Udenrigsudvalget 2011-12

URU Alm.del Bilag 159

Offentligt

DIIS REPORT

DIIS REPORT 2012:04

DIIS REPORT

ADDRESSING CLIMATE CHANGEAND CONFLICT IN DEVELOPMENTCOOPERATIONEXPERIENCES FROM NATURAL RESOURCEMANAGEMENTMikkel Funder, Signe Marie Cold-Ravnkilde andIda Peters Ginsborg- in collaboration with Nanna Callisen BangDIIS REPORT 2012:04

DIIS . DANISH INSTITUTE FOR INTERNATIONAL STUDIES1

DIIS REPORT 2012:04� Copenhagen 2012, the authors and DIISDanish Institute for International Studies, DIISStrandgade 56, DK-1401 Copenhagen, DenmarkPh: +45 32 69 87 87Fax: +45 32 69 87 00E-mail: [email protected]Web: www.diis.dkCover photo: Tuareg men shaking hands. Copyright 2005Mark BrunnerLayout: Allan Lind JørgensenPrinted in Denmark by Vesterkopi ASISBN 978-87-7605-495-3Price: DKK 50.00 (VAT included)DIIS publications can be downloadedfree of charge from www.diis.dkHardcopies can be ordered at www.diis.dk

2

DIIS REPORT 2012:04

List of contents

AcknowledgementsAcronymsAbstract1. Introduction2. Climate change and conflict in Africa2.1 The link between climate change and conflict2.2 Climate change as a conflict multiplier2.3 Impacts of climate-related conflicts3. Examining the lessons from natural resource management4. The nature and causes of natural resource conflicts4.1 Types of natural resource conflicts4.2 Root causes of natural resource conflicts5. Conflict prevention, management and resolution in natural resourcemanagement5.1 Conflict prevention in natural resource management6. Experiences from the local level6.1 Local conflict prevention and management in natural resourcemanagement6.2 Lessons learnt7. Experiences from the national level7.1 National conflict prevention and management in natural resourcemanagement7.2 Lessons learnt8. Experiences from the transboundary level8.1 Transboundary conflict prevention – lessons learnt8.2 Transboundary conflict management – lessons learnt

5679111112131517171821212424263131323535383

5.2 Conflict management and resolution in natural resource management 22

DIIS REPORT 2012:04

9. Addressing climate-related conflicts in development cooperation9.1 Guiding principles for addressing climate-related conflicts indevelopment cooperation9.2 Key questions to consider9.3 Recommended entry points for support9.3.1 The link between climate change and conflict9.3.2 Climate change as a conflict multiplier9.3.3 Impacts of climate-related conflicts9.4 Monitoring conflict prevention and management interventionReferencesAnnex 1 - Case Study: The Peace Wells in NigerAnnex 2 - Case Study: Drought and conflict in northern KenyaAnnex 3 - Case Study: The Nile Basin Initiative

404041434446495052637076

4

DIIS REPORT 2012:04

Acknowledgements

This report has been prepared by the Danish Institute for International Studies (DIIS)for the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, who funded the study. The report waswritten by Mikkel Funder, Signe Marie Cold-Ravnkilde and Ida Peters Ginsborg ofDIIS in collaboration with Nanna Callisen Bang of CARE.The authors would like to thank the following individuals and institutions for theirassistance with and comments on the report: Gilbert Muyumbu and Yussouf Artain(ActionAid, Kenya); Olga Mutoro, Tabitha Kilatya and Dhahabu Daudi (PeaceNetKenya); Eric Kisinagani and Benedict Mukoo (Practical Action); Prof. KennedyMkutu (USIU, Kenya); Jeanette Clover (Regional Coordinator, UNEP, Kenya);Klaus Ljørring Pedersen (Regional Coordinator, Danish Demining Group DDG,Kenya); Troels Bruun Jørgensen (NIRAS, NEMA, Kenya); Keith Fisher (DFID)and Prof. Kassim Farah, ASAL Secretariat, Kenya); Mohammed Halakh, (Ministryof the Northern Regions and Other Arid Lands, Kenya); Marie Haug Jørgensen andAnne Nyaboke Angwenyi (the Danish Embassy, Nairobi); Jens Emborg (KU LIFE);Vibeke Vindeløv (KU); Mogens Laumand Christensen (Danida); Ced Hesse (IIED,London); Oli Brown (UNEP, Sierra Leone) for useful discussion, comments andadditional input into the report.

5

DIIS REPORT 2012:04

Acronyms

ADRASALASEANCBOCBNRMDACDPCFAOIISDIWRMNAPANGONPCNPPCMNRMOECDRBOREDDSADCUNUNEP

Alternative Dispute ResolutionArid and Semi-arid LandsAssociation of Southeast Asian NationsCommunity Based OrganisationsCommunity Based Natural Resource ManagementDevelopment Assistance CommitteeDistrict Peace CommitteeFood and Agriculture OrganisationInternational Institute for Sustainable DevelopmentIntegrated Water Resources ManagementNational Adaptation Plan of ActionNon Governmental OrganisationNational Peace CommissionNational Policy on Peace-building and Conflict ManagementNatural Resource ManagementOrganisation for Economic Co-operation and DevelopmentRiver Basin OrganisationReduced Emissions from Deforestation and DegradationSouthern African Development CommunityUnited NationsUnited Nations Environment Programme

6

DIIS REPORT 2012:04

Abstract

This report presents the main findings of a desk study of experiences with conflictprevention and resolution in natural resource management, and how these can beapplied in development cooperation in relation to climate change.The report briefly discusses the link between climate change and conflict, includingthe need to see climate change as a conflict multiplier rather than as a major directcause of conflict in itself. The report then goes on to review approaches and lessonslearnt from conflict prevention, management and resolution in natural resourcemanagement at the local, national and transboundary levels respectively.On this basis, the report provides recommendations on how development coopera-tion can address the potential conflict multiplier effects of climate change, includingguiding principles and key entry points for support. The latter include (i) enhanc-ing so-called structural conflict prevention measures, (ii) supporting institutionalmechanisms for managing and resolving conflict, and (iii) ‘conflict proofing’ policiesand development interventions.

7

DIIS REPORT 2012:04

8

DIIS REPORT 2012:04

1. Introduction

This report presents the main findings of a desk study on experiences with conflictprevention and resolution in natural resource management, and how these can beapplied in development cooperation in order to address the potential conflict multipliereffects of climate change. The study was undertaken by the Danish Institute forInternational Studies, with funding from the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs.A number of previous studies have addressed the topic of climate change and conflictfrom an overall perspective and/or in relation to security studies (Brown & Crawford2009). The current study examines the issue from the perspective of natural resourcemanagement and -governance, which is closely related to that of climate change andwhere stakeholder conflicts are a well-known issue. On this basis, the study providesrecommendations for possible approaches and key elements when addressing climate-related conflict in development cooperation.The study has a particular focus on land and water aspects, and an emphasis on theAfrican setting. However, many of the findings and recommendations also apply toother aspects of climate-related conflict and natural resource management in theSouth. The main implications for development cooperation can also be found ina shortened version of the current report, which has been published as a Danida‘How to Note’.The study has drawn its information and analysis from several sources, namely:(i) A review of literature on addressing conflict in natural resource management,with a particular emphasis on land and water in the African setting. Thisinvolved an initial literature search which produced a longlist of titles on thesubject, including both academic articles and ‘grey’ literature which reportedthe findings from studies related to specific projects etc. The literature in thislonglist was categorised by type into case studies of natural resource conflicts(stand-alone and comparative), and general reviews and recommendations onaddressing conflict in natural resource management. A total of 50 referenceswere selected for review from the ‘case study’ category. These were studied withthe aim of extracting information on (a) what caused natural resource conflictsand (b) what are the experiences from efforts seeking to prevent conflicts and(c) what are the experiences from efforts to manage and resolve conflicts? This9

DIIS REPORT 2012:04

information was entered into a matrix for each title, allowing us to gain anoverview of cross-cutting issues and approaches. To this was added the findingsand recommendations from the more general (non-case specific) literature.(ii) Three desk-based case studies of particular natural resource conflict/cooperationsituations, namely (i) the ‘Wells of Peace’ in Niger; (ii) conflict and conflictresolution in Northern Kenya, and (iii) the Nile Basin Initiative.(iii) A general review of the literature on climate change and conflict, conflictresolution methods and conflict sensitive development.(iv) Consultations with relevant practitioners, policymakers and researchers, includinginterviews in Kenya, and comments on draft versions of this document fromstaff at relevant policy and action research institutions.The following section provides an introduction to the relationship between climatechange and conflict (chapter 2). This is followed by the review of experiences fromnatural resource management (chapter 3), the nature and causes of conflict (chapter4), conflict prevention, resolution and management (chapter 5) at local, national andtransboundary level (chapters 6, 7 and 8). The final section provides recommendationsfor addressing climate-related conflict in development cooperation (chapter 9).

10

DIIS REPORT 2012:04

2. Climate change and conflict in Africa

2.1 The link between climate change and conflictAccording to most studies, the impacts of climate change in Africa and beyond willbe severe, and are already ongoing in many places. It is nevertheless important toavoid across-the-board assumptions that climate change will automatically lead toconflict. There are a number of reasons for this:• Predicting the nature of climate change in individual countries and locationsis notoriously difficult. In fact, increasingunpredictabilityof rainfall, droughtand flooding patterns seems to be a key characteristic of climatic change on thecontinent (Brown & Crawford 2009). Several studies have furthermore pointedout that different regions will be differently affected, with some areas due toexperience increasing overall rainfall, and others less (Stern 2006).• Human responses to climate change will also most likely be varied and unpredictable:the particular social, cultural and economic context in any given location playsan important role in determining how its institutions and individuals respondto climate change. Whether or not climate change contributes to conflict in agiven society will, to a large extent, depend on its resilience and character – e.g.the magnitude of shock that it can absorb, the nature and capacity of socialorganisation, and the ability to adapt (Adger & Thomkins 2004; Bob 2010).• The scientific evidence for the relationship between climate change and conflictis as yet limited, and frequently also inconclusive. In 2009 it was widely reportedthat a statistical study had established a historical link between rising temperaturesand civil war in Africa (Burke et al. 2009). Shortly afterwards, another study usedthe same data to arrive at the opposite conclusion (Buhaug 2010a/b). A key issuehere is that conflict tends to be caused by numerous factors, and it is thereforeoften difficult to identify and single out individual causes.• Scarcity of natural resources frequently leads tocollaborativeactions andarrangements rather than conflict. This has been documented in recent studiesof water governance, both at the transboundary and local levels (Wolf et al.2005; Ravnborg et al. 2012) and is also evident in the way many local Africansocieties organise the management of scarce natural resources through commonproperty arrangements. Often, conflict is simply too costly or too risky for statesor individuals to engage in.• Climate change is rarely the only or even main cause of conflict. Typically, whenclimate conflicts are examined in detail they turn out to be rooted in a number11

DIIS REPORT 2012:04

of other or additional issues. Examples of this include the pastoralist conflicts inNorthern Kenya, which have been described as some of the world’s first climateconflicts (Christian Aid 2006; Yale Environment 2011).However, as recountedlater in this report, these conflicts are by no means only about climate change.2.2 Climate change as a conflict multiplierClimate change is therefore best seen as a conflictmultiplier,rather than as a majordirect cause of conflict in itself. Climate change may aggravate and extend the scopeof existing conflicts, or trigger underlying and latent conflicts to break out into theopen.Previous studies have identified a number of areas in which climate change maycontribute to a worsening of conflicts (Brown & Crawford 2009). These include:• Land and water access. Access and use rights to land are a key feature in mostsituations where climate change has contributed to natural resource conflicts sofar. Climate change can intensify existing conflicts over land, as land becomes lessfertile or is flooded, or if existing resource sharing arrangements between differentusers and land use practices are disrupted. In some parts of Africa, climate changemay lead to a decline in available water resources of some 10–20% by the end ofthe century (op cit.). This may intensify existing competition for access to waterat intra-state and/or subnational levels.• Food security. Reduced rainfall and rising sea levels may lead to a decline inagricultural production and a substantial loss of arable land in some parts ofAfrica. Reduced yields for own consumption and increasing domestic food pricesmay in some cases lead to civil unrest, and competition over access to land mayintensify.• Migration and displacement. In some cases, increased scarcity of and competitionover access to water and arable land may contribute to internal or regional migration,and disasters such as floods may lead to temporary or long-term local displacement.This may in turn strengthen conflicts between host societies/communities andmigrants looking for access to new land and resources.• Increasing inequality and injustice. Through processes such as the above, somepopulation groups may be particularly hard hit, leading to increased inequality anda sense of injustice. This may intensify existing grievances and disputes betweennatural resource users and/or between resource users and outside actors such asgovernments – thereby increasing the risk and intensity of conflict.12

DIIS REPORT 2012:04

• A further and sometimes overlooked way in which climate change can contributeto conflict is through the adaptation and mitigation efforts themselves. Forinstance, the demand for climate-friendly fuels has meant that large agriculturalareas have been set aside for production of crops used in biodiesel or ethanol inseveral African countries. In some places this has meant that local farmers havelost access to important land and water resources, leading in turn to local protestsand disputes. Another example is the controversies surrounding the proposedglobal mechanism for Reduced Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation(REDD), which if handled poorly could trigger or intensify conflicts over rightsto forest areas between local forest users and external stakeholders and within theparticipating communities, e.g. over benefit sharing.It should be noted, however, that there are still only a few cases where the contributionof climate change to conflict has been clearly and thoroughly documented.Many examples of climate-related conflicts provided in the current literature areanecdotal or hypothetical, and our knowledge of the processes involved is thereforeincomplete.2.3 Impacts of climate-related conflictsConflict is an inevitable feature of human society, and can lead to important socialchanges when grievances are brought out into the open and social injustices arechallenged. Not all conflicts are necessarily negative, but when they escalate intoviolence and/or abuse of power they can have significant negative impacts in bothhuman and developmental terms. In this respect, experiences from natural resourceconflicts in general suggest that:• Conflicts over natural resources often have particularly negative impacts on thepoor, who typically lack the necessary means to defend their interests and rights,and who are frequently the worst hit when conflict leads to breakdown of locallivelihoods or displacement.• Conflicts over land and other natural resources may, in some cases, have significantmacro- economic costs, including reduced food production and capital flight.Conflicts may also impact significantly on the structure and vulnerability ofnational economies, which tend to see decline in manufacturing and a greaterreliance on exports of primary resources.• Natural resources conflicts may, in some cases, contribute to institutional erosionand reduce the reach and capacity of statutory or customary institutions to govern,13

DIIS REPORT 2012:04

regulate and deliver services. Implementation of particular development policiesand programmes may be constrained or misdirected in situations where conflictsover natural resources persist. This includes cross-sectoral impacts, e.g. wherehealth and education programmes are constrained by ongoing natural resourceconflicts.• Conflicts may also lead to degradation of the natural resource base itself, e.g.when rules and enforcing authorities lose legitimacy, or when natural resourcesare drawn upon to finance armed conflict.While these potential impacts are serious, care should be taken to avoid assumptionsabout vicious circles whereby local societies disintegrate in a spiral of poverty, resourcedegradation and violence. Studies suggest the need for a balanced understanding,which avoids undue romanticism, but which also recognises that community membersfaced with environmental change continuously seek to innovate and adapt withintheir available circumstances (Leach et al. 1997).It is furthermore important to emphasise that the responses of local stakeholders tonatural resource conflicts do notnecessarilyhave negative impacts on local societies ornational economies. Migration, for example, is a livelihood strategy already appliedby millions of households across Africa, and plays an important part in economicdevelopment through e.g. the provision of a labour force in cities and rural economicdevelopment through remittances. Conflict may also have positive outcomes, suchas in cases where it provides opportunities for local stakeholders to learn about eachother’s ways of life and different strategies for coping in times of stress.

14

DIIS REPORT 2012:04

3. Examining the lessons from natural resourcemanagement

The potential contribution of climate change to conflict is strongly related to thegovernance and management of natural resources.1Firstly, factors such as increasedflooding, more frequent drought and a general increased unpredictability of rainfall,all impact directly on the quantity and quality of natural resources in a given setting.Secondly, many of the already existing conflicts that climate change may exacerbateand multiply take place within the realm of natural resource management and itsassociated institutions. And thirdly, because natural resource management has alwaysbeen subject to conflict, a range of efforts and mechanisms to prevent and resolveconflicts already exists.A review of the experience of efforts to address conflict in natural resource managementcan therefore provide important pointers for how to understand, approach and addressclimate-related conflicts in development cooperation.Specifically, our review of experiences with conflicts in natural resource managementexamined:(a)The nature and causes of natural resource conflicts.Conflict studies have repeatedlyshown that successful prevention and management of conflicts requires an understandingof their nature and their root causes (e.g. OECD 2001; Brown & Crawford 2009).While this will differ from case to case, it was possible to draw out a number of cross-cutting features that are also highly relevant to climate-related conflict prevention andmanagement.(b)Approaches and measures to address conflict.Efforts to address conflicts typicallyinclude an emphasis on one or more of the following elements:• Conflictpreventionmeasures, that seek to prevent new conflicts from developing• Conflictmanagementmeasures, that seek to contain, limit and mitigate ongoingconflicts1

In the following, we use the term ‘natural resource management’ as shorthand for both the governance ofnatural resources (including access to and control over resources), and the more technical management aspectsas well, as it emphasises the more positive dynamics through which parties may develop constructive responsesto difficult situations of conflict.

15

DIIS REPORT 2012:04

• Conflictresolutionmeasures, that seek to end conflicts by resolving the underlyingincompatibilities(c)Levels of intervention.Prevention, management and resolution may take placethrough a variety of different mechanisms and at different scales. In natural resourcesmanagement, this typically includes:• Local mechanisms, e.g. customary and informal mechanisms, local governmentetc.• National frameworks, e.g. statutory institutional systems and legal frameworksat national level• Intergovernmental mechanisms, e.g. regional or transboundary water managementbodiesOn this basis, we conducted a review of experiences to be found in the literature, asking(i) what are the causes of natural resource conflicts; (ii) what are the experiences ofconflict prevention in natural resource management, and (iii) what are the experienceswith conflict management and resolution. These questions were stratified accordingto the intergovernmental, national and local level.The following section reviews the nature and causes of natural resource conflicts, whilethe subsequent sections presents the findings on experiences with conflict preventionand management/resolution at local, national and transboundary levels.

16

DIIS REPORT 2012:04

4. The nature and causes of natural resource conflicts

4.1 Types of natural resource conflictsNatural resource-related conflicts are essentially social conflicts (violent or non-violent)that primarily revolve around how individuals, households, communities and statescontrol or gain access to resources within specific economical and political frameworks(Turner 2004). Such conflicts may express disagreements about distribution of resources,inequalities, land rights and maintenance issues. Natural resource conflicts are a commonfeature in many areas in the developing world, and reflect the widespread dependenceon access to natural resources for local livelihoods (FAO 2005). Particularly in ruralareas, where material conditions are poor, local conflicts are often resource-related.Natural resource conflicts typically involve one or more of the following: (i) micro–micro conflicts, i.e. between or among local stakeholders; (ii) micro–macro conflicts,e.g. between local and national or international stakeholders, and (iii) macro–macroconflicts, e.g. intergovernmental conflicts. The table below shows examples of thedifferent types of conflicts arising in natural resource management.

Examples of natural resource conflictsMicro–micro conflicts:• Intra-community conflicts where some households are excluded or furtherdisadvantaged and benefits captured by other community members• Conflict over land access between pastoralists and crop farmers• Conflicts over water access between long-standing resident groups and new-comer households• Conflicts between neighbouring clan leaders over the control of pastureMicro–macro conflicts:• Conflicts between customary and government authorities over control ofland allocation• Conflicts between local farmers and the state over protected areas• Conflicts between fishermen and the state over hydropower productionMacro–macro conflicts• Conflicts between two riparian states sharing a river course• Conflicts between international NGOs and the state over logging• Conflicts between international companies over diamond and fossil fuelresourcesSource:Format adapted from Warner 2000, with examples from the reviewed literature

17

DIIS REPORT 2012:04

In practice, a particular area or river may be the subject of all three types of conflictat the same time, and the stakeholders involved may move across both local, nationaland transboundary dimensions. The above distinction should therefore not be takentoo literally. It does however highlight how different institutional mechanisms andforms of organisation (or different combinations of these) may be necessary fordifferent types of conflict.4.2 Root causes of natural resource conflictsThe causes of natural resource conflicts are often complex and multi-layered. Abasic distinction can be made between contributing causes (e.g. climate change, orproliferation of arms), and root causes (e.g. governance, inequality etc.). Understandingthe root causes of conflicts is considered crucial in conflict-sensitive developmentcooperation as it provides the basis for assessing the potential for future conflicts, thedynamics of existing conflicts, and the necessary strategies for conflict preventionand resolution (OECD 2001).In the literature reviewed, the following root causes of natural conflicts frequentlyoccurred:Natural resource scarcity/distribution.The natural scarcity of a resource is sometimesa root cause of climate-related conflicts. This includes competing interests amongpowerful stakeholders at various levels over the control of resources, or conflicts overaccess between different types of production systems. However, absolute scarcity ofwater and other resources are in many cases managed without major conflict. At heart,many conflicts are often more about how land and water resources aredistributedamong stakeholders, and the failure of institutions to manage scarce resources of highvalue in a peaceful and equitable manner (Ashton 2002; Fiki & Lee 2004; Odgaard2006; Thébaud 2002).State policies and priorities.National policies such as collectivisation or privatisationof land have in some cases had unintended effects and can ignite land and waterconflicts. Policies that deliberately or inadvertently prioritise some sectors, producersand regions at the cost of others have historically been the source of numerous landand water conflicts (Bob 2002; Castro 2005).Market changes.The advent of new markets and associated changes in productionpatterns, ownership and resource values, are an underlying factor in some conflicts over18

DIIS REPORT 2012:04

e.g. land grabbing, new commercial water users and rising land values (Hughes 2001;Van Leeuwen 2009; Odgaard 2006). For instance in Somalia pastoral communities arehighly affected by land degradation due to the charcoal industry for export to SaudiArabia. Before these trade mechanisms existed, communities were more resilient toclimate change (Baxter 2007).Competing and insecure rights.Insecurity and inequality in land and water rightsis a key factor in many natural resource conflicts. Customary rights systemshave been undermined in many areas, but have frequently not been replacedwith clear and defensible rights (Odgaard 2006; UNEP 2009). The overlappingand competing nature of resource rights in many areas means that they can berepeatedly challenged and tend to be captured by the more resourceful local orexternal stakeholders.Governance constraints.Authoritarian approaches and poor accountability in thegovernance of natural resources, and in society more generally, is another key factorunderlying many conflicts. Government institutions at international, national andlocal levels also frequently lack the capacity and legitimacy to effectively collaborateand fairly enforce rights and legal frameworks. In some cases customary conflictprevention and resolution mechanisms have been eroded or are unable to respond tolarge-scale conflicts. More generally, wider political struggles over power, influenceand territory may be rhetorically or symbolically linked to land and water, and/or mayfinancially exploit these resources to finance such struggles (Campbell & Crawford2009; Huggins et al. 2005; Matthew et al 2009).Poverty and inequality.Poverty does not necessarily lead to overt conflict, as the poormay lack the necessary means to express discontent and engage in conflict. However,from a development point of view, latent conflicts between poor and better-offstakeholders will often be important to address, and may in any case eventually eruptinto explicit conflict if livelihoods come under extreme stress. Unequal access topolitical representation and rights of different population groups is also a commonfactor in natural resource conflicts (Castro 2005; Grahn 2005).Demographic change.In some locations population growth has led to increasedcompetition over land and water, e.g. through the reduction of land plot sizes.Likewise, internal or regional migration and displacement may, in some cases, cause orcontribute to natural resource conflicts (Theron 2009; Baechler 1999). Nevertheless,universal assumptions should be avoided. Some studies have shown the opposite19

DIIS REPORT 2012:04

effect, e.g. that ‘more hands’ improve farming outputs, and that migrants contributeto economic growth in host communities (Blaikie & Brookfield 1987; Kessides 2005;Lambin et al. 2001).

20

DIIS REPORT 2012:04

5. Conflict prevention, management and resolution innatural resource management

5.1 Conflict prevention in natural resource managementConflict prevention forms an implicit and often unspoken part of natural resourcemanagement practices (Baechler 1999). Traditions, norms, common rules, laws,institutions and policies in natural resource management are ideally all basic elementsof conflict prevention, which essentially aims to clarify rights and uses and to bringcoexistence to situations of potential resource competition and conflicts of interest(UNEP 2009). The following discussion cannot explore all of these issues, but insteaddraws out a selection of features related to conflict prevention measures, as found inthe literature review.Conflict analysis typically operates with three overall types of conflict preventionmeasures namely (i) early warning; (ii) direct conflict prevention and (iii) structuralconflict prevention. Natural resource management mechanisms and interventions havenot typically operated with these concepts. Nevertheless, elements of all three typesof conflict prevention can be found in the natural resource management practicesand interventions reviewed:��������������������������������������������������������������

���

�������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������

�����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������

�������������������������

�����������������������������

21

DIIS REPORT 2012:04

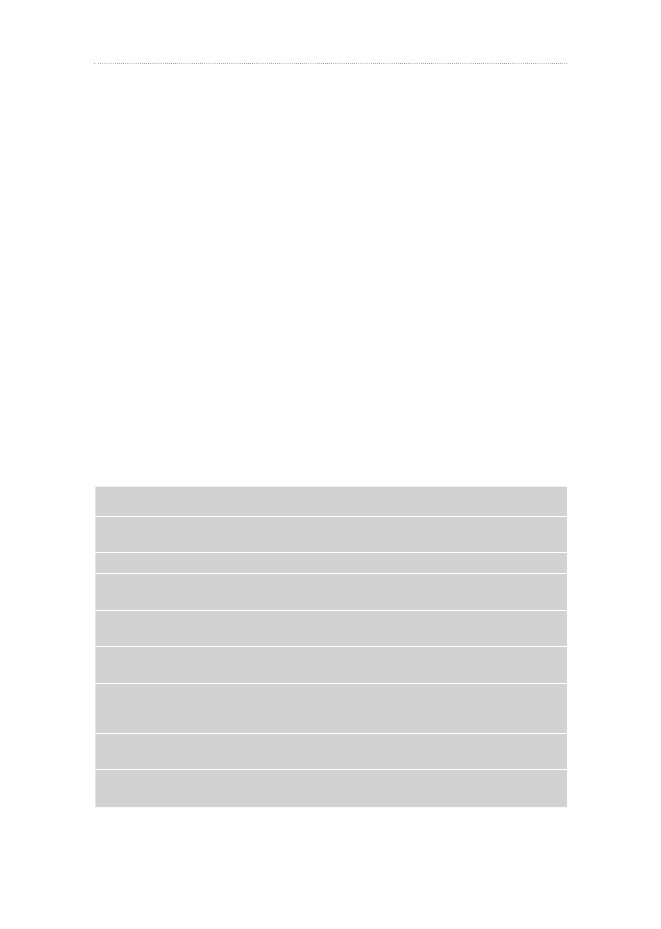

All three elements of conflict prevention may be carried out at local, national andinternational levels. While each type of prevention is important in its own right, theliterature reviewed indicates that early warning systems and direct conflict preventionmeasures are of limited effect if they are not backed by structural conflict preventionefforts that address the root causes of conflicts e.g. by addressing inequalities inresource access, institutionalising rights and agreements, and providing supportingnational frameworks (Benjaminsen & Ba 2009; Brockhaus et al. 2004). If this is notdone, the duration of agreements made through direct prevention measures may beshort-lived, and new conflicts may erupt and escalate.5.2 Conflict management and resolution in natural resourcemanagementConflictmanagementmeasures seek to contain, limit and mitigate ongoing conflicts,and conflictresolutionmeasures seek to end conflicts by resolving the underlyingincompatibilities. However, in both practice and in much of the literature, the twoaspects flow together and thus they are discussed together in the following sectionsunder the overall heading of ‘conflict management’. This can take a variety of forms,but typically involve one or more of the following elements:�������������������������������������������������������������������������������

����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������

�����������������������Source:Castro 200522

DIIS REPORT 2012:04

In many parts of Africa, conflict management measures will take place in a contextof legal pluralism in which different legal orders coexist, contradict, overlap and/orcompete with each other. Drawing on Castro’s analysis of local capacity for managementof natural resource conflicts in Africa, the table below gives an overview some of themost dominant conflict resolution measures.

���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������

�����������

�����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������

����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������

Source:Developed from Castro 2005

Customary systems may be legally recognised by law, but are distinguished fromnational statutory systems by their customary and often localised nature, specific to,for example, a particular ethnic group or production system.Different settings may require a different emphasis on each of these differentmechanisms, depending on the history and outlook of conflicts, the existing meansfor governing conflicts, and the nature and aim of policies and of developmentcooperation. No single approach is necessarily superior and fits all. They all possessstrengths and weaknesses, and their success depends upon analysis of the contextand conflicts in question.

23

DIIS REPORT 2012:04

6. Experiences from the local level

Documented experiences from addressing conflicts in natural resource managementin the South typically have a strong focus on the local level. This is likely a result ofthe strong emphasis on locally-based natural resource management in recent years,as well as the fact that many conflicts emerge locally, even if they are partially or fullycaused by larger scale factors. Local conflict prevention mechanisms identified in thereviewed literature include:

6.1 Local conflict prevention and management in naturalresource managementCustomary mechanismsThese frequently consist of general ‘traditional’ authorities in communities such as,for example, chiefs or headmen who are asked to settle disputes through mediation,arbitration or adjudication (Baechler 1999; Edossa et al. 2005). In addition oralternatively, conflict prevention and management may involve village councilssuch as a ‘council of elders’ whose mandates often include explicit reference toensuring harmony and peace in communities (Adan & Pkalya 2006 a/b). Whilemost interventions in support of conflict prevention and management tend to focuson these traditional authorities, there are also a range of other important conflictprevention and management mechanisms which are ingrained in local customs andnot necessarily visible to outsiders. Such measures described in the literature include:(i) village assemblies and inter-community meetings (Grahn 2005); (ii) naturalresource management agreements between different resource users, e.g. irrigationmanagement agreements (Wolf 2000) or mutually agreed timing of when herdersmove cattle across the fields of sedentary farmers; (iii) reciprocal benefit systems, e.g.mutually dependent pastoral and farming systems; (iv) inter-community alliances, e.g.alliances and intermarriages between different communities or ethnic groups with theaim of avoiding conflict over resources (Adan & Pkalya 2006 a/b); and (v) everydaycultural practices that are indirectly aimed at fostering mutual understanding andreducing tension, e.g. ‘dilemma stories’ and family banter in Burkina Faso (Brockhauset al 2003).In addition to this, individual livelihood coping strategies contain important conflictavoidance aspects, such as seeking off-farm benefits or regulating herd size with the24

DIIS REPORT 2012:04

indirect aim of increasing room for action to avoid conflict with fellow farmers(Baechler et al. 2002; Campbell et al. 2009). Ongoing climate change adaptationpractices employed by herders in dryland areas can also be seen as indirect butimportant conflict prevention efforts (Beyene 2010; Mwangi & Dohrn 2008).Community-based natural resource managementIn most cases, customary conflict prevention and management measures have beenapplied to address conflicts between users at the local level (i.e. micro–micro conflicts,although the geographical extent of the ‘local level’ may be far-reaching and cut acrossnational boundaries). Community-based natural resource management (CBNRM)interventions have typically had a different point of departure, namely addressingconflicts between local users and the state or other national or international stakeholders(i.e. micro-macro conflicts). Efforts found in the reviewed literature that are relevant toconflict prevention include: (i) full or (more commonly) partial transfer of use rightscommunities, either for communal resource management among community members,or as joint resource management with state authorities or private entrepreneurs; (ii)transfer of responsibility for specific resource management tasks to communities, e.g.implementation of management actions, enforcement of regulations, monitoring ofresources etc.; (iii) development of resource sharing agreements and ParticipatoryLand Use Planning; (iv) establishment of Community Based Organisations (CBOs)as the management entity for such resources, frequently with national or internationalNGOs as facilitators, and in some cases involving capacity development to enhancethe voice and networks of CBOs; (v) development of benefit-sharing arrangementsas incentives for sustainable use, e.g. transfer of forest and wildlife revenues from stateto community, and (vi) alternative incomes and livelihoods as a means of reducingpressure from scarce or protected resources.Multi-stakeholder fora and committeesThese constitute collaborative mechanisms for the management of natural resourcesbetween the national and community level. They include mechanisms that aretypically defined by resource boundaries rather than administrative ones, such asWater user Associations, Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM) basinor sub-basin committees, Protected Area management boards or Participatory LandUse Planning fora. They typically consist of stakeholder representatives from resourceuser organisations, as well as government sector bodies and/or Local Governmentauthorities, and may be charged with collaborative planning and development ofregulations. Some fora, such as sub-basin IWRM committees may also have a conflictmanagement mandate, and may be charged with organising public consultations.25

DIIS REPORT 2012:04

District level institutionsLocal government authorities and government agencies at district level sometimesplay an important de facto role in everyday conflict prevention and management.For instance, district staff who work in water affairs or other technical departmentsfrequently engage in close contact with community members and may be informallyused as mediators or arbitrators if they are trusted and respected. This aspect is rarelymentioned in the literature, and has not been a frequent focus of interventions toaddress conflicts. Specific conflict prevention and management fora involving multiplestakeholders have been developed at district level in some countries, frequently inpost-conflict situations where broader security concerns are involved.Private sector engagementThe private sector can, in some cases, play a part in innovating and disseminating newtechnologies and practices that may provide access to new resources or reduce demandfor existing ones. This can ideally help reduce the pressure on scarce resources andthereby indirectly contribute to conflict prevention and resolution. Examples includenew water technologies (e.g. deep pumps) that can provide access to groundwaterresources previously beyond reach and/or associated payment and managementschemes. Traditionally private sector engagement in such areas has focussed ontechnology development, but increasingly also involves broader schemes, such aswater payment and management schemes.6.2 Lessons learnt• A cross-cutting finding in the cases reviewed is that customary mechanisms arekey in local level conflict prevention. Much of the literature highlights the positivepotential of customary dispute settlement mechanisms because of their accessibilitydue to low cost, flexibility in scheduling and procedures, their knowledge of localcustoms and values, and use of local languages. Moreover, local customs can helpreconciliation of the parties after an agreement is reached (Castro 2005). Conflictprevention efforts that have engaged customary institutions have thus in severalcases been successful, whereas other efforts that have sought to bypass them havefrequently not. However, customary measures are frequently described as beingeroded, as a result of increasing pressure on natural resources and/or impositionof new rules and regimes by the state. This suggests that supporting and engagingcustomary conflict prevention mechanisms should be a priority.• Most prior support to customary conflict prevention measures seems to have hada rather narrow emphasis on supporting traditionalauthorities.While these are26

DIIS REPORT 2012:04

clearly very important, there appears to be scope for a more integrated approachthat works with the wider range of customary prevention mechanisms, such asdeveloping reciprocal relationships between land users, supporting agreementsfor shared management between local users, and integrating support to localadaptation practices as part of a conflict prevention strategy.• CBNRM interventions have in some cases succeeded in reducing or overcomingconflicts between local stakeholders and the state or other external parties (e.g.Child & Jones 2006; Mustalahti & Lund 2010), but have failed in others (e.g.Turner 1999; Oldekop et al. 2010). Where CBNRM interventions have failed toreduce conflicts, two key factors are that (i) incentives/benefits for communitymembers have been insufficient compared to the associated restrictions in resourceuse and access under CBNRM; and (ii) thede factodevolution of rights andauthority to communities has been limited, and frequently remains with stateagencies. In addition to this, alternative income generating activities and livelihoodoptions have in some cases failed due to a lack of understanding of local livelihoodstrategies, or insufficient attention to market needs (Wollenberg et al. 2001).Hence while CBNRM includes a number of elements that can help address futurenatural resource conflicts, particular attention is needed to ensure that they arebased on an in-depth understanding of local livelihood and market dynamics,and that they arede factosupported by national policies and legal systems.• While both customary and CBNRM measures for conflict prevention can provideimportant entry points to conflict prevention in natural resource management,they also have limitations. Firstly, they may not be legally recognised and cantherefore sometimes be easily undermined by external actors. Secondly, local leadersmay benefit from disputes to pursue their own interests. Thirdly, both types ofmechanisms are frequently dominated by local elites and are not necessarily pro-poor: while poor local households may prefer dealing with customary institutionsin local conflicts, it is not necessarily in their long-term interest to do so. Exclusionof women (who often bear the heaviest consequences of conflict) and young men(who are sometimes key actors in local conflicts) from both customary institutionsand CBOs is also frequently reported as a problem, and may contribute toconflict (Baechler et al. 2002; Brown & Crawford 2009). Community level forafurthermore tend to emphasise consensus-based decisions, which in some casesdisfavours stakeholders with limited negotiating power.• Addressing the issue of exclusion in customary and CBNRM institutions istherefore an important aspect of ensuring pro-poor and sustainable conflictprevention and management. Research on local water conflict and cooperationsuggests that excluded groups can benefit from using alternative institutional spaces27

DIIS REPORT 2012:04

for venting their grievances when the ‘normal’ spaces are dominated by elites withopposing interests (Funder et al. 2012.)2Other checks and balances that can helpsupport marginalised stakeholders include regular monitoring and supervision ofwhether agreements and decisions are upheld by the involved parties (e.g. Child2006).• In general the role of women in both conflict and peace building efforts isunderestimated. In armed conflicts, women are often victims, suffering fromphysical, economic and psychological stress as armed conflict tends to exacerbateexisting gender discriminations. Furthermore, relative resource scarcity has differentimpacts on men and women’s coping strategies. For example, in pastoral settingswomen are often responsible for children and cannot easily migrate, and femaleheaded households are particularly vulnerable due to tenure insecurity (Omolo2011). Studies from the upper eastern region in Kenya, however, also show thatwomen may take part in the cultural reproduction of conflict, by e.g. singingsongs that encourage men to raid cattle and carry out revenge attacks. In theKaramoja region in Kenya and Uganda pastoralist women may also be involvedin ammunition trading (Mkutu 2008). Efforts to work with women throughsensitisation to address these issues have proved successful in some cases.3Womenare also potentially important peacekeepers as they play a key role in establishingcontinuity, which enables families and communities to move forward in post-conflict situations. The development of District Peace Committees in Kenya isthus based on an initial initiative taken by a group of women in Northern Kenya(see Annex 2).• Customary institutions and CBOs do not necessarily in themselves have thereach to address conflicts that take place across multiple communities or on awider geographical scale. They may be most suited to reconcile members of thesame social group, as they may not be considered legitimate by people coming infrom the outside or other countries, as they may be biased towards members oftheir own social group. It may therefore be necessary to engage other institutionsat other levels.• In some cases district authorities are mentioned as imposing authoritarianapproaches to community members in situations of conflict (Berger 2003; Castro2005). However, while this is clearly the case in some locations, they may also serveimportant de facto roles in conflict prevention and management as mentionede.g. where a chief or headman is biased against the grievances of a poor household, the latter may benefit fromseeking the support of a local government councillor or a CBO. Or vice versa.3Author interview with PeaceNet Kenya, 2010.2

28

DIIS REPORT 2012:04

•

•

•

•

above. Cases from Ethiopia, Kenya and some other sites furthermore point to thebenefits of approaches that foster collaboration between customary institutionsand local government and district agencies in conflict prevention and resolution,for example the District Peace Committees (DPC) in Kenya (see annex).Multi-stakeholder fora and committees such as IWRM committees or water userassociations at sub-basin level or joint protected area management boards are stillunder development in many areas. Experiences so far suggest that such fora canbe beneficial for aligning interests and planning between stakeholders in somerespects, but also that they suffer from challenges of equitable representation(Höynck & Rieser 2002). They may also, in some cases, be too far removed from ornot aligned with the de facto patterns of decision making and conflict resolutionsought by local stakeholders. Hence, while such institutions may be beneficialfor specific resource planning exercises, it should not be assumed that they are apanacea for resolving conflicts at e.g. community level (Barham 2001).The range of third parties that community members choose to involve may be wide,and are not necessarily exclusively either customary or statutory mechanisms. Thirdparties may be elders, local chiefs, judges and/or local government representatives(Beyene 2010; Grahn 2005; Theron 2009). Third party involvement does notnecessarily entail that conflicts get resolved (Castro 2005; Lund 1998; von Benda-Beckman 1981; Moore 1992). If local authority structures or other circumstanceschange, cases may be retried or reopened by losing parties (Barrière & Barrière 2002;Moore 1992). This is not necessarily because the conflict managing mechanismsdo not function properly; it rather reflects how things often work at the local level,and that institutions should be supported in ways that allow them to handle theinevitable re-emergence of some conflicts (Moore 1992). It is moreover importantto pay attention to petty corruption and bribery in third party involvement as thisreproduces inequality and may aggravate conflicts (Benjaminsen & Ba 2009).In general, the above experiences point to the benefits of involving a broad rangeof institutions and mechanisms in local conflict prevention and resolution. Thisnot only helps avoid conflicts over authority between the various institutionsinvolved, but also helps draw on the comparative advantages of different institutions.For example, the degree of trust often afforded to customary institutions can becomplemented by the options for advocacy by civil society institutions, while localgovernment agencies can provide alternative options for voicing grievances, andcoordinate activities across locations and upwards to central government (Swatuk2005).Private sector engagement in the innovation of new technologies and approacheshas in some cases helped to introduce improved technologies and management29

DIIS REPORT 2012:04

schemes in rural areas, especially within water development. This has frequentlyhelped address important local stakeholder needs. However, the extent towhich it has contributed to conflict prevention and resolution in practice is lessclear. In some situations, the development of new water resources can in itselfinduce conflict between local stakeholders who compete for access to new waterinfrastructure (Bolwig et al. 2009; Funder et al. 2010). As private sector engagementis furthermore based on marketing terms, technologies may not be equally attractiveor affordable to different stakeholder groups (e.g. upstream/downstream; poor/wealthy; or farmers/pastoralists), leading to bias and possible conflict as a result.The contribution of the private sector to innovation and dissemination of newtechnologies and practices thus needs to be balanced by careful attention to issuesof access and ownership of the resources in question.

30

DIIS REPORT 2012:04

7. Experiences from the national level

Apart from military interventions to stop violence, three types of national levelmeasures to prevent and manage conflict in natural resource management are reflectedin the literature reviewed:

7.1 National conflict prevention and management in naturalresource managementDevelopment of national institutional frameworks for conflict prevention andmanagementThis can include developing the legal system in order to resolve conflicts throughstandard judicial procedures, or developing specific national bodies aimed at conflictprevention (Theron 2009; van Leeuwen 2009. See also Danida 2010 a/b). The basicprinciple of the latter is to provide mechanisms that prevent emerging and existingtensions from developing into actual conflict, by e.g. monitoring through early warningsystems, and addressing key issues of concern early on. Typically such institutionsalso have a conflict management and resolution mandate, and the emphasis is notnecessarily on natural resources specifically. A case in point is the National SteeringCommittee on Peace Building and Conflict Management in Kenya (see annex).Cross-sectoral policy coordination and planning related to natural resourcesA recurrent finding in the study is the call for better harmonisation between differentland use and development policies and interests. At the national level, measuresto address this typically include cross-sectoral policy integration and provision ofappropriate frameworks for practical planning efforts such as IWRM, strategicenvironmental assessment, land use planning etc.Reforms and revisions of the allocation and governance of land, water and othernatural resourcesThis includes measures such as land reform, development of new processes andprinciples for water allocation and payment, and devolution of authority and revenuesin natural resource management (Bob 2002; Hughes 2001; Herrera & Gugliema daPassano 2006; UNEP 2009). While such reforms may have a number of purposes,they ideally address basic aspects of resource allocation and can serve to address rootcauses of many conflicts, such as conflicts over unequal land access for example, and31

DIIS REPORT 2012:04

unclear land tenure or infringement of local water rights. Examples include a range ofoptions such as land reform (Hughes 2001), incorporating customary law and localrights into the formal legal system and policy frameworks (Mwangi & Dohrn 2008),or devolution of forest and wildlife management rights and revenues (Mustalahti &Lund 2010).Alternative Dispute Resolution approachesAlternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) is a range of processes and techniques fordispute resolution outside the judicial process (Herrera & Guglielma da Passano2006). It can be used at local, national and transboundary levels, but is discussed hereas there is increasing attention to develop ADR capacity among NGOs and (so farto a lesser extent) government institutions. ADR processes may include:•Conflict assessment:to identify issues, interested parties, and possible pathwaysfor action early on•Interest-based negotiation:between different groups or individuals to understanddifferent parties interests and ways to address them•Mediation:intervention by a neutral third party to assist the parties in reachinga solution•Arbitration:third party listens to facts and arguments presented by the parties ortheir representatives to render a binding or non-binding decision•Negotiated rulemaking:multiparty negotiations to formulate environmentalregulations•Policy dialogues:discussions among different interest groups to encourage mutualunderstanding.•Quasi-judicial processes:expert opinions to interest groups through techniques suchas early neutral evaluations, mini-trials, settlement judges, and fact-finding.

7.2 Lessons learnt• Cross-sectoral efforts and structural reforms such as those mentioned above areconsiderable and challenging tasks, but are nonetheless key elements of structuralconflict prevention in natural resource management. In a number of the casesreviewed, such national level measures are lacking, and this is frequently describedas a major reason why conflicts develop and persist in the first place, or why localefforts to address conflicts fail.• A recurrent finding in the literature is thus that while conflicts should ideallybe prevented locally and through local institutions, national frameworks and32

DIIS REPORT 2012:04

•

•

•

•

reforms are essential to provide the overall regulatory frameworks and coordinatea concerted nationwide effort towards replication of successful institutions andarrangements (e.g. Kameri-Mbote et al. 2007).Elements of ADR can be seen in civil society approaches to conflict resolutionin a number of countries in the South, although experiences within naturalresource management are still limited (Castro 2005). The case study on thePeace Wells in Niger (see annex) applies several approaches that can be foundunder the overall ADR umbrella. ADR approaches are also subject to critiquein some of the reviewed literature, namely that they do not necessarily addressstructural inequalities and may serve to perpetuate or exacerbate powerimbalances (Cousins 1996).The benefits of using official legal systems in dispute resolution are that it strengthensthe rule of law and fosters the principle of equity before the law. However, theliterature review found that national legal systems can be inaccessible to the poor,women, remote communities or other marginalised groups due to cost, distance,language barriers, ethnicity, political obstacles, and discrimination (Herrera &Guglielma da Passano 2006; Huggins et al. 2005). People may lack knowledgeof procedures and, moreover, adjudication of cases may take a long time. ‘Accessto justice’ initiatives have sought to address this, although primarily outside thenatural resource management sector (e.g. Danida 2010 a/b).Attempts to make official governance systems more accessible and accountablehave been taken in the form of bureaucratic reforms. For example, decentralisationreforms have been widely implemented both in the form of deconcentration(delegating responsibility to field units of ministries) and devolution (transferringsubstantive power to the local level). In practice, however, decentralisationprocesses have often been slow to implement in reality, and power inequalitiesat the local level have sometimes undermined the democratic reform intendedby decentralisation. Evidence from the literature review thus suggests thatdecentralisation sometimes exacerbates, rather than reduces local naturalresources conflicts (Ribot 1999; 2002), because local political and economicelites take advantage of pursuing new opportunities provided by decentralisation(Castro 2005).In many cases appropriate national level frameworks for preventing and managingconflict in natural resource management are thus in fact in place on paper, but arenot de facto implemented. Reasons described in the literature include capacityand funding constraints, resilient institutional cultures and conflicting sectoralinterests. Control of the productive resources and their associated revenues canbe important funding and power bases for central sector institutions, who may33

DIIS REPORT 2012:04

be reluctant to actually devolve resources. International stakeholders that bypassnational policies and legislation have, in some cases, added to this, e.g. land-grabbingas a result of corruption and/or individual exemptions (Cotula et al. 2009).Approaches that have had some success in reducing these constraints include:• Highlighting and demonstrating to national policymakers the actual benefits ofcross-sectoral coordination and reforms, as well of particular types of land use,e.g. in terms of national economic benefits, efficiency savings and the costs ofconflicts to national budgets (UNEP 2009; Uitto & Duda 2002).• Anchoring reforms and policies in broad public consultation processes, therebyenhancing legitimacy and reducing the scope for central government retrenchmenton the issue (Campbell et al. 2009; Nielsen Raakjær et al. 2004).• Ensuring that reform and policy development is accompanied by appropriate andinclusive conflict prevention, management processes and fora that can monitorand address key issues during formulation and implementation, and provide forafor expressing grievances (Campell et al. 2009; Edossa et al 2005).• Enhancing the capacity and frameworks for civil society advocacy and monitoringof natural resource governance, including ensuring that policies and laws arefollowed through in practice (Theron 2009).• Strengthening platforms and networks for local government authorities orcustomary institutions to claim revenues and authority vis-à-vis central authoritiesas provided in formal policies and laws (Yurdi et al. 2006; Van Leeuwen 2009).• Supporting integration of customary tenure and resource management institutionsin formal national legislation and policy, where this is in accordance with pro-poordevelopment (Byene 2010, Castro 2005; Mwangi & Dohrn 2008).

34

DIIS REPORT 2012:04

8. Experiences from the transboundary level

Transboundary conflict prevention and management in Africa has especially focussedon river basin management. Apart from this, major lakes such as Lake Victoria andLake Chad also have transboundary, intergovernmental collaboration. In addition, inrecent years cross-border protected area management has developed in various partsof the region in the form of so-called ‘Peaceparks’ that help ensure collaboration andconflict prevention across international borders. There have also been emerging effortsto address issues of cross-border conflicts, for example between pastoralists in theHorn of Africa, through cross-border collaboration between local authorities.The following section draws mainly on experiences generated by transboundaryriver basin management, which is where the bulk of documentation currently exists.However, many of the emerging experiences from Peaceparks and local cross-bordercollaboration are similar to these.8.1 Transboundary conflict prevention – lessons learntOf the 63 river basins in Africa, approximately one third are covered by some formof collaborative River Basin Organisation (RBO) (Boege and Turner 2006). Inaddition to this, more than 150 bi- or multilateral agreements have been developedfor international river basins on the continent (Lautze & Giordanio 2005). Thesegenerally consist of three overall types, namely (a) agreements that cover all shared waterbodies between countries (e.g. between Namibia and South Africa); (b) single watercourse agreements (e.g. the Niger, Zambezi and Nile basins), or (c) agreements thatcover specific shared water course projects such as dams (Boege & Turner 2006).Many of the current RBO frameworks and collaborative agreements are – at leastnominally – based on the UN Convention on International Water Courses, whichsets down (i) a principle of equitable and reasonable utilisation; (ii) a do no harmprinciple, and (iii) a duty to cooperate with other, co-riparian states. In accordancewith these principles, ratifying governments are obliged to notify other basin statesof any major developments they plan to undertake on the water course, and canproceed if other signatories have no objections.Although disagreements between riparian states have frequently occurred, actualacts of violence and military aggression over transboundary water resources have35

DIIS REPORT 2012:04

been very rare between African states.4This is also evident on a global scale, asdocumented in the Transboundary Freshwater Dispute Database, which has shownthat the vast majority of actions between riparian states are collaborative rather thanconflictive (Wolf et al. 2003; see also Ravnborg 2004). Indeed, analysis shows thatsuch agreements have often proved surprisingly enduring in the longer term (Wolfet al 2003op cit.).This does not, however, mean that all is well. Although most of the major river basinsin Africa are now covered by transboundary agreements, two thirds of the continent’sbasins remain without agreements. Moreover, only 25% of the existing agreementsinclude all riparian nations (Lautze & Giordanio 2005). Progress in developingtransboundary collaboration has furthermore been protracted in many river basinsacross the continent, and differences of interest abound. Even where more substantialcollaborative mechanisms have materialised, they have typically developed out oflong-term processes over several decades, involving an erratic but gradual build-upfrom single-issue agreements via setbacks and diversions to a gradually wider scope ofcollaboration. An extreme example of this includes the Nile Basin Initiative describedelsewhere in this report, but a similar process is evident in the long-standing efforts todevelop a collaborative mechanism for the Zambezi River. Increasing demand for waterin the face of recurring droughts and increasing economic development is, in somecases, adding further to intensify competing demands, as in the case of negotiationsbetween Uganda, Tanzania and Kenya on the extraction of water resources fromLake Victoria (Kagwanja 2007).Our review of the literature also found a number of more specific experiences relevantto conflict prevention and management at transboundary levels:• National interests override all other concerns in negotiation processes. This isrepeatedly found throughout the literature. Collaboration for the sake of a highercollective purpose is rare. Collaborative agreements therefore need to generategenuine added value for the involved nation states – whether in terms of economic,political, cultural, security – or environmental benefits (Qaddumi 2008).• Approximately half of the existing agreements lack clear allocation of water rightsbetween riparian states (Lautze & Giordanio 2005). In some cases this is the resultof a deliberate strategy which seeks to develop mutual benefits (e.g. mobilising4

One of the few exceptions cited in the literature is South Africa’s military intervention in Lesotho in 1998 which– despite claims to the contrary - was reportedly conducted with the intention of ensuring water supply from thecontested Lesotho Highlands Water Project (Boege and Turner 2006).

36

DIIS REPORT 2012:04

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

investments and addressing joint risks) before addressing thorny issues of resourcesharing. While such a strategy has been successful in the short term in some cases,it also means that critical issues of allocation are only postponed and may lead tobreakdown of collaboration at a critical point – especially if water scarcity increasesas in the case of climate change (Lautze & Giordanio 2005; Mekkonen 2010).A dual process is therefore needed which works simultaneously on optimisingbenefits and negotiating clear user rights (Mason 2004).Cost sharing arrangements can be as important as benefit sharing arrangements.Options for economic compensation are frequently not fully exploited, e.g.compensation from one country to another for loss of downstream water flow(Qaddumi 2008).Collaborative programmes that foster economic interdependence and economicintegration across boundaries have a stabilising effect on transboundaryrelationships (Mason 2004), e.g. joint projects to sustainably exploit waterresources or the tourism potential of transboundary protected areas.Generation of mutual information and data for water course management can act asan important initial platform for collaboration, upon which further collaborationcan be built. Positive experiences are quoted from jointly conducted assessments ofresources, conflicts and common risks in river basins, and collaborative productionof technical data on e.g. water flows and climate change (including early warningof flooding etc.).Anchoring transboundary agreements and collaborative activities in widerregional frameworks (e.g. SADC for the Zambezi) has contributed to fosteringpolitical will and momentum in some cases, and, furthermore, helps ensureintegration with wider regional policies and development efforts.Bilateral agreements are far more numerous than multilateral ones, and typicallyeasier to establish Building on bilateral relationships and exploiting thecomparative advantages of two states has proved successful in several instances.However, developing bilateral agreements in a context of multiple riparianstates can also be risky, because it may preclude multilateral agreements byexcluding other riparians, and can defeat the purpose of basin-wide approaches.Bilateral efforts therefore need to be carefully coordinated with multilateralefforts.Support to enhancing water use efficiency and policies in individual countriescan help facilitate and sustain transboundary agreements, because the projectedwater demands of individual countries are reduced (Qaddumi 2008).Multi-track negotiation and communication approaches have generally shownfavourable results (Mason 2004). This entails working at several levels and in37

DIIS REPORT 2012:04

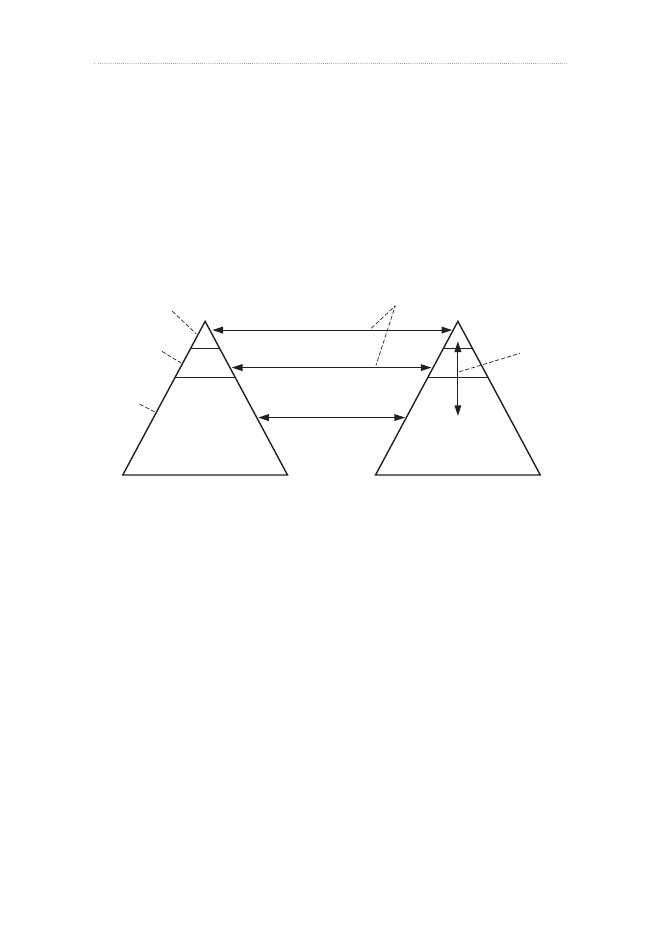

multiple fora to discuss, negotiate and review collaborative arrangements. Thefigure below illustrates one approach to multi-track conflict prevention andmanagement. In extension of this, development of river basin organisations hasoften had an exclusive focus on formal, inter-governmental, decision-makingprocedures, while engagement of civil society and private sector stakeholdershas sometimes been ‘forgotten’ or underestimated This may increase the risk ofconflicts emerging at other levels, including across national boundaries (e.g. Hirschand Jensen 2006).������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������

����������������

“Multi-track” = communication between different tracks of different countries, “Cross-track” = communicationbetween different tracks within one country. Track one (official), Track two (non-official) and Track three(grass-root) diplomacy or conflict management are complementary.Source:Mason 2004

8.2 Transboundary conflict management – lessons learntJust over half of Africa’s existing transboundary agreements contain conflict resolutionmechanisms, which is in fact a higher proportion than in some other parts of theworld (Lautze & Giordanio 2005). Such mechanisms may stipulate provisions fora designated body within the RBO to act as a third party and oversee negotiationsbetween two disputing riparians. If disputes cannot be settled they may, in somecases, be referred to a higher authority outside the RBO, e.g. a regional collaborativebody. Mechanisms described in the agreements are, however, not necessarily clearor applied in practice (see e.g. Schulz 2007). Attention to development of clear andwell-functioning conflict resolution mechanisms in RBOs is therefore frequentlycalled for (Boege & Turner 2006).38

DIIS REPORT 2012:04

Power asymmetries and economic inequity between states has been a core challengein transboundary conflict resolution (e.g. Jägerskog & Zeitoun 2009). Attempts toaddress this have included:• Identification of incentives for powerful states to shift from conflictive tocooperative behaviour, e.g. through collaborative projects in poor upstream statesthat help ensure the water security of powerful downstream states.• Capitalising on the increasing water demands from powerful economies (whethercaused by increasing demand or water scarcity) to engage them in collaborativeschemes. For example, South Africa consumes some 80% of water resources inSouthern Africa, but contributes only 8% and has escalating demands (Scheumann& Neubert 2006). While such a situation poses a potential risk of conflict, it alsoprovides a potential opportunity to engage the country in collaborative negotiationsover riparian rights, as is currently the case.• Enhancing the capacity of weaker states to engage in negotiations and technicalmanagement issues (op cit.).• Undertaking the above activities alongside efforts to develop frameworks inaccordance with UN principles on equitable sharing of water courses (Mekonnen2010).Experiences from such efforts suggest a need for long-term engagement andinvolvement of third parties, and may be particularly challenging in situations wherethe powerful riparians are located upstream. Other experiences related to conflictresolution in transboundary water governance include:• Building human resources capacity for transboundary conflict resolution, includingtraining of legal experts for mediation and brokerage at the regional level, whichare often lacking• Initiating practical, on the ground, projects as vehicles for collaboration• Addressing local transboundary conflicts by establishing joint border commissionsor regular exchange visits between local authorities, as applied in parts of NorthernKenya• Engaging international donors as third parties/facilitators to support dialogueand practical collaboration, although care should be taken to avoid agreementsand collaborative frameworks becoming essentially donor-driven

39

DIIS REPORT 2012:04

9. Addressing climate-related conflicts in developmentcooperation

The following section proposes key principles and elements for addressing climate-related conflict in development cooperation. The recommendations are based on thereview of experiences from natural resource management discussed above, as well ason literature relating to climate change and development specifically. Experiencesfrom conflict and security studies and ‘conflict sensitive development’ approachesare also drawn upon.9.1 Guiding principles for addressing climate-related conflicts indevelopment cooperationGuiding principles for addressing climate-related conflict resolution include:•Climate-related conflicts should be seen in the perspective of other developmentchallenges.Conflicts are serious and should be addressed. However, climate-relatedconflict is not necessarily the only or indeed the biggest development challengein a given setting, and it should not divert attention or funding from efforts toaddress other fundamental development issues.•Interventions should be based on careful analysis of the links between climate change,conflict and development.Climate-related conflicts are typically complex andmulti-layered, and prior assumptions about the role of climate change in conflictsoften turn out to be wrong or only part of the story. Thorough analysis is thereforeneeded prior to interventions.•Interventions should help prevent and resolve conflicts, not suppress them.The aimof addressing climate change conflicts is not to suppress or subdue them, but toprevent and resolve them to the satisfaction of those involved. Experience showsthat interest-based negotiation is often more effective than agreements based onnominal consensus.•Attention to poverty alleviation and inequality.Mechanisms for addressingclimate-related conflicts should have an emphasis on equitable access and pro-poor outcomes. This may include special efforts such as innovating means for theinterests of the poor to be considered in consensus-based mechanisms, which arenot necessarily pro-poor in themselves.•Draw on existing mechanisms and principles for resolving conflict as far as possible.Where relevant, existing principles and mechanisms for addressing conflicts40

DIIS REPORT 2012:04

should be supported and built upon. These may range from customary conflictresolution mechanisms, through the emerging body of private sector institutionsand NGOs specialised in conflict resolution in e.g. Africa, to national frameworksand the various initiatives on conflict prevention and resolution in the AfricanUnion.•Balancing support to micro and macro scales.Experience show that local conflicts arebest solved locally, and that the principle of subsidiarity should apply in addressingconflicts. However, the underlying causes of many climate-related conflicts arenot generated locally, but from the national and even international level. Reformsand efforts may be needed at these levels to provide the frameworks that makelocal conflict prevention and resolution possible and sustainable.•Cross-sectoral approach.Addressing climate-related conflicts will typically takeits outset in the ‘green’ sectors, i.e. agriculture, natural resource management andenvironment, etc. However, conflict prevention and resolution requires engagementwith institutions and efforts in other sectors, e.g. governance, legal systems, socialdevelopment etc.•Donor harmonisationis particularly critical when addressing climate-relatedconflicts. Engaging with the root causes of climate-related conflicts requires effectiveharmonisation across development efforts. Moreover, because interventionsthemselves may cause or contribute to such conflicts, it is essential that effortsare coordinated. DAC principles on conflict-sensitive development can form apoint of departure for this.9.2 Key questions to considerKey questions and issues to consider when addressing climate-related conflict preventionand resolution in the programming of development cooperation include:Is climate-related conflict actually an issue?As discussed earlier, climate change doesnot necessarily contribute to conflict. A careful assessment of the situation is thereforenecessary, which avoids prior assumptions about the links between climate changeand conflict in the target area for support, and which considers whether externalintervention may actually do more harm than good to existing conflict preventionand resolution processes.What types of conflicts may be fuelled by climate change?In order to determine how andto what extent development cooperation can help address climate-related conflicts, anassessment must be made of the nature and scope of such conflicts in the target area41

DIIS REPORT 2012:04