Sundheds- og Forebyggelsesudvalget 2012-13

SUU Alm.del Bilag 337

Offentligt

www.discoverymedicine.comISSN: 1539-6509; eISSN: 1944-7930

DISCOVERY MEDICINE�

201

Personalized�Medicine:�Theranostics�(TherapeuticsDiagnostics)�Essential�for�Rational�Use�of�TumorNecrosis�Factor-alpha�AntagonistsKlAuSBeNdtzeNAbstract: With the discovery of the central patho-genic role of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α in manyimmunoinflammatory diseases, specific inhibition ofthis pleiotropic cytokine has revolutionized thetreatment of patients with several non-infectiousinflammatory disorders. As a result, geneticallyengineered anti-TNF-α antibody constructs nowconstitute one of the heaviest medicinal expendituresin many countries. All currently used TNF antago-nists may dramatically lower disease activity and, insome patients, induce remission. Unfortunately,however, not all patients respond favorably, andsafety can be severely impaired by immunogenicity,i.e., the ability of a drug to induce anti-drug antibod-ies (ADA). Assessment of ADA is therefore an impor-tant component of the evaluation of drug safety inboth pre-clinical and clinical studies and in theprocess of developing less immunogenic and saferbiopharmaceuticals. Therapeutics diagnostics, alsocalled theranostics, i.e., monitoring functional druglevels and neutralizing ADA in the circulation, iscentral to more effective use of biopharmaceuticals.Hence, testing-based strategies rather than empiri-cal dose-escalation may provide more cost-effectiveuse of TNF antagonists as this allows therapies tai-lored according to individual requirements ratherthan the current universal approach to diagnosis.The objective of the present review is to discuss thereasons for recommending theranostics to imple-ment an individualized use of TNF antagonists andto highlight some of the methodological obstaclesthat have obscured cost-effective ways of using thesetherapies.[DiscoveryMedicine15(83):201-211, April 2013]IntroductionThe last decade has seen a revolution in the treatment ofpatients with various immunoinflammatory diseases,for example arthritic diseases [e.g., rheumatoid arthritis(RA) and ankylosing spondylitis], inflammatory boweldiseases [e.g., Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative coli-tis], skin diseases (e.g., psoriasis and hidradenitis sup-purativa), non-infectious diseases of the eye (e.g., dia-betic macular edema and age-related macular degener-ation), and refractory asthma (Langford, 2008; Linetal.,2008; Emeryet al.,2009; Allezet al.,2010; Desaiand Brightling, 2010; Furstet al.,2011; Jemec, 2013).Thus, antibody constructs that specifically antagonizethe inflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor(TNF)-α have dramatically improved outcomes forpatients refractory or intolerant to conventional treat-ments, reducing corticosteroid requirements and, insome cases, inducing long-term remission (Tanaka,2012).The anti-TNF-biopharmaceuticals for systemic admin-istration are the human TNF receptor/IgG1 fusion pro-tein, etanercept/Enbrel; the chimeric human/mousemAb, infliximab/Remicade; the human mAbs, adali-mumab/Humira and golimumab/Simponi; and themAb/Fab fragment, certolizumab pegol/Cimzia. Theyall target both soluble and membrane-associated formsof TNF-α, thus inhibiting TNF-α from triggering cellu-lar TNF-receptors. The effects have been so dramatic,and the number of patients who benefit so large thatTNF-α-targeting drugs now constitute one of the heav-iest medicinal expenditures in many countries.The massive use of TNF antagonists has confronted cli-nicians with several challenges. Apart from immuno-suppression and other side-effects, up to 50% ofpatients sooner or later experience treatment failure(Cassinotti and Travis, 2009; Afifet al.,2010; Aikawaet al.,2010; Allezet al.,2010; Krieckaertet al.,2010;Barteldset al.,2011; Ben-Horin and Chowers, 2011;

Klaus Bendtzen,M.D., D.M.Sc., is at the Institute forInflammation Research (IIR 7521), RigshospitaletUniversity Hospital, 9 Blegdamsvej, Copenhagen2100, Denmark.Corresponding email: [email protected].�Discovery�Medicine.All rights reserved.

Discovery Medicine,Volume 15, Number 83, Pages 201-211, April 2013

202

theranostics essential for Rational use of tNF-α Antagonists

Daneseet al.,2011; Yanai and Hanauer, 2011; Atzenietal.,2012; Chaparroet al.,2012; Colombelet al.,2012;Garceset al.,2012). As there is currently no establishedstandard for handling patients with insufficient effect ofTNF antagonists, clinicians are left with only a fewchoices when the drugs fail -- all based on clinical out-come. They can wait and see, empirically intensifytreatment with the existing drug, switch to another TNFantagonist, or switch to an entirely different class ofdrugs. This ‘trial-and-error’ approach has several disad-vantages. Patients with inflammation in the presence ofotherwise therapeutic drug levels are not identified, suf-fering continues if the new and empirically chosen drugis also ineffective, and there is a risk of irreversible tis-sue damage while physicians search for an effectivenew drug. It is also important to realize the enormousfinancial consequences of unsuccessful ‘trials.’One approach to deal with these problems is to use ther-apeutics diagnostics, or theranostics, so that clinicianscan identify patients for whom a medication, or achange in medication is likely to work (Palekar-Shanbhaget al.,2012). It offers the possibility of tailor-ing therapy according to individual needs as opposed tothe standard generic approach to diagnosis, and it aimsat reducing delays in effective treatment. Testings foranti-drug antibodies (ADA) may also help assessing therisk of potentially dangerous reactions caused by drugimmunogenicity. Finally, theranostics has the potentialto improve the cost-effectiveness of already expensivetherapies.Clinical Use of TNF AntagonistsApart from infliximab, which is given intravenously, allsystemically used biological TNF antagonists are for-mulated for self-administration through subcutaneousinjections. Because of the high costs associated withprolonged therapies, episodic treatment with discontin-uation of the drugs during clinical remission is used insome patients even though this strategy is associatedwith insufficient responses and adverse reactions(Steenholdtet al.,2011a).Inadequate effect of TNF antagonistsMost patients respond favorably to TNF antagonists, atleast initially, but some do not. It is for exampleunknown why certain TNF antagonists are effective insome but not in other chronic inflammatory disorders(Assasiet al.,2010). In general, patients with inade-quate effects either do not respond at all (primaryresponse failure) or they respond initially but have laterrelapses (secondary response failure) despite increaseddosage and/or more frequent administration of theDiscovery Medicine,Volume 15, Number 83, April 2013

drugs (Strandet al.,2007; Bendtzenet al.,2009; Allezet al.,2010; Krieckaertet al.,2010; Furstet al.,2011).The mechanisms underlying these failures are notentirely clear, partly because the problem has receivedlittle attention. Proposed explanations for drug failureinclude problems related to bioavailability, pharmaco-kinetics (PK), and pharmacodynamics (PD) in addtionto immunogenicity with development of ADA(Ainsworthet al.,2008; Wijbrandtset al.,2008;Bendtzen, 2012).PK, PD, and primary response failureIt is likely that at least some of the above mentionedproblems could be overcome if therapists had knowl-edge of the PK and PD of the drugs in individualpatients. For example, drug levels in sera sampled at theend of a therapeutic cycle (trough) are surrogate PKmarkers, and these levels have been shown to vary con-siderably between patients on standardized dose regi-mens with low levels correlating with (later) loss ofresponse (Bendtzenet al.,2006; Ternantet al.,2008).These variations relate to structure and formulation ofthe drugs, and route and frequency of administration,but they also seem to depend on patient-related featuressuch as age, sex, weight, intercurrent diseases, con-comitant medications, and the ability of an individual tomount an immune response.If primary nonresponders are routinely monitored forcirculating levels of the TNF antagonist or, better yet,for levels of TNF-α-neutralizing activity, one would beable to adjust treatment on the basis of patient-relevantevidence which is likely to be much more cost-effec-tive. For example, in the absence of ADA it would belogical to increase the dosage of a drug, or to shortenthe dosing interval in patients with insufficient TNF-α-neutralizing capacity. On the other hand, some patientswith primary response failure have therapeutic or evensupra-therapeutic drug levels (Ainsworthet al.,2008).These patients are not likely to benefit from intensifiedtherapy, and because the patients are unresponsivedespite already high blood levels of anti-TNF-α activi-ty, switching to another TNF antagonist is also likely tobe ineffective. Indeed, the presence of supra-therapeu-tic concentrations of bioactive drug in unresponsivepatients raises the question whether TNF-α is of keypathogenetic importance in all cases diagnosed as a sin-gle disease entity (Ainsworthet al.,2008; Wijbrandtsetal.,2008). If not, RA, CD, psoriasis, and many otherdiseases, where the diagnoses rest primarily or solelyon clinical criteria, may constitute pathophysiologicallyheterogeneous groups of diseases, some of whichresponding to TNF antagonists, others not (Bendtzen,2012). Nonetheless, monitoring functionally active

theranostics essential for Rational use of tNF-α Antagonists

203

drugs in the circulation is warranted in patients with pri-mary response failure because demonstration of highdrug levels may save months of futile and expensivetherapy and allow earlier shift to effective treatment(Bendtzen, 2011).Immunogenicity and secondary response failureMany patients who meet the criteria for an initial clini-cal response sooner or later lose effect of TNF antago-nists, and the one-year drug survival rates may in somecases decline to less than 20% mainly due to loss ofefficacy (Allezet al.,2010; Furstet al.,2011; Brunassoet al.,2012; Emery, 2012). Secondary response failurecan in some patients be related to individual differencesin drug bioavailability and PK, as this may lead to inad-equate drug levels in the circulation and in affected tis-sues. PD issues involving the mechanisms underlyinginflammation in the affected tissues, may also beinvolved. Infections and alterations in concomitanttherapies, or the introduction of new ones, may forexample affect pathophysiological processes in tissuesalso affected by the original disease. The major contrib-utor to secondary response failure, however, appears tobe immunogenicity leading to production of ADA withremoval of the drug from the circulation and/or directneutralization of drug activity.Anti-drug antibodies (ADA)Repeated injections of biopharmaceuticals may trigger

production of ADA (Kromminga and Schellekens,2005; Shankaret al.,2006; Strandet al.,2007). This ishardly surprising because administration of many pro-tein drugs resemble vaccination procedures: repetitivesubcutaneous injections of non-self proteins. All cur-rently used anti-TNF biopharmaceuticals arenon-selfglycoproteins, including the so-called fully human anti-bodies (adalimumab and golimumab) that contain TNF-binding idiotopes that are not part of a normal humanantibody repertoire (Bendtzen, 2012). It is therefore tobe expected that TNF antagonists also induce ADA(Fefferman and Farrell, 2005; Bendtzenet al.,2006;Wolbinket al.,2006; Aardenet al.,2008; Ebertet al.,2008; Westet al.,2008; Bendtzenet al.,2009;Cassinotti and Travis, 2009; Karmiriset al.,2009;Petitpainet al.,2009; Wolbinket al.,2009; Aikawaetal.,2010; Allezet al.,2010; Jamnitskiet al.,2010;Krieckaertet al.,2010; Lecluseet al.,2010; Makoletal.,2010; Barteldset al.,2011; Bendtzen, 2011; Furstetal.,2011; Korswagenet al.,2011; Steenholdtet al.,2011a; Yanai and Hanauer, 2011; Emery, 2012). What issurprising is that it has taken more than a decade to real-ize this important problem. In RA and CD patients, forexample, half the patients with initial response to inflix-imab experience flare of disease after months of thera-py, and several studies have now shown that ADA areclosely associated with these events. This frequency iseven likely to be a low estimate, because the full impactof drug immunogenicity is realized only if patients aremonitored for ADA on a routine basis or, at the veryleast, every time treatment failure or side-effect occur.

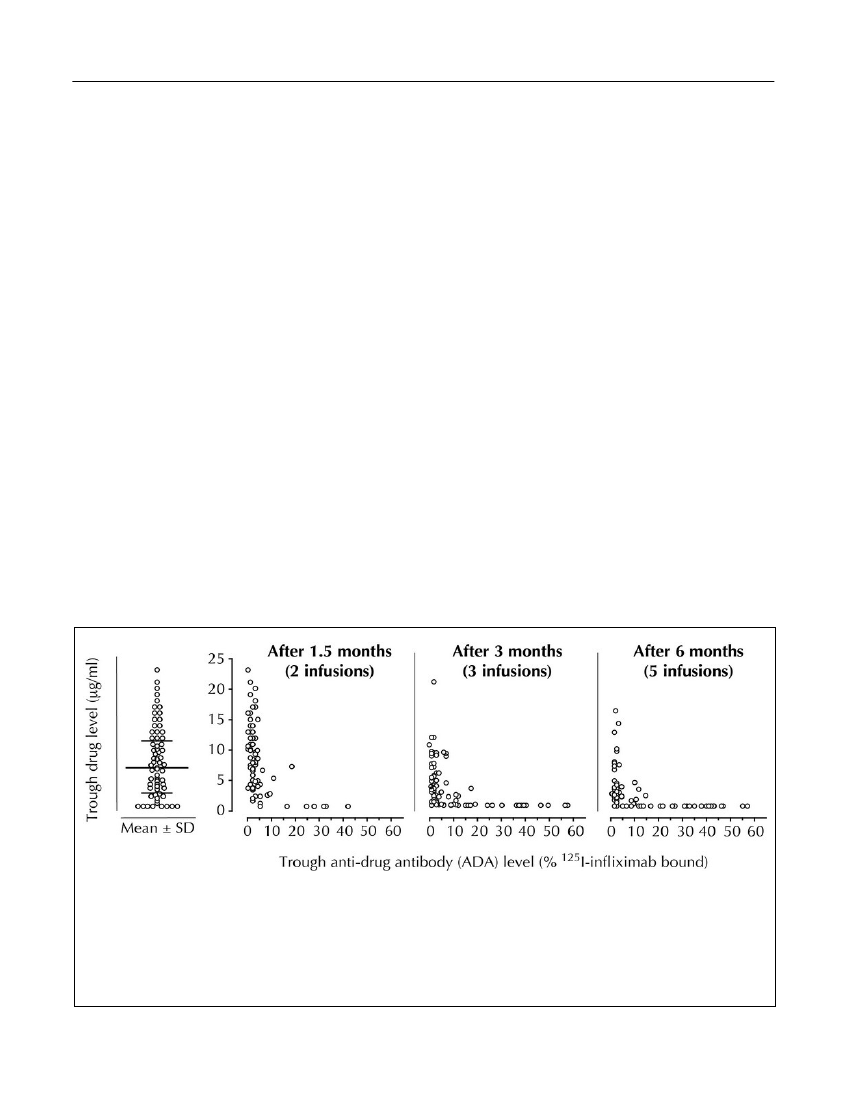

Figure 1.Interindividual differences in serum levels of infliximab, and dynamic influence of ADA on drug PK. Serumlevels of infliximab (Y-axes) and anti-infliximab ADA were measured in 106 RA patients using RIA. Trough leveltestings were carried out on sera drawn immediately before the 3rd intravenous infusion of infliximab 1.5 months afterstart of therapy, and before the 4th and 6th infusions, respectively (right panels). The drug was administered at therecommended dosage of 3 mg/kg. The left panel is a scatter plot showing mean value � standard deviations (SD) ofthe drug levels achieved after the 2nd infusion. Note the gradual disappearance of the drug as soon as ADA develop.Approximately half the patients (44%) were ADA-positive after 6 months of therapy. Extended with permission fromArthritis and Rheumatism(Bendtzenet al.,2006).Discovery Medicine,Volume 15, Number 83, April 2013

204

theranostics essential for Rational use of tNF-α Antagonists

If not, as is the usual approach today, clinicians willnever know that ADA could be the underlying cause oftherapeutic failure, and side-effects.The latter is highlighted by reports on potentially seri-ous side-effects that seem to be mediated by drug-ADAimmune complexes, for example, infusion reactions,serum sickness, bronchospasm, and Arthus reactions(Wolbinket al.,2005; Bendtzenet al.,2006; Wolbinket al.,2006; Descotes and Gouraud, 2008; Dubeyet al.,2009; Bendtzen, 2011; Korswagenet al.,2011). Theproblem of drug immunogenicity becomes even moreimportant as evidence from infliximab-treated CDpatients show highly variable kinetics of ADA in thecirculation (Steenholdtet al.,2012). In some patients,ADA persist for years even after discontinuation oftherapy, whereas others clear ADA from the circulationduring continued therapy. In view of the above find-ings, it is remarkable that the vast majority of patients

still receive TNF antagonists without consideration ofthe fact that development of ADA poses a safety risk(Cheifetz and Mayer, 2005; Hwang and Foote, 2005;Tangriet al.,2005; De Groot and Scott, 2007;Bendtzen, 2011; 2012).Investigations have shown that drug bioactivity disap-pears from the circulation as soon as ADA appears(Bendtzenet al.,2006; van den Bemtet al.,2011)(Figure 1). Not surprisingly, several other investiga-tions of RA and CD patients have shown that low bloodlevels of infliximab, adalimumab, and etanercept, andthe presence of ADA correlate with the requirement fordose increase, therapeutic failure, and infusion reac-tions (St. Clairet al.,2002; Wolbinket al.,2005;Mullemanet al.,2009; Radstakeet al.,2009; Afifet al.,2010; Barteldset al.,2011; Jamnitskiet al.,2011;Steenholdtet al.,2011a; Yanai and Hanauer, 2011).

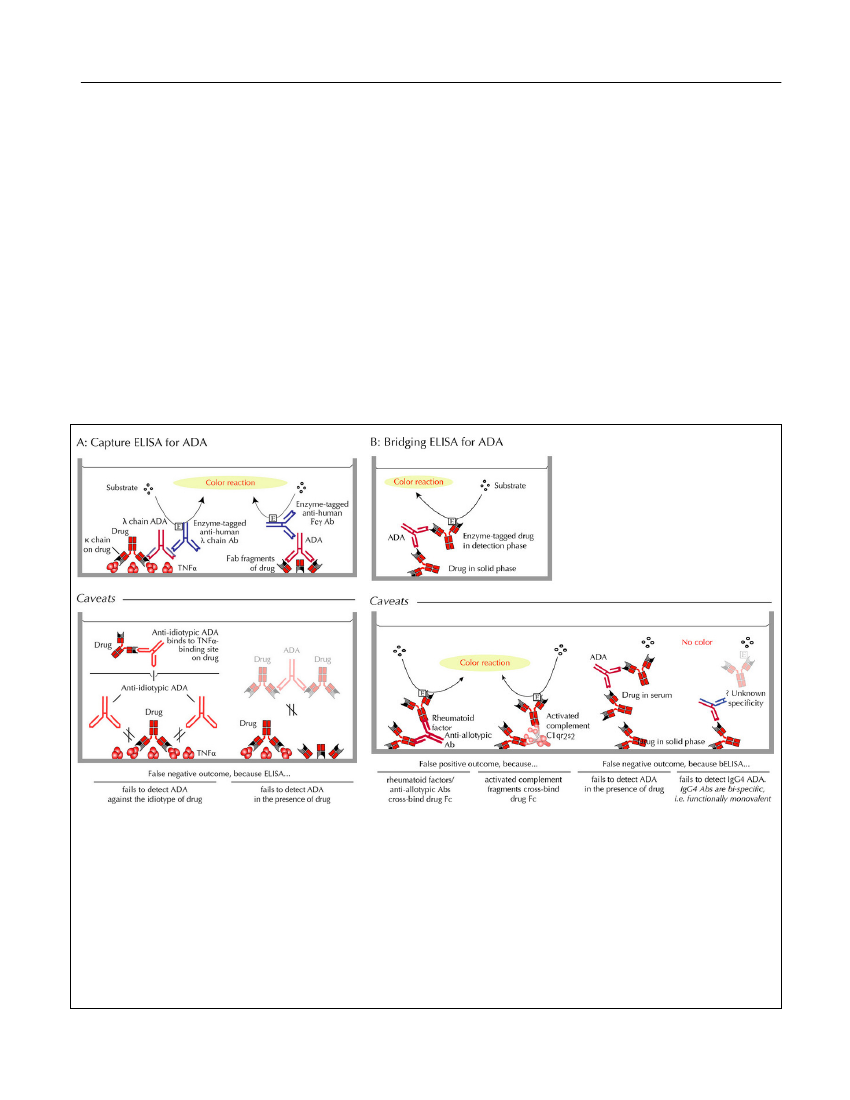

Figure 2.ELISAs for ADA.A:Capture ELISA. Left upper panel: λ light-chain ADA, bound to the TNF antagonistcaptured on TNF-α-coated plastic wells, are detected by enzyme-labeled anti-human λ light-chain antibody (Ab). Rightupper panel: Alternatively, ADA captured on plastic-adherent Fab fragments of the drug, are detected by enzyme-labeledanti-human Fcγ Ab. Left lower panel: False negative ADA testings may arise from failure to detect anti-idiotypic ADA.Right figures in the lower panel: False negative ADA testings due to high drug-sensitivity, i.e., inability to detect ADA inthe presence of drug.B:Bridging ELISA. Upper panel: Bridging ELISA depends on the bivalency of primarily IgG Ab(and multivalency of IgA and IgM Ab) and, hence, the ability of these immunoglobulin classes to ‘bridge’ a drug mole-cule preabsorbed to a plastic plate with an added enzyme-labeled drug molecule. Left two figures in the lower panels:False positive ADA testings may arise from cross-binding of drug Fc-fragments by sera containing rheumatoid factorand/or anti-allotypic Abs, or activated complement components in sera of patients with high inflammatory activity. Righttwo figures in the lower panels: Most often, however, bridging ELISA generates false negative results for ADA becausethey are highly drug-sensitive and/or because of failure to detect IgG4 ADA which predominate after prolonged immu-nizations.Discovery Medicine,Volume 15, Number 83, April 2013

theranostics essential for Rational use of tNF-α Antagonists

205

Assays for TNF Antagonists and ADAAn important and often overlooked aspect of using test-ing-based strategies is the ability of assays to accurate-ly and reliably measure levels of functionally activedrug and ADA (Bendtzen, 2012). Detections of ADA,for example, are generally hampered by the fact thatmost TNF antagonists are by themselves immunoglob-ulins, and by the complexity of measuring antibodiesagainst antibodies in non-functional binding assays.Immunoassays for ADA bindingEnzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs)arethe most commonly used tests for ADA in patientserum. Unfortunately, however, all solid-phase assayshave several notable limitations for clinical use(Bendtzen, 2012) (Figure 2). These include difficultiesfor certain capture ELISAs to detect anti-idiotypic anti-bodies because idiotopes residing in the TNF-α bindingsite(s) of an antibody drug are masked by TNF-α in thecapture phase (Figure 2A). The frequently used bridg-ing ELISA modification also fails to detect IgG4 anti-bodies, a major isotype of ADA after prolonged immu-nizations (Svensonet al.,2007; Bendtzen, 2012; vanSchouwenburget al.,2012). This is because IgG4 anti-bodies are functionally monovalent and therefore can-not ‘bridge’ in this type of binding assay (Figure 2B).Perhaps more importantly, ELISA is highly sensitive tothe presence of drug in the sample being tested forADA, giving rise to false negative findings (Hartet al.,2011; Bendtzen, 2012). Some investigators conse-quently report ADA status as inconclusive in sera test-ed with ELISA if drug is detectable (Yanai andHanauer, 2011). This has been estimated to be the casein about half the patients in clinical trials.ELISAs and other solid-phase assays are also known toreport false positive findings for example from neoepi-tope formation and from nonspecific binding of low-affinity antibodies, including heterophilic antibodies,and also from rheumatoid factors and/or activated com-plement which may cross-bind IgG Fc fragments inbridging ELISA (Figure 2B).As tools for therapeutic guidance, it is essential to real-ize that binding assays do not discriminate betweenneutralizing and non-neutralizing ADA, an issue recog-nized in 2007 by the European regulatory authorities(European Medicines Agency, 2007). With this in mindand the limitedin vivorelevance of solid-phase tech-niques in general, the wide use of ELISA in recentyears may have contributed to the confusion surround-ing drug immunogenicity -- and will continue to do soas long as therapeutic relevance is ignored when

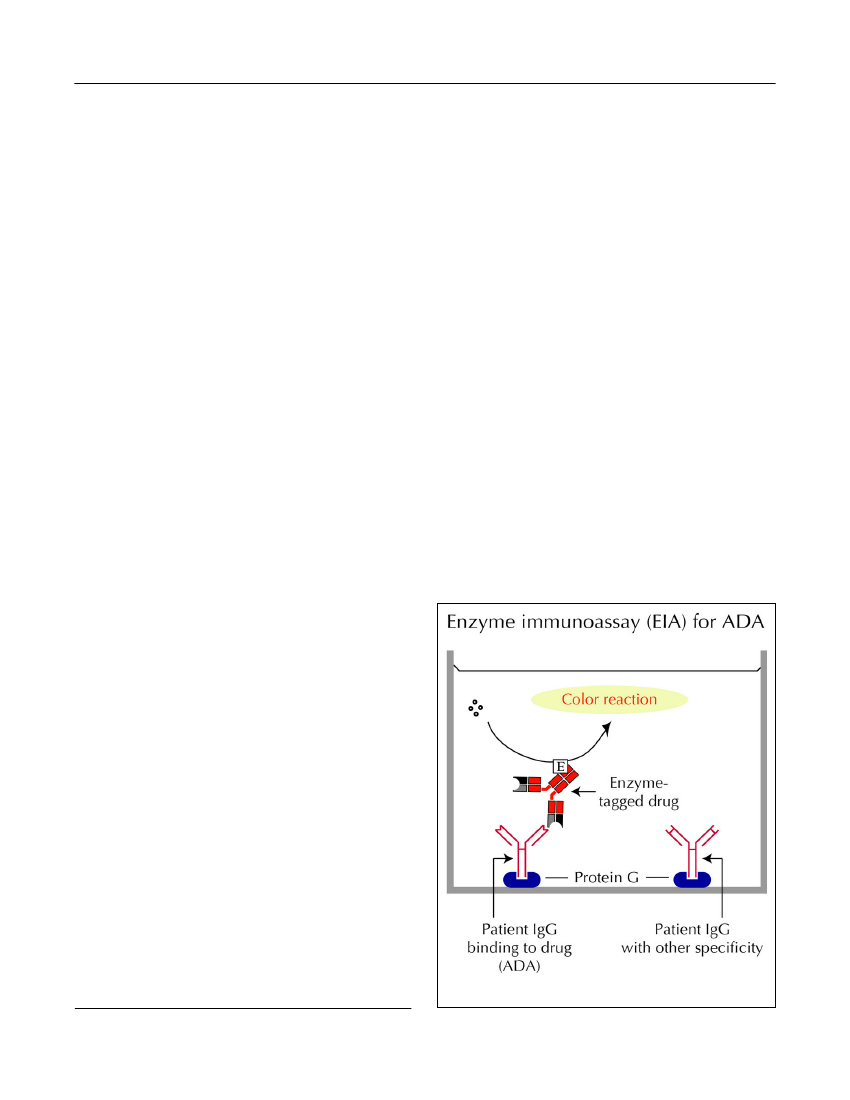

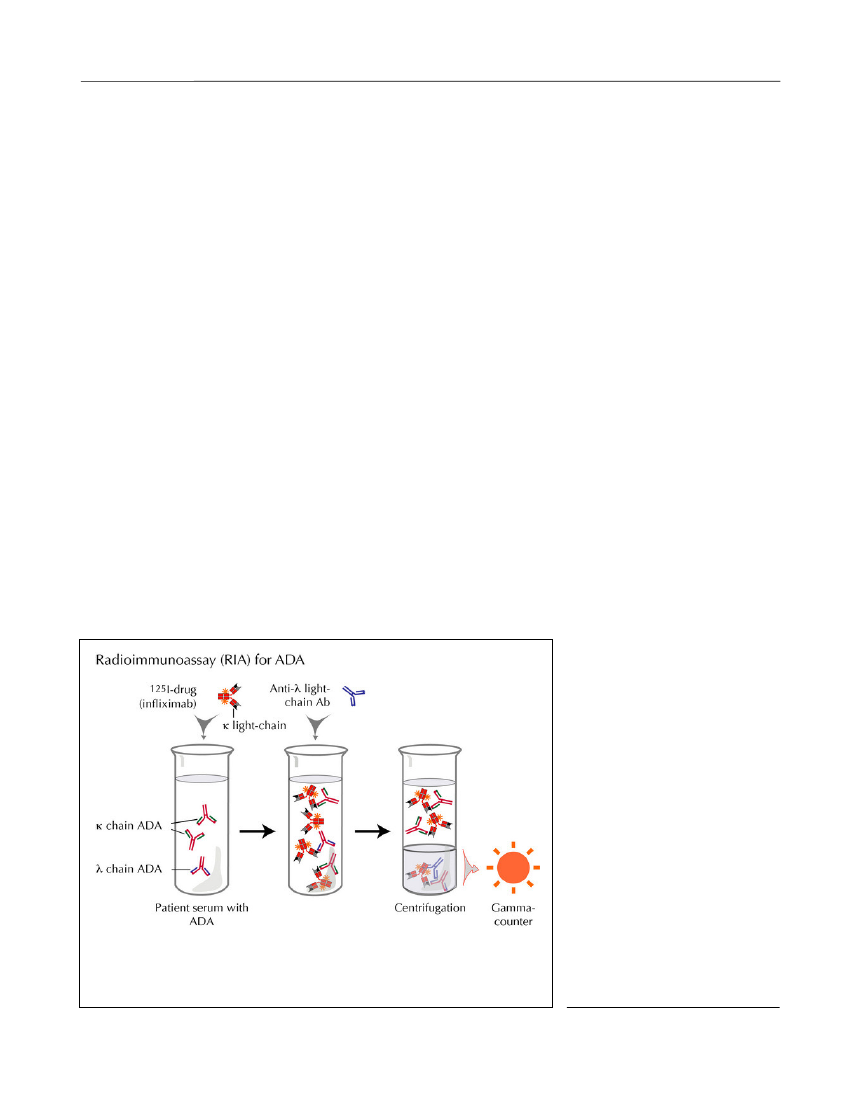

assessing ADA in the clinical setting. Newer solid-phase binding assays, including those based on bead-and chip technologies, may have similar disadvantagesas they report antibody binding to drugs in a non-homogeneous and, possibly, aggregated or otherwisedenatured form (Bendtzen, 2012).Semi fluid-phase enzyme-immunoassay (EIA).Inthis ‘reverse’ EIA, patient serum and biotinylated drugare allowed to preincubate in solute phase before beingdeveloped on avidin-coated plates (Bendtzen andSvenson, 2011). In a newer modification, serum is firstadded to plastic wells precoated with protein G whichselectively binds to the Fc parts of IgG molecules irre-spective of their antigen specificities (Figure 3). Afterremoval of all non-IgG serum components (by wash-ing), any immobilized IgG ADA are visualized by addi-tion of the enzyme-tagged drug. This modification alsoallows ADA to bind to drug that has not been denaturedby prior plastic absorption as in an ELISA setup.Fluid-phase radioimmunoassay (RIA)for ADA hasgenerated promising results in patients with RA andCD (Bendtzenet al.,2006; Barteldset al.,2011;Bendtzen and Svenson, 2011; Steenholdtet al.,2011b;Krieckaertet al.,2012). Most of these assays are lesssensitive to artifacts encountered in solid-phase assaysand therefore thought to better reflect thein vivocondi-tions (Figure 4). In contrast to ELISA, RIA is highlysensitive and measures ADA also in the presence of

Figure 3.EIA for ADA.Discovery Medicine,Volume 15, Number 83, April 2013

206

theranostics essential for Rational use of tNF-α Antagonists

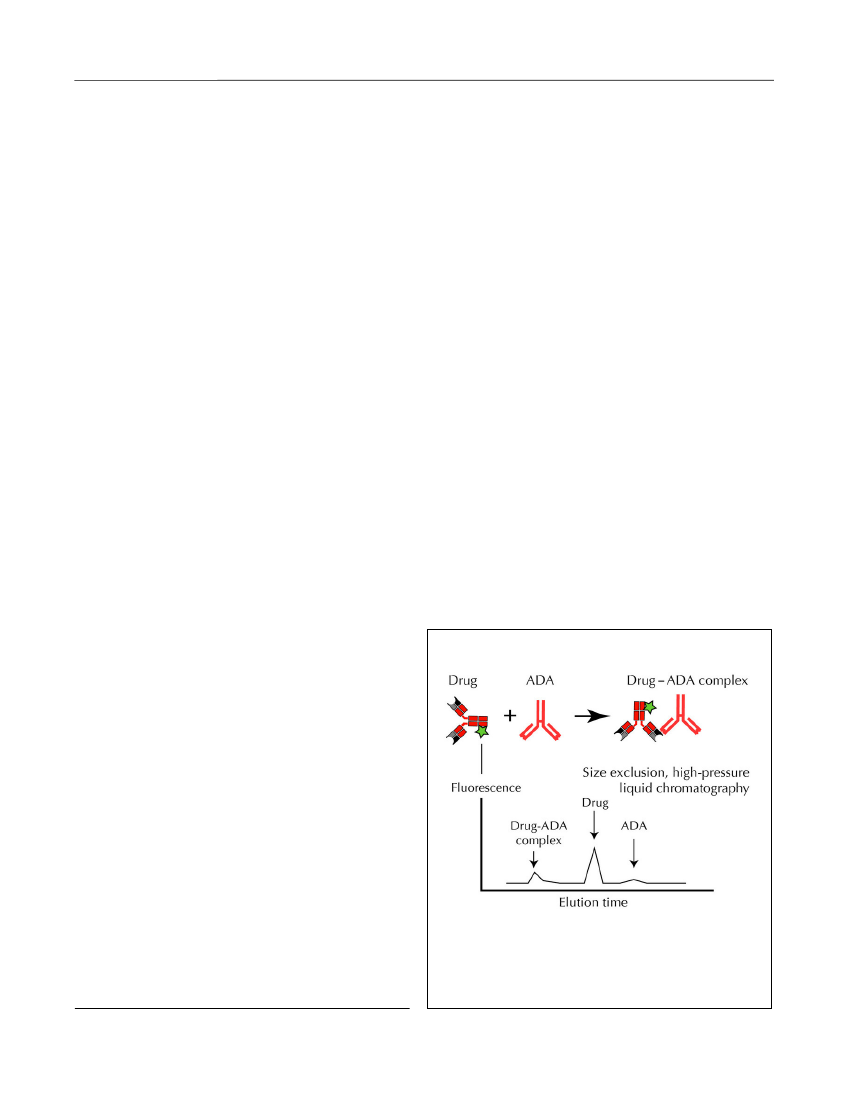

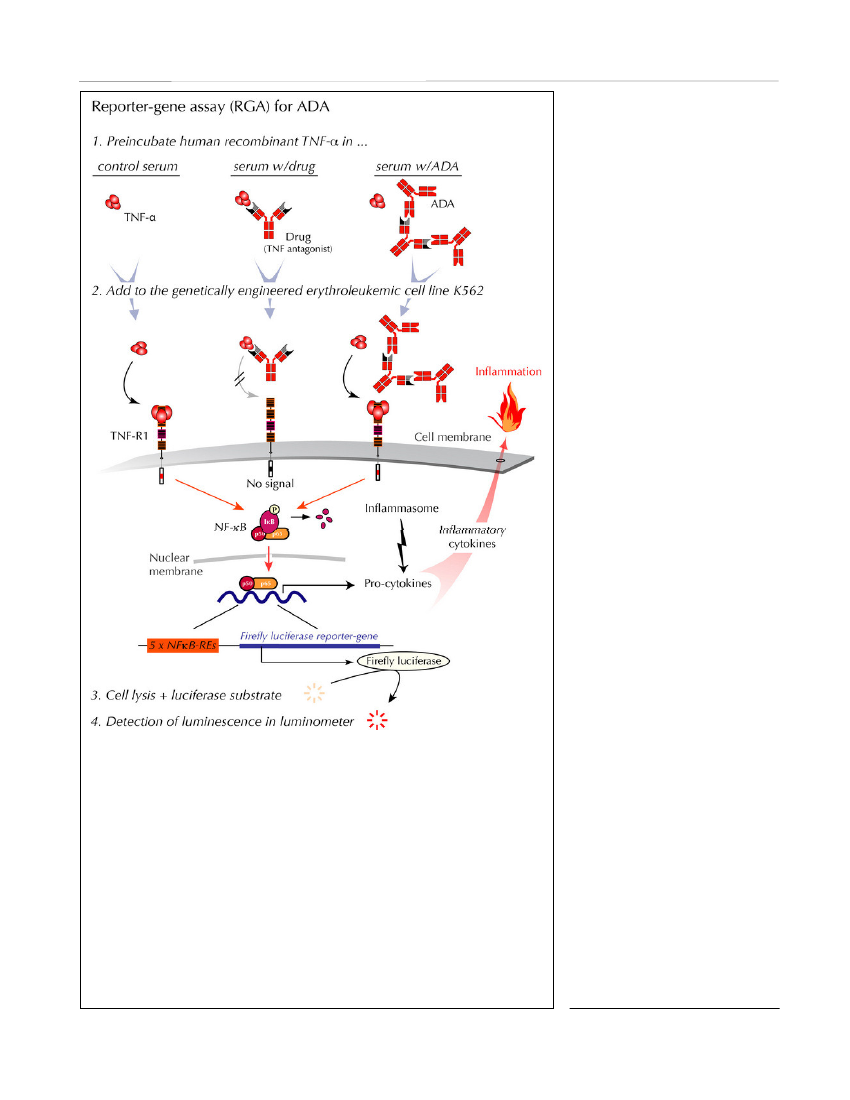

limited amounts of drug. In addition, RIA detects allisotypes and subclasses of immunoglobulins that bindto the drug, including IgG4. The major limitation ofRIA is the need for advanced laboratory facilities andthe fact that these assays also fail to detect whether thereported ADA are neutralizing or not.Homogeneous mobility-shift assay(HMSA) uses sizeexclusion high-performance liquid chromatography todetermine concentrations of ADA (Figure 5). This tech-nology was recently introduced in North America as areplacement for ELISAs for ADA detection (Wangetal.,2012). The clinical potential of HMSA is underinvestigation, but its rather expensive setup may limitroutine use. The fact that immune complexes may splitduring chromatography giving rise to drug detection inthe presence of ADA is a potential problem. As withother binding assays, HMSA does not inform on thefunctionality of the reported ADA.Cell-based assay for neutralizing ADAReporter-gene assay (RGA)is the most recent devel-opment (Lallemandet al.,2011; Bendtzen, 2012)(Figure 6). In contrast to binding assays, RGA measuresthe functionality of both drugs and ADA, i.e., the TNF-inhibitory effect of drugs and neutralizing ADA, respec-tively. Though at present largely unexplored in clinicaltrials, it may be desirable to use RGA for patient moni-toring as it reports ADA that bind with sufficient avidi-ty and to a locality on the drug that interferes with drugactivity at the cellular TNF-receptor level. This assay

therefore seems to resemble thein vivoconditions underwhich TNF antagonists are believed to function.The usual limitations of cell-based assays have beenovercome by the development of an RGA that allowsboth drug activity and neutralizing ADA to be quanti-fied independent of serum matrix effects and cell-num-bers. In addition, the use of assay-ready cells stored at-80�C for extended periods without loss of sensitivityobviates the need for continuous cell cultivation. Theassay reports ADA within a few hours, and it is easilymodified for quantification of residual drug activity andneutralizing ADA in patients treated with all knownanti-TNF biopharmaceuticals.Testing-based Strategies as Clinical UtilitySome investigators hold the view that there is little needto monitor drug levels, let alone ADA levels, if patientsare doing well on standard regimens. Some even feelthat ADA are of limited importance because there arenot always observable consequences of ADA develop-ment. These assumptions are fostered by the use ofassays that have little clinical relevance, and even onassays known to yield false results in the clinical setting(Aardenet al.,2008; Bendtzen, 2012).The wide use of bridging ELISA for detecting ADA inpatient serum is perhaps the most problematic example,as this type of assay as mentioned previously cannotdetect ADA in the presence of drug (Hartet al.,2011).Consequently, the extensive use of bridging ELISA andother assays that underestimateADA in the circulation and/or donot reflect thein vivoconditions inpatients may have contributed con-siderably to the confusion manyinvestigators feel regarding thetherapeutic importance of drugimmunogenicity.Some clinicians also find it suffi-cient to monitor drug levels alone(without ADA). The rationalebehind this is that ADA shouldreflect itself in sub-therapeutic orundetectable drug levels in the cir-culation. This is unfortunate forseveral reasons:1. There are other causes of lowdrug levels than ADA, for exampleimproper handling/storage (caus-ing drug aggregation), complianceproblems (most TNF antagonists

Figure 4.RIA for ADA. This RIA detects all immunoglobulin isotypes of ADAagainst all currently registered TNF antagonists. Free and immunoglobulin-bound tracer are separated by spinning down only the radiolabeled drug bindingto λ light-chain ADA in complex with anti-λ light-chain Ab.Discovery Medicine,Volume 15, Number 83, April 2013

theranostics essential for Rational use of tNF-α Antagonists

207

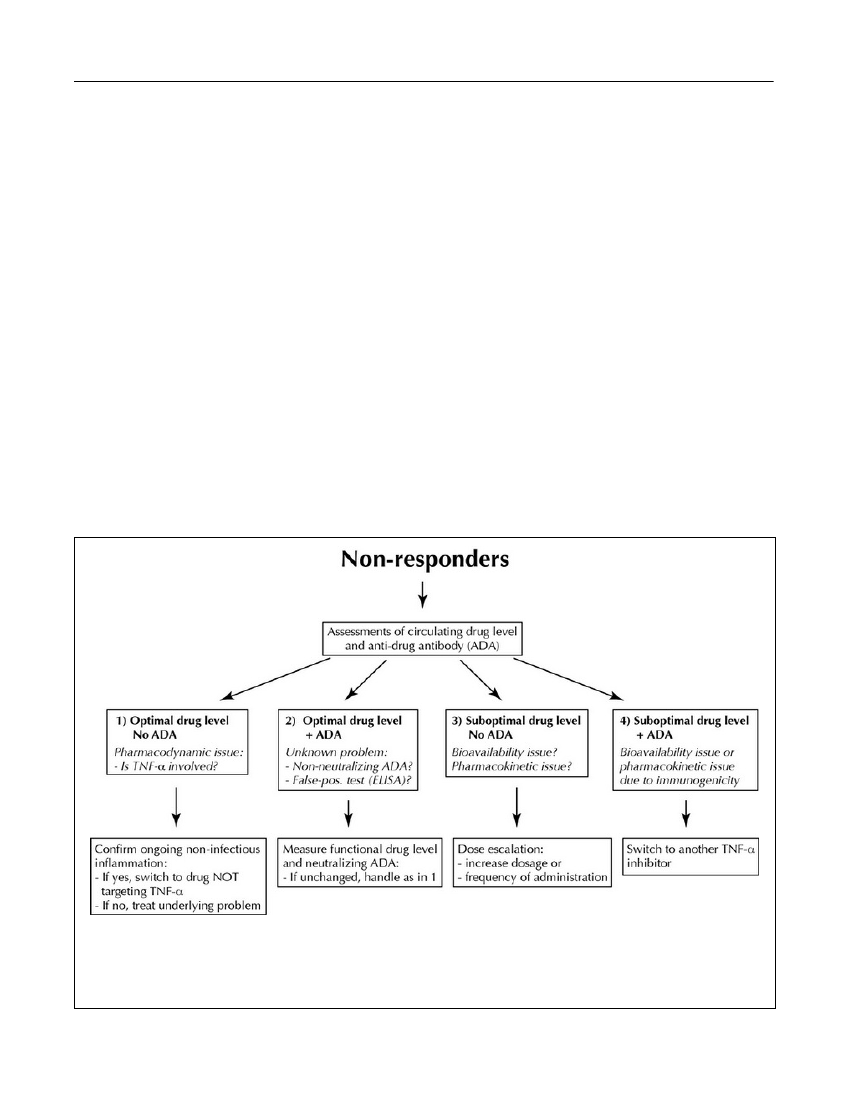

are administered by patients themselves), and serumsampling after prolonged injection intervals (resultingin lower than ‘normal’ drug levels). Non-ADA induceddegradation and/or elimination of antibody constructsmay also play a role (Ordaset al.,2012).2. If therapists continue to immunize a patient withundiscovered ADA, possibly even with increased dosesbecause of low drug levels, extended therapy becomesboth costly and ineffective (van der Maaset al.,2012).It also compromises safety because the risk of adverseevents increases in the presence of ADA.3. If low drug levels are being determined by ELISA orother binding assays, these data do not reveal the func-tion of the drug, i.e., the TNF-α neutralizing capacity.Several serum factors are known to interfere withELISA, including normally occurring serum compo-nents such as C-reactive protein and albumin, and non-neutralizing antibodies (Ordaset al.,2012).Assuming the use of accurate and sensitive assays thatreflect thein vivoconditions, how should theranosticsbe implemented in order to optimize efficacy and safe-ty in individual patients? In case of an insufficientresponse to a TNF antagonist, one should initially con-firm that symptoms originate from increased activity ofthe underlying disease. Non-inflammatory symptomsshould be realized, as should inflammatory activity dueto reasons other than relapse of the disease being treat-ed (infections, ischemia, etc.). In case of assumed drugfailure, it is suggested to measure serum levels of bothdrug and ADA to better understand the pharmacoim-munological realities in each individual patient. A pre-viously proposed algorithm considers four principal sit-uations (Bendtzenet al.,2009) (Figure 7):1. A PD issue where loss of response occurs in the pres-ence of moderate or even high TNF-α-neutralizingserum capacity. This is speculated to arise from activa-tion of alternative immunoinflammatory pathwaysbypassing TNF-α as a central pathogenic factor. Manypatients with primary response failure appear to belongto this subgroup, and these patients are not likely tobenefit from dose escalation -- or change to anotherTNF antagonist. They should be switched directly toanother therapeutic principle.2. Optimal levels of drug in the presence of ADA mayarise from false positive ELISA testings, or they may bedue to detection of low-avidity and/or otherwise func-tionally inactive ADA. In such cases sera should beretested with a cell-based assay both for functionallyactive drug and drug-neutralizing ADA. In case ofunchanged findings, patients are considered suffering

from a PD issue, and they should be treated as those ingroup 1.3. Suboptimal levels of drug despite assured compli-ance, and no demonstration of neutralizing ADA. Thiscondition is considered due to non-antibody-mediatedinadequate bioavailability and/or PK issues withincreased drug turnover for example due to increased‘inflammatory load’ with elevated expression of TNF-αin the affected tissues and/or increased drug clearance.As there is only limited information regarding factorsother than ADA that influence the turnover of TNFantagonists, it is suggested that patients in this groupreceive intensified therapy with the already adminis-tered TNF antagonist.4. Immunogenicity with generation of drug-neutralizingADA resulting in insufficient TNF-α blockade and/orincreased drug clearance. Because ADA are usuallydrug specific, patients in this category should benefitfrom switching to a different TNF antagonist.The above algorithm has been supported by other inves-tigators (Afifet al.,2010; Yanai and Hanauer, 2011;Ordaset al.,2012) and has recently been tested in aprospective, randomized, controlled, and blinded trialinvolving CD patients treated with infliximab(Steenholdtet al.,2013). Compared to routine escala-tion of drug dosage, therapy guided by the algorithmreduced the average treatment costs per patient by 30%to 50% without compromising clinical efficacy.Homogeneous mobility-shift assay (HMSA) for AdA

Figure 5.HMSA for ADA. HMSA detects allimmunoglobulin isotypes of ADA by size-exclusionhigh-performance liquid chromatography and subse-quent quantification of fluorescence-labeled drug in freeform and in complex with ADA (Wanget al.,2012).Discovery Medicine,Volume 15, Number 83, April 2013

208

theranostics essential for Rational use of tNF-α Antagonists

Conclusions1. Therapies with anti-TNF-α anti-body constructs are often effectivein patients suffering from a host ofchronic immunoinflammatory dis-eases.2. Unfortunately, about one thirdof patients with RA and CD do notrespond to TNF antagonists, andone third lose effect over timedespite ongoing therapy.3. PK issues correlate with inade-quate responses to TNF antago-nists. This results in insufficientdrug levels to adequatelyneutralize TNF-α in the circula-tion and in target tissues. Drugimmunogenicity is the underlyingfactor in many patients, but PDissues with predominantly TNF-independent disease mechanismsmay also play a role.4. Immunogenicity of TNF antag-onists may cause hypersensitivityreactions, both local and systemic.Immune-complex diseases withsevere and even lethal vascularinvolvement have been reported.5. Determining optimal therapyafter drug failure is complicated.The current strategy of initial doseescalation followed by change toother TNF antagonists may lead toirreversible tissue damage whilesearching for an effective seconddrug, and it carries a high cost.6. Theranostics, i.e., monitoringcirculating levels of drug andADA, appears to be essential foroptimal and cost-effective inter-ventions, and may prevent adversereactions.7. Assays should be designed tomimic thein vivosituation andreport functionality of both drugs(TNF-α neutralization) and ADA(drug neutralization).8. Solid phase binding assays,

Figure 6.RGA for neutralizing ADA (and functional drug levels). This cell-based assay reports functional levels of drug-neutralizing ADA and, in addition,TNF-α-neutralizing activity of all currently used anti-TNF-α drugs (Lallemandet al.,2011). Steps 1 to 4 of one assay are indicated in italic. When humanrecombinant TNF-α in normal serum is added to the cells (left upper part), thecytokine initiates intracellular signalling through the surface TNF-receptor, type1 (TNF-R1), thus activating the cytoplasmic nuclear factor (NF)-κB. The activecomponents of this transcription factor are then transported to the nucleus wherethey bind to NF-κB response elements (NF-κB-REs) in the genome. This acti-vates more than a hundred genes, including an inserted reporter-gene constructencoding the enzyme Firefly luciferase. After cell lysis and addition of sub-strate, luciferase-catalyzed light emission is quantified in a luminometer. WhenTNF-α is preincubated with patient serum containing a TNF antagonist and thenadded to the cells (middle upper panel), the drug, if functional, neutralizes theeffect of TNF-α, and no cell-signal is initiated. When TNF-α is preincubatedwith patient serum containing drug-neutralizing ADA and then added to thecells (right upper panel), the drug no longer interferes with TNF-α-mediatedsignalling resulting in a luminescence output.Discovery Medicine,Volume 15, Number 83, April 2013

theranostics essential for Rational use of tNF-α Antagonists

209

e.g., ELISA, are considered inappropriate for safe ther-apeutic guidance as they do not reveal the functions ofdrugs and ADA, and their artificial setup has severelimitations in clinical use.9. Screening for ADA is now required for marketing ofall new biological drugs, including biosimilars(European Medicines Agency and U.S. FDA). Despitethis, monitoring individual patients for ADA is not yetpart of routine clinical practice.AcknowledgmentsI am indebted to the many colleagues who over theyears have contributed to the basic and clinical researchdiscussed in this article.DisclosureWithin the last three years, Klaus Bendtzen has servedas a speaker for Pfizer, Roche, Novo-Nordisk, Bristol-Meyers Squibb, and Biomonitor, and owns stocks inNovo-Nordisk and Biomonitor.ReferencesAarden L, Ruuls SR, Wolbink G. Immunogenicity of anti-tumor necro-

sis factor antibodies - toward improved methods of anti-antibody meas-urement.Curr Opin Immunol20(4):431-435, 2008.Afif W, Loftus EVJ, Faubion WA, Kane SV, Bruining DH, Hanson KA,Sandborn WJ. Clinical utility of measuring infliximab and human anti-chimeric antibody concentrations in patients with inflammatory boweldisease.Am J Gastroenterol105(5):1133-1139, 2010.Aikawa NE, JF dC, Silva CAA, Bonfa E. Immunogenicity of anti-TNF-alpha agents in autoimmune diseases.Clin Rev Allergy Immunol38:82-89, 2010.Ainsworth MA, Bendtzen K, Brynskov J. Tumor necrosis factor-alphabinding capacity and anti-infliximab antibodies measured by fluid-phase radioimmunoassays as predictors of clinical efficacy of infliximabin Crohn’s disease.Am J Gastroenterol103:944-948, 2008.Allez M, Karmiris K, Louis E, Van Assche G, Ben-Horin S, Klein A, Vander Woude J, Baert F, Eliakim R, Katsanos K, Brynskov J, Steinwurz F,Danese S, Vermeire S, Teillaud J-L, Lémann M, Chowers Y. Report ofthe ECCO pathogenesis workshop on anti-TNF therapy failures ininflammatory bowel diseases: Definitions, frequency and pharmacolog-ical aspects.J Crohn’s Colitis4(4):355-366, 2010.Assasi N, Blackhouse G, Xie F, Marshall JK, Irvine EJ, Gaebel K,Robertson D, Campbell K, Hopkins R, Goeree R. Patient outcomes afteranti TNF-alpha drugs for Crohn’s disease.Expert Rev PharmacoeconOutcomes Res10(2):163-175, 2010.Atzeni F, Talotta R, Benucci M, Salaffi F, Cassinotti A, Varisco V,Battellino M, Ardizzone S, Pace F, Sarzi-Puttini P. Immunogenicity andautoimmunity during anti-TNF therapy.Autoimmun Rev,epub ahead ofprint, Nov. 30, 2012.Bartelds GM, Krieckaert CL, Nurmohamed MT, van Schouwenburg PA,

Figure 7.Decision algorithm for patients with primary and secondary response failure to TNF-α antagonists. Four sce-narios encountered in patients with insufficient clinical response to TNF antagonists. Serum trough levels of function-ally active drug and drug-neutralizing ADA are measured. Relevant cut-off levels for both drug and ADA depend onpre-determined clinical validation. Adapted with permission fromScandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology(Bendtzenet al.,2009).Discovery Medicine,Volume 15, Number 83, April 2013

210

theranostics essential for Rational use of tNF-α Antagonistsnecrosis factor alpha monoclonal antibody, injected subcutaneouslyevery four weeks in methotrexate-naive patients with active rheumatoidarthritis: Twenty-four-week results of a phase III, multicenter, random-ized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of golimumab beforemethotrexate as first-line therapy for early-onset rheumatoid arthritis.Arthritis Rheum60(8):2272-2283, 2009.Emery P. Optimizing outcomes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis andan inadequate response to anti-TNF treatment.Rheumatology (Oxford)51(Suppl 5):v22-v30, 2012.European Medicines Agency (EMA). Guideline on immunogenicityassessment of biotechnology-derived therapeutic proteins (http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guide-line/2009/09/WC500003946.pdf). pp1-18, 2007.Fefferman DS, Farrell RJ. Immunogenicity of biological agents ininflammatory bowel disease.Inflamm Bowel Dis11(5):497-503, 2005.Furst DE, Keystone EC, Braun J, Breedveld FC, Burmester GR, DeBenedetti F, Dorner T, Emery P, Fleischmann R, Gibofsky A, Kalden JR,Kavanaugh A, Kirkham B, Mease P, Sieper J, Singer NG, Smolen JS,Van Riel PL, Weisman MH, Winthrop K. Updated consensus statementon biological agents for the treatment of rheumatic diseases, 2010.AnnRheum Dis70(Suppl 1):i2-i36, 2011.Garces S, Demengeot J, Benito-Garcia E. The immunogenicity of anti-TNF therapy in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases: a systematicreview of the literature with a meta-analysis.Ann Rheum Dis,epubahead of print, Dec. 6, 2012.Hart MH, de Vrieze H, Wouters D, Wolbink GJ, Killestein J, de GrootER, Aarden LA, Rispens T. Differential effect of drug interference inimmunogenicity assays.J Immunol Methods372:196-203, 2011.Hwang WY, Foote J. Immunogenicity of engineered antibodies.Methods36:3-10, 2005.Jamnitski A, Bartelds GM, Nurmohamed MT, van Schouwenburg PA,van Schaardenburg D, Stapel SO, Dijkmans BA, Aarden L, Wolbink GJ.The presence or absence of antibodies to infliximab or adalimumabdetermines the outcome of switching to etanercept.Ann Rheum Dis70:284-288, 2010.Jamnitski A, Krieckaert CL, Nurmohamed MT, Hart MH, DijkmansBA, Aarden L, Voskuyl AE, Wolbink GJ. Patients non-responding toetanercept obtain lower etanercept concentrations compared withresponding patients.Ann Rheum Dis64(12):3850-3855, 2012.Jemec GB. Predicting response to anti-TNF-alpha treatment inHidradenitis suppurativa.Br J Dermatol168(2):233, 2013.Karmiris K, Paintaud G, Noman M, Magdelaine-Beuzelin C, FerranteM, Degenne D, Claes K, Coopman T, Van Schuerbeek N, Van Assche G,Vermeire S, Rutgeerts P. Influence of trough serum levels and immuno-genicity on long-term outcome of adalimumab therapy in Crohn’s dis-ease.Gastroenterology137(5):1628-1640, 2009.Korswagen LA, Bartelds GM, Krieckaert CL, Turkstra F, NurmohamedMT, van Schaardenburg D, Wijbrandts CA, Tak PP, Lems WF, DijkmansBA, van Vugt RM, Wolbink GJ. Venous and arterial thromboembolicevents in adalimumab-treated patients with antiadalimumab antibodies:a case series and cohort study.Arthritis Rheum63(4):877-883, 2011.Krieckaert C, Rispens T, Wolbink G. Immunogenicity of biological thera-peutics: from assay to patient.Curr Opin Rheumatol24(3):306-311, 2012.Krieckaert CL, Bartelds GM, Lems WF, Wolbink GJ. The effect ofimmunomodulators on the immunogenicity of TNF-blocking therapeu-tic monoclonal antibodies: a review.Arthritis Res Ther12(5):217, 2010.Kromminga A, Schellekens H. Antibodies against erythropoietin andother protein-based therapeutics: An overview.Ann N Y Acad Sci1050:257-265, 2005.

Lems WF, Twisk JW, Dijkmans BA, Aarden L, Wolbink GJ.Development of antidrug antibodies against adalimumab and associa-tion with disease activity and treatment failure during long-term follow-up.JAMA305(14):1460-1468, 2011.Ben-Horin S, Chowers Y. Review article: loss of response to anti-TNFtreatments in Crohn’s disease.Aliment Pharmacol Ther2011.Bendtzen K, Geborek P, Svenson M, Larsson L, Kapetanovic MC,Saxne T. Individualized monitoring of drug bioavailability and immuno-genicity in rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with the tumor necrosisfactor alpha inhibitor Infliximab.Arthritis Rheum54:3782-3789, 2006.Bendtzen K, Ainsworth M, Steenholdt C, Thomsen OO, Brynskov J.Individual medicine in inflammatory bowel disease: monitoringbioavailability, pharmacokinetics and immunogenicity of anti-tumournecrosis factor-alpha antibodies.Scand J Gastroenterol44(7):774-781,2009.Bendtzen K. Editorial: Is there a need for immunopharmacologicalguidance of anti-TNF therapies?Arthritis Rheum63(4):867-870, 2011.Bendtzen K, Svenson M. Enzyme immunoassays and radioimmunoas-says for quantification of anti-TNF biopharmaceuticals and anti-drugantibodies. In:Detection and Quantification of Antibodies toBiopharmaceuticals. Practical and Applied Considerations.Tovey MG,ed. pp 83-101. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., West Sussex, UK, 2011.Bendtzen K. Anti-TNF-α biotherapies: perspectives for evidence-basedpersonalized medicine.Immunotherapy4(11):1167-1179, 2012.Brunasso AM, Puntoni M, Massone C. Drug survival rates of biologictreatments in patients with psoriasis vulgaris.Br J Dermatol166(2):447-449, 2012.Cassinotti A, Travis S. Incidence and clinical significance of immuno-genicity to infliximab in Crohn’s disease: A critical systematic review.Inflamm Bowel Dis15:1264-1275, 2009.Chaparro M, Guerra I, Munoz-Linares P, Gisbert JP. Systematic review:antibodies and anti-TNF-alpha levels in inflammatory bowel disease.Aliment Pharmacol Ther,epub ahead of print, Mar. 22, 2012.Cheifetz A, Mayer L. Monoclonal antibodies, immunogenicity, andassociated infusion reactions.Mt Sinai J Med72(4):250-256, 2005.Colombel JF, Feagan BG, Sandborn WJ, Van Assche G, Robinson AM.Therapeutic drug monitoring of biologics for inflammatory bowel dis-ease.Inflamm Bowel Dis18(2):349-358, 2012.Danese S, Colombel JF, Reinisch W, Rutgeerts PJ. Review article:infliximab for Crohn’s disease treatment -- shifting therapeutic strate-gies after 10 years of clinical experience.Aliment Pharmacol Ther33(8):857-869, 2011.De Groot AS, Scott DW. Immunogenicity of protein therapeutics.Trends Immunol28(11):482-490, 2007.Desai D, Brightling C. TNF-alpha antagonism in severe asthma?RecentPat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov4(3):193-200, 2010.Descotes J, Gouraud A. Clinical immunotoxicity of therapeutic proteins.Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol4(12):1537-1549, 2008.Dubey S, Kerrigan N, Mills K, Scott DG. Bronchospasm associated withanti-TNF treatment.Clin Rheumatol28(8):989-992, 2009.Ebert EC, Das KM, Mehta V, Rezac C. Non-response to infliximab maybe due to innate neutralizing anti-tumour necrosis factor-alpha antibod-ies.Clin Exp Immunol154:325-331, 2008.Emery P, Fleischmann RM, Moreland LW, Hsia EC, Strusberg I, DurezP, Nash P, Amante EJ, Churchill M, Park W, Pons-Estel BA, Doyle MK,Visvanathan S, Xu W, Rahman MU. Golimumab, a human anti-tumor

Discovery Medicine,Volume 15, Number 83, April 2013

theranostics essential for Rational use of tNF-α AntagonistsLallemand C, Kavrochorianou N, Steenholdt C, Bendtzen K, AinsworthMA, Meritet JF, Blanchard B, Lebon P, Taylor P, Charles P, Alzabin S,Tovey MG. Reporter gene assay for the quantification of the activity andneutralizing antibody response to TNFalpha antagonists.J ImmunolMethods373(1-2):229-239, 2011.Langford CA. Drug insight: anti-tumor necrosis factor therapies for thevasculitic diseases.Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol4(7):364-370, 2008.Lecluse LL, Driessen RJ, Spuls PI, de Jong EM, Stapel SO, van DoornMB, Bos JD, Wolbink GJ. Extent and clinical consequences of antibodyformation against adalimumab in patients with plaque psoriasis.ArchDermatol146(2):127-132, 2010.Lin J, Ziring D, Desai S, Kim S, Wong M, Korin Y, Braun J, Reed E,Gjertson D, Singh RR. TNFalpha blockade in human diseases: anoverview of efficacy and safety.Clin Immunol126(1):13-30, 2008.Makol A, Grover M, Guggenheim C, Hassouna H. Etanercept andvenous thromboembolism: a case series.J Med Case Reports4:12, 2010.Mulleman D, Meric JC, Paintaud G, Ducourau E, Magdelaine-BeuzelinC, Valat JP, Goupille P. Infliximab concentration monitoring improvesthe control of disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis.Arthritis Res Ther11(6):R178, 2009.Ordas I, Mould DR, Feagan BG, Sandborn WJ. Anti-TNF monoclonalantibodies in inflammatory bowel disease: pharmacokinetics-based dos-ing paradigms.Clin Pharmacol Ther91(4):635-646, 2012.Palekar-Shanbhag PS, Jog SV, Gaikwad SS, Chogale MM. Theranosticsfor cancer therapy.Curr Drug Deliv,epub ahead of print, Dec. 31, 2012.Petitpain N, Gambier N, Wahl D, Chary-Valckenaere I, Loeuille D,Gillet P. Arterial and venous thromboembolic events during anti-TNFtherapy: a study of 85 spontaneous reports in the period 2000-2006.Biomed Mater Eng19(4-5):355-364, 2009.Radstake TR, Svenson M, Eijsbouts AM, van den Hoogen FH, EnevoldC, van Riel PL, Bendtzen K. Formation of antibodies against infliximaband adalimumab strongly correlates with functional drug levels andclinical responses in rheumatoid arthritis.Ann Rheum Dis68(11):1739-1745, 2009.Shankar G, Shores E, Wagner C, Mire-Sluis A. Scientific and regulato-ry considerations on the immunogenicity of biologics.TrendsBiotechnol24(6):274-280, 2006.St. Clair EW, Wagner CL, Fasanmade AA, Wang B, Schaible T,Kavanaugh A, Keystone EC. The relationship of serum infliximab con-centrations to clinical improvement in rheumatoid arthritis. Results fromATTRACT, a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-con-trolled trial.Arthritis Rheum46:1451-1459, 2002.Steenholdt C, Svenson M, Bendtzen K, Thomsen O, Brynskov J,Ainsworth MA. Severe infusion reactions to infliximab: aetiology,immunogenicity and risk factors in patients with inflammatory boweldisease.Aliment Pharmacol Ther34(1):51-58, 2011a.Steenholdt C, Bendtzen K, Brynskov J, Thomsen OO, Ainsworth MA.Cut-off levels and diagnostic accuracy of infliximab trough levels andanti-infliximab antibodies in Crohn’s disease.Scand J Gastroenterol46(3):310-318, 2011b.Steenholdt C, Al-khalaf M, Brynskov J, Bendtzen K, Thomsen O,Ainsworth MA. Clinical implications of variations in anti-infliximabantibody levels in patients with inflammatory bowel disease.InflammBowel Dis18(12):2209-2217, 2012.Steenholdt C, Brynskov J, Thomsen O, Munck LK, Fallingborg J,Christensen LA, Pedersen G, Kjeldsen J, Jacobsen BA, Oxholm AS,Kjellberg J, Bendtzen K, Ainsworth MA. Treatment of secondary inflix-imab failure in Crohn’s disease based on serum levels of infliximab andantibodies against infliximab: the Danish study of Optimizing

211

Infliximab Therapy in Crohn’s Disease (DO IT CROHN) randomizedclinical trial.Digestive Disease Week,Orlando, Florida, USA, 2013.Strand V, Kimberly R, Isaacs JD. Biologic therapies in rheumatology: les-sons learned, future directions.Nat Rev Drug Discov6(1):75-92, 2007.Svenson M, Geborek P, Saxne T, Bendtzen K. Monitoring patients treat-ed with anti-TNF-alpha biopharmaceuticals - assessing serum infliximaband anti-infliximab antibodies.Rheumatology46:1828-1834, 2007.Tanaka Y. Next stage of RA treatment: is TNF inhibitor-free remission apossible treatment goal?Ann Rheum Dis72(Suppl 2):ii124-ii127, 2013.Tangri S, Mothe BR, Eisenbraun J, Sidney J, Southwood S, Briggs K,Zinckgraf J, Bilsel P, Newman M, Chesnut R, Licalsi C, Sette A.Rationally engineered therapeutic proteins with reduced immunogenic-ity.J Immunol174(6):3187-3196, 2005.Ternant D, Aubourg A, Magdelaine-Beuzelin C, Degenne D, Watier H,Picon L, Paintaud G. Infliximab pharmacokinetics in inflammatorybowel disease patients.Ther Drug Monit30(4):523-529, 2008.van den Bemt BJ, den Broeder AA, Wolbink GJ, Hekster YA, van RielPL, Benraad B, van den Hoogen FH. Anti-infliximab antibodies arealready detectable in most patients with rheumatoid arthritis halfwaythrough an infusioncycle: an open-label pharmacokinetic cohort study.BMC Musculoskelet Disord12:12, 2011.van der Maas A, van den Bemt BJ, Wolbink GJ, van den Hoogen FH,van Riel PL, den Broeder AA. Low infliximab serum trough levels andanti-infliximab antibodies are prevalent in rheumatoid arthritis patientstreated with infliximab in daily clinical practice: results of an observa-tional cohort study.BMC Musculoskelet Disord13(1):184, 2012.van Schouwenburg PA, Krieckaert CL, Nurmohamed M, Hart M,Rispens T, Aarden L, Wouters D, Wolbink GJ. IgG4 production againstadalimumab during long term treatment of RA patients.J Clin Immunol32(5):1000-1006, 2012.Wang SL, Ohrmund L, Hauenstein S, Salbato J, Reddy R, Monk P,Lockton S, Ling N, Singh S. Development and validation of a homoge-neous mobility shift assay for the measurement of infliximab and anti-bodies-to-infliximab levels in patient serum.J Immunol Methods382(1-2):177-88, 2012.West RL, Zelinkova Z, Wolbink GJ, Kuipers EJ, Stokkers PC, Van derWoude CJ. Immunogenicity negatively influences the outcome of adal-imumab treatment in Crohn’s disease.Aliment Pharmacol Ther28(9):1122-1126, 2008.Wijbrandts CA, Dijkgraaf MG, Kraan MC, Vinkenoog M, Smeets TJ,Dinant H, Vos K, Lems WF, Wolbink GJ, Sijpkens D, Dijkmans BA, TakPP. The clinical response to infliximab in rheumatoid arthritis is in partdependent on pretreatment tumour necrosis factor alpha expression inthe synovium.Ann Rheum Dis67(8):1139-1144, 2008.Wolbink GJ, Voskuyl AE, Lems WF, de Groot E, Nurmohamed MT, TakPP, Dijkmans BA, Aarden L. Relationship between serum trough inflix-imab levels, pretreatment C reactive protein levels, and clinical responseto infliximab treatment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.Ann RheumDis64(5):704-707, 2005.Wolbink GJ, Vis M, Lems W, Voskuyl AE, de Groot E, NurmohamedMT, Stapel S, Tak PP, Aarden L, Dijkmans B. Development of antiin-fliximab antibodies and relationship to clinical response in patients withrheumatoid arthritis.Arthritis Rheum54(3):711-715, 2006.Wolbink GJ, Aarden LA, Dijkmans BA. Dealing with immunogenicityof biologicals: assessment and clinical relevance.Curr Opin Rheumatol21(3):211-215, 2009.Yanai H, Hanauer SB. Assessing response and loss of response to bio-logical therapies in IBD.Am J Gastroenterol106:685-698, 2011.

Discovery Medicine,Volume 15, Number 83, April 2013