Forsvarsudvalget 2012-13, Det Udenrigspolitiske Nævn 2012-13

FOU Alm.del Bilag 83, UPN Alm.del Bilag 113

Offentligt

CENTRE FOR MILITARY STUDIESUNIVERSITY OF COPENHAGEN

Get it TogetherSmart Defence Solutions to NATO’s CompoundChallenge of Multinational Procurement

Henrik Ø. BreitenbauchGary Schaub Jr.Flemming Pradhan-BlachKristian Søby KristensenFebruary 2013

This report is a part of the Centre for Military Studies’ (CMS) policy research service for thepolitical parties to the Danish Defence Agreement 2009-2014. The purpose of this report is toexamine and further the follow-up to the Chicago Summit declaration on Allied militarycapabilities in 2020. In particular, the report analyses impediments and possible solutions toNATO’s compound political problem of multinational defence procurement.The CMS is a research centre located at the Department of Political Science, University ofCopenhagen. The centre carries out research and offers policy research services within thefields of security and defence policy and military strategies. Academic research at the CMSprovides a foundation for the policy research services that the centre provides to the Ministryof Defence and the political parties behind the Defence Agreement.This report is an analysis based on research methodology. The conclusions of this reportshould not be interpreted as the view and opinions expressed by the Danish government, theDanish armed forces or by any other authorities.Read more about the centre and its activities on the website http://cms.polsci.ku.dk/.

Authors:Dr. Henrik Ø. Breitenbauch, Senior researcher, Centre for Military StudiesDr. Gary Schaub Jr., Senior researcher, Centre for Military StudiesMA Flemming Pradhan-Blach, Military analyst, Centre for Military StudiesDr. Kristian Søby Kristensen, Researcher, Centre for Military Studies

ISBN: 978-87-7393-687-0

i

ContentsSAMMENFATNING ................................................................................................... 1EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................... 6INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................... 10Focus of the analysis.......................................................................................................................... 10How we did it ....................................................................................................................................... 12Overview .............................................................................................................................................. 13

A COMPOUND POLITICAL PROBLEM.................................................................. 15Defence cooperation – economics and efficiency or politics and security? ................................ 15The political defence market in the Euro-Atlantic region ............................................................... 19International frameworks: A first round of NATO and EU perspectives ....................................... 23Domestic chokepoints ........................................................................................................................ 24

INITIATIVES FOR A POSITIVE SPIRAL ................................................................. 27General approach: Break the stalemate, create a positive spiral .................................................. 28NATO’s internal processes and multinational procurement .......................................................... 29EU defence cooperation initiatives ................................................................................................... 32NATO harmonisation through synchronisation and standardisation ........................................... 36NATO Defence Planning Process (NDPP) ........................................................................................ 38NATO Procurement Organisation (NPO) .......................................................................................... 39Allied Command Transformation’s Framework for Collaborative Interaction (FFCI) .................. 41Domestic level initiatives ................................................................................................................... 42

CONCLUSIONS ....................................................................................................... 45Pathways to a positive spiral ............................................................................................................. 45Reasons for measured pessimism.................................................................................................... 47

BIBLIOGRAPHY ...................................................................................................... 50NOTES ..................................................................................................................... 55

ii

SammenfatningIndhold:•••••Baggrund: Smart Defence i NATO og i aftale om forsvarsområdet 2013-2017Hovedargument: Multinationalt indkøbssamarbejde er god Smart DefenceFørste del: Dødvandet ift. multinationale forsvarsindkøb skabes hjemme og udeAnden del: Løsningsforslag til at styrke multinationale forsvarsindkøbPerspektivering: Multinationalt samarbejde er alliancepolitik for mindre lande

Baggrund: Smart Defence i NATO og i aftale om forsvarsområdet 2013-2017

Ved NATOs topmøde i Chicago i maj 2012 vedtog regeringslederne en fælles deklaration forudvikling af alliancens forsvarskapaciteter frem mod 2020.1Her spiller ’Smart Defence’-initiativet en vigtig rolle. NATO forsøger med dette initiativ at forstærke forsvarssamarbejdeti form af en øget harmonisering og koordinering af nationernes forsvarspolitiske valg. SmartDefence-initiativet har tre hoveddimensioner: samarbejde, prioritering og specialisering.Initiativet minder i indhold om tidligere kapacitetsinitiativer indenfor NATO og internationaltforsvarssamarbejde, selvom det i anslaget er mere ambitiøst. Smart Defence ses derfor somen fundamentalt ny måde at tænke forsvarspolitik på (nyt ’mindset’).IAftale på forsvarsområdet 2013-2017fremgår det, at forligspartierne er ’enige om, atNATO’s Smart Defence initiativ skal søges udnyttet til at opnå større operativ effekt for desamme eller færre ressourcer’, at Danmark ’målrettet’ skal ’virke for at opretholde sin statussom NATO kerneland’, herunder igennem Smart Defence, ligesom multinationalitetfremhæves som et særskilt hensyn indenfor dansk forsvarspolitik, herunder i form af SmartDefence.2Hovedargument: Smart Defence begynder med multinationalt indkøbssamarbejde

Denne rapport beskæftiger sig med et specifikt og underbelyst aspekt af Smart Defence.Overordnet fokuserer Smart Defence-dagsordenen mest påoutput,det vil her sige operativemilitære kapaciteter. Stigende priser på forsvarsmateriel i kombination med faldendebudgetter udgør en tilskyndelse til øget multinationalt samarbejde i hele Alliancen, men isærhed for de mindre lande. Rapporten argumenterer derfor for, at der er fordele ved atfokusere på at styrke samarbejdet påinput-siden,i forhold til indkøb af militære platforme.Logikken er, at det er mindre følsomt at købe ind sammen tilhver sinkapacitet, end det er atkøbe ind sammen til enfælleskapacitet. Til gengæld vil man opnå stordriftsfordele over hele1

udstyrets levetid, nemmere operativt samarbejde og en dybere forankring af Alliancen. Mender findes imidlertid et dødvande indenfor multinationale indkøb. Dødvandet er forårsaget afen kombination af nationale, internationale, administrative, politiske og industrirelateredefaktorer. For at fremme Smart Defence-dagsordenen analyserer denne rapport, hvordan mankan skabe en positiv spiral for multinationale indkøb indenfor NATO.Første del: Dødvandet ift. multinationale forsvarsindkøb skabes hjemme og ude

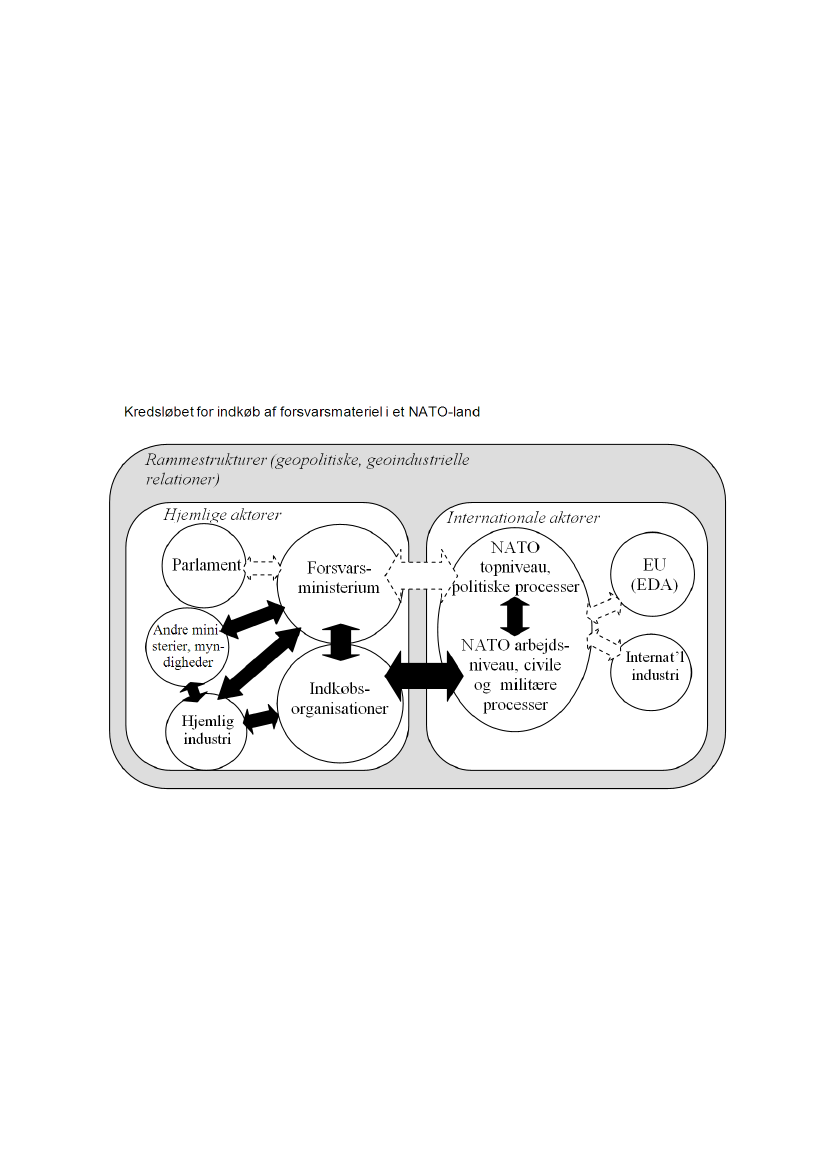

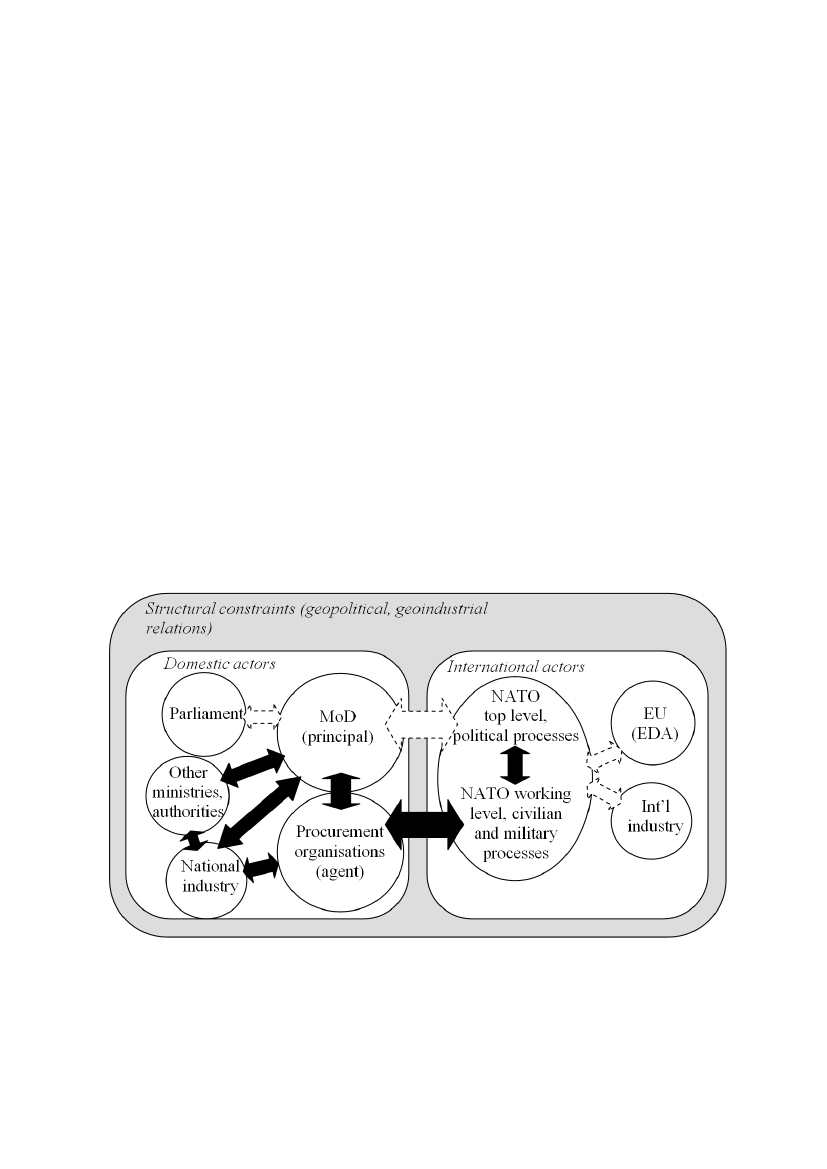

Rapportens første del beskriver udfordringer for forsvarsindkøb i en international kontekst.Multinationale forsvarsindkøb begrænses af en række sammenhængende faktorer. Derskelnes her mellem tre hovedområder som er indeholdt i den nedenstående figur, ’Kredsløbetfor indkøb af forsvarsmateriel i et NATO-land’.

Disse er for det første de bagvedliggende rammestrukturer som udgøres af geopolitiske oggeoindustrielle forhold. USA, Storbritannien, Frankrig og Tyskland tegner sig for over 85%af Alliancens forsvarsudgifter. Kun disse lande har meget væsentlige forsvarsindustrier, ogkun USA kan meningsfuldt siges at være selvforsynende med forsvarsmateriel. Italien,Holland, Spanien, Tyrkiet og Canada tegner sig for endnu ca. 10% – og de mindste 19 lande,herunder Danmark, står for under 5% af Alliancens forsvarsudgifter. Forholdet mellemNATO og EU, og USA’s og de store europæiske landes respektive syn herpå er et afgørendeforhold i disse rammebetingelser (den grå baggrund i figuren).

2

For det andet er der i alle NATO-landene hjemlige aktører som er involveret i indkøb afforsvarsmateriel. De indbefatter det politiske niveau, indkøbsorganisationerne, parlamentet,andre relevante ministerier og myndigheder, og den hjemlige forsvarsindustri. Den størsteudfordring for øget multinationalt samarbejde er, at indkøbsorganisationer og militære værn ipraksis i vidt omfang kan modarbejde politiske ønsker om flere multinationaleindkøbsløsninger. Det skyldes, at de besidder en særlig teknisk indsigt eller formel ret til atbestemme over doktriner, som ministerier og politikere kun vanskeligt kan udfordre.For det tredje er der det internationale niveau som her primært udgøres af NATO – hvor derigen skelnes mellem de politiske processer på topniveau, og civile og militære administrativeprocesser – samt EU og EU’s forsvarsagentur EDA, og endelig den internationaleforsvarsindustri. På figuren er ikke medtaget bilaterale relationer landene imellem samt andreformer for mellemstatsligt samarbejde vedrørende indkøb af forsvarsmateriel, såsom indenforOCCAR. Det skyldes rapportens fokus på, hvordan særligt NATOs egne processer kanstyrkes med henblik på at forøge andelen af multinationalt indkøbt forsvarsmateriel.Anden del: Løsningsforslag til at styrke multinationale forsvarsindkøb

Den dagsorden, der blev vedtaget i Chicago, er ved at blive implementeret. Anden delredegør for implementeringen og undersøger først – af særlig interesse for Danmark som stårudenfor EDA – hvilke EDA-initiativer NATO vil kunne lære noget af, særligt i forhold tilmultinationale indkøb. Dernæst beskrives både en overordnet tilgang og konkrete forslag til,hvordan landene i Alliancen fremadrettet kan styrke den multinationale andel afforsvarsindkøbene.Vigtigst kan multinationale indkøb styrkes ved at øge det politisk niveaus involvering, især iforholdet mellem nationerne og NATO. Selvom NATO-samarbejdet ofte er mindre juridiskbindende end EU-samarbejdet, så kan det alligevel bruges som løftestang af det politiskeniveau i medlemslandene. Videre har de nationale parlamenter en vigtig rolle at spille i formaf tilsyn, kvalitetskontrol og godkendelse i forhold til beslutningsprocesser. Endelig vil entilnærmelse til EDA i praksis være en oplagt udviklingsmulighed for de dele af NATO, derskal udvikle og fastholde Smart Defence-dagsordenen, ligesom industriens repræsentanterkan inddrages bedre. På figuren ovenfor vises dette udviklingspotentiale i kraft af de stipledepile, mens de sorte pile viser eksisterende relationer.Hvis NATO-landene i fællesskab skal bryde med det nuværende dødvande i forhold tilmultinationale forsvarsindkøb og skabe en positiv spiral bør de derfor:3

••

Forpligte sig politisk til som udgangspunkt altid at forfølge en multinational løsning(det vil sige i fællesskab med mindst et andet land)Fremme reformer af NATOs forsvarsplanlægning NDPP så det multinationale aspekt(hvordan vi køber forsvarsmateriel) gøres ligeså vigtigt som kvalitet og kvantitet(hvad vi køber), herunder i form af krav til afrapportering

••••

Fremme reformer af NATOs processer og institutioner med henblik på en øgetharmonisering af indkøbsplaner for forsvarsmaterielStyrke sådan harmonisering ved at anvende standardiserede indkøbsplaner og deledisse med alliancen med henblik på synkronisering af behovUdvikle grundlaget for en standardisering af tekniske materielbeskrivelser i NATO-regi såvel som af relaterede doktrinerLøfte behandlingen af det multinationale indkøbsprocesser op fra Konferencen afnationale materieldirektører (CNAD) til det politiske niveau, og herunder integreremålsætninger og afrapporteringer i NDPP

•

Give NATO til opgave at indsamle og udgive løbende data om forsvarspolitik,herunder budgettal vedrørende nationale og multinationale indkøb i Alliancen for atsikre et debatgrundlag

•

Udvikle og udvide Parlamenternes rolle i forhold til tilsyn og kvalitetskontrol iforhold til større materielindkøb, herunder om de foretages som et multinationaltindkøb

Perspektivering: Multinationalt samarbejde er dansk alliancepolitik

Kun USA er i realiteten selvforsynende med forsvarsmateriel. Hvis det at væreselvforsynende med forsvarsmateriel er en forudsætning for handlefrihed, så er de flestelande i Alliancen i praksis kun suveræne i kraft af internationalt samarbejde. For de 19mindste lande betyder det, at det er særligt vigtigt at skabe et udbygget samarbejdevedrørende indkøb af forsvarsmateriel – både for at fastholde de større lande i et forpligtendesamarbejde, og for at sikre, at Alliancen har de bedst mulige militære kapaciteter i 2020. Detgælder dermed også for Danmark, som må se det som en vigtig opgave at bidrage tilstyrkelsen af både en fælles ramme i NATO-regi for multinationale indkøb, og overveje atimplementere rapportens forslag til styrkelse af det multinationale aspekt.Relevans for beslutningstagere

Rapportens analyse og løsningsforslag er relevante for beslutningstagere i forhold til:4

•••••

Forsvarsforligets implementeringIndkøb af nyt kampflyIndkøb af andre større materielgenstande, herunder pansrede mandskabsvogne ogvåbensystemer med videre til fregatterneForsat effektivisering indenfor forsvarspolitikkenStørre åbenhed indenfor forsvarspolitikken, herunder i form af Folketingetsinddragelse

5

Executive summaryAt the Chicago Summit in May 2012, NATO political leaders agreed to theSummitDeclaration on Defence Capabilities: Toward NATO Forces 2020.The Smart Defenceinitiative is an important component of the declaration. Compared to earlier allied capabilityefforts, this initiative is unique given the high-level involvement and emphasis on a newmindset. This report proposes ways of institutionalising the new mindset through increasedmultinational procurement.Some of the most difficult aspects of the Smart Defence efforts deal with outputs, that is withthe integration of operational defence capabilities. We propose beginning instead by focusingon the input side. It is easier to agree on buying the same defence equipment together than toagree on buyingand operatingdefence equipment together. In enabling increasedmultinational procurement, ministers of defence from different countries will likely reapbenefits of economies of scale for both the actual acquisition and during the entire platformlife-cycle, as there will be partners with whom to share development and maintenance costs.By operating identical equipment, nations will also be ready for a high degree ofinteroperability in terms of both operations and maintenance. This also renders them capableof engaging in more ambitious sharing and capability-pooling arrangements. Raising the ratioof multinational to national procurement is therefore a positive policy goal for the Allianceand a promising way of implementing the Smart Defence agenda.But if enhanced multinational procurement appears to be less ambitious than other aspects ofthe Smart Defence agenda, it is not a straightforward task. It is in fact a compoundinternational political problem with diverse and interlocked problem areas. Some of these arefound within the NATO organisation and processes and in other international contexts, butmany are of a domestic character. The current system is therefore in a stalemate with regardto multinational procurement. Adopting the solutions proposed here offer an opportunity toNATO and its member states to break this stalemate.This report assesses the stalemate and proposes a general approach and concrete initiatives tocreate a positive spiral of enhanced multinational procurement in the Alliance. The generalapproach should be for NATO organisations and processes to further the harmonisation ofnational defence policies with regard to capability development and planning. With regard toprocurement, harmonisation means both standardisation and synchronisation – thestandardisation of capability requirements, of doctrine and national reporting, and6

synchronisation of plans and planning requirements. In concrete terms, this means elevatingthe principle of multinational procurement to a main focus of political level NATOcooperation, including in the NATO Defence Planning Process, and helping nations to pursuethe principle of going multinational first.Even if nations should push for reforms of NATO organisations and processes which shouldenable such a development, the greatest challenges are found in the capitals. Some of thestrongest impediments to multinational procurement are found in the relationships betweenministries of defence (MoDs) and subordinate armaments organisations, including themilitary services. We propose that the political level leadership in nations – MoDs – shouldreform and employ the NATO processes, including the Defence Planning Process, to dealwith this issue. Political level attention to making commitments and reporting requirements atthe international level can create a substantial downward pressure at the domestic level, fromministers and their cabinets down to National Armaments Directors, armamentsorganisations, and service bureaucracies. NATO processes should be used in capitals as alever in this domestic tug of war. While NATO will not acquire any of theformalcharacteristics of a supranational organisation in the foreseeable future, it can acquire suchfunctionalcharacteristics when MoDs use NATO processes as leverage in their respectivedomestic management processes.In order for this to happen, we propose a set of initiatives at both NATO and national levels.In particular, NATO organisations and processes should be adapted to:•Elevate the principle of multinational procurement (how we buy things) at par withthe quality and quantity of capabilities (what we buy), including in the NATODefence Planning Process (NDPP).••Establish a permanent staff for the NATO Procurement Organisation (NPO).Establish a ministerial-level governing board for the NPO to replace the Conferenceof National Armaments Directors (CNAD) so that responsibility for multinationalprocurement rests at the political level rather than the technical level.•••Institutionalise reporting requirements to include the ratio of national to multinationalprocurement projects and explanations of deviations from multinational procurement.Gather and publish transparent data on defence expenditures.Propagate international standards for military requirements so as to achievestandardisation of capabilities.7

••

Enhance contracting transparency through accessible projects databases for nationsand companies.Harmonise doctrine in order to avoid differing requirements.

These NATO-level initiatives could enable Alliance member states to engage in multinationalprocurement if they choose to do so. Yet this is a compound political problem, and loweringbarriers to cooperation at the NATO level is not sufficient. Member states must take actionand reform their own processes if they are to engage in multinational procurement moreeasily. To achieve this, initiatives such as the following should be undertaken by MoDs:••••Pledge to increase multinational procurement by making it the default principle.Adopt standardised national procurement plans (for NATO reporting purposes).Share these with Allied nations so that procurement can be synchronised in time andstandardised in capability.Link national procurement plans to the NDPP so that capability shortfalls andsurpluses can be coordinated and avoided more easily and multinational potential canbe identified.••••Gather and publish transparent data on defence expenditures.Adopt international requirement standards so that equipment purchases can beharmonised more easily.Institutionalise relations with industry based upon transparent requirements andcontracting opportunities, both nationally and internationally.Enhance parliamentary oversight in order to strengthen the transparency andaccountability of the involved actors and processes.These domestic reforms mirror those proposed at the NATO level. The synchronisation ofprocesses at each level will facilitate cooperation by removing key impediments as theprocess moves from one level to the next. Harmonising these processes will allow nationalpolitical leaders to utilise NATO processes to enforce their will upon their subordinateprocurement agencies, thereby solving the principal–agent issue that hampers multinationalprocurement. The strategic challenge of maintaining military capabilities in an era of severefiscal constraints requires the exercise of political leadership in the Alliance.No single country outside the United States has the money, expertise, and political will tohave a full-fledged defence. No Western country – even the European NATO countries8

together – is able to be self-sufficient in defence affairs regarding both capabilitydevelopment, sustainment, and operational use. In this context, cooperation, coordination,and sharing in defence matters increasingly constitute a precondition for sovereignty –especially if sovereignty is to be understood less as an abstract legal term than as a practicalissue of maintaining autonomy and freedom of action. Nations engaging in multinationalprocurement are likely to increase their autonomy and freedom of action via the benefitsaccrued in the form of economies of scale and increased interoperability.

9

IntroductionAt the Chicago Summit in May 2012, NATO political leaders agreed to theSummitDeclaration on Defence Capabilities: Toward NATO Forces 2020.3The declaration includesdescription of the Smart Defence initiative. Smart Defence is about creating value for moneyin European defence by encouraging synergies through economies of scale. Smart Defencehas three components: aligning national capability investments with NATO’s capabilitypriorities, pooling Allied military capability among Allies to generate economies of scale andimprove inter-operability, and achieving a more effective division of labour throughspecialisation.4Compared to earlier allied capability efforts, this initiative is particular givenhigh-level involvement and emphasis on a new mindset.This report proposes ways of institutionalising the new mindset through increasedmultinational procurement. Some of the most difficult aspects of the Smart Defence effortsdeal with outputs, that is with the integration of operational defence capabilities. Clearly,issues of sovereignty and burden-sharing at the international level come to the fore when suchprospects are being considered. It therefore makes sense to focus especially on cooperation inthe input side aimed at enhancing multinational procurement – regardless of how thecapabilities are employed, whether in national or multinational settings. By purchasingdefence materiel together – with at least one other member nation – NATO nations will gainboth economies of scale along the life-cycle of the platforms and ensure betterinteroperability, thereby improving future allied operational cooperation.

Focus of the analysisThe Smart Defence initiative covers a wide-ranging agenda to strengthen cooperation inNATO in ways that touch upon sovereignty-related issues. We focus on a specific subset ofthis agenda: investments in military capabilities, which is where the future of Alliedcapabilities is laid down. This report therefore examines challenges related to enhancing themultinational procurement of defence capabilities, discusses the agenda agreed to at theChicago summit, and proposes a set of recommendations for policy-makers at various levels.Like issues further downstream in the defence policy process, such as force employment,multinational procurement poses many challenges. Structural geopolitical and geo-industrialtensions also expressed in the unresolved NATO–EU relationship are clearly relevant whenaccounting for the limitations to the harmonisation of Allied procurement processes.

10

Despite these challenges, the specific focus on multinational procurement is smart. The futureof the Alliance is being made at this public–private intersection in the form of armamentsorganisations and industry, domestic and international processes through national and NATOdefence planning, and civilian and military with ministers and MoDs in combination withmilitary establishments. Despite the challenges – which are many – this is also the obviousstarting point for a renewed push for stronger harmonisation of allied defence policies. Itsidesteps many of the political sensitivities related to operational requirements andgeostrategic differences of perspective. Moreover, procurement is also basically a politicalissue that political leaders have the power to change.To be clear, the argument concerns multinational defence procurement. This is understoodhere as defence materiel procured by at least two NATO nations, or a NATO nation and apartner nation, at the same time. The focus is solely on procurement, not what is referred to inNATO parlance as multinational capabilities and common funding.5It is important toemphasise that the multinationally procured capabilities can then be deployed as either purelynational capabilities, as part of a multinational framework, or some combination of the two.From a life-cycle management perspective, the possibilities for multinational cooperation ontraining, platform development, operational deployment and sustainment, and retirement aremuch greater when the starting point is capabilities that have been procured together by atleast two allied nations. While these issues provide reason to pursue multinationalprocurement, they involve their own challenges and are not covered here. The focus is onenhancing multinational procurement only, as a first and important stepping stone towardsbetter and more affordable future allied capabilities. Furthermore, our focus is on equipmentmanufactured or intended primarily for military use, such as tanks, armoured personnelcarriers, fighter aircraft, and frigates. Our analysis excludes goods and services purchased byMoDs that are generic or intended for civilian use, such as office furniture, informationtechnology, or catering services.6The report focuses primarily on NATO, even if EU developments are included. NATO is thecentral Western security actor and the centrepiece of security and defence matters in theNorth Atlantic area. More than an alliance, NATO is also the most important organisation forcommunicating and harmonising defence and military policy standards, including thenecessary knowledge of the art of war as it develops in the global security environment.NATO’s internal processes for communication and harmonisation are therefore of crucialimportance. The NATO Smart Defence initiative aims at reinforcing these processes so that a11

more effective use of the defence budgets will mean a higher relative output througheconomies of scale. While the United States is and will remain the Alliance’s most importantmember, in this context the other nations – mid-sized and smaller nations with or withoutsignificant defence industries – play the main role. For ease of language, this group of stateswill be referred to in the report as ‘European NATO’.7Specific examination of the Europeanangle to NATO matters, as this is where the most efficiencies to pursue are found. Moreover,the arguments here will likely be of special interest to the smaller European NATO nationsfor whom the business case of multinational procurement and cooperation is the mostpressing and evident.While we have spoken with many defence industry executives in the course of the researchdone in preparation for the report, the focus is not on supply but rather on demand. This isbecause the defence industry is one of the most politically conditioned industries: supply isultimately determined by whatever states demand. This is not to say that the issue of industryis unimportant; rather, industry and geo-industrial relations largely underlie the currentstalemate. This means that a higher degree of involvement with industry in everyday andformalised terms is necessary just to make small amounts of progress, and also that somekind of grand transatlantic bargain or agreement is necessary for the materialisation of atransatlantic defence market. Less is perhaps necessary to further multinational defenceprocurement in European NATO, but drawing up the parameters of the possible in order toknow what can be achieved nevertheless matters.

How we did itAs part of the production and service contract for 2012 between the Danish MoD and theCentre for Military Studies/University of Copenhagen, the Centre for Military Studies (CMS)was tasked with preparing a report on Smart Defence as part of the analyses for the parties tothe Danish Defence Agreement.8In addition to following the procedures laid out in the CMSproject manual, including external peer review, the analyses underlying the report wereorganised in the following way:9One member of the project team was involved inpreparatory international think-tank workshops organised by the Center for Strategic andInternational Studies (CSIS), the Atlantic Council of the US (ACUS), and the InternationalInstitute for Strategic Studies (IISS) in cooperation with NATO Public Diplomacy Division(PD) in the six month run-up to the Chicago Summit. These observations resulted in an op-edon industry and Smart Defence publishedDefense News’sinternational edition during thesummit.10As part of our research, we have made desk studies and carried out dozens of12

interviews with high-ranking international defence industry representatives, seniorinternational officials, and think-tank researchers. Apart from doing research in Denmark, theteam travelled in September‒November 2012 to NATO HQ, NATO Allied CommandTransformation’s (ACT) Industry Day in Riga, a NATO Parliamentary Assembly Rose-RothMeeting in Montenegro, NATO ACT’s Strategic Foresight Workshops, a NATO PD and IISSworkshop on Smart Defence in Brussels, and conferences organised by the Danish AtlanticCouncil and the Nordic Atlantic Councils on Smart Defence and Nordic Security Cooperationin Copenhagen and Helsinki.During this process, we have developed and examined various hypotheses about the existingimpediments to multinational procurement. Our consistent approach has been to ask all typesof stakeholders, civilian and military, as well as representatives of the defence industry aboutthe often complex and technical issues surrounding defence materiel procurement.Interviewing international defence industry representatives has several advantages. Defencecompanies are profit-driven and motivated to achieve the highest possible sales, including theinternational context. Defence companies (beyond a certain size or with specific internationalexport capabilities) therefore have an incentive to further multinational procurement. Defencecompanies have a unique understanding of the political conditions of the market andtherefore also of the impediments government officials may be reluctant to mention. Finally,industry appeared to be a crucial partner for future NATO HQ efforts to organise the NATOEurope defence market, as mentioned in theDefense Newsop-ed.

OverviewThis introduction is followed by two main analytical sections and a conclusion. The first ofthe analytical sections examines the system of relations constituting the compound politicalproblem of multinational defence procurement in NATO. This means that the sectioncontains a review of each of the different problem areas and a discussion of their relativechallenges and impediments to multinational procurement. In this way, the analysis alsoidentifies chokepoints within the problem areas and discusses how they are interlocked,making for a certain balance in the overall system. The second analytical section thenemphasises the political character of the compound political problem. This means looking forinitiatives that may become solutions to change the current balance in the system in favour ofa positive spiral for enhancing multinational defence procurement in NATO. The sectiontherefore contains both an overall approach to reshaping and breaking the current stalemate

13

as well as some concrete proposals for doing so. Even if these proposals can be implementedin relatively straightforward terms on the various institutional levels they are aimed at, theyalso indicate the possibility of applying the general approach to breaking the stalemate inother ways. The second section therefore also emphasises the importance of an explicit andshared political understanding of the stalemate as a compound political problem requiringmulti-level initiatives that reach into shared NATO processes as well as national procurementand strategic planning processes in order to succeed with this important part of the SmartDefence agenda. Finally, the conclusion sums up the argument and offers further suggestionsfor how progress can be achieved.

14

A compound political problemAs the Alliance proposes the further harmonisation of defence policies under the SmartDefence headline, defence procurement merits special attention. The procurement of newdefence capabilities not only amounts to a significant part of the aggregate defence budgets ofthe Alliance, it also paves the way for the Alliance of tomorrow, as these capabilities areliterally the means of our future armed forces. In numerous different ways, the current systemof defence procurement impedes a higher ratio of multinational to national defenceprocurement. This section argues, first, that the challenge is of a fundamentally political, noteconomic, nature. Second, it describes the system of actors and multinational defenceprocurement processes and their relations in the context of NATO. Third, it sums up thedifferent chokepoints and assesses the overall stalemate as a way of introducing thesubsequent chapter’s review of on-going reforms as well as an agenda for change.

Defence cooperation – economics and efficiency or politics andsecurity?Normally, the story of European defence inefficiencies is presented something like this: TheEuropean states have developed armed forces and their favoured approaches to equippingthem in light of their indigenous resources and the primary security challenges that they haveeach traditionally faced. For various reasons – limited resources concentrated in a relativelysmall area, the difficulty of power projection, and the heterogeneity of peoples – mostEuropean states developed the capacity to arm themselves and focused upon territorialdefence against the possible aggression of their neighbours. The few exceptions to thisfunctional imperative have been the great powers, which possessed a surplus of resources andthe desire to devote them towards what we now call expeditionary operations. Yet even thesegreat powers were forced to grant priority to territorial defence during the Cold War. Thecommon threat of the Soviet Union and the institutional frameworks developed under thebanners of NATO and the European Community facilitated historic levels of cooperation.This cooperation even extended into the realm of military equipment requirements, withNATO’s Military Agency for Standardization being founded in 1951.11Despite steady andincremental improvement in the area of common military procurement, significant challengesremain.12Unlike the United States, Europe has long suffered the deleterious effects of a fragmentedmilitary equipment market. Sovereignty in the realm of national security led to an exemption15

for the production and trade in armaments, munitions, and war materiel in the 1958 Treaty ofRome that established the European Economic Community.13It also allowed member statesto retain information concerning their national security secrets from one another.Consequently, the market for military supplies has remained fragmented, competition hasbeen limited to suppliers within national boundaries, and transparency has been lacking.Demand has also been fragmented, with national governments developing their ownrequirements for military capabilities and relying primarily upon national suppliers so as toretain control over sensitive information, technology, and economic opportunities. The resulthas been national monopolies or oligopolies in the defence industry sector and a patchwork ofnational regulations, processes, and practices. Together, these have reduced the incentivesand increased the barriers for suppliers to cooperate with one another, even as they facereduced demand from their primary customers.Thus, opportunities for cooperation leading to economies of scale in the production ofmilitary equipment and for larger purchases that could further reduce the unit cost have beenlost. From a purely economic perspective, the Alliance is allocating its defence spending in asuboptimal manner. This argument has been underlying efforts in the context of NATO andthe EU with respect to integrating defence investment policies since the birth of NATO andthe first continental European defence project with the European Defence Community in themid-1950s.14The longevity of the argument demonstrates the value of examining theAlliances’ defence budgets from such a utilitarian viewpoint. It allows us to see howimprovements can be made under the assumption that everything else is equal.There is a lot of truth to this story – it is also a driver of the Smart Defence initiative – but itis not the whole story. Everything else is not equal. While global and European politicscertainly have seen considerable integration since the end of World War II, there has beennothing inevitable about this grand integration process. Rather, these processes have been andwill always remain deeply political. They are acts of conscious choice rather than acts of fate.This is good because the power of politics is that it can change the framework within whichother decisions are made. Thus, reducing the issue to an economic problem of allocation is tomiss its essence: it discounts the geopolitical and political‒administrative dimensions of theproblem.Enhancing multinational defence procurement is therefore best understood as a compoundpolitical problem. A compound political problem consists of a set of distinct but interlocked16

problem areas. Each of the problem areas contains their own particular dynamics that impedesolutions. These areas include the relations between actors at the national level, such asministers and MoDs, military procurement agencies, other ministries, parliament, andindustry. They also include actors at the international level, including the relations betweenstates within NATO processes, and their interaction with the international defence industrymarketplace. The intersections of these actors and processes present chokepoints that workagainst an increase in the number of multinational defence procurement projects. The overallsystem results in a stalemate.Despite their apparent technical content, all of the issues are of a political character and canbe solved by political means. Consequently, this report proposes a general approach tobreaking the stalemate as well as a set of concrete proposals for how political leaders andcivil servants may start a positive spiral of multinational defence procurement. History showsthat problems that are inherently political can be solved through political means. The EU andindeed NATO itself offer clear examples of this. Moreover, the interlocked character can beutilised to devise solutions in one area that will alleviate some of the challenges in others.Figure 1: The procurement process actors

The system of multinational defence procurement can best be conceptualised as a series ofrelations between domestic and international actors and processes. These different locationsand problem sets are described in Figure 1.17

Figure 1 describes the actors and problem areas in multinational defence procurement in ageneric perspective, including the domestic and international levels (where we find concreteactors and processes) with geopolitical and geo-industrial structural conditions in thebackground (limiting and influencing the specific actors and processes). On the left side, thedomestic level contains a number of typical actors and processes: the MoD and its underlyingprocurement-related authorities, including dedicated and general armaments organisations,service specific organisations, and other relevant organisations formally answering to theMoD. Formal defence procurement almost always proceeds within this top-downrelationship. Next (to the left), we find a set of supporting domestic actors: industry (nationaland international), other relevant authorities such as ministries of finance, industry, labour,technology, foreign affairs, and the equivalent of a prime minister’s cabinet. Finally, we findthe parliament, which plays an important role regarding oversight, ensuring transparency, andthe democratic legitimacy of major defence policy decisions.The arrows indicate the most important relations with regard to the procurement process.They are not exhaustive. Industry can have direct contact with parliamentarians, for example.The darker the arrow, the more significant the relationship. The major domestic relationshipis between the MoD and its armaments organisations (and their underlying authorities in themilitary services). These subordinate and implementing organisations naturally deal with theproviders of the services and products that they are created to procure; that is, they deal withindustry in its various forms, including national and international industry representatives.The least developed arrow is for the role of parliament in providing quality control to majordecisions, oversight, and democratic legitimacy. Another less-emphasised arrow is crucial forimproving multinational procurement: the relationship between the MoD (at its highest level)and the political level processes in NATO. As argued in the next chapter, that relationshipshould be leveraged by MoDs in order to deal with the most difficult chokepoint at thedomestic level: the management of their subordinate agencies.The right side of the figure provides a generic description of the international actors andprocesses with a NATO focus. Here, distinction can be drawn between NATO top-levelforums and processes, such as ministerial meetings, meetings in the North Atlantic Council(NAC), the Military Committee (MC), and political/civilian high-level working groups – andthe working level day-to-day processes carried out in meetings among nations or beingprepared by NATO personnel, such as the NDPP and others. Here, the arrow is again bold,emphasising a main component in the multinational procurement framework. At the same18

time, crucial components of the multinational procurement framework at the internationallevel are left to underlying national authorities. This is expressed in the black arrow, whichconnects the domestic and international systems at the working levels. Outside NATO, theEU and its European Defence Agency (EDA) are underutilised resources for NATO, whilethe same is the case for international industry, especially in the shape of the NATO IndustrialAdvisory Group (NIAG). We have left out important international relations such as bilateralrelations and international groupings in defence procurement such as OCCAR. This omissionis based on the subsequent focus on how NATO’s own processes can be strengthened tosupport further multinational procurement among member nations.Connecting the domestic and international levels, we find two arrows: a black arrow at theworking level and a dotted arrow at the political level. The difference between the lowerblack arrow and the higher white arrow indicates a main issue impeding multinationalprocurement: the lack of elevation of the issue to the highest political levels.When taken together, the black arrows show the main elements in the current stalemate. Inthe domestic sphere, national industry and underlying armaments authorities can stall orimpede multinational procurement policy decisions at the political level. As they are alsoresponsible for managing and developing multinational procurement at the working level inBrussels, there is limited opportunity for feedback from NATO to domestic armamentorganisations to spur multinational cooperation.Multinational procurement will become a much sturdier fixture on the political agenda,particularly by emphasising the relations captured by the middle, upper white arrow betweenthe domestic and international political domestic levels. Moreover, by letting NATOdevelopment be inspired by the EDA and by building a better working relationship with theEDA, many things will be gained. Finally, giving Parliaments a substantial function in majordefence policy decisions will not only boost democratic legitimacy but possibly also providemuch-needed transparency and oversight to such decisions.

The political defence market in the Euro-Atlantic regionThe generic description captured in Figure 1 shows how the domestic‒international interfaceboth conditions the current stalemate and offers possibilities for dealing with the stalemate.As also indicated in Figure 1, however, there are a number of geopolitical and geo-industrialstructural conditions behind the generic setup that limit and shape the forms and amounts ofmultinational procurement. The geopolitical tensions behind the Alliance – divisions over19

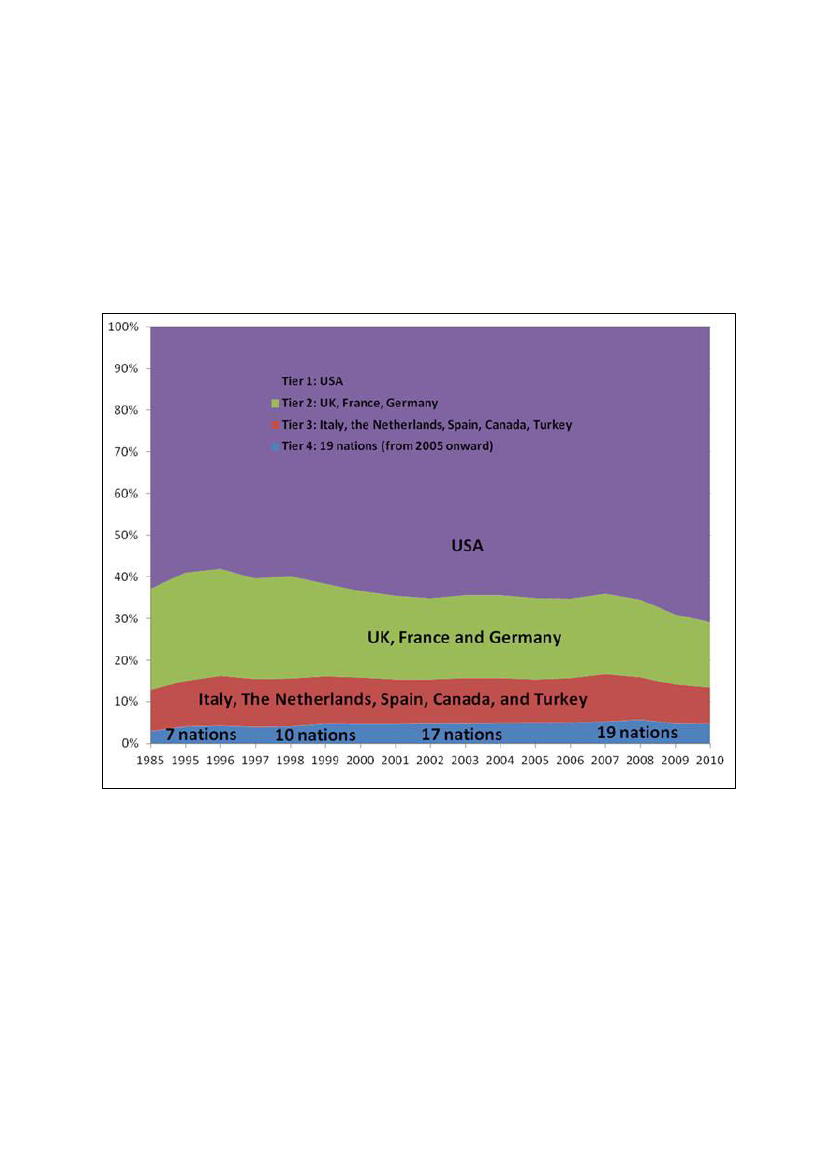

what purpose the alliance should serve, the transatlantic relationship, and the unsettledrelationship and division of labour between NATO and the EU – are all constraining factors.In Figure 1, such unsettled issues form the deep structural background for the development offurther allied cooperation in defence. Some of the resulting practical impediments are likelyto remain unresolved as long as the deep ones persist. Until then, the space for bettercooperation is limited by these structural constraints.Figure 2: Relative NATO Defence Expenditures (data fromThe Military Balance)

When it comes to defence expenditures, industries, and the dynamics of multinationaldefence procurement, the Allied nations are quite different. Overall, there are fourdistinguishable state types in the Alliance:•••Tier one: the United StatesTier two (defence expenditure over USD 25 billion, 2010 data from theMilitaryBalance):the UK, France, and GermanyTier three (defence expenditure of USD 10‒25 billion): Italy, the Netherlands,Canada, Spain, and Turkey20

•

Tier four: 19 states with defence spending under USD 10 billion. To this group maybe added a number of partner nations in geographical Europe.

Over time, the relative importance of the four groupings has developed as described in Figure2: Relative NATO defence expenditures. Figure 2 illustrates the development of defencespending in the Alliance over time.15The US relative contribution has risen from around 60per cent in the mid-1990s to about 70 per cent of the Alliance’s defence expenditures adecade and a half later. At the same time, it is noteworthy that the relative share of thesmallest countries (Tier 4) has not grown despite NATO enlargement. These four tiers facedifferent challenges with regard to multinational procurement. We will describe these in turn.The American role and position is paramount for how the Alliance works – including anymovement with respect to the overall stalemate. American defence industry consolidationcorresponded to the structural adjustments that occurred in the 1980s and were accelerated bydefence spending cuts in the 1990s. Consolidation of the defence sector proved too importantto be left solely to the market, and the US Department of Defense concluded that it wouldprotect key defence industry capabilities as well as allowing for efficiencies that wouldreduce expenditures.16In practice, the American approach has since been the development ofa hub-and-spokes model, exemplified by the Joint Strike Fighter programme, for anincreasing number of capability development programmes. US defence market policy alreadyencourages a partial globalisation of the US market, especially in terms of buyers.17Thismeans that the political economy of the American defence industry and defence industry baseincreasingly depends on – or rather, is interdependent with – its international allies andpartners.Unlike the United States, ‘there has so far never been a genuine pan-European defenceprocurement market but rather 27 national markets fenced off with regulatory barriers toentry aimed at protecting national defence industries’.18This situation of fragmented nationaldemand, fragmented national-based supply, and hence duplication of productive capacity andR&D spending has had significant consequences for European defence procurement and thedefence industry base. To this may be added politically and economically motivatedprotectionism on both sides of the Atlantic.Turning to Tier 2, great powers such as Great Britain, France, and Germany retained a self-sufficient defence industry base into the 1990s.19The prevailing conditions driving the

21

consolidation of the American market also affected the more heavily state-owned defencesector in Europe.20Defence industry consolidation through mergers, acquisitions, and cross-national partnerships allowed suppliers to reap some of the benefits of a larger market,including economies of scale derived from horizontal and vertical integration. This resultedin the formation of numerous large multinational defence companies around the primaryfirms within these countries, each with sufficient scale to develop and produce high-technology products at prices competitive with those of American companies. This hasresulted in transnational oligopolistic competition replacing national monopolies for majorsystems across the continent. Indeed, the companies of the Tier 2 states account ‘for morethan 80% of armament production and for 90% of military R&T expenses in Europe’.21In Tier 3 and 4 countries, defence industries have long been unable to supply theirgovernments with all of their military equipment needs.22These countries generally buymajor platforms produced by companies located in larger countries. Nor can the defenceindustries of these countries survive on domestic sales alone. Under pressure from the waveof industrial consolidation of the 1990s, they have taken to specialising in niche componentsand often assumed the role of subcontractors to larger, foreign companies. Such industries arevulnerable to market fluctuations and their home governments have thus utilised the off-setmechanisms under Article 296 of the Treaty of Rome to ensure their survival.23While thecompanies in mid-sized countries are concerned with becoming second-tier subcontractorsfor American firms, the companies in small countries are often more reluctant to partner withlarger companies from Tier 2 countries.Under the impression of rising platform prices and austerity budget cuts, defence analystChristian Mölling has warned that European countries will only have ‘bonsai armies’ at theirdisposal in the not-so-distant future.24This argument is especially pertinent for the Tier 4states whose share of the overall defence expenditures has not risen with the enlargements.Because they have less operational capability, however, the Tier 3 and 4 nations have aparticular opportunity to move forward on multinational defence procurement. In terms ofindustry, they have less strategic reason to be protective, as they are not sovereign in anypractical sense if sovereignty is to mean self-sufficiency in capability development.25If youcannot provide for your own security even in theory, including the development, production,procurement, and deployment of the platforms needed within your own borders, then youneed to cooperate in order to achieve security. Only Tier 1 and 2 countries can theoreticallyaspire to this status and, as seen with the US example, even these countries are increasingly22

dependent on allied markets. This means that Tier 3 and 4 countries are freer to act from amarket perspective when shopping for arms on the international market. They can go for bestvalue instead of being tied to specific producers. Moreover, cooperation is a precondition forthem for sovereignty, not an impediment to it. As should be clear to decision-makers at alllevels in these national capitals, Tier 4 nations are optimal candidates for moving forwardwith multinational procurement.This argument is strengthened by trends in relative defence procurement. The relativespending gaps shown in Figure 2 are only exacerbated when considering defenceprocurement.26Smaller countries generally spend a smaller percentage of their overalldefence budget on procurement and research and development. Based on numbers providedby the EDA’s annual defence data publication, the Tier 2 and 3 nations are estimated toprocure about 23‒27 per cent of their equipment in cooperation with others. The fewavailable numbers for Tier 4 nations suggest that the multinational procurement ratio issomewhat or even far lower here,27meaning that the smallest nations are playing catch up tothe larger nations in terms of multinational procurement.

International frameworks: A first round of NATO and EU perspectivesThis constellation of actors with divergent interests poses a complex challenge ofbureaucratic, political, industrial, and geopolitical nature that must be overcome ifmultinational procurement is to be enhanced. In principle, NATO possesses centralmechanisms for addressing these issues – some longstanding and well-known, such as theNDPP, and others that are under development, such as the NPO. These processes aim to copein various ways with the issue of coaxing sovereign countries towards increased integrationof their defence capability development processes. NATO Secretary General Anders FoghRasmussen has called for NATO to act as an ‘honest broker’ in the Smart Defence attempt toachieve greater allied coherence. In this way, it is clear that the NATO processes are intendedto enable market coordination, from demand to supply. On the demand side, the NDPP andNPO focus on standardising and synchronising defence capability development projects. Onthe supply side, they provide opportunity for dialogue with industry and encourage thedevelopment of multinational rather than national programmes. We will return to theseinternational level NATO processes in the following chapter on solutions.Because NATO is not a supranational organisation, its processes are not legally binding fornations. Yet 21 NATO nations are also EU members. EU defence-related market reforms will23

increasingly shape the capacity of these countries to do multinational procurement. Europeandefence industrial consolidation has been facilitated by reductions in the scope of goodsconsidered to be validly exempted from the common market under Article 296. Although the1992 Maastricht Treaty did not revise Article 296, the definition applied to goods intendedfor ‘purely military purposes’28has been progressively narrowed over the past twenty years.29As military forces have turned to commercial and dual-use technologies, the percentage ofequipment that can be excluded from pan-European market competition has narrowedsignificantly.30The EU Defence and Security directive solidifies this requirement to justifydeviations from EU law.31Thus, we might expect some barriers to multinational procurementof defence equipment to be eroded progressively by EU regulations in NATO nations that arealso EU members.Whether NATO nations are EU members or not, the domestic level remains the mostsignificant dimension with regard to multinational defence procurement.

Domestic chokepointsThere are barriers to enhanced multinational procurement at the domestic level. The issue isless about market functions than political control in a multi-layered political‒administrativesystem.Taking the political level announcements made at the Chicago Summit at face value, then theMoDs and their cabinets support the Smart Defence agenda, as they have signed up for theoverall vision. In a multi-layered political‒administrative system, however, nominallysubordinate authorities often have their own agendas, not least with regard to defendingbudget shares. Other turfs to defend include national defence industries, either through formalor informal networks between government and industry, and military service-specificdimensions. As anyone who has worked with political‒administrative systems knowsintuitively, organisational self-interest makes for non-linear implementations of policy, evenwithout ascribing bad faith to any of the actors. These impediments can be derived from thestructural organisation of the administrative‒political system in general. For procurementspecifically, we may add the particular element of technical expertise in combination withever-developing technology. Together, they place a special premium on the subordinateorganisation or organisations possessing the necessary knowledge to make technically soundrecommendations, including descriptions of capability requirements descriptions.

24

This is what is known as a principal‒agent issue.32Principal‒agent issues arise in publicadministration when strategic authorities are faced with managing underlying organisationsthat possess special technical expertise. In this case, it is a challenge for the principal (MoD)to compel agents (their subordinate procurement organisations) to prioritise multinationalsolutions. Services and armament organisations possess extensive technical expertise that isimpractical to mirror in ministries and other oversight authorities. Added to the purelytechnological knowledge, military services also sometimes possess the formal authority overtraining, tactics, and procedures (TTPs) and other doctrine which can shape the definition ofrequirements descriptions. The ability to enforce a clear line of command and implementpolicy vanishes somewhere between the MoDs and the regiment workshops. As a matter ofcommon sense, procurement agencies and armed forces branches know so much about theships, planes, and guns they are supposed to buy that it becomes very difficult for the politicallevel – especially at the top of the MoDs – to monitor processes effectively and makeinformed decisions. In practical terms, MoDs are at the mercy of procurement agencies.Procurement agencies and armed forces branches thus retain large decision-making powerregarding materiel investment. This is especially the case when processes are in their earlyformal or even informal stages and still under development. Requirements descriptions arenot innocuous, as seemingly small differences may rule in or out specific platforms availableon the international market. Even in competitive processes, technical arguments may helpselect or deselect qualified candidates which service organisations, for instance, find are toodangerous for their preferred candidates, resulting in false competitions. The knowledgemonopoly of the underlying organisations makes it difficult for the formally directingorganisations to impose their will.Furthermore, procurement agencies often rely upon industry to know what is possible andwhat it will cost. This three-level game renders the monitoring and enforcement of politicalguidance even more difficult. Finally, the legislative branch provides an alternative source ofpolitical guidance to which the procurement agency and industry can appeal if theirpreferences are not supported by the cabinet. This ‘iron triangle’ poses significantopportunities to prevent cooperation in procurement, even after it has been agreed upon bythe head of government.In sum, we may describe the challenge of furthering multinational defence procurementwithin NATO Europe as involving three sets of interlocking issues: geo-industrial rivalry;25

complex domestic relations between aspects of the executive, industry, and the legislature;and international NATO processes. There may be sufficient impediments to multinationalprocurement at any of these levels. Their combination into interlocking impediments makesfor additional difficulties. So how are we to approach solutions to the stalemate? This is thetheme of the next chapter.

26

Initiatives for a positive spiralThe problem of multilateral cooperation in military procurement might seem intractable.Issues on several levels impede enhancing multinational defence procurement. There are,however, reasons for guarded optimism. The most important of these is that the challenge isfundamentally one of politics. Politics can remedy negative structures, create newinstitutions, and change patterns of behaviour, even if such change may be incremental andonly visible in the long term. This chapter draws up a general approach for doing so andproposes concrete policy initiatives to go with the approach.This section consists of four main parts. The first introduces the general approach –advocating a political choice of multinational solutions as a default policy and theharmonisation of procurement plans. The two following sections then discuss initiatives atthe domestic and international levels. At the domestic level, we focus especially on ways ofaddressing principal‒agent issues by revitalising the political and international dimensions ofprocurement processes. At the international level, we focus on NATO processes and howthey can be further developed to increase multinational procurement. Finally, we bring thesetwo strands together in a set of recommendations for the further harmonisation of nationaldefence policies in the shape of synchronisation and standardisation in procurement planningand policy.

To break the stalemate and create a positive spiral, nations should:

•Commit politically to pursuing multinational procurement as a default policy; report toeach other on their multinational-to-domestic procurement ratio; and offer transparentand systematic arguments about decisions not to procure multinationally.•Promote institutional reform in NATO in order to further the harmonisation of defenceprocurement plans – not only of the NPO, but also make multinationality a part of theNDPP.•Offer to further such harmonisation at home through the adoption of standardisedprocurement plans (for sharing with allies and partners), such that they can besynchronised over time.•Promote the standardisation of capability requirements as well as of doctrine and TTPsthat stand in the way of multinational procurements.•Promote the reform of NATO processes such that the political level sees the multinationalaspect of procurement at par with the quality and quantity of new capabilities. How theyare acquired matters increasingly as much as what and how much – withoutmultinationality, there will be fewer and sub-optimal new capabilities.•Take the responsibility for multinational procurement away from CNAD and elevate it tothe political level.27

General approach: Break the stalemate, create a positive spiralEven if the challenge is great, the solutions need not necessarily be revolutionary. Rather, theapproach most likely to succeed is a combination of institutional changes in NATO andinitiatives by a group of nations’ ministers of defence. Change must come from the nations,supported by NATO, and under the pressure of economic and strategic necessity. For thesmaller NATO nations – and increasingly for the larger ones as well – more extensivecooperation is a precondition for sovereignty, not an impediment to it. It is therefore thehighest strategic levels in capitals – including both the political, administrative, and militarytop – that must embrace and further a principle of multinational procurement as adefaultoptionfor defence acquisitions. This means always pursuing new procurement with anothernation first. It also means supporting and promoting NATO processes that advance thisprinciple.In particular, nations and NATO should create processes that can be leveraged in the capitalsin order to address the blocking power of services and armament organisations. Bothparliaments and ministries should be mobilised for this purpose. The principle of choosingmultinational solutions first and national ones only after systematic and transparent scrutinyshould be furthered by general reforms of national defence planning processes. These shouldaim at harmonising defence planning cycles – synchronising specific future needs – as well asharmonising defence requirements, equipment specification, and ultimately doctrine. To sumup: efforts in both nations and in NATO are needed. But the centre of gravity is in thecapitals, and NATO processes should be designed for the strategic and political levels to beable to set this priority. By deciding on such a matter of principle in public, ministers ofdefence can increase their ability to compel their subordinate agencies.As a whole, NATO must therefore further the harmonisation of defence procurement plans,both in terms of synchronisation (when to buy something) and standardisation (what to buytogether). Because change can only be achieved in NATO if it happens in capitals, it is thenations which must push for these reforms in NATO and adopt their respective domesticcomponents at home. Nevertheless, NATO has a very important role to play as the forum andframework for defence procurement cooperation. The following section therefore deals withon-going and future possible reforms within NATO, inspired especially by the EDA.

28

NATO’s internal processes and multinational procurementThis section briefly introduces relevant reforms underway in NATO followed by discussionof related EU initiatives. It does so in order to lay the ground for the subsequent presentationof a set of concrete initiatives intended to remedy the chokepoints identified above, includingthrough the international level processes within NATO.Since the 1991 Strategic Concept, NATO has cast itself as a defence and securityorganisation. It has developed institutions for addressing collective defence, securitycooperation, and crisis management. These three tasks are emphasised in the 2010 StrategicConcept. Although legacy institutions and processes remain, NATO is adapting to deal withthese roles more efficiently. The most important elements in this adaptation are the NATODefence Planning Process, the NATO Support Agency (NSPA), the NATO Communicationsand Information Agency (NCI), and the NATO Procurement Organisation (NPO). Wediscuss each in turn.33The NDPP is the most important of these processes. It is an iterative, multi-annual processthat creates the basis for the implementation of the politically agreed level of ambition andforce goals. It is overseen by the Defence Policy and Planning Committee (DPPC), aworking-level group of delegation ‘defence counsellors’ chaired by the Assistant SecretaryGeneral for Defence Policy and Planning.34It reports directly to the North Atlantic Council(NAC). The process constitutes the major defence policy planning elements within NATO.The NDPP is the largest game in NATO HQ and the one that most consistently draws nationsand national processes into the overall allied framework as it compares the plans of individualnations to the agreed and shared allied force goals. Importantly, the NDPP is institutionalisedand iterative, making it useful for measuring and furthering defence planning andprocurement harmonisation.The NDPP consists of five steps following its April 2009 revision:35establishing politicalguidance, determining requirements, apportioning requirements and setting targets,facilitating implementation, and reviewing results.36A central outcome in the first step is thedimensioning description of NATO’s Level of Ambition, which describes the character andnumber of military missions NATO armed forces are required to have the capability to carryout concurrently.37The second step of determining requirements is implemented by theDefence Planning Staff Team,38with the Allied Command Transformation in the lead. Thethird step is to apportion requirements for each Alliance member. ‘Minimum Capability29

Requirements’ are negotiated with member states and agreed to by ministers of defence. Thefourth step of facilitating implementation ‘is done by encouraging national implementation,facilitating and supporting multinational implementation, and proceeding with the collective(multilateral, joint, or common-funded) acquisition of the capabilities required by theAlliance.’39This is a key step in which the principle of multilateral procurement could beimplemented.Perhaps the key NDPP element is the review of results. Reviewing national progress towardsthe mutually-agreed-to allocations, first bilaterally and then in plenum, at the ‘reinforced’DPCC enables diplomatic ‘naming and shaming’ of relative laggards following ‘the workingpractice of consensus-minus-one’.40The process is not legally binding, but the diplomaticpressure to follow through on commitments is increasing. The United States continuouslydecries the European lack of burden-sharing.41Indeed, the United States has unofficiallyindicated that it will encourage Allied contributions by limiting its own pledges to fillcapability gaps – as it did in Operation Unified Protector. The United States is not the onlymajor ally raising the equity of burden sharing. As one interviewee put it, it is well knownthat the top five members of the Alliance account for almost 90 per cent of its combineddefence budgets and provide 70 per cent of common funding.42The bottom fourteen accountfor 1 per cent of NATO’s collective defence budget and utilise fifteen per cent of thecommon funds. Even without a permanent staff, the NDPP provides a systematic process forairing such issues and does as much as one could expect of a non-legally binding framework.In political terms, it can be fairly successful in creating a common framework for settingshared goals for defence policy.Apart from the NDPP, NATO offers a set of procurement-related processes and institutions,some of which were already being reformed by the Chicago Summit, while others havereceived increased impetus after the Summit’s declaration on Alliance Capabilities in 2020.With the Smart Defence concept, NATO has agreed to improve the procurement process bothwithin NATO and in its member states. To this end, new bodies are being developed and theexisting structures will be eased into the new structure in the 2012‒2014 period while theseprocesses are on-going. The new agencies cover three areas: procurement, support, andcommunications and information. The reform is to improve efficiency and effectiveness inthe delivery of capabilities and services.43The new bodies of interest to the procurementprocess are the NATO Support Agency (NSPA), the NATO Communications andInformation Agency (NCI), and the NATO Procurement Organisation (NPO).30

The new reform process resulted in the establishment of the NATO Support Agency(NSPA).44One of the NSPA’s functions is to combine logistics and procurement support intoone organisation capable of providing these capabilities to nations.45It utilises two publiclyaccessible databases to inform potential suppliers of contracting opportunities with NATO, orthe procurement agencies of member and partner states.46This offers suppliers the advantageof dealing with a single entity – and the Alliance and its members the opportunity to increasecompetition between potential suppliers. It does so particularly for logistics operations,wherein it provides ‘cooperative logistics services to ... NATO nations and other NATObodies’ under the principle of ‘consolidation’, by which NSPA means the ‘consolidation oflogistics requirements expressed by two or more customers. The consolidation ofrequirements means larger quantities can be ordered, resulting in economies of scale.’47Thus,in the realm of logistics support, the NSPA has already adopted the principle of multinationalprocurement and has developed processes for implementing it.The second reformed institution is the NATO Communications and Information Agency(NCIA).48Among its other duties, it has undertaken to ‘provide support to the establishmentand the execution of the multinational [command, communication, intelligence, surveillance,and reconnaissance] projects between nations, national and international organizations andindustries.’49This support comes in the form of facilitating ‘consultation and liaison with theNATO Strategic Commands, Agencies and other entities to ensure coherence with otherNATO programmes and activities in the area of multinational projects.’50Unlike the NSPA,the NCIA has not taken steps to pool procurement opportunities from either the demand orsupply side of the equation.The NATO Procurement Organisation (NPO) is the final institutional pillar of Smart Defencethat can be used to facilitate multinational defence procurement. Previously, NATO set upadhocagencies to facilitate multinational procurement projects, such as the NATO HelicopterManagement Agency and Airborne Early Warning Programme Management Agency.51TheNPO is currently under development. Its organisational concept is to be completed in 2014.The concept is to establish a single, permanent agency to oversee all common andmultilateral procurement projects. The agency will benefit from resident expertise that can beapplied across programs and reduce administration costs. The NPO was established by theNorth Atlantic Council and will be a subsidiary body of NATO. During the design phase, thegoverning body will be the CNAD.

31

The CNAD is a crucial element in NATO’s efforts to improve the amount of multinationaldefence procurement. Even if it consists of national representatives, the CNAD technicallyreports directly to the NAC and meets twice annually. In these biannual meetings, the CNADagrees on overall policies and conducts oversight of underlying processes. There are roughly50 working groups underlying the CNAD, while daily processes are handled in NATO HQby the representatives of the National Armament Directors or NADREPs.52In order tofurther cooperation, including in the form of co-operative, joint, multi-national, andcommonly funded programmes, CNAD adopted the Phased Armaments ProgrammingSystems (PAPS) in 1990.53PAPS was last revised in 2010. PAPS is a non-binding frameworkfor furthering multinational procurement cooperation and, as such, merely an offer to membernations. It provides a ‘systematic and coherent, yet flexible, framework for promotingcooperative programmes on the basis of harmonised military requirements.’54The frameworkconsists of the description of a structured process consisting of a number of phases with anemphasis on aiding decision-makers at all levels at each of the decision points.55PAPS offersthe conceptual description of best practice, a shared terminology, and planning logic thatpotentially can alleviate national concerns over multinational projects.Each of these institutions represents a consolidation of NATO procurement efforts, yet theyshould be treated as an intermediate step. Substantial overlap will remain between these threeagencies, with NCIA handling the C4ISR procurement portfolio, NSPA handling the life-cycle support portfolio for some national and common-funded systems, and the NPOhandling all others. If multinational procurement is to be elevated as a principle under SmartDefence, then ideally these procurement areas ought to be consolidated in a single agency.This will facilitate ownership and accountability at the political level and preclude buck-passing strategies at the working level when shortfalls in capability occur. Moreover,responsibility for the NPO and multinational procurement cannot be reduced to CNAD butmust be elevated to the political level. We will return to these arguments below.

EU defence cooperation initiativesAs emphasised in the NATO Summit Declaration on Alliance Capabilities in 2020, the SmartDefence efforts are both a continuance of ‘60 years of allied cooperation in defence’ and anambition to install a new defence harmonisation mindset. NATO’s own reforms mirror boththe continuity and tentatively the new, more ambitious agenda. Yet more remains to be done.NATO’s Smart Defence project was spurred by the 2008 financial crisis and clear shortfallsin capability highlighted by Operation Unified Protector in 2011. These provided renewed32