Forsvarsudvalget 2013-14

FOU Alm.del Bilag 43

Offentligt

DIRECTORATE-GENERAL FOR EXTERNAL POLICIES

POLICY DEPARTMENT

POLICY BRIEFING

The European Council on defence matters:Time to deliver

AbstractDefence matters. This was the clear message of the Thessaloniki European Council of 19and 20 June 2003. The moment the conference took place, one decade ago, was also thetime of the first EU missions and operations, the birth of the European Security Strategyand the starting shot for the European Defence Agency. Since then, the key change forthe EU and for defence has been the entry into force of the Lisbon Treaty, in December2009. Yet European efforts to collectively reform defence have been marked from theoutset by drawbacks, criticism and resistance, punctuated by occasional successes andincremental advancements. Progress in this field has been held hostage to politicaldisagreements between those who clearly support and those who are fiercely scepticalabout defence integration. Their divergence has meant that security and defence policyin the EU has been rather toothless, and its institutions feeble. Gathering in December2013, the heads of state and government have the privilege and – given the past decadeof neglect – the duty to end this perpetual beginning.

DG EXPO/B/PolDep/Note/2013_260PE 522.315

December 2013EN

Policy Department, Directorate-General for External Policies

This Policy Briefing is an initiative of the Policy Department, DG EXPO

AUTHOR:

Ulrich KAROCKDirectorate-General for External Policies of the UnionPolicy DepartmentWIB 06 M 45rue Wiertz 60B-1047 BrusselsEditorial Assistant: Elina STERGATOU

CONTACT:

PUBLICATION:

English-language manuscript completed on 05 December 2013.�European Union, 2013Printed inBelgiumThis Policy Briefing is available on the intranet site of the Directorate-General for External Policies, in theRegions and countriesorPolicy Areassection.

DISCLAIMER:

Any opinions expressed in this document are the sole responsibility of theauthor and do not necessarily represent the official position of theEuropean Parliament.Reproduction and translation, except for commercial purposes, areauthorised, provided the source is acknowledged and provided thepublisher is given prior notice and supplied with a copy of the publication.

2

The European Council on defence matters: Time to deliver

Table of contents12345The end of beginning or the beginning of the end?In the hands of the Member StatesThe EU aspect... and NATO?What next?4581012

3

Policy Department, Directorate-General for External Policies

1

The end of beginning or the beginning of the end?Defence matters. This was the clear message of the Thessaloniki EuropeanCouncil of 19 and 20 June 2003. The moment the conference took place, onedecade ago, was also the time of the first EU missions and operations, thebirth of the European Security Strategy and the starting shot for theEuropean Defence Agency. Since then, achievements have been modest:only than the European Council of 2008, which 'reloaded' the EuropeanSecurity Strategy, achieved something in the domain. Yet the 2013 iterationis expected to deliver strategic impetus on the defence policy in the Union.The key change for the EU and for defence since Thessaloniki is the entry intoforce of the Lisbon Treaty, in December 2009. The treaty, borne of the failureof the constitution treaty, brought significant changes to the Union’sCommon Security and Defence policy (CSDP). New provisions supersededthe security and defence policy provisions of the Amsterdam Treaty, whichhad entered into force a decade earlier, on 1 May 1999.From the very beginning, European efforts to collectively reform defencehave been marked by drawbacks, criticism and resistance, punctuated byoccasional successes and incremental advancements. Progress in the fieldhas generally been held hostage to political disagreements between thosewho clearly support and those who are fiercely sceptical about defenceintegration. Their divergence has meant that security and defence policy inthe EU is rather toothless, and its institutions feeble. Gathering in December2013, the heads of state and government have the privilege and – given thepast decade of neglect – the duty to end this perpetual beginning. Withoutproper attention, the Union’s defence will vanish, and the upcomingEuropean Council will mark the beginning of the end.

Defence matters. Thiswas the clear message ofthe ThessalonikiEuropean Council of 19and 20 June 2003.

In December 2012, theEuropean Council againsent a signal to defencestakeholders thatEuropean defencematters.

The European Council will consecrate at most a couple of hours to thedefence debate. Even this may make a difference; when the Council merelydecided in December 2012 to address the topic, it sent a signal to defencestakeholders in Member States, the North Atlantic alliance and the EUinstitutions that European defence matters. The Council charged thecompetent institutions to reflect on defence and the EU, and to address threetopics: improving the effectiveness, visibility and impact of the CSDP;developing the necessary capabilities; and strengthening the technologicaland industrial base underpinning defence.Over the course of 2013, many political gatherings, conferences, reports andarticles have addressed the current state of defence policy in the EU. Manyproposals have been advanced to reform and to improve it – or, in somecases, to end it. This lively public debate accompanied the preparation anddelivery of the institutional contributions requested of the EuropeanCommission1, the Council of the European Union2and the High

Communication 'Towards a more competitive and efficient defence and security sector' of24/07/20132Council conclusions on Common Security and Defence Policy of 25&26 November 20131

4

The European Council on defence matters: Time to deliver

Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy / Head of the EuropeanDefence Agency (EDA)3. The European Parliament adopted two non-legislative reports on the CSDP4and on the European Defence Technologicaland Industrial Base5(EDTIB) on 21 November 2013.The numerous political, industrial and academic views expressed in recentpreparations for the Council have highlighted that the current decade iscrucial for defence and for the EU. There are reasons to believe that neitherthe EU nor European defence can survive without the other, and that bothmust live by the rule,'use it, or lose it!'

2

In the hands of the Member StatesDefence matters. That the European Council will conclude this is a certainty.But the words that are added to this conclusion will be scrutinised withextreme attention in the capitals of Europe and beyond.Three European capitals will have a key role to play. Pieter De Crem, BelgianDeputy Prime Minister and Minister of Defence, clearly named the countriesthat would lead the strategy in his speech to the Subcommittee on Securityand Defence European Parliament on 26 September 2013: ‘To advance in theright direction, the European Union must necessarily demonstrate moredetermined and visible leadership. For Belgium, that leadership mustprincipally derive from greater military cooperation among the great powersin Europe – Great Britain, France and Germany, in no particular order6.’The political and economic punch of Berlin, the strategy and will of Paris andthe global – in particular transatlantic – understanding of London will need tobe united. These three governments’ expenditures account for two thirds ofEU defence outlays. When Italy is included, the four represent more thanthree quarters of the EUR 190 billion spent by the EU on defence in 20127.Much of the industrial and technological base of European Defence – and agood deal of European military capabilities – is also concentrated in thesefour Member States. Not coincidentally, these four are also key allies in NATOand deeply involved in international cooperation and many missions andoperations.Yet just how committed these states are remains to be established. In fact,Final Report by the HR/Head of the EDA on the CSDP of 15/11/ 2013Report on the Implementation of the Common Security and Defence Policy (based on theAnnual Report from the Council to the European Parliament on the Common Foreign andSecurity Policy) adopted on 21/11/20135European Parliament Report on the European defence technological and industrial base(based on the communication from the European Commission 'Towards a morecompetitive and efficient defence and security sector') adopted on 21/11/20136In French: ‘Pour progresser dans la bonne direction, l’Union européenne doitnécessairement afficher un leadership plus déterminé et visible. Pour la Belgique, il doitémaner avant tout d’une coopération militaire accrue entre les plus grandes puissancesmilitaires en Europe, à savoir le Royaume-Uni, la France et l’Allemagne, l’ordre importantpeu’.http://www.pieterdecrem.be/index.php?id=36&tx_ttnews%5BbackPid%5D=144&tx_ttnews%5Btt_news%5D=3460&cHash=55c77c5f474695a0ab9804f7f808335c&L=17EDA defence data,http://www.eda.europa.eu/info-hub/defence-data-portal34

The EU needs aleadership determined toprogress in the rightdirection.

5

Policy Department, Directorate-General for External Policies

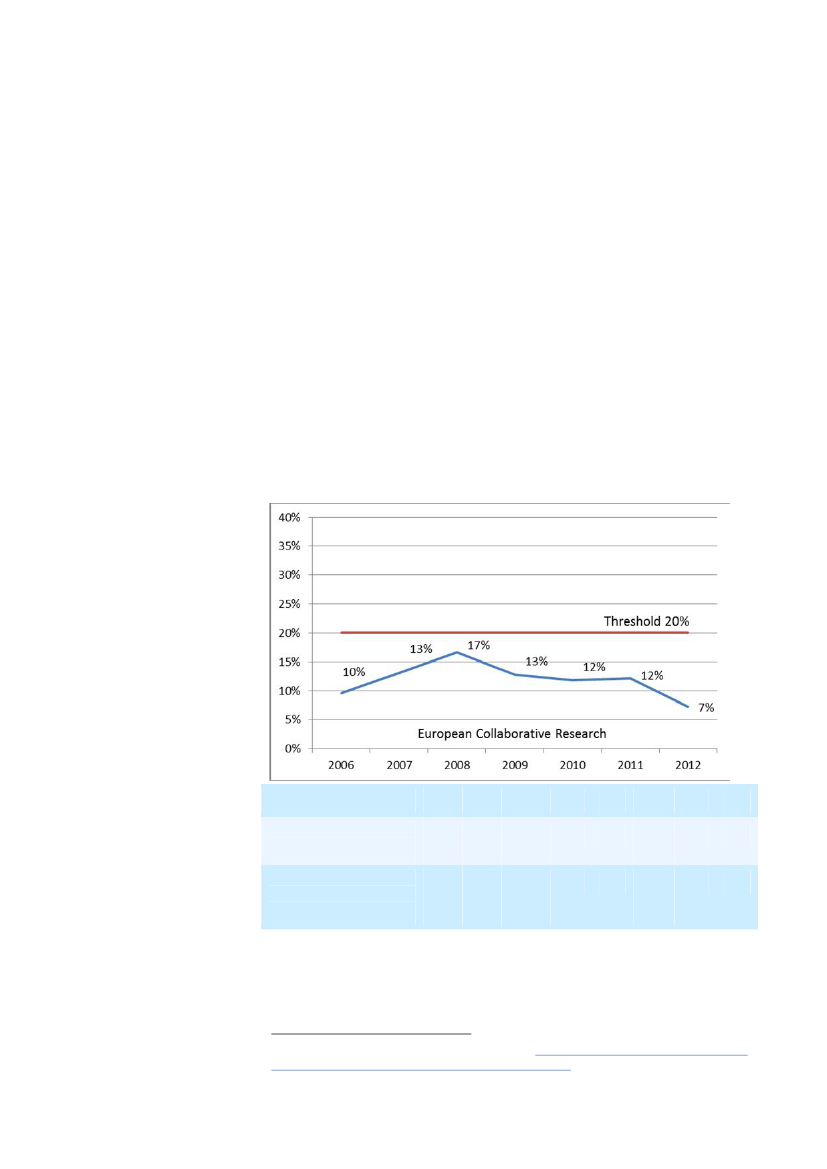

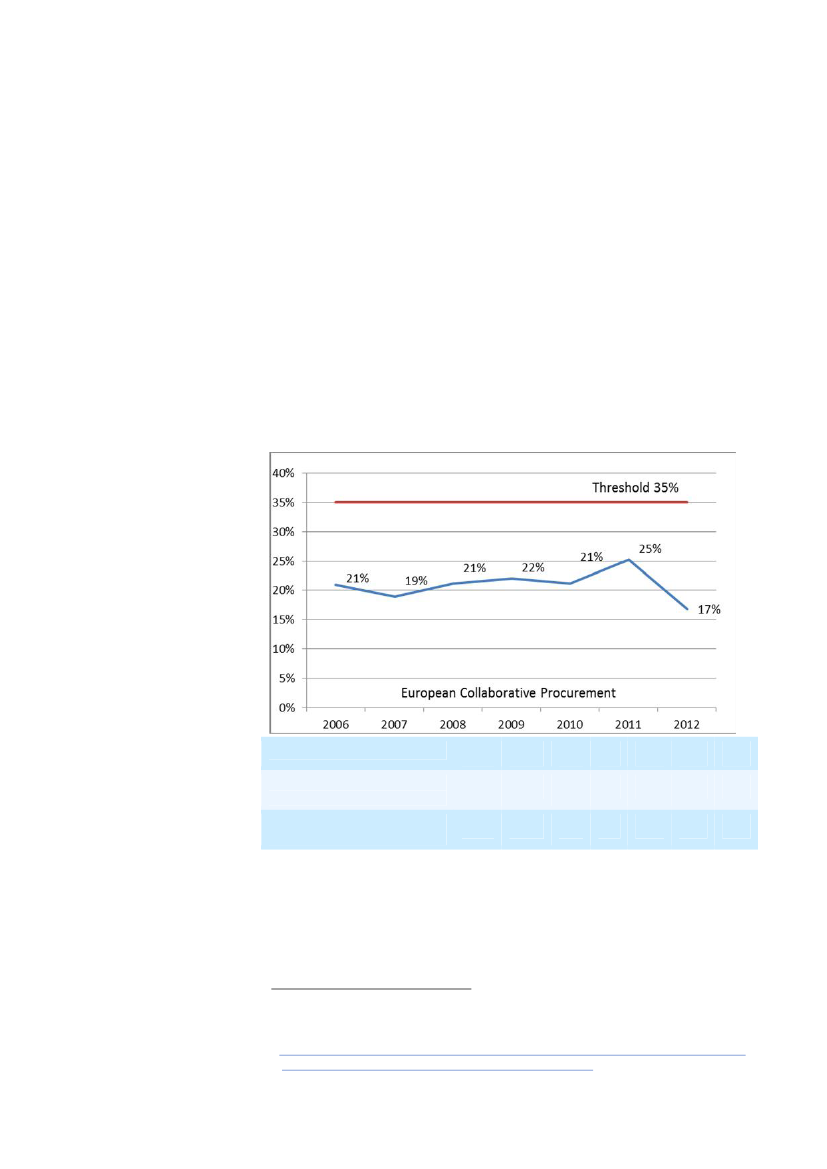

other EU countries – the ‘small ones', who have realised that cooperation iskey for defence – are calling on 'the big ones' to work together. In the wordsof former NATO Secretary General Javier Solana, ‘It is an absoluterequirement for us to spend more, spend better, and spend more together’.Trans-European dividesexist and need to beovercome.One answer is certainly that there exists a trans-European divide, in additionto the well-described transatlantic one. This European rift is nourished bymultiple frustrations: ill-perceived (or explained) clubs (such as 'LancasterHouse'), States’ abandonment of common programmes before completion,lack of solidarity and of collegiate behaviour in international organisationsand military operations, and distorting competition in the defence market. Inthe name of national (security) interests, national sovereignty or politicalengagements at home, Member States do not always act in Europeanharmony.This has consequences. In 2007 EU defence ministers established severalhigh-level aggregate benchmarks to better target their defence expenditureand match their objectives. They agreed to spend – on a voluntary basis –20 % of their defence research budget and 35 % of their defenceprocurement on joint projects8(seeFigures 1 and 2 below).Figure 1:European collaborativedefence research aspercentage of totaldefence research2006-2012

YearTotal defence researchin million EuroCollaborative defenceresearchin million Euro

2006 20072 660 2 540

20082 480

20092 260

20102 080

20112 150

20121 930

20062 660

380

380

450

320

260

310

210

380

Source: European Defence Agency, Defence data 2012

Voluntary engagements

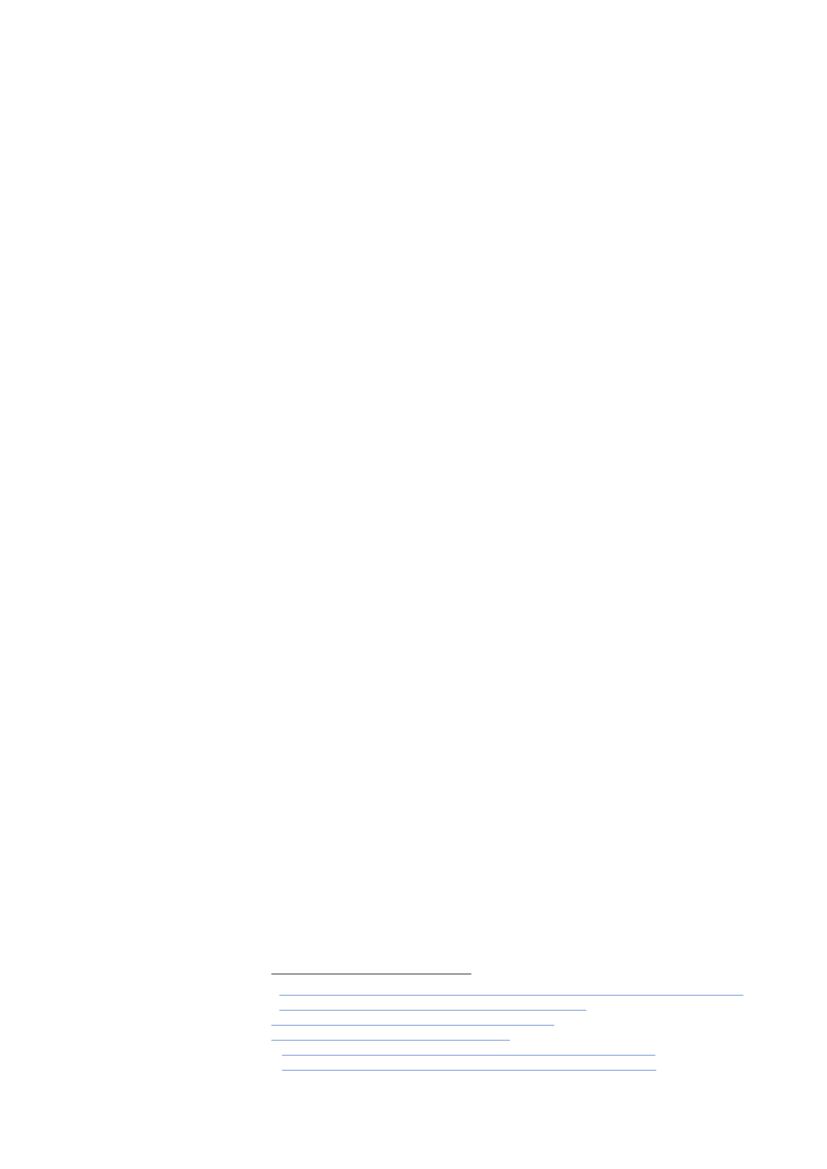

Until 2012, neither of these benchmarks was met. In 2012, collaborativespending accounted for as little as 7 % of the research budget and 17 % ofEuropean Defence Agency, Defence Data 2012;http://www.eda.europa.eu/docs/default-source/eda-publications/defence-data-booklet-2012-web8

6

The European Council on defence matters: Time to deliver

have not worked;collaboration in researchand procurement iswaning.

the procurement budget – the lowest values recorded since data collectionstarted. This drop was not unexpected. As the former Chief and Deputy ChiefExecutive of the EDA noted as early as in October 2010 (at the dawn of thedebt crisis), 'Ministers preside over defence establishments which do not liketo co-operate, or to change9.' The EDA's former top officials have cited manyexamples of the wastefulness this practise – and the examples are still validtoday10.It is worth noting that the 2006-2009 data comprise EUR 54.93 million fromthe EDA's Joint Investment Programme Force Protection11– the first jointprogramme – and other major new research and technology programmesand projects launched within the EDA framework. In 2012 the EDA’scollaborative research had dropped to EUR 33 million – 16 % of the amountdevoted to European collaborative defence research and technology, andonly 2 % of the amount spent on European defence research and technology.The willingness of Member States' defence establishments to work togetherand use the institutions foreseen for that purpose has clearly faded.

In its first years, the EDAmanaged majorcollaborative defenceresearch programmes.Today less than 16 % ofdefence research andtechnology expendituresare collaborative.

Figure 2:European collaborativedefence procurement aspercentage of totaldefence procurement,2006-2012

YearTotal defence procurementin million EuroCollaborative defence procurementin million Euro

200629 1006 700

2007 2008 200932 200 3 300 2 5006 800 8 100 8 200

2010

2011

2012

4 300 29 200 34 2007 7007 9006 000

Source: European Defence Agency, Defence data 2012

The EuropeanCommission hasincreased its footprint in

At the same time, the European Commission increased its investment insecurity research – which often addresses technologies and capabilitiessimilar to those in defence research – to EUR 241.7 million in 2012 and EUR307.6 million in 201312. In other words, the Commission has increasingly

'Time to get pedalling'; Witney, Nick and Linnenkamp, Hilmar; in European VoiceRefer to the examples in the 'The cost on non-Europe' report; Ballester, Blanca; EuropeanAdded Value Unit, European Parliament, 2013;11http://www.eda.europa.eu/docs/documents/Background_Note_on_Force_Protection.pdf12http://ec.europa.eu/research/fp7/index_en.cfm?pg=budget910

7

Policy Department, Directorate-General for External Policies

security and defence-related research.

invested where the Member States have cut. If the downward trend ofdefence research and technology expenditure is confirmed for 2013, theCommission will have spent twice as much this year as the Member Statescollectively. This makes the Commission one of the top spenders in securityand defence-related research, alongside France, Germany and the UK.In November 2010 EU Defence Ministers proposed 'pooling and sharing' tointensify military cooperation in Europe13. In 2012 the NATO summit inChicago endorsed the concept of 'smart defence'14, which complements'pooling and sharing' in areas led by NATO. However, if the defenceestablishments do not actively participate, these top-down initiatives willremain ineffective.Alternatively, the cracks may become irreparable ruptures. In such a scenario,the UK leaves the EU, France must survive alone in a globalised world, andGermany is the next Switzerland. Is it that what Pieter De Crem voiceddiplomatically? This vision demands debate at the top level of the EU.Because defence matters.

Defence establishmentsneed to cooperate or allefforts to fortify EUdefence will be in vain.

3

The EU aspectDefence matters. This is the message that the Union's institutions havebroadcast over the past year, each in its area of competence. The EU'sadministrative and political machinery has delivered a coherent set ofproposals underscoring that much is possible, but nothing is mandatory.How is this new?Allinstitutions are buying in into defence, and are doing soin a coordinated manner.Since the entry into force of the Lisbon Treaty on 1 December 2009, the EU’spolitical and institutional agenda has focused on establishing newarrangements and an altered institutional configuration for the CommonForeign and Security Policy. Of the provisions on security and defence policy,however, only the statue of the EDA has been adapted to the new legal base.Even this involved little more than copying and pasting the provisions ofArticle 45 of the Treaty on European Union (TEU) into a Council Decision15.

For the first time, all EUinstitutions have agreedon the importance ofdefence.

The potential of theLisbon Treaty remainsuntapped.

The debate on establishing permanent structured cooperation (PESCO,Article 46 TEU), on entrusting CSDP tasks to a group of Member States (Article44 TEU), on establishing a start-up fund for CSDP military activities (Article41(3) TEU) and on realising the full potential of the EDA foreseen by Articles42(3) and 45 TEU have either never started or were launched with littleenthusiasm. Clearly, neither the provisions nor the spirit of the Lisbon Treatyhave made their way into the European Union’s security and defencebusiness.Many of these Lisbon Treaty provisions create the opportunity for 'more

The move to qualified

http://www.europarl.europa.eu/meetdocs/2009_2014/documents/sede/dv/sede260511deseinitiative_/sede260511deseinitiative_en.pdf14http://www.nato.int/cps/en/natolive/topics_84268.htm15Council Decision 2011/411/CFSP of 12 July 201113

8

The European Council on defence matters: Time to deliver

majority decision makingwill change defencedecisions.

Europe' in defence. Some decisions that would contribute to this 'more' nolonger require unanimity and may not be vetoed; this is the case, forexample, for Article 45 TEU on (the EDA) and Article 46 TEU (on permanentstructured cooperation). Compared to past procedures, this represents adramatic change, which diplomatic and military structures in Brussels and inthe Member States capitals well understand. Yet without-top level guidance,defence establishments in the in the European capitals will not advance. Andeven with top-level guidance, an early and wholehearted participationshould not be expected.There are good reasons that the two provisions on the EDA and PESCO donot require unanimity and are not subject to veto. Decisions requiringunanimity and permitting vetoes regularly produce faint results representingto the least common denominator. A telling example is the budget of theEDA, which the Council has failed even to adapt to inflation16. After increasingby almost 50 % between 2005 and 2009 (the entry into force of the LisbonTreaty), this budget has been frozen at slightly above EUR 30 million since,owing to the sole and constant opposition of the United Kingdom to anyincrease.In 2012, in the European Parliament urged the Council and the MemberStates to provide the EDA with adequate funding for the full range of itsmission and tasks. The parliament suggested that this would be bestaccompanied by financing the Agency’s staff and operating costs throughthe Union budget17. Yet the Parliament’s request to address this issue has sofar been taken up by neither the Council nor the High Representative, VicePresident of the Commission and Head of EDA.PESCO is the other instrument in the Lisbon Treaty with significant potentialto rationalise defence expenditure, improve military capabilities and fosteroperational effectiveness. However, since the first broad debate was held inthe summer of 201018, little progress has been made in the EU to deepenunderstanding of PESCO and its potential added value.Some academics have, on the other hand, contributed usefully to thequestion, with the following observations19:Even though PESCO no longer requires unanimity, it is nonetheless verydemanding as it requires a significant majority of Member States.Although PESCO is an instrument of coordination and planning whose termsof reference are set by qualified majority, decisions about subsequentimplementation measures require consensus among the participants.PESCO comprises an assessment mechanism through the EDA foreseen inArticles 42(3) and 45 TEU.http://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/docs/pressdata/EN/foraff/139633.pdfhttp://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?pubRef=-%2f%2fEP%2f%2fNONSGML%2bREPORT%2bA7-2012-0252%2b0%2bDOC%2bPDF%2bV0%2f%2fEN18http://www.egmontinstitute.be/press/10/100716-Press-release-sem.pdf19http://www.egmontinstitute.be/papers/10/sec-gov/SPB-11_PSCD_II.pdf1617

The European Parliamenthas called for the EDA toreceive appropriatefunding … so far in vain.

Permanent structuredcooperation is the key tothe future of defence inthe Union.

9

Policy Department, Directorate-General for External Policies

As PESCO is treaty-based, it provides the appropriate legal framework forrunning permanent military structures, such as the European Air TransportCommand, as well as for running EU operations among PESCO memberstates – an option foreseen in Articles 42(3) and 44 TEU.Once established, PESCO has institutional characteristics. It is permanent andstructured, generates forces for the CSDP, and provides for commoncapabilities and military structures. As an institutionsui generis,its runningand staffing costs could be part of the Union budget. If operational activitiesunder PESCO have an added value for the EU, or if EU investment would addvalue to PESCO activities, the Union budget should be used, as is alreadyforeseen in the EDA's legal basis20. This could comprise operatingexpenditures other than those arising from operations – i.e. PESCO's'peacetime' operational costs, as well as those relating to common capabilityprogrammes.The European Defence Agency plays a key role in PESCO. As both require aqualified majority for decisions, the same Member States are likely tocompose their core membership group. The PESCO group could also lead thedevelopment of the common capabilities and armaments policy referred toin Article 42(3) TEU.The configuration introduced by the Lisbon Treaty allows Member States tobe member of the EDA without being part of PESCO. It is even possible toparticipate in a 'group of the willing' without being in either the EDA orPESCO, although this would be disadvantageous to interoperability. It is alsopossible to not participate at all.PECSCO operates under the auspices of the Council. As for the EDA, theCouncil could decide to entrust the High Representative with representingPESCO institutionally in the Council. Through the HR/VP and through theEDA, PESCO is connected to the work of the European Commission. It wouldmake sense to give the EEAS and the Commission non-voting seats inPESCO's steering structures.The European Parliament is linked to PESCO and EDA through Article 36 TEU,which allows the Parliament to take political initiatives and to makerecommendations. If the running and staffing costs were to be allocated tothe EU budget, the Parliament would be fully involved in the budgetaryplanning, decision making and scrutiny processes.

Permanent structuredcooperation couldbecome an EUinstitution.

The Lisbon Treaty allowsdefence policy to betailored to MemberStates' needs.

4

... and NATO?Defence matters. This belief is shared by the EU and NATO. Cooperation withNATO is required by both politics and the Lisbon Treaty21, which describesNATO's role in European security in Articles 42(2) and (7). Yet NATO is todaysignificantly different from the organisation to which EU treaties since

Today's NATO is differentfrom the organisationreferred to in all EU

Refer to Article 15 of the Council Decision 2011/411/CFSP of 12 July 2011http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/briefing_note/join/2013/491515/EXPO-SEDE_SP(2013)491515_EN.pdf2021

10

The European Council on defence matters: Time to deliver

treaties since Maastricht.

Maastricht have referred. For any defence policy to be effective and credible,both inside and outside, it requires both solidarity and commitment. This inturn requires a high level of consensus. An awareness of this has led NATO formany decades, driven by the pressure of a common, existential threat. Nowthat the threat is fading, so is consensus:As the Director of the Research Division of NATO’s Defence College wrote:'One fundamental and arguably the most important issue will overarch thesummit debates and will require political guidance from the highest level:how can NATO’s existence in the post 2014 era be justified22?'NATO's Strategic Concept, adopted at the Lisbon summit in November 2010,and the decision to restructure the organisation, taken at theStrasbourg / Kehl Summit in April 2009, mark significant turns towards aleaner NATO. The 2010 Strategic Concept underlines the organisation’schanges and new features, and describes NATO'S future missions ascollective defence, crisis management and cooperative security. The UN andthe EU are identified as key partners in this regard.

NATO needs a newraisond’être...

As NATO seeks a newraison d'être,and as the EU reiterates its own reasoningon defence, and as the EU and NATO select new personnel to top posts, it istime to adopt a clear position on the importance of the NATO-EUrelationship, and to assign the organisation’s new authorities a common task.The EU and NATO face the same challenges of globalisation. The EuropeanCouncil could therefore suggest that the HR/VP consider the changes thathave occurred in the European and global environments since 2003 and2008, and report back on the implications at the next European Council ondefence. The HR/VP could liaise with the NATO Secretary General on this, andif requested, could also contribute to a similar exercise in NATO. In eithercase, it will be necessary to consult with Member States and the relevant EUinstitutions.The NATO summit in Wales in September 2014 could also serve as a momentto rejuvenate the NATO-EU relationship. The framework for cooperation willbe more than ten years old then, and the EU now has much more to offer indefence than it did in 2003. What is more, a number of new members havejoined both organisations. A review process could be launched to reflectwhat is needed over the coming decade. Further efforts could be made toallow Cyprus to participate in formal EU-NATO meetings. This could involvepractical steps, as well as liaising on capability planning and strategicdevelopments; for example, the EU battle group preparations could be betteraligned with NATO response force exercises, and EU civilian capabilities couldbe coordinated with NATO-led exercises.The European Parliament could also review the NATO-EU relationship andconsider addressing the topic in depth, including in the EP’sinterparliamentary work.

... and the EU isreiterating its ownreasoning in defence.

The EU and NATO shouldwork together adaptingto changes in theEuropean and globalenvironment.

The 2014 NATO summitcould launch a review ofthe NATO-EUrelationship.

NATO’s 2014 Summit Agenda; KAMP, Karl-Heinz; in Research paper No. 97, p. 7; NatoDefence College; Rome; September 201322

11

Policy Department, Directorate-General for External Policies

5

What next?Defence matters. Once this is reiterated, and once the related tasks havebeen distributed by the European Council, work will start in the institutionsand the Member States. The most important outcome, however, will be thedate fixed for the next European Council to address defence.Some work could still be done before the European elections and the changeof the EU's top personnel. However, the critical activity will take place onlyonce the EU machinery has been restarted after these changes, early in thesecond half of 2014.Given what the European Council is expected to do, a first 'hard' date is likelyto be 30 September 2015. This is when the annual budget proposal for 2016will be presented by the Commission. This proposal should comprise thepreparatory work on CSDP research suggested by the Commission andwelcomed by the HR/VP, the EDA, the Council and the European Parliament.If the September deadline is not met, the credibility of the EU's institutions indefence would be at risk.Prior to that, Member States will have to develop their views on what thatpreparatory work should look like, what it should address, and what it shouldprepare. This effort – likely to take place between the autumn of 2014 and theautumn of 2015, with a meeting of the European Council somewhere in thatstretch – would allow Member States and EU institutions to frame their ideason defence and the EU in such a way as to ensure that preparatory workwould be driven by capabilities and be linked to 'pooling and sharing', 'smartdefence', HORION 2020 or European non-dependence strategies.The Commission should begin the work proposed in its communication assoon as possible. In particular, its green paper on the control of defence andsensitive security industrial capabilities and its work on hybrid civil-militarystandards should be launched early in 2014, as these may well haveramifications for the defence business in Europe and across the Atlantic.The European Parliament also has a role to play. The Parliament shouldadvocate that EU defence and defence policy constitute key politicalengagements of the future High Representative, Vice President of theCommission and Head of the European Defence Agency.Because defence matters.

The European Councilshould set cleardeadlines to properlyrestart the machineryafter the Europeanelections and thechanges to the EU's toppersonnel.

The critical date forestablishing a‘Preparatory Action onCSDP’ research is30 September 2015.

From the autumn of 2014to the autumn of 2015,Member States andinstitutions should frametheir ideas on the futureof defence and the EU.

12