Udenrigsudvalget 2012-13

URU Alm.del Bilag 208

Offentligt

2012:8Mary BetleyAndrew BirdAdom Ghartey

Joint Evaluation

Evaluation of PublicFinancial Management Reformin Ghana, 2001–2010Final Country Case Study Report

Joint Evaluation 2012:8

Evaluation of Public FinancialManagement Reformin Ghana 2001–2010Final Country Case Study Report

Mary BetleyAndrew BirdAdom Ghartey

Submitted by fiscus Public finance consultants and Mokoro ltdtotheEvaluation Management groupJune 2012

Authors:Mary Betley, Andrew Bird, Adom GharteyThe views and interpretations expressed in this report are the author and do notnecessarily reflect those ofthe commissioning agencies, Sida, Danida and AfDB.

Joint Evaluation 2012:8Commissioned by Sida, Danida and AfDBDate of final report:June 2012Published by:Sida, 2012Copyright:Mary Betley, Andrew Bird, Adom GharteyDigital edition published by:Sida, 2012Layout and print:Citat/Edita 2012Art.no.SIDA61499enurn:nbn:se:sida-61499enISBN:978-91-586-4196-9This publication can be downloaded/ordered from: www.Sida.se/publications

Acronyms and AbbreviationsAAPADMDAfDBAFROSAIARICBDUBMZBPEMSCABRICAGDCEPSCFAACHRAJCIDACPIACSODACDANIDADCDFIDDPECERPFMEUFAAFARFCFMISGASGBS(HIPC) Annual Assessment & Action PlanAid and Debt Management DivisionAfrican Development BankAfrica Organisation of Supreme Audit InstitutionsAudit Recommendation Implementation CommitteesBudget Development UnitGerman Ministry of Cooperation and DevelopmentBudget and Public Expenditure Management SystemCollaborative African Budget Reform InitiativeController and Accountant General’s DepartmentCustoms, Excise and Preventative ServiceCountry Financial Accountability AssessmentCommission on Human Rights and Administrative JusticeCanadian International Development AgencyCountry Policy & Institutional AssessmentCivil Society OrganisationsDevelopment Assistance Committee (of the OECD)Danish International Development AssistanceDeveloping CountryDepartment for International Development of the UKDevelopment PartnerEuropean CommissionExternal Review of the Public Finance ManagementEuropean UnionFinancial Administration ActFinancial Administration RegulationsFinance CommitteeFinancial Management SystemsGhana Audit ServiceGeneral Budget Support5

ACroNymS AND ABBrEvIAtIoNS

GDPGIFMISG-JASGNIGoGGPRSGRAGSGDAGTZHDIHIPCIAAIAUICRIDAIEGIFMSIMFINTOSAIIPPDLGAMDAsMDBSMDBS-FMDGMMDAsMoFEPMoLGRDMPsMTEFNAONDCNDPC6

Gross Domestic ProductGhana Integrated Financial Management Information SystemGhana Joint Assistance StrategyGross National IncomeGovernment of GhanaGrowth and Poverty Reduction StrategyGhana Revenue AuthorityGhana Shared Growth and Development AgendaGerman Technical CooperationHuman Development IndexHighly Indebted Poor CountriesInternal Audit AgencyInternal Audit UnitImplementation Completion ReportInternational Development AssistanceIndependent Evaluation Group (World Bank)Integrated Financial Management SystemInternational Monetary FundInternational Organisation of Supreme Audit InstitutionsIntegrated Personnel and Payroll Database systemLocal Government AuthorityMinistries, Departments and AgenciesMulti-Donor Budget SupportMulti-Donor Budget Support FrameworkMillennium Development GoalMetropolitan, Municipal, and District AssembliesMinistry for Financial and Economic PlanningMinistry of Local Government and Rural DevelopmentMembers of ParliamentMedium Term Expenditure FrameworkNational Audit OfficeNational Democratic CongressNational Development Planning Commission

ACroNymS AND ABBrEvIAtIoNS

NPMNPPODAOECDOHCSPACPAFPBAsPDPEFAPERPETSPFMPIUPPBPPPPSCRAGBSAPSBSSECSECOSMTAPSSAST/MTAPTATINTSAUNDPUNICEFUSDWB

New Public ManagementNew Patriotic PartyOfficial Development AssistanceOrganisation for Economic Cooperation & DevelopmentOffice of the Head of Civil ServicePublic Accounts CommitteeProgress Assessment FrameworkProgramme Based ApproachesParis DeclarationPublic Expenditure & Financial AccountabilityPublic Expenditure ReviewPublic Expenditure Tracking SurveyPublic Finance ManagementProject Implementation UnitPublic Procurement BoardPurchasing Power ParityPublic Service CommissionRevenue Agency Government BoardStrategic Action PlanSector Budget SupportState Enterprises CommissionSwiss – State Secretariat for Economic AffairsShort and Medium Term Action Plan for PFMSub-Saharan AfricaShort & Medium Term Action Plan (for PFM Reform)Technical AssistanceTaxpayer Identification NumberTreasury Single AccountUnited Nations Development ProgrammeUnited Nations Children’s FundUnited States DollarWorld Bank7

PUFMARP Public Financial Management Reform Programme

Table of ContentsExecutive Summary ...................................................................................101Summary of objectives and Approach .............................................131.1 Objectives of the evaluation ..............................................................131.2 Evaluation approach .........................................................................131.3 Evaluation questions.........................................................................171.4 Fieldwork process ............................................................................181.5 Report Structure ...............................................................................19Inputs and Context: the design of PFm reform............................... 202.1 The Reform context...........................................................................202.2 PFM reform baseline........................................................................252.3 Direct Reform Inputs ........................................................................272.4 Structures to design and manage PFM reform inputs .................312.5 Complementary Donor inputs to PFM reform ...............................332.6 Civil Society pressure for PFM reform ...........................................352.7 Relevance of PFM Reform Inputs ....................................................36outputs: the Delivery of PFm reform .............................................. 433.1 Key reform outputs ..........................................................................433.2 Efficiency and coordination of reform outputs ..............................503.3 External drivers and blockers of change .......................................52outcomes and overall Assessment ................................................ 564.1 Changes in PEFA scores ..................................................................564.2 Relevance of PFM improvements for servicedelivery, especially for women ........................................................ 614.3 The effectiveness of PFM reforms: from inputsto intermediate outcomes ...............................................................63Conclusions and Wider Lessons ......................................................675.1 Summary of key conclusions ...........................................................675.2 Wider lessons....................................................................................685.3 Recommendations for the Design and Managementof PFM reform processes ................................................................71

2

3

4

5

Annex A: Summary matrices of responses to Evaluation Questions forCountry and Component Case Histories.................................. 77Annex B: List of Persons Consulted........................................................117Annex C: List of references ....................................................................120Annex D: Summary of PFm reform inputs, outputsand intermediate outcomes.....................................................124Annex E: terms of reference ..................................................................1308

Joint Evaluations ......................................................................................142

tABLE oF CoNtENtS

table of Figures & tablesFigure 1.The Evaluation Framework and the place of the EvaluationQuestions within the Intervention Logic ........................................16table 1:Overall Budgetary Trends, 2001-2010 .............................................22table 2:DP allocations to PFM reform activities ..........................................28table 3:Overview of Development Partner fundingfor PFM reform ..................................................................................28table 4:Total MDBS Commitments and Disbursements2003-2010 ...........................................................................................29table 5:Poverty-Reducing Expenditures...................................................... 61Box 1:Evaluation questions ............................................................................17Box 2:Summary of Key PFM Events, Late 1990s-present...........................24Box 3:Summary of PUFMARP 1997-2003.....................................................26Box 4:Summary of GoG’s PFM Short and MediumTerm Action Plan 2006-2009 ...............................................................27Box 5:Comparison of 2006-09 Short & MediumTerm Action Plan with identified weaknesses ...................................37Box 6:Alignment of 2006-2009 Short & MediumTerm Action Plan with PEFA Results..................................................40Box 7:Overview of PFM Reform Outputs and DP Contributions .................46Box 8:Summary of changes in intermediate outcomesbased on PEFA assessments ..............................................................58Box 9:Summary of PFM reform inputs, outputs, and intermediateoutcomes ...............................................................................................73

9

Executive Summaryoverview of findingsThis Country Report has been prepared by Fiscus Limited, UK, in collabora-tion with Mokoro Ltd, Oxford, as one of three country reports in the JointEvaluation of Public Financial Management Reform, managed by the Afri-can Development Bank, Denmark and Sweden. The evaluation looked at twomain questions: (i) where and why do Public Finance Management (PFM)reforms deliver results and (ii) where and how does donor support to PFMreform efforts contribute most effectively to results? Our overall conclusionsare presented in the Summary Matrix contained in Annex A, which summa-rises, for the overall Ghana PFM reform programme 2001 -2010 and for fourcomponent areas within the reform programme, our answers to the 12 Evalu-ation Questions, posed within the study.The study’s main conclusion is that, relative to the significant funds expendedon Public Finance Management (PFM) reform over the study period, successhas been largely disappointing. The most substantial progress was found in astronger legislative base. However, similarly to other countries, Governmentof Ghana (GoG) has experienced significant challenges in implementing thenew laws. Otherwise, the most effective reforms appear to have been the rev-enue management activities, as they have led to a sustained output in the formof changed processes and a significant increase in revenues as a share of GrossDomestic Product (GDP) during the period studied.During the period studied, PFM outcomes deteriorated in a number of keyareas, including budget credibility, the build-up of expenditure arrears, andcompliance with expenditure controls. The deterioration in outcomes islargely a consequence of the failure to achieve a number of desired PFMreform outputs, including a fully-functioning Medium Term ExpenditureFramework (MTEF), a workable Financial Management Information System,and greater efficiency in resource flows to Ministries, Departments and Agen-cies (MDAs) and MMDAs. The limited improvements in intermediate out-comes were largely independent of PFM reform actions.On the other hand, Ghana has experienced significant improvements inregard to external oversight. The most notable achievements have been theclearance of the backlog of audits, the introduction of open Public AccountsCommittee (PAC) hearings on audit reports, and the timely submission of cen-tral government audit reports to Parliament.The degree of political commitment and leadership was found to be the mainbinding constraint to the relative success of PFM reform. Commitment tend-10

ExECutIvE SummAry

ed to be relatively strong at the beginning of reforms, which enabled legisla-tion to be enacted and reform programmes to be initiated, but commitmenthas tended to wane over time as other political priorities have taken prece-dence, thus hampering the completion of reforms under way and the imple-mentation of the new legislation. Political incentives for reform were found tobe strongest at the beginning of a new government. However, progress was attimes hampered by disruptions to the continuity of senior management per-sonnel following electoral change. The political cycle also led to a recurringpattern of rapid fiscal expansion, followed by fiscal consolidation and theimposition of stronger expenditure controls. As a consequence, for two yearseither side of each election both administrative effort and political attentionhave been repeatedly diverted away from the implementation of reforms.In terms of the role of DPs in the success, or otherwise, of reforms, it did notappear that Development Partner (DP) support was a key positive factor inachieving PFM reform progress. While the total amount of resourcesappeared to be sufficient, and disbursement delays were not a critical hin-drance to reform, the effectiveness of DP contributions was undermined bypolicy space constraints, particularly in terms of the appropriate design of spe-cific reforms. In particular, there has been a tendency to focus on technologi-cal solutions rather than changes to the underlying processes. There has alsobeen a failure to adapt reform designs in the light of implementation results.External support has therefore appeared to have greater traction at the earlystages of reforms, in facilitating design and the initial implementation, thansubsequently in sustaining or deepening reform initiatives, which would clear-ly call for adaptation of initial designs and the application of the lessons ofimplementation experience. Exceptions to this have occurred where therehave been sustained DP contributions over a longer period of time, with sup-port demand-driven, targeted to specific needs, and adaptable in terms ofdesign and re-design. Reforms to revenue administration are the most salientexample.

implicationsAs Ghana, a newly middle-income country enters a phase characterised bylikely changes in its partnership with DPs, including in terms of the MDBS, itsgovernment and senior management are likely to exercise greater active con-trol of its reform programme, including the provision of resources. The studyhighlighted the following areas of potential risk management for both GoGand DPs in its future PFM reforms.• GoG and DPs should recognise the importance of continuity in reform initiatives and consider longer-term and flexible approaches to supportthat can take advantage of windows of opportunity (e.g. political space)while allowing for scaling back when conditions for making progressare less favourable.

11

ExECutIvE SummAry

• Explicit analyses should be undertaken of stakeholder readiness for reform, particularly for Information Technology (IT) projects andreforms involving functions to be devolved. A technological (IT) solu-tion may not always be appropriate, particularly if the underlyingmanual processes (e.g. internal controls) are inadequate.• Identify demand and management factors that are likely to facilitate successful reform, including the role of Civil Society Organisations(CSOs) and peer-to-peer learning opportunities.• Allow adequate time to plan and sequence reforms, including plan-ning, designing, testing (piloting), reviewing, and taking action basedon reviews of the testing, and completing reforms. Successful reformprogrammes should not be led by systems (and technology).• Consider the provision of training in leadership for senior political and administrative levels, particularly for those in newly-appointed posi-tions.• Improve incentives for active senior management linked to reform per-formance.• In light of the impact of the electoral cycle, build into the reform pro-gramme periods of review or a pause in the timetable for bringing onboard new stakeholders.

12

1. Summary of Objectivesand ApproachThis Country Report has been prepared by Fiscus Limited, UK, in collabora-tion with Mokoro Ltd, Oxford, as one of three country reports in the JointEvaluation of Public Financial Management Reform, managed by the Afri-can Development Bank, Denmark and Sweden. It incorporates the commentsreceived on the first draft by the Management Group and the peer reviewer aswell as those of the in-country stakeholders, who attended the presentation ofthe draft report in Accra during January 2012. This report, together with theevaluation of PFM Reforms in Malawi and Burkina Faso, has been incorpo-rated into an accompanying synthesis report and will be the subject of a widerprocess of dissemination within the Africa region and beyond.

1.1 ObJECTivES OF ThE EvAluATiOnThe evaluation aims to address two core questions presented in the Terms ofReference:a) Where and why do PFM reforms deliver results (i.e. improvements in thequality of budget systems)?;andb) Where and how does donor support to PFM reform efforts contribute mosteffectively to results?It is thus a dual evaluation, involving first an evaluation of the overall pro-grammes of PFM reform conducted over 2001 to 2010 in Ghana, and second-ly, an evaluation of the external support provided to these reforms by donors.

1.2 EvAluATiOn APPROAChThe evaluation framework has been defined in the Inception Report for the3-country study1. It utilises the Organisation for Economic Development(OECD-DAC) evaluation criteria and thus assesses the relevance, efficiency,effectiveness and sustainability of both the overall programme of PFM reformand the external support provided. The overall goal is to draw lessons on (i)the types of PFM reform pursued and their interaction with the Ghana con-text and (ii) the mechanisms of external support that most contributed to theirsuccess. Success is associated with improvements in the quality of budget sys-tems, as measured primarily by changes in the Public Expenditure and Finan-cial Accountability (PEFA) assessment framework indicators and the narrative1Lawson, A. (2011). Joint Evaluation of PFM Reforms in Burkina Faso, Ghana andMalawi: Inception Report. Oxford, Fiscus Limited, Mokoro Limited.13

1. SummAry oF oBJECtIvES AND APProACH

PEFA reports. The evaluation framework characterises these changes as inter-mediate outcomes in a ‘PFM Theory of Change Framework’, which underliesthe evaluation.The Framework (presented in Figure 1 below) requires the detailing ofPFM Reform inputs, outputs and intermediate outcomes and the examinationof the relationship between them. In addition, it allows for the analysis of howexternal constraints – conceptualised as political, financial and policy spaceconstraints – impact on the translation of reform inputs into outputs.Inputsare defined as the resources and other inputs provided in order topromote PFM reform. These are divided between direct funding by govern-ments to internal PFM reform efforts, external funding by Donors of PFMreform efforts and complementary inputs by Donors, aimed at facilitating bet-ter PFM through the use of country systems and the provision of budget sup-port, or improving the design and implementation of PFM reforms throughpolicy dialogue and external monitoring (often linked to budget support or toIMF supported arrangements).Outputsare defined as the immediate changes in the architecture andsubstance of the PFM system generated by the combined set of inputs. Theseare categorised into four groups: i) Changes in human resource endowments(people and skills); ii) Changes in laws, procedures and rules; iii) Changes insystems and business processes; and iv) Changes in Organisational factors (thequality of management, the work culture, the degree of organisational devel-opment).Intermediate Outcomesare the changes generated in the quality ofthe PFM system, as measured by changes in the quality of:i) Strategic budgeting;ii) Budget Preparation (including budget deliberation by the Legislature);iii) Resource management (covering both inflows and outflows);iv) Internal controls, audit and monitoring;v) Accounting and reporting; andvi) External Accountability.The framework utilises the PEFA assessment framework to measure changesin each of these clusters of functions, based on a categorisation of the sub-dimensions of the PEFA indicators between each of them. The categorisationis based on Andrews (2010) and is also applied by De Renzio et al (2010). Thecharacteristics of (a) transparency and comprehensiveness, (b) the quality oflinks to policies and plans, and (c) the efficiency and effectiveness of control,oversight accountability are subsumed within this categorisation.External constraints are seen to impinge on the PFM reform ‘productionfunction’, in other words with the capacity of PFM reform inputs to generatethe planned outputs. Key constraints are “political constraints” related to thedegree of ownership and support for given PFM reforms, “financial con-straints” related to the ability to finance PFM reforms in the face of compet-ing priorities, and “policy space constraints”, related to the nature of policyideas which might potentially be considered in designing PFM reforms.14

1. SummAry oF oBJECtIvES AND APProACH

A key task for the evaluation of PFM reforms in Ghana was therefore toexamine whether there have been external constraints which have preventedor slowed down the translation of reform inputs into reform outputs and whichof the three types of constraint have been most significant in this respect. Thepurpose has been to identify what have been the binding constraints on differ-ent types of reforms and to reach a judgement on whether reform challengeswere due to reform models which lay beyond the prevailing “production pos-sibility frontier”, examining also the role of donor support in this process.

15

16

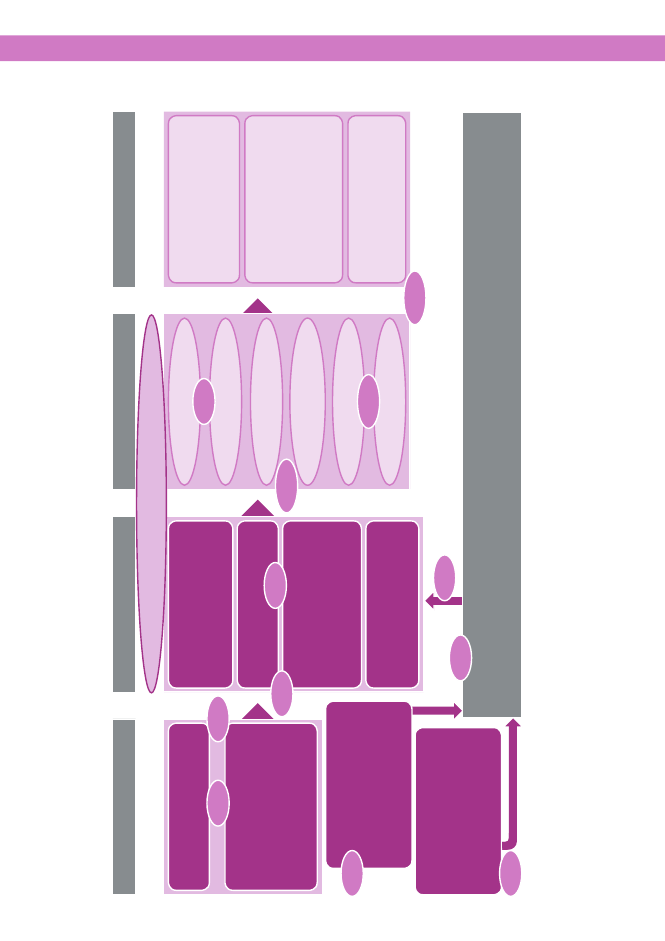

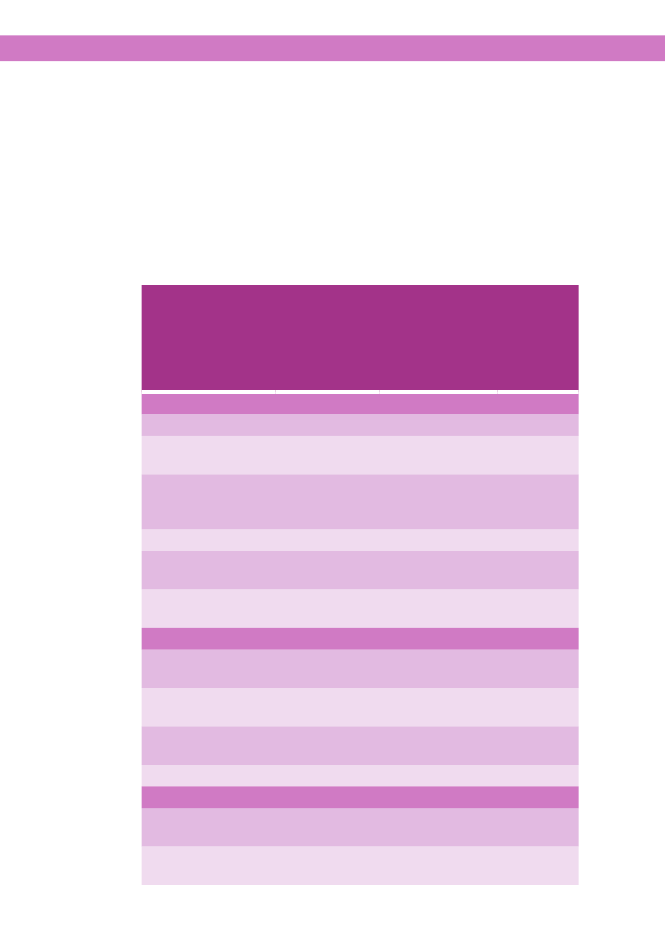

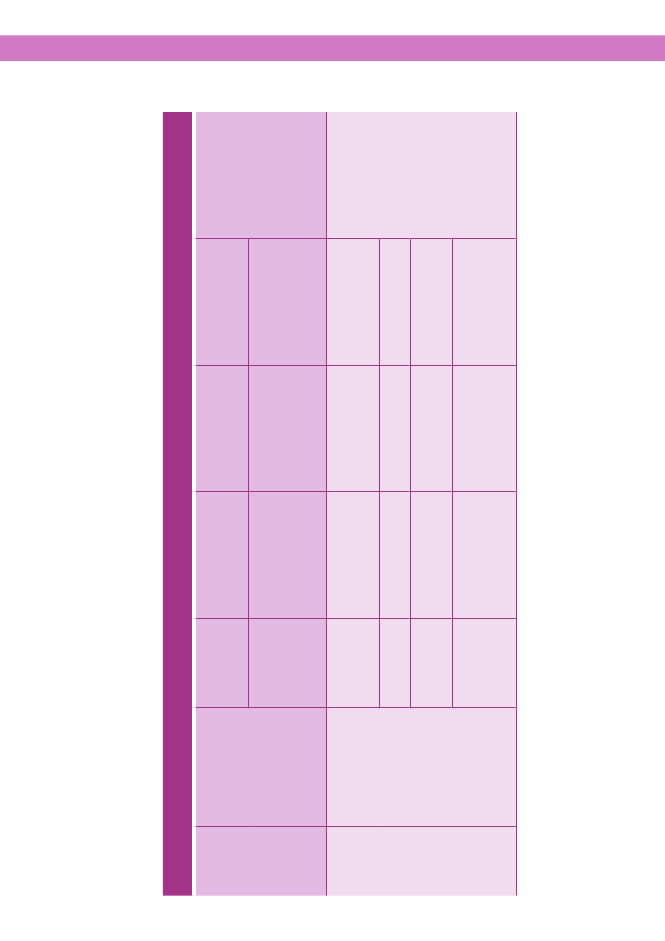

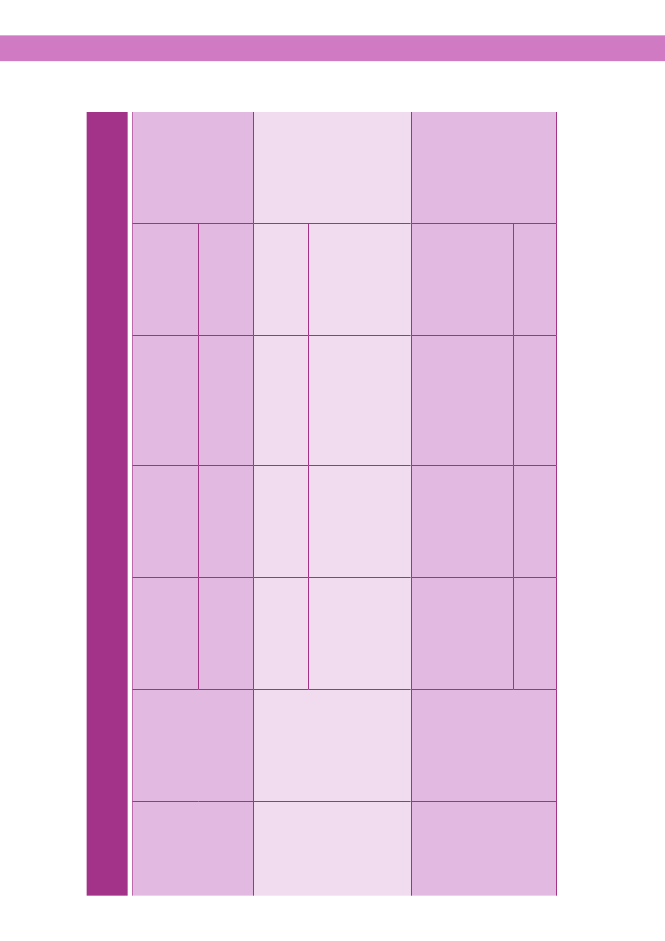

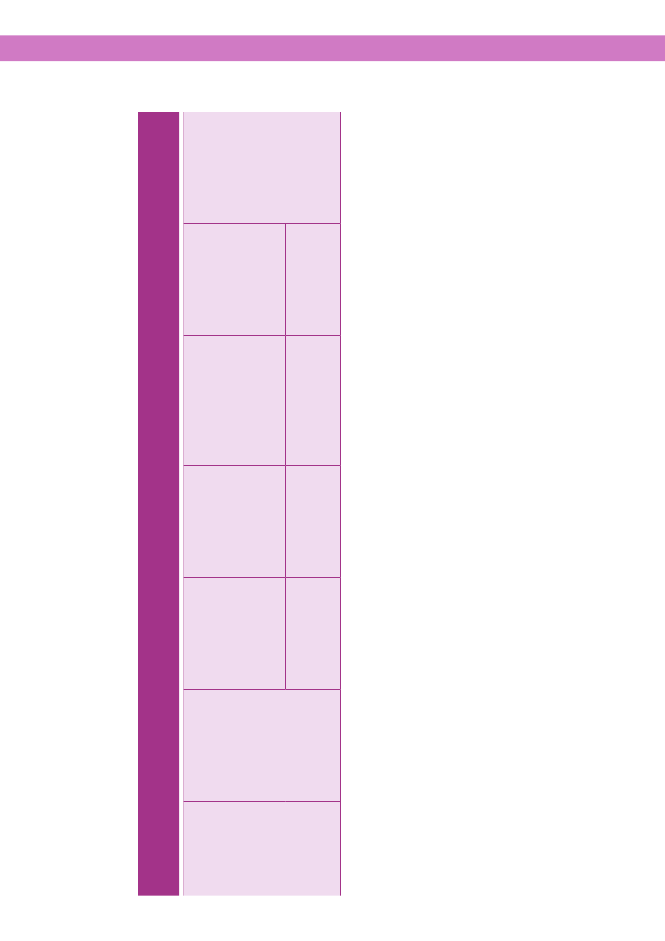

figure 1. the Evaluation framework and the place of the Evaluation Questions within the intervention logicOUTPUTSINTERMEDIATE OUTCOMESFINAL OUTCOMES

INPUTS

PFm reform Intervention LogicPeople &Skills:Strategic BudgetingEQ 9

• Government-funded inputs

Government PFm reformInputsBudget PreparationresourcemanagementEQ 11

Fiscal Discipline:

EQ 1

EQ 2

• umbers of PFM professionals N(auditors, etc.)• evpt of specific skills, D(incl. reform management)

• ulfillment of planned fiscal Ftargets• aintenance of Sustainable MDeficit

DP funded support to PFmreform

1. SummAry oF oBJECtIvES AND APProACH

(delivered in aharmonised&aligned manner):• Institutional strengthening• Advisory TA• Diagnostca Work

EQ 7

• hanges in Laws. Rules &CProceduresEQ 6

Laws, rules &procedures

Strategic Allocationofresources:• onsistency of executed C&approved aggregate /departmental budgets• onsistency of revenue Ctargets &coIIecfions

Systems &BusinessProcesses:Internal control.Audit &monitoringAccounting & reportingEQ 10

EQ 3

Complementary DevelopmentPartner inputs:External Accountability

• omputer systemsC• pecific approaches to budget-Sing, accounting addit, treasurymanagement, etc.

• Use of Country Systems• Provision of Budget SupportP• olicy Dialogue &monitoring ofPFM reform

• mproved managementI• rganisational developmentO• mproved work culture.IEQ 8

organisational factors:

• volution of Unit costs ofpublic EservicesEQ 12

operational Efficiencyin Public Spending

Public &Civil Society pressurefor improved PFm:

EQ 5

• Voting preferences• Political lobbying• Research &advocacy• Regional/ international norms

EQ 4

• olitical Constraints:Degree of leadership /ownership of PFM reform at Administratve and Politcal levels.P• Financial Constraints:Availability &timeliness of funding for PFM reform, presence.' absence of economic crisis.• olicy Constraints:Openness of the policy reform agenda, receptivity to new ideas. policy space for long-term reforms.P

External Constraints on the PFm reform “production possibility frontier”

1. SummAry oF oBJECtIvES AND APProACH

1.3 EvAluATiOn quESTiOnSbox 1 : Evaluation questionsA Inputs & context: the design of PFm reformWhat has been the nature and the scale of PFM reform inputs pro-vided by Government and by Donors?What types of structures have been used for the design and man-agement of these reform inputs? Have these structures served toprovide a coordinated and harmonised delivery framework?What types of complementary actions have Donors taken to sup-port PFM reforms and what has been their significance? Have theyhad any influence on the external constraints to reform?To what extent has there been domestic public pressure or re-gional institutional pressure in support of PFM reform and whathas been the influence on the external constraints to reform?How relevant was the PFM reform programme to the needs andthe institutional context? Was donor support consistent with na-tional priorities? To what extent were adaptations made in re-sponse to the context and the changing national priorities?

EQ. 1:EQ. 2:EQ. 3:EQ. 4:EQ. 5:

B outputs: the delivery of PFm reformEQ. 6:What have been the outputs of the PFM reform process and towhat extent has direct donor support contributed to these out-puts?EQ. 7:How efficiently were these outputs generated? Was the pacingand sequencing of reforms appropriate and cost-effective? Wasthe cost per output acceptable?EQ. 8:What have been the binding external constraints on the deliveryof PFM reform outputs: political, financing or policy factors? Howhas this varied across different PFM reform components?C outcomes: overall assessment of PFm reform & of donorsupport to PFm reformEQ. 9:What have been the intermediate outcomes of PFM reforms,in terms of changes in the quality of PFM systems?EQ. 10:To what extent have the outcomes generated been relevant toimprovements in the quality of service delivery, particularly forwomen and vulnerable groups?EQ. 11:Have reform efforts been effective? If not, why not? If yes, towhat extent PFM reform outputs been a causal factor in thechanges identified in intermediate outcomes?EQ. 12:To what extent do the gains identified at the Intermediate Out-come levels appear sustainable? Is the process of PFM reformsustainable?17

1. SummAry oF oBJECtIvES AND APProACH

The Ghana study was based on twelve evaluation questions common to thethree country cases (see Box 1 above and the fuller presentation of responsesto evaluation questions and corresponding judgement criteria in Annex A).The Evaluation Questions are structured so as to provide a standardisedframework for assembling evidence, so that the results of the country studiescan be easily synthesised to provide answers to the overall high-level ques-tions, which the evaluation addresses. The questions marry core OECD DACevaluation questions with the concerns specific to the study.

1.4 FiEldwORk PROCESSThe research for the country study was undertaken in two phases. The firstphase, an initial desk phase, involved reviewing background documents andgathering published data on the Ghana context and the specific PFM reformscarried out from the late 1990s to the present. The output from this phasewas a desk report, whose findings have been included in the current report.2The study’s second phase, the field visit, involved extensive interviews andfocus group meetings with stakeholders in Accra and in one district adminis-tration. An Aide-Memoire setting out the findings was circulated followingthe field visit.3While each of the three country case studies examines PFM reforms dur-ing the 10-year period from 2001 through 2010, the Ghana case study includ-ed the late 1990s in its review. This extended time period was considered rel-evant in order to include the whole of the PUFMARP reforms, which beganin 1998, and which provided the foundation for many of the reforms, whichtook place during the study period. In addition, the study makes references inpassing to recent reforms that were initiated during 2010 (e.g. in budget for-mulation [programme-based budgets] and the GIFMIS) in order to commenton the extent to which they respond to previous reform experience, since it istoo early to evaluate the performance of these reforms.In Ghana, as in the other two country studies, an assessment was made ofthe overall progress of the PFM reform programme and of a number of spe-cific reforms, as case histories. The case histories focussed on four specificPFM reforms, specifically, (i) Financial Management Information Systems(FMIS), including Budget Planning and Expenditure Management System(BPEMS) and the Integrated Payroll and Personnel Database (IPPD2); (ii) theMedium Term Expenditure Framework (MTEF); (iii) revenue management;and (iv) internal audit. Together, these components cover the majority (interms of monetary value spent) of the reforms that were carried out duringthe period studied. At the same time, they provide for comparative results tobe studied, with two of these reforms (FMIS and MTEF) enjoying significantDP support, whilst a third (internal audit) had very limited external support.2318

Gordon, A, and M Betley (2011), Evaluation of Public Financial Management Reformin Ghana 2001-2010: Desk Report, Fiscus/Mokoro: Oxford.Betley, M, A Bird, and A. B. Ghartey (2011), Joint Evaluation of Public FinancialManagement Reform in Burkina Faso, Ghana & Malawi: Ghana Country Case Study– Field Visit: Aide-Mémoire, Fiscus/Mokoro: Oxford.

1. SummAry oF oBJECtIvES AND APProACH

The fourth reform, revenue management, is common to the three case studycountries and provides a contrast in terms of being relatively technical innature and relatively self-contained (i.e. predominantly managed by a singleinstitution).Reviews of documentation and data, stakeholder interviews and focusgroups provided the main evidence for the analyses against the evaluationquestions. The stakeholders consulted are shown in Annex B, and the docu-ments examined during the study are listed in Annex C. The former includedrepresentatives from central agencies (specifically, Ministry of Finance andEconomic Planning [MoFEP], Controller and Accountant-General’s Depart-ment [CAGD], and Ghana Revenue Authority [GRA]), as well as sector min-istries (Ministry of Health and Ministry of Tourism), and one local govern-ment unit (a district assembly, known collectively in Ghana as Metropolitan,Municipal, and District Assemblies [MMDAs]).While every attempt has been made to ensure that the responses to theevaluation questions are based on the best evidence available, the lack of rel-evant, consistent and comprehensive data represents a significant shortcomingto the analysis. This is particularly true for actual GoG expenditures forPFM-related activities, as well as for disaggregated data on DP PFM commit-ments and disbursements. Furthermore, the change in government in 2009,following a period of 8 years, meant that many of those who were in leader-ship or management positions during the implementation of the reforms beingstudied were no longer in post. This was also true for DP officials involved inPFM reforms, many of whom moved on to other positions outside of Ghana.Nonetheless, the study team managed to consult with a number of formerGoG officials who had been involved in the implementation of the reformsunder the previous government.

1.5 REPORT STRuCTuREThe report follows the standardised structure for the three country studies. Inaddition to this chapter on the Study objectives and approach, it comprises (i)a chapter describing the context and evaluating the inputs to PFM reforms inGhana; (ii) a chapter on the planned and actual outputs; (iii) a chapter discuss-ing the intermediate outcomes; and iv) a chapter providing conclusions andwider lessons.A series of annexes contain summary matrices of the responses to the 12Evaluation Questions for Ghana as a whole and for the four PFM reform“case histories” (Annex A), a list of those consulted during the study (AnnexB), bibliographic references (Annex C), and an overall summary of PFMreform inputs, outputs and intermediate outcomes over the 2001 – 2010 evalu-ation period (Annex D).

19

2. inputs and Context: the designof PFM reform2.1 ThE REFORM COnTExTGhana has a population of 23 million people, of whom around 51% live inrural areas. Per capita gross national income (GNI) was US$1,530 in 2009.4The country is divided into 10 administrative regions (Ashanti, Brong Ahafo,Central, Eastern, Greater Accra, Northern, Upper West, Upper East, Voltaand Western). Ghana has seen progress in reducing poverty in recent yearsalthough there are considerable differences in socio-indicators between thenorth and the south, with relatively greater poverty in the northern regions.The absolute number of poor declined sharply in the south between 1992 and2006 (2.5 million fewer poor), while it increased in the north (0.9 million morepoor).5In 2010 the country’s ranking in the United Nations Development Pro-gramme’s (UNDP) human development index (HDI) was 130 out of 182 coun-tries. Ghana became the first African country to reach the first MillenniumDevelopment Goal (MDG) on halving its poverty and hunger rates before2015.

overview of economic and fiscal performanceWhen the New Patriotic Party (NPP) won the elections in 2000, it inheritedan economy that had suffered a macroeconomic shock in 1999. Inflation wasrunning at 41%. The budget deficit and external and domestic debts were atunsustainable levels and this inevitably had a negative impact on expenditurein social sectors and poverty reduction activities as the Government struggledto service its debt and stabilise public finances.However, the anti-inflationary monetary policy and the fiscal consolida-tion that was implemented by GoG facilitated a subsequent period of positivegrowth that was also helped by strong commodity prices. In 2007, the annualreal growth rate reached 6.3%; only the second consecutive year that thegrowth rate had been in excess of 6% since the 1980s. Between 2000 and2007, the average real gross domestic product (GDP) growth rate was 5.2%, afigure higher than the sub-Saharan average of 4.8% in the same period.6In2008 growth rates reached their highest for two decades rising to 7.3%.7Morerecently economic growth has slowed in Ghana as it has globally. In Ghanaeconomic growth in 2009 dropped to 4.7% – the lowest since 2002. Economic456720

PPP, current international US$ – World Bank (2011)World Bank, 2011Allsop et al, 2009.Using rebased GDP, this figure would be 8.4%.

2. INPutS AND CoNtExt: tHE DESIGN oF PFm rEForm

growth began to recover in 2010 and is projected to accelerate to almost 14%in 2011 on the back of global recovery, exceptional public investment in therising oil sector, and revenues from anticipated new oil discoveries.8Ghana’s macroeconomic situation is considered to be “delicate” by theWorld Bank.9This is in part due to its reliance on primary products but alsoto instability in the region, which has led to Ghana’s hosting refugees fromother countries. Agriculture accounts for about a third of GDP, while theindustrial sector contributes 28%. Ghana continues to be overly dependent ona few primary commodities. A narrow range of exports constitutes a signifi-cant part of Ghana’s GDP, specifically, gold (42%) and cocoa (30%), whichtogether accounted for over 70% of exports in 2009. Despite government poli-cies over a number of years, which aimed to encourage industrialisation, man-ufacturing accounts for just 9% of exports.10The discovery of substantialreserves of oil and gas in Ghana will provide a new source of revenue but onewhich is vulnerable to shocks in global oil prices.The global financial crisis has had an impact on the Ghanaian economy,with lower export values, a fall in commodity prices, less and more expensiveforeign capital, lower remittances and fewer tourists. This in turn has had animpact on income growth, job losses and budgetary pressures, leading toreduce government spending on social protection systems. However, with thestart of oil production in late 2010, GDP per capita is projected to exceed$1,400 in 2011.11For 2010, the Ghana Statistical Services projected a 6.6%growth in real GDP.12The impact of oil-related investment expenditures (e.g.construction, information and communication technologies, hotels, financialintermediation) and continuously favourable climatic and terms of trade con-ditions were seen to trigger a slight increase in economic growth in the firsthalf of 2010. This was reinforced by the moderate rebound in private sectorcredit growth which has occurred since June 2009.The Government’s stabilisation policies led to improved fiscal perfor-mance post-2001 (Table 1). Revenue generation has been stronger, assisted inpart by improved tax administration, greater collection of internally generat-ed funds (IGFs), and higher levels of remitted profits, while expenditures havebeen contained, partly through reductions in debt servicing requirements.Domestic revenues increased to nearly 24% of GDP by 2005. This revenuemobilisation effort, supported by HIPC debt relief, allowed Government bothto reduce its reliance on domestic financing of the deficit and to increasedomestically financed primary expenditure to just fewer than 30% of GDP in2005, up from 23% in 2002. Fiscal performance has also benefited from lowerdomestic interest rates.

891011

African Economic Outlook, 2011World Bank, 2010.African Economic Outlook, 2011This figure differs from the GNI figure above as the latter also includes its incomereceived from other countries (notably interest and dividends), less similar paymentsmade to other countries.12 World Bank, 2010

21

2. INPutS AND CoNtExt: tHE DESIGN oF PFm rEForm

table 1: overall budgetary trends, 2001-2010% of GDPActual Actual Actual Actual Actual Actual Actual Actual Actual2Actual2

2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010

Total25.0 21.1 25.5 30.2 28.3 27.3 28.8 27.5 16.4 17.4Revenues1Total32.7 26.1 29.0 33.3 30.7 34.3 37.3 41.0 20.4 23.5Expendi-turesAggregate(7.7) (5.0) (3.6) (3.1) (2.5) (7.0) (8.5) (13.5) (4.0) (6.1)Deficit11Including grants2Figures shown are as % of non-oil GDP (re-based)Source: IMF, WB

Political contextThe current political structure in Ghana is framed by the 1992 Constitution.This established the fourth republic, multi party elections, and a return toconstitutional rule with an elected administration. The period covered by thisstudy has seen a consolidation of democratic rule in Ghana. The NationalDemocratic Congress (NDC) party’s rule came to an end in 2000, and theNPP government took over for 8 years, after which NDC regained power.There has been evidence over this period of a deepening of democracy,including a strengthened role for Parliament, and a more active civil societyand media. In 2002, the then-President inaugurated a reconciliation commis-sion to look into human rights violations that had occurred during the mili-tary rule.The NPP Government focused on poverty reduction and, in 2003, the firstGhana Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper (GPRS I) was published, covering2003-2005. This was to be the framework for co-ordinating social and eco-nomic development in Ghana. It was to inform government programmes inall sectors, and set out a number of priorities for government. The strategyhad a strong emphasis on poverty reduction and improving living standards.In December 2004, national elections with a strong turn-out (85%) wereheld, and the incumbent President was re-elected. In 2006 the new Govern-ment published the second GPRS (2006-2009), entitled the “Growth and Pov-erty Reduction Strategy”, marking its emphasis on economic growth and itsaim of facilitating Ghana’s promotion to the status of a middle-income coun-try by 2015, a goal which was achieved in July 2011, following the rebasing ofGDP.13

22

13 As indicated by the World Bank.

2. INPutS AND CoNtExt: tHE DESIGN oF PFm rEForm

Following close elections (including a run-off election) in December 2008, agovernment led by the NDC was elected and took office in January 2009.14The new government prepared its national development strategy, known asthe Ghana Shared Growth and Development Agenda (GSGDA), covering2010-2013. The NDC Government also prepared a longer-term strategy doc-ument, “An Agenda for Shared Growth and Accelerated Development for aBetter Ghana (2010 – 2016) which, as per Ghanaian Constitution requires “...within two years after assuming office, the President shall present to Parlia-ment a coordinated programme of economic and social development policies,including agricultural and industrial programmes at all levels and in allregions of Ghana”. The implementation of the Coordinated Programme isplanned to be undertaken through Medium-Term National Development Pol-icy Frameworks. The Ghana Shared Growth and Development Agenda(GSGDA), 2010 to 2013, covers the first phase of this Coordinated Pro-gramme. It is expected to form the basis for the preparation of developmentplans and annual budgets at the sector and district levels throughout the coun-try. The Coordinated Programme is expected to be read alongside the GhanaShared Growth and Development Agenda (GSGDA), 2010 to 2013 and othersector specific policy documents mentioned elsewhere in the CoordinatedProgramme document.Box 2 summarises key PFM events from the late 1990s, with the full chro-nology set out in Annex A of the Ghana Desk Report.

14 It has been noted that the 2008 election provided a test of the country’s democraticstrength; in spite of a very close margin of votes between the two dominant parties,state institutions, in particular the judiciary and the electoral commission, withstoodsignificant tension (Allsop et al, 2009).

23

2. INPutS AND CoNtExt: tHE DESIGN oF PFm rEForm

box 2: Summary of Key PfM Events, late 1990s-presentF rom late 1990s-early 2000s••Introduction of new classification system, which simplified thecategorisation of economic expendituresRemoving dual budgeting

2003-2005•••••Greater macro-fiscal stability achievedFirst GPRS, 2003-2005Greater links between planning and budgeting process and GPRS inthe form of MTEF workshops with MoFEP and MDAs to determine thelinkage of policy proposals in budget submissions to the GPRSAPR process (first APR in 2003)Achieving of HIPC completion point, leading to greater availability ofresources, to be targeted to investment; included in medium-termmacro-fiscal framework

2005-2006•••••2006 budget was first one passed before beginning of the comingbudget yearGPRSII 2006-2009STAP, emphasising the strengthening of MTEFGreater PAC involvement in budget processIncorporation of MDRI resources in medium term macro-fiscalframework

2007-2008••••••Greater analysis of links between budgets and GPRSChanges in classification; streamlining of MTEF activitiesFirst introduction of policy hearingsGreater focus on technical hearings: attempts to place greateremphasis on justification of budget submissions for allocation ofadditional resourcesPreparation of initial MTEF submissions by pilot MMDAsMTEF training

2009-2010•••••Ghana Revenue Authority Act passedProcess of initiating Ghana Revenue Authority beginsWork on GIFMIS (to replace BPEMS) beginsPlans for the introduction of programme budgeting under wayPreparation work on Petroleum Revenue Management Bill begins

24

2. INPutS AND CoNtExt: tHE DESIGN oF PFm rEForm

2.2 PFM REFORM bASElinEDuring the last 15 years, there have been two main PFM reform agendas, (i)the Public Financial Management Reform Programme (PUFMARP), from1997-2003; and (ii) GoG’s Short and Medium Term Action Plan (ST/MTAP),covering 2006-2009. The suite of reforms associated with the Ghana Integrat-ed Financial Management Information System (GIFMIS), begun in 2010,may be considered to represent a significant part of the current PFM reformprogramme; however, the study focuses on the reforms pre-2009/10, as thesehave been under way for a significant enough amount of time to review theireffect.15These PFM reform programmes have been set in the overall contextof GoG’s national medium-term development plans, the GPRS I, GPRS II,and the GSGDA. Overall, in comparison with other countries in the region,Ghana was an early adopter in sub-Saharan Africa of key PFM reforms, suchas the Medium Term Expenditure Framework (MTEF).The main central GoG agencies relating to PFM are the Ministry ofFinance and Economic Planning (MoFEP), the Controller and AccountantGeneral’s Department (CAGD)16, the Public Services Commission (PSC), theOffice of the Head of the Civil Service (OHCS), the State Enterprises Com-mission (SEC), and the National Development Planning Commission(NDPC). The Bank of Ghana is the Government’s banker; GoG also operatesaccounts at commercial banks. Also part of the central management frame-work, and critical for PFM, are the Public Procurement Authority (PPA)17, theIAA, and the Ghana Revenue Authority (GRA); these agencies operate underseparate Acts and have a statutory mandate. External scrutiny agenciesinclude the Ghana Audit Service (GAS), headed by the Auditor-General, andtwo Parliamentary committees, the Finance Committee (FC), and the PublicAccounts Committee (PAC).

15 This is for practical reasons but is not to give the impression that PFM reforms havestalled under the new government or that the evaluation has not been balanced in itsreview.16 The Controller and Accountant General reports to the Minister of Finance.17 Formerly, the Public Procurement Board

25

2. INPutS AND CoNtExt: tHE DESIGN oF PFm rEForm

box 3: Summary of PufMaRP 1997-2003the Public Financial management reform Programme (PuFmArP)was a 6-year multi-component GoG programme to strengthen PFM. TheProgramme, which was under way between 1997 and 2003 was supportedmainly by funding from IDA, with co-financing provided by DFID, CIDA, andthe EU. The Programme’s components included:1. Budget preparation – introduction of an MTEF;2. BPEMS, an integrated financial management information system;3. Cash management – introduction of a modern cash managementsystem;4. Aid and debt management – improving data on aid and debt managementand the links with CAGD and BoG;5. evenue management – introduction of VAT, unique Taxpayer RIdentification Number, IT system for tax assessment, collection andreporting, and strategy for managing customs data;6. Procurement – formulation of national procurement code anddevelopment of mechanisms for compliance with code;7. Auditing – development of national audit standards, specification of auditreports, and introduction of value-for-money audits;8. Legal framework – review of legislative framework and development ofrevised financial rules and regulations for Parliamentary approval;9. Human resources development – training for staff in programmecomponent areas.Components in italics indicate those where the scope was scaled down during projectimplementation, due in part to make way for the additional resource requirements ofBPEMS.

26

2. INPutS AND CoNtExt: tHE DESIGN oF PFm rEForm

box 4: Summary of gog’s PfM Short and Medium-term actionPlan 2006-2009At the beginning of 2006, MoFEP published its three-year strategic plan andits short and medium-term PFM Action Plan (ST/MTAP), covering the period2006-2009, in line with GPRSII. The Government updated the Action Planin August 2006, following the PEFA assessment. Theshort-term ActionPlansets out reforms currently being introduced, which focus on improvingthe efficiency of resource and information flows through the system. Thespecific measures in the short-term Action Plan include:• The on-going building of an improved Integrated Personnel and Payroll Database system (IPPD2);• The Government’s integrated financial management system: the Budget and Public Expenditure Management System (BPEMS);• The introduction of a decentralised payment system, beginning initially in pilot ministries, including the Ministry of Education;• Strengthening of internal audit and procurement processes, focusing mainly on establishing effective internal audit and procurementinstitutions and processes in MDAs and MMDAs and accompanying stafftraining.In addition to these short-term measures, the Government’smedium-termaction planconsists of a matrix of reforms centred on 9 focal areas. Withineach focal area, output targets are given, the main agencies responsibleas well as other agencies involved are named, activities to be undertakenare detailed, and the risks are identified. The reforms are comprehensiveand cover most areas of the PEFA framework. The action plan was revisedfollowing the 2006 PEFA assessment, and the short and medium-termmeasures were prioritised and sequenced and a rough estimate of costswas added.

2.3 diRECT REFORM inPuTSEQ 1:What has been the nature and scale of PFM reform inputs providedby Government and Donors?

country overviewTable 2 summarises DP allocations to PFM reform activities from 1998 to2010. DPs represented the bulk of funding for PFM reform activities. Themajority of funds have been spent on the FMIS reforms (BPEMS, IPPD2 andGIFMIS), followed by strategic budgeting (specifically, MTEF-related activi-ties). Significantly fewer amounts were spent on resource management (reve-nue, expenditure, aid, and debt), and audit. Additionally, limited diagnosticwork has been undertaken by both the World Bank and the IMF, as well as byother DPs in preparation for the provision of their programmatic support.27

2. INPutS AND CoNtExt: tHE DESIGN oF PFm rEForm

table 2: DP allocations to PfM reform activitiesPFm Support by main DPWorld BankEUBMZOthertotal12

Estimated specific PFm projectsupport, 1998-2010 (mn uS$)118.411.210.8210.751.1

Data represent best estimates, based on, in some cases, very limited available data.€10.5 million.Sources: WB, EC, BMZ, DFID, MoFEP

With the exception of FMIS (where the majority of funds were spent on hard-ware and software), the bulk of the funds on PFM reforms have been spent ontechnical assistance. GoG support has been spent primarily on training staffon existing reform initiatives under way or rolling out such reforms.18Themain DPs supporting PFM reforms (by value) during the study period includeDFID, the EC, BMZ/GTZ, the IMF, and the World Bank. Others includeDanida, CIDA, Japan, KFW, Switzerland, and UN.Table 3 summarises the funding from the main DPs on PFM activitiesduring the study period. PFM-specific DP support was in the form of multi-component programmes, managed by either a single DP (e.g. Good FinancialGovernance), or a pooled-funding arrangement (e.g. GIFMIS).19

table 3: overview of Development Partner funding for PfM reformPFm Focal AreaStrategic budgeting/budgetpreparationResource managementInternal controls, audit,monitoringAccounting, reporting (BPEMS)External accountabilitytotal1

Estimated specific PFm projectsupport, 1998-2010 (mn uS$)14.619.00.715.611.251.1

Data represent best estimates, based on, in some cases, very limited available data.

28

18 It is to be noted that the GoG expenditure estimates given in this section are specifi-cally related to reform activities (i.e. excluding day-to-day activities of relevant institu-tions) and do not include personnel-related expenditures.19 GIFMIS is a pooled fund with a joint steering committee and common funding ofagreed activities. Some harmonisation of M&E has taken place in order to ensure onereporting standard; this was funded by DFID.

2. INPutS AND CoNtExt: tHE DESIGN oF PFm rEForm

There was a marked reduction in DP funding for PFM activities between2004 and 2006. This coincided with the commencement of a programme ofmulti-donor budget support (MDBS), which provided significant funds to theConsolidated Fund (annual average of just over US$300 mn since 2003)(Table 4). These funds were available to support GoG’s budget, but were notaimed specifically at PFM reform activities, nor can it be assumed that theywere used as such. A recent study20of the benefits of MDBS examined wheth-er or not the shift to MDBS: (i) resulted in increased DP project funding forPFM reform (i.e. to support MDBS); and/or (ii) facilitated greater governmentspending on PFM reform through a substitution effect. The study found noevidence to support either proposition.

table 4: total MDbS commitments and Disbursements 2003-20102003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 20092

2010

Commitments (mn US$)1281.4 302.2 285.3 372.4 319.6 347.9 601.1 451.5Actual disbursements(mn US$)MDBS (actual) as %of dev. assistanceMDBS (actual) as %of gov’t expend.12

277.9 309.0 281.9 312.2 316.6 368.1 525.2 403.030.0% 26.7% 29.3% 33.0% 26.5% 25.7% 34.6%N/A 12.7% 10.2% 8.3% 7.7% 8.3% 9.3%––

Data refer to pledges, as officially recorded by MoFEP.Commitments and disbursements reflect funding provided in response to the impact onthe economy of the global financial crisis.Sources: MoFEP, GAS (audited accounts), BoG (exchange rates)

component case historiesThe FMIS case history includes two main FMIS-related reforms, the intro-duction of the Budget Planning and Expenditure Management System(BPEMS) under PUFMARP, and the Integrated Personnel and Payroll Data-base (IPPD2). For BPEMS, external support was provided mainly between1997 and 2003 under PUFMARP, with minimal external amounts providedthereafter. The main sources of funding under PUFMARP were IDA(US$15.3 mn), and GoG ($4.6 mn). Following the conclusion of PUFMARP,GoG continued providing funding to BPEMS from its annual budget. It isnotable that the final expenditures under PUFMARP were 50% higher thanoriginally programmed; this additional expenditure was financed by transfer-ring part of the budget originally intended for the revenue management com-ponents (specifically, covering support to Customs, Excise and PreventativeService (CEPS)). Inputs centred on TA for system design (re-engineering busi-ness processes), the provision of hardware (including networks), and financialmanagement software (based on Oracle Financials).For IPPD2, DP support was provided by DFID, largely for system specifi-cation, hardware, application licence, customisation costs and training staff inMDAs.20 Betley and Burton, 2011.29

2. INPutS AND CoNtExt: tHE DESIGN oF PFm rEForm

MtEfThe majority of funding for the MTEF came from PUFMARP; total fundingunder the programme for the MTEF was estimated at US$4.58 million(external) and US$ 0.18 million (GoG). The reform inputs, which werefocused primarily on MoFEP and MDAs, were provided mainly as technicalassistance. They involved two main areas of support: (i) the development andspecification of the MTEF at MDA level (mainly activity-based), and (ii)improvements to the formulation of the annual budget, including budget cir-cular, installation of budget preparation software in MDAs and staff training.Following PUFMARP, some limited financing was available from CIDA(long-term advisory support), GTZ (MTEF training), and UNICEF (interna-tional site visits and advisory support).Revenue managementUnder the PUFMARP programme, disbursed IDA funding amounted toUS$0.95 mn. Under the subsequent Good Financial Governance programme,supported by BMZ, disbursed funding for each phase was: (i) Phase I (9/2003– 8/2006): €2.8 mn; (ii) Phase II (9/2006 – 3/2010): €5.0 mn; Phase III(4/2010-13) €9 mn. Co-financing of around €2.6 mn has also been providedby Switzerland (SECO). Otherwise, during 2005/06, DFID provided an advi-sor on improving non-tax revenue collection in the natural resources sector.internal auditThe introduction of a formal internal audit function began with the passage ofthe Internal Audit Agency Act in 2003. Previously, internal audit had beenfocussed largely on compliance checking of payment vouchers (pre-audit),rather than on systemic reviews on behalf of management of internal controlsystems.Very limited DP funding was spent during the study period, mainly ontraining. This included EC support (estimated at less than €0.5 mn)21that wasprovided towards the end of the study period (in 2008) to train staff in MDAs’Internal Audit Units (IAUs). Some limited support for training and ICTequipment was also provided by the World Bank.GoG funding during the period in question was focussed on getting theIAA operational, and initiating an internal audit function in MDAs andMMDAs, including staff familiarisation and training. GoG funds spent onintroducing internal audit amounted to an estimated �12 mn per year.22

30

21 Study team estimates based on project documentation.22 Based on estimates by the IAA.

2. INPutS AND CoNtExt: tHE DESIGN oF PFm rEForm

2.4 STRuCTuRES TO dESiGn And MAnAGEPFM REFORM inPuTSEQ 2:What type of structures has been used for the design andmanagementof these reform inputs? Have these structures served to providea coordinated and harmonised delivery framework?

country overviewAs described above, the main reform activities during the period studied werethose under the PUFMARP reform programme, the GTZ/BMZ-support forresource management, the EC support to external audit, and wholly-GoG-financed reform activities. As such, the institutional structures involved inPFM reform followed those of the relevant reform programmes.For the PUFMARP, the governance structure involved ultimate oversightby a Government Steering Committee, chaired by the Deputy Minister ofFinance, and representatives of senior management of MoFEP, including theChief Director, CAGD (Deputy Controller), as well as representatives of majorspending MDAs. Day-to-day functions were the responsibility of the PUF-MARP Implementation Team, headed by the Project Manager.As indicated below, the PUFMARP Project Completion Report noted sig-nificant concerns about the relevance of the design of different aspects ofPUFMARP, including mis-specification and over-estimation of the readinessof the implementing agencies for the reforms.Immediately following the PUFMARP, solely GoG-financed reformactivities were co-ordinated by the individual divisions concerned, largely inMoFEP. Following the publication of its ST/MTAP, MoFEP created a specif-ic unit in 2007, the Budget Development Unit (BDU), under the Budget Divi-sion, to facilitate and drive forward budget reforms. From 2001 through 2008,the overall public sector reform programme was co-ordinated by the Ministryof Public Sector Reform.With a limited number of PFM reforms during the study period, andresources channelled through large PFM programmes, donor harmonisationof these programmes was less of an issue. As indicated above, from 2003, asignificant proportion of DPs’ annual resources to GoG (around 30%) havebeen channelled through MDBS. One of the benefits of MDBS was greaterDP harmonisation of its support, including on PFM, with GoG’s priorities andprogrammes.23

23 See Betley and Burton (2011), and Betley (2008).

31

2. INPutS AND CoNtExt: tHE DESIGN oF PFm rEForm

component case historiesfMiSThere were marked differences in the design and management arrangementsfor BPEMS and IPPD2 that reflected differences in the scope and complexityof the respective reform initiatives:• BPEMS. There were fundamental weaknesses in the technical designand management arrangements for BPEMS. It was conceptualised pri-marily as technology driven reform with insufficient attention given tochanges in PFM processes and procedures that should have precededthe reform, to change management, and to the assessment of capacityissues and training requirements. Furthermore, BPEMS was initiallymanaged through the PUFMARP project implementation unit, whichhad no functional or operational responsibility for the reform. Thisresulted in implementation of BPEMS being distanced from its two cli-ent departments (CAGD and the Budget Division), contributing to alack of ownership for the reform. It was only following completion ofPUFMARP in 2003 that the responsibility for BPEMS was transferredto the CAGD. However, coordination between the CAGD and theBudget Department remained weak, particularly as by then BudgetDivision had developed its own software application for budget plan-ning and managing budget releases.• IPPD2. By comparison, IPPD2 was a more narrowly specified andsimpler reform, involved only a limited number of users of the sys-tem, and presented fewer change management issues. It was man-aged by the CAGD and implemented through a contract with a con-sultancy firm.MtEfLike BPEMS, the MTEF reforms were financed through PUFMARP,although through parallel funding provided by DFID. The PUFMARPappraisal document provided only a very general specification of the reformwhich emphasised its technical features rather than its institutional and pro-cess aspects. The reform was implemented independently from the other com-ponents of PUFMARP through a separate MTEF Project Unit which subse-quently became the Budget Development Unit that has continued to beresponsible for overseeing the preparation of the Budget and overseeing fur-ther development of the reform.Although these arrangements facilitated strong ownership of the reformwithin the Budget Division, they may have undermined coordination andharmonisation between the MTEF and the other elements of the PFMreforms being supported through PUFMARP. For example, the Budget Divi-sion developed its own ACTIVATE software application for budget prepara-tion rather than using the budget preparation module of the BPEMS system.Delays in the implementation of the BPEMS meant that the performance ele-ment of the chart of accounts that was meant to support the MTEF budgetingreforms was not implemented.

32

2. INPutS AND CoNtExt: tHE DESIGN oF PFm rEForm

The design of the MTEF process allows for a review of the experience fromthe most recent MTEF/budget planning cycle to be fed into the planning ofthe subsequent MTEF. A number of external reviews of the MTEF reformhave been undertaken including a 2003 case study undertaken by the Over-seas Development Institute as part of wider study of the design and applica-tion of MTEFs as a tool for poverty reduction, the 2004 PUFMARP projectcompletion report, and the 2009 External Review of PFM.

Revenue managementThe revenue management component of PUFMARP was co-ordinated andmanaged through the programme’s Steering Group and the PIU. The moresignificant BMZ-funded support was provided directly to the relevant revenueagencies, specifically the Revenue Agencies Governing Board (RAGB), theInternal Revenue Service, and the VAT Service. Subsequently, the Secretariatcovering the Taxpayer Identification Numbering (TIN) programme, whichwas previously managed by the PUFMARP PIU, was brought under theRAGB. With only one DP providing support at a time, harmonisation amongDPs was not an issue in practice.internal auditAn IAA steering committee was established to provide oversight for thereform, with the Auditor General as the Chair and the Director General ofthe IAA as the Vice Chair. A formal memorandum of understanding betweenGAS and IAA spells out the operational relationships between the two organ-isations, including the sharing of information, reports, resources, and train-ing. Internal audit standards from International Organisation of SupremeAudit Institutions (INTOSAI) and African Organisation of Supreme AuditCommission (AFROSAI-E) were adopted.However, the reforms have left the IAs confused as to where they belong.They have dual reporting responsibilities at MDA and MMDA levels betweenthe IAA and MDA and between IAA and MMDA. The IAA posts the Inter-nal Auditors to MDAs and MMDAs and, although they report directly to theIAA, they are expected to be part of the MDA/MMDA. This dual allegiancehas created tensions and suspicion among the IAUs, MDAs and MMDAs.

2.5 COMPlEMEnTARy dOnOR inPuTSTO PFM REFORMEQ 3:What types of complementary actions have Donors taken tosupport PFM reforms and what has been their significance? Havethey had any influence on the external constraints to reform?

country overviewThe primary complementary action undertaken by DPs was the Multi-DonorBudget Support (MDBS) Framework. In particular, the introduction ofMDBS in 2003 provided a useful forum for policy dialogue around reform in

33

2. INPutS AND CoNtExt: tHE DESIGN oF PFm rEForm

general, but particularly in terms of PFM systems, as well as issues around ser-vice delivery.24It provided a forum for shared PFM assessments, with themeetings for the annual External Reviews of Public Financial Managementand the initial PEFA assessment being open for all stakeholders. The MDBSframework also facilitated information sharing and harmonisation of DPreform activities.However, the more direct way in which the MDBS framework sought toinfluence reform actions was primarily through the MDBS triggers. All of thePFM MDBS triggers were met or declared to be met25, although it may beargued that there was some interpretation in the achievement of some of thetriggers, particularly with BPEMS.26Ironically, the MDBS policy dialogue was least successful in dealing withPFM outcomes. The fiscal crisis of 2008, and the subsequent political fall-out,had an impact on the collective nature of MDBS dialogue, with the WorldBank opting to undertake its own adjustment programme with GoG outsideof the MDBS framework. This, together with strong future economic growthprospects, and with the rebased GDP, and DPs’ own fiscal pressures, can beexpected to have an impact on future levels of MDBS.27In terms of the extent of aid-on-budget for funding for PFM reform meas-ures, as the majority of funding for the PUFMARP reforms was from an IDAcredit, the resources were on-budget. However, since they used World Bankprocedures, they were not on-Treasury or on-accounting. Reporting on theuse of funds was also separate. Grant-funded programme support tended touse the DPs’ own procedures28, and was not systematically on budget.29Underthe MDBS framework, KFW, CIDA and Danida sponsored a number of par-tial audits of MDAs and MMDAs, known as selected flows audits. Overall,less than 50% of all external resource flows use government procedures.30One potential external constraint to PFM reform was the predictability ofexternal disbursements, on which the PEFA reports indicate that there wereweaknesses in the early part of the period studied, but that predictability hadimproved after 2004.31

component case historiesfMiSBPEMS was initially implemented as part of PUFMARP, which supported arelatively comprehensive programme of PFM reforms. In practice, the242526272829See Betley and Burton, 2011.See the Ghana desk report for this study (Gordon and Betley, 2011).See Betley and Burton, 2011.On the other hand, Japan joined the MDBS group.With some exceptions (e.g. Danida)The Budget Statement contains a table of estimated current year-to-date spend on ex-ternally financed projects, but this is not comprehensive, and the information is oftendifferent to that held by the MDAs and the DPs.30 A D score was recorded for the D-3 indicator in both the 2006 and 2009 PEFAs.31 A C score was achieved in the 2006 PEFA for D-2(i), but this had improved to an Ascore in the 2009 PEFA.

34

2. INPutS AND CoNtExt: tHE DESIGN oF PFm rEForm

reforms were not well sequenced and were implemented independently ofeach other. This meant that the potential benefits of managing the reformswithin a wider reform agenda were not realised.The subsequent MDBS dialogue had minimal influence on the FMISreforms although two triggers were linked to FMIS implementation. The firstrequired complete deployment of all six BPEMS modules in eight pilot MDAsby 2006. This was not achieved but was “declared met” by the 2007 MDBSReview even though it was only partially met. The second involved the inte-gration of 50% of subverted agencies into the IPPD2 by May 2008 was met inAugust 2008.

MtEfFollowing the completion of the DFID assistance in 2003, the government hascontinued to finance and sustain the MTEF reforms. This has been comple-mented by limited assistance from CIDA (long-term advisory support), BMZ(training and short-term advisory support), and UNICEF (MoFEP interna-tional experience familiarisation and short-term advisory support). Therehave been no MDBS triggers relating to the MTEF, and there is no evidencethat the MDBS dialogue has influenced the evolution of the MTEF initiative.

2.6 Civil SOCiETy PRESSuRE FOR PFMREFORMEQ 4:To what extent have there been domestic public pressure orregional institutional pressure in support of PFM reform and whathas been the influence on the external constraints to reform?

country overviewThere appears to have been limited domestic public pressure for PFM reforms,partly due to the perceived technical nature of such reforms. There are fewCSOs undertaking budget analysis and advocacy and little fiscal and budget-ary analysis undertaken by academia. Non-availability of budget executiondata remains a major constraint to independent budget analysis, and MoFEPhas not actively facilitated such analysis. However, the recent opening of PAChearings on external audit reports to the public and the televising of the hear-ings has increased public awareness of the role of the PAC and led directly topressure on the PAC to increase its technical capacities and improve the qual-ity and timeliness of its scrutiny of GAS reports.32Regional (African) peer-to-peer experience-sharing is cited as an impor-tant factor in enabling GoG officials to learn about international experience.For the Budget Division in MoFEP, CABRI is seen as having been particular-ly influential. In addition, MoFEP has a programme of enabling staff to gaininternational experience (through international degree programmes) andpotentially job-swaps or job placements.32 We note the request by PAC for support to the Secretariat on analysing external auditreports.35

2. INPutS AND CoNtExt: tHE DESIGN oF PFm rEForm

component case historiesfMiSThere was no discernible engagement with civil society, academia or themedia over the implementation of BPEMS and IPPD2. This was consistentwith the view of the FMIS as technological reform. Similarly there has beenlittle pressure from regional and international organisation in support of thereforms, although MoFEP increasingly recognises that the experience withBPEMS compares unfavourably with the implementation of FMIS initiativesin other African countries.MtEfUnlike some other countries where similar reforms have been introduced,Ghana’s MTEF has not involved specific measures to involve civil society,academics and the media in the budget process. MoFEP organises consulta-tions with CSOs in October each year, but these take place too late in thebudget process to influence resource allocations. Prior to the consultations,there is a call for submissions from CSOs that is published in the newspapers.Similarly the MTEF reform has not led to any strengthening of parliamentaryinvolvement in the budget process, which remains limited to the period fol-lowing presentation of the draft budget.There are few CSOs undertaking budget analysis and advocacy and lim-ited fiscal and budgetary analysis undertaken by academia. Non-availabilityof budget execution data remains a major constraint to independent budgetanalysis, and MoFEP has done little to encourage such analysis.There is evidence that regional PFM fora have begun to influence theMTEF reform. For example, a meeting of Collaborative African BudgetReform Initiative (CABRI) in the second quarter of 2010 was influential inconvincing officials in the Budget Division to adopt a more strategic pro-gramme-based approach to budget planning.

2.7 RElEvAnCE OF PFM REFORM inPuTSEQ 5:How relevant was the PFM reform programme to the needs and theinstitutional context? Was donor support consistent with nationalpriorities? To what extent were adaptations made in response tothe context and the changing national priorities?

country overviewAs indicated above, there were a few formal domestic PFM reform strategydocuments during the period studied. It is notable that the ST/MTAP wasrevised and re-released in early 2007 following the publication of the firstPEFA assessment; the revised version reflected GoG’s revised policy objectivesin response to weaknesses identified in the PEFA. Specifically, the changesinclude: a reprioritisation of activities based on the PEFA assessment; explicitsections added to explain the prioritisation and the sequencing of reforms;estimates of the likely cost of activities were included, and for each focal area,

36

2. INPutS AND CoNtExt: tHE DESIGN oF PFm rEForm

the likely outcome (mainly, expected changes in processes) in 2009 (the finalyear of the Action Plan) was indicated. However, there was no indication ofthe potential impact on service delivery – both original and revised STAPsfocussed more on actions and outputs rather than on outcomes. At the sametime, the issue of how change was to be managed was not addressed, specifi-cally, the organisational development, capacity development and motivationalinitiatives needed to drive each objective.

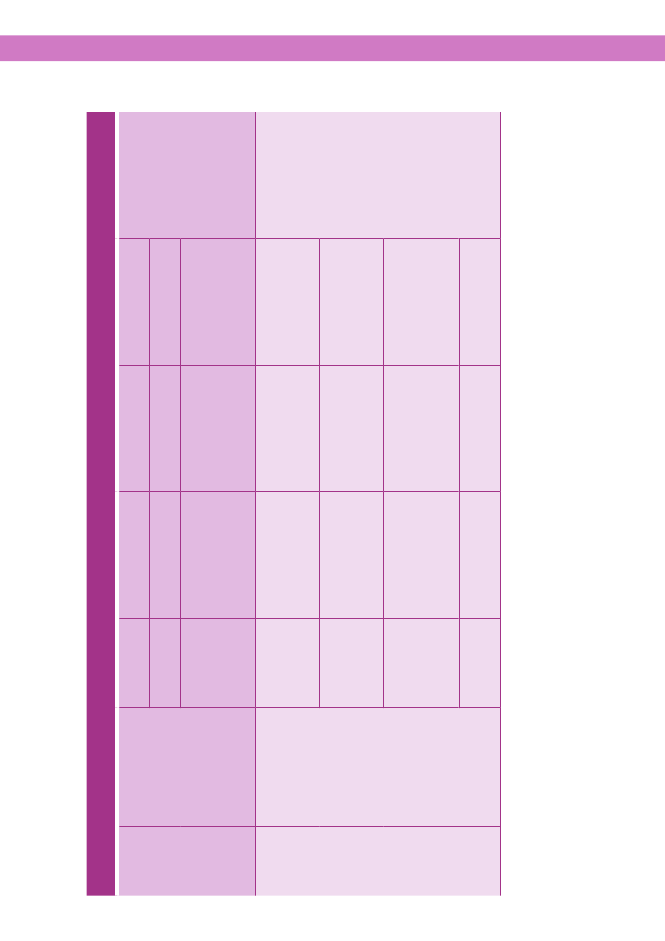

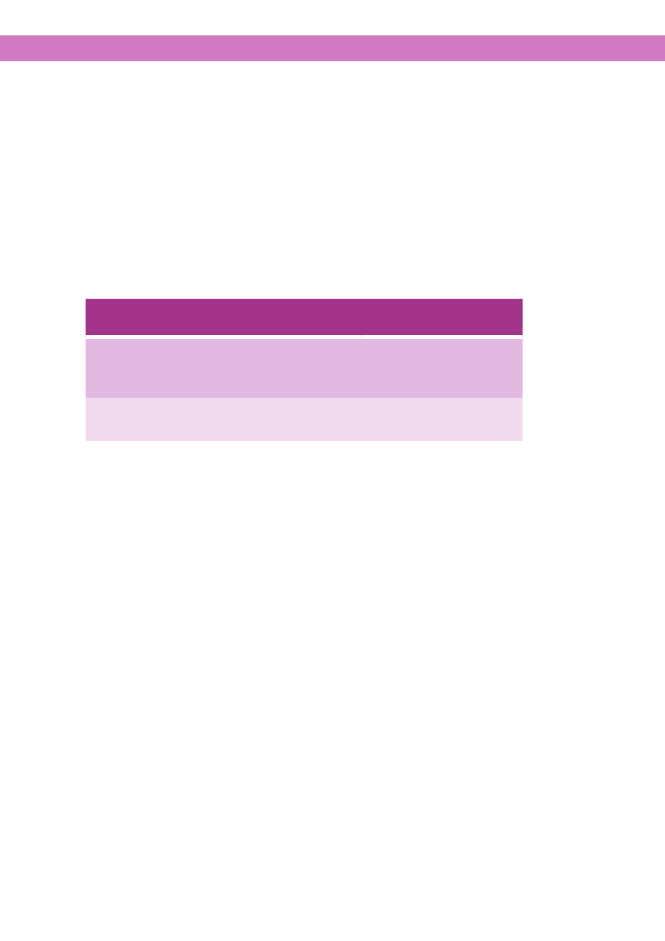

box 5: comparison of 2006-09 Short & Medium term action Planwith identified weaknessesInclusion inWeakness2006-09 reformIdentifiedProgramme(2001 HIPC,(St=Short-term2004 CFAA,Action; mt=med.-2006/09 PEFA) term Action)DP SupportHIPCHIPC, CFAASTMTDFID, DE,UNDP

Elements of PFmSystema. cross-cuttingLegal FrameworkCapacity buildingOrganisationalstructure/functionalreviewsIFMSCo-ordinationacross PFM systemsBudget policymanagementb. budget credibilityBudget deviations inaggregateBudget deviationsby MDARevenue projec-tions/outturnsExpenditure arrears

HIPC

STMT

WB, DFID

PEFA(-/C)PEFA(D/C)HIPCMTMT

c. comprehensiveness/transparencyBudgetclassificationComprehensivenessof budget docsHIPC, CFAA,PEFA(-/C)MTMT37

WB,IMF

2. INPutS AND CoNtExt: tHE DESIGN oF PFm rEForm

Elements of PFmSystemBudget comprehen-siveness & unre-ported opsInter-governmentalfiscal managementAggregate fiscalrisk/SOEsPublic access tofiscal info

Inclusion inWeakness2006-09 reformIdentifiedProgramme(2001 HIPC,(St=Short-term2004 CFAA,Action; mt=med.-2006/09 PEFA) term Action)DP SupportCFAA,PEFA(C/-)PEFA(-/D+)PEFA(C/D+)MTMTMTUNDP

D. Policy-based budgetingStructure of budgetprocessMTEF/multi-yearbudgetingE. budget executionTax administrationreformDomestic resourcemobilisationPEFA(C/C)PEFA(C/-)MTMTMTMTCFAAHIPCCFAA,PEFA(C/D+)HIPC, CFAA,PEFA(D+/D+)HIPC, CFAA,PEFA(C/C)MTMTMTMTEC, WBGIZGIZ, DFIDUSHIPC, CFAAHIPC, CFAAPEFA(C/-)ST, MTDFID, CIDA,GIZ,UN

Expend. Predictabil-HIPC,ity/commitmentPEFA(C/D+)controlsDebt, cash manage-mentPayroll controlsProcurementInternal controlsInternal audit

IMF,USDFIDWB, DFID.GIZ

f. accounting, recording and reporting38

Reconciliationof accounts

MT

IMF

2. INPutS AND CoNtExt: tHE DESIGN oF PFm rEForm

Elements of PFmSystemResources rec’d byservice deliveryunitsIn-year budgetreportsAnnual financialstatementsExternal auditLegis. scrutiny ofannual budget law

Inclusion inWeakness2006-09 reformIdentifiedProgramme(2001 HIPC,(St=Short-term2004 CFAA,Action; mt=med.-2006/09 PEFA) term Action)DP SupportPEFA(D)CFAAHIPC, CFAAHIPC, CFAAHIPC;PEFA(-/D+)DFIDMTMTMTMTEC

g. External scrutiny/audit

Legis. scrutiny of ex-HIPC (-/D+)ternal audit reports12

HIPC refers to 2001 HIPC action plan recommendations.CFAA refers to recommendations in the 2004 CFAA Action Plan.3PEFA refers to 2006 and 2009 PEFA scores C or D (central government). 2006 & 2009scores separated by “/”.4DP support may not be comprehensive due to lack of available information.

The alignment between the PFM reforms and Government needs (i.e. PFMweaknesses) may be analysed in two ways: firstly, whether or not the reformsundertaken adequately reflected PFM weaknesses, and secondly whether ornot DPs’ contributions were appropriately targeted. Box 5 shows the align-ment between the weaknesses identified (in the 2001 HIPC survey, 2004CFAA, and 2006 PEFA), their inclusion in the GoG’s 2006-09 PFM reformprogramme and the availability of DP support for reform.In terms of the alignment of DP support with PFM weaknesses, the analy-sis indicates that, in general, DP support was focussed on those areas with thegreatest needs. Based on the link between DP support on the one hand andGoG’s PFM needs on the other, as measured by HIPC, CFAA assessmentsand the scores of Cs and Ds in the 2006 PEFA assessment, there is a reason-able correspondence between DP support and those PFM areas assessed asrequiring strengthening. DP support is concentrated disproportionately – butfor good reasons – on budget execution, followed by the MTEF.DP support has not been provided to any area, which was assessed as beingreasonably strong, although there are relatively few of those. One of the areasnot identified as requiring assistance and without DP support is the establish-ment of a system to identify and monitor expenditure arrears, although DPsare reported to have consistently raised this issue with GoG over the past yearsbut GoG did not request support for such a system during the period studied.

39

2. INPutS AND CoNtExt: tHE DESIGN oF PFm rEForm

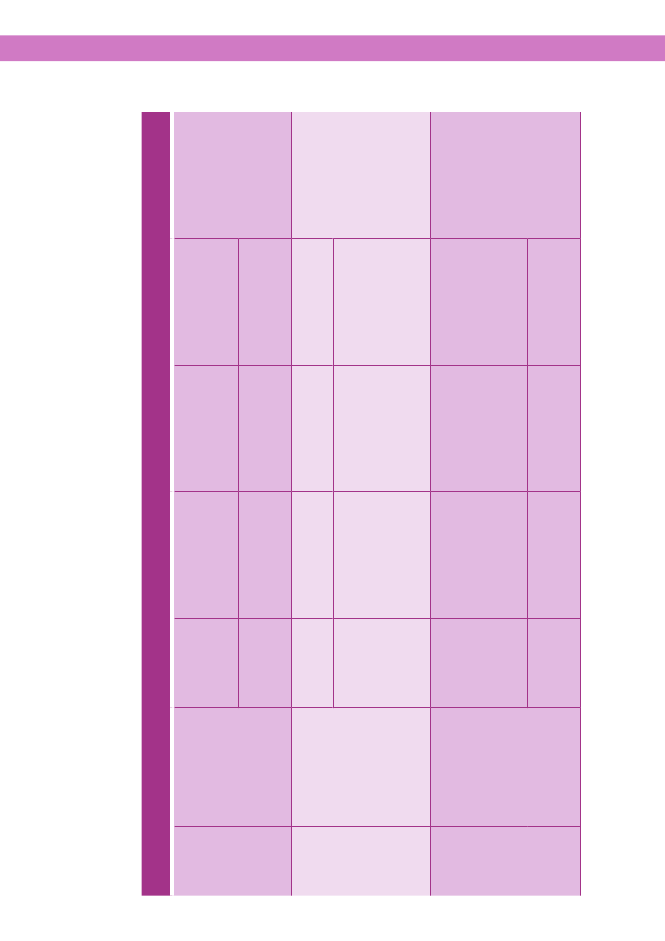

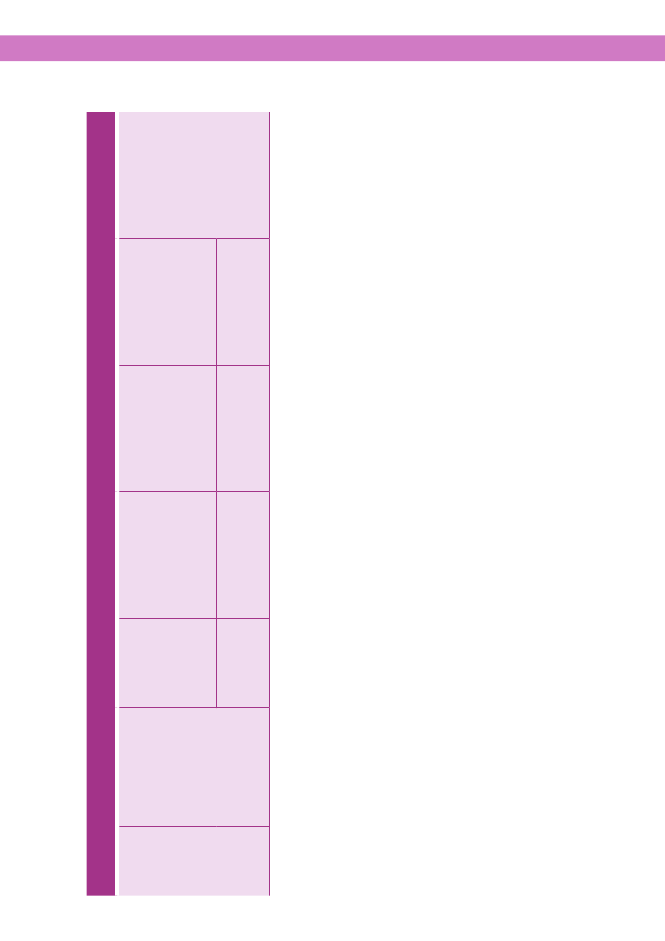

The lack of such a system enabled GoG to build up a large stock of newarrears during 2007 and 2008, which reached an estimated 4% of GDP.33Box 6 below examines GoG’s reform programme in more detail andassesses how close it is in practice to the PFM weaknesses as indicated by thePEFA and to GoG’s PFM medium-term Action Plan. The analysis indicatesthat nearly all PEFA indicators are included in the Plan. This was partly bydesign, as the Action Plan was revised following the 2006 PEFA assessment.However, the measures are not prioritised, which undermines the Plan’s use-fulness. It is interesting to note, however, that the reform programme is inreality a MoFEP Action Plan since those aspects of PFM undertaken by otheragencies (e.g. internal audit, external audit) largely do not feature (except rev-enue administration measures).

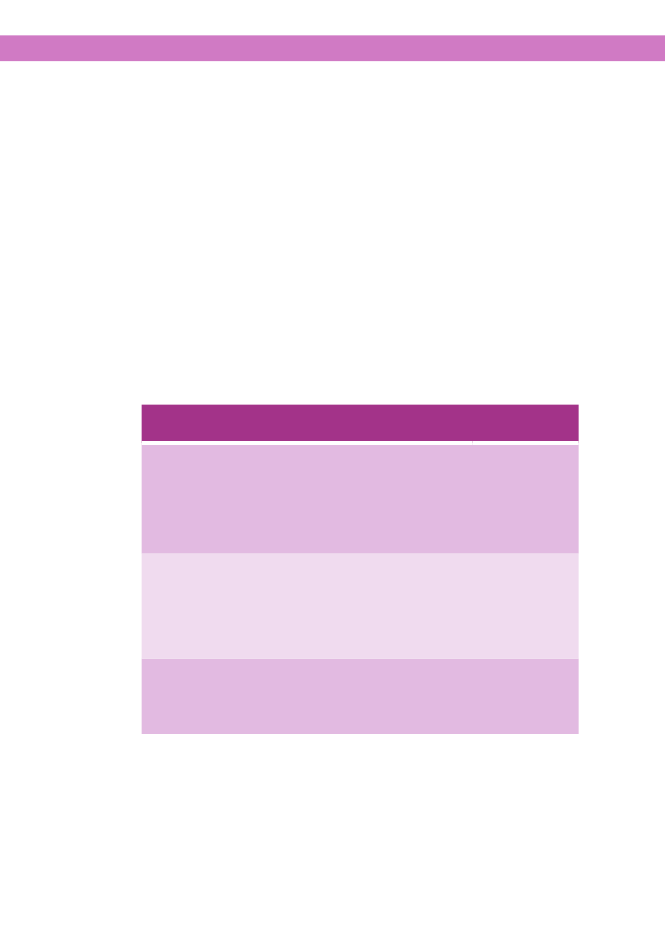

box 6: alignment of 2006-2009 Short & Medium term action Planwith PEfa ResultsSt/mtAP FocalAreas1/Key objectives• To improve fiscalresourcemobilisation• Formulate andimplement soundmacro-economicpoliciesrelated2006 PEFAIndicator/resultsPI-14 (C)PI-16 (C)PI-8 (C)PI-23 (D)PI-2 (C)

Selected WorkPlan Activity• Linking/integrating revenuesystems• Improving monitoring ofexpenditure commitments• Consolidating of fiscal data• Public Expenditure TrackingSurveys• More accurate wage billplanning• Improving MTEF throughcapacity development• Harmonising central/localclassification systems• Facilitating SOE inputs into thebudget• Budget classification• Budget reporting• Cash releases• Donor harmonisation

1. fiscal Policy Management – Macro-Economic Stability