Det Udenrigspolitiske Nævn 2011-12, Udenrigsudvalget 2011-12

UPN Alm.del Bilag 204, URU Alm.del Bilag 192

Offentligt

BAhrAIn fAIls to AchIEvE justIcEfor protEstErs

Flawed reForms

amnesty international is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters,members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaignto end grave abuses of human rights.our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the universaldeclaration of human rights and other international human rights standards.we are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest orreligion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations.

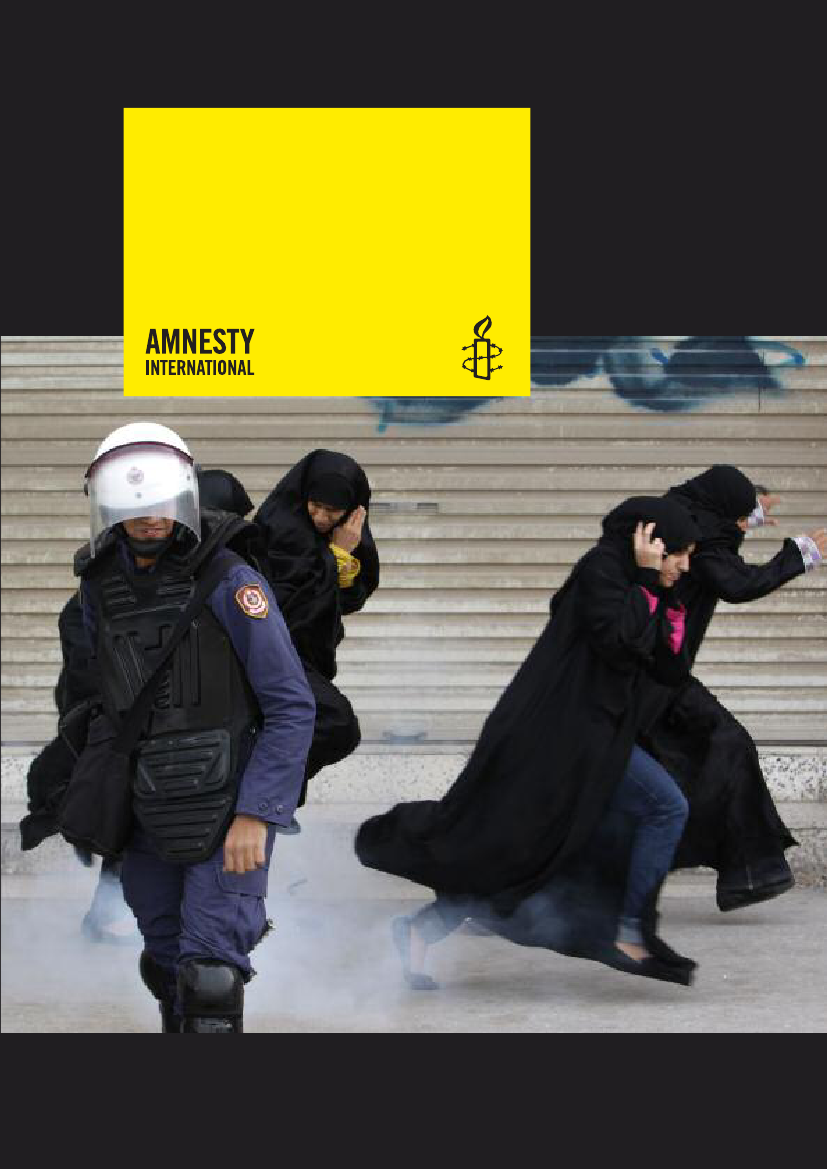

First published in 2012 byamnesty international ltdpeter Benenson house1 easton streetlondon wc1X 0dwunited Kingdom� amnesty international 2012index: mde 11/014/2012 englishoriginal language: englishprinted by amnesty international,international secretariat, united Kingdomall rights reserved. this publication is copyright, but maybe reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy,campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale.the copyright holders request that all such use be registeredwith them for impact assessment purposes. For copying inany other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications,or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission mustbe obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable.to request permission, or for any other inquiries, pleasecontact [email protected]Cover photo:Bahraini anti-government protesters react as riotpolice throw sound bombs at their feet to disperse them inQadam, Bahrain, 17 February 2012.� ap photo/hasan jamali

amnesty.org

CONTENTSTT1. Introduction..........................................................................................................5February-March 2011 protests ....................................................................................6Piecemeal reforms .....................................................................................................8Lack of political will.................................................................................................10About this report......................................................................................................112. Mechanism for implementing recommendations .........................................................133. Accountability for violations during protests ...............................................................15Deaths in custody and killing of civilians....................................................................17Tortured in custody ..................................................................................................194. Unfair trials of political activists ...............................................................................24National Safety Court cases ......................................................................................26Death sentences ......................................................................................................335. Continuing violations by police in the midst of reforms................................................35Excessive use of force ..............................................................................................36Arbitrary detention and torture and other ill-treatment .................................................396. Workers and students dismissed, punished ................................................................43Waiting to return to work ..........................................................................................447. Compensation to the victims ....................................................................................478. Prospects for reconciliation ......................................................................................499. International human rights groups and foreign journalists restricted .............................52

10.

Conclusion and recommendations ...................................................................... 54

Endnotes ................................................................................................................... 58Annex ....................................................................................................................... 65

Flawed reformsBahrain fails to achieve justice for protesters

5

1. INTRODUCTION“The Bahraini authorities need to urgently takeconfidence-building measures includingunconditionally releasing those who wereconvicted in military tribunals or are still awaitingtrial for merely exercising their fundamentalrights to freedom of expression and assembly.”UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Navanethem (Navi) Pillay, 21 December 2011

The human rights crisis in Bahrain is not over. Despite the authorities’ claims to the contrary,state violence against those who oppose the Al Khalifa family rule continues, and in practice,not much has changed in the country since the brutal crackdown on anti-governmentprotesters in February and March 2011.

The King, the Prime Minister and the Crown Prince during the Bahrain Independent Commission ofInquiry's ceremony � Amnesty International

Index: MDE 11/014/2012

Amnesty International April 2012

6

Flawed reformsBahrain fails to achieve justice for protesters

The Bahraini authorities have been vociferous about their intention to introduce reforms andlearn lessons from events in February and March 2011. In November 2011, the BahrainIndependent Commission of Inquiry (BICI), set up by King Hamad bin ‘Issa Al Khalifa,submitted a report of its investigation into human rights violations committed in connectionwith the anti-government protests. The report concluded that the authorities had committedgross human rights violations with impunity, including excessive use of force againstprotesters, widespread torture and other ill-treatment of protesters, unfair trials and unlawfulkillings.So far, however, the government’s response has only scratched the surface of these issues.Reforms have been piecemeal, perhaps aiming to appease Bahrain’s international partners,and have failed to provide real accountability and justice for the victims. Human rightsviolations are continuing unabated. The government is refusing to release scores of prisonerswho are incarcerated because they called for meaningful political reforms, and is failing toaddress the Shi’a majority’s deeply-seated sense of discrimination and politicalmarginalization, which has exacerbated sectarian divides in the country.In recent months, the Bahraini authorities have become more concerned with re-buildingtheir image and investing in public relations than with actually introducing real human rightsand political reforms in their country. Indeed, for the authorities, much is at stake. They arekeen to portray Bahrain as a stable and secure country in order to stave off internationalcriticism. But as the country is about to host the Formula 1 Grand Prix on 20-22 April, afterthe event was cancelled last year in response to the instability in the country, daily anti-government protests continue to be violently suppressed by the riot police that use tear gasrecklessly and with fatal results. Acts of violence by some protesters against the police havealso considerably increased in the last three months.Holding the Grand Prix in Bahrain in 2012 risks being interpreted by the government ofBahrain as symbolizing a return to business as usual. The international community must notturn a blind eye to the ongoing human rights crisis in the country. The government mustunderstand that its half-hearted measures are not sufficient - sustained progress on realhuman rights reform remains essential.

FEBRUARY-MARCH 2011 PROTESTSOn 14 February 2011, inspired by the uprisings in Egypt, Tunisia and other countries in theMiddle East and North Africa, tens of thousands of Bahrainis took to the streets to voice theirdemands. The vast majority of protesters were Shi’a Muslims, who despite being the majorityof Bahrain’s population, have resented being politically marginalized and discriminatedagainst by the ruling Sunni Al Khalifa family which dominate all aspects of political andeconomic life in Bahrain.The government’s response to the protests was brutal. The security forces used excessiveforce, including shotguns and live ammunition as well as the reckless use of tear gas, todisperse protesters who mostly camped in the Pearl Roundabout in the capital Manama.Seven protesters were killed by the security forces in the first week alone in February 2011.

Amnesty International April 2012

Index: MDE 11/014/2012

Flawed reformsBahrain fails to achieve justice for protesters

7

As demonstrations continued to grow, negotiations between the opposition, led by Bahrain’slargest Shi’a political organization, the al-Wefaq Society, and the royal family, led by CrownPrince Shaikh Salman bin Hamad Al Khalifa, collapsed in early March 2011.1The oppositionreportedly had demanded that the government resign before negotiations could take place.Al-Wefaq’s 18 members of parliament resigned in February 2011 in protest against policebrutality.After the first week of March 2011, anti-government protesters began to organize peacefulmarches to key government buildings. Many were openly calling for an end to the monarchyin Bahrain, and for a republican system to be established instead. Thousands went on strike.With members of the Sunni community going on large pro-government rallies, sectarianrelations in the country became extremely tense, and violence ensued. On 12 March 2011,thousands of anti-government protesters marched to the Royal Court in al-Riffa’a. The marchturned violent amid reports that government supporters armed with knives and sticks wereplanning to prevent the demonstrators from approaching the Royal Court. A day later, the twosides violently clashed at Bahrain University.13 March 2011 brought a further escalation in violence when anti-government protesterssealed off the main roads in Manama and occupied the capital’s Financial Harbour area,causing considerable disruption. The anti-government protests were by and large peaceful,but there were a few violent incidents. Some anti-government protesters attacked Asianmigrant workers, killing two and injuring others.

Bahrain demonstration, 22 February 2011 � Amnesty International

On 15 March 2011, Saudi Arabia sent at least 1,200 troops to Bahrain across the causewaylinking the two states, reportedly at the request of the Bahraini government. The same day,the King of Bahrain declared a three-month state of emergency, known as the State ofNational Safety, and gave the security forces sweeping powers to arrest and detain protesters

Index: MDE 11/014/2012

Amnesty International April 2012

8

Flawed reformsBahrain fails to achieve justice for protesters

and ban all protests. On 16 March 2011, security forces, backed by helicopters and armytanks, stormed the Pearl Roundabout area and evicted the protesters by force. At least twoprotesters and two police officers were reported killed and dozens of people were injured.Protesters were also forced out of the nearby Financial Harbour area. The Pearl Monument,which had become a symbol for the pro-reform protesters, was torn down.Manama’s main hospital, the Salmaniya Medical Complex, also became a target. The securityforces stormed it and took control of the hospital. Many wounded protesters weresubsequently too afraid to go there for treatment. Some of those who did were detained.In the weeks that followed, hundreds of activists, including opposition leaders, medicalworkers, teachers, journalists and students were rounded up and detained. Most werearrested at dawn, without arrest warrants, and held incommunicado in police stations or atthe Criminal Investigations Directorate (CID) in Manama. Many said that they were tortured orotherwise ill-treated during interrogation. At least five people died in custody as a result oftorture. Detainees were forced to sign “confessions”, which were then used against them incourt. Hundreds of people were later tried by the National Safety Court, a military courtestablished under the state of emergency, and sentenced to prison terms, including lifeimprisonment, after grossly unfair trials.At least 35 people died during the February-March protests, including five security officers.More than 4,000 people, among them teachers, students and nurses, were dismissed fromtheir jobs or university positions for taking part in the anti-government protests.About 38 Shi’a mosques were demolished in the aftermath of the February-March events.The government has argued that these mosques had been built illegally, but the timing of thedemolitions led many in the Shi’a community to believe that this mass demolition wascollective punishment for the unrest.

PIECEMEAL REFORMSKeen to pacify the international community about the government’s crackdown, particularlyover allegations of torture and deaths in custody, the King lifted the state of emergency on 1June 2011. On 29 June 2011, the King decreed that the National Safety Court, which hadalso attracted international criticism, would no longer deal with cases linked to the February-March protests. However, the National Safety Court continued to function for feloniesconsidered to be the most serious crimes until early October 2011, when all cases werefinally transferred to civilian courts. The National Safety Court closed down after convictinghundreds of people following unfair proceedings.The King’s most noteworthy response to international pressure was setting up the BahrainIndependent Commission of Inquiry (BICI). In an unprecedented step, the authoritiesappointed five renowned international legal and human rights experts2to investigate humanrights violations committed in connection with the protests. On 23 November 2011, to muchmedia fanfare, BICI Chairman Professor Mahmoud Cherif Bassiouni, submitted theCommission’s report to the King. According to the report, the BICI had examined more than8,000 complaints; interviewed more than 5,000 people, including detainees; and visitedvarious prisons, detention centres and the Salmaniya Medical Complex in Manama.

Amnesty International April 2012

Index: MDE 11/014/2012

Flawed reformsBahrain fails to achieve justice for protesters

9

The report concluded that dozens of detainees had been tortured by security officials,including by members of the National Security Agency (NSA), who believed they could actwith impunity; that police and other security forces had repeatedly used excessive forceagainst protesters, resulting in unlawful killings; and that proceedings before the NationalSafety Court did not meet international standards for fair trial. The BICI made variousimportant recommendations, including the establishment of an independent human rightsbody to investigate all torture allegations, deaths in custody as a result of torture, killings ofprotesters and bystanders during the protests and other human rights violations. It alsorecommended that all those responsible be brought to account, including high-rankingmembers of the government, security forces and the army who gave orders to commit suchhuman rights violations. Other recommendations included rebuilding demolished Shi’amosques; establishing a national reconciliation programme to address the grievances ofgroups which felt marginalized or discriminated against; ending discrimination against Shi’ain the security forces and preventing incitement to hatred by the government-controlledmedia. The King accepted the findings of the report, and publicly expressed thegovernment’s commitment to implement all its recommendations.The Bahraini government has so far failed to ensure accountability that guarantees truth,justice and adequate reparation for the victims of arbitrary arrests, torture and unfair trials,as well as for those injured during protests, or the relatives of those killed. In response to theBICI recommendations, the government set up a new investigative unit within the PublicProsecutor’s Office (PPO). Lacking independence and impartiality, the new unit is unlikely todeliver real accountability. Only 11 low-ranking police and security officers, including fivePakistanis and a Yemeni national, are currently being tried for their part in specific humanrights violations committed during and after the February and March 2011 protests. On 21March 2012, a day after the King received the report by the BICI, the Public Prosecutor wasquoted in the Bahrain News Agency as saying that 50 policemen were being or were about tobe tried in connection with torture and other abuses.Hundreds of protesters are still in prison after being detained, tried unfairly by militarycourts, and receiving harsh prison sentences. Dozens have been imprisoned for life. Many ofthem are prisoners of conscience, punished solely for leading or participating in anti-government demonstrations, and did not use or advocate violence. They include 14 leadingopposition figures and a prominent trade unionist. Among them is prominent human rightsdefender ‘Abdulhadi Al-Khawaja, who is said to be nearing death as he continues his hungerstrike in protest at his imprisonment.The government’s promise to reinstate all those who were dismissed from work or universityfor participating in protests is yet to be fulfilled. At the time of writing, more than 200 peoplestill have not been allowed to return to their jobs. Many of those who have returned havecomplained of various administrative sanctions, such as a change of position or loss ofincrements. Only five out of the at least 38 Shi’a mosques that were demolished by thegovernment last year are being reconstructed.The government has not taken any steps to tackle discrimination or incitement to hatred, orwork towards real reconciliation between the ruling family and the Shi’a population.

Index: MDE 11/014/2012

Amnesty International April 2012

10

Flawed reformsBahrain fails to achieve justice for protesters

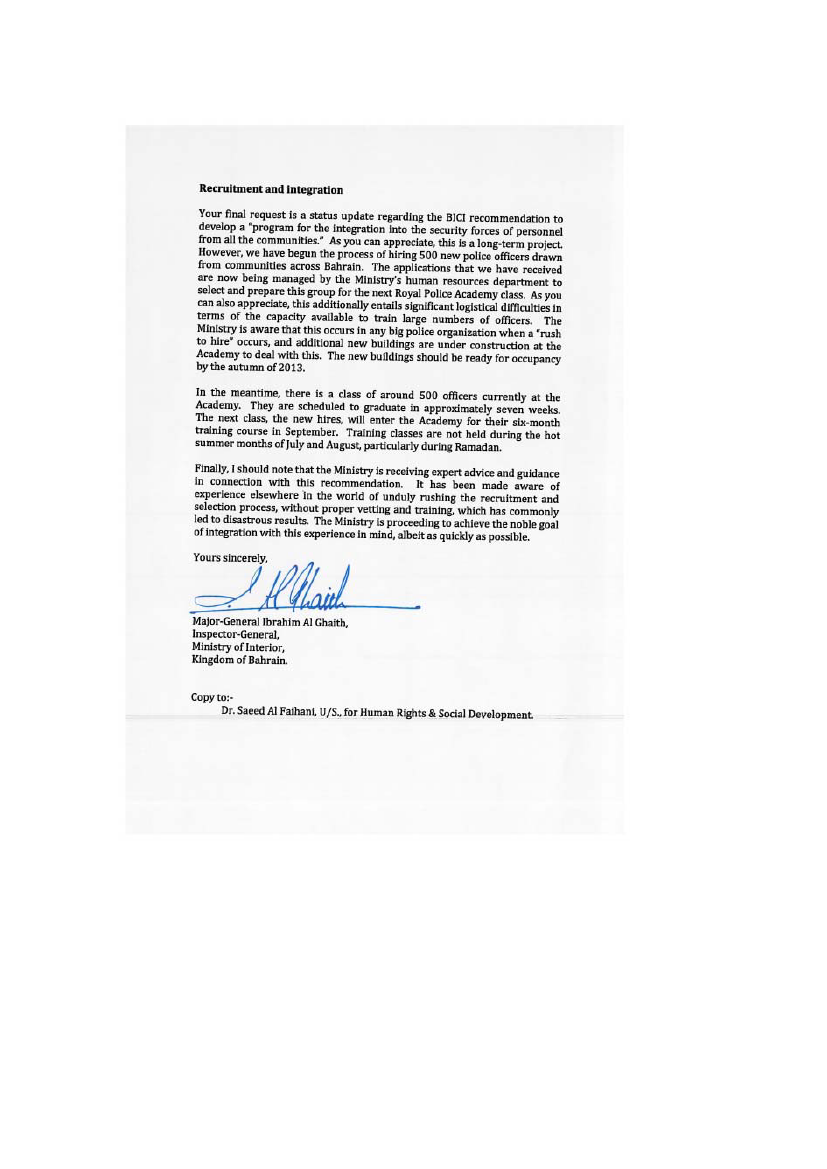

There have been some positive institutional and other reforms within the Bahraini police. Thegovernment has introduced a new code of conduct, established a new office in the Ministry ofInterior, dedicated to investigating complaints against the police, and embarked on humanrights training for police officers.In practice, however, the security forces remain unaffected by these institutional changes.They continue to respond to protesters with unnecessary and excessive force, particularly thereckless use of tear gas which has resulted in several deaths in recent months. AmnestyInternational is still receiving reports of torture and other ill-treatment. With calls for reformsand social justice continuing, the numbers of deaths had reached at least 60 by April 2012.The government has taken some potentially positive steps in reviewing, or proposing to reviewcertain provisions in the Criminal Procedure Code and the Penal Code. Such steps are longoverdue as many provisions in Bahrain’s domestic legislation, including the Penal Code, donot comply with a number of international human rights treaties to which it is state party.These include, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR); theInternational Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD),the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC); and the UN Convention against Tortureand Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT).3The Bahrainigovernment is required to honour its obligations under these and other human rights treatiesit is a party to. Under these treaties, Bahrain is also required to investigate all allegedviolations of international human rights and humanitarian law and prosecute thoseresponsible. In ratifying these treaties, the Bahrain government promised both the people ofBahrain and the wider international community that it would uphold and respect theirprovisions. Bahrain’s international human rights commitments will be put under the spotlightin Geneva in May and June 2012 when the country’s rights record is assessed under theUniversal Periodic Review of the UN Human Rights Council.

LACK OF POLITICAL WILLThe government has recruited a number of foreign experts in international human rights law,policing and the media, with the ostensible aim of helping it understand and implement theBICI recommendations. Advisors have been hired by several ministries, including the Ministryof Interior and the Ministry of Human Rights and Social Development, as well as the PPO andthe Information Affairs Authority. The government has also hired a number of public relationsexperts to help it re-build its image internationally ahead of this year’s Grand Prix.Such steps will only lead to results if they are matched by the genuine will to reform and realcommitment toward human rights. However, so far the signs have not been encouraging.Despite welcoming international media and human rights groups to witness the King receivethe BICI report in November 2011, in January 2012, the government began to restrict theaccess of foreign journalists and human rights delegations. On 29 February 2012, a day afterthe Minister of Human Rights and Social Development solemnly announced to the UNHuman Rights Council that the UN Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhumanor degrading treatment or punishment would be visiting Bahrain from 8-17 March 2012, hisvisit was postponed, at the government’s request, until July 2012. Also in February 2012,Amnesty International was left with no choice but to cancel a visit to Bahrain because of newrestrictions to the way human rights groups are able to work in the country, only

Amnesty International April 2012

Index: MDE 11/014/2012

Flawed reformsBahrain fails to achieve justice for protesters

11

communicated at the last minute before a scheduled visit by the organization.The establishment of the BICI was a real breakthrough and raised expectations that thingswould be different in Bahrain. Yet, nearly five months later, real change has not materialized.People are still waiting for the significant changes that would demonstrate the political will toreform. The piecemeal nature of the reforms, and the persistence of some of the sameviolations documented in the BICI report, have cast a shadow over the whole process, andraised doubts over the authorities’ political will to reform.This Amnesty International report shows the discrepancy between the Bahraini government’spublic pronouncements and its failure to make real steps toward accountability for humanrights violations. In doing so, the report evaluates the government’s implementation of theBICI recommendations and for ease of reference follows the structure of the BICI report. Thereport highlights patterns of human rights violations committed by Bahraini security forcesand provides testimonies of victims of human rights violations who are still awaiting justice.In its conclusion, Amnesty International calls on the Bahraini government to show realpolitical will for reform in the country and makes a series of recommendations to the Bahrainigovernment, key of which are:

Immediately and unconditionally release all prisoners of conscience who were tried andsentenced by the National Safety Court, or ordinary criminal courts, solely for peacefullyexercising their rights to freedom of expression and assembly, including the 14 prominentleaders of the opposition;

Set up prompt, thorough, impartial independent investigations (by an independent bodyoutside the PPO) into all allegations of torture, deaths in custody and unlawful killings,including those resulting from unnecessary and excessive use of force, committed since thebeginning of the February 2011 protests;

Ensure that all those suspected of torture and unlawful killing, including those withcommand responsibility, or those who condoned or committed torture, unlawful killings andother human rights violations, regardless of their position or status in the government andranking in the security and military forces, are held accountable, including in a trialconsistent with international fair trial guarantees and without recourse to the death penalty.

ABOUT THIS REPORTThis report is based on individual testimonies, including of victims of human rightsviolations, lawyers and human rights defenders, gathered by Amnesty International during afact-finding visit to Bahrain in November 2011. Unfortunately, its scheduled visit to Bahrainin March 2012 was cancelled following a communication by the Ministry of Human Rightsand Social Development of new restrictions imposed on international NGOs wishing to visitBahrain. Considering the late communication of such restrictions, Amnesty International feltunable to go ahead with its planned visit.The report also relies on official documents published by the government. AmnestyInternational has been unable to raise some of the concerns articulated in this report directlywith the authorities given its cancelled visit. However, the organization has continued to raise

Index: MDE 11/014/2012

Amnesty International April 2012

12

Flawed reformsBahrain fails to achieve justice for protesters

directly its concerns with the Bahraini authorities since the beginning of the human rightscrisis in the country. For the purpose of this report Amnesty International has addressed anumber of questions to the Ministry of Interior as well as to the Public Prosecutor. Answersprovided by the government of Bahrain are reflected in this report. Amnesty International isgrateful to all those individuals who met with or provided information to its delegates.Amnesty International also appreciates the time and assistance provided by Bahraini humanrights activists and civil society organizations.

Amnesty International April 2012

Index: MDE 11/014/2012

Flawed reformsBahrain fails to achieve justice for protesters

13

2. MECHANISM FOR IMPLEMENTINGRECOMMENDATIONSSignificantly, the first recommendation of the BICI report (No.1715)4calls for an impartialbody to drive and oversee the implementation process of its recommendations. A few daysafter 23 November 2011, when the BICI submitted its report, the King established theNational Commission to Follow Up on the Implementation of the Recommendations of BICI(the National Commission) and appointed its members (Royal Orders No.45 and No.48,issued on 26 and 28 November 2011 respectively). The Commission was made up of 19people, including the current Minister of Justice Shaikh Khaled bin ‘Ali Al Khalifa, who is amember of the royal family, and chaired by ‘Ali Bin Saleh al-Saleh, President of the ShuraCouncil, the upper house of Bahrain’s bicameral national assembly (parliament), whose 40members are appointed by the King, and a key Shi’a pro-government politician. The NationalCommission was to study the BICI recommendations and make suggestions on theirimplementation, as well as on amendments to Bahraini legislation. It was given until the endof February 2012 to complete its work in a “transparent way” and then to publish itsconclusions.5The Commission set up three working groups: the first to focus on legislativereform, the second to focus on human rights issues and the third to deal with nationalreconciliation issues.The lack of transparency in setting up the National Commission angered many in Bahrain,including main-stream opposition political organizations such as the al-Wefaq Society, aswell as human rights activists. Reportedly, the government confidentially contactedindividuals to invite them to join the National Commission. When two al-Wefaq formermembers of parliament were contacted in this way, the Society objected. Al-Wefaq thenrefused to join the National Commission, arguing that the way it was set up went against thecontent and spirit of BICI recommendation No.1715. Fifteen members of the NationalCommission are believed to be pro-government and, in addition to the Minister of Justice,they include actual and former members of parliament, businessmen, lawyers andacademics.The National Commission held weekly meetings to discuss its progress and regularlyrequested information from various ministries on their implementation of relevantrecommendations. On 31 December 2011 Chair ‘Ali Bin Saleh al-Saleh submitted a letter ofresignation to the King in response to attacks in the media. The letter was published innewspapers in Bahrain.Some pro-government figures had attacked ‘Ali Bin Saleh al-Saleh, in the media and duringmosque sermons, for helping four members of the Shura Council back into the Council afterthey were dismissed because of their participation in anti-government protests in Februaryand March 2011.6However, ‘Ali Bin Saleh al-Saleh’s resignation was not accepted and hecontinued in his position. On 2 March 2012, the King extended the mandate of the NationalCommission until 20 March 2012 (Royal Order 9 for 2012).7The National Commissionsubmitted its report to the King in a ceremony hosted by the King and the Crown Prince andattended by foreign diplomats and the media.

Index: MDE 11/014/2012

Amnesty International April 2012

14

Flawed reformsBahrain fails to achieve justice for protesters

The King invited BICI Chairman Professor Mahmoud Cherif Bassiouni to Bahrain in earlyFebruary 2012 to prepare a report on how the BICI recommendations had been implementedby the government. Professor Mahmoud Cherif Bassiouni was due to submit his report at theend of March 2012, but as of 10 April 2012 it was not known if he had submitted it or not.The National Commission’s report, submitted on 20 March 2012, includes correspondencebetween the Head of the Commission and the various government ministries on theimplementation of BICI recommendations relevant to their ministries. The report alsoincludes advice and recommendations made by the international human rights experts.Judging from the report it submitted on 20 March 2012 and from the decree setting it up itappears that the National Commission did not have much power to drive the implementationprocess. The working methods of the Commission were unknown and its remit did not includereceiving individual complaints of human rights violations, or the power to compel officials tofollow-up on cases highlighted in the BICI report. Amnesty International regrets that no clearcriteria of expertise, independence and impartiality in the selection of members of theCommission were set out from the outset, which opened the door to the actual or perceivedpoliticization of the National Commission. Its mandate and its powers, including the power tosummon officials to obtain information and documents, or to compel them to testify, werenot spelled out in the decree establishing the National Commission, limiting its effectivenessfrom the outset.

Amnesty International April 2012

Index: MDE 11/014/2012

Flawed reformsBahrain fails to achieve justice for protesters

15

3. ACCOUNTABILITY FOR VIOLATIONSDURING PROTESTS“They started punching me on the back of myhead. I lost consciousness.”A former detainee who was tortured in police custody, interview by Amnesty International on 4 December 2011

Scores of protestors were tortured by Bahraini security forces, including members of the NSA.Methods of torture included beatings, punching, the use of electric shocks on different partsof the body and threats of rape. Detainees were also verbally abused. At least five detaineesdied in custody as a result of torture.In response to the National Commission’s request on the government’s implementation ofRecommendation17168regarding accountability for“deaths,torture and mistreatment ofcivilians”, the Bahraini government stated:“To implement this recommendation, prominent international legal experts were appointed,namely Sir Jeffrey Jowell and Sir Daniel Bethlehem to head the team charged withformulating a method to assess how an independent mechanism can be created, and tocommence taking action to ensure independence and neutrality as stated in therecommendation. This team will also help clarify and determine relevant legal criteria toevaluate accountability issues, including special directions on the implementation ofinternational standards on upper leadership accountability in Bahrain…”9.Although the Bahraini government ratified the Convention against Torture it did not translateinto domestic law the provisions of the Convention. In addition, no independent and impartialinvestigations have been conducted in allegations of torture, deaths in custody and deaths asa result of excessive use of force. A few other recommendations contained in the BICI reportalso deal with independent investigations, including171910and1722(a,b).11In early January 2012, the government announced that two British lawyers, Sir DanielBethlehem KCMG QC, former Legal Advisor to the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office,and Sir Jeffrey Jowell QC, Emeritus Professor of Public Law at University College of London,were appointed to assist the Bahraini government on issues relating to accountabilitymechanisms, including “establishing a national watchdog to bring to justice police officersresponsible for torture, death or mistreatment of civilians.”12Several other internationalexperts were hired by the government to help the authorities implement the BICIrecommendations.13

Index: MDE 11/014/2012

Amnesty International April 2012

16

Flawed reformsBahrain fails to achieve justice for protesters

The government’s implementation of BICI recommendation1716on setting up anindependent and impartial mechanism to determine accountability is inadequate and raises anumber of concerns. On 27 February 2012, one day before the end of the original deadlinefor the implementation of the recommendations, Public Prosecutor ‘Ali al-Bou’ainain issued adecree establishing a Special Investigative Unit (SIU) within the PPO to investigate crimes oftorture and other ill-treatment, killings and other violations, and to determine thegovernment’s accountability for these violations. According to Article 5 of the Decree, theSIU will first focus on all violations that took place during last year’s protests and that areincluded in the BICI report. The Public Prosecutor can refer any other case to the SIU forinvestigation. The unit is now headed by Nawaf ‘Abdallah Hamza, a senior public prosecutorwho will be supported by seven prosecutors, as well as criminal investigators and forensicexperts.14The Public Prosecutor directly supervises and manages the SIU. The governmentstated that US and German lawyers were expected in Bahrain to train prosecutors in effectiveinvestigations.15According to Article 3 of the decree, the SIU will use international standards, in particularthe Manual on Effective Investigation and Documentation of Torture and Other Cruel,Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, commonly known as the Istanbul Protocol,in its investigations. However, the new SIU as a body within the PPO does not meet the“minimum requirements of independence, impartiality and effectiveness” as recommendedby the international human rights experts hired by the government.16Indeed, the PPO in Bahrain is not an independent body, contrary to government claims. Infact, serious doubts about the independence and impartiality of the Bahraini judiciary havebeen cast, including by local human rights defenders. Courts often come under governmentpressure on sentencing, verdicts and appeals. Judges in Bahrain are appointed by RoyalOrder (Article 24 of the Law of Judicial Authority), based on the recommendation of theJudicial Supreme Council. Prosecutors are also appointed by Royal Order (Article 58).According to Article 69 of the Law of Judicial Authority, the King chairs the Supreme JudicialCouncil, which is made up of seven senior judges and the Public Prosecutor.17The King mayalso appoint a representative to head the Supreme Judicial Council.18This lack of independence has also been demonstrated by the fact that the PPO has oftenfailed to investigate allegations of torture and it has used “confessions” by detaineesextracted under torture or other ill-treatment to convict them. Such a track record casts ashadow on the ability of the SIU as part of the PPO to deal with the widespread allegations oftorture in Bahrain and does not augur well for victims of torture and other abuses.Trial proceedings against several policemen allegedly implicated in human rights violationsstarted before the establishment of the new unit in the PPO. On 8 December 2011, theMinister of Interior, Shaikh Rashid bin Abdullah Al Khalifa, issued an order to “refer all casesrelated to deaths, torture and inhuman treatment implicating the police to the PublicProsecutor’s Office to implement recommendation No. 1716 of the BICI report.”19On 25December 2011, the Public Prosecutor stated that his office had received cases andcomplaints relating to torture and other ill-treatment from the Ministry of Interior. He addedthat investigative teams, under his supervision, would start work within a week and that theywould summon victims and complainants to hear their testimonies.20A number of formerdetainees, some still on trial, were summoned to the PPO for questioning regarding their

Amnesty International April 2012

Index: MDE 11/014/2012

Flawed reformsBahrain fails to achieve justice for protesters

17

torture allegations. At the end of January 2012, several medical doctors who had beenreleased on bail and who were on trial were interviewed by the Public Prosecution inconnection with complaints they had made about their alleged torture.In a press conference on 22 January 2012, the Public Prosecutor stated that, as of that day,the PPO had received from the Ministry of Interior 113 cases of torture and deaths, whichinvolved 62 suspects from the security forces.21As of 10 April 2012, only a handful of low-ranking security and police officers have been put on trial.However Bahrain’s record in providing accountability for human rights violations does notinspire confidence. In fact, impunity has been rampant. No senior member of the securityforces, including the Public Security Forces (PSF), NSA, or the Bahrain Defence Force (BDF)have been held to account for their role, either in last year’s killings of protesters or fortorture of detainees. No members of the extended royal family have been held to account forhuman rights violations, despite continuing accusations made against at least two membersin senior positions in the security forces. Ten years ago, the King sanctioned impunity inBahrain: Decree No.56 of 2002 granted immunity from investigation or prosecution togovernment officials alleged to be responsible for torture or other serious human rightsabuses committed prior to 2001.22A number of senior security officials alleged to have beeninvolved in torture, especially in the 1990s when Bahrain had another human rights crisis,and who are known to Bahraini victims, have been given immunity. Also, a number ofsecurity officers, including in the NSA, accused by detainees and former detainees of beingresponsible for their torture and other ill-treatment during last year’s protests, are said to bestill in their positions and have reportedly not been investigated. The King removed the headof the NSA, Shaikh Khalifa bin ‘Abdallah Al Khalifa from his post, but only to promote him asSecretary General of the Supreme Defence Council and a security advisor to the King.Under Article 12 of the Convention against Torture, Bahrain is required to initiate “… aprompt and impartial investigation, wherever there is reasonable ground to believe that an actof torture has been committed….”. Article 13 states that “Each State Party shall ensure thatany individual who alleges he has been subjected to torture in any territory under itsjurisdiction has the right to complain to and to have his case promptly and impartiallyexamined by its competent authorities. Steps shall be taken to ensure that the complainantand witnesses are protected against all ill-treatment or intimidation as a consequence of hiscomplaint or any evidence given.”

DEATHS IN CUSTODY AND KILLING OF CIVILIANSTTSix cases of deaths, three in custody as result of torture and three during protests, wererecently referred to the ordinary criminal courts. On 11 January 2012, the High CriminalCourt held its first trial session in the case of two people who died in custody as a result oftorture last year.Zakaraya Rasheed Hassan al-‘Asheri,aged 40, married with two children,died on 9 April 2011 in the Dry Dock Prison. He was arrested for his leading role in theprotests from his home in al-Dair on 2 April. The Ministry of Interior attributed ZakarayaRasheed Hassan al-‘Asheri’s death to ill-health but at his burial the body reportedly hadmarks that indicated torture. According to the BICI report a “forensic report confirmed thecause of death and concluded that the deceased had large bruises on his back and thighsand smaller bruises on his face and hands.”23

Index: MDE 11/014/2012

Amnesty International April 2012

18

Flawed reformsBahrain fails to achieve justice for protesters

‘Ali ‘Issa Ibrahim al-Saqer,aged 31, also died in custody on 9 April 2011. He was arrestedsix days earlier in Hamad Town, after he was summoned to a police station duringinvestigations into the killing of a police officer during the March 2011 protests. The Ministryof Interior said ‘Ali ‘Issa Ibrahim al-Saqer had died while being restrained by police. His bodywas returned to his family for burial and had visible marks of severe bruises on different partsof his body, suggesting that he had been tortured. A forensic report seen by the BICI“confirmed the cause of death and concluded that the deceased had dark red bruises acrossthe body but mostly around the back of the hands and right eye. His wrists had red flakingmarks because of handcuffing and these marks were of recent origin.”24Five policemen, allPakistanis, have been charged in connection with the deaths of the two detainees. Two of thefive have been charged with “assaulting the detainees and beating them with a plastic hose,which unintentionally led to their deaths”. The other three were charged with “failure toreport the crimes”.The five policemen had initially been acquitted by a military court. A Military Court of Appealrejected the verdict and sent the case to a civilian court. The defence lawyers, 15 of themreportedly appointed and paid by the government, called for the case to be dismissed on thebasis that the acquittal by the military court was not cancelled by the Military Court ofAppeal. According to lawyers acting on behalf of the families of the deceased, investigationscarried out by the Military Prosecution did not address who gave the orders for the allegedtorture. The court did not summon the investigators in the case, although their names werementioned in the investigation report. On 26 March 2012 the High Criminal Court decided torefer the case back to the Public Prosecution because the latter had reportedly notinvestigated the crimes as stipulated for in Article 81 of Bahrain’s Criminal Procedure Codewhich requires the Public Prosecution to investigate all felony cases (cases of serious crime).‘Ali Ahmed ‘Abdullah ‘Ali al-Momen,aged 23, died in hospital of multiple gunshot wounds.He was one of five protesters shot at the Pearl Roundabout on 17 February 2011.That sameday,‘Issa ‘Abdulhassan,aged 60, died instantaneously from a massive head wound causedby a shot fired at close range. An eyewitness told Amnesty International that ‘Issa‘Abdulhassan walked over to the police as they were storming the Pearl Roundabout andasked why they were shooting. The witness recalled a policeman putting a gun to ‘Issa‘Abdulhassan’s head and shooting him. Two policemen, one Yemeni and another Bahraini,are being tried in connection with the two deaths. The Yemeni policeman is charged withshooting ‘Isa ‘Abdulhassan in the head with a shotgun which “unintentionally” led to hisdeath. The second defendant is charged with shooting ‘Ali Ahmed ‘Abdullah ‘Ali Al-Momen inthe leg with a shotgun which led to his “accidental” death. Both defendants have denied thecharges against them in court. However, during the investigations by the Military Prosecution,they reportedly confessed that they had shot the victims. The defence witnesses in the caseare all policemen. Lawyers acting on behalf of the families of the deceased told the court thatthere are witnesses for the victims, who should be heard. The representative of the PublicProsecution told the court that the role of lawyers acting on behalf of the families should beconfined to seeking compensation only. The lawyers for the families of the victims wanted tocall witnesses and on 28 March 2012 the court heard testimonies of four witnesses,including the father of ‘Ali Ahmed ‘Abdullah Ali Al-Momen, before it adjourned the trial to 17April 2012.

Amnesty International April 2012

Index: MDE 11/014/2012

Flawed reformsBahrain fails to achieve justice for protesters

19

Hany ‘Abdelaziz ‘Abdullah Jumaa,aged 32, was shot three times with a shotgun in thevillage of Bilad al-Qadeem on 19 March 2011. His family did not receive his body until 25March 2011. A Bahraini policeman has been charged with shooting at Hany ‘AbdelAzizAbdullah Jumaa three times, “unintentionally” leading to his death. Lawyers representing thefamily of the deceased asked the court for maximum sentence and for the charges to bechanged to premeditated murder. The defendant has denied the charge. The case is stillongoing at the time of writing.All eight policemen being tried in the cases above are reportedly still working in the Ministryof Interior and their trials are ongoing as of 10 April 2012. Their lawyers have called for thedismissal of the cases and their acquittal. The policemen should be suspended until thecompletion of the trial and other disciplinary proceedings that may take place.On 5 March 2012, the High Criminal Court held its first session in the case of the death of‘Abdelkarim al-Fakhrawi.Two security officers working in the NSA are charged with assault,resulting in his “accidental” death. The two men have denied the charge. ‘Abdelkarim al-Fakhrawi, a 49 year-old businessman, member of al-Wefaq and one of the founders ofal-Wasatnewspaper, was arrested on 3 April 2011. According to the death certificate he waspronounced dead at 1:10pm on 11 April and died of injuries sustained while in the custodyof the NSA.25The BICI report stated that ‘Abdelkarim al-Fakhrawi’s death was attributed to“torture while in the custody of the NSA”.26At the time, the authorities attributed his deathto kidney and heart failure. No family members were present at the court hearing on 5 March2012 – they apparently had not been informed that the hearing was taking place.The High Criminal Court did not order a new investigation into the case of ‘Abdelkarim al-Fakhrawi’s death, and has relied on the investigation carried out by the Military Prosecution.During the second court session on 19 March 2012, one of the lawyers acting on behalf of‘Abdelkarim al-Fakhrawi’s family asked the court to open a new investigation. He asked for ajudge to be sent to interview all security officers who were at the prison and who interrogated‘Abdelkarim al-Fakhrawi to determine their role in his death, including those in seniorpositions who gave the orders. The lawyer also urged the court to use appropriate provisionscontained in the Penal Code, including Article 208 relating to the use of torture byofficials27, rather than provisions selected by the Military Prosecution, which are deemed tobe lenient. The trial was adjourned until 9 April 2012 and on that day the court adjournedthe trial again until 13 May 2012.

TORTURED IN CUSTODYBahrain’s 1976 Penal Code criminalizes the use of torture through Article 208, which statesthat “a prison sentence shall be the penalty for every civil servant or officer entrusted with apublic service who uses torture, force or threat, either personally or through a third party,against an accused person, witness or expert to force him to admit having committed a crimeor give statements or information in respect thereof.” Article 232 of the Code stipulates that“a prison sentence shall be the penalty for any person who uses or threatens to use torture orforce, either personally or through a third party, against an accused person, witness or expertto make him admit the commission of a crime or give statements or information in respectthereof. The punishment shall be imprisonment for at least six months if the torture or use offorce results in harming the integrity of the body.”

Index: MDE 11/014/2012

Amnesty International April 2012

20

Flawed reformsBahrain fails to achieve justice for protesters

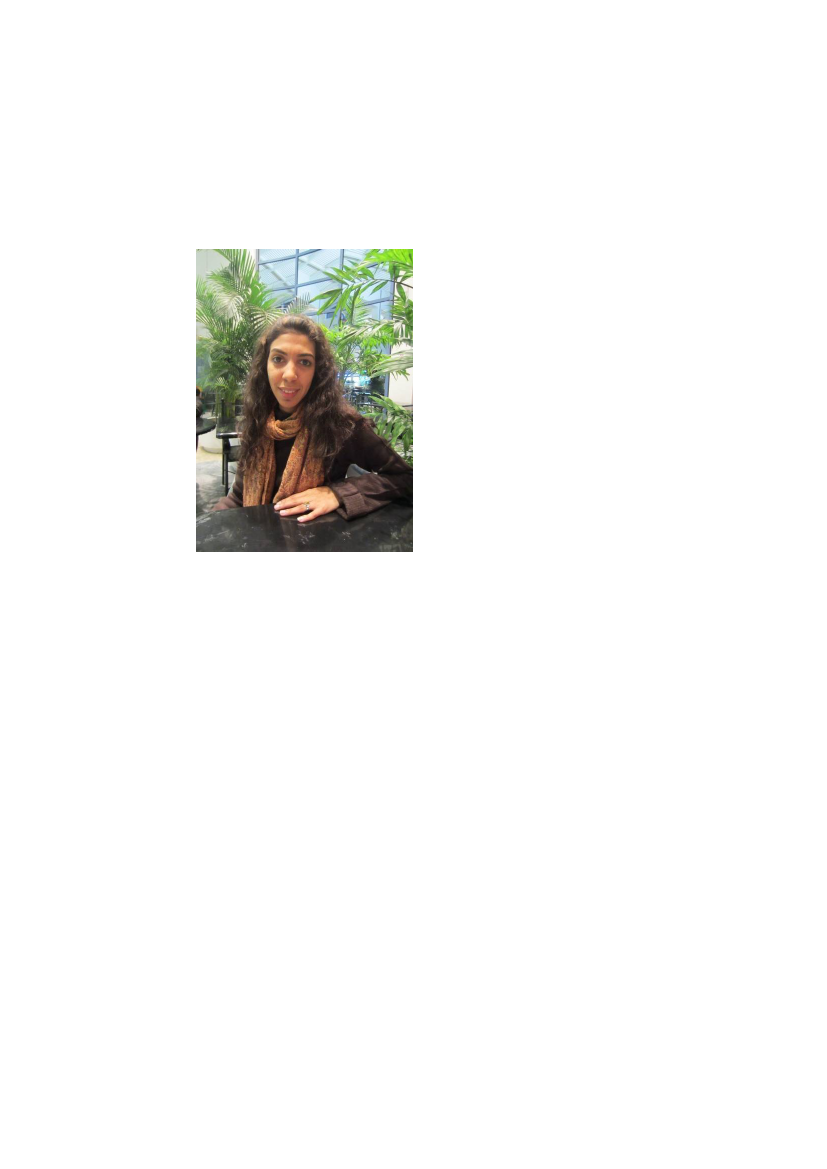

In spite of this prohibition and Bahrain being a party to the CAT, torture and other ill-treatment have been routinely used in Bahrain’s response to the protests which started in2011.On 4 March 2012, a lower criminal court referred the torture allegation made by journalistNazeeha al-Saeedagainst a policewoman to the PPO, because it involved a felony and notmisdemeanour, and so did not fall under the jurisdiction of a lower criminal court.The Public Prosecutor is expected to refer Nazeehaal-Saeed’s case to the High Criminal Court. Thepolicewoman, who works in a police station inWestern al-Riffa’a in central Bahrain, and who isalleged to have been involved in Nazeeha al-Saeed’s torture, has been tried by a military courtand found guilty of neglect. She was fined BD400(just over US$1,000) for physical assault andinsults against the victim.Nazeeha al-Saeed, aged 30, had worked as acorrespondent for French television news channelFrance 24 since June 2009 and for Monte-Carlo TVsince 2004. According to the information receivedby Amnesty International, on the evening of 22 May2011, she received a phone call from al-Riffa’apolice station asking her to go there. She was firstquestioned by a policeman who told her that shewas accused of being a member of a group thatNazeeha al-Saeed � Amnesty Internationalwanted to overthrow the monarchy and that shehad spoken to some of the leaders of theopposition. She denied the accusation. Nazeeha al-Saeed was then taken to another room,where a group of policemen and policewomen reportedly started beating her with a hose-pipe,punching and kicking her. She was then taken to another room, blindfolded and pulled byher hair into other rooms. She was then reportedly beaten by one policewoman on her backand feet. The policewoman used electric shocks on Nazeeha al-Saeed, who suffered burns onher right arm as a result. The policewoman also made her pretend to be a monkey and forcedher to drink an unidentified liquid while she was blindfolded. The police woman pushedNazeeha al-Saeed’s head down a toilet and said, “This water is cleaner than you, you Shi’a”.She also accused Nazeeha al-Saeed of fabricating her television reports.Nazeeha al-Saeed was then questioned again. She was asked who the sources of her mediareports on deaths of protestors were. When she replied she had received the information fromdoctors, her investigators told her that these doctors were lying and that she had fabricatedthe information. When her blindfold was finally removed, Nazeeha al-Saeed could see therewere nurses detained in the room with her. Ten hours after she arrived at the police station,Nazeeha al-Saeed was taken to the officer in charge, who asked her to sign some papers. Butshe was too afraid to ask to read them before signing. The officer told her, “whateverhappens in this police station is my reputation and you don’t want to ruin it.”

Amnesty International April 2012

Index: MDE 11/014/2012

Flawed reformsBahrain fails to achieve justice for protesters

21

Scores of people were subjected to similar torture or other ill-treatment by the Bahrainisecurity forces, especially at the height of the repression from mid-March 2011 to the end ofJune 2011. The victims are still waiting for those responsible to be held accountable.Aayat Alqormozi,a student in ateaching faculty, read out poemscritical of the Prime Ministerand the King during theFebruary and March 2011protests. She presented herselfto the authorities on 30 March2011 after masked members ofthe security forces twice raidedher parents' house andthreatened to kill her brothers ifshe did not surrender. AayatAlqormozi was arrested and heldincommunicado for the first 15days (in the CID and then in aAayat Alqormozi � Amnesty Internationallpolice station in al-Wustaprovince in central Bahrain). From the date of her arrest and Tuntil she was brought to courtfor the first time on 2 June 2011, she only had communication with her family via phonecalls and her family did not know her place of detention.She said that during that time she was punched and kicked, given electric shocks to theface, forced to stand for hours, verbally abused and threatened with rape. She could onlyaccess her two lawyers in court, not before court sessions. She appeared in court again on 6June 2011 and then following the third session held on 12 June 2011, the National SafetyCourt sentenced her to one year in prison after convicting her of participating in “illegalprotests”, “disrupting public security” and “inciting hatred towards the regime”. She wasconditionally released on 13 July 2011 after pledging not to participate in protests orcriticize the government. While in prison, she was coerced to let herself be filmed apologizingfor her actions. The footage was broadcast on Bahrain State television. Her case was referredto the High Criminal Court of Appeal, which on 21 November 2011 ruled that the case besuspended but did not clarify her legal status. It took many months before Aayat Alqormoziwas finally admitted back to Bahrain University after she was expelled. She returned touniversity in March but left days later following harassment and abuse by pro-governmentstudents. No independent investigation into her torture allegations is known to have beenconducted. In July 2011 the Ministry of Interior summoned her and interviewed her in thepresence of her lawyer in connection with her allegations. As of 10 April 2012 no securityofficial has been tried in connection with her torture allegations.

Index: MDE 11/014/2012

Amnesty International April 2012

22

Flawed reformsBahrain fails to achieve justice for protesters

Mohammed al-Tajer,a prominenthuman rights lawyer who hasdefended many cases of oppositionand human rights activists, wasarrested at his house in Manama onthe night of 15 April 2011 and latertortured. According to his wife, over20 security officers entered theirhouse in the middle of the night.Some were in uniforms, others werein plain clothes. All except one werewearing masks. They searched all thebedrooms and confiscated personalitems such as mobile phones,laptops and papers. Following theMohammed al-Tajer � Amnesty Internationalraid, Mohammed al-Tajer wasarrested without any explanation. Noarrest order was shown to him or his family. He called his family for two minutes on 17 April2011 to let them know he was in the CID and wanted them to bring him clothes. He toldthem that he did not know what the charges against him were. On 12 June 2011, he wasbrought before the National Safety Court of First Instance and formally charged with offencesthat included “spreading rumours and malicious news” and “incitement of hatred against theregime”. He pleaded not guilty. He was released on 7 August 2011. His trial was thenreferred to a civilian court. He appeared before a lower criminal court and his trial wasadjourned. On 9 April 2012 the trial resumed. His six defence lawyers requested from thecourt to add a torture complaint made by the defendant against the PPO to his case file. Thetrial was adjourned to 8 May 2012. He told Amnesty International that he was tortured whenhe was in detention: “On the first day I was forced to stand opposite a wall, they put a bag onmy head and I had to raise my arms up in the air. They started punching me on the back ofmy head. I lost consciousness. That first torture lasted for about half an hour. I was torturedtwice more, each time for about 20 minutes. They told me they arrested me because I wasdefending traitors.”Mohammad Hassan Jawwad,one of the 14 opposition leaders (see section on unfair trials)was tried and sentenced by a military court. He is in Jaw Prison serving a 15-year-prisonsentence. He is reportedly suffering from ill-health and on 3 or 4 April 2012 he was taken tothe Military Hospital. He had described his torture after his trial before a military court, indiaries smuggled out of prison, as follows:“…I am an old man, I am 65 years old and I felt the terrible pains in my pelvis, back,head and bones. They dragged me like an animal again into the Na’aim police station andthey ordered me to stand near a wall and it took a bit more than two hours without saying aword to defend myself.“…later I was surprised to hear that the National Security [Agency] ordered to take me toAl Qalaah, the main office of the Ministry of Interior in Manama. They took me there totorture me! When I got [there] … I was subjected to many insults and vile words …. Therewas a big number of men thrown sleeping in the hallways waiting for their turn to be tortured

Amnesty International April 2012

Index: MDE 11/014/2012

Flawed reformsBahrain fails to achieve justice for protesters

23

including Shaikh MohammedHabib Al Meqdad and ShaikhMerza Al Mahroos who I personallyknow and are accused with me inthe same case. I sometimes heardscreams of pains of some orwitness the torture of others. Theirscreams are so bad that they go outof breath and you don’t knowwhether they’re alive or dead. Theirvoice goes away and you see theirblood spilling and they disappear…Sometimes they hang me,sometimes they hit me, other timesthey chain me to the groundMohammad Hassan Jawwad � Privatebecause I occasionally tried todefend myself out of frustration. In one of the hallways they tried to sexually rape me with apiece of wood, trying to get it into my genitals, out of self defence I pulled one of them andtrapped him inside my handcuffed hands, he got stuck inside, I hit him with my knee. Aspunishment 20 other security men came in and hit me so terribly, they wondered why I woulddefend myself. Later in prosecution I was accused of resisting security men, for God’s sakewhy wouldn’t I defend myself against those trying to abuse my body and my dignity?“…So I entered the torture room, they asked me to stand with groups of three or four peopleall masked holding a hose and some other torture tools including an electrocuting machine.They made me hear its sound on purpose so they’d scare me, I was wondering whether they’lluse it or not. But after they tied my hands and my legs with a steel cuff I knew they wantedto. They started torturing me from the bottom of my feet and the pain was terrible, it was sobad that I felt my soul was being sucked into a different world…”28

Index: MDE 11/014/2012

Amnesty International April 2012

24

Flawed reformsBahrain fails to achieve justice for protesters

4. UNFAIR TRIALS OF POLITICALACTIVISTS“We wrote to the court three times requesting itto bring witnesses to the court so that we cross-examine them, but the court refused… I askedthe court to write down what I said about thetorture of my client, but the president of the courtdid not”A defence lawyer talking to Amnesty International about trials before the National Safety Court, 4 December 2011

Hundreds of protesters, including leading opposition activists who led the protests inFebruary and March 2011, were tried by the National Safety Court. Trial proceedings beforethis court did not meet international standards for fair trial. The court, headed by a militaryjudge and with two other civilian judges, was located in the headquarters of the BahrainDefence Force. Prominent opposition activists, health workers, teachers, students and humanrights activists appeared before this court on a wide range of charges, including“participation in illegal demonstrations”, “attempting to overthrow the regime by force”,“inciting hatred against the regime”, “propagating false information” and “occupying publicplaces by force”. Many of the charges are broad, vaguely worded, and criminalize the exerciseof the right to freedom of expression and peaceful assembly.Most detainees were denied access to their lawyers before the start of their trial. Many toldthe court that they had been tortured and that “confessions” obtained under torture wereused to incriminate them. However, the court did not investigate their allegations of torture ordismiss their “confessions” marred by torture allegations. Nor did they refer defendants forindependent medical examination. Some of the defendants were released on bail to awaitappeals after being sentenced. Lawyers complained that they were told in court that some ofthe information used by the prosecution to incriminate defendants was deemed confidentialand obtained from intelligence sources. The lawyers could not cross-examine those whogathered the information. On many occasions, the court rejected lawyers’ requests to call andcross-examine witnesses. Amnesty International categorically opposes the trial of civiliansbefore military courts.

Amnesty International April 2012

Index: MDE 11/014/2012

Flawed reformsBahrain fails to achieve justice for protesters

25

At the end of August 2011, the King issued a decree referring all cases being examined bythe National Safety Court to civilian courts and by early October 2011 all such cases werereferred to civilian courts.The BICI recommendations do not explicitly call for the immediate and unconditional releaseof all protesters who did not use violence or advocate the use of violence. Instead,recommendation172029calls for sentences and verdicts issued by the National Safety Courtto be reviewed by ordinary courts. Recommendation1722(h)30also calls on the governmentto review sentences issued by courts against people who did not use violence.A month after the BICI report, on 24 December 2011, the Public Prosecutor ordered that allcharges related to the right to freedom of expression be dropped.31He stated that this wouldapply to 43 cases and that 334 of those accused would benefit from such a measure.32However, in reality, very few detainees have benefited from this measure because the vastmajority of people detained for participating in the protests were charged with severaloffences. One of the most frequent charges is “participation in an illegal gathering of morethan five people”, which is set out in Article 178 of the Penal Code.The Penal Code and other Bahraini legislation, including Law 18 (1973) on Public Meetings,Processions and Gatherings (and amendments made through Law 32 of 2006), and the2005 Political Societies Law severely restrict the right to freedom of expression andassembly. In fact the Penal Code contains an array of articles (for example articles 165-169;172-174 and 178-182) which are broad, vaguely worded and which impose prison sentenceson people violating these articles. Provisions in these articles deal mainly with criticism ofthe King, the royal family and the government and amount to undue restrictions to the rightsto freedom of expression and peaceful assembly as guaranteed in international law.Under international human rights law and standards Bahrain has a duty to uphold the rightsto freedom of assembly and freedom of expression (articles 21 and 19, ICCPR). According toArticle 21 of the ICCPR, any restrictions on the right to freedom of assembly must be inaccordance with the law and strictly necessary to preserve national security or public safety,public order, public health or morals, or protect the rights and freedoms of others. Any suchrestrictions must be proportionate to a legitimate purpose and without discrimination,including on grounds of political opinion. Even when a restriction on the right to protest isjustifiable under international law, the policing of demonstrations (whether or not they havebeen prohibited) must be carried out in a manner that ensures full respect for human rights.On 3 January 2012, the President of the Court of Cassation and Vice President of theBahrain Supreme Judicial Council Shaikh Khalifa Bin Rashed Al Khalifa stated that acommittee made up of a number of judges had been set up to review all final verdicts andsentences issued by the National Safety Court.33On 25 February 2012, the Supreme Judicial Council announced that the new committee hadcompleted its work. It found that the National Safety Court had handed down 165 convictionverdicts, which included the sentencing of 502 people. Many received lengthy prison terms,including life in prison. The committee also noted, “135 verdicts were appealed before andare being processed by ordinary courts according to the law.” The committee recommendedthat charges against only six prisoners were dropped.34At the time of writing the identity of

Index: MDE 11/014/2012

Amnesty International April 2012

26

Flawed reformsBahrain fails to achieve justice for protesters

the six people who benefited from this measure had not been made public.

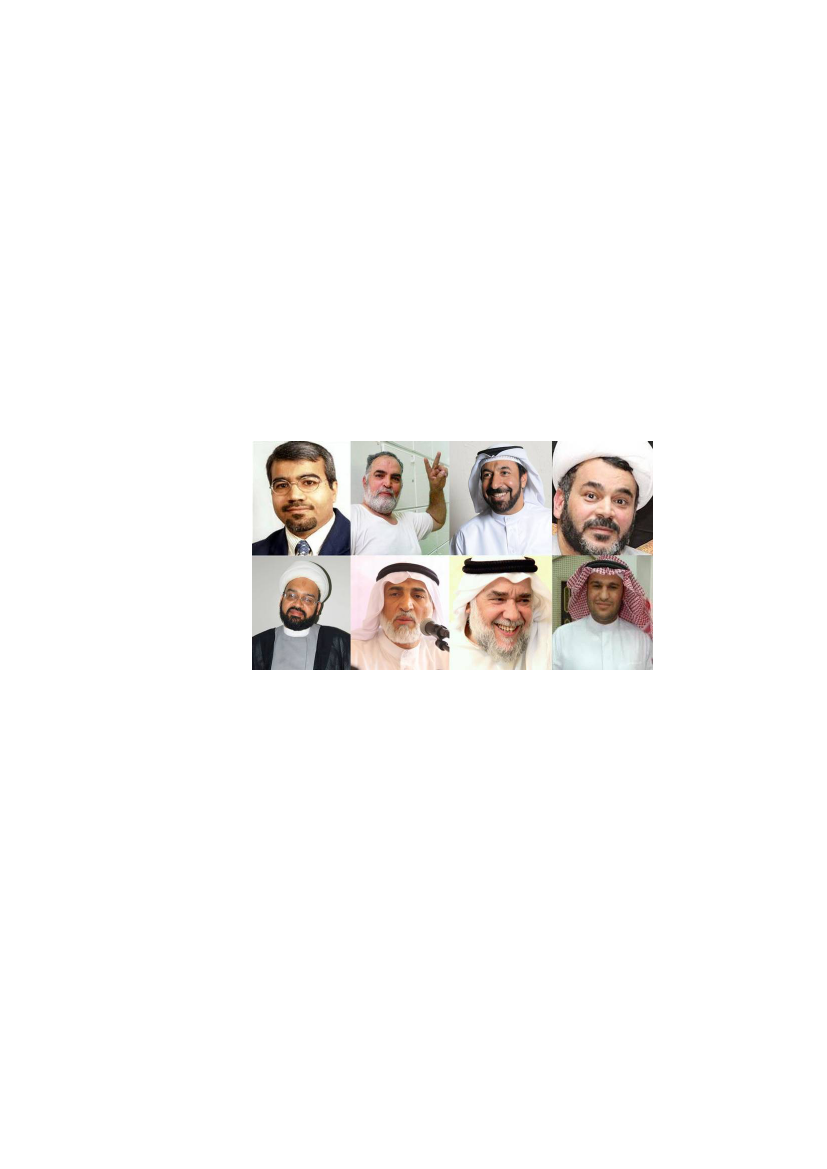

NATIONAL SAFETY COURT CASESScores of people who were tried and sentenced by the National Safety Court, and whosesentences were upheld by the National Safety Court of Appeal, also a military court, haveappealed before the Court of Cassation, a civilian court.One of the cases is of 21 prominent opposition figures arrested in March and April 2011. Ofthe 21, 14 were tried in person and seven were tried in absentia. On 22 June 2011, themilitary court sentenced seven of the 14 defendants who were present to life in prison. Theseven areHassan Mshaima’(leader of the al-Haq Movement, an unauthorized oppositiongroup),‘Abdelwahab Hussain(leader of the al-Wafa Movement, also unauthorized)35,‘Abdulhadi Al-Khawaja, Dr ‘Abdel-Jalil al-Singace, Mohammad Habib al-Miqdad, Abdel-Jalilal-MiqdadandSa’eed Mirza al-Nuri.Four people,Mohammad Hassan Jawwad, Mohammad‘Ali Ridha Isma’il, Abdullah al-Mahroosand‘Abdul-Hadi ‘Abdullah Hassan al-Mukhodher,were sentenced to 15 years in prison.Ebrahim SharifandSalah ‘Abdullah Hubail Al-Khawaja,the brother of ‘Abdulhadi Al-Khawaja, were given five-year prison terms.Al-HurYousef al-Somaikhreceived a prison sentence of two years.

Clockwise from top left Dr ‘Abdel-Jalil al-Singace, Mohammad Hassan Jawwad, Mohammad ‘Ali Ridha Isma’il Mohammad Habibal-Miqdad, Al-Hur Yousef al-Somaikh, Hassan Mshaima’, ‘Abdelwahab Hussain and Sa’eed Mirza al-Nuri. Some of the 14opposition activists sentenced by a military court in Bahrain in 2011 � Private

Charges against the 21 included “setting up terror groups to topple the royal regime andchange the constitution”. Some of the 14 prisoners publicly called for an end to themonarchy and its replacement with a republican system. They have not used or advocatedviolence, and Amnesty International considers them as prisoners of conscience who shouldbe immediately and unconditionally released.Several were reportedly tortured following their arrest.‘Abdulhadi Al-Khawaja,a prominenthuman rights defender and former Protection Co-ordinator for Front Line, an internationalNGO that works for the protection of human rights defenders, was arrested on 9 April 2011at his daughter’s house. According to his family, he was beaten during the arrest, taken away

Amnesty International April 2012

Index: MDE 11/014/2012

Flawed reformsBahrain fails to achieve justice for protesters

27

barefoot and not allowed to take his medication with him. He was not permitted family visitsfor weeks.When ‘Abdulhadi Al-Khawaja was admitted to the BDF military hospital in al-Riffa’a incentral Bahrain around the end of April 2011, he had cracks on his jaw and skull and blackmarks on his arms, allegedly caused by torture. He was admitted for six days and had severaloperations to his head and face. He was then hastily returned to prison where he wasreportedly tortured again. During the first session of the trial of the 21 opposition figures on8 May 2011, ‘Abdulhadi Al-Khawaja was not allowed to address the court. On his way out atthe end of the session he shouted that he was being tortured in detention. After that, securityofficers reportedly beat him and threatened him with rape. The court did not investigate hisallegation. He later gave an account of his torture to investigators from the BICI and histestimony featured in the BICI report.As of 10 April 2012 ‘Abdulhadi Al-Khawaja had been on hunger strike forover 60 days protesting against historture, unfair trial and arbitraryimprisonment. At the end of March 2012he told his family and his lawyer that hewas starting to reduce his glucose intake,which he had been taking along withwater to sustain his health. His heathdeteriorated significantly. He wasadmitted to the Military Hospital for twodays at the end of March. His weightdropped to 51 kilos, 16 less than beforehis imprisonment. On 31 March 2012, ashis health deteriorated further, he wastransferred to the Ministry of Interior‘Abdulhadi Al-Khawaja � PrivateHospital, where he was kept for a fewdays and then transferred to a military hospital. As of 10 April 2012 he was still being keptthere and was not allowed visits by his family and his lawyer. Abdulhadi Al-Khawaja has dualDanish and Bahraini nationality. The Danish government formally requested that he bereleased and sent to Denmark for treatment. The authorities rejected this request.On 6 September 2011, the appeal hearing of the 21 defendants took place before theNational Safety Court of Appeal.36The defence lawyers asked the presiding judge to testifyabout their torture and other ill-treatment in detention. They also urged the court to withholdits verdict until the publication of the BICI report and for the court to examine the evidenceof torture obtained by the BICI. The lawyers also asked to challenge the legality of the royaldecrees that provide for civilians to be tried before the National Safety Court. The appealhearing was postponed until 28 September 2011. Then, in a brief session that lasted only afew minutes, the appeal court decided to uphold all the convictions and sentences imposedon the 21 defendants on 22 June 2011. The defence lawyers later appealed the sentencesand the verdict before the Court of Cassation. On 2 April 2012 the Court of Cassation startedreviewing the case and then adjourned the hearing until 23 April 2012 when it is expected toissue its verdict. The court refused to release the defendants, as requested by the defence

Index: MDE 11/014/2012

Amnesty International April 2012

28

Flawed reformsBahrain fails to achieve justice for protesters

lawyers. The 14 people, who had been held in al-Gurain Military Prison in central Bahrainunder the control of the BDF, were transferred to Jaw Prison on 28 November 2011.Throughout the trial of the 21 defendants, the Military Prosecution failed to provide anyevidence that the accused used or advocated violence during last year’s protests.Other opposition activists and religious figures were also tried and sentenced by militarycourts. On 4 October 2011 the National Safety Court gave its verdict in the trial of theleaders of the Islamic Action Society (Amal), an authorized Shi’a political group whosemembers are said to be followers of the Najaf-based Ayatollah Hadi al-Mudarrassi, they arealso known as “the Shirazi faction”.Shaikh Mohammad ‘Ali Al-Mahfoodh,the SecretaryGeneral,Abdullah Ibrahim Ahmad Al-Saleh, Sayed Mahdi Hadi Al-Mossawi, Hadi Mohammadal-Muderrassi, Jassim Ali Mohammad Yousef Al-DumistaniandTalal ‘AbdulhameedMohammad al-Jamri,received 10 years’ imprisonment each. Eight others37received five-yearprison term each.The 14 were charged with, among other things,“attempting to overthrow the regime by illegalmeans”, “incitement to hatred of the regime”,“illegal gatherings” and “propagation of falseinformation”. The group’s lawyers appealed theverdict and sentences before the High CriminalCourt of Appeal. In a court session held on 20February 2012 defence lawyers requested that theBICI report be added to the case file and thatallegations of torture be independently investigated.The court agreed to appoint a medical team toexamine the defendants and decided to adjourn thetrial until 8 April 2012. On that date the trial wasadjourned again until 2 May 2012 because thecourt had not added the BICI report to the case fileand defendants had also not been referred forindependent forensic examinations.Younis Ashoori,a 60-year-old administrator in al-Muharraq Maternity Hospital, who is married withInternationalchildren, was arrested on 20 March 2011 at the hospital. He was unwell and staying at homewhen he received a phone call from his supervisor asking him to return to work because of anemergency. He drove to the hospital but was arrested by a large group of security officers. Hiswife inquired about him and searched for him in several police stations, with no success. Thefamily later heard that Younis Ashoori was being held in Hid police station, and that his carhad been confiscated. When his wife took his medication to the police station, the policedenied that he was being held there and refused to take the medicine. Eighteen days later,Younis Ashoori contacted his family by phone for the first time. He did not know where hewas being held. Amnesty International considers that he was held in conditions amounting toan enforced disappearance.Shaikh Mohammed ‘Ali A-Mahfoodh � Amnesty

During the first two weeks of detention Younis Ashoori was reportedly tortured. Reportedmethods included beatings with a hosepipe, punches to his face and his stomach,

Amnesty International April 2012

Index: MDE 11/014/2012

Flawed reformsBahrain fails to achieve justice for protesters

29

suspension upside down and electric shocks. He was told that if he did not sign a“confession”, his wife and sisters would be brought to the police station and raped in front ofhim. He was denied medicine for his prostate, kidney problems and migraine. As a result ofrepeated torture Younis Ashoori signed papers when blindfolded and without knowing whattheir content was. Later he discovered that he had signed three documents incriminatinghimself: taking gas cylinders from the hospital to the Financial Harbour (where protesters haderected a camp), replacing political leaders’ portraits with those of religious ones, preparing award within the hospital for injured protesters and “inciting hatred against the regime.”The Military Prosecution charged him with one formal criminal offence: stealing materialfrom the hospital and dropped the other charges. He was tried bythe National Safety Court and on 28 September 2011 he wassentenced to three years in prison. A day later, he was transferred toJaw Prison. His case was later transferred to the High Criminal Courtof Appeal which adjourned the hearing several times. On 25 March2012, the trial resumed. His lawyer told the court that thedefendant had been tortured and requested copies of medicalreports issued on behalf of his client. The lawyer told AmnestyYounis Ashoori � PrivateInternational that as of the end of March 2012 Younis Ashoori’s“confession”, extracted under torture, is still being used as evidence, together withinformation received from “secret witnesses”. The main prosecution witness has notappeared in court. The trial was adjourned until 11 April 2012.Two leaders of the teachers’ association,Mahdi ‘Issa Mahdi Abu DheebandJalila al-Salman,former President and Vice-President of the Bahrain Teachers’ Society (BTS), were sentencedon 25 September 2011 by the National Safety Court of First Instance to 10 and three yearsin prison respectively. They were charged with, among other offences, using their positionswithin the BTA to call for a strike by teachers during the 2011 unrest, “halting theeducational process”, “inciting hatred of the regime” and attempting to “overthrow the rulingsystem by force”, “possessing pamphlets and disseminating fabricated stories andinformation”.Mahdi ‘Issa Mahdi Abu Dheeb has been indetention since his arrest on 6 April 2011 after araid on his uncle’s house. Both he and his unclewere detained; his uncle was released 72 dayslater. Mahdi ‘Issa Mahdi Abu Dheeb’s family didnot know where he was for 24 days. He spent 64days in solitary confinement during which he sayshe was tortured. His family and lawyer were onlyallowed to see him during the first session of thetrial on 7 June 2011. He said he was repeatedlybeaten on the head, back and legs and wasforced to remain standing for prolonged periods oftime.Jalila al-Salmanwas released on bail on 21August 2011 after spending nearly five months inMahdi ‘Issa Mahdi Abu Deeb � Private

Index: MDE 11/014/2012

Amnesty International April 2012

30

Flawed reformsBahrain fails to achieve justice for protesters

detention. Her house in Manama was raided on 29 March 2011 by more than 40 securityofficers. She was taken to the CID in Manama where she was reportedly ill-treated andverbally abused. She remained there for eight days until she was transferred to a women’sdetention centre in ‘Issa Town and kept there in solitary confinement for 18 days. She wasthen transferred to a cell with other women within the same facility. She is currently not injail, although she was briefly arrested and held for several days in late October 2011.

Jalila al-Salman � Private

There is no evidence that Mahdi ‘Issa Mahdi Abu Dheeb or Jalila al-Salman used oradvocated violence. They were targeted solely for their leadership of the BTS and forpeacefully exercising their rights to freedoms of expression, association and assembly,including calling for strikes. The lawyers of the two appealed the verdict and the sentences.The appeal hearing was held in late December 2011, then postponed to 9 February 2012. Itwas again postponed until 2 April 2012, and then until 2 May 2012.Mahmood AbdulSaheb,an artist and photographer who is marriedwith three children, was arrested at a checkpoint on 15 March 2011on his way home. For 10 days his family did not know what hadhappened to him. He then called and asked them to bring clothes toal-Riffa’a police station where he was being held. He wasreportedly tortured and burn marks were still visible on hishands when his family saw him for the first time two months later. Amonth after his arrest, he was transferred to Dry Dock Prison inManama. He was charged by the Military Prosecution with “illegalassembly” and “fabricating and leaking photos of injuredprotesters”. His trial before the National Safety Court of FirstInstance started on 12 May 2011, and on 31 May he was

Mahmood Abdulsaheb �Private

Amnesty International April 2012

Index: MDE 11/014/2012

Flawed reformsBahrain fails to achieve justice for protesters

31