Udenrigsudvalget 2011-12

URU Alm.del Bilag 245

Offentligt

Denmark’s engagement in multilateral de-velopment and humanitarian organiza-tions 2012

Ministry of Foreign Affairs, January 2012.

List of contentsExecutive Summary ............................................................................................................................. 4The policy and financial environment ............................................................................................. 4Alignment with Danish development policy priorities .................................................................... 6Recommendations.......................................................................................................................... 8Part 1 - Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 13Challenges facing the multilateral organisations in a changing world .......................................... 14General trends ............................................................................................................................ 14Changing growth patterns and shifts in global decision-making capacity...................................................... 14Trends in the multilateral funding....................................................................................................... 16Specific challenges ..................................................................................................................... 21Conflict-affected and fragile states........................................................................................................ 21Rio+20 with focus on green economy................................................................................................... 23Part 2 – Denmark’s engagement in the multilateral organisations .................................................... 25General Remarks ............................................................................................................................ 25UN Funds and Programmes, WHO, GFATM and UNAIDS ......................................................... 26UNDP ......................................................................................................................................... 27UNICEF ..................................................................................................................................... 30UNFPA....................................................................................................................................... 33UNEP ......................................................................................................................................... 35WHO .......................................................................................................................................... 38The Global Fund ........................................................................................................................ 39UNAIDS..................................................................................................................................... 41The International Financial Institutions ......................................................................................... 42The World Bank ......................................................................................................................... 43The African Development Bank ................................................................................................ 46The Asian Development Bank ................................................................................................... 49The International Fund for Agricultural Development .............................................................. 52The Humanitarian Organisations ................................................................................................... 54OHCA ........................................................................................................................................ 55UNFPA.......................................................................................................................................57UNHCR ...................................................................................................................................... 58UNICEF ..................................................................................................................................... 58UNRWA..................................................................................................................................... 59WFP ........................................................................................................................................... 60

2

I C R C ....................................................................................................................................... 62OHCHR ...................................................................................................................................... 64Part 3 – Conclusions and recommendations ...................................................................................... 65Alignment with Denmark’s development policy priorities............................................................ 65Adaptation to new framework conditions and new challenges...................................................... 68Recommendations .......................................................................................................................... 69Appendix 1 – List of abbreviations .................................................................................................... 73

3

Executive SummaryThe Danish Government has undertaken a first comprehensive review of its engagement in multilateraldevelopment- and humanitarian organisations. The purpose is to strengthen the strategic orientationand coherence of Denmark’s cooperation with these organizations. This review examines trends anddevelopments in the policy and financial environment for multilateral development cooperation as wellas the activities of key partner organisations1during the past year and the degree of alignment of theirprogrammes with Danish development policy priorities.

The policy and financial environmentOver the past decade,economic growth in developing countries has been considerably higherthan growth in advanced economies,and developing countries now account for 35 per cent of glob-al GDP and 65 per cent of global economic growth. In addition, low-income countries as a group haveachieved per capita annual growth of over 3 per cent over the past decade, reversing the trend of slowor stagnating growth, foreign direct investments and integration in international trade that characterisedthe previous decades. The largest number of developing country citizens ever recorded, have workedtheir way out of poverty, and the efforts to improve people’s access to health care, education and infra-structure have been largely successful.The shift of wealthfrom the current advanced economies to-wards the dynamic economies and eventually the low-income countrieswill continue in the comingdecade.The change in the distribution of economic power also means that global decision-making no longerresides predominantly with the great powers of the 20th century, but is diffused in an international sys-tem withmultiple centres of power.The G20 is now a leading forum for tackling the global financialand economic crisis, with dynamic developing economies playing a central role. The G20 is based onrecognition of the growing importance of developing countries for the global economy. It providesnew opportunities for promoting a global enabling environment, investments and cooperation,which can help more citizens in developing countries work their way out of poverty and enable theirgovernments to finance the delivery of public services. In addition,South-Southinvestments and tradeare becoming ever more important factors for growth in low-income countries.The global diffusion of power challenges the international system of multilateral organisations.Several emerging economies benefited considerably from support received from multilateral organisa-tions earlier on and are now seeking to influence the leading multilateral fora such as the UN SecurityCouncil, the IMF and the World Bank, resulting in amore intensive debate on values and para-digms.The economic dependence of low-income countries on external development assistance willgradually diminishand the presence of bilateral development agencies is likely to be scaled down as aconsequence. The development agenda will increasingly be set by the need to deliver support in con-flict-affected and weak states and by climate and environmentally related challenges. Therefore, an in-ternational institutional machinery will still be required to respond to countries in need of external assis-tance to address security, humanitarian and development challenges.1

Major organisations are here defined as organisations receiving more than 35 million DKK (approx. 6 million USD)annually in 2010, or otherwise deemed to be strategically important for the pursuit of Danish development objectives.Denmark’s development cooperation through the European Union is not included in this analysis.

4

Thelegitimacythat multilateral organisations confer on international cooperation is absolutely vitalfor the development and endorsement of the standards, ideas, platforms and frameworks that serve asthe backbone of the international partnership for development. One of the major successes of multilat-eral cooperation during the past decade has been the formulation in the UN of theMillennium De-velopment Goals,which became the compass around which international development cooperationsubsequently was oriented. This success must now be followed up by the formulation of a new set ofpost 2015 goals that keep up the momentum to finish the outstanding work and supplement with goalsfor handling new challenges. In Denmark’s pursuit of arights-based approach to developmenttheUN system is a natural starting point, with its long-standing and globally recognized roles as a normsetter and monitor of progress.Since the end of the Cold War, and despite progress made on aid effectiveness against the Paris andAccra goals,the trend has been towards increasing fragmentation of development assistanceand proliferation of development actorsin many developing countries. The trend is partly driven bya rapid increase in the earmarkingof member state financial contributions to multilateral organisa-tions. This development tends to undermine the absolute advantages of multilateral organisations asactors – i.e. their legitimacy and accountability as well as their ability to provide access to sufficientlyfungible and predictable ODA in response to global needs, also for countries that are not the preferredchoice of bilateral donors.The analysis ofmultilateral financingshows a multilateral system that issqueezed in relation tofunding of core budgetsand subject to anincreasing inflow of funds earmarked for specific ac-tivities and interventions,which in many cases lie outside or at the margin of their mandates. Fur-thermore, earmarked funds do not necessarily fall under the governance and reporting structures of theorganizations and may not be administered according to the principle of partner country ownership. Tomaintain an efficient and effective multilateral system, multilateral organisations should not be asked todeliver in areas outside their core mandate. On the contrary, they should be supported in their effortsto maintain their specific character and specialisation based on their absolute and comparative ad-vantages. This requires adequate funding of their core budgets. At the same time,the multilateral sys-tem’s capacity to act in a coordinated and coherent manner must be enhanced.The analysis of the challenges in relation toconflict-affected and fragile statesindicates a clear needfor a credible, flexible and adequate response from the international community on this main priorityfor Denmark. There is a need to adopt aholistic approach to security, humanitarian needs anddevelopmentand for a concerted effort by the entire international community to build country capaci-ty. The multilateral organisations with theirmandates and legitimacyconstitute the natural startingpoint for coordination of efforts and adaptation to changing country needs. The World DevelopmentReport 2011 on conflict-affected and fragile states has paved the way for more explicit acknowledge-ment among relevant organisations of their respective roles and the need to work together accordingly.To meet Denmark’s and the EU’s ambition for atransition to a green global economymultilateralorganisations must act asstandard-setters, platforms for negotiation and partners of developingcountries.Key priorities for Denmark on the multilateral agenda are: 1. Formulation of sustainabledevelopment goals (SDGs) as a supplement to the MDGs; 2. agreement on a methodological frame-work for the green economy; 3. establishment of amore powerful body in the UNfor providingadvisory support on and monitoring of the countries’ follow-up; and 4. more effective orchestration ofsupport provided by multilateral organisations to developing countries in their efforts to transit to sus-tainable forms of production and consumption. UNEP in particular, but also other UN funds and pro-

5

grammes, as well as the World Bank and the regional development banks have key roles to play in theseefforts.

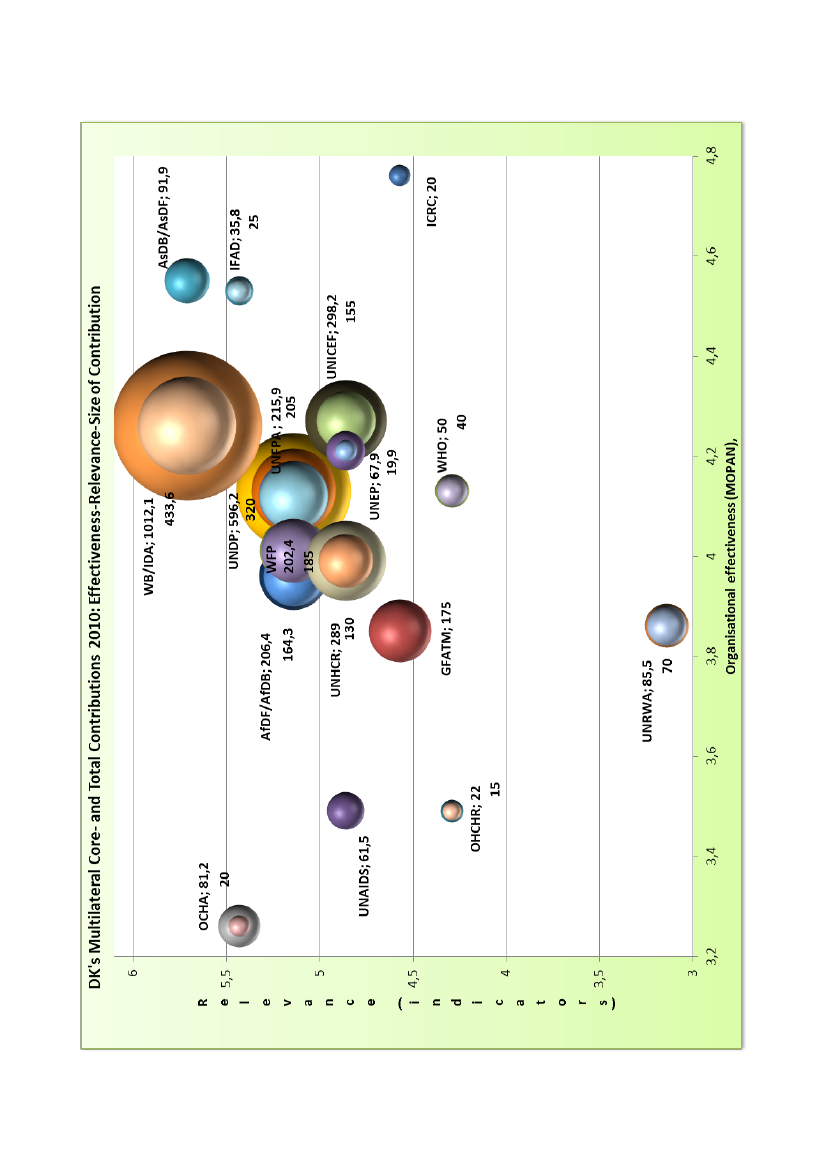

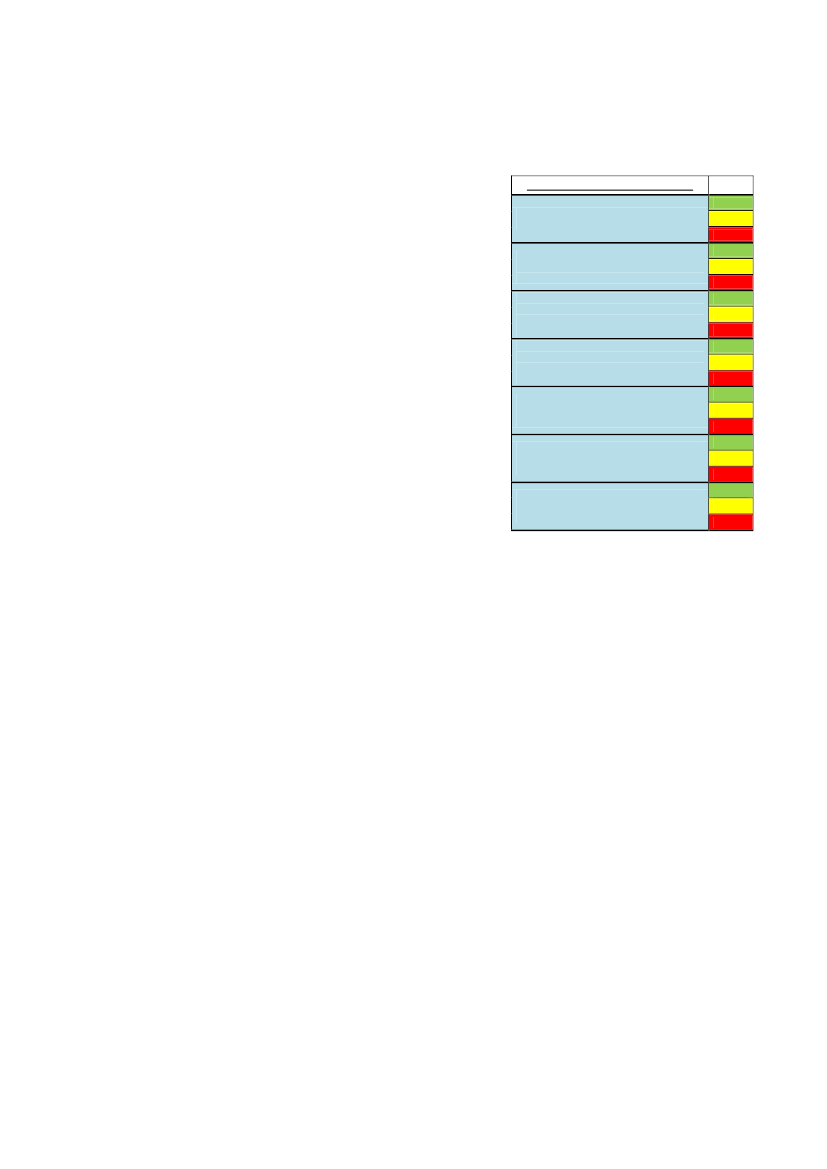

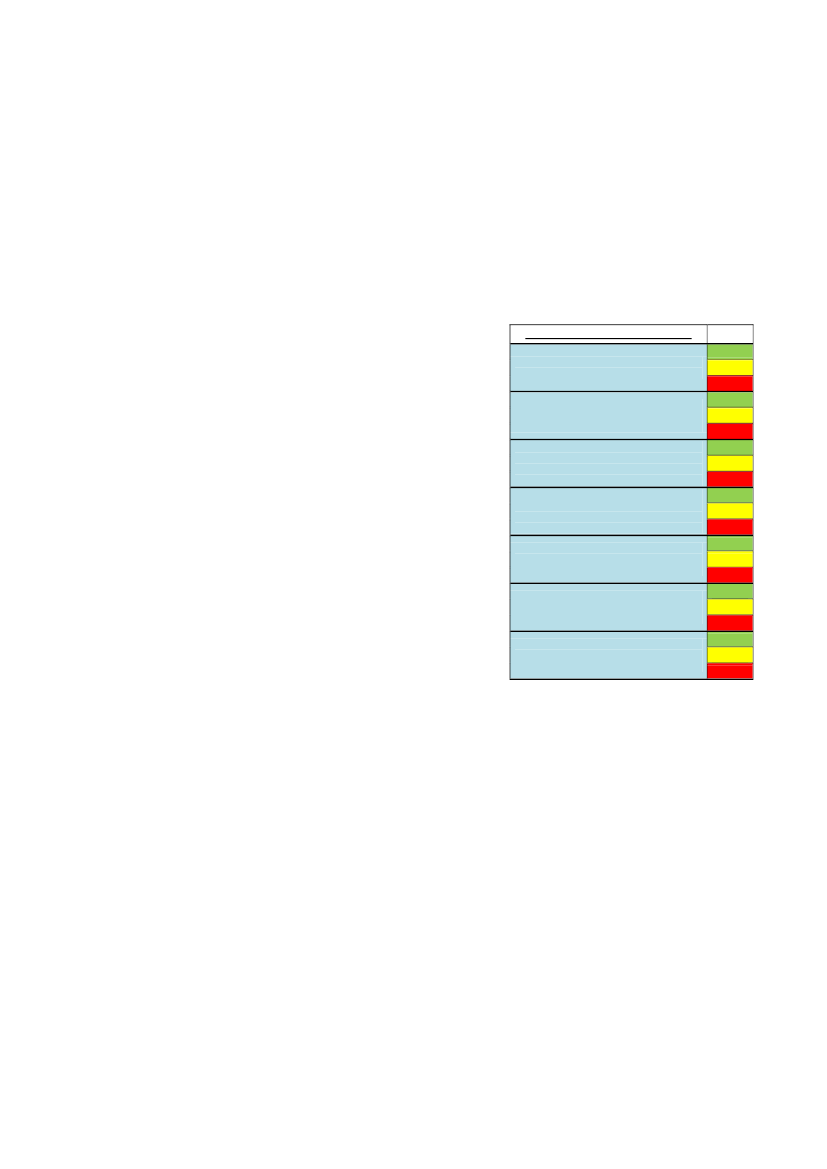

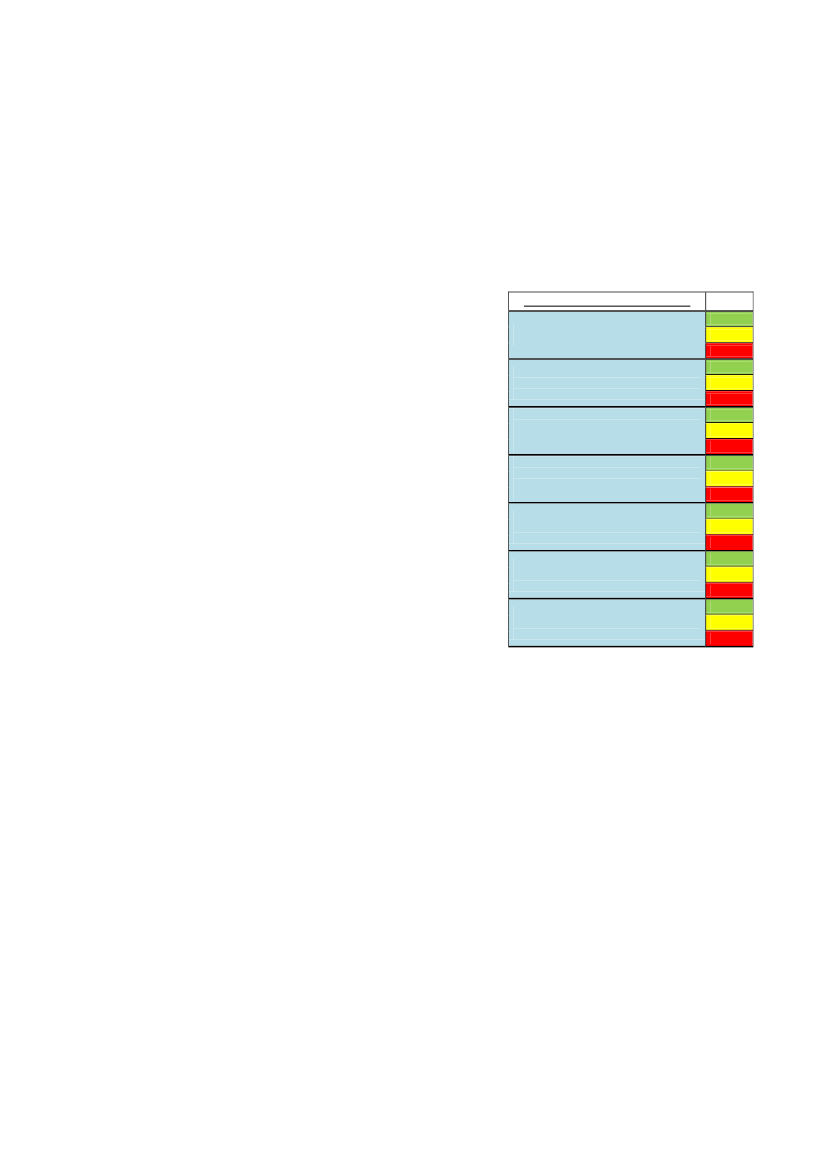

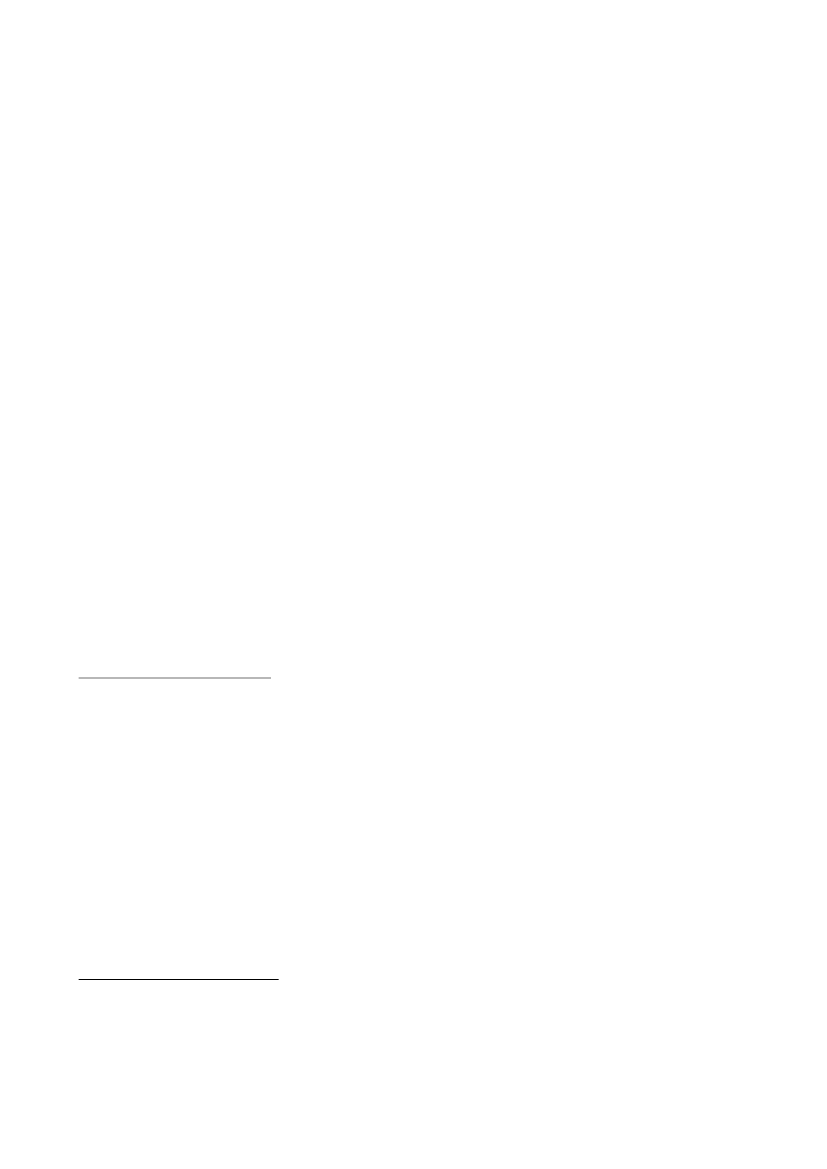

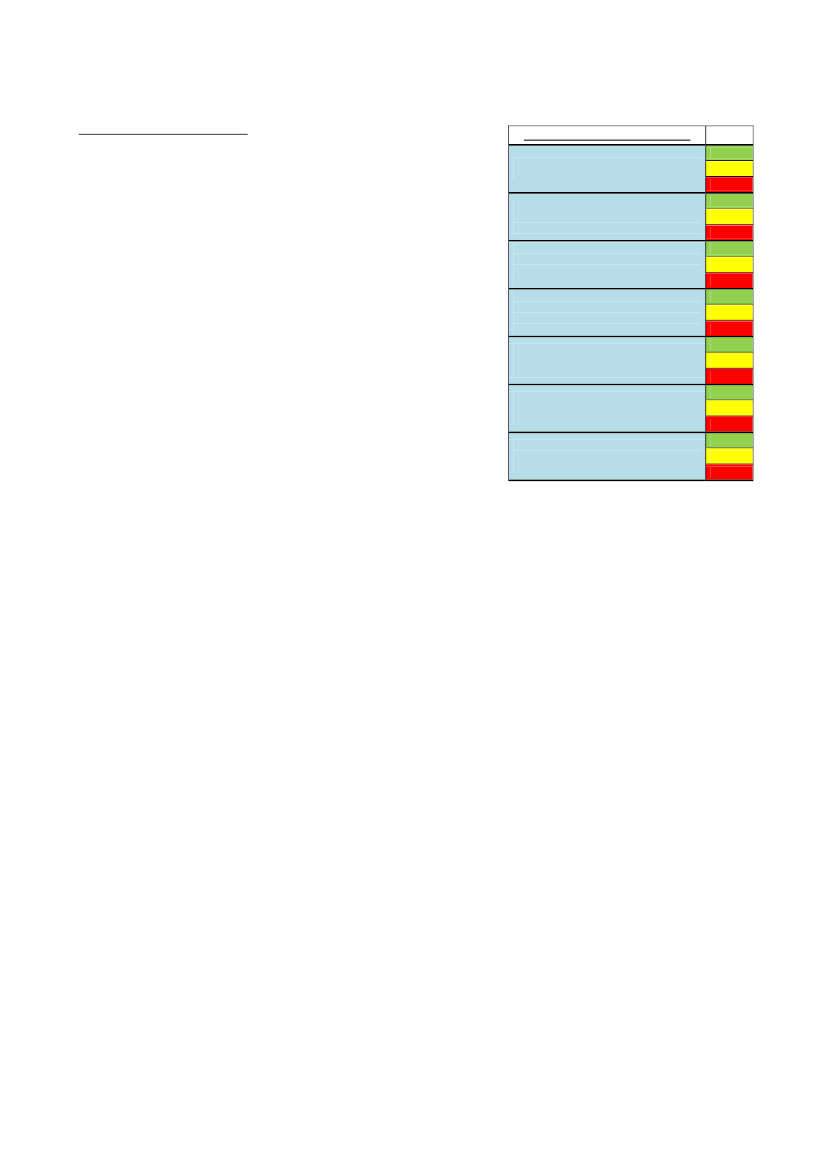

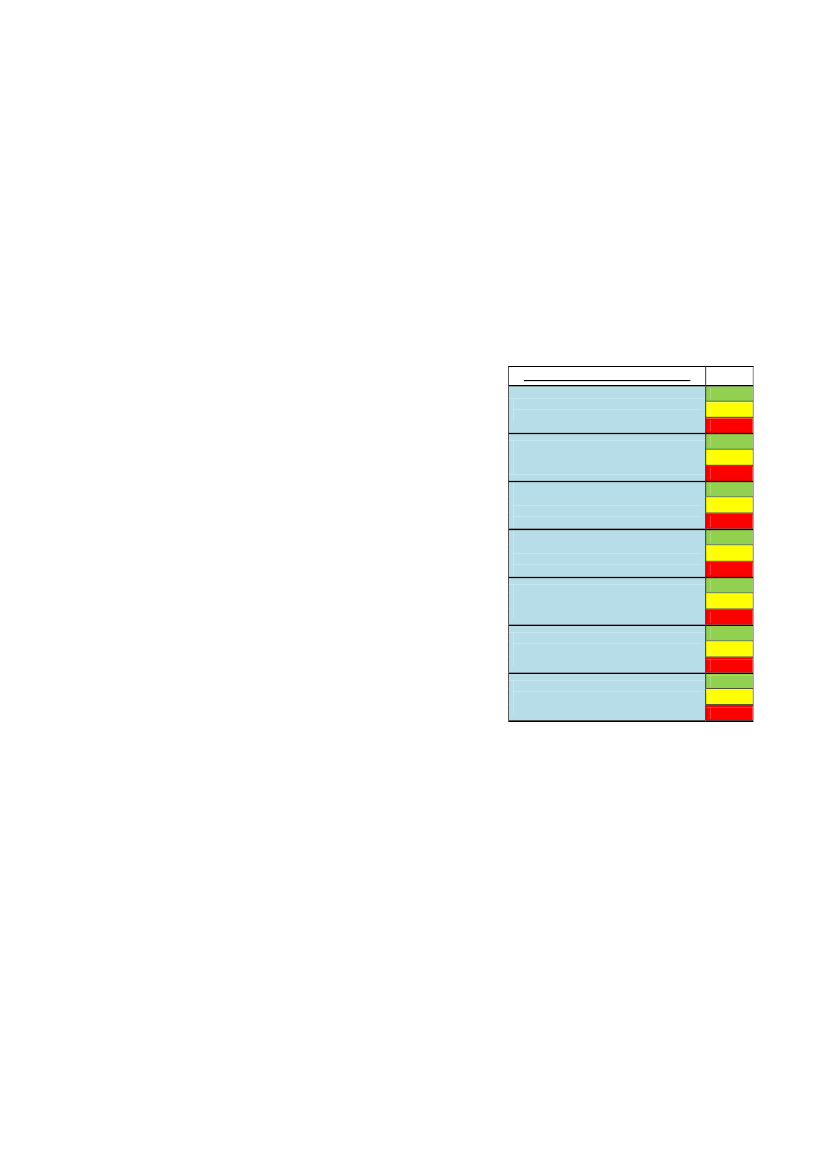

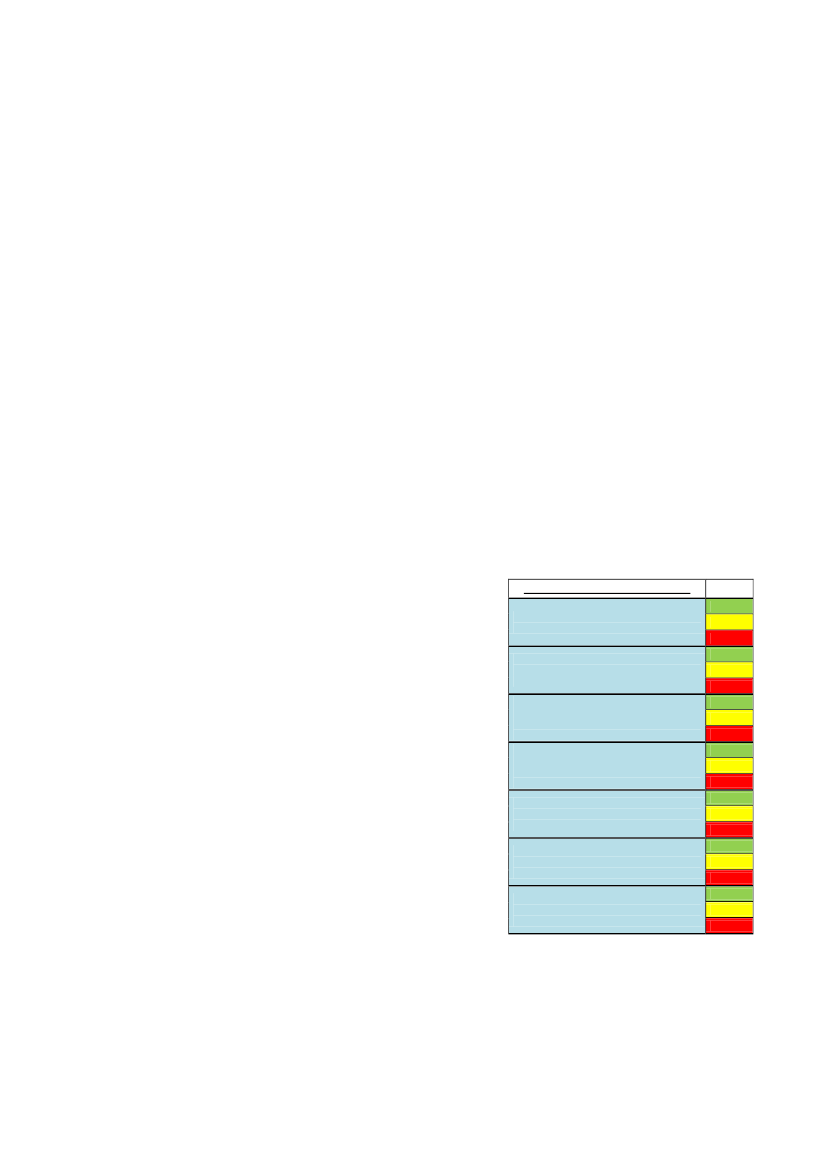

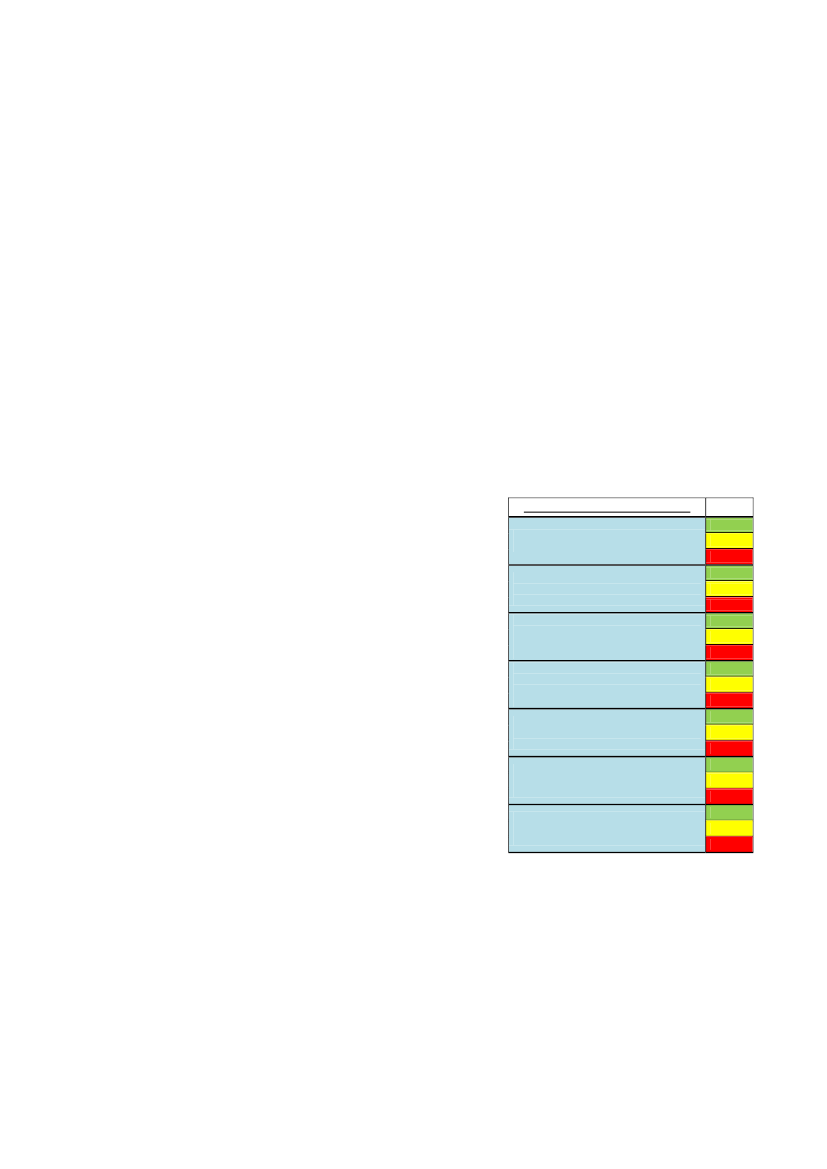

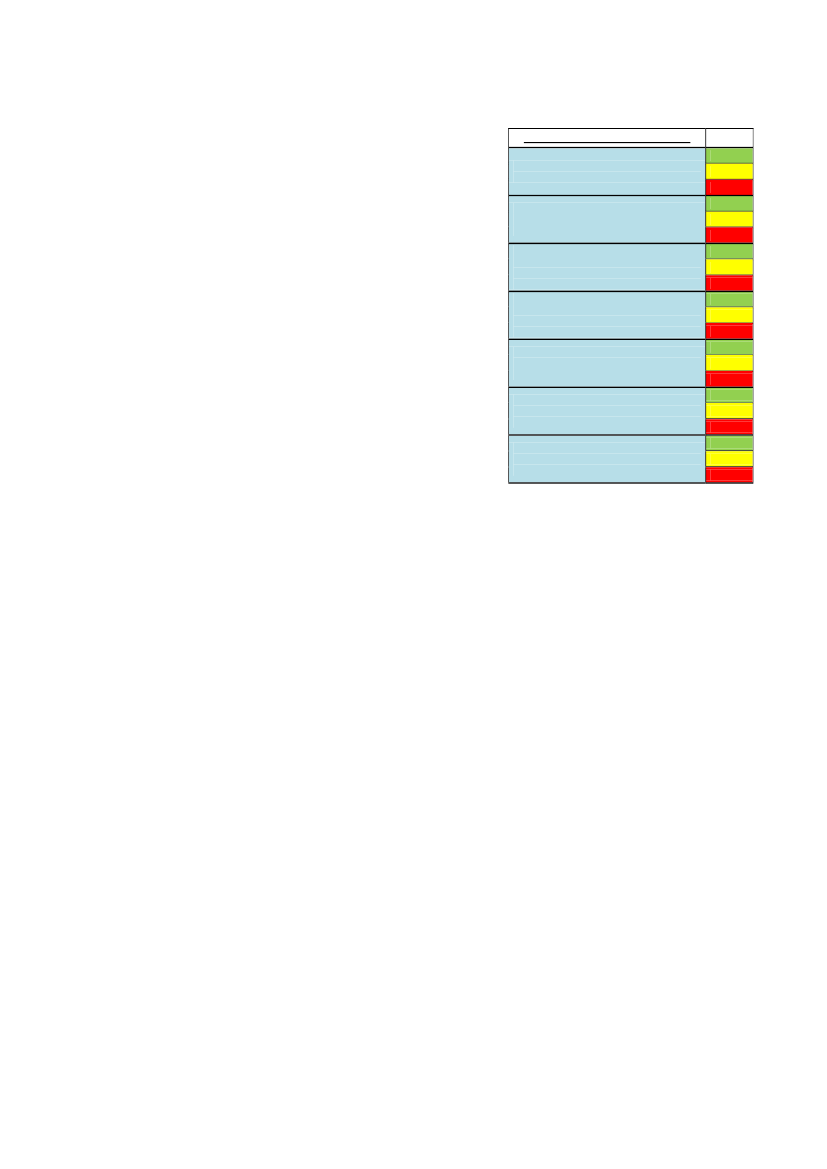

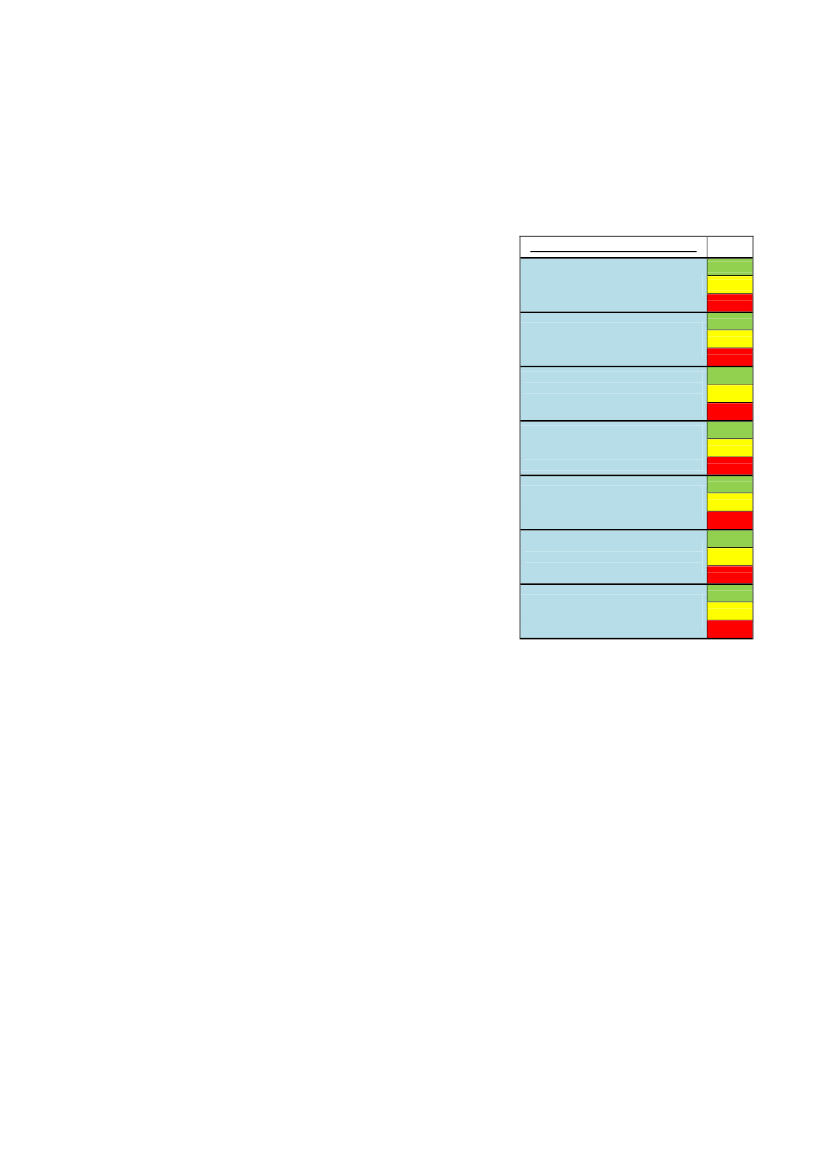

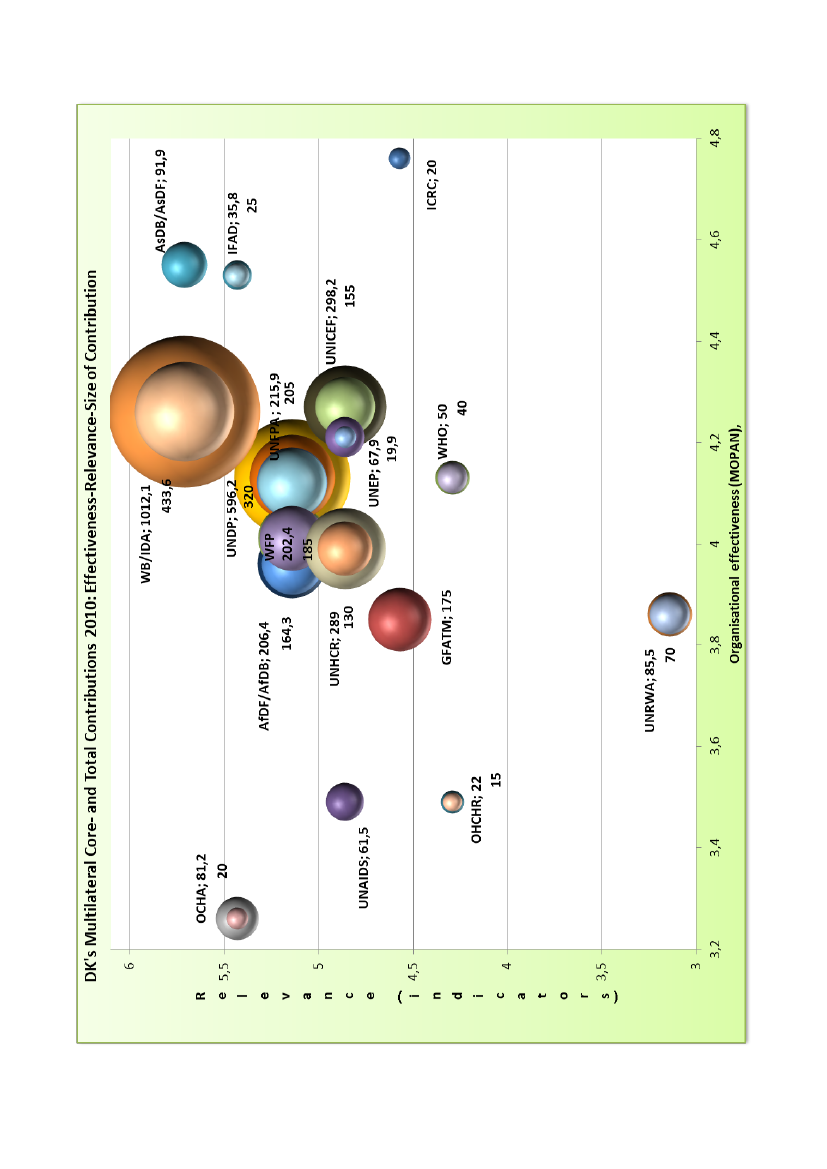

Alignment with Danish development policy prioritiesThe review of Denmark’s cooperation with individual organisations generally shows a high degree ofalignment with Danish development priorities. It also indicates that Denmark, with its decentralisedmodel of cooperation, is consistently able to ensure that its priorities are pursued through the organisa-tions whose mandates best cover them. As a supplement to the assessment carried out of each organi-sation’s performance on goals agreed for its partnership with Denmark, departments in the Ministry ofForeign Affairs as well as Danish UN missions abroad have been asked to answer a set of cross-cuttingquestions regarding the consistency between the activities of the institutions and Danish developmentpriorities. The use of these indicators2introduces a substantial element of subjectivity. However, theambition is to strengthen the element of objectivity in future assessments.The diagram on the following page shows the relative position of organisations when rated against thecross-cutting indicators mentioned above and indicators of their institutional efficiency. Data regardinginstitutional efficiency has been drawn from MOPAN and DFID’s multilateral analysis. The diagramalso shows the relative size of Denmark’s contributions to the 17 multilateral organisations examined inthis report, as indicated by the size of the bubble showing both the Denmark’s core budget contribu-tion and total contribution to the organisation.The diagram indicates relatively good alignment betweenthe scale of Danish cooperation with theorganisations and the assessment of the efficiency and relevance of the institutions.It should beunderlined, however, that the diagram does not reflect either the development impact of the organiza-tions on specific goals selected for monitoring progress in their partnership with Denmark or their rel-evance in relation to Denmark’s specific policy priorities. These key dimensions will be strengthened infuture assessments.Overall, the analysis showsgood correspondence between the specific development contribu-tions made by the multilateral organisations and Danish development priorities.The analysisalso indicates good alignmentbetween the relative size of the Denmark’s partnership with theorganisations and the assessment of their efficiency and relevance.

2

The indicators include the degree to which the organisation 1. Is innovative and agenda-setting within its mandate, 2.is relevant to Danish development priorities, 3. has satisfactory systems for responsible financial management and re-porting, including risk management and anti-corruption, 4. provides a satisfactory level of information on results andchallenges, 5. complies with the Paris and Accra Declarations, 6. is actively involved in the multilateral reform agendaand 7. is actively attempting to include new development actors in its work.

6

7

RecommendationsThe analysis contained in this paper covers the financing of multilateral organizations, their role in con-flict-affected and fragile states and in promoting sustainable development as well as at Denmark’s co-operation with individual organisations. The analysis demonstrates a need for a continuedactive en-gagement by Denmark in the work of multilateral organizations.Denmark will work toinfluencethe development of the overall multilateral institutional machinery and the individual organisa-tionsto ensure that these institutions can effectively deliver their part of the international agenda inrelation to stabilisation, humanitarian efforts and development in general, and more specifically on theDanish policy priorities. Denmark will work for a moreefficient, well-coordinated and flexible sys-tem of multilateral organisations,capable of effectively meeting emerging security, development andhumanitarian challenges and of ensuring a better transition between peace-making, stabilisation, hu-manitarian interventions and development, with therequired legitimacy and capacity to respondgloballywherever and whenever necessary.Denmark will seek influence in organisations through its work on the executive boards, its funding pol-icy, bilateral contacts and a sharper focus on secondment of staff in areas of strategic importance toDenmark. The impact of Denmark’s views and priorities will be enhanced through cooperation withlike-minded countries, including within the Nordic+ and the Utstein Group, as well as through the EU.Denmark will work across executive boards and other decisions-making bodies to ensure that mandatesand divisions of labour are respected and built upon to create added value in the overall effort. Thisalso applies to bilateral programmes at country level, where Danish embassies will be expected to helppull organisations in the right direction in accordance with their core mandates. Engaging effectively inthe strategic dialogue in the organisations requires professional involvement and input from the entireDanish Foreign Service, including at times participation from headquarters in important meetings.The overall approach outlined above will be followed while observing the following specific recom-mendations for Denmark’s engagement in the multilateral cooperation.

FundingThe analysis contained in this review does not provide justification for significant im-mediate realignment of the financial contributions to the various organisations.Denmark will cooperate with Nordic and other like-minded countries to ensure ade-quate financing of core budgets to enable these organisations to effectively executetheir mandate and bring their absolute advantages into play.With the objective of securing a sound financial framework for multilateral organiza-tions Denmark will work to:oCreate clarity and consensus regarding the size of resources necessary to main-tain a critical mass in individual organizations;oEnsure that the growing tendency to earmark multilateral contributions is re-versed and that attention is paid to securing sufficient funding of general budg-ets to enable organisations to deliver on their core mandate;

8

oEnsure that the remaining trust funds are aligned with core mandates andstreamlined within governance structures and processes, and that the agreedmandates and governance mechanisms are fully respected in those cases whereinstitutions have been asked to administer multi-donor trust funds in the ab-sence of a designated organisation.The modality of Danish multilateral assistance will be decided on following the samephilosophy that guides allocation of bilateral assistance, namely that generalised con-tributions are best suited to strengthening development effectiveness through promo-tion of partner ownership and use of country systems. Denmark’s contributions to mul-tilateral organisations will be provided as core contributions as a default, and deviationsfrom this principle – in the form of earmarking – should be the exception requiring jus-tification in each specific case.Earmarked contributions through multilateral organisations must be focused on deliv-ery of support in conflict-affected and fragile states and generation of global publicgoods (GPG) within climate, health and education, in areas not covered by existing in-stitutions.Denmark will work to ensure that emerging economies contribute to financing multi-lateral organisations in line with their economic standing and that the multilateral or-ganisations attract financing from private funds and serve as facilitators for South-Southand triangular cooperation.

Results-based managementIn its efforts to help enhance the effectiveness of multilateral organisations, Denmarkwill pay particular attention to: 1) establishment of satisfactory systems of financial ac-countability, 2) strengthening of the organisations’ own systems of results-based man-agement, monitoring and evaluation, 3) follow-up on action plans for alignment andharmonisation, and 4) intensification of the efforts on the part of the organisations toinvolve new actors.Denmark will work for an agreement within the UN on a new set of global goals for in-ternational development that takes into account the need to follow through on the un-finished agenda in relation to the Millennium Development Goals after 2015, supple-mented with goals for addressing new challenges, including specific sustainable devel-opment goals.Denmark will work to ensure that the UN strengthens its global norm-setting functionin relation to the formulation and promotion of internationally recognised rights andthat it brings its recognised advantages in relation to pursuing a rights-based approachto development at the country level fully into play.

9

Conflict-affected and fragile statesDenmark will work to ensure that relevant multilateral organisations more effectivelybring their particular advantages in conflict-affected and fragile countries into playthrough a clearer division of labour and observance of mutual respect for this divisionamong organisations. Among the most important organisations within the humanitari-an and development fields are OCHA, UNDP, UNICEF, OHCHR, the World Bankand the regional development banks. This ambition will also be pursued in the contextof the EU.Denmark will increasingly build on the advantages offered by the multilateral frame-work in post-conflict and fragile states, including in countries such as Afghanistan, So-malia, South Sudan and Zimbabwe.Denmark will work to strengthen the coherence among security, humanitarian and de-velopment efforts – both within and between organisations - and to ensure that effortsto prevent conflicts are intensified. Deeper analysis of the underlying conflict factors,use of joint risk assessment and greater willingness to run a calculated risk are im-portant elements of this agenda.Denmark will support the implementation of the New Deal in Afghanistan, Liberia andSouth Sudan and help ensure that multilateral organisations contribute to the imple-mentation of the New Deal generally. Denmark will also work for an outcome in whichthe UN assumes the key role in the rebuilding of Afghanistan, acting on the recom-mendations of the cross-cutting analysis of the performance of the various UN actors inAfghanistan currently underway.

Sustainability and the green economyDenmark will work to ensure that the multilateral system of organisations intensifies itsefforts to support the transition of the global economy in general, and the economies ofdeveloping countries in particular, to forms of production and consumption that safe-guard the planet’s natural resource and ecosystems. Organisations should supportcountries in their efforts to develop specific responses to the challenges caused by pov-erty, unequal distribution of wealth and intensified consumption of resources and as-sume leadership in providing advice and support to countries making the transition.Denmark will work to ensure that global sustainable development goals (SDGs) areformulated in the context of the UN as part of the transition to a green global economyand as a supplement to the MDGs, and that all the multilateral organisations subse-quently contribute to achieving these goals.

10

Denmark will call on multilateral organizations to cooperate in the effort to develop andachieve international recognition of a common methodological framework for the greeneconomy, building on methodological advances already made with regards to green na-tional accounting, cost-benefit analyses and similar instruments.Denmark will use the multilateral system to forge closer cooperation with new donors(the BRICS countries and second-wave economies) with a view to attract more financialsupport for programmes with a green dimension.

Follow-upDenmark will evaluate the degree of alignment between Denmark’s development priori-ties and the core mandate of organizations continuously as part of future reports on itsengagement in multilateral organizations, and strengthen its monitoring of their contri-butions towards achieving agreed development results.

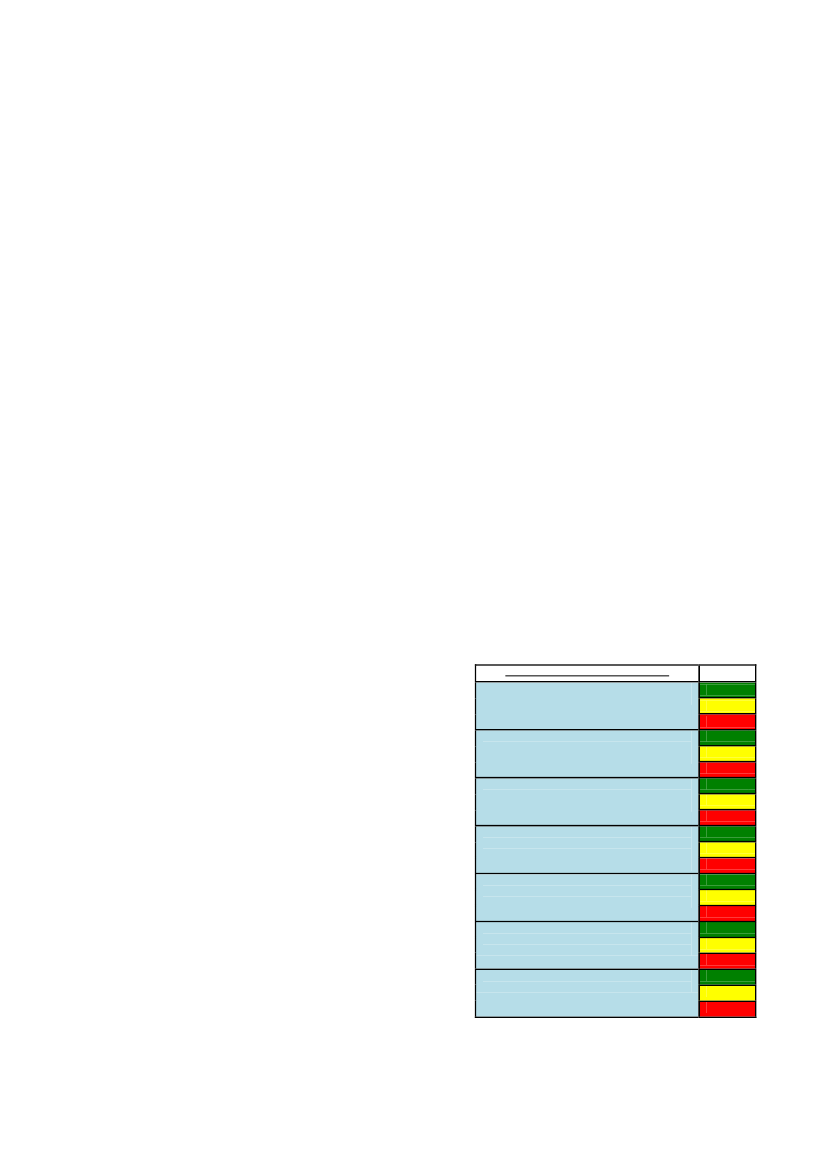

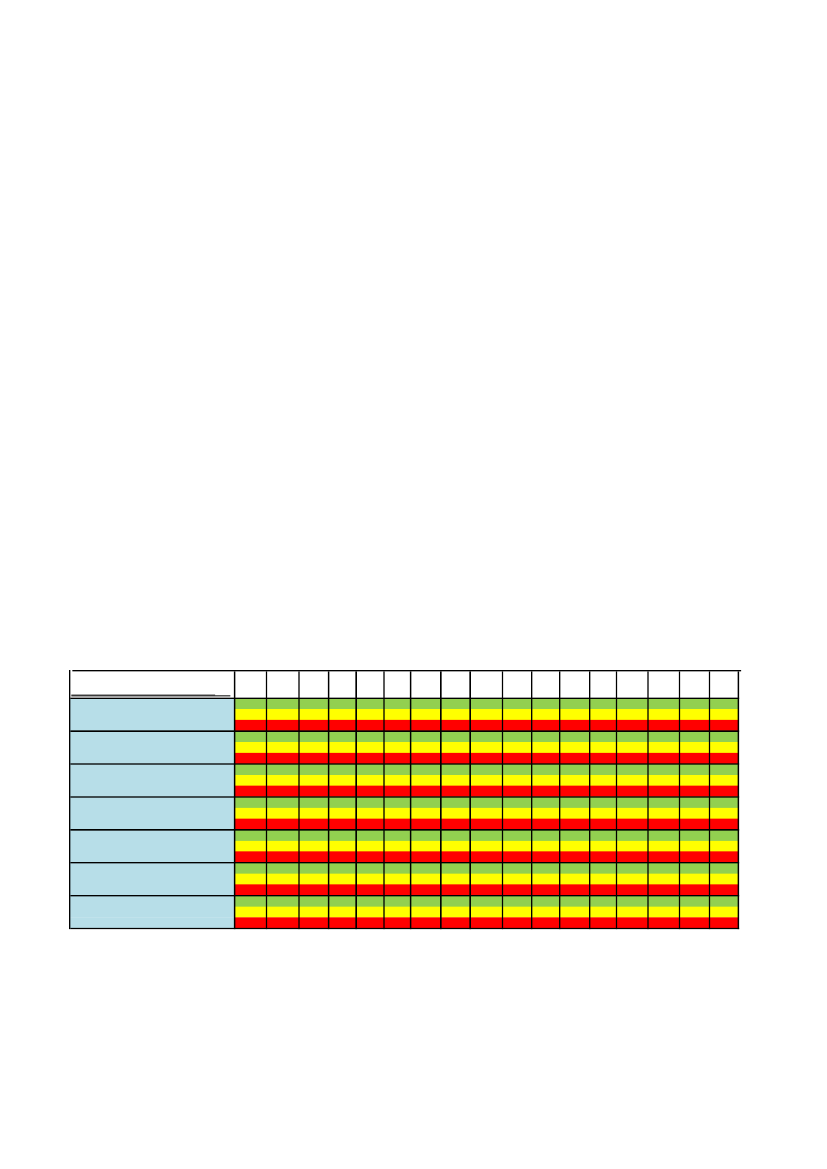

The above mentioned recommendations will serve as the basis for structuring Denmark’s cooperationwith multilateral organisations. The specific strategies for Denmark’s cooperation with individual or-ganizations will include indicators that reflect these aspects. The follow-up will be monitored throughannual reviews to be included in future multilateral assessments. The recommendations listed above aremedium and long term in scope and may re-appear in future multilateral reviews, adjusted to changes inthe circumstances as need be. Denmark will address these issues and encourage collective action inconsultation with like-minded donors in the Nordic+ and Utstein contexts, and in connection withjoint reviews and evaluations of the multilateral organisations, including MOPAN.The next page contains a schematic overview of the Danish priorities for the 17 organisations.

11

ORGANISATIONContribution 2010(DKK mil.)UNDPCore contribution 320.0Total contribution 596.2UNICEFCore contribution 155.0Total contribution 298.2

MandatePoverty reduction. MDGs.Strengthening of democracy. Crisisprevention and rebuilding.Environment/ sustainabledevelopmentMobilises resources for children’srights to health, clean water,education, and protection.Humanitarian key actorPromote reproductive health andgender equality. Develop popula-tion programmes to reducepoverty. Leading role in the follow-up of the action plan from theconference on population anddevelopment in 1994Reducing poverty and hunger by50 per cent in 2015 throughcreating increased income in thepoorest rural areas. Professionaladvice to the agricultural sectorand support to increased marketaccess and insight.Save and protect lives. Fighthunger and promote food security.Distribution of food. Developmentmandate which Denmark does notsupportProtection and assistance topersecuted people due to race,religion, nationality, political beliefs,or belonging to a specific group ofsociety. Key role with regard toprotection, administration etc. ofcamps for IDPs.Established to mobilise resourcesto funding of initiatives to supportMDG 6 with regard to fighting aids,tuberculosis and malaria in theareas of the world with the greatestneedsEnsure integrated and holisticapproach to fighting of HIV andaids within the UN family, includingimprovement of the coordination ofUN’s efforts at country level.Partnership of ten multilateralorganisationsContribute to improved health forall, and leading cooperating organfor international health cooperation.Considerable normative role inhealth policy. Obliged to contributeto fulfil the 2015 goals on healthImpartial, neutral and independentprivate organisation. Mission toprotect and assist victims of armedconflicts. In addition strengthen,and dissimate awareness on IHLand universal humanitarianprinciplesPromote and protect human rightsand protest when these areviolated. Through normativedevelopment of human rights,surveillance of compliance andwork to ensure strengthening ofUN’s approachHandling basic needs such aseducation, health social services,and humanitarian assistance toapprox. 4.5 million registeredPalestinian refugees in Lebanon,Syria, Jordan, Gaza, and on theWest BankPoverty reduction throughassistance to sustainable growth.Focus on poor and vulnerablegroups particularly in Africa, createfoundation for economic growth,promote global collective action,and good governanceAssist in poverty reduction andfulfilment of MDG 15 in Asia andPacific by offering professionalsupport, loans, and grants toauthorities and the private sector inentitled Asian member statesContribute to economic and socialdevelopment in Africa throughsupport of good governance anddevelopment of the private sector,infrastructure, and education.Strengthen efforts in fragile statesand increased regional integrationCoordinate and support interna-tional humanitarian efforts. Mobiliseresources to save lives and reducevulnerability in humanitariansituations. Develop humanitarianpolicy in cooperation with partners.Advocate for people in need.Deliver communication on andanalysis on humanitarian challeng-es and needs.Strengthen global cooperation andpolicy development on environ-ment. Primarily normative.Increased emphasis on environ-ment and development. Assist toensure integration of environmentin development

Main focus areas for Danish cooperation and dialogue with the individual organisations

Overall policy developmentand coordination

Conflict-affectedand fragile states

Sustainable develop-ment, sustainableenergy, MDGs+

Democratic governance

Gender equality and human rights

Support of the weakestgroups. Children’s rights

Health. Reductionin child mortality

Education

Conflict-affected andfragile states

Support of UNICEF’s humanitarianrole through partnership agreement

UNFPACore contribution 205.0Total contribution 215.9

Support to maintain theaction plan from the Cairoconference in 1994

Individual rights,in particularsexual andreproductivehealth and rights

Ensure involvement ofpopulation dimensionon sustainability

(Conflict-affected andfragile states)

Gender equality

IFADCore contribution 25.0Total contribution 35.8

Increase focus on low-income countries and Sub-Saharan Africa and thesouth-south cooperation

Conflict-affectedand fragile states

Increased efforts withregard to climateadaption, value chaindevelopment, marketaccess for wom-en/smaller businessMaintain pressure toensure WFP continuesto contribute tocoordination insituations of crisesIntern reform process:results-based leader-ship, resourcemanagement andevaluationFocus on means for thepoorest countries.Strengthening ofharmonisation andalignment

Continued decentralisa-tion to country offices andstrengthened efforts forharmonisation

Involvement of new actors andstrengthening of OPEC countries’involvement

WFPCore contribution 185.0Total contribution 202.4

Support protection ofWFP’s humanitarian work

Support WFP’srole in conflict-affected andfragile statesSexual andgender basedviolence and on-going solutions.Voluntaryreturn/integrationCapacity andpolicy building:gender equalityand sexual rights

Maintain focus ontransition towards anincreased strategic foodassistanceMaintain UNHCR’s focuson coordination responsi-bility and partnershipbehaviour

Maintain WFP’s focus on itscomparative strengths and coretasks.

UNHCRCore contribution 130.0Total contribution 289.0

Protection including:environment and children

Increased HR-policy among otherthings with regard to improvedemergency relief and focus onsecurity for envoys in the field

GFATMCore contribution 175.0Total contribution 175.0

Central partner for fightingof HIV/aids + MDG 6 (+MDG 4-5)

Maintain role model forpublic-private partnership

Support thorough reform processacross the organisation

UNAIDSCore contribution 61.5Total contribution 61.5

Support movementtowards rights-basedapproach

Support efficientcooperation withpartner organisa-tions – post-2015goals

Ensure maintaining ofkey role for coordina-tion between partnerorganisationsSupport centralcompetence areas:development of normsand standards tosupport fulfilment ofhealth related 2015goalsSupport ICRC’s effortsin acute humanitariancrises.

Strengthened focus onUNAIDS’ technicalsupport facilities

Protect UNAIDS’s specific possibili-ties to handle sensitive themes andproblems

WHOCore contribution 40.0Total contribution 50.0

Ensure continued role askey actor of improvementof health in developingcountries with regard to2015 goals

Support essentialreform process toensure focus andefficiency acrossthe organisationSupport work toextend humanitar-ian law in relationto handling ofprisoners(CopenhagenProcess)Oppose othercountries’attempts tonarrow the HighCommissioner’sindependenceAssist instrengtheningUNRWA viabilityduring increasing-ly difficultconditionsEnsure positionas leading role assupport todevelopmentcountries’ effortsof good govern-anceIncrease efforts inenergy, integra-tion of environ-ment, adaptationto and preventionof climate changeMaintain AfDBcontributesactively to Rio+20follow-up

Support WHO’s globalrole in the area of non-communable diseases

ICRCCore contribution 20.0Total contribution 20.0

Strengthen support ofdetainees and protectionof ICRC’s right ofconfidentiality

Contribute to campaignfor access to healthbenefits in conflicts andother situations ofviolence

Support ICRC’s efforts on disarma-ment, primarily with regard to clusterarms and light hand weapons

OHCHRCore contribution 15.0Total contribution 22.0

Support the HighCommissioner’s work assecretariat for treatyorgans and professionalsupport to other UNorganisations

Cooperate on ques-tions of torture andintegration of humanrights in relation toefforts in conflict-affected statesSupport improvementof cooperation betweenUNRWA, donors, andhost countries – focuson improving ”humani-tarian access”.Work to increaseintegration of environ-ment and climate incountry and sectorstrategiesMaintain that AsDBinvests in education,distribution policy,infrastructure etc. toincrease growth andreduce povertyMaintain AfDB’sinvolvement inrebuilding fragile states,including strengtheningstaff expertise

Cooperate on themesrelated to the develop-ment in the Middle Eastand North Africa duringthe Arab Spring

UNRWACore contribution 70.0Total contribution 85.5

Support work to ensure therights of Palestinianrefugees

Put pressure on establish-ing transparent andconsolidated budget andgreater openness in thedialogue with donorsSupport that WDR2011recommendation onconflict-affected andfragile states is followedwith UN in leading role inthe transition phaseSupport AsDB’s contin-ued focus on corruptionand bad governance asthe biggest threats toregional developmentEnsure AfDB strengthensefforts on good govern-ance – analytical and viaactive advocacy togovernments

Shifting assistance to pure corecontributions to support efforts inincreased budget transparency

WB/IDACore contribution 433.6Total contribution 1.012.1

Growth and employment –the World Bank as keyadvisor on and source offunding of growth

Ensure that the Bank strengthens itsgender equality aspects in design,implementation, and evaluation ofprogrammes and projects

AsDB/AsDFCore contribution 91.9Total contribution 91.9

Ensure AsDB continues itshigh level and high qualityof assistance to Afghani-stan and PakistanEnsure support ofeconomic developmentfrom an inclusiveapproach. Priority tocreating jobs in formal andinformal sectors

Ensure increased priority to genderequality

AfDB/AfDFCore contribution 164.3Total contribution 206.4

Put pressure on AfDB to increaseoperative capacity with regard togender equality, and integratesgender equality in all relevantactivities

OCHACore contribution 20.0Total contribution 81.2

Ensure support of OCHA’skey role in the coordinationof humanitarian efforts.And from the entire UNsystem

Support strength-ening of OCHA’shumanitarianadvocacy

Continue dialogue onefficiency in theorganisation andimprovement ofmonitoring andreporting systems

Ensure Danish participa-tion in OCHA DonorSupport Group – inbriefings as well as in theannual High Levelmeeting

UNEPCore contribution 19.9Total contribution 67.9

Prioritise development andimplementation of a robustsystem for results-basedmanagement

Support work toensure states’ability to includeclimate in nationaldevelopmentstrategies

Considerate emphasisto UNEP’s work on agreen agenda,including supply of solidknowledge and advice

Support UNEP’scoordinating role in theUN system’s efforts forsustainable development

Ensure a key role for UNEP withregard to integration of environmentand poverty reduction

12

Part 1 - IntroductionIn 2011 it was decided tostrengthen the policy focus and coherencein Denmark's participation inmultilateral development cooperation. The preparation and reporting on cooperation with multilateralorganizations would henceforth be anchored inone annual cycle.The cycle starts each year in Sep-tember with preparation of an analysis of changes in the policy and financial environment in whichmultilateral organizations operate and formulation of strategic orientation for Denmark’s future en-gagement in multilateral cooperation. Against this background, representations and entities in charge ofmultilateral organizations prepare a report on progress made over the past year in cooperation withorganizations receiving more than 35 million DKK in annual contributions from Denmark. In this re-port, suggestions are also made for priorities for Denmark’s engagement in the organization in questionand an assessment is made of its relevance based on a set of cross-cutting indicators.Building on these various contributions,a comprehensive strategic paperis put together and pre-sented to the management of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs for discussion on the status and the sug-gested orientation of Denmark’s participation in multilateral development cooperation in the followingyear. The paper is subsequently revised and submitted to the Minister for Development Cooperationfor consideration and approval. The annual cycle replaces the previous briefings of the Board on strate-gies and action plans for individual organizations.This paper consists of three parts.Part 1 contains an assessment of trends and challengesfor mul-tilateral cooperation.Part 2 contains an assessment of progress in the cooperation with individu-al multilateral organizationsin the year under review and suggests priorities for Denmark's engage-ment in the organization in 2012 and beyond.In Part 3 general conclusionsand overall recommen-dations for Denmark’s engagement in multilateral cooperation in the future are provided.The 2011 multilateral analysis reviewed the shifting global patterns of growth and the accompanyinggeopolitical changes as well as their implications for the role of multilateral organizations. The 2012multilateral analysis focuses on a number of more specific dimensions, namelythe funding of multi-lateral organizations and the sustainability agenda as it evolves around the Rio+20 Conferenceas well as the need to ensure a more effective international response to the requirements ofconflict-affected and fragile states.These topics were chosen because of the attention they currentlycommand internationally. They do not constitute the entire policy universe of multilateral cooperationand Danish multilateral missions have been asked to contribute supplementary relevant information intheir submissions on specific organizations.This paper isbased on the current strategy for Denmark’s participation in international devel-opment cooperation entitled “Freedom from Poverty”.The new overall strategy now under prepa-ration will be reflected fully in next year’s multilateral analysis. However, the paper covers two of thegovernment's announced new priorities,namely green growthandstability and security. Therights-based approach to development and food security– the two other priorities of the newstrategy - are also raeas where multilateral organizations have a clear role to play. These dimensions willbe covered in the 2013 analysis. It is also anticipated that Denmark’s contributions to international de-velopment through the EU will be subject to assessment and priority setting in future analyses.

13

Challenges facing the multilateral organisations in a changing worldGeneral trendsChanging growth patterns and shifts in global decision-making capacityOver the past decade, economic growth in developing countries has been faster than growth in ad-vanced economies, and developing countries currently account for 35 per cent of global GNP and 65per cent of global economic growth. Whilst the success of a number of dynamic developing economiesis the most frequently publicized part of this growth story, low-income countries as a group have alsoexperienced elevated rates of real annual growth of above 3 per cent during the past decade, thusre-versing the trend of slow or stagnating growth, foreign investments3and participation in inter-national trade of previous decades.And the positive development in the economic sphere has beenaccompanied by significant advances on the social front. The largest number of citizens ever recordedhas worked their way out of poverty, and the massive efforts to improve public access to health care,education and infrastructure have largely borne fruit. Despite the current serious economic crisis, thereis no reason to believe that the shift of prosperity from the currently advanced economies towards thedynamic economies and subsequently the low-income countries will not continue in the coming dec-ade. In its wake, competition for access to energy and raw materials will intensify.This fundamental shift in economic power also means that decision-making no longer predominantlyresides with the great powers of the 20th century, but is diffused in an international system withseveralpower centres.The G20 has manifested itself as the leading forum for tackling the global financial andeconomic crisis, with dynamic developing economies playing a central role.The prominence of the G20 also reflects the increasingly interwoven and interdependent nature of theglobal economy. On the one hand the welfare implications for developing countries of decisions takenby the G20 countries’ decisions are increasingly evident. On the other hand economic progress in de-veloping countries contributes as a driver of growth in the global economy with growing strength. Therecognition of this interdependenceprovides a new rationale and implies new opportunities forinternational collaboration to build a global policy and economic environment and strengtheninvestments and development cooperation which wouldhelp more citizens in developing coun-tries work their way out of poverty and enable their governments to finance the delivery of public ser-vices. In addition,South-Southinvestments and trade are becoming increasingly important elementsfor the economic growth in low-income countries.However, the shift in global power and the establishment of new alliances and fora challengethe international system of global governance and multilateral decision-making.Many emergingeconomies have benefited considerably from cooperation with the multilateral organisations them-selves. Not surprisingly they now demand – and acquire – greater influence in leading multilateral forasuch as the UN Security Council, the IMF and the World Bank. This also means thatthe internationaldebate about values and paradigms of development is becoming more intensified.Led by theemerging economies, developing countries oppose attempts by the rich countries to persuade them toaccept higher standards regarding worker protection, environment and climate than advanced countriesthemselves observed during their industrialisation.

3

In the last decade, direct foreign investment in low-income countries has grown from USD 2.8 billion to USD 16.9billion and remittances from USD 4.1 billion to USD 24.8 billion.

14

If growth continues in the developing countries as anticipated,the economic dependence of low-income countries on external development assistance will gradually diminish,and traditionaldonor countries will focus more of their energy on forging commercial ties to the new potential part-ners. Such a scenario will likely be accompanied by a decreasing relative demand for the presence ofbilateral donors in emerging countries. At the same time, the need to be able to respond more resolute-ly, flexibly and coherently to the requirements of conflict-affected and fragile states, possibly accentuat-ed by new geopolitical tensions, will command more attention, as will a developmental agenda increas-ingly set by climate and environmentally related challenges. In this scenario there will still be a need foran institutional machinery capable of ensuring that countries which continue to need access to externalassistance to address their security, humanitarian and developmental challenges also receive this assis-tance. Traditional donors will in all likelihood look to the multilateral institutions as those who can en-sure that the ambition behind six decades of international development cooperation is followedthrough, including in countries where they themselves have no strategic interest in being present. Like-wise, in a world characterised by competing ideas and paradigms and influenced by new actors seekingnew platforms, the multilateral organisations are likely to appear as increasingly relevant partners forboth middle-income and low-income countries.Thelegitimacythat the multilateral organisations confer on international cooperation is absolutelyvital for the development and endorsement of the standards, ideas, platforms and frameworks thatserve as the backbone of the international partnership for development and the point of departure formeasuring its developmental impact. To the multilateral system’s absolute advantages in the develop-ment field can be added its advantages in initiating and delivering security and humanitarian interven-tions and in fostering coherence between security, humanitarian efforts and development. While emerg-ing economies have so far not participated strongly in formalised donor cooperation in multilateralfora, they are becoming ever more important commercial partners for low-income countries. The chal-lenge is to enhance the development impact of all efforts by seekingsynergy between private in-vestments from the emerging economies and the private and public transfers from the tradi-tional donors– a challenge that the multilateral organisations are well placed to help tackle.It is in Denmark’s clear interest to help maintain an effective, well-coordinated and flexiblesystem of multilateral organisationscapable of meeting outstanding and emerging challenges of asecurity, development, humanitarian and global public goods nature as well as of ensuring a better tran-sition between peace-making, stabilisation, humanitarian and development efforts, with the requiredlegitimacy and capacity to respond globally where and when needed.Since the end of the Cold War, and notwithstanding progress made on the Paris and Accra goals on aideffectiveness, there has been atrend towards increasing fragmentation of development assistanceand proliferation of actorsengaged in the development cooperation in many developing countries.This trend has partly been driven by anincrease in the earmarkingof multilateral funding, whichtends to undermine the absolute advantages of multilateral organisations as actors – i.e. their legitimacyand accountability as well as their ability to ensure access to funding with the required scope and pre-dictability, including for countries that may not be the preferred partners of bilateral donors. The op-portunities of the organisations to bring their advantages into play require adequate and predictablefinancing of their general budgets and their core mandate - the point of departure for discussions re-garding goals, results and reforms – also with the new actors. Despiteprogress in relation to ensur-ing better coordination in the multilateral system,there is still a long way to go before the cogs inthe multilateral machinery mesh smoothly.

15

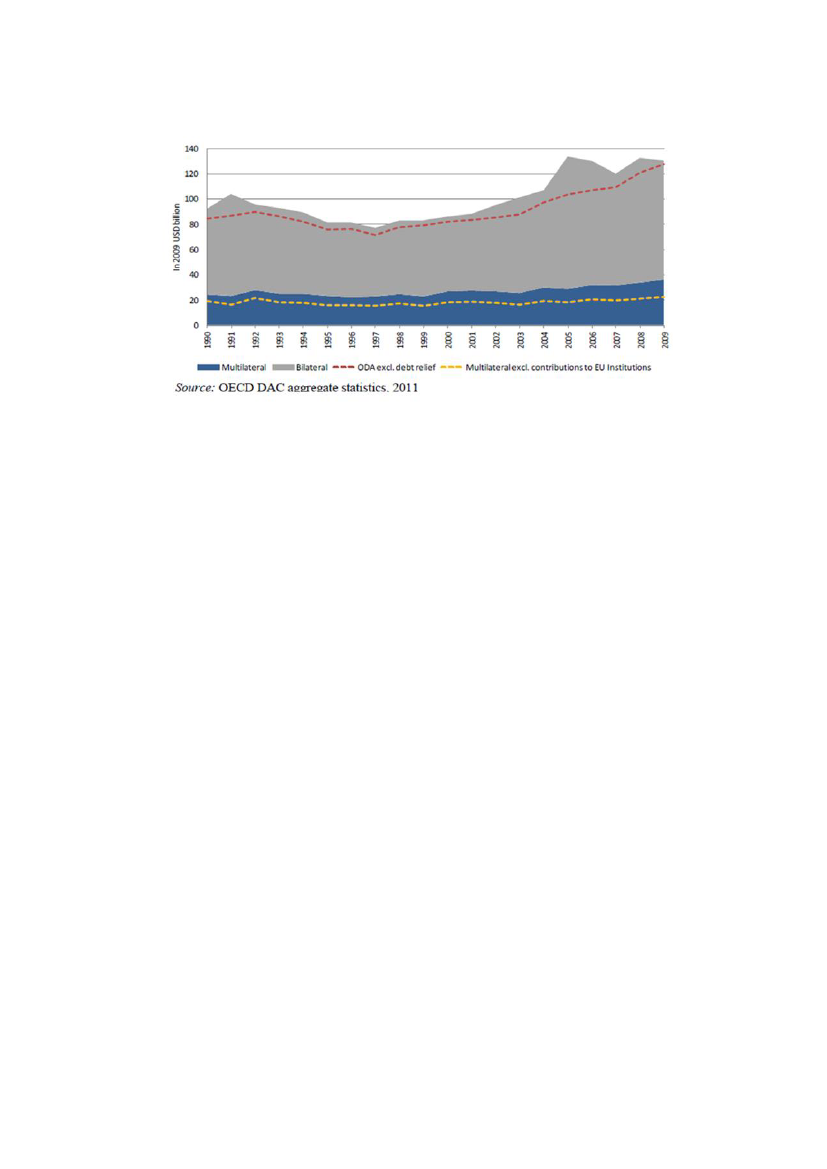

One of the major successes of the multilateral system during the past decade has been the formulationof theUN Millennium Development Goals.Rather than gathering dust on the shelves next to pre-vious UN goals, the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) have become the compass around whichnot just the multilateral organisations but the whole of international development cooperation today isoriented. This success must now be followed up by the formulation of a new set of goals that ensurethe continuation of efforts on outstanding challenges and supplement with goals to address new chal-lenges.Trends in the multilateral fundingDespite advances made on the Paris and Accra agendas, the overall picture of development coopera-tion is one characterised by anincreasingly complex architecture,with agrowing diversityof or-ganisations that channel aid and byincreasing fragmentationandearmarkingof development assis-tance. The average number of donors per country grew from three in the 1960s to thirty in the 2000s.Fragmentation and proliferation have gathered pace particularly since the end of the Cold War. In thisperiod the number of countries with more than 40 active donors has risen from zero to 24. More than100 organisations operate in the health sector alone, which hampers the ambition to build their healthsystems based on a holistic approach. The number of multilateral organisations, funds and programmesis now larger than the number of countries they were created to help.At the 4th High-Level Forum on Aid Effectiveness in November - December 2011 in Busan,South Korea, the fragmentation and proliferation of development assistance was acknowledged as is-sues that needed to be addressed. One of the commitments emerging from the forum is that countrieswill work to reverse the proliferation of multilateral funding channels and reach agreement on guide-lines to this effect by the end of 2012. The multilateral organisations have promised to honour theircommitments to harmonise and adapt their contributions to development to the partner countries’ ownsystems in accordance with the Paris and Accra declarations.The total funding of the multilateral organisations’ development programmes topped USD 51 billion or40 per cent of total ODA in 2009, compared to 37 per cent in 2007. However, the international finan-cial crisis is now also influencing the multilateral funding. The DAC’s 2011 report on multilateral assis-tance confirms the tendencies identified in the 2010 report, namely that the general trends in funding ofthe multilateral system observed over the past 20 years are continuing.One significant trend is the fall in the relative share of the core contributionschannelled to themultilateral organisations in relation to total ODA (see the table on next page). If the assistance chan-nelled through the EU is deducted, the assistance to other institutions dropped to 20 per cent in 2009.If the EU is included4, the multilateral contributions rose from USD 26.6 billion in 2000 to USD 36.2billion in 2009 – an average annual increase of 3 per cent compared to an increase of 4 per cent fortotal ODA. In total, the core contributions to the multilateral organisations dropped from 33 per centin 2001 to 28 per cent of total ODA in 2009.

4

TheEU is not a multilateral actor in the conventional sense. In this respect, the EU does not have a global normativefunction, nor does it have a mandate to cover needs globally. The EU channels a considerable proportion of its assistance toother multilateral actors.

16

ODA from DAC Member Countries in the Period 1990-2009

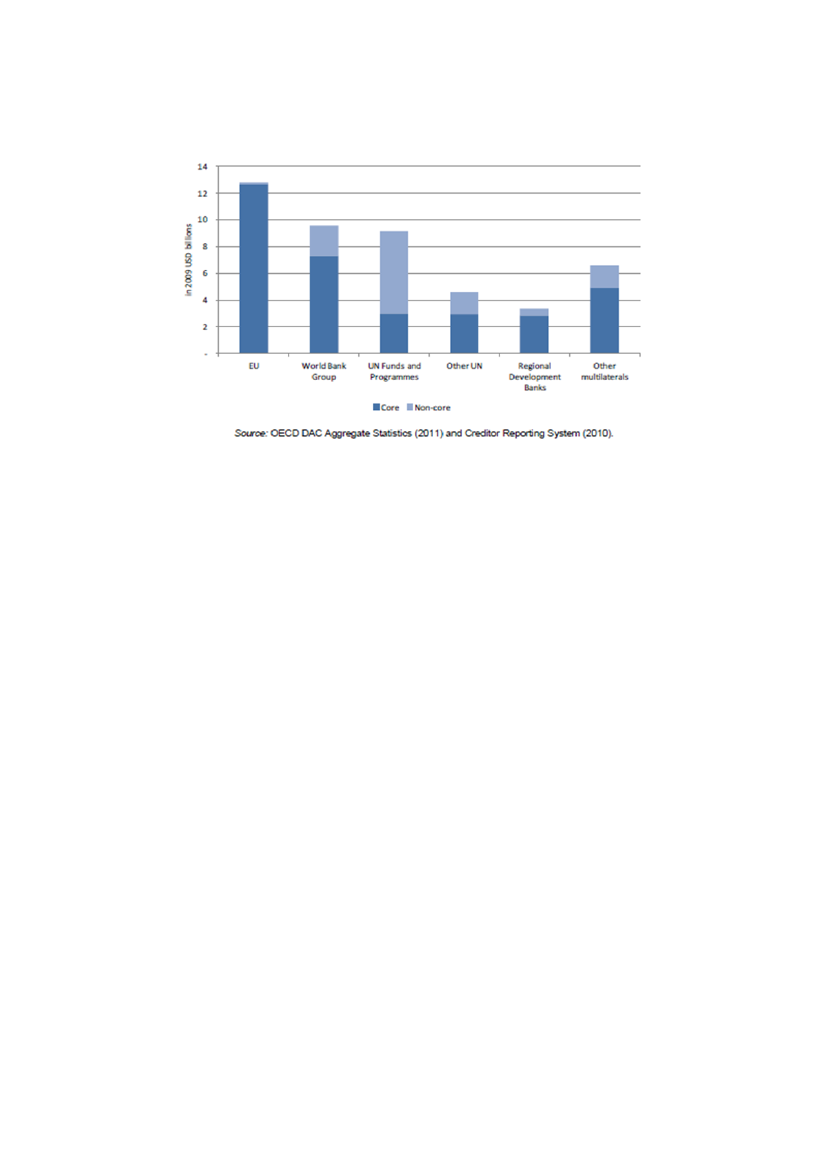

Since 1990, the disbursements of core contributions to the EU have grown from 25 per cent to 37 percent of total multilateral assistance, whilst the proportion going to the UN and the development bankshas shrunk correspondingly. In contrast to the UN funds and programs the level of activity of the mul-tilateral development banks (MDBs) and IFAD in low-income countries depends not only on the in-flow of new grant funds, but also on reflows from countries’ repayment of loans. Growing reflowsfrom past loans have enabled MDBs to increase the level of activity in their soft windows, IDA, AfDF,AsDF and FSO/IDB.The other significant trend in multilateral funding is the growing volume of earmarked fundsplaced at the disposal of the multilateral organisations. Earmarked contributions to multilateral organi-sations constitute the fastest rising form of ODA. Besides core contributions, multilateral organisationsreceive 12 per cent of total ODA, corresponding to USD 15 billion in earmarked funding – an increasefrom USD 13.4 billion in 2008. This is channelled through the multilateral organisations and earmarkedfor use in specific sectors, regions, countries or themes. The diagram next page shows the distributionbetween core contributions and earmarked funds in the financing of different parts of the multilateralsystem, as an average for the years 2007-2009. As can be seen, UN funds and programmes in particularare financed by earmarked funds. Six UN funds and programmes receive more in earmarked funds thanin core contributions. However, the World Bank and other UN agencies also receive substantial contri-butions in earmarked form.

17

Core Contributions and Earmarked Multilateral Funding (Average Annual Contributions 2007-2009)

Whilst the core contributions fall fully under the management and governance structures in the organi-sations, including the planning and reporting processes and procedures agreed with the member states,this is not necessarily the case for earmarked funds, which according to DAC fall “under a kaleidoscopeof accountability arrangements that very few ordinary citizens, and not many experts fully compre-hend”.Forpartner countriesearmarked funds can provide advantages in the form of better adaptation totheir own systems compared to alternative bilateral arrangements, and that they gain direct influence inthose cases where governance mechanisms have been established that provide developing countrieswith a stronger voice compared with the executive boards. However, this is not often the case, andtheir influence will typically be limited. Significant disadvantages include lack of clarity regarding thecriteria for allocation, in that the allocation of funds does not necessary follow the principles for alloca-tion of core funds, as well as lack of clarity regarding responsibility for the management of the funds.Earmarking hampers efficient allocation of resources on the national budget, weakens financial disci-pline and carries a higher transaction cost in terms of administrative effort.Forthe organisations,earmarking can increase the volume of funds available. Furthermore, earmark-ing through a trust fund can be the most suitable vehicle for performing specific tasks limited in time,rather than setting up a new organizational entity where no designated organisation exists. The disad-vantages are that earmarking can undermine the organization’s governance structures, tilt the balance inits general activity, and erode its mandate and policies as well as its mechanisms for allocating funds,including performance-based allocation mechanisms. The organisations often see earmarking as a “bi-lateralization” of the multilateral assistance.Forthe donors,the advantages include the possibility to focus on specific sectors, regions and coun-tries as well as to supplement their bilateral efforts, ensure greater visibility and facilitate circumventionof more complicated executive board decision-making structures. The disadvantages can be increasedadministration and cross-subsidisation between core and earmarked contributions. The donors perceiveearmarking as a “multilateralization” of the bilateral assistance.

18

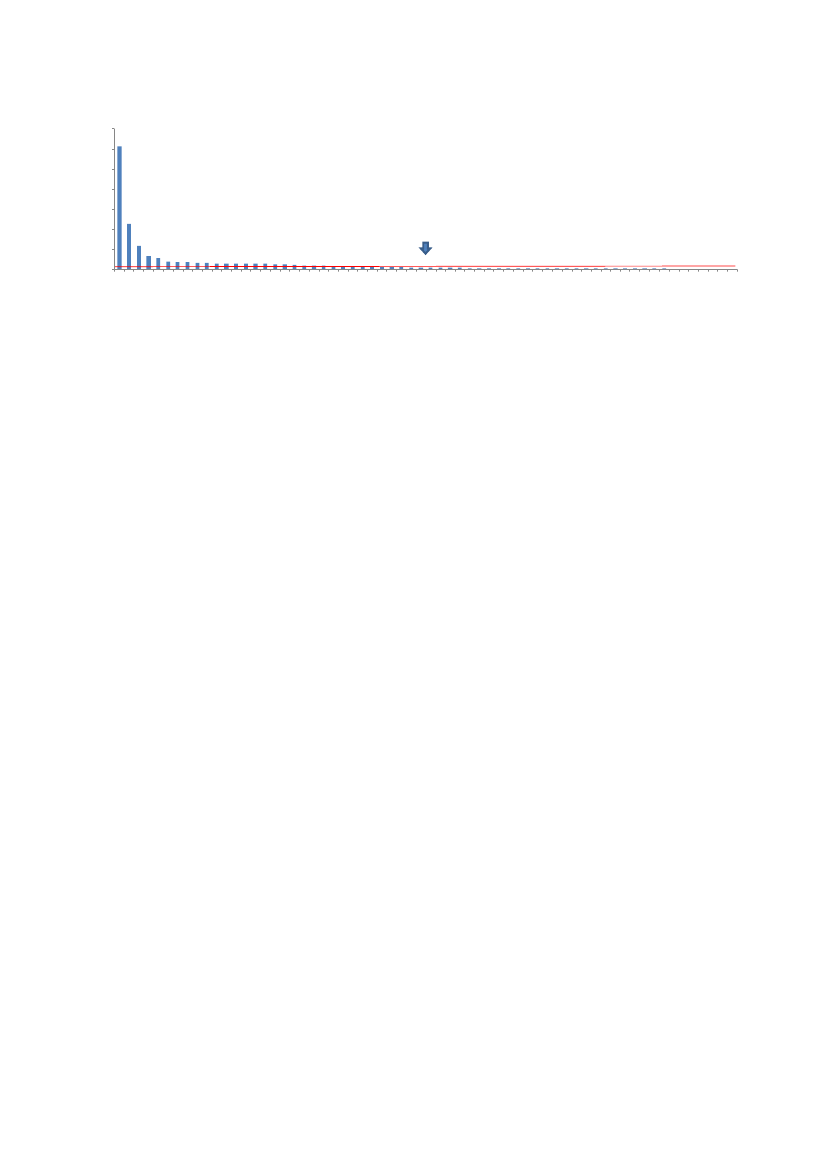

The earmarking/core budget contribution issue is not simple.In this respect, it is not possible toidentify which of the factors examined in the previous sections that have been most important in moti-vating the donors to increase earmarking of their multilateral funding. It is likely that a mixture of caus-es have been at play, including also a lack of confidence and inadequate influence in the organisationsas well as a growing pressure on the bilateral organisations’ administrative budgets. And it must be em-phasised that there can be good reasons for earmarking funds for particular purposes, for example inconflict-affected countries, for starting up in emerging areas of activity and as a means of attracting newsources of development funding in situations where the multilateral organisations are unable to mobi-lise adequate resources from their own budgets to tackle challenges which they are otherwise particular-ly qualified to handle.However, the multilateral organisations’ ability to bring their unique and absolute advantages into playrequires a critical mass of institutional capacity and reach in relation to their core mandate, and themaintenance of this critical mass is premised on predictable and adequate funding of their budgets.When budgets continually shrink on account of decreasing core contributions from member states, thecritical mass is reduced. Unchecked growth in earmarked funds can affect the overall balance in theactivities and interventions and undermine governance and management structures.Circumvention of “cumbersome” executive boards by means of earmarking also sows doubt about thewill to pursue multilateral solutions. And earmarking weakens the donor countries’ demands for resultsand performance in the organisations – an ambition that requires focusing attention around the execu-tive boards, management processes and the organisations’ own systems. Yet, amore robust and flexi-ble multilateral system is needed which can fill the gaps expected to be left in the future bybilateral donorswishing to focus on fewer countries and leaving outstanding work to the multilateralorganisations as low-income countries transit to middle-income status during the next 10-15 years.5Robustness and the ability to respond globally and with flexibility is best promoted through the use ofpredictable and untied contributions to the general budgets.The proportion of multilateral assistance of individual donors’ total assistance varies considerably.Denmark lies at the higher end of the scale with approx. 25 per cent channelled to multilateral organisa-tions, excluding the EU. Approx. 28 per cent of DAC’s multilateral assistance is earmarked. With ap-prox. 11 per cent in reported6earmarked assistance, Denmark lies relatively low in DAC’s comparison.At the top end of the scale are Australia, the USA and Norway with more than 50 per cent of theirmultilateral aid earmarked. The Netherlands has approx. 37 per cent, Sweden approx. 35 per cent andthe UK approx. 39 per cent.7As an example of Denmark’s earmarked contributions to multilateral organisations, it can be stated thatDenmark in 2010 contributed to a total of 49 active budget lines in the UNDP, one for core contribu-tions and 48 for earmarked contributions. Another example is Denmark’s contributions to active trustfunds in the World Bank Group in the period 2007-2011, which is presented in the diagram next page.

5

57 % of the multilateral funds are channelled directly to low-income countries compared with 34 % of the bilateralfunds, and 49 % of the multilateral assistance reaches countries in Sub-Saharan Africa compared with 26 % of the bilat-eral assistance.640 % of the assistance channelled to the 17 organisations covered by this analysis review was earmarked.7These comparisons must be taken with a very large grain of salt and compared with the countries’ total ODA, ODApercentages and contributions to the multilateral system.

19

20.00

40.00

60.00

80.00

100.00

120.00

140.00

50.00

Approx. 82 per cent of global multilateral assistance is provided through the EU, the World Bank, UNfunds and programmes, the Global Fund, the AfDB and the AsDB. The remaining 18 per cent is allo-cated to more than 200 organisations. Many of these organisations do not have a mandate to assistcountries directly, but can be important standard-setters or providers of frameworks and knowledge.

Lastly, there is growingSouth-Southcooperation and tripartite cooperation, in which the multilateralorganisations often play the role of catalyst or coordinator. New donors and partners are often middle-income countries who believe that multilateral organisations should not focus only on low-incomecountries and conflict-affected states, but also respond to the needs of middle-income countries –countries that are home to more than half of the people living in absolute poverty and some of whichappear to be caught in a middle-income trap.

In addition,private funds and companiesincreasingly contribute to the financing of multilateral or-ganisations. Different estimates indicate that the annual contributions from these sources for develop-ment could total between USD 22 billion and USD 53 billion. These actors do not participate in execu-tive board work and contribute predominantly with earmarked funds. However, models should be de-veloped to allow them to participate in relevant discussions and gain access to the necessary reports onthe use of their funds.

A total of 20non-DAC donorsreport their multilateral assistance to DAC. Brazil, India, China andRussia are not among them. The total reported multilateral commitment from non-DAC donors wasUSD 1,096 million, corresponding to 4.15 per cent of all donor contributions reported. Many new do-nors are middle-income countries, acknowledging the assistance they themselves received from theorganizations. Based on indications from different sources, the total ODA contribution from BRICcountries can be estimated to be USD 3.9 billion, corresponding to approx. 3 per cent of ODA in 2009.How large a proportion is channelled through the multilateral organisations is unknown.

20

5 million

Education for All Fast Track Initiative…Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust FundTrust Fund to Co-finance the Eighth, Ninth…Nile Basin Initiative Trust FundSupport Facility for the National Program…Municipal Development ProjectDenmark - Donor Funded Staffing ProgramKP/FATA/Balochistan Multi-Donor Trust…Trust Fund for Mainstreaming Disaster…MDTF for Trade Related Assistance in…Trust Fund for the Provision of Junior…Readiness Fund of the Forest Carbon…Water and Sanitation Program-Danish…Trust Fund for Local Government Capacity…Second Emergency Municipal…Trust Fund for Energy Sector Management…Danish Carbon FundMDTF for the Adolescent Girls InitiativeMulti Donor Nordic Trust FundMDTF for Water Partnership ProgramEnergy Sector Management Assistance…State- and Peace- Building MDTFMDTF for Co-financing of Private Sector…Financing for the Consultative Group to…MDTF for Strengthening Public…Integrated Land and Water Management…MDTF for the Public Sector Technical…MDTF for the South-South Experience…Callable Funds for the Standby Recovery…MDTF for Southern Sudan (MDTF - SS)MDTF for the Kosovo Sustainable…Learning for Equality, Access and Peace…MDTF to Support Public Financial…Java Reconstruction Fund (JRF)The MDTF for the Gender Action PlanMDTF for Country Environmental AnalysisAfrican Capacity Building Foundation-…MDTF for Forced DisplacementMDTF to Support Analytical Work within…The Sub-Saharan Africa Transport Policy…Economic Development and Structural…Development Marketplace 2009 Multi-…Africa Stockpile ProgramMulti-Donor Trust Fund for Bangladesh…The Multi Donor Low Income Countries…MDTF for COM+, Alliance of…MDTF for the Secretariat for the…MDTF for Uganda Emergency…Nepal Public Financial Management…MDTF for the Strategic Partnership with…Technical and Administrative Support to…Multi-Donor Trust Fund for Zimbabwe…MDTF for Communities and Small-Scale…MDTF for Migration and Remittances for…Palau - Petroleum MDTFGlobal Environment Facility (GEF)…Special Initiative of the Global…Financing for the Consultative Group to…Water and Sanitation Programme (WSP)…African Capacity Building Foundation…Global Environment Facility (GEF)…MDTF for Aceh and North Sumatra (…Danish Carbon Fund - Prepaid Trust FundMulti-Donor Trust Fund for Justice Sector…

Specific challengesIn the following sections two particular sets of challenges for the multilateral system are examined,namely those related to fostering stability and development in conflict-affected and fragile states andthose associated with supporting developing countries in their transition to a green economy. Thesetwo rapidly emerging issues are expected to strongly affect the work of multilateral organizations andtest their ability to adapt to a changing global agenda. At the Rio+20 Conference to be held in June2012 it is anticipated that new directions will be decided for the transition to a green economy and sus-tainable development.Conflict-affected and fragile statesFragile and conflict-affected states constituteone of the greatest development challenges today.The latest MDG report makes this abundantly clear. Whilst considerable progress has been made bymany developing countries, fragile and conflict-affected states lag far behind economically and have notachieved any of the MDG. Indications are therefore, thatan increasingly larger proportion of totaldevelopment assistance will go to conflict-affected and fragile states.There is a need for innova-tive approaches and genuine change, if peace, stability and development are to gain a strong foothold incountries affected by conflict and fragility. Geographically,the focus is likely to be on Africa, whereseven of the world’s ten most fragile states are situated.Bilateral donors often lack the necessarylegitimacy as well as technical and administrative capacity to operate in conflict-affected and fragilestates, and therefore act primarily through multilateral organisations.The need for a new international approach is documented in a number of pioneering reports such asthe World Bank’s World Development Report 2011, the Report of the Secretary-General on peacebuilding in the immediate aftermath of conflict from 2009, the UN review of civilian capacities from2011, and a number of reports from the conflict network in OECD/DAC, including the monitoring offragile state principles, which unfortunately shows that there is still a long way to go in terms of puttingthe principles into practice.As an innovation, a group of fragile states (G7+) have taken the initiative to engage in discussions re-garding a new international structure. The International Dialogue on Peace Building and State building,comprising G7+ and donors, has launched the“New Deal”– a new international approach to fragilestates – at the High-Level Forum on Aid Effectiveness held in Busan. Five goals for peace building andstate building have been identified that must be accomplished as a prerequisite for achieving theMDGs. The “New Deal” calls for much greater national ownership and strengthened cooperation be-tween international actors and national actors within the framework of a simple agreement structureunder multilateral leadership – typically provided by the UN.It is difficult to operate in fragile states. Lack of security as well as insufficient legitimacy and accounta-bility of governments that are often politically and economically marginalised contribute to the chal-lenge. Efforts in conflict-affected and fragile states are therefore complex and often very politically sen-sitive. This has led toa state of affairs in which the international community’s engagement infragile states is fragmented and primarily based on short-term interventions.Therefore, the mul-tilateral system needs to work more effectively in fragile states. The multilateral organisations play apivotal role in delivering aid in these countries and in the dialogue with national actors. This is partlydue to their particular legitimacy in situations characterised by precarious security and sensitive politicaland social controversies, and partly because few countries have bilateral missions in fragile states.

21

The multilateral organisations provide unique platforms for cooperation with new actors, particularlythe emerging economies such as China, India, Brazil, South Africa, which play a major role in manyfragile states. The opportunities for engaging in dialogue with new actors and influencing their policiesas part of the total international engagement in fragile states should be used. Strengthening the linkagebetween peace-making, peace building and state building requiresa sharp division of labour as wellas enhanced cooperation and coordination between the different multilateral actors –the UN,the World Bank, the EU and the regional organisations and development banks. In the WDR11, theWorld Bank recognizes that the UN should play the leading role in the transition phase. The review ofthe UN’s civilian capacities underpins and operationalizes this recommendation. This is an importantstep in the right direction In addition, a greater recognition of the importance of the regional organisa-tions and development banks for ensuring regional stability is needed. It is particularly important thatDenmark works in a targeted way to strengthen the international architecture – also through our influ-ence in the EU.The dialogue on the international architecture has a tendency to become centred at headquarter level. Itis, however, important to hold on to the notion that the key objective is to deliver concrete results forthe people who are affected by instability and poverty on the ground. The success of the efforts to cre-ate a more effective structure should consequently be monitored through theperformance of actorsat the country level.On the one hand, we must become better at feeding lessons learned from coun-try-level activities into the policy dialogue. On the other hand, we must also have the courage to whole-heartedly support policy decisions and provide key multilateral actors with the real means to deliverresults.Peacekeeping is keyin conflict-affected states. Security is a precondition for development, and thelinkage between peace building and state building is two-way.Coordinationbetween the differenttypes of operations is therefore of great importance. The individual UN mission mandates have gradu-ally become more ambitious, and the emphasis now is primarily on integrated operations rather than onconventional peacekeeping buffer missions. Integrated missions require intensive cooperation betweenthe military and civilian components of the mission.A key task in fragile states is to prevent unstable and fragile situations from developing into conflicts.Conflict preventionis supported, among other things, by strategic regional efforts or through the UNand other actors who are working to reduce tensions and strengthen dialogue, mediation and capacitybuilding. The interplay between preventive diplomacy and development intervention is central. Thechallenge in relation to preventive efforts is to make the link between activities and results clear.In the UN review ofcivilian capacitiesparticular attention was paid to constraints associated withrapid deployment of people with the right personal profile in fragile and conflict-affected states. Expe-rience shows that the difference between success and failure in many cases is highly dependent on indi-viduals – particularly those in leading positions. We must focus much more on identifying people withthe right technical, cultural and interpersonal skills through targeted efforts to recruit, train and deployDanish civilian personnel – to the EU, the OSCE, the UN and NATO – and persuade multilateral or-ganisations to do the same. The UN itself identifies a number of inappropriate administrative proce-dures and rules that should be eliminated. In addition, the prospects of intensified South-South cooper-ation bring new opportunities. The UN, and in particular the UNDP, is in a perfect position to con-tribute to building capacity in the South. A stronger effort should also be made to promote more ex-change of staff between organisations – e.g. the World Bank and the UN – partly to facilitate moreflexible and versatile use of human and other resources, and partly to enhance mutual cooperation.

22

The normative sphereplays an immensely important role in relation to conflict-affected and fragilestates – as demonstrated by Responsibility to Protects (R2P) and other initiatives related to protectionof civilians, children and women in conflict situations, as well as peace and security (SR1325). In rela-tion to protection of civilians, prevention is a key element. Closer cooperation between the UN, region-al organisations and states in responding to early signs of ethnic cleansing, war crimes, genocide andcrimes against humanity is crucial for the success of the R2P standard.Rio+20 with focus on green economyThe UN Conference on Sustainable Development (Rio+20) will be held in Rio de Janeiro in June 2012during the Danish EU Presidency.The two key themes will be the green economy in the contextof sustainable development and poverty eradication as well as the institutional framework forsustainable development.The major challenge is to reach a common global understanding of the fact that the economic, socialand environmental dimensions of development need not be mutually exclusive but can be mutuallyreinforcing. The G-77 countries are sceptical about the green economy, which is viewed as a Westernconcept that may lead to imposition of new conditionality and green trade barriers obstruct them intheir efforts to pursue economic growth and job creation through industrialisation.The G-77countries cliam that the new commitments accompanying the transition to a green economyshould be accompanied by economic compensation in the form of development assistance, capacitybuilding and technology transfers from the Western countries, particularly if they are to be subject tomore stringent standards than the advanced economies were subject to at the time of their own take-off.The countries in the G-77 group, including countries such as China, India and Brazil, have so far stead-fastly maintained the principle of common, but differentiated responsibility (CBDR principle). Accord-ing to this principle countries have different responsibilities according to their level of development.Advanced economies must provide the development aid necessary to allow them to make the transitionto a green economy. Traditional donor countries, on their part, demand that middle-income countriescontribute to the transition. The COP17 reconfirms that the CBDR principle. This will hopefully makeit easier to reach agreements in Rio that also commit the BRICs.EU Member States, and particularly Denmark with inspiration from the work of the Global GreenGrowth Fund (3GF), argue in favour of a model in which growth and sustainability go hand in handand require the involvement of the private sector as a partner in Rio+20.Denmark believes that Rio+20 will focus on scarcity of resources such as water, energy and foods, inaddition to the general issue of preventing irreparable damage to the ecosystems.Denmark therefore also supports the UN Secretary-General’sSustainable Energy for All(SE4ALL)Initiative which proposes a new global goal for sustainable energy comprising three objectives: univer-sal access to electricity, doubling the rate of improvement in energy efficiency globally, and doublingthe share of renewable energy in the global energy mix. All three objectives are to be achieved by 2030.In multilateral organisations, Denmark will work to ensure that all three elements in the current dia-logue about energy – access, improved efficiency and renewable energy – are addressed.The Secretary-General’s energy initiative can be seen as a significant contribution to the debate on set-ting global sustainable development goals (SDGs), which has become an overriding theme in the prepa-23