Udenrigsudvalget 2012-13

URU Alm.del Bilag 19

Offentligt

The State of

Food Insecurity in the WorldEconomic growth is necessary but not suf cientto accelerate reduction of hunger and malnutritionKey messages

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The State of Food Insecurity in the World 2012presents new estimates of the numberand proportion of undernourished people going back to 1990, de ned in terms of thedistribution of dietary energy supply. With almost 870 million people chronicallyundernourished in 2010–12, the number of hungry people in the world remainsunacceptably high.The vast majority live in developing countries, where about 850million people, or slightly fewer than 15 percent of the population, are estimated to beundernourished.Improved undernourishment estimates, from 1990, suggest that progress in reducinghunger has been more pronounced than previously believed.Most of the progress, however, was achieved before 2007–08. Since then, globalprogress in reducing hunger has slowed and levelled off.The revised results imply that the Millennium Development Goal (MDG) target ofhalving the prevalence of undernourishment in the developing world by 2015 is withinreach,if appropriate actions are taken to reverse the slowdown since 2007–08.Despite signi cant improvements this year to the FAO methodology for estimatingundernourishment, further improvements and better data are needed to capture theeffects of food price and other economic shocks.Therefore, the undernourishmentestimates do not fully re ect the effects on hunger of the 2007–08 price spikes or theeconomic slowdown experienced by some countries since 2009, let alone the recent priceincreases. Other indicators are also needed to provide a more holistic assessment ofundernourishment and food security.In order for economic growth to enhance the nutrition of the neediest, the poor mustparticipate in the growth process and its bene ts:(i) Growth needs to involve and reachthe poor; (ii) the poor need to use the additional income for improving the quantity andquality of their diets and for improved health services; and (iii) governments need to useadditional public resources for public goods and services to bene t the poor and hungry.Agricultural growth is particularly effective in reducing hunger and malnutrition.Mostof the extreme poor depend on agriculture and related activities for a signi cant part oftheir livelihoods. Agricultural growth involving smallholders, especially women, will bemost effective in reducing extreme poverty and hunger when it increases returns tolabour and generates employment for the poor.Economic and agricultural growth should be “nutrition-sensitive”.Growth needs toresult in better nutritional outcomes through enhanced opportunities for the poor todiversify their diets; improved access to safe drinking water and sanitation; improvedaccess to health services; better consumer awareness regarding adequate nutrition andchild care practices; and targeted distribution of supplements in situations of acute micro-nutrient de ciencies. Good nutrition, in turn, is key to sustainable economic growth.Social protection is crucial for accelerating hunger reduction.First, it can protect themost vulnerable who have not bene ted from economic growth. Second, socialprotection, properly structured, can contribute directly to more rapid economic growththrough human resource development and strengthened ability of the poor, especiallysmallholders, to manage risks and adopt improved technologies with higher productivity.To accelerate hunger reduction, economic growth needs to be accompanied by purpose-ful and decisive public action.Public policies and programmes must create a conduciveenvironment for pro-poor long-term economic growth. Key elements of enabling environ-ments include provision of public goods and services for the development of the produc-tive sectors, equitable access to resources by the poor, empowerment of women, anddesign and implementation of social protection systems. An improved governancesystem, based on transparency, participation, accountability, rule of law and humanrights, is essential for the effectiveness of such policies and programmes.

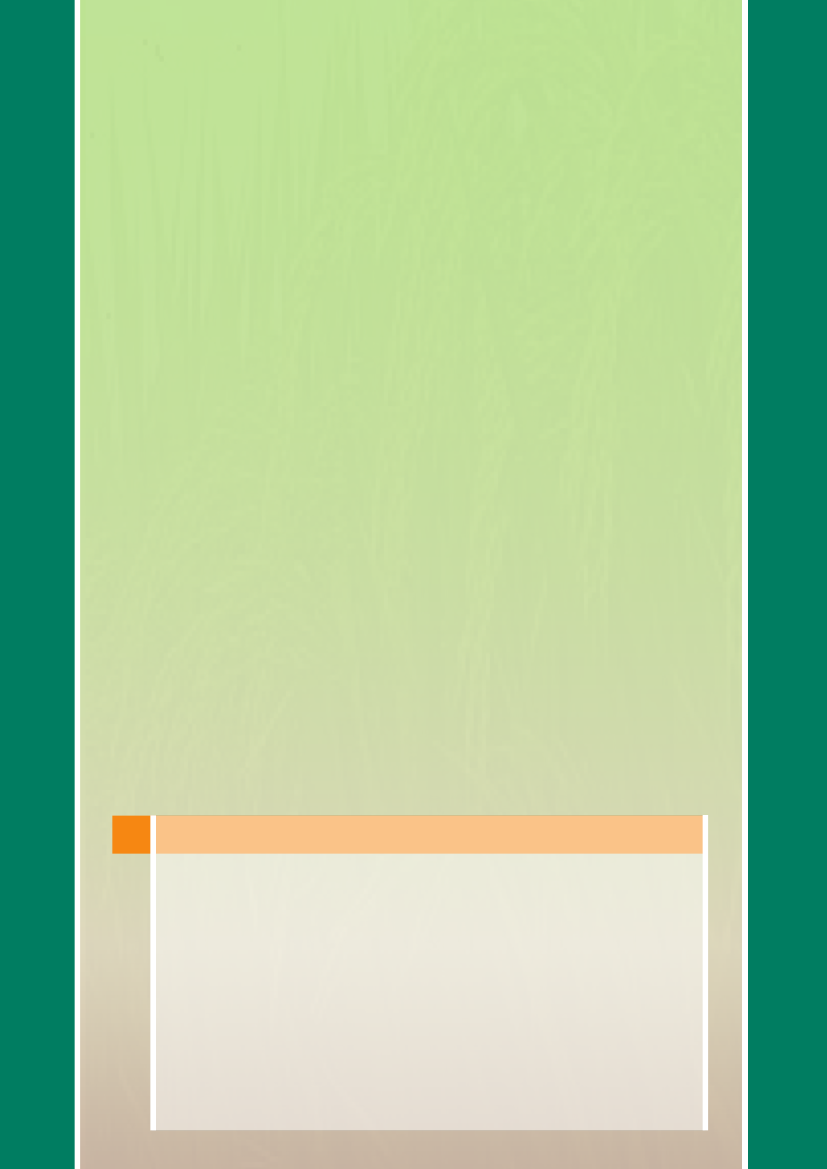

The State of

Food Insecurity in the WorldEconomic growth is necessary but not suf cientto accelerate reduction of hunger and malnutritionUndernourishment around the worldAbout 870 million people are estimated to have beenundernourished in the period 2010–12. This represents12.5 percent of the global population, or one in eightpeople. The vast majority of these – 852 million – live indeveloping countries, where the prevalence ofundernourishment is now estimated at 14.9 percent of thepopulation (Figure, below left). Undernourishment in theworld is unacceptably high.The updated gures emerging as a result ofimprovements in data and the methodology FAO uses tocalculate its undernourishment indicator suggest that thenumber of undernourished people in the world declinedmore steeply than previously estimated until 2007,although the rate of decline has slowed thereafter(Figure, below left). As a result, the developing world as awhole is much closer to achieving the MillenniumDevelopment Goal (MDG) target of reducing by half thepercentage of people suffering from chronic hunger by2015. If the average annual decline of the past 20 yearscontinues through to 2015, the prevalence ofundernourishment in the developing country regionswould reach 12.5 percent – still above the MDG target,but much closer to it than previously estimated.Considerable differences among regions and individualcountries remain, however. A reduction in both thenumber and proportion of undernourished in Asiaobserved in recent years has continued, resulting in Asiabeing roughly on track for achieving its MDG hungertarget. The same holds true for Latin America. Africa, bycontrast, is continuing its large and rising deviation awayfrom what is needed to meet its target; the trend forprogress in reducing undernourishment is broadly mirroredby those for poverty and child mortality. In Western Asiaalso, the prevalence of undernourishment hasprogressively increased since 1990–92 (regionalaggregations follow standard UN classi cation; abreakdown of country composition is provided in theannex to the report).As regions have differed in their rates of progresstowards reducing hunger, the distribution of where hungrypeople are concentrated in the developing regions haschanged over the past 20 years (Figure, below right).The shares of South-Eastern Asia and Eastern Asia in thedeveloping regions’ undernourished people have seen themost marked decline between 1990–92 and 2010–12(from 13.4 to 7.5 percent and from 26.1 to 19.2 percent,respectively), while that of Latin America also declined,from 6.5 to 5.6 percent. Meanwhile, the shares haveincreased from 32.7 to 35.0 percent in Southern Asia,from 17.0 to 27.0 percent in sub-Saharan Africa and from1.3 to 2.9 percent in Western Asia and Northern Africa.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Undernourishment in recent yearsThe new estimates also suggest that the increase inhunger during 2007–10 – the period characterized byfood price and economic crises – was less severe thanpreviously estimated. There are several reasons for this.First, the FAO methodology estimateschronicundernourishment based on habitual consumption ofdietary energy and does not capture the effects of pricespikes, which are typically short-term. As a result, theprevalence should not be used to draw de nitiveconclusions about the effects of price spikes or othershort-term shocks. Second, the transmission of economicshocks to many developing countries was less pronouncedthan initially thought. More recent GDP estimates suggestthat the “great recession” of 2008–09 resulted in only amild slowdown in many developing countries, andincreases in domestic staple food prices were very small inChina, India and Indonesia (the three largest developingcountries).

Undernourishment in the developing world

Undernourishment in 2010 –12, by region (millions)Total = 868 million

Millions1 00090080070060050040023.218.3980901

Percentage undernourished4035885852852

OceaniaCaucasus and Central AsiaDeveloped regionsWestern Asia and Northern AfricaLatin America and the CaribbeanSouth-Eastern Asia

1616254965

3025

WFStarget

201510

14.916.815.5MDGtarget

Eastern Asia167

01990–921999-20012004–06 2007–09 2010–122015

0

Sub-Saharan Africa234Southern Asia304Source:FAO.

Number(left axis)Source:FAO.

Prevalence(right axis)

Improvements to the FAO hunger indicatorThis year’s edition ofThe State of Food Insecurity in theWorldpresents new estimates of the number andproportion of hungry people in the world going back to1990, re ecting several key improvements in data and inthe methodology used by FAO to derive its prevalenceof undernourishment indicator (PoU). The new estimatesincorporate:•the latest revisions of world population data;•new anthropometric data from demographic,health and household surveys that suggestrevised minimum dietary energy requirements,by country;

•updated estimates of dietary energy supply,••

by country;country-speci c estimates of food losses atthe retail distribution level; andtechnical improvements to the methodology.

It should be noted that the current methodologydoes not capture the impact of short-term price andother economic shocks, unless these are re ected inchanges in long-term food consumption patterns.

However, even when higher prices cannot be directlylinked to a reduction in the total amount of caloriesconsumed by the population, higher food prices maynevertheless have had other negative impacts, for examplea deterioration in the quality of the diet and reducedaccess to other basic needs such as health and education.Such impacts are dif cult to quantify using informationcurrently available in most countries, and certainly cannotbe captured by an indicator based only on the adequacy ofdietary energy. In an effort to ll this information gap, FAOhas identi ed a preliminary set of more than 20 indicators,available for most countries and years. Data for these areavailable from the companion website for this report(www.fao.org/publications/so /en/) and will allow foodsecurity analysts and policy makers to assess morecomprehensively the various dimensions andmanifestations of food insecurity, and thus inform policyfor more effective interventions and responses.

Economic growth – necessary but not suf cientto accelerate reduction of hunger and malnutritionProgress in reducing undernourishment has slowedconsiderably since 2007, and strong economic growth willbe an essential component for successful and sustainablehunger reduction. Indeed, regions that have grown morerapidly have generally witnessed more rapid reductions inhunger; throughout the world, people with more incomehave greater dietary diversity (see Figure, below). Duringthe past decade, per capita income growth was positive inall developing country regions, but in many countriesgrowth did not signi cantly reduce hunger, suggestingthat growth alone is unlikely to make a signi cant impacton hunger reduction.Economic growth must involve and reach the poorthrough increased employment and other income-earningopportunities. Furthermore, women need to share in these

As incomes rise, dietary diversity increases

Share of food groups in total dietary energy supplies (percentage)1009080706050403020100Q1AsiaSource:FAO, analysis of household surveys.Q5Q1Q5Latin Americaand the CaribbeanQ1Q5North AfricaQ1Q5Sub-Saharan Africa

OtherSugarsFats and oilsAnimal-source foodsFruits and vegetablesPulsesRoots and tubersCerealsNote:Data refer tohouseholds of lowest andhighest income quintiles in47 developing countries.

developments, because when women have morecontrol over household income, more money tends tobe spent on items that improve nutrition and health.In addition to economic growth, governmentaction is also required to eliminate hunger. Economicgrowth should bring additional government revenuesfrom taxes and fees, which should be used to nanceeducation, skills development and a wide variety ofpublic nutrition and health programmes. Goodgovernance is also indispensible, including theprovision of essential public goods, political stability,rule of law, respect for human rights, control ofcorruption, and effective institutions.One example of growth that often reaches thepoor is agricultural growth, especially when based onincreased productivity of smallholders. Agriculturalgrowth is especially important in low-incomecountries, where agriculture’s contribution to reducingpoverty is greatest. Agriculture is also particularlyeffective in reducing poverty and hunger wheninequality in asset distribution is not high, becausesmallholders are then able to bene t more directlyfrom growth. A greater focus on integratingsmallholders into markets will not only help meetfuture food demand, but will also open up increasedopportunities for linkages with the rural non-farmeconomy, as smallholders are likely to use most oftheir additional income to purchase locally producedgoods and services.In order to reduce undernourishment as rapidly aspossible, growth must not only bene t the poor, butmust also be “nutrition-sensitive”. Improving foodsecurity and nutrition is about more than justincreasing the quantity of energy intake – it is alsoabout improving the quality of food in terms of dietarydiversity, variety, nutrient content and safety. To date,

the linkage between economic growth and nutritionhas been weak, with long lags before growth istranslated into real changes in nutritional status.Policies in support of such objectives should bepursued within an integrated agriculture–nutrition–health framework. And while economic growth isimportant for progress in improving people’s nutrition,the links run in the other direction as well – nutritiousdiets are vital for people’s full physical and cognitivepotential and health, thus contributing to economicgrowth. Improved childhood nutrition and access toeducation can improve cognitive development andthereby raise income levels when those childrenbecome adults, with personal bene ts as well asbene ts for society as a whole.Equitable and strong economic growth based ongrowth of the rural economy of low-income countriesgoes a long way towards enhancing access to foodand improving the nutrition of the poor. However,some of the changes made possible through economicgrowth take time to bear fruit, and the neediestpopulation groups often cannot take immediateadvantage of the opportunities it generates. Thus,in the short-term, social protection is needed tosupport the most vulnerable so that hunger andundernourishment can be reduced as soon as possible.But social protection can also reduce undernourishmentin the long term. First, it improves nutrition for youngchildren – an investment that will pay off in the futurewith better educated, stronger and healthier adults.Second, it helps mitigate risk, thus promotingtechnology adoption and economic growth. Bydesigning a well-structured system of social protectionto support and complement economic growth,undernourishment and malnutrition can be eliminatedas quickly as possible.

F

U

R

T

H

E

R

I

N

F

O

R

M

A

T

I

O

N

The State of Food Insecurity in the Worldraises awareness about global hunger issues,discusses underlying causes of hunger and malnutrition and monitors progress towardshunger reduction targets established at the 1996 World Food Summit and the MillenniumSummit. The publication is targeted at a wide audience, including policy-makers,international organizations, academic institutions and the general public with an interestin linkages between food security, human and economic development.ENQUIRIES:

so @fao.orgMEDIA RELATIONS:

[email protected]FAO PUBLICATIONS CATALOGUE:

www.fao.org/icatalog/inter-e.htmFood and Agriculture Organization of the United NationsViale delle Terme di Caracalla,00153 Rome, ItalyTel.: +39 06 57051WEBSITE:

www.fao.orgI0000E/1/09.12