Europaudvalget 2012-13

EUU Alm.del Bilag 212

Offentligt

Should non-euro area countries join the SSM?Zsolt Darvas and Guntram B. Wolff1Bruegel18 February 2013This paper was prepared for a hearing at the Danish Parliament on 26 February 2013.1. IntroductionFollowing the summit of 29 June 2012, Europe is determined to move ahead with a banking union. Thedecision stemmed partly from the recognition of the discrepancy between the integrated Europeanbanking market and the largely national banking policies. But perhaps even more importantly, thedecision was a response to the increasing market pressure on several interlinked banks and sovereignsof the euro area, and the increasing financial fragmentation, which risked having major negative impactson the economy of the euro-area and beyond. It is worthwhile repeating the first sentence of the 29June 2012 Euro Area Summit Statements: “We affirm that it is imperative to break the vicious circlebetween banks and sovereigns.” The vicious circle had been previously highlighted by differentresearchers (e.g. Gerlach, Schulz and Wolff (2010), Véron (2011), Darvas (2011), Merler and Pisani-Ferry(2012), Angeloni and Wolff (2012)). The European Banking Union initiative aims to address this viciouscircle, to improve the quality of banking oversight and thereby to reduce the probability of bank failuresand the ensuing costs to taxpayers.The following elements are generally seen as central to addressing the vicious circle and completing thebanking union: a common banking supervision based on a single rulebook, a single resolutionmechanism, agreement of fiscal burden sharing and some degree of common deposit insurance (Pisani-Ferry et al 2012). Better banking oversight would reduce the probability of bank failures and the ensuingcost to taxpayers while resolution equally aims at reducing costs to the tax payer. The element of fiscalburden sharing is the logical complement to fully overcome the doom-loop. Most of the discussion inthe second half of 2012 was focused on the supervisory mechanism leading to a Council agreement onthe legislative proposal for the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM) on 13 December 2012 (see Council,2012) and an accompanying agreement on modifying the regulation of the European Banking Authority(EBA). The discussion on the single resolution mechanism, including its fiscal backstop, is currentlyundergoing and the European Commission has announced its intention to publish first proposals beforethe summer (see Véron and Wolff 2013 for more details). The most contentious part of the discussioncertainly relates to the fiscal burden sharing arrangements (Pisani-Ferry and Wolff 2012).The final design of the future banking union is still very much unclear. While euro-area members will beincluded in all element of the banking union, the December 2012 agreement allows non-euro area1

Thanks are due to Carlos de Sousa and Giuseppe Daluiso for excellent research assistance.1

� Bruegel 2013

members of the EU to participate in the SSM. Presumably, further elements of the banking union willalso allow the participation of non-euro area members in certain forms. For these countries, therefore,an important strategic question is whether and when to join parts or all elements of the emergingbanking union. Currently, these non-euro countries have to decide about participation in the SSM oncethe December 2012 legislative proposal has entered into force, without knowing the design of the otherelements. While the SSM as such is just a part of the banking union and as such cannot deliver the fullbenefits, a single supervision can bring a number of benefits. In particular the supervision of cross-border banks should be improved and supervisory practices should be made more consistent.On September 12, 2012 the Commission had put forward its initial proposal for the single supervisorymechanism.2It was perceived by many non-euro area countries as not sufficiently catering for theinterests of countries outside of the euro area. The core difficulty relates to the defined treaty base andthe resulting decision making structure. Following the European Council conclusions of June 2012, theRegulation proposal employs as a Treaty base Article 127(6) TFEU. The Article puts the ECB at the centreof the mechanism. The ultimate decision making body of the ECB is the Governing Council (Art. 129(1)TFEU), in which the non-euro area countries do not have a vote. This Treaty base was seen by many non-euro area countries as essentially preventing them from participating in the mechanism.3. In thesubsequent negotiations, significant modifications were undertaken also with the aim of addressing theconcerns of non-euro area members (Council 2012).In this note we assess the current legislative proposal from the perspective of EU member states outsidethe euro area and evaluate various arguments against, and in favour of, joining the SSM. The nextsection analyses the legal text, while section 3 discusses the arguments. The last section concludes.2. The SSM regulation proposal: key aspects for non-euro area countriesIn this section, we briefly discuss some the key aspects of the adopted regulation proposal (hereafter:Regulation), which are most relevant to non-euro area participating member states. We also review thesafeguards for non-participating EU member states.Legal FrameworkArticle 6 of the Regulation defines the terms of cooperation of participating member states whosecurrency is not the euro. The SSM is open to participation of EU countries that are not members of theeuro area on the basis of “closecooperation”(Article 6). Close cooperation essentially requires that non-euro member states that wish to join the SSM, adopt the necessary legal framework and cooperate withthe ECB along the lines codified in the Regulation. This means, in particular, that the nationalSee the assessment of this proposal in Véron (2012).The alternative treaty base, Article 352, was not pursued and the Council had to find a compromise solutionbased on Article 127(6) which refers to the ECB.32

� Bruegel 2013

2

authorities, as those authorities within the euro area, will be bound to abide by guidelines and requestsissued by the ECB and be responsible to provide the adequate information.Right to exitThe Regulation’s Article 6 also allows for exit of non-euro area participating member states by threeways: (1) after three years without qualification (Article 6(6a)); (2) exclusion by the ECB in the event of amajor non-compliance by the authorities of the non-euro area country (Article 6(6)); (3) expedited exitprocedure on the request of the non-euro area country in case of a major disagreement with asupervisory decision impacting this country (Article 6(6aab)). Following an exit, re-entering the SSM ispossible after three years.Decision makingSupervisory draft-decisions of the SSM will be taken by a Supervisory Board that the new Regulationcreates. These draft decisions will be deemed adopted unless the Governing Council of the ECB objectswithin a period to be defined but less than 10 days (Article 19(3)). The Supervisory Board will consist ofthe Chair, the Vice Chair, who is an ECB executive Board member, 4 representatives from the ECB andone representative from the supervisory authority of each member state participating in the SSM.4Decisions of the Supervisory Board shall be taken by simple majority of its members with every memberhaving one vote (Article 19(2ab)), except for decisions on regulations adopted by the ECB (Article 4(3)).This compromise considerably improves the influence of non-euro area countries on supervisorydecisions and it probably reached the maximum which is possible under the adopted legal framework.Nevertheless, additional safeguards are provided for the non-euro area countries. First, the draftdecision by the Supervisory Board is transmitted to the Member States concerned at the same timewhen it is transmitted to the Governing Council of the ECB. Whenever a non-euro area participatingmember states objects a draft decision prepared by the Supervisory Board, the Governing Council willinvite the representatives of that member state to the meeting. Appeal to the European Court of Justiceis possible. There is also the procedure (discussed above) allowing for an expedited exit of the memberstate (Article 6(6aab)), in which case the decision of the Governing Council will not apply to thatmember states.AccountabilityThe accountability of the ECB in the exercise of its supervisory tasks is broad based. The ECB isaccountable towards the European Parliament and the Council of Ministers for the implementation ofthe Regulation. There are regular reporting requirements and the chair of the Supervisory board needsWhen the national supervisor is not the central bank, then a representative of the central bank can alsoparticipate in the Supervisory Board. But for voting they will have only one vote (Article 19(1)).� Bruegel 201334

to present the report to the European Parliament and the Eurogroup extended by those ministers ofcountries participating in the SSM. The chair may also be heard by the relevant committees on theexecution of its tasks. Finally, the ECB is also required to answer in writing to any questions raised bynational parliaments and national parliaments may invite the chair or any other member of thesupervisory board for an exchange of views. Overall, in terms of accountability the Regulation thereforeputs non-euro area countries on equal terms with euro area countries.Supervisory convergenceOne pre-requisite for the establishment of the SSM is the passing of the Capital RequirementsRegulation (CRR) and its complement the fourth Capital Requirements Directive (CRD4). This isnecessary so that the SSM can implement a harmonized supervisory rulebook based on the Basel IIIaccord instead of the currently in place and different national regulations. To ensure consistence ofstandards throughout the EU, the regulation foresees that the EBA continues to ensure supervisoryconvergence and consistency of supervisory outcomes. From the point of view of the rules determiningbanking supervision, there should be no material difference between countries in the SSM and thoseoutside of the SSM. Whether in practice there will be differences, remains to be seen. It appears,however, possible that the ECB will de facto become a standard setter in supervisory practices and mostmember states would eventually have to apply those standards.CoverageAs a general rule, only “significant” financial institutions (and their subsidiaries and branches) will bedirectly supervised by the ECB, but the ECB will have the right to supervise any institution, if aninstitution is suspected to cause a significant risk for financial stability. In Box 1 we aim to quantify theshare in total assets under direct ECB supervision in each non-euro country if it was to join the SSM. Ourresults indicate that participation would lead to a large coverage in terms of assets but relatively lownumber of banks (de Sousa and Wolff 2012 document a similar result for the euro area countries). Forcountries outside the SSM, only branches of large banks that are located in a participating member statewill be falling under the ECB supervision while subsidiaries remain under the supervision of nationalsupervisors.Box1: SSM Coverage of non-euro area member statesWe use the extensive but not comprehensiveThe Banker Databaseto estimate the percent of totalbanking assets covered by the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM) in non-euro area member states,should they decide to join. This database includes 1,032 bank holding companies and subsidiaries out ofthe 7,533 monetary and financial institutions standing in the EU at the end of 2011. Since theinstitutions not included are small, the database has a good coverage of the total banking assets in theEU (Table 1).

� Bruegel 2013

4

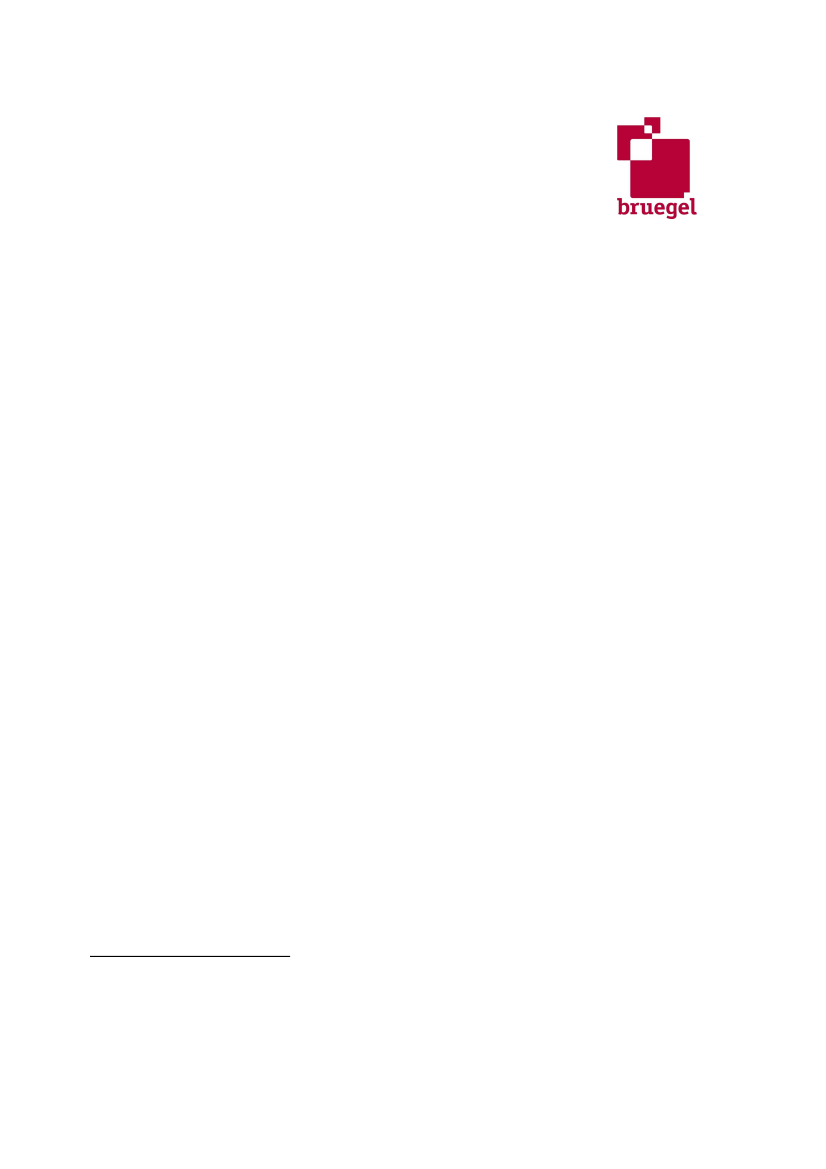

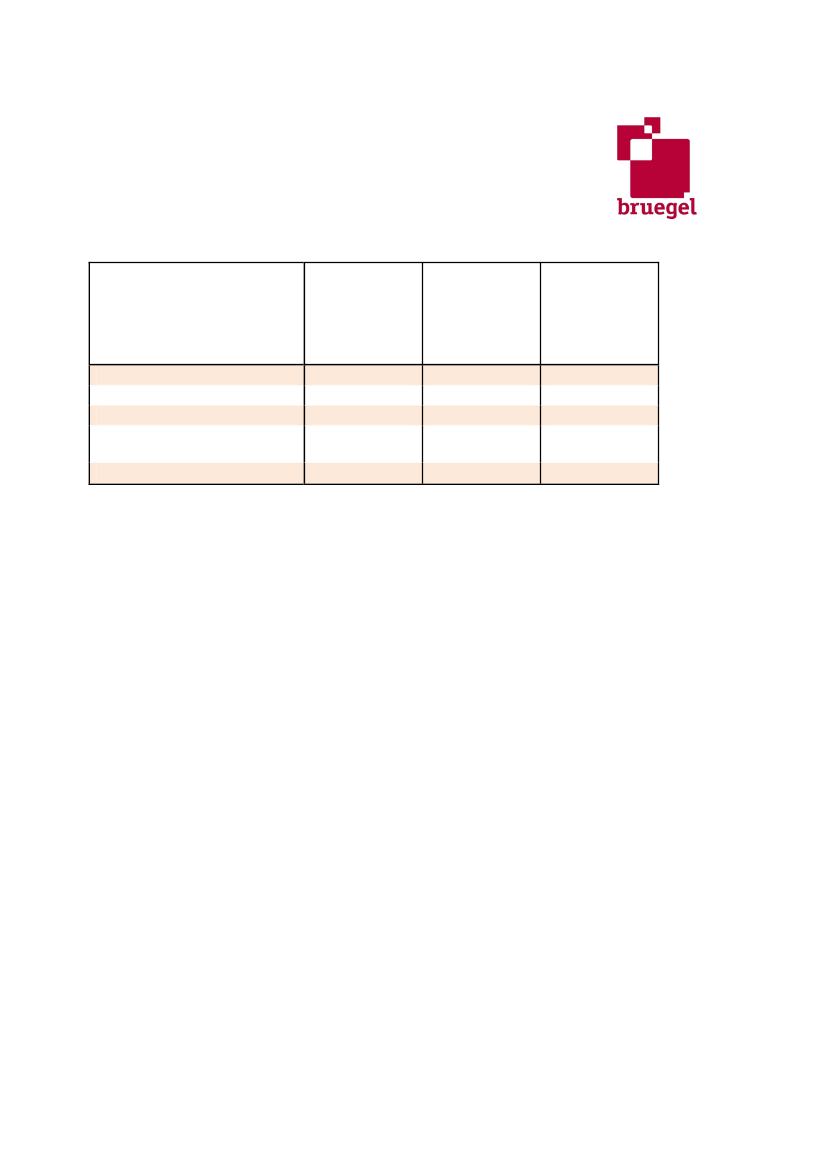

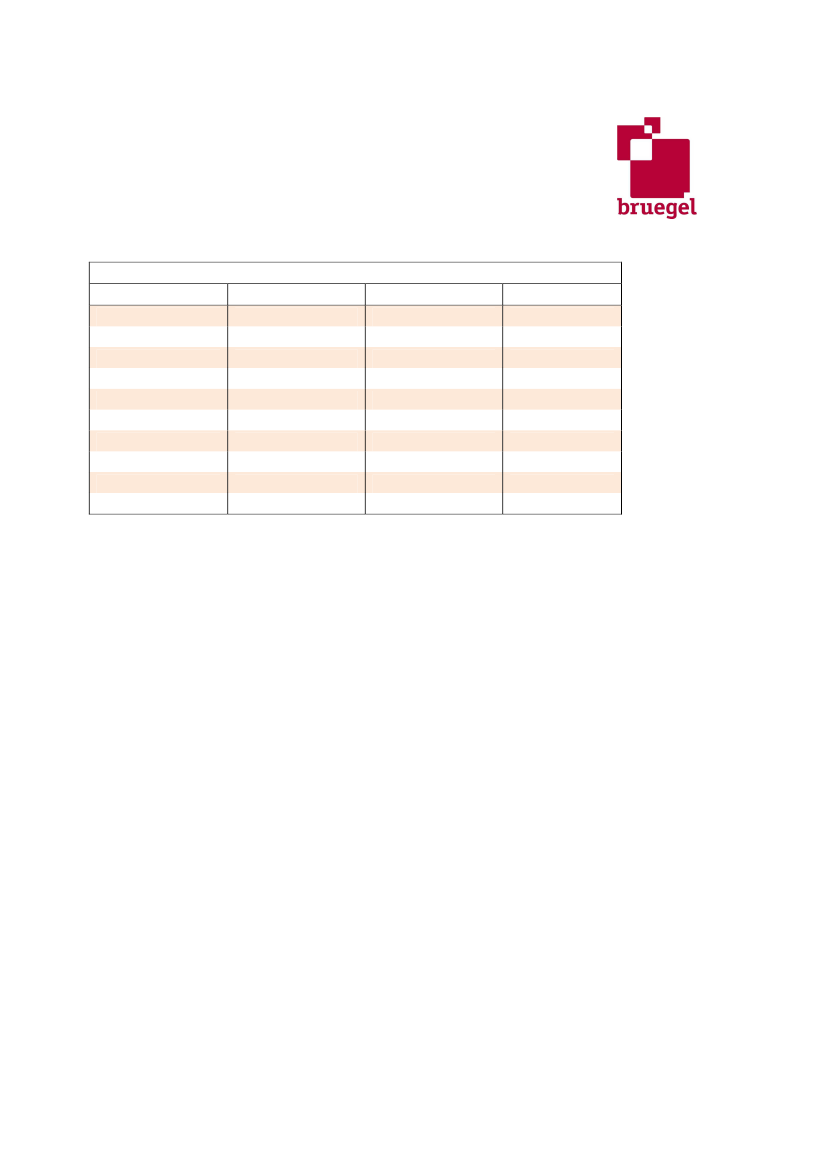

Table 1: coverage of The Banker Database of total assets in the national financial systemsTotal assets (million euro, end of 2011)ECBThe BankerCoverageBulgaria40,60429,03672%Czech Republic175,276138,84279%Denmark932,590920,37199%UK11,353,73911,147,56498%Hungary110,98689,38281%Lithuania22,85522,42198%Latvia27,01923,49987%Poland318,368252,26579%Romania84,09465,31378%Sweden1,647,7401,515,65992%Sources: ECB and The Banker Database

A drawback of this dataset is that it does not include most of the branches and it misses some smallsubsidiaries as well. Given that we use the total assets reported by the ECB as denominator whichincludes all financial institutions, our estimates presented in Figure 1 (below) should be taken as theminimum share of total assets that would be under the SSM if a non-EA member state would decide tojoin.From the Regulation proposal, we used the following criteria to assess if a financial institution will fallunder the supervision of the ECBi.ii.iii.iv.The total value of its assets exceeds 30 billion euro; or,The ratio of its total assets over the GDP of the participating Member State of establishmentexceeds 20%, unless the total value of its assets is below 5 billion euro; or,It is among the three most significant credit institutions in the participating Member state,unless justified by particular circumstances; orIt is subsidiary or branch of a banking group which fall under the SSM.

Note that other institutions which are concluded to have a significant relevance with regard thedomestic economy, and institutions, in which cross-border assets or liabilities represent a significantpart of total assets, will also be covered by the SMM, but we did not incorporate these considerations.Also, all institutions for which public financial assistance has been requested or received directly fromthe EFSF or the ESM will be covered by the SSM, but such direct support has not yet been granted and,according to current legislation, non-euro area countries cannot benefit from the EFSF and ESM.In Figure 1 we distinguish between financial institutions that would fall under supervision by complying� Bruegel 20135

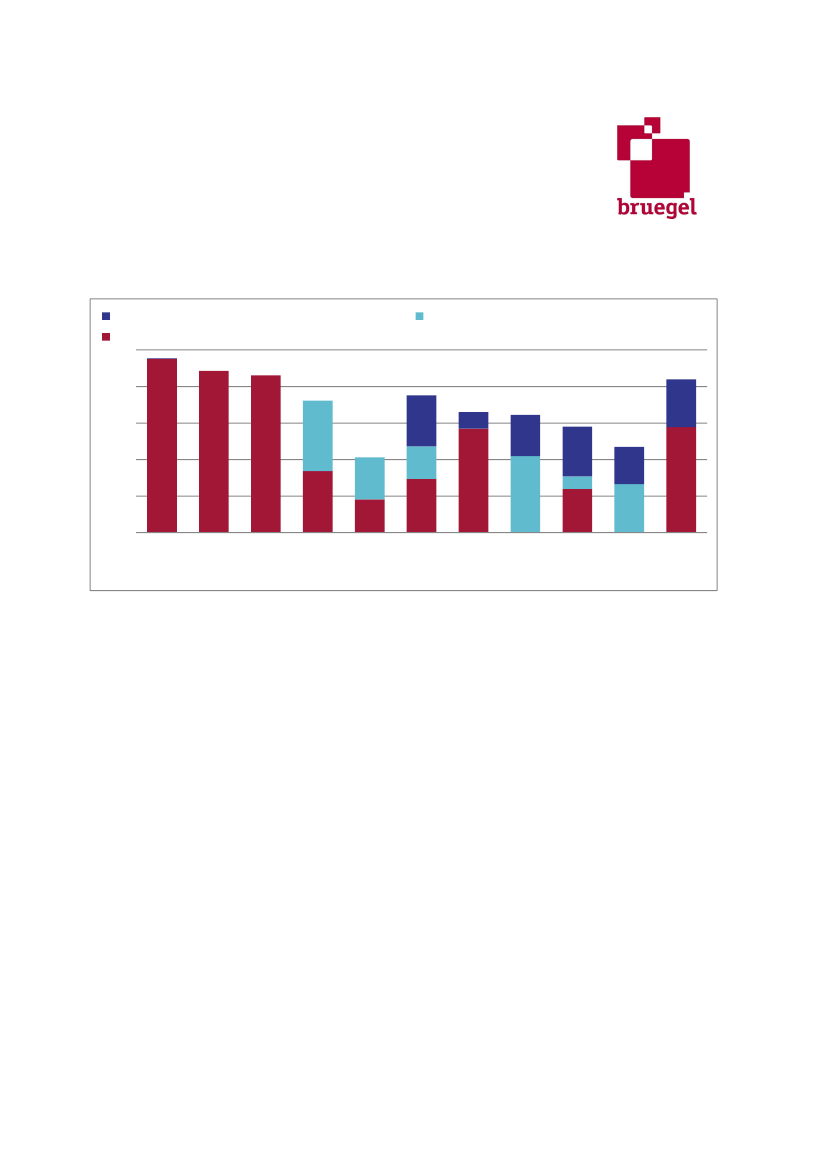

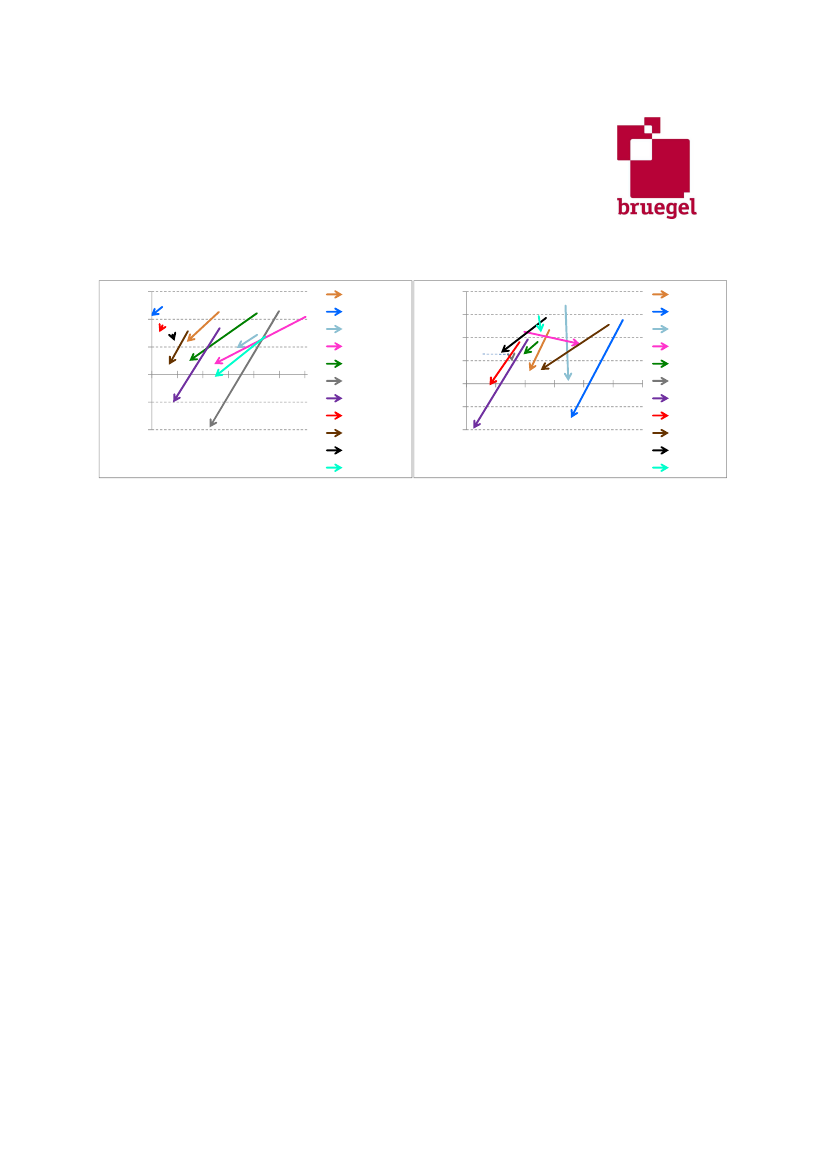

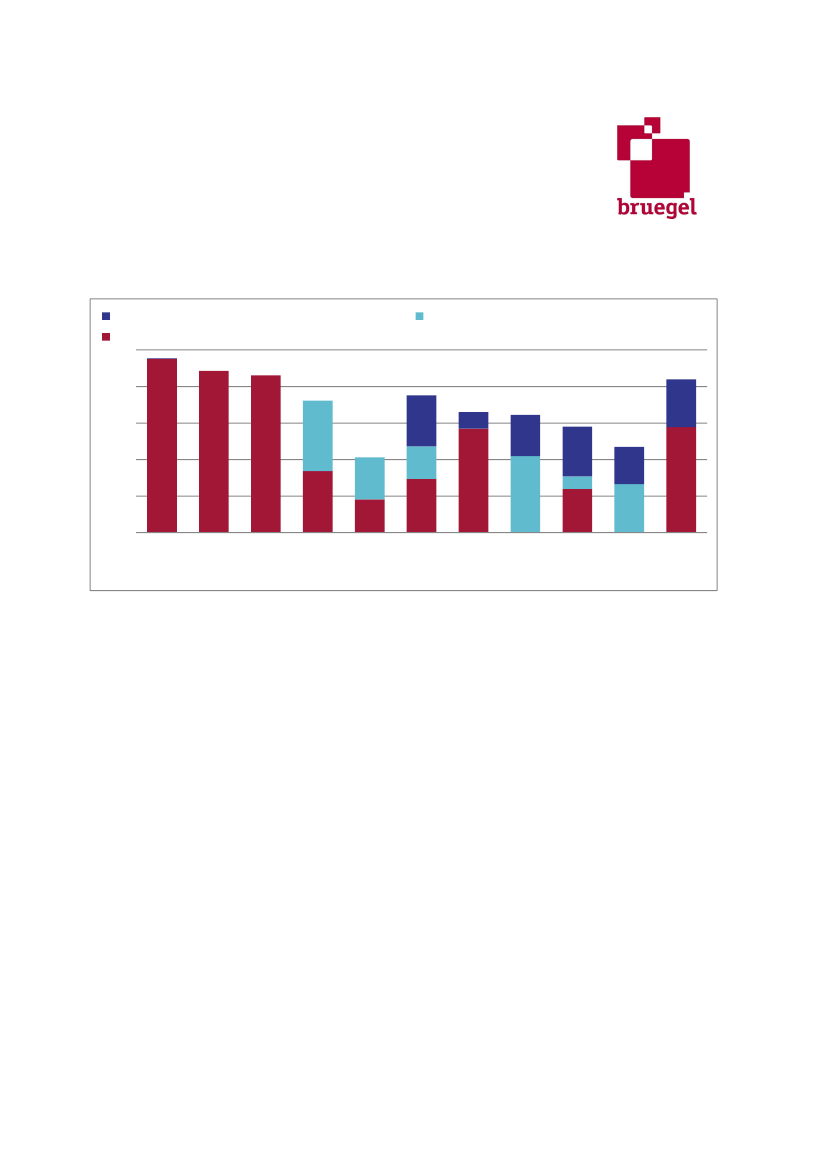

one of the first two criteria, i.e. ‘big enough’, and those that fulfil only the third or the fourth one.Figure 1: Percent of assets falling under the SSM in the case of participationShare of assets under supervision by criteria ivShare of assets under supervision by criteria i, or ii100%80%460%1940%20%0%UKSweden DenmarkLithuania Latvia Hungary Czech Romania Poland Bulgaria CroatiaRepublic2442111233113111281233Share of assets under supervision by criteria iii

Sources: The Banker Database, ECB and Bruegel calculationsNote: numbers over the bars indicate the number of banks that could be under ECB’s supervisionIn Central and Eastern Europe, where the banking systems are mostly dominated by subsidiaries and branches of euro-areaparent banks, the inclusion in the SSM would mainly come from these subsidiaries and the criteria concerning the three biggestbanks. In the case of Hungary, for example, the OTP Group is the only Hungarian banking group that has consolidated assetsthat exceed 20 percent of GDP.

In Lithuania, only three institutions could be under SSM: Swedbank (Swedish), SEB Group (Swedish) andDanske Bank (Danish). In Latvia, Swedbank, SEB Group and Aizkraukles Banka (third biggest Latvianbank) would be included.In order to check the precision of our estimates from The Banker Database in the case of a particularcountry, we compared our results with the comprehensive dataset of the Hungarian FinancialSupervisory Authority which includes all financial institutions, including branches (Table 2).

� Bruegel 2013

6

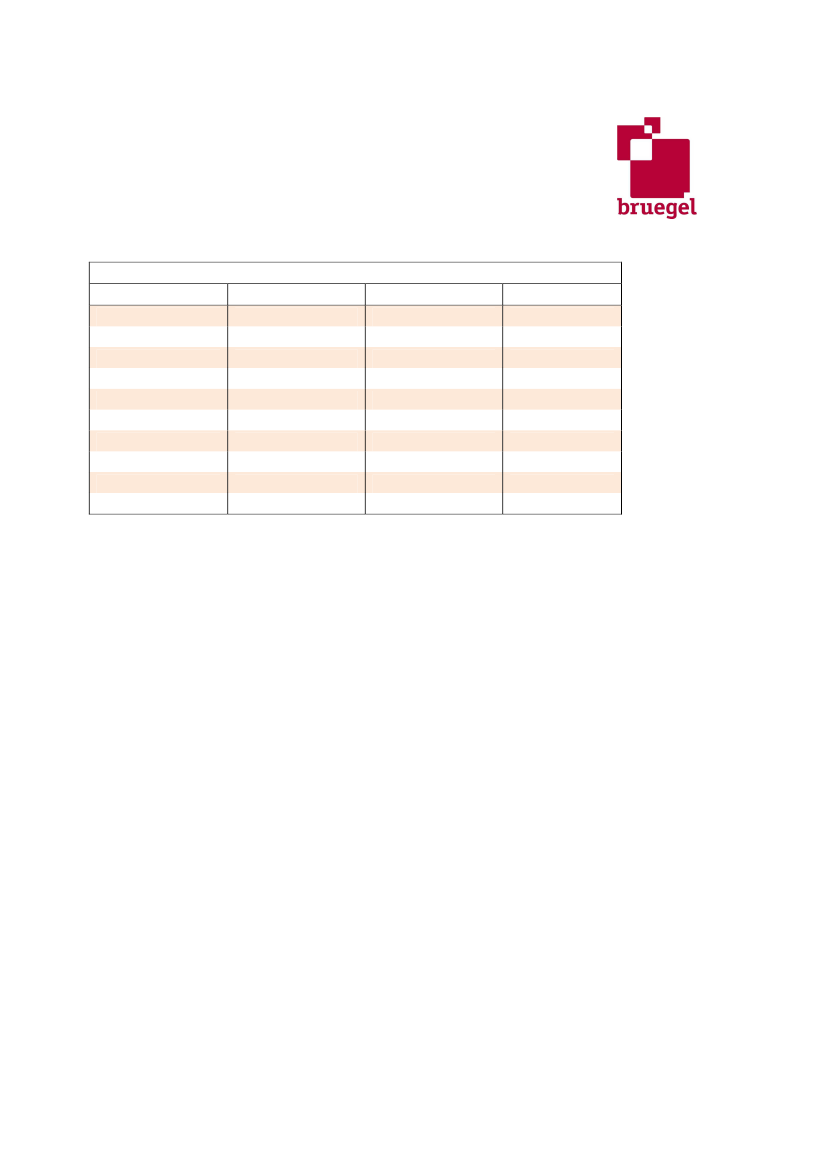

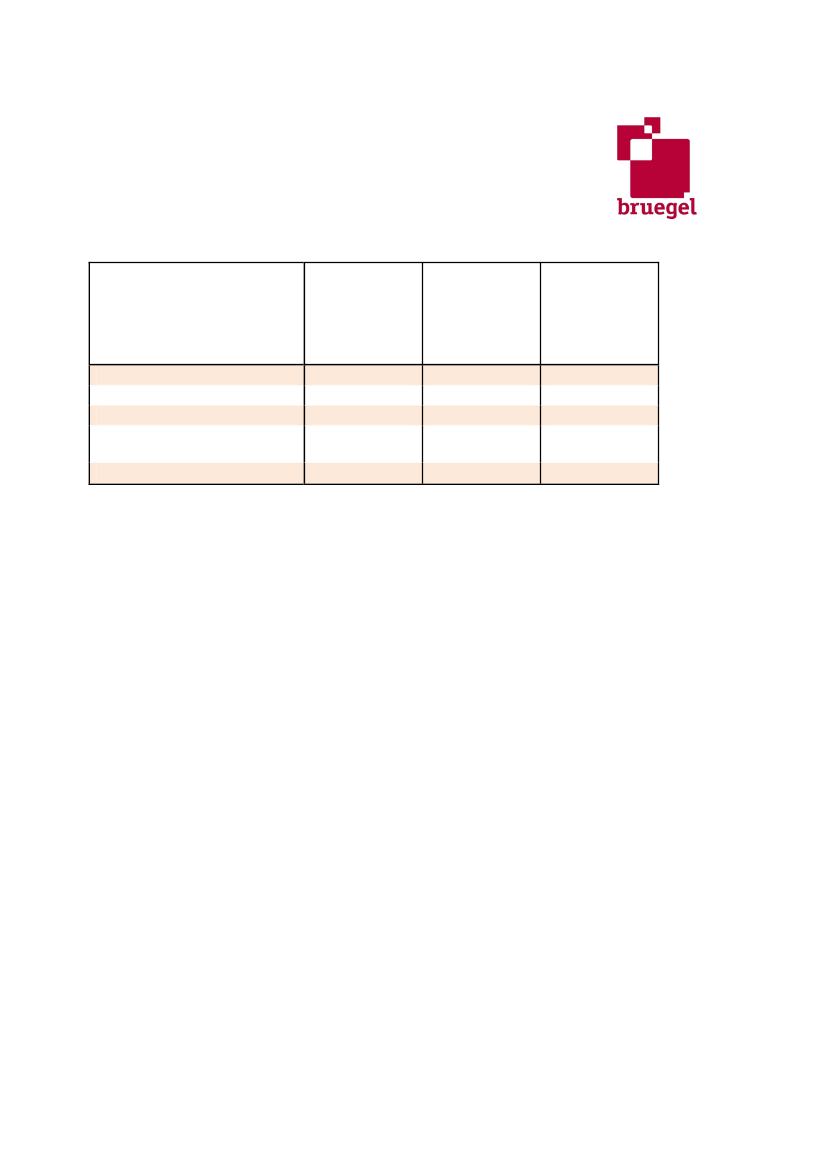

Table 2: Hungary: comparison of our estimates from The Banker Database with the official dataHungarianFinancialSupervisoryAuthority118,29791,6904355478%The BankerDatabaseThe BankerDatabasecombined withECB data ontotal assets110,98683,427201475%

(Million euro; end-2011)

Total assetsAssets under SSMTotal number of institutionsNumber of institutions underSSMShare of assets under the SSM

89,38283,427201493%

Source of the Hungarian Financial Supervisory Authority data:https://www.pszaf.hu/bal_menu/jelentesek_statisztikak/statisztikak/aranykonyv (available only in Hungarian)The two main reasons for the difference are that The Banker Database does not include (a) most of the branches and (b)smaller banks. As Table 2 shows, in the case of Hungary, the difference in assets under the SSM is not large and when we usetotal assets from the ECB and relate to it the assets to be covered from The Banker Database, the difference in the estimatedshare of assets to be covered by the SSM is small (78 percent versus 75 percent).

This box was prepared by Carlos de Sousa.END OF BOX 1Another interesting aspect in terms of coverage is the case of the subsidiaries established in the euroarea of those banking groups that are headquartered in a non-participating member states. Forexample, in Box 2 we look at the composition of Danske Group and the Hungarian OTP Group. IfDenmark stayed outside the SSM, then still, Danske’s subsidiaries in euro-area countries would bedirectly supervised by the ECB because they would collectively be larger than the defined thresholds.This would not happen to the OTP group, because OTP’s subsidiaries in euro-area countries are small.But OTP has significant exposure to Russia and Ukraine and some smaller subsidiaries in non-EU Balkancountries. Therefore, if Hungary was to join the SSM, 61 percent of OTP’s activities would be covered forsure, but about one-fifth of the group’s total activity would be surely outside the jurisdiction of the SSM(activities in non-EU countries) and another one-fifth would depend on the SSM participation ofBulgaria, Croatia and Romania.Box 2: Danske and OTP: two major banking groups headquartered outside the euro-areaUnfortunately, we did not find a decomposition of all activities of Dankse Bank among the countries ofits operation, but only a decomposition of lending activities, which account for 48 percent of totalassets. Yet the banking activities in Finland and Ireland, two euro area countries, pass the €30 billionthreshold and therefore these subsidiaries will be supervised by the ECB, irrespective of Denmark’s� Bruegel 20137

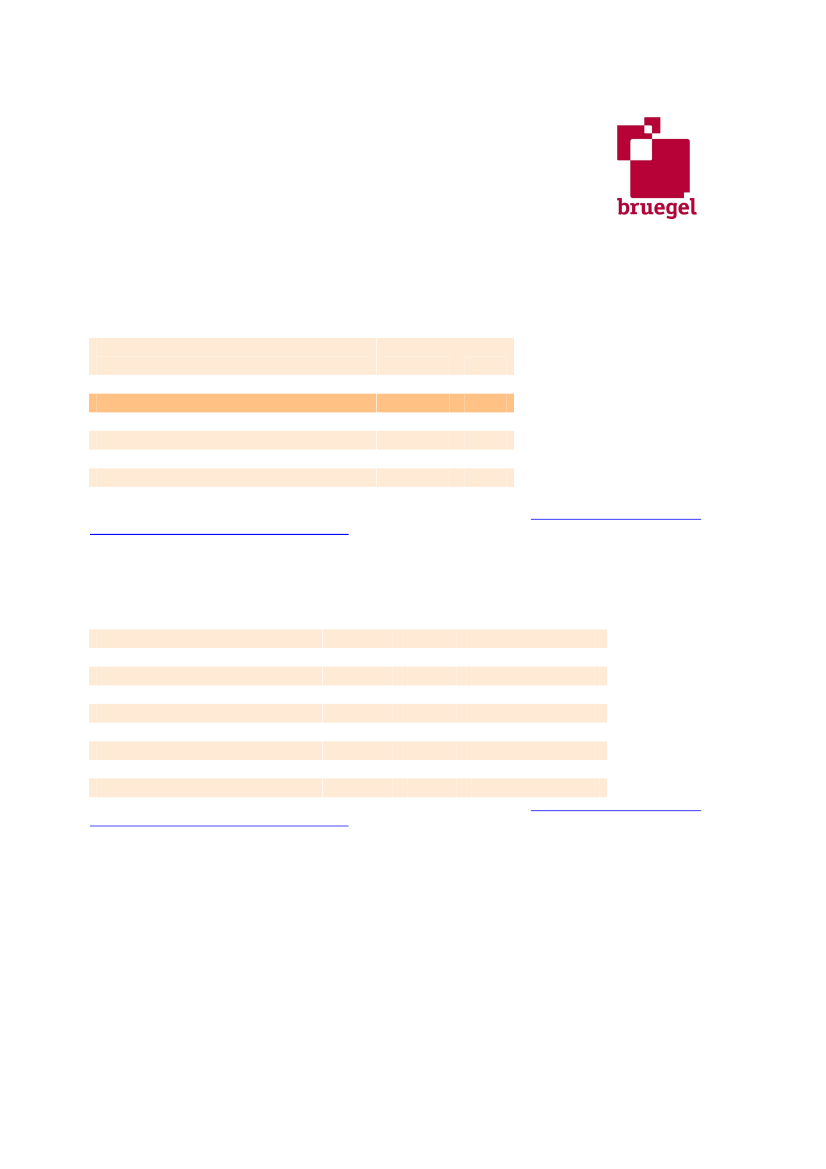

participation in the SSM (Tables 3 and 4).Table 3: Composition of the consolidated balance sheet of Danske Group€ billionsDue from credit institutions and centralbanksRepo loansLoans and advancesTrading portfolio assetsInvestment securitiesAssets under insurance contractsOther assetsTotal assets15.241.2224.4108.914.432.330.6467.1Share3%9%48%23%3%7%7%100%

Source: The Danske Bank Group Annual Report 2012 (published on 7th February 2013)http://www.danskebank.com/en-uk/ir/Documents/2012/Q4/Annualreport-2012.pdf

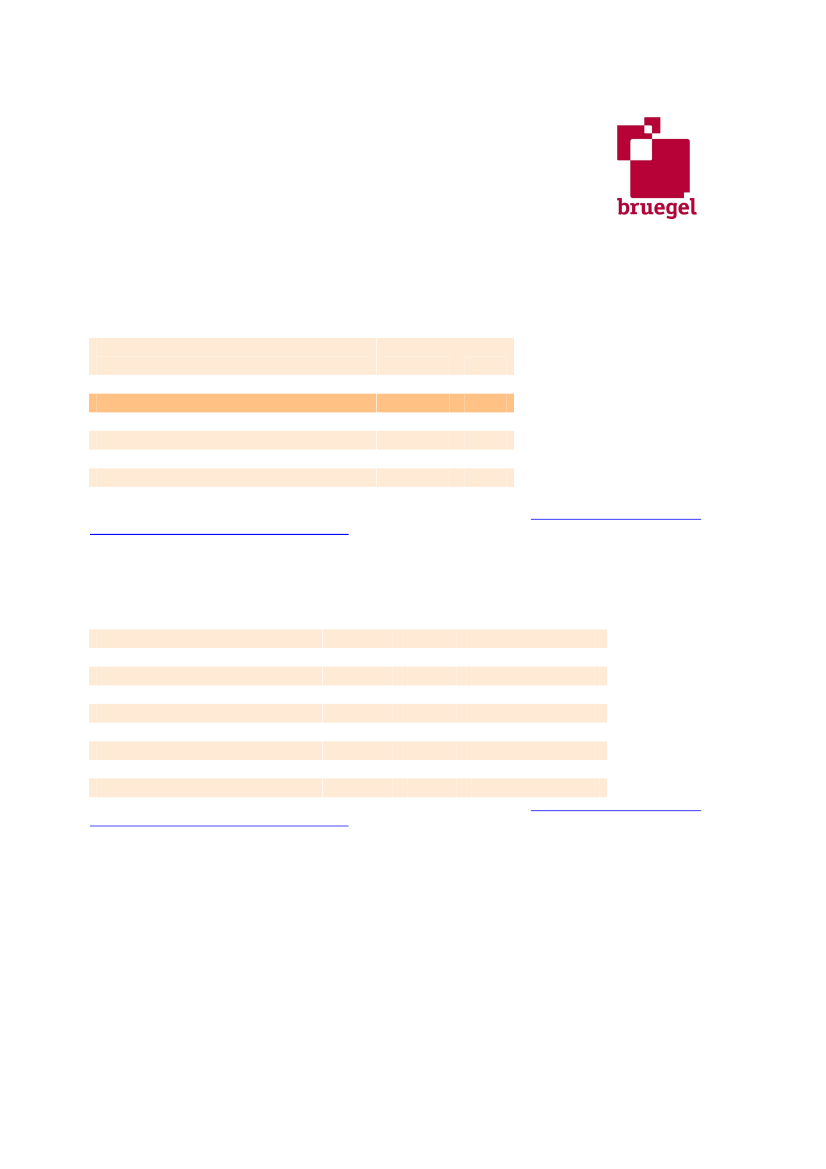

Table 4: Geographical distribution of banking activities of the Danske GroupShare in TotalAssets27%5%4%4%3%1%1%3%48%

Retail Banking DenmarkRetail Banking SwedenRetail Banking FinlandRetail Banking NorwayRetail Banking IrelandBanking Activities BalticsOther Banking ActivitiesCorporate & Institutional BankingTotal Banking Activities

€ billions127.824.720.419.013.32.52.313.4223.2

Share57%11%9%8%6%1%1%6%100%

Source: The Danske Bank Group Annual Report 2012 (published on 7th February 2013)http://www.danskebank.com/en-uk/ir/Documents/2012/Q4/Annualreport-2012.pdf

For the OTP Group, a decomposition of the consolidated balance sheet is available across countries ofoperations (Table 5).

� Bruegel 2013

8

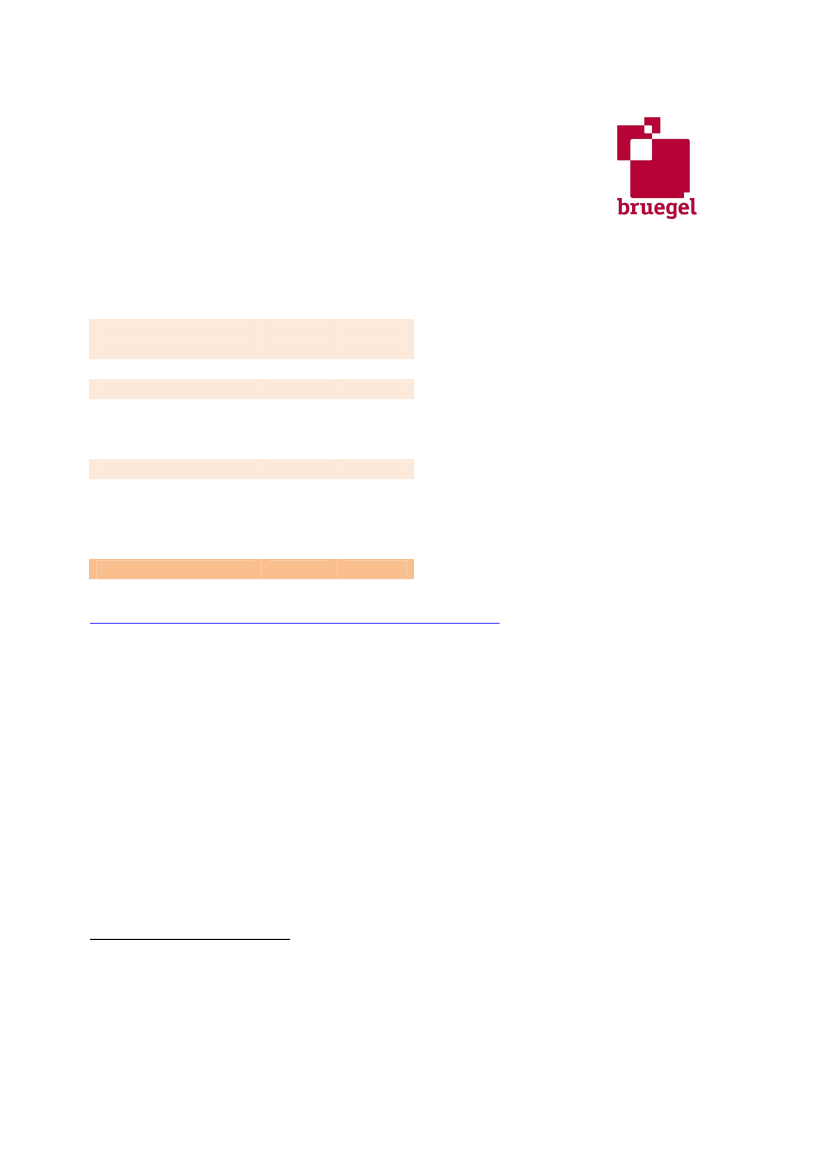

Table 5: Distribution of the consolidated balance sheet of the OTP Group among countries ofoperations, 2012Q3€ billion21.31.31.38.04.61.81.66.80.80.43.42.337.5share57%4%4%21%12%5%4%18%2%1%9%6%100%

(a) Hungary(b) Euro-area countriesSlovakia(c) Other EU countriesBulgariaCroatiaRomania(d) Non-EU countriesMontenegroSerbiaRussiaUkraineConsolidated

Source: Interim Management Report, First nine months of 2012 results (English translation of the original report submitted tothe Budapest Stock Exchange), 15 November 2012, OTP Bank Plc.https://www.otpbank.hu/static/portal/sw/file/121114_OTP_20123Q_e_final.pdf

END OF BOX 2Non-participating member statesAs regards countries outside the SSM, the regulation foresees that they would conclude a Memorandumof Understanding describing how they will cooperate with the ECB. This would involve regularconsultations as well as an agreement of how to manage emergency situations. The change in EBAdecision making by the accompanying EBA regulation, whereby double majority (majority of both SSMparticipating member states and also the majority of the non-participating member states) is needed,strongly improves the position of the non-participating member states in EBA decisions.5

Also, the Preamble of the Proposal states that: “EBAis entrusted with developing draft technical standards andguidelines and recommendations ensuring supervisory convergence and consistency of supervisory outcomeswithin the Union. The ECB should not replace the exercise of these tasks by the EBA”,but to adopt regulationsbased on the guidelines and recommendations of the EBA.� Bruegel 20139

5

3. Pros and cons of joining the SSMA number of arguments need to be carefully weighed when considering whether to join or not join theSSM.First, let’s consider the major earlier worries6regarding the first proposal of the European Commissionand assess the extent to which the compromise Regulation addresses these issues. Here, we do notdiscuss the multiple questions related to the single bank resolution mechanism, whose shape remainsstill largely unexplored.1) Inadequate inclusion of non-euro participating member states in decision makingIt was feared that the SSM only caters for the interest of euro area countries, while countries outsidethe euro would either not be able to participate in the system, or if they would, they will not have asufficient voice in the decisions. The Treaty’s Article 127(6) provides a relatively weak basis for theinvolvement of non-euro area member states as the article puts the ECB in the centre of decisionmaking. Indeed, the final decision making body of the ECB is the Governing Council, consisting of theECB executive board and the central bank governors of the countries belonging to the euro. As aconsequence, final supervisory decisions will have to be passed in the Governing Council. As arguedabove, within these limits, the compromise text has arguably achieved the maximum decision makingpower and involvement for non-euro area members possible.Also, whenever a non-euro area participating member state disagrees with a draft proposal of theSupervisory Board and this proposal is passed by the Governing Council, or when such a member statesagrees with the draft proposal, but that proposal is overturned by the Governing Council,7then thespecial opt-out clause for non-euro participating member states can apply, so that the member state isnot bound by the decision. This is, of course, a radical decision and the regulation therefore foreseesthat it is impossible to re-enter the SSM within a three year delay. The opt-out clause caters forconcerns but comes at a significant price. In particular, it introduces a significant uncertainty as to thepermanency of the geographical coverage of the SSM.8Furthermore, the Preamble of the regulation keeps the option open of adjusting the treaty base of theSSM so as to enshrine a full participation of non-euro area countries.9Overall, we would argue that non-The source of some of these earlier worries is Zettelmeyer, Berglöf and de Haas (2012), while others emergedduring our interviews with various stakeholders.7It is, however, quite unlikely that the majority on any major supervisory decision is so thin in the SupervisoryBoard that there would be a different majority in the Governing Council.8This option provides the non-euro area countries with a very special status in which purely national interestsunder certain conditions can be put ahead of the common interest.9Wolff (2012) called for a sunset clause in the regulation so as to force the reconsideration of the treaty base. Theregulation’s preamble now reiterates the Commission proposal (which was put forward in its Blueprint for a deep� Bruegel 2013106

euro area participating member states will have sufficient voice in decision making in the steady state.2) Inattention to small countriesSome feared that the ECB might devote insufficient attention to the supervision of a small country’sfinancial system. However, this is not a concern that is in any way specific to non-euro area countries.Moreover, the Regulation defines the clear goal of safeguarding financial stability both at the EU levelas well as in each individual participating member states. The ECB will supervise credit institutions at aconsolidated basis with regard to the group, but also on an individual bases with regard to subsidiariesand branches in participating member states. While the primary focus of the SSM will be on large banks,whenever there is a risk that a small bank poses a threat to financial stability, the ECB can exercisesupervisory tasks to this credit institution, even if it is a branch from a parent bank outside the SSM. Wedo not see the risk therefore that the ECB would miss important supervisory tasks in countries with fewand small banks.3) Macroprudential toolsSome non-euro area member states were concerned that the centralisation of macro-prudential tools atthe ECB would prevent them from taking appropriate macroprudential regulatory action in response tothe issues specific to countries outside the euro, especially with regards to capital buffers. Thecompromise regulation grants the right to adopt national macro-prudential regulations (Article 4a).While the ECB can express objections to the proposed measures, the concerned national authority onlyhas to “dulyconsider the ECB’s reasons prior to proceeding with the decision”,but the ECB cannot blocksuch measures unless they violate a relevant EU law. On the other hand, the ECB can apply higherrequirements for capital buffers and more stringent measures aimed at addressing systemic ormacroprudential risks.4)Supervisorycoordination failures with respect to banks with cross-border activitiesAs argued by Zettelmeyer, Berglöf and De Haas (2012), a major drawback of the September 2012proposal of the Commission was not addressing the supervisory coordinator failures with respect tomultinational banks, for which either the parent or the subsidiary is located outside the SSM countries.These failures arise from direct conflict of interest over how to share the burden of bank resolution, andthe anticipation of such a situation during good times. National authorities’ main concern is theeventual burden to their domestic taxpayers and they pay much less attention to cross-border

and genuine economic and monetary union) to amend Article 127(6) of the TFU to eliminate some legalconstraints, such as “toenshrine a direct and irrevocable opt-in by non-euro area Member States to the SSM,beyond the model of "close cooperation", grant non-euro area Member States participating in the SSM fully equalrights in the ECB's decision-making, and go even further in the internal separation of decision-making on monetarypolicy and on supervision.”.A re-consideration of the legal framework is thus not fully of the table.� Bruegel 201311

externalities of their actions.Despite the establishment of the EBA, which aims to coordinate between home and host supervisors inthe EU, several unilateral actions were adopted by national supervisors to ring-fence banking activities.While Article 1 of the Regulation states the importance of the unity and integrity of the single market,there is not much in the Regulation that could help to resolve such cross-border supervisory conflicts.There will be cooperation between the ECB and authorities of both EU countries not in the SSM andwith countries outside the EU. It needs to been if such cooperation will improve the aforementionedsupervisory coordinator failures. However, since most banks and subsidiaries established in non-eurocountries are headquartered in euro-area member states, if non-euro countries would join the SSM, thisproblem would have a lesser relevance thereafter, because the ECB will be the supervisor of both theparents and the subsidiaries in participating member states.Still, as discussed above, national supervisory authorities in the SSM could apply variousmacroprudential measures which may also serve ring-fencing and the ECB will not be able to block suchmeasures.But arguably, addressing cross-border supervisory coordination issues should be easier if both theparent and the subsidiary will belong to the SSM, which calls for entering the SSM by those non-euroarea member states in which subsidiaries of euro-area parent banks have a large role.Beyond these earlier worries, a number of additional factors have to be considered.5) Effect on the activities of major banking groups in non-participating countriesSome observers speculate that large banking groups headquartered in euro-area countries may re-consider the geographical scope of their business and may reduce the activities of their subsidiariesestablished in countries that will not participate in the SSM. This may in particular be a concern, whenone sees the decision to join the SSM as a clear decision to also join the forthcoming Single ResolutionMechanism. If that was to happen, it may bring economic costs to these countries and may prove to bedifficult to re-establish the currently strong cross-border financial integration, once a country has joinedthe SSM later.A number of arguments need to be considered carefully in this regard. First, delaying a decision onjoining the SSM increases the uncertainty for the concerned banks. Banks do not know whether theywill eventually fall under the joint supervision, whether they will be supervised as a group or whethersubsidiaries will remain under national supervision only. This represents an important uncertainty whichwill justify delaying decisions on bank operations as well as investments. When bank regulation and thescrutiny of bank supervision will be very much different under the SSM than under the nationalsupervisors, then this uncertainty is compounded.

� Bruegel 2013

12

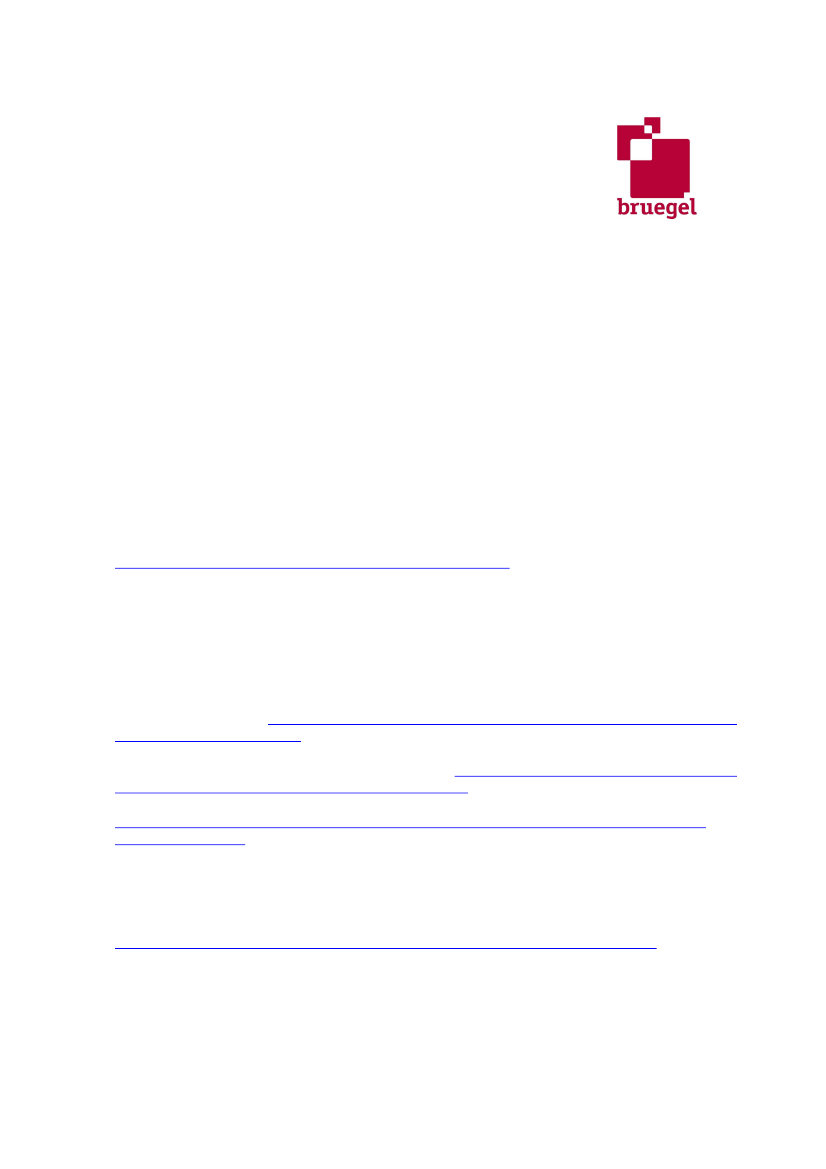

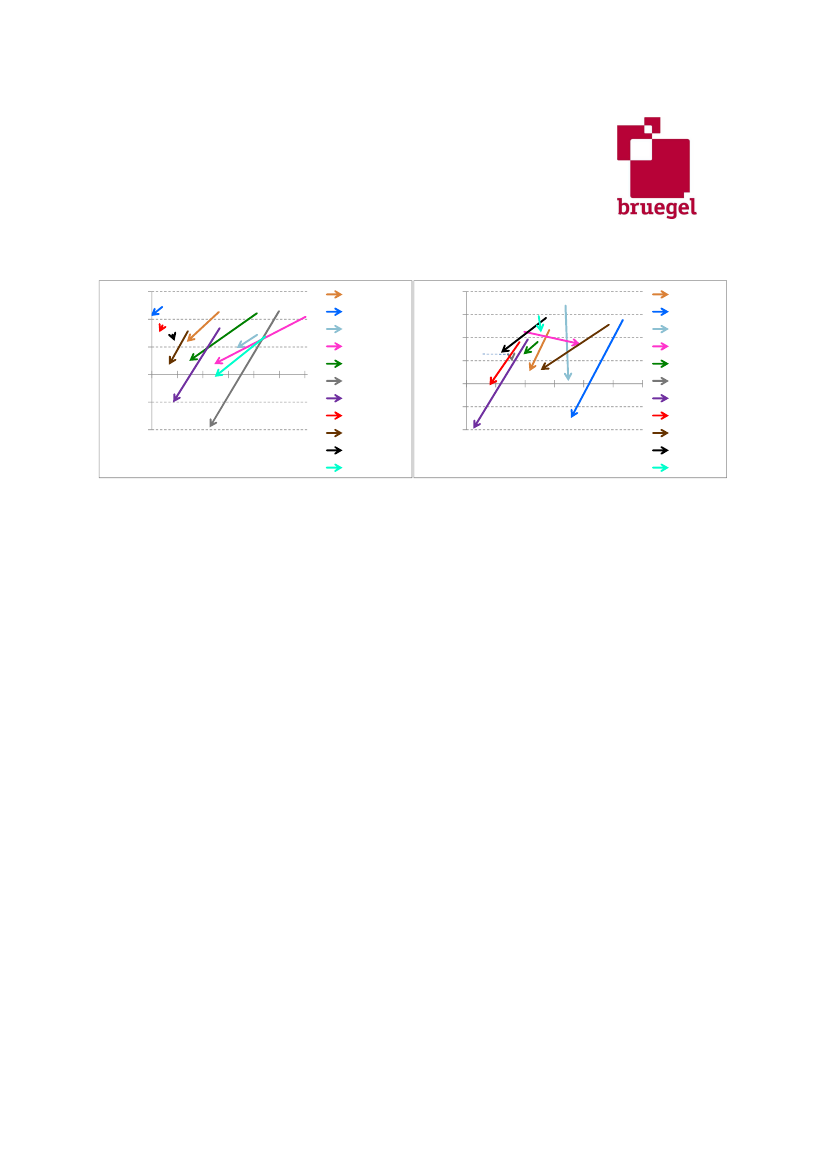

But more importantly, some of the cross border banks are already now affected by regulatory practicesas regards cross-border liquidity and capital operations. There is a risk that the home supervisor of theparent bank adopts measures discriminating against non-participating member states. Indeed, anumber of home supervisors tried to ring-fence banking activities inside the home country during thecrisis and even recently, the European Commission had to issue a statement on 4 February 2013 tryingto limit such activities.10While this risk will remain, one of the goals of the proposal regulation on theSSM is to preserve the integrity of the single market. Yet it remains to be seen to what extent the ECBwill be able and willing to change the currently reported ring-fencing of banking activities.At the same time, there are also factors suggesting that the participation in the SSM, or the lack of it,may not be a key factor for cross-border investment decision of major banking groups. Banking groupsengaged in activities outside the country of their headquarters based on strategic decisions. Regardingnon-euro are member states in central and eastern Europe (CEE), banking business was much moreprofitable than in EU15 countries before the crisis, and also during the crisis.11While the growth rates ofCEE will likely be smaller compared to the pre-crisis growth rates, these countries continue to have abrighter economic outlook than euro-area countries according to medium term forecasts. Therefore,banking in these countries will likely remain more profitable than banking in euro-area countries.Clearly, major euro-area banking groups have started to decrease their exposure to region, but mostlikely because either their exposure have grown too high or because they faced serious capital andliquidity needs in their home countries or regulatory pressure with similar effects. These laterconsiderations may remain and therefore their exposure to the region may be reduced further.Figure 2 confirms that the change in exposure to CEE countries from 2008Q3 to 2011Q3 was largerwhen (a) the exposure was larger in 2008Q3 and (b) where bank profitability declined significantlyduring 2008-2011. Foreign banks may be more selective in cross-border investments, but we see littleincentives to reduce the exposure to eg the Czech Republic and Poland, two countries in which bankingbusiness remained highly profitable during the crisis and the exposure of foreign banks is not too high.

Some quotes from the 4 February 2013 statement of the EC: “TheCommission took this action because it hadbeen made aware that, on several occasions, national bank supervisors acted independently to impose allegedlydisproportionate prudential measures on national banking subsidiaries of cross-border EU banking groups. Thealleged measures in question include capital controls, restrictions on intra-group transfers and lending, limitingactivities of branches or prohibiting expatriation of profits. These would have the effect of ‘ring-fencing’ assets,which could, in practice, restrict cross-border transfers of banks’ capital and potentially constrain the free flow ofcapital throughout the EU.”11During the crisis, return on equity was highly negative in the three Baltic counties that went throughunsustainable credit booms before the crisis and an extreme bust and economic hardship. Bank profitability alsoturned negative in Hungary by 2011 due unusually high bank taxes and other measures.� Bruegel 201313

10

Figure 2: Return on equity of banks and the change in foreign banks’ exposure to the domesticeconomy from 2008Q3 to 2012Q330BulgariaCZBGLTHUHRSILVEE

24

Return on equity (%)

20100-10-2020

Czech RepublicCroatiaEstoniaHungaryLatviaLithuaniaPolandRomania

Return on equity (%)

DKSEFIFRDEITESATPTBE

AustriaBelgiumDenmarkFinlandFranceGermanyGreece

PL ROSK

181260-6-1220GR

ItalyPortugal

30 40 50 60 70 80Exposure (% of 2008 GDP)

SlovakiaSlovenia

406080 100 120Exposure (% of 2008 GDP)

140

SpainSweden

Note: the starting coordinate of an arrow is the exposure of BIS reporting banks (ie all banks of the world, not just euro-areabanks) in 2008Q3 as a percent of 2008 GDP of the host country on the horizontal axis and the average return on equity during2003-2007 on the vertical axis. The end coordinate of an arrow is the exposure in 2012Q3 (on an exchange rate adjusted basisso that exchange rate changes do not influence the reported magnitude of the change in exposure) on the horizontal axis andthe average return on equity during 2008-2011 on the vertical axis. Data for six EU countries are not reported due to very highvalues. In these countries, the exposure declined from 2008Q3 to 2011Q3: in Cyprus from 271 percent to 242 percent; inIreland from 486 percent to 299 percent; in Luxembourg from 1778 percent to 1748 percent; in Malta from 546 percent to 450percent; in the Netherland from 177 percent to 143 percent; and in the United Kingdom from 202 percent to 179 percent (allare expressed as a percent of 2008 GDP and are based on exchange-rate adjusted changes).Source: Bruegel calculations using IMF Financial Soundness Indicators tables and BIS data.

Also, supervisory differences may not be a major concern. Major banking groups have developed theircentral European subsidiaries under the supervision of national authorities and hence the absence ofchange in the supervisor should not immediately imply a change in their strategic engagements. It canbe assumed that the headquarters anyway have strong controls over their subsidiaries and thereforeeven if the remaining local supervisor may be viewed less careful than the ECB, it may not matter much.Too-stringent national macro-prudential tools limiting business opportunities may be implementedunder the SSM as well as outside of it.Overall, the immediate risk related to reducing the activities of subsidiaries established in non-participating countries of major banking groups may not be very high, but uncertainty, including aboutdiscriminatory measures against non-participating member states by the home supervisor of the parentbank could limit the activities of large financial groups in non-participating member states (and also innon-EU countries).6) Competitive disadvantage of banks not owned by a parent bank headquartered in an SSM countryWhen a country stays outside of the SSM, then domestically owned banks and those banks that do nothave a parent bank in a SSM participating member state may face a competitive disadvantage. Ifsupervision by the ECB will be regarded as an important safeguard in the assessment of the soundness� Bruegel 201314

of banks, then staying out may imply higher financing costs: both the cost of wholesale funding may berelatively higher and the depositors may also require a higher interest rate. While it is difficult to assessthe risk and the magnitude of such competitive disadvantages, they call for a membership in the SSM.7) Implicit obligation to join other elements of the banking union after SSM membershipClearly, there is uncertainty about the next steps of the banking union and belonging to the SSM may atleast implicitly imply an obligation to join other elements of the banking union when they are adopted.However, the experience with the negotiations for the SSM showed that the interests of non-euro areamember states were considered to perhaps the greatest possible extent allowed by the TFEU. As in thecase of the SSM, the next steps of the banking union, the SRM, will be agreed upon by the co-legislatorsto which the non-SSM members are full party. We do not see how non-SSM countries would have asmaller impact on policy choices than SSM members. At the same time, non-euro area countries arealready excluded from important debates, in particular when they relate to the European StabilityMechanism, but SSM membership would not make a material difference in these debates.8) Contribution to the shaping of the practical operation of the SSMThe governing council as well as the supervisory board will have to set the rules of the practicaloperation of the SSM. This will be done at an early phase and will likely shape in a fundamental way theeffectiveness and inclusiveness of the new mechanism. While according to the regulation, non-euromember states will be members only if this decision is published in the Official Journal of the EuropeanUnion (Article 6(4) of the Regulation) and therefore most likely they can join formally only after thesystem has been set up, a clear and early signal to join the SSM is likely to increase the voice of non-euro member states in shaping the modalities. At the same time, however, the modalities have to be inline with the draft technical standards and guidelines and recommendations prepared by the EBA. Thisargument therefore calls for an early indication of the intention to join.9) Access to supervisory informationNon-participating EU member states will sign a memorandum of understanding of the ECB with regardsto cooperation during good times (ie consultations relating to decisions of the ECB having effect onsubsidiaries and branches established in the Member State) and cooperation in emergency situations.While this may improve the flow of information related to supervisory matters from the SSM towardsnon-participating countries, but undoubtedly, participating member states will have full access tosupervisory information. This would be especially valuable for countries in which several subsidiariesand branches of euro-area banking groups are established. Therefore, access to supervisory informationcalls for participation in the SSM.

� Bruegel 2013

15

4. ConclusionsThis paper has reviewed the new legislation for the establishment of a Single Supervisory Mechanismfrom the point of view of non-euro area countries. The Treaty base provides a relatively narrow basis forthe involvement of non-euro area countries. Yet, the achieved compromise provides strong safeguardsto protect the interests of non-euro area countries.The paper has outlined a number of arguments speaking in favour and against an early entry into theSSM. While it is too early to come to an overall conclusion, on balance, in our assessment an earlydecision to join may bring more benefits than drawbacks.References••Angeloni, Chiara, and Guntram Wolff (2012), “Are Banks Affected by their Holdings of Sovereign Debt?”Bruegel Working Paper 2012/7, MarchCouncil (2012), “Proposal for a Council Regulation conferring specific tasks on the European Central Bankconcerning policies relating to the prudential supervision of credit institutions” [SSM Regulation], Brussels,CounciloftheEuropeanUnion,December,http://register.consilium.europa.eu/pdf/en/12/st17/st17812.en12.pdfDarvas, Zsolt (2011), ‘A tale of Three Countries: Recovery after Banking Crises’, Policy Contribution 2011/19,BruegelDe Sousa, Carlos and Guntram B. Wolff (2012), “A banking union of 180 or 91%?” Bruegel blog 13 December2012Gerlach, Schulz and Wolff (2010), “Banking and sovereign risk in the euro area”, CEPR discussion paper 7833.Merler, Silvia and Jean Pisani-Ferry (2012) “Hazardous tango:sovereign-bank interdependenceand financialstability in the euro area”, Financial Stability Review No. 16, Banque de France, AprilPisani-Ferry, Jean, and Guntram B. Wolff (2012), “The Fiscal implications of a Banking Union” Bruegel PolicyBrief 2012/2, September,http://www.bruegel.org/publications/publication-detail/publication/748-the-fiscal-implications-of-a-banking-union/Pisani-Ferry, Jean, André Sapir, Nicolas Véron, and Guntram B. Wolff (2012), “What Kind of European BankingUnion?” Bruegel Policy Contribution 2012/12, June,http://www.bruegel.org/publications/publication-detail/publication/731-what-kind-of-european-banking-union/Véron, Nicolas (2011) ‘Euro area banks must be freed from national capitals’, Bruegel blog, 20 September,http://www.bruegel.org/publications/publication-detail/publication/611-euro-areabanks-must-be-freed-from-national-capitals/Véron, Nicolas (2012) ‘Europe’s Single Supervisory Mechanism and the Long Journey towards Banking Union’,Policy Contribution 2012/06, BruegelVéron, Nicolas and Guntram B. Wolff (2013), “From Supervision to Resolution: Next Steps on the Road toEuropean Banking Union”, Bruegel Policy Contribution 2013/04.Wolff, Guntram B. (2012), “A sunset clause for Europe’s banking union”, Bruegel blog November 7.http://www.bruegel.org/nc/blog/detail/article/936-a-sunset-clause-for-europes-banking-union/Zettelmeyer, Jeromin, Erik Berglöf and Ralph de de Haas (2012) ‘Banking union: The view from emergingEurope‘, in: Beck, Thosten (ed): ‘Banking union for Europe: Risks and Challenges‘, Centre for Economic POlicyResearch, London, p. 63-76.

•••••••••••

� Bruegel 2013

16