Udenrigsudvalget 2013-14

URU Alm.del Bilag 16

Offentligt

AidWatch

20�3

THE UNIQUE ROLEOF EUROPEAN AIDThe fight againstglobal poverty

�

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSABOUT THIS REPORTSince 2005, development NGOs from all the EU countries (now28) have come together every year through the AidWatch initia-tive, under the umbrella of CONCORD, to produce the annualAidWatch reports. CONCORD is the European NGO Confedera-tion for Relief and Development. Its 27 national associations,�7 international networks and two associate members repre-sent �,800 NGOs which are supported by millions of citizensacross Europe. CONCORD leads reflection and political action,and regularly engages in dialogue with the European institu-tions and other civil society organisations. At the global level,CONCORD is actively involved in the Beyond 20�5 campaign,the CSO Partnership on Development Effectiveness and the In-ternational Forum of NGO platforms.More at: www.concordeurope.org.AidWatch has monitored and made recommendations on thequality and quantity of aid provided by EU member states andthe European Commission since 2005. The AidWatch initiativecarries out ongoing advocacy, research, media activities andcampaigns on a wide range of aid-related issues throughoutthe year. More at: www.aidwatch.concordeurope.org.Report editing: Anna Thomas.Report writing and data analysis: Gideon Rabinowitz and JavierPereira.The AidWatch Advocacy Group has given overall guidanceand made substantial inputs to the writing of the report. Thegroup includes: Amy Dodd (UKAN), Jennifer Young (Bond),Luca De Fraia (ActionAid), Pauliina Saares (Kepa), CatherineOlier (Oxfam), Jeroen Kwakkenbos (Eurodad), Peter Sörbom(Concord Sweden), Liz Steele (PWYF), Fotis Vlachos (HellenicCommittee of NGOs) and Wiske Jult (��.��.��.).The writers of the Country pages were: Austria: Globale Ve-rantwortung – Michael Obrovsky, Hilde Wipfel and JakobMussil; Belgium: CONCORD Belgium – Oumou Zé, Koen De-tavernier and Griet Ysewyn; Bulgaria: BPID – Ventzislav Kirkov;Cyprus: CYINDEP – Michalis Simopoulos, Sophia Arnaouti andKerstin Wittig; Croatia: Tihomir Popovic and Gordan Bosana;Czech Republic: FoRS – Jana Milerova, Zuzana Sikova; Den-mark: CONCORD Denmark – Mathias Ljørring; Estonia: AKÜ– Evelin Andrespok; Finland: Kehys – Pauliina Saares andReetta Hahlen; France: Coordination SUD – Gautier Centlivre;Germany: VENRO – Jana Rosenboom; Greece: Hellenic Com-mittee of NGOs – Marina Savrami and Fotis Vlachos; Hungary:HAND – Réka Balogh; Ireland: Dóchas – Hans Zomer; Italy:CONCORD Italy – Luca De Fraia and Francesco Petrelli; Latvia:Lapas – Evija Goluba; Lithuania: LU – Julius Norvila; Luxem-burg: Cercle – Christine Dahm; Malta: SKOP – Paola Prinzis;Netherlands: Partos – Mieke Olde Engberink and Koos de Bru-ijn; Poland: Grupa Zagranica – Jan Bazyl; Portugal: PlataformaONGD – Pedro Cruz; Romania: Fond – Adela Rusu and AdrianaZaharia; Slovakia: MVRO – Andrea Girmanova, Lenka Nemcovaand Nora Benakova; Slovenia: SLOGA – Anita Ramsak, AnaKalin and Marjan Huc; Spain: CoNgDe – Cristina Linaje; Swe-den: CONCORD Sweden – Peter Sorbom; UK: Bond – JenniferYoung, Amy Dodd and Joanna Rea.The positions taken in this report are thoseof CONCORD AidWatch.Copy-editing by Veronica Kelly.Design and layout by: www.atelier3�4.eu.For further information about this report:[email protected]

2

CONTENTSExecutive summaryPART ONE – OVERVIEWIntroductionChapter � – The unique role of aidChapter 2 – Aid effectivenessChapter 3 – The quantity of genuine aidRecommendationsPART TWO – COUNTRY PAGESAppendix � – Inflated aid: notes on methodologyAppendix 2 – Acronyms4679�4�823245455

3

EXECUTIVE SUMMARYIn these challenging political and economic times, leadership onaid is needed more than ever. Unfortunately, however, Europe’sleadership appears to be waning – on the boundaries of aid, onits effectiveness, and on its quantity. This needs to change.This eighth Concord AidWatch Report focuses on the uniquerole of aid. It shows that, while all sources of finance are impor-tant for development, aid can achieve things that other sourcescannot.

Aid effectivenessIt might be expected that, under current economic pressures,the EU would be working hard to maximise the effectivenessof every cent of aid, and to lead the rest of the world in reach-ing the same objective. The evidence, disappointingly, is thatdespite the major Busan conference in December 20��, and theresulting Global Partnership for Effective Development Coop-eration (GPEDC), progress on aid effectiveness has slowed:•Only seven EU member states (MSs) have a full strategyin place for implementing the Busan commitments.•Many CONCORD members report that, in recent years,their government’s commitment to Paris and Accra principlessuch as country ownership has weakened.•Only �0 MSs have undertaken, or said they intend toundertake, ambitious or moderately ambitious actions on aidtransparency.•Only two MSs make their aid predictable by providing three-to five-year rolling plans for all their development partners.•Since Busan, only five MSs have declared strong ambi-tions to untie their aid further.In addition, the quality of aid effectiveness informationhas declined significantly since Busan. The implementation ofthe Paris and Accra agreements was monitored globally, andreasonably comprehensively. The implementation of Busan, onthe other hand, is to be monitored mainly at country level.

The unique role of aidPoverty is still widespread, and growth alone cannot eradicateit. Other finance is needed, therefore, and some of it needs tobe in the form of aid. Ten arguments for aid:�Effective aid can target public services and support pri-vate enterprise for poor people2Effective aid is available now, and helps establish longer-term resource collection3Aid has to be focused on generating genuine resourcetransfers for development4Effective aid can help support accountable institutionsand improve governance5Effective aid means a transparent, accountable publicfinancing mechanism6Aid is a suitable mechanism for investing in sectors thatare key to eradicating poverty7Loans have to be repaid8Aid is necessary until developing countries can raise ad-equate domestic resources through fair tax systems9Unlike aid, foreign direct investment does not have a de-velopment objective�0 Aid is the most powerful expression of global solidarity.Aid is defined as finance provided to support develop-ment activities, and only funds that meet strict criteria can becounted towards the politically important quantitative aid tar-gets. Currently there are signs in the EU, the OECD and else-where that aid, defined in this way, may potentially be margin-alised, and other forms of development finance brought to thefore. Because of aid’s unique and important role, this would bea grave error.Yet aid could be improved – it could be more effective,and aid quantity figures could be less inflated. In addition, theEU needs to take its aid quantity commitments seriously.

4

>Quantity of genuine aidWhile a few EU member states are standing by their aid quan-tity commitments, many others appear not to be fulfilling theirpublic promises on them.In 20�2, aid from the EU-27 countries represented only0.39% of the EU’s GNI, bringing us back to the lowest levelsince 2007, when aid was 0.37% of EU’s GNI. And, for the sec-ond year in a row, aid also dropped well below the objective of0.7% GNI by 20�5. The EU-27 countries delivered €50.6 billionin aid in 20�2, a 4% drop compared to the previous year. Aidhas either been cut or remained stagnant in �9 EU memberstates. The deepest cuts between 20�� and 20�2 took placein Spain (49%), Italy (34%), Cyprus (26%), Greece (�7%) andBelgium (��%).Nor are there any signs of imminent improvement. In 20�3-20�4, total EU aid is expected to remain almost stagnant at ap-proximately 0.43% of GNI. The estimated funding gap betweenprojected aid levels and EU commitments will be approximately€36 billion in 20�5 alone. Despite this, European leaders are stillinsisting that they will honour their aid commitments, without giv-ing any tangible sign of how they plan to do so.This aid was inflated, moreover, by an estimated €5.6billion, bringing genuine aid in 20�2 down to €45 billion or0.35% of GNI. The inflated aid comprises several components:imputed student costs, refugee costs in donor countries, debtrelief double-counted as aid, tied aid and interest on loans allcounted as official development assistance (ODA).

RecommendationsEurope urgently needs to take leadership again and reversethe declining trends in aid practice. Concretely, it should dothe following:On protecting the unique role of aid•Ensure that the definition of ODA is not diluted by the in-corporation of elements of dubious development impact whichwould further inflate commitment estimates. Ensure that aid-effectiveness principles are firmly ingrained in any discussionabout the future of the ODA definition, and that civil societyorganisations (CSOs) and southern partners play a central rolein any decisions on it.•Monitor and report on other forms of development fi-nance more effectively, without including them in quantitativeODA commitments by donors.On the effectiveness of development cooperation•Publish Busan implementation strategies by the endof 20�3, focusing in particular on the elements of the Busanagreement that derive from the Paris and Accra agreements.•Fully untie all aid.•Make information on aid more useful by publishing infor-mation in the IATI standard and by continuing to improve dataquality and coverage in time for the Busan deadline at the endof 20�5.•Inject political impetus into the GPEDC, ensure partnercountries become more fully involved in the process, and reviewwhether the partnership’s constituency structure is working.•Strengthen the EU’s role in monitoring Busan implemen-tation, and improve the coordination of this monitoring.On aid quantity•Meet the longstanding commitment to devote 0.7% ofincome to ODA in a way that is transparent, predictable andaccountable.•Increase EU pressure on member states that decreaseaid or are very far from meeting their targets.•Reduce the inflation of aid by:•ending the inclusion of refugee costs, imputed stu-dent costs, debt relief and future interest on cancelledloans in aid budgets;•providing climate finance that is additional to ODA.

5

>

PART ONE– OVERVIEW

6

INTRODUCTIONAid is a unique and valuable resource in the global fight againstpoverty, inequality and marginalisation. As the deadline forthe 20�5 Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) approachesand ongoing economic difficulties sap the political will to meetaid promises, we must continue to promote the importance ofhigh-quality aid and encourage the political drive necessary toensure it.This eighth Concord AidWatch report focuses on the uniquerole of aid. It shows that, while all sources of finance are impor-tant for sustainable development, aid can achieve things that othersources cannot. No other financial flows can replace it.up in 20�3. Vital preparation is needed this year to ensure thatthe ministerial meeting in early 20�4 can move the agenda for-ward and showcase some genuine successes. This meetingwill be a crucial test of global commitment to improving aidquality, and will show us whether the GPEDC will blaze a trail toa bold new future for aid quality, or whether it will turn out to beoverblown hype.

The economic and political contextfor aid in 20�3At the same time as these two major aid-related processes areplaying out, the final push to reach the MDGs is underway. Thisis happening in the context of a number of developments in Eu-rope, where one factor challenging aid quantity is the continu-ing poor economic situation. The euro crisis has not yet ended,some EU member states really are in dire straits, and there islittle fiscal space in the others. In this situation, politicians whohave always been against aid are buttressed, and even someof those who support it are increasingly nervous in a climate ofperceived public hostility (which is actually less than is often im-plied: in 20�2, according to Eurobarometer, 85% of EU citizensthought that supporting developing countries was important).5The overall political will to support aid is thus diminishing.The economic situation provides a platform for politiciansto focus on aid quality rather than quantity, at least in rhetoricalterms. Here, geopolitical relations are shifting, and the aid anddevelopment landscape has to adapt. Emerging and developingcountries are taking their place on the world stage, and Europeis negotiating new relationships with them. These countrieswant to throw off the perception that they are supplicant aidrecipients (although most of them do receive development as-sistance, some of it as ODA); instead they want equal economicand political partnerships. This affects how their aid relation-ship with Europe works. Meanwhile, they are becoming donorsthemselves, albeit not under the auspices of the OECD DAC (co-ordinating instead through UN DESA). This provides a greaterchoice of sources for countries that receive aid,6and representsan additional context for developments in aid quality.

20�3, an important year for aidAs 20�5 approaches, assessments of the world’s achieve-ments on the MDGs multiply. And the news is, on the whole,good. Overall the proportion of people living in extreme povertyhas dropped to less than half its �990 value, and it has fallenin every region of the world. Two billion people now have betterdrinking water. Remarkable gains have been made in fightingmalaria and TB. The proportion of slum dwellers in cities is de-clining. The hunger target is within reach.�Aid cannot claim solecredit, but it has certainly contributed to this progress, some-times directly and sometimes by sparking other processes.At the same time, there is still a very long way to go.Many people continue to live in poverty. From households togovernments, women are still denied decision-making powerequal to men’s. There needs to be more progress on child andmaternal survival, and on HIV. The poorest children are stillthose most likely to be out of school. Sanitation has improved,but not enough.2Discussions on the post-20�5 successor to the MDGsare growing serious. The post-20�5 debate is a landmark one,and is underpinning renewed debate about what resources areneeded for development, how to mobilise them, and the roleand definition of ODA. The UN High-Level Panel is proposingthat “eradicating extreme poverty from the face of the earth”should be central to the post-20�5 agenda.3This will be a trulyhistoric aim, albeit still too limited. But if the political will toprovide more, higher-quality aid is lacking, this aim will be hardto achieve, and the commitment of the countries of the globalnorth will be perceived by those in the global south as beinghypocritical and hollow. The UN is saying that falls in aid arejeopardising even current strides towards the MDGs, not tomention the post-20�5 agenda.4Meanwhile, global discussions at the GPEDC, which wascreated in Busan in 20�� and is the successor to the Rome,Paris and Accra commitments, must also be seriously stepped� UN (20�3),The Millennium Development Goals Report 20132Ibid.3 UN (20�3),A New Global Partnership: eradicate poverty and transformeconomies through sustainable development4 UN (20�3),The Millennium Development Goals Report 2013

5 European Commission (20�2),Solidarity that Spans the Globe: Europe andDevelopment Aid.Special Eurobarometer 3926 Greenhill R, Prizzon A and Rogerson A (20�3),The Age of Choice – howare developing countries managing the new aid landscape?Overseas Develop-ment Institute

7

>Responses in Europe and beyondEurope has generally performed well on aid quality and quantity– but just when adequate, effective aid is needed most, theEU appears to be weakening its commitment. ODA levels fellin 20�2, with cuts in most EU member states and an overallfour per cent reduction from the EU-27 in 20�2 compared with20��. Not surprisingly, with Europe being the largest donor,global trends are similar: in 20�2 aid was four per cent less inreal terms than in 20��, following a two per cent reduction theyear before.It is now evident that some member states will find it dif-ficult indeed to meet their aid target while also providing aid ef-fectively. Perhaps even more worrying than cuts is the very littleevidence of any real will to get back on track. Most EU memberstates have confirmed their intention to continue honouring the40-year-old commitment to achieving a certain percentage ofGNI as aid.7But the trend in their actual contributions, and theirfuture projections, make this commitment feel hollow indeed.In this context, we might expect donors to at least redou-ble their efforts to ensure that every euro of aid is well spent.But this is not the case. There is political rhetoric on aid qual-ity, but action or implementation through the GPEDC is so farlargely lacking.Finally, in the OECD, the EU institutions and some mem-ber states, a discussion is starting about where the boundariesaround aid should be, and whether they should be reviewed.The debate is unfortunately not about reducing inflated aid(such as student fees and refugee costs, which have no directimpact on development), but instead about creative accounting:making more flows count as aid without any certainty eitherthat this will augment financial flows, or that these flows willcontribute to development. For example, according to Venro– the umbrella organisation for non-governmental developmentorganisations (NGDOs) in Germany – the German governmenthas announced that it wants to revise the definition of ODA andits monitoring system, and to incorporate other areas of spend-ing into it. This would be truly bad news for the world’s poorpeople, and could reinforce the wrong-headed idea that ODAshould serve the self-interest of states.The countries that are maintaining political willDecline is not inevitable. This report shows that:Several countries have substantially increased their aid, thelargest relative increases being in Latvia (�7%), Luxembourg(�4%), Poland (�4%), Austria (8%), Lithuania (8%) and the Unit-ed Kingdom (7%). Those already reaching the 0.7% target areDenmark (0.8%), Luxembourg (�%) and Sweden (0.99%), andin 20�3 the UK will join them, at 0.7%.In six countries, less than 4% of bilateral aid comprises inflatedaid (Ireland, Luxembourg, UK, Lithuania, Estonia and Poland).Given aid’s unique and vital role, negative trends can andshould be turned around. This report contributes to this effort.It focuses first on aid’s unique contribution to development. Itthen looks at trends in EU aid quality, and quantity (includingdistinguishing between genuine aid and inflated aid). Finally, itproposes recommendations for Europe to follow.Europe has stood shoulder to shoulder with the world’spoor people for a long time. Now – paradoxically, just when itis most needed – it is doing less to improve aid performance.But it could, instead, continue to play its previous global leadingrole on aid. It should abide by its commitment to share 0.7%of its income, while also ensuring that it continues to make itsaid more effective for poor people. Even while facing its owninternal challenges, Europe would surely prefer to find the dig-nity, capacity and strength to continue to uphold the principle ofglobal solidarity with poor people.

7 E.g. European Commission (20�3),Beyond 2015: towards a comprehen-sive and integrated approach to financing poverty eradication and sustainabledevelopment,�6 July 20�3, COM (20�3) 53� Final

8

CHAPTER 1– THE UNIQUE ROLE OF AIDThese are challenging economic times, but aid plays a uniquerole in tackling poverty, and is needed more than ever. Aid canbe targeted to support essential public services. It is availablenow and helps establish longer-term resource collection. Ef-fective aid can support accountable governance, and is itselfa transparent and accountable form of finance. Other forms offinance are important in addition to aid – but they are no sub-stitute for it: loans have to be repaid, adequate levels of taxationare only feasible when there is an adequate tax base, and for-eign private investment does not always support development.This chapter looks at why aid is still very much needed in devel-oping countries, both because poverty and inequality are still areality, and because aid plays a unique role in tackling both.Despite the importance of aid, discussions are startingin the EU, the OECD, donor countries and elsewhere aboutwhether the focus of development finance should move awayfrom aid and towards other forms of finance. While recognisingthe importance of how other kinds of financial flows impacton development, and welcoming the growing attention to this,AidWatch feels strongly that any changes that marginalise aid,or blur its essential characteristic of being focused on develop-ment and poverty reduction, would be a grave mistake.nificant role in ending poverty in future decades.��This is verydifferent from arguing that, because of growth, aid might aswell be cut right now. Other influential authors focus on howthe majority of poor people live in large countries which arenow classified as middle-income ones. However, they do notargue for an end to aid either – rather, they show that aid is stillneeded in a middle- as well as a low-income context, perhapsplaying a game-changing and human-rights-supporting role indevelopment there.�2There is a genuine debate on the focus ofaid along these lines, although not on its relevance per se.Furthermore, the most recent major studies that predictdramatic falls in poverty in the next �0-�5 years use a $2-a-day (€�.5)�3or $�.25-a-day (€0.94) poverty line.�4Just abovethese extreme poverty lines are many more poor people. Also,as these measures focus only on income they fail to incorporatean understanding of broader forms of poverty, represented bymeasures such as the MDGs, which most developing countriesare still some way from achieving.

The role of growthOn average, growth is associated with some reduction in pov-erty (and an increase in inequality).�5This average masks verydifferent situations in different countries, however. A 20��study showed that many countries with very high growth rateshad experienced no concurrent drops in poverty, while in some,poverty had even increased.�6This is not to say that growth indeveloping countries is unimportant – it is very important – butit must be complemented by other measures (e.g. redistributivepolicies) if it is to succeed in creating, sustainably, a high qualityof life for all.In fact, this is a rerun of an old debate. Several decadesago it was thought that the benefits of growth would ”trickledown” to the poorest people. Then we realised that other poli-cies were needed alongside growth. We should not return to the�950s hope that we can rely on growth alone: we also need totackle poverty, and inequality, directly.

The end of poverty?The ambition of eradicating poverty within a generation is bothinspirational and laudable, but we must also remember thatthis ambition is a long way off. One in five people – �.25 bil-lion – still live below the extreme poverty line of $�.25 dollars(€0.94) per day.8Many more live on only a little more (half theworld’s population is estimated to live on £3-4 (around €3.50to €4.70 a day),9and have nothing like the resources needed tolive a life in which they can reach their full potential. Developingcountries face a financing gap of over $�50 billion (€��2 billion)annually in the coming years, purely in relation to the provisionof basic social goods like education, health, water and sanita-tion, and food security.�0Global poverty is still very much with us. A view that hasattracted growing support in recent years is that, based on pro-jected growth rates, the worst forms of poverty will soon bea feature of a small number of countries, and therefore aid isbecoming significantly less relevant. This conclusion, however,is not as solid as it sounds. For example, one such projectionspecifically discusses the future role of aid, and speculatesabout how, if aid is not cut, it could potentially play a very sig-8 Chandy L (20�3),Counting the poor – methods, problems and solutionsbehind the $1.25 per day poverty estimates,Development Initiatives/Brook-ings9 Hammondet al.(2007),The Next 4 Billion: Market Size and Business Strat-egy at the Base of the Pyramid,World Resources Institute and IFC�0 Greenhill R and Ali A (20�3),Paying for progress: how will emergingpost-2015 goals be financed in the new aid landscape?,Overseas Develop-ment Institute

�� Kharas H and Rogerson A (20�2),Horizon 2025: creative destruction inthe aid industry,Overseas Development Institute�2 Sumner A (20�0),Global Poverty and the New Bottom Billion,Institute forDevelopment Studies�3 Karveret al.(20�2),MDGs 2.0: What Goals, Targets, and Timeframe?,Centre for Global DevelopmentKharas and Rogerson (20�2),op. cit.�4 Chandy L and Gertz G (20��),Poverty in Numbers: The Changing State ofGlobal Poverty from 2005 to 2015,Brookings InstitutionHillebrand E (2008),The Global Distribution of Income in 2050,World Develop-ment 36:5Ravallion M (20�2),Benchmarking Global Poverty Reduction,World BankPolicy Research Working Paper 6205�5 http://www.scribd.com/doc/575�2672/Human-Development-in-LICs-LMICs-and-UMICs�6 Bond (20��),Growth and Development

9

>Ten reasons why aidis irreplaceablePoverty is still widespread, and growth alone cannot eradicateit. So other forms of finance are needed. But does this financeneed to be aid? The answer is: yes, some of it does. Effec-tive aid has a unique and important role to play amongst thevarious possible sources. It cannot be replaced, and should beincreased. There are a number of reasons for this.So when a country has very few resources, aid is the financesource that can start to fund development that provides a basisfor the future, such as education and the growth of accountableinstitutions. Aid’s ability to do this, in contrast to other kinds offinance, is recognised, for example in the context of the MDGs.�9Aid is needed in the short term to fund development that canmean, in the longer term, that less will be needed. Developingcountries that depend on aid now will depend on it less in thelonger term.20In practice, of course, aid is not always as speedyas it should be – but that is something to fix (through policieson aid and development effectiveness). It is not a fundamentalproblem with aid.None of this means that aid should only be spent on quickfixes, or that challenging sectors, or fragile contexts, or lesstangible areas, such as institution-building, should be ignored.The point is that aid as a source of finance can be availablemore rapidly than others, to enable work in all areas of devel-opment to happen. Sometimes, for instance where aid is usedto support the development of fair tax systems, this link is veryclear. For example, with support from international donors,starting in the late �990s Rwanda overhauled its tax system. In�998 the government collected a mere £60 million (€70 million)in tax revenue; by 2006 this had quadrupled to £240 million(€280 million).2�

1

Effective aid can target public servicesand support private enterprise for poor people

Aid in developing countries can support investment in servicesand intervention targeting poor people, in areas such as educa-tion, health and water. These kinds of areas are absolutely cru-cial for poverty reduction and development, but are much lesslikely to attract sufficient investment – in a way that createsaccess for everyone – from profit-seeking private investmentor commercial loans.Public goods like these are not meant to create privateprofit; hence the state and public financing should play animportant role in providing them. If a financial return has tobe generated, the services are unlikely to be targeted at poorpeople, because they cannot afford them. If a fee is charged,this restricts access dramatically, and the poor are likely to bebypassed. For example, when school fees were abolished inGhana in 2004, primary-school enrolment increased by morethan a million virtually overnight.�7Where national governmentsin developing countries do not have the resources to provide allthese goods themselves, aid can help to support the delivery ofsuch vital public services.It is not only in relation to government investment thatgrants and concessional loans are vital by targeting poor peo-ple. Recent research highlights how mainstream private inves-tors are avoiding supporting enterprises that can provide em-ployment, goods and services targeted at the very poorest, asthe returns on such investments are limited and the risks arehigher.�8Aid, however, could be used to help generate a step-change in investment in such local enterprises.

3

Aid has to be focused on generating genuineresource transfers for development

The main objective of ODA must, by definition, be the devel-opment and welfare of developing countries.22This result inchecks on the levels of resources donors have genuinely trans-ferred to developing countries with the explicit intention of sup-porting development, ensures political pressure to maintainthis finance, and focuses public and political attention on it. Noother form of development finance does this.

4

Effective aid can help support accountableinstitutions and improve governance

2

Effective aid is available now and helps establishlonger-term resource collection

Aid should be a rapid form of development finance. Othersources, such as revenues from fair fiscal systems, will takelonger to materialise in developing countries or to show impact.�7 Tran M (20�2), Pearson to invest in low-cost private education in Asiaand Africa,Guardian,3 July 20�2�8 Bannick and Goldman (20�2),Priming the Pump: The Case for a Sector-Based Approach to Impact Investing,Omidyar Network

This is an area increasingly agreed to be vital for development.A unique role of aid here is to support the emergence of strongparliaments, media, auditors and civil society organisations,which in turn hold their governments to account. In countrieswhere there is no enabling environment in which these actorscan fulfil their duties, the role of aid is absolutely crucial. It isalso an area where technical assistance from donors – if re-quested by the recipient government – may bear fruit.�9 Atisophon Vet al.(20��),Revisiting MDG cost estimates from a domesticresource mobilisation perspective,OECD Development Centre Working Paper30620 ActionAid (20��),Real Aid 3 – Ending Aid Dependency2� OECD (2008),Taxation, State Building and Aid,OECD Factsheet22 OECD (2008),Is it ODA?Factsheet

�0

>Aid also has a role to play in improving governance (assuggested in Agenda for Change, the EU development strat-egy). If aid is effective in supporting democratic ownership – forexample, if it is reported in the developing country’s budget,and if it uses national financial and procurement systems ratherthan parallel ones23– then it will in itself support improved gov-ernance by supporting the development of institutions throughwhich the government is accountable to its own people.Donor support tackles misuse of funds24Donors have supported the strengthening of public financialmanagement systems in Uganda through pooled funding.A priority has been to support the government audit office(OAG), and to support parliament in acting on the audit find-ings. The OAG has thus attained greater independence, cleareda backlog of reports and recruited more skilled staff.Recently, the OAG led efforts to uncover the circum-stances behind the misuse of funds in the prime minister’s of-fice, and it provided parliament and the police with the informa-tion needed to undertake an extensive investigation.

6

Aid is a suitable mechanism for investingin sectors that are key to eradicating poverty

Investment in infrastructure is an important and neglected areaof investment in many developing countries.25But the pendulumhas swung, and indeed, listening to the current political rhetoricone might think it was the only area that needed investment.This is incorrect: essential services, support for women’s rights,support for smallholder farmers, support for accountable insti-tutions, and so on, are still needed too. Moreover, infrastructuremay sometimes (not always) be a suitable area for private in-vestment, and it is also attracting investment from south-southdevelopment cooperation. This is all the more reason for OECDDAC donors to divide labour rationally and continue to provideaid in areas that have a direct impact on poverty reduction (e.g.health, education and food security), where possible throughbudget support.26Moreover, there is no guarantee that spending on infra-structure will benefit poor people specifically. The EU is startingto lend for more large-scale infrastructure projects, but there isno guarantee that these will build local markets or benefit poorpeople in the relevant countries.

5

Effective aid means a public finance mechanismthat is transparent and accountable

7

Loans have to be repaid

Transparency in public financing is a cornerstone of democraticaccountability, enabling parliament and citizens to influencebudget-setting (and therefore spending priorities) and to moni-tor implementation. It also enables parliaments and citizens,via media and audit bodies, to discover and challenge any inap-propriate or corrupt spending. So transparency and the subse-quent accountability are, in turn, central to good governance.This applies to the whole of public finance (in both develop-ing and developed countries). There has been particular progressin recent years on aid transparency, however, with a concertedglobal campaign and, for the first time, a focus on transparencyin the GPEDC. Currently, therefore, there is particular potential foraid transparency to contribute to and support the developmentof budget transparency in developing countries. Aid transpar-ency can be focused mainly on the parliaments and citizens ofdeveloping countries; that same transparency can then also beused by the donors to demonstrate to their own citizens how ef-fectively public money has been used in funding aid.

23 As specified, for example, in the Busan Partnership Document24 Glennie J and Rabinovitz G (20�3), Localising Aid – a whole-of-societyapproach, Overseas Development Institute Centre for Aid and Public Expen-diture

A move away from ODA towards more commercially basedsources of development finance would impact on the debtsof developing countries, and excessive debt prevents coun-tries from spending on essential public services. Civil societyorganisations campaigned for over a decade for the cripplingdebt of developing countries to be reduced through recent debtrelief processes. It is therefore important for aid to be providedin the form of grants (and suitably concessional loans) in orderto help prevent a repeat of such a debt crisis. There are realrisks involved: recent increases in the debt levels of sub-Saha-ran African countries, for example, have caused their paymentson debts to increase from $�3 billion (€9.75 billion) in 2009 to$�5.2 billion (€��.4 billion) in 20��.27This is partly because do-nors have become less willing to provide aid as grants, and alsobecause of debts taken on during the financial crisis.This issue links with the current EU debate on leveraging:using aid funds to reduce risk for private lenders, in particularfor infrastructure in developing countries, thereby “leveraging”more funds. There is much current European enthusiasm forthis practice, yet in development terms it is highly problematic.There is no guarantee that the funds leveraged would be addi-tional to investment that would have been made anyway; wherethey are not, leveraging simply diverts scarce aid from invest-ment in essential public services. Moreover, the funds are oftenloans, which increase the indebtedness of developing coun-25 Greenhill R, Prizzon A and Rogerson A,op. cit.26 Ibid.27 World Bank (20�3), International Debt Statistics 20�3, World Bank

��

>tries; there is no safeguard to ensure that the projects funded inthis way are developmentally beneficial, and no transparency tohelp us find out. Also, much of the support goes to developed-world companies, and thus does not benefit small or medium-sized enterprises in developing countries.28

8

Aid is necessary until developing countries canraise adequate domestic resources througha fair tax system

transferring technology and skills, and providing tax revenue.In reality, however, it often generates few jobs or linkages, thetechnology stays within the company, and taxes are avoided.34It is certainly not a finance mechanism targeted specifically atproviding development outcomes, nor is it under any obligationwhatsoever to facilitate development if this is not the optimumcommercial path.

Donors are giving increasing (and welcome) consideration tothe idea of mobilising additional domestic resources for devel-opment, and this is indeed crucial. However, it is only possibleto raise adequate and sustainable revenues if some pre-con-ditions are in place – for example, if enough wealth is beinggenerated in the country by a sufficient pool of individual andcorporate taxpayers, and if there is adequate legislation inplace (mostly in donor countries) for fighting tax evasion andavoidance. Furthermore, while it is essential for a governmentto develop fair fiscal systems, it is a politically sensitive issue.This certainly gives governments no excuse not to act, but itdoes explain why in many countries it genuinely cannot be doneovernight. Until taxation has been more widely developed, aidwill still be needed as a source of public finance. In addition,if fair fiscal systems (once introduced) are to tackle inequal-ity effectively, they need to be coupled with strong domesticaccountability mechanisms and a commitment to progressiveredistribution.29Moreover, while even the poorest countries can raise do-mestic resources to pay for a basic social protection floor, noneof them can yet end poverty through taxation alone, simply be-cause the tax base is not yet large enough.30This is also truefor middle-income countries: one study showed that India, forexample, would have to tax at a marginal rate of over �00% if itwere to raise enough resources to end poverty.3�

10Aid is the most powerful expression of globalsolidarityEffective aid acts as a proxy for political support for sustain-able development and rights, and aid is one of the most obvi-ous ways for a European country to express its commitment todevelopment and global solidarity. Aid also provides a meansfor people to be active global citizens with a world view that iswider than their own community, nation or region. While riddledwith potential traps, this wider worldview is absolutely vital, notonly for development and poverty reduction but also for otheraspects of geopolitics, such as maintaining peace and security,and fighting racism. It is a matter of taking responsibility andensuring that internationally supported values, for example thehuman rights declaration, are put into practice.Some of aid’s achievements in health and education•During the period 2000-2008, efforts to increase vac-cinations for measles, whooping cough and tetanus across Af-rica, for which ODA provided the vast majority of funding, led toa reduction of 509,000 in the deaths from these diseases (Savethe Children 20�3)•Across 2� priority countries in sub-Saharan Africa, newHIV/AIDS infections in children have been reduced by �30,000– a drop of 38% – since 2009, primarily thanks to the provisionof anti-retroviral drugs by donors, to prevent transmission frominfected mothers (UNAIDS 20�3)•In Sierra Leone, donors – who fund 70% of the govern-ment’s health budget – supported the government in introduc-ing free health care for children under five and pregnant andlactating mothers; as a result, consultations for children underfive increased by almost one-third from 0.93 million in 2009/�0to 2.93 million in 20�0/�� (MoHS 20��)•Between 2004 and 20�0 an additional 5.3 million chil-dren gained access to primary school, with donors providing20% of the funding to the education sector (UNESCO 20�2)

9

Unlike aid, foreign direct investment does nothave a development objective

Foreign direct investment in developing countries is increasingrapidly,32although it is very uneven and is still concentratedmainly in just a few countries.33It is praised for generating jobs,boosting related areas of the economy by generating demand,28 Concord AidWatch (20�2), Global Financial Flows, Aid and Development;Kwakkenbos J (20�2), Private profit for public good? Eurodad29 Concord (20�3),Spotlight Report – Policy coherence for development30 Atisophon Vet al.(20��),Revisiting MDG cost estimates from a domesticresource mobilisation perspective,OECD Development Centre Working Paper3063� Ravallion M (20�2), http://blogs.worldbank.org/developmenttalk/should-we-care-equally-about-poor-people-wherever-they-may-live32 UNCTAD (20��),World investment Report33 Prada F et al. (20�0), Supplementary study on development resourcesbeyond the current reach of the Paris declaration

34 UNCTAD (20�2),World Investment Report;UNCTAD (20�2),Trade andDevelopment Report

�2

>What is aid?Aid funding is precious and needs to be protected. One waythis protection is provided is through tight definition. “Officialdevelopment assistance”, or ODA, is defined by the OECD DACessentially as grants or concessional loans provided to supportdevelopment activities. To be more precise, ODA must be ad-ministered with the promotion of economic development andthe welfare of developing countries as its main objective, and itmust be concessional in character, with a grant element of atleast 25% (calculated at a discount of �0%).35Only finance thatmeets this definition can be reported to the OECD as ODA, andcount towards the politically important 0.7% ODA/GNI ratio.Although the ODA concept has been debated and refinedthroughout its history, in recent years there have been increas-ingly concerted attempts by donors to challenge the politicalemphasis it receives and to overhaul its definition. These ef-forts began in 2009 with the EU and G8 (led mainly by the gov-ernments furthest from meeting their aid commitments) callingfor greater political recognition for the flows of developmentfinance other than ODA that emerge from their countries. Thishas led to the OECD DAC’s being given a mandate to explorehow this could be achieved and (in December 20�2) to launcha formal process to develop new, broader, statistical waysof measuring development finance, which are to be adoptedas part of the post-20�5 development goals agreement. Thisprocess could also lead, ultimately, to ODA’s being re-defined.Meanwhile, the EU is getting involved. In its July 20�3 commu-nication on development finance, it said that all countries andinternational actors should agree to “reform ODA and monitorexternal public finance in the context of a comprehensive mu-tual accountability mechanism”.36Among the sources of development finance that are be-ing explored as potential elements for these new developmentfinance measures are: officially supported export credits, non-concessional loans, guarantees and other financial products of-fered by development finance institutions (DFIs) and internationalfinance institutions (IFIs), private grants and remittances.37It is important to have a better understanding of the leveland development outcomes of these flows, as well as theirimpact on ODA, in order to support relevant policy processes.However, pushing ODA down the political agenda in order tofocus on these forms of development finance could undermineefforts to support development. Moreover, donors have not yetmet their existing aid commitments. A debate on the definitionof ODA is inappropriate until donors have succeeded in keepingtheir promises – changing the rules to try and meet their targetsis simply not acceptable.35 OECD (2008),Is it ODA?Factsheet36 European Commission (20�3),Beyond 2015: towards a comprehensiveand integrated approach to financing poverty eradication and sustainable de-velopment,�6 July 20�3, COM (20�3) 53� Final37 OECD DAC(20�3),Initial roadmap for improved DAC measurement andmonitoring of external development finance

How aid could be betterThere is currently a wave of intellectual, political and (in somecountries) public critique of aid that threatens to delegitimiseand undermine the agenda for it. Some of this is driven by theself-interested agendas of governments whose commitment toaid has been in question for some time, and critics who havenever really given aid a chance. Some, however, stems fromaid’s genuine current shortcomings: it is true to say that, whileaid is important, it is not currently working at maximum ef-ficiency to reduce poverty and support human rights. Aid’sshortcomings arise in two main areas: aid needs to be effec-tive, and it needs to be genuine.Aid needs to be effective for development. Significantefforts have been made to improve aid and development co-operation effectiveness through the Rome (2003), Paris (2005),Accra (2008) and Busan (20��) agreements. These have shonea spotlight on a range of fundamental challenges relating toODA, and although much more remains to be done we havecome a long way from the donor-driven and un-transparentODA of the past. Effectiveness is covered in the second chapterof this report.Aid also needs to be genuine. The ODA definition ex-cludes a number of financial flows, but it also includes somethat AidWatch believes should not be there. Among these arefinance that never reaches the developing country (for example,spending on students or refugees in the donor country), financethat is double-counted (for example as climate finance, or debtrelief), finance that never existed (future interest on cancelleddebts) or finance where the primary objective is the benefit tothe donor, not the developing country (tied aid). AidWatch refersto this non-genuine aid as “inflated aid”, and this report’s thirdchapter provides a detailed analysis of its extent in the EU in20�2.Aid plays a vital and unique role in development, butthere is room for improvement. The rest of this report analyseshow this improvement could take place.

�3

CHAPTER 2– AID EFFECTIVENESSIf aid is to play the unique role that it could play, it is essential forit to be effective. This chapter looks at the available informationabout global progress on aid effectiveness since the last majorconference on the issue in Busan in December 20��, focusingon the areas of democratic ownership, transparency, predict-ability and untying.It might be expected that, under current economic pres-sures, the EU would be working hard to maximise the effective-ness of every cent of aid, and to lead the rest of the world inreaching the same objective. The evidence, disappointingly, isthat despite the continuing rhetoric, actual progress on makingdevelopment cooperation more effective has slowed – so it is vitalfor the EU to seize the reins and lead a new push for progress.

Glacial progresson aid effectiveness across the EUWhile some major progress in implementing the GPEDC hasbeen made over the past year by EU MSs, it has been unevenacross these countries, where action has been focused on anarrow range of priorities, past commitments are slipping downthe agenda, and political attention is on the wane. The GPEDC’sgrowing pains have not spared EU MSs, but all the same, ratherthan succumbing to malaise, they could have seized the reinsand driven a more ambitious response.Concord AidWatch’s special report on Busan,39publishedalmost a year ago, reported that a year after the GPEDC hadbeen endorsed only one EU MS had developed a strategy toguide its implementation. Such a strategy is necessary, tosignal the political importance of implementing the GPEDC’scommitments and to guide and coordinate action across therelevant implementing agencies. Last year’s report thereforeraised concerns about the very limited progress EU MSs hadmade in developing such strategies.The period since has seen some progress – but it is stillslow. In June 20�3, our survey found that only seven EU MSshave a full Busan strategy in place (Denmark, Finland, France,Germany, Italy, Portugal and Sweden); a handful of others have apartial strategy, or claim to have a strategy that is not public, orhave progressed only on the transparency elements of Busan.

The global process for improvingthe effectiveness of aidand development cooperationThe efforts made by EU MSs to address the challenges im-pacting on how effectively their aid supports development havebeen shaped by, and have in turn shaped, the internationalagreements on aid and development cooperation effectivenessthat have emerged over the past decade.The latest of these agreements, the Busan Partnershipfor Effective Development Cooperation (BPa), was endorsedwith much fanfare in December 20��. Its supporters heraldedthe BPa’s combined promises to:•reaffirm the commitment to address the unmet reformtargets set by the Paris (2005) and Accra (2008) agreements;•address a range of additional priorities for action;•establish the GPEDC – a broader community of actors(including emerging economies as donors) working together toimprove the effectiveness of their development cooperation.Today, however – almost two years after the GPEDC wasendorsed – it is clear that this agreement has barely begun todeliver on its promises. Its broadened agendas brought withthem a worrying neglect of past commitments, a loss of focus,and confusion about future priorities.This assessment of the situation of development coop-eration effectiveness since Busan applies to EU MSs as muchas anyone. The EU’s joint position for Busan prioritised the EUtransparency guarantee and a move towards joint program-ming, some areas of the Paris/Accra aid effectiveness agenda,and the inclusion of south/south cooperation and the privatesector in development cooperation effectiveness. The Euro-pean Commission (EC) is the only European actor with a seat atthe GPEDC table, so the EU has to speak with one voice in theGPEDC process.3838 Concord AidWatch (20�2), Making sense of EU development cooperationeffectiveness: Special Report

Weakening political attentionto democratic ownershipand other Paris and AccracommitmentsOne of the issues many CONCORD members were keen tohighlight following the endorsement of the GPEDC was that itsalmost cursory (although unambiguous) reaffirmation of theParis and Accra commitments, combined with its broadening ofthe agenda for action, potentially opened the doors for donorsto scale back their political attention on implementing the Parisand Accra commitments.Our survey of EU MSs reveals that these fears werenot unfounded. Although CONCORD members report that themajority of EU MSs still see these commitments as binding,they also report that the commitment of their governments toimplementing Paris and Accra has weakened in recent years,especially in areas such as use of country systems. These EUMSs include several who were previously at the forefront ofnegotiating and implementing these agreements.39Ibid.

�4

>Democratic ownership, whereby developing countries(including government and civil society) are in the driving seatof their own development, is the principle at the heart of theBusan agreement and of the continuation of Paris and Accra;the Busan document says that “partnerships for developmentcan only succeed if they are led by developing countries”. Yetpolitical commitment to this, too, appears to be on the wane.Globally, budget support – an aid modality that gives developingcountries maximum autonomy in the use of aid – has been cutdramatically, from $4.4 billion (€3.3 billion) in 20�0 to $3 bil-lion (€2.25 billion) in 20�� and just $�.3 billion (€�.73 billion) in20�2. Rwanda’s thorough mutual accountability process, whichrates its donors for the effectiveness of their aid, finds mixedresults. In Rwanda, EU institution aid using country systems isdown from 87 to 70%, although aid-on-budget is up.40The GPEDC’s time-bound commitments�8e – Pursuant to the Accra Agenda for Action, we will acceler-ate our efforts to untie aid. We will, in 20�2, review our plansto achieve this23c – Implement a common, open standard for electronic pub-lication of timely, comprehensive and forward-looking informa-tion on resources provided through development cooperation…We will agree on this standard and publish our respectiveschedules to implement it by December 20�2, with the aim ofimplementing it fully by December 20�524a – By 20�3, [we] will provide available, regular, timely roll-ing three- to five-year indicative forward expenditure and/orimplementation plans as agreed in Accra [for] all developingcountries with which [we] cooperate25a – We will, by 20�3, make greater use of country-led co-ordination arrangements, including division of labour, as wellas programme-based approaches, joint programming and del-egated cooperation25b – We will improve the coherence of our policies on multilat-eral institutions, global funds and programmes… We will workto reduce the proliferation of these channels and will, by the endof 20�2, agree on principles and guidelines to guide our jointefforts25c – We will accelerate efforts to address the issue of coun-tries that receive insufficient assistance, agreeing – by the endof 20�2 – on principles that will guide our actions to addressthis challenge

Limited progresson time-bound GPEDCcommitments – transparency,predictability and untyingThe GPEDC includes a limited number of time-bound commit-ments (see box). The fact that the number is limited is likelyto limit the pressure on signatories to undertake timely imple-mentation.Recent analysis by Publish What You Fund (PWYF), theOECD and G8 has assessed the degree to which donors haveimplemented the time-bound commitments relating to trans-parency, predictability and tied aid respectively. The commit-ments have not yet been reported on publicly, but this analysis(which covers mainly the EU-�5), is available. It is presentedbelow, together with additional insights from our members andother sources.

TransparencyAt Busan donors agreed to reach a new “common standard” ofaid transparency, to publish implementation schedules by theend of 20�2, and to implement them fully by the end of 20�5.The EU reaffirmed its commitment to implementing the commonstandard as part of the European Transparency Guarantee in Oc-tober 20�2, which was also reflected in the G8 Communiqué inJune 20�3. A core component of the common standard is theInternational Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI). The IATI is themost significant international standard for publishing data on aid,judged on the basis of its ambition to ensure that the informationpublished is comprehensive, comparable, timely and accessible.PWYF has produced the most comprehensive analysis4�of progress made by donors in meeting their GPEDC transpar-ency commitments and their ambition to take steps to maketimely, comparable information publicly available. The table be-low presents the results of their analysis of “donors” schedulesfor implementing the IATI component of the common standard,and shows that EU performance is mixed. The European Com-mission and �9 EU member states have published.424� http://tracker.publishwhatyoufund.org/plan/organisations/.42 http://www.oecd.org/dac/aid-architecture/acommonstandard.htm

40 Thomas A (20�3),Country ownership – the only way forward on develop-ment cooperation,Bond/UKAN

�5

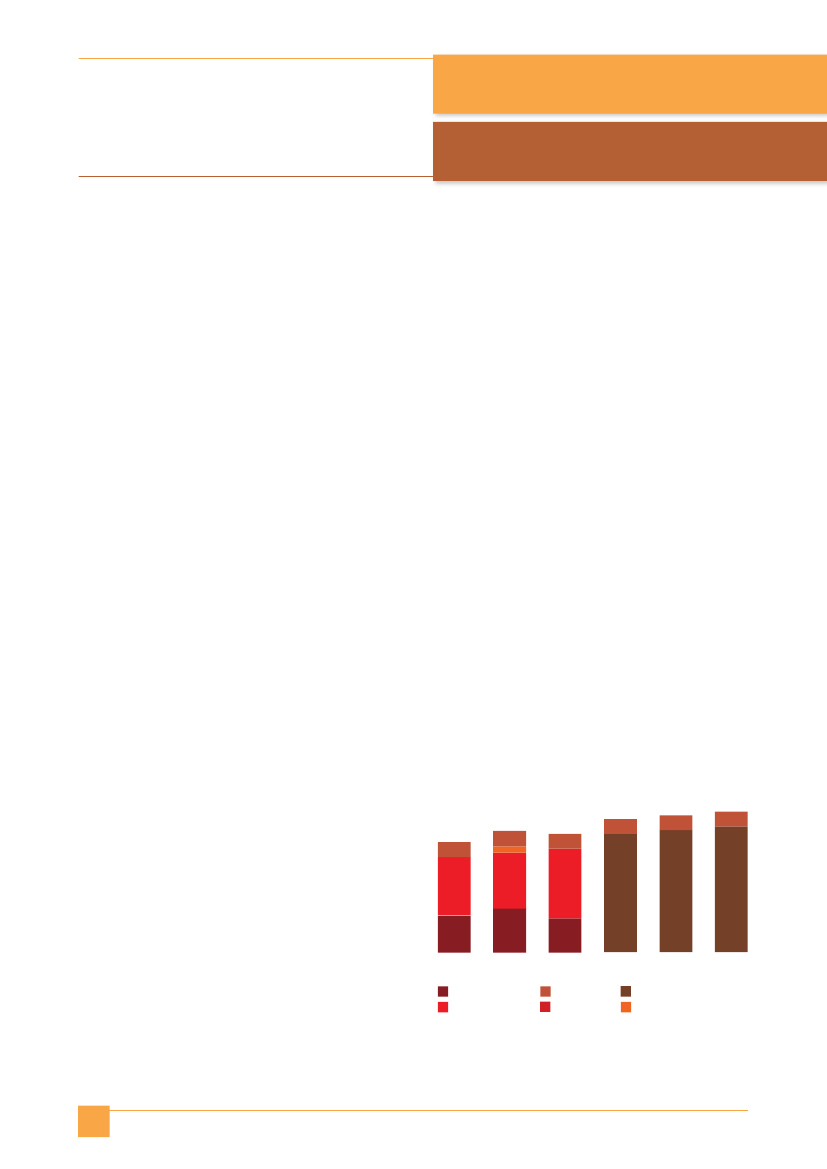

>Of these:•the EC and �3 MSs have drawn up plans for full imple-mentation of IATI by 20�5 (the Busan commitment);•the EC and �0 MSs have either undertaken or signalledtheir intention to undertake ambitious or moderately ambitiousaction to implement IATI;•two EU MSs are in the process of considering the publi-cation of their aid information to IATI;•four EU MSs have yet to signal any intention to publishtheir aid information to IATI.•eight EU MSs have not yet published a schedule, all ofwhich are EU-�5 Member States (excluding Croatia, the mostrecent member of the EU).AmbitiousBelgium, Denmark, (European Commission: EuropeAid,Enlargement and FPI), Netherlands, Sweden and UKModerately ambitiousCzech Republic, Finland, Germany, Ireland and SpainUnambitiousSlovak RepublicUnder considerationFrance and ItalyIncompleteLuxembourg and PolandNo publication(of current, comparable data)Austria, Greece, Portugal and Sloveniaas DFID’s Development Tracker43and Open Aid platforms in theNetherlands and Sweden.44

PredictabilityIn July 20�2 the OECD undertook a review (based on self-re-porting) of its members’ efforts to implement the Busan (andAccra) commitment to provide partner countries with three- tofive-year forward spending plans for their aid.45This analysis,which is presented in the table below and is available only forthe EU-�5, shows that:•only two EU MSs (plus the EC) provide three- to five-yearindications to all their partner countries (and this information isnot provided on a rolling basis);•seven EU MSs provide three- to five-year indications tosome of their partner countries;•two EU MSs provide none of their partner countries withsuch information;•four EU MSs provided inadequate information or none forthe OECD to use in making its assessment.Provide three- to five-year indications to all partnercountries(although not on a rolling basis)Sweden, UK (and EU institutions)Provide three- to five-year indications to some of theirpartner countriesAustria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Ireland, Portugal andSpainProvide no partner country with three- to five-yearindicationsFrance and GreeceProvided insufficient / no information to the OECDGermany, Italy, Luxembourg and Netherlands

Implementationof transparency commitmentsIn 20�3 Germany and Ireland joined the European Commissionand the six European Member States already publishing theirinformation to the IATI Registry since 20�� (Denmark, Finland,Netherlands, Spain, Sweden and UK) representing over 68% ofEU-28 ODA. The European Commission as a whole has madeconsiderable progress since 20�2 by publishing ambitious im-plementation schedules and beginning publication to the regis-try. All major EC departments managing EU external assistanceare publishing their data to IATI and as a result collective EUpublication to IATI currently represents 87% of EU ODA.Apart from this, approaches to implementation have variedamongst MSs, from fundamental culture change and the tech-nical reform of information systems (e.g. Netherlands, Swedenand UK) to basic implementation through conversion of OECDCreditor Reporting System information (e.g. Finland). There arealso significant attempts to roll out the coherent publication ofIATI data across departments, especially in Sweden, the UKand the EC, in addition to positive accessibility initiatives such

Untying aidOf the GPEDC’s commitments, the one on tied aid was perhapsthe furthest from meeting the ambitions of partner countries.Throughout the negotiations on the GPEDC, developing coun-tries (and NGOs, including CONCORD) were calling for donorsto make a commitment to untie their aid fully. In the end, thetext of the GPEDC simply committed donors to reviewing theirplans to untie aid during 20�2 in an effort to accelerate effortsto take action, and to improving their reporting on the tied sta-tus of their aid.The G8 reviewed its members’ performance in this area43 http://devtracker.dfid.gov.uk/44 http://harmonia.openaid.nl/; http://openaid.se/45 OECD DAC (20�2), 20�2 DAC Report on Aid Predictability: Survey onDonors’ Forward Spending Plans, OECD Development Assistance Committee20�2-20�5 and efforts since HLF4

�6

>in 20�3.46Of EU MSs, this review is relevant only to France,Germany and Italy, as the UK has already officially untied itsaid. The best the report could say was that Italy had taken somesteps to improve its reporting.This was consistent with an earlier piece of analysis bythe OECD, published in October 20�2,47which (based on self-reporting) assessed the progress of its members in implement-ing the Busan commitments on tied aid. This analysis revealedthat:•of the EU MSs whose level of untied aid is above the DACaverage, since Busan two (Finland and Netherlands) have de-clared strong ambitions to untie it further, and five (Belgium,Denmark, France, Luxembourg and Sweden) have either mod-est or no plans to untie further;•of the EU MSs whose level of untied aid is below the DACaverage, three (Greece, Italy and Portugal, plus the EU) havedeclared strong ambitions to untie further since Busan, and two(Germany and Spain) have modest or no plans to untie further;•Austria did not report on its intentions;•the UK and Ireland have already untied their aid.

Teething problems with GlobalPartnership governanceThe GPEDC signatories spent much of 20�2 negotiating, de-signing and agreeing a governance framework for it, includ-ing its structures, how different stakeholder groups would berepresented and its decision-making procedures. Inevitably,this reorganisation since Busan has led to a slowing of dialogueand decision-making on aid and development cooperation ef-fectiveness issues. Despite its new governance framework, theGPEDC has yet to shake off its sluggishness, as is illustratedby the decision to delay the first full ministerial meeting of itsmembers (which had been due to take place in the second halfof 20�3) until early 20�4 – over two years after Busan.In addition, the largest aid-recipient countries are weaklyrepresented in the GPEDC’s decision-making structures (noneof the co-chairs fits into this category, and only one countryfrom sub-Saharan Africa is included). This has contributed tothe Partnership’s mission-drift into issues beyond developmentcooperation effectiveness, and its tentativeness in addressingareas of major concern to the largest recipients of aid, such asthe use of country systems.

Unclear progress acrossother effectiveness prioritiesCONCORD members reported that Busan had shaped theirgovernments’ agendas in other ways over the last two years,especially in terms of increasing their focus on results monitor-ing and reporting, promoting the role of the private sector indevelopment and engaging on issues to do with fragility andconflict. In the absence of detailed monitoring of performancein these and other areas, however, it is difficult for us to drawany conclusions about progress or ambitions.This conclusion highlights a concern raised by a numberof our members when reviewing the EU’s performance on aideffectiveness over the last year. Since Busan it has been agreedthat the OECD’s role in monitoring will be scaled back, andmonitoring will take place primarily through country-level initia-tives rather than a comprehensive international survey (in 20��:78 countries and 33 donors). These monitoring processes arecurrently taking place in only a limited number of countries,which means that in future we will have less comprehensive,comparable data across countries and donors – somethingthat is likely to take the pressure off EU MSs to improve theirperformance. This is clearly one way in which more ambitiousmonitoring by the EC (building on the EU Accountability Reporton Financing for Development) could make an important contri-bution to driving progress on implementation.

A leadership opportunityOne of the main factors that has contributed to the limited am-bitions across the board in implementing Busan and taking theGPEDC forward is the palpable lack of political attention beingfocused on this area of international cooperation. As we havepointed out, EU MSs are as guilty as any of the GPEDC’s stake-holders in this respect.Preparations for the GPEDC’s first ministerial meeting inearly 20�4, however, and the meeting itself, provide an impor-tant opportunity for EU MSs to take a leadership role in ensur-ing that this forum takes a comprehensive and honest look atprogress since Busan, and plots an ambitious course for futureaction on commitments to aid and development cooperation ef-fectiveness.

46 G8 (20�3), Lough Erne Accountability Report47 OECD DAC (20�2),Aid Untying – 2012 reportDCD/DAC(20�2)39

�7

CHAPTER 3– THE QUANTITY OF GENUINE AIDThe quantity of aid is the first and most obvious measure bywhich aid progress is usually judged, as without quantity therecan be no quality. Because of huge absolute differences in na-tional income between EU countries, the targets for aid contri-butions are set as a proportion of national income – 0.7% for“old” Europe, the EU-�5, and 0.33% for new member states,the EU-�3. It is an important principle that every donor mustcontribute a proportion of its income. But this figure is not theonly factor in aid quantity: it is just as important for aid to havea real chance of contributing to poverty reduction and develop-ment. In other words, it must be “genuine” aid.This chapter looks at the EU’s progress – or lack of it– on aid quantity, and finds that while a few member states arestanding by their commitments, many appear not to be fulfill-ing their public promises on them. It continues to analyse thetrends in the proportion of aid that is inflated – in other words,aid that does not really contribute towards development.The sluggishness of European aid progress is simply unaccept-able. The aid targets are a proportion of national income, soeconomic stress should not mean that they need to be aban-doned: if an economy shrinks, so does its absolute level of aidresponsibility. The political repetition of the targets negates thereality and compounds this unacceptability. It will now be verydifficult for some EU MSs to meet their 20�5 targets, but thetrend should be upwards rather than downwards.Moreover, Europe as a whole cannot afford to miss the0.7% target. European aid has been crucial to progress towardsthe MDGs and other international development goals, and aidcuts threaten this. Europe will lose credibility in global proc-esses if it steps back from its commitments. More importantly,millions of poor people across the world are counting on theEU’s promise to support them.Although 20�5 is only two years away, there is still timefor Europe to make progress towards the 0.7% target.The impact of aid cutsIn 20�2 Spanish ODA reached its lowest level since �989 (0.�5%of GNI). As a result of the massive cuts over the last couple ofyears, the Spanish aid agency (AECID) and many developmentNGOs have had to wind up their operations in many countries.Making progress towards poverty reduction and other develop-ment issues such as gender equality is a long-term quest. TheSpanish cuts jeopardise the progress achieved through hun-dreds of projects across the world. For example, the cuts haveforced organisations like Entrepueblos to cancel a seven-yearpartnership with indigenous communities in Peru to empowerrural women and help them claim their rights.52It is very likelythat, without external support, progress will be halted, andeven reversed.In other cases, budget cuts have a more immediate impacton developing countries. Austria, for instance, has stoppedits bilateral cooperation with Nicaragua after a revision of itsdevelopment priorities. In addition to cancelling developmentcooperation programmes, Austria also suspended its directsupport for Nicaragua’s health budget. This decision causedhavoc in the Nicaraguan government’s short- and long-termhealth planning.

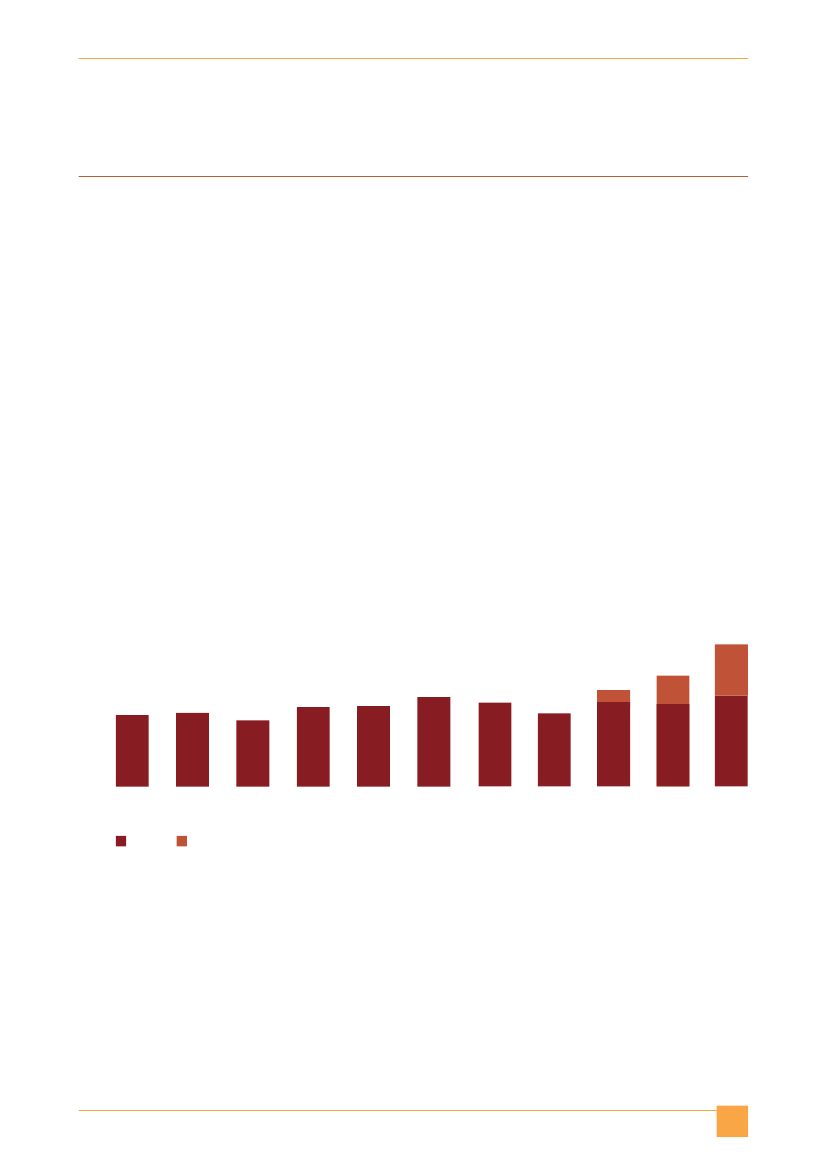

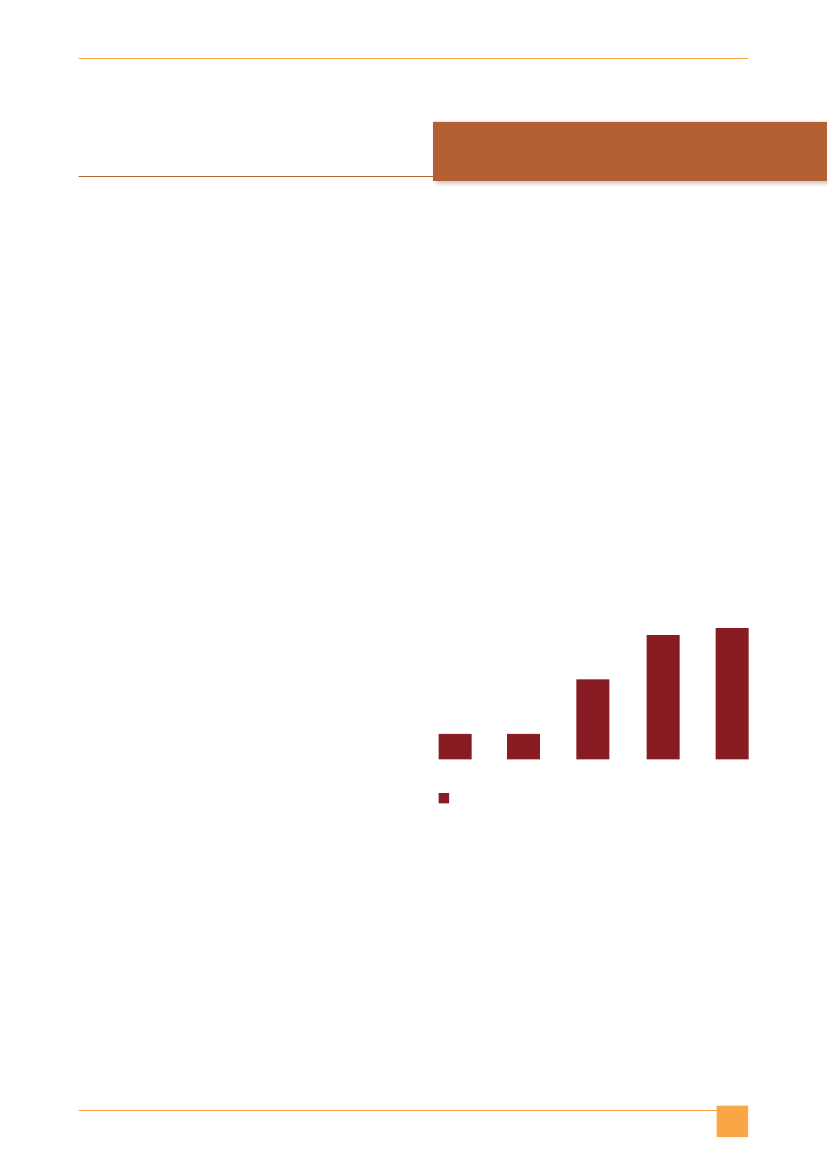

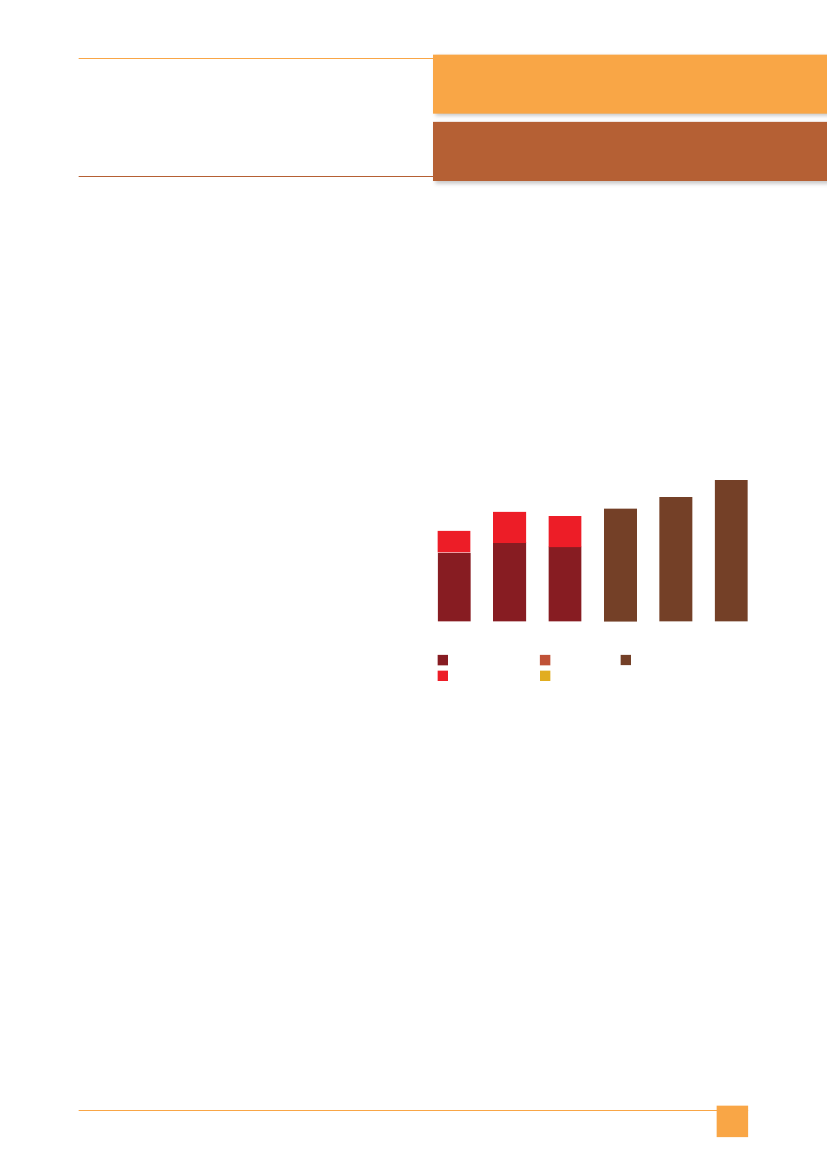

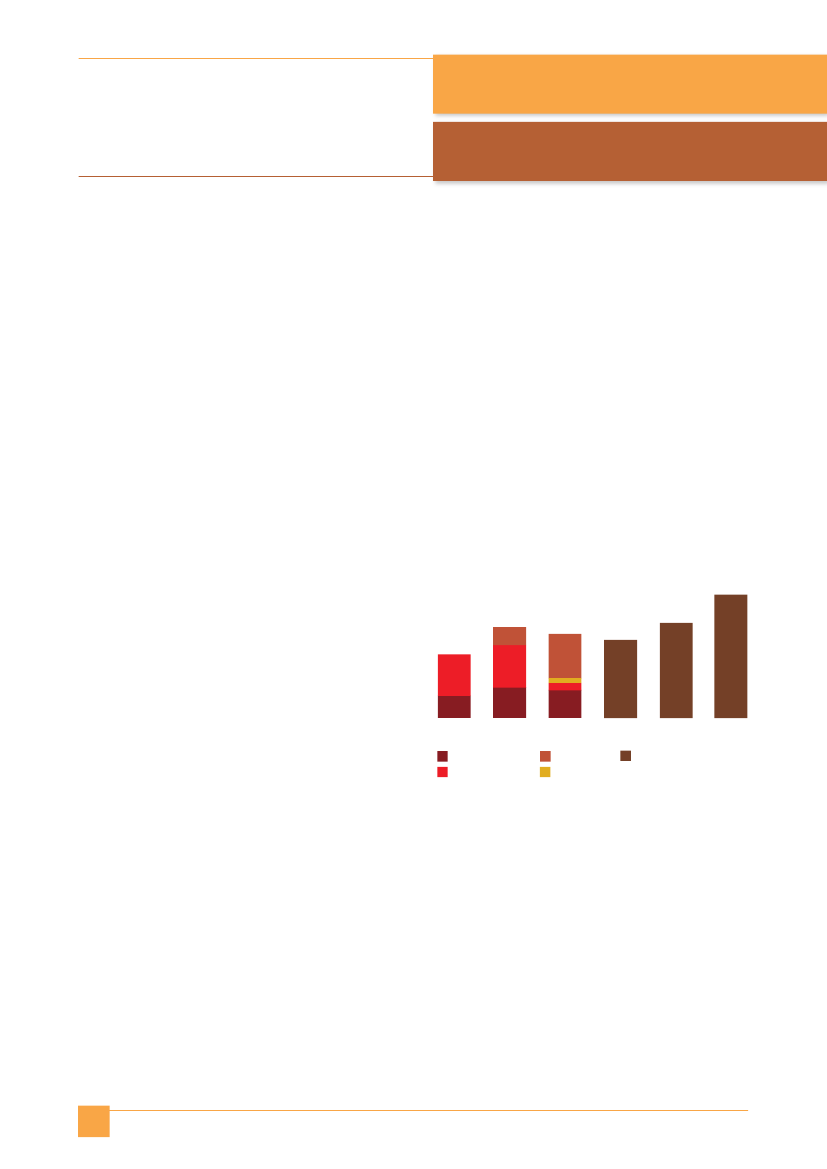

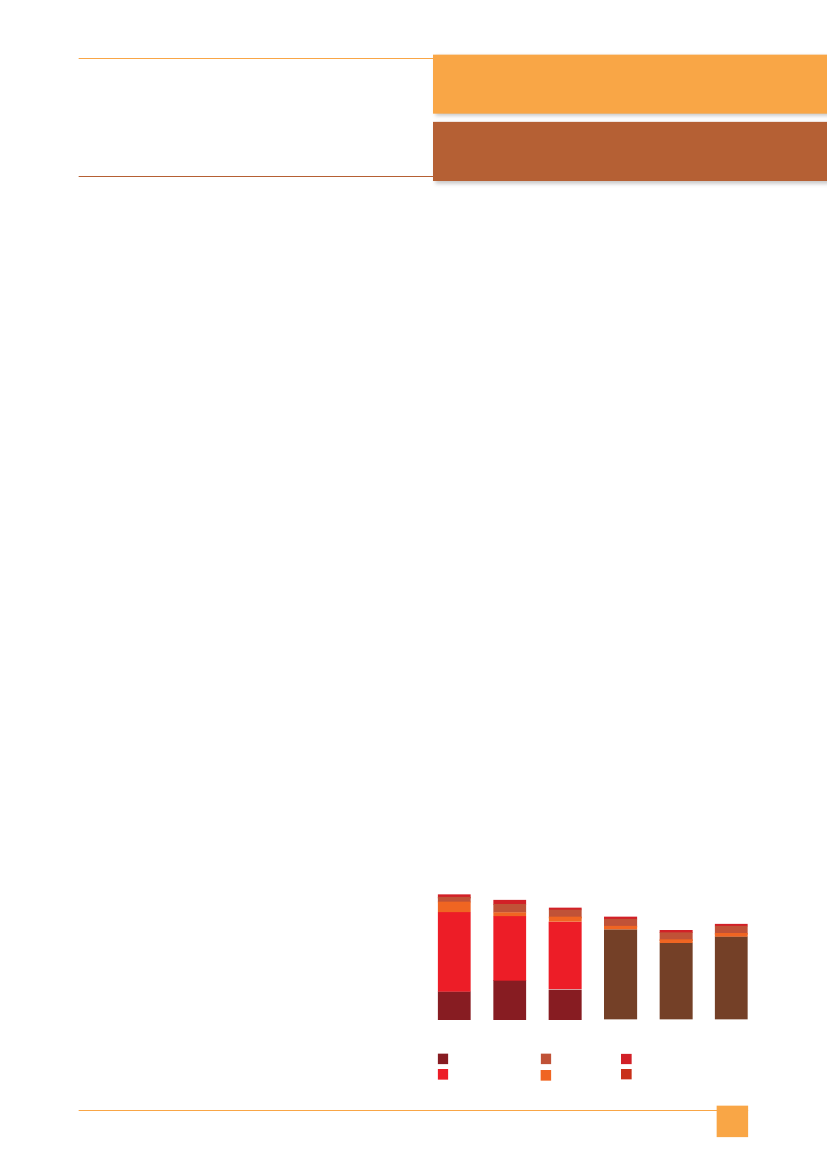

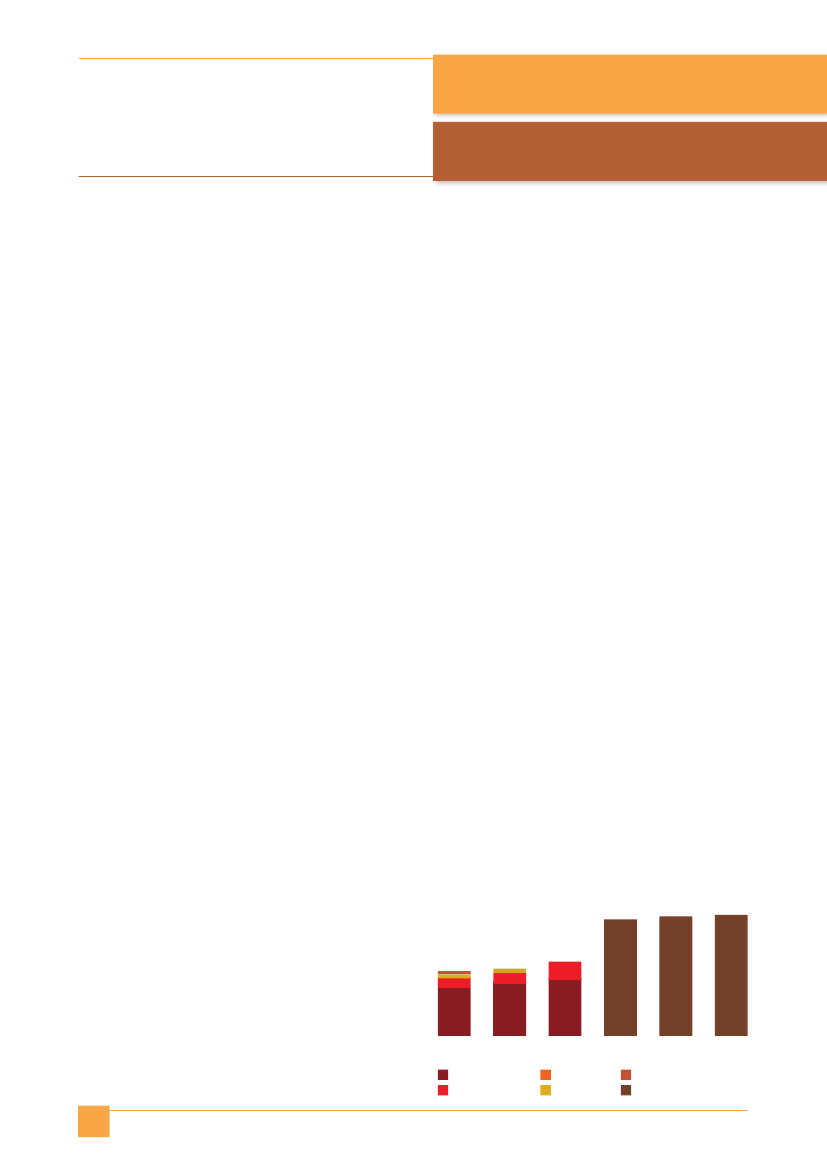

Europe going backwardsAt 0.39% of the EU’s GNI, aid from the EU-27 countries in 20�2was at its lowest since 2007, when it was at 0.37%. Aid alsodropped in absolute terms, for the second year in a row. TheEU-27 countries delivered €50.6 billion in aid in 20�2,48a 4%drop when compared to the previous year (€52.6 billion). Aidhas been cut or remains stagnant in �9 EU member states.The deepest cuts between 20�� and 20�2 took place in Spain(49%), Italy (34%), Cyprus (26%), Greece (�7%) and Belgium(��%).Proving that this is not inevitable, several countries havemanaged to increase their aid substantially, thereby helping tomake the total reduction less than it might have been. The larg-est increases since 20�� took place in Latvia (�7%), Luxem-bourg (�4%), Poland (�4%), Austria (8%), Lithuania (8%) andthe United Kingdom (7%).Overall, however, European aid is shrinking, and it is cer-tainly failing to progress towards the aid targets. Recent Europeanprojections show that total EU aid is expected to remain almoststagnant at approximately 0.43% of the GNI in 20�3-20�4.49Theactual estimated funding gap between projected aid levels andthe EU commitments will be approximately €36 billion in 20�5alone.50Nevertheless, European leaders insist that they willhonour their aid commitments. The most recent example is theCouncil Conclusion of 28 May 20�3, in which EU foreign affairsministers stated that “the Council remains seriously concernedabout ODA levels and reaffirms its commitment and politicalleadership to achieve EU development aid targets”.5�48 All the figures in this chapter are in current prices, except in the com-parative graph where they are constant.49 EC (20�3),Publication of preliminary data on Official Development Assist-ance, 2012.EC, Brussels50 CONCORD (20�3),AidWatch 2013. Policy Paper.CONCORD, Brussels5� Council of the European Union (20�3),Annual Report to the European

Council on Development Aid Targets – Council Conclusions52 http://www.alandar.org/spip-alandar/?Los-recortes-mas-alla-de-las

�8

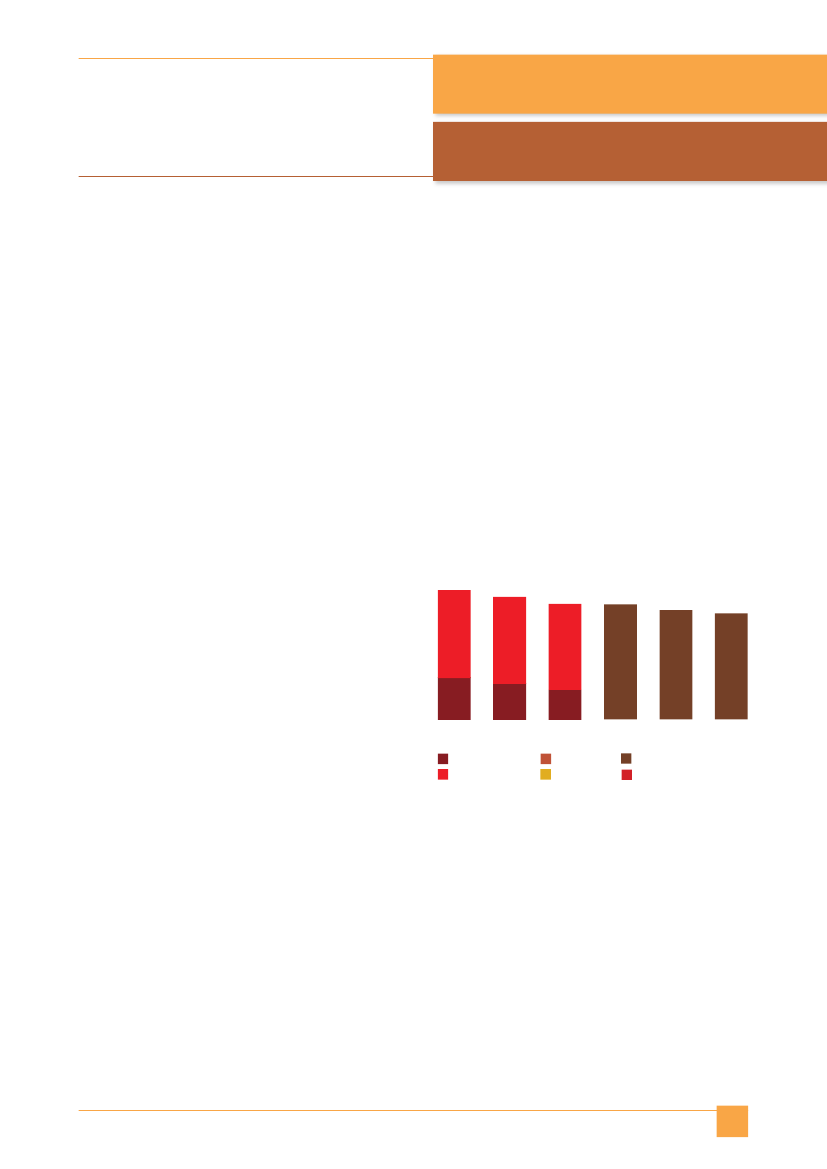

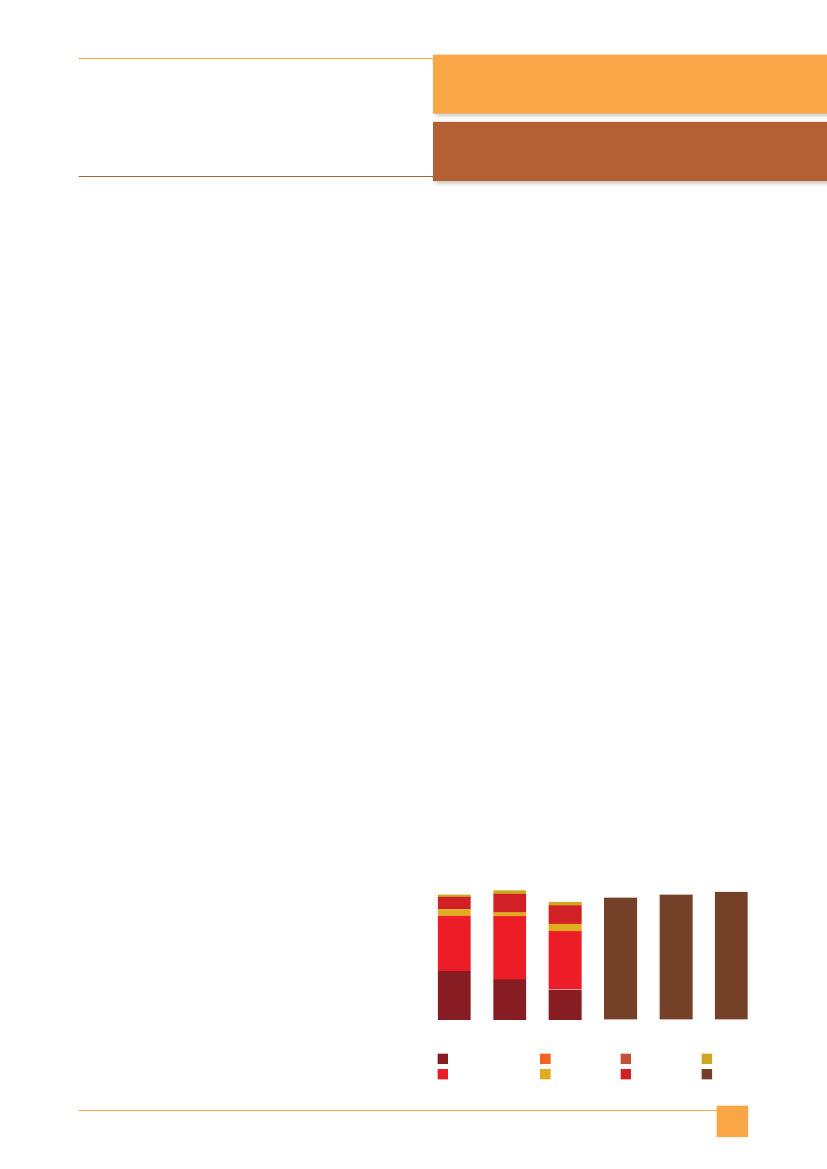

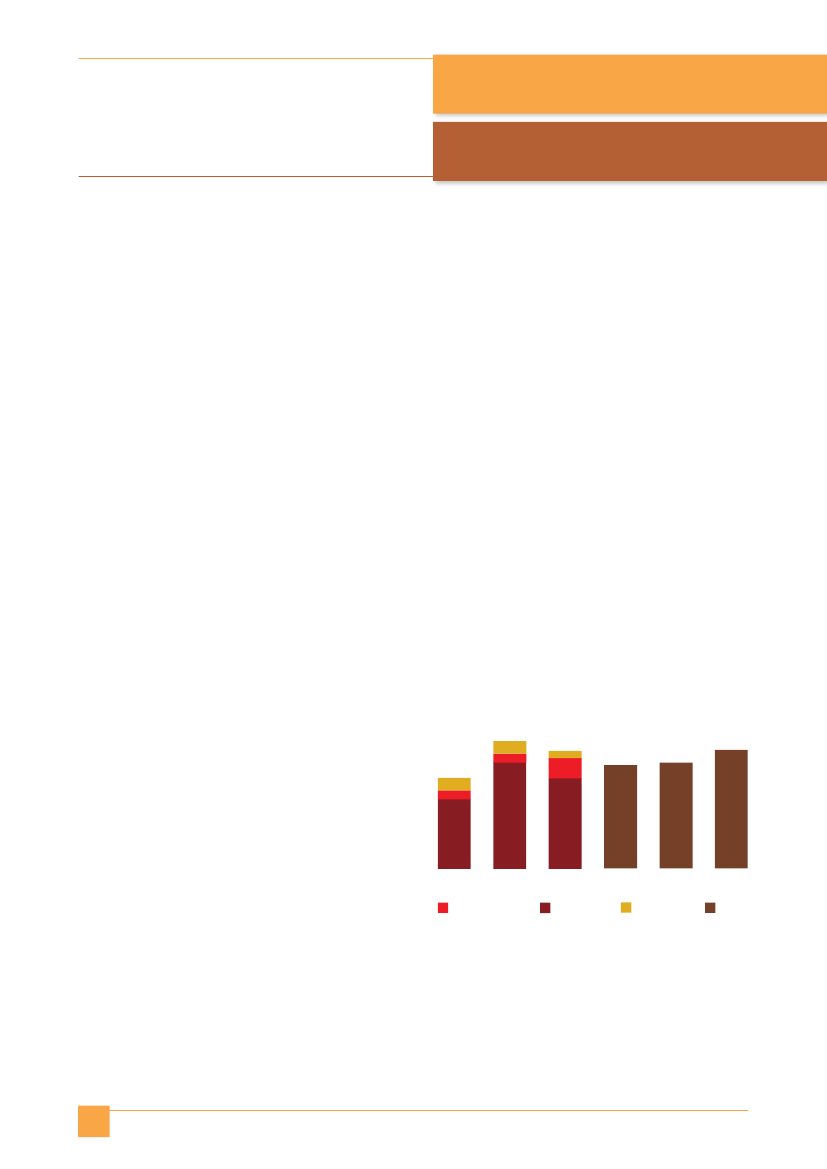

>Genuine and inflated aidAid statistics include flows of money that do not genuinely con-tribute to development. Instead, some of the items recorded inaid budgets represent funds that, in AidWatch’s view, shouldnot count as aid. We have developed a methodology for sub-tracting these items from aid figures, to provide a more ac-curate picture of aid flows, and for distinguishing genuine frominflated aid.The components of inflated aid, explained further in theAppendix, are:•costs for students from developing countries•refugee costs•debt relief•ied aid•nterest on loans.AidWatch also considers climate finance which has beendouble-counted as aid to be aid inflation, but it is not possible toquantify this dimension of inflated aid using the data currentlypublished.In 20�2, EU donors reported approximately €5.6 billion ofinflated aid expenditure. This brings the amount of genuine aiddelivered by the EU down to €45 billion, or 0.35% of aggregatedGNI.Table � shows the proportions of genuine and inflated aidfor each EU donor.53

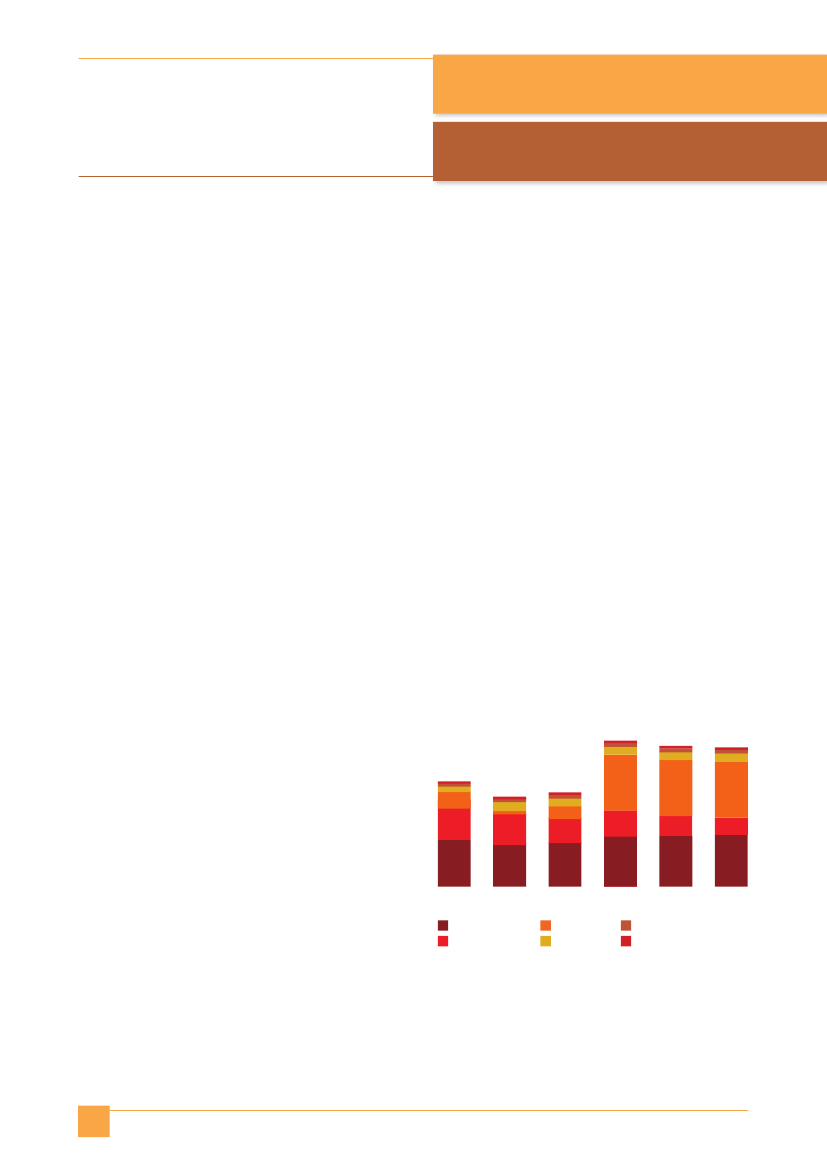

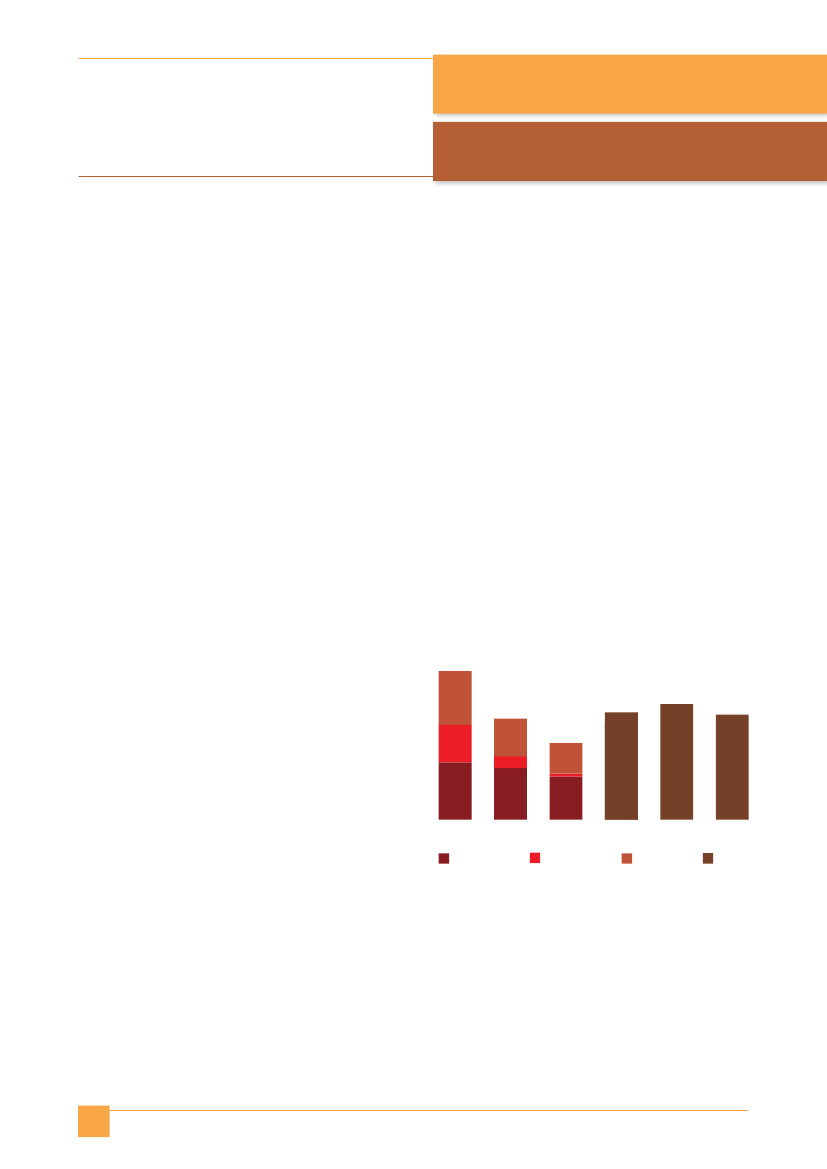

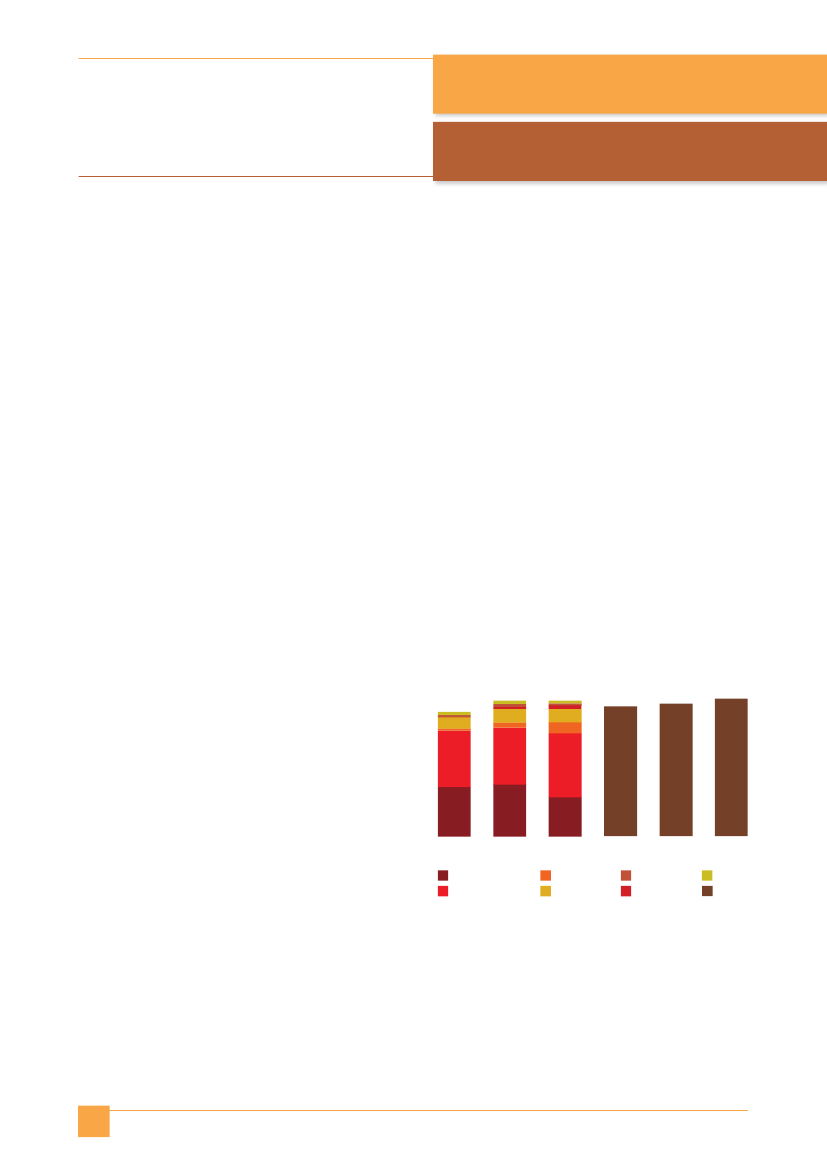

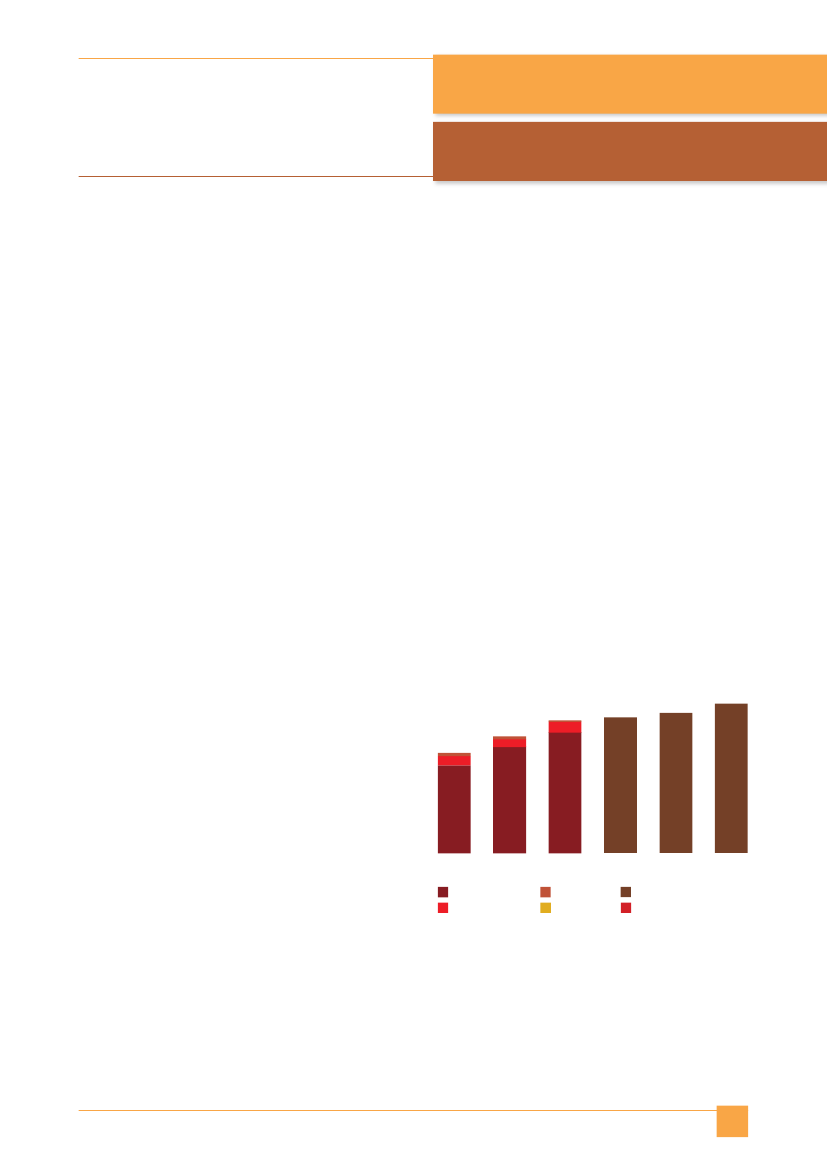

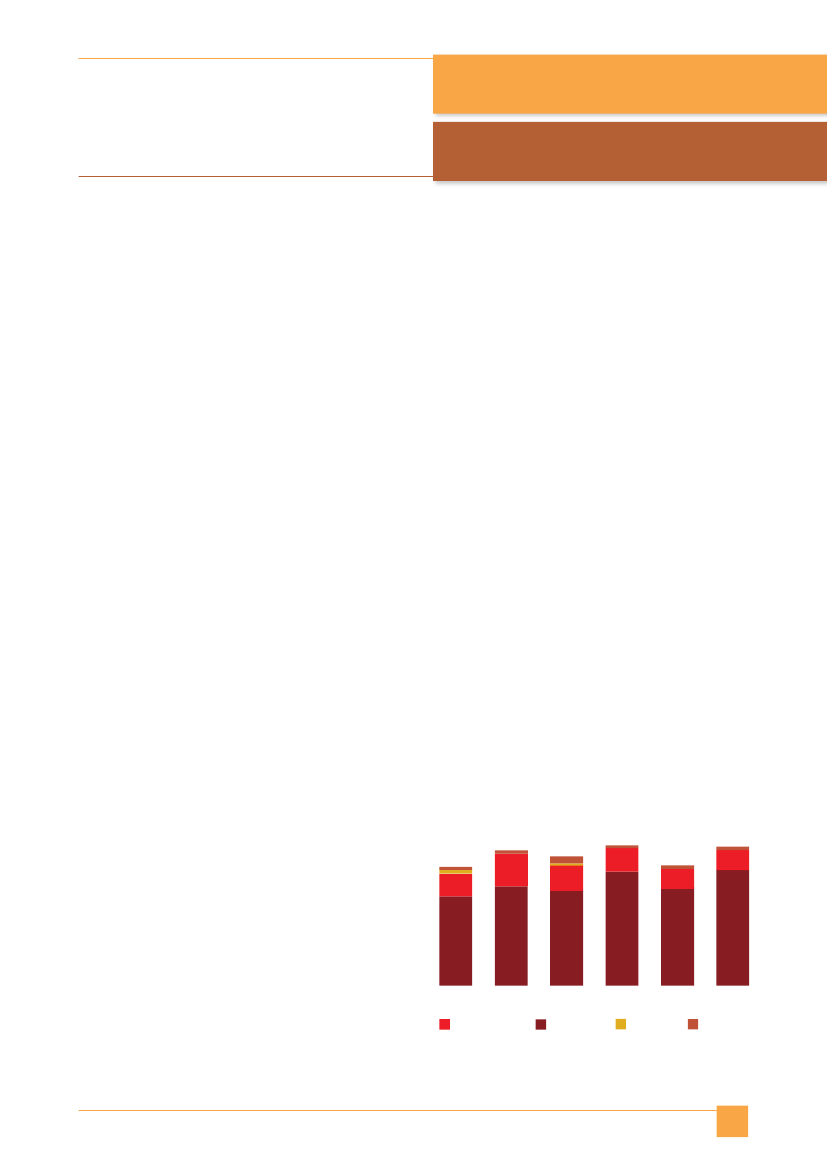

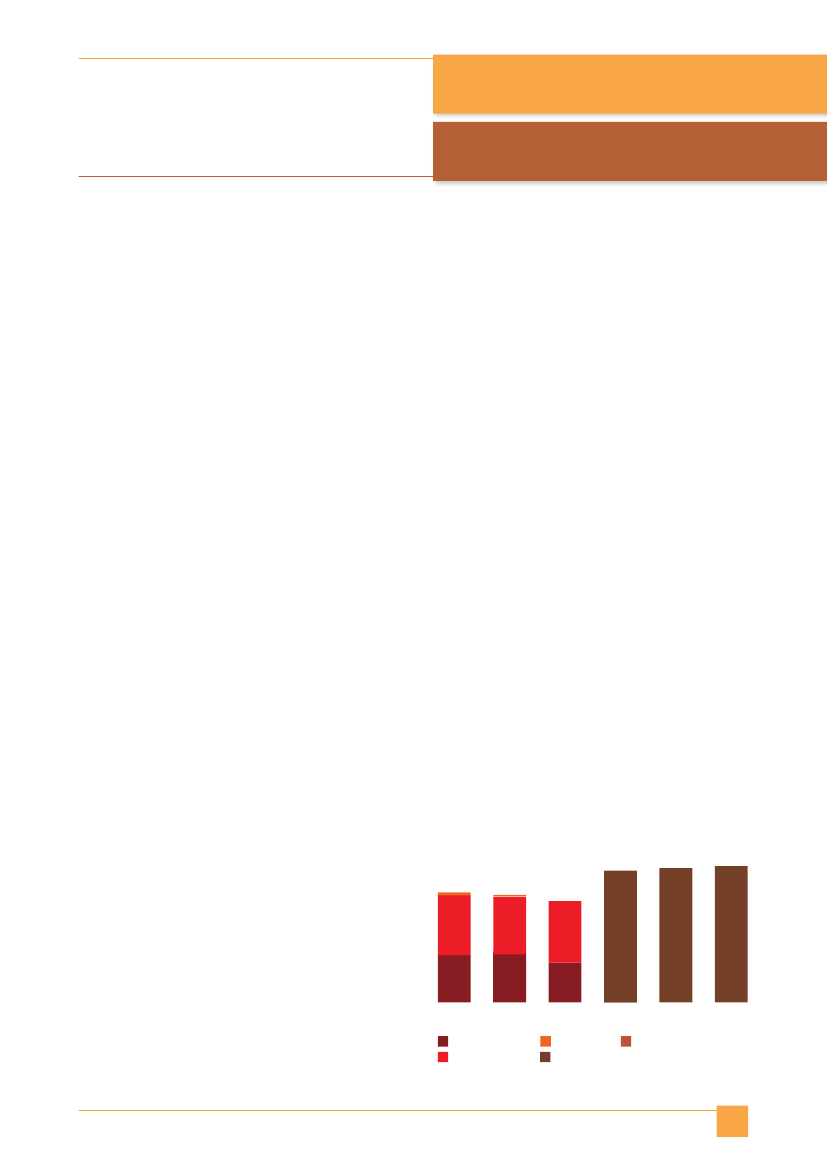

Graph 1. EU aid 2005-2015 including gap in achieving0.7% aid by 2015 (in € billion at constant prices, 2011�00ODA € billion (constant prices 20��)36,3802�,7604020048,349,65�,446,85�,354,352,88,852,85�,954,5

49,0

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

20�0

20��

20�2

20�3*

20�4*

20�5*

*Based on EU projectionsAidGap

Graph drawn by the author: see Methodology for further information and sources

53 Inflated aid can only be calculated as a proportion of bilateral aid. Thusgenuine aid as a proportion of total aid and of GNI is a conservative estimate,because a proportion of multilateral aid is also inflated (e.g. as climate fi-nance).

�9

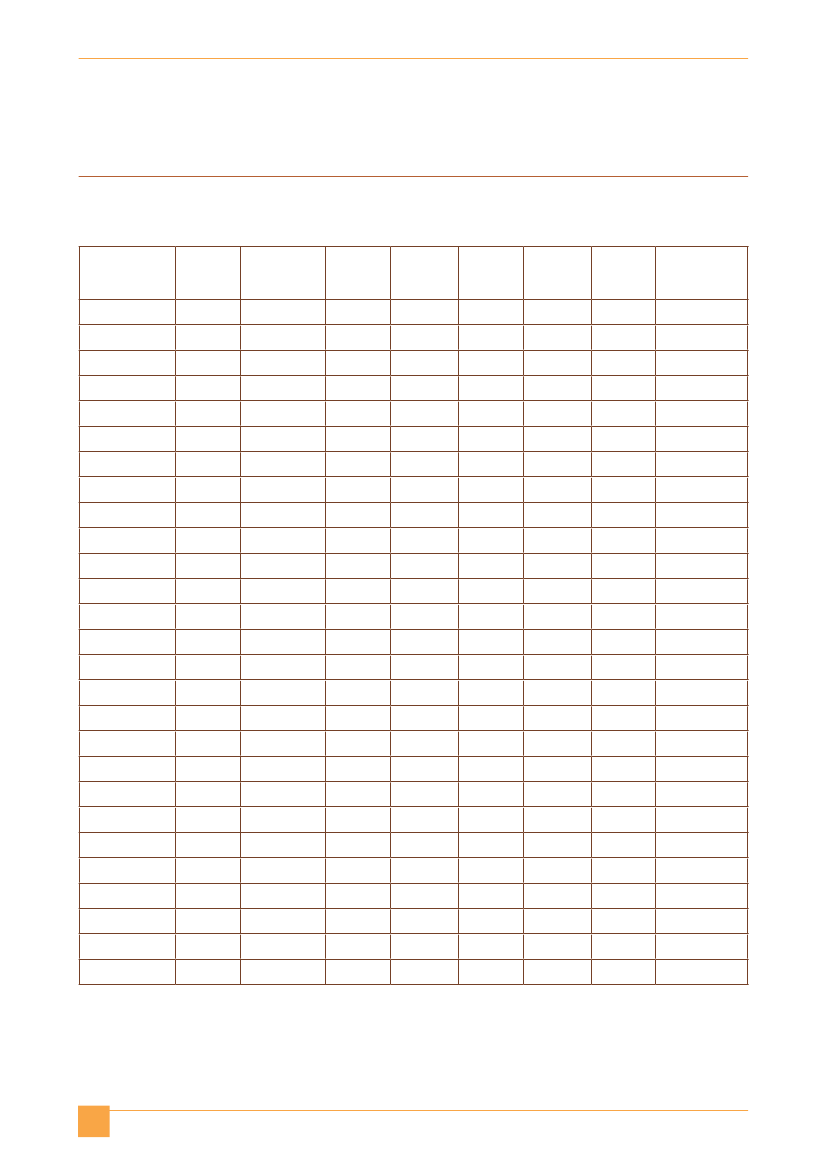

>Table 1.Total and genuine aid 201254Total aid(€m)AustriaBelgiumDenmarkFinlandFranceGermanyGreeceIrelandItalyLuxembourgNetherlandsPortugalSpainSwedenUnited KingdomBulgariaCyprusCzech RepublicEstoniaHungaryLatviaLithuaniaMaltaPolandRomaniaSlovak RepublicSlovenia865.4�792.�2��4.8�026.794�8.7�0�98.2252.0629.52053.3336.24297.644�.3�5�5.54078.3�0627.030.020.0�70.6�7.692.5�6.040.0�4.0340.5��3.060.844.8Bilateral aid(€m)4�8.7����.7�522.4620.76230.86787.768.94�7.2385.2237.63038.2299.9656.42833.76926.�0.�6.949.04.9�7.50.9�7.�9.�85.9�9.3�3.8�4.6Inflatedaid (€m)229.8358.7�32.�6�.32086.2�492.265.90.556.60.7456.995.6��2.7400.876.20.��2.97.40.�5.40.�0.28.02.6��.32.4�.7Genuineaid (€m)635.6�433.4�982.7965.47332.48706.0�86.�629.0�996.8335.53840.7345.6�402.83677.4�0550.829.97.��63.2�7.487.��5.939.86.0337.9�0�.758.443.�Inflatedaid as %of total aid26.6%20.0%6.2%6.0%22.2%�4.6%26.�%0.�%2.8%0.2%�0.6%2�.7%7.4%9.8%0.7%0.3%64.7%4.4%0.8%5.9%0.8%0.5%57.2%0.8%�0.0%3.9%3.7%Inflatedaid as %of bilateralaid54.9%32.3%8.7%9.9%33.5%22.0%95.7%0.�%�4.7%0.3%�5.0%3�.9%�7.2%�4.�%�.�%83.6%92.9%�5.2%2.7%3�.0%�3.9%�.2%87.6%3.�%58.7%�7.3%��.4%Total aidas % ofGNI0.28%0.47%0.84%0.53%0.46%0.38%0.�3%0.48%0.�3%�.00%0.7�%0.27%0.�5%0.99%0.56%0.08%0.�2%0.�2%0.��%0.�0%0.08%0.�3%0.23%0.09%0.08%0.09%0.�3%Genuine aid as% of GNI0.2�%0.38%0.79%0.50%0.35%0.32%0.�0%0.48%0.�3%�.00%0.63%0.2�%0.�3%0.89%0.56%0.08%0.04%0.��%0.��%0.09%0.08%0.�3%0.�0%0.09%0.07%0.08%0.�2%

54 Figures compiled by Concord AidWatch authors from a combination ofOECD data (prioritised for this table where it was available for consistencypurposes), national platforms and estimations where data points were nototherwise available. There may be some discrepancies between these figuresand those on the country pages (all of which were supplied by the nationalplatforms). The figures in the table are in current terms, while some of thosesupplied by the national platforms are in constant terms because severalyears are compared.

20

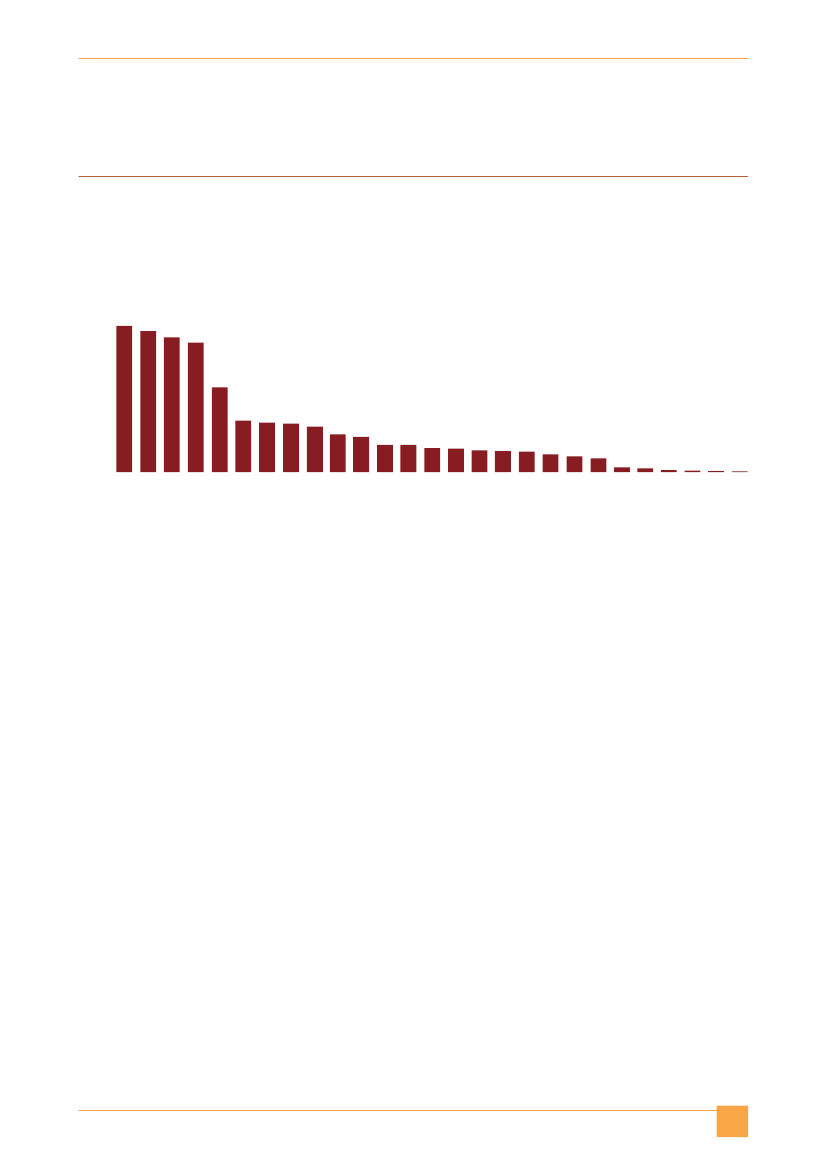

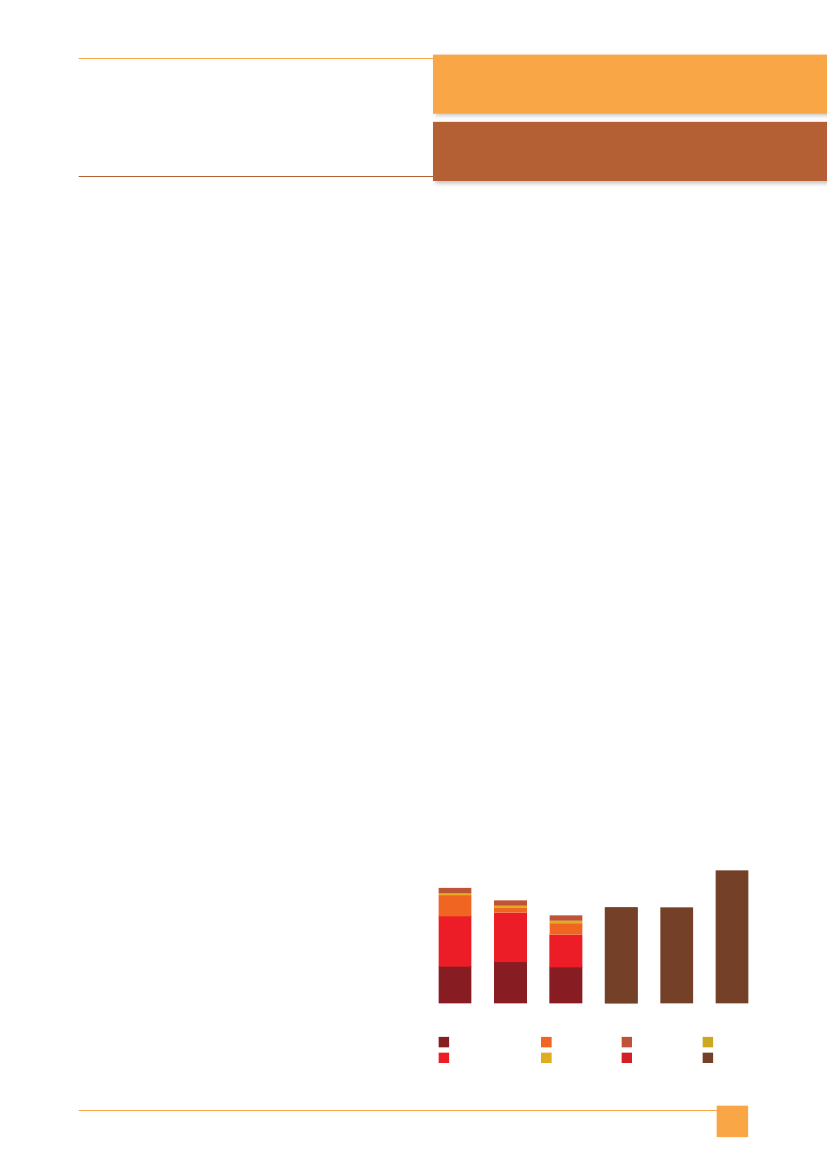

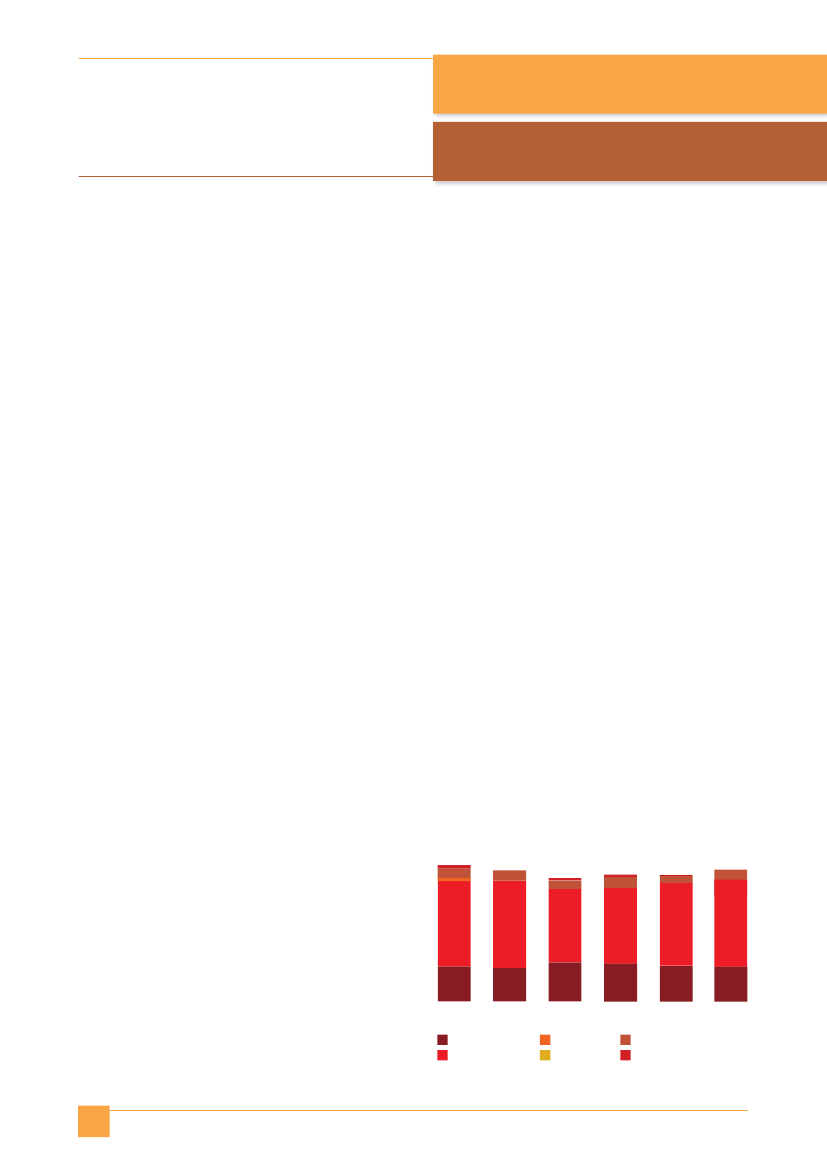

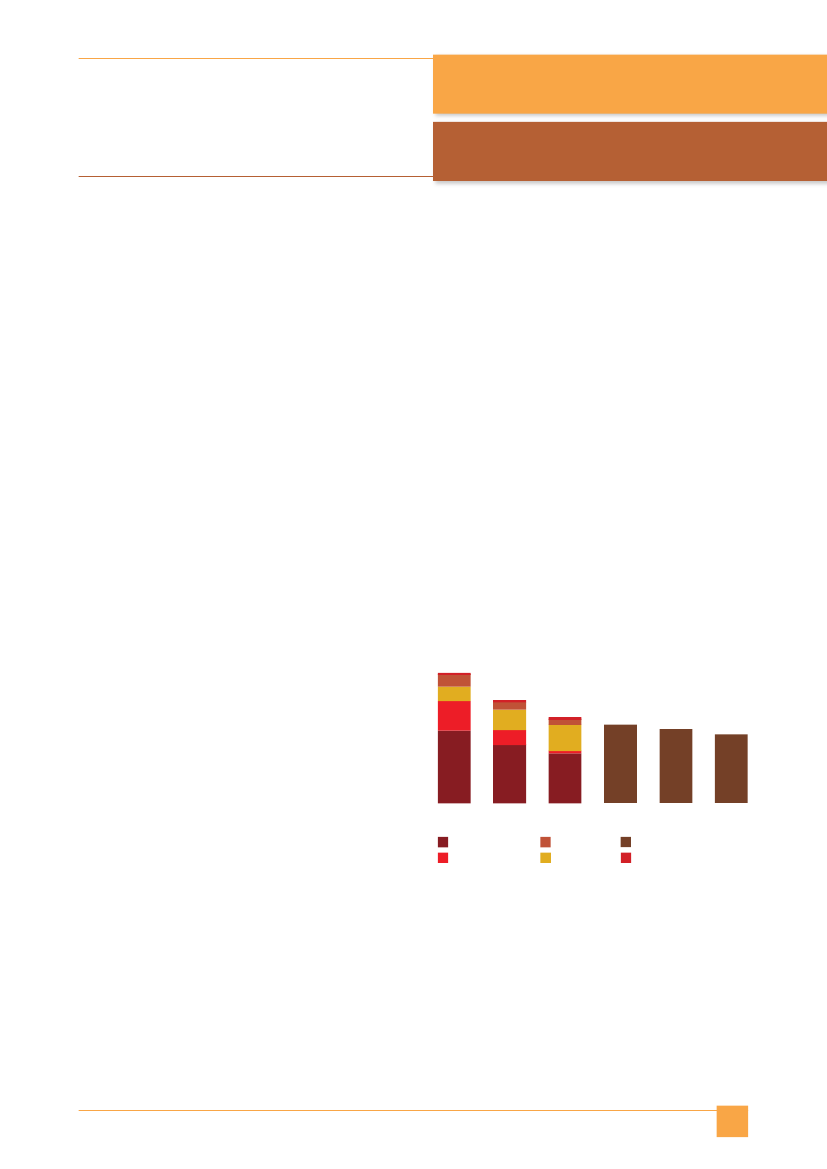

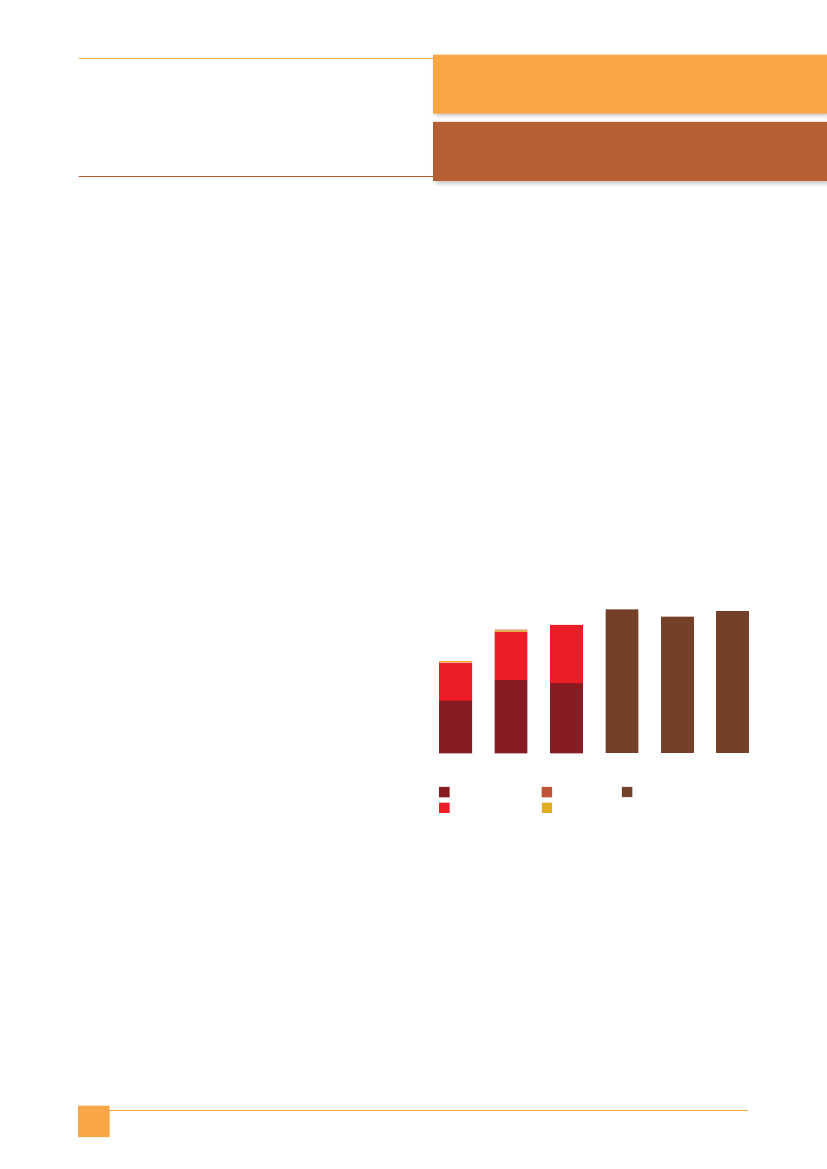

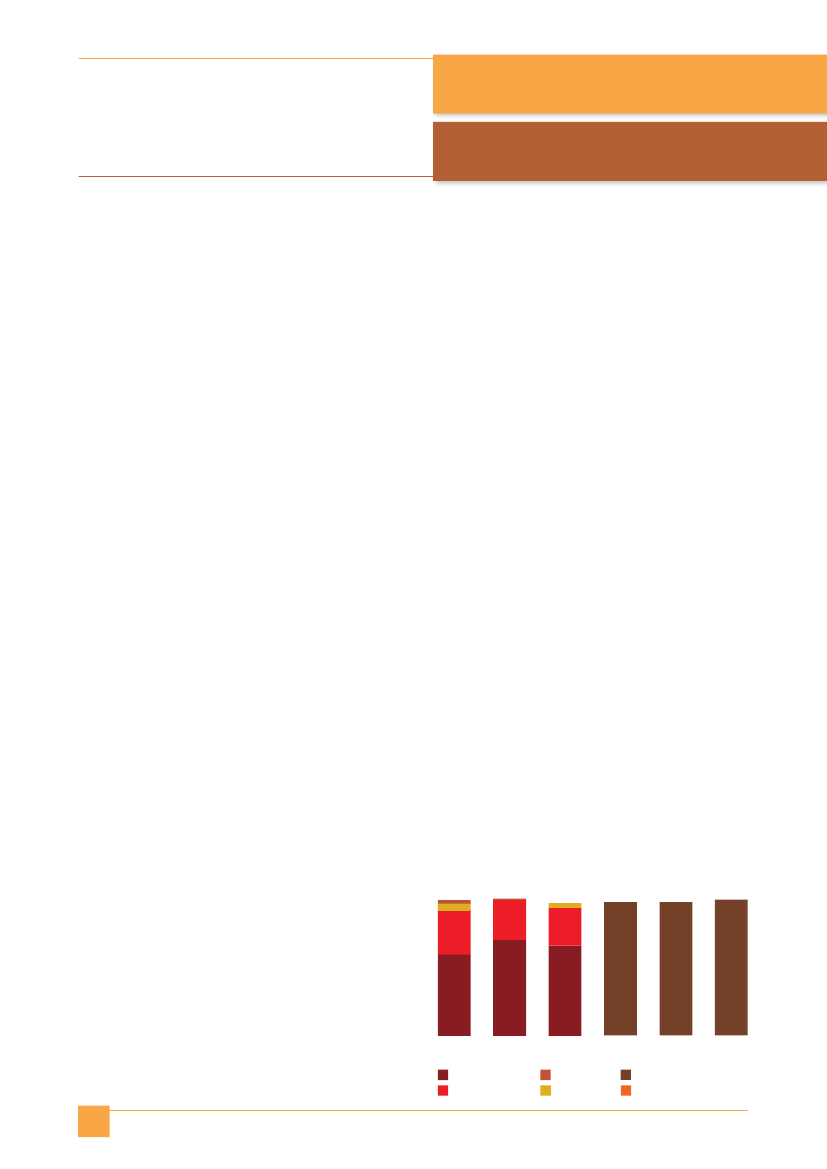

Inflated aid as % of bilateral aid402080�00600Greece95,7%

>

Cyprus92,9%

Malta87,6%

Bulgaria83,6%

Austria54,9%

France33,5%

Portugal3�,9%

Hungary3�,0%

Belgium28,7%

Graph 2.Inflated aid as a percentage of total bilateral aid

Romania23,8%

Germany22,0%

Slovakia�7,3%�7,2%�5,2%�5,0%�4,7%�4,�%�3,9%��,4%9,9%8,7%3,�%2,7%�,2%�,�%0,3%

SpainCzech RepublicNetherlandsItalySwedenLatviaSloveniaFinlandDenmarkPolandEstoniaLithuaniaUnited KingdomLuxembourgIreland

2�

0,�%

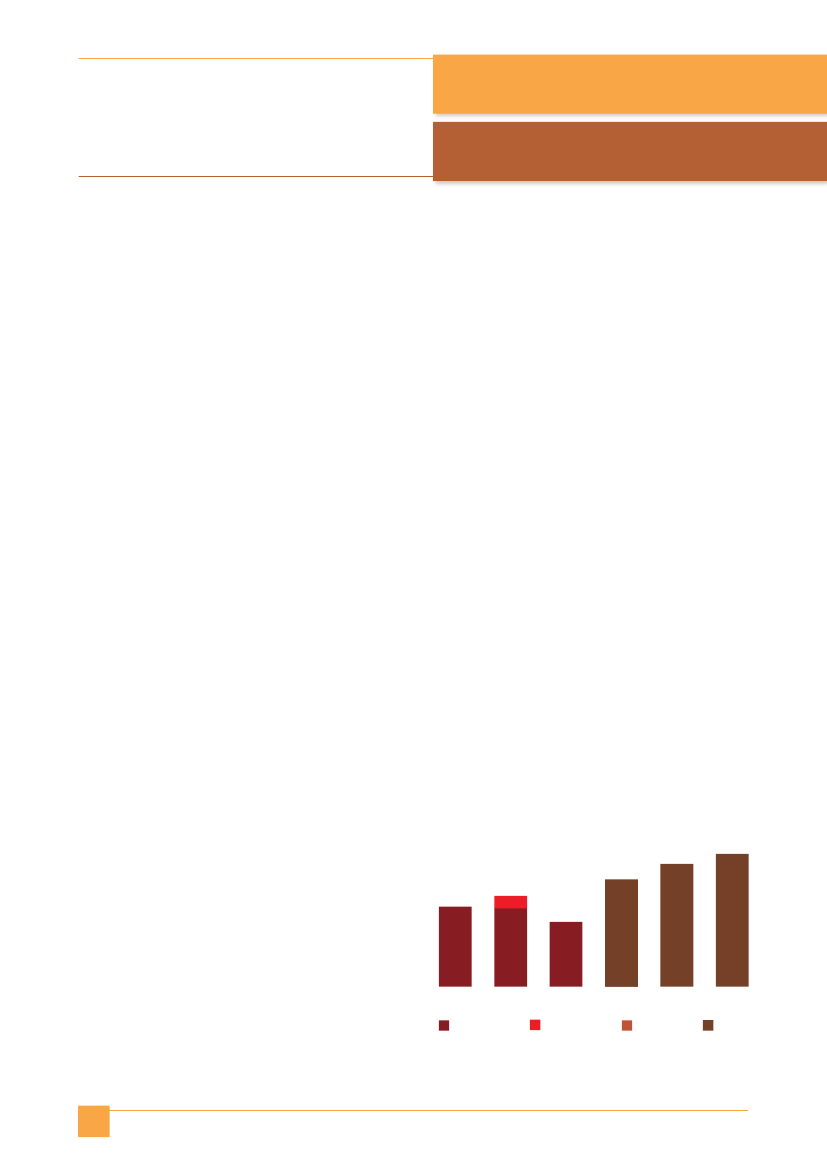

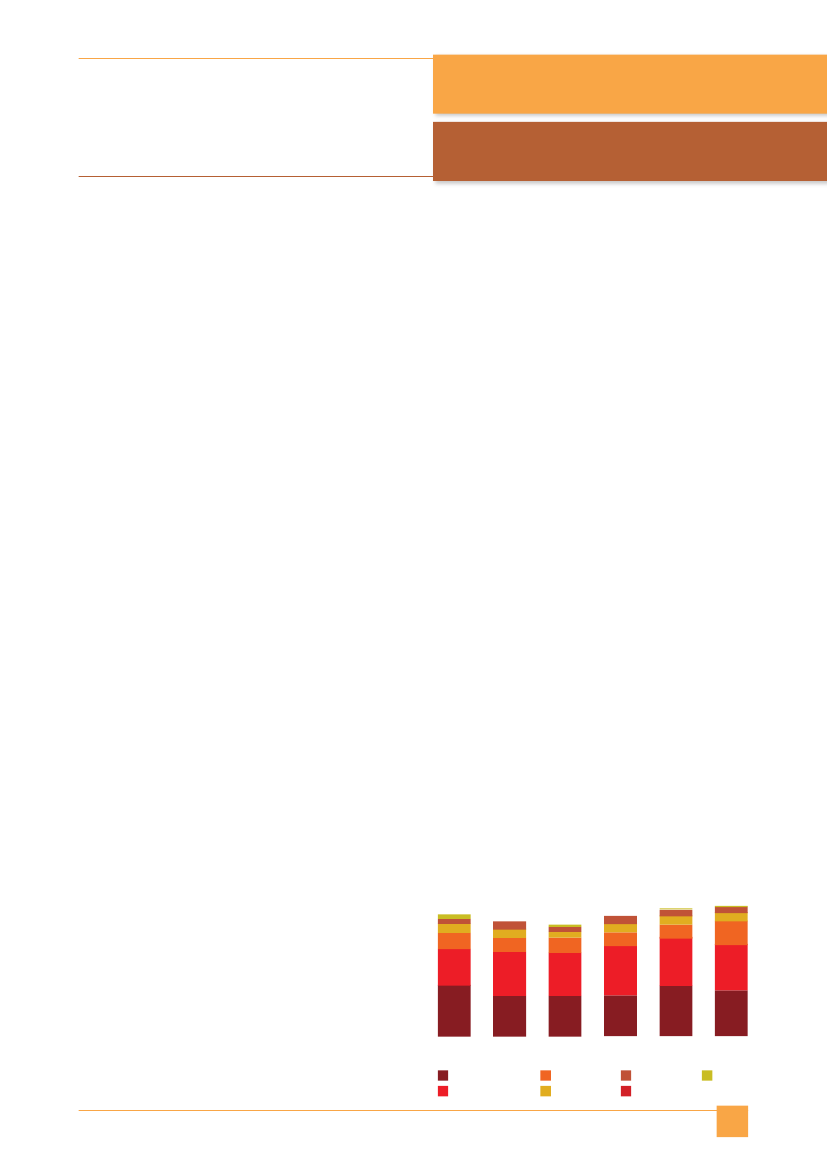

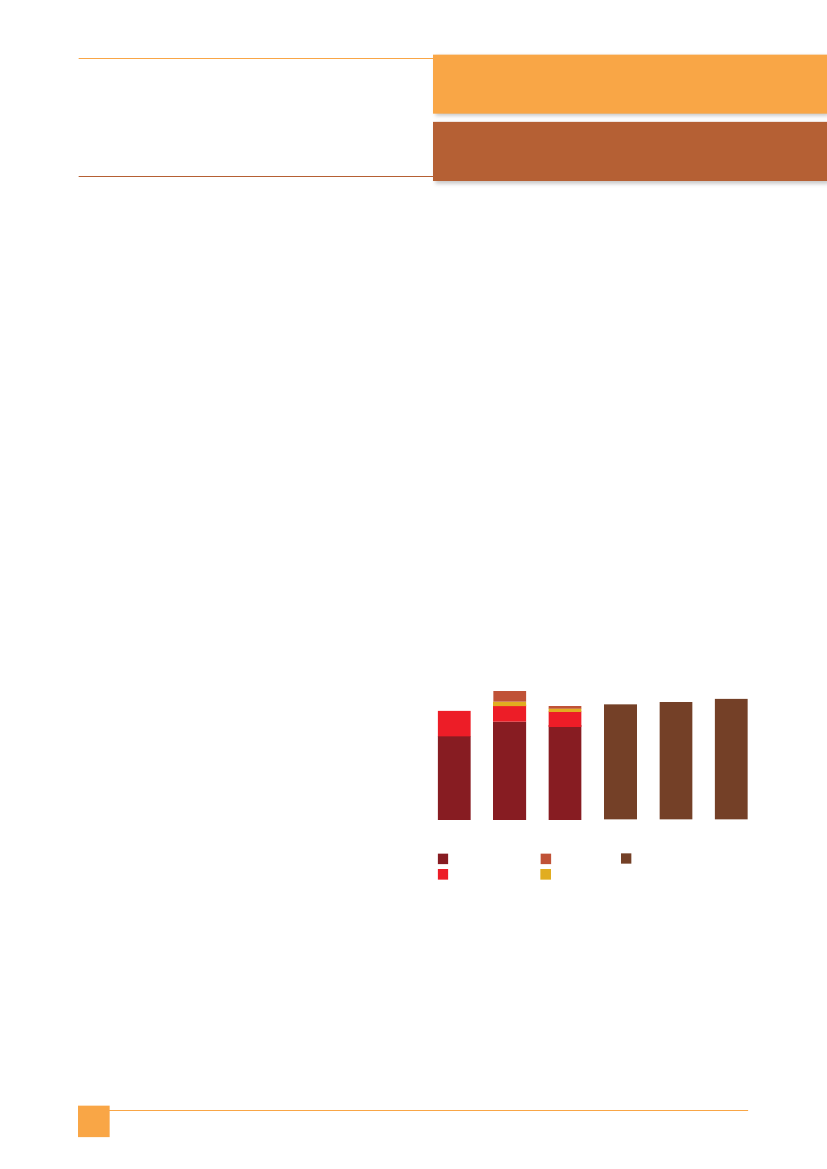

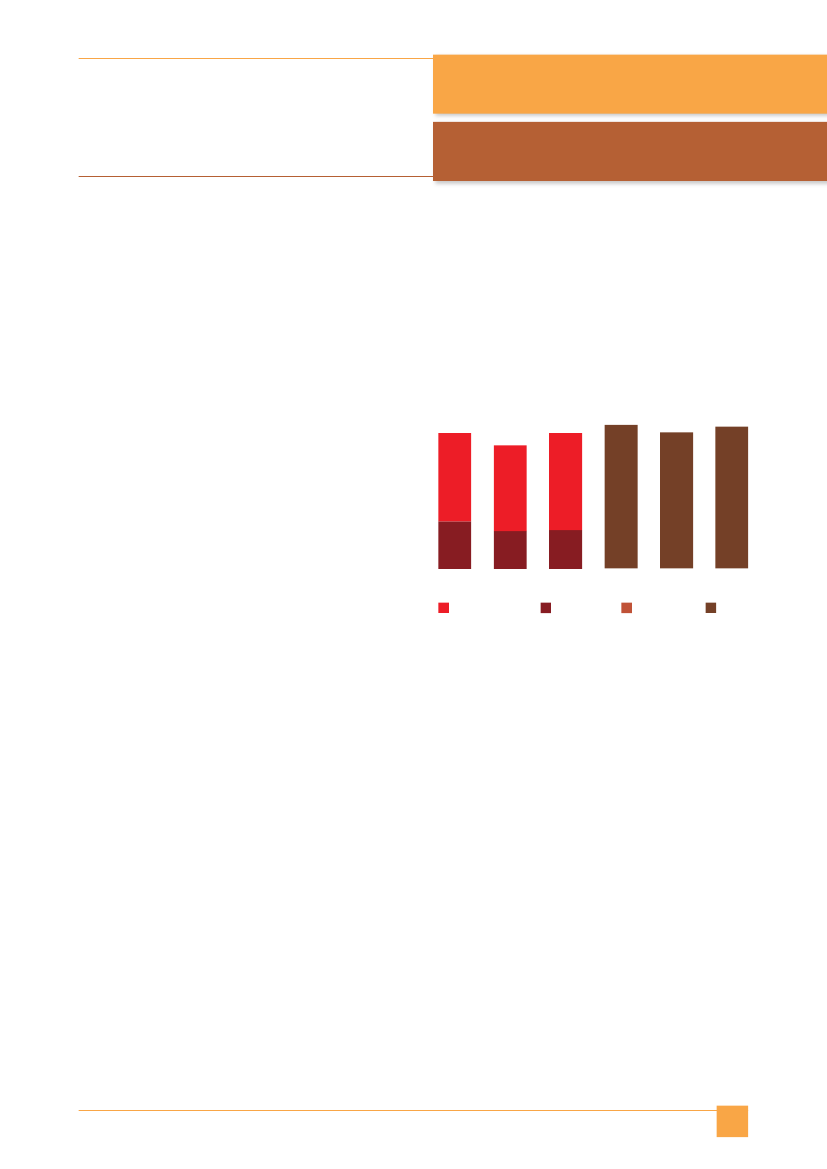

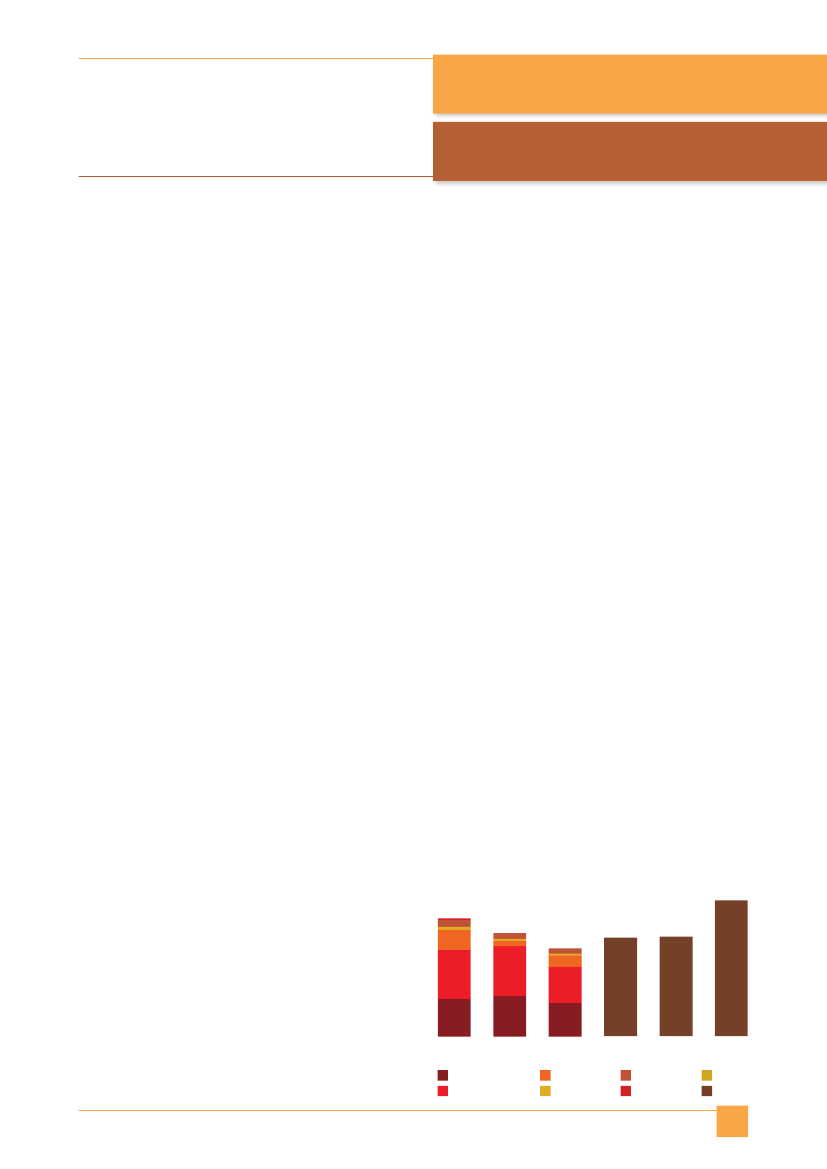

>Components of inflated aidImputed student costsImputed student costs represent a proportion of donor countries’expenditure on education. In 20�2, student costs accounted for€�.4 billion of European aid. The largest amounts were reported inGermany (€7�5 million), France (€500 million), Austria (€67 million),Greece (€47 million) and Belgium (€38 million). When measured asa percentage of bilateral assistance, they significantly inflate theaid budgets of Greece (69%), Romania (59%), Austria (�6%), Hun-gary (�5%), Germany (�0%), Slovenia (9%) and France (8%).Refugee costs in donor countriesUnder the definition, donors are allowed to count as ODA theamount of money they spend supporting refugees who arrivein their own country.In 20�2, refugee costs represented approximately €�.3 billionof European aid. The largest absolute refugee costs were recordedin Sweden (€400 million), France (€320 million), the Netherlands(€254 million) and Denmark (€�03 million). When we measure inpercentage terms, however, we see a different picture: this showsrefugee costs representing more than half the bilateral aid flowsreported by Cyprus (93%), Bulgaria (84%) and Malta (8�%). Theyalso represent a large proportion of other countries’ bilateral aid:Greece (23%), Hungary (�6%), Sweden (�4%), Latvia (�4%), Slo-vakia (�2%), Belgium (8%), the Netherlands (8%), Austria (7%) andDenmark (7%). As far as we can confirm, the only EU country thatcounts no refugee costs as ODA is Luxembourg.Debt reliefThe cancellation of unpayable debts is important, but it shouldnot be double-counted as aid. Debt relief accounted for ap-proximately €2 billion of EU aid in 20�2. Almost all this amountis concentrated in the EU-�5 countries. In 20�2, significantamounts of debt relief were recorded in France (€�.� billion),Germany (424 million), Belgium (€2��.62 million), the Nether-lands (€94 million), Austria (€82 million), the United Kingdom(€76 million) and Spain (€59 million).Tied aidSometimes donors make aid conditional on the purchaseof goods and services from their own country or a restrictednumber of countries. This practice is known as tied aid.Tied aid accounted for approximately €�.4 billion of theEU’s inflated aid in 20�2. This figure covers only the EU-�5countries; data on the EU-�3 countries is sparse, and mostof their aid goes through multilateral channels. The countrieswith the highest levels of tied aid in 20�2 were Germany (€��2million), the Netherlands (€�09 million), Portugal (€70 million),Austria (€50 million), Italy (€49 million), France (€4� million),Finland (€29 million) and Spain (€2� million).5555 Estimated figures

Interest on loansConcessional loans to developing countries count as ODA.When donors estimate their net ODA, they discount the repay-ment of the principal by recipient governments, but not inter-est payments. AidWatch regards these interest payments asinflated aid.In 20�2, interest repayments came to €590 million. Mostof this amount is accounted for by a handful of donors: theEU institutions (€248 million), Germany (€�74 million), France(€�20 million), Spain (€33 million) and Portugal (€9 million).Several other countries provide concessional loans to develop-ing countries and do not report interest payments.Climate financeEuropean countries are committed to “scaled-up, new and ad-ditional, predictable and adequate funding” for climate-changemitigation and adaptation.56AidWatch is concerned that EUcountries are failing to ensure that climate finance is new andadditional.The Fast-Start Finance initiative provides an example. InCopenhagen, EU countries committed themselves to deliver-ing €7.2 billion in fast-start financing in the period 20�0-20�2.In 20�2, they actually mobilised €2.67 billion, thus bringingthe total amount of money disbursed as part of the Fast-Startinitiative to €7.34 billion, a figure slightly larger than that origi-nally promised. These funds, however, are neither additionalnor new. AidWatch research finds that least �9 EU MSs reportthese figures as ODA. In the other cases it is not clear how thefigures are reported.Apart from Sweden and Denmark – which regard fund-ing above 0.7% and 0.8% respectively as “new and additional”57– we have not found any other EU country that clearly separatesclimate finance from aid commitments. Without such a definition,EU countries cannot differentiate between flows, and they arecounting the same funds for two separate targets. If climate fi-nance were truly new and additional, then many European coun-tries would be a good deal farther from their aid targets.The problem will only get worse in the coming years, asdonor countries move towards the climate finance target of de-livering US$ �00 billion (€75 billion) a year by 2020. It is essentialto agree and implement a common definition of additionality thatcan be used by developing countries and European citizens tohold EU governments to account for their international commit-ments.However, because the necessary data are not published,climate finance double-counted as aid is not included in ourfigures for inflated aid.

56 Copenhagen Accord, FCCC/CP/2009/L.7, �8 December 200957 AidWatch survey, 20�3

22