Udenrigsudvalget 2011-12

URU Alm.del Bilag 65

Offentligt

sECuriTY WiTHHuMaN riGHTs

sauDI arabIa

rEPrEssiONiN THE NaMEOF sECuriTY

amnesty international is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters,members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaignto end grave abuses of human rights.Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the universaldeclaration of Human rights and other international human rights standards.We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest orreligion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations.

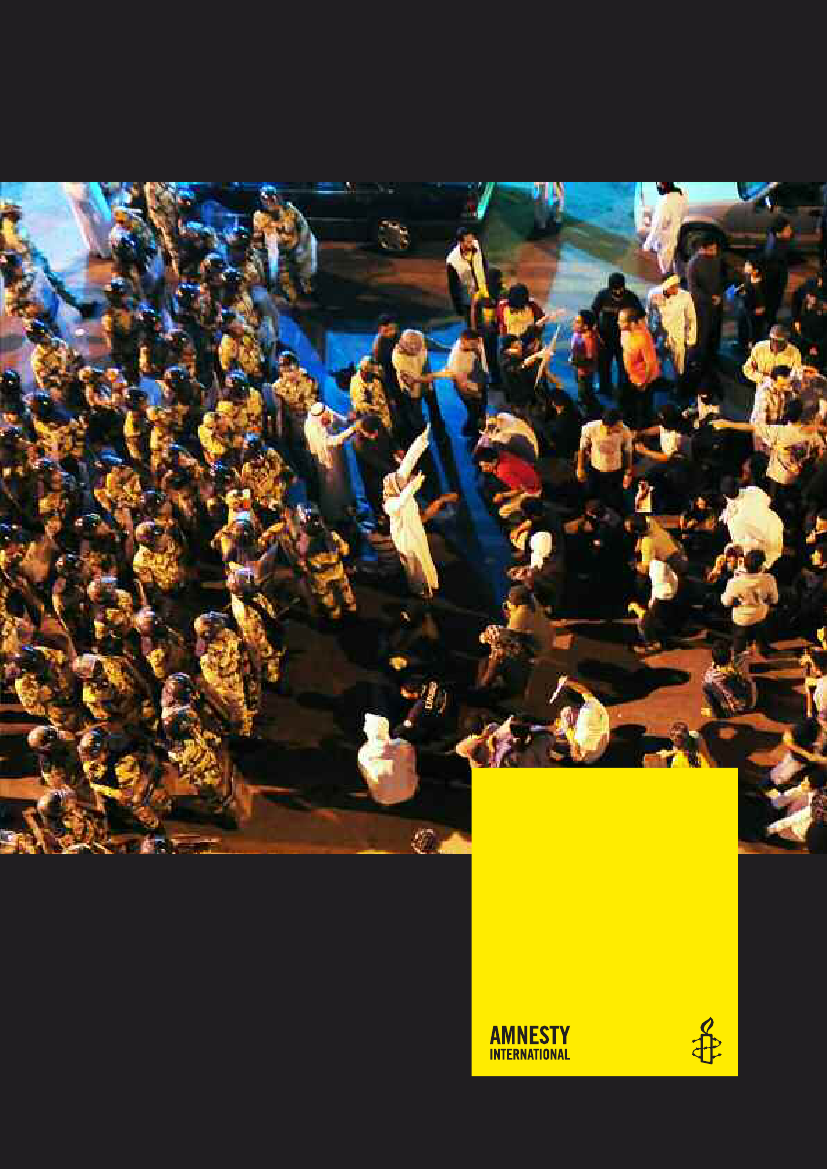

First published in 2011 byamnesty international LtdPeter benenson House1 Easton streetLondon WC1X 0dWunited Kingdom� amnesty international 2011index: MdE 23/016/2011 EnglishOriginal language: EnglishPrinted by amnesty international,international secretariat, united Kingdomall rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but maybe reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy,campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale.The copyright holders request that all such use be registeredwith them for impact assessment purposes. For copying inany other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications,or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission mustbe obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable.To request permission, or for any other inquiries, pleasecontact [email protected]Cover photo:anti-riot police in a stand-off with protestersin awwamiya, a town in the Eastern Province of saudi arabia,March 2011. The protesters were demanding the release ofshi'a prisoners being held without charge or trial since the1990s. � rEuTErs/Zaki Ghawas

amnesty.org

CONTENTS1. Introduction.............................................................................................................3Amnesty International’s work ......................................................................................52. Draft anti-terror law...................................................................................................7Law in preparation .....................................................................................................7Threat to human rights ...............................................................................................9a) Vague and broad definition of terrorism offences....................................................9b) Unlawful restrictions on freedom of expression ....................................................10c) Lack of definitions for key terms.........................................................................12d) Violations of rights of detainees..........................................................................12e) Broad Interior Ministry powers without judicial supervision....................................15f) Wide scope for the death penalty ........................................................................16Conclusion..............................................................................................................163. Detentions and trials in the name of counter-terrorism................................................18Offical figures .........................................................................................................18Prolonged detention without charge or trial.................................................................20Unfair trials ............................................................................................................26Case study I: Reformists...........................................................................................29Case study II: Abdullah Abu Bakir Hassan and Abdel Hakim Gellani .............................35“Counselling” programme.........................................................................................384. Crackdown on freedom of expression.........................................................................40Repression of protests ..............................................................................................41

a) Protests by members of the Shi’a minority...........................................................41b) Other protests ..................................................................................................43Arrests of advocates of reform ...................................................................................475. Recommendations..................................................................................................51To the Saudi Arabian government ..............................................................................51To the UN and international community.....................................................................52Endnotes ...................................................................................................................53

Saudi Arabia:Repression in the name of security

3

1. INTRODUCTION“I am here to say we need democracy. We needfreedom. We need to speak freely. We need noone to stop us from expressing our opinions.”Khaled al-Johani speaking to reporters at a protest where no one but he turned up on 11 March 2011 and was arrested shortly after.

Since March 2011 the Saudi Arabian authorities have launched a new wave of repression inthe name of security. They have cracked down on demonstrators protesting over human rightsviolations in the context of calls for reform at home and the uprisings and mass protests inthe region. At the same time, they are in the process of creating a new anti-terror law whichthreatens to exacerbate an already dire situation for freedom of expression, in which any realor perceived dissent is almost instantly suppressed. It would also legalize a number ofabusive practices including arbitrary detention, thus consolidating draconian and abusivecounter-terrorism measures imposed since 2001 against the backdrop of an extremely weakinstitutional framework for the protection of human rights.State power in Saudi Arabia rests almost entirely with the King and the ruling Al Saud family.The Constitution1gives the King absolute power over government institutions and the affairsof the state,2and severely curtails political dissent and freedom of expression.3The country’s27 million4residents have no political institutions independent of government, and politicalparties and trade unions are not tolerated. The media is severely constrained and those whoexpress dissent face arrest and imprisonment, whether political critics, bloggers oracademics. King Abdullah announced on 25 September 2011 that women will have the rightto vote and run in municipal elections, the kingdom’s only public poll, from 2015 and beappointed to the Shura Council, a body that advises the monarchy. However, women remainsubject to severe discrimination in both law and practice. Women are unable to travel, engagein paid work or higher education, or marry without the permission of a male guardian.5It is against this background that some Saudi Arabians have been insisting publicly that it istime for change and for their human rights to be respected. Many have tried to assert theirright to peaceful protest on the streets. Some have demanded political and social reforms;others have called for the release of relatives detained without charge or trial on terrorism-related grounds. In response, the security forces have arrested hundreds of people forprotesting or voicing their opposition to government policies this year. Most have beenreleased without charge; others remain in detention without charge or trial; and others stillhave been charged with vague security-related and other offences. Amnesty Internationalconsiders many of those detained to be prisoners of conscience, held solely for peacefullyexpressing their rights to freedom of expression and assembly.

Index: MDE 23/016/2011

Amnesty International December 2011

4

Saudi Arabia:Repression in the name of security

The formulation of a new anti-terror law is another apparent sign of the authorities’ to use thelaw to silence discontent in the Kingdom. A copy of the draft law was leaked to AmnestyInternational in late June 2011. Among other things, it would provide for the prosecution ofacts of peaceful dissent as a “terrorist crime” such as “harming the reputation of the state orits position”. Questioning the integrity of the King or the Crown Prince would be punishableby a minimum of 10 years in prison. The law would also give the authorities carte blanche todetain security suspects indefinitely without charge or trial. The draft law has been criticizedby members of civil society in Saudi Arabia who see it as an attempt to justify the arrest,detention and punishment of pro-reform activists. Adapting the mantra repeated throughoutthe region during mass protests this year - “the people want to overthrow the regime” - oneactivist in Saudi Arabia said in reference to the draft law that “the regime wants to arrest thepeople”.Thousands of people have been detained in the past decade on security grounds, many ofwhom remain behind bars. Among them are clerics and people suspected of belonging to orsupporting armed Islamist groups such as al-Qa’ida or other groups opposed to the SaudiArabian government or its links with the West. Typically, they have been detained for monthsin conditions of virtual secrecy, held without charge or trial for years and without any meansof challenging their detention. Most have been held initially in prolonged incommunicadodetention for interrogation for varying periods and have subsequently at times been deniedaccess to lawyers, medical assistance and family visits. Some, it appears, have been tried insecret and sentenced to prison terms. Some have been held for “re-education”.Torture and other ill-treatment facilitated by incommunicado detention remain rife becauseinterrogators know that they can commit their crimes without fear of punishment. The abuseis also encouraged by the ready acceptance by courts of “confessions” forced out ofdetainees using beatings, electric shocks and other forms of torture and other ill-treatment.Those who have been charged with security-related offences and brought to trial have facedgrossly unfair and in many instances secret proceedings. Since its establishment in October2008 such trials have generally been heard by the Specialized Criminal Court.Caught up in the sweeping repression are an unknown number of human rights defenders,peaceful advocates of political reform, members of religious minorities and many others whohave committed no internationally recognized offence. At least some of them are prisoners ofconscience.Saudi Arabia has witnessed sporadic incidents of political violence over the years, with stateinstitutions, oil installations and Western nationals the most common targets. AmnestyInternational has repeatedly and unreservedly condemned killings and other abuses by armedgroups and individuals in Saudi Arabia, and called for the perpetrators to be brought tojustice in accordance with international standards and without recourse to the death penalty.It has also appealed to armed groups to respect the humanity of all individuals, and urgedthem to respect international law and standards that prohibit abuses such as the targeting ofcivilians and hostage-taking.Amnesty International fully recognizes the duty and responsibility of the Saudi Arabianauthorities to protect the public from violent attacks, including by bringing to justice people

Amnesty International December 2011

Index: MDE 23/016/2011

Saudi Arabia:Repression in the name of security

5

involved in such attacks. However, the Saudi Arabian authorities must at all times complywith their obligations under international human rights law and never violate the rights ofsuspects. Combating terrorism and other threats against public safety must not be used as apretext or justification for violations of human rights or for allowing officials to commit suchviolations with impunity.

AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL’S WORKResearching human rights in Saudi Arabia is extremely difficult. The government does notallow Amnesty International to visit the country to research human rights issues; many otherinternational observers have similar access problems. The state and its justice system operatelargely in secret, and the media is severely censored and otherwise constrained. Independenthuman rights organizations and other NGOs are not permitted to operate freely,6and civilsociety remains weak because of government repression. As a result, little information isrecorded or published about human rights. Websites of organizations critical of the SaudiArabian authorities have been blocked at times inside the country. After AmnestyInternational published a copy of the draft anti-terror law along with its concerns about it, itswebsitewww.amnesty.orgwas reportedly blocked within Saudi Arabia for around a week.7The block appeared to be lifted after the blocking was widely reported in the internationalmedia and social media sites.

Screenshot of web page that appeared when internet users attempted to access Amnesty International’s websitewww.amnesty.orginside Saudi Arabia after the organization published the draft anti-terror law on it � Private

This report is based on information divulged to Amnesty International by people in SaudiArabia and Saudi Arabians or foreign nationals, including former prisoners, who have left thecountry. It is also based on government statements, where they exist, local and internationalmedia reports and other research carried out despite the obstacles.

Index: MDE 23/016/2011

Amnesty International December 2011

6

Saudi Arabia:Repression in the name of security

The report follows up on issues covered in Amnesty International’s 2009 publication,SaudiArabia: Assaulting human rights in the name of counter-terrorism.8It updates cases andtrials covered in that report, and includes information on new cases that have emerged since2009 and others from previous years that have been brought to the organization’s attentionsince 2009. It also covers the crackdown on protests since early 2011.Amnesty International regularly writes to the Saudi Arabian authorities about its concerns andto seek permission to visit the country, including to observe trials of security detainees, butgenerally does not receive substantive responses. On 26 August 2011 Amnesty Internationalsubmitted a memorandum to the Saudi Arabian government to seek clarifications on theconcerns and cases raised in this report. The government replied with a letter dated 20September 2011 focusing on its concerns about Amnesty International’s publication of aleaked copy of the draft anti-terror law and clarifying some aspects of the legislative processwith respect to the law (see Chapter 2: Draft anti-terror law for further details oncommunication between Amnesty International and the Saudi Arabian government on thisissue). The letter did not, however, provide any response to the memorandum’s request forinformation and comments on the issues and cases in this report. Amnesty International sentanother letter to the Saudi Arabian government on 20 November, reminding it of theoutstanding request and providing additional time for a response, but had not received anyfurther reply as of writing.Amnesty International is publishing the information in this report to puncture the wall ofsecrecy around the gross and widespread human rights violations being committed in SaudiArabia, and to help stop these violations. To this end, Amnesty International is calling on theSaudi Arabian authorities to take urgent action, including to:

immediately release all prisoners of conscience, such as those held solely for thepeaceful exercise of their rights to freedom of opinion, expression, assembly or association;end all arbitrary arrests and detentions;

provide prompt and public trials meeting international standards of fairness withoutrecourse to the death penalty to all detainees charged or held, including on suspicion ofterrorism-related offences, or else release them;investigate thoroughly and independently all allegations of torture and other ill-treatmentand bring those found responsible to justice;

considerably amend the draft Penal Law for Terrorism Crimes and Financing of Terrorismand bring all of Saudi Arabia’s terrorism-related laws and practices into line withinternational human rights law and standards.

Amnesty International December 2011

Index: MDE 23/016/2011

Saudi Arabia:Repression in the name of security

7

2. DRAFT ANTI-TERROR LAWLAW IN PREPARATIONThe draft Penal Law for Terrorism Crimes andFinancing of Terrorism, as the new draft anti-terror lawis formally known, was prepared initially by theMinistry of Interior and then reviewed by the ShuraCouncil, which can recommend amendments to draftlaws but has no binding legislative powers. Althoughthe text of the law has been kept confidential, asusually happens with draft legislation in Saudi Arabia,in late June 2011 sources within Saudi Arabia leakeda copy of what was believed to be the then latestversion of the draft to Amnesty International. Theyalso leaked a report on the draft law prepared by theCommittee on Security Affairs of the Shura Council.9The preparation of the draft law comes against thebackdrop of a number of other security-related lawsFirst page of draft anti-terror lawissued by royal decree in recent years. They include� Amnesty International10laws governing offences related to explosives, andarms and ammunitions,11as well as two on money laundering and IT offences in which“terrorism” is mentioned but not defined.12Saudi Arabia’s legal system contains no writtencriminal code, but is rather largely based on an uncodified form of Shari’a, as interpreted bythe country’s judges.The sources who leaked the draft law said they did so because, despite the risks tothemselves of taking such action, they believed that the law went far beyond the frameworkof legitimate measures to combat terrorism and so needed to be exposed to public debate.Amnesty International analysed the draft in detail and came to the conclusion that the lawrisked entrenching existing patterns of human rights violations in the context of counteringterrorism and providing a further tool to suppress peaceful political dissent at a time whenpeople were taking to the streets across the Middle East and North Africa to demand greaterfreedoms.Amnesty International was also concerned that the virtual secrecy surrounding thepreparation of the law was denying people in Saudi Arabia the opportunity to debate animportant development that was a matter of genuine and wide public interest. In thisconnection, it is relevant to note the view of the Special Rapporteur on the promotion andprotection of human rights and fundamental freedoms while countering terrorism, MartinScheinin, who wrote in 2010 that the implications of counter-terrorism legislation were so“potentially profound” that governments should “seek to ensure the broadest possiblepolitical and popular support for counter-terrorism laws through an open and transparentprocess.”13

Index: MDE 23/016/2011

Amnesty International December 2011

8

Saudi Arabia:Repression in the name of security

Amnesty International published the draft law, along with a summary of its concerns(detailed later in this chapter) and the report of the Shura Council’s Committee on SecurityAffairs, on 22 July 2011, writing to the Saudi Arabian government the day before to requestinformation on the status of the law.14Its aim was to try and ensure that these concerns weremade known and considered in the context of a public debate in Saudi Arabia. The report ofthe Shura Council’s Committee on Security Affairs reveals that some Saudi Arabianauthorities, including the Ministry of Justice, the Human Rights Commission and the PublicProsecution, had raised concerns themselves about, for instance, the detention proceduresprovided for in the draft.The authorities replied in a letter dated 24 July in which they described the concerns as“baseless, mere supposition and without foundation”, but neither addressed the substance ofthe concerns nor provided further details on the process or timeline which would lead to thelaw being brought into force.15Similar messages were given at a meeting between AmnestyInternational and the Saudi Arabian embassy in London on 29 July. Amnesty Internationalpublished the letter of 24 July at the authorities’ request, along with its response to it.16On 26 August Amnesty International submitted a memorandum to the government in which,as well as raising other human rights issues, it asked again for clarification on the status ofthe law and whether concerns raised about the draft were being taken into consideration. Thegovernment sent a response dated 20 September 2011 in which it provided a number ofdetails related to the progress of the draft law:1. The draft law was submitted to the Shura Council in 72 articles and referred tothe Committee on Security Affairs for review. The committee held a series ofmeetings to discuss the draft, interviewed government agencies, experts and subjectspecialists, and submitted a detailed report to the Council.2. During a further series of discussions, 85 interventions to the law was raised.3. Among the changes made were the deletion of 15 draft articles relating to penallaw for crimes of terrorism and terrorist financing. Amendments were also made to31 articles, including those relating to investigations, the issue of contact with thefamily of accused persons, and a reduction in the duration of initial detention.4. The Council highlighted in its amendments the difference between crimes ofterrorism, state crimes, and other crimes.5. The final draft approved by the Board comprises 58 articles. The Kingdom wouldlike to point out that the threat of terrorism is a global issue and remains a seriouschallenge for all governments. We will continue to tackle this threat to the securityof our country in every way necessary.17The letter repeated its view that Amnesty International had behaved improperly, saying that ithad “published an unfair analysis” of the draft law which had generated “inflammatory,baseless remarks about the content of the document”. The letter did not, however, providethe latest draft text of the law, making it impossible to assess the amendments that had beenmade. Neither did it clarify whether the law had been finalized or remained in draft form and,

Amnesty International December 2011

Index: MDE 23/016/2011

Saudi Arabia:Repression in the name of security

9

if so, what the process still to be followed was. Amnesty International’s understanding is that,once a final draft is completed, it would have to be approved by the King as the head of theCouncil of Ministers and head of state before the law comes into effect. This could happenimminently.

THREAT TO HUMAN RIGHTSThe Saudi Arabian government has told Amnesty International that the “fight againstterrorism requires appropriate legislation” and has justified the draft law and its provisions byreferring to the need to ensure security and pointing to the challenges faced by Saudi Arabiain relation to terrorism.18Amnesty International fully recognizes that Saudi Arabia has suffered serious attacks byarmed groups in recent years and continues to face security concerns and that thegovernment has a responsibility to ensure public safety in the face of threats of such actsoccurring in the future. It condemns all violent attacks targeting civilians unreservedly andcalls for those responsible to be brought to justice. Amnesty International acknowledges thatthe authorities can and should take measures to counter such attacks, but contends thatwhen doing so they must adhere to their obligations under international law, including theinternational human rights treaties to which Saudi Arabia is party, such as the UNConvention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment orPunishment.In setting out its counter-terrorism strategy, the UN General Assembly has adopted a similarapproach:The promotion and protection of human rights for all and the rule of law is essentialto all components of the Strategy, recognizing that effective counter-terrorismmeasures and the protection of human rights are not conflicting goals, butcomplementary and mutually reinforcing…19Amnesty International considers that the version of the draft law that it has seen is seriouslydeficient in a number of respects. Below are some of the key concerns that the organizationhas identified about the text of this version.

A) VAGUE AND BROAD DEFINITION OF TERRORISM OFFENCESThe definition of terrorism offences in the draft law is so vague and broad that it lends itselfto abuse. Article 1 defines “the crime of terrorism”:a) The crime of terrorism:All crimes referred to in this law and all actions taken by the accused through wordsor action in the pursuance of a personal or collective enterprise aimed atundermining the public policy of the state; destabilizing society or the security ofthe state; endangering its national unity; revoking the Basic Law of Governance orsome of its articles; harming the reputation of the state or its standing; damaging itsinfrastructure or natural resources; or threatening to carry out actions that lead tothe above mentioned aims.

Index: MDE 23/016/2011

Amnesty International December 2011

10

Saudi Arabia:Repression in the name of security

The crime of terrorism includestakfeerof the state [deeming the state an infidelstate] and adopting the approach oftakfeer[deeming others as infidels] that leadsto committing a terrorist crime or inciting it, as well as anything that is likely toproduce intellectual or doctrinal bases to justify these crimes or to promote theseideas or to incite them or to publish material or information that incites or leads tothe implementation of a terrorist activity.20Under international law, the definition of crimes has to be clear and narrowly defined. In thecontext of national security laws, the UN Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protectionof human rights and fundamental freedoms while countering terrorism has explained that theprinciple of legality (the requirement that crimes must be enshrined in laws that are clear,ascertainable and predictable21) means that legal provisions “must be framed in such a waythat: the law is adequately accessible so that the individual has a proper indication of howthe law limits his or her conduct; and the law is formulated with sufficient precision so thatthe individual can regulate his or her conduct.”22Analogously, the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention has expressed particular concernabout “extremely vague and broad definitions of terrorism in national legislation”, stating,“[i]n the absence of a definition of the offence or when the description of the acts oromissions with which someone is charged is inadequate… the requirement of a precisedefinition of the crimes - the key to the whole modern penal system – is not fulfilled and thatthe principle of lawfulness is thus violated, with the attendant risk to the legitimate exerciseof fundamental freedoms.”23In contrast, the draft law, while it criminalizes some well-defined acts such as hostagetaking,24provides a general definition of terrorist crimes which is extremely vague and broadand not restricted for example to acts of violence against members of the general public. Thevague acts criminalized by the definition in Article 1 include “destabilizing society”,“endangering… national unity”, “revoking the Basic Law of Governance” and “harming thereputation of the state”.

B) UNLAWFUL RESTRICTIONS ON FREEDOM OF EXPRESSIONThe draft law contains numerous provisions that either restrict the legitimate exercise offreedom of expression or may be used as a convenient vehicle to criminalize dissent orcriticism of the authorities or even calls for reform, and could be used to punish the peacefulexpression of opinions under the pretext of protecting security.For example, under Article 1 an action which is deemed by the authorities as “harming thereputation of the state” may be considered as “terrorism”. Since under the same article it isalso considered “terrorism” to “publish material or information that incites or leads to theimplementation of a terrorist activity”, it appears to follow that publication of criticism of theauthorities may be deemed to be an act of “terrorism”.Under Article 29 “anyone who describes the King – or the Crown Prince – as an infidel,questions his integrity or defames his trustworthiness, or revokes his allegiance [to the King]or incites this” shall be “punished with a prison term of no less than 10 years”.

Amnesty International December 2011

Index: MDE 23/016/2011

Saudi Arabia:Repression in the name of security

11

Under Article 45 “anyone who intentionally broadcasts – for the purpose of committing aterrorist crime by any means – a news item, a statement or a false or tendentious rumourlikely to stir up people or spread panic among them or shake the confidence of citizens in thestate or the King or the Crown Prince” shall be “punished with a prison term of no less thanthree years”.Under Article 51 “anyone who publicly transgresses on any of the established principles ofShari’a or the established principles of the legitimacy of the state, if this was likely to upsetstability or lead to a terrorist crime” shall be “punished with a prison term of no less than 10years”.These articles explicitly provide for restrictions on peaceful dissent and other limitations onfreedom of speech which are not allowed under international human rights law andstandards. Those provide only for narrowly defined restrictions for considerations of respect ofthe rights or reputations of others, the protection of national security, public order, publichealth or morals and the prevention of incitement to discrimination, hostility, violence andwar propaganda.25Other articles of the draft law refer to terrorist offences which by their nature are too broadand vague and as such may also have the impact of restricting freedom of expression. Forexample, under Article 44 “anyone who openly praises a terrorist crime” shall be “punishedwith a prison term of no less than two years”. Likewise, “anyone who promotes – orally or inwriting by any means – a terrorist crime or any matter contrary to the Kingdom’s politicalapproaches or any idea that affects national unity or calls for sedition or shakes nationalunity” shall be “punished with a prison term of no less than five years”. Article 52criminalizes the holding of meetings “to plan a terrorist act”. Since “the crime of terrorism”under the draft law includes peaceful expressions of dissent, holding peaceful politicalmeetings could be deemed to come within the definition of a “terrorist crime”.One of the articles that the Committee for Security Affairs of the Shura Council proposedremoving when it reviewed the draft law is Article 47, under which “anyone who organizes ademonstration, participates in its organization, assists it, calls for it, or incites it” shall be“punished with a prison term of no less than three years” and “anyone who raises a slogan orimage likely to infringe upon the country’s unity or its safety or to call for sedition anddivision and disunity among individuals in society, or incites such acts” shall be “punishedwith a prison term of no less than seven years”. It is not clear, however, if the proposedremoval of the article has been or will be accepted or rejected.The proposed restrictions in the draft law come in a context of increasing constraints onfreedom of expression in Saudi Arabia. On 29 April 2011, the authorities amended thePrinting and Publications Law of 2000.26The amendments include new restrictionsprohibiting the publication of anything that “contradicts rulings of the Shari’a or regulationsin force”, “calls for disturbing the country’s security, or its public order, or serves foreigninterests that contradict national interests”, “causes sectarianism or that spreads divisionsbetween citizens” or “damages public affairs in the country”. They also include a prohibitionon violating the “reputation or dignity” of the Grand Mufti, members of the Council of SeniorUlema (Religious Scholars), or any other government official or government institution, aswell as on slandering or libelling them, and on publishing without official consent

Index: MDE 23/016/2011

Amnesty International December 2011

12

Saudi Arabia:Repression in the name of security

proceedings from any investigations or court trials.27A decree issued three months earlierhad already extended provisions of the Printing and Publications Law to onlinecommunications.28

C) LACK OF DEFINITIONS FOR KEY TERMSWhile instances of “the crime of terrorism” are defined, albeit in broad and excessive terms,as described above, the draft law contains key terms that have not been defined at all,leaving room for abusive application, in particular against groups engaged in peacefuldissent.For example, the draft law fails to define what constitutes a “terrorist group”, “a terroristorganization”, “a terrorist gang” and “a terrorist entity” despite the fact that it containsseveral provisions to which these terms are central. Article 43 criminalizes the setting up ofwebsites to “facilitate communication with the leaderships of terrorist organizations or any oftheir members or to promote their ideas”. The offence carries a prison term of at least 15years. Under Article 44, anyone who praises or promotes a terrorist crime “or any mattercontrary to the Kingdom’s political approaches” is to be sentenced to no less than 10 years’imprisonment “if he is connected to a terrorist group or organization” – otherwise thepunishment is five years. Article 52 similarly criminalizes holding “a meeting with membersof any terrorist organization, group or gang or any other terrorist entity – of whatever kind… topursue a terrorist purpose, to harm the country and its security, to shake its stability orreligious standing, or to damage its international relations”.This opaqueness could be exploited to charge peaceful meetings of a group of people whomake political demands or even engage in academic discussions with a “terrorist crime”under this draft law.Another term for which no definition is provided for in the draft law istakfeer(deemingothers as infidels). While it is true that stating that someone is an infidel can have seriousrepercussions for the person regarded as an infidel, the draft law does not define what wouldamount totakfeer.

D) VIOLATIONS OF RIGHTS OF DETAINEESThe draft anti-terror law provides for measures constituting serious violations of the rights ofdetainees.The draft law explicitly provides for prolonged, indeed indefinite, incommunicado detention.Under Article 9 the “investigating authority” may “prohibit contact with the suspect for aperiod not exceeding 120 days if the interest of the investigation requires it”. The mattermust be raised with the Specialized Criminal Court if the investigating authority requests “alonger period”, at which point the Court “decides as it deems appropriate”. No restrictions onthe length of such an extension is provided for.The Saudi Arabian government has explained to Amnesty International why the draft law“gives judges discretion over the reporting of the detention of a suspected terrorist and thecircumstances in which such a suspect can be held in prison prior to trial”:For those who work in counter-terrorism, the reasons for this are clear. There are

Amnesty International December 2011

Index: MDE 23/016/2011

Saudi Arabia:Repression in the name of security

13

cases in which revealing that a suspect has been apprehended could undermine anongoing operation against a larger terrorist cell and thus seriously damage counter-terrorism efforts.29There can, however, be no justification for provisions which would allow for incommunicadodetention for periods up to 120 days, let alone for an indefinite period. The UN GeneralAssembly has stated that “prolonged incommunicado detention or detention in secret placescan facilitate the perpetration of torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment orpunishment and can in itself constitute a form of such treatment,”30the UN Human RightsCommittee has stated that provisions should be made against the use of incommunicadodetention,31and the UN Committee against Torture has consistently called for itselimination.32The UN Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degradingtreatment or punishment, recognizing that “torture is most frequently practised duringincommunicado detention”, has also called for such detention to be made illegal.33In the words of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights:The mere subjection of an individual to prolonged isolation and deprivation ofcommunication is in itself cruel and inhuman treatment which harms thepsychological and moral integrity of the person, and violates the right of everydetainee under Article 5(1) and 5(2) to treatment respectful of his dignity.34In 2001, referring to allegations of torture by Israeli security forces, the Special Rapporteuron torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment stated thefollowing:The Special Rapporteur accepts that not all allegations [of torture] will be wellfounded. Nevertheless, as long as the Government continues to detain personsincommunicado for exorbitant periods, itself a practice constituting cruel, inhumanor degrading treatment (as repeatedly confirmed by the [UN Human Rights]Commission), the burden will be on the Government to prove that the allegations areuntrue. This is a burden that it will not generally be able to dischargeconvincingly.35[emphasis added]Saudi Arabia’s Law on Criminal Procedures of 2001 introduced safeguards prohibiting tortureor degrading treatment and “bodily or moral harm” of those arrested or detained (Articles 2and 35) and requiring interrogators “not to affect the will of the accused” in making astatement (Article 102).36However, these safeguards do not appear to be enforced inpractice and have not curbed the use of torture or other ill-treatment against detainees.37Also, even though Saudi Arabia is a state party to the Convention against Torture and OtherCruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, which places an obligation on statesto take effective legislative, administrative, judicial or other measures to prevent torture asdefined in Article 1 of that treaty, including by making it a criminal offence punishable bypenalties which take into account their grave nature, the Law on Criminal Procedures doesnot define torture in terms consistent with the definition in the treaty, nor does it make it acriminal offence.38The UN Committee against Torture in its report on Saudi Arabia in 2002 stated that Saudi

Index: MDE 23/016/2011

Amnesty International December 2011

14

Saudi Arabia:Repression in the name of security

Arabia’s domestic law did not expressly reflect the prohibition on torture as laid out in theConvention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishmentand nor did it impose criminal sanctions.39The draft law also permits prolonged detention without charge or trial, effectively legalizingarbitrary detention. Under Article 8, the “investigating authority” may detain a suspect for aperiod of up to six months without charge or trial and may extend the detention for anothersix months “if the investigation procedures require that”. It may apply for a “longer period”of detention with the Specialized Criminal Court, which “decides as it deems appropriate”.Here too, no restrictions are imposed on the maximum period, raising concerns that sucharbitrary detention may be imposed indefinitely. This extends beyond the current limit ondetention without trial under the Law on Criminal Procedures, which has a maximum limit ofsix months.40The draft law’s provisions restrict detainees’ right to access legal counsel during the period ofinvestigation. Under Article 13, a suspect may appoint a lawyer to defend himself within“adequate time” prior to the case being transferred to the court. The investigating authoritydetermines what amounts to “adequate time”.Article 15 sanctions secret evidence; under this article the testimony of “experts” and“witnesses” may be heard “without the presence of the suspect and his lawyer”. The accusedis to be “informed of the content of the expert report without the identity of the expert beingrevealed”. The provision does not extend to entitling an accused person or their lawyer tocross-examine such an expert or witness, leaving the accused without access to the details ofevidence against them.Article 11(1) of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states:Everyone charged with a penal offence has the right to be presumed innocent untilproved guilty according to law in a public trial at which he has had all theguarantees necessary for his defence.Article 14 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which lists thecomponents of the right to a fair trial, stipulates, among other things:In the determination of any criminal charge against him, everyone shall be entitledto the following minimum guarantees, in full equality… to examine, or haveexamined, the witnesses against him and to obtain the attendance and examinationof witnesses on his behalf under the same conditions as witnesses against him.41Saudi Arabia is not a state party to the ICCPR. However, the principle known as “equality ofarms”, that is, the right of both sides in a court case to be treated without discrimination,including having equal access to documents and equal ability to question witnesses, hasbeen recognized as a general principle of law, that is, a procedural principle so widelyaccepted and deeply ingrained in judicial tradition and practice that it is binding on allstates, irrespective of whether or not they are parties to a treaty that provides for thisprinciple.42This principle is clearly breached by these provisions in the draft law.

Amnesty International December 2011

Index: MDE 23/016/2011

Saudi Arabia:Repression in the name of security

15

E) BROAD INTERIOR MINISTRY POWERSWITHOUT JUDICIAL SUPERVISIONThe Ministry of Interior, the instigatorof this draft law, is set to enjoy verywide powers, some of them usuallyreserved for the judiciary or the publicprosecution, if the law is passed.These wide powers range fromauthorizing the Minister of Interior “totake the necessary measures toprotect internal security from anyterrorist threat”, under Article 4, tohaving the sole say in determining if aSaudi Arabian Ministry of Interior building in Riyadh � Jon Rawlinsonsuspect may be released temporarily,that is on bail, under Article 10. Moreover, there are no provisions in the draft law subjectingthese powers to judicial supervision or oversight.Articles 5 and 6 further undermine the role of the judiciary. For example, under Article 5 theMinistry of Interior is entrusted with investigating “terrorist crimes and their financing”, andthe Minister of Interior has the role of issuing “a decision to co-ordinate and organize thework between the investigating authority and the public prosecution”. Article 6 provides forthe creation of a Security Cases Division within the Bureau of Investigation and PublicProsecution. Its members are to be appointed by the Minister of Interior, to bring casesbefore the Specialized Criminal Court and “to monitor and inspect prisons and places ofdetention dedicated to the detention of those convicted of and those suspected of crimes ofterrorism or its financing, and to oversee the implementation of the punishments in this law”.The draft law gives the Minister of Interior the right to issue orders for the arrest of a“terrorism” suspect or for entering a building to search it, including without a warrant(Articles 7 and 22). The Minister of Interior may delegate these powers to anyone he sees fit.The Minister may order the monitoring of communications (Article 23). These provisions donot state that the order should provide an opportunity to challenge it. Such provisions gobeyond what is provided for in the Law on Criminal Procedures.43Under Article 17, a decision to drop charges is not valid unless approved by the Minister ofInterior or anyone he delegates.One of the most far-reaching powers which might be conferred on the Ministry of Interior iscontained in an article that the Shura Council’s Committee for Security Affairs opposed,arguing that it undermined the independence of the judiciary. Article 65 stipulates that acommittee headed by a judge and comprising two other members, one of them a “religiousadvisor”, will be set up in the Ministry of Interior to look into the case of prisoners whoseforthcoming release is “considered dangerous to the security and safety of the state”. Thecommittee could decide to take “any appropriate procedures and measures to avert the threatfrom him”, including to prolong his detention. An affected prisoner would have the right toappeal the committee’s decision before the Specialized Criminal Court.

Index: MDE 23/016/2011

Amnesty International December 2011

16

Saudi Arabia:Repression in the name of security

An accused person or a sentenced prisoner who has suffered harm as a result of theirdetention or imprisonment being unduly prolonged has no recourse to the judiciary to bring acriminal or civil case but may apply to a committee to be set up by the Ministry of Interior forcompensation (Article 61). This effectively means that the Ministry could act with impunity.The Minister of Interior also has the authority to release detainees or anyone sentenced forterrorist crimes while they are serving their sentences (Article 59).Articles 62 and 63 stipulate that special centres will be set up to “educate detainees andthose convicted of terrorist crimes” in order to “rectify their ideas and deepen their sense ofnational belonging”. The draft law does not, however, provide clarity as to whether adetainee’s attendance of these centres is voluntary or not or whether refusal to attend suchcentres invites any sanction or punishment. As an exception to the rules on banking secrecy,under Article 18, the Minister of the Interior – “in exceptional cases which he determines” –may allow the investigating authority, through the Saudi Arabian Monetary Agency, to accessor obtain information relating to funds held in financial institutions. It is of concern that nojudicial oversight is provided for.

F) WIDE SCOPE FOR THE DEATH PENALTYThe draft anti-terror law contains 27 instances where the death penalty can be applied.Amnesty International opposes the death penalty in all circumstances and so is concerned atthe wide scope which the draft law gives to capital punishment. In addition, it notes that thedraft law would lead to several specific violations of international standards:i) Under international human rights law, people charged with crimes punishable by death areentitled to the strictest observance of all fair trial guarantees and to certain additionalsafeguards. Such guarantees and safeguards are absent.ii) Under international human rights law, death sentences may be imposed only for the mostserious crimes. According to the UN Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary orarbitrary executions “the death penalty can only be imposed in such a way that it complieswith the stricture that it must be limited to the most serious crimes, in cases where it can beshown that there was an intention to kill which resulted in the loss of life.”44Given the vaguedefinitions in the draft law, discussed above, the death penalty could be imposed in relationto offences which do not fall in the “most serious crimes” category, contrary to internationallaw.iii) The draft law does not prohibit the imposition of the death penalty on juvenile offenders(those aged under 18 at the time of the alleged crime), as provided in the UN Convention onthe Rights of the Child, to which Saudi Arabia is a state party,45or on the mentally ill.46These concerns are exacerbated when the shortcomings in Saudi Arabia’s justice system areconsidered. Amnesty International has documented the use of the death penalty and the fairtrial concerns surrounding it.47

CONCLUSIONThe draft law currently available to the organization contains serious flaws as set out abovethat contravene Saudi Arabia’s international obligations to ensure that security legislationdoes not come at the expense of human rights. Instead it authorizes the violation of the rights

Amnesty International December 2011

Index: MDE 23/016/2011

Saudi Arabia:Repression in the name of security

17

of detainees, threatens the legitimate exercise of freedom of expression, including peacefulpolitical dissent, undermines the independence of the judiciary, and gives the Ministry ofInterior wide-ranging powers without judicial oversight.If passed, the draft law would consolidate anti-terrorism measures that breach internationalhuman rights standards by sanctioning them in law. Such measures have been and continueto be documented by Amnesty International and include arbitrary detention, incommunicadodetention, detention without charge or trial, and unfair trials (see Chapter 3: Detentions andtrials in the name of counter-terrorism).

Index: MDE 23/016/2011

Amnesty International December 2011

18

Saudi Arabia:Repression in the name of security

3. DETENTIONS AND TRIALS IN THENAME OF COUNTER-TERRORISM“For about 7 months we did not know if he wasalive or dead.”Wife of detainee Hamad al-Neyl Abu Kassawy speaking to Amnesty International.

OFFICAL FIGURESDespite maintaining secrecy about many aspects of their workings, the Saudi Arabianauthorities have, through statements issued in recent years, given some sense of the numberof detainees they have arrested, detained and put on trial for what they consider security-related reasons.In July 2007 the Minister of Interior announced that 9,000 people had been arrested duringcounter-terrorism operations between 2003 and 2007 and that 3,106 of them remainedheld.48In October 2008 the Interior Ministry announced that it would refer to court thecases of 991 people accused of being part of the “deviant organization… named al-Qa’ida”.49In the same month a new special court called the Specialized Criminal Court wasestablished to try detainees held on terrorism-related charges.50In mid-March 2009, theMinister of Interior was reported to have stated that the trials had started and that the fullresponsibility for them had been passed on to the Ministry of Justice.51In early July 2009 the government announced that the trials of 330 people charged with“terrorism offences” that had begun in March that year had concluded.52Virtually all of thedefendants were convicted before the Specialized Criminal Court in trials closed to observersand members of the public, with sentences ranging from fines to the death penalty. Theauthorities did not disclose their names or details of the charges. However, it was reportedthat one defendant had been sentenced to death and 323 others had received prison termsranging from a few months to 30 years. Some of the 323 received additional punishments offines or forced residence; others were told they would be released only after “repenting”. Ofthe remaining six defendants, three were sentenced to travel bans and three were acquitted.No further information was given.53On 24 March 2010, the Interior Ministry announced the detention of 113 suspectedmembers of al-Qa’ida in the previous five months – 58 Saudi Arabians, 52 Yemenis, oneSomali, one Bangladeshi and one Eritrean. Among them was a woman who has since beentried and sentenced (see below Unfair trials). The statement said the detainees weresuspected of planning to carry out attacks on oil installations and other targets in Saudi

Amnesty International December 2011

Index: MDE 23/016/2011

Saudi Arabia:Repression in the name of security

19

Arabia.54On 26 November 2010, the Interior Ministry announced the arrest of 149suspected members of al-Qa’ida in the previous eight months – 124 Saudi Arabians and 25foreign nationals who, it said, included Arabs, Africans and South Asians. The statementadded that a woman online activist who had been arrested was released after investigation.55In January 2011, the Justice Ministry announced that the Specialized Criminal Court inRiyadh had issued by early December 2010 preliminary verdicts in 442 cases involvingindividuals who were accused of belonging to al-Qa’ida or “plotting against nationalsecurity”. It said that the cases involved 765 detainees and that the detainees had lodgedappeals against verdicts in 325 cases.56The preliminary verdicts ranged from fines, travelbans and house arrest to terms of imprisonment and the death penalty. The Ministry said thatthe accused had been tried on charges that included “joining al-Qa’ida”, “embracing the al-Qa’ida methodology and supporting its crimes” and “financing and communicating with its[al-Qa’ida] leaders”.On 2 April 2011, the security spokesperson for the Ministry of Interior, General Mansour al-Turki, gave an update to the Ministry’s 2008 statement on the referral to court of 991accused relating to the crimes of al-Qa’ida. He stated that 5,831 detainees had beenreleased “in recent years”, including 184 earlier in 2011; that of 5,696 detainees, 5,080had been questioned and referred for trials; 616 detainees were still being questioned; andthat 1,931 others had been questioned with a view to referring them to the SpecializedCriminal Court. In addition, according to the statement, 486 convicted persons had beencompensated for periods of detention exceeding the term to which they had beensentenced.57An official from the Bureau of Investigation and Public Prosecution stated thesame day that 2,215 people had been referred to the Specialized Criminal Court in casesinvolving “terrorist offences” and that, of these, 612 detainees had received verdicts and603 were still undergoing trials.58In late April 2011,Arab News,a Saudi Arabian English-language daily newspaper, reportedthat an Interior Ministry spokesperson told them that 1,325 foreign nationals were beingtried for their direct or indirect involvement in “terror plots or for conspiracy to participate interror-group activities”.59He also said that 1,612 people had been convicted of “terrorismcharges” and that some women, albeit “very few” in number, were among those who havebeen detained.60While these government statements provide some indication of the scale of the detentionsand trials of people held for what the authorities consider security-related reasons, AmnestyInternational has been unable to obtain further information from the authorities on the detailsof the persons and cases concerned, such as their names, the reasons for their arrest, thelegal basis and conditions of their detention, including their access to family and lawyers, thedetails of their charges and conviction, where applicable, and the dates when they werearrested and, where relevant, charged, brought to trial and convicted. The informationappears not to be available on the Saudi Arabian government’s websites and when AmnestyInternational has written to the authorities to request further details, as it did following theannouncement of the trials of 330 people by the Ministry of Justice in July 2009, theannouncement of the arrests of 113 people by the Interior Ministry in March 2010 and theannouncement of the arrests of 149 people by the Interior Ministry in November 2010,61ithas received no response.62To obtain such details, the organization has therefore had to rely

Index: MDE 23/016/2011

Amnesty International December 2011

20

Saudi Arabia:Repression in the name of security

on the limited information available in the Saudi Arabian media about trials where thepresence of some state media has been authorized and on testimonies of former detainees,their families and lawyers, and human rights activists in the country.

PROLONGED DETENTION WITHOUT CHARGE OR TRIALAmnesty International fully recognizes that the Saudi Arabian authorities have a duty toensure public safety and, in particular, to bring to justice those responsible for carrying out orplanning violent attacks. However, it is seriously concerned about what appears to be apattern of people being detained for months or years on the stated grounds of securitywithout being convicted of any crime. In some cases, the authorities may have evidence ofthe detainees’ involvement in internationally recognized criminal activities, but are failing touse due legal process against them. In many others, the detainees appear to be held on avague suspicion that they pose a threat to Saudi Arabia’s security or because of their real orperceived opposition or criticism of the authorities. In all cases, their detention appears to bearbitrary.

PROHIBITION OF ARBITRARY DETENTIONInternational human rights law and standards clearly prohibit the arbitrary arrests and detentions seen inSaudi Arabia. Article 9 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights provides that: “No one shall be subjectedto arbitrary arrest, detention or exile.” The UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention considers that detentionbecomes arbitrary when it falls into one or more of the following categories:A) When it is clearly impossible to invoke any legal basis justifying the deprivation of liberty (aswhen a person is kept in detention after the completion of his sentence or despite an amnesty law applicableto him) (Category I);B) When the deprivation of liberty results from the exercise of the rights or freedoms guaranteed byarticles 7, 13, 14, 18, 19, 10 and 21 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and, insofar as Statesparties are concerned, by articles 12, 18, 19, 21, 22, 25, 26 and 27 of the International Covenant on Civil andPolitical Rights (Category II);C) When the total or partial non-observance of the international norms relating to the right to a fairtrial, spelled out in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and relevant international instrumentsaccepted by the states concerned, is of such gravity as to give the deprivation of liberty an arbitrary character(Category III).63Many detainees held for stated security reasons have been held for prolonged periods withoutbeing brought to trial, or even charged, despite the six-month limit on detention without trialintroduced under the 2001 Law on Criminal Procedures.64They rarely have any idea of whatis going to happen to them. They are invariably held incommunicado following arrest andduring the period of interrogation, which can last for months, before they are allowed familyvisits. They are often detained for months or years without access to a lawyer, informationabout the progress of legal proceedings against them or any opportunity to challenge thelegality of their detention. Many remain held until the authorities decide they are not asecurity threat or, in some cases, until they promise not to engage in opposition activities.Some have been rearrested immediately or shortly after release. Others have been repeatedlyarrested without charge.

Amnesty International December 2011

Index: MDE 23/016/2011

Saudi Arabia:Repression in the name of security

21

In the instances when individuals are charged and brought to trial, the proceedings invariablyfail to meet the most elementary standards of fairness (see below Unfair trials).

“Please put him on trial and sentence him to a hundred years in prison even. At least we know ahundred years will end. But you can’t keep us like this.”Relative of a detainee held without charge or trial for years

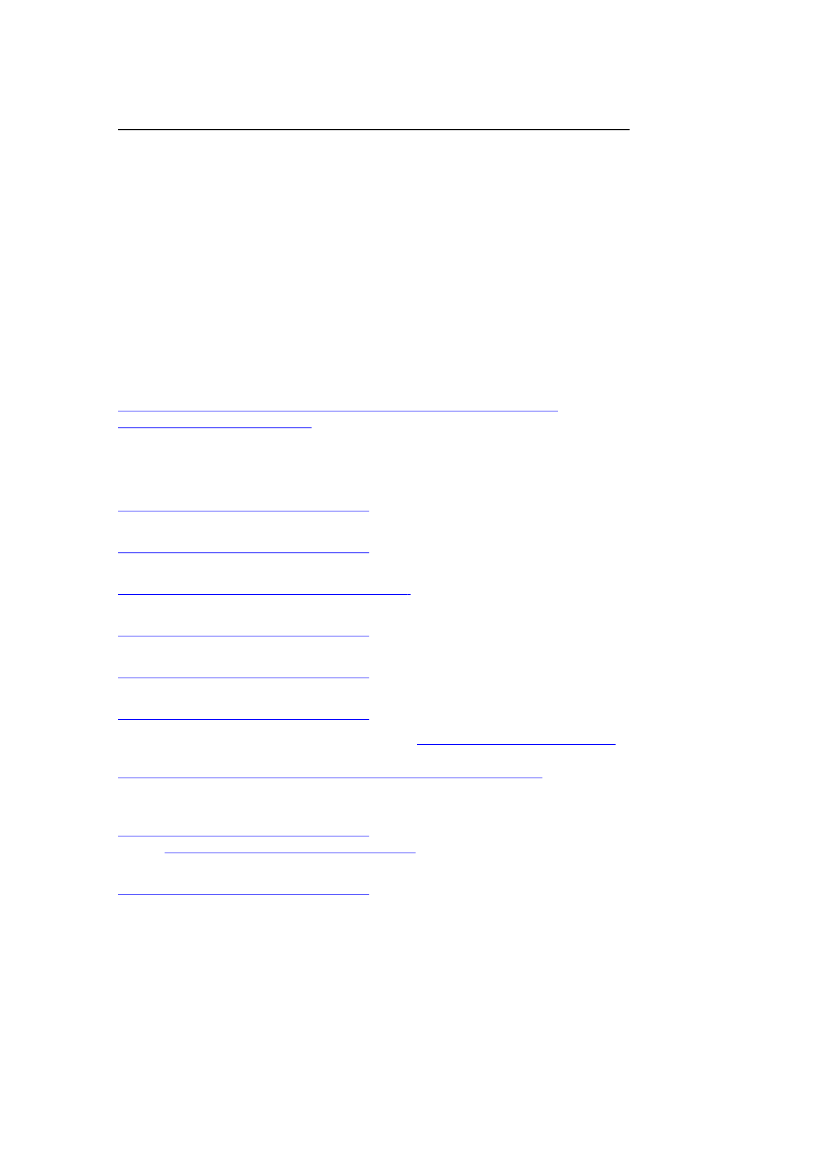

The Interior Ministry’s General Directorate of Investigation (GDI)65is the main internalsecurity force responsible for arresting and detaining people in the name of security.66It hasused fear and repression to counter critics of the state and monitors without accountabilitythose it sees as political opponents and imprisons those it sees as a threat.67Amnesty International has received information that many of those detained have beentortured or otherwise ill-treated, particularly during incommunicado detention to extractconfessions or undertakings. Methods of torture and other ill-treatment reported include:beatings with sticks, punching, suspension from the ceiling or cell doors by the ankles orwrists, the application of electric shocks to the body, prolonged sleep deprivation and beingplaced in cold cells. Many are held in solitary confinement for long periods of time.Some of the cases cited below have come to Amnesty International’s attention since its lastreport of 2009; others include updates on cases that the organization included in thatreport.68Among the Saudi Arabian nationals who have been detained without charge or trial for yearsisMuhammad bin Abdul Rahman al-Sulaiman,a 34-year-old teacher in Islamic studies whohas two children. He has apparently been detained without charge or trial, or access to alawyer, since September 2004. He was arrested by members of the GDI at the school wherehe worked, apparently accused of being in contact with a “deviant group”. He was apparentlyheld for seven months in solitary confinement. He is said not to be in good health, havingsuffered from blood clotting and complications with his eyes, apparently exacerbated by theconstant lights in prison. He is said not to be allowed glasses for his eyes. The family are saidto have reported the case to the National Human Rights Commission but to have beeninformed that it could not do anything regarding the case.Former university professorDr Sa’id bin Zu’air,69a 62-year-old cleric and critic of the government,was arrested in Riyadh on 6 June 2007.70He washeld incommunicado at an unconfirmed locationand denied required medication at times. He wasarrested by the GDI at a police checkpoint on theroad into Riyadh on his way home from Meccawith his 30-year-old sonSa’ad bin Zu’air.Theauthorities reportedly said that Dr Sa’id bin Zu’airwas arrested for collecting money to “helpterrorism”. Other sources believe that he wasDr Sa’id bin Zu’air � Privatedetained to prevent him from taking part inbroadcasts on Al Jazeera television as he had criticized the government, including itsapproach to tackling terrorism, in previous broadcasts. He is currently on trial. Some Saudi

Index: MDE 23/016/2011

Amnesty International December 2011

22

Saudi Arabia:Repression in the name of security

Arabian media have reported on the trial, referring to anacademic but without naming him. The trial began inlate October 2011.71He has been charged with 19offences, one report cited charges including “incitingagainst the ruler and stirring sedition”, “harming thenational cohesion”, “undermining the prestige of thestate and its security and judicial institutions” and“publishing through the internet what will stirsedition”.72Other reports stated that he had “adoptedthe Kharijite73methodology in jihad” and had engagedin “financing terrorism and terrorist acts”.74He isreported to have denied all charges in a session on 23Sa’ad bin Zu’air � PrivateNovember which some members of his family were75allowed to attend. His son Sa’ad bin Zu’air, however, continues to be held without charge.Both Dr Sa’id and his son Sa’ad bin Zu’air have been held in solitary confinement since theirarrest and are currently detained in al-Ha’ir prison in Riyadh. On 21 November 2008 the UNWorking Group on Arbitrary Detention concluded that Dr Sa’id bin Zu’air was a victim ofarbitrary detention.76In 2011, another of Dr Sa’id bin Zu’air’s sons, 38-year-oldMubarak binZu’air,was arrested after he staged a protest calling for the release of them and otherpolitical prisoners (see Chapter 4: Crackdown on freedom of expression).77Khaled Abdul Rahman Hamad al-Tuwaijari,a 32-year-old father of two from Buraydah inQasim Province, who served as a vice sergeant in the Saudi Arabian air force, has been heldin al-Ha’ir prison in Riyadh for almost three years without charge or trial. He was initiallyarrested in Jordan in September 2008 and held there for about four months. In January2009 he was extradited to Saudi Arabia and taken immediately to al-Ha’ir prison. His familywas not told of his arrest or extradition until some five months after his arrest in Jordan, andonly found out then after a family member of a former inmate at al-Ha’ir prison visitedKhaled’s family and told them that Khaled was there. When the family contacted the Ministryof Interior to enquire about him, they denied that they were holding him. However, a monthlater the family was contacted by officials and told that they could visit Khaled. When theyfinally did, some two years had reportedly passed since his arrest. According to informationreceived by Amnesty International, he was held in solitary confinement for a year and a half,during which time he was alleged to have been subjected to beatings on five consecutivedays as a punishment for having olive oil in his possession. He is said to suffer from healthproblems in his back as a result of such treatment, and his health is said to be deteriorating.Khaled is allowed to call his wife once every 15 days and receive a one-hour visit from hisfamily every 35 days. However, there have been occasions where their visits have beencancelled at the last minute despite the fact that the family have to make a 350km journeyfrom Buraydah to Riyadh. He is said to have been accused of “breaking allegiance to theKing” and of making trips to Afghanistan and Pakistan.Some have been held without charge of trial for even longer. Nine people from the Shi’acommunity in the Eastern Province believed to have been arrested in 1998 in connectionwith the bombing of the Khobar Towers Complex, a US military housing complex, in June1996 in the city of al-Khobar which killed 19 US servicemen are reported to be still heldwithout charge or trial. The nine were interrogated and allegedly tortured following theirarrests and appear to have been denied access to lawyers and the opportunity to challenge in

Amnesty International December 2011

Index: MDE 23/016/2011

Saudi Arabia:Repression in the name of security

23

court the legality of their detention. They are saidto be held at Dammam Prison. Among them isHani al-Sayegh,who had sought asylum in theUSA but was forcibly returned to Saudi Arabia on11 October 1999.78The other eight are:AbdullahAhmad al-Jarrash, Hussain Abdullah Al Maghiss,Abdulkareem Hussain al-Nimr, al-Sayyed Mustafaal-Qassab, al-Sayyed Fadhel al-Alawi, MustafaJa’far al-Mu’allam, Ali Ahmad al-MarhounandSaleh Mahdi Ramadan.A 10th man,MuhammadHassan al-Hayek,was said to have been arrestedPoster of the nine men held since 1998 in connection within connection with the al-Khobar attack in Julythe 1996 al-Khobar bombing � Rasid News Network1996 and transferred to al-Ha’ir prison in Riyadh.About two years after his arrest, his brother was said to have been summoned by the SaudiArabian authorities to go to Riyadh, where he was told that Muhammad had died and beenburied in Riyadh.Among the foreign nationals detained in recent years on suspicion of threatening SaudiArabia’s security isKhaled Hussein al-Jubeihi,79a Jordanian national aged 41, whograduated in computer science in the USA in 2002, was arrested on 17 June 2003 at hisworkplace in Dammam during a wave of mass arrests following bomb attacks in May 2003.He is said to have been held incommunicado during the first three months of his detentionbefore he was allowed visits by his parents. He was reportedly kept in solitary confinement foralmost a year. He was also said to have been beaten. He has been held in Dammam prisonfor the last six months. In 2006 Amnesty International wrote to the National Human RightsCommission seeking clarification of his legal status, the reasons for his arrest and his placeof detention.80The Commission undertook to seek such a clarification, but no furtherinformation has been provided to Amnesty International.81In May 2007, the UN WorkingGroup on Arbitrary Detention considered his detention to be arbitrary.82He is apparently dueto be taken to trial soon, but Amnesty International is not aware on which charges. He isreported to have been provided with a state-appointed lawyer.His wife, who is a foreign national, has had difficulties in obtaining a visa to visit herhusband, partly because she does not have amahram(male guardian). She was able to visithim one time as she was able to travel forUmrahand visit him when he was detained inJeddah in 2010. However, anUmrahvisa would not allow her to travel to Dammam, where heis currently held. Their eight-year-old son has only seen his father once. She told AmnestyInternational that the Saudi Arabian authorities do not respond to her visa applications. Shesaid: “I cannot go by car, or plane. I feel like my legs and arms are cutoff. Without a visa I cannot do anything. It’s not fair. I behave... I havenot done anything wrong.”Hamad al-Neyl Abu Kassawy,a 36-year-old Sudanese national, wasarrested by members of the GDI in June 2004 when he arrived atMedina airport from Syria on his way to carry outUmrah.He thendisappeared for eight months. His family believe he came undersuspicion because of his frequent journeys as a trader. He had made aliving as a “suitcase trader,” travelling between Sudan, SyriaHamad al-Neyl Abu Kassawy � Private

Index: MDE 23/016/2011

Amnesty International December 2011

24

Saudi Arabia:Repression in the name of security

and the United Arab Emirates buying and selling household goods and clothes. He has beenheld without charge or trial since his arrest. He is reported to have attempted to commitsuicide a number of times and on one occasion he was reported to have gone on hungerstrike for 21 days. He is believed to be suffering from stomach problems.

Family of Hamad al-Neyl Abu Kassawy � Amnesty International

WIFE OF HAMAD AL-NEYL ABU KASSAWY SPEAKING TO AMNESTYINTERNATIONALFor about seven months we did not know if he was alive or dead. We lived in unbearable anxiety. We went tothe Sudanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs and asked them to look for my husband as we did not know hiswhereabouts, but they couldn’t help me; we could not get any information from them regarding my husband’slocation, or maybe they couldn’t figure out what was going on themselves… After seven months orapproximately eight months a Saudi Arabian man called us and told us that he was visiting his relative inMedina prison where my husband, Hamad al-Neyl, gave him our home telephone number and asked him tocontact us and tell us that he’d been detained in Saudi Arabia.Then we knew that he was detained in Saudi Arabia, so we went back to the Sudanese Ministry of ForeignAffairs asking them to do anything that could help us; but we didn’t get any help. So we contacted our relativewho was residing in Saudi Arabia and informed him that my husband was detained in Medina Prison, andasked him to look for him and try to find out what was happening. He looked for him, and found him in MedinaPrison and started to visit him immediately to get his news and tell him our news and reassure both of us.Then after two years he was transferred to Jeddah.My husband used to call us sometimes and the contact would be cut off at other times; the contact betweenus was completely cut off for two whole years. He only called us again around a year or so ago, at Eid al-Adha

Amnesty International December 2011

Index: MDE 23/016/2011

Saudi Arabia:Repression in the name of security

25

last year to be precise. We asked him about his conditions and his news. He said he was fine and that he hadbeen transferred to the city of Abha, where he is detained currently; so we contacted several organizations,human rights and other organizations. He has been allowed to call us for 10 minutes every month so far.This was for mere suspicion of his belonging to al-Qa’ida. He has said that there is absolutely no evidence orproof of this suspicion; nothing is proved until now. Some periods of time pass without any investigations orinterrogations with him, and other times he is interrogated, and until now he was not brought to trial, and nocharge was proved.The situation is very hard of course, very difficult and very terrible, especially as he is the only man in thefamily and the only provider for the family. In addition to me and three children he also provides for hisparents and his sick elder brother; his parents are very old and he is the only person who provides for them.Also he is the only provider for some of his relatives such as his widowed aunts and some of his elderlyrelatives.Our situation is very bad, for a man who has responsibility towards a family and children. I am unemployed soI came back to live with my big extended family. Our life continues, but it continues with great hardship.My demands to the Saudi authorities are to prosecute my husband; otherwise to release him and let him gobecause we really need him. Things cannot continue the way they are because at the end this is a family withan uncertain future…I ask the international community to help us, support us and remove this injustice, and return my husband tous by God’s will.Ali Hilal al-Hussain,a 40-year-old Syrian national with three children, appears to have beenheld without charge or trial for nearly three years. He was arrested by members of the GDI inMarch 2006, when he was working as a carpenter in Saudi Arabia. He was held initially in‘Ulaysha prison for 22 days, during which time he said he was interrogated every day andtortured. He told Amnesty International that he was beaten with a metal stick and plasticcables on his back. He was interrogated about a trip he had made to Iraq and about moneyhe had given to an Islamic organization. He responded that he had gone to Iraq from Syriawhen US-led forces invaded in 2003 with the intention of offering his help to the Iraqipeople, but returned to Syria after a week and, that at another point he had sent money to anorganization that was teaching people to memorize the Qu’ran in rural areas of Syria.He told Amnesty International that he was denied contact with his family for over two yearsand during different periods spent months in solitary confinement. During interrogations hesaid he was made to fingerprint “confessions”. He said he was taken in front of a court over ayear after his arrest and asked to confirm his confessions by fingerprinting them. He said hedid so because he was threatened by interrogators that he would be beaten until he agreed todo so. He was brought before the Specialized Criminal Court in Riyadh to be charged andtried in January 2009. He described being asked by a judge if he had gone to Iraq and if hehad sent money to an organization, replying yes to both questions, and then being sentencedto six months’ imprisonment. He said he was later brought back to the Specialized CriminalCourt on two separate occasions and informed that an appeal court had raised his sentence,firstly, in October 2010, to one year’s imprisonment and then in early 2011 to two years. Hesaid he did not have a lawyer at any time during the legal process. In May 2011 he was

Index: MDE 23/016/2011

Amnesty International December 2011

26

Saudi Arabia:Repression in the name of security

deported to Syria after signing a pledge whose content he claimed not to know. He toldAmnesty International: “Saudi Arabia has destroyed me and my family completely. Mychildren haven’t seen me in five years and now they don’t know me,” but added: “My case isnothing compared to others”.Ahmed Muhammad Abdulle,a 26-year-old Danish national of Somali origin, was arrested on14 March 2009 by members of the GDI at the Islamic University of Madinah where he wasstudying. He is still held without charge or trial in Jeddah without access to lawyers.

UNFAIR TRIALS

“This is to report that prisoners in KSA [Kingdom of Saudi Arabia] are being taken by the dozens tofake courts and arbitrarily receiving 30 to 40 year sentences. They cannot speak while theirsentence is read to them; they are forced to sign it and then are sent back to jail. This is the ‘fair’trial of Saudi Arabia.”Message received at the end of March 2009. Name of person withheld for fear of reprisal against the detainee.

Trials of political and security detainees fall woefully short of international standards offairness in Saudi Arabia. Court hearings are often held in secret. Defendants are rarelypermitted the help of a lawyer, and foreign detainees are often denied consular assistance orany translation services during interrogation and trial. Detainees, defendants in trials, formerprisoners and relatives of prisoners routinely say that confessions were extracted using tortureor other ill-treatment. These statements are sometimes the sole evidence used to convictpeople. In many cases, defendants and their families are not even aware of the progress oflegal proceedings against them. The range of offences punishable by death is extremely wide,and confessions obtained by torture are accepted as evidence even in cases of capitaloffences.

PRINCIPLES OF FAIR TRIALUnder international law, everyone has the right to a fair trial by a competent, independent and impartialtribunal established by law, as reflected in Article 10 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. All trialsof those charged with a recognizably criminal offence must conform to the minimum procedural guarantees.The fairness of proceedings before a court depends on several factors including: whether the defendants wereassisted by a lawyer of their own choosing and the right to appeal against their conviction and sentence to ahigher court; whether the trial proceedings were public; whether the court’s jurisdiction complies with theprinciples of non-discrimination and equality before the law; and whether the judges are impartial andindependent from the executive. Further, any information obtained under torture or other ill-treatment must beexcluded from use in the judicial proceedings and may not be used as evidence to obtain conviction.The UN Basic Principles on the Independence of the Judiciary emphasize the absolute indispensability ofjudicial independence. Principle 5 states:Everyone shall have the right to be tried by ordinary courts or tribunals using established legalprocedures. Tribunals that do not use the duly established procedures of the legal process shall not be createdto displace the jurisdiction belonging to the ordinary courts or judicial tribunals.The Universal Declaration of Human Rights also states: “Everyone is entitled in full equality to a fair andpublic hearing by an independent and impartial tribunal, in the determination of his rights and obligations

Amnesty International December 2011

Index: MDE 23/016/2011

Saudi Arabia:Repression in the name of security

27