Beskæftigelsesudvalget 2012-13

BEU Alm.del

Offentligt

Ref. Ares(2012)763789 - 25/06/2012

Final Study

Authors:

Yves JorensSaskia PetersMijke HouwerzijlJune 2012

Study on the protection of workers' rights in subcontracting processes in theEuropean UnionProject DG EMPL/B2 - VC/2011/0015Contractor:Ghent University, Department of Social Law, Universiteitstraat 4, B-9000 Gent (in consortiumwith University of Amsterdam)Disclaimer:The information contained in this publication does not necessarily reflect the position oropinion of the European Commission.

National ExpertsFlorian BurgerYves JorensKrassimira SredkovaEva SoumeliPetr HurkaMartin Gräs LindMerle MudaUlla LiukkunenBarbara PalliMonika SchlachterCostas PapadimitriouJózsef HajdúMichael DohertyGiovanni OrlandiniKristine DupateTomas DuvalisGuy CastegnaroAriane ClaverieRoselyn KnightLucy van den BergSaskia PetersStein EvjuMonika TomaszewskaJulio GomesMaria Cristina AnaAndrea OlsovskaLuka TicarJoaquin Garcia MurciaAngeles Ceinos SuárezKerstin AhlbergLinda ClarkeIan FitzgeraldLucinda HudsonAustriaBelgiumBulgariaCyprusCzech RepublicDenmarkEstoniaFinlandFranceGermanyGreeceHungaryIrelandItalyLatviaLithuaniaLuxembourgLuxembourgMaltathe Netherlandsthe NetherlandsNorwayPolandPortugalRomaniaSlovak RepublicSloveniaSpainSpainSwedenUnited KingdomUnited KingdomUnited Kingdom

2/192

ContentsChapter 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 5I.II.Background/policy context of the project ...................................................................................................... 5Aims, method and outline of the study .......................................................................................................... 7A. Aims and outline of the study ................................................................................................................ 7B. Research method.................................................................................................................................... 8Definitions of key terminology used ............................................................................................................... 8

III.

Chapter 2 Setting the scene ................................................................................................................................. 12I.II.III.Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 12Relevant measures at EU level ...................................................................................................................... 12An overview of ‘general’ responsibility/liability measures ........................................................................... 15A. Measures regarding wages, including holiday payments ..................................................................... 15B. Measures regarding social fund payments........................................................................................... 17C. Measures regarding occupational health & safety, including working time ........................................ 18D. Measures regarding tax on wages and social security contributions ................................................... 20E. Functional equivalents/alternatives, including corporate social responsibility ................................... 24An overview of ‘specific’ responsibility/liability measures ........................................................................... 27A. Measures regarding undeclared/illegal (migrant) labour .................................................................... 27B. Measures regarding temporary agency workers.................................................................................. 28C. Measures within the framework of public procurement/public works ............................................... 29An overview of responsibility/liability measures from a country perspective ............................................. 34A. No measures, government measures or measures initiated by social partners .................................. 34B. Sectoral or general scope ..................................................................................................................... 37C. Nature of responsibility/liability measures .......................................................................................... 38Liability systems and the case Law of the European Court of Justice ........................................................... 40Summarising and concluding remarks .......................................................................................................... 44A. A brief summary of the findings ........................................................................................................... 44B. Concluding remarks .............................................................................................................................. 45

IV.

V.

VI.VII.

Chapter 3 A detailed review of relevant national laws on responsibility and joint and several liability insubcontracting processes .................................................................................................................... 46I.II.Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 46(Statutory, conventional, soft law) arrangements on wages ........................................................................ 46A. Origins and main objectives ................................................................................................................. 46B. Nature and coverage ............................................................................................................................ 50C. Preventive measures ............................................................................................................................ 58D. Sanctions .............................................................................................................................................. 61(Statutory, conventional) arrangements on social funds payments ............................................................. 63A. Origins and objectives .......................................................................................................................... 63B. Nature and coverage ............................................................................................................................ 64C. Preventive measures ............................................................................................................................ 66D. Sanctions .............................................................................................................................................. 67Health & Safety arrangements ...................................................................................................................... 67A. Origin and objectives ............................................................................................................................ 67B. Nature and coverage ............................................................................................................................ 68C. Preventive measures ............................................................................................................................ 75D. Sanctions & complaint mechanisms ..................................................................................................... 763/192

III.

IV.

V.

Other arrangements ..................................................................................................................................... 76A. Origins and objectives .......................................................................................................................... 76B. Nature and coverage ............................................................................................................................ 81C. Preventive measures ............................................................................................................................ 88D. Sanctions .............................................................................................................................................. 90Concluding remarks ...................................................................................................................................... 92

VI.

Chapter 4 The practical impact of the rules – particularly in the framework of cross-border subcontracting ......... 97I.II.Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 97Application of the rules in practice – specifically in cross-border situations ................................................ 98A. Wages and other employment conditions ........................................................................................... 99B. Health & safety arrangements ........................................................................................................... 108Enforcement of the implemented norms and instruments – specifically in cross-border situations......... 113A. Wages and other employment conditions ......................................................................................... 113B. Health and safety................................................................................................................................ 118C. Collaboration with foreign actors and institutions ............................................................................. 120D. The relevance of EU level cross-border legal instruments in force allowing foreign administrationsand other creditors to be paid............................................................................................................ 122E. The place and role of the measures in the overall system of enforcement of labour law ................. 123Social fund payments .................................................................................................................................. 124Temporary agency work ............................................................................................................................. 125SMEs............................................................................................................................................................ 128A comparative examination of positive issues, problems, deficiencies or shortcomings ........................... 134

III.

IV.V.VI.VII.

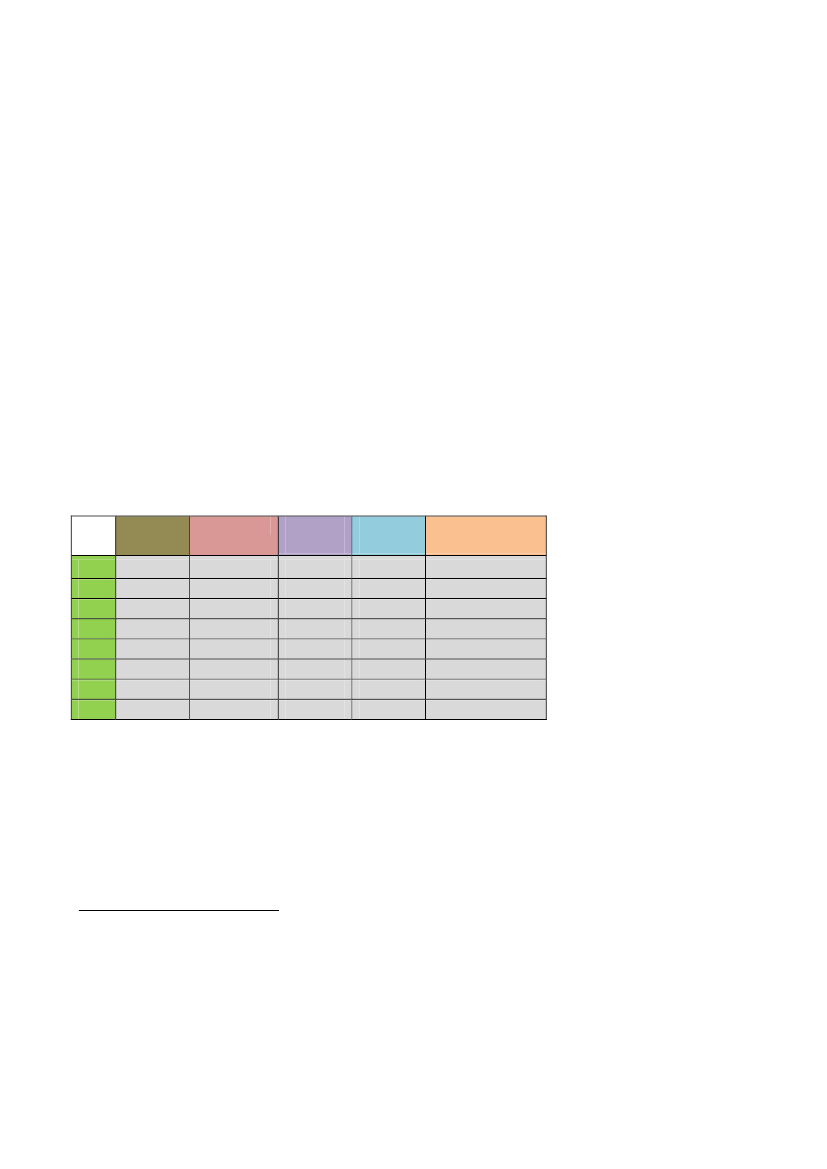

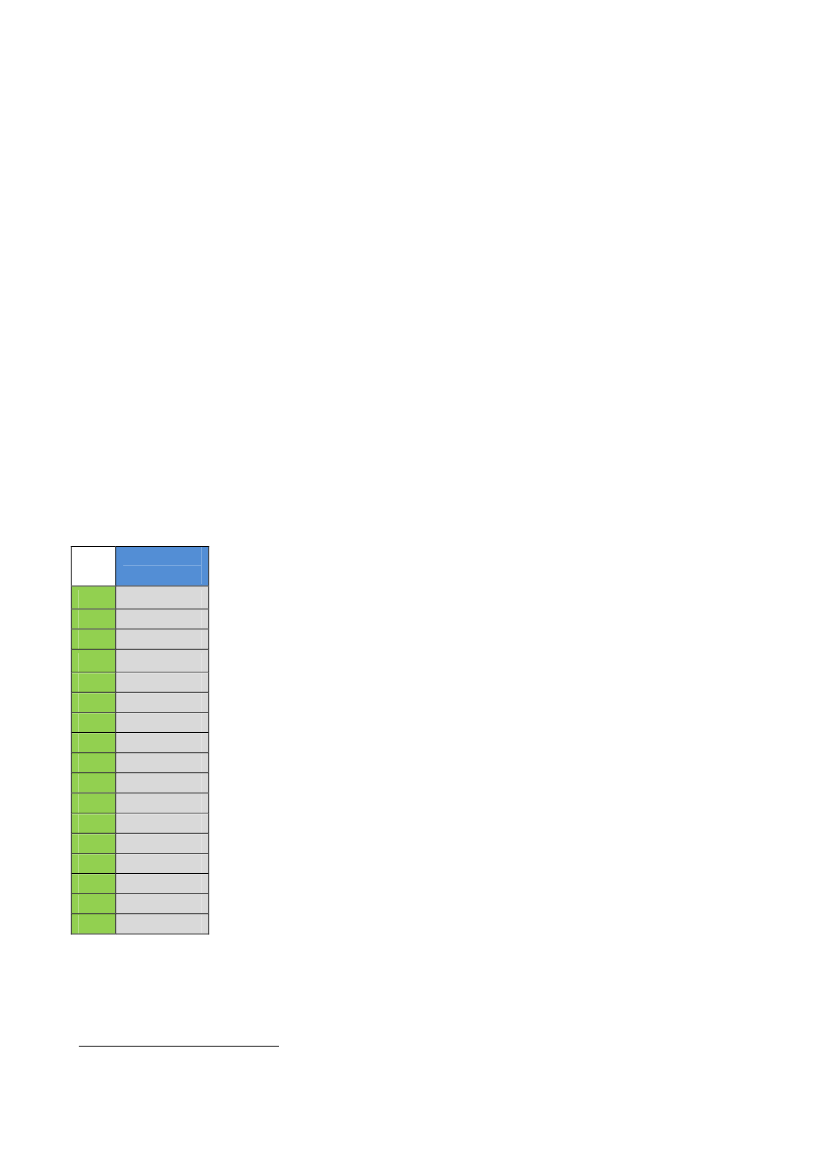

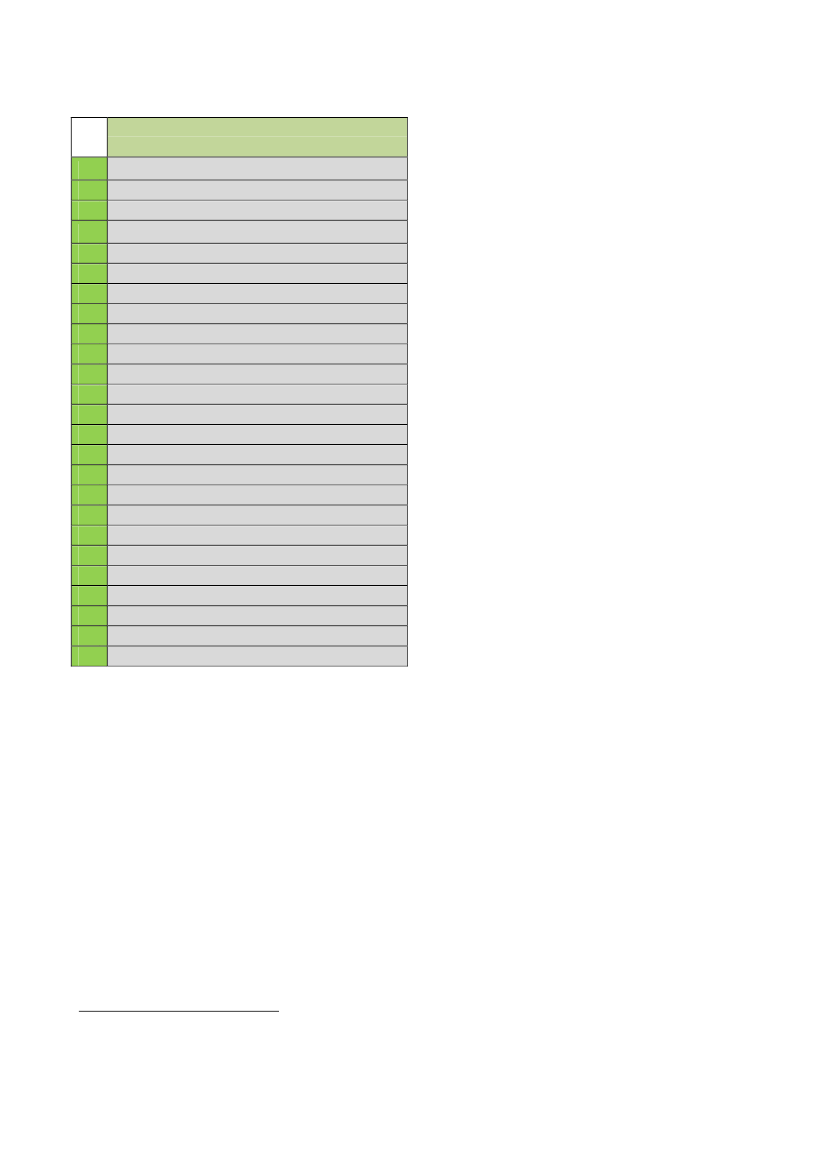

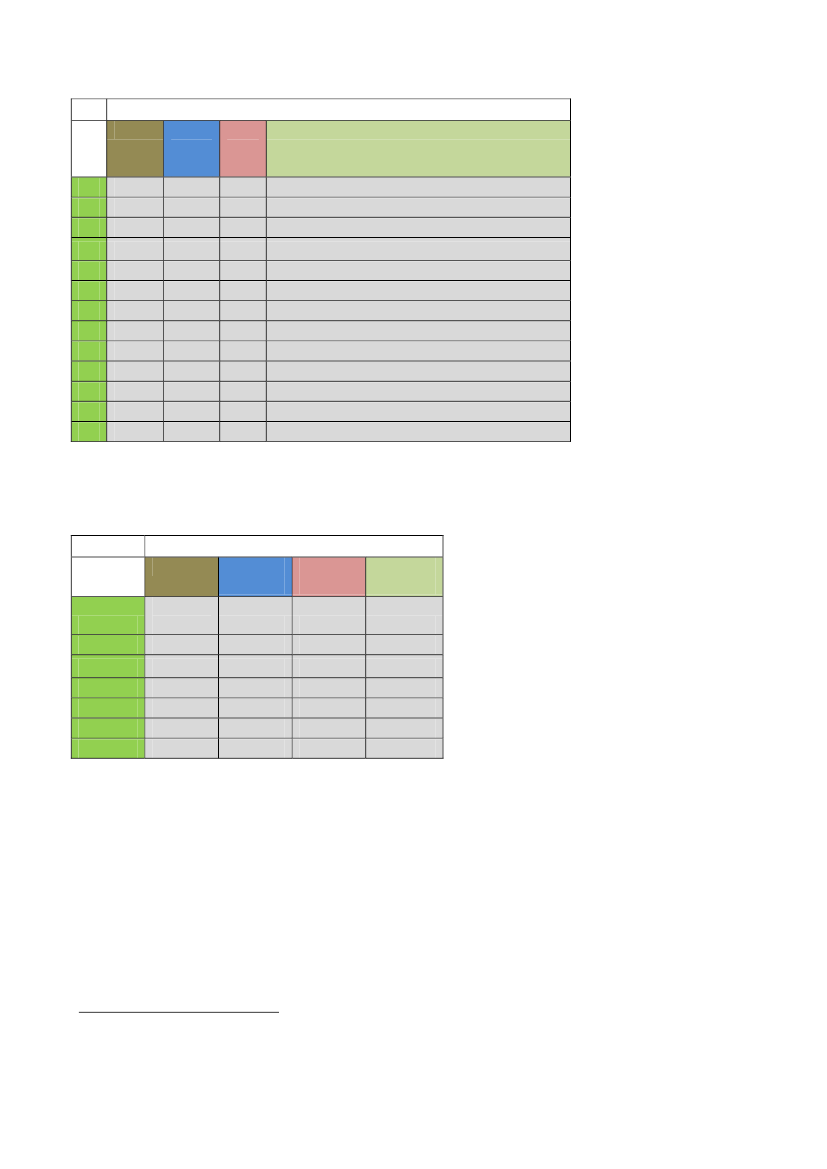

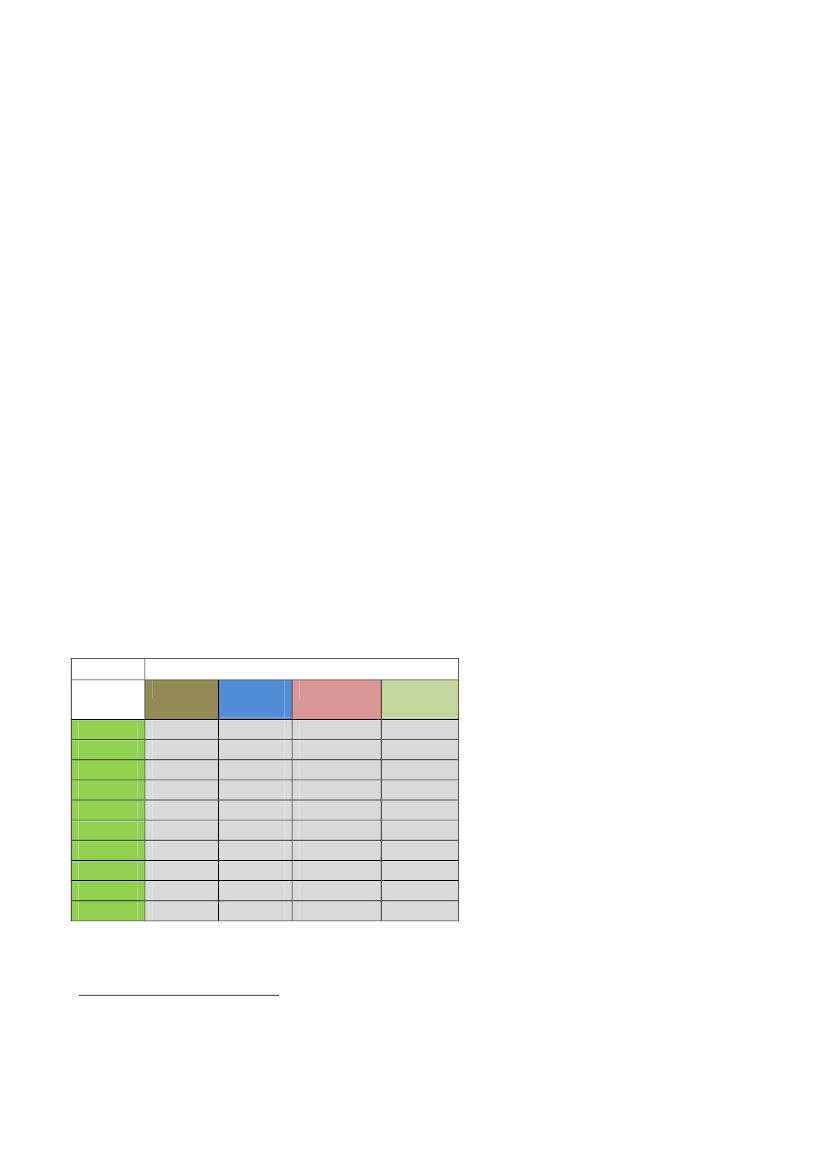

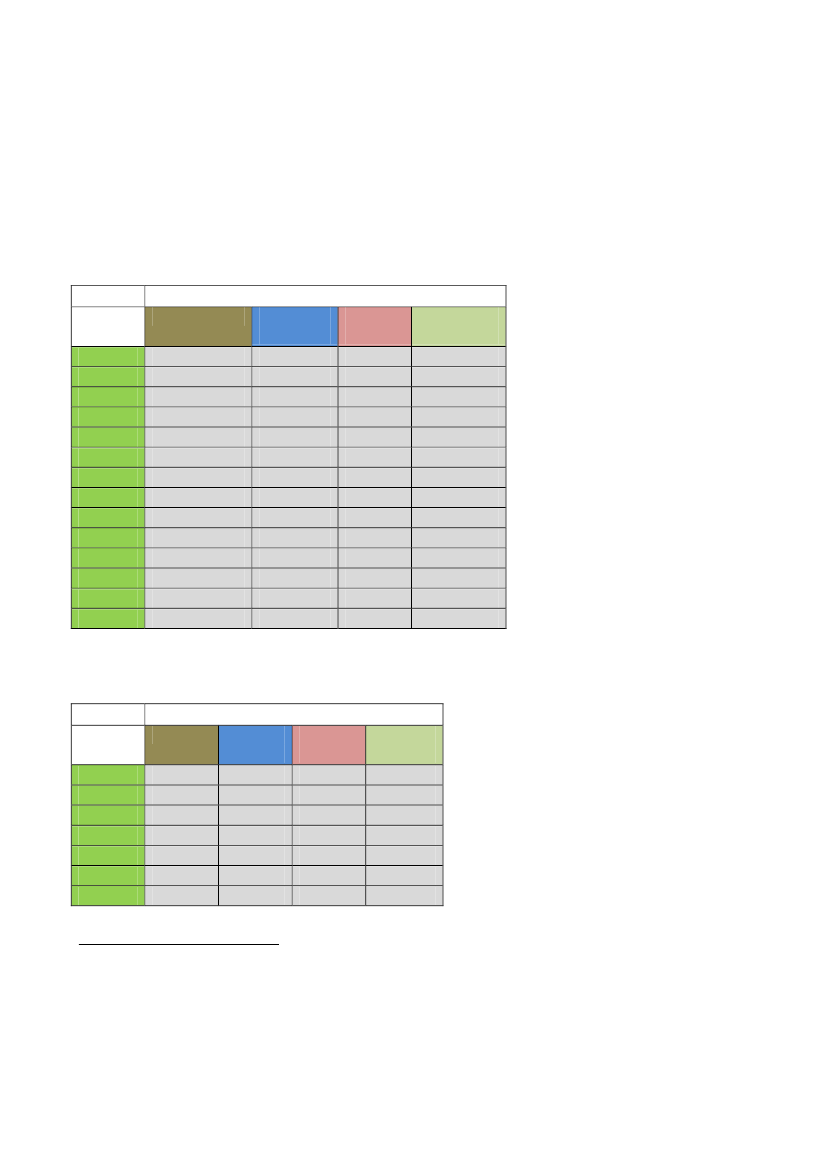

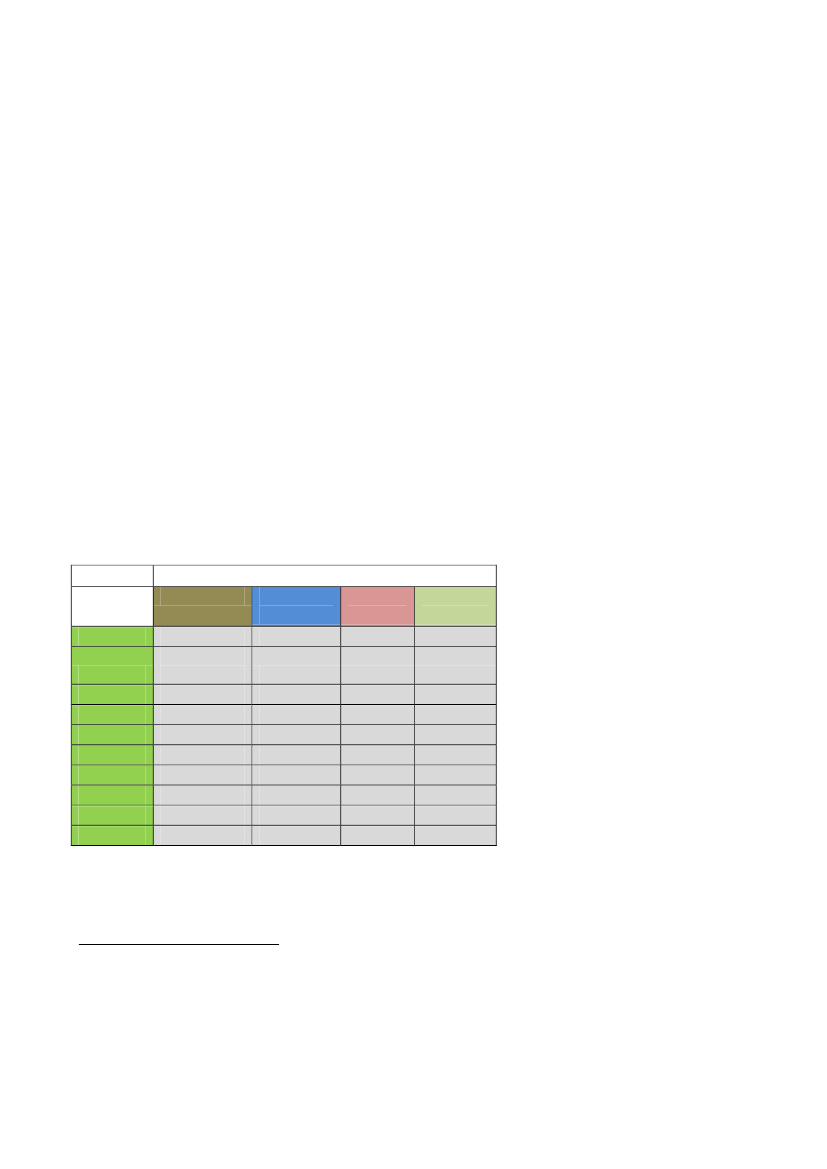

Chapter 5 Conclusions and recommendations ................................................................................................... 144I.A schematic overview ................................................................................................................................. 144A. Joint and several liability mechanisms for labour conditions: a widespread phenomenon in theEuropean Union? ................................................................................................................................ 144B. Occupational health and safety .......................................................................................................... 145C. Illegal Employment ............................................................................................................................. 146D. The legal nature of the provisions ...................................................................................................... 148E. A limited scope? ................................................................................................................................. 150F. Direct versus chain liability ................................................................................................................. 151G. Possibilities to exclude liability ........................................................................................................... 152H. Conclusion .......................................................................................................................................... 153Some general conclusions and recommendations ..................................................................................... 154A. The reasons why the introduction of a system of joint and several liability for the protection ofworkers’ rights and to fight unfair competition is called for .............................................................. 154B. Arguments pro and contra the introduction of a system of joint and several liability ...................... 157C. Up to the future: How to protect the workers of subcontractors? Joint and several liability and theneed for flanking measures ................................................................................................................ 160National jurisprudence on liability (core reports) ....................................................................................... 165Interviewed organizations (core reports) ................................................................................................... 171National legislations and liability ................................................................................................................ 175Summary table identifying the different types of measures and variables upon which authorities canintervene to enforce joint liability in the field of wages. ............................................................................ 191

II.

Annex I:Annex II:Annex III:Annex IV:

4/192

Chapter 1I.

Introduction

Background/policy context of the project

Since the late 1980s, the Member States of the European Union have witnessed a rapid growth ofsubcontracting as a method for firms and organisations to externalise certain tasks, encompassingincreasingly long and sometimes parallel chains of interconnected companies. Due to the steadily evolvingintegration and enlargement of the internal market, leading to a greater movement of capital and labouracross countries, subcontracting chains more and more often involve companies from different MemberStates. The phenomenon is particularly widespread in the construction sector, but it is also a commonfeature of other economic sectors such as transport, tourism or the cleaning industry. On the one hand,subcontracting has been encouraged by national and European policy makers and stakeholders because ofthe flexibility it creates for companies, which was deemed to benefit economic activity and job creation. Onthe other hand, the growing use of subcontracting especially in labour intensive industries led to concernsabout the possible deterioration of workers’ rights at the lower ends of long subcontracting chains, sincethe client and/or the principal contractor have no direct legal and social responsibility for the payment ofwages, taxes and social security contributions on behalf of the employees of their subcontractors.The European Commission has addressed this issue in the 2006 Green Paper on ‘Modernising labour law tomeet the challenges of the 21st century’ and in its Communication of 2007 on the outcome of the EU-widepublic consultation on the green paper. The latter reflected the conflicting opinions of various stakeholdersabout the systems of joint and several liability adopted by several Member States to tackle the problematicprotection of workers’ rights in subcontracting processes. The question whether such joint and severalliability arrangements are in accordance with Community law, in particular the free provision of services inthe internal market, was raised in two judgements of the European Court of Justice in 2004 and 2006. Inthe Wolff-Müller case (C-60/03), the Court ruled that the German liability scheme for wage payments couldbe assessed (under certain conditions) as a justified measure, whereas the Belgium scheme of joint liabilityfor tax debts was deemed to be a disproportionate and thus an unjustified measure in the Commission vBelgium case (C-433/04).Meanwhile, the issue of workers’ rights protection in subcontracting processes also caused debate in theEuropean Parliament, which adopted several resolutions on the issue. The last one, dating from 2009,called on the Commission to develop a legal instrument introducing joint and several liability for general orprincipal undertakings. Indeed, by adopting Directive 2009/52/EC on sanctions and measures againstemployers of illegally staying third-country nationals, the EU legislator did for the first time introduce chainliability rules in the framework of subcontracting processes. Where the employer is a subcontractor, theDirective, under certain conditions, provides for a mechanism of joint and several liability with respect tofinancial sanctions as well as back payments relating to outstanding remuneration; liability may also beextended to those in the subcontracting chain who knew that the subcontractor employed illegally stayingthird-country nationals.In its resolution of 2009, the European Parliament also asked the European Commission to launch a cross-sectoral impact assessment on the added value and feasibility of such an instrument at Community level,referring to the study carried out in 2008 by the European Foundation for the Improvement of Living andWorking Conditions (Dublin) on 'Liability in subcontracting processes in the European construction sector'(hereinafter ‘the Dublin study’). The Dublin study identified eight Member States where legislative and/orself-regulatory instruments on joint and several liability in subcontracting chains have been introduced. Thestudy was limited to the construction sector and did therefore neither cover possible arrangements inother sectors nor protective measures which are neither part of nor linked to any liability scheme. One ofthe study’s findings was that most of the liability arrangements did not seem to be very effective in theprotection of workers' rights in cross-border subcontracting processes.

5/192

In this regard, Directive 1996/711is of specific relevance. This so-called Posting of Workers Directive(hereinafter PWD) sets the employment conditions of workers who are temporarily posted to provideservices in a Member State different from the one where they have their original employment contract. Itestablishes a hard core of clearly defined terms and conditions of work and employment for minimumprotection of workers (laid down in Article 3 (1) a - g) that must be complied with by the service provider(for the purpose of this study: the subcontractor) in the host Member State. So, the PWD establishes forwhich subject matters mandatory (minimum) local labour standards must be fulfilled by the employer vis-à-vis the workers he posts in e.g. the framework of providing cross-border services in his capacity as asubcontractor.Despite the protection offered by the PWD, the phenomenon of the posting of workers in the framework ofthe provision of services still raises complex issues that have made this one of the most controversialaspects of EU labour legislation. Especially after the 2004 enlargement, the difficulties with the applicationof the PWD have become more numerous, in particular in situations where transitional measures withrespect to the free movement of workers were applied. Moreover, the judgements of the European Courtof Justice in the Viking, Laval, Rüffert and Commission vs Luxembourg cases gave rise to an intense debatebetween EU and national policy makers, academics and social partners on the interpretation of the PWD, aswell as more generally on their consequences for the protection of workers' rights and the right to takecollective action by trade unions.In this context, several research projects were launched by or supported by the EC, which are closelyconnected to the cross-border aspects of the topic covered by the present study.2The impression thatposted workers may be vulnerable given their situation (temporary employment in a foreign country,difficulty to obtain proper representation, lack of knowledge of local laws, institutions and language) wasclearly confirmed by the commissioned or supported research and recommendations that were made toaddress identified shortcomings. In the meantime, the EC’s Single Market Action Plan adopted as one of itskey actions “Legislation aimed at improving and reinforcing the transposition, implementation andenforcement in practice of the Posting of Workers Directive, which will include measures to prevent andsanction any abuse and circumvention of the applicable rules, together with legislation aimed at clarifyingthe exercise of freedom of establishment and the freedom to provide services alongside fundamental socialrights.”3An impact assessment study is currently being undertaken.For the situation of posted workers involved in subcontracting processes, the studies by Van Hoek andHouwerzijl on the implementation, application and enforcement of the Posting of Workers Directive in all27 Member States are of particular relevance.4In these two legal studies, firstly a detailed overview can befound of the obligations of the direct employer (for the purposes of the current study: the subcontractor)with regard to his cross-border posted workers. Where appropriate, explicit reference is made to thesereports, under the abbreviation PWD1 and PWD2.51

2

34

5

Directive 96/71/EC of 16 December 1996 concerning the posting of workers in the framework of the provision ofservices.These projects resulted in the following studies: “Posted workers in the European Union", by EIRO October 2010;"The legal aspects of the posting of workers in the framework of the provision of services in the EuropeanUnion", by Aukje van Hoek and Mijke Houwerzijl, March 2011; "Economic and social effects associated with thephenomenon of posting of workers in the EU", by IDEA consult/Ecorys, March 2011; “In search of cheap labour inEurope", by CLR/EFBWW, December 2010; "Information delivered as regards posted workers", by FabienneMüller/ Strasbourg, October 2010; “Joining up in the fight against undeclared work in Europe. Feasibility study onestablishing a European platform for cooperation between labour inspectorates, and other relevant monitoringand enforcement bodies, to prevent and fight undeclared work” by Regioplan, December 2010.COM (2011) 206, April 2011.See for the ‘PWD1 study’ of 31 March 2011: ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=6677&langId=en . This studyconcerns the following 12 EU Member States: BE, DE, DK, EE, FR, IT, LU, NL, PL, RO, SE, UK. The complementaryPWD2 study of November 2011 on the other 15 Member States (AT, BG, CY, CZ, EL, ES, FI, HU, IE, LT, LV, MT, PT,SI, SK) is not yet published.See in particular section 2.3 of PWD1 and section 2.3 of PWD2.6/192

Norway is not included in the PWD1 and PWD2 studies. Therefore, we provide here a brief description ofthe extent to which labour standards in Norway as a host country apply to posted workers. In this country,the General Applicability Act (GAA) may be seen as a statutory machinery for fixing minimum standards,including minimum wages. The Act itself does not provide for any substantive rules, but grants devolvedlegislative power to issue regulations regarding terms and conditions of employment toTariffnemnda– anindependent administrative law body, with representation from the relevant social partners. Theseregulations apply to all employees, domestic and foreign, irrespective of whether they are posted workersor not and regardless of whether they are EU/EEA or third country nationals. The General Application Actwas adopted in 1993 with a view to counteracting social dumping and safeguarding prevailing standards ofwages and working conditions. The PWD was implemented in 2000 by, inter alia, separate Regulations onPosted Workers. These Regulations refer to the General Application Act with regard to pay. In case of cross-border postingTariffnemndamay only extend minimum wage standards in collective agreements.

II.A.

Aims, method and outline of the studyAims and outline of the study

The overall objective of this project is to describe, analyse and assess the aims, objectives, functioning andeffectiveness of existing mechanisms, notably joined and several liability and chain liability schemes, withrespect to ensuring the protection of workers' rights in subcontracting processes in the EU and Norway,understood in the broadest possible way. Subcontracting refers to situations where an entity (B) contractsout to another entity (C) the provision of goods or services for its own needs. This includes cases commonlydenoted “outsourcing”, i.e. where B’s contracting-out to C is not directly linked to A having ordered theprovision of certain goods or services by B.On the basis of this comparative study, the analysis will further focus on the degree of effectiveness ofprovisions aimed at ensuring the protection of workers’ rights in subcontracting processes and identifyfeatures, which are common to several Member States, as well as to their interaction with other existinginstruments and mechanisms.Finally, this study will also formulate recommendations for possible improvements in the protection ofworkers' rights in the framework of subcontracting, including in cross-border situations.To these ends:In Chapter 2, a comparative survey is given of (legislative, administrative and conventional) measurescurrently applied in the EU Member States and Norway, which were identified as aiming, directly orindirectly, at making actors other than the direct employer co-responsible or liable for ensuring the socialprotection of workers employed by undertakings acting as subcontractors for a client undertaking.

In Chapter 3 and 4, a detailed review of relevant national law on responsibility and joint and several liabilityin (cross-border) subcontracting processes is presented. For this reason, the measures and mechanismsapplicable in a representative sample of ‘core’ countries were explored more in detail than the situation inthe other countries. The ‘core countries’ are : Austria, Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy,Luxembourg , the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Spain, Sweden and United Kingdom.Chapter 3 deals with the details of the relevant protective measures regarding workers in subcontractingprocesses, predominantly concerning wages and other employment conditions. The origin of legislation,objectives, coverage, types of tools (preventive measures and sanctions) and common features and

7/192

elements between the liability arrangements in the Member States are identified. Subsequently, Chapter 4describes and analyses their degree of relevance and effectiveness in practice. Here again, we identifycommonalities and differences and we assess the overall difficulties and best practices encountered in theapplication and enforcement of the national liability arrangements.In Chapter 5, conclusions are drawn and recommendations are made as to the ways and means to ensureand/or improve the protection of the employment conditions of workers in subcontracting processes,including in cross-border situations, as well as the formulation of relevant mechanisms.

B.

Research method

In light of the exploratory nature of the study, the research in all the countries studied (the 27 MemberStates and Norway) was based on qualitative review and analysis of primary sources such as legislative andself-regulatory measures, as well as secondary sources such as existing literature, (case) studies, policystatements, reports and publications by social partners and policy makers, relevant statistical data –if any –and case law.Although in this manner a systematic review has been undertaken with a view to measures andmechanisms that make actors other than the direct employer co-responsible or liable for ensuring thesocial protection of workers in subcontracting processes, it must be noted here that the findings in somecountry studies are more often highlighted than others. The reason for this rather uneven spread ofattention is that in many of the countries reviewed, the kind of responsibility/liability measures looked forare virtually non-existent. Hence, we would like to emphasise that all the country studies have contributedto the comparative overview and analysis in this study, also the ones which are not highlighted because not(m)any relevant measures were found.Next to the abovementioned method of qualitative review and analysis of primary and secondary sources,information for the representative sample of 14 core countries was also collected by approaching thecompetent authorities and/or offices of the countries covered by the study, employers' associations,businesses and trade unions, especially in sectors where subcontracting is widespread (e.g. construction).For this purpose, the national experts conducted, where appropriate, face-to-face or telephone interviewswith the national authorities, such as labour inspectors, the relevant social partners and other professionalbodies involved (for an overview see Annex II) , based on questionnaires drafted by the lead researchers ofthis research project.

III.

Definitions of key terminology used6

Below, we introduce the key terminology used in this report.The actors involved in subcontracting processesIn terms of the parties involved, subcontracting processes usually feature a ‘client’, ‘owner’, ‘principalcontractor’ and one or more ‘subcontractors’.

6

Mainly drawing from Chapter 1 of the ‘Dublin report’, where, in turn, the definitions of the client, owner andcontractor were drawn from the GAIPEC report of 1992 coordinated by FIEC on product liability in theconstruction industry.8/192

The clientThe subcontracting chain starts with the client, who is defined as: ‘any natural or legal person, public orprivate, who orders and/or pays for the works that are the object of a contract’ (the term ‘customer’ issometimes used but avoided in this study).The ownerOften, the client will also be the ‘owner’. The latter term refers to ‘any natural or legal person, public orprivate, who has for the time being, whether permanently or temporarily, legal title to the building or whois legally responsible for its care and maintenance’. In this study, the use of the term ‘client’ is preferredand shall be taken to include the term ‘owner’, except where the context does not permit this.The contractorThe client hires one or more ‘contractors’. A contractor may be defined as ‘any participant who agrees tocarry out the physical execution of the works that are the object of a contract’.The principal contractorIf the client only engages the services of one contractor to carry out all the work, then obviously no chain ofsubcontracting exists. However, the client may also employ the services of a single contractor who isresponsible for the entire building project, but who, in turn, outsources part of the work to othercontractors. In this case, the first contractor is referred to as the ‘principal contractor’ (sometimes alsoreferred to as the ‘main contractor’).The subcontractorsThe contractors hired by the principal contractor are known as the ‘subcontractors’, sometimes alsoreferred to as intermediary contractors (apart from the last contractor in a chain).The recipientIn their contractual relationship, the principal contractor and also the intermediary contractor in the chainare deemed the ‘recipient’ parties, who order and pay for the work or services. The recipient party mayalso be labelled the ‘order provider’, since this party gives the order to carry out the work. However, inorder to avoid confusion, this term is not used in this study.The providerThe subcontractor – who may also be an intermediary contractor – is considered the ‘provider’, who carriesout the work or services requested.Temporary work agencies (labour-only subcontracting)Apart from outsourcing work to specialised subcontractors – who may carry out the work themselves asself-employed operators or through their own employees – contractors may also engage external labour toperform some of the work under their supervision. In some sectors and/or countries, the practice of hiringworkers from temporary work agencies is less accepted than in others. In this study, the parties that onlyoffer the services of their workers to a contractor are referred to as ‘temporary work agencies’ (the moregeneral term ‘supplier’ may also be used, but is avoided in this study).Agency workerThe term ‘agency worker’ is used to refer to those employed by temporary work agenciesHirer/user companyThe terms ‘hirer’ and ‘user company’ refer to the parties that hire the agency workers.

9/192

The subcontracting chainTogether, the principal contractor and all the subcontractors may be labelled as a ‘subcontracting chain’. Itis also possible that the client himself carries out, or could have carried out, part of the physical works. Inthis case, he may function in a double capacity as both the client and principal contractor towards (someof) the subcontractors.A subcontracting chain constitutes a logistical chain, as well as a value chain of an economic and productivenature – ‘from conception to completion’. Single specialities or tasks are often ‘externalised’ to smallcompanies or self-employed workers. Subcontracting chains may sometimes take the form of a multiplechain of production – a chain which has both lengthened and broadened.These activities are carried out simultaneously or in several, subsequent phases. The chain can be seen as ahierarchical, socioeconomic dependency network, based on a linked series of contract sand connections.LiabilityFrom the Dublin study it is known that the problems at the lower ends of a subcontracting chain have led toso-called liability arrangements in the eight Member States examined in that study. In the context ofliability arrangements, relevant parties may include the ‘guarantor’, ‘debtor’ and ‘creditor’.GuarantorA ‘guarantor’ is someone who is made liable for paying the debts of the subcontractor if the latter partydefaults; in practice, this is usually the principal contractor and/or client.DebtorA ‘debtor’ in the context of this study is someone who is in debt regarding the obligation to pay wages(social security contributions and income tax), In practice, this mostly concerns the subcontractor, beingthe employer of the employees involved.CreditorIf the debtor does not fulfil the said obligations in respect of the ‘creditor’, he will therefore be indebted tothis party – for instance to the employee, the social fund, the Inland Revenue, social security authorities.Thus, the creditor can be a person, company or institution to whom or which the money is owed.Joint and several liabilityThe concept of joint and several liability in subcontracting processes can be explained as follows. If, forexample, a subcontractor does not fulfil its obligations regarding wages in respect of the Inland Revenue,the contractor together with the subcontractor can be held liable by the Inland Revenue authorities for theentire tax debt of the subcontractor. Therefore, the creditor – in this case the Inland Revenue – can recoverthe whole indebtedness from either the contractor (guarantor) or the subcontractor (debtor). Thecontractor is made liable for the total tax debt, regardless of its degree of fault or responsibility. Theguarantor (contractor) and debtor (subcontractor) are then left to sort out their respective contributionsbetween themselves. The logic behind this concept is that it should enable the creditor to address the partywith the best financial resources, which is usually a contractor higher in the subcontracting chain – oftenthe principal contractor.Chain liabilitySometimes, the liability is not only of a joint and several nature, but is a ‘chain liability’ as well. This meansthat the joint and several liability not only applies to the contracting party, but also to the whole chain. Inthe example cited above, this would mean that the Inland Revenue can address all parties in the chain,which are all jointly and severally liable, for the entire debt. In other words, it could include not only thecontractor but also, for instance, the principal contractor.

10/192

Preventive measuresSeveral (soft and/or hard law) tools have been developed to either prevent the possibility forliability/responsibility among the relevant parties or to sanction the parties which did not follow the rules.Preventive tools may be divided into two main categories:measures seeking to check the general reliability of the subcontracting party;measures aiming to guarantee working conditions such as the payment of wages.SanctionsParties who do not abide by the rules in place for the protection of workers’ rights in subcontractingprocesses may be sanctioned through a number of means, notably back payment obligations, fines and/oralternative or additional penalties.(Corporate) social responsibilityAt several levels of governance actions are taken which may be labelled as (corporate or sector-based)social responsibility initiatives in subcontracting processes. These actions can be seen as a voluntarycommitment by clients or contractors to manage their relationships with subcontractors in a responsibleway. Contractor selection is of crucial importance in chain responsibility arrangements. For example, in thecontext of public procurement, Directive 2004/18/EC and Directive 2004/17/EC as well as Convention No.94 of the International Labour Organization (ILO) on labour clauses in public contracts respectively enableand require provisions or social clauses in government procurement contracts to ensure the compliance ofsubcontractors with labour standards. The objective is to ensure that conditions imposed by publicauthorities in their role as clients, such as low pricing policies or tight deadlines, do not undermine thecapacity of subcontractors to comply with relevant labour and social standards.Effectiveness / effective impact / practical impactIt is important that no misunderstandings arise from the use of terms such as ‘effectiveness’ and ‘effectiveimpact’ or ‘practical impact’. For this study, these terms refer to whether a specific regulation/mechanismin operation produces the intended result. In other words, the report examines whether the objectives of aregulation are fulfilled in practice. An important indication for the effectiveness of a regulation is its level ofcompliance.However, the extent to which a regulation is effective may only be estimated in an approximate manner,since – up until now – no standard, quantifiable indicators exist in this field. When purely based oninterviews, the assessment of the practical impact or effectiveness of a regulation may inevitably involvesome subjective elements. In the national reports, this problem will be tackled in two ways: firstly, theinterviews will be conducted with all of the most important stakeholders which represent different andsometimes opposing views on the issue addressed – the government, employer organisations and tradeunions. Secondly, wherever possible, other sources of factual evidence will be used and referred to, such ascase law or policy reports.

11/192

Chapter 2I.

Setting the scene

Introduction

This chapter consists of an overview of measures currently applied in the 27 EU Member States andNorway which were identified as aiming directly or indirectly at making actors other than the directemployer co-responsible or liable for ensuring the social protection of workers employed by undertakingsacting as subcontractors for a client undertaking. For a more detailed perspective on existingresponsibility/liability arrangements concerning employment law protection, we refer to Chapters 3 and 4.For the purpose of the current Chapter, the 28 country experts gathered and analysed information on awide range of protective measures, not only limited to wages and other working conditions, but alsoincluding social security contributions and income tax. The results of this exploration of relevant measuresand mechanisms currently applied in the Member States and Norway are compiled below.Although in this manner a representative picture is given with a view to measures and mechanisms thatmake actors other than the direct employer co-responsible or liable for ensuring the social protection ofworkers in subcontracting processes, it must be noted from the outset that the findings in some countrystudies are much more often highlighted than others. The reason for this rather uneven spread of attentionis that in many of the countries reviewed, the kind of responsibility/liability measures we looked for arevirtually non-existent.7Hence, as already emphasised in Chapter 1-II B, it is important to note that all thecountry studies have contributed to the comparative analysis in this chapter, also the ones which are not(often) highlighted because not (m)any relevant measures were found.The chapter is organised as follows. Since the national mechanisms are partly based on existing EUinstruments, in the next section (Chapter 2-II) we identify relevant EU law in the context ofresponsibility/liability for employee protection in subcontracting processes. For the rest of this chapter wefocus on applicable rules at the national level. One way to categorise the different measures andmechanisms is by their material scope. We did this in Chapter 2-III, where we subsequently present anoverview of tools related to (minimum) wages, social funds, health & safety, social security premiums andincome tax, as well as a category of functional equivalents/alternatives including corporate socialresponsibility. Next, in Chapter 2-IV, we provide an overview of measures from a different angle. Here, themeasures are classified per group of workers or the client they aim at (illegal workers; temporary agencyworkers; procuring public entities). In Chapter 2-V, we take yet another point of view: here, we look at the(non-)existence of said measures from a country perspective. As some liability systems were the subject ofreview by the European Court of Justice, Chapter 2-VI consists of an analysis of this rather succinct caselaw, with the aim to find out what guidance the ECJ gives with respect to the possible benefits anddrawbacks of such measures in place in the Member States. This may also be useful knowledge withrespect to a possible introduction of an EU-wide liability system. The chapter ends with some concludingremarks (Chapter 2-VI).

II.

Relevant measures at EU level

As was confirmed in the country reports, several provisions that directly or (more often) indirectly benefitworkers involved in subcontracting processes are based on EU law. In particular the following Directives arerelevant: Directive 89/391 (general framework on health & safety) and Directive 92/57 (regarding health

7

For more details see Chapter 2-V A, where the (non-)existence of responsibility/liability measures is looked atfrom a country perspective and also Chapter 2-VI and the schematic overview in Chapter 5-I.12/192

&safety on temporary and mobile construction sites);8Directive 2004/18 and 2004/17 (on publicprocurement);9Directive 2008/104 (on temporary agency work, to be implemented before 5 December2011)10and Directive 2009/52 (sanctions on employment of illegally staying third-country national workers,including as an option joint & several liability, to be implemented before 19 June 2011).11Few country reports also mention legislation implementing Directive 80/987 (now repealed and replacedby Directive 2008/94 on employee rights in the event of insolvency of their employer) (IE),12legislation8

9

1011

12

Directive 89/391/EEC on the introduction of measures to encourage improvements in the safety and health ofworkers at work – OJ L 183, 29 June 1989, pp. 1-8. Directive 92/57/EEC on the implementation of minimumsafety and health requirements at temporary or mobile construction sites (eighth individual Directive within themeaning of Article 16 (1) of Directive 89/391/EEC) – OJ L 245, 26 August 1992, pp. 6-22. In particular, article 6 ofDirective 89/391/EEC states “4. Without prejudice to the other provisions of this Directive, where severalundertakings share a work place, the employers shall cooperate in implementing the safety, health andoccupational hygiene provisions and, taking into account the nature of the activities, shall coordinate theiractions in matters of the protection and prevention of occupational risks, and shall inform one another and theirrespective workers and/or workers' representatives of these risks”. Furthermore, Article 8 of said Directivestates:“3. The employer shall:(a) as soon as possible, inform all workers who are, or may be, exposed to serious and imminent dangerof the risk involved and of the steps taken or to be taken as regards protection;(b) take action and give instructions to enable workers in the event of serious, imminent andunavoidable danger to stop work and/or immediately to leave the work place and proceed to a place ofsafety;(c) save in exceptional cases for reasons duly substantiated, refrain from asking workers to resume workin a working situation where there is still a serious and imminent danger.”.Moreover, Article 10 of this Directive stipulates:“2. The employer shall take appropriate measures so that employers of workers from any outside undertakingsand/or establishments engaged in work in his undertaking and/or establishment receive, in accordance withnational laws and/or practices, adequate information concerning the points referred to in paragraph 1 (a) and (b)which is to be provided to the workers in question.” Article 12 of Directive 89/391/EEC provides: “2. Theemployer shall ensure that workers from outside undertakings and/or establishments engaged in work in hisundertaking and/or establishment have in fact received appropriate instructions regarding health and safety risksduring their activities in his undertaking and/or establishment.”Article 7 of Council Directive 92/57/EEC of 24 June 1992 on the implementation of minimum safety and healthrequirements at temporary or mobile construction sites (eighth individual Directive within the meaning of Article16 (1) of Directive 89/391/EEC) clearly states the responsibilities of clients, project supervisors and employers:“1. Where a client or project supervisor has appointed a coordinator or coordinators to perform the dutiesreferred to in Articles 5 and 6 [regarding the duties of the coordinators for safety and health matters], this doesnot relieve the client or project supervisor of his responsibilities in that respect. 2. The implementation of Articles5 and 6, and of paragraph 1 of this Article shall not affect the principle of employers' responsibility as providedfor in Directive 89/391/EEC. “.Directive 2004/17/EC coordinating the procurement procedures of entities operating in the water, energy,transport and postal services sectors – OJ L 134, 30 April 2004, pp. 1-113. Directive 2004/18/EC on thecoordination of procedures for the award of public works contracts, public supply contracts and public servicecontracts – OJ L 134, 30 April 2004, pp. 114-240.Directive 2008/104/EC of 19 November 2008 on temporary agency work.Directive 2009/52/EC providing for minimum standards on sanctions and measures against employers of illegallystaying third-country nationals – OJ L 168, 30 June 2009, pp. 24-32.Directive 2008/94/EC of 22 October 2008 on the protection of employees in the event of the insolvency of theiremployer. This Directive protects the interests of employees in respect of old-age benefits, also of thoseemployees who left the business before the insolvency occurred. In particular article 8 stipulates: Member Statesshall ensure that the necessary measures are taken to protect the interests of employees and of persons havingalready left the employer’s undertaking or business at the date of the onset of the employer’s insolvency inrespect of rights conferring on them immediate or prospective entitlement to old-age benefits, includingsurvivors’ benefits, under supplementary occupational or inter-occupational pension schemes outside thenational statutory social security schemes.13/192

and/or case law based on Directive 2001/23 (consolidating the old Directives 98/50 and 77/187) on thesafeguarding of employees’ rights in the event of transfers of undertakings, businesses or parts ofbusinesses or undertakings (LU, MT),13and legislation (partly) transposing Directives 2002/14/EC andDirectives 98/59/EC and 2001/23/EC that bring obligations of information and consultation into play (NO,NL).It is important to note that almost all relevant provisions in the Directives mentioned above only establishprotection of worker’s rights by defining obligations of the employer. This is not surprising, since saidDirectives are not specifically meant for the protection of workers employed by subcontractors. Instead,they aim at protecting workers in general or in a certain sector (the construction and the sector of thetemporary work agency), or, in the case of Directives 2004/17 and 2004/18 the aim is coordination ofprocurement procedures. Although the focus of Directive 2009/52 is neither specifically on workersemployed by subcontractors, the EU legislator did in this Directive for the first time introduce adirect wayof extending the responsibility/liability for protectingworker’s rights in subcontracting processes to othersthan the direct employer only.14For this purpose, chain liability rules were adopted in the framework ofsubcontracting processes covering illegally staying employees with a third country nationality. Where theiremployer is a subcontractor, the Directive, under certain conditions, provides for a mechanism of joint andseveral liability with respect to financial sanctions as well as back payments relating to outstandingremuneration. The liability may also be extended to those contractors further in the subcontracting chainwho knew that the subcontractor employed illegally staying third-country nationals.Another important point to note from the outset is that this existing EU acquis of directives is based onminimum harmonisation. This means that Member States are free to stick to the lowest commondenominator as provided by the set of rules in a directive. In fact, in several of the Member States whichjoined the EU in 2004 and 2007, the national implementation of said EU Directives was reported to be of aminimalist character – for instance (in LT), it was reported that the legislative provisions just repeatrelevant provisions from the Directives with no particular emphasis on their implementation mechanisms inthe national context. However, Member States can also choose to go beyond the degree of protectiongranted by a directive by introducing or maintaining rules with a higher level of protection.See for instance the Preamble of Directive 2009/52, which states that:As this Directive provides for minimum standards, Member States should remain free to adoptor maintain stricter sanctions and measures and impose stricter obligations on employers.Hence, a uniform application of national law on the topic covered by said Directives is neither aimed at, norguaranteed. As a consequence, great differences exist in the level of protection implemented and appliedby the Member States.

1314

The Acquired Rights Directive 2001/23/EC of 12 March 2001 (‘Business Transfers Directive’).See article 8 Directive 2009/52:“1. Where the employer is a subcontractor and without prejudice to the provisions of national law concerningthe rights of contribution or recourse or to the provisions of national law in the field of social security, MemberStates shall ensure that the contractor of which the employer is a direct subcontractor may, in addition to or inplace of the employer, be liable to pay… any back payments (outstanding remuneration).… Here a directcontractual relationship is required.2. Where the employer is a subcontractor, Member States shall ensure that the main contractor and anyintermediate subcontractor, where they knew that the employing subcontractor employed illegally staying third-country nationals, may be liable to make the back- payments in addition to or in place of the employingsubcontractor or the contractor of which the employer is a direct subcontractor.” Here there is a chain liability.

14/192

Finally, it must be noted that all Directives mentioned above primarily focus on establishing substantiverules to be implemented in the national legal orders. Although their scope may include situations with across-border element (or even specifically aim at that in the case of Directive 2009/52), no particularsolutions are provided for problems that may arise in this context.

III.

An overview of ‘general’ responsibility/liability measures

Below, we present an overview of measures establishing responsibility and/or liability of other parties thanthe direct employer with regard to (minimum) wages, social funds, health & safety, social securitypremiums and income tax, as well as any functional equivalents/alternatives, including corporate socialresponsibility (soft law codes of conduct).The measures are partly of a statutory nature and partly embedded in collective agreements or in codes ofconduct and other ‘soft law’ tools. Where we refer to ‘statutory law’, this is meant as a commondenominator for Acts and Regulations.15Where we refer to ‘collective agreements’, it must be noted thatthis term does cover various kinds of agreements that are not in use (in exactly the same way) in allMember States and Norway. In some countries (e.g. BE, NO16) national collective agreements exist. Thesecontain ‘basic agreements’ on general and overarching issues, mostly concluded on the confederationslevel. Sometimes, specific agreements of an industry or part of an industry, setting out provisions on wages,working time, and other concrete terms and conditions, are also included (NO). However, in this study wealways refer to such specific agreements as ‘sectoral agreements’, regardless of whether a country has orhas not linked these to national collective agreements. Sometimes, mention may also be made of(subordinate) local collective agreements concluded at the workplace. A brief overview of collective labourlaw systems in the 27 Member States was recently given in the PWD1 and PWD2 studies.17A.Measures regarding wages, including holiday payments18

With regard to the extension of responsibility and/or liability for wages to other parties than the employerof the employees involved in subcontracting processes, several instruments were identified in ten MemberStates in total, which may be distinguished in (full) chain liability and social clauses.General wage liability arrangementsIn eight countries (AT, DE, EL, ES, FI, IT, NL, NO) some kind of ‘general’ wage liability is established. With‘general’ we mean here that the liability arrangement protects the wages of all workers employed by asubcontractor. This general wage liability may be enacted at a national or at a sectoral level. Next to this, inseveral Member States also ‘specific’ wage liability instruments exist, either limited to a specific group of

15

16

1718

Definition taken from the Norwegian report by S. Evju. We also adopt his description of Acts, Regulations andCirculars: WhereasActsare legislative instruments adopted by Parliament,Regulationsare legislativeinstruments adopted by the government, by a Minister, or by an administrative body. Regulations may only beadopted in accordance with devolved (delegated) power in pursuance of an Act and are thus subordinate to Acts.Circularsetc are (internal) instructions / policy guidelines to the administrative bodies concerned.In Norway a basic agreement contains provisions of a general nature and is designed to span all or mostindustries within the umbrella of the employer side organisation.See section 2.3 of PWD1 and section 2.3 of PWD2.See in the particular context of posted workers also section 3.6 of PWD1 from p. 72 onwards, and section 3.5 ofPWD2 from p. 109 onwards.15/192

workers (such as agency workers or illegal/undeclared workers) or in the framework of publicprocurement.19These more specific tools are grouped together in Chapter 2-IV.In six of these countries (AT, DE, EL, ES, IT, NO) general wage liability tools are based on statutory rules.Additional arrangements in collective agreements exist in Greece (only in the sandblasting profession) andItaly. Regarding Norway, the General Applicability Act (GAA) contains a joint and several chain liability.Hence, Norway uses a statutory tool, which can be invoked by social partners with regard to their specificcollective agreements.Applicable to all sectorsIn Austria, a statutory liability regime regarding wages applies to all sectors, but it is not a full chain liability.There are in fact two different regimes depending on whether the subcontractor is based inside or outsidethe European Economic Area. If the subcontractor is based within the European Economic Area, adistinction is made between legitimate and illegitimate situations of subcontracting. In the latter case, astricter regime of liability applies (see also below in Chapter 2-IV A).Italy and Spain have enacted a statutory liability system for minimum wages encompassing all sectors ofindustry and binding all contractors in the chain. In the Italian and the Spanish construction sectoradditional requirements exist for the client and the contractors. The Italian law implementing the PWD,includes a special rule on joint and several liability for the Italian recipient with regard to the obligations ofthe foreign service provider.Limited to one or more sectorsIn Germany, the different rules on joint and several liability differ with respect to the sectors they apply to.The main provision on liability for minimum wage is in principle applicable to a wide category of industries,ranging from construction to industrial cleaning, postal delivery services, security services, special miningwork, laundry services, waste management and education and training services.In Greece, there are specific (mostly statutory, one conventional) rules regarding different branches of theeconomy such as construction, temporary agency employment, public works, etc. These rules coverresponsibility/liability regarding wages, including holiday payments. In the Netherlands a liabilityarrangement is set up in several extended collective agreements (for a specific statutory minimum wageliability regarding agency workers, see below under Chapter 2-IV B).Also in Finland, wage liability is incorporated in (only) some nation-wide collective agreements for instancein the construction industry. This liability of the principal contractor is however only a (albeit strong) moralobligation.20Not yet (fully) adopted and implementedNext to the arrangements in the seven Member States mentioned, in Belgium the social partners and inparticular the construction sector recently agreed to a kind of liability system with respect to the labourconditions of the employees of subcontractors including wages. However, the legal implementation is notyet finished.Social clausesSeven Member States (DK, FI, IE, IT, NL, NO, UK) are familiar with so-called ‘social clauses’ in collectivelabour agreements. In Danish collective agreements, through either a direct or an indirect clause,employees of foreign subcontractors often have to be treated like Danish employees. In Finland, several19

20

For social clauses and/or liabilities in the context of public procurement law (AT, BE, DE, EL and NO), see belowunder Chapter 2-IV C. For social clauses and/or liabilities in the context of illegal work (e.g. FR, NL), see belowunder Chapter 2-IV A.See in this regard also the Dublin study, p. 3016/192

collective agreements, for instance in the construction sector, state that a contract on subcontracting(including temporary agency work) must include a provision obliging the subcontractor (and the temporarywork agency) to respect the sector’s national collective agreement regarding the terms and conditions ofemployment. Also in the Irish and Italian construction sector and in some other branches (more or less far-reaching) social clauses are laid down in binding collective agreements.21In the Netherlands, several generally applicable collective agreements contain ‘social clauses’ which imposeon principal contractors the obligation to contract subcontractors only on the condition that they will applythe provisions of the collective agreement concerned to their employees. Under the General ApplicationAct in Norway the client is under the obligation to inform a contractor of the duty to abide by the relevantprovisions on wages and other terms and conditions of employment by the contractor himself and by allsubcontractors, and to include this in the contract for the assignment.In the UK, the main objectives of collective agreements in the construction industry are to maintaindifferentials for the differing trades and to detail all other agreed payments. They often provide a minimumrate for jobs which can be exceeded at site level. Overall, they have been the first means to maintain labourstandards in the industry and apply to all workers, including posted and migrant workers, with the NAECIagreement in particular recognising that foreign workers have been used to undermine labour standards.Measures regarding social fund payments22

B.

Responsibility/liability arrangements regarding social fund payments exist in five Member States (AT, BE,DE, IT and NL).In Austria, a liability system is applied with regard to outstanding contributions to be paid to the AnnualLeave and Severance Payment Fund by the subcontractor.In Germany, a similar system exists with regard to the contributions to be paid to the holiday pay funds.In Belgium, a liability system is enacted including social fund payments, combining this with liability for taxon wages and social security contributions.In Italy, in the construction sector a tripartite regulation exists concerning contribution payments (SingleInsurance Contribution Pay Certificate, abbrev. ‘DURC’) to e.g. social funds which contains a liability clause.A generally applicable collective agreement in the Dutch construction industry establishes two social fundschemes (a vacation fund and a risk fund). The first scheme mentioned is strengthened by a guaranteescheme, which may be invoked by the employee in case his employer defaults – this also applies in case ofsubcontracting and temporary agency work. Moreover, the collective agreement establishes, in case ofnon-compliance with the collective agreement provisions, several liability of the recipient next to thesupplier.

21

22

Under Part III of the Irish Industrial Relations Act 1946, collective agreements made between unions andemployers that are registered with the Labour Court are legally binding. While many of these are companyagreements, they can be applied to all employers and employees working in a particular sector or industry, solong as the parties to such agreements are ‘substantially representative’ of workers and employers in that sector.The most important of these so-called Registered Employment Agreements (REAs) are undoubtedly the REA forthe Construction Industry and the related, but separate, REA for the Electrical Contracting Industry.See in the particular context of posted workers also section 3.6 of PWD1 from p. 73 onwards, and section 3.5 ofPWD2, p. 118.17/192

C.

Measures regarding occupational health & safety, including working time23

With regard to health & safety, at least a certain minimum layer of responsibility of other actors in thesubcontracting chain than the immediate employer is established all across the EU and Norway, thanks torelatively elaborate EU law in this field. Below, an impression is given of arrangements in several MemberStates which clearly shows how similarities and differences go hand in hand.24A distinction is madebetween measures which pertain to jointly securing health & safety at the workplace and measures whichpertain to the prevention of or liability in case of industrial accidents.Responsibilities and liability for a healthy and safe working environmentIn Austria, the legislation on health and safety knows specific regulations containing the respectiveobligations of the employer-client and the employer-subcontractor, dealing with the exchange ofinformation, coordination and cooperation, leading to a liability system. An elaborated system exists thatdeals with occupational health and safety. In this system, the contractor has certain obligations whenemployees of the subcontractor execute their work in their business premises. It is also foreseen that incase employees of the contractor and the subcontractor are working in a joint place of work, on aconstruction site or an external place of work, the employers have to cooperate regarding theimplementation of the guidelines for the health and safety conditions. They do not only have to coordinatetheir activities, but they also have to inform each other as well as their employees about possible dangers.This can lead to certain obligations with liability aspects.Also in Belgium, the legislation on health and safety knows specific regulations containing the respectiveobligations of the employer-client and the employer-subcontractor, dealing with the exchange ofinformation, coordination and cooperation, leading to a liability system.In Bulgaria, securing health and safety work conditions is a duty of the client who makes use of theworkforce. For instance, natural persons and legal entities using workers made temporarily available byanother company must notify the contractor/subcontractor-employer about the specific characteristics ofthe workplace, the professional hazards and the professional qualification required. In Estonia in the fieldof occupational health and safety, employers have specific obligations and responsibility when employeesof at least two employers work at the workplace at the same time.In Greece, regarding health & safety, several liability arrangements exist, most importantly in theconstruction sector and the shipbuilding sector.In Spain, there are specific statutory obligations regarding health and safety in case of subcontracting. Non-compliance with these obligations also leads to joint and several liability. The latter (Act 32/2006) containsspecial rules for subcontracting in the construction sector.25In Hungary, responsibility for health and safety issues is in fact the only issue concerning employeeprotection in subcontracting processes at construction sites, which is widely discussed. The employers’liability for various types of damage is under debate regarding the contract between general contractorsand subcontractors. Formerly, the subcontractor was in principle liable for any kind of damage caused. Thatsituation changed when Hungary joined the EU in May 2004, as a ministerial decree regulated the ‘minimalhealth and safety standards at construction sites and in the course of construction processes’. This decree23

2425

See in the particular context of posted workers also section 3.7 of PWD1 from p. 78 onwards, and section 3.6 ofPWD2For a more developed account of applicable arrangements in the field of health & safety, see Chapter 3-IV below.See for more information on the specific measure in the shipbuilding industry Chapter 3-IV B under ‘additionalmeasures’.18/192

prescribes the nomination of a coordinator – that is, a natural person responsible for health and safetyissues for the overall construction project; prior to the actual work, this individual’s name must be reportedto the Labour Inspectorate (OrszágosMunkavédelemiés Munkaügyi Főfelügyelőség,OMMF).In Ireland, under the Construction Registered Employment Agreement, principal contractors are required toengage only ‘approved’ subcontractors, which they must ensure are compliant with e.g. health and safetylegislation (section 10 of the Construction REA).26In Italy, the legislation provides for some specific obligations for the client and the contractor regardinghealth & safety aiming at preventing the risk that arises from the fact that two or more parties are involved.For example, the client (as every other contractor in the subcontracting chain) is held to check the technicaland professional qualifications of the contractor (by means of a certificate of registration at the Chamber ofCommerce and a certification delivered by the contractor him or herself). All employers involved in thechain of subcontracting must also cooperate in the implementation of prevention and protection measuresthat have to be taken and coordinate their activities informing each other, as well as eliminate or minimisethe risks due to interference between the work of each undertaking. To this aim, the client is required toprepare the DUVRI (single document of interferential risk assessment), which lists all measures taken tocombat the risk of interference. The contractor and subcontractor must also equip al workers with a specialidentification card.In the report on Latvia, mention was made of requirements regarding a joint health & safety plan and thesupervision of all workers of subcontractors employed at a construction site, including those subcontractorswhich are employed at a site in their capacity of a self-employed subcontractor. Furthermore, the lawrequires the joint and coordinated liability of all employers involved where several undertakings share aworkplace or where an employer sends his workers to perform work in a workplace of another employer.In Sweden, the client or user undertaking is directly responsible for the health and safety of employees ofthe subcontractor or the temporary work agency.Responsibility for the prevention of and/or liability for industrial accidentsAlthough in France the client or user undertaking has no direct and automatic liability for accidents thatoccur at the workplace, he is responsible for the coordination of preventive measures (put in place by the(sub)contractor).Notwithstanding the fact that in Greece liability arrangements are as a rule only regulated sector-specifically, Art. 8 of Act 551/1915, which provides that the client, the contractors and the subcontractorsare jointly liable for compensation of workers in the event of an accident at work, seems to have a generalpersonal scope.In Italy, with regard to health and safety there is a joint liability for injuries suffered by the contractor’s orsubcontractors’ employees.In order to protect workers from accidents at work and occupational diseases in Lithuania, employers mustcooperate and coordinate actions in the implementation of provisions of the legal acts concerning safetyand health at work. Moreover, they must inform each other, the workers’ representatives, the employers’representatives for safety and health at work, as well as the workers about possible dangers and riskfactors. Where necessary, the employers must draw up a description of the procedure to coordinatecooperation and actions. Despite the lack of a clear liability regulated by the legislator, the case law gave avery broad interpretation to the provisions just mentioned. Both the Supreme Court of Lithuania and the26

For more information, e.g. on how principal contractors and ‘approved’ subcontractors in practice ensurecompliance and how this is enforced, see in subsections C (preventive measures), p. 58 and D (sanctions), p. 61of Chapter 3-II under ‘conventional liability arrangements and (soft law) social clauses’.19/192

Court of Appeal of Lithuania embraced the principle of several (proportional) liability of companies involvedin the accident at work level. This means that, in practice, under certain circumstances not only the directemployer, but also other contractors and the principal contractor (and/or client) can be held responsible.Regulation in the Netherlands makes the ‘actual employer’ (e.g. the contractor/user undertaking)responsible for the health and safety (i.e. working conditions and working time) of the hired/postedworkers. There is a joint safety obligation and joint liability for the agency or company which posts theworker together with the user undertaking with regard to industrial accidents or work related diseases (incertain cases of subcontracting). Furthermore, there is a special liability for user undertakings regardingworking time in cases of cross-border subcontracting.27Measures regarding tax on wages and social security contributions28

D.

In the field of tax on wages and social security contributions,twelveMember States haveresponsibility/liability arrangements in place. Measures that extend the liability for the fulfilment ofemployer’s obligations in the field of both income tax and social security contributions are enacted insixMember States (AT, BE, DE, ES, IT and NL).Fourother Member States (EL, FR, IT and LU) have such a systemin place only regarding social security contributions. Below follows a brief description per category.29Nextto this, two Member States have imposed a certain responsibility on the client and/or principal contractor(FI, IE).Liability systems regarding both subject mattersAT knows a liability system with respect to the obligations of a subcontractor to pay social securitycontributions in the country, as well as with respect to tax on wages. This is also the case in Belgium, wherea combined liability system deals with tax on wages and social security contributions and social fundpayments. Dutch statutory rules stipulate a joint and several liability for social security contributions andincome tax in case of subcontracting (including temporary agency work).However, in Germany, Italy and Spain, two separate mechanisms exist with respect to liability for taxationof wages and social security contributions. In Germany, these are both limited to the construction sector.In Austria the liability provided by Sect. 67a of the General Social Security Act is, in legal terms it is linked toSect. 19(1a) of the Turnover Tax Act. The contractor is liable for all social security contributions of thesubcontractor.30The liability of the contractor vis à vis the subcontractor is limited to a maximum of 20% ofthe wage paid. This liability is a direct liability. However, in some cases, the direct liability can become achain liability: according to Sect. 67a(10) of the General Social Security Act, the liability of the contractorincludes all (sub-)subcontractors, when the subcontracting is considered a transaction with the aim tocircumvent the liability. This way, the contractor does not succeed to evade the liability by formallyinterposing a subcontractor between himself and a sub-subcontractor. Sect. 67a of the General SocialSecurity Act provides two possibilities for the client to avoid liability: in the first place, when thesubcontractor appears on theHFU-Gesamtliste,a comprehensive listing of the companies which are2728

29

30

For more detailed information see Ch. 3-IV B, p.74, just above ‘some additional measures’.For detailed information on liability arrangements regarding this subject matter in AT, BE, DE, FI, FR, IT, NL and ES(the ‘Dublin countries’), see the Dublin report, Dublin 2008, Chapter 2.Although slightly more information is given on arrangements in the ‘non-Dublin countries’ presented under thisheading (EL, IE and LU).These include not only the contributions for the statutory health, accident or pension insurance, but alsocontributions for the statutory unemployment insurance, for the insurance against non-payment in case ofinsolvency, and for the statutory licensed severance and retirement funds, the apportionment of the employeeto the Federal Chamber of Labour, and the contribution for housing subsidies.20/192

exempted from liability and, in the second place, a money transfer of 20% of the wage to the ServiceCentre. The confirmation provided for in Sect. 7 of the Guidelines for the Consistent Enforcement of theInsurers in the Area of the Employers’ Liability 2011 doesn’t exclude the contractor’s liability, but limits it.Sect. 82a of the Austrian Income Tax Actprovides for a liability of the contractor, which is linked to theliability according to Sect. 67a of the General Social Security Act, partially by a literal repetition, partiallythrough a direct reference to Sect. 67a of the General Social Security Act, which shall ensure wage-relatedcontributions, collected by the tax authorities (Sect. 82a of the Income Tax Act).31Similar rules are provided by Article 30 bis of the RSZ-Act and the Code of Income Tax for Belgium32and by§ 28e para. 3aSozialgesetzbuchIV (SGB IV) and by § 48 para. 1 of the Income Tax Act(Einkommenssteuergesetz– EStG)for Germany.Again, these mechanisms are characterised by fierce limitations. In Austria, as well as in Belgium and inGermany, the liability for social security contributions and taxes is not only limited to a certain amount,relative to both the debt of the subcontractor as to the amount the client owes the latter. The scope is alsolimited to the construction sector.The Netherlands have an interesting system: Articles 34 and 35 of the Collection of State Taxes Act 1990(Invorderingswet1990(Dutch abrevv: IW) provide for the liability of the user firm or the principalcontractor, relating to social security contributions and wage tax.33These provisions stipulate a joint andseveral liability for the user firm (client) as well as for the principal contractor for the whole chain oftemporary work agencies and/ or (sub)contractors, who follow in line and who are at work on the sameproject at the building site, concerning their obligations about social security contributions and wage tax.34The liability does not apply in the case the whole chain is not culpable. Employers may escape this liabilityby opening a special blocked account, known as a Guarantee account or G-account. This is a blocked bankaccount in the agency’s or subcontractor’s name. This account may only be used for paying social securitycontributions and wage taxes to the Inland Revenue. User companies and (principal) contractors that use31

32

33

34