Udenrigsudvalget 2011-12

URU Alm.del Bilag 236

Offentligt

EVALUATION OF DANISHDEVELOPMENT SUPPORTTO AFGHANISTAN

Evaluation

2012

Evaluation of Danishdevelopment supportto Afghanistan

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark

August 2012

� Ministry of Foreign Affairs of DenmarkAugust 2012

Production:Cover photo:Graphic Production:e-ISBN:

Evaluation Department, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of DenmarkFranz-Michael MellbinPh7 kommunikation, Århus978-87-7087-667-4

This report can be obtained free of charge by ordering from www.evaluation.dk or fromwww.danida-publikationer.dk.This report can be downloaded through the homepage of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs www.um.dk ordirectly from the homepage of the Evaluation Department www.evaluation.dk.Contact:[email protected]

The opinions expressed in this document represent the views of the authors, which are not necessarilyshared by the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs or other stakeholders.

ContentsPrefaceEvaluation of Danida Support to the Education Sector in AfghanistanEvaluation of the Danish Region of Origin Initiative in AfghanistanEvaluation Study:Danish support to statebuilding and improved livelihoods in Afghanistan

3

4

PrefaceOver the last decade, Denmark has provided substantial development support to thereconstruction of Afghanistan, with the main purposes of contributing to national, re-gional and global security as well as to poverty reduction. In Denmark, as well as in thedonor community in general, there is a wish to learn from the experiences with differenttypes of support to Afghanistan implemented through the last decade. Against this back-ground, the Evaluation Department in 2010 decided to initiate preparation of an inde-pendent evaluation of the Danish support to Afghanistan.Preparatory work for the evaluation established that the total disbursement of Danishdevelopment support to Afghanistan over the period 2001-2012 amounted to approxi-mately DKK 3.8 billion. Support during this period was mainly concentrated within fourthematic areas: (1) State-building, (2) Livelihoods, (3) Education, and (4) Regions ofOrigin Initiative (ROI) support.The preparatory work also found that support to state-building and livelihoods hadmainly been channeled through joint/pooled funding mechanisms covered by a consid-erable amount of existing reviews, studies and evaluations. EVAL therefore decided tocover these two thematic areas by means of an Evaluation Study comprising a desk basedreview of existing documentation. The review was conducted by Oxford Policy Manage-ment Institute (UK).The two other thematic areas – i.e. education and Regions of Origin (ROI) support inAfghanistan – had not to the same extent been covered by previous evaluation work. Inthese two areas of support, EVAL therefore decided to commission full evaluations, in-cluding both desk and field work.Field work for the two evaluations was conducted during the period from September2011 to March 2012 by independent evaluation teams selected through internationaltendering processes. The evaluation of support to the education sector was conducted bya consortium comprising Particip (Germany) and Niras (Denmark), while the evaluationof the ROI support was conducted by a consortium comprising GHK (UK) and tana(Denmark).The two evaluations and the evaluation study were supplemented by two additionalevaluation studies entitled Economic development and service delivery in fragile states(conducted by UN-Wider) and Effective statebuilding? A review of evaluations of inter-national statebuilding support in fragile contexts (conducted by German DevelopmentInstitute). These evaluation studies were published in Spring 2012 and are available atwww.evaluation.dkEvaluation DepartmentMinistry of Foreign Affairs/Danida

5

6

Evaluation of DaniDa Supportto thE EDucation SEctorin afghaniStan

Evaluation

2012.02

CH INA

AFGHANISTANMaryMu

64

Dary

�

mu

Darya

66

68��UZBEKISTAN

70

�

a-ye

72

�

Murgho74b

�

Te

A

QurghonteppaKerkiKiroyaKeleftAndkhvoy

(Kurgan-Tyube)

TA J I KI STA N

izrm

DustiRostaq

BADAKHSHANKhorughFayz AbadFayzabadJormEshkashemrmiPa

TURKMENISTANTedzhen

rgab

JAWZJAN

Jeyretan

Qala-I-Panjeh

Shiberghan Mazar-e-Sharif

Kunduz

KUNDUZTaluqanTaloqanKhanabadTAKHAR

Dowlatabad36

BALKHSari PulTokzarShulgarah

Kholm

�

BaghlanAybak

shgy

MaymanaQeysar

Gu

FARYAB

SAMANGAN

nar

GushgyTaybadTowraghondi

BADGHISQala-e-NawMorghab

Ku

SARI PULBAMYANBamyan

LAGH

Ha

rirud

HeratHirat

Karokh Owbeh

DowlatChaghcharanYar

BazarakMahmud-e-NURISTANRaqirunsKUNARChaharikarNPoKAPISAAsad AbadPARWANMehtarlamMA

dBAGHLANniHPANJSHER

FarkharDowshi

Ku

u

s

h

36

�

GilgitAFGHANISTAN

34

ruHa

FA RA HFaraharahF

Now ZadKajaki

Tirin Kot

ghAr

t

andab

32

T

Indus

shKha

Lashkar Gah

wd-e

NIMROZCheharBorjakHilmand

KANDAHARDeh Shu

Chaman

✈

30

Zahedan62

Map No. 3958 Rev. 7 UNITED NATIONSJune 2011

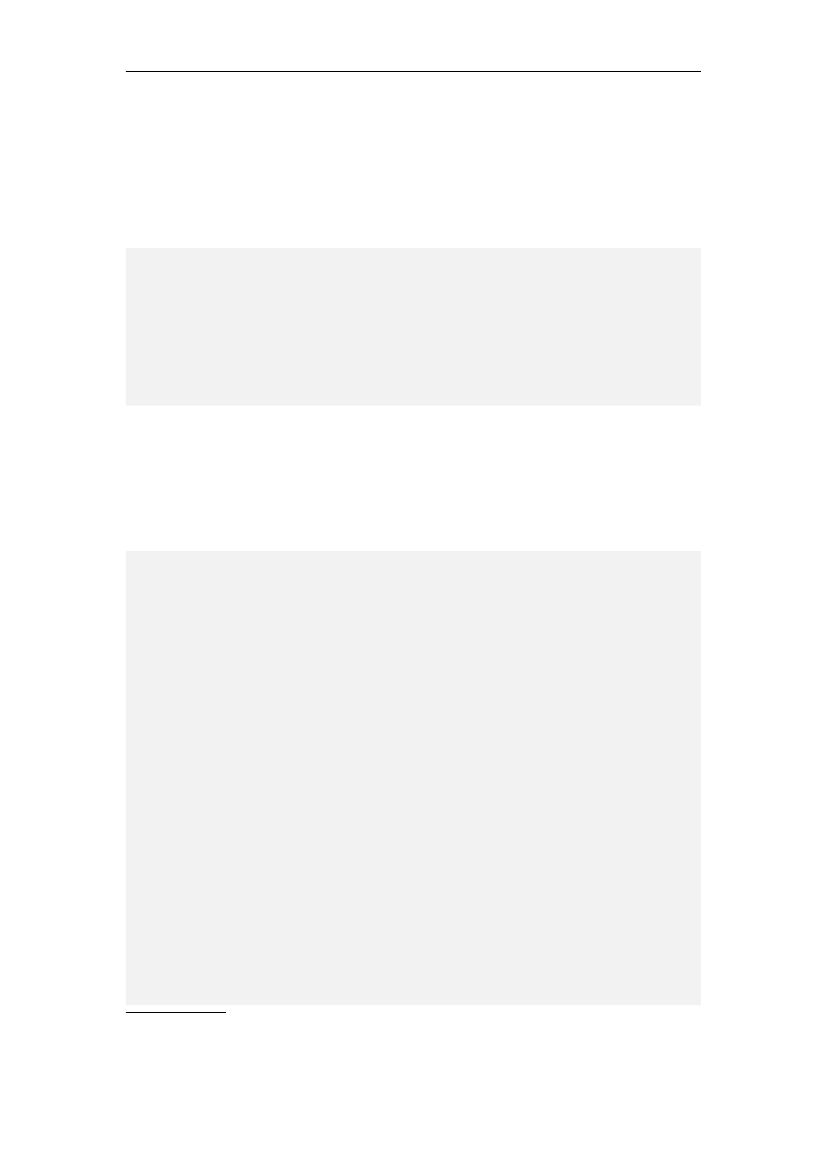

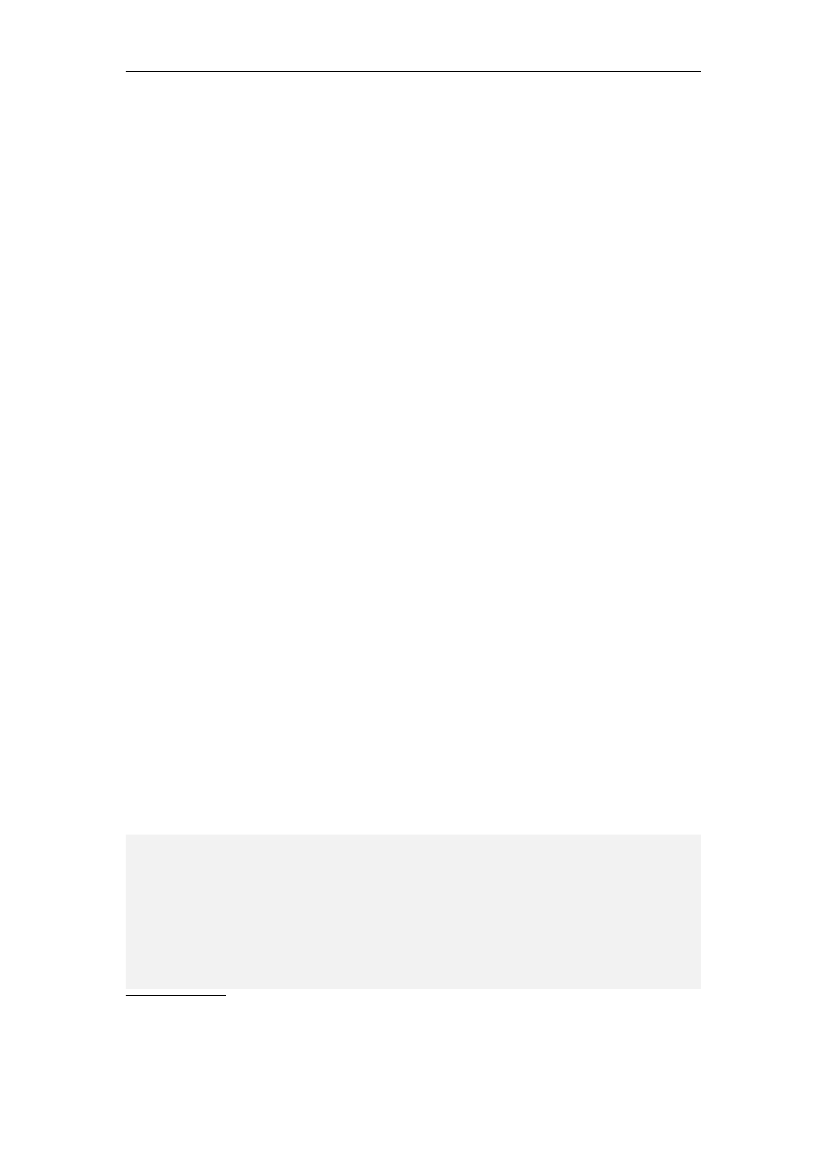

for administrative purposes the government has grouped afghanistan’s 34 provinces intothree main zones (from: 2008-09 EMiS School Summary report). these are shown in the tablebelow:Northern Mainland Afghanistan1.1 north Eastern afghanistan1.1.1Badakhshan1.1.2 Baghlan1.1.3 Kunduz1.1.4 takhar1.2 north Western afghanistan1.2.1 Balkh1.2.2 faryab1.2.3 Jowzjan1.2.4 Samangan1.2.5 Sare polCentral Mainland Afghanistan2.1 Eastern afghanistan2.1.1 Kunar2.1.2 laghman2.1.3 nangarhar2.1.4 nuristan2.2 central afghanistan2.2.1 Kabul2.2.2 Kabul city2.2.3 Kapisa2.2.4 logar2.2.5 panjshir2.2.6 parwan2.2.7 Wardak2.3 Western afghanistan2.3.1 Badghis2.3.2 Bamyan2.3.3 farah2.3.4 ghor2.3.5 heratSouthern Mainland Afghanistan3.1 South Eastern afghanistan3.1.1 ghazni3.1.2 Khost3.1.3 paktia3.1.4 paktika3.2 South Western afghanistan3.2.1 Daykundi3.2.2 helmand3.2.3 Kandahar3.2.4 nimruz3.2.5 urozgan3.2.6 Zabul

ISLAMIC

JammuandKashmir

�

HERA THIRA T-ShindandAnar Darreh

GHOR

DAYKUNDINililmHedan

MaydanShahrWARDAK

KABUL

Kabul

JalalabadMardanbeKhy

LOGARPul-e-Alam

NANGARHARPeywar PassrPass

34

�

Peshawar

IslamabadRawalpindi

REPUBLIC

Ghazni

GHAZNIQarah Bagh

GardezPAKTYA KHOSTKhost (Matun)SharanBannu

URUZGAN

Khas Uruzgan

PAKISTAN�

�

ZABULQalatnakarRo

PAKTIKAhraLu

Delara

m

Tank

32

OF

Kandahar

National capitalZhob

IRAN�

Zabol

Kadesh

Provincial capitalTown, villageAirportsInternational boundaryProvincial boundaryMain roadSecondary roadRailroad72

Zaranj

HILMAND

Spin Buldak

The boundaries and names shown and the designationsused on this map do not imply official endorsement oracceptance by the United Nations.Dotted line represents approximately the Line of Controlin Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan.The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has not yet beenagreed upon by the parties.

INDIAINDIA

QuettaGowd-eZereh

00

50

10050

15010070

200

250 km150 mi

30

�

�

64

�

66

�

68

�

�

�

74

�

Department of Field SupportCartographic Section

Evaluation of Danida Supportto the Education Sectorin Afghanistan

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark

June 2012

� Ministry of Foreign Affairs of DenmarkJune 2012

Production:Cover photo:Graphic Production:Print:ISBN:e-ISBN:

Evaluation Department, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of DenmarkFranz-Michael MellbinPh7 kommunikation, ÅrhusRosendahls - Schultz Grafisk978-87-7087-644-5978-87-7087-645-2

This report can be obtained free of charge by ordering from www.evaluation.dk or fromwww.danida-publikationer.dk.This report can be downloaded through the homepage of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs www.um.dk ordirectly from the homepage of the Evaluation Department www.evaluation.dk.Contact:[email protected]

The opinions expressed in this document represent the views of the authors, which are not necessarilyshared by the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs or other stakeholders.

Table of ContentsAcknowledgementsExecutive Summary1Introduction1.1 Background to the evaluation1.2 Structure of the report1.3 MethodologyEducation in Afghanistan2.1 The cultural context2.2 The development of education2.3 The administration of education2.4 Education and society2.5 Education and conflict2.6 The futureDanish support to the education sector in Afghanistan 2003-103.1 Danish aid to Afghanistan before the 2000s3.2 Danish assistance to education from 20013.3 Implementation modalitiesThe activities and objectives of other development partners inthe education sector in Afghanistan4.1 Introduction4.2 Principal donors in educationFindings on Danish support to the education sector inAfghanistan 2003-105.1 2001-03 The baseline situation5.2 2003-06 Primary Education Programme Support (PEPS)5.3 2007-08 Extension of PEPS5.4 2008-10 Further extension of PEPS5.5 Overall performance on extensions 2007-105.6 2010-13 Education Support Programme to AfghanistanOverall assessment and conclusions6.1 Evaluation Criterion 1: Relevance6.2 Evaluation Criterion 2: Effectiveness6.3 Evaluation Criterion 3: Efficiency6.4 Evaluation Criteria 4/5: Sustainability and ImpactRecommendations and lessons learned59242424253232323334363941414245484848525256717882849696101108113118

2

3

4

5

6

7

3

Table of Contents

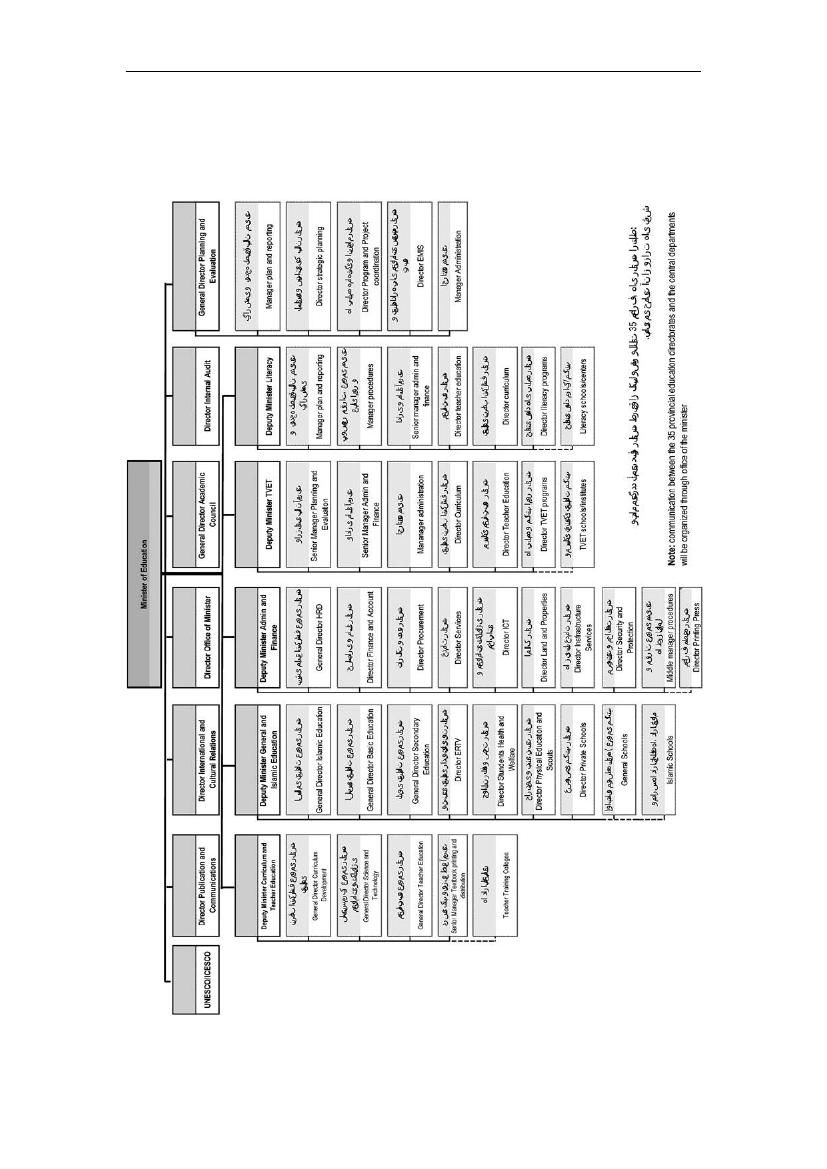

AnnexesAnnex A Terms of ReferenceAnnex B List of informantsAnnex C List of documents consultedAnnex D Organogram of the Ministry of EducationThe following annexes to the Evaluation Report can bedownloaded from www.evaluation.dkAnnex EAnnex FAnnex GAnnex H

121121132137148

Education sector aid programmes and projects 1388 (2009)Donor assistance to education over the period covered by the evaluationList of feedback session participants in KabulCase studies

4

AcknowledgementsThe evaluation was led by George Taylor and included Henrik Jespersen, Leo Schellek-ens, Ahmad Parwiz Yosufzai, Habiba Wahaj and Nazifa Aabedi. Project management wasprovided by Anchoret Stevens and Beatriz Bohner, and quality assurance by Georg Ladjand Gunnar Peder Jakobsen. Additional support for the evaluation was provided by EricSarvan and Tino Smail.The evaluation team would like to express their gratitude to representatives of the Gov-ernment of Afghanistan especially those in the Ministry of Education who generouslygave their time to the evaluation, the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Royal Dan-ish Embassy in Kabul, the members of the Reference Groups and all others who providedvaluable input in one form or another during discussions, interviews, meetings or provin-cial visits.

5

List of abbreviationsADBAFANDSAPEPARTFCIDACNADACDACAARDAARTTDEDDfIDDKKDOFDPECEECGEFAEIPEMISEQUIPESPAESWGEQEQIPEUEVALFDGFTIGDPGIZGMUGPEHDIHRDBIDPIIEPINEEInSeTISDISAFJICALEGLTTAMDGMDUMFA6Asian Development BankAsia FoundationAfghanistan National Development StrategyAfghanistan Primary Education Program (World Bank)Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust FundCanadian International Development AgencyADB’s Comprehensive Needs AssessmentDevelopment Assistance CommitteeDanish Committee for Aid to Afghan RefugeesDanish Assistance to Afghan Rehabilitation and Technical TrainingDistrict Education DepartmentDepartment for International Development (UK Government)Danish KronerDepartment of FinanceDevelopment PartnerEarly Childhood EducationEducation Consultative GroupEducation For AllEducation Interim PlanEducation Management Information SystemEducation Quality Improvement Program (World Bank)(Danish) Education Support Programme to AfghanistanEducation Sector Working GroupEvaluation QuestionEducation Quality Improvement ProjectEuropean UnionEvaluation Department,Focus Discussion GroupFast Track InitiativeGross Domestic ProductDeutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale ZusammenarbeitGrant Management UnitGlobal Partnership for EducationHuman Development IndexHuman Resource Development BoardInternally Displaced PersonInternational Institute for Educational PlanningInter-Agency Network for Education in EmergenciesInservice TrainingInfrastructure Development Services DepartmentInternational Security Assistance ForceJapan International Cooperation AgencyLocal Education GroupLong Term Technical AssistanceMillennium Development GoalsMaterials Development UnitMinistry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark

List of abbreviations

MoEMoFMoHEMTNATONDFNESPNGOOECDP&GPARPEDPEPSPIUPRAPRDCPRRPRTQAQRFRBMRDEREURIMUROIRRASBSSidaSQSTTATATEPTLToRTRCTRTTTCTVETUNUNESCOUNHCRUNICEFUPEUSAIDWFPWHODanida

Ministry of EducationMinistry of FinanceMinistry of Higher EducationMaster TrainersNorth Atlantic Treaty OrganisationNational Development FrameworkNational Education Strategic PlanNon-Governmental OrganisationOrganisation for Economic Cooperation and DevelopmentPay & GradePublic Administration ReformProvincial Education DirectoratePrimary Education Programme SupportProject Implementation UnitParticipatory Rural AppraisalProvincial Reconstruction Development CommitteePriority Restructuring & ReformProvincial Reconstruction TeamQuality AssuranceQuick Response FundResults Based ManagementRoyal Danish EmbassyResearch and Evaluation UnitReform Implementation Management UnitRegions of Origin InitiativeRapid Rural AppraisalSector Budget SupportSwedish International Development Cooperation AgencySub-evaluation QuestionShort Term Technical AssistanceTechnical Assistance/Technical AdvisorsTeacher Education ProgramTeam LeaderTerms of ReferenceTeachers’ Resource CenterTeachers’ Resource TeamTeacher Training CollegeTechnical and Vocational EducationUnited NationsUnited Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural OrganisationUnited Nations High Commissioner for RefugeesUnited Nations Children’s FundUniversal Primary EducationUnited States Agency for International DevelopmentWorld Food ProgrammeWorld Health OrganisationThe Danish aid administration until the 1990s, but now a collective termfor the development activities of the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairsrather than a separate entity.

7

List of abbreviations

Exchange Rates (November, 2011)1 Euro = 7.44 Danish Kroner (DKK)1 Euro = 1.42 United States Dollars (USD)1 DKK = 0.19 USD (However, actual exchange rates are used in the report)Afghan Calendar:1382 = 2002 - 20031383 = 2003 - 20041384 = 2004 - 20051385 = 2005 - 20061386 = 2006 - 20071387 = 2007 - 20081388 = 2008 - 20091389 = 2009 - 2010

8

Executive SummaryBackground to the evaluationBetween 2003 and 2010 Denmark disbursed Danish Kroner (DKK) 431 million foreducation in Afghanistan mainly through bilateral programmes, including in Helmand,but also through other channels, e.g. the Afghan Reconstruction Trust Fund (ARTF)1.To learn from the experience the Evaluation Department of the Danish Ministry of For-eign Affairs (EVAL) commissioned the current evaluation. The main purposes are to as-sess Denmark’s contribution and to assist the continued improvement of Danish support.The objectives are to assess strategy, implementation and results and to identify conclu-sions, lessons learned and recommendations. The evaluation has used the DAC evalua-tion criteria of relevance, effectiveness, efficiency and sustainability, taking into consid-eration the context, including the security situation, in which the support is provided.The evaluation was conducted from mid-2011 to early 2012. It was planned to includefour phases: i. Preparation and fact finding; ii. Desk study; iii. Evaluation visit and fieldstudies; and iv. Final data analysis. Arrangements were made for a further documentsearch and a visit to Kabul and Helmand province. Results of the additional work havebeen incorporated into the evaluation report.

MethodologyDanish support policy, as exemplified in the programme documents, was to workthrough and strengthen host institutions, using an ‘on-budget’ modality. This approachrelied on regular, documented results to guide joint programme management by theMinistry of Education (MoE) and the Royal Danish Embassy (RDE). Planning andmodifying activity would specify outputs and programme outcomes. Immediate resultswould feed into next steps in the management process, keeping ownership with the MoEand raising capacity.The approach taken by this evaluation also relies on documented results. Consistent withthe logic of the support programme it draws on Results Based Management (RBM), astrategy focusing on outputs, outcomes and impacts. The evaluation seeks to show thelinks between what was planned, what was carried out (inputs) and the immediate results(outputs), and the eventual broader outcomes. Where possible it also points to longer-term impact.Documentation for programme management and evaluationEssential tools for all programmes were the Annual Work Plans and Budgets, whichwould guide each cycle. The fragile situation and weak capacity meant managementwould be a challenge. This was the risk inherent in the support strategy. To mitigate this,flexibility in resource allocation was a central part of the design, therefore, and docu-mented Annual Reviews were to inform the feedback loop (e.g. PEPS 1 Programme1Note: References have been kept to a minimum in this Executive Summary. Full details of quotedsources are given in the main text or in footnotes in the report. A list of the main documents con-sulted is given in Annex C.

9

Executive Summary

Documents, para 6 and para 41). Programme documents detail the roles of the GrantsManagement Unit (GMU) and the Steering Committee in using annual and quarterly pro-gress reports, monitoring, accounts and audits to monitor progress and make decisions. Thelogic, as stressed by Programme Documents, was that this would strengthen capacity, notonly to manage Danida’s programmes, but for the education system in general.The GMU was also to be a magnet and coordination mechanism for other DevelopmentPartner (DP) programmes. The logical assumption was that as efficiency and effectivenesswere demonstrated, other donors would provide funding through government systemsfollowing Danida. Danish aid was to be a “test case” (term used in the Programme Docu-ments) to encourage harmonisation and alignment. Thus documentation was fundamen-tal to management and aid effectiveness.Management as central to Danida’s modalityThe modality also assumed that use of the Afghan public administration (a Ministry ofFinance (MoF) account for Danish funds with earmarking of programme components)and MoE service delivery would contribute to national reconstruction. In particular, themodality relies on development of a strong monitoring framework. Popular participa-tion in governance to increase stability in a very fragile situation was also a broad aim.National policies linked to local activity were to build confidence in Government. Theseincluded community participation in location of schools, promoting access to educationfor girls, training for female teachers and students, school management, etc. The Afghanand Danish Governments explicitly linked national policy and local realisations as ameans of nation-building.A fundamental aspect of Danida’s support model was the implementation of a two trackdevelopment approach, i.e. to attend not only to local, emergency intervention, butalso to long-term systems and policy development. Sustainability and ownership by theAfghan Government as well as collaboration with other donors would be built on docu-mentation of shared strategy.In sum, management mechanisms with documented outputs (accounts, reviews, min-utes, reports, plans, etc.) were foreseen as the basis of Danish support and continue to beessential for programme management and for broader system development. They permit,flexible budget allocation (inputs) in response to need as it becomes clearer, as data andreduced levels of conflict allow this to be specified; they provide a means to manage thefunding risk, through transparency and accountability; at the level of outcomes they sup-port confidence-building in government systems among other donors and the Afghanpublic, and they link immediate, local action to long-term national strategy, and buildsustainable capacity in MoE and government departments.Evaluation approach and constraintsSimilarly, the evaluation itself depended heavily on written records. Security and time didnot permit direct observation or statistical sampling of programme results. Interviews andvisits allowed only an impression of the Afghan education system, although fact-findingand field visits in 2011 and 2012 included a mix of urban and rural areas in different re-gions with experience of different ethnic groups. During these visits informants at MoE,provincial and district education offices, schools, communities and teacher training col-leges (TTCs) were interviewed; girls’ schools were visited and issues of marginalisationdiscussed. Representatives of key NGOs and DPs were met (see Annex B). The interplaybetween education support and security issues in Helmand and elsewhere was discussed.10

Executive Summary

During the 2011 field mission schools were sitting national exams, meaning little obser-vation of structured teaching or use of books or materials was possible. Data collectionbased on the evaluation questions (EQs) and sub-questions (SQs) provided in the Termsof Reference (ToR), were used in the field mission. However, data on many indicators wasnot available (e.g. net and gross enrolment ratios (NER) and (GER), numbers of qualifiedteachers by year, etc.). Other constraints matched those for programme management:• Frequent changes of staff in Government and DPs and weak institutional memo-ry;• • • • • Lack of continuity between international staff, including technical assistance (TA);Donor projects (including military) operating in the same technical area;Weak individual, institutional and data management and administrative capacity;Frequent reorganisation in Afghan government institutions;Changing patterns of security and stability throughout the country.

The evaluation, moreover, covered a period of more than 10 years. Technical and man-agement reports covered a lengthy and unstable period. However, a comprehensive data-base of over 800 documents was assembled and largely formed the basis for the evalua-tion.

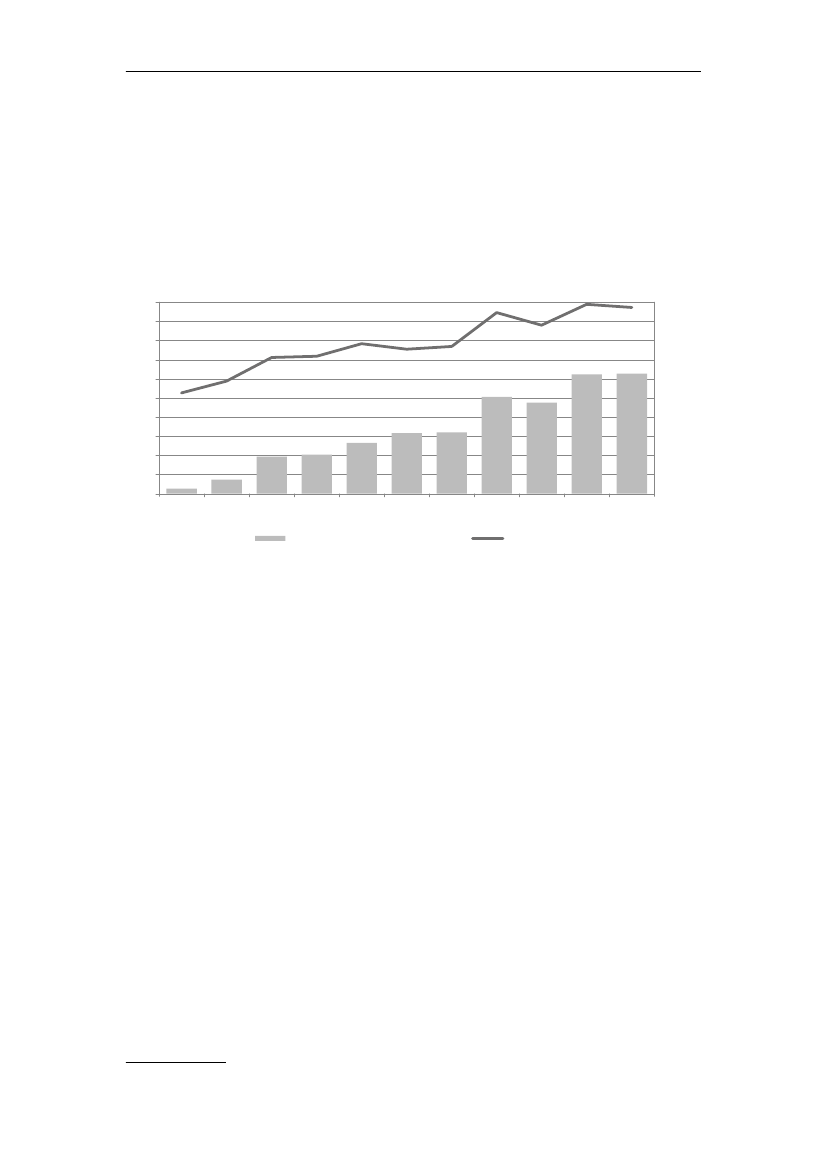

Education in AfghanistanThe cultural contextThe Islamic tradition has permeated Afghan society and religious leaders have influencedcommunity life, including educational development. Education indicators have alwaysbeen low (literacy has never risen above 25%) and the central state’s role in provision hasbeen limited. In 1979, when the Soviets invaded, the literacy rate was 18% for males and5% for females.This period was followed by two decades of conflict when 80% of school buildings weredestroyed and qualified teachers were killed or left the country. After Soviet occupationin 1989 factional fighting between Mujahedeen parties delayed reconstruction. In 1993,NGOs assisted 1,000 of the 2,200 schools. 90,000 Afghan children were supportedin refugee camps in Pakistan. Between 1996 and 2001, the Taliban took control andbanned female participation in education. Only limited services were provided by MoE,which by 2001 needed to be rebuilt from scratch.Provision has greatly improved with support from donors including Denmark. Accord-ing to MoE, more than 7 million children are enrolled, (39% or 2.7 million girls); usableclassrooms were increased from fewer than 1,000 in 2002 to over 71,000 in 2010; thereis an eight-fold increase in teacher numbers; over 8,500 school Shuras (community edu-cation committees) have been established, and there is a Provincial Education Depart-ment (PED) in each of the 34 provinces.

11

Executive Summary

Education and societyThe socio-economic and political situation varies within the 34 provinces. GDP hasgrown since 2003/04 at an average of 9.1% p.a., though with high volatility. In 2010/11international aid was about USD 15.7 billion, or about the same size as nominal GDP.Afghanistan has made notable progress on some Human Development Index (HDI) in-dicators. In 2011 48% of the population had access to clean water, i.e. double 2007/08figures; 72,500 women are attending 2,900 literacy centres. Education is a basic right forall children. The country is committed to Education for All (EFA) and the MillenniumDevelopment Goals (MDGs), with a revised target date of 2020. However, it remainsamong the poorest countries in the world (HDI ranking 172 of 187).Education and conflictEducation is a means of building stability and is free of charge. However, continued vio-lence undermines protection and almost 50% of the population is insecure. This limitsservice delivery.According to the Asia Foundation (AF), access to education and widespread illiteracywere the biggest problems for women in 2011, but security, peace and education inter-act in a complex manner. Stakeholders have a range of interests, capacities and motives.Government legitimacy continues to be challenged and links between Government andpeople depend on central and local structures. The state is only slowly becoming animportant part of people’s lives. Danish support to education in Afghanistan recognisesthat where donor support is outside the Government it undercuts state capacity andmay reduce legitimacy. Moreover, in areas where international military and PRTs pro-vide assistance, schools may be more vulnerable to attack precisely because they havebeen constructed by foreign forces. Some donors have begun to address this throughbroader approaches, at least within education, and recent reports indicate the Talibanand Government are finding common ground, though progress is vulnerable to fre-quent setbacks.

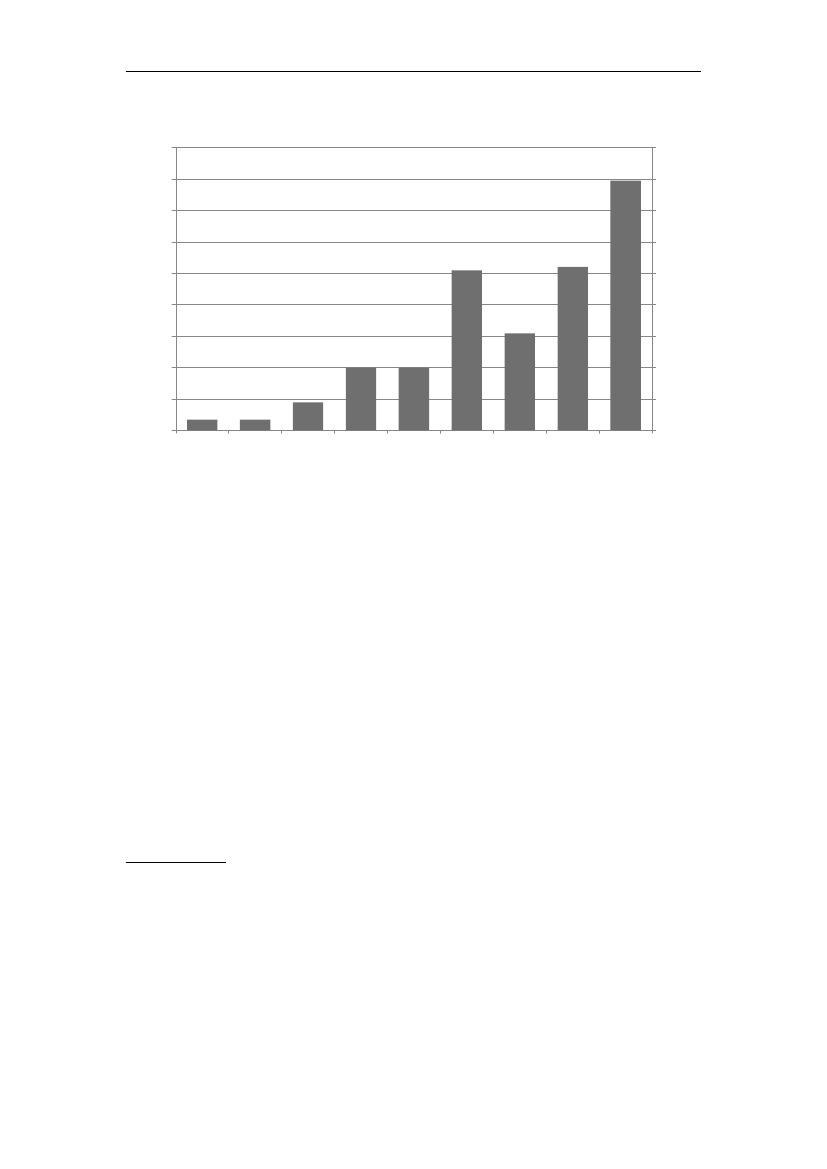

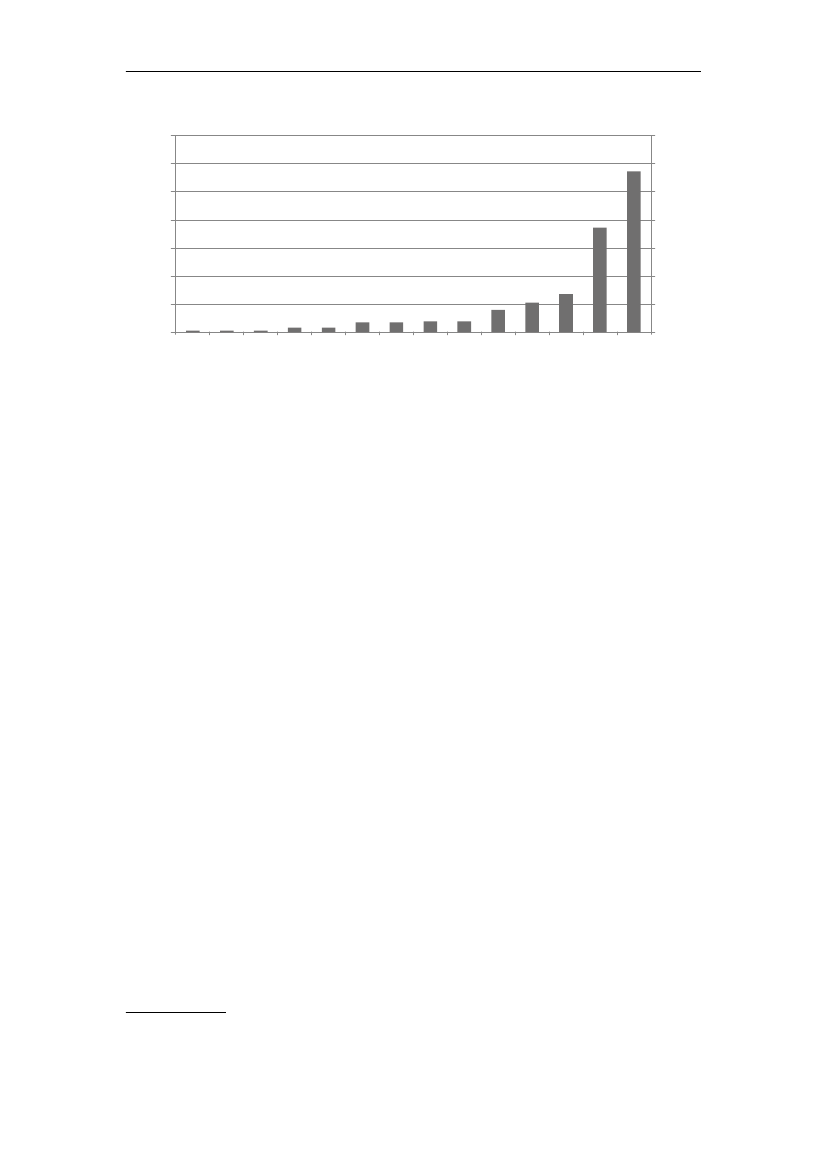

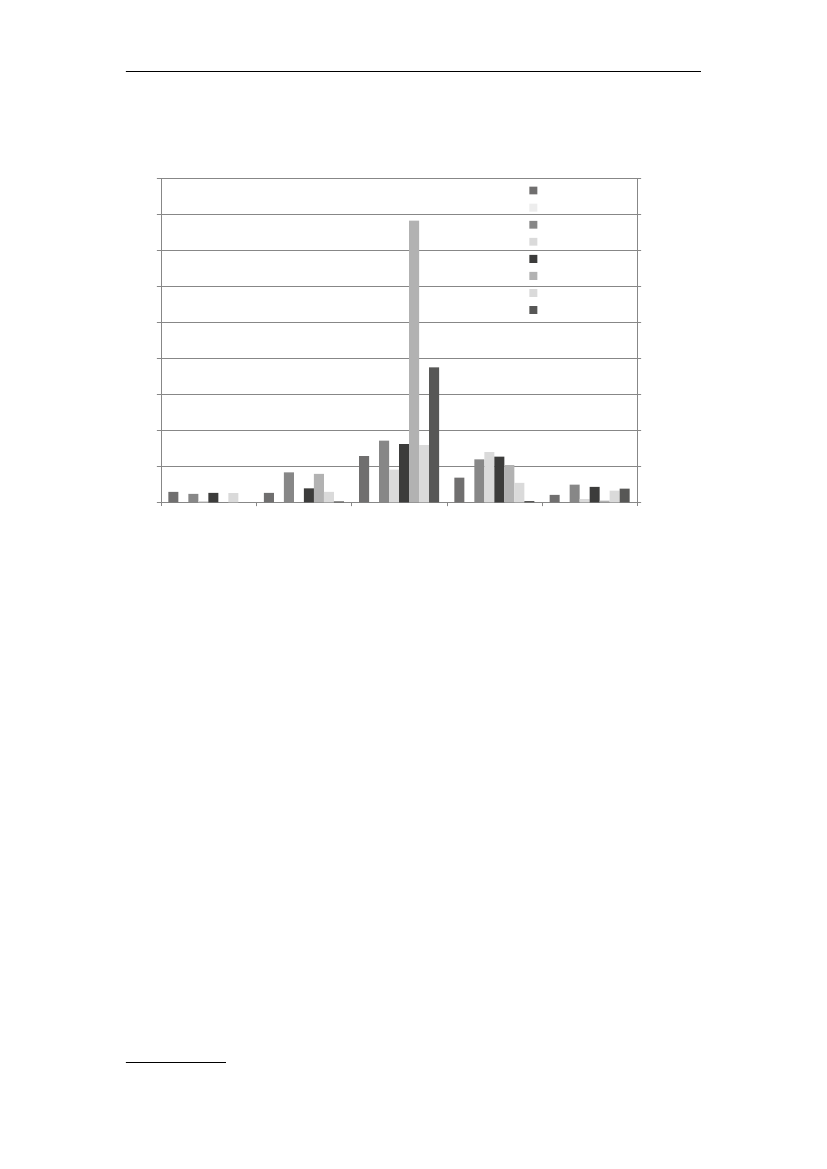

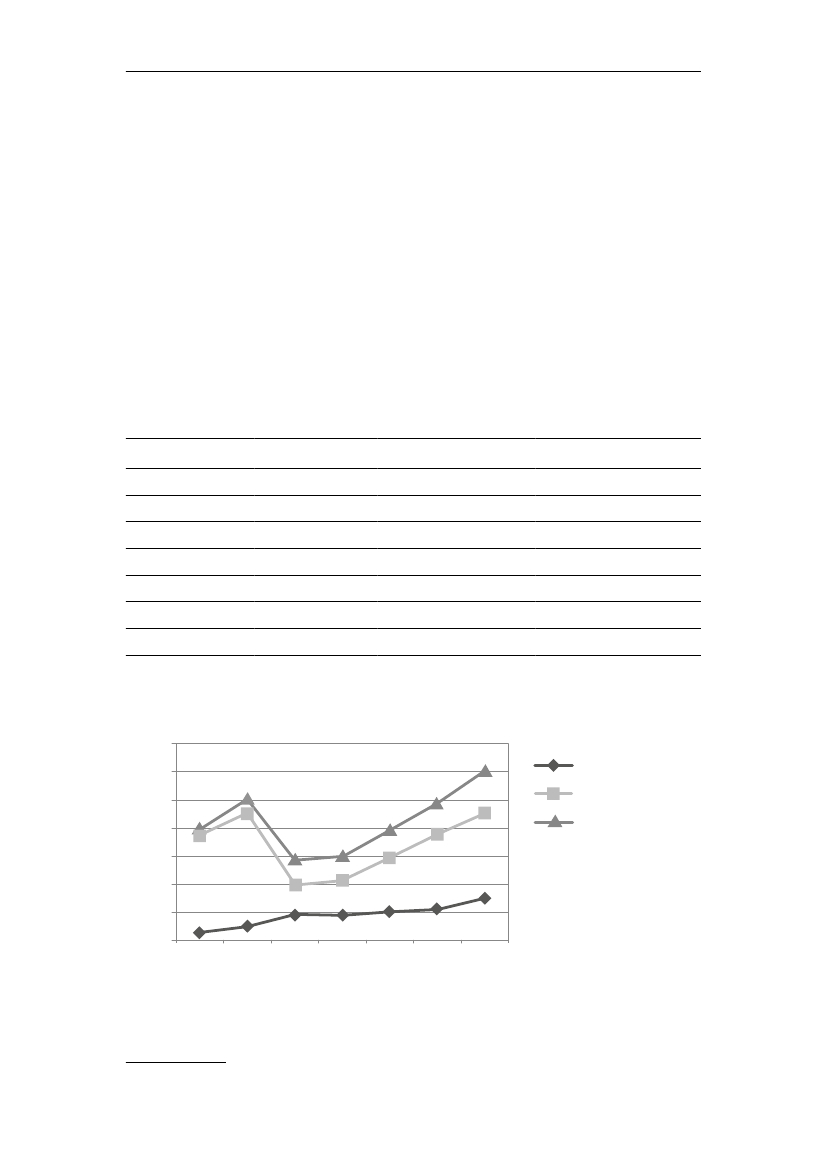

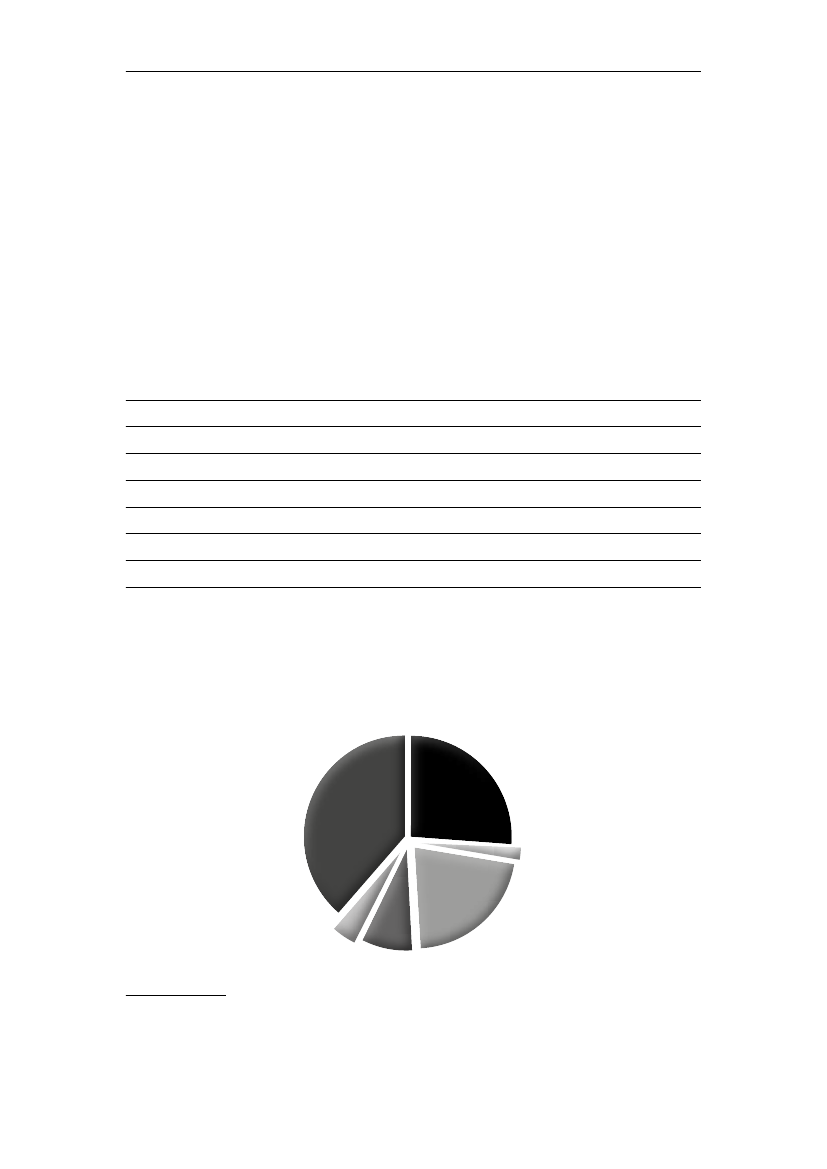

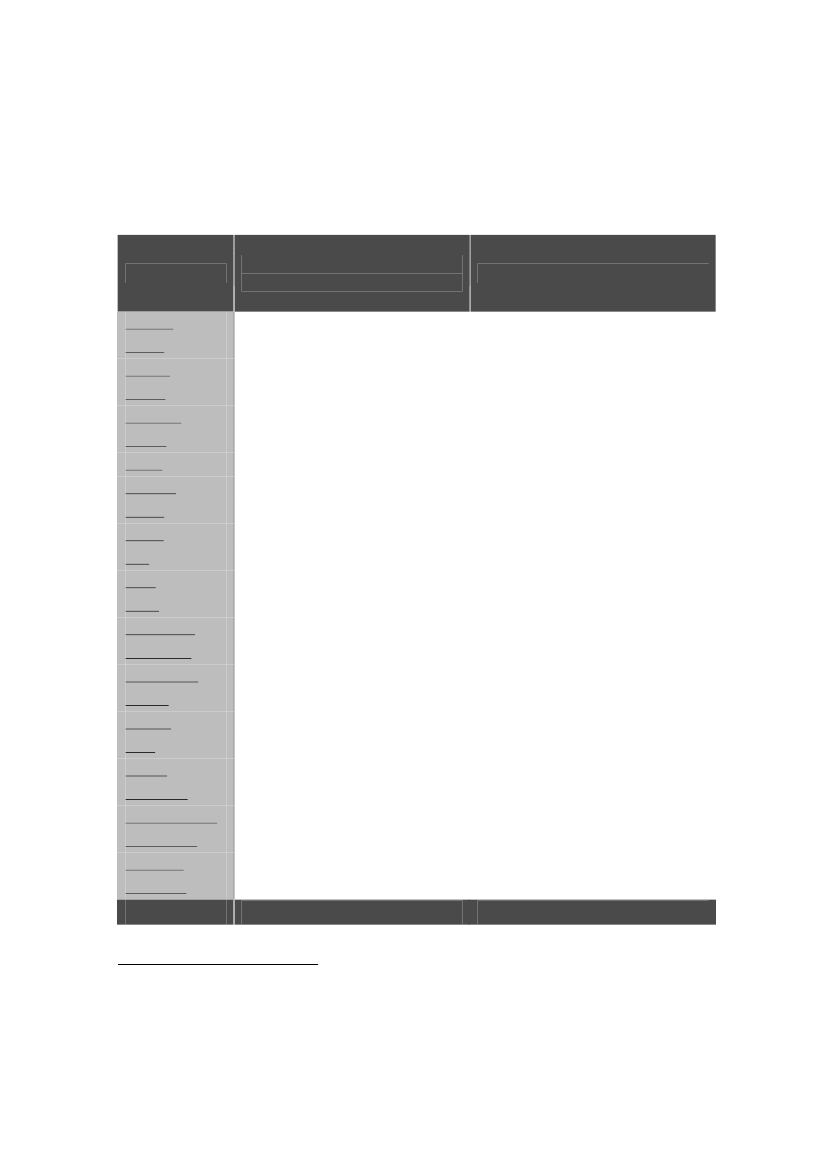

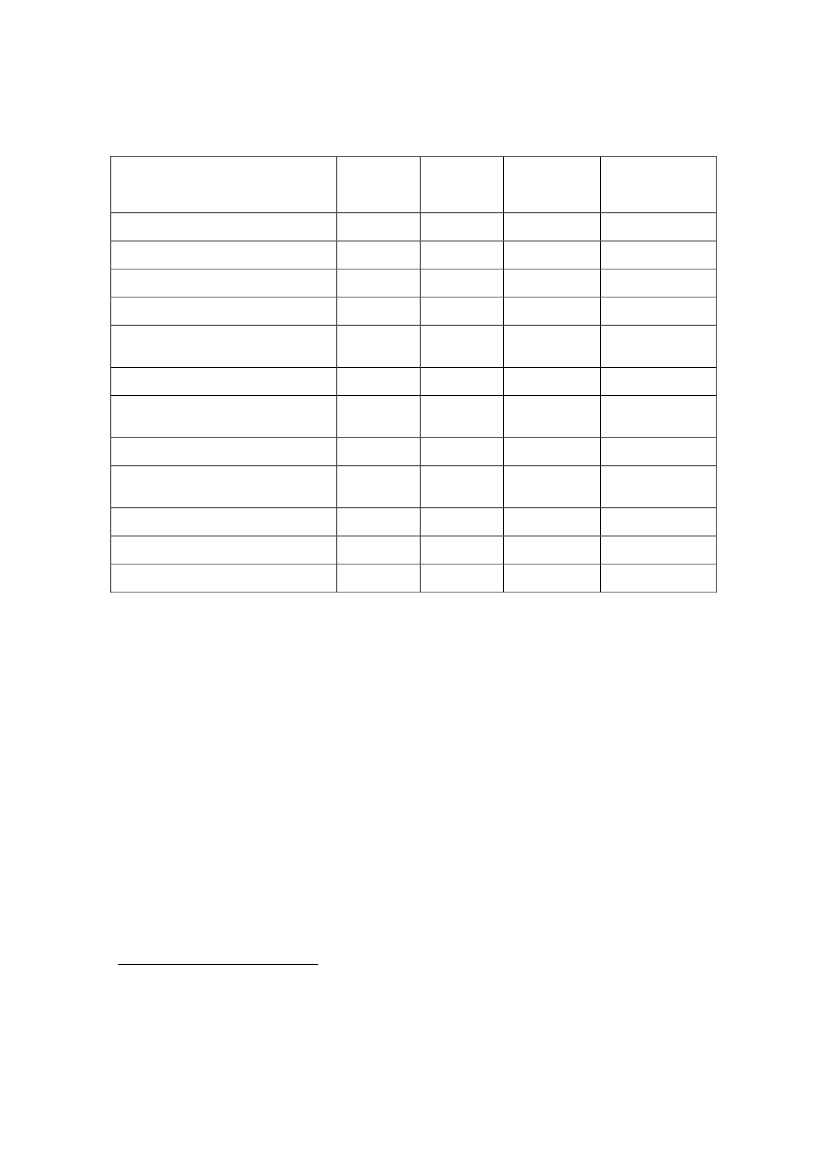

Brief overview of Danish supported areas in educationThe two tables below provide a summary of Danish support from 2003 to the present,showing the programme components supported with amounts, by period, and the mainmodalities. It will be noted that the current programme budget represents a substantialincrease in funding (2003-10, USD 50.5 million; 2010-13, USD 60 million). The pro-gramme components supported in 2003 included Curriculum development, Construc-tion, Teacher training, Textbooks and Management including aid management. Apartfrom construction, funded separately through the NGO Danish Assistance to AfghanRehabilitation and Technical Training (DAARTT), and some funding through the ARTF,Danish support used an on-budget modality.Over the whole period there is a broadening of scope (to include all education grades1-12) and reduction in earmarking, aligning with Afghan strategic planning for educa-tion as set out in the Education Interim Plan (EIP). This reflects Danish developmentguidelines and strategy. Support for education in Helmand was specifically included from2008.

12

Executive Summary

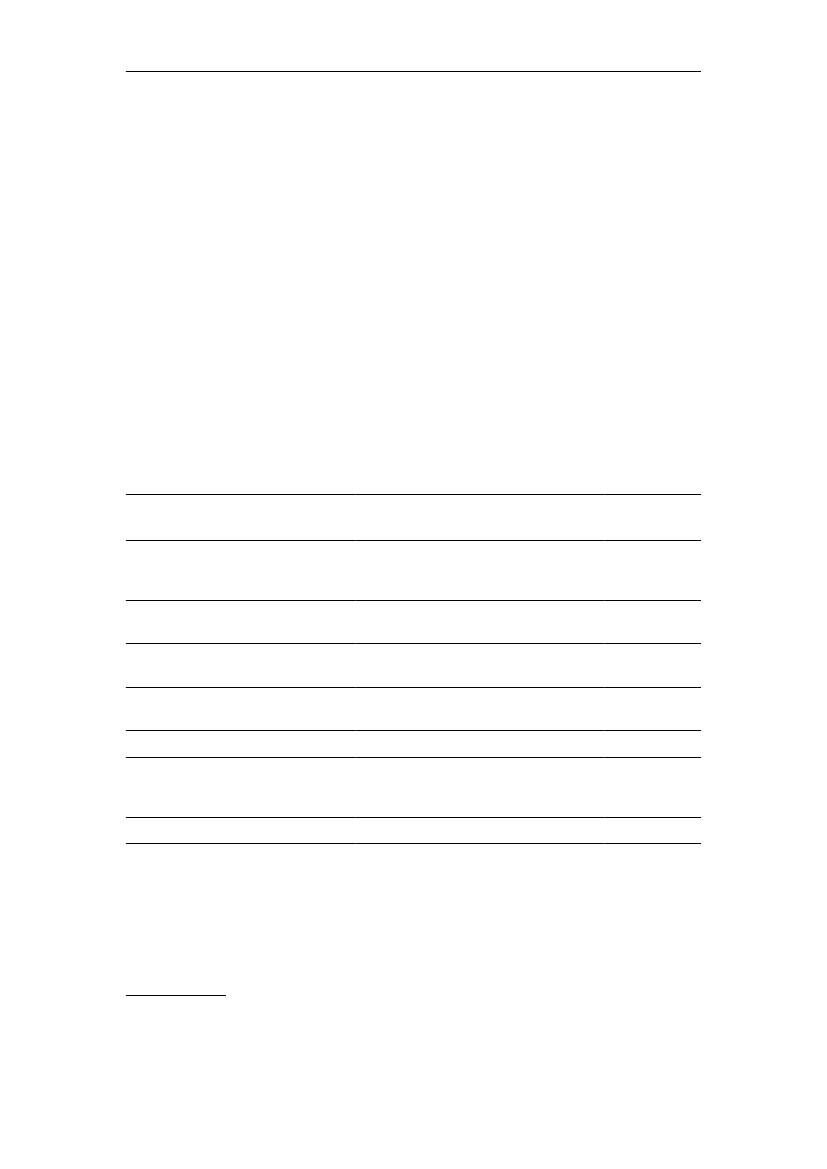

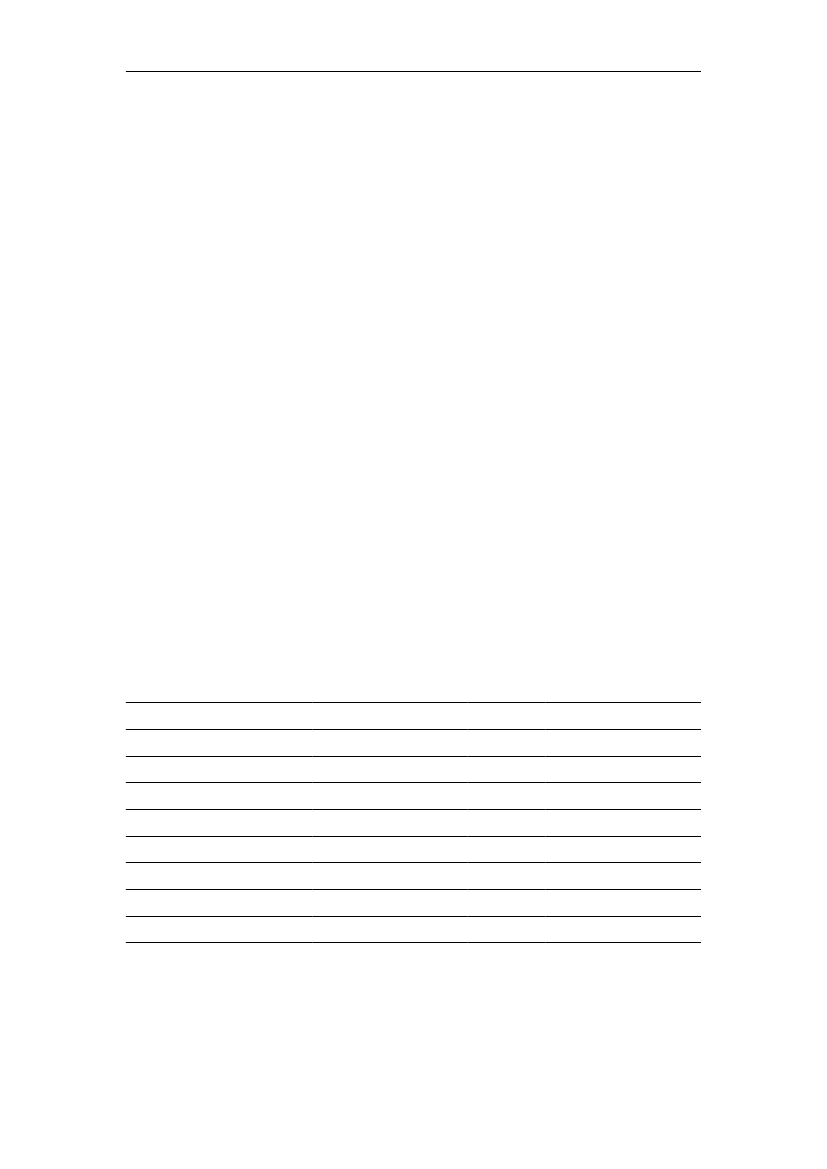

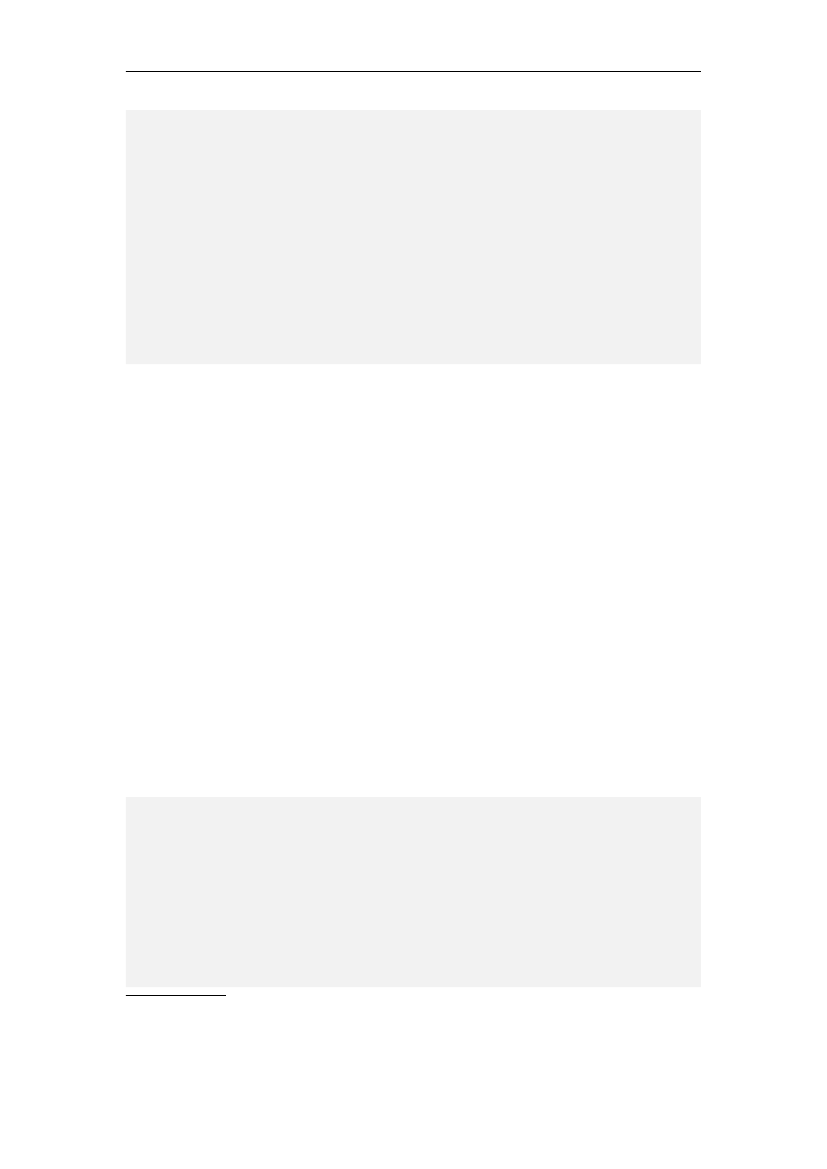

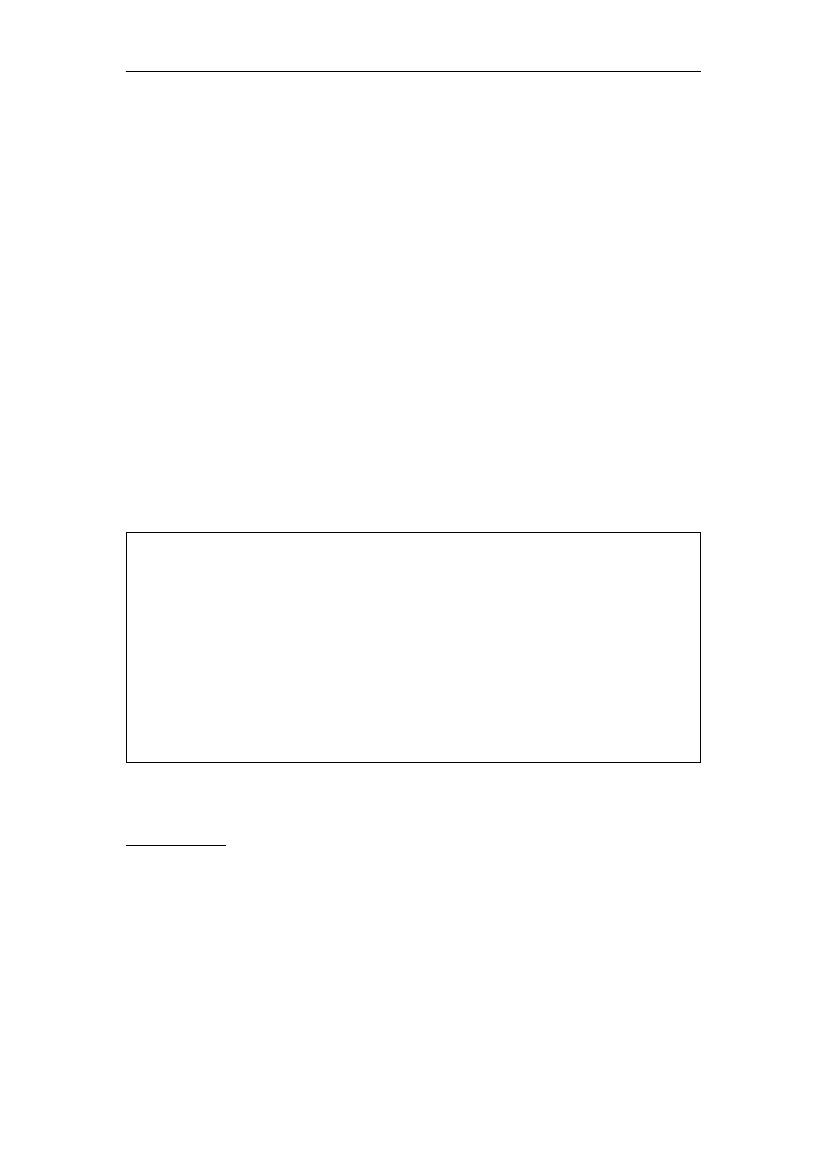

Table 1Programme

Programmes and budget allocations2Agreement date4.12 2003Years2003-06(Extendedto March 2007)2007-082008 onwards2009-10DKK110.0 millionUSD215.7 million

Primary EducationSupport Programme(PEPS 1)Extension (includinggrades 1-12)Helmand Schools andDormitoriesExtension of funding foreducationTotal 2003-10Education SupportProgramme toAfghanistan (ESPA)Total incl. (ESPA)

17.5 200719.11 2008??

72.0 million34.2 million92.5 million308.7 million

12.6 million6.0 million16.2 million50.5 million60 million

2010

2010-13

340 million

648.7 million

110.5 million

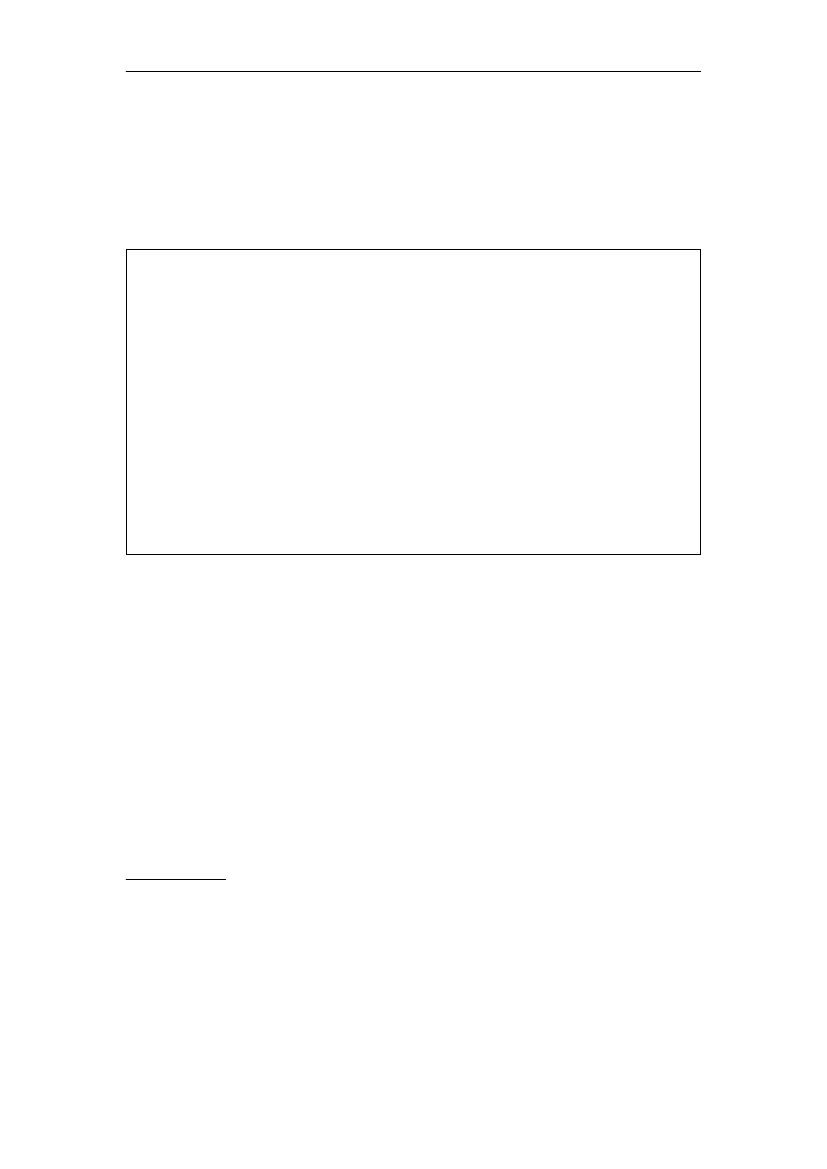

Source: Programme documentation and meetings during the evaluation mission.Table 2Summary of programme components 2003-103Primary EducationSupport Programme(PEPS)2003-061-6XXXXXXXXXXXXXExtension of Danishsupport to Educationin Afghanistan2007-081 - 12Hel-mand2008-??1 - 12Extension of fund-ing for education2009-101 - 12

Component*

GradeCurriculumConstructionTeacher trainingText BooksEducationadministrationHelmandMultilateralassistance

During the period Danida provided multilateral funding (in 2009 at leastthrough the ARTF) earmarked for teacher salaries3Danida also supportedUNICEF’s “Back-to-School-Campaign” in 2002.

23

USD 1= DKK 7.00 in 2003 and DKK 5.70 for the remaining years.Letter from WB to RDE, January 2009.

13

Executive Summary

Component*

Primary EducationSupport Programme(PEPS)2003-06Covered by a separatecontract signedbetween Danida andDACAAR/DAARTTfor construction ofschools.

Extension of Danishsupport to Educationin Afghanistan2007-08Covered by aseparate contractsigned betweenDanida andDACAAR/DAARTTfor construction ofschools

Hel-mand2008-??

Extension of fund-ing for education2009-10In 2009 DAARTTwas contractedfor an acceleratededucations projectfor Danida fundedfrom the bilateralsector support foreducation.

Assistancethrough NGOs

*Capacity Development: Staff training, institutional and professional development are explicitlymentioned as priorities or under implementation arrangements (with budget in PEPS) in allcomponents from 2003 onwards (including in current ESPA documents). Capacity developmentwas the principal element in the Education Administration component.

Source: Programme documents.

The activities and objectives of other development partners in AfghanistanIn 1990 NGOs and UN agencies supported 70% of Afghan schools with teacher salaries,training, student supplies, and textbooks. In 2001 the new development agenda attractedinternational organisations and NGOs and increased the need for coordination.Principal donorsDetails of donor contributions are given in Annex F (can be found on www.evaluation.dk). Inaddition, a 2009 report listed the principal donors with the United States Agency for Interna-tional Development (USAID) as the largest bilateral, contributing USD 97 million directly(almost USD 300 million in total) for education over the decade. The Embassy of Japan andJICA were also major contributors with the multilateral agencies (World Bank (WB), AsianDevelopment Bank (ADB), and United Nations (UN) agencies, including the World FoodProgramme (WFP)) also providing very substantial sums. Danida, Canadian InternationalDevelopment Agency (CIDA), Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency(Sida) and German aid, (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ))were the major contibutors bilaterally after USAID. Few donors have provided funds throughGovernment via MoF. While others use MoE systems, they contribute little directly to sup-port MoE’s control of sector resources. In this sense Danida’s approach is unique. USAID andthe United Kingdom’s Department for International Development (DfID) also implementeducation programmes in Helmand through the PRT. WB manages the largest donor pro-gramme in the MoE with three components under the ARTF, all on-budget:• the World Bank’s Education Quality Improvement Program (EQUIP) – basic and secondary education• • Technical/Vocational trainingHigher education

The 10 ARTF donors have provided USD 88 million for EQUIP I and II, covering Gen-eral Education, Teacher Education and Working Conditions, Education Infrastructure14

Executive Summary

Rehabilitation and Development. PRTs, funded primarily by the Provincial Reconstruc-tion and Development Committee (PRDC) and Quick Response Fund (QRF) underISAF, also support the sector.

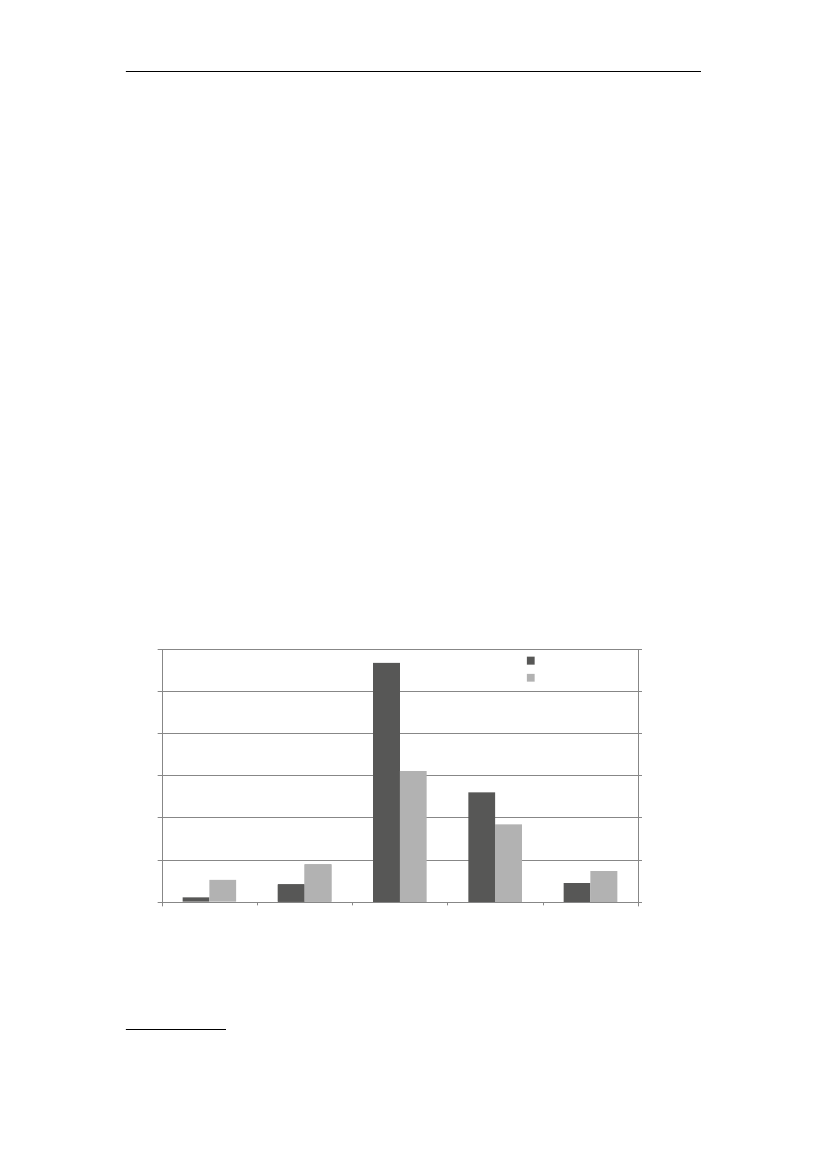

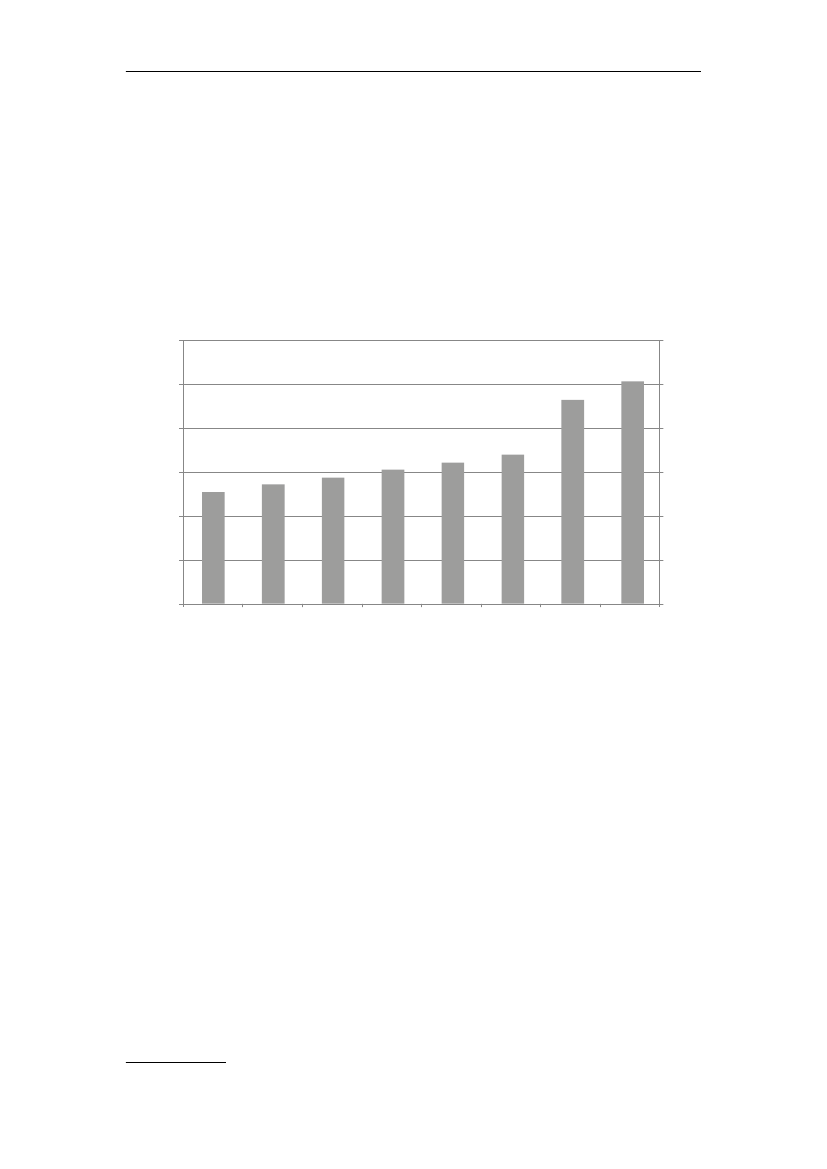

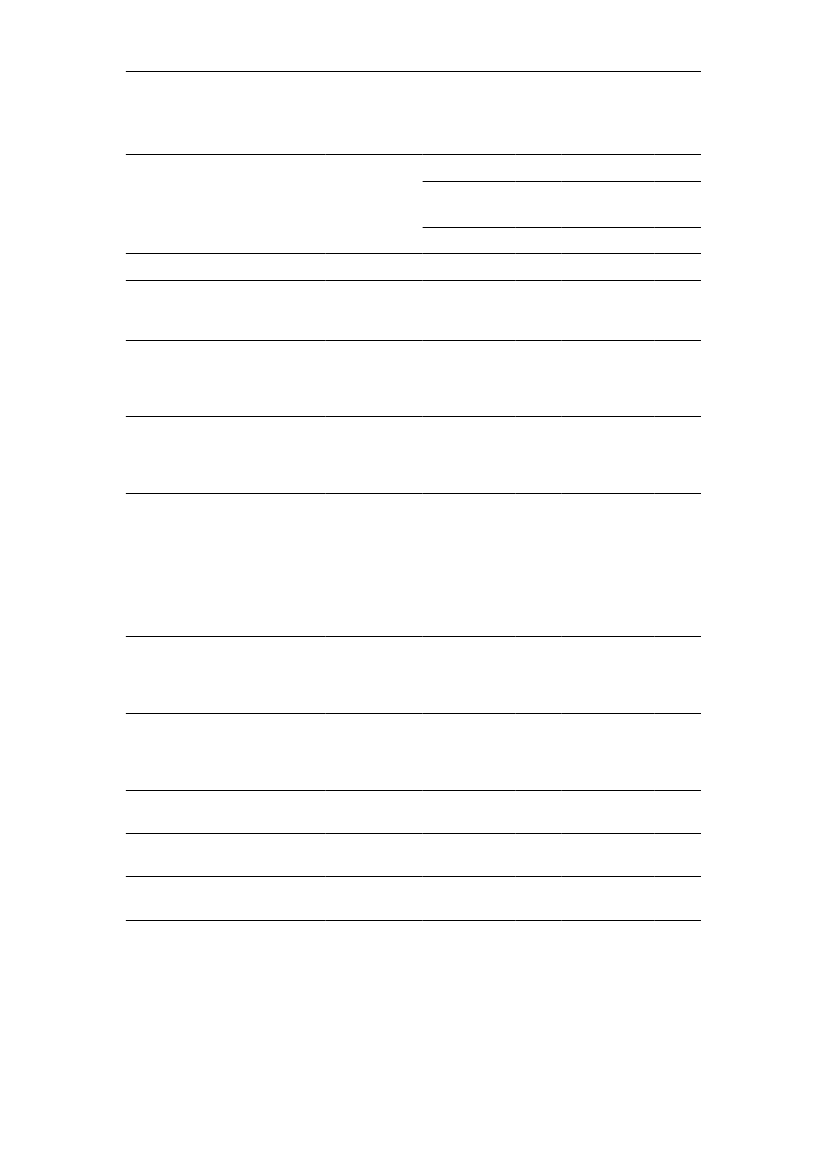

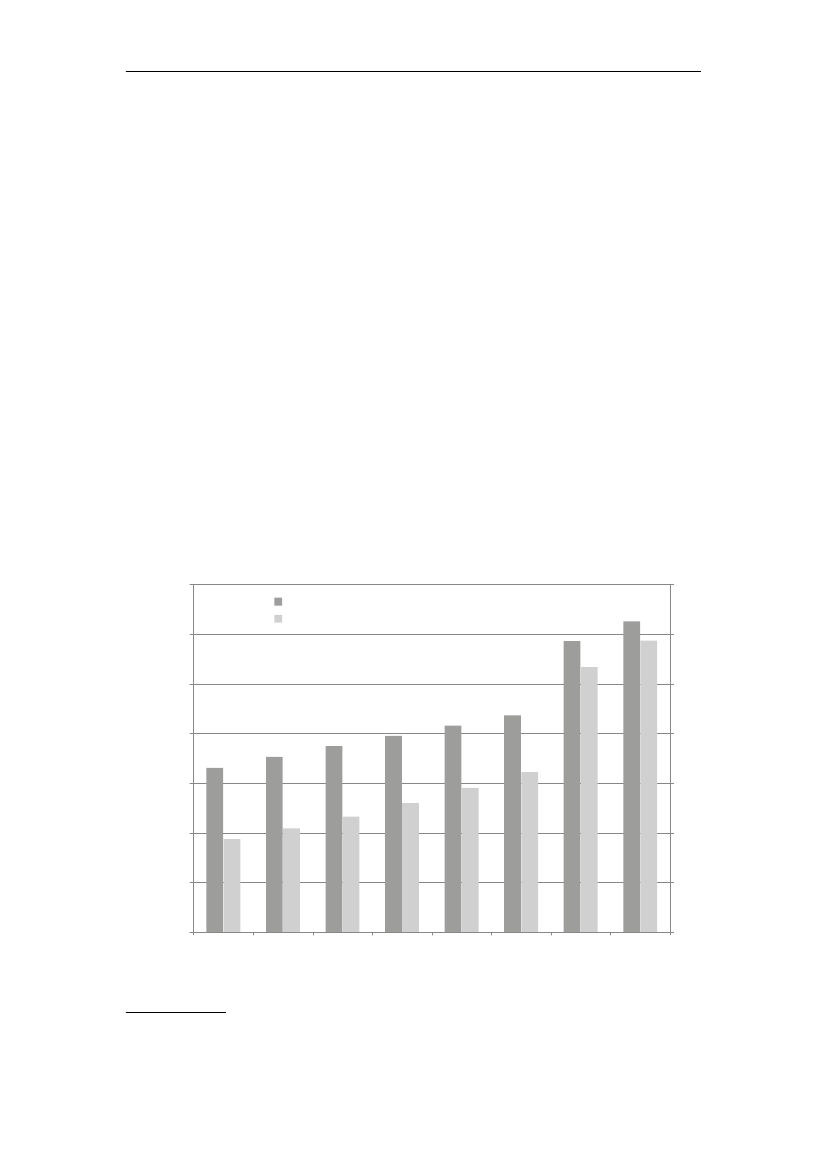

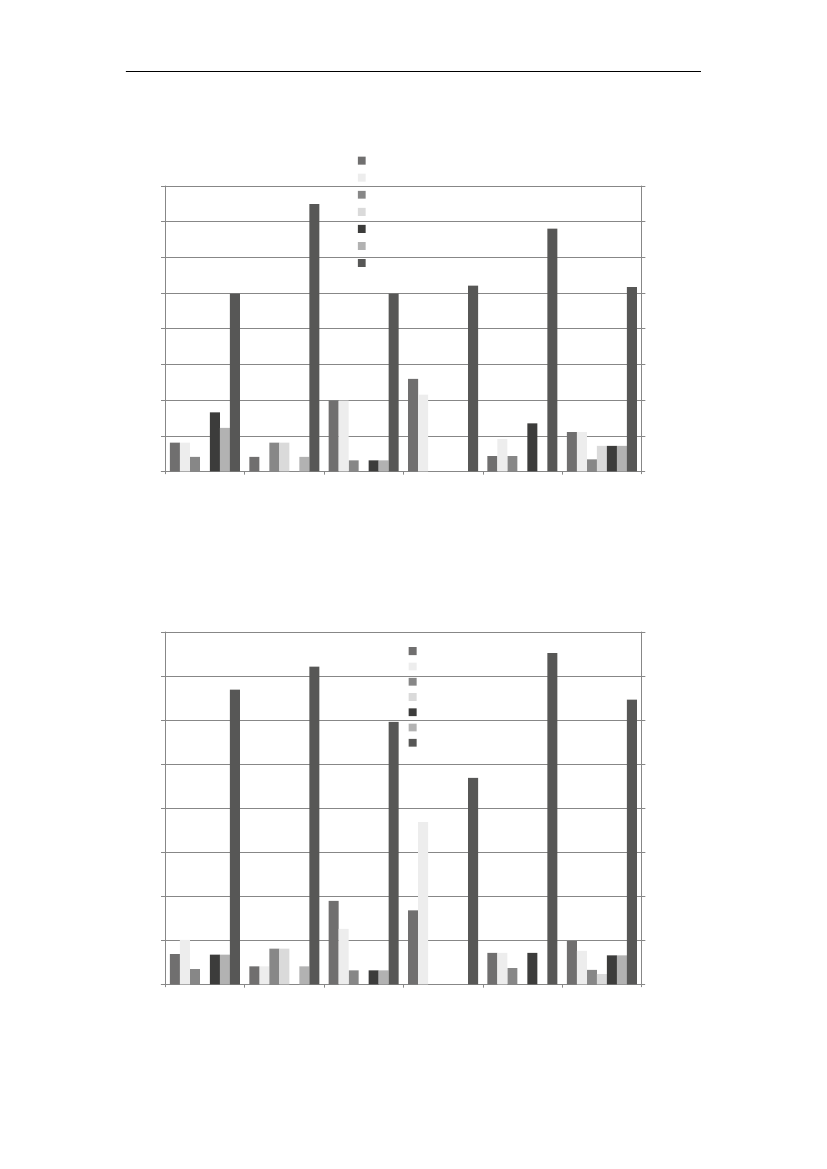

Achievements of Danish support to education in Afghanistan 2003-10Achievements are summarised for three periods of programme support. It was expectedthat inputs would take time to show progress and that sustainable results would not beestablished in one three year programme, but that periods of support would strengthenearlier gains. This has been the case with a remarkable expansion in education provisionin Afghanistan over the past decade with an increase of schools under MoE ownershipby approximately 10,000 (in 2002, there were 3,400 schools in MoE ownership and in2010 the MoE reported owning 13,363 schools; including 12,421 general education and626 islamic education), recruitment and training of 93,000 new teachers, printing ofmillions of textbooks based on a new curriculum and significantly strengthened manage-ment capabilities. Denmark has made a major contribution to this progress.Overall performance of PEPS 1Between 2003 and 2006 the Afghan education system expanded substantially. Accessimproved dramatically through the construction of 1,424 primary schools and class-rooms. Quality was addressed through a new curriculum, printing millions of books andby greatly expanding teacher provision. These outcomes relate to Danida’s programmeoutputs: building 21 schools, rehabilitation of the Curriculum Development Centreand contributions to writing the primary curriculum and textbook printing. Danida’smanagement inputs were documented and the whole programme budget was disbursedmaking use of in-built flexibility. The on-budget modality, management controls and ear-marking allowed spending to be monitored with evidence of ownership and responsive-ness to need in terms of inputs.The evidence shows that, through a very unsettled period in the establishment of theAfghan MoE, Denmark contributed significant and much appreciated support. Theonly other programme to use direct funding, EQUIP, which became effective in July2004, was in problem project status before June 2006. These are important achievementsagainst considerable obstacles.However, recognition of great progress in Afghan education and the Danish contributionmust be tempered by acknowledgement of differences between planned interventions and theactual experience of support. Budget disbursement and management were not as planned.Management, through the Steering Committee (the GMU did not function), relied heav-ily on Danida TA. Flexibility was anticipated, but variations from programme plans weremarked, and reasons not always documented. Inputs and activities were recorded, but thereare limited records of outputs especially in the areas of system and policy development.Spending was very largely on printing books (twice the original allocation and three times thatspent on all other components), and yet there was no book distribution system. For this pe-riod there are no central records of how many of the books printed with donor support actu-ally reached the schools. Systems for sustainable printing and distribution were only discussedat the end of 2006. Plans for capacity development and coordination of construction werenot addressed. Danida’s planned contribution to teacher training was reallocated. Immediateneeds tended to crowd out systems rather than operating an expected two track approach.

15

Executive Summary

For these reasons overall programme relevance is evaluated as good, though effective-ness and efficiency are moderate. Sustainability took longer to emerge. It is too early toevaluate performance in terms of impact. Limited records of outputs make contributionanalysis difficult. That Danida supported improved outcomes in access and quality areasis clear. Its overall contribution, however, was not as anticipated. Individual programmeoutputs where documented show marked differences from original plans.Overall performance on extensions 2007-10During the following period the Afghan education system continued to expand ac-cess and to address quality issues. By 2008 there were almost 8,000 more schoolsand 6 times as many enrolled students compared to 2001. 87 million textbooks wereprinted in the period and teacher and education administration staff reached almost170,000 (from 64,000 teachers in 2001). In 2008 also MoE produced the first Edu-cation Management Information System (EMIS) report, showing improved capacityfor planning and management. The Ministry was gradually able not only to gatherand present data at provincial level, but also to begin analysis of quality issues as wellas access. Recorded Danish aid outputs for the period include: Completion of 72classrooms by August 2009 with a further 130 classrooms almost finished by the endof 2010; contribution to textbook printing and some attention to distribution prob-lems.In general, records for Danish programme outputs are scarce for this period. As shown,Afghan education outcomes improved substantially and Danida clearly contributed.Budget disbursement and achievement of outputs are not reported in any detail. Howev-er, as far as can be seen, the funding modality functioned reasonably well in very difficultcircumstances in Afghanistan. Aid effectiveness and management improved somewhatalso, with ARTF acting as a donor coordination forum. The Education DevelopmentBoard (EDB) and subsequently the Human Resource Development Board (HRDB) andWorking Groups began to meet in late 2008. Danida has been active in the HRDB, andwas co-chair from May 2010 to 2011.However, it is less easy to see where Danish programme inputs occurred until SteeringCommittee Meetings resumed in late 2009. Improvements in management capacity atthe level of policy, strategy and systems are seen from later evidence from school surveys,staff management, etc. Danida contributed to reforms in these areas. Achievements inmanagement and aid management were slower to emerge than expected. Fragmentationof inputs was reportedly still a problem in 2009, and the capacity to formulate commonplans and provide objective feedback on performance (outputs) was still weak, meaningintended programme outputs were still highly relevant.Analysis of Danish contribution to overall system outcomes is harder than for the previ-ous period, therefore. 2008 and 2009 Danida reports draw attention to this problemand issues began to be addressed from late 2009 when Steering Committee meetings re-sumed, documentation improved and monitoring of TA workplan outputs began.

Education Support Programme to Afghanistan (ESPA) from 2010From March 2010 Denmark began a three-year programme worth DKK 340 million(approximately USD 60 million) to support Government’s Afghan National Develop-ment Strategy (ANDS) and what would become the NESP/Education Interim Plan16

Executive Summary

2011-13. Danish support is provided under the Education Support Programme for Af-ghanistan (ESPA) April 2011-13. Under the Danish Helmand Plan (2011) 15% of thedevelopment support is for Helmand.ESPA provides direct support to MoE budgets and plans with TA and capacity devel-opment. The ESPA Programme Document lists five EIP priority programmes. Theyinclude, i. General and Islamic education; ii. Curriculum development and teacher edu-cation; iii. TVET; iv. Literacy; v. Education governance and administration. Due to thelimited implementation period this evaluation covers only a limited analysis of ESPAfocusing on links and follow up from PEPS, etc.The largest budget item in EIP is Construction, also the most seriously underfunded.However, a recent (Danida-funded) report has improved the basis for MoE policy de-velopment in this area, coordination of inputs, setting of targets, standards, etc. EMISreports the number of classrooms in 2009 was 71,592. The projected need was 127,253,rising to 144,191 in 2011. The relevance of support is still clear.There is growing confidence in government systems. In addition to improved access(through construction) quality continues to improve through materials provision andteachers. MoE capacity to estimate need with increasing accuracy is a significant achieve-ment and Danida supports this area through TA and funding of training. However,programme documents emphasise continued monitoring of progress in areas of ongoinginterest, using MoE systems.The demand for teachers remains very large (EMIS records a shortfall of 131,929 in2009) despite progress. The proportion of female teachers has risen, from 28% of thetotal in 2006 to 52% in 2011. Several training initiatives continue. Danida’s interest re-mains in improved programme coordination, systems for measuring and increasing learn-ing, and improved efficiency.The Steering Committee is still responsible for management of ESPA using EIP workplans as“the primary references”with clear annual targets according to programme docu-ments. The stated intention, following the strategy for earlier interventions, is to reportoutputs and outcomes not activities. Monitoring is against targets, budget and DPs’ con-tributions. ESPA foresees some training before this can happen, and Danida is currentlyfunding workshops by the International Institute for Education Planning (IIEP).The GMU, revived from 2008, has functioned as coordinator for the Steering Com-mittee Meetings. It is staffed by national TA. In late 2009 there were 1,157 TA in MoE,mostly Afghan nationals. Danida was funding some 155 of these. “Capacity buying” ofsuch a large TA cohort represents a significant strategic choice and merits shared discus-sion on management and staged future planning. More specific output targets for capcitydevelopment would be welcome.The GMU’s function as coordinator for Danida’s programmes and its role in broader aidcoordination, the support logic consistently detailed in programme documents, are notdemonstrated, and the transaction cost of monthly Steering Committee Meetings is high.There has been progress with donor coordination as indicated by successful submissionof a coordinated proposal to the Global Partnership for Education (GPE) in 2011, andby MoE’s preparation with DPs of a first Joint Sector Review for mid-2012. However,there is some duplication of function between the Department of Finance (DoF), GMU17

Executive Summary

and the Education Development Board (EDB later the Human Resources DevelopmentBoard, HRDB). Danida supports both the HRDB and the GMU.HelmandNESP/EIP as a national plan directs priority activities, without earmarking by province.ESPA supports national level planning with specific, indicative activities and budget allo-cations for Helmand (15% of Danish development support for Afghanistan). Since 2008Afghan priorities for Helmand have focused on access as the number of students in safeareas has increased.According to MoE’s EMIS system there were 89,615 students enrolled in Helmand(17,720 girls, 20%) attending 332 schools in 2010. The school numbers have increasedsince 2008, when 238 schools were reported with 106,881 students (16% more thancurrent). Fluctuating trends show the difficulty of getting reliable data and the changingsecurity situation. However, there seems to be an encouragingly consistent growth in en-rolment of female students.From 2010, Denmark has support programmes aimed at stabilisation and develop-ment. Development activities are related to ESPA, with funding for school and dor-mitory construction and capacity building initiatives implemented through MoE.Stabilisation activities are funded through the UK and US military budgets andhave included community outreach, teacher training, material supply and schoolconstruction. Danida, as education lead, has increased alignment and harmonisa-tion of donor programmes over 2011, reflecting the overall support strategy. This isan achievement of Danida support and deserves expansion. More donors and NGOsshould join the Provincial Education Sector Working Group, adopt common policiesand report progress jointly to PED.In terms of infrastructure achievements, Denmark has funded construction of nine schoolsand two dormitories. Progress has been reported since 2010 at Steering Committee Meet-ings. Ongoing plans include construction of a Mini-TTC and administrative building inGereshk to increase female teacher recruitment; the extension of a school in Abazaan intoa high school to have an impact on girls’ enrolment in the area, and the development of abranch of the National Institute for Administration and Management in Lashkar Gah.Textbooks and materials for over 4,000 students and 100 teachers were distributed to dis-trict centres in 2009. In 2010, students and teachers received sets of children’s books tobroaden reading opportunities in Pashto.On teacher training, as with all data from the province, the figures are not reliable. How-ever, between 2005 and 2008 numbers increased from 1,437 teachers to 1,629 (20% fe-male). In 2010 there were 200 women enrolled in the Lashkar Gah TTC. Over 2009 andearly 2010, in-service training was provided to 200 female literacy teachers and over 400district based teachers. Teachers in Helmand also make use of the Radio in a Box distancetraining programme. Upgrading through national exams has enabled Helmand teachers(over 90%) to be included on the new MoE Pay & Grade system leading to higher indi-vidual salaries.A challenge in Helmand as elsewhere is to apply Danida’s policy on programme sup-port to develop MoE capacity for more confident and convincing projections, and to usethem jointly with partners for reporting, planning and decision-making.18

Executive Summary

ConclusionsThis section summarises the performance of Danida’s programmes against the DAC cri-teria. It constitutes a set of conclusions drawn from the evaluation. The relevant chapterin the main report gives detail on the inputs, components, discussions and outputs foreach period of support.RelevanceDanish support has been in line with Afghan needs. Despite the challenge of on-budgetsupport in the early 2000s the strategic decision to work closely with the new Govern-ment has had great value. Denmark is, consequently, seen as a trusted partner. Accesshas been MoE’s greatest priority and Denmark continues to support this through con-struction. Need for inputs to quality areas has also increased with the huge expansion inenrolments and Danida has provided the bulk of funding for textbook development andprinting. Budget flexibility in particular increased ownership and responsiveness to need.Collaboration on management has also been appreciated by MoE and other donors. Da-nida has contributed to increased MoE capacity to collect and analyse data on nationalneeds and performance, which has justified reduced earmarking in recent programmes.The integrated, two track attention to policy and system development and immediateneed was appropriate. Cross-cutting issues were consistent and appropriate policy priori-ties in Danida support, as were the emphases on harmonisation of donor support.However, the challenge of establishing systems for on-budget modality, were under-estimat-ed and there was insufficient assessment of the implications of possible failure. In the eventearly management relied much more than intended on Danish TA. The Steering Commit-tee and GMU were expected to develop policy and capacity without explicit details of howthis was to be done. Target outputs and mechanisms for development of MoE managementcapacity were not detailed and results not documented. Sustainability and efficiency werereduced, therefore. The decision to fund school construction through DAARTT mademanagement by the Steering Committee more difficult. Funding for teacher training wasswitched to textbook printing in response to need, but fuller documentation of how budgetflexibility operated would have allowed valuable lessons to be learned. There are few ex-planations of what activities or outputs were projected in many of the cross-cutting areasapart from expansion in female enrolment and teacher numbers. The mechanisms for pro-gramme harmonisation were also not detailed and the need to capture all annual donor andgovernment contributions (funds and activities) in annual strategic plans, with joint sectorprogress reporting is only now being addressed in 2012. It would be helpful to see plans ofhow attention to urgent needs is balanced with long-term strategic capacity building.EffectivenessThere have been significant improvements in the sector during a highly insecure periodand Danida has provided major inputs. Male and female access to education, a consti-tutional right and a MoE policy priority, has increased as schools were built or restored.Denmark has funded high quality construction with local involvement in site selectionand building. Education quality issues have been addressed through curriculum and syl-labus development, writing and printing of textbooks and training of teachers. Danidamade its largest contribution to textbook and other material printing. Flexible budget al-location largely benefited this component.MoE capacity to report improvements and to estimate annual demand for teachers, class-rooms, etc. with greater accuracy has grown. There is now considerable M&E capacity at19

Executive Summary

central level related to IIEP support funded through Danida. Full programme ownershipby government institutions is established (with caveats regarding TA). Successful intro-duction of the staff pay and grading (P&G) system indicates growing capacity to monitorand reward performance. Danida funding of the Reform Implementation ManagementUnit (RIMU) helped develop this system.Management and aid management have made clearer progress recently and Danida hasshown the lead towards better alignment with government priorities. It helped coordinatedevelopment of the GPE support proposal. Danida’s“flexible and non-bureaucratic”ap-proach in dialogue with MoE has allowed rapid response in the uncertainties of Afghani-stan. A joint donor/MoE review in June 2012 will move this process forward significantly.Danida’s success in applying aid effectiveness principles in difficult circumstances (even inHelmand) merits greater publicity especially in the face of objections that such coordina-tion is premature for Afghanistan. Security constrained programme implementation in itsaccess to provinces, schools and communities even for Afghan staff. Access to Helmand hasbeen severely restricted for civilian advisers. Danida is said by DPs to be doing a“remarkablejob”there, aligning with local and government priorities and approaches.Nevertheless, in all component areas there were aspects of planned support that tooklonger to show progress. Management capacity to control construction, though repeat-edly emphasised, was not addressed until recently and there is no evidence of systems orpolicies for vulnerable groups and minorities. Support for these is mainly handled locallyby individual NGOs or donors. Danida’s collaboration in teacher development ceasedearly. Funding was switched and the intended unified policies, programmes and nationalrecords are still in development. Donor training remains fragmented and still needs in-tegration into national career pathways (e.g. the P&G structure). MoE records booksprinted, but there is no system for monitoring distribution to schools.Contrary to the planned use of Afghan systems, programme management dependedlargely on TA inputs before 2006, and from mid-2006 to late 2009 largely stopped re-porting inputs and results. From limited records, funding was not disbursed as expectedand important elements in the planned support were not fully achieved.Ministry capacity still rests with staff designated as TA and not in systems or in the growingskills of establishment counterparts. TA numbers remain very large and key staff are paid bydonors under different systems with unclear links between salary and performance. The riskalso is that“bought capacity”will not stay in the public service if outside funds are reduced.EfficiencyThe ability to direct funding to areas of need contributed to efficient use of budgets. Inearlier periods, built-in flexibility allowed response to emerging need in a very uncertaincontext and ensured a high burn-rate. Major re-allocations from curriculum develop-ment and teacher training to printing went smoothly. Management decision-making bythe Steering Committee was efficient, though reliant on outside TA to 2006 and then onhold until late 2009. Funding efficiency through pooled arrangements was developed asplanned where Danida took the lead (e.g. in Helmand). Separate funding for infrastruc-ture has a mixed evaluation for efficiency. Speedier construction may have been offset byraised costs, increased duplication and complicated management by MoE.The security situation affected the efficiency and effectiveness of all activity. Insecuritywith poor distribution systems and road conditions limited delivery of textbooks printed20

Executive Summary

with Danida support. The cost of precautions is high, especially where use of interna-tional TA is necessary.The GMU coordinating mechanism did not operate consistently or efficiently as for-seen in implementation plans for managing aid in general or Danish aid in particular.Currently, it runs in parallel to the HRDB. The continued frequent, dedicated Steer-ing Committee Meetings are still valued by MoE despite the serious transaction cost.Absence of Joint Sector Reviews (with all donors), intended to increase alignment andharmonisation, reduced efficiency. The first Joint Sector Review is now planned for mid-2012.Measurement of inputs and related outputs was generally not used to measure Danida’sprogramme performance and increase efficiency. The modality made enormous demandson RDE capacity. Effectiveness and efficiency increased where sufficient permanent Da-nida staff with education sector specific expertise were in place.Sustainability and impactIn line with its programme strategies, Danish support follows Afghan priorities. Owner-ship by MoE of Danida supported interventions contributes to sustainable alignmentand partnership. In addition, interventions comply with Danish Government policy on“Whole of Government approaches”.Consequently Government is seen by the Afghanpublic as the main education provider, the most important public service. Awareness ofdonor initiatives is encouragingly limited, strengthening sustainable ownership. SchoolShura also strengthen ownership, planning and liaison with the community, promotingeducation, reducing suspicion, etc. including in Helmand.In more stable parts of the country there is evidence of economic progress contribut-ing to stability and long-term development. Perceptions of improved prosperity aregrowing, though unevenly. There is steady confidence in the Afghan National Armyand National Police and growing confidence in print media, provincial and communitycouncils and other forms of local government, indicating sustainable stability and pro-gress. There is a respect for free speech and exchange of opinion (e.g. through the LoyaJirga).Support to central and provincial planning units is important for targeting and sustain-able development of education services as well as measurement of performance. The ca-pacity of the EMIS unit to make projections of education need is developing and Danidahas funded training and continues to pay staff supplements. There were questions overthe reliability of data on need in 2004 and later, but recent improvements are encourag-ing. Sustainable capacity at provincial and district levels has yet to be developed. The de-ployment of Afghan TA or supplemented Afghan staff promotes national ownership andensures skills are available within MoE. However, buying capacity is vulnerable to adjust-ments in donor support and of weak sustainability.As noted, trends in female school attendance, sometimes in discouraging circumstances,are encouraging even in Helmand. Supply of female teachers is also expanding, whichencourages sustainable female enrolment. Needs remains double the supply, however. At-tendance at literacy classes continues to grow even in Helmand. Positive trends are revers-ible however, and sustained growth in enrolment trends relies on improved quality andopportunities for graduates to make use of learning when they leave school.

21

Executive Summary

Recommendations and lessons learnedThe evaluation presents six recommendations below. Each draws from various conclu-sions and links to lessons learned. In general, the recommendation is that Danida shouldcontinue to support education priorities in Afghanistan in those areas and through themodality that has been used to date. The programme support approach is the more ap-propriate as capacity in MoE has grown. The EIP provides the necessary basis for jointsector performance monitoring.1.Danida’s on-budget modality reflected emerging aid effectiveness priorities, wasappropriate and should be continued.At the time of its application it was innova-tive and applied in a context of high risk (acknowledged in programme documen-tation). Nevertheless, the benefits outweighed the risk.However, to reduce this risk, to implement policies underlying Danida’s supportstrategy, to allow all stakeholders to draw more fully on experiences and lessonslearned from the modality and programme implementation, the following recom-mendations should be introduced.2.To reduce risk and promote capacity development, it is recommended thatdocu-mentation be kept more fully and in a form that facilitates use by managers inMoE, Danida and development partners.This was not always done and, at times, seriously threatened the value of the assis-tance. Moreover, at best, documentation referred more to activity and process thanoutput. Management needs to focus more on planning and monitoring of outputs,targeting medium-term outcomes and eventual impact. This needs to be explicit inToR of TA and managers and monitored as an important aspect of performance.3.For the host institution the maintenance of records in a form that focuses on re-sults serves a strong capacity development purpose and should be given greaterprominence. Counterpart managers should receive training and support in writing,keeping and using documented results, identification of significant expected out-puts and setting realistic targets. MoE, provincial, district and school managementstill needs help to cost annual interventions and to report on performance andtrends.It is recommended that Danida ensure that results-based managementskills are included in the training programmes they currently support for MoEand PED staff. In addition, RDE education programme management should bestrengthened and increased to ensure the assistance MoE receives is tailored tothe monitoring task involved.The use of the on-budget modality was intended to promote donor coordination.Plans for a Joint Sector Review are currently being developed, and it is recom-mended that this is capitalised on for explicit mapping of phased progress towardsimproved coordination including programme budgeting, capturing all annual do-nor and government contributions (funds and activities) to annual strategic plans.It isrecommended that Danida develop an explicit results chain to show howprogramme activity will lead to the improved harmonisation and alignment ofsupport.This should be done in collaboration with MoE and other donors, butneeds to be both planned and monitored.

4.

22

Executive Summary

5.

Danida’s further support to education quality at the level of systems, coordinationand policy development is appropriate, consistent with the modality, in line withearlier planning, and plays to Danida’s strengths in partnership and dialogue. Itshould continue to balance attention to urgent needs with support for long-termstrategic planning. More explicitbenchmarking is needed to ensure these inputstranslate into not just immediate outputs but medium-term outcomescloser tobeneficiaries, i.e. students, parents, etc.4Danida should support the further de-velopment by MoE of systems that record and report quality improvements atschool level.It is recommended thatDanida should support rationalisation of the different TAand supplementation systems, either by provision of specialist advice to MoE, orthrough advocacy in Ministry/donor forums.Performance of TA with counterpartdevelopment roles should be monitored against ToRs, preferably in collaborationwith the HR department. Where funding is provided to government establish-ment staff, development of a single scheme with government-led reporting criteriashould be established. Since it supports both, Danida should advocate a rationalisa-tion of the roles ofthe GMU and HRDB.

6.

4

For example, through support to MoE on follow up of issues raised in the 2006 report on text-books.

23

1

Introduction

1.1 Background to the evaluationDenmark has provided substantial development assistance to the reconstruction of Af-ghanistan since 2001, with the main purposes of contributing to national, regional andglobal security as well as to poverty reduction. It has been active in the education sectorsince 2003 and between 2003 and 2010 disbursed approximately Danish Kroner (DKK)431 million (US Dollar (USD) 82 million at 5.24 DKK=1 USD) in support to Afghaneducation through bilateral programmes, including the efforts in the Helmand province,mainly through the bilateral education sector programmes. A relatively minor portion offunding has been given through other channels, e.g. through the Afghan ReconstructionTrust Fund (ARTF) and, in the early years, through UN organisations.Denmark wishes to learn from the experience of development assistance to Afghanistanover the above period, and the Evaluation Department of the Danish Ministry of ForeignAffairs (EVAL) has, therefore, commissioned the current evaluation. The main purposesare to assess and document the contribution to results of the Danish support to educationin Afghanistan and to contribute to the continued improvement of Danish support. It willalso contribute to continued learning in relation to sector support in ‘fragile’ situations.The main objectives of the evaluation are to assess the strategy, implementation and re-sults of Danish support and to identify conclusions, lessons learned and forward-lookingrecommendations for continued support. The evaluation has used the DAC evaluationcriteria of relevance, effectiveness, efficiency and sustainability as a basis for assessments,while taking into consideration the context, including the security situation, in which thesupport is provided. This evaluation is one of two Danida evaluations concerning Danishsupport to different development cooperation activities in Afghanistan. The other evalua-tion covers the Region of Origin Initiative.

1.2 Structure of the ReportThe report firstly sets out the methodology used for the evaluation including discussionof the underlying logic, and a description of the data collection tools and processes usedduring the evaluation. This is followed by chapters outlining the background to educa-tion in Afghanistan to the present day and an overview of Danish support to Afghan ed-ucation in the past decade. Both include some analysis of the ongoing conflict situation.These chapters are followed by an in-depth analysis of the Danida programmes: PrimaryEducation Programme Support (PEPS 1) 2003-06; the extension from 2007 to 2008;the further extension from 2008 to 2010, and the current support through the (Danish)Education Support Programme to Afghanistan (D/ESPA) 2010-13. Each programmecomponent (curriculum, textbooks, training, construction, management) is discussed interms of the DAC evaluation criteria and the modality selected for delivery of Danishsupport. There are sections on Technical Assistance (TA) and on support activity in Hel-mand Province. This is followed by a chapter summarising the conclusions of the evalu-ation in answer to each of the Evaluation Questions (EQ) and Sub-evaluation Questions(SQ). The report ends with six key recommendations drawn from the analysis.24

1 Introduction

The report includes annexes and with a summary of the Terms of Reference (ToR), listsof documents consulted and persons interviewed and an organogram of the Ministry ofEducation (MoE).

1.3 MethodologyThe ToR ask for an evaluation with a focus on results taking account of the context ofhistorical isolation, poverty, fragmentation, fragility and insecurity and the causal chainleading to the results.Danish support policy, as exemplified by the strategies detailed in programme documents,was to work through and strengthen host institutions, using an on-budget modality. Supportrelied on regular, documented results to guide joint programme management by the MoEand the Royal Danish Embassy (RDE). Planning and modifying activity would specify out-puts, and programme outcomes. Immediate results would feed into next steps in the man-agement process, keeping ownership with MoE and raising capacity.The support strategy also assumed that use of Afghan public administration (a Ministryof Finance (MoF) account for Danish funds with earmarking of programme compo-nents) and MoE service delivery would contribute to national reconstruction. Wheredevelopment partner (DP) support over the last 10 years has been provided off budget ithas thereby undercut state capacity and missed the opportunity to strengthen legitimacy.To this extent it has reduced its assistance to the Afghan State. Danida’s strategy specifi-cally addressed this through its emphasis on use of government systems.A further fundamental aspect of Danida’s support strategy was the implementation of atwo track approach referred to also in programme documents as “interrelatedstrategic ap-proaches”(PEPS 1 p. 4 and Extension Document p. 6). This required attention not onlyto local, emergency intervention but also to long-term systems and policy development.As an example of emergency intervention, the Education Materials component was to begiven priority in the first year of programme operation (2003-04) and the largest portionof the budget. This was because a major investment was urgently required“to establish thecapacity for production on the scale and quality required for the new curriculum”5. As noted,the need for books, even based on earlier, low estimates of demand, was huge.A further aspect of Danida’s programme strategy was the emphasis on harmonisation andalignment of support. These aspects, as shown in sustainability and ownership by theAfghan Government as well as collaboration with other donors would be built on docu-mentation of shared strategy.The approach taken by this evaluation also places a strong emphasis on documentedresults. Consistent with the logic of the support programme it draws on Results BasedManagement (RBM), a strategy focusing on outputs, outcomes and impacts. The basictechnique in RBM is formulation of a results chain, mapping inputs and activities toproduce intended results. The key distinction in RBM between inputs/activities and re-sults places emphasis on measurement of the latter, where possible using indicators andtargets. Also fundamental is the distinction between short-term outputs and longer-termoutcomes and impact. The evaluation seeks to show the links between what was planned,5PEPS 1 Programme Document, 2003-06, p. 5.

25

1 Introduction

what was carried out (inputs) and the immediate results (outputs), and the eventualbroader outcomes. Where possible it also points to longer-term impact.Evaluation approach and constraintsRBM principles are relevant to planning, management and evaluation of aid pro-grammes6. Danish support to education in Afghanistan from 2003 was not informedexplicitly by RBM, but logic in Danida’s PEPS and ESPA depends explicitly on a similarresults focus to guide programme management7. Planning and modifying activity toproduce expected outputs leading to outcomes continue to be essential responsibilities ofprogramme management. Programme management and the methodology used for thisevaluation, though distinct, thus share an emphasis on documentation of results. In theformer the documentation of results is to guide programme inputs and activity. In thelatter, to draw broader conclusions against EQs grouped under the headings: Relevance,Effectiveness, Efficiency, Sustainability and Impact. This chapter of the evaluation under-lines the ways in which both management and evaluation rely on and make use of docu-mentary evidence.Security and time did not permit direct observation or statistical sampling of programmeresults. Interviews and visits allowed only an impression of the Afghan education system,although fact-finding and field visits in 2011 and 2012 included a mix of urban and ruralareas in different regions with experience of different ethnic groups. During these visitsinformants at MoE, provincial and district education offices, schools, communities andteacher training colleges (TTCs) were interviewed; girls’ schools were visited and issuesof marginalisation discussed. Representatives of key NGOs and DPs were met (see An-nex B). The interplay between education support and security issues in Helmand andelsewhere was discussed. During the 2011 field mission schools were sitting nationalexams meaning little observation of structured teaching or use of books or materials waspossible. Data collection based on the EQs and SQs provided in the ToR, were used inthe field mission. However, data on many indicators was not available (e.g. net and grossenrolment ratios (NER) and (GER), numbers of qualified teachers by year, etc.). Otherconstraints matched those for programme management:• Frequent changes of staff in Government and DPs and weak institutional memo-ry;• • • • • Lack of continuity between international staff, including technical assistance (TA);Donor projects (including military) operating in the same technical area;Weak individual, institutional and data management and administrative capacity;Frequent reorganisation in Afghan government institutions;Changing patterns of security and stability throughout the country.

The evaluation, moreover, covered a period of more than 10 years. Technical and man-agement reports covered a lengthy and unstable period. However, a comprehensive data-67See inter alia: Defining the role of evaluation vis-à-vis Performance Measurement in Results BasedManagement in the Development Cooperation Agencies: A Review of Experience, The Develop-ment Assistance Committee, Working Party on Aid Evaluation, 1999.E.g. PEPS 1 Programme Document, 2003-06, paragraph 6 p. 1, paragraphs 41 and 45 p. 8.

26

1 Introduction

base of over 800 documents was assembled and largely formed the basis for the evalua-tion.Documentation for programme management and evaluationPage 1 of the Executive Summary of the first PEPS 2003-06 specifies,“Annual Work Plansand Budgets will serve as tools for determining and identifying next steps in each componentof the programme”.Given the fragile situation, weak capacity and lack of data records,management was always going to be a challenge. This was the risk inherent in the inter-vention logic. Flexibility in resource allocation linked to planning was part of the design,therefore, and Annual Reviews were to contribute to the constant feedback loop.In addition to annual plans, budgets and reviews, the mechanisms consistently identifiedfor management of Danida’s programmes were the Grants Management Unit (GMU)and the Steering Committee. Responsibilities of both are set out in detail in the 2003,2007 and 2010 programme documents. They include widespread and comprehensivereporting, monitoring and accounting functions, including, in the case of the SteeringCommittee, approval of plans and budgets (annual and quarterly revisions if needed),annual and quarterly progress reports, ToR for annual audits, etc. The logic explained inthe programme documents was that this would strengthen capacity, not only to manageDanida’s programmes, but for the education system in general8.Moreover, through its key management function the GMU was intended to act as both amagnet and a coordination mechanism for other DP programmes. The assumption wasthat other donors would begin to provide funding through the GMU in the same way asDanida9. The modality selected for Danida’s Afghan education programmes, i.e. use ofgovernment systems with a degree of earmarking linked to management assistance, is de-scribed as on-budget support10. To increase fiduciary reliability funding was to be chan-nelled to the MoE through a special bank account allowing the Finance Ministry (MoF)to withdraw money for utilisation by MoE, while MoE would report to the Danish Rep-resentation in Kabul on the use of funds and activities carried out. Danish aid would be a‘test case’ to encourage harmonisation and alignment, a“shift from parallel disbursement oftheir funds to channelling into the official Afghan system.”11Thus documentation was fun-damental to management and aid effectiveness.Management as central to Danida’s modalityHost capacity and a strong monitoring framework are recognised as essential elementsin deployment of an on-budget modality12. And yet weaknesses in Afghan monitoringand management capacity were repeatedly acknowledged in documents throughout theperiod. For this reason, the development of management capacity in MoE (includingplanning and performance monitoring) was included as a formal component of the aidprogramme. To mitigate risk entailed by the on-budget modality, where institutions and89101112PEPS 1 Programme Document, p. 27 paragraph 151.Explicitly stated in PEPS 1 Programme Document, p. 30 paragraph 163.See Danida’s Guidelines for Programme Management, 2011 and earlier versions of documentationon Danish aid modality from 1994 and 2000.PEPS 1 Programme Document 2003-06 p. 5.Danish policy on host management and monitoring capacity has been developed and refined inofficial documentation at least since the Strategy for Danish Development Policy towards the year2000, 1994. Documentation includes Guidelines for Programme Management Support, 1998,Partnership 2000, Guidelines for Programme Management, 2003 (1stversion), 2006, 2007, 2009and 2011, and Modalities for the Management of Danish Bilateral Development Cooperation, June2005.

27

1 Introduction

management were known to be fragile, substantial management capacity developmentwas, and continues to be, essential.The rationale for use of the on-budget modality included recognition of the importanceof strengthening the Afghan state in provision of public services as part of national,economic and social reconstruction. Poverty reduction, social development and equity,including access by girls to education, are Afghan state policy and have also been stronglyadvocated by Danida from PEPS onward. Popular participation in governance as a meansto build stability is a broad aim of Danish support, just as the drafting of coherent Af-ghan national policies and their presentation through local activities, building confidencein Government are also accepted as critical in this process.Danida programme documents stress the need for strong links between national policyand local implementation including community participation in dialogue on location ofschool buildings, access to education for girls, promotion of training for female teachersand students, unified national curricula, systems for school management, etc. The Af-ghan and Danish Governments explicitly linked national policy and local realisations in acritical nation-building relationship.And finally, Danida’s support was always foreseen as a collaborative effort. Danida wouldnot take sole responsibility for a sub-sectoral component, but would work with the Af-ghan Government and other donors. The development of a common policy frameworkwas always essential, therefore. Danida’s objectives were not simply to train teachers orto print textbooks, but to do these things within a unified national programme. Thisexplains the stress on balance between policy development and urgent, local implemen-tation,“the inter-related strategic approaches (i) immediate action, and (ii) longer-termdevelopment”.13The availability of shared documentation was fundamental to the ap-proach.In sum, the management mechanisms identified in the PEPS programme documentstogether with associated documentation (accounts, reviews reports, plans, etc.) wereforeseen as the basis of Danish support and continue to be essential for programmemanagement and for broader system development. They were also essential to the evalu-ation. The meetings, records, reviews, etc, made possible and demonstrated the flexiblebudget allocation (inputs) in response to need as it becomes clearer, as data and reducedlevels of conflict allow this to be specified; they provide a means to manage the fund-ing risk, through transparency and accountability; at the level of outcomes they supportconfidence-building in government systems among other donors and the Afghan public,and they link immediate, local action to long-term national strategy for development andreconstruction14, and build sustainable capacity in MoE and government departments.Limitations of the evaluation approachEvaluation of Danida support, thus, depends on documentation (as well as institutionalmemory, informants’ impressions, etc.) in the same way that the above management pro-cesses did and do. The conflict situation and weak institutional capacity in Afghanistanplaced a serious burden on management of aid programmes. They also made evaluationdifficult. But the fragile situation, weak institutional capacity and need for changes ofstrategy also made the role of management especially important. Constraints common toevaluation, aid and sector management include:1314PEPS 1, 2003-06 Programme Document p. 4.PEPS Extension 2007-08 Programme Document, para 68.

28

1 Introduction

• • •

Frequent changes of staff at all host government and DP institutions resulting in weak institutional memory;Lack of continuity of inputs from key international staff, including Technical Advi-sors (TA) (short periods in-country followed by leave);A tendency for several donor projects (including the aid activities implemented by military or associated mechanisms) to operate in the same technical area increasingthe risk of duplication, fragmentation and increasing transaction costs;Uneven capacity in institutions and individuals;Frequent reorganisation of structures and responsibilities in Afghan government institutions;Changing patterns of security and stability throughout the country.

• • •