Udvalget for Udlændinge- og Integrationspolitik 2012-13

UUI Alm.del Bilag 133

Offentligt

FRONTIEREUROPEHUMAN RIGHTS ABUSES ONGREECE’S BORDER WITH TURKEY

Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters,members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaignto end grave abuses of human rights.Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the UniversalDeclaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards.We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest orreligion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations.

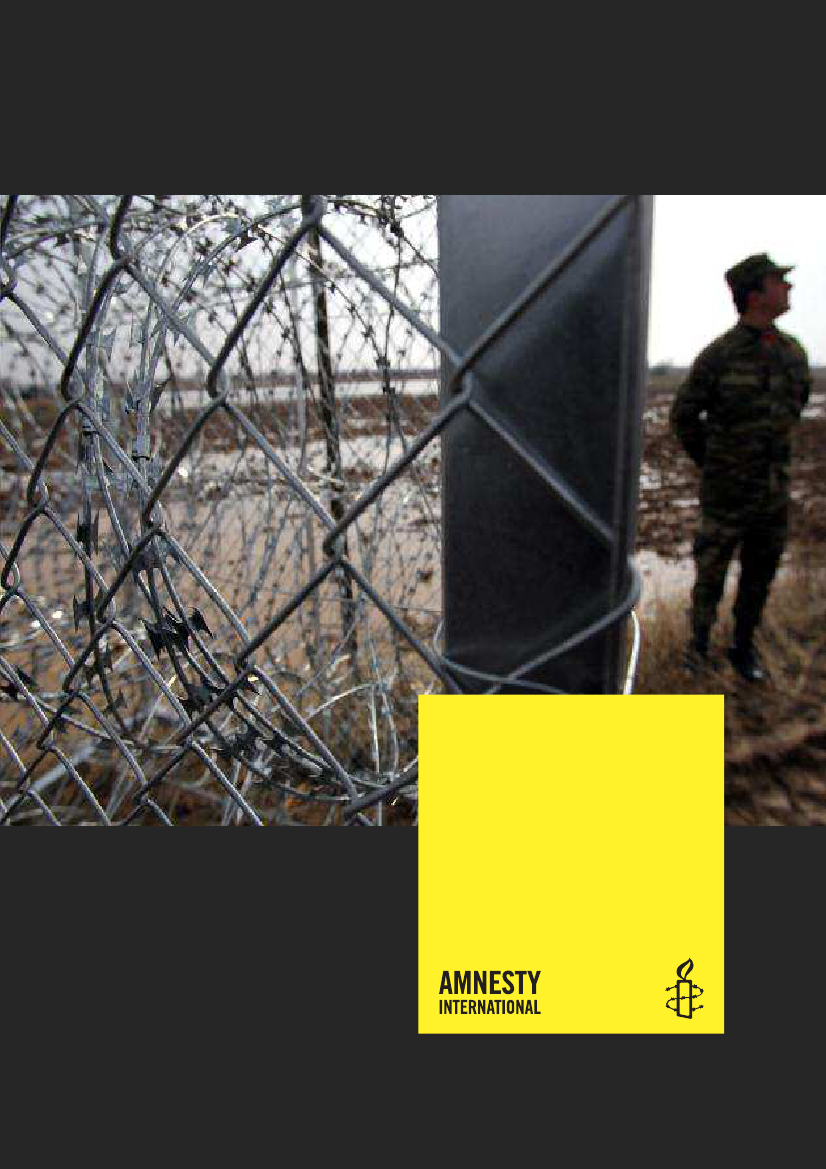

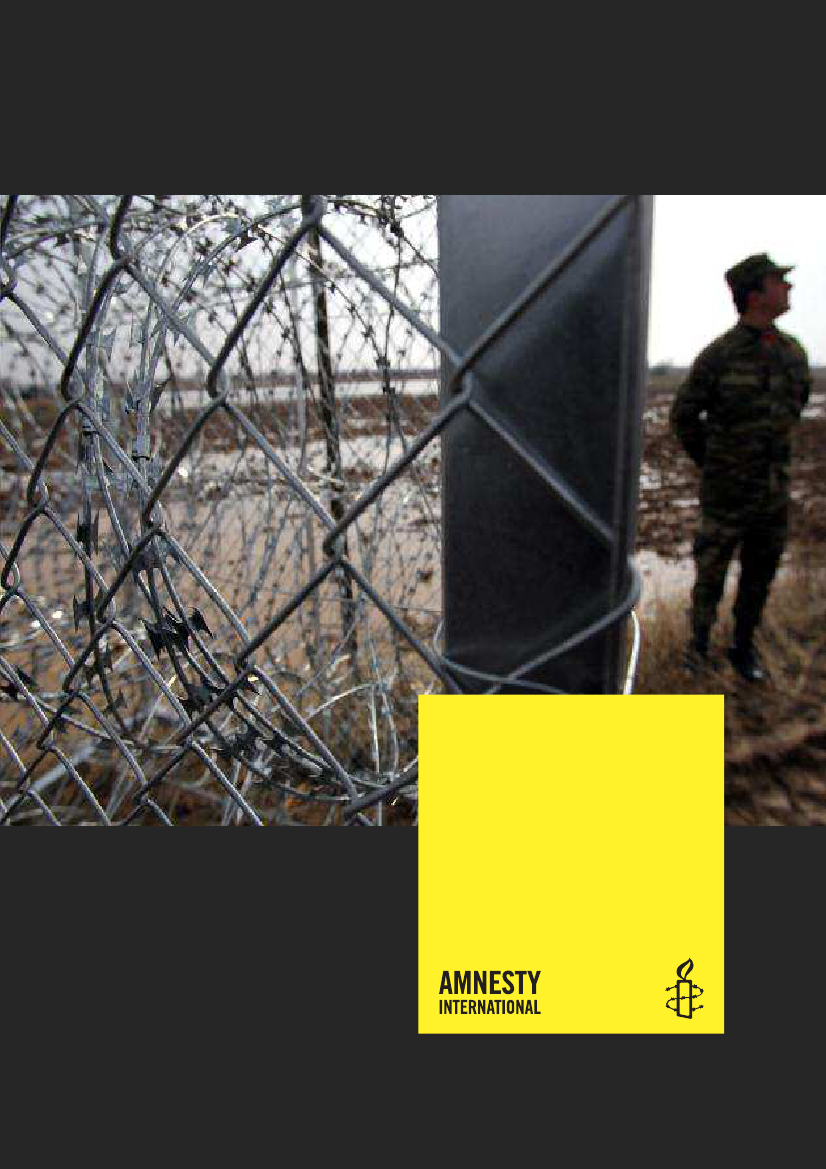

First published in 2013 byAmnesty International LtdPeter Benenson House1 Easton StreetLondon WC1X 0DWUnited Kingdom� Amnesty International 2013Index: EUR 25/008/2013 EnglishOriginal language: EnglishPrinted by Amnesty International,International Secretariat, United KingdomAll rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but maybe reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy,campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale.The copyright holders request that all such use be registeredwith them for impact assessment purposes. For copying inany other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications,or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission mustbe obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable.To request permission, or for any other inquiries, pleasecontact [email protected]Cover photo:Construction of the border fence in Evros region,Greece, February 2012. The 10.5km fence now shields thenorthern part of Greece’s land border with Turkey, which usedto be one of the busiest transit points for irregular migration toEurope.� AP Photo/Nikolas Giakoumidi

amnesty.org

CONTENTS1. Introduction: EU’s Frontier in the Eastern Mediterranean: the Greece-TurkeyBorder ........52. Crossings from Turkey to Greece .................................................................................73. Collective expulsions (push-backs) on the Greece-Turkey Border ....................................93.1. Push-back operations putting lives at risk ............................................................113.2. Ill-treatment during push-back operations ...........................................................134. Sweep operations resulting in collective expulsions ....................................................155. Prolonged detention of asylum seekers and irregular migrants ......................................175.1. Detention conditions .........................................................................................195.2. Detention of children ........................................................................................216. Conclusion: Shared EU Responsibility for its External Borders .....................................24Recommendations ......................................................................................................26Glossary .....................................................................................................................28Endnotes ...................................................................................................................29

FRONTIER EUROPEHuman rights abuses on Greece’s border with Turkey

5

1. INTRODUCTION:EU’S FRONTIER IN THEEASTERNMEDITERRANEAN: THE GREECE-TURKEY BORDER“Don't you know they built a wall in the North? It isimpossible to cross the land border now. Greecedoesn't accept refugees anymore.”A., 27-year-old Palestinian refugee, said that the Greek coastguard pushed him back to Turkey along with 52 others in earlyFebruary 2013. He was in detention in Turkey on 18 February 2013 when he was interviewed by Amnesty International.

“The creation of the fence built by Greek resources is not the solution of the problem. But it is a measure, anoption with a powerful symbolism, a message that shall reach nationals of third countries, smugglers andtraffickers who want to use our country as a transit country for their migration to the countries of EuropeanUnion.”Greek government’s response to the report of the UN Special Rapporteur on the human rights of migrants, 19 April 2013.1

The external frontier of the EU between Turkey and Greece is made up of a 203km landborder in the Evros region in the North and a sea border on the Aegean in the South. Thisborder has long been one of the main entry routes for migrants and refugees trying to findsafety or a better life in Europe. In 2012, it saw the largest number of irregular entries to theEU out of all the EU's external borders.2A large number of those arriving are from conflict-torn countries like Afghanistan and Syria. Research by Amnesty International has foundinstances of shocking human rights violations against them by the Greek authorities.In the last few years Greece has invested millions of euros in keeping migrants out. In 2012it completed a 10.5km fence along its land-border with Turkey and deployed almost twothousand new border guards there. In the meantime, a new body established by law in 2011to process asylum requests first began functioning–and then only partially–in June 2013.Amnesty International acknowledges the prerogative of states to control the entry into andstay of non-nationals in their territory and of the EU to support member states in carrying outlegitimate bordercontrol. However, the manner in which Greece’s border with Turkey is beingcontrolled is leading to serious human rights violations.

Index: 25/008/2013

Amnesty International July 2013

6

FRONTIER EUROPEHuman rights abuses on Greece’s border with Turkey

The Greek government is trying to seal its borders not only through increased surveillance andthe construction of a fence; but research by Amnesty International shows that those who doarrive are sometimes pushed straight back to Turkey. Those returned to Turkey under suchcircumstances are denied the chance to apply for asylum in Greece or explain whether theyhave other needs, in flagrant violation of international law.Amnesty International’s research also shows that the way in which such push-backoperationsare carried out by the Greek border guard or coastguard is putting lives at risk. Several ofthose interviewed by Amnesty International claimed they were abandoned in the middle ofthe sea on unseaworthy vessels or left on the Turkish side of the land border with tied hands.As Turkey only recently passed its first law on international protection and does not providerefugee status to those coming from countries that are not members of the Council of Europe,the support individuals sent back to Turkey receive remains highly limited. Various humanrights bodies and non-governmental organizations have also highlighted the difficulties ofaccessing protection in Turkey and the risk of being sent back to a country where some mightface persecution or other serious harm.3Migrants intercepted at borders and irregular migrants identified in the course of sweepoperations within Greece, face lengthy detention–often in appalling conditions–without anassessment of the necessity and proportionality of detention as required by law.Other EU member states appear only too happy for Greece to act as their gatekeeper. But thepolicies and practices along the Greek border do not just shame Greece: they shame theEuropean Union as a whole. They expose the bitter irony of European countries pressing forpeace abroad while denying asylum to, and risking the lives of those who seek refuge inEurope from conflicts in their homelands.

METHODOLOGYThis report is prepared based on information collected from migrants, refugees, non-governmentalorganisations, lawyers, relevant government authorities and the United Nations High Commissioner forRefugees (UNHCR) in Greece in the course of research visits to Turkey and Greece in March and April 2013.Updated information was also gathered through telephone interviews in May and June 2013. Amnestyinternational researchers conducted almost 80 individual interviews with refugees and migrants who hadrecently crossed, or attempted to cross, the border between Greece and Turkey. This report also draws ondiscussions with groups of detainees and observations at nine facilities in Greece and one facility in Turkey(Edirne Removal Centre), where irregular migrants and asylum seekers were detained. Individual intervieweesincluded women, men and unaccompanied children from Afghanistan (24), Algeria (1), Bangladesh (1),Cameroon (1), Eritrea (3), Iran (2), Iraq (2), Ivory Coast (1), Morocco (1), Nigeria (1), Palestine (4), Somalia(14), Sudan (10) and Syria (14).

Amnesty International July 2013

Index: 25/008/2013

FRONTIER EUROPEHuman rights abuses on Greece’s border with Turkey

7

2. CROSSINGS FROM TURKEY TOGREECEUp until 2010, most migrants and refugees sought to reach Greece by crossing the AegeanSea in small boats.4That year the main route shifted to the land border in the Evros region,which for the most part runs along the River Evros. This was partly because of increasedsurveillance at sea by Greek coastguards supported by Frontex–the European BorderAgency5- and partly because the Greek government had removed the anti-personnel minesalong the land border, making it less dangerous for migrants to cross on foot from Turkey.6In mid-August 2012, however, Greece launched Operation Aspida (Shield) to stop migrantsentering irregularly across the Evros border by deploying more than 1,800 additional policeofficers7and constructing a 10.5km fence along the northern section of this land border.According to Frontex these developments have had such an impact that less than tenirregular migrants a week were detected crossing this border at the end of October 2012,down from 2,000 in the first week of August 2012.8With heightened security on the land border, more and more refugees and migrants are againtaking the more dangerous sea route to Greek islands on small boats. According to the Greekpolice, the number of migrants apprehended crossing the land border irregularly droppedfrom 15,877 in the first five months of 2012 to 336 in the same period in 2013;apprehensions on the Greek islands or in the Aegean rose from 169 in 2012 to 3,265 in2013 for the same period.9This shift of the migration route back to the Aegean Sea is claiming lives. Since August2012, 101 individuals–mostly Syrians and Afghans, among them children and pregnantwomen–have lost their lives in at least six known incidents in this stretch of water.10

FRONTEX ON THE GREECE-TURKEY BORDER: POSEIDON LANDAND SEA OPERATIONSThe EU and its member states have provided support to Greece to police its borders as part of efforts to controlirregular migration to the EU through Greek land and sea borders. Since 2006, border patrol operations, named“Poseidon Joint Operations”,have been carried out with the participation of more than 20 EU member statesand Schengen Associated Countries. Participating states have provided technical equipment and guestofficers to patrol the borders, identify countries of origin (“screening”) andinterview migrants to gatherinformation on trafficking networks and routes used by smugglers (“debriefing”).11At the time of Amnesty International’s visit to Greece in April 2013, Frontex had only one screener, stationed onthe island of Lesvos, who was interviewing people apprehended while trying to enter Greece by sea to identifytheir nationality. There were also around 20 guest officers in the Evros region, mainly carrying out patrollingduties and operating thermal vision cameras.12Frontex publishes very little information about its ongoingoperations.13The latest publically available information on its operations in Greece dates back to 2011 forland operations and 2010 for sea operations providing only cursory details.

Index: 25/008/2013

Amnesty International July 2013

8

FRONTIER EUROPEHuman rights abuses on Greece’s border with Turkey

Frontex activities are governed by its founding regulation (as amended)14and by the EU Charter ofFundamental Rights.15In 2011 Frontex adopted a Fundamental Rights Strategy. In 2012, Frontex appointed aFundamental Rights Officer and established a Consultative Forum on Fundamental Rights. In instances wherebreaches of fundamental rights are alleged, Frontex can resort to a number of measures ranging from “letterof concern to relevant member states, letter of warning; discussion at the Management Board level; report tothe European Commission; withdrawal or reduction of the financial support to member states; appropriatedisciplinary measures both in the member states and in Frontex; temporary suspension of the joint operationor the pilot project; or termination of the joint operation or thepilot project.”16

Amnesty International July 2013

Index: 25/008/2013

FRONTIER EUROPEHuman rights abuses on Greece’s border with Turkey

9

3. COLLECTIVE EXPULSIONS (PUSH-BACKS) ON THE GREECE-TURKEYBORDERCollective expulsions are deportations of a group of people without considering theindividual circumstances of each person separately. Collective expulsions are specificallyprohibited by EU law and protection from collective expulsion applies to everyone,including irregular migrants.17Greece is therefore obliged to examine the situation of eachperson arriving to its territory if they wish not to be removed and allow them the chance tochallenge any deportation decision. Collective expulsions may lead to direct or indirectrefoulement(the forced return of individuals to countries in which they are at risk ofserious human rights violations).Refoulement,direct or indirect is prohibited underEuropean and international law.18Of the 79 migrants and refugees Amnesty International interviewed between March and May2013, 28 described at least 39 separate instances of collective expulsions from Greece toTurkey, which they claimed to have experienced themselves between August 2012 and May2013. Seven interviewees claimed they were pushed back more than once. 26 instancesconcerned push-backs across the land border with Turkey and 13 concerned push-backs onthe Aegean. The number of alleged push-backs reported by this small sample size still worksout an average of roughly one such incident a week.The alarming number of testimonies collected by Amnesty International alleging collectiveexpulsion suggests that these practices are regularly employed by Greek border guards andcoastguards. In April 2013, the UN Refugee Agency, UNHCR, in Greece also reported that“[s]ome testimonies of Syrians received by UNHCR make reference to informal forced returns(push-backs) or attemptedinformal returns to Turkey.”19In response to a query by AmnestyInternational, Frontex also wrote on 6 June 2013 that since 2012, Frontex Headquarters hadreceived 18 reports of alleged violations of fundamental rights which included “unofficialreturns(“push-backs”) involving groups of migrants (up to ten people) or single individualsthat had allegedly been returned to Turkey by the Hellenic Police.”20Frontex informedAmnesty International that it had raised such allegations with the Greek authorities in writingon three separate occasions and received a response denying that such push-backs had takenplace.Those who used the land route told Amnesty International that they had been caught byGreek border guards, sometimes hours and sometimes days after arriving in Greece, havingcrossed the River Evros. In most cases, they were held in a police station until nightfallbefore being taken back to the Turkish side of the river by boat and dropped on Turkish landor left on one of the small islands in the river.Some of those seeking to reach the EU through a Greek island in the Aegean said that theirinflatable boats were towed by the Greek coastguard to Turkish waters; some said that they

Index: 25/008/2013

Amnesty International July 2013

10

FRONTIER EUROPEHuman rights abuses on Greece’s border with Turkey

were taken on board the coastguard vessel only to be forced back into their own inflatablesonce in Turkish waters.All those who claimed to be pushed back in this way reported that they were never given anopportunity to explain their situation or challenge their deportation. This is a breach ofGreece’s internationaland regional obligations - most importantly thenon-refoulementobligation as well as Greece’s domestic law. It also risks the lives and well-beingof thepeople sent back either as a result of the manner in which they are sent back or by puttingthem at risk of being further sent back to a country where they may face persecution or otherharm (indirectrefoulement)once they are in Turkey.

DIFFICULTIES ACCESSING PROTECTION IN TURKEY AND RISK OFREFOULEMENTTestimony collected by Amnesty International from returned migrants and refugees, aswell as information provided by local non-governmental organisations (NGOs) show thatonce returned from Greece to Turkey, many are apprehended and detained,21althoughsome manage to escape detection by the Turkish gendarmerie, coastguard or police.Despite some positive legislative reforms by Turkey in the field of asylum22, most notablythe adoption of the Law on Foreigners and International Protection in April 2013,23access to asylum procedures in detention is still problematic.24Detention facilities forirregular migrants, currently called “removal centres,” are not independentlymonitored.25NGOs do not have access to detention facilities and free legal aid is verylimited.26International protection needs may go undetected or are at times ignored.27Asa result, those in need of international protection are at risk of being sent back to transitcountries or countries of origin where they may face persecution or other serious humanrights abuses.28Turkey has never lifted the geographical limitation found in the original text of the 1951UN Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees,29limiting refugee status to refugeescoming from member countries of the Council of Europe. Non-Europeans currently canonly obtain a national protection status, which allows them to stay in Turkey on atemporary basis until they can find another country for resettlement with the help of theUN Refugee Agency (UNHCR). In practice, this means that integration is not possiblefor refugees from outside of Europe; they have little access to social services or tolegitimate employment.30As a result, most live in destitution or work illegally underexploitative conditions.31Although the new Law on Foreigners and InternationalProtection improves access to healthcare for non-European asylum seekers in Turkey; itfails to ensure access to other rights; most importantly access to lawful employment.Most of the Amnesty International interviewees who claimed to have been pushed backfrom Greece to Turkey, stated that they had been detained in Turkey for periods rangingfrom a few days to three months in removal centres in Edirne, Aydin, Izmir and Mugla.Some of the people interviewed told Amnesty International that they feared persecutionin their countries of origin. However, the majority said that they did not apply for asylum

Amnesty International July 2013

Index: 25/008/2013

FRONTIER EUROPEHuman rights abuses on Greece’s border with Turkey

11

in Turkey either knowing that as a non-European they would not be able to have apermanent refugee status there or claiming that they lacked information on thepossibility of seeking asylum in Turkey. Two claimed that the police in the detentionfacility they were held in told them that their release from detention would be delayed ifthey applied for asylum.

3.1 PUSH-BACK OPERATIONS PUTTING LIVES AT RISK“We were left inthe middle of the sea, with nothing but a damaged boat.”B., 17-year-old Afghan boy detained in a removal centre in Turkey.

First-hand testimony collected by Amnesty International reveals that people's lives arefrequently put at risk by the actions of the Greek border guard and coastguard while carryingout push-back operations along the border with Turkey.Some of the refugees and migrants navigating the Aegean Sea on small inflatable boats,overloaded far beyond capacity, described how they were at first relieved to see Greekcoastguard boats only to discover what they believed to be a rescue was in fact an operationto send them back to their point of departure. In some cases people deliberately damagedtheir boats once they spotted Greek coastguard, hoping they would be rescued and taken toGreece.B., a 17-year-old from Afghanistan, was detained in a removal centre in Turkey, close to theAegean coast, when Amnesty International talked to him by telephone in March 2013. Hewas held in the centre with his two sisters, aged 15 and 16, as well as the three children ofhis late sister; two boys, aged seven and three, and a girl of five.“Iam here with my two sisters and the children of my older sister who is dead. I have to takecare of them all butthe Greek coastguard took all my money. I don’t know what to do.”He explained that his parents and older sister died in a bomb blast in Ghazni, Afghanistan.Fearing for his life and the lives of the five children placed in his charge, B. left Afghanistan inSeptember 2012 with his sisters, nephews and niece. He recounted how he went to Iran, wherehe irregularly worked for five months, and then came to Turkey with the hope of entering theEuropean Union. He went to the large coastal city of Izmir, where most refugees and migrantsstart their journey across the Aegean Sea to Greece. There he negotiated with smugglers to takehim and his family to Greece. On a cold night in late February 2013, they were put on board - arubber dinghy - with 36 others from Syria, Sudan and Iran. The smugglers told them to aimtowards the lights in the distance, which they said was a Greek island.“We left at 11:15pm. This was in late February, 2013. But we couldn’t reach the island. Wewere at sea for three and a half hours. Then the Greek boat with Greek police found us. Theytook us onto their boat. They beat us very badly. They took all our money, our mobile phones,our clothes. Everything we had. They beat my sister so badly she has bruises all over her now.… So, we wereon [the] Greek boat for three hours. At around 6am they took us back toTurkish waters; they put us back on our own boat, they scratched one side of our boat withtheir knife, they damaged our boat and they took away the motor and left us in the middle ofthe sea. We were 42 people all together. There were three small children with us: my nieceand nephews. There were also other children, but they were older… We were left in themiddle of the sea, with nothing but a damaged boat.”

Index: 25/008/2013

Amnesty International July 2013

12

FRONTIER EUROPEHuman rights abuses on Greece’s border with Turkey

B. said that the Turkish coastguard rescued him and his fellow travellers. They were thendetained in a removal centre for irregular migrants awaiting deportation.B.’sstory and the testimonies of other refugees and migrants point to the blatant disregardshown by the Greek coastguard for human life during push-back operations carried out in theAegean Sea. 13 of the 14 interviewees who described being pushed-back to Turkey in theAegean Sea described similar experiences of their inflatable boats being rammed or knifed,or nearly capsized while they were being towed or circled by a Greek coastguard boat, theirengines disabled, their oars removed, and their occupants left in the middle of the sea onunseaworthy vessels. B.’sstory also demonstrates that even children are put at risk,are ill-treated and deprived of their belongings.On 12 April 2013, Y., a Syrian woman in her early 30s, explained to Amnesty Internationalthat she left Syria with her six children to reach her husband in Switzerland. She boarded asmall boat in Turkey with approximately 30 others. She claimed that their boat was rammedby the Greek coastguard near Agathonisi island, when the coastguard steered their boattowards theirs to scare them off to go back to Turkey. In the chaos, Y.’sfour-year-olddaughter fell into the sea:“AGreek policeman jumped into the sea and rescued my daughter. Then they took us toAgathonisi Island where we were detained for seven days. We were incredibly dirty and wet.But there was no shower and they did not give us dry clothes. They only gave us water; noteven food. I had 100 euros with me. I spent it all to buy food in detention. A week later, theytransferred us to Samos Island. I had no money left, so I couldn’t even buy food. A policemanbrought cookies for my children.”Similar life-endangering practices are also reported by those apprehended after crossing theRiver Evros. N. from Darfur told Amnesty International that he was left on a small island inthe middle of the river with his hands tied:“Ifirst tried to go to Greece on 25 December 2012 with three other men I met in Istanbul.We arrived in Orestiada and were captured by the Greek police. They took us to a policestation and put us in a small room. There were already seven others in this room. There weretwo Nigerian women; the rest were all men. We were kept there for 14 hours or so. I think itwas in the afternoon when they brought water and bread. They threw them at us. That was allthey gave us.“Ataround 9pm the Greek police tied our hands behind our backs with plastic. I saw themthrow our bags into the garbage and then they took us in a small bus back to the river. Therewere two boats waiting in the river. They untied the hands of one of the Nigerian women; shelooked sick. Then they forced us onto the boats. I was scared of falling off into the river withtied hands. They told us to get off on a small island in the middle of the river; and then theyleft. They didn’t even untie our hands but left us like that in the middle of the river. Afterabout 40 minutes, the Turkish police found us on the island.”Such treatment was also reported by D., aged 28, from Sudan. He told Amnesty Internationalthat he almost drowned because he fell into the water as the Greek police were putting himashore on the Turkish side of the River Evros in August 2012:

Amnesty International July 2013

Index: 25/008/2013

FRONTIER EUROPEHuman rights abuses on Greece’s border with Turkey

13

“They(the Greek border guard) tied my hands and then put me on a boat with several others.Everyone's hands were tied except three who spoke English. I don’t know why they untiedtheir hands. There were two Greek policemen on the boat. When we approached the riverbankon the Turkish side, they pushed some of us on to the bank on the Turkish side. But thenthey (the Greek border guard) thought that the Turkish gendarmerie were nearby. So theycouldn’t drop the rest of us there. We moved away a bit and then the police pushed the restof us off the boat towards the Turkish land. However, I fell into the water. The water waschest high and very fast. It was very difficult to get out of the water with my hands tied on myback. We had to help some others because they couldn't make it out of the river themselves.”The allegations raised in the testimonies above and provided by others who were interviewedby Amnesty International do not only demonstrate a blatant disregard for life, but alsoinclude ill-treatment, the confiscation of property, and the failure to screen and identify thosewith protection or other needs, such as unaccompanied children. These practices representviolations of human rights and Greece’s obligations under international law and should ceaseimmediately. The Greek authorities must investigate such allegations and bring thoseresponsible to justice.

3.2 ILL-TREATMENT DURING PUSH-BACK OPERATIONS“We asked for water from the Greek police, but they laughed at us and said ‘you arelike dogs’.”X., from Palestine, said he was on the Aegean near a Greek island in a boat with 11 others from Palestine and Syria, including atwo-month-old baby on 6 March 2013. He said that the Greek coastguard towed them back to Turkish waters.

“When we saw the Greek coastguard boat, one of us punctured our boathoping thatthey will rescue us and take us to Greece. The coastguard took us on to their boat;they didn’t ask anything, they just beat us; they told us not to look up, not to look attheir faces.”E., a 27-year-old Sudanese man, described to Amnesty International how he was treated by the Greek coastguard in February 2013before being taken back to Turkish waters and left on a punctured boat along with three families with small children aged around four.

“He (the officer) was searching me roughly. He slappedmy face when I told him tobe slow– I looked straight into his face when he slapped me… (then) he started tobeat me on my face… One of my daughters held on to his leg but he pushed heraway.”M., a Syrian man, describing his ill-treatment in front of his small children while undergoing a body search on the island of Chiosin February 2013. M reported that he and his family had previously been unlawfully sent back to Turkey by the Greek border guardthrough the River Evros in November 2012.

Almost all who claimed to have experienced collective expulsion - whether at the land borderor at sea–said that they either experienced or witnessed violence or degrading treatment.People described being slapped, beaten and manhandled. Almost all interviewed describedbeing searched and their mobile phones, money, jewellery, baggage containing clothes andfamily photographs confiscated or thrown into the sea. In one incident recounted by twointerviewees who said they were searched, they claimed to have been stripped naked.

Index: 25/008/2013

Amnesty International July 2013

14

FRONTIER EUROPEHuman rights abuses on Greece’s border with Turkey

U., an 18-year-old Afghan asylum seeker in Turkey told Amnesty International how Greekborder guards beat up his friend while they were being unlawfully sent back to Turkey on 19November 2012:“Wecrossed the river at night-time and walked for almost a day. Near a Greek town, thepolice caught us. They called a van and this van took us back to the river. There were alreadyaround 20 people in the van when they picked us up. They were all Afghans. When wearrived at the river, the police kept us there in the van for three hours. It was very difficult asthe van was very crowded and it smelled horrible. While we were in the van, my friend calledthe UN and some other organizations to ask their help. Shortly after this call, the policeopened the van and asked who called the organizations. They took us out one by one andasked this. I guess one of us told them who had made the call because they then took myfriend and beat him up with batons. Then they took our phones and our belts and deportedus back to Turkey.”

Amnesty International July 2013

Index: 25/008/2013

FRONTIER EUROPEHuman rights abuses on Greece’s border with Turkey

15

4. SWEEP OPERATIONS RESULTINGIN COLLECTIVE EXPULSIONS“Weare scared of the police. If we see apoliceman on the street, I freeze. I don’t knowwhat to do. Should I continue walking or should Igo back? I am scared to go out.”R., a Syrian woman in her 30s alone in Athens with her three children aged seven, five and one.

In addition to tightening border controls in the Evros region, in August 2012 Greece alsointensified sweep operations in urban areas to round up and detain irregular migrants.Migrants and refugees that Amnesty International met in Athens in April 2013 said that theyfeared going out as they were scared of being apprehended during one of these sweepoperations, code-named Xenios Zeus.While carrying out research in Turkey in March 2013, Amnesty International interviewed twoSudanese men, D. and C., who claimed to have been subjected to collective expulsions fromthe Evros region following such sweep operations. One had lived in Greece since 2008 andthe other since 2006. Both said that they had wives and daughters (aged three and five), whohad been left behind in Athens when they were sent to Turkey across the River Evros. Thesestories show that unlawful expulsions to Turkey without being given a chance to explain theirsituation is not only a danger for people who have only just entered Greece but also for thosewho have been in Greece for years and have established family ties there.D., who had lived in Greece since 2008, described how he was picked up by police at the carwash where he was working in Athens in August 2012. He told Amnesty International that hewas registered as an asylum seeker in Greece, but had left his asylum seeker card at home onthe date he was apprehended:“Itold the police I had this red card at home (asylum seeker card) and that I had a wife andchild here; but they didn't listen to me, they punched me in the stomach and pushed me intoa bus. There were about 25 others in the bus; from Sudan, Senegal, Bangladesh... We drovefor about eight hours. Then they held us in a very bad place. Then at 1am, they took us insmall cars to the river at the border with Turkey. I begged them not to send me to Turkey; Itold them about my document, my wife and child; asked them to check their computers. Butthey told me to shut up.”C. said that he similarly tried to explain to the Greek police that he had lived in Greece sinceAugust 2006; that he had an asylum-seeker card and a child and wife in Athens. However,he was sent back to Turkey under cover of night in November 2012 with others who had beenapprehended in sweep operations. When Amnesty International met him in Turkey in March

Index: 25/008/2013

Amnesty International July 2013

16

FRONTIER EUROPEHuman rights abuses on Greece’s border with Turkey

2013, he had tried to reunite with his family in Athens four times; failing at each attempt.When Amnesty International delegates met C.'s wife and daughter in their basementapartment the following month in Athens, they learned that he had once again tried to jointhem by crossing the River Evros. However, this time he was caught by the Turkishgendarmerie before he made it into Greece and was being held in detention in Edirne.Both D. and C. claimed to have lodged asylum applications in Greece, which would meanthat their expulsion from Greece was a clear violation of the 1951 Refugee Convention andrelated EU law. Furthermore, where migrants illegally residing in Greece are expelled in asimilar manner, without any procedures to assess their individual circumstances, it would bein violation of the prohibition on collective expulsion and Greece’s international obligationsunder EU law.32

Amnesty International July 2013

Index: 25/008/2013

FRONTIER EUROPEHuman rights abuses on Greece’s border with Turkey

17

5. PROLONGED DETENTION OFASYLUM SEEKERS AND IRREGULARMIGRANTS“Whatkind of a law can keep us here for a year? Iam not a murderer, not a criminal. I am just amigrant. I just came here for a good life.”A young Afghan man detained in Fylakio Immigration Detention Centre.

The extensive and indiscriminate use of detention is a central plank of Greece’s migrationpolicy. The EU law33and the Greek law allows the detention of irregular migrants for thepurposes of deportation or return up to six months, which can be extended for a maximum of12 months if certain conditions apply.34Since October 2012, asylum seekers can now bedetained also for up to 18 months.35Many of the irregular migrants and asylum seekers thatAmnesty International met during the organization's mission to Greece in April 2013 hadbeen held for periods of six to nine months. On the islands, reportedly due to limiteddetention capacity, people are released more quickly with orders to leave the country inperiods ranging from seven to 30 days.36However, as Greece aims to increase the detentioncapacity of its six major immigration detention centres from 5,00037to 10,000 through EUco-financing, longer periods of detention can be expected in the future.38The possibility of being detained and re-detained for up to 18 months solely because of theirirregular status in Greece caused serious distress for the refugees and migrants AmnestyInternational met. They were unable to understand why they were being held for so long; andsaid that they received no information about how much longer they might be detained.

“I have been here for nine months: they say they can keep me another nine. Then they will give me apaper to leave Greece in seven days. How can I arrange to leave Greece in seven days? I cannot evenmake a phone call here. They will just arrest me again.”A Guinean migrant in one of the large detention facilities in the Evros region.

Under international and EU law,39Greece should prove - in each individual case–thatdetention of a person for immigration purposes is both necessary and proportional, and thatless coercive measures would not be sufficient. Greek authorities must use and makeavailable alternative measures to detention both in law and in practice.40However in Greece,irregular migrants and asylum seekers are automatically detained if they are apprehended inan irregular situation, either while entering the country or during their stay. Testimony

Index: 25/008/2013

Amnesty International July 2013

18

FRONTIER EUROPEHuman rights abuses on Greece’s border with Turkey

collected by Amnesty International and interviews with representatives of the Greekauthorities responsible for detention of irregular migrants and asylum seekers as well asinterviews with lawyers and non-governmental organizations show that less coercive measuresare almost never considered before detention.41Greece’s obligations under EU law42also require people to be released when deportationcannot be carried out within a reasonable time. However, information provided by detentionauthorities and detainees in the facilities visited, as well as interviews with lawyers and localnon-governmental organizations confirmed that people without any possibility of beingreturned to their countries of origin, such as Somalia and Eritrea, are held in detention forprolonged periods.

“Please,all the responsible authorities (Greece and European Union), discuss andnegotiate about our situation, we have been kept enough in detention.- Help us, we have nowhere to go back, we have nowhere to be deported, (ifpossible, we would choose any 3rdcountry for deportation)”From a letter handed to the Amnesty International delegation by Eritrean detainees in an immigration detention centre in the Evrosregion on 14 April 2013

Some migrant detention facilities that Amnesty International visited in Greece did not haveinterpreters for the most needed languages and migrants said that often they were being usedas interpreters for other detainees. Many of those interviewed did not have a clearunderstanding of their rights in relation to their detention or the asylum system in Greecealthough the authorities claim that all detainees are advised by the police on their rights andprovided information in writing.43In May 2013, Amnesty International was informed that the Greek Council for Refugees, anNGO which was the only source of free legal aid for asylum seekers in detention in the Evrosregion had to cease its operations on 30 April 2013 in the region due to lack of funding.44Several of the interviewees who had applied for asylum while in detention had withdrawn orwished to withdraw their applications after hearing about the extension of the detentionperiod for asylum seekers in October 2012. During Amnesty International’s visit to theKomotini Immigration Detention Centre on 17 April 2013, the officer responsible forexamining asylum claims told Amnesty International that 17 of the detainees in Komotiniwithdrew their applications before they had their first instance interviews.Indeed, many detainees who wished to lodge asylum applications in detention reported toAmnesty International that they were discouraged from doing so as they believed that theywould be held longer in detention while their asylum application was processed. In interviewswith Amnesty International the Greek authorities confirmed that asylum seekers would beheld in detention until their asylum application had been processed. They stated that thiswas necessary arguing that the asylum system had previously been abused.45AITIMA is an NGO providing legal aid to asylum seekers and refugees. They confirmed thatthe lengthening of the detention period for the asylum seekers to 18 months - in accordancewith Presidential Decree 116/2012 - deters refugees from seeking protection while indetention in Greece. AITIMA further informed Amnesty International that at the Corinth

Amnesty International July 2013

Index: 25/008/2013

FRONTIER EUROPEHuman rights abuses on Greece’s border with Turkey

19

Immigration Detention Centre (near Athens) and various detention facilities in the Evrosregion police released detainees who have not lodged an asylum application sooner thanthose of the same nationality with asylum applications. This practice had contributed to thebelief among detainees that they might be held longer if they apply for asylum and resultedin some of them withdrawing their asylum applications.Greece established a civilian body, the New Asylum Service, in 2011 to receive and assessfirst instance asylum claims.46However, this new service did not begin operating until 7 June2013. According to the information provided by the Director of the Asylum Service, theservice will currently only receive applications through its Regional Office in Attica. Detaineeselsewhere in the country will have to be transferred to detention facilities in Attica region inorder to submit their asylum applications. A mobile unit is expected to start receivingapplications from Fylakio Initial Reception and Immigration Detention Centres in June, and aRegional Office in Alexandroupolis is expected to open in the coming months to cater to theregions of Evros, Rodopi and Xanthi.47However it remains to be seen how those wishing toseek asylum in other facilities will be transferred to Attica until these expected changes takeplace.

5.1 DETENTION CONDITIONS“If you die here, no one would know.”Somali man detained in Feres Border Guard Station in the Evros region.

Refugees and migrants who are apprehended for their irregular stay in the country or afterirregularly entering Greece end up being detained, if not immediately returned to Turkey.Detention conditions and the lack of procedural safeguards surrounding detention in Greecehave been regularly criticized by human rights organisations48as well as the EuropeanCommittee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment andPunishment (CPT)49and the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA).50Mostrecently, the UN Special Rapporteur on the human rights of migrants described theconditions in eleven detention facilities he visited in Greece between 25 November and 2December 2012 as “inappropriate” pointing out in some facilities limited access to fresh air,lack of leisure activities, limited access to toilets, lack of artificial lighting, lack of heatingand hot water, and complaints concerning “insufficient amounts and poor quality of food,lack of soap and other hygiene products, as well as insufficient clothing, shoes andblankets.”51In April 2013, Amnesty International visited three detention centres (Komotini and FylakioImmigration Detention Centers and the Fylakio Initial Reception Centre52), four border guardstations (Metaxades53, Tychero, Soufli, Feres), and a police station (Iasmos) in the Evrosregion and the neighbouring Rodopi Prefecture. Some of those detained in these facilitieshad been apprehended shortly after their arrival in Greece, but many were arrested duringsweep operations carried out by the Greek police in urban areas. Amnesty researchers alsovisited the Mytilini Police Station on the island of Lesvos where those who had newly arrivedthrough the Aegean route were being held.Some of the detention facilities visited (Iasmos, Mytilini and Tychero) lacked any outsidespace for fresh air and exercise. Although the authorities agreed that these cells weredesigned to hold people overnight, those detained–mostly young men, but also some womenand even unaccompanied children–often spend months there because of lack of space in

Index: 25/008/2013

Amnesty International July 2013

20

FRONTIER EUROPEHuman rights abuses on Greece’s border with Turkey

the larger immigration detention centres.54In other facilities with outside yards,55detaineesclaimed that they were not regularly taken outside except at the Fylakio Initial ReceptionCentre where detainees were free to use the yard.Communication with the outside world is severely restricted. Mobile phones are banned atalmost all facilities and pay phones available charge high rates for international calls.Detainees spoken to reported that phone cards costing €4 each lasted only a few minuteswhen making international calls. Many detainees told Amnesty International that they had notbeen able to speak to their families for months once their money had ran out. Many Somalisand Afghans felt deep distress at not knowing if the families they had left behind were stillalive.

“We cannot speak to anyone. We don’t know what happens in the world outside.There is no TV, no radio. All we can do is think. We think too much. Two Afghansattempted suicide by hanging themselves. It is too difficult here. Our blanketshaven’t been washed for nine months.”A Rwandan man detained in Komotini Immigration Detention Centre since August 2012.

In the Tychero Border Guard Station–a converted warehouse–there was mould on the wallsthe floors were dirty, and some cells were damp despite renovations. In Feres and Metaxadesdetainees complained that they had to call the police whenever they needed to use the toilet,as there were no toilets in their cells. They claimed that their calls sometimes wentunanswered for hours so they had to urinate in bottles.Detainees also complained that they lacked access to proper medical care.56As a member ofa minority clan, P. said she had to flee Mogadishu, Somalia. She told Amnesty Internationalthat she left behind her three children in the hope that they would join her once she wassettled somewhere safe. She said that she first tried to reach Europe in November 2012. Shecrossed the River Evros along with other refugees and migrants, all men unknown to her.Shortly after arriving in Greece, they were reportedly caught by the Greek police and returnedto Turkey:“Itwas night, so we couldn’twalk and spent the night next to the river. That night,two men travelling with us attacked me. They raped me.”Despite the risks, she gathered her strength and crossed the border again to Greece in earlyMarch. However, while she was trying to continue into Former Yugoslavian Republic ofMacedonia, the Greek police caught her once again. P. said that she was initially detained fortwo weeks near the Macedonian border, and then transferred to the Fylakio ImmigrationDetention Facility. When Amnesty researchers met her there on 14 April 2013, she had beenin Fylakio for more than three weeks. P. said that she had heavy vaginal bleeding which shebelieved was due to being raped. Although the director of the centre told AmnestyInternational that the doctors at the facility would have been aware of her situation and herneed for care, P. and other women detained with her claimed that she has not been givenmedical assistance.Amnesty International was not given access to the detention area in the KomotiniImmigration Detention Centre and inside the cells of most of the other facilities so it was notpossible to make a detailed assessment of hygiene and accommodation conditions. Detaineesthemselves reported sewage leaks at the Komotini Immigration Detention Centre. In

Amnesty International July 2013

Index: 25/008/2013

FRONTIER EUROPEHuman rights abuses on Greece’s border with Turkey

21

detention facilities in Komotini, Fylakio [the immigration detention centre], Metaxades,Feres, and Tychero detainees also complained that they had to sleep on bedding that was notwashed for months and of a lack of personal hygiene products, such as soap, shampoo andsanitary towels. Poor sanitation may have contributed to health problems with manydetainees observed during interviews to have skin and respiratory problems.

MEDICAL CARE IN DETENTIONMédecins Sans Frontières (MSF) had until April 2013 been providing medical services as well as distributingmaterials such as personal hygiene items in many of the facilities in the Evros region. Detainees said this wastheir only source of medical help. MSF representatives told Amnesty International that the majority of healthproblems (skin infections, gastrointestinal problems, upper respiratory tract infections, musculoskeletalproblems and psychological complaints) detected in detention facilities in the Evros region were linked toextended incarceration and to detention conditions. This was based on data from 2,000 consultations MSF hadwith patients in detention in the Evros region between December 2012 and March 2013. MSF halted its work inthe region after KEELPNO (Hellenic Centre for Disease Control and Prevention) began providing medicalservices to the detainees in Evros and Rodopi regions in March 2013. However, Amnesty International waslater informed by KEELPNO that its programme had ceased as of April 2013 owing to a lack of funding.57The absence of firm information on how long each detainee might end up being held, thepossibility of being detained for 18 months, the poor living conditions,58the lack of access tofresh air and the scant communication with the outside world all have an acute impact on thepsychological state of detainees. The majority of those that Amnesty International spoke tocomplained that they were unable to sleep and that suicide attempts are not uncommon.Psychologists and social workers in Komotini Immigration Detention Centre cited suicideattempts, self-harm and self-mutilation, post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, andsleeping disorders among the psychological problems they encountered at the centre.KEELPNO reported that their social workers in Evros and Rodopi regions recorded threesuicide attempts reported to them during their presence there in March and April 2013.59

5.2 DETENTION OF CHILDRENUnder international law, states are required to consider “the best interest of the child” inevery decision concerning them.60EU legislation allows detention of unaccompanied childrenand families with children, but only as a last resort.61However, in Amnesty International’sview, children and in particular unaccompanied children, should never be detained forimmigration purposes, as detention can never be in their best interest.62In Greece, the process for identifying unaccompanied children and other vulnerableindividuals is weak. Even when identified, support that is extended to them isinsufficient.63According to the numbers provided by the UN Refugee Agency, the totalcapacity in Greece to house unaccompanied children and asylum seekers in need was only1,006 in February 2013.64In January 2011 a law was introduced to establish an Initial Reception Service“to effectivelymanage the flow of illegally entering third-countrynationals in the country.”65Amongst otherduties, the Service is tasked with registering and verifying the identity and nationality of newarrivals, providing information about rights and obligations, and identifying persons belonging

Index: 25/008/2013

Amnesty International July 2013

22

FRONTIER EUROPEHuman rights abuses on Greece’s border with Turkey

to vulnerable groups. Under the new law arrivals can be held in initial reception centres forup to 25 days.The first initial reception centre began operating in March 2013 in Fylakio. At the time ofAmnestyInternational’s visit in April 2013, this first centre was only receiving individualsapprehended after it became operational and only those arrested in the Evros region. Manyvulnerable individuals including unaccompanied children apprehended during sweepoperations elsewhere were therefore directly sent to detention facilities rather than being firstscreened in the Initial Reception Centre in Fylakio. At the time of Amnesty International’svisit, there was no other initial reception centre in Greece apart from the one in Fylakio,including the islands where most arrivals were taking place and more were expected. TheDirector of the Initial Reception Service responded to an Amnesty International query statingthat the Service expects mobile units to be operational on the islands of Chios and Samos bythe end of June at the latest.66In several facilities such as Tychero, Fylakio [immigration detention centre] and Komotini,where adults were being held, Amnesty International was approached by young detainees whosaid that they were children. Some of them said that they were ignored by the detentionauthorities when they told the authorities that they were under 18; others reported that theywere judged to be adults after an age assessment that took into consideration only physicalexaminations such as dental examination or radiological tests looking at bone developmentwithout assessing psychological and developmental factors.67Four young boys from Afghanistan were being held at the Soufli Border Guard Station formore than three months already at the time of Amnesty International’s visit. They claimedthey were under 18 and were therefore held in a cell separate from adults. Authorities toldAmnesty International that a shelter space was finally found for the boy whose claimed agewas confirmed and he would be transferred there soon. However, one of them wasdetermined to be over 18 as a result of medical tests and the other two were still waiting fortheir age test results. They shared a small cell without much space to walk around. Althoughthe facility had a fenced yard, the boys said that they were not able to go out daily to getfresh air or exercise because the weather had been cold.Those identified as children remained detained in conditions unsuitable for children until aspace was found for them in a shelter. In May 2013, Amnesty International was told by UNRefugee Agency in Greece that already limited shelter space for children was further strainedfor want of funding to cover the shelters’ operationalcosts.68The lack of funding was a resultof gaps in the distribution of EU funding by the Greek government to the organizationsrunning the shelters. In May 2013, this reportedly led some shelters such as Agiassos on theisland of Lesvos to stop receiving newly-arrived children.69Amnesty International interviewed two unaccompanied boys aged 16 and 17 held in theIasmos police station. They were previously detained at the Komotini Immigration DetentionCentre, but were transferred to Iasmos to be separated from adult detainees, when they wereeventually documented as children. H. from Afghanistan was arrested in a sweep operation inAthens in August 2012. He explained to Amnesty International that he repeatedly told theauthorities that he was a minor but had been ignored. He was finally documented as a minorafter being detained alongside adults for more than eight months following the intervention of

Amnesty International July 2013

Index: 25/008/2013

FRONTIER EUROPEHuman rights abuses on Greece’s border with Turkey

23

the Greek Council for Refugees.When Amnesty International spoke to them, the two boys were being held in adjoining cellsin Iasmos, sleeping on mattresses on the cement floor. The facility had no outside space orindoor exercise or leisure area. H. had already been there for about a month; the second boy,from Ivory Coast, had been there a few weeks. Neither had any information about how muchlonger they might be held until space opened up in a shelter for children where they could betransferred. They were visibly distressed and appeared in need of psychological support.

Index: 25/008/2013

Amnesty International July 2013

24

FRONTIER EUROPEHuman rights abuses on Greece’s border with Turkey

6. CONCLUSION: SHARED EURESPONSIBILITY FOR ITS EXTERNALBORDERS“Already, new pre-departuredetention centres,initial reception centres, a new asylum serviceand an appeals authority have been established.We are managing all those who come to Greece inthe best way ... We are trying to convince them ina humane way ... to pass the message for themnot to come to Greece because Greece is goingthrough a crisis and that we are not going to allowthem to go to other European countries–which iswhat most of them wish”.Major General E. Katriadakis, Ministry of Public Order and Citizens' Protection, 5 June 2013 70

Along with other countries on the EU’s southern frontier,Greece has been confronted with alarge flow of migrants and refugees most of whom wish to go further west to other EUcountries rather than stay in Greece. This responsibility is particularly difficult for Greece asan EU Member State greatly impacted by economic crisis.The European Commission has been supporting Greece in the area of migration and asylumthrough funding as well as through technical assistance provided by Frontex and theEuropean Asylum Support Office (EASO). However, the emphasis of the support extended toGreece in this area has been on securing Europe’s external borders byenhancing bordercontrol measures and increasing detention capacity.71While the Commission allocatedalmost €227,576,503 million for Greece under the Return Fund and the External BordersFund for the period from 2011 to the end of 2013;72only €19,950,000 was allocated toGreece under the European Refugee Fund for the same period.73As evidenced by AmnestyInternational’s research presented above, the emphasis on border control and detention iscosting lives and leading to human rights abuses on the Greece-Turkey border.

Amnesty International July 2013

Index: 25/008/2013

FRONTIER EUROPEHuman rights abuses on Greece’s border with Turkey

25

The EU and its member states should support the Greek government in ensuring the rights ofall migrants and refugees’ regardlessof their legal status by shifting the emphasis away fromsealing off EU’s external borders and towards enhancing reception capacity and receptionconditions for asylum seekers, refugees and other vulnerable migrants as well as theidentification of vulnerable migrants and those in need of international protection at Greece’sborders. At the same time, the EU should explore new ways of sharing responsibility withGreece for the management of the mixed-migration flows it faces.

Index: 25/008/2013

Amnesty International July 2013

26

FRONTIER EUROPEHuman rights abuses on Greece’s border with Turkey

RECOMMENDATIONSTo the Government of Greece:Ensure that all those intercepted in the Aegean or apprehended at the land border withTurkey have access to individualized procedures to seek international protection or raise otherprotection needs;�Ensure that all those intercepted in the Aegean or apprehended at the land border withTurkey have access to an effective remedy against any deportation decision;�Investigate allegations of collective expulsions (push-backs) and ill-treatmentat Greece’sland border with Turkey and in the Aegean and prosecute officials involved;�End indiscriminate and automatic detention of irregular migrants; and instead usealternatives to detention;�End systematic prolonged detention of those who apply for asylum while in detention;and increase reception capacity for asylum seekers and other vulnerable groups;�Prohibit the detention of children by law and end it in practice; and increase sheltercapacity for unaccompanied children;�Improve detention conditions by ensuring adequate sanitation of the facilities, access tohealth care, hygienic materials, and outside space for fresh air and exercise for all detainees;�Improve procedural safeguards in detention by ensuring the availability of necessaryinterpreters and informing all detainees of the reason for their detention, its duration, theirright to have access to a lawyer, to challenge their detention and to seek asylum;�Ensure that all migrants detained are able to contact their families, consular servicesand a lawyer regularly and free of charge;�Ensure independent monitoring of all facilities where migrants and asylum-seekers aredetained;�Ensure that the Initial Reception Service offers effective services to the newly arrivedmigrants on the Greek islands; providing information on their rights, extending medicalservices, and identifying international protection needs as well as vulnerabilities to refer themto necessary services.�

To the Government of Turkey:�Ensure that all those detained in removal centres are informed of their rights in alanguage they can understand; such as legal remedies against their detention anddeportation, and their right to seek asylum;�Ensure that no one with international protection needs is returned to a country where heor she may face persecution or other serious harm;�Allow independent monitoring of all facilities where migrants are detained.

To the European Union and its member states:Share responsibility for asylum seekers more equally, taking into account actualprotection standards and asylum seekers’ needs;�Support Greece in increasing its open reception capacity for asylum seekers and othervulnerable groups;�Help Greece increase its capacity for sheltering unaccompanied children in age-appropriate facilities;�Assist Greece in providing minimum services to refugees, asylum seekers and irregularmigrants in need, such as health care and housing;�

Amnesty International July 2013

Index: 25/008/2013

FRONTIER EUROPEHuman rights abuses on Greece’s border with Turkey

27

Abide by the rulings of the European Court of Human Rights and the Court of Justice ofthe European Union by maintaining the halt of transfers of asylum seekers back to Greeceand take responsibility for those asylum seekers;74�Continue monitoring the situation in Greece for migrants and refugees, particularly indetention, and take appropriate action as required from the Commission under the Treaty onthe Functioning of the European Union (Article 258).�

To Frontex:�

In a transparent manner, follow up allegations of mistreatment and collective expulsionsreceived from guest officers in Greece or third parties, such as non-governmentalorganizations or the media, until the situation is remedied.

Index: 25/008/2013

Amnesty International July 2013

28

FRONTIER EUROPEHuman rights abuses on Greece’s border with Turkey

GLOSSARYArefugeeis a person who has fled from their own country because their human rights havebeen violated. This means that they have been deprived of their fundamental freedoms, theyhave been discriminated against or they have suffered violence because of who they are, theirbeliefs or their opinions, and their government cannot or will not protect them.Asylumproceduresare designed to determine whether someone meets the legal definition of arefugee or not. When a country recognizes someone as a refugee, it gives theminternationalprotectionas a substitute for the protection of their country of origin.Anasylum seekeris someone who left their country seeking protection but has yet to berecognized as a refugee. During the time an asylum claim is being examined, the asylumseeker cannot be forced to return to their country of origin.Amigrantis someone who leaves their country to live in another country for work, study, orfamily reasons and does not have international protection needs. A migrant who is authorizedto stay in a country, for example by having a valid visa or residency permit, is aregularmigrant.Anirregular migrantis someone who enters a country without authorization (for example;without travel documents, without a valid visa or at border crossings that are not official entrypoints) or someone who might have entered the country through regular channels but is nolonger authorized to stay there (for example, because their visa has expired). Governments areobligated to respect the rights of all people within their jurisdiction regardless of their status.Irregular migrants must not be mistreated, arbitrarily deprived of their liberty. If they are tobe returned to their country of origin, this should be done in a manner consistent with thatstate’s human rights obligations.Refoulementis the forcible return of an individual to a country where they would be at risk ofserioushuman rights violations (the terms ‘persecution’ and ‘serious harm’ are alternativelyused). Individuals in this situation are entitled to international protection; it is prohibited byinternational law to return refugees and asylum seekers to the country they fled–this isknown as the principle ofnon-refoulement.The principle also applies to other people whorisk serious human rights violations such as torture and the death penalty, but do not meetthe legal definition of a refugee.Indirect refoulementoccurs when one country forcibly sendsthem to another country that subsequently sends them to a third country where they riskserious harm; this is also prohibited under international law.Collective deportation or collective expulsionis the deportation of a group of people(migrants, asylum seekers and/or refugees) without looking at each case individually andconsidering the individual circumstances of each person separately. It is prohibited underinternational law.This report uses the term refugees to refer to those that have fled persecution or conflict,regardless of whether they have been recognized as such. The term ‘migrants’ is used to referto people who have crossed or attempted to cross the border between Turkey and Greece foreconomic reasons, regardless of how they entered the country or the legality of their stay.

Amnesty International July 2013

Index: 25/008/2013

FRONTIER EUROPEHuman rights abuses on Greece’s border with Turkey

29

ENDNOTESUN General Assembly,Report of the Special Rapporteur on the human rights of migrants,Fran§ois Crépeau: Addendum–Mission to Greece: comments by the State on the report ofthe Special Rapporteur,19 April 2013, Paragraph 11, available at:http://ap.ohchr.org/documents/dpage_e.aspx?si=A/HRC/23/46/Add.5.1

According to Frontex’ migratory routes map, the Eastern Mediterranean Route includingBulgaria, Cyprus and Greece, is by far the most used, accounting for 37,220 irregular entriesinto the EU in 2012. The Central Mediterranean Route (Italy and Malta) is the next largestwith 10,380 detected irregular entries. The Migratory Routes Map is available at:http://www.frontex.europa.eu/trends-and-routes/migratory-routes-map.See also EuropeanCommission,Second biannual report on the functioning of the Schengen Area 1 May 2012-31 October 2012,23 November 2012, pp. 2-3, available at:http://ec.europa.eu/dgs/home-affairs/what-is-new/news/pdf/2_en_act_part1_v7_schengen.pdf;European Commission,Thirdbiannual report on the functioning of the Schengen Area 1 November 2012-30 April 2013,31 May 2013, p. 2, available at:http://ec.europa.eu/dgs/home-affairs/what-is-new/news/pdf/2_en_act_part1_v7_schengen.pdf;Frontex,Annual Risk Analysis 2013,April2013, p. 20, available at:http://frontex.europa.eu/assets/Publications/Risk_Analysis/FRAN_Q4_2012.pdf; andPACE,Migration and asylum: mounting tensions in the Eastern Mediterranean,23 January 2013,available at:http://assembly.coe.int/ASP/XRef/X2H-DW-XSL.asp?fileid=19349&lang=en.See for example, UN General Assembly,Report of the Special Rapporteur on the humanrights of migrants, Fran§ois Crépeau: Addendum–Turkey,17 April 2013, Paragraph 60,available at:http://ap.ohchr.org/documents/dpage_e.aspx?si=A/HRC/23/46/Add.2and Euro-Mediterranean Human Rights Network,An EU-Turkey Readmission Agreement–Undermining the rights of migrants, refugees and asylum seekers?,20 June 2012, pages 9-10, available at:http://www.euromedrights.org/eng/2013/06/20/an-eu-turkey-readmission-agreement-undermining-the-rights-of-migrants-refugees-and-asylum-seekers/.Difficultiesaccessing international protection while in detention was also confirmed through interviewswith local legalaid organizations, Helsinki Citizens’ Assembly and Multeci-Der.Updates weregathered from these organizations on 30 May 2013 and 18 June 2013 respectively.345

2

See Glossary for definitions of refugees and migrants and other terms used in the report.

Agency for the Management of Operational Cooperation at the External Borders of theMember States of the European Union6

Landmine & Cluster Munition Monitor reports that “in 2009, Greece completed clearanceof antipersonnel mines in the 57 mined areas it laidalong the border with Turkey.” Availableat:http://www.the-monitor.org/custom/index.php/region_profiles/print_theme/1822#_ftnref11.European Commission,Commission reports on EU free movement,3 June 2013, availableat:http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-13-496_en.htm.At the time of AmnestyInternational’s visit, the number ofadditional border guards deployed there under the7

Index: 25/008/2013

Amnesty International July 2013

30

FRONTIER EUROPEHuman rights abuses on Greece’s border with Turkey

Operation Aspida was around 800, according to information provided by the Orestiada andAlexandroupolis Police Directorates in the Evros region on 14 April and 16 April 2013respectively.8

Frontex,Annual Risk Analysis 2013,April 2013, p. 20, available at:http://frontex.europa.eu/assets/Publications/Risk_Analysis/FRAN_Q4_2012.pdf.9

Relevant statistics are available on the website of the Greek Police:http://www.astynomia.gr/images/stories//2013/statistics13/stat_allod/etsynora.JPG.Hurriyet Daily News,Refugee boat sinks in Aegean Sea: 1 dead, 5 missing,6 June 2013,available at:http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/refugee-boat-sinks-in-aegean-sea-1-dead-5-missing.aspx?pageID=238&nid=48314;EnetEnglish.gr Greek Independent Press,6-year-olddrowns off Farmakonisi coast,15 May 2013, available at:http://www.enetenglish.gr/?i=news.en.article&id=920;Al Arabiya News,Syrian refugeesdrown on their way to Greece,21 March 2013, available at:http://english.alarabiya.net/en/News/2013/03/21/Syrian-refugees-drown-on-their-way-to-Greece.html;Kayiki Press Release,Grief itself is not enough,18 January 2013, available at:http://www.kayiki.org/2013/01/kayiki-press-release-grief-itself-is.html;Amnesty International(Livewire blog), ‘Iwant all the world to know about us,’18 February 2013, available at:http://livewire.amnesty.org/2013/02/18/i-want-all-the-world-to-know-about-us/;and HurriyetGundem,63 gö§menin ölümüyle ilgili 9 kişi gözaltında,22 May 2012, available at:http://www.hurriyet.com.tr/gundem/23343092.asp.10

According to the latest information available on Frontex’ websiteon these two operations,the budget for the Poseidon Land operation (covering both Greece and Bulgaria’s borderswith Turkey) in 2011 was almost€9 million. The budget for the Poseidon Sea operation in2010 was over€12.4 million. Available at:http://www.frontex.europa.eu/operations/archive-of-operations/?year=®ion=&type=&host=Greece.Based on information provided by the Frontex Operational Coordinator in Alexandroupolis(in the Evros Region) on 17 April 2013.1312

11

Letter dated 6 June 2013 from the Executive Director of Frontex to Amnesty InternationalEuropean Institutions Office in response to a query dated 13 May 2013 stated that “[t]hedetailed figures about deployment of experts and technical means of an ongoing jointoperation cannot be publicly disclosed, as they might jeopardize the fulfilment of theoperation objectives.”14

Regulation (EU) No 1168/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25October 2011 amending Council Regulation (EC) No 2007/2004 establishing a EuropeanAgency for the Management of Operational Cooperation at the External Borders of themember states of the European Union, available at:http://frontex.europa.eu/assets/About_Frontex/frontex_amended_regulation_2011.pdf.15

Charter of Fundamental Rights of The European Union (2000/C 364/01), available at:http://www.europarl.europa.eu/charter/pdf/text_en.pdf.16

Frontex,Frontex Response to Ombudsman own-initiative inquiry 01/5/2012/BEH-MHZ,29May 2012, available at:http://www.ombudsman.europa.eu/en/cases/correspondence.faces/en/11758/html.bookmark.

Amnesty International July 2013

Index: 25/008/2013

FRONTIER EUROPEHuman rights abuses on Greece’s border with Turkey

31

Article 19(1) of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (the Charter)prohibits collective expulsions (push-backs). Explanations on the Charter published in theOfficial Journal of the European Union on December 2007 state that the purpose of theArticle “is to guarantee that every [expulsion] decision is based on a specific examination.”The explanations further add that Article 19(1) has “the same meaning and scope as Article4 of Protocol No 4 to the ECHR (European Convention on Human Rights) concerningcollective expulsion.” The European Court of Human Rights case law provides detailedguidance on how the Article 4 of Protocol 4 should be interpreted. See for example, HirsiJamaa and others v. Italy (Application no. 27765/09). Despite not having signed the Protocol4, Greece is still bound by the prohibition of collective expulsions through the Charter. TheCharter of Fundamental Rights of The European Union (2000/C 364/01) is available at:http://www.europarl.europa.eu/charter/pdf/text_en.pdfand the explanations relating to theCharter of Fundamental Rights (14.12.2007) are available at:http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:C:2007:303:0017:0035:EN:PDF.According to a study published by the Directorate General for Internal Policies of theEuropean Parliament, Article 19(1) of the Charter obligesstates to “ensure that in fact inevery expulsion decision the individual concerned has a real opportunity to be representedand put forward his or her arguments against expulsion before any decision is taken.” Thestudy further states that the same standardshould apply “to persons who are irregularly onthe territory or indeed those who have recently arrived and are still at or near the border.”European Parliament, Policy Department C: Citizens' Rights and Constitutional Affairs, CivilLiberties, Justice and Home Affairs,Implementation of the EU Charter of FundamentalRights and its Impact on EU Home Affairs Agencies Frontex, Europol and the EuropeanAsylum Support Office,August 2011, page 54, available at:http://www.europarl.europa.eu/meetdocs/2009_2014/documents/libe/dv/02_study_fundamental_rights_/02_study_fundamental_rights_en.pdfCharter’s provisionson collective expulsion (Article 19) as well as other fundamental rights(such as Article 18 on the right to asylum and the Article 47 on the right to an effectiveremedy and to a fair trial) would be invoked when Greece acts within the scope of the EUlaw. See for example, Judgment of the Court of Justice of the European Union,Åklagaren vHans Åkerberg Fransson,Case C-617/10, 26 February 2013, Paragraph 21. With regards topush-backs in the Evros region and the Aegean sea, the applicable EU law could, forexample, include the 2011 Qualifications Directive (Directive 2011/95/EU of the Europeanparliament and of the Council of 13 December 2011 on standards for the qualification ofthird-country nationals or stateless persons as beneficiaries of international protection, for auniform status for refugees or for persons eligible for subsidiary protection, and for thecontent of the protection granted), the 2005 Asylum Procedures Directive (Council Directive2005/85/EC of 1 December 2005 on minimum standards on procedures in member statesfor granting and withdrawing refugee status), and the 2006 Schengen Borders Code(Regulation (EC) No 562/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 March2006 establishing a Community Code on the rules governing the movement of persons acrossborders).18

17

See for example, UN General Assembly,Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees,28July 1951, United Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 189, p. 176, Article 33(1), available at:

Index: 25/008/2013

Amnesty International July 2013

32

FRONTIER EUROPEHuman rights abuses on Greece’s border with Turkey

http://www.refworld.org/docid/3be01b964.html;the Charter of Fundamental Rights of TheEuropean Union (2000/C 364/01), available at:http://www.europarl.europa.eu/charter/pdf/text_en.pdf;Article 3 of the European Conventionon Human Rights; Council Directive 2005/85/EC of 1 December 2005 on minimumstandards on procedures in Member States for granting and withdrawing refugee status; andthe Directive 2008/115/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December2008 on common standards and procedures in Member States for returning illegally stayingthird-country nationals.UNHCR,Syrians in Greece: Protection Considerations and UNHCR Recommendations,17April 2013, available at:http://www.unhcr.gr/fileadmin/Greece/News/2012/Syria/pc/Greece_Syria_Note_for_Pressconference_English.pdf.1920

Letter dated 6 June 2013 from the Executive Director of Frontex to Amnesty InternationalEuropean Institutions Office in response to a query dated 13 May 2013.Also see, UN General Assembly,Report of the Special Rapporteur on the human rights ofmigrants, Fran§ois Crépeau: Addendum–Turkey,17 April 2013, Paragraphs 40 and 41,available at:http://ap.ohchr.org/documents/dpage_e.aspx?si=A/HRC/23/46/Add.2.2122

See for example, the Ministry of Interior Circular on Refugees and Asylum Seekers No.B.050.OKM.0000.12/2010/19 of March 19, 2010 (Mültecive Sığınmacılar) and Circular onCombating Illegal Migration of March 23, 2010 (Yasadışı Gö§le Mücadele ile ilgili GenelgeNo. 2010/22).23

The law on foreigners and international protection (Law No.6458) was adopted by theGrand National Assembly of Turkey on 4 April 2013. However, most of its provisions willcome into force on 11 April 2014, one year after its publication in the Official Gazette andwhether it will lead to real improvement in practice remains to be seen.See for example, UN General Assembly,Report of the Special Rapporteur on the humanrights of migrants, Fran§ois Crépeau: Addendum–Turkey,17 April 2013, Paragraph 60,available at:http://ap.ohchr.org/documents/dpage_e.aspx?si=A/HRC/23/46/Add.2and Euro-Mediterranean Human Rights Network,An EU-Turkey Readmission Agreement–Undermining the rights of migrants, refugees and asylum seekers?,20 June 2012, page 10,available at:http://www.euromedrights.org/eng/2013/06/20/an-eu-turkey-readmission-agreement-undermining-the-rights-of-migrants-refugees-and-asylum-seekers/.Difficultiesaccessing international protection while in detention–especially at the Edirne RemovalCentre–was also confirmed through interviews with local legal aid organizations, HelsinkiCitizens’ Assembly and Multeci-Der.Updates were gathered from these organizations on 30May 2013 and 18 June 2013 respectively.24