Research Article

Genetic and Metabolic Diseases

JOURNAL

OF HEPATOLOGY

Alcohol consumption in late adolescence is

associated with an increased risk of severe liver

disease later in life

Graphical abstract

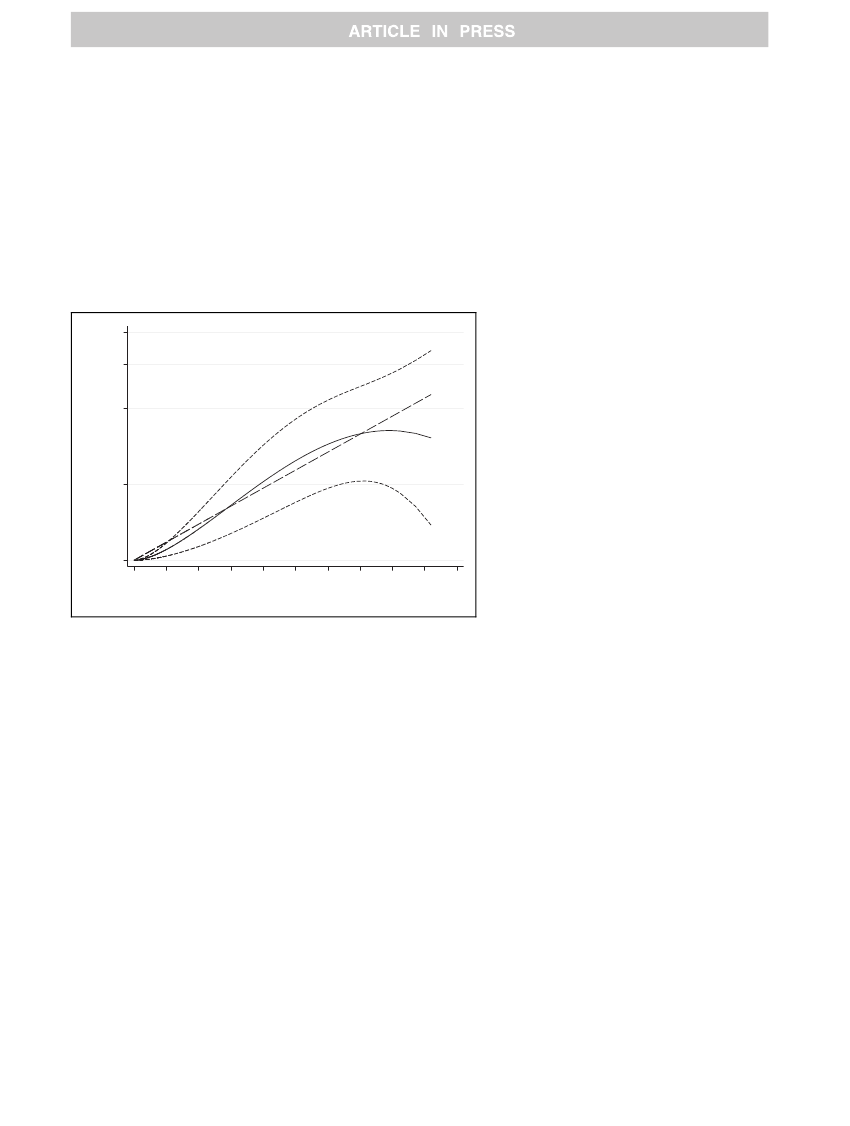

8.00

6.00

Authors

Hannes Hagström, Tomas Hemmingsson,

Andrea Discacciati, Anna Andreasson

Correspondence

4.00

Hazard ratio

(H. Hagström)

Lay summary

2.00

1.00

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

Alcohol consumption (grams per day)

90

100

Highlights

Alcohol consumption early in life was associated with an

increased risk for development of severe liver disease after

39 years of follow-up.

The risk increased in a dose-response pattern, with no

evidence of a threshold effect.

Trend towards an increased risk of severe liver disease in

men consuming less than current recommendations for a

safe alcohol intake.

We investigated more than 43,000 Swed-

ish men in their late teens enlisted for

conscription in 1969–1970. After almost

40 years of follow-up, we found that

alcohol consumption was a significant

risk factor for developing severe liver

disease, independent of confounders. This

risk was dose-dependent, and was most

pronounced in men consuming two

drinks per day or more.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2017.11.019

Ó

2017 European Association for the Study of the Liver. Published by Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. J. Hepatol. 2018, xxx, xxx–xxx