Erhvervs-, Vækst- og Eksportudvalget 2013-14

ERU Alm.del Bilag 55

Offentligt

SAFETY REPORTOctober 2013

LEOPARDPirate attack on 12 January 2011

The Danish Maritime Accident Investigation BoardCarl Jacobsens Vej 29DK-2500 ValbyTel. +45 91 37 63 00E-mail:[email protected]www.dmaib.dkOutside office hours, the Danish Maritime Accident Investigation Board is available on +45 23 34 23 01.

This safety report is issued on 29 October 2013Case no.:2013007348Front page: LEOPARD. Source: Admiral Danish Fleet.The marine accident report is available from the webpage of the Danish Maritime Accident Investi-gation Board www.dmaib.dk.The Danish Maritime Accident Investigation BoardThe Danish Maritime Accident Investigation Board is an independent unit under the Ministry ofBusiness and Growth that carries out investigations with a view to preventing accidents and pro-moting initiatives that will enhance safety at sea.The Danish Maritime Accident Investigation Board is an impartial unit which is, organizationally andlegally, independent of other parties.PurposeThe purpose of the Danish Maritime Accident Investigation Board is to investigate maritime acci-dents and to make recommendations for improving safety, and it forms part of a collaboration withsimilar investigation bodies in other countries. The Danish Maritime Accident Investigation Boardinvestigates maritime accidents and accidents to seafarers on Danish and Greenlandic merchantand fishing ships as well as accidents on foreign merchant ships in Danish and Greenlandic wa-ters.The investigations of the Danish Maritime Accident Investigation Board procure information aboutthe actual circumstances of accidents and clarify the sequence of events and reasons leading tothese accidents.The investigations are carried out separate from the criminal investigation. The criminal and/or lia-bility aspects of accidents are not considered.Marine accident reports and summary reportsThe Danish Maritime Accident Investigation Board investigates about 140 accidents annually. Incase of very serious accidents, such as deaths and losses, or in case of other special circum-stances, either a marine accident report or a safety report is published depending on the extentand complexity of the subject matter.

Page 2 of 27

Contents1.2.SUMMARY .............................................................................................................................. 4FACTUAL INFORMATION....................................................................................................... 52.12.22.32.42.52.63.3.13.23.33.4Photo of the ship ............................................................................................................... 5Ship particulars ................................................................................................................. 5Voyage particulars ............................................................................................................ 6Weather data .................................................................................................................... 6Marine casualty or incident information ............................................................................. 6The ship’s crew ................................................................................................................. 7Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 8Background ...................................................................................................................... 8Sequence of events .......................................................................................................... 9The ship's anti-piracy preparedness................................................................................ 15On-board measures ................................................................................................. 15Guards..................................................................................................................... 19

NARRATIVE ............................................................................................................................ 8

3.4.13.4.23.53.63.74.4.14.25.6.

Piracy in the area in January 2011 .................................................................................. 20Breakdown of the propulsion machinery ......................................................................... 21Danish and international legal basis and recommendations ............................................ 22Sequence of events ........................................................................................................ 23On-board measures ........................................................................................................ 24

ANALYSIS ............................................................................................................................. 23

CONCLUSIONS .................................................................................................................... 26PREVENTIVE MEASURES ................................................................................................... 27

Page 3 of 27

1. SUMMARYOn 12 January 2011 at 1650, the cargo ship LEOPARD was attacked by Somali pirates appr. 200nautical miles southeast of the coast of Oman. When the pirates had taken control of the ship andthe crew, they tried in vain to tow the LEOPARD to the Somali coast. Later in the evening, the crewwere transferred to the pirates’ mother ship as hostages.The ship as such was not captured, but had to be left in open sea, due to a defect in the propulsionsystem that the pirates had inadvertently caused during the attempted capture.The Danish Maritime Accident Investigation Board has investigated the safety aspects of the anti-piracy measures launched by the shipowner, the operator and various crews in connection with thepassage of the Gulf of Aden.During a number of years, the shipowner, the operator, and the various crews had launched anumber of measures meeting the recommendations that later became international. However,these measures did not prevent the pirates from boarding the ship.The Danish Maritime Accident Investigation Board has noted that anti-piracy measures may havean inappropriate impact on the preparation and use of ships’ life-saving appliances.The Danish Maritime Accident Investigation Board has received information about the safetymeasures implemented following the attack on the LEOPARD.

Page 4 of 27

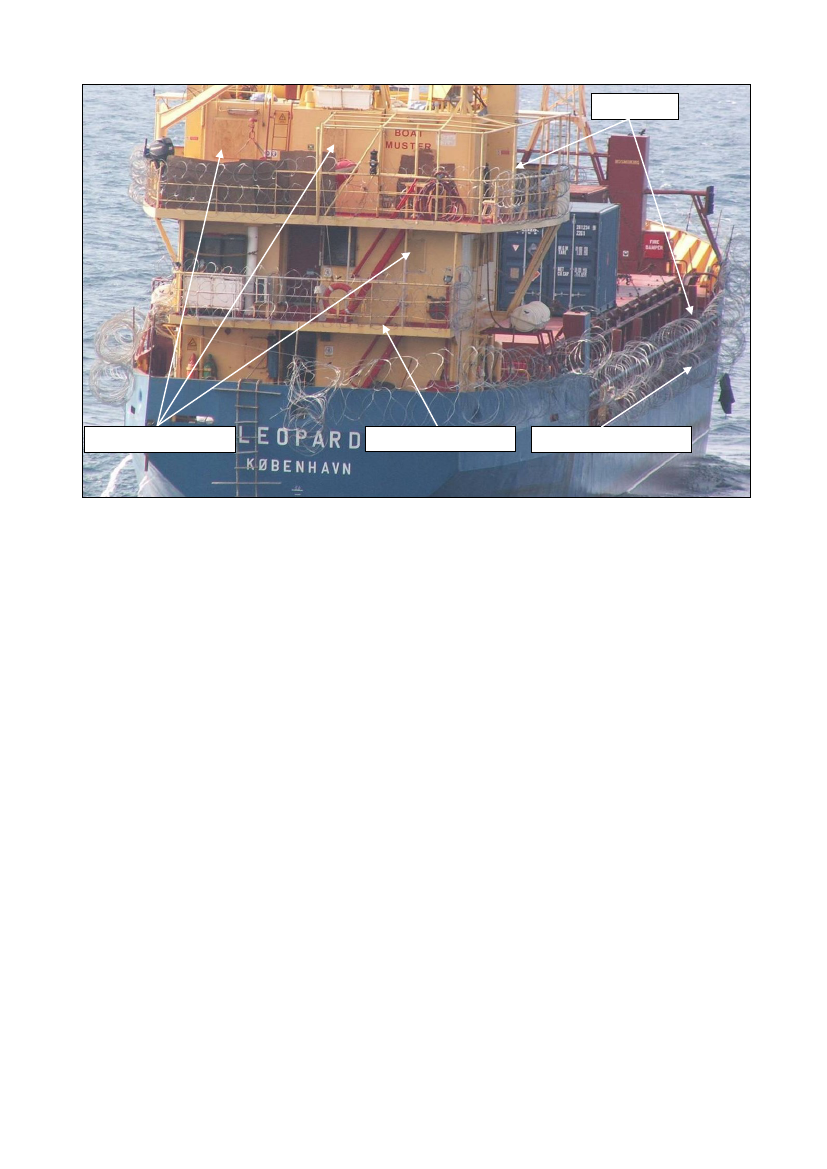

2. FACTUAL INFORMATION2.1 Photo of the ship

Figure 1: LEOPARD.Source: Jörg Zogel.

2.2 Ship particularsName:Type of vessel:Nationality/flag:Port of registry:IMO number:Call sign:DOC company:IMO company no. (DOC):Year built:Shipyard/yard number:Classification society:Length overall:Breadth overall:Gross tonnage:Deadweight:Draught max.:Engine rating:Service speed:Hull material:Hull design:LEOPARDDry cargo carrierDanish (Danish International Register of Shipping – DIS)Copenhagen, Denmark8902096OWOD2Nordane Shipping A/S10859151989Sakskøbing Skibsværft/1989/40Lloyd's Register of Shipping67.00 m10.20 m1,0931,780 t5.60 m749 kW11.0 knotsSteelSingle hull

Page 5 of 27

2.3 Voyage particularsPort of departure:Port of call:Type of voyage:Cargo information:Manning:Pilot on board:Number of passengers:Bar, MontenegroMumbai, IndiaInternationalGeneral cargo, IMO class 16No0

2.4 Weather dataWind – direction and speed:Wave height:Visibility:Light/dark:Current:North-easterly 4 m/sUnknownGoodLightUnknown

2.5 Marine casualty or incident informationType of marine casualty/incident:Location:Position:Ship’s operation, voyage segment:Consequences:Piracy attackAppr. 264 nautical miles southeast of Salalah, Oman15�13.29’ N – 058�17.34’ EAt seaSix crew members abducted.Minor damages to the ship.

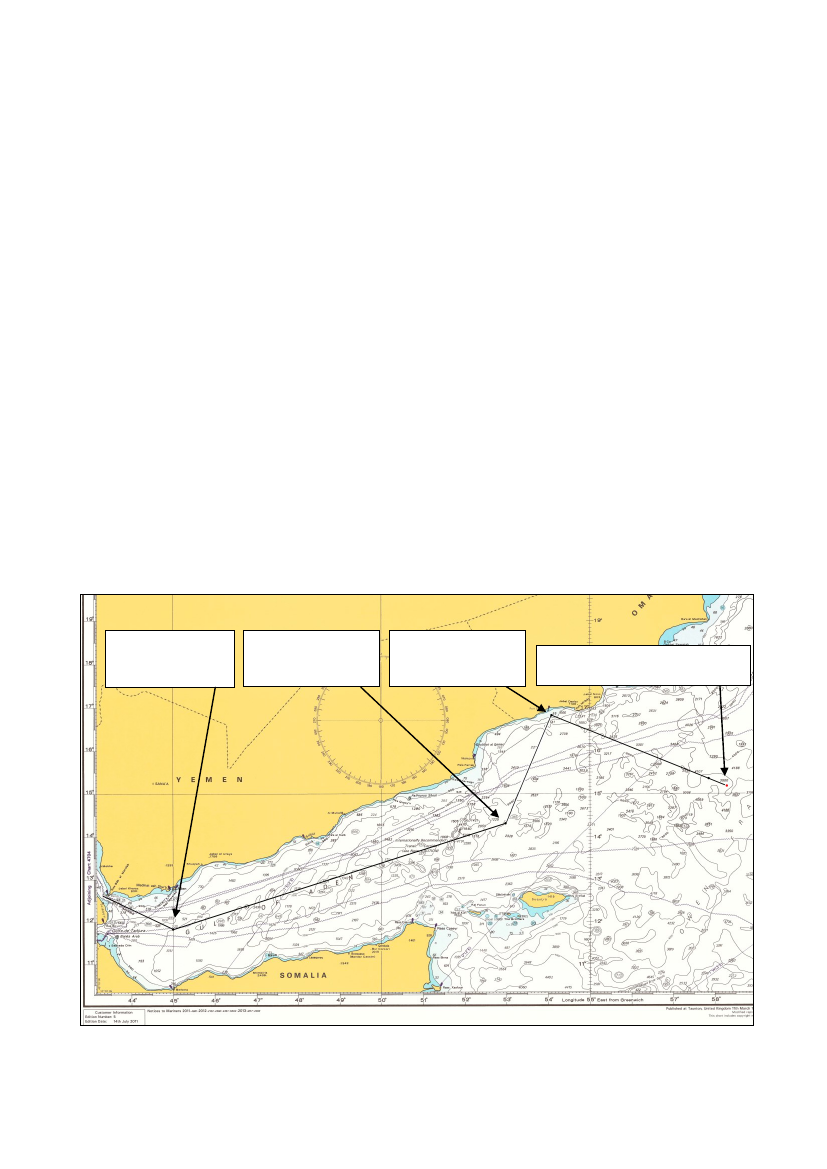

9 January 2011at 0127 hoursIRTC point A

10 January 2011at 2357 hoursIRTC point B

11 January 2011at 1420 hoursSalalah, Oman

Appr. position of attack on12 January 2011 at appr. 1650hours

Figure 2: Extract of chart 4705.Source: The United Kingdom Hydrographic Office/DMAIB.

Page 6 of 27

2.6 The ship’s crewMaster:Certificate of competency STCW II/3.43 years old. Had been at sea for 17 years, as a navigatingofficer since 1999. Had been employed by the shipownersince 2000 and had had several voyages with the LEOPARDand other company ships. Became master of the LEOPARD in2007.Certificate of competency STCW II/3.46 years old. Had been at sea for more than 30 years, as anavigating officer since 1991. Had been employed by theshipowner since 2010. This was his first voyage on board theLEOPARD.40 years old. Had been at sea for appr. 20 years and hadbeen employed by the shipowner since 2001.47 years old. Had been at sea for appr. 20 years and hadbeen employed by the shipowner since 2001.58 years old. Had been at sea for more than 25 years and hadbeen employed by the shipowner since 2002.58 years old. Had been employed by the shipowner for appr. 1year.

Mate:

AB:AB:Motorman:Cook:

Page 7 of 27

3. NARRATIVE3.1 IntroductionFor many years, piracy as defined in the Convention on the Law of the Sea1has been part of thereality of modern shipping on most continents. In this report, the term piracy is used to cover actsagainst a ship and its crew in open seas and is covered by article 10 of the Convention on the Lawof the Sea (in general referred to as piracy attacks) as well as similar armed robbery of an espe-cially dangerous nature on ships in the territorial waters or in a port of another country.Today, piracy is a large problem for shipping worldwide. Previously, piracy attacks on merchantships were especially common in the Strait of Malacca. In recent years, Somalia-based attackshave become the predominant problem. The attacks have spread from the coast off Somalia tolarge parts of the Indian Ocean. Armed attacks on ships off the West African coast at Nigeria alsooccur, but armed attacks against ships may also occur in other places around the world. In recentyears, much focus has been on the situation in the waters off Somalia because these incidentshave been extensive and especially risky for the crew. These attacks are characterised by shipsbeing captured and the crew being held hostage for rather long periods of time, while negotiationsfor a ransom take place. In other places of the world, piracy typically manifests itself as armed andviolent robbery, where the pirates rob the crew’s belongings, the ship’s equipment and cargo and,subsequently, leaves the ship fast.Most Danish ships on international voyages have a preparedness against piracy or armed robbery.Therefore, the Danish Maritime Accident Investigation Board will shed light on this issue from amaritime safety perspective the purpose of which is to generate knowledge that may improveships’ safety. This report will only include the event until the crew on board the LEOPARD weredisembarked and the situation developed into a hostage-taking that the Danish Maritime AccidentInvestigation Board has no legal basis for investigating.The report is based on the operational reality that formed the basis for the behaviour and decisionsof the shipowner, the operator and the crew during the last voyage until the attack in January 2011.In this context, it should be mentioned that the information that subsequently seemed decisive wasnot necessarily available or recognised by the involved parties. Consequently, the probability of agiven incident occurring may not seem clear to those involved. This premise for the investigationsof the Danish Maritime Accident Investigation Board is decisive in order to understand how andwhy incidents develop. In this manner, the most effective safety learning is acquired.In the report, all indications of time are given as the ship’s local time.

3.2 BackgroundIn the shipping industry, it is quite common for the owner(s) to divide the operation of the ships intoa commercial part, a technical part and a manning part, where each individual area is handled bydifferent companies specialized within their individual area of expertize.At the time of the attack, the LEOPARD was owned by Lodestar Shipholding Ltd. and bareboatchartered to Shipcraft A/S (the shipowner) that handled the commercial parts of the ship’s opera-tion. The technical operation and management of the ship, including accounting, manning issuesand measures related to safe operation of ships in accordance with the international regulations inthis field (ISM2), ship and port facility security (ISPS3) and inspection and technical surveys, were12

United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, article 101.International Safety Management Code.3The International Ship and Port Facility Security Code.

Page 8 of 27

handled by Nordane Shipping A/S (the operator). Shipcraft A/S was responsible for contracts withthe security company and the administrative issues in this connection.The master and mate of the ship were employed by the shipowner Shipcraft A/S, whereas the rat-ings were hired by a manning agency in Manila, the Philippines, with whom the operator had coop-erated for quite some time. Nordane A/S carried out the tasks related to the crew administration.The majority of both the crew on board the ship at the time of the attack and the substitute crewhad served on board the shipowner’s ships for a number of years and were, consequently, familiarwith the ship and the ship’s trading area.The ship was in a specialised trade carrying IMO class 1 cargo (explosives) and was typically en-gaged in voyages between Europe and Asia, and during a return voyage the ship would typicallycall at 20-25 different ports depending on the orders received while underway.Normally, the LEOPARD would have a crew of six persons, two of which were navigating officerson a two-shift watch of six hours’ duration, and four ratings consisting of two ABs, one cook andone motorman. According to the provisions4of the Danish Maritime Authority, the ship was notrequired to have an engineering officer since the engine rating was below 750 kW. The ship’s ma-chinery was otherwise of such a nature that an experienced motorman could take care of the dailyoperation and maintenance of the engine room. The two ABs were engaged in ordinary deck workand also operated the ship’s cranes. The safe manning document of the ship, which had been is-sued on 19 February 2010, required four crew members two of whom should be navigating officersand two ABs. The shipowner had assessed that the operational pattern of the ship additionally re-quired one cook and one motorman.

3.3 Sequence of eventsOn 29 September 2010, the LEOPARD departed from Bar, Montenegro. Here, the ship had loadedappr. 29 tonnes of cargo, thus having a total cargo of appr. 300 tonnes. The mean draught of theship was appr. 3.0 metres, which resulted in an average freeboard of appr. 2.6 metres.The next port of call was Port Said, Egypt, whereupon the ship was to pass the Suez Canal on itsvoyage towards Mumbai, India, which was the first port of discharge.In the afternoon of 3 January 2011, when the LEOPARD had passed the Suez Canal and was atanchor at Suez, Egypt, four unarmed security guards arrived who were transported to the ship by aservice boat. The shipowner had arranged for the security guards to be on board until the ship hadpassed the Gulf of Aden as an anti-piracy measure in the area around the Horn of Africa, and ac-cording to the agreement they were to be disembarked in Salalah, Oman. Should it be considerednecessary, it would be possible to negotiate an extended presence of the guards on board.As there were no vacant cabins on board the ship, the guards were accommodated in a containeron deck. Previous crew members had made it possible to arrange the container with lighting andair-conditioning. In everyday life on board, the guards used the ship’s accommodation, which alsofunctioned as the crew mess where they would eat, watch films, and sometimes sleep.The security company, which provided the guards, had carried out assignments for the shipownersince 2009 and, therefore, some of the guards were familiar with the ship and had met several ofthe crew members before.The day after the guards’ embarkation, they and the ABs routinely started rigging the securitymeasures. Razor wire was placed along the gunwale and the accommodation and iron plates wereplaced over the external stairs. The plates covering the accommodation windows had been ar-4

Act on the manning of ships (no. 15 of 13 January 1997).

Page 9 of 27

ranged as a permanent solution and were therefore already in place. The secured area in the shiphad also been arranged as a permanent solution, consisting of the stores room, workshop andaccess to engine room and lockable by means of a reinforced door (figure 7). In addition, it waspossible to mount a device on the external doors to the accommodation, making it possible to lockthem from the inside. The deck was cleared of material that could be used by any pirates thatmight board the ship.On 5 January 2011 during the voyage through the Red Sea, a routine fire drill was held with theparticipation of the guards. In addition to the drill, a safety meeting was held on the bridge wherethe piracy situation was discussed as well as the measures to be launched by the crew in casepirates were observed. Since the ship's crew were familiar with the area and the threat of piracy,the subject of the meeting was well-known to most crew members. It was agreed that, in case ofan attack, the crew should muster on the bridge and the master would decide when to go to thesecured area. The guards would launch their initiatives while the crew were on the bridge or in thesecured area. If the pirates came to the door leading to the secured area, the crew should presumethat the guards had been overpowered. The use of fire hoses against the pirates was also dis-cussed, as mentioned in the BMP35(section 3.7), but this idea was abandoned since the waterpressure was not sufficient to be effective, and the fire hoses would have to be operated manuallyin order to have any effect. It was considered too dangerous to operate the fire hoses if the pirateswere so close that it could have any effect.Furthermore, the mate and the master discussed on an on-going basis how to act vis-à-vis thethreat of piracy. It was, inter alia, agreed that, if small vessels were identified on the radar or visu-ally, the watch keeping officer should turn away instantly and increase the distance to the vesselthough it might be a fishing vessel.When the ship was in the middle of the Red Sea, the guards initiated a two-shift watch on theweather deck both during the night and day. From the same point in time, reports were being re-ceived by the ship’s INMARSAT-C6about various observations of pirates. The mate plotted themessages in a general chart (a large-scale chart), and the ship's master took care of the manda-tory reporting.The mate planned several different routes from the Gulf of Aden to Mumbai. The decision on theroute to be used depended on the reports received during the voyage. The routes went in a north-easterly direction along the coast of Oman, then in a directly easterly direction towards India and,later, in a south-easterly direction towards Sri Lanka. The immediate plan was to use the route in anortherly direction along the coast of Oman and subsequently change the course in an easterlydirection towards Mumbai.Most of the crew members had experience from voyages in this area and were attentive to thethreat of piracy, but they did not have the perception that there was any imminent danger. Theyexpected that the measures taken would suffice. The concern about attacks was the greatest in theareas adjacent to the Gulf of Aden, where there was no military presence – i.e. in the area beforeand after the corridor (IRTC7, figure 2), such as at Bab el Mandeb which occasionally is character-ised by dense, crossing traffic by small boats. In addition, the eastern part of the IRTC corridorwhere the crew considered the military presence to be more sporadic was perceived as being acritical part of the voyage.When the ship was approaching the strait at Bab el Mandeb at the western mouth of the Gulf ofAden, there was quite some traffic by small boats crossing the strait at high speed. They were pre-5

The 3rd edition of the shipping industry’s Best Management Practice to deter Piracy off the Coast of Soma-lia and Arabian Sea Area.6Satellite communication equipment.7Internationally Recommended Transit Corridor.

Page 10 of 27

sumed to be fishing boats and ordinary traffic across the strait. The mate discovered that he couldtrace the small boats at a distance of 4 nautical miles on the 3 cm radar in the port side if it was setfor the 6 nautical mile area and had trails indicating the direction of movement on the echo. It wasdifficult to maintain a plot of each individual echo, but by means of trails they became more distinct.The setting was used to ascertain whether there were any vessels in the vicinity that were ap-proaching the LEOPARD and could thereby represent a threat. In addition, the 10 cm radar wasused to monitor a larger area.On 9 January at 0130, the LEOPARD arrived at point A in the IRTC and started its voyage throughthe Gulf of Aden and along the coast of Somalia. The mate was navigating, and the master wasconducting the requisite reporting to the naval forces and to the UKMTO.8No special incidentsoccurred during the voyage, and a couple of times the crew had radio contact with nearby navalforces. Just before midnight on 10 January 2011, the ship passed point B (figure 2 above) and wasout of the IRTC. The course was set for a north-easterly direction towards Salalah where theguards were to disembark. When point B was passed, the ship’s AIS9was turned off to preventpirates from tracing the ship. Shortly before the LEOPARD arrived at Salalah, the ship received areport about piracy activities north of Oman. The master had a conversation with Shipcraft A/S,and he assessed that it would be the most convenient to disembark the guards in Salalah as wasgeneral practice.In the afternoon of 11 January 2011, the LEOPARD arrived at the waters off Salalah, where it wasdrifting appr. 13 nautical miles from the port. Here, the four guards were disembarked and broughtashore by a service boat that they themselves had arranged for. Subsequently, the LEOPARDimmediately continued its voyage towards Mumbai.Later in the afternoon, there was a message about a piracy attack close to the planned route nearthe coast of Oman in an area where there had also been reports of piracy earlier that day. Then,the course was changed and set for a waypoint appr. 100 nautical miles south of the latest attack.At the waypoint, the course was to be changed to an easterly direction towards Mumbai.The weather was fine, slightly cloudy with a light north-easterly wind. The sea was calm with noswell.That afternoon, the mate practised zigzagging the ship without losing too much speed. This ma-noeuvre was recommended by the BMP to prevent pirates from getting along the ship's side andboard it. The mate learned that he would have to turn the helm 10 degrees and count to ten beforedoing the same to the other side. In this manner, the ship would lose as little speed as possible(section 3.4). During the voyage from Salalah, they could keep a speed of 10-11 knots under theprevailing weather conditions.Shortly before noon on 12 January 2011, the mate came to bridge to relieve the master. The mas-ter was just about to change the course from southeast to east. They agreed to change the coursein a northerly direction towards Mumbai at 1800 when the mate was to be relieved. The master andthe mate assessed that they had now left the risk area since 24 hours had elapsed since they hadlast heard any message about possible piracy activities in the area.At appr. 1600 in the afternoon, there was some interference noise on the VHF radio and an echoappeared on the radar in a distance of appr. 15 nautical miles. The echo was too weak to be plot-ted effectively. The mate immediately changed the course to starboard to a south-south-easterlycourse in order to increase the distance to the suspicious echo.

89

United Kingdom Marine Trade Operations.Automatic Identification System.

Page 11 of 27

The mate went to the bridge wing and warned the AB working on the cargo hold hatch. As previ-ously agreed the ratings immediately started locking up the ship and, subsequently, assembled onthe bridge. The echo on the radar was now plotted on the radar.The radar plot showed that the suspicious ship stopped, and on board the LEOPARD the mate hadno doubt in his mind that the ship was manning the skiffs to be used for an attack. The master wasinformed about the imminent attack and also came to the bridge.Now, the mate could see the echo on the radar astern of the ship and that two fast-going skiffswere heading for the LEOPARD. At appr. 1650 hours, the master pushed the alarm button(SSAS10) and the mate activated the VHF DSC distress call. The mate turned off the automaticsteering and started manoeuvring manually in order to zigzag on the course to prevent the piratesfrom coming alongside the ship. Meanwhile the master contacted the operator Nordane A/S andinformed them about the situation. At this point in time, the two skiffs were at a distance of appr.2.5 nautical miles and were approaching fast, and gunshots were heard. The LEOPARD was doing10 knots on a south-easterly course.The operator immediately contacted the UKMTO and the MSCHOA11that said that they did nothave any naval vessels nearby. Shortly hereafter, the UKMTO tried in vain to reach the LEOPARDby telephone. Later in the afternoon, it became clear to the operator that the nearest naval vesselwas appr. 400 nautical miles from the position of the LEOPARD and would reach the position inthe afternoon on the next day.Before the skiffs came alongside the LEOPARD, the motorman was sent to the engine room todisengage the shaft generator and start the auxiliary engine.The two skiffs came along each side of the LEOPARD. The crew saw that the fast-going skiff onthe starboard side had brought along an aluminium ladder for boarding the ship. In the skiff on theother side, there was a pirate armed with an RPG.12Machine guns were fired against the bridgefrom both boats. The projectiles went through the bridge windows and hit the ceiling and someelectronic equipment. Most of the crew members threw themselves on the floor.While the LEOPARD was zigzagging on the course, the pirates tried to get alongside by position-ing the skiffs in the ship's turning centre where the ship had little movement. At one point in timewhen the pirates had come very close to the ship, the master took over the steering and gave fullhelm to starboard. Thereby, the ship lost speed and came to an almost complete stop.The pirates’ skiff overtook the ship, turned around and came along the side amidships on the star-board side and started ripping down the razor wire by means of the ladder. Shortly hereafter, thefirst pirates boarded (figure 3 and figure 4). The master disengaged the propeller, stopped the en-gine and told the crew of the LEOPARD to go to the secured area.

1011

Ship Security Alert System.Maritime Security Centre Horn of Africa.12Rocket Propelled Grenade.

Page 12 of 27

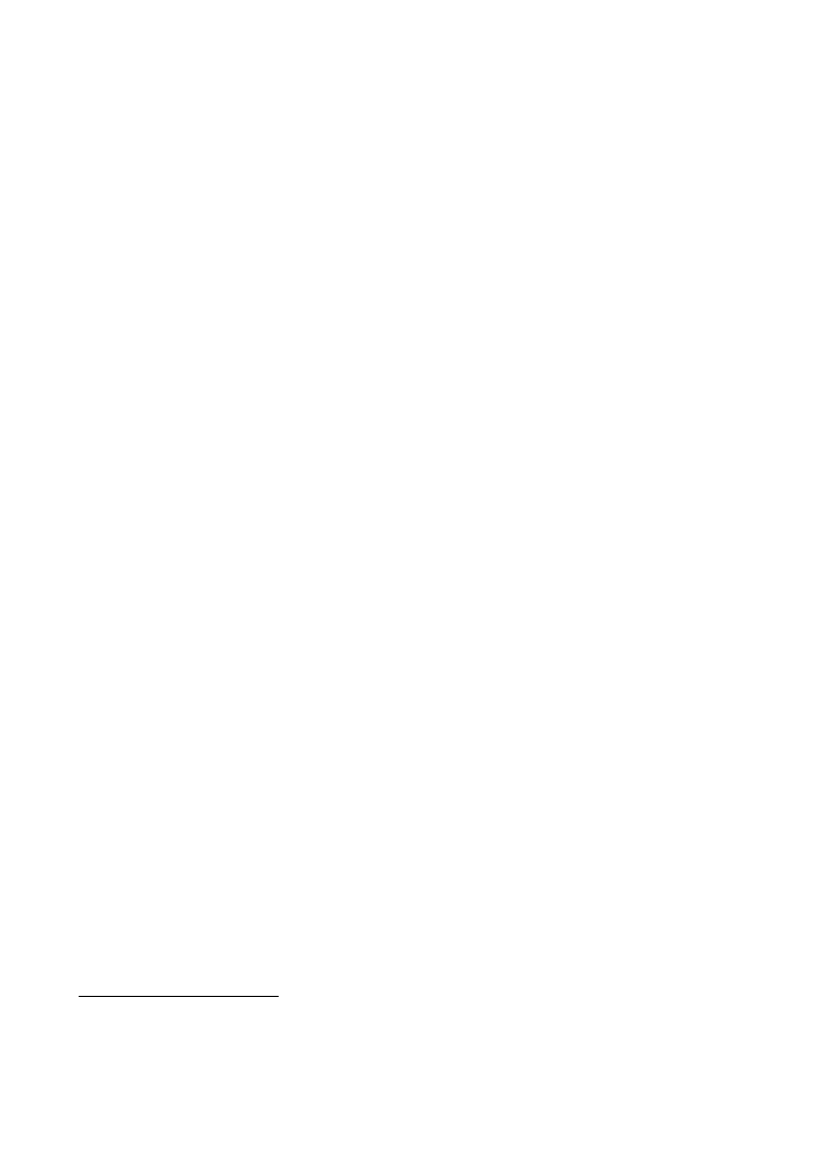

Pirates’ place of boarding

Guards’ accommodation container

Figure 3: The guards’ accommodation container and the pirates’ approximate place of boarding. The picture is from aprevious voyage.Source: Private photo.

Quite some time elapsed before the crew could hear the pirates rummaging on deck and in theaccommodation where it sounded as if they were trying to break into different rooms. They alsoheard the pirates working on the after deck, where it subsequently turned out that they had riggedthe ship’s pilot ladder in order to get more men on board. The pilot ladder had not been removedfrom the deck because the ladders for the life rafts were available anyway. The crew had not re-moved these ladders for general safety reasons.The operator was in contact with the shipowner on on-going basis and called the ship severaltimes, but the phone was answered by the Somali pirates. The operator did not engage in anyconversation.Several times, the master tried to get assistance over the VHF, but receiving no answer. After awhile, the pirates reached the reinforced door for the secured area and tried to force it open. Whilethe pirates were striving to open the door, the CO2alarm sounded in the engine room.13The crewin the secured area were aware that the consequence of sitting in the secured area in case CO2leaked from the engine room could be fatal. Since they could not escape through the emergencyexit in the engine room due to the CO2risk, they decided to surrender. They approached the rein-forced door that the pirates were trying to open, but by then it had been too damaged to be openedfrom the inside. Subsequently, they decided to move to the workshop because the air-breathingapparatuses were stored there and could be used should it become necessary.The control levers for releasing CO2in the engine room were located in a cabinet in the starboardbridge wing. However, the pirates had only opened the cabinet, thus activating the CO2alarm, butwithout touching the release mechanism.The pirates tried to break up the door to the secured area for appr. 3-4 hours until they succeededlater in the evening at around 2000 hours.

13

A CO2 fire-extinguishing system was installed covering the engine and cargo spaces.

Page 13 of 27

From the secured area, the crew could see that the pirates were using fire, but they did not knowwhether they were trying to burn down the door or to smoke them out. At a point in time, the firealarm sounded. Later, it has become clear that the fire originated from a cutting blowtorch bymeans of which the pirates tried to open the reinforced door by cutting off the hinges. They hadbrought along the cutting blowtorch equipment themselves, but since they probably did not knowhow to use it, they only managed to melt the hinges so that they got stuck instead of cutting themoff.During their efforts to open the door, the floor and the bulkhead around the door caught fire, andthe pirates extinguished it by means of a fire extinguisher that was positioned immediately outsidethe door. However, the pirates managed to weaken the door hinges so much that they could breakit open and create an opening, thus getting access to the secured area. Before the pirates pene-trated the door, they fired several shots into the area.The crew were led from the workshop to the port side of the bridge, and during this transfer thepirates were being violent to them. The crew noticed that the front window on the port side of thebridge had been smashed and that there was blood in the glass fragments. This was an indicationthat one or more of the pirates had cut themselves before getting in through this window via theventilation duct below (figure 4).

Window on the bridge where thefirst pirates came in

Ventilation duct

Figure 4: Accommodation on the LEOPARDSource: Admiral Danish Fleet

It is not clear how the pirates came from the platform on top of the ventilation duct up to the bridgewindow, but it is likely that they used the boarding ladder that they had brought along.

Page 14 of 27

On the bridge, the pirates wanted the master to start the propulsion machinery, and the masterordered the motorman to proceed to the engine room to start the engine. The motorman was ac-companied by two pirates. Once the engine had been started, the master could not connect it tothe propeller shaft. Gradually, the master realised that the pirates – in their attempt to navigate theship – had randomly pushed the buttons for the emergency operation of the propeller pitch, and heconcluded that the gear had been damaged. During the entire period, the master was threatenedby his life to start the propulsion. Apparently, the pirates had got the impression that there was infact no technical problem. Since the pirates could not communicate effectively in English, the pi-rates contacted an English speaking person ashore with whom the master could communicate.The master told him that they did not have an engineer officer or an electrician on board and, con-sequently, could not repair the gear themselves.Once again the motorman was sent to the engine room by the master to remedy the problem. Themaster made it clear that, if they were to get out of there alive, they would have to solve the prob-lem with the propulsion and get the ship underway.The ship’s cook was taken into the galley where he was ordered to procure food for the pirates.When he asked for how many persons he was to cook, the pirates said appr. 20 persons.When it became clear later in the evening that the propulsion could not be repaired, the pirateswanted to try to tow it after their mother ship, the Taiwanese fishing vessel SHIUH FU no. 114,which they had previously captured and where the Chinese crew were still held hostage on board.An AB was sent down to rig a mooring line between the ships, but the mooring line broke eachtime the towing operation started. During the towing operation, the rudder was not amidships,which made towing difficult. After a couple of hours, the pirates abandoned the attempt to tow theship.Around midnight, the mate and the ratings were forced by the use of violence through the accom-modation to the aft deck and from there down a pilot ladder to skiff. They were taken to the fishingvessel and placed in the forepart of the ship. The master was still on board the LEOPARD.Later, the motorman and a Chinese engineer officer who had been taken hostage were brought onboard the LEOPARD in an attempt to have the propulsion repaired, but in vain. The master, themotorman and the Chinese engineer officer were brought back to the fishing vessel, and theLEOPARD was abandoned with the main and the auxiliary engine running.In the evening of 12 January 2011, a Turkish naval vessel was tasked with countering the situationon board the LEOPARD. On 13 January 2011 at appr. 1300 hours, the Turkish naval vessel’s heli-copter arrived at the LEOPARD and did not observe any crew members or pirates on board. Thehelicopter crew did not succeed in establishing radio contact with the ship.

3.4 The ship's anti-piracy preparedness3.4.1 On-board measuresThe risk of piracy in, inter alia, the Gulf of Aden, the Strait of Malacca, and the waters around thePhilippines had always been part of the ship's operational reality. On several occasions, the chang-ing crews on board the ship had observed pirates or directly repelled attacks by pirates and hadtherefore gained experience with the initiatives that could be effective in various situations were theship would be attacked. Thus, the ship had for a number of years been fitted with a number ofmeasures to counter the increasing threat from piracy, especially in the Gulf of Aden.

14

SHIUH FU no.1 was a fishing vessel registered in Taiwan that had been captured on 25 December 2010.

Page 15 of 27

Especially after the capture of the Danish cargo ship DANICA WHITE on 1 June 2007, making thethreat of piracy real and, subsequently, causing it to be perceived as imminent, the structural andoperational securing of the ship became more extensive.In general, the BMP recommendations were used, the BMP3 being the most recent version (sec-tion 3.7). The various versions of the BMP were by the crew and guards considered to be of a toogeneralising and overall nature to contribute with additional new knowledge. They were considereduseful for ships not previously engaged in voyages in the area. In addition, the pirates were ex-pected to develop their methods as the BMP recommendations became known and, consequently,additional measures would be necessary.Since the different crews had different experiences with piracy, the measures used varied to someextent. For example, previous crews had tried rigging lines secured to the stern and dragged afterthe ship. The intention was that, in case a pirate vessel came from abaft, the lines would be caughtby the propeller of the pirate vessel and, thus, the attack would be interrupted. However, the cur-rent crew on the LEOPARD had concerns about the effect of the anti-piracy measures in the Gulfof Aden since the pirates had considerable resources, such as fast-going vessels, boarding lad-ders and firearms and displayed a determination to board the ship.Experience had been gained from previous incidents in the area by other crews on the LEOPARDthat the firing of flares against pirates had a deterrent effect, presumably because the small pirateskiffs carried considerable quantities of fuel in plastic containers that could catch fire. Conse-quently, previous crews had made various pyrotechnics ready in the ship's bridge wing for voyagesin the Gulf of Aden.Due to the still more aggressive behaviour of the pirates in the Gulf of Aden, the crew on board theLEOPARD at the time of the attack did not consider the use of pyrotechnics a real option becausethey would be exposed in case the pirates fired gunshots against the ship.The various crews on board the LEOPARD had never used fire hoses as an anti-piracy measurebecause the ship's fire pumps did not have sufficient capacity to have an effect against pirates. Inaddition, the crew assessed that they would be too exposed if they were standing on open deckwith a fire hose while the pirates were firing against the ship. The intention behind the use of firehoses was to fill the relatively small pirate vessels with water so that they lost their manoeuvrabilityand/or stability or to cause damage to the electrical parts of the outboard engine.At some point in time before 2006, the ship had been fitted with steel plates in front of the windowsin the accommodation (figure 5) as a measure against the general threat of piracy in Asia and Afri-ca. The plates had been bolted on and, subsequently, welded, but only to such an extent that itwould still be possible to loosen the bolts by means of an extended spanner, which could becomerelevant in case of a fire necessitating access to the accommodation. The steel plates had beenperforated so that daylight could get into the accommodation.During the period after the capture of the DANICA WHITE in 2007, fittings were welded onto thegunwale over the entire length of the ship for mounting sceptres on which to secure the razor wire.During the voyage through the Red Sea, two layers of razor wire were extended along the entireship's side as well as three layers on the accommodation (figure 5).

Page 16 of 27

Razor wire

Perforated steel plates

Steel plate over stairway

Pirates' place of boarding

Figure 5: Razor wire on the LEOPARD.Source: Admiral Danish Fleet.

Razor wire differs from traditional barbed wire in that small steel blades have been mounted on therazor wire functioning as small knives. Consequently, clothes will be caught in it, just as it couldcause serious cutting injuries to persons. The type of razor wire used on the LEOPARD could havea strong springing effect and would retract if released. It was recognized that the razor wire wouldnot be effective in stopping the pirates' access to the ship, but it could possibly delay it.On the external stair on the aft side of the accommodation, a steel plate was mounted on eachdeck and secured by means of bolts, thus blocking the stair to the accommodation.All external doors were made of steel and locked from the inside by means of fasteners secured bysplit-pins.The establishment of the secured area (figure 7) was a process that took place over a period ofappr. one year. The fire door was reinforced in 2007, and a VHF radio was installed in the area in2008, i.e. before the publication of the first BMP.

Page 17 of 27

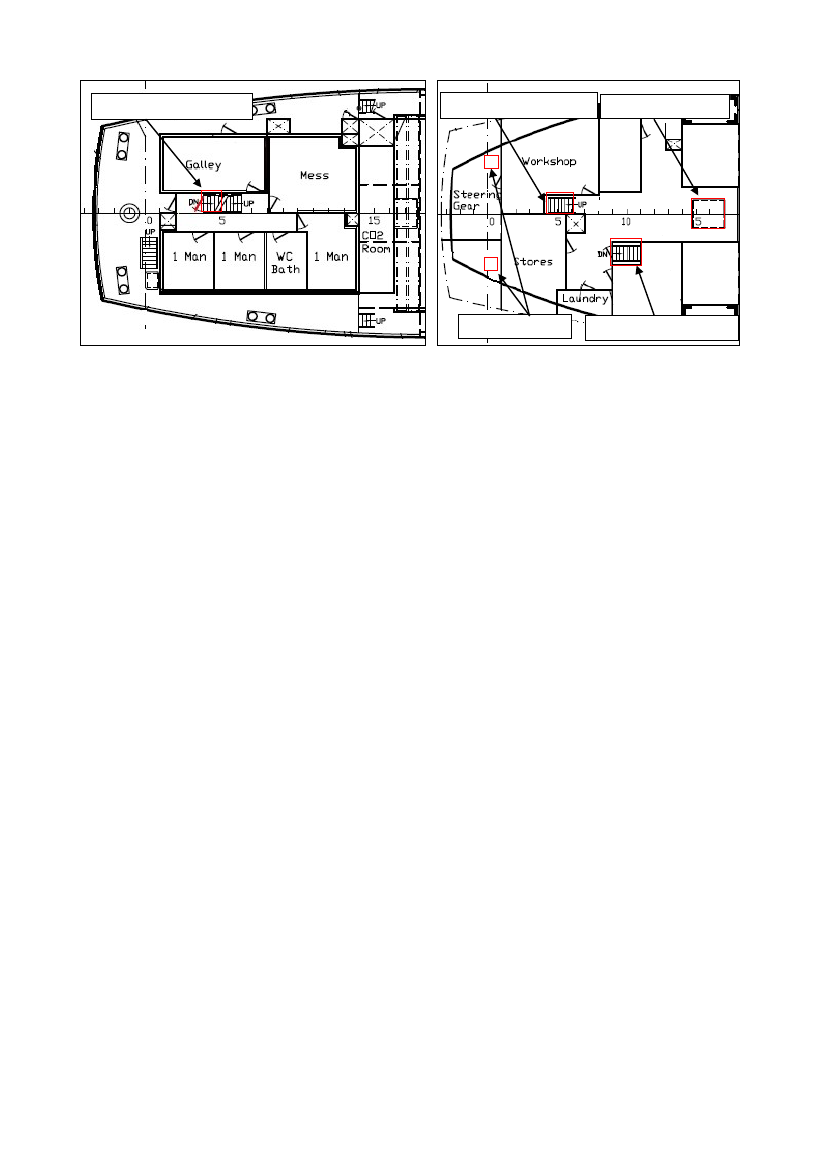

Entrance to secure area

Entrance to secure area

Engine room hatch

Emergency exitFigure 6: Drawing of main deck and companionway to se-cured area.Source: Nordane A/S and DMAIB.

Exit to engine room

Figure 7: Drawing of secured area.Source: Nordane A/S and DMAIB.

The companionway to the secured area is marked in red in figure 6. The door to the secured area,which opened outwards as indicated in the figure, was a fire door fitted with locking latches on theinside. Furthermore, it was reinforced by means of stainless steel plates so that it could be re-sistant in case pirates forced themselves into the area.The area was located below the main deck and consisted of a workshop, store room, laundry roomand steering gear room. At a switchboard in the room, a VHF radio was installed that the crewcould use for communication with the outside during an attack. Since the store room was a part ofthe secured area, food and beverages were available.The only means of access to the area – in addition to the staircase in the accommodation – was anemergency exit from the steering gear, which was a steel hatch locked from the inside by means offasteners and split-pins. In addition, access was provided to the machinery space through a steelhatch in front of the accommodation (figure 7). It was normally used for loading spare parts, etc. Itwas secured by means of a chain pulley on the inside.From the secured area, access was provided to the machinery space. A CO2system had beeninstalled as a fixed fire-extinguishing system covering both the machinery and cargo space. Notuntil the time of the attack, it became clear that the crew could not seek refuge in the machineryspace or get out through the machinery space hatch if the CO2system was released and that arisk might be related to accommodation in the secured area.The purpose of the secured area was for the crew to seek refuge in this area during an attack and,thus, be protected against the random shots fired by the pirates against the ship. In addition, it wasexpected that the military units nearby would launch liberation activities.Different crews had different perceptions of the importance of the AIS being turned on or off, re-spectively. Some considered it important that the naval vessels could see the ship all the time anddoubted the sophistication of the pirates' equipment and, thus, always had the AIS turned on. Oth-er crews turned it off in the area outside the IRTC. When the LEOPARD left the IRTC on 10 Janu-ary 2011, the master chose to turn off the AIS. It is uncertain whether it was turned on again duringthe attack.The recommendation of the BMP3 was that the ship's master should practise manoeuvring theship so that it would not loose much speed. The purpose would be to create the most difficult sea

Page 18 of 27

conditions for the pirate skiffs trying to attack. The crew on board the LEOPARD practised thesemanoeuvres, but they turned out to reduce the speed considerably.The ship had an SMS15procedure on piracy, describing inter alia the risk areas, which measures tobe launched and how the ship's crew were to act following an attack. Furthermore, it contained areference to the BMP.The ship's Ship Security Plan had been approved by Bureau Veritas on behalf of the Danish Mari-time Authority. Thus, the plan contained the mandatory parts under the ISPS Code, but the ship'screw had an operational approach to their safety measures that was more comprehensive thandescribed in the plan.The ship was fitted with a mandatory alarm system – SSAS – in accordance with the ISPS Codethat, when activated, transmits an alarm containing information about the ship's position, courseand speed to the operator and to the Maritime Assistance Service under the Admiral Danish Fleet.It was possible to activate the alarm from the bridge and from one other place in the ship knownonly by the ship's officers.

3.4.2 GuardsThe shipowner had used civilian, unarmed guards on its ships in the Gulf of Aden since 2009. Atthe time of the attack, it was not permitted pursuant to Danish arms legislation16to have arms onboard Danish ships.The use of guards was motivated by the shipowner's and the crews' assessment of the increasingthreat from pirates in the area and of the shippers' requirements. In general, the guards were hiredto take care of the ship's security in the IRTC area, which was in the autumn of 2010 by the ship-owner considered to be the area presenting the highest risk of an attack. The task of the guardswas to assist the crew in rigging the anti-piracy measures. In addition, they were to provide theship protection against pirates in case of an attack. In general, there would be four-five guards onboard who were accommodated in a container on deck fitted with lighting and an air-conditioningsystem. The guards would eat in the crew mess and in general use the crew's dayroom when theywere off duty. The guards were unarmed since, at this point in time, it was only in extraordinarycircumstances that permits were issued by the authorities to have armed guards on board Danishships.Because the number of persons on board had been increased considerably, the operator had fittedthe ship with one extra life raft. The extra life raft was intended to be moved from one side to theother depending on the circumstances of an evacuation.During the period from 2009 to 2010, the market for guards was characterized by many new play-ers in the field that were not experienced with piracy or with the conditions applicable in the mer-chant fleet. Consequently, the security companies' approach to the task differed, as did the ship-owner and the crew's expectations of the effect of the guards.Before armed guards were used on board Danish registered ships in the spring of 2011, the secu-rity companies had different approaches to the task. Some companies considered the guards to bemerely consultants who could assist the crew in rigging the anti-piracy measures and, if relevant,assist with the reporting in case of an attack by pirates.In addition to their consultative task, the guards on board the LEOPARD also had an offensive ap-proach to their task. Therefore, they had developed an operational approach on how to counter1516

Safety Management System.Consolidated act no. 704 of 22 June 2009.

Page 19 of 27

piracy attacks while being unarmed. That is, they would actively try to prevent the pirates fromboarding. They had previously had experience with this approach from an attack on the LEOPARDand on the PUMA, which was another one of the shipowner's ships. However, the previous inci-dents had not been as aggressive as this more recent attack on the LEOPARD and, in one case,the crew contributed greatly to the interruption of the attack.Already at an early stage, the guards used the BMP as guidelines, but gradually they realized thatthe measures described were not sufficient to prevent an attack; therefore, the security companyhad its own measures, primarily because the recommended measures followed a pattern that wasknown by the pirates and that the pirates were constantly developing methods for countering.Some of the crew members were concerned that, if they were attacked by pirates, the guards' be-haviour could escalate the situation in such way that the crew could risk being killed if the piratescame on board.Previously, the guards had embarked in the southern part of the Red Sea, but as the threat of pira-cy became more present and moved to the north, the shipowner started taking the guards onboard in the Suez roads. Usually, the guards were disembarked in Salalah or Mumbai, but the In-dian authorities were to an increasing degree unwilling to let the guards disembark in Mumbai. It isuncertain for which reason, but this was a problem that was also known by other shipowners. Onthe other hand, Salalah was considered a suitable place for embarking and disembarking guardsbecause the authorities had a favourable approach and a developed infrastructure that wouldmake this easy.On board the ships owned by the company Shipcraft, the crews had varying experiences with howthe guards were to form part of the daily routines. The LEOPARD had an accommodation intendedfor a crew of six persons. Therefore, four to five guards were a considerable increase in the num-ber of persons on board. On limited space, this could create social tension that could be intensifiedby the guards' lacking experience with the normal interaction between crew members on boardsmall ships.The crew's perception of the guards' presence on board the ship had been characterized by thefact that the LEOPARD was a rather small ship that had not been designed to accommodate tenpersons. Though accommodation had been arranged for the guards on deck, the guards spentquite a lot of time in the ship's mess/accommodation, and conflicts could arise about the use of thespace. Furthermore, the crew members doubted the value of the guards since they were unarmedand, therefore, the crew believed that they could not deter an attack by pirates.Consequently, they were of the view that it would be the most convenient to disembark the guardsin Salalah. The operator and the officers were certain that, if they had wanted guards on board theship for the voyage across the Indian Ocean, they would have been made available by the ship-owner.

3.5 Piracy in the area in January 2011The LEOPARD was attacked on the afternoon of 12 January 2011. During the period from Novem-ber 2010 to February 2011, there were a total of 168 incidents in the area around the high risk areacovering most of the Indian Ocean.1727 of these were captures, 103 failed attempts at capturesand 37 suspicious incidents. Within 250 nautical miles from the position of the seizure of theLEOPARD, there were six other seizures and 22 failed capture attempts. It is hard to set the num-ber of ships in the area since aggregate overviews of the traffic in the area are not made. In addi-tion to the transit voyages via Suez, there is considerable local trade as well as quite a lot of trafficbetween Africa and the Arabian peninsula. During the relevant period, appr. 4,300 ships passedthe Suez Canal.17

From Suez in the north to 10� S and 78� E.

Page 20 of 27

The piracy threat had changed from primarily being in the Gulf of Aden to also being a threat in theArabian Sea. This was likely a result of the presence of naval forces in the Gulf of Aden and thatthe pirates had the capability of operating in a larger area, which would include shipping going toand from the Persian Gulf.

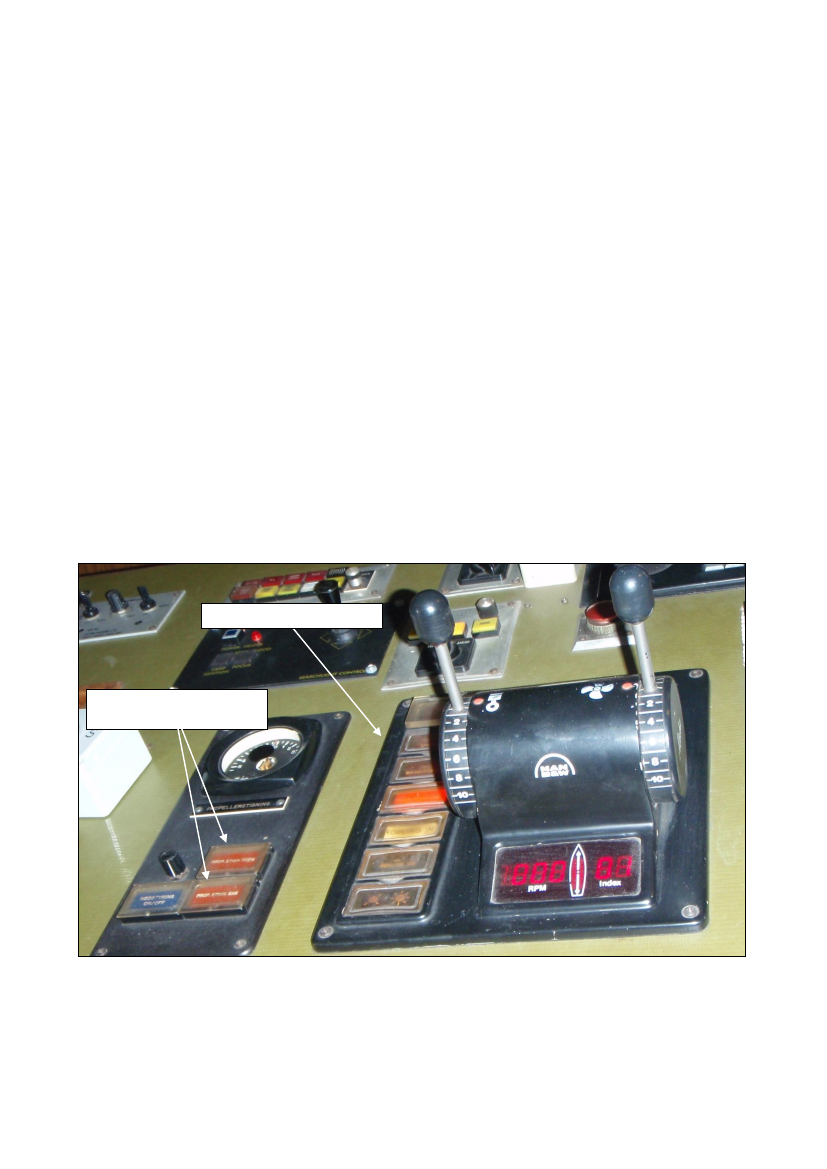

3.6 Breakdown of the propulsion machineryAs the pirates were boarding the ship, the ship's master disengaged the gear and stopped the en-gine before the entire crew went to the secured room.It was the pirates' intention to seize the ship and bring it along. They did not succeed because theship's propulsion machinery was disengaged in connection with the pirates' ravage on board, whilethe crew were locked in the secured area of the ship.In an attempt to make the ship sail, the pirates had pressed the buttons on the control panel on thebridge at random (figure 8) and thereby made it impossible to engage the gear again though thecrew succeeded in starting the engine.The machinery was such that it was only possible to engage the gear when the propeller pitch waszero. However, the pirates had constantly pressed the emergency steering for the propeller pitch,thus destroying the system's built-in signalling of the propeller pitch. Consequently, the systemcould not measure that the pitch was zero, and the automatics made it impossible to engage thegear. The motorman who was responsible for the daily maintenance in the engine room was or-dered by the pirates to engage the engine. He thought that the problems were related to the gearas such and, in the situation, he did not realize that it was a question of a defect in the system'sinternal measurement of the propeller pitch.

Engine control panel

Emergency steering of pro-peller pitch

Figure 8: Engine control panel.Source: Private photo.

Page 21 of 27

3.7 Danish and international legal basis and recommendationsDenmark has been committed to the fight against piracy for several years. The efforts made arecomprehensive, including military activities carried out by naval vessels and requirements for ship-owners and ships regarding anti-piracy procedures, the solving of the legal challenges persecutingpirates as well as long-term capacity-building enabling the countries in the region to meet the pira-cy challenge by themselves. This is reflected in the Danish anti-piracy strategy 2011-2014, which isbased upon the principle of an overall approach to the piracy problem, and the purpose of which isto contribute to making the waters in the Indian Ocean safe for Danish and international shipping.In Denmark, the combat against piracy is spread over a number of ministries: The Ministry of Busi-ness and Growth, the Ministry of Defence, the Ministry of Justice and the Ministry of Foreign Af-fairs.In 2008, the Danish Maritime Authority prepared a technical regulation on piracy prevention, con-taining requirements for ships and shipowners' procedures when navigating or calling at ports inareas presenting a risk of piracy and armed robbery against ships. The procedures must containprovisions on the prevention of attacks, including an assessment of the risk and relevant measuresfor protecting the ship and its crew. The procedures must be drawn up in consideration of the IMOrecommendations and guidelines for voyages in areas presenting a risk of piracy and armed rob-bery. The technical regulation was revised in 2011 as part of the Danish anti-piracy strategy so thatfrom 1 January 2012 it has, inter alia, been a requirement for Danish ships engaged in voyages inthe high-risk area in the Indian Ocean to register their voyages with the international naval forcesand UKMTO.In practice, the use of the BMP is an important tool when navigating the high-risk area. The BMPhas been developed by the international shipping industry in cooperation with the naval forces andhas also been issued by the IMO. The purpose of the guidelines is to advise ships about how toavoid, deter or delay piracy attacks off the coast of Somalia, in the Gulf of Aden and in the ArabianSea.The BMP is a dynamic tool, which is updated on an on-going basis. The use of the BMP is notmandatory. On the other hand, the BMP recommends carrying out a specific risk assessment foreach individual ship. The BMP contains recommendations on piracy prevention, primarily in theform of practical measures on board the ship and a description of the occurrence of a typical attackby pirates.Furthermore, it is recommended that the ships register with the coordination centre of the navalforces (MSCHOA) and report to the central coordination centre which functions as a connectinglink between the merchant ships and the military naval forces (UKMTO). In August 2010, the Inter-national Chamber of Shipping forwarded the 3rdversion of the BMP to the IMO. The IMO issuedthis BMP3 as an annex to circular MSC.1/Circ.1337 of 4 August 2010. Thus, this BMP3 was validwhen the LEOPARD was attacked.Since piracy came into focus, Denmark has been working internationally in the IMO to maintain theinternational commitment regarding the combat of piracy and armed robbery against ships. Now,this work is performed both by the UN and the IMO. The IMO has adopted a considerable numberof guidelines and recommendations on piracy and has also issued the BMP. The IMO has, interalia, issued guidelines for ships, shipowners and seafarers on the prevention and avoidance ofpiracy and armed robbery against ships. Similarly, the IMO has drawn up guidelines for the authori-ties to be taken into consideration by flag states in their anti-piracy policies. Guidelines have alsobeen developed for shipowners on what to consider when selecting guards and security com-panies.At the request of the UN Security Council, an international contact group on piracy off the coast ofSomalia has been established. The contact group coordinates the efforts made by the international

Page 22 of 27

community through five sub-working groups, focusing on the operational and capacity-building as-pects, the legal challenges, the industry's protection of itself, as well as communication.

4. ANALYSIS4.1 Sequence of eventsThe voyage from Suez until the time of the attack did not differ considerably from other voyagesundertaken by either the LEOPARD or other of the company's ships in the area in the recent year.A practice had developed on the basis of the shipowner, the operator and the crew's perception ofthe threat of piracy, and the international recommendations.From 2009, the shipowner had chosen to use private security guards, not only in the Gulf of Aden,but sometimes also on voyages in other waters.In the view of the shipowner, the guards' presence was a necessity out of safety and commercialconsiderations. The commercial consideration was typically based on shippers who wanted tohave guards on board during a part of the voyage. In addition, it was important that the shippersfelt that the manner in which their cargoes were carried was safe and secure. However, the guardsembarking the LEOPARD in January 2011 were part of the general safety-related response to pi-racy in the Gulf of Aden, and it was customary for them to be disembarked in Salalah. Nothing in-dicates that the motivation for disembarking the guards was based on economic considerations bythe shipowner. Ultimately, it was the master's decision because he was the one closest to theevents and, consequently, in a position to make the best assessment. The master had the ship-owner's support for the assessments made.The master decided to disembark the guards in Salalah because they were not considered by themaster and the crew to contribute considerably to the security, primarily because they were un-armed and only kept their watch in the IRTC. In addition, they constituted a strain on the socialconditions on board. Furthermore, the guards' offensive approach to their task made some of thecrew members feel unsafe.It shall be emphasized that unarmed guards would not necessarily take measures against attacksby pirates, but that some guards exclusively functioned as consultants. If the guards took offensive,improvised measures against the pirates, such as pyrotechnics or other things, this could escalatethe situation to such an extent that the crew would fear reprisal measures should the pirates suc-ceed in getting on board.The BMP did not recommend the use of private security guards, but left the decision to be basedon an assessment made by the shipowner. The BMP advised against the use of armed, privatesecurity guards18.It is uncertain whether the guards' presence on board could have deterred the attack by pirates.Previous piracy attempts on the LEOPARD and the PUMA cannot shed light on how events couldhave evolved on board the LEOPARD with guards present under the attack because they werevery different incidents. When attacking the LEOPARD, the pirates fired shots against the ship at avery early point in time and showed signs of their intention to use an RPG. In addition, the officerswere not prepared to take part in and assist in an open confrontation with the pirates as were someother crews.The attempt to manoeuvre the ship so as to prevent the pirates from boarding turned out not to beeffective. The LEOPARD had a speed of 10-11 knots, which was not sufficient to get away from18

BMP3, 6.11.

Page 23 of 27

the pirates and it turned out not to be difficult for the pirates to get along the ship's side at its turn-ing point, which was relatively fixed in connection with avoidance manoeuvres, and to board. Inaddition, there was almost no sea, which made the conditions very favourable for the pirates.The LEOPARD had a freeboard of appr. 2.6 metres. The freeboard may be of importance whenunarmed guards are to prevent pirates' attempts to board ships. In this case, where the ship didnot have any guards on board, it was probably of no importance since the freeboard height as suchdoes not prevent pirates from boarding ships.The pirates' inability to bring the ship to Somalia was caused by the impossibility of engaging thegear due to misoperation of the emergency steering of the propeller pitch. The ship's motorman,who was otherwise familiar with the functioning of the gear, did not recognize which technical rea-sons prevented the engagement of the engine to the propeller shaft. It is probable that the pres-sure that he was subject to made it impossible for him to assess the technical circumstances andreasons for the breakdown. The Chinese chief engineer who was brought to the ship from theSHIUH FU no. 1 has not been able to contribute with decisive knowledge about machinery withwhich he was not familiar. The fact that the pirates were operating under a pressure of time hasprobably contributed to the psychological pressure imposed on the motorman and the Chinesechief engineer.The BMP3 recommended the ship's operator and master to make a risk assessment before theship entered the high-risk area.19The risk assessment should be made on the basis of the proba-bility and consequence of an attack based on the latest information available. However, this turnedout to be difficult because the statistic approach to the risk did not offer the crew the opportunity topredict whether an attack would occur or whether the measures launched would be effective.It would be difficult for the ship’s master to decide which route to sail based on the reported pirateattack. The choice was to sail to the latest reported area of attack, with the presumption that a pi-rate attack would not happen the same place twice within a short time frame, or to divert to anotherroute entirely. The master of the LEOPARD chose another route than the one first planned, expect-ing that they would sail away from the pirates.In accordance with the practice trained, the crew sought refuge in the ship's secured area. Thesecurity companies recommended that the crew sought refuge in areas with a minor risk of beinghit by random shooting. It was the perception of the crew that the room could, in addition, functionas a refuge until military units came to their rescue. It is beyond the terms of reference of the Dan-ish Maritime Accident Investigation Board to investigate to what extent the crew could expect themilitary forces in the area to rescue them in what may be termed a hostage situation on board.

4.2 On-board measuresThe shipowner, the operator and the different crews on board the LEOPARD had fitted the shipwith what they considered the necessary anti-piracy measures. These measures had been devel-oped on the basis of their experience and of the development of the BMP. Though the internationalrecommendations were followed, the measures turned out not to be sufficiently effective to preventthe pirates' boarding and access to the accommodation.The secured room had been established during a couple of years and appr. one year before theissue of the first version of the BMP. It turned out to be effectively secured for preventing the pi-rates' immediate access to the room though they were in possession of a cutting blowtorch. But ofcourse pirates who have this type of equipment and competence to use it can force themselvesinto any room in the ship. Consequently, the secured area turned out to be effective in that it re-sisted the pirates' attempt to penetrate the door for several hours. The fact that the machinery19

BMP3, p. 5.

Page 24 of 27

space was fitted with a CO2fire-extinguishing system constituted a potential risk in case it was re-leased by the pirates.The crew on board the LEOPARD chose not to use the ship's fire hoses as a part of their anti pira-cy measures. The ship's fire pump could not have delivered a pressure capable of pressurizing somany fire hoses that the ship would be protected over its entire length. An attempt to manually di-rect a nozzle against the pirates would have involved considerable danger to the crew.It was recommended to turn on the AIS again during an attack so that the military forces could lo-cate the ship. The crew did not do so, but it was of no importance to the localisation of theLEOPARD because the SSAS alarm transmitted the ship's position continuously during the entireperiod, and the shipowner forwarded these positions to the military forces in the area.Razor wire had been fitted all around the ship and on the accommodation. The wire did not preventthe pirates from boarding. The razor wire was part of the overall measures to delay the pirates'boarding of the ship, but the ship's crew did not expect the wire to prevent the pirates from gettingaccess to the ship, but rather that it would make the boarding more difficult and, thereby, delay thepirates.In connection with the investigation, the Danish Maritime Accident Investigation Board has becomeaware that anti-piracy measures could have an unintended impact on the use of the ship's life-saving appliances. In figure 10 below the starboard liferafts of the LEOPARD are shown. Theywere mounted on a frame making it possible to launch them without having to lift them over theship's side. They had been secured by means of lashings and hydrostatic releases that would au-tomatically release the lashings in case the ship foundered.

Figure 10: Picture of the liferafts on the starboard side on the LEOPARD.Source: Private photo.

As is evident from the figure, the launching and embarkation of the liferaft will be made difficult bythe razor wire. However, the ship's crew had fitted wire cutters in the vicinity so that it was possible

Page 25 of 27

to release the razor wire and make room for launching the liferaft. Though it may be possible tofind an apparently simple operational solution, a number of overall problems arise as regards theeffect of anti-piracy measures on the use of the ship's safety and life-saving appliances. In general,it is inexpedient that prescribed safety and life-saving appliances have a conditional use, i.e. that itis necessary to carry out a number of acts before the crew can use the equipment. Specifically, thismeans that the crew will first have to cut and release the razor wire and maybe even pick it up inorder to avoid it getting in the way and damaging the liferaft and injuring the crew. Furthermore, thewire will make the improvisation that might be necessary in an emergency difficult, for example ifthe crew decide to embark the liferaft from another place on board the ship and, consequently, willhave to draw the liferaft along the ship's side. In addition, the liferaft and the crew could get caughtin the wire in case of a loss that evolves fast and where the crew do not have time to release andembark the liferaft and, therefore, will have to leave the ship by jumping into the sea.In connection with the investigation of the death on board the NORD GOODWILL20on 23 October2012 in the Tema roads, Ghana, the Danish Maritime Accident Investigation Board has found thatthe crew could not immediately launch the ship's rescue boat due to the razor wire fitted.In addition, the Danish Maritime Accident Investigation Board has, in connection with current in-vestigations of another accident, found that the use of the ship's fire-extinguishing system as ananti-piracy measure where the fire hydrants on deck are open could have an unfortunate impact onthe ship's fire-fighting response because all the fire hydrants will have to be turned off first beforeinitiating the fire-fighting as such.When persons from the shipowner and the operator subsequently inspected the ship in Dubai, theUnited Arab Emirates, they found a bollard that had been torn from its base. This probably oc-curred when the ship was subsequently towed ashore and did not originate from the pirates' at-tempt to tow the ship.

5. CONCLUSIONSThe attack on the LEOPARD and the subsequent abduction of the crew on 12 January 2011 wascarried out by Somali pirates who had the equipment and will to capture the ship. The pirates suc-ceeded in boarding the ship and abducting the ship's crew despite the extensive anti-piracymeasures implemented on the basis of the experiences gained by the crew, the operator, the ship-owner and the international recommendations. The ship was not captured and had to be left in theopen sea due to damage to the ship's propulsion system that the pirates had inadvertently causedduring the attempt to seize the ship.The recommendations of the BMP3 were unclear as regards the use of unarmed guards, and leftthis issue to the shipowner's assessment. The BMP3 dissuaded the use of armed guards. At thetime of the attack, it was under Danish law only in extraordinary circumstances that permits wereissued by the authorities to have armed guards on board Danish ships.It was decided to disembark the guards in Salalah. It is not possible to explain why this decisionwas taken without understanding the operational and social aspects. The master's motive was that,because the guards were unarmed, he and the rest of the crew did not find that they contributedconsiderably to the ship's safety. This perception may have been reinforced by the fact that theirpresence on board created social tensions among some crew members.It is uncertain whether the guards' presence would have prevented an attack and a comparisonwith previous episodes would be comparable to the situation on board the LEOPARD becausethey differ in decisive ways.20

http://www.dmaib.dk/Ulykkesrapporter/NORD%20GOODWILL.pdf

Page 26 of 27

It was a potential threat to the crew that the secured area was in the immediate vicinity to the ma-chinery space that was fitted with a CO2fire-extinguishing system. Considering the size and layoutof the ship it was difficult to arrange for a secure area elsewhere on the ship.The Danish Maritime Accident Investigation Board has found that some of the measures launchedaffected the use of the ship's life-saving appliances, but it had no effect on the events on the 12January 2011. This problem may also be found on other ships. In general, most merchant shipshave not been designed to resist attacks by pirates, and the introduction of anti-piracy measuresmay have an effect on the designed functioning of life-saving appliances. In this connection, it isimportant to notice that in emergencies unexpected events and complex circumstances may occurwhere it is not always possible to foresee the effect of anti-piracy measures on the functioning oflife-saving appliances. Therefore, seemingly simple solutions, such as the fitting of wire cuttersetc., may turn out to be insufficient in complex emergencies where the crew will have to improvise.

6.

PREVENTIVE MEASURES

Following the attack on the LEOPARD, the shipowner and the operator have implemented a num-ber of preventive measures. In consideration of the effect of these measures and the ships' safety,it would not be expedient to publish these measures.In March 2011, the Ministry of Justice – in consultation with the involved authorities and the indus-try organisations – decided that Danish ships could, following a specific application on the basis ofthe general assessment of the threat, be permitted to use civilian, armed guards in the area off theHorn of Africa.On 13 June 2012, the Danish Parliament (Folketinget) adopted an amendment of the arms act21,which entered into force on 30 June 2012. This ensures that shipowners can, faster and in a moreflexible manner, acquire a general permit to use armed guards on board Danish cargo ships inareas presenting a risk of piracy and armed robbery against ships.The Danish Shipowners' Association and The Shipowners' Association of 2010 will in their com-mon committee, Piracy Group, discuss and exchange best practises on implementation of anti-piracy measures and the effect the measures can have on the use of life-saving appliances.

21

Act no.564 of 18 June 2012.

Page 27 of 27