Europaudvalget 2013-14

EUU Alm.del Bilag 87

Offentligt

Information note prepared for the Members of the Danish Parliament's European Affairs committeeTopics: Nord Stream and Southern Gas Corridor (including Nabucco)

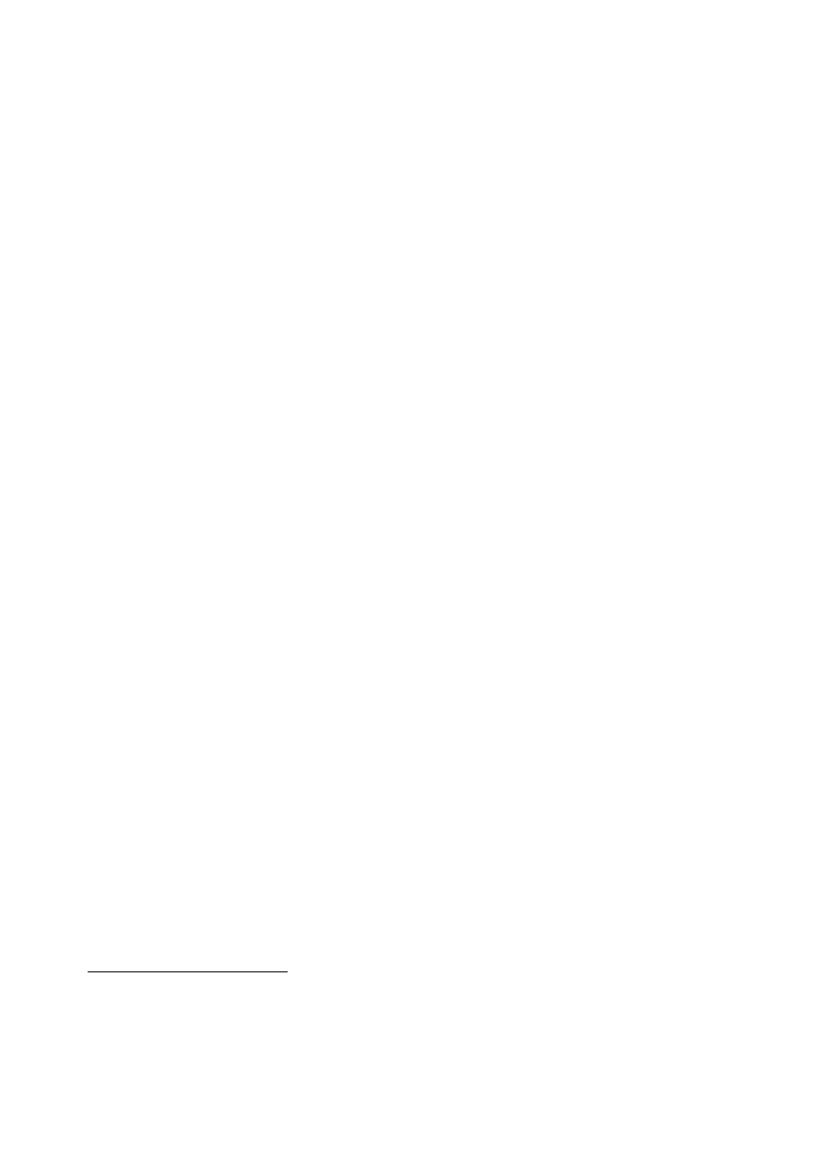

Nord StreamNord Stream is an offshore natural gas pipeline from Vyborg in Russia to Greifswald in Germany (map inthe annexe). It is owned and operated by Nord Stream AG1. Nord Stream crosses the Exclusive EconomicZones of Russia, Finland, Sweden, Denmark and Germany, as well as the territorial waters of Russia,Denmark, and Germany. The project includes two parallel gas pipelines each 1,224 km long2. The firstline of the pipeline was laid by May 2011 and was inaugurated on 8 November 2011. The second linewas completed by September 2012 and began transporting gas in October 2012.Each of the pipelines has the capacity to deliver up to 27.5 billion cubic metres (bcm) of gas a year. Thetwin pipelines can deliver combined total of about 55 bcm of gas a year i.e. more than 10% of the EU gasconsumption. At the moment, however, Nord Stream's capacity remains underutilised. In 2013 theaverage use of the capacity has been ca 37% which nevertheless represents an improvement from 2012when ca 31% of the capacity was effectively used. Nord Stream AG claims that more gas will be flownonce the pipelines connecting to Nord Stream in Germany and beyond (OPAL (DE), NEL (DE) and Gazelle(CZ)) will be completed.Nord Stream AG is said to be currently considering options for adding further transmission capacity toNord Stream by building pipeline 3 and 4. The latter could be extended to reach the UK market. InAugust 2012, Nord Stream AG applied to Finnish and Estonian governments for route studies in theirexclusive economic zones for the third and fourth linesNord Stream has been included in the list of Project of European Interest under the Trans-EuropeanEnergy Network (TEN-E) regime (2006 guidelines adopted by the Council and the European Parliament).The guidelines has been recently revised and replaced by a new regulation3- the possible constructionof Nord Stream 3 and 4 has not been proposed for the status of Project of Common Interest in thisprocess.As regards the regulatory and legal framework for Nord Stream, the Commission has voiced concernsabout the lack of a public law framework for this pipeline. This is not a standard approach for buildingand operating supply pipelines in the EU4. Such a framework, normally in a form of anintergovernmental agreement, on the one hand contributes to the stability and security of gas supplyand regulates safety related aspects of pipeline operation (e.g. hydrocarbon leakage affecting theenvironment) and on the other hand protects and decreases the risk for the investors and financiers ofthe project.

Southern Gas CorridorThe Southern Gas Corridor (SGC) is a strategic initiative to connect the EU's Internal Energy Market (theworld's largest integrated gas market) with the largest concentration of hydrocarbons in the world,loosely defined as the Caspian and Middle East region. The Caspian / Middle East region stretches fromNord Stream AG, based in Zug, Switzerland, is an international consortium of 5 companies: OAO Gazprom (51%), WintershallHolding GmbH (a BASF subsidiary) (15.5%), E.ON Ruhrgas AG (15.5%), N.V. Nederlandse Gasunie (9%) and GDF SUEZ (9%).Thecompany was established in 2005 for the planning, construction and subsequent operation of the twin pipelines through theBaltic Sea2It is the longest sub-sea pipeline in the world, surpassing the Langeled pipeline.3http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:32013R0347:EN:NOT4For instance there is such a framework in place between all EU concerned Member States and Norway1

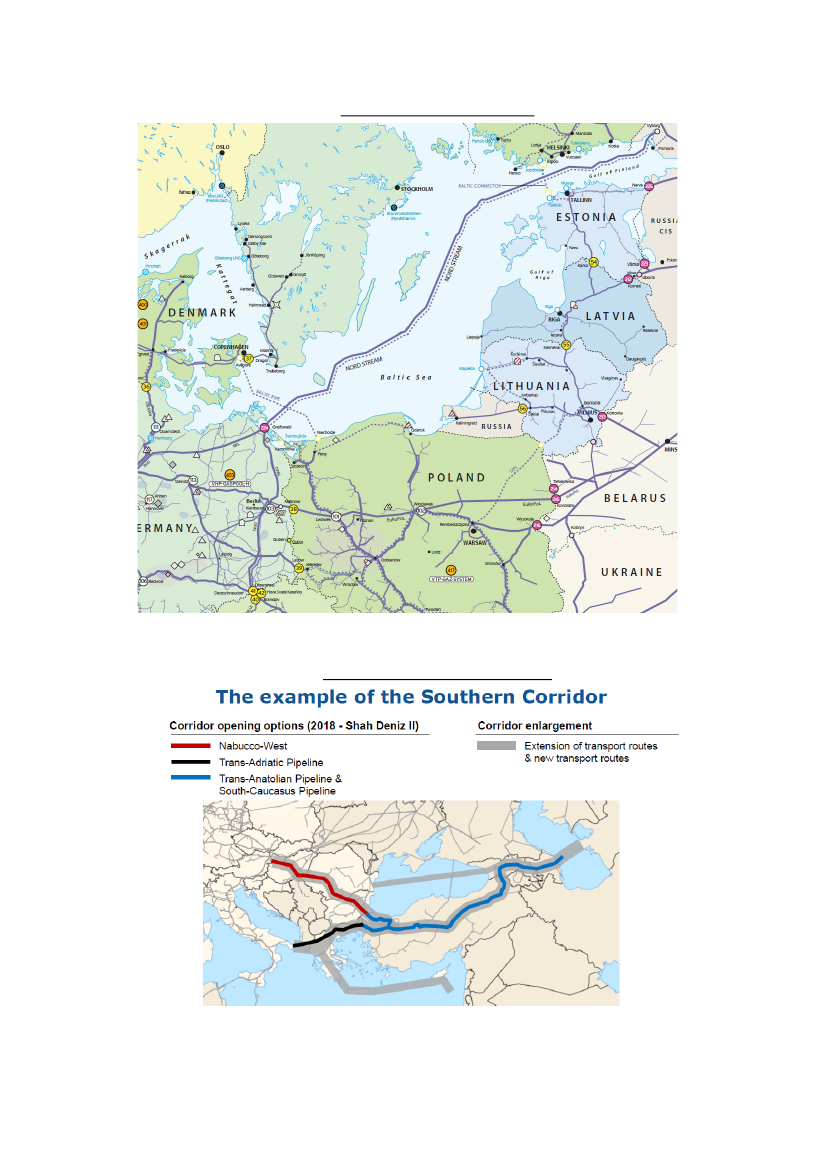

Central Asia to Eastern North Africa, and is constituted by a wide range of countries; the area is smallerthan Russia, but collectively has far more hydrocarbon resources. The wide range of source countriesmeans that political risk on the side of producers is dispersed, but the high number of countriesbetween the EU and the source countries means that transit risk is a serious concern. Ultimately, SGCshould give access to 90-100 bcm/a5(billion cubic meters per annum) of gas annually and create anadditional meaningful source of supply, in addition to the existing supply oligopoly i.e. gas importedmainly from Russia and Norway, some from Northern Africa and LNG.From an EU policy perspective, SGC has been identified as one of the EU's highest energy securitypriorities in the Second Strategic Energy Review in 2008 and as one of the twelve priority corridors in therecent Regulation on guidelines for trans-European energy infrastructure (Regulation 347/2013).Of the possible source countries, only one – Azerbaijan – is clearly capable of supplying gas to the EU inthe short-term (before 2020). Azerbaijan is therefore judged to be the 'enabler' of the SouthernCorridor. Other possible sources of gas include Iraq, Turkmenistan and, once there is suitable politicalcircumstance, Iran. Indeed, in the right circumstances, other sources of supply could be linked in to theSouthern Corridor, such as the Arabian Peninsula countries (where gas is still flared), and other CentralAsian states. Supplies from the Eastern Mediterranean (e.g. Israel) could also be envisaged, but thepolitical circumstances would have to improve considerably.It is now expected that Azerbaijan will supply gas as of early 2019 to the EU from its Shah Deniz 2 gasfield, which is majority owned by BP (UK – 25.5%) and Statoil (Norway – 25.5%), and includes Total(France – 10%), Socar (Azerbaijan – 10%), LukAgip (Russia/Italy – 10%), NICO (Iran – 10%) and TPAO(Turkey – 9 %) . The current phase of the Southern Corridor work has therefore focused on securing thisgas and the final investment decision for the entire project is expected in December 2013.The key element of European Union and European Commission policy has been the effort to establish adefined, dedicated, scalable and legally protected physical pipeline connection through Turkey and theCaucasus to Azerbaijan (to minimise the transit country risk and avoid the difficulties EU had with 2006and 2009 gas disruptions in Ukraine). This has been mutually agreed between the EU (President Barroso)and Azerbaijan (President Aliyev) in their Joint Statement issued in January 2011. The two pipelineprojects that have been promoted that deliver this connection within Turkey are firstly Nabucco (Classic)and secondly the Trans-Anatolian Pipeline (TANAP – controlled by Azerbaijan).TANAP is now the favourite for construction in 2017 but even though international legal framework hasbeen set with the ratification of IGA between Turkey and Azerbaijan, the European Union has no finalassurances that it will be physically built. The pipeline connection in the Caucasus is called the SouthernCaucasus Pipeline (SCP-X) and its physical strengthening (to take more gas) and its legal regime arealready assured. The European Union has to insist that the scalability criterion is designed to assure thatSGC can grow as more gas becomes available from Azerbaijan and elsewhere.The downstream pipeline connections within the EU should be considered as interconnectors within theinternal energy market, and since the internal energy market is integrated, increasingly interconnectedand resilient, European Commission policy has been not to discriminate between the downstreamcommercial options. Two options, namely Nabucco (West) [promoted by AT, HU, RO, BG and DE] andthe Trans-Adriatic pipeline (TAP) [promoted by IT, GR, Albania, DE and Switzerland] were competing forShah Deniz 2 gas in this respect. The SD2 Consortium announced on 28 June 2013 its decision in favour

5

Which is c.a. 15%-20% of EU's gas consumption

of TAP, thus favouring the Greek and Italian markets and signed the associated gas sales agreements inSeptember 2013.Following the dismissal of Nabucco-West, the Commission is now working with the Member States toaccelerate the work on interconnectors towards South East Europe, so that these markets can benefitalso from the opening of SGC at an early stage. This will namely be achieved through theimplementation of Projects of Common Interest in the Region (as defined in Regulation 347/20136).Shah Deniz 2 will deliver 16 bcm, of which 10 bcm/a to the EU and 6 bcm to Turkey. With regard tofurther supply opportunities and the expansion of SGC, several options are available:•Firstly, more gas can come from Azerbaijan, which considers that up to 50 bcm/a is ultimatelypossible (2020 onwards). Such levels of gas supply could underpin the building of both TAP andanother dedicated pipeline reaching Central Europe.Secondly, the EU is in discussion with Turkmenistan for a further 30 bcm/a. On the basis of anegotiating directives received from the Council (in September 2011), the Commission isnegotiating with Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan a legal framework for the construction of a Trans-Caspian pipeline. Furthermore, the Commission is currently organising commercial interest inthis option through the Caspian Development Corporation (CDC). A 30 bcm/a commitmentwould allow the construction of another pipeline from Turkmenistan to the EU (e.g. NabuccoClassic).Thirdly, an accommodation within Iraq to allow gas exports will eventually come, and once thatis agreed, it is felt that Iraqi gas can be profitably used in Turkey and within the EU;infrastructure choices made today must allow this hence the need for a pipeline across Turkeyto allow for it.

•

•

6

http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:32013R0347:EN:NOT

AnnexeSchematic map of Nord Stream

Source ENTOS-G

Schematic map of the options in SGC

Source: Energy priorities for Europe, Presentation of J.M. Barroso to the European Council of 22 May 2013