Udenrigsudvalget 2012-13

URU Alm.del Bilag 185

Offentligt

THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S CHILDREN2013

Children withDisabilities

� United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF)May 2013Permission is required to reproduce any part of this publication. Permission will befreely granted to educational or non-profit organizations. Others will be requestedto pay a small fee. Please contact:Division of Communication, UNICEFAttn: Permissions H6F3 United Nations Plaza, New York, NY 10017, USATel: +1 (212) 326-7434Email: [email protected]This report and additional online content are available at <www.unicef.org/sowc2013>. Perspective and Focus essays represent the personal views ofthe authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the United NationsChildren’s Fund.For corrigenda subsequent to printing, please see <www.unicef.org/sowc2013>.For latest data, please visit <www.childinfo.org>.ISBN: 978-92-806-4656-6eISBN: 978-92-806-4662-7United Nations publication sales no.: E.13.XX.1Cover photo:Schoolchildren queue to enter their classroom in this 2007 photograph from theSyrian Arab Republic. � UNICEF/HQ2007-0745/Noorani

THE STATE OF THEWORLD’S CHILDREN 2013

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSThis report is the result of collaboration among too many individuals and institutions to acknowledge here. The editorial and research teamthanks all who gave so willingly of their time, expertise and energy, in particular:Vesna Bosnjak (International Social Services); Shuaib Chalklen (UN Special Rapporteur on Disability); Maureen Durkin (University of Wisconsin); Nora Groce and Maria Kett(Leonard Cheshire Disability and Inclusive Development Centre, University College London); Nawaf Kabbara (Arab Organization of Disabled People); Lisa Jordan (Bernardvan Leer Foundation); Connie Laurin-Bowie (International Disability Alliance); Barbara LeRoy (Wayne State University); Charlotte McClain-Nhlapo (United States Agency forInternational Development); Helen Meekosha (Women with Disabilities Australia); Peter Mittler (University of Manchester); Roseweter Mudarikwa (Secretariat of the AfricanDecade on Persons with Disabilities); David Mugawe (African Child Policy Forum); Ghulam Nabi Nizamani (Pakistan Disabled Peoples’ Organization); Victor Santiago Pineda(Victor Pineda Foundation); Tom Shakespeare (World Health Organization); Aleksandra Posarac (World Bank); Shantha Rau Barriga (Human Rights Watch); Eric Rosenthal(Disability Rights International); Albina Shankar (Mobility India); and Armando Vásquez (Pan American Health Organization) for serving on the External Advisory Board.Judith Klein (Open Society Foundations); Gerrison Lansdown (independent); Malcolm MacLachlan and Hasheem Mannan (Trinity College Dublin); Susie Miles (independent);Daniel Mont (Leonard Cheshire Disability); and Diane Richler (International Disability Alliance) for authoring background papers.Sruthi Atmakur (City University of New York); Parul Bakshi and Jean-Francois Trani (Washington University in St. Louis); Nazmul Bari and Amzad Hossain (Centre for Disabilityin Development); Simone Bloem and Mihaylo Milovanovitch (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development); Johan Borg (Lund University); Megan Burke,Stephane De Greef and Loren Persi Vicentic (Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor); James Conroy (Center for Outcome Analysis); Audrey Cooper, Charles Reilly and AmyWilson (Gallaudet University); Alexandre Cote (International Disability Alliance); Marcella Deluca, Sunanda Mavillapalli, Alex Mhando, Kristy Mitchell, Hannah Nicolls andDiana Shaw (Leonard Cheshire Disability/Young Voices); Avinash De Souza (De Souza Foundation); Catherine Dixon (Handicap International); Fred Doulton (Secretariat of theConvention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities); Natasha Graham (Global Partnership for Education); Jean Johnson (University of Hawaii); Chapal Khasnabis and AlanaOfficer (World Health Organization); Darko Krznaric (Queen’s University); Gwynnyth Llewellyn (University of Sydney); Mitch Loeb (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/National Center for Health Statistics); Rosemay McKay (Australian Agency for International Development); Amanda McRae (Human Rights Watch); Sophie Mitra (FordhamUniversity); David Morissey, Sherzodbek Sharipoo and Andrea Shettle (United States International Council on Disabilities); Zelda Mycroft (The Chaeli Campaign); EmmaPearce (Women’s Refugee Commission); Natalia Raileanu (Keystone Human Services); Richard Rieser (World of Inclusion); Marguerite Schneider (Stellenbosch University);Morsheda Akter Shilpi (Organization for the Poor Community Advancement); Silje Vold (Plan Norway) for writing background material or providing advice and information.Tracy Achieng; Grace Okumu Akimi; Sophia Rose Akoth; Abeida Onica Anderson; Washinton Okok Anyumba; Beatrice Atieno; Ssentongo Deo; Ivory Duncan; Argie Ergina;Mary Charles Felix; Michael Salah Hosea; Amna Hissein Idris; Tiffany Joseph; Hannah Wanja Maina; Saitoti Augustin Maina; Dianne Mallari; Modesta Mbijima; ShidaMganga; Nicole Mballah Mulavu; Joseph Kadiko Mutunkei; Ann Napaashu Nemagai; Rachael Nyaboke Nyabuti; Alice Akoth Nyamuok; Sarah Omanwa; Benson Okoth Otieno;Nakafu Phiona; Shalima Ramadhani; Rosemarie Ramitt; Nambobi Sadat; Veronicah Shangutit Sampeke; Ladu Michel Seme; Josephine Kiden Simon; Muhammad Tarmizi binFauzi; Elizabeth Mamunyak Tikami; Shemona Trinidad; and the 20 other young people who participated anonymously in surveys and focus groups conducted specially for thisreport by facilitators from the Leonard Cheshire Disability Young Voices network.Bora Shin and Matthew Manos (veryniceDesign) for the infographic on universal design published online at <www.unicef.org/sowc2013>.UNICEF country and regional offices and headquarters divisions contributed to this report or to related online content or advocacy materials by submitting findings or photo-graphs, taking part in formal reviews or commenting on drafts. Many UNICEF offices and national committees arranged to translate or adapt the report for local use.Programme, policy, communication and research advice and support were provided by Yoka Brandt, Deputy Executive Director; Geeta Rao Gupta, Deputy Executive Director;Gordon Alexander, Director, Office of Research and colleagues; Nicholas Alipui, Director, Programme Division and colleagues; Ted Chaiban, Director, Office of EmergencyOperations and colleagues; Colin Kirk, Director, Office of Evaluation and colleagues; Jeffrey O’Malley, Director, Division of Policy and Strategy and colleagues; and EdwardCarwardine, Deputy Director, Division of Communication and colleagues. This edition also benefited from the close cooperation of Rosangela Berman-Bieler, Chief, andcolleagues in the Disability Section of UNICEF’s Programme Division.Special thanks to David Anthony, Chief, Policy Advocacy Section; Claudia Cappa, Statistics and Monitoring Specialist; Khaled Mansour, Director of Communication untilJanuary 2013; and Julia Szczuka, deputy editor of this report until September 2012, for their generosity of intellect and spirit.

REPORT TEAM

EDITORIAL AND RESEARCHAbid Aslam, EditorChristine Mills, Project ManagerNikola Balvin, Sue Le-Ba, Ticiana Maloney, Research OfficersAnna Grojec, Perspectives EditorMarc Chalamet, French EditorCarlos Perellon, Spanish EditorHirut Gebre-Egziabher (Lead), Lisa Kenney, Ami Pradhan, Research AssistantsCharlotte Maitre (Lead), Carol Holmes, Pamela Knight, Natalie Leston,Kristin Moehlmann, Copy EditorsAnne Santiago, Nogel S. Viyar, Judith Yemane, Editorial support

PUBLISHING AND DISSEMINATIONCatherine Langevin-Falcon, Chief, Publications Section; Jaclyn Tierney, ProductionOfficer; Germain Ake; Christine Kenyi; Maryan Lobo; Jorge Peralta-Rodriguez;Elias Salem

STATISTICAL TABLESTessa Wardlaw, Associate Director, Statistics and Monitoring Section, Divisionof Policy and Strategy; David Brown; Claudia Cappa; Liliana Carvajal; ArchanaDwivedi; Anne Genereux; Elizabeth Horn-Phathanothai; Priscilla Idele; ClaesJohansson; Rouslan Karimov; Rolf Luyendijk; Colleen Murray; Jin Rou New;Holly Newby; Khin Wityee Oo; Nicole Petrowski; Tyler Porth; Chiho Suzuki;Andrew Thompson; Danzhen YouDesign by Prographics, Inc.Printed by Hatteras Press, Inc.

ii

THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S CHILDREN 2013: Children with Disabilities

FOREWORDIs there a child who does not dream of being counted and having her or his giftsand talents recognized? No. All children have hopes and dreams – including childrenwith disabilities. And all children deserve a fair chance to make their dreams real.This edition ofThe State of the World’s Childrenincludes contributions byyoung people and parents who show that, when given that chance, children withdisabilities are more than capable of overcoming barriers to their inclusion, of taking their rightful placeas equal participants in society and of enriching the life of their communities.But for far too many children with disabilities, the opportunity to participate simply does not exist. Fartoo often, children with disabilities are among the last in line for resources and services, especiallywhere these are scarce to begin with. Far too regularly, they are the objects simply of pity or, worse,discrimination and abuse.The deprivations faced by children and adolescents with disabilities are violations of their rights and theprinciple of equity, at the heart of which lies a concern for the dignity and rights ofallchildren – includingthe most vulnerable and marginalized members of society.As this report documents, the inclusion of children with disabilities in society is possible – but it requiresfirst a change of perception, a recognition that children with disabilities hold the same rights as others;that they can be agents of change and self-determination, not merely the beneficiaries of charity; thattheir voices must be heard and heeded in our policymaking and programmes.We contribute to their exclusion by failing to gather enough data to inform our decisions. When we failto count these children, we are failing to help them count for all they should in their societies.Fortunately, progress is being made – albeit unevenly. This report not only examines the challengesinvolved in ensuring that children with disabilities have the fair access to services that is their right. Italso explores initiatives that show promise in such areas as health, nutrition, education and emergencyprogramming – and in the data collection and analysis needed to improve policies and operations in allthese fields. Other chapters also discuss principles and approaches that can be adapted to advance thesechildren’s inclusion.Somewhere, a child is being told he cannot play because he cannot walk, or another that she cannotlearn because she cannot see. That boy deserves a chance to play. And we all benefit when that girl,and all children, can read, learn and contribute.The path forward will be challenging. But children do not accept unnecessary limits. Neither should we.

Anthony LakeExecutive Director, UNICEF

iii

CONTENTSACKNOWLEDGEMENTS................................................. iiFOREWORDAnthony Lake, Executive Director, UNICEF .............................. iiiCHAPTER 4

ESSENTIALS OF PROTECTION........................... 41Abuse and violence .................................................................... 41Institutions and inappropriate care .......................................... 42Inclusive justice .......................................................................... 43

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION................................................................ 1From exclusion to inclusion ........................................................ 1On the numbers............................................................................ 3A framework for action ............................................................... 3

CHAPTER 5

HUMANITARIAN RESPONSE............................... 49CHAPTER 6

MEASURING CHILD DISABILITY....................... 63Evolving definitions ................................................................... 63Putting disability in context ..................................................... 64Data collection ............................................................................ 65Questionnaire design ................................................................. 66Purpose and consequences ....................................................... 67A way forward ............................................................................ 68

CHAPTER 2

FUNDAMENTALS OF INCLUSION................... 11Changing attitudes ..................................................................... 12It’s about ability .......................................................................... 13Supporting children and their families .................................... 13Community-based rehabilitation .............................................. 16Assistive technology .................................................................. 18Universal design ......................................................................... 18

CHAPTER 7

AN AGENDA FOR ACTION.................................... 75CHAPTER 3

Ratify and implement the Conventions ................................... 75Fight discrimination ................................................................... 75Dismantle barriers to inclusion ................................................. 77End institutionalization ............................................................. 80Support families ......................................................................... 81Move beyond minimum standards .......................................... 81Coordinate services to support the child ................................ 81Involve children with disabilities in making decisions........... 84Global promise, local test ......................................................... 85

A STRONG FOUNDATION...................................... 23Inclusive health ........................................................................... 23Immunization .............................................................................. 23Nutrition ...................................................................................... 24Water, sanitation and hygiene ................................................... 25Sexual and reproductive health and HIV/AIDS ........................ 26Early detection and intervention ............................................... 26Inclusive education .................................................................... 27Starting early .............................................................................. 29Working with teachers ............................................................... 32Involving parents, communities and children ........................ 33Lines of responsibility ................................................................ 36

iv

THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S CHILDREN 2013: Children with Disabilities

FOCUSViolence against children with disabilities .............................. 44Risk, resilience and inclusive humanitarian action ................. 52Explosive remnants of war ....................................................... 54Lessons learned .......................................................................... 69From screening to assessment ................................................. 70

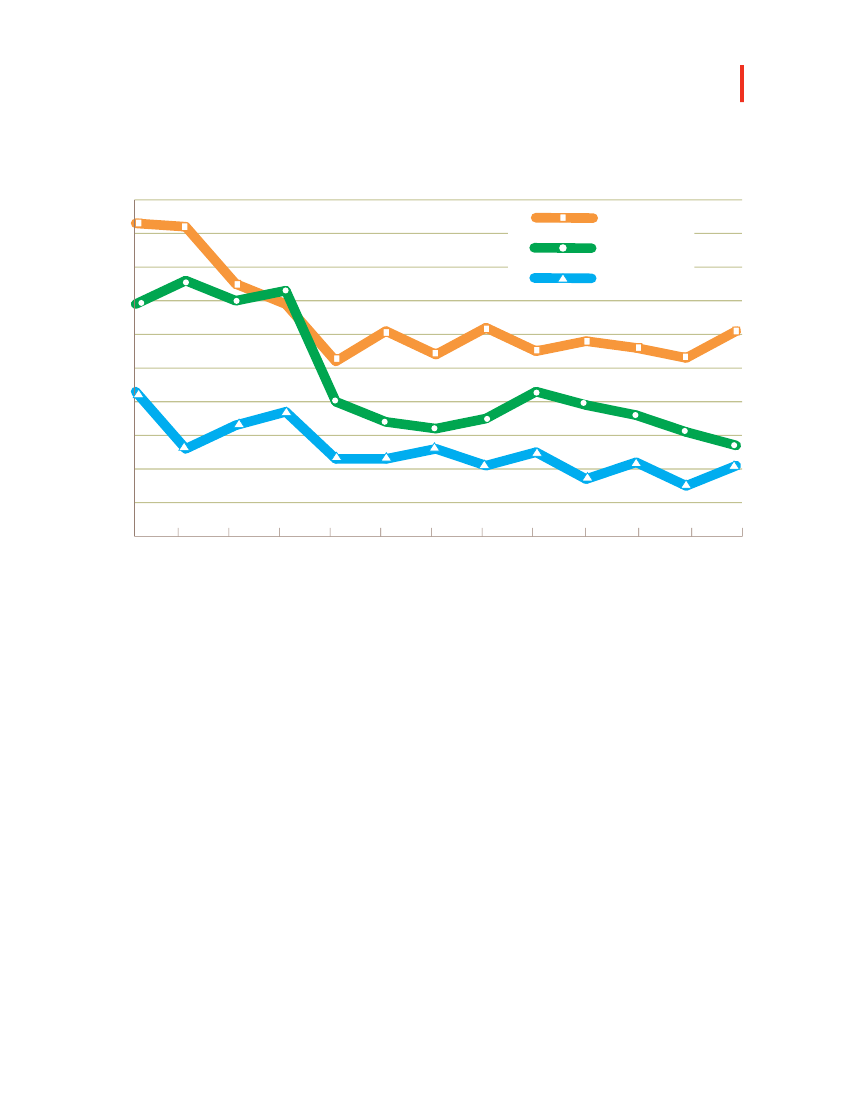

FIGURESEstimated rates of primary school completion ....................... 12Community-based rehabilitation .............................................. 16Assistive technology products.................................................. 19Children with disabilities and secondary education .............. 42Last to benefit............................................................................. 43Child casualties in countries heavily affected bymines and explosive remnants of war, 2011 ........................... 56

PERSPECTIVEFrom pioneer to advocate for inclusionNancy Maguire............................................................................. 4Living with albinism, discrimination and superstitionMichael Hosea.............................................................................. 6I want good memoriesNicolae Poraico............................................................................. 8For deaf young people, language is the keyKrishneer Sen............................................................................. 20My son HanifMohammad Absar..................................................................... 30The new normalClaire Halford.............................................................................. 34Adjusting, adapting and empoweringYahia J. Elziq............................................................................... 38Segregation and abuse in institutionsEric Rosenthal and Laurie Ahern.............................................. 46One bite of the elephant at a timeChaeli Mycroft............................................................................. 60From invisibility to inclusion forindigenous children with disabilitiesOlga Montufar Contreras........................................................... 72Open the doors to education – and employmentIvory Duncan............................................................................... 78End the ‘book famine’ with bettertechnology, attitudes and copyright lawKartik Sawhney........................................................................... 82Children with disabilities anduniversal human rightsLenín Voltaire Moreno Garcés................................................... 86Additional Focus and Perspective essays are available online at<www.unicef.org/sowc2013>.

Child casualties in the most affectedcountries (1999–2011) ................................................................ 57Child casualties by type of explosive ....................................... 59Four case studies: Percentage of populationreporting some form of disability............................................. 64Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilitiesand Optional Protocol: Signatures and ratifications .............. 76

REFERENCES....................................................................... 88

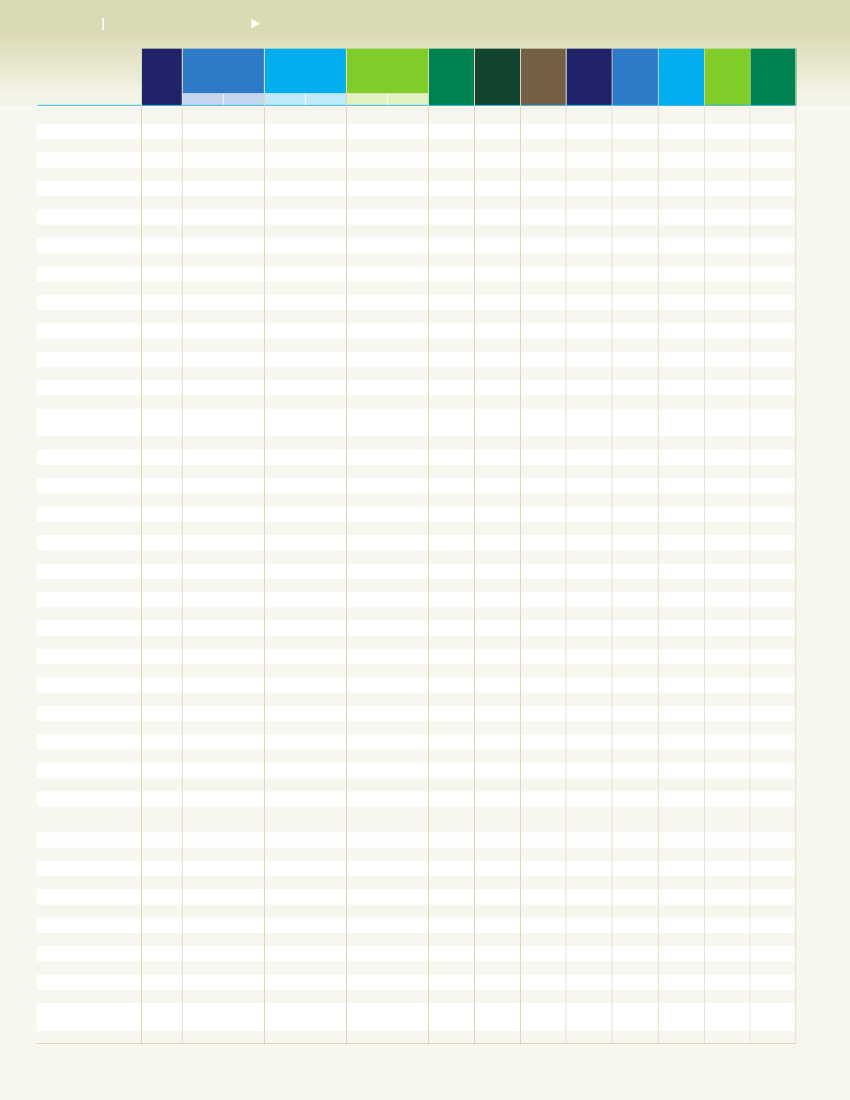

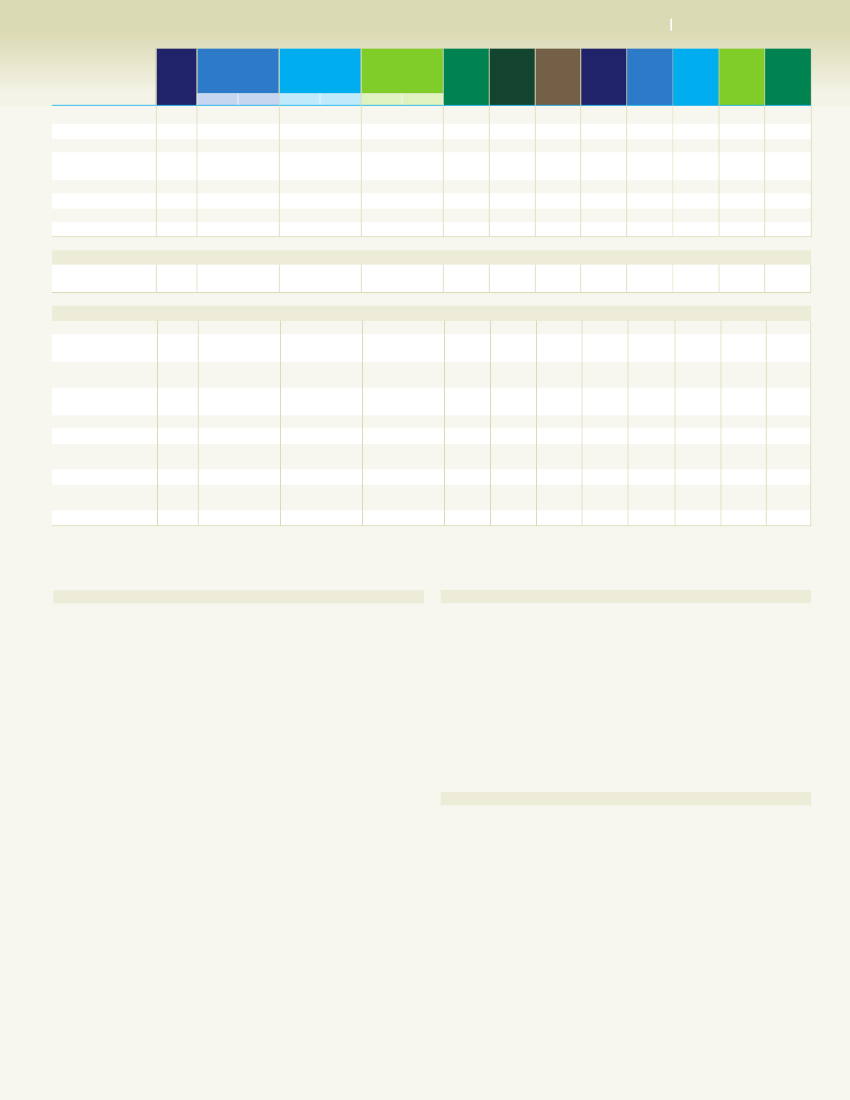

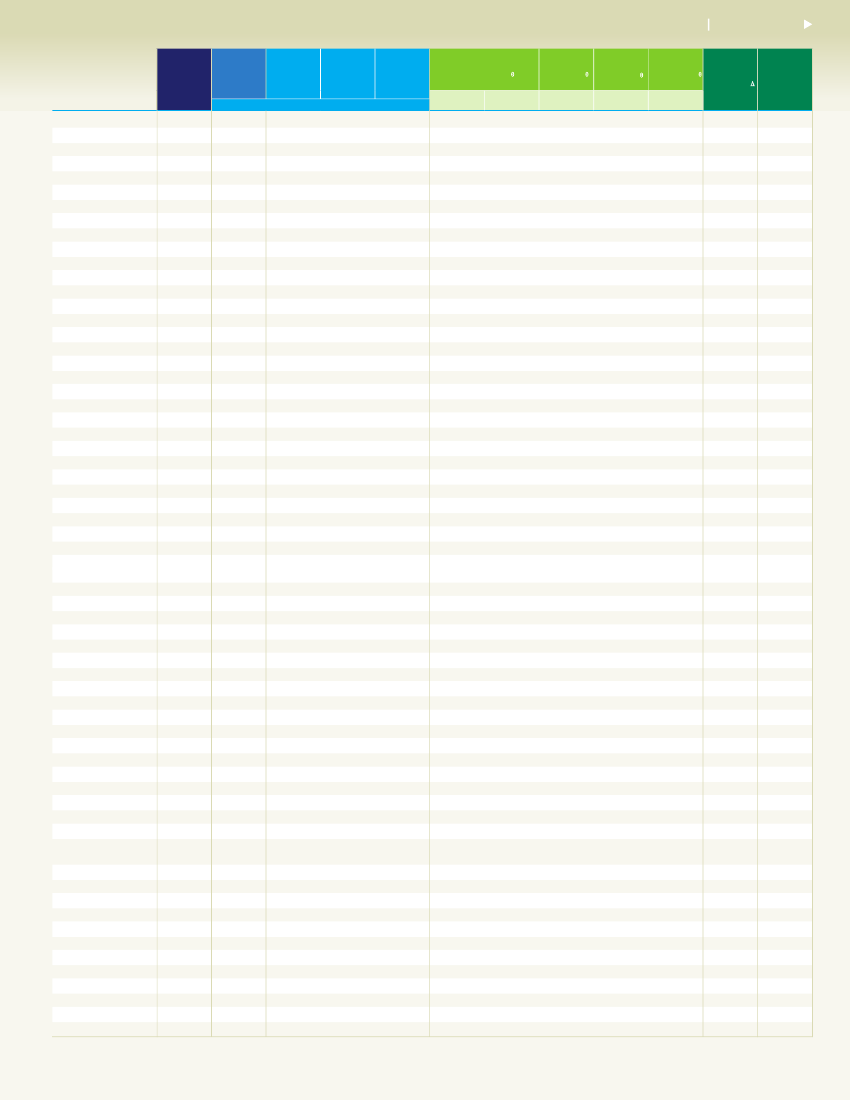

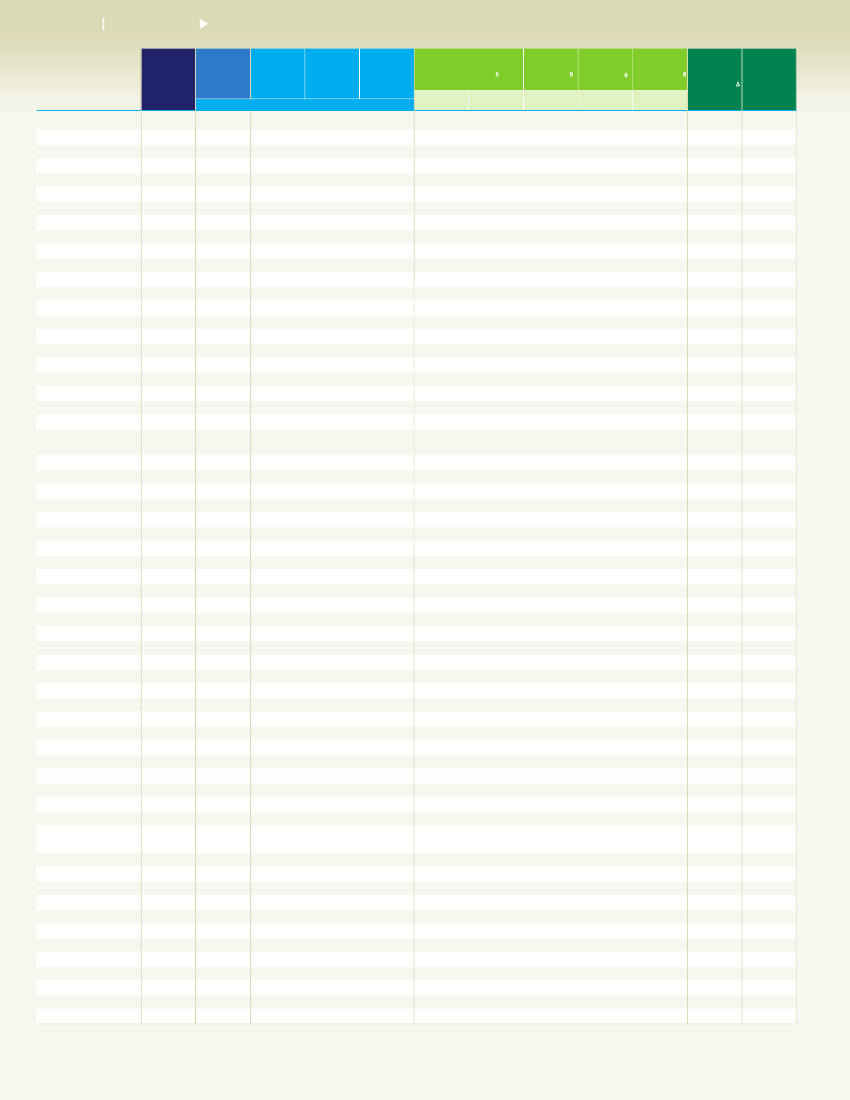

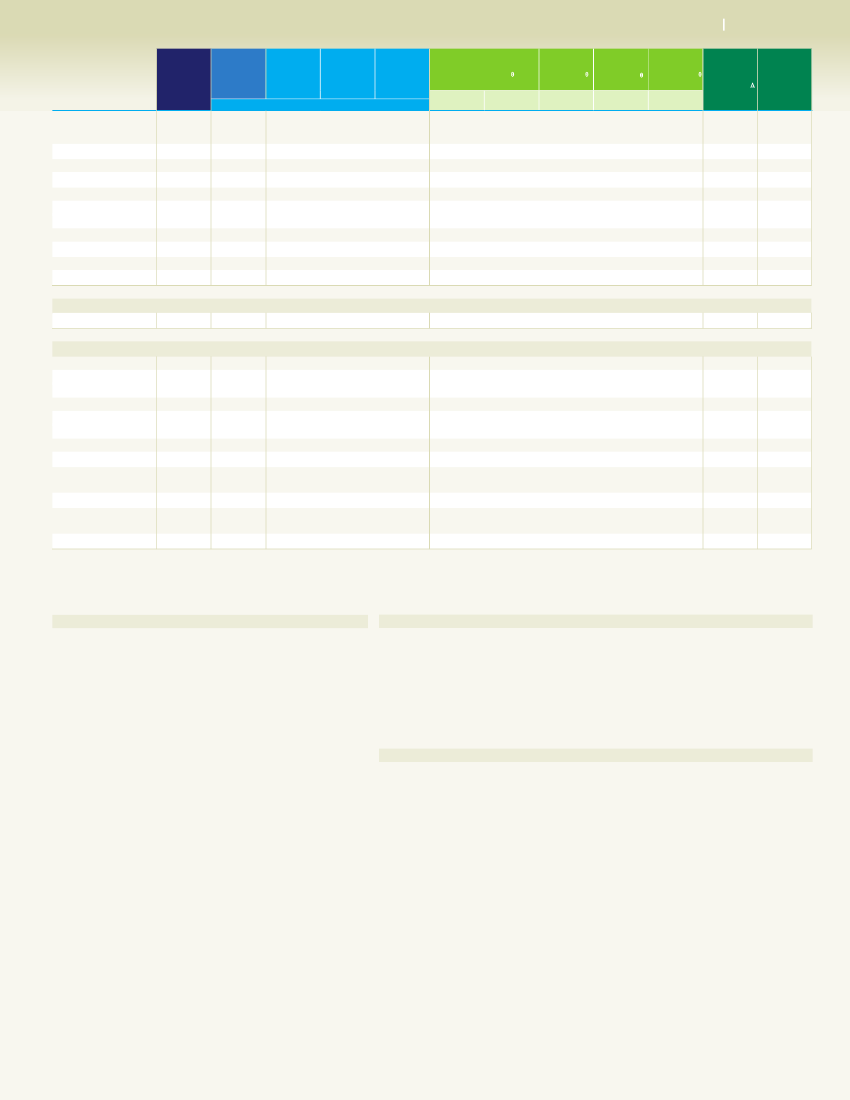

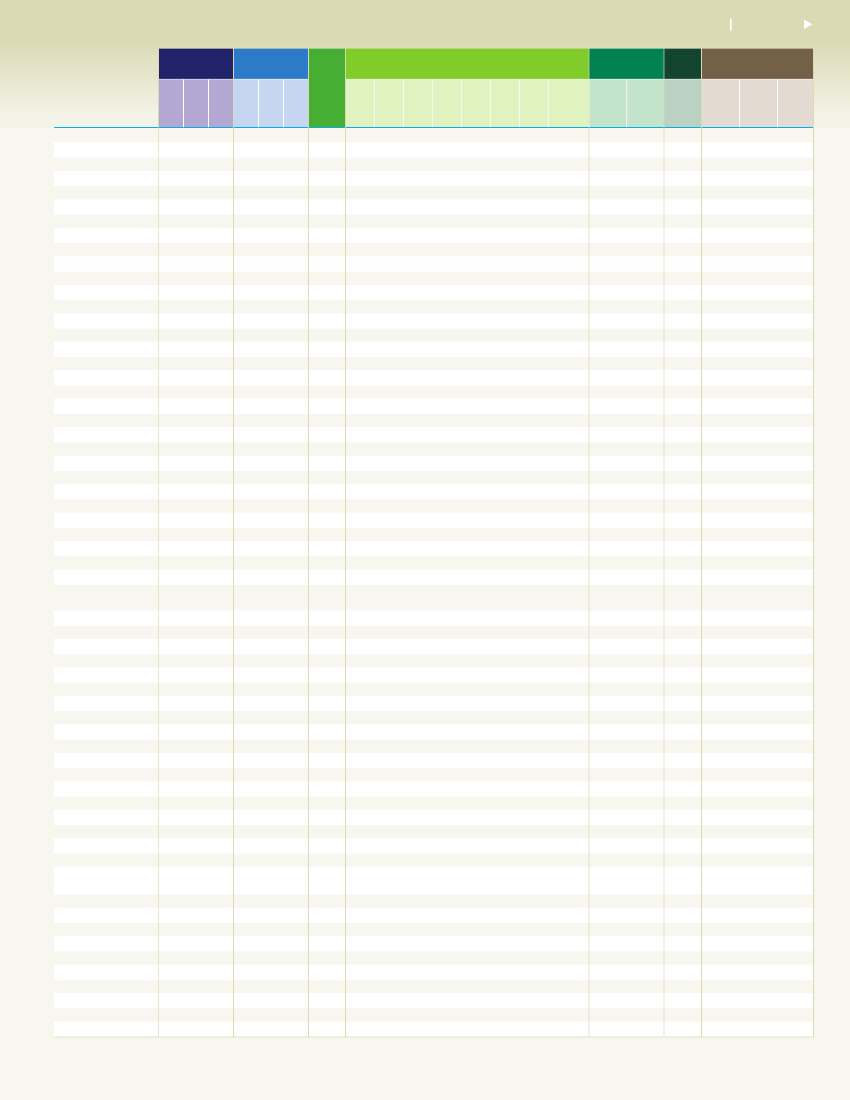

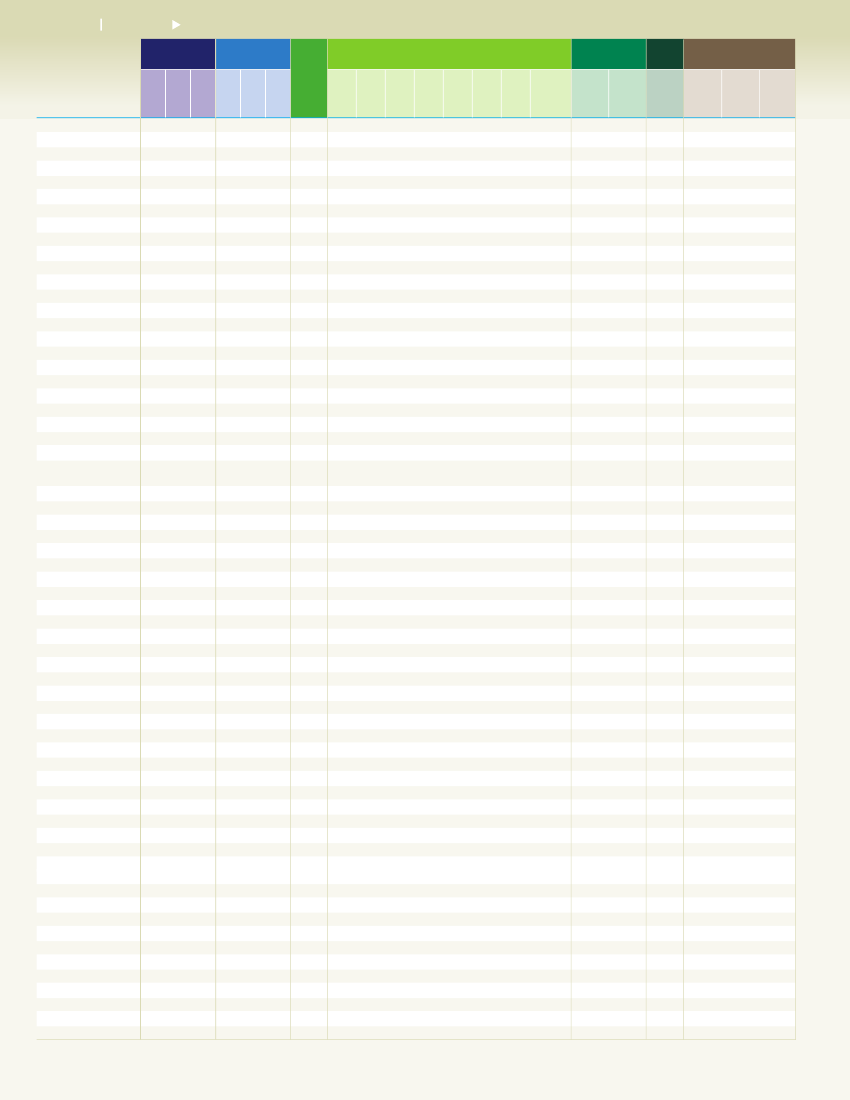

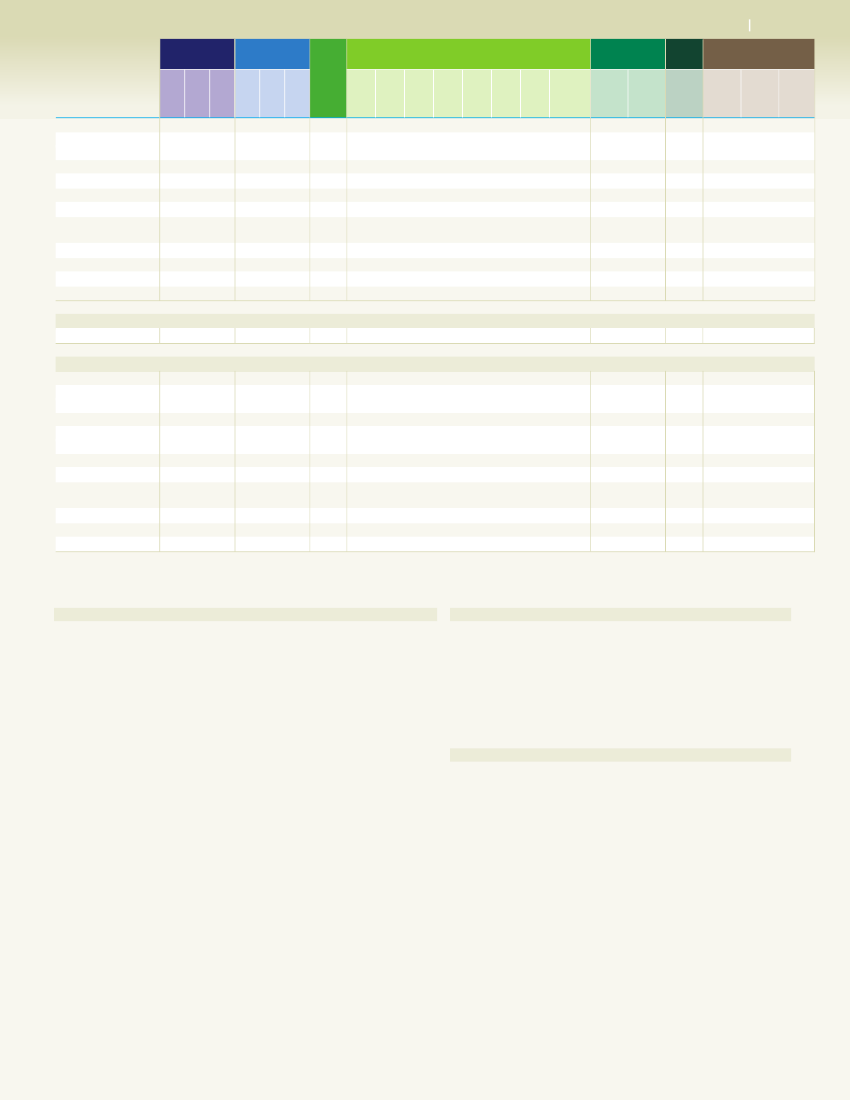

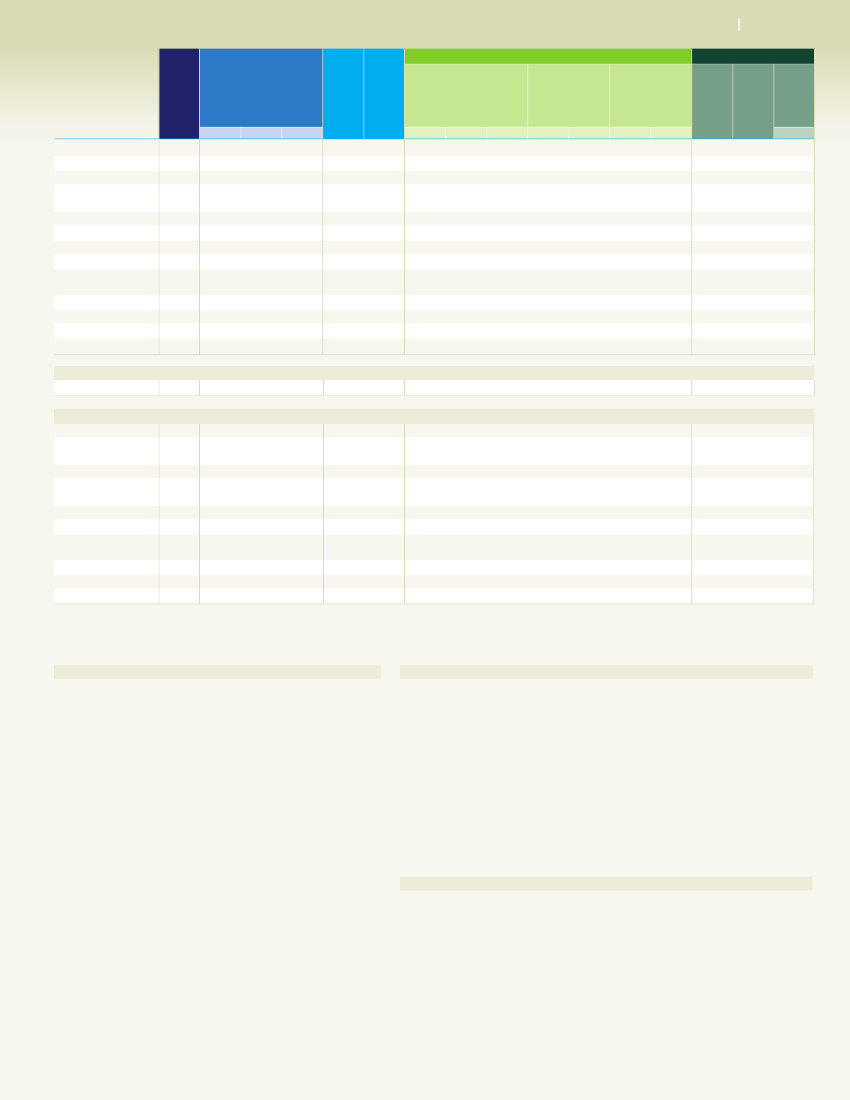

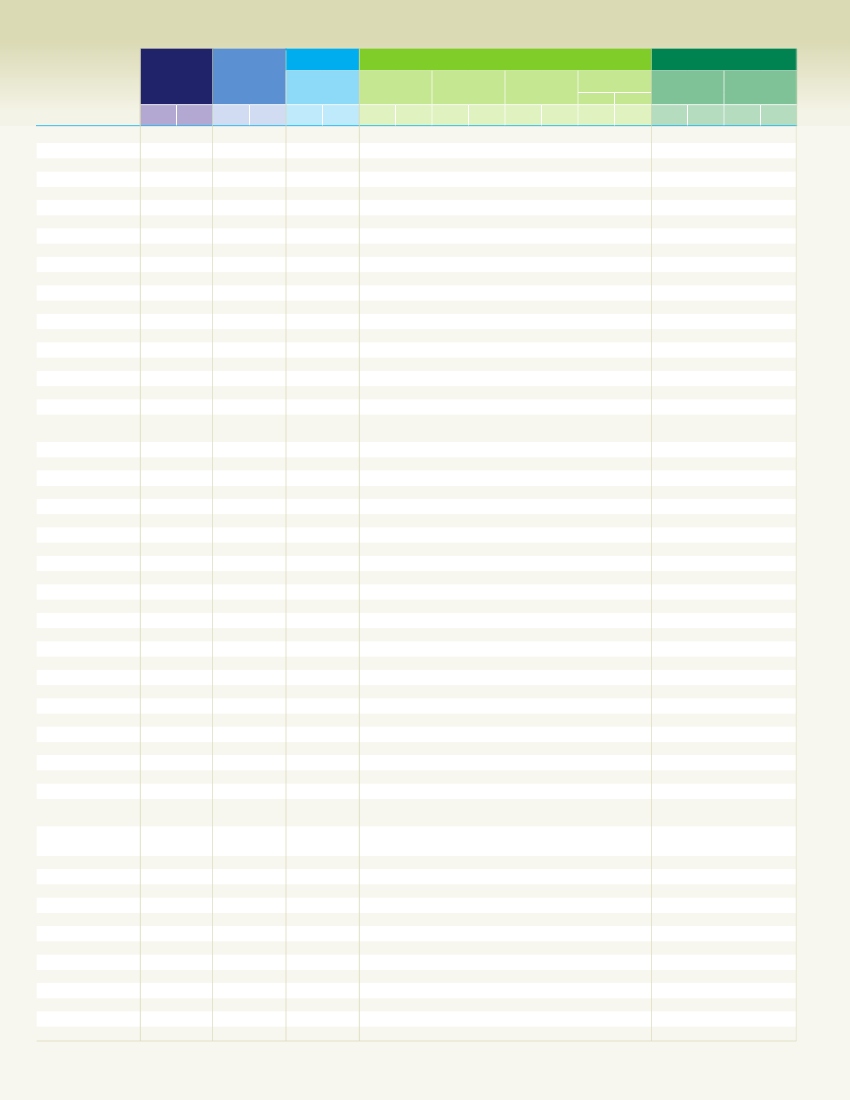

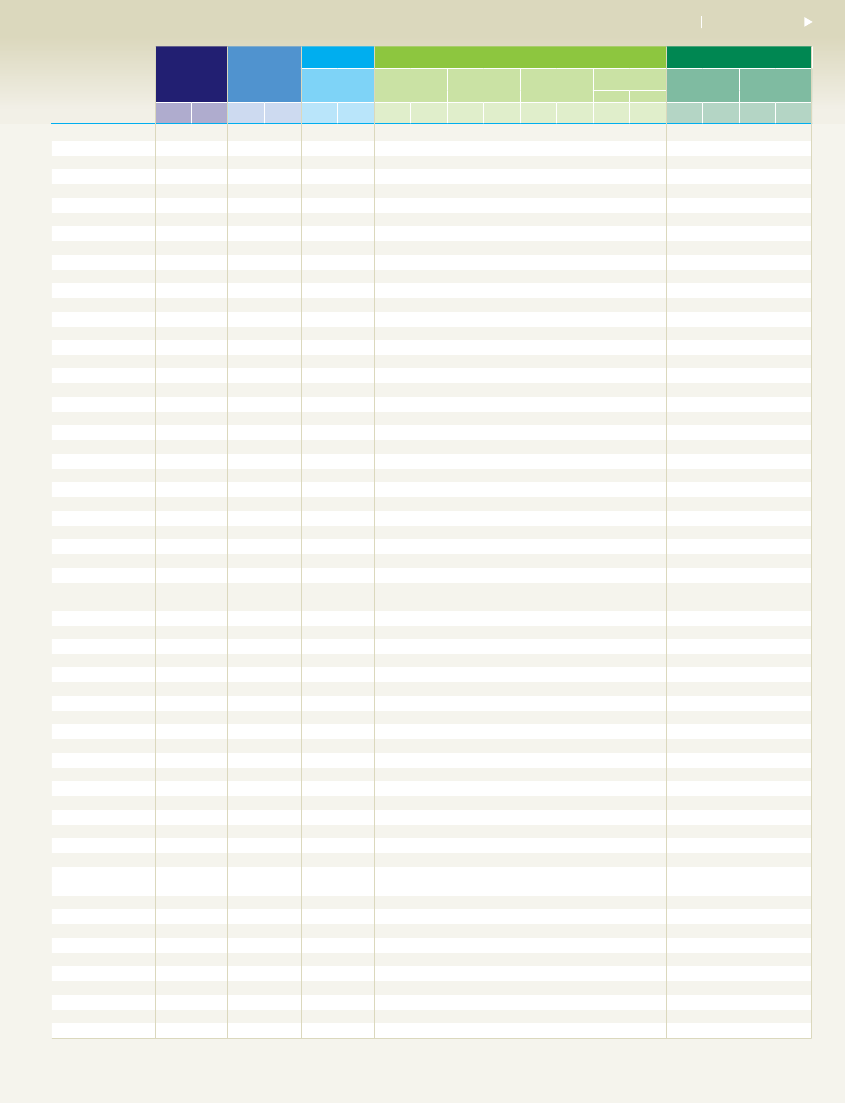

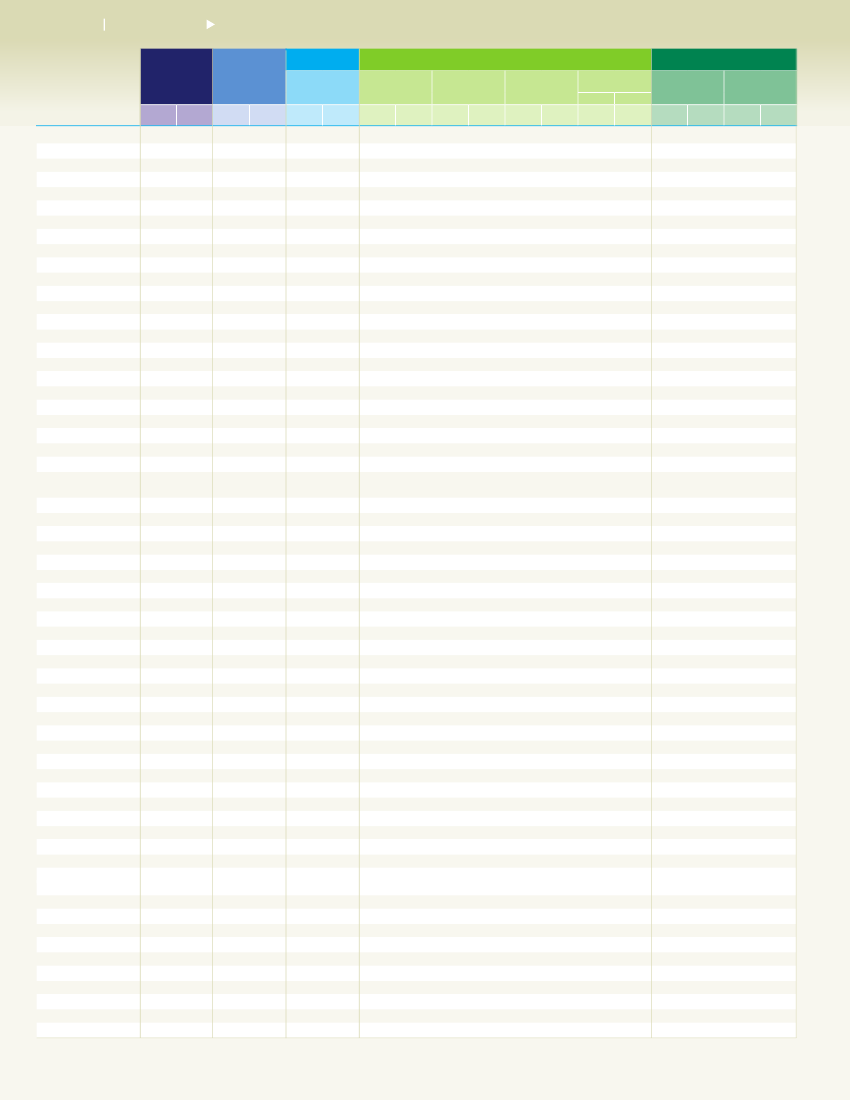

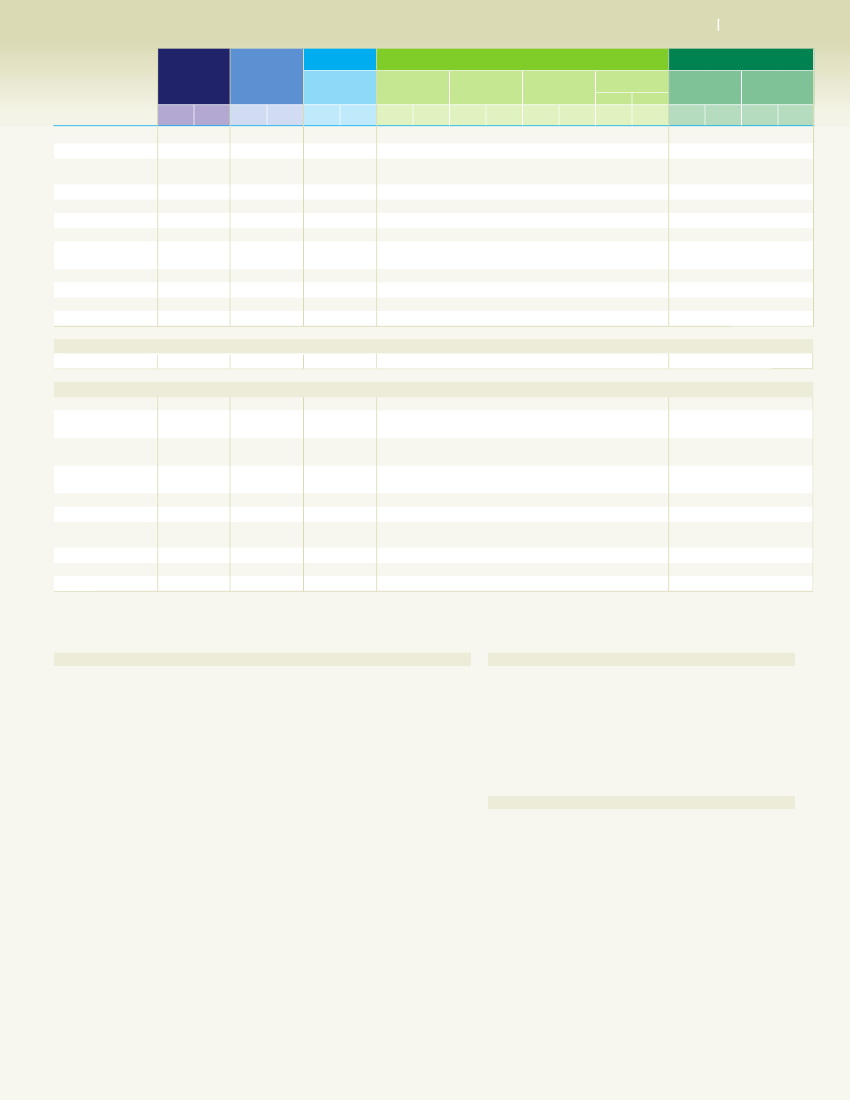

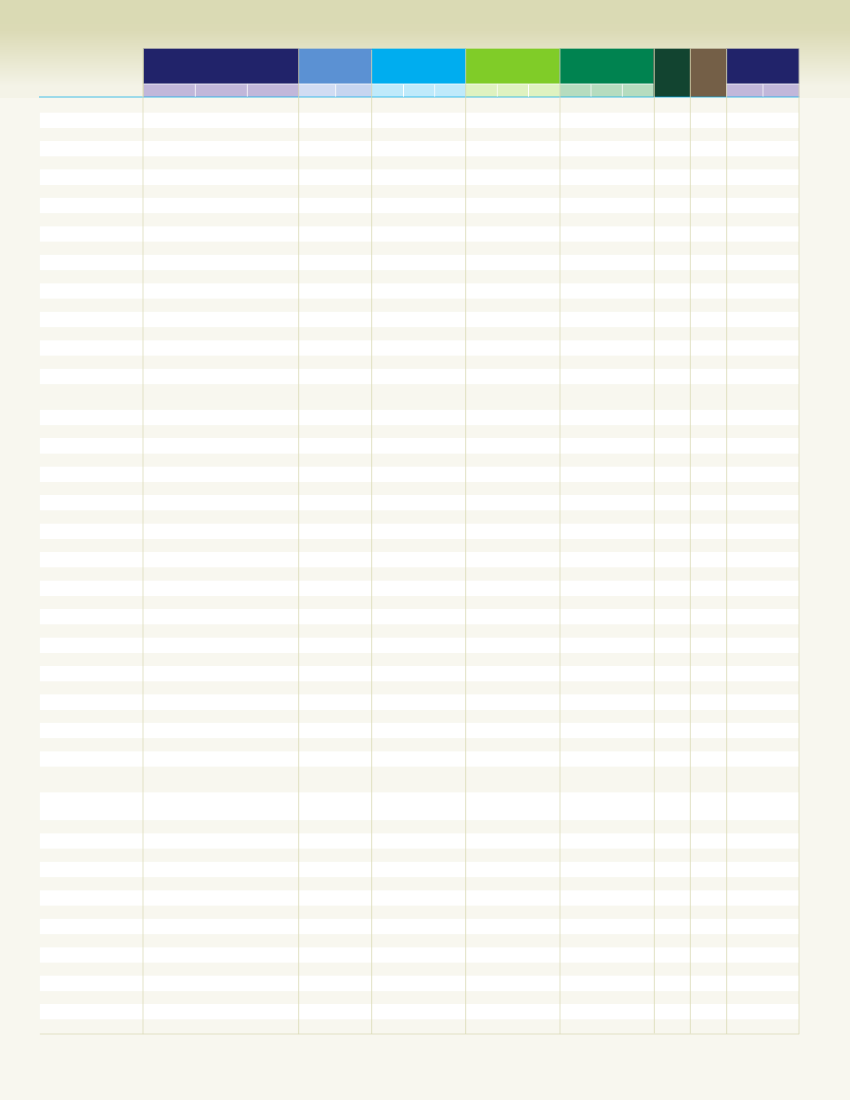

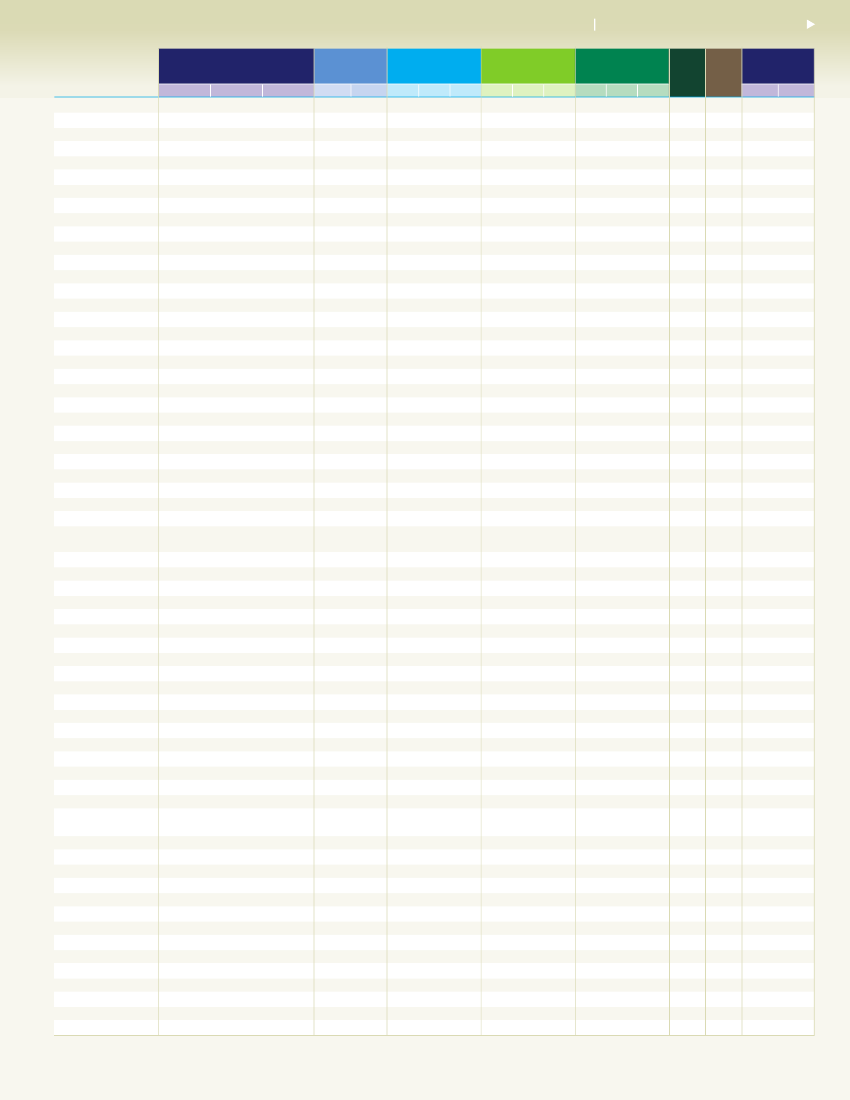

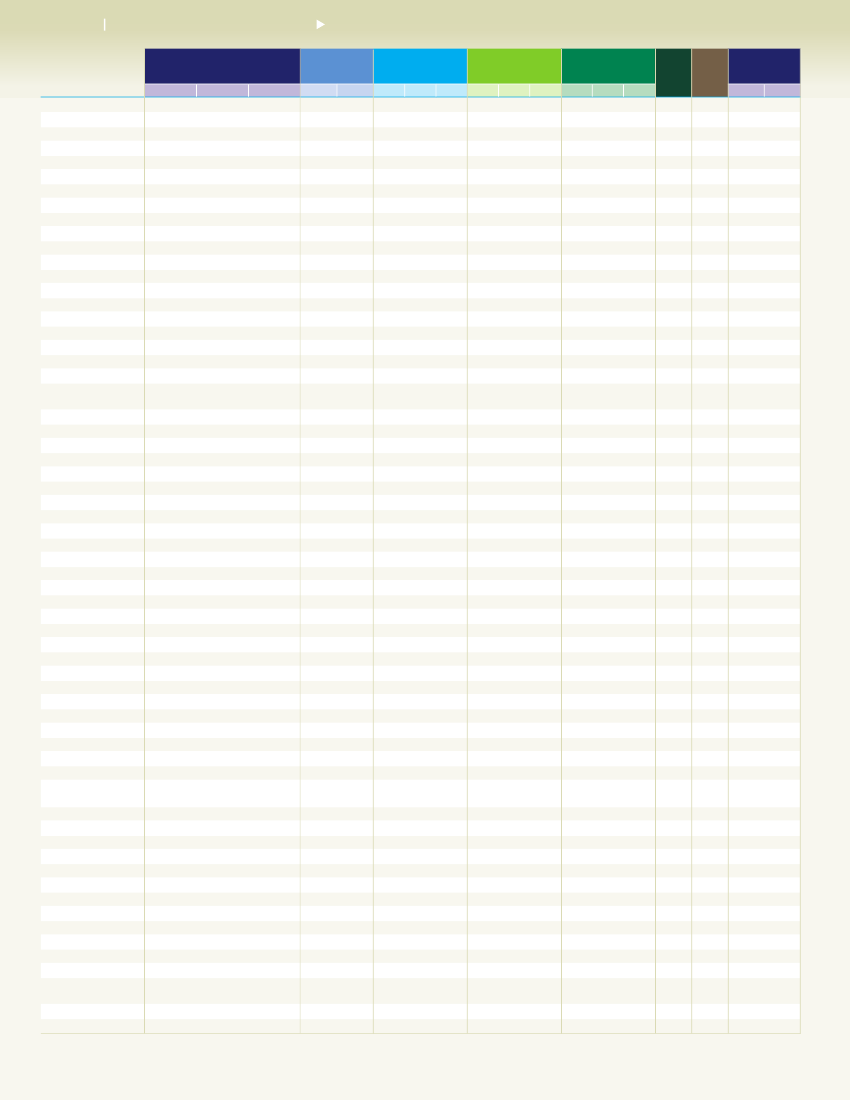

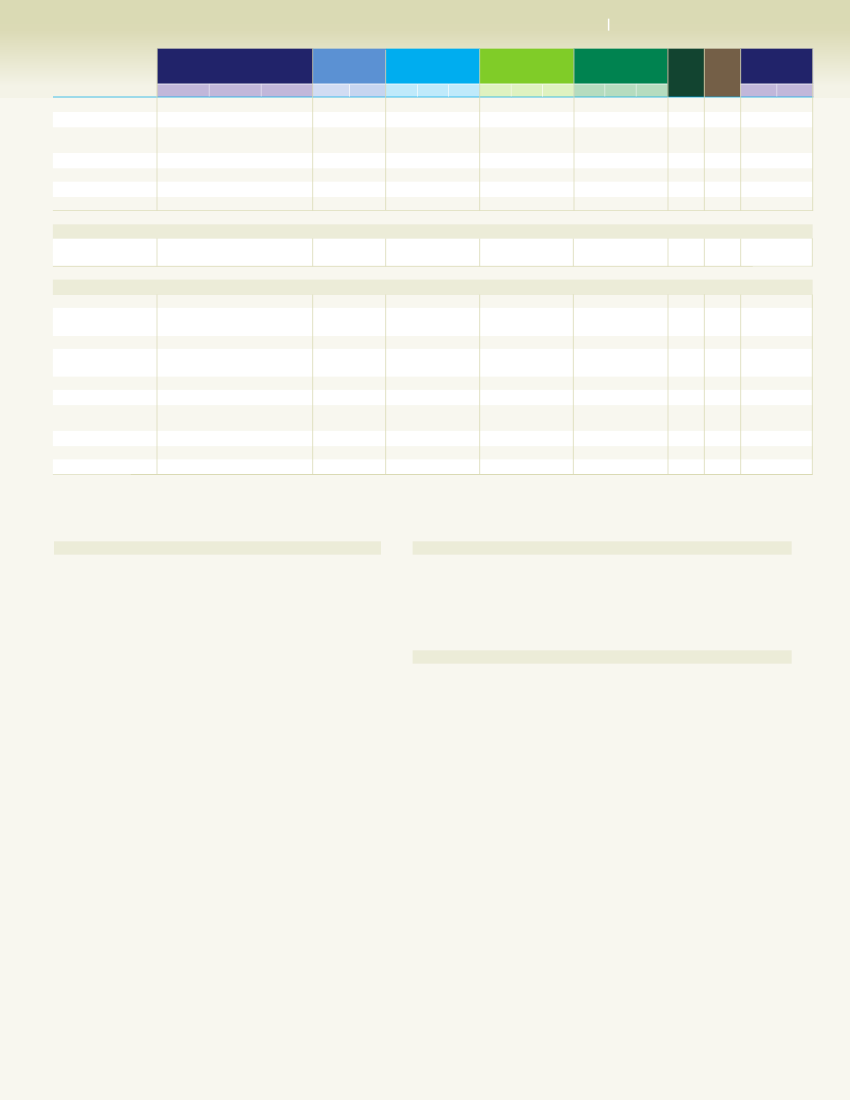

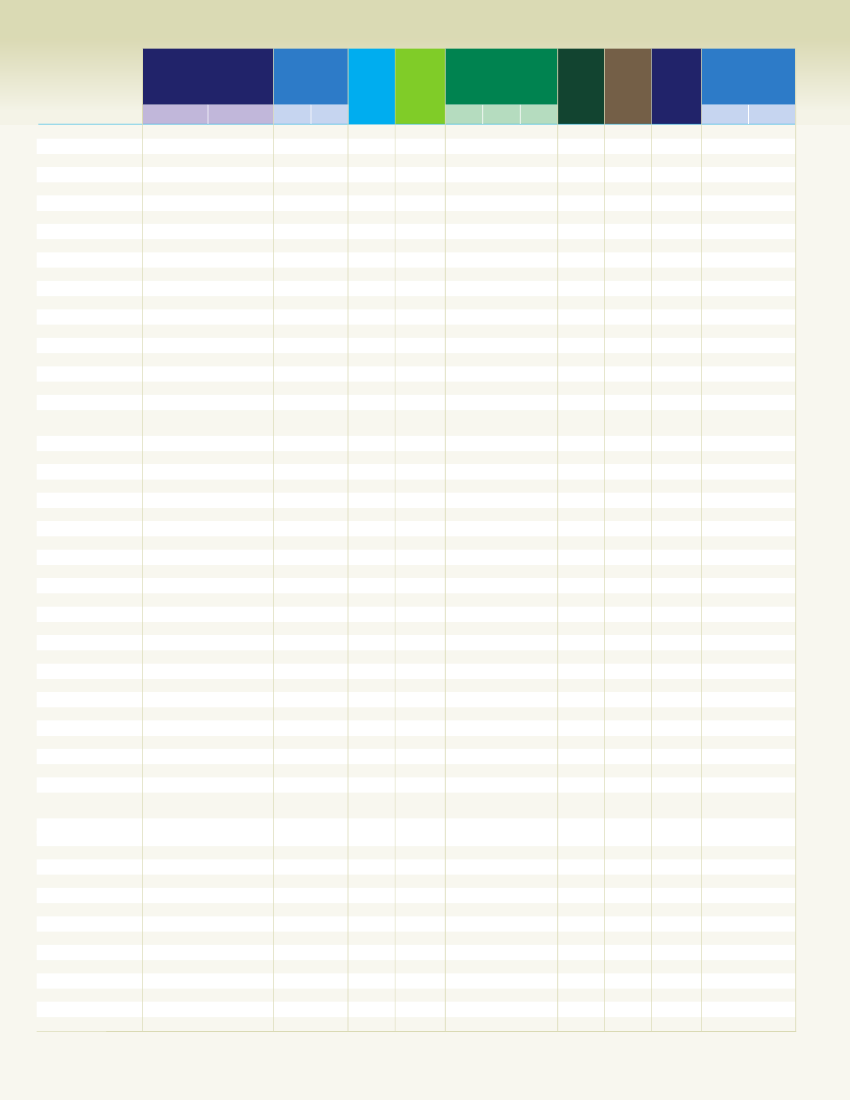

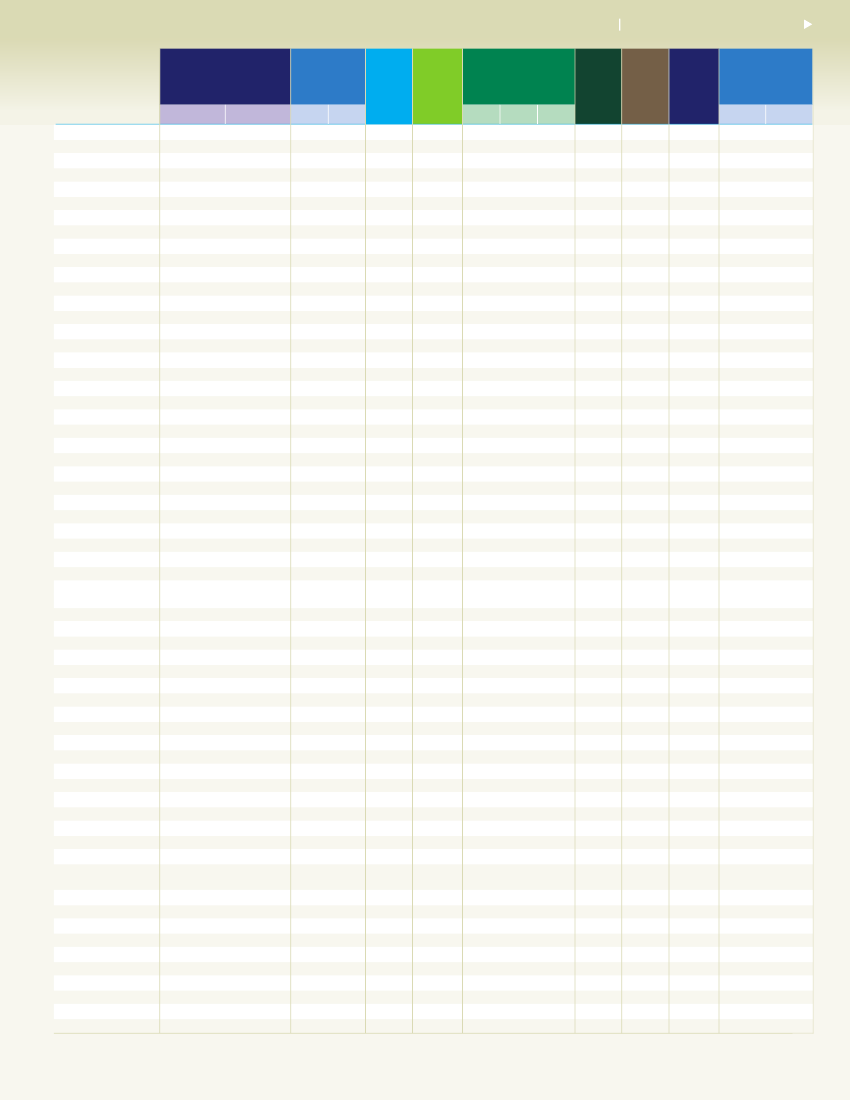

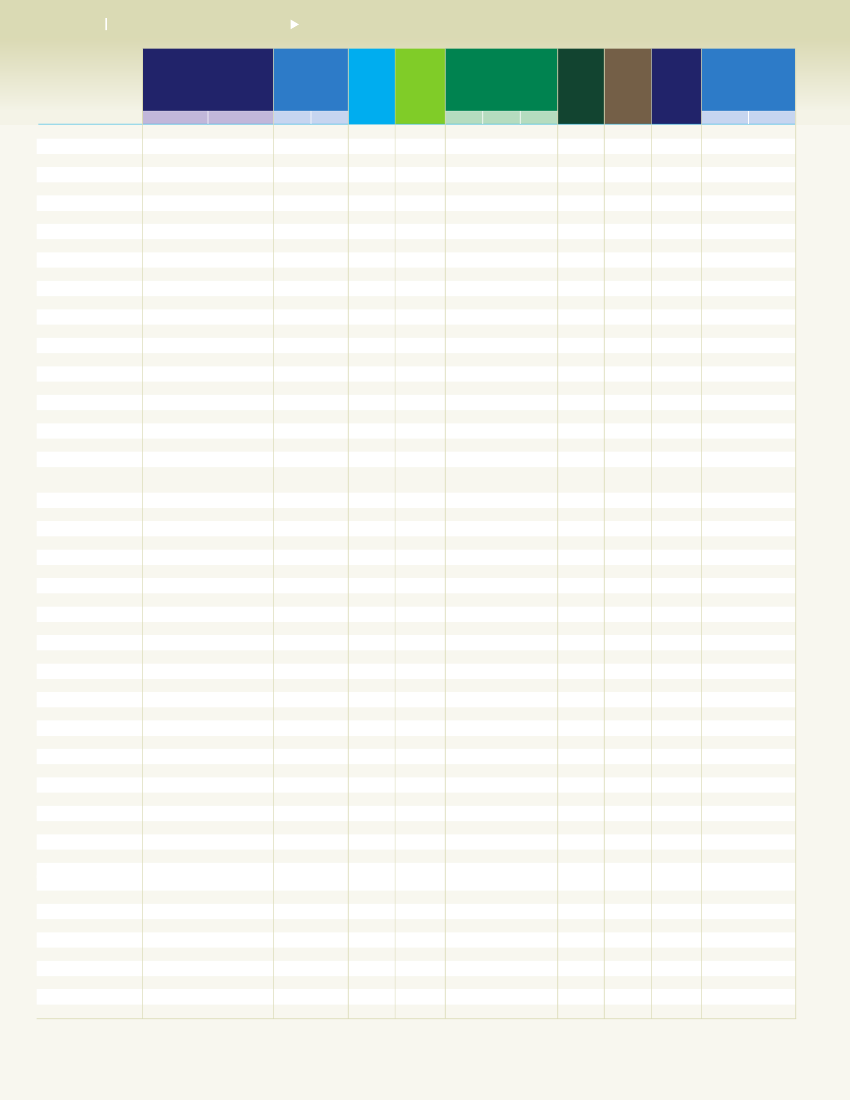

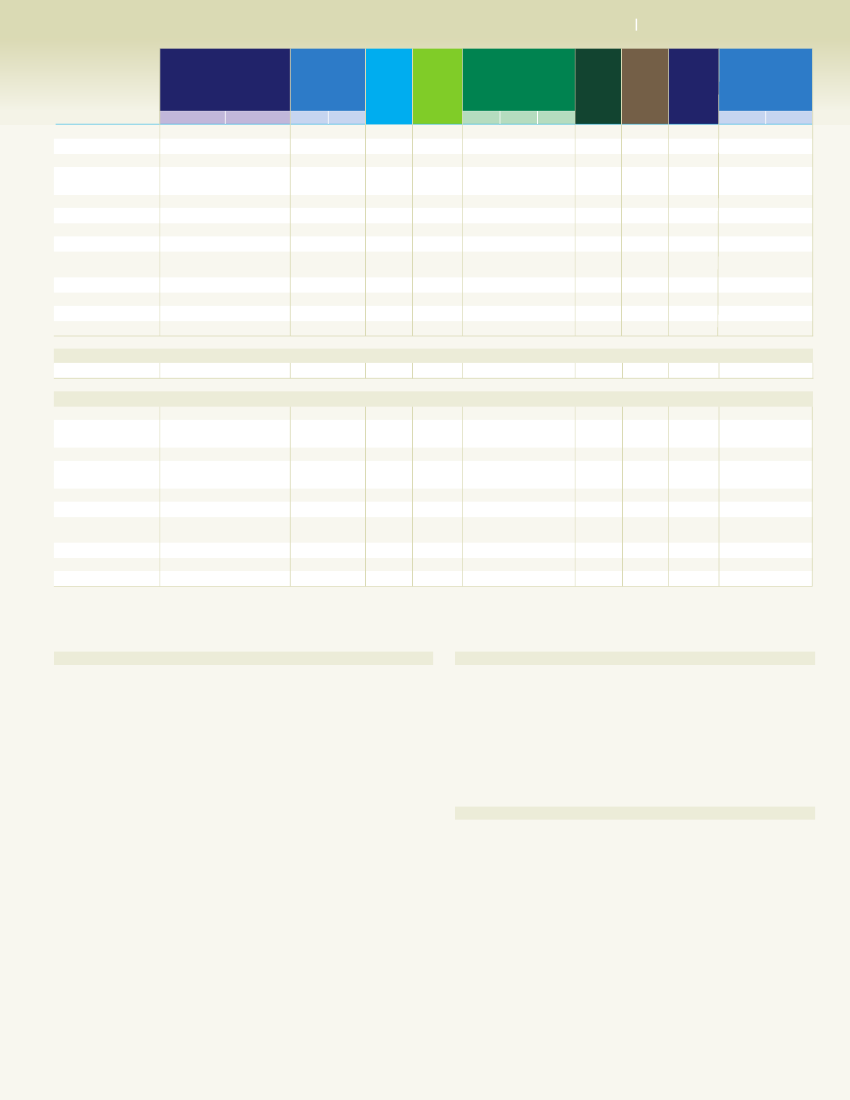

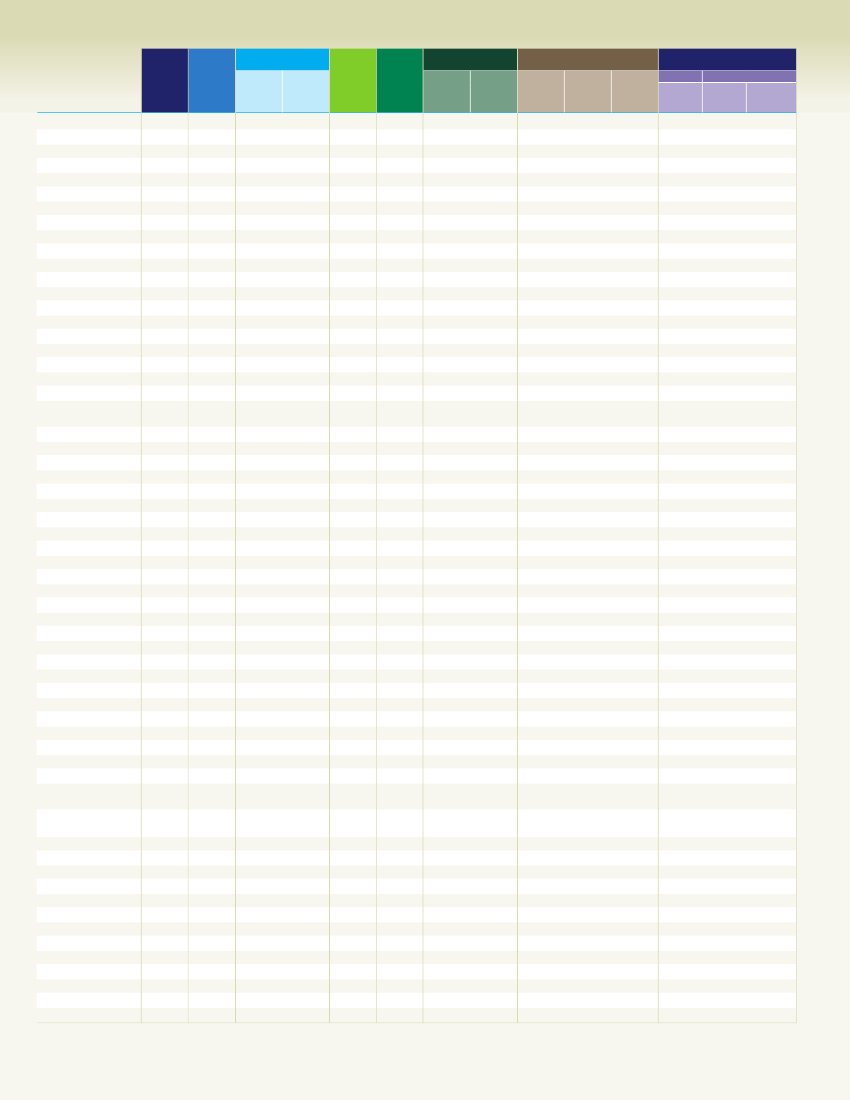

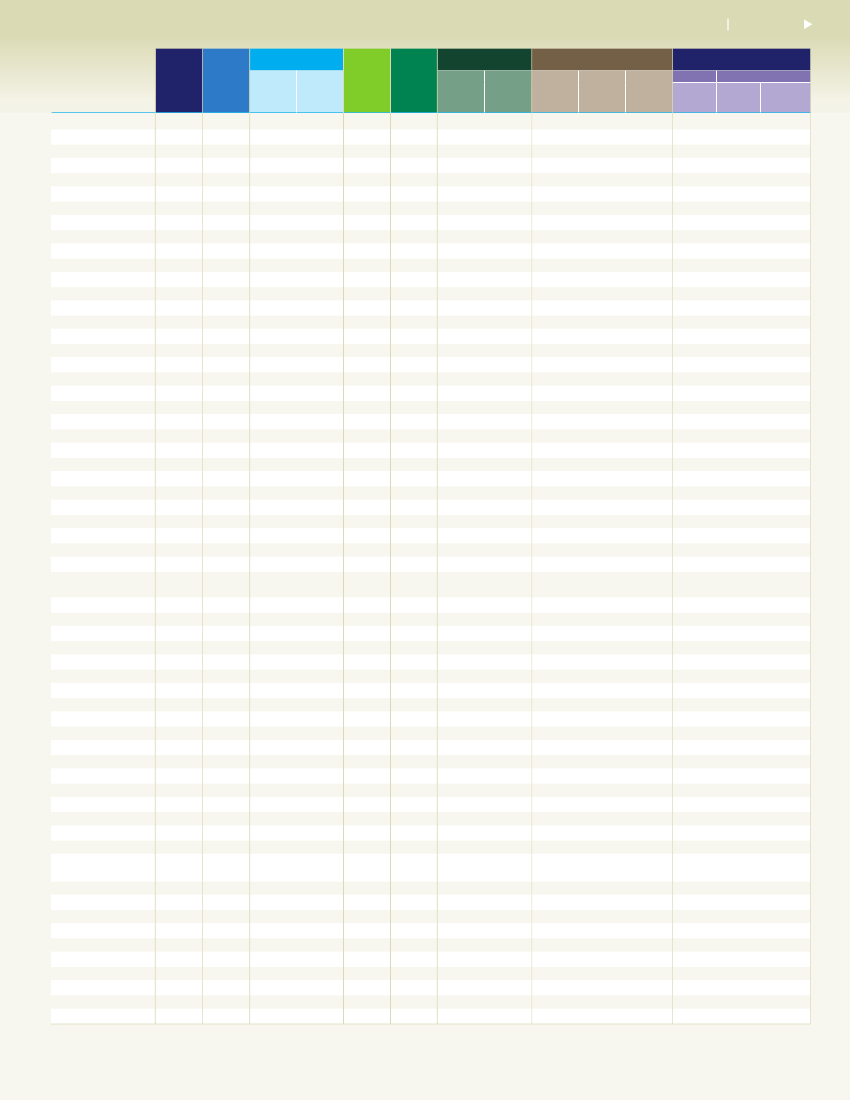

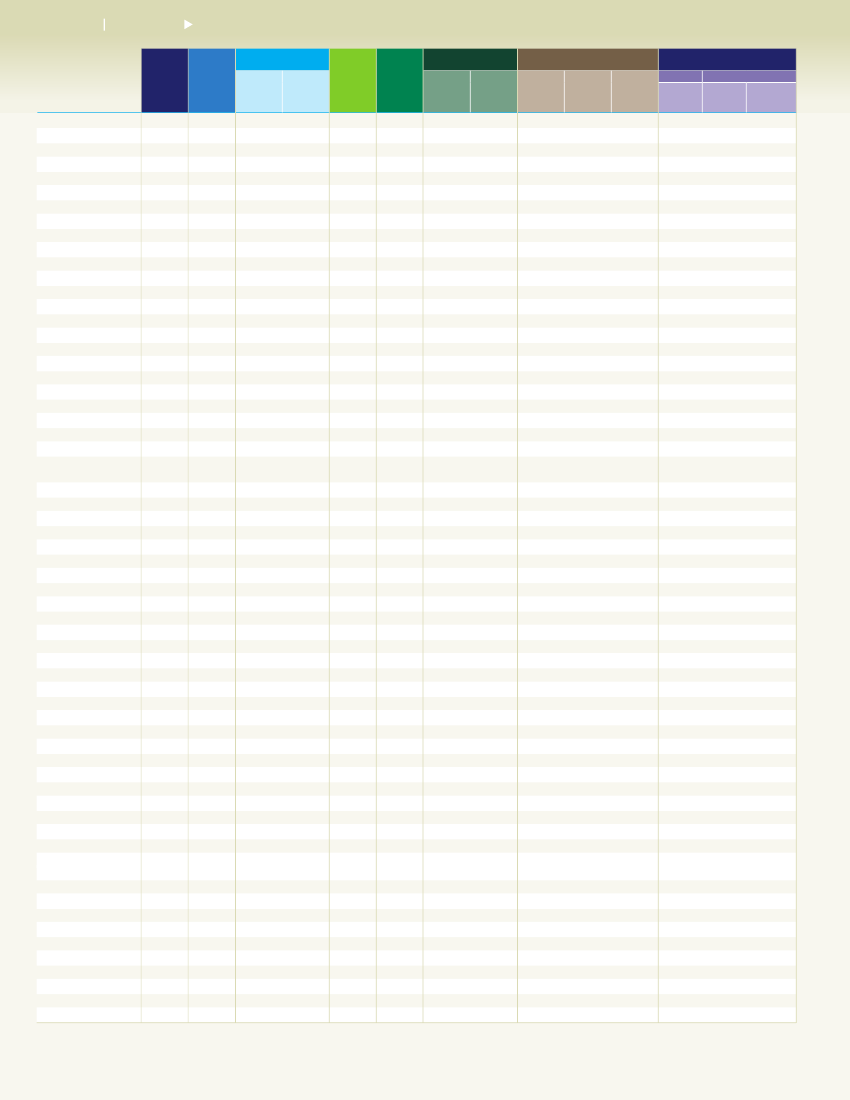

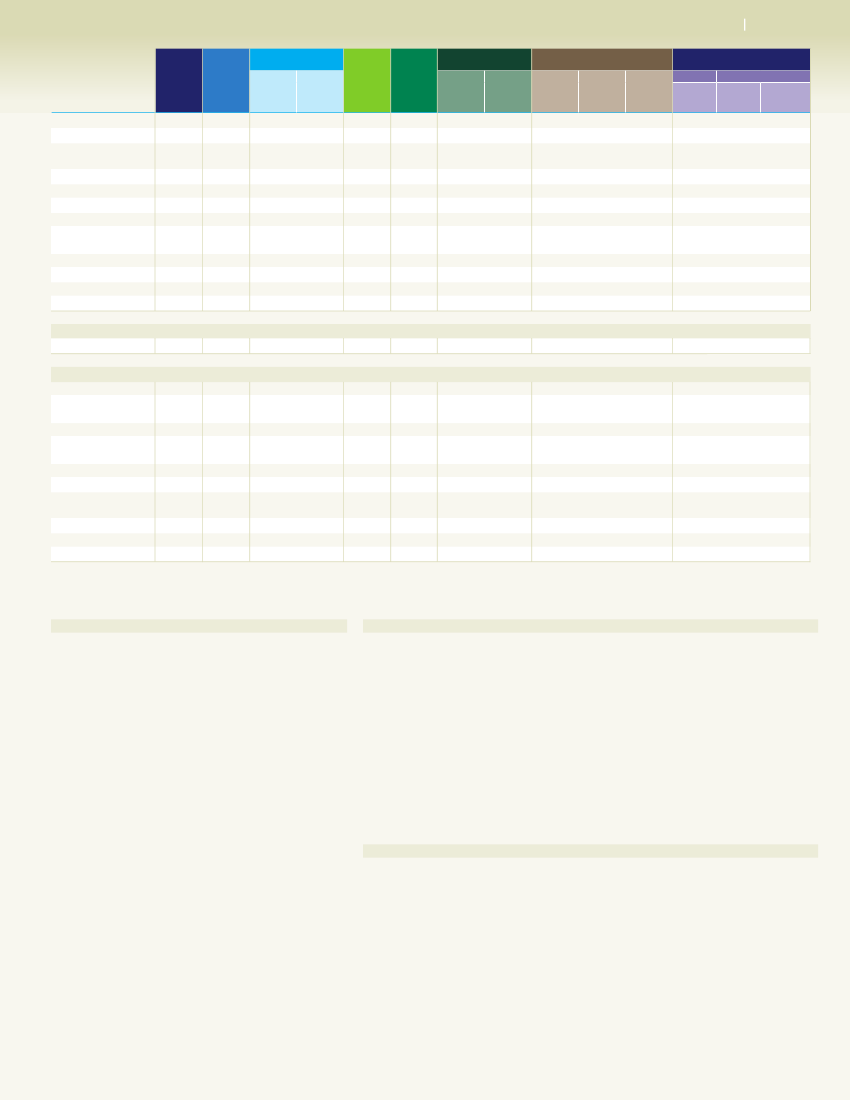

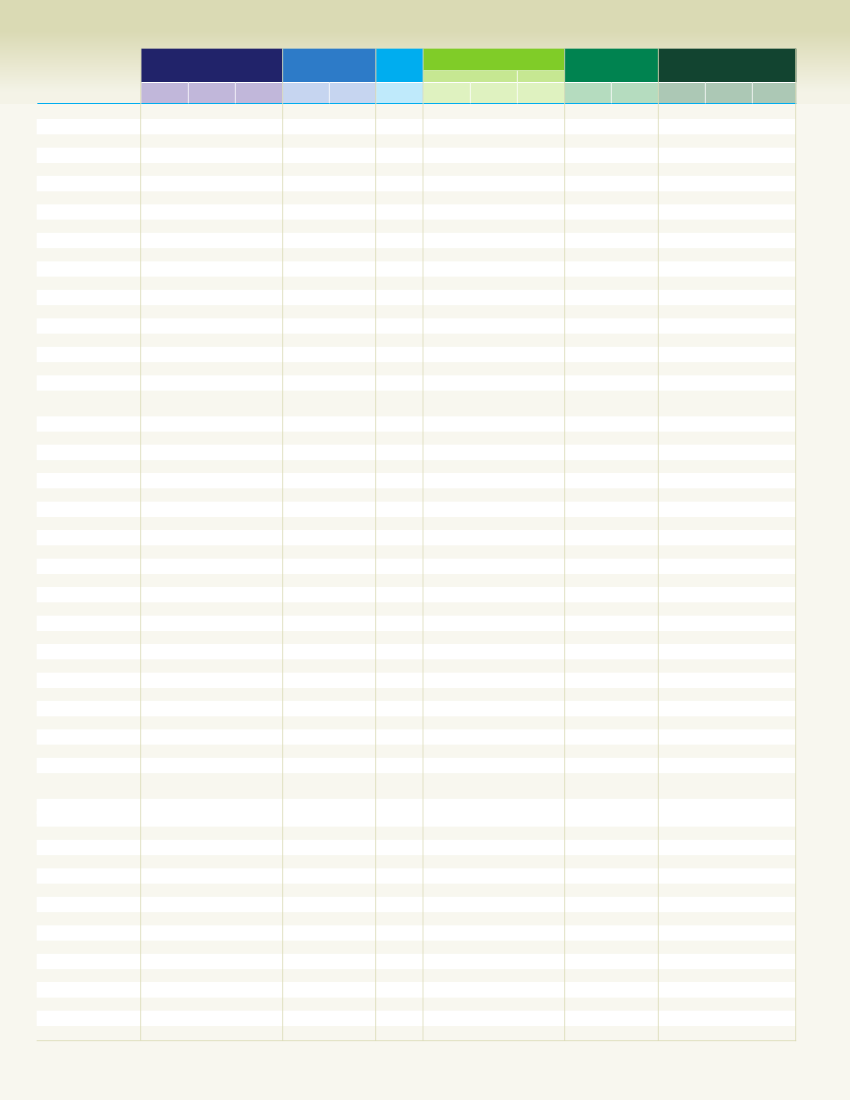

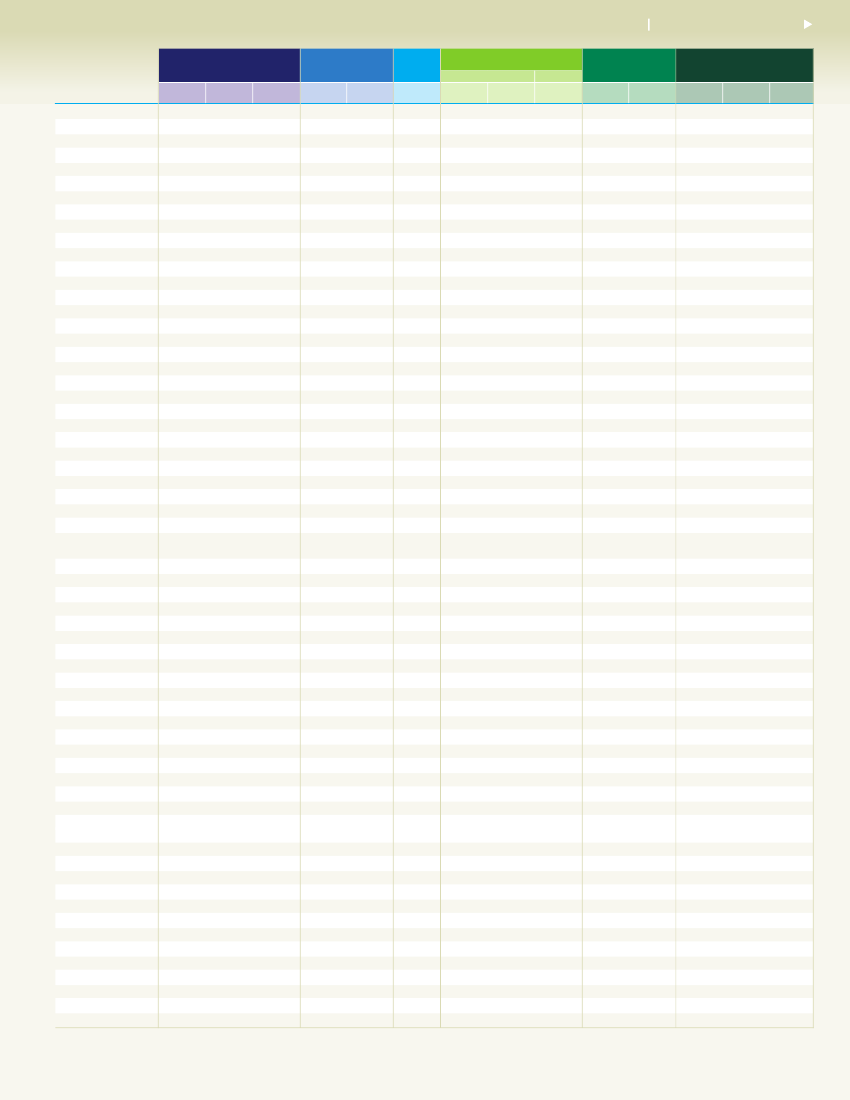

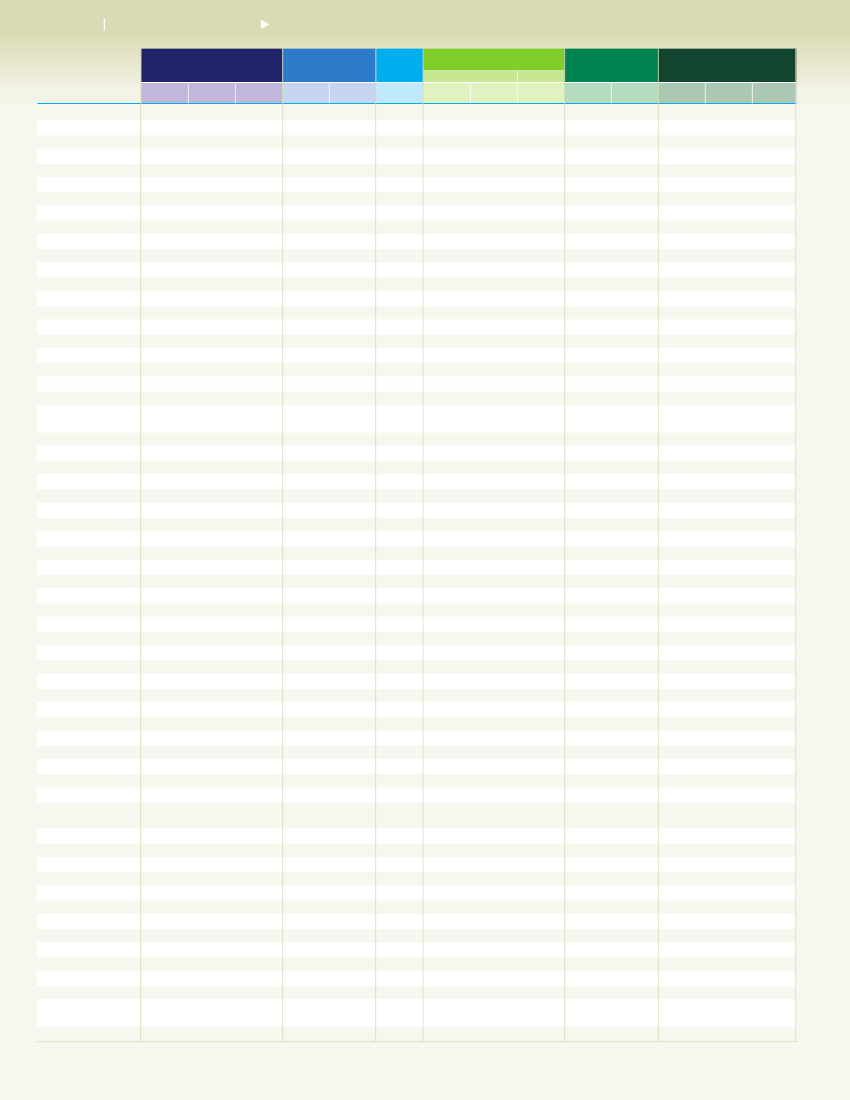

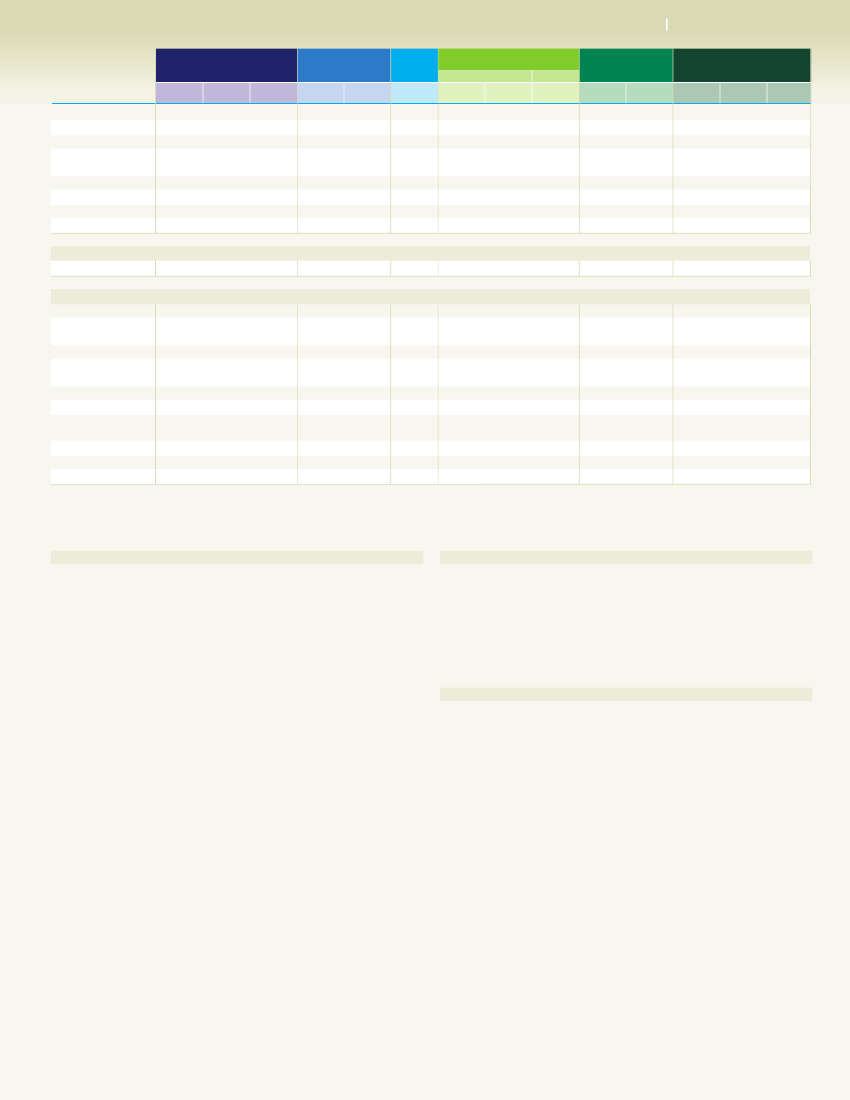

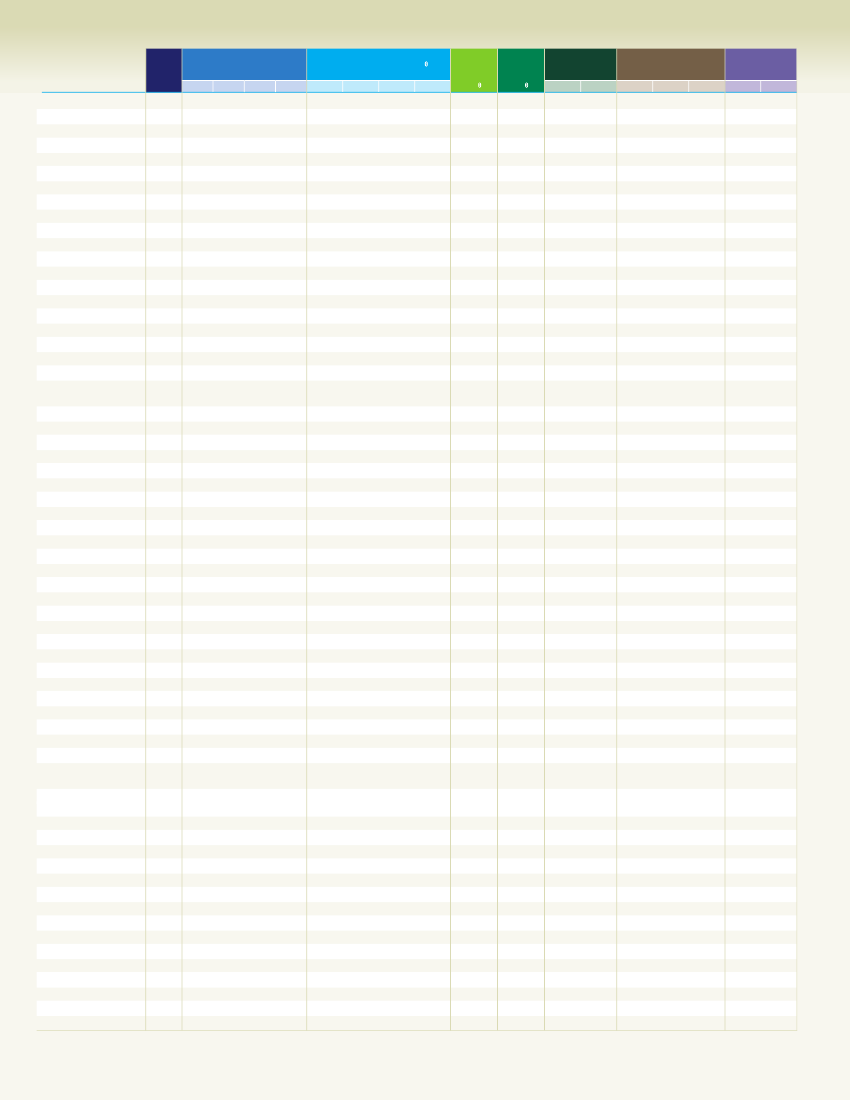

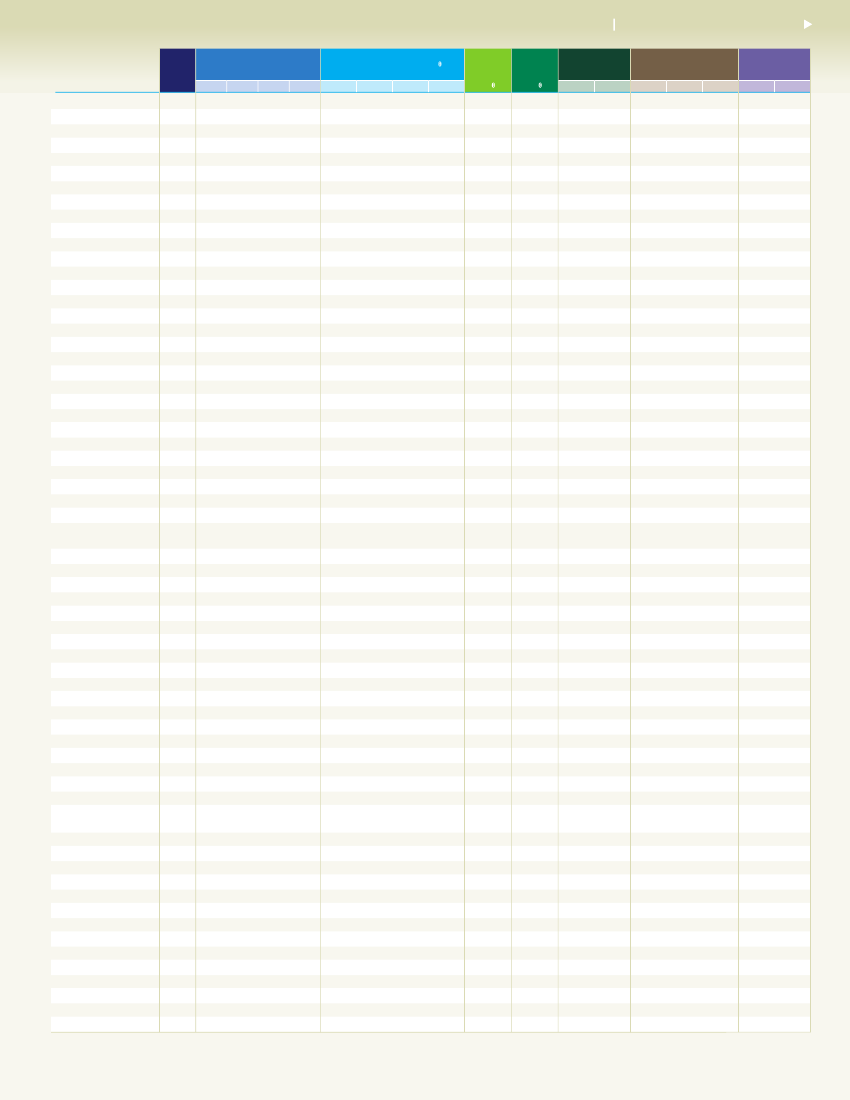

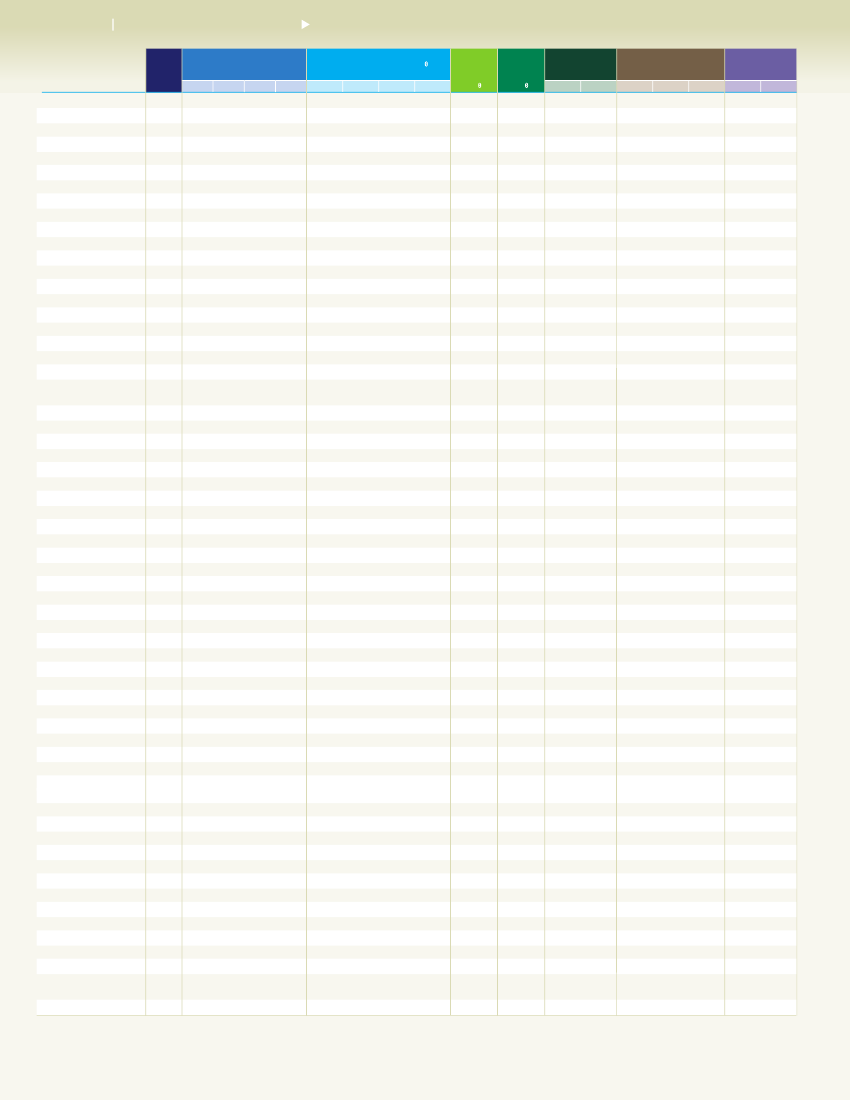

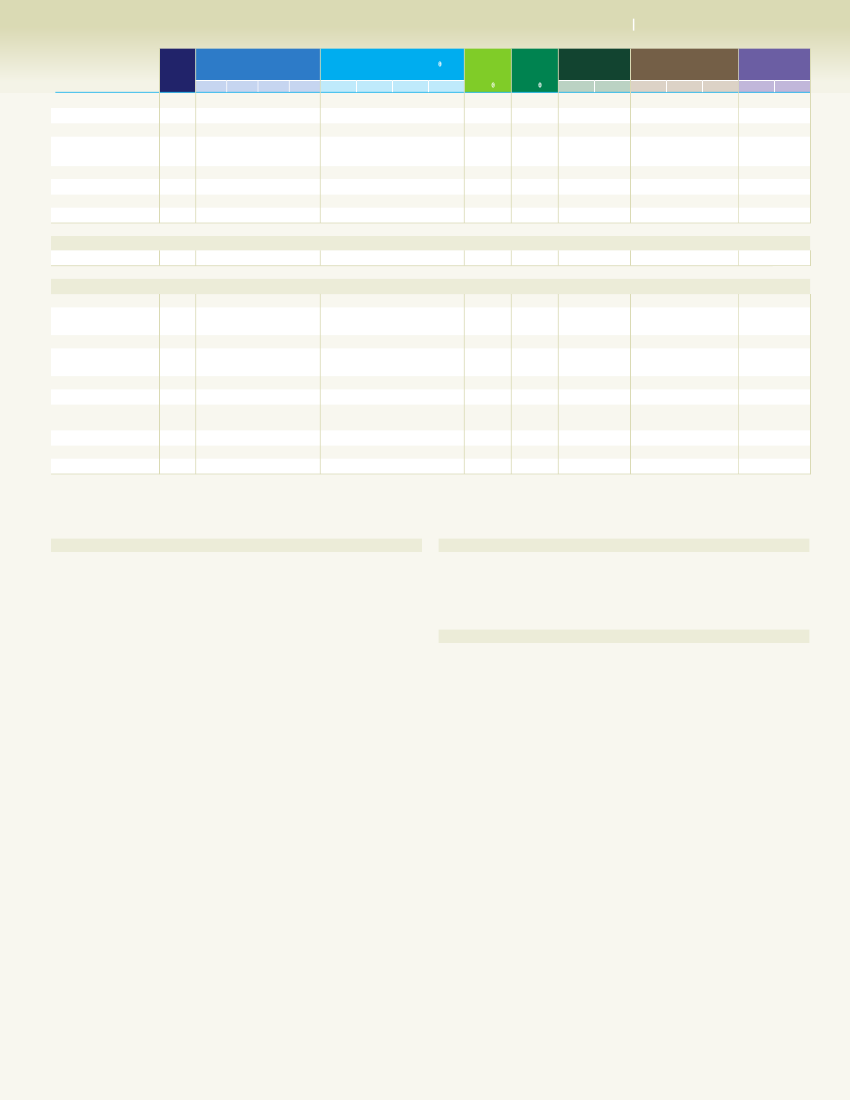

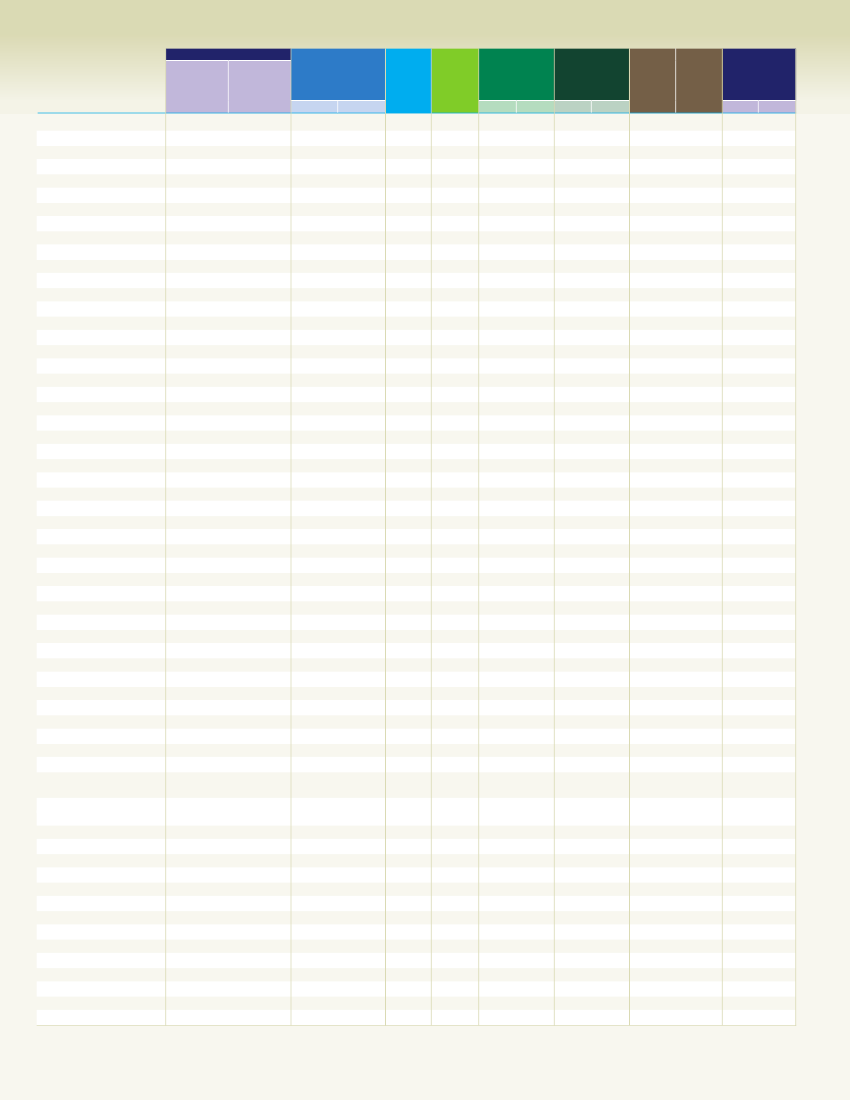

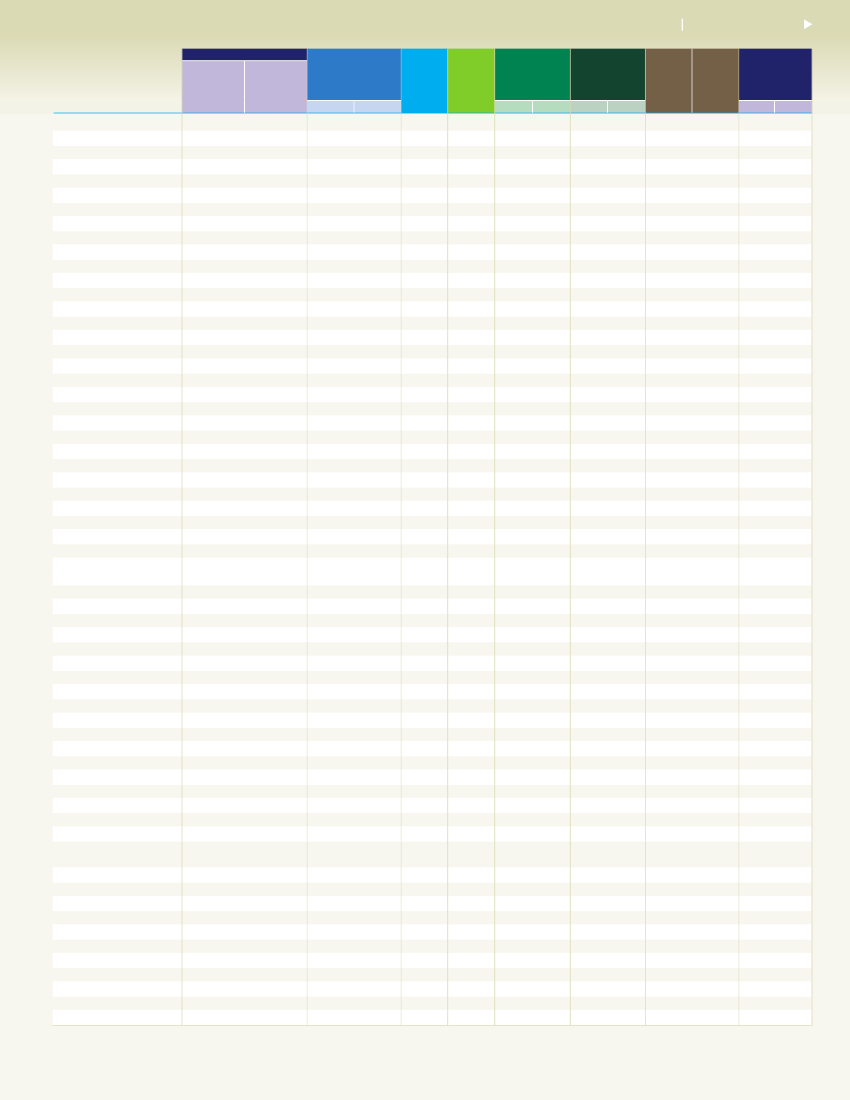

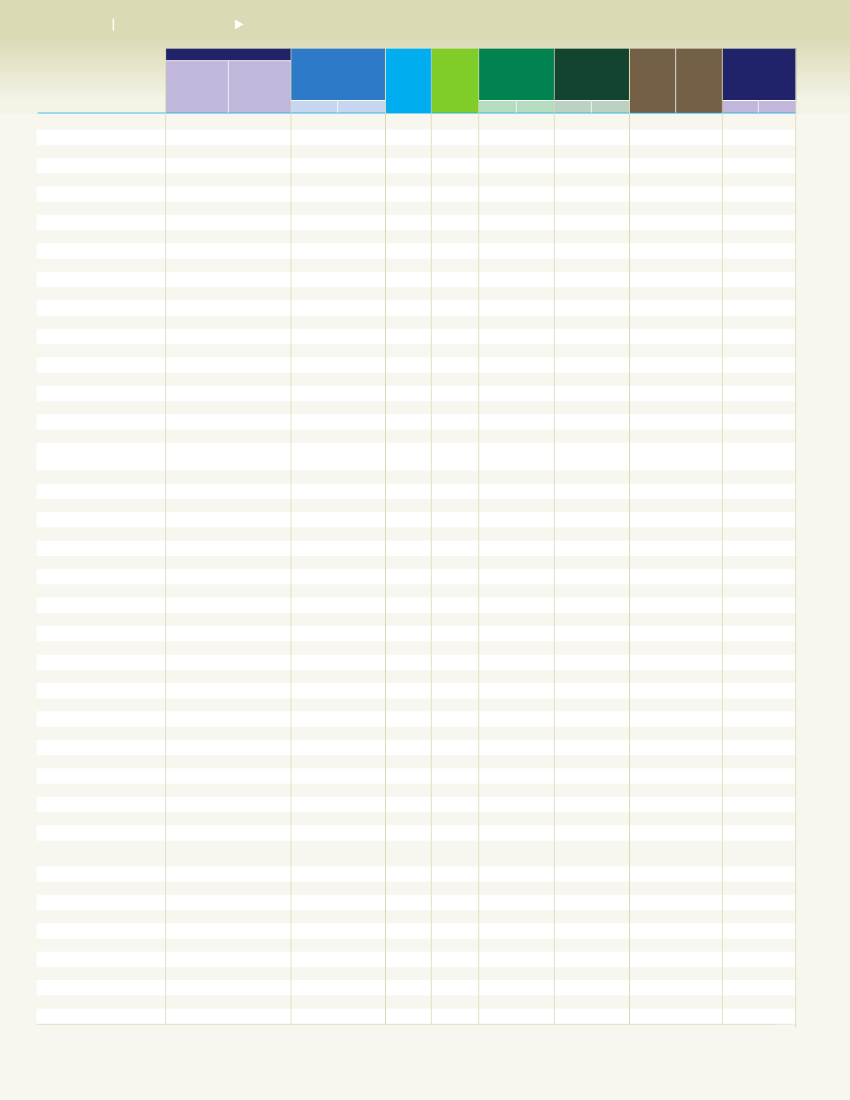

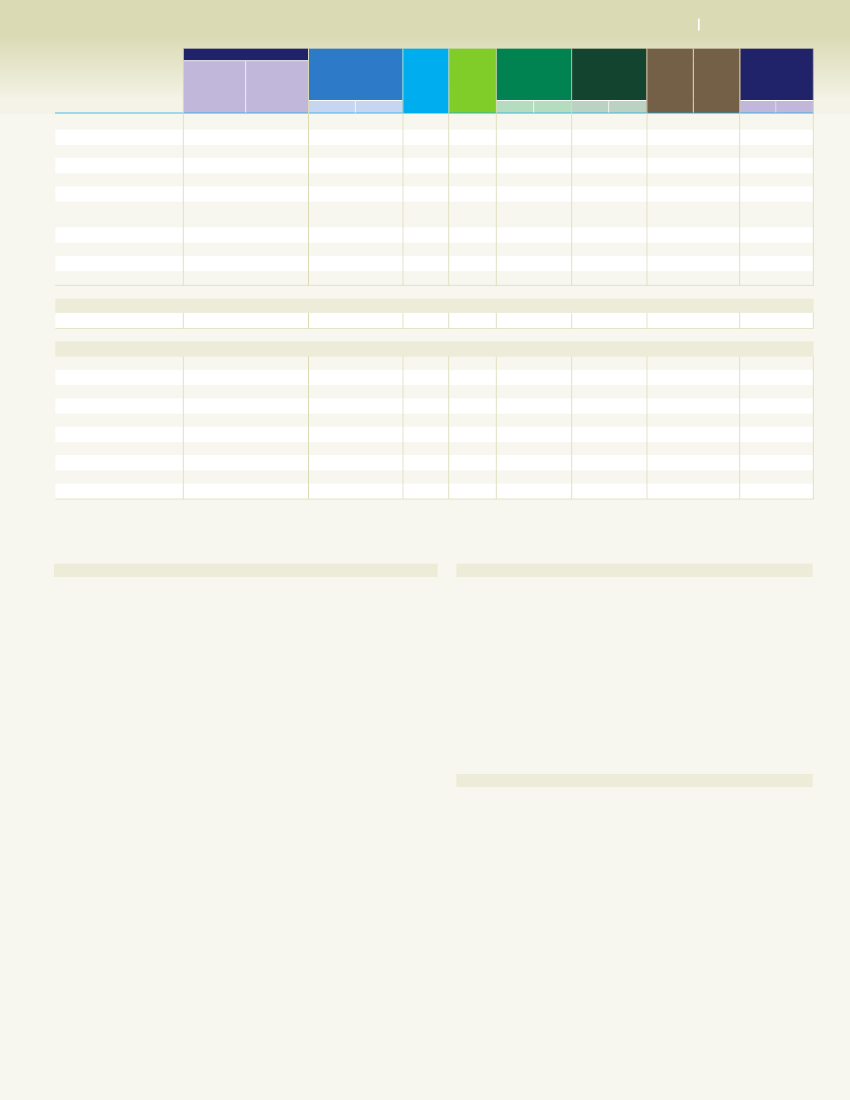

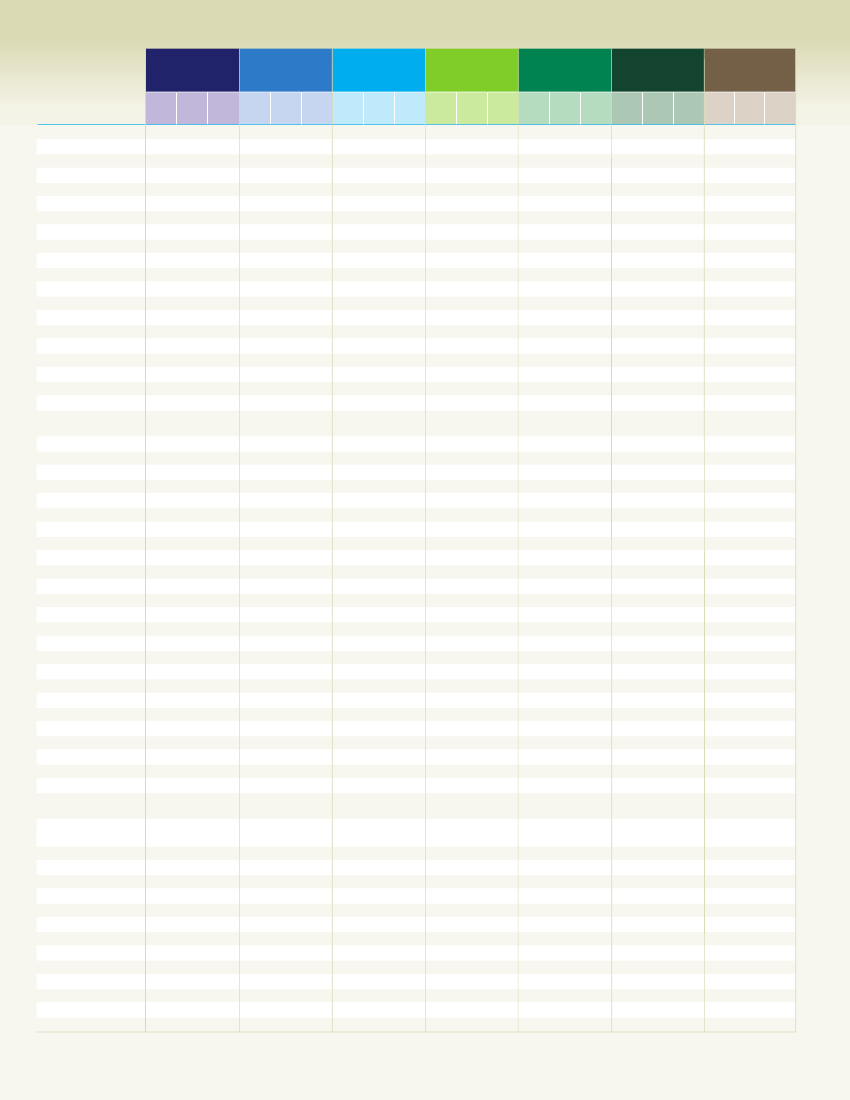

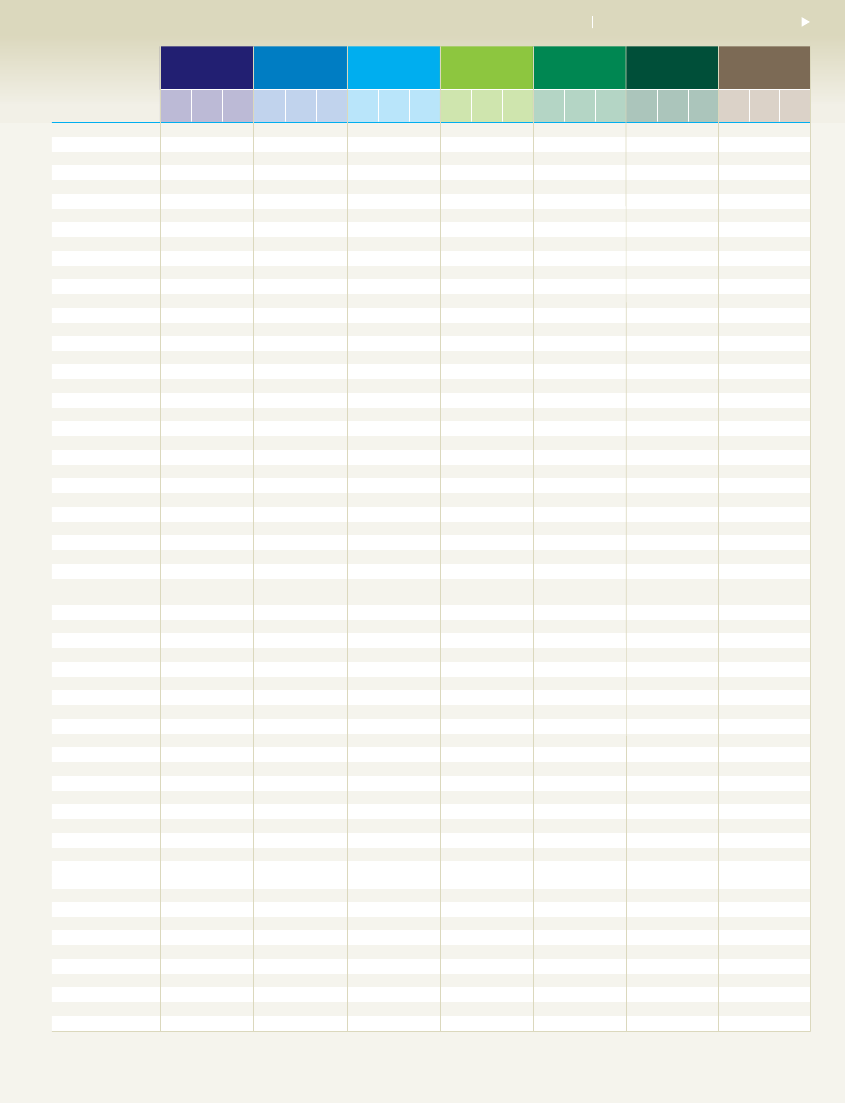

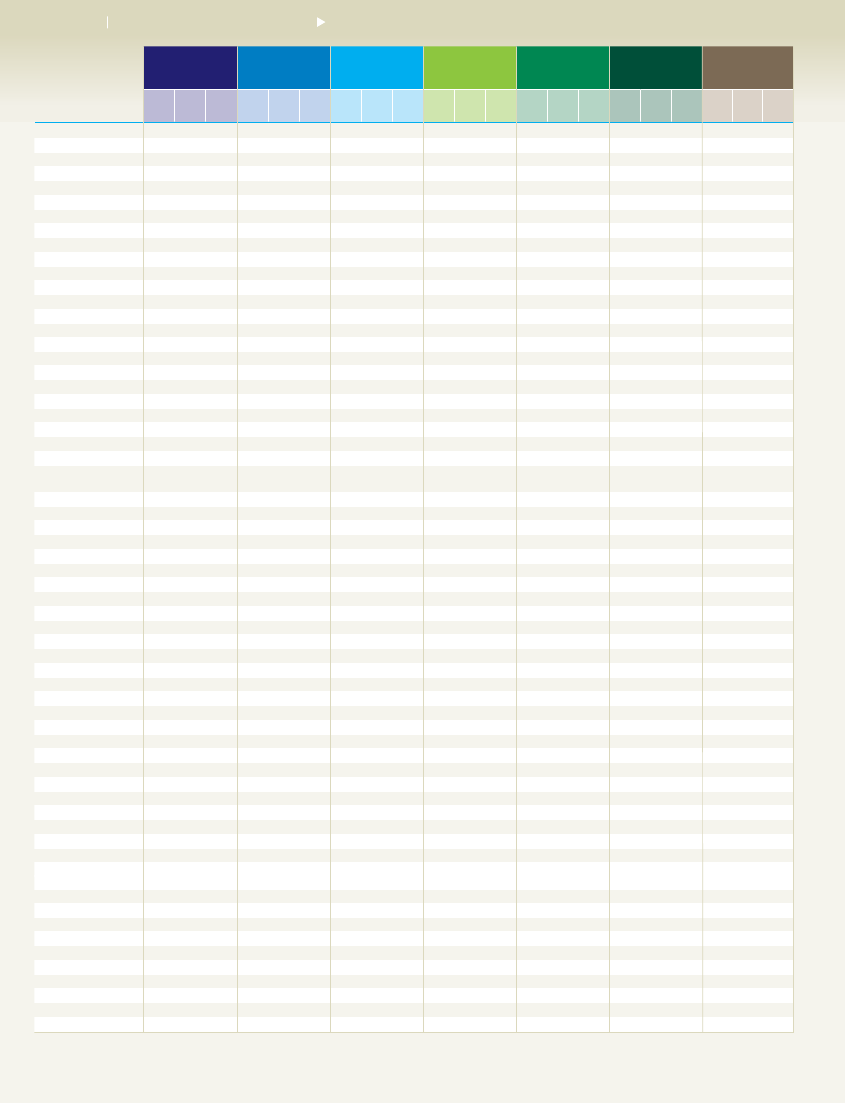

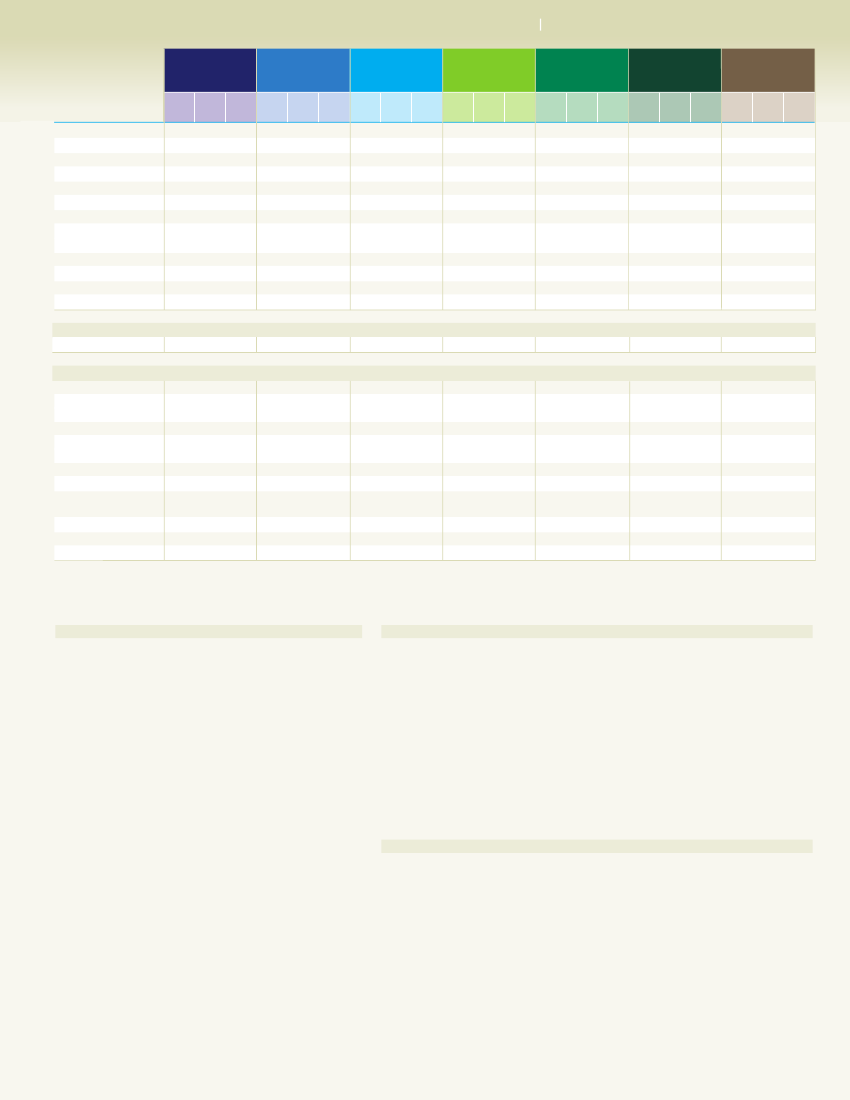

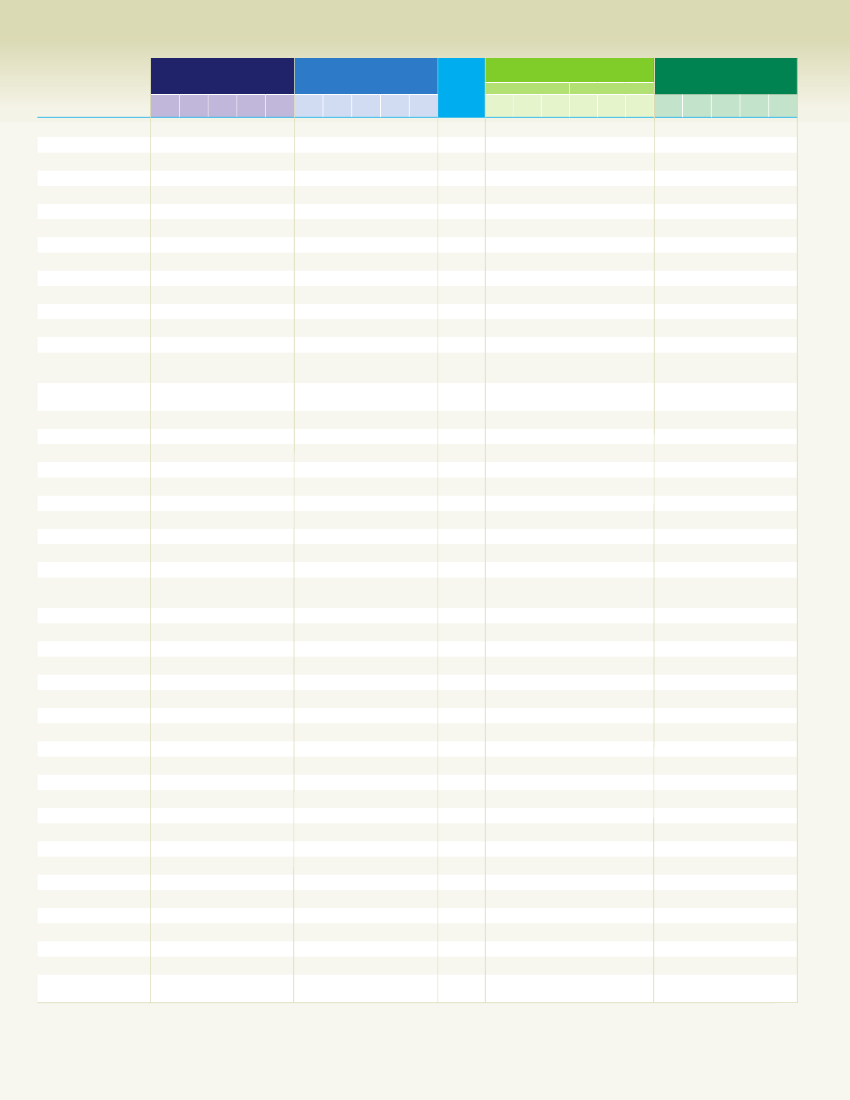

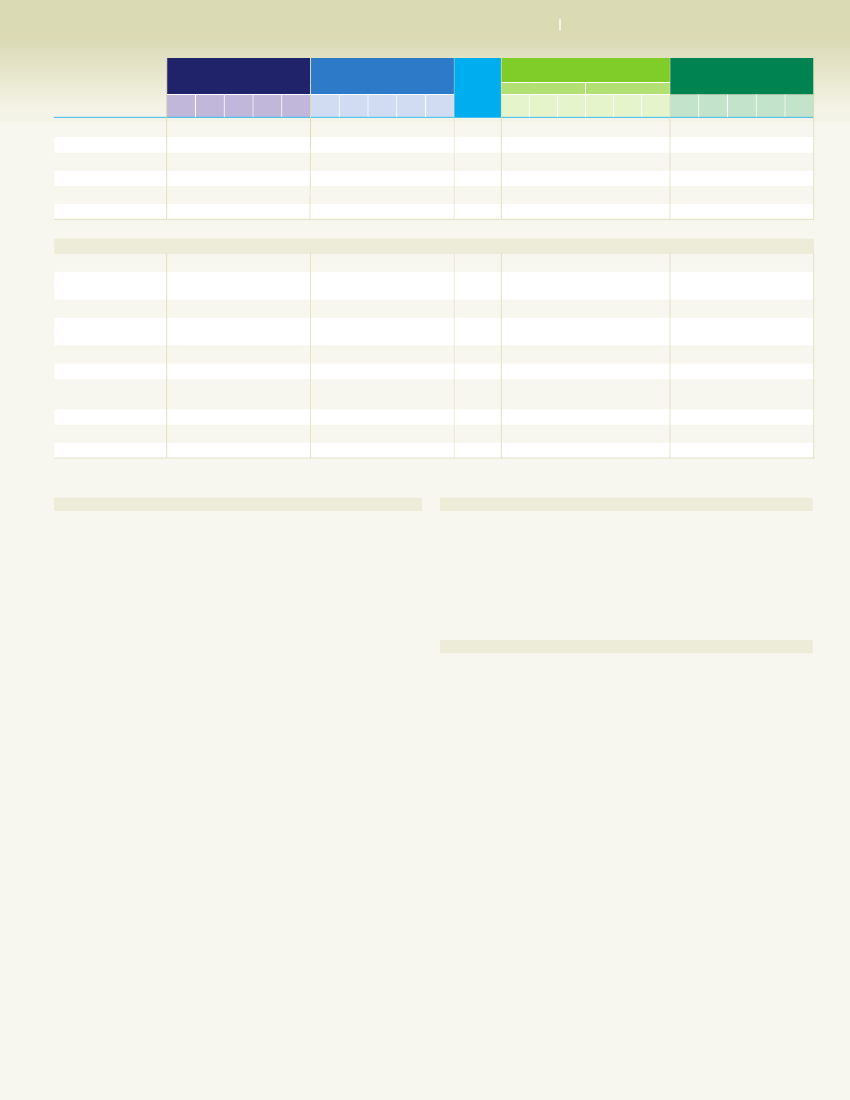

STATISTICAL TABLES................................................ 93Overview ..................................................................................... 94Under-five mortality rankings ................................................... 99Table 1. Basic indicators .......................................................... 100Table 2. Nutrition ...................................................................... 104Table 3. Health .......................................................................... 108Table 4. HIV/AIDS ..................................................................... 112Table 5. Education .................................................................... 116Table 6. Demographic indicators ............................................ 120Table 7. Economic indicators .................................................. 124Table 8. Women ........................................................................ 128Table 9. Child protection.......................................................... 132Table 10. The rate of progress ................................................ 136Table 11. Adolescents .............................................................. 140Table 12. Disparities by residence .......................................... 144Table 13. Disparities by household wealth ............................ 148Table 14. Early childhood development ................................. 152

A NOTE ON TERMSConventions, optional protocols, signatures andratifications ............................................................................... 154

v

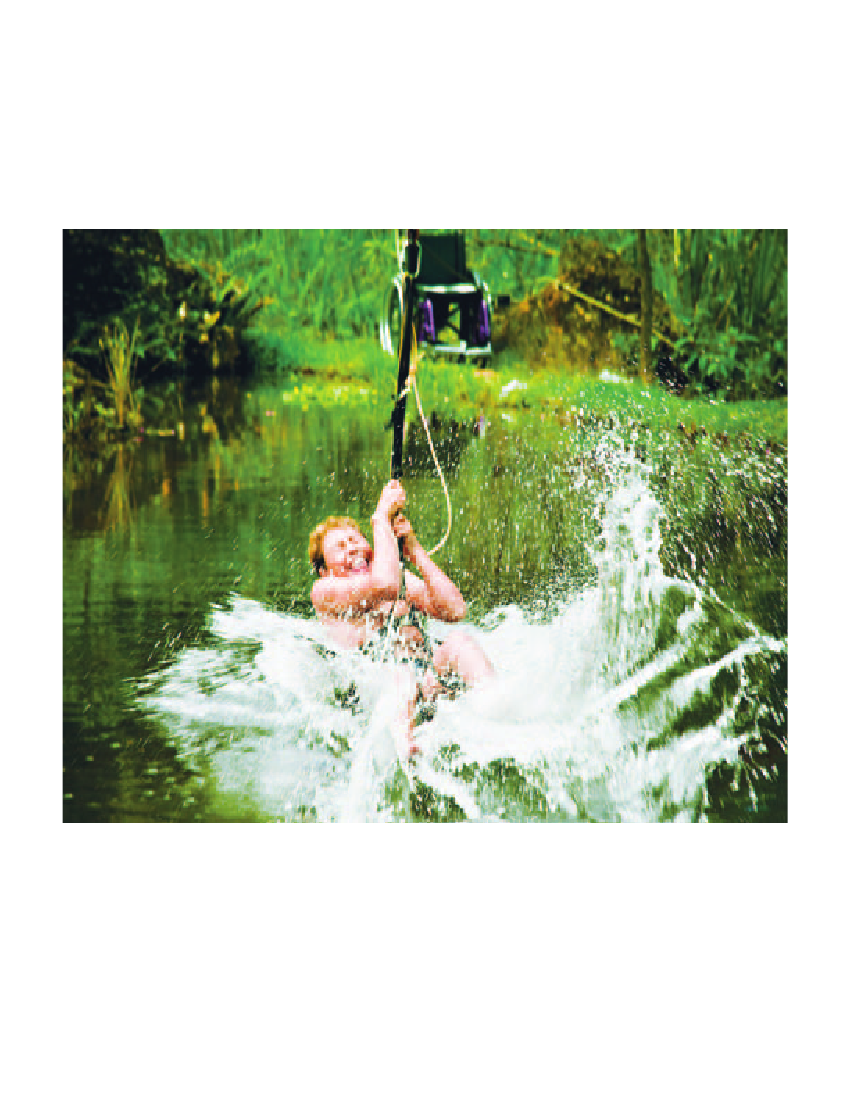

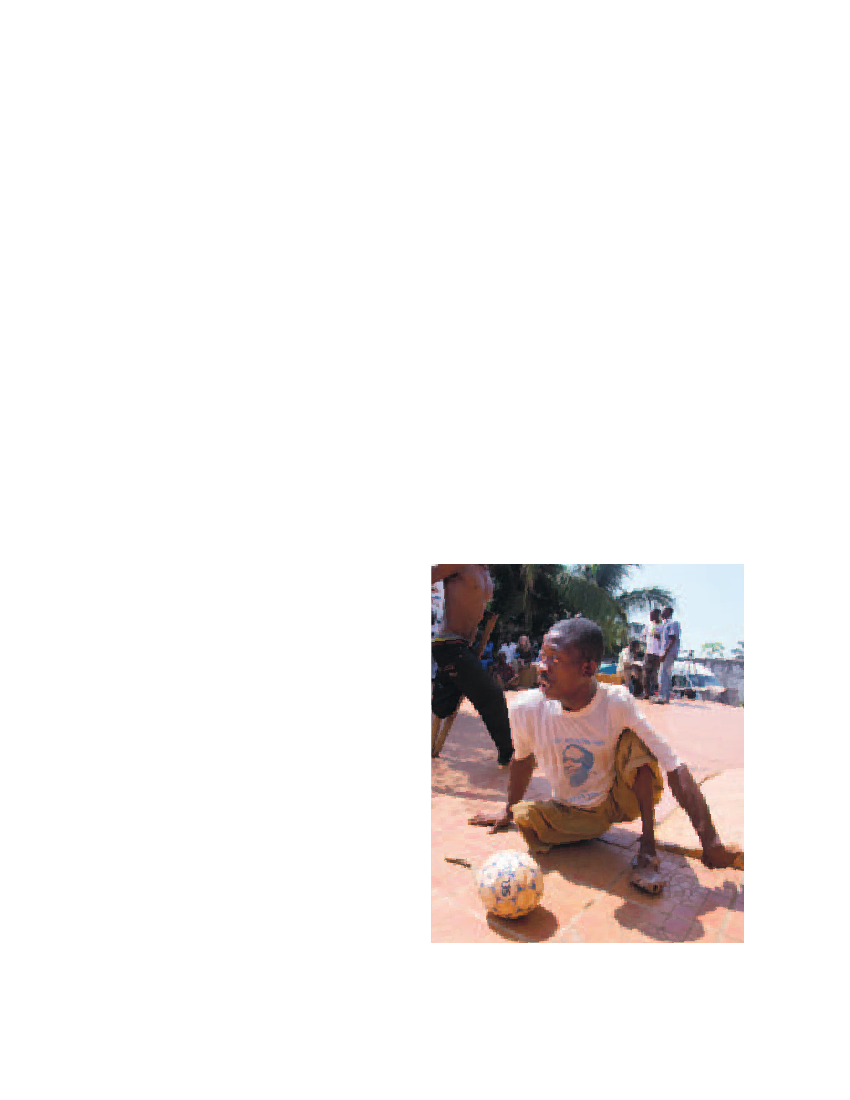

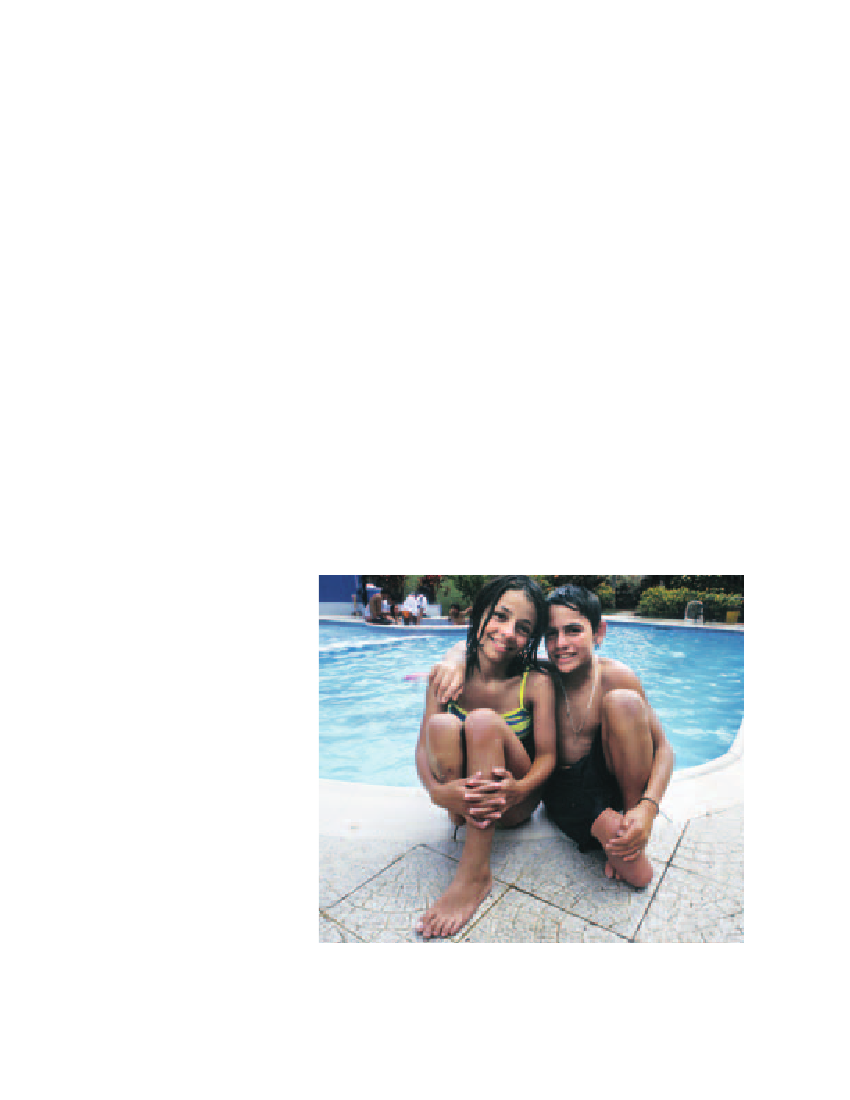

Victor, a 13-year-old with cerebral palsy, has fun in the water in Brazil. � Andre Castro/2012

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTIONReports such as this typically begin with a statisticdesigned to highlight a problem. The girls and boys towhom this edition ofThe State of the World’s Childrenis dedicated are not problems.Rather, each is a sister, brother or friend who hasa favourite dish, song or game; a daughter or sonwith dreams and the desire to fulfil them; a childwith a disability who has the same rights as anyother girl or boy.Given opportunities to flourish as others might,children with disabilities have the potential tolead fulfilling lives and to contribute to thesocial, cultural and economic vitality of theircommunities – as the personal essays in thisvolume attest.Yet surviving and thriving can be especiallydifficult for children with disabilities. They areat greater risk of being poor than peers withoutdisabilities. Even where children share the samedisadvantages – of poverty or membership in aminority group, say – children with disabilitiesconfront additional challenges as a result of theirimpairments and the many barriers that societythrows in their way. Children living in poverty areamong the least likely to enjoy the benefits of edu-cation and health care, for example, but childrenwho live in poverty and have a disability are evenless likely to attend their local school or clinic.In many countries, responses to the situationof children with disabilities are largely limitedto institutionalization, abandonment or neglect.These responses are the problem, and they arerooted in negative or paternalistic assumptionsof incapacity, dependency and difference that areperpetuated by ignorance. Unless this changes,children with disabilities will continue to have theirrights neglected; to experience discrimination,violence and abuse; to have their opportunitiesrestricted; to be excluded from society.What is needed is a commitment to thesechildren’s rights and their futures, giving priorityto the most disadvantaged – as a matter of equityand for the benefit of all.

From exclusion to inclusionChildren with disabilities encounter differentforms of exclusion and are affected by them tovarying degrees, depending on factors such asthe type of disability they have, where they liveand the culture or class to which they belong.Gender is also a crucial factor: Girls are lesslikely than boys to receive care and food and aremore likely to be left out of family interactionsand activities. Girls and young women withdisabilities are ‘doubly disabled’. They confrontnot only the prejudice and inequities encounteredby many persons with disabilities, but are alsoconstrained by traditional gender roles andbarriers.1Girls with disabilities are also less likelyto get an education, receive vocational training orfind employment than are boys with disabilitiesor girls without disabilities.2

INTRODUCTION

1

At the heart of these differing forms and degreesof exclusion, however, lies the shared experienceof being defined and judged by what one lacksrather than by what one has. Children with disabili-ties are often regarded as inferior, and this exposesthem to increased vulnerability: Discriminationbased on disability has manifested itself in margin-alization from resources and decision-making, andeven in infanticide.3Exclusion is often the consequence of invisibility.Few countries have reliable information on howmany of their citizens are children with disabili-ties, what disabilities they have or how thesedisabilities affect their lives. In some countries,families raising children with disabilities faceostracism. Because of this, even loving parentsand family members can be reluctant to reportthat a child of theirs has a disability – whetherbecause they are trying to avoid being shunned,because they are being overprotective of the

child, or both. If the child is born with an impair-ment, its birth might not even be registered.Children excluded in this way are unknown to,and therefore cut off from, the health, educationand social services to which they are entitled.Childhood deprivations can have lasting effects– by limiting access to gainful employment orparticipation in civic affairs later in life, forexample. Conversely, access to and use ofsupportive services and technology can positiona child with a disability to take her or hisplace in the community and contribute to it.Indeed, the future is far from grim. Effectivemeans are available to build inclusive societiesin which children with and without disabilitiescan enjoy their rights equally. Physical, attitudi-nal and political barriers are being dismantled,although the process is uneven and has farto go.

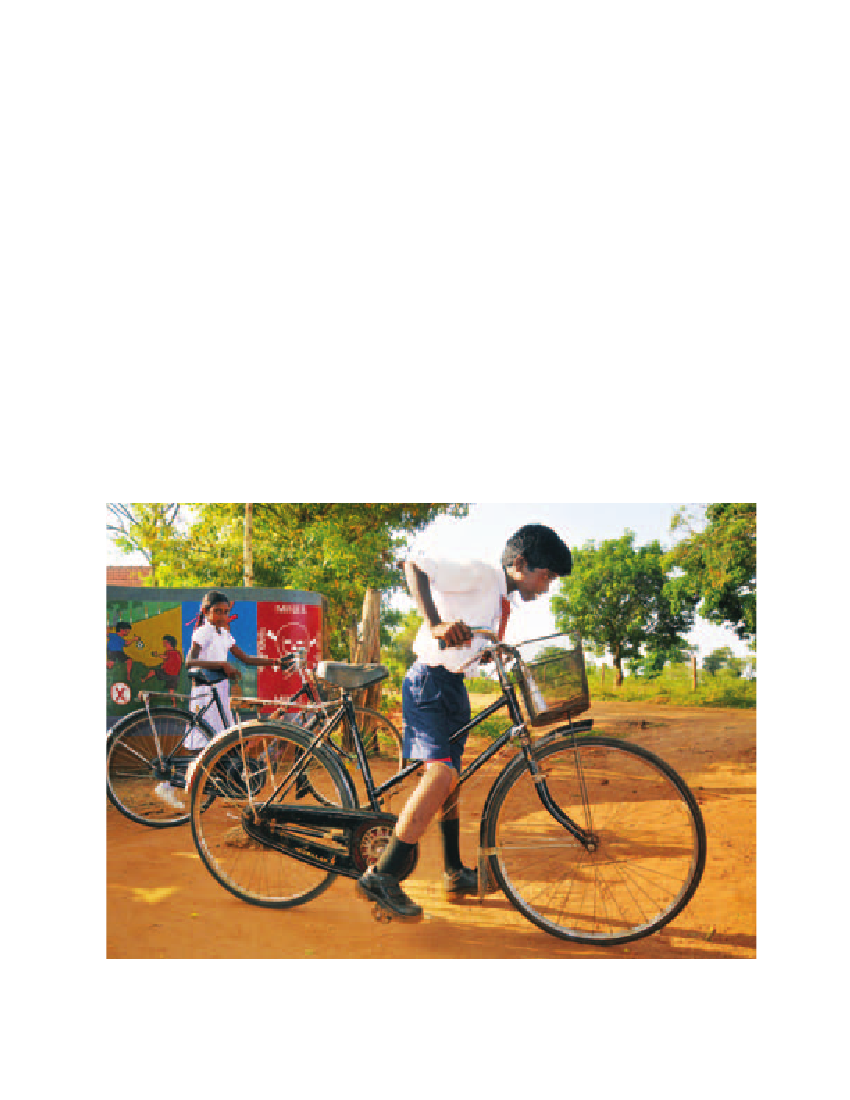

Rahmatuallah, 14, who lost his leg in a landmine explosion, takes part in a training workshop for electricians at a centre forwar-affected children in Kandahar, Afghanistan. � UNICEF/AFGA2007-00420/Noorani

2

THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S CHILDREN 2013: Children with Disabilities

Under the Convention on the Rights of theChild (CRC) and the Convention on the Rights ofPersons with Disabilities (CRPD), governmentsaround the world have taken upon themselvesthe responsibility of ensuring that all children,irrespective of ability or disability, enjoy theirrights without discrimination of any kind. As ofFebruary 2013, 193 countries had ratified the CRCand 127 countries and the European Union hadratified the CRPD.These two Conventions bear witness to a grow-ing global movement dedicated to the inclusionof children with disabilities in community life.Concern for inclusion is rooted in the recognitionthat all children are full members of society: thateach child is a unique individual who is entitledto be respected and consulted, who has skillsand aspirations worth nurturing and needs thatdemand fulfilment and whose contributions areto be valued and encouraged. Inclusion requiressociety to make physical infrastructure, informa-tion and the means of communication accessibleso all can use them, to eliminate discriminationso none is forced to suffer it and to provide pro-tection, support and services so every child witha disability is able to enjoy her or his rights asdo others.Inclusion goes beyond ‘integration’. The latterimplies that children with disabilities are to bebrought into a pre-existing framework of pre-vailing norms and standards. In the context ofeducation, for example, integration might beattempted simply by admitting children withdisabilities to ‘regular’ schools. This would fallshort of inclusion, which is possible only whenschools are designed and administered so thatall children can experience quality learning andrecreation together. This would entail provid-ing students with disabilities with such neededaccommodations as access to Braille, signlanguage and adapted curricula that allowthem equal opportunity to learn and interact.Inclusion benefits everyone. To continue with theexample of education, ramps and wide doorways

On the numbersBy one widely used estimate, some 93 million children– or 1 in 20 of those aged 14 or younger – live with amoderate or severe disability of some kind.Such global estimates are essentially speculative. Theyare dated – this one has been in circulation since 2004– and derived from data of quality too varied and meth-ods too inconsistent to be reliable. In order to providea context for and illustrate the issues under discussion,this report presents the results of national surveys andindependent studies, but even these must be interpret-ed with caution and should not be compared to oneanother. This is because definitions of disabilitydiffer by place and time, as do study design, methodol-ogy and analysis. These issues, and promising initia-tives aimed at improving the quality and availabilityof data, are discussed in Chapter 6 of this report.

can enhance access and safety for all children,teachers, parents and visitors in a school, notjust those who use wheelchairs. And an inclusivecurriculum – one that is child-centred and thatincludes representations of persons with disabili-ties in order to reflect and cater to a true crosssection of society – can broaden the horizons notonly of children whose disabilities would other-wise limit their ambitions or options, but also ofthose without disabilities who stand to gain anappreciation of diversity and of the skills and pre-paredness necessary to build a society inclusiveof all. Where educational attainment leads to a jobor other means of earning a living, the child witha disability is able to advance and to take her orhis place as a full and equal member of the adultworld, one who produces as well as consumes.

A framework for actionChildren with disabilities should not be treated orregarded simply as the recipients of charity. Theyhave the same rights as others – among these,the right to life and to the opportunities that flowfrom good health care, nutrition and education,(continued on p. 9)

INTRODUCTION

3

PERSPECTIVE

From pioneer to advocatefor inclusionBy Nancy Maguire

Nancy Maguire is a disabilityactivist from the United Kingdom.She is a qualified social worker but,after travelling abroad, decided tocampaign for the rights of peoplewith disabilities, especially youngwomen. She has worked withdisabled people’s organizationsin Asia and Southern Africa, andhopes to obtain a Master’s degreein policy and development.

In the 1980s, inclusive educationwas still a fairly new concept.Like most parents of a disabledchild, mine were advised tosend me to a special school.My mother is a teacher, andafter visiting the recommendedschool she was convinced thatit would provide a substandardeducation. My parents havealways used my older sisterKaty, who did not have a dis-ability, to gauge what is accept-able for me: If they thoughtsomething wasn’t good enoughfor Katy, then it wasn’t goodenough for me.I was the first child with a dis-ability to attend my primaryschool, and in many ways I feltlike a guinea pig for inclusion.For example, despite having apositive attitude towards includ-ing me in all aspects of schoollife, my teachers lacked experi-ence in how to adapt physicaleducation so that I could getinvolved in a meaningful way.Like most childhoods, minewasn’t always easy. I spent alot of time in hospital, and evenwithin an ‘inclusive’ mainstreameducation system, there weretimes when I was excluded.For example, I wasn’t allowedto go to my nursery Christmasparty because the teachers wereworried I would break a bone.

Also, at high school they had aseparate table in the canteen forchildren with disabilities and theteachers could not understandwhy I refused to sit at it. Despitesetbacks and obstacles, how-ever, I managed to flourish botheducationally and socially.I was always encouraged to trynew things. My extracurricularactivities included swimming,ballet, wheelchair tennis, dramaand singing. In many of these,I was also the only child with adisability. Interestingly, I oftenfound these groups more inclu-sive than school in terms ofhow much I could participateand contribute. I felt wantedand people found creativeways for me to get involved.Nonetheless, there were manythings I found difficult to dobecause of my limited mobility.I would sometimes feel upsetbecause I couldn’t do things aswell as the other children, andas I grew older and more self-conscious, I became reluctant toput myself in situations wheremy difficulties were on show.In my teenage years a lot of myfriends went through phasesof being a ‘goth’ or a ‘rudegirl’, which involved dressingor behaving in ways designedto attract attention. Whilst theywere doing everything they

I was born in London in 1986and have a condition calledosteogenesis imperfecta, com-monly known as brittle bones.Many children with brittle bonesgrow up protected – overpro-tected, some might say – fromany possibility of hurting them-selves. My parents wanted meto be safe, but they also wantedme to have the opportunity toplay, make friends and lead asnormal a childhood as possible.

4

THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S CHILDREN 2013: Children with Disabilities

People with disabilities are becoming more visible in many walksof life – in politics and the media, for example. This is instrumentalin improving children’s perceptions of what they can achieve.

could to stand out and be dif-ferent, I was desperate to be‘normal’ and fit in. Growing upwith a disability, I received a lotof attention. People in the streetwould often stare at me, makecomments and ask my parents,“What’s wrong with her?” I haddays when I was able to brush itoff, but no amount of resilienceor family support can stop thatfrom affecting you.I developed extremely low self-esteem and poor body image,made worse because I wassignificantly overweight. I foundexercise difficult, and like manygirls my age, I ate to comfortmyself. I had also internalizedthe medical terminology thatwas used to describe me – inparticular the word ‘deformed’(I had a curvature of the spine,since corrected). When I was 14,I developed an eating disorder,partly because I wanted to loseweight – but also because myweight felt like one aspect of myphysical appearance that I couldactually control.Although I had incrediblysupportive family and friends,being disabled was never some-thing I viewed as a positivething. I thought I had to over-come it, like adversity. I becameobsessed with being as ‘undis-abled’ as possible, and I was

convinced that if I could walk,my life would be a lot better.Ironically, although I no longeruse a wheelchair, in many waysI feel more aware of my disabilitythan ever. People still make com-ments about me because I havesmall stature, and make assump-tions about my life and ability;I always have to prove myself,particularly in the workplace.Though I am not defined by mydisability, it has been pivotal inshaping who I am and whatI have achieved. Having a disabil-ity is now something I embrace:I no longer see it as a negativething or something I should beembarrassed about. In manyways being disabled has workedto my advantage and createdopportunities that might neverhave been available to me –like writing this article.Every child’s experience isdifferent. I come from a lower-middle-class family in the UnitedKingdom, where I had accessto free health care and a goodeducation. But I strongly believethat the issues of belonging,self-esteem and aspirationtranscend such distinctions asgender, class and nationality.To develop a greater sense ofself-worth, children withdisabilities need the opportunityto participate and contribute inall aspects of their lives.

People with disabilities arebecoming more visible in manywalks of life – in politics andthe media, for example. Thisis instrumental in improvingchildren’s perceptions of whatthey can achieve. When I wasgrowing up, the only role modelI had was Stevie Wonder.I admired him because he wasa successful and respectedmusician despite being blind.However, it would have helpedme to see people with disabili-ties doing everyday jobs – asteachers, doctors or shopkeep-ers. I think that would also havehelped my parents. My mumsaid that when I was a child,she tried not to think aboutmy future because it made herscared. She knew that I wascapable but feared that myoptions would be limited.As it turns out, my disability hasnot prevented me from achiev-ing any of the important things.I am a qualified social worker,passed my driving test whenI was 16, left home when I was19 and have lived and workedin Asia and Africa. In the futureI hope to be an advocate forchildren with disabilities on aninternational level, as I passion-ately believe in the inalienablehuman rights and untappedpotential of these children.

INTRODUCTION

5

PERSPECTIVE

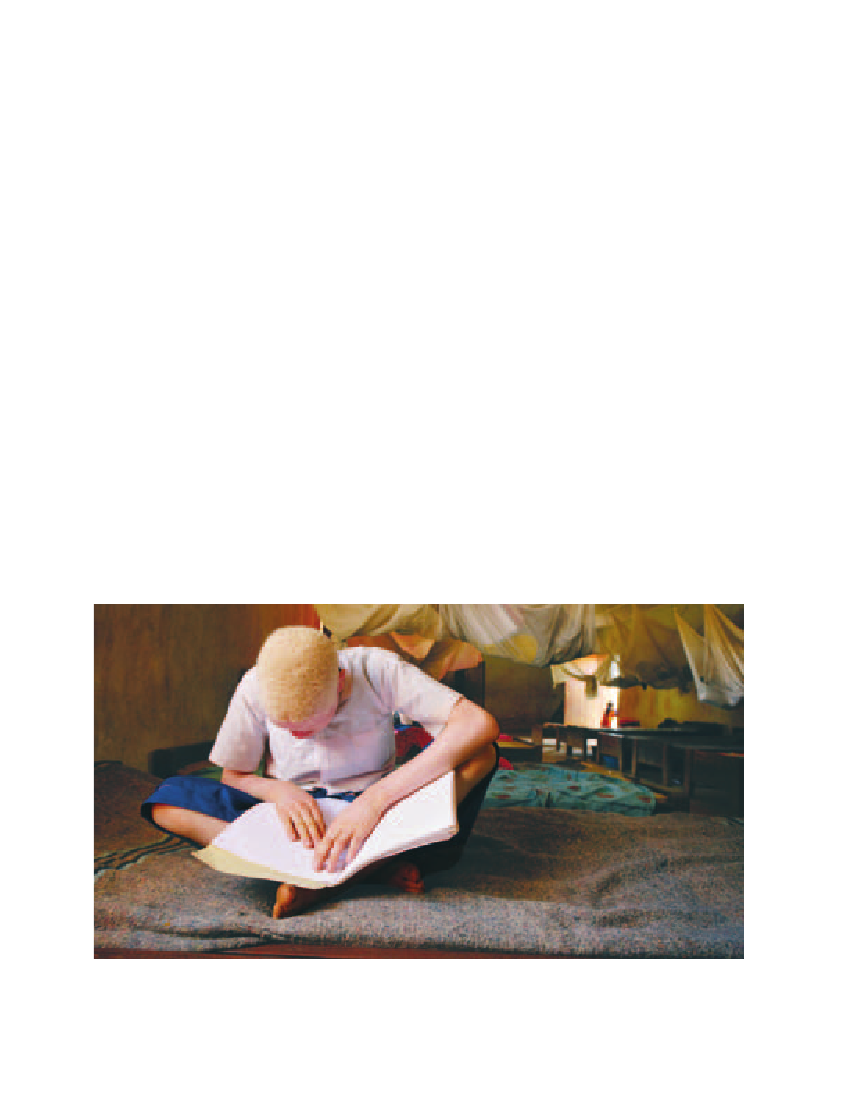

Living with albinism,discrimination and superstitionBy Michael Hosea

to protect my eyes. I also havetroubles at school. SometimesI can’t see the blackboard, andI always have to sit in theshade. This country doesnot have sufficient vision-enhancing technology, suchas glasses, magnifiers andspecial computer equipment,and without it children withalbinism have a hard timegraduating from school andfinding employment. My familyis poor, so getting money forschool fees is also difficult.Life is complicated even moreby the way people treat us.There is a lot of discriminationagainst people with albinism,and I sometimes lack the com-pany of friends. Some peoplealso believe horrible mythsabout us: that we are nothuman and never die, thatalbinism is a curse from thegods and that anyone whotouches us will be cursed.Worst of all, practitioners ofwitchcraft hunt and kill us touse our hair, body parts andorgans in charms and potions.For centuries some peoplehave believed that if they goto a witch doctor with albino

Michael Hosea was born in 1995.He is the eldest of six children andone of three persons with albinismin his immediate family. He livesin Dodoma, United Republic ofTanzania, and is about to graduatefrom school. He advocates forthe rights of young people withdisabilities, particularly those withalbinism, through the LeonardCheshire Disability Young Voicesnetwork.

I was born in Mwanza, thesecond largest city in theUnited Republic of Tanzania.I am the eldest son and livewith my siblings and parents inDodoma, the capital. There aresix children in our family; oneof my sisters and one of mybrothers are also albinos.The impairments caused bymy condition make life verydifficult. I always have troublewith the sun and have to coverup with heavy, long-sleevedclothing and wear sunglasses

6

THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S CHILDREN 2013: Children with Disabilities

Education is the key to stopping the murder, abuse anddiscrimination. It is important that others – even members ofmy extended family – learn that we are people just like them.

body parts, they will becomerich and prosperous. Eventhough it is illegal to kill peoplewith albinism, it still happens –it’s greed that makes peopledo it. But it’s all based on lies:There are people who havedone these terrible things, yettheir lives have remainedthe same.A few months ago, thanks to afriend of my father, my siblingsand I escaped being the victimsof murder for witchcraft. Myfather’s friend came to warn himthat his three albino childrenwere in danger of being hunted,and he begged my father toleave Mwanza. This wasn’t easybecause my parents’ financialsituation was not good, but wepacked up everything and leftat 3 a.m. that night.We travelled over 500 kilome-tres to Dodoma and after twodays received news from homethat people had broken into ourhouse in Mwanza looking tokill us.When these people found thatwe had escaped, they wentto our next-door neighbour’shouse. He was our local albino

representative and had done somuch to help us and advocatefor albino rights in our commu-nity. They cut off his genitalsand arms, and left him there todie. We later received a phonecall from another neighbourtelling us what they did to him.This news hurt me so muchthat I cried a lot, but whatcould I do? This is the waythings are.I don’t understand why peopledo such things to fellow humanbeings. But I think education isthe key to stopping the murder,abuse and discrimination. It isimportant that others – evenmembers of my extendedfamily – learn that we arepeople just like them. Weare all the same.To escape life’s difficulties, I loveto write songs and sing. I havejust written a song about albinosand our struggle. My dream isto one day be able to record mymusic in a studio and spreadmy message. I pray that peoplearound the world can one dayunderstand that albinos are nodifferent from them. We are allhuman beings and deserve to betreated with love and respect.

Note:Albinism is a rare, geneticallyinherited condition found in allethnicities. People with albinismhave little or no pigmentation intheir eyes, hair and skin owing to alack of melanin. They are sensitive tobright light and have a higher thanaverage risk of skin cancer from sunexposure. Most people with albinismare also visually impaired. Underthe Same Sun, a Canadian non-governmental organization, estimatesthat albinism affects 1 in 2,000Tanzanians. Although the medicalcondition itself does not affect lifeexpectancy, in the United Republicof Tanzania the average lifespanof a person with albinism is around30 years.

INTRODUCTION

7

PERSPECTIVE

I want good memoriesBy Nicolae Poraico

I was 11 when I went to the insti-tution with my brother Grisha. Iam now 16. Our mother sent usthere because we did not haveenough money to buy or renta house, and she had to worknights. She came to see us often.I do not remember the day Iwent to the institution. I evenforgot some of my memories ofbeing there, and I hope in time Iwill forget the other ones. I wantnew memories, good memories.At holidays the food was good. Itwas also good on other days; wewere fed four times a day. Aftereating I cleaned the kitchen.The teachers taught us to recitepoems and sing songs andshowed us different games.I know a poem about Gigeland two about Mother.We had naptime from 1 to4 p.m. I would not sleep:I laughed, talked to other boys.I put my head on the pillow, keptmy eyes open and looked at theboys. We were all living in oneroom, all 16 boys from my class.There was one boy, Victor. Heworked in the kitchen. We wentto the stadium nearby. He tookjust me to the stadium; he hadbread and sour milk, and we atetogether. When my mother took

me and my brother home, Victordid not know as he was sleep-ing. He gave me his picture so Iwould not forget him, but I for-got it there.Sometimes the staff beat us. Ido not know why. They beat meso much with different sticksthat my back was injured. I wasnot the only one. Other boyswere injured, too. And someboys had knives. Some boys hitothers, and sometimes I foughtwith them, with fists. Whatcould I do? If I did not defendmyself, they could kill me. Theybeat Grisha, but I defended him.I didn’t want to stay there. If mymother had left us there, theadministration could have sentus to different families and mymother would never find us. ButI want to visit the institution, justto see Victor and take his phonenumber.At home, it is very good.I now play with Colea, Igorand Dima. Here, nobody beatsme. Sometimes we discussproblems with our motherand ask for advice. We getalong very well and I go toschool every day. I like physicaleducation and Romanianlanguage classes. I am gladI came here. I am happy thatI am in Lapusna.

Nicolae Poraico and his brotherGrisha spent several years in aresidential home for children withmental disabilities in the Republicof Moldova. Nicolae was diagnosedwith a moderate intellectualdisability and his brother with asevere intellectual disability. In2010 Nicolae and Grisha reunitedwith their mother in the villageof Lapusna. This was madepossible with the assistance ofthe Community for All – Moldovaprogramme, which is implementedby the Keystone Human ServicesInternational Moldova Associationwith financial support from theOpen Society Mental HealthInitiative and the Soros FoundationMoldova.

8

THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S CHILDREN 2013: Children with Disabilities

(continued from p. 3)

the right to express their views and participatein making decisions, and the right to enjoy equalprotection under the law. They belong at thecentre of efforts to build inclusive and equitablesocieties – not only as beneficiaries, but asagents of change. After all, who is in a betterposition to comprehend their needs and evaluatethe response?In any effort to promote inclusion and fairness,children with disabilities should be able to enlistthe support of their families, disabled people’sorganizations, parents’ associations and com-munity groups. They should also be able tocount on allies further afield. Governments havethe power to help by aligning their policies andprogrammes with the spirit and stipulations ofthe CRPD, CRC and other international instru-ments that address or affect child disability.International partners can provide assistancecompatible with the Conventions. Corporationsand other entities in the private sector canadvance inclusion – and attract the best talent– by embracing diversity in hiring.The research community is working to improvedata collection and analysis. Their work will helpto overcome ignorance and the discriminationthat often stems from it. Furthermore, becausedata help to target interventions and gauge theireffects, better collection and analysis helps inensuring an optimal allocation of resources andservices. But decision-makers need not wait forbetter data to begin building more inclusive infra-structure and services: As some have alreadyfound, inclusion involves and benefits entirecommunities, and its elements can be applied tonew projects across the board. All that is neededis for these efforts to remain flexible so they canbe adapted as new data come to light.The next chapter of this report discusses exclu-sion and the factors that propagate it, along withsome philosophical and practical fundamentalsof inclusion. Subsequent chapters – each ofwhich applies the same approach of explor-ing barriers as well as solutions that show

promise – are dedicated to specific aspects ofthe lives of children with disabilities. Chapter 3examines the health, nutritional and educationalservices that can provide a strong foundationon which children with disabilities can buildfull and fulfilling lives. Chapter 4 explores theopportunities and challenges of ensuring legalrecognition and protection against exploitationor abuse. Chapter 5 discusses inclusion in thecontext of humanitarian crises.Many of the deprivations endured by childrenwith disabilities stem from and are perpetuatedby their invisibility. Research on child disabilityis woefully inadequate, especially in low- andmiddle-income countries. The resulting lack ofevidence hinders good policymaking and servicedelivery for children who are among the mostvulnerable. Therefore, Chapter 6 of this reportexamines the challenges and opportunitiesconfronting researchers – and ways in whichchildren with disabilities can be rendered vis-ible through sound data collection and analysis.Chapter 7, which concludes this edition ofTheState of the World’s Children,outlines necessaryand feasible actions that will enable govern-ments, their international partners, civil societyand the private sector to advance equity throughthe inclusion of children with disabilities.

Wenjun, 9, walks with her foster mother in China.� UNICEF/China/2010/Liu

INTRODUCTION

9

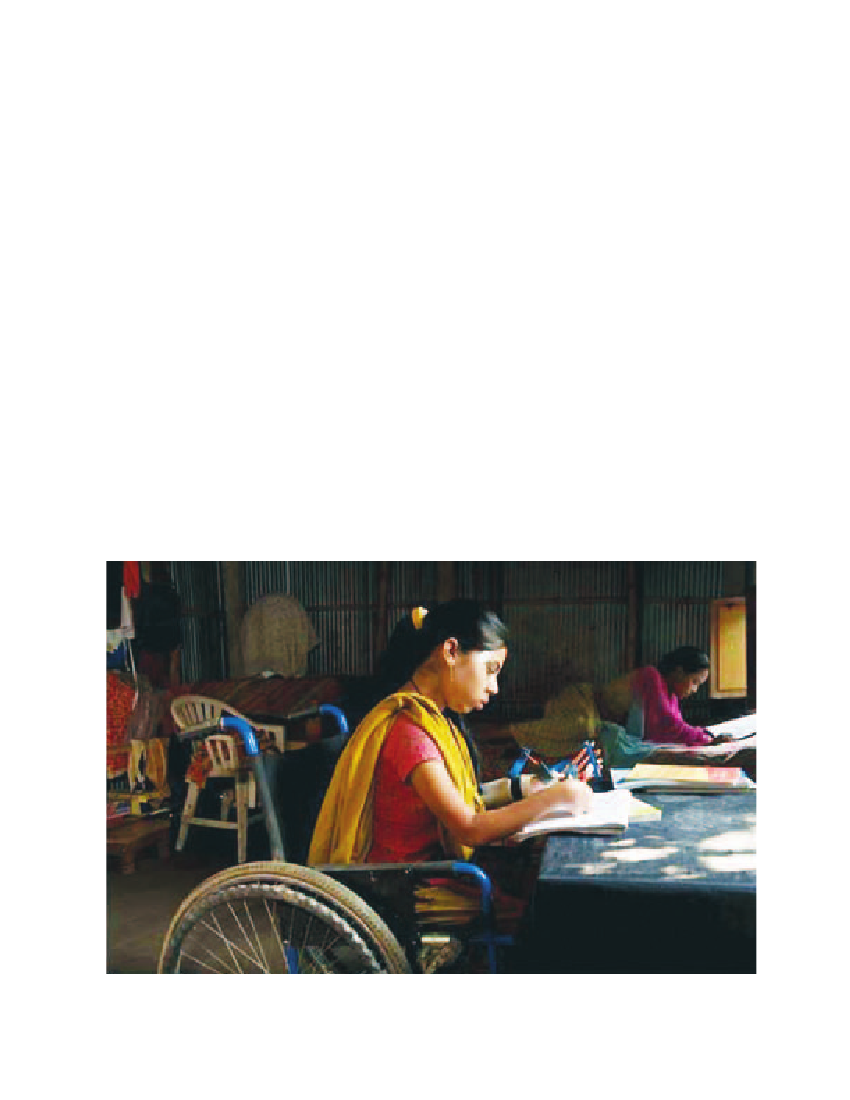

Children with and without disabilities participate in school festivities in Bangladesh. � UNICEF/BANA2007-00655/Siddique

CHAPTER 2

FUNDAMENTALS OFINCLUSIONAdopting an approach grounded in respect for the rights,aspirations and potential of all children can reduce thevulnerability of children with disabilities to discrimination,exclusion and abuse.The Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC)and the Convention on the Rights of Persons withDisabilities (CRPD) challenge charitable approach-es that regard children with disabilities as passiverecipients of care and protection. Instead, theConventions demand recognition of each childas a full member of her or his family, communityand society. This entails a focus not on traditionalnotions of ‘rescuing’ the child, but on investmentin removing the physical, cultural, economic, com-munication, mobility and attitudinal barriers thatimpede the realization of the child’s rights – includ-ing the right to active involvement in the makingof decisions that affect children’s daily lives.It is often said that whenyouchange, the worldchanges. Underestimation of the abilities ofpeople with disabilities is a major obstacle totheir inclusion. It exists not only in society atlarge but also in the minds of professionals,politicians and other decision-makers. It can alsooccur in families, among peers and in individualswith a disability, especially in the absence of evi-dence that they are valued and supported in theirdevelopment. Negative or ill-informed attitudes,from which stem such deprivations as the lack ofreasonable accommodation for children withdisabilities, remain among the greatest obstaclesto achieving equality of opportunity.Negative social perceptions may result in chil-dren with disabilities having fewer friends andbeing isolated or bullied, their families experi-encing additional stress, and their communi-ties treating them as outsiders. Early studiesof the way children with disabilities are treatedby their peers have found that even at the pre-school level, they may be overlooked as friendsor playmates, sometimes because other chil-dren believe that they are not interested or ableto play and interact.4A survey of families ofchildren with disabilities in the United Kingdomfound that 70 per cent thought that understand-ing and acceptance of disability among theircommunity was poor or unsatisfactory, andalmost half encountered problems in accessingsuch support services as childcare.5Accordingto a 2007 UK study involving children with spe-cial educational needs, 55 per cent said thatthey had been treated unfairly because of theirdisability.6In Madagascar, one study found thatignorance about disability was common amongparents – and that even among the presidentsof parents’ associations, 48 per cent believed,mistakenly, that disability is contagious.7A2009 study in the Vietnamese city of Da Nangreported that although the community adoptedgenerally tolerant attitudes towards childrenwith disabilities and their families, instancesof stigmatization and discrimination persisted.The appearance of children with disabilities inpublic on such holidays as Tet, which marks thenew lunar year, was considered detrimental togood fortune.8

FUNDAMENTALS OF INCLUSION

11

It is no wonder, then, that children with disabili-ties are among the most vulnerable to low self-esteem and feelings of isolation. No child shouldbe defined by a disability. Each child is uniqueand has the right to be respected as such. Whensocieties embrace inclusive principles and dem-onstrate this support for equity in practice, chil-dren with disabilities are able to enjoy the samerights and choices as other children. Enablingparticipation in the community and providingeducational, cultural and recreational options isof paramount importance for the healthy physi-cal and intellectual development of every child.Where specialized support – for communicationsor mobility, for example – is needed to facilitateinteraction and promote self-reliant participationin everyday activities, access should be free andavailable to all.

change. Ignorance about the nature and causesof impairments, invisibility of the children them-selves, serious underestimation of their potentialand capacities, and other impediments to equalopportunity and treatment all conspire to keepchildren with disabilities silenced and marginal-ized. Major public awareness campaigns thatare sponsored by governments, include childrenas key presenters and are supported by all civilsociety stakeholders can inform, challenge andexpose these barriers to the realization of rights.Furthermore, parents and disabled persons’ orga-nizations can – and often do – play pivotal rolesin campaigning for acceptance and inclusion.Bringing disability into political and social dis-course can help to sensitize decision-makers andservice providers, and demonstrate to society atlarge that disability is ‘part of the human condi-tion’.9The importance of involving children withdisabilities cannot be overstated. Prejudice canbe effectively reduced through interaction, andactivities that bring together children with andwithout disabilities have been shown to fostermore positive attitudes.10Social integration ben-efits everyone. It follows that if societies seekto reduce inequalities, they should start withchildren who are best fitted to build an inclusivesociety for the next generation. Children whohave experienced inclusive education, forexample, can be society’s best teachers.Inclusive media also have a key part to play.When children’s literature includes children andadults with disabilities, it sends out positive mes-sages that they are members of families andneighbourhoods. It is important for membersof all groups, and especially those that may bediscriminated against on the grounds of race,gender, ethnicity or disability, to be included instories and textbooks for children – not neces-sarily as the main protagonists but simply tonote their presence and participation. Books, filmand media portrayal play an important role inteaching children about social norms. Just as theportrayal of girl characters in mainstream chil-dren’s media carries implicit notions of gender

Changing attitudesLittle will change in the lives of children withdisabilities until attitudes among communities,professionals, media and governments begin to

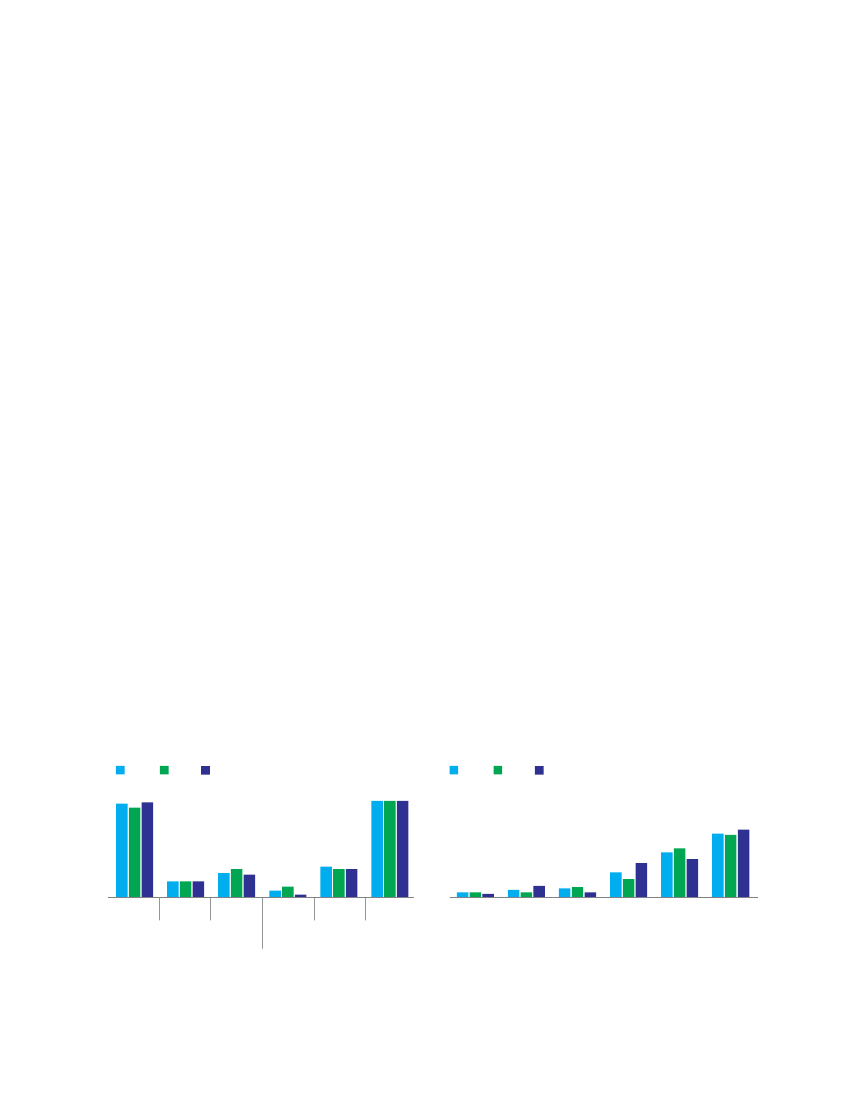

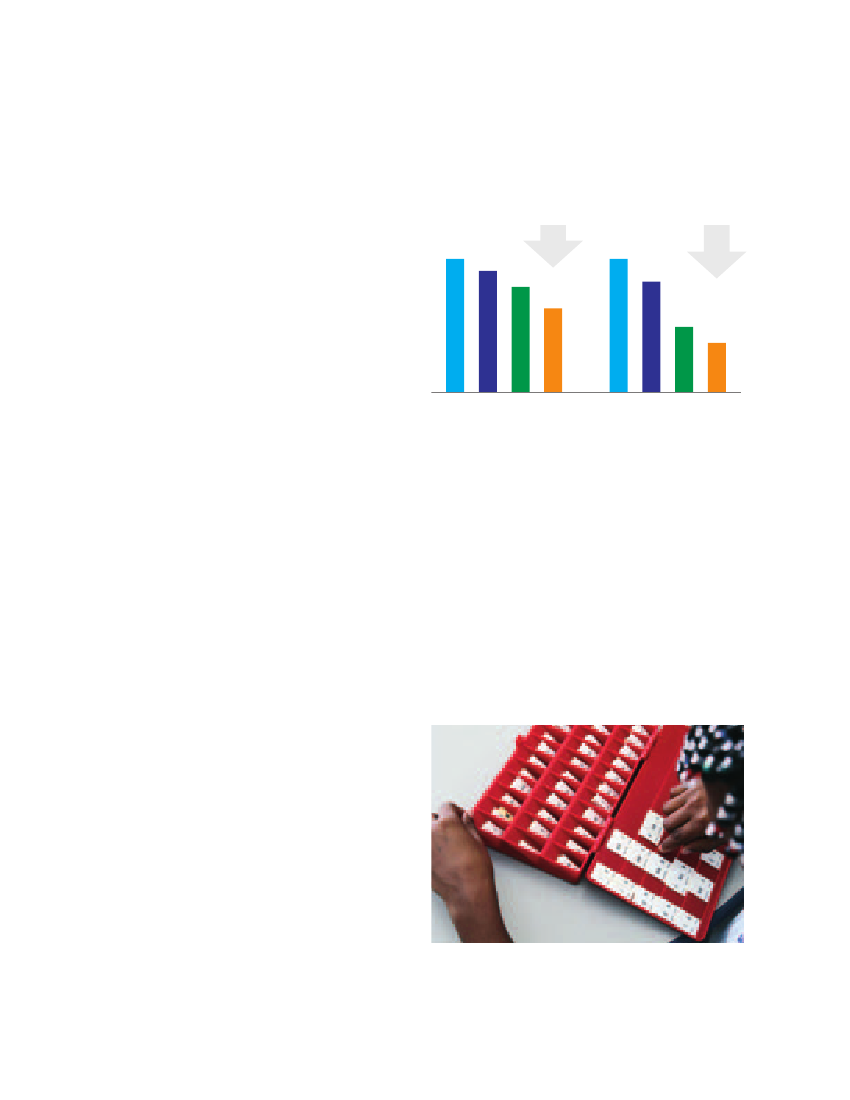

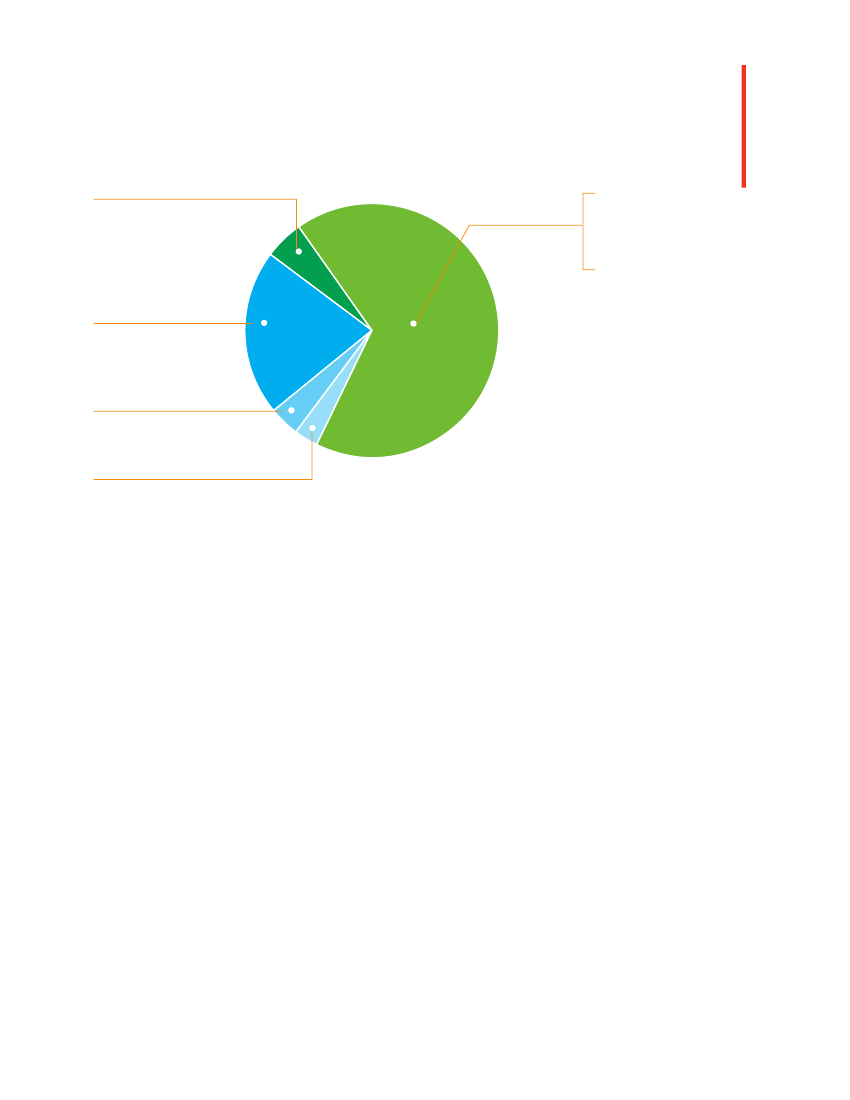

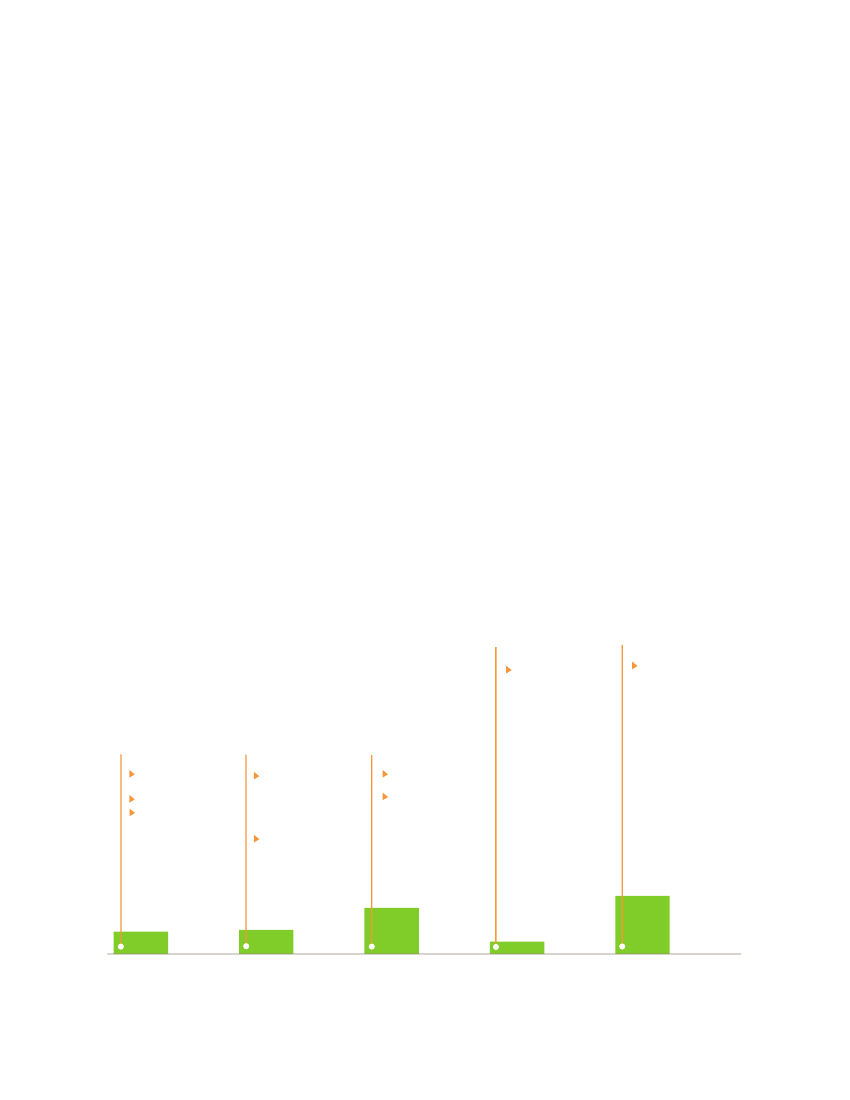

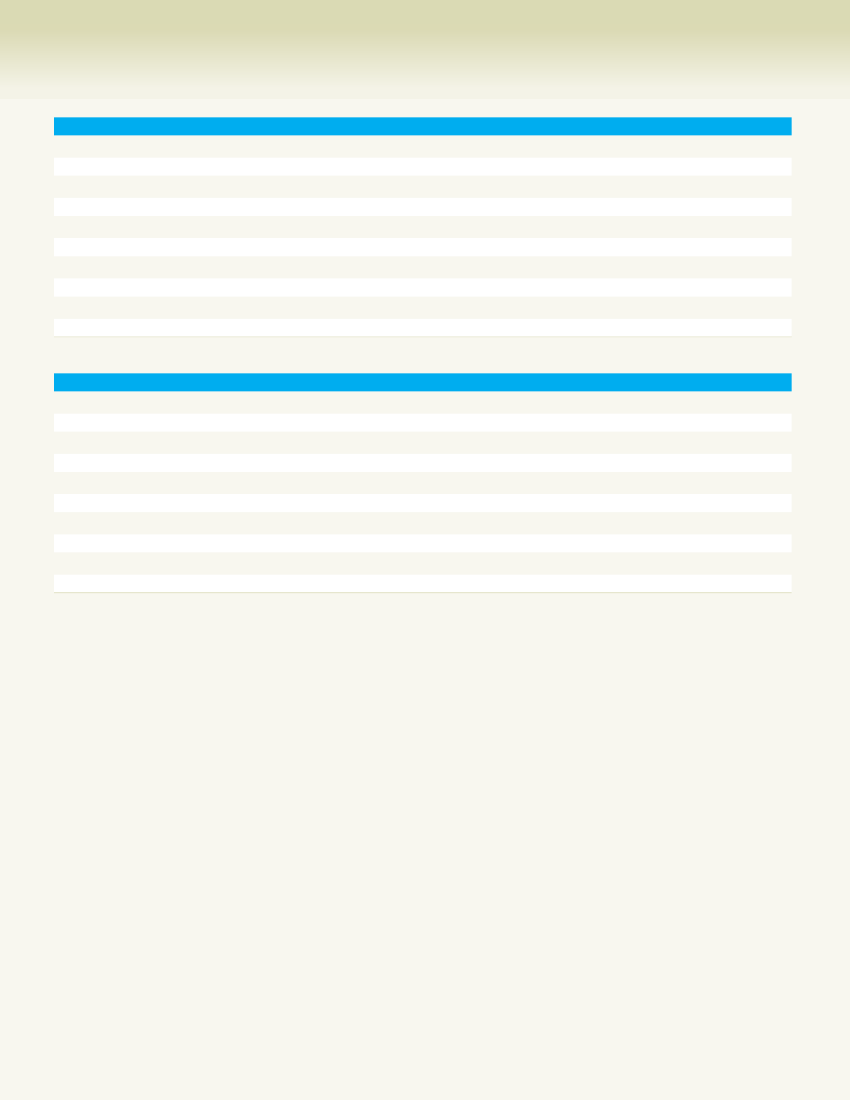

Estimated rates of primaryschool completionwithdisabilitywithoutdisability

51%61%42%53%

withdisabilitywithoutdisability

Source:World Health Organization, based on surveys in 51 countries.

12

THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S CHILDREN 2013: Children with Disabilities

hierarchy and traditional expectations of gender,so the routine absence, misrepresentation orstereotyping of people with disabilities createsand reinforces social prejudices and leads to theunderestimation of the roles and place of peoplewith disabilities in society.Similarly, participation in social activities helpsto promote a positive view of disability. Sport, inparticular, has helped overcome many societalprejudices. Physical activity can be a powerfulmeans of promoting respect – it is inspirationalto see a child surmount the physical and psycho-logical barriers to participation, including lackof encouragement and support or limited adap-tive equipment. In one study, physically activechildren with disabilities were rated as morecompetent than their non-disabled counterparts.11However, care must be taken not to create anartificial atmosphere in which children with dis-abilities who demonstrate physical heroism aredeemed worthy and those who do not are madeto feel inferior.Sport has also been helpful in campaigns toreduce stigma. Athletes with disabilities areoften among the most recognized representa-tives of people with disabilities, and many usesuch platforms as the Paralympics and SpecialOlympics to campaign and to become rolemodels for children with physical or intellectualimpairments. Moreover, experiences in Bosniaand Herzegovina, the Lao People’s DemocraticRepublic, Malaysia and the Russian Federationshow that access to sport and recreation is notonly of direct benefit to children with disabilitiesbut also helps to raise their standing in the com-munity as they are seen to participate alongsideother children in activities valued by society.12Encouraging children with disabilities to takepart in sport and recreation in company with alltheir peers is more than a matter of changingattitudes. It is a right and a specific requirementof the CRPD, which instructs States parties to“ensure that children with disabilities have equalaccess with other children to participation in play,

It’s about abilityMontenegro’s ‘It’s About Ability’ campaign waslaunched in September 2010 and has had an impact onthe public’s knowledge of and attitudes and practicestowards children with disabilities. The campaign bringstogether a broad coalition of 100 national and inter-national organizations ranging from the Governmentof Montenegro to the European Union, the Council ofEurope, the Organization for Security and Co-operationin Europe, United Nations agencies, embassies, asso-ciations of parents of children with disabilities, printand electronic media, the private sector, local officialsand children with and without disabilities. One of thecampaign’s strategies involved the use of billboards allover the country to show children with disabilities asactive members of society, portraying them as athletes,friends, musicians, dancers, students, daughters, sons,brothers and sisters.A November 2011 survey measuring the impact of thecampaign reported that it contributed to an 18 percent increase in the number of people who considerchildren with disabilities as equal members of society.Behaviour toward children with disabilities andcommunication between them and people withoutdisabilities were also seen to improve.

recreation and leisure and sporting activities,including those activities in the school system.”

Supporting children andtheir familiesThe CRPD underlines the role of the family as thenatural unit of society and the role of the Statein supporting the family. It says that “personswith disabilities and their family members shouldreceive the necessary protection and assistanceto enable families to contribute towards the fulland equal enjoyment of the rights of personswith disabilities.”13The process of fulfilling the rights of a child witha disability – of including that child in community

FUNDAMENTALS OF INCLUSION

13

Social protection for children with disabilitiesand their families is especially important becausethese families often face a higher cost of livingand lost opportunities to earn income.Estimates of the additional costs of disabilityborne by families range from 11–69 per centof income in the United Kingdom to 29–37 percent in Australia, 20–37 per cent in Ireland, 9 percent in Viet Nam and 14 per cent in Bosnia andHerzegovina.14Costs associated with disabilityinclude such direct expenses as medical treat-ment, travel, rehabilitation or assistance withcare, and such opportunity costs as the incomeforgone when parents or family members giveup or limit their employment to care for a child orchildren with disabilities.15The International Labour Organization has esti-mated that in 10 low- and middle-income coun-tries, the economic costs of disability amount to3–5 per cent of gross domestic product.16A reviewof 14 developing countries found that peoplewith disabilities were more likely to experiencepoverty than those without disabilities.17Peoplewith disabilities tended to be less well off in termsof education, employment, living conditions,consumption and health. In Malawi and Uganda,households with members who have disabilitieshave been found more likely to be poorer thansimilar households without disabled members.18Households with members with disabilities gener-ally have lower incomes than other householdsand are at greater risk of living below the povertyline.19In developing countries, households with amember or members who have disabilities spendconsiderably more on health care.20This meansthat even a household that technically standsabove the poverty line but includes a memberor members with disabilities can actually havea standard of living equivalent to that of a house-hold below the poverty line but without memberswith disabilities.The evidence is clear that childhood disabilitydiminishes a person’s life chances. Children withdisabilities grow up poorer, have less access

Marmane, 8, looks over her shoulder in a rehabilitationcentre run by the international non-governmentalorganization Médecins sans Frontières in Port-au-Prince,Haiti. � UNICEF/HQ2005-1970/LeMoyne

life – begins with establishing a home settingconducive to early intervention. It involves stimu-lation and interaction with parents and caregiversfrom the first days and weeks of life through thedifferent stages of the child’s educational andrecreational development. Inclusion is importantat all ages but the earlier children with disabilitiesare given the chance to interact with peers andthe larger society, the greater the likely benefitsfor all children.Under the CRPD, children with disabilities andtheir families have the right to an adequate stan-dard of living, including adequate food, clothingand housing. Children with disabilities and thoseresponsible for their care are also entitled to suchsubsidized or free support services as day care,respite care and access to self-help groups.

14

THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S CHILDREN 2013: Children with Disabilities

to education and health-care services, and areworse off on a host of measures including thelikelihood of family break-up and abuse.States can tackle the consequent, increased risk ofchild poverty with such social protection initiativesas cash transfer programmes. These programmesare relatively easy to administer and provide forflexibility in meeting the particular needs of par-ents and children. They also respect the decision-making rights of parents and children.Cash transfer programmes have been shownto benefit children,21although it can be diffi-cult to gauge the extent to which they are usedby and useful to children with disabilities andthose who care for them.22A growing number oflow- and middle-income countries are buildingon promising results from these broader effortsand have launched targeted social protectioninitiatives that include cash transfers specificallyfor children with disabilities. These countriesinclude Bangladesh, Brazil, Chile, India, Lesotho,Mozambique, Namibia, Nepal, South Africa,

Turkey and Viet Nam, among others. The typeof allowances and criteria for receiving themvary greatly. Some are tied to the severity ofthe child’s impairment. Routine monitoring andevaluation of the transfers’ effects on the health,educational and recreational attainment of chil-dren with disabilities will be essential to makesure these transfers achieve their objectives.Another tool governments can use is disability-specific budgeting. For instance, a governmentthat has committed to ensuring that all childrenreceive free, high-quality education would includespecific goals regarding children with disabilitiesfrom the outset and take care to allocate a suf-ficient portion of the available resources to cover-ing such things as training teachers, making infra-structure and curricula accessible, and procuringand fitting assistive devices.Effective access to services including education,health care, habilitation (training and treatmentto carry out the activities of daily living), reha-bilitation (products and services to help restore

A young boy with albinism reads Braille at school in the town of Moshi, United Republic of Tanzania.� UNICEF/HQ2008-1786/Pirozzi

FUNDAMENTALS OF INCLUSION

15

function after an impairment is acquired) andrecreation should be provided free of charge andbe consistent with promoting the fullest possiblesocial integration and individual development ofthe child, including cultural and spiritual develop-ment. Such measures can promote inclusion insociety, in the spirit of Article 23 of the CRC, whichstates that a child with a disability “should enjoya full and decent life, in conditions which ensuredignity, promote self-reliance and facilitate thechild’s active participation in the community.”23States parties to the CRPD have obligatedthemselves to take action to eliminate discrimi-nation against children with disabilities andto make their inclusion in society a priority.Comprehensive national strategies with mea-surable outcomes will make it more likely forall children to realize their rights. Internationalcooperation and exchange of information andtechnical assistance – including advances inteaching or community-based approaches to

early intervention – could further these aims.Development assistance programmes focusingon children can help by taking into account theneeds of children with disabilities and their fami-lies, particularly in low-income settings wheresystems to protect and promote the rights ofchildren with disabilities may be weak.Services for children with disabilities aredelivered by a range of government andnon-governmental institutions. Appropriatemulti-sectoral coordination involving familymembers would help to avoid gaps in provisionand should be attuned to changes in the child’scapacities and needs as she or he grows andexperiences life.

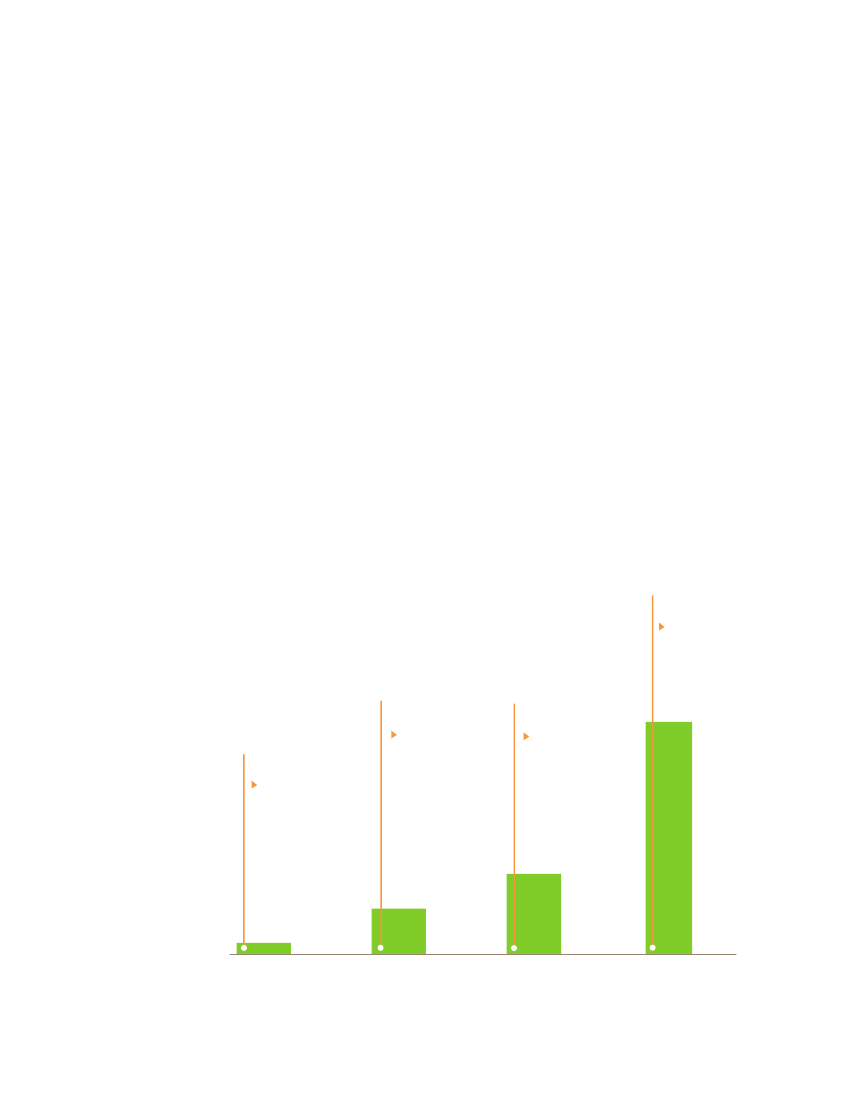

Community-based rehabilitationCommunity-based rehabilitation (CBR) pro-grammes are designed and run by local com-munities. CBR seeks to ensure that people with

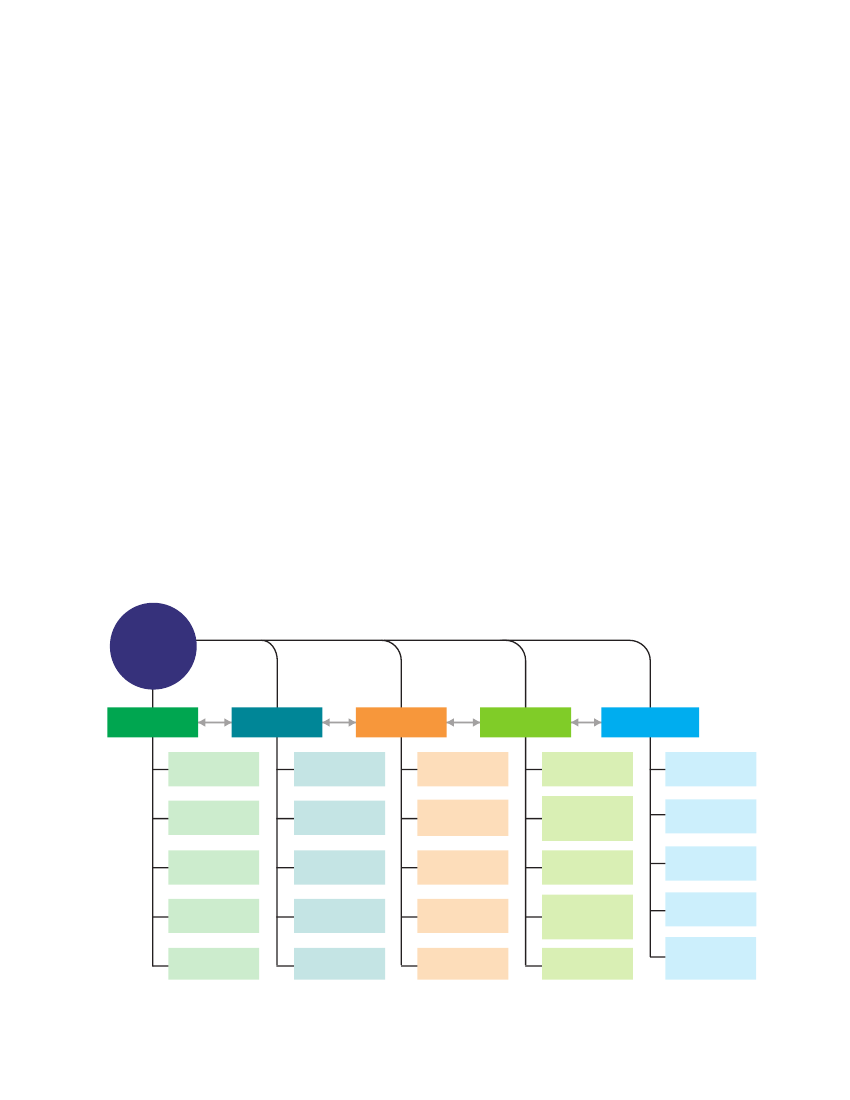

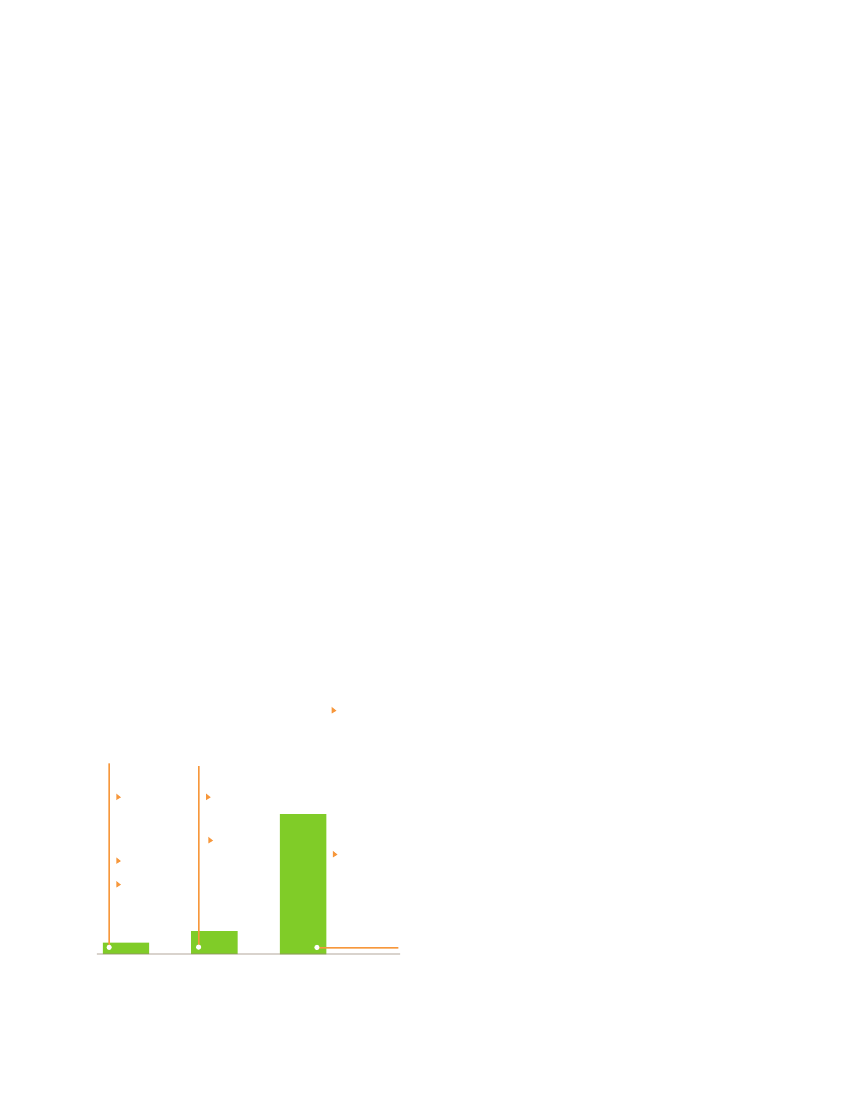

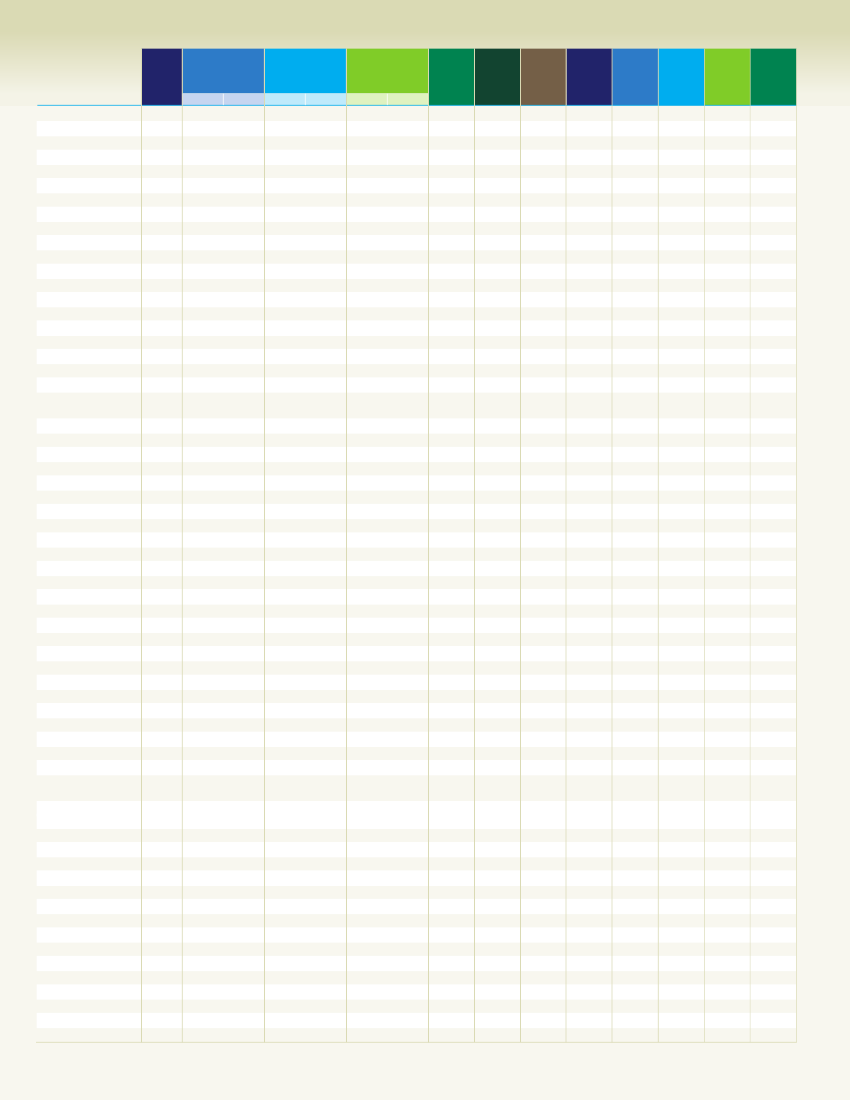

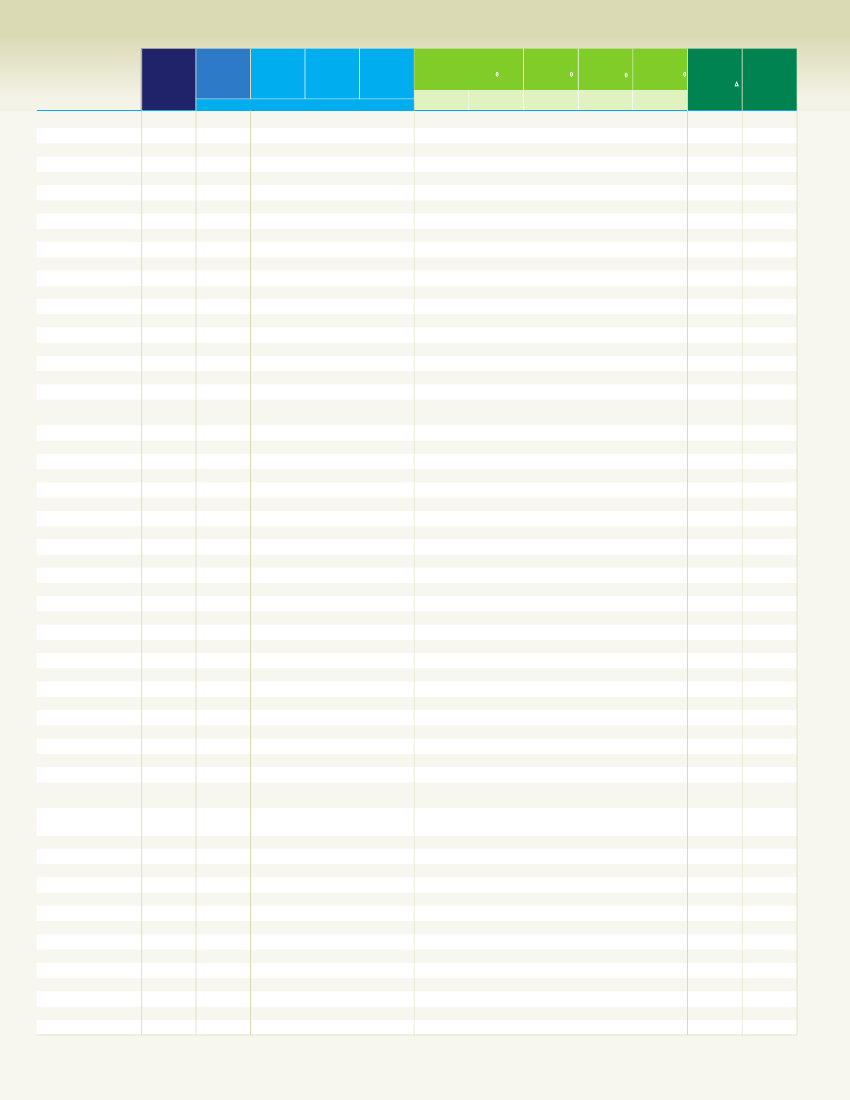

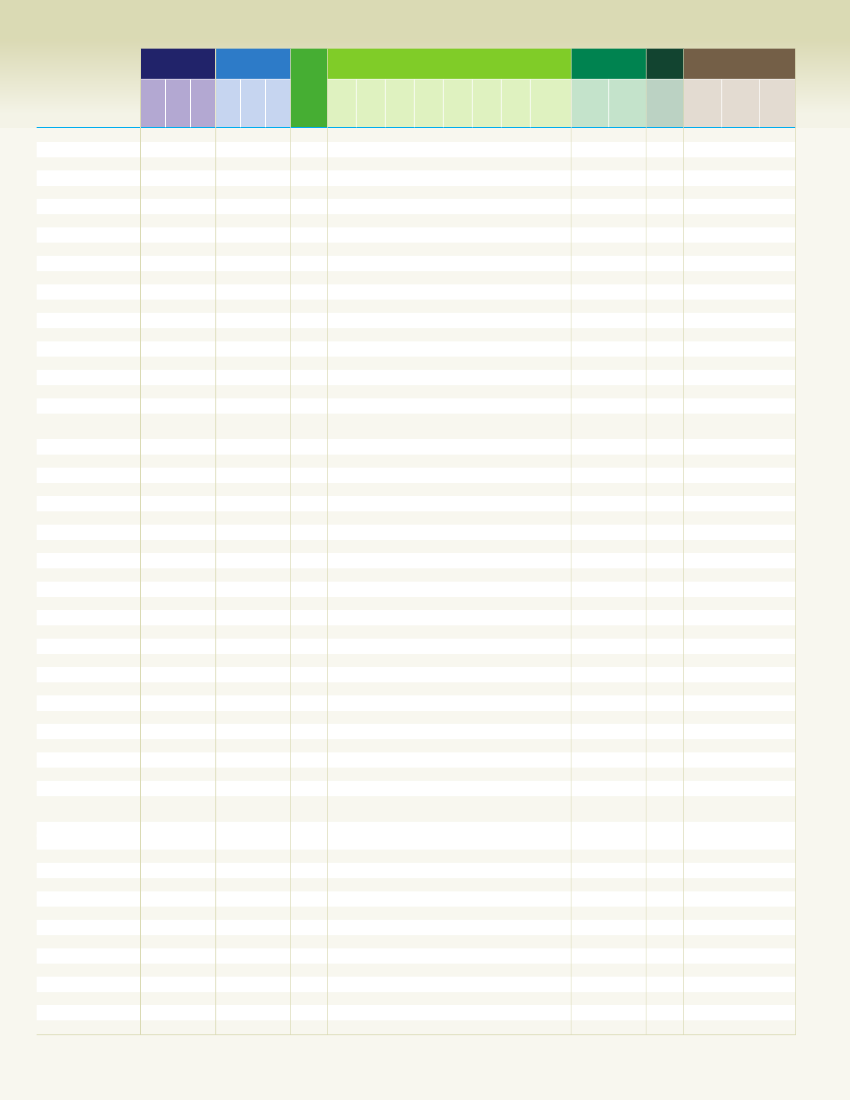

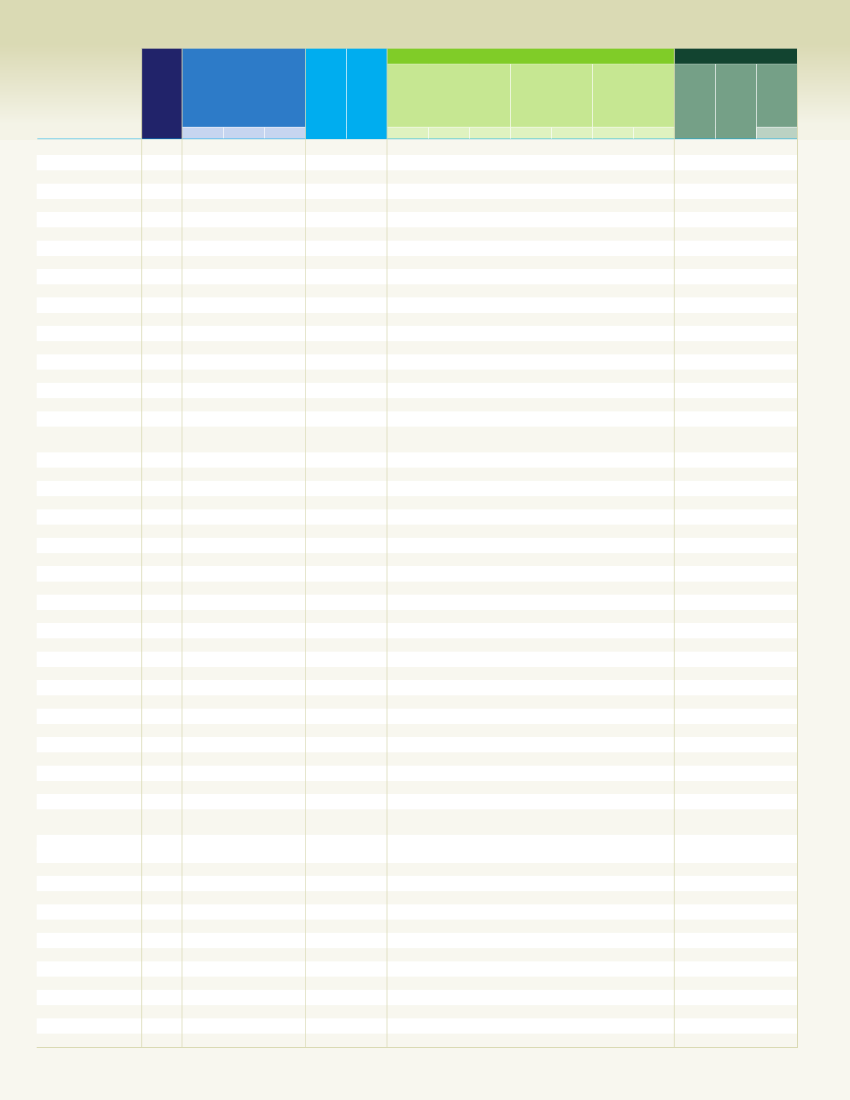

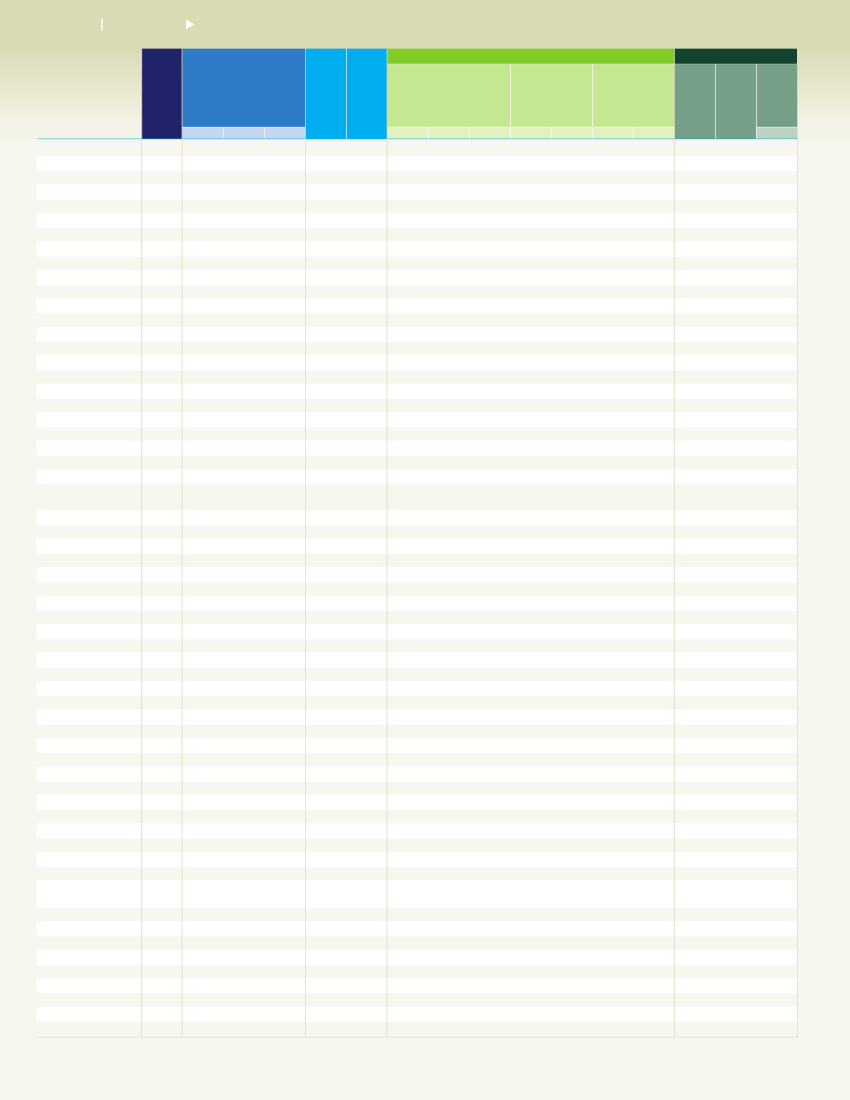

Community-based rehabilitationCBRMATRIXHEALTHPROMOTION

EDUCATIONEARLYCHILDHOODPRIMARY

LIVELIHOODSKILLSDEVELOPMENTSELF-EMPLOYMENTWAGEEMPLOYMENTFINANCIALSERVICESSOCIALPROTECTION

SOCIAL

EMPOWERMENTPERSONALASSISTANCERELATIONSHIPSMARRIAGE &FAMILYCULTURE &ARTSRECREATION,LEISURE &SPORTSJUSTICEADVOCACY &COMMUNICATIONCOMMUNITYMOBILIZATIONPOLITICALPARTICIPATIONSELF-HELPGROUPSRECREATION,LEISURE &SPORTS

PREVENTION

MEDICAL CARE

SECONDARY &HIGHERNON-FORMALLIFELONGLEARNING

REHABILITATIONASSISTIVEDEVICESSource:World Health Organization.

16

THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S CHILDREN 2013: Children with Disabilities

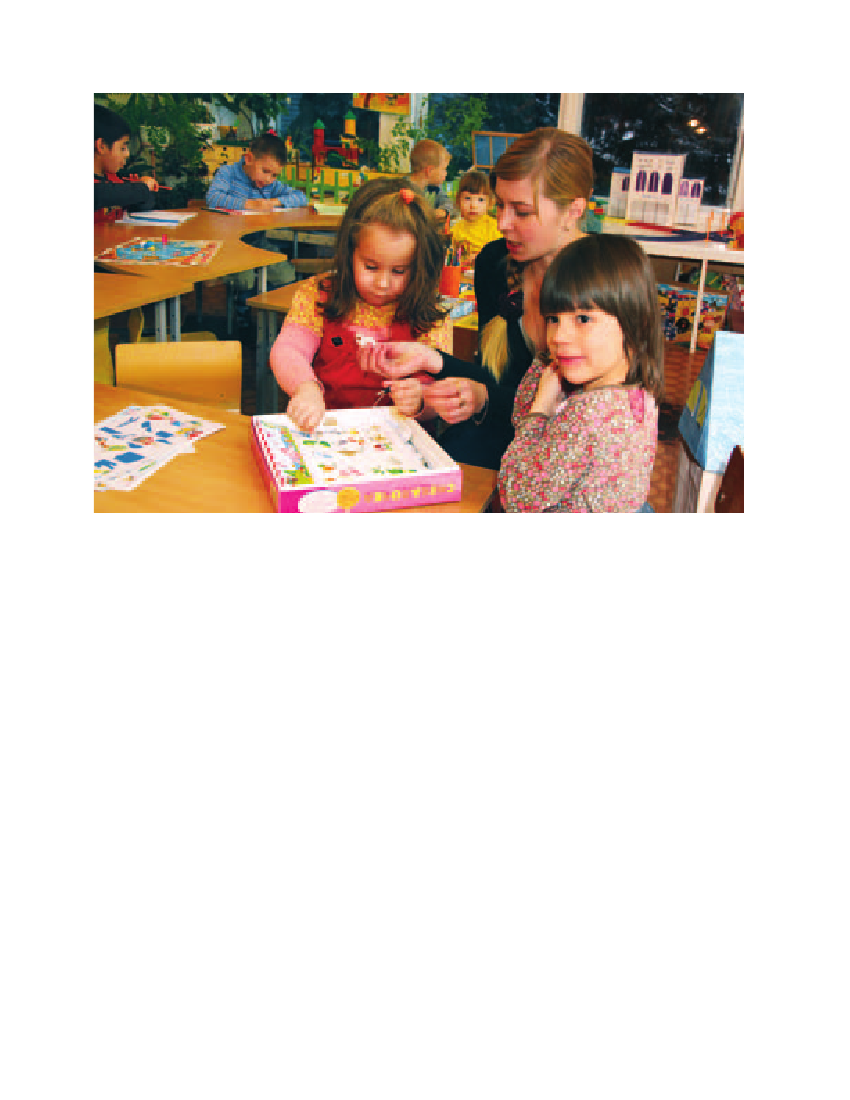

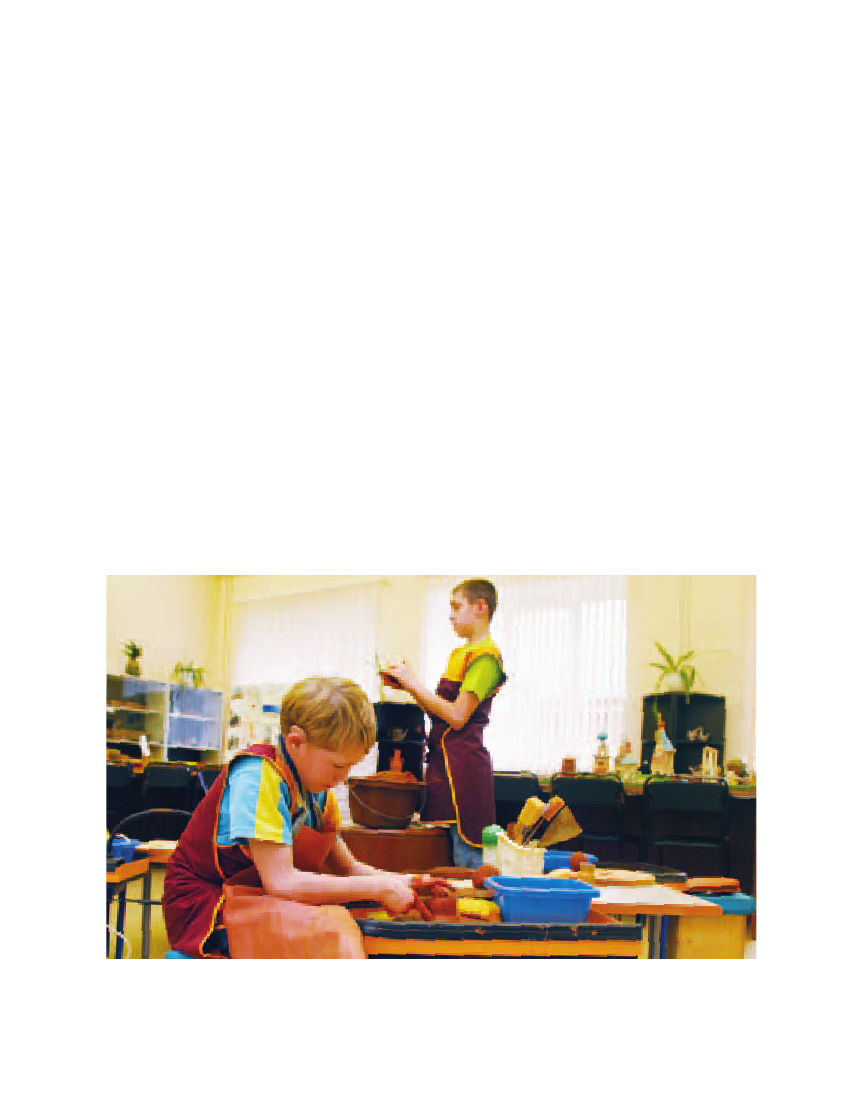

An inclusive kindergarten in Nizhny Novgorod, Russian Federation. � UNICEF/RUSS/2011/Kochineva

disabilities have equal access to rehabilitationand other services and opportunities – health,education, livelihoods. Developed by the WorldHealth Organization (WHO) in the late 1970s andearly 1980s, it is practised in more than 90 coun-tries and represents a move away from the con-centration of care in institutions and at the handsof specialists towards community self-reliance,collaboration and ownership in addressing theparticular needs of people with disabilities –critically, with their own active participation.24CBR can prove effective in addressing multipledeprivations. Children with disabilities who livein rural and indigenous communities contendwith multiple disadvantages: They have dis-abilities, they belong to a marginalized groupand they live in remote locations. They havelittle or no access to services that could ensuretheir development, protection and participationin community life.25An outreach initiative led

by the Centre for Research and Post-SecondaryStudies in Social Anthropology (CIESAS) inOaxaca, Mexico, provides an example of CBRfor indigenous children with disabilities, theirfamilies and community. In collaboration withUNICEF and with financing from the state welfareagency DIF-Oaxaca, CIESAS used CBR to advancethe inclusion of children with disabilities in fourremote rural communities26with large indigenouspopulations and low Human Development Indexscores. Teams – made up of a doctor, a physicalor occupational therapist, an educator and twocommunity activists fluent in local indigenouslanguages – were trained and sent into the com-munities to conduct workshops on discrimina-tion, inclusion and children’s rights. They pro-moted the formation of local support networksamong the families of children with disabilitiesand, where appropriate, provided referrals to med-ical treatment or therapy. During the three-yearperiod 2007–2010, the initiative led to increased

FUNDAMENTALS OF INCLUSION

17

acceptance of indigenous children with disabilitiesby their own families and communities. Benefitsalso included improved provision of social ser-vices, community-led construction of wheelchairramps to make public spaces accessible, agree-ment by state and federal hospitals to provideservices free of charge to children with disabilitiesreferred by the project – and 32 new enrolments ofchildren with disabilities in mainstream schools.27

technology.30The provision and uses of assistivetechnology are discussed in a Focus article pub-lished online at <www.unicef.org/sowc2013>.

Universal designInclusive approaches are built around the con-cept of accessibility, with the aim of making themainstream work for everyone rather than creat-ing parallel systems. An accessible environmentis essential if children with disabilities are toenjoy their right to participate in the community.For instance, access to all schools is necessaryif children with disabilities are to take part ineducation. Children who are educated along-side their peers have a much better chance ofbecoming productive members of their societ-ies and of being integrated in the lives of theircommunities.31Accessibility can refer to the design of anenvironment, product or structure. Universaldesign is defined as the design of products

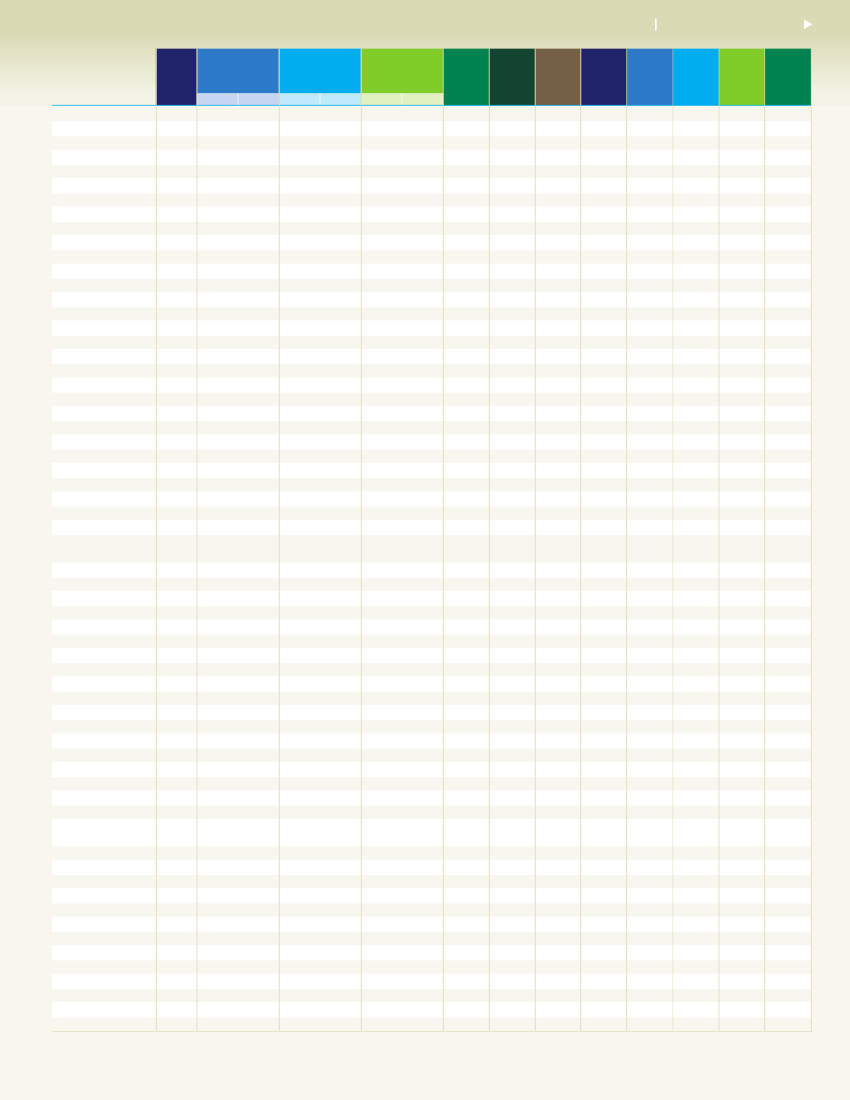

Assistive technologyDepending on the type of disability, a child mayneed any of a number of assistive devices andservices (seenext page).According to the WorldHealth Organization, however, in many low-income countries only 5–15 per cent of the peoplewho need assistive technology are able to obtainit.28Reasons for this include costs, which can beespecially prohibitive in the case of children, whoneed their assistive devices replaced or adjustedfrom time to time as they grow.29Children areoften less likely than adults to access assistive

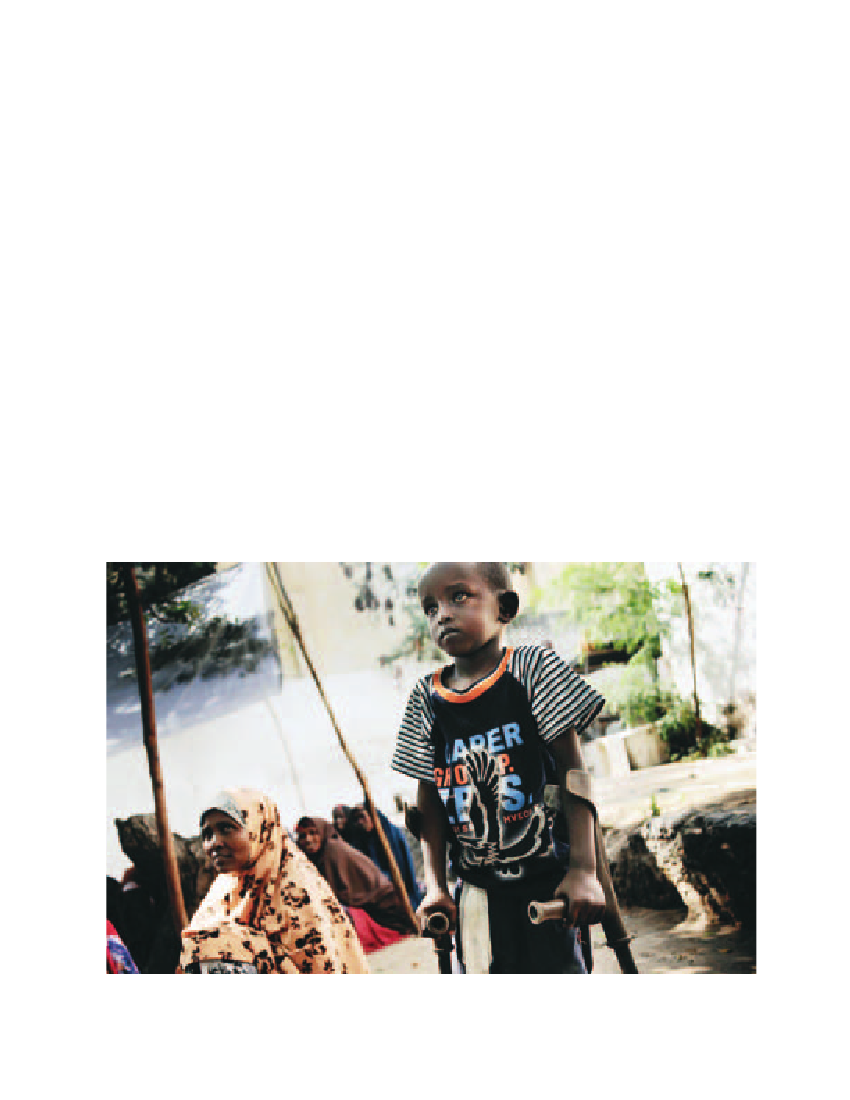

Liban, 8, uses crutches after losing a leg to a bomb explosion in Mogadiscio, Somalia. � UNICEF/HQ2011-2423/Grarup

18

THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S CHILDREN 2013: Children with Disabilities

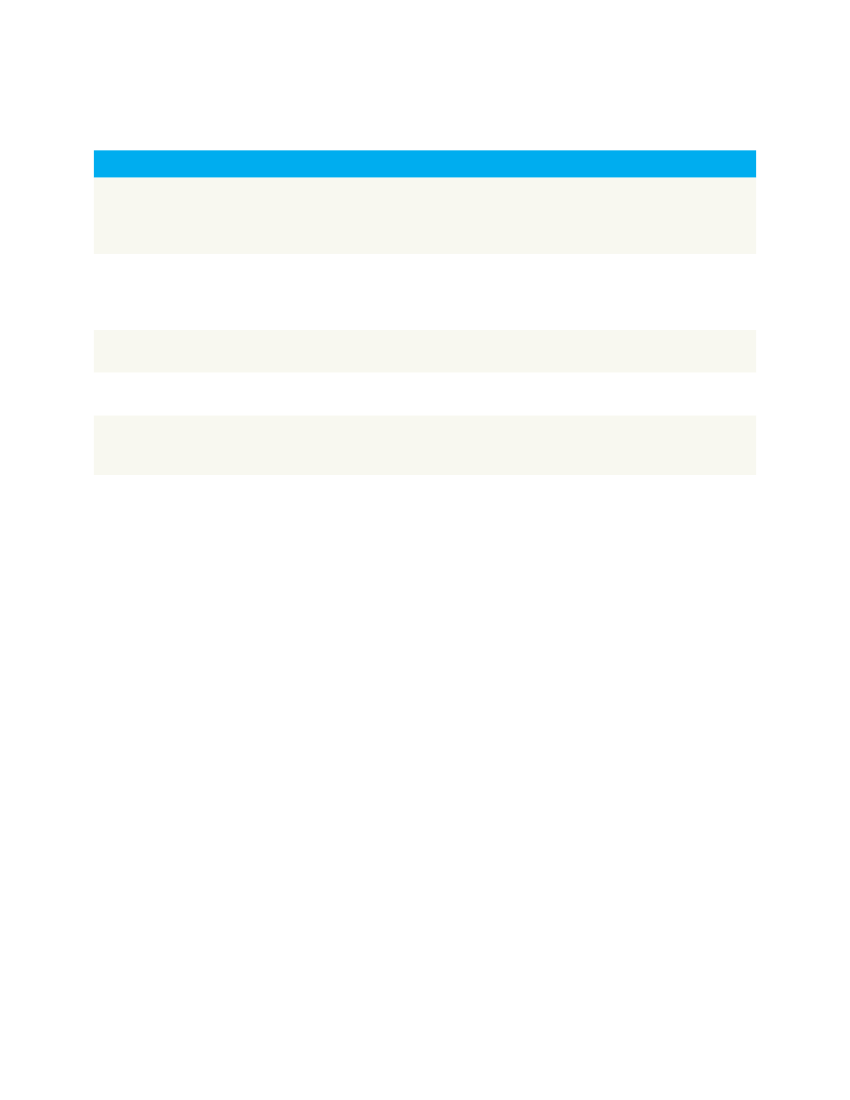

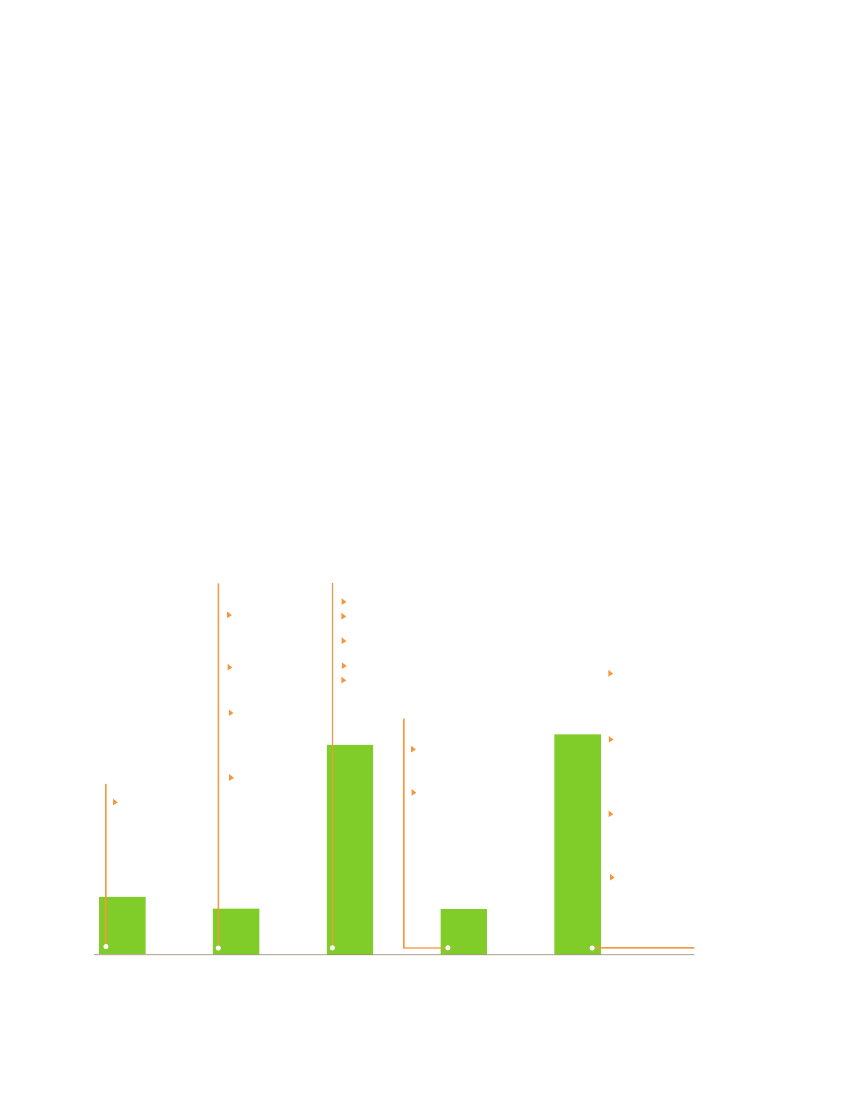

Assistive technology productsCategoryMobility

Examples of products• • • • • • • • Walking stick, crutch, walking frame, manual and powered wheelchair, tricycleArtificial leg or hand, caliper, hand splint, club foot braceCorner chair, special seat, standing frameAdapted cutlery and cooking utensils, dressing stick, shower seat, toilet seat, toilet frame, feeding robotEyeglasses, magnifier, magnifying software for computerWhite cane, GPS-based navigation deviceBraille systems for reading and writing, screen reader for computer, talking book player, audio recorder and playerBraille chess, balls that emit sound

Vision

Hearing

• Headphone, hearing aid• Amplified telephone, hearing loop

Communication• Communication cards with texts, communication board with letters, symbols or pictures• Electronic communication device with recorded or synthetic speechCognition• Task lists, picture schedule and calendar, picture-based instructions• Timer, manual or automatic reminder, smartphone with adapted task lists, schedules, calendars and audio recorder• Adapted toys and games

Source:Johan Borg; International Organization for Standardization (2008), <http://www.iso.org/iso/home/store/catalogue_tc/catalogue_tc_browse.htm?commid=53782>.

and environments to be usable by all people,to the greatest extent possible, without theneed for adaptation or specialized design.The approach focuses on design that worksfor all people regardless of age, ability orsituation.The principles of universal design were devel-oped by architects, product designers, engi-neers and environmental design researchers.They cut across design disciplines and may beapplied to guide the design process or evaluateexisting designs. There are seven principles:equitable use; flexibility in use; simple andintuitive use; perceptible information; toler-ance for error; low physical effort; and sizeand space for approach and use.

In practice, universal design can be found inthe form of curb cuts or sidewalk ramps, audiobooks, Velcro fastenings, cabinets with pull-outshelves, automatic doors and low-floor buses.The cost of integrating accessibility into newbuildings and infrastructure can be negligible,amounting to less than 1 per cent of the capitaldevelopment cost.32However, the cost of makingadaptations to completed buildings can be muchhigher, especially for smaller buildings, whereit can reach 20 per cent of the original cost.33Itmakes sense to integrate accessibility consid-erations into projects at the early stages of thedesign process. Accessibility should also be aconsideration when funding developmentprojects.

FUNDAMENTALS OF INCLUSION

19

PERSPECTIVE

For deaf young people,language is the keyBy Krishneer Sen

Access to information andmeans of communication areessential for anyone to realizetheir rights as a citizen. Withoutways to gather knowledge,express opinions and voicedemands, it is impossible toobtain an education, find a jobor participate in civic affairs.In my country, Fiji, lack ofaccess to information andmeans of communication arethe biggest issue facing deafchildren. Information andcommunication technology(ICT), which I am studyingat university, is helping deafpeople around the world, creat-ing opportunities that simplywould not have been possiblea generation ago. Where avail-able, ICT provides deaf peoplewith the chance to communi-cate and connect with friends,reduces their isolation andopens up avenues for their par-ticipation in political, economic,social and cultural life. Thosewho lack access – because theylive in rural areas, are poor orlack education, or for whomappropriately adapted devicesare not yet available – experi-ence frustration and exclusion.Deaf Fijians like me havelimited access to the media,

emergency services – and evensimple telephone conversa-tions. In the absence of suchassistive technology as cap-tioned telephones, we mustrely on people who can hear toserve as interpreters, or resortto text messaging. This will notchange until ICT and mediapolicy for people with disabili-ties become a top governmentpriority.Deaf people can succeed andcontribute to society just likehearing people. Developingtheir abilities begins with edu-cation and language. Becausedeaf children grow up in ahearing world, quality educa-tion necessarily means bilin-gual education. In Fiji, deafchildren should be taught FijiSign Language in additionto the languages commonlytaught to hearing Fijian chil-dren (English, Fijian and Hindi),and this should start at birth.Bilingual education helps deafchildren develop their abilityto communicate using the lan-guages of hearing people: Deafchildren who can communicateeffectively in sign language willfind it easier to learn other lan-guages, like English. I believethat bilingualism will give deafchildren better access to the

Krishneer Sen, a deaf youth activistfrom Suva, Fiji, and recipient of theWorld Deaf Leadership scholarship,is studying information technologyat Gallaudet University, UnitedStates. In 2012, he served as anintern with UNICEF Fiji.

20

THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S CHILDREN 2013: Children with Disabilities

We need to make media more accessible to deaf childrenby captioning or interpreting television programmes anddeveloping children’s programmes that use sign language.

education they need to functionas equal citizens.As a kid, I used to watch car-toon programmes on Fijian TVwith no subtitles or sign lan-guage interpreters. My familydidn’t know sign language well.Later on, I realized that the rea-son I was still struggling withmy English was that I had notbeen exclusively taught usingsigns at home. Parents havean important role in facilitatingdeaf children’s ability to com-municate and access informa-tion; along with other peoplewho interact with deaf children,they need to take the initiativeand use sign language to com-municate in their daily lives, athome and school.We need to make media moreaccessible to deaf children bycaptioning or interpreting tele-vision programmes and devel-oping children’s programmesthat use sign language. Weneed an environment freeof communication barriers. Iwould like to see Fijian SignLanguage used in a range ofprogrammes, from news tocartoons. In addition to televi-sion, social media can providepowerful tools to enhanceknowledge about Fiji and

international affairs and ensurethat everyone, including peoplewith disabilities, has access toinformation about the politi-cal situation and can cast aninformed vote during elections.Making ICT available to deafchildren can facilitate theirsocial and emotional devel-opment, help them learn inmainstream schools and pre-pare them for future employ-ment. I took a basic computerclass at a special school, andit changed my life for the bet-ter: It was through the Internetthat I learned about GallaudetUniversity, where I now study.In addition to enhancing edu-cation, ICT provides deaf andother young people with dis-abilities to learn about theirrights and band together tocampaign for their realization.By facilitating activism, ICTmay thus help increase theprofile of persons with dis-abilities within society at largeand allow them to participateactively.My dream is to see deaf peoplecommunicate freely with hear-ing people through the use ofassistive technologies. OnceI graduate, I plan to start a

project to set up communica-tion technologies in Fiji in orderto facilitate communicationbetween hearing and deaf peo-ple, using sign language inter-preters as well as video calling.I will be working with the FijiAssociation for the Deaf, ofwhich I have been a memberfor many years, to advocatefor human rights, opportunitiesand equality.If the government is to con-sider the needs of deaf peoplea priority, deaf people mustadvocate on our own behalf.To facilitate activism amongdeaf people, we must educatedeaf children to use both signlanguage and the languages ofthe hearing communities theylive in, and we must work toexpand access to technologiesthrough which they can findinformation and communicatewith others, deaf and hearing.

FUNDAMENTALS OF INCLUSION

21

A teacher with a hearing impairment teaches a class of hearing-impaired children in Gulu, Uganda. � UNICEF/UGDA2012-00108/Sibiloni

CHAPTER 3