Udenrigsudvalget 2012-13

URU Alm.del Bilag 41

Offentligt

briefing paper

Brazil in Africa:Just Another BRICSCountry Seeking Resources?Christina StolteAfrica Programme and Americas Programme | November 2012 | AFP/AMP BP 2012/01

Summary pointszzOver the last decade, Brazil has expanded its engagement with Africa, doubling

its diplomatic presence from 17 to 37 embassies.zzNew economic partnerships have been forged, raising trade with Africa in thesame period from US$4.2 billion to US$27.6 billion.zzOil and other natural resources account for 90% of Brazil’s imports from thecontinent and Brazilian investment is focused mainly on Lusophone Africa.zzBrazilian policy-makers see Africa’s biggest potential as providing a consumermarket for their country’s manufactured goods.zzBrazil also uses its Africa policy as a means to achieve its foreign policy goal ofbeing recognized as a major power.zzSouth–South cooperation is a key driver of Brazil’s Africa policy as it is seekingsupport for a permanent UN Security Council seat.zzBrazil advocates South–South cooperation projects that are based on its owndevelopment experience. Biomedical and health research and agriculturalresearch have been turned into effective foreign policy instruments.

Pontos de resumo em português na página 19.

www.chathamhouse.org

page 1

Brazil in Africa: Just Another BRICS Country Seeking Resources?

page 2

Introduction‘Brazil is not coming to Africa to expiate the guilt of acolonial past. We also don’t see Africa as an extensivereserve of natural riches to be explored. Brazil wants to bea partner for projects of development. We want to shareexperiences and lessons, add efforts and unite capacities.’1Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, President of Brazil 2003–10, at the OpeningCeremony of the 13th African Union Summit, Sirte, Libya, 1 July 2009.

States (ECOWAS), the New Partnership for Africa’sDevelopment (NEPAD) and the African Union (AU)complement Brazil’s new engagement with regional inte-gration schemes in Africa and underpin its quest for amore active role there.Another indication of Brazil’s new commitment toAfrica is also the number of visits by its heads of state.Former president Lula da Silva (2003–10) visited 29 Africancountries on a total of 12 journeys during his eight years inpower. His successor, President Dilma Rousseff, despite herreluctance to travel and her rather low interest in foreignpolicy,4has paid a visit to three African countries duringher first year in office. Numerous journeys by foreignand economic ministers, accompanied by large businessdelegations, have further contributed to the development ofrelations and a growing Brazilian presence in Africa.Moreover, Brazil has initiated a great number ofpolitical and cultural forums to deepen ties, rangingfrom broadly defined, multi-thematic events such as theBrazil–Africa Forum, which brings together academics,government officials and civil society representatives, tohigh-ranking biennial summits such as the Africa–SouthAmerica Summit of heads of state. Thematic events suchas the Dialogue on Food Security, Fight against Hungerand Rural Development further add to the intensificationof contacts and exchange of knowledge.Brazil has also made an effort to contribute to Africa’sdevelopment by transferring technical expertise andproviding assistance to African countries. Although still arecipient of development assistance itself, it has emergedas a new donor in Africa. Noteworthy in this context isnot only its decision to relieve African countries’ debts ofmore than US$ 1 billion,5but also the fact that more thanhalf of Brazil’s technical cooperation resources is directedtowards the continent.6

Largely unnoticed by international media and academia,South America’s economic powerhouse Brazil has activelyenhanced its presence on the African continent duringthe last decade. In the shadow of its BRICS partners Chinaand India, whose engagement with Africa has attractedinternational attention and spurred a heated debate, Brazilhas implemented an equally active, though less controver-sial policy towards Africa and has emerged as a relevantplayer on the continent.In less than ten years, Brazil has more than doubled itsdiplomatic presence in Africa from 17 to 37 embassies, andit is now among the countries with most diplomatic repre-sentations there.2In parallel, relations in the economicrealm have intensified, with trade increasing sixfold. Neweconomic partnerships have been forged, linking Brazil’sCommon Market of the South (Mercado Comun delSur – MERCOSUR)3with the Southern African CustomsUnion (SACU) and the Southern African DevelopmentCommunity (SADC). In addition to its traditionally closeties with Lusophone Africa, united in the Community ofPortuguese-Speaking Countries (Comunidade de Países deLingua Portuguesa – CPLP), Brazil has further establishedpartnerships with other African regional or sub-regionalorganizations on a bilateral basis. Cooperation agree-ments with the Economic Community of West African

1 Translation by the author, see full speech at http://www.imprensa.planalto.gov.br.2 In terms of the number of embassies in Africa, Brazil ranks fourth, with 37 embassies, after the United States (49), China (48) and Russia (38).3 The other members are Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay and Venezuela.4 Some analysts maintain that Dilma Rousseff’s reluctance to travel is due to health problems and not to a lack of interest. In any event, in contrast to herpredecessor Lula who maintained an intensive travel diplomacy schedule, she has chosen to limit her visits to Brazil’s most important partners.5 K.R. Rizzi, C. Maglia, M. Kanter and L. Paes (2011), ‘O Brasil na África (2003–2010): Política, Desenvolvimento e Comércio’,Conjuntura Austral1(5),pp. 1–21, cited in World Bank/Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada (IPEA) (2011),Bridging the Atlantic. Brazil and Sub-Saharan Africa: South-SouthPartnering for Growth(Washington, DC/Brasília), p. 42.6 World Bank/IPEA (2011), p. 43; Agência Brasileira de Coopera§ão (2009),A Coopera§ão Técnica do Brasil para a África,Brasília.

www.chathamhouse.org

Brazil in Africa: Just Another BRICS Country Seeking Resources?

Clearly, Brazil has a great interest in Africa, but it is lessobvious what this interest is about. Is Brazil just ‘anotheremerging power in the continent’,7disguising its economicinterests by offering aid projects to its partner countries?Is it striving to secure African resources in order to ensureits economic development, following the same pattern asits BRICS partner China? Or is the Brazilian engagementin Africa driven by a ‘Southern solidarity’, as Braziliangovernment officials and academics maintain?8Is there aspecific pattern in Brazil’s Africa policy that distinguishesit from other emerging powers on the continent?This briefing paper sets out to give an overview of Brazil’sactivities in Africa and analyse its motives for engagement.It starts by detailing the different activities, highlightingthe basic principles and peculiarities of Brazil’s Africapolicy. In addition to outlining the country’s engagementin traditional economic sectors such as natural resourcesand construction, the paper draws particular attention toBrazil’s remarkable recent efforts and commitment in thepolicy fields of health, rural development and energy. The

underlying motives and interests of Brazil’s Africa engage-ment are then traced within the context of the country’sgeneral foreign policy orientation.

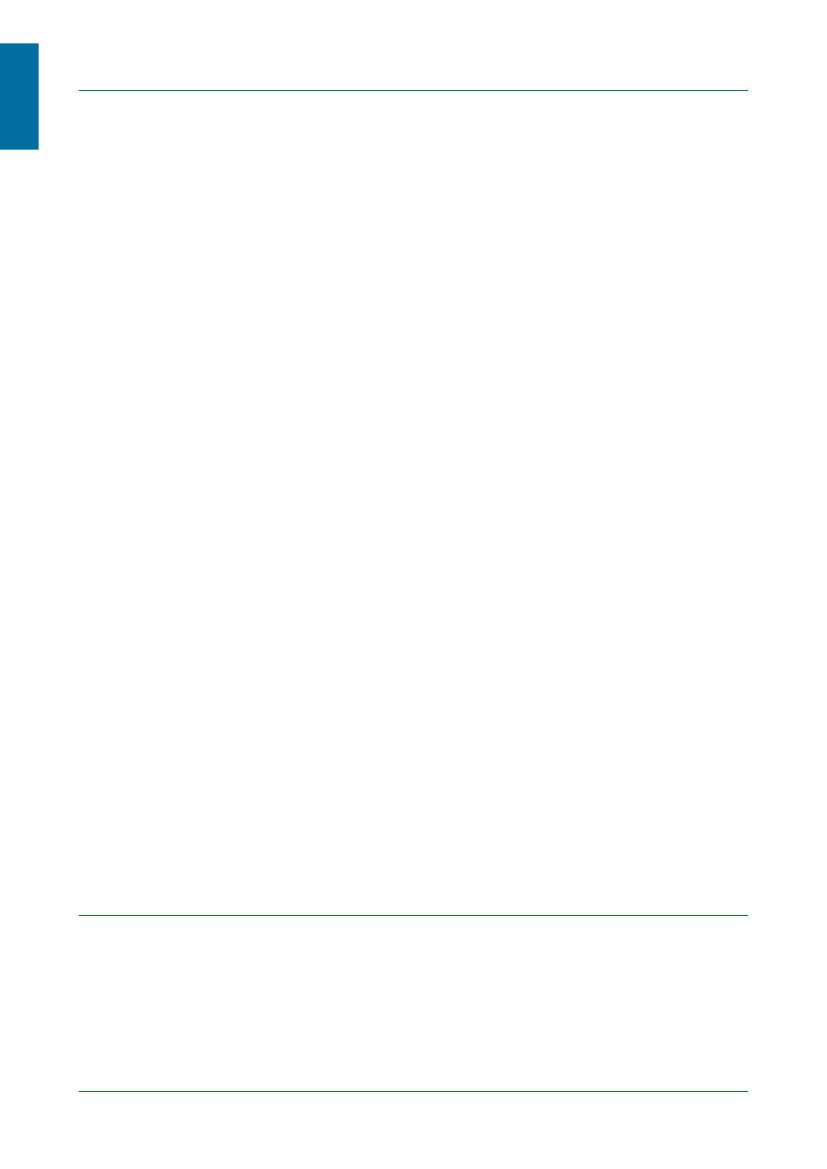

Brazil’s economic engagement in AfricaDuring the last decade, Brazil has significantly steppedup its economic engagement in Africa. There has been asharp rise in trade since the beginning of the millennium.As Figure 1 shows, between 2000 and 2011 it increasedmore than sixfold, from US$4.2 billion to US$27.6 billion.After suffering an interim drop in 2009 owing to theglobal financial and economic crisis, trade had alreadyresumed its upward trend the following year. Since 1990trade between Brazil and Africa has registered impressivegrowth rates of 16% p.a. Compared with its BRICS part-ners, Brazil has seen the second highest increase in tradewith Africa, after China.9Although Brazil has put great effort into extendingcommercial ties with African countries, the trade balanceis still in favour of Africa: Brazilian imports from the

Figure 1: Development of Brazil–Africa trade, 2001–11 (US$bn)30,00025,000Trade between Brazil and Africa20,000Brazilian exports to Africa15,000Brazilian imports from Africa10,0005,000020012002200320042005200620072008200920102011

Source: Ministério do Desenvolvimento, Indústria e Comércio Exterior, Secretaria de Comércio Exterior: Intercâmbio Comercial Brasileiro Africa (exclusiveoriente médio), 06/08/2012. (Ministry of Development, Industry and Foreign Trade, Secretariat for Foreign Trade: Commercial Exchange Brazil-Africa(without Middle East), 6 August 2012.

7 Alexandre Barbosa de Freitas, Thais Narciso and Marina Bianclalana (2009), ‘Brazil in Africa: Another Emerging Power in the Continent?’,Politikon,36(1),pp. 59–86.8 Between March and June 2012 the author conducted interviews on Brazil’s Africa policy at the Brazilian Foreign Ministry (Itamaraty), the BrazilianCooperation Agency (ABC), the Brazilian Ministry for Development, Industry and Trade (MDIC) and other Brazilian governmental, economic, and academicinstitutions. The vision of a ‘foreign policy towards Africa driven by solidarity’ was frequently expressed.9 Simon Freemantle and Jeremy Stevens (2009), ‘Tectonic Shifts Tie BRIC and Africa’s Economic Destinies’, Standard Bank Economics,BRIC and Africa,14 October 2009, p. 10.

www.chathamhouse.org

page 3

Brazil in Africa: Just Another BRICS Country Seeking Resources?

page 4

continent accounted for US$15.43 billion in 2011, whereasits exports to Africa accounted for US$12.22 billion. Moresignificantly, as data from the African Development Bankshow, imports from the continent are more importantfor Brazil than imports from Brazil are for Africa. WhileAfrican countries accounted for 6.6% of Brazil’s totalimports in 2009, Brazil represented only 3.4% of totalAfrican imports.10This imbalance is also reflected in theranking of Africa’s most important trade partners: whileBrazil is the 10th most important export destination forAfrica, it is only the 16th most important trade partnerfor imports. In terms of the ranking of Africa’s emergingtrade partners, Brazil is in fourth place, behind its BRICSpartners China and India, and South Korea.11Africancountries combined are currently Brazil’s fifth biggesttrading partner for exports and imports.12

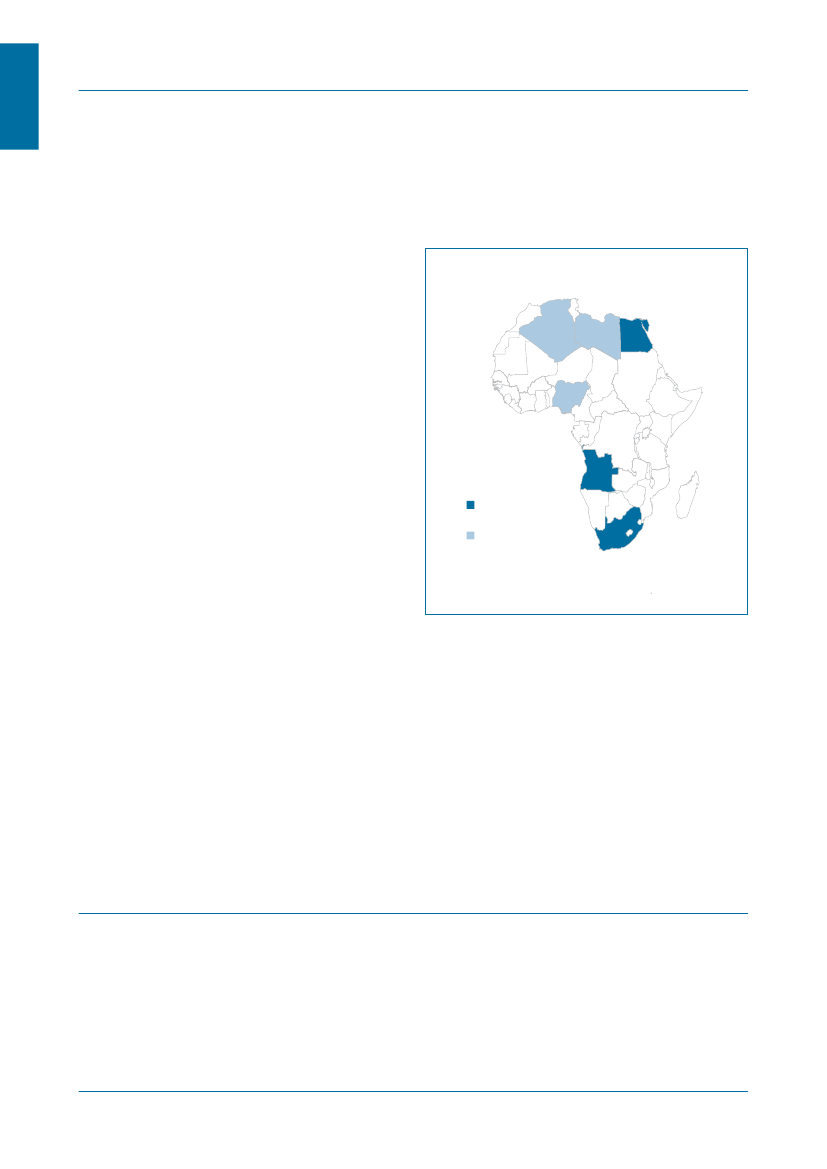

resource sector is explained by the fact that the majorityof the country’s large-scale enterprises are specializedin resources. It is therefore not a strategy of securingresources but rather their attempt to internationalize anddiversify away from the Brazilian market.Figure 2: Brazil’s most important trade partners inAfrica

Is it all about resources?In terms of the composition of trade, Brazil’s resourceinterests seem to dominate the picture: oil and othernatural resources make up almost 90% of its importsfrom Africa.13Its most important trade partners on thecontinent also seem to fit neatly into the pattern of aresource-hungry BRICS country coming to Africa: itsmajor trade partners Nigeria, Angola, South Africa andLibya are all rich in resources. Moreover, nearly all thebig Brazilian companies investing in the continent areinvolved in the resource sector.Yet the pattern is not as clear as it might seem at firstglance. Brazil, in contrast to its BRICS partners Chinaand India, is a resource-rich country itself and is notdependent on Africa’s resources. In fact, natural resourcesaccount for an important part of Brazil’s total exports,and some analysts maintain that it is even too dependenton exporting these.14Brazil’s engagement in Africa’s

Most important exportdestinations for BrazilMost important importcountries for Brazil

Source: MRE/Divisao de Inteligencia Comercial 2012 [Brazilian ForeignMinistry/Economic Intelligence Division 2012], pp. 12–13.

The current pattern of oil imports seems to reflectthe past rather than indicate likely future developments.Economic engagement in resource-rich countries datesback to the 1970s when the Brazilian military regimetried to meet the country’s growing energy demand byimporting oil from Africa.15At that time Brazil was almosttotally dependent on foreign oil imports and sufferedseverely from the effects of the first oil crisis. Economicties with oil-rich countries in Africa also proved to bevaluable in the first years of the new millennium, when awave of energy nationalism in South America led Brazilto try to diversify away from politically motivated oil

10 African Development Bank (2011), ‘Brazil’s Economic Engagement with Africa’,Africa Economic Brief,Vol. 2, No. 5, 11 May 2011.11 African Economic Outlook (2011), ‘Africa’s Emerging Partners. The Broad Range of Emerging Partnerships’, http://www.africaneconomicoutlook.org/en/in-depth/emerging-partners/africa-pushes-aside-post-colonialism/the-broad-range-of-emerging-partnerships/ (last accessed 17 October 2012).12 Ministério do Desenvolvimento, Indústria e Comércio Exterior (2011) Balan§a Comerical Brasileira. Dados Consolidados [Brazilian Ministry of Development,Industry and Foreign Trade, Brazilian Trade Balance. Consolidated Data], Brasília, pp. 18 and 28.13 Ibid., p. 28.14 Ruchir Sharma (2012), ‘Bearish on Brazil. The Commodity Slowdown and the End of the Magic Moment’,Foreign Affairs,Vol. 91, No. 3, May/June 2012.15 Ricardo Sennes and Thais Narciso (2009), ‘Brazil as an International Energy Player’, in Lael Brainard and Leonardo Martinez-Diaz (eds),Brazil as an EconomicSuperpower? Understanding Brazil’s Changing Role in the Global Economy(Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press), pp. 17–54.

www.chathamhouse.org

Brazil in Africa: Just Another BRICS Country Seeking Resources?

exporters in its own neighbourhood.16Since 2007–08,however, when the world’s largest oil discovery in 20years was made in Brazil, it has become clear that in thenear future the country will no longer be dependent onforeign oil imports.17As it becomes a major oil exporteritself, its demand for oil from Africa will considerablydiminish.18This trend is already reflected in the strategyof Brazil’s energy giant Petrobras: whereas its 2007–11plan envisaged a doubling of investment in Africa, thecurrent plan (2012–15) envisages 95% of total invest-ment going to activities in Brazil, with a focus on theproduction of the so-called pre-salt reserves found on theBrazilian coast.19While this certainly does not mean that Brazil willcompletely cease importing oil from Africa in the years tocome, the trade balance is likely to shift in favour of Brazilwhen oil imports from Africa start to diminish. WithBrazilian industrial production in need of resources, theshare of other mineral and metallic raw materials such assteel, iron, cement etc. (currently less than 3% of Brazilianimports from Africa)20might increase in the future.However, they will not compensate for the reduction in oilimports. Brazil’s economic dependence on Africa is thuslikely to be reduced in the next decade.Brazil’s exports to Africa are more diversified than itsimports, comprising many agricultural products (sugar,dairy, meat, cereals) but also manufactured and semi-manufactured goods (vehicles, vehicle parts). In fact,Africa has become a growing market for Brazil’s processedproducts.

Investment focused on Lusophone AfricaDespite this growth in trade, Brazilian investment inAfrica remains relatively limited.21There are no precisedata available, although estimates range between US$10billion and US$20 billion.22According to the BrazilianFunda§ão Dom Cabral, Africa currently ranks only fifthamong Brazil’s preferred investment regions. However,the continent is gaining interest among Brazilian compa-nies, registering the third highest growth in Braziliandirect investment in 2010.23Interestingly, this investment pattern is not fullycongruent with Brazil’s major trade partners. LusophoneAfrica is clearly the main destination for Brazilian directinvestment in the region; its oil-rich trade partners inNorthern Africa are of only minor importance in thisregard. A common language and historical ties havefacilitated heavy investment by Brazilian companies inPortuguese-speaking Angola and Mozambique.In fact, Angola is Brazil’s main destination for directinvestment and franchising.24The former Portuguesecolony has had a special relationship with Brazil sincethe first hours of its independence, as Brazil was the firstcountry to officially recognize Angola as a sovereign state.Despite Brazil’s anti-communist military dictatorship andclose relations with Portugal, it took the opportunity toestablish ties with Angola’s communist MPLA movement.It was soon rewarded with the MPLA leader’s personalinvitation to Petrobras to invest in the newly independentstate, and the company started operations there shortlyafter independence. Other big Brazilian companies, such

16 Genaro Arriagada Herrera (2006), ‘Petropolitics in Latin America. A Review of Energy Policy and Regional Relations’, Inter-American Dialogue: AndeanWorking Paper, December 2006; and Paul Isbell (2008), ‘Energía y geopolítica en América Latina’, inDocumento de Trabajo,No.12/2008 (Madrid: RealInstituto Elcano).17 Sennes and Narciso (2009), ‘Brazil as an International Energy Player’.18 In 2011 oil accounted for 85% of imports from Africa. Ministério de Rela§ões Exteriores (MRE), Divisão de Inteligência Comercial (2012), ‘África. DadosBasicos e Prinicipais Indicadores Economico-Comerciais’ [Brazilian Foreign Ministry/Economic Intelligence Division, ‘Africa. Basic Data and Principal Economicand Commercial Indicators’], p. 11.19 Petróleo Brasileiro S.A. – Petrobras (2006): 2007–2011 Business Plan, Rio de Janeiro. And: Petróleo Brasileiro S.A. – Petrobras (2011): 2012–2016Business Plan, Rio de Janeiro, www.investidorpetrobras.com.br/en/business-plan/ (last accessed 17 September 2012).20 MRE (2012), p. 10.21 Roberto Magno Iglesias and Katarina Costa (2011), ‘O investimento direto brasileiro na África’,Textos CindesNo. 27, December 2011, p.16.22 See African Development Bank (2011), ‘Brazil’s Economic Engagement with Africa’, p. 4;Folha de São Paulo(2011), ‘Aumenta influência do Brasil na África’,14 December 2011.23 Funda§ão Dom Cabral (2010), ‘Ranking Transnacionais Brasileiras 2010. Repensando as Estratégias Globais’, www.fdc.org.br (last accessed 17 September2012).24 Iglesias and Costa (2011), ‘O investimento direto brasileiro na África’.

www.chathamhouse.org

page 5

Brazil in Africa: Just Another BRICS Country Seeking Resources?

page 6

as the construction firm Odebrecht, soon followed suit. Asthey stayed in the country despite almost three decades ofcivil war (1975–2002), Brazilian companies were amongthe first to win contracts for the reconstruction of thecountry. Today, Brazil figures among the three mostimportant and influential investor countries in Angola25and its footprint is still growing. Odebrecht has contrib-uted significantly to rebuilding the infrastructure – fromdams to housing and hospitals – in the war-ravagedcountry. Apart from construction, Odebrecht is alsoinvolved in the oil, biofuel, diamond and supermarketsector.26It is the biggest private employer in Angola andenjoys close relations with President José Eduardo dosSantos.27Furthermore the Brazilian private companiesTV Globo and Record broadcast on Angola’s television,attracting millions of Angolans to Brazilian culture withsoap operas, sport and lifestyle programmes. Last but notleast, Petrobras has significantly stepped up its activitiesby acquiring further exploration rights and increasingproduction.In the wake of Brazil’s multinationals, a large numberof small and medium-sized businesses have come toAngola. Whereas the presence of the large companies isthe most visible sign of its footprint in Angola, it is thegrowing number of small business that indicates Brazil’snew interest in the country. Studies by the Brazilian Trade

Promotion and Investment Agency (APEX) and the deci-sion by the agency to establish a regional APEX officein Luanda confirm an increasing interest among smallercompanies in extending their business activities to Africa.The established presence of other Brazilian companiesmeans that Angola has become an easy departure point fortheir internationalization plans. However, Mozambiquetoo has seen an increase in Brazilian direct investment.Like Angola, it has historical and cultural ties that facilitateinvestment, and there is no language barrier.28

Focus on resources and constructionAs regards the preferred sectors of Brazilian investmentin Africa, the picture is once again dominated by a clas-sical pattern. As with other BRICS countries, Brazilianinvestment has so far been concentrated in the resourceand construction sector. But this is again explained by thefact that the majority of Brazil’s biggest companies – thosethat possess the necessary financial resources to investinternationally – are specialized in the areas of civil construc-tion and resources (e.g. Odebrecht, Andrade Gutierrez,Petrobras, Vale).29It is important to note that their activitiesare not a recent trend but date back to the 1970s when theBrazilian military regime supported the internationalizationof domestic companies as a means of securing resources andfostering the country’s development.

Table 1: Brazil’s big players in AfricaCompanyOdebrechtPetrobrasValeBusiness sectorConstructionOilMiningPresence in African countriesAngola, Botswana, Congo, Djibuti, Gabon, Libya, Liberia, Mozambique, South AfricaAngola, Benin, Gabon, Libya, Namibia, Nigeria, TanzaniaAngola, Congo, Gabon, Guinea, Liberia, Malawi, Mozambique, South Africa, Zambia

Source: Company websites (last accessed 13 September 2012).

25 Júlia Vilas-Bôas (2011), ‘Os investimentos brasileiros na África no governo Lula: Um mapa’,Meridiano 47,Vol. 12, No. 128, November–December 2011,pp. 3–9.26 João Fellet (2012), ‘Com BNDES e negócios com políticos, Odebrecht ergue “império” em Angola’, BBC Brasil, 18 September 2012.27 Ibid.28 Iglesias and Costa (2011), ‘O investimento direto brasileiro na África’.29 For a ranking of Brazil’s biggest companies in 2012 see http://exame.abril.com.br/negocios/empresas/melhores-e-maiores/ranking/2012/ (last accessed24 August 2012).

www.chathamhouse.org

Brazil in Africa: Just Another BRICS Country Seeking Resources?

Table 2: Africa credit lines granted by Brazil’s Development Bank BNDESCountrySouth AfricaCredit volume (US$)35mSectorTransportBuses, electronic payment systems for public transportConstructionEngineering services and products for the construction of Nacala airportConstructionStreets, basic sanitation, housing, technological centresIndustry and agricultureMachinery and technical equipment for the modernization of Angola’s fire brigade;agricultural machinerySource: BNDES, 2012.

Mozambique

80m

Angola

3.2bn

As Africa is known for its vast potential in naturalresources and its need for infrastructure, resources andcivil construction have traditionally been the most promi-nent sectors for international investment. It is thus nosurprise that Brazil’s investment activities have so far beenconcentrated on these sectors. Especially when it comes tomining and drilling for oil, Brazilian companies also claima natural advantage over their international competitors:as the two continents were united in a single landmass(‘Gondwana’) 200 million years ago, they have geologicalsimilarities.An additional factor is that financing modalities inBrazil have so far privileged the big companies and thuscontributed to the concentration of Brazilian firms in theabove-mentioned sectors. Since the credit lines by theBrazilian Development Bank BNDES were designed tosupport Brazil’s big players in their internationalizationefforts, smaller companies, especially those affiliated withother branches (foods, beverages, clothing, etc.) have beenmore reluctant to invest in Africa because of a lack offunding.It was not until 2007 that BNDES granted the first creditline to companies willing to invest in Africa. From itsinitial rather limited credit volume of US$149 million, thebank has extended its grants, peaking at US$766 millionin 2009 before settling back to a total of US$466 million in30 Data provided to author by BNDES.31Financial Times(2012), ‘BTG launches $1bn Africa buyout fund’, 3 May 2012.32 Data provided to author by BNDES.33 Fellet (2012) ‘Com BNDES e negócios com políticos’.

2011.30In addition to state-financed lending, BTG Pactual,a leading Brazilian investment bank, has launched a US$1billion fund focused on investing in Africa in 2012.31Construction and engineering top the list of businesssectors privileged by BNDES lending schemes. However,the export of machinery and technical equipment is alsogrowing in importance since the construction servicesof Brazilian companies often use Brazilian goods andproducts. Currently, BNDES credit lines benefit Braziliancompanies investing in South Africa, Mozambique andAngola, with the last being granted the biggest creditvolume, in line with Brazil’s investment focus. Since 2007four credit lines worth US$3.2 billion were approved byBNDES and safeguarded by guarantees linked to Angola’sgrowing oil industry;3249% of these credit lines have beendedicated to projects carried out by Odebrecht.33

Competition with ChinaDuring the last decade, China’s activities in Africa havefurther drawn international attention to the continent’snatural resource potential and have led to competition forwhat is today considered the world’s last resource frontier.Brazilian companies have joined in this new ‘scramble forAfrica’ and have stepped up their activities, using theirpre-existing presence in some African countries to extendtheir engagement and influence.

www.chathamhouse.org

page 7

Brazil in Africa: Just Another BRICS Country Seeking Resources?

page 8

Brazilian companies such as Petrobras (oil sector) andVale (mining) are actively competing with Chinese compa-nies for exploration rights in Africa. Brazil may lack thefinancial resources to support its companies in Africa in thesame way as China, but while it sees this as a comparativedisadvantage, it can claim a cultural advantage. Althoughthe Brazilian government has made a great effort to provideBrazilian companies with financial and political support intheir competition for markets and influence in Africa, itsees ‘cultural affinity’ as the real trump card against morepowerful Chinese state-backed companies.34Brazilian businessmen and government officials aliketherefore stress their common cultural roots with Africaand maintain that, unlike China, they enjoy a commonbusiness culture. The fact that the majority of Brazil’spopulation is of Afro-Brazilian origin – it has the world’slargest black population after Nigeria – serves as a popularillustration of these cultural similarities.Brazil is very keen to highlight the differences in itsapproach towards Africa and has not shied away fromopen criticism of its BRICS partner. On a journey toTanzania, for example, President Lula referred to a miningproject that the Brazilian mining giant Vale had lost to aChinese company and declared openly: ‘Nothing againstmy Chinese friends. Quite the contrary. China is a greatpartner for us and we want to maintain our strategic rela-tionship. But the truth is that they sometimes win a mineand take only Chinese there to work, without generatingany opportunity for the local workers.’35Stressing the benefits of their country’s engagement inAfrica, Brazilian officials therefore frequently refer to theemployment and training that Brazilian firms provide forthe local workforce. In Angola, Odebrecht is, as noted,already the biggest employer and Brazil maintains that its

approach towards Africa is generally focused on gener-ating development and benefiting the local population.president Rousseff therefore has pledged that Braziliancompanies willing to invest in Africa will leave a legacy tothe local population by transferring technology, providingvocational training and offering social programmes.36Like her predecessor, she is convinced that the Brazilianapproach ensuring benefits on both sides comparesfavourably with China’s.

Brazil’s bet on Africa’s growing marketDespite the current focus on resources and construction,Brazilian business representatives maintain that Africa’sbiggest potential for their country lies in the export ofmachinery, technical equipment and construction mate-rials, as well as food, beverages and agricultural products.Promising markets for Brazilian products are also seen forfashion, cosmetics and pharmaceutics.37Here, a positive effect is attributed to China’s Africaengagement: Brazil calculates that Chinese investment inAfrica will boost incomes among the local population andeventually create a growing consumer market for food andprocessed goods. A representative of a Brazilian govern-mental institution confirmed this in 2007 by stating:‘China is going to Africa after mining, copper, iron,manganese as well as oil and gas. We [Brazil] are goingafter the vacuum left by them […].’38Already, 42% of the goods that Brazil exports to Africaare manufactured products.39As the average share ofmanufactured goods in Brazil’s total exports is only 36%,the African market ranks significantly above average inthis regard. In fact, Africa is the export region with thethird highest share of manufactured goods for Brazil, afterLatin America and the United States. This makes Africa an

34 David Lewis (2011), ‘In Africa, Can Brazil be the Anti-China?’, Reuters Special Report, 23 February 2011.35 ‘“Nada contra os meus amigos chineses. Pelo contrário [a China], é um grande parceiro nosso e queremos manter nossa parceria estratégica. Mas a verdadeé que, às vezes, eles ganham uma mina e trazem todos os chineses para trabalhar naquela mina. E fica sem gerar oportunidade para os trabalhadores dopaís”, disse Lula.’ SeeValor Económico,‘Avan§o de chineses na África preocupa Brasil’, 8 July 2010.36Valor Econômico,‘Dilma revê estratégia para a África’, 8 November 2011.37 See, for example, studies by Brazil’s Trade Promotion Agency APEX (2010), ‘Angola. Estudo de Oportunidades 2010’, Brasília; APEX (2011), ‘África do Sul.Perfil e Oportunidades Comerciais 2011’, Brasília.38Valor Econômico,25 April 2007, quotation from de Freitas, Narciso and Bianclalana (2009), ‘Brazil in Africa: Another Emerging Power in the Continent?’.39 MRE (2012), p. 9; semi-manufactured goods account for a further 27% of its exports to the continent.

www.chathamhouse.org

Brazil in Africa: Just Another BRICS Country Seeking Resources?

interesting market as the Brazilian economy endeavoursto step up its manufactured exports and diversify awayfrom the export of simple raw materials.Brazil sees a special potential in the African market whenit comes to technological products. Industry representa-tives and officials from the governmental export promotionagency maintain that Brazilian technology has a specialcomparative advantagevis-à-visproducts from high-tech-nology countries, as it is adaptable to tropical conditions(‘tropicalized technology’).40By presenting its products inAfrican fairs, Brazilian industry hopes to further increase itsexports to a growing African market.Brazilian companies eager to exploit this potentialusually sail in the wake of the big Brazilian companiesalready established in Africa, thereby taking advantageof the their presence and knowledge of the market. TheBrazilian Ministry of Development, Industry and ForeignTrade calculates that every investment by a large-scaleBrazilian company provides for the establishment ofaround 10 small or medium-sized firms that act assuppliers or subcontractors for the bigger companies orseize opportunities to sell Brazilian consumer products.

relations with Brazil’s most important trade partners, theUnited States and the EU, without being able to assert thecountry’s economic and political interests against thesepowerful players. The new government set out to reduceBrazil’s dependence on the industrialized countries byforging ties with the developing world.42At first, Lula’sefforts to establish a ‘new trade geography of the South’were dismissed as an ideological project and economicnonsense by Brazil’s economic elite.

Already, 42% of the goodsthat Brazil exports to Africa aremanufactured products. As theaverage share of manufacturedgoods in Brazil’s total exports isonly 36%, the African marketranks significantly above average

More driven by government than by themarketAlthough Brazil has already enhanced its trade links withAfrica, its real economic interest in Africa is only justawakening. The intensification of economic ties, particu-larly trade, over the past decade was driven by governmentinitiatives during the left-wing Lula administration ratherthan by Brazilian business itself.41President Lula had declared Africa a priority for hisgovernment in 2003 and set out to deepen relations atall levels. Under his predecessor, Fernando Cardoso(1995–2002), the government had concentrated on

As the country’s economic relations had traditionallybeen directed towards the big markets of the industrializedcountries, trade routes with the developing world wereeither non-existent or very expensive. Business associa-tions therefore accused the Lula government of ignoringthe economic realities and neglecting Brazil’s dependenceon the consumer markets in Europe and the United States.Furthermore, at that time, Brazilian businesses saw littleeconomic potential in a poor and crisis-prone continent.Their reservations were based on a mixture of prejudiceand bad experiences in the past, when African countrieshad not been able to pay their bills for Brazilian imports,and Brazilian investors were affected by civil wars.43

40 Interview with the Câmera de Comércio Afro-Brasileira (AfroChamber), São Paulo, May 2012.41 Interviewees at the Brazilian National Federation of Industry CNI (Confedera§ão Nacional de Indústria) and the Brazilian Development Bank BNDES (BancoNacional do Desenvolvimento) in June 2012 commonly expressed this view.42 It should be noted that Lula was not the first Brazilian president to forge ties with Africa. Already at the beginning of the 1960s the then military dictatorshipestablished relations with African countries. However, in the 1980s and 1990s, owing to economic problems and a shift in foreign policy, the Brazilian focuson Africa declined. For a good overview of the history of Brazil–Africa relations see José Flávio Sombra Saraiva (2012),África parceiro do Brasil atlântico.Rela§ões internacionais do Brasil e da África no início do século XXI,Chapter 1 (pp. 25–50) (Belo Horizonte: Editora Fino Tra§o).43 Interview at the Brazilian National Confederation of Industry (CNI) in Brasília, June 2012.

www.chathamhouse.org

page 9

Brazil in Africa: Just Another BRICS Country Seeking Resources?

page 10

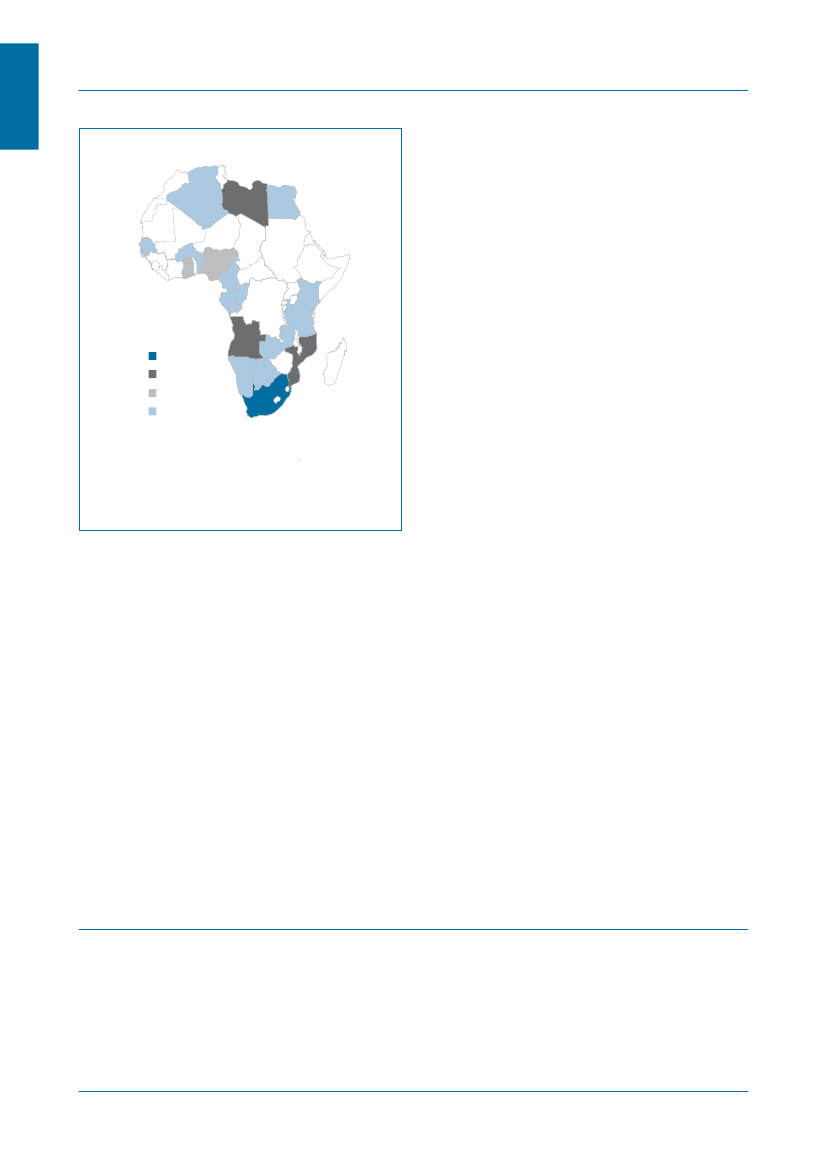

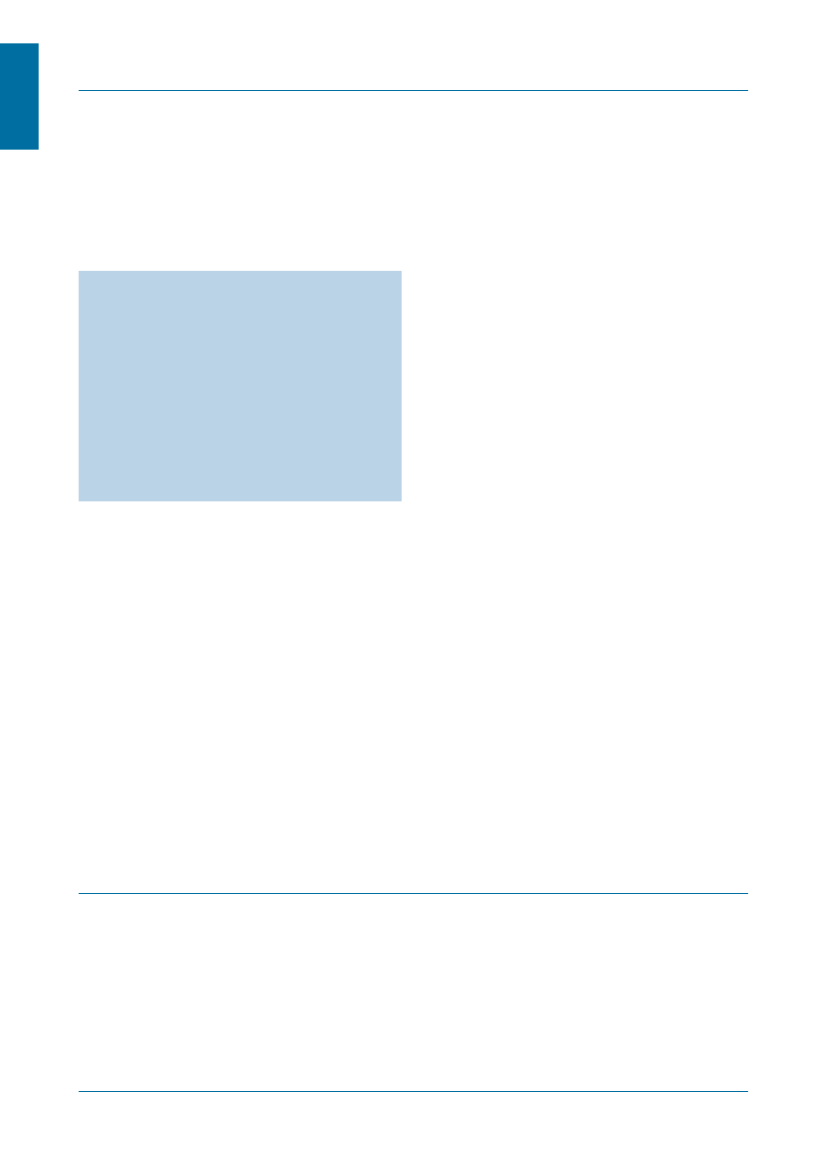

Figure 3: Brazilian presidential visits to Africa

Criticism of President Lula’s courtship of Africa easedwith the growing commercial exchange. Today Africa’seconomic potential is widely acknowledged amongBrazilian business circles, especially at a time of economicrecession in the industrialized countries.45It is perceivedas the last economic frontier to be explored, and Africainitiatives have gained momentum in Brazil’s foreigntrade strategy. Under President Rousseff, Brazil has evendevised a special Africa strategy to gain markets there.46

5–6 visits3–4 visits2 visits1 visitSource: MRE (2011), ‘Relatório de visitas internacionais do PresidenteLuiz Inácio Lula da Silva e de visitas ao Brasil de Chefes de Estado e deChefes de Governo entre janeiro 2003 e dezembro de 2010’ [BrazilianForeign Ministry, ‘Report on the international visits of President LuizInácio Lula da Silva and visits of Heads of State or Heads of Governmentto Brazil between January 2003 and December 2010’].

Going beyond commercial interestsBrazil’s profile in Africa, however, is not only shaped byits business activities. In fact, the economic engagement ofBrazilian enterprises is only one aspect of Brazil’s footprint.President Lula’s Africa strategy went far beyond commer-cial interests. Whereas his personal commitment to theintensification of relations with Africa has undoubtedlygenerated economic benefits for Brazil, his South–Southcooperation strategyvis-à-visAfrica was driven rather byforeign policy ambitions than by economic calculations.47As an emerging power striving to win a seat at the UnitedNations Security Council, Brazil has turned engagementin Africa into a centrepiece of its strategy to gain supportfor this ambition.48Brazil has positioned itselfvis-à-visAfrica as a partnerfor development, rather than a business partner. Havingonly recently joined the club of economic powers, Brazilhas presented itself as a ‘rising power of the South’ familiarwith the development challenges faced by African coun-tries. Strengthening its discourse on Southern solidarity, ithas provided so-called South-South cooperation projectsthat are based on its own development experiences.49In contrast to classical development cooperationprovided by rich countries (North–South cooperation),South–South cooperation is conceptualized as a ‘horizontal

Despite these concerns, the Lula administration paved theway for an intensification of both political and commercialties with Africa. Against severe criticism by the opposi-tion, Lula promoted the continent as an under-exploredopportunity for Brazilian business and actively encour-aged Brazilian companies to engage with Africa. From thestart, he invited Brazilian businessmen to accompany himon his visits and to take advantage of the political contactsforged with African countries. To support their interna-tionalization efforts in developing regions, a special tradepromotion strategy was devised;44in cooperation withAPEX, founded in the first year of his administration,the government organized gatherings of Brazilian andAfrican businessmen and actively supported the partici-pation of Brazilian firms in African fairs to promote theirproducts.

44Carta Capital(2008), ‘O vendedor do Brasil’, 25 June 2008.45 Stuart Grudgings (2011), ‘As rich world sputters, Brazil looks to Africa’, Reuters Business and Financial News, 17 November.46Valor Econômico(2011), ‘País elabora estratégia para se tornar mais competitivo na África, 08.11.2011’.47 Cepal Workshop on South–South Cooperation, Brasília, 30.03.2010. Summary (in Portuguese) under: http://www.cepal.org/brasil/noticias/paginas/2/38422/Coopera%C3%A7%C3%A3o_SUL-SUL.pdf (last accessed 19 September 2012).48 Danilo Marcondes de Souza Neto (2011), ‘Brazil and Africa: Challenges and Opportunities’,Africa Quarterly,Vol. 51, No. 3–4, p. 76–86.49 Bruno Ayllón Pino and Iara Costa Leite (2010), ‘La cooperación Sur-Sur de Brasil: Instrumento de política exterior y/o manifestación de solidaridadinternacional?’,Mural Internacional,Vol. 1, No. 1 (January/June).

www.chathamhouse.org

Brazil in Africa: Just Another BRICS Country Seeking Resources?

partnership’ between countries that share common prob-lems and development challenges. Having been a recipientof development aid for decades, Brazil claims that it hasa better understanding of the needs and sensitivities ofrecipient countries. It stresses that its cooperation projectsare fundamentally different from those formulated in anindustrialized country, being based on expertise generatedand implemented within a developing-country context.50Historical cultural ties between Brazil and Africa furtherfacilitate cooperation and enhance the applicability of thesedevelopment projects. Operating largely free of a legacy ofcolonialism, Brazil maintains that its cooperation is moti-vated by a feeling of solidarity with its African partners.However, former president Lula also framed South–Southcooperation with Africa as a moral obligation to ‘givesomething back’ to the African people that ‘helped to buildBrazil’.51Apologizing for centuries of slavery, he frequentlydeclared that Brazil owed a moral debt to Africa.52As acountry that has overcome key problems of developmentby finding innovative solutions, Brazil has offered Africancountries its know-how in a range of relevant policy fields.Especially in the area of poverty reduction, energy andhealth, Brazil has shown significant commitment by trans-ferring technical expertise and offering cooperation projects.Key to Brazil’s South–South cooperation projects withAfrica have been two state-financed research institutions:the biomedical research and public health institute Fiocruz(Oswaldo Cruz Foundation) and the Agricultural ResearchInstitute Embrapa (Empresa Brasileira de PesquisaAgropecuária). The former made crucial contributions

to Brazil’s success in tropical agriculture and the latter tocombating and preventing tropical diseases. Both havereceived worldwide acclaim.53Capitalizing on this broadinternational recognition, the Lula government turnedboth institutions into foreign policy instruments, encour-aging them to start activities abroad54and selling them asshowpieces of Brazil’s successful development.

Brazil as a partner in Africa’s fight againsthunger and povertyPoverty reduction and the alleviation of hunger werepriorities of Brazil’s Lula administration for both domesticand foreign policy.55The president, raised in conditionsof poverty himself, declared the fight against poverty aleading topic for his presidency after coming to power in2003. His programmes to alleviate hunger and povertysoon delivered results and enabled the country to achievethe Millennium Development Goals for poverty andhunger five years ahead of schedule.Convinced that ‘hunger is the real mass destructionweapon’,56Lula also put the fight against poverty at thetop of his foreign policy agenda. In his first year in officehe proposed a global hunger fund to the world’s leadingeconomies at the G8 Summit in France and promoted thealleviation of poverty as one of the most pressing securityproblems of the 21st century.57Making Africa the test case for its commitment tofight poverty, Brazil has implemented a great variety ofprojects to foster African development. Actions are basedon its own experiences in the fight against poverty58and

50 Sean Burges (2012), ‘Developing from the South: South-South Cooperation in the Global Development Game’, Austral.Brazilian Journal of Strategy &International Relations,Vol. 1, No. 2, July-December, pp. 225–49.51 BBC (2010), ‘Brazil’s Lula pays tribute for Africa’s historic role’, 4 July, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/10500100 (last accessed 31 October 2012).52 BBC (2005), ‘Brazil’s Lula “sorry” for slavery’, 14 April, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/4446647.stm (last accessed 31 October 2012).53 In 2006 two Embrapa scientists were awarded the World Food Prize for ‘one of the greatest achievements of agricultural science in the 20th century’. Seehttp://www.worldfoodprize.org/en/press/news/index.cfm?action=display&newsID=808 (last accessed 16 October 2012). See alsoThe Economist(2010),‘The miracle of the Cerrado’, 26 August. Fiocruz was nominated the ‘best public health institution in the world’ by the World Federation of Public HealthAssociations in 2006. See http://www.fiocruz.br/~ccs/novidades/news/fiocruz_thebestp.htm (last accessed 16 October 2012).54 Under the Lula administration, both Embrapa and Fiocruz established special international relations departments and opened branch offices in Africa.55 Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva (2011): ‘Our battle to end hunger’,Guardian,19 June 2011.56 Cited by Brazil’s Minister of Foreign Affairs Celso Amorim (2010), in ’Brazilian–African Talks on Food Safety, Hunger Alleviation and Rural Development’, inAgencia Brasileira de Coopera§ão (ed.),Brazilian–African Talks on Food Safety, Hunger Alleviation and Rural Development,Brasília, p. 94.57 BBC (2003), ‘Lula proposes hunger fund’, 6 February 2003. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/2954990.stm (last accessed 26 October 2012).58 Between 2003 and 2010 Brazil managed to lift 32 million people out of poverty. It has been internationally recognized for its success in poverty reductionand social promotion programmes, and promoted by Global institutions such as the World Bank and the United Nations as a model for successful povertyreduction. See for example OECD (2010),Tackling Inequalities in Brazil, China, India and South Africa. The Role of Labour Market and Social Policies.

www.chathamhouse.org

page 11

Brazil in Africa: Just Another BRICS Country Seeking Resources?

page 12

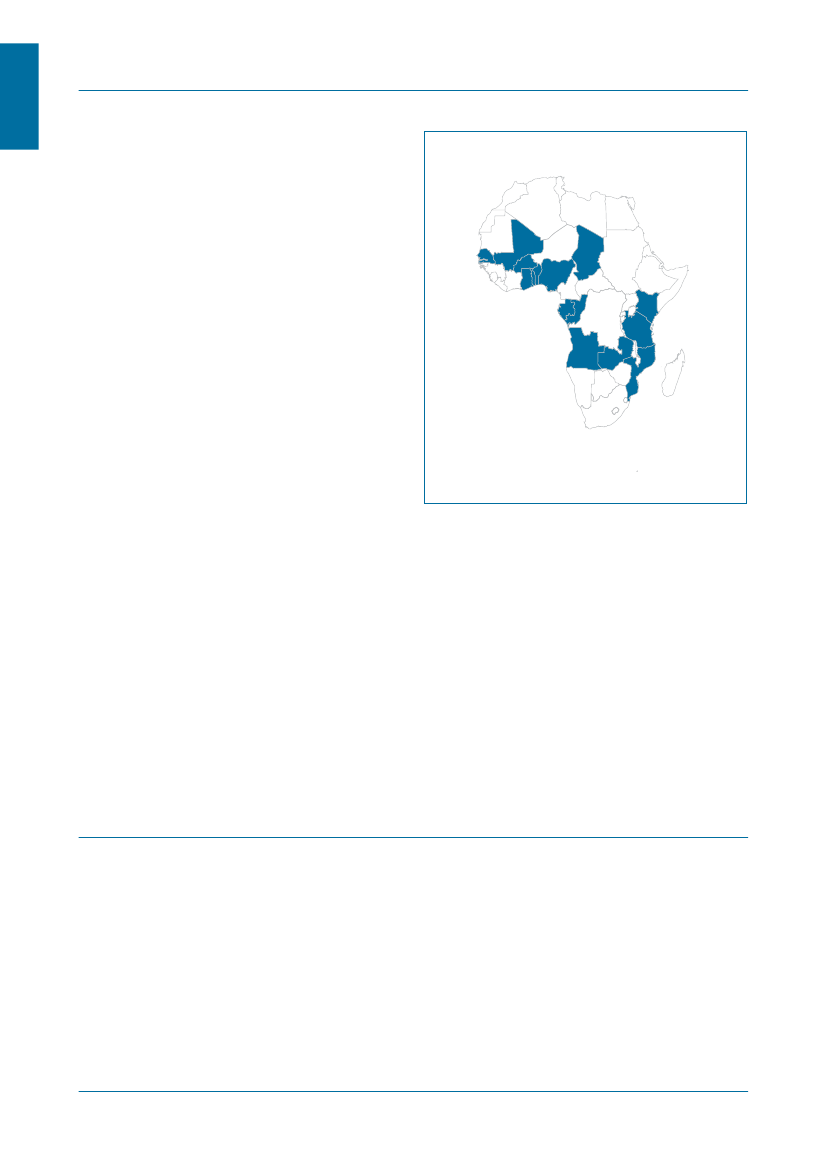

comprise assistance in the development of the continent’sagricultural sector as well as the implementation of socialprogrammes.As the leading power in tropical agriculture and thirdlargest food exporter in the world,59Brazil has positioneditself as an important partner in Africa’s quest for foodsecurity. Since the 1960s, the continent has transformeditself from a net food exporter to a net importer andits population growth rate has outstripped its annualincrease in food production.60Brazil has gone in theopposite direction, developing from a net food importerin the 1970s to an agricultural superpower.61As a tropicalcountry with similar climatic and geological conditionsto those of a great part of sub-Saharan Africa, Brazilhas found it easier to adapt its agricultural expertiseand technology to the African context than traditionalagricultural powers such as the United States or theEuropean Union.62Since the opening of the first Africa office of theAgricultural Research Institute Embrapa in Ghana in2008, Brazil has presented itself to Africa as a providerof technical assistance in tropical agriculture. It offers itsAfrican partners free transfer of know-how in techniquesfor improving the soil, adapting seeds and strengtheningcrop resistance to drought and pests. Today, Embrapais implementing agricultural cooperation projects in 15African countries, ranging from the support of horti-culture in Senegal and the improvement of cashew nutpost-harvest technologies in Tanzania to technical coop-eration on native seed rescue, production and breeding infamily-based agriculture in Namibia.63

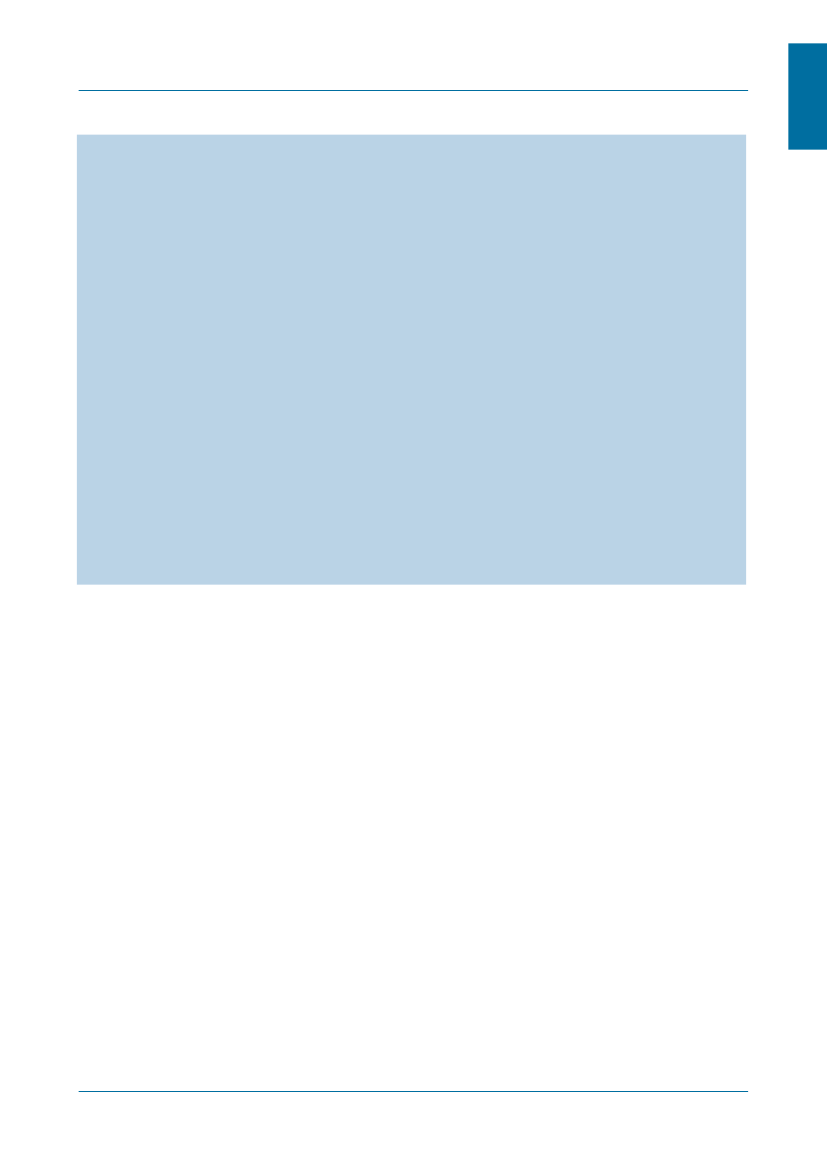

Figure 4: Brazilian agriculture projects in Africa

Source: Embrapa/Ministério da Agricultura, Pecuária e Abastecimento[Embrapa/Brazilian Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Supply] (2011),Africa. Continent of Opportunities,Brasília.

Embrapa’s showcase projects include a model cottonfarm in Mali that aims to increase productivity and qualityin production in the ‘Cotton-4’ countries (Benin, BurkinaFaso, Chad and Mali), as well as an experimental rice farmin Senegal that trains technicians from Senegal, Guinea-Bissau and Mauritania in rice production and processingtechnologies. The Africa–Brazil Agricultural InnovationMarketplace, launched by Brazil in 2010, has establisheda platform to link professionals from African institutionswith Embrapa research centres; it currently has ten coop-eration projects in seven African countries.Brazil also supports African family farming. Based on itssuccessful experiences with the ‘More Food Programme’64

59 See WTO International Trade Statistics 2011, ‘Leading exporters and importers of food 2010’, Table II.20, http://www.wto.org/english/res_e/statis_e/its2011_e/its11_merch_trade_product_e.htm.60 Simon Freemantle and Jeremy Stevens (2010), ‘Brazil Weds Itself to Africa’s Latent Agricultural Potential’, Standard Bank Economics,BRIC and Africa,1 February 2010, p. 2; and Manitra A. Rakotoarisoa, Massimo Iafrate and Marianna Paschali (2011), ‘Why has Africa become a net food importer?’, FAOTrade and Markets Division, Rome.61 Geraldo Barros (2008), ‘Brazil. The Challenges in becoming an Agricultural Superpower’, in Brainard and Martinez-Diaz (eds),Brazil as an Economic Superpower?.62 World Bank/IPEA (2011),Bridging the Atlantic,pp. 50–51.63 For a full overview of Brazilian agricultural projects in África, see Agência Brasileira de Coopera§ão (ABC) (2010),A Coopera§ão Técnica do Brasil para aÁfrica,Brasília.64 Between 2008 and 2010 alone, Brazilian family farmers increased their productivity per area by 89% and their income by 30%. Caio Fran§a et al. (2009), ‘Ocenso agropecuário 2006 e a agricultura familiar no Brasil’, Ministério do Desenvolvimento Agrário (MDA) [Ministry of Africultural Development], Brasília. For agood overview of the More Food for Africa Programme see Thomas Cooper Patriota and Francesco Maria Pierri (2012), ‘Brazil´s Cooperation for AgricultureDevelopment and Food Security in Africa: Assessing the Technology, Finance, and Knowledge Platforms’, in Fantu Cheru and Renu Modi (eds),AgriculturalDevelopment and Food Security in Africa: The Impact of Chinese, Indian and Brazilian Investments(London: Zed Books).

www.chathamhouse.org

Brazil in Africa: Just Another BRICS Country Seeking Resources?

and the demands voiced by African ministers of agri-culture participating in the Brazil–Africa Dialogueon Food Security, Fight against Hunger and RuralDevelopment,65it has designed a project line especiallyto support local food production by family farmers inAfrica. The ‘More Food for Africa Programme’, whichwill be implemented in cooperation with the Food andAgriculture Organization (FAO) and the World FoodProgramme (WFP), supports African family farmersacross the value chain, offering special credit lines forthe purchase of agricultural machinery and insuranceagainst harvest losses. It is linked to food purchaseor national school feeding schemes and other publicprocurement programmes that guarantee family farmerssecure market access.66Although Brazil’s main focus in supporting Africa’sfight against hunger has been on helping the continent toboost its agricultural sector, it has also provided assistancein other anti-poverty measures. Having lifted more than 30million people out of poverty in less than a decade, Brazil isseen as a model for effective social programmes.67Africancountries have shown interest in cash transfer programmessuch as the successful ‘Zero Hunger Programme’ andespecially the ‘Bolsa Familia’ scheme.68Since 2005 Brazilhas offered to provide technical support to Africangovernments interested in implementing cash transferprogrammes, arranging study tours and visits to theMinistry of Social Development and Hunger Alleviation,which is in charge of the programme.69Representativesfrom Ghana, Guinea Bissau, Mozambique, Nigeria, SouthAfrica and Zambia have been invited to Brazil to learnfrom the experiences with the ‘Bolsa Familia’ programmeand gain insights into the design, implementation andmanagement of this social scheme.

In addition, in 2008 Brazil launched the Africa–BrazilCooperation Programme on Social Development toprovide a more systematic coordination of cooperationprogrammes with African countries. The previous year, ithad already provided Ghana with technical assistance inthe design of a pilot social grants programme. Currently, apilot project on the implementation of the ‘Bolsa Familia’programme is under negotiation with Benin.70Through its efforts in transferring its technical exper-tise in poverty alleviation measures Brazil has become animportant partner in Africa’s fight against hunger andpoverty. The region’s appreciation of its commitmentwas demonstrated by the invitation to Brazil to join theAfrican Union’s regional conference of African Ministersof Social Development in October 2008 as the only non-African country.

Brazil as provider of health developmentassistanceBrazil has also dedicated itself to another key challenge forAfrica. Having included the right to health in its consti-tution, it has put great emphasis on health developmentassistance in its South–South cooperation with Africa.Indeed, all of President Lula’s 12 journeys to the conti-nent had a health component.71In total, Brazil has signed53 bilateral agreements on health topics with 22 Africancountries.A clear focus of Brazil’s health diplomacy towards Africahas been the fight against HIV/AIDS. Having dramaticallyreduced AIDS-related mortality and morbidity, Brazil haswon international recognition for its highly successfulAIDS programme.72It has effectively implementedHIV education and prevention campaigns (includingnationwide condom distribution and HIV testing) and

65 This dialogue convened more than 40 African ministers in Brasília on 10–12 May 2010.66 Cooper Patriota and Pierri (2012), ‘Brazil´s Cooperation for Agriculture Development and Food Security in Africa’.67 World Bank (2012), ‘Bolsa Familia: Changing the Lives of Millions in Brazil’, in World Bank News & Broadcast, http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/NEWS/0,,contentMDK:21447054~pagePK:64257043~piPK:437376~theSitePK:4607,00.html (last accessed 5 September 2012).68 José Graziano da Silva, Mauro Eduardo del Grossi and Caio Galvão de Fran§a (2012), ‘Fome Zero (Programa Hambre Zero). La Experiencia Brasileña’,FAO/ Ministerio de Desarrollo Agrario del Brasil, Brasília.69 Ibid.70 ABC (2010),A Coopera§ão Técnica do Brasil para a África,Brasília.71 World Bank/IPEA (2011),Bridging the Atlantic,p. 67.72 BBC (2003) ‘Brazil’s pioneering Aids programme’, 14 July 2003, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/3065397.stm (accessed 26 October 2012).

www.chathamhouse.org

page 13

Brazil in Africa: Just Another BRICS Country Seeking Resources?

page 14

Table 3: Brazil’s health projects with AfricaTopicMalariaHIV/AIDSPartner countriesAngola, Cape Verde, Cameroon, Congo, Guinea-Bissau, São Tomé and PríncipeBotswana, Burkina Faso, Congo, Ghana, Liberia, Mozambique, Kenya, SierraLeone, (South Africa), Tanzania, ZambiaAngola, Benin, Ghana, SenegalCape Verde, Angola, Algeria, Mozambique, São Tomé and Príncipe, Sierra Leone

Sickle cell anaemiaOtherTuberculosis, cancer, oral health, community-based therapy, primaryhealth care, cardiac and paediatric surgical procedures, prenatal andneonatal care

Source: ABC (2010),A Coopera§ão Técnica do Brasil para a África,[Brazilian Technical Cooperation with Africa], Brasília.

provides free universal access to AIDS treatment withantiretroviral drugs for people affected by HIV.73Itsexperience in designing and implementing an efficientAIDS programme as an indebted middle-income countryis therefore of great interest to Africa, the continent mostafflicted by the AIDS pandemic.Against this background, President Lula pledged toassist Africa in its fight against the deadly disease. Since therevitalization of Brazil–Africa relations in 2003, AIDS hasbeen among the key topics of their South–South coopera-tion. Brazil has carried out AIDS projects with Botswana,Burkina Faso, Congo, Ghana, Liberia, Mozambique,Kenya, Sierra Leone, Tanzania and Zambia.74It supportsthese African countries in formulating multidisciplinaryresponses to HIV/AIDS. Measures include capacity-building in the field of prevention, care and treatment, aswell as logistic and supply-chain management for medi-cine distribution. Brazil also shares its experience on waysof mobilizing NGOs and strengthening the participationof the private sector in national HIV/AIDS prevention andtreatment programmes.Brazil’s showcase project in its commitment to Africa’sfight against HIV/AIDS is a factory for antiretroviral drugsin Mozambique. Indeed, the construction of the plant toproduce generic drugs is the most ambitious and most

expensive South–South cooperation project ever launchedby Brazil.75Announced during a visit by President Lula toMozambique in 2003, it was meant to be officially inaugu-rated in 2010 but suffered various delays, while investmentcosts soared from the expected US$23 million to aroundUS$100 million. The plant finally started operations inmid-2012 and is set to produce 21 types of medicines tofight HIV/AIDS. Initially, it will produce drugs to meetthe demand in Mozambique only. However, productionis set to expand in the next few years to supply all of sub-Saharan Africa.76Brazil is providing further capacity-building measuresto enable production of the generic drugs to be takenover by Mozambican technicians. They are being trainedby Fiocruz, which is responsible for the pharmaceuticalproduction process at the plant. Brazil’s National SanitarySurveillance Agency (ANVISA) and the Brazilian Ministryof Health are also supporting Mozambique in establishinga drug regulatory authority to control the safety, qualityand price of these pharmaceuticals.In another flagship project on AIDS, Brazil developedan Awareness and Prevention Campaign with SouthAfrica during the FIFA World Cup in 2010. This firstjoint effort, based on Brazil’s experiences with preventioncampaigns during Carnival, included the distribution of

73 Amy Nunn et al. (2009), ‘AIDS Treatment in Brazil: Impacts and Challenges’, inHealth Affairs,July/August 2009, 28:4, ProQuest, pp.1103–13.74 ABC (2010),A Coopera§ão Técnica do Brasil para a África.75 Paulo Sotero (2009), ‘Brazil as an Emerging Donor. Huge Potential and Growing Pains’,Development Outreach,Vol. 11, No. 1, pp. 18–20.76 ABC(2012), ‘Brazil to open factory to produce AIDS medicines in Africa, 13 July 2012. http://www.abc.gov.br/ABC_Eng/webforms/interna.aspx?secao_id=37&s=CTI-News-&c=Brazil-to-open-factory-to-produce-AIDS-medicines-in-Africa&campo=423 (accessed 26 October 2012).

www.chathamhouse.org

Brazil in Africa: Just Another BRICS Country Seeking Resources?

30,000 condoms and leaflets about the prevention of HIV/AIDS and other sexually transmitted diseases in fan parksand public viewing areas.77Brazil has also been active in the fight against otherdiseases in Africa, including malaria. In Ghana, it is estab-lishing a centre on haemophilia and sickle cell anaemiathat will be dedicated not only to treatment but also toresearch and training. The centre is one of Brazil’s largehealth-related projects and will be open to other countriesin the region.78In the effort to intensify South–South cooperationon health, Fiocruz opened its first regional Africa officein Mozambique in 2008. The office aims to coordinate,monitor and evaluate the growing number of Brazilianhealth projects in Africa and offers training and coursesto African professionals in different health-related areas.A particular aim of the Fiocruz office in Maputo is toprovide partner countries of the Community of PortugueseSpeaking Countries with assistance to strengthen theirhealth systems and establish national institutes of health.79Aiming at the exchange of knowledge on neglected tropicaldiseases, Brazil has also set up the Africa-Brazil HealthResearch Network. Launched in May 2010, this will developa framework for cooperation between Brazilian and Africanresearchers and foster further research and cooperationprojects on tropical diseases.80

than that of Spain. Moreover, around 90% of the ruralpopulation have no access to modern energy.81Recognizing energy scarcity as one of the main obsta-cles to African development, Brazil has offered Africanpartner countries its expertise on a variety of energy-related topics ranging from the production of renewableand non-renewable energy to public policies that aim toextend energy access to poor and remote areas. In thiscontext, Brazil has signalled its willingness to transfer its‘Luz para Todos’ [Light for All] Programme to Africa.82This programme has sought to assure access to electricityto homes and businesses in Brazil’s poor rural areas. Ithas provided access for almost three million rural familiessince its launch in 2003, and is considered to be the biggestand most ambitious electric inclusion programme in theworld. In recognition of its contribution to poverty reduc-tion in rural communities by facilitating the integration ofhealth, water supply and sanitation services through theprovision of electricity, the UN refers to this programmeas a model for rural electrification.83In May 2012 Brazilsigned a cooperation agreement with Mozambique tohelp the country implement the Light for All Programme.Technical cooperation programmes based on Brazil’sexperience have also been established with South Africa,Angola, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Nigeria, Kenya andZambia.84Brazil’s effort in supporting African countries to attainenergy security is not limited to the provision of accessto electricity. Having attained energy independence itselfin 2006, it is also supporting African partners seekingto reduce their dependence on expensive oil imports.Through the development of special technology (biofueland deepwater drilling), Brazil transformed itself from a

Brazil as a partner in Africa’s quest forenergy securityDespite its vast energy resources, Africa has a significantlack of energy generation capacity. According to AfricanDevelopment Bank data, the entire installed generationcapacity of 48 sub-Saharan African countries is no more

77 Brazilian Embassy South Africa (2010), ‘Brazil and South Africa join efforts on HIV/AIDS prevention during World Cup’, Pretoria, http://www.brasil.gov.br/para/press/press-releases/june/brazil-and-south-africa-join-efforts-on-hiv-aids-prevention-during-world-cup/br_model1?set_language=en.78 ABC (2010),A Coopera§ão Técnica do Brasil para a África,p. 68.79 Fiocruz Africa, http://www.fiocruz.br/cgi/cgilua.exe/sys/start.htm?infoid=4496&sid=10 (last accessed 7 September 2012).80 African Development Bank (2011), ‘Brazil’s Economic Engagement with Africa’, p. 10.81 Danald Kaberuka, President of the African Development Bank Group, in FIESP/Electrobras/African Development Bank (2011),Energy Markets in Africa,SãoPaulo, p. 5.82Valor Econômico(2012), ‘Brasil exporta programa‚ Luz para Todos’, 8 May 2012.83 UN Global Compact (2011), ‘A Global Compact for Sustainable Energy. A Framework for Business Action’, http://www.unglobalcompact.org/docs/publications/A_Global_Compact_for_Sustainable_Energy.pdf (last accessed 10 September 2012).84 Government of Brazil (2012), ‘Programa Luz para Todos’, http://www.brasil.gov.br/energia-es/programa-luz-para-todos (last accessed 10 September 2012).

www.chathamhouse.org

page 15

Brazil in Africa: Just Another BRICS Country Seeking Resources?

page 16

net energy importer to a net energy exporter. This impres-sive achievement has aroused interest among Africanstates seeking to follow the Brazilian example. In viewof soaring global energy prices, energy-importing coun-tries without fossil fuel resources have shown particularinterest in Brazil’s energy expertise.

an interesting partner for those striving for energy inde-pendence. Inviting African countries to ‘join the biofuelsrevolution’,88it has launched various initiatives to shareits expertise on the production and use of renewable fuels.Among those are the ‘Structured Programme for Supportto Other Developing Countries in the Area of RenewableEnergy’ (Pro-Renova), a memorandum of understandingwith the West African Economic and Monetary Union forcooperation on biofuels,89and biofuel technology transferin the framework of the IBSA Dialogue Forum with SouthAfrica and India.90Spearheaded by the Africa office of Embrapa, Brazilhas also forged a great number of bilateral biofuel coop-eration agreements with African countries. South–Southcooperation accords on biofuels production exist withAngola, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ghana,Kenya, Mozambique, Nigeria, Senegal, Sudan, Ugandaand Zambia. By providing technology transfer andtraining, Brazil assists these countries in developing theirown biofuel industries and reducing their dependence onoil. However, its biofuel cooperation has not been limitedto oil-importing African countries. Large oil exporterssuch as Nigeria and Angola have also shown interest inits expertise, seeing it as an instrument for diversifyingenergy sources on the local market and creating jobsin rural areas. In Nigeria, for example, plans to builda ‘Biofuel Town’ composed of rural migrants who aretrained to become biofuel producers were announced in2007 by a consortium of Brazilian and Nigerian researchorganizations and private companies.91With Angola,Brazil has set up a joint venture called the BioenergyCompany of Angola (BIOCOM). The plant will produce30 million litres of ethanol and 250 tons of sugarper year, predominantly supplying Angola’s domestic

By offering oil-importingAfrican countries free transfer ofits biofuels technology, Brazil haspositioned itself as an interestingpartner for those striving forenergy independence

Brazil has offered to transfer its energy technology tointerested African states through South–South coopera-tion projects. At the forefront of this energy cooperationhas been its initiative on biofuels production. Brazil is theworld’s biggest exporter of sugar-cane-based ethanol andmeets about half of its fuel demand with biofuels.85Thecountry’s efficient biofuel sector, based on the ‘ProAlcool’programme initiated under the military dictatorship inthe 1970s and relaunched under the Lula administrationin 2003, has enabled it to significantly reduce its depend-ence on oil imports86and has provided growing exportrevenues. President Lula therefore promoted his country’sexperience in the production of biofuels as a developmentmodel for resource-poor African states.87By offering oil-importing African countries free transferof its biofuels technology, Brazil has positioned itself as

85El País(2006), ‘Brasil, vanguardia verde’, 28 September 2006; US Energy Information Administration (2012),Country Analysis Briefs. Brazil,28 February2012.86 Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (2006), ‘Join Brazil in planting oil’,Guardian,7 March 2006.87 BBC Brasil (2006), ‘Tecnologia brasileira pode beneficiar a África, diz Lula’, 30 November 2006, http://www.bbc.co.uk/portuguese/reporterbbc/story/2006/11/061130_lulaafricacoletivarwdt.shtml (last accessed 26 October 2012).88 Reuters (2007), ‘Brazil urges Africa to join “biofuel revolution”’, 16 October 2007, http://uk.reuters.com/article/2007/10/16/environment-brazil-africa-dc-idUKL1638910920071016 (last accessed 26 October 2012).89 FIESP/Electrobras/African Development Bank (2011),Energy Markets in Africa,p. 132.90 African Development Bank (2011), ‘Brazil’s Economic Engagement with Africa’, p. 10.91 Freemantle and Stevens (2010), ‘Brazil Weds Itself to Africa’s Latent Agricultural Potential’, p. 6.

www.chathamhouse.org

Brazil in Africa: Just Another BRICS Country Seeking Resources?

Table 4: Brazilian energy cooperation with AfricaType of energy cooperationRural electrification programmeTransfer of biofuel technologyDeepwater oil explorationCountriesAngola, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Mozambique, Nigeria, Kenya, South Africa, ZambiaAngola, Ghana, Kenya, Mozambique, Nigeria, Republic of Congo, Senegal, Sudan, Uganda, ZambiaAngola, Benin, Gabon, Libya, Namibia, Nigeria, Tanzania.

Source: Author’s compilation based on data by ABC, Brazilian Ministry of Mining and Energy, Petrobras and Brazilian media articles.

market.92Other countries are set to explore the potentialfor becoming energy exporters through the develop-ment of a biofuel industry. Ghana, which has developeda biofuel sector with the help of Embrapa, will host asugar-cane plantation financed by Brazil that is expectedto produce ethanol for both domestic supply and export.In fact, ethanol is expected to become the country’sfourth major export after cocoa, gold and timber.93UsingBrazilian technology, oil-rich Sudan has already becomean exporter of ethanol. In 2010 it exported 15 million litresof ethanol to Europe, diversifying its range of exports andcreating new sources of revenue.94While focusing its energy cooperation projects with Africaprimarily on renewable energy, Brazil has also pledged toassist African partner countries in the exploration of oilreserves. It has raised hopes in West African countries ofreplicating the Brazilian discoveries on the African Atlanticcoast, given the geological similarities.95Petrobras has thusconcentrated its Africa activities on the west coast of thecontinent, exploring deep and ultra-deep waters using thespecialized technology that enabled the Brazilian discoveries.

influence and trade deals. Like its BRICS partners, itseconomic engagement has been predominantly concen-trated in the resource and construction sector. Whiletrade ties between Brazil and Africa have become moreintensive in general, trade with resource-rich Africancountries in particular has been on the rise. In fact,Brazil’s biggest trade partners are all resource-rich coun-tries.Yet, although this pattern of economic engagementseems to indicate clear resource interests, Brazil’s profilein Africa is more complex. Brazil has been involved inthe exploitation of African commodities since Petrobras’first investment in the 1970s. Activities have intensifiedduring the last decade with soaring prices for oil andother natural resources and the growing internationali-zation of Brazilian commodity firms. However, being amajor exporter of natural resources itself, Brazil is notcoming to Africa for resources. Commercially, its long-term interest lies in Africa’s growing consumer market.The dynamic growth of African economies despite theglobal economic and financial crisis96has led Brazilto look to the continent as a promising market for itsgoods and services, especially manufactured or semi-manufactured products, as it can offer ‘tropicalizedtechnology’ to meet the demands of developing coun-tries.

Conclusion: Brazil’s profile in AfricaDuring the last decade Brazil has actively forged closerrelations with Africa and has become a major playeron the continent, competing with China and India for

92 Ibid.93 African Development Bank (2011), Brazil’s Economic Engagement with Africa, p. 3.94 FIESP/Electrobras/African Development Bank (2011),Energy Markets in Africa,p. 132.95 See Petrobras Global Activities, http://www.petrobras.com/en/about-us/global-presence/ (last accessed 11 September 2012).96 International Monetary Fund (2012), ‘Regional Economic Outlook: Sub-Saharan Africa Maintains Growth in an Uncertain World’, 12 October 2012,http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/survey/so/2012/CAR101212B.htm (last accessed 26 October 2012).

www.chathamhouse.org

page 17

Brazil in Africa: Just Another BRICS Country Seeking Resources?

page 18

However, Brazil’s engagement in Africa goes beyondthe economic realm. Its profile in Africa has been signifi-cantly shaped by its commitment to Africa’s developmentchallenges. Building on its own successful developmentexperiences, Brazil has pledged to assist African partnercountries in their efforts to fight hunger and poverty,provide healthcare and attain energy security. By trans-ferring its experience and technical know-how in theimplementation of social promotion programmes, Brazilhas presented itself as a partner for the continent’s socialand economic development and has tried to gathersupport for its pursuit of a seat at the United NationsSecurity Council. While Brazil’s strategy of South–Southcooperation has contributed to its growing economicfoothold in Africa and has been used as a trump cardin the competition with China, the benefit of Brazil’sAfrica policy goes far beyond pure economic profit. Byproviding technical assistance, Brazil has raised its profileas a leading power of the South and ‘champion of devel-opment nations’.97By underpinning its quest for a ‘newmultilateralism of the South’ with cooperation projectsin Africa, Brazil has gained credibility among developingnations and an international voice as a speaker on theirbehalf.Forging ties with African countries through the provi-sion of development assistance has enhanced Brazil’sbargaining power and international status. Whereas thebenefits in terms of support for its campaign to gain a seatat the UNSC remain uncertain,98Brazil has profited fromits Africa engagement in an indirect way. By engaging ina foreign continent and offering development assistance,this Latin American country has achieved an impressiverole change. Associated until recently with a broad rangeof economic and social challenges itself, it has transformeditself into a model for successful development. Through

its Africa engagement, Brazil has discarded its status asan aid-receiving developing country and joined the pres-tigious club of donor countries. Furthermore, by offeringtechnical assistance to African countries, it can demon-strate its willingness and ability to make a contribution tothe solution of global problems. By embracing key globalissues such as poverty, health and energy and exercisingleadership on these development and security challengesof the 21st century, Brazil has become increasingly recog-nized at the top tables of decision-making in internationalrelations.99

By embracing key globalissues such as poverty, healthand energy and exercisingleadership on these developmentand security challenges of the21st century, Brazil has becomeincreasingly recognized at thetop tables of decision-making ininternational relations

Brazil’s Africa engagement should thus not be seen as apure economic strategy and even less as a simple policy tosecure resources. Its involvement and growing presence inAfrica reflects the country’s broader foreign policy ambi-tion of being recognized among the key players in wordpolitics. Gaining economic presence and conquering newmarkets has been only one element of this ‘grand strategy’towards Africa.

97 Peter Dauvergne and Déborah Farias (2012), ‘The Rise of Brazil as a Global Development Power’,Third World Quarterly,Vol. 33, No. 5, pp. 903–17.98 This has been only partially successful so far. While it is said that its successful campaigns for the FAO Director General and the head of the World CoffeeOrganization were only possible owing to the broad support of African countries, Brazil’s ultimate goal of winning a seat at the UN Security Council has beenobstructed, not least by Africa’s resistance to reform that body.99 Kelley Lee and Eduardo J. Gómez (2012), ‘Brazil’s Ascendance: The Soft Power Role of Global Health Diplomacy’,European Business Review,http://www.europeanbusinessreview.com/?p=3400 (last accessed 13 September, 2012); Council on Foreign Relations Task Force Report (2012),GlobalBrazil and U.S.–Brazil Relations(New York: CFR).

www.chathamhouse.org

Brazil in Africa: Just Another BRICS Country Seeking Resources?

O Brasíl na África – Mais um Páis dos BRICS Buscando Recursos?Pontos de ResumozzDurante a última década o Brasil ampliou o seu engajamento na África e a sua presen§a diplomática no continente

aumentou para o dobro – de 17 para 37 embaixadas.zzForjaram-se novas parcerías financeiras e o comércio com a Africa aumentou de US$4,2 bilhões para US$27,6

bilhões.zzO petróleo e outros recursos naturais representam 90% dos produtos importados pelo Brasil do continente. Os

investimentos brasileiros dirigem-se principalmente à África lusófona.zzOs decisores brasileiros consideram que o maior potencial africano seja a viabiliza§ão de um mercado de consumo

para os produtos manufacturados pelo Brasil.zzO Brasil também emprega a sua política africana como meio de alcan§ar a meta da sua política externa: o

reconhecimento do país como grande potência.zzA colabora§ão Sul-Sul é uma das for§as motrizes da política africana do Brasil na sua procura de apoio para

obten§ão de um lugar no Conselho de Seguran§a da ONU.zzO Brasil defende projectos de coopera§ão Sul-Sul que se baseiem na sua própria experiência de desenvolvimento.

Exitos na pesquisa médica e biomédica assim como na pesquisa agrícola foram transformadas em eficazesinstrumentos de política externa.

www.chathamhouse.org

page 19

Brazil in Africa: Just Another BRICS Country Seeking Resources?

page 20

Christina Stolteis junior research fellow at the GIGAInstitute of Global and Area Studies and member ofthe Hamburg International Graduate School for theStudy of Regional Powers (HIGS). She served as deskofficer for Brazil at the Latin America and CaribbeanDivision of the German Federal Foreign Office inBerlin from 2010 to 2011. Her main research area isBrazilian foreign policy, with a special focus on Brazil’sengagement in Africa. Her publications include policypapers on Brazil’s regional role in South America andBrazilian biofuels policy.AcknowledgmentsPublication of this paper was supported by a grant fromBG Group and the Chatham House Director’s ResearchInnovation Fund.

Chatham Househas been the home of the RoyalInstitute of International Affairs for ninety years. Ourmission is to be a world-leading source of independentanalysis, informed debate and influential ideas on howto build a prosperous and secure world for all.

Chatham House10 St James’s SquareLondon SW1Y 4LEwww.chathamhouse.orgRegistered charity no: 208223Chatham House (the Royal Institute of International Affairs) is anindependent body which promotes the rigorous study of internationalquestions and does not express opinions of its own. The opinionsexpressed in this publication are the responsibility of the author.� The Royal Institute of International Affairs, 2012This material is offered free of charge for personal andnon-commercial use, provided the source is acknowledged.For commercial or any other use, prior written permission mustbe obtained from the Royal Institute of International Affairs.In no case may this material be altered, sold or rented.Cover image � Getty imagesDesigned and typeset by Soapbox, www.soapbox.co.uk

www.chathamhouse.org