Miljøudvalget 2012-13

MIU Alm.del Bilag 277

Offentligt

Rigsrevisionen, DenmarkNational Audit Office of FinlandState Audit Office of the Republic of LatviaNational Audit Office of LithuaniaOffice of the Auditor General of NorwayPolish Supreme Audit OfficeSwedish National Audit Office

Emissions trading to limitclimate change:Does it work?A cooperative audit

www.eurosaiwgea.org

Joint report

Seven European Supreme Audit Institutions have been partners in this cooperative audit onemissions trading:Rigsrevisionen, Denmark•www.rigsrevisionen.dkNational Audit Office of Finland•www.vtv.fiState Audit Office of the Republic of Latvia•www.lrvk.gov.lvNational Audit Office of Lithuania•www.vkontrole.ltOffice of the Auditor General of Norway•www.riksrevisjonen.noPolish Supreme Audit Office•www.nik.gov.plSwedish National Audit Office•www.riksrevisionen.se

Content Overview

Message from Heads of Supreme Audit Institutions.........................Summary.................................................................................................Acronyms and glossary.........................................................................Report......................................................................................................

24610

Reviewer of the joint report:National Audit Office of Estonia•www.riigikontroll.ee

Supreme Audit InstitutionsThis document is available at www.eurosaiwgea.orgPrinted copies may be ordered from:Office of the Auditor General of Norway / EUROSAI WGEA SecretariatP.O. Box 8130 DepNO-0032 OsloNorwayE-mail: [email protected]Tel.: (+ 47) 22 24 10 00Fax: (+ 47) 22 24 10 01ISBN (print): 978-82-8229-209-2ISBN (web): 978-82-8229-210-8Print: 07 Gruppen AS

The role of Supreme Audit Institutions (SAIs) is to conduct independent auditsof governments’ activities. These assessments provide the national parliamentswith objective information to help them examine the government’s publicspending and performance. The International Organisation of Supreme AuditInstitutions (INTOSAI) is the international umbrella organisation for SupremeAudit Institutions. The aim of the institutionalised framework is to promotedevelopment and transfer of knowledge, improve government auditing world-wide and enhance professional capacities, standing and influence of memberSAIs in their respective countries. The regional organisation for Supreme AuditInstitutions on the European level is EUROSAI. One of its working groups isthe EUROSAI Working Group on Environmental Auditing (EUROSAI WGEA).The aim of the working group is to contribute to increase the SAIs’ capacity inauditing governmental environmental policies, to promote cooperation, andto exchange knowledge and experiences on the subject between SAIs.

Messages from Heads ofSupreme Audit InstitutionsThe Supreme Audit Institutions play an important accountability roleby reporting to parliaments on the efficient, effective and cost-effectiveimplementation of, amongst other things, environmental and energypolicies.Ms Lone Lærke StrømAuditor GeneralRigsrevisionenDenmark

There has been significant Value Added Tax (VAT) fraud related toemissions trading, which challenges the credibility of the system andresults in a loss of state income. Some count ries have introducedtemporary measures against VAT fraud in trading allowances, but acomprehensive and long-term solution is not yet in place.Based on these conclusions, we recommend consideration of thefollowing:• In order to ensure adequate incentives for long-term reductions of emissions, it should be ensured that instruments are in place and used to limit any excessive amounts of allowances/credits for the next emissions trading period.• Governments should consider making full use of their discretionary power provided by EU legislation to improve the effectiveness of the system.• Vigilance is still needed in the area of VAT fraud, and cooperation between tax authorities and EU ETS administrators, as well as cross-border cooperation remains important.• To speed up the project process, simplifying procedures for CDM projects should be considered, without giving up the strict require-ments for control and verification. It is also important that the buyer countries conduct proper risk analyses in order to detect and handle problems at an early stage.

Mr Vesa JatkolaAssistant Auditor GeneralNational Audit Office ofFinland

Climate change is considered by both United Nations (UN) and EU asone of the biggest environmental, economic and social challenges, andneeds to be addressed in a coordinated effort at an international level.Emissions trading is a key policy instrument in meeting national andthe Kyoto Protocol emissions targets in a cost-effective way. Theimplementation of the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) and theproject-based mechanisms under the Kyoto Protocol (the Clean Devel-opment Mechanism (CDM) and Joint Implementation (JI)) have been ahuge administrative undertaking and entail new tasks and roles forgovernments and companies. There are potential risks related to theimplementation of these systems as well as to their effectiveness.The aim of the cooperative audit has been to assess the trustworthiness,reliability and effectiveness of the EU ETS and project-based mecha-nisms under the Kyoto Protocol. This report draws on findings gainedfrom individual audit reports from seven countries in the years 2008–2012.The cooperative audit has established that the governments of theNordic–Baltic–Polish partnership have implemented the EU ETS in linewith current EU legislation and the provisions under the United NationsFramework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The effective-ness of the system in contributing to long-term emissions reductionsis however a major challenge as allowance prices have been low dueto a general surplus of allowances in the system during the period2008–2012.Moreover, the full potential of the JI and CDM mechanisms is not beingrealised. The main reasons are slow approval and verification proce-dures. The cooperative audit has also identified weaknesses in the riskmanagement in the buyer countries.

Mr Jørgen KosmoAuditor General /Chair of EuROSAiWGEAOffice of the AuditorGeneral of Norway

Mr Jacek JezierskiPresidentSupreme Audit Officeof Poland

Ms Inguna SudrabaAuditor GeneralState Audit Office ofthe Republic of Latvia

Mr Claes NorgrenAuditor GeneralSwedish NationalAudit Office

Ms Giedrė ŠvedienėAuditor GeneralNational Audit Office ofLithuania

2

EUROSAI WGEA

EMISSIONS TRADING TO LIMIT CLIMATE CHANGE: DOES IT WORK?

3

Summary

The Nordic–Baltic–Polish cooperative audit on emissions trading was performed in2012 and involved the Supreme Audit Institutions (SAIs) of Denmark, Finland, Latvia,Lithuania, Norway, Poland and Sweden.1The report builds on 13 individual nationalaudit reports.The aim of the cooperative audit was to assess:• the effectiveness of the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) in reducing national greenhouse gas emissions or fostering technology development• the proper functioning of the EU ETS: national registries, greenhouse gas emis-sions permits and emissions reporting• the implementation and administration of Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) and Joint Implementation (JI) programmesThere are clear indications from the cooperative audit that the emissions limitationtargets adopted in the Kyoto Protocol or through the EU Burden Sharing Agreementare likely to be met in all seven countries by the end of the first Kyoto Protocolcommitment period (end of 2012). The countries have implemented the EU ETS inline with the current EU legislation and the provisions under the UNFCCC. However,the effectiveness of the system in reducing emissions is a major challenge. For theNordic countries the EU ETS provided little incentive for long-term reductions in CO2emissions as allowance prices have been low due to a general surplus of allowancesin the system during the period 2008–2012. Taking into account the slower economicgrowth than expected, emissions trading did not provide a strong market mechanismthat has raised the costs of emissions related to production and given a competitiveadvantage to cleaner production.The audits for Latvia, Lithuania and Poland have shown that emissions have increasedat a slower pace than economic growth. However, in this audit it has not been pos-sible to measure whether this can be attributed to the effectiveness of the EU ETS.

Most governments have not used their discretion provided in the EU legislation toauction 10% of the allowances to operators or to set restrictions on the use ofoperators’ revenues from selling allowances. Both of these factors have led to lesscontrol of the system.The EU ETS has been complicated to put into place, but overall the system has beenproperly implemented. Verification procedures for operators’ monitoring and report-ing of emissions are in place. However, the data security of the national registrieshas been challenged by fraudsters. Major concerns relating to IT security have beenaddressed through national initiatives and system changes. The recent centralisationof the registry is expected to strengthen security further.There have been major cases related to cross-border VAT fraud in trading allowances.These were caused by lack of a proper verification of the identity of individuals andby criminals who were abusing normal VAT reimbursement procedures. The identi-fication problems were solved and a temporary change to reverse charge VAT inseveral countries has reduced the risk of fraud, while a long-term and more compre-hensive solution is still to be established.All the Nordic countries have established purchase programmes for CDM and JIprojects. Delivery of credits has generally taken longer than planned. The audit froma host country concluded that the full potential for JI projects has not been realisedyet. Furthermore audits in the Nordic countries have found that better risk assessmentcould improve effectiveness.

1

Estonia participated as a reviewer of the report.

4

EUROSAI WGEA

EMISSIONS TRADING TO LIMIT CLIMATE CHANGE: DOES IT WORK?

5

Acronyms and glossary

AAU– Assigned Amount Unit: a Kyoto Protocol unit equal to one tonne of carbondioxide equivalent. The industrialised countries in Annex I to the United NationsFramework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) are issued AAUs up to thelevel of their assigned amount. AAUs may be exchanged through international emis-sions trading.Allowance– An allowance to emit one tonne of carbon dioxide equivalent during aspecified period. Allowances are part of the EU Emissions Trading System and aretransferable. An allowance from the project-based mechanisms (Clean DevelopmentMechanism and Joint Implementation) is often called credit.Carbon leakage– An increase in emissions outside a country or region as a directresult of a policy to limit emissions in a country or region, for example in the form ofa cap or a tax on emissions.Cap and trade principle –A cap is set on the total amount of greenhouse gasemissions that can be emitted by the installations in the system. Companies receiveemissions allowances within a fixed limit that they can use to compensate for theiremissions, sell or buy. The limit on the total number of allowances available ensuresthat allowances have a value.CDM– Clean Development Mechanism: A mechanism under the Kyoto Protocolthrough which developed countries finance greenhouse gas emission reduction orremoval projects in developing countries.CER– Certified Emission Reduction: A Kyoto Protocol unit equal to one tonne ofcarbon dioxide equivalent. CERs are issued for emission reductions from CleanDevelopment Mechanism projects.CO2– Carbon dioxide: A gas produced by burning carbon and organic compoundsand by respiration. It is the principal anthropogenic greenhouse gas that affects theEarth’s radiative balance.CO2 equivalent –a unit for measurement of greenhouse gas emissions. It states thequantity of a greenhouse gas expressed in terms of the amount of carbon dioxidethat has the same impact on the climate: the impact of, for example, 1 kg of methanecorresponds to 21 kg CO2.

Community Independent Transaction Log– Monitors, registers and validates all trans-actions between accounts in the National registries. Replaced by the European UnionTransaction Log upon activation of the Union Registry.Cost-effectiveness– The degree to which objectives are achieved in comparison torelative expenditure.Credit –refer to “allowance”.Effectiveness– The extent to which objectives are achieved and the relationshipbetween the intended impact and the actual impact of an activity.Efficiency– The relationship between the output, in terms of goods, services orother results, and the resources used to produce them.ERU– Emission Reduction Unit: A Kyoto Protocol unit equal to one tonne of carbondioxide equivalent. ERUs are generated for emission reductions from Joint Imple-mentation projects.ETS– Emissions Trading System: A climate policy instrument based on a cap andtrade principle, aiming to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by providing economicincentives.EU Burden Sharing Agreement– Under the Kyoto Protocol, the pre-2004 EU-15group of Member States has taken on a common commitment to reducing emissionsby 8 % on average between 2008 and 2012, compared to base-year emissions (1990).Within this overall target, differentiated emissions limitation or reduction targetshave been agreed for each of the 15 pre-2004 Member States under an EU accordknown as the “Burden-Sharing Agreement”.EUROSAI– European Organisation of Supreme Audit InstitutionsEUROSAI WGEA –EUROSAI Working Group on Environmental AuditingEU ETS– EU Emissions Trading System, formerly also referred to as Emissions TradingScheme.

6

EUROSAI WGEA

EMISSIONS TRADING TO LIMIT CLIMATE CHANGE: DOES IT WORK?

7

European Union Transaction Log– Automatically checks, records and authorises alltransactions that take place between accounts in the Union Registry.Flexible Mechanisms– The Kyoto Protocol introduced three market-based mecha-nisms, thereby creating what is now known as the “carbon market.”The Kyotomechanisms are: Emissions Trading, the Clean Development Mechanism and JointImplementation.GHG– GreenHouse Gas: Gaseous constituents of the atmosphere, both natural andanthropogenic, which absorb infrared radiation in the atmosphere.Hacking– Unauthorised attempt to bypass the security mechanisms of an electronicsystem.INTOSAI –International Organisation of Supreme Audit InstitutionsIPCC –The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change was set up in 1988 to provideauthoritative scientific assessments on climate change.International Transaction Log– Related to the United Nations Framework Conven-tion on Climate Change, verifies transactions proposed by national registries toensure they are consistent with rules agreed under the Kyoto Protocol.JI– Joint Implementation: A mechanism under the Kyoto Protocol through which adeveloped country can receive emission reduction units when it helps to financeprojects that reduce net greenhouse gas emissions in another developed country.Kyoto Protocol –The Kyoto Protocol was adopted under the United Nations Frame-work Convention on Climate Change in 1997 and sets binding targets for the reduc-tion of greenhouse gas emissions by industrialised countries.LULUCF –Land Use, Land Use-Change and ForestryNational Allocation Plan– Each member of the EU Emissions Trading System has todevelop a National Allocation Plan. The plan defines the total amount of emissionsallowances for a given period and how it intends to allocate these to operators.Operator– A company subject to the EU Emissions Trading System.OECD –The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.Phishing– An attempt to get access to confidential information under the pretenceof being a trustworthy part of the electronic system in question.

Project-based mechanisms– Established under the Kyoto Protocol, see JI and CDM.Reverse charge VAT collection– Value Added Tax collection system whereby thebuyer – and not the seller, as in the general rule – is responsible for calculating andpaying the value added tax on the sales.SAI– Supreme Audit InstitutionsUNFCCC –United Nations Framework Convention on Climate ChangeVAT –Value Added Tax

8

EUROSAI WGEA

EMISSIONS TRADING TO LIMIT CLIMATE CHANGE: DOES IT WORK?

9

rEport

Table of Contents

1 Background.........................................................................................1.1 The EU Emissions Trading System............................................1.2 The Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) andJoint Implementation (JI)..........................................................1.3 Scope of the cooperative audit................................................1.4 Audit methods...........................................................................2 Findings...............................................................................................2.1 The effectiveness of the EU Emissions Trading System inreducing GHG emissions..........................................................2.2 National registries, GHG emissions permits andverification of emissions reporting...........................................2.3 The implementation and administration of CDM andJI programmes...........................................................................3 Conclusions and Recommendations................................................4 Lessons learned.................................................................................5 Acknowledgements...........................................................................6 National Abstracts..............................................................................7 Audit matrix.........................................................................................8 Partners...............................................................................................9 Audit Criteria.......................................................................................9.1 Relevant UNFCCC and EU legislation and audit criteria........9.2 UNFCCC legislation...................................................................9.3 EU legislation.............................................................................9.4 National audit criteria................................................................10 References.........................................................................................

131316181920202941525557587579808081818283

EMISSIONS TRADING TO LIMIT CLIMATE CHANGE: DOES IT WORK?

11

1 Background

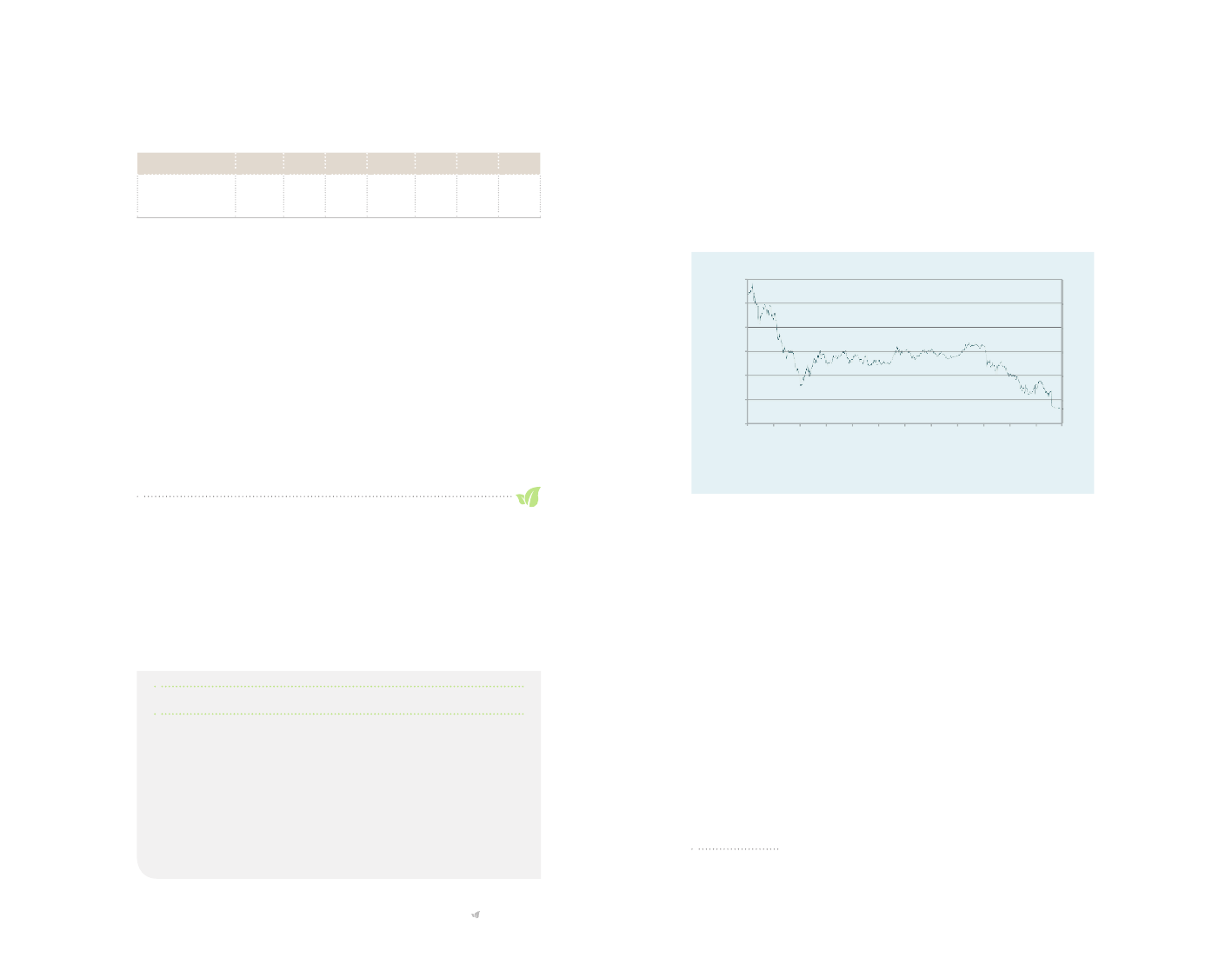

1.1 the EU Emissions trading SystemThe Kyoto Protocol under the United Nations Framework Convention on ClimateChange (UNFCCC) has worked out the so-called flexible mechanisms to meet nationalemissions targets. These mechanisms consist of Emissions Trading Systems (ETS),the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) and Joint Implementation (JI). The KyotoProtocol provides individual country targets for greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.2The EU has within the framework of the Kyoto Protocol established an EmissionsTrading System (EU ETS) as a key policy instrument to mitigate GHG emissions. Figure1 illustrates the relation between the EU ETS and non-ETS sectors and the differentKyoto mechanisms.

Figure 1: The relation between the EU ETS and non-ETS sectors

Kyoto target

Emissionstrading sector

Non-emissions-trading sector

Domestic emission reductionsGopu vernrch meas nteFlexible mechanisms- Emissions trading- Project mechanisms(JI, CDM)Sector policies- Transport- Agriculture- Waste-…2The pre-2004 15 EU Member States are committed to reducing their average emissions by 8% in theperiod 2008–2012 compared with base year levels (1990). For the EU to reach its reduction targets, in1998 a political agreement was reached to divide the burden of reaching this target unevenly amongMember States.

EMISSIONS TRADING TO LIMIT CLIMATE CHANGE: DOES IT WORK?

13

The EU ETS is one of the cornerstones in the EU “20-20-20” energy and climate target.Its purpose is to reduce GHG emissions in a cost-effective and economically efficientmanner. It is based on the “cap and trade” principle. The cap represents the amountof total allowed emissions for the system as a whole and for each installation emittingGHG. That means that the effectiveness of the system is in principle equal to the totalemissions reductions according to the cap. One carbon credit unit, or emissionsallowance, is the right to emit one tonne of CO2equivalent.The EU implemented its first ETS in 2005. In 2008 the system was expanded. TheETS now operates in 30 countries (the 27 EU Member States, Iceland, Liechtensteinand Norway). The system covers GHG emissions from installations such as powerplants, combustion plants, oil refineries and iron and steel works, as well as factoriesproducing cement, glass, lime, bricks, ceramics, pulp, paper and board. The instal-lations currently in the system account for almost half of the EU’s CO2emissions and40% of its total GHG emissions.If the operator has a deficit of allowances in relation to its emissions, the operator canbuy more allowances on the market. If the operator has a surplus of allowances, theoperator can sell them. The cost of buying allowances is meant to trigger investmentsthat will reduce emissions, or reduce the demand for carbon-intensive products. Theprice of allowances is determined by the market (supply and demand). The numberof allowances in the ETS is consequently an important factor for its effectiveness.National Allocation Plans (NAPs) set out the total quantity of allowances that govern-ments grant to operators in the first (2005–2007) and the second (2008–2012) tradingperiods. Before the start of these periods, each country had to propose how manyallowances to allocate in total for the trading period and the amount each installationwould receive. The plans were subject to approval or rejection by the EuropeanCommission or the EFTA Surveillance Authority. For the 2008–2012 trading periodthe cap corresponds to the sum of allowances in the NAPs which have been approved.The total number of allowances in the EU ETS can only be changed if the cap in theEU ETS is modified. Operators may, however, buy CDM and JI credits up to a certainlimit – and in this way the actual number of allowances in the EU ETS is increasedabove the cap.From 2012 the EU ETS also covers airlines. When the third trading period (Phase III,2013–2020) starts, the system will be extended to cover more sectors, petrochemicals,ammonia and aluminium industries and to additional gases. Further, the EU sets thecap for each Member State and allocates free allowances to the Member States. InPhase III the EU has put in place a single European cap on emissions in the ETS. TheEuropean Commission has proposed to amend the ETS Directive to postpone someof the allowances to a later part of Phase III in order to increase the allowance pricesin the first part of Phase III by limiting supply.3

During Phase II operators could receive their allowances free of charge from thestate, or buy some of them. For the trading period 2008–2012, at least 90% of theallowances had to be allocated free of charge. The remaining allowances could besold, by for example auctioning. Within the EU, six Member States have informedthe European Commission that they would auction allowances. In Phase III the EUexpects to give half of the allowances away for free and auction the other half.Operators must be in possession of a GHG emissions permit including a monitoringplan which defines the methods for measurement or calculation of emissions. Athorough assessment of operators’ GHG emissions permit applications is essentialin order to provide a sound basis for subsequent emissions reporting.Correct emissions monitoring and reporting is the basis for operators’ annual allow-ance settlement, but also the basis for future allocation periods on an aggregatedcountry level as well as on the operator level. Adequate verification of emissionsmonitoring and reports is therefore crucial. The Commission has within the frameworkof the ETS Directive adopted repor ting guidelines for GHG emissions. The Directive(Article 14 ) requires governments to ensure that operators of installations monitorand report their GHG emissions in accordance with these guidelines. Operators haveto submit emissions reports electronically each year within a fixed deadline. Thecompetent authority for GHG emissions has then to verify these reports and approvethe amount of reported emissions. Operators must surrender the equivalent numberof allowances by 30 April of the same year.Each state participating in the EU ETS must operate a national ETS registry. Theregistry system is similar to a banking system, which keeps track of the ownership ofmoney in accounts, but does not look into the deals that lead to money changinghands. To participate in the EU ETS, a company or a natural person must open anaccount in one of the national registries.These registries are online databases that record:• accounts to which allowances have been allocated• transfers of allowances (“transactions”) performed by account holders• annual verified GHG emissions from installations• annual reconciliation of allowances and verified emissions, where each operatormust have surrendered enough allowances to cover all its emissionsThe National registry shall ensure the accurate accounting of allowances as well asthe accuracy of data, the security of data storage and exchange, and the transparencyand auditability of transactions. Given the significant monetary value of the ETS forboth the state and the operators, it is paramount that the national registry is secureand functioning properly. In addition, well-functioning control mechanisms and trans-parency are important factors to instil confidence in the system. The trust worthiness

3

Commission prepares for change of the timing for auctions of emissions allowances.News article, 25 July2012.

14

EUROSAI WGEA

EMISSIONS TRADING TO LIMIT CLIMATE CHANGE: DOES IT WORK?

15

of the EU ETS depends on its capacity to protect itself from different kinds of fraud,such as hacking4, phishing5and VAT fraud.

Box 1:COUNTRIES WITh qUANTIFIED COmmITmENTSIn July 2012, the national registries have been replaced by a single EU registry oper-ated by the European Commission. The European Union Transaction Log (formerlyCommunity Independent Transaction Log) records and authorises all transactionsthat take place between accounts in the EU ETS registries. This verification is doneautomatically and ensures that any transfer of allowances from one account to anotheris consistent with the EU ETS rules.Industrialised countries listed in Annex I to the UNFCCC, which have accepted emissions targets for the period 2008–2012 in ccordance awith the Kyoto Protocol. They include • most of the original OECD members, except USA and Canada (including Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden)• he European Union members, except Cyprus and Maltat• countries with economies in transition including Latvia, (Lithuania and Poland)Of the countries participating in this audit, in particular Latvia, ithuania Land Poland are otential sellers pof allowances and hosts of JI Icelandprojects. Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden are potential buyers of credits from CDM and JI projects.NorwayEstoniaSwedenLatviaDenmarkIrelandUnitedKingdomLithuania

1.2 the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) andJoint Implementation (JI)The so-called project-based Kyoto mechanisms, CDM and JI, allow for the use ofcertified reductions from third countries to meet own emissions targets. These arebased on the principle that it does not matter for climate change where the GHGemissions occur, and that emission-reducing measures can be implemented wherethey give the greatest emissions reduction per unit of money invested. The purposeof the CDM is to assist countries without quantified commitments in achieving sustain-able development and in contributing to the ultimate objective of the UNFCCC, aswell as to assist the Annex I Parties under the UNFCCC (see box 1) in meeting theirquantified emission commitments. It is also a goal of the Kyoto Protocol that CDMprojects should result in real, measurable, long-term benefits and reductions inemissions which are additional to any that would have occurred in the absence ofthe certified project activities. JI, like CDM, is a project-based mechanism, but JIprojects are carried out in countries with quantified commitments under the KyotoProtocol (see box 1).The Parties to the Kyoto Protocol have adopted detailed rules for the verification ofCDM and JI projects. All CDM projects must go through an extensive certificationprocess in which emissions reductions and their contribution to sustainability in thehost country must be documented. This process is intended to ensure that projectsare implemented in accordance with CDM regulations negotiated by the parties tothe Kyoto Protocol. The project must be approved by an external designatedoperational entity, by the CDM Executive Board appointed by the UNFCCC and bythe host country. The CDM Executive Board evaluates and certifies projects. Anexternal certified company checks the project at two different stages: on validationand on verification. A similar system is in place for JI projects.

Finland

Russia

■ ountries potentially Chosting JI projects■ ountries potentially Cbuying JI and CDM credits

Belarus

NetherlandsGermanyBelgiumLuxemburg

PolandUkrainaCzech RepublicSlovakiaMoldova

FranceSwitzerland

AustriaSloveniaCroatia

HungaryRomania

SerbiaBosnia &HerzegovinaItalyPortugalMontenegroKosovo

Bulgaria

MacedoniaSpainAlbaniaGreeceTurkey

45

Hacking attacks may occur if internal security is not strictly ensured such as by logging into an unsecu-red network.Phishing is attempting to acquire account holders’ user names and passwords under the pretence ofbeing a trustworthy part of the electronic system, and thus gain access to the system.

16

EUROSAI WGEA

EMISSIONS TRADING TO LIMIT CLIMATE CHANGE: DOES IT WORK?

17

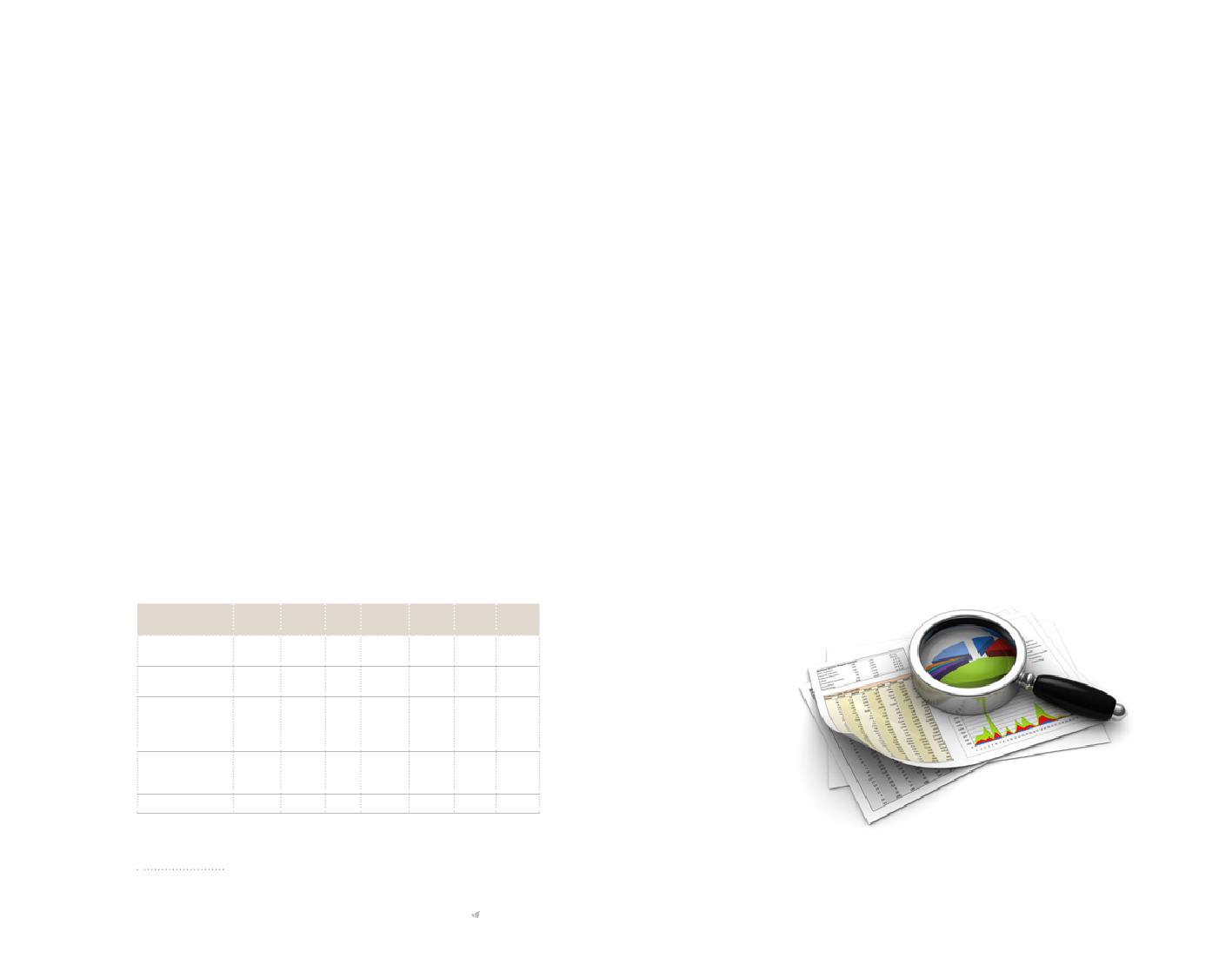

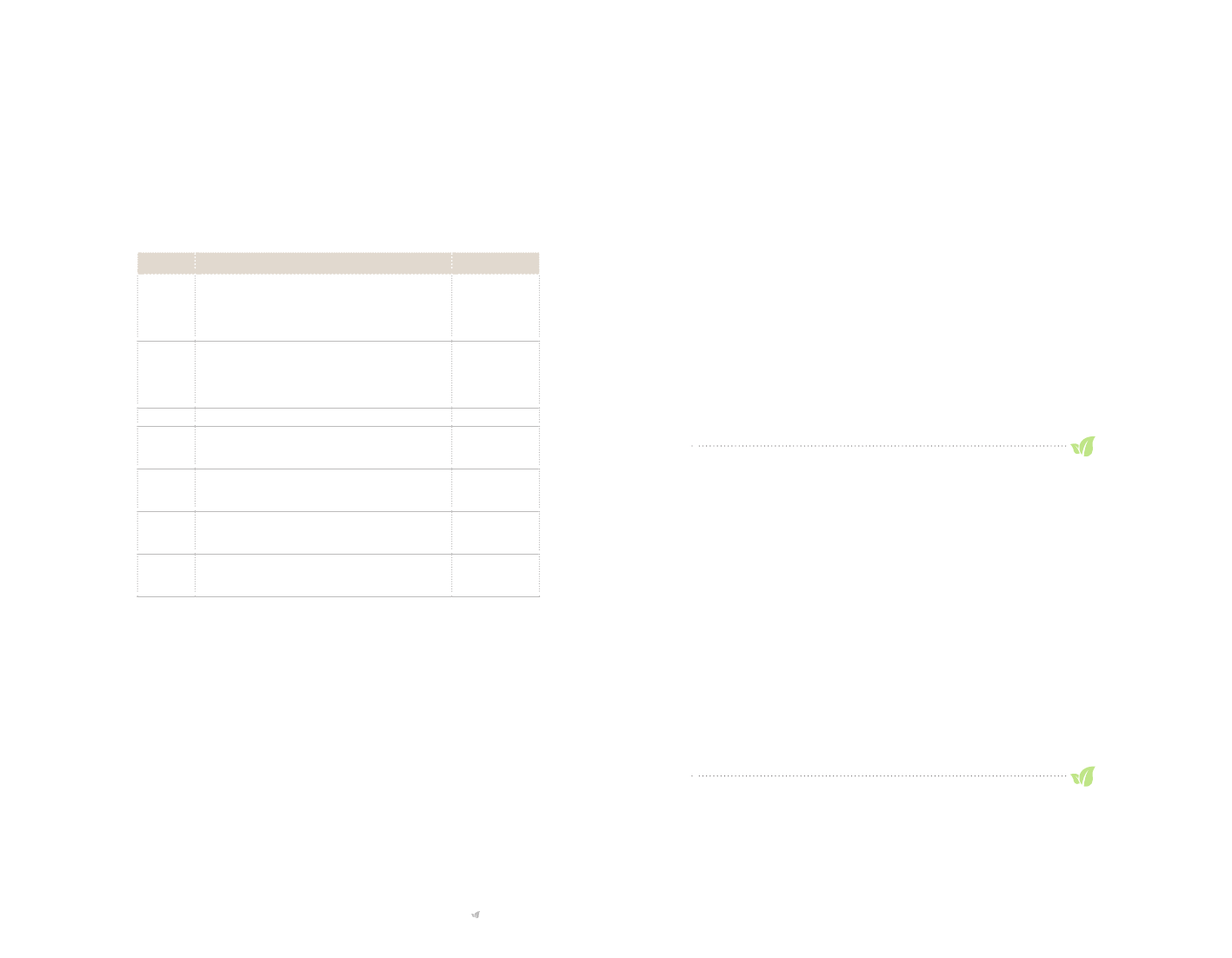

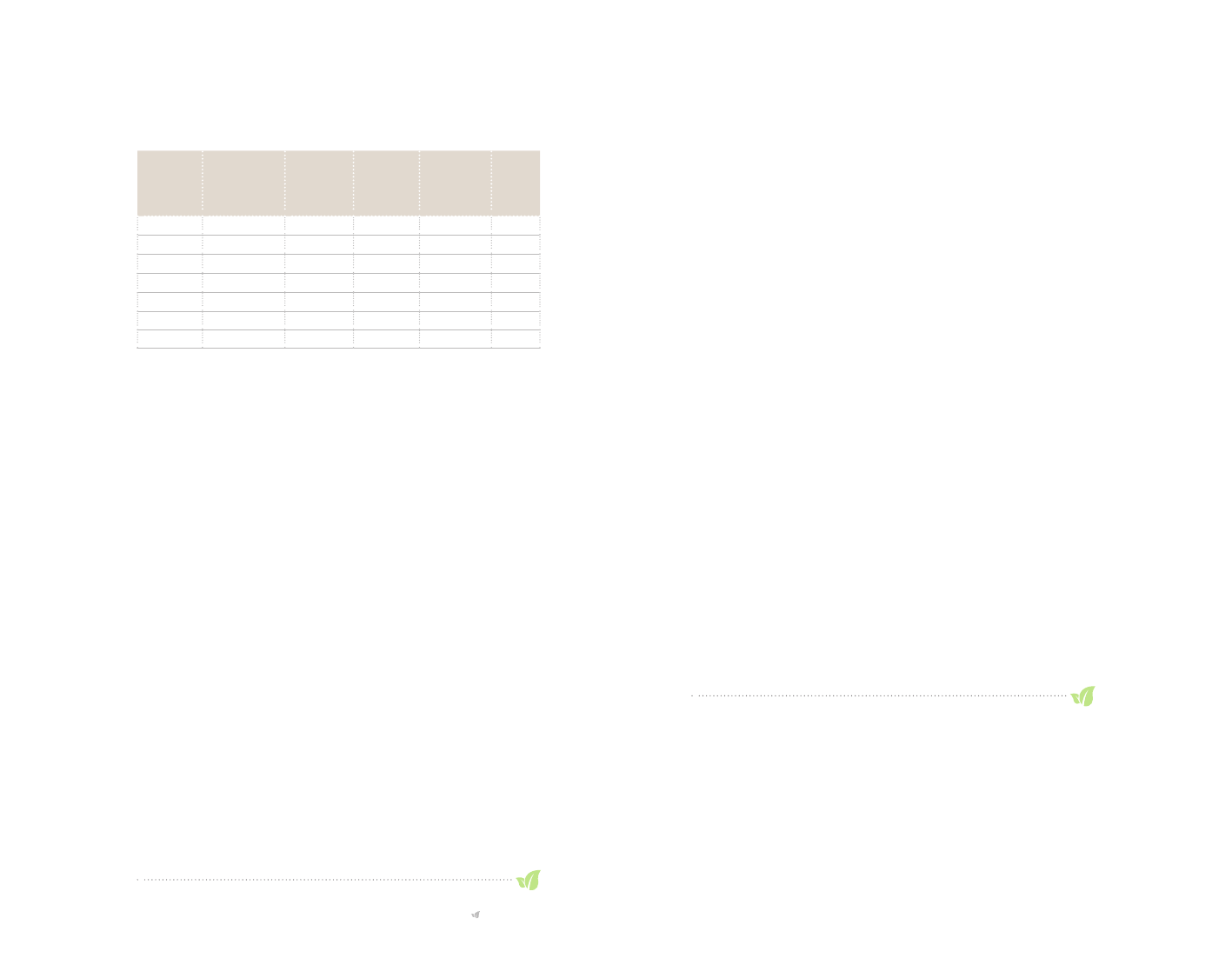

1.3 Scope of the cooperative auditThe aim of the cooperative audit was to assess:• the effectiveness of the EU ETS in reducing national GHG emissions or fosteringtechnology development• the proper functioning of the EU ETS: national registries, GHG emissions permitsand emissions reporting• the implementation and administration of CDM and JI programmesThe audit has focused on the first commitment period of the Kyoto Protocol and thesecond phase of the EU ETS, i.e. 2008–2012.The scope of the individual audits of the participating SAIs naturally varies, as bothrisks and implementation differ between the countries. An overview of the scopeand time of audits is provided in table 1. Abstracts of the individual national auditsare provided in chapter 6.• All partner countries to the audit except Finland have audited effectiveness interms of either emissions target achievement or emissions trading as a means toachieving the target.• Registry systems were audited by Denmark, Latvia, Lithuania, Norway and Polandand emissions reporting by Latvia, Lithuania, Norway and Poland.• The implementation and administration of CDM and JI programmes were auditedby all partner countries, except Latvia6. Denmark only audited the contribution inthe form of credits from CDM/JI projects.

1.4 Audit methodsCooperative auditThe overall findings, conclusions and recommendations as well as the case studiesin this report are based on the SAIs’ answers to a set of common audit questions(see chapter 7) and on the national audit abstracts. Supplementary information hasbeen provided by SAIs on request. The interpretation and incorporation of theindividual national findings in the cooperative audit’s findings, conclusions andrecommendations have been quality controlled by each individual SAI.

National auditsThe national audits’ approaches, including audit criteria, methodology, quality controland publication of the national results, have been carried out in accordance with thecountries’ standard procedures. The audit criteria applied in the national audits arebased on national criteria, EU legislation and international commitments. The commonbasis for the audit criteria is provided in chapter 9. The actual criteria used can varyfrom audit to audit. Standard auditing methodologies like interviews, documentanalysis, spot checks and questionnaires have been applied.

Table 1: Partner countries’ auditsDenmark Finland Latvia Lithuania Norway Poland SwedenNational targets /Kyoto ProtocolEffectiveness ofemissions tradingImplementationand admini-stration of CDM/JI programmesEmissionsreporting andregistriesNo. of reports2011201220122009 +follow-up in201120112011201120082012201220102010201020092012200920122012200920122011

2012

2012

2009201223

2

1

1

2

2

6

Where there are no accepted CDM and JI programmes.

18

EUROSAI WGEA

EMISSIONS TRADING TO LIMIT CLIMATE CHANGE: DOES IT WORK?

19

2 Findings

2.1.1 targets under the Kyoto protocol and the EU BurdenSharing Agreement are likely to be metThe cooperative audit shows that in some of the countries, the EU ETS is a significantmechanism in reaching the Kyoto Protocol targets. Overall, the EU has a reductiontarget of 8%, with individual country targets according to the EU Burden SharingAgreement (see table 2).

2.1 the effectiveness of the EU Emissions tradingSystem in reducing GHG emissionsIn order to assess the effectiveness of the EU ETS in reducing GHG emissions, thefollowing audit objectives have been addressed:1.2.3.Will the countries fulfil their GHG emission targets under the Kyoto Protocol forthe period 2008–2012?Has the EU ETS given incentives for operators to invest in GHG emission reduc-ing technologies?Has the implementation of the EU ETS in each country been conducive to ensureeffectiveness?

Table 2: GHG emissions and Kyoto Protocol targets (excluding LULUCF)Change Base year Target emissions 2008–2012, base %-change year– (Mill. 2008 tonnes CO2 base year equi-(%)valents)DenmarkFinlandLatviaLithuaniaNorwayPolandSweden707127495056473-210-8-8+1-6+4-7.1-0.2-55.8-51.0+8.1-28.9-12.6Change base year– 2009 (%)-11.3-6.0-58.7-59.1+3.3-32.3-18.0Change Emissions Emissions Emissions base 20082009 2010year– (Mill. (Mill. (Mill. 2010 tonnes CO2 tonnes CO2 tonnes CO2 (%)equi-equi-equi-valents)valents)valents)-10.5+6.0-54.5-57.1+8.2-28.9-9.0657012245440164626611205238260637512215440166

Box 2:EFFECTIvENESS OF ThE EU ETS IN REDUCING GhGEmISSIONSIn assessing the effectiveness of the EU ETS in reducing GHG emis-sions, two factors have been examined:- hether the objectives of the system in terms of reaching the GHG wemission targets have been achieved- hether the achievement of the objective of reaching the GHG emis-wsion targets can be attributed to the EU ETS

Source: Annual European Union greenhouse gas inventory 1990–2010 and inventory report 2012.Technical report No 3/2012. The European Environment Agency, 27 May 2012 and UNFCCC.

Table 2 shows that the emissions from Latvia, Lithuania and Poland have been sub-stantially below the average target each year from 2008–2010. It is therefore practi-cally certain that these countries will meet the target. For the participating Nordiccountries, except Sweden, actual emissions in the period 2008–2010 have been eitherabove or close to the target. However, the final accounts indicating whether thesecountries will meet the target will not only depend on national emissions reductionsin the remaining part of the period, but also on the countries’ use of the flexiblemechanisms. The audits show that in these countries, overall the reduction targetsare likely to be met by a combination of the EU ETS and the other flexible mechanisms.Whether the countries will meet the target for 2008–2012 cannot be assessed defi-nitely until data for the remaining part of the period are available.The EU ETS covers substantial parts of emissions from different sectors (see chapter 1)but its scope varies between the countries. Table 3 shows that the ETS sectors arerelatively biggest in Finland and Poland and relatively smallest in Latvia and Lithuania.In Finland, annual emissions vary considerably, e.g. depending on weather conditions.In 2010, the emissions in Finland were unusually high due to a shortage of hydroelectricpower in the Nordic electricity market.

20

EUROSAI WGEA

EMISSIONS TRADING TO LIMIT CLIMATE CHANGE: DOES IT WORK?

21

Table 3: Per cent of GHG emissions covered by the EU ETS in 2010 (% of total emissions excluding LULUCF)Denmark Finland Latvia Lithuania Norway Poland Sweden% of GHGemissions coveredby EU ETSSource: The SAIs

43%

55%

27%

31%

36%

50%(CO2only)

34%

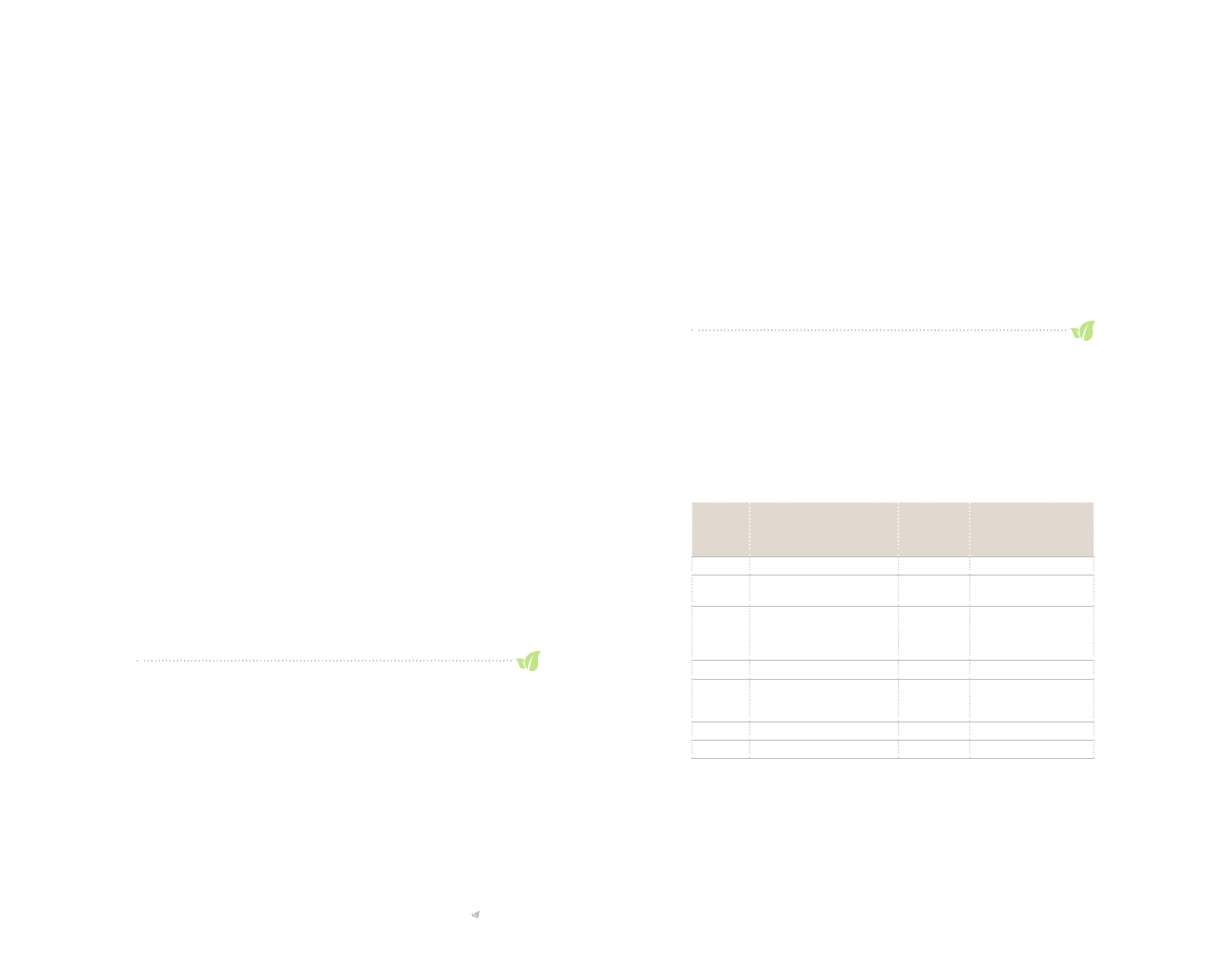

Figure 2 shows the actual price of allowances in Phase II of the EU ETS. The price ofallowances was only for a short period, in 2008, above EUR 20. After this, the pricestabilised at around EUR 15 from end of 2008 until mid-2011. Since second half of2011, the price has gradually decreased to below EUR 5. By the beginning of December2012 the price was EUR 6.

Figure 2: The price of allowances 2008–2012 (EUR)

Table 3 shows that the EU ETS covers a large share of emissions in all countries. Case1 shows that the ETS sector in Denmark has contributed to the overall GHG emissionsreductions with a share which is in line with what was expected in the NationalAllocation Plan (NAP).

30252015

Case 1:

Expected and actual share of emissions from the ETSsector in Denmark are the same

1050

In Denmark, the actual share of GHG emissions from the ETS sectors was 43%in 2010, almost the same as the expected share for the period 2008–2012, whichwas 44%. The Danish audit concludes that this is more likely because of theeconomic crisis than because of the EU ETS.

1

8

0

0

1

9

9

08

10

11

201y2Ju

09

01

00

01

00

00

01

20

01

20

20

20

y2

y2

r2

y2

r2

r2

ne

r2

ne

ne

be

be

ar

ne

be

be

ar

ar

Ju

ru

Ju

Ju

to

ru

to

ru

to

to

Ju

Feb

Oc

Feb

Feb

Source: Thomson Reuters

2.1.2 In some countries, the EU EtS has not providedadequate incentives for operators to invest in GHG emissionreducing technologyThe price of allowances has been lower than expectedFor the EU ETS to have long-term effects on GHG emissions, it should lead to moreclean technology investments than would have been the case without the ETS.

A Green Paper7from the European Commission from 2000 estimated that a price ofEUR 33 is necessary to make the EU ETS effective. The expected price of allowancesused when Denmark drew up its NAP was EUR 20. Thus, the actual allowance pricehas – with an exception of a short period – been lower than the price projected toensure the effectiveness of the system.According to a EU Commission working document8, it is likely that the financial crisisis the main reason for the low price of allowances compared with the projected price.The crisis has led to lower than expected industrial production, which again has ledto a lower demand for allowances.Case 2 from Denmark and Norway illustrates that alternatives to buying allowancesmay be more costly. Furthermore, replacing the previous tax system with the EU ETShas resulted in fewer incentives to reduce domestic emissions in Norway. Case 3from Sweden illustrates that due to the low prices in the EU ETS the Swedish ETScompanies pay considerably less for their emissions than the companies outside theETS.78Green Paper ( COM(2000) 87 final) on greenhouse gas emissions trading within the European Union.Brussels, 8.3.2000.The EC Staff Working Document (2012) 234 final, 25.7.2012.

Box 3:ECONOmIC INCENTIvES TO REDUCE EmISSIONSAccording to standard economic theory, if reducing an operator’s emissions is cheaper than the price of allowances, the operator has an incentive to reduce GHG emissions and sell possibly freely allocated surplus allowances rather than buying extra allowances. On the other hand, if reducing GHG emissions costs more than the price of allow-ances, it is in the interest of the operator to buy allowances corre-sponding to its emissions. In these considerations, the operator will also have to assess the need for reductions under future ETS systems.

22

Feb

Oc

Oc

Oc

ru

ar

ne

20

12

EUROSAI WGEA

EMISSIONS TRADING TO LIMIT CLIMATE CHANGE: DOES IT WORK?

23

Case 2:

Alternatives to buying allowances are moreexpensive

Case 4:

Carbon tax on Norwegian petroleum activities hasreduced the growth in emissions

Estimates from the Danish audit (2012) on Denmark’s GHG emissions reductionsshow that the price of allowances needed to be considerably higher than EUR20 for it to have been cost-effective for energy-producing enterprises to investin land wind energy instead of coal.In Norway the EU ETS has replaced a CO2tax in several sectors. The audit from2010 concluded that the current price of allowances gives weaker incentivesfor implementation of national measures in most sectors than the tax did,because the tax implied a price of emissions which was higher than the currentallowance price. The effect of the ETS in reducing national emissions wasestimated to only 0–0.5 mill. tonnes per year.

Energy generation causes about 90% of the emissions from Norway’s petroleumsector. A CO2tax on petroleum activities offshore was introduced in Norwayin 1991. The 2010-audit found that this tax level translates into a cost per tonneof CO2emitted that is higher than in other sectors. In addition, emissions fromthis sector have been lower than they would have been without the tax.Operators report that measures to improve energy efficiency have beenmotivated by taxation. The audit found that this effect has decreased in recentyears because available reduction measures are no longer considered cost-effective by the companies.

Allocated allowances have exceeded actual emissions

Case 3:

Polluters’ costs for emissions in Sweden

Both the EU ETS and the CO2tax provide a price on CO2emissions,but companies in the trading sector have in practice paid very little, in somecases nothing, for emissions. This is due to reductions in and exemptions fromclimate-related taxes. This is also due to Swedish companies having obtaineda completely free allocation of more allowances than they have needed (seecase 6).In principle the CO2tax was abolished for Swedish companies within the ETSfrom 2011. For companies outside the ETS, the CO2tax has been increasedduring 2010–2015. According to the Swedish NAO’s calculations, Swedishcompanies in the trading sector are expected to see a decrease in expenditureon CO2tax of EUR 750 mill. per year for the period 2009–2015. In the non-trading sector, the companies are expected to see an increase in expenditureon CO2tax of EUR 209 mill. per annum during the same period.

Table 4 and 5 show the projected emissions compared to the allocations requestedby each country from the European Commission, as well as the allowances allocatedin the ETS sectors for each country.

Table 4: ETS Phase II: Projected emissions compared to requested allowances and allocated allowances. Annual average 2008–2012. Mill. tonnes CO2 equivalents Projected GHG emissions in Allocations Actually allocated the ETS sectors as submitted asked for by allowancesto the European Commission the countryfrom each countryDenmarkFinlandLatvia29.745.3(average per year 2008–2011)6.2524.539.66.2523.937.63.4(until 31 July 2011)*6.25(as per 1 Aug. 2011)*8.815.0*(of which 6.3 wereauctioned)205.6 *22.5 **Including reserve for new entrants

LithuaniaNorway

18.421.0(2010)208.5 (including new entrants)27.1

16.615.0

Carbon tax could be effective in reducing growth in emissionsCase 4 from Norway shows that a higher tax – and thus a higher price on emissions– provides an incentive for companies to invest in emissions-reducing technologies.PolandSwedenSource: The SAIs

208.525.2

In Phase II each country decided the total amount of allowances for its ETS sectors asa whole in its National Allocation Plan. The replies from the countries show that themethodologies used to calculate projected emissions and decide the total quantityof allowances differ between the countries. For most countries, the amount of allow-ances asked for were lower than the projected emissions and the finally approved

24

EUROSAI WGEA

EMISSIONS TRADING TO LIMIT CLIMATE CHANGE: DOES IT WORK?

25

number of allowances were the same as or lower than the amount asked for. All planshave been approved by the European Commission or the EFTA Surveillance Authority.Exept for Norway, Denmark (2008–2010) and Finland (2010), table 5 shows thatallocated allowances have been higher than the actual GHG emissions in the ETSsector taken together for all of the countries in all four years.

The audits for Latvia, Lithuania and Poland have shown that emissions have increasedat a slower pace than economic growth. However, in this audit it has not been possibleto measure whether this can be attributed to the effectiveness of the EU ETS.

2.1.3 the governments have not designed the parts of thesystem under their discretion optimallyIn general, all allowances were handed out for freeIn Phase II, each country decides the amount of allowances to be allocated to thesectors which are part of the ETS and, within the framework of the ETS Directive,whether the allowances are handed out for free to individual operators or auctioned.Governments in six out of seven countries handed out allowances for free, therebyreducing their own control over the system. Only Norway auctioned a large share ofits allowances. (See cases 5 and 6).

Table 5: Allocated allowances for EU ETS Phase II compared with actual emissions. Mill. tonnes CO2 equivalentsAllocated allowances for ETS Phase II, average per year, including reserve according to the NAPDenmarkFinlandLatvia24.537.6Actually allocated allowances for 2008–2011, average per yearActual emis-sions 2008Actual emis-sions 2009Actual emis-sions 2010Actual emis-sions 2011

23.937.6

26.5362.7

25.534.42.5

25.341.53.2

21.535.12.9

3.43.4(until 31 July 2011) (until 31 July 2011)6.254.41(as per 1 Aug.(as per 1 Aug.2011)2011: informationat 4 July 2012)8.8415208.522.52,0816.07.9204.022.21,983

Case 5:

Allocation of allowances in Norway

According to the EU ETS Directive, at least 90% of the allowanceswill be allocated free of charge. Norway, as an EEA/EFTA country, has beenexempt from this provision for the period 2008–2012. Norway decided to sellapproximately half of the allowances. No free allowances were allocated in thepetroleum sector.

LithuaniaNorwayPolandSwedenEU ETSoverall –for com-parison

6.119.3204.120.12,120

5.819.2191.217.51,880

6.419.4199.722.71,938

5.619.2203.019.81,854

Source: Data provided by each SAI and EC home page (http://ec.europa.eu/clima/policies/ets/registries/documentation_en.htm and http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-07-1614_en.htm )

When actual emissions are below the allocated allowances, there is no incentive forthe operators to buy extra allowances. Thus in the present Kyoto period (2008–2012),the operators have had very limited need to buy extra allowances or invest inemissions-reducing technologies. However, there is no accurate information onwhether the reductions have been achieved via lower production, investment in cleantechnology or by other means. As is seen in table 5, an average total of 1,983 mill.allowances have been allocated for the period 2008–2011, while actual emissionshave been on average 1,948 mill. tonnes per year. In Denmark, the amount of allow-ances allocated free of charge was 97% of the actual emissions in the period2008–2011.

26

EUROSAI WGEA

EMISSIONS TRADING TO LIMIT CLIMATE CHANGE: DOES IT WORK?

27

Case 6:

Surplus of allowances in Sweden

Every year from the start of the ETS in 2005, the trading sector inSweden has been allocated far more allowances than it has required. Due tothis, some installations and trade and industry sectors may have receivedconsiderable income without having had to take action to reduce emissions.To date, the surplus of allowances that have been allocated free of charge toSwedish companies has constituted a redistribution of capital which can beestimated to a value of approximately EUR 104 mill. per trading period. Compa-nies in certain trade and industry sectors have, however, had to purchaseallowances.

Case 7:

Not all operators spent revenues on emission-reductions measures in Latvia and Lithuania

The Latvian SAI collected information from a sample of energy operatorsregarding their use of revenues from the sale of allowances in Phase I from2005 to 2007. This showed that 17% of the energy sector operators in the sampleused the revenues to cover expenses which were not related to the reductionof GHG emissions.During the audit, tariff calculation methodologies for heat energy and cogen-eration envisaged that operators must use the revenue from emissions tradingto cover the costs of emissions reduction, such as renovating existing equipmentand purchasing of new equipment; these costs must not be included in therelevant tariff. After publishing the audit report, which included findings of alack of control over correct use of profits, the Public Utilities Commissionamended the tariff calculation methodologies and abolished the requirementthat the revenue from emissions trading must be used to cover the costs ofemissions reduction, arguing that the EU legislation does not prescribe theobligation to invest revenues from emissions trading to cover the costs ofemissions reduction.In Lithuania, in 2009 two operators did not spend the revenues as required.One operator did not provide complete information on received and usedincomes. In 2010, two operators did not submit required information to theMinistry of Environment.

Limited possibility to withdraw allowances In five of the countries, if an operator does not use its production capacity as fullyas assumed in the NAP, the operator is free to sell unused allowances. In two othercountries, allowances can be cancelled or given to other operators in some cases:in Finland cancelled in case of malpractice, and in Lithuania if the operator goesbankrupt. In Norway, the annual allocation is conditional on the operator holding avalid pollution permit and not having ceased activity. In Sweden, if an operator’spollution permit is revoked, the remaining yearly part of the allowances attributedto that operator may not be issued.

Few restrictions on the use of revenues from the sale of allowances In all of the partner countries to this audit except for Lithuania, private enterprisesmay use profits from selling allowances as they wish. This is in line with the marketprinciple the system is based upon. However, private enterprises in Lithuania andpublic operators in Latvia and Lithuania must use revenues from the sale of allowancesto invest in emissions reductions. In these two countries, some investment in emis-sions-reducing technologies is ensured to the extent that operators have sold allo-wances and that there is adequate control of the correct use of the profits. However,audits from the two countries conclude that the governments cannot prove that thecontrol is adequate. Furthermore, one of the audits concluded that not all operatorsspent the revenues as required, i.e. on emissions-reduction measures, nor did theyall report in line with requirements. This is demonstrated by case 7 from Latvia andLithuania.The Latvian audit has shown that in public service sectors, competitive conditionsare not fully met, and therefore it is easy for enterprises to transfer costs of buyingallowances to electric and heating energy consumers instead of investing in emissionsreductions. Consequently enterprises in public service sectors are not always moti-vated to find the cheapest ways of reducing emissions themselves, contrary to theETS basic principle.

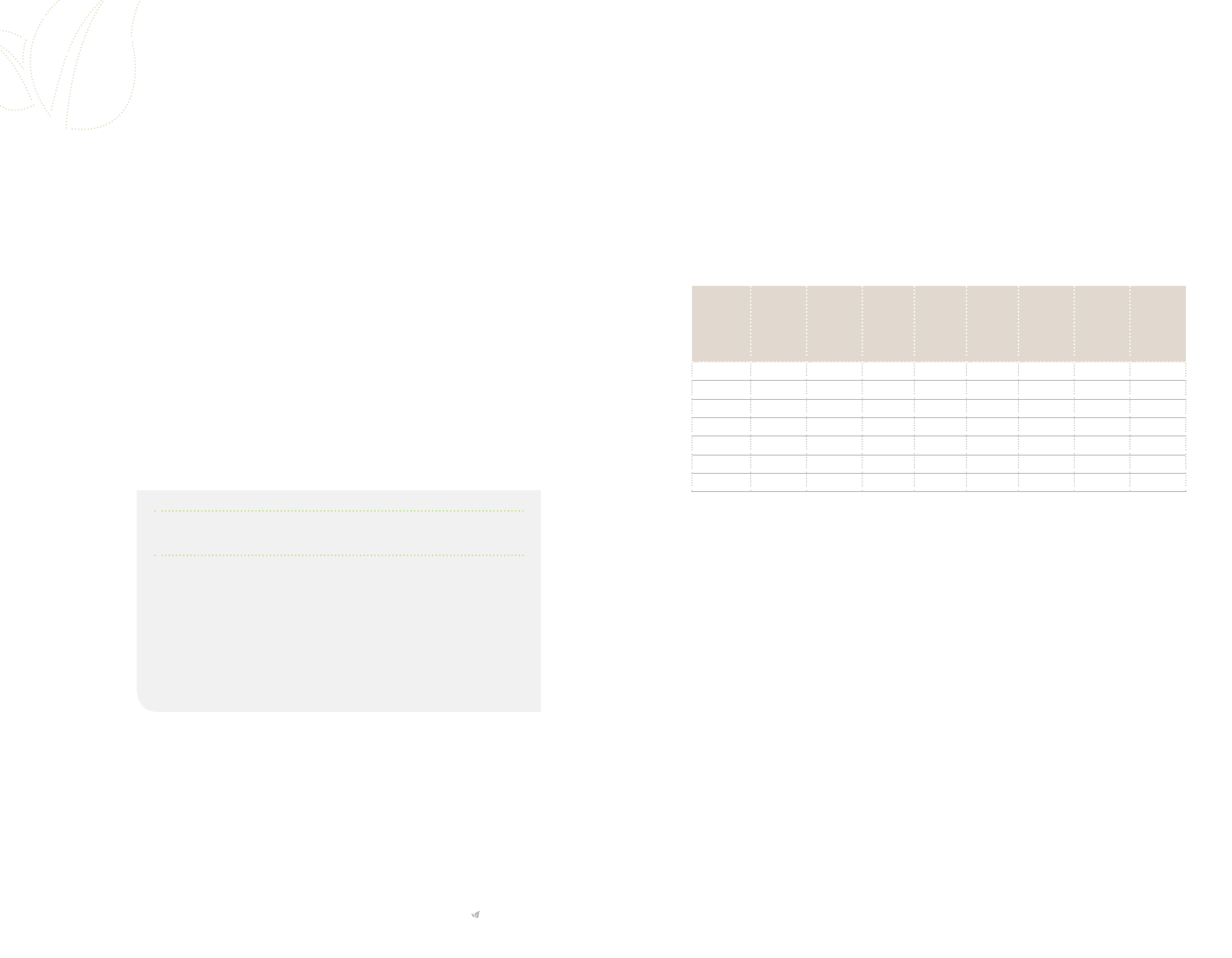

2.2 National registries, GHG emissions permitsand verification of emissions reportingCountries participating in the EU ETS must operate a national ETS registry, issueGHG emission permits to operators and verify emissions reporting. The objectiveof this part of the cooperative audit is to assess:• whether all relevant operators are issued a GHG emissions permit and monitoringplan, and are allocated a correct number of allowances• whether the national registry operates properly and securely• whether the issue of fraud has been dealt with• the adequacy of the emissions monitoring and reporting by operators

28

EUROSAI WGEA

EMISSIONS TRADING TO LIMIT CLIMATE CHANGE: DOES IT WORK?

29

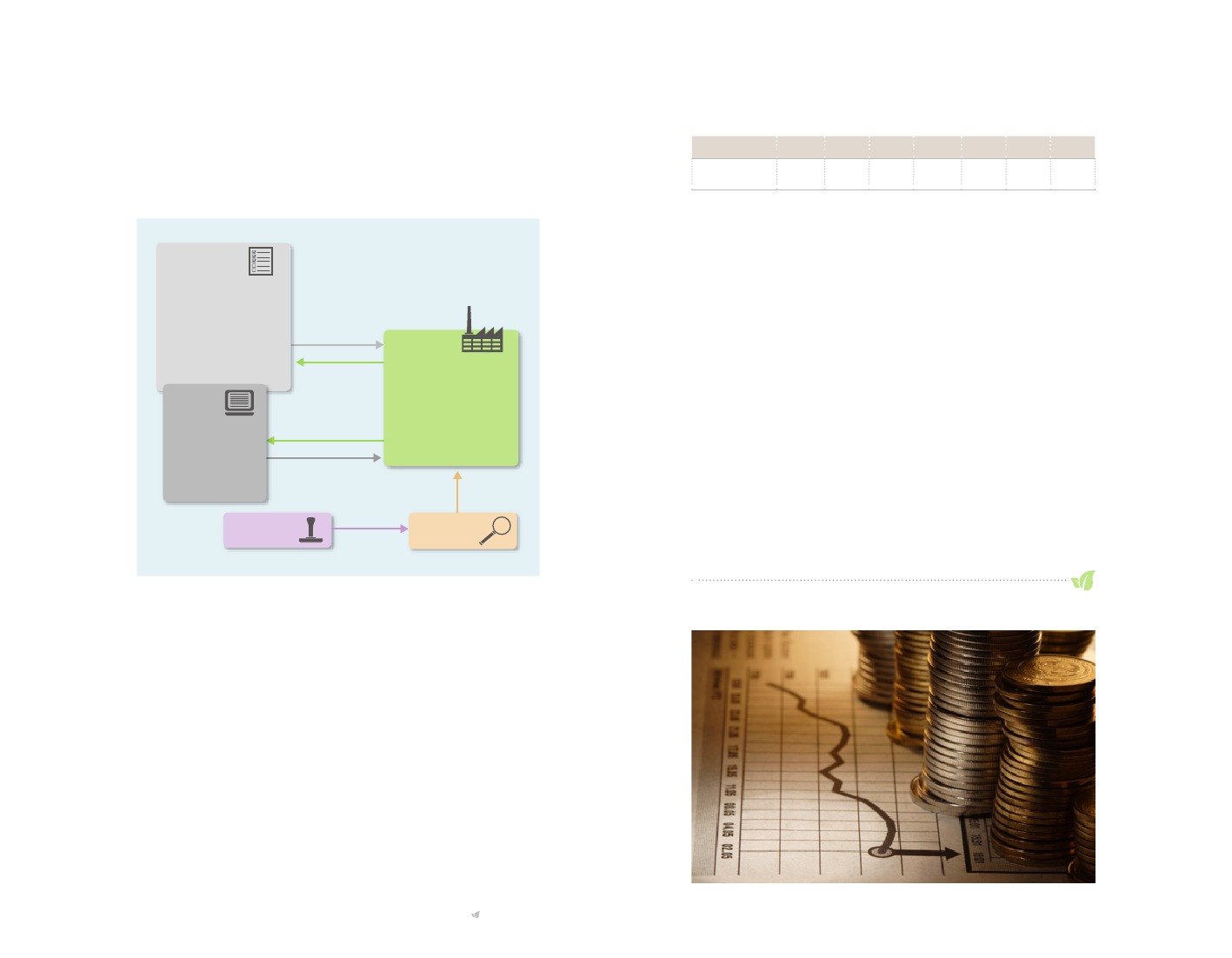

The organisation for issuing GHG emission permits and verifying emissions report-ing is illustrated in figure 3, showing the roles of the competent authority, the nationalregistry, independent verifiers and the accreditation body in relation to operators’obligations under the ETS.Figure 3: The key roles in the ETS system

Table 6: Number of installations subject to the EU ETS in each country in 2010Denmark FinlandNumber ofinstallationsSource: SAIs

Latvia Lithuania Norway Poland Sweden77101110811754

380

589

Competentauthority• identifies relevant operators/new entrants and assessesGHG permit applications (1)• issues GHG permits (2)• assesses allowanceapplications and approvesallowance quota (3)• assesses and approvesannual emissions report

Issuance of a GHG emissions permit and check of monitoring plan (see figure 3 point 2, page 30)On the whole, the competent authority ensures that operators are issued an appro-priate GHG emissions permit and that monitoring plans are in place.Operator• applies for a GHG emissionspermit• applies for emissionsallowances• submits verified annualemissions report• applies for account• surrenders allowances

Nationalregistry• opens accountsupon document check• allocates freeallowances uponverification annually• verifies surrender ofallowances

Case 8 and 9 illustrate the importance of a proper assessment of emissions permitapplications and the necessity of amending emissions permits and monitoring plansin case of changes at operator installations. The cases also give insight into acompetent authority’s assessment background.

Verification of annualemissions report

Case 8:

Assessment of permit applications in Latvia

Accreditationbody

Accreditationand control

Independentverifier

The Latvian audit has found instances where the competentauthority did not verify whether the amount of fuel consumption indicated inthe operator’s pollution permit corresponded to the amount stated in the GHGemissions permit application. As a result, the fuel quantity stated in the GHGemissions permits in the audit sample exceeded the maximum permissiblevolume of consumption by approximately 20 million m3or 29%.

2.2.1 operators are issued a GHG emissions permit andallocated a correct number of allowancesIdentification of relevant operators subject to the ETS (see figure 3 point 1)Although the institutional organisation of government bodies in charge of GHGemissions permits (competent authority) varies to some degree from country tocountry, the audit shows that the competent authority ensures that all installationssubject to the ETS are identified. Information is provided by environmental agenciesat national or regional level. Table 6 shows the number of installations subject to theEU ETS in each country.

30

EUROSAI WGEA

EMISSIONS TRADING TO LIMIT CLIMATE CHANGE: DOES IT WORK?

31

Case 9:

Assessment of permit applications in Norway

The Norwegian audit shows that many operators had already beenpart of the Nor wegian ETS from 2005, but had to update their permit andmonitoring plan for the next period. These operators were therefore alreadywell known, as the same authority had evaluated their initial application andthree annual emissions reports. In addition, on site-inspection with follow-upprocedures had been carried out at these operators’ installations.The authority assessed the applications of operators new to the ETS. In itscapacity as the national pollution authority, the authority was already acquaintedwith these operators as subjects to the Pollution Control Act and had a goodbackground for assessing these applications. The audit also shows that in caseof discrepancies between annual reports and emissions permits and monitor-ing plans, the authority demands that operators apply for a change in thepermits and plans.

Case 10 and 11 describe two situations where the national registry was not operatingnormally due to the intervention of supervisory mechanisms at EU and UNFCCClevel. In the first case the European Commission was responsible for a delay in theuploading of allocation plans in Latvia which caused late settlement. The secondcase relates to Lithuania, which has been partially suspended from trading allowancesand Kyoto units with other countries as a result of inaccuracies identified in thecountry’s reporting submitted under the Kyoto Protocol.

Case 10:

Delayed allowance allocations in Latvia

The Latvian audit shows that allowances were not allocated tooperators in time, thus impeding timely settlement. This was the case in 2008and 2009 when awaiting the European Commission’s internal decision onuploading allocation plans meant that approximately 19% of allowance alloca-tions were delayed by an average of 58 days.

Allocation of GHG allowances to operators(see figure 3, page 30)The audits establish that each country’s National Allocation Plan sets out the totalquantity of allowances to be granted to operators. In order to be allocated free allow-ances for the period 2008–2012, operators had to apply to the competent authoritywhich assessed the operators’ historical emissions before fixing their quota. In caseswhere historical data was unsuitable, due to substantial changes in activity, operatorshad to provide adequate documentation. Altogether, the national registry allocatesannually the stipulated number of allowances allocated for free to each operator by28 February after making sure that the operator is still entitled to receive these allowances.

Case 11:

Suspension of Lithuania from Kyoto mechanisms

2.2.2 National registries operate according to UNFCCC andEU requirementsRegistry operation (seefigure 3, page 30)The audit shows that the required registry procedures are in place. The prescribedprocedures are described in internal regulations and instructions, and are also to alarge extent taken care of by the different national registries’ software. In the courseof the period 2008–2012, a number of technical problems have arisen. However,registry software has been continuously updated, and new software versions wereimplemented.

The Lithuanian audit shows that the decision by the KyotoProtocol Compliance Committee in December 2011 to suspend Lithuania fromparticipating in the mechanisms under articles 6, 12 and 17 of the Kyoto Proto-col has led to negative consequences for the country and operators:• Operators could not trade allowances and Kyoto units with foreign countries.• Lithuania cannot trade assigned amount units (AAUs) and is not able to receivefunds for the Special Climate Change Programme until the suspension iscancelled. According to the decision Enforcement Branch of the ComplianceCommittee taken 24 October 2012, Lithuania is now fully eligible to participatein the mechanism under Articles 6, 12 and 17 of the Kyoto Protocol.

Registry security and control National registries are regularly assessed by the EU and UNFCCC. The commonsoftware and hardware platform which the common Union Registry has providedsince July 2012, is supposed to eliminate earlier problems and increase the system’sreliability and security.

32

EUROSAI WGEA

EMISSIONS TRADING TO LIMIT CLIMATE CHANGE: DOES IT WORK?

33

Public access to non-confidential informationThe majority of audits show that national registries make non-confidential informationavailable in accordance with UNFCCC and EU requirements at the InternationalTransaction Log and Community Independent Transaction Log (now European UnionTransaction Log) and national websites. Although information as listed in the casestudy by Latvia is publicly available, the Latvian audit (case 12) found that informationhad not been published concerning GHG emissions permits for 20% of the operatorsand 36% of the cancelled emissions permits, thus not providing the general publicwith information regarding operators’ activities. As a result of the national audit, theLatvian authorities have now published the missing information.

Phishing and hacking attacksPhishing as well as hacking attacks aim at getting access to the system for the purposeof embezzling allowances. None of the audits has positively identified hacking attacks.However, several phishing attacks have occurred in Denmark, Norway and Poland,but did not succeed in obtaining confidential information as was the case in otherEuropean countries.9The phishing attacks exploited the open access to the e-mailaddresses of account representatives on the website of the Community IndependentTransaction Log. This information is no longer publicly available. All the countriesaffected by phishing attacks cooperated with national registries in other countries.The Polish case (case 13) illustrates actions taken by national registries such as tem-porary shut-down of the registry, an alert message on the registry’s website and sentto account holders, and notification of the national authorities in charge of IT security.

Case 12:

Information is publicly available on the Latvian ETSRegistry web page

The following information is publicly available on the Latvian ETS Registry web page:• operators’ permits and permit amendments• operators’ annual emissions reports• verification reports• decisions on approving operators’ annual verified emissions reportsIn addition, the web page of the Ministry of Environmental Protection andRegional Development publishes information about decisions on allowanceallocation and cancellation.

Case 13:

Phishing attack in Poland in January 2010

Users of the Polish registry received an e-mail with a link to thewebsite www.tradingprotection.com the purpose of which was to steal loginand password information. The sender of the e-mail referred to cooperationwith the European Commission and the national registry administration. Upondiscovery of the fraud attempt, the following actions were taken:• Access to the registry was blocked for 24 hours.• An alert message was put up on the registry’s website.• Users were sent an alert e-mail.• Users who responded to this warning had their password changed.• The incident was reported to the Governmental Computer Security IncidentResponse Team and to the Central Investigation Bureau.

2.2.3 phishing and fraud have not succeeded in harmingnational registriesTable 7 gives an overview of detected cases of VAT fraud, hacking and phishing inDenmark, Latvia, Lithuania, Norway and Poland. Finland and Sweden have not carriedout audits on their national registry.

Temporary action has been taken against cross-border VAT fraudAs trade in allowances can involve transactions across borders, there is an inherentrisk of VAT fraud, as with other commodities. Box 4 explains how cross-border VATfraud is committed with GHG allowances.Of the countries taking part in the cooperative audit, Denmark and Norway havereported cases of cross-border VAT fraud, whereas Latvia and Lithuania have reportednone. The Polish case of VAT fraud hasn’t been confirmed for its cross-bordercharacter. The Swedish and Finnish SAIs have not audited their national registries.

Table 7: Detected cases of VAT fraud, hacking and phishing DenmarkDetected cases of VAT fraudDetected cases of attemptedhackingDetected cases of attemptedphishingYesNoneYesLatviaNoneN/AN/ALithuaniaNoneNoneNoneNorwayYesNoneYesPolandYesNoneYes

Source: Denmark, Norway: national audits; Lithuania: Ministry of the Environment; Latvia andPoland: competent authority.

9

Other European countries such as Austria, Greece, Italy, Romania and the Czech Republic.Source: The Norwegian investigation into the Norwegian authorities' control of the NorwegianEmissions Trading System.

34

EUROSAI WGEA

EMISSIONS TRADING TO LIMIT CLIMATE CHANGE: DOES IT WORK?

35

Box 4:mEChANISmS OF CROSS-BORDER vAT FRAUD WIThALLOWANCES IN ThE EUROPEAN ECONOmIC AREA10Cross-border VAT fraud exploits the fact that VAT is zero-rated on transactions with goods or services between VAT registered compa-nies in different countries of the Euro ean Economic Area. A company pbuys VAT-free (zero-rated) from a foreign country and resells to another company in its own country. The selling company collects VAT on the resale, but fails to settle the VAT with the tax authorities. Instead the company transfers the money out of the country to where it is not readily possible to seize the funds.The following figure illustrates cross-border VAT fraud: Company A buys a substantial quantity of allowances which are then sold to company B in another EEA country. No VAT is charged on the trans-action. Company B now resells the allowances to company C in its own country and charges VAT in connection with the resale. After company B has received the VAT from company C, company B fails to settle the VAT with the tax auth rities. There may be several innocent buffer ocompanies in between before the allo nces are resold cross-border wato company E (or back to A), after which the last company in the chain is reimbursed by the government for its VAT paid. The govern ent mhas now reimbursed the VAT without receiving the tax from company B. Company B goes bankrupt or missing. This kind of fraud is also called carousel or Missing Trader Intra Com-munity fraud.C2Cn

The only available overall estimate of cross-border VAT fraud relating to GHG allow-ances in the EU ETS is Europol’s estimate11of a total VAT loss of EUR 5 billion incurredby the treasuries. Europol’s estimate was made in December 2009 when cross-border VAT fraud was at its peak. Case 14 shows the results from the Danish auditof the occurrence of cross-border VAT fraud in Denmark.

Case 14:

Danish VAT cross-border fraud linked to emissionstrading

The Danish 2012 audit of the Danish ETS Registry showed that the Danish taxauthorities identified a VAT loss of EUR 200,000 for the Danish treasury byexamining trading patterns for accounts that had links to Denmark. However,the audit concluded that there is a risk that the actual VAT loss incurred by theDanish treasury may be higher. Moreover, 14 EU Member States have statedthat they suspect VAT fraud in the amount of EUR 200 mill. through the Danishregistry. Several countries have not quantified their suspected losses, and totallosses may therefore exceed this sum.The Danish registry ranked among those registries that had opened the largestnumber of person holding accounts in 2009; indeed, a calculation by theEuropean Commission’s central European registry shows that the approx. 1,000person holding accounts that were opened through the Danish registry in 2009,equal to approx. 45 per cent of all the accounts opened throughout the entireEU during the same period.The Danish audit showed that the Danish registry did not comply with EUregulations because it did not require account holders to provide documenta-tion of their identities. This meant that from 2005 to 2009 it was possible forpersons using false identities to trade in allowances in the Danish registry. TheDanish authorities have taken action to limit the risk of fraud in the future: theVAT system has been changed to reverse charge, which limits the risk of fraud,and documentation of identities is now required. International cooperationhas been improved.

Company C1

Company BBuys VAT-free from A, chargesVAT to C1, fails to report orpay collected VAT to taxauthorities and goes missing

Buys from B paying VATand sells furtherto otherbuffer companies whomaybe innocent

Company D (marketplace)Buys from Cnpaying VAT,then sells VAT-free crossborderto E, reclaiming VAT fromtax authorities

Company A

Company E

1110The European Economic Area comprises EU members, Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway.

Carbon credit fraud causes more than 5 billion Euros damage for European taxpayer. Europol pressrelease9 December 2009.

36

EUROSAI WGEA

EMISSIONS TRADING TO LIMIT CLIMATE CHANGE: DOES IT WORK?

37

Fraud detectionThe tax authorities or the entity responsible for the national ETS registry in thecountries concerned detected cross-border VAT fraud. Suspicious trading could bea high number of transactions – up to 100,000 per day – or transactions betweencompanies or persons already known to the tax authorities from other fraud cases.If criminal action was suspected to have taken place, the case was reported to thepolice for further investigation and, if possible, assets belonging to the suspectswere frozen.In Denmark and Norway, the two countries which have known cases of cross-borderVAT fraud, the audits of the registries have shown that the tax authorities and theagencies responsible for the ETS registry have worked closely together to detectand investigate possible cases of such fraud. (See case 15 from Norway.)

the trading and VAT payments between EU countries is limited. However, in thisregard, the Danish and Norwegian audits have shown that both countries collaboratedwith other countries and international bodies to detect fraud and to limit the oppor-tunities for future fraud.

Amendment of VAT rulesAs a consequence of the cross-border VAT fraud in relation to trade in emissionsallowances, the EU amended the VAT directive in March 2010 so that Member Stateswere allowed to introduce reverse charge VAT12on a temporary basis, i.e. until June2015.13Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden now have reverse charge systems on atemporary basis. With a reverse charge system, the risk of cross-border VAT fraud isconsiderably reduced. In Latvia, Lithuania and Poland, VAT is collected by normalcharge system.

Case 15:

The detection of cross-border VAT fraud in Norway

In September 2009, the Norwegian Climate and Pollution Author-ity (Klif) and the Norwegian Tax Administration (SKD) were made aware thatsuspicious trading activities had been discovered in other countries’ registries.Klif monitored transactions in the registry on behalf of SKD, who did not havedirect access to the registry. Klif noticed that large numbers of transactionshad been made on two accounts within the space of a few minutes. In February2010, several addresses were raided, resulting in the discovery of VAT fraud ofapproximately EUR 18.3 million between December 2009 and February 2010.Assets belonging to the companies involved have been frozen. Seven personshave been charged.Klif supplied SKD with a list of 107 rejected applications for person holdingaccounts for further investigation, of which 16 had been uncovered as havingcommitted document fraud and a further three that had been consideredsuspicious.

Proper verification of identities The cases of cross-border VAT fraud committed via the Danish ETS registry demon-strate the importance of proper monitoring of the registries. Conversely, the Nor-wegian audit (see case 16) has shown that the Norwegian registry’s strict applicationof documentation requirements for person holding accounts has meant that Norwayto a large extent has avoided dubious account holders. Documentation controlremains the responsibility of each country even though the registry has now beencentralised at EU level.

Case 16:

Compliance with legal requirements for openingaccounts in the Norwegian registry

The Danish audit showed that the work of the tax authorities was facilitated whenthe tax authorities got direct online access to the Danish ETS registry. According tothe Danish audit, most tax authorities in countries which are part of the EU ETSacquired direct access to their respective registries after the Danish case.Uncovering suspicious chains of allowance transactions and identifying the fraudstersis a particularly complex task, because companies and persons from all over theworld may open accounts and trade in any EU ETS registry. The Danish audit showedthat tax authorities’ efforts to combat cross-border VAT fraud in the EU are hamperedby the fact that in cases of transnational economic crime, access to information on

The Norwegian Climate and Pollution Agency registered a dramatic increasein account applications during the first months of 2010. Out of 100 applicationsfor person holding accounts only six were accepted in 2010 and three in 2011.Several incidents of falsified documentation were uncovered. Account openingrequirements had been further strengthened following Commission Regulation(EC) No. 920/2010, demanding that at least one account representative has tobe either Norwegian or resident in Norway for the last six months and providecertified documentation. Since 2011, account holders have to nominate anadditional account representative.

1213

Reverse charge VAT means that VAT is paid and deduced by the same company. Normally, VAT ischarged by the seller with the buyer later reclaiming this amount from the tax authorities.Council Directive 2010/23/EU of 16 March 2010 amending Directive 2006/112/EC on the common systemof value added tax, as regards an optional and temporary application of the reverse charge mechanismin relation to supplies of certain services susceptible to fraud. The Directive applies until 30 June 2015.

38

EUROSAI WGEA

EMISSIONS TRADING TO LIMIT CLIMATE CHANGE: DOES IT WORK?

39

2.2.4 Emissions monitoring and reporting is generally adequateIn all countries but Norway, where the competent authority itself has assumed therole of verifier, emissions reports submitted by operators are verified by accreditedthird-party verifiers. The competent authority then checks the completeness of thereports, the correctness of calculations and compliance with regulations and condi-tions in the monitoring plan. The interaction between the competent authority,operators, verifiers and the national registry is as illustrated in figure 3, page 30.The audit in Latvia has shown that the national framework does not define criteriafor assessment of emissions reports by the competent authority. Monitoring andreporting are in general considered to be adequate. Case 17 describes the verifica-tion process in Norway. As a result of control procedures sanctions have been appliedin Poland, as exemplified in case 18.

Case 18:

Sanctions following infringements by operators

In Poland, the National Centre for Emissions Management hasblocked accounts in the Polish national registry in the period 2008–2012 in thefollowing cases:• Verified reports on emissions were not delivered to the Centre (337 cases).• The fee for account administration was not paid (92 cases).• Breach of regulations, liquidation of the installation, unpaid fee for allowancesissued and first entry in registry, unclear legal situation of the installationowner, owner change (11 cases).

2.3 the implementation and administration ofCDM and JI programmesAll the partners in the cooperative audits have quantified commitments under theKyoto Protocol and have the right to host JI projects as well as to purchase creditsfrom CDM and JI projects. The Parties to the Kyoto Protocol have adopted compre-hensive rules for CDM and JI. The cooperative audit has looked into:• the organisation of CDM/JI purchase programmes or JI hosting programmes• whether JI projects are hosted and managed properly. The audits have looked intocompliance with rules, not into what extent the JI projects actually deliver as intended.• whether the management system for purchase of credits functions well• whether goals for purchase are met• whether there is transparency in the budgeting of funds for CDM/JI credits• whether CDM/JI credit purchases are supplementary to national reductions

Case 17:

Evaluation and verification of annual reporting inNorway

The competent authority checks that all emission sources are reported on. Itverifies activity data for each emissions source, emissions factors and relateduncertainty levels. The information is assessed comparing reported data withearlier reports, comparing cross-sector data and by means of on-site inspec-tions. In Norway, on-site verification of annual emissions reports is chiefly carriedout by the competent authority and not accredited third-party verifiers. Sanc-tions in case of non-conformity in relation to on-site inspections are rarely usedas cautioning of coercive fines is usually sufficient to achieve compliance.

Different organisational structuresClear roles and responsibilities are an important prerequisite for efficient CDM andJI programmes. All countries have appointed a main responsible ministry or agency.This is either a ministry or an agency responsible for environmental, energy orfinancial matters (see table 8). In most of the countries, several ministries and agen-cies are responsible for the implementation. However, several audits concluded thatthere have been some problems with respect to how the organisation functions:• Finland: Complicated decision-making process in bilateral purchase, overlapbetween ministries’ responsibilities and in monitoring of purchasing. Personnelresources were not optimally targeted.• Norway: The Ministry of Finance is using its competence as an actor in financialinvestments in this area. The Ministry had initially little experience in emissionstrading. The Ministry can if necessary seek advice from the Ministry of ForeignAffairs or the Ministry of Environment.• Sweden: The Swedish Energy Agency spends little time on follow-up. The Agencyhas not documented evaluations of the projects or funds despite the projectsrunning for seven or ten years (see case 22).

40

EUROSAI WGEA

EMISSIONS TRADING TO LIMIT CLIMATE CHANGE: DOES IT WORK?

41