Forsvarsudvalget 2012-13

FOU Alm.del Bilag 79

Offentligt

Treatment of Conflict-RelatedDetainees in Afghan Custody

One Year On

United Nations Assistance Mission in AfghanistanUnited Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human RightsJanuary 2013Kabul, Afghanistan

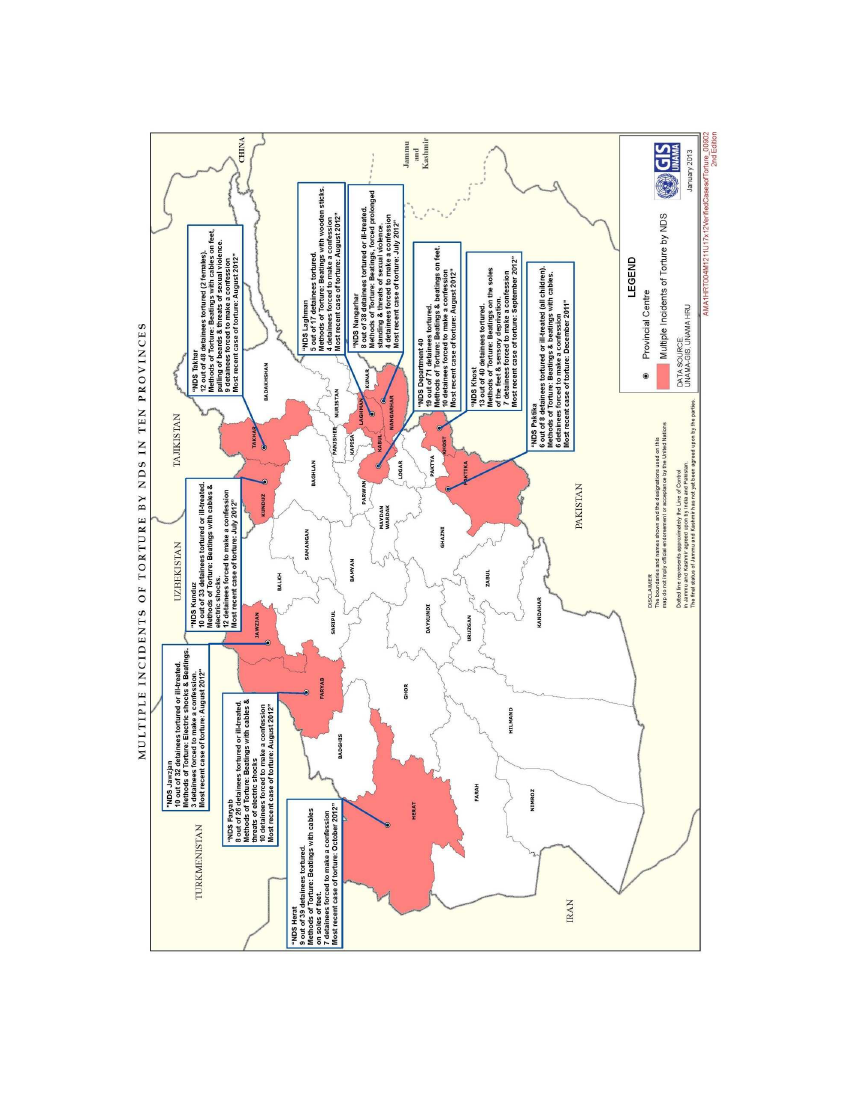

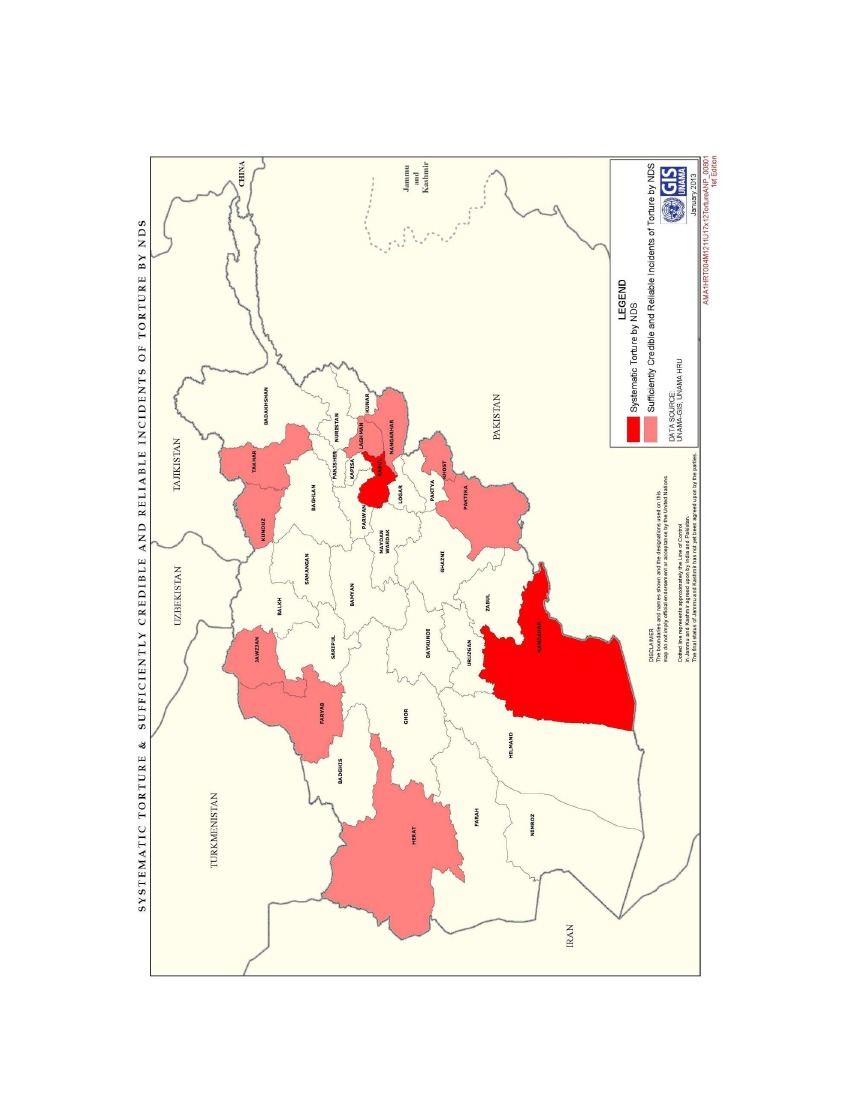

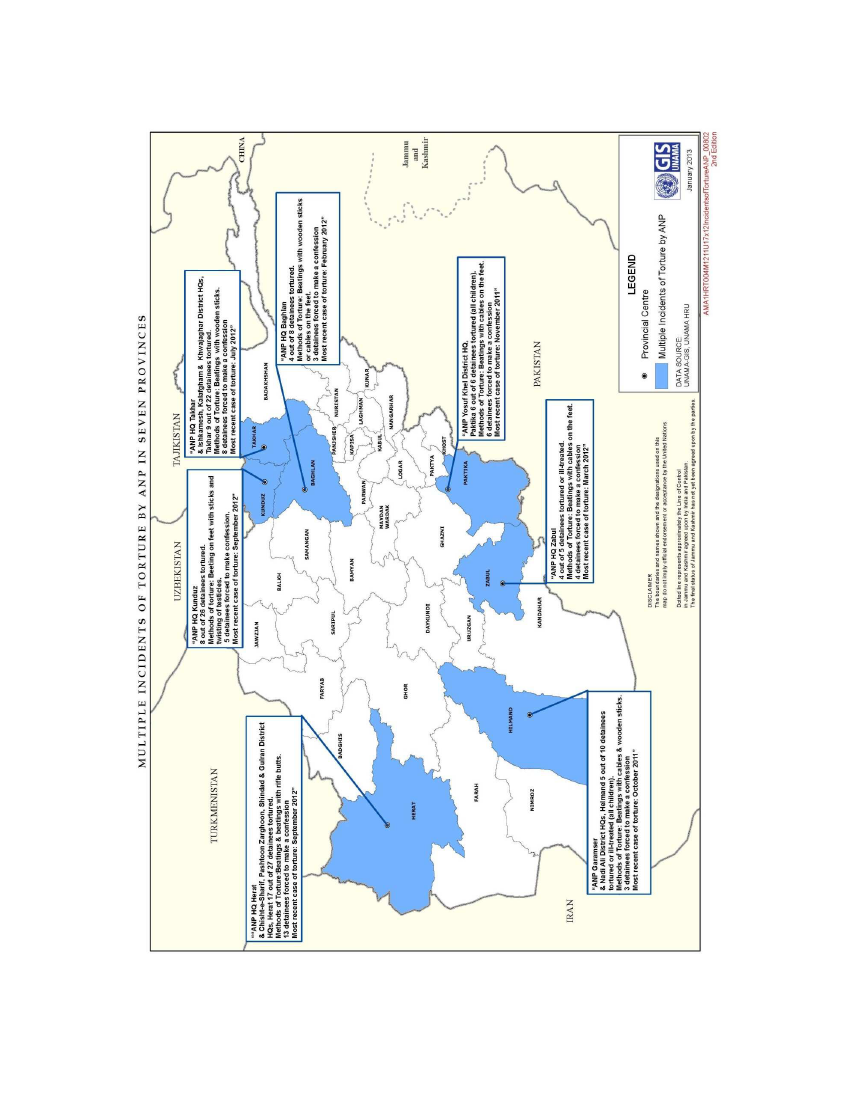

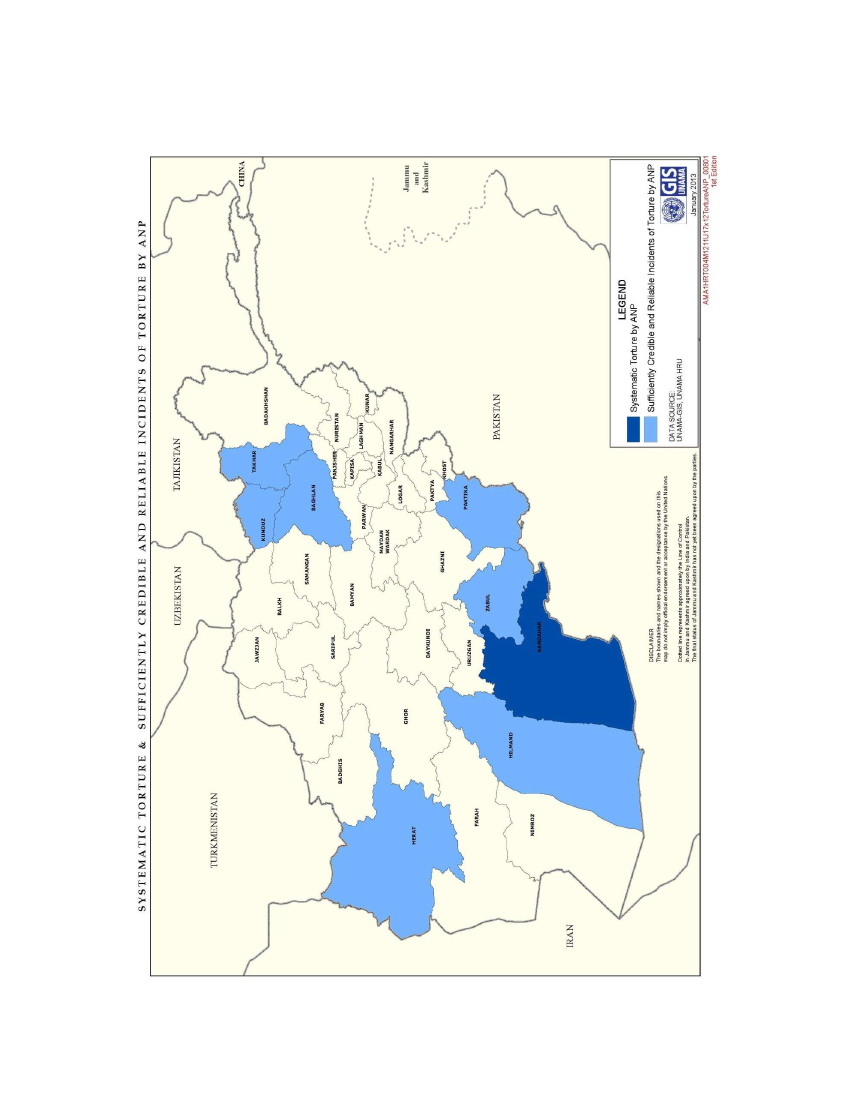

ContentsGlossary ........................................................................................................................................................... iUNAMA’s Mandate ......................................................................................................................................iiAccess and Methodology ..........................................................................................................................iiExecutive Summary.................................................................................................................................... 1Map 1: Detention Facilities Visited by UNAMA.............................................................................. 26Map 2: Detention Facilities where Incidents Occurred.............................................................. 27Map 3: Detainee Accounts of Treatment in ALP, ANA, ANP and NDS Locations ................ 28Treatment of Detainees by the National Directorate of Security ........................................... 29Map 4: Multiple Incidents in NDS Custody in Ten Provinces ................................................... 42Map 5: Systematic and Sufficiently Credible and Reliable Incidents in NDS Custody ..... 45Treatment of Detainees by the Afghan National Police and Afghan National BorderPolice ............................................................................................................................................................ 46Map 6: Multiple Incidents in ANP Custody in Seven Provinces ............................................... 55Map 7: Systematic and Sufficiently Credible and Reliable Incidents in ANP Custody..... 60Treatment of Detainees by the Afghan National Army .............................................................. 61Treatment of Detainees by Afghan Local Police ........................................................................... 61Treatment of Detainees Transferred to NDS and ANP by International Military Forces63Measures Taken by the Government of Afghanistan to Address Torture and Ill-Treatment................................................................................................................................................... 65Due Process and the Criminal Justice System’s Response ........................................................ 72ISAF’s Detainee Facility Inspection Programme .......................................................................... 76International Support to the NDS and the Ministry of Interior ............................................... 81Way Forward: Proposal for Future Detention Monitoring ....................................................... 83Recommendations................................................................................................................................... 85ANNEX I: UNAMA’s Detention Observation Programme 2010-12 .......................................... 91ANNEX II: Status of Implementation of UNAMA’s Recommendations from October 2011Report .......................................................................................................................................................... 93ANNEX III: Applicable Law .................................................................................................................... 97ANNEX IV: Response of the Government of Afghanistan, National Directorate of Securityand Ministry of Interior to this Report dated 14 January 2013 ............................................103ANNEX V: Letter of Commander ISAF to UNAMA dated 11 January 2013..........................125

GlossaryAcronymsAIHRCALPANAANBPANPANSFCIDCoPCPDCRCHQICPCICRCISAFJRCMoIMoJMoUNDSNPMsOHCHRUNAMAUNDPAfghanistan Independent Human Rights CommissionAfghan Local PoliceAfghanistan National ArmyAfghanistan National Border PoliceAfghanistan National PoliceAfghanistan National Security ForcesCriminal Investigations DepartmentChief of PoliceCentral Prisons DirectorateConvention on the Rights of the ChildHeadquartersInterim Criminal Procedure CodeInternational Committee of the Red CrossInternational Security Assistance ForceJuvenile Rehabilitation CentreMinistry of InteriorMinistry of JusticeMemorandum of UnderstandingNational Directorate of SecurityNational Preventive MechanismsOffice of the High Commissioner for Human RightsUnited Nations Assistance Mission in AfghanistanUnited Nations Development Programme

Arabic, Dari and Pashto wordsHawzaShuraTalibanTaqninCadastral zone within a cityConsultation or council of community eldersArmed opposition group fighting against the Government ofAfghanistan and International Military ForcesMoJ Department of Legislative Drafting

i

UNAMA’s MandateSince 2004, the United Nations Security Council has mandated the United NationsAssistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA) to support the establishment of a fair andtransparent justice system, including the reconstruction and reform of the prison sector,and to work towards strengthening the rule of law. UNAMA includes a Human RightsUnit with field staff across the country, supported technically by the UN Office of theHigh Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR).UN Security Council Resolution 2041 (2012)1mandates UNAMA to improve respect forhuman rights in the justice and prisons sectors as follows:37.Reiteratesthe importance of the full, sequenced, timely and coordinatedimplementation of the National Priority Programme on Law and Justice for All, by all therelevant Afghan institutions and other actors in view of accelerating the establishmentof a fair and transparent justice system, eliminating impunity and contributing to theaffirmation of the rule of law throughout the country;38.Stressesin this context the importance of further progress in the reconstruction andreform of the prison sector in Afghanistan, in order to improve the respect for the ruleof law and human rights therein,emphasizesthe importance of ensuring access forrelevant organizations, as applicable, to all prisons and places of detention inAfghanistan,andcalls forfull respect for relevant international law includinghumanitarian law and human rights law, noting the recommendations containedin the report of the Assistance Mission dated 10 October 2011.

OHCHR in AfghanistanThe UN Human Rights Council in decision 2/113 of 27 November 2006 mandatesOHCHR to address the human rights situation in Afghanistan, and urges its continuedcooperation as follows:The Council requests the High Commissioner to continue, in cooperation with theUnited Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan, to monitor the human rights situationin Afghanistan, provide and expand advisory services and technical cooperation in thefield of human rights and the rule of law, and report regularly to the Council on thesituation of human rights in Afghanistan.2

Access and MethodologyFrom October 2010 to August 2011, in response to repeated concerns and reports abouttorture and ill-treatment of conflict-related detainees from communities acrossAfghanistan and in consultation with the Government of Afghanistan, UNAMAconducted an intensive programme of observation of conflict-related detaineesthroughout Afghanistan. UNAMA produced a public report on its findings with 25recommendations to relevant authorities entitledTreatment of Conflict-Related

UN Security Council Resolution 2041, S/RES/2041 (2012) was adopted on 22 March 2012.Report of the Human Rights Council to the 62ndSession of the General Assembly,Supplement No. 53,A/62/53, Decision 2/113, 28 November 2006.12

ii

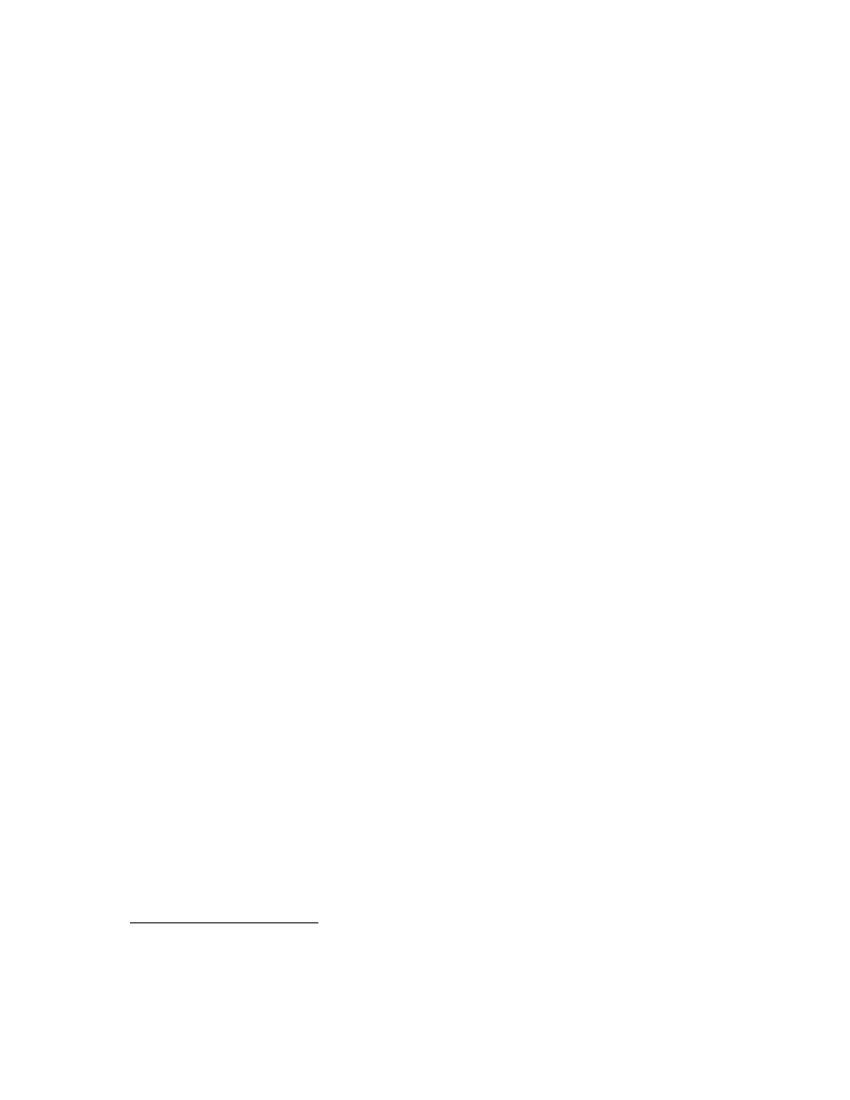

Detainees in Afghan Custodyreleased in October 2011.3See Annex 1 of this report for asummary of the findings and Annex II for information on the status of implementationof recommendations from UNAMA’s October 2011 report.Current ReportThis report presents findings from UNAMA’s observation of conflict-related detentionfor the period October 2011 to October 2012. Government officials from the ANP,Afghan National Border Police, NDS, Ministry of Interior (MoI) and other departmentscooperated with UNAMA during the period of detention observation.From October 2011 to October 2012, NDS provided access to detainees at NDS facilitiesthroughout Afghanistan, except the national detention facility of NDS Counter-Terrorism Department 124 (formerly known as Department 90) in Kabul to whichUNAMA has not been permitted access.The Ministry of Interior provided access to all ANP and ANBP lock-ups and detentionfacilities. The transfer of responsibility for prisons through the Central PrisonsDirectorate (CPD) from the Ministry of Justice to the Ministry of Interior on 10 January2012 caused some obstacles for UNAMA in accessing several CPD prisons and ininterviewing detainees.4Sample of DetaineesBetween October 2011-2012, UNAMA interviewed 635 pre-trial detainees andconvicted prisoners detained by the ANP, ANBP, Afghan National Army (ANA), AfghanLocal Police (ALP) and/or by NDS. Detainees were interviewed at ANP or ANBP lock-ups or ANP provincial centers or at NDS provincial headquarters, a Central PrisonsDirectorate (CPD) prison or a juvenile rehabilitation centre (JRC). UNAMA’s interviewscovered treatment of detainees interviewed in 89 facilities in 30 provinces acrossAfghanistan (detainees held in Wardak and Nimroz were interviewed following transferto Kabul and Farah respectively).5Map 1 provides an overview of detention facilitiesvisited by UNAMA between October 2011 and October 2012.

of Conflict-Related Detainees in Afghan Custody(UNAMA/OHCHR, October 2011) available athttp://unama.unmissions.org/Portals/UNAMA/Documents/October10_%202011_UNAMA_Detention_Full-Report_ENG.pdf.4Directors of some provincial CPD prisons informed UNAMA they had received instructions from theMinistry of Interior to seek authorization from the provincial chief of police prior to permitting any visits.This occurred in Kandahar when UNAMA sought to visitSarpoza Prisonin December 2011 and January2012 when authority for CPD facilities was initially transferred from the Ministry of Justice to theMinistry of Interior (MoI). UNAMA resolved the issue by referring the matter to the Head of CPD in Kabul,General Jamshed who intervened and authorized UNAMA’s access. It remains unclear, however, whetherthe MoI or the CPD has overall authority to grant access to independent monitoring bodies/organizationsto prisons. CPD directors have indicated that the chief prosecutor, the Head of NDS and the Chief of Policeare the authorities that UNAMA should contact to authorize monitoring visits. UNAMA is concerned thatthis lack of clarity may jeopardize efforts to continue to observe and report on detainee treatment andcompliance with due process obligations by Afghan authorities.5NDS provincial facilities UNAMA visited: Faizabad (Badakhshan), Qala-e-Naw (Badghis), Pul-e-Khumri(Baghlan), Mazar (Balkh), Bamyan city (Bamyan),Nili (Daikundi), Farah city (Farah), Maimana (Faryab),Herat city (Herat), Sherbergan (Jawzjan), Kabul (Departments 1 and 40), Kandahar city (Kandahar),Mahmud-e-Raqi (Kapisa), Khost city (Khost), Asad Abad (Kunar), Kunduz city (Kunduz), Mehtarlam(Laghman), Jalalabad (Nangarhar), Sharan (Paktika), Gardez city (Paktya), Chaharikar (Parwan), Sari Pulcity (Sari Pul), Taloqan (Takhar), and Qalat (Zabul). ANP provincial facilities UNAMA visited: Faizabad(Badakhshan, Pul-e-Khumri (Baghlan), Mazar (Balkh), Bamyan city (Bamyan), Nili (Daikundi), Farah city

3Treatment

iii

At almost all of these detention facilities, UNAMA met with detaining authorities andother relevant Government officials, visited parts of each detention facility andexamined its registry. At some NDS facilities, UNAMA was denied access to the registryor logbook and/or access to all parts of the detention facility. When this occurred, thematter was first referred to the senior management of the facility concerned and then tothe NDS human rights department at NDS headquarters in Kabul. After intervention bythe NDS human rights department, UNAMA was granted access to logbooks in all NDSfacilities visited.Of 635 detainees UNAMA interviewed, 552 were held on suspicion of or were convictedof offences related to the armed conflict. UNAMA found that ANP counter terrorismunits and/or NDS had detained another 78 detainees who were categorized as suspectsfor “common crimes.” Many had been arrested for kidnapping or abduction, classified asa common crime which NDS is responsible for investigating; many of these detaineeswere also suspected members of Anti-Government Elements (AGEs) or relatives ofsuspected AGEs. UNAMA included these detainees in the sample because NDS and ANPtreated them as conflict-related detainees and held them with other conflict-related orpolitical detainees.UNAMA found that 330 out of 552 conflict-related detainees were alleged to be Talibansupporters and 57 were alleged to be members of other Anti-Government armedgroups. Among the 552, 87 were alleged to have been in possession of explosives andother lethal devices, 18 were alleged to have committed murder or assault, 13 werealleged to have participated in failed suicide attacks, seven were alleged to havecommitted abduction, two were accused of forgery, two detainees were detained forbeing the relative of an accused suspect, one was accused of human trafficking and 16were alleged to have committed other crimes. A further 19 detainees did not know thespecific crime for which they were detained.Of the 635 detainees, 514 were held or had been held in NDS detention facilities6, 286were held or had been held in ANP facilities, nine were held or had been held by ANBP7,34 had been held in ANA detention facilities8, 12 detainees were held or had been held(Farah), Maimana (Faryab), Herat city (Herat), Sherbergan (Jawzjan), Kabul city (Kabul), Mahmud-e-Raqi(Kapisa), Kandahar city (Kandahar), Khost city (Khost), Asad Abad (Kunar), Kunduz city (Kunduz city),Mehtarlam (Laghman), Jalalabad (Nangarhar), Sharan (Paktika), Gardez (Paktya), Chaharikar (Parwan),Taloqan (Takhar) and Qalat (Zabul). CPD provincial prisons that UNAMA visited: Faizabad (Badakhshan),Qala-e-Naw (Badghis), Pul-e-Khumri (Baghlan), Mazar (Balkh), Bamyan city (Bamyan), Nili (Daikundi),Farah city (Farah), Maimana (Faryab), Chaghcharan (Ghor), Herat city (Herat), Sherbergan (Jawzjan),Pul icharkhi(Kabul),Sarpoza(Kandahar), Mahmud-e-Raqi (Kapisa), Khost city (Khost), Asad Abad (Kunar),Kunduz (Kunduz), Mehtarlam (Laghman), Jalalabad (Nangarhar), Chaharikar (Parwan), Sari Pul city (SariPul), Taloqan (Takhar) and Qalat (Zabul). JRCs that UNAMA visited: Faizabad (Badakhshan), Qala-e-Naw(Badghis), Pul-e-Khumri (Baghlan), Farah city (Farah), Lashkar Gah (Helmand) Herat city (Herat), Kabulcity (Kabul), Kandahar city (Kandahar), Mahmud-e-Raqi (Kapisa), Khost city (Khost), Kunduz city(Kunduz), Mehtarlam (Laghman), Pul-e-Alam (Logar), Jalalabad (Nangarhar), Sharan (Paktika), Taloqan(Takhar) and Qalat (Zabul).6Out of 514 detainees, 68 detainees were held in two NDS detention facilities at different times, 18 wereheld in three NDS detention facilities at different times and three detainees were held in four NDSdetention facilities at different times totaling 601 instances of NDS detention in the sample.7Out of 286 detainees, 61 detainees were held in two ANP detention facilities at different times and twodetainees were held in three ANP detention facilities at different times totalling 347 instances of ANPdetention in the sample.8Out of 34 detainees, three detainees were held in two ANA detention facilities at different times in thesample.

iv

by ALP and 79 detainees had been captured and/or held by international military forcesor foreign government intelligence agencies either alone or with Afghan security forcesand transferred to NDS or ANP custody. The number of detainees held by both NDS andANP or ANBP at different times was 151. The total number of detainees appears higherthan 635 because numerous detainees were detained by both NDS and ANP or ANBPand/or by ANA, Afghan Local Police and/or international military forces.Of the 635 detainees UNAMA interviewed, 267 individuals were arrested by NDS (actingalone); 212 arrested by ANP and/or ANBP; 79 captured or arrested by internationalmilitary forces (operating alone or jointly with ANSF or campaign forces); 31 capturedby ANA (acting alone), 26 by others (Afghan Local Police, MoI Criminal InvestigationDivision or local commanders); and five detainees captured by ANSF (acting alone).Fifteen of the 635 detainees were unable to reliably identify the capturing or arrestingauthority in their case.Of the 79 detainees initially arrested or captured by international military forces orforeign government intelligence agencies acting alone or jointly with Afghan forces, 52were initially transferred to NDS custody, 20 were transferred to ANP, four weretransferred to ANA, one was transferred to a MoI prison, one was transferred to aDistrict Governor’s office and one detainee was transferred to a Juvenile RehabilitationCentre (JRC).UNAMA interviewed three female detainees held on conflict-related offences. In general,Afghan authorities detain very few women for such offences. 105 child detainees wereinterviewed who were under the age of 18 years at the time of their detention.9UNAMA also interviewed and met frequently with members of the judiciary,prosecutors, defence counsel, medical personnel, humanitarian and human rightsorganizations and other relevant interlocutors over the observation period.The focus of UNAMA’s interviews with the 635 detainees was on their treatment by NDSand ANP or ANBP personnel, as well as ANA and ALP officials. Every detaineeinterviewed was asked about their treatment at each detention facility in which theywere held. UNAMA also observed the Government’s compliance in detainee’s cases withits due process obligations under Afghan and international human rights law.10Interview Safeguards, Modalities and Standard of ProofUNAMA randomly selected detainees held on conflict-related offences and interviewedthem in private in their mother tongue (Pashto or Dari) without the presence ofdetention facility staff, other Government officials, or other detainees. All detaineesinterviewed provided their informed consent to be interviewed.UNAMA interviewers visited the same detention facilities on numerous occasions and atdifferent times over the course of the 12-month observation period. A significantnumber of visits were conducted unannounced; however, visits to detention facilities inKabul and Kandahar were conducted by a protocol arrangement with visits carried outby prior appointment.Under theConvention on the Rights of the Child(CRC) the legal definition of a child is any person underthe age of 18 years (0-17 years).10UNAMA’s Rule and Law and Child Protection Units provided expert research and analysis support toUNAMA’s detention observation programme and preparation of this report.9

v

UNAMA used internationally accepted best practices and standards in designing andcarrying out its detention observation programme and interviews with detainees.UNAMA issued detailed guidance notes and instructions to all interviewers andtranslators.11These documents incorporated instructions from the UN Office of the HighCommissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) training manual on interviewing detaineesand visiting detention facilities.12All UNAMA interviewers received standardized training on how to conduct interviews,assess credibility, protect confidentiality and corroborate and cross-check informationon matters of detention, torture and ill-treatment with extensive supervision andoversight from experts and supervisors in UNAMA’s Human Rights Unit. Interviewersavoided leading questions and asked each detainee to tell his story in an open-endedmanner (interviews ranged in length from 30 minutes to two and half hours with anumber of detainees interviewed on multiple occasions).13For each interview, UNAMAinterviewers recorded a detailed verbatim transcript and note of the interview whichwas assessed for credibility and cross checked.Where UNAMA was not satisfied about the credibility or veracity of a detainee’saccount, it was not included in the sample of sufficiently credible and reliable cases oftorture or ill-treatment. UNAMA’s sample of 635 detainees included detainees who didnot allege torture or ill-treatment and whose allegations of torture or ill treatment werenot assessed as credible or verified. Of the 635 detainees interviewed, 377 detaineesalleged they were subjected to torture or ill-treatment, while 258 did not allege tortureor ill-treatment.14UNAMA did not find the accounts of 51 of the 377 detainees whoalleged torture and ill-treatment to be sufficiently credible and reliable. UNAMA verified

See UN endorsed guidelines: http://www1.umn.edu/humanrts/monitoring/chapter9.html#C1.OHCHR Training Manual on Human Rights Monitoring (2011). Available athttp://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Publications/training7Introen.pdf.13Expert practitioners in obtaining and verifying detainee accounts of treatment in detention havedetermined that the most reliable way to uncover false allegations is to obtain the "true version" of adetainee’s statement and subject it to detailed analysis. The true version is a detainee’s statement of thealleged incident in his or her own words without interruption, as opposed to a version provided inresponse to a series of questions. The true version better enables and supports expert analysis of whetherthe account is being provided through a real memory. With a falsified, embellished or enhanced account,the detainee will have memorized details and will be recalling them in response to questions. However, atrue story will be described using the senses and displaying other characteristics associated with a realmemory. Comparative analysis of detainee accounts has determined that real memories tend to reflectand include greater sensory detail (such as colours, size, shape and sound), greater mention of geographicdetail, more mention of cognitive or other internal processing e.g. thoughts, emotions, reactions andfewer verbal qualifications or hedges. For this detention study, UNAMA interviewers asked questions thatallowed detainees to tell their stories in their own words and at their own pace. Initial questions wereopen-ended providing the best possible means of assessing the veracity of a detainee’s statements. Once adetainee had provided the basic information in response to these open-ended questions, interviewersfollowed up with closed-ended questions to elicit further details or clarify areas of a detainee’s account.For further information, see Gudjonnsen (1992) and Schooler, Gerhard and Loftus (1986) referenced inOHCHR’s Training Manual.14UNAMA’s sample of 635 detainees included 326 detainees who made allegations of torture or ill-treatment (125 by ANP or ANBP, 178 by NDS, 10 by ALP and 13 by ANA totaling 326) found to besufficiently credible and reliable. UNAMA observed that six detainees were tortured or ill-treated by bothANP and NDS and one detainee was ill-treated by both ANA and ANP.12

11

vi

as sufficiently reliable and credible allegations of torture and ill-treatment of 326 of the377 detainees who alleged torture.15Interviewers exercised due diligence to corroborate information from detaineesthrough various methods including interviews with relatives, community members,defence lawyers, local experts, humanitarian agencies, medical personnel and othernational and international interlocutors directly involved in the detainee’s case or thedetention facility, and through inspections of physical evidence and review of otherrelevant material. UNAMA also obtained photographic and other evidence of tortureand ill-treatment of detainees from a range of interlocutors and sources.16UNAMA interviewers observed injuries, marks and scars on numerous detainees thatappeared to be consistent with torture and ill-treatment and/or bandages and otherevidence of medical treatment for such injuries.1758 of the detainees interviewedreported they required medical treatment due to injuries sustained during theirinterrogation and detention.Standard of ProofWhile UNAMA interviewed individual detainees and made determinations on theplausibility of allegations of torture, UNAMA does not purport to be an alternative to thecriminal justice system. UNAMA’s detention observation programme is designed toprovide sufficiently credible and reliable information on the occurrence of torture thatrequires impartial, credible and independent criminal investigations by the Governmentof Afghanistan together with appropriate remedial actions.UNAMA weighed all available information (including individual accounts and relatedcorroborating evidence) to determine whether the information obtained was“sufficiently credible and reliable” to permit UNAMA to make findings, raise concernsabout specific facilities and recommend criminal investigations and other measures.18The standard of “sufficiently credible and reliable” information was also used as thebasis to determine whether consistent patterns of torture and ill-treatment as definedunder international law had occurred within the detention system.19This reportThis sample of 51 detainee accounts included 31 from NDS: Detainees 130, 134, 135, 142, 195, 216,254, 318, 371, 399, 406, 409, 412, 416, 430, 444, 453, 531, 536, 548, 551, 552, 583, 585, 591, 606, 612,614, 635, 641, 661; Nine from ANP: Detainees 44, 168, 231, 339, 455, 496, 510, 617, 623; Five from ALP:Detainees 65, 197, 233, 568, 598; Five from ANA: Detainees 238, 372, 576, 599, 604 and one (detainee220) who had been held by international military forces totaling 51.16The Government of Afghanistan in its response to this report dated 14 January 2013 (attached as AnnexIV) commented on the structure and methodology of this report and statedUNAMA Human Rights Unit forpurposes of establishing facts in preparing the report only used interviews with accused persons andsuspects and some staff which is not sufficient to prove their claims.UNAMA indicates as outlined above therange of sources it used to make its findings.17Detainees 3, 24, 71, 74, 219, 270, 288, 306, 458, 485, 508, 511, 553, 578, 605, 610 and 627.18Stephen Wilkinson,Standards of Proof in International Humanitarian and Human Rights Fact-Findingand Inquiry Missions(2012), Geneva Academy of International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights, pp.32.19Under Article1(1) of theConvention against Torture,torture means any act by which severe pain orsuffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person for such purposes as obtainingfrom him or a third person information or a confession, punishing him for an act he or a third person hascommitted or is suspected of having committed, or intimidating or coercing him or a third person, or forany reason based on discrimination of any kind, when such pain or suffering is inflicted by or at theinstigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official15

vii

indicates those facilities where “sufficiently credible and reliable” information wasfound in multiple cases establishing that torture was very likely used on conflict-relateddetainees.In facilities identified as using systematic torture,20numerous detainees interviewedwho had been held in the specific detention facility provided sufficiently credible andreliable information meeting the standard of proof above. This indicated that numerousdetainees in the particular facility were very highly likely subjected to torture meaningthat facility directors and investigators must have known, ordered or acquiesced to theuse of torture. As such, it can be concluded that torture was an institutional policy orpractice of the specific facility and was not used by a few individuals in isolated cases orrarely.While all claims of torture should be investigated, UNAMA has chosen to use“sufficiently credible and reliable” as a standard of proof rather than a basic “reasonablesuspicion” standard (which is regularly used to trigger investigations within thecriminal justice system).21Due to the gravity of torture and the vulnerability of victimsof such gross human rights violations, the higher standard of proof is intended to ensurethat UNAMA is in the best position possible to recommend well-founded and concreteactions to stop its use.UNAMA did not take or use cameras, cell phones, video equipment or recording devicesin interviews with detainees in compliance with NDS instructions.Data from all interviews with detainees as well as findings from all meetings andinterviews with third party witnesses and Afghan and international officials weredocumented and recorded in a dedicated database.For reasons of security and confidentiality, this report refers to detainees by number. Inthis context, to protect the identity of individual detainees, the term “detainee” refers topersons suspected, accused or convicted of crimes.Questions about UNAMA’s Methodology and UNAMA’s ResponseNDS and ANP officials and international interlocutors have raised questions andcomments about UNAMA’s methodology outlined below. UNAMA addressed thesequestions about methodology by analyzing patterns of allegations in the aggregate andat specific facilities which permitted conclusions to be drawn about abusive practices at

capacity. It does not include pain or suffering arising only from, inherent in or incidental to lawfulsanctions. Torture distinguishes itself from other cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment (ill-treatment)due to the severity of pain inflicted, the intentionality of the infliction of pain and the fact that severe painis inflicted for a specific purpose, namely obtaining a confession, intimidation or coercion. Both tortureand ill-treatment are prohibited under international law, including by the International Covenant on Civiland Political Rights and the Convention against Torture (both ratified by Afghanistan).20For purposes of this report, UNAMA uses the term “systematic” to reflect the presence of a policy orpractice within an individual facility. This report does not argue that the use of torture and ill-treatmentwas part of a systematic national or institutional Government policy. In its comments to this report dated14 January 2013 (attached as Annex IV), the Government of Afghanistan noted that UNAMA said in thisreport thattorture and harassment of detainees was part of the policy and procedure of Government legaland arresting bodiesand that UNAMA had not properly defined the purpose and use of the termsystematic torture. UNAMA addresses these matters in this and the previous footnote.21Ibid, pp. 49-52.

viii

specific facilities and suggested fabricated accounts were uncommon as summarizedbelow.Questions/Comments of Afghan authorities(1) There is a high likelihood of lying or false allegations of torture from detaineeshighlighting the training some insurgents receive in making false allegations ofill-treatment as a form of anti-Government propaganda.22(2) The Taliban provide members with instructions or code of conduct that directmembers detained by Afghan authorities to offer a bribe to be released and/orto allege torture when seen by foreigners during detention.UNAMA’s Response•The nation-wide pattern of allegations from the large sample size (635 detaineesat 89 facilities) is inconsistent with a substantial proportion of detaineesinterviewed having been trained prior to their capture and detention in what liesto tell about their treatment if detained. First, the nature of the ill-treatmentreported was generally distinctive and specific to the facility at which it wasalleged to have occurred. It is improbable that training would be so well tailoredto specific facilities. Second, the same forms of ill-treatment at the same facilitieswere reported by different detainees interviewed at different times and oftenmonths apart. Interviewees also belonged to a variety of networks, such as localkidnapping gangs and a range of insurgent groups. Training is unlikely to havebeen provided consistently across this diverse range of groups, and the patternof allegations of ill-treatment did not correspond with any identifiableideological agenda.The Taliban’s most recent Code of Conduct orLahyaof 30 May 2010 does notinclude a directive instructing members to bribe Afghan detaining authoritiesand allege torture to foreign observers.UNAMA received a copy of an alleged Taliban manual on detentions andinvestigations (undated in Pashto and English). Independent expert analysis ofthe document indicates that it is unlikely the document is an authentic Talibantext. In addition, while the document discusses members paying money to NDS toget detainees released it does not appear to directly instruct members to allegeor lie about being tortured to foreign observers.At facilities visited and observed, UNAMA ruled out the possibility of collectivefabrication – where a group of detainees would share stories of real or rumoredill-treatment and, either spontaneously or by design, arrive at and deliver acommon account. When a significant portion of interviews regarding a facilitywas conducted at that facility, knowledge of that facility’s practices forsegregating detainees made it possible for UNAMA to ascertain that specificdetainees who provided highly similar accounts had not had any opportunity tocommunicate since arriving at the facility.UNAMA conducted numerous interviews with detainees at various locations andfacilities who had previously been detained at the same NDS facility over periodsof time before transfer to different locations. It is highly unlikely these detainees

••

•

•

See Annex II to UNAMA’s October 2011 report:Comments of the Government of Afghanistan, theNational Directorate of Security and the Ministry of Interiorto UNAMA’s report onTreatment of Conflict-Related Detainees in Afghan Custodydated 6 October 2011.22

ix

•

•

collectively or individually fabricated similar accounts of their treatment at thesame facility during their different detention periods.At facilities where UNAMA interviewed substantial numbers of detaineeswithout receiving any allegations of ill-treatment, no detainees within thesegroups alleged physical ill-treatment. This finding further suggests that detaineesgenerally gave truthful accounts, free from collusion, sharing of stories andcollective fabrication.Even if some portion of detainees were trained to lie about being tortured,UNAMA’s methodology, guidance and training to interviewers is designed todetect and weed out fabrication as explained above. UNAMA assessed as notcredible 51 allegations of torture and ill-treatment by detainees.

Question/Comment of Afghan authorities(3) UNAMA did not share evidence with NDS of torture allegations made bydetainees at the time when the allegations were made. NDS did not thereforehave an opportunity to verify and follow up on specific allegations of torture orill-treatment received.23UNAMA’s Response•Throughout UNAMA’s 12-month detention observation, UNAMA regularlyrequested meetings with provided relevant information about allegations oftorture and ill-treatment to NDS and ANP interlocutors permitting them to act asthey determined appropriate. In some instances, NDS advised UNAMA that it hadundertaken investigations into specific allegations/cases or to specific facilitiesincluding those referred by UNAMA and reported that it had found no torture orill-treatment in all such instances.As noted in the 11 January 2013 letter of Commander ISAF to UNAMA (attachedas Annex V to this report), over the last 18 months, ISAF reported 80 allegationsof detainee abuse to Afghan authorities requesting action and offering assistanceto support investigations with Afghan officials acting on only one case to date.

•

Question/Comment of Afghan authorities(4) UNAMA did not produce evidence of methods of specific acts of torture by NDS,in particular electric shocks, sexual threats and beatings to sexual organs e.g.pulling of testicles.24UNAMA’s Response•Since NDS and ANP did not permit UNAMA to take cameras into interviews it wasoften difficult for UNAMA to obtain direct first hand photographic evidence ofelectric shocks to detainees’ bodies or other evidence of beatings to sexualorgans. In some cases, detainees were not able to receive medical treatment forinjuries sustained during interrogation and medical providers were reluctant toprovide UNAMA with information or records regarding such injuries, often forsecurity reasons.

2324

Ibid.Ibid.

x

xi

Executive Summary“NDS has several secret places in which they detain and torture people. The office waslocated inside the NDS HQ compound in XXX25and I can tell you that all tortureddetainees were taken out of their cells that are located in one building and they weretransferred to another building inside the same compound to hide them….from anydelegation visiting NDS HQ.”(NDS Official, April 2012)26“I was arrested 12 days ago at a checkpoint in Panjwayi district on the outskirts ofKandahar city by the ANP. I am accused of being a Talib. I was taken directly to KandaharANP HQ. I was interrogated on the first day of my arrival in the ANP counter-terrorismdepartment. Four ANP officers beat me with a cable on my back and on my legs. Theinterrogation lasted two hours. The next day, I was given electric shocks on my arms andlegs. Another time, they threatened me with a gun saying that they would kill me if I didnot confess. I was forced to put my thumb print on a document and I was not interrogatedagain.”(Detainee 509, ANP HQ Kandahar, September 2012)27Further to its mandate from the United Nations Security Council to assist theGovernment of Afghanistan to improve respect for the rule of law and human rightsincluding in the prison sector, the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan(UNAMA) visited 89 detention facilities in 30 provinces between October 2011 andOctober 2012 to observe treatment of conflict-related detainees and the Government’scompliance with due process obligations under Afghan and international human rightslaw.28During these visits, UNAMA interviewed 635 pre-trial detainees and convictedprisoners including 105 children detained by the Afghan National Police, NationalDirectorate of Security, Afghan National Army or Afghan Local Police for nationalsecurity crimes or crimes related to the armed conflict.29All references to names and individuals (alleged perpetrators and detainees) that could lead toidentification of sources have been omitted to preserve security and confidentiality of sources.26UNAMA interview with NDS official, April 2012, Kabul. The reference to the location of the NDSdetention facility has been omitted for security reasons.27All dates referenced in the accounts of detainees refer to the month of torture and not to the month oftheir interview(s) with UNAMA.28UN Security Council Resolution 2041 (2012) paragraph 38:Stresses in this context the importance offurther progress in the reconstruction and reform of the prison sector in Afghanistan, in order to improve therespect for the rule of law and human rights therein, emphasizes the importance of ensuring access forrelevant organizations, as applicable, to all prisons and places of detention in Afghanistan, and calls for fullrespect for relevant international law including humanitarian law and human rights law, noting therecommendations contained in the report of the Assistance Mission dated 10 October 2011.See the sectionof this report on UNAMA’s mandate. See Map 1 for overview of detention facilities visited by UNAMAbetween October 2011 and October 2012. UNAMA does not currently visit the Detention Facility inParwan (DFIP) run by the United States Government or the Afghan National Detention Facility at Parwanso these facilities were not included in UNAMA’s sample and detention observation. The AfghanistanIndependent Human Rights Commission and the International Committee of the Red Cross visit thesefacilities. On 9 March 2012, the Governments of the United States and Afghanistan signed a Memorandumof Understanding reaffirming the transfer of Afghan nationals detained at Detention Facility in Parwan(DFIP) to Afghan control with most transfers completed at the time of writing.29Of the 635 detainees UNAMA interviewed, 514 had been held in NDS custody in 32 detention facilitiesin 30 provinces. 286 of the 635 detainees had been held by ANP in one of 37 facilities in 24 different25

1

The National Directorate of Security and the Ministry of Interior cooperated withUNAMA and provided access to almost all detention facilities and detainees. UNAMAregularly requested meetings with the National Directorate of Security and the Ministryof Interior/Afghan National Police and met numerous times with officials in Kabul andacross the country over the 12-month observation period to share appropriateinformation, and discuss concerns and follow up measures.The International Security Assistance Force (ISAF), other international military forcesand foreign intelligence agencies continue to have a role in detention of individuals forconflict-related offences through involvement in the capture and transfer of detainees toAfghan custody. In September 2011, ISAF launched a six-phase detention facilitymonitoring programme that initially covered 16 NDS and ANP facilities. DuringUNAMA’s 12-month observation period, UNAMA met with ISAF officials to discussISAF’s detention programme and related matters.Using internationally accepted methodology, standards and best practices, UNAMA’sdetention observation from October 2011 to October 2012 found that despiteGovernment and international efforts to address torture and ill-treatment of conflict-related detainees, torture persists and remains a serious concern in numerousdetention facilities across Afghanistan.30UNAMA found sufficiently credible and reliable evidence that more than half of 635detainees interviewed (326 detainees31) experienced torture and ill-treatment in

provinces. Nine of the detainees interviewed had been held by Afghan National Border Police (ANBP), 34had been detained in facilities operated by the ANA, 12 had been detained by the ALP and 79 detaineeshad been initially captured and held by either international military forces or other internationalgovernment agencies acting alone or together with Afghan security forces and transferred to NDS or ANPcustody. The total number of detainees as noted is higher than 635 because numerous detainees weredetained by both NDS and ANP or ANBP and/or by ANA, Afghan Local Police and/or international militaryforces. The majority of detainees were alleged to be members, supporters and foot soldiers of the Talibanor other Anti-Government armed groups. See theAccess and Methodologysection of this report. Under theConvention on the Rights of the Childthe legal definition of a child is any person under the age of 18 years(0-17 years). UNAMA made no assumptions or conclusions on the guilt or innocence of those detainees itinterviewed for crimes of which they were suspected, accused or convicted.30Other organisations also documented and reported on the use of torture and ill treatment in Afghandetention facilities during the observation period. For example, in March 2012, the AfghanistanIndependent Human Rights Commission and Open Society Foundations released a report that foundcredible evidence of torture and ill-treatment at nine NDS and several ANP detention facilities, andwidespread and deliberate violations of detainees’ fundamental due process rights. The report alsoexamined the transfer of detainees from international military and security forces to Afghan authoritiesand noted the lack of monitoring of transfer of detainees by US Special Forces outside ISAF’s chain ofcommand. SeeTorture, Transfers, and Denial of Due Process: The Treatment of Conflict-Related Detainees inAfghanistan,Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission/Open Society Foundations, 17 March2012. Available athttp://www.aihrc.org.af/media/files/AIHRC%20OSF%20Detentions%20Report%20English%20Final%2017-3-2012.pdf.31Of the 635 detainees interviewed, 377 made allegations of torture or ill-treatment. UNAMA found theaccounts of torture and ill-treatment of 326 of the 377 detainees to be sufficiently credible and reliable.To address concerns about the likelihood of lying and false allegations of torture as a form of Anti-Government propaganda, UNAMA analysed patterns of allegations of torture and ill-treatment in theaggregate and at specific facilities to corroborate allegations, to identify abusive practices at specificfacilities and to detect and rule out fabricated accounts. In addition to interviews with detainees and arange of interlocutors and sources, UNAMA obtained or reviewed documentary and photographic

2

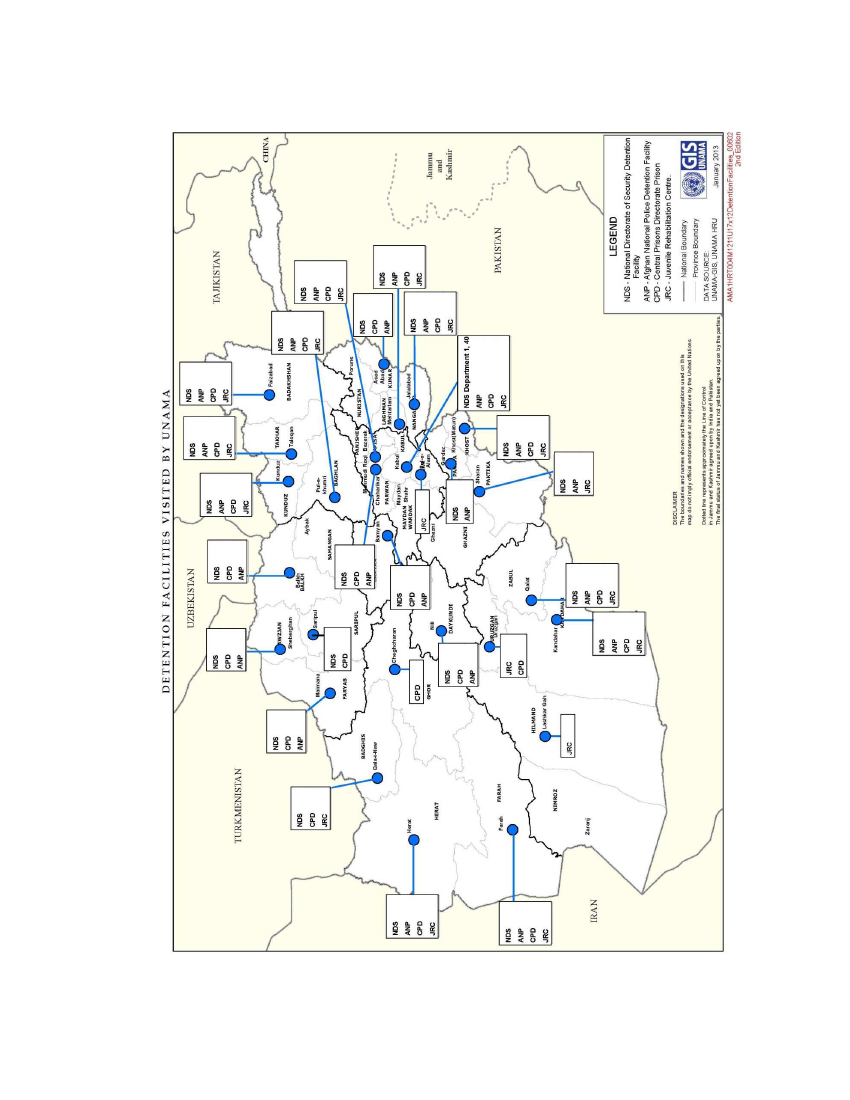

numerous facilities of the Afghan National Police (ANP), National Directorate of Security(NDS), Afghan National Army (ANA) and Afghan Local Police (ALP) between October2011 and October 2012.32This finding is similar to UNAMA’s findings for October 2010-11 which determined that almost half of the detainees interviewed who had been heldin NDS facilities and one third of detainees interviewed who had been held in ANPfacilities experienced torture or ill-treatment at the hands of ANP or NDS officials.33(SeeMap 2).UNAMA’s new study noted that while the incidence of torture in ANP or ANBP facilitiesincreased compared to the previous period, detainees interviewed in NDS custodyexperienced torture and ill-treatment at a rate that was slightly lower than the previousperiod. UNAMA observed that of the 105 child detainees interviewed, 80 children (76percent) experienced torture or ill-treatment, an increase of 14 percent compared toUNAMA’s previous findings.34UNAMA also interviewed a small number of detainees who had been held by ALP orANA forces and found sufficiently credible and reliable evidence that 10 of the 12detainees held by the ALP experienced torture or ill-treatment. One third (13) of the 34detainees interviewed who were held in ANA custody experienced torture or ill-treatment.UNAMA found sufficiently credible and reliable evidence that 25 of the 79 (31 per cent)detainees interviewed who had been transferred by international military forces orforeign intelligence agencies to Afghan custody experienced torture by ANP, NDS orANA officials. This represents an increase of seven percent compared to UNAMA’sfindings for the prior one-year period when 22 of 89 detainees (24 percent) transferredby international military forces experienced torture. This situation raises continuing

evidence of torture and ill-treatment. Such material was appropriately shared with Government officialsincluding at the highest levels. See the section of this report onAccess and Methodology.32This report uses the definition of torture in theConvention against Torture (CAT) article 1:For thepurposes of this Convention, the term “torture” means any act by which severe pain or suffering, whetherphysical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person for such purposes as obtaining from him or athird person information or a confession, punishing him for an act he or a third person has committed oris suspected of having committed, or intimidating or coercing him or a third person, or for any reasonbased on discrimination of any kind, when such pain or suffering is inflicted by or at the instigation of orwith the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity. It doesnot include pain or suffering arising only from, inherent in or incidental to lawful sanctions. Thisdefinition includes four elements: (1) the act of inflicting severe pain or suffering (2) the act is intentional(3) the act is for such purposes as obtaining information or a confession, punishment, intimidation orcoercion, or discrimination and (4) the perpetrator is a public official or other person acting in an officialcapacity. The “elements of intent and purpose . . . do not involve a subjective inquiry into the motivationsof the perpetrators, but rather must be objective determinations under the circumstances.” Committeeagainst Torture, General Comment No. 2 (“Implementation of article 2 by States parties”), CAT/C/GC/2(24 January 2008), Para. 9.33See UNAMA’s October 2011 reportTreatment of Conflict-Related Detainees in Afghan Custody(UNAMA/OHCHR, 10 October 2011). Available athttp://unama.unmissions.org/Portals/UNAMA/Documents/October10_%202011_UNAMA_Detention_Full-Report_ENG.pdf. Also see Annex I of this report for a summary onUNAMA’s Detention ObservationProgramme 2010-12.34UNAMA observed that 33 child detainees experienced torture by NDS, 45 by ANP, one by ANA and oneby ALP totalling 80 child detainees.

3

concerns about States’ legal obligations prohibiting them from transferring detainees toanother State’s custody where a substantial risk of torture exists.35ISAF rules also stipulate that consistent with international law, individuals should notbe transferred under any circumstances where there is a risk they will be subjected totorture and ill-treatment. Addressing concerns about transfer to a risk of torturerequires international military forces to conduct rigorous oversight and monitoring ofall transfers of detainees to Afghan custody and to suspend transfers to facilities withcredible reports and risks of torture in compliance with their legal obligations.Where torture occurred, it generally took the form of abusive interrogation techniquesin which NDS, ANP, ALP or ANA officials deliberately inflicted severe pain and sufferingon detainees during interrogations aimed mainly at obtaining a confession orinformation. Such practices amounting to torture are among the most serious humanrights violations under international law and are crimes under Afghan law.36Described methods of torture and ill-treatment were similar to practices previouslydocumented by UNAMA. Fourteen different methods of torture were described.Detainees said they experienced torture in the form of suspension (hanging from theceiling by the wrists or from chains attached to the wall, iron bars or other fixtures sothat the victim’s toes barely touch the ground or he is completely suspended in the airwith his body weight on his wrists for lengthy periods), prolonged and severe beatingwith cables, pipes, hoses or wooden sticks (including on the soles of the feet), punchingand kicking all over the body, twisting of genitals, and threats against the detainee ofexecution and/or sexual violence.Other forms of torture and ill-treatment reported included increased incidents ofelectric shock, stress positions, prolonged standing, standing and sitting down orsquatting repeatedly and forced standing outside in cold weather conditions for longperiods. Many detainees interviewed reported they had been subjected to severalmethods of torture often inflicted with escalating levels of pain particularly when theyrefused to confess to the crime they were accused of or failed to provide or confirminformation.UNAMA found that multiple credible and reliable incidents of torture and ill-treatmenthad occurred particularly in 34 facilities of the ANP, ANBP and NDS. UNAMA foundsufficiently credible and reliable evidence that NDS officials at two facilities

Article 3 of theConvention against Tortureonnon-refoulementobliges States not to transfer “a personto another State where there are substantial grounds for believing that he would be in danger of beingsubjected to torture.” Further, “If a person is to be transferred or sent to the custody or control of anindividual or institution known to have engaged in torture or ill-treatment, or has not implementedadequate safeguards, the State is responsible, and its officials subject to punishment for ordering,permitting or participating in this transfer contrary to the State’s obligation to take effective measures toprevent torture.” See Committee against Torture, General Comment No. 2 (“Implementation of article 2 byStates parties”), CAT/C/GC/2 (24 January 2008), Para. 19.36The Government of Afghanistan ratified theConvention against Torturein June 1987. Article 29 of theConstitution of Afghanistanprovides “No one shall be allowed to or order torture, even for discovering thetruth from another individual who is under investigation, arrest, detention or has been convicted to bepunished.” TheAfghan Penal Codecriminalizes torture and article 275 prescribes that public officials(including all NDS and ANP officials) found to have tortured an accused for the purpose of obtaining aconfession shall be sentenced to imprisonment in the range of five to 15 years.”

35

4

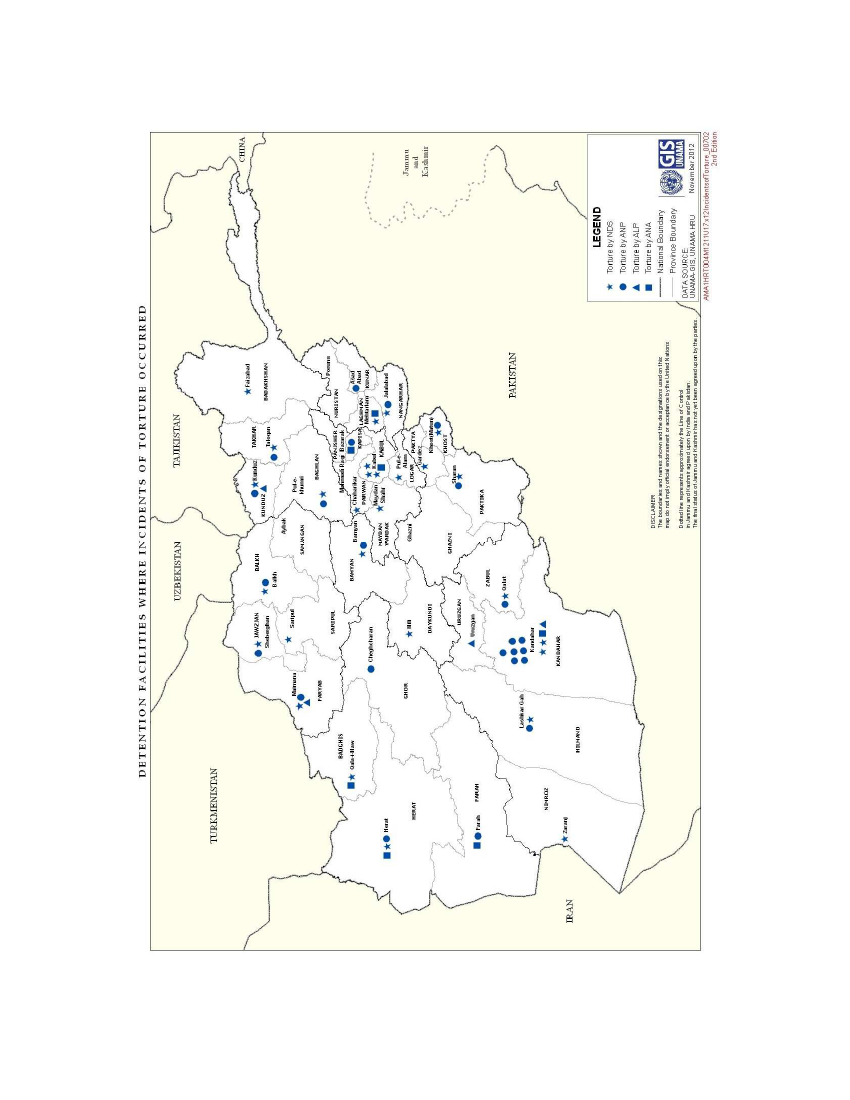

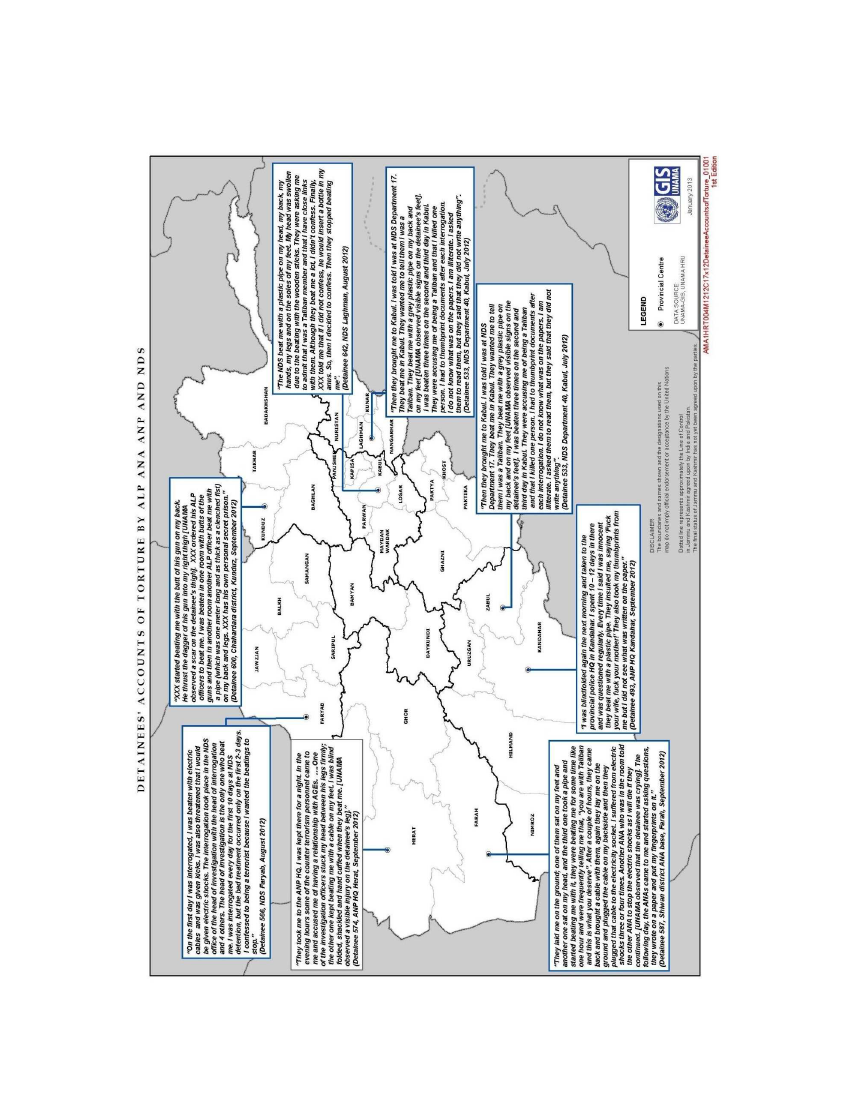

systematically tortured detainees mainly to obtain confessions and information.37Multiple credible and reliable cases of torture and ill-treatment were documented in tenother NDS facilities. The systematic use of torture was found in six ANP facilities andone ANBP location. In 15 other ANP provincial headquarters and district police stations,UNAMA found numerous credible and reliable cases of torture or ill-treatment.38UNAMA observed more conflict-related detainees detained and interrogated by the ANPin several regions with an increase in reports of torture by ANP. UNAMA also receivedsufficiently reliable and credible information that in some NDS facilities, officials hiddetainees from international observers and held them in underground or otherlocations. Multiple credible reports were received about the existence of unofficialdetention facilities in a few locations. Similar to previous findings, UNAMA observedthat credible and reliable evidence of torture was most prevalent in NDS and ANPfacilities in Kandahar.UNAMA also received credible reports of the alleged disappearance39of 81 individualswho reportedly had been taken into ANP custody in Kandahar province from September2011 to October 2012 and whose status remains unknown.Over the one-year period, UNAMA observed early improvement in some NDS facilitieswith a decrease in allegations of torture. This reduction corresponded with a decreasein transfers by international military forces and increased monitoring including by ISAF.However, after ISAF resumed transfers to these facilities and reduced its monitoring,UNAMA observed an increase and resumption in incidents of torture.Government Measures to Address Torture and Ill-TreatmentFrom October 2011 to October 2012 and in response to UNAMA’s October 2011 report,the Government of Afghanistan instituted a range of measures aimed at addressingtorture and ill-treatment in Afghan detention facilities.40The NDS and the Ministry ofInterior continued to provide UNAMA and international and national organizations withaccess to most facilities, stating they investigated allegations of torture and ill-See the section in this report onAccess and Methodologyfor the definition used in this report of asystematic practice or pattern of the use of torture within specific detention facilities.38See Map 3 for a sample of detainees’ accounts of torture by location.39International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearancedefines “enforceddisappearance” under article 2: “the arrest, detention, abduction or any other form of deprivation ofliberty by agents of the State or by persons or groups of persons acting with the authorization, support oracquiescence of the State, followed by a refusal to acknowledge the deprivation of liberty or byconcealment of the fate or whereabouts of the disappeared person, which place such a person outside theprotection of the law”. Afghanistan has not signed or ratified the convention. Multiple sources sharedconcerns with UNAMA that following arrest, some detainees may have been killed while in police custody.40In October 2011, UNAMA released a report entitledTreatment of Conflict-Related Detainees in AfghanCustody.Based on in depth interviews from October 2010 to August 2011 of 379 detainees at 47 facilitiesin 22 provinces, the report found the use of interrogation practices by ANP and NDS officials thatconstituted torture and ill-treatment under international law and crimes under Afghan law. The reportalso found compelling evidence that a number of detainees whom international military forces hadtransferred to NDS or ANP custody had been tortured by NDS or ANP officials. The report made 25recommendations to the NDS, Ministry of Interior, the Government of Afghanistan and Afghan judicialinstitutions, troop contributing countries and ISAF. Annex II of the report is the Government’s commentsto UNAMA’s October 2011 report available athttp://unama.unmissions.org/Portals/UNAMA/Documents/October10_%202011_UNAMA_Detention_Full-Report_ENG.pdf.37

5

treatment, implemented training programmes on prevention of detainee ill-treatmentand issued policy directives to their officials throughout Afghanistan which stated thattorture of detainees is a violation of Afghan law.41In 2012, NDS also created a sub-directorate of human rights charged with investigatingallegations of torture and ill-treatment that reports directly to the Director of NDS.42Former NDS Director Rahmatullah Nabil informed UNAMA that he participated directlyin several internal investigations into human rights violations in NDS facilities.43Insome instances, NDS advised UNAMA that it had investigated specific allegations andreports of torture and ill-treatment or investigated specific facilities including thosereferred by UNAMA. NDS informed UNAMA that in all such instances it found no tortureor ill-treatment. NDS officials also told UNAMA that it had reassigned several provincialNDS chiefs although the reasons for reassignment were not made clear.44While NDS and ANP acknowledged problems in their facilities, they stopped short ofrecognizing that their officials were responsible for torture.45To UNAMA’s knowledge,these internal investigations have not resulted in the prosecution or loss of jobs of NDSofficials for involvement in torturing detainees or for having failed to prevent the use oftorture. UNAMA is not aware of any instance in which an ANP officer has beenprosecuted in recent months for abusing detainees.On 17 September 2012, the NDS issued a statement46indicating that NDS welcomedand supported all organizations interested in observing and scrutinizing conditions ofdetainees and detention facilities. The NDS statement noted that NDS was working on anew mechanism to create a timetable for human rights organizations to visit NDSdetention facilities and detainees and that NDS was planning training programmes onhuman rights for NDS employees throughout Afghanistan. The statement asked allnational and international institutions to help and support NDS in this regard andreiterated NDS’s commitment to protecting the rights of detainees.

UNAMA meetings with Ministry of Interior Gender, Human Rights and Child Rights Department, 9 May2012, Kabul, and UNAMA meeting with NDS Human Rights Department, 14 May 2012, Kabul. Copies ofthe orders of the Ministry of Interior and NDS are on file with UNAMA.42Letter from NDS Human Rights Department to UNAMA dated 2 January 2012.43See Annex II: Comments of the Government of Afghanistan, the NDS and the Ministry of Interior toUNAMA’s October 2011 reportTreatment of Conflict-Related Detainees in Afghan Custody(UNAMA/OHCHR, 10 October 2011). Available athttp://unama.unmissions.org/Portals/UNAMA/Documents/October10_%202011_UNAMA_Detention_Full-Report_ENG.pdf.Asadullah Khalid was appointed Director of NDS on 3 September 2012 andRahmatullah Nabil was appointed deputy advisor of the National Security Council of Afghanistan.44As a result of some of these investigations, the Ministry of Interior and NDS improved hygiene inseveral facilities. UNAMA noted that physical conditions, including cleanliness, availability of basicmedical care, and quality of nutrition improved in some detention facilities. While these humanitarianissues were not the focus of UNAMA’s detention observation, such improvements are welcome.45See Annex II: Comments of the Government of Afghanistan, the NDS and the Ministry of Interior toUNAMA’s October 2011 report on theTreatment of Conflict-Related Detainees in Afghan Custody(UNAMA/OHCHR, October 2011). Available athttp://unama.unmissions.org/Portals/UNAMA/Documents/October10_%202011_UNAMA_Detention_Full-Report_ENG.pdf.45 Press Statement by NDS dated 27/06/1391 (17 September 2012). On 7 December 2012, a deputydirector of NDS, Hisamuddin Hisam was named as acting director of NDS following an attack on NDSDirector Assadullah Khalid requiring a period of medical treatment.

41

6

Government of Afghanistan Response to Findings of this ReportIn response to this report’s findings, the Government of Afghanistan, the NDS and theMinistry of Interior prepared a detailed written response and comments dated 14January 2013 attached as Annex IV to this report.47The response notes that while theGovernment “does not completely rule out abuse and ill-treatment by detention centerstaff due to lack of capacity and sound training in these institutions, the level of allegedtorture reflected in this report is exaggerated.” The Afghan authorities outlinenumerous measures they have undertaken to address allegations of ill-treatment todate including expanded training, investigations into a range of human rights concerns,issuance of orders and policy directives, and inspections.48Both the Ministry of Interior and NDS stated they reject the existence of systematictorture in their facilities and NDS noted that it rejects reports of hidden and alternatedetention centers. The Government together with NDS and the Ministry of Interiorstated they are ready to consider all recommendations for the consolidation of law andorder in detention centers, ensuring rights of detainees and the realization of justice.International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) Measures to Address Torture and Ill-TreatmentIn September 2011, ISAF suspended detainee transfers to 16 NDS and ANP locationswhich UNAMA had identified as practicing systematic torture.49As noted above, ISAFalso designed and rolled out a six-phase detention facility monitoring programme tosupport Afghan authorities in reforming their interrogation and detainee treatmentpractices prior to resumption of international transfers. The programme requiredregular inspections of facilities and interviews with detention center personnel anddetainees as the primary means of identifying abusive detention practices by NDS andANP. Inspections were accompanied by training seminars for detention facilitymanagers and investigative staff focused on humane treatment of detainees, includingnon-coercive interview techniques.Following training and a second round of unannounced facility inspections, NDS andANP facilities were considered for certification that permits international militaryResponse of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan on Draft Annual Report of Human Rights Section ofHuman Rights of UNAMA (Office of National Security Council, Ministry of Interior and NationalDirectorate of Security), 14 January 2013 attached as Annex IV to this report. The Government providedits response to UNAMA in the Dari language which UNAMA’s translation unit translated into English.48In their 14 January 2013 response to this report, the Ministry of Interior and NDS stated they havetaken measures to identify perpetrators of human rights violations and punish them, but reject thatincidents of torture and ill-treatment were discovered in their investigations. The Ministry of Interiorstated “In line with its legal obligations, the Ministry of Interior of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan hastaken legal actions against dozens of national police personnel who violated their legal terms of referenceand, in some cases, dismissed the violators and referred them to prosecutors’ offices.” NDS stated they donot “…claim perfection in our work…,” but attributed “flaws and faults” because of a “…lack of adequatework experience of our officials in some regions, because of insecurity in some regions and due to theirinability to access crime scenes and lack of technical equipment to prove material evidence of crimes…Insuch cases, the leadership of NDS has applied serious legal measures.” UNAMA notes this informationdoes not indicate what violations were committed particularly any torture and ill-treatment of detaineesor the reasons NDS and the Ministry of Interior took the stated actions.49ISAF suspended transfers on 4 September 2011 to NDS national counter-terrorism department 124 inKabul, NDS provincial facilities in Laghman, Kapisa, Takhar, Herat, Khost and Kandahar District 2 NDSoffice, and ANP district facilities in Kandahar including Daman, Arghandab, District 9 and Zhari, ANPdistrict facility in Dasht-e-Archi, Kunduz and ANP headquarters in Khost, Kunduz and Uruzgan.47

7

forces to resume transfers of detainees to specific facilities. Once certified, internationalmilitary personnel made regular monitoring visits to facilities where they transferreddetainees to track their treatment through the pre-trial process. ISAF’s position is thataccountability of perpetrators of torture of detainees is the sole responsibility of Afghanauthorities, and that ISAF’s role is limited to sharing information from their inspectionsand monitoring with the relevant Afghan authority on its follow up action. According toISAF, over the last 18 months, it reported 80 allegations of detainee abuse to Afghanauthorities requesting action and offering assistance to support investigations withAfghan officials acting on one case to date.50The Commander of ISAF began certifying facilities on 8 November 2011 and by 8 March2012 ISAF announced that it had fully or conditionally certified 14 of the 16 detentionfacilities that UNAMA named as locations where torture had occurred permittingresumption of international transfers to the facilities.51To UNAMA’s knowledge, ISAFcertification was not an endorsement by the Commander of ISAF that a facility was“torture-free” or a guarantee that the personnel of such facilities had been thoroughlyre-trained not to use abusive interrogation methods. Rather certification reflected thatNDS or ANP facilities had completed the first three stages of ISAF’s remediationprogramme and that ISAF was not aware of further torture or ill-treatment.In response to new credible reports of torture at several NDS and ANP facilitiesincluding from UNAMA, on 24 October 2012, ISAF de-certified and suspended for asecond time detainee transfers to NDS Department 124 in Kabul, NDS Laghman, NDSKhost, NDS Herat, ANP headquarters in Khost and ANP headquarters in Kunduz and forthe first time suspended detainee transfers to NDS Department 40 in Kabul.52ISAF alsoinformed UNAMA that it was reviewing its detention facility monitoring programme tostrengthen monitoring and undertaking a new round of detention facility inspectionsand investigations including joint investigations of facilities with NDS and Ministry ofInterior officials with representation from the Afghanistan Independent Human RightsCommission.53Further Measures Needed to Address Torture and Ill-TreatmentThe Government’s efforts to address torture and those of ISAF, although significant,have not resulted in a marked improvement and reduction in the use of torture. Thisraises concerns at a time when the Government is taking over almost full responsibilityfor conflict-related detainees from international military forces.

Letter of Commander ISAF to UNAMA dated 11 January 2013 attached as Annex V to this report.UNAMA interviews with ISAF personnel, March 2012, Kabul. By 8 March 2012, ISAF had resumedtransfers to 14 facilities: NDS national counter-terrorism department 124 in Kabul, NDS provincialfacilities in Laghman Kapisa, Takhar, Herat, Khost and ANP district facilities in Kandahar includingDaman, Arghandab, District 9 and Zhari, ANP district facility in Dasht-e-Archi, Kunduz and ANPheadquarters in Khost, Kunduz and Uruzgan. ISAF resumed transfers to NDS Takhar in March 2012 butsuspended transfers to the facility a second time on 6 August 2012 following multiple credible accounts oftorture resulting from NDS Takhar’s investigations of alleged poison attacks on girl’s schools in May 2012.ISAF has not resumed transfers to NDS Department 2, NDS Headquarters and ANP Headquarters’detention facilities in Kandahar. Also note ISAF’s suspension of detainee transfers to seven facilities on 24October 2012 referenced in the text above.52UNAMA meeting with ISAF personnel, 24 October 2012, Kabul.53UNAMA meetings with ISAF HQ personnel, October - December 2012, Kabul. Also see the letter ofCommander ISAF to UNAMA dated 11 January 2013 attached as Annex V to this report.51

50

8

Similar to previous findings, UNAMA found a persistent lack of accountability forperpetrators of torture with few investigations and no prosecutions or loss of jobs forthose responsible for torture or ill-treatment. The findings in this report highlight thattorture cannot be addressed by training, inspections and directives alone but requiressound accountability measures to stop and prevent its use. Without effective deterrentsand disincentives to use torture, including a robust, independent investigation processor criminal prosecutions, Afghan officials have no incentive to stop torture. A wayforward is clear.To bolster current measures underway to address torture, UNAMA recommends thecreation of an independent preventive body, similar to the national preventivemechanism model prescribed in theOptional Protocol to the Convention against Torture.Such a mechanism could be considered possibly within the Afghanistan IndependentHuman Rights Commission with authority to inspect all detention facilities, conductfollow up investigations and make recommendations for action including prosecution ofperpetrators of torture by criminal justice institutions or other bodies. Establishing sucha mechanism requires concerted and sustained international support.54This initiative could be reinforced through explicit instructions from the AttorneyGeneral’s Office and Supreme Court to all judges and prosecutors requiring them in allcases to actively investigate and reject any confessions gained through torture or ill-treatment. Failure to do so should result in professional sanctions and/or criminalprosecutions of such officials. UNAMA stands ready to continue to work constructivelywith Afghan authorities, and international and national partners to end and prevent theuse of torture in Afghan detention facilities.Continuing Torture and Ill-treatment of Detainees by NDS, ANP, ALP and ANA(October 2011-October 2012)The 635 detainees UNAMA interviewed from October 2011 to October 2012 represent a59 percent increase over the total sample of 379 detainees UNAMA interviewed in 2011.UNAMA increased the total number of detainees interviewed to improve the analyticaland statistical validity of the overall data and the sub-samples.55The new studyinterviewed twice as many NDS detainees and two and a half times the number ofdetainees held in ANP facilities than the previous year.

A joint press statement issued by President Obama and President Karzai on strengthening the enduringUS-Afghan partnership was issued on 11 January 2013, stating “Building upon significant progress in2012 to transfer responsibility for detentions to the Afghan Government, the Presidents committed toplacing Afghan detainees under the sovereignty and control of Afghanistan, while also ensuring thatdangerous fighters remain off the battlefield. President Obama reaffirmed that the United Statescontinues to provide assistance to the Afghan detention system. The two Presidents also reaffirmed theirmutual commitment to the lawful and humane treatment of detainees, and their intention to ensureproper security arrangements for the protection of Afghan, U.S., and coalition forces.”http://president.gov.af/en/news/1645.55The margin of error for the 2012 total sample of 635 detainees is plus or minus 3.7 percent, while themargin of error for the 2011 total sample of 379 detainees was plus or minus 4.8 percent. The 2012 and2011 studies are considered statistically comparable, taking into account the small difference in themargins of error. For the 2012 sub-sample of 514 NDS detainees, the margin of error is plus or minus 3.9percent, and for the sub-sample of 286 ANP or ANBP detainees, the margin of error is plus or minus 5.3percent. These margins of error are based on an estimated total detainee population of 5,000 and aresubject to a 95 percent confidence rating, i.e. 19 times out of 20.54

9

The new study found sufficiently reliable and credible evidence that 125 of arepresentative sample of 286 conflict-related detainees held in ANP or ANBP facilities,or 43 percent, had been tortured or ill-treated while in custody, compared with 35percent in the previous 12-month period.UNAMA determined that 178 out of 514 detainees held in NDS facilities, or 34 percent,experienced torture or ill-treatment, down 12 percent from the previous year, when 46percent reported torture or ill-treatment in NDS custody.56This reduction may be partlyexplained by the lower number of detainees found in NDS facilities including severalNDS facilities in ISAF’s inspection programme namely NDS Laghman, NDS Takhar, NDSKapisa and NDS Herat.UNAMA found sufficiently credible and reliable evidence of torture by ALP in fourprovinces. 10 of the 12 detainees UNAMA interviewed who had been held by the ALPreported torture or ill-treatment: seven of the 10 were in Chahardara district in Kunduzprovince, while the remaining cases occurred in districts of Faryab, Kandahar andUruzgan. Although ALP are allowed to hold individuals temporarily as part of theirmandate to “conduct security missions in villages” they have no role in or powers of lawenforcement and lack the authority to arrest and detain. The inferred power to holdsuspects temporarily is not defined in scope or timeframe.57Regarding ANA, UNAMA found sufficiently credible and reliable evidence that 13 of the34 detainees interviewed who were held in ANA custody experienced torture or ill-treatment in seven provinces. Nine of the 13 incidents occurred inChisht-e-Sharif ANAbase, Shindand ANA base(Herat),Shiwan ANA base, Bala Buluk, Bekwa (Farah) and BalaMurghab (Badghis)in the western provinces (five in Farah, two in Herat and two inBadghis) with the remainder occurring in Kabul, Kapisa, Kandahar and Laghman.Detainees interviewed in NDS, ANP, ALP and ANA detention reported that torture or ill-treatment took place during interrogation sessions, often in separate interrogationrooms, or in corridors and hallways of smaller facilities. During these sessions,interrogators, officers or prosecutors usually wanted detainees to confess to beingmembers or supporters of the Taliban or other anti-government groups, confirm namesof alleged Taliban or Anti-Government Elements, admit to planting or makingimprovised explosive devices, having weapons, being failed suicide attackers orotherwise assisting the Taliban. In most cases, the main reason for the use of torturewas to obtain a confession or information and to intimidate detainees. As noted above,NDS, ANP, ALP and ANA officials used a range of torture methods including prolongedbeatings often with cables, pipes or hoses, suspension and electric shocks.The replication or pattern of torture methods consistently used on detainees suggeststhe use of torture was systematic at two NDS facilities.58These were the NDSheadquarters in Kandahar city and NDS Counter-terrorism Department 124 in Kabul(formerly known as NDS Department 90).

The total number of detainees noted is higher than 635 because numerous detainees were detained byboth NDS and ANP or ANBP and/or by ANA, Afghan Local Police and/or international military forces. SeetheAccess and Methodologysection of this report and footnote 29.57Afghan Local Police Establishment Procedure adopted August 2010 and adjusted January 2012.58See theAccess and Methodologysection of this report for a full definition of a systematic pattern,practice or use of torture within a detention facility.56

10