Udenrigsudvalget 2013-14

URU Alm.del Bilag 127

Offentligt

DIRECTORATE-GENERAL FOR EXTERNAL POLICIES

POLICY DEPARTMENT

BRIEFING

South Sudan:The roots and prospectsof a multifaceted crisisAuthor: Manuel MANRIQUE GIL,with contributions from Marion EXCOFFIER (trainee)

AbstractThe violent conflict that erupted in South Sudan during the night of 15 December 2013had many triggers, the closest being political disputes between the country's toppoliticians, President Salva Kiir and former Vice-President Riek Machar. The fact theDecember crisis escalated into an open civil war reflects underlying tensions and widermisgivings within the South Sudanese population, especially between ethnic Dinka andethnic Nuer. External actors – mainly the Intergovernmental Authority on Development(IGAD), the United Nations, the EU and the US – have played a crucial role in supporting apopulation that has faced significant human rights abuses and humanitarian shortfalls.These actors have also worked to find a negotiated solution to the crisis from the outset,brokering the ceasefire agreement signed on 23 January 2014. However, the peace dealbetween the two parties marks only the beginning; the process of reconciliation,rehabilitation and nation-building will be long, and reports of violations of the ceasefiredemonstrate the fragility of the situation. Immediate, as well as medium- and long-term,challenges must be addressed swiftly, so that Africa's youngest state can embark acredible path to development.

DG EXPO/B/PolDep/Note/2014_55PE 522.328

March 2014

EN

Policy Department, Directorate-General for External Policies

This Briefing is an initiative of the Policy Department, DG EXPO

AUTHOR:

Manuel MANRIQUE GILWith contributions from Marion EXCOFFIER (trainee)Directorate-General for External Policies of the UnionPolicy DepartmentWIB 06 M 83rue Wiertz 60B-1047 BrusselsEditorial Assistant: Simona IACOBLEV

CONTACT:

PUBLICATION:

English-language manuscript completed on 5 March 2014.�European Union, 2014Printed in BelgiumThis Policy Briefing is available on the intranet site of the Directorate-General for External Policies, in theRegions and countriesorPolicy Areassection.

DISCLAIMER:

Any opinions expressed in this document are the sole responsibility of theauthor and do not necessarily represent the official position of theEuropean Parliament.Reproduction and translation, except for commercial purposes, areauthorised, provided the source is acknowledged and provided thepublisher is given prior notice and supplied with a copy of the publication.

2

South Sudan: The roots and prospects of a multifaceted crisis

Table of contents12IntroductionThe different causes of the crisis2.12.2The immediate triggerThe root causes2.2.12.2.22.2.3Institutional dimensionPolitical dimensionEthnic dimension

4445567

3

The crisis3.13.2Human rights violations and humanitarian crisisRole of external actorsDifficulties, content and reactionsFuture challenges

778

4

Signing the ceasefire4.14.2

101011

5

Outlook and policy options for the European Parliament

12

3

Policy Department, Directorate-General for External Policies

1

IntroductionOn 23 January 2013, South Sudan's government and rebels signed a ceasefireagreement after nearly six weeks of violence in the country. This marks thebeginning of a ‘second chance’ for the building of the world's newest state.After more than fifty years of intermittent civil war between the northern andthe southern parts of Sudan, South Sudan gained its independence in July2011 following a self-determination referendum. Relations with Sudan havesince improved although they remain volatile due to different disputes,including sharing of oil resources, questions over citizenship and, notably,the status of the contested area of Abyei. The overall economic and socialsituation of South Sudan since independence has been however very fragile.The country is characterised by a very high poverty rate (50.6% of SouthSudanese citizens live below the poverty line), weak public service deliverysystems (especially in rural areas), rapid population growth and anoverdependence on oil exports and numerous imports. Moreover, it iscomposed of more than 200 ethnic groups, with the Dinka and the Nuer asthe largest communities. Due to its fragility, South Sudan's economic andpolitical stability are highly vulnerable to both internal and external events.This was first revealed in the rocky relation with Sudan, which led to thehalting of oil exports in early 2012 and mid-2013, provoking a massive loss ofrevenues for South Sudan's economy. Protracted political rivalries, whichhave sometimes relied on ethnic mobilisation for support, have recentlydemonstrated that they constitute an important threat to stability. Despitebeing aware of South Sudan's fragility, the outbreak of violence on 16December 2013, and notably its speed and intensity, surprised theinternational community. Although the precarious situation in the countrycould have made South Sudan's crisis predictable, its causes andconsequences remain multidimensional and complex.

Gaining itsindependence in 2011,South Sudan became theworld's youngest state.

The overall economicand social situation of thecountry remains veryfragile, increasing thepotential for instability.

22.1

The different causes of the crisisThe immediate triggerThe violent conflict that erupted in South Sudan and pushed the countrytowards civil war is the result of diverse factors, most directly the politicaldisputes between the country's leadership. The political crisis began in July2013 when President Salva Kiir announced a major cabinet reshuffle in whichVice-President Riek Machar and several other key officials were removed fromoffice. The Secretary General of the ruling party, the Sudan Peoples'Liberation Movement (SPLM), Pagan Amum, was also suspended without anyclear justification. This formalised the first 'visible' fissure in the ruling party.One month later, President Kiir also removed two state governors, suspectedof representing a treat to national security. This power restructuringcontinued with the dissolution of all SPLM structures on 15 November. Inreaction, dismissed SPLM leaders accused ina press statementPresident Kiirof using dictatorial manners violating the party and national constitutions.On 14 December 2013, after several postponements, the National LiberationCouncil of SPLM - second highest organ in the party decision-making

The political crisis wastriggered by thedismissals of seniorleaders of the SudanPeoples' LiberationMovement (SPLM) and amajor cabinet reshuffle.

4

South Sudan: The roots and prospects of a multifaceted crisis

The outbreak of fightingduring the night of 15December marked thebeginning of the civilwar.

structures - was finally held. A meeting in which the dismissed membershoped to make their voices heard. However, the day after the meeting theopposition stated that no space for true dialogue was provided by PresidentKiir during the meeting, which meant that reconciliation was far from beingachieved. This became obvious the following day as, according to reports,fighting broke out during the night between the Nuer and the Dinkafractions of the Presidential Guard in Juba. The events of 15-16 Decembermarked the beginning of the violent conflict and its escalation into an opencivil war. On 16 December President Kiir, in a public address, accused Macharof organising a failed coup attempt. Machar in turn denied any involvementin the events. The same day 11 SPLM leaders were arrested and Machar wasdeclared wanted as he escaped Juba. On 21 December, Riek Machar officiallytook leadership of an armed rebellion based in the northern part of thecountry and involving mainly Nuer commanders and people. The fightingrapidly escalated as the armed forces split along political and ethnic lines andconflict spread to important parts of the country.

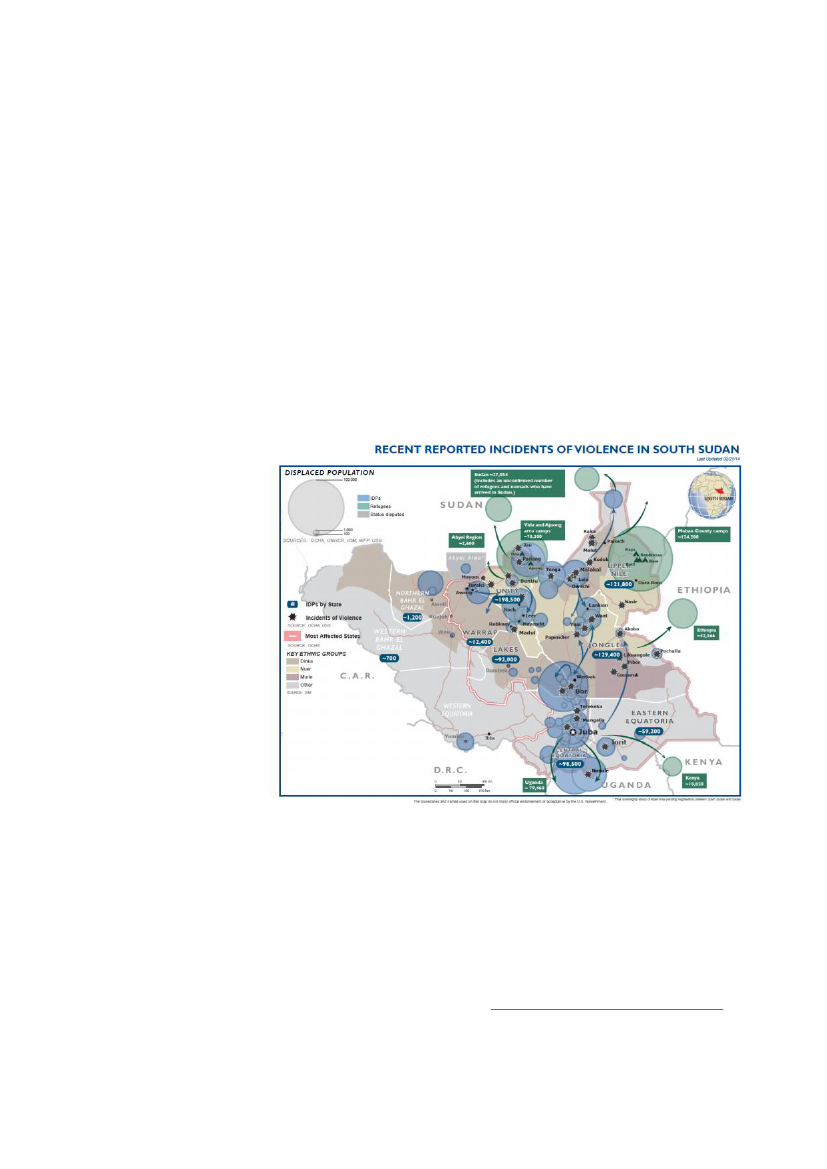

Figure 1:

Reported incidents ofviolence in South Sudan,as of 21 February 2014Source: USAID, 21 February 2014

2.22.2.1

The root causesInstitutional dimensionThe deeper roots of violence lie in the political and civil crisis that has affectedSouth Sudan since its independence in July 2011. Since becomingindependent South Sudan has had to develop its institutional framework,establishing laws, public services and infrastructures. The internationalcommunity, especially through theUN Mission deployed in South Sudan(UNMISS), has accompanied the country in this process. Consisting of 7 000military and 900 civilian police personnel, the UN Mission was established on8 July 2011 for an initial period of one year (since then renewed twice). Its5

Policy Department, Directorate-General for External Policies

South Sudan isconsidered a 'fragilestate', lacking theinstitutional tools to facean insurgency throughpolitical and democraticmeans.

mandate covers three main areas: first, support for peace consolidation(thereby fostering longer-term state building and economic development);second, support South Sudan's government in exercising its responsibilitiesfor conflict prevention and protect civilians and third, support thegovernment in developing its capacity to provide security, to establish rule oflaw and to strengthen the security and justice sectors. Despite these efforts,allegations of corruption, lack of good and fair institutions as well as a verypoor delivery of public goods remain the main features of the country as it iswell stated inVeronique De Keyser's reporton South Sudan's state-buildingand development adopted by the Development Committee on 5 Novemberand in plenary on 10 December 2013. South Sudan, considered a 'fragilestate' due to these shortcomings, presents thus a potential for instabilityhigher than any other developing countries. This fragile institutional situationwas compounded by the precarious security situation, due to the difficultiesfaced by the government to disarm the population after the independence.Because of the on-going and emergent rebellions by various militias in thecountry notably in the Greater Upper Nile (Jonglei, Unity and Upper Nilestates), many local communities have sought to retain their weapons for self-defence. Moreover, Kiir's government has sought to integrate these militiafighters into the police and the military forces, which has resulted in thecreation of over-sized forces with very little professional training leading toloose command and control. Consequently, South Sudan’s security situationis extremely complex, with armed civilians on one side and disorganisedpolice and military forces on the other, incapable of handling any significantunrest and often causing it.

2.2.2

Political dimensionLong before the outbreak of violence in December 2013, political stability inSouth Sudan was threatened by the unresolved and protracted rivalriesbetween President Kiir and former Vice-President Machar, which date back tothe 1990s. After being a major in Sudan's national army, Kiir joined the SPLMled by John Garang in 1983, and helped him form the Sudan People’sLiberation Army (SPLA). By contrast, Machar entered the SPLM and SPLA in1984 after having completed a doctorate in the UK. Disapproving Garang'sobjective of a united Sudan with recognition of the South, and fightinginstead for South Sudan's secession, Machar broke away and formed theSPLM/A Nasir dissident group in 1991. His movement evolved, and becamethe 'South Sudan Independence Movement/Army' (SSIM/A) in 1995. As aresult of internal tensions within his group, Machar finally agreed to mergeback into Garang’s SPLA in January 2002. After Garang's death in 2005, Kiirbecame SPLM's leader and Machar, Vice-President. After independence, inJuly 2011, Kiir became President and kept Machar as Vice-President, largely toappease ethnic tensions and launch a process of reconciliation and nationalcohesion. However, political rivalries between the two men remained. Kiirand Machar have significant disagreements on fundamental aspects of theparty and country's leadership, governance and direction. They believe intwo different kinds of relations with Sudan. Contrary to Machar, Kiir is willingto keep good relations with Sudan and cooperate with Khartoum regarding

Unresolved andprotracted politicaldisagreements betweenPresident Salva Kiir andformer Vice-PresidentRiek Machar haveprolonged andaggravated the crisis.

6

South Sudan: The roots and prospects of a multifaceted crisis

their respective insurgents. Machar also disagrees with Kiir's way of runningthe country and has criticised his dictatorial tendencies. Article 101 ofSouthSudan's Transitional Constitution,concentrates numerous powers on thePresident, who can run state affairs with very limited consultation, includingremoval of elected officials. President Kiir overused these powers, notablyafter Machar declared in March 2013 his intention to contest for the partychairmanship. The numerous dismissals of SPLM officials from any executivepositions consequently express the result of a long-term struggle for powerbetween Kiir and Machar. Political disputes are also fuelled by theinstrumentalisation of ethnic identities by both sides, leading to an evenmore complex crisis.

2.2.3

Ethnic dimensionThe crisis in South Sudan also reflects underlying tension and mistrust amongSouth Sudanese belonging to the country’s two main different ethnic groups:the Nuer and the Dinka. This largely dates back to Sudan's civil war (1983-2005) when the SPLM and SPLA (and factions within them) competed forpower by mobilising supports around ethnic lines. In fact, the ethnic targetedkillings reported during the current crisis resonate with the 1991 inter-ethnicviolence generated by the SPLM/A split between the Garang faction (Dinka),supported by Kiir, and the Machar one (Nuer). As a result of this division, abloody conflict exploded mainly between ethnic Dinka and ethnic Nuer,leading to the killing of thousands of civilians on both sides and massstarvation. One of the grossest human rights violations at that time andattributed to troops commanded by Machar was the 'Bor massacre' in whichat least 2 000 Dinka were killed in Bor, Jonglei State's capital. Twenty yearslater, in August 2011, Machar publicly apologised for his part in the massacrehoping that it would bring unity to the Dinka and Nuer tribes. The apologyreceived mixed reactions by individuals belonging to the Nuer communitywhom regretted that reconciliation was not a two-way process.As it was the case in 1991, ethnicity was not the initial cause of the sparkingof violence last December, although it was used in the conflict to target theopposition. Also, the unhealed wounds and lack of justice and reconciliationfrom atrocities in the past may have contributed to spread and intensifyfighting as well as to some of the human rights violations committed duringthe crisis.

The instrumentalisationof ethnicity by both sidesfuelled the conflict.

33.1

The crisisHuman rights violations and humanitarian crisisAccording toHuman Rights Watch(HRW), numerous human rights abuses,ranging from illegal detentions to attacks on civilians and targeted killings,were reported during the conflict. In the week of 16 December, mass arrestswere conducted by forces loyal to President Kiir. Eleven senior SPLM partyofficials were arrested, accused by Kiir of having plotted a coup against him.The release of these prisoners became an important sticking point during thenegotiations of a ceasefire (See below), and on 29 January, seven of them7

Policy Department, Directorate-General for External Policies

Numerous human rightsabuses, committed byboth sides, were reportedduring the conflict.

Over seven millionpeople were estimated inneed of humanitarianassistance.

Protecting civiliansrepresented a majorhumanitarian challengeduring the armedconflict.

were finally released. Attacks on civilians include beatings, rapes, destructionof houses and acts of torture. According to HRW, both parties committedatrocities. Widespread killings of Nuer men by members of the government'sarmed force were documented by the NGO between 15 and 19 December inJuba, including a massacre of more than 200 men in the Gudeleneighbourhood on 16 December. Intense attacks and abuses against civiliansof Dinka ethnicity in Bor and Bentiu were also reported the same week.International Crisis Grouphas estimated the death toll of the conflict as closeto 10 000 after four weeks of fighting. The conflict also caused a significanthumanitarian crisis. On 10 February 2014, over 865 000 people weredisplaced in South Sudan, compared to 125 000 at the beginning of theconflict. This rising number includes 110 000 South Sudanese seeking refugein neighbouring countries notably in Uganda' West Nile region and Ethiopia'sAkobo area. The conflict has furthermore affected a country that was alreadyfacing a worrying humanitarian situation before the outbreak of violence as4.3 million people were estimated to be in need of humanitarian assistanceand 3.4 million to suffer from food insecurity. There are now 7 million peopleat some risk of food insecurity and 4.9 million people in need of water,sanitation and hygiene assistance. Already in an extremely precarioussituation, with most people lacking access to basic services, includingadequate sanitation, clean water nor healthcare, the current crisis isworsening the situation. The government also failed to ensure the security ofany humanitarian corridors leading to very difficult conditions forhumanitarian relief as the on-going clashes seriously limited the access topeople in need. Reports of looting of medical and humanitarian facilities aswell as some government denials of flight authorisation were also reported.Protection of civilians was also a major humanitarian challenge of the armedconflict. In the aftermath of the outbreak of fighting, UNMISS took urgentsteps to host civilians in their compounds in South Sudan and in transitcentres in neighbouring countries. The number of people sheltering in theirbases is estimated at 74 790. Nevertheless, these shelters rapidly becameovercrowded and living conditions deteriorated. For instance, the UN Dzaipicentre (in Uganda), originally designed to host only 400 people, wassheltering over 32 500 people!

3.2

Role of external actorsExternal actors, notably African regional organisations, the United Nations,the EU and the United States, have been involved in finding a negotiatedsolution to the crisis since the start, and have brokered the peace talks held inAddis Ababa. These have been led bythe Intergovernmental Authority onDevelopment(IGAD) and its current Chair Ethiopia, which have played acrucial mediating role multiplying visits between Addis Ababa and Juba andorganising face-to-face talks between all stakeholders. Several communiquéswere also issued by the African Union (AU) to express its firm support toIGAD's mediation efforts in the negotiations and urge for the immediatecessation of hostilities. On 30 December, the AU also declared its intention tocreate a Commission of Enquiry to investigate the human rights abuses and

The IntergovernmentalAuthority onDevelopment IGAD)played a crucial role inmediating the ceasefire.

8

South Sudan: The roots and prospects of a multifaceted crisis

other violations committed during the armed conflict as well as to makerecommendations to ensure accountability and reconciliation among allSouth Sudanese communities. On 18 January, it was announced that the firststeps to establish the Commission have been undertaken.The presence of Ugandantroops in Juba wasconsidered animpediment to peacetalks.Another IGAD member, Kenya, through the appointment of General LazaroSumbeiywo as Special IGAD Envoy for South Sudan also played an importantpart in the negotiations process. A more direct involvement has come fromUganda, whose Uganda People's Defence Force (UPDF) were deployed inSouth Sudan shortly after the outbreak of hostilities. Fist announced as adeployment aiming to secure key locations in Juba, it has since been shownthat UPDF troops have played a much more important role in the conflict,supporting the Kiir government. Whilst the Ugandan Foreign Ministerjustified their presence as only aiming at ’supporting regional objectives toend the conflict’, their presence has become a sticking point in thenegotiations and criticised by different actors.The UN contribution has been essential in terms of humanitarian assistancenotably with regards to protection of civilians. On 24 December 2013, theSecurity Council adoptedResolution 2132that temporarily increased UNMISSmilitary component up to 12 500 troops while the police component wasincreased up to 1323, from 900. The UN also supported IGAD's mediation andAU's idea concerning the establishment of a Commission of enquiry.Nonetheless, some worrying developments have taken place, with PresidentKiir questioning the neutrality of the UN in South Sudan, and accusing it ofrunning a ’parallel government’ on its own.The EU, through the active participation of the EU Special Representative forthe Horn of Africa, Alexander Rondos, monitored the peace talks andsupported IGAD as well as the AU's commitment with regards to the end ofthe crisis. AEUR 1.1 million financial contributionto help holding thenegotiation process was also provided, using the African Peace Facility EarlyResponse Mechanism. On 23 December 2013, Kristalina Georgieva, EuropeanCommissioner for International Cooperation, Humanitarian Aid and CrisisResponse,announcedthat additional humanitarian funding of EUR 50 millionwill be made available in 2014, amounting to overEUR 251 millionfor 2013-2014 EU total support (including Member states' contribution).The United States also sought a mediated solution to the crisis. Its specialenvoy for Sudan and South Sudan, as well as the US Ambassador to SouthSudan, were actively engaged in the negotiations process, supporting IGAD'sdetermination to reach an agreement. Giving almost 77 % more than the EU,the US isthe largest bilateral donorof South Sudan, providing over USD 323million in humanitarian assistance for 2013-2014, and making available USD50 million of additional funding to face the crisis' consequences.

UN humanitarianassistance has beenessential.

The EU monitored thetalks and financiallysupported IGAD's efforts.

As the largest bilateraldonor to South Sudan,the US was also activelyengaged in the peaceprocess.

9

Policy Department, Directorate-General for External Policies

44.1

Signing the ceasefireDifficulties, content and reactionsThe signing of a ceasefire agreement between Kiir's allies and Machar's allies,finally achieved on 23 January, was not an easy task. During almost threeweeks of talks, no progress in negotiations was made mainly due to thecontinued fighting and sticky issues such as the status of detainees and thepresence of Ugandan troops. Four days after the outbreak of fighting in thecapital, the IGAD took the decision to dispatch a delegation of Foreign AffairsMinisters to Juba with the participation of the AU Commissioner for Peaceand Security and the UN Special Envoy. Although President Kiir committedhimself to engage in an inclusive political dialogue with the opposition, notalk was initiated between the two sides. Eventually, peace talks begun on 4January in Addis Ababa. However, fighting continued in the meantime andnegotiations appeared to be deadlocked over the government'simprisonment of 11 political leaders. On 16 January, the opposition alsodeclared that no ceasefire would be signed unless Uganda stops supportinggovernment forces. One week later however, on 23 January, two agreementswere reached between the two sides: one on thecessation of hostilitiesandone on thestatus of detainees.Although many expressed scepticism onwhether armed groups would abide to the cessation of hostilities, the dealrepresents ‘a critical step toward building a lasting peace’ between the twogroups.The agreement, negotiated by Nhial Deng Nhial on the government side andTaban Deng Gai for the opposition, states that ‘cessation of hostilities shouldtake effect within 24 hours after the signing of the agreement’. Furthermore,it commits both sides to an ‘all inclusive dialogue’. With regards to the 11political detainees, South Sudan Government agreed to envisage an amnestybut declared that he will only do so after their cases had been heard in court.However, on 29 January seven of them were released sending thus a positivesign for South Sudan's future. According to the deal, Kiir also agreed that allforces and armed groups ‘invited by either side’ should be redeployed or‘progressively withdrawn’ from the ‘theatre of operations.’ On 21 February,Ugandan troops were however still present on the South Sudanese territorywhich did not facilitate the true respect of the peace talks. Reopening ofhumanitarian corridors and facilitation of the reunion of families separatedduring the fighting were also part of the deal. Last but not least, both sidesagreed for an end to ‘hostile propaganda’ and attacks against civilians.President Kiir has declared that people will be held accountable for their acts.Reactions from the international community were numerous.PresidentBarack Obamawas one of the first ones of having hailed the agreement,urging both sides to 'fully and swiftly implement it'.UN Secretary General BanKi-moonalso welcomed the deal pressing the two sides in the conflict tokeep the momentum going with a 'national political dialogue to reach acomprehensive peace agreement, with the participation of all SouthSudanese political and civil society representatives, including the SPLM

On 23 January, twoagreements werereached, one on thecessation of hostilitiesand one on the status ofpolitical detainees

The internationalcommunity welcomedthe deal, calling for itsrapid implementationand the opening of aninclusive dialoguebetween the two leaders.

10

South Sudan: The roots and prospects of a multifaceted crisis

detainees'. On the same path and whilst welcoming the ceasefire,the HighRepresentative of the EU for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy,CatherineAshton, called for its 'quick implementation' by both sides and 'in good faith'stressing the importance of the end of any summary executions so thatcivilians feel safe again and humanitarian assistance be delivered to all inneed.

4.2

Future challengesThe signing of a peace deal between Kiir and Machar only marks thebeginning of a long process of reconciliation, rehabilitation and nation-building. For Seyoum Mesfin, IGAD's chief mediator, 'the post-war challengeswill be greater than the war itself. The process will be unpredictable anddelicate.' A second round of negotiations, first supposed to take place on 10February 2014, opened in Addis Ababa on 11 February in the evening asopposition negotiators announced they would not take part unless certainconditions were met such as the release of the four remaining politicaldetainees and the withdrawal of Ugandan troops from Juba. The rebelsfinally agreed to attend the peace talks as IGAD gave them guarantees thatthese issues will be addressed. The seven former political detainees are alsotaking part in the talks. Even though the proposed agenda remains unclear,the resumption of talks is aimed at better defining the content of the broaderpolitical agreement by tackling the root causes of the crisis. On 3 MarchIGADmediators announcedthe suspensions of the talks for two weeks , 'to allowthe parties to further reflect and consult on guiding documents of theprocess, as well as (...) to hear from civil society and ensure their views arereflected'. Other sources however stated that the talks were on the verge offailure.On 5 March gunfire erupted on the military barracks in Juba where theconflict started in December. While the situation is not yet clear, thisunderlines the importance of the first challenge for South Sudan: theimplementation of the agreement and maintaining peace. On 29 January,theAUunderscored that a Monitoring and Verification Mechanism set up byIGAD, will be operationalised soon to scrutinise the correct implementationof the agreement. On 2 February, IGAD deployed a team of 14 observers tomonitor the cease fire. A first preliminary report was sent on 7 February butits content is not yet known. Despite IGAD's efforts, the implementation ofthe agreement has seemed to be questioned every day since the signing ofthe ceasefire. Both sides have indeed repeatedly traded accusations that theother has violated the ceasefire deal. Attacks on 3 and 5 February on rebel-held positions in both Unity and Jonglei States notably at Leer, Machar'shometown, demonstrate the fragility of the ceasefire and the necessity forfurther talks between the two parties. Furthermore, it is not yet clear exactlyhow much control Riek Machar has over all the anti-government forces. On 3February 2014, Machar announced the creation of a new resistance forcecalled the SPLM/SPLA. Although he declared this movement will aim to movethe country towards democracy, free elections and good governance, it isunclear to what extent peaceful means will be used. Indeed, many on the11

Talks resumed on 11February to address theroot causes of the crisis.They were adjourned on3 March until 20 March.

Persistent attacksthreatened theimplementation of theagreement.

Disarmament and thewithdrawal of Ugandantroops will determineSouth Sudan's future.

Policy Department, Directorate-General for External Policies

Reconciliation anddemocratic reformsshould be the core of thegovernment's newstrategy.

rebel side are civilians who took up arms and who are not military disciplined.The existence of the White Army, a group of armed Nuer youths, couldconstitute a real threat to the preserving of peace since they may not want togive up arms. Disarmament should be very well controlled if both partiesseek restoration of peace and stability in the country. Second, the withdrawalof Ugandan troops represents an important element with regards to thequick implementation of the agreement considering that their presence isperceived as illegitimate by both the opposition and Ethiopia. Third, deliveryof humanitarian assistance must be secured and facilitated by theGovernment so that the population could have access to basic services again.On 5 February 2014,the UNannounced that the humanitarian crisis in SouthSudan had reached a 'level three emergency', the highest level under theUN's categorisation, putting the country on the same level to that of thehumanitarian situation in Syria.Regarding the medium and long-term process, it seems essential that in thecontext of 'an all-inclusive dialogue' between Kiir and Machar, the root causesof the crisis are addressed. The international community has also animportant role to play in defining the main priorities for the upcomingmonths and years. Reconciliation among South Sudanese leaders and ethniccommunities should be at the core of the new Government's strategy.Therefore, a national cohesion program should be adopted and a permanentConstitution recognising all ethnicities on an equal footing should beestablished so that trust among all South Sudanese citizens could be rebuilt.At the same time, South Sudanese leaders should address the organisationand the functioning of the period between now and the next elections,scheduled for 2015. A government of transition, gathering a broadendorsement, should be put in place and a reform of the ruling party shouldbe envisaged in order to solve the political divergences.

5

Outlook and policy options for the European ParliamentThe ceasefire agreement, signed on 23 January 2013 by the two parties,represents a sign that the situation in South Sudan may stabilise in theupcoming months. However, immediate – as well as medium- and long-term– challenges remain and must be addressed during the forthcomingnegotiations rounds.

To achieve a lastingpeace in South Sudan,the root causes of thecrisis should be tackledduring the comingmonths.

The European Parliament closely follows the evolution of the political,humanitarian and security situation in South Sudan. On 16 January 2014, theEP issued aresolutionaffirming its strong support of IGAD's mediation effortsin the peace talks, condemning the human rights abuses, calling for therelease of all political prisoners and urging the High Representative to re-establish a Special Representative for Sudan/South Sudan (this positionexisted, but was fused with that of the EUSR for the Horn of Africa inNovember 2013).The27thsession of the ACP-EU Joint Parliamentary Assemblyto be held inStrasbourg (France) from 17 to 19 March 2014 and theEU-Africaparliamentary pre-summitin Brussels (on 31 March and 1 April) constitute

12

South Sudan: The roots and prospects of a multifaceted crisis

opportunities for the EP to debate South Sudan's future and how the EU andAfrican states can contribute to the country's nation-building process. In thisregard, the European Parliament could consider the following policy options:In collaboration withAfrican states, the EPshould continuemonitoring the peaceprocess and thediscussions on SouthSudan's future.Underline the importance of the ceasefire agreement and stress theimportance of its rapid and genuine implementation by both sides. TheEP could also underscore the willingness of the internationalcommunity to remain involved in helping South Sudan face itsnumerous challenges and to define its immediate and long-termpriorities.Stress the importance of granting humanitarian access and ofrespecting UN neutrality.Reiterate the appeal for the establishment of a national cohesionprocess to treat all ethnic community as equals. A permanentconstitution should integrate such a principle in its text.Call for the re-establishment of the rule of law and governance in thecountry and demand that human rights abuses committed during theconflict be prosecuted. Political prisoners should be released. Atransitional government should also be endorsed and empowered asquickly as possible to ensure the delivery of basic public services.Express the need for a comprehensive and inclusive peace agreementthat also reforms institutional governance, including political parties,and that involves civil society. Note the importance of respectingpluralism and freedom of opinion.Stress the regional dimension. Commend IGAD's efforts and call for thewithdrawal of foreign troops to avoid escalation into a regional conflict.Monitor and support the organisation of general elections in 2015.With the agreement of the government, an EU and EP electionobservation mission could be sent. Later, the European Parliamentmight institute a parliamentary democracy mechanism to support localparliamentarians as they establish an effective institution that monitorsand balances the executive power.

13