Udenrigsudvalget 2012-13

URU Alm.del Bilag 208

Offentligt

2012:7

Joint Evaluation

Andrew Lawson

Evaluation of PublicFinancial Management ReformBurkina Faso, Ghana and Malawi 2001–2010Final Synthesis Report

Final Synthesis Report 2012:7

Evaluation of Public FinancialManagement Reformin Burkina Faso, Ghana and Malawi 2001–2010Andrew Lawson

Submitted by Fiscus Public Finance Consultants and Mokoro LtdtotheEvaluation Management GroupApril 2012

Author:Andrew LawsonThe views and interpretations expressed in this report are the author´s and do not necessarily reflect thoseofthe commissioning agencies, Sida, Danida and AfDB.

Joint Evaluation 2012:7Commissioned by Sida, Danida and AfDBDate of final report:April 2012Published by:Sida, 2012Copyright:Andrew LawsonDigital edition published by:Sida, 2012Layout and print:Citat/Edita 2012Art.no.SIDA61498enurn:nbn:se:sida-61498enISBN:978-91-586-4194-5This publication can be downloaded/ordered from: www.Sida.se/publications

ForewordThe evaluation of public financial management reform is one of several joint evalua-tions, undertaken under the umbrella of the OECD’s Development Assistance Com-mittee, which are focused on issues identified as key for using country systems andwhere looking at donor assistance collectively makes more sense than trying to attrib-ute results to a single actor.The evaluation involved three main components, a literature review (publishedin 2009) a quantitative study (published in 2011) and finally three country casestudies. It is through the three cases – Burkina Faso, Ghana and Malawi – that theevaluation has been able to look in detail at the context and mechanisms that makePFM reforms successful.The importance of good public financial management for the effectiveness ofthe state has become increasingly clear over the years. Good public financial man-agement supports not only good governance and transparency but is also crucial foreffectively delivering the services on which human and economic development rely.For these reasons, many bilateral organisations and multilateral institutions consid-er public financial management to be a priority. The evaluation units of the AfricanDevelopment Bank (AfDB), the Swedish International Development Agency (Sida)and Danish International development Assistance (DANIDA) commissioned thisevaluation on behalf of a larger group of donors.We are now entering a second generation of PFM reforms, so learning the les-sons from past experience is crucial. The added value of the country case studies isthat they analyse the context and mechanisms which make for successful PFMreforms. The report identifies lessons for countries going through PFM reforms,including the importance of high-level buy-in and leadership, alongside effectivecoordination. It also identifies lessons for development partners, which includeresisting the temptation to push for reforms where the context is not right, and mak-ing sure the advice they provide is high quality and relevant to the setting. Theevaluation observes a general improvement in donor coordination and alignment,while noting that it is those inputs which are not integrated into government-ownedprogrammes that most often fail. And on both sides, flexibility is needed – even thebest planned projects often need adjustments.Beyond this evaluation, the challenge now – for both countries going throughreforms and for their development partners – is to apply those lessons in practice, toget better results in future.The three organisations that commissioned the evaluation and the teams thatcarried it out would like to express sincere thanks to those individuals and groupsthat played a role in the evaluation process. In particular, this third phase of theevaluation would not have been possible without the cooperation of governmentofficials and local PFM experts in the three country case study countries.5

Acronyms and AbbreviationsAAPAFDAfDBAfroSAIBCEAOBPEMSCABRICAGDCAPA/FPCdCCDMTCFCFAACIDCIDACIECIRCOCPARCPIACRSCSLPCSOsDACDanidaDFIDDGB(HIPC) Assessment & Action Plan (for PFM)Agence Fran§aise de DéveloppementAfrican Development BankAfrican Organisation of Supreme Audit InstitutionsBanque Centrale des Etats d’Afrique de l’OuestBudget and Public Expenditure Management SystemCollaborative African Budget Reform InitiativeController and Accountant General’s DepartmentCadre Partenarial d’Appui au renforcement des Fi-nances PubliquesCour des Comptes (Court of Accounts: the SupremeAudit Institution)Cadre de dépenses à Moyen Terme (MTEF)Contrôleur FinancierCountry Financial Accountability AssessmentCircuit Intégré de la DépenseCanadian International Development AgencyComptabilité Intégrée de l’EtatCircuit Intégré des RecettesControlling OfficerCountry Procurement Assessment ReviewCountry Policy & Institutional AssessmentCreditor Reporting System (of the OECD-DAC)Cadre Stratégique de Lutte contre la Pauvreté (PovertyReduction Strategy)Civil Society OrganisationsDevelopment Assistance Committee (of the OECD)Danish International Development AssistanceDepartment for International Development of the UKDirection Générale du Budget

6

ACroNymS AND ABBrEvIAtIoNS

DGIDGTCPDPDPLDSIENAREFEUFAAFARFCFAGBSGoBFGDPGFSGoGGoMGIFMISG-JASGNIGPRSGTZHDIHIPCIAAIEGIFMS/ IFMISIFUIMFINTOSAIIPPDIPSASLGA

Direction Générale des ImpôtsDirection Générale du Trésor et de la ComptabilitéPubliqueDevelopment PartnerDevelopment Policy LendingDirection des Services InformatiquesEcole nationale des régies financières(National Financial School, Burkina Faso)European UnionFinancial Administration ActFinancial Administration RegulationFrancs de la communauté financière africaineGeneral Budget SupportGovernment of Burkina FasoGross Domestic ProductGovernment Finance StatisticsGovernment of GhanaGovernment of MalawiGhana Integrated Financial Management InformationSystemGhana Joint Assistance StrategyGross National IncomeGrowth and Poverty Reduction StrategyGerman Technical CooperationHuman Development IndexHighly Indebted Poor CountriesInternal Audit AgencyIndependent Evaluation Group (World Bank)Integrated Financial Management SystemIdentifiant Financier Unique (Tax Identification Number)International Monetary FundInternational Organisation of Supreme AuditInstitutionsIntegrated Personnel and Payroll Database systemInternational Public Sector Accounting StandardsLocal Government Authority7

ACroNymS AND ABBrEvIAtIoNS

MDAsMDBSMDGMEFMFBMoFMoFEPMGDSMPsMTEFNAONDCNDPCNGONPMNPPOBIODAODPPOECDPACPAFPEFAPFMPIDPPIUPPBPPPPRGB

Ministries, Departments and AgenciesMulti-Donor Budget SupportMillennium Development GoalMinistère de l’Economie et des FinancesMinistère des Finances et du BudgetMinistry of FinanceMinistry for Financial and Economic PlanningMalawi Growth and Development StrategyMembers of ParliamentMedium Term Expenditure FrameworkNational Audit OfficeNational Democratic CongressNational Development Planning CommissionNon-Governmental OrganisationNew Public ManagementNew Patriotic PartyOpen Budget InitiativeOfficial Development AssistanceOffice of the Director of Public Procurement (Malawi)Organisation for Economic Cooperation & DevelopmentPublic Accounts CommitteePerformance Assessment FrameworkPublic Expenditure & Financial AccountabilityPublic Finance ManagementPublic Institutional Development ProjectProject Implementation UnitPublic Procurement BoardPurchasing Power ParityPlan de Renforcement de la Gestion Budgétaire(Burkina Faso Plan of Action to Strengthen BudgetManagement)Poverty Reduction and Growth FacilityPoverty Reduction Strategy CreditPoverty Reduction Strategy (Paper)Public Service Commission

PRGFPRSCPRS(P)PSC8

ACroNymS AND ABBrEvIAtIoNS

PUFMARPROSCSADCSBSSECOSidaSMTAPSP PPFSRFPSWApTATSAUSDVATWAEMUWB

Public Financial Management Reform Programme(Ghana)Report on the Observance of Standards & CodesSouthern African Development CommunitySector Budget SupportSwiss Secretariat for Economic CooperationSwedish International Development CooperationAgencyShort and Medium Term Action Plan for PFM (Ghana)Secrétariat Permanent pour le suivi des Programmeset Politiques FinancièresStratégie de Renforcement des Finances Publiques(Burkina Faso)Sector Wide ApproachTechnical AssistanceTreasury Single AccountUnited States DollarValue Added TaxWest African Economic and Monetary Union (UEMOA)World Bank

9

Table of ContentsExecutive Summary............................................................................... 121objectives and Approach.....................................................................181.1 Objectives of the evaluation .........................................................181.2 The research context for the evaluation.....................................291.3 The Tunis Inception Workshop ....................................................211.4 The Choice of Case Study Countries ...........................................221.5 Evaluation Framework ................................................................241.6 The Evaluation Questions & the Approach to the CountryStudies ...........................................................................................281.7 The Approach to the Synthesis process .....................................311.8 Limitations of the Analysis...........................................................321.9 Report Structure ..........................................................................34overview of PFm reform experience in the Study countries.........352.1. Economic and political background............................................352.2. Reform Inputs ............................................................................... 412.3. Reform Outcomes ........................................................................432.4. The PFM reform processes in overview: the resultingC-M-O combinations ....................................................................49Successful PFm reform: what is the right context?.........................603.1 Introduction...................................................................................603.2 Refining our Programme Theory................................................653.3 Why and how is political commitment to PFM reformimportant?.....................................................................................683.4 Understanding “Policy Space” constraints................................723.5 Additional contextual factors for further investigation.............75Successful PFm reform: what are the right mechanisms?............794.1 Introduction...................................................................................794.2 The most important aspects of the managementmechanisms for PFM reform ......................................................794.3 The continuing weaknesses in the coordinationof technical assistance.................................................................824.4 The lack of an effective learning and adaptation process ........85Conclusions and emerging lessons....................................................875.1 Key Conclusions ...........................................................................875.2 Lessons for Development Agencies supportingPFM reforms.................................................................................885.3 Lessons for Governments managing PFM Reforms ................90

2

3

4.

5.

10

tABLE oF CoNtENtS

Bibliography.....................................................................................................93Annex one: Biographical details of Finance ministers..............................96Annex two: Quantitative Study sample of 100 Countries.........................99Annex three: the 6 Clusters of PFm functions........................................102Annex Four: Consultant terms of reference............................................103

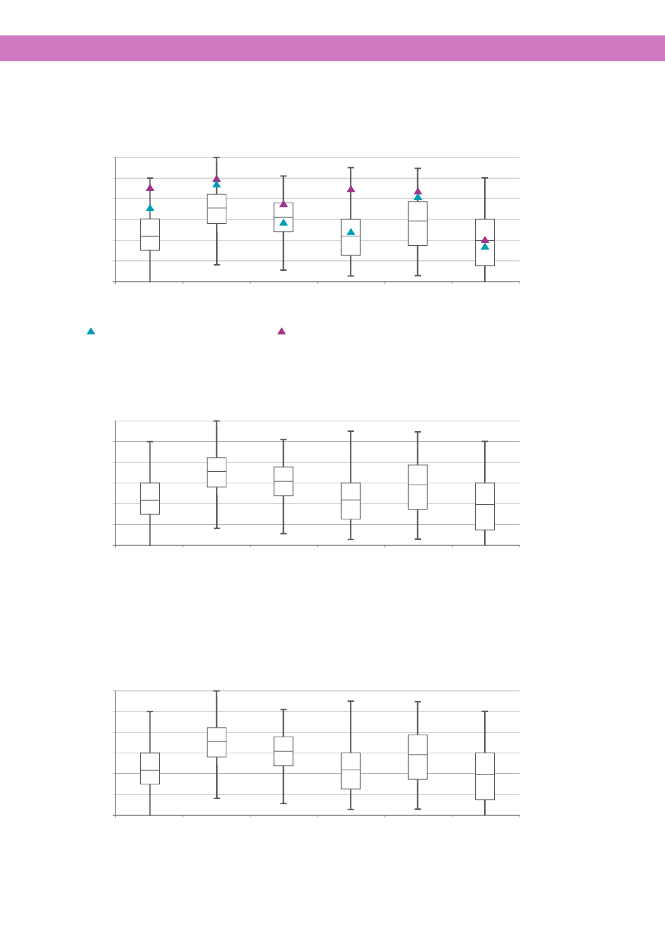

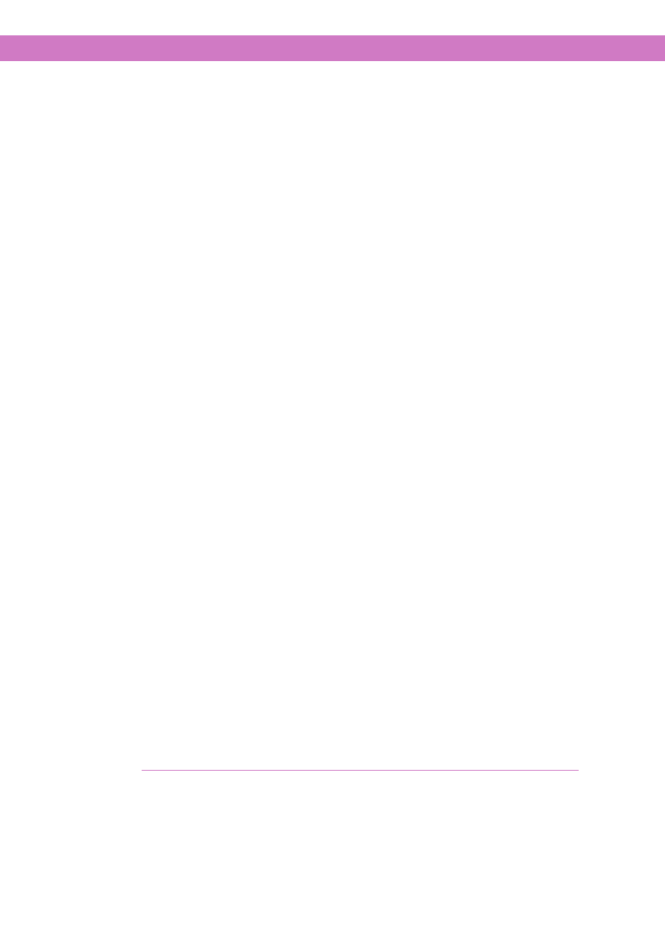

table of Figures & tablesFigure 1.The Evaluation Framework and the place of theEvaluation Questions within the Intervention Logic ..................25Figure 2.Overview of the Case History Approach to the CountryStudies ...........................................................................................30Figure 3.Overview of PFM Performance in Study Countries,2001–2010......................................................................................43Figure 4.Burkina Faso PEFA Scores 2007 & 2010, comparedto median score for 100 countries ..............................................46Figure 5.Malawi PEFA Scores 2006 and 2011, comparedto median score for 100 countries ..............................................46Figure 6.Ghana PEFA Scores 2006 and 2010, comparedto median score for 100 countries ..............................................46Table 1.Preliminary Estimation of Relative Impact of DonorSupport to PFM reforms in SSA ..................................................23Table 2.The Selection of 9 Case Histories from the StudyCountries .......................................................................................31Table 3.Key Economic, Social & Political Indicators forthe Study Countries (2010) ...........................................................35Table 4.Ministers, Deputy Ministers and Members of Parliamentrelative to the population in Case Study Countries ................... 41Table 5.Funding of PFM Reform Inputs in the Case StudyCountries 2001–2010 ....................................................................42Table 6.Average PEFA Scores by Cluster for the Case StudyCountries, 2006/07 and 2010/11..................................................45Table 7.Overview of PFM Reform in the Case Study Countries:the C-M-O Combinations ............................................................. 61Table 8.Results of 2008/ 09 Afrobarometer survey questionregarding citizens’ attitudes to their Government.....................78Table 9.Burkina Faso: Ministers of Finance 1996–2011 .....................96Table 10.Malawi – Ministers of Finance 1994–2011 ............................96Table 11.Ghana: Ministers of Finance 1982–2011 ................................97

11

Executive SummaryThis Synthesis Report provides a summary of the conclusions of the JointEvaluation of Public Financial Management Reform, managed by theAfrican Development Bank, Denmark and Sweden. The report synthe-sises the results of Country Studies prepared for Burkina Faso, Ghanaand Malawi, based upon desk research and fieldwork, and followinga standardised evaluation framework. The selection of the case studiesand the design of the framework drew upon a previous literature review,an Approach Paper and an extensive quantitative study, examining thelessons that might be drawn for the design of PFM reform processes fromthe data available on 100 countries that have completed PEFA assess-ments.The evaluation looked at two main questions: (i) where and why do PFMreforms deliver results and (ii) where and how does donor support to PFMreform efforts contribute most effectively to results? Our conclusions andthe corresponding lessons for Governments and Development Partnersare detailed below.The evaluation framework and its origins are fully explained in Chapter1 of the report, while details of the results of the country studies for Burki-na Faso, Ghana and Malawi are presented in Chapter 2. Chapter 3 anal-yses the key features of the context for PFM reform, which emerge as crit-ical to its success, while Chapter 4 examines the critical features of themechanisms for the management and coordination of PFM reform.Chapter 5 presents the conclusions and the corresponding policy lessonsfor Governments and Development Partners.Where and why do PFM reforms deliver results?I.PFM reforms deliver results when three conditions coincide: there is a strong political commitment to their implemen-whentation, reform designs and implementation models are well tai-whenlored to the institutional and capacity context; and strong coordination arrangements – led by governmentwhenofficials – are in place to monitor and guide reforms.

II. Strong leadership and commitment to reform are also needed at thetechnical level. In the case study countries, this emerged naturallywhere there was political commitment and leadership. By contrast,

12

ExECutIvE SummAry

commitment at the technical level was not sufficient to generate polit-ical commitment.III. External donor pressure and domestic pressure from the Legislatureor Civil Society will generally contribute to preserving political com-mitment for reform, where it already exists but, in the case studies, itproved insufficient to generate political commitment for PFMreform, where it was lackingIV. PFM reform designs and implementation models will almost inevita-bly have flaws; hence a learning process is essential to permit the con-tinuous evolution and adaptation of reform designs and models.Where management and coordination mechanisms for PFM reformbuild in adequate provision for the regular, independent evaluationof performance, these learning processes are more likely to be effec-tive.V. Reform outcomes are generally more favourable where a wide rangeof policy options is available at the outset or where the mechanismsfor monitoring and coordination of reforms promote active lesson-learning and adaptation during the implementation process. By con-trast, the case study countries frequently found themselves facinga constraint in respect of the policy space for reforms, where themenu of available policy designs and models for PFM reform was notappropriate to the institutional and capacity context, and where thelearning and adaptation processes were rarely effective enough topromote quick changes to faulty design and implementation models.VI. Advocacy work by CSOs and activism by the Legislature are morelikely to be useful, when focused on a narrow objective, such as theimprovement of budget transparency. In the case study countries, theinfluence of the Legislature and Civil Society on PFM reform provedlimited, in part because of the limited expertise of these stakeholdersin this regard but more significantly because of the relative absenceof a culture of public accountability.Where and how does donor support to PFM reform effortscontribute most effectively to results?I.Donor funding for PFM reform has facilitated its implementation inthose countries where the context and mechanisms were right forsuccess, and where external funding was focused on the Govern-ment’s reform programme. On the other hand, governments in thecase study countries showed a willingness to fund PFM reformsdirectly and their ability to do so was significantly facilitated by theGeneral Budget Support inflows they were receiving. Hence, inmany cases, direct external funding for PFM reform may not be thedeciding factor.13

ExECutIvE SummAry

II. Donor pressure to develop comprehensive PFM reform plans and toestablish clearly defined monitoring frameworks has been a positiveinfluence in countries receiving Budget Support.III. By contrast, attempts to overtly influence either the pace or the con-tent of PFM reforms through Budget Support conditionality havebeen ineffective and often counter-productive.IV. Donor promises to enhance the utilisation of country systems havenot generally advanced very far. In the case study countries, the latedisbursement of Budget Support and the partial use of country pro-cedures have been inimical to good public finance management.V. External technical assistance and advisory support helped toadvance the PFM reform processes in the study countries when theywere focused on clear objectives and outputs, directly linked to theGovernment’s reform programme. However, too many TA activitiesdid not fulfil these conditions: there is a need for all TA activities insupport of PFM reform to be explicit about their objectives and theiranticipated outputs and outcomes and to be subjected to independentevaluation on a more systematic basis.VI. The provision of poor advice and the promotion of inappropriatereform models by external agencies remain an unfortunate feature ofmany PFM reform programmes. Greater attention to the appropri-ateness of reform models is needed, within an adaptive, learningapproach to PFM reform implementation.Key lessons for Development Partners Be more discriminating in the provision of financial sup- port to PFM reforms.PFM reforms deliver results when there isa strong political commitment to their implementation, when reformmodels are tailored to the institutional and capacity context and whenstrong coordination arrangements – led by government officials – arein place to monitor and guide reforms. Where these conditions are notin place, PFM reforms are unlikely to be successful. In such circum-stances, external support would be more appropriately used to developcore PFM skills, and to undertake diagnostic work, which might raiseawareness at the political level of the need for reform. A lign support as closely as possible to the Governmentprogramme and avoid pursuing independent technicalassistance initiatives.In the country cases, externally financedsupport to PFM reform was most efficient and effective, when it directlyfinanced, or supported through technical assistance, actions and inter-ventions identified within the Government PFM reform programme.The least efficient interventions were those, which supported actionsoutside of the programme or only tangentially related to it. Thus,technical assistance and institutional support should focus on specific14

ExECutIvE SummAry

outputs to which there is a shared commitment, and should be com-bined with Budget Support, where appropriate. Ensure that aid policy and practise works in favour of thePFM system and not against it.Aid dependent countries facethe perpetual problem of having to adapt their domestic PFM systemsto the requirements of their external aid partners. In the study coun-tries – and elsewhere – significant problems have been created by aidmechanisms making partial use of government systems. Three par-ticular problems arose, which undermined the good management ofpublic finances in the study countries: (i) the late disbursement of budgetsupport; (ii) the imposition of special reporting requirements for “basketfunds” or “trust funds” managed through the national budget process;(iii) the opening of special project accounts outside of the Single Treas-ury Account. Ensure that advice is up to date and informed by the ex-perience within country, within the region and by widerinternational experience.External support can play a useful role inbringing to bear new and more widely informed perspectives on PFMproblems, with which the Government is struggling. By opening “policyspace” in this way, it can help to resolve problems but when externaladvice is not well informed, it serves to close policy space. Externalagencies have a duty to ensure their advice is right, and, where this isnot immediately possible, to ensure that they work jointly with Govern-ment to learn from initial mistakes until an adequate solution is found. Ensure that internal procedures for the supervision andpeer review of initiatives to support PFM reform are effec-tive in providing acontinuous check on progress.Each of thecase study countries suffered from the continued implementation overseveral years of inappropriate reform models and approaches. Policyadvice will not always be right from the outset, in particular when work-ing on PFM reform issues where a degree of experimentation is oftennecessary, but it is important to ensure there are mechanisms in placeto ensure mistakes do not go uncorrected for too long. This requires thecreation – both within the Development Agencies and within Govern-ments – of a learning and adaptation culture, supported by a process ofcontinuous evaluation. Provide support, where necessary, to regional institutionsand professional associations working on PFM reform is-sues.In the case study countries, both regional governmental institu-tions – such as WAEMU – and regional professional associations – suchas CABRI and AfroSAI – were found to be influential in generatingimproved practises on public finance management. In so far as thescope of influence of such bodies could be expanded by more substan-tial external support, then clearly such investments would be of benefit.However, it should be recalled that much of the value of these bodiesderives from their ability to promote peer-to-peer learning: an excessive15

ExECutIvE SummAry

amount of external funding by DPs might undermine the effectivenessof this role. Continue to provide support to CSOs and Legislative bodieson PFM reform issues but accept that their inf luence mayonly be effective in the longer term.The experience of the casestudy countries suggests that CSOs and the Legislature are unlikely tohave significant effects on the pace and content of PFM reforms in theshort to medium term. However, broader international experience – in-cluding in the OECD countries – suggests that their influence over thelonger term may be important. Hence, support to such activities shouldbe continued but not as a substitute to direct support to the Executive.In addition, support should be concentrated on a narrower set of objec-tives, such as the improvement of public access to fiscal information.

Lessons for Developing Country Governments: It is essential to ensure clear and coherent support for PFM reform within the Executive and, over time to broadensupport across the political spectrum.PFM reforms are oftenperceived as purely “technical” measures and this perception needs tobe corrected. This must start within the Executive, with the Ministerof Finance and his/ her team working closely with the President and/or Prime Minister to promote reforms and then widening the scope ofconsultations to include the Cabinet and other members of the rulingparty. In time, it should be an objective to sensitise opposition membersto the need for PFM reforms, so as to ensure continuity over time, in theevent of changes of government. Serious attention needs to be given to the design and staff-ing of the structures established to coordinate and managePFM reforms.Those responsible for coordinating reforms shouldhave both technical competence and authority. The model of a techni-cal secretariat reporting directly to the Minister of Finance is a goodone. Another key feature of an effective model is that authority for im-plementation should be retained at the level of the relevant competentauthority (the President of the Court of Audit, the Directors General ofTreasury, the Budget, etc.) This will avoid doubts over the responsibilityfor implementation and will ensure that the coordinating body is notover-burdened with both implementation and coordinating/ monitor-ing responsibilities. Those responsible for coordinating PFM reforms should ex-ert control over external support to PFM and over dialoguewith Budget Support donors,related to PFM reform. This can bepromoted through the unification of responsibilities for attracting andmanaging external support to PFM reform with those for coordinatingimplementation by the departments and institutions of Government.

16

ExECutIvE SummAry

structures established for monitoring PFM reformTheshould also evaluate performance in order to promotelearning from experience and the corresponding adaptionof implementation plans.PFM reform is inevitably complex andinitial plans are likely to need adaptation and adjustment. If implemen-tation of reform is to be efficient, the monitoring process must identifyreform bottlenecks quickly and take speedy corrective measures. Inorder to ensure this happens effectively, management structures mustembody not only monitoring of progress but also periodic – ideallyindependent evaluation of performance. Finally, the regular training of PFM staff needs to beaconsistent priority.The most important aspect of this is to ensurea consistent output of people with core skills in auditing, accounting,economics, procurement and financial management. In many coun-tries, investment needs to be made to re-establish PFM training institu-tions of adequate quality, and to ensure their recurrent funding overtime.

17

1. Objectives and ApproachThis Synthesis Report is submitted by Fiscus Limited, UK in collaborationwith Mokoro Ltd, Oxford. It summarises the key conclusions and lessons ofthe 2011 Joint Evaluation of Public Financial Management Reform, managedby the African Development Bank, Denmark and Sweden. The report synthe-sises the results of Country Studies for Burkina Faso, Ghana and Malawi1,based upon both desk research and fieldwork. It also draws upon an earlier lit-erature review2, an Approach Paper3and a Quantitative Study4, which exam-ined PEFA data and HIPC AAP data for 100 countries.The evaluation management group and the external peer reviewerreviewed the first draft of the Synthesis Report over October and November2011. Its results were also presented and discussed during January 2012 ineach of the case study countries. This final version of the Synthesis Report hasbeen revised so as to incorporate the comments received from each of thesesources. It is now expected that it will be the subject of a wider disseminationand consultation process, and it is hoped that it may also lead to further coun-try studies – in Africa, Asia, Latin America and Eastern Europe, whichshould serve to deepen its findings and clarify the extent of their applicabilityinternationally.

1.1 OBjECTivES OF ThE EvAluATiOnThe evaluation aimed to address two core questions:a) Where and why do Public Finance Management (PFM) reforms deliverresults, in terms of improvements in the quality of budget systems?; andb) Where and how does donor support to PFM reform efforts contribute mosteffectively to results?

It has thus been a dual evaluation, involving both an evaluation of the overallprogrammes of PFM reform conducted over 2001 to 2010 in Burkina Faso,Ghana and Malawi and an evaluation of the external support provided tothese reforms by Development Agencies. This Synthesis Report focuses in1234Lawson, Chiche & Ouedraogo (2011), Betley, Bird & Ghartey (2011) and Folscher,Mkandawire & Faragher (2011).Pretorius, C. and Pretorius, N (December, 2008), Review of the Public FinancialManagement Literature, DFID, London.Lawson, A. and De Renzio, P, Approach & Methodology for the Evaluation of DonorSupport to PFM Reform in Developing Countries: Part A ( July 2009) and PartB (September 2009), Danida, Copenhagen.De Renzio, P., M.Andrews and Z.Mills (November 2010), Evaluation of DonorSupport to PFM Reforms in Developing Countries: Analytical Study of quantitativecross-country evidence, Overseas Development Institute, London.

18

1. oBJECtIvES AND APProACh

particular on the wider lessons of the evaluation for future design and man-agement of PFM reforms by Governments and for the design and manage-ment of support to such reforms by Development Agencies.

1.2 ThE RESEARCh COnTExT FORThEEvAluATiOnThe evaluation forms part of a wider sequence of research activities, whichwere initiated by a management group comprising the evaluation depart-ments of the African Development Bank, DFID, Danida and Sida in order toaddress the gaps in knowledge regarding the design of effective PFM reformsand of effective external support to PFM reforms. As noted above, the initialresearch activities comprised a literature review, background analytical workto define an approach to the evaluation, and a quantitative analysis.The Literature Review(Pretorius & Pretorius, 2008) demonstrated theabsence of cross-country evaluation and research work to assess the effective-ness of PFM reforms. It identified and reviewed a substantial number of singlecountry assessments of PFM reform efforts, as well as a smaller number ofcross-country analyses of specific types of reforms – such as Medium TermExpenditure Frameworks (MTEFs), but found no existing comprehensivecross-country evaluations. It concluded that, beyond broad generalisations –drawn essentially from evaluations of structural adjustment processes andbroader public sector reforms, there was little knowledge of what made PFMreform efforts more or less successful and of what made financial and techni-cal support to PFM reforms more or less effective.Given this important gap, theApproach Paper(Lawson & De Renzio,2009) focused on deepening the literature review initially conducted, onextending the debate through a structured process of consultations, and ondefining more carefully how success in PFM reform could be defined andmeasured. Drawing on the literature on budget institutions across differentdisciplines, it provided a definition of three key dimensions that could be usedto track the impact of budget reforms over time, namely transparency andcomprehensiveness, the quality of links between budgets, plans and policies,and the quality of control, oversight and accountability. It considered themain sources of data on budget institutions, and demonstrated that by com-bining the results of IMF/World Bank HIPC tracking studies with PEFAassessments, the changes in the quality of budget institutions could be meas-ured against these criteria for 19 developing countries over the period 2001–2007. This background analytical work thus paved the way for the quantita-tive study undertaken during 2010 and also laid out the elements of the evalu-ation framework, later developed in the Inception Report to this evaluation5.Theanalytical study of quantitative cross-country evidenceofthe impact of PFM reforms was completed in November 2010 (De Renzio,5Lawson, A (2011), Joint Evaluation of Public Finance Management Reforms inBurkina Faso, Ghana and Malawi: Inception Report, Fiscus Limited and Mokoro:Oxford, UK.

19

1. oBJECtIvES AND APProACh

Andrews & Mills, 2010). It drew on information from PEFA assessmentsundertaken in 100 countries over 2006–2010, financial data on donor supportto PFM reforms collected from the donor agencies most active in this area,and a large data set on economic/social, political/institutional and aid-relatedvariables. Its key findings were as follows: conomic factors are most important in explaining differences in the qual-E ity of PFM systems. Specifically, countries with higher levels of per capitaincome, larger populations and a better recent economic growth record arecharacterised by better quality PFM systems. By contrast, state fragility,has a negative effect on the quality of PFM systems. onor PFM support is also positively associated with the quality of PFMD systems. On average, countries that received more PFM-related technicalassistance have better PFM systems. However, the association is weak. he share of total aid provided as general budget support is positively andT significantly associated with better PFM quality. Thus, the choice of aidmodalities contributes to explaining differences in the quality of PFM sys-tems in the poorer countries where donor efforts are concentrated. he level of donor PFM support is more strongly associated with improvedT scores forde jureand concentrated PFM processes, highlighting how donorPFM support seems to focus more on rules, procedures and specific actorswithin government. Results are reversed when it comes to upstream vs.downstream processes. Here, the association is stronger with downstreamprocesses, possibly highlighting the large amounts of funding devoted toIFMIS projects, a typical downstream PFM reform.The study emphasised that these results suffered from a number of limitations,including weaknesses in data quality and problems in interpreting causalityrather than merely association. The study authors accordingly stressed theneed to interpret the results with a lot of caution, and noted that the results‘highlight the need to complement these quantitative findings within-depth qualitative research at country level’.There is thus a direct link between the quantitative study and our countrycase studies in Burkina Faso, Ghana and Malawi. This is reflected in theselection of case studies, in the evaluation questions and in the overall evalua-tion framework, which is presented below. This linkage is emphasised in twoparticular lines of investigation: irstly, the quantitative study confirmed, in general terms, the observationsF made in earlier analysis of countries with PEFA assessments (Andrews,2010), that‘countries make budgets better than they execute them, pass laws better thenthey implement them and progress further with reforms for which responsibility lies witha concentrated group of actors in the Ministry of Finance.’The country studiesallowed a qualitative investigation of the factors explaining these trends. econdly, the most significant uncertainty thrown up by the quantitativeS study related to the direction of causality between high levels of PFM relat-ed donor investment (both in the form of Budget Support and as support toPFM reform) and PFM performance. The study found an association butwas unable to determine, whether it simply reflected the tendency of donor

20

1. oBJECtIvES AND APProACh

agencies to invest more resources in countries, which have already demon-strated their willingness and capacity to reform their PFM systems, ora genuine causal relationship between the donor actions and the improvedPFM performance.

1.3 ThE TuniS inCEPTiOn WORkShOPIn order to initiate activities under the evaluation, on the 3rdand 4thMay2011, PFM experts and practitioners from across Africa were invited by theAfrican Development Bank to Tunis to share PFM reform experiences.22 African government representatives from 10 separate countries6talkedopenly about their PFM reform experiences. The points below reflect the keyobservations made by participants7: uccessful PFM reform depends on political support and lead-S ership:reform works well when it has strong political leadership. Hence,it is essential to take into account the political context when designingreform. Coordination between the technical level and the political level iscrucial. Communication of PFM reform across government and transpar-ency over reform results and challenges can be beneficial in building sup-port. Reforms need to be ‘sold’ to the politicians (including the opposition)especially when the political situation is fluid and changing. eforms must be country owned:reform should not be imposed asR a donor condition. While it seems to be the case that reform happens fasterwhen linked to budget support, it is more likely to be sustained if ownership isdeveloped. Without ownership, reform stops when the money stops. lan big, implement small:The “Big bang” approach has advantagesP as everything related to the PFM cycle moves together, although it seems bestto design the whole picture but implement piece by piece. It is important toconsider the breadth, speed and depth of PFM reform. The notion of the “Bigbang” suggests all of these, whereas African experience suggests the need forbreadth – the need to be holistic, covering the whole PFM system, while im-plementing gradually based on priorities and human capacity, and choosinga ‘depth’ of reforms (degree of sophistication), which is consistent with the realneeds and the capacity to implement. ake account of existing capacity:PFM reform is capacity constrained.T It tends to work well when donors finance the initial stages of the PFM reformprocess but then stand back and allow reform to occur in line with existingcapacity. .. and of the magnitude of the change management involved:. Change management aspects of PFM reform are often neglected. Reformprogrammes tend to under-estimate the time and effort involved in fomentingsustainable changes in work culture and work practises.

67

Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Ethiopia, Malawi, Mali, Mozambique, Senegal, SouthAfrica, Uganda, Zambia.These points are taken from the AfDB’s summary of the workshop posted on itsweb-site, with certain points more fully elaborated based on the notes on proceedingsprepared by the evaluation team.

21

1. oBJECtIvES AND APProACh

ecognize that donors are part of the problem:especially when itR

is difficult for governments to account for donor expenditure, because ofthe use of off-budget processes and the lack of reports to the relevantauthorities. tructure diagnostic work around the PEFA assessment frame-S work:the use of the PEFA diagnostic on a periodic basis was reported bymost countries represented to have been useful in creating a shared under-standing of PFM strengths and weaknesses and a shared perception of thedegree of progress being achieved in PFM reforms. In these countries, it hadhelped to break with past approaches in which donors pursued separate diag-nostic assessments, often leading to separate PFM reform programmes andprojects.

Therefore, in relation to the direction of causality between high levels of PFMrelated donor investment (both as Budget Support and as support to PFMreform) and PFM performance, the African government officials who partici-pated in the Tunis conference shared two perceptions relevant to this ques-tion. Firstly, there was unanimous agreement that successful PFM reformrequired political support and leadership and needed to be country-owned.The question of whether donor investment in PFM reform could help to gen-erate political support was not explicitly discussed, however. Secondly, theview was expressed that the pace of reforms needed to be consistent withcapacity and that external support often encouraged a pace of reform thatexceeded domestic capacity. The case studies allowed each of these themes tobe explored further.

1.4 ThE ChOiCE OF CASE STudyCOunTRiESThe 2009 Approach Paper for the evaluation8recommended the use of a pur-posive methodology for the selection of the country case studies for the evalua-tion. Bringing together data from the 2001 and 2004 HIPC AAP assessmentsand the early PEFA assessments undertaken up to 2007, the Approach paperfirst classified the 14 African countries for which this data was available intotwo groups, comprising countries where budget institutions appeared toimprove over the period and countries where budget institutions appeared notto have improved or to have deteriorated. Secondly, drawing on data from theOECD-DAC CRS database, an estimation was made of the donor inputs toPFM reform provided per capita to these same countries over 1998–2007. Theresulting table is presented below.

22

8

Specifically Part A of the Approach Paper (De Renzio, 2009; pp 31–33).

1. oBJECtIvES AND APProACh

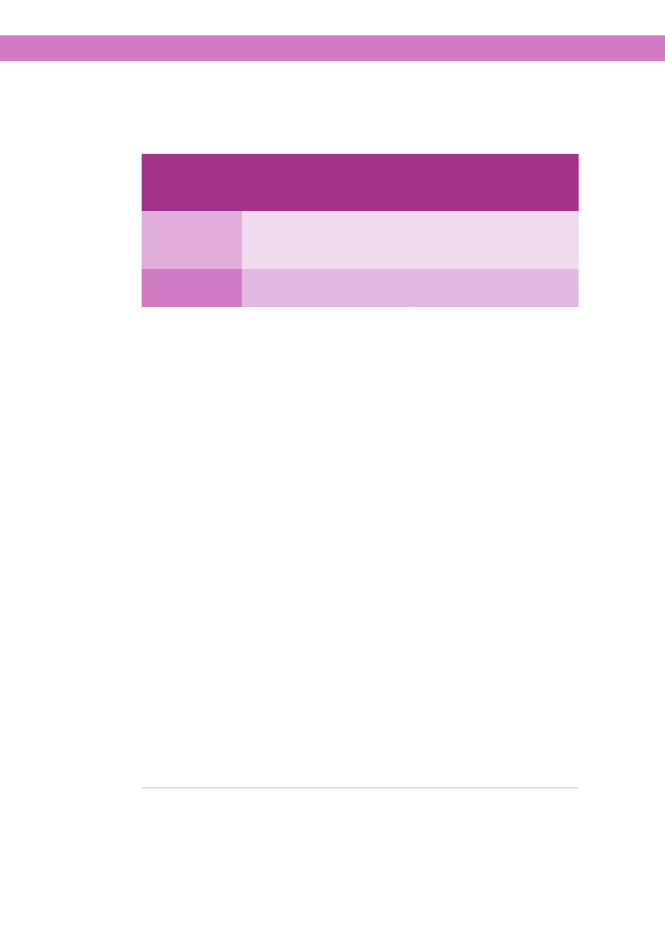

Table 1:Preliminary Estimation of Relative Impact of Donor Supportto PFM reforms in SSA (1998–2007)Countries where budgetinstitutions improvedhigh donoreffortLow donoreffortBurkina Faso, Tanzania,ZambiaEthiopia, Ghana, MaliCountries where budgetinstitutions did not im-prove or deterioratedBenin, Malawi, Mozam-bique, Rwanda, São Toméand Principe, UgandaGuinea, Madagascar

This analysis suggested that there were only three countries (Burkina Faso,Tanzania and Zambia) where donor support had been associated with suc-cessful reforms and three others (Ethiopia, Ghana9and Mali) where reformsappeared to produce positive outcomes even in the presence of more limiteddonor effort. The Approach Paper stressed that no firm conclusions could bedrawn from ‘this simple comparative exercise’ but it suggested that it pointedto ‘a range of situations which merited further investigation in the selection ofcase studies’.Specifically, the Approach paper suggested that, ‘excluding the countriesin the shaded box, the ideal way of applying the evaluation framework wouldbe to select a limited number of case studies focusing on countries from theremaining three boxes, possibly pairing them in ways that keep constant fac-tors such as the administrative heritage (for example, by pairing Francophoneand Anglophone countries). In this way, it would be possible to examine threetypes of situations:a) One in which donor support appeared to be positively correlated with PFMimprovements;b) One in which donor support appeared to be negatively correlated with PFMimprovement;c) One in which significant PFM improvements appear to have occurred de-spite relatively low levels of donor support.’

The Evaluation Department of the African Development Bank thenapproached these 14 countries to enquire which would be interested in collab-orating with the evaluation process, in order to find ways of strengtheningtheir PFM reform programmes and of improving the quality of external sup-9 Various PFM specialists consulted on the Approach Paper expressed surpriseat the resulting categorisation of Ghana, suggesting that it was misleading intwo respects. Firstly, there appeared to be a significant under-recording ofthe level of donor funding for PFM reforms. Secondly, the results of the 2001HIPC AAP were considered by many to have been unfeasibly low, giving animpression of significant improvements in subsequent years, which was notconsistent with other reports on the status of PFM systems in Ghana.

23

1. oBJECtIvES AND APProACh

port to those programmes. Three countries agreed to collaborate in the pro-cess, which appeared at first sight to fall into these three groups, namelyBurkina Faso [Group a)], Malawi [Group b)], and Ghana [Group c)].Information from the case studies themselves has demonstrated that someof the preliminary estimates underlying Table 1 were in fact wrong. In partic-ular, all three countries were found to have been recipients of relatively highlevels of donor support to PFM. In addition, more recent PEFA assessmentsundertaken in 2009, 2010 and 2011 convey a more nuanced picture of the per-formance of PFM systems in each of these countries. Nevertheless, the casestudies do present interesting variations in the performance of PFM reformsas well as some striking similarities. A fuller description is presented in Chap-ter 2.

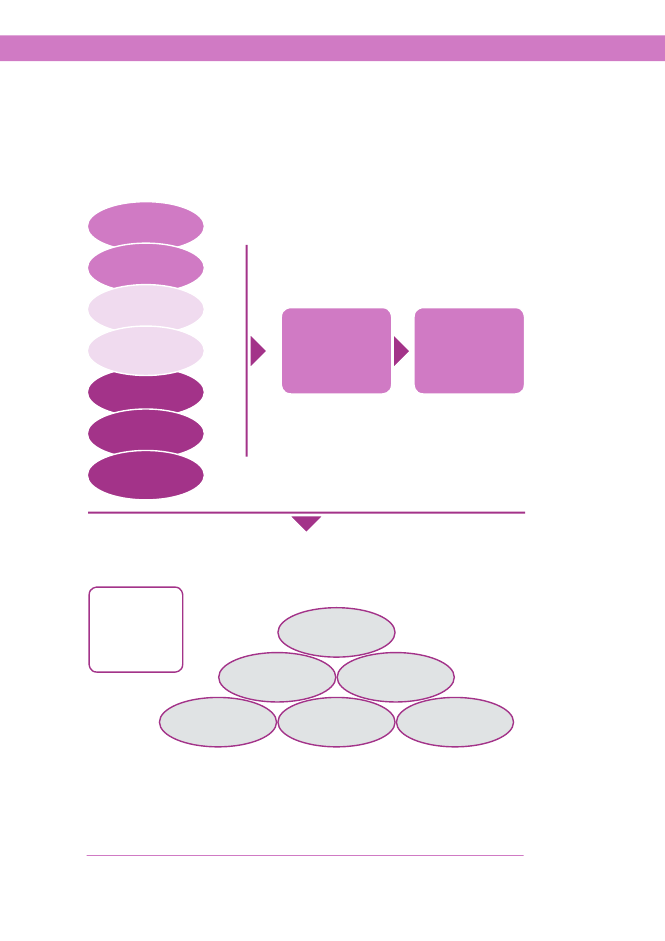

1.5 EvAluATiOn FRAMEWORkThe evaluation framework was defined in the Inception Report for the evalua-tion (Lawson, 2011). It utilises the OECD-DAC evaluation criteria and thusassesses the relevance, efficiency, effectiveness and sustainability both of coun-try programmes of PFM reform and of the external support provided to thoseprogrammes. It gives particular attention to three dimensions of PFM reformprocesses: heContexts,in which reforms have taken place;T heMechanismsadopted for the design, management and delivery ofT reforms; and he consequentOutcomesachieved.T Success is associated with improvements in the quality of budget systems, asmeasured primarily by changes in the Public Expenditure and FinancialAccountability (PEFA) assessment framework indicators and the narrativePEFA reports. The evaluation framework characterises these changesasintermediate outcomesin a ‘PFM Theory of Change Framework’, whichis presented in Figure 1 below10. The Framework details PFM Reform inputs,outputs and intermediate outcomes and examines the relationship betweenthem, and with key contextual factors.

10 A preliminary version of this framework was developed in Part B of the ApproachPaper for the evaluation (Lawson & De Renzio, 2009), which was widely commentedupon by PFM practitioners, academics and Development Partners. The refinementspresented in the Inception Report drew upon these comments. The final version ofthe framework, which was used in the country studies, was presented at the launchworkshop for the evaluation held at the African Development Bank in Tunis.(See above.)24

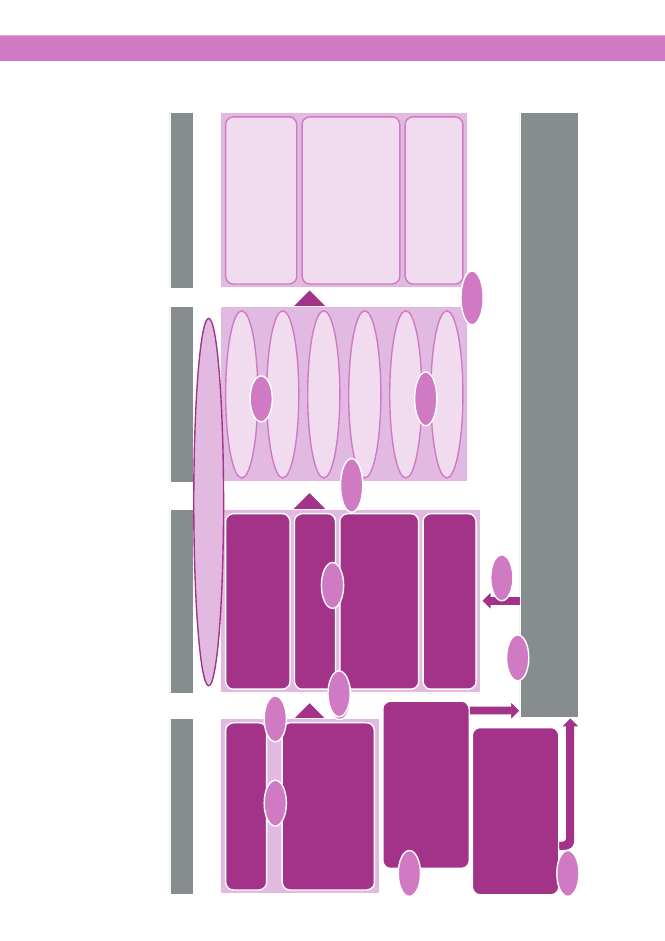

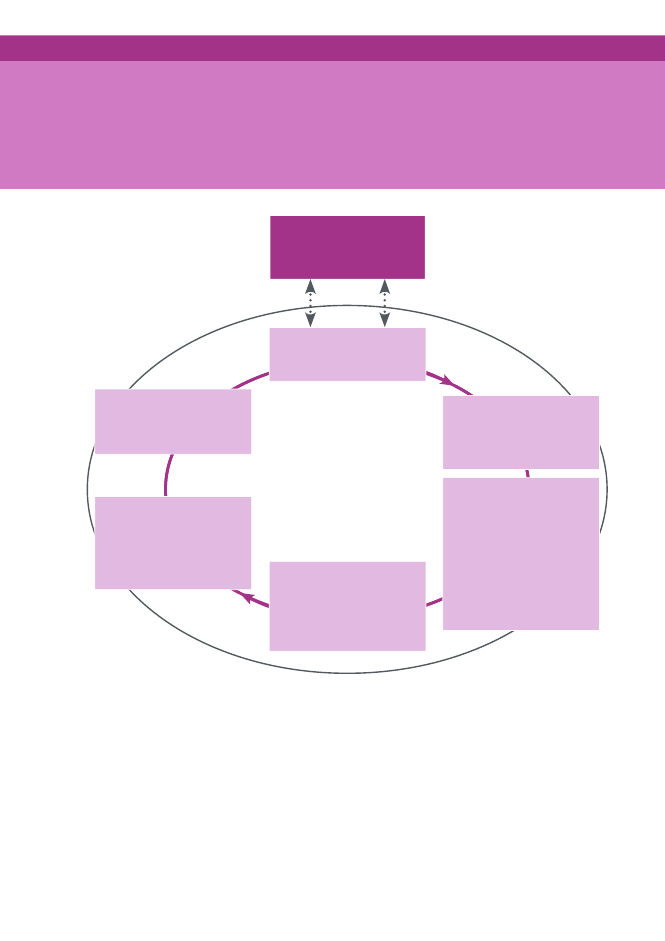

Figure 1. The Evaluation Framework and the place of the Evaluation Questions within the Intervention LogicOUTPUTSINTERMEDIATE OUTCOMESFINAL OUTCOMES

INPUTS

pFM reform intervention Logicpeople & skills:strategic budgetingEQ 9

• Government-funded inputs

Government pFM reforminputsbudget preparationresourceManagementEQ 11

Fiscal discipline:

EQ 1

EQ 2

• umbers of PFM professionals N(auditors, etc.)D• evpt of specific skills, (incl. reform management)

• ulfillment of planned fiscal tar-Fgets• aintenance of Sustainable Defi-Mcit

dp funded support to pFMreform

(delivered in aharmonised &aligned manner):• Institutional strengthening• Advisory TA• Diagnostca Work

• hanges in Laws. Rules & Proce-CduresEQ 6EQ 7EQ 2

Laws, rules & procedures

strategic allocationofresources:

systems & businessprocesses:

internal control. audit& Monitoringaccounting 8. reportingEQ 10

complementary developmentpartner inputs:EQ 3Organisational factors:

• omputer systemsC• pecific approaches to budgeting, Saccounting addit, treasury manage-ment, etc.

• onsistency of executed C&approved aggregate / depart-mental budgets• onsistency of revenue Ctargets & coIIecfions

Operational efficiencyin public spending

• Use of Country Systems• Provision of Budget Support• olicy Dialogue & monitoring PofPFM reform

• mproved managementI• rganisational developmentO• mproved work culture.IEQ 8

external accountabilityEQ 12

• volution of Unit costs ofpublic Eservices

public & civil society pressurefor improved pFM:

EQ 5

• Voting preferences• Political lobbying• Research & advocacy• Regional/ international norms

1. Objectives and apprOach

EQ 4

• olitical constraints: Degree of leadership / ownership of PFM reform at Administratve and Politcal levels.p• Financial constraints: Availability & timeliness of funding for PFM reform, presence.' absence of economic crisis.• olicy constraints: Openness of the policy reform agenda, receptivity to new ideas. policy space for long-term reforms.p

external constraints on the pFM reform “production possibility frontier”

25

1. oBJECtIvES AND APProACh

Inputsare defined as the resources and other inputs provided in order to pro-mote PFM reform. These are divided between direct funding by governmentsto internal PFM reform efforts, external funding by Development Partners(DPs) of PFM reform efforts and complementary inputs by DPs. These com-plementary inputs might be aimed at facilitating better PFM through the useof country systems and the provision of budget support, or at improving thedesign and implementation of PFM reforms through policy dialogue andexternal monitoring (often linked to budget support).Fourcontextual factorsare considered. One is internal and relates topublic and civil society pressure for PFM reform11. It examines the relativeimportance for the design and implementation of PFM reform of the votingpreferences of the electorate (to what extent good PFM is prioritised by voters),of research and advocacy work by CSOs, of political lobbying by CSOs andothers, and of regional and international norms for PFM, which might pro-vide “rallying points” for civil society groups and for the design of advocacycampaigns12.Also included within the contextual factors are external constraints – con-ceptualised as political, financial and policy space constraints. These externalconstraints are seen to impinge on the PFM reform ‘production function’, inother words on the capacity of PFM reform inputs to generate the plannedoutputs. Political constraints relate to the degree of political ownership andsupport for PFM reforms. Financial constraints relate to the ability to financePFM reforms in the face of competing priorities, and “Policy space con-straints” relate to the nature of policy ideas, which might potentially be con-sidered in designing PFM reforms. This latter constraint reflects the prevail-ing conventional wisdom over the types of reforms that could be contemplatedand the influence on that conventional wisdom of government stakeholdersand academic and civil society organisations, as well donor agencies andinternational and regional institutions. Another potential way of describingthis would be in terms of the “space for novelty”13in PFM reform policies andstrategies.Outputsare defined as the immediate changes in the architecture andsubstance of the PFM system generated by the combined set of inputs. Theseare categorised into four groups: i) Changes in human resource endowments(people and skills); ii) Changes in laws, procedures and rules; iii) Changes in11 Advocacy work by CSOs in support of greater transparency and accountability mayattract funding support from Development agencies and international foundations. Inthis sense, it is an “output” of PFM reform efforts. However, such funding is modestin relation to the direct funding available for core components of the PFM reformprogramme. Hence, in the case studies, funding to CSOs for advocacy work was notincluded within the financial estimates of PFM reform inputs and it was dealt withpurely as a contextual input.12 For example, amongst the country case studies, the West African Economic & Mon-etary Union (WAEMU or UEMOA in French) establishes both convergence criteriafor macroeconomic and fiscal management, and norms for certain aspects of PFM, towhich its eight members subscribe, including Burkina Faso.13 This is considered in Pritchett, Woolcock & Andrews (2010) as a key characteristic bywhich to judge systems.

26

1. oBJECtIvES AND APProACh

systems and business processes; and iv) Changes in Organisational factors (thequality of management, the work culture, the degree of organisational devel-opment).Intermediate Outcomesare the changes generated in the PFM sys-tem, as measured by changes in the quality of:i)ii)iii)iv)v)vi)Strategic budgeting;Budget Preparation (including budget deliberation by the Legislature);Resource management (covering both inflows and outflows);Internal controls, audit and monitoring;Accounting and reporting; andExternal Accountability.

The framework uses the PEFA assessment framework to measure changes ineach of these clusters of PFM functions, based on a categorisation of the sub-dimensions of the PEFA indicators between each of these clusters. The catego-risation14is based on Andrews (2010) and was also applied by De Renzio et al(2010) in the quantitative study, which examined data on 100 separate coun-tries which had completed PEFA assessments between 2006 and 2010.The PEFA Performance Measurement Framework for PFM (PEFA 2005)is to date the most comprehensive attempt at constructing a framework toassess the quality of budget systems and institutions. It comprises 28 indica-tors, which assess system performance at all stages of the budget cycle, as wellas crosscutting dimensions and indicators of budget credibility. It also includesthree additional indicators on donor practices. (See www.pefa.org.)In order to derive the PEFA scores by budget “cluster”, Andrews (2010)and De Renzio et al (2010) follow four steps, which were also used in the coun-try studies to convert scores from the PEFA assessments in each country intonumerical averages for each cluster. De Renzio et al (2010, pp. 11–12) explainthe methodology very clearly:“First, we only considered indicators PI-5 to PI-28, as indicators PI-1 to PI-4 coverPFM system outcomes and performance, and not the quality of PFM systems per se. Second,for multi-dimensional indicators we used sub-indicator/dimension scores rather than sum-mary indicator scores in order to fully exploit the information contained in the PEFA scores.This also allowed us to avoid the downward bias introduced by the M1 scoring methodol-og y, where summary indicators are based on the lowest scoring dimension, or ‘weakest link’.Third, we converted the letter scores included in PEFA reports into numerical scores, withhigher scores denoting better performance (from A=4 to D=1). Fourth, we constructed ourdependent variable in three different ways: 1) as an overall simple average of the 64 numeri-cal scores that include all sub-indicators/dimensions for indicators PI-5 to PI-28; 2) asaverages of numerical scores for sub-indicators/dimensions in each of six clusters of indica-tors grouped by phase of the budget cycle. This generates six sub-indices to be used separatelyas dependent variables; 3) as individual scores for each of the 64 sub-indicators/dimensionsin indicators PI-5 to PI-28. This generates a panel-type dataset of64 dimensions * 100 countries.”14 These clusters are slightly different from the ones included in the PEFA methodology,as they have been rearranged to increase their level of internal consistency. For furtherdetails, see Annex 3, as well Andrews (2010:8) and Andrews (2007).

27

1. oBJECtIvES AND APProACh

1.6 ThE EvAluATiOn QuESTiOnS &ThEAPPROACh TO ThE COunTRy STudiESEach of the Country studies was based on twelve evaluation questions, whichare presented in Box 1 below15. The evaluation questions were structured so asto provide a standardised framework for assembling evidence, so that theresults of the country studies could be easily synthesised to provide answers tothe overall high-level questions.Each of the Country Studies generated a set of“case histories”ofchange in PFM systems. The aim of this approach was to ensure that the eval-uation did not miss patterns of change, which might be obscured by looking atthe average changes in the system as a whole. For example, even in a countrymaking limited progress with its overall PFM reforms, there would probablybe specific sub-components progressing faster. This is unlikely to be a merecoincidence: it would be more likely to reflect the relative balance for thosesub-components of the positive and negative forces, driving or blockingchange. By examining the patterns of change within the sub-components ofthe PFM reform programme, we believe that more significant insights havebeen revealed. The approach is illustrated in Figure 2 below.

28

15 The Inception Report presents the Evaluation Questions, with the correspondingjudgement criteria used to assess them.

1. oBJECtIvES AND APProACh

Box I. The Evaluation questionsA. Inputs & context: the design of PFM reformEQ 1:What has been the nature and the scale of PFM reform inputs provid-ed by Government and by Donors?EQ 2:What types of structures have been used for the design and manage-ment of these reform inputs? Have these structures served to provide a coordi-nated and harmonised delivery framework?EQ 3:What types of complementary actions have Donors taken to supportPFM reforms and what has been their significance? Have they had any influ-ence on the external constraints to reform?EQ 4:To what extent has there been domestic public pressure or regionalinstitutional pressure in support of PFM reform and what has been the influenceon the external constraints to reform?EQ 5:How relevant was the PFM reform programme to the needs and theinstitutional context? Was donor support consistent with national priorities? Towhat extent were adaptations made in response to the context and the changingnational priorities?

B. Outputs: the delivery of PFM reformEQ 6:What have been the outputs of the PFM reform process and to whatextent has direct donor support contributed to these outputs?EQ 7:How efficiently were these outputs generated? Was the pacing andsequencing of reforms appropriate and cost-effective? Was the cost per outputacceptable?EQ 8:What have been the binding external constraints on the delivery ofPFM reform outputs: political, financing or policy factors? How has this variedacross different PFM reform components?

C. Outcomes: overall assessment of PFM reform & of donor supportto PFM reformEQ 9:What have been the intermediate outcomes of PFM reforms, in termsof changes in the quality of PFM systems?EQ10:To what extent have the outcomes generated been relevant toimprovements in the quality of service delivery, particularly for women and vul-nerable groups?EQ 11:Have reform efforts been effective? If not, why not? If yes, to whatextent PFM reform outputs been a causal factor in the changes identified inintermediate outcomes?EQ 12:To what extent do the gains identified at the Intermediate Outcomelevels appear sustainable? Is the process of PFM reform sustainable?

The case histories were compiled from a process of reconstruction of the chro-nology of events, drawing on interviews and focus group discussions to iden-tify the potential causes of change and triangulating across these sources to

29

1. Objectives and apprOach

arrive at aset of validated hypotheses. In broad terms, they followed the tech-nique of “process tracing”.16

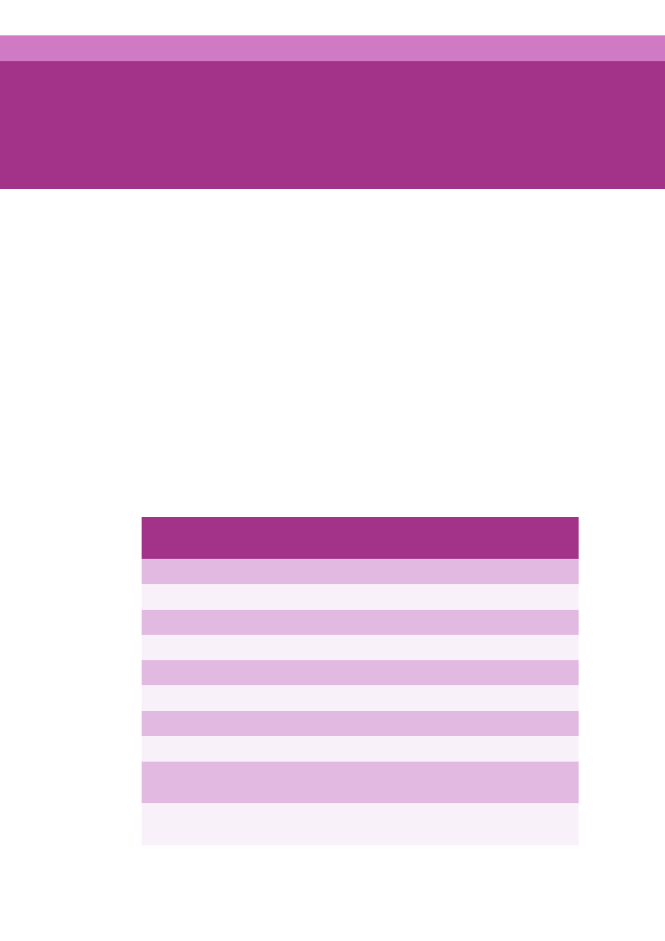

Figure 2 Overview of the Case History Approachto the Country StudiesGovernment fundedPFM reformsDonor funded PFMreformsComplementaryDevelopment partnerinputsPublic &CSO pressurefor improved PFMEvolving PoliticalConstraintsEvolving FinancingConstraintsEvolving Policy SpaceConstraints

Factors driving/ blocking Change(Independent Variables)

PFM REFORMOUTPUTS

(INTERMEDIATEOUTCOMES OFPFM REFORMS)

RESULTS

...analysed through Case Histories...and for specific sub-componentstargeted by Reforms...for the PFMsystem asawholeStrategic BudgetingResourceManagementInternal Con-trol, Audit& Monitoring

Budget Preparation

Accounting &Reporting

External Audit

With the available budget, it was not possible to recreate the reform case histo-ries for each of the 6 PFM clusters in each country. Hence, reform processeswere analysed in relation to the PFM system as awhole and in relation to3specific PFM clusters targeted by reforms. Table 1 shows the case studies16 Process tracing is amethod for the reconstruction of causal relationships throughthe recreation of case histories. [George, A.L, & A. Bennett (2005), Case studies andtheory development in the social sciences.]

30

1. oBJECtIvES AND APProACh

chosen. Each of these comprised a case history of some historical longevity, sothat the evolving process of reform over time could be examined and a judge-ment on sustainability could be reached. They included cases of success andcases of failure, whilst also providing a basis for cross-country comparisons byexamining certain types of reforms in more than one country.

Table 2. The Selection of 9 Case Histories from the Study CountriesBurKINA FASoThe integrated finan-cial management in-formation system: theCircuit Intégré de laDépense (CID), and itsvarious complemen-tary sub-systemsIntroduction of mediumterm programmaticbudgeting through theCadre des DépensesàMoyen Terme (CDMT)and the budgets-pro-grammes.Reform of the Reve-nue AdministrationsystemGhANAThe Integrated Finan-cial Management sys-tem (BPEMS– Budget& Public ExpenditureManagement System)mALAWIThe Integrated Finan-cial Management sys-tem (IFMIS).

Introduction of the Me- Reform of the Procure-dium Term Expendi-ment Systemture Framework(MTEF)

Reform of the Reve-nue AdministrationSystem

Reform of the InternalAudit system

1.7 ThE APPROACh TO ThE SynThESiSPROCESSThis Synthesis report has thus brought together information from 3 countryhistories and from 9 case histories at the “PFM cluster” level. The objectivehas been to address the high level questions identified in the terms of refer-ence:‘The purpose of the evaluation is to identify what factors–institutional and contextual– contribute to successful PFM reformand how donors can best support PFM reform given the influenceof contextual factors on the process of change.’(Terms of Reference,pp.3–4)The adopted approach to analysis is that of ‘realist synthesis’ (Pawson &Tilley, 1997; Pawson 2002). The starting assumption of the realist school isthat most programmes of reform or social change work only in limited cir-cumstances. Therefore, the discovery and documentation of the ‘scope condi-tions’ within which a programme works becomes the main objective of theprocess of synthesis. Realist synthesis does this through the analysis of change

31

1. oBJECtIvES AND APProACh

Mechanisms (M) working within different Contexts (C) and producinga range of Outcomes (O). By careful examination of these C-M-O combina-tions, it is possible to define to a certain level of detail the “boundary condi-tions” within which a programme theory will work, leading to a more tailoredtheory and to a better understanding of its transferability.Thus, the systematic analysis of a range of C-M-O combinations producesa continual refinement of programme theory, by learning both from success(favourable outcomes) and failure (unfavourable outcomes). In this sense, real-ist synthesis builds on the ideas of Karl Popper (Popper, 1959) regarding theimportance of being able to falsify a theory. Where a theory is open to falsifi-cation, it then becomes possible to refine the theory through the experience offailure. Learning from mistakes through ‘analytical induction’ (Lindesmith,1968) is essential to the process.The evaluation questions provide a template for documenting the C-M-Ocombinations generated by the case histories: ontextis captured by the questions relating to complementary DP inputsC (EQ3) and demand-side pressures (EQ4), as well as to binding externalconstraints (EQ8). echanismsare documented through questions on inputs (EQ1) andM outputs (EQ6) and on efficiency (EQ7) as well as through more detailedexamination of the structures for design and management of reform inputs(EQ2). utcomesare directly documented (EQ9) and also examined withO respect to their relevance for service delivery, especially for women andvulnerable groups (EQ10). elationships between Context-Mechanism-OutcomesareR examined from the perspective of relevance (EQ5), effectiveness (EQ11)and sustainability (EQ12.)By examining these different combinations, at the country level and then atthe PFM cluster level, we have been able to develop a tailored programmetheory regarding firstly the critical aspects of context, which contribute to suc-cessful PFM reform, and secondly the most important features of the mecha-nisms adopted for delivering PFM reform. This analysis has allowed us tocrystallise a number of lessons, which are presented in our conclusions.

1.8 liMiTATiOnS OF ThE AnAlySiSClearly, the value of the conclusions presented in this synthesis is limited bythe fact that they are derived from only nine case histories within three casestudy countries in Sub Saharan Africa. The three country studies do illustratea variety of situations – covering Anglophone and Francophone administra-tive systems – and include cases (and specific periods within the same cases) ofsuccessful and unsuccessful PFM reform. Moreover, by going down to thePFM reform “component” level in the case histories, the range of experiences32

1. oBJECtIvES AND APProACh

covered has been further broadened. We have also drawn comparisons withthe quantitative study and with the existing literature on PFM reform wher-ever possible. Nevertheless, it is a small sample from which to develop a pro-gramme theory.It is therefore vital to disseminate and discuss the results of this work, inorder to assess whether there are other PFM reform experiences, which havenot been accessed and which might serve to enrich the conclusions. It is alsoimportant to assess whether the insights here presented are supported by theimpressions and by the experiences of seasoned PFM practitioners andresearchers. The dissemination process envisaged by the Evaluation Manage-ment Group should allow for the results to be tested through such feedback.Moreover, in the medium term, it is essential that this study should becomplemented by further case study work, which might build upon itsinsights. Wherever possible, additional case study work should deliberatelyseek to test the “boundary conditions” of the conclusions reached, by choosingcontrasting case study countries. If additional case study work were to utilisethe same evaluation framework and the same approach to the synthesis ofresults, this would permit the continuous updating of the “programme theo-ry” here presented.In terms of the approach to fieldwork, the results are also subject to a num-ber of limitations. Most notably, fieldwork comprised only 6 person weeks ofwork (three consultants for two weeks) and within such a short time period, therange of stakeholders who could be interviewed was, of course, limited. Asa consequence, the depth of analysis possible for the three detailed cases stud-ies undertaken in each country was uneven, although in our opinion adequateto justify the resulting conclusions. It is also the case that the analysis mighthave been biased by the perspectives of the stakeholders directly involved inthe reforms, as the government and donor staff managing and undertakingthe PFM reforms in each country comprised the majority of those inter-viewed. Whilst members of Civil Society Organisations dealing with PFMissues were interviewed in each country, either individually or within focusgroups, they were relatively limited in number. With regard to members of theLegislature, it did not prove possible to interview MPs in Burkina Faso andonly small numbers in Ghana and Malawi.On the other hand, in drawing conclusions from fieldwork, the evaluatorswere careful to triangulate findings wherever possible. For many issues, sys-tematic comparisons of the perspectives of central agency staff, sector minis-try staff and donor representatives were possible. In other cases, comparisonswere made between the views of different donors or the opinions of public sec-tor managers and junior staff. The fieldwork also built on detailed desk stud-ies17that were undertaken prior to the fieldwork, drawing on the extensivedocumentation available on each of these countries either on the Internet or17 The desk studies were undertaken by experienced research assistants, who wereclosely supported by the other team members for each country. Reports were allpublished in advance of the field work and amounted to documents in excess of 100pp each including annexes: Chiche, M., June 2011 (Burkina Faso), Faragher, R. June2011(Malawi) and Gordon, A. & Betley, M, June 2011 (Ghana).

33

1. oBJECtIvES AND APProACh

from reports and data explicitly requested from Government departments andDonor agencies.In short, our judgement is that such biases as might have been introducedinto fieldwork by the time limitations or by the composition of the personsinterviewed were for the most part corrected for, and were certainly no greaterthan in other case study work of this kind. We are confident in the quality ofthe evidence for our conclusions, and have introduced explicit caveats withinthe text for the small number of cases, where we have reservations in thisrespect.

1.9 REPORT STRuCTuREFollowing this introduction to the objectives and approach, the SynthesisReport comprises four further chapters: hapter 2 provides an overview of the reform experience of the three caseC study countries, detailing theOutcomesof reforms for each country, andsummarising the differentC-M-O combinations,which emerged for thethree country cases and for each of the nine individual case histories. hapters 3 and 4 present in more detail the analyses ofContextandC Mechanisms,leading to a refinement of the initial programme theory. hapter 5 presents overall conclusions, drawing out the wider lessons forC Governments and Development Agencies.

34

2. Overview of PFM reformexperience in the Study countriesIn this chapter, we present an overview of our main findings, before analysingmore deeply in chapters 3 & 4 the contextual factors and the aspects of thePFM reform design and delivery mechanisms, which have proved critical. Inorder to set the scene, we begin first with a simple comparative analysis of theeconomic and political frameworks in each of the three countries. We thenconsider the relative levels of inputs to PFM reform provided in each coun-try – both directly by Governments and by Development Agencies – and theoutcomes achieved, before presenting a summary of the C-M-O combinations(Context-Mechanism-Outcomes) generated by the three country studies andby the 9 more detailed case histories.

2.1 ECOnOMiC And POliTiCAlBACkGROundTable 3. Key Economic, Social & Political Indicators for the StudyCountries (2010)Indicator

GDP per Capita PPP, 2005international $Population, milliona% Population Living on < $1.25ppp/DayLife Expectancy at BirthLiteracy Rateaabba

Burkina

Faso

1078.015.856.553.7293739.6bGhana

1410.023.830.057.1731442.82.02.1911.2malawi

779.015.373.954.6661639.02.71.177.2Child malnutrition (% of children under 5)Gini CoefficientbAnnual Population Growth Rate

3.1

Average Annual ODA Disbursements 2002–2009, 1.03cconstant 2008 $billionTotal GBS as a% of total aid disbursement 2002– 15.92009 c

35

2. ovErvIEW oF PFm rEForm ExPErIENCE IN thE StuDy CouNtrIES

Indicator

Average Annual ODA Disbursements per capitaa,cPolitical Openness 2010 (indicationof general state of freedom in acountry)Political Rights (1= high freedom;17= low)Civil Liberties(1= high freedom; 7=2low)Corruption Perceptions Index 2010 (0 = highly3ecorrupt; 10 = no corruption)Sources:abcded

533.1

124.1

343.4

World Bank Development Indicators 2010;Human Development Report 2010;OECD DAC Database, accessed 10/1/11;Freedom In the World 2010, Freedom House;Corruption Perceptions Index 2010, Transparency InternationalThe ratings process is based on a checklist of 10 political rights ques-tions. Scores are awarded to each of these questions from which a rating of1 to 7 is derived, with 1 representing the highest and 7 the lowest level offreedom.The ratings process is based on a checklist of 15 civil rights questions. Again,a rating of 1 to 7 is derived, with 1 representing the highest and 7 the lowestlevel of freedom.The CPI measures the degree to which public sector corruption is perceivedto exist within a country on a scale of 0 (highly corrupt) to 10 (very clean).

Notes:

1

2

3

Economic and Social contextTable 3 above shows key economic, social and political indicators for each ofthe study countries. There are certain similarities but also important differ-ences. They are all high recipients of aid and each can be described in a broadsense as a Developing Country but income per capita is considerably higher inGhana – a coastal, natural resource rich country, which became formallya middle income country in 2011 - than it is in Burkina Faso or Malawi, bothland-locked low income countries, which are predominantly reliant on rain-fed agriculture.Their recent economic development paths have also been quite different inseveral important respects: urkina Fasohas been through a process of wide-ranging macroeco-B nomic and monetary reform over the last two decades. The change ofregime in 1987 signalled a move away from a socialist model to a moremarket-oriented economic policy. A devaluation of the currency in 1994resulted in a remarkable acceleration of growth, and in the last 20 yearsBurkina Faso has experienced higher economic growth and lower inflation

36

2. ovErvIEW oF PFm rEForm ExPErIENCE IN thE StuDy CouNtrIES

than the average in the WAEMU and Sub-Saharan African (SSA) coun-tries. Between 2000 and 2010, it maintained an average growth rate ofover 5.2 % per annum, and except for a short-lived spike following thedevaluation, average inflation has remained below 3 % since 1995. How-ever, with a population growth rate of 3.1 % per annum, and a continuingsusceptibility to droughts and floods and a vulnerability to regional con-frontation among its trading partners (such as in Cote d’Ivoire), this level ofGDP has not been sufficient to be transformational. Its economic perfor-mance has been steadily positive rather than exceptional18, although therecent growth in mining exports does open up new opportunities for thefuture19. hanaalso experienced major macroeconomic and structural reformG over the decade of 1985–1995, as the Rawlings government managed thetransition from a protectionist state-led model of development to a liberal-ised, export driven model and from military rule to civilian rule, culminat-ing in the 1992 Constitution and the 1996 elections. It was helped by nar-row but robust export growth, based upon gold and cocoa, and by thesteady growth of its services sector. The period since the mid ‘90s has beencharacterised by a “boom and bust” cycle, linked closely to the electoralcycle20. In 1999 and 2000, as the incumbent National Democratic Con-gress (NDC) Government reached the end of its term, public spending wasdramatically expanded, allowing the fiscal deficit to mushroom, financedthrough domestic borrowing, and inflation, which hit 41 % in 1999. Theincoming New Patriotic Party (NPP) government introduced a period offiscal consolidation and tight monetary policy, paving the way for growthin excess of 6 % in 2006 and 2007, and of 7.3 % in 2008. Yet, as the NPPgovernment reached the end of its second term, 2008 also saw big increasesin public expenditure, with negative effects on the fiscal deficit, whichreached 13.5 % of GDP, as well as on inflation, and domestic interest rates.The returning NDC government has introduced a new period of fiscalconsolidation over 2009 and 2010. Helped by the start of oil production in2010 and the related investment, growth rates of 6.6 % and 8.3 % are fore-cast for 2010 and 2011.

18 Steady economic growth, increasing social expenditures and improvements in ac-cess to basic services saw a decline in the incidence of poverty from 54 % in 1998 to46.4 % in 2003, and to an estimated 43 % in 2010. Sustained efforts and investmentshave resulted in positive trends in human development, with strong increases in grossprimary enrolment, use of health services, vaccination rates, percentage of assistedbirths, and an improved access to clean water but it remains one of the poorest coun-tries in the world, ranked 161$1-$2 out of 169 countries in the 2010 Human Develop-ment Index.19 In 2009, gold replaced cotton as Burkina Faso’s most valuable export. Mining isexpected to increase export earnings by 25 %, bringing $450 million in added fiscalrevenue between 2010 and 2015 (World Bank, 2010a.)20 In common with Burkina Faso, Ghana also averaged 5.2 % annual growth in GDPover 2000 to 2007 but annual fluctuations around this average were much greater,and inflation was considerably higher than in neighbouring Burkina Faso.

37

2. ovErvIEW oF PFm rEForm ExPErIENCE IN thE StuDy CouNtrIES

alawishares many of the economic features of Burkina Faso, being alsoM