Socialudvalget 2011-12, Ligestillingsudvalget 2011-12, Beskæftigelsesudvalget 2011-12, Retsudvalget 2011-12, Udvalget for Udlændinge- og Integrationspolitik 2011-12

SOU Alm.del Bilag 173, LIU Alm.del Bilag 33, BEU Alm.del Bilag 86, REU Alm.del Bilag 233, UUI Alm.del Bilag 71

Offentligt

Child Traffickingin the Nordic CountriesRethinking strategies andnational responses

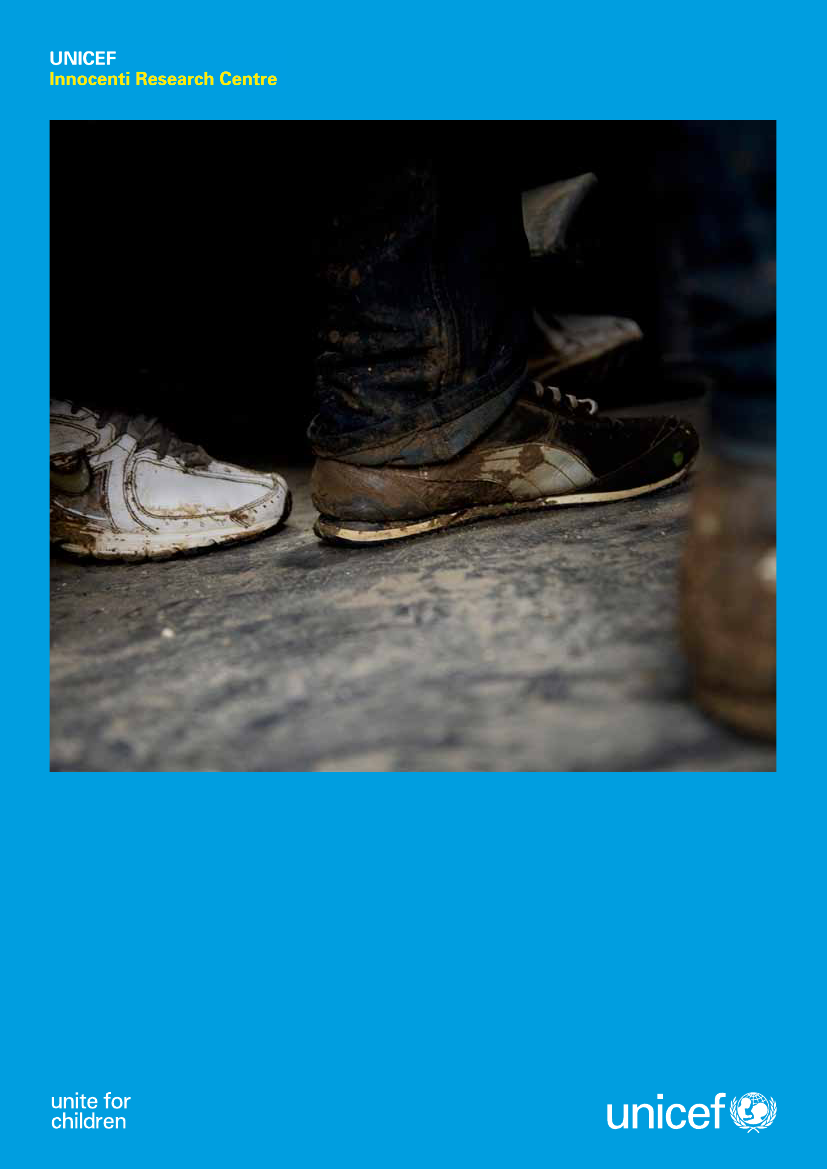

Cover photo: Muddy feet of illegal immigrants who, after crossing the Turkish-Greek border,have been detained by officers of the European Union border police, Frontex.� Jeroen Oerlemans / Panos

Child Trafficking in the Nordic Countries:Rethinking strategies and national responses

Prepared by the UNICEF Innocenti Research Centrein collaboration with the National Committees for UNICEFin Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden

The UNICEF Office of Research, Innocenti

The Innocenti Research Centre (IRC) was established in Florence, Italy in 1988 to strengthen theresearch capability of the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and to support its advocacy forchildren worldwide. The Centre helps to identify and research current and future areas of UNICEF’swork. Its prime objectives are to improve international understanding of issues relating to children’srights and to help facilitate full implementation of the Convention on the Rights of the Child indeveloping, middle-income and industrialized countries.IRC is the dedicated research hub of the UNICEF Office of Research (OOR), which providesglobal leadership for the organization’s strategic research agenda around children. The Officeaims to set out a comprehensive framework for research and knowledge within the organization,in support of its global programmes and policies. Through strengthening research partnerships withleading academic institutions and development networks in both the North and South, the Officeseeks to leverage additional resources and influence in support of efforts towards policy reform infavour of children.IRC’s publications are contributions to a global debate on children and child rights issues andinclude a wide range of opinions. For that reason, the Centre may produce publications that do notnecessarily reflect UNICEF policies or approaches on some topics. The views expressed are thoseof the authors and/or editors and are published by the Centre in order to stimulate further dialogueon child rights.The Centre collaborates with its host institution in Florence, the Istituto degli Innocenti, in selectedareas of work. Core funding for the Centre is provided by the Government of Italy, while financialsupport for specific projects is also provided by other governments, international institutions andprivate sources, including UNICEF National Committees.Design and layout: TOMCOM, Konzeption und Gestaltung, Postdam, Germany� United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF)December 2011ISBN: 978-88-6522-003-0Requests for permission to reproduce or translate UNICEF IRC publications should be addressedto: Communications Unit, UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre, [email protected].Correspondence should be addressed to:UNICEF Innocenti Research CentrePiazza SS. Annunziata, 1250122 Florence, ItalyTel: (39) 055 20 330Fax: (39) 055 2033 330[email protected]www.unicef-irc.org

ii

Acknowledgements

This publication was coordinated by the UNICEF Office of Research, Innocenti, assisted by aninternational panel of advisers and reviewers. The research was conducted in close collaborationand consultation with the National Committees for UNICEF in Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norwayand Sweden, which also kindly provided financial contributions for this study.ResearchersDaja Wenke, Principal Researcher, Independent ConsultantPhil Marshall, Writer and Editor, Director, Research Communications Group, New ZealandSusanna Nordh, Research Assistant, UNICEF Office of Research, InnocentiDanish Committee for UNICEFAnne-Mette Friis, Head of Education for DevelopmentKarin Aaen, Director of Communication and AdvocacyJakob Colville-Ebeling, Communication and Advocacy OfficerFinnish Committee for UNICEFInka Hetemäki, Programme DirectorTanja Suvilaakso, Child Rights AdvisorSara Park, former Advisor, Advocacy and CommunicationJohanna Kurki, Advocacy Manager, Domestic Child PolicyIcelandic National Committee for UNICEFBergsteinn Jónsson, Project Coordinator for Education and YouthLóa Magnúsdóttir, Fundraising and AdvocacyNorwegian Committee for UNICEFNina Kolbjørnsen, Project ManagerAnita Daae, Head of CommunicationSwedish Committee for UNICEFChristina Heilborn, Advocacy DirectorUNICEF Office of Research, InnocentiGordon Alexander, DirectorJasmina Byrne, Child Protection SpecialistAndrew Mawson, Chief of Child ProtectionClaire Akehurst, Executive AssistantAesa Pighini, ConsultantUNICEF technical support/adviceJyothi Kanics, Advocacy and Policy Specialist, UNICEF GenevaSusu Thatun, Child Protection Specialist, UNICEF New YorkKarin Heissler, Child Protection Specialist, Planning and Evidence-Building, UNICEF New YorkMargaret Wachenfeld, Senior Policy Adviser, UNICEF BrusselsYu Kojima, International Consultant and former Child Protection Specialist,UNICEF Office of Research, InnocentiExternal advisers/peer reviewersLena Karlsson, Director, Child Protection Initiative, Save the ChildrenLars Lööf, Head of the Children‘s Unit, Council of the Baltic Sea StatesJulia O’Connell Davidson, Professor of Sociology, School of Sociology and Social Policy,University of NottinghamMike Dottridge, International ConsultantMaria Indiana Alte, Project Coordinator, Counter Trafficking Unaccompanied Minors,International Organization for MigrationHanne Mainz, Social Consultant, Danish Centre against Human TraffickingVenla Roth, Senior Officer, Office of the Ombudsman for Minorities, NationalRapporteur on Trafficking in Human Beings, Finland

iii

Stacks of folders containing applications for asylum in the Office of the CommissionerGeneral for Refugees and Stateless Persons in Brussels.� Dieter Telemans / Panos

Contents

AcknowledgementsForewordIntroductionAbout the StudyKey Concepts: Child protection and best interestsPart I:The Convention on the Rights of the Child as a framework for protectionThe definition of traffickingDifficulties in identifying trafficked childrenTrafficking in the Nordic countriesOther risks faced by vulnerable migrant childrenProvision of services based on identification as a victim of traffickingMoving beyond the trafficking frameworkSafeguarding children through the ConventionPart II:Responses of the Nordic Countries to child traffickingOverall response to child traffickingBroader child protection responsesExpanding services from identified trafficking victims to ‘potential victims’Part III:Guiding principles of the Convenion of the Rights of the ChildGuiding principlesThe right to non-discriminationThe best interests of the childThe right of the child to have his or her views heard and taken into accountChild-sensitive complaint mechanismsThe right of the child to life, survival and developmentPart IV:Vulnerable migrant children and legal, judicial andadministrative processesNon-punishmentDeprivation of libertyIssues relating to return of children to their home countriesTransfers under the ‘Dublin II Regulation’Part V:Promising interventionsConclusions and recommendationsConclusionsRecommendationsCountry-specific recommendationsAcronymsNotes

iiivi1335578899101111121315151516181919232324242529313132353839v

Regularization of stay: Reflection periods, temporary residence permits and asylum26

Foreword

This study,Child Trafficking in the Nordic Countries: Rethinking strategies and national responses,was initiated with twin aims: improving understanding of child trafficking and responses in the region;and contributing to the international discourse on child trafficking by examining the linkages betweenanti-trafficking responses and child protection systems. With these objectives in mind, in early 2010the UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre and the National Committees for UNICEF in Denmark,Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden set out to gather data and information. Two years later, followingan intensive period of literature review, interviews, round-table discussions, analysis and peer review,the final product has brought us further than we originally anticipated.Although the study was conceived with a primary focus on trafficking, its scope is much broader.It analyses how the general principles of the Convention of the Rights of the Child are applied inrelation to those children vulnerable to trafficking and other forms of exploitation. By examiningchild trafficking responses from a child rights perspective, the study was able to identify effectiveresponses as well as gaps in policy and practice. These related not only to children vulnerable tochild trafficking specifically, but to all migrant children at risk of exploitation.The study confirms that the Nordic countries have indeed made significant – and continuouslyevolving – attempts to address the issue of child trafficking, including through setting up relevantinstitutions, developing action plans and allocating budgets. However, while this has meant thatspecialized expertise is available for specific groups of children, it has sometimes led to fragmentationof services, leaving some children unprotected.The research also finds that many existing gaps may be bridged by consistent and strengthenedimplementation of the Convention on the Rights of the Child. This simple message resonates all overthe world. The Convention has been in existence for more than 20 years, and its far-reaching andholistic nature provides a framework for addressing even the most serious crimes against children.One of the many advantages of addressing child exploitation within such a framework is thatservices available to exploited and at-risk children need not depend on their identification as victimsof trafficking. This is particularly important in light of the study’s finding that there is little or noconsistency in the way the concept of trafficking is understood among stakeholders within the region.This in turn prohibits the fair and consistent application of the definition of trafficking to children.At the same time, the study highlights that there is a way to achieve a fuller realization of rights forchildren who are vulnerable in the context of migration. In particular, we still need to improve ourunderstanding of how to interpret and apply the concept of a child’s ‘best interests’; we need to learnhow to strengthen our ability and determination to seek and listen to the views of the child, includingallowing them to express concerns or complaints; and we need to put a stop to discrimination basedon factors such as a child’s nationality, status or citizenship, so that no child is left without theprotection or services that he or she is entitled to. For, irrespective of status or administrative category,a child is first and foremost a child.

Gordon AlexanderDirectorUNICEF Office of Research, Innocenti

vi

Introduction

It has now been 11 years since the adoption of the Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and PunishTrafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children, supplementing the United Nations Conventionagainst Transnational Organized Crime (‘UN Trafficking Protocol’). This period has been marked bya major increase in international attention to trafficking, the adoption of new international guidelines,and the implementation of multiple initiatives aimed at preventing trafficking in persons, identifyingand providing support for victims, and apprehending and prosecuting perpetrators of the crimeof trafficking.As yet, however, information on the issue remains limited. There is no consensus on the number ofpeople trafficked and scant evidence of success of these actions and initiatives, with few evaluationsof the outcomes and impact of trafficking programmes. From the information that is available, itis clear that there is usually no single factor that leads to a person being trafficked; children’svulnerability to trafficking is complex and multifaceted. Patterns in reported cases suggest thatchildren who have been trafficked have often had earlier exposure to domestic violence, social andeconomic marginalization, or exclusion and exploitative relationships. Structural issues, including aprecarious migration status, or patterns of discrimination against children on the grounds of theirgender, ethnic or national origin, and legal or other status, constitute additional risk factors that maycause, sustain or exacerbate a child’s vulnerability to exploitation.1In line with these findings on multiple causes of vulnerability, and also noting the difficulty ofapplying the definition of child trafficking to individual cases in a way that is both consistent andbeneficial to trafficked children, there has been a growing recognition among practitioners thatresponses to child trafficking might be more effective when embedded in comprehensive andsystemic approaches that are based on the rights of the child as afforded under internationalstandards.2One of the features of such approaches is that they seek to cater to children‘s individualneeds and rights, rather than on a ‘categorization’ of children according to a specific legal or otherstatus, such as ‘trafficked’ or ‘not trafficked’.It was against this background that the UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre (IRC), in partnershipwith the UNICEF National Committees in Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden, initiateda study on child trafficking in the Nordic region in early 2010. Covering the five Nordic countries, thestudy aims to generate a better understanding of child trafficking and national responses to the issue,from a child rights perspective.Although primarily focused on child trafficking, the authors of this study sought at the outset tolocate their analysis within a discussion of child protection responses to other vulnerable migrantchildren in the Nordic countries. This decision has proved significant. As evidence was gathered,it became increasingly clear that child trafficking cannot be adequately addressed independentlyof other vulnerabilities faced by children, migrant children in particular. This leads to the core findingof the study: that the Convention on the Rights of the Child offers a stronger framework for the protec-tion of trafficked (and other exploited) children than the child trafficking framework. In line with thisfinding, the study goes considerably beyond identifying strengths and gaps in existing responsesto child trafficking. It examines the potential that strategies for implementation of the Conventionon the Rights of the Child hold for addressing child trafficking in a broader context, as well as for theprotection of those referred to in the report as vulnerable migrant children.The Convention offers a number of advantages over a narrow child trafficking focus, notably intranscending the challenges of how trafficking is defined, understood and applied in practice.It can also help ensure that services for exploited children are geared more to the nature of their

introduction

1

exploitation than to how they came to be in an exploitative situation, e.g. by ensuring that similarservices are available for child victims of sexual exploitation, whether or not they are identified ashaving been trafficked. Although the question of resource allocation was not specifically addressedin the study, a framework that safeguards the right of all exploited and abused children to specialprotection measures would appear to facilitate a more efficient use of resources, particularly where,as in the Nordic countries, the number of confirmed trafficking cases is low.At the same time, the child trafficking lens proves a useful one through which to identify both effectiveinitiatives and response gaps within existing child protection systems. Using trafficking as a startingpoint, the study has also been able to identify several areas in which the countries concernedmight do more to fulfil their commitments to child protection, as set out in the Convention on theRights of the Child.This report seeks to highlight the major themes and key points identified in the accompanying technicalstudy. It is divided into five main parts, followed by a section on conclusions and recommendations.Each part starts with a general finding, followed by additional specific findings, as appropriate.Part I of the report outlines the considerations involved in the core finding on the relative protectionmerits of the child trafficking framework and the Convention on the Rights of the Child. It examinesthe concept of trafficking in human beings and identifies variations in how this is understood in theNordic region, particularly in relation to children. It highlights difficulties in applying the traffickingdefinition in a consistent and equitable manner, and also questions the value of determining servicesfor children based on their categorization as trafficking victims or otherwise. Lastly, Part I coversemerging attempts to address the difficulties identified with the trafficking framework and brieflyintroduces the Convention as an alternative.The considerable action taken by the Nordic countries in addressing child trafficking and relatedissues is the focus of Part II. This includes legal reform, establishment of specialized institutions,cooperation and coordination mechanisms, and development of tools and measures for theidentification of adults and children who have been trafficked. It also encompasses a wide rangeof assistance measures for trafficked persons. These have gradually been extended to possibletrafficking victims and others who may be vulnerable through the introduction of the concept of‘potential victim of trafficking’.Part III examines responses to trafficking and related issues in the Nordic countries againstConvention on the Rights of the Child commitments, focusing on the four general principles ofthe Convention: best interests of the child; right to non-discrimination; right to participation; and right tolife, survival and development. Several potential gaps are identified in each area, many relating todifferential treatment of children based on nationality and/or legal or other status. The differencein guardianship arrangements for officially identified child trafficking victims and other vulnerablemigrant children is highlighted as an example. The importance of strengthening child complaintmechanisms across the region is also discussed.Part IV of the report outlines issues relating to vulnerable migrant children and the associated legal,judicial and administrative processes. These include the rights of children as victims of crime, theimportance of protection from prosecution for crimes committed as part of the trafficking process,and concerns identified with regard to the deprivation of liberty among child victims of traffickingand other non-national children. Part IV goes on to examine the question of return or transfer tocountries of origin and other countries, with particular reference to the ‘Dublin II Regulation’

2

child trafficking in the nordic countries

(Council Regulation (EC) No 343/2003 of 18 February 2003 establishing the criteria and mechanismsfor determining the Member State responsible for examining an asylum application lodged in oneof the Member States by a third-country national). The short and long-term alternatives to return,including asylum, are also addressed.The study found numerous examples of promising policies and interventions that are worthy ofwider consideration throughout the region and beyond. Brief information on selected interventions isincluded in Part V. Based on the issues raised, the study then concludes with recommendations forstrengthening systemic and rights-based approaches to prevent the exploitation of vulnerable migrantchildren, and to assist children who have already been exploited, including, but not restricted to,victims of trafficking.About the StudyThis study was based primarily on a comprehensive literature review, complemented by key informantinterviews and a consultative review process. Selected country examples were also documented.The research was guided by international standards, in particular the Convention on the Rights ofthe Child and the ‘UN Trafficking Protocol’, as well as regional standards, instruments and initia-tives developed within the Council of Europe (COE) and the European Union (EU). The study wasalso informed by the work of the Council of the Baltic Sea States (CBSS) and its Expert Groupfor Cooperation on Children at Risk, and the Separated Children in Europe Programme.The research was implemented in consultation with a steering committee, made up of the focal pointsfor this study from the National Committees for UNICEF in each of the five countries, and an advisorygroup. Members of the advisory group included representatives from the Centre on Migration, Policyand Society (COMPAS) at the University of Oxford; CBSS; Save the Children; School of Sociologyand Social Policy at the University of Nottingham; Child Rights Advocacy and Education Section,UNICEF Private Fundraising and Partnerships (PFP) Division, Child Protection Section, UNICEFNew York; and an independent expert. The preliminary findings and recommendations from the studywere presented at technical round-table discussions in four Nordic countries (excluding Iceland).During the meetings, initial results were shared with key informants and further input, commentsand clarifications solicited. Between May and June 2011, the study was also peer reviewed byexperts from each of the countries.Key Concepts: Child protection and best interestsIn this report, the term ‘child protection’ refers to the protection of children from all forms of violence,exploitation and abuse. UNICEF defines child protection as “preventing and responding to violence,exploitation and abuse against children – including commercial sexual exploitation, trafficking, childlabour and harmful traditional practices.”3International agencies such as UNICEF and Save theChildren are increasingly advocating the benefits of a holistic response to issues affecting children,rather than an issues-based approach that can lead to fragmentation of services. The ‘best interests ofthe child’ is a central and all-embracing principle under the Convention on the Rights of the Child.Article 3 of the Convention stipulates that “in all actions concerning children, whether undertakenby public or private social welfare institutions, courts of law, administrative authorities or legislativebodies, the best interests of the child shall be a primary consideration.”4The right to non-discrimination,survival and development, and respect for the child’s views are all considered relevant in theassessment and determination of the best interests of the child.5However, there are no internationalinstruments that specify how best interests considerations should be applied in practice. The guidingprinciple has been introduced into several sectoral laws, regulations and policy plans in the Nordiccountries. The application of this principle in practice is a core focus throughout this study.

introduction

3

A variety of passports used as props at the Medininkai Border Guard School in Lithuania, where students learn to distinguish betweenreal and fake passports. The students here will work along the border between Lithuania and Belarus.� Fredrik Naumann / Panos

Part I: The Convention on the Rights of the Childas a framework for protection

General finding 1: The Convention on the Rights of the Child offers a stronger framework forthe protection of trafficked (and other exploited) children than the child trafficking framework.Specific finding 1:Significant differences exist across and within Nordic countries as to howtrafficking is defined and understood.Specific finding 2:Some migrant children face risks and exploitative practices that are not adequatelycovered by the ‘trafficking’ / ‘non-trafficking’ distinction.Specific finding 3:The provision of services for children based on the categorization ‘trafficked’versus ‘not-trafficked’ may be neither feasible nor desirable.

The definition of traffickingAn internationally recognized definition of trafficking in persons is contained in the ‘UN TraffickingProtocol’, which states in article 3:(a)“Trafficking in persons” shall mean the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouringor receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, ofabduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or ofthe giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person havingcontrol over another person, for the purpose of exploitation. Exploitation shall include, at aminimum, the exploitation of the prostitution of others or other forms of sexual exploitation,forced labour or services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude or the removalof organs;(b)The consent of a victim of trafficking in persons to the intended exploitation set forth insubparagraph (a) of this article shall be irrelevant where any of the means set forth insubparagraph (a) have been used;(c)The recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of a child for the purpose ofexploitation shall be considered “trafficking in persons” even if this does not involve any of themeans set forth in subparagraph (a) of this article;(d)“Child” shall mean any person under eighteen years of age.6The Protocol supplements the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime,a criminal justice instrument. It has been extremely influential in raising the profile of traffickingand has stimulated a wide range of responses. Not surprisingly given its origins, the provisions ofthe Protocol are particularly relevant in relation to the apprehension and prosecution of criminalsinvolved in human trafficking. While in many jurisdictions most of the composite crimes involved intrafficking are already offences, the crime of trafficking allows targeting of the entire trafficking chain,across borders and jurisdictions where necessary.At the same time, however, there are major complications related to how the definition of traffickingis understood and applied to real situations (seeBox 1, page 6).One consequence is limitedeffectiveness as a protective instrument for those who are victims of, or vulnerable to, human trafficking.

part i:the convention on the rights of the child as a framework for protection

5

Box 1: Definitional and conceptual challenges related to traffickingThe Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Woman andChildren, supplementing the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime(‘UN Trafficking Protocol‘) defines trafficking in adults as comprising at least one ‘act’ of recruitment,transfer, harbouring or receipt of persons, at least one illicit ‘means’ such as coercion, threat anduse of force, and a ‘purpose’ of exploitation. The definition of child trafficking is essentially derivedfrom the definition related to adults, modified to require only an act and an exploitative purpose,not an illicit means.There are, however, challenges related to applying this definition in practice. These include:1. The term ‘exploitation’ is not clearly defined in the ‘UN Trafficking’ Protocol or any otherinternational legal instrument. Further, the Protocol explicitly leaves it up to individual states todecide what constitutes ‘sexual exploitation’, increasing the likelihood of inconsistent definitionsbeing used across different jurisdictions. The term ‘trafficking victim’ is also not defined.2. There are differences in the way the definition is understood among policymakers andpractitioners. For example, as shown in Figure 1 below, the study did not find consensus onwhether trafficking requires a movement component. A significant proportion of officials andpractitioners view kidnapping for adoption as a form of trafficking.7Thetravaux preparatoires(official records of the negotiations) of the Protocol, however, state that only “where illegaladoption amounts to a practice similar to slavery…it will also fall within the scope of theProtocol”.8Figure 1Key informants’ responses to the question “Do you consider‘movement’ to be a part of the trafficking concept?”YES 5No clearresponse 10

NO 24N = 39

3. It is often difficult to consistently apply the trafficking definition to on-the-ground realitiesacross different organizations and states. Indeed, it seems logical that a victim supportagency, with the primary role of assisting those in need, would wish to apply a more generousdefinition of what constitutes a trafficking victim than a criminal justice agency, which ischarged with applying finite resources to the investigation and prosecution of criminal cases.Responding to child trafficking in the context of the protection framework provided by theConvention on the Rights of the Child has the major advantage of transcending thesedefinitional and conceptual difficulties. From a child protection perspective, the importanceof the trafficking definition can be greatly reduced by focusing on the needs and rights ofindividual children, independently of their status as a trafficking victim.

6

child trafficking in the nordic countries

Difficulties in identifying trafficked childrenIdentifying child victims of trafficking in the Nordic countries poses numerous challenges. Some arerelated to definitional issues, as noted above. While the ‘act’ of human trafficking, i.e. the “recruitment,transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of persons” is reflected in the relevant sections ofthe criminal codes of all five countries, differences occur in relation to what constitutes exploitativepurposes. In Denmark, Iceland and Norway, national law provides an exhaustive list. In Finland andSweden, the scope of exploitation is left open by the reference to “other demeaning circumstances” or“other (exploitative) activity”.9An exhaustive list is in effect more limited than the ‘minimum’ provisionof the ‘UN Trafficking Protocol’, since new and emerging forms of exploitation may not be covered.Although each country has an agency with specific responsibility for victim identification, the processoften involves many different agencies, which sometimes use different screening tools.10At present,the authorities responsible for victim identification may also not be in contact with all groups ofchildren affected by trafficking. National authorities report, for example, that it is difficult to reachand identify accompanied children who may have been trafficked, and that limited means exist toidentify children trafficked within the EU.11Even where authorities are in contact with trafficked children, they may not be identified as havingbeen trafficked. For example, the study highlighted that there is limited consideration of traffickingexperiences or risks for children transferred under the ‘Dublin II Regulation’, which regulates whichcountry is responsible for examining a person’s asylum application (seePart IV).In Finland andSweden, children may not be identified as victims of trafficking if their exploiters are charged witha crime other than trafficking, such as procurement.12Further, while under the definition of childtrafficking a child “cannot consent to being trafficked”, study respondents suggested that thisconcept has not yet been fully understood and applied in criminal proceedings.13Victims of trafficking are often perceived to undergo severe psychological distress but may notalways show signs of harm when in contact with the authorities or service providers. If signs ofdistress are absent, authorities may not recognize the child in question to be a victim of trafficking.Exploitative situations may cause severe psychological distress to some children, but may also beaccepted by others as a harsh reality of life and as the only way to earn an income in the absenceof safer or more viable alternatives.14Children may also resist being assigned the status of a victimof trafficking particularly when, as highlighted throughout this study, it may serve to limit their mobilityand freedom of choice. Some children who are exploited in illegal activities may not consider themsel-ves victims but simply children in trouble with the law.15Taken together, these factors suggest major difficulties in the fair and consistent application of thetrafficking definition as it relates to children. In terms of consistency at least, this appears to besupported by the differences in national statistics. Only two child victims of trafficking wereidentified in Denmark between 2006 and 2010,16while Norway, which uses the broader definitionof ‘potential victim’, found 217 potential cases of child trafficking in a shorter period, 2007–2009.17Itseems unlikely that this signifies a much greater trafficking problem in Norway than in Denmark.Certainly, policymakers and service providers in the Nordic countries recognize that children whoare victims of trafficking or vulnerable to trafficking and associated exploitation may somehow slipthrough the existing web of protection systems.

part i:the convention on the rights of the child as a framework for protection

7

Trafficking in the Nordic countriesAcross the Nordic region, the number of officially identified trafficking victims is low.18From existinginformation, it can be concluded that adults and children are trafficked to and within the region andthey experience different forms of exploitation. Sexual exploitation takes place in prostitutionand pornography.19Labour exploitation was reported or considered probable in labour-intensivesectors and those that primarily employ non-nationals, such as construction, restaurants, cleaning,agriculture and berry picking. Trafficking is also possible in relation to domestic work, begging,forced marriage and child marriage.20The recruitment of children into trafficking is believed to take place mostly outside the Nordic region,with traffickers ranging from small groups of people to larger international networks.21Case analysis fromSweden noted differences in forms of exploitation according to the age of the child. Children traffickedinto sexual exploitation were mostly between 15 and 17 years. Children aged 10–14 years wereexploited in begging and thievery under the control of organized criminal groups. The age ofcriminal liability (15 years in Sweden) was considered relevant in this context, since youngerchildren do not risk prosecution when identified by the police.22Limited information and analysis is available on the backgrounds of children identified as actualor potential victims of trafficking. Even where common characteristics have been identified amongvictims, such as difficulties in finding employment in countries or areas of origin,23it is not clearwhether these factors also apply to non-trafficked migrants or indeed to most citizens of thecountries concerned. This lack of information hampers the development of responses to childtrafficking, particularly preventive responses.Other risks faced by vulnerable migrant childrenWhile, as noted above, few children are officially identified and registered as trafficking victims, the studyhighlighted a range of other risks and vulnerabilities faced by migrant children, both accompaniedand unaccompanied. Across the region, there are reports of exploitation of migrant children in variousforms at source, in transit and at destination countries. Such children often face severe risks to theirhealth and even to their lives.24The necessity for many migrants, notably asylum-seekers, to engagewith criminal networks (smugglers) adds to their vulnerability, although in some cases such networkscan also protect children from harm.25Studies have suggested that the risk factors faced by vulnerablemigrant children tend to be intertwined and cumulative.26Other groups specifically identified as vulnerable to exploitation in the context of migration includechildren who have disappeared from the asylum-seeking process, children from Roma migrantcommunities, and children who are unaccompanied but not seeking asylum, including EU citizens.27Little information is currently available on issues affecting the third group, or how local child protectionservices, which have the responsibility to care for these children during the three months they are entitledto remain in the Nordic countries, would become aware of and respond to their needs and concerns.28Overall, the information gathered with respect to vulnerable migrant children supports the viewthat clear identification or ‘categorization’ of children according to a specific status may not alwaysbe practical, and that a child’s status does not necessarily reflect the needs of the individual childconcerned. Children may be victims of trafficking or other crimes while they are also accompaniedor unaccompanied asylum-seekers, regular or irregular migrants, or members of minority groups.Moreover, children often move between different statuses or ‘categories’ depending on their options

8

child trafficking in the nordic countries

and choices of migration, as well as on decisions taken by immigration authorities when theirapplications are being assessed or reassessed.29Provision of services based on identification as a victim of traffickingAgainst this backdrop, there are major questions related to the underlying protection value of thetrafficking categorization. The concept of trafficking distinguishes cases based on how children andadults came into an exploitative situation, rather than the nature of the exploitation itself. In otherwords, the presence or absence of factors such as recruitment, transportation, harbouring or receiptis treated as more significant than how children have actually been exploited. Among children whohave been exposed to trafficking, however, service and assistance needs vary according to the ageand sex of the child, and the way in which he or she has been exploited. A child who has beensexually exploited, for example, is likely to have different needs than a child who has been exploited inbegging. The need for psychosocial counselling, access to health care and legal assistance maybe common among child victims of trafficking and other crimes, as well as migrant and asylum-seeking children. Access to the asylum procedure and return programmes is potentially relevant toall non-national children. Safety and security are essential considerations for all child victims andwitnesses of crime, including child victims of trafficking, as well as for other vulnerable child migrantsand asylum-seekers.This does not mean that the concept of trafficking should be ignored. Trafficking is an importantand often not very visible means by which children are placed and held in exploitative situations.It is thus very important that all those working with migrant children are fully aware of the risks,nature and manifestations of child trafficking. This offers important opportunities to identify andassist children at risk as well as children who have been exploited. Incorporating training on childtrafficking into the standard curricula of all relevant professionals and officials working with and forchildren can improve the rate at which vulnerable children are identified.From a child protection point of view, however, the value of providing services solely based on adetermination of a child as a victim of trafficking is not readily apparent. In short, a child should beafforded special protection and assistance not only on the grounds of being a victim of trafficking,but on the grounds of being a child.Moving beyond the trafficking frameworkThe limitations of the trafficking concept are increasingly being recognized by different countries andorganizations, particularly in regard to support for exploited and vulnerable persons. The Council ofEurope Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings, for example, has broadened theapproach to victim assistance. It provides that a person should have access to appropriate serviceswhen the competent authorities have ‘reasonable grounds’ to believe that he or she has been trafficked.30The International Organization for Migration (IOM) is expanding its trafficking victim assistanceprogrammes to include other ‘vulnerable migrants’, making services less dependent on a personbeing categorized as a victim of trafficking. This initiative was endorsed by a recent evaluation ofIOM, funded by the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD).31Within the Nordic region, Denmark, Finland and Norway have introduced the concept of ‘poten-tial victim’ to describe persons who may be victims of trafficking or are considered at risk. Morewidely, several international organizations are exploring the concept of ‘children on the move’, whichseeks to address issues relating to migrant children in a holistic manner.32

part i:the convention on the rights of the child as a framework for protection

9

These initiatives are essentially attempts to ensure a better fit between the existing traffickingparadigm and the realities faced by vulnerable and exploited migrants. Yet, while a solution to thedefinitional problems described above is not readily apparent in relation to adults, an alternative,grounded in international law, does exist in relation to children. This is the framework provided bythe Convention on the Rights of the Child.Safeguarding children through the ConventionThe Convention on the Rights of the Child prohibits the exploitation of children in any form and context.Significantly, it affords the same rights and safeguards to all children who have been exposed toexploitation, irrespective of the context in which the exploitation has occurred. Children who havebeen exposed to exploitation in any form are considered ‘child victims of crime’ and as such areentitled to the same support and assistance for recovery and (re)integration, and enjoy specialrights and protection in the context of legal and judicial proceedings, as child victims of trafficking.Further, the Convention provides broad protections for children, irrespective of their status.Responding to child trafficking in the context of the protection framework provided by the Conventionthus has the major advantage of transcending definitional and conceptual difficulties. It facilitatesa focus on the needs and rights of individual children, independently of their status as a traffickingvictim or otherwise. Assigning a specific label to a case of child exploitation, such as ‘trafficking’,‘sale’, ‘procurement’ or other, can be considered secondary. In prevention and response measuresunder the framework of the Convention, the primary obligation is that the individual situation andneeds of a child are assessed, and that his or her rights are fully safeguarded to prevent exploitationor to offer appropriate services once exploitation has occurred.This study has demonstrated how, in responding to child trafficking and related forms of exploitation,a review of existing and planned responses vis-à-vis the rights guaranteed by the Convention canguide the process of policy and planning.

10

child trafficking in the nordic countries

Part II: Responses of the Nordic countries to child trafficking

General finding 2: To date, all the Nordic countries have made serious and continuouslyevolving attempts to address the issue of child trafficking.Specific finding 4:The response could be further strengthened by additional measures to ensurethat the specialized mandates of the many agencies working in the child protection field, an advantagein terms of expertise, do not result in the fragmentation of services.Overall response to child traffickingAll of the Nordic countries have ratified the ‘UN Trafficking Protocol’ and the Convention on theRights of the Child. They have all introduced special articles or sections in their national criminallaws that prohibit and criminalize trafficking in human beings, including special provisions tocriminalize child trafficking, as well as laws around composite crimes such as rape and kidnapping.In all of the countries, except for Denmark, the offence is considered ‘aggravated’ or ‘gross’ whencommitted against a person under 18 years of age, and it carries a higher sentence.Significant progress has been achieved in regard to incorporating the general principles of theConvention into constitutions, child rights statutes and sectoral laws, as recommended by theCommittee on the Rights of the Child. In Norway, the Convention and several other internationalhuman rights standards have been incorporated into the Human Rights Act and its provisions are totake precedence over national law.33In Finland, the Convention is also applicable law.34In Denmark, ithas the status of a relevant source of national law and can be invoked in court and applied directlyby courts and administrative authorities.35The Danish Institute for Human Rights, however, suggeststhat its application is limited in practice.36Sweden has not yet incorporated the Convention and itsOptional Protocols into law. In its October 2011 ‘Concluding Observations’ on the Optional Protocolto the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the sale of children, child prostitution and childpornography, the Committee on the Rights of the Child recommends that the Swedish Governmentaddress the issue as a matter of urgency.37All of the Nordic countries have also developed national plans of action to address trafficking inhuman beings, all of which provide special measures for children. These cover multiple forms ofexploitation, with the exception of the Swedish plan, which is limited to prostitution and exploitationfor sexual purposes. In Denmark and Sweden, a specific budget has been allocated to the plans.The plans in Finland and Sweden have expired but their provisions are considered to continue toguide policy and practice in the respective countries.38Four Nordic countries have interministerial working groups or comparable institutionalized mechanismsthat are mandated to coordinate and oversee implementation of the national action plans againsttrafficking in human beings. The exception is Sweden, where the National Method Support Teamagainst Prostitution and Human Trafficking plays a key role by providing a forum for the collaborationof agencies involved in the response. Along with Finland, Sweden has also established a NationalRapporteur on Trafficking in Human Beings.39Each country has assigned a specific authority with an official mandate to assess and verify a person’svictim status although, as noted previously, in practice this role is played by many different institutions.Denmark, Finland and Norway have generous interpretations of the definition of a trafficking victim.In Norway, there is a particularly low threshold for persons who are assessed by service providersas ‘potential victims of trafficking’ to access services.40Denmark and Finland also provide broaddefinitions and simply require ‘reasonable grounds’ to believe that a person has been trafficked.41

part ii:responses of the nordic countries to child trafficking

11

Other than some instances involving deprivation of liberty and child participation, both discussedlater in this report, few concerns have been raised about services for children who have beenofficially identified as ‘trafficked’ or ‘potentially trafficked’.Numerous examples of good practice have been developed, several of which are highlighted in Part Vof this report. Moreover, the study discusses how trafficking responses have continued to evolve inlight of new challenges, recent information and ongoing developments at policy level in Europe.Although outside the scope of this study, it should be noted that Nordic countries also continue tofund anti-trafficking initiatives in lower-income countries.Broader child protection responsesIn the Nordic countries, the responsibility for policy planning and operational tasks relating to therights and protection of national and non-national children is often divided among different institutions.Furthermore, matters concerning child victims of trafficking, and migrant and asylum-seeking children,usually fall under the mandates of different ministries, with multiple institutions and authoritiesinvolved in their implementation. As elsewhere, it is also not always clearly established how actionplans and strategies addressing child trafficking relate to other action plans and strategies that arerelevant to specific child rights and protection themes.Local authorities adopt a more unified approach to the provision of services for child protection andcare and are responsible for all children who reside in a particular municipality. However, they maynot be fully aware of national standards and obligations. Key informants for this study reportedthat little information appears to be available, for example, on the extent to which Best InterestsDeterminations take place in regard to the return of non-national children directly from municipalities.42Study respondents further noted that state authorities and services assess the best interestsof the child from the perspective of their specific mandates and areas of work. As noted by theGovernment Migration Policy Programme in Finland, “the concept of a child’s best interests isused in different meanings in refugee and asylum policy. Different sectors of [the] administrationhave different ideas of how the best interests of a child should be established and what expertiseshould be employed in doing so.”43Evidence from Finland, Norway and Sweden suggests that immigration authorities, for example, tendto carry out formal Best Interests Determinations with a specific focus on whether a child shouldremain in the country or return to his or her country of origin. Social welfare and child protectionauthorities on the other hand, are likely to assess best interests with a specific focus on carearrangements, possible risks or experiences of violence, exploitation or abuse. Representativesand guardians for unaccompanied children, including child victims of trafficking, may assess thechild’s best interests in relation to accommodation and well-being.44Taken together, these issuescan lead to fragmented approaches. In Denmark, for example, an evaluation of the Action Plan toCombat Trafficking in Human Beings concluded that the responsibilities and mandates of the variousauthorities and organizations involved in working with vulnerable migrant children lacked cohesionand required further refinement.45As a first step towards identifying and addressing possible gaps and discrepancies resulting fromdifferent organizational mandates, each country may consider undertaking a detailed mapping ofhow child trafficking, exploitation and the broader situation of non-national children are addressed inpolicy and practice, with a view to making any necessary adjustments.

12

child trafficking in the nordic countries

Expanding services from identified trafficking victims to ‘potential victims’Assistance and services for child victims of trafficking are generally provided through existingprotection structures for unaccompanied asylum-seeking children. Local child protection orsocial welfare services play a key role in providing care for these children. Under nationallegislation, many provisions regulating children’s access to protection and care are availableregardless of a child’s status, and the provision of services is based on individual case andneeds assessments. In practice, however, the study has highlighted how a child’s status matters inmultiple ways, including in relation to immigration status, national origin and status as a victim,or potential victim, of trafficking. Examples are provided in Part III of the paper, particularly in thesection relating to the principle of non-discrimination.One measure that countries have taken to address this issue is the adoption of the concept of‘potential victim of trafficking’, initially promoted by the Group of Experts on Trafficking in HumanBeings of the European Commission and the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe(OSCE), and taken up by the Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking in HumanBeings.46In Norway, this concept is applied in a particularly broad manner.47It describes bothpersons who are considered likely to be victims of trafficking but not yet formally identified as such,and those thought to be at risk. They may be referred to the specific services in place for victims oftrafficking while their cases are further assessed.The status of ‘potential victim of trafficking’ appears to offer opportunities for prevention when itallows the early identification of children at risk of exploitation and their referral to assistance. At thesame time, as highlighted throughout the study, a child should be afforded special protection andassistance not only on the grounds of being a victim of trafficking, but on the grounds of being a child.It is important to ensure that the concept of potential victim does not reinforce existing disparitiesin the ability of children to access their rights. Customized services for specific ‘categories’ of childrenshould not create discrimination, but rather should be tailored to the needs of individual children andcomplement basic child protection services.

part ii:responses of the nordic countries to child trafficking

13

A Georgian migrant travelling on the so-called ‘patera’ train without a visa reaches the French-Spanish border. The train, whichtraverses French, Italian and Spanish boundaries, has acquired a reputation for carrying undocumented migrants, largely fromEastern European territories, into the affluent EU communities in the west.� Lorena Ros / Panos

Part III: Guiding principles of the Convention onthe Rights of the Child

General finding 3: Despite considerable efforts by the Nordic countries, some gaps remain inpolicy and practice with respect to ensuring implementation of the general principles of theConvention on the Rights of the Child.Specific finding 5:The general principle of the best interests of the child has been introduced intolaws, policies and plans in the Nordic countries.Specific finding 6:Best Interests Determinations and assessments for non-national children,including child victims of trafficking, are often conducted in a sector-specific way.Specific finding 7:Discrimination against children can be found across the region based on factorsranging from nationality and language to age and, most commonly, status.Specific finding 8:Gaps exist with regards to the right of the child to have his or her views heard andtaken into account. Child-sensitive complaint mechanisms could be strengthened throughout the region.General principlesThis part of the report assesses the current policies and practices relating to child trafficking andassociated exploitation in the Nordic countries in accordance the Convention on the Rights of theChild. While it contains a total of 54 articles, a solid basis for analysis is provided by the four‘general principles’ of the Convention, as articulated by the Committee on the Rights of the Child.These are:Article 2:The right to non-discriminationArticle 3:The best interests of the child as a primary considerationArticle 6:The right to life, survival and developmentArticle 12:The right of the child to have his or her views heard and taken into accountThe right to non-discriminationThe Convention affords children broad and comprehensive protection against discrimination.It provides that State parties shall ensure that the rights in the Convention apply to all children withintheir jurisdiction without discrimination of any kind – race, colour, sex, language, religion, politicalor other opinion, national, ethnic or social origin, property, disability, birth or other status. The rightsafforded under the Convention therefore apply to non-national children, including children who arevisiting a state, refugees, children of migrant workers and undocumented children.48The right to non-discrimination is reflected in different ways in the national legislation of the Nordiccountries, although to date only Finland has ratified Protocol No. 12 to the Council of EuropeConvention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, which provides for ageneral prohibition of discrimination and guarantees fundamental rights to all persons within itsjurisdiction. All countries have enacted specific anti-discrimination laws in addition to generalprovisions in their constitutions. Most have also established institutions to promote the right tonon-discrimination and monitor implementation of national anti-discrimination laws.49The above prohibitions are, however, often limited to discrimination on specific grounds or in specificsectors. A general prohibition of discrimination in line with article 2 of the Convention on theRights of the Child is not yet fully guaranteed. The study identified examples across a wide range

part iii:guiding principles of the convention on the rights of the child

15

of areas, notably in relation to immigration status and status as a trafficking victim. This hasaffected access to, among other things, health and education, social services, guardianship andBest Interests Determinations.In Norway, for example, outreach workers reported that authorities usually took action immediatelyto assist children who had received a residence permit. In the cases of non-national children withoutsuch permits, however, it is often less clearly established which authority is responsible, particularlywhen a child’s legal status and place of registry in Norway cannot be clearly identified.50Differencesin funding availability for services at the local level, based on children’s nationality and immigrationstatus, were noted throughout the region. In Finland, for example, while the right to free basic educationfor ‘everyone’ is provided for under the Constitution, this is interpreted to apply only to childrenwho are permanent residents or have temporary residence status.51Victims may also be discriminated against based on the crimes with which their exploiters are charged.In Finland, a child victim involved in a trafficking case is an interested party in criminal proceedings,whereas a child victim involved in a procurement case is regarded solely as a witness.52This severelyaffects children‘s entitlements in terms of legal assistance, compensation and access to services.Similar concerns were reported in Sweden, including specifically with regard to children exploitedin procurement.53In Norway, the broad law on human trafficking makes it easier to try cases ofprocurement that involve children under child trafficking charges and grant trafficking victim status tothe exploited child.54In some cases, victims are discriminated against due to their age. In Norway, for example, care forunaccompanied children over the age of 15 falls under the responsibility of immigration authoritiesrather than social services. The Ombudsman for Children states that “the level of follow-up…isconsiderably inferior to that provided to Norwegian children without caregivers in the country andunaccompanied minor asylum-seekers under the age of 15”.55Undocumented children are a particularly vulnerable group and are not always afforded access tothe same services as children who have regularized status or national children. Even where rightsclearly exist on paper, service providers are not always aware of them. There may be a need to moreclearly stipulate rights in relation to issues such as education and health in the national legislation,since this is often left to the discretion of municipal authorities.56The best interests of the childThe general principle of the ‘best interests of the child’ is a central and all-embracing principleunder the Convention on the Rights of the Child. Article 3 of the Convention stipulates that “in allactions concerning children…the best interests of the child shall be a primary consideration”.The Committee on the Rights of the Child recommends that this principle be integrated in alllegal provisions, projects and services relevant for children as well as judicial and administrativeprocedures and decision-making processes affecting children, including in the context of parentalcustody, alternative care and migration.57Progress has been made in this regard throughout the Nordic countries, particularly in relation to childprotection, parental custody and alternative care, as well as the reception and assessment of childrenseeking asylum.58The wording of best interests provisions is often vague, however, with the resultthat other decision-making processes relating to more precisely worded laws may take precedence.59As noted in Part II, the implementation of formal Best Interests Determinations, as well as best

16

child trafficking in the nordic countries

interests assessments for children, tends to differ among the Nordic countries, and among differentprofessionals, sectors and groups of children.60Concerns were also raised in a 2010 study by theUnited Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) on unaccompanied Afghan children inEurope, which noted that there was no clear understanding of the meaning and scope of the conceptof the best interests of the child, in particular in relation to unaccompanied asylum-seeking children.61Operational guidelines for the determination of the best interests of the child have been developedby UNHCR.62Although intended for use in the specific context of refugee children, many of themethodological and procedural elements might inform processes in other areas, including childtrafficking cases. The guidelines distinguish between best interests assessments and Best InterestsDeterminations. A best interests assessment is made by staff taking action with regard to anindividual child, such as deciding on the child’s accommodation. A Best Interests Determination, onthe other hand, is a formal process for particularly important decisions affecting the child, such asidentifying a “durable solution” (seebelow),which involves return to the child’s country of origin. Themethods and outcomes of both processes should always be documented and explained in writtenform, and give due consideration to the child‘s views and to assessing a child’s psychosocialsituation, including past and present experiences of violence, exploitation and abuse.Despite some potential shortcomings, as noted above, there have been several positive initiativeswithin the Nordic region to ensure an increase in coverage, quality and consistency of best interestsassessments and Best Interests Determinations. One example comes from the Child Welfare Actin Finland, which states that when assessing the interests of the child, consideration must be givento the extent to which alternative measures and solutions safeguard the following seven criteria:balanced development and well-being and close, continuing human relationships; understandingand affection as well as supervision and care; education; personal safety and physical and emotionalfreedom; a sense of responsibility and independence; the right to participation; the child’s linguistic,cultural and religious background.63Another Finnish initiative, which is to develop a psychosocialinterviewing model that strengthens best interest assessments, is discussed in Part V, along withanother relevant programme, the Children’s House models in Iceland and elsewhere.Overall, concerns with regard to upholding the general principle of the best interests of the childcan be summarized in two categories. First, the current sectoral approach appears to contributeto a situation in which some children may be excluded from having their best interests assessedand determined by the competent authorities. Second, current arrangements do not ensure thatprocedures to assess and determine the best interests of the child are consistent for all children andtake into account all the rights of the child, including the right to be heard. In the case of non-nationalchildren, mechanisms to combine assessments made by social welfare or child protection servi-ces with those conducted by the immigration authorities can inform a holistic approach and promotegreater understanding of a child’s best interests. Countries that have not already done so may alsoconsider elaborating criteria to be considered in assessing the best interests of the child.In doing so, countries may draw on the concept of durable solutions. In its General Comment No. 6,the Committee on the Rights of the Child stated that the “ultimate aim in addressing the fate ofunaccompanied or separated children is to identify adurable solution[emphasis added] that addressesall their protection needs, takes into account the child’s view and, wherever possible, leads toovercoming the situation of a child being unaccompanied or separated.”64As opposed to short-termmeasures such as emergency assistance, reflection periods or temporary residence permits, a durablesolution is oriented towards longer-term objectives that ensure the child’s safety and promote his orher development.65

part iii:guiding principles of the convention on the rights of the child

17

In an effort to ensure more systematic identification of durable solutions, the Committee of Ministersof the Council of Europe adopted a recommendation on ‘life projects’ in 2007 that called upon memberStates to strengthen their policies and practices in responding to the situation of unaccompaniedmigrant children.66The ‘life project’ is an individual tool designed to help unaccompanied childrenand competent State authorities to jointly confront the challenges that result from the child’s migration.Stronger consideration of implementation of the Council of Europe recommendation, in light of theinternational standards that it refers to, would help to shape more systematic and rights-basedapproaches to assisting vulnerable migrant children, including victims of trafficking.The right of the child to have his or her views heard and taken into accountThe Convention on the Rights of the Child imposes legal obligations on states to ensure that a childwho is capable of forming his or her views has the right to express those views in all matters affectinghim or her, and that these views be given due weight in accordance with the age and maturity of thechild. This right has been enshrined in numerous sectoral national laws and policies in the Nordiccountries. The study found that the practical application of this principle was inconsistent, however,notably in regard to the judicial and administrative proceedings and services provided to traffickedand potentially trafficked children. This includes issues related to deprivation of liberty, court hearings,opportunities for employment, and return or transfer to countries of origin or other countries, particularlyunder the ‘Dublin II Regulation’.Decentralization poses particular challenges to the consistent implementation of a child’s right tobe heard. Feedback from Denmark, Norway and Sweden has highlighted concerns about gapsin the systematic recognition of this right at the local level, particularly in cases relating to care andimmigration issues.67The Committee on the Rights of the Child noted that in Finland, in somecases a child’s views were related to the court by a third party, with the risk that the third partyhad not consulted with the child before submitting these views to the court.68A useful example ofhow application of the child’s right to be heard may be improved comes from Sweden. Whenevera judgement or ruling that affects children is made, the court or government agency is requiredto explain how they have assessed the investigation. At present, however, they are not similarlyrequired to explain how the views of the child have been taken into account.69Addressing this gapwould appear a relatively easy matter since it involves a small modification to an existing process.Other countries may wish to consider adopting a similar requirement.In relation to the provision of services, in Norway, for example, children designated as potentialvictims of trafficking cannot refuse the assistance offered.70By contrast, children in Finland arefree to choose whether they wish to accept or decline the services available to victims of trafficking.71Children without a valid permit of stay who decline these services will remain in the reception centrefor asylum-seekers and receive the general assistance available to children seeking asylum.Different age limits have been defined in relation to the right of the child to be heard in judicial andadministrative procedures. As a result, the right of younger children to be heard is not addressed inthe same way as the right of adolescents.72Specific concerns in several countries were also notedin regard to the role of interpreters.73In Sweden, for example, problems included inaccurate translations,editing of responses, and even pressure exerted by interpreters on the children. A lack of sufficienttraining for interpreters, for example on asylum procedures, was also noted.74In Norway, concernswere raised by the Norwegian Ombudsman for Children about difficulties in gaining access toqualified interpretation services for children who do not speak or understand Norwegian.75

18

child trafficking in the nordic countries

Confirmation of these concerns about children’s views not being taken into account by authoritiescomes from one of the few documents identified in this study that emphasized the views of children.Twenty asylum-seeking children interviewed by the Swedish Committee for UNICEF reported thatthey had not been consulted or listened to during the asylum procedure, and in many instanceshad not received information about their rights in relation to the asylum procedure, access to healthservices and education at school.76Notwithstanding the above responses, surprisingly little information is available from the Nordiccountries on how children are consulted on the services available to them, how they perceive theseservices, how they view their situations, and the aspirations guiding their decisions and actions.The creation of standard procedures to address child participation across all relevant sectors mayhelp to overcome these challenges. Areas addressed by these procedures might include: participationin court proceedings; use of interpreters; and measures to ensure children’s views are taken intoaccount with regard to services provided, Best Interests Determinations and decisions on return.Child-sensitive complaint mechanismsGiven the gaps and difficulties in the practical implementation of the child’s right to be heard,the lack of easily accessible child-sensitive complaint mechanisms across the Nordic region is ofconcern. The main barrier does not appear to be a lack of suitable institutions, but rather that theseinstitutions follow processes that are not particularly appropriate for children.Functioning national human rights structures are already in place in the Nordic countries, includingombudspersons for children and parliamentary ombudsmen. The exception is Denmark, wherethe National Council for Children acts as an independent body for children’s rights. However, noneof the ombudspersons for children in the Nordic countries are mandated to receive individualcomplaints, a source of repeated criticism from the Committee on the Rights of the Child. Whileparliamentary ombudsmen in all of the countries may receive individual complaints on violationsof children’s rights, before a complaint can be lodged, the complainant needs to seek administrativeredress through the relevant national authorities, ministries, or specialized appeals bodies.77Thiscondition poses significant obstacles to children who wish to lodge a complaint on their own initiative.These issues are recognized within the countries themselves. Numerous institutions and organizationshave called for the establishment of easily accessible and child-sensitive reporting and complaintmechanisms where children can seek information, advice and counselling.78As well as upholding thechild’s right to be heard, effectively functioning mechanisms are likely to provide new and relativelyup-to-date information on problems and gaps in current responses. With this in mind, governmentsthroughout the Nordic region are encouraged to view this as a priority.The right of the child to life, survival and developmentThe Committee on the Rights of the Child has stated that the right to life, survival and development“can only be implemented in a holistic manner, through the enforcement of all the other provisions ofthe Convention, including rights to health, adequate nutrition, social security, an adequate standardof living, a healthy and safe environment, education and play.”79While this section has a primaryfocus on education and health, these issues are briefly discussed throughout the study.While the right of the child to education is subsumed under the right to life, survival and development,it is also specifically recognized in articles 28 and 29 of the Convention. The study highlighted

part iii:guiding principles of the convention on the rights of the child

19

difficulties in policy and practice with regard to access to education for children who are undocumentedor irregular migrants, asylum-seeking children and children whose asylum claims have been denied.For example, while asylum-seeking children, including child victims of trafficking who are assisted atasylum reception centres, have the right to access school education, concerns were expressed thatthe quality of education offered in reception centres is significantly lower than in public schools. InDenmark, for example, national non-governmental organizations (NGOs) have noted that the level ofeducation in reception centres may not be comparable to the standard of regular education, whichwould facilitate children‘s integration into the mainstream education system.80Across the region the responsibility for organizing school education, including for asylum-seekingchildren, lies with the municipal authorities and is often subject to their discretion.81Reports existof children with undocumented status being excluded from school, while research from Denmark,Finland and Norway shows that many non-national children, including in some cases traffickingvictims, are not consistently guaranteed access to education of a quality commensurate with thatafforded to local children.82Similar difficulties were noted with regard to the responsibility to provide children with “the highestattainable standard of health”, as recognized in the Convention. In all the Nordic countries, accessto emergency health care is guaranteed for every child.83Provisions regulating the access ofnon-national children to more comprehensive medical treatment differ, however, and problemswith implementation at the local level are reported from several countries. Differences were noted inSweden, for example, in the ways in which asylum-seekers and undocumented migrants are grantedaccess to health services at the local level, based on local interpretations of national guidelines.84Similar concerns have been expressed in Denmark and Norway.85In Finland, non-national children may access health care under the same conditions as Finnishcitizens and permanent residents, only after having obtained a residence permit.86Further, whiletrafficked children have access to mental health care through the Children’s House (described inPart V) there are few services for mental health care or therapy for child asylum-seekers.87

20

child trafficking in the nordic countries

Box 2: Representation and guardianship88In all of the Nordic countries, the system of guardianship is administered primarily by public authorities.Guardians or representatives of non-national children (including unaccompanied children and childvictims of trafficking) hold a key function in representing non-national children in specific situations.A strong guardianship system is thus important to ensure that the views of each child are heardand taken into account, that their best interests are respected, and that services provided to child-ren contribute to durable solutions in line with the child’s right to life, survival and development. Theissue of non-discrimination based on status is also relevant in this context.The study identified a number of issues with regard to existing guardianship arrangements. InDenmark, for example, the appointment of a guardian is obligatory for unaccompanied children whoare victims of trafficking, but optional for unaccompanied asylum-seeking children. The situation wassimilar in Finland until 1 September 2011, when a change in the law made guardianship mandatoryfor unaccompanied asylum-seeking children.89In Denmark, guardians appointed for child victimsof trafficking are paid professionals, while the comparable support persons for unaccompaniedchildren work as volunteers. They do not receive a salary and, in some cases, even meet expensesfrom their own pockets.90In Sweden, consultations in the context of the development of theUNICEF Guidelines on theProtection of Child Victims of Traffickingwere instrumental in clarifying that the existing guardianshipsystem applies equally to all children, irrespective of their status.91Prior to this, professionalswere left without clear instructions on what to do when a child victim was in need of a guardian butnot seeking asylum. There is now a uniform system of guardianship in Sweden, as well as Iceland,that covers all unaccompanied children, irregular migrant children and victims of trafficking.In recent years Sweden has, however, experienced a large increase in asylum applications fromunaccompanied children. Save the Children reported in 2011 that a guardian is not always appointedpromptly and, in some cases, children may have to wait for several weeks or a couple of months.92Problems were also noted in Finland, where it was reported that “some of the persons appointed asrepresentatives have had no contact with social welfare or child welfare work and do not necessarilyeven have an understanding of the asylum process.”93In Norway, a guardian is appointed to support all children, independent of their age, during theasylum process. The guardian is paid for participation in interviews and has expenses covered.There is no difference between victims and non-victims of trafficking as long as they are seekingasylum; however, no information was obtained about arrangements for children who do not fit intoeither of these categories.94The study also found that the use of volunteer guardians creates difficulties in ensuring appropriatetraining and qualifications. Further, in at least one country (Finland), the laws regulating thescreening of a person for a possible criminal record do not apply to volunteers who will be workingwith and for children.95It may be useful for Nordic countries to review the system of guardianship/representation with a view to confirming and addressing such issues, to ensure the system providesgood quality and non-discriminatory support for non-national children.

part iii:guiding principles of the convention on the rights of the child