Klima-, Energi- og Forsyningsudvalget 2023-24

KEF Alm.del Bilag 426

Offentligt

Denmark’s position on the post 2030

architecture for agriculture and LULUCF

Denmark’s main priorities to strengthen the climate architecture for agriculture, land

and forestry after 2030

The EU needs a new and more effective climate architecture for agriculture, forestry and land post-2030. Total

EU agricultural greenhouse gas emissions have been stable since 2005 and agriculture will account for an

increasing share of EU emissions towards 2040. In addition, the EU is not on track to meet the 2030 net removal

target under LULUCF. Changes must be made in the architecture to accommodate some of these challenges

and to provide a better baseline for regulation. Therefore, Denmark strongly advocates for combining agricultural

emissions and net emissions from agricultural land in a new agricultural pillar. This pillar should be regulated with

emission trading as the central instrument. Thereto, Denmark proposes a separate forestry pillar with a common

EU regulation of emissions and removals from forests and other land use. Such a design would be simple, cost-

effective, and would allow for a more coherent policy making in the respective sectors.

Promoting agricultural synergies while accommodating the distinctive properties for forest land

Denmark proposes a new climate architecture constructed as follows:

1.

Livestock, farm management and agricultural land; regulated through emissions trading

Agricultural non-CO

2

emissions and net removals in agricultural soils should be considered together to allow for

a more coherent policy-making of the agricultural sector. Such a framework, in which all farm emissions are

accounted for (including e.g. livestock, manure handling, slurry, fertilizer management and soils), would

encourage farmers to make more cost-efficient mitigation efforts across the various emissions in the sector.

2.

Forestry and other land use; regulated with a common EU regulation

The vast majority of the EU’s GHG removals occur on forest land and could be handled in a separate pillar. With

agricultural soils separated from this pillar, the scope becomes more homogeneous than the scope of the current

LULUCF Regulation. This allows for a more focused approach to overcome some of the challenges identified

with regulating greenhouse gas fluxes in forests:

1)

At this point, forestry seems less fit for emissions trading. In New Zealand, where forestry is integrated

in the national emissions trading system, there are recognized challenges with ensuring permanence

and forest integrity.

There are general issues with obtaining accurate and timely data for emissions and removals on forest

land, which should be handled separately in order not to jeopardize the credibility of a combined

forestry and agricultural sector.

Moreover, a common challenge with climate regulation of forests is how to ensure more long-term

goals. A climate regulation specifically designed for forests may in a higher degree than today manage

to incorporate incentives for long-term effects that can contribute positively to climate neutrality and net

negative emissions.

2)

3)

Denmark supports looking into options for designing incentives for individual forest owners to increase long-term

net removals of carbon from the atmosphere. Looking ahead, several initiatives such as the revision of the

LULUCF-regulation as well as the Soil and Forest Monitoring Laws could increase knowledge on how to best

optimize a consistent, long-term and sustainable contribution from forests. Moreover, the implementation of the

EU carbon removal certification framework could turn out to be a valuable tool by paving the way for efficient

results-based payment schemes and by facilitating private finance on the voluntary market for climate credits.

KEF, Alm.del - 2023-24 - Bilag 426: Non-papirer fra regeringen inden for klima og energi ifm. tidlig EU interessevaretagelse, fra klima-, energi- og forsyningsministeren

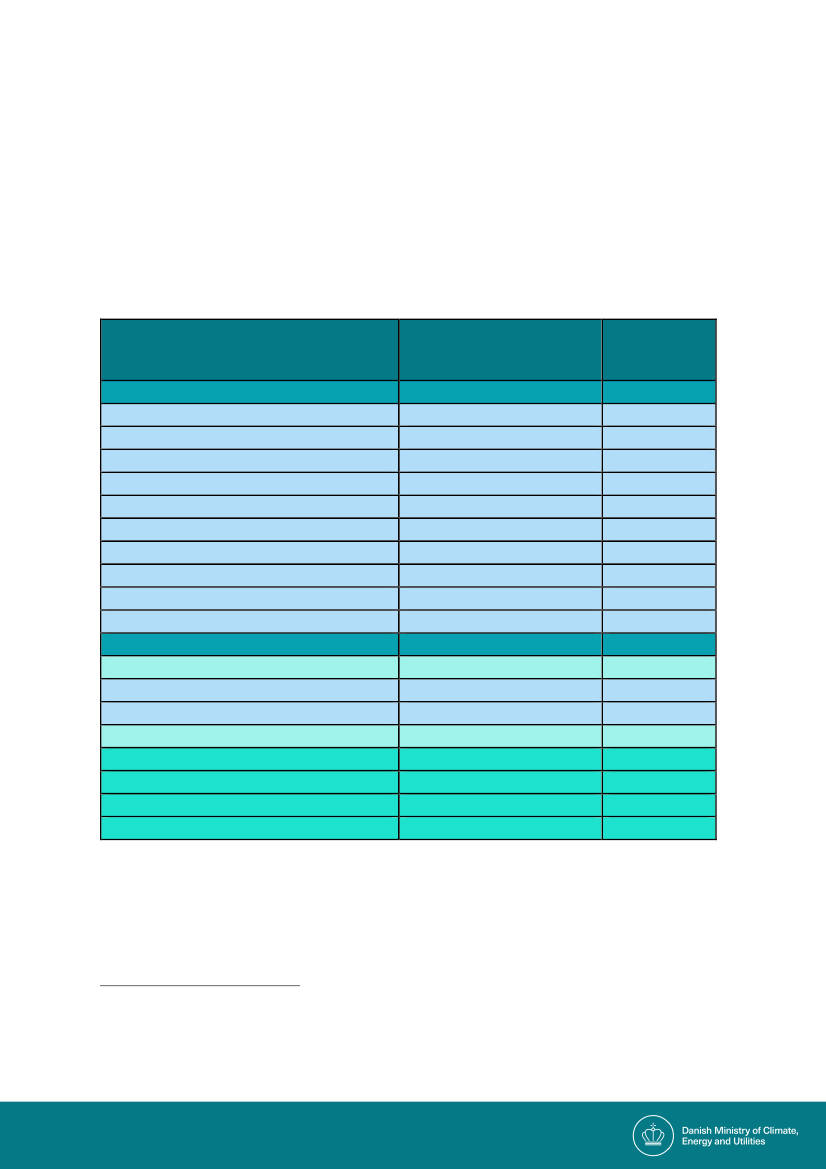

A suggestion for technical adjustments for a new climate architecture for agriculture, forestry and land

The

livestock, farm management and agricultural land

pillar should include all non-CO

2

emissions from

agricultural activities as well as emissions and removals from “B. Cropland” and “C. Grassland.” In turn, the

Forestry and other land use

pillar should include “A. Forest land” as well as the land reporting categories “4.D

Wetlands”, “4.E Settlements”, “4.F Other land” and “4.H Other”.

The majority of recently deforested land in the EU is converted to settlements or wetlands, which makes it

reasonable to govern emissions from these land conversions together with emissions and removals from

managed forest land. Moreover, an ETS or other price mechanism for agriculture would not be an appropriate

measure to drive mitigation action on the parcels of land falling under the scope of these categories. A concrete

proposal for the design can be viewed in Table 1.

Table 1. Overview of reporting categories within each pillar and their associated emissions figures

GHG emissions,

(Mt CO2e yr

-1

)

383

Livestock and agricultural land

Livestock and agricultural land

Livestock and agricultural land

Livestock and agricultural land

Livestock and agricultural land

Livestock and agricultural land

Livestock and agricultural land

Livestock and agricultural land

Livestock and agricultural land

Livestock and agricultural land

184

64

3

119

-

1

5

4

1

2

-245

Forestry and other land use

Livestock and agricultural land

Livestock and agricultural land

Forestry and other land use

Forestry and other land use

Forestry and other land use

Forestry and other land use

Forestry and other land use

-297

24

21

21

28

1

-44

0

Reporting category (including subcategories)

3. Agriculture

A. Enteric fermentation

B. Manure management

C. Rice cultivation

D. Agricultural soil

E. Prescribed burning of savannas

F. Field burning of agricultural residues

G. Liming

H. Urea application

I. Other carbon-containing fertilizers

J. Other

4. Land use, land-use change and forestry

A. Forest land*

B. Cropland

C. Grassland

D. Wetlands*

E. Settlements

F. Other land

G. Harvested wood products

H. Other

Pillar

1

Note: *This suggested split includes the subcategories, such as land use conversions. Emission figures are the

EU average for the years 2017-2021 according to the 2023 submission.

The suggested design requires additional comprehensive analysis; including further investigation concerning

incentive structures and how the design interplays with future regulations on national emissions on land-use.

Moreover, it raises key questions on how to deal with areas in transition. It will be important that the architecture

supports and rewards mitigation efforts for farmers. A way forward could be to include cropland and grassland

1

Note that both pillars need policies to consider the scope for both emission reductions and removal enhancements. There

would be gross removals embedded in cropland and grassland, just like there will be gross emissions embedded in forest

land; in some Member States, grassland is a sizable net sink while in others, forest land is a net source.

KEF, Alm.del - 2023-24 - Bilag 426: Non-papirer fra regeringen inden for klima og energi ifm. tidlig EU interessevaretagelse, fra klima-, energi- og forsyningsministeren

converted to forest land in the

Livestock, farm management and agricultural land

pillar as to better reflect the

entirety of mitigation actions taking place on agricultural soils and reward farmers for afforestation measures.

Emissions and removals from agroforestry activities are already reported under cropland, in line with IPCC 2006

guidelines. The same approach could apply to wetlands in order to ensure that wetland conversions are made

solely when it is cost-efficient

2

.

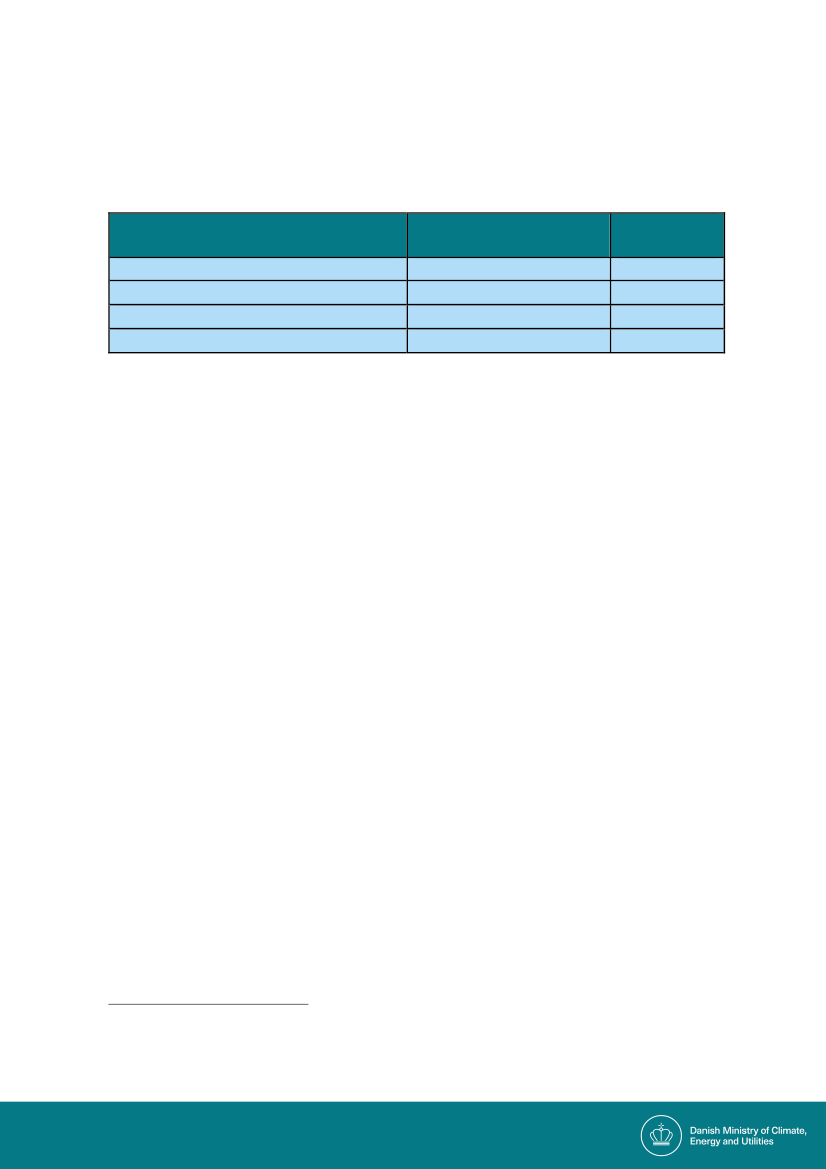

Table 2. Forest land in transition

Reporting subcategories

A. 2.1 Cropland converted to forest land

A. 2.2 Grassland converted to forest land

B. 2.1 Forest land converted to cropland

C. 2.1 Forest land converted to grassland

Pillar

Livestock and agricultural land

Livestock and agricultural land

Livestock and agricultural land

Livestock and agricultural land

GHG emissions,

(Mt CO2e yr

-1

)

-17

-20

8

7

Note: Emission figures from the year 2021 according to the 2023 submission.

2

Wetlands have not been included in table 2 due to their nature of the reporting scheme, and their inclusion remains for

further analysis.