OSCEs Parlamentariske Forsamling 2013-14

OSCE Alm.del Bilag 2

Offentligt

a comparative studyof structures for womenmps in the osce region

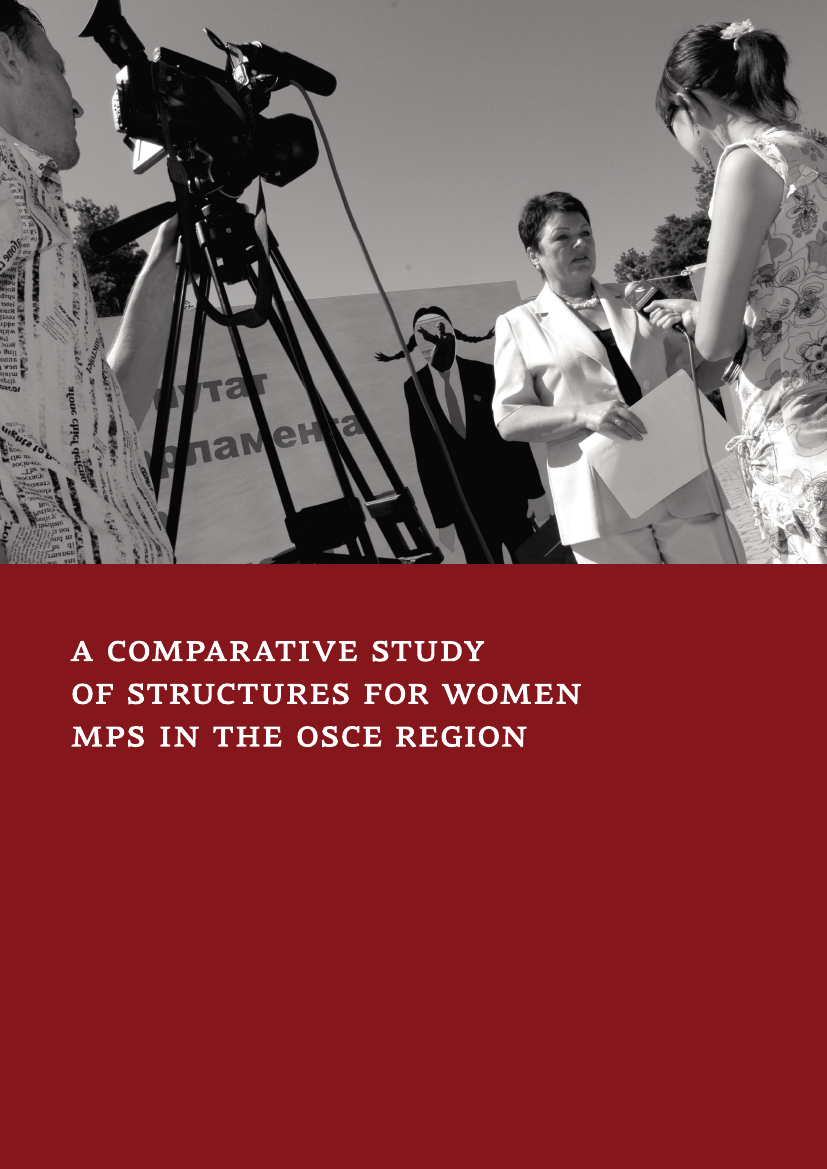

Front page photo:A press conference “For Equality in Policy!” held in May 2007 in front of the Jogorku Kenesh(Parliament) in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan, organized by public associations and an initiative group of citizens.Credit:Eric GourlanThis study was commissioned by the OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR).The opinions and information it contains do not necessarily reflect the policy and position of ODIHR.September 2013Designed by Homework, Warsaw, PolandPrinted in Poland by AGENCJA KARO

Table of contents

Acknowledgements Executive summary

6

5

1. Introduction: Institution building for gender equality 9Women’s parliamentary bodies: Parameters of the researchResearch framework and methodology2. Defining a women’s parliamentary body1316171910

The benefits of having a women’s parliamentary body

Presence of women’s parliamentary bodies in the OSCE regionOne size does not fit all: The design of women’s parliamentarybodiesConclusion2021242525Typology of women’s parliamentary bodies

3. Enabling factors

Parliamentary and political systems in the OSCE regionmeasures26

Enhancing women’s parliamentary presence: The use of specialCase Study 1: The Albanian experience of a Women’s CaucusThe existence of women’s movementsA question of timingBody in SerbiaConclusion32333331302928

Case Study 2: Towards the establishment of a Women’s Parliamentary

4. Organizing for effectiveness

Mode of operation and internal organizationKosovoparliamentMembership34373839

Case Study 3: Women’s Caucus (GGD) of the Assembly ofWomen’s parliamentary bodies and their relationship to the

Case Study 4: The Equal Opportunities Groupof the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine

Leadership, decision-making and procedural issuesformer Yugoslav Republic of MacedoniaObjectives and mandatesConclusion46474442

41

Case Study 5: Women Parliamentarians’ Club of the Assembly of the

Does structure and organization impact on effectiveness?

45

5. Achieving positive outcomesActivities47

Case Study 6: Women’s Union of the Estonian ParliamentThe role of parliamentary and political party systemsEmpowering membersParliamentConclusion525355555250

48

Case Study 7: The Network of Women Members of the Finnish

6. Fostering strong relationships

Connecting with communities of interestRelationship building for gender mainstreamingEquality Issues60

Case Study 8: The Polish Parliamentary Group of Women58

56

Case Study 9: The Swedish Speaker’s Reference Group on GenderFormalizing parliamentary relationshipsBosnia and HerzegovinaConclusion65666462

Case Study 10: The Women’s Parliamentary Club at entity level in

7. Impeding progress: What challenges remain?Latvia6972

Case Study 11: The Women’s Parliamentary Co-operation Group in

8. Conclusions and the way forwardparliamentary body9. Recommendations7377

An eight-step framework for the establishment of a women’s

Recommendations to women’s parliamentary bodiesRecommendations to parliamentsSelected resources 8078

77

Appendix 1: OSCE Ministerial Council Decision 7/09 on Women’s Participation in Political and Public Life, Athens, 2009Appendix 2: List of respondentsAppendix 3: Questionnaire858382

Foreword

5

Acknowledgements

This study was drafted by Dr. Sonia Palmieri, an international expert on gender and women’sparliamentary representation. The study was commissioned by the OSCE Office for DemocraticInstitutions and Human Rights (ODIHR), and the information it contains does not necessarilyreflect the policy and position of ODIHR.The study would not have been possible without the support provided by the OSCE ParliamentaryAssembly (PA) and its Special Representative on Gender Issues, Dr. Hedy Fry. The OSCE PAcommitment has been extremely valuable in the dissemination of a specially designed ques-tionnaire to all OSCE participating States, as well as in the provision of comments and ideas tocontinuously improve this study and to promote women’s parliamentary participation acrossthe OSCE region.The study also benefitted from all those who generously contributed their time to sharing theirexperiences on the establishment and running of women’s parliamentary bodies (a list of re-spondents can be found in Appendix 2). Similar thanks are extended to the National DemocraticInstitute in Ukraine, the Inter-Parliamentary Union, and well-known experts on gender issues,including Lolita Cigane, Lenita Freidenvall, Sonja Lokar, Melanie Sully, Kristina Wilfore andOlena Yena. Special gratitude is extended to OSCE field operations for their invaluable supportthroughout the drafting of the study, to the Parliament of Austria for supporting the ODIHRRegional Workshop on Parliamentary Structures for Women MPs in the OSCE Region, heldin Vienna in December 2012, and, last but not least, to the representatives who participated inthis event.

6

Executive summary

While the goal of gender parity in parliamentary representation has not yet generally beenachieved, women have still managed to make a significant contribution to the political land-scape across the OSCE region. Policy and legislative change on gender equality issues, for ex-ample, has frequently been the result of concerted, collaborative efforts between women insideand outside parliament.As a first of its kind in the OSCE region, this study is concerned with the presence and operationof dedicated women’s parliamentary bodies (alternatively referred to as parliamentary struc-tures for women members of parliament (MPs)) that promote gender equality and women’srepresentation. Women’s parliamentary bodies are a particular form of gender mainstreaminginfrastructure commonly initiated by women parliamentarians in order to promote solidarity,enhance parliamentary capacity, and advance women’s policy interests.1Where they have beenestablished and retained, women’s parliamentary bodies have been recognized as important fo-rums for advancing gender equality issues, for facilitating cross-party co-operation and agree-ment on legislative priorities, and for influencing political agendas from a gender perspectivewithin parliaments.2This study is the result of a research commissioned by the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe’s (OSCE) Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR)across parliaments in the OSCE region between June and December 2012 to identify the differ-ent types of women’s parliamentary bodies in existence. Within the framework of the ODIHRproject “Strengthening parliamentary structures for women MPs in the OSCE region”, parlia-ments were surveyed on good practices in establishing and running such structures, as wellas on the international and OSCE support provided to them. The project forms part of, anddirectly feeds into, ODIHR’s broader programming on women’s political participation and par-liamentary strengthening.The study initially identifies the women’s parliamentary bodies that have been established inthe OSCE region. In particular the study finds that, among the 36 OSCE participating States

12

Sonia Palmieri,Gender-Sensitive Parliaments: A Global Review of Good Practice,Reports and Documents No. 65(Geneva: Inter-Parliamentary Union, 2011).Anna Mahoney, “Politics of Presence: A Study of Women’s Legislative Caucuses in the 50 States”, State Politicsand Policy Conference Dartmouth, Hanover, New Hampshire, 2011.

Executive summary

7

surveyed, there are 16 structures for women MPs currently functioning.3These bodies appearto be structured and organized in a variety of ways across the OSCE region, indicating thatthere is no one model for success.But what conditions favour the establishment of these parliamentary bodies in the first place?Are there any enabling factors that can support women MPs in establishing such structures?While the type of parliamentary and political system in place does not appear to affect directlythe emergence of a women’s parliamentary body, the study finds that the political environmentcan influence what type of body emerges. Likewise, the existence of legal gender quotas or vol-untary measures to support women’s election to parliament does not appear to be a direct in-dicator of the likelihood that a women’s parliamentary body will be established. Nonetheless,many women’s parliamentary bodies have played a key role in advocating for the introductionof gender quota provisions in electoral laws, in lobbying for amendments to gender quota pro-visions, and/or in monitoring the implementation of quota provisions.As regards potential enabling factors, the study recognizes and highlights the important roleplayed by women’s movements. Women’s movements and organizations often facilitate theestablishment of women’s parliamentary bodies, providing women MPs with expertise andfirst-hand knowledge of gender issues, and connecting them to the electorate. Furthermore,women’s movements often serve as the institutional memory of past achievements, currentrealities, and lessons learned in the struggle for women’s rights and gender equality.Having identified women’s parliamentary structures in existence in the OSCE region, thestudy goes on to map their mandates, structures, activities and memberships. The main find-ing here is the broadly informal nature of these bodies across the OSCE region, with meetingsscheduled only as required, and limited dedicated financial and logistical support provided tothese bodies. Notwithstanding the informal structure of these bodies, their approach towardsleadership and procedure is more commonly observed as formalized. Agendas are typicallycirculated in advance of a meeting, written rules determine meeting procedure, and leadershipterms are often fixed. Membership options differ widely: while some bodies include men, oth-ers prefer to restrict their membership to women only. With respect to objectives, it was foundthat women’s parliamentary bodies are overwhelmingly committed to influencing policy andlegislation from a gender perspective, and to lobbying on gender equality issues.On the basis of these findings, the study outlines good practices, and identifies challenges aswell as lessons learned in relation to the establishment and operation of women’s parliamen-tary bodies. The study finds that political partydisciplineremains a significant challenge forwomen who wish to co-operate across party lines, but does not constitute an insurmountableobstacle per se. Where women’s parliamentary bodies focus on specific gender issues, theyare often able to work within parliamentary environments characterized by strong party dis-cipline. This is particularly evident when they focus on issues where parties themselves donot have conflicting ideological or political stances. By contrast, parliamentary environmentscharacterized by strong politicalpolarizationare shown to render cross-party communicationand co-operation extremely difficult.The study concludes by presenting an eight-step framework for action and a number of rec-ommendations aimed at strengthening women’s parliamentary bodies and the way in which

3

A similar structure was also surveyed in the Assembly of Kosovo, thus bringing the total number of structures to17. All reference to Kosovo, whether to the territory, its institutions, or population, in this text should be under-stood in full compliance with United Nations Security Council Resolution 1244.

8

parliaments work with them. In particular, women’s parliamentary bodies are encouraged towork towards building consensus on issues that can be supported across the political spec-trum, and to develop and maintain strong relationships both inside and outside the parliament– notably with other organizations that work towards the achievement of gender equality.Parliaments, in turn, are urged to support the work of these parliamentary bodies, for example,by implementing pro-active policies to increase the number of women MPs and promote themto leadership positions within the parliament. At the same time, parliaments should provideadequate resources to these bodies. Where resources are not available, they should facilitatethe meetings of women’s parliamentary bodies and encourage the establishment of strongerlinks between these bodies and the more institutionalized organs of the parliament, such asdedicated committees on gender equality, social policy issues or human rights, and/or otherinstitutions of parliamentary leadership.Overall, the study aims to help women MPs in the OSCE region interested in strengtheningtheir role within their respective parliaments through mechanisms such as women’s parlia-mentary bodies, and to promote a greater understanding of the value and functioning of thesebodies. This is intended as a first step towards the implementation of future projects and re-search on the topic, to further advance women’s political participation and their substantiverepresentation within national parliaments.

Executive summary

9

Introduction: Institutionbuilding for gender equality

In 2013, women held just over 20 per cent of the seats in national parliaments worldwide; in theOSCE region, this figure has currently reached 24.4 per cent in lower houses of parliament.4While the march towards gender equality in political life continues, at the very least thisfigure acknowledges women’s now irreversible place in politics. To support this trend, OSCEparticipating States have agreed, through a series of commitments, to “encourage and promoteequal opportunity for full participation by women in all aspects of political and public life, indecision-making processes and in international co-operation in general.”5Nevertheless, scope for even greater change in the way parliamentary institutions themselvesare structured and run still remains. A consistent finding in research on women in parliamentsis that the onus for continued change – in terms of increasing the number of women elected,eradicating the ‘masculine’ culture of parliament, and making ‘substantive’ legislative changein favour of gender equality – is on women.6Where parliaments have made steps towards thesemilestones, more often than not it has been because of the tireless work of women members ofparliament (MPs).As Childs, Lovenduski and Campbell have argued, laying the responsibility for such change atthe hands of women alone sets up ‘unhealthy expectations’ of women parliamentarians.7Whenthese expectations are not met, women’s contribution to the political sphere is questioned:“why do we need women in parliament?”8

45678

Inter-Parliamentary Union,Women in national parliaments,http://www.ipu.org/wmn-e/world.htm, accessed July2013.Document of the Moscow Meeting of the Conference on the Human Dimension of the CSCE, 1991, Art. 40.8.Julie Ballington,Equality in Politics: A Survey of Women and Men in Parliaments,Reports and Documents No. 54(Geneva: Inter-Parliamentary Union, 2008).Sarah Childs, Joni Lovenduski, and Rosie Campbell,Women at the Top: 2005 Changing Numbers, Changing Politics?(London: Hansard Society, 2005).See the 2012 debate on women’s participation in parliament initiated by Joshua Foust and Melinda Haring:http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2012/06/22/who_cares_how_many_women_are_in_parliament and theresponse from Susan Markham, Director of the National Democratic Institute: http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2012/06/29/the_missing_50_percent.

10

For some researchers, the proportion of women in parliament makes a difference. Based on thework of Kanter, the commonly cited ‘critical mass’ target has presented commentators withthe promise of difference (e.g., that women will change the institution, will introduce moregender-sensitive legislation, will be represented in positions of parliamentary and politicalleadership) once they represent at least 30 per cent of the legislature.9The theory has comeunder pressure, however, considering that women parliamentarians do not act in isolation ofthe institutions in which they work, and that parliaments are ‘gendered institutions’. That is,parliaments, having been dominated by men since their creation, have historically tended toresist the equal participation of women and have often perpetuated established norms aboutwhat is appropriate work for men and women.10A more comprehensive line of inquiry focuses on the role of the parliament itself in addressinggender equality. Not only does this shift the weight of responsibility for change from womento the institution as a whole, but it also provides an opportunity for more systemic and sus-tainable change. The question is now more about the circumstances under which the institu-tion allows for or facilitates change, rather than how many women are needed to achieve it.Parliamentary institutions and procedures – and their level of gender-sensitivity – can play animportant role in supporting MPs in exercising the power entrusted to them by the electorate.One effective way to do so could be through the establishment of mechanisms, or infrastruc-ture, that allow all parliamentarians – men and women – to work towards gender equality.Such infrastructure might come in the form of a women’s caucus, a dedicated committee ongender equality, or an advisory group on gender issues. Accordingly, this study looks in detailat one type of gender mainstreaming infrastructure – parliamentary structures for womenMPs – and how these structures can make parliaments more gender-friendly and enhancewomen’s substantive representation in legislatures.

Women’s parliamentary bodies: Parameters of the researchThe establishment of parliamentary structures for women MPs is not a completely new phe-nomenon. Indeed, mechanisms for enhancing women’s political influence have been createdand prioritized in many parliaments in Africa, Latin America and Asia.11With strong supportfrom international actors, the bulk of existing research and good practices emerges from struc-tures established in these regions. These regions are likely to have established cross-partywomen’s parliamentary bodies in order to affect policy processes and outcomes, specificallyby influencing the political agenda and setting priorities, channelling women’s interests inlegislative reform processes, and facilitating capacity development for women parliamentar-

910

11

Rose Kanter, “Some effects of proportions on group life: Skewed sex ratios and responses to token women”,American Journal of Sociology,Vol. 82, No. 5, 1977, pp. 965–990.Drude Dahlerup, “From a small to a large minority: Women in Scandinavian Politics”,Scandinavian PoliticalStudies,Vol. 11, No. 4, 1988, pp. 275–298; Georgia Duerst-Lahti and Rita Mae Kelly (eds.)Gender Power, Leadershipand Governance(Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1996); Janice Yoder, “Rethinking Tokenism: Lookingbeyond numbers”,Gender & Society,Vol. 5, No. 2, 1991, pp. 178–192. Yoder’s critique of Kanter is premised inthe argument that the critical mass thesis confounds four factors: “numeric imbalance, gender status, occupa-tional inappropriateness, and intrusiveness”. That is, “increases in the number of lower-status members threatendominants, thereby increasing gender discrimination in the forms of harassment, wage inequities and limitedopportunities for promotion” (pp. 178–180).Keila Gonzalez and Kristen Sample,One Size Does Not Fit All: Lessons Learned from Legislative Gender Commissionsand Caucuses(Lima: International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA) and NationalDemocratic Institute (NDI) for International Affairs, 2010); Claire McLoughlin and Seema Khan, “HelpdeskResearch Report: Cross-party Caucuses”, Governance and Social Development Resource Centre, 2009.

Introduction: Institution building for gender equality

11

ians. Thus far, however, there has been no systematic assessment of parliamentary structuresfor women MPs in the OSCE region.12There is little comparative information in the OSCEregion about the real impact of women’s parliamentary bodies in terms of influencing policyoutcomes, and still less about correlations between impact on the one hand, and structure,mandate and activities on the other. This study aims at beginning to fill this gap.This study takes a comparative approach to women’s parliamentary bodies. It seeks to identifythe range of women’s parliamentary bodies that have been created, the circumstances underwhich they were created, and the extent to which they have become effective mechanisms forpromoting gender equality issues and empowering women parliamentarians in the OSCE re-gion. In particular, the following analysis aims to:•identify parliaments in the OSCE region that currently host such structures, have estab-lished or attempted to establish these structures in the past, or plan to create them in thefuture;map the mandate, structure, membership and activities of these structures;analyse the data collected in order to outline good practices, success stories, challenges andlessons learned; andoffer an eight-step framework for action to support the establishment or re-vitalizationof a women’s parliamentary body, and present a number of tailored recommendations towomen’s parliamentary bodies as well as to parliaments more broadly.

•••

This study is based on data collected from specially designed questionnaires sent to 55 parlia-ments13within the OSCE region, with the support of the OSCE Parliamentary Assembly (PA),its Special Representative on Gender Issues, Dr. Hedy Fry, and its secretaries of delegations,between June and November 2012. Responses were received from 36 parliaments14plus oneresponse from the Assembly of Kosovo (producing a response rate of 66 per cent).15As the study will demonstrate, a wide variety of women’s parliamentary structures have beenestablished in the OSCE region. Among all the respondents to the survey, 16 OSCE participat-ing States acknowledged the existence of a body that ‘brings women together’.16Keeping in mind that 11 of the 16 women’s parliamentary bodies surveyed among OSCE partic-ipating States have been established since 2008, the present study can only begin to examinethe impact that such structures may have and to assess the influence of the political environ-ment on their functioning. Accordingly, the study does not aim to derive correlations or causallinkages between women’s parliamentary bodies on the one hand, and the broader politicaland parliamentary context on the other. Nor does it attempt to draw conclusions regardingregional trends in the emergence of such structures, or predict the best environment in whichthese bodies will flourish. Further research will be necessary, in order to better understandpolitical complexities, patterns and regional trends.

12

13141516

The 57 States of the OSCE include countries from Europe, Central Asia and North America, and comprise theworld’s largest regional security organization. As Mongolia officially joined the OSCE in November 2012, its par-liament was not surveyed as part of this project.Questionnaires were disseminated to all OSCE participating States with the exception of the Holy See andMongolia. In addition, a questionnaire was sent to the Assembly of Kosovo.Kyrgyzstan and Armenia sent in two responses each.See Appendix 2 for the complete list of respondents.The existence of a similar body was also surveyed in the Assembly of Kosovo, thus bringing the total number ofstructures to 17.

12

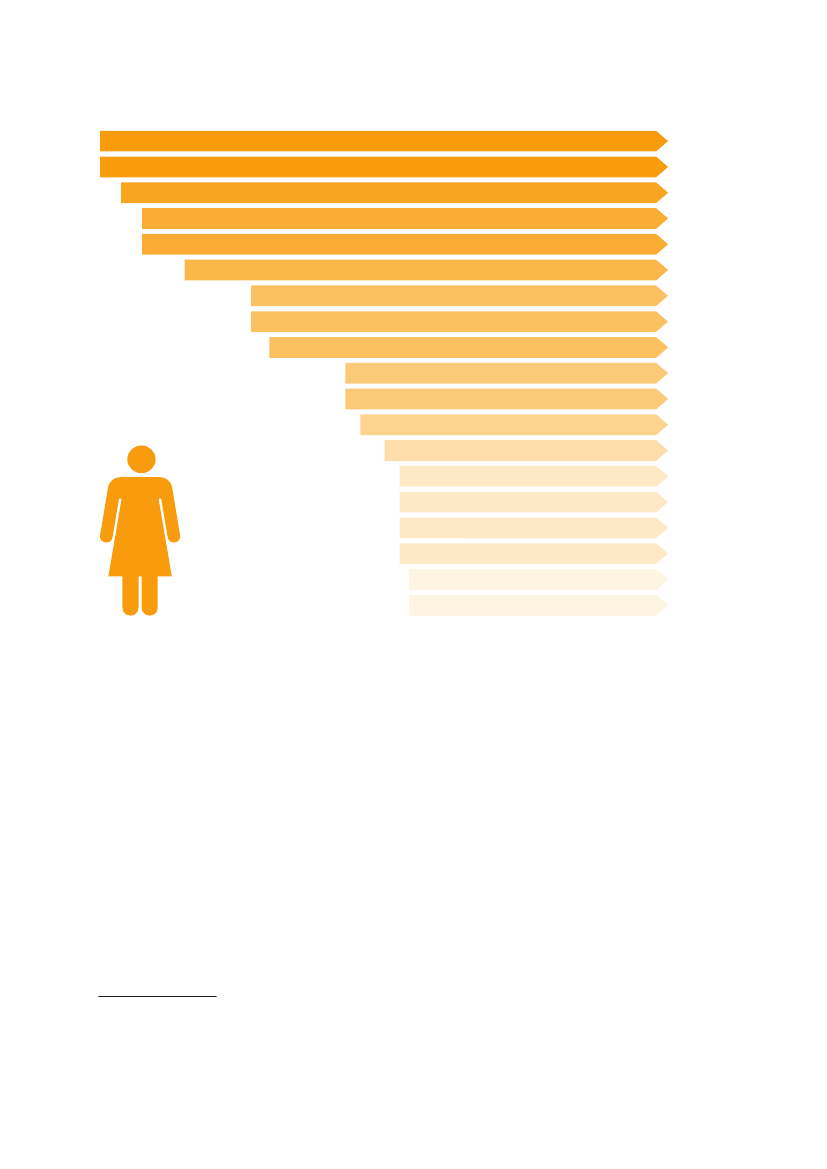

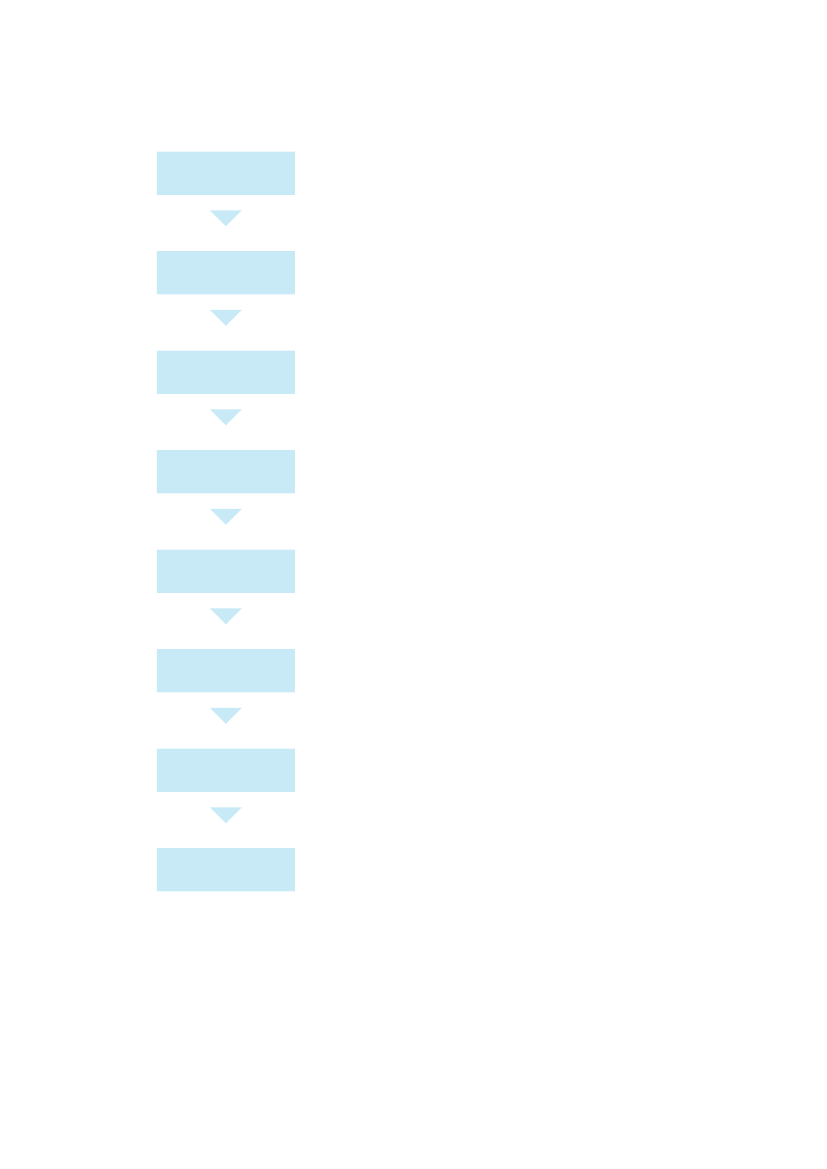

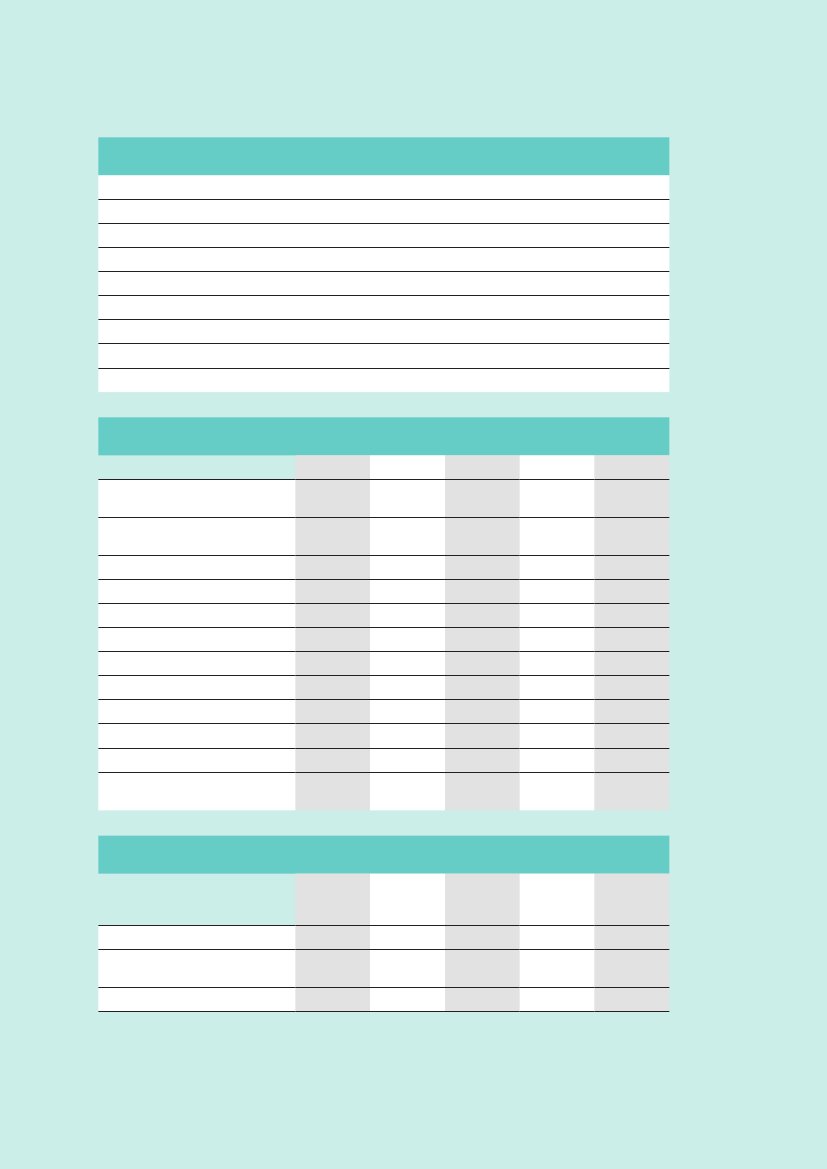

Figure 1.1 Chronological overview of the ‘bodies that bring women together’ surveyed in the OSCE region1991Women’s Network,Finland1991Parliamentary Group of Women,Poland1993The Liberal Women’s Caucus,Canada

1995Women’s Caucus,Albania; re-established in 2005 and functioned until 20091995Speaker’s Reference Group on Gender Equality Issues,Sweden1999Women Delegation,France2002–20072002–20102003Network of Women Politicians,DenmarkWomen’s Parliamentary Co-operation Group,Latvia

Women Parliamentarians’ Club,former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia20082008Women’s Network,NorwayLadies Breakfasts,AustriaGender Equality Council,GeorgiaUnion of Women’s Groups,TajikistanEqual Opportunities Group,UkraineCaucus on Women’s Issues,United StatesWomen’s Union,EstoniaWomen’s Forum,KyrgyzstanWomen’s Network,Serbia

2009

2010

20112011201120112013

2013Women’s Parliamentary Club,Bosnia and Herzegovina

Importantly, this study embraces the idea that ‘one size does not fit all’. The functioning ofwomen’s parliamentary bodies is influenced by different external factors; indeed, women’s par-liamentary bodies are shaped by unique political and parliamentary contexts at the nationallevel, the presence of women’s movements or other civil society groups, as well as the influenceof international organizations.17In this vein, the study does not attempt to advocate for onetype of structure to be established over another. Women parliamentarians and their supportersare the best judges of the political and parliamentary context in which they are operating, andthe type of structures that will best suit their environment.Having said this, the study does aim to identify common factors that support the establishmentand running of these bodies, as well as good practices that can possibly be replicated in otherparliamentary contexts. To this end, it introduces an analytical framework for understandingparliamentary structures for women MPs in the OSCE region and the ‘enabling environment’in which these structures implement their mandates and functions most effectively.Following an outline of the research framework and methodology, the study begins with ananalysis of what defines a women’s parliamentary structure in the parliaments of the OSCE

17

See Gonzalez and Sample.

Introduction: Institution building for gender equality

13

region. A series of enabling factors for the establishment of such structures is then presented,followed by a more in-depth analysis of women’s parliamentary bodies by organization, activi-ties and relationships. The study then presents some of the reported challenges in establishingand running such bodies, and concludes by outlining an eight-step framework to guide theestablishment or re-vitalization of a women’s parliamentary body, as well as recommendationsto enhance the work currently being done by these structures within the OSCE community.

Research framework and methodologyThrough its work, ODIHR has supported initiatives to increase women’s participation in politi-cal and electoral processes, as members of political parties, as political leaders, and as candi-dates for public office. ODIHR also supports parliamentary support programmes (PSP) imple-mented by OSCE field operations. In fact, support to parliamentary structures for women MPsis an important component of PSP programming in different OSCE participating States, for ex-ample, in the Western Balkans. ODIHR has long-standing relationships with these PSPs, actingas a hub for the exchange of knowledge and good practice, including by co-ordinating regionaljoint events and contributing expertise and advice on projects. This study was designed withthe intention of collecting information and good practices, to be disseminated and shared withOSCE field operations, MPs, and other parliamentary stakeholders across the OSCE region.Existing research conducted in recent years18suggests that numerous parliamentary bodies forwomen MPs have been established, and that they vary widely in design, structure, activitiesand degrees of formality. This variety gives rise to the following set of questions:1) Which parliaments in the OSCE currently host these bodies, have established or attemptedto establish these in the past, or plan to create these in the future?2) How are such bodies organized, in terms of mandate, structure and membership?3) What activities do these bodies generally engage in?4) What relationships do they build both internally and externally to the parliament?5) How does the parliamentary regime and level of parliamentary development affect the es-tablishment and efficacy of these bodies?6) Are there any good practices or success stories that can be learned from existing bodies?7) What challenges and lessons can be drawn from them?For the purposes of this study, a parliamentary body for women is defined according to threemain criteria: organization, activities and relationships. Each of these criteria can be under-stood in the following terms:Organization:••Mode of operation and internal organization: including format, status and frequency ofmeetings, staffing and resources;Membership, leadership and procedures: including recruitment of members (nominated,appointed,ex officio),leadership structures, established procedures (agendas, decision-mak-ing process), required documentation for its establishment and renewal; andMandate and objectives of the body.

•

18

See, for example, Gonzalez and Sample and McLoughlin and Khan. Further documents can be found in theSelected Resources section at the end of this study.

14

Activities:•Main activities of the parliamentary body, the ability of the body to implement those activi-ties in light of political realities, and the perceived impact of those activities.

Relationships:•Relationships within the parliament with other parliamentary bodies on gender equality(e.g. committees or Secretariat entities), with other parliamentary bodies more generally,with the political leadership as well as the parliamentary administration; andRelationships with external stakeholders, namely civil society, academia, the media, the ex-ecutive, gender equality machinery, international donors, and international organizations.

•

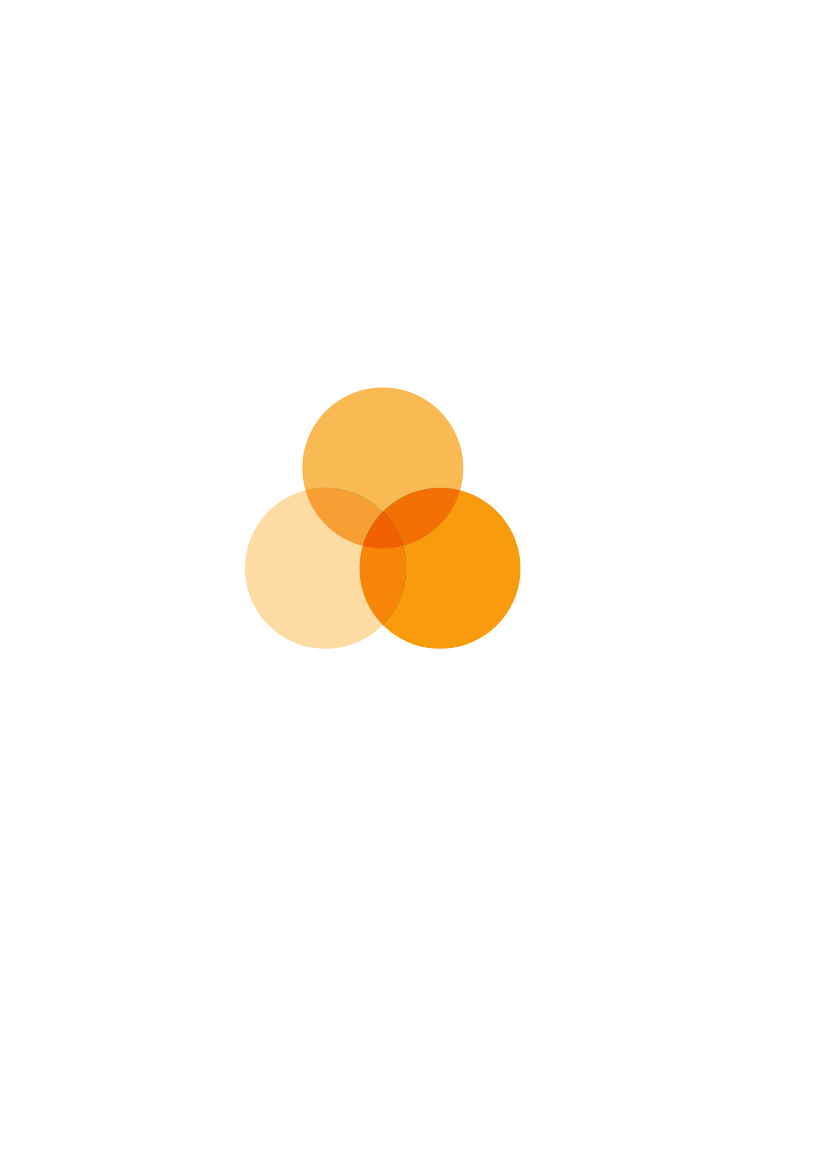

Figure 1.2 Criteria defining a women’s parliamentary body

Organization

Activities

Relationships

Recognizing that MPs work within the confines of their parliamentary institution, it is alsoimportant to assess the broader enabling environment for the effective functioning of suchstructures. Where possible, the study has considered the following factors:•Parliamentary regime:Where relevant, distinctions have been made between presidentialor parliamentary systems, bicameral or unicameral parliaments, strong versus weak politi-cal party systems, and proportional representation, majority and mixed electoral systems;Number and position of women in parliament:The relationship between a ‘criticalmass’ of women (e.g. 30 per cent) and the effectiveness and sustainability of a women’s par-liamentary structure has been considered. The position of key women or gender equalityadvocates in the parliament (e.g. in the Executive, or as Committee chairs) has also beentaken into account.Special measures to promote women’s political participation:The prevalence of spe-cial measures in place to promote women’s political participation has been noted, witha focus on legal and voluntary gender quotas.

•

•

Introduction: Institution building for gender equality

15

•

Position of body in relation to parliament as a whole:The effectiveness of the bodyand its ability to influence mainstream parliamentary processes, as determined by its rela-tionship to the rest of the parliament, has been considered (e.g. whether the body is a mar-ginalized structure, integrated into the parliament’s broader processes, or supported byparliamentary leadership).

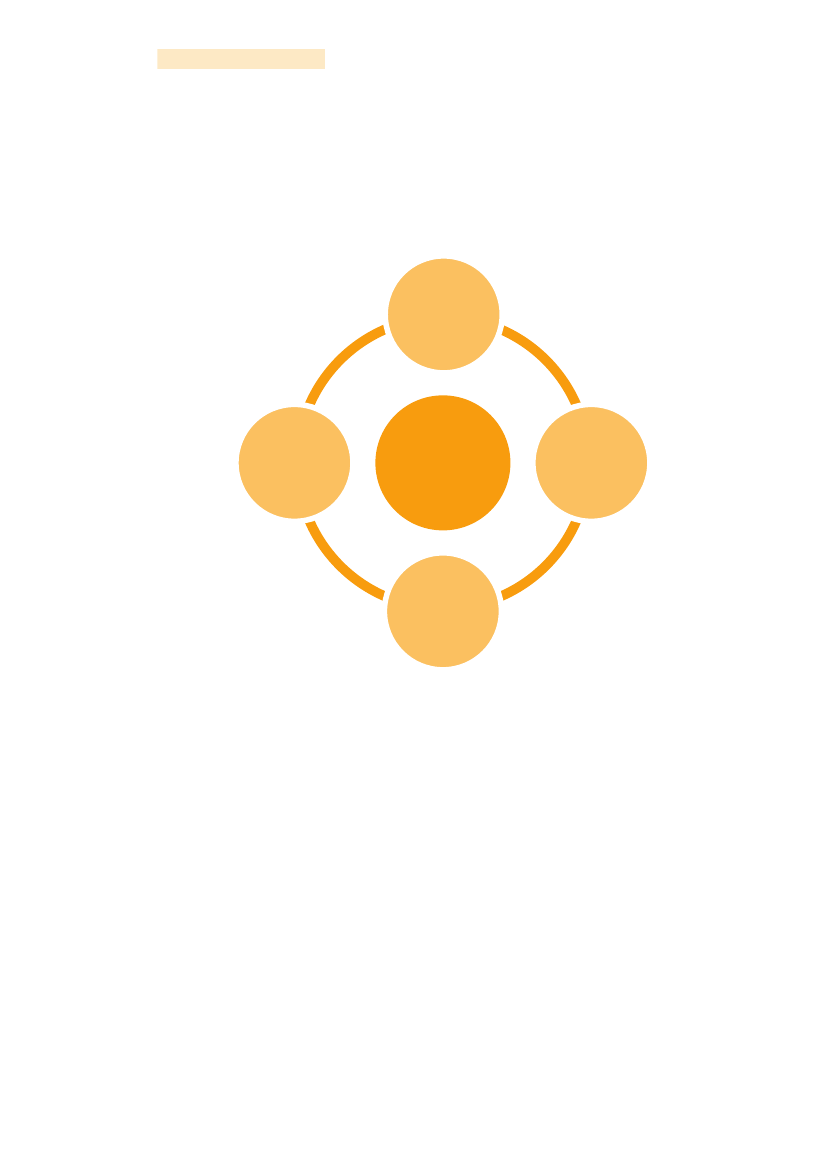

Figure 1.3 Enabling environment for the effective functioning of a women’s parliamentary body

ParliamentaryRegime

Existenceof SpecialMeasures

Women’s parliamentarybody

Number and Positionof Women inParliament

Position of Bodyin Relation toParliament

To identify the women’s parliamentary bodies currently in existence in the OSCE region, ques-tionnaires were developed on the basis of a literature review; the questionnaires also incorpo-rated questions previously used in similar research conducted by ODIHR and other organiza-tions (the questionnaire can be found in Appendix 3).Data collected from the questionnaires was supplemented by additional desk and field researchconducted in the OSCE region. The research began with a review of existing literature onwomen’s parliamentary bodies (see the section on Selected Resources at the end of this study).Selected parliaments, which indicated that a women’s parliamentary body existed or used toexist, were contacted to provide additional information, forming the basis of more detailedcase studies. These case studies, incorporated throughout the body of the study, serve to high-light what aspects of women’s parliamentary bodies have contributed to their successes and topinpoint the challenges encountered in establishing and running these bodies.

16

2. Defining a women’s parliamentary body

This chapter looks into the different types of women’s parliamentary bodies established in theOSCE region, as well as the different definitions that have been created to attempt to distin-guish these bodies from other types of parliamentary structures. A list of potential benefitsconnected with the establishment and presence of a women’s parliamentary body is then of-fered.To systematize the analysis of women’s parliamentary bodies surveyed by this study, this sec-tion also introduces a new framework, or typology, for these bodies. In the survey, parliamentswere asked to identify their own women’s parliamentary body, and these results are matchedwith the typology proposed in the questionnaire.

Defining a women’s parliamentary bodyPerhaps reflecting the diversity of experience around the world, the existing literature offersdiverse definitions of what represents a women’s parliamentary body. They have been defined as:•“voluntary associations […] which seek to have a role in the policy process. These groupshave standard organizational attributes: a name, a membership list, leadership, and staffingarrangements”;19“[a body] that meets weekly or monthly during session, hires staff, is policy oriented and/orpays dues”;20and“an institutionalized, bipartisan association of only women legislators who meet more thanonce during the legislative session”.21

••

Thus, for some experts, a women’s parliamentary body is a voluntary association, while forothers, it is something more institutionalized; some researchers require such bodies to be

192021

Susan Webb Hammond, Daniel P. Mulholland, and Arthur G. Stevens, Jr., “Informal Congressional Caucuses andAgenda Setting”,Western Political Science Quarterly,Vol. 38, No. 4, 1985, pp. 583–605.See Leah Olivier, “Women’s Legislative Caucuses”, National Conference of State Legislatures, Briefing Paper onthe Important Issues of the Day, Vol. 13, No. 29, 2005.Mahoney,op. cit.

2. Defining a women’s parliamentary body

17

policy focused, while others do not specify their activities. Some bodies have resources allo-cated to them by the parliament, while others collect membership fees or are partially fundedby non-governmental or international organizations.There is, then, no single model of organization, and, as Gonzalez and Sample found, ‘one sizedoes not fit all’.22Indeed, women’s parliamentary bodies tend to reflect women legislators’needs and political leverage, as well as the parliamentary system and the political culture ofa specific country. Their purpose, decision-making mechanisms, attributes, operations, andareas of activity are commonly decided by those establishing the structure.23Women’s struc-tures have also evolved over time, for example, by setting rules for the election of leaders longafter their creation, developing a formal agenda previously non-existent, or even becominginstitutionalized as a gender equality committee.24Contrary to permanent parliamentary committees specialized on gender equality issues, thesestructures tend to remain outside the formal organs of parliament and often benefit froma higher degree of flexibility of operation. In some cases, both types of structures find a way toco-operate, combining their strengths to advance policy and legislative initiatives.Importantly, women’s parliamentary bodies do not always restrict their membership to wom-en MPs. Some have included men parliamentarians in a clear attempt to ensure that genderequality issues are not only advanced by women. Other bodies also include the participation ofcivil society organizations or representatives of international organizations.Because of the multiplicity of experiences, scholars have either focused on the formal/infor-mal aspect of women’s parliamentary bodies,25or have developed more restrictive definitionsthat reflect specific national circumstances.26This study maintains that, more important thandefining a women’s parliamentary body, is the process of identifying the different factors thatfacilitate the establishment and running of these bodies.

The benefits of having a women’s parliamentary bodyRegardless of the way a women’s parliamentary body is structured and/or organized, the find-ings of this and other studies27suggest that these bodies serve a number of purposes and func-tions. The reported benefits of establishing such bodies are as follows:•They promote women’s numerical and substantive representation.As chapter 3 willexplain in more detail, women’s parliamentary bodies often advocate for the introductionof legal or voluntary gender quotas and other special measures in order to increase wom-en’s representation in parliaments. For example, the Women Parliamentarians’ Club of theAssembly of the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, established in 2003, achieved anamendment to the Election Code, which ensured that every third place on the political par-

22232425

2627

Gonzalez and Sample,op. cit.National Democratic Institute, “Women’s Caucuses Fact Sheet” (Washington: NDI, 2008).Mahoney,op. cit.See Kristin Kanthak and George Krause, “Can Women’s Caucuses Solve Coordination Problems among WomenLegislators? Logic, Lessons, and Evidence from American State Legislatures”, Paper presented at Annual Meetingof the American Political Science Association, Washington DC; 2010, and Palmieri,op. cit.See Mahoney,op. cit.See Gonzalez and Sample,op. cit.;Mahoney,op. cit.;McLoughlin and Khan,op. cit.;and Palmieri,op. cit.

18

ty’s candidate list is allocated to the less represented gender. This measure helped securethe election of 28 per cent of women MPs in 200628(see Case Study 5 below).•They highlight the importance of gender issues within parliamentary processes. Canada provides a valuable example in this regard. A 2001 article on the effectiveness ofthe Liberal Women’s Caucus stated that many women MPs admit that simply asking ques-tions (for example, on the impact of budget cuts on girls and boys, women and men), ratherthan agreeing with the proposed solution, has contributed to important shifts in the politi-cal culture on Parliament Hill.29They serve to ensure that gender equality issues are mainstreamed into legisla-tive and policy processes. Suchbodies can serve to influence the drafting of legislationand policies in line with gender equality standards, as well as monitor their implementa-tion. Moreover, these bodies can also lobby for the introduction of processes to review leg-islation and policies from a gender perspective.30They can lobby for the development and adoption of gender equality legislation. While most women’s parliamentary bodies do not enjoy the power to initiate legislation,they can nonetheless support the development of legislation on issues of concern to the body,including gender equality. In Ukraine, for example, the parliamentary Equal OpportunitiesGroup, established in 2011, indicated that it would concentrate its efforts on ensuring thatthe Ukrainian legislation related to equal rights and opportunities conforms to Europeanstandards, and on the drafting of amendments to legislation concerning violence againstwomen and domestic violence (see Case Study 4 below).They influence, and sometimes shape, policy and legislative agendas through cross-party co-operation.In some contexts, women’s parliamentary structures can influ-ence legislative and policy agendas by uniting women (and like-minded men) across partylines in the form of a voting bloc. The voting bloc can use the power of numbers to pass orblock the adoption of legislation. Where party discipline hinders the emergence of formalcross-party voting blocs, women’s parliamentary bodies can still bring women (and men)together to develop a stance on specific issues of concern that can be used to influence howparliamentarians vote.They facilitate communication and dialogue within and across parties.In line withthe point above, women’s parliamentary bodies can provide a forum where MPs from dif-ferent parties come together in an informal, neutral environment to discuss interests ofmutual concern. Where political polarization makes cross-party co-operation difficult, ifnot impossible, women’s parliamentary bodies can provide a platform for discussion of top-ics on which party leaders have not adopted a particular stance. Such topics may includegender-based violence, non-discrimination, healthcare, and/or children’s rights.

•

•

•

•

282930

National Democratic Institute, “Women’s Caucuses Fact Sheet” (Washington: NDI, 2008); Cvetanka Ivanova, “Women’sParliamentary Club in the Assembly of the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia”, iKNOW Politics, 2007.Jackie Steele, “An effective player in the parliamentary process: the Liberal Women’s Caucus 1993–2001”,(Ottawa: Institute on Governance, 2011), www.iog.ca/publications/alfhales2001.pdf.For example, the women’s structure established in the Assembly of Kosovo, the Women’s Caucus Group (GDD),has among its specific objectives the “harmonization, amendment and drafting of legislation with a genderperspective lens”. The GDD has successfully lobbied for the adoption of a policy which requires all draft lawsdiscussed by the Assembly of Kosovo to be screened by the GDD from a gender equality and equal representationperspective (see Case Study 3).

2. Defining a women’s parliamentary body

19

•

They provide information to their members and engage in advocacy.Such bod-ies can engage in research or advocacy on issues of concern to all women parliamentar-ians, providing support, for example, to individual women parliamentarians engaged inthe drafting or amendment of specific pieces of legislation. They can also raise awarenesson gender equality issues by facilitating dialogue on certain issues between governmentand civil society. For example, women’s parliamentary bodies can liaise with NGOs andmembers of women’s movements, in order to ensure that the priorities of civil society, andwomen’s groups in particular, are conveyed to the parliament. Polish women MPs, for in-stance, have co-operated with representatives of civil society to raise awareness of genderequality issues. Members of the Parliamentary Group of Women established in the PolishSejm participate regularly in the annual Polish Congress of Women, an event gatheringthousands of women (and men) from across all sectors of Polish society to discuss key is-sues of concern to women across the country (see Case Study 8 below).They provide training and support to their membersin the form of mentoring, ca-pacity building, confidence building, networking, discussion and information sharing.This helps women MPs but also parliaments to institutionalize gender equality learning,and, where appropriate, can also facilitate the revival of a previously established women’sparliamentary structure. In this regard, the Network of Women Members of the FinnishParliament organizes seminars and informal events meant to bring together women par-liamentarians. Such events can enhance the individual capacities of women by providinga platform for exchange and training (see Case Study 7 below).31

•

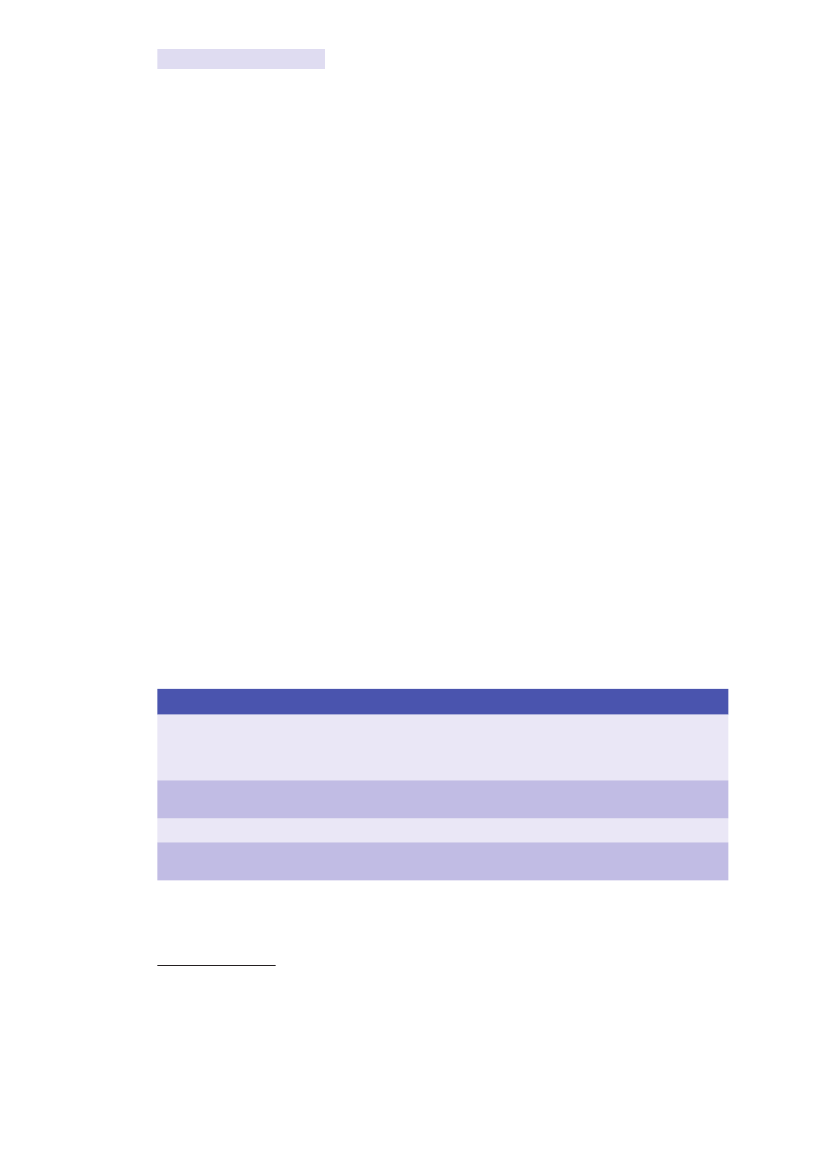

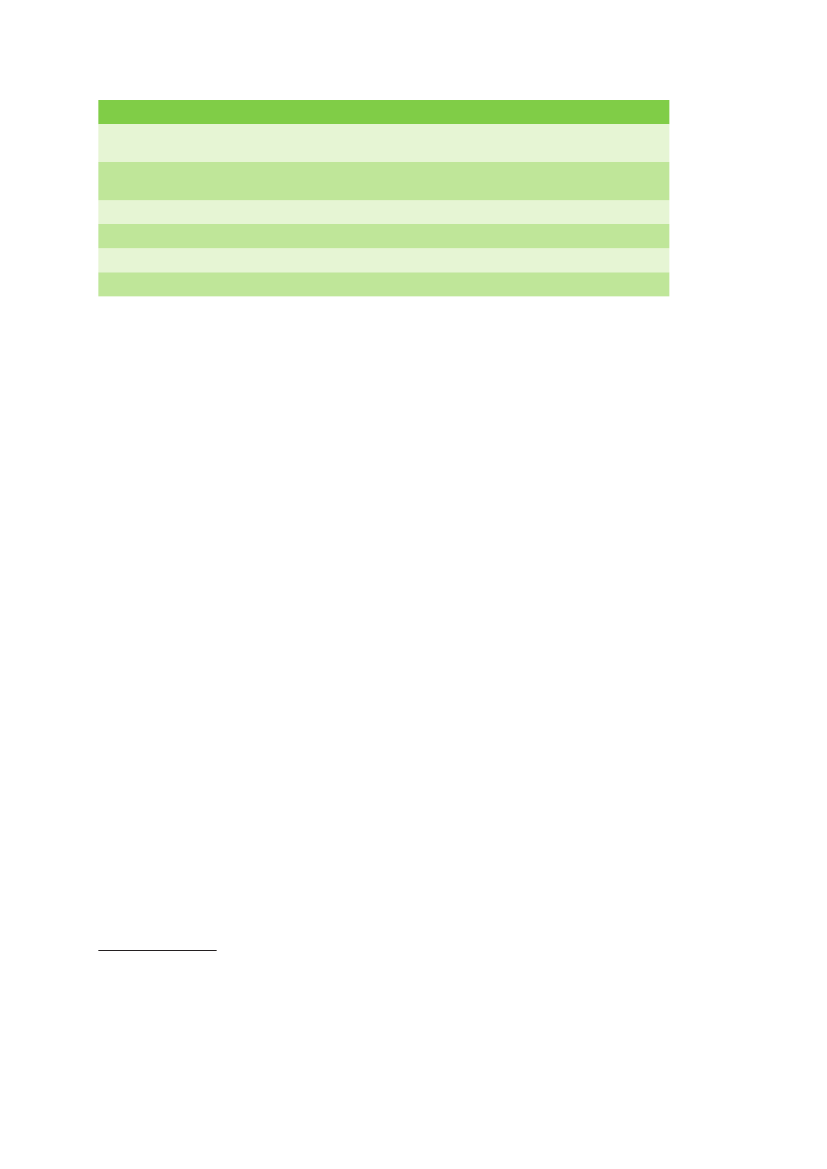

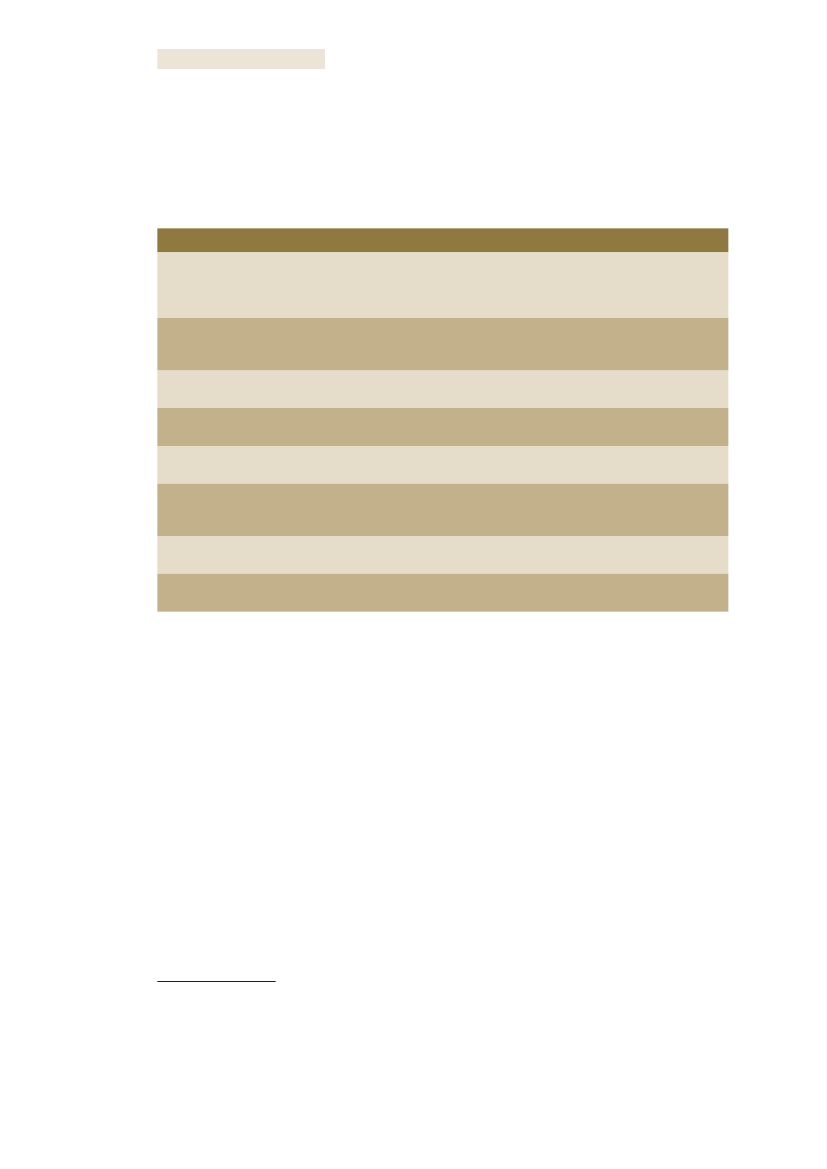

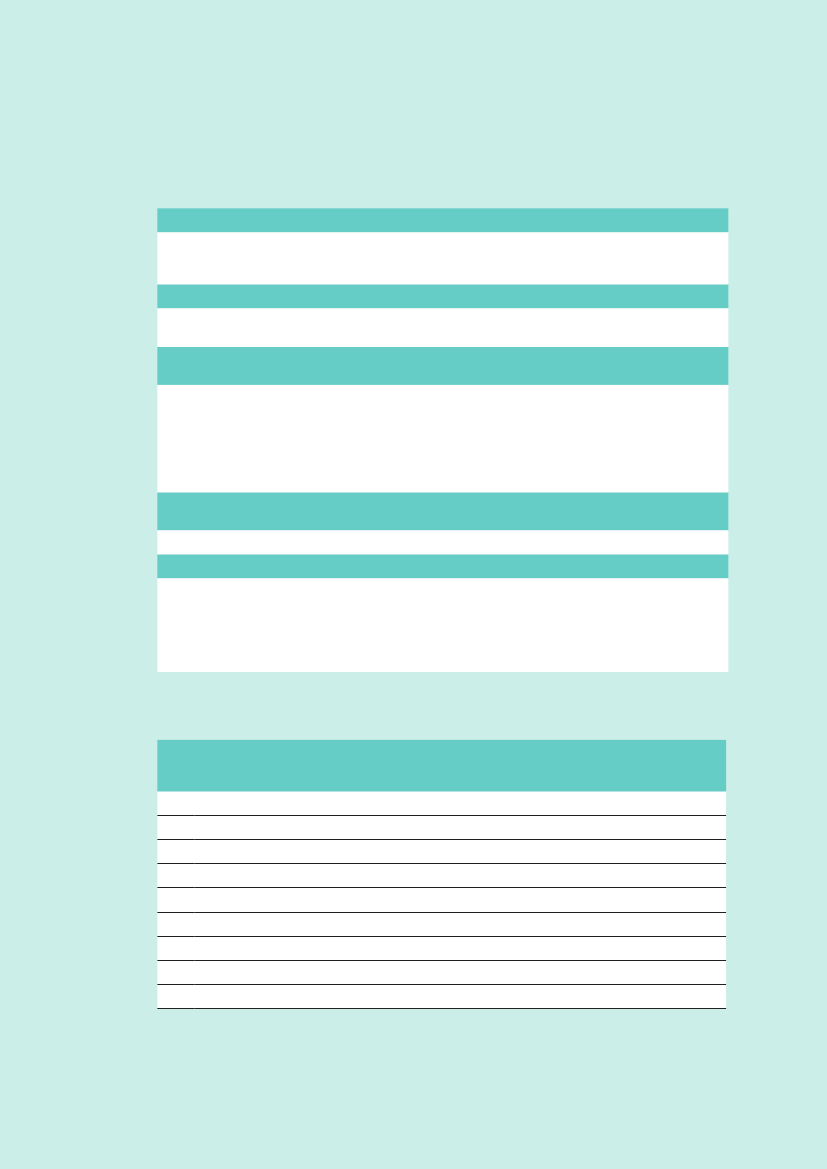

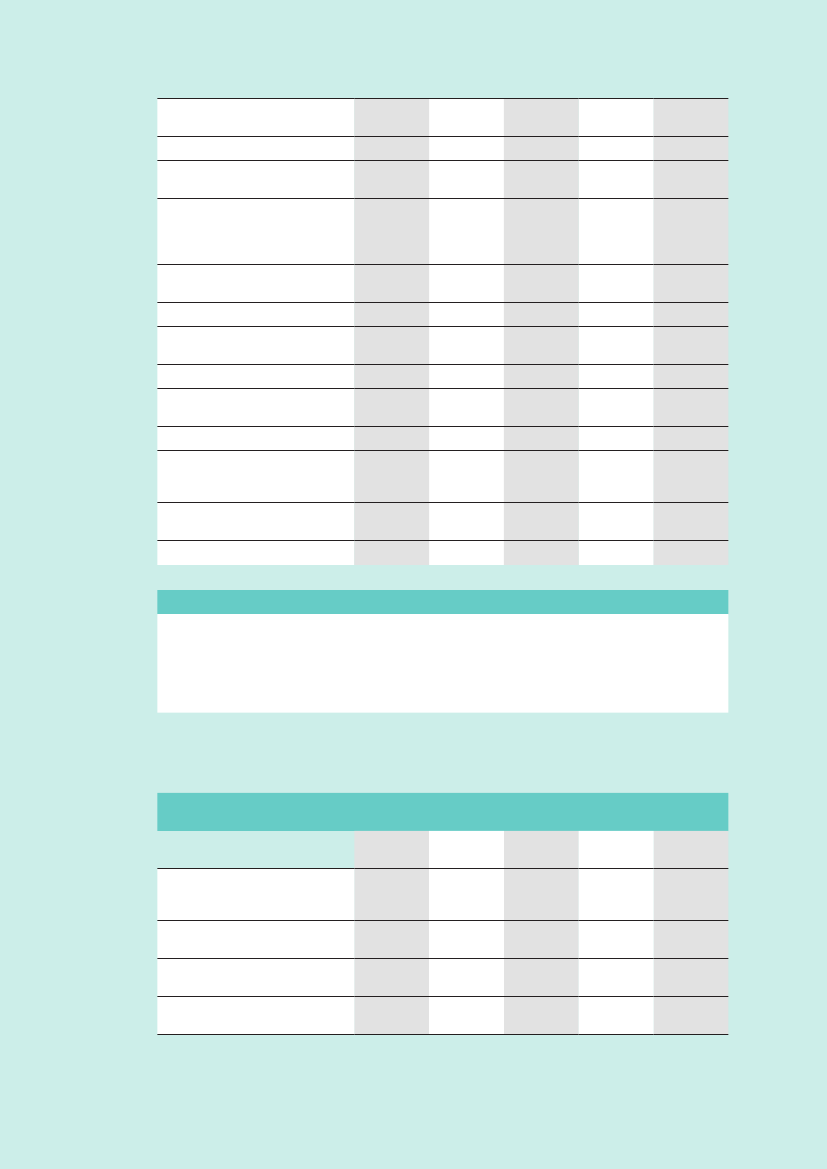

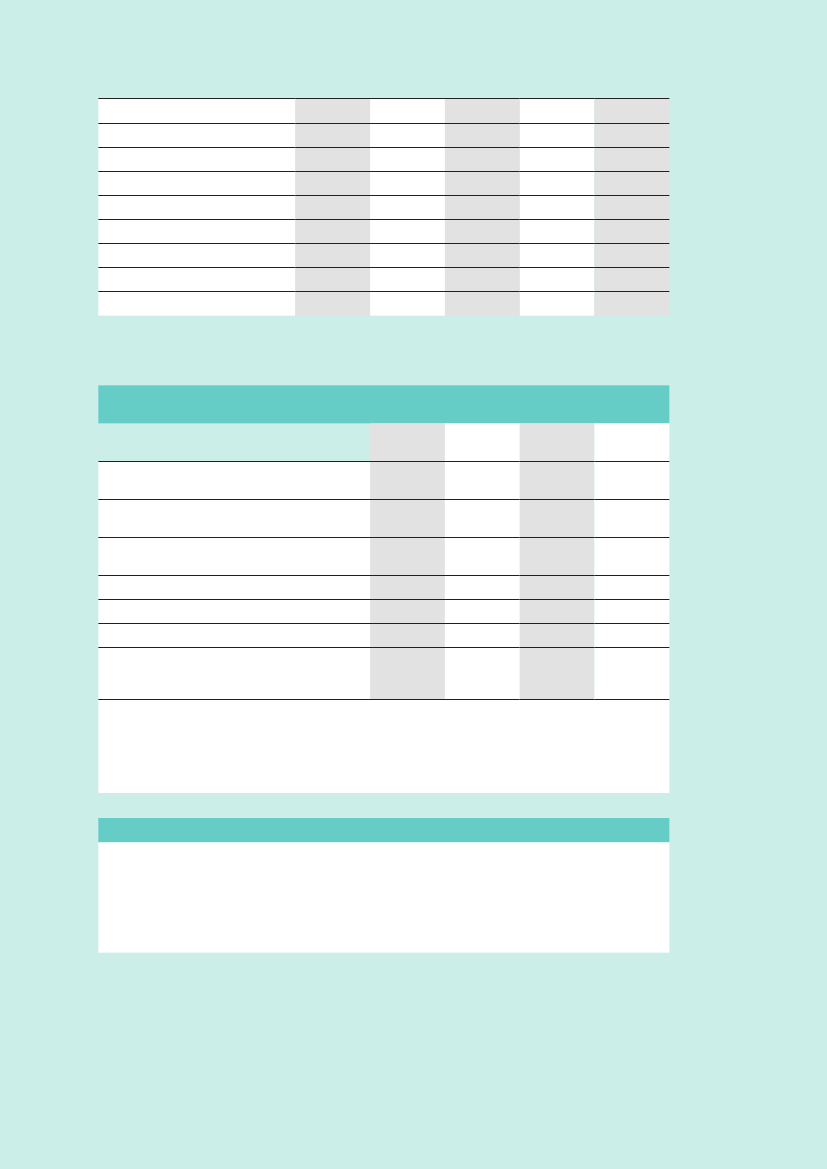

Presence of women’s parliamentary bodies in the OSCE regionThe study found that a number of parliaments in OSCE participating States have establishedwomen’s parliamentary bodies. As Table 2.1 shows, of the 36 respondents to the survey, 16,or just over 40 per cent, acknowledged the existence of a body that ‘brings women together’.A structure for women MPs used to be present in six of the OSCE participating States, and inanother two, women MPs expressed their desire to establish such a body in the near future.Twelve OSCE participating States responded that there was no such body.Table 2.1 Presence and number of bodies that bring women MPs together in the OSCE region (n=36)Yes, there is one (or more) currently16Austria, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Canada, Estonia, Finland, France,Georgia, Kyrgyzstan, the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia,Norway, Poland, Serbia, Sweden, Tajikistan, Ukraine, United Statesof America33Albania, Andorra, Armenia, Denmark,Latvia, Slovak RepublicHungary, MoldovaBelgium, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Germany, Italy, Kazakhstan,Liechtenstein*, Netherlands, Portugal, Romania, Slovenia, Spain

Yes, there used to be oneNo, but there are plans to create oneNo, there is no such body

6212

*

The questionnaire response from Liechtenstein noted that there was not a ‘body that brings women together’, butnonetheless detailed the activities of similar bodies.

3132

National Democratic Institute, “Women’s Caucuses Fact Sheet” (Washington: NDI, 2008).The existence of a similar body was also surveyed in the Assembly of Kosovo, thus bringing the total number ofstructures to 17.

20

According to these numbers, women’s parliamentary bodies have been established in partici-pating States across the whole OSCE region. Moreover, the number of responding parliamentsthat currently host a body (16), have hosted a body in the past (six), or intend to do so in thefuture (two) totals 24, which is double the number of parliaments that indicated that no suchbody has been established (12).It is important to identify the different reasons given as to why women’s parliamentary bodieshave not been established or are no longer functioning. Where such bodies no longer function,an analysis of the reasons why can bring to light lessons learned that may be of use to otherwomen’s parliamentary bodies. In Armenia, Latvia and Slovenia, the parliaments reportedthat the mandate of the body had simply not been renewed, sometimes because there weretoo few women elected to the parliament following elections to justify the continuation of thestructure, or too few women MPs were interested in re-establishing the body. This is particu-larly problematic where the women who created the body are not re-elected, as was the casein Denmark. In Armenia, a body close to being established was ultimately not formed, due todifficulties surrounding the question of leadership. In other cases, the renewal of the body wasnot achieved due to a lack of support from political parties, a lack of sufficient resources, orchanges in the parliamentary environment that rendered a women’s parliamentary body lessrelevant. A further reason was identified in Andorra, where the body’s functions were formallycommissioned to the parliamentary Social Affairs Committee.Understanding the potential challenges to the establishment or renewal of such bodies canhelp women parliamentarians better prepare to address these obstacles.

One size does not fit all: The design of women’s parliamentary bodiesWhile there is a plethora oftypesthat fall under the category of a women’s parliamentary body,differences essentially arise around their organizationalstructure.A core focus for such bodies is the desire to bring women (and sometimes men) parliamentar-ians together with the broad aim of facilitating discussion on issues of concern to them. Theway in which a group is formed to facilitate that discussion, however, can vary greatly. Asoutlined in Table 2.2 below, the differences essentially revolve around seven criteria: mandate,formality, structure (or modes of operation), leadership, resources, membership and activities.Table 2.2 Points of differentiation between women’s parliamentary bodiesCriteriaMandateAlternatives•••••••Formal issue-based advocacy and awareness raisingInformal forum for discussionInformation gathering mechanismPolicy and legislative review mechanismLegislative initiativesEmpowerment and capacity building of women MPsResearch body

2. Defining a women’s parliamentary body

21

Formality

• Formal body of the Parliament, follows parliamentary rules, has specific powers andprivileges• Formal parliamentary committee or sub-committee (not the focus of this study)• Informal group recognized by the Parliament• Informal group not recognized by the Parliament•••••••••••Accepted plan of activitiesRegularly scheduled meetings (more than 3/year)Infrequent meetings ‘as required’ (less than 3/year)Minutes of meetings recordedDecisions taken by consensusDecisions taken by a voteLeadership positions given to members of governing partyLeadership positions rotated across partiesLeadership via a co-chairing mechanismNo leadership positions (non-hierarchical leadership structure)Leadership positions held for a fixed term

Mode of operation

Leadership

Resources

• Staff, budget and meeting rooms provided by the Parliament• Staff and budget partly provided by the Parliament and partly provided by otherorganizations• Staff and budget provided entirely by other organizations• Budget derived from membership fees• Meetings held outside Parliament••••••••••Women onlyMen also includedWomen (and men) across all partiesWomen (and men) from one party only, or from the majority coalition onlyCivil society and/or international organizations includedFormer parliamentarians included

Membership

Activities

Writing letters, general advocacyConducting inquiries into legislation or policyDrafting and sponsoring gender equality legislationMonitoring the implementation of laws and international obligations from a genderperspective• Organizing social events• Mentoring of current and future MPs• Advocating for more gender-sensitive parliaments

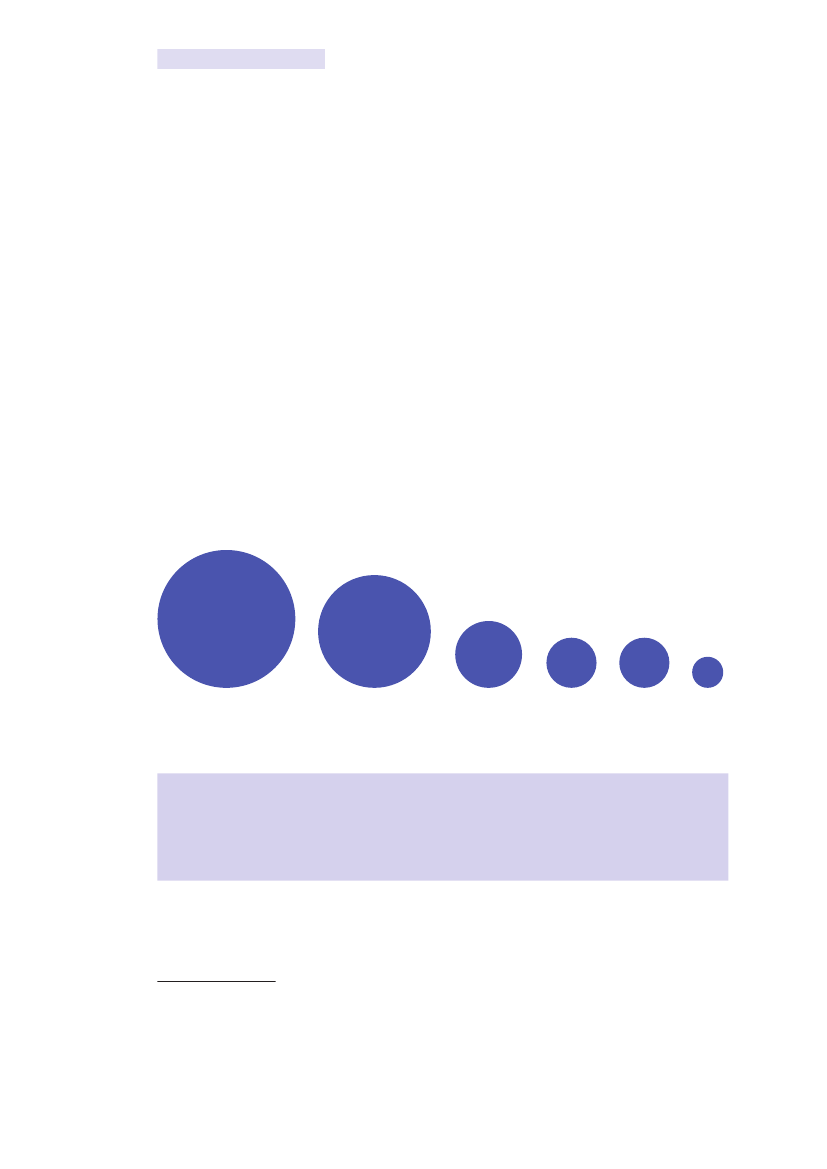

Typology of women’s parliamentary bodiesGiven the multiple ways in which women’s parliamentary bodies can be organized and struc-tured, making sense of the diversity of such structures can be a challenge. Therefore, for thepurpose of this study, the seven criteria identified in Table 2.2 – mandate, formality, structure(or modes of operation), leadership, resources, membership and activities – have been com-bined into two groups which form two continuing axes.Structureis a composite of formality,mode of operation, leadership, membership and resources. On this axis, bodies can be classi-fied as predominantly formal or informal. At one end of the spectrum, a formal body is onethat meets regularly with a pre-determined agenda, in accordance with pre-defined meetingrules and is supported (and possibly resourced) by the parliament. It might have a hierarchicalleadership structure and clear procedures by which members are included in the group. At theother end of this continuum, an informal body would meet as required, has no supporting staffor resources provided by the parliament, and can include a loose affiliation of members.The second axis delineates the parliamentary bodies’focus,which combines the mandate andactivities criteria outlined in Table 2.2. At one end of this spectrum, bodies that demonstratea parliamentary focus are those that have as their main goal the scrutiny and influencing of parlia-

22

mentary legislation, through the tabling of amendments or promotion of gender equality issueswithin the parliamentary agenda. At the other end, a body focused on advocacy would concentrateon lobbying on selected policy issues as well as with gender mainstreaming in a broader sense.A mapping of the various types of women’s parliamentary bodies according to this typology ispresented in Figure 2.1, and further explained below.Figure 2.1 Typology of women’s parliamentary bodies*

FORMAL STRUCTUREBody that is part of aninternational network ofparliamentary women’s groupsProfession-Focused Group

INFORMAL STRUCTUREPlatform involving civil societyStudy GroupResearch Body

ADVOCACYFOCUSED

Issue-Focused GroupPARLIAMENTARYFOCUSEDAdvisory GroupCross-Party Women’s Caucus

Parliamentary Friendship GroupInternal Party Women’s CaucusVoluntary Association, Network or Club

*For a detailed description of the various types of women’s parliamentary bodies see Appendix 3.

Formal, parliamentary focused groupssuch as cross-party women’s caucuses, advisory groups,or issue-focused groups are those established and recognized by the parliament, which may beprovided with resources (including parliamentary staff, budget and/or meeting rooms). They areprimarily concerned with the review of policy and legislation from a gender perspective, support-ing the introduction of amendments to such legislation, or advocating for women’s substantiverepresentation in parliament. These groups tend to restrict their membership to women.Formal, advocacy focused groupsare those that may be similarly resourced by the parlia-ment (although not to the same extent as parliamentary focused groups) and run as formalgroups with clear leadership structures and meeting rules. They are more concerned withadvocacy on a specific issue or profession, or with similar parliamentary groups in other coun-tries (e.g. an international network of women’s parliamentary bodies). These bodies may in-clude the participation of men.Informal, parliamentary focused groupssuch as voluntary associations, clubs or networks,or parliamentary friendship groups, can be differentiated in that they are generally not pro-vided with resources from the parliament (but may attract some funding from internationalor non-governmental organizations). They have less rigid meeting rules and leadership struc-tures (e.g. may rotate their leadership positions), but are still focused on parliamentary activi-ties, such as legislative reviews. These bodies may include the participation of men.Informal, advocacy focused groups tend to be composed of women and men, have a non-hierarchical leadership structure, meet infrequently on an as-required basis, and have no re-sources provided by the parliament. They are primarily focused on information gathering, writ-ing letters, and general advocacy. Platforms involving civil society and research or study groupsare usually very well connected with civil society (and other) organizations outside parliament.

2. Defining a women’s parliamentary body

23

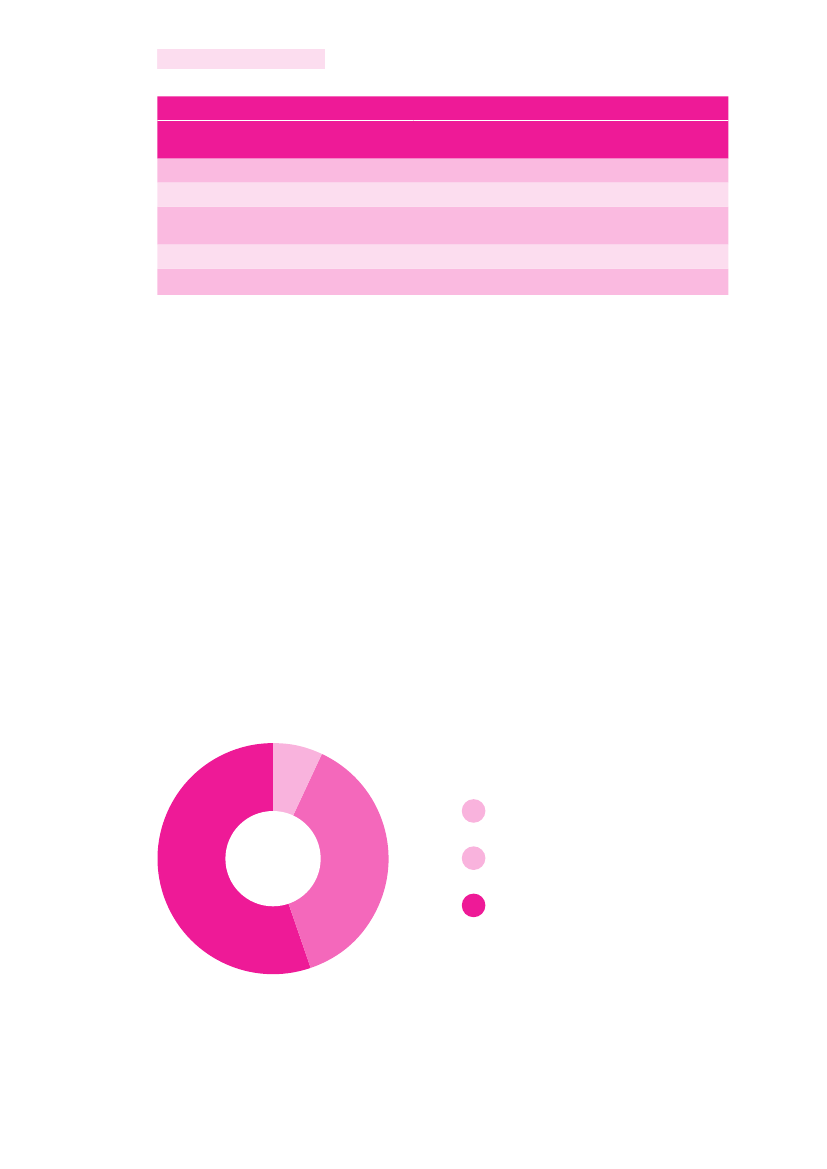

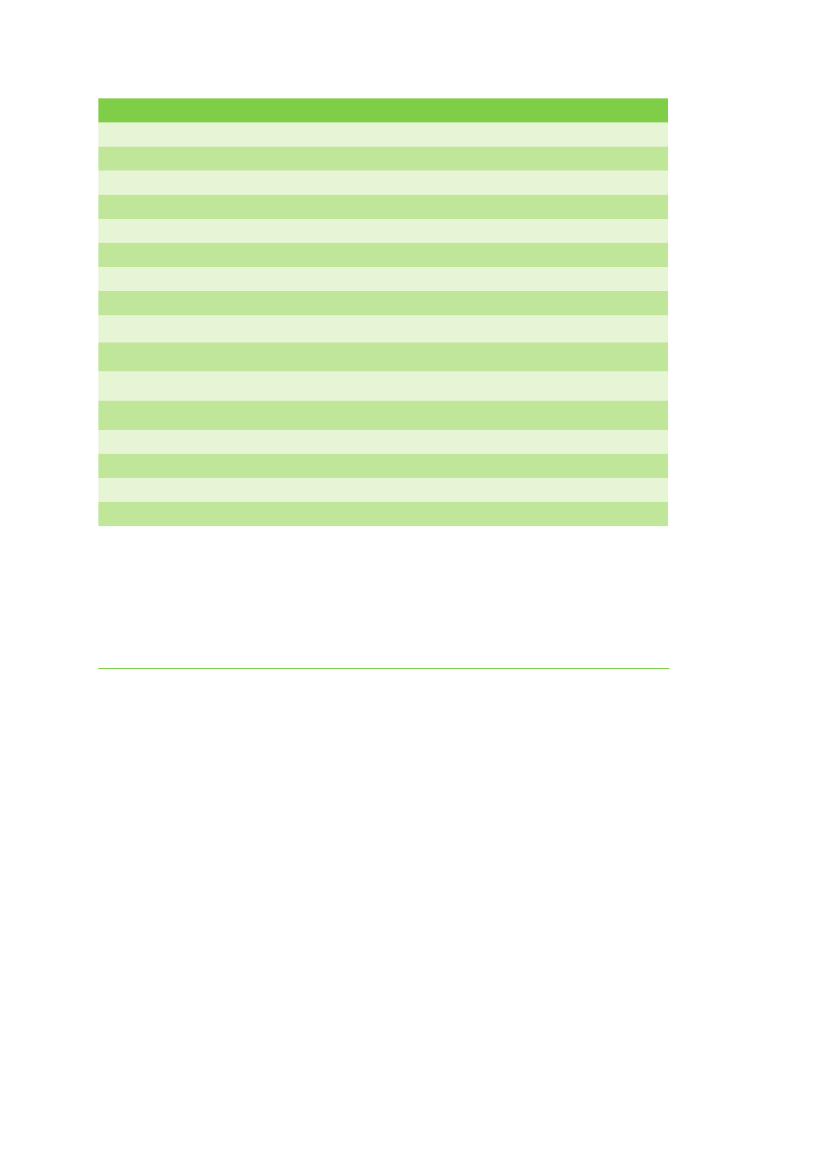

The range of women’s parliamentary bodies was presented to respondents in the question-naire. Each respondent was asked to match the women’s parliamentary body in his or her par-liament with one of the types identified in Figure 2.1 (the results are presented in Figure 2.2).Most respondents identified their body as a cross-party women’s caucus, followed closely bya voluntary association, club or network. A cross-party caucus is particularly prevalent amongthe Western Balkan states. With the exception of Canada, it might be said that the parliamentswhich include a cross-party women’s caucus generally have less disciplined party structuresthan those where an internal party caucus has been identified. The case of Canada, however,is interesting. In practice, the Canadian cross-party caucus generally has not been as active assome parties’ internal women’s caucuses precisely because of the rigid party discipline thatexists in that (Westminster) parliamentary system.33The prevalence of a voluntary association, club or network is also noteworthy. These bodies, bydefinition, are less reliant on the parliament for resources and support, but perhaps their advan-tage is a degree of flexibility to address issues of concern to their members (as is the case withthe Swedish Speaker’s Reference Group on Gender Equality Issues; see Case Study 9 below).The responses reveal that among those parliaments surveyed, there are both formal and in-formal bodies that tend to be focused on parliamentary work (that is, legislative and policy re-view), and informal bodies that are focused on advocacy (that is, raising awareness on specificissues, engaging the community and the electorate in these activities).Figure 2.2 Categorizing structures for women MPs in the OSCE region*

10

943Issue-focusedGroup

3InternalPartyWomen’sCaucusAustria,Canada,Norway

1PlatformInvolvingCivilSociety/OthersGeorgia

Cross-PartyWomen’s Caucus

VoluntaryAssociation,Network or Club

ParliamentaryFriendshipGroup

Albania, Bosnia andHerzegovina, Canada,Kyrgyzstan, Latvia, theformer Yugoslav Republic ofMacedonia, Poland, SlovakRepublic, United States ofAmerica36

Andorra, Denmark,Finland, Kazakhstan,Norway, Serbia, Sweden,Tajikistan, Ukraine

Canada,Georgia, Latvia,Tajikistan

Canada,Estonia,UnitedStates ofAmerica

Note: *The total number is greater than the 16 structures for women MPs reported in Table 2.1, because it includes cur-rent, former and/or future parliamentary bodies. Also, multiple answers were possible.

3334

See Jackie Steele, “The Liberal Women’s Caucus”,Canadian Parliamentary Review,Summer, 2002, pp. 13–19.The figure (10) includes a similar structure for women MPs established in the Assembly of Kosovo.

24

There were no reported bodies that were primarily formal in structure and focused on advo-cacy work, or a body that forms part of a larger international network of women parliamentar-ians. This does not mean that such bodies do not exist at all or indeed that this work is not doneto some extent by any of the bodies surveyed across the OSCE region. Rather, it suggests thatwhen a parliamentary body is formed in this region, it is either more focused on parliamentarywork, or is a more informal body engaged in advocacy work.Finally, it is interesting that some parliaments reported more than one type of women’s par-liamentary body. The case of the United States is illustrative, having both a cross-party andan issue-specific women’s caucus. This may suggest that where one type of body (for example,the Cross-Party Women’s Congressional Caucus) has not catered to the specific needs and ob-jectives of a sub-group of women, that sub-group has simply chosen to form a second caucus(for example, the Pro-Life Women’s Caucus). This also implies that the formation of a women’scaucus is more readily accepted in this parliamentary environment.

ConclusionA number of women’s parliamentary bodies have been established in OSCE participatingStates. Around 68 per cent of the parliaments surveyed noted that a women’s parliamentarybody is currently functioning, had previously been established, or there were plans to createone in the future. Conversely, 32 per cent of the parliaments surveyed indicated that they didnot have one or that they did not have any plans to create one in the future. These bodies ap-pear to be structured and organized in a variety of different ways across the OSCE region. Inparticular, this study noted that these bodies tend to differentiate themselves along seven cri-teria (mandate, formality, structure, leadership, resources, membership and activities), whichcan be further classified along two axes according to their structure and focus.Presenting this typology to parliaments in the OSCE region, the study found a predominanceof women’s parliamentary bodies that are parliamentary focused, such as cross-party women’scaucuses and voluntary networks or associations. At the same time, however, the wide range ofbodies already established and functioning in OSCE participating States indicates that there isno one model for operational success. Rather, the needs and preferences of potential membersare the best guides for deciding what type of body is most suitable for each parliamentarysetting, and for achieving some of the goals and benefits connected with their establishment.Regardless of how they are structured, women’s parliamentary bodies can provide a widerange of benefits to their members and parliamentarians more broadly. These benefits will beexplored in more detail through country case studies in the following chapters.

2. Defining a women’s parliamentary body

25

3. Enabling factors

Women’s parliamentary bodies do not exist in a vacuum. Taken alone, their internal organi-zation and activities do not define their ability to achieve positive outcomes. It is important,therefore, to consider whether and to what extent political and parliamentary systems, institu-tional arrangements, as well as the activities of broader civil society, play a role in facilitatingthe establishment and eventual running of a women’s parliamentary body. In other words,what factors facilitate or hinder the establishment and running of women’s parliamentary bod-ies in the OSCE region?This chapter looks in more detail at the ‘enabling factors’ that can have a positive impact onwhether women’s parliamentary bodies are established in the first place, and what type ofstructure and focus these bodies may have. The chapter focuses on external factors, whilesubsequent chapters focus on the internal dimensions of how women’s parliamentary bodiesfunction.

Parliamentary and political systems in the OSCE regionThe OSCE region is composed of different parliamentary regimes, as defined by electoral sys-tems, parliamentary systems, and political party composition. Thirty-three of the parliamentsin the OSCE region are unicameral; 22 are bicameral. Each of the lower houses and unicam-eral chambers are directly elected. The upper houses of Germany, the Netherlands, Slovenia,Canada and Tajikistan are indirectly elected or appointed.Of the 36 OSCE participating States surveyed, proportional representation is used to elect atleast one chamber in 23 legislatures; mixed electoral systems (being those that include ele-ments of both proportional representation and plurality or majority systems)35exist in ten leg-islatures, and majority systems are used in four. Parliamentary systems predominate amongthose States that responded to the questionnaire. Only four of the respondents had presidentialsystems, and another three reported a semi-presidential system. The vast majority of these

35

Louis Massicotte and André Balais, “Mixed electoral systems: a conceptual and empirical survey”,ElectoralStudies,Vol. 18, No. 3, 1999, pp. 341–366.

26

States are defined as having a multi-party system; two are defined by the Inter-ParliamentaryUnion as using ‘dominant’ party systems.36Survey results indicate that parliamentary women’s bodies have been established in parlia-ments elected according to all three types of electoral systems (proportional representation,mixed and majoritarian). Furthermore, these bodies have been established in both parliamen-tary and presidential systems, and in systems where certain parties have dominated the politi-cal landscape over long periods of time. It is possible to conclude, therefore, that the type ofparliamentary regime and electoral system in place is not necessarily a predictor of whether ornot a women’s parliamentary body will be established or, indeed, of its effectiveness.By contrast, some respondents indicated that the politicalcontext– for example, the degreeof multi-party co-operation and dialogue that takes place in general, the degree of polariza-tion characterizing the political environment, and the strength of political party discipline –rather than politicalsystems,has a potentially greater impact on the emergence and effectivefunctioning of women’s parliamentary bodies.37Where political polarization creates a level ofpolitical party discipline that makes cross-party co-operation difficult or unlikely, the estab-lishment of formal cross-party women’s parliamentary bodies may prove extremely challeng-ing. This does not mean that cross-party bodies do not emerge under these circumstances, butrather that they may take another form – for example, as an informal network. In these cases,cross-party dialogue can be facilitated from the outside, by non-political actors such as inter-national organizations or civil society.

Enhancing women’s parliamentary presence: The use of special measuresAs of July 2013, women’s parliamentary representation in the OSCE region amounted to anaverage of 24.4 per cent in unicameral or lower houses, and 22.6 per cent in upper houses.Although there is some diversity in the proportion of women’s representation across the OSCEregion, this percentage compares favourably with the world average of 21.3 per cent in unicam-eral or lower houses, and 18.8 per cent in upper houses.38Nonetheless, it falls short of the 30per cent recommended by the United Nations.39

3637

3839

Inter-Parliamentary Union,PARLINE Database on National Parliaments,http://www.ipu.org/parline/, accessedMarch 2013.Discussions with participants held during the OSCE/ODIHR Regional Workshop on Parliamentary Structuresfor Women MPs in the OSCE Region, organized 11 to 12 December 2012 in Vienna, within the framework of theODIHR project “Strengthening Parliamentary Structures for Women MPs in the OSCE Region”.Inter-Parliamentary Union,Women in national parliaments,http://www.ipu.org/wmn-e/world.htm, accessed July2013.The UN Economic and Social Council originally proposed the 30 per cent target to be achieved by 1995. In its1995 Beijing Platform for Action, the United Nations recalled that few countries had achieved this goal and urgedmember states to take actions to achieve the target as a means to build a ‘critical mass’ of women’s representa-tion in political and public life. See http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/beijing/pdf/BDPfA%20E.pdf.

3. Enabling factors

27

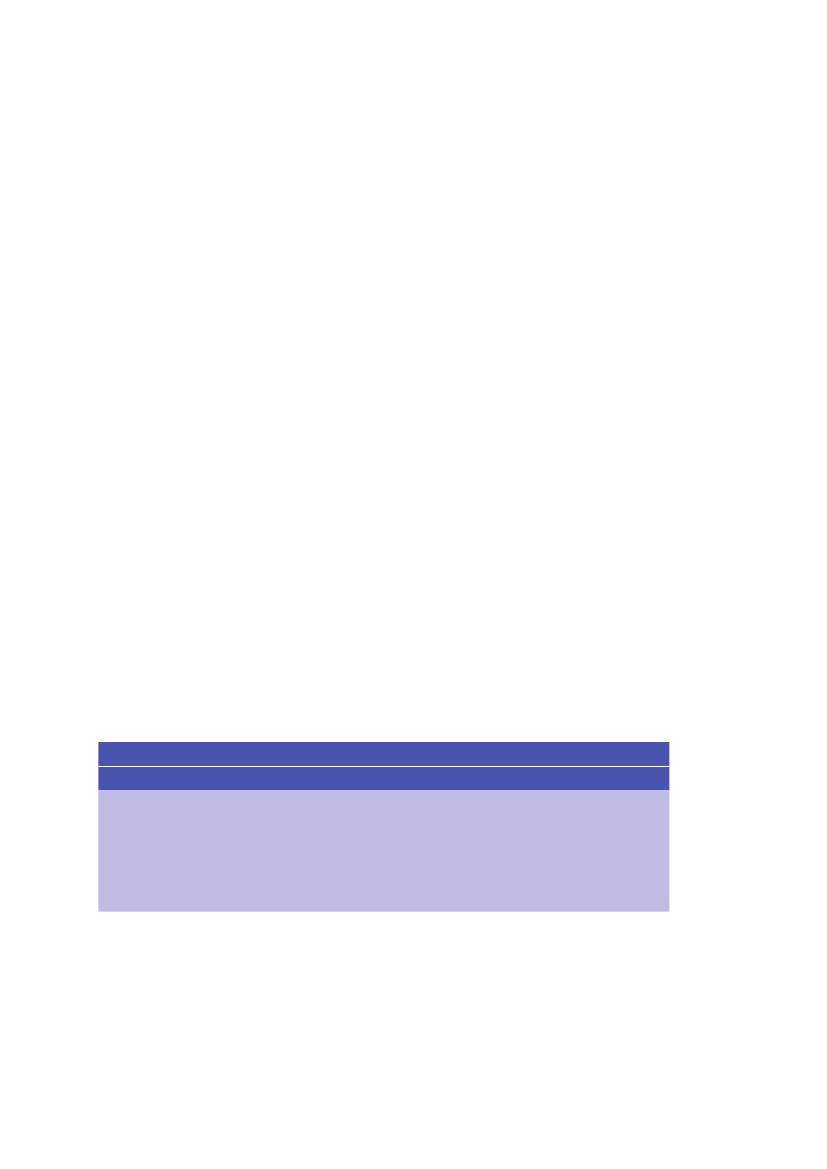

Table 3.1 Women in national parliaments in the OSCE, by regionRegionOSCENorthern EuropeEurope and North America (excluding NorthernEurope)Western BalkansCommonwealth of Independent StatesSource : IPU (2013) http://www.ipu.org/parline/Lower or Unicameral houses (%)24.442.022.720.415.5Upper houses (%)22.6--22.65.812.3

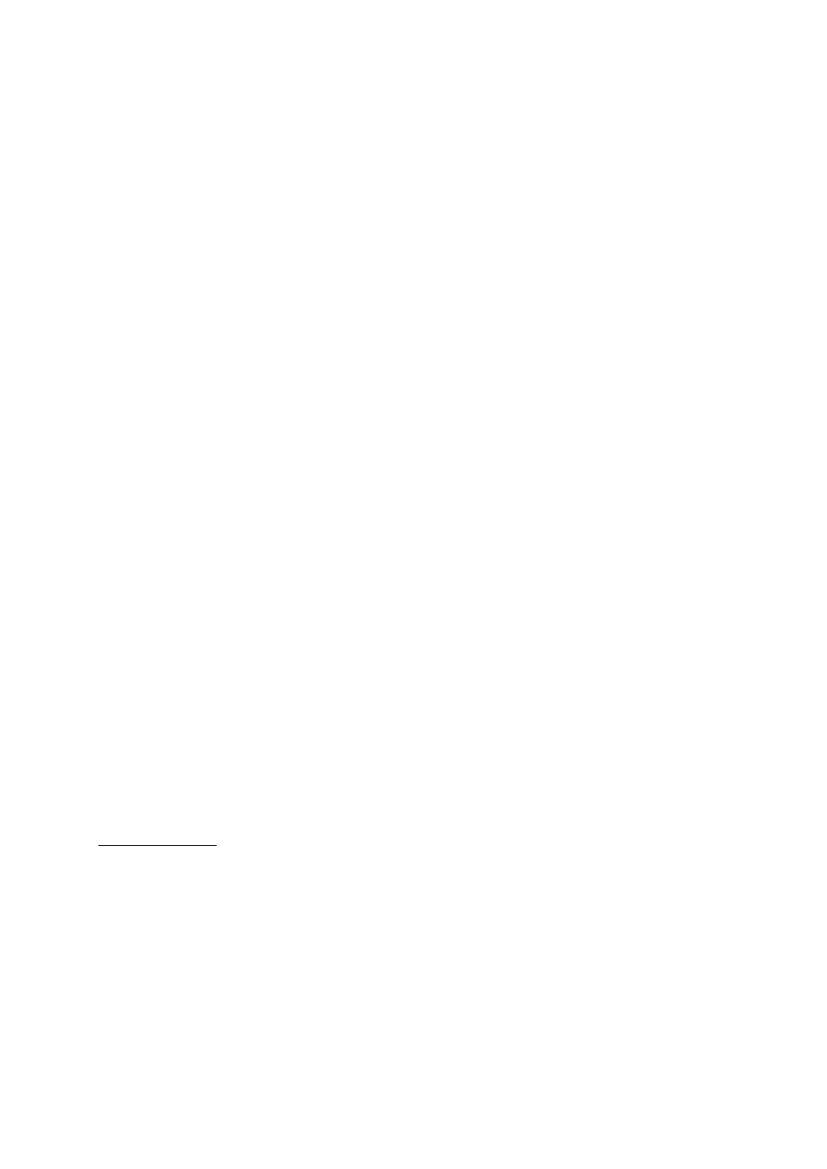

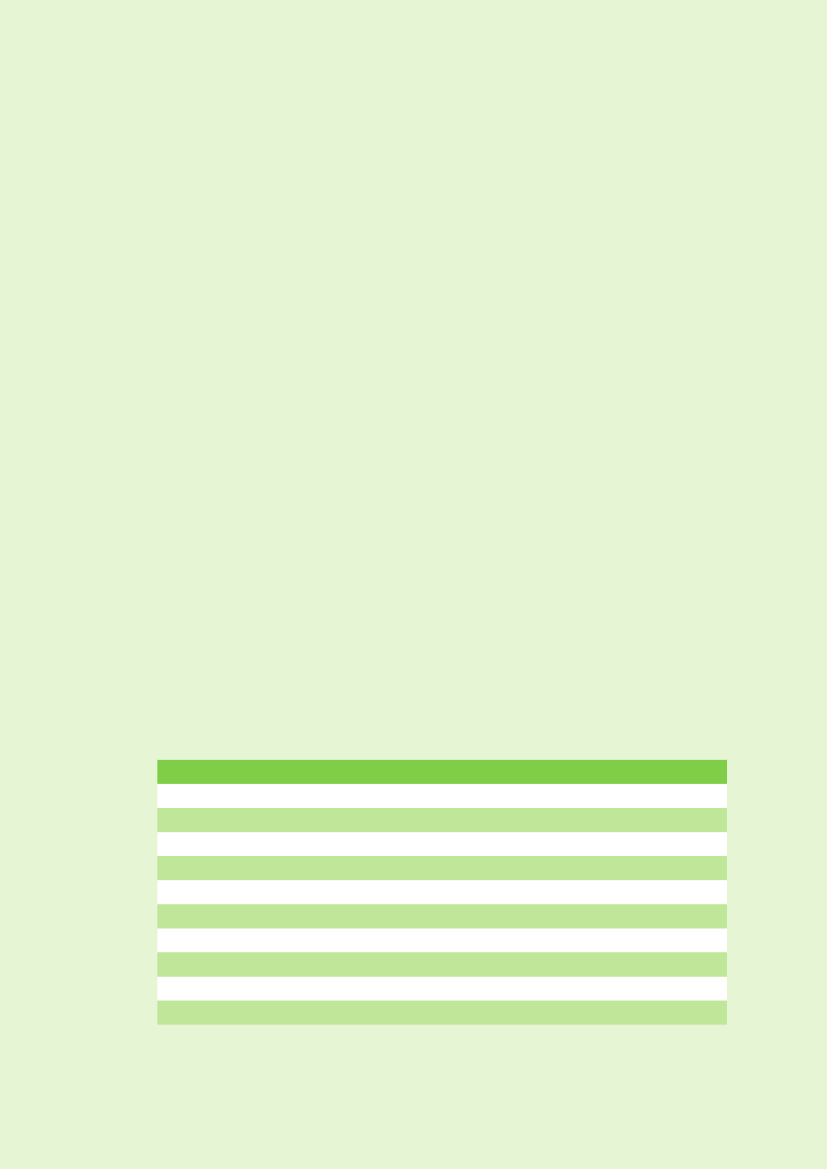

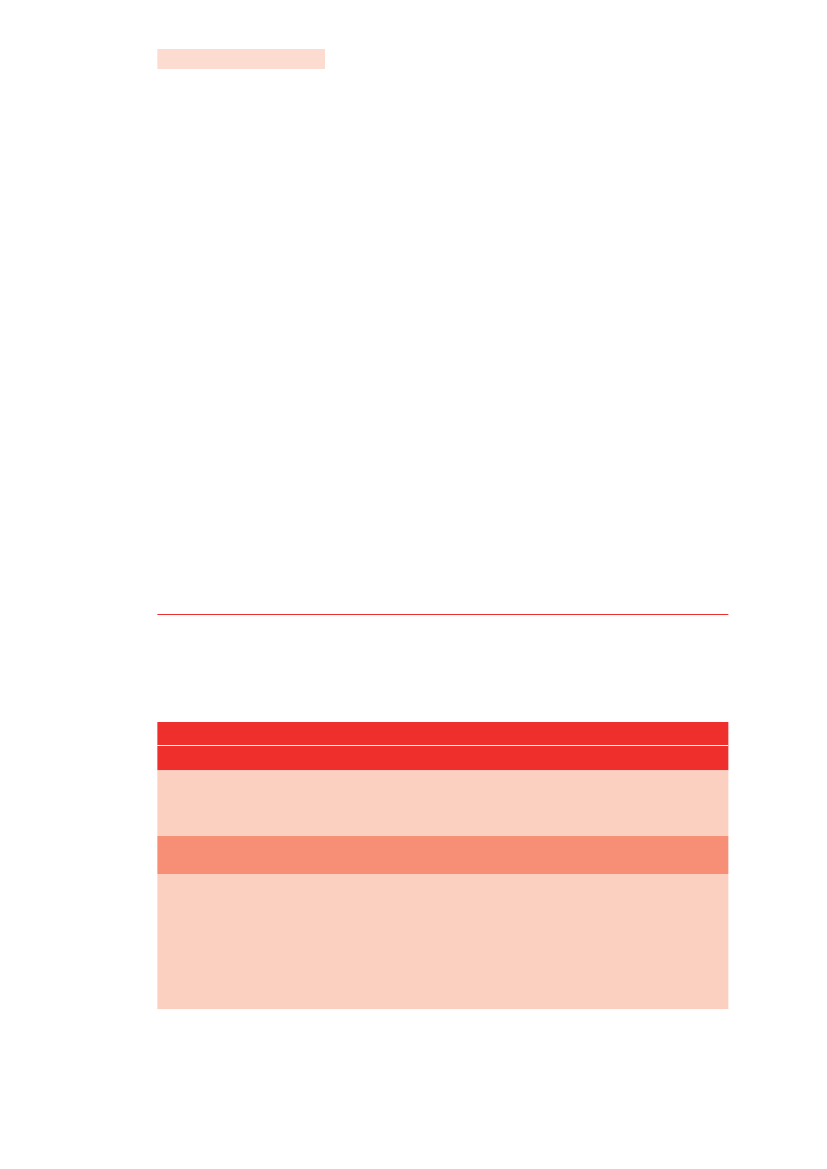

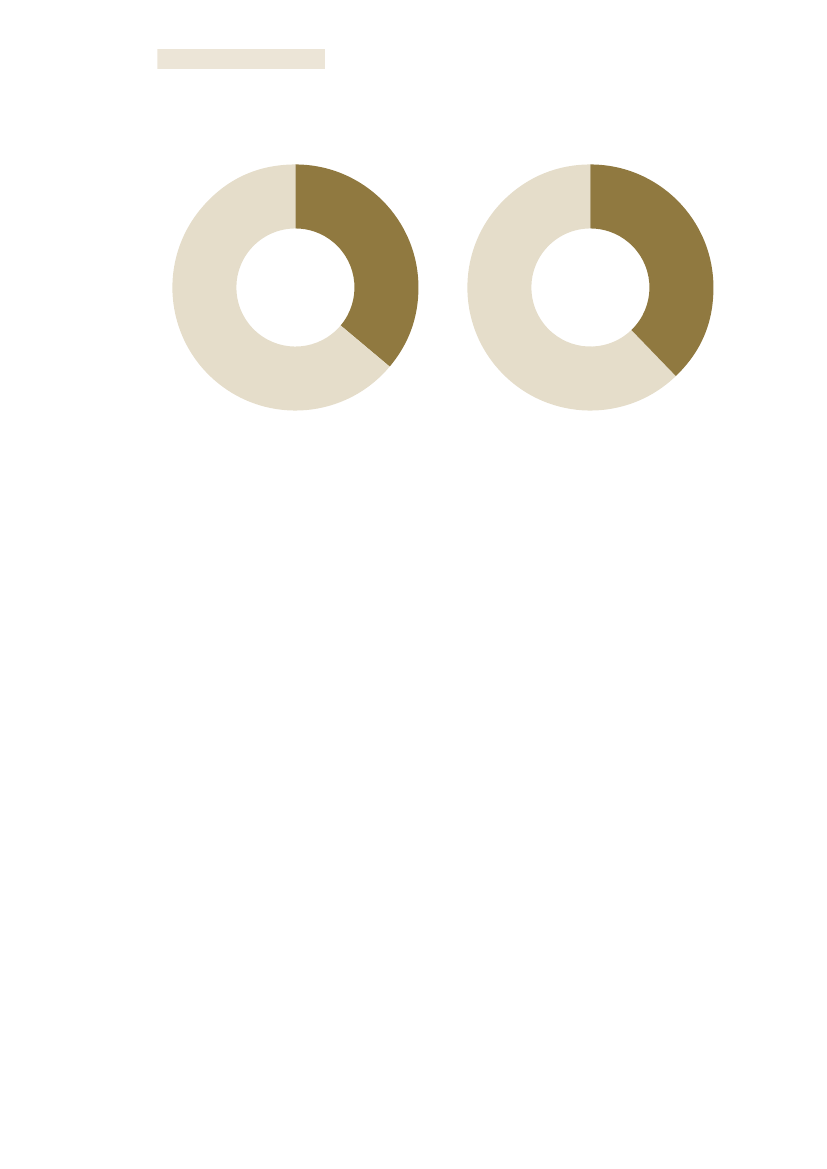

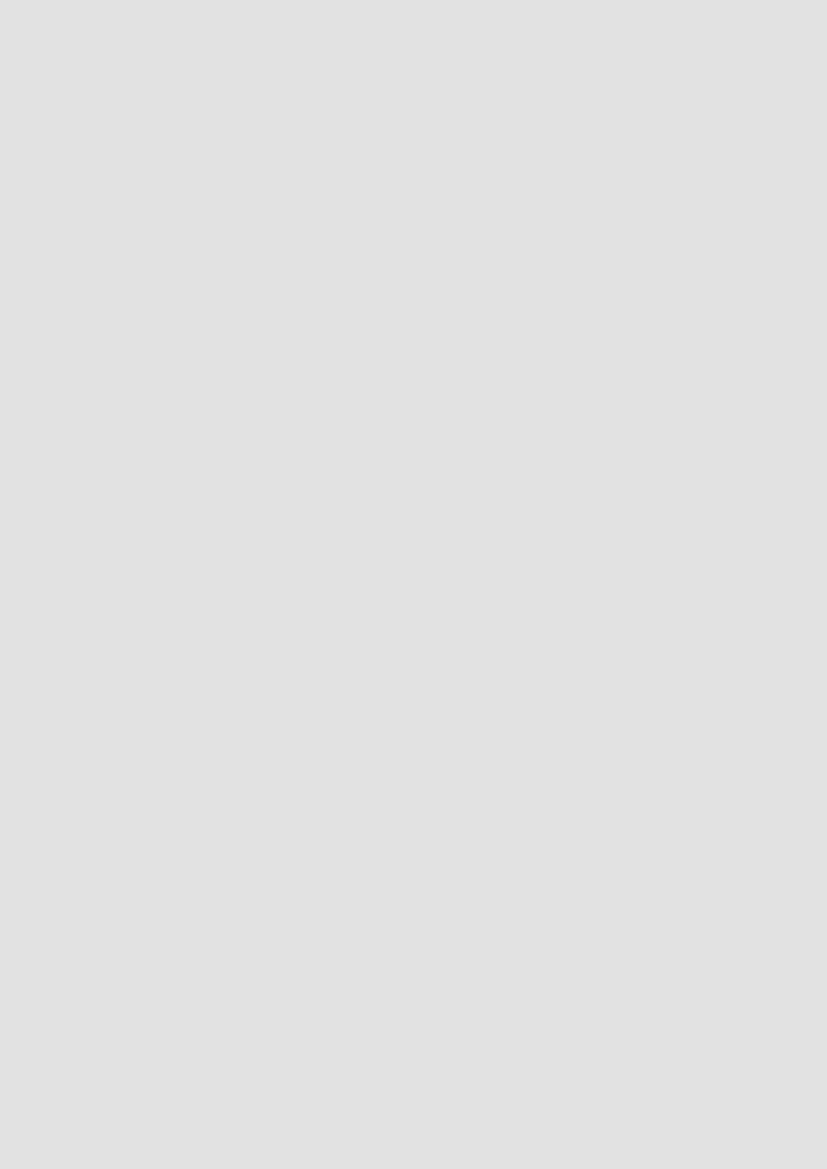

High numbers of women in parliament are often associated with the presence of special meas-ures to promote women’s political participation. In the OSCE Ministerial Council Decision 7/09on Women’s Participation in Political and Public Life, adopted during the 2009 Athens OSCEMinisterial Council, participating States were called upon to “consider possible legislativemeasures which would facilitate a more balanced participation of women and men in politi-cal and public life, especially in decision-making” (see Appendix 1 for key provisions of thisDecision). In the 18 participating States surveyed where at least one chamber has over 25 percent of women MPs, special measures (most commonly legislated gender quotas) are used inten. Conversely, in those countries where women are least represented, legal quotas have notbeen implemented, although some have introduced voluntary party quotas.Reserved seats, or quotas that legally mandate in a Constitution or an electoral law that a cer-tain percentage or number among those elected must be women, appear to be used sparinglyamong the OSCE participating States, and continue to be marred by some controversy. Morefrequently, political parties have introduced voluntary party quotas – quotas voluntarily de-termined by political parties themselves (see Figure 3.1). In 23 of the States surveyed, oneor more political parties have nominated a target number (or percentage) of women or of theunder-represented sex to be included on party lists or to be elected.3Figure 3.1 Presence of special measures in OSCE participating States

23

16

Reserved seats/Executive appointmentsLegislated party/candidate quotasVoluntary partyquotas

Source: Quota Project (2012) http://www.quotaproject.org

28

The data suggests that there is no direct correlation between the percentage of women MPs and theexistence of legal or voluntary measures to promote women’s representation on the one hand, andthe existence of women’s parliamentary bodies in OSCE participating States on the other. Indeed,women’s parliamentary bodies have been established in countries with both high and low percent-ages of women MPs, in countries that have adopted legal quotas (for example, Poland, Kyrgyzstanand the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia), in countries where some political parties haveadopted voluntary quotas or other measures (for example, Austria, Canada, Finland, France, Georgia,Norway, Sweden and Ukraine), as well as in countries that have not introduced any legal or volun-tary quotas per se to advance gender representation in parliamentary structures or political parties,but have introduced other types of special measures, including policy and legal instruments andprogrammes, to promote gender equality and women’s participation in political and public life.Notwithstanding the above, it is worth noting that several women’s parliamentary bodies havebeen actively involved in advocating for the introduction of such special measures and/or inmonitoring their implementation. For example, the Polish Parliamentary Group of Women advo-cated alongside civil society and gender equality organizations for the introduction of an elector-al quota for candidate lists in the run-up to parliamentary elections in Poland in 2011. Likewise,the Women’s Caucus of the Albanian Parliament (see Case Study 1 below), which existed in the2005 to 2009 sitting of the legislature, lobbied together with civil society for the introduction ofa legal gender quota, which was finally achieved in 2008. Alternatively, where electoral genderquotas have been introduced, women have often grouped together to ensure that increased par-liamentary representation translates into increased substantive participation of women in par-liament or to achieve amendments to existing special measures, as was the case of the WomenParliamentarians’ Club of the Assembly of the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia.Therefore, it is possible to conclude that, while the existence of special measures (legal orvoluntary) is not a pre-condition for the establishment or running of a women’s parliamentarybody, such measures can provide a common purpose or issue around which women MPs, andspecifically women’s parliamentary bodies, can organize and mobilize.

Case Study 1: The Albanian experience of a Women’s CaucusAlbanian women MPs first established a Women’s Caucus in 1995. In 2005, with the support of theOSCE, the Caucus was renewed, gathering ten women MPs from the main political parties. TheCaucus forged an effective and co-operative relationship with the Sub-Committee on Juveniles andEqual Opportunities, which formed part of the Committee on Health, Labour and Social Issues.Between 2007 and 2009, the Caucus focused its activities on advocating for the adoption of theLaw on Gender Equality in the Albanian Society, which was passed in 2008 with the support ofthe national women’s movement, as well as on the reform of the Electoral Code, advocating for theintroduction of a 30 per cent legislated party quota for the less represented gender on party lists.The Electoral Code was successfully changed in 2008 to require, “for each electoral zone, at leastthirty per cent of the multi-name list and/or one of the first three names on the multi-name list [to] befrom each gender.” In the parliamentary elections of 2009, 23 women were elected, increasing wom-en’s representation in that chamber from 7 per cent to 16.4 per cent. It has been suggested that oneof the reasons why more women were not elected was the differing interpretations of the electorallaw, with “weaknesses in the formulation of the legal provisions undermin[ing the quota] objective”.40

40

OSCE/ODIHR Election Observation Mission to the Republic of Albania, 14 September 2009, p. 18. Available at:http://www.osce.org/odihr/elections/albania/38598.

3. Enabling factors

29

In addition to the quota, the electoral law was also amended in 2008 to introduce a list pro-portional representation system, whereby the 140 members of parliament are elected across 12constituencies corresponding to the country’s 12 administrative regions. Under this electoralsystem, the lists of candidates are prepared by the political parties. It has been argued thatthe change in the electoral system resulted in MPs becoming more loyal to their political par-ties, and less able to pursue political issues independently, outside their party. Political partytensions following the 2009 elections eventually culminated in a six-month parliamentaryboycott by the Socialist Party.In this context, women MPs found it extremely difficult to leave behind their party politics.Women elected for the first time in 2009, who had actively campaigned on gender issues whileworking in the civil society sector and were passionate about those issues, were unable to putparty loyalties aside and find a space for cross-party dialogue. In this political climate, there-establishment of a women’s caucus proved too challenging. Nonetheless, it is clear that theWomen’s Caucus that previously functioned in the parliament played a key role in introducingspecial measures to promote women’s political participation in Albania.While women MPs have found it difficult to raise the profile of gender issues and women’spolitical representation at the national level, at the local level, several women networks havehad more success. In this regard, the National Platform for Women (NPfW), a network of1500 women politicians active in local and national-level politics, and supported by the OSCEPresence in Albania, has successfully raised awareness of gender issues in recent years. Inaddition, the main political parties have formed their own internal party women’s leagues/forums operating at the local level, lobbying for an increased presence of women and theirempowerment within the respective party structures.In 2012, the Electoral Code was the subject of further reform.41With the support of several in-ternational organizations, different women’s networks pulled together to advocate for a strong-er quota provision, and stronger enforcement provisions. Lack of political will from the mainpolitical parties, however, together with divisions among the women’s groups and their inabil-ity to find a united position, meant that no substantial amendments were introduced. As a con-sequence, there were concerns that the gender quota would not be enforced by electoral bodiesduring the parliamentary elections in June 2013, and that again this would affect the numberof women elected to the Albanian parliament. In this environment, women parliamentarianscontinue to seek ways in which to co-operate across party lines, acknowledging the role thatthe previous Women’s Caucus played in lobbying for women’s representation in the past.

The existence of women’s movementsThe presence of a women’s movement and/or other women’s civil society groups, coupled withthe degree of their support for a women’s parliamentary body, especially in the phases priorto and just after its establishment, can be considered an important enabling factor. While thequestionnaire did not survey the existence of a women’s movement in the OSCE participatingStates as a mechanism for promoting women’s political participation as such, several respond-ents noted that the presence of a women’s movement did influence the emergence of women’sparliamentary bodies.

41

The Electoral Code of the Republic of Albania, 2012, Art. 67, p. 57. Available at: http://www.osce.org/alba-nia/14464.

30

In the Western Balkans, for example, strong women’s movements functioned before, duringand following the transitions to democracy. In fact, many of the women eventually elected toparliament in this region were leaders or members of the civil society women’s movement.Several members of women’s parliamentary bodies in the Western Balkans noted that women’sparliamentary bodies are more likely to be successful where they maintain strong links to andrelationships with the broader women’s movement.42This is because women’s movements of-ten constitute the ‘institutional memory’ of the struggle for women’s rights and gender equal-ity in a country or region, and, as such, also tend to enjoy the support of society more broadly.Women’s parliamentary bodies that capitalize on this knowledge and experience are morelikely to be perceived as legitimate by the electorate. The Women Parliamentarians’ Club ofthe Assembly of the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia is one example of a parliamen-tary body that has maintained strong links with women civil society activists; the Club ofteninvolves these activists in its activities and outreach. A similar relationship with the women’smovement was noted by the Women’s Caucus of the Assembly of Kosovo.Likewise, gender equality outcomes in Slovenia have been achieved, in large measure, due tothe work of a coalition of women from both inside and outside the parliament. In fact, whenpartisan competition and personal divisions between women MPs became too strong for a par-liamentary caucus to function, a broad-based national Parity Coalition was formed, includingindividual leaders of women’s organizations, trade unions, experts and leaders of politicalparty women’s organizations from the left, centre and right wing parties. The Coalition also in-cluded three highly prominent men. This Coalition is credited with having lobbied successfullyfor the introduction of a gender quota in the law on the election of members to the EuropeanParliament (MEPs), requiring at least 40 per cent of the under-represented sex on party lists.As a result, the first delegation of Slovenian parliamentarians to the European Parliament wascomposed of 42 per cent women.The Coalition also pressured competing political parties during the 2011 elections to increasethe number of women candidates selected. Two parties which collectively won 35 per cent ofthe vote in these elections ran women in 50 per cent of their eligible constituencies.