Udenrigsudvalget 2012-13

URU Alm.del Bilag 129

Offentligt

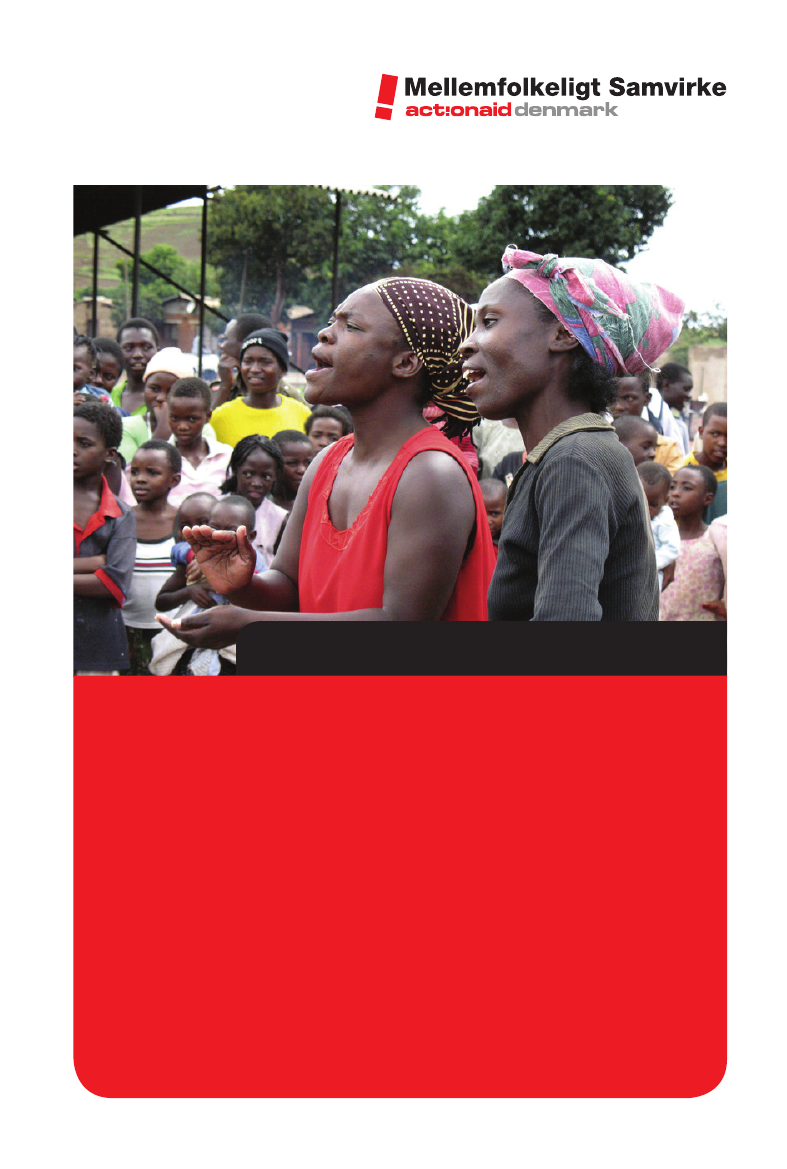

EAGER ORSLUMBERING?Youth and politicalparticipation in ZimbabweActionAidDenmarkMarch 2013

s. 2

This paper has been written by Peter Tygesen, Konsulentnetværket

s. 3

FOREwORd BYACTIONAId dENMARKIt is my pleasure to introduce this analysis of thepolitical participation of youth in Zimbabwe. As inother countries in Africa, the youth makes up a hugepart of the population and holds the future of thecountry in their hands. Yet, as the paper will show,they also bear the brunt of economic and politicalmismanagement.Still the youth in Zimbabwe has an admirable beliefthat the future has positive change in store for them.Therefore, it is of crucial importance that government,political parties and civil society organisationsinclude youth and let them have a say in how theircountry is governed. The reluctance to do so couldhave devastating consequences as a disillusioned,disenfranchised youth is a time bomb under a positiveand stable development of Zimbabwe.MS / ActionAid Denmark has supported civil societyand the work for participatory democracy in Zimbabwefor more than 20 years and we are passionate aboutsupporting and following the developments closely.We are hopeful that the youth of Zimbabwe will be adriving force for change and creation of a sustainabledemocracy.We support civil society organisations, amongthem youth organisations, in the important work ondemanding increased decentralisation and devolutionof power in Zimbabwe. We support civil societyactors in pushing for accountable and transparentmanagement of resources and in their systematicmonitoring of human rights violations. In this work wehave a special focus on including young people.The analysis in this paper points to the possibility ofcreating national and even international platformsacross political and geographical divides. ActionAidInternational is presently prioritising the creation of aninternational youth movement, Activista. Activista is aglobal youth network involving more than 50 ActionAidpartners and thousands of volunteers in more than 25countries including Zimbabwe. Activista is made upof youth activists working with artists, film-makers,musicians and with other campaigning organisationsto create powerful and creative campaigns. Activistaempowers and enables young people to activelyparticipate in the decision making and politicalprocesses that affect their lives.Given the fact that general elections are comingup in Zimbabwe, the time is now for government,political parties and civil society organisations to actand find new ways to include and listen to the poolof engaged youth that this paper shows is out there.Also international actors such as the UN agencies,Western donors and SADC should keep their eyesfirmly fixed on the inclusion of youth in the electionpreparation process.This briefing paper is the latest in a series of reportsand papers on the political situation in Zimbabwe (ref.www.ms.dk/afrika/zimbabwe). The paper is publishedby MS / ActionAid Denmark and solely represents theopinions of this organisation. The paper consists ofan analysis of: A) Political participation of youth seenfrom a youth perspective, B) Government efforts toinclude youth, C) The efforts of political parties toinclude youth, D) Civil society organisations’ efforts toinclude youth, E) Recommendations.Happy reading!Secretary General, Frans Mikael JansenMellemfolkeligt SamvirkeCopenhagen 15thMarch 2013

s. 4

AbbreviationsCSOMDCMDCMDC-TMPOINCASADCZanu PFZBCZECZESNCivil Society OrganisationMovement for Democratic ChangeMovement for Democratic ChangeMovement for Democratic Change - TsvangiraiMass Public Opinion InstituteNational Constitutional AssemblySouthern African Development CommunityZimbabwe African National Union – Patriotic FrontZimbabwe Broadcasting CorporationZimbabwe Election CommissionZimbabwe Election Support Network

Print and design: MSPhoto: ActionAid International

s. 5

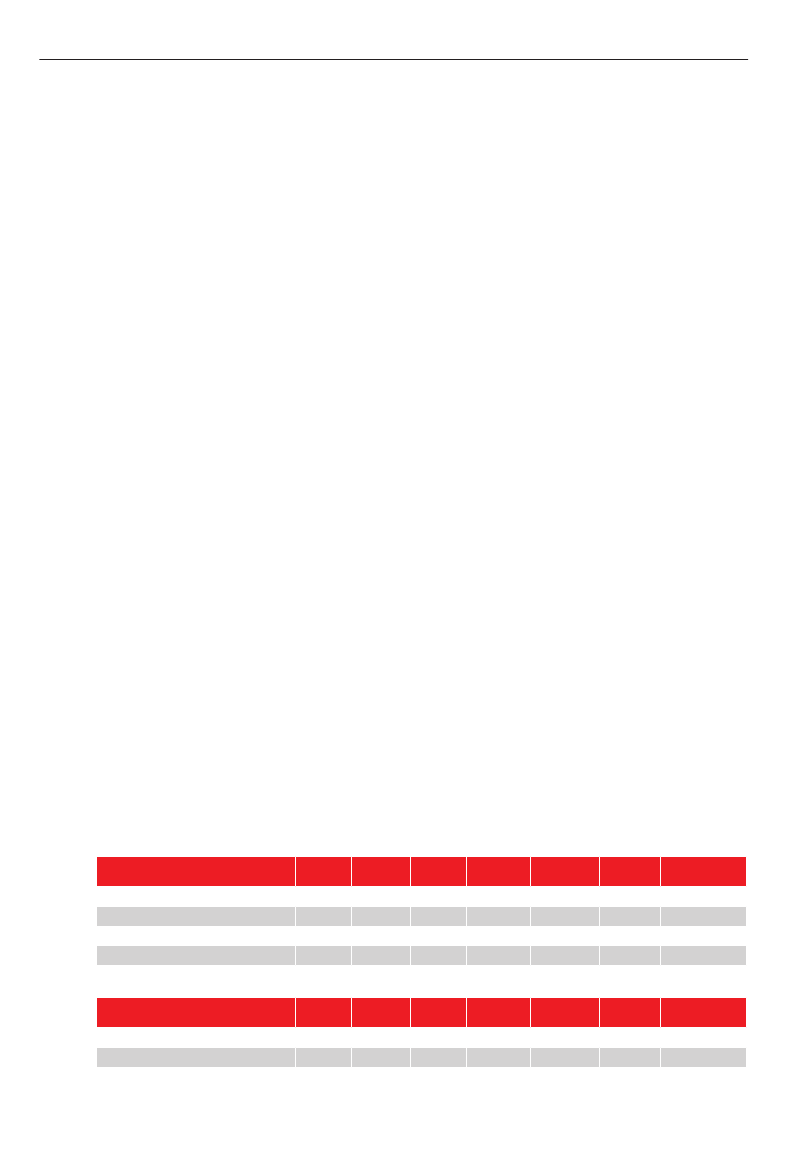

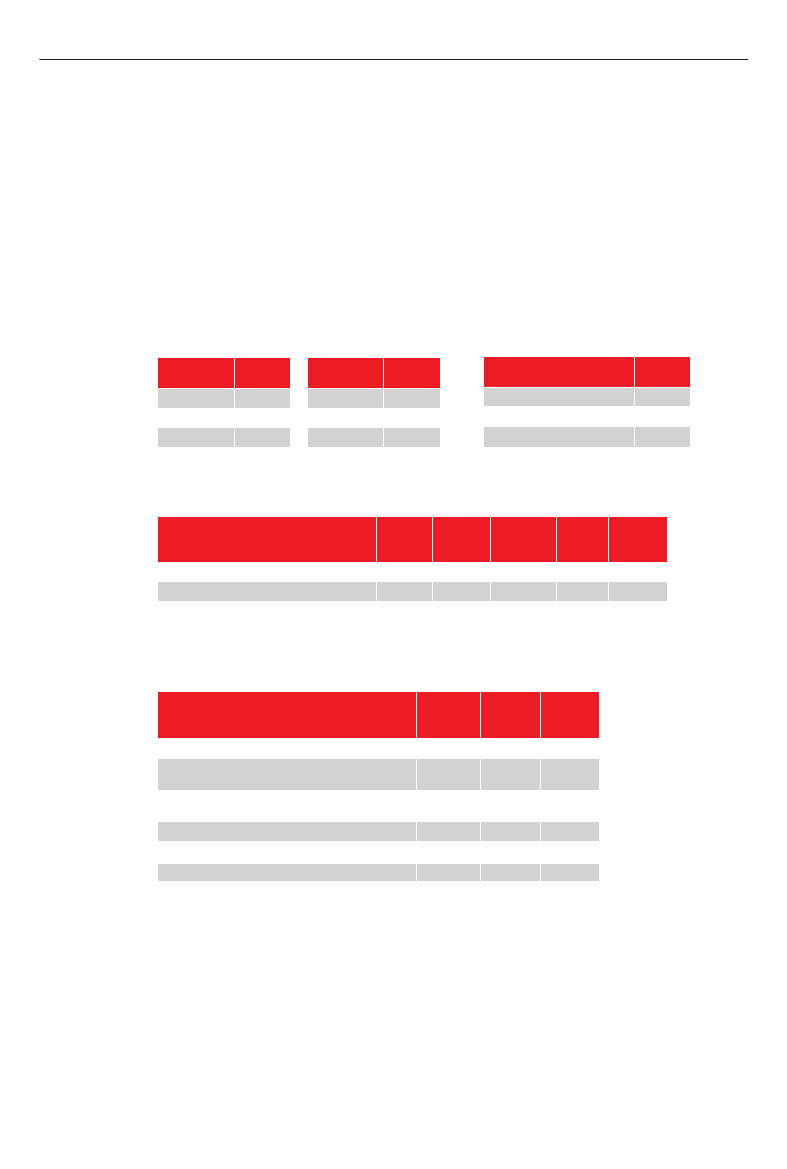

Table of contents1. Introduction.............................................................................. 62. Survey results .......................................................................... 82.1 Background ...............................................................................................82.2 Young people’s present social situation...................................................82.3 Young people’s participation in political and public affairs .....................102.4 Youth abhors political violence .................................................................12.5 Youths feel restrained................................................................................122.6 The rural/urban divide is distinctive but not large ...................................122.7 Gender aspects .........................................................................................143. Youth and the upcoming referendum and elections .................. 173.1. Youth and the draft constitution ............................................................173.2. Youth and elections; preparations still lacking.....................................184. Governmental and institutional efforts to include youth ........... 194.1. The voters roll ...........................................................................................194.2. Zimbabwe Election Committee ...............................................................204.3. Electoral reforms ......................................................................................204.4. Creating a climate conducive for free and fair elections ........................215. The Political Parties’ efforts to include youth ........................... 225.1. Political parties marginalise youth...........................................................226. Civil Society’s efforts to include youth ..................................... 236.1. Youth organisations and the challenges before the elections ...............247. Conclusion ............................................................................... 26Annex A ........................................................................................ 28Table 1 ..............................................................................................................8Table 2 ..............................................................................................................9Table 3 ..............................................................................................................10Table 4 ..............................................................................................................10Table 5 ..............................................................................................................11Table 6 ..............................................................................................................11Table 7 ..............................................................................................................12Table 8 ..............................................................................................................13Table 9 ..............................................................................................................15Table 10 ............................................................................................................16Table 11 ............................................................................................................24Table 12 ............................................................................................................24

s. 6

1.

introductionas victims. During election campaigns, there havebeen examples of youth being drafted into vigilantegroups terrorising and torturing fellow citizens.The patronising attitude of older politicians in thisregard was recently displayed by Deputy Prime MinisterThokozani Khupe as she lambasted politicians formanipulating the youths and using them to hold ontopower: “The youths should wake up and turn againstanyone who wants to use them as pawns in the dirtygame of political violence. These old and tired leadersdo not have an eye for tomorrow,” Khupe said.Perhaps Zimbabwean youth is already wide awake, butnobody is really ready to listen to them? Khupe’s ownparty is not particularly open to youth’s participation.Zimbabwe is also a deeply divided society. Fordecades, a divide has existed between urban andrural realities in which access to paid employment,modern medicine, democratic local government,and to information from independent media wasskewered in favour of the urban. In the early years ofindependence a deliberate government policy activelycontributed to diminish such differences, but thelast decade’s devastating economic crisis has onceagain exacerbated the differences. Often ignored,a major recent change besides the consequencesof the economic divide has been government’s re-introduction of indirect rule giving ‘traditional’ leaders(chiefs, headmen, etc.) strong powers over everydaylife in the rural areas (allocation of land, arbitrationof disputes, the authority to declare areas non-accessible to outsiders, etc.). During the years of ZanuPF’s rule, the party successfully co-opted many such

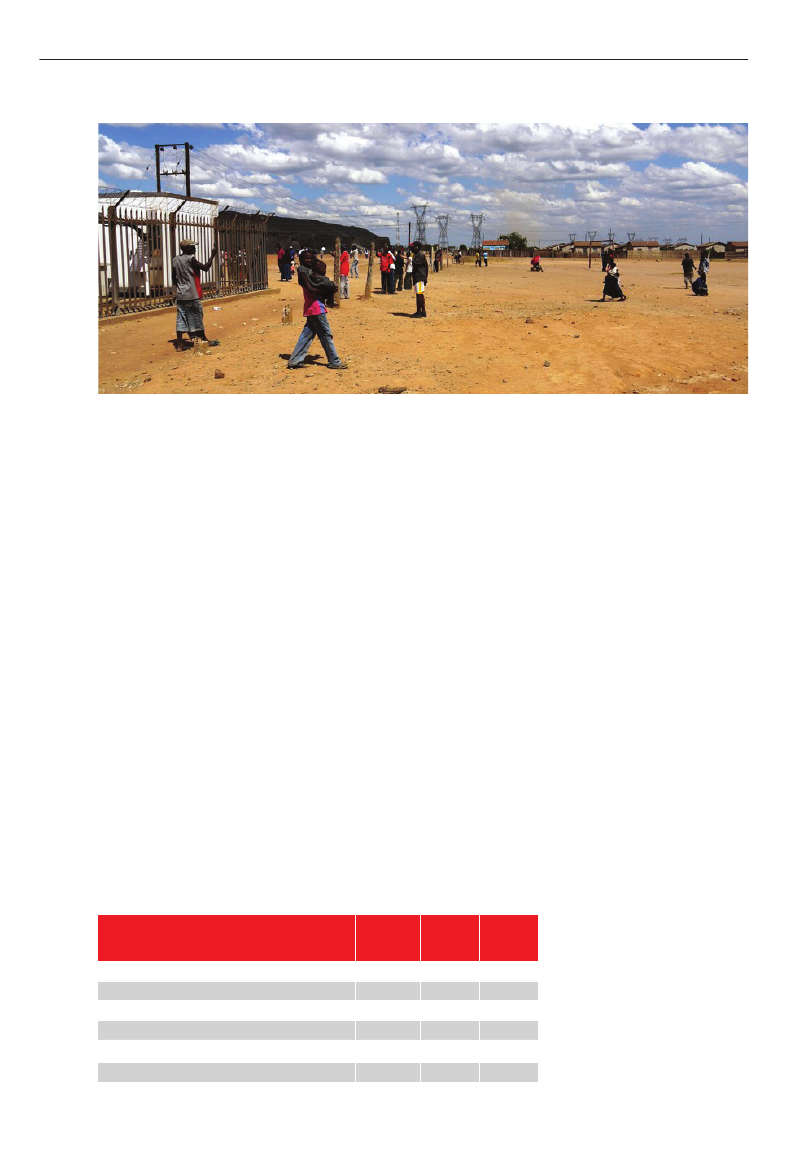

Zimbabwe is a youthful country; youth defined (inthis report) as those between 18 and 30 years of ageconstitute around half of the adult population. As such,youth is a crucial segment of Zimbabwean society -and the country’s voters. No wonder then, that politicalparties make frequent references to youth and youthaffairs. As a sign of how acutely aware the parties areof youth’s role in the coming elections, Zanu PF at itsrecent congress in December 2012 declared that theyouth vote “could make or break” the party’s regainingof power.However, in spite of these realisations of theimportance of youth it does not play any conspicuousrole in the country’s public affairs. Rather, throughZimbabwe’s history since dependence in 1980, thecountry’s political elite has gradually grown older andis now dominated by the parents or grandparents oftoday’s youth. The presidents of the three dominantpolitical parties are 89, 61 and 51 years old and thevast majority of their leadership colleagues are agegroup peers. Similarly, though the country has morethan 60 ministers in government, only one is youngerthan 40 years old. The parties’ interest in youth ismainly manifested in attempts to control and directits activities.How do young people react to this? Is this spawningapathy amongst them? Are parties and civil societyaware of the age gap and do they actively seek toclose it? Is youth participation in political and publicaffairs actively encouraged?Zimbabwean politics is regularly marred by violenceand it is generally perceived that youth play a majorrole in this, mainly as perpetrators, but simultaneously

s. 7

‘traditional’ leaders as its local instruments. This hasfurther aided to stifle rural life and to diminish spacefor political debate, especially for youth, as many suchnon-elected older ‘traditional’ leaders expect youth todefer to them.A deep political divide between supporters of ZanuPF and the opposition MDC parties has furtherthreatened to tear the country apart. Since the MDCfirst contested political office in 2000, most electionshave been marred by political violence. MDC and civilsociety organisations have since the late 1990’iesrepeatedly documented breaches of human rights onthe part of authorities in order to suppress the viewsand supporters of critical Civil Society Organisations(CSOs) and the MDCs. This is still the case in spite ofZanu PF having been forced to enter into a coalitiongovernment with the MDC parties.There is a long tradition in the country for suchpolitical intolerance; pre-independence politics wasalso characterised by intolerance, exclusion andsuppression. Throughout this tradition, youth hasalways been used as foot soldiers for enforcingvarious parties’ viewpoint, both literally as soldiers andtheir auxiliaries, and for violent vigilantism.There is however nothing particularly Zimbabwean inthis, all over the world youth has always constituted thecore group of soldiers and vigilantes. There is similarlyno reason to believe that Zimbabwean youth aremore violently inclined than their contemporary globalpeers. As will be shown below, the vast majority ofZimbabwean youth is deeply against political violence.12

It is however a fact, demonstrated below, thatZimbabwean youth feels politically excluded and thattheir voices are hardly heard in the public domain.Perhaps a higher degree of inclusion could give youthincreased strength and possibility to withstand anyconscription, voluntarily or not, into violent actions?To provide a fact-based framework for the discussionof youth and political representation, the Mass PublicOpinion Institute, MPOI, in January 2013 executeda nation-wide survey of youth1.A statistically re-presentative (urban/rural, female/male, regions, age-groups, etc.) sample of 1,0002youth answered anarray of questions about their situation and their viewson this as well as on public and political affairs. Inaddition, views and comments have been sought froma number of youth organisations and their leaders andmembers as well as from Action Aid Zimbabwe.As the results are presented below, this paper willseek to pose some of the most crucial questions tobe answered in relation to understanding the realitiesof Zimbabwe’s youth and its feeling of being excludedfrom political life.Along with the old, the sick and the handicapped,young people have generally borne the brunt of the last10-15 years’ economic downturn in Zimbabwe. Thedeterioration of schools and the educational serviceshas obviously impacted severely upon their ability toperform in society, and secondly, the unavailability ofemployment or paid work has been felt most severelyby this group.

”Youth Survey January 2013”, to be published during March 2013 by MPOI.The margin of error in a sample this size is +/- 3% at 95% level of confidence. It is consequently not possibly to distinguish confidentlybetween a score of, say 43% and 47%. Differences have to be larger than 3 points to be significant.

s. 8

2.

Survey resultsFor the present generation of youth, the consequencesof the educational and economic crisis are dire.Reports from the south of the country speak of entirevillages and indeed districts almost devoid of youth asthese have left for job-hunting abroad, mainly in SouthAfrica (reliable figures does not exist for this migration).

2.1 BackgroundAmidst national unrest, teaching was particularlydisrupted from 2006 to 2009. In addition to sufferingfrom insufficient funding, Zimbabwe’s schools lostpart of 2006, the entirety of 2007 and segments ofthe 2008 and 2009’s academic years (UNICEF foundthat 94% of rural schools were closed by 2009).20,000 teachers left the country between 2004 and2009. With few mechanisms to help pupils catch upor re-take years when they returned, thousands foundthemselves unable to gain a meaningful education.Data from the Ministry of Education, Sports, Art andCulture reveals that between 2000 and 2008 morethan 2 million children and young people failed theirexam in national ordinary (‘O-level’) examinations ordropped out aged 13.Whereas one may view the above figures asrepresenting the crest of the crisis, its aftershocks arestill severely felt with 82% of all students sitting fortheir 0-level exams in 2012 failing these. Though theminister of education valiantly tried to put a positivespin to this as a sign of progress compared to thefail rate of 86% in 2009, when he and the rest of thepresent Inclusive Government took office, the figuresare reflecting dramatically poor outlooks for theafflicted children and youth.

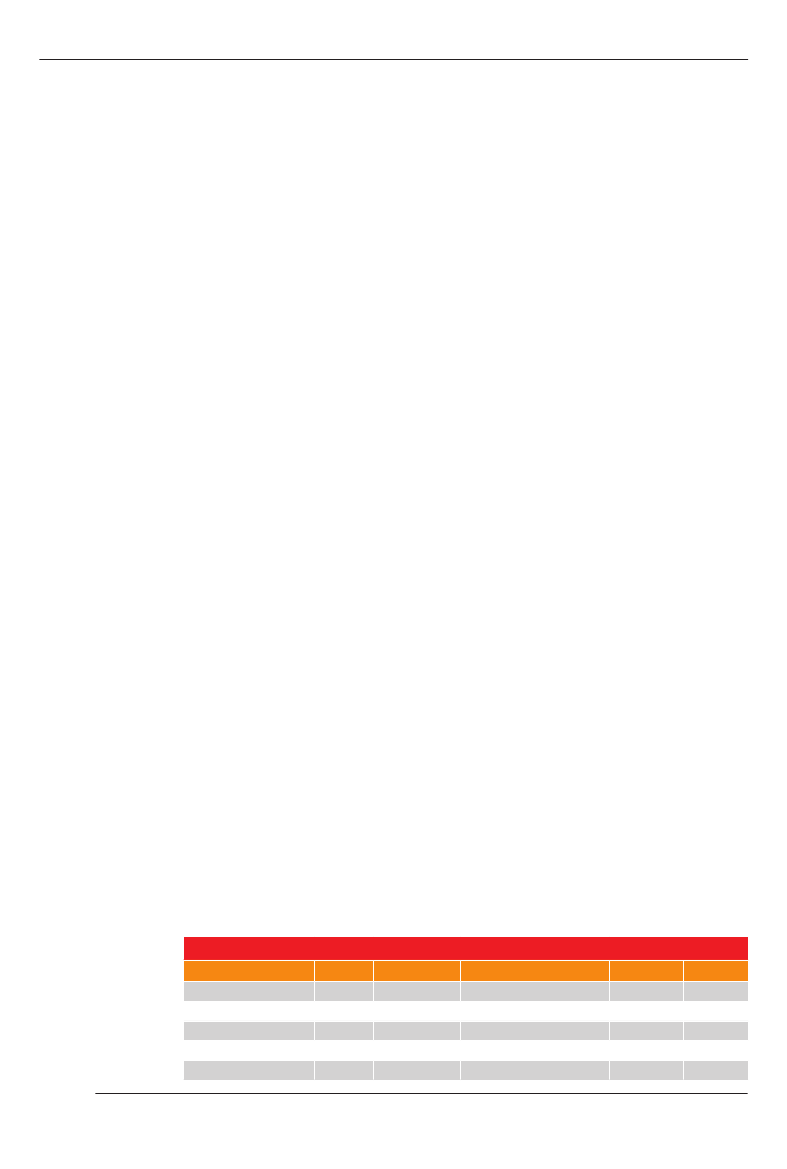

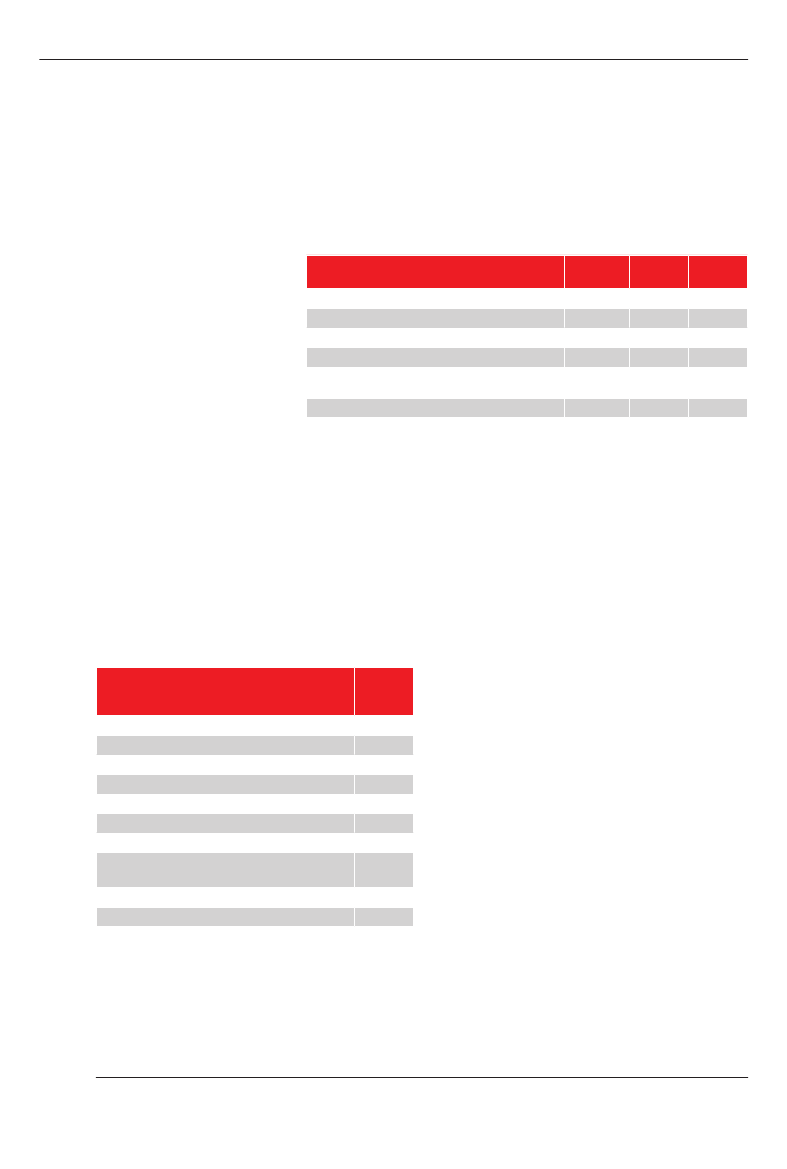

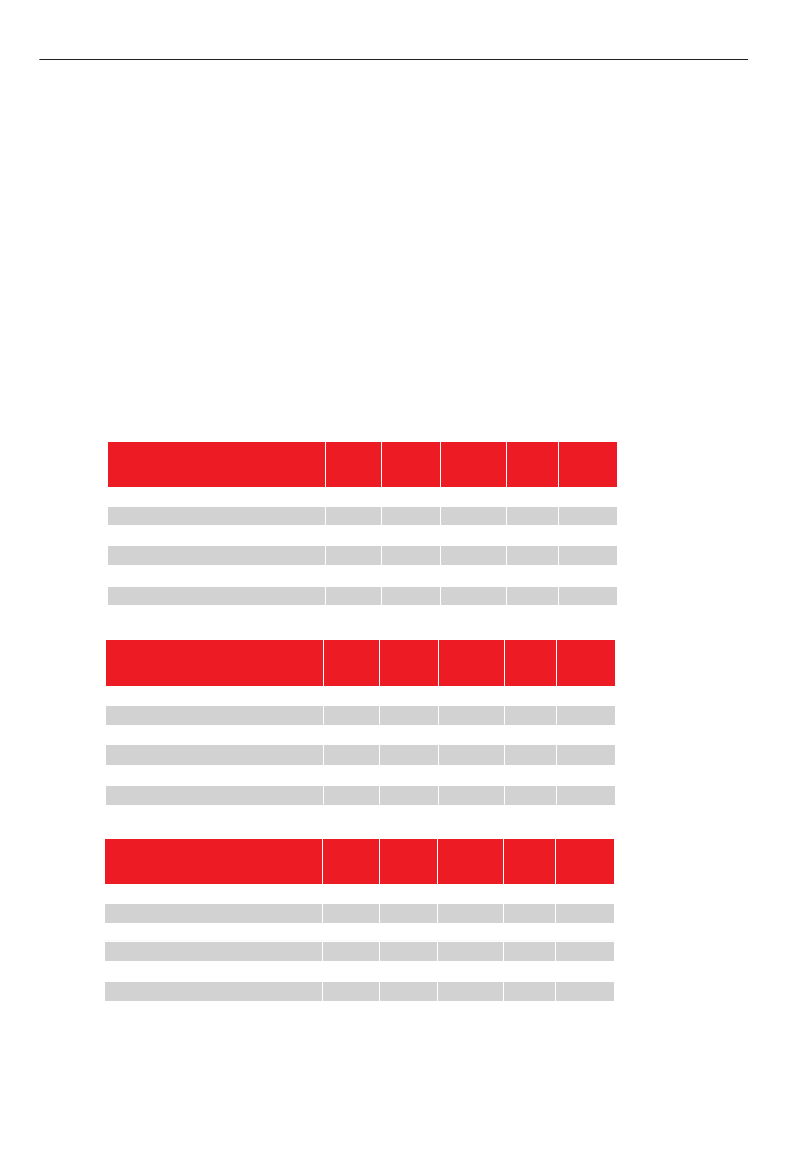

2.2 Young people’s present socialsituationThe figures for those remaining in the country speakvolumes: According to our survey 73% of youth doesnot have any job that pays them a cash income;almost half of these have given up looking for suchincome. Only 13% have a full-time job giving them acash income (in formal and informal sectors). Morethan a quarter (28%) is “always” or have “many” or“several” times gone without enough food to eat.Such dire economic and educational conditions islocking youth into prolonged dependency on olderfamily members and consequently bleeding theirsense of personal freedom. It blocks youth’s inductioninto adult society and hinders marriage and theestablishment of normal family life; a large proportion ofyouth are forced to rely on parents or family for shelterand whatever little money can be spared for them;they feel they are begging for alms. It’s humiliating,Gone without enough food to eat?

Table 13

Do you have a job that pays cash income

#No (not looking)No (looking)Yes, part timeYes, full timeTotal3

%34 Never39 Just once or twice13 Several times14 Many times100 Always

#418303203669

%42302071

342386133135996

When reading the tables please note that as figures have been rounded up/down to avoid decimals, you might in some instances find whenadding up the figures that the total will be 99% or 101%.

s. 9Table 2

Looking ahead, do you expect thefollowing to be better or worse?% of respondentsEconomic conditions in five years’ time?Your living conditions in five years’ time?

MuchWorse33

Worse54

Same1515

Better4438

MuchBetter2229

Don’tknow1211

debilitating and may bred both apathy and anger.Young women are especially vulnerable in this situationof limbo in delayed adulthood. 75% of female youthsbetween 15 and 24 years have at least once fallenpregnant, a recent survey for Swedish SIDA found4.Given their poor economic means, their unstablesocial conditions, the unavailability of legal abortionbut widespread use of illegal ones combined with thedeteriorated health services, such statistics give aBox1

glimpse into the difficulties in for instance reproductivehealth that young women face in their daily lives.In spite of all this, youth in Zimbabwe is optimisticabout the future, especially for themselves. A solid twothirds are convinced that both the country’s economiccondition as well as their own will have improved in 5years’ time.The survey does not explore deeper into the beliefsand presumptions behind youth’s optimism. Theymay be founded on a range of economic, socialand political issues. This would be crucial to explorefurther in order to map areas of importance to youthand to better adjust policies and programmes toaccommodate this.

Tsitsi: The ElectoralAmbassadorTsitsi is 21 years old and dedicated to bring herself forward.Her parents both died when she was 16, she had to leaveschool and she has since had to fend for herself.I started to make decorations and catering for churchfunctions. I think I am good at my business, because I nowmake enough money from this to pay for myself, so I’mback in school again. I want to be a journalist. I’m staying atmy sisters’ place but she loves her children more than me.Sometimes I think she mainly looks at me as a maid servingher family – but I can’t afford to live somewhere else.”I think when I’m older, I can go out and teach other womento be brave and take part in society, because I know what ittakes – and I know it can be done. A lot of women are scaredof politics, they fear for the violence and the intimidation. Inmy area there’s a group of Zanus, most of them men in their30’ies or 40’ies, very, very, very rough. You can see that theyare dangerous people; they have scars all over and meaneyes. But they don’t stop me, I know them and I know how toavoid them. I have become an ‘Electoral Ambassador’ in myarea, organised by a youth organisation. We try to encouragethe untapped youth vote, by arranging workshops, teachingabout the electoral law, training people to be observers, etc.So I try to recruit more youths for training.I think that there are three main groups of youth. 1) Thosethat are at school. 2) Those who failed at school and don’treally do anything. They have little, if no hope. They are verydifficult to connect with, because they almost have lost hope.3) Those whose family have connections. They go to work orhave managed to get back to school again. This is the easiestgroup to connect with; they’re ‘alive’, and ready to look at thefuture with a sense that they belong in it.Of course I’ll vote I’m already registered: It was easy – you justgo to the office and insist on being registered.”

2.3 Young people’s participation in poli-tical and public affairsPerhaps surprisingly, given the above description ofyouth’s lack of political representation, our surveyshows that young Zimbabweans are generally imbuedwith a will and dedication to be competent citizens,and they place great trust in the Zimbabwean society.This attitude is persistently displayed by a solidmajority ranging from two thirds to three quartersrelative to a wide variety of questions on relatedissues: Two thirds have participated in communitymeetings, almost half has ’raised an issue’ at suchmeetings, they believe no-one is above the law, noteven the president, whom they consider should beheld accountable by the parliament and by the mediaas well. They take a lively interest in political affairs- more than a quarter of them seek information onpolitical issues every day. One out of twenty do so onthe internet (6%, see Table 14).They seem to act according to these values; duringthe elections in 2008, 17% actively campaigned for aparticular party or candidate in (remember that 30%

4

Youth Sector Analysis Zimbabwe, p. 126. Probe Market Research 2012 for SIDA.

s. 10

of the present sample were too young to vote at thattime) - but even more, a quarter (25%), intends to doso in the forthcoming elections (see table 19).

means that their trust is fraying. Youth’s attitude tothe police is telling in this respect: When asked aboutpublic service delivery, half of the youth (51%) find it“easy” or “very easy” to get help from the police. What

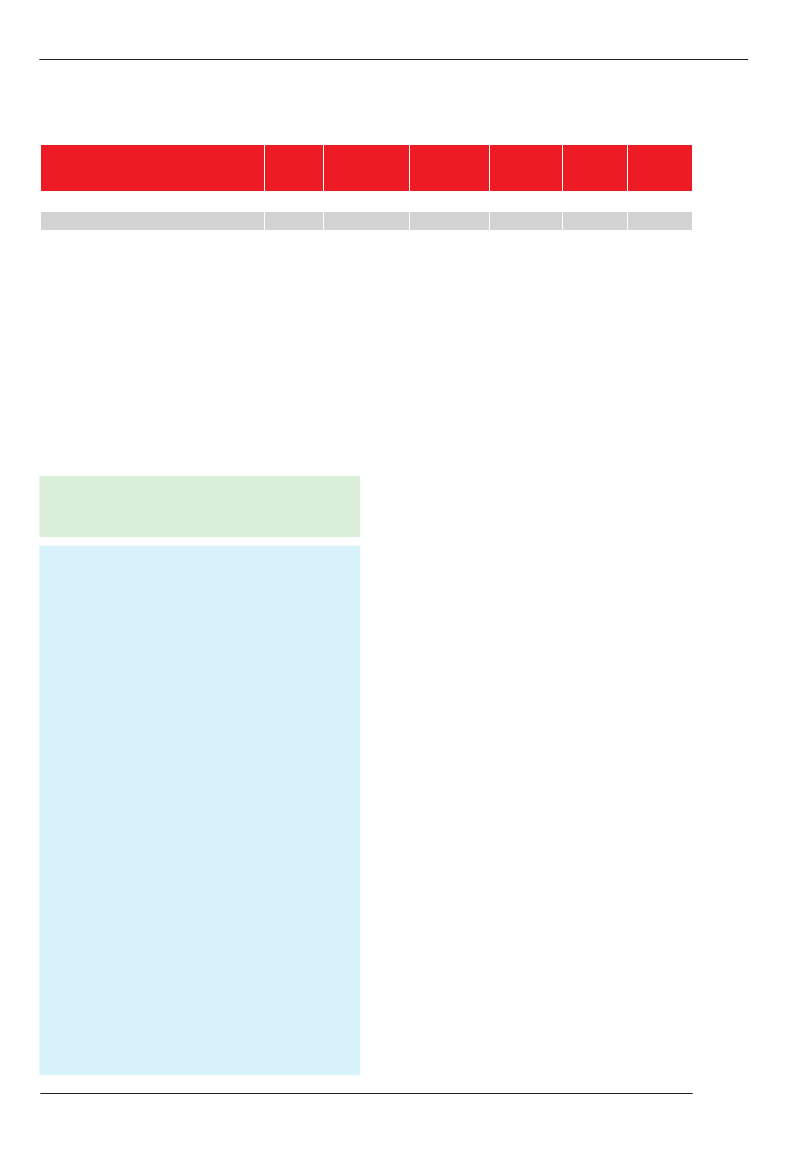

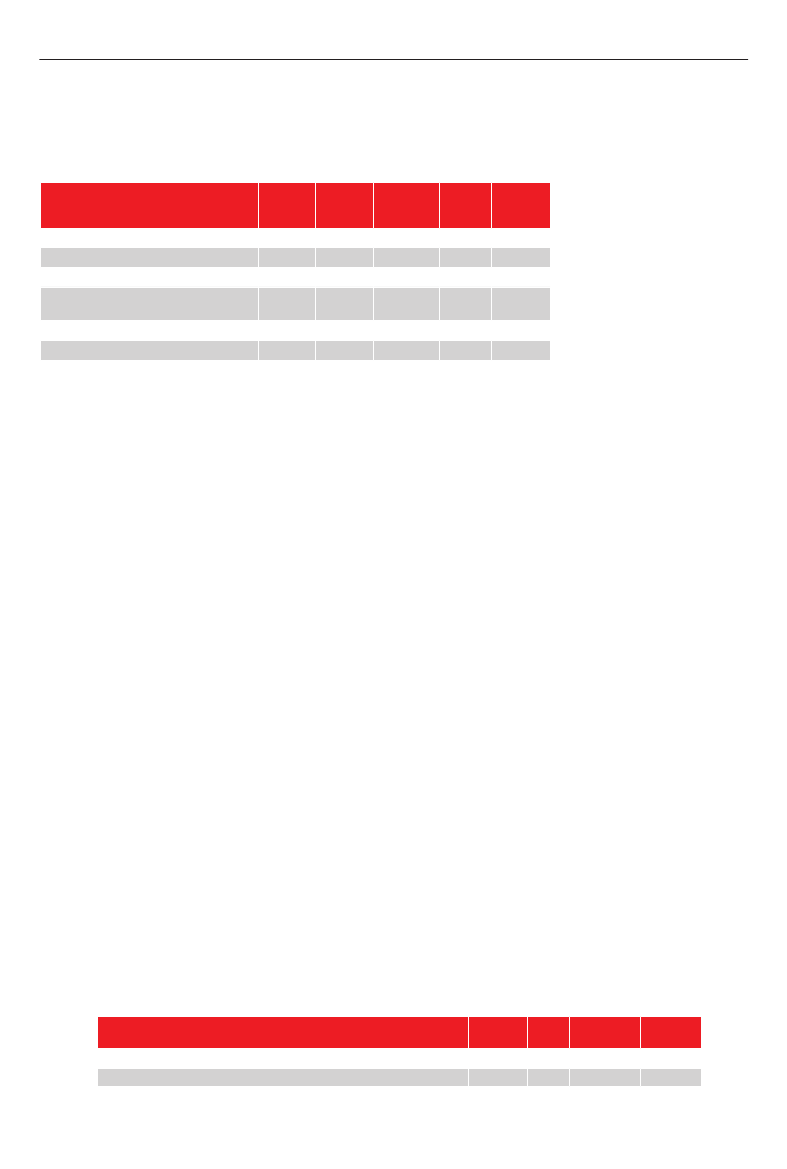

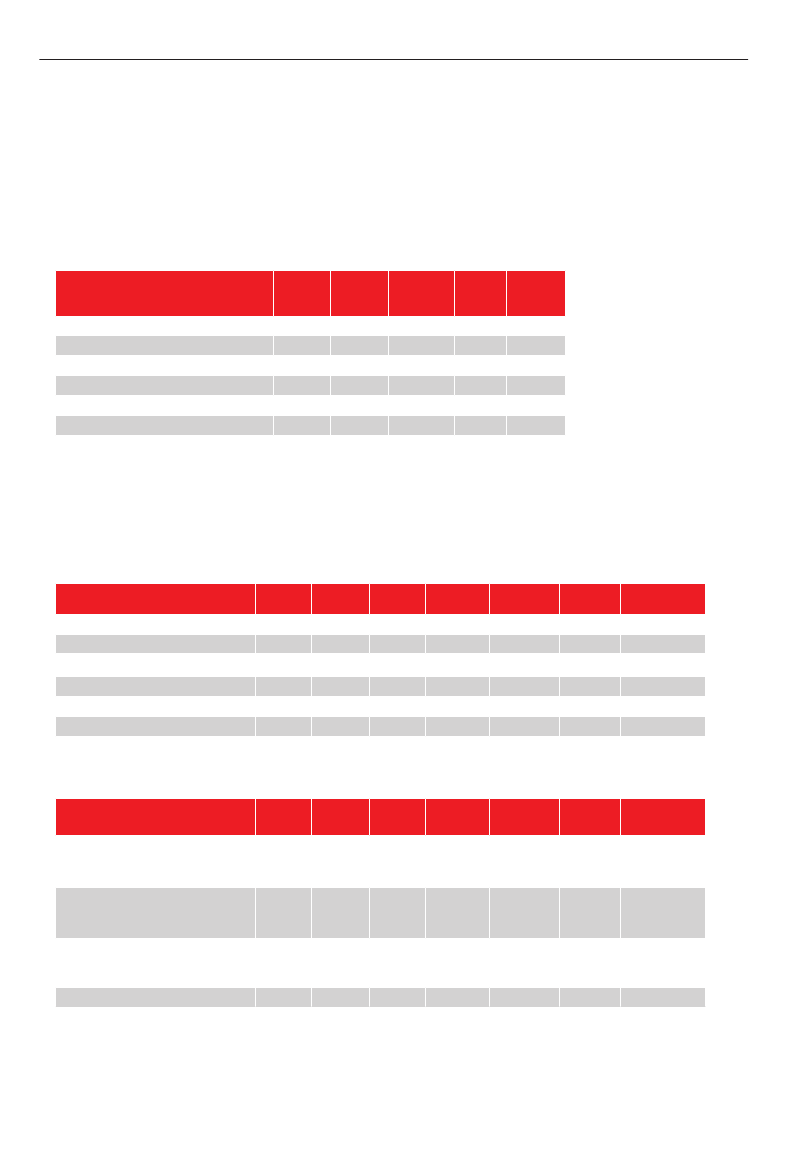

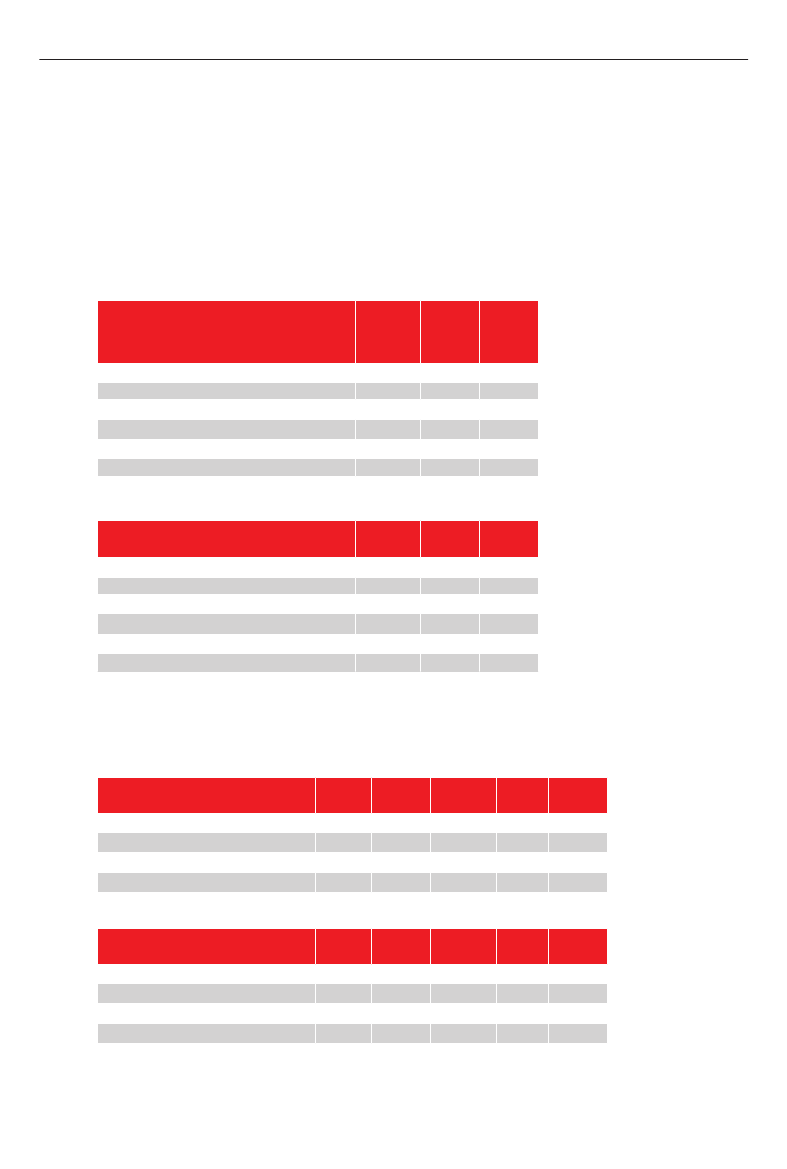

The youth is eager participantsTable 4in building democracy throughIn your opinion how much of a democracyFemale %Male %Total %is Zimbabwe today?participation: Half of Zimbabwe’sNot a democracy132017youth is registered to vote (theA democracy, with major problems323232majority of the non-registeredA democracy, but with minor problems292728being young first-time voters- seeA full democracy131514Table 9). Of the non-registered,Do not understand question /do not understand31250% say they will go registerwhat ‘democracy’ isbefore elections; most knowsDon’t know1158the requirements for registering;only a small minority lack thenecessary documents - however, most of these are about the other half? 40% says it is “difficult” or “veryfirst-time voters lacking a personal ID (see Table 24). difficult”6(see Table 22). That’s a very high proportionOnly 10% say outright that they are not interested of dissatisfaction and disapproval.in voting - a figure many ’developed’ democraticsocieties would look upon with envy. Zimbabwe’s The approving yet critical attitude to the country’spresent youth have grown up with respect for the institutions is repeated in almost similar proportionscountry’s institutions, and this seems to be imbued when its democratic merits are summed up. Not evenin them. The vast majority (3/4) think that youth has half of the youth, only 42%, think Zimbabwe is eitherthe same ability as others to influence their country a full democracy or one with only minor problems.and community, and they are convinced that their The proportion of the disapproving is larger; almosthalf, 49%, say the country has major problems inTable 3democracy, of these more than a third doesn’t evenWith regard to the most recent nationalthink the country is a democracy (17%).Presidential run-off election held in June2008 which statement is true for you?You were too young to voteYou were not registered to voteYou voted in the electionsYou decided not to voteYou could not find the polling stationYou were prevented from votingYou did not have time to voteYou did not vote because you could not findyour name in the voters’ registerDid not vote for some other reasonDon’t Know / Can’t rememberTotal %3015376-110100

2.4 Youth abhors political violenceA resounding majority of Zimbabwean youth (88%)say they will not accept political violence under anycircumstance. Given the volatile situation that manycommunities sometimes find themselves in, and giventhat political violence is an almost daily event in thecountry as such, this is a very high proportion who hasdecided to refrain from this means – especially sincequite a number of youth themselves have been victimsof the violence (see below). Their constraint is furtherconfirmed by the fact that only a small minority of 6%think that they might find themselves in a situationwhere they might use violence “for a just cause”.The table describes the respondents’ stated intentionnot to be violent so the question is how many youthhas actually personally taken part in violence? Firstlyone should consider whether youth can be expected

vote counts (see Table 20). They also elicit as theirfirst choice, to go to the police if they were violentlyand physically attacked by a supporter of anotherpolitical party (71%)5; only 9% would try to get back tothe person, “using the same method” (see Table 21)But their experience with the country’s harsh realities5

The police are rarely perceived in the Zimbabwean population as direct instigators of political violence, though there is a clear perception of the forcebeing abused to suppress opposition or critical voices.9% ”had never tried” and 1% answered ”do not know”.

6

s. 11

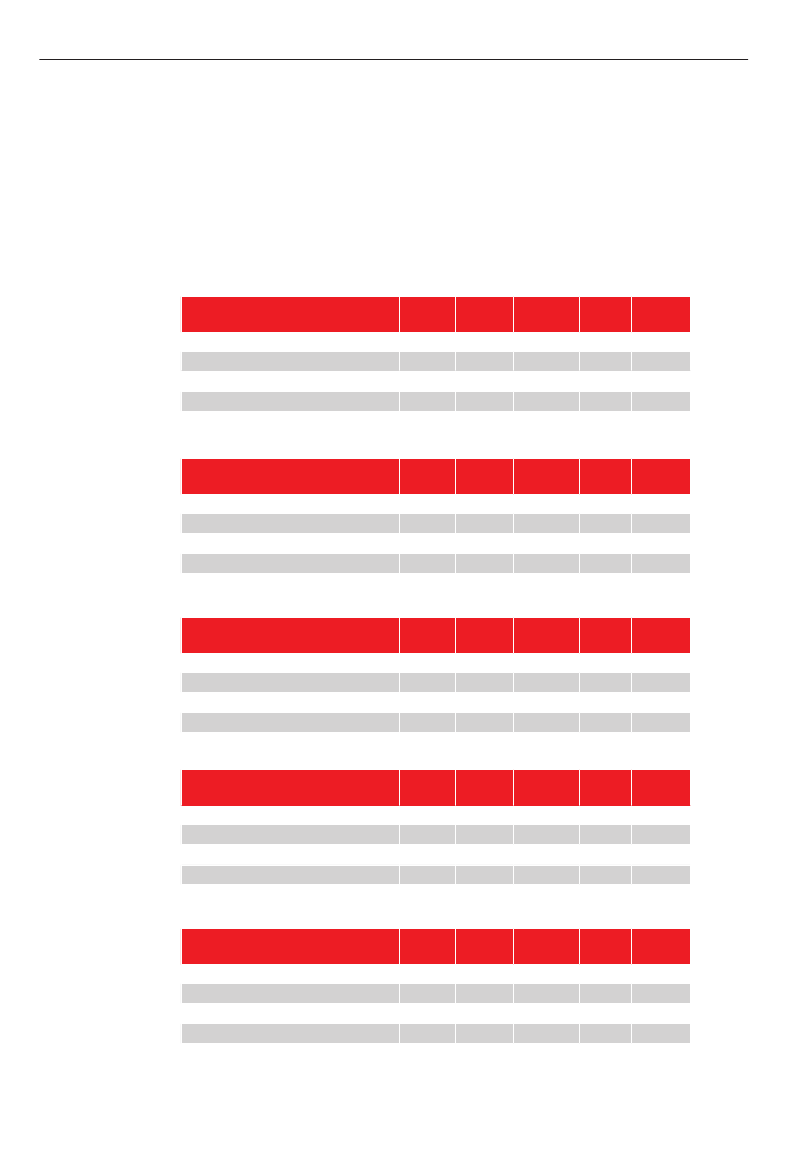

Table 5Statement 1: The use of violence is never justified in Zimbabwean politics today. Statement 2: In this country,it is sometimes necessary to use violence in support of a just cause.

Which of the following statementsis closest to your view? ChooseStatement 1 or Statement 2.Agree Very Strongly With Statement 1Agree With Statement 1Agree With Statement 2Agree Very Strongly WithStatement 2Agree With NeitherDon’t know

Rural % Urban %5234443458322135

Female % Male %5335312654323533

Total %54343334

to reveal such activity to a researcher? According toMPOI, who conducted the survey, chances are quitegood that respondents will answer honestly. Firstly,the survey is conducted anonymously. Secondly,perpetrators might want to get it off their chest. Thirdly,MPOI makes sure that the question is approachedfrom various angles and at intervals in the survey.If we list the answers youth gives to these questions,we see the following responses: 10 individuals of the1,000 questioned (1%) answered “once or twice” tothe following question: “Have you ever used forceor violence for a political cause”. Nobody answeredin the category “Several times”, and one personanswered in the category “Often”. When the essenceof the question is repeated later in the survey,25 individuals reply confirming to the question “Haveyou ever participated in any way in an act of politicalviolence?” giving a frequency of 2,5%.Based on this it should be safe to state that only1-3% has actually ever been involved in perpetrationof political violence. This is a very hopeful finding:The culture of violence is not ingrained. So much forolder politicians’ perception that youth is easy prey tomanipulative elders.The country’s generally violent culture is however alsoreflected amongst youth. Many have been victims ofpolitical violence, and a vast proportion feel intimidatedeven in their daily lives by this.Table 6

Who does youth see as the best agents for stoppingpolitical violence? Once again, their trust in society andits institutions is worth noting. As the most importantagency to stop political violence, most youth point tothe police (56%) and community leaders (30%). 14%find that Zanu PF could stop the political violence; halfthat number (8%) suggest that MDC-T might be ableto do so - perhaps a reflection of whom they fingeras the violence’s instigators? Church leaders andwar veterans may play some role too (7-8%), as mayNGOs (5%), whereas headmasters, radio and TV areconsidered having practically no effect on stoppingviolence (see Table 23).Overall, Zimbabwean youth embrace the social valuesoften associated with the stabilising and developmentaleffect of democratic values of the middleclass.Development of such middleclass values is oftenseen as a crucial step towards creating a modern,economically sound and stable society. From thisperspective, the future of Zimbabwe should look bright.

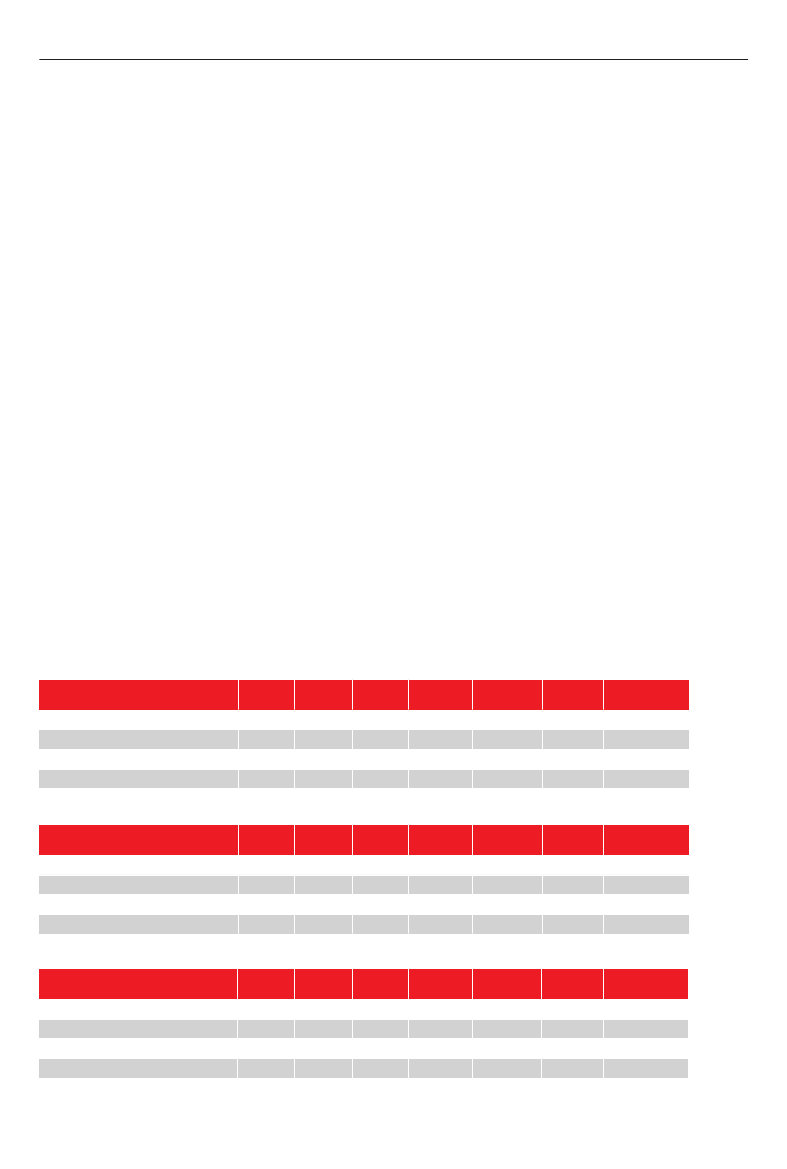

2.5 Youths feel restrainedYet Zimbabwean youth feels restrained. They areable and ready to contribute, but some institutionalrealities restrain them. Sure, two thirds say they haveparticipated in community meetings - but almost theentire remaining group (30%) say they would too, ”ifthey’ve had the chance”. Why did they not have thisopportunity?Yes % No %Refuse toanswer %01Don’tknow %01

Have you ever been a victim of political violence?Were any of your family or close friends victims of political violence

1343

8756

s. 12

We observe the same sentiment of feeling restrainedin further areas of public life - ”if given the chance”,41% would also ’raise an issue’ (47% have doneso) and 29% would participate in a march ordemonstration (only 6% have done so) (see Table13). Our survey does not reveal specifically whythese large proportions of youths have not beenable to participate in such activities. But it over-whelmingly points to the fact that these large proportionsof youths feel ‘un-used’ or ‘under-engaged’ in suchpolitical activities of representation.

Zimbabwean daily life is full of examples of howparty, state or patriarchal structures tend to defineanypublicagenda.Table 7One such example isIn this country, how oftenNever % Rarely % Often %AlwaysDon’tdo people:% know %the recent constitution-Have to be careful about51436432making exercise. At thewhat they say about politics?local outreach meetingsHave to fear political intimidation51333482meant for the populationduring election campaigns?to be able to expressHave to fear political intimidation153231212as they go about their daily lives?their desires for the newconstitution, officials cameto poll them with set questionnaires. Thus, the issuesthat citizens could express their views on were pre- In conclusion it is obvious that Zimbabwe’s youth isdefined. For youth, this was yet another example of geared toward taking over society from their elders,how adults decide the issues and the agenda for they have interest in country and society, are eager tothem. There was no room for youth’s own input. Youth be active participants - but do not feel free or welcomein some rural areas can also give examples of how to fully do so.they were invited to take part in outreach meetings,but not to speak, as party and village heads had2.6 The rural/urban divide is distinctivedecided beforehand who should speak.but not largeIn many issues there is little distinction between thendAs recently as March 2 , another glaring example standpoints of youth according to their residence inwas presented as national television broadcasted rural or urban areas; they equally distance themselvesPresident Robert Mugabe’s 89thbirthday party in from political violence, are equally insisting onBindura. A young representative of the 21st February promoting women’s and girls’ rights, even when itMovement7was asked to step forward and present goes against tradition. Furthermore, they are equally“the youth’s” wishes. What did he demand? This inclined to vote yes or no in the referendum on theyoung man firstly wished for Zanu PF to stop imposing new constitution, and they are equally convinced thatleaders on local or youth organisations. And secondly, their vote counts.that in the party’s primary election, locals were allowedto decide more freely on their own candidates.But there are significant differences. Rural youth is farless optimistic about the future than their urban peers.A crucial source of youth’s feeling of exclusion and They also have a pervading sense of being poorer offbeing restrained is revealed in the survey, as a large than other youths, not surprisingly, as they are poorerproportion of Zimbabwe’s youth do not “feel free”. off: they are more frequently without any cash income7

Almost four out of five (79%) say they have to becareful about what they say about politics. Half ofthe youth population fear political intimidation dailyand even more, 81% fear political intimidation duringelections. These are highly disturbing figures. Thesense of restraint from lack of freedom is persistentand pervading; almost half of Zimbabwean youth donot feel free to join any party (45%) or to say whatthey think (45%) (see Table 8). In addition, 13% feelpowerless towards intimidation and violence andindicate that they have to “suffer in silence as theyare not physically able to retaliate” (Table 21). Perhapsmost disturbingly, almost half (41%) feel underpressure to vote in a particular way (Table 8c).

Created by Zanu PF publicity officials with the aim of celebrating Robert Mugabe; named after his birthday.

s. 13

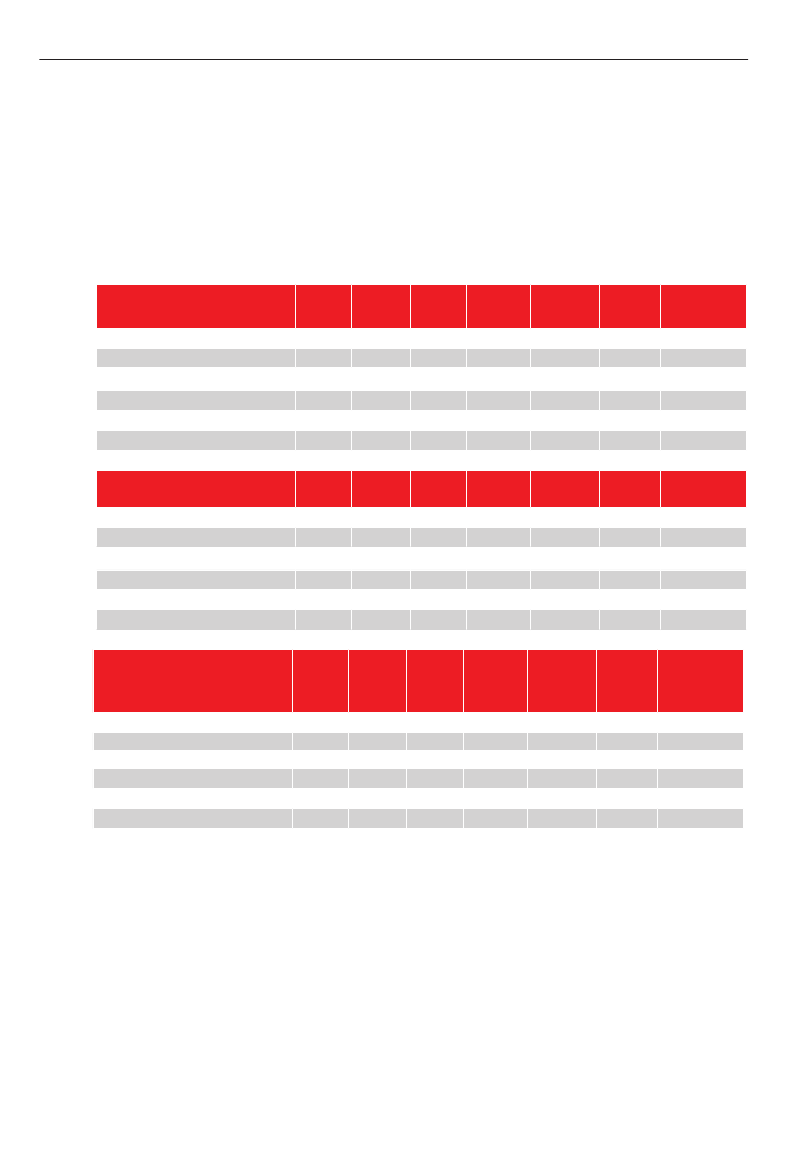

or sufficient food, have less access to clean water,medical treatment and fuel for cooking.There are also differences regarding political affairs: Aslightly larger proportion of rural youth indicate thatthey or their families have been victims of politicalviolence - but still, they are markedly more interestedin politics than urban youth. This latter manifests itselfin several areas: Compared to urban youth, the ruralyouth is more likely to attend rallies, to be registeredas voters (53% rural, 43% urban - and a significantsmaller proportion of non-registered rural youth willnot register (11% vs. 16% urban). More of those whocould vote in 2008 actually did so in the rural areas,more look forward to participating in forthcomingelections, and the rural youth has also more frequentlytaken part in community meetings or raised issues.Differences in political values are also clear, though notmassive. An increased fraction of rural respondents(5-10%) have a slightly more authoritarian tilt than theirurban counterparts (Table 17 - finding it acceptablethat government ban organisations opposed to itspolicy, let the army govern, allow only one party tostand, limit media freedom), and find Zimbabwe aTable 8In this country, how free are you:

”full” democracy or one with ”minor problems”.There’s however a marked distinction in the feelingof freedom/restraint. In general, rural youth feel lessinhibited than their urban peers - however it should benoted that more than a third of rural youth do not feelfree to say what they think, join a political party or votewithout feeling pressured.Not surprisingly, there’s also a marked differencein urban and rural youth’s access to news media,especially TV and internet, but also newspapers -though it should be noted that a fifth, 20%, of ruralyouth say they access the internet weekly. Also,though youth in general has very good access totelephones, rural youth is still lacking behind (64%of rural youth use the phone daily vs. 90% of urbanyouth), (table 11).This lesser exposure to the national discoursethrough diminished access to media might assist inexplaining some of the differences noted above. Itmight also be reflected in the fact, that when askedwho the respondents believe sent the researchers

A

To say what you think

Rural162231311Rural201928303Rural192025343

Urban302825161Urban322521193Urban262222282

Female212231250Female272027224Female221925294

Male202627261Male222323311Male202122342

18-24 25-3021223125118-24 25-3025192724518-24 25-30222022316212125331242324281212528260

Total212429261Total242125263Total212024323

Not at all free %Not very free %Somewhat free %Completely free %Don’t know %BTo join any politicalorganization you wantNot at all free %Not very free %Somewhat free %Completely free %Don’t know %CTo choose who to vote forwithout feeling pressuredNot at all free %Not very free %Somewhat free %Completely free %Don’t know %

s. 14

for this survey, a considerable larger proportionof rural youth (59%) thinks that it is some or otherbranch of government (compared to 46% of urbanyouth). Similarly, only a tenth of the rural respondentshave really understood that it is a private researchcompany, half the proportion of their urban peers(19%) who understood this fact8. These divergencesin media exposure and perception of whom they areresponding to is perhaps also influencing the ruralrespondents’ answers to questions of a more politicalnature, perhaps inducing them to answer in a moreconservative, authoritarian way. From this perspective,however, it is quite remarkable that almost 40% ofrural youth consistently say they feel un-free in variousaspects.

quarter of young women (63%) say they are not atall or not very interested in politics compared to lessthan half (40%) amongst their male peers – and viceversa, only 9% of young women find politics ‘veryinteresting’ in contrast to 25% of the young men.Consequently, fewer young women are registered tovote and actually take part in voting. Whereas 55% ofthe young men are registered, only 44% of the youngwomen are likewise, (table 9).The reasons for this is likely complex and mainlylinked to traditional notions of men’s and women’ssocietal limits and obligations, including a strongerfeeling amongst (young) women of being outside thisrealm. 62% of young women feel that “sometimespolitics and government seem so complicated that aperson like me cannot really understand it” (see Table15). Globally, this is a classical response of peoplefeeling outside decision-making, whether in national

2.7. Gender aspectsYoung women tend to be less interested and activein political issues than their male peers. Almost three

8

Standard procedure during MPOI questionnaire research is to explain twice to respondents that the survey is conducted by a privateorganisation unlinked to government, NGOs etc.; this is done before the actual questioning.

s. 15

Box 2

Lucia:The Football CoachLucia is a 20-year old woman, deeply involved in communityaffairs and in sports – and desperate to improve her educationalstatus. Her parents live in Masvingo and have only limitedresources, so she lives with an aunt in a Harare high-densitysuburb. She is almost completely dependent on her aunt to giveher a few dollars to survive on.Apart from educating myself, my thing is football! I used to playbut injured my one ankle, so now I am a football coach for theunder-15 players, both girls and boys. In addition, I’m involved inthe Youth Forum’s local programmes of community activity. We goto old peoples’ homes, orphanages, clean up streets and help withincome-generating projects. Last year we made scarves with logosfor our local school. I like designing and organised a cousin whohas a printing business to print t-shirts for the school’s students aswell. We made a tiny surplus that we used for the football teams.My school fell apart some years ago and I was stranded. I triedlooking for a job but it was hard. I felt I was being pushed aroundfor nothing, and then thinking about what people think about you,what they say about you, since I did not really do anything. I crieda lot, as I didn’t think I had a future.Finally, last year an uncle arranged to help me to go back to school– but I had to finalise two years’ classes in only nine months.However, I managed and actually got the highest marks of all inclass. So now I have my O-levels, and I want to push on, but lackthe money as my aunt has other children to help. I want to go touniversity and study sociology or become a social worker.I’m not interested in politics, and I don’t think I’ll vote. I’m notregistered. Politics have ruined the country. Politics doesn’t makesense, like the violence at last election. The problem is that to beinvolved, you will have to belong to one particular camp and thatimmediately cuts you off from the other side. You can’t’ be neutral.I hate that!

young women than young men feel that “for someonelike me, it doesn’t matter what kind of governmentwe have” (13% young women vs. 8% young males- see Table 16).This could be a result of young women beingespecially constrained in finding space in which toexpress themselves. In their outreach, governmentinstitutions, political parties and civil societyorganisations do not always consider the realitiesof young women. As an example, some meetingstake place at night, but according to the survey,young women generally feel more insecure “walkingat night” than young men. Traditional family patternstend to gravitate against evening meetings as parentsoften demand that young women stay at home after5 pm.It is the experience of Action Aid Zimbabwe thateven in youth organisations young women often feelconstrained, as the organisations are dominated bymen. Moreover, young women often complain thatthey don’t get room in the women’s organisations asthese are dominated by ‘aunties’, older ladies.The survey does however also point to some importantpossible entry points to connect with young women.They have similar access to mobile phones as youngmen and they are similarly eager to raise an issue “ifgiven the chance” as their male peers (table 11, table13). Though young women are less active in youthorganisations and at meetings compared to youngmen, the survey shows that young women are farmore active in other types of civic organisations andin church meetings outside services. Perhaps this is

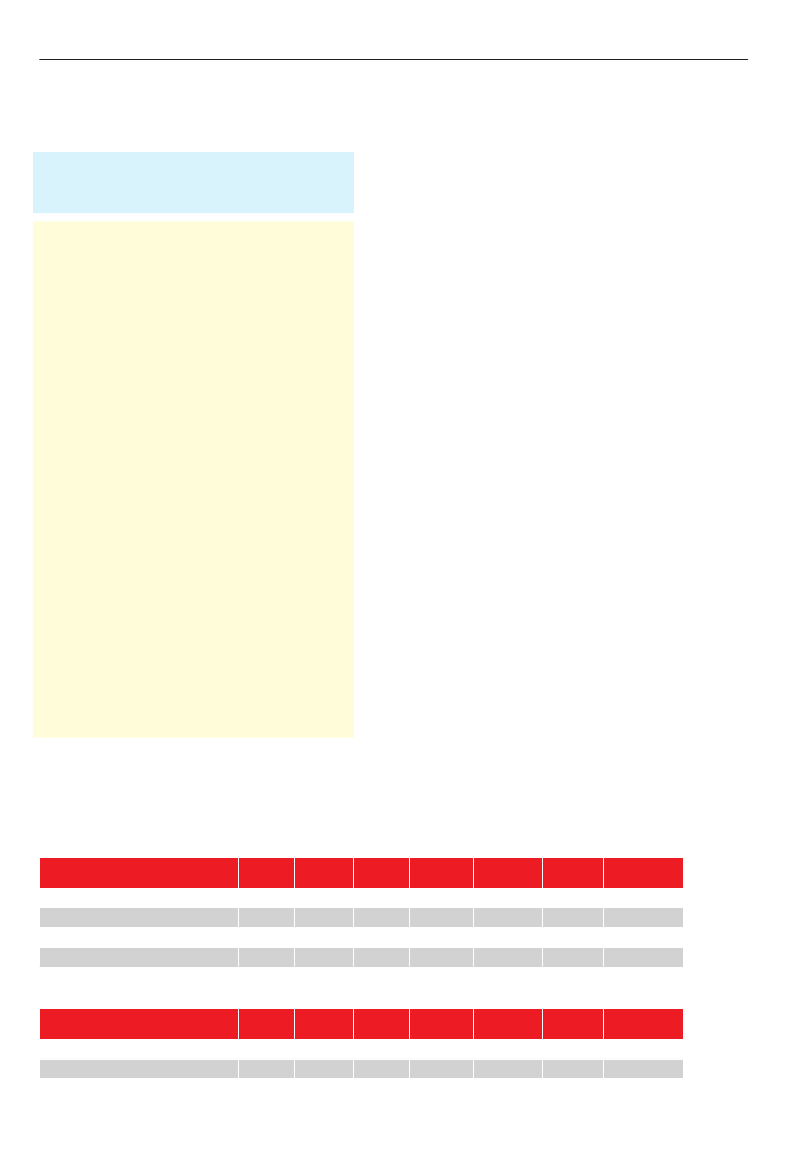

or local (or even domestic) issues. It’s a feeling ofhelplessness, or at least of “being outside” and notrespected. This interpretation of young women’sattitude is underscored by the fact that 50% moreTable 9

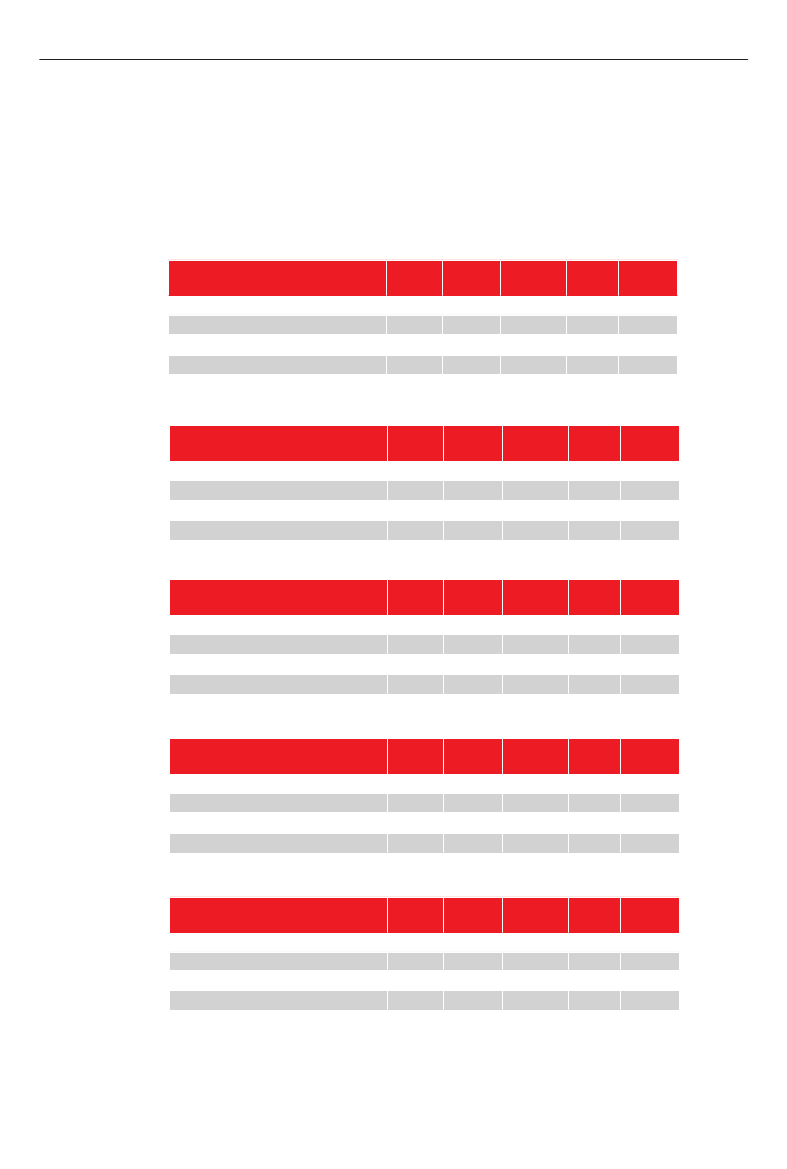

How interested would you sayyou are in politics?Not at all interested %Not very interested %Somewhat interested %Very interested %Don’t know %Are you a registered voter ofZimbabwe?Yes %No %Not sure %

Rural183033181Rural53471

Urban193927141Urban43560

Female24392791Female44560

Male132735250Male55441

18-24 25-302740258118-24 25-301387080181112736250

Total173331171Total50501

s. 16

where young women are more easily approached?The fact that young women feel particularly excludedis a democratic shortcoming in itself. Looking at thefigures from the survey, one might further detectominous warnings of the consequences of this, asmore young women tend to hold authoritarian viewsthan their male peers. Though the vast majority ofyoung women (78%) and men (85%) want their leadersto be elected through open and honest elections, asmall group of young women do seem less confidentin democracy and the democratic obligations of thosein power than young men; 50% more young womenthan young men discard completely the choosingof the country’s leaders through open and honestelections (12% vs. 8%).Similarly, young women are less than their male peersdisapproving of allowing only one party, letting thearmy govern and abolishing elections and parliament(see Tables 16, 17).Table 10Statement 1: We should choose our leaders in this country throughregular, open and honest elections. Statement 2: Since electionssometimes produce bad results, we should adopt other methodsfor choosing this country’s leaders.

The pattern is consistent in all of the survey’s series ofquestions gauging respondents’ democratic attitudes.Young women’s less democratic attitude could be aconsequence of the level of understanding of issues.They are, after all, the main losers in the educationcrisis; more girls leave schools than boys and theyoften do so at an earlier age. The less educated ismore likely to go for ‘brute force’ in governance,feeling that force is the only efficient tool for solvingserious problems. It’s also a reflection of lack of spaceto discuss alternatives, and lack of space in whichthey can involve themselves in local decision-makingor even in decisions on their own affairs.Constitutional issues have been at the heart of modernZimbabwe’s political contest. All political camps havefor years agreed that the present “Lancaster House”constitution should be substituted by a modernand more democratic one. After pressure from civilsociety, a government-proposed draft was presentedto voters in 2000. The MDC and the umbrella civilsociety organisation National Constitutional Assemblyrejected this draft and a majority of voters backed

Which of the following statements isclosest to your view?Choose Statement 1 or Statement 2.Agree Very Strongly With Statement 1 %Agree With Statement 1 %Agree With Statement 2 %Agree Very Strongly With Statement 2 %Agree With Neither %Don’t know

Female %532571222

Male %60256810

Total %562571011

s. 17

3.

Youth and the upcomingreferendum and electionsappeal to youth feeling constrained by the presentset-up. Should such change actually take place, itmight even result in renewed opportunity for youthto improve their lives and partake in public affairs. Atpresent, more than half of the youth, 59%, feel close toa particular political party and are consequently likelyto feel especially involved in the upcoming elections.

them in this; since then the issue has been an integralpart of opposition and mainstream politics. It has alsobeen a consistent and crucial civil society demand.As the present forced coalition government was formedon the foundation of the General Political Agreementof 2008, this agreement also included a definedprocedure for a constitution-making process leadingto a referendum on the proposed draft. After years ofdelay and hard negotiating, the parties finally agreedon a draft in early February 2013. Most of Zimbabwewas taken by surprise at the announcements by thepolitical leaders that the referendum on the draft newconstitution will take place on March 16th. This leftless than five weeks for debating the draft.Zanu PF’s leaders have for years insisted on “earlyelections”, latest at its conference in December 2012.The MDC parties have urged caution, demandingextensive electoral reforms to create conditions forfree and fair elections. SADC has backed the MDCparties in this demand as far as insisting that all partiesmust agree to the conditions under which electionsare held.The elections hold hope of change of politicalleadership. Even as Zanu PF honours PresidentMugabe’s leadership, its supporters and leaders oftenexpress a wish for renewal. For supporters of theMDC parties, there’s the hope of finally succeedingin coming to power. The MDC parties draw supportfrom a wide variety of quarters in the country. Theirdifferent aspirations are all condensed into the party’sone-word slogan: Chinja!, change. This is likely to

3.1. Youth and the draft constitutionThe draft constitution specifically mention youthas a group for which government holds a certainresponsibility. It confirms their rights, for instance toeducation, to opportunities for employment or otherforms of empowerment, and obliges government toprotect youth from abuse or exploitation.In its analysis of the draft, the Zimbabwe Lawyers forHuman Rights note this as amongst “an impressivelist of objectives that can guide interpretation andapplication of constitutional rights and duties. Howeveractual compliance with these by duty-holders will beharder to achieve in practice.”

A number of civil society groups have condemnedthe March 16th date as giving inadequate time for thecountry’s voters to study and discuss the content ofthis crucial document. Also, in January the ZimbabweElection Committee, ZEC, which by law is tasked withthe holding of elections and referendums and withvoter education, stated that it would need at least 10weeks to prepare for the holding of the referendum.They were in reality given less than half of that time.Further, controversy is brewing over the issue of

s. 18

sourcing funds for the referendum; government doesnot have the necessary means, estimated at $80-100million, and the short notice has made it impossiblefor donors to find the funds. The minister of justice,Patrick Chinamasa has however indicated that privatecompanies are ready to donate the necessary funds– spawning speculation that illegally siphoned offdiamond revenue will be used.The National Constitutional Assembly, NCA, tookgovernment to court over the issue of the shortnotice for the referendum, but courts have dismissedthe claim. Along with a small group of civil societyorganisations, NCA has long argued for voting no atthe referendum, finding the entire process excludingand flawed to the extent of being illegitimate. Manyyouth organisations have historical bonds with NCAand share its criticism of the process, representing theyouth group that feels marginalised in the process.This sentiment is further exacerbated by the presentmood of defeat as it is expected the ‘Yes’-side hasalready won. The three main parties have all agreedto the draft constitution after a long and gruellingprocess of negotiation and compromising. They seemdetermined to bring about a speedy referendum inorder to proceed to the ensuing elections as quicklyas possible; all of them apparently convinced thatthey will gain by acting hastily. In doing so they riskdisenfranchising a large part of the population, notablythe young first-time voters, as these do not have thenecessary documents for being allowed to vote (31%,see Table 24).Presenting a national ID will provide access to votingin the referendum. However, our survey shows thatquite a large proportion of youth does not possessa national ID (17%). This is particularly true for many

first-time voters as almost a third of the 18-24 year oldyouth does not possess this document. The problemis slightly more widespread in rural than in urbanareas, and is generally a larger problem for youngwomen than young men. It is further compounded bythe fact that most youth find it difficult to obtain an ID(see Table 22).

3.2. Youth and elections; preparationsstill lackingThere are a number of controversial, contentious is-sues pertaining to the upcoming elections, mainlyregarding the lack of service provided by ZimbabweElection Committee, ZEC, and the state of the votersroll. In spite of his earlier insistence on thorough elec-toral reform, Tsvangirai has recently repeatedly sug-gested this should happen as early as July this year.Along with the haste for holding referendum, this givesworry that MDC-T is ready to compromise on reforms.Civil Society has consistently demanded a numberof changes before the holding of elections (see forinstance MS/Action Aid Denmark’s briefing paper“Along the Winding Road” from June 20129). If thereforms are not implemented, there is not sufficientspace for political expression.As the survey has shown, youth is particularly vulne-rable to being disenfranchised or further marginalisedin elections. Contrasting with their high hopes for thefuture, there’s a serious risk that this particular genera-tion of youth might get seriously disappointed.At the time of writing there were no signs of the gover-nment making a particular effort to alleviate youth’simmediate problem of lack of documents and voterregistration. This points to two further major issuespertaining to the upcoming elections.

9

Ref: www.ms.dk/afrika/zimbabwe

s. 19

4.4.1. The voters roll

Governmental and institution-al efforts to include youthIn spite of this, ZEC has not managed to prove theyhave as yet accomplished the task.Before the 2008 elections, the voter registration func-tion was performed by the Office of the Registrar-General (RG) but since then the electoral laws statethat custody of the voters roll is vested in the ZEC.However, the actual management of the voters roll isstill in the hands of the RG, perceived as being a sta-unch Zanu PF member in whom neither the MDCs northe civil society have much trust. In March 2012, thisdistrust was further exacerbated as the Registrar Ge-neral claimed to the state-controlled Zimbabwe Bro-adcasting Corporation (ZBC) that the voters’ registeris “perfect”.ZEC in late 2012 announced that beginning January,it would embark on a voter registration campaign (in-cluding the deployment of mobile registration units),but so far, nothing has come of this - ostensibly dueto lack of funds.

Zimbabwe’s electoral system requires that an eligibleperson must first register before s/he is allowed to voteand this has been the law and practice since the 1985elections. As a consequence, voter registration is acritical function in the overall electoral process. It hasbeen a highly contested function and Zimbabwean ci-vil society has consistently over the last years showedthe present voters roll to be in a very sorry state. Toomany voters are missing from the roll and among tho-se registered a large proportion seems to be dead ormissing. Indeed, the recently resigned10ZEC chairmanJustice Simpson Mutambanengwe publicly concededin August 2010 that: “As it is, the voters roll is in disar-ray” and that it needed cleaning up. Civil society andthe two MDC parties have persistently sought to holdZEC accountable to this task, but so far have achie-ved few results. One of the ZEC commissioners esti-mated that the agency would need at least a year toclean up the voters roll, however in February 2011 theZEC chairman said it could be done in three months.

10

High Court Judge Rita Makarau has been nominated for the post.

s. 20

Police has recently initiated a clampdown on civil so-ciety organisations that had taken a special interest inassisting voters to register11. Civil Society often findsthat officials responsible for registering new voters arenon-cooperative. “They have so many ways of impe-ding it, for instance saying, ‘we can only register 5per day’, etc.”, says a youth organisation leader. Therehave however been a number of media reports thatthe RG’s office is assisting in mass registering per-ceived Zanu PF voters.All point to the need for ZEC to take fully charge of animpartial and thorough campaign to both clean the rolland add interested new voters to it. This is of particularimportance for youth as a large majority (87%) of poten-tial first-time voters are not yet registered (Table 9 above).

On ZEC, the umbrella civil society organisation Zim-babwe Election Support Network, ZESN, in a January2013 report concluded, that:“Over the years, the reputation of the ZEC (and itspredecessor) has never been above mediocre, thanksto its performance that has never been perceived aslaudable. Though there have been changes at thegovernance level, to date there is no convincing evi-dence that it has become more autonomous, impar-tial and professional. The new ZEC should change theway it does business and needs to be assisted to doso. The fact of ZEC being inadequately resourced, un-derstaffed and undertrained is a legendary historicalfact… It will not obtain the good will from the politicalstakeholders and the public unless it exhibits profes-sionalism at all levels of its structure and operations.”And, “ZEC must, without undue delay, begin the criti-cal process of voter education. Indeed, education ofvoters should be taken as a continuous process; itmust not be tied to electoral cycles. Voter educationshould be regarded as a collective and national ef-fort.”12Youth in particular, especially first-time voters,has only limited experience with democratic procedu-res and are obviously the most needy of learning howthe electoral system works – this is also a measureagainst young people accidentally spoiling their ownballot when finally in the election booth.

4.2. Zimbabwe Election CommitteeAlthough commissioners are appointed by the threemain political parties to the ZEC, the MDCs and ci-vil society place little trust in the organisation’s ope-rational impartiality. Indeed, in January Prime MinisterTsvangirai iterated an oft-proposed civil society de-mand that the entire staff of ZEC be vetted and large-scale changes introduced, as a substantial proportionof the staff is former army personnel or Central Intel-ligence Organisation agents, popularly regarded asZanu PF supporters or instruments. These are mainlythe same staff that manned the commission duringthe 2008 presidential elections, whose results wereconsidered by the opposition parties and civil societyas fraudulent and manipulated. Tsvangirai has on ear-lier occasions included such changes in the necessa-ry electoral reforms crucial to establishing conditionsfor free and fair elections. The demand is rejected byZanu PF and by the management of ZEC.ZEC is also the government agency charged withvoter education, and NGOs need accreditation fromZEC to do voter education. Further, they’ll need ZECaccreditation for all material to be used or utilize ZECmaterial. They are not allowed to use donor fundingfor this. It is however a widespread practice for CSorganisations to approach such issues through “civiceducation” or “social studies” for which they have nolegal constraints.11

4.3. Electoral reformsThe long-awaited adjustment of the country’s elec-toral laws were passed by parliament in 2012 andsigned into law by the president during September2012. A contentious issue was whether voters shouldbe able to vote at any polling station within their wardor should be consigned to a specific polling station.The latter procedure is perceived as the one givingleast room for fraud – but may also, as was seen inthe run-off presidential elections in 2008 provide thebasis for violent retaliation towards those who “votedwrongly” in the first round. Consequently, the act willallow voters to cast their vote at any polling stationwithin their ward.Further changes to the electoral law will have to be in-troduced and passed by parliament after the expectedapproval of the new constitution to align the laws with

During December-February, a number of Zimbabwe Human Rights Association and one National Youth Development Trust staff were arrested. Theformer organisation’s cases are still pending. Further, police raided the offices of the Habakkuk Trust, the Zimbabwe Peace Project and ZESN lookingfor what they called subversive material.”Zimbabwe’s Electoral Preparedness for the 2013 Harmonised Elections: Ready or Not”, p. 26. ZESN, January 2013.

12

s. 21

the new constitution. Among important changes isthe introduction of a semi-proportional system with anumber of seats reserved for women in parliament.Preparations for these revisions have already been ini-tiated, according to the responsible minister.

In a move directly targeted at youth organisations, theZanu PF minister for Youth Development, Indigeniza-tion and Empowerment recently had regulations in-troduced that compel youth organisations to registerwith the government-run Youth Council or risk beingshut down.13The regulations also dictate that youth groups shouldsubmit annual reports and accounts, as well as workplans and budgets to the Youth Council, which is lar-gely viewed as an extension of President Robert Mu-gabe’s Zanu PF party. In addition, youth organizati-ons are also compelled to pay an annual levy to thecouncil. The regulations were mooted by the ministerlast year and then apparently shelved. However, theywere without warning or publicity suddenly gazettedearly this year with very little time for youth organi-sations to react. The organisations generally regardthe measures as an attempt to discipline and controlyouth organisations presently not under the control ofthe ministry.As demonstrated above, government is not at presentinvolved in any activities targeting youth for increasedparticipation. The political parties are rallying their sup-porters, but youth will find themselves marginalised inthis, apart from being urged to vote for their party.

4.4. Creating a climate conducivefor free and fair electionsOutside these institutional shortcomings, the authori-ties are apparently intended on putting a heavy lid onany discussion in civil society of the merits of the draftconstitution. A meeting in Harare scheduled for Fe-bruary debating the draft constitution was cancelledby police for a number of reasons including the issueof the selection of panellists. Even more worrisome,the police on this occasion said they are “no longerallowing public meetings to be convened by NGOsoutside the arrangements of government.”In addition to the police harassment of civil society andyouth organisations mentioned above, police also inFebruary banned citizens from owning or using radiosable to pick up short wave signals from radio stationsoutside the country. The broadcasts are produced byexiled Zimbabwean journalists based in Europe andthe US.

13

Zimbabwe Youth Council (General) Regulations [SI 4/2013]

s. 22

5.

The Political Parties’efforts to include youthstructures are further likely to widen the party’s fac-tional cracks as youths’ parliamentary aspirants arecurrently pushing for wholesale leadership renewal,fuelling divisions with the old guard which still prefersthe seniority and hierarchical approach. Overall, theparty is faced with the fact that tying its agenda tothe liberation and anti-imperialism history and rhetoricdoes not appeal to youth.In reality, none of the parties seems really interestedin youth as active participants, but are happy to havetheir backing as voters, vigilantes, and campaigners.In all main camps these practices is bound to limityouth’s enthusiasm for political participation.

5.1. Political parties marginalise youthThe optimistic Zimbabwean youth risk being disap-pointed in regards to their induction into the realm ofpolitical participation. The present political field with itselected representation in parliament and local councilsis hotly contested with individuals and parties loath togive up whatever positions have been conquered.Zimbabwe’s political parties are not very open to re-cruiting active youth. In preparations for the comingelections, MDC-T has decided to “spare” incumbentMPs and councillors for contesting primary elections,in effect ring fencing these positions for the age groupalready represented. This has prompted MDC-T youthto demand a quota system that would ensure they arerepresented at every level of the party.“We demand a quota system along the lines of gen-der parity system and our leadership should be awarethis is our right,” said MDC-T Youth Assembly nationalsecretary for information Clifford Hlatshwayo recently.“We will persuade our leaders and tell them a peacefuland smooth transition in the future can only be rea-lised if the youths have practical experience now.”Similarly, Zanu PF has always gone for tried and tru-sted candidates and is seen as even more exclusive toyouth participation. It is indicative that a raft of estab-lished Zanu PF politicians known as the party’s “youngturks”, eager to take over from the old guard, are allin their 40’ies or 50’ies. Consequently, it has becomepractice in the party to relegate eager younger candi-dates to constituencies where they have no chance ofwinning. Deliberate moves to inject new blood into the

s. 23

6.

Civil Society’s efforts toinclude youthwith youth. The most immediate interests of youthmay not be national politics but other areas such as(lack of) education, the (lack of) platforms allowingyouth to be heard, the lack of ‘freedom’ – and this iswhere youth may be reached.One youth organisation leader broadly place youthin two major categories, ‘the youth voice, in realitythose active’ and ‘the rest’: “The first group is look-Box 3

A large number of civil society organisations are in-volved in projects targeting youth. They are aiming atthe group from many different angles and with varioustools: income generating projects, livelihood projects,small loans schemes, sports, youth activities andmuch more. And yet, youth still feel marginalised.One reason could be that a number of youth organi-sations are not that effective. Zimbabwe has a largenumber of youth organisations14, so large actually,that the sector appears fragmented with most of theorganisations unable to perform their mandate due tolack of capacity. “There’s a lot of repetition with toomany organisations too small to do anything of mea-sure,” comments one youth organisation leader.In the remaining ‘serious’ organisations, advocacyand inducements to political participation play a pro-minent role, explaining the nature of democracy, therole of elections, the need for youth to be active in the-se, not least local elections. Yet, some youth organi-sations involved in advocacy and providing platformsfor youth find youth uninterested or outright apathetic.They look at youths as a slumbering group who needsto be woken up.To civil society organisations working with youth, thissurvey’s findings of a politically interested and enga-ged youth should come as encouraging news. Per-haps civil society organisations need to reflect overthe discrepancy between the expressed wish of youthto be involved and their own perception of youth asbeing apathetic. This should have implications for theirstyle or content of communications and cooperation

Experiencedorganiser ofyouth activities:Listen to the Youth!Young people first and foremost need to feel that they arelistened to and respected. For any organisational work withthem you have to depart in ideas to activities that makes senseto them – and this they ultimately have to define themselves,be it sports, theatre, expressing themselves and above all: Tomake money.At beginning of meetings you might be quite demoralised: Theysit there with blank eyes, seemingly apathetic. Then you startasking them what they find interesting or how they spend theirdays and suddenly you notice that eyes light up! They see theyare listened to; they start conversing amongst themselves andsoon you might have a notion of, yes! We can do something!It may be difficult beforehand to imagine what will actually be amotivating factor. Relax; you’ll get there. They don’t mind beingmotivated, but they prefer themselves to be the motivator! Anddon’t worry; if you get the process going there’ll always emergea ‘natural leader’ out of the groups so that there’s someone torely upon for the follow-up.

14

The SIDA analysis of the youth sector mentioned above counts more than 600 organisations.

s. 24

ing forward and wants to be enthusiastic. They findthat being active gives them a chance to be heardand they aim to spread this enthusiasm. The majorityhowever, is immobilised - they want to see an end topoverty and misery. For them elections is understoodnot of opportunity, but of threats. They do not see theconnection between ‘politics’ and their private situa-tion of lack of opportunities.”Furthermore, there is obviously a special challengefor civil society in general and youth organisations inparticular to reach out to young women, given theirdescription of the lack of space available to them.Only few civil society organisations cater for this. Oneimportant entry point to connect with young womencould be social media especially mobile phones.Another entry point could be civic organisations otherthan youth organisations e.g. church related activities.Overall, experience from the interviewed youth orga-nisations demonstrate that bringing together youth, initself is a starting point to help breaking down barriersand create space for “breathing freer”. This is whereyouth may discover their individual strength as theyinvolve themselves in collective activities. Youth or-ganisations provide frameworks for this, but they andcivil society organisations in general need to find al-ternative ways of engaging with the youth in order totap in to the pool of engaged young women and men.Table 11

6.1. Youth organisations and the chal-lenges before the electionsEven before the announcement of the short campaignperiod ahead of the referendum, youth organisationleaders interviewed for this report did not regard thisas an important event. “It will come and pass as anon-event,” comments one. “It could be utilised as astep to hype up interest for voting as such, but I don’tthink it will work, as the ’no’-vote will not be able tomobilise. It will just be yes-yes-yes.”Enthusiasm is likely to grow considerably when theelections draw nearer. In contrast to the referendum,where all major parties are advocating a ‘yes’ vote, theelections are seen as involving a real contest betweenthe camps. This will present considerable challengesto the youth organisations overcoming their percep-tion of the majority youth as being “immobilised”.There is however, optimism too: “Youth is more easilyswept by excitement than older groups, and this is ourchance”, says one youth organisation leader. “Youthis more susceptible to peer pressure and popular cul-ture, so if we can manage to get out there in a sty-lish, fashionable way, we will improve our chances ofbreaking through.”As the survey shows, there is a real opportunity for rea-ching youth through social media, not least via mobilephones and the internet. A few politicians have shown

How often do you accessa cell phone?Daily %Once or twice weekly %A few times a month %

Rural6419314

Urban90773

Female7216310

Male7414110

18-247117210

25-307414210

Total7315210

No Answer %Table 12

Do you use a cell phone toaccess news on the internet?Yes %No %No Answer %

Rural16777

Urban451739

Female23968

Male291160

18-24251363

25-3027865

Total261064

s. 25

themselves to be deft users of especially Facebook,two of them (both representing Zanu PF) even rack-ing up a similar number of ‘friends’ as prominent popstars (app. 5,000). Though this number seems smallin the national context, one youth organisation leaderoffers this perspective: “Given that many youth feelsmarginalised they are often extremely grateful for anycontact with people of influence. If they get a respon-se through Facebook from a politician – who mighteven respond to their name, they feel respected, at-tracted, attached. And who-ever appears to be closeto someone of influence has influence themselves intheir peer group.”One youth organisation leader warns however againstcivil society’s tendency to focus on negative and ad-verse conditions in their communications – “do weuse the social media platforms to enforce hopeles-sness if we keep hammering on how much ‘the sy-stem’ is clamping down?” he asks.

s. 26

7.

Conclusioncrisis, it will be nearly impossible to create enough jobsin the next five years for the huge number of youthwithout a regular source of income. Furthermore, thelack of space for young people in the political partiesand government structures threatens to exclude theyouth from decision-making instead of tapping intothe potential.How will this generation of Zimbabwean youth react tosuch disappointing developments? What will happen ifthe past five years of getting nowhere is perpetuated?It was long-term disappointment, build up over manyyears that sparked recent uprisings in the Arab world.Years of bitterness over getting no-where and livingwith the prospect of no jobs, no money, no freedom,not even space to express all that disappointment.Such sentiments may turn to anger and revolt. Onthe one hand such developments carry the risk ofcementing authoritarian or violent methods. But onthe other hand a Zimbabwean youth uniting acrossthe country and bridging political affiliation could usherin change.

The above analysis of youth’s perception of politicalparticipation along with the role that government,political parties and civil society play in engaging youthpolitically, presents both hope and risks regarding thefuture of Zimbabwe.The Zimbabwean youth displays a striking optimismregarding the future in five years’ time, they embracedemocratic values and they show eagerness toparticipate in decision-making. As for their space toparticipate, the two electoral events could hold hopefor youth if they are given the opportunity to maketheir own choices. Also, the proposed constitutionincludes specific government obligations to youth.Regarding the unity of the youth voice, it shouldbe noted how the wishes expressed by the Zanu-loyal 21stFebruary movement youth representativeresonate with those of a huge number of their peers,regardless of political affiliation: Even amongst themost privileged of the Zimbabwean youth, thoseclosest to Zanu PF power and patronage, the senseof exclusion, of marginalisation is clear. This is quiteremarkable and might point towards the possibilityof youth uniting on a platform reaching across partydivisions to strengthen their collective voice.Yet, there is also a risk of serious disillusion anddisappointment among the youth. Given the depthand the magnitude of the last decade’s economic

RecommendationsZimbabwean youth seems to be willing and eager toparticipate in decision-making at different levels, buta variety of institutional and structural barriers blocktheir actual involvement. All actors can do much moreto facilitate a higher degree of youth involvement.

s. 27

The Government• Should act speedily to facilitate youth’s ac-cess to crucial documents (e.g. national ID)allowing them to participate in the referendumand facilitate their access to be registered asvoters.ZEC should assist with campaigns targeteddirectly at registering young voters, includingsending mobile registration units to ruralareas.Voter education should be carried out ex-tensively and non-biased e.g. via civil societyorganisations.The demands for electoral reform shouldbe met speedily and the harassment of civilsociety organisations halted immediately.

Civil Society Organisations• Must change the form and content of outreachactivities in order to overcome the differencebetween youth’s own expressed wish to berecognised and to participate actively, andthe perception in many (not all) civil societyorganisations of youth as being passive andapathetic.Should analyse more in depth, ‘what stopsthe youth?’/‘what really gets them started?’ inorder to tap in to the pool of engaged youngwomen and men.Youth organisations need to constantly revisetheir ways of communicating with youth. So-cial media and the utilisation of mobile phonesas platforms for communications seem to bean opportunity to reach new and large groupsof youth.Civil society organisations in general shoulddo more and find alternative ways to ac-commodate young women, since the youngwomen don’t feel the traditional ways oforganising and meeting are embracing them.

•

•

•

•

•

The Political Parties• Should take heed of youth’s sense of exclusionfrom the political sphere. Thus they shouldinvite youth to have real influence within theparties’ own structures and give access forthem to take up positions of importance.Should encourage young women to becomecandidates for positions of importance inparties and as duty bearers.Could increasingly utilise social media e.g.Facebook to interact with youth. Not onlyto profile older politicians but to listen to thevoices of youth.•

•

•

s. 28

Annex A

Table 13Here is a list of actions that people sometimes take as citizens. For each of these, please tell me whetheryou, personally, have done any of these things during the past year. If not, would you do this if you had thechance?

A

Attended a communitymeeting

Rural % Urban %322263118-945555050

Female % Male %632242613-4272529140

Total %5302427140

Would never do thisWould if had the chanceOnce or twiceSeveral timesOftenDon’t know

B

Got together with othersto raise an issue

Rural % Urban %1134252111-16551793-

Female % Male %164221156-940231910-

Total %134122178-

Would never do thisWould if had the chanceOnce or twiceSeveral timesOftenDon’t know

C

Attended a demonstrationor protest march

Rural % Urban %62306111682650-0

Female % Male %7322400155358101

Total %64296101

Would never do thisWould if had the chanceOnce or twiceSeveral timesOftenDon’t know

s. 29

Table 14

How often do you get political newsfrom the internet?NeverLess than once a monthA few times a monthA few times a weekEvery dayDon’t know

Rural % Urban %8543540568915120

Female % Male %796564071451090

Total %7555860

Table 15Do you agree or disagree with the following statement: Sometimes politics and government seem so complicated that a person like youcannot really understand what is going on.

RuralStrongly agreeAgreeNeither agree nor disagreeDisagreeStrongly disagreeDon’t know / Don’t understand27291614113

Urban25301813131

Female3428161093

Male18301717152

18-243329151093

25-3021291717152

Total26291614123

Table 16Which of these three statements is closest to your own opinion?

RuralSTATEMENT3:For someone likeme, it doesn’t matter what kind ofgovernment we haveSTATEMENT 2: In somecircumstances, a non-democraticgovernment can be preferable.STATEMENT 1: Democracy ispreferable to any other kind ofgovernment.Don’t know12

Urban8

Female13

Male8

18-2414

25-307

Total10

11

12

10

13

11

12

11

73

78

72

77

71

78

75

5

3

5

2

5

3

4

s. 30

Annex A

Table 17There are many ways to govern a country. Would you disapprove or approve of the following alternatives?

A

Only one political partyis allowed to stand forelection and hold office.Strongly agreeAgreeNeither agree nor disagreeDisagreeStrongly disagreeDon’t know

Rural3232914104Rural432815734Rural

Urban51245982Urban61229612Urban

Female333191395Female463191395Female

Male4427612102Male442714525Male

18-2439289109618-2449281162518-24

25-30373071510125-3050241573325-30

Total3829181293Total492613624Total

B

The army comes in togovern the country.

Strongly agreeAgreeNeither agree nor disagreeDisagreeStrongly disagreeDon’t knowCElections and Parliamentare abolished so that thePresident can decideeverything.

Strongly agreeAgreeNeither agree nor disagreeDisagreeStrongly disagreeDon’t know

373215654

57268432

403214635

492812552

452913535

433113652

443013543

s. 31

Table 18A: Thinking about the lastnational election, did you tryto persuade others to votefor a certain candidate orparty?

B: Do you intend to try topersuade others to vote fora certain candidate or partyin the next national election

Table 19Do you think that the youths have thesame ability as others to exercise politicalinfluence or pressure through the votingprocess?

Total %Yes %No %Maybe %17830Yes %No %Maybe %

Total %25705Yes %No %Not sure/Don’t know %

Total %721018

Table 20

Do you think your vote counts (i.e.affects policy and politics)?YesNoNot sure/Don’t know

Rural % Urban %741313711711

Female % Male %701614761312

Total %731513

Table 21Which is the one most likely step you would take?