Det Udenrigspolitiske Nævn 2013-14

UPN Alm.del Bilag 92

Offentligt

The Secretary General’sAnnual Report2013

Future NATO:towards the 2014 Summit

Foreword

I

n an unpredictable world, NATO remains anessential source of stability. Against the backgroundof an economic crisis, the new Strategic Conceptthat we adopted at our 2010 Lisbon Summit hasguided the continuous adaptation of the Alliance to meetthe demands of a fast-moving security environment. WhileNATO is now more effective and efficient than at any timein its history, we will need to maintain the momentum oftransformation at our next Summit in Wales in September.

In 2013, we worked with our global network of partnersto bring security where it is needed, and trained withthem to make sure that we maintain the ability to operatetogether. We also made steady progress in improving theway we work and the way we manage our resources,by reforming the NATO Command Structure, NATO’sAgencies, and our Headquarters in Brussels. Thesereforms will provide our taxpayers with greater securityand better value for money.Building on the strong foundation that we have laid, theWales Summit will deliver an Alliance that is ready, robustand rebalanced.The Summit will take place as we prepare to completeour combat mission in Afghanistan, and plan the launchof a new, non-combat mission to train, advise and assistthe Afghan security forces after 2014. In Afghanistan andour other operations, we have learnt many lessons thatwe need to apply to shape “Future NATO”.First, capabilities. We must invest in the capabilitieswe need to deal with the risks and challenges thatwe face, from terrorism, piracy and instability in ourneighbourhood, to missile and cyber attacks. I expectEuropean Allies to play their full part in developing criticalcapabilities, such as joint intelligence, surveillance andreconnaissance, heavy transport and missile defence.As our economies start to recover, we need to show thepolitical will to keep defence in Europe strong. This willalso keep NATO strong.Second, connectivity. ISAF brought together over onequarter of the world’s nations: 28 NATO Allies and22 partners in the largest coalition in recent history.Beyond 2014, our forces must stay connected, as Alliesand with partners, so that we stand ready to operatetogether when called upon. At the Wales Summit,we should commit to a broad programme of realisticexercises, demanding training and comprehensiveeducation as part of our Connected Forces Initiative.

Throughout 2013, NATO continued to protect our commonvalues and our shared security. The men and women of ourarmed forces showed constant courage, determination andprofessionalism in a wide range of deployments on land,in the air, and at sea. This Annual Report is, above all, atestimony to their service and sacrifice.In Afghanistan, we reached an important milestonein mid-2013, when Afghan forces assumed leadresponsibility for security across the country. Havingreached their full strength of 352,000 soldiers and police,their growing capability allowed ISAF to shift from acombat to a support role and prepare to complete itsmission at the end of 2014, as agreed at the Lisbonsummit. We also saw significant progress in Kosovo,where NATO is providing vital support to the EuropeanUnion-brokered agreement on the normalisation ofrelations between Belgrade and Priština.To continue fulfilling our core tasks effectively, weagreed at Lisbon to strengthen our defences against21st century challenges. And at our Chicago Summitin 2012, we adopted the Smart Defence mindset,through which Allies work together to acquirecapabilities more efficiently than they could on theirown. We have been working together in 29 differentcapability areas, ranging from precision-guidedmunitions to maritime patrol aircraft, and two projectshave already been completed. We also continued todevelop our own missile defence system, and enhanceour ability to defend against cyber attacks.

2

Finally, cooperative security. This is one of the pillars ofour Strategic Concept and a vital element of “FutureNATO”. At a time of global risks and threats, NATOmust continue to look outwards. We must deepen andwiden our unique network of political and operationalpartnerships with over 40 countries and organisationson five continents. One area of cooperative security thatoffers significant potential benefits for Allies and partnersis defence capacity building. We have unique expertise,acquired over years of active engagement, on securitysector reform, building defence institutions, developingarmed forces, disarmament and reintegration, which canadd value to broader international efforts. In 2013, weresponded positively to the request by the Libyan PrimeMinister for advice on the development of his country’ssecurity sector. I believe that similar support from NATOcould help others too, and enable us to project stabilityand help prevent conflict.As we prepare for the Wales Summit, we draw strengthand inspiration from the values that unite North Americaand Europe in a unique bond. The transatlantic

relationship remains the bedrock of our security andour way of life, and 2014 will bring that relationshipnew vigour and new vitality. A Transatlantic Trade andInvestment Partnership can give a real boost to theeconomic link between the United States and theEuropean Union, while the NATO Summit will reaffirmthe essential security link between our two continentsand our determination to share the responsibilities andrewards of security.As this Annual Report shows, over the past four yearswe have laid a firm foundation for the future. We set out aclear vision in our Strategic Concept, and we are turningit into reality. Our forces are more capable and connectedthan ever before. We have a record of achievement inchallenging operations and world-wide partnerships.And we are continuing to adapt to make NATO moreagile and more efficient. Our Wales Summit will build onthis foundation to shape “Future NATO”.■

Anders Fogh RasmussenNATO Secretary General

3

Active engagementBuilding security through operationsrises and conflicts beyond NATO’s borderscan pose a direct threat to the securityof Alliance territory and populations. WithNATO’s Strategic Concept adopted atthe Lisbon Summit in 2010, Allies agreed to engage,where possible and when necessary, to prevent crises,manage crises, stabilise post-conflict situations andsupport reconstruction.In 2013, NATO was actively engaged through operationsto enhance security and stability in the Euro-Atlanticarea and beyond. NATO-led missions and operationshave involved contributions from all 28 NATO membercountries and over 20 partners. From training securityforces in Afghanistan, to monitoring shipping in theMediterranean and countering piracy off the Horn ofAfrica to providing airlift in support of the African Union,ensuring stability in Kosovo, and providing Patriot missilesin support of Turkey, NATO forces were engaged overthree continents.

C

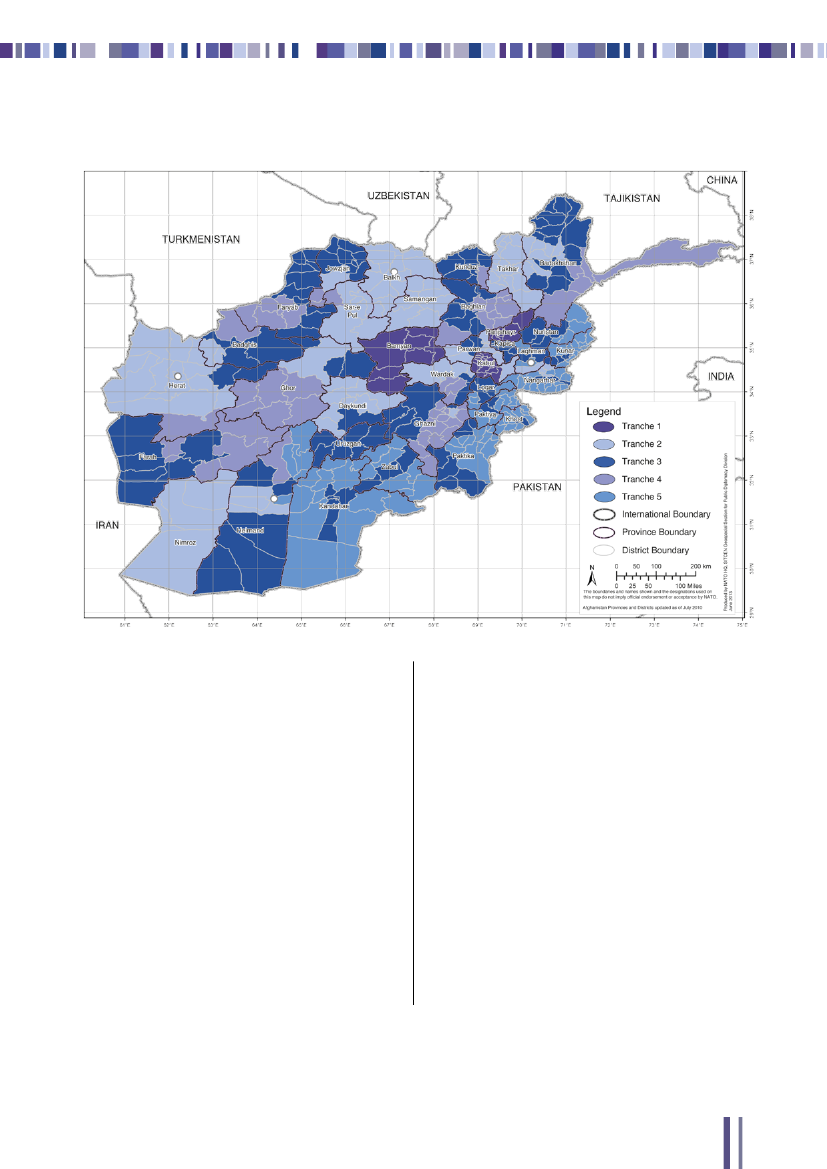

Afghans in the leadOn 18 June 2013, President Karzai announced the startof the fifth and final tranche of the security transitionprocess agreed in 2010. Afghan forces are in the leadfor security across the entire country. During the firstfighting season in which it has had the lead, the ANSFdemonstrated its capacity to provide security for theAfghan population. The ANSF conducted 95 per cent ofthe conventional operations and 98 per cent of specialoperations in Afghanistan. These achievements in 2013built confidence within the Afghan forces and among theAfghan people.

AfghanistanNATO and its partners in the International SecurityAssistance Force (ISAF) continue their commitment toAfghanistan, pursuing the same fundamental objectivethat has always underpinned the mission: to ensurethat the country never again becomes a safe haven forinternational terrorists.2013 was a year of progress and evolution forAfghanistan. At NATO’s Lisbon Summit in 2010,leaders of the countries contributing to ISAF, togetherwith the President of Afghanistan, launched theprocess of transition, whereby Afghanistan wouldsteadily take lead responsibility for its own security.They agreed on a clear timetable for handoverof security responsibility from ISAF to the AfghanNational Security Forces (ANSF) by the end of2014. Each year since then, the ANSF, which hasgrown to 352,000 soldiers and police, has taken onmore responsibility. And each year, ISAF’s role hascorrespondingly shifted from provision of security tosupport for the ANSF.

The Afghans are now firmly in the lead. And in line withthis shift in requirements and responsibilities, ISAFforces have begun to draw down. At the beginning of2013, approximately 105,000 personnel and 184 basesor facilities comprised ISAF’s presence in Afghanistan.By the end of the year, there were approximately75,000 personnel and 88 bases and facilities. At the endof 2013, the only unilateral actions taken by ISAF werefor its own security, for route clearance to maintain itsown freedom of movement, and for the redeployment ofequipment and vehicles no longer required.Similarly, Provincial Reconstruction Teams (PRTs), set up asone mechanism to channel development aid and assistancein Afghan provinces, are evolving and gradually closing aslocal Afghan authorities are able to take over responsibilityfor these efforts in each province. During 2013, the number

4

Afghanistan: transition tranches 1-5

of active PRTs was reduced from twenty-two to four. Theselast four PRTs will be closing in 2014.The ANSF, which includes the Afghan National Army(ANA), the Afghan National Police (ANP) and the AfghanAir Force (AAF), is now capable of a wide range ofoperations: large and small, ground and air, responsiveand preventive. In 2013, the Afghan forces led a number ofjoint and combined arms operations, including OperationSeemorgh, the largest such endeavour ever undertakenby the ANSF. During this operation the AAF and ANAworked together to support troop movements, re-supplyfielded forces, and conduct casualty evacuation acrossAfghanistan. While this kind of large-scale operation is notregularly called for in counter-insurgency, the skills involvedin planning and carrying out these operations can apply inpreparation for election support or in response to naturaldisasters and build confidence in and among the ANSF.Many of the challenges the Afghan forces face requiresmaller, specialised responses. With ISAF support, the

ANSF is working to ensure that it has the right toolsand structures to meet these challenges. Within theANP, for example, there are units specialised in counter-narcotics, counter-terrorism, and crisis response in urbanenvironments. Special operations forces within the ANAare trained to interact with local populations and includefemale soldiers, who are well-placed to interact withwomen and children.While ground forces comprise the majority ofAfghanistan’s security apparatus, airborne capabilitiesare an essential component of the ANSF. The size of theAfghan fleet grew during 2013 with the addition of twoC-130 transport aircraft and 12 Mi-17 helicopters that willenable Afghanistan to better support the movement oftroops and equipment throughout the country.

Training a sustainable forceWhen ISAF’s mission began in 2001, there were nounified Afghan National Security Forces. The ANSF now

5

includes approximately 350,000 personnel, consisting ofsix ANA combat corps, a special operations command,hundreds of ANP units and a growing air force. TheAfghan government has built structures and ministriesthat support and complement not only these forces butthe range of functions that contribute to the security andprosperity of any country.As agreed in 2010, ISAF has worked to prepareAfghanistan by training Afghan forces, advising Afghanofficials, and standing shoulder to shoulder with Afghansas they build the capabilities and gain the experiencethat will support their future security. During 2013, thefocus of ISAF support was on building the systems,processes and institutions necessary to make the gainsto date sustainable. This included capacity-building workwithin the government and in the military. As part of thissupport, 375 Security Force Assistance Teams providedadvice and assistance to Afghan army and police units,and training was provided to nearly 22,000 members ofthe Afghan forces.

and the lessons learned are incorporated into the trainingthat their forces receive.Because of threats posed by improvised explosivedevices (IEDs), NATO has developed methods to detectand destroy these weapons. Throughout 2013, NATOimproved its ability to detect and neutralise IEDs, clearaffected routes and protect vehicles, personnel andstructures. These lessons are also being adopted by theANSF and incorporated into their training. Compared tothe 2012 fighting season, the 2013 fighting season inAfghanistan saw a 22 per cent drop in IED incidents.

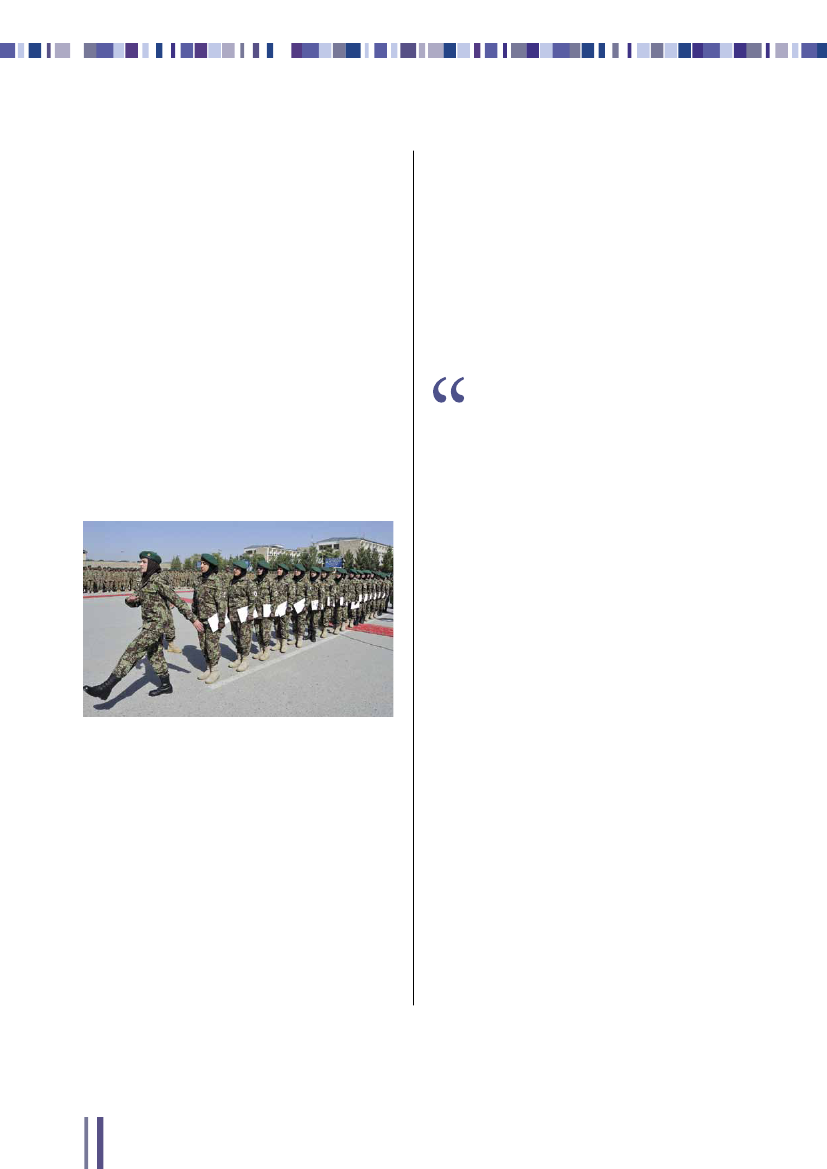

In 2013, over 90 per centof training was providedby the AfghansIn addition to instruction on technical skills and sharingof lessons learned, Afghan forces and ministries receivedtraining related to the international norms endorsed bythe United Nations (UN), including on human rights andgender sensitivity.ISAF and the Office of the NATO Senior CivilianRepresentative work with Afghan security ministries,with the international community and with local andinternational non-governmental organisations tocoordinate efforts aimed at women’s empowerment.In 2013, ISAF welcomed its highest-ranking genderadviser, a brigadier general, who will help to consolidatethese efforts and support further progress. ISAF alreadyincludes training on gender issues for the ANSF andsupports the recruitment and retention of women in thesecurity sector. There are currently over 2,000 womenin the ANSF, a 10 per cent increase since 2012.In preparation for the 2014 elections, ISAF is working withAfghan officials to ensure that there are sufficient numbersof female personnel to support the voter registrationprocess and to provide support at the polling stations.The ANSF has become an organised and professionalforce, with progress outpacing earlier estimates, and hasachieved impressive standards in a short time under difficultcircumstances. While violent incidents, including high-profileattacks, continued in 2013, the Afghan forces demonstratedthat they can react to those incidents quickly, efficiently, andincreasingly without direct ISAF assistance.

Photo: MCpl Frieda Van Putten, Canadian Armed Forces

As the Afghan forces are increasingly capable ofproviding security, they are also providing more of theirown training. In 2013, over 90 per cent of training wasprovided by the Afghans, often in their own languages.And as transition continues, the structures through whichNATO provides training are also being adapted. Since2009, the NATO Training Mission in Afghanistan (NTM-A)has served as the umbrella for NATO and nationalinstitutional training efforts; in 2013 it was integrated intothe ISAF Joint Command.Part of what NATO offers through its training is lessonsfrom its own experience. During over a decade inAfghanistan, ISAF has worked to prevent civiliancasualties. That experience is shared with the Afghans

6

Looking aheadThe conclusion of ISAF at the end of 2014 will markthe opening of a new chapter in NATO’s relationshipwith Afghanistan. At the Chicago Summit in 2012, theAfghan government welcomed NATO’s offer to deploya follow-on mission when ISAF concludes. The aim ofthis new mission, Resolute Support, is to continue tosupport Afghanistan as it develops the self-sustainingcapability to ensure that it never again becomes a safehaven for international terrorism.At the meeting of NATO Defence Ministers in June2013, a detailed concept for the new mission wasendorsed, which guides NATO military experts in theiroperational planning. Resolute Support will not be acombat mission; this train, advise, and assist missionwill focus its efforts on national and institutional-leveltraining, to include the higher levels of army and policecommand. Provided that a proper legal framework is inplace, Resolute Support will begin in January 2015.Beyond ISAF and the planned Resolute Supportmission, NATO is building a formal partnershipwith Afghanistan, working on a range of issuesthat contribute to the development of a stable andprosperous country. In 2013, areas of cooperationincluded development of the civil aviation sector,facilitation of internet connectivity for Afghan universities,support for programmes to develop professionalmilitary education, and efforts to build integrity in themanagement of ministries. This Enduring Partnership,announced at the Lisbon Summit in 2010, is the basisupon which NATO is widening its cooperation withAfghanistan, developing a partnership similar to thosethat NATO has with numerous other countries as part ofthe Alliance’s efforts toward cooperative security.NATO’s partnership with Afghanistan is based onmutual respect and accountability. The internationalcommunity, of which NATO is a part, has made anenormous investment in Afghanistan and has pledgedits long-term support. In return, the Government ofAfghanistan has also made clear commitments: to holdinclusive, transparent and credible elections; to fightcorruption and improve good governance; to upholdthe constitution, particularly as regards human rights;and to enforce the rule of law. The ongoing efforts of theGovernment of Afghanistan to meet its commitmentswill pave the way for the continued support of theinternational community in the years to come.

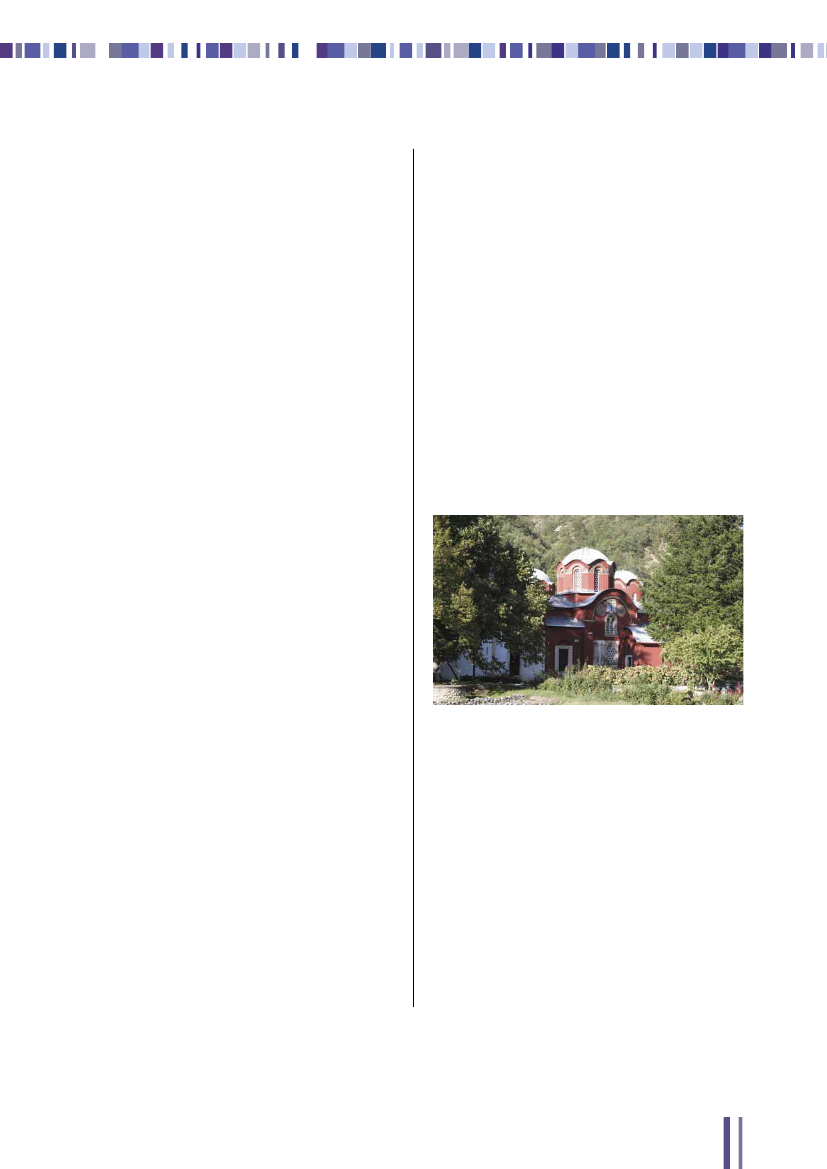

Kosovo2013 was a year of progress toward creating a more secureenvironment in Kosovo, where NATO and its operationalpartners continue to fulfill the UN-mandated mission. Thebenefits of that secure environment are increasingly evident.Belgrade andPrištinasigned a landmark agreement on19 April 2013, providing a political way forward to overcomepersistent disagreements. The agreement, facilitatedby the European Union, covers a wide range of issuessupporting a normalisation of relations and improvementsin the northern part of Kosovo. NATO played an importantrole in this agreement, with both parties requesting thatNATO support the implementation. The NATO-led KosovoForce, KFOR, remains a key enabler of the political process,providing guarantees to both parties of a safe and secureenvironment. When there were attacks on polling stationsin north Mitrovica in November, KFOR deployed quickly tothe area, later supporting a re-run of the elections. KFORalso ensured freedom of movement on the routes used totransport election ballots to the counting centre.

The process of “unfixing” properties with designated specialstatus in Kosovo – transferring their protection from KFORto local authorities – continued in 2013. In September,the responsibility for the protection of the Serb OrthodoxPatriarchate inPeć/Pejawas transferred from KFOR to localKosovo police forces. The Patriarchate was the eighth siteto be unfixed, from nine sites originally designated.In July 2013, the North Atlantic Council declared fulloperational capability of the Kosovo Security Force (KSF).The KSF is a multi-ethnic, civilian-controlled, lightly armedprofessional force. Unlike the police, the KSF is primarilyresponsible for civil protection, disposing of explosiveordnance, fire fighting and other humanitarian assistancetasks. The Alliance continues to support the KSF inthis new phase of its development and will continue tosupport peace in Kosovo according to the UN mandate.

7

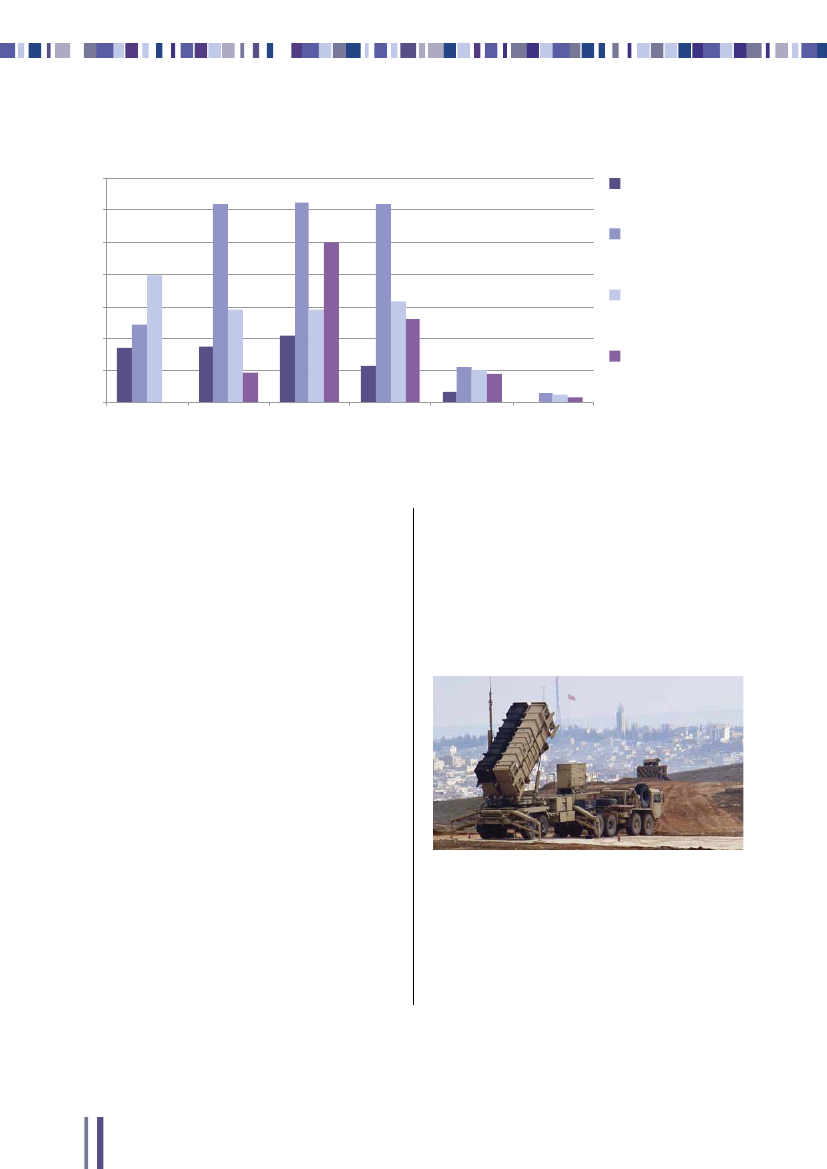

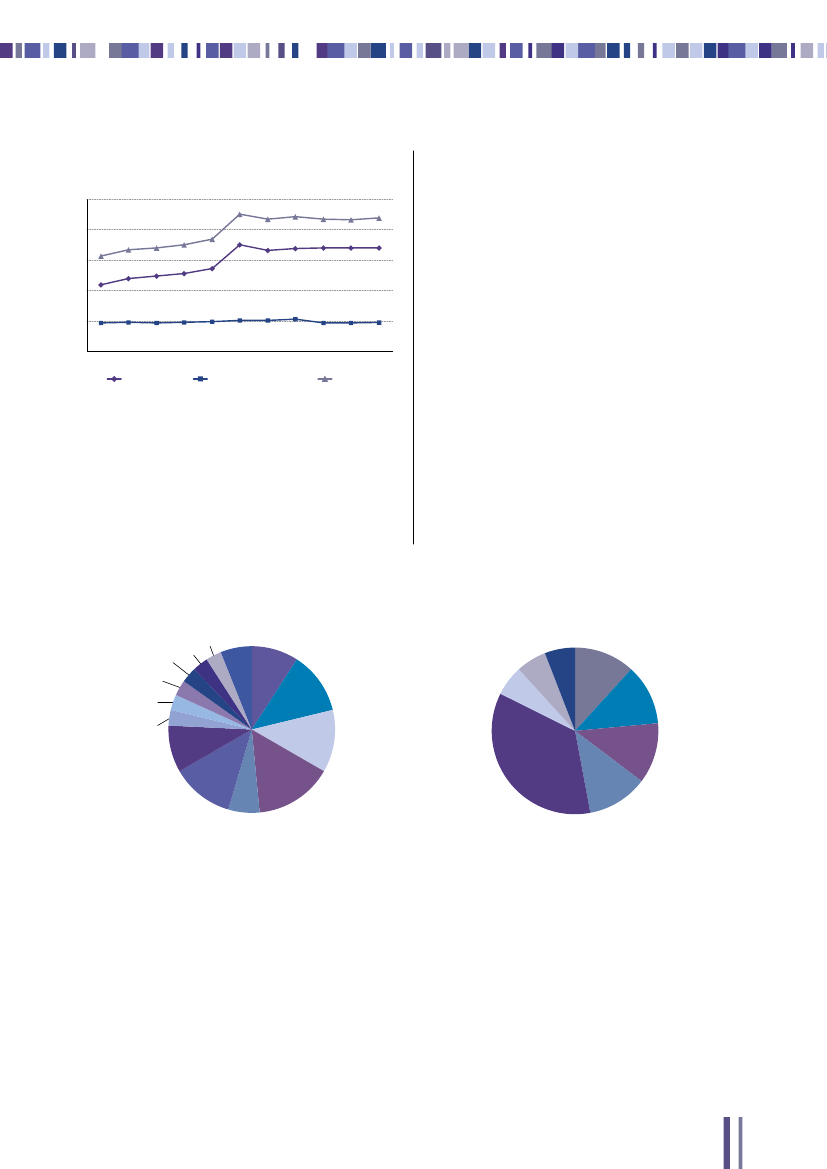

140120100806040200200820092010

Piracy incidents2008-2013Pirated - Where piratesgain control of the vesseland crew.Attack - Where piratesfire at or make contactwith a vessel in an attemptto board.Approach - Where the visibilityof weapons and ladders meanspirate intent is clear, but an attackis not conducted.Disruption - Where militaryforces intercept a pirategroup and removetheir capability to conductfurther acts of piracy.201120122013

Note: Disruptions in this chart occurred before pirates could attack or approach a vessel. Disruptions after piracy incidents are not included since that would imply more pirate activity than was actually occurring.Figures for piracy incidents involve vessels greater than 300 tons engaged on international voyages as defined in Regulation 19 of Chapter V of the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) Convention of theInternational Maritime Organization.Statistics provided by NATO's Maritime Command Headquarters, Northwood, United Kingdom − the command leading NATO's counter-piracy operation.

Counter-piracy2013 marked a significant reduction in pirate activityoff the Horn of Africa and in the Gulf of Aden. Therewere no successful attacks in the area in 2013. Thepresence of the international navies off the coastof Somalia has been a determining factor, togetherwith measures taken by the international merchantshipping community.With the global annual impact of Somali piracyestimated at US$18 billion by the World Bank, effortsto counter piracy are an important investment.Throughout 2013, NATO continued to deter anddisrupt pirate attacks and protect vessels in the region,working closely with other international actors. In theframework of Operation Ocean Shield, NATO forcescooperate with the EU-led Operation Atalanta, withUS-led Combined Maritime Forces, and with countriessuch as China, Japan and Russia. This collective efforthas allowed the international community to maintainpressure on Somali pirates and strengthen partnershipsin the maritime domain.While these efforts have yielded positive results in theshort term, they cannot address the root causes ofpiracy ashore. For a lasting solution, more work needsto be done in the area of regional capacity-building.Although not in the lead in these efforts, NATO iscommitted to continuing to provide expertise in this field.

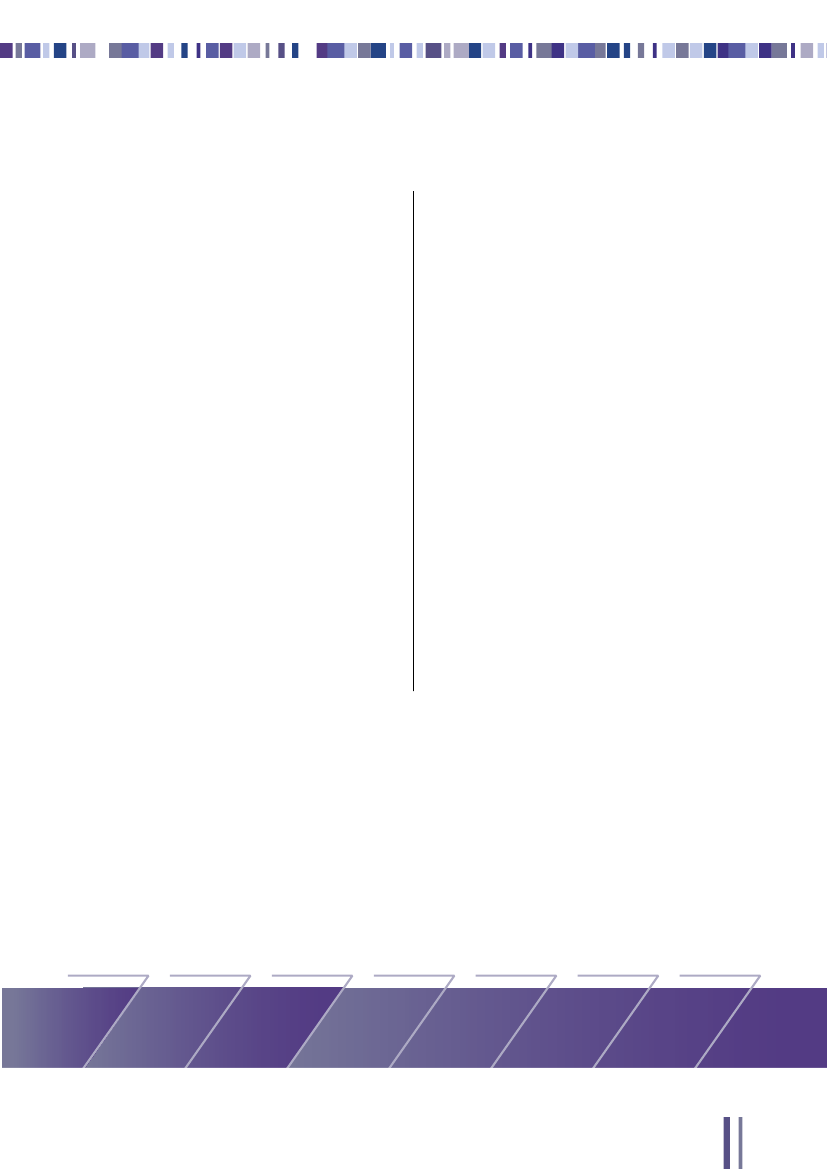

NATO support to TurkeyIn November 2012, repeated violations of Turkey’s territoryfrom Syria, along NATO’s southeastern border, led to arequest from Turkey for Alliance support. NATO ForeignMinisters agreed to deploy Patriot missiles to augmentTurkey’s air defence capabilities, helping to defend andprotect Turkey’s population and territory and to contributeto the de-escalation of the crisis along NATO’s border.

By early 2013, six defensive Patriot missile batterieswere operational in Turkey helping to protect Turkishcitizens from possible ballistic missile attacks. As part of aregular review of deployment in November, Allies agreedto maintain this support in 2014. The command andcontrol of the Patriot missile batteries rests with the NATOCommand Structure, and NATO continues to keep thesituation in Syria under close review.

8

Broadening partnerships for global securityToday’s global challenges require a cooperativeapproach to security. Complementing the closerelationships among NATO member countries,partnerships are an increasingly important part of theAlliance’s core business. NATO has actively engagedwith partners for over two decades. As the securityenvironment has evolved, and as the number ofcountries and institutions working with NATO hasgrown, so have the Alliance’s approaches to andmechanisms for working with partners.In 2010, NATO leaders agreed that the promotion ofEuro-Atlantic security is best assured through a widenetwork of partner relationships with countries andorganisations around the globe. They recognised thevalue of partners’ contributions to operations andthe importance of giving those partners a structuralrole in shaping strategy and decisions on NATO-ledmissions to which they contribute.To expand the areas of cooperation with partnercountries and organisations and facilitate increaseddialogue, Allies endorsed a new partnership policyin 2011. Since then, one of NATO’s aims hasbeen to improve flexibility so that partners caneasily join political consultations and integrate intoNATO operations on the basis of their individualinterests and their specific capabilities. In 2013,NATO engaged with more partners in moresubstantive areas than ever before.

Extending partnership networksMiddle East and North AfricaThroughout 2013, the Alliance’s engagement in theMiddle East and North Africa continued to developthrough and beyond the established frameworks of theMediterranean Dialogue and the Istanbul CooperationInitiative. In October, following preparatory discussionsamong experts in Tripoli and Brussels, NATO DefenceMinisters agreed to respond positively to a request forassistance from Libya. Specifically, Libya asked NATOto assist the country in strengthening its security anddefence sector. This engagement signals the Alliance’scommitment to projecting stability in its neighbourhoodby helping to build local capacity and foster accountableand effective security institutions.In September, NATO and Djibouti agreed to developcloser cooperation that includes the establishment ofa liaison office in support of NATO’s counter-piracyoperation, Ocean Shield. Despite civil unrest in Egypt,NATO continued its training programme in landminedetection. And NATO is working with Mauritania toestablish a national operational coordination centre tostrengthen national civil protection services.

Asia-PacificIn 2013, NATO continued to build its relations with keypartners in the Asia-Pacific. In April, NATO and Japan

NATO adopts abroader approachto partnership inits new StrategicConcept, openingthe way to deepercooperation witha wider networkof partners.NATO andAfghanistan signa Declarationon EnduringPartnership.

Five non-NATOcountriesparticipate inthe NATO-ledoperation, UnifiedProtector, inLibya: Jordan,Morocco, Qatar,Sweden andthe United ArabEmirates.

NATO launchesa more flexiblepartnership policyand operationalpartners aregiven a greaterrole in shapingdecisions relatedto the operationsto which theycontribute.

ISAF troopcontributorMongolia adoptsa programmeof cooperationwith NATOcovering areassuch as crisismanagement,capacity-building andinteroperability.

Leaders fromthe 50 countriescontributingto ISAF, joinedby PresidentKarzai andrepresentativesfrom Russia,Japan, Pakistan,Central Asianstates, the UNand the EU, meetduring NATO’sChicago Summit.

New Zealandfocuses oncyber defence,disaster relief,crisis managementand joint educationand training in itsnew programmeof cooperationwith NATO.

NATO andAustralia committo developinga strongerrelationship throughthe signing ofa Joint PoliticalDeclaration and,later, adopt anew cooperationprogramme.

r

ril

e

rch

be

rch

Ma

Jun

Ma

2010

Nov

em

2011

2012

Ma

Jun

Ap

e

y

9

signed a Joint Political Declaration, highlighting theirshared strategic interests in promoting global peace,stability and prosperity, and outlining areas for increasedcooperation. NATO and Japan cooperate broadly inAfghanistan, where Japan has been a catalyst for andleading provider of financial support and developmentassistance. Other areas of cooperation includecoordination in crisis management and in dealing withchallenges including disaster relief, terrorism, piracyand cyber attacks. April 2013 also marked the first visitof a NATO Secretary General to the Republic of Korea,a valuable contributor to the ISAF mission which is alsointerested in expanding cooperation with the Alliance.NATO’s partnerships in the Asia-Pacific are groundedin a global perspective of today’s security challenges.NATO’s partners in the Asia-Pacific region, which alsoinclude Australia, New Zealand, and Mongolia, havebeen valuable troop contributors to the InternationalSecurity Assistance Force (ISAF) in Afghanistan. Buildingon these experiences in the field, NATO coordinates withthese partners to retain the ability to work together inoperations while expanding cooperation in other areas,including counter-terrorism and cyber defence. Theseinitiatives complement expanding NATO ties to othercountries of the Asia-Pacific region, including Malaysiaand Singapore. Senior staff from NATO and Chinacontinued their informal security dialogue in 2013.

Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia*, and Georgia. In2013, good progress was made in implementing thereforms necessary to meet the Alliance’s standards,even if further progress is required for these countries toachieve their membership aspirations. Specific areas ofwork include: registering immovable defence propertiesas state property in Bosnia and Herzegovina; bringingsecurity agencies up to NATO standards and addressingcorruption in Montenegro; and continuing progress towardcivilian and military reform goals as set out in the AnnualNational Programme in Georgia. An invitation to the formerYugoslav Republic of Macedonia* will be extended as soonas a mutually acceptable solution to the issue over thecountry’s name has been reached with Greece.

RussiaThe 2010 Lisbon Summit launched a new phase inrelations between NATO and Russia, with agreements todo more together on Afghanistan, enhance training oncounter-narcotics, and fight terrorism. In 2013, practicalcooperation grew, despite continuing disagreements ona number of issues including missile defence. Russiacontinued to provide important transit facilities for NATOand partner forces in Afghanistan, and progress wasmade in counter-narcotics cooperation. NATO andRussia also sustained their joint support to the AfghanAir Force through the NATO-Russia Council HelicopterMaintenance Trust Fund. In April, the second phase ofthe project expanded the support provided to the Afghanforces, and at the end of 2013, 40 Afghan maintenancestaff had completed initial training.* Turkey recognises the Republic of Macedonia with its constitutional name.

Countries aspiring to join NATOParticularly close relationships are maintained with thefour partner countries that aspire to NATO membership– Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, the former

The Republicof Korea andNATO step upcooperationwhile, in parallel,Seoul continuesto contributeto ISAFin Afghanistan.

Iraq formallyenters NATO’spartnership familywith the signingof a cooperationaccord withthe Alliance.

First-ever visitof a NATOSecretary Generalto the Republic ofKorea.

Japan– a long-standingcontributor anddonor to NATOoperations –signs a JointPoliticalDeclaration withthe Alliance.

The helicoptermaintenanceproject funded byNATO and Russiais expanded tohelp the AfghanAir Force developthe ability tooperate andmaintain its fleetof helicoptersindependently.

Military-to-militarycooperation isstrengthenedwith Pakistan.

The NATOSILK-Afghanistaninternetconnectivityprogramme shiftsfrom satelliteto fibre-opticcommunications.

mber

mber

ril

ril

ril

y

Ma

Ap

Ap

pte

Se

Se

pte

2013

10

Ap

Ma

y

In December 2013, NATO and Russia agreed to launcha new trust fund project for the safe disposal of obsoleteand dangerous ammunition in the Kaliningrad region. Thefirst phase will focus on the disposal of tens of thousandsof obsolete bombs and shells, making the area saferfor those who live there and creating the conditions forformer military sites to be converted to civilian use.

International organisationsCooperation with other international organisations hasbecome integral to NATO’s crisis management. In 2013,the Alliance worked to reinforce links with other keyregional and global institutions. In September, NATO andthe United Nations (UN) marked five years of enhancedpartnership since the signing of the Joint Declarationon UN/NATO Secretariat Cooperation in 2008. Thesefive years have been characterised by growing practicalcooperation and an increasingly effective politicaldialogue between the two organisations to supportregional capacity-building and crisis management, with astrong focus on Afghanistan.NATO and the European Union continued their closecooperation in 2013. In December, NATO’s SecretaryGeneral addressed the European Council during theirmeeting on defence. This was the first address by aNATO Secretary General to the European Council. Thishigh-level engagement was matched by cooperationon the ground in Afghanistan, Kosovo, and Bosnia andHerzegovina; structured dialogue continued at the stafflevel to exchange information and avoid duplication.Similar staff-to-staff contacts also continued with theOrganization for Security and Co-operation in Europeand with a number of other key organisations, such asthe League of Arab States, the Gulf Cooperation Council,and the International Committee of the Red Cross.NATO’s planning and capacity-building support to theAfrican Union Mission in Somalia also continued in 2013,including with a small NATO military liaison team at theAfrican Union Headquarters in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Photo: NATO-Russia Council

Further progress was made on counter-terrorism. InSeptember, NATO and Russian fighter aircraft flewtogether during a live counter-terrorism exercise, VigilantSkies 2013, where the capacity to respond to the hijackingof civilian aircraft in mid-air was tested. This was preceded,in early summer, by the testing in real-life conditions of theSTANDEX project technology developed jointly by NATOand Russian scientists to detect explosives concealedon suicide bombers in public spaces with particularlyhigh transit rates such as airports and train stations. Thistechnology is now under commercial development.

NATO and theUN join effortsin supportingchildren affectedby armed conflictand launchan e-learningtraining course toraise awarenessamong troops.

The North AtlanticCouncil visitsGeorgia, which isa top non-NATOtroop contributorin Afghanistan.

Ukraineengages in themodernisationof its militaryeducation, inpartnership withNATO. Of themany educationalprogrammes theAlliance embarkson with partnercountries, thisone is by farthe biggest.

Djibouti andNATO decide todevelop closercooperation inefforts to fightpiracy, includingthrough theestablishment ofa liaison office.

Russia andseveral NATOmembers testtheir real-timecapacity todetect and directthe response toa civilian aircrafthijacked byterrorists in theair, in exerciseVigilant Skies.

A Ukrainianfrigate joinsOperation OceanShield off theHorn of Africa –the first time apartner countrydeploys as part ofNATO’s counter-piracy operation.

NATO agreesto establish anadvisory teamspecialisedin defenceinstitution buildingfor Libya, atthe requestof the LibyanPrime Minister.

mber

mber

er

Jun

Jun

Ju

tob

pte

pte

Oc

Se

2013

Se

Oc

tob

er

e

e

ly

11

Remaining connectedIn 2013, the Alliance updated its Political-Military Frameworkwhich ensures that partners can participate more effectivelyin Allied assessments, planning, and decision-making oncurrent and potential operations. This and other measuresbuild on the experiences of partner country involvement inNATO-led operations in Afghanistan, Kosovo, Libya andthe counter-piracy operation, Ocean Shield. Through theseexperiences, NATO and its operational partners improvedtheir political consultations and gained higher levels ofinteroperability. To secure these gains, NATO’s partnerswill be more systematically integrated into NATO’s regulartraining and exercise programmes.As part of these efforts, NATO is fostering partnerparticipation in the NATO Response Force (NRF), NATO’srapid-reaction force. In 2013, Sweden joined the NRFalongside Finland and Ukraine, while Georgia pledged tomake forces available to the NRF in 2015. In the autumn,four partners participated in the Alliance’s largest exerciseof the last seven years, Steadfast Jazz, which served tocertify the NRF rotation for 2014.Partners also participated in other major exercises in2013. One example is Capable Logistician, which wassponsored by the Czech Republic and conducted inSlovakia in June 2013. Thirty-five countries, includingnine partner countries, participated in this major logistics

field exercise that addressed support activities asdiverse as movement and transportation, water supply,infrastructure engineering and smart energy.

NATO’s partners willbe more systematicallyintegrated into NATO’sregular training andexercise programmesEducation is another area where cooperation expanded in2013. Through its training programmes, NATO is helpingto support institutional reform in partner countries. Initially,these programmes focused on increasing interoperabilitybetween NATO and partner forces. They have expandedto provide a means for Allies and partners to collaborateon how to build, develop and reform educationalinstitutions in the security, defence and military domains.NATO has developed individual country programmeswith Afghanistan, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Iraq,Kazakhstan, Mauritania, Moldova, Mongolia, Serbia,Ukraine and Uzbekistan.■

In a joint effort toprevent suicideattacks in publicareas, NATO andRussian expertscomplete thefirst phase of aproject for thereal-time stand-off detectionof explosives(STANDEX).

Finland, Sweden,the formerYugoslav Republicof Macedonia*and Ukraineparticipate inSteadfast Jazz,a large-scale jointexercise aimed attesting the NATOResponse Force.

NATO supportsthe OSCE inrunning themunicipalelections inKosovo.

First address by aNATO SecretaryGeneral to theEuropean Council.

er

r

r

be

be

tob

em

em

Oc

* Turkey recognises the Republic of Macedonia with its constitutional name.

12

Dec

Nov

Nov

em

be

r

Modern defence

S

ince the end of the Cold War, NATO’s forces haveundergone a dramatic transformation. Armour-heavyland forces previously prepared for the defenceof continental Europe are now capable of beingdeployed and sustained over great distances in diverse rolesand in challenging, often unfamiliar environments. Many havebeen re-equipped with wheeled armoured vehicles that havegreater mobility, as well as protection against land mines andimprovised explosive devices. A new generation of mediumtransport helicopters facilitates the rapid movement of groundforces and their supplies.

larger, longer-range transport aircraft and air-to-air refuellingtankers to give combat aircraft longer reach. Allied navieshave improved their capacity for long-term deploymentsand for supporting joint operations from the sea as a resultof the development and introduction into service of larger,more capable aircraft carriers and large amphibious ships.All services are also better integrated to contribute toa comprehensive approach to stabilisation operations.These efforts to make NATO forces more deployable,flexible and agile have accelerated in recent years withthe NATO-led operation in Afghanistan, Operation UnifiedProtector in Libya and the counter-piracy operation,Ocean Shield. It will be essential for Allies to maintainthese hard-won gains in deployability as the operationaltempo varies in the years to come.

Allies’ air forces, once tied logistically to their homeairbases, are now able to quickly deploy overseas. Thisis due, in part, to the acquisition of deployable airbaselogistic support modules, as well as the procurement of

Smart solutions to security challengesDelivering modern defence requires securing cutting-edge capabilities and training forces to operateseamlessly together. With the agreement of the StrategicConcept in 2010, Allies affirmed the primacy of theircommitment to defence of Allied territory and populationsand deterrence against potential threats. To ensurethe credibility of this commitment, Allies pledged tomaintain and develop a range of capabilities. Acquiringthese capabilities and forces in a climate of prolongedausterity is not easy but remains essential. Through aseries of initiatives, NATO is on track to provide innovativesolutions to deliver a modern defence.In 2011, the Secretary General launched the SmartDefence initiative, promoting prioritisation, specialisationand multinational approaches to acquisition. At theChicago Summit in 2012, NATO Heads of State andGovernment endorsed the initiative and agreed ona package of 22 Smart Defence projects. They alsoendorsed the Connected Forces Initiative (CFI) to sustainand enhance the high level of interconnectedness andinteroperability Allied forces have achieved in operationsand with partners. In 2013, Allies completed two SmartDefence projects, broadened the portfolio of projects, andmade considerable progress on those already underway.Within the framework of CFI, Allies began to implementplans to revitalise NATO’s exercise programme.In 2010, Allies adopted a package of critical capabilitiesthat included the Alliance Ground Surveillance (AGS)system, enhanced exchange of intelligence, surveillanceand reconnaissance data, and improved defencesagainst cyber attacks. NATO leaders also agreed todevelop the capability to defend their populationsand territories against ballistic missile attack. Steadyprogress has been made in each of these areas. In 2012,the procurement contract was signed for AGS, Alliesendorsed an initiative on Joint Intelligence, Surveillance,and Reconnaissance (JISR), improvements were made toNATO’s cyber defence capabilities, and Allies declared aninterim NATO ballistic missile defence capability. In 2013,the first NATO AGS aircraft was produced, JISR conceptswere refined and advanced, NATO’s Computer IncidentResponse Capability was improved, and the commandand control structures for NATO’s missile defence systemwere enhanced.

13

NATO Forces 2020At the Chicago Summit in 2012, NATO adopted the goalof NATO Forces 2020: a coherent set of deployable,interoperable and sustainable forces equipped, trained,exercised and commanded to operate together andwith partners in any environment. Two key programmessupport this goal: the Smart Defence initiative and theConnected Forces Initiative.With the Smart Defence initiative, NATO provides aframework for using scarce resources more efficiently bypromoting the joint acquisition of important capabilities.This approach builds on existing mechanisms forcooperation among Allies, and promotes prioritisation,specialisation and multinational approaches to acquisition.The Connected Forces Initiative is another catalystfor achieving a modern defence and deliveringNATO Forces 2020. While Smart Defence addressesthe acquisition of some of the key capabilities requiredby the Alliance, the Connected Forces Initiative focuseson the interoperability of NATO’s forces – their ability towork together. It aims to ensure that Allies and partnersretain the benefits of the experience gained while workingtogether during multinational deployments to Afghanistan,Libya, the Horn of Africa and the Balkans.In addition to these initiatives, NATO is pursuingprogrammes to improve its capabilities in certain keyareas – specifically in the fields of intelligence, surveillanceand reconnaissance (ISR) capacities, ballistic missiledefence, and cyber defence.

Launched in early 2011, Smart Defence has begun todeliver concrete savings for NATO Allies. Two projectswere completed in 2013. Through the US-led HelicopterMaintenance project, Allies work collectively to maintaindeployed helicopters in Afghanistan instead of maintainingthem individually. Participating countries report savingmillions of euros in maintenance costs while reducingrepair time by up to 90 per cent. The other Smart Defenceproject completed in 2013 facilitates proper disposal ofmilitary equipment that countries no longer need. TheNATO Support Agency has developed a way for countriesto use off-the-shelf legal and financial tools that significantlyreduce the costs of disposal. The clear benefits of thesecoordinated approaches have motivated national andNATO officials to pursue collective solutions in other areas.

Smart Defence hasbegun to deliver concretesavings for NATO AlliesIn 2013, Allies broadened the portfolio of Smart Defenceprojects and made considerable progress on a number ofprojects already underway.Multinational Cyber Defence Capability Development:thisproject improves the means for sharing technical informationand promotes awareness of threats and attacks. Participatingcountries signed a Memorandum of Understanding in 2013,providing the basis for future progress.Pooling CBRN Capabilities:this project will pool existingchemical, biological, radiological and nuclear (CBRN)protection equipment and forces to create a multinationalCBRN battalion framework and conduct multinationaltraining and exercises. Several CBRN projects exist and areorganised around different regional groupings. They aim togenerate synergies and increase interoperability.Multinational Aviation Training Centre:building onoperational experience gained in Afghanistan, this projectwill provide top quality training for helicopter pilots andground crews. The training will focus on the deploymentof helicopter detachments in support of NATO operations,as well as preparing Aviation Advisory Teams that providetraining for the Afghan National Security Forces.Multinational Military Flight Crew Training:this projectaims to rationalise pilot training to reduce costs, as well

Smart DefenceMany of the modern defence capabilities required to facetoday’s challenges are extremely expensive to develop andacquire. It is increasingly prohibitive for individual Allies toobtain specific capabilities on their own. Moreover, it doesnot always make good economic sense for an individualAlly to acquire these expensive technologies when thereare mechanisms available for a cooperative approach.NATO’s Smart Defence initiative builds on the strengthsof the Alliance to deliver essential capabilities whilereducing unit costs. Drawing on existing mechanisms,it aims to better coordinate defence efforts by aligningnational and Alliance capability priorities. And it providesa platform for Allies to build on their individual strengthsthrough coordination with the Alliance and each other, thusachieving specialisation by design rather than by default.

14

as the number of training facilities required by Allies.It will facilitate closer cooperation and ultimatelyimproved interoperability.Multinational Joint Headquarters Ulm:this project istransforming an existing German joint command intoa deployable multinational joint headquarters. Officiallyopened in July 2013, it addresses NATO’s deployableheadquarters needs in a multinational context, facilitatingenhanced coordination while reducing costs.Pooling Maritime Patrol Aircraft:by pooling a range ofmaritime patrol aircraft capabilities owned by Allies, thisproject will allow more flexible use of assets. It will lead toa more efficient allocation of assets to specific missionsand tasks and continued access to this capability for Alliesthat are significantly reducing their inventories. A technicalagreement has been in place since January 2013 andthe handover to Allied Maritime Command (Northwood,United Kingdom) for activation is scheduled for July 2014.NATO Universal Armaments Interface:in 2013, furtherprogress was made to standardize weapons integration onfighter aircraft. This project will provide Allies with greaterflexibility for using ammunition in operations. In addition, itwill reduce future costs, increase interoperability and reducethe time needed for the integration of new weapons.NATO plans to build on initial achievements, pursuingprojects at the high end of the capabilities spectrum. In thisrespect, at their meeting in October 2013, NATO DefenceMinisters discussed the capability areas they would like todevelop in the context of more demanding Smart Defenceprojects. This work will continue into 2014 and beyond.

allow countries to continue to develop their operationalcompatibility, and provide an opportunity to test and validateconcepts, procedures, systems and tactics. Allies are alsoencouraged to open national exercises to NATO participation,adding to the opportunities to improve interoperability.CFI includes a technology element to ensure that Alliesidentify and exploit advances in this area. It encompassesa range of solutions to seamlessly connect forces duringtraining, exercises and, most importantly, when workingside-by-side in operations. For instance, building onNATO’s Afghan Mission Network, which interlinks thecommunication and information systems of Allied andpartner forces in Afghanistan, NATO is developing a FutureMission Network, which will ensure that NATO has asimilar capability for all of its future operations. This projectexemplifies the underlying logic of CFI – to preserve thegains achieved in operations as the Alliance moves forward.NATO has already begun to increase the scope ofmultinational exercises. In November 2013, NATOconducted its largest live exercise since 2006 in a collectivedefence scenario. Steadfast Jazz brought togetherthousands of personnel from Allied and partner countries totrain, test, and certify the units serving in the 2014 rotationof the NATO Response Force (NRF). This exercise wasconducted at sea, in the air, and on the territories ofEstonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Poland. It incorporated aheadquarters component provided by Allied Joint ForceCommand Brunssum (The Netherlands) to test the newNATO Command Structure.Allies agreed in 2013 to hold a large NATO exerciseafter the conclusion of the ISAF mission in Afghanistan.This major exercise involving partners will take place in2015 and will be hosted jointly by Spain, Portugal andItaly. A comprehensive programme of exercises is beingdeveloped for 2016 and beyond.

Connected Forces InitiativeThe Connected Forces Initiative (CFI) aims to enhancethe high level of interconnectedness and interoperabilityAllied forces have achieved in operations and withpartners. CFI combines a comprehensive education,training, exercise and evaluation programme with the useof cutting-edge technology to ensure that Allied forcesremain prepared to engage cooperatively in the future.In February 2013, NATO Defence Ministers endorsed plansto revitalise NATO’s exercise programme; implementationbegan in October. These plans set the course for a morerigorous multi-year training schedule to ensure NATO andpartner forces retain the ability to work efficiently together.They broaden the range of exercise scenarios and increasethe frequency and the level of ambition of exercises. This will

15

NATO Response Force rotations2003-2013Land component HQDNK5%FRA5%TUR19 %

Maritime component HQUSA***14 %ESP29 %DEU14 %

Air component HQFRA10 %

ESP9%

GRC9%GBR19 %Eurocorps*9%DEU/NLD**9%ITA14 %

GBR19 %NATOCommandStructure****57 %

FRA19 %

ITA19 %

GBR19 %

Note: For 2012 and 2013, the rotations lasted 12 months, compared to six months for the period 2003-2011.* Eurocorps rotations involve a headquarters provided by Belgium, France, Germany, Luxembourg and Spain together.** Germany and the Netherlands together as part of the HQ 1st German/Netherlands Corps.*** The United States is the framework nation for HQ Naval Striking and Support Forces, NATO (STRIKFORNATO).**** The applicable NATO Response Force rotations between 2003 and 2013 were filled by the Allied Air Command HQs Ramstein and Izmir.Source: NATOFigures have been rounded off.

The NRF, activated in 2003, is NATO’s most deployableforce, able to operate globally and react to a widespectrum of challenges. Made up of air, land, maritime,special operations forces elements and componentcommand headquarters from across the Alliance, itcan be appropriately scaled to quickly meet any threat,providing a targeted and flexible response to crises.Contributing to the NRF is an important way for Alliesto demonstrate their commitment to the Alliance. Alliesprovide troops and component command headquarterson a yearly cycle, which allows NRF units to buildexpertise and lasting relationships between Allies’forces. Improving the interoperability and readiness ofthe NRF is an important element of CFI. It will thereforebe heavily involved in training and exercise programmesbeyond 2013.

and “when”. This gives a commander the informationneeded to make the best possible decision.NATO’s JISR initiative aims to provide the Alliance with amechanism to bring together data and information gatheredthrough these and other systems. It will enable coordinatedcollection, processing, dissemination and sharing ofthis data and information within NATO, maximisinginteroperability without hampering the performance ofeach system. It will also provide common standards and acommon vision of the theatre of operations.JISR was endorsed as a NATO initiative at the ChicagoSummit in May 2012. A revised concept was approved in2013 and measures were agreed to coordinate the strandsof work pertaining to the three main lines of development:procedures for data sharing, training and education, andthe networking environment. In addition, there is needfor a longer-term JISR strategy; work to that end alsobegan in 2013. Progress in 2013 built on a technical trialheld in 2012 (Unified Vision 12). This exercise, testingthe interoperability of national systems and developingpragmatic solutions for improved coordination, was animportant step, and a follow-on exercise is being plannedfor 2014. Future NRF exercises will also be used tocontinue developing JISR to ensure seamless compatibilityas NATO develops these important capabilities.

Joint Intelligence, Surveillance andReconnaissance (JISR)Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissanceprovides the foundation for all military operations andits principles have been used for centuries. However,although these principles are not new, the militarytechnological advances made since NATO operationsbegan in Afghanistan have meant that surveillance andreconnaissance can better answer the “what”, “where”,

16

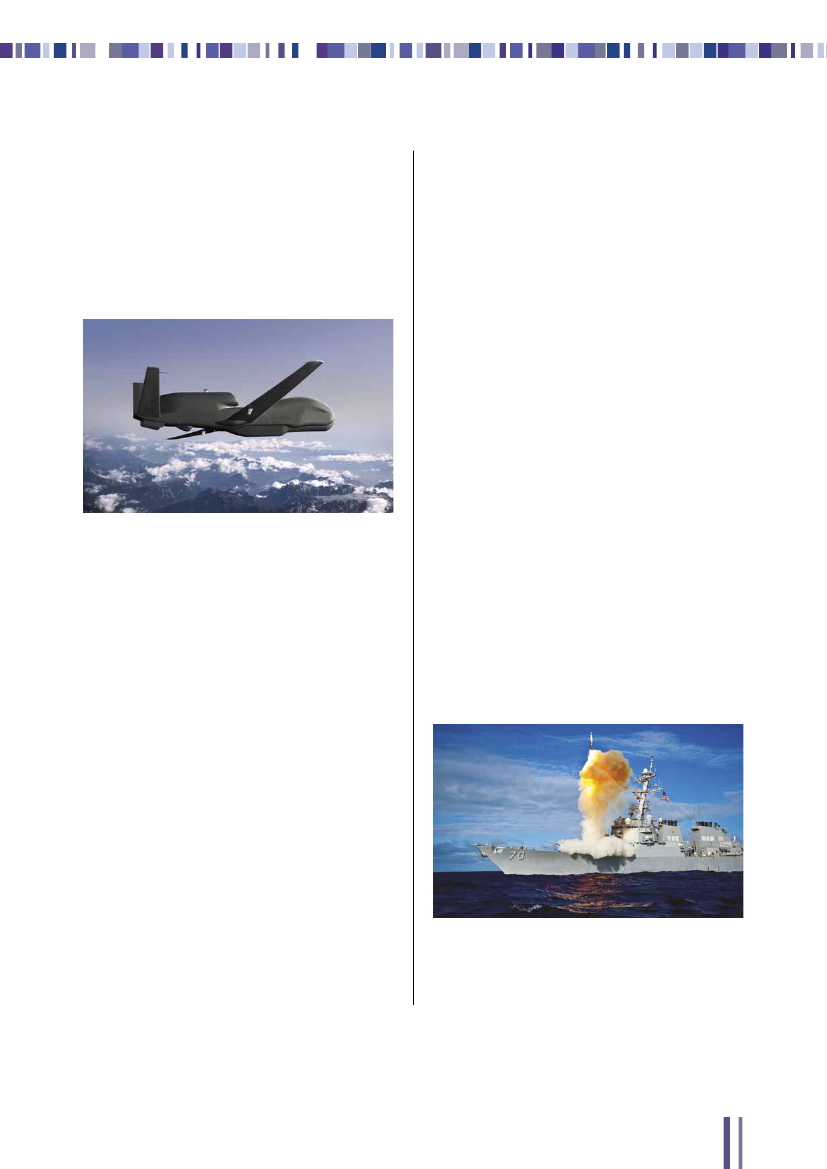

Alliance Ground SurveillanceAs part of JISR, the NATO-owned and -operatedAlliance Ground Surveillance (AGS) capability willgive commanders a comprehensive image of what ishappening on the ground before, during and after anoperation. It is therefore a critical capability that willenable surveillance over wide areas from high-altitude,long-endurance, unmanned aircraft.

In 2012 and 2013, NATO built on this interim capability,working towards a fully operational capacity in theyears to come. Recent efforts enhanced the commandand control structures of both territorial and theatremissile defence and will significantly increase theoperational value of NATO’s integrated air and missiledefence system. Individual Allies have offered additionalsystems, are upgrading national equipment, and aredeveloping or hosting capabilities that contribute to thestrength of the system.The US European Phased Adaptive Approach (EPAA)is a major contribution to the NATO ballistic missiledefence architecture. In early November 2013, thegroundbreaking ceremony for the missile defence facilityin southern Romania was a significant step forward forPhase 2 of the US EPAA – two of three phases in total.Phase 4 was cancelled by the US government, with noimpact on the coverage provided for NATO memberson the European continent.

� Northrop Grummann

The AGS core capability is composed of five GlobalHawk unmanned aerial vehicles and associated fixed anddeployable ground and support segments. Fifteen Alliesare participating in the acquisition of the system that willbe made available to the Alliance in 2017.Progress in 2013 included the production of the first NATOAGS aircraft. Additionally, all the requirements for the AGSproject were confirmed in November, opening the way forthe finalisation of design activities scheduled for May 2014,after which production of the numerous componentsof the system can commence. In parallel, Allies havestarted work to establish the AGS main operating base atSigonella (Italy) and have made significant progress towardestablishing the AGS force, which in time will be mannedby personnel from the Alliance.

In parallel, NATO and Russia continue to explorepossibilities for cooperation in this domain. In 2013,discussions made little headway. However, the offerNATO has made to cooperate with Russia in buildinga missile defence architecture that would protect bothNATO and Russia from the growing ballistic missile threat,still stands. Due to the design and configuration of itsarchitecture, NATO’s ballistic missile defence systemcannot pose any threat to Russia’s strategic deterrentforces. NATO-Russia cooperation on missile defence,however, would raise the partnership to a strategic leveland enhance security across the Euro-Atlantic area.

Ballistic missile defenceThe proliferation of ballistic missiles, carryingconventional, chemical or nuclear warheads, continuesto pose a grave risk to the Alliance. At the Lisbon Summitin 2010, NATO agreed to extend its own ballistic missiledefence capability beyond the protection of forces toinclude all NATO European populations and territory.In May 2012 at the Chicago Summit, Allies took a firststep towards operational status by declaring an interimcapability for NATO’s missile defence system.

In 2013, NATO also began discussions and exchangedinformation with a number of other partner countries onNATO’s ballistic missile defence system, and agreed tocontinue regular exchanges in the future.

17

Cyber defence2013 was a year of considerable progress in NATO’sability to defend itself against cyber attacks. NATOhas implemented NATO Computer Incident ResponseCapability (NCIRC) centralised protection at NATOHeadquarters, Commands and Agencies. This isa major upgrade of NATO's protection against thecyber threat. NATO networks in the 51 NATO locationsthat make up NATO Headquarters, the NATO CommandStructure and NATO Agencies are under comprehensive24/7 surveillance and protected by enhanced sensorsand intrusion detection technologies.While NATO’s primary role in the cyber domain isto defend its own networks, in 2013 the Alliancebroadened its efforts to address cyber threats. For thefirst time, cyber defence has been included in NATO’sdefence planning process. This will help to ensure thatAllies have the basic organisation, capabilities, andinteroperability to assist each other in the event of cyberattacks. NATO also continued to feature cyber defencescenarios in its exercises, training, and education.NATO’s annual Cyber Coalition exercise was held inNovember 2013 and included the participation of sevenpartner countries and the European Union. Duringthe exercise, 400 national and NATO cyber defence

experts participated remotely from their locations, and80 experts participated from Tartu, Estonia where theexercise was hosted.

Counter-terrorismNATO’s work to counter terrorism is an area ofcontinued advancement within the Alliance and withnational and institutional partners, both in the laband in the field. Through its 2013 activities, NATOcontinued to develop capabilities to protect its soldiersfrom many of the devices terrorists use, includingimprovised explosive devices. It also pioneered workin biometrics, non-lethal capabilities, and harboursecurity. Operation Active Endeavour, in which NATOships are patrolling the Mediterranean and monitoringshipping to help detect, deter and protect againstterrorist activity, was initiated immediately after 9/11and is ongoing.Allies increased exchanges of intelligence and expertanalysis of the evolving terrorist threat. NATO alsoincreased interaction with the UN Counter-TerrorismCommittee and its Executive Director, and the EUCounter-Terrorism Coordinator briefed the NorthAtlantic Council on developments in Syria related tointernational terrorism.

18

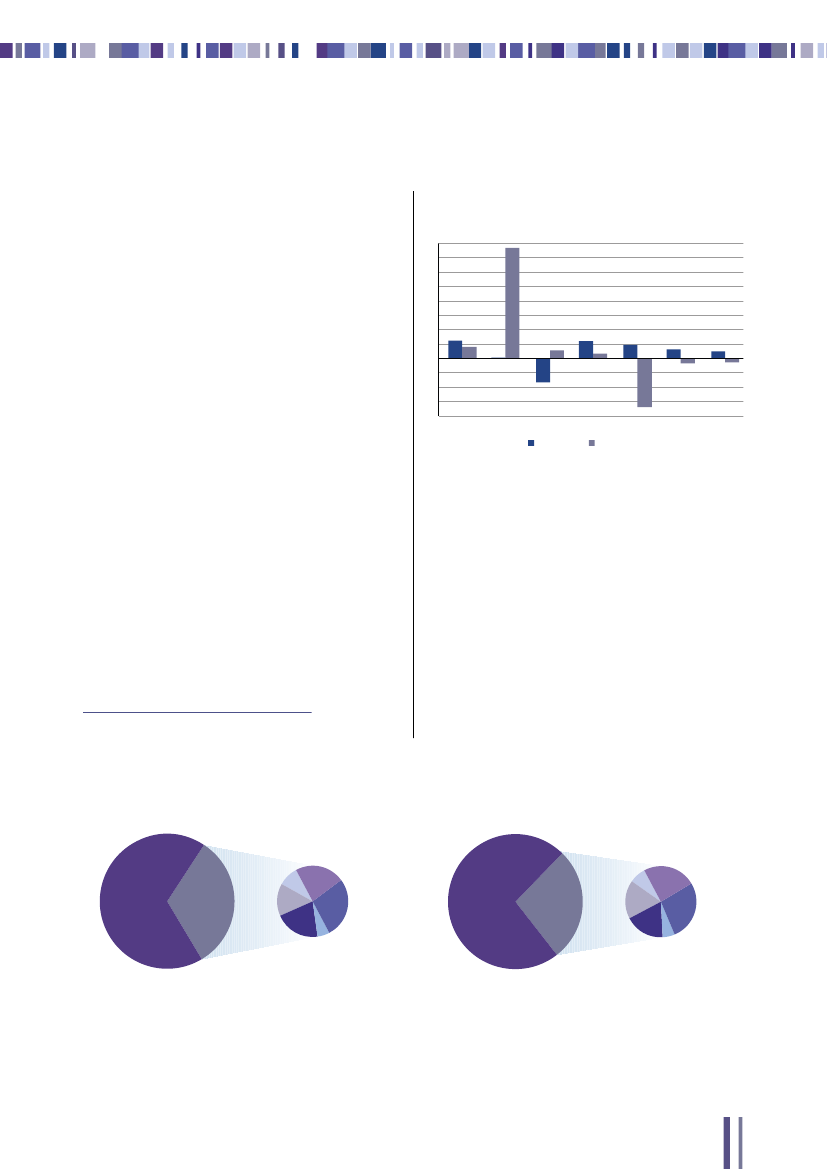

Defence in an age of austerityEconomic pressures on defence spendingSince 2008, economies in Europe and North Americahave been challenged by the persisting global economiccrisis. Declining or low-level economic growth amongmany member states has increased government budgetdeficits, raised the levels of government indebtedness andprompted tighter constraints on government spending.The weaker economic performance in Europe and NorthAmerica has, in many cases, been reflected in consistentlydeclining defence spending.1As economic conditions in many NATO countries havebegun to stabilise, the cuts to defence spending havebegun to level off. However, the need to maintain defencespending levels will remain crucial in order to retainthe capacity to provide security across the Alliance.Investment in defence is a long-term requirement; whatmay appear to be savings in the near term can havelasting consequences. Further reductions in defencespending risk undermining NATO’s efforts to ensure amodern and capable Alliance.%161412108642-2-4-6-8200720082009GDP20102011201220130

Alliance real GDP and defence expendituresPercentage changes from previous year2007-2013

Defence exp.

Source: NATO Defence Planning Capability Review 2013-14, OECD, ECFIN and IMF.Based on 2005 prices and exchange rates. Estimates for 2013.

Sharing responsibilitiesMembers of NATO are committed to the collectivedefence of the Alliance. That mutual commitment isreflected in the principle that members should contributefairly to the provision of the forces and capabilities1For all the graphs in this chapter of the report, it should be noted that Albania andCroatia joined the Alliance in 2009 and that Iceland has no armed forces.

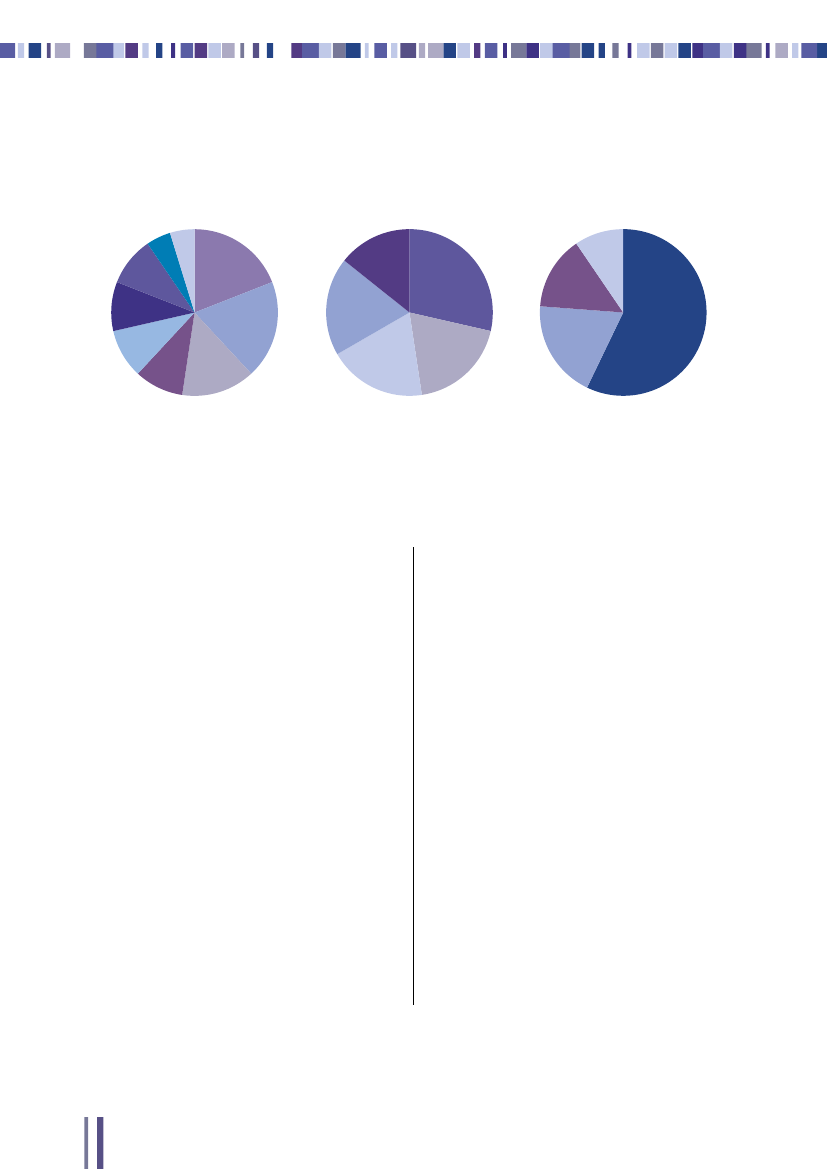

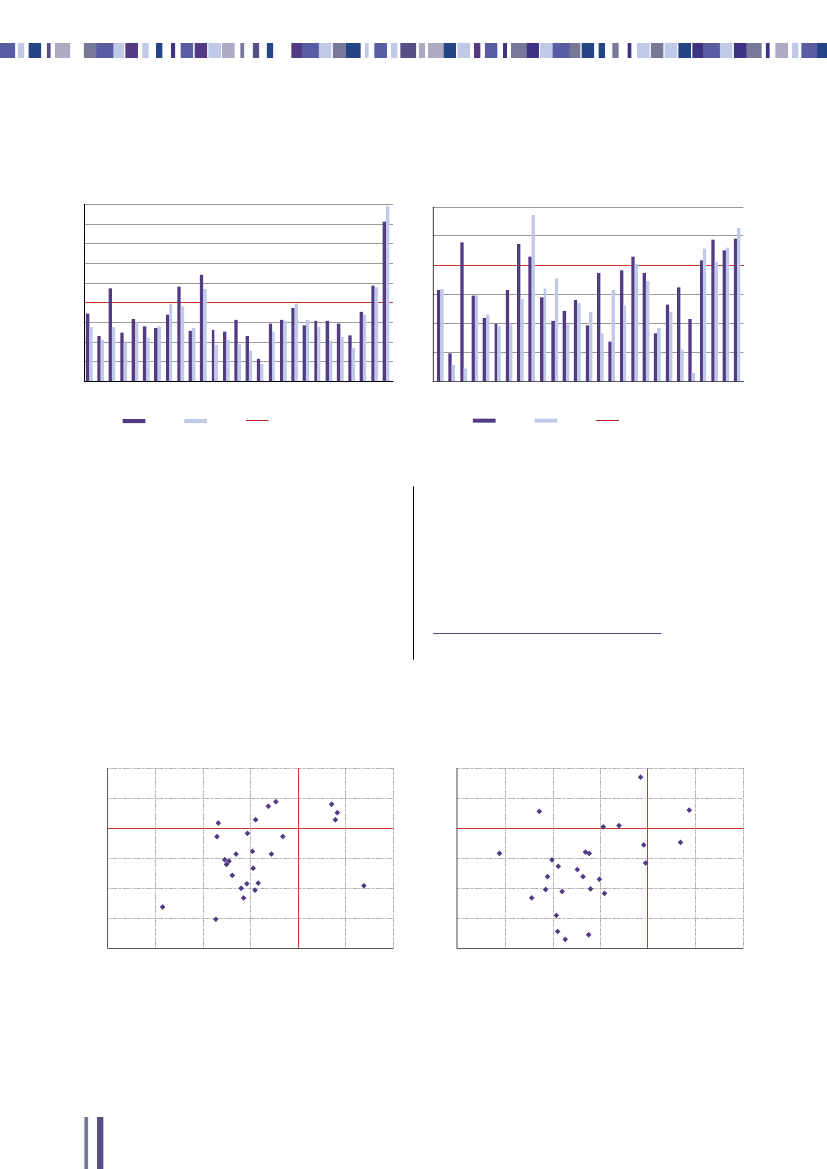

needed to undertake the roles and tasks agreed inNATO’s Strategic Concept. While there is a criticaldifference between what any Ally chooses to investin its defence and what it makes available for anyAllied undertaking, overall investment in defence hasimplications for any Ally’s ability to share the overallresponsibility. The gaps in defence expenditures withinthe Alliance are growing, as illustrated by the pie chartsbelow. Between 2007 (taken as the pre-crisis baseline)and 2013, the share of US expenditures has increasedfrom 68 to 73 per cent. In 2013, the European shareof the total Alliance defence expenditures continued todecrease as a whole.

Percentage of Alliance defence expenditures2007Italy2.9 %Germany4.7 %France Canada6.6 %1.8 %UK7.3 %USA73 %NATOEurope+ Canada27 %

2013Italy2.0 %Germany4.7 %France Canada4.9 %1.5 %UK6.6 %

USA68 %

NATOEurope+ Canada32 %

Others8.8 %

Others7.4 %

Source: NATO Defence Planning Capability Review 2013-14. Based on 2005 prices and exchange rates. Estimates for 2013.Note: Figures have been rounded off in the small pie charts.

19

%4.54.03.53.02.52.01.51.00.5

Alliance defence expendituresas a percentage of Gross Domestic Product2007 and 2013

%302520151050

Alliance major equipment expendituresas a percentage of defence expenditures2007 and 2013

ALBBELBGRCANHRVCZEDNKESTFRADEUGRCHUNITALVALTULUXNLDNORPOLPRTROUSVKSVNESPTURGBRUSA

2007

2013

NATO 2% guideline

Source: NATO Defence Planning Capability Review 2013-14. Based on 2005 prices.Estimates for 2013.

It is essential that all Allies contribute to developing thecapabilities that will underpin NATO’s role in the future.This is possible only if Allies hold the line on defencespending and focus investment on key capabilities.Allies have collectively agreed to two guidelines to helpencourage an equitable sharing of roles, risks andresponsibilities. First, members should devote at least2 % of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) to defence.Second, at least 20 % of those funds should be allocatedtowards major equipment.

The financial crisis has impacted upon both goals. Whilethe United States has reduced defence expenditures inthe last five years, reductions made by European Allieshave been more extreme in relative terms. As the graphsabove show, only three members met the 2 % guidelinein 2013, down from five in 2007. Moreover, where majorequipment expenditures2are concerned, many Allies arefalling short of the 20 % guideline.2Major equipment expenditures also include research and development spendingdevoted to major equipment.

Defence expenditures as a percentage of GDP versusmajor equipment expenditures as a percentage of defence expendituresMajor equipment exp. as % of defence expendituresMajor equipment exp. as % of defence expenditures%3025201510500.0NATO 20 % guideline

2007NATO 2 % guideline

0.5

1.01.52.02.5Defence expenditures as % of GDP

3.0 %

Source: NATO Defence Planning Capability Review 2013-14. Based on 2005 prices. Estimates for 2013 except Spain 2012 figure for major equipment.Note: United States is not included.

20

ALBBELBGRCANHRVCZEDNKESTFRADEUGRCHUNITALVALTULUXNLDNORPOLPRTROUSVKSVNESPTURGBRUSA20072013NATO 20% guidelineSource: NATO Defence Planning Capability Review 2013-14. Based on 2005 prices.Estimates for 2013 except Spain 2012 figure.

0.0

%3025201510500.0

2013NATO 2 % guideline

NATO 20 % guideline

0.5

1.01.52.02.5Defence expenditures as % of GDP

3.0 %

BillionUS$250200150100500

Alliance major equipment expenditures2003-2013

Nevertheless, recent efforts by a number of Allies serveas an important example. Several have effectivelyincreased their major equipment expenditures over thelast six years, investing in future requirements despitethe pressures of the economic crisis.Moreover, sharing responsibilities is not only a matter ofthe percentage of any country’s GDP spent on defence.The provision of forces and capabilities to NATO-ledoperations and missions is a meaningful demonstrationof Alliance solidarity. Despite budget cuts, contributionsto NATO operations remain strong. European Allies inparticular have taken the lead in a number of operationsand missions, including in Kosovo and Libya. EuropeanAllies have also consistently contributed the bulk offorces to the NATO Response Force and to Baltic airpolicing, as well as to a majority of air surveillance andinterception rotations in Iceland.■

2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013United StatesNATO Europe+CanadaNATO Total

Source: NATO Defence Planning Capability Review 2013-14. 2005 prices and exchange rates.Estimates for 2013.

The negative trend is particularly visible in the twoscatter graphs where the defence expenditures of allAllies, except those of the United States, feature inrelation to the 2 % guideline on defence expendituresand the 20 % guideline on major equipmentexpenditures for 2007 and 2013.

Air policing rotations, Baltic States2004-2013PRT CZEROU 3 % 6 %ESP 3 %BEL9%DNK12 %

Air surveillance and interception rotations, Iceland2008-2013PRT6%ITA6%CAN12 %DNK12 %

3%TUR3%NLD3%GBR3%USA9%

FRA6%

FRA12 %

DEU12 %USA35 %

POL12 %

NOR6%

DEU15 %

NOR12 %

Source: NATONote: Figures have been rounded off.

21

Reforming the AllianceATO has continually evolved over the last twodecades, building on operational experience,expanding partnership networks and innovatingto develop capabilities for modern defence.In 2010, NATO Heads of State and Government agreedon a new Strategic Concept to guide this current phase ofNATO’s evolution and tasked the Secretary General and theNorth Atlantic Council with reforming NATO’s structures.Since then, NATO has been hard at work to ensure that thistransformation results in an Alliance that is fit for purpose inaddressing 21st century security challenges.In the years since 2010 there has been significantprogress toward these goals. As agreed by Allies in 2011,the number of operational entities comprising the NATOCommand Structure has been reduced from thirteen toseven; fourteen NATO Agencies have been consolidatedinto four. Resulting cost savings are already apparentin 2013 and are expected to increase in the years tocome. In addition to more streamlined structures, a focuson key priorities has helped a smaller workforce to meetthe changing needs of the Alliance. NATO is on trackto deliver an Alliance that is efficient and effective in itsoperations and prepared for the future.

N

In 2013, NATO developed tools to clearly illustratethe current performance of individual Allies across anumber of areas, as well as wider trends in capabilitydevelopment over time. NATO forces need to be flexible,agile and deployable, with all the supporting infrastructureand logistics this entails so that they can respond to avariety of threats.

NATO Command StructureThe NATO Command Structure enables NATO toimplement political decisions through the coordinationof military means and is part of what makes the Allianceunique. These military command and control bodies whichmake up the command structure coordinate contributionsfrom member and partner countries during operations andexercises. They are permanently manned and ready toreact at very short notice to any contingency.

Defence planningAddressing the challenge of orienting national andAlliance resources to address new threats has beencentral to NATO’s defence policy efforts in recent years.NATO cannot dictate how Allies allocate their resources,and it is the Allies (individually or in groups) thatultimately provide defence capabilities. However, NATOcan facilitate national and multinational efforts in waysthat build on the strengths of the Alliance to ensurethese efforts are harmonised through NATO’s defenceplanning process.The 2010 Strategic Concept laid down the parameters forthe next ten years of planning. Further political guidanceas well as the comprehensive Deterrence and DefencePosture Review of 2012 provide the framework for theongoing work of improving the defence planning process.

NATO forces need tobe flexible, agile anddeployable, with all thesupporting infrastructureand logistics this entailsIn 2010, Allies agreed to reform this command structure.The aim was a leaner, more affordable structure thatwould be flexible and more deployable. 2013 was ayear of steady progress toward this goal, with the newcommand structure attaining its initial operational capabilityin December. The number of operational entities hasbeen reduced from thirteen to seven. In November 2013,Allied Joint Force Command Brunssum (The Netherlands)provided the headquarters component for the majorNATO Response Force exercise Steadfast Jazz. This wasan important demonstration of the Command’s ability tosupport a diverse, deployable force, the exercise havingtaken place at sea, in the air, and on land, with participantsfrom Allied and partner countries.

22

At the end of 2015 when the implementation of thecommand structure reform is complete, the manning andfootprint of the overall structure will have been reducedby one third, resulting in savings of€123million to themilitary budget.

NATO AgenciesNATO Agencies are responsible for a range of servicesnecessary to support the work NATO does, includingprocurement of goods and services as well as logisticalsupport for current operations. Because of the complexlinks between the functions of the NATO CommandStructure and the services provided by NATO Agencies,planning for and implementation of agency reform has beencoordinated to ensure continuous provision of support.The aims of the agency reform process agreed in 2011are improved governance and enhanced efficiency. Whenthe process began, there were fourteen entities; thesehave now been consolidated into four bodies, focused onsupport, procurement, communications and information,and science and technology. This consolidation provides abetter coordinated, more effective structure.In 2013, agency reform efforts focused on consolidatingservices and programmes while preserving the ability toprovide for ongoing operations. Cost-saving programmeshave delivered a five per cent reduction in 2013 and remainon track for a 20 per cent reduction in coming years.During 2013, 88 per cent of all agency personnel weretransferred into the new organisations for support,communication and information, and science andtechnology. Work also progressed on the developmentof a new procurement body to better integrate existingacquisition programmes, provide a flexible framework forfuture projects and improve cost-effectiveness.Also in 2013, as part of agency reform, NATO establishedthe Office of Shared Services, which is working torationalise service delivery across NATO bodies. It isfocused on three areas: finance and accounting, generalprocurement, and human resources.

modernise the working practices of the International Staff.By 2018, the size of the International Staff will have beenreduced by nearly 20 per cent. More importantly, dozensof staff positions have been reassigned to higher priorities.These efforts to craft a more adaptable civilian workforceare part of a new human resources policy, implementationof which began in 2013.NATO’s International Military Staff, numbering around500, is also under review. An extensive report wascompleted in 2013 that will guide the efforts to refine thatstructure so that it, too, is properly equipped to serve thegoals of a 21st century Alliance.NATO’s committee structure is also part of theHeadquarters reform. NATO members come together incommittee meetings to discuss and decide. Since 2010,there has been a 65 per cent reduction in the number ofcommittees – this leaner, more coherent structure allowsfor swifter, better integrated responses to tasks delegatedby the North Atlantic Council.The new NATO headquarters, which is currently underconstruction, will provide the Alliance with a modernbase. The current headquarters was designed and builtin the 1960s as a temporary structure for 15 countries.NATO now has 28 member countries and requires afacility able to flexibly adapt to shifting priorities.■

NATO HeadquartersNATO’s International Staff numbers just over 1,000,making up a relatively small but important element of theAlliance’s overall structure. As part of the broader reform,and in preparation for the move to a new headquarters,NATO has been working to streamline the workforce and

23

24

NATO Public Diplomacy Division1110 Brussels – Belgiumwww.nato.int

� NATO 2014

1462-13 NATO Graphics & Printing - SGAR13ENG