June ����, �������� ����:����AM EDT

Available In

ﺔﻳﺑﺭﻌﻟﺍ

English

Egypt: Cancel Military Court Death Sentences

Convicted Civilians Alleged Torture, Forcible Disappearances

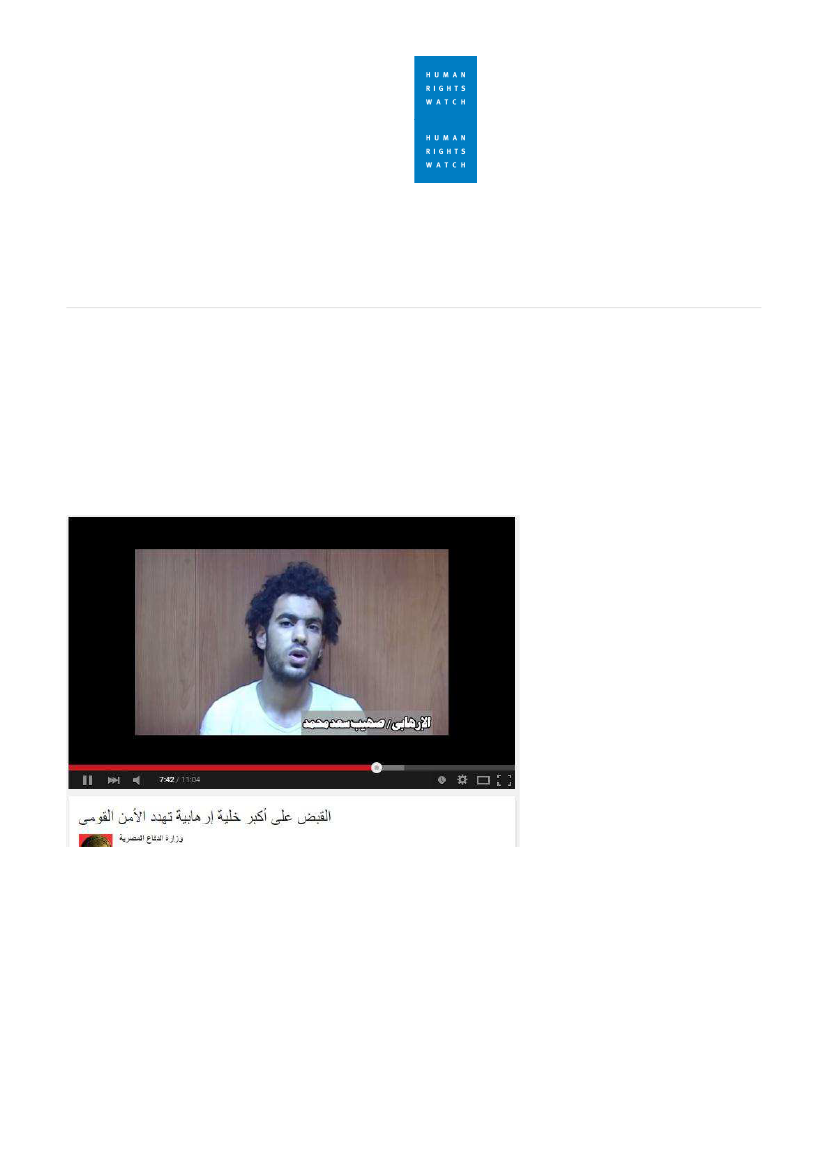

Souhaib Sa’ad in a still from a video released by the Defense Ministry

several weeks after his disappearance. His brother told Human Rights

Watch that Sa'ad was forced to repeat dictated confessions after being

tortured for 3 days.

(Beirut) – The case of eight men who could face

imminent execution following a military trial shows why

Egyptian

authorities should place a moratorium on the

death penalty, Human Rights Watch said today.