Sundheds- og Ældreudvalget 2017-18

SUU Alm.del Bilag 291

Offentligt

Environmental Research 165 (2018) 40–45

Contents lists available at

ScienceDirect

Environmental Research

journal homepage:

www.elsevier.com/locate/envres

Long-term exposure to wind turbine noise at night and risk for diabetes: A

nationwide cohort study

Aslak Harbo Poulsen

a,

, Ole Raaschou-Nielsen

a,c

, Alfredo Peña

b

, Andrea N. Hahmann

b

,

Rikke Baastrup Nordsborg

a

, Matthias Ketzel

c

, Jørgen Brandt

c

, Mette Sørensen

a,d

a

T

⁎

Diet, Genes and Environment, Danish Cancer Society Research Center, Copenhagen, Denmark

DTU Wind Energy, Technical University of Denmark, Roskilde, Denmark

c

Department of Environmental Science, Aarhus University, Roskilde, Denmark

d

Department of Natural Science and Environment, Roskilde University, Roskilde, Denmark

b

A R T I C LE I N FO

Keywords:

Wind turbine noise

Diabetes

Epidemiology

A B S T R A C T

Focus on renewable energy sources and reduced unit costs has led to increased number of wind turbines (WTs).

WT noise (WTN) is reported to be highly annoying at levels from 30 to 35 dB and up, whereas for traffic noise

people report to be highly annoyed from 40 to 45 dB and up. This has raised concerns as to whether WTN may

increase risk for major diseases, as exposure to traffic noise has consistently been associated with increased risk

of cardiovascular disease and diabetes. We identified all Danish dwellings within a radius of 20 WT heights and

25% of all dwellings within 20–40 WT heights from a WT. Using detailed data on WT type and hourly wind data

at each WT position and height, we estimated hourly outdoor and low frequency indoor WTN for all dwellings,

aggregated as nighttime 1- and 5-year running means. Using nationwide registries, we identified a study po-

pulation of 614,731 persons living in these dwellings in the period from 1996 to 2012, of whom 25,148 de-

veloped diabetes. Data were analysed using Poisson regression with adjustment for individual and area-levels

covariates. We found no associations between long-term exposure to WTN during night and diabetes risk, with

incidence rate ratios (IRRs) of 0.90 (95% confidence intervals (CI): 0.79–1.02) and 0.92 (95% CI: 0.68–1.24) for

5-year mean nighttime outdoor WTN of 36–42 and

≥

42 dB, respectively, compared to < 24 dB. For 5-year

mean nighttime indoor low frequency WTN of 10–15 and

≥

15 dB we found IRRs of 0.90 (0.78–1.04) and 0.74

(95% CI: 0.41–1.34), respectively, when compared to and < 5 dB. The lack of association was consistent across

strata of sex, distance to major road, validity of noise estimate and WT height. The present study does not

support an association between nighttime WTN and higher risk of diabetes. However, there were only few cases

in the highest exposure groups and

findings

need reproduction.

1. Introduction

Focus on renewable energy sources has increased globally during

the last decades, which together with reduced costs has led to an in-

creased number of wind turbines (WTs). WT noise (WTN) has con-

sistently been associated with annoyance among people living by.

Schmidt and Klokker (2014), Michaud et al. (2016a), Janssen et al.

(2011), Michaud et al. (2016b).

Also, reviews and meta-analyses have

found WTN to be associated with self-reported disturbance of sleep,

(Schmidt

and Klokker, 2014; Onakpoya et al., 2015)

although recent

studies using objective measures of sleep have failed to

find

an asso-

ciation (Michaud

et al., 2016; Jalali et al., 2016).

This has raised con-

cern as to whether WTN may increase risk for major diseases.

Recent studies have found exposure to road traffic and aircraft noise

to be significantly associated with higher risk of diabetes, (Sorensen

et al., 2013; Eze et al., 2017a; Clark et al., 2017)

whereas no association

was found for railway noise (Roswall

et al., 2018).

In support of this,

traffic noise has been associated with major risk factors for diabetes,

including fasting blood glucose, (Cai

et al., 2017)

glycosylated he-

moglobin, (Eze

et al., 2017b)

obesity (Eriksson

et al., 2014; Pyko et al.,

2015, 2017; Christensen et al., 2016)

and physical inactivity (Roswall

et al., 2017; Foraster et al., 2016).

The believed pathophysiologic

pathways behind noise as a metabolic risk factor are activation of a

general stress response and disturbance of sleep, which may lead to

reduced insulin secretion and sensitivity, reduced glucose tolerance and

altered levels of appetite-regulating hormones (Spiegel

et al., 2004;

Taheri et al., 2004; Mazziotti et al., 2011; McHill and Wright, 2017).

Also, reduced sleep quality and quantity have both consistently been

⁎

Correspondence to: Danish Cancer Society Research Center, Strandboulevarden 49, 2100 Copenhagen, Denmark.

E-mail address:

Aslak@Cancer.dk

(A.H. Poulsen).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2018.03.040

Received 5 December 2017; Received in revised form 23 February 2018; Accepted 26 March 2018

0013-9351/ © 2018 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

SUU, Alm.del - 2017-18 - Bilag 291: Orientering om undersøgelse vedr. vindmøllestøj og diabetes, fra sundhedsministeren

A.H. Poulsen et al.

Environmental Research 165 (2018) 40–45

shown to increase risk of diabetes (Cappuccio

et al., 2010).

Findings on traffic noise and diabetes are not readily applicable to

WTN. Levels of WTN are generally much lower than noise from traffic

in urban settings. However, WTN has been associated with a higher

proportion of annoyed residents than traffic noise at comparable sound

levels (Janssen

et al., 2011).

While people start reporting WTN to be

highly annoying at levels from 30 to 35 dB and up, traffic noise is

generally not reported as highly annoying at levels below 40–45 dB

(Michaud

et al., 2016).

A potential explanation is that WTN depends on

wind speed and direction making it less predictable than traffic noise,

where the latter e.g. often abates at night. Also, amplitude modulation

may give WTN a rhythmic quality different from e.g. road traffic noise.

It has therefore been suggested that the characteristics of WTN relevant

for annoyance may be better captured by metrics focusing on amplitude

modulation or low frequency (LF) noise, rather than the full spectrum

A-weighted noise as typically used in studies of traffic noise (Jeffery

et al., 2014).

A review from 2016 on LF noise (from various sources)

indicated that LF noise was associated with annoyance and potentially

sleep disturbance, although it was added that research in this area was

scarce and with methodological short-comings (Baliatsas

et al., 2016).

Lastly, WTs are often placed in rural areas, where the auditory impact

of WTs may be more pronounced as compared to more densely popu-

lated areas, due to less background noise from traffic, industry and

others.

Two studies have investigated associations between WTN and self-

reported diabetes: (Michaud

et al., 2016a; Pedersen, 2011)

A Canadian

study of 1238 participants living within 12 km of a WT, among whom

113 reported to have diabetes, found no associations between estimated

A-weighted residential WTN and prevalent diabetes (Michaud

et al.,

2016a).

In the second study, results from two Swedish and one Dutch

study population(s) were presented. In one of the Swedish study po-

pulations (N = 744), A-weighted residential WTN was associated with

an odds ratio (OR) for prevalent diabetes of 1.13 (95% confidence in-

tervals (CI) 1.00–1.27) in analyses adjusted for age and sex. However,

no association was seen for the other two study populations (N = 1011,

ORs of 0.96 and 1.00) (Pedersen,

2011).

Both of these studies were

cross-sectional, which prevent conclusions on causality and chron-

ological order of events, and with risk of selection and recall bias. No

prospective studies have investigated associations between WTN and

diabetes.

We aimed to prospectively investigate associations between long-

term residential exposure to WTN and risk for diabetes in a nationwide

register based study, combining data on WTN, meteorology, WT posi-

tion and type, residential addresses, development of disease and so-

cioeconomic indicators over the period 1996–2012.

2. Methods

2.1. Study base and estimation of noise

The study was based on the entire Danish population, where all

citizens since 1968 can be tracked in and across all Danish health and

administrative registers by means of a personal identification number

(PIN) maintained by the Central Population Register (Schmidt

et al.,

2014).

We identified all WTs (7860) in operation in Denmark any time

between 1980 and 2012 from the administrative Master Data Register

of Wind Turbines maintained by the Danish Energy Agency. It is

mandatory for all WT owners to report cadastral codes and geo-

graphical coordinates of their WT(s) to the registry. Furthermore, for

WTs in operation at the time of data extraction, the register also con-

tained coordinates from the Danish Geodata Agency. In case of dis-

agreement between the recorded geographical locations, the WT loca-

tion was validated against aerial photographs and historical

topographic maps of Denmark. Of the 7860 WTs, we excluded 517

(6.6%) offshore WTs. Furthermore, we excluded 87 (1.1%) WTs with

41

two (or three) different registered locations, for which we were unable

to identify the correct location based on aerial photographs and his-

torical topographic maps. Moreover, 314 (4.0%) WTs wrongly recorded

in the Master Data Register were assigned new coordinates based on

maps and aerial photographs, leaving 7256 WTs for investigation. On

the basis of information on height, model, type and operational settings

(when relevant) from the register for all WTs each WT was classified

into one of 99 noise spectra classes, with detailed information on the

noise spectrum from 10 to 10,000 Hz in thirds of octaves for wind

speeds from 4 to 25 m/s. These noise classes were made from existing

measurements of sound power for Danish WTs (Backalarz

et al., 2016;

Sondergaard and Backalarz, 2015).

For each WT location, we estimated the hourly wind speed and

direction at hub height for the period 1982–2012, using mesoscale

model simulations performed with the Weather Research and

Forecasting model (Hahmann

et al., 2015; Peña and Hahmann, 2017).

The WTN exposure modelling has been described in details else-

where (Backalarz

et al., 2016).

In summary, using a two-step approach

we

first

identified buildings eligible for noise modelling defined as all

dwellings in Denmark that could experience at least 24 dB outdoor

noise or 5 dB indoor low frequency (LF, 10–160 Hz) noise under the

unrealistically extreme scenario that all WTs ever operational in Den-

mark were simultaneously operating at a wind speed of 8 m/s with

downwind sound propagation in all directions. In the second step, we

performed a detailed modelling of noise exposure for the 553,066

buildings identified in step one, calculating noise levels in 1/3 octave

bands from 10 to 10,000 Hz using the Nord2000 noise propagation

model (Kragh

et al., 2001),

taking into account the time varying

weather conditions. The Nord2000 model has been successfully vali-

dated for WTs (Sondergaard

et al., 2009).

For each dwelling, the noise

contribution from all WTs within a 6000 m radius was calculated hour

by hour. These modelled values were then aggregated over the period

10 p.m. to 7 a.m. (nighttime), which we considered the most relevant

time-window because people are most likely to be at home and sleep

during these hours. We calculated outdoor A-weighted sound pressure

level, which is the metric most commonly used in noise and health

studies, (Pedersen,

2011; Michaud et al., 2016d).

as well as A-weighted

indoor low frequency (10–160 Hz) sound pressure level, as LFN easier

penetrates buildings, and has been suggested to be an important com-

ponent of WTN in relation to health (Jeffery

et al., 2014).

The quality of noise spectra available for different wind turbine

models differed and these spectra were typically only described at

certain wind speeds. We therefore determined a validity score that for

each night and dwelling summed up information for all contributing

WTs on the number of measurements used to determine the WTN

spectra class, and how closely the simulated meteorological conditions

of each night resembled the conditions under which the relevant WTN

spectra were measured.

For the calculation of indoor LFN, all dwellings were classified into

one of six sound insulation classes based on building attributes in the

Building and Housing register (Christensen,

2011):

“1�½-story

houses”

(residents assumed to sleep on the second

floor),

“light

façade” (e.g.

wood),

“aerated

concrete” (and similar materials including timber

framing),

“farm

houses” (remaining buildings in the registry classified

as farms),

“brick

buildings” and

“unknown”

(assigned the mean at-

tenuation value of the

five

previous classes). The frequency-specific

attenuation values for each of the six classes are shown in (Backalarz

et al., 2016).

2.2. Study population

When defining the study population, we identified all dwellings ever

situated within a radius of 20 WT heights of a WT as well as a random

selection of 25% of all dwellings situated between 20 and 40 WT

heights from a WT, thus including all living close to WTs as well as a

large population living in the same areas, but with little or no exposure.

SUU, Alm.del - 2017-18 - Bilag 291: Orientering om undersøgelse vedr. vindmøllestøj og diabetes, fra sundhedsministeren

A.H. Poulsen et al.

Environmental Research 165 (2018) 40–45

We excluded hospitals, residential institutions- and dwellings situated

within 100 m of areas classified as

“town

centre” (using GIS data from

the Danish Geodata Agency), as type of dwelling, traffic conditions and

lifestyle in town centres may differ substantially compared to the main

study population. We subsequently identified all adults aged 25–84

years of age living at least one year in these

“inclusion

dwellings” from

five

years before erection of a WT until end of 2012, using the Danish

Civil Registration System (Schmidt

et al., 2014).

This extended time-

frame ensured inclusion of subjects living in exactly the same dwellings

before erection (or after decommissioning) of a WT. People entered the

study population after living one year in the dwelling. For this popu-

lation, we then established complete migration histories from

five

years

before study entry and until

five

years after moving from the inclusion

dwelling. Subjects without complete address history for the period

five

years before entry were excluded.

The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency

(J.nr: 2014-41-2671). By Danish Law, ethical approval and informed

consent are not required for entirely register-based studies.

2.3. Covariates

Selection of potential confounders was done

a priori.

From Statistic

Denmark, we obtained information on age and sex, highest attained

educational level, personal income, marital status, occupation and areal

level (10,000 m

2

) mean household income. Information on type of

dwelling was obtained from the building and housing register

(Christensen,

2011)

As proxies for local road traffic noise and air pol-

lution we identified the distance from each dwelling to the nearest road

with an average daily traffic count of

≥

5000 vehicles (in 2005) as well

as total amount of kilometres driven by vehicles within 500 m of the

residence each day as the product of street length and traffic density.

2.4. Identification of outcome

registered partnership and other), education (basic or high school, vo-

cational, higher and unknown), occupation (employed, retired and

other), personal income (20 equal sized annual categories and un-

known), area level average disposable income (20 equal sized cate-

gories and unknown), dwelling classification (farm, single-family de-

tached house and other), distance to road with

≥

5000 vehicles per day

(< 500 m, 500- < 1000 m, 1,000- < 2000 m and

≥2000

m), and traffic

load within 500 m radius of dwelling (1st and 2nd quartile and above

median). Subjects were allowed to change between categories of cov-

ariates and exposure variables over time.

We used Poisson models including an interaction term and stratified

analyses, to investigate the following potential effect-modifiers: sex,

validity of cumulated noise estimate (above or below the median va-

lidity score among those exposed to indoor WTN

≥

10 dB or outdoor

WTN

≥

36 dB), tree coverage (above or below 5% of area within 500 m

of dwelling covered by forest, thicket, groves, single trees and hedge-

rows according to GIS data from the Danish Geodata Agency; we hy-

pothesize that there is less noise from vegetation among people living

with low tree coverage and that a potential association thus would be

more conspicuous in this group), distance to major road (above or

below 2000 m to nearest road with > 5000 vehicles/day; we hypothe-

size that there is less background noise among people living > 2000 m

from a major road and that a potential association thus would be

stronger in this group), dwelling classified as farm (yes or no; a large

proportion of the highly exposed lives on farms, and we hypothesize

that there is less variation in lifestyle and other exposures among this

sub-population compared to the whole population, potentially reducing

susceptibility to residual confounding in this group) and total height of

closest WT (above or below 35 m; higher WTs have been suggested to

emit relatively more LF noise than smaller WTs (Moller

and Pedersen,

2011)).

Data were analysed using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc. Cary, NC,

USA).

3. Results

Diabetes cases were identified by linking the PIN of each member of

the study population to the nationwide Danish National Diabetes

Registry (Carstensen

et al., 2011),

applying the following inclusions

criteria: a hospital discharge diagnosis of diabetes in the National Pa-

tient Register (International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision:

E10–14, H36.0 and O24); National Health Insurance Registry in-

formation indicating podiatry (chiropody) for diabetic patients, and/

or > 1 purchase of insulin or oral glucose-lowering drugs within 6

months registered in the Register of Medicinal Product Statistics. The

register has been found reliable from January 1995 (Carstensen

et al.,

2011).

As patients diagnosed upon start of the register could include

prevalent cases from before register start, we excluded all cases of

diabetes diagnosed before 1996.

2.5. Statistical methods

Log-linear Poisson regression analysis was used to compute in-

cidence rate ratios (IRRs) for diabetes according to outdoor (< 24,

24– < 30, 30– < 36, 36– < 42, and

≥42

dB) and indoor LF WTN (< 5,

5– < 10, 10– < 15, and

≥15

dB) exposure calculated as running means

over the past 1- and 5-years. For dwellings so far from WTs as to never

have WTN above 24 dB outdoor or 5 dB indoor, or when WTs were not

operating due to wind conditions, a value of

−

20 dB was used in cal-

culating the average. Follow-up was started after living one year in the

recruitment dwelling, turning 25 years or Jan 1st 1996, whichever

came last, and ended at time of diabetes, death, age 85 years, dis-

appearance or having no recorded address for more than seven days,

Dec 31st 2012 or

five

years after moving from inclusion dwelling,

whichever came

first.

All analyses were adjusted for sex, calendar year (1996–1999,

2000–2004, 2005–2009, and 2010–2012) and age (25–84 years, in

five-

year categories). Additionally, we adjusted for marital status (married/

42

We identified 735,384 adults (age 25–84 years) living

≥

one year in

the inclusion dwellings. We excluded persons who had emigrated

(n = 40,190; 5.5%) or been recorded as disappeared (n = 1475; 0.2%)

prior to entry, who had unknown address for eight or more consecutive

days in the

five

years prior to entry (n = 57,668; 7.8%), who lived in

hospitals or institutions at study start of follow-up (n = 1599; 0.2%) or

who had diabetes before start of follow-up (n = 19.721; 2.7%). The

final

study population was 614,731 persons, of whom 25,148 devel-

oped diabetes during 5,213,194 person-years.

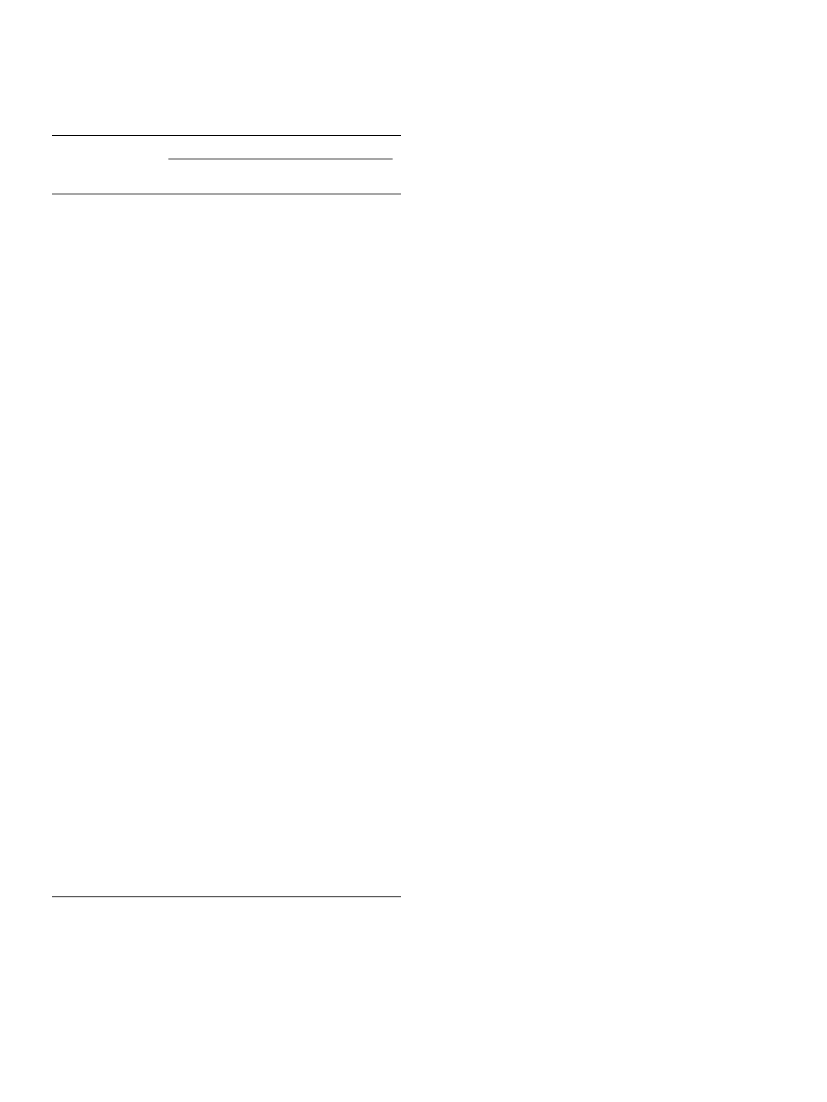

When compared to people with 1-year mean outdoor A-weighted

WTN < 36 dB, person with higher exposure levels at entry were more

likely to be men, below 40 years of age, working, living in a farm house,

living in areas with higher average household incomes, living >

2000 m from a major road and have a low traffic load and less tree

coverage within 500 m of dwelling (Table

1).

Personal income and

education did not show marked differences according to exposure level.

Similar tendencies were seen when comparing people exposed to indoor

LF WTN above and below 10 dB, except that we here observed an al-

most equal proportion of men and women at all exposure levels and

that an even higher proportion of the highly exposed lived on farms,

were younger at entry and entered the study later, as compared with

outdoor WTN (Supplement

Table 1).

At entry, more than 79% of the study population lived in dwellings

exposed to < 24 dB outdoor WTN and 97% had indoor LF

WTN < 5 dB. Among dwellings exposed to

≥

36 dB outdoor WTN, the

vast majority were located less than 500 m from a WT. With regard to

height of the nearest WT, only small differences were seen when

comparing the people exposed to < 36 dB with the 36–42 dB exposure

group, whereas for the highest exposure group (≥ 42 dB), there was a

much higher proportion of dwellings located near low WTs (Table

2).

In

comparison with outdoor exposure

≥

36 dB, a larger proportion of

SUU, Alm.del - 2017-18 - Bilag 291: Orientering om undersøgelse vedr. vindmøllestøj og diabetes, fra sundhedsministeren

A.H. Poulsen et al.

Environmental Research 165 (2018) 40–45

Table 1

Characteristics of the study population at start of follow-up according to re-

sidential A-weighted exposure to outdoor wind turbine noise calculated as

mean exposure during the preceding year.

Outdoor wind turbine noise

Characteristics at entry

< 36 dB

(N = 606,275)

50%

42%

19%

16%

22%

55%

15%

22%

8%

20%

24%

26%

25%

6%

36–42 dB

(N = 7010)

53%

49%

20%

15%

15%

55%

20%

17%

8%

21%

26%

25%

22%

6%

≥

42 dB

(N = 1446)

53%

44%

23%

19%

15%

73%

17%

8%

2%

21%

21%

23%

29%

5%

Men

Age

< 40 years

40–50 years

50–60 years

≥

60 years

Year of entry

1996–2000

2000–2005

2005–2010

2010–2012

Personal income

Quartile 1 (low)

Quartile 2

Quartile 3

Quartile 4 (high)

Unknown

Highest attained

education

Basic or high school

Vocational

High

Unknown

Marital status

Married

Divorced/widow(er)

Never married

Occupation

Working

Retired

Other

Area-level income

a

Quartile 1 (low)

Quartile 2

Quartile 3

Quartile 4 (high)

Unknown

Type of dwelling

Farm

Single-family detached

house

Others

Distance to major road

b

< 500 m

500–2000 m

≥

2000 m

Traffic load within 500 m

(10

3

vehicle km/

day)

< 2.5

2.5–5.3

5.3–9.7

> 9.7

Tree coverage within 500

m

< 5%

5–20%

> 20%

a

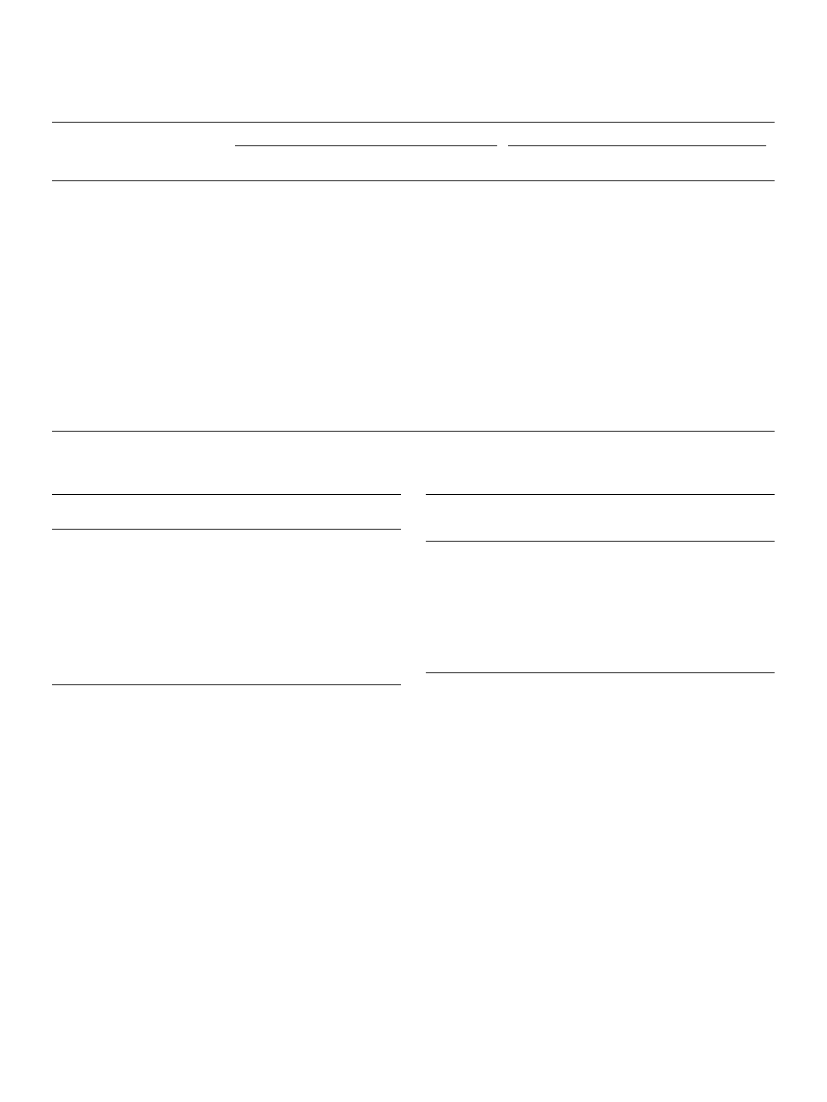

We found no overall association between long-term exposure to

outdoor WTN or indoor LF WTN and risk of diabetes, for any of the

exposure time-windows (Tables

3 and 4).

In the crude analyses, we

found all IRRs to be below one; some with confidence limits below

unity. Adjustment for potential confounders resulted in estimates

markedly closer to unity. For outdoor WTN, the risk estimate among

people exposed to 36–42 dB remained borderline significant (IRR: 0.87;

95% CI: 0.77–0.99). However, there was no indication of an exposure-

response relationship, with IRRs of 1.01 and 1.02 in the 24–30 dB and

30–36 dB exposure groups, respectively, and of 1.06 in the highest

exposure group (≥ 42 dB,

Table 3).

For indoor LF WTN

≥

15 dB, the

IRRs in adjusted analyses remained below unity, although not statisti-

cally significant and based on only few cases (Table

4).

We found no

indications of positive dose-response relationship in any analyses.

For outdoor WTN, we found no effect-modification of the risk esti-

mates in analyses stratified by sex, type of dwelling, distance to major

road, validity of noise estimate, tree coverage or WT height, with no

estimate substantially above unity and all p-values for interaction ex-

ceeding 0.3 (Supplement

Table 3).

Similarly, we found no statistically

significant effect-modification of the indoor LF WTN and diabetes as-

sociation (all P-values > 0.1;

Supplement Table 4).

4. Discussion and conclusion

35%

41%

17%

7%

55%

15%

29%

67%

21%

13%

23%

28%

28%

19%

2%

13%

61%

25%

35%

27%

37%

36%

44%

16%

4%

52%

13%

35%

73%

14%

13%

12%

28%

34%

20%

7%

39%

51%

10%

17%

26%

57%

37%

38%

21%

4%

62%

12%

26%

75%

13%

12%

14%

21%

36%

23%

6%

40%

51%

9%

17%

25%

58%

33%

25%

19%

23%

68%

13%

13%

6%

67%

15%

10%

8%

13%

63%

24%

29%

63%

7%

29%

63%

9%

Average disposable household income among

100×100 m grid cell.

b

Major road defined as

≥

5,000 vehicles per day.

all

households

in

those exposed to indoor LF WTN

≥

10 dB lived

≥

500 m from a WT at

entry (especially in the 10–15 dB group) and a much lower proportion

of people exposed to LF WTN

≥

10 dB lived near a WT < 35 m

(Table

2).

Median exposure levels for all exposure categories are pro-

vided in supplement

Table 2,

43

We did not

find

long-term nighttime exposure to outdoor or indoor

LF WTN to be associated with increased risk of diabetes in a large

prospective study based on the full Danish population ever exposed to

WTN. The lack of association between WTN and diabetes was consistent

across various strata, including sex, distance to a major road, validity of

the noise estimate and total height of the nearest WT.

A major strength of the present study is the prospective nationwide

design with information on potential socioeconomic and environmental

confounders, the large number of incident cases identified through a

high-quality nationwide register (Carstensen

et al., 2011),

and access to

complete residential address history for the entire exposure and follow-

up period. Also, we estimated long-term exposure to WTN using high

quality input data (hourly wind speed and direction at each WT posi-

tion, combined with detailed WTN spectra for all WT types) and state-

of-the art exposure models, allowing us to estimate noise levels speci-

fically

for nighttime, when people are most likely to be at home

sleeping. Additionally, we estimated exposure to the potentially more

biologically relevant indoor noise, accounting for different housing

sound insulation properties, although it is important to note that we

could only differentiate into few insulation categories, based on rela-

tively crude information. Further strengths were estimation of WTN for

all dwellings in Denmark that might experience WTN, and that our

design ensured that all members of the study population where re-

cruited from similar geographical areas. Furthermore, we had access to

a number of individual and area-level socioeconomic variables re-

vealing almost no differences in income and educational level between

people exposed to high (≥ 36 dB) versus lower (< 36 dB) levels of

WTN, which indicates low risk for residual confounding from individual

SES. Also, we accounted for living on a farm, which is conceivably

associated with many differences in lifestyle and environment. Due to

the register-based nature of the study, we did not have information to

adjust for potential lifestyle confounders, such as dietary habits, obesity

and physical activity. This may have biased the results, although it is

not clear in which direction.

Fewell et al. (2007)

It is, however, im-

portant to note that adjusting for lifestyle in studies of noise is not

straight-forward, as traffic noise has been associated with e.g. obesity

and physical activity, (Eriksson

et al., 2014; Pyko et al., 2015; Roswall

et al., 2017; Foraster et al., 2016; Christensen et al., 2015).

suggesting

that these are intermediates and not confounders on the pathway be-

tween noise and disease. Another limitation is the rather crude ad-

justment for local road traffic noise, using traffic load and distance to

major road. However, residual confounding by traffic noise is unlikely

SUU, Alm.del - 2017-18 - Bilag 291: Orientering om undersøgelse vedr. vindmøllestøj og diabetes, fra sundhedsministeren

A.H. Poulsen et al.

Environmental Research 165 (2018) 40–45

Table 2

Characteristics of wind turbines at the dwellings of the study participants at start of follow-up, according to residential exposure to outdoor and indoor low frequency

(LF) wind turbine noise calculated as mean exposure during the preceding year.

Wind turbine characteristics at of the

study population dwellings at entry

Outdoor wind turbine noise

< 36 dB

(N = 606,275)

Outdoor wind turbine noise (1-year mean)

a

< 24 dB

24–30 dB

30–36 dB

36–42 dB

≥

42 dB

Indoor LF wind turbine noise (1-year mean)

a

< 5 dB

5–10 dB

10–15 dB

≥

15 dB

Distance to nearest wind turbine

< 500 m

500–2000 m

≥

2000 m

Total height, nearest wind turbine

< 35 m

35–70 m

70–100 m

≥

100 m

36–42 dB

(N = 7010)

≥

42 dB

(N = 1446)

Indoor LF wind turbine noise

< 10 dB

(N = 610,429)

10–15 dB

(N = 3990)

≥

15 dB

(N = 312)

79%

16%

5%

–

–

97%

3%

0%

0%

7%

57%

36%

31%

56%

11%

1%

–

–

–

100%

–

28%

48%

22%

2%

94%

5%

1%

33%

58%

8%

1%

–

–

–

–

100%

7%

37%

45%

11%

97%

2%

1%

66%

33%

1%

0%

78%

16%

5%

1%

0%

97%

3%

–

–

8%

56%

36%

31%

56%

11%

1%

–

1%

45%

38%

16%

–

–

100%

–

67%

32%

1%

12%

58%

28%

3%

–

–

2%

47%

51%

–

–

–

100%

93%

6%

1%

20%

62%

16%

2%

Table 3

Associations between mean 1- and 5-year exposure to residential A-weighted

outdoor wind turbine noise and risk of diabetes.

Outdoor wind turbine noise

N cases

1-year mean exposure

< 24 dB

24–30 dB

30–36 dB

36–42 dB

≥

42 dB

5-year mean exposure

< 24 dB

24–30 dB

30–36 dB

36–42 dB

≥

42 dB

a

Table 4

Associations between mean 1- and 5-year exposure to residential A-weighted

indoor low frequency wind turbine noise and risk of diabetes.

Indoor low frequency wind

turbine noise

N cases

Crude

1.

IRR (95%

CI)

ab

Adjusted

IRR (95% CI)

ac

Crude

IRR (95% CI)

ab

Adjusted

IRR (95% CI)

ac

18,340

4926

1598

241

43

18,419

4913

1529

244

43

1 (ref)

0.98 (0.94–1.01)

0.94 (0.89–0.99)

0.76 (0.67–0.86)

0.86 (0.64–1.16)

1 (ref)

0.98 (0.95–1.01)

0.93 (0.88–0.98)

0.79 (0.69–0.89)

0.77 (0.57–1.03)

1 (ref)

1.01 (0.98–1.04)

1.02 (0.96–1.07)

0.87 (0.77–0.99)

1.06 (0.78–1.43)

1 (ref)

1.00 (0.97–1.04)

1.00 (0.94–1.05)

0.90 (0.79–1.02)

0.92 (0.68–1.24)

1-year mean exposure

< 5 dB

5–10 dB

10–15 dB

≥

15 dB

5-year mean exposure

< 5 dB

5–10 dB

10–15 dB

≥

15 dB

a

23,692

1197

244

15

23,857

1097

183

11

1 (ref)

0.89 (0.84–0.95)

0.84 (0.74–0.95)

0.64 (0.39–1.07)

1 (ref)

0.91 (0.86–0.97)

0.77 (0.67–0.89)

0.60 (0.33–1.07)

1 (ref)

0.99 (0.93–1.05)

0.98 (0.86–1.11)

0.80 (0.48–1.33)

1 (ref)

1.00 (0.94–1.07)

0.90 (0.78–1.04)

0.74 (0.41–1.34)

IRR: incidence rate ratio; CI: confidence interval.

b

Adjusted for age, sex and calendar-year.

c

Adjusted for age, sex, calendar-year, personal income, education, marital

status, occupation, area-level socioeconomic status, type of dwelling, traffic

load in 500 m radius and distance to major road.

IRR: incidence rate ratio; CI: confidence interval.

Adjusted for age, sex and calendar-year.

c

Adjusted for age, sex, calendar-year, personal income, education, marital

status, occupation, area-level socioeconomic status, type of dwelling, traffic

load in 500 m radius and distance to major road.

b

to be a major issue in the present study, as adjusting for the proxies only

resulted in minor changes in estimates, and we found no effect mod-

ification by distance to major roads.

There is inevitable uncertainty in the modelled noise exposure

metrics, but we expect this to be non-differential, which in most cases

will influence the estimates towards the null. Although our validity

score does not cover all aspects of uncertainty pertaining to the noise

estimates, we

find

that the observed lack of marked differences in risk

estimates when stratifying by this estimator, speaks against exposure

misclassification as explanation for the null

finding.

This is further

supported by the similar estimates observed in strata of environmental

factors, which could influence sound reception and perception (tree

coverage and major roads). Lack of information on a number of factors

that may influence the personal exposure to WTN, including window

opening habits, bedroom location and hearing impairment, are likely to

have resulted in exposure misclassification. Such misclassification is

thought non-differential and influence risk estimate towards unity.

Finally, despite including all relevant cases in Denmark, statistical

44

power was impaired by having relatively few cases with high exposure

to WTN.

Overall, our results do not support the hypothesis that exposure to

outdoor WTN or indoor LF WTN, or aspects of WTN directly associated

with these metrics, are risk factors for diabetes. However, we observed

that adjustment in our analyses consistently drew the estimates from a

reduction in risk (statistical significant for many estimates) in the crude

analyses towards unity in the adjusted analyses, and with regard to

indoor LF WTN the point estimates among those with high exposure

remained below unity even after adjustment. We can therefore not

entirely rule out that residual confounding is present, which could

change the results.

In support of a null-finding, we, however, found no suggestions of a

positive association in any of the stratified analyses. The lack of a po-

sitive association between WTN and diabetes observed in the present

study is mostly in line with the few cross-sectional studies on WTN and

diabetes, which found ORs of 1.13 and 0.96 in two Swedish popula-

tions, of 1.00 in a Dutch population and an equal distribution of cases

across

five

WTN exposure categories in a Canadian population

SUU, Alm.del - 2017-18 - Bilag 291: Orientering om undersøgelse vedr. vindmøllestøj og diabetes, fra sundhedsministeren

A.H. Poulsen et al.

Environmental Research 165 (2018) 40–45

confounding in epidemiologic studies: a simulation study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 166 (6),

646–655.

Foraster, M., Eze, I.C., Vienneau, D., Brink, M., Cajochen, C., Caviezel, S., Heritier, H.,

Schaffner, E., Schindler, C., Wanner, M., Wunderli, J.M., Roosli, M., Probst-Hensch,

N., 2016. Long-term transportation noise annoyance is associated with subsequent

lower levels of physical activity. Environ. Int. 91, 341–349.

Hahmann, A.N., Vincent, C.L., Pena, A., Lange, J., Hasager, C.B., 2015. Wind climate

estimation using WRF model output: method and model sensitivities over the sea. Int.

J. Climatol. 35, 18.

Jalali, L., Bigelow, P., Nezhad-Ahmadi, M.R., Gohari, M., Williams, D., McColl, S., 2016.

Before-after

field

study of effects of wind turbine noise on polysomnographic sleep

parameters. Noise Health 18 (83), 194–205.

Janssen, S.A., Vos, H., Eisses, A.R., Pedersen, E., 2011. A comparison between exposure-

response relationships for wind turbine annoyance and annoyance due to other noise

sources. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 130 (6), 3746–3753.

Jeffery, R.D., Krogh, C.M., Horner, B., 2014. Industrial wind turbines and adverse health

effects. Can. J. Rural Med. 19 (1), 21–26.

Kragh. J., Plovsing, B., Storeheier, S.Å., Jonasson, H.G., 2001. Nordic environmental

noise prediction methods, Nord 2000 summary report general nordic sound propa-

gation model and applications in source-related prediction methods. In: DELTA

Danish Electronics, Light & Acoustics, Lyngby, Denmark, Report 45.

Mazziotti, G., Gazzaruso, C., Giustina, A., 2011. Diabetes in Cushing syndrome: basic and

clinical aspects. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 22 (12), 499–506.

McHill, A.W., Wright Jr., K.P., 2017. Role of sleep and circadian disruption on energy

expenditure and in metabolic predisposition to human obesity and metabolic disease.

Obes. Rev. 18 (Suppl. 1), 15–24.

Michaud, D.S., Feder, K., Keith, S.E., Voicescu, S.A., Marro, L., Than, J., Guay, M.,

Denning, A., McGuire, D., Bower, T., Lavigne, E., Murray, B.J., Weiss, S.K., van den

Berg, F., 2016a. Exposure to wind turbine noise: perceptual responses and reported

health effects. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 139 (3), 1443–1454.

Michaud, D.S., Keith, S.E., Feder, K., Voicescu, S.A., Marro, L., Than, J., Guay, M., Bower,

T., Denning, A., Lavigne, E., Whelan, C., Janssen, S.A., Leroux, T., van den Berg, F.,

2016b. Personal and situational variables associated with wind turbine noise an-

noyance. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 139 (3), 1455–1466.

Michaud, D.S., Feder, K., Keith, S.E., Voicescu, S.A., Marro, L., Than, J., Guay, M.,

Denning, A., Murray, B.J., Weiss, S.K., Villeneuve, P.J., van den Berg, F., Bower, T.,

2016c. Effects of wind turbine noise on self-reported and objective measures of sleep.

Sleep 39 (1), 97–109.

Michaud, D.S., Feder, K., Keith, S.E., Voicescu, S.A., Marro, L., Than, J., Guay, M.,

Denning, A., Bower, T., Villeneuve, P.J., Russell, E., Koren, G., van den Berg, F.,

2016d. Self-reported and measured stress related responses associated with exposure

to wind turbine noise. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 139 (3), 1467–1479.

Moller, H., Pedersen, C.S., 2011. Low-frequency noise from large wind turbines. J. Acoust.

Soc. Am. 129 (6), 3727–3744.

Onakpoya, I.J., O'Sullivan, J., Thompson, M.J., Heneghan, C.J., 2015. The effect of wind

turbine noise on sleep and quality of life: a systematic review and meta-analysis of

observational studies. Environ. Int. 82, 1–9.

Pedersen, E., 2011. Health aspects associated with wind turbine noise

–

results from three

field

studies. Noise Control Eng. J. 59, 47–53.

Peña, A., Hahmann, A.N., 2017. 30-year mesoscale model simulations for the

“noise

from

wind turbines and risk of cardiovascular disease” project. DTU Wind Energy E 0055.

Pyko, A., Eriksson, C., Oftedal, B., Hilding, A., Ostenson, C.G., Krog, N.H., Julin, B.,

Aasvang, G.M., Pershagen, G., 2015. Exposure to traffic noise and markers of obesity.

Occup. Environ. Med. 72 (8), 594–601.

Pyko, A., Eriksson, C., Lind, T., Mitkovskaya, N., Wallas, A., Ogren, M., Ostenson, C.G.,

Pershagen, G., 2017. Long-term exposure to transportation noise in relation to de-

velopment of obesity-a cohort study. Environ. Health Perspect. 125 (11), 117005.

Roswall, N., Ammitzboll, G., Christensen, J.S., Raaschou-Nielsen, O., Jensen, S.S.,

Tjonneland, A., Sorensen, M., 2017. Residential exposure to traffic noise and leisure-

time sports

–

a population-based study. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 220 (6),

1006–1013.

Roswall, N., Raaschou-Nielsen, O., Jensen, S.S., Tjonneland, A., Sorensen, M., 2018. Long-

term exposure to residential railway and road traffic noise and risk for diabetes in a

Danish cohort. Environ. Res. 160, 292–297.

Schmidt, J.H., Klokker, M., 2014. Health effects related to wind turbine noise exposure: a

systematic review. PLoS One 9 (12), e114183.

Schmidt, M., Pedersen, L., Sorensen, H.T., 2014. The Danish civil registration system as a

tool in epidemiology. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 29 (8), 541–549.

Sondergaard, L.S., Backalarz, C., 2015. Noise from wind turbines and health effects

–

investigation of wind turbine noise spectra. In: International Conference on Wind

Turbine Noise. Glasgow, UK.

Sondergaard, L.S., Plovsing, B., Sorensen, T., 2009. Noise and energy optimization of

wind farms, Validation of the Nord 2000 propagation model for use on wind turbine

noise. Report Nr. 53 from DELTA, Hørsholm, Denmark.

Sorensen, M., Andersen, Z.J., Nordsborg, R.B., Becker, T., Tjonneland, A., Overvad, K.,

Raaschou-Nielsen, O., 2013. Long-term exposure to road traffic noise and incident

diabetes: a cohort study. Environ. Health Perspect. 121 (2), 217–222.

Spiegel, K., Tasali, E., Penev, P., Van, C.E., 2004. Brief communication: Sleep curtailment

in healthy young men is associated with decreased leptin levels, elevated ghrelin

levels, and increased hunger and appetite. Ann. Intern. Med. 141 (11), 846–850.

Taheri, S., Lin, L., Austin, D., Young, T., Mignot, E., 2004. Short sleep duration is asso-

ciated with reduced leptin, elevated ghrelin, and increased body mass index. PLoS

Med. 1 (3), e62.

(Michaud

et al., (2016a; Pedersen, 2011).

As the present study is the

first

prospective study on WTN and diabetes, more studies are needed

before

firm

conclusions can be drawn.

In conclusion, the results of the present study do not support an

association between long-term nighttime exposure to WTN and higher

risk of diabetes.

Acknowledgements

We wish to express our gratitude to DELTA, who even in the face of

enormous datasets, has shown great expertise, diligence and ingenuity

in all steps of the process towards estimating detailed wind turbine

noise data useable for the epidemiological analyses. We are also in-

debted to Geoinfo A/S who made it possible to extract the GIS in-

formation relating to all address point covered in our study.

Source of funding

This study was supported by a grant [J.nr. 1401329] from the

Danish Ministry of Health (the grant was co-funded by the Danish

Ministry of Food and Environment and the Danish Ministry of Energy,

Utilities and Climate).

Appendix A. Supporting information

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the

online version at

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2018.03.040.

References

Backalarz, C., Sondergaard, L.S., Laursen, J.E., 2016. Big noise data for wind turbines. In:

Wolfgang Kropp Ove, Brigitte Schulte-Fortkam (ed.) Inter-noise. Hamburg; German

AcousticalSociety (DEGA).

Baliatsas, C., van Kamp, I., van Poll, R., Yzermans, J., 2016. Health effects from low-

frequency noise and infrasound in the general population: is it time to listen? A

systematic review of observational studies. Sci. Total Environ. 557–558, 163–169.

Cai, Y., Hansell, A.L., Blangiardo, M., Burton, P.R., BioShaRe, de Hoogh, K., Doiron, D.,

Fortier, I., Gulliver, J., Hveem, K., Mbatchou, S., Morley, D.W., Stolk, R.P., Zijlema,

W.L., Elliott, P., Hodgson, S., 2017. Long-term exposure to road traffic noise, ambient

air pollution, and cardiovascular risk factors in the HUNT and lifelines cohorts. Eur.

Heart J. 38 (29), 2290–2296.

Cappuccio, F.P., D'Elia, L., Strazzullo, P., Miller, M.A., 2010. Quantity and quality of sleep

and incidence of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes

Care 33 (2), 414–420.

Carstensen, B., Kristensen, J.K., Marcussen, M.M., Borch-Johnsen, K., 2011. The national

diabetes register. Scand. J. Public Health 39 (Suppl. 7), 58–61.

Christensen, G., 2011. The building and housing register. Scand. J. Public Health 39

(Suppl. 7), 106–108.

Christensen, J.S., Raaschou-Nielsen, O., Tjonneland, A., Nordsborg, R.B., Jensen, S.S.,

Sorensen, T.I., Sorensen, M., 2015. Long-term exposure to residential traffic noise and

changes in body weight and waist circumference: a cohort study. Environ. Res. 143

(Pt A), 154–161.

Christensen, J.S., Raaschou-Nielsen, O., Tjonneland, A., Overvad, K., Nordsborg, R.B.,

Ketzel, M., Sorensen, T., Sorensen, M., 2016. Road traffic and railway noise exposures

and adiposity in adults: a cross-sectional analysis of the Danish diet, cancer, and

health cohort. Environ. Health Perspect. 124 (3), 329–335.

Clark, C., Sbihi, H., Tamburic, L., Brauer, M., Frank, L.D., Davies, H.W., 2017. Association

of long-term exposure to transportation noise and traffic-related air pollution with

the incidence of diabetes: a prospective cohort study. Environ. Health Perspect. 125

(8), 087025.

Eriksson, C., Hilding, A., Pyko, A., Bluhm, G., Pershagen, G., Ostenson, C.G., 2014. Long-

term aircraft noise exposure and body mass index, waist circumference, and type 2

diabetes: a prospective study. Environ. Health Perspect. 122 (7), 687–694.

Eze, I.C., Foraster, M., Schaffner, E., Vienneau, D., Heritier, H., Rudzik, F., Thiesse, L.,

Pieren, R., Imboden, M., von Eckardstein, A., Schindler, C., Brink, M., Cajochen, C.,

Wunderli, J.M., Roosli, M., Probst-Hensch, N., 2017a. Long-term exposure to trans-

portation noise and air pollution in relation to incident diabetes in the SAPALDIA

study. Int J. Epidemiol. 46 (4), 1115–1125.

Eze, I.C., Imboden, M., Foraster, M., Schaffner, E., Kumar, A., Vienneau, D., Heritier, H.,

Rudzik, F., Thiesse, L., Pieren, R., von Eckardstein, A., Schindler, C., Brink, M.,

Wunderli, J.M., Cajochen, C., Roosli, M., Probst-Hensch, N., 2017b. Exposure to

night-time traffic noise, melatonin-regulating gene variants and change in glycemia

in adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 14, 12.

Fewell, Z., Davey Smith, G., Sterne, J.A., 2007. The impact of residual and unmeasured

45