Beskæftigelsesudvalget 2012-13

BEU Alm.del Bilag 161

Offentligt

JOEM

•

Volume 48, Number 11, November 2006

1199

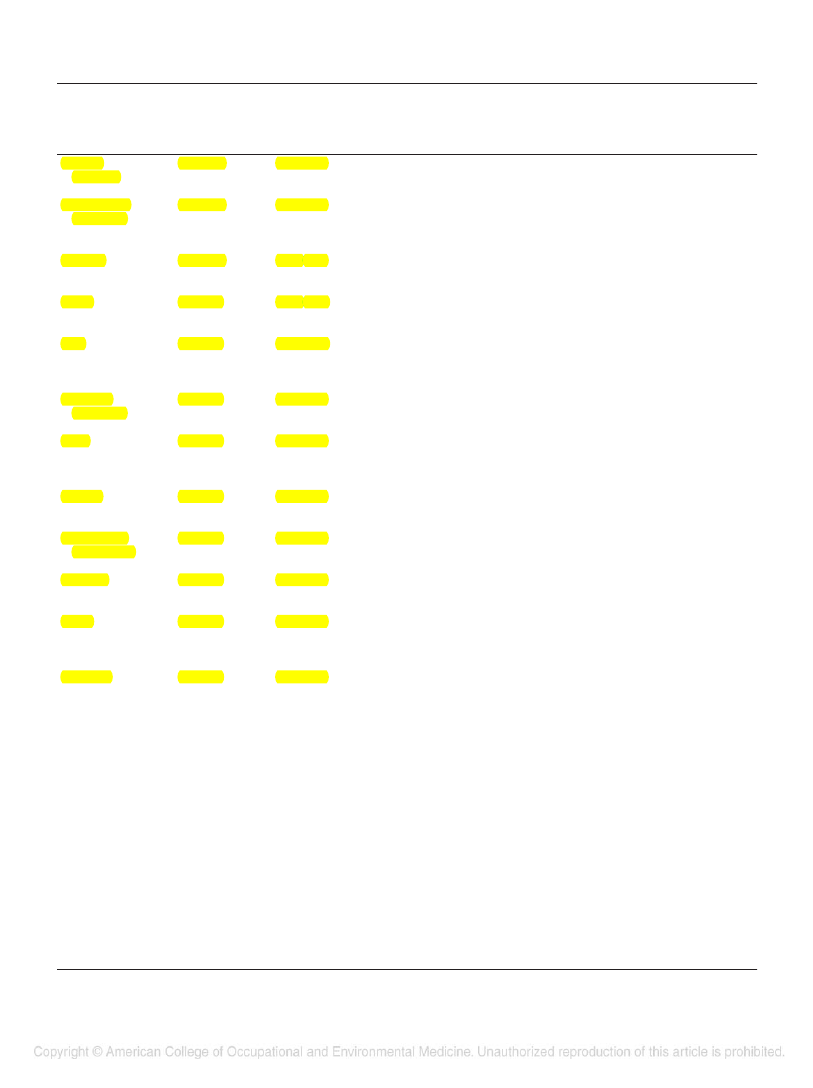

TABLE 5Summary of Likelihood of Cancer Risk and Summary Risk Estimate (95% CI) Across All Types of Studies for All CancersCancer SiteMultiplemyelomaNon-HodgkinlymphomaLikelihood of CancerRisk by CriteriaProbableSummary RiskEstimate (95% CI)1.53 (1.21–1.94)CommentsConsistent with mSMR and PMR (1.50, 95% CI 1.17–1.89)Based on 10 analysesHeterogeneity—not significant at the 10% levelOnly two SMR and another PMR studiesSlightly higher than mSMR and PMR (1.36, 95% CI 1.10 –1.67)Based on eight analysesHeterogeneity—not significant at the 10% levelConsistent with mSIR (1.29, 95% CI 1.09 –1.51)Based on 13 analysesHeterogeneity—not significant at the 10% levelSlightly higher than mSIR (1.83, 95% CI 1.13–2.79)Based on four analysesHeterogeneity—not significant at the 10% levelSlightly lower than mSMR and PMR (1.44, 95% CI 1.10 –1.87) – derivedon basis of PMR studiesBased on eight analysesHeterogeneity—not significant at the 10% levelSlightly higher than mSMR and PMR (1.29, 95% CI 0.68 –2.20)Based on 10 analysesHeterogeneity—not significant at the 10% levelSlightly higher than mSMR and PMR (1.27, 95% CI 0.98 –1.63)Based on 19 analysesHeterogeneity—not significant at the 10% level; there washeterogeneity among SMR studiesSlightly lower than mSMR and PMR (1.39, 95% CI 1.12–1.70)Based on 13 analysesHeterogeneity—not significant at the 10% levelSlightly higher than mSMR (1.18, 95% CI 0.81–1.66)Based on nine analysesHeterogeneity—not significant at the 10% levelLower than mSIR (1.58, 95% CI 1.12–2.16)Based on 13 analysesHeterogeneity—not significant at the 10% levelSlightly lower than mSMR and PMR (1.31, 95% CI 1.08 –1.59)Based on 25 analysesHeterogeneity—significant at the 10% level; there washeterogeneity among SMR and PMR studiesSimilar to mSMR and PMR (1.14, 95% CI 0.92–1.39)Based on eight analysesHeterogeneity—not significant at the 10% levelHigher than mSMR (0.58, 95% CI 0.25–1.15)Based on seven analysesHeterogeneity—not significant at the 10% levelSimilar to mSMR and PMR (1.24, 95% CI 0.83,1.49)Based on 11 analysesHeterogeneity—significant at the 10% level; there washeterogeneity among SMR studiesHigher than mSMR (0.68, 95% CI 0.39 –1.08)Based on eight analysesHeterogeneity—not significant at the 10% levelSlightly higher than mSMR (0.98, 95% CI 0.75–1.26)Based on 13 analysesHeterogeneity—not significant at the 10% levelSimilar to mSMR and PMR (1.23, 95% CI 0.94 –1.59)Based on 12 analysesHeterogeneity—significant at the 10% level; there washeterogeneity among SMR studies(Continued)

Probable

1.51 (1.31–1.73)

Prostate

Probable

1.28 (1.15–1.43)

Testis

Possible

2.02 (1.30 –3.13)

Skin

Possible

1.39 (1.10 –1.73)

MalignantmelanomaBrain

Possible

1.32 (1.10 –1.57)

Possible

1.32 (1.12–1.54)

Rectum

Possible

1.29 (1.10 –1.51)

Buccal cavityand pharynxStomach

Possible

1.23 (0.96 –1.55)

Possible

1.22 (1.04 –1.44)

Colon

Possible

1.21 (1.03–1.41)

Leukemia

Possible

1.14 (0.98 –1.31)

Larynx

Unlikely

1.22 (0.87–1.70)

Bladder

Unlikely

1.20 (0.97–1.48)

Esophagus

Unlikely

1.16 (0.86 –1.57)

Pancreas

Unlikely

1.10 (0.91–1.34)

Kidney

Unlikely

1.07 (0.78 –1.46)

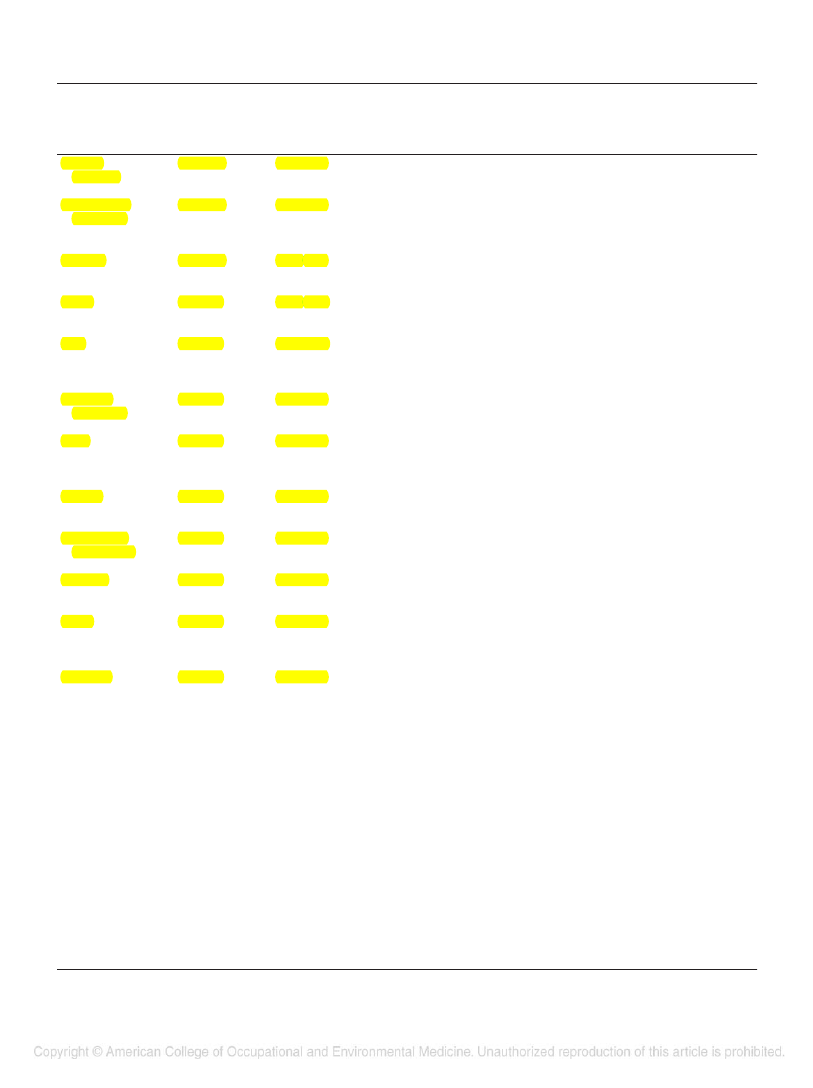

1200TABLE 5ContinuedCancer SiteHodgkin’sdiseaseLiverLikelihood of CancerRisk by CriteriaUnlikelySummary RiskEstimate (95% CI)1.07 (0.59 –1.92)

Cancer Risk Among Firefighters

•

LeMasters et al

CommentsHigher than mSMR (0.78, 95% CI 0.21–2.01)Based on three analysesHeterogeneity—not significant at the 10% levelSimilar to mSMR (1.00, 95% CI 0.63–1.52)Based on seven analysesHeterogeneity—not significant at the 10% levelSimilar to mSMR and PMR (1.05, 95% CI 0.96 –1.14)Based on 19 analysesHeterogeneity—not significant at the 10% level; there washeterogeneity among PMR studiesSimilar to mSMR and PMR (1.06, 95% CI 1.02–1.10Based on 25 analysesHeterogeneity—significant at the 10% level; there washeterogeneity among SMR studies

Unlikely

1.04 (0.72–1.49)

Lung

Unlikely

1.03 (0.97–1.08)

All cancers

Unlikely

1.05 (1.00 –1.09)

CI indicates confidence interval; SMR, standardized mortality ratio; PMR, proportional mortality ratio; SIR, standardized incidence ratio.

SIR1.39, 95% CI0.2–5.0; 11to 20 years: SIR 4.03, 95% CI1.3–9.4. In those exposed greaterthan 20 years, the risk estimate re-mained elevated but declined (SIR2.65, 95% CI0.3–9.6), possiblybecause testicular cancer generallyoccurs at a younger age. Bates et al30argued that, although the reason forthe excess risk of testicular cancerremained obscure, the possibility thatthis is a chance finding was lowbecause incident studies are likelythe most appropriate methodologyfor a cancer that can be successfullytreated.The 1990 findings of Howe andBurch4showing a positive associa-tion with brain cancer and malignantmelanoma are compatible with ourresults because both had significantsummary risk estimates. Brain can-cers were initially scored as probablebut then downgraded to possible (Ta-ble 5). There was inconsistencyamong the SMR studies, which re-sulted in the use of the random-effects model, yielding confidencelimits that were not significant(SMR 1.39, 95% CI 0.94 –2.06)(Table 2). This inconsistency primar-ily resulted from the Baris et alstudy,13a 61-year follow up of 7789firefighters demonstrating a markedreduction in brain cancer (SMR0.61, 95% CI0.31–1.22). As

noted in Table 4, however, therewere elevated, but not significant,risk estimates across all studies, ie,mSMR, mPMR, mRR, and mSIR.This consistency is all the more re-markable given the diversity of rarecancers included in the category“brain and nervous system.” Further-more, there was a 2003 study byKrishnan et al65published after oursearch that examined adult gliomasin the San Francisco Bay area of menin 35 occupational groups. Thisstudy showed that male firefighters(six cases and one control) had thehighest risk with an odds ratio of5.93, although the confidence inter-vals were wide and not significant. Inaddition, malignant melanoma wasalso initially scored as probable butwas downgraded to “possible” due tostudy type. This study downgradewas related to the negative SMR ( )and reliance primarily on a PMRstudy. Thus, in conclusion, our studysupports a probable risk for multiplemyeloma, similar to Howe andBurch’s4findings, and a possibleassociation with malignant mela-noma and brain cancer.

SummaryWe implemented a qualitativethree-criteria assessment in additionto the quantitative meta-analyses.Based on the more traditional quan-

titative summary risk estimatesshown in Table 5, 10 cancers, or half,were significantly associated withfirefighting. Three cancers were des-ignated as a probable risk based onthe quantitative meta-risk estimatesand our three criteria assessment.These cancers included multiple my-eloma, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma,and prostate. A recommendation isalso made, however, for upgradingtesticular cancer to “probable” basedon the twofold excess summary riskestimate and the consistency amongthe studies. Thus, firefighter risk forthese four cancers may be related tothe direct effect associated with ex-posures to complex mixtures, theroutes of delivery to target organs,and the indirect effects associatedwith modulation of biochemical orphysiologic pathways. In anecdotalconversations with firefighters, theyreport that their skin, including thegroin area, is frequently covered with“black soot.” It is noteworthy thattesticular cancer had the highestsummary risk estimate (2.02) andskin cancer had a summary risk esti-mate (1.39) higher than prostate(1.28). Certainly, Edelman et al3atthe World Trade Center, althoughunder extreme conditions, revealedthe hazards that firefighters may en-counter only because air monitoringwas performed.