Udvalget for Udlændinge- og Integrationspolitik 2012-13

UUI Alm.del Bilag 52

Offentligt

� REUTERS/Yannis Behrakis

GREECETHE END OF THE ROAD FORREFUGEES, ASYLUM-SEEKERSAND MIGRANTS

2

GREECETHE END OF THE ROAD FOR REFUGEES,ASYLUM-SEEKERS AND MIGRANTS

� Uriel Sinai/Getty Images

“IN SYRIA YOU DIE ONCE, HERE YOU DIE MANYTIMES… WE SLEEP ROUGH AND ARE SCAREDOF RACIST ATTACKS”.A Syrian asylum-seeker in Athens, Greece, speaking to Amnesty International inOctober 2012very year, tens of thousands ofirregular migrants and asylum-seekerscross the Greek border in search ofshelter, refuge or just a better life withinthe European Union. Few of them find itin Greece.

E

of valid documents. Those detained areoften held in poor or inhuman conditionsand can languish in detention forprolonged periods.The shortage of places in receptionfacilities means that many asylum-seekersand unaccompanied children are lefthomeless, or forced to live in squalidaccommodation. On top of that, a newthreat is the dramatic increase in thenumber of racist attacks by membersof extreme right-wing groups.

Refugees, asylum-seekers and migrantsin Greece are highly exposed to a range ofhuman rights abuses. Greece still does nothave a fair and effective asylum system,and asylum-seekers face major obstaclesjust to register their claims. Those unableto demonstrate that they have applied forasylum face arrest and detention ordeportation as it is common practice inGreece for the police to detain asylum-seekers and migrants not in possession

Amnesty International December 2012

Index: EUR 25/011/2012

GREECETHE END OF THE ROAD FOR REFUGEES,ASYLUM-SEEKERS AND MIGRANTS

3

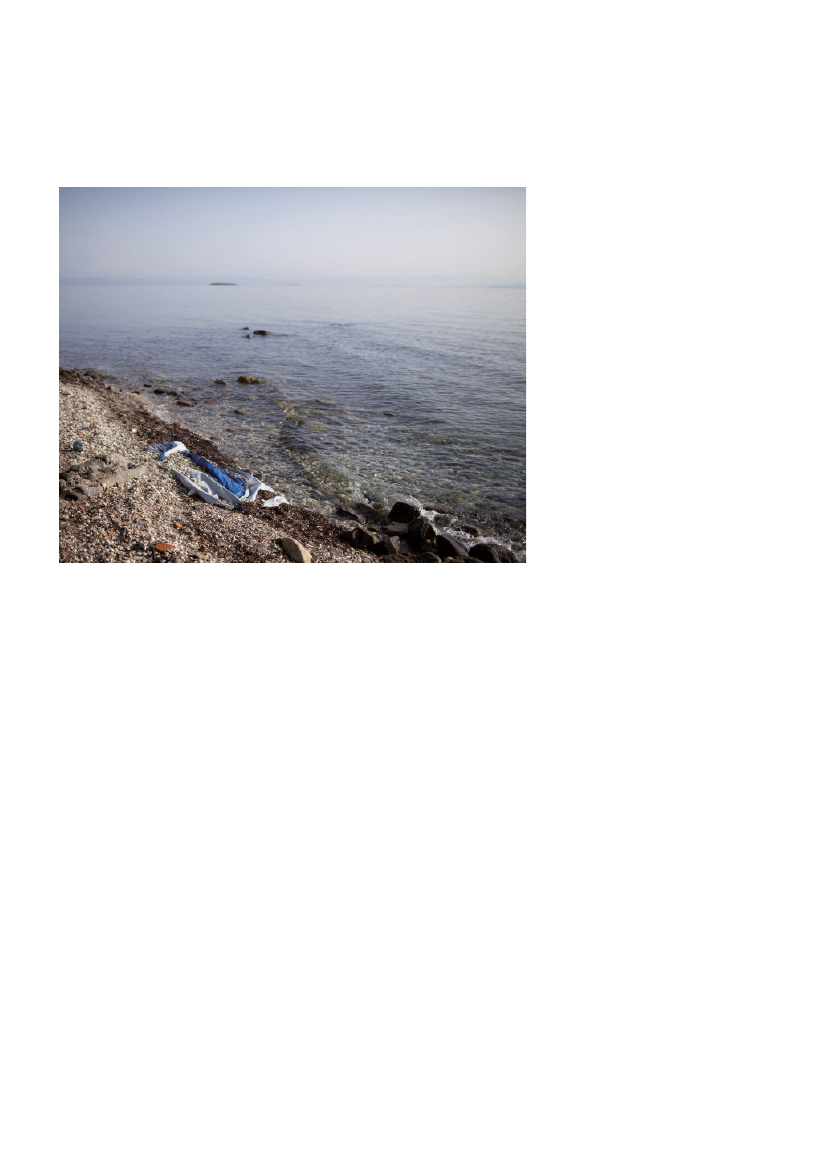

ARRIVING IN GREECEThe main land route into Greece andtherefore into the European Union (EU)is across the Evros River from Turkey. In2012, however, the number of migrants andasylum-seekers arriving through that routereduced significantly while summer arrivalsby sea increased significantly.By November 2012, a 10.5km fence wasconstructed along the part of the Greek-Turkish border where the highest numbersof entries had been recorded (on account ofthe border in that part being on land ratherthan running through the River Evros).Amnesty International believes that thefence is inconsistent with, and will lead tothe violation of, the right to seek and enjoy

asylum from persecution, since it willprevent people who are seeking internationalprotection from reaching Greece.

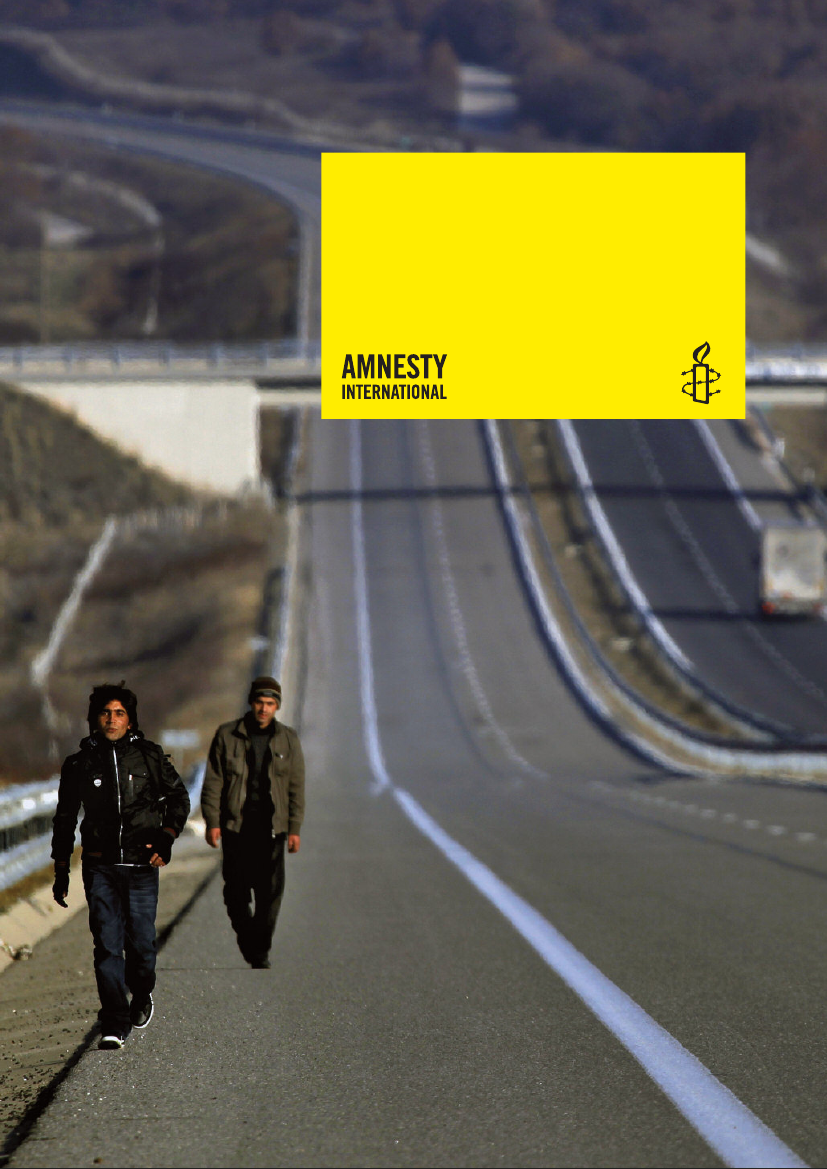

Cover:Migrants from Pakistan make their wayalong the Egnatia motorway heading south,near Feres, after crossing the Turkish-Greekborder in Evros Region, northern Greece, 25December, 2011.Above left:The remains of a rubber boat usedby migrants to cross the Aegean Sea fromTurkey to the Greek island of Lesvos is washedto shore, May 2010 in Lesvos, Greece.Above:A military officer on the site of theborder fence between Greece and Turkey,aimed at stemming irregular immigration, inthe village of Kastanies, northern Greece,February 2012.

Many of those arriving in 2012 by sea,on islands such as Leros, Lesvos, Symi,Samos and Farmakonisi, were fleeingthe conflict in Syria; among them manyfamilies with small children. Despitethis, the new arrivals were – and continueto be – detained in police stations inovercrowded, often unhygienic, conditionsor provided with no shelter at all.

Index: EUR 25/011/2012

Amnesty International December 2012

� AP Photo/Nikolas Giakoumidis

4

GREECETHE END OF THE ROAD FOR REFUGEES,ASYLUM-SEEKERS AND MIGRANTS

� Bradley Secker/Demotix

PUSH BACKS AND UNSAFE CROSSINGSSome people trying to enter Greece across theRiver Evros told Amnesty International that theyhad been pushed back to Turkey by the Greekauthorities.In June 2012, a boat carrying seven Syrians wasreportedly sunk by a Greek police boat. N., fromAleppo, Syria, described to Amnesty Internationalin October 2012 how their boat reached themiddle of the river, where supposedly the Greekborder starts, when the Greek police arrived in apatrol boat and started pushing their inflatabledinghy back towards Turkey. Then a police officerused a knife to stab the plastic fabric of theboat, which then sank, leaving people to swim tothe Turkish shore.F., another Syrian man aged 31, said that inAugust, a group of 11 people from Syria,including families with children, crossed theRiver Evros and entered Greece. He said thatthey walked to a nearby village where, at around7am the police arrested them and kept them inthe courtyard of a police station along with otherpeople, around 40 in total. At midnight, thepolice bussed them all back to the river andloaded them into two boats. The police directedthe boats into the middle of the river and hemaintained that two armed policemen pushedeveryone into the river, without life-jackets.When they made it across the river to the Turkishshore, he could only count 25 out of the groupof 40 people that the police had brought tothe river.F. made a second attempt to enter Greece, thistime via the islands. He shared the same boatfrom Turkey with C., another asylum-seeker fromSyria aged 21, who explained how he fled Syriato avoid killing or being killed; “Would you kill ababy?’’ he asked, “I saw this happening when Iwas a soldier and left when they called me upagain.”C. described how they arrived to the remoteGreek island of Farmakonisi in the followingterms: “There were 27 of us on the boatincluding three families, with three babies… Wewere taken to Farmakonisi by Turkish traffickerswho threw us in the sea with nothing but ourlife-jackets.’’ said C.F. described the conditions on Farmakonisi,where there is only a military outpost: “Therewere 100 of us, we had to sleep on the groundwithout beds or even a mattress… there wereno toilets.” One day they decided to protestabout the poor, inappropriate food and theirliving conditions. “We went on a hunger strike.In response, the soldiers began shooting, toscare and intimidate us. They used their riflesto shoot three times on the ground and twice inthe air, two metres away from us. The babieswere crying, we were scared, fearing for ourlives, especially as we were coming from a warzone ourselves.”

Amnesty International December 2012

Index: EUR 25/011/2012

GREECETHE END OF THE ROAD FOR REFUGEES,ASYLUM-SEEKERS AND MIGRANTS

5

� Bradley Secker/Demotix

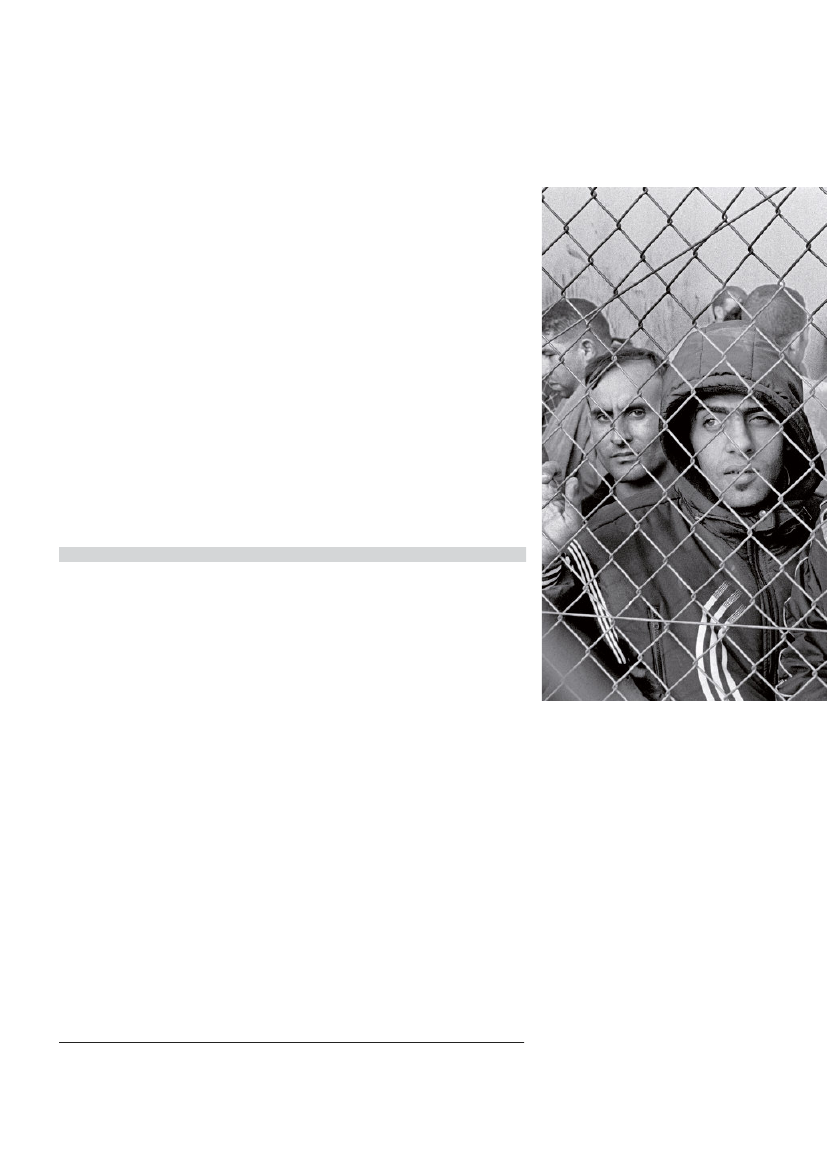

Far left:A man from Algeria is detained inFylakio detention centre, north eastern Greece.Migrants are often arbitrarily detained formonths.Left:Detained migrants in the border policestation in Tychero, Evros Region, Greece, 2kmfrom the Turkish border.

nights. “Day and night here, on the ground,in the cold and rain, we are waiting patientlyand then they send us away. Why do theyaccept only 20 people?”The rest are sent away without papers and riskdetention and deportation. This risk hasincreased since August 2012, when policesweep operations on irregular migrantsintensified. These operations, coupled with thevery limited access to asylum procedures,mean that anyone without a “pink card” (apaper proving a registered asylum claim) risksbeing detained and possibly deported withouttheir asylum claim having been registered, letalone fully and fairly determined as individualsdetained for immigration purposes also facenumerous obstacles to applying for asylum.There was no improvement by the time of alater Amnesty International’s visit to PetrouRalli in October 2012. C. from Syria (see casepage 4) said that he had been trying for fiveweeks to lodge an application, and that manypeople he knew had just given up trying. He,along with many others, complained that“now people come up to us, asking for up to€700 to secure a place for you, all under thenose of the 20 police officers standing by.”

NO SAFETY WITHOUT PAPERSUnder international law, including EU law,Greece has obligations to uphold, respect,protect and fulfil the human rights of allmigrants, asylum-seekers and refugees whoarrive in the country, however they arrive.This means that asylum-seekers must, forexample, be able to submit their applicationand to have access to a fair and effectiveprocedure to determine whether or not theyare entitled to international protection.

Attika Aliens Police Directorate in Athens, whowere hoping to have their asylum applicationsregistered by the authorities. Men and womenwere sitting or lying down in the mud andrubbish, some of them had been there fortwo or more days. These people were queuingup as part of a weekly ritual – the chance tobe one of the 20 or so applicants received bythe Greek authorities each Saturday morning.Such is the desperation in the queue thatfights can break out as people jostle for aposition. “Sometimes they end up inhospital”, said a man from Bangladesh.An asylum-seeker from the DemocraticRepublic of the Congo described how hehad already been waiting for four days and

QUEUING AT PETROU RALLIIn January 2012, Amnesty Internationalrepresentatives joined the scores of asylum-seekers queuing in the early hours of a Saturdaymorning on Petrou Ralli Avenue, outside the

Index: EUR 25/011/2012

Amnesty International December 2012

6

GREECETHE END OF THE ROAD FOR REFUGEES,ASYLUM-SEEKERS AND MIGRANTS

He had to fight for his place in the queueand was injured, but succeeded in submittinghis application the following morning.

WHO SHOULD PROTECT ASYLUM-SEEKERS AND REFUGEES?‘’Everyone has the right to seek and to enjoyin other countries asylum from persecution.’’Universal Declaration of Human Rights

The Dublin Regulation, which is part ofEU asylum policy, aims to determine whichmember state is responsible for an asylumapplication lodged within the EU (and insome other European countries to which theRegulation also applies). It usually requiresasylum-seekers be returned to the firstcountry they entered upon arrival in the EU.The Regulation is based on the assumption thatall member states have equivalent standardsof protection, which in practice is not the case.Up until 2011, most EU member states andother countries participating in the Dublinsystem used to return asylum-seekers toGreece, rather than processing their claimsfor international protection. The fact that alarge number of asylum applicants in the EUand other Dublin system participating stateshad entered the EU via Greece meant thatvery large numbers of asylum-seekers wereforcibly returned to that country withouthaving had their applications examined,which, in turn, exacerbated the already direcircumstances for asylum-seekers in Greece.This was the background to the landmarkruling in the case ofM.S.S. v. Belgiumand

� Bradley Secker/Demotix

Greece in January 2011, in which theEuropean Court of Human Rightsconcluded that Greece lacked an effectiveasylum determination system. The findingsof the European Court of Human Rightswere confirmed in December 2011 by theCourt of Justice of the European Union inthe judgement ofN.S. and Others v. UK.In light of these rulings, many Dublinsystem participating countries have haltedthe return of asylum-seekers to Greece.They should continue to do so.Despite international condemnation, Greece’sprogress towards establishing a fair andeffective asylum system has been limited.Improvements at the appeal stage of theasylum determination procedure have been

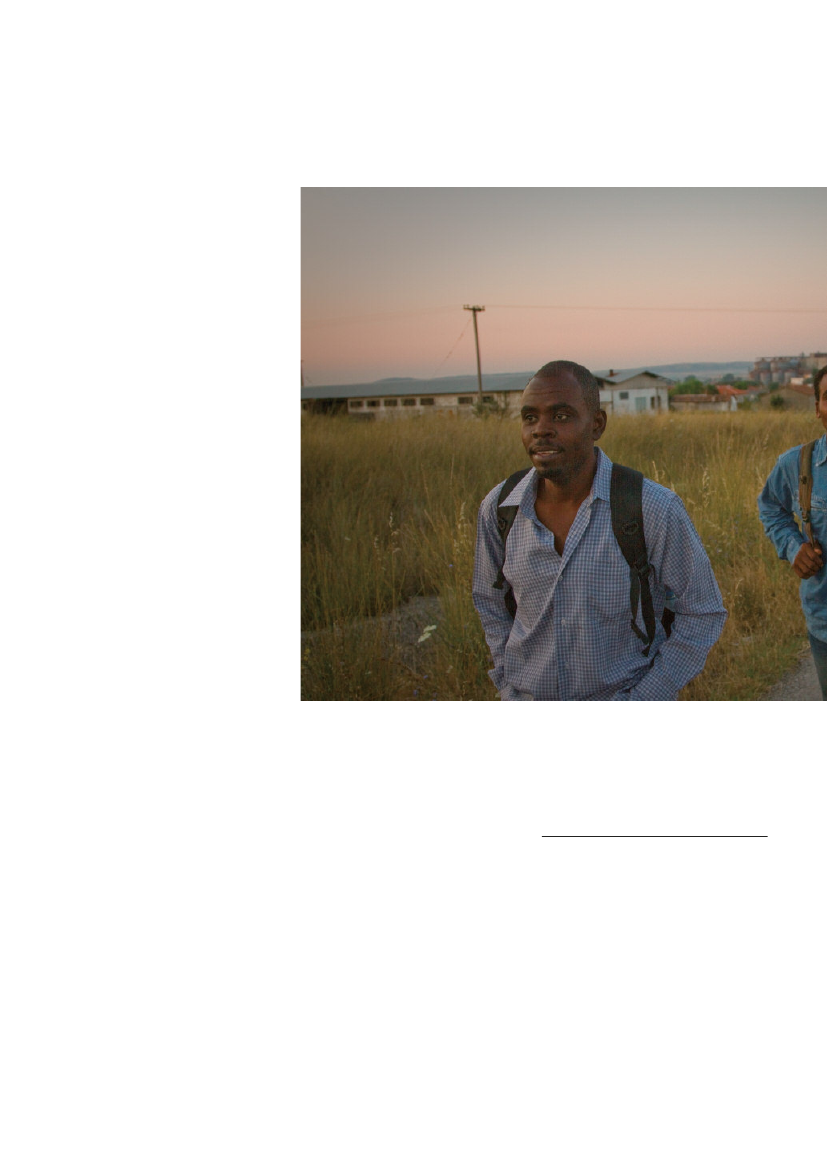

Two men from Eritrea who crossed into Greeceirregularly earlier in the morning, by swimmingacross the River Evros from Turkey, July 2011.They are searching for a police station to handthemselves in and register themselves, afterwhich they can stay in Greece for 30 days.

reported but serious impediments to accessto asylum remain as well as a major backlogof pending applications. In January 2011, anew law was adopted that promises achange to the system. It provides for theestablishment of a new, civilian authoritywith no police involvement to receive, examineand decide on asylum applications at theinitial stage. However, the Asylum Authority, asit is called, has yet to receive and process asingle application as a result of the significantstaff recruitment problems that it is facing.

Amnesty International December 2012

Index: EUR 25/011/2012

GREECETHE END OF THE ROAD FOR REFUGEES,ASYLUM-SEEKERS AND MIGRANTS

7

PRINCIPLE OFNON-REFOULEMENTGreece is obliged under international law torespect the principle ofnon-refoulement,according to which no-one should beremoved to any country or territory where heor she would face a real risk of persecutionor other forms of serious harm. In violation ofthis principle, in the past few years, severalasylum-seekers in Greece have beenreportedly deported without their claimshaving been registered, let alone fully andfairly determined.

DETENTION FIRST, QUESTIONSLATERSweep operations by the police to round uppeople with no papers intensified in 2012.Those wishing to apply for asylum who donot manage to do so are at risk of arrest,detention and – if they also do not manageto apply for asylum while in detention –possible deportation. Detention forimmigration purposes in Greece is used as amatter of course rather than, as internationalhuman rights standards require, as a lastresort. Under EU law, detention may only beused after the authorities have demonstratedthat it is both necessary and that lessrestrictive measures are insufficient.In October 2012 a new law on asylumdetermination procedures gave police the

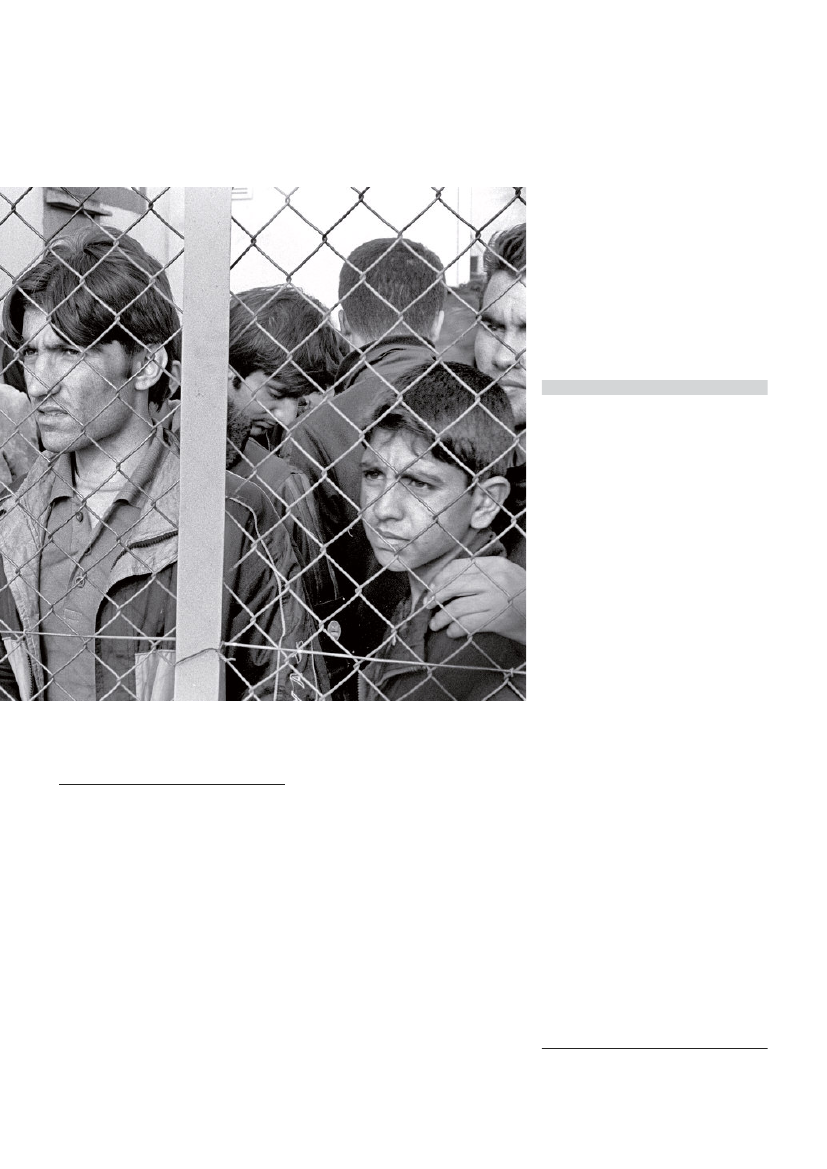

Asylum-seekers outside Attika Aliens PoliceDirectorate on Petrou Ralli Avenue, 28 January2012, queuing for days and nights, with limitedchances of lodging their application.

discretion to extend the maximum three orsix-month period that an asylum-seeker canbe held to a further 12 months. The threatof being held for up to 18 months, inappalling conditions, may deter asylum-seekers from applying for internationalprotection, particularly in view of theauthorities’ practice of holding people whoapply for asylum while in detention forprolonged periods.

Index: EUR 25/011/2012

Amnesty International December 2012

� Amnesty International (photo: Kusha Bahrami)

8

GREECETHE END OF THE ROAD FOR REFUGEES,ASYLUM-SEEKERS AND MIGRANTS

THE STORY OF K.Amnesty International interviewed several peoplequeuing at Petrou Ralli. On 7 July 2012, AmnestyInternational representatives talked to K., anasylum-seeker of African origin who requested toremain anonymous. K. told Amnesty Internationalthat he arrived in Greece after a long andperilous journey. “I have been trying to apply forasylum for the past six months” he explained. Hesaid that the other day, somebody threatenedhim with a broken bottle to make him abandonhis place: “When we ask the police for protectionthey tell us ‘fight back’.”K. called Amnesty International at the beginningof August to say that he had been arrestedduring a sweep operation in Athens and that hewas being held at the Petrou Ralli detentionfacility.He had not succeeded in registering his asylumclaim as he did not manage to get to the front ofthe queue. As a result, he was detained as anirregular migrant. A few days later he wastransferred to a detention centre somewhere innorthern Greece.K. kept on trying to apply for asylum while indetention: “the officer says ‘tomorrow’ everytime I ask him” he told Amnesty Internationalrepresentatives when they saw him at the end ofAugust and in later telephone conversations.Finally, in October, two months after his arrest,K.’s asylum application was registered, followingmultiple interventions by non-governmentalorganizations. However, in December 2012, hewas still being held in detention.In October, many detainees at the centre went onhunger strike in protest over their detentionagainst a backdrop of poor detention conditionsand alleged ill-treatment. A riot broke out inNovember reportedly sparked by the tearing of aKoran by police guards.

� Georgios Giannopoulos

CONDITIONS IN DETENTIONThe conditions in various immigrationdetention centres and police stations whereasylum-seekers and irregular migrants areheld have frequently been criticized byinternational organizations. The EuropeanCourt of Human Rights has found Greeceto be violating the prohibition of inhumanor degrading treatment in several cases inrecent years, relating to the conditions ofdetention for people held for immigrationpurposes.In July and August 2012, AmnestyInternational visited various detentionfacilities in Athens, and the Komotini policeacademy, which was being used to holdpeople for immigration purposes followingthe sweep operations against irregular

Amnesty International December 2012

Index: EUR 25/011/2012

GREECETHE END OF THE ROAD FOR REFUGEES,ASYLUM-SEEKERS AND MIGRANTS

9

THE STORY OF H.A.In late August 2012 Amnesty International visitedthe Komotini Police Academy in north-east Greece,having been told that at least one child was beingheld. The Director initially claimed that there wereno children, but eventually acknowledged thatH.A., aged 15, was detained there.H.A. had arrived in Greece in September 2011from Afghanistan with his mother and hisyounger brothers and sister. His father is seekingasylum in the Netherlands.H.A. was arrested during a police sweep operation inAugust and separated from his family. When talking toAmnesty International H.A. was evidently scared anddid not know how long he would have to stay indetention. He said that the toilets were dirty (thoughthey had clearly been cleaned shortly before thedelegates’ visit), there was no warm water and that hewas first allowed to exercise outside just the day beforethe organization’s visit – two weeks after he arrivedat the detention facility. He said that there were threeother children in the same facility, although the Directorinsisted that this was not the case. He did, however,promise to move H.A. to an appropriate facility.H.A. was moved to the police cells of the Iasmosdetention facility in Rhodopi the same day, afacility purportedly appropriate for minors. However,according to the Greek Council of Refugees lawyerwho visited him, H.A. was detained with adults andsometimes even with people facing criminal charges.The lawyer said that the police cell in which H.A.was held was very small, with no outside exercisespace and with little natural light. On 7 October2012, H.A. was transferred to a reception facilityfor minors in Konitsa (north-west Greece).

Asylum-seekers and migrants held in theFylakio Detention Centre, Evros Region,northern Greece, October 2010.

DETENTION OF UNACCOMPANIEDCHILDRENUnaccompanied or separated children inGreece continue to be routinely held indetention, and for prolonged periods, until aplace in a reception centre is available. TheAmygdaleza immigration detention centrefor unaccompanied male children washolding children in substandard conditionsfor up to three months in August 2012because of the insufficient number ofplaces in reception centres. AmnestyInternational visited centres in Athens andEvros where children were being detainedwith adults and/or were registered as adults.

migrants conducted in August. In theElliniko detention facilities, conditionsamounted to inhuman and degradingtreatment. In both the New and Old Ellinikodetention facilities, bedding was old anddirty, toilets were filthy and detainees hadaccess to poor quality drinking water.Those held at Old Elliniko had no accessto outside exercise and no natural lightreached their cells.

Index: EUR 25/011/2012

Amnesty International December 2012

10

GREECETHE END OF THE ROAD FOR REFUGEES,ASYLUM-SEEKERS AND MIGRANTS

� EPA

RACIST ATTACKSSince 2010, asylum-seekers, refugees andirregular migrants, as well as the unofficialmosques, shops and community centresthey have developed, have been targeted inracially-motivated attacks. There was adramatic rise in the number of attacksthroughout 2012. The economic crisis andsevere austerity measures have heightenedxenophobic feelings in some sectors ofsociety and played into the hands of extremeright-wing groups. Golden Dawn, a far-rightpolitical party with an aggressive anti-migrantrhetoric gained 18 seats in the Greekparliament in the June 2012 elections.Victims are usually unwilling to report theattacks to the authorities, particularly thosewhose irregular migration situation renders

them vulnerable to arrest and detentionthemselves. This contributes to the generalclimate of impunity for the perpetrators ofsuch attacks.In November 2012, the Minister of PublicOrder and Citizens’ Protection presented adraft presidential decree providing for theestablishment of specialized police units atthe Athens and Thessaloniki policedirectorates to tackle racially motivatedcrime. However, the draft decree does notinclude a provision that would protect victimswho are in an irregular situation from arrestand deportation during the investigation andpossible prosecution of alleged perpetrators.In October 2012, the Racist ViolenceRecording Network published their findings

Amnesty International December 2012

Index: EUR 25/011/2012

� EPA

on incidents of racially motivated violencebetween January and September 2012. TheNetwork found that more than half of the 87recorded incidents were connected withextremist groups that acted in an organizedand planned manner. In certain cases, thevictims or witnesses reported that theyrecognized individuals associated with thefar-right political party, Golden Dawn amongthe perpetrators.On 7 September 2012, in Rafina, GoldenDawn supporters were joined by one of theirmembers of parliament (MPs) and attackedmarket stalls belonging to migrants withsticks and batons. A few hours later, asimilar incident took place in another city,Messolongi, again with the participation ofan MP for Golden Dawn. In October 2012,

GREECETHE END OF THE ROAD FOR REFUGEES,ASYLUM-SEEKERS AND MIGRANTS

11

Below:The blood stained clothes of a victim ofa racist attack, Greece, August 2012.� Toumpanos Leonidas

Above left:A racist attack on a migrant in thecentre of Athens, Greece, 12 May 2011. Thegroup wear Greek flags and carry a variety ofimprovised weapons.Above:A racist attack on a migrant in thecentre of Athens, Greece, 12 May 2011. Oneof the attackers carries a knife.

NEIGHBOURHOOD ATTACKSOn 10 September 2012, at around 8.30pm twomen dressed in black entered a barbershop runby a Pakistani man. “At first they verballyattacked the Greek customer who was present,asking him why he was having a haircut in ashop owned by Pakistanis”, said S.I. who waspresent in the shop, “he reacted and the twoguys stabbed him.” Z.A., who worked in theshop, said, “then they started destroying theshop and throwing Molotov cocktails… onecame so close to my head that part of my hair isburned.” However, this was not the only incident.“We have often seen the people who attacked usthat day” said S.I., “they are boys, around 18 to20 years old, who pass by nearly every week andthreaten to shut down the shop. A week beforethe attack they were throwing rocks andbreaking the shop windows.”The police came to investigate the incident andafter a brief questioning they arrested both Z.A.and S.I. because they had no documents. InOctober, they were both in detention, pendingdeportation. There were no reports of arrests ofthose responsible for the attacks.

the Greek parliament lifted the immunityfrom prosecution of the two Golden DawnMPs who participated in the events. InNovember 2012, a prosecutor broughtcharges for, among other things, unlawfulviolence, damage to property and violationsof the law on racial discrimination, againstK. Barbarousis, one of the Golden DawnMPs, in relation to the incident at themarket of Messolongi.

Index: EUR 25/011/2012

Amnesty International December 2012

12

GREECETHE END OF THE ROAD FOR MIGRANTS ANDASYLUM-SEEKERS

� Socrates Baltagiannis/Demotix

CONCLUSIONDue to its position, Greece remains one ofthe main entry points for refugees, asylum-seekers and migrants seeking to enter theEU. The burden on Greece is great and,given the current economic crisis,increasingly difficult for it to deal with alone.Greece clearly needs support from the EUto carry this burden. However, this cannotexcuse the impediments that deny peopletheir rights, the xenophobic rhetoric, or theracist attacks. It is time that Greece and theEU act to put an end to the violations of therights of asylum-seekers and migrants.

RECOMMENDATIONSTo the Greek authorities:To European Union member states and otherparticipating countries in the Dublin system.

Implement the reforms of the Greekasylum system, and ensure unimpededaccess to asylum determinationprocedures particularly in the Attika AliensPolice Directorate in Athens;n

n

Prohibit the detention ofunaccompanied migrant and asylum-seeking children in law and end it inpractice.Combat the increase in racialdiscrimination and related violence,including by publicly condemning all suchintolerance, and by prosecuting andpunishing the perpetrators of such acts.

Abide by the rulings of the EuropeanCourt of Human Rights and the Courtof Justice of the European Union bymaintaining the halt of transfers of asylumseekers back to Greece and takeresponsibility for those asylum seekers.n

n

n

Share responsibility for asylumseekers more equally, taking into accountactual protection standards and asylumseekers' needs.

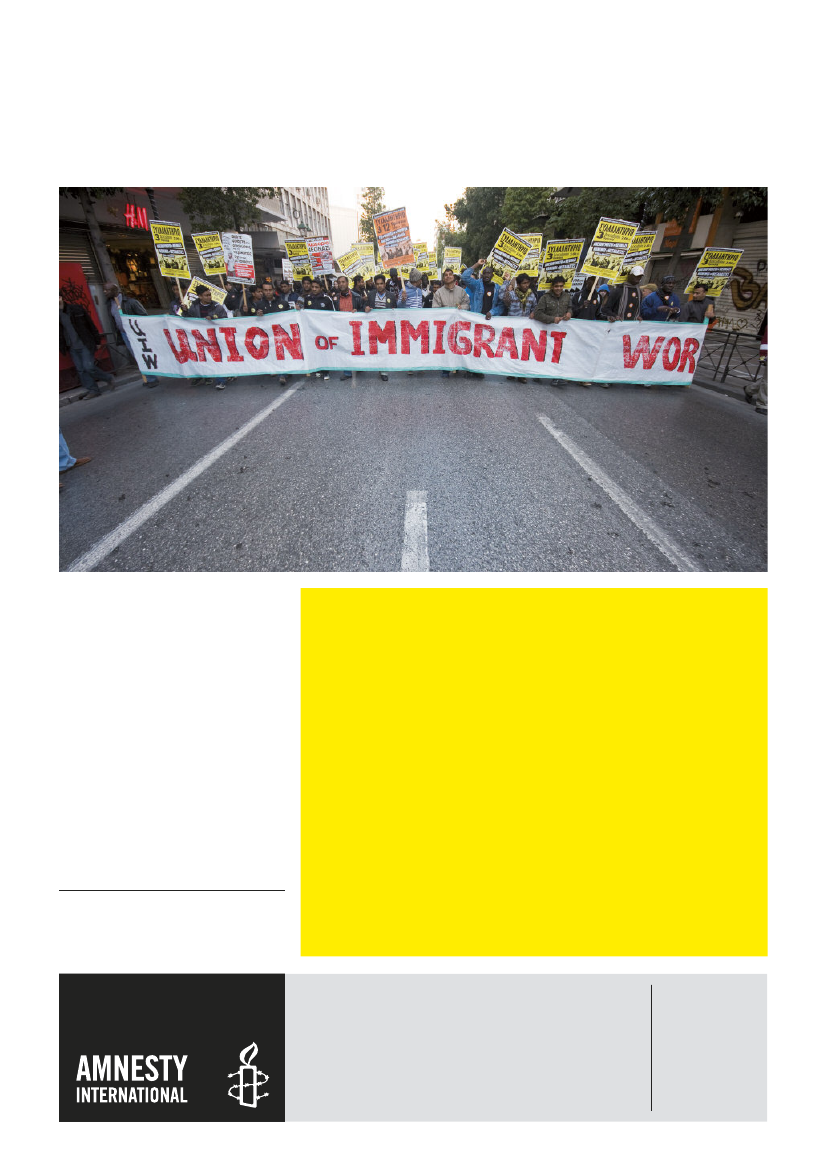

Above:People march through the streets ofAthens, Greece, to protest against racism andin favour of immigrants' rights, December2011.

Amnesty Internationalis a global movement of more than 3 millionsupporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries andterritories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights.Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in theUniversal Declaration of Human Rights and other international humanrights standards.We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interestor religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations.

Index: EUR 25/011/2012EnglishDecember 2012Amnesty InternationalInternational SecretariatPeter Benenson House1 Easton StreetLondon WC1X 0DWUnited Kingdom

amnesty.org