Børne- og Undervisningsudvalget 2013-14

BUU Alm.del Bilag 168

Offentligt

Northern Lights onTIMSS and PIRLS 2011Differences and similarities in the Nordic countries

Northern Lights onTIMSS and PIRLS 2011Differences and similarities inthe Nordic countries

Kajsa Yang Hansen, Jan-Eric Gustafsson, Monica Rosén,Sari Sulkunen, Kari Nissinen, Pekka Kupari, Ragnar F. Ólafsson,Júlíus K. Björnsson, Liv Sissel Grønmo, Louise Rønberg,Jan Mejding, Inger Christin Borge and Arne Hole

TemaNord 2014:528

Northern Lights on TIMSS and PIRLS 2011Differences and similarities in the Nordic countriesKajsa Yang Hansen, Jan-Eric Gustafsson, Monica Rosén, Sari Sulkunen, Kari Nissinen,Pekka Kupari, Ragnar F. Ólafsson, Júlíus K. Björnsson, Liv Sissel Grønmo, Louise Rønberg,Jan Mejding, Inger Christin Borge and Arne HoleISBN 978-92-893-2772-5ISBN 978-92-893-2773-2 (EPUB)http://dx.doi.org/10.6027/TN2014-528TemaNord 2014:528ISSN 0908-6692�Nordic Council of Ministers 2014Layout: Hanne LebechCover photo: ImageSelectPrint: 07 Media a.sCopies: 416Printed in Norway

This publication has been published with financial support by the Nordic Council of Ministers.However, the contents of this publication do not necessarily reflect the views, policies or rec-ommendations of the Nordic Council of Ministers.www.norden.org/en/publicationsNordic co-operationNordic co-operationis one of the world’s most extensive forms of regional collaboration, involv-ing Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, and the Faroe Islands, Greenland, and Åland.Nordic co-operationhas firm traditions in politics, the economy, and culture. It plays animportant role in European and international collaboration, and aims at creating a strongNordic community in a strong Europe.Nordic co-operationseeks to safeguard Nordic and regional interests and principles in theglobal community. Common Nordic values help the region solidify its position as one of theworld’s most innovative and competitive.Nordic Council of MinistersVed Stranden 18DK-1061 Copenhagen KPhone (+45) 3396 0200www.norden.org

ContentForeword ........................................................................................................................................... 91. Introduction Northern Lights Report on TIMSS and PIRLS 2011 ..................... 111.1 What are TIMSS and PIRLS?................................................................................ 111.2 Why participate in international studies? ..................................................... 131.3 Northern Lights Report: secondary analyses across Nordiccountries .................................................................................................................... 162. Summary of the articles ..................................................................................................... 192.1 School performance differences and policy variations in Finland,Norway and Sweden .............................................................................................. 192.2 Characteristics of low and top performers in reading andmathematics. Exploratory analysis of 4th grade PIRLS and TIMSSdata in the Nordic countries. .............................................................................. 202.3 Teacher attitudes and practices in international studies andtheir relationship to PISA performance: Nordic countries in aninternational context ............................................................................................. 212.4 Mathematics in the Nordic countries – Trends and challenges instudents’ achievement in Norway, Sweden, Finland and Denmark ..... 222.5 A Nordic comparison of national objectives for readinginstruction and teachers’ responses about actual readingpractice ....................................................................................................................... 23

3. School performance differences and policy variations in Finland,Norway and Sweden ........................................................................................................... 253.1 Introduction.............................................................................................................. 253.2 Policy changes in Finland, Norway and Sweden ......................................... 263.3 Research on determinants of school and classroom variation inperformance ............................................................................................................. 293.4 Method........................................................................................................................ 323.5 Results......................................................................................................................... 363.6 Discussion and Conclusions ................................................................................ 413.7 References ................................................................................................................. 45

5. Teacher attitudes and practices in international studies and theirrelationships to PISA performance: Nordic countries in an internationalcontext ......................................................................................................................................855.1 Summary.....................................................................................................................855.2 Introduction ..............................................................................................................865.3 Models of cultural differences ............................................................................865.4 A culture of observation, feedback and improvement...............................885.5 The link with progress...........................................................................................895.6 Methods ......................................................................................................................915.7 Analysis .......................................................................................................................925.8 Results .........................................................................................................................925.9 Discussion ..................................................................................................................995.10 The Nordic countries........................................................................................... 1015.11 References............................................................................................................... 1045.12 Appendix. Data Analysis..................................................................................... 105

4. Characteristics of low and top performers in reading and mathematics.Exploratory analysis of 4thgrade PIRLS and TIMSS data in the Nordiccountries ..................................................................................................................................494.1 Summary.....................................................................................................................494.2 Introduction ..............................................................................................................504.3 Previous findings on predicting performance in reading andmathematics ..............................................................................................................524.4 Materials and methods ..........................................................................................554.5 Low and top performers in the Nordic countries ........................................584.6 Characteristics predicting low performance in reading and inmathematics ..............................................................................................................604.7 Characteristics predicting top performance in reading and inmathematics ..............................................................................................................664.8 Conclusions................................................................................................................694.9 References..................................................................................................................754.10 Appendix.....................................................................................................................80

6. Mathematics in the Nordic countries – Trends and challenges instudents’ achievement in Norway, Sweden, Finland and Denmark ................ 1076.1 Summary.................................................................................................................. 1076.2 Introduction ........................................................................................................... 1086.3 Mathematics Performance and School Emphasis on AcademicSuccess (SEAS)....................................................................................................... 1126.4 What Characterises Mathematics Performance in the Nordiccountries? ................................................................................................................ 1186.5 Students’ Opportunity to Learn (OTL) Mathematics ............................... 1216.6 Summary and Conclusions – Discussions on How to ImproveStudents’ Achievement in Mathematics in the Nordic Countries........ 1286.7 References............................................................................................................... 133

8. Sammendrag ........................................................................................................................ 167

7. A Nordic comparison of national objectives for reading instruction andteachers’ responses about actual reading practice ................................................ 1377.1 Summary .................................................................................................................. 1377.2 Introduction............................................................................................................ 1387.3 The present study ................................................................................................. 1427.4 Formal objectives of reading in the Nordic countries ............................. 1437.5 The Nordic countries’ definition of reading ability .................................. 1457.6 Research-based elements in the national objectives ............................... 1477.7 Analysis of Nordic teachers’ reading instruction based on datafrom PIRLS 2011 ................................................................................................... 1507.8 Materials and genres as a basis or supplement for readinginstruction ............................................................................................................... 1517.9 The use of literary and informational text types during readinginstruction ............................................................................................................... 1527.10 Activities during and after reading instruction ......................................... 1567.11 Emphasis on the evaluation of students’ progress in reading .............. 1597.12 Discussion................................................................................................................ 1617.13 References ............................................................................................................... 164

ForewordThis publication is the first Northern Lights edition based on the TIMSSand PIRLS studies. Earlier editions in the Northern Lights series havemainly focused on PISA. As with former editions, this one has receivedfinancial support from the Nordic Council of Ministers.An editorial group appointed by the Nordic Evaluation Network hasbeen responsible for developing the report. Ann-Kristin Boström, JouniVälijärvi, Ragnar F. Olafsson, Elsebeth Aller, Anne Berit Kavli and RolfVegar Olsen has participated in the editorial group. The group has beenled by Hallvard Thorsen. All the articles in this publication have been re-viewed by the editorial group.On behalf of the editorial group I would like to thank the authors whohave contributed with articles.We hope that this publication will be of interest for policymakers inthe Nordic countries and that we achieve our ambition to give input tofurther policy development.Oslo March 2014Hallvard Thorsen

1.

IntroductionNorthern Lights Report onTIMSS and PIRLS 2011

By Anne Berit Kavli and Hallvard Thorsen, The Norwegian Directorate forEducation and Training•How is reading literacy taught in Nordic classrooms, and how is thisinfluenced by the curricula?

These are some of the questions that are discussed in this collection of arti-cles that are based on the results of the IEA studies TIMSS and PIRLS 2011.Some of the articles also use data from the OECD studies PISA and TALIS.

•What characterizes the top performing pupils, and how can westimulate more pupils to perform at the highest levels?

•What is the relationship between school performance and policyvariations?

•How do teachers’ attitudes, beliefs and practices influence pupils’learning outcomes?

•How can we improve mathematics teaching in Nordic classrooms?

1.1 What are TIMSS and PIRLS?

Trends in Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) and Progress in Read-ing Literacy Study (PIRLS) are both large-scale international comparativestudies developed and conducted by the International Association for theEvaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA).

IEA was founded as a non-governmental membership organisation in1958, and it now has 70 members representing countries and educationsystems all over the world. The main goal for the IEA is to conduct largeinternational comparative studies of educational achievement and otheraspects of education, with the aim of gaining an in-depth understanding ofthe effects of policies and practices within and across systems of educa-tion. The IEA studies are grade-based studies designed to measure theeffect that schooling has on a variety of subjects. The subjects range frombasic skills in reading literacy to pupils’ skills in mathematics and science,computer literacy focusing on information and communication skills andpupils’ knowledge and understanding of democracy and citizenship. Inaddition to the tests, the IEA studies also contain surveys of backgroundinformation for pupils, teachers, principals and sometimes also parents.PIRLS is a trend study of the reading literacy capacity of pupils that arein their fourth year of compulsory schooling. The development of ade-quate reading literacy is crucial for learning in all other subjects; there-fore, it is of high importance for education systems to both assess andfollow the pupils’ reading skills development at an early stage, and to seehow this relates to reading instruction. Beginning in 2001, PIRLS has beenconducted every fifth year. A number of countries also participated inIEA’s first Reading Literacy Study, which was conducted in 1990–91, andit is possible to see trends even from that study’s findings.TIMSS assesses pupils’ knowledge and skills in mathematics and sci-ence at the end of Grade 4 and Grade 8. TIMSS has been conducted everyfourth year since 1995. In 2011, both TIMSS and PIRLS were conducted atthe same time, and many countries then used that opportunity to test thesame pupils in all three subjects at Grade 4.All of the Nordic countries except Iceland participated in TIMSS andPIRLS 2011 at Grade 4, and Finland, Norway and Sweden also participatedin TIMSS at Grade 8. Finland, Norway and Sweden tested the same pupilsin both in TIMSS and PIRLS at Grade 4, while Denmark chose to have dif-ferent samples for the two studies.TIMSS and PIRLS are comparative studies designed to test the out-comes of schooling in the tested subjects. The grade-based design hasstrong analytical powers because entire classes are tested. The tests arefollowed by background questionnaires sent to principals, parents, pupils12Northern Lights on TIMSS and PIRLS 2011

and teachers. The questions in those surveys address important aspects ofthe environment for teaching and learning. The studies are also followedby a system-level questionnaire that is sent to countries. That survey de-scribes the various curricula and school systems.Because the age for starting school varies across countries, the grade-based samples have caused some challenges in comparing results acrossthe Nordic countries. In Norway, children start school the year they turn 6without any preschool, while in Denmark, Sweden and Finland most pu-pils attend preschool the year they turn 6 and then start school at the ageof 7. In Denmark, this preschool year is compulsory, while in Finland andSweden most children attend preschool even if doing so is optional. Thecontent of the preschool year in Denmark, Finland and Sweden is quitecomparable to the Grade 1 curriculum taught in Norwegian schools. Thismeans that in Grade 5 Norwegian pupils are the same age and have hadthe same amount of schooling as pupils in Grade 4 in Denmark, Swedenand Finland. For this reason, Norway has tested a smaller additional sam-ple at Grade 5, in order to be able to perform more relevant comparisonswith other Nordic countries.The variation in average age across all participating countries at thetime of testing is quite large, ranging from 9.7 to 10.9 years for pupils inGrade 4. In Norway, the mean age in Grade 4 is 9.7 years, and in Grade 5the mean age is 10.7 years. In Denmark, Finland and Sweden the mean ageat the time of testing varies from 10.7 to 10.9 years. The effect of one yearof age difference is around half a standard deviation, approximately 40points on the scales. For the next rounds of TIMSS and PIRLS in 2015 and2016, it has been decided that Norway will participate by using pupils inGrade 5 and Grade 9 as their main sample in order to make the compari-sons more relevant.

1.2 Why participate in international studies?

In all the Nordic countries, participation in large scale international stud-ies of learning outcomes is an important part of the national strategy forthe quality assessment of educational systems. Textbox 1 and Textbox 213

Northern Lights on TIMSS and PIRLS 2011

provide an overview of the current international comparative studies andNordic participation in those studies.Participation in international comparative studies provides countrieswith an opportunity to assess the strengths and weaknesses of their educa-tional systems. The studies provide important measures of trends in stu-dents’ learning outcomes, and through surveys the countries also receiverich background information on students, their learning environment andthe organisation of the schools. This combination of tests and backgroundquestionnaires offers a unique basis for in-depth analyses of the relation-ship between the learning environment and learning outcomes.The results from these international studies should also always be ana-lysed in a national context. The studies can never give a complete pictureof a country´s educational system; however, combined with national dataand research they provide an important background assessing the qualityof schools. Basic skills, like reading and mathematics literacy, are of cru-cial importance for learning across all subjects, and longitudinal analyseshave shown that these competencies are also highly correlated with fur-thering the students’ educational achievement.

Textbox 1: Overview of current international studiesIEA Studies•

Trends in Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) aims to study interna-reports students’ achievement in mathematics and science. TIMSS also col-advanced mathematics and physics. The study also collects policy-relevantconducted again in 2015.

lects detailed information about curriculum and curriculum implementa-•

tional trends in mathematics and science achievement at the fourth andeighth grades. TIMSS has been conducted every four years since 1995, and itTIMSS Advancedassesses final-year secondary students’ achievement inand training. TIMSS Advanced was conducted in 1997 and 2008. It will be

tion, instructional practices and school resources.

data about curriculum emphasis, technology use and teacher preparation

14

Northern Lights on TIMSS and PIRLS 2011

•

Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) is an assessment of

reading comprehension that has been monitoring trends in achievement atinternationally-comparative data about how well children read after fourplementation, instructional practices and school resources in each partici-pating country.

five-year intervals in countries around the world since 2001. PIRLS provides

years of primary schooling. In addition, the study also collects extensive in-ePIRLSis a new extension of PIRLS that will be implemented in 2016.ePIRLS is an innovative assessment of online reading, making it possiblestudents to read, comprehend and interpret online information.ines the outcomes of student computer and information literacy (CIL)vember 2014. Grade 8 is the main target grade for ICILS.

formation about home supports for literacy, curriculum and curriculum im-•

for countries to assess how successful they are in preparing fourth gradeacross countries. CIL refers to an individual’s ability to use computers toinvestigate, create and communicate in order to participate effectively athome, at school, in the workplace and in the community. ICILS was con-

•

The International Computer and Information Literacy Study (ICILS) exam-ducted for the first time in 2013, and its findings will be reported in No-

OECD Studies•

designed to assess the extent to which students at the end of compulsoryeducation can apply their knowledge to real-life situations and becation of that knowledge, which can help analysts interpret the results.national, large-scale survey that focuses on the working conditions ofequipped for full participation in society. The information collectedthrough background questionnaires also provides a context for the appli-The OECD Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) is an inter-teachers, the school climate and school leadership.

Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) is a triennialby testing the skills and knowledge of 15-year-old students. The tests areinternational survey that aims to evaluate education systems worldwide

•

teachers and the learning environment in schools. TALIS covers themessuch as initial teacher education and professional development, teachers’instructional beliefs and pedagogical practices, appraisal and feedback to

Northern Lights on TIMSS and PIRLS 2011

15

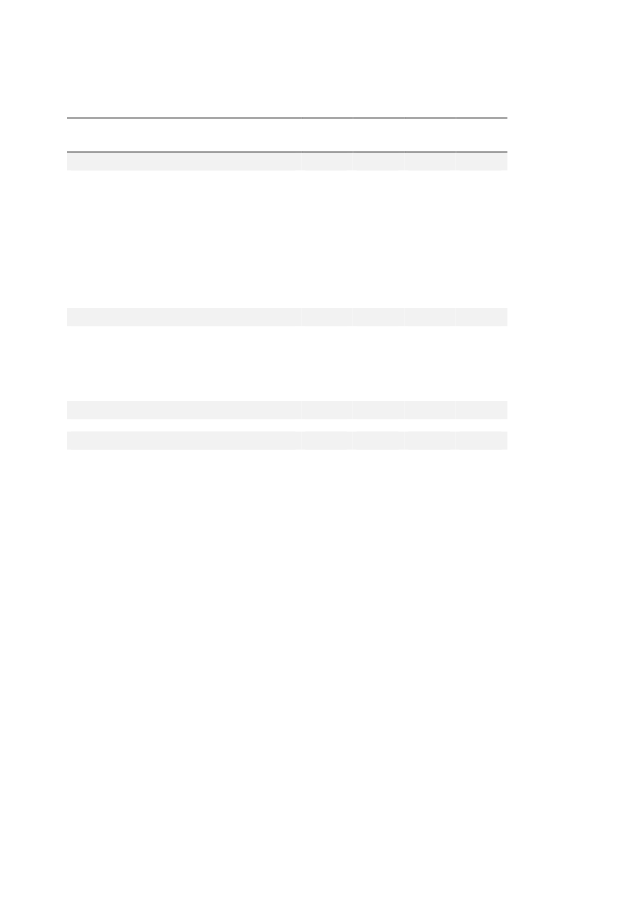

Tabel: Nordic participation in international comparative studiesOrganisationIEAStudyTIMSS 2011TIMSS 2015TIMSS Advanced 2015PIRLS 2011PIRLS 2016ICILS 2013ICCS 2016PISA 2012PISA 2015TALIS 2013Participating CountriesDK, F, N, SDK, F, N, SN, SDK, F, N, SDK, F, N, SDK, NDK, N, SallallallTarget GroupGrade 4 (5) and 8Grade 4(5) and 8(9)Grade 11(12)Grade 4(5)Grade 4(5)Grade 8 (9)Grade 8 (9)15 year olds15 year oldsTeachers and principals

IEA

IEAIEAOECD

OECD

The Nordic countries provide a unique opportunity for relevant cross-country analyses. To a large extent, these countries share a common cul-tural background; however, at the same time they have chosen differentways of developing and organising their educational systems. The patternof achievement has also been rather different among these countries, andthis provides a background for relevant policy analyses where countriescan learn from each other.Since PISA 2000, the Nordic Council of Ministers´has funded Nordicanalytical reports after each PISA study; these are known as the “NorthernLights on PISA” reports. This report is the first Northern Lights reportbased on TIMSS and PIRLS, and the future intention is to use the entirerich datasets based on all the international studies.The aim of these analytical reports is to conduct common Nordic anal-yses, which can shed light on the equalities and differences between theNordic educational systems; this enables the countries to learn from eachother and use the results as input to further policy development. Theseanalyses will also provide input to the joint Nordic initiatives on educa-tional development and further research.16Northern Lights on TIMSS and PIRLS 2011

1.3 Northern Lights Report: secondary analysesacross Nordic countries

The articles in this volume aim to provide input for important policydiscussions and further policy development within the Nordic countries.Therefore, the main target groups are educational ministers and policy-makers at all levels.Since the first PISA results were published in 2001, we have seen alarge increase in the interest in and the impact of international studies,and especially the impact of PISA. A major policy-related message fromthese studies has been the focus on basic skills, like reading and mathe-matics literacy, and the importance of developing these skills as a basis forlearning across all subjects. Furthermore, the comparative internationalstudies have emphasised the importance of a qualified teacher force and,by that, they have also identified teacher education and professional de-velopment of teachers as being the main strategic measures for the im-provement of learning outcomes. As a consequence of this focus on thedevelopment of learning outcomes, many countries have also establishedand improved their national systems for quality assessment.All results from these international studies have to be analysed in a na-tional context in order to be relevant for further policy development. Bystimulating secondary analyses in a Nordic context, the Nordic countriescan receive valuable input to further the development of their educationalsystems. In this report, Nordic researchers have used data from TIMSS andPIRLS to gain research-based knowledge on important issues, such as thelearning environment and the opportunity for learning, characteristics oftop and low performers, the relationship between curriculum and teachingpractice, school performance differences and policy variations and teacher’sbeliefs and practices and their influence on learning outcomes.Researchers representing all the Nordic countries have contributed tothe articles in this book.

Northern Lights on TIMSS and PIRLS 2011

17

2. Summary of the articles2.1 School performance differences and policyvariations in Finland, Norway and Sweden

By Kajsa Yang Hansen, Jan-Eric Gustafsson and Monica Rosén, University ofGothenburgThis article focuses on the differences in the amount of variation in thelevel of performance between schools and classrooms in Grade 4 andGrade 8 in Finland, Norway and Sweden. Variability in the level of perfor-mance between different schools is of great interest both from a researchperspective and from a policy perspective. A large amount of observeddifferences in the level of performance between schools may be indicativeof a segregated school system in which students of different levels of abil-ity are sorted into different schools through processes of selection or self-selection. However, the performance variability between schools may alsoreflect differences in the level of the quality of the education offered bydifferent schools. Therefore, it is essential both to describe the amount ofperformance variability between schools and to determine which factorscould account for that variation.However, teaching typically is organised within more or less flexiblyorganised groups of students within a school, normally in the form of clas-ses. Given that different classes are normally taught by different teachersand that the students within a particular class influence one another, sys-tematic variation in the level of performance of different classes may beexpected. Therefore, in order to correctly determine the amount of schoolperformance differences, it is also necessary to determine the amount ofdifferences between the classes within different schools.This article concludes that there are substantial performance differ-ences between schools in Norway and Sweden, which may be due to both

segregation of living and school choice. In Finland, there are no schooldifferences; instead, very substantial classroom differences have beenidentified. It will be interesting for further research to determine thesources of these school and classroom differences.

2.2 Characteristics of low and top performers inreading and mathematics. Exploratory analysisof 4th grade PIRLS and TIMSS data in the Nordiccountries.By Sari Sulkunen, Kari Nissinen and Pekka Kupari, University of Jyväskylä

This article focuses on studying the background variables that predict lowand top performance in reading and mathematics during the primaryyears of school in four Nordic countries: Denmark, Finland, Norway andSweden. The purpose of the study is to provide information about low andtop performance in the two important key competences in order to devel-op educational systems to better meet the students’ diverse needs.PIRLS and TIMSS 2011 datasets were used in the analysis, which con-sisted of country-specific, three-level logistic regression models. Potentialpredictors for low and top performance were selected on the basis of ear-lier research findings.The results of the study showed that students’ basic skills in reading,their home resources, as well as the attitudes and activities related toreading and mathematics, predicted their performance in all the Nordiccountries. Class and school level variables predicted the students’ perfor-mance only in Denmark and Sweden, and they clearly played a less im-portant role in predicting performance than the student-level variables.The article emphasises the importance of providing individual supportfor pupils who need it. The individualized approach provides a solidframework for learning for students who have a weak start and studentswho have a disadvantage at school for one reason or another. In addition,top performers need individualized education, which includes materials20Northern Lights on TIMSS and PIRLS 2011

and tasks challenging enough to develop their competencies to the level oftheir full potential.The need for an individual approach places a great deal of pressure onteachers’ education and continuous professional development in topicssuch as teaching materials and methods, assessment and diagnosinglearning problems. Still, this article states that resources and opportuni-ties for continuous professional development for teachers are not ade-quate in the Nordic countries, particularly in Finland.

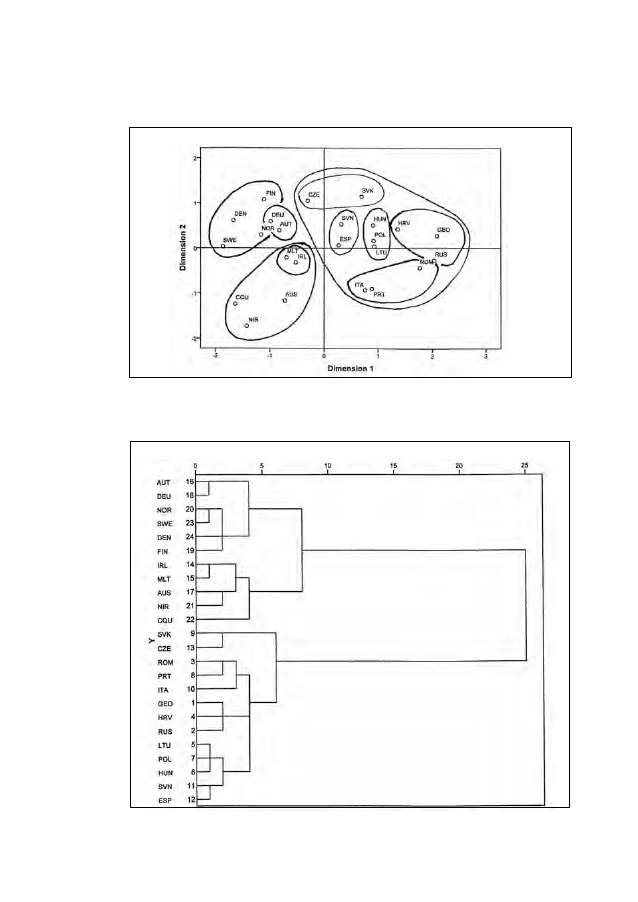

By Ragnar F. Ólafsson and Júlíus K. Björnsson, Educational Testing Institute– ReykjavikThe objective of this article is to explore cultural differences in teachingpractices and attitudes among European countries, with a special focus onNordic countries. The international PIRLS and TIMSS studies provide in-formation about teachers’ attitudes and practices as well as indicators ofpupils’ achievement in reading, math and science. This data provides anexcellent opportunity in which to explore cultural differences in the con-text of teaching and the findings could be used to identify certain types ofteaching practices that may be conducive to higher achievement in read-ing, mathematical and science literacy, which are assessed by PISA, anoth-er international OECD educational research program.Teachers’ responses to the PIRLS and TIMSS questions about theirteaching practices and their attitudes towards teaching in general, includingmath, reading and science, were subjected to Multidimensional ScalingAnalysis, based on OECD country means on each of 325 questionnaire items.Country groups (or clusters) were identified. These groups/clusters con-sisted of East-European, Mediterranean, Anglo-Saxon, Germanic and Nordiccountries, with some overlaps, indicating differences in teaching cultureNorthern Lights on TIMSS and PIRLS 201121

2.3 Teacher attitudes and practices ininternational studies and their relationship toPISA performance: Nordic countries in aninternational context

across these OECD countries. A main dimension of engagement was identi-fied differentiating largely between Eastern European and Western coun-tries. The former showed greater engagement, which consisted of greaterteacher self-confidence, greater use of specific teaching strategies, more testadministration and home-work follow up. In the PISA survey, a correlationwas found between engagement and progress in reading and math literacy,indicating that more engaging teaching practices are associated with moreprogress. The limitations of the approach are discussed.

2.4 Mathematics in the Nordic countries – Trendsand challenges in students’ achievement inNorway, Sweden, Finland and Denmark

By Liv Sissel Grønmo, Inger Christin Borge and Arne Hole, University of OsloThe aim of this article is to provide an overview of the important charac-teristics of mathematics as a school subject in Nordic countries, and topoint out the issues that should be addressed in order to improve stu-dents’ learning of mathematics. The analyses in the article provide evi-dence of the important educational factors that can explain the trends instudents’ achievement.The article presents results from analysing several factors that mayhave contributed to an understanding of trends in Norway, Sweden andFinland. This includes analyses and discussions of factors such as SchoolEmphasis on Academic Success (SEAS) and Students’ Opportunity toLearn (OTL) mathematics. The results of the analyses of what characteriz-es mathematics in schools in Nordic countries are also presented. Thisarticle also refers to the results from other international comparativestudies, such as PISA, TIMSS Advanced and TEDS-M, in order to obtain asolid basis for discussions about how to make improvement in students’achievement in mathematics.The analyses show that the increased School Emphasis on AcademicSuccess and improvement on students’ Opportunity to Learn that is meas-ured in Norwegian schools is an important factor for explaining the im-22Northern Lights on TIMSS and PIRLS 2011

proved results measured in Grade 8. This is likely to reflect changes ineducational policy and curriculum in Norway, with an increased emphasison students’ performance in schools. Another issue stressed in the articleis the low emphasis that Nordic countries place on pure mathematics,such as algebra. This low emphasis is likely to influence the possibility ofstudents pursuing studies and professions using advanced mathematics.

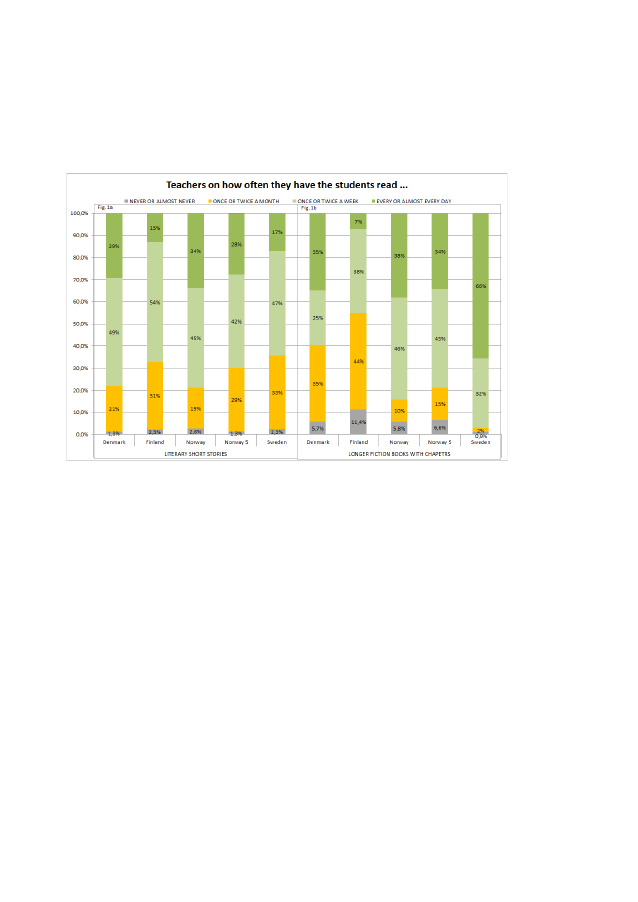

2.5 A Nordic comparison of national objectives forreading instruction and teachers’ responsesabout actual reading practice

By Louise Rønberg and Jan Mejding, Aarhus University, Department ofEducation (DPU)This article presents a comparison of the Nordic countries’ official objec-tives for reading and analyses of 1005 Nordic teachers’ responses regard-ing their reading instruction. The specificity and transparency vary greatlyin the objectives, from broad outlines in Norway to more specific andfunctional goals in Finland. It appears that the Finnish descriptions aremore aligned with current empirical research on reading comprehension.Swedish and Norwegian teachers have the most varied used of bothliterary and informational text types during a week, whereas Finnishteachers give informational texts a higher priority than literary texts – andthe opposite is apparent for Danish teachers. The Finnish and Norwegianteachers prioritise activities that enhance students’ oral reading fluency,which is important for reading comprehension development, to a greaterextent than teachers in Denmark and Sweden do. The Nordic teachers ingeneral appear to prioritise advanced comprehension activities to a lesserextent than teachers in the English-speaking countries do. Furthermore,Danish teachers put the least emphasis on formative assessments com-pared to the other Nordic countries.It is important that national objectives correspond with empirical re-search on reading instruction and that they are functional and transparentas they set the stage for the actual instruction in class.Northern Lights on TIMSS and PIRLS 201123

It is important that national objectives correspond with empirical re-search on reading instruction and that they are functional and transpar-ent as they set the stage for the actual instruction in class.

3. School performancedifferences and policyvariations in Finland,Norway and SwedenBy Kajsa Yang Hansen, Jan-Eric Gustafsson and Monica Rosén, University ofGothenburg

The present study focuses on differences in the amount of variation in levelof performance between schools and classrooms for Grade 4 and Grade 8 inFinland, Norway and Sweden. Variability in the level of performance be-tween different schools is of great interest both from research and policyperspectives. A large amount of observed differences in level of perfor-mance between schools may be indicative of a segregated school system inwhich students of different levels of ability are sorted into different schoolsthrough processes of selection or self-selection. However, performancevariability between schools may also reflect differences in the level of quali-ty of the education offered by different schools. It is therefore essential bothto describe the amount of performance variability between schools and todetermine which factors can account for the variation.However, teaching typically is organised within more or less flexiblyorganised groups of students within a school, normally in the form of clas-ses. Given that different classes are usually taught by different teachersand that the students within a particular class influence one another, sys-tematic variation in the level of performance of different classes may beexpected. In order to correctly determine the amount of school perfor-

3.1 Introduction

mance differences, it is, therefore, also necessary to determine the amountof differences between the classes within different schools. In the presentstudy, we use multi-level modelling techniques which separate the totalobserved variation into factors due to students, classes and schools. Datafrom the International Association for the Evaluation of EducationalAchievement (IEA) 2011 Trends in International Mathematics and ScienceStudy. (TIMSS) for Grade 4 and Grade 8 and Progress in InternationalReading Literacy Study (PIRLS) for Grade 4 form the basis of form thebasis of these analyses.We use a comparative approach focusing on differences between theNordic countries, and originally we aimed to include all five Nordic coun-tries in the analyses. Regrettably, however, Iceland did not participate inthe 2011 TIMSS and PIRLS studies, so we had to exclude Iceland from thestudy. For Denmark, data are available for Grade 4, but the sampling de-sign of the study was such that it does not allow separation of variationdue to schools and classes, so we had to exclude Denmark as well.Our study is, therefore, restricted to comparisons between Finland,Norway and Sweden. One main aim is to determine the magnitude ofschool and classroom performance differences for Grade 4 and Grade 8 inthe three countries, and another main aim is to investigate school andclassroom performance differences as a function of the location of theschool (urban or rural) and the students’ socio-economic status.Given that school and classroom performance differences are likely tobe determined by educational policies, we first review educational policychanges in Finland, Norway and Sweden.

3.2 Policy changes in Finland, Norway and Sweden

The educational systems in the Nordic countries share common valuesand ideologies for geographic, cultural and historical reasons. During thelast 50 years, the Nordic welfare state has been established as a uniquemodel, with a strong emphasis on equity of access to education of a highlevel of quality. During the 1960s and 1970s, the organisationally differen-tiated compulsory education was, in the Nordic countries, replaced withcomprehensive compulsory schooling for at least nine years.26Northern Lights on TIMSS and PIRLS 2011

The comprehensive education system in Finland was introduced in the1970s, following the introduction of comprehensive schooling in Swedenin the 1950s and in Norway in the 1960s (Kerr, Pekkarinen, & Uusitalo,2013). Since that time, Finland has not made any major school-reform(Sahlberg, 2010, 2011).However, in Finland too decision making has been decentralised. In1993, local authorities were given more autonomy in the allocation ofschool resources. They no longer received earmarked funds from the cen-tral government; instead, a lump sum was allocated that the local govern-ment could distribute to different purposes (see, e.g., Aho, Pitkänen, &Sahlberg, 2006; Rinne et al., 2002). Since there is no central regulationconcerning the allocation of school funds, there has been great diversityamong the principles of funding used by different local authorities.In 1998, it was made explicit that parents could choose any school fortheir child within the municipality. However, Finland has very few schoolsthat have providers other than the municipality. Since Finnish schools aredecentralised in terms of curricula, teaching methods and other pedagogi-cal practices and profiles, choice of school was a meaningful policy change.However, admission to school still gives priority to the local students.Schools are allowed to recruit students from outside the local catchmentarea only when there are places left after enrolment of the local students.

One global trend in educational reforms since the 1980s has been toadopt market principles in the realm of schooling. The reforms thus havebeen characterised by an orientation towards output of schooling ratherthan on input of resources. Decentralisation and deregulation of decisionmaking, accountability, choice and competition have also been clearlyvisible global trends (e.g. Sahlberg, 2011). Such educational reform ideashave also influenced the Nordic countries, albeit to a different extent andin different ways.

3.2.1

Finland

Northern Lights on TIMSS and PIRLS 2011

27

3.2.2

Norway has also implemented several reforms. During the 1980s and1990s, the previously strongly centralised school system was decentral-ised in several respects. A radical step towards decentralisation and localautonomy was the introduction of a new funding system in 1986, whichimplied a change from state-determined and earmarked allocation offunds to municipally decided priorities. The 1992 Local Government Actgave the local authorities and school leaders greater responsibility forallocating funds, providing education and assuring its quality. Schools alsogot an increased amount of autonomy, which included budgeting, re-cruitment, education management and competence development. Thelength of compulsory education in Norway was extended to 10 years in1997 (see Helg, Oslash, & Homme, 2006 for a more detailed comparisonbetween Norway and Sweden).The Norwegian Independent School Act of 2003 made it easier to startindependent schools and for authorised independent schools to receivefinancial support from the state. The number of independent compulsoryschools has increased since 2003, but still the great majority of students,approximately 98%, attend public schools. This is because enrolment inprimary and lower secondary schools still largely follows the proximityprinciple. However, in the large cities of Norway, systems of school-choicehave now been introduced, which are similar to those introduced in Fin-land, as is described above.

Norway

3.2.3

The Swedish school system has undergone fundamental changes since thelate 1980s (see SOU 2014:5 for a thorough description and analysis). In1989 the municipalities took over responsibility from the state as employ-ers for the teachers and other categories of school personnel. Further-more, decision-making concerning the organisation of schooling was de-centralised to the municipalities and considerable local autonomy wasallowed (Björklund et al., 2004). The decentralisation was thus followedby a deregulation of principles of funding, giving the municipalities con-siderable freedom to allocate funds. Many decisions, such as hiring teach-28Northern Lights on TIMSS and PIRLS 2011

Sweden

ers, were also decentralised to municipalities and schools, and here, too, apreviously strict system of eligibility of employment was deregulated.A voucher system to support free school choice was launched in thebeginning of the 1990s. It allows students to choose the school of theirpreference, which broke with the proximity principle and made it possiblefor students to choose schools outside of their neighbourhood. A system ofindependent (private) schools was introduced at the same time, and thenumber of students attending independent schools has successively in-creased. Currently, over 16% of the compulsory schools are independentschools, and around 13% of the comprehensive school students attendindependent schools.In 1994, new curricula, primarily describing which goals were to bereached but not how to reach them, were introduced for both compulsoryschool and for upper secondary school. New criterion-related gradingsystems were also introduced.These reforms, and others, have thoroughly transformed the Swedishschool system from being highly centralised and regulated to being verydecentralised and deregulated (Lundahl, 2002; Lundahl, et al., 2013).In summary, different educational policy changes in Finland, Norwayand Sweden have taken place, even though they all tend to be in the direc-tion of decentralisation and deregulation of decision making.

In this section, we provide a brief overview of research on factors influ-encing variation between schools and classrooms.

3.3 Research on determinants of school andclassroom variation in performance3.3.1Selection of students to different schools

Previous research has shown that the most important determinant ofschool level performance differences is the composition of the schools’student body with respect to social and ethnic background, and with re-spect to previous level of performance (e.g. Coleman, et al., 1966; Jencks &Mayer, 1990; Thrupp & Lupton, 2006; Yang, 2003).Northern Lights on TIMSS and PIRLS 2011

29

Explicit selection of students into schools on the basis of previous per-formance is an important factor in causing school differences. Thus, schoolsystems which use organisational differentiation to track students intoacademic and non-academic schools are characterised by very substantialschool performance differences, which may amount to 40–50% of thetotal amount of performance differences (see, e.g., OECD, 2013; Yang,2003). Germany and Austria are two examples of countries with suchorganisational differentiation. In the 1960s and 1970s, the Nordic coun-tries abolished organisational differentiation and introduced comprehen-sive compulsory schooling; so, in these countries, school performancedifferences are smaller and typically account for less than 10% of the totalperformance variation. However, even school differences of this magni-tude may be of substantial importance (e.g. Yang, 2003).Given that students often attend neighbourhood schools, the socio-economic and ethnic composition of schools tends to reflect the socio-demographic characteristics of the neighbourhood that the school serves.Therefore, residential segregation with respect to socio-economic back-ground and ethnicity affects school performance differences. If students andparents are allowed free school choice, this may also affect school perfor-mance differences. Students sorting themselves into schools on the basis ofsocio-economic and ethnic factors may cause school performance differ-ences to increase over and above the differences caused by residential seg-regation. However, students sorting themselves into schools on the basis ofambition and ability may reduce the effects of residential segregation butincrease segregation on the basis of performance (Gustafsson, 2006).There is quite a rich body of literature of international research on dif-ferent mechanisms of school segregation and their relative importance (see,e.g., Palardy, 2013; Sahlgren, 2013). However, results tend to be incon-sistent across studies, and so far little consensus has been achieved. Themain reason for this is probably that the mechanisms to a large extent arespecific to different cultures and school systems. This suggests that it isimportant to investigate these issues within the Nordic countries as well.As has been described above, there have in Finland, Norway and Swe-den been reforms of the educational systems, which to a varying extenthave allowed students and parents increased possibilities of school choice.30

Northern Lights on TIMSS and PIRLS 2011

This may influence the amount of school differences, and particularly so inurban areas where there are real possibilities of choice.If attendance at different schools is determined by residential segrega-tion and/or school choice, it may be expected that this will cause differ-ences between schools with respect to the students’ socio-economic status(SES). Such differences will also be reflected in performance differencesbetween schools, given the strong relationship between SES and perfor-mance, particularly at the school level (Sirin, 2005). These performancedifferences are likely to be observed primarily at the school level unlessallocation of students to different classrooms is made on the basis of pre-vious levels of performance.

Previous research has shown that classroom differences in level of per-formance often are of substantial magnitude and that they often are largerthan school differences (see e.g., Creemers & Kyriakides, 2008). Whileclassroom differences may be due to the sorting of students into differentclasses, they also may reflect differences in quality of instruction and dif-ferences between classrooms with respect to teacher–student relations,for example. Thus, the determinants of classroom differences in perfor-mance are likely to differ from those causing differences in level of per-formance between different schools.Furthermore, many studies confound variation between schools andclassrooms, by not separating their relative contributions. This is some-times due to the fact that this is not possible because it requires that thedifferent schools be represented by two or more classrooms and also thatthe classroom to which each student belongs is correctly represented inthe data. When school and classroom variance is confounded, the resultstypically are reported in terms of school differences. However, such esti-mated school differences may to a considerable extent reflect classroomdifferences. Confounding of the two sources of variation may thus system-atically bias the findings from studies on school variation.

3.3.2

Classroom differences in performance

Northern Lights on TIMSS and PIRLS 2011

31

3.3.3

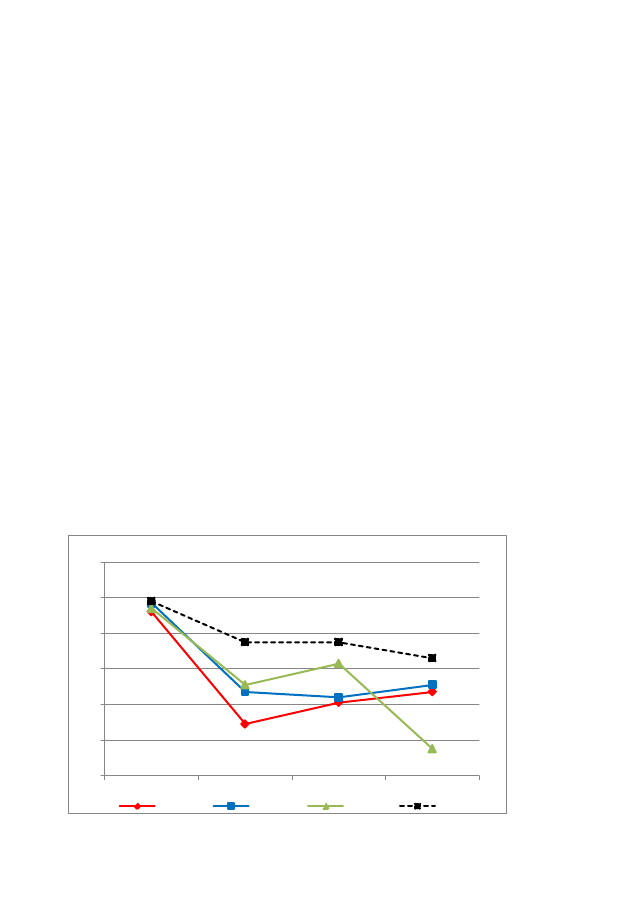

The TIMSS and PIRLS data include information about different character-istics of the schools, such as location (urban/rural) and students’ socio-economic background. This information can be used to investigate thedifferent mechanisms behind school variation more closely. Thus, schoolchoice is mainly an urban phenomenon, and the effects of school choicecan therefore primarily be expected to be seen in urban areas. Residentialsegregation is also primarily an urban phenomenon, and it may be ex-pected that this is a more important factor for students in lower gradesthan in higher grades. Comparisons of differences in the amount of ob-served school performance differences in urban and rural schools forGrades 4 and 8 in the three countries may therefore be a way to investi-gate the impact of school choice and residential segregation.The following research questions will be focused upon:•What differences are there in the magnitude of school and classroomperformance differences for Grade 4 and Grade 8 in Finland, Norwayand Sweden?•To what extent are school and classroom performance differencesrelated to students’ SES in Finland, Norway and Sweden?•What differences are there in the magnitude of school and classroomperformance differences in urban and rural schools in Finland, Norwayand Sweden?

Research questions

3.4 Method3.4.1

Grade 4 and Grade 8 data from the TIMSS 2011 study were included in theanalyses. For Grade 4, data from the PIRLS 2011 study, take away “literacytest” were also included.32Northern Lights on TIMSS and PIRLS 2011

In this section, samples, variables and analytical methods used in theanalyses are presented.

Samples

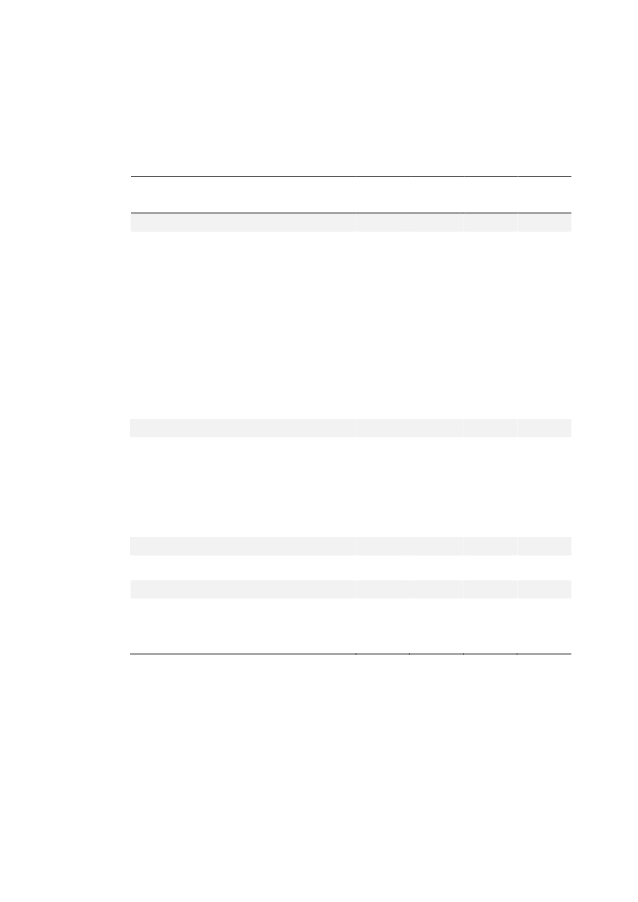

Table 1: Number of Students, Classes and Schools Included in the AnalysesGrade 4FinlandRuralN studentsN classesN schoolsTotalN studentsN classesN schools2,11413378Urban2,38312563NorwayRural Urban71455402,29013575SwedenRural Urban1,62291612,52513174FinlandRural2,13713378Urban1,79110258Grade 8NorwayRural2,8334844UrbanSwedenRural Urban2,27711063

3,778 2,3901181118764

4,638268145

3,004185115

4,663252152

4,622258145

3,862170134

5,573266153

Note:The number of urban and rural students does not sum up to the total number of observa-tions due to missing information in the urban/rural variable for some schools.

As is shown in Table 1, there were 12,305 students, 412 schools and 705classes from Grade 4, and there were 14,057 students, 432 schools and694 classes from Grade 8 included in the analysis. The students were dis-tributed over urban and rural schools, and in general there were moreurban schools than rural and more students enrolled in urban schoolsthan were enrolled in rural schools.

3.4.2

The variables used in the analyses are presented in Table 2, along withdescriptive statistics.Information about number of books at home was used to measure SES.This variable in particular captures differences in cultural capital (Bour-dieu, 1997) among the homes, which has been shown to be the aspect ofSES most strongly tied to achievement (Gustafsson, Yang, & Rosén, 2013;Yang, 2003; Yang & Gustafsson, 2004). While there are also other indica-tors of SES available in the TIMSS and PIRLS data, such as level of parentaleducation, the variable representing number of books is the only onewhich is comparable across Grade 4 and Grade 8. We therefore use thisvariable as the sole indicator of SES.Mathematics and science achievement scores were outcome varia-bles for both Grade 4 and Grade 8, and for Grade 4 reading achievementwas also measured. These are estimated as so called “plausible values”which are multiple imputed scores, taking advantage of all availableNorthern Lights on TIMSS and PIRLS 201133

Variables

responses to both test items and background variables (von Davier,Gonzalez, & Mislevy, 2009).The variable “Type of community” is dummy coded, with rural schoolscoded as 0 and urban schools coded as 1. This variable is based a questionasking about “the type of immediate area of the school’s location”. Theresponse alternatives “Urban”, “Sub-urban” and “Medium size city” werecollapsed into the “urban” category, while “Small town” and “Remote ru-ral” were collapsed into the “rural” category. However, this information ismissing in the Grade 8 data for Norway. The question “how many peoplelive in the area where the school is located” was therefore used for classi-fying urban vs. rural schools in the Norwegian data. For both Grade 4 andGrade 8, communities where over 15,001 people live were defined asurban, while communities with less than 15,000 people were defined asrural. This implies that comparisons with respect to urban-rural differ-ences between Norway on the one hand, and Finland and Sweden on theother hand, should be interpreted with caution.

34

Northern Lights on TIMSS and PIRLS 2011

Table 2: Descriptive Statistics of the Variables Involved in the Analysis for Grade 4 and Grade 8 in Finland, Norway and SwedenGrade 4FinlandMeanSDMeanSDMeanSDMeanSDMeanSDMeanNorwaySwedenFinlandNorwaySwedenSDGrade 8

Variables

RuralNumber of books in the home (5 categories)Mathematics AchievementScience AchievementReading achievement3.265455715673.345465695693.295465705680.451.066866630.503.194964955080.661.136862610.483.255045355420.501.146674650.503.29514553-0.421.176466-0.491.096967633.224984975101.146864613.265065335441.186878673.33515553-1.206567-3.40479497-3.36475494-0.681.246474-1.236473-0.471.036765633.094894905031.136560603.255015345381.126571633.26512552-1.136264-3.27468486-1.216472-

3.17479507-3.32490516-3.23484510-0.49

1.266578-1.316984-1.296781-0.50

UrbanNumber of books in the home (5 categories)Mathematics AchievementScience AchievementReading achievement

TotalNumber of books in the home (5 categories)Mathematics AchievementScience AchievementReading achievement1Type of community (Urban vs. Rural)

Note: 1. The variable “Type of community” is a dummy variable, coded 1 for schools in urban areas and 0 for schools in rural areas.

Multi-level regression techniques were used to separate the total varia-tion in outcomes into three different parts: one that is due to the differ-ences among individual students within classrooms, a second that is dueto differences between classrooms within schools, and a third that is dueto performance differences between schools. The SES-related variable“Number of books at home” was then introduced into the analysis as anindependent variable, and it was investigated as to how much variancethis variable accounted for at each of the three levels of observation.The analyses were done with the Mixed Models procedure in the SPSSsystem, using individual case weights. The models were estimated usingthe first plausible value of the mathematics, science and reading achieve-ment scores.

3.4.3

Analytical method

3.5 Results3.5.1

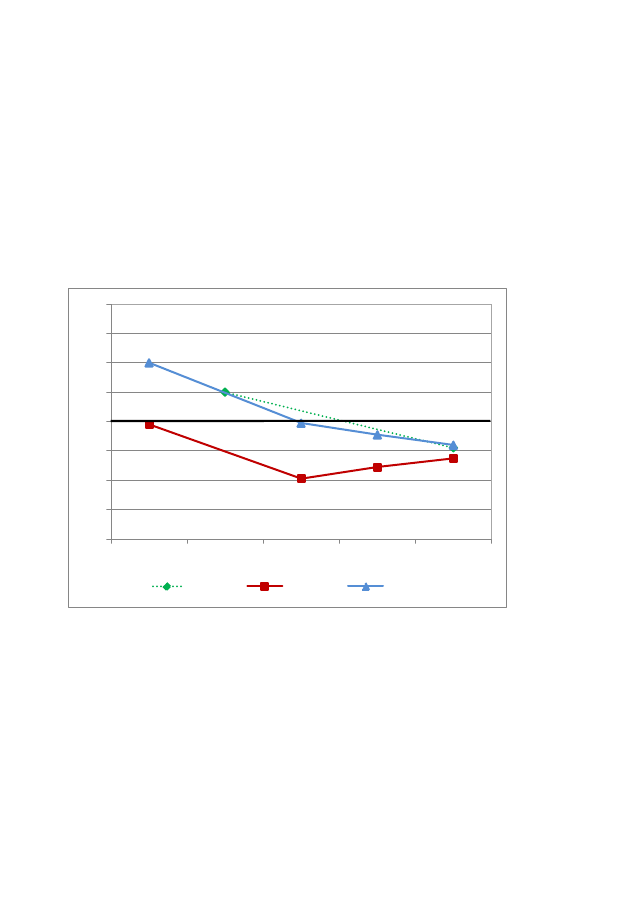

The magnitude of between-school and between-class differences in math-ematics, science, and reading performance can be measured by the Intra-class Correlation Coefficient (ICC), which expresses the proportion of var-iation in a variable that can be explained by belonging to different groups,such as schools or classrooms. When there are large mean differences inthe level of performance between the different groups, the ICC becomeslarge. It may be noted though that even though the ICC is referred to as acorrelation measure, it is rather a squared correlation, expressing amountof variance explained. Table 3 shows the estimated ICCs for TIMSS andPIRLS 2011 in Finland, Norway and Sweden for Grades 4 and 8.

Results pertaining to the research questions are presented below.

School and classroom performance differences

36

Northern Lights on TIMSS and PIRLS 2011

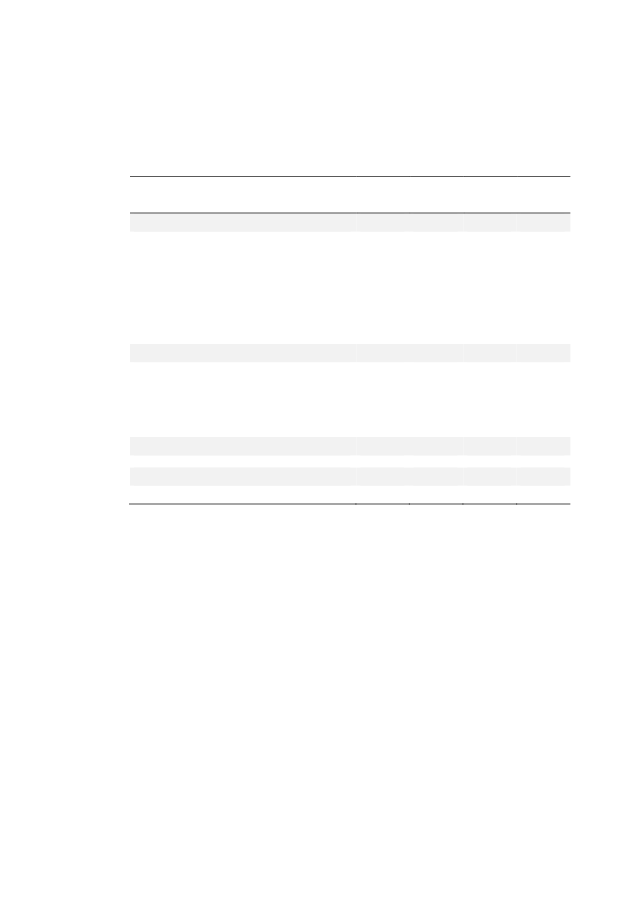

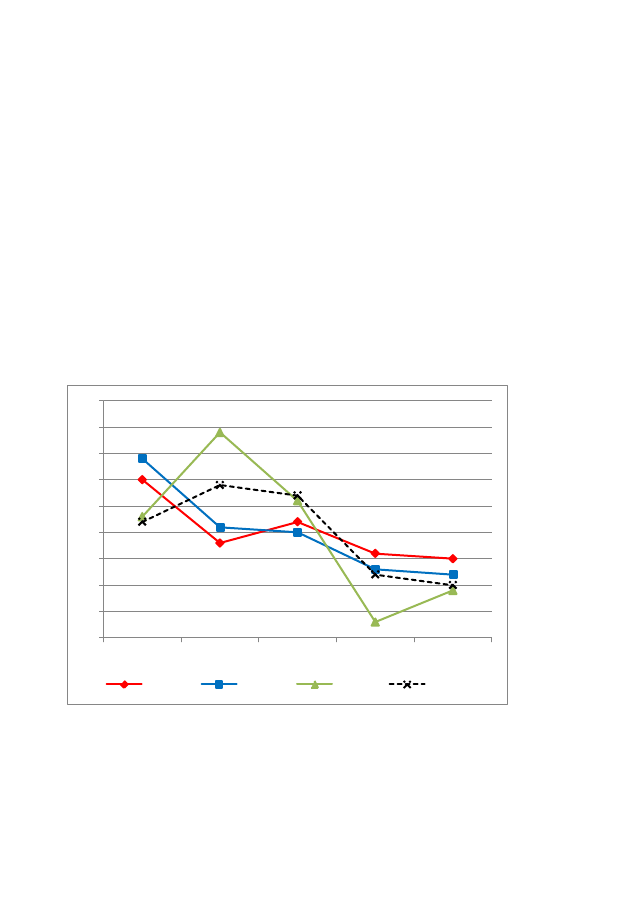

Table 3: Estimated School- and Class-level ICCs of Mathematics, Science and Reading Achieve-ment for Grade 4 and Grade 8CountryLevelMathematicsFinlandClassSchoolClassSchoolClassSchool.13.04.08.10.03.15Grade 4Science.12.04.05.07.03.19Reading.13.02.02.09.04.15Grade 8Mathematics.26.02.02.10.07.08Science.30.03.03.10.09.12

Norway

Sweden

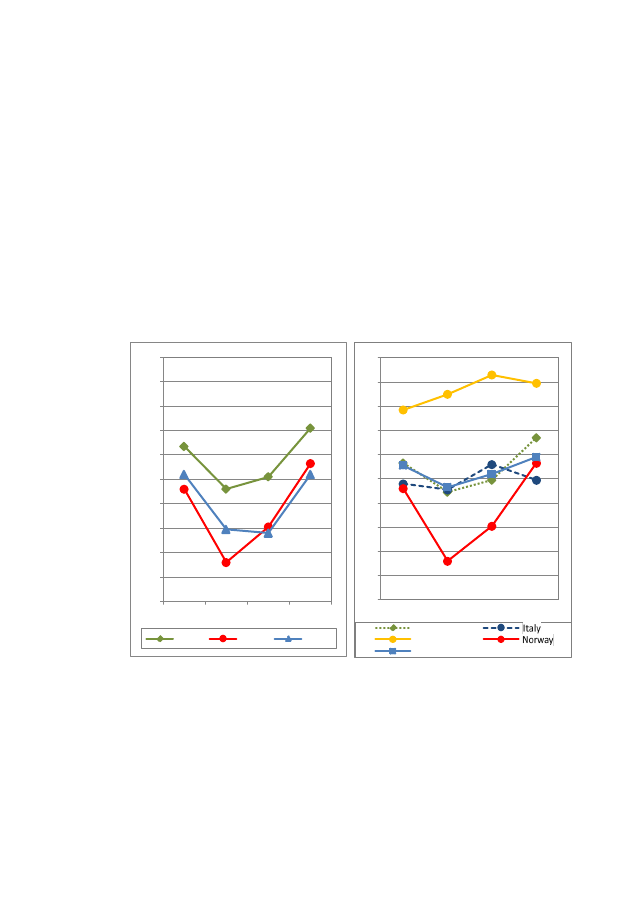

Different patterns of ICCs were observed in the three countries. For Fin-land, the school ICCs were close to zero, while the classroom ICCs werelarge, and particularly so for Grade 8 where the ICC approached .30 forboth mathematics and science. For Norway, the school ICCs were relative-ly large (around .10) for both Grade 4 and Grade 8. The classroom ICCswere small, even though estimates were somewhat higher for mathemat-ics and science for Grade 4. For Sweden, the school ICCs were large, andparticularly so for Grade 4. In Grade 8, there were both classroom- andschool-differences. These results thus show substantial differences be-tween the countries in terms of whether there are performance differ-ences at the classroom- or the school-level.One reason for these differences may be that students are sorted intoschools and classrooms according to different principles. In particular, it isof interest to investigate to what extent student SES accounts for the per-formance differences at different levels. Table 4 presents results from amodel in which the variable “Number of books at home” (or SES) has beenadded to the model. For each component of variance in the model, it isshown how much variance in performance the SES variable accounted for.However, for ICCs .06 or lower, the percentage estimates have been set tozero so as not to disturb the pattern of results with trivially small esti-mates. The .06 limit was somewhat arbitrarily chosen on the basis of con-siderations of both practical and statistical significance.

Northern Lights on TIMSS and PIRLS 2011

37

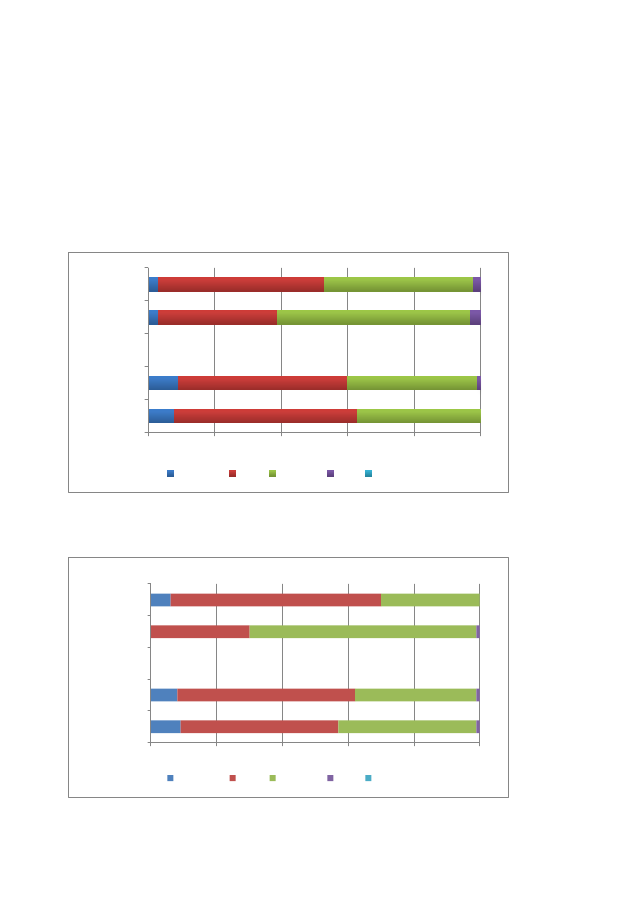

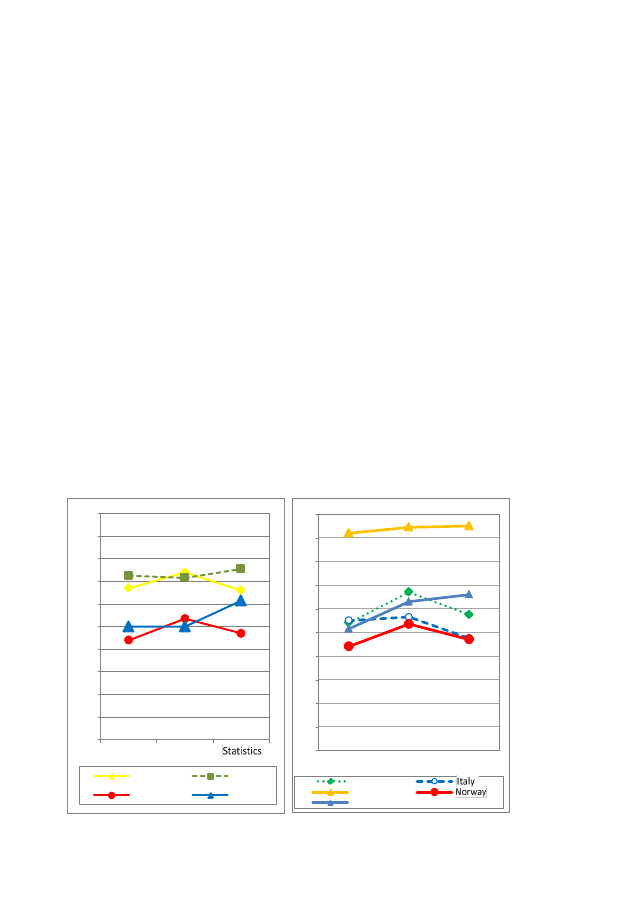

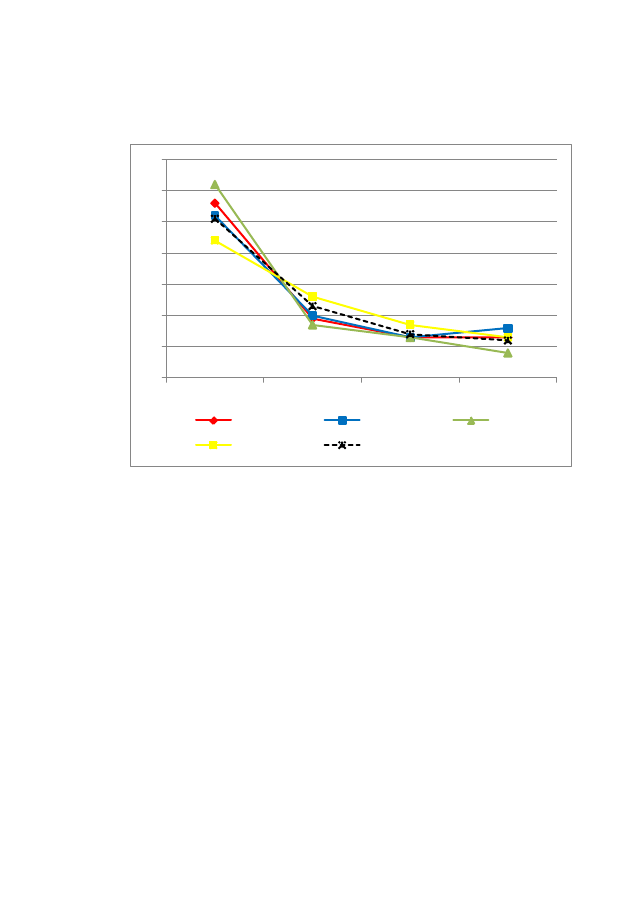

Table 4: Percentage of Variance in Mathematics, Science and Reading Achievement at School-,Class- and Student-levels Explained by Number of Books at HomeExplained VarianceMathematicsFinlandStudentClassSchoolStudentClassSchoolStudentClassSchool57051187041Grade 4Science813070299042Reading613060216044Grade 8Mathematics52001403692747Science1024014050132952

Norway

Sweden

In Sweden, school performance differences were to a substantial degree(40–50%) accounted for by the SES variable for both Grade 4 and Grade 8.For Norway, a similar pattern of results was observed for Grade 8, while theestimates were lower, but still large, for Grade 4 (20–30%). In Finland, SESdifferences did not account for any school performance differences, but itshould be noted that such differences were almost non-existent in Finland.In Finland, classroom differences were of substantial magnitude and,particularly for Grade 8, they could be accounted for by SES differences. InSweden, too, SES accounted for a part of the classroom differences (a littleless than 30%) for Grade 8, while for Grade 4, the amount of classroomdifferences was too small to make it meaningful to try to account for thesein terms of SES. In the Norwegian data, there were no classroom differ-ences, neither for Grade 4 nor in Grade 8.At the student level, SES accounted for more variance in Grade 8 than inGrade 4, with the exception of mathematics in Grade 8 in Finland, whereSES accounted for only 5% of the variance. This low relationship at the stu-dent level may be related to the large magnitude of classroom differences inFinland, which to a certain extent could be accounted for by SES.

Note:The explained variance has been set to zero for ICC estimates 0.06 or lower (see Table 3).

38

Northern Lights on TIMSS and PIRLS 2011

3.5.2

School and classroom performance differences

Table 5: Estimated School- and Class-level ICCs by Urban and Rural Schools for Grade 4 andGrade 8Grade 4MathematicsRuralFinlandClassSchoolClassSchoolClassSchool.13.03.07.09.04.06Urban.12.05.09.10.04.21ScienceRural.12.03.03.11.05.05Urban.10.05.06.07.03.27ReadingRural.14.00.02.07.05.04Urban.11.04.03.10.05.21Grade 8MathematicsRural.22.00.01.05.06.02Urban.22.06.02.11.09.14

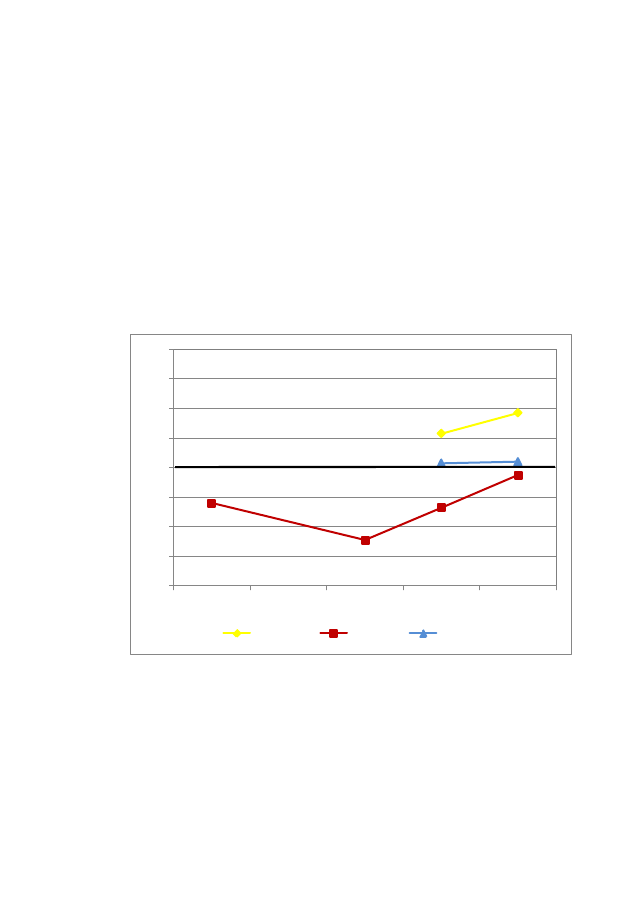

Given that opportunities for choice of school vary across urban and ruralareas, it is of interest to investigate to what extent the amount of varianceassociated with schools and classrooms was different for schools locatedin different types of areas. Table 5 presents estimates of the ICCs for Grade4 and Grade 8.

among urban and rural schools

ScienceRural.26.01.01.05.06.05Urban.25.06.03.11.13.20

Norway

Sweden

For both Finland and Norway, the patterns of results were quite similaracross schools located in urban and rural areas, even though there was atendency for the magnitude of school differences to be larger for urbanschools than for rural schools for Grade 8. For Sweden, the results werestrikingly different – the amount of school differences being larger in ur-ban than in rural areas for both Grade 4 and Grade 8.Only small school differences in level of performance could thus be ob-served among rural schools in all three countries. Among urban schools,there were at least some school differences, and the pattern of differencesamong countries was similar for Grade 4 and Grade 8 – the largest differ-ences being observed for Sweden, the lowest for Finland and Norway inbetween. In Finland, there were large classroom differences among bothurban and rural schools in both grades, while in Sweden there were class-room differences primarily among urban schools for Grade 8. This sug-gests that the classroom differences observed in Sweden and Finland maybe due to different determinants.Northern Lights on TIMSS and PIRLS 201139

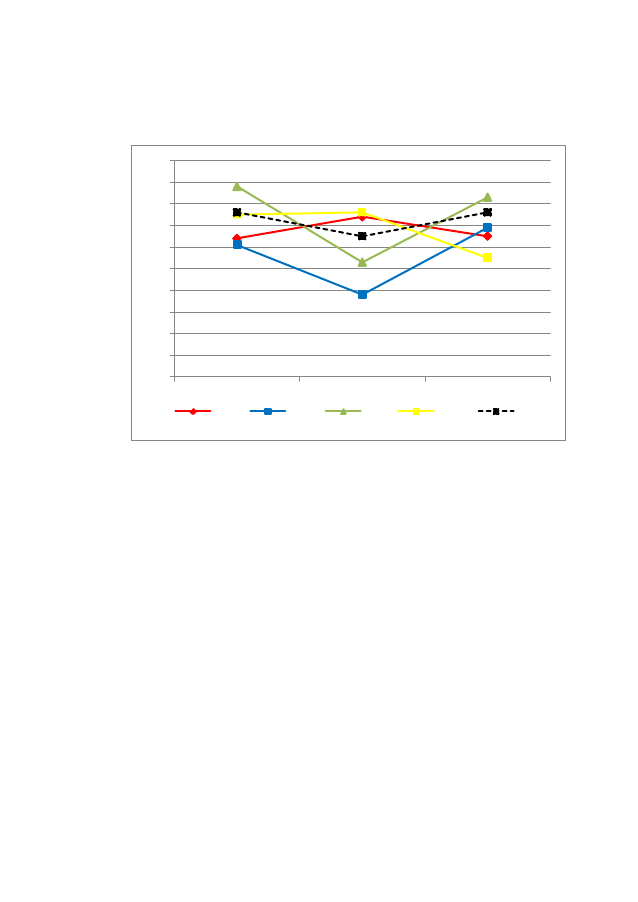

Table 6: Percentage of Variance Explained by Number of Books at Home in Urban and RuralSchools (%)Explained variance (%)MathematicsRuralFinlandStudentClassSchoolStudentClassSchoolStudentClassSchool4105012600Urban612047197044Grade 4ScienceRural7506011900Urban1021070318041ReadingRural4130500600Urban816070257044Grade 8MathematicsRural4160900900Urban72101704092859ScienceRural91508001100Urban1226017052143556

Norway

Sweden

Table 6 presents the amount of variance accounted for by SES. For Swe-den, the school differences for urban schools in both Grade 4 and Grade 8were to a large degree accounted for by SES. For the Swedish ruralschools, the ICCs were too small to allow estimation of SES impact. In theNorwegian data, school differences were accounted for by SES in bothrural and urban schools for both grades, except that estimates were notcomputed for Grade 8 in rural schools. For Finland, SES did not accountfor any school differences. Thus, for Sweden and Norway, SES accountedfor school variance in urban schools, and in Norway, this also held true forGrade 4 in rural schools. However, as has already been pointed out thesomewhat different definition of the urban-rural distinction in Norwaymakes it necessary to interpret this result with caution. For Grade 8 urbanschools, SES accounted for quite large amounts of school variance in Nor-way and Sweden.In Sweden, there were classroom differences in performance particu-larly among urban Grade 8 schools. These differences could, to around30%, be accounted for by SES, suggesting that in urban Grade 8 schoolsstudents may be allocated to different classrooms on the basis of level ofachievement. In Finland, there were classroom differences among bothrural and urban schools for both Grade 4 and Grade 8, but differenceswere larger in Grade 8. The classroom differences among urban Grade 440Northern Lights on TIMSS and PIRLS 2011

Note:The explained variance has been set to zero for ICC estimates 0.06 or lower (see Table 7).

schools could to a certain extent be accounted for by SES, as could theclassroom differences among urban Grade 8 schools.At the student level, SES accounted for somewhat less variance inachievement in rural schools than in urban schools in all three countries.In other respects, the patterns of relationships with SES were similar tothose observed in the overall analysis.One main aim of the current study is to determine the amount of schooland classroom performance differences in Grade 4 and Grade 8 in Finland,Norway and Sweden. Another main aim is to find explanations for thepatterns of differences between the countries and the grades, particularlyin terms of mechanisms related to the sorting of students across schools.The results show a clear pattern of school-level differences in perfor-mance between the three Nordic countries. In Finland, there are no schooldifferences, neither in Grade 4 nor in Grade 8. In Sweden, in contrast, theschool differences in level of performance are quite substantial, and this isalso the case for Norway. In Norway around 10% of the student differ-ences in performance are accounted for by school differences for bothGrade 4 and Grade 8. In Sweden, the school differences for Grade 8 are ofthe same size, but they are larger for Grade 4 (15–19%).In the academic year 2010–2011, 9% of the Swedish Grade 4 studentsattended independent schools, while 15% of the Grade 8 students did.These numbers indicate that the frequency of school choice in Sweden islarger in the higher grades of compulsory school than it is in the lowergrades. Therefore, the larger magnitude of school differences in Grade 4 isan unexpected result, given that the school differences are hypothesisedto be partly due to school choice.The Swedish results also show that for both Grade 4 and Grade 8, theschool differences are to a considerable extent accounted for by SES dif-ferences among the students. Thus, the quite substantial decrease in theamount of school differences between Grade 4 and Grade 8 is associatedwith a fairly stable, or slightly increasing, relationship to SES. This patternof results suggests that in Grade 4, the school differences are mainly dueNorthern Lights on TIMSS and PIRLS 201141

3.6 Discussion and Conclusions

to segregation of living, the SES impact being driven by cost of living indifferent parts of the three metropolitan areas in Sweden. The increasedopportunity for school choice in the higher grades may have been takenadvantage of by high SES students representing both lower and higherlevels of performance, but to some extent also by low SES students of highability and ambition. The combined effect of these different categories ofstudents sorting themselves into attractive schools could be decreasedperformance differences between schools, while the strength of relation-ship to SES is maintained. One possible explanation of the decrease in theamount of school differences in the higher grades in Sweden thus is thatincreased school choice counteracts the effects of segregation of living(see, e.g., Yang Hansen & Gustafsson, 2012). However, there also are otherpossible explanations. In 2010–2011, there were in Sweden about twiceas many Grade 8 students in each school than there were Grade 4 stu-dents. This implies that the catchment areas are larger in Grade 8 thanthey are in Grade 4, which in turn should imply that the catchment areasare more heterogeneous in Grade 8 than in Grade 4. This larger heteroge-neity could explain the smaller magnitude of school differences in Grade 8.In Norway, the amount of school differences remained constant be-tween Grade 4 and Grade 8, but SES accounted for a larger part of theschool differences for Grade 8 than for Grade 4. The smaller school differ-ences in level of performance and the relatively weak SES relationship forGrade 4 suggests that the impact of segregation of living is lower in Nor-way than it is in Sweden. It may be hypothesised that in Norway, too,more opportunities of school choice are made available for Grade 8, whichmay cause the SES impact on school differences to increase. It is interest-ing to note, however, that the magnitude of school differences does notincrease between Grade 4 and Grade 8, which suggests that the high SESstudents who actively choose their schools do not as a group performbetter than other students.For Swedish Grade 4 schools, there is a much higher school variationamong urban schools than among rural schools. Assuming that schoolvariation in the early school years is determined most of all by segregationof living, this suggests that such segregation is primarily an urban phe-nomenon in Sweden, and it may be hypothesised that it is particularlyconnected to the three metropolitan areas in Sweden. In Norway, there is42Northern Lights on TIMSS and PIRLS 2011

no difference in the amount of school variation for Grade 4 betweenschools in rural and urban areas, suggesting that there is an equal amountof segregation of living in the two categories of areas in Norway. ForGrade 8, there is only little school variation among rural schools in bothNorway and Sweden. This may be explained by the fact that such schoolstend to be larger than those for Grade 4 and therefore have more hetero-geneous catchment areas. In Norway, both the amount of school varianceand the SES impact is for Grade 8 higher in urban than in rural schools,which pattern suggests an impact of school choice. It should also be notedthat the classification of urban and rural schools in Norway was based onthe number of inhabitants in the community, rather than the communitytype, as used in Sweden and Finland.Perhaps the most striking empirical result of the present study is thevery substantial amount of classroom variation in Finland, amounting to12–13% for Grade 4 and at least twice as much for Grade 8. The estimatesare highly similar across rural and urban schools. This was an unexpectedfinding, and our study includes few variables that could help us understandthis result. In urban schools, a part of the between-class variance (around20–25%) is due to SES, and for rural Grade 8 schools, SES accounts forabout 13%. Thus, a part of the classroom variance may be due to the sortingof students into different classrooms on the basis of level of performance.Kupari and Nissinen (2013) also conducted three-level analyses of theTIMSS 2011 data and reported that the three-level model for the TIMSS 2011data suggests that about a quarter of the total variation is contributed by theclassroom differences. However, they did not report results from analyseswhich included explanatory variables, so this still remains to be done.One of the things that is clearly brought out in descriptions of the Finn-ish school system is the high degree of autonomy of the Finnish teachers(e.g. Sahlberg, 2011). With the exception of the matriculation exam at theend of upper secondary school, there is little external accountability andcontrol. Furthermore, the curriculum gives the teacher considerable free-dom in making decisions about what to teach and how to teach. A systemwhich decentralises much of the control of the teaching process to theteachers may, of course, also cause considerable variation both in how theteaching is organised and in the results that are achieved. Given that aconsiderable amount of information from the teachers is available in theNorthern Lights on TIMSS and PIRLS 201143

While the analyses reported in this article are based upon high qualitydata, it must be observed that the data and the analyses are also afflictedby limitations. One main limitation of the study is that it did not provepossible to include all Nordic countries, which was originally planned.Iceland did not participate at all in TIMSS 2011. While Denmark partici-pated in the TIMSS and PIRLS 2011 studies, the sampling design was suchthat the school and classroom variance could not be separated. It was,therefore, only possible to include three of the Nordic countries in thestudy. In future research, it may be worthwhile to try to take advantage ofthe data available in all the TIMSS and PIRLS studies. This could allowfurther countries to be included in the analyses, and it could also provideinteresting information about trends in the development of contributionsof variance at the school-, class-, and student-levels.It must also be emphasised that in some cases, the information was notoptimal for the purpose of separating school and classroom variance.Thus, for rural schools, it was quite common to have only one classroom,which caused standard errors for the estimated variance components tobe large. We also observed that in some cases, there were schools withonly one class comprising some 50–60 students. This is most likely a prob-lem of coding to which class the students belong, and it does seem essen-tial that care be taken to enter the full and correct information about this.Another limitation of the current study is that we have relied on thesingle measure of “Number of books at home” to represent SES. While thisis a simple and powerful indicator of cultural capital for both younger andolder students, it does not represent other important aspects of SES, suchas economic capital (Yang, 2003; Yang & Gustafsson, 2004). It is conceiva-ble that the mechanisms of segregation of living and school choice relatedifferentially to cultural and economic capital, so for both theoretical andempirical reasons, it may in future research be important to try to captureaspects of SES other than cultural capital.44Northern Lights on TIMSS and PIRLS 2011

questionnaires that are part of the TIMSS study, this information could beanalysed to see to what extent there are similarities and differencesamong the teachers at different schools.

3.6.1

Limitations

3.6.2

This article had the aim of describing and understanding sources of per-formance variation at different levels of observation in three Nordic coun-tries. We have found that there are performance differences betweenschools in Norway and Sweden, which may be due to both segregation ofliving and school choice. In Finland, there are no school differences, butinstead we have identified very substantial classroom differences. It willbe interesting tasks for further research to find the sources of these schooland classroom differences.Aho, E., Pitkänen, K., & Sahlberg, P. (2006). Policy development and reform princi-ples of basic and secondary education in Finland since 1968. Working Paper Se-ries: the World Bank.Björklund, A., P-A. Edin, P. Fredriksson, & A. Krueger (2004). Education, equality,and efficiency – An analysis of Swedish school reforms during the 1990s. IFAUreport, Uppsala. http://www.ifau.se/upload/pdf/se/2004/r04-01Bourdieu, P. (1997). The forms of capital. In A. H. Halsey, H. Lauder, P. Brown & A.Stuart-Wells (Eds.), Education: culture, economy, and society, (pp. 46–58). Ox-ford: Oxford University Press.Coleman, J. S., Campbell, E., Hobson, C., McPartland, J., Mood, F., Weinfeld, F. et al.(1966). Equality of educational opportunity. Washington, DC: U.S. GovernmentPrinting Office.

Yet another limitation of the study is that very few explanatory varia-bles were included in the study. This was partly intentional because of theexploratory nature of the three-level modelling approach that was adopt-ed. However, while SES does seem to be a powerful variable in accountingfor school differences, the school questionnaire includes many interestingmeasures of school characteristics that should be systematically analysedto better understand the sources of the school-level differences in perfor-mance observed in Norway and Sweden. As has already been discussed, italso is important to establish a deeper understanding of the substantialclassroom differences identified in the Finnish data.

Conclusions

3.7 References

Northern Lights on TIMSS and PIRLS 2011

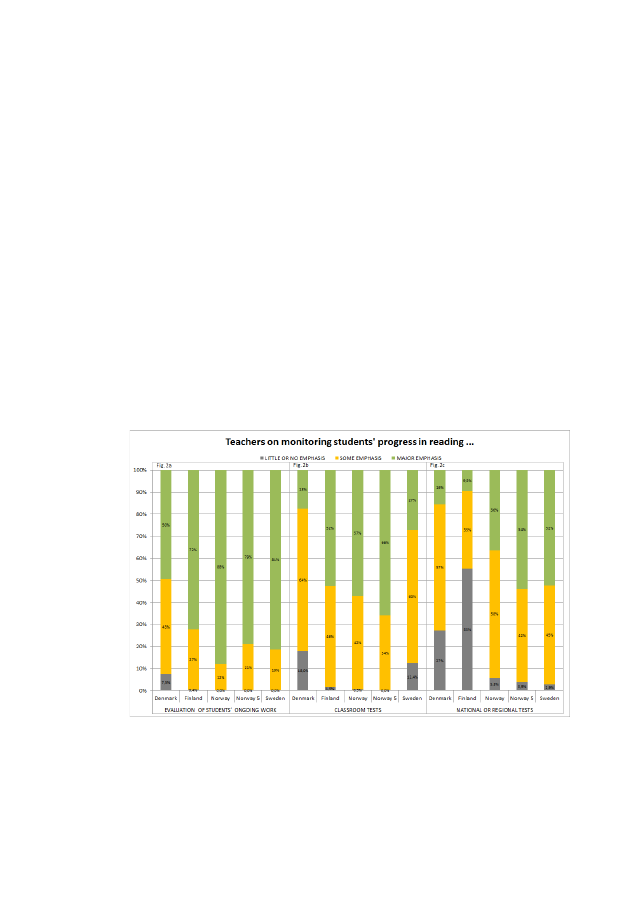

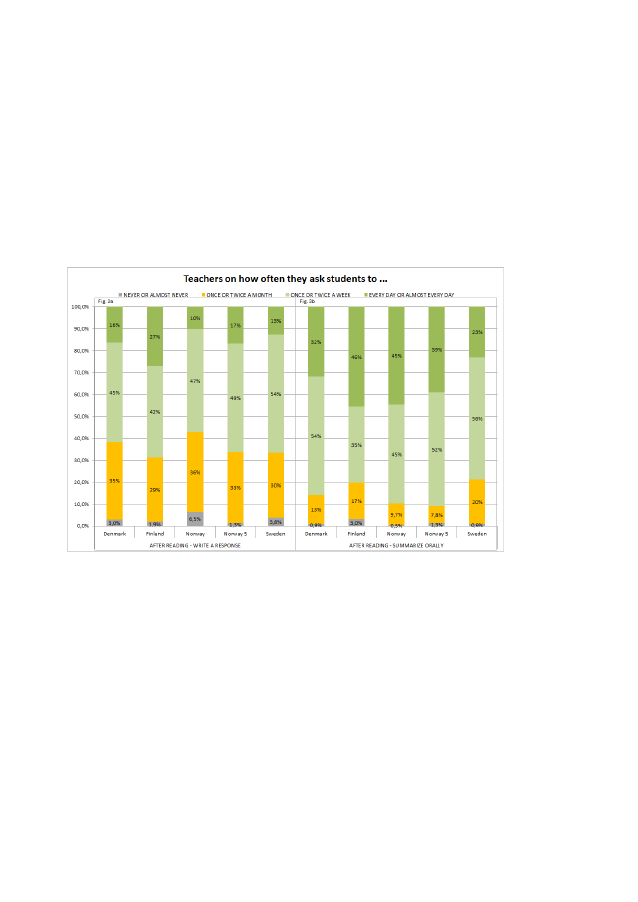

45