ART

ANALYSIS AND RESEARCH TEAM

16 February 2023

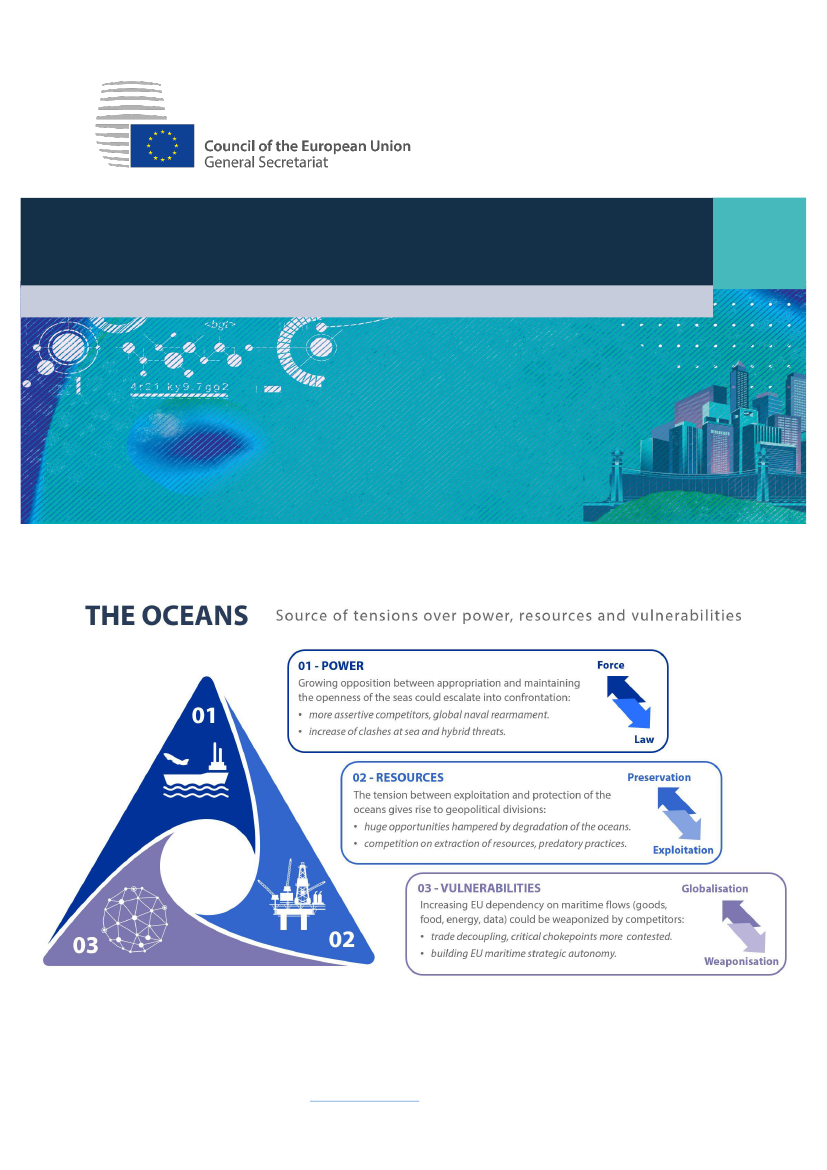

THE EU: FROM MARITIME ACTOR

TO SEA POWER

Source: ART

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed are solely those of the author(s). In no case should they be considered or construed as representing an official position of the

Council of the European Union or the European Council. © European Union, 2023 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged.

Any question or comment should be addressed to