Socialudvalget 2012-13

SOU Alm.del Bilag 62

Offentligt

UNICEFOffice of Research

ChampioningChildren’s RightsA global study of independent human rightsinstitutionsfor children – summary report

THE UNICEF OFFICE OF RESEARCHIn 1988 the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) established a research centre to support itsadvocacy for children worldwide and to identify and research current and future areas of UNICEF’swork. The prime objectives of the Of ce of Research, until 2011 known as the Innocenti Research Centre,are to improve international understanding of issues relating to children’s rights and to help facilitatefull implementation of the Convention on the Rights of the Child in developing, middle-income andindustrialized countries.The Of ce aims to set out a comprehensive framework for research and knowledge within theorganization in support of its global programmes and policies. Through strengthening researchpartnerships with leading academic institutions and development networks in both the North and South,the Of ce seeks to leverage additional resources and in uence in support of efforts towards policyreform in favour of children.Publications produced by the Of ce are contributions to a global debate on children and child rightsissues and include a wide range of opinions. For that reason, some publications may not necessarilyre ect UNICEF policies or approaches on some topics. The views expressed are those of the authorsand/or editors and are published in order to stimulate further dialogue on child rights.The Of ce collaborates with its host institution in Florence, the Istituto degli Innocenti, in selected areasof work. Core funding is provided by the Government of Italy, while nancial support for speci c projectsis also provided by other governments, international institutions and private sources, including UNICEFNational Committees.Extracts from this publication may be freely reproduced with due acknowledgement.Requests to translate the publication in its entirety should be addressed to:Communications Unit, [email protected].For further information and to download or order this and other publications, please visit the websiteat www.unicef-irc.org.Design and layout: BlissDesign.comCover photo: � UNICEF/INDA2010-00730/Pirozzi; Globe, Thinkstock� United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF)October 2012ISBN: 978-88-6522-010-8Correspondence should be addressed to:UNICEF Of ce of Research - InnocentiPiazza SS. Annunziata, 1250122 Florence, ItalyTel: (+39) 055 20 330Fax: (+39) 055 2033 220[email protected]www.unicef-irc.org

UNICEFOffice of Research

ChampioningChildren’s RightsA global study of independent human rightsinstitutions for children – summary report

AcknowledgementsThis executive summary presents the findings of acomprehensive study, which is the outcome of severalyears’ research, collaboration and consultation involvingmany partners.Vanessa Sedletzki, Child Rights Specialist at theUNICEF Office of Research, is the main author and leadresearcher for the study. Andrew Mawson, Chief of theChild Protection and Implementation of InternationalStandards Unit, supervised the study in its final twoyears, reviewing this text and overseeing its finalizationunder the guidance of Göran Holmqvist, AssociateDirector Strategic Research, and Gordon Alexander,Director of the Office of Research. Thanks go toAnastasia Warpinski, editor.The study was initiated by and has benefited fromthe guidance and expertise of Trond Waage, formerOmbudsman for Children in Norway and a formerSenior Fellow at the Innocenti Research Centre (IRC).The study began under the supervision of Susan Bissell,then Chief of the Implementation of InternationalStandards Unit, under the direction of Marta SantosPais, at the time Director of the IRC. Rébecca Stewardand Katherine Wepplo contributed research andanalysis; Claudia Julieta Duque carried out backgroundresearch on Latin America and the Caribbean; andNoortje van Heijst provided research assistance.Administrative support was provided by ClaireAkehurst and previously Sarah Simonsen.We extend warm thanks to Shirin Aumeeruddy-Cziffra, Jean-Nicolas Beuze, Marvin Bernstein,Richard Carver and Peter Newell, who reviewedthe complete draft of the technical report. Weare also grateful to the numerous individuals,ombudsperson network members and organizationsthat have supported the research process at variousstages by attending consultations and/or reviewingsections of earlier drafts: GeorgeAbuAl-Zulof,BegoñaArellano, PolinaAtanasova, Julien Attuil-Kayser,AudronéBedorf, Akila Belembago, Karuna Bishnoi,Xavier Bonal, SabrinaCajoly, Eva MariaCayanan,Clara Chapdelaine, Laurent Chapuis, MaryClarke,Janet A. Cupidon-Quallo, Anna Dekker, BrigetteDeLay,Jaap Doek, European Network of Ombudspersonsfor Children, HuguesFeltesse, ElizabethFraser,EmilioGarciaMendez, BrianGran, KarlHanson, KarinHeissler, CharlotteHelletzgruber, MariaCristinaHurtado,Inter-American Children’s Institute of the Organization ofAmerican States, Jyothi Kanics, Lena Karlsson, JaneKim,CindyKiro, Maarit Kuikka, Jean-Claude Legrand,Fran§oisLevert, Heidi Loening-Voysey, EmilyLogan,JeanneMilstein, GeorgiosMoschos, John Mould,Aida Oliver, DavidParker, DominiquePierre Plateau,RonPouwels, Paul Quarles vanUfford, BernardRichard,RobertaRuggiero, LioubovSamokhina, JohannaSchiratzki,Helen Seifu, ShanthaSinha, DianeSwales, TselisoThipanyane, JorgeValencia Corominas, Lora Vidovic,Christian Whalen, CorneliusWilliams and Lisa Wolff.The UNICEF Office of Research is very grateful to theGovernments of Norway and Sweden, whose supportas the main funders of the research made this initiativepossible. It also gratefully acknowledges additionalfinancial support provided by the Governments ofFrance, Italy and Switzerland.

Championing Children’s Rights2

ContentsAcknowledgementsForewordChampioning Children’s Rights:A global study of independent human rights institutions for children1. Introduction2. What do independent human rights institutions for children do?2.1 Making children and their best interests visible in policymaking2.2 Promoting environments that nurture child rights2.3 Promoting equitable approaches for the most marginalized children2.4 Promoting child participation in society2.5 Addressing individual or specific situations3. What makes independent human rights institutions for children effective?3.1 Independence3.2 Child participation3.3 Receiving complaints on specific child rights violations3.4 International engagement4. Conclusion and recommendations245581011111213161619232629

Contents3

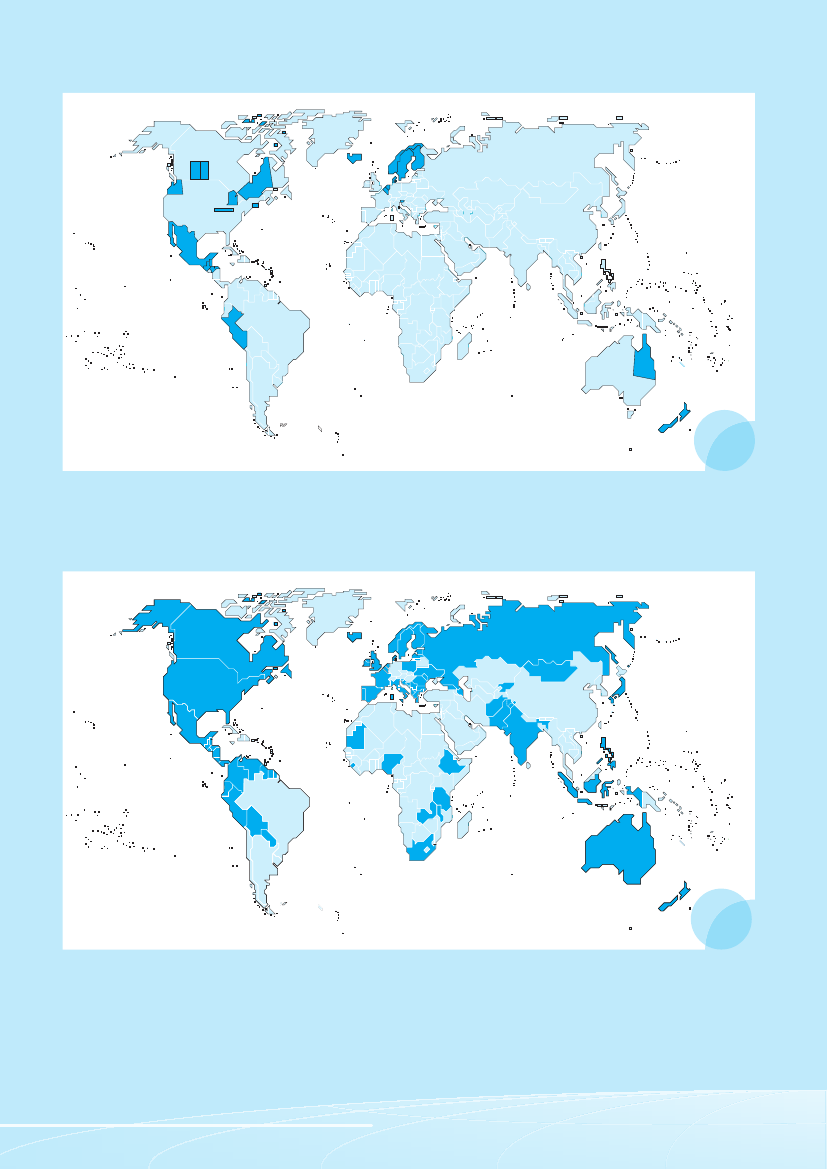

ForewordOver the last two decades, progress in the developmentof independent human rights institutions for childrenhas been remarkable. In 1989, there were far fewerthan the more than 200 independent institutionsthat exist today in over 70 countries. Taking manyforms – children’s ombudspersons, human rightscommissions or children’s commissioners – they sharethe unique role of facilitating governance processesfor children, and have emerged as important actors forthe implementation of the Convention on the Rights ofthe Child. Their work remains little known, however,and their specification as both public and independentinstitutions is often difficult to grasp.Independent institutions bring an explicit children’sfocus to traditionally adult-oriented governancesystems. Often offering direct mechanisms for greateraccountability of the state and other duty bearers forchildren, they fi ll gaps in checks and balances and makesure that the impact of policy and practice on children’srights is understood and recognized. They supportremedy and reform when things have gone wrong orresults are inadequate. Far from taking responsibilityaway from the plethora of often better-knowninstitutions affecting children – schools, health services,government departments, local authorities, privatesector actors and parents themselves – the work ofindependent institutions complements and strengthenstheir performance to realize the rights of all children.Amidst the current global economic uncertainty,inequities between rich and poor are widening in somecountries. It is a period, too, of reflection on progresstowards achieving the Millennium DevelopmentGoals and in defining sustainable and equitable goalsto follow them. During such times, independentinstitutions are key players in promoting systems thatadvance and are responsive to the rights of children; theCommittee on the Rights of the Child has been theirmost unwavering supporter.Yet the role and position of independent institutionsare contested. Their recommendations are toooften left unattended by the very governments andparliaments responsible for their creation. In thecontext of significant economic constraint, thesetypically small offices are the targets of budgetarycuts. They need to constantly demonstrate theirrelevance in an area where the direct attribution ofresults is difficult. Challenges can also be internal; theeffectiveness of these institutions depends on theirability to reach out to the most marginalized childrenand provide an adequate remedy for rights’ violations.Leadership and capacity are core aspects of theirability to fulfi l their mission.This study, globally the fi rst comprehensive reviewof independent human rights institutions forchildren, takes stock of more than 20 years of theirexperience. It represents the fi rst phase of a body ofwork that will also explore, among other topics, goodgovernance, decision-making and coordination for theimplementation of children’s rights.An associated technical report provides practitionerswith a more extensive discussion of the issuessummarized in the pages that follow as well as aseries of regional analyses from around the world. Ouraim is to help readers understand the purpose andpotential of independent human rights institutionsfor children, what it is they do and how they operate.Both reports invite policymakers and practitionersto consider how the role of such institutions can bestrengthened and enhanced.What is at stake here is the place of children, andespecially the most marginalized and excluded, in oursocieties. In a political system made for adults, whatmakes an institution fit for children? Independentinstitutions are a window not only on the characterof childhood in a given country, but also on the wayadults and the policies they create really view andrespect childhood.

Gordon AlexanderDirector, UNICEF Office of Research

Championing Children’s Rights4

Championing Children’s Rights: A global study ofindependent human rights institutions for children1. IntroductionSince the 1990s, independent human rights institutionsfor children1have emerged globally as influential bodiespromoting children in public decision-making anddiscourse. More than 200 such public institutions havebeen established to independently monitor, promote andprotect children’s rights, and are now at work in over 70countries located on all continents around the world. Inthe vast majority of cases their creation has followed stateratification of the Convention on the Rights of the Child(CRC), which is core to their operation.These institutions take a variety of forms and go bymany different names: in English, ombudsperson, childcommissioner, child advocate, child rights or humanrights commission; in French,défenseurormédiateur;in Spanish,defensoríaorprocuraduría;and in otherlanguages, alternative designations. Their role is tomonitor the actions of governments and other entities,advance the realization of children’s rights, receivecomplaints, provide remedies for violations, and offer aspace for dialogue about children in society and betweenchildren and the state. Defending the best interestsof the child and acting as champions for children arecentral to their mission. Their achievements span manylevels, ranging from influencing significant change innational policy to delivering interventions on behalf ofindividual children.The United Nations Committee on the Rights of theChild is one of their main advocates. But why haveit and so many states decided that such institutionsare needed? In most countries, there already existsa plethora of better-known institutions that deal insome respect with children’s rights, and many have along heritage. Implementation of the CRC is a nationalresponsibility requiring all the organs of the State to playtheir part. Legal action through the courts is a principalremedy for addressing violations of children’s rights.Parliaments are responsible for enacting legislation toenshrine child rights, and specialized parliamentarycommittees often play an essential role in overseeingthe implementation of policy and legislation. Lineministries or ministries for children have key practicalresponsibilities for developing and implementinggovernment policy that realizes children’s rights.Coordination mechanisms exist in principle to ensurethat all areas of government recognize the obligationsinherent in the Convention on the Rights of the Child.1The terminology commonly used by the Committee on the Rights of theChild has been retained for this study. The Committee on the Rightsof the Child General Comments 2, 5 and 12 refer to “independentnational human rights institutions” but the denomination has since beenmodified slightly, most likely to take into account the fact that many suchinstitutions are also established at subnational level.

Children’s observatories monitor children’s rights inorder to provide evidence to influence policy. Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and otherelements of civil society, including the media, often playan important monitoring and advocacy role.Independent human rights institutions for children do notremove responsibility from these actors but work alongsidethem to strengthen their performance. Their key role isto facilitate governance processes involving others. Theyare the ‘oil in the machine’, bringing an explicit children’sfocus to traditional adult-oriented systems, filling gaps inchecks and balances as direct accountability mechanisms,making sure that the impact of policy and practice onchildren’s rights is understood and recognized, andsupporting processes of remedy and reform when thingshave gone wrong or procedures or policies are inadequate.They bring flexibility to political and institutional systemsthat can otherwise be rigid and inaccessible to thepublic, especially to children or those working on issuesconcerning them.While the precise mandate of independent humanrights institutions for children differs from placeto place, their ability to effect change results fromtheir combination of independence and ‘soft power’:the capacity to report, to convene, to mediate andto influence lawmakers, government bodies, publicinstitutions and public opinion. Indeed, it is the abilityto influence those with direct responsibility for policyand practice that distinguishes an effective institution.Yet the challenges faced by such institutions are many.Translating the vision of the child embodied in theConvention on the Rights of the Child into social andpolitical reality is never straightforward. Neither isnavigating national governance systems and the sociallysensitive issues – including normative attitudes tochildhood – that can lie at the heart of children’s rights.It is not uncommon for child rights to remain low on theagenda, whether because of a limited understanding ofthe practical implications, competing budgetary priorities,political or institutional inertia, or social resistance basedon anxiety that principles are irrelevant or inappropriate.Independent institutions often contribute to the creationof a concrete child rights framework, with national orlocal discussions around their establishment involvingdebate about child rights concepts and what they meanin practice. Once formed, the institutions demonstraterights in action, by advancing the rights of childrenthrough their interventions. The social, political andeconomic context to which they belong and contributeis a constantly shifting landscape, however, andcompeting interests continually affect institutions’ability to effectively carry out their mandate. While they

Inroduction5

Independent human rights institutions for children in 1996

PERU

Map No. 4136 Rev. 10 UNITED NATIONSDecember 2011

Department of Field SupportCartographic Section

Independent human rights institutions for children in 2012

Map No. 4136 Rev. 10 UNITED NATIONSDecember 2011

Department of Field SupportCartographic Section

Championing Children’s Rights6

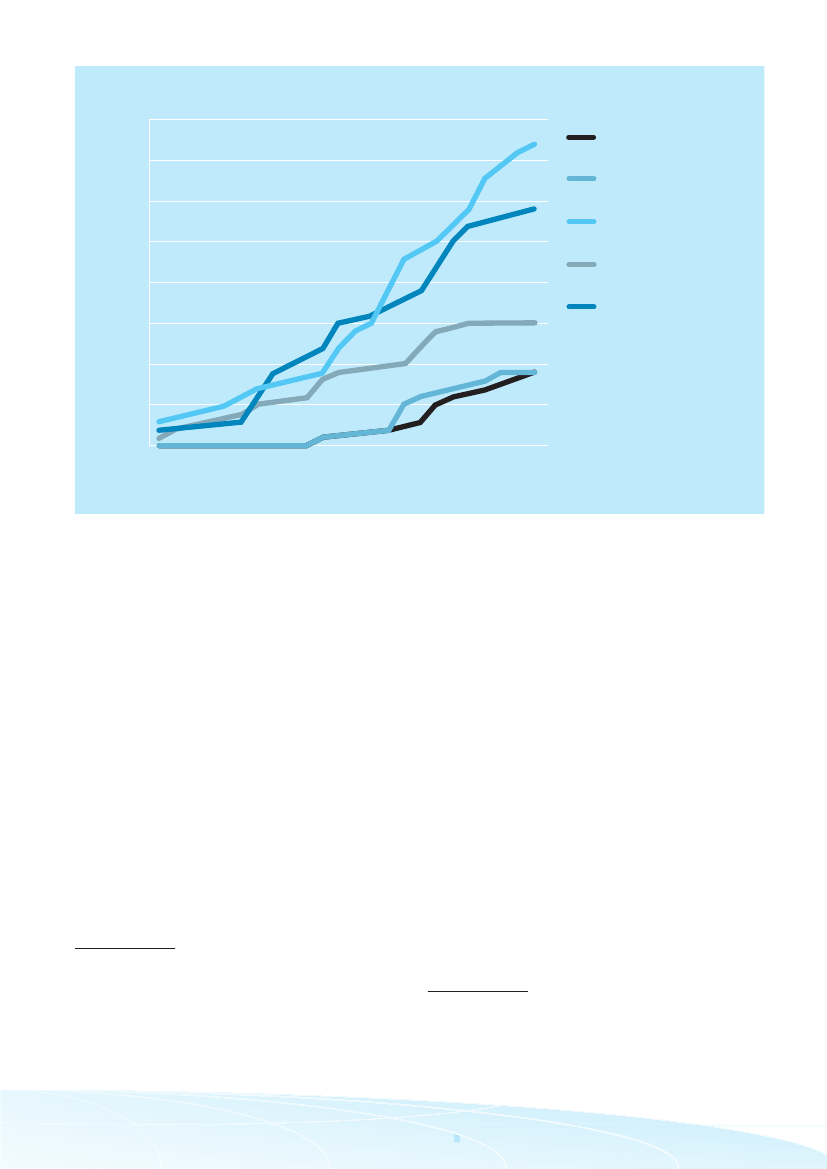

Regional expansion of independent human rights institutions for children 1989–201240Africa35AsiaNumber of IHRIs for children30Europe25Latin America20151050198919941999Year20042009Note: For each country, the year consideredis that of the rst independent human rightsinstitution for children established, evenif at subnational level, except *.

Australia*Canada*New ZealandUnited States of America*

may remain independent of government and impartialin principle, numerous forces can, for good or for ill,impact on their actual independence, institutionalcapacity, funding, reputation, profi le and authority –even their existence.The Committee on the Rights of the Child – theinternational body in charge of monitoring and guidingStates Parties in the implementation of the Conventionon the Rights of the Child – considers that anindependent institution with responsibility forpromoting and protecting children’s rights2is a coreelement of a State Party’s commitment to the practicalapplication of the Convention. The Committee’s GeneralComment No. 2, adopted in 2002, provides guidance onthe role and characteristics of these institutions. Itbuilds on the Paris Principles – adopted by the UNGeneral Assembly in 19933as the primary set ofinternational standards for the mandate, function,composition, operations and competencies of nationalhuman rights institutions – and adapts these to thechild rights framework enshrined in the Convention.42Committee on the Rights of the Child General Comment No. 2: The role ofindependent human rights institutions in the promotion and protection ofthe rights of the child, CRC/GC/2002/2, 15 November 2002, pp. 1–2.Principles relating to the Status of National Institutions (the ParisPrinciples), adopted by General Assembly Resolution 48/134 of 20December 1993.Committee on the Rights of the Child General Comment No. 2: The role ofindependent human rights institutions in the promotion and protection ofthe rights of the child, CRC/GC/2002/2, 15 November 2002, pp. 1–2.

The Committee on the Rights of the Child hassubsequently systematically recommended inconcluding observations to state party reports thecreation and strengthening of independent institutionsfor children’s rights. It has gone on to act as a primarydriving force for the development of such institutionsacross regions.This report, which summarizes a longer studyentitledChampioning Children’s Rights,published bythe UNICEF Office of Research, takes stock of thedevelopment of independent human rights institutionsfor children globally and identifies the specific roles theyperform. It also pinpoints core elements, characteristicsand features that contribute to their institutional successor otherwise.The origins of the research initiative lie in a long-standing interest in the progress of these institutions,manifest in previous publications produced by UNICEFIRC (now Office of Research).5Since 2001, the Centrehas received many enquiries about independentinstitutions from practitioners seeking advice andguidance, including policymakers, NGOs, donors,international organizations and ombudspersons5Flekkøy, M. G.,A Voice for Children: Speaking out as their Ombudsman,Jessica Kinsley Publishers, London, 1991; United Nations Children’sFund, ‘Ombudswork for Children’,Innocenti Digest 1,UNICEF InnocentiResearch Centre, Florence, 1997; United Nations Children’s Fund,‘Independent Human Rights Institutions Protecting Children’s Rights’,Innocenti Digest 8,UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre, Florence, 2001.

3

4

Introduction7

HistoryThe path to the creation of each institution is unique – each context differs socially, politically,economically and institutionally. Some bodies have originated in response to tragic failures toprotect children from abuse. Others have emerged as part of wider governance reform during timesof political transition or following social upheaval.While a handful of countries had a children’s ombudsperson before the adoption in 1989 of theConvention on the Rights of the Child – the first being Norway in 1981, followed by Costa Rica in1986 and the region of Veneto (Italy) in 1988 – the creation of independent human rights institutionsfor children has accelerated since its adoption.Early front-runners were countries in Europe and Latin America.In Europe, the Norwegian example was an influential model, with other institutions – usuallyspecialized ombudspersons – first set up in countries with democratic governance and strongindividual human rights traditions. Northern and western Europe led the way, with furtherinstitutions soon emerging in southern and eastern Europe, often in the context of democratictransition and usually integrated into general human rights bodies. In the same period,democratization in Latin America and the recognition of children as subjects of rights in law andpolicy paved the way for the creation of children’s offices within public defender’s institutions.Around the mid-2000s, countries in Africa (mainly in eastern and southern parts of the continent)and in Asia (chiefly in south and east Asia) began to set up independent human rights institutionsfor children as part of efforts to comply with international standards. Typically these wereestablished within existing human rights commissions and ombudsman offices; only India andMauritius have specialized structures.Common law countries, from North America and Jamaica to the United Kingdom, Australiaand New Zealand, have usually established specialized children’s advocates or commissionerswith a strong child protection mandate. This is often focused – at least initially – on protectingmarginalized children from violence and abuse.In federal states such as Australia, Austria, Canada,India, and also in Italy, the model was often established early on in a few states or provinces and thenprogressively adopted by most federated entities or regions.

themselves. The aim is to respond to some of thequestions often asked by providing a palette oflessons and experiences for use when establishing,strengthening and working with such institutions.Neither this executive summary nor the technical reportpurports to be a manual, however, but are invitations toreflection and dialogue informed by evidence.Both the summary and technical report are based oninformation from a review of different kinds of bodiesacross regions. This involved direct interaction viadialogue and a survey answered by 67 institutions, andthe review of academic literature, legislation, institutionreports, and reports and studies from relevantinternational bodies and NGOs. A limitation of thereview is that institutions with the most documentationavailable are likely to be those featured most often.The fact that a particular piece of work is given asan example does not necessarily reflect an overall

assessment of the work of an institution; it is simplyan illustration of the type of activities in which suchinstitutions can engage.

2. What do independenthuman rights institutions forchildren do?The starting point for the work of independent humanrights institutions for children lies in the broad spectrumof rights enshrined in the Convention on the Rights ofthe Child, which uniquely brings together in one legalstandard civil, political, economic, social and culturalrights as they pertain to children. The Convention takesthe perspective of the ‘whole child’, and this same visioninforms the work of independent institutions. Fourgeneral principles of the Convention guide the analysis

Championing Children’s Rights8

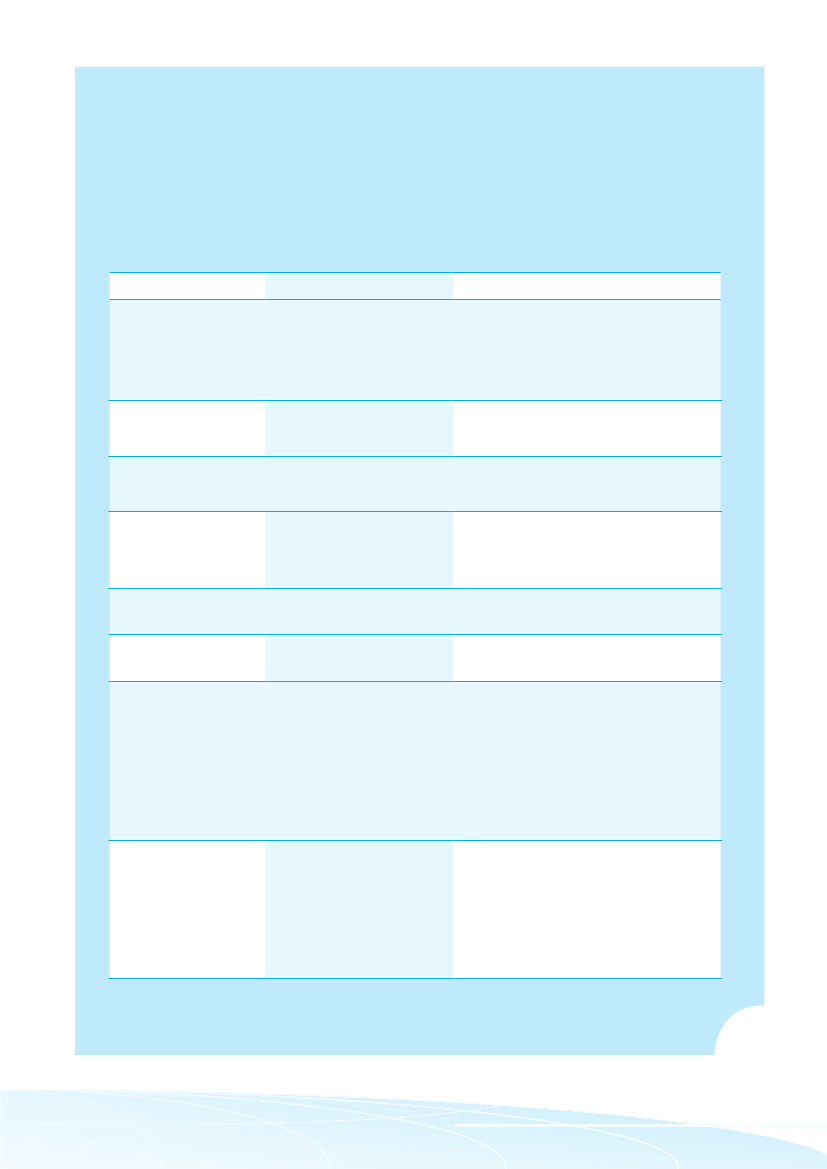

The Paris Principles and CRC General Comment No. 2Although fundamentally rooted in the Paris Principles (formally known as the Principles relatingto the Status of National Institutions), CRC General Comment No. 2 introduces significant newelements that reflect the child rights perspective. Important concepts include the best interests ofthe child and the significance of child participation. For example, children are citizens who do not– because of their age – have easy avenues for making their views known about issues that affectthem (children do not, for example, have the right to vote). Actively establishing ways of seeking andexpressing the views of children is therefore a fundamental responsibility.The Paris PrinciplesLegal and political statusAdopted by UN GeneralAssembly (all UNMember States)Non-binding but strongpolitical endorsementGeneral Comment No. 2Adopted by the Committee on the Rights ofthe Child (committee of independent expertsmonitoring States Parties’ compliance with theConvention on the Rights of the Child)Non-binding but significant practicalguidance valueConvention on the Rights of the Child must beincluded in mandate

Mandate

Generic reference tointernational humanrights instrumentsMonitoring public authorities(executive, legislative, judicial andother bodies)No mention

Competency

Monitoring all relevant public andprivate authorities

Establishment process

Consultative, inclusive and transparentSupported at the highest level of governmentParticipation of all relevant elements of the state,the legislature and civil society

Composition

Pluralistic representation of thesocial forcesOptional

Pluralistic representation of civil societyInclusion of child and youth-led organizationsMandatory

Individualcomplaint mechanismAccessibilityand information

Address public opinion directlyor through any press organ

Geographically and physically accessible toall childrenProactive approach, in particular for the mostvulnerable and disadvantaged childrenDuty to promote the views of childrenDirect involvement of children throughadvisory bodiesImaginative consultation strategiesAppropriate consultation programmes

Activities

Advocate for and monitor humanrights

Promote visibility and the best interests ofthe child in policymaking, implementationand monitoringEnsure that views of children are expressedand heardPromote understanding and awareness ofchildren’s rightsHave access to children in care and detention

What do independent human rights institutions for children do?9

and implementation of all other rights, namely non-discrimination; the best interests of the child; the right tolife, survival and development; and the right to expressviews with due regard to age and maturity.An important aspect of the Convention is that itdoes not consider the child as an isolated individual.Instead, it situates the child as a member of a familyand community, recognizing his or her need for supportto develop and thrive. Action to realize the rights ofchildren can thus be envisaged as taking place withinand through a triangular set of relations involving thestate, parents (and/or guardians) and child.6Independent human rights institutions for children areone of the general measures of implementation of theConvention identified by the Committee on the Rightsof the Child.7As such they complement other measures,including law reform, resource allocation, governmentalbodies and strategies, data monitoring systems,awareness-raising and the role of civil society.The distinctive significance of independent institutions liesboth in the activities they undertake and the approach theypromote. Where other actors may tackle specific issues(e.g., justice for children, education, health or women’sissues) from a particular governmental or non-governmentalvantage point, independent institutions foster child-centredstrategies that reflect the multiple dimensions of childhood,the indivisibility of the many rights children enjoy, and thefactors that directly or indirectly affect a child’s life and thefulfilment of those rights. A holistic analysis of child rightsissues lays the foundations for institutions’ policyrecommendations. Their public yet independent natureplaces them midway between government and civil society,enabling them to create a space for dialogue between thetwo.8They seek to bring together different parts of thepolitical and institutional system and society in the bestinterests of the child. They are bridge-builders – a role that isneither easy nor highly visible.

The institutions scrutinize policy decisions not onlyfollowing their implementation but also duringdiscussions prior to their adoption. It is common forchildren’s ombudspersons to be involved in draftinglegislation through the submission of advice toparliament, participation in drafting meetings andthe taking of public positions. Illustrative examples ofactivities include the systematic review of child-relatedlegislation by the Ombudsperson for Children inMauritius and the National Commission for Protectionof Child Rights in India. In 2009, the Australian stateand territory children’s commissioners made variousrecommendations in the context of federal tax systemreform for evidence on the impact on child developmentof various policies and practices to be taken intoaccount. The Australian Government took up someof their proposals, including in relation to tax benefitsfor families, parental leave and the cost of adolescents’schooling.9The National Human Rights Commissionof Indonesia recommended changes to citizenshiplegislation for children with non-national fathers, whichwere reflected in the nationality law adopted in 2006.10Taking a systematic approach, Scotland’s Commissionerfor Children and Young People (United Kingdom)has developed a methodology for carrying out childrights impact assessments of proposed policy. Severalindependent institutions and related organizationsin other parts of the world have since adopted thisframework for their own purposes.Many institutions carry out enquiries and producereports based on hearings and investigations. Thesehave often proven influential in identifying wrongdoingor weaknesses in practice and in effecting institutionalreform. In early 2012, for example, the Children’sCommissioner for England (United Kingdom) shedlight on the treatment of unaccompanied asylum-seeking children arriving in the United Kingdom fromFrance and their potential rapid return without dueconsideration of their best interests. As a result, theborder authorities undertook to stop the practice.11Numerous institutions conduct research to examine theroot causes of children’s problems. An example is ananalysis carried out in 2006 by the Defensoría del Puebloin Colombia of risk factors leading to vulnerability tochild soldier recruitment. This subsequently informed

2.1 Making children and their bestinterests visible in policymakingAs virtually all policy decisions affect children, ensuringthat the best interests of the child principle is brought tothe attention of policymakers is a critical role of humanrights institutions and one that they have extensivelyassumed. Analysis of law, policy and practice – whetherexisting or proposed – from the perspective of theConvention on the Rights of the Child is a core activityof many such institutions.6Convention on the Rights of the Child, Articles 5 and 18.SeeDoek, J. E.,‘Independent Human Rights Institutions for Children’,Innocenti WorkingPaperNo. 2008-06, UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre, Florence, 2008.Committee on the Rights of the Child General Comment No. 5: Generalmeasures of implementation of the Convention on the Rights of the Child,CRC/GC/2003/5, 27 November 2003.Smith, A., ‘The Unique Position of National Human Rights Institutions: AMixed Blessing?’,Human Rights Quarterly,28(4), 2006, pp. 908–911.

9

Submission to Australia’s Future Tax System Review Panel, 2008, andvarious press releases at ‘Treasury Ministers Portal’, <http://www.treasurer.gov.au>, Australian Treasury website accessed 31 August 2012.

10 The National Human Rights Commission of Indonesia, Annual Report,2006, p. 31; Law of the Republic of Indonesia Number 12, Year 2006, onCitizenship of the Republic of Indonesia, Art. 4.11 Matthews, A., ‘Landing in Dover: The immigration process undergone byunaccompanied children arriving in Kent’, Children’s Commissioner forEngland, January. 2012.SeeAnnex 4: ‘Correspondence between MaggieAtkinson, Children’s Commissioner for England and Rob Whiteman,Chief Executive of UKBA’, p. 69.

7

8

Championing Children’s Rights10

recommendations for effective programming to supportthe reintegration of demobilized child combatants.12Even the best resourced institutions can find it achallenge to influence law and policy developmenteffectively. Providing quality advice on the breadth oftopics that affect children requires highly specializedskills and corresponding resources, which institutionswith limited staff may not be able to access easily.Institutions often have to rely on policymakers toinform them of a policy initiative early enough so theymay have the opportunity to influence its outcome.Policymakers may not even consider recommendations,let alone follow them. The success of advocacy activitiesshould therefore also be measured against theircollateral impact, for example, defining the best interestsprinciple in debate, fostering coalitions around specificthemes and building capacities.

to one third of the countries reviewed, independentinstitutions are specifically mandated to monitorchild care institutions; many more make regularvisits to children in alternative care in order to assesschild well-being, respect for children’s rights andthe quality of services provided. For example, Peru’sDeputy Ombudsman for Children and Adolescentsvisits state residential centres for children and assessestheir functioning and the level of respect they affordchildren’s rights. The Deputy Ombudsman’s startingpoint is to consult children on their perceptions andexperiences, in order to guide further investigation.15Visiting detention centres and reviewing the conditionsof detention of children represents a major competencyfor these institutions. It is a function performed by theoverwhelming majority of institutions across regions– including human rights institutions that do not havea dedicated child rights department – as part of theirdetention centre monitoring activities. Independentinstitutions regularly advocate the separation ofjuveniles from adults and make recommendationsfor the improvement of juvenile detainees’ livingconditions. The Human Rights Commission ofMalaysia, for example, monitors the conditions ofdetention of juveniles as part of its review of detentionfacilities, which includes immigrant detention centres.16

2.2 Promoting environments thatnurture child rightsIndependent human rights institutions for children seek topromote environments conducive to children’s enjoymentof their rights. They are also concerned with the socialchanges needed to ensure the realization of child rights.As befits the centrality of families to child well-being,it is common for independent institutions to supportadvocacy on state obligations to provide families withnecessary assistance13and to advocate policies thatsupport families’ capacity to care for their children,including to prevent institutionalization. Examplesinclude advocating policies that assist poor families inAzerbaijan, and calling for legislation to recognize therole of grandparents in Mauritius and step-parents inFrance in response to changing social contexts.Independent human rights institutions for childrenoften address dimensions of education, includingaccessibility, quality of education and the school as asafe, healthy and protective environment that respectschildren’s rights and dignity. Many institutions carryout regular visits to schools and organize training andworkshops; they produce and disseminate child-friendlymaterial for schoolchildren and guidance tools to helpteachers address human rights.The situation of children in alternative care requiresspecific monitoring.14Independent institutions havea unique capacity to advocate on behalf of individualchildren as well as for children as a group. In close12 Defensoría del Pueblo Colombia and UNICEF,Caracterización de las niñas,niños y adolescentes desvinculados de los grupos armados ilegales: inserciónsocial y productiva desde un enfoque de derechos humanos,Defensoría delPueblo and UNICEF, 2006.13 Doek, J. E., ‘Independent Human Rights Institutions for Children’,Innocenti Working PaperNo. 2008-06, UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre,Florence, 2008.14 Guidelines for the Alternative Care of Children, adopted by GeneralAssembly Resolution 64/142 of 24 February 2010, para. 130.

2.3 Promoting equitable approaches forthe most marginalized childrenIndependent human rights institutions for children playan important role in advocating policies that aim tocorrect the disadvantages experienced by some childrenand address exclusion.The majority of institutions reviewed address thesituation of the most excluded groups of children,although they are explicitly mandated to do so inonly one third of the countries studied. A number ofindependent institutions take a proactive approach(e.g., by disseminating specific material and visitingareas, places and institutions where vulnerable childrenare) to ensure their accessibility to these groups; onefinding of this study, however, is that this work could bestrengthened in many countries.In relation to children belonging to minority groupsor indigenous peoples, our review found that issuessurrounding education and language are commonlyaddressed. These can be particularly important becauseof the role of education and language in transmitting

15 República del Perú Defensoría del Pueblo, ‘El derecho de los niños, niñas yadolescentes a vivir en una familia: la situación de los Centros de AtenciónResidencial estatales desde la mirada de la Defensoría del Pueblo’,Informedefensorial No. 150,Lima, April 2010.16 Human Rights Commission of Malaysia, ‘The State of Prisons andImmigration Detention Centres in Malaysia: 2007–2008’, SUHAKAM,2010.

What do independent human rights institutions for children do?11

culture.17For example, in 2010, the Canadian Councilof Child and Youth Advocates called for a nationalplan to improve the well-being and living conditions ofCanada’s Aboriginal children and youth. In particular,it recommended a coordinated strategy to narrowthe significant gaps in health, education and safetyoutcomes apparent between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal children.18Several independent institutions have developedspecific strategies to reach children with disabilities andensure their accessibility to them. These institutionsadvocate accessibility to all services and inclusion insociety for children with disabilities. For example, sincethe intervention in 2009 of the Persons with DisabilitiesUnit of the Afghanistan Independent Human RightsCommission, most schools and other public buildingsbuilt in the country are equipped with ramps.19A few countries have specialized national human rightsinstitutions to address specific issues or protect certaingroups, e.g., the Equality Ombudsman in Sweden,the Ombudsman for Minorities in Finland and theNational Commission for Women in India. Effectivecollaboration between children’s rights offices and theseand other thematic offices (e.g., offices dealing withwomen, people with disabilities, migrants or indigenouspeoples) is crucial in promoting a holistic approach tochildren’s rights and in helping children in these groupsto realize their rights.Overall, however, the review of independent humanrights institution activities and reports suggests thatcollaboration across thematic programmes – whetherwithin a broad-based institution or among specializedoffices – remains limited. In the case of integratedinstitutions, paying attention to internal coordinationamong various departments is important.Many of the challenges of promoting equitableapproaches lie in the marginalization of the issuesconcerned in the wider social and political context.Bringing about change for excluded children requiressignificant efforts to increase the visibility of the issuesthat affect them and for these to be deemed worthy ofpolitical attention.Other challenges concern the nature of the individualinstitution itself. An institution’s ability to promotethe rights of the most excluded children oftenrequires specific consideration of its internal profi leand workings. For example, some institutions have17 Sedletzki, V., ‘Fulfi lling the Right to Education for Minority andIndigenous Children: Where are we in international legal standards?’,State of the World’s Minorities and Indigenous Peoples, Minority RightsGroup International/UNICEF, July 2009, p. 43.18 Canadian Council of Provincial Child and Youth Advocates, ‘AboriginalChildren and Youth in Canada: Canada must do better’, position paper, 23June 2010.19 Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission, Annual Report,January 1–December 31 2009, AIHRC, 2010, p. 31.

specifically encouraged ethnic diversity and gendermainstreaming in staffing. Anecdotal evidence suggeststhat some institutions have deliberately hired staff fromminority or indigenous groups to help meet the needs ofthe most marginalized children.20

2.4 Promoting child participationin societyIndependent human rights institutions for children arein a unique position to promote child participation inthe community and broader society. They can contributeto challenging and dismantling the legal, political,economic, social and cultural barriers that impedechildren’s opportunity to be heard and to participate inall matters affecting them.21Institutions have becomea source of expertise and support to governments andother stakeholders in creating opportunities for childparticipation; several have issued guides and handbookson the subject.22Institutions promote children’s right to be heardthroughout their many activities: monitoring,research, advocacy, handling complaints, carryingout investigations and advising. They have supportedprocesses, for example, aimed at involving childrenin school life and promoting children’s political voice.In 2010, the Northern Ireland Commissioner forChildren and Young People (United Kingdom) set upDemocra-School, a programme aimed at promotingdemocracy and youth participation in schools. TheCommissioner issued a guidance pack on the inclusionof pupils in school councils and various tools includingelection guidelines and sample ballot papers, formsand reports.23The initiative is endorsed by the mainteaching unions and led to a commitment from theDepartment of Education to set up children’s councils inall schools in Northern Ireland.In Europe, institutions in Austria, Flanders (Belgium)and Norway have advocated lowering the voting age(usually set at 18 years old) to give voting rights tochildren. This has delivered successful results in Styria(Austria), where the voting age has been lowered to16years, and in Norway, where several municipalitiesare testing a lower voting age.

20SeeHon. T. Hughes, ‘Final Progress Report on the Implementation of theRecommendations of the BC Children and Youth Review’, Representativefor Children and Youth, 2010, pp. 38–39, which recognizes the presenceof Aboriginal staff, including at senior level, within the office and theimportance of a specific mention in staffi ng advertisements in order toencourage Aboriginal candidates to apply.21 Committee on the Rights of the Child General Comment No. 12: The rightof the child to be heard, CRC/C/GC/12, 20 July 2009, para. 135.22 For example, in Australia (New South Wales, South Australia and WesternAustralia).23 Northern Ireland Commissioner for Children and Young People, AnnualReport and Accounts, for the year ended 31 March 2011, NICCY, 15December 2011, p. 16.

Championing Children’s Rights12

In Asia, Nepal’s National Human Rights Commission helped to organize regional workshops togive children a voice in the drafting of the country’s new constitution.24Unlike its predecessor, theInterim Constitution of Nepal includes a section on child rights, providing for rights to a name andidentity, to the provision of services and to protection from labour and exploitation, especially whenindifficultcircumstances.2524 Nepal National Human Rights Commission, Status of Child Rights in Nepal (2008), p. 43.25 The Interim Constitution of Nepal, 2063 (2007), Article 22.

The review of independent human rights institutionsfound that the promotion of child participation hasreceived uneven attention. Institutions in high-income countries – often stand-alone, specializedchildren’s ombudspersons – have usually developedthis aspect of their work to a much greater extent thaninstitutions elsewhere.

with particular features and advertising that targetedadolescents. The Ombudsperson mobilized relevantministries on the issue, leading the company to changeits strategy, put in place measures to prevent youngpeople under 18 years old from accessing the service,and introduce a special warning about the riskstousers.29In 2011, the National Commission for Protection ofChild Rights in India fi led a report with the policeagainst the owner of a mine in which nine childrenwere employed.30Involvement in judicial proceedingsis a major function of the Jamaican Office of theChildren’s Advocate; it has followed numerous cases,either by reporting on the case, monitoring proceedingsor representing a child. In 2007, for example, the Officeinvestigated and reported to the police a case of violenceagainst a child by his uncle, following which the unclewas arrested and prosecuted, while at the same timeobserving proceedings on behalf of the child.31Addressing specific situations is important forindependent institutions as it enables them to havedirect contact with children’s experiences; resolvinga problem also allows them to demonstrate concreteresults. There is the dilemma, however, that institutionsthat gain public recognition of their effectiveness can intime become overwhelmed with individual complaints,reducing their capacity to work on broader policy andsystemic issues.

2.5 Addressing individual orspecific situationsMost independent human rights institutions forchildren have the ability to address specific situationsin which child rights are at stake. The complaintmechanism is the route by which to remedy individualand collective child rights violations. Access to aneffective remedy for rights violations is integral to therealization of all human rights and is implicit in theConvention on the Rights of the Child. States Partiesare obliged to provide effective and child-sensitivemeans for children to have their complaints heardbefore competent bodies.26Additional internationalstandards relating to two groups of children identifiedas particularly vulnerable to rights violations –those in contact with the justice system and thosein alternative care – also require child-sensitivecomplaintmechanisms.27Examples of action based on complaints are many;what follows are just some examples. In Peru, theDefensoría del Pueblo intervened when the relevantauthorities failed to act upon reports of the sexual abuseof children by a teacher. The teacher was subsequentlyprosecuted together with those who had obstructedthe judicial process, and the education authoritiesinitiated administrative proceedings against him.28InMauritius, the Ombudsperson for Children receivednumerous complaints from parents concerned about amobile phone company’s new text messaging system26 Committee on the Rights of the Child General Comment No. 5: Generalmeasures of implementation of the Convention on the Rights of the Child,CRC/GC/2003/5, 27 November 2003, para. 24.27 United Nations Guidelines for the Prevention of Juvenile Delinquency(The Riyadh Guidelines), adopted and proclaimed by General AssemblyResolution 45/112 of 14 December 1990; Committee on the Rights of theChild General Comment No. 10: Children’s rights in juvenile justice,CRC/C/GC/10, 9 February 2007, para. 89; Guidelines for the AlternativeCare of Children, adopted by General Assembly Resolution 64/142 of 24February 2010, para. 130.28 Defensoria del Pueblo de Peru, Annual Report 2009, pp. 167-168.

29 Ombudsperson for Children in Mauritius, Ombudsperson for ChildrenAnnual Report 2009–2010, chapter IX.30 See ‘Media and Communications’, <http://www.ncpcr.gov.in/childlabour_education.htm>,National Commission for Protection ofChild Rights website, accessed 13 October 2012.31 Office of the Children’s Advocate – Jamaica, Office of the Children’sAdvocate Annual Report, 2007–2008 Fiscal Year, 2008, p. 30.

What do independent human rights institutions for children do?13

The role of parliamentsParliaments have a special role in relation to independent human rights institutions for children, whichwork with many public bodies that have a responsibility to advance children’s rights. Parliaments adoptthe law establishing the institution and its mandate and competencies – as well as any subsequentmodifications. In many instances, they have a say in the selection and appointment of the individualombudsperson or commissioner. Parliaments also oversee the performance of institutions.The majority of institutions reviewed submit an annual report on their activities to parliament; theyalso provide an analysis of the state of childhood in the country and outline gaps to be addressed. Theannual report and any additional publications are important sources of knowledge and information forparliamentarians and others. The study also found that ombudspersons for children often informallyinteract with and lobby key parliamentarians to press for legislative and other measures to advancethe realization of children’s rights.

Independent human rights institutions for childrenandnon-governmental organizationsThe work of NGOs complements and supports that of independent human rights institutions forchildren in numerous ways. In addition to being involved in establishing institutions32in line withthe Paris Principles, representatives of NGOs in many places are also members of human rightscommissions and therefore have the ability to influence an institution’s priorities.33Human rights NGOs are a source of knowledge and expertise, and independent institutions oftenuse the research that NGOs undertake. NGOs can also raise public awareness of the existence of anindependent mechanism for children’s rights and can work to redress violations. In some places,like Indonesia,34Jordan and Mexico, individual complaints received by independent human rightsinstitutions for children are channelled through NGOs, which have a more extensive field presence.Independent human rights institutions for children also have the potential to support NGOs.Because they have direct access to decision makers, the independent institutions can reiterate NGOrecommendations, enhancing their influence. Independent institutions can help to foster coalitionsthat can benefit NGOs working towards children’s rights. The Ombudsman for Children in Greece,for example, set up an NGO network for monitoring the implementation of the Convention on theRights of the Child and facilitating cooperation between civil society and the State.35Developing good relationships with children’s rights organizations can help institutions toprotect their independence and enhance their effectiveness. Connections can help an independentinstitution to deepen public legitimacy, reflect public concerns and priorities, receive feedback onits own work and tap into valuable information, expertise and networks.36Direct collaboration withchildren’s organizations enriches the work of independent institutions by supporting access to adiversity of children’s perceptions, opinions and experiences.

32 For example, in Sweden, NGOs established an ombudsman mechanism that paved the way for the creation of a public independent humanrights institution for children.33 Vuˇckovi´ -Šahovi´ , N., ‘The Role of Civil Society in Implementing the General Measures of the Convention on the Rights of the Child’,ccInnocenti Working PaperNo. 2010–18, UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre, Florence, 2010, p. 39.34 International Council on Human Rights Policy, ‘Performance & Legitimacy: National human rights institutions’, ICHRP, Versoix, 2004, p. 99.35 Ombudsman for Children – Greece, Ombudsman for Children Annual Report 2009, p. 54.36 International Council on Human Rights Policy, ‘Assessing the Effectiveness of National Human Rights Institutions’, ICHRP, Versoix, 2005,p.15; Reif, Linda C., ’Building Democratic Institutions: The Role of National Human Rights Institutions in Good Governance and HumanRights Protection’,Harvard Human Rights Journal,vol. 13, 2000, p. 26.

Championing Children’s Rights14

Practical question:Whatstructure should anindependent institution take?The question of what an independent human rights institution forchildren should look like arises again and again. Research suggeststhat institutional structure influences certain capacities, for example,the accessibility of an institution to children. Yet there is no singlemodel that fits all.Of all the countries with an independent human rights institution forchildren, approximately one third has a stand-alone institution, onethird has an institution integrated into a broad-based human rightsinstitution with a legislated child-specific mandate, and one third hasan institution with an integrated child rights office without a mandatebased in legislation.37What are the considerations in deciding upon a stand-aloneombudsperson for children or one that is integrated into a broaderhuman rights institution?1. Children as specific rights-holders.The distinctive feature of astand-alone institution is its specialization in children; a broad-basedhuman rights institution, in contrast, concerns itself with all humanrights. Many stand-alone institutions were created in recognitionthat the protection of children’s rights requires specific action. Thefirst ombudspersons for children in the world appeared in Europeas stand-alone institutions; one such was created in Norway, forexample, a country that has a legal tradition of recognizing children asrights-holders.382. Accessibility to and participation of children.Research showsthat accessibility to, and involvement of, children is specified almostexclusively in the mandates of stand-alone institutions. An overviewof institution activities aimed at promoting systematic, direct contactwith children shows that it is primarily stand-alone institutions thatperform these activities. Where an integrated office is very active inthis area, it often features a highly identifiable ombudsperson forchildren with significant autonomy in carrying out its mandate, asis the case in Greece. Across all institutions, however, adults submitthe overwhelming majority of complaints, suggesting that childrenthemselves are generally unaware of the institution and its role.3. Indivisibility of human rights and coordination issues.Themain argument for an integrated institution is that it is needed to buildon the interdependence and indivisibility of all human rights and tomainstream children’s rights across all areas. A single institution islikely to foster greater communication, which can enhance the cross-fertilization of ideas and sharing of good practices,39and to favour aunified approach to issues affecting all children’s rights.40This can alsomitigate potential jurisdiction issues, where a particular problem (e.g.,discrimination against a child with a disability or an indigenous girl)could fall under the scope of various specialized institutions.4137 A few countries, including Spain and Serbia, have institutions at the local levelwith a combination of these features.38 Flekkøy, M. G.,A Voice for Children: Speaking out as their Ombudsman,JessicaKinsley Publishers, London, 1991.39 Carver, R., ‘One NHRI or Many? How Many Institutions Does It Take to ProtectHuman Rights? Lessons from the European Experience’,Journal of Human RightsPractice,vol. 3, issue 1, 2011, p. 9. For an example,see alsoDefensoría de losHabitantes de Costa Rica, Annual Report 2010–2011, DHR, San José, 2012, p.122,concerning a case related to refugee status involving women’s and children’srights, and the corresponding departments within the Defensoría.40 Carver, R., Dvornik, S., and Redžepagi c, D., Rationalization of the Croatian´Human Rights Protection System – Report of Expert Team, February 2010, p.50.41 Carver, R., (2011) op. cit., p. 9.42 Ibid. p. 1.

Child rights of ceintegratedwithoutspeci c legislationChild rights of ceintegratedwithspeci c legislationStand-alone children’sombudsperson

Yet an integrated structure alone does not guarantee a highly unifiedapproach to human rights; there must also be willingness within theinstitution to undertake cross-disciplinary work.4. Status and ability to influence child rights policies.Astrongargument for an integrated institution is the visibility and authorityof a single body as the beacon of human rights promotion andprotection in a country. In fact, a number of broad-based human rightsinstitutions have mandates established by the constitution and benefitfrom the high status this incurs; in contrast, specialized child rightsinstitutions are virtually always established by law and almost neverfounded in the constitution.There are risks associated with placing all work around rightsprotection under a single umbrella, however. An institution thatis weak – due to a restrictive mandate, its limited capacities, aninadequate institutional head or its failure to inspire trust – canjeopardize the whole human rights protection system. Furthermore,the vision of child rights enshrined in the Convention on the Rightsof the Child encompasses the responsibility of actors beyond thestate: parents, civil society and, by implication, the private sector. Itis only relatively recently that action by private bodies has begun tobe considered a legitimate concern of the wider international humanrights framework, and its extent and nature remains debated. For thisreason, the mandates of some broad-based human rights institutionsdo not yet provide for work in relation to the behaviour of the privatesector, which can limit the scope of action on behalf of children’s rights.Another related and significant issue is the visibility of children’srights within a broad-based institution. When one voice (the broad-based institution) speaks for all rights, topics across a wide range ofissues must be prioritized. A legislative basis for work on child rights istherefore crucial in giving a long-term voice to children’s rights. Stand-alone independent human rights institutions for children have directaccess to parliament and the government to raise matters of concern –and influence policies – with respect to children’s rights.5. Cost.Cost-effectiveness is often a major determinant of institutionalstructure. A broad-based institution can pool a number of functions,e.g., logistics and infrastructure. Innovative proposals to uniteadministrative functions while retaining specialized mandates on asubstantive level have also emerged.Should existing institutions be merged?An increasing number of countries are considering reforming andmerging existing human rights institutions, an impulse that oftenarises from a desire to rationalize administration and cut costs oris articulated at a time when a new, specialized institution is underconsideration.42Political factors can also prompt discussion aroundinstitutional merger. Merging pre-existing institutions is complex, andthe potential benefits that stand to be gained (e.g., cost savings) mustbe balanced against the potential risks (e.g., compromising advancesmade to date, uncertain added value and loss of capacity or profile onchild rights).

What do independent human rights institutions for children do?15

3. What makes independenthuman rights institutions forchildren effective?The effectiveness of an independent human rightsinstitution for children is a function of both the workof the institution itself and the responsiveness andsupport it receives from wider society and the otherpublic institutions around it. The elements that combineto advance child rights agendas differ from society tosociety and issue to issue and, of course, change overtime. While they may be agents of change, effectiveindependent institutions for children also need tobe able to adapt to changing circumstances in orderto remain significant. Attributing success in policydevelopment or reform to a single institution can becomplex, especially when that institution’s role is largelyto facilitate governance processes involving others.Nevertheless, in analysing how independent institutionsoperate, the dilemmas they face and the positiveoutcomes they yield, this study has identified a numberof features that underpin their ability to advance therealization of children’s rights.

There is an inherent tension related to an institution’sindependence and its existence as a public body. Withinmost countries’ traditional institutional landscape –which includes government, parliament and a judiciary– independent human rights institutions for childrenare both part of the public arena and beyond it, as theyare set up to monitor these institutions yet also workwith them.Being perceived as independent helps an institutioncarry out its mandateThe perception of an institution’s independence,particularly on the part of children, excludedcommunities and other actors engaged in rights-related work, is crucial to its ability to carry out itsmandate. Perceptions of independence may influencethe willingness of injured parties to fi le complaints withthe ombudsperson; the ability of the ombudspersonto engage children and vulnerable communities in itswork; the trust of all political factions and actors; andthe strength of the relationships and opportunities forcollaboration with NGOs.Perceptions of independence are influenced by a numberof elements including pluralistic representation withinan institution (e.g., gender balance and presence of stafffrom various social, ethnic and cultural backgrounds);its legal basis and mandate; its physical location (havingits own premises separate from other institutions isimportant); and its impartiality, often related to a fair andtransparent appointment process of its leadership.Establishment and appointment processes impact onan institution’s experience of independenceEnjoying a legal and especially a constitutional statusconfers on an institution a certain rank and legitimacy.For adoption of legislation, a vote by parliament istypically required, and there is some form of democraticdebate. Such an establishment process is likely toresult in institutions that are more independent andsustainable in the long term than those created bydecree of the executive branch. This latter process maylimit broader political ownership, create the perceptionthat the institution is a creature of the governmentof the day and leave the institution at risk of beingdismantled when a new government comes to power.Virtually all independent children’s rights institutionsacross the globe are created by law. In nearly half ofthe countries with an independent institution whosemandate includes children’s rights, the institution isprescribed by the national constitution. In addition toproviding guarantees of sustainability, constitutionalstatus indicates that the institution is considered a pillarof the state system.The legislative mandate of many institutionsstipulates independence. Such an explicit mention

3.1 IndependenceIndependence is the defining feature of human rightsinstitutions for children. It is their main strengthand their source of legitimacy and authority. It is thequality that allows them to keep child rights front andcentre regardless of political trends.43The degree ofindependence is pivotal in determining the success orfailure of institutions.44At the same time, independence is also their mostfragile quality.An institution’s actual experience of independence isa function of its mandate, resources and management.It is influenced by politics and, to a lesser extent, thestrength of the media and civil society surroundingit. Political conditions are a potent factor, determiningwho is appointed to lead the institution, how strongits mandate, its level of resources and whethergovernment pays attention to its recommendations.A strong institution, in turn, is able to influence all ofthese factors.43 Preparatory meeting for the Second Global Meeting of IndependentHuman Rights Institutions for Children, UNICEF Innocenti ResearchCentre, Florence, 11–12 November 2002.44 International Council on Human Rights Policy, ‘Assessing theEffectiveness of National Human Rights Institutions’, ICHRP, Geneva,2005, p. 12. Also, John Ackerman argues that four determinants forwhether an independent agency ends up as an “authoritarian cover-up”or a “positive force for accountable governance” are public legitimacy,institutional strength, second-order accountability and bureaucraticstagnation;seeAckerman, J. M., ‘Understanding IndependentAccountability Agencies’ in Rose-Ackerman, S. and Lindseth, P. (eds.),Comparative Administrative Law,Edward Elgar, London, 2010.

Championing Children’s Rights16

of independence in the founding legislation is anadditional guarantee of actual independence, as itdetermines the nature and status of the body within thenational institutional system.As previously described, mandates can cover a widerange of activities and powers, and explicitly definingthese can be important in giving an institutionauthority and a clear identity. Examples of significantlimitations inserted into institutional mandates in lawand practice exist in all regions of the world, however.Some institutions, for example, require government orjudiciary approval, or may face a government veto, whenundertaking an investigation. This is the case for theHuman Rights Commission of Malaysia, which needsgovernment permission to conduct visits to detentioncentres.45A review of the Children’s Commissioner forEngland (United Kingdom) found that the institution’sobligation to consult the Secretary of State for Educationbefore holding an enquiry, and the latter’s power todirect an enquiry and to decide whether to amendfindings or keep them from the public, are factors thatsignificantly reduce its independence.46The leadership appointment process for ombudspersonsand commissioners for children is also crucial to theindependence of institutions. It sets the tone for thelevel of trust institutions enjoy and creates a layer ofaccountability. The personal qualities and authorityof the individual ombudsperson or commissioner arefundamental to the actual experience of independenceenjoyed by the institution he or she leads.Financial autonomy: A key to independencein practiceInstitutions need sufficient and sustainable financialresources to carry out their mandates. At the sametime, funding sources must respect the legitimacyand independence of an institution. Human rightsinstitutions with no say over their finances willbe dependent on whichever body exerts financialcontrol.47While financial dependence on the statemight compromise the independence of an institutionwhen funds are restricted or unduly controlled, statefunding provides legitimacy to an institution as a public,regulatory agency.The Committee on the Rights of the Child hasconsistently noted in its concluding observations to45 Human Rights Commission of Malaysia Act 1999, Act 597, 1999, Section 4(2).See alsoAsian NGOs Network on National Human Rights Institutions,2010 ANNI Report on the Performance and Establishment of NationalHuman Rights Institutions in Asia, ANNI, 2010, p. 18.46 Dunford, J., Review of the Office of the Children’s Commissioner(England), Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for Educationby Command of Her Majesty, November 2010, p. 33. A reform process isunder way as of mid-2012.47 United Nations Centre for Human Rights,National Human RightsInstitutions: A Handbook on the Establishment and Strengthening of NationalInstitutions for the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights,United NationsCentre for Human Rights, Geneva, 1995, para. 73.

state party reports that efforts to provide reasonableand secure funds to child-related institutions areinsufficient.48External funding is necessary in manyplaces – especially for child rights programmes –because of resource shortages. In these countries,private and foreign donors have become involvedin supporting the work on children’s rights withinnationalinstitutions.49Such support is a double-edged sword: it keeps aninstitution operational and potentially shields it fromthe political fallout that a solely state-determinedbudget can elicit, but it can also compromise theindependence and sustainability of the institution,particularly over the long term. Donor agendasmay affect an institution’s own long-term strategy,especially where funding strategies are subject tochange. Our study shows that this is a particularconcern for children’s departments within broaderhuman rights institutions, whose funding is oftenproject based and provided directly by donors50rather than drawn from the institution’s own budget.Donor strategies therefore need to be geared towardsguaranteeing both sustainability and nationalownership, by promoting diversification of fundingsources and contributions by the institution andthe state. This also helps to address the perceptionthat the institution is a creature of foreign interests.In Morocco, for example, funding for recruitmentto the Consultative Council for Human Rights of astaff member specializing in child rights came fromUNICEF during the fi rst year but was subsequentlyincorporated into the Council’s budget.51Accountability mechanisms can help topreserve independenceIndependent human rights institutions for childrenare one kind of accountability mechanism. Othertypes of accountability mechanisms provide ongoingfeedback on the strengths and weaknesses ofthe institution itself, which is crucial in fosteringits independence and helping it to becomestronger over time. Like any other public body, aninstitution must be held accountable for its ownactions and performance, in a way that preservesits independence.Clear accountability mechanisms can build publictrust and reinforce legitimacy in the eyes of the public48See,for example, Committee on the Rights of the Child ConcludingObservations on Colombia, CRC/C/OPAC/COL/CO/1, 21 June 2010, para.11; on Guatemala, CRC/C/GTM/CO/3-4, 25 October 2010, para. 23; onNicaragua, CRC/C/NIC/CO/4, 20 October 2010, para. 16; on Panama,CRC/C/PAN/CO/3-4, 21 December, 2011, para 15; on Bangladesh, CRC/C/BGD/CO/4, 26 June 2009; on Maldives, CRC/C/OPSC/MDV/CO/1, 4 March2009; on the Philippines, CRC/C/PHL/CO/3-4, 22 October 2009; and onUzbekistan, CRC/C/UZB/CO/2, 2 June 2006.49 For example, in Afghanistan, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Malawi,Nepal, Pakistan and Zambia, among many others.50 As has been the case in Honduras and Nepal, for example.51 Interview with UNICEF Country Office, August 2012.

What makes independent human rights institutions for children effective?17

by helping to make action transparent.52They arealso a means to officially inform state bodies of theinstitution’s recommendations – and reinforce theresponsibility of state bodies to implement them.Accountability mechanisms include:Written reports of activities to parliament,government or the public on an annual or regularbasis. The level of accountability and oversightachieved by this process is highly dependent uponthe level of engagement by these other actors.Informing the general public. Research forthis study suggests that this practice is not yetwidespread; aside from the increased use ofwebsites and social media by institutions in somemiddle- and high-income countries, only a fewpublish regular bulletins on their activities.Monitoring by civil society. In Asia, for example,theAsian NGO Network on National Human

Rights Institutions issues an annual report on thefunctioning and independence of national humanrights institutions.Monitoring as part of network membership.The International Coordinating Committee ofNational Human Rights Institutions periodicallymonitors and accredits human rights institutionsthat comply with the Paris Principles. It does not,however, assess stand-alone independent humanrights institutions for children or those that areestablished solely at the local level.Assessment by international monitoring bodies(e.g., the Committee on the Rights of the Childand other treaty bodies, the Human RightsCouncil Universal Periodic Review, specialprocedures). The Committee on the Rights ofthe Child systematically considers the mandate,independence, financing and overall state supportof children’s ombudspersons during its periodiccountry reviews. Other treaty bodies also reviewthe role of national human rights institutions.The Universal Periodic Review of the HumanRights Council provides the opportunity to debatethe effectiveness of human rights institutions ineach country and makes recommendations tostrengthen them.

52 Ackerman, J. M., ‘Understanding Independent Accountability Agencies’,in Rose-Ackerman, S. and Lindseth, P. (eds.),Comparative AdministrativeLaw,Edward Elgar, London, 2010; International Council on HumanRights Policy, ‘Assessing the Effectiveness of National Human RightsInstitutions’, ICHRP, Geneva, Switzerland, 2005, p. 23.

A 2007 review of democratic institutions in South Africa, including the South African Human RightsCommission, pointed to the lack of engagement by the National Assembly. Institutions’ interactionswith Parliament were restricted to annual meetings with portfolio committees of very limited duration(e.g., two to three hours). Challenges to greater engagement included the workload of parliamentarycommittees and uncertainty among parliamentarians about their role in preserving the independenceof institutions.Recommendations from the review included creating a unit within the Office of the Speaker tocoordinate the oversight of these institutions; strengthening the relevant parliamentary committees (inparticular by ensuring their access to relevant expertise); and adopting legislation on accountabilitystandards to regulate the relationship between Parliament and the institutions concerned.53Followinga resolution by the National Assembly in 2008, the Office on Institutions Supporting Democracy wasformally established in 2010..54

53 Parliament of the Republic of South Africa, Report of the ad hoc Committee on the Review of Chapter 9 and Associated Institutions, A report to the NationalAssembly of the Parliament of South Africa, Cape Town, 2007, pp. 30–32.54 ‘Office on Institutions Supporting Democracy’, <http://www.parliament.gov.za/live/content.php?Category_ID=320>, Parliament of the Republic ofSouthAfrica website, accessed 20 July 2012.

Championing Children’s Rights18

Practical question: How can institutions withstand threats?The sustainability of an independent human rights institutionand, even more fundamentally, the regard for child rights, isnot guaranteed even in those countries with the most effectiveinstitutions. While ineffectiveness is the primary risk, thefindings and recommendations of human rights institutionscan sometimes be uncomfortable for those in authority or mayjar with different factional interests. In this context, a record ofachievements and strong independence can create a backlash,leading political decision makers to question the need for aninstitution. In other situations, financial challenges may leadto the questioning of institutions’ viability, perhaps especiallyif a country has multiple bodies to address different areas ofhuman rights.Independent human rights institutions for children have beendismantled in contexts as diverse as Ghana, Madrid (Spain)and New Jersey (United States of America). Their existence asstand-alone institutions has been questioned in a number ofcountries, including Croatia, England (United Kingdom), France,Ireland and Sweden. Motivations have included a combinationof the rationalization of institutional structures, concerns overcosts and political considerations. In light of the specificity ofchildren’s rights and the mobilization of child rights advocates,institutions were eventually maintained in all of the countriescited above except France. Here the institution became integratedinto a broad-based human rights institution in 2011; advocacyled to the specific visibility of children’s rights in the newlegislation, however.In the case of British Columbia’s Representative for Childrenand Youth (Canada), vocal support for the Representative byindigenous communities played an important role in reminding55 ‘Open Letter: UBCIC Supports Representative For Children And YouthPetition To Access Cabinet Documents’, dated 11 May 2010, IndigenousPeoples Issues and Resources website, <http://indigenouspeoplesissues.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=5165:open-letter-ubcic-supports-representative-for-children-and-youth-petition-to-access-cabinet-documents&catid=52:north-america-indigenous-peoples&Itemid=74>, accessed on 2 October 2012.

the public and judiciary that the institution’s responsibility is toaddress the rights and needs of the province’s most marginalizedchildren – something these communities felt would have beencompromised had the institution’s legislation been weakened.55These examples point to the importance of institutions buildingrelationships beyond government and parliament, connectingwith partners that can mobilize and speak out on behalf ofthe institution if necessary. The media can be instrumental inhelping an independent human rights institution for children toestablish itself as a unique and permanent feature of the nationallandscape. Partnerships forged with civil society, and with childrights NGOs in particular, play an important role in enhancinginstitutional legitimacy; these are also the primary constituenciesto provide support if or when the institution faces threat.56Another way to withstand threats is to set up internalmechanisms that can identify and anticipate them. TheNorthern Ireland Commissioner for Children and YoungPeople (United Kingdom) has established an Audit and RiskCommittee composed of external representatives, whichprovides independent oversight and regularly identifies risksto the effectiveness of the office. These can be both strategic, forexample, risks to resources and independence, and substantive,for example, an adverse judicial decision on a child rights issue.The Commissioner also maintains a Corporate Risk Register,which it reviews monthly.57Effectiveness, measured through concrete results andcapitalizing on partnerships and public trust, is the bestprotection for and guarantee of institutional sustainability.