Udenrigsudvalget 2012-13

URU Alm.del Bilag 173

Offentligt

Childhoodunder firethe impact of two yearsof conflict in Syria

Childhoodunder fireThe impact of two years of conflict in Syria

Save the Children works in more than 120 countries.We save children’s lives. We fight for their rights.We help them fulfil their potential.

AcknowledgementsThis report was written by Nick Martlew, Senior Humanitarian Advocacy Adviserat Save the Children. The research was supported by Nick Pope, with additionalassistance from Misty Buswell.Testimonies were collected by Mona Monzer, Cat Carter, and Mohamad Al Asmar.Photos by Jonathan Hymans. (All are Save the Children staff.)The report also includes findings from an unpublished study, the Bahcesehir Studyof Syrian Refugee Children in Turkey, conducted by a team of researchers forBahcesehir University in Istanbul, Turkey. The research team was led by Dr SerapOzer of Bahcesehir University, Dr Selcuk R Sirin of New York University, andDr Brit Oppedal of the Norwegian Institute of Public Health. The study findingsare available from the authors on request.The children’s drawings in this report were gathered as part of the Bahcesehir study.

All names of children and parents who shared their stories have beenchanged to protect identities.

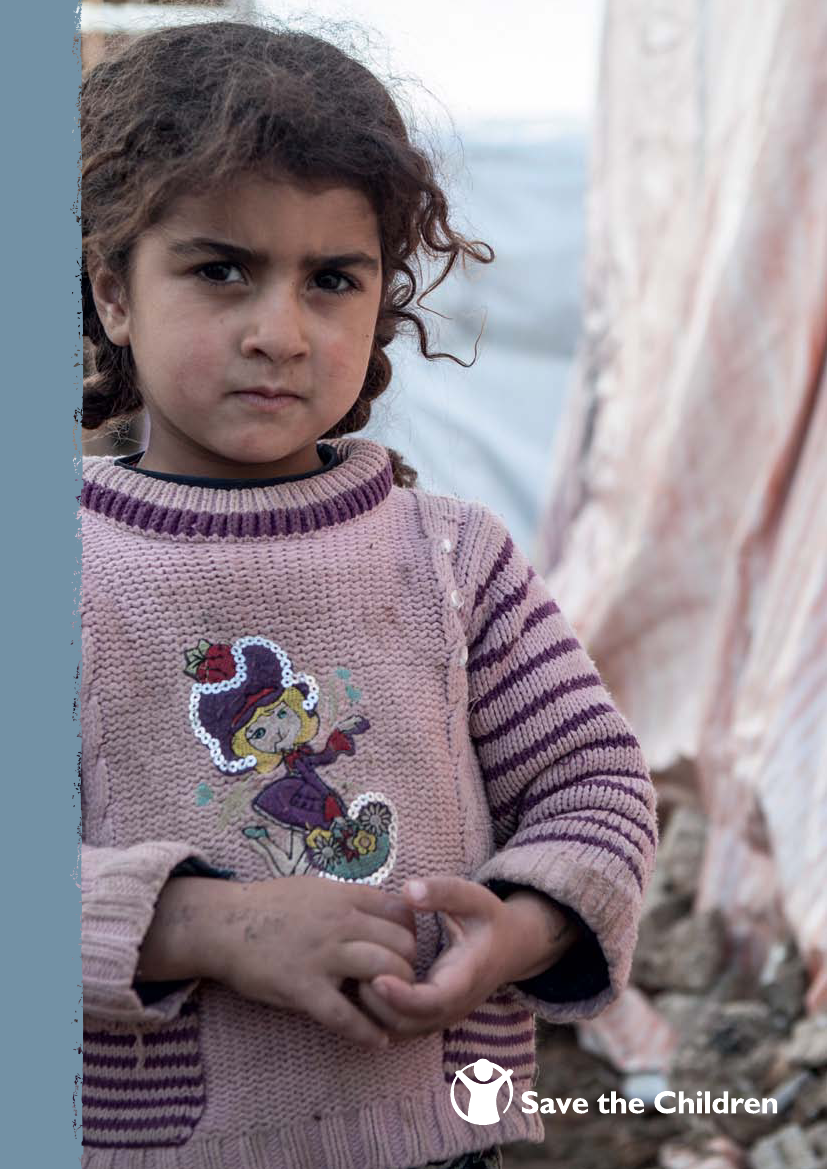

Published bySave the Children1 St John’s LaneLondon EC1M 4ARUK+44 (0)20 7012 6400savethechildren.org.ukFirst published 2013� The Save the Children Fund 2013The Save the Children Fund is a charity registered in England and Wales (213890)and Scotland (SC039570). Registered Company No. 178159This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee orprior permission for teaching purposes, but not for resale. For copying in any othercircumstances, prior written permission must be obtained from the publisher, and afee may be payable.Cover photo: Hanane, four, at a refugee camp near the Syrian border (Photo:Jonathan Hyams/Save the Children)Typeset by Grasshopper Design Company

conTenTS

Executive summaryIntroductionThe impact of war on childrenSheltering from the stormStaying alive, staying healthyDanger on all sidesEducation under attackGoing hungry

iv

1

337101214

Humanity’s best efforts?RecommendationsEndnotes

16

19

22

execuTive Summary

“My message to the world? The war shouldstop in Syria so we could be able to go back toour country.”

Nidal,*6

From the very beginning of the crisis in Syria, childrenhave been its forgotten victims – facing death, traumaand suffering, and deprived of basic humanitarian aid.Save the Children estimates that nearly 2 millionchildren are in need of assistance in Syria.Through Save the Children’s work in Syria and theregion, we are witnessing what is happening tochildren and the misery and fear they are living withevery day. The only way to stop their suffering is tobring an end to the war. A larger humanitarian actionresponse is absolutely essential, but we also recognisethat, without peace, for children in Syria there willonly be more death, and more destruction.

children interviewed had lost a loved one becauseof the fighting. Children are being killed and maimedtoo, including by the indiscriminate use of shells,mortars and rockets. In one area of Damascus thatwas formerly home to almost 2 million people,heavy weapons were used in 247 separate recordedincidents in January 2013 alone.Children are increasingly being put directly in harm’sway as they are being recruited by armed groups andforces. There have even been reports that children asyoung as eight have been used as human shields.Conflict is threatening children’s lives in Syria fromtheir first days of life. Mothers and their newbornsare at greater risk of complications during childbirth.Many hospitals and health workers are beingdeliberately attacked, so people are reluctant to takethe risk of going to hospital; across the country, athird of hospitals have been put out of action. Thismeans more births are taking place at home, withouta skilled birth attendant. There is also a worryingtrend of attacks, mostly by Syrian government forces,on hospitals in contested areas. We have seen howeven hospitals that have managed to stay open arefinding it difficult to provide a high standard of care,with little or no heating, exhausted doctors, andintermittent electricity supply.Children’s access to healthcare is massively reducedwhile the risks to their health grow. In many areas,water and sewage systems have been destroyed ormade inaccessible by violence or displacement; in onearea where Save the Children works, almost everyfamily told us they did not have safe access to cleantoilets. These unsanitary conditions are contributingto the growing number of cases of children sufferingdiarrhoea – the biggest killer of children globally.Schools should be a safe haven for children. But2,000 schools in Syria have been damaged duringthe conflict, and many are closed because they havebecome temporary shelters for displaced people.

“We had to stay in one room, all of us… Iwatched my father leave, and watched as myfather was shot outside our home… I started tocry, I was so sad. We were living a normal life, wehad enough food… Now, we depend on others.Everything changed for me that day.”

Yasmine, 12

This report shows how the conflict is affecting allaspects of children’s lives. Families are struggling tofind a safe place to stay, as nearly 3 million buildingshave been damaged or destroyed. The lines offighting move almost daily, so families often do notknow if the place they’ve settled in today will be safetomorrow. Most displaced families share overcrowdedapartments and houses, but an estimated 80,000internally displaced people are sleeping out in caves,parks or barns.With more than 5,000 people being killed eachmonth, the killing is touching everyone: a newstudy by a research team at Bahcesehir Universityin Turkey found that three in every four Syrian

*

All names of children and their family members who shared their stories have been changed to protect identities.

iv

Experience in other conflict settings where Save theChildren works shows that the longer children areout of school, the less likely they are to ever go back,threatening their own futures and the future ofthe country.

taking time; and it only takes one checkpoint to refusepassage for the entire aid delivery to be halted.There are also few organisations – local orinternational – with the skills and systems in placein Syria to respond to the massive scale of needs.Some Syrian agencies delivering assistance have strongpolitical affiliations with one side of the conflict,representing a challenge to the principles of humanityand impartiality, which are essential to reach thosemost in need.Save the Children is calling on the internationalcommunity to take urgent action to address someof these challenges so that children and their familiescan receive the assistance they so desperately need.First and foremost,the UN Security Council mustunite behind a plan that will bring about an endto the violence and ensure that humanitarianaid reaches children throughout Syria.In addition:• The international community must press urgently and explicitly for parties to the conflictto end the recruitment and use of children inmilitary activities, and cooperate with the UN toensure that all violations of children’s rights aredocumented so that those responsible can be heldto account.• International donors should quickly turn pledges into funding and deliver assistance on the groundin a way that is needs-based, sustained, flexible,and coordinated.

“I liked going to school… We used to write andplay. When I want to remember somethinghappy, it is playing with my friends on the swings.We laughed. I miss them.“At the beginning… there wasn’t shelling at myschool, but after some time the shelling started.I stopped going to school when the shellingstarted. It wasn’t safe. I feel sad that my schoolwas burned because my school reminds me ofmy friends. I love going to school.”

Noura, 10

Mills, factories and roads are also being damaged andfarmland threatened by shelling. As a result, mostparts of the country are experiencing shortages offlour, forcing food prices beyond the reach of thepoorest families. Combined with an alarming drop inthe proportion of mothers breastfeeding their infants,this is leading to the first signs of increasing levels ofchild malnutrition in Syria.It is not just Syrian citizens whose lives are beingaffected by the war. Non-nationals who were living asrefugees in Syria (including large numbers of Iraqis andPalestinians) have limited access to assistance and arebecoming ever more vulnerable.Despite the efforts of the United Nations (UN) andnon-governmental organisations (NGOs), millions ofpeople in desperate need in Syria are not receivingenough humanitarian assistance. Some areas havehad very little aid or none at all. Insecurity is oneof the biggest constraints: 15 aid workers in Syriahave lost their lives in the past two years. Access isanother huge obstacle, as control of access routesshifts continually with the fighting. This means thatagencies sometimes have to negotiate more than20 checkpoints for one journey, with each negotiation

“I wasn’t thinking; I just wanted to protect mychildren. I didn’t want anything else. I wasn’t eventhinking; I just wanted to keep my children safe.If I die it is fine… but not my children. I want tokeep them safe…“Syria is our country and we want to go backthere. We don’t know who is right and whois wrong, but I know we civilians are payingthe price.”

Hiba

v

Safa

“I want to tell the world about the situation inSyria… There is no fuel, no electricity, no food.This is the situation. There is shelling, explosions,gunfire… violence, death. No one is working,there are no jobs. People are just surviving day today, living for the sake of living.

years… killing, fleeing. I wish the world could seethe truth. I wish you could.“I don’t think there is a single child untouchedby this war. Everyone has seen death, everyonehas lost someone. I know no one who has notsuffered as we have. It is on such a scale.

“Every human being should act – they should“When the world finally sees what is happeningstop this violence. It is killing women and children.in Syria, when you go to villages beyond those youPeople are fleeing. We cannot bear this… This,are ‘allowed’ into – you will not have the words.this is too much…Everything is destroyed. A people is destroyed.“I hope that you can tell the entire world what“You… will not be able to bear what you willI have said here, what I have seen. I am onlysee in Syria. We know what is happening, but theone person, but every person will say the same.world is not listening.”We are tired… tired of this. It has been two

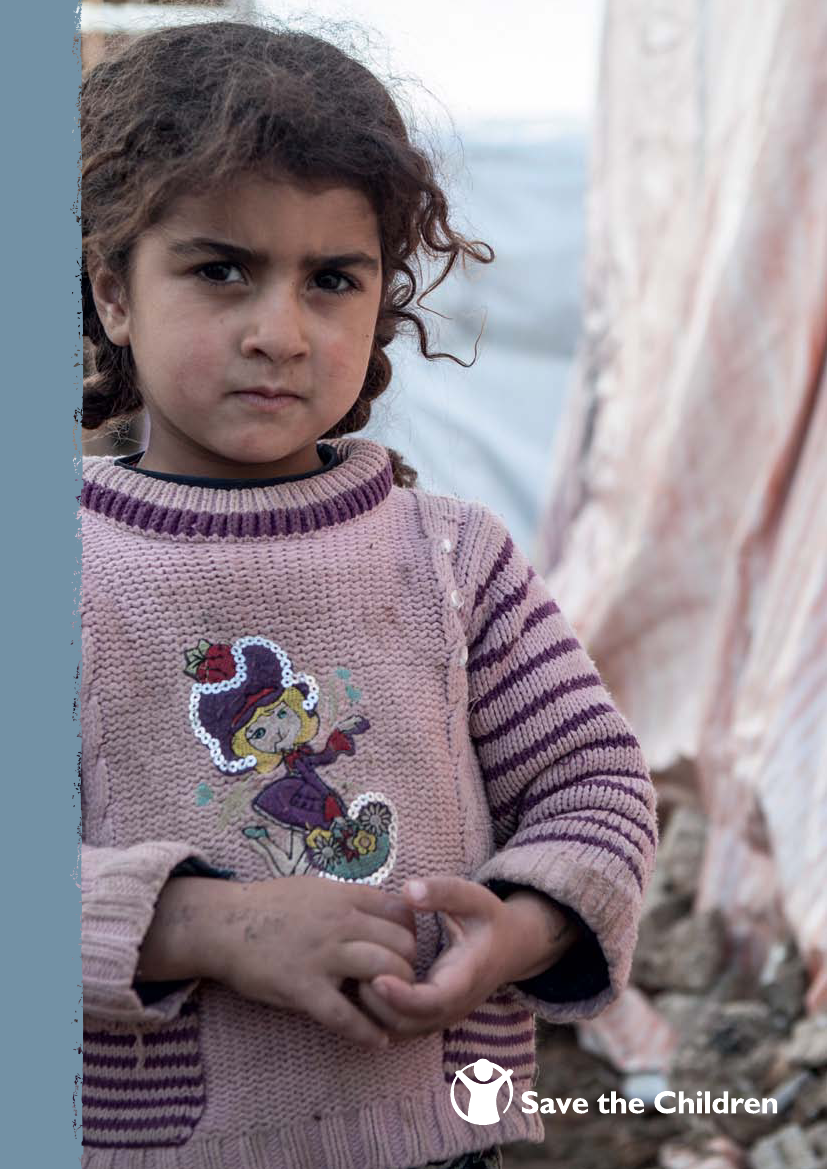

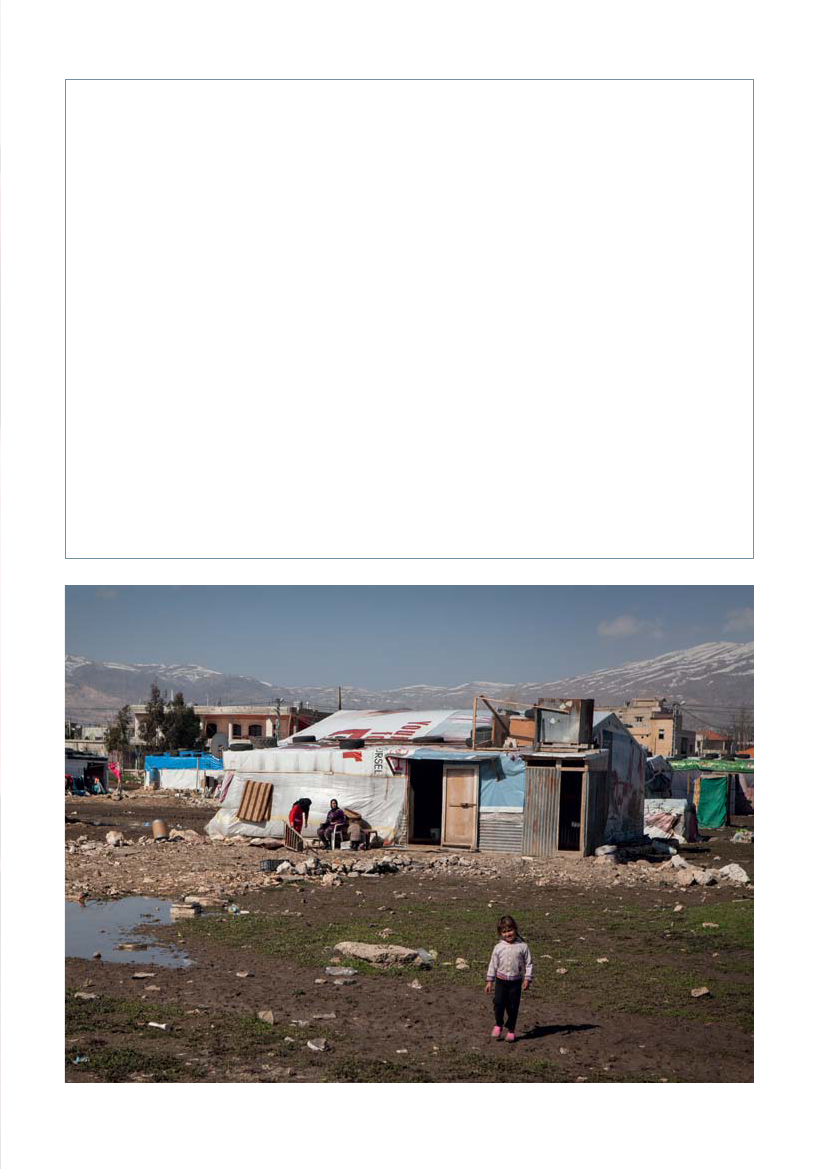

PHOTO: JONATHAN HYAMS/SAvE THE CHILDREN

A refugee settlement near the Syrian border

vi

inTroducTion

“Once, armed men chased us. They shot at [thethree of] us and it hit the ground near my foot soI jumped. It hit below my foot and it touched myshoe but I kept running. We reached a wall andcouldn’t run any more.“I was scared, very scared. I was scared and myfriends too. We were surrounded by walls. Sowe chose to jump over one wall. When we ranthrough the garden, we saw men with guns. Theyasked us why we were running. We told them wewere being followed. They came with us and ranwith us and we reached another wall, and oneof them carried me over and my other friendjumped by himself. Another friend they caught,I don’t know what happened to him.“My message to the world? The war shouldstop in Syria so we could be able to go back toour country.”

From the very beginning, children have been theforgotten victims of Syria’s horrendous war. Today,nearly 2 million children are in need of assistance.1Six months into the conflict, 1,000 people were dyingeach month; now, it is 5,000 people each month.2Thefighting is on such a scale that few children have beenspared feeling its effects. Three in every four Syrianrefugee children interviewed as part of new researchby Bahcesehir University, Turkey, had experienced thedeath of a loved one due to the conflict.3This report bears testimony to the suffering of Syria’schildren. Deprived of food, water, healthcare; deniedsafety; their homes and communities destroyed; in awar being fought ferociously throughout the country,children above all are paying the price.The chaotic reality of the conflict makes it difficult togather comprehensive, definitive data. The informationon which this report is based has been gatheredthrough Save the Children’s response to the crisison the ground, as well as the experience of other

Nidal, 6

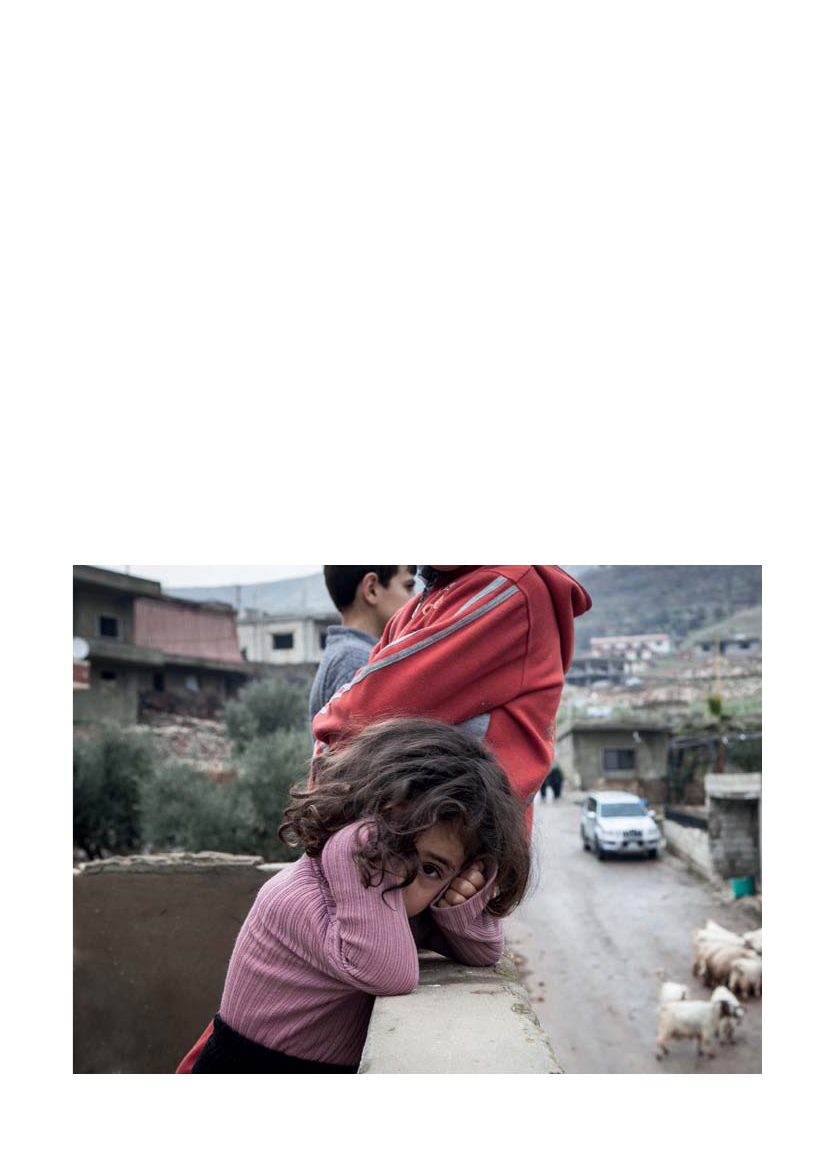

PHOTO: JONATHAN HYAMS/SAvE THE CHILDREN

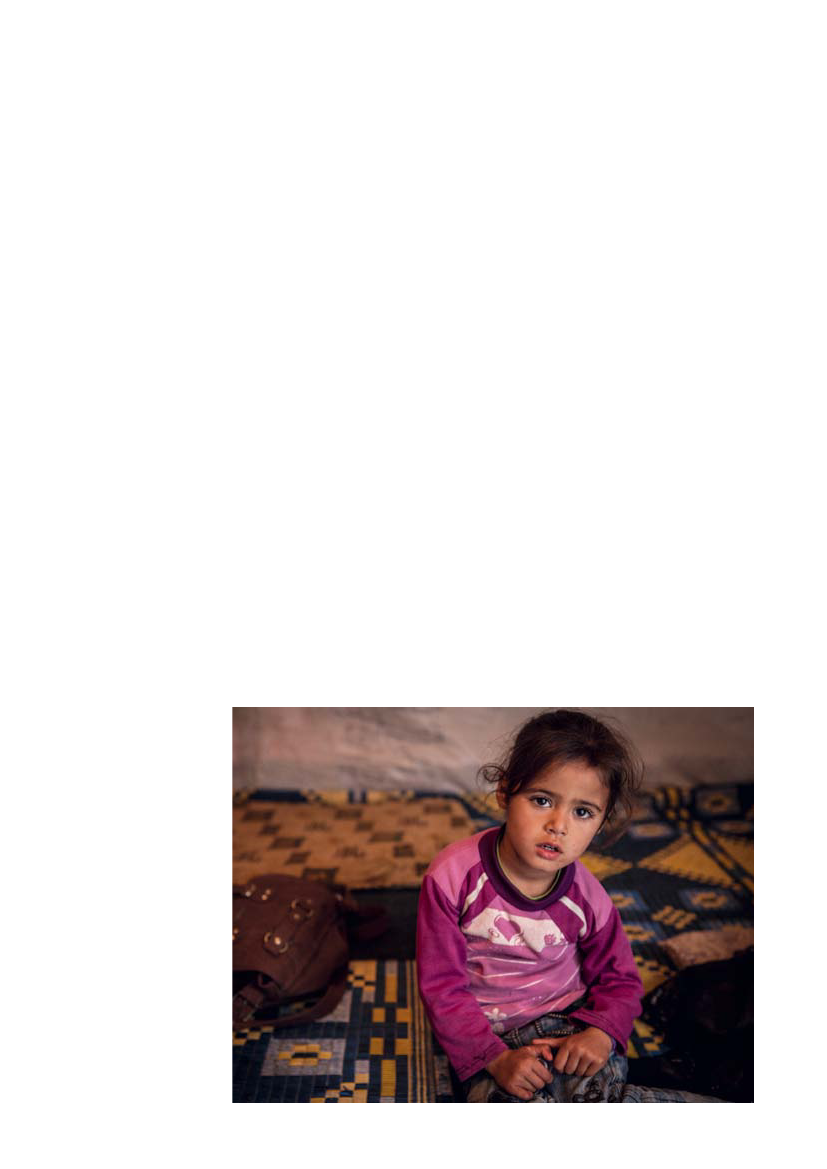

Sana, three. Her older sisterYasmine explains whathappened to their familyon page 4.

1

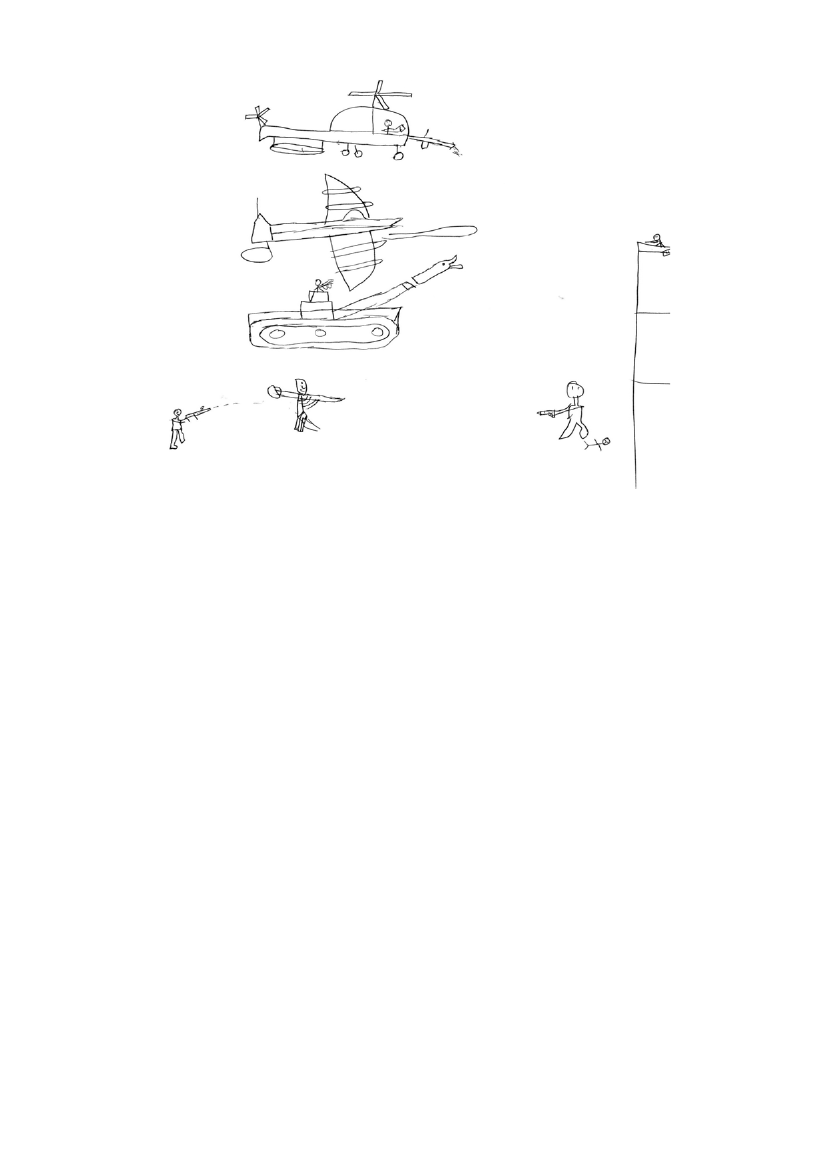

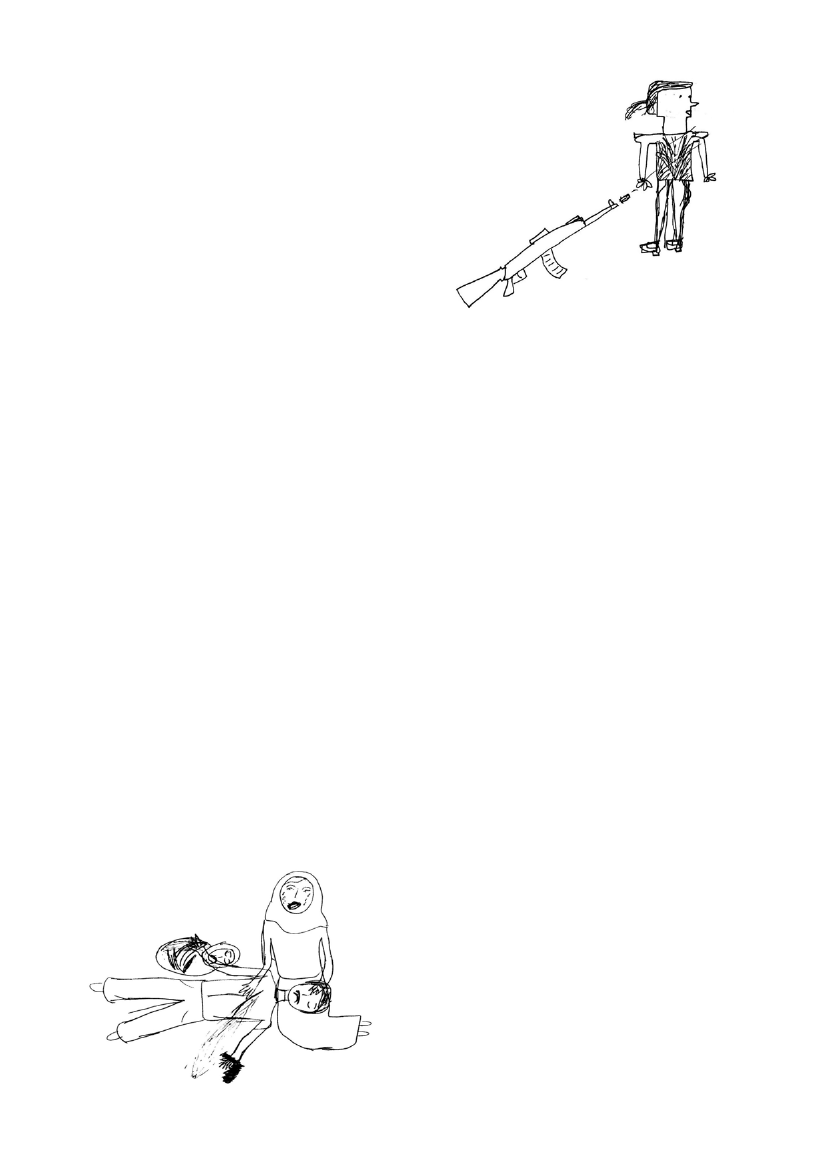

CHILDHOOD UNDER FIREDrawing by a Syrian refugee child

agencies working in the country. The interviewscarried out with children and their parents – all ofwhose names have been changed – provide powerfultestimony to the devastating impact of the war onevery aspect of children’s lives today.Through our work in Syria and the region, Save theChildren is witnessing first-hand the misery beinginflicted on children. They are telling us their storiesand they want them to be heard. We are workingtirelessly in Syria – and with refugees in Iraq, Jordan,and Lebanon – to meet the enormous humanitarianneeds of children and their families.An estimated 4 million people are in need ofassistance within Syria, in addition to more than1 million who have fled to neighbouring countries.4The United Nations (UN) and non-governmentalorganisations (NGOs) are doing what they can toreach people in need by whatever channels availableto them, and millions of people have already receivedfood or other forms of assistance. Despite theseefforts, children are not receiving the help theyneed.5This report is an urgent call to action: theinternational community must take stronger actionto support humanitarian efforts, based solely on theneeds and rights of those affected by the conflict,

and independent of any political interests. The scaleof the crisis demands a concerted, coordinated, andlarge-scale response.Stopping the war is the fastest way to stop thesuffering and start the process of reconciliation andrebuilding. Humanitarian action is absolutely essential,but we also recognise that without peace, forchildren in Syria there will only be more death, moredestruction; the legacy of this conflict grows morepainful and costly with every day of fighting. The onlyway to stop the suffering is to bring an end to the war.The first part of this report sets out how Syrianchildren’s lives are being affected by the conflict,from the places they have to live to the violencethey have to fear; the impact on their educationand on their health. Children and parents describein their own words how the war has affected theirlives and the lives of their loved ones. The reportthen gives an overview of the challenges involved indelivering a humanitarian response of the scale andquality needed. Finally, we present Save the Children’srecommendations for how to overcome thesechallenges to ensure that children’s needs for basicsurvival and protection are met.*

*

The report includes information from different parts of Syria, but where that information could compromise the securityof children, their families and communities, or the agencies involved in the humanitarian response, we do not cite a location.

2

The impacT of waron childrenAs Safa’s story shows (see page vi), the civilwar raging throughout Syria is devastatingall aspects of children’s lives. This sectiondescribes some of the ways the fighting isaffecting children, beginning with the desperateshelter conditions for the millions of peopleinside Syria who have had to flee their homes.It then looks at the impact of the war onchildren’s health, protection, education, andfood security.up to 50 children living in one house.13Thousandsof people either have no extended family to turn toor cannot reach them. It is estimated that 80,000internally displaced people (IDPs) are sleeping out incaves, parks or barns.14Displaced people are receiving some temporaryshelters and basic items provided by Syrianor international humanitarian agencies, butimplementation challenges (described below) meanthe level of assistance is far below internationalstandards. Save the Children is seeing how thisparticularly affects girls: the shelters that thousandsof families are living in are cramped, affording littlepersonal privacy; girls are often afraid to go outside,especially at night, as the presence of armed mencontributes to a pervasive fear of sexual violence.15Families seeking refuge inside Syria have had toendure two winters that saw snow fall across muchof the country, with temperatures as low as -8�C.16Families fled, often without enough time to gatherwinter clothing for children.17This winter, rationingof the power supply severely limited electric heating.Shortages of fuel pushed the price of kerosene up byas much as 500%, making it impossible for the poorestfamilies to heat their shelters; in one area, 80% ofhouseholds could not afford heating.18This makeswarm shelters and blankets all the more important,but in 2012 only 30% of those who needed blanketsor mattresses received them.19This lack of safe and protective shelter is puttingchildren’s health at risk. In the depths of this winter,children aged 5 to 14 suffered the largest proportionof flu-like illness – 38% of all registered cases inSyria.20In some cases, children’s lives have been putdirectly at risk: some shelters have accidentally caughtfire, killing several children, because people made openfires as the only way of keeping warm.21The next section shows in more detail the manyways in which the health of Syria’s children is underconstant assault.

SHELTERING FROM THE STORMThe fighting has damaged or destroyed an estimated2.9 million buildings.6As a result of the destruction,3 million people (one in seven Syrians) – people likeHiba and her family – have had to flee their homes.7A third of them have sought refuge in neighbouringcountries (see box on page 5), but 2 million peopleremain displaced within Syria.In some areas, the entire population of a town hasfled. In others, people who had held on for monthsamid heavy fighting finally had to flee as they couldno longer meet their basic needs. As Abu, a father inDamascus, told Save the Children:“Why did we leave?We left because of the explosions, the constant shelling.Everything was a struggle, nothing was available – no food,no water.”For many people, ongoing fighting makes ittoo risky to move to the border. For others, especiallythe poorest families, fleeing the country is not anoption as they simply cannot afford the transport toget to the border.8The options open to families displaced within Syriaare bleak. The lines of fighting move almost daily,so people often do not know if the place they havesettled in today will be safe tomorrow. Most peopleseek refuge with friends or relatives in whatever spacethey can spare – apartments, outhouses, even chickensheds. The result is often extreme overcrowding, with

3

yaSmine, 12“Most of the houses were being hit.We had to stay in one room, all ofus. The other rooms were being hit…The shelling was constant, I wasvery scared.“I felt so afraid. I knew we could notmove from that one room. Therewere 13 of us… crammed into oneroom. We did not leave that room fortwo weeks. It was always so loud.“My father left the room. I watchedmy father leave, and watched as myfather was shot outside our home…I started to cry, I was so sad. Wewere living a normal life, we hadenough food. Now, we dependon others. Everything changedfor me that day.”

PHOTO: JONATHAN HYAMS/SAvE THE CHILDREN

4

THE IMPACT OF WAR ON CHILDREN

THE REGIONAL REFUGEE CRISISThis report focuses on the situation for childreninside Syria, but the humanitarian crisis hasspilled over the country’s borders as more andmore people flee their homes and seek refuge inneighbouring countries. As of March 2013, therewere more than 1 million people – 52% of themchildren – registered as refugees or awaitingregistration, with nearly 5,000 more every day.9The real number of refugees is likely to be muchhigher, as around 40–50% of refugees outside theestablished camps have not registered with theUnited Nations Refugee Agency, UNHCR – oftenin order to protect their identities.10Jordan and Lebanon are home to the largestnumber of refugees, each with more than a quarterof a million Syrian people registered or awaitingregistration. More than 180,000 Syrians have soughtrefuge in Turkey and more than 100,000 in Iraq,nearly 10% of whom are in Anbar province, whereagencies like Save the Children have to manage theinsecurity to try to meet refugees’ basic needs.11The refugee crisis is most visible at Za’atari campin Jordan, where the government and humanitarianagencies are working hard to expand the provisionof essential services like shelter and water. However,across the region, 70% of refugees are not in campsbut are instead living in informal settlements orwith extended family and friends, many of whomare themselves very vulnerable.12Save the Children is working with UNHCR andother UN agencies, and the host governmentsin Jordan, Lebanon, and Iraq, to ensure that allvulnerable groups get the assistance and protectionthey need. We are providing support to refugees(whether registered or unregistered) and hostcommunities, as well as non-Syrians fleeing thecountry, such as Palestinians and Iraqis. As of March2013, we had provided much-needed assistanceto more than 240,000 people across the region,including shelter, food, and protection for children.

A refugee settlement near the Syrian border

PHOTO: JONATHAN HYAMS/SAvE THE CHILDREN

5

hibaHiba fled Syria with her daughter and severelydisabled son.“Hospitals in Syria are being targeted with shelling. Theone I took my son to for physiotherapy sessions is notoperating any more. I couldn’t put him in a car and takehim to a doctor, and then to which hospital? The roadswere too difficult.“I don’t know why some hospitals were shut down. Somewere hit in the shelling, others were untouched; yet theroads were too dangerous for us to travel anyway. Anytime I want to take him out, it’s dangerous for us. We stayat home, we call the doctor, but we can never reach him.“How do I feel? Any mother’s heart would break seeingher son in this state… I am helpless. When I see him tired,I wish it’s me instead. He gets stiff and faints; his eyesstare in vain, and this is very hard for me… SometimesI cry, but I can’t do anything.”“Everyone is affected by this war. My daughter is 13 yearsold and goes crazy every time she hears a noise. Oncethe bombs started we ran… I couldn’t take my son’swheelchair, so I had to carry him, and run. We thought it isbetter for us to die in the street than under the rubble ofour house. We ran at 3 in the morning and we didn’t knowwhere to go. We were just running because we didn’t wantto die under the rubble.“I wasn’t thinking; I just wanted to protect my children.I didn’t want anything else. I just wanted to keep mychildren safe. If I die it is fine… but not my children.I want to keep them safe.“In the morning we came back to our home, but it wasruined. There’s no place for us to go to, no safe space to goto at all. I think there is no safe space in Syria. It is beyondimagining.“I cried and shouted but there was nothing else I could do.What can we say? Nothing.There is no human being livingthat wouldn’t be sad. We worked all our life to build ourhome and suddenly we lose it all.“Syria is our country and we want to go back there. Wedon’t know who is right and who is wrong, but I know wecivilians are paying the price.”

PHOTO: JONATHAN HYAMS/SAvE THE CHILDREN

Hiba with hergranddaughter

6

STAYING ALIvE, STAYING HEALTHYThe civil war is being waged in every city in Syria,affecting everyone’s health and their ability to gethealthcare when they need it. Most of those injuredby gunshots are young men, over the age of 18. Butacross the country, from being unable to find or affordmedication to being injured by explosive weapons,children are feeling the effects. As Ara’s story shows,some children’s health is at risk from the momentthey are born.Stories like Ara’s are far from unique. Save theChildren has found that getting access to safe birthingfacilities can be a dangerous, sometimes impossiblestruggle for mothers and midwives. The lack ofneo-natal care and specialist medics, as well as thedamage to health facilities, mean that many birthsare now taking place in people’s homes, temporary

homes or shelters, without a skilled birth attendantwho can assist with any complications. Given thedifficult living conditions and the huge challenge ofadequate sanitation for displaced people and theirhost families (described below), mothers and theirnewborns are at greater risk.22Young children’s health is also at greater risk nowbecause the civil war has disrupted or completelystopped routine vaccinations, including for measlesand polio. While UNICEF managed to conducta vaccination campaign that reached 1.4 millionchildren, often in very difficult circumstances, gettingvaccinations into Rural Damascus governorate andalso into opposition-controlled areas of northernSyria has proved immensely challenging. By January2013, no more than a third of children had beenvaccinated in the north of Syria; with every passingday, the potential for an epidemic increases.23

THE IMPACT OF WAR ON CHILDREN

ARAAra has three children.“I was very sick during my pregnancy but there wereno doctors, no hospitals. It wasn’t like my otherpregnancies – I had no scans, no check-ups.“It was morning when the contractions started. Theycarried on all day, I remember that I was so tired. I’vealways delivered in hospital before, never at home. Afternightfall, I told my family that I must go to hospital, butthey knew there was no way we could get through safely,shells were already falling. “Men shoot at everythingthey see at night, and there are so many checkpoints– we would never get past. Even if we did get through,where would we go? There are no hospitals now, only amakeshift clinic far away.“Around 4am, I started to deliver, I was terrified. I was inso much pain, I thought I would die. There was a terriblecomplication in my birth – and I thank God some of myneighbours helped a brave midwife to get through to me.The cord was wrapped around my baby’s neck – themidwife saved my baby boy’s life, and mine too I think.“My daughter was there for the birth, and she wasterrified about the whole situation. She couldn’t dealwith what happened all around her – especially theshelling, and the screaming.“It’s because of these shells, the endless explosions,that I left my home. I left a few months after this birth,coming from my home only three days ago. For thejourney, I carried my baby. I have other children and Iwished I could carry all of them, but I couldn’t – so theyhad to run for themselves. People were dying all aroundus, houses became rubble.“If you ever went into Syria you will see somethingyou’ve never seen before. It is not something you canbelieve…“The children that are still in Syria… they are dying. Itfeels as though no one is helping, nothing is changing.Why can’t you help them?”

7

CHILDHOOD UNDER FIRE

ATTACKS TARGETING HEALTH FACILITIESAND HEALTH WORKERSThese growing threats to children’s health in Syria areall the more alarming given the increasing devastationto health facilities and attacks on health workers, asHiba’s experience (see case study) vividly shows.24This destruction is all too often the result of atargeted attack on health facilities: agencies workingin Syria report that they are seeing a continued trendof attacks, mostly by Syrian government forces, onhospitals in contested areas. This appalling trend is incontravention of international humanitarian law, andmeans people are afraid to go to hospitals even whenthey are in urgent need of treatment.25In Deir ezZor governorate, for example, every single hospitalhas been damaged, while in Aleppo governorate,two-thirds of hospitals are no longer functioning.Across the country, more than half of Syria’s hospitalshave been damaged, and nearly a third have been putcompletely out of action.26Even hospitals that are still functioning are not ableto deal with the growing numbers of people who

need treatment. In one area, Save the Children foundhospitals with little or no heating, exhausted doctors,intermittent electricity supply, and woeful conditionsfor paediatric patients – despite the best efforts ofcourageous and committed staff who were continuingto work in such difficult conditions.27The fighting in cities and reports of targeted attackson doctors mean that many medical staff fear fortheir lives when they travel to work. Understandably,many decide they simply cannot take the risk: 50%of doctors are reported to have fled Homs, andaccording to one account, the number of medicspractising in and around Aleppo has fallen from 5,000to just 36.28TRAPPED IN WAR AND POvERTYThe fighting has made it much more difficult forpeople to get to hospitals and other health facilitiesfor treatment, and it has also led to a major shortageof medicines in many areas, as Save the Childrenhas witnessed. Before the conflict began, almost alldrugs used in Syria were produced in-country.29

PHOTO: JONATHAN HYAMS/SAvE THE CHILDREN

Souha, three, at a refugee settlement near the Syrian border

8

Now, shortage of fuel and hard currency, disruptionto supply chains and damage to factories have allmassively slowed production of medical supplies.Wealthier Syrians are reportedly travelling toneighbouring countries for healthcare; but, as withheating and food, the medicines that are available arepriced beyond the reach of the poorest families.30The poorest families’ health is also at greaterrisk, because they are more likely to be living inovercrowded communal shelters with little or noaccess to clean water and adequate sanitation. Moreand more children are suffering from diarrhoea,hepatitis A, upper respiratory tract infections, andskin rashes because of the deterioration in sanitationconditions.31In one rural area where Save theChildren is responding to the crisis, almost everydisplaced family said they lacked safe access to cleantoilets. In many cases, parents feared for the safety oftheir daughters with the presence of so many mencarrying weapons.32

Even in cities, children now have to go to the toiletin public spaces because damage to the water andsewage system means that toilet flushes no longerwork. In addition, the proportion of sewage beingtreated in Syria has halved since the conflict began.This presents a huge risk of disease outbreak,especially as clean water becomes more and morescarce. In some areas, water supply is now down to athird of pre-crisis levels; in some parts of Aleppo, forinstance, water is only pumped for four hours a day.33AN UNSAFE REFUGEBefore the conflict began, thousands of peoplefleeing conflict from elsewhere in the region hadsought refuge in Syria. These people are particularlyvulnerable now (see box). For example, before theconflict, an estimated 10,000 Palestinian refugees wereliving in Der’a camp in south-west Syria. Water andsanitation provision was poor even then; now, thefacilities have closed altogether.34

THE IMPACT OF WAR ON CHILDREN

PALESTINIAN AND IRAqI REFUGEES IN SYRIANot all those affected by the conflict are Syrians.Hundreds of thousands of Palestinians, Iraqis,Afghans and others are in Syria having sought refugefrom violence and insecurity back home. Thereare believed to be more than 500,000 Palestinianrefugees and 480,000 Iraqi refugees in Syria.35Approximately 40% of these are children – thoughchildren under five are often not registered, so thisis probably an underestimate.36Refugees in Syria were particularly vulnerable evenbefore the conflict. For example, children born toPalestinian refugee families were less likely to beenrolled in school than Syrian children, and morelikely to die before their fifth birthday.37Also, ahigh proportion of Iraqi refugees – two in everyfive – had special protection or medical needs thatrequired targeted support.38The outbreak of conflict in the country theserefugees originally came to for protection meansthey are now much more vulnerable and face newrisks. For instance, Yarmouk camp, a Palestinianrefugee settlement in Damascus, has become abattleground; there is fighting almost every dayin or around the camp. Three-quarters of the150,000 residents have once again had to flee, andbecause some borders to neighbouring countriesare closed to Palestinians, they remain trappedinside Syria.39The United Nations Relief and WorksAgency (UNRWA) provides essential assistanceto Palestinian refugees, but insecurity has forced itto halt its operations in many camps in Syria. As aresult, only 40% of its clinics are still open, and morethan 80% of school-age Palestinian refugee childrenare unable to attend school.40Tens of thousands of Iraqis have already fled Syria,and UNHCR estimates that a third of those stillin Syria will leave during 2013.41Most of them willprobably go back to Iraq, despite the continuinginsecurity there and the lack of jobs and basicsocial services.42Refugees in Syria already faced difficult anduncertain futures. Now, finding themselves engulfedin conflict once again, their options are even morelimited, their situation even more desperate.

9

CHILDHOOD UNDER FIRE

DANGER ON ALL SIDESThe conflict in Syria has had terrible repercussionsfor children’s lives and health. When the conflict isvisited directly on children, the consequences aretruly harrowing. These threats to children are whatthe next section describes.When we ask parents how their children are copingwith their experiences, the most common replyis that it has left children with a pervading andpersistent feeling of fear. When children are giventhe opportunity to draw pictures of their recentexperiences, they fill the pages with violent andangry images of bloodshed, explosions, and thetrappings of war. Parents also say that their childrenare showing signs of significant emotional distress,such as nightmares, bed wetting, or becominguncharacteristically aggressive or withdrawn; anyloud noise reminds the children of the violencethey fled from.43A new study by a research team from BahcesehirUniversity in Turkey, found some chilling evidence ofwhat children are experiencing. Two-thirds of thoseinterviewed had been in a terrifying situation wherethey felt they were in great danger; one child in threehad been hit, kicked, or shot at. And three in everyfour children interviewed – children like nine-year-oldIbrahim – had experienced the death of at least oneloved one.44As documented in the UN Secretary-General’s 2012report on children and armed conflict, some abusesin Syria are so heinous that they represent graveviolations of children’s rights under UN SecurityCouncil Resolution 1612.45Children are beingkilled and maimed every day in Syria. The conflicthas claimed the lives of some 70,000 people and anestimated 300,000 are believed to have been injured.46

IBRAHIM, 9Ibrahim’s mother and two older brothers diedwhen their home came under attack.“When I heard shelling in Syria at night, it alwayswoke me up. Sometimes I stood outside to see wherethe noise was coming from and sometimes it mademe really afraid, so I just stayed inside. I used totell my siblings they better stay inside because ofthe shelling.“I miss the days my mum took me to the playgroundin Syria. My mum is dead, and my two older brotherstoo… They died from the shelling of our home.Nadeem was my brother and my best friend. I wishI can have fun with him and go to school with himagain.“I just wish they were still alive. It makes me want togo back to Syria. When I return, I want to visit theirgraves and say ‘I miss you’.”

While we do not know just how many of thesecasualties are children, hospital reports show that anincreasing number of children are being admitted withburns, gunshot wounds, and injuries from explosions.47Every day, children remain at risk of death and injury,including permanent disability. Children are not beingspared from the violence.The use of explosive weapons in populated areas haskilled and maimed children as well as adults. In January2013 alone, there were more than 3,000 recorded‘security incidents’ – clashes or attacks – in Syria;80% of them involved heavy weapons such as mortars,shells and rockets. This fighting was concentratedin urban areas; in Damascus, 247 incidents wererecorded in just two communities that were formerlyhome to 1.8 million people.48The blast and fragmentation effects of explosiveweapons cover a wide area, and do not discriminatebetween civilians and military targets. All partiesto the conflict are using these kinds of weapons inbuilt-up areas where many families remain trapped,with government forces in particular using air strikesand Scud missiles.49There are multiple reports fromacross Syria of blasts from explosive weapons killingseveral children at once – sometimes from the samefamily, sometimes infants less than three months old.50

NOOR, 8“We were all scared. Because of the shelling, wewere hiding in the bathroom and the kitchen. Theshelling happened every day for a while… Every day,in the evening.“This is what I remember of Syria. No, nothing good,no good memories. I remember how my uncle andmy grandmother died, because I saw it… What do Iremember of Syria? Blood.This is it.”

10

Aside from their devastating immediate impact,explosive weapons also leave a potentially fatal legacy.As much as 11% of explosive ordinance does notexplode on impact; these explosive remnants of warare now scattered across Syria, a country wherepeople have had no previous experience of dealingwith such hazards. Children face the risk of death orserious injury either from playing with unexplodedshells or simply through being forced to live and movearound in a landscape scattered with unexplodedremnants. Even fighters have been killed from tryingto deal with unexploded grenades.51THE THREAT OF SExUAL vIOLENCESexual violence is another grave violation of children’srights. There is some evidence that girls and boys asyoung as 12 are being subjected to sexual violence,including physical torture of their genitals, and rape.52The prevalence of such abuses is hard to establish, assurvivors often do not report the attacks for fear ofdishonouring their family or bringing about reprisals.But fear of sexual violence is repeatedly cited to Savethe Children as one of the main reasons for familiesfleeing their homes.There are also reports that early marriage of younggirls is increasing. This can be understood as desperatefamilies like Um Ali’s struggling with ever-narrowingoptions to survive. They may be trying to reduce thenumber of mouths they have to feed or hoping thata husband will be able to provide greater securityfor their daughter from the threat of sexual violence.However, anecdotal reports from organisations workinginside Syria indicate that early marriage is sometimesbeing used as a ‘cover’ for sexual exploitation, wheregirls are divorced after a short time and sent backto their families.53In such a chaotic and dangerousenvironment, children and young girls in particularare at much greater risk of abduction and trafficking,especially for purposes of sexual exploitation.DISPLACEMENT AND SEPARATIONFaced with appalling and indiscriminate violence, theonly choice left to millions of people has been toflee their homes. These displaced people may findshelter, but they may not find security: once theyhave left their homes, families may be repeatedlydisplaced as the fighting spreads, each time carryingwith them harrowing memories and fewer and fewerpossessions. According to one survey of Syrians whofled to Mafraq governorate in Jordan, more than 60%had been displaced twice or more before crossing theborder, each time settling for a week or more beforebeing forced to flee again.54In some situations, peoplehave no time to pick up even a coat or proper shoes;they literally have to run for their lives.In the panic of escape, many children becomeseparated from their families. In other cases,parents make the tough decision to send childrenaway to relatives in areas deemed less insecure.This is why, in one area of Syria where Save theChildren is responding to the crisis, a quarter offamilies are hosting other people’s children. As thesituation deteriorates further, many foster familieswill no longer be able to cope, increasing the riskthat children may be handed over to institutionsor abandoned to live on the street and fend forthemselves in a country at war.55THE RECRUITMENT OF CHILDRENBY ARMED GROUPS OR FORCESThere is a growing pattern of armed groups on bothsides of the conflict recruiting children under 18as porters, guards, informers or fighters. For manychildren and their families, this is seen as a source ofpride. But some children are forcibly recruited intomilitary activities, and in some cases children as youngas eight have been used as human shields.56Drawings by Syrian refugee children

THE IMPACT OF WAR ON CHILDREN11

The use of children in combat is a grave violationof their rights; it contravenes international law andcommitments made by both parties to the conflict.It also puts the children involved at enormous riskof death, injury or torture. One monitoring groupaffiliated with the opposition, the Syria violationsDocumenting Center, has documented the deathsof at least 17 children associated with armed groupssince the start of the conflict. Many other children inarmed groups have been severely injured; some havebeen permanently disabled.57Thousands, if not millions of children in Syria haveexperienced appalling abuses during the war. In frontof high-level representatives of the internationalcommunity in Kuwait in June 2012, the UN’s Under-Secretary General for Humanitarian Affairs, valerieAmos, highlighted the urgent need for psychosocialsupport for infants and children – like Hamma’syoungest daughter – to deal with what they aregoing through.

CHILDHOOD UNDER FIRE

Children like Noura, fleeing from the fighting, justwant to be back at school, back to normality, learningand playing with their friends.“I liked going to school in Syria. We used to write and play.When I want to remember something happy, it is playingwith my friends on the swings. We laughed. I miss them.“At the beginning… there wasn’t shelling at my school, butafter some time the shelling started. I stopped going toschool when the shelling started. It wasn’t safe. I feel sadthat my school was burned because my school remindsme of my friends. I love going to school.“I would hear the shelling… I would get scared and tryto hide. One day I was with my friends playing in the sunand sand. We were collecting the sand, and putting it ina bucket, then we flipped it. We made a castle like that,always.Then a sound from the mosque shouted ‘RUN,RUN’. We ran away to our houses, and sat inside becausewe knew the shelling started. We ran very fast. I wasafraid that shrapnel would hit me.“We were terrified, and cried a lot when this happened.The mosque speaker sounds the alarm on the incomingshelling, so we can seek shelter and hide. Sometimes weheard the mosque alarms and sometimes we didn’t.“I came home, we hid in the living room and we prayed.I prayed that my brother and sisters will stay safe. I alsoprayed for my school not to be destroyed.”Noura, 10

HAMMA“My other daughter, Sham, is one year and sevenmonths. Do you know what her first word was?‘Enfijar’ [Explosion]. Her first word! That’s why weleft, that’s why we ran. My daughter’s first word isexplosion. It is a tragedy. We felt constantly as if wewere about to die.”

EDUCATION UNDER ATTACKIt is difficult to know the full extent of the disruptionto children’s education caused by the war in Syria,given the relative scarcity of data. But the illustrativedata that do exist, and the information Save theChildren has been able to gather, are deeply worrying.It is clear that education is part of the front lineof the war on children. Schools are protected byinternational human rights law; they should be safeplaces for children to play, learn and develop. But inSyria, schools have come under direct attack, denyingchildren their right to education in a safe learningenvironment. An eight-year-old boy from Alepporefused to talk for more than two weeks after fleeingSyria. When he eventually did speak, his first wordswere, “They burned my school.”58

In Syria, before the conflict, access to basic educationwas free and more than 90% of primary school-agedchildren were enrolled – one of the highest rates inthe Middle East.59But the conflict is undoing all thoseachievements, denying children the right to education,depriving them of a safe learning environment, andthreatening their futures as well as that of the country.In other conflict settings where Save the Childrenworks, once children have been forced to drop outof school, their aspirations and faith in the educationsystem (especially state schools) are severely dashed.The longer children are out of school, the less likelythey are ever to return. Millions of children and youngpeople in Syria may never regain the chance to fulfiltheir true potential.Some schools have closed because displaced familiesare living in them, as they had nowhere else to stay.An estimated 1 million people are living in schoolsand public buildings not designed to be lived in, and solacking proper heating and sanitation.60In one area ofSyria where Save the Children is responding, during

12

PHOTO: JONATHAN HYAMS/SAvE THE CHILDREN

um aliUm Ali has three children.“There has been no school for twoyears. Because of this, my son missedhis baccalaureate, and my daughtermissed her 11th grade. It’s too dangerousto go to school – they are being shelled,and even if they are still there, you getshot at if you try to get there.“My daughter, she is 16 and she loved school.She was the first in her class, and she wantedto become an architect. But this war…we were too worried for her. We could notprotect her, so we had to marry her. I knowthat men are hurting women, old women,single women – everyone. We needed her tohave a protector.“We couldn’t let her go outside at all. And ifsomeone comes inside your house, you cannotdefend yourself as just a woman. If theycome in, what will her father do? Sit asideand watch? They were attacking women.Her father told her this is the only solution.There are no schools. One year, two years, noschools. What about marriage? ‘Your cousinis a good man, take him, he is good.’ So shesaid ‘As you wish’. But she did not want to getmarried, she wanted to study. But there wereno more schools. So… she was married. Thisis happening a lot within Syria, many womenI know are marrying their daughters – evenyounger than 16 – to protect them.“What do people need most? People in Syrianeed everything. They need help, they needto be saved. People are dying. People aredying and there is slaughter and the rest ofthe world is just watching. There is no helpfrom outside. They keep holding meetings andthat’s it. They are just… watching. We arecalling for them, but no one is listening.”

13

CHILDHOOD UNDER FIRE

the bitter winter months, school benches were stolenfor firewood; desperate, understandable measuresto stay warm, but further erosion of children’sopportunities to learn and play.Thousands more schools have been put out of useby the fighting. Attacks on schools represent graveviolations of children’s rights because of their directand lasting impact on children. Yet according to theSyrian government, 2,000 schools have been damagedin the conflict; one UN survey found that a quarter ofschools in one area had been damaged or destroyed.61This not only makes children’s place of learningunsafe or unusable; it can also make children afraidof returning to school even when the fighting is over.There have also been reports of parents not allowingtheir children – especially girls, like 13-year-old Saba– to go to school for fear of being attacked, caught incrossfire, or directly shot at.62As a result, attendancerates, particularly for displaced children, vary widely.According to one estimate, more than 200,000children displaced by the fighting in Syria are missingout on education.63In one area, Save the Children has witnessedincredible dedication on the part of teachers whohave no materials to work with, but teach what theycan remember by heart. Despite threats againstthem, displacement, and the destruction of schools,do not lessen their conviction that children need tocontinue their education. These dedicated efforts areenough to keep education going for 200 children.64But they are not able to provide the standard of basiceducation that the children have a right to, and thereare hundreds of thousands more who are getting noformal education at all.The next section describes how the war isdepriving children and their families of enough foodto survive on.

GOING HUNGRY“What we struggled for the most in Syria was to get food.Even the water tanks were shot at to leave houses withoutwater.We almost starved to death.“During the conflict, bread supplies were completely cutoff from my town. I saw it with my own eyes – a truckcarrying flour into the town to supply the bakeries, and thetruck was forced to turn back, and this is how our breadsupply was cut.“They cut our water, they cut our electricity, our food andour bread. We managed to make it through, by uniting. Ifone of the neighbours was able to get bread, they shared itwith the rest… This is reality.”Faris, father of six

Before the conflict began, although Syria wasconsidered a middle-income country, it hadrelatively high levels of stunting – a result of chronicmalnutrition.65Acute malnutrition was rare, andremains so.66However, as the fighting continues andfamilies are finding that accessing nutritious foodbecomes ever more difficult, expensive, and evendangerous, there are the first signs of an increase inthe number of children suffering malnutrition.67According to the United Nations Office for theCoordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA),2.5 million Syrians are in need of emergency foodassistance.68However, one recent assessment inthe north of the country estimated that 3.2 millionpeople need food assistance in 58 sub-districts alone,suggesting that the situation may be much worse thanpreviously thought.69The fighting has drastically curtailed food productionin the country. Jamal, like 20% of farmers, reportsthat it was too unsafe to harvest any of his crops.Insecurity has also hampered cross-border trade

SABA, 13“We left Syria because there were lots of explosions butwe didn’t want to leave our house. We were injured andwe got scared, that’s why we left. What do I remember?People being hurt. People dying… In front of my eyes.“They were hitting schools. Many children would die, sowe got scared and stopped going to school. No childrenwould go to school, it was too dangerous. It makes mesad that I’m not going to school.“Before the crisis we used to play outside. We weren’tscared. Now? We stay inside and be afraid. That is it.“We should stop the shelling. For me, explosions leadto destruction. And more than that – the shelling makespeople get injured, and it makes people die.The onlyeffect is destruction, death and wounded people. Myhome has been destroyed. We were in it when it washit, and when it fell. I feel as though all of Syria hasbeen destroyed.”

14

of food and other essentials like cooking oil; and insome cases, road closures and fighting have disrupteddeliveries of food relief (this is discussed further inthe next section).70Shortages of flour – a key staple –have been reported in most parts of the country dueto damage to mills, closure of factories, lack of fuel fordelivery, road closures, and insecurity.71“We stopped leaving our houses because of the danger,which meant no work and no more income. It wasimpossible to go to the field and check on my crops.Before the conflict, we harvested our olives and grapes, butfor the past year, I swear to you not one farmer harvesteda single olive. Not one human being.Whoever decided tovisit his crops, knows he is going to die.”Jamal, father of eight

to cut down on the number of meals they and theirchildren eat each day.74“We were living from the foodwe had stored away – jam, a little bread,”Hamma toldus. She was heavily pregnant when she fled Syria withher one-year-old daughter.“Prices are so high – food isten times as much as it was. All I want for my baby is asafe life. That is my only hope.”Access to affordable food is a daily challenge forfamilies in Syria, but malnutrition in infants and veryyoung children can be staved off if they get the rightfood and micronutrients, for which breastfeedingis essential. Traditionally in Syria, the majority ofmothers do not breastfeed their infants, but Save theChildren has seen indications of a further reduction –between 15% and 50% – in the proportion of mothersbreastfeeding.75This is because of a widespreadperception that the stress women are under reducestheir ability to produce enough breast milk. Anotherfactor is that there has been uncontrolled distributionof breast milk substitutes such as infant formula.76Given the poor sanitation conditions many familiesare living under, described earlier in the report, wehave seen how this is contributing to more infantsand children suffering diarrhoea.77This is just one small indication of the complexity ofthe situation facing children and their families in Syria.The next section outlines some of the main challengesthat Save the Children and other agencies face intrying to help children in Syria in the context of theconflict raging around them.

THE IMPACT OF WAR ON CHILDREN

The scarcity of food has contributed to soaringfood prices, exacerbated by the closure of manyfood markets due to insecurity. This has ended upcentralising supply in private bakeries and leavingprice-setting in fewer hands.72In Aleppo, which hasseen heavy fighting, the price of bread is now up toten times what it was when the conflict began twoyears ago.73For many people, the price rises mean they are unableto feed their families. Even for those who have enoughmoney to buy food, the risk of being caught up in thefighting makes joining the long queues at bakeriestoo dangerous to attempt. As we see through Savethe Children’s response to the crisis, few displacedfamilies have any food stocks at all. They are having

15

humaniTy’S beST efforTS?

The enormous humanitarian needs in Syriaand the widespread violations of children’srights demand action. Humanitarian agencies,including Syrian and international NGOs andUN agencies, have already mobilised to helpall those people they can reach.But the challenges involved in the humanitarianresponse in Syria are immense. Some of the biggestissues concern ongoing insecurity, limited access,constraints on implementation capacity, challenges tocoordination, and insufficient funding, which are alldescribed in more detail below.While it is impossible to say with any certainty, thereare believed to be millions of people in Syria whoneed assistance and who are not receiving enough,if any at all.78There have been recent breakthroughsin humanitarian access, with some UN agenciessucceeding in negotiating access across conflict linesto deliver essentials such as food and blankets.79While these are much-needed positive signs, theoverall picture remains bleak. It is likely that millionsof children are not getting the help and protectionthey need.Insecurity:The most evident constraint to reachingthe millions who need assistance is insecurity.Crossfire, indiscriminate use of force, explosiveweapons, landmines, unexploded remnants of war,kidnapping; the list of threats to aid workers goeson, and the threats are real – 15 aid workers in Syriahave lost their lives in the past two years, trying toget assistance to civilians caught up in the conflict.80Some of them were directly targeted despite wearinginternationally recognised humanitarian emblems.81Ambulances have been directly attacked too: four outof five Syrian ambulances have been damaged duringthe conflict.82Whether indiscriminate or targeted, attacks onaid workers and aid convoys make some areas toorisky to operate in. For instance, the UN agencyresponsible for providing assistance for half a millionPalestinian refugees in Syria (UNRWA) had to close16

most of its operations in Yarmouk, where 150,000Palestinians had been living.83Crossfire, shellingand aerial bombardment mean agencies are takingsignificant risks to reach those in need.Assent of parties to the conflict:The conflict inSyria has created a complex patchwork, with differentarmed groups and forces active in different areas.There are some large areas where control is relativelyunified, and where large numbers of people cangain assistance, if security allows. In other areas, thesituation is much more fragmented and dynamic, soaid agencies must negotiate with numerous factionsto move around and reach people affected by thecrisis. Sometimes more than 20 checkpoints mustbe negotiated for one journey, with each negotiationtaking time; it only takes one checkpoint to refusepassage to mean that the agency has to halt an aiddelivery, with no one gaining assistance.For Save the Children, humanitarian impartialityis our only passport to respond in Syria, meaningwe have already been able to provide assistance tothousands of children. Denying children their right toreceive humanitarian assistance by denying agenciesaccess to them is a grave violation of children’s rightsand contravenes international humanitarian law.Experience tells us that negotiations to secure accessbased on humanitarian principles will continue to bedifficult, and necessary.Capacity to deliver:Prior to the conflict therewere very few organisations – local or international– with sufficient technical and operational capacityfor a humanitarian response in Syria. As the conflicthas escalated, the UN and NGOs have been tryingto increase the scale of their operations, within theconstraints of access and insecurity. To complementdirect operations, many agencies, including Savethe Children, work with Syrian partners who areable to deliver a humanitarian response on a largescale. However, there are not enough experiencedlocal organisations working in accordance withhumanitarian principles of impartiality and neutralityto match the enormous needs.

naziha, 17“One evening I was at my house with myhusband and I was holding my daughter inmy arms, breastfeeding. We heard a noiseoutside. Something hit the house and I don’tremember anything after that… All I knowis that after, I became disabled – I can’tmove my arm or my leg. Now I can’t standor sit without help.“There were many people who wereinjured or who became disabled in Syrialike this. This cannot go on. Someone shouldput an end to it. People are losing theirchildren, brothers, parents. Some peopleare getting shot. Others are unable to leavethe country. Children in Syria are dying, orbecoming disabled like I was. Until whenwill this keep going?”

PHOTO: JONATHAN HYAMS/SAvE THE CHILDREN

CHILDHOOD UNDER FIRE

For most agencies – international and Syrian – gettinghold of the commodities needed to deliver life-savingassistance can be extremely challenging. Whether itis medicines, food, blankets and tents, or people withthe necessary expertise and visas, there are significantobstacles to increasing the scale of operations in Syriato meet the immense and urgent needs.Humanitarian principles and coordination:Due to the difficulties of access and insecurity, thereis no central focus in the country for ensuring thathumanitarian community has a clear, impartial, nationalpicture of the needs and the response. For example,many of the humanitarian organisations operatingin Syria are not present in Damascus. Conversely, ofthose organisations operating from Damascus, manyare not present in places like Aleppo, in the north.The UN Office for the Coordination of HumanitarianAffairs (OCHA) has been proactively working withnon-governmental partners to find creative solutionsto this dilemma. It is not simply an issue of avoidingduplication and filling the gaps, important thoughthis is. It is also about ensuring that the response isbased on humanitarian need, rather than politicalconsiderations.Some Syrian diaspora groups with strong politicalaffiliations have given substantial financial and technicalsupport to groups on whichever is ‘their side’ of theconflict. In addition, the Syrian conflict has deeplydivided the international community, with someindividuals, groups or governments funding onlyone side or the other, regardless of what is best forchildren and their families in need. The humanitarianimperative is that the priority for the flow of essentialaid to Syria must be to reach those who need it most.Acting on that imperative gives agencies best chance ofsecurity in what is a complex and fast-moving conflict.

Operating in this context requires constant vigilanceand negotiation. Given the access challenges describedearlier, all sides to the conflict want to have a role inthe targeting of aid into the country. However, it isvital that agencies delivering humanitarian assistanceremain impartial.Funding:In 2012, funding for the internationalhumanitarian appeal for Syria fell $130 million shortof the requirements identified by the UN – a shortfallof more than a third.84As the humanitarian needsescalated throughout the year, this not only meantthat agencies in Syria could not provide much of thenecessary assistance; it also meant that they were stilltrying to increase the scale of their operations.By the end of January 2013, the appeal received ahuge boost: international donors pledged $1.5 billionto support the aid effort, including substantialamounts from the European Commission, Kuwait,the United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom, andthe United States.85These promises of funding are very welcome, butthey need to be urgently translated into real funds foragencies on the ground. At the time of writing thisreport, UN figures showed only 2.9% of the requiredfunding for the emergency education response hadbeen provided, only 2.6% for community services(which includes programmes to improve childprotection), and a shortfall of $72 million for health –88% of the requested funds.86While sufficient funding is vital for an effectivehumanitarian response in Syria, the challenges setout here make one thing clear: funding alone is notsufficient. The next section sets out what Save theChildren believes needs to happen to help addressthe humanitarian suffering.

18

recommendaTionS

As the conflict continues, so does theimpact of the war on children. Aboveall else,Save the Children calls on theUN Security Council to overcome itsdivisions and urgently unite behind aplan that will bring about an end tothe violence in Syria.Ending the pain that this report sets out will not beeasy, but it is possible. Just as the waging of this waris a result of human actions and decisions, so can beits end. The appalling suffering of Yasmine and Ibrahimand Naziha and the thousands like them demands anend to the conflict now.Tragically, but realistically, peace will take some time torealise, and many more lives will be lost or destroyedin the meantime.The international communitymust press urgently and explicitly for partiesto the conflict to take specific measures toimprove and secure humanitarian access andto ensure the protection of children.Otherrecommendations addressed to specific actors aredetailed below.

•

• •

•

protection, and clearance of unexploded remnantsof warensure that children and all civilians and civilian objects are not targeted by armed action.This should include targeting, occupation, ormilitary use of medical facilities and personnel,schools, sites for internally displaced people, andhumanitarian agencies and workers. Civiliansshould be allowed safe passage out of areas ofactive military engagementend the use of explosive weapons in populated areascease the recruitment and use of children under the age of 18 in armed groups and forces, releaseall children currently associated with armed groupsand forces, and cooperate with the return of thesechildren to their families, as well as necessarysystems for recovery and reintegrationcooperate with the UN to ensure that all violations of children’s rights are documented sothat those responsible can be held to account.

THE UNITED NATIONSThe UN has classified the Syria response as a level 3– the highest category possible. This is a clearrecognition of the scale and urgency of humanitarianneed in Syria. This categorisation requires theappointment of a ‘Super’ Humanitarian Coordinator,activation of Clusters for coordination, and theagreement of a strategic approach. The UN shouldtake action on the following areas:The UN Secretary-General, the UN-LAS(League of Arab States) Joint SpecialRepresentative for Syria, the SpecialRepresentative of the Secretary-General forChildren and Armed Conflict, and OCHAshould expressly urge parties to the conflict to endviolations of children’s rights and to take the specificsteps outlined above with utmost urgency to ensurethat children are protected from the conflict.

PARTIES TO THE CONFLICTSave the Children takes no side in this conflict. Allthose who are fighting in Syria have a responsibilityunder national and international humanitarian andhuman rights law to protect civilians and specificallychildren, who are entitled to special protection.Allparties to the conflict should commit publicly,and take immediate measures, to:• allow unfettered, safe access by humanitarian agencies trying to provide assistance to thosein need, including access across the lines ofthe conflict• ease any bureaucratic constraints on agencies increasing their capacity to respond, allowinghumanitarian agencies, their staff and suppliesto reach those in need. This should apply toall sectors of humanitarian activity, including

19

OCHAshould:• work towards a sustained staff presence, where security allows, in its coordination hubs outside ofDamascus to work with government and non-government actors to improve humanitarian access• use its presence in the region to complement the work of the Damascus Humanitarian CountryTeam to develop a ‘whole of Syria’ picture of thehumanitarian needs and response. This is a meansto identifying gaps in coverage and pressing forhumanitarian access through all channels to reachthose people• press for activation of all Clusters, including education and protection• prioritise, at the highest levels, strengthening coordination with donors and all aid actors fromthe Gulf and the Middle East. This should alsopromote decision-making based on impartial needsassessments, as well as avoiding duplication, andmaximising coverage by all actors in the response• undertake contingency planning for humanitarianneeds in Syria with all relevant partners, ensuringthat this informs planning for the refugee response,emergency preparedness, and post-conflict planning.

INTERNATIONAL DONORS,INCLUDING THOSE FROMTHE GULF REGIONThe pledges made at the Kuwait donor conference inJanuary 2013 for the Syria response and the refugeecrisis will allow a significant increase in life-savingassistance. The crisis will be prolonged, however: theneed for emergency relief and help with recovery willcontinue long beyond any cessation of hostilities. Withthis and the wider context in mind, all donors should:• commit to supporting agencies that are delivering assistance on the ground, with support that is:–needs-based:in line with the principles ofGood Humanitarian Donorship, prioritisationshould not be linked to any political agenda butrather according to greatest need, including forSyrians, Iraqis, Palestinians, or any other group.87To facilitate this, donors should strengthenimplementing partners’ capacity to undertakeneeds assessments inside Syria

–quickly disbursed:recent pledges shouldbe turned into committed funding as soon aspossible and disbursed to agencies deliveringassistance on the ground–sustained:humanitarian needs will continueto increase as long as the conflict lasts, andpeople will need assistance long after theconflict is over–flexible,including supporting humanitarianpreparedness to respond if the situationchanges and access improves–coordinated:donors should ensure that theirhumanitarian funding is coordinated with otherdonors’ funding• advocate for increased humanitarian access by any possible channel, and for greater humanitarianpresence on the ground• fund integrated approaches across all sectors for an effective holistic response, including:–protection:children need psychosocialsupport; mapping and clearing explosiveremnants of war is essential; and protectionfrom all abuses, including grave violations ofchildren’s rights, must be supported–education:this is to protect children now,but also to protect their development and thatof Syria once the conflict is over• continue to support the humanitarian response reaching refugees in neighbouring countries andwork with regional governments to ensure thatborders are kept open for refugees.

CHILDHOOD UNDER FIRE

ACTORS DELIvERINGHUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCEThere is a range of actors delivering humanitarianassistance in Syria, from established internationalNGOs to relatively new community groups that mayhave strong affiliations with one side to the conflict.We urge all these groups to:• commit to sharing information regularly with other humanitarian partners, including OCHA, to ensurethat a full picture of needs and responses can bedeveloped, notwithstanding the need to managerisks to the security of programme staff andbeneficiaries

20

• commit to upholding the Red Cross/Red Crescent and NGO Code of Conduct, ensuring thatassistance is not linked to any political agendabut is delivered according to where there isgreatest need88• conduct joint needs assessments, coordinating with other agencies to ensure that the methodologyis compatible with that used in other areas ofthe country. All assessments should include childprotection elements• work with communities to have IDP camps, schools, and hospitals declared as ‘zones of peace’,agreed with armed groups and forces (learningfrom experience in other countries such as Nepal,for instance).

NEIGHBOURING COUNTRIESAs of March 2013, more than 1 million Syrians hadfled to neighbouring countries, along with thousandsof Palestinian and Iraqi refugees who had been living inSyria. Those governments who have maintained openborders and are generously facilitating the responseto refugees’ needs are performing an essentialhumanitarian service. Neighbouring countries should:• keep borders open for humanitarian purposes, including allowing entry for all those fleeing Syriato find safe refuge• continue to work with humanitarian agencies to ensure a reliable humanitarian supply chain forrefugee response and for operations in Syria.

RECOMMENDATIONS21

endnoTeS

1

UNICEF (2013) ‘Syria Crisis – UNICEF Response and Needs’, http://reliefweb.int/map/syrian-arab-republic/syria-crisis-unicef-response-and-needs-enar, last accessed 1 March 2013UN News Service (2013) ‘UN officials alarmed by effect of systematicviolence on civilians in Syria’, 18 January, http://reliefweb.int/report/syrian-arab-republic/un-officials-alarmed-effect-systematic-violence-civilians-syria,last accessed 1 March 2013S Ozer, SR Sirin and B Oppedal (2012) ‘Bahcesehir Study of SyrianRefugee Children in Turkey’, Bahcesehir University, Istanbul, Turkey. Thisreport,Childhood Under Fire,cites statistics from the Bahcesehir study,which is available from the authors on request.OCHA (2013) ‘Humanitarian Bulletin: Syria’, Issue 18, 22 January–4 February 2013, p 1; UNHCR (2013) Syria Regional Refugee Response:Information Sharing Portal, http://data.unhcr.org/syrianrefugees/regional.php, last accessed 1 March 2013This is an estimate based on different indications of a) need, andb) response. According to the Syria Humanitarian Assistance ResponsePlan (SHARP), 4 million people are in need across Syria. However, the jointassessment overseen by the Assistance Coordination Unit (ACU) in 58 ofSyria’s 128 sub-districts found that 3.2 million people in these areas aloneneeded assistance, suggesting that the true figure may be much higher thanthe SHARP estimate. Food assistance has reportedly reached 1.5 millionpeople out of the 2.5 million identified by the SHARP as in need of foodassistance. Distributions of non-food items have reached only 30% of the1.5 million people identified as in need of such items. OCHA (2013) ‘SyriaHumanitarian Assistance Response Plan (SHARP, 1 January–30 June 2013).’www.unocha.org/cap/appeals/humanitarian-assistance-response-plan-syria-1-january-30-june-2013, last viewed 1 March 2013Syrian Network for Human Rights, cited in Syria Needs Analysis Project(SNAP) (2013) ‘Regional Analysis for Syria, 28 January 2013’, AssessmentCapacities Project (ACAPS), www.acaps.org/disaster-needs-analysis, p 7,last accessed 1 March 2013. This figure could not be confirmed withoutextensive satellite surveys.UNHCR (2013) Syria Regional Refugee Response: Information SharingPortal, http://data.unhcr.org/syrianrefugees/regional.php, last accessed7 March 2013Observation from Save the Children’s work; Al Jazeera (2012) ‘Syriandisplaced seek shelter in ruins’, 27 November, video clip, www.youtube.com/watch?v=8N6ShEWPSZI&feature=youtu.be, last accessed 1 March2013UNHCR (2013) (see note 7)Based on NGO assessment data, including from Save the ChildrenUNHCR (2013) (see note 7); also interview with Save the Children staff

2

Observation from Save the Children’s work; see also RefugeesInternational (2012) ‘Syrian Women & Girls: No Safe Refuge’,16 November, http://refugeesinternational.org/sites/default/files/Syrian%20Women%20&%20Girls%20letterhead.pdf last accessed 1 March 201315

WeatherSpark (2013) ‘Historical weather for 2012 in Damascus, Syria’,http://weatherspark.com/history/32874/2012/Damascus-Rif-Dimashq-Governorate-Syria, last accessed 1 March 2013161718

3

Observation from Save the Children’s work

4

5

USAID (2013) ‘Syria Complex Emergency’, Fact Sheet #7, 17 January,p 2, United States Agency for International Development, http://transition.usaid.gov/our_work/humanitarian_assistance/disaster_assistance/countries/syria/template/fs_sr/fy2013/syria_ce_fs07_01-17-2013.pdf, last accessed1 March 2013; Avaaz (2012) ‘Suffering Syria confronts another winter’,http://en.avaaz.org/1255/suffering-syria-confronts-another-winter, lastaccessed 4 February 2013; DFID (2012) ‘Syrian refugees in Jordan’,podcast from Liz Hughes, Humanitarian Advisor for Jordan and Iraq, UKDepartment for International Development, www.dfid.gov.uk/Stories/Case-Studies/2012/Syrian-refugees-in-Jordan/, last accessed 1 March 2013OCHA (2013) ‘Syrian Arab Republic: Non-food items distribution(1 Jan–31 Dec 2012)’, distributed to Inter-Agency Standing Committee(IASC) Emergency Directors’ meeting, 17 January 201319

OCHA (2013) ‘Humanitarian Bulletin: Syria’, Issue 17, 8–21 January, p 3,http://foodsecuritycluster.net/sites/default/files/Syria%20Humanitarian%20Bulletin%20Issue%2017.pdf, last accessed 1 March 201320212223

Observation from Save the Children’s workObservation from Save the Children’s work

6

Observation from Save the Children’s work; see also ACAPS (2012)‘Disaster Needs Analysis: Update: Syria; 22 December 2012’, p 19; OCHA(2013) ‘Syrian Arab Republic: Measles, Polio and vit. A vaccination Coverageof 1,370,000 Children by Status of Location (as of 14 Jan 2013)’WHO (2012) ‘Syria: Key Health Facts & Figures; Impact on public healthinfrastructure & workforce’, Monitoring Report, December 2012, WorldHealth Organization, p 224

7

8

ACU (2013) ‘Joint Rapid Assessment of Northern Syria – InterimReport (draft)’, pp 18, 31; OHCHR (2013) ‘Report of the independentinternational commission of inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic’,pp 21–22, www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/HRC/IICISyria/Pages/IndependentInternationalCommission.aspx last accessed 1 March 201325262728

9

WHO (2012), p 1 (see note 24)Observation from Save the Children’s work

101112

IRC (2013)Syria: A Regional Crisis – The IRC Commission on SyrianRefugees,p 8, www.rescue.org/sites/default/files/resource-file/IRCReportMidEast20130114.pdf last accessed 1 March 2013Observation from Save the Children’s work; SNAP (2013) (see note 6);OCHA (2013) ‘Humanitarian Bulletin: Syria’, Issue 17, 8–21 January, http://foodsecuritycluster.net/sites/default/files/Syria%20Humanitarian%20Bulletin%20Issue%2017.pdf, last accessed 1 March 20131314

WHO (2012) ‘Health Situation in Syria and WHO Response’,26 November, p 2, World Health Organization Regional Officefor the Eastern Mediterranean www.who.int/hac/crises/syr/Syria_WCOreport_27Nov2012.pdf last accessed 1 March 2013; see also IRC(2013) Syria: A Regional Crisis, p 7 (see note 12)2930

WHO (2012) p 3 (see note 28)

Middle East Monitor (2013) ‘Syria: A Modern Humanitarian Failure’,4 January, www.middleeastmonitor.com/articles/middle-east/4931-syria-a-modern-humanitarian-failure, last accessed 1 March 20133132

SNAP (2013) (see note 6)

ACU (2013) p 34 (see note 25)Observation from Save the Children’s work

22

ACU (2013) pp 41–2 (see note 25); see also SNAP (2013) (see note 6);and UNICEF (2013) ‘Running dry: water and sanitation crisis threatensSyrian children’, http://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/Running%20dry%20Water%20and%20sanitation%20crisis%20threatens%20Syrian%20children%20Eng_0.pdf last accessed 1 March 2013333435

5152

Interview with expert in unexploded remnants, Amman, 3 February 2013

ENDNOTES

SNAP (2013) (see note 6)

Child Protection Working Group (2013) ‘Child Protection in Syria:Current situation and priorities’, p 2; also observation from Save theChildren’s work. The Child Protection Working Group (CPWG) is theglobal level forum for coordination and collaboration on child protectionin humanitarian settings.Observation from Save the Children’s work; Refugees International(2012) (see note 15) ; IRC (2013) p 2 (see note 12)53