Udenrigsudvalget 2012-13

URU Alm.del Bilag 241

Offentligt

Committing to Child Survival:A Promise RenewedProgress Report 2013EXECUTIVE SUMMARYUNICEF has committed to producing annual progress reports on child survival in support of theCommittingto Child Survival: A Promise Renewedglobal movement. The reports are intended to track progress and pro-mote accountability for global commitments made to children.The 2013 progress report is the second report in the series. It covers:Trends and levels in under-five mortality over the past two decades.Analysis of progress towards Millennium Development Goal 4 (MDG 4).Causes of and interventions against child mortality.Highlights of national and global initiatives by governments, civil society and the private sector toaccelerate progress on child survival.Statistical tables of child mortality and causes of under-five deaths by country and UNICEF regionalclassification.This 2013 progress report is released in conjunction with the child mortality estimates of the United NationsInter-Agency Group on Mortality Estimation.

KEY MESSAGESDespite rapid progress in reducing child deaths since 1990,the world is still failing to renew the promise of survival forits most vulnerable citizens.•Global progress in reducing child deaths since 1990 hasbeen significant. The world rate of under-five mortality hasroughly halved, from 90 deaths per 1,000 live births in 1990to 48 per 1,000 in 2012. The annual number of under-fivedeaths has fallen from 12.6 million to 6.6 million over thesame period.Put another way, 17,000 fewer children died each day in2012 than did in 1990 — thanks to more effective andaffordable treatments, innovative ways of deliveringcritical interventions to the poor and excluded, and sus-tained political commitment. These and other vital child

•

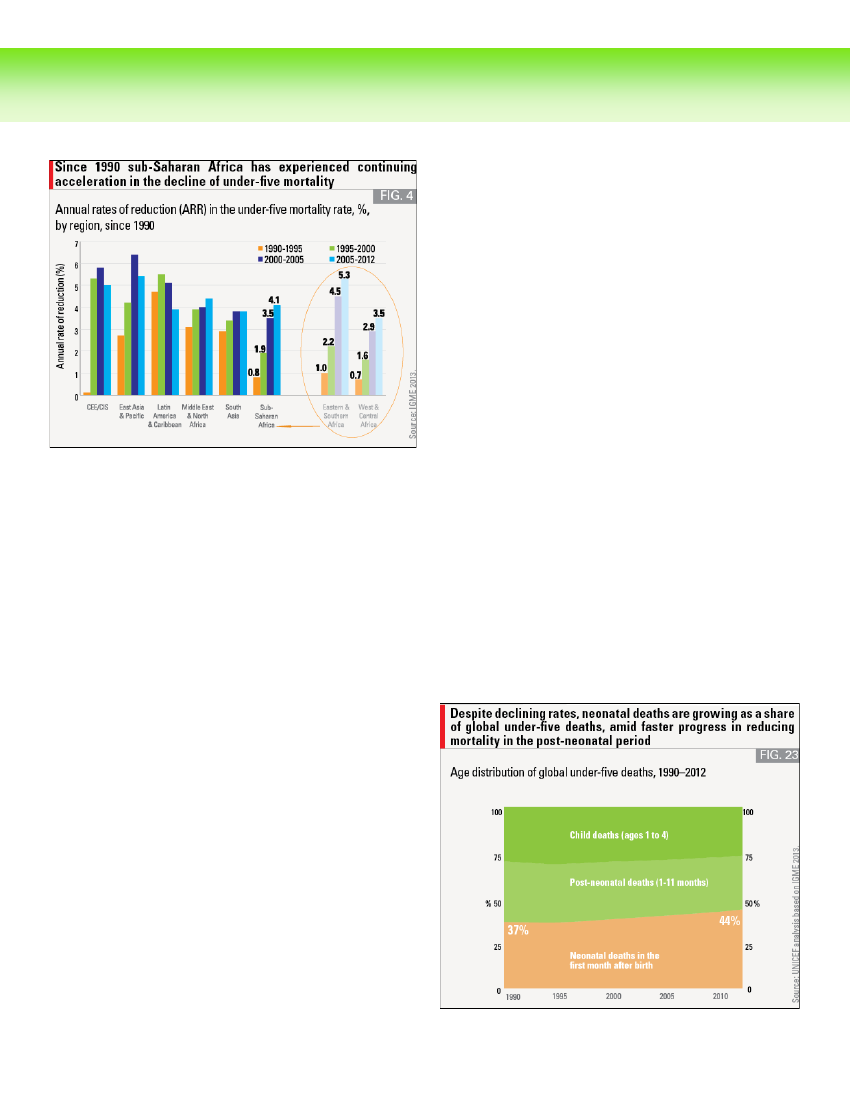

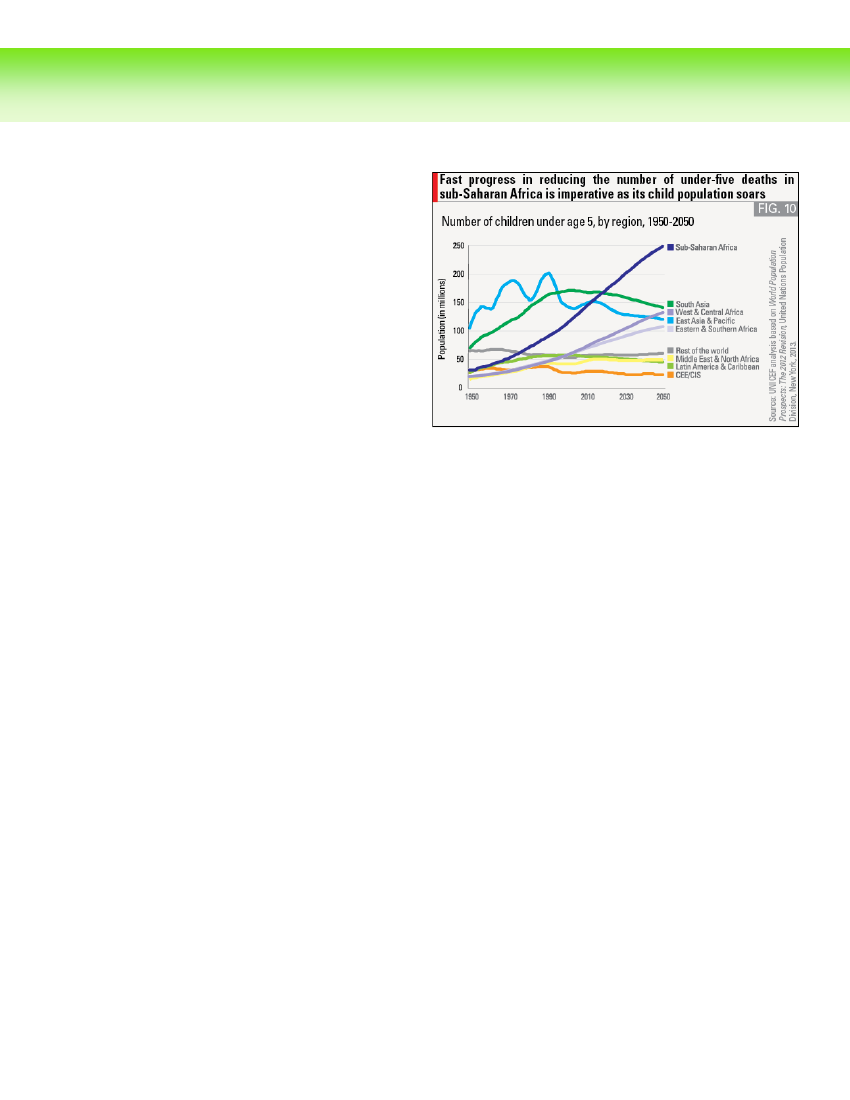

survival interventions have helped to save an estimated90 million lives in the past 22 years.Encouragingly, the world is currently reducing under-five deaths faster than at any other time during thepast two decades. The global annual rate of reductionhas steadily accelerated since 1990–1995, when itstood at 1.2 per cent, more than tripling to 3.9 percent in 2005–2012. Both sub-Saharan African regions— particularly Eastern and Southern Africa but alsoWest and Central Africa — have seen a consistent ac-celeration in reducing under-five deaths, particularlysince 2000. And all regions with the exception of Westand Central Africa and sub-Saharan Africa as a wholehave at least halved their rates of under-five mortalitysince 1990.See Figure 4 on next page.

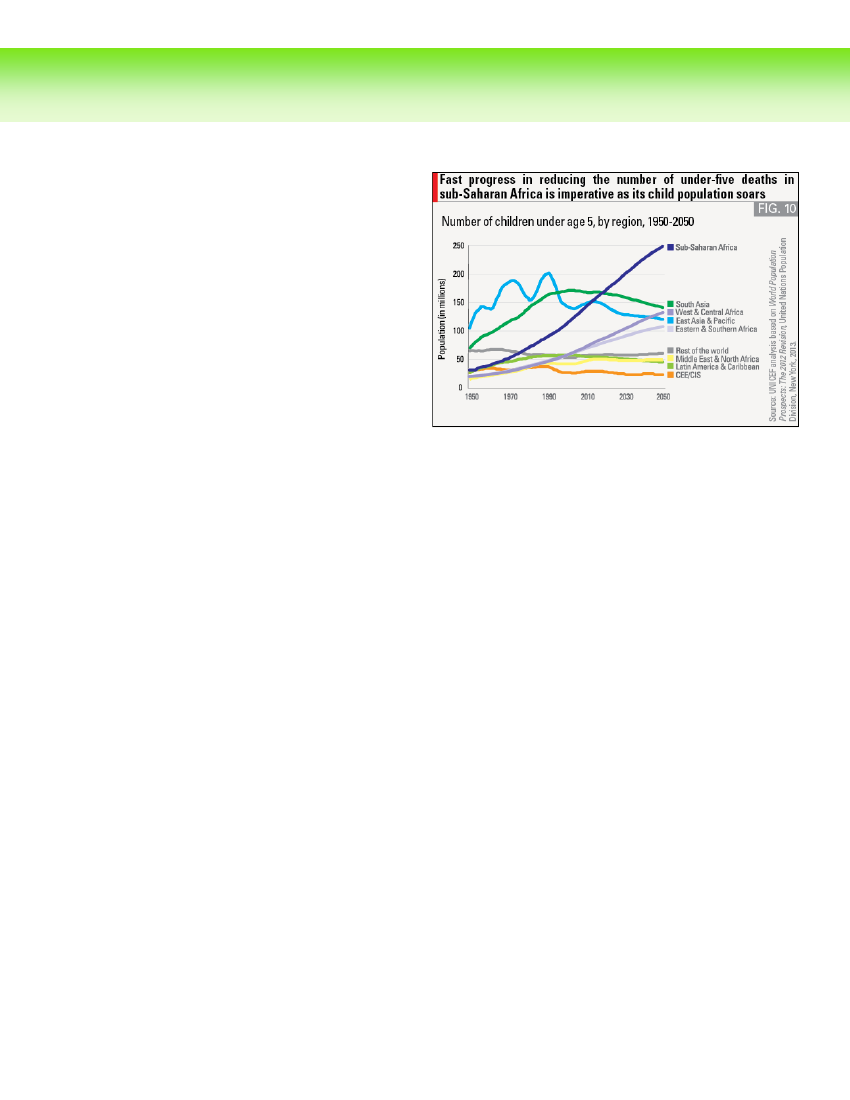

goal were met on time in 2015 and that trend continued.Only two regions — East Asia and Pacific, and Latin Amer-ica and Caribbean — are currently on track to meet the2015 deadline for MDG 4.Of the 6.6 million under-five deaths in 2012, most were frompreventable causes such as pneumonia, diarrhoea or malaria;around 44 per cent of deaths in children under 5 occurredduring the neonatal period.•Even though there have been strong advances in fightingchildhood diseases, pneumonia and diarrhoea remainleading causes of death among children under 5, killingalmost 5,000 children under 5 every day. The distributionof these diseases is highly concentrated, with three quar-ters of global pneumonia and diarrhoea deaths occurringin just 15 countries.Malaria remains a significant cause of child death, killing1,200 children under 5 every day. It remains strongly con-centrated in sub-Saharan Africa, where it accounts for 14per cent of child deaths, despite major gains in life-savinginterventions in recent years.Despite declining rates globally, neonatal deaths aregrowing as a share of global under-five deaths amid fasterprogress in reducing mortality in the post-neonatal peri-od. Most neonatal deaths are preventable.See Figure 23.

•

Despite these gains, child survival remains an urgent con-cern. In 2012, approximately 6.6 million children died be-fore their fifth birthday, at a rate of around 18,000 perday. And the risk of dying before age 5 varies enormouslyaccording to where a child is born. In Luxembourg, theunder-five mortality rate is just 2 per 1,000 live births; inSierra Leone, it is 182 per 1,000.Since 1990, 216 million children have died before theirfifth birthday — more than the current total population ofBrazil, the world’s fifth most populous country.

•

•

Without faster progress on reducing preventable diseases, theworld will not meet its child survival goal (MDG 4) until 2028 —13 years after the deadline — and 35 million children will die be-tween 2015 and 2028 who would otherwise have lived had thegoal been met on time.To reach MDG 4 — which seeks to reduce the global under-five mortality rate by two thirds between 1990 and 2015 —the pace of reduction would need to quadruple in2013–2015. And even if the world were to achieve MDG 4 ontime, 15 million children under 5 would still die between 2013and 2015, mostly from preventable causes. To achieve MDG 4by 2015, an additional 3.5 million children’s lives must besaved between 2013 and 2015 above the current trend rate.At the current rate of reduction in under-five mortality,the world will only meet MDG 4 by 2028 — 13 years afterthe deadline — and 35 million more children will die be-tween 2015 and 2028 whose lives could be saved if the2

•

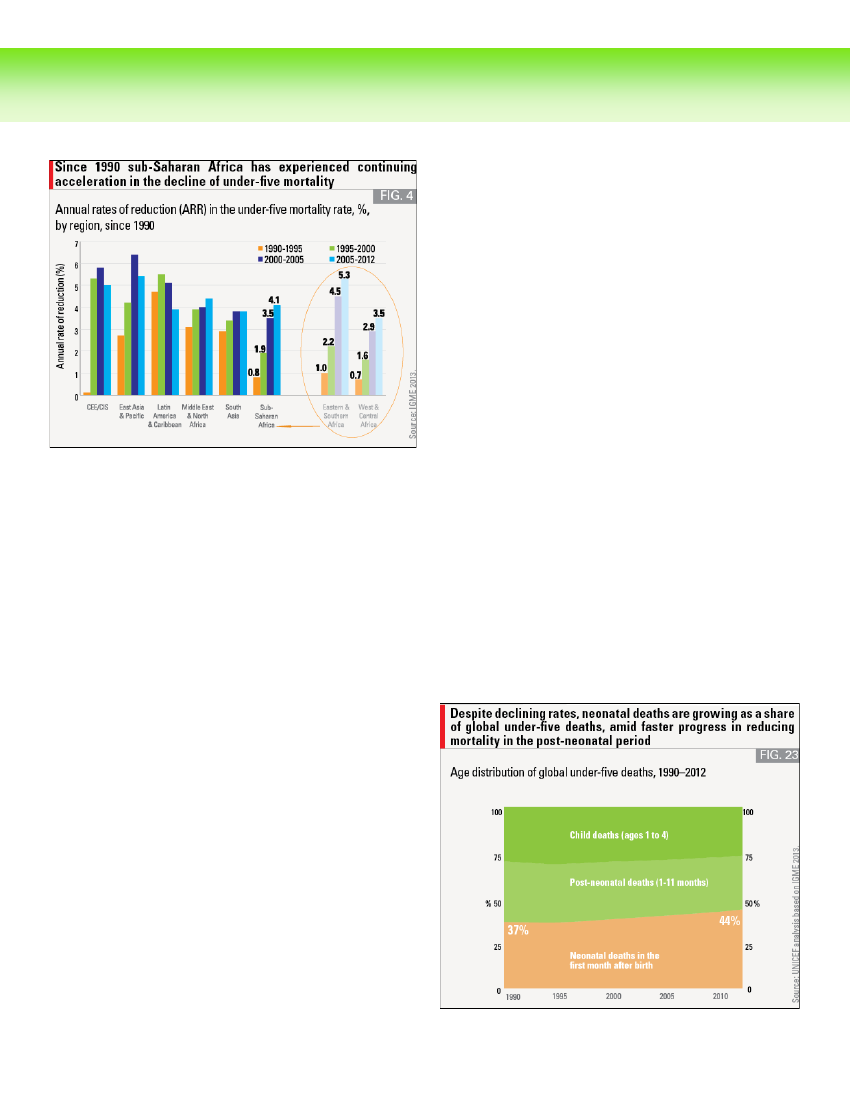

Accelerating progress in child survival urgently requiresgreater attention to ending preventable child deaths in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, which together account for 4out of 5 under-five deaths globally.South Asia has made strong progress on reducing preventa-ble child deaths, more than halving its number of deathsamong children under 5 since 1990. But nearly one in everythree under-five deaths still takes place in this region, and ithas not seen a major acceleration in the rate of reduction.Sub-Saharan Africa faces a unique and urgent challenge inaccelerating progress. By mid-century it will be the regionwith the single biggest population of under-fives, ac-counting for 37 per cent of the global total and close to40 per cent of all live births. And it is the region with leastprogress on under-five mortality to date.See Figure 10.

West and Central Africa in particular requires a special focusfor child survival, as it is lagging behind all other regions,including Eastern and Southern Africa, and has seen virtual-ly no reduction in its annual number of child deaths since1990.•Within sub-Saharan Africa, there is beginning to be adivergence in child survival trends between Eastern andSouthern Africa, and West and Central Africa. This hasimportant implications for strategies, priorities, re-sources and leadership in the global drive to end pre-ventable child deaths.Eastern and Southern Africa has managed to reduce itsunder-five mortality rate by 53 per cent since 1990 —and in the past seven years has been among the bestperforming regions in the world, reducing under-fivemortality at an annual rate of 5.3 per cent in 2005–2012.But it still has high rates of mortality, with 1 in every 13children dying before the age of 5.In contrast, West and Central Africa has seen a drop ofjust 39 per cent in its under-five mortality rate since1990, the lowest among all regions. Moreover, its annu-al rate of reduction, while accelerating, is still the slow-est in the world. The region also has the highest rate ofmortality, with almost one in every eight children dyingbefore the age of 5.

West and Central Africa is also the only region not to haveat least halved its rate of under-five mortality since 1990,and the only region to have seenvirtually no reduction inthe absolute number of children dyingover the past 22years. Its burden of child deaths now stands at about 2million annually, almost identical to the level in 1990.

The good news is that much faster progress is possible. Coun-try experience shows that sharp reductions in preventablechild deaths are possible at all levels of national income andin all regions.Some of the world’s poorest countries in terms of nationalincome have made the strongest gains in child survival.Seven high-mortality countries (Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Li-beria, Malawi, Nepal, Timor-Leste and the United Republicof Tanzania) have already reduced their under-five mortal-ity rates by two thirds or more since 1990; six of thesecountries are low-income, proving that low national in-come is not a barrier to making faster and deeper gains inchild survival. A further 18 high-mortality countries havealso managed to at least halve their under-five mortalityrates over the same period.See Figure 5 on the next page.Many middle-income countries have also made tremen-dous progress in reducing under-five deaths, and mosthigh-income countries have also seen sharp declines since1990 — proving that even in high-income countries, rapiddeclines in child mortality are possible.

•

•

3

A Promise Renewedis a movement based on shared responsibil-ity for child survival, and is mobilizing and bringing together gov-ernments, civil society, the private sector and individuals in thecause of ending preventable child deaths within a generation.A Promise Renewed is a global movement that seeks toadvance Every Woman Every Child — a strategy launchedby United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon to im-prove the health of women and children — through actionand advocacy to accelerate reductions in preventable ma-ternal, newborn and child deaths.Since its launch just over a year ago,A Promise Renewedhas driven several important developments. A current totalof 176 governments have signed theCommitting to ChildSurvival: A Promise Renewedpledge and thousands of civilsociety groups and private individuals have mobilized ac-tions and resources in support of the goal.A diverse array of governments, from Bangladesh to Zambia,India to Liberia, Ethiopia to the Democratic Republic of theCongo, are setting bold new targets for maternal, newbornand child survival. Every month, more governments are fol-lowing suit.Around the world, civil society is increasingly holding gov-ernments accountable for their promises, facilitated bynew communication technologies and tools such asUganda’s SMS-based U-report.A Promise Renewedrecognizes that leadership, commit-ment and accountability are vital if we are to end prevent-able child deaths. And since child survival is increasinglyrecognized as a shared responsibility, everyone has a roleto play.

•

•New analysis suggests that disparities in under-five mortal-ity rates between the richest and the poorest householdshave declined in most regions of the world. And under-fivemortality rates have fallen among the poorest householdsin all regions.These examples show that it is possible to sharply reducepreventable child deaths, even from initially high rates andamong the poorest households, when concerted action,sound strategies, adequate resources and political will areconsistently applied in support of child and maternalhealth.

•

•

Excerpted from:United Nations Children’s Fund,Committing to Child Survival: A Promise Renewed, Progress Report 2013,UNICEF, New York, 2013.� United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), September 2013For information, contact: UNICEF, 3 United Nations Plaza, New York, NY 10017. <www.unicef.org>More details onA Promise Renewedare available at <www.apromiserenewed.org>.

4