Ligestillingsudvalget 2012-13

LIU Alm.del Bilag 73

Offentligt

Gender Equality Index

ReportReport

The Gender Equality Index is the result of three years ofwork by various contributors.The principal authors of the main Report and CountryProfiles are: Laura de Bonfils, Dr Anne Laure Humbert,Dr Viginta Ivaškaitė-Tamošiūnė, Dr Anna Rita Manca,Ligia Nobrega, Dr Jolanta Reingardė and Dr Irene RiobóoLestón. A particular thank you goes to colleagues at theEuropean Institute for Gender Equality for their intel-lectual contributions, administrative support and encou-ragement.This work builds upon the initial study for the develop-ment of the basic structure of a European Union GenderEquality Index, developed for EIGE by Prof Dr JannekePlantenga, Prof Colette Fagan, Prof Dr Friederike Maierand Dr Chantal Remery. Important contributions to theGender Equality Index were also made by Prof EileenDrew, Dr Maris Goldmanis, Eva Heckl and Dr Irene Pim-minger. A special gratitude goes to Dr Michaela Saisanafrom the European Commission’s Joint Research Centreand Linda Laura Sabbadini from ISTAT.

The construction of the Gender Equality Index has alsogreatly benefited from expert advice received from:EIGE’s Working Group on the Gender Equality Index, itschair and external experts; EIGE’s Management Board andExperts’ Forum. The acknowledgements are also extend-ed to the European Commission, in particular the Gen-der Equality Unit at the Directorate-General for Justice,Freedom and Security, Eurostat and Joint Research Cen-tre; the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights(FRA); the European Foundation for the Improvement ofLiving and Working Conditions (Eurofound); National Sta-tistics offices, European Women’s Lobby, Social Partners(European Trade Union Confederation, BusinessEurope)and international organisations (ILO, UNECE, OECD, WorldEconomic Forum, Social Watch).The European Institute for Gender Equality is very grate-ful to many other individuals and institutions which pro-vided valuable contributions and support to the buildingof the Gender Equality Index.

Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to yourquestions about the European Union.Freephone number (*):00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11(*) Certain mobile telephone operators do not allow access to 00 800 numbersor these calls may be billed.

More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu).Cataloguing data can be found at the end of this publication.Gender Equality Index ReportISBN: 978-92-9218-224-3doi:10.2839/69597Gender Equality Index – Country ProfilesISBN 978-92-9218-265-6doi:10.2839/87720� European Institute for Gender Equality, 2013Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged.Printed in Germany

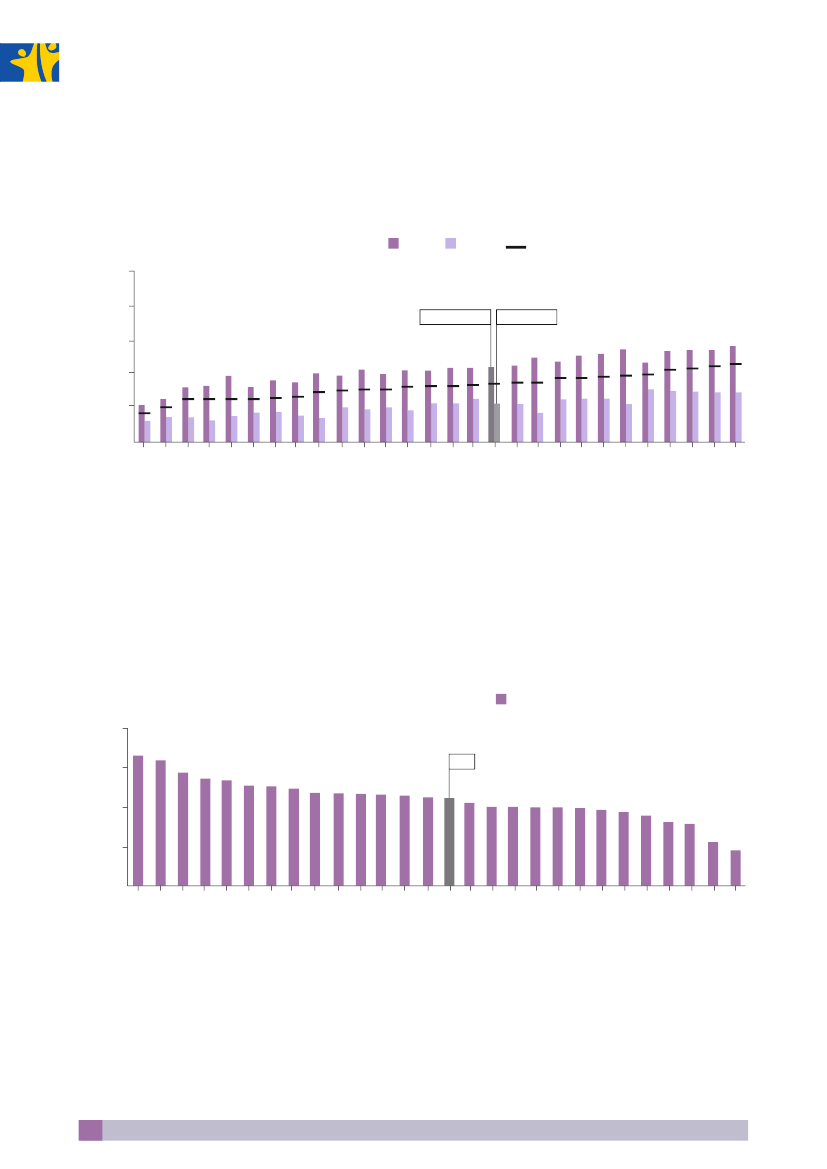

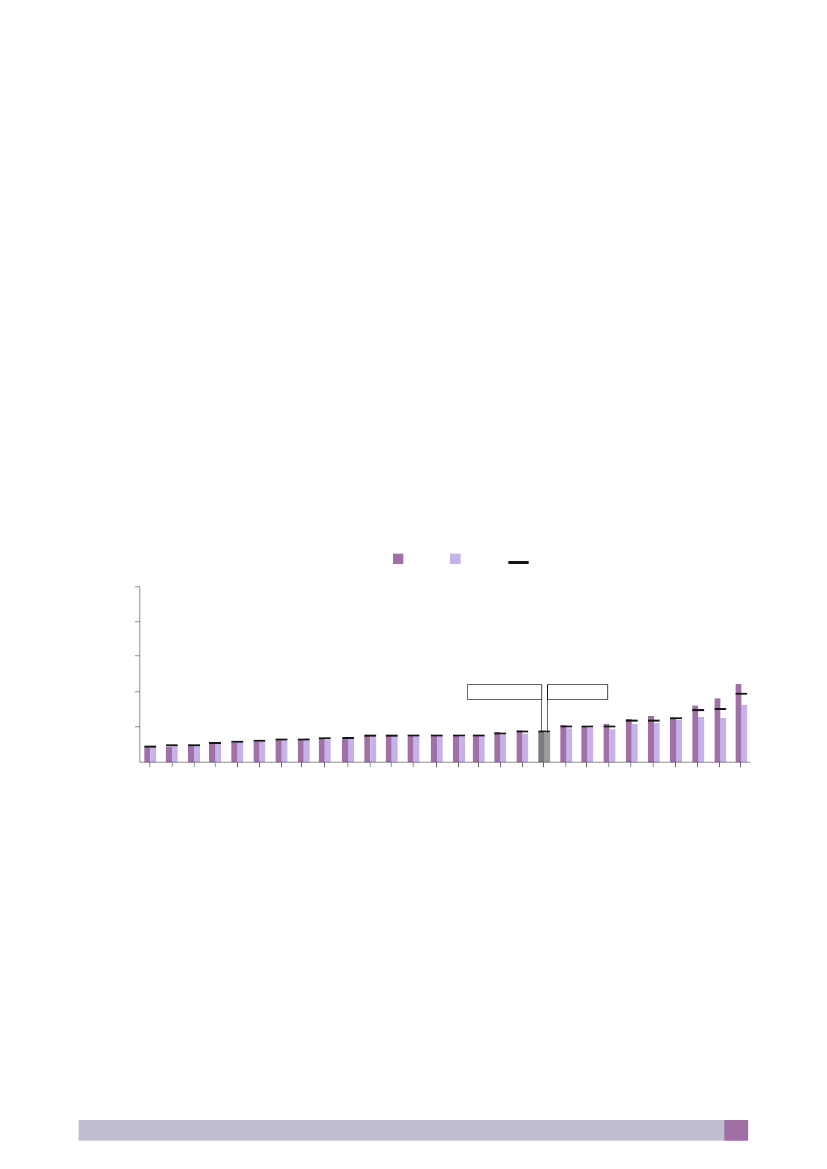

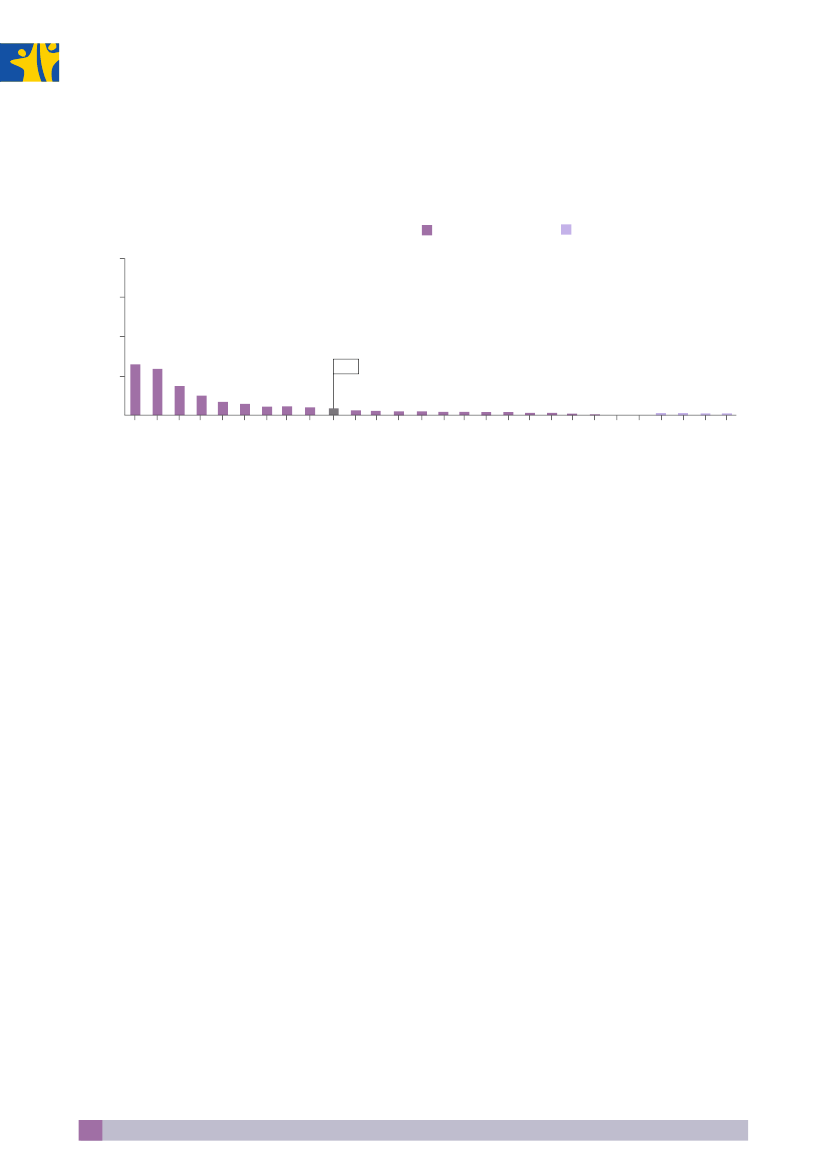

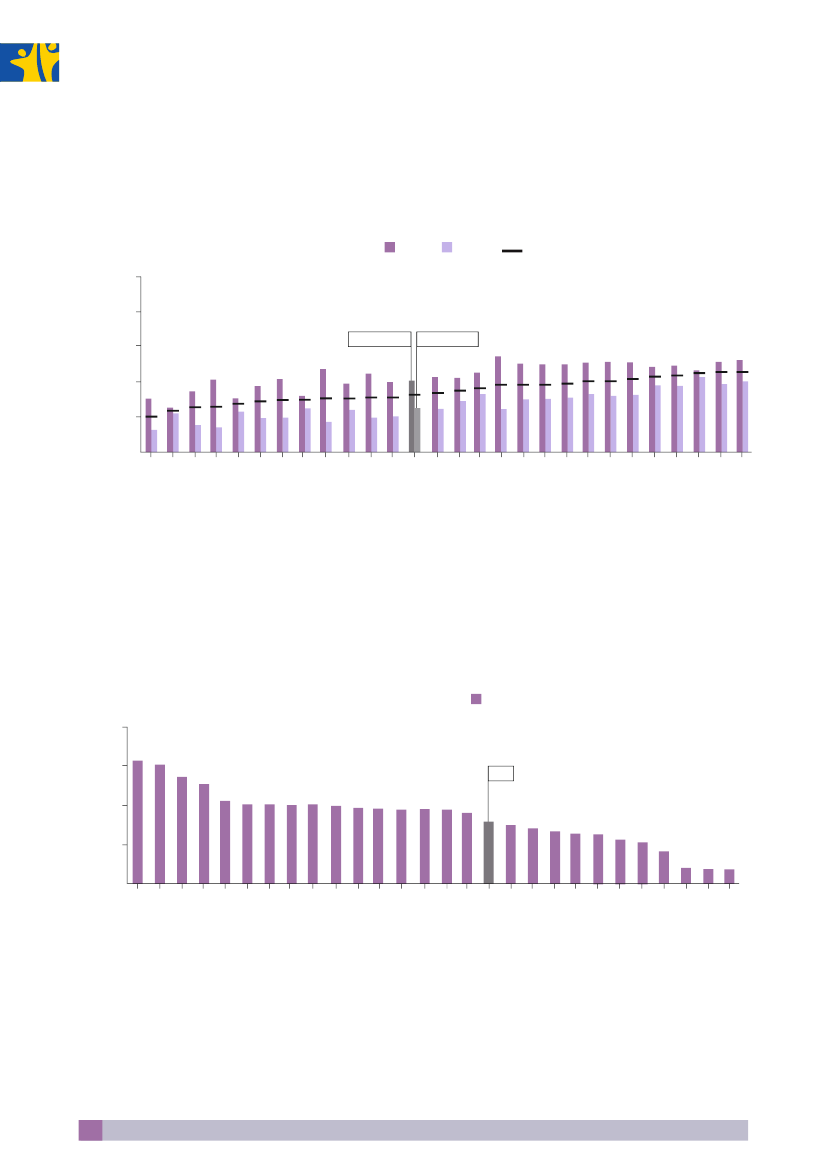

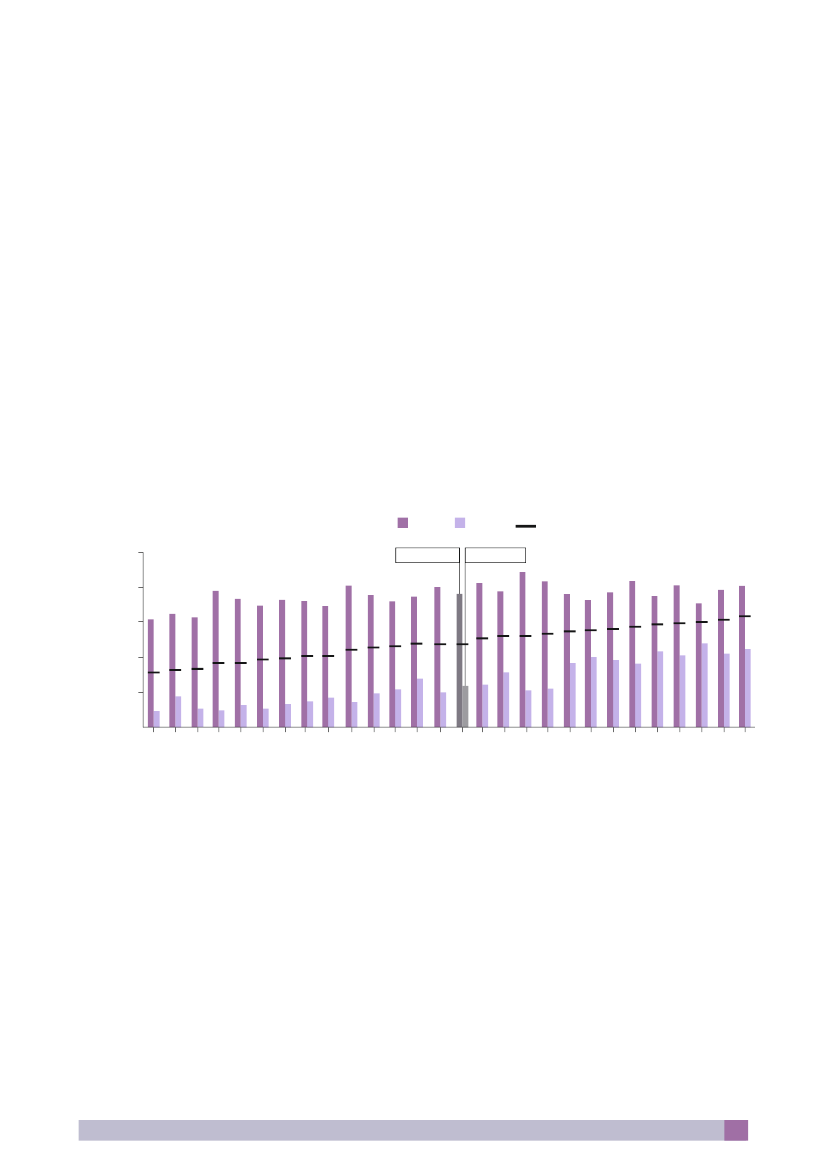

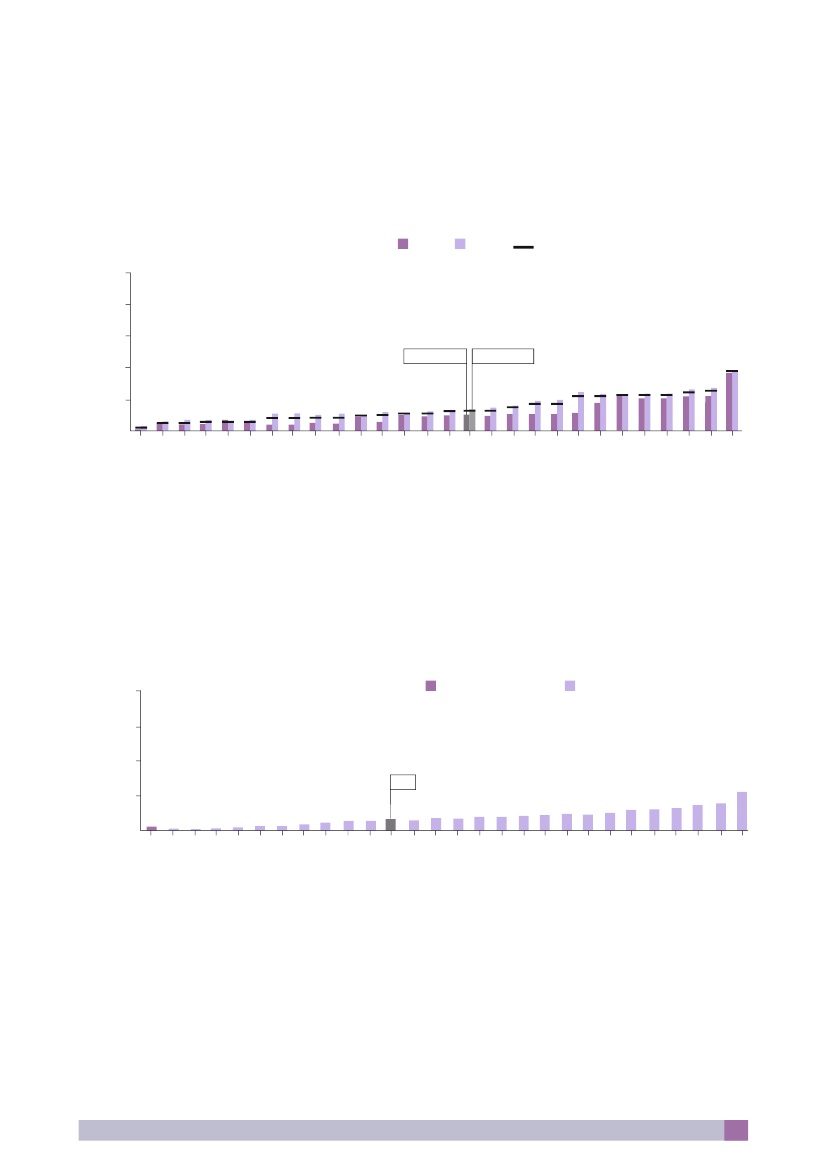

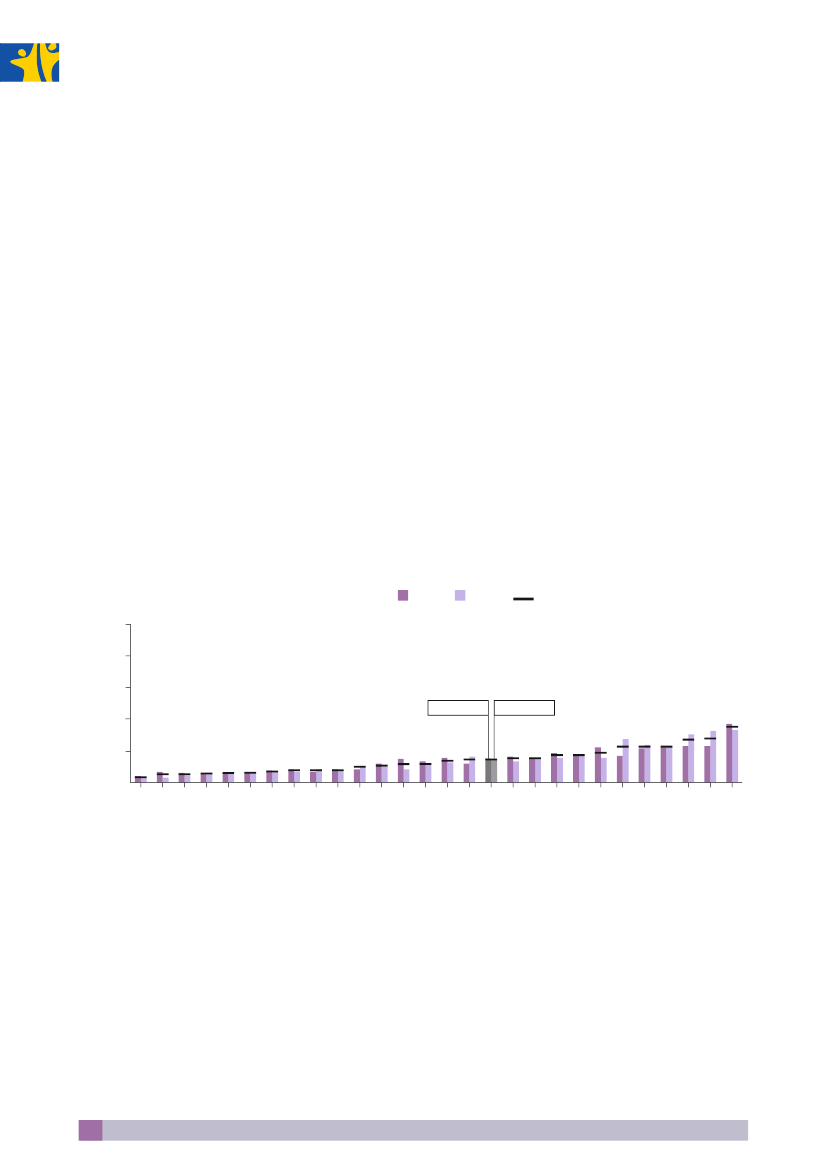

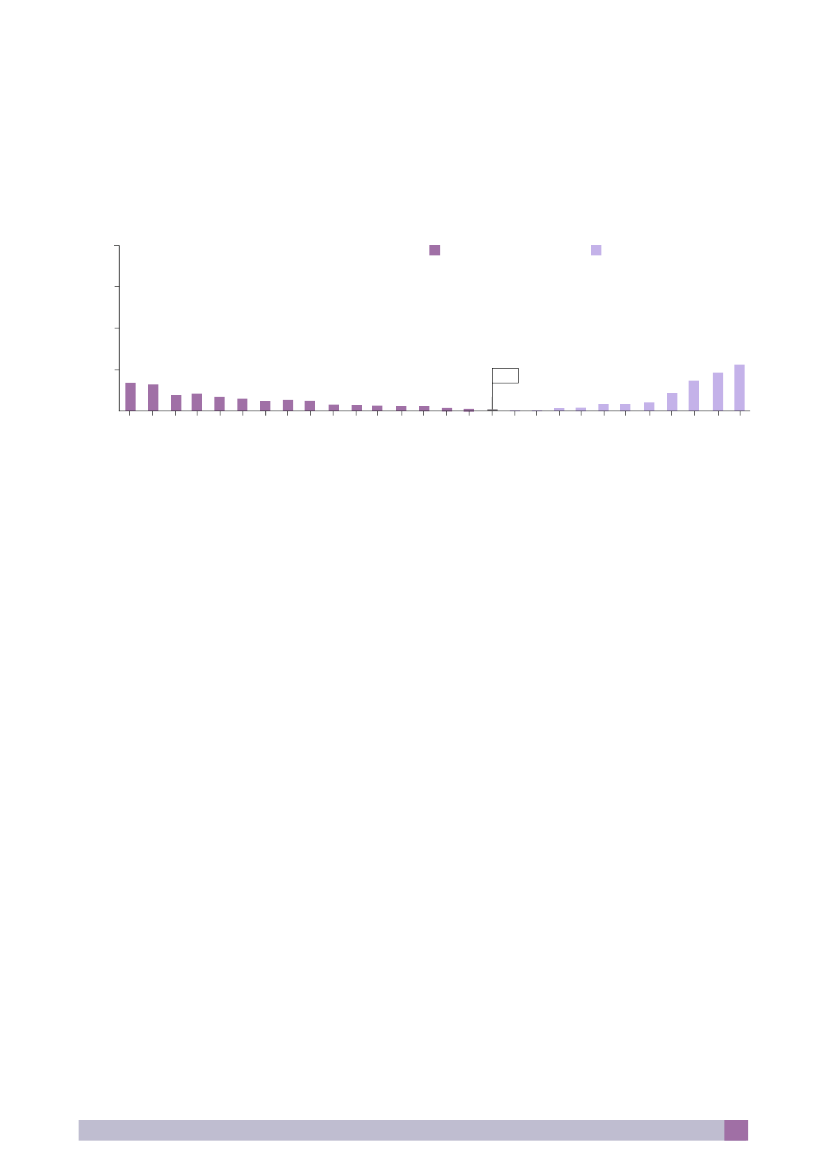

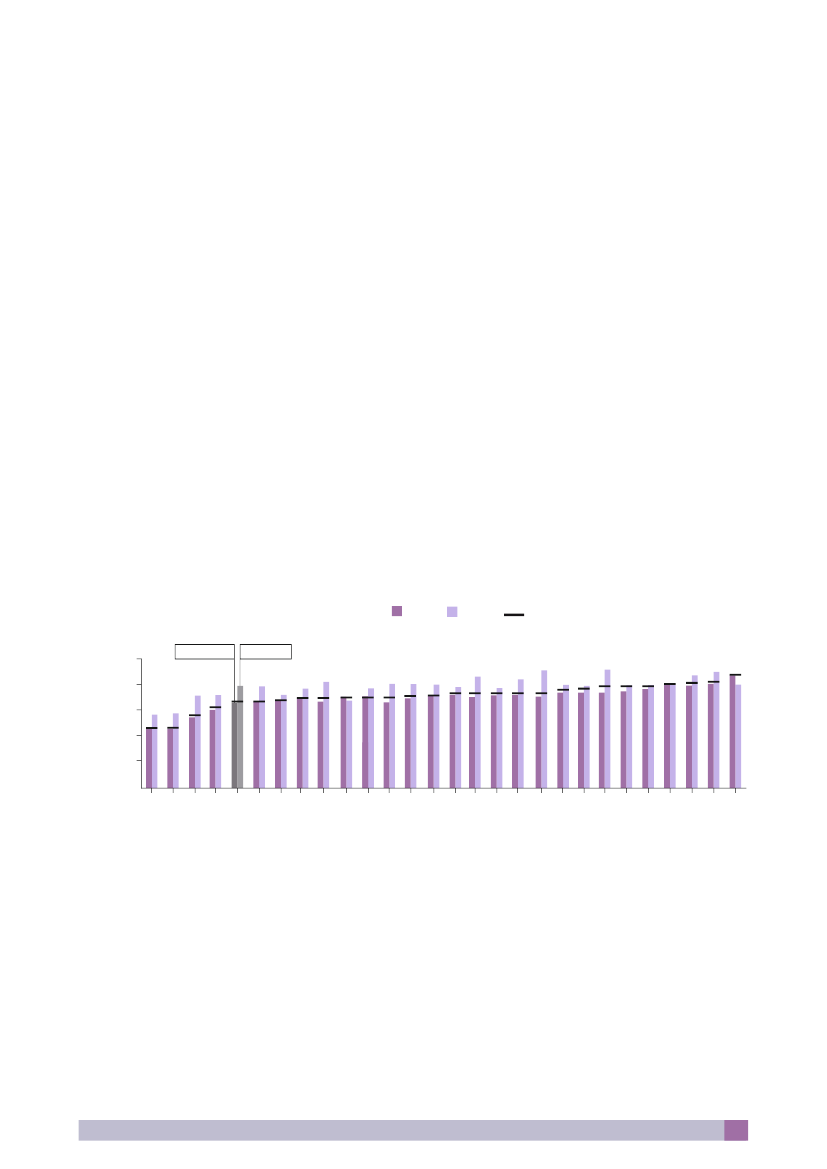

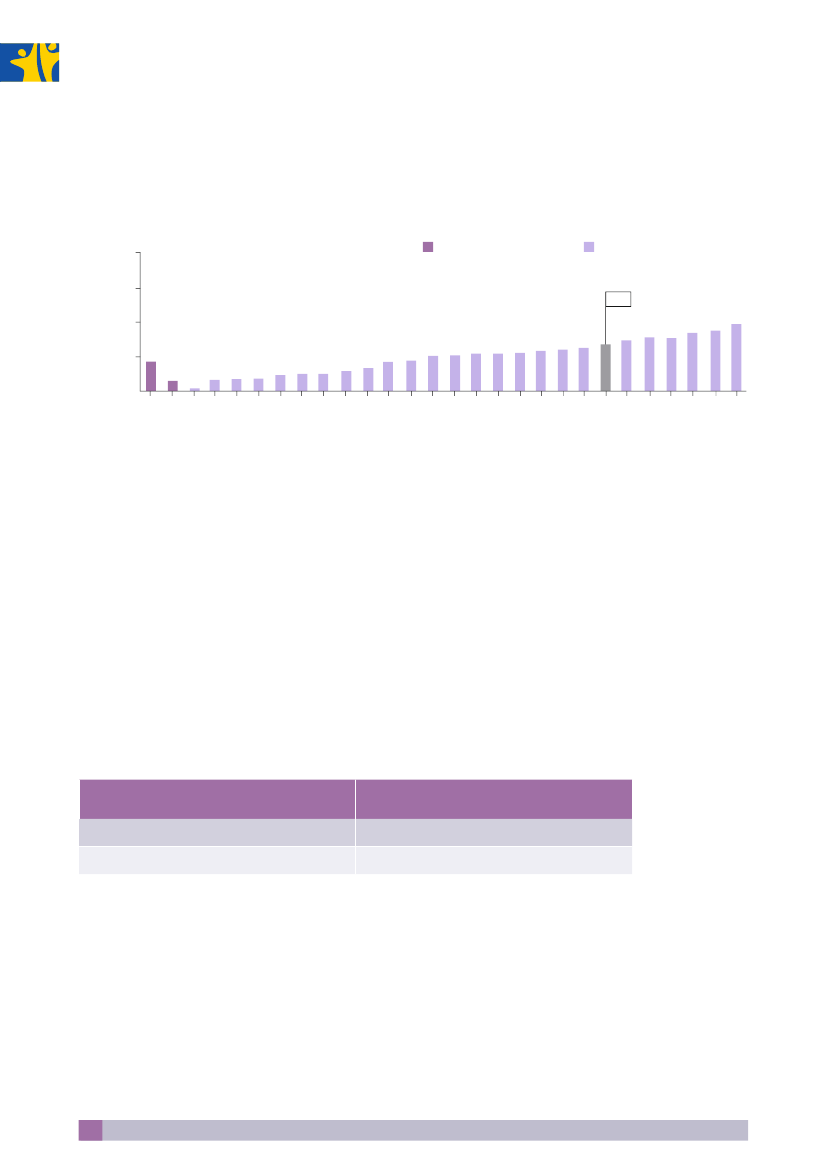

Halfway towards equalityEquality between women and men is a fundamental valueof the European Union and is vital to its economic and so-cial growth. To reach the objectives set by the EU in theEurope 2020 growth strategy; face current economic andsocial challenges; secure social justice; and achieve smartand sustainable development, gender equality has to beincluded at the very centre of political debate in Europe.Despite 50 years of policies and actions at European level,Member States have not yet managed to overcome gen-der gaps, thus there is a need for further efforts.Policy improvement cannot bear fruit without systematicand consistent measurement of gender gaps at EU andMember States level. The process began when the Europe-an Commission proposed to introduce an assessment toolon gender equality in the Roadmap for Equality betweenWomen and Men 2006–2010, and subsequently includedit in the Action Plan of its Strategy for Equality betweenWomen and Men 2010–2015. The creation of the assess-ment tool was undertaken by the European Institute forGender Equality (EIGE) since the start of its operations, inJune 2010.This report is a result of the Institute’s work of the pastthree years, which presents a synthetic measure of genderequality – the Gender Equality Index. I am proud to saythat it is the only index that gives a comprehensive map ofgender gaps in the EU and across Member States based onthe EU policy framework.The Gender Equality Index relies on a trustworthy statisti-cal methodology. In spite of the scarcity of data, stringentcriteria are applied to the gender indicators, requiring thatvariables are available and comparable across all Mem-ber States. The computation of the Gender Equality Indexavoided subjective decisions in the way a weighting andaggregation method for the Index was selected. The proc-ess relied on a computation of more than 3,000 alterna-tives in order to choose the best and most robust Index.In the report, scores for each Member State and an EUaverage are presented to enable a detailed assessment ofhow close the EU and Member States have come towardsachieving gender equality in each of the critical domainsand within the EU policy agenda. It is also evident thatgender equality is correlated more with social indicatorssuch as public expenditure on education and research,rather than with traditional economic indicators such asGDP. With an average score of 54.0, (where 1 stands forabsolute gender inequality and 100 for full genderequality), the European Union is only halfway towards agender equal society.The results obtained show that the domain of power high-lights the biggest gender gaps, with an average score ofonly 38.0 at EU level. The wide differences in the propor-tion of women and men in decision-making across theEU-27 is a strong call for the improvement of policy anddecisive action, such as the introduction of quota systems,initiated by the European Commission in 2012. The domainof time is marked by wide differences between womenand men when it comes to time spent on unpaid caringand domestic activities. This is the second domain wherethe widest gender gaps can be observed, with an averagescore of 38.8 at the EU level.The Institute foresees regular updates of this first GenderEquality Index, which is specifically tailored towards the EU’sneeds in a present policy context and hopes to offer EUpolicy makers a reliable tool in assessing the progress andeffectiveness of policies and initiatives aimed at improv-ing gender equality in general and specific policy areas.On behalf of the Institute and its team, I would like tothank all institutions and experts who contributed to thecreation of the Gender Equality Index, and especially tothe European Commission: Directorate-General for Justice;Joint Research Centre; Eurofound; International LabourOrganisation; European Women’s Lobby; EIGE’s Manage-ment Board; Experts’ Forum; Working Group on the Gen-der Equality Index; and my colleagues at EIGE. We firmlybelieve that the Index will give impetus for broader debateon the challenges of gender equality, and will contributeto making equality between women and men in Europea reality for all.

Virginija Langbakk,DirectorThe European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE)

Gender Equality Index – Report

3

The European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE) is anautonomous body of the European Union, established tocontribute to and strengthen the promotion of genderequality, including gender mainstreaming in all EU policiesand the resulting national policies, and the fight againstdiscrimination based on sex, as well as to raise EU citizens’awareness of gender equality. Further information can befound on the EIGE website (eige.europa.eu).

European Institute for Gender EqualityGedimino pr. 16LT-01103 VilniusLITHUANIATel. +370 52157444E-mail: [email protected]http://eige.europa.euhttp://www.twitter.com/eurogenderhttp://www.facebook.com/eige.europa.euhttp://www.youtube.com/eurogender

4

Gender Equality Index – Report

ContentsAcknowledgements1. Introduction2. Conceptual framework3. Methodology4. Indicators5. Index results6. Conclusion7. Annexes8. References26143456108136145165

Gender Equality Index – Report

5

1. IntroductionEquality between women and men is a fundamental valueof the European Union, enshrined in its Treaties, includingthe Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Un-ion. The capacity of EU institutions to help shape genderrelations in its Member States has been present since itsearliest days (Verloo and Lombardo, 2007). Although theTreaty of Rome was signed at a time when the genderequality landscape looked substantially different from thecontemporary one, it nevertheless contained a clause onequal pay between women and men, a precursor to thelegislation and policy approaches that emerged through-out Europe in later years. Gender equality is recognised asvital to economic growth, prosperity and competitiveness,as exemplified by the Council’s commitment to fulfil EUambitions on gender equality through the adoption of theEuropean Pact for Gender Equality (2011–2020) (7349/11adoption of the European Pact) and the European Com-mission’s Strategy for Equality between Women and Men(2010–2015) (COM(2010) 491 final). The EU, as a multi-levelgovernance framework, plays a crucial role in enabling aconcern for gender equality in Member States’ policies,gender norms and cultures to filter down from the interna-tional and EU level to national, regional and local levels.The acknowledged importance of gender equality in theEU manifests itself in the development of distinct gender-aware policies. The evaluation of the effectiveness of thesepolicies is, however, a complex and challenging endeavourgiven that the EU is a multi-level polity, comprising ofsubnational, national and supranational institutions, withactors and discourses interacting in complex ways to en-act gender legislation and policy. The development anddissemination of EU-wide, comparable and reliable gen-der statistics and indicators have contributed to bet-ter monitoring and assessment of progress, for example,through the process of Gender Mainstreaming in the EU. Itis therefore important to develop further monitoring andevaluation indicators. To assist with the measurement ofgender equality at EU level, and in order to demonstratethe success of promoting gender equality in each Mem-ber State, the creation of a composite indicator on genderequality, a Gender Equality Index, as a common assess-ment tool was initially introduced by the European Commis-sion in The Roadmap for Equality between Women andMen (2006–2010) (COM(2006) 92 final) and proposed in theAction Plan of the Strategy for Equality between Womenand Men (2010–2015) (SEC(2010) 1079/2) that followed.The elaboration of the Gender Equality Index became oneof the major assignments decided by the European Insti-tute for Gender Equality (EIGE) in its first Mid-term WorkProgramme (2010–2012), following its establishment. TheGender Equality Index is a composite indicator that pro-vides a measure, across Member States and eventually overtime, of the concept of gender equality as a multi-dimen-sional concept. It is a sophisticated tool that synthesisesthis complexity into a user-friendly and easily interpretablemeasure. It is formed by combining gender indicators ac-cording to a conceptual framework, into a single summarymeasure.

1.1. Structure of the reportThe first section positions the Gender Equality Index as ameasure of gender equality for the EU. It shortly reviewsthe definitions and approaches to gender equality, as wellas main existing gender equality indices along with theirmain shortcomings. The rationale behind producing aGender Equality Index is also set out.The second part of the report outlines the conceptualframework used for the Gender Equality Index. It describesthe major areas of concern in the field of gender equalitythat are of particular interest to European policy.Subsequently, the methodology employed is described.It gives information on how the conceptual structure(underpinned by policy and theory) was translated into ameasurable structure (underpinned by data and statisticalconsiderations), as well as the steps followed to computethe Index.The fourth section presents an overview of the gender in-dicators, by domain, used to construct the Gender EqualityIndex. For each indicator, a detailed analysis of both levelsof achievement and gender gaps is provided, at EU level,across Member States and where possible over time.The report then provides with a detailed breakdown ofthe Gender Equality Index score for each country. It alsodiscusses the contribution of each indicator to the Gen-der Equality Index. Lastly, this section analyses the resultsin conjunction with other contextual variables in MemberStates such as GDP and spending on key policy areas.

6

Gender Equality Index – Report

Finally, the report concludes with the main findings of theGender Equality Index.Accompanying this report is a set of 27 Country Profileswhich provide an overview of the score of the GenderEquality Index for each Member State, along with listedmain policy initiatives for the promotion of gender equalityand key data at national level. The profiles aim to supportdecision-makers and researchers alike in drawing conclu-sions to feed into national and EU level debates on closingthe gender equality gap even further.

national level. In those Member States that see womenas primary carers, the bulk of policy aims at supportingwomen in those roles. In other Member States, the focusis on challenging gender roles with a policy frameworkthat tends to focus on changing the behaviours of bothwomen and men (Rubery, 2002).To counter the difficulties of agreeing on a definition ofgender equality, and in light of the imperative need tooperate from an agreed definition, the Gender Equality In-dex bases itself on a simplified overarching definition ofgender equality:equal share of assets and equal dignity andintegrity between women and men.

1.2. Definitions of genderequality in the EUGender equality is a complex and multi-dimensional con-cept, as well as a normatively and politically controversialsubject, with a diversity of meanings across Europe (Verlooand Lombardo, 2007). Gender equality is not consistentlydefined in EU policy texts. Furthermore, although defini-tions attempt to be gender neutral, there is a general ten-dency to conflate this approach with one that focuses onwomen specifically.At EU level, treaties and policy documents (for example,Art. 2 and 3(3) TEU and Art. 8 TFEU) discuss gender equalityin different ways, including conceptualisations that en-compass a mixture of equal access to resources and assetsand equal access to dignity and integrity. The EuropeanCommission defines gender equality as ‘the result of theabsence of discrimination on the basis of a person’s sex inopportunities and the allocation of resources or benefitsor in access to services’ (European Commission, 2010). Anexpanded definition is provided in the European Commis-sion’s Women’s Charter (2010) (COM(2010) 78 final) whichfocuses on the following elements:life choices and economic independence;the full realisation of women’s potential and the fulluse of their skills;a better gender distribution in the labour market, morequality jobs for women;the promotion of genuine opportunities for bothwomen and men to enjoy a work-life balance;human dignity, the right to life and the right to theintegrity of the person.At national level, there are also various meanings of genderequality across individual Member States. Differences mostlyreside in the ideology of gender roles most represented at

1.3. Gender equality approachesThe task of developing the Gender Equality Index calls fora clear direction of what is the purpose of gender equal-ity. However, this is greatly hampered by the insufficientagreement of what constitutes gender equality and whatit should achieve. There are contrasting ways in which toaddress the purpose of gender equality, with three broadapproaches: equality through sameness (equal opportu-nities or equal treatment); equal valuation of difference(special programmes) and the transformation of genderedpractices and standards of evaluation (Walby, 2005). Thissection presents these three approaches before outlininghow they are incorporated into the Gender Equality Index.

1.3.1. The sameness approachThe sameness approach highlights the necessity to includewomen into a world from which they have typically been ex-cluded. Equality policies should seek gender-neutrality andextend the dominant practices and values to all individuals(Verloo, 2005). Differences between women and men are of-ten attributed to a gender identity which is inscribed in theprocess of a lifetime of learning experiences (Epstein, 1988)and which as a consequence often characterises women ina disadvantageous position as opposed to men.In this approach, the emphasis is on women becomingequal to men. This entails women entering previously maledomains, and has the unintended consequence that themale norm remains the standard (Walby, 2005). Equalitystrategies based on the male as norm may in fact disad-vantage women (Plantenga et al., 2009). This is problematicin that it may place women in a position of defensiveness,to be explained and justified, as well as falsely constructsmen as belonging to one homogenous category (Bacchi,1996). In addition, encouraging women to become more

Gender Equality Index – Report

7

like men does not tackle the need to re-examine and re-evaluate social roles and values including ‘caring roles’ andcare itself (Maddock, 1999).

1.3.2. The difference approachThe second approach reflects a move towards the equalvaluation of the existing and different contributions ofwomen and men in a gender segregated society (Wal-by, 2005). This approach suggests that women’s physi-cal difference from men results in different life patterns,psychology and moral values. This approach often seesa call for parity rather than sameness (Cockburn, 1991).Men and male cultures and practices are often prob-lematised and the need to construct new spaces thataccommodate non-hegemonic gender identities andcultures are called for (Verloo, 2005).A number of difficulties exist with this approach. It is difficult torecognise differences, while avoiding the trap of essentialismand relying on essentialist notions of femininity and mascu-linity. It can reinforce existing stereotypes and the currentorganisation of labour and care (Fraser, 1997). The debate onthe sameness/difference approach was criticised becauseit provides limited possibilities for change (Cockburn, 1991),may divert attention to other problems such as the prob-lem of caring for children and the elderly (Bacchi, 1996) andmaintains a political frame of arguments that reifies maledefinitions in order to be heard (Maddock, 1999). It is alsounclear as to whether there can be an effective route togender justice in which existing separate gender norms/standards are retained, in that it is not possible to be ‘differ-ent but equal’ because differences are too entwined withpower and resources (Fraser, 1997).

sal caregiver model’, gender equality implies a change inthe lives of both women and men through the promotionof greater equality in the distribution of paid and unpaidwork, while also indicating that an equal distribution ofpaid and unpaid work is not enough.

1.3.4. Drawing on all three approachesIndeed, these three approaches are intertwined with, andbuild on, one another (Daly, 2005). In practice, the threeapproaches are not mutually exclusive but can be (andare) combined: the sameness approach can be seen asan integrationist approach which may lead to culturalchanges, while the approach of difference could be trans-formative in questioning both femininity and masculinity(Verloo, 2005).These steps remain necessary in order to achieve deepcultural changes, create new structures and transform thegendered nature of society (Martin, 2003). It is important tointegrate these different approaches under the same goal:that of achieving greater gender equality.These three approaches can be observed in the EuropeanCommission’s approach to gender equality over the lastthree decades (Rees, 1992):Tinkering – equal treatment (legal redress to treatwomen and men the same);Tailoring – positive action (recognising that thereare differences between men and women and thatspecific measures are required to address disadvantagesexperienced by women as a consequence of thosedifferences);Transforming – gender mainstreaming (how existingsystems and structures cause indirect discriminationand altering or redesigning them as appropriate).This perspective of gender equality as a particular com-bination of sameness, difference and transformation, isclearly reflected in key EU policy documents. The Women’sCharter (2010) (COM(2010) 78 final) presents the commit-ment of the European Commission to five priorities basedon agreed principles of equality between women and menthat draw on these several perspectives. These five priori-ties are translated into concrete measures in the Commis-sion Strategy for Equality between Women and Men (2010–2015) (COM(2010) 491 final).

1.3.3. The transformative approachThe third approach is one where, rather than having tochoose between the sameness and difference approach, anew standard for both men and women is created, that is,the transformation of gender relations (Walby, 2005; Walby,2009). It aspires to move ‘beyond gender’ and attempts toproblematise not only the exclusion of women, or men asa norm, but the gendered world in itself (Verloo, 2005).For example, Fraser (1997) provides a vision of what thismay entail and calls for men to change their lifestyles sothat they resemble more that of women’s. In the ‘univer-

8

Gender Equality Index – Report

The measures range from getting more women into com-pany boardrooms and tackling gender-based violence toraising the transparency of pay structures. The Strategyunderlines that gender equality is not only equated withequal positions of women and men within paid employ-ment (equality-as-sameness strategy), but embedded intoa more broadly defined ‘gender equal regime’, as a resultof which relevant policies might also refer to, for example,equal sharing of power between women and men, reducingthe school drop-out rate for boys, improving fathers accessto parental leave and combating domestic violence.The perspective of gender equality adopted in the GenderEquality Index attempts to combine these different ap-proaches, by reflecting this plurality of drawing on same-ness and difference of outcomes, but also on engagingwith a broader reflection on how to transform gender rela-tions to achieve greater gender equality for both womenand men in Europe.To combine these positions, the Gender Equality Index con-siders gender gaps, in an attempt to distance itself from thesameness-difference debate inherent in measuring levels ofachievement. Gender gaps, indeed, provide an opportunityto reflect on gender equality from a transformative perspec-tive, as they provide a single equality point to be achieved.By focusing on measuring gender gaps, the Gender EqualityIndex places the equality point between women and menas a benchmark, meaning that women and men shouldhave equality in outcomes. In some instances, it is alsonecessary to consider the approach of difference, by rec-ognising the specificities of women or other groups, forexample, in terms of violence or social exclusion where thefocus is on protecting the integrity and dignity of indi-viduals, and where certain groups are more at risk becauseof power relations in society. Finally, the transformative ap-proach can be introduced through opening up a debateon the division of time between women and men.It is, however, not possible to focus solely on genders gapsand ignore levels of achievement altogether. In light ofthe crisis for example, gender gaps have greatly reducedacross the EU in some areas. Unfortunately, this is not asign of greater gender equality, but shows the hard rea-lity of how much the life of women and men have beenaffected over the past few years (European Commission,2013). In order to ensure that gender gaps cannot be

regarded positively where they point to an adverse situa-tion for women and men, the Gender Equality Index alsotakes levels of achievement into consideration by adjust-ing gender gaps to reflect these. This is the case, for exam-ple, where gender gaps are low in employment rates, butwhere that is associated with low, and possibly worsening,participation rates.

1.4. Measuring gender equalitythrough indicesThe Gender Equality Index does not represent the firstattempt to measure gender equality through a compositeindicator. Several indices that measure gender equality atinternational level already exist (a summary is provided inTable 1.1.). They represent an extremely valuable startingpoint to assist in the measurement of the effectivenessof gender equality policies at EU level. However, there arealso a number of drawbacks, which are discussed in thissection.The evolution of indices can be traced back to the GrossNational Product (GNP) and the Gross Domestic Product(GDP) as internationally applicable measures of a nation’seconomic development. Subsequently, the United NationsDevelopment Programme’s (UNDP) ‘Human DevelopmentReport’ sought to extend this measure to capture some as-pects of human as distinct from purely economic develop-ment. This led to the Human Development Index in 1990.By 1995, along with the elaboration of the Beijing Platformfor Action, a strong case emerged for a more comprehen-sive investigation of gender inequality in economic and so-cial arrangements throughout the world that would requireanalyses and empirical research. Two initial gender indiceswere thus developed. The Human Development Index wasadjusted to build the Gender-related Development Index(Bardhan and Klasen, 1999) by adding disaggregation ofthe indicators by sex. The Gender Empowerment Measuredeparted from these initial indices by focusing on indica-tors related specifically to women’s empowerment issues(Bardhan and Klasen, 1999). It does not attempt to measurewomen’s progress in well-being, but, rather, their roles asagents in society. Other gender indices have since beendeveloped, expanding on the theoretical positions andconceptual frameworks of these initial gender indices.

Gender Equality Index – Report

9

1.4.1. Theoretical positionsThe theoretical positions of gender indices are differ-ent and have developed from several theoretical per-spectives including human development, women’sempowerment or, increasingly, gender equality. TheGender Development Index supported the premise ofseeing gender inequality as a human development is-sue (not primarily an issue of women’s empowerment)that would facilitate policy discussions on gender in-equality and further the collection of sex-disaggregateddata for analysis and policy (Bardhan and Klasen, 1999).Other indices were built with an explicit focus on adopt-ing women’s empowerment position. Examples of suchindices include: the Relative Status of Women Index, basedon the same indicators as the Gender Development Indexand Human Development Index, but instead using relativemeasures that assess the position of women compared tothat of men (Dijkstra and Hanmer, 2000); the Gender In-equality Index which is designed to capture women’s dis-advantage in the dimensions of empowerment, economicactivity and reproductive health.

The European Union Gender Equality Index (Plantenga etal., 2009) departs from a perspective of women’s empow-erment and embraces a gender approach. It does so byencompassing the universal caregiver model outlined byFraser (1997), in which gender equality, as ‘equal sharingof paid work, money, knowledge, decision-making powerand time’, is seen as central (Plantenga et al., 2009).

1.4.2. Enlarging the frameworksNumerous studies attempted to expand on the concep-tual frameworks of the initial gender indices, with someattempting to construct alternative indices. Examples ofalternative indices along with their main conceptual frame-works are provided below in Table 1.1.

10

Gender Equality Index – Report

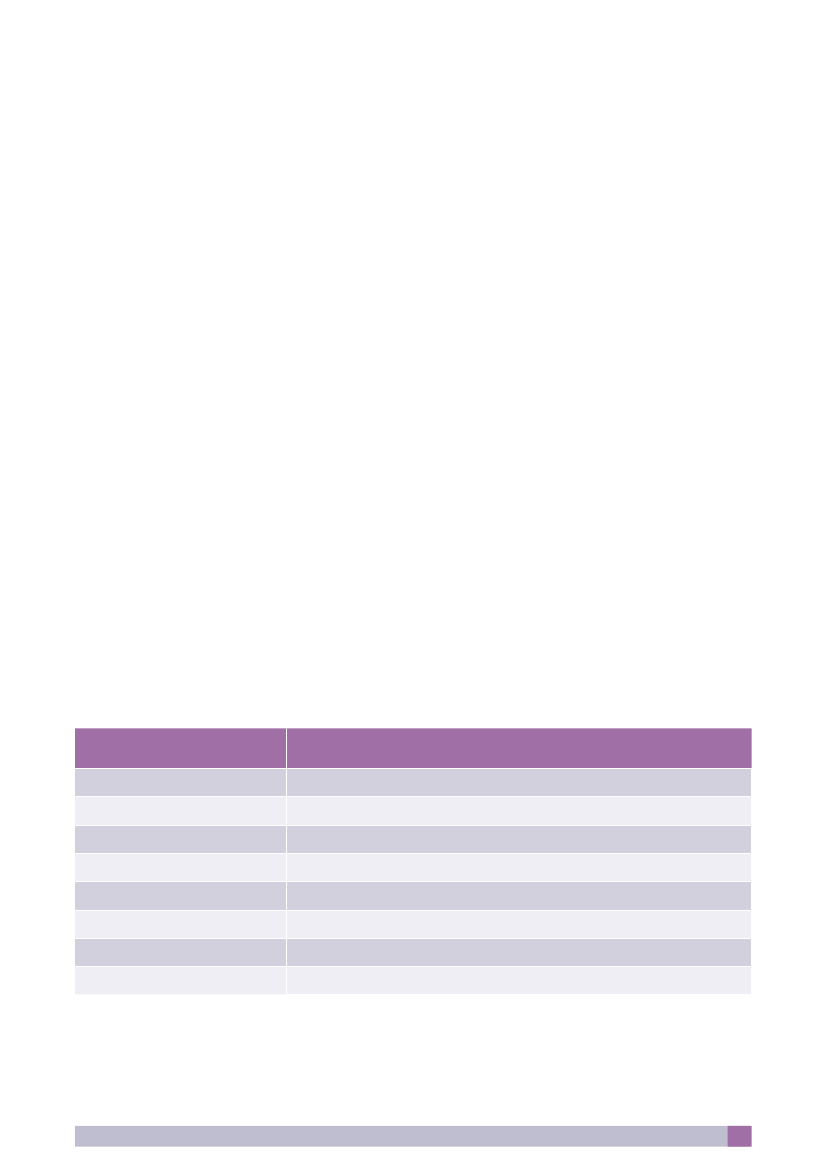

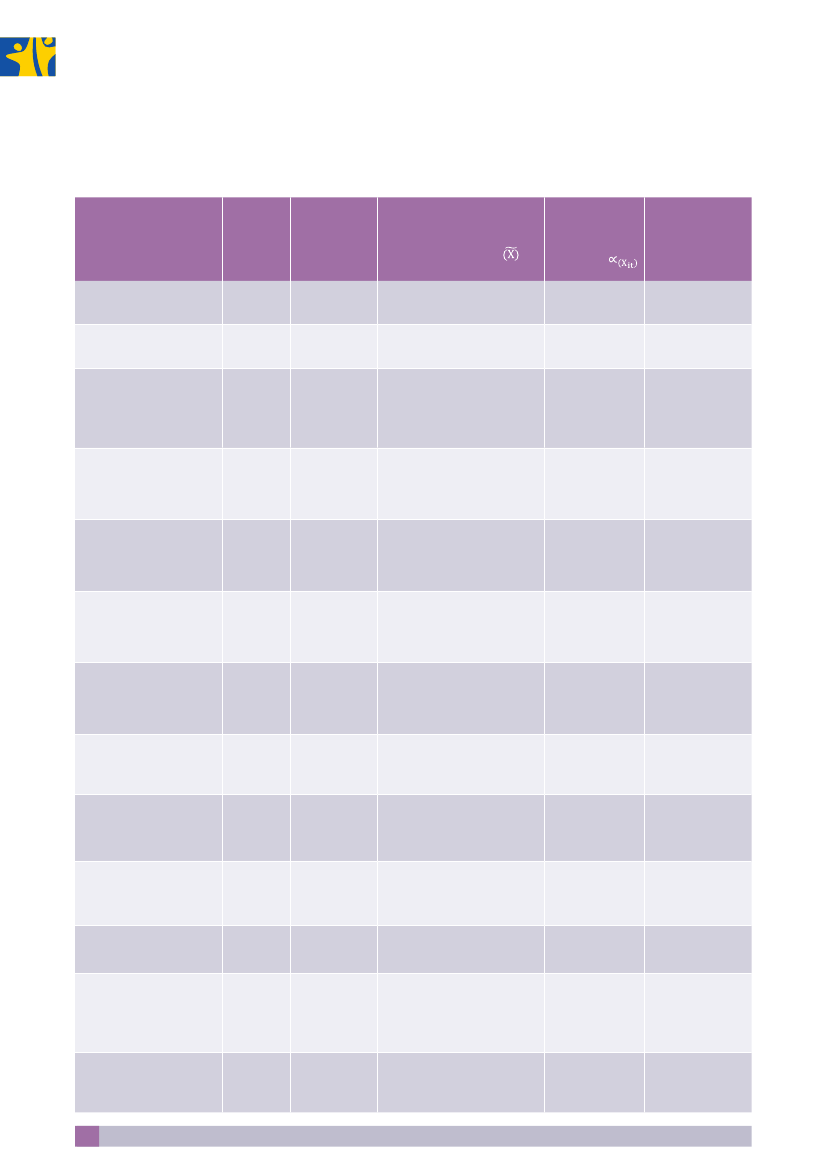

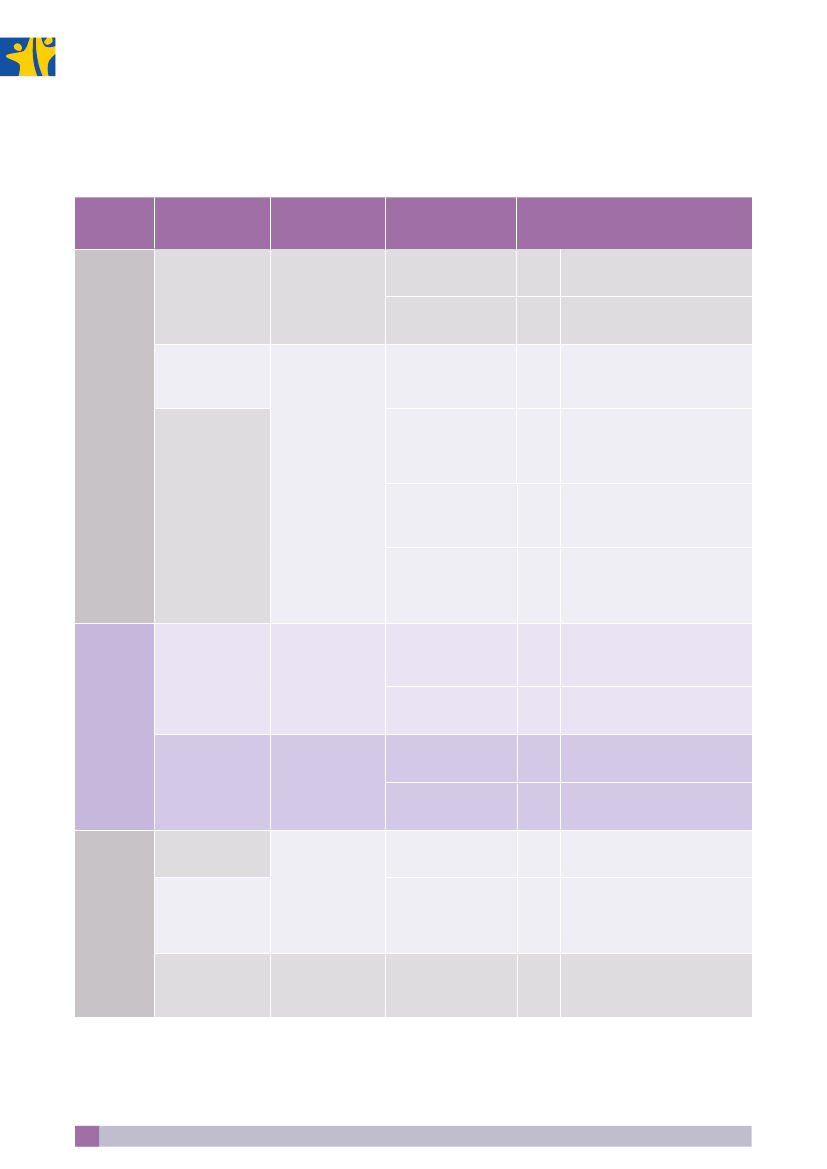

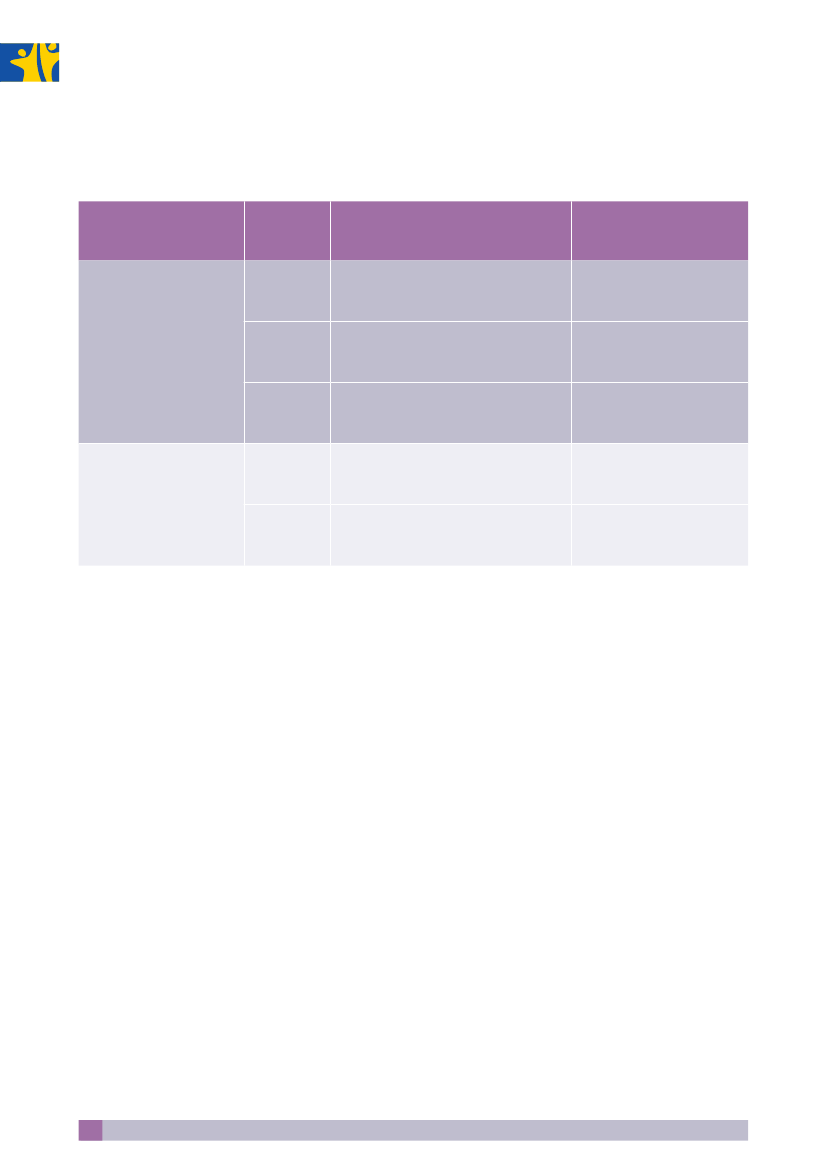

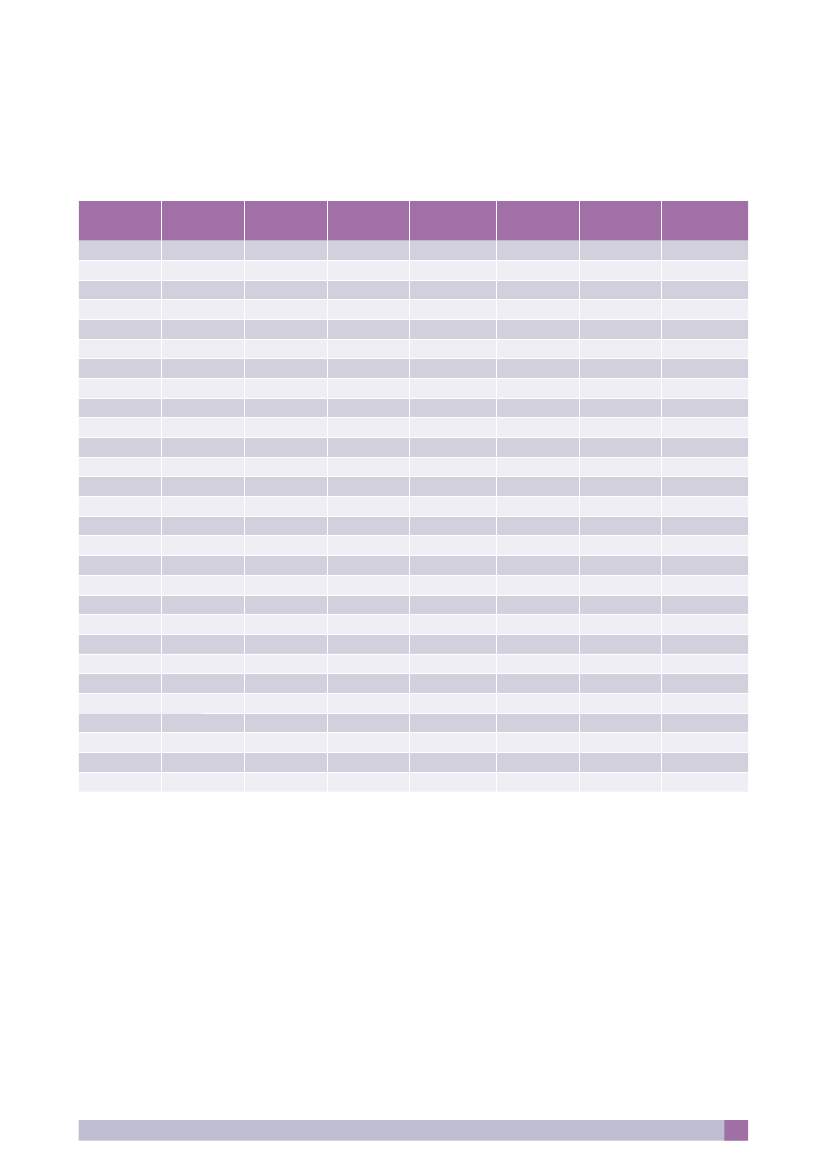

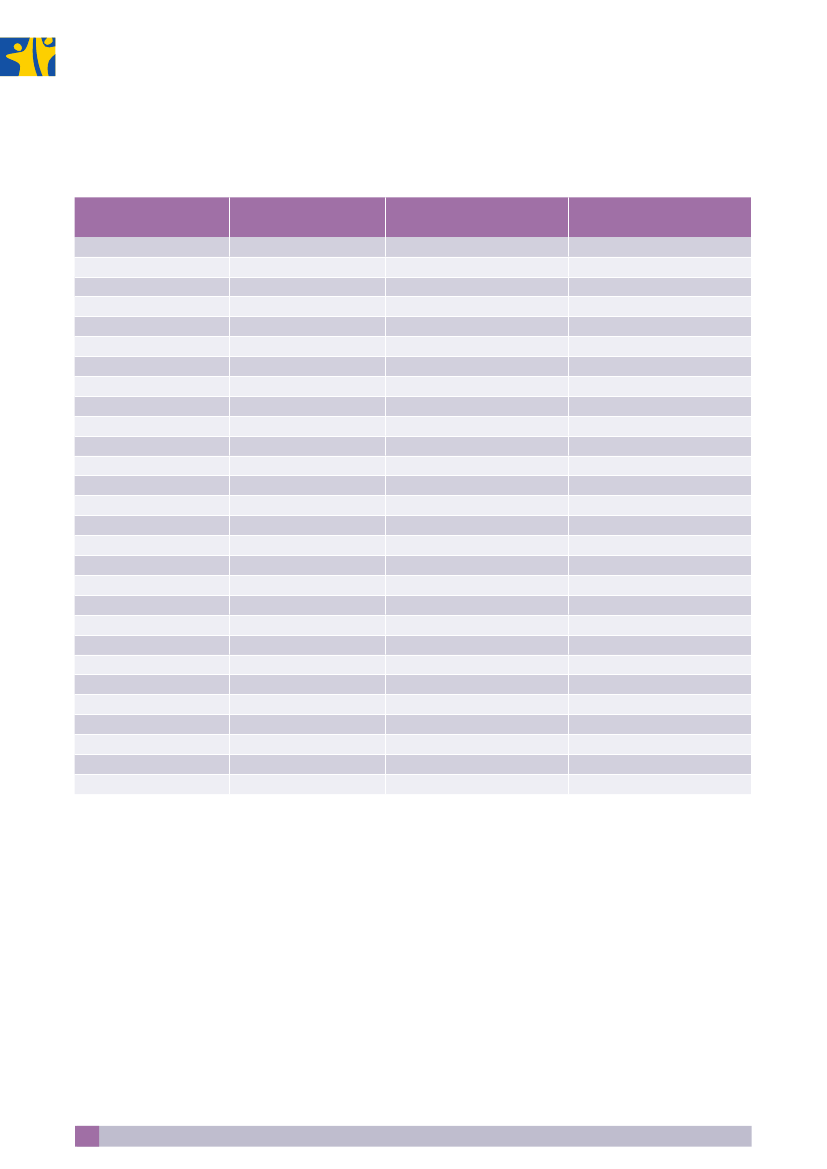

Table 1.1. Existing gender indices and their conceptual frameworkIndicesConceptual frameworkEducational attainmentLongevityIncomeParticipation in governmental, managerial decision-makingParticipation in professional roles and in economic activities in general

Source

Gender Development Index

UNDP

Gender EmpowermentMeasure

UNDP

Gender Inequality Index

Labour marketEmpowermentReproductive healthEconomic participation and opportunityEducational attainmentHealth and survivalPolitical empowermentEducationEconomic participationWomen empowermentDiscriminatory family codeRestricted physical integritySon biasRestricted resources and entitlementsRestricted civil libertiesRatio of the female and male index for education(educational attainment)Ratio of the female and male index for life expectancy (longevity)Relative female and male returns to labourHealth (inequality-adjusted life expectancy index)Education (inequality-adjusted education index)Income (inequality-adjusted income index: Quintile income ratio;income Gini)Equal sharing paid work (labour force participation,unemployment)Money (gender pay gap, income)Decision-making power (political power, socio-economic power)Knowledge (gender gap in education and training,gender gap in educational attainment)Unpaid time (caring time, leisure)Education (education level, lifelong learning and internet,educational segregation)Work (participation, contract conditions, occupational andpay segregation)Power (political, managerial)

UNDP

Gender Gap Index

World EconomicForum

Gender Equity Index

Social Watch

Social Institutionsand Gender Index

OECD

Relative Status of Women

Dijkstra and Hanmer (2000)

Inequality-adjusted HumanDevelopment Index

UNDP

European UnionGender Equality Index

Plantenga et al. (2009)

European GenderEquality Index

Bericat (2011)

Gender Equality Index – Report

11

The multiplicity of domains in the different conceptualframeworks of existing indices reflect the specificity of theobjectives and region that the index targets. For this rea-son, they may not provide an adequate tool for MemberStates comparisons at EU level.Criticisms of existing gender related indices also pointto the sometimes over-simplistic nature of what is beingmeasured and point to the need to extend to other dimen-sions that better reflect critical areas of gender equality, aswell as take into account more subtle and relevant indica-tors of gender equality. This section summarises the short-comings identified within the perspectives of human de-velopment, women’s empowerment and gender equality.While crude indicators such as life expectancy suggestthat women have a major advantage over men (and thismight also apply to levels of educational attainment) this isnot mediated by reference to quality of life and levels of illhealth and disability in later life. Critics are thus calling foran index that measures gendered well-being (Chant, 2006)or captures gender gaps in mortality and disability-free lifeexpectancy (Hooper, 2006).The uneven sharing of (paid and unpaid) work and theconsequences of this in terms of access to financial re-sources and the likelihood of falling into the poverty trap ispointed out as an important area. A gender equality indexshould therefore focus on sex-specific employment andunemployment rates (Cueva, 2006), on disposable income(Klasen, 2006), and on the economic returns of women’sand men’s labour (Chant, 2006). It needs to measure thetime spent on care (Schüler, 2006; Chant, 2006; Klasen,2006; Permanyer, 2011) and the time spent in the informalsector, including leisure activities (Permanyer, 2011; Klasen,2006). The importance of measuring individual disposabletime, net of financial and time responsibilities associatedwith care, has also been raised (Folbre, 2006).The absence of any provision in gender equality indicesin relation to gender-based violence and violence againstwomen, which ignores a major sphere in which gender in-equalities are sustained and magnified, in the home, work-place and society, has been heavily criticised. It is impera-tive that a gender equality index focus on forms of violenceagainst women (Ellsberg et al., 2008); more particularly, onphysical security and absence of violence (Klasen, 2006)or empowerment at the household level, related to vio-lence, control over one’s body, sexuality and reproduction(Cueva, 2006). The focus on gender-based violence against

women also calls for measures of gender equality normsand values (Klasen, 2006) as these are the root of genderinequality in the first place (Inglehart and Norris, 2003).Finally, there is a call for a gender equality index to takeinto consideration other vulnerable groups such as poorwomen, (Chant, 2006) in order to avoid a situation whichsolely reflects the position of economically advantagedwomen (Cueva, 2006; Bericat, 2011).Collectively, researchers agree on the need for a com-parative index that broadens the measures of genderequality, but such measures have not yet been collatedinto a cohesive inter-country index. Due to the lack ofavailable harmonised data, computation remains heavilyconstrained. However, this lack of data should not con-strain the conceptual base of the domains of genderequality to be measured. In summary, existing gender in-dices have fallen short of providing the kind of measuresthat would illuminate debate and contribute to decision-making at EU and national levels. It points to the needfor a more comprehensive, EU based index that feedsinto key policy decisions at EU and national levels.

1.5. The added-value of aGender Equality IndexThe Gender Equality Index provides a synthetic measureof gender equality that is both easy to understand and tocommunicate. This tool should play an important role bysupporting decision-makers in assessing how far a givenMember State is from reaching gender equality. The use ofthe Gender Equality Index allows meaningful comparisonsto be made between different policy areas. Last but notleast, it will give visibility to gender equality by making itpossible to measure its progress over time.In response to the shortcomings of other gender equalityindices, the Gender Equality Index provides a more com-prehensive framework of gender equality. In line with theEU’s framework on gender equality for both women andmen, the Index adopts a gender approach rather than fo-cusing on women’s empowerment. Moreover the GenderEquality Index benefited from the consultation processwith the National Statistics Offices and with the expertsfrom the National Machineries of the EU Members States.Their contribution has determined an important addedvalue to this Index.

12

Gender Equality Index – Report

The Gender Equality Index ensures that it draws upon allthree approaches to gender equality (sameness, differenceand transformative). It does so by relying on gender gaps,that is the difference in the levels of achievement betweenwomen and men on a given gender indicator. No distinc-tion is made as to the direction of this gap, meaning thatthe gender approach takes into account the situation ofwomen and men in various domains of economic and so-cial life, including those where men are in disadvantagedsituations. The target is the equality point, and a givenMember State is equally treated whether a gap is to theadvantage of women or men. However, levels of achieve-ment are also taken into account in order to avoid situationswhereby gender gaps are low, despite an adverse situationfor both women and men.A limitation of existing global gender equality indices isan apparent lack of sensitivity to location. There is a needto provide a more informative tool within a narrower geo-graphical area (Hooper, 2006; Plantenga et al., 2009). Theglobal approach of the Gender Development Index and theGender Empowerment Measure, in the context of Europe,may lose the subtleties of differences between MemberStates (Permanyer, 2011). As its purpose is to offer an arenafor debate and to support the development of policy andresearch at EU level, it is imperative that the GenderEquality Index remain closely aligned with domains perti-nent to both EU policy and specific gender equality policy.To sum up, in line with its policy foundations, the objec-tives of the Gender Equality Index are not only to measuregender equality throughout the Member States and the EU,but also to allow an analysis of gender equality both overtime and geographical areas; to give more visibility to thesituation of women and men in the Member States overalland in selected areas of concern for gender equality; andto support the evaluation of the degree of effectivenessbetween different measures and policies implemented inthe field of gender equality at EU level.Having set out the definition and approach taken by theGender Equality Index, and defined its added value, theReport now turns to the development and presentation ofits conceptual framework.

Gender Equality Index – Report

13

2. Conceptual frameworkA conceptual framework for gender equality is a prere-quisite to guide the way in which gender indicators willbe selected and combined to provide a suitable meas-ure of gender equality relevant to the EU policy context.Describing the dimensions of gender equality is a chal-lenging exercise. It is necessary to deal with the complex-ity of the concept, since it draws on different perspec-tives and disciplines, different age groups and a moregeneral heterogeneity within the population itself, addingfurther complexity to the attempt to construct a concep-tual framework of gender equality.It is also essential for the Gender Equality Index to renderwhat it seeks to describe as simple as possible. It is crucialto bear in mind that this simplicity is not a marker oftriviality. Instead, users should be aware that it representsthe main elements of an intricate concept. This process ofsimplification is the result of carefully negotiating thebalance of drawing out the main elements without losingthe essence of gender equality.The conceptual framework aims to provide a hierarchicaltree structure that can adequately map the main equalityconcerns within the framework of EU policy and EU gen-der equality policy. It establishes the domains and associ-ated sub-domains into which gender gaps within relevantindicators can be measured. The development of thisstructure is driven by both policy objectives and explicitreference to (gender) equality frameworks, which this sec-tion outlines before presenting in detail the domains andsub-domains of the conceptual framework.ness, difference and transformative frameworks to genderequality also adopted in the Gender Equality Index, andprovide various domains of gender equality to be takeninto account.

2.1.1. Equality and equity frameworksSeveral equality and equity frameworks, sometimes appliedspecifically to gender, have been developed. A perspectiveof ‘equality of condition’ is proposed by Baker et al. (2004)in a social equality framework. Although this concept ofequality is not specifically dedicated to the question ofgender equality, but rather to social equality in general,it provides a possible approach to determine relevantdomains of gender equality. This approach is particularlyrelevant to contemporary developed societies and aims ateliminating major inequalities. It sees inequalities as rootedin changing and changeable social structures, particularlyin structures of domination and oppression. Instead of see-ing individuals as responsible for their successes and failures,the approach of equality of condition emphasises the in-fluence of social factors on people’s choices and actions.The framework offers some interesting dimensions whichare adaptable to the context of gender and which includefive dimensions of equality which are seen to cover mostissues that contemporary egalitarians are concerned with:equal respect and recognition; equality of resources; love,care and solidarity; equality of power; and working andlearning as equals.Another framework that is focused specifically on genderhas been proposed by Pascall and Lewis (2004). This frame-work names five areas as key elements of gender regimes,for the purpose of analysing and assessing welfare systemsand social politics with respect to gender equality. It mapssocial politics for gender equality across the domains of paidwork, care work, income, time and voice. It argues that gen-der equality policies have been limited in effect, becausethey have addressed only part of the system rather thanthe whole, in particular, individual women’s possibilities forequal earning (Pascall and Lewis, 2004), which shows the im-portance of ensuring that a conceptual framework of gen-der equality is as comprehensive as possible.

2.1. Gender equality theoreticalframeworksIn order to make sense of the variety of meanings ofgender equality observed in EU policy documents, somekey frameworks that could explicate gender equality atthe macro level were analysed. They broadly cover twomain areas: equality or equity frameworks and capabilityapproaches. These, taken together, combine the same-

14

Gender Equality Index – Report

The gender framework developed by Fraser (1997) departsfrom the concept of gender equality, instead using the termgender equity and establishing principles for thinking sys-tematically about gender equity in the context of welfarestate models. This change in terminology reflects the ideathat equity is concerned with fairness and justice betweenwomen and men in relation to the share of benefits andresponsibilities. The equity concept moves from allocatingtasks equally to allocating them fairly. It suggests that genderequality can only be reached when both women and menchange their lifestyles and the way in which they allocateshares of social and economic participation. Gender equityis defined as a complex idea, and relies on shattering thedichotomy between sameness and difference. Against thebackground of a multi-dimensional concept, it determinesthe dimensions of gender equity as a compound of sevendistinct principles, to which welfare systems must conform inorder to meet the claim of gender equality: anti-poverty; anti-exploitation; income equality; leisure time equality; equalityof respect; anti-marginalisation; and anti-androcentric.

Some researchers have extended the original capability ap-proach and applied it to gender, such as Nussbaum (2003),whose considerations on gender equality build upon Sen’scapability approach. She argues that, in order to supplyconcrete and useful guidance, a definite list of the mostrelevant capabilities have to be formulated, even one thatis tentative and revisable. She has thus developed a list ofcentral human capabilities (in terms of universal humanneeds and entitlements) of which everyone should be en-titled to a minimum threshold, even while considering thislist as open-ended and subject to ongoing revision andrethinking. Nussbaum lists these capabilities as: life; bodilyhealth; bodily integrity; senses, imagination and thought;emotions; practical reason; affiliation; other species; play;control over one’s environment; and equal worth of indi-viduals. Each of these capabilities is seen as crucial to fullequality. Neglecting one or more of them is construed as afailing in gender justice.Robeyns (2003), like Nussbaum (2003), argues against com-pleting a definitive list of universal capabilities but sug-gests a procedural approach to defining relevant capabili-ties for determining what to measure and how to observegender inequality, where interested parties can proposefurther capabilities pending a reasonable argument. Thelist of gender equality capabilities she proposes consistsof: life and physical health; mental well-being; bodily in-tegrity and safety; social relations; political empowerment;education and knowledge; domestic work and nonmarketcare; paid work and other projects; shelter and environ-ment; mobility; leisure activities; time-autonomy; respect;and religion (Robeyns, 2003).These frameworks provide a solid basis on which to con-ceptualise gender equality in the EU policy context, in-cluding a list of overlapping domains. Before proceeding,however, the report provides an overview of the develop-ment of the concept of gender equality within legal andstrategic documents at EU and international level in orderto identify the domains of gender equality present in thesedocuments, and to map the concept of gender equality.

2.1.2. Capability approachesThe meaning of gender equality has also been taken fromthe perspective of capabilities. Attempts to measure gen-der equality, notably the Human Development Index andGender-related Development Index, have largely adoptedthis approach and drawn upon the framework of Sen’s ca-pability approach (Sen, 1980; 1993). It argues that a con-cept of equality should be concerned with what peopleare able to be and to do, and not with their income, orwhat they can consume. The focus should be on the realopportunities that people have for well-being and leadinga valuable life. According to this equality concept, it is notimportant to equate people with the distribution of mate-rial resources, but rather to ask how, against the concretebackground of their different individual situations, resourcescan be used to open options for choice and secure people’swell-being. People with physical disabilities, for example,require more resources to attain an equal degree of mobil-ity, power to act and choice. The parameters for equalityare capabilities, which are necessary for the realisation ofmeaningful activities and positive states of being. Sen’s ca-pability approach itself only provides a general frameworkwithout proposing a concrete list of capabilities because,in his opinion, it is not up to the theorist to make thesedecisions, but rather to a democratic process among therelevant agents (Robeyns, 2007).

Gender Equality Index – Report

15

2.2. Gender equalitypolicy contextTo understand the concept of gender equality in EU policy, athorough analysis of some key documents was undertaken.The EU treaties were the first main reference as the bindingagreement between EU Member States, complemented bythe body of other EU strategic documents promoting com-pliance with the principle of gender equality. Finally, relevantinternational frameworks such as the UN are discussed. Thefields of action and priority areas that appear in these policydocuments are set out in this section.

2.2.2. Gender equality in the EUstrategic policy documentsIn light of the increasing impetus for gender equality andin order to fulfil these gender equality ambitions, the trea-ties of the EU, the European Commission and other EU in-stitutions have developed several strategic and/or legisla-tive documents.Since 1996 the European Commission has followed a dualapproach to gender equality by both implementing gen-der mainstreaming and initiating specific measures the firstcomprehensive policy was introduced in the a Commu-nity Framework Strategy on Gender Equality (2001–2005)(COM(2000) 335 final) in 2000, having as its main objectiveto ‘establish a framework for action providing for gendermainstreaming in all Community activities in such a waythat they help to attain the goal of removing inequalitiesand promoting gender equality’. The framework identifiedseveral inter-related fields of action in the promotion ofgender equality in economic life: equal participation andrepresentation; equal access and full enjoyment of socialrights for women and men; gender equality in civil life;change of gender roles and stereotypes.Following this, the European Commission developedthe Roadmap for Equality between Women and Men(2006–2010) (COM(2006) 92 final), outlining six priority areas,each with specific key objectives and actions, and thereforemarking a clear advance in terms of providing measuresand targets. To measure progress, the roadmap calls for thedevelopment of comparable sex-disaggregated statistics,gender sensitive indicators to monitor progress towardsgender equality and the creation of a Gender Equality In-dex. Its priority areas consist of: equal economic independ-ence for women and men; the reconciliation of private andprofessional life; equal representation in decision-making;the eradication of all forms of gender-based violence; theelimination of gender stereotypes; and the promotion ofgender equality in developing countries.In 2010, on the occasion of International Women’s Day,the European Commission unveiled the Women’s Charter(COM(2010) 78 final), which aims at strengthening the Eu-ropean Commission’s commitment to ‘making equality be-tween women and men a reality’. This includes strengthen-ing gender perspectives in all policy work undertaken bythe Commission and dedicating the necessary resources toits realisation. The Charter is based on five gender equalityprinciples: equal economic independence; equal pay for

2.2.1. Gender Equality in the EU TreatiesPolicies in the area of gender equality have been drawnup since the creation of the European Economic Commu-nity in 1957 with the Treaty of Rome. Following the estab-lishment of this founding treaty, this basic principle wasgradually clarified and developed by several Council Direc-tives, which dealt mostly with economic perspectives, in-cluding pay, participation, health and safety, maternity andparental leave, as well as other issues pertinent to work-lifebalance (European Parliament, 2009). None of these legalmeasures, however, dealt specifically to the principle ofgender equality.The principle of gender equality has been strengthened,notably since the 1997 Treaty of Amsterdam (97/C 340/05),by inscribing the principle of gender mainstreaming ina foundation text of the EU. The perspectives of gen-der equality started to widen and, although still largelyadopting an economic perspective, it sought an im-proved understanding of gender equality and requestedthat gender mainstreaming be applied to all activities ofthe Community.Subsequently, the introduction of the Lisbon Treaty (2007/C306/01) in 2009 marked a turning point, as it directly ad-dressed the principle of gender equality, and the policiesto support it, as a central element of EU policy. It empha-sised the importance of eliminating all types of discrimina-tion, including those based on sex, through the Charter ofFundamental Rights of the European Union (2000/C364/01),and gave renewed attention to how gender-based vio-lence of the European Union (2000/C 364/01) threatenedthe integrity and dignity of women and men in the EU.

16

Gender Equality Index – Report

equal work and work of equal value; equality in decision-making; dignity, integrity and an end to gender-basedviolence; gender equality beyond the EU.In the same year, and following on from the Roadmap, theEuropean Commission developed the Strategy for Equal-ity between Women and Men (2010–2015) (COM(2010) 491final), which, building upon the Women’s Charter (COM(2010)78 final), presents current priorities. The Strategy aims at con-tributing ‘to improving the place of women in the labourmarket, in society and in decision-making positions both inthe European Union and the world’, and reiterates the callfor increased cooperation between all European institutionsand Member States. The main priority areas it identifies are:economic independence of women; equal pay; equality indecision-making; dignity, integrity and an end to gender-based violence; gender equality in external actions; andhorizontal issues. Importantly, in its action plan, the Strat-egy for Equality between Women and Men mandates theconstruction of the Gender Equality Index to the EuropeanInstitute for Gender Equality.The year 2010 also saw the launch of the European Union’s10-year growth strategy, Europe 2020 (IP/10/225), which,although it does not refer specifically to gender equality,emphasises the need to foster growth that is smart, sus-tainable and inclusive. Under both the smart and inclusivegrowth agendas, EU targets look at employment (makingspecific references to gender inequality and other groundsof inequality) and education. The employment target aimsfor 75 % of 20- to 64-year-olds to be employed, while theeducation targets aim to reduce school drop-out rates be-low 10 % and ensure that at least 40 % of 30- to 34-year-olds have completed third level education or equivalent.The inclusive agenda has an additional EU target for reduc-ing the number of people in or at risk of poverty and socialexclusion by at least 20 million.The work undertaken at European level by the EuropeanCommission was reinforced in 2006 by a commitment atMember State level. In the first European Pact for GenderEquality (2006) (7775/1/06 REV 1), the European Councilrequested that Member States strengthen attention togender equality and support the objectives of the road-map. In 2011 a new Pact for the period 2011–2020 (7349/11)was adopted. It urges the EU and Member States towork towards achieving equality, to close gender gaps inemployment, education and social inclusion, ensure equalpay for equal work and promote the equal access andparticipation of women and men in decision-making. The

Pact also calls for the promotion of work-life balance forboth women and men and action to reduce all forms ofviolence against women.

2.2.3. Gender equality ininternational platformsOutside of the EU context, United Nation (UN) institutionshave been significant actors in terms of their work in thefield of gender equality. The United Nations General Assem-bly adopted the Convention on the Elimination of All Formsof Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) on 18 Decem-ber 1979, providing a historic document positioning dis-crimination against women as a violation of fundamentalrights. Its scope is very wide and includes, for example, SexRole Stereotyping and Prejudice (Article 5); Prostitution (Ar-ticle 6); Political and Public Life (Article 7); Representation(Article 8); Education (Article 10); Employment (Article 11);Health (Article 12); or Marriage and Family Life (Article 16).At the conclusion of the United Nations 4th World Confer-ence on Women in 1995, the Beijing Platform for Action(BPfA) was unveiled. It highlighted 12 critical areas of con-cern for gender equality, which include: Women and Pover-ty; Education and Training of Women; Women and Health;Violence against Women; Women and Armed Conflict;Women and the Economy; Women in Power and Decision-making; Institutional Mechanisms for the Advancement ofWomen; Human Rights of Women; Women and the Me-dia; Women and the Environment; The Girl-child. The BPfAwas ratified by the EU Member States who have commit-ted to regularly monitor progress in each area. In addition,following the ratification of the BPfA, the establishment ofgender mainstreaming became a major global strategy forthe promotion of gender equality. Within this context, all27 Member States committed to a dual approach of gen-der equality, namely specific actions and gender main-streaming. Although the primary responsibility lies withthe EU Member States to advance the BPfA agenda, theEuropean Council committed the EU to its principles in thesame year. The High Level Group on Gender Mainstream-ing, established and chaired by the European Commission,undertook to review the implementation of each of thecritical areas of concern in an annual work programme,with which each EU Presidency country collaborates.The UN also adopted the Millennium Declaration in 2000,listing eight international development goals to be reachedby 2015. The third Millennium Development Goal (MDG3)is promoting gender equality and empowering women,

Gender Equality Index – Report

17

with targets that aim at tackling issues in employment, pay,political representation, education or poverty. The fifth Mil-lennium Development Goal (MDG5) also highlights thepromotion of maternal health and access to reproductivehealth, particularly when it comes to contraception andantenatal care coverage.The Council of Europe also works actively to promote gen-der equality. Article 14 and Protocol 12 of the EuropeanConvention for the Protection of Human Rights and funda-mental Freedoms, whose implementation is monitored bythe Council, have helped to improve the legal protectionand status of women in recent decades. In April 2010, theCommittee of Ministers of the Council of Europe adopt-ed a Convention on preventing and combating violenceagainst women and domestic violence, also known asIstambul Convention.This review of the main developments of gender equalitypolicy at EU and international level provides a solid baseon which to derive critical areas of gender equality for thepurpose of building the Gender Equality Index. They, to-gether with the theoretical frameworks reviewed above,have been mapped to provide a comprehensive concep-tualisation of gender equality issues at EU policy level.

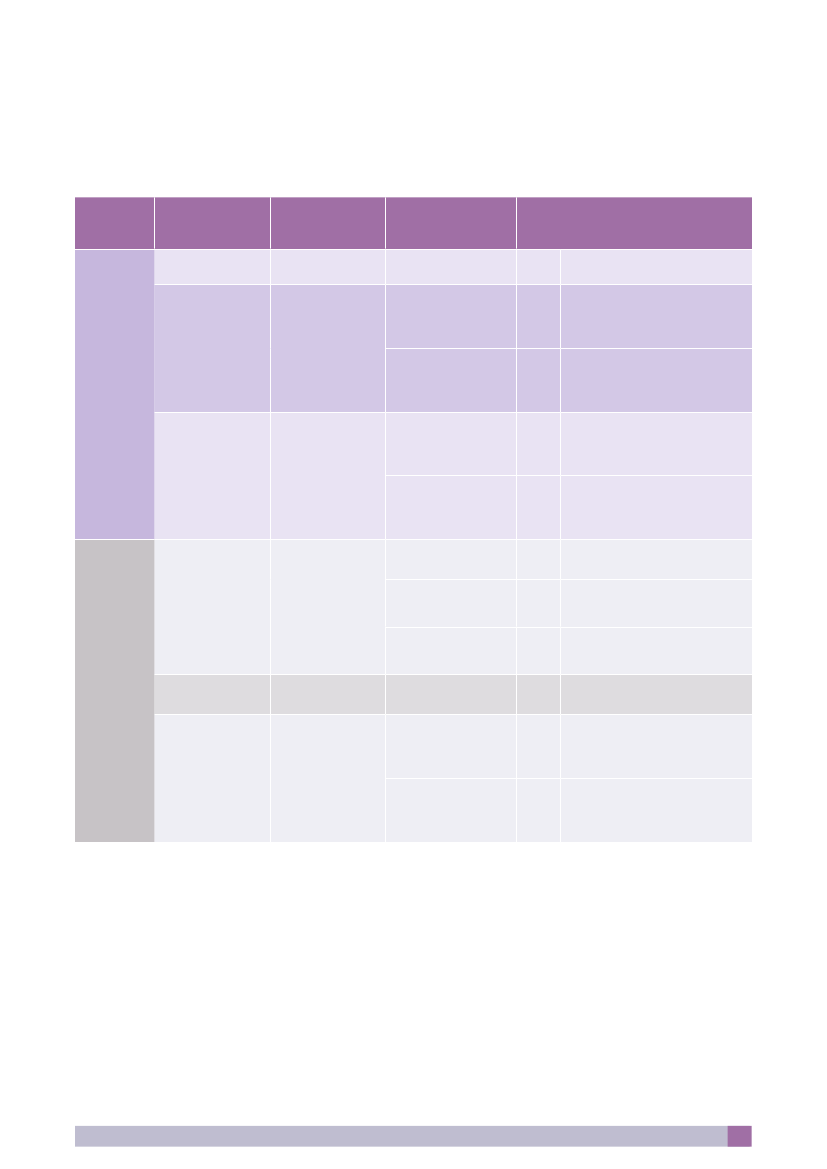

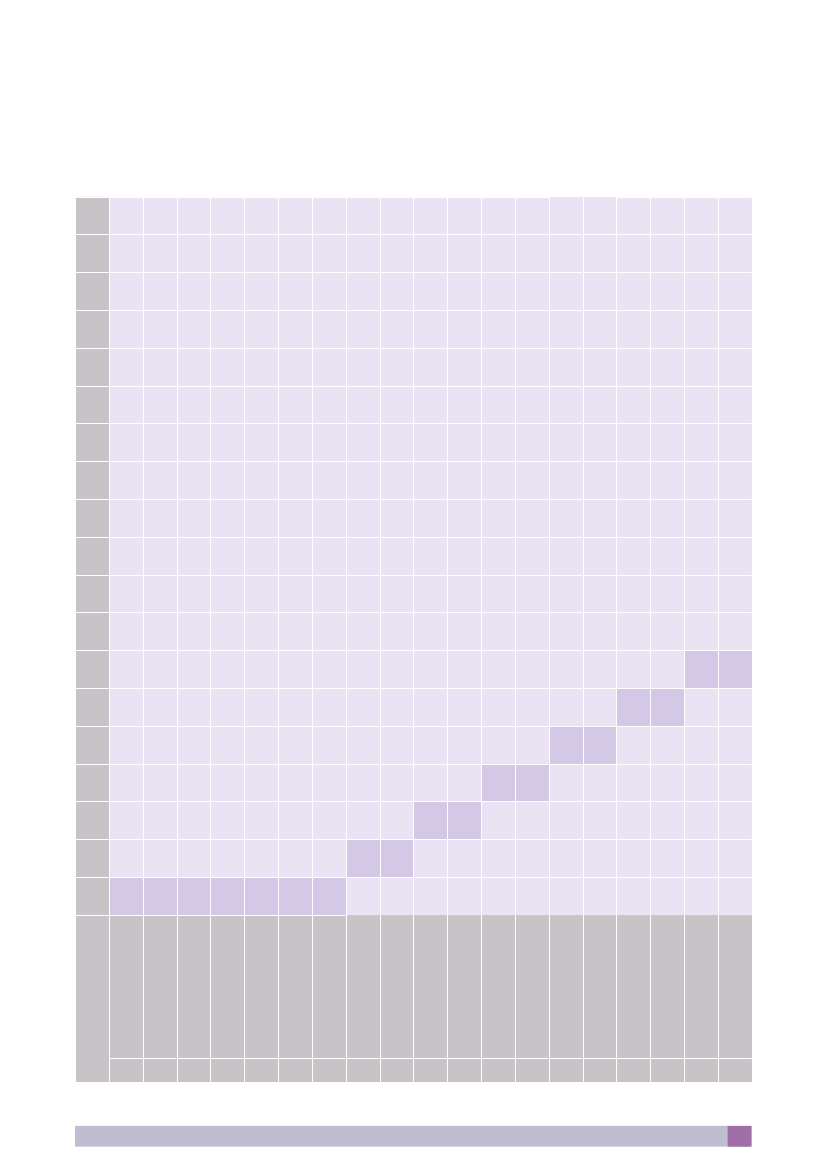

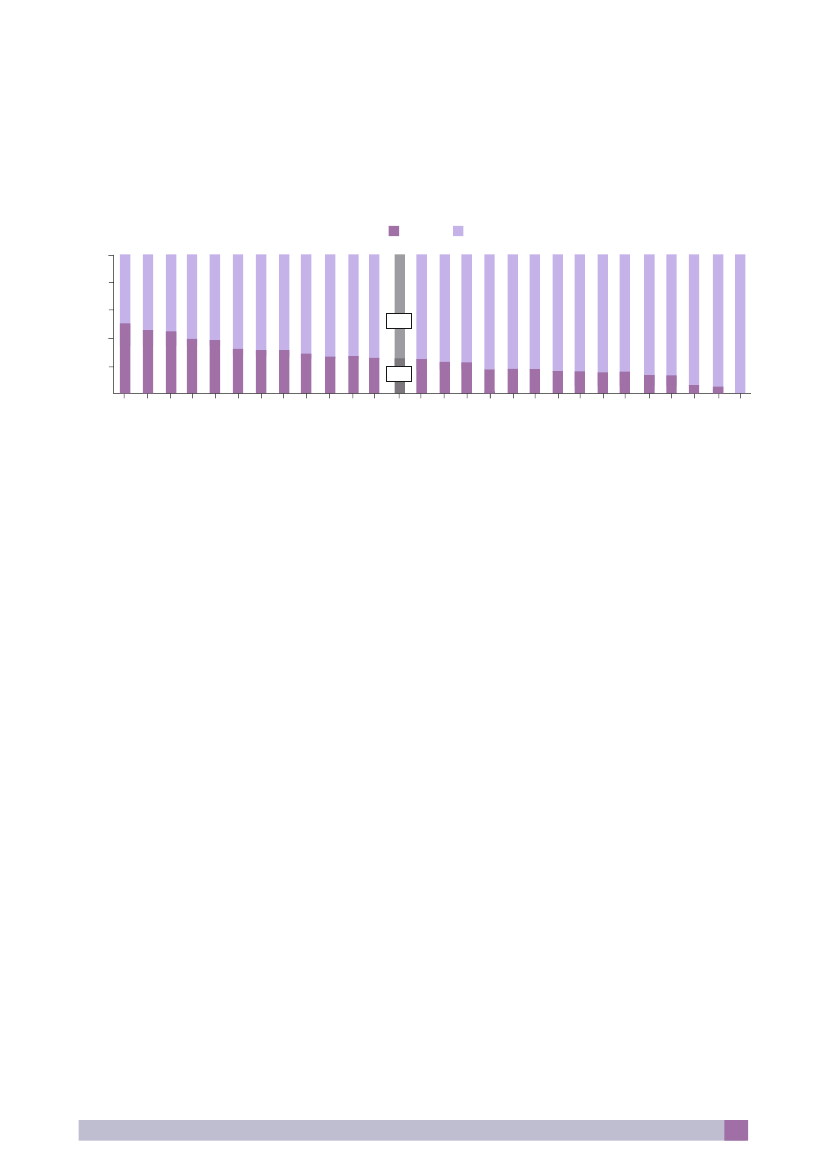

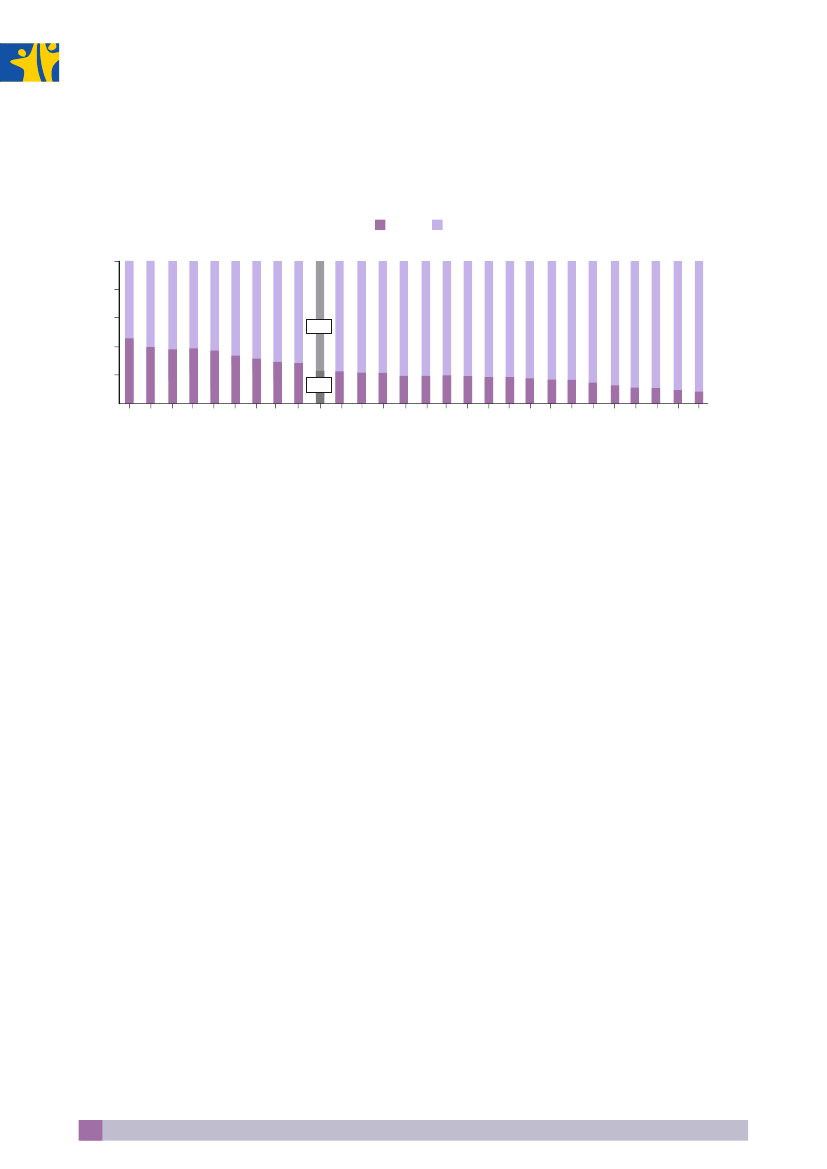

into a hierarchical tree structure. Each domain was thenfurther subdivided into sub-domains. The process of de-signing this structure1was carried out with the advice ofthe members of EIGE’s Experts Forum and Working Groupon the Gender Equality Index1. It was also based on a studyfor the development of the basic structure of a EuropeanUnion Gender Equality Index commissioned by the Euro-pean Institute for Gender Equality (Plantenga et al., 2011)and a feasibility study commissioned by and presented tothe European Commission (Plantenga et al., 2003).During this process, the domains and sub-domains werealso developed against the backdrop of wider interna-tional framework agreements, such as the CEDAW andthe BPfA. Where possible, the critical areas of the BPfAwere taken into account because they provide a world-wide framework and because a commitment exists bythe European Union to continue to review its indicatorsto review the progress of gender equality. A detailed ac-count of how each domain relates to the framework ex-amined is provided in Annex 1.Using some of the conceptualisations of gender equalityand key frameworks of gender equality reviewed above,the domains used in the Gender Equality Index are nowpresented (Figure 2.1.). It consists of eight domains, the firstsix being combined into a core index, and an additionaltwo satellite indices. The satellite indices are conceptu-ally related to gender equality, but cannot be included inthe core index because they measure an illustrative phe-nomenon – that is, a phenomenon that only applies to aselected group of the population. This occurs when con-sidering issues that are related to women only, as in thecase of gender-based violence against women, or whenexamining gender gaps among specific population groups(people with a disability; lone parents or carers; etc).Creating a framework of a core index with satelliteaccounts, as was initially proposed in the work of Plantengaet al. (2011), provides more flexibility to the Gender EqualityIndex and thus increases its usefulness.

2.3. Domains of gender equalityHaving reviewed the main domains of gender equality con-sidered by some leading theoretical frameworks, as well as in-ternational policy documents, this section now turns to howthese were organised into a coherent framework for the Gen-der Equality Index, before describing them in more detail.

2.3.1. From theory and policy to domainsAn analysis of key policy documents and gender equalityframeworks enabled the translation of the concept of gen-der equality, with all its complexity and layers of meaning,

1

The Working Group on the Gender Equality Index is a board officially established by EIGE’s Management board in 2011 to provide the technicalsupport in the construction of the Gender Equality Index and in developing a strategy to disseminate it. The Experts’ Forum is the Institute’s advisorybody. Its principle function is to provide expertise knowledge in the field of gender equality.

18

Gender Equality Index – Report

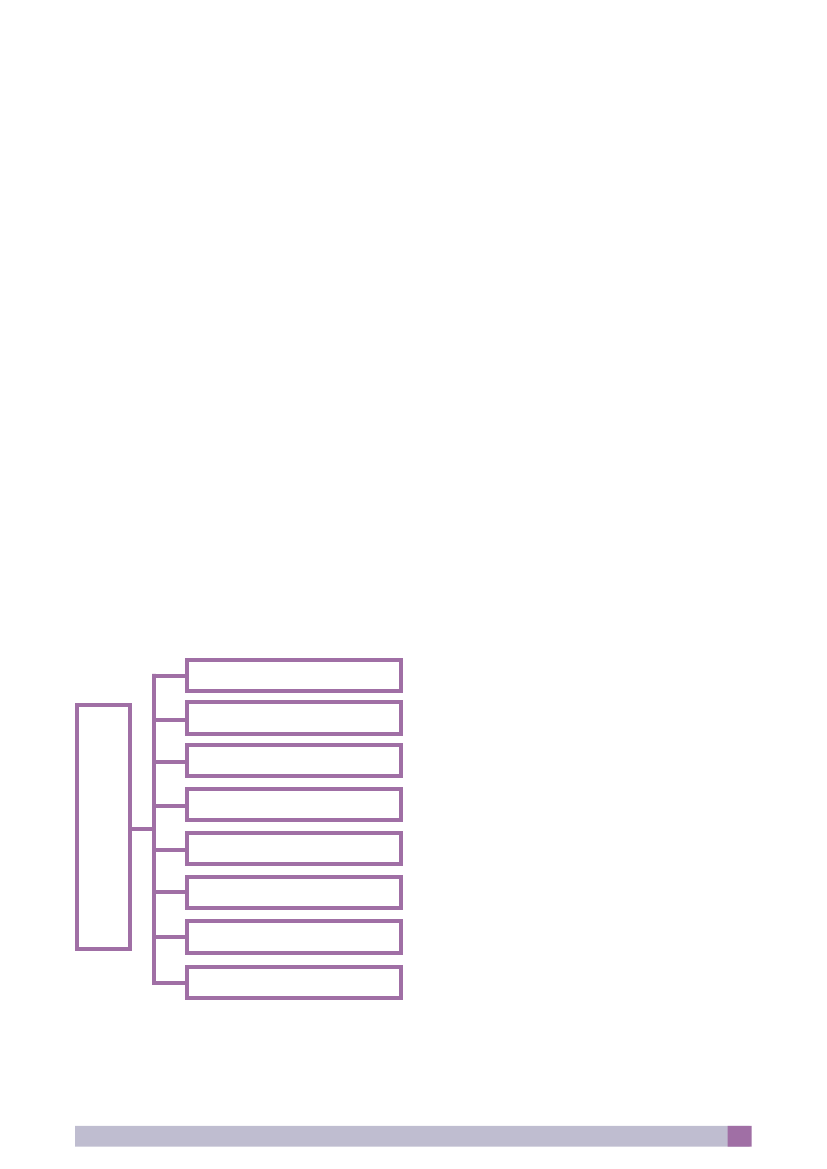

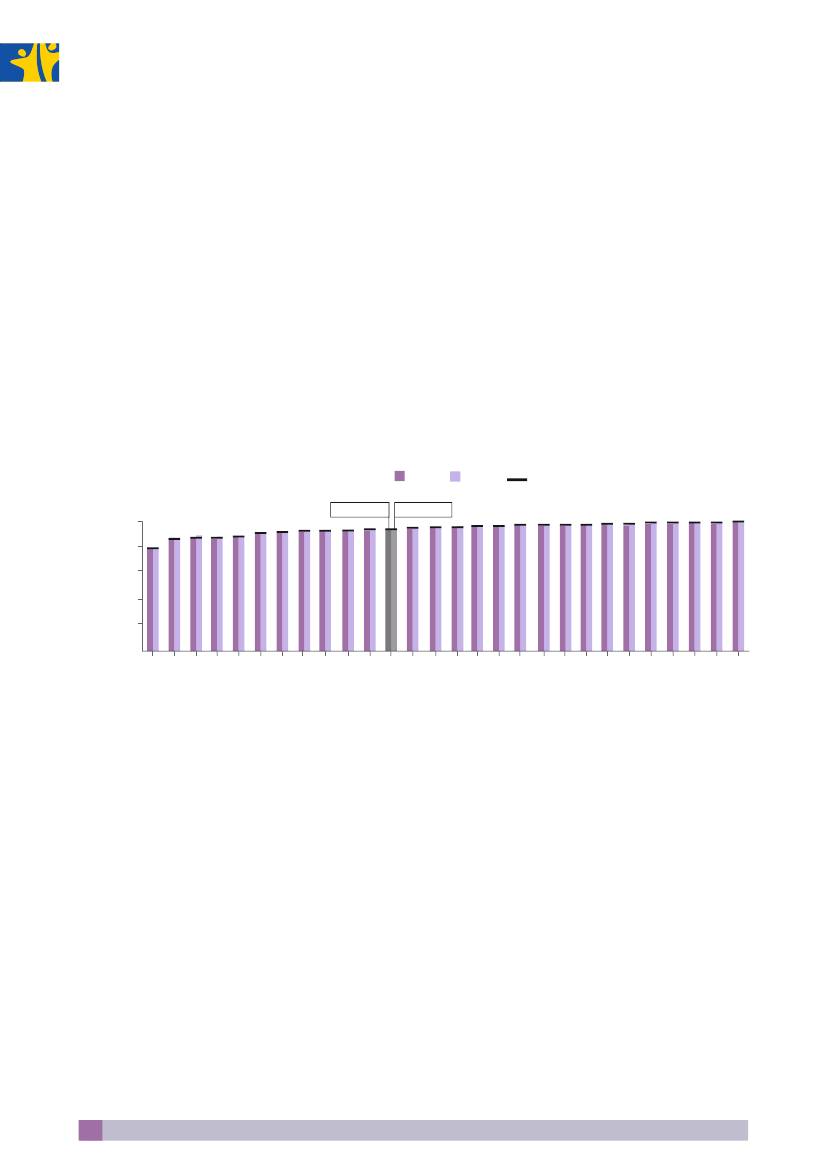

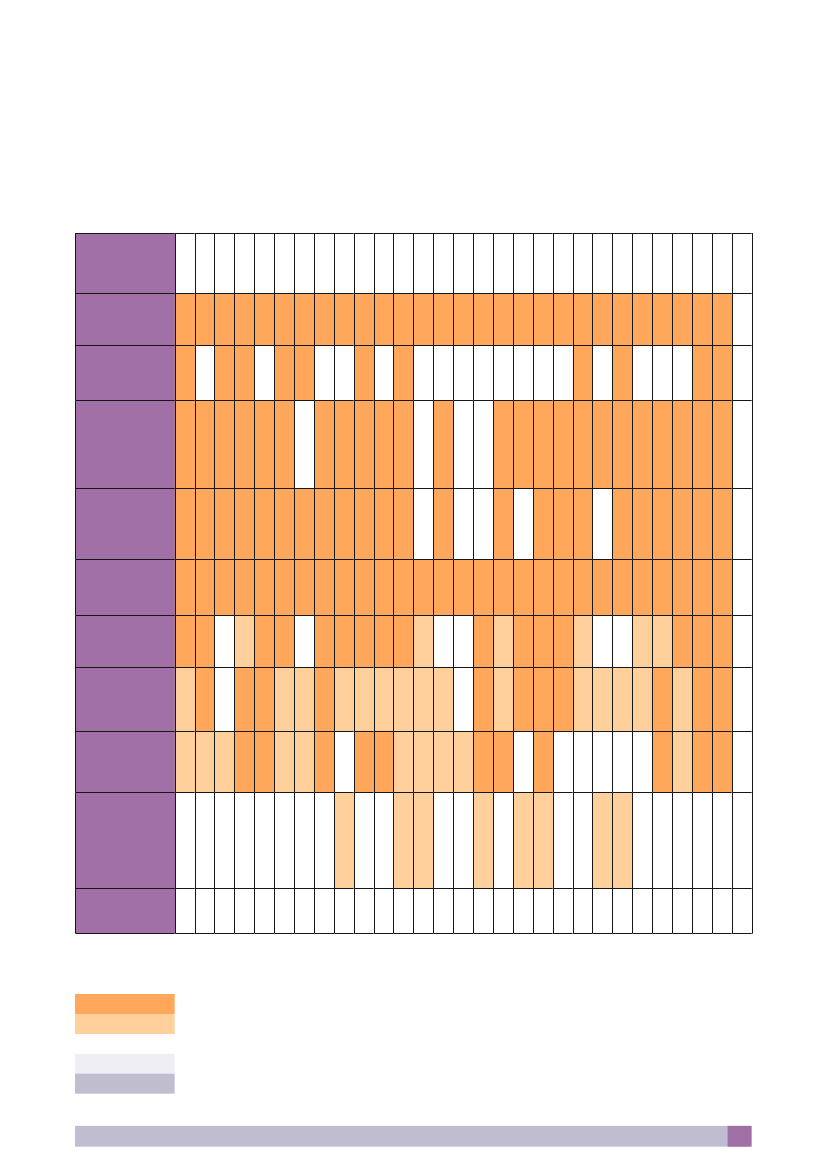

Figure 2.1. Domains of the Gender Equality Index

WorkViolenceMoney

Intersectinginequalities

Gender Equality inthe EU PolicyFramework

Knowledge

HealthPower

Time

Each of the domains is discussed in greater detail below,along with associated sub-domains. The link betweenthe concept of gender equality and each domain is out-lined, and the section expands on how domains relate totheoretical approaches of gender equality, as well as howeach addresses a gender equality policy concern at the EUlevel.

2.3.2. Domain 1: WorkThe first domain,work,relates to gender gaps in the posi-tion of women and men in the European labour market.This means that, in line with EU policy focus, it mostlyconsiders paid work. It is an important area to consider, asgender gaps in employment have been linked to slowerrates of economic growth because of an artificial reduc-tion in the pool of talent in the labour market (Klasen andLamanna, 2009).The domain ofworkrelates to the conceptual models ofgender equality identified in the literature. Access is em-phasised in equality frameworks with a focus on the ca-pability of individuals to work in the labour market or toundertake projects (Robeyns, 2003). Importance is given tothe equal value and share of work between women and

men (Pascall and Lewis, 2004), and to the equal distribu-tion of burdens and benefits of work. In addition to equalshare, the conditions under which people work need to bemuch more equal in character to achieve equality (Bakeret al., 2004). This may mean being capable of controllingone’s environment, including exercising practical reasonand entering into meaningful relationships of mutual rec-ognition with other workers (Nussbaum, 2003). This focuson the conditions in which work is undertaken to achievegender equality can be framed as a more general anti-ex-ploitation principle (Fraser, 1997).At policy level, the domain ofworkis relevant becauseof the importance given to increasing both the numberof jobs and labour market participation. Some of the keybenchmarks in this domain of EU policy are the Europe 2020(IP/10/225) and the European Employment (COM(2003) 6 fi-nal) strategies, with a target to achieve a participation ratein employment of 75 % of 20- to 64-year-old Europeans.Gender differences are tackled by a number of documents.The Treaty on the Functioning of the EU (Article 153) (2010/C83/01) includes a commitment to support Member Statesin achieving equality between women and men with re-gard to labour market opportunities and treatment atwork. This is reinforced by the European Commission, the

Gender Equality Index – Report

19

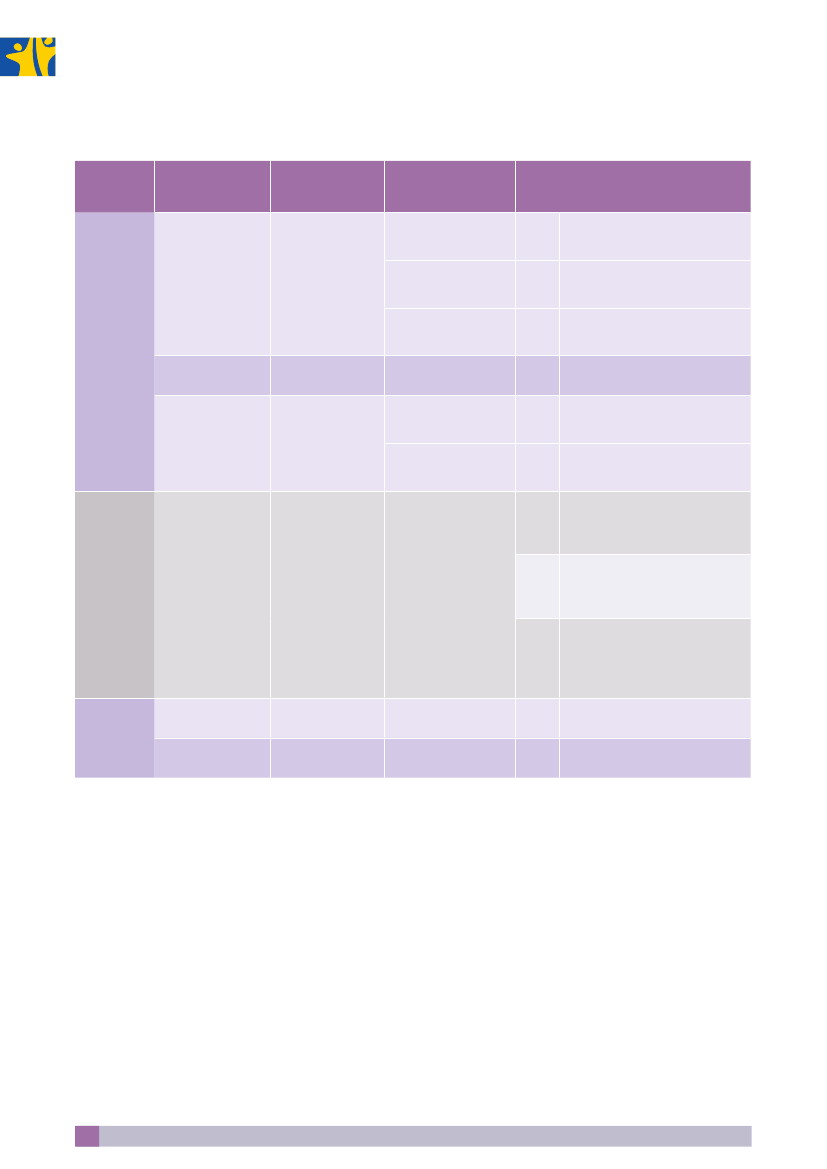

European Parliament and the European Council with Direc-tive 2006/54/EC, which deals with the implementation ofthe principle of equal opportunities and equal treatmentof women and men in matters of employment and oc-cupation. Furthermore, strategic documents such as theRoadmap (2006–2010) (COM(2006) 92 final), the Women’sCharter (2010) (COM(2010) 78 final), the Pact (2011) (7349/11)or the Strategy (2010) (COM(2010) 491 final)have translatedthese concerns mainly in terms of increasing women’s em-ployment, currently well below that of men’s, as well asreducing labour market segregation.The focus of EU policy has moved away from only attempt-ing to provide more jobs, to also ensuring that these arebetter jobs. Quality of work, for example, is at the heart ofthe European Social Model and the European EmploymentStrategy (COM(2003) 6 final). The Lisbon Strategy (2000)and Europe 2020 (IP/10/225) call not only for the creationof more jobs for women, but also better jobs for womenand men. The issue of quality can refer to a number of jobcharacteristics and may also be defined as the match be-tween the characteristics of the job and the worker, and theworkers’ subjective assessment of their job in terms of sat-isfaction, job security, career prospects and so forth (Green,2006; European Commission, 2001) (COM(2001) 313 final).The principles of quality of work were developed followingstatements from the Lisbon and Nice European Councils in2000, where there was an emphasis on the promotion ofquality in all areas, including quality of work (EMCO, 2010).Under the Lisbon Strategy, Member States have acknowl-edged the major contribution that guaranteeing qualityand productivity at work can play in promoting economicgrowth and employment (COM(2003) 728 final). The focusof EU policy on quality of work also includes the promotionof flexible working arrangements, with a strong emphasison work-life balance, often translating into policies relatedto family leave or childcare arrangements, for both womenand men, seen, for example, in the Pact (2011) (7349/11).Quality of work became a priority area of the Social PolicyAgenda of the European Union (2006–10) (COM(2005) 33final) and subsequently developed into the Europe 2020’scall for more and better jobs.The domain ofworkis divided into three sub-domainswhich consist ofparticipation, segregationandquality ofwork(Figure 2.2.).

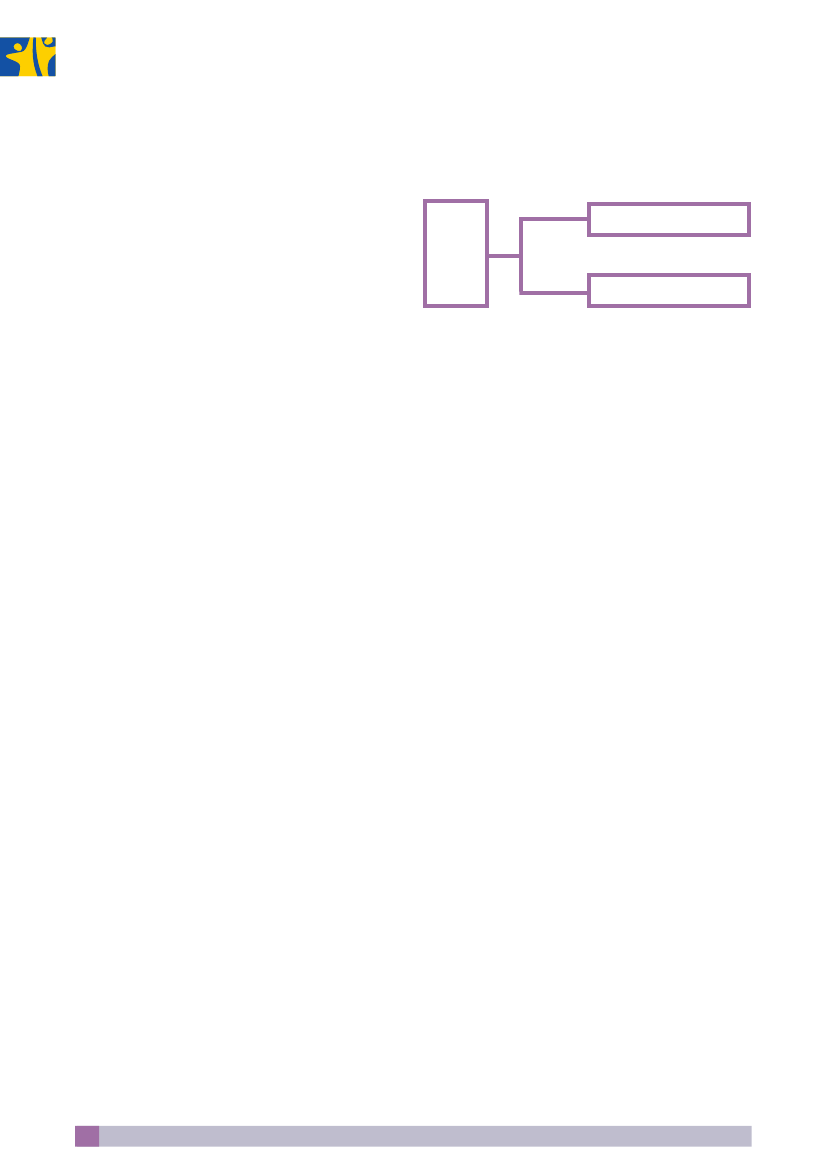

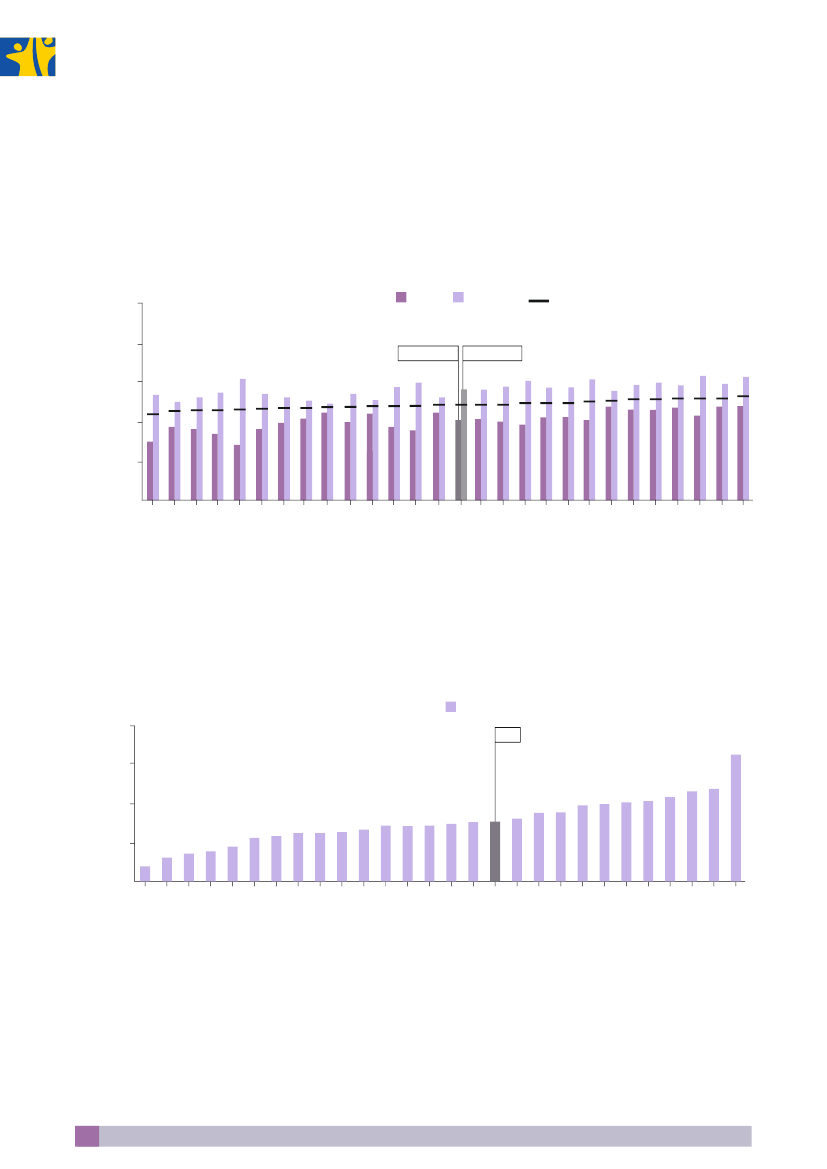

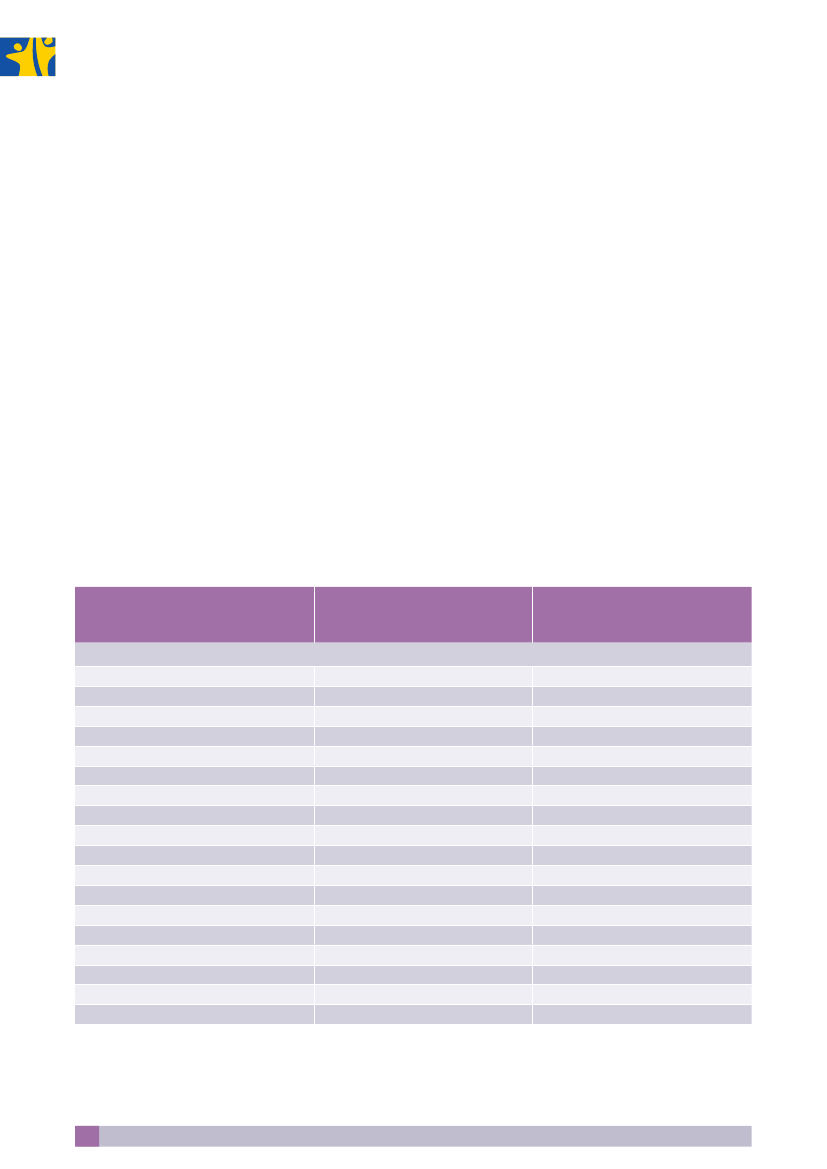

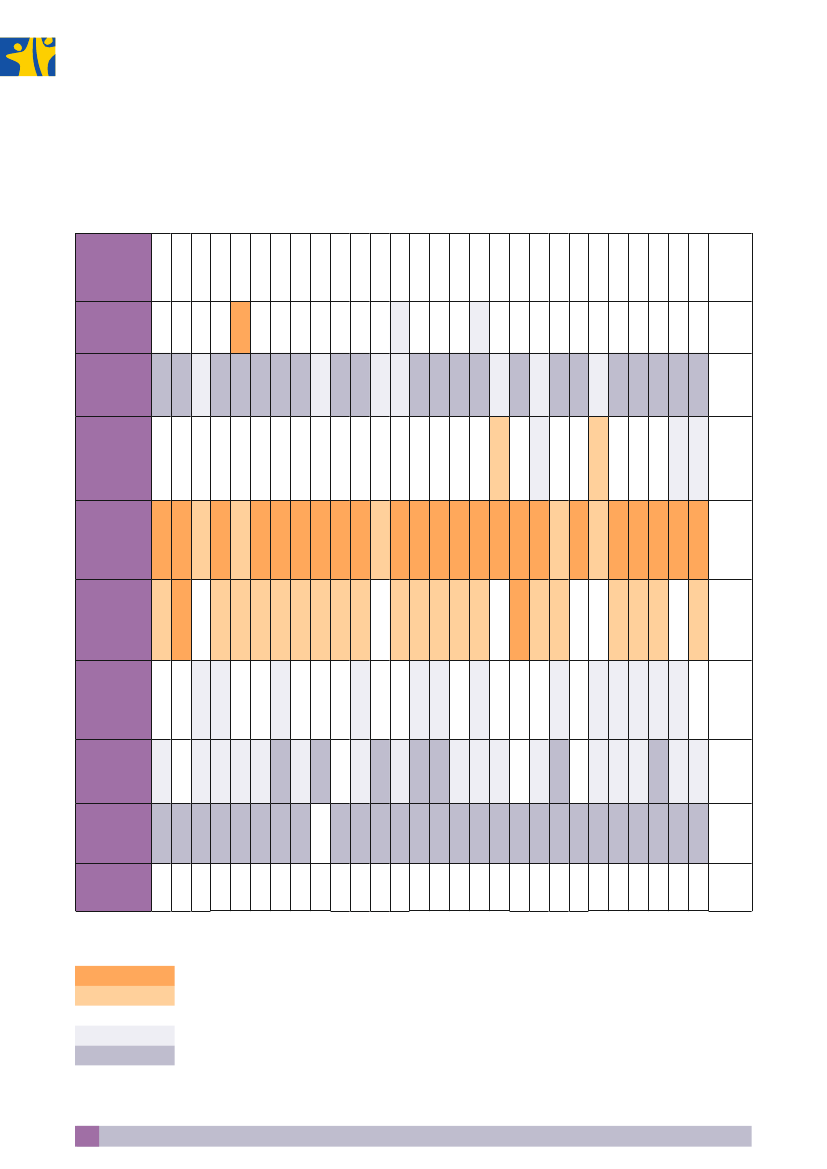

Figure 2.2. Domain ofworkand its sub-domains

Participation

Work

SegregationQuality of work

The first sub-domain,participation,is important for genderequality given that gender gaps in participation have nar-rowed dramatically across the lifespan of the EU, althoughwomen remain less likely than men to participate in thelabour market. Furthermore, when women do participate,it is more frequently on a part-time basis, leading to in-creased patterns of segregation and lower quality of work(European Commission, 2009). Despite the EU policy focuson paid employment, it is important to point out that par-ticipation is also highly gendered by patterns of participa-tion in the formal and informal labour market. While theparticipation of women in paid employment has reachedone of the highest levels in history, women’s involvementin so-called ‘invisible’ areas should not be forgotten. Thiscan take the form of work performed at home (piece-ratelabour), in the black economy or working undeclared in afamily business (Chant and Pedwell, 2008).Women are more likely to move in and out of the labourmarket, because their disproportionate responsibility totake on caring roles leads to more career interruptionscompared with men (Annandale and Hunt, 2000). Theparticipation of women and men in work is fundamen-tally different and can be summarised by the so-called‘30:30:40’ model (Hutton, 1995). In this model, society isdivided into approximately 30 % of the population that areunemployed or inactive, a further 30 % that are active butin some form of precarious conditions (such as some formsof self-employment or forced part-time employment) andthe remaining 40 % in permanent employment or estab-lished and secure self-employment. Of course, adoptinga gender perspective for this model shows that a funda-mental difference is that women are disproportionatelyrepresented in the last two categories (Crompton, 1997).Many forms of policy can influence the participation rateof women, including fiscal policies; benefits, allowances orsubsidies; various forms of leave; flexible forms of workingincluding part-time work (Jaumotte, 2003).

20

Gender Equality Index – Report

The second sub-domain examines gendersegregation,asit continues to contribute to gender inequality in Europeand also results in less efficient economies (Anker, 1998).Segregation refers directly to patterns of segregation inthe labour force both horizontally and vertically. Segrega-tion in the labour market has been a pervasive issue over along period of time. Occupational, or horizontal, segrega-tion is defined as the concentration of women and menin different types and levels of activity and employment,with women being confined to a narrower range of oc-cupations than men. Often, the most feminised sectors arethose that provide market substitutes for services womenhistorically provided in the household, such as childcare,elder care, nursing or teaching (Folbre, 2006). The segrega-tion of the labour market has detrimental effects on thelabour market generally because it contributes to the gen-der pay gap, and impacts career advancement and accessto training (Magnusson and Nermo, 2009).Hierarchical, or vertical, segregation refers to the under-representation of women at the top of career ladders andover-representation in roles that are deemed more menial,with the ordering of occupations often done on the basisof desirable attributes such as income, prestige and condi-tions (Bettio and Verashchagina, 2009). Horizontal segrega-tion has had a tendency to shift towards fewer differencesover time, with an increase in the proportion of womenin most sectors. However, some sectors, such as scienceand technology, still lag behind. Vertical segregation alsoremains strong despite the increase in the number ofwomen entering top positions. A symbolic and very tellingexample of this is the lack of progress made regarding thenumber of women on company boards. Furthermore, evi-dence suggests that some degree of tokenism prevails, orthat within equal job descriptions, the tasks of women andmen remain fundamentally different. Importantly, researchsuggests that the power structures of the labour markethave remained largely intact despite women infiltrating alllevels and areas, with the most attractive positions still outof reach of women (Annandale and Hunt, 2000).The third sub-domain,quality of work,refers not only towork participation, but also looks at the features of thatemployment (COM(2001) 313 final). Indeed, the increase inthe number of jobs in response to EU policy may have beenat the expense of quality (Leschke et al., 2008), and the pat-terns of segregation of the labour market may heightendifferences in the quality of jobs between men and wom-en (European Commission, 2009). For example, segrega-tion entails that women-dominated jobs may hold fewer

opportunities for training and ensuing promotion, whichin turn contributes to further segregation and a wideningof the gap (Eurofound, 2012). The nature of employment,and thereby its quality, is being affected by new ways ofworking, the rise of new Internet technologies allowingfor a greater permeability between the private and publicspheres. The greater need for flexibility on the part of organ-isations has given rise to greater low-paid and less securetypes of employment, often on a part-time or temporarybasis, with positions that are filled by more women thanmen (Bradley and Healy, 2008). This is gendered, as it oftenentails that women become disproportionately involvedin non-standard and/or precarious work (Rubery, 2002).Quality of work can be examined at the individual level,but it is also possible to adopt a social (stemming fromquality of work) or an organisational (ensuring a productiveworkforce) perspective (UNECE, 2010). But only the individ-ual perspective can be implemented in a composite indi-cator. Quality of work is a multi-dimensional concept thatcan be summed up under several pillars (Eurofound, 2002).The first pillar is career and employment security. This isvery gendered because, despite their upward mobility,women’s progress in many sectors is still very uneven dueto a ‘glass ceiling’, masculine culture and lack of transpa-rent promotional processes (European Commission, 2007a).In addition, women hold a slightly higher percentage thanmen of fixed-term contracts, including involuntary short-term contracts (European Commission, 2009). The secondpillar is that of the health and well-being of workers, wherealthough historically men were more exposed to womenbecause of their greater involvement in industrial occupa-tions, the gaps are now starting to close (European Com-mission, 2009). The third pillar concerns skills and compe-tences, notably their under-utilisation in work (EuropeanCommission, 2009).The experience of women and men within the domainofworkvaries significantly, mostly to the detriment ofwomen because the tendency is for lower participation,greater segregation and differences in quality of work.Narrowing the segregation gender gap would positivelyimpact both women and men, as it would contribute toreducing the gap in participation and quality. Overall, it isimportant not to lose sight of the fact that quality of workshould also be improved for both women and men.

Gender Equality Index – Report

21

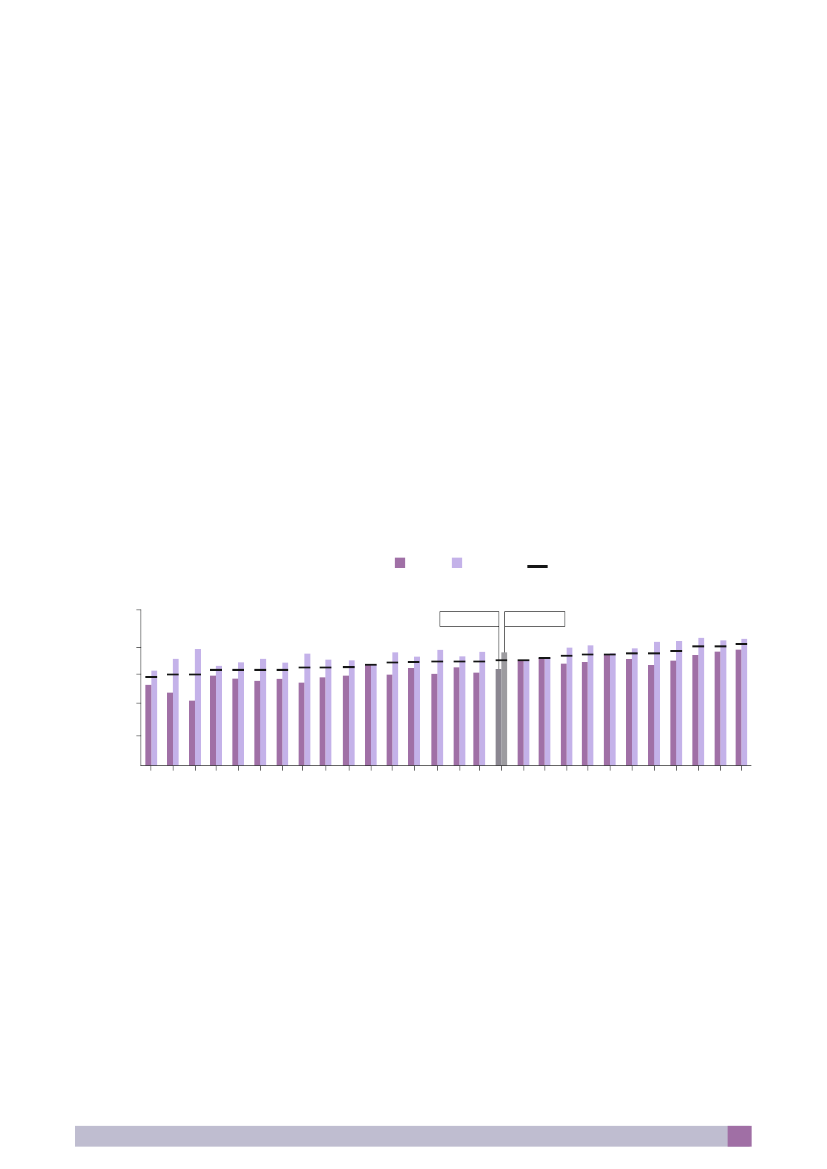

2.3.3. Domain 2: MoneyThe second domain,money,examines gaps between thefinancial resources and economic situation of women andmen. It is an important domain of gender equality giventhat women are generally disadvantaged financially, ex-posing them to greater risks of social exclusion.This domain echoes the majority of the theoretical frame-works of equality reviewed above. Equality can be viewedas having approximately the same range of key resourcesas others, such as income and wealth (Baker et al., 2004).Gender equality in pay and income rules out unequal payfor equal work and emphasises the importance of equalis-ing pensions and benefits between women and men (Fra-ser, 1997; Pascall and Lewis, 2004). This goes together witha call for a substantial reduction in the vast discrepancy be-tween women’s and men’s income – following divorce, forexample, when women’s income tends to decrease sharplywhile men’s increases (Fraser, 1997). Because of interruptedcareers, women tend to rely more often on social transfersand may be disadvantaged by transfer incomes which arecalculated on the basis of former income from employ-ment. Finally, because of the predominance of traditionalgender roles in the household, a considerable number ofwomen do not have a market income of their own, placingthem in a situation of financial dependence.Equalising money needs to be combined with prevent-ing poverty to achieve gender equity as seen in Fraser’s(1997) anti-poverty dimension. Eradicating gender-basedpoverty is achievable through the introduction of a decentminimum wage (Pascall and Lewis, 2004) and being ableto hold property (both land and movable goods) on anequal basis with others (Nussbaum, 2003).At EU policy level, the domain ofmoneyis part of the LisbonTreaty (2007/C 306/01), which requires Member States toensure that the principle of equal pay for male and femaleworkers for equal work or work of equal value is applied.This is central to the work of the EU and its commitmentto equal pay (Article 141 (ex 119) of the Treaty EC) (2010/C83/01). The elimination of the gender pay gap is empha-sised in all key policy documents (Roadmap 2006–2010(COM(2006) 92 final), Women’s Charter 2010 (COM(2010)78 final), Commission’s Strategy 2010–2015 (COM(2010)491 final), Pact 2011 (7349/11)). This includes not only pay,but also income in the form of transfers. This is flaggedby Europe 2020 (IP/10/225), which states that Mem-bers States need to ‘fully deploy their social security andpension systems to ensure adequate income support’.

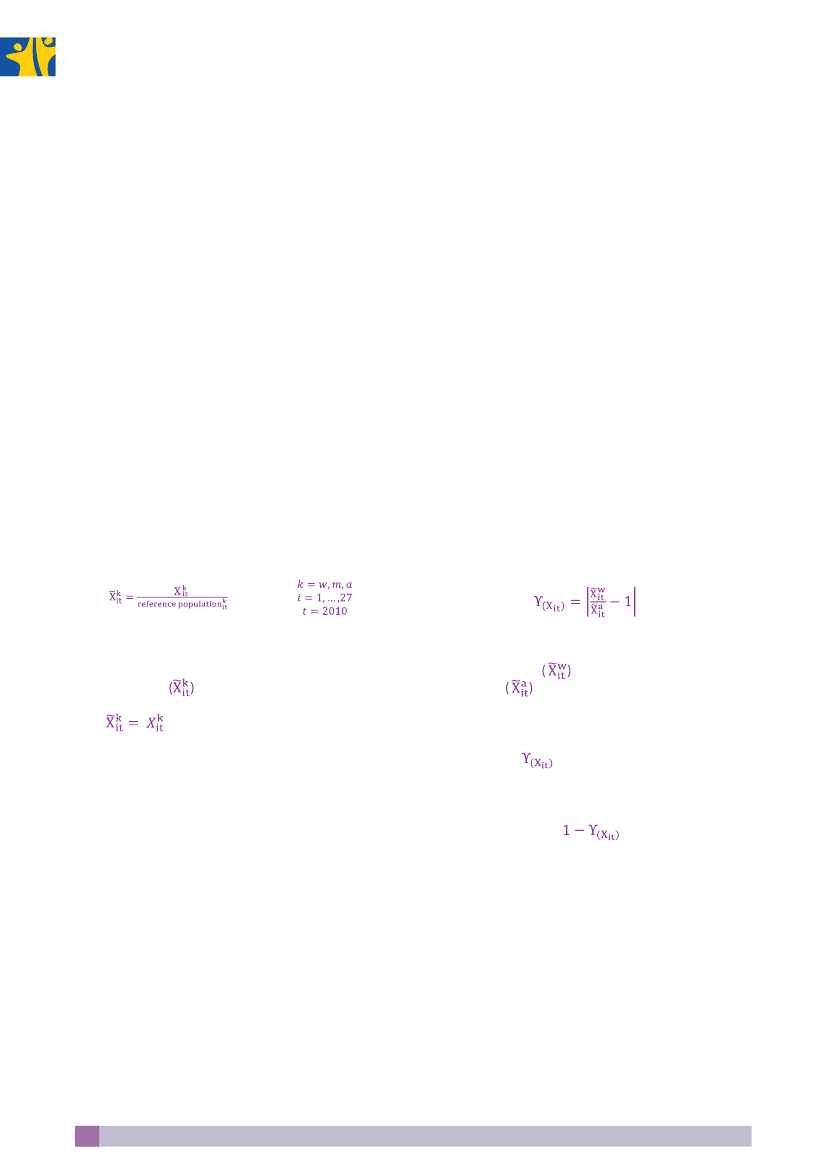

Another key priority of the European Union, related to eco-nomic situation, is the fight against poverty (Pact, 2011)(7349/11). Women have a higher risk of poverty, and tack-ling gender-based poverty can lead to equal economic in-dependence. Poverty can be defined as the non-fulfilmentof a person’s human rights to a range of basic capabilities(Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, 2002).Europe 2020 (IP/10/225) has a strong focus on poverty withthe aim to reduce the number of individuals living belowthe national poverty lines by 25 %, thereby decreasing thenumber of individuals at risk of poverty by 20 million.The domain ofmoneyexamines two sub-domains:financial resourcesandeconomic situation(Figure 2.3.).Figure 2.3. Domain ofmoneyand its sub-domains

Financial resources

Money

Economic situation

Examining gender gaps infinancial resourcesis importantbecause there are strong differences between womenand men’s income. Gender equality in pay can contrib-ute to an increase in economic growth, as it could leadto higher rates of savings, improved investments, bettercredit reimbursing and investing in the human capital ofthe next generation (Klasen and Lamanna, 2009). The maincauses of the gender pay gap in the EU have been attrib-uted to: discrimination in the workplace; structural factors;as well as workplace practices and promotion procedures(European Commission, 2011a).In addition to earnings, other incomes (for example, in-come from property, stock, and other financial assets) con-stitute another realm of unequal distribution among wom-en and men. Women are generally less likely than men tohold economic assets, such as property, with legislation fortransfer in the case of divorce often working to the detri-ment of women (UNECE, 2010). At the same time, womenare also less likely to be able to control economic assets,including their use of disposable income, which may berelated to their bargaining position in the household. Forexample, in a situation of necessity, women deplete theirassets to a greater extent than men (UNECE, 2010).

22

Gender Equality Index – Report