Beskæftigelsesudvalget 2012-13

BEU Alm.del

Offentligt

Liability in subcontracting processesin the European construction sector

Wyattville Road, Loughlinstown, Dublin 18, Ireland. - Tel: (+353 1) 204 31 00 - Fax: 282 42 09 / 282 64 56email: [email protected] - website: www.eurofound.europa.eu

Authors:Mijke Houwerzijl and Saskia PetersInstitute:Radboud University, Nijmegen, the NetherlandsResearch managers:Gregorio de Castro, John Hurley and Stavroula DemetriadesProject:Liability in subcontracting

ContentsExecutive summaryIntroduction1. Liability in subcontracting chains2. Detailed review of relevant national laws on joint and several liability3. Practical relevance and effective impact of rules4. ConclusionsReferencesAnnex: National summaries of liability arrangements1471030445052

Executive summaryThe unprecedented rate of economic activity in the European construction industry over the last quarter of a century hasplayed a major role in raising employment levels across most economies of the European Union. This development hasbenefited large and small companies, as well as driven entrepreneurship, with self-employed people making up about25% of the total labour force in the sector. As a result of the construction boom, the industry has witnessed a rapid spreadof the practice of subcontracting, encompassing increasingly long chains of interconnected companies.This scenario has redefined employment relations in the construction sector and, at the same time, reduced the directsocial responsibility of the ‘principal contractor’, as labour has been externalised by the use of subcontractors andemployment agencies.Such changes have raised questions over the impact of subcontracting on employment conditions in the sector, morespecifically in terms of: the legal implications of subcontracting for employers and workers; its impact on employeerights; the increased potential for ‘social dumping’ and a potential avoidance of fiscal responsibilities.Against a backdrop of increased European and national policy attention regarding this highly sensitive issue, Eurofoundset out to conduct a pioneering piece of research by analysing existing national legislation on liability in subcontractingprocesses.

Policy contextThe steadily evolving integration and enlargement of the internal market, together with the free movement of capital,goods, services and workers, has led to a greater movement of labour across countries. This has been particularlynoticeable at the lower ends of the subcontracting chains, where foreign companies and/or posted workers often operate.In response to this outsourcing of tasks, and in an attempt to guarantee decent employment conditions and security forworkers, eight EU Member States have over the years introduced provisions relating to ultimate liability in thesubcontracting chain – that is, Austria, Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands and Spain. In four ofthese countries – Belgium, Germany, Italy and Spain – liability legislation applies particularly and exclusively to theconstruction sector. In half of the countries, the Sectoral Social Partners have played a significant role in the law makingprocesses.At EU level, the European Commission has emphasised that employment conditions offered to posted workers must bein line with the minimum conditions established by law or negotiated under generally applicable national collectiveagreements. The issue of liability has also been addressed in a recent European Commission Communication on the1posting of workers in the framework of the provision of services (COM(2007) 0304 final) and been the subject ofdiscussion in the context of the debates on modernising labour law and combating undeclared work.

Key findingsOrigins and aims of legislationThe research shows that legislation on liability in subcontracting processes in most of the countries dates back to the1960s (Italy, the Netherlands) or 1970s (Belgium, Finland, France). Legislation was introduced at a later date in Spain(1980), Austria (1990s) and Germany (1999–2000). The regulations were introduced in order to prevent the abuse ofemployees’ rights and the evasion of the rules, as well as to combat undeclared work and illegal or unfair businesscompetition.

1

http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:52007DC0304:EN:NOT1

� European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, 2008

Liability in subcontracting processes in the European construction sector

From this common background emerges the more indirect aim of securing social security schemes and tax payments,along with safeguarding the public interest. Furthermore, in three of the eight Member States – Austria, France and Italy– the rules were developed in a cross-border context, in order to prevent social dumping in the construction sector.Nature of the liabilityThe study differentiates between two main types of liability:joint and several liability – this only applies at one level of the employment relationship, that is, when a subcontractordoes not fulfil its obligations regarding payments, for example, to the Inland Revenue; in such instances, thecontractor, together with the subcontractor, can be held liable by the Inland Revenue for the entire debt of thesubcontractor;chain liability – this applies not only in relation to the contracting party, but also to the whole chain. In this case, theInland Revenue may address all parties in the chain for the entire debt of a subcontractor.Different variations of chain liability arrangements can be found in Finland, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands and Spain.Whereas, a purely contractual liability – restricted to the direct contracting party - is established in the regulations of fivecountries and joint liability in three of them.Coverage of liabilityCoverage of the liability laws contains a material, personal and territorial scope for all of the Member States underconsideration. In relation to the material scope of the liability, three main categories of obligations covered by theliability arrangements can be distinguished: minimum wages, social security contributions and tax on wages. Theresearch found that the liability schemes of all the Member States covered at least two of these categories of obligations.Concerning the personal scope, a differentiation is made between the employer and the workers. In the case of theformer, the scope of the regulations varies greatly between the countries, while for the latter the scope of the liability issimilar across the Member States. Territorially, the main part of the rules examined apply throughout the country, whichin principle covers all parties established in other Member States when providing services in the country concerned.Preventive toolsAll of the eight Member States, except Belgium, were found to have preventive tools in place which seek to diminishthe possibility of liability for the parties concerned. These may be divided into two categories: measures which aim tocheck the general reliability of the subcontracting party and/or temporary work agency; and measures which seek toguarantee the payment of wages, social security contributions and wage tax.SanctionsSanctions for parties who do not abide the liability rules fall under three main categories across the eight Member States:back-payment obligations, fines and/or alternative additional penalties.EnforcementSimilarly, all of the countries under consideration reported facing serious problems regarding the enforcement andapplication of their liability arrangements on foreign subcontractors and/or temporary work agencies. Regarding liabilityfor wages, the main obstacles concerned problems with the language, non-transparent or inaccessible legislativeinformation, difficulties in proving abuses and problems in cross-border judicial proceedings. Concerning liability forsocial security and taxes, the main problem cited was that foreign subcontractors and their foreign workers are most oftencovered by the regulations in their country of origin instead of those of the host country.

2

� European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, 2008

Liability in subcontracting processes in the European construction sector

Role of social partnersIn all but one of the countries examined, the national authorities play either a monitoring role and/or act as potentialclaimants involved in the liability regimes at stake. The social partner organisations play multiple roles – for example,acting as advisers, representatives and providers of legal aid to individual members, as well as being parties to CollectiveLabour Agreements, or providing assistance with monitoring and compliance tasks alongside the local or regionalauthorities.

ConclusionsThe report underlines the significant differences that exist between the various national liability regulations in place inthe eight Member States under consideration. The varying legal tradition and industrial relations cultures in the countriescovered mean that research results are highly specific to each national situation and that few elements are transferable.Overall, the liability rules were deemed to be effective in achieving the specified objectives. Preventive tools offeringincentives to clients or principal contractors through the limitation of or exemption from liability were largely considereda positive element of successful liability regulations. Likewise, developing simple, accessible and understandable normswas identified as essential in the effective implementation of the regulations and in guaranteeing compliance. Moreover,the regulations should not be altered, amended or modified too frequently to avoid confusion.The involvement of the social partners in the development and implementation of the arrangements has proved to be asalient feature of most of the measures categorised as ‘good practice’. One possible way to diminish abuses at the lowerends of the subcontracting chain might be to further develop corporate or sector-based social responsibility initiatives.These could easily be developed through the normal social partner channels of consultation and negotiation, thus leadingto largely binding agreements.The current study may serve to facilitate the exchange of experiences and good practice among Member States on thesubject of liability in subcontracting processes. At the same time, it may enable social partners and legislators to becomebetter informed in relation to an increasingly important policy debate.

� European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, 2008

3

IntroductionOver the last 25 years, the European construction sector has seen a rapid spread of the practice of subcontracting, withthree main trends developing. The first trend concerns the concept of the ‘umbrella organisation’ – or ‘managementcontracting’ – where core activities are developed within the company and all other activities are realised throughsubcontracting. The second noticeable trend relates to companies that exclusively organise the sale of building worksand subcontract the whole building process. The third main trend concerns the subcontracting of bulk work, such as thecleaning of a building site (see Hellsten, 2007, p. 36).Furthermore, subcontracting chains in the construction industry are becoming increasingly long due to the structure ofthe construction sector, which is characterised by a considerable number of large companies and a big proportion ofsmall and micro enterprises, with self-employed people making up about 25% of the total workforce (see Cremers,2007). These one-person enterprises reflect the labour market tendencies: on the one hand, skilled workers recognise anopportunity to use their skills and experience as an enterprise rather than an employee; on the other hand, some peoplein the sector are working under questionable circumstances and for pay below that set by collective agreements – asituation that can be considered as ‘bogus’ self-employment. A recent example of the latter was revealed by the Unionof Construction, Allied Trades and Technicians (UCATT) in the United Kingdom (UK), where a subcontracting companyemployed a dozen Lithuanian workers. The workers were paid below the agreed minimum wage for the site, did notreceive payment for overtime and were charged excessive deductions for rent, tools and utility bills (see UCATT2press release, 30 June 2008).According to one researcher (Cremers, 2008):‘Thegrowing use of subcontracting for the labour intensive segments of the execution of construction projects doesnot necessarily lead to a deterioration of the working conditions, but it certainly has created a decrease of the directsocial responsibility of the principal contractor. Labour has been “externalised” by the use of subcontractors andagencies.’Mainly in reaction to this outsourcing of tasks and corresponding employers’ obligations, eight Member States of theEuropean Union have introduced provisions relating to the ultimate liability in the subcontracting chain, which largelyapply to the construction and building industry. Indeed, some of these countries – Belgium, Finland, France, Italy andthe Netherlands – have had legal provisions in place for many years. Other countries – Austria, Germany and Spain –have more recently developed legislation to address this issue. The different laws introduced in these Member Statesreflect the different legal traditions of each country in the field of labour law and social policy and, as a result, introducevery diverse instruments to deal with the situation in each national territory.The steadily evolving integration of the Member States’ economies in the internal market of capital, goods, services andpersons – together with the recent EU enlargements – have also led to the greater movement of workers across countries,with the construction industry being particularly affected by this trend. It is at the lower ends of these subcontractingchains, in particular, that foreign companies and/or posted workers are operating. The European Commission recently3emphasised in itspress releaseof 3 April 2008 the importance of ensuring that the employment conditions offered toposted workers are in line with minimum conditions established by law or negotiated under generally applicablecollective agreements (see for example Cremers, 2007; Cremers and Donders, 2004, pp. 48–51). For instance, in one

23

http://www.ucatt.info/content/view/515/30/2008/06http://europa.eu/rapid/pressReleasesAction.do?reference=IP/08/514&format=HTML&aged=0&language=EN&guiLanguage=en

4

� European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, 2008

Liability in subcontracting processes in the European construction sector

case covered by the European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions (Eurofound), thePolish company ZRE Katowicz Ireland Construction Ltd had been contracted by a German enterprise to carry outscaffolding work on a large contract which the German company had with the Irish power plant operator, the ElectricitySupply Board (ESB), for the €380 million refurbishment of its plant. When the German company discovered that ZREhad not been complying with Irish employment law, it terminated its contract, forcing ZRE to dismiss 200 of it Polishemployees (Eurofound, 2007, pp. 11–13).In this context, when gaps in the enforcement of national and Community law were becoming increasingly visible,policymakers began to search for effective compliance tools. This also prompted a debate on the chain liability ofprincipal contractors in subcontracting chains. At European level, this debate has been launched by the EuropeanParliament and partly fuelled by the judgement of the European Court of Justice (ECJ) in the case of Wolff and Müller4(C-60/03 ). The liability issue was included by the European Commission (2007) in its Communication on the postingof workers in the framework of the provision of services (COM (2007) 0304 final) and in its questionnaire on Europeanlabour law in the Commission Green Paper ‘Modernising labour law to meet the challenges of the 21st century’5(COM(2006) 708 final).Against the backdrop of the European and national political attention given to this highly sensitive issue, the regulationson liability in subcontracting processes in the construction industry have been explored in the eight Member States understudy – Austria, Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands and Spain. This research report,commissioned by Eurofound, is based on the material provided by the eight country reports and explains and comparesthe national liability arrangements. In particular, it highlights the similarities and differences between the systems, aswell as the positive components, challenges and problems that they pose for the actors involved in the different MemberStates.

Methodology, aims and limitations of studyThe material gathered for the eight country reports consists of a literature study analysing the regulations on joint andseveral liability in force, along with the case law, policy statements and publications by social partners and policymakers;it also examines the empirical research conducted on the practical relevance and effective impact of the laws, withparticular emphasis on the construction sector where relevant. For the empirical part of the study, the national expertsconducted face-to-face and telephone interviews with the relevant national authorities, social partners and otherprofessional bodies involved. The country reports served as the basis for the present comparative report.The aim of the combined literature study and empirical research was to create a methodological overview of the existinglegislation and the way the laws are working in practice. The analysis sought to pinpoint best practice, shortcomings andcommon denominators in order to facilitate policy debates at national and European level on the liability issue.For a proper interpretation of the present study and its results, it is important to acknowledge both its strengths andlimitations. Since it is the first time that comparative research on the theme of liability in the context of subcontractingprocesses has been undertaken at European level, this study fills a knowledge gap. Thus, given the societal relevance of

45

http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:62003J0060:EN:NOThttp://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:52006DC0708:EN:NOT

� European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, 2008

5

Liability in subcontracting processes in the European construction sector

the issue addressed, the added value of this study for policymakers and for future research is clear. Furthermore, thetripartite involvement and collaboration of social partners in each country and at European level in the constructionsector, as well as of national government representatives, guarantees that different perspectives on the research themeare incorporated in all of the reports.However, certain limitations may also arise given the uniqueness and political sensitivity of the research theme, on theone hand, and the fact that the research had to be conducted in a relatively short time frame and with a limited budget,on the other hand. In this respect, it is important to note that the comparative and the national reports are predominantlyof an exploratory, descriptive and explanatory nature, and may only serve as an introductory overview in this context. Itshould also be highlighted that the circumstances for research were not the same in each country. Firstly, differencesarose in relation to the ‘maturity’ and quantity of the regulations in force. Secondly, it proved to be more difficult in onecountry, especially Italy, than in others to gain access to the most relevant stakeholders.

Structure of reportThis comparative report is divided into four chapters. Chapter 1 introduces the subject of liability in subcontractingprocesses, giving a brief account of the practice of subcontracting and joint liability, as well as the terminology used inthis highly technical area of law.Chapter 2 provides a detailed overview of the national laws and actors involved in the eight Member States in respectof liability arrangements and largely concerning wages, social security and financial matters. It also identifies the originof the legislation, objectives, coverage, types of tools (preventive measures or sanctions), and common features andelements of the liability arrangements in the eight Member States.Chapter 3 examines the practical implementation of the liability arrangements and the effectiveness of the instrumentsas regards the centre of responsibility for discharging employees’ entitlements and also in combating bogussubcontracting practices. The focus is partly on cross-border subcontracting, as this trend affects the application of thenational instruments on liability in subcontracting chains. Here again, the similarities and differences are identified,while the overall difficulties and best practices encountered in the application of the national liability arrangements areassessed.Finally, Chapter 4 makes some concluding remarks and gives an assessment of the recommendations and options forpolicymakers and social partners, based on the findings reported in Chapters 2 and 3.

6

� European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, 2008

Liability in subcontracting chainsKey actors and terminology

1

Liability in subcontracting chains is a highly complex matter and encompasses many different actors. In terms of the6parties involved, the subcontracting chain usually features a ‘client’, ‘owner’ and ‘subcontractor’.The subcontracting chain starts with the client, who is defined as: ‘any natural or legal person, public or private, whoorders and/or pays for the works that are the object of a contract’ (the term ‘customer’ is sometimes used but avoided inthis study). Often, the client will also be the ‘owner’. The latter term refers to ‘any natural or legal person, public orprivate, who has for the time being, whether permanently or temporarily, legal title to the building or who is legallyresponsible for its care and maintenance’. In this study, the use of the term ‘client’ is preferred and shall be taken toinclude the term ‘owner’, except where the context would not permit this.The client hires one or more ‘contractors’. A contractor may be defined as ‘any participant who agrees to carry out thephysical execution of the works that are the object of a contract’. If the client only engages the services of one contractorto carry out all the work, then obviously no chain of subcontracting exists. However, the client may also employ theservices of a single contractor which is responsible for the entire building project but which, in turn, outsources part ofthe work to other contractors. In this case, the first contractor is referred to as the ‘principal contractor’ (sometimes alsoreferred to as the ‘main contractor’), while the contractors hired by the principal contractor are known as the‘subcontractors’.In their contractual relationship, the principal contractor and also the intermediary contractor in the chain are deemed the7‘recipient’ party, which orders and pays for the work or services. Meanwhile, the subcontractor – which may also be anintermediary contractor – is considered the ‘provider’, which carries out the work or services requested. Together, theprincipal contractor and all the subcontractors may be labelled as a ‘subcontracting chain’. In relation to ambitiousbuilding projects, the client may also attract several contractors for separate services. In such cases, multiplesubcontracting chains may exist next to each other. It is also possible that the client itself carries out, or could havecarried out, part of the physical execution of the works. In this instance, it may function in a double capacity as both the8client and principal contractor towards (some of) the subcontractors.Apart from outsourcing work to specialised subcontractors – that may carry out the work themselves as self-employedoperators or through their own employees – contractors may also engage external labour to perform some of the workto be done under their supervision. In the last decade, the practice of hiring workers from temporary work agencies hasonly gradually become accepted in the construction industry – although considerable differences still arise between the

6

The definitions of client, owner and contractor are drawn from the 1992 report by GAIPEC (Groupedes AssociationsInterprofessionelles Europeénes de la Construction)on product liability in the construction industry, coordinated by the EuropeanConstruction Industry Federation (Fédérationde l’Industrie Européenne de la Construction,FIEC).The recipient party may also be labelled the ‘order provider’, since this party gives the order to carry out the work. However, inorder to avoid confusion, this term is not used in this study.This is the case in relation to the Dutch liability rules for social security contributions and wage tax. These rules do not apply tothe client, but a specific client is considered equivalent to a principal contractor: the so-called ‘self-constructor’ (see section oncoverage in Chapter 2).

7

8

� European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, 2008

7

Liability in subcontracting processes in the European construction sector

Member States in this respect. In this study, the parties that only offer the services of their workers to a contractor arereferred to as ‘temporary work agencies’ (the more general term ‘supplier’ may also be used but is avoided in this study).The term ‘agency worker’ is used to refer to those employed by temporary work agencies, while the terms ‘hirer’ or ‘usercompanies’ refer to the parties that hire the agency workers. Temporary work agencies may be functioning at the lowestlevels of the subcontracting chain.A subcontracting chain constitutes a logistical chain, as well as a value chain of an economic and productive nature –‘from conception to completion’. Single specialities or tasks are often ‘externalised’ to small companies or self-employed workers. Over time, the subcontracting chains have tended to take the form of a multiple chain of production– a chain which has both lengthened and broadened. Arising from this practice are construction activities consisting ofdifferent parts of an overall project, executed by various contractors and subcontractors with problems arising in relation9to coordination and efficiency. These activities are carried out simultaneously or in several, subsequent phases. Thechain can be seen as a hierarchical, socioeconomic dependency network or triangle, based on a linked series of contractsand connections.At the top of this triangle, regular and completely legal undertakings exist. In the positive sense, the whole chain wouldbe based on, or could result in, healthy relationships between a main contractor and specialised, preferred subcontractors.However, companies at a lower level in the value chain – with the exception of specialised subcontractors with highlytechnical or other sophisticated activities – are not in a position to act on an equal footing with the main contractor. Animbalance of power in the lower parts of the chain can lead to questionable contracts that define the market transactionsbetween the different levels (paragraph mainly extracted from Cremers, 2008). The problems at the lower ends of thechain have led to the liability arrangements in the Member States examined.In the context of liability arrangements, relevant parties may include the ‘guarantor’, ‘debtor’ or ‘creditor’. A ‘guarantor’is someone who is made liable for paying the debts of the subcontractor if the latter party defaults; in practice, this isusually the principal contractor and/or client. A ‘debtor’ in the context of this study is someone who is in debt regardingthe obligation to pay wages, social security contributions and wage tax; in practice, this mostly concerns thesubcontractor, being the employer of the employees involved. If the debtor does not fulfil the said obligations in respectof the ‘creditor’, it will therefore be indebted to this party – for instance, to the Inland Revenue, social security authoritiesor employees. Thus, the creditor can be a person, company or institution to whom or which the money is owed.

9

This has led to Directives on health and safety at work – that is, Directive 92/57 (temporary and mobile sites) and Directive 92/58(safety signs at work). Moreover, the European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (OSHA) has established the European Forumfor Safety in Construction in order to promote the exchange of experience between players in the sector and, in particular, amongsmall and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). The Senior Labour Inspectors Committee (SLIC) has also devised awareness-raisinginitiatives in the sector, including European inspection campaigns.

8

� European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, 2008

Liability in subcontracting processes in the European construction sector

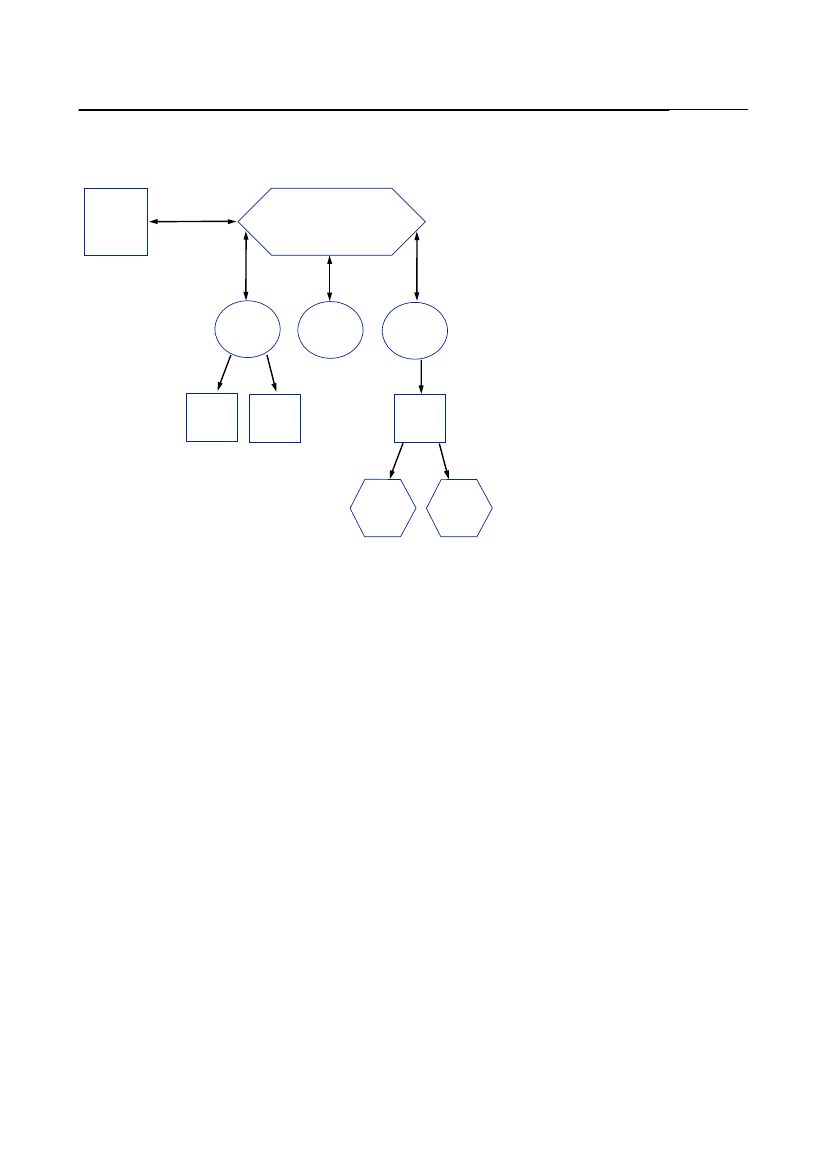

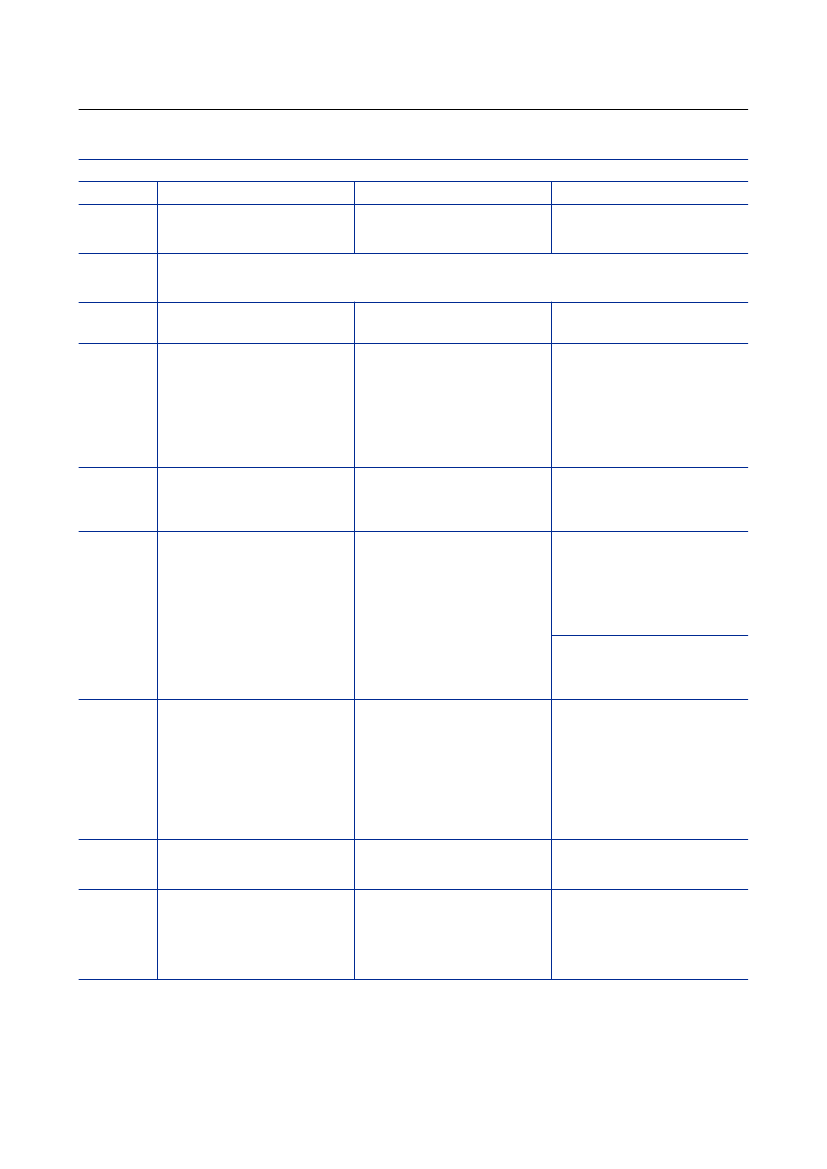

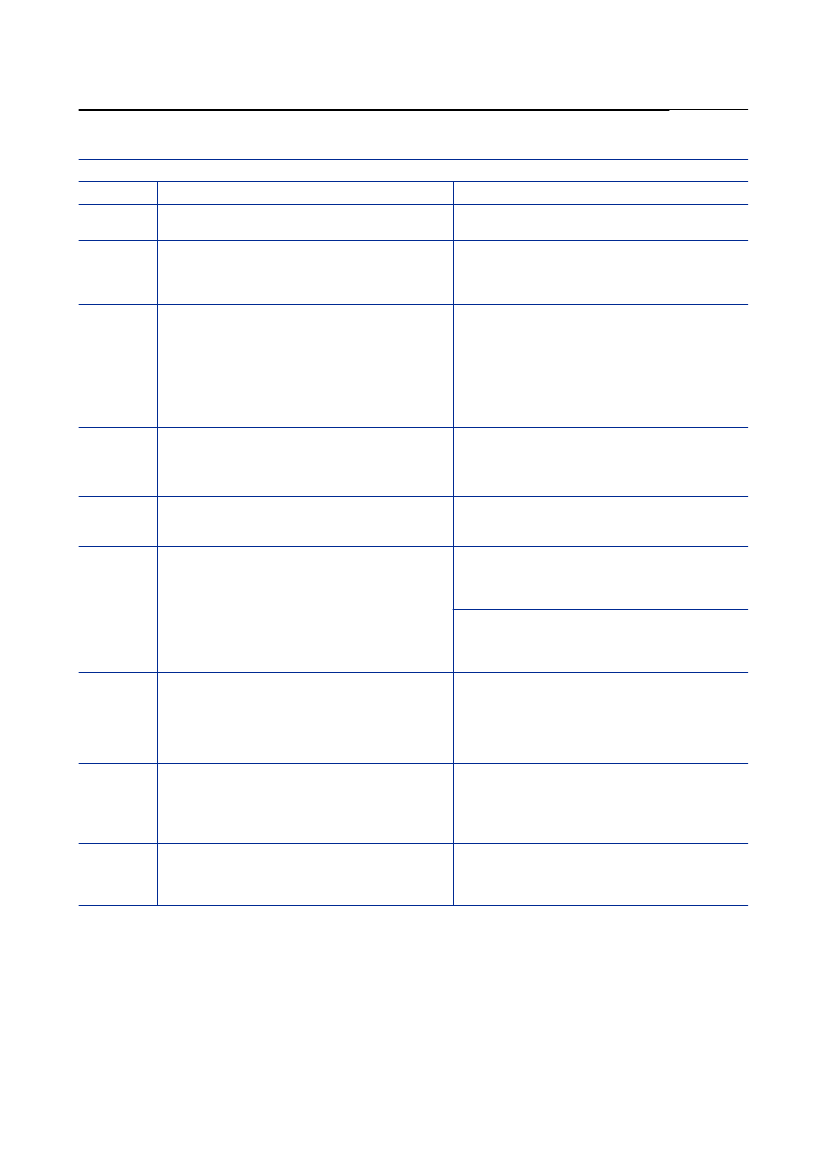

Figure 1:Example of chains of contractors in subcontracting processes

Client/owner

Principalcontractor

Sub 1

Sub 2

Sub 3

Sub1.1

Sub1.2

Sub3.1

Sub3.1

Sub3.1

Source:Adapted from Figure 1 of report by International Labour Organization (ILO, 2008, p. 21)

Joint and several liabilityThe concept of joint and several liability in subcontracting processes can be explained as follows. If, for example, asubcontractor does not fulfil its obligations regarding wages in respect of the Inland Revenue, the contractor togetherwith the subcontractor can be held liable by the Inland Revenue authorities for the entire tax debt of the subcontractor.Therefore, the creditor – in this case the Inland Revenue – can recover the whole indebtedness from either the contractor(guarantor) or the subcontractor (debtor). The contractor is made liable for the total tax debt, regardless of its degree offault or responsibility. The guarantor (contractor) and debtor (subcontractor) are then left to sort out their respectivecontributions between themselves. The logic behind this concept is that it should enable the creditor to address the partywith the best financial resources, which is usually a contractor higher up in the subcontracting chain – often the principalcontractor. Sometimes, the liability is not only of a joint and several nature, but also a ‘chain liability’. This means thatthe joint and several liability applies not only to the contracting party, but also to the whole chain. In the example citedhere, this would mean that the Inland Revenue can address all parties in the chain, which are all jointly and severallyliable, for the entire debt. In other words, it could include not only the contractor but also, for instance, the principalcontractor (see also Chapter 2).

� European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, 2008

9

2

Detailed review of relevant national lawson joint and several liability

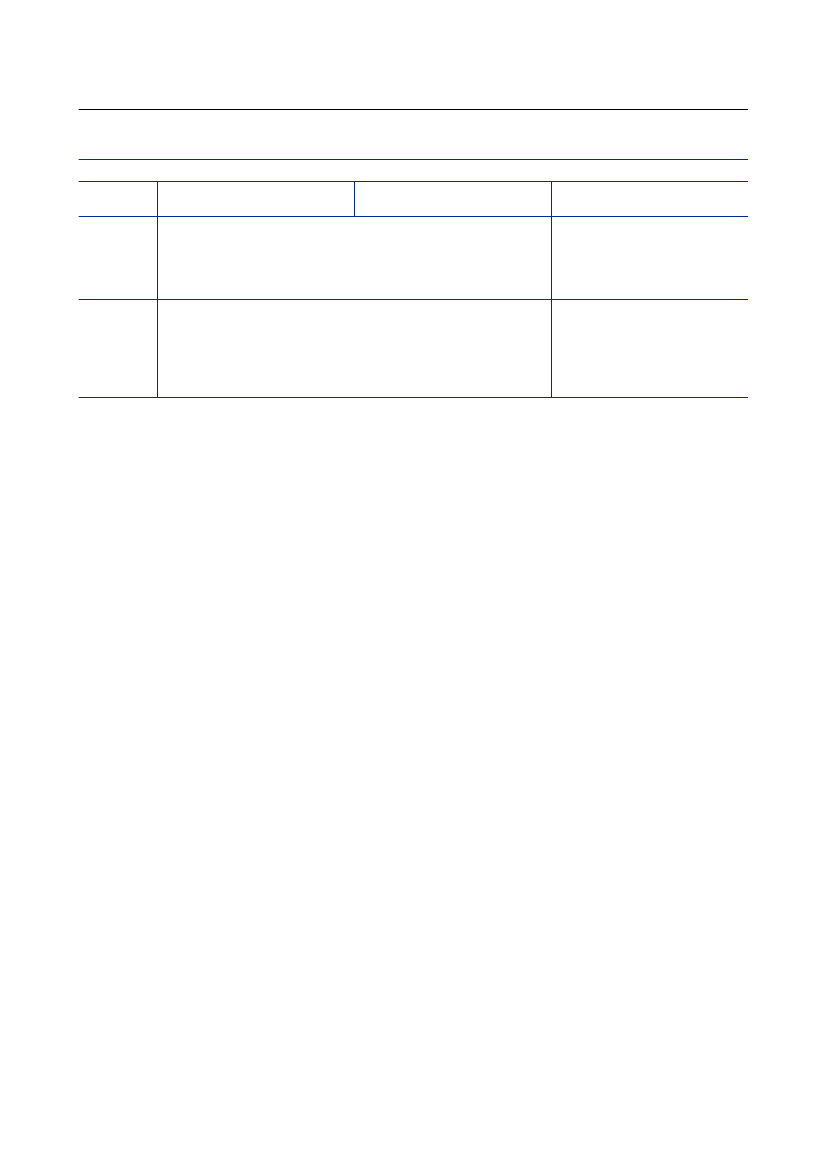

Liability regulationsIn all the Member States under consideration, most of the liability regulations are laid down in legislation. In Finland, itis noteworthy that part of the legislation – more specifically, that concerning the payment of unacceptably low wages toposted workers – is laid down in the country’s Penal Code. In some Member States – Finland, the Netherlands and Spain– part of the relevant rules can be found in the countries’ generally applicable collective agreements. In Italy, along withliability acts and decrees, a tripartite regulation concerning contribution payments in the construction sector exists; thissystem has been established by three parties – the national public institute for pensions, the national public institute forinsurance against labour accidents and a private joint institute for holiday payments in construction.It is also noteworthy that in some of the Member States – Austria, Belgium, Finland and Spain – social partners in theconstruction sector have played a significant role in the lawmaking process and/or the particular legislation is based onsystems developed by the social partners. In the case of Austria, a new bill to this effect is expected to come into forceon 1 January 2009.In four of the Member States – Belgium, Germany, Italy and Spain – liability legislation is in force particularly andexclusively for the construction sector. In Belgium, the Liability Act on subcontracting is applicable to contractorscarrying out ‘certain work’, which mainly covers the construction industry. In Germany, liability provisions for taxobligations are only applicable in the construction sector. In Italy, as mentioned, a tripartite regulation concerningcontribution payments exists in the construction sector. In Spain, more stringent rules exist regarding subcontracting inthe construction industry. Furthermore, in Austria, a bill which was recently put forward and which is set to tackle theproblem of bogus or ‘bubble’ companies will only apply in the construction sector.The liability arrangements of nearly all the Member States investigated include separate regulations for subcontractingand temporary employment through temporary work agencies. In the four Member States Austria, Belgium, France andGermany, these regulations on subcontracting and temporary employment are laid down in separate legislation; in thecase of Germany, a special liability regime for temporary employment regarding social security contributions exists. InFinland, Italy, the Netherlands and Spain, these partly separate regulations are laid down in the same legislative act.In Italy, the temporary work provisions are significantly more rigorous than the provisions regarding subcontracting.Meanwhile, in France, along with separate legislation on bogus subcontracting and temporary employment, a specialliability regulation exists regarding undeclared or illegal work.The liability arrangements of nearly all the Member States under consideration cover the payment of social securitycontributions, wages and tax on wages. Sometimes, the liability is limited to certain percentages or amounts relating tothe contract concerned or to any outstanding debts (see section on ‘Coverage of liability’ in this chapter).

Origins and main objectivesThe legislation on liability in subcontracting processes dates back to the 1960s in the case of Italy and the Netherlands,and to the 1970s in Belgium, Finland and France. The liability legislation was introduced at a later date in Spain (1980),Austria (1990s) and Germany (1999–2002).

10

� European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, 2008

Liability in subcontracting processes in the European construction sector

A considerable number of similarities were found between the Member States with regard to the background andobjectives of this legislation. Before examining these elements in more detail in each Member State, it is worth givinga short overview of the background and objectives which are common to these eight countries.In all the Member States under consideration, the regulations were introduced mainly against a background of employersevading their obligations and of employees’ rights being abused in subcontracting chains. In Austria, such regulationswere specifically introduced in a cross-border context, while in Germany the rules sought to combat illegal activity inthe building industry in particular. Therefore, the main objectives of the regulations in this context have been to preventabuse of employees’ rights and the evasion of the rules, as well as to combat undeclared work and illegal or unfairbusiness competition. Alongside this common objective is the more indirect aim of securing social security schemes andtax payments – that is, collecting the relevant social and fiscal charges – or, in more general terms, of safeguarding thepublic interest (see for instance the case of Belgium).In the three Member States Austria, France and Italy, the regulations have been developed also or mainly – in the caseof Austria – in a cross-border context. In Austria, they have sought to prevent social dumping in the construction sectorwith foreign companies and workers. In France and Italy, the central aim has been to fight the abuse of posted workersby fraudulent employers in the context of cross-border subcontracting.Despite certain similarities between the countries, the regulations have also arisen against the backdrop of the particularcircumstances prevailing in each Member State. In Austria, the introduction of the Anti-Abuse Act(Antimissbrauchsgesetz) can be attributed to two factors. On the one hand, it is related to the situation in neighbouringGermany in the early 1990s, when a construction boom occurred following the fall of the Berlin Wall: during this period,social dumping with foreign companies and workers emerged as a significant problem in the construction sector; this, inturn, led Austria to establish in 1995 legislation aimed at preventing similar instances of social dumping. At the sametime, Austria’s specific geographical situation can be considered an influential factor: the country had to cope with awide pay gap with the neighbouring countries of the Czech Republic, Hungary, Slovakia and Slovenia. As a result, it wasattractive for companies from these countries – and indeed from all EU Member States – to work in Austria using their10own workers, who might partly be remunerated at the level of their country of origin. This affected the level of wagesand the Austria’s labour market situation.In Belgium, the liability rules were established in the 1970s in response to the appearance of so-called ‘gangmasters’,who declared workers to the social security and tax administration but never paid social security contributions and taxeson wages. This legislation was based on a system developed by the social partners in the construction sector and hasundergone many changes since. Up until 1 January 2008, the liability rules were based on a registration system (whichstill exists): under this system, a contractor could be registered if it met certain reliability requirements. Under the oldrules, principals and contractors that (sub)contracted with foreign partners not registered in Belgium had to withhold15% of the sum payable for work carried out; non-compliance gave rise to a joint and several liability for the tax debtsof such contracting partners. However, this system was abandoned following a ruling by the ECJ of 9 November 2006,which stated that this system violated the freedom to provide cross-border services within the EU as the obligatory nature11of the registration system could have a deterrent effect on foreign companies (Commissionv. Belgium, C-433/04).

10

Note that until 16 December 1999, the EU posted workers directive still had to be implemented in the Member States. Since then,while differences still exist between wages which might indeed constitute a pull factor, in practice the gap should at least havediminished as, according to Article 3, Paragraph 1 of the directive: the foreign service providers will have to comply with a‘nucleus’ of mandatory rules applicable in the host country, among which are mandatory minimum wage levels stipulated inlegislation and/or in generally applicable collective agreements.http://curia.europa.eu/jurisp/cgi-bin/gettext.pl?where=&lang=en&num=79938890C19040433&doc=T&ouvert=T&seance=ARRET11

11

� European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, 2008

Liability in subcontracting processes in the European construction sector

In Finland in the 1970s, a liability clause was included in the national collective labour agreement (CLA) in the housingconstruction sector. Nowadays, other important national CLAs in the construction industry also include such a clause.Since May 2004, the country’s Penal Code defines the payment of unacceptably low wages to posted workers as acriminal offence. In 2007, the Liability Act entered into force, which is based on the incomes policy agreement for theperiod 2005–2007, concluded by the central social partners. A tripartite governmental committee prepared the details inthe system and the governmental bill reproduced it with only minor modifications.In France, the first legal provisions – introduced in the mid 1970s – regarding liability in subcontracting processes soughtto protect subcontractors rather than their workers if the principal contractor became insolvent. In 1990, a system of jointliability between a principal contractor and its subcontractor was introduced for the payment of wages and social securitycontributions. This legislation must be seen in the context of efforts to combat bogus subcontracting and the abuse ofworkers’ rights. It seeks to stabilise employment and adapt precarious forms of work. In 1979, specific liability rules fortemporary agency workers were introduced to enhance the protection of these workers. Subsequently, in 1992, liabilityprovisions regarding illegal or undeclared work were introduced due to the inadequacy of previous provisions forcombating undeclared work in the context of subcontracting chains. The rules provide an additional guarantee for thepayment of wages, social security contributions and taxes in the case of a fraudulent or disappearing contractor. Mentionshould also be made of the French legislation regarding the cross-border posting of workers, based on EU12Directive 96/71/ECconcerning the posting of workers in the framework of the provision of services; this legislationwas amended in 2005 for the benefit of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).In Germany, the liability regulations were introduced in the period 1999–2001, mainly against the background ofnational and cross-border illegal activity in the construction industry – such as the fraudulent use of (sub)contractingarrangements. The opportunity for such activities increased after the removal of the internal EU frontiers and with theincreasing permeability of its external borders. In 2001, the liability provisions for tax obligations in construction weresubstantially changed. Along with the main objectives, stated above, the liability provision for minimum wages also aimsto protect German SMEs against unfair competition by subcontractors from ‘cheap wage countries’ and to combatunemployment in the German labour market.Since 1960, Italian legislation has provided for a number of regulations regarding liability in subcontracting processes.Since 2004, this legislation has been affected by many profound changes and the liability has been extended. Thebackground for the current legislation was the need to ensure greater protection for workers involved in subcontractingand to safeguard fair competition.In the Netherlands, the legislation has provided for joint and several liability in subcontracting processes since 1960.Initially, this was limited to social security contributions and only applicable to agency workers. However, since 1982,the liability also embraces wage tax and applies to contracting for work. The main objectives of this legislation havebeen to deter unreliable temporary work agencies and subcontractors and the abuse of legal persons, as well as to combatunfair competition. Until 1998, the generally applicable CLA for the construction industry contained a real liabilityprovision. Since 2000, this provision has been a mere social clause. From 2007 onwards, the social clause obliges bothassociated and non-associated employers (main contractors) to contract subcontractors only on the condition that theyapply the provisions of the CLA to their employees. The objective is to ensure greater compliance with correct wagelevels and other labour conditions, as stipulated in the CLA.

12

http://eur-lex.europa.eu/smartapi/cgi/sga_doc?smartapi!celexapi!prod!CELEXnumdoc&lg=EN&numdoc=31996L0071&model=guichett

12

� European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, 2008

Liability in subcontracting processes in the European construction sector

In Spain, the legislation on joint liability dates back to 1980. The general aims of such legislation are to protect workersand ensure compliance with the regulations by all companies involved in the subcontracting process. A noteworthyobjective is that the law on subcontracting in the construction industry also aims to improve health and safety conditionsand to reduce accidents; at the same time, it seeks to promote the quality and solvency of companies and to introduce amechanism of transparency in work sites by limiting the amount of subcontracting to three links in the chain – althoughit allows for some exceptions to this general rule, for example when specialised work is required, in the case of technicalcomplications, or inforce majeurecircumstances – and by increasing control of this chain.

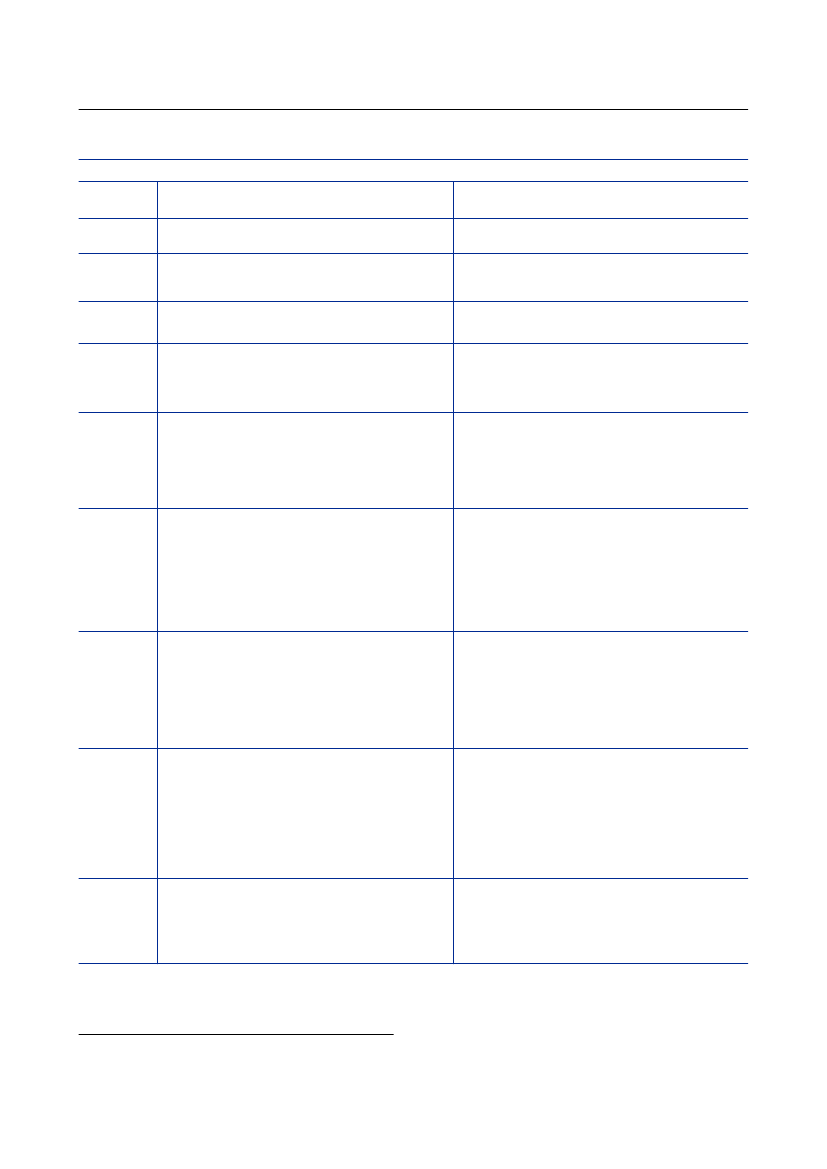

Coverage of liabilityIn terms of the coverage of the Members States’ liability provisions, this can be further categorised according to: 1) theobligations which fall within the liability, that is, the ‘material scope’; 2) the personal scope; and 3) the territorial scope.Material scopeThe material scope – or employers’ obligations which are covered by the liability provisions – can be distinguishedaccording to three main categories:(minimum) wages;social security contributions;tax on wages.France, Germany, Italy and Spain have liability legislation in place regarding all these obligations. Finland haslegislation that covers social security contributions and wage tax, while wages as well as holiday pay are covered byCLAs. Furthermore, the liability regime of Finland’s Penal Code includes the payment of unacceptably low wages, orthose below the relevant generally binding collective agreement, to posted workers. In the Netherlands, legislation is inplace regarding social security contributions and wage tax, in addition to a generally applicable CLA for the constructionindustry that applies to all material obligations deriving from the CLA, such as wages and paid holidays. In Belgium,the liability regulations on subcontracting cover social security contributions, social fund payments and wage tax, whilethe liability law on agency work covers social security contributions and wages, as well as all work-related benefits. InAustria, the liability rules apply to social security contributions and wages.In some of the Member States, as already mentioned, the liability is limited to certain percentages or amounts relatingto the contract concerned or to any outstanding debts. In Belgium, for instance, regarding social debts, the liabilityextends to 100% of the value of the work. However, the share devoted to social debts is limited to 65% when the liabilityis also established for tax debts, the latter receiving 35%, excluding value-added tax (VAT). In Germany, one of theconditions for joint and several liability regarding social security contributions is that the total value of building servicesis above €500,000. In France, the liability regarding (bogus) subcontracting is limited to contracts for services worthmore than €3,000.13

13

The aforementioned tripartite regulation concerning contribution payments in Italy covers contributions for holiday payments,pensions and health insurance for occupational accidents in the construction sector.

� European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, 2008

13

Liability in subcontracting processes in the European construction sector

Personal scopeThe personal scope of the liability regulations differs between countries and also frequently between regulations withineach country. Nevertheless, a considerable number of similarities are also evident, especially with regard to theregulations on temporary agency work. In this section, the personal scope of regulations on subcontracting will first beexamined; this will be followed by an analysis of the personal scope of the rules on temporary agency work. For thepurposes of this analysis, the study will distinguish between the employers’ side and the workers’ side. Finally, somespecific conditions for the liability will be mentioned in the last part of this section.SubcontractingEmployers’ sideThe liability provisions may apply to the principal contractor only or to all contractors that subcontract part of the workor services. Furthermore, the liability may also or exclusively apply to the client.Principal contractor onlyIn Austria, liability for wages under the Anti-Abuse Act applies only to the principal contractor, under certaincircumstances. The ‘principal contractor’ is defined as: ‘someone who passes within his business at least a part of aservice that he owes due to a contract to another company (subcontractor)’ (Article 7c, subparagraph 2 of theEmployment Contract Law Adaptation Act (Arbeitsvertragsrechts-Anpassungsgesetz, AVRAG)). In the Netherlands, thesocial clause of the CLA for the construction industry – for wages and other obligations deriving from the CLA – onlyapplies to the principal contractor. In Spain, the liability for wages and social security contributions, as laid down in theWorkers’ Statute, covers the principal contractor, but only if the subcontracted work falls within the scope of the principalcontractor’s ‘own activity’ (see below). The liability also covers the developer if it is acting in the capacity of acontractor. In Finland, the liability for wages as laid down in several CLAs applies only to principal contractors –including user companies – bound by the collective agreement.All contractors that subcontract part of the work/services‘All contractors’ includes the principal contractor as well as (sub)contractors lower down in the chain (the degree ofliability of the contractor, either in terms of liability for the whole chain or only for the direct subcontractor, will bediscussed in the section on ‘Nature of liability’ in this chapter). At least part of the liability provisions in Belgium,Finland, France, Germany, Italy and Spain apply to all contractors. The same is true for the liability legislation in theNetherlands, as laid down in the country’s Wages and Salaries Tax and Social Security Contributions Act (Wetkoppeling14met afwijkingsmogelijkheid,WKA).In Belgium, the liability on wages and social security contributions under the country’s Liability Act applies to allcontractors carrying out certain work; this work mainly covers the construction sector. In Finland, the liability provisionsof the Liability Act apply to contractors in whose Finnish premises the subcontractor’s workers perform works that relateto the contractor’s normal operations. In the building industry, the scope is broader: the provisions apply to allcontractors contracting out part of the work at a shared workplace. Therefore, in subcontracting a link to the contractor’snormal operations is needed, while in building this link is not a prerequisite for the application of the act, which meansthat all construction activities are covered. However, the liability provisions do not apply if the value of compensationis less than €7,500. Finally, the provisions of the Penal Code apply to all (sub)contractors.

14

http://www.eurofound.europa.eu/emire/NETHERLANDS/CONDITIONALINDEXATIONACTWKA-NL.htm

14

� European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, 2008

Liability in subcontracting processes in the European construction sector

In France, the liability regarding (bogus) subcontracting applies to all (sub)contractors. The liability concerningundeclared or illegal work applies to the client together with the contractors, regarding the direct subcontractingrelationship all along the subcontracting chain. This means that the liability is contractual in nature. In Germany, theliability for tax obligations in the construction sector applies to all contractors that subcontract part of the work orservices; the liability for minimum wages also applies to principal and other contractors in the subcontracting chain, butwith the exception of private individuals, building owners and administrative organs. In Spain, the liability for wagesand social security contributions, as laid down in the Law on subcontracting in the construction industry, covers allcontractors that subcontract part of the job to either companies or self-employed workers. The same is true for theliability regarding wage tax under general tax law, but on condition that the subcontracted work falls within the principaleconomic activity of the contractor (see below).Client15The liability provisions concerning subcontracting also include the client in Finland and France. In Finland – in thecase of building activities – the liability provisions of the Liability Act and the Penal Code also apply to clients actingas builders. In Germany, the liability for tax also applies to the client, except where it is the building owner. In Italy, theliability for wages and social security contributions – in accordance with Legislative Decree No. 276/2003 – applies tothe client with regard to the contractor and any subcontractors. In the Netherlands, the liability rules for social securitycontributions and wage tax under the WKA do not apply to the client. However, a specific type of client is consideredequivalent to a principal contractor: the so-called ‘self-constructor’ (eigen-bouwer). A characteristic feature of the ‘self-constructor’ is that the realisation of the subcontracted work belongs to its ordinary course of business, so that it couldhave carried out the work itself. A ‘self-constructor’ is, for instance, a manufacturer that subcontracts a part of themanufacturing process to another company. In this case, the manufacturer is considered to be both the client and theprincipal contractor.Workers’ sideIn general, the liability regulations of the eight Member States under consideration cover all workers employed by thesubcontractor; this includes ‘flexible’ workers, such as those employed on fixed-term contracts or part-time workers.Therefore, freelance workers and other workers who do not have an employment contract with the subcontractor are notcovered. Moreover, in Austria, employees in public services, that is, those who have a contract with the government, areexcluded from the scope of the Anti-Abuse Act.Temporary employmentEmployers’ sideIn all eight Member States, the liability regulations concerning temporary employment are applicable to the usercompany and the temporary work agency. The user company – which hires workers from the temporary work agency –is liable if the agency does not comply with certain obligations. In Finland, however, the Liability Act only applies touser companies if the duration of temporary work exceeds a total of 10 days.Workers’ sideIn seven of the Member States, the liability regulations concerning temporary employment cover all the workersemployed by the temporary work agency. Only in Belgium is the scope of these regulations less broad: the Law on

15

See Chapter 1 for the distinction between a client and a (principal) contractor. A client does not physically execute any part of thework which is the object of the contract.

� European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, 2008

15

Liability in subcontracting processes in the European construction sector

agency work covers all agency workers, except posted workers from abroad. In Austria, on the other hand, the scope isbroader than the general scope: the Law on agency work also covers ‘workers’ who are similar to employees and‘workers’ who are not gainfully employed but economically dependent (arbeitnehmerähnlich).Specific conditionsIn some of the Member States’ legislation, the extent of the liability depends on the place where the work is carried outor the nature of the subcontracted work. In France, for example, the coverage of the liability provisions regardingsubcontracting may be extended or limited, depending on whether the work is performed at the workplace or site of theprincipal contractor or client. In Spain, the liability on wages and social security contributions under the Workers’Statute, along with the liability on wage tax under general tax law, only apply if the subcontracted work falls within thescope of the ‘core business’ activities of the contractor. In Finland, the Liability Act applies to any temporary agencywork, whereas in subcontracting a link to the contractor’s normal operations is needed. However, such a link is notrequired in the case of building works; therefore, all (subcontracted) construction activities are covered, unless subjectto specific derogations.With regard to temporary employment, the German legislation is noteworthy. In this country, a liability regime for theuser company exists regarding social security contributions. However, in the building industry, the supply of agencyworkers is only allowed by temporary work agencies that are subject to the same generally applicable frameworkagreements and collective agreements on the social fund scheme as the hiring party for at least three years. For temporary16work agencies from other Member States of the European Economic Area (EEA ), it is sufficient if they predominantlyperform activities that are covered by the scope of this framework for at least three years. Thus, in the building industry,temporary employment business is largely restricted to the so-called ‘colleague assistance’ (Kollegenhilfe) form.Territorial scopeIn all of the eight Member States under study, the liability regulations on subcontracting and temporary agency workapply throughout the country. In principle, this means that the regulations also cover contractors and temporary workagencies established in other Member States when providing services in the country concerned. However, the liabilityrules only come into effect if the cross-border subcontractor has obligations concerning wages, social fund payments,social security contributions and wage tax towards or on behalf of its posted workers in the Member State where it istemporarily carrying out its work in the framework of the provision of services. Whether this is the case dependsprimarily on the European and/or bilateral ‘conflict of law’ rules concerning the following:labour law –Rome Convention 1980and Directive 96/71/EC;social security law –Regulation (EEC) No. 1408/71on the application of social security schemes to employedpersons and their families moving within the Community and/or, in the case of third country nationals, internationalbilateral agreements;tax law – bilateral treaties mainly based on the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)19model tax convention.1817

16171819

http://ec.europa.eu/external_relations/eea/http://www.rome-convention.org/instruments/i_conv_orig_en.htmhttp://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:31971R1408:EN:HTMLThe OECD model tax convention serves as a model used by countries when negotiating bilateral tax agreements. These agreementsare entered into by countries to clarify the situation when a taxpayer might find themselves subject to taxation in more than onecountry. The first OECD model tax convention was launched in 1963 and is regularly updated, most recently in 2005 (see OECD,2004).

16

� European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, 2008

Liability in subcontracting processes in the European construction sector

According to Article 3, Paragraph 1 of the EU posted workers directive, such workers are entitled to minimum wagelevels in the host country, as laid down by national law and/or generally applicable CLAs, provided that these providefor more favourable wages than those owed on the basis of their employment contract. With regard to social securitycontributions, posted workers will generally be covered by the benefit schemes in their country of origin for the first yearand, with the consent of the host country, also for the second year of posting. In terms of wage tax, depending on thespecific bilateral agreement at stake, it may depend on the length and nature (whether or not as an agency worker) of theposting, whether the tax law of the host country applies from day one or only when the duration of the posting exceeds183 days.In certain Member States, some specific rules and exceptions apply in the case of cross-border contracting with theinvolvement of workers. In Austria, the Anti-Abuse Act has separate liability provisions for, on the one hand, EUcompanies, including Austrian companies; these provisions are applicable to domestic and cross-border postedemployees within the EU. On the other hand, the Act also encompasses liability provisions that exclusively apply to non-EU companies; these provisions are applicable to cross-border posted employees from outside the EU.In France, the liability regarding temporary agency work also applies to foreign agencies when active in France.However, these foreign agencies may be exonerated from certain obligations if they have already complied withformalities of the same or of an equivalent effect in their country of origin.In Germany, the Law on the posting of workers (concerning minimum wages and leave fund contributions) provides forthe following: if foreign posted workers are not taxed in Germany, the provider – subcontractor or temporary workagency – may apply for an exemption certificate. If the provider does not apply for an exemption certificate and therecipient – principal contractor or user company – withholds the tax on compensation for construction work, the providercan apply for a tax refund.In Italy, all liability regulations also cover foreign contractors and agencies when active in Italy. Furthermore, they applyto activities abroad pursuant to Italian jurisdiction. In the case of cross-border contracting, foreign Inland Revenue andsocial security authorities can also demand payment by Italian clients of contributions and taxes owed in relation tosubcontracted work or services supplied in Italy by staff who have retained the right to pay taxes and contributions inthe country of origin. The same applies to the payment of taxes and contributions relating to subcontracted work andservices supplied abroad, when the posting abroad cannot be considered temporary or no bilateral agreements existbetween the foreign country and Italy.In the Netherlands, the liability legislation on social security contributions and wage tax may also apply when the workis carried out abroad by Dutch subcontractors.

Nature of liabilityJoint and several liabilityThe concept of joint and several liability in subcontracting processes has already been explained in Chapter 1.The twin concepts ‘joint and several’ are defined in Italian legislation (Article 1292 of the Civil Code) as follows: ‘Anobligation is considered joint and several when each of a number of debtors involved in a single operation can be forcedto comply on behalf of all the others, and the compliance by one of the debtors frees the others from their obligation.’In Italy, according to Legislative Decree No. 223/2006, the contractor is – in relation to the subcontractor – ‘jointly andseverally’ liable for wage tax and social security contributions relative to the employees of the subcontractor.

� European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, 2008

17

Liability in subcontracting processes in the European construction sector

According to the regulations of several Member States, the liability is not only of a joint and several nature, but is alsoa chain liability. This means that the joint and several liability applies to the whole chain, instead of only the directcontracting party.Chain liability (including joint and several liability)Various types of chain liability, as described here, were found in the liability arrangements of Finland, Germany, Italy,the Netherlands and Spain.In Finland, according to the Penal Code, the payment of unacceptably low wages to (posted) workers is a criminaloffence, which may lead to confiscation by the state of the illegal benefit gained by paying the illegally low wages. Theconfiscation claim may also be directed against a (principal) contractor or user company. Confiscation cannot be orderedif the (posted) workers concerned present their wage claims. This represents a kind of chain liability for the part of theconfiscation possibility, but not with regard to real wage claims.In Germany, the liability provision for minimum wages contains an unconditional chain liability, that is, joint and severalliability; accordingly, the principal contractor, client, intermediary contractor or user company are jointly and severallyliable. In addition, regarding social security contributions, a joint and several liability exists – under certain conditions;the conditions are, for instance, that the transaction must aim to circumvent the law and that the total value of thebuilding services amount to €500,000 or over. If such conditions are fulfilled, the health insurers as collecting agencieshave the right to choose to claim on the client, principal contractor, intermediary contractor or user company (thebuilding owner is excluded); these parties are all jointly and severally liable.In Italy, the liability for social security contributions, wage tax and wages (Legislative Decree No. 276/2003) is a chainliability. The client or contractor is liable with regard to the contractor and any subcontractor(s). The subcontractor’semployees can bring a direct action against the contractor and the client. However, concerning wage tax, the liability ofthe client will be abolished in the near future under Legislative Decree No. 97/2008 of 3 June 2008.In the Netherlands, the liability legislation under the WKA stipulates a joint and several liability for the user company,as well as for the (principal) contractor, for the whole chain of temporary work agencies and/or subcontractors thatfollow in line and that are working on the same project at the building site.The Spanish Workers’ Statute contains a joint and several chain liability with regard to the principal contractor only forsocial security contributions and wages; however, this liability only applies if the subcontracted work falls within thescope of the principal’s ‘own activity’. Principal contractors in the construction sector are, on the other hand, subject toan unconditional chain liability – that is, joint and several liability – regarding social security contributions and wagesunder the Law on subcontracting in the construction industry.Contractual liability‘Contractual liability’ means that the liability is restricted to the direct contracting party and therefore to one level ofsubcontracting. As a result, no chain liability arises. For instance, the principal contractor is liable only for its directcontractor, and that contractor only for its direct subcontractor in turn. This kind of liability can be found in Austria(Anti-Abuse Act); Finland (Liability Act), France (liability regarding (bogus) subcontracting and liability regardingillegal or undeclared work) and Germany (liability provisions for tax obligations in construction). In Austria, this liabilityis restricted to the highest level in the subcontracting chain – that is, to the principal contractor, according to the Anti-Abuse Act (Article 7c.3 of AVRAG). Finally, the Belgian Liability Act of 2008 contains mainly a contractual liability;nevertheless, under certain circumstances, this liability may acquire a joint nature.

18

� European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, 2008

Liability in subcontracting processes in the European construction sector

Joint liabilityIn Belgium, the liability acquires a joint nature if the contracting party of the contractor with social security and tax debtshas failed to meet its obligations after being formally pressed for payment by the administration. Only if these conditionsare fulfilled will the next level in the chain be addressed. In France, the user company is jointly liable if the temporarywork agency defaults and its insurance proves insufficient to pay the wages and social security contributions. Theliability of the user company is proportional to the duration of the temporary employment contract. Regardingundeclared or illegal work, under certain conditions, a joint liability of the client together with the contractors arisesregarding the direct subcontracting relationship. Finally, in Spain, the temporary employment provisions of the Workers’Statute provide for a subsidiary liability of the user company, which becomes a joint liability if certain provisions havebeen infringed.Special types of liabilityAccording to the Belgian Law on agency work, a liability arises if the employment agency transfers part of its authorityto the user company. In this case, the employment contract of the agency worker with the agency will automatically betransformed into an open-ended contract with the user company.In Finland, the CLA in the housing construction sector includes a clause which stipulates that the principal contractor isliable for the subcontractor’s or temporary work agency’s unpaid wages and holiday pay, under certain conditions. Thisobligation is, however, ultimately a moral obligation.The CLA for the construction sector in the Netherlands does not contain a real liability, but only a social clause. Thisplaces an obligation on the principal contractor to monitor the compliance of the CLA’s provisions in all individualemployment contracts covered by the agreement; the principal contractor is obliged to agree on this in the subcontractingarrangement.Finally, it should be mentioned that, in Austria, several types of liability can be found in one regulation. The Anti-AbuseAct contains three types of liability: joint and several liability (Article 7a, subparagraph 2); ‘normal’ liability, whichmeans that the precondition for the liability is that the principal debtor received a warning but has still failed to pay(Article 7c, subparagraph 2); and ‘secondary’ liability, which means that the contractor is only liable if the subcontractorcannot pay the debt (Article 7c, subparagraph 3). Furthermore, the Law on agency work contains a normal liability(Article 14, subparagraph 1) and a secondary liability (Article 14, subparagraph 2). The secondary liability exists if theuser company can prove that it has fulfilled its financial obligations deriving from the contract with the temporary workagency.

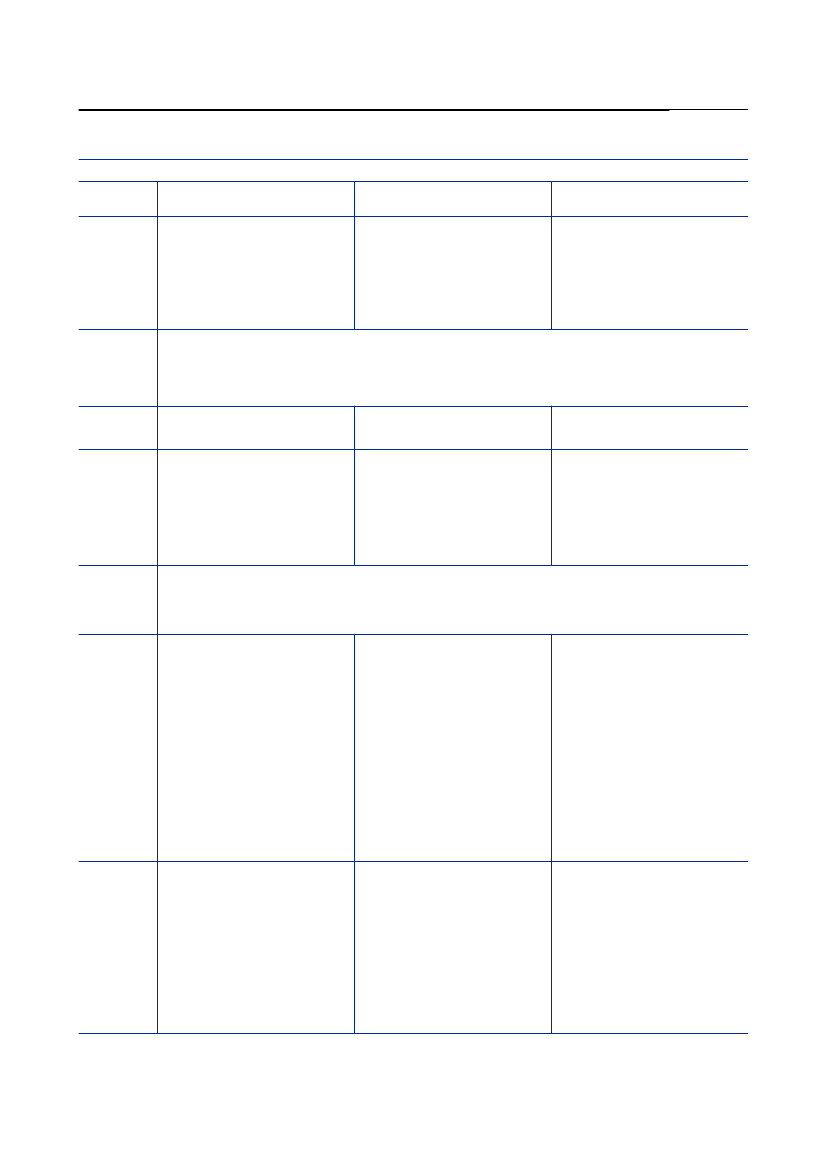

Preventive measures used in framework of liability arrangementAs part of, or in connection with, the liability arrangements in the different Member States, several tools have beendeveloped to either prevent the possibility for liability among the relevant parties or to sanction the parties which did notfollow the rules. An overview of the different sanctions will be provided in the next section of this chapter.In terms of the preventive tools in place, these may be divided into two main categories:measures seeking to check the general reliability of the subcontracting party;measures aiming to guarantee the payment of wages, social security contributions and wage tax.

� European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, 2008

19

Liability in subcontracting processes in the European construction sector

With regard to these preventive tools, three possible scenarios may occur in the eight Member States underconsideration: no preventive tools may exist; the preventive tools may be optional; or they may be obligatory preventivetools. Moreover, when such measures are established, they may either be embedded in a self-regulatory framework orin a legal framework.Before describing these measures, it is interesting to observe that, in Spain, a comparatively different preventive tool wasintroduced in 2006. In this particular country, the monitoring and surveillance obligations of Law 32/2006 aim to restrictthe length of the subcontracting chain, with no more than three vertical levels allowed in the chain; some exceptions tothis limitation are, nevertheless, foreseen in situations where specialised work is required, where technical complicationsarise or inforce majeurecircumstances. In addition, the certification of adequate training and organisation in the area ofoccupational hazard prevention are prescribed by the measures. The certificates issued by the relevant Register ofAccredited Companies for this purpose are of special importance.Checking reliability of subcontractor or temporary work agencyIn five of the eight Member States – Austria, Belgium, Germany, Italy and the Netherlands – no general obligation existsfor the client or the principal contractor to check the reliability of the subcontractor or temporary work agency. However,in practice, not checking can result in a higher chance of liability and/or sometimes failure to do so is sanctioned with amore strict liability regime. Private parties may therefore choose to voluntarily include a clause on reliability checks intheir contract as a safeguard against liability. The Italian national report, in particular, refers to regular use of thispossibility. Prior to entering into a contracting or subcontracting agreement with a contractor, the client must first verifythat the contractor and any subcontractor(s) it chooses have their affairs in order regarding the payment of wages, socialsecurity contributions and taxes. Similar verifications may also be implemented during the execution of the contractingor subcontracting agreement.Although not mentioned in most of the national reports, it may be safely assumed that the option to make suchcontractual clauses exists in all of the Member States under consideration. In the Netherlands, optional tools have beenintroduced by the legislator for the client and principal contractor to avoid becoming involved in the effects of joint andseveral liability and thus having to sustain high economic costs. The fact that no general obligation to check thereliability of the subcontractor exists in Germany is not very relevant, since the reliability check in this country is anintegral part of the obligation to take due care of the payment behaviour of the subcontractor with respect to minimumwages, social security (optional) and tax debts (see next section). In Finland and France, legal obligations of a preventivenature do exist. This report will describe the optional and obligatory measures next. As in some Member States thepossibilities or obligations to take preventive measures differ for contractors involved in public procurement and forcontractors involved in a purely private building project, attention will also be paid to measures in the context of publicprocurement.Optional reliability checkIn the Netherlands, before the user company decides to hire workers, or before the principal contractor decides tocontract the subcontractor, they may do the following: check the temporary work agency’s or (sub)contractor’sreferences; request proof that these parties possess a (Dutch) payroll tax number; and request proof that the supplier or(sub)contractor actually files a return. The incentive to do this is high because the liability clause will not apply if no-one in the chain, including the employer of the workers involved, can be blamed for the tax and contribution debt. Thecountry’s Inland Revenue issues leaflets with guidance on how to screen the supplier or subcontractor and offerspossibilities to ask for declarations of good behaviour concerning payment of tax and social security contributions bythe relevant temporary work agency or subcontractor in the past. One recommendation of the Inland Revenue is toinclude a clause in the contract with the supplier or subcontractor that they may not, in turn, outsource the work withoutprior acceptance of the user company or principal contractor.

20

� European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, 2008

Liability in subcontracting processes in the European construction sector