Udenrigsudvalget 2011-12

URU Alm.del Bilag 132

Offentligt

THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S CHILDREN2012

Children inan Urban World

EM28BAFebr RGua Ory ED2012

EM28BAFebr RGua Ory ED2012

THE STATE OF THEWORLD’S CHILDREN2012

EM28BAFebr RGua Ory ED2012

� United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF)February 2012

Permission is required to reproduce any part of thispublication. Permission will be freely granted toeducational or non-profit organizations. Others willberequested to pay a small fee. Please contact:Division of Communication, UNICEF3 United Nations Plaza, New York, NY 10017, USATel: +1 (212) 326-7434Email: [email protected]

This report and additional online content are availableat <www.unicef.org/sowc2012>.PerspectiveandFocusOnessays represent the personal views of theauthorsand do not necessarily reflect the position ofthe UnitedNations Children’s Fund.For corrigenda subsequent to printing,please see <www.unicef.org/sowc2012>.

For latest data, please visit <www.childinfo.org>.ISBN: 978-92-806-4597-2eISBN: 978-92-806-4603-0United Nations publication sales no.: E.12.XX.1

EM28BAFebr RGua Ory ED2012Photographs

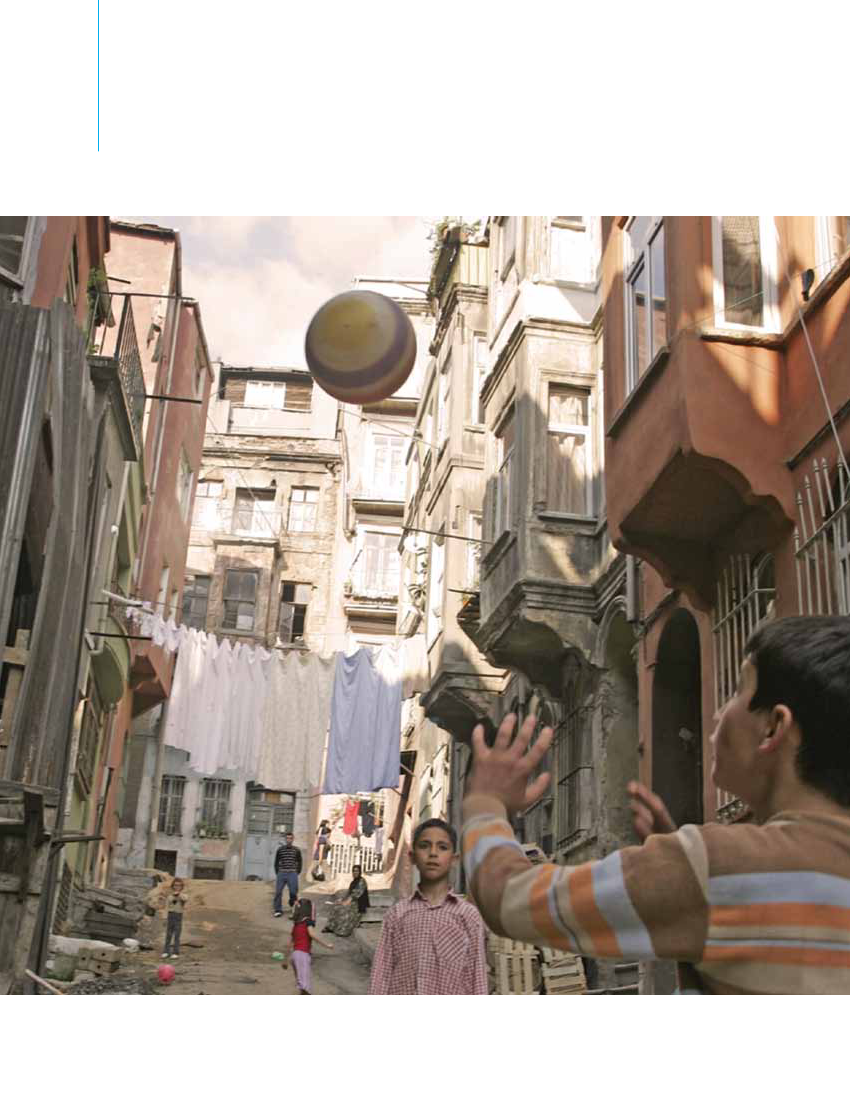

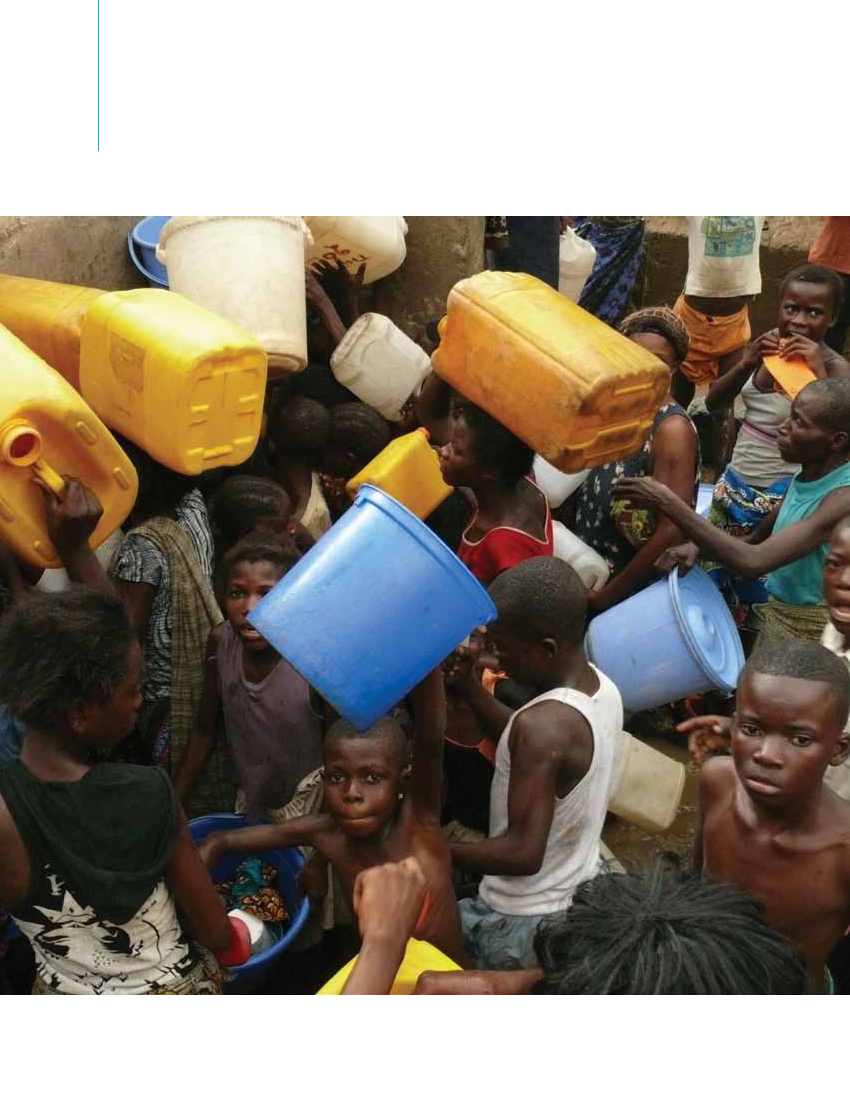

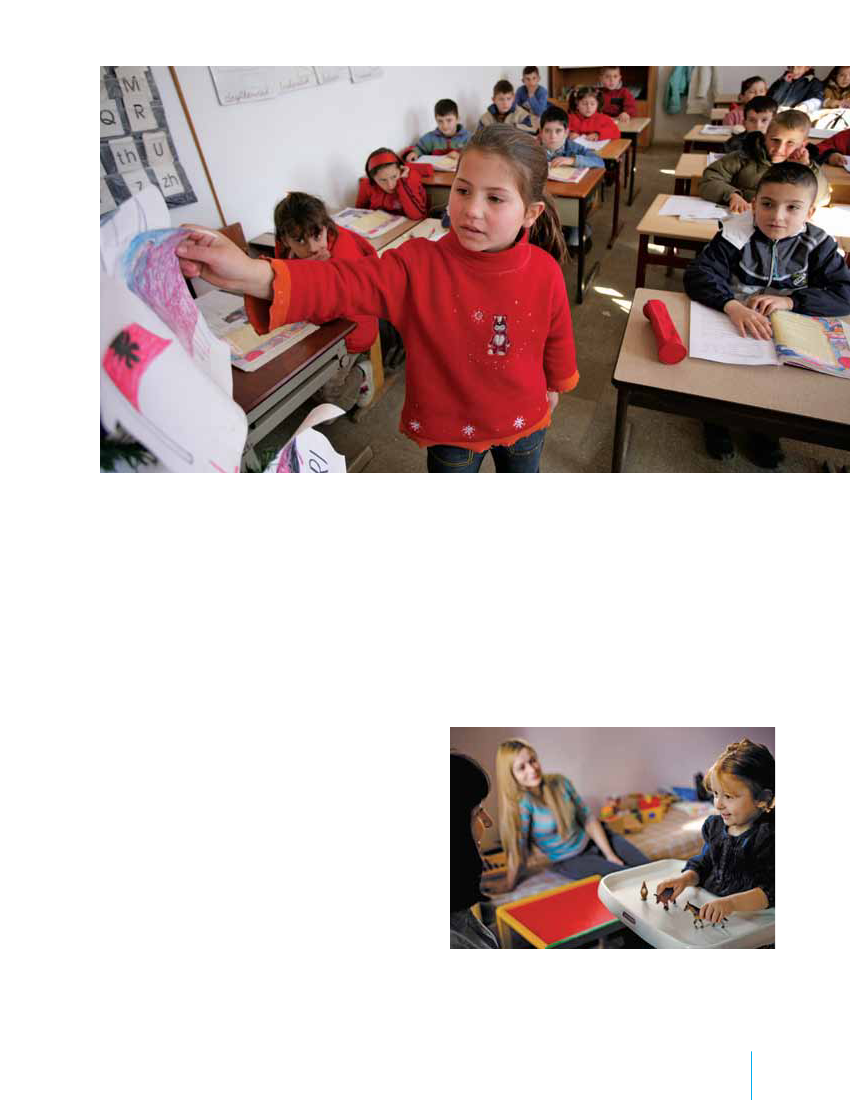

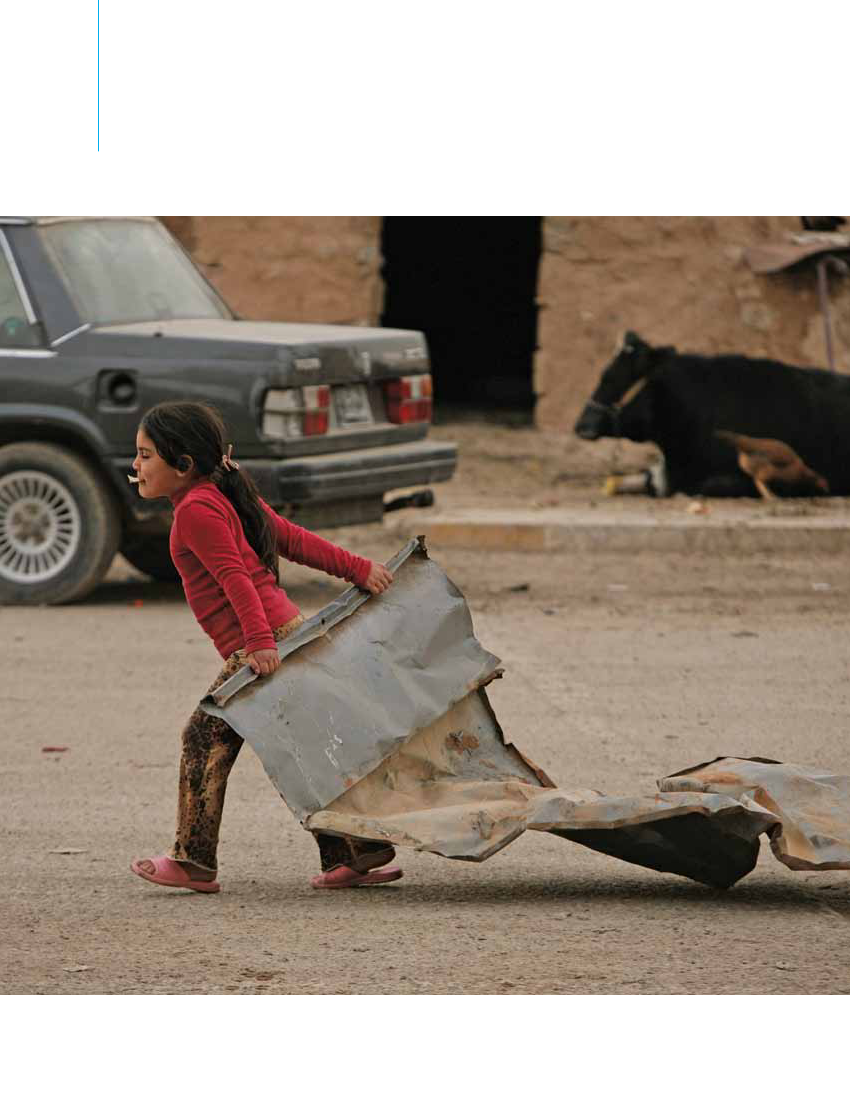

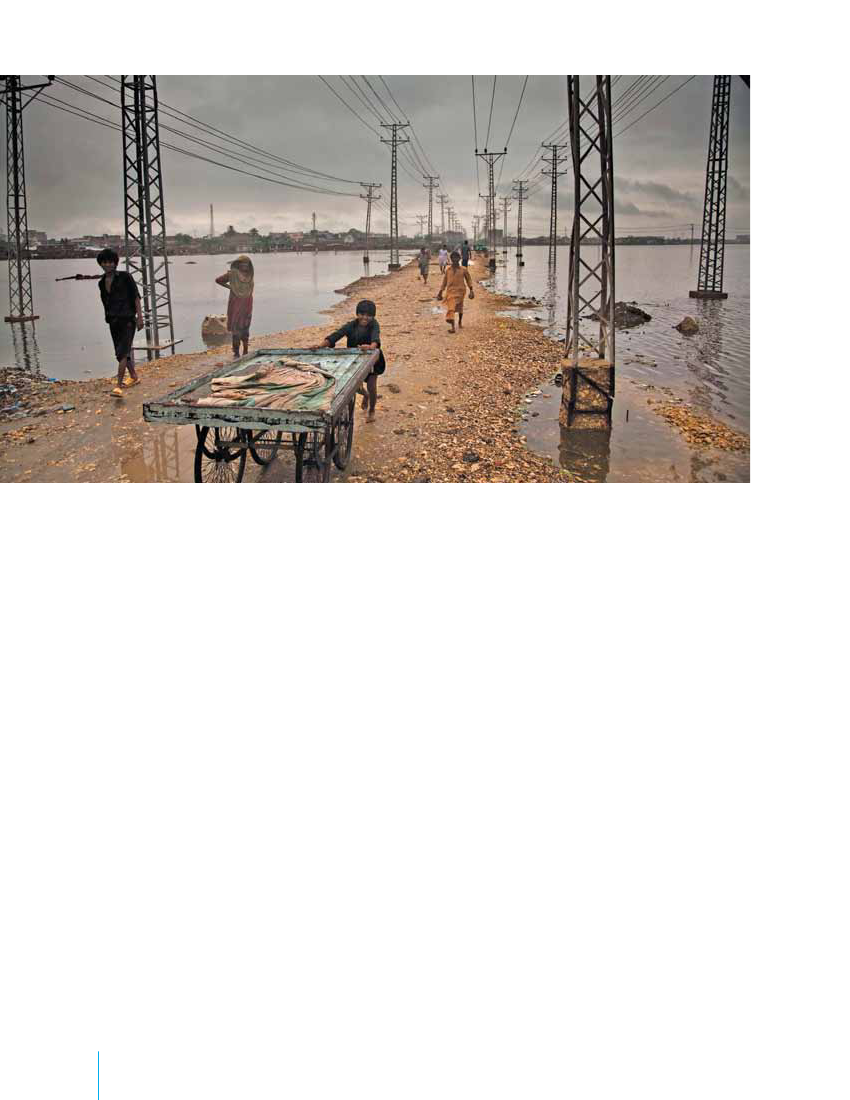

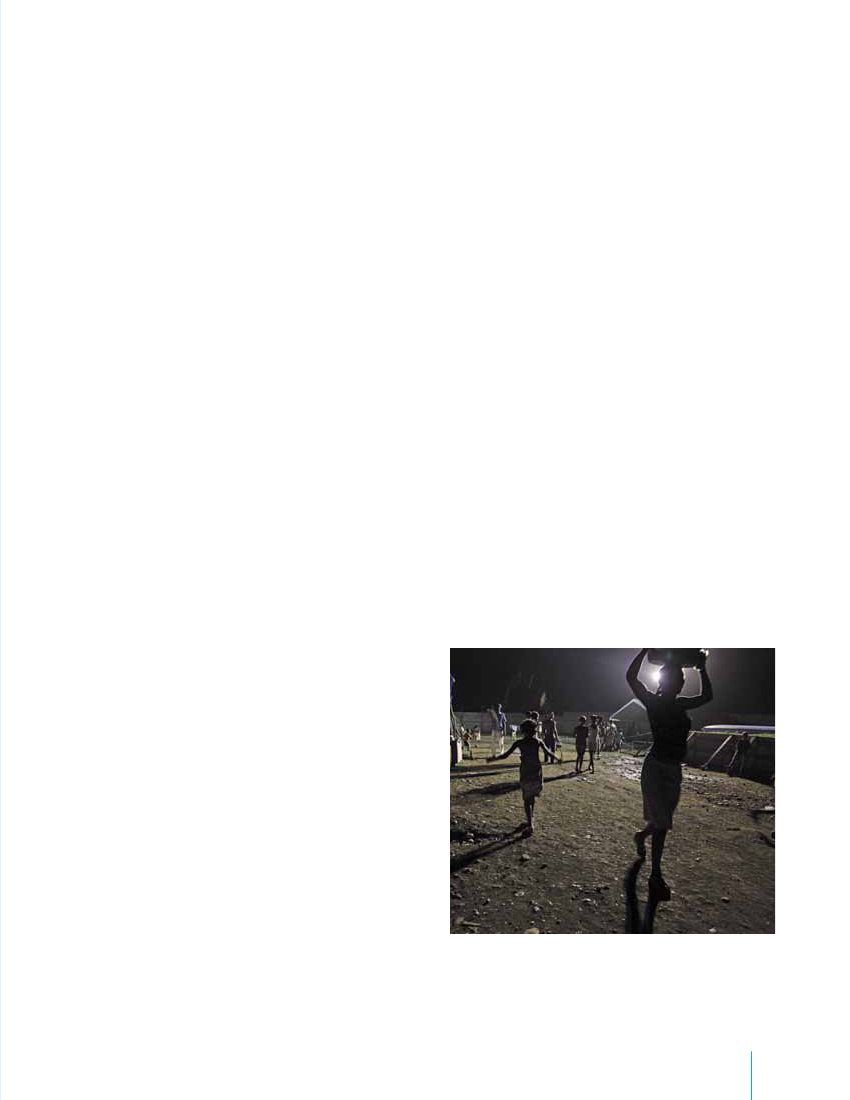

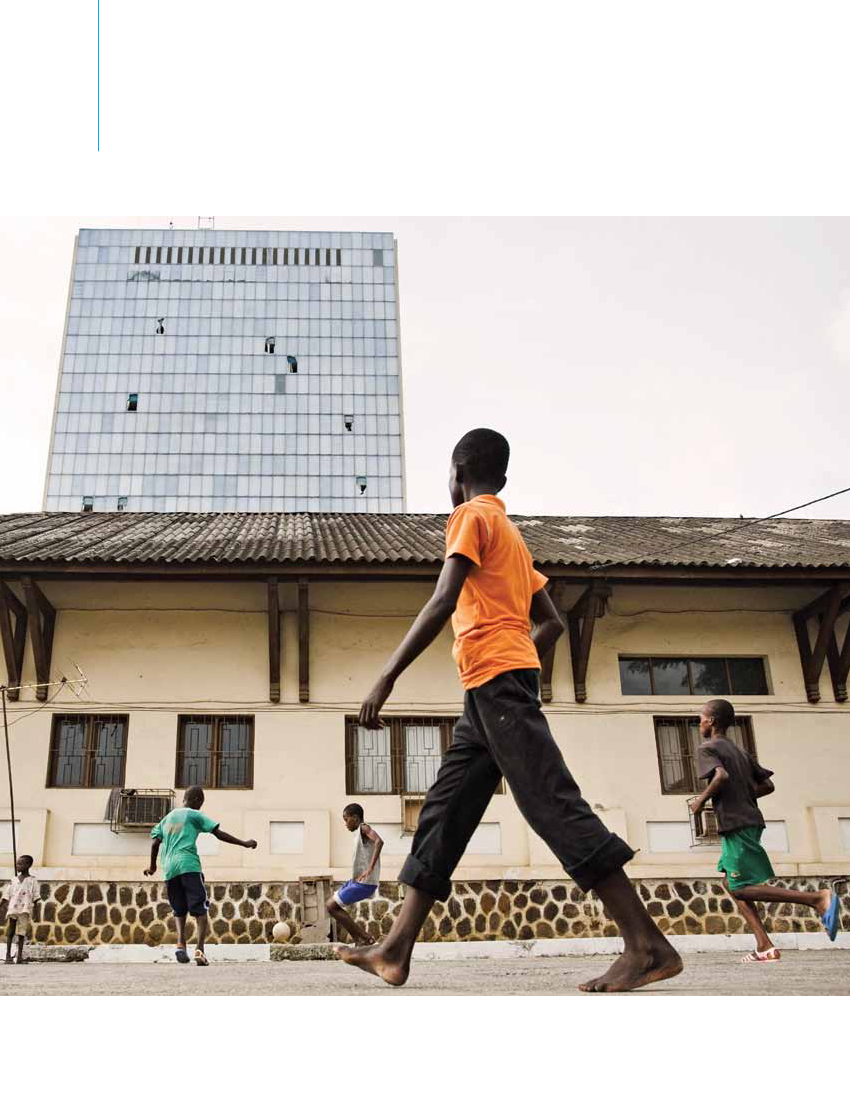

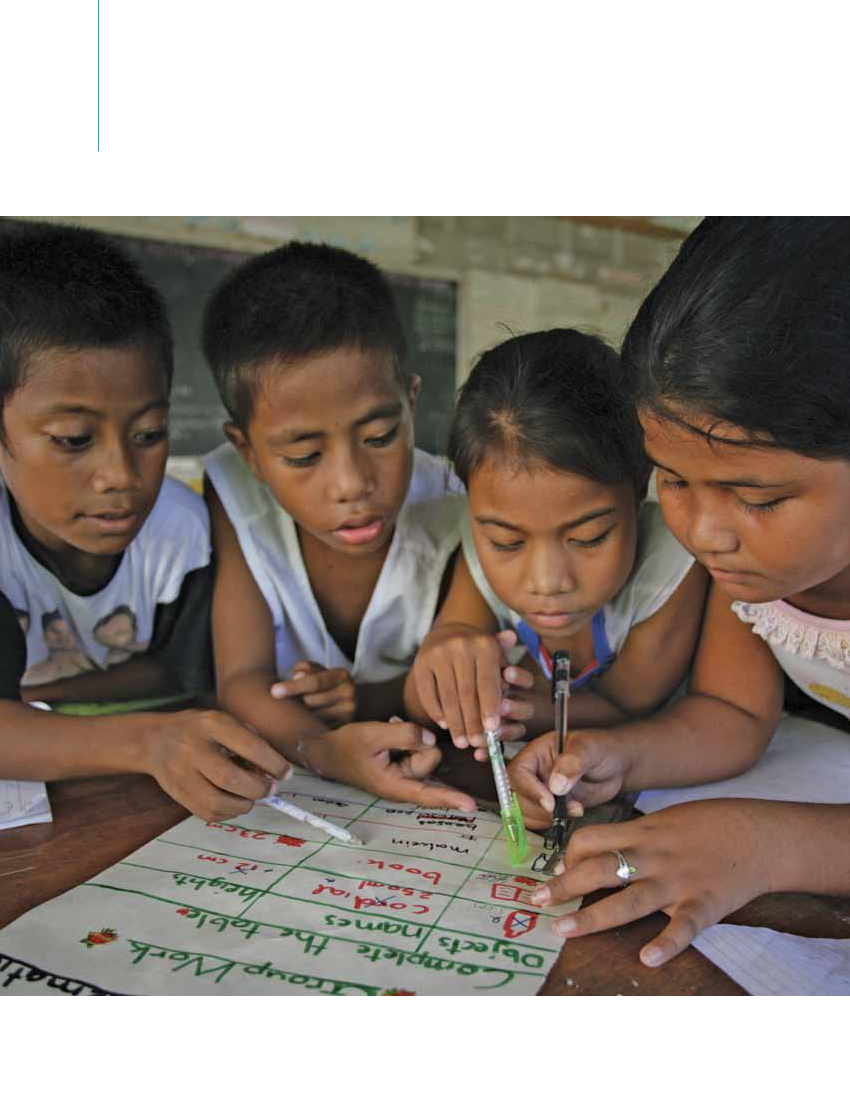

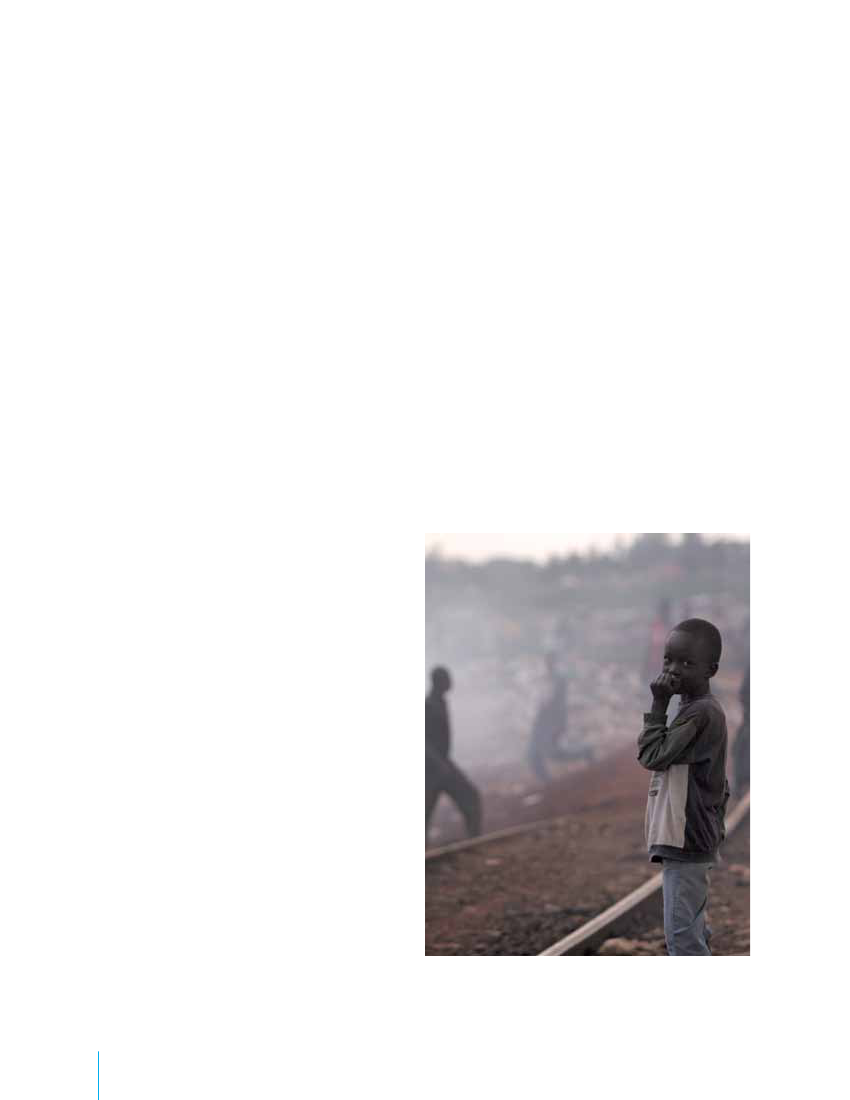

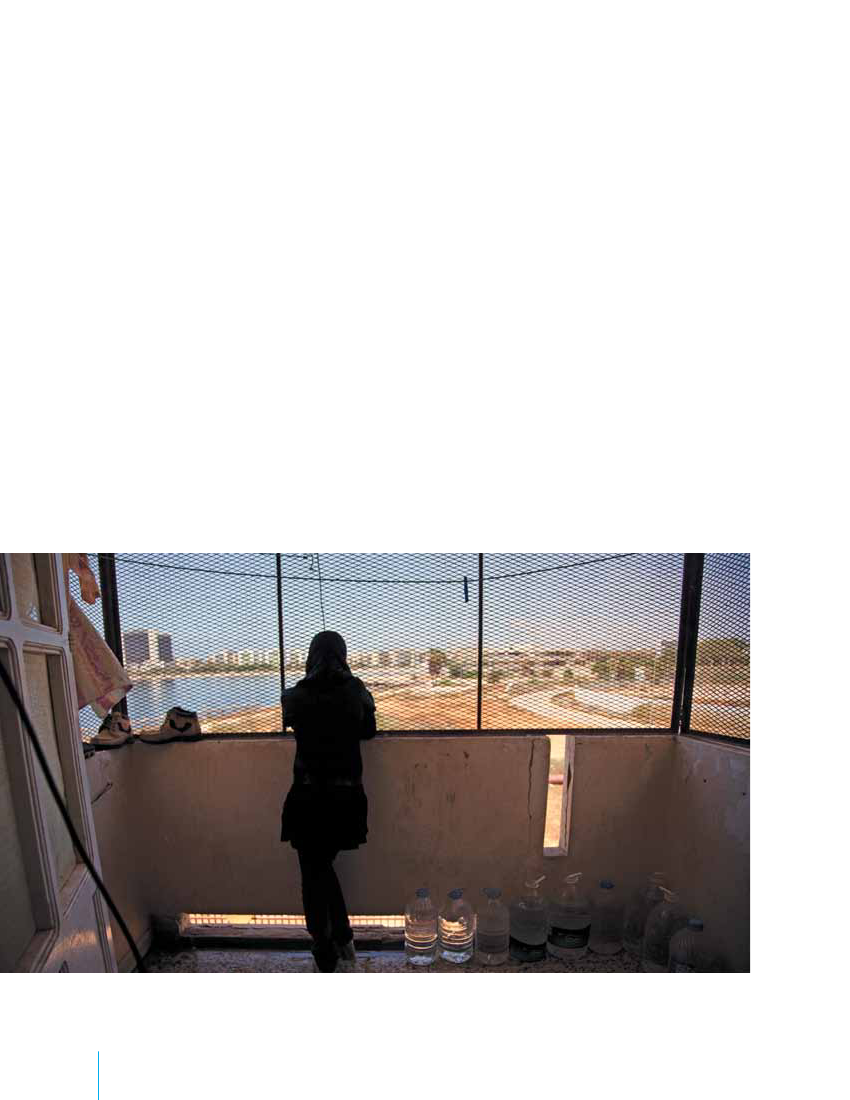

CoverChildren dance in an informal settlement ona hillsidein Caracas, Bolivarian Republicof Venezuela (2007).� Jonas Bendiksen/Magnum PhotosChapter 1, page xChildren play in Tarlabasi, a neighbourhood thatis home to many migrants in Istanbul, Turkey.� UNICEF/NYHQ2005-1185/Roger LeMoyneChapter 2, page 12Queuing for water at Camp Luka, a slum on theoutskirts of Kinshasa, Democratic Republic ofthe Congo.� UNICEF/NYHQ2008-1027/Christine NesbittChapter 3, page 34A girl in Kirkuk, Iraq, drags scrap metal that herfamily will use to reinforce their home – a smallspace with curtains for walls on the top floor ofa former football stadium.� UNICEF/NYHQ2007-2316/Michael KamberChapter 4, page 48Boys play football in the courtyard of the CentreSauvetage BICE, which offers residential andfamily services for vulnerable children in Abidjan,Côte d’Ivoire.� UNICEF/NYHQ2011-0549/Olivier AsselinChapter 5, page 66Girls and boys work on a group project in a primaryschool in Tarawa, Kiribati.� UNICEF/NYHQ2006-2457/Giacomo Pirozzi

ACkNOWLEDGEMENTSThis report is the fruit of collaboration among many individuals and institutions. The editorial and research team thanks allwho gave so generously of their expertise and energy, in particular:Sheridan Bartlett (City University of New York); Jean Christophe Fotso (APHRC); Nancy Guerra (University of California);Eva Jesperson (UNDP); JacobKumaresan (WHO Urban HEART); Gora Mboup (UN-Habitat); Sheela Patel (SDI);Mary Racelis (Ateneo de Manila University); Eliana Riggio; David Satterthwaite (IIED); Ita Sheehy (UNHCR);Nicola Shepherd (UNDESA); Mats Utas (Swedish Academy of Letters); and Malak Zaalouk (American University of Cairo),for serving on the External Advisory Board.Sheridan Bartlett; Roger Hart and Pamela Wridt (City University of New York); Carolyn Stephens (London School ofHygiene and Tropical Medicine and National University of Tucuman, Argentina); and Laura Tedesco (Universidad Autonomade Madrid), for authoring background papers.Fred Arnold (ICF Macro); Ricky Burdett (London School of Economics and Political Science); Elise Caves and Cristina Diez(ATD Fourth World Movement); Michael Cohen (New School); Malgorzata Danilczuk-Danilewicz; Celine d’Cruz (SDI);Robert Downs (Columbia University); SaraElder (ILO); Kimberly Gamble-Payne; Patrick Gerland (UNDESA); FriedrichHuebler (UNESCO); Richard Kollodge (UNFPA); MaristelaMonteiro (PAHO); Anushay Said (World Bank Institute);Helen Shaw (South East Public Health Observatory); MarkSommers (Tufts University); Tim Stonor (Space Syntax Ltd.);Emi Suzuki (World Bank); Laura Turquet (UN-Women); HenrikUrdal (Harvard Kennedy School); and Hania Zlotnik(UNDESA), for providing information and advice.Special thanks to Sheridan Bartlett, Gora Mboup and Amit Prasad (WHO) for their generosity of intellect and spirit.UNICEF country and regional offices and headquarters divisions contributed to this report by submitting findings andphotographs, taking part in formal reviews or commenting on drafts. Many field offices and UNICEF national committeesarranged to translate or adapt the report for local use.Programme, policy, communication and research advice and support were provided by Geeta Rao Gupta,Deputy ExecutiveDirector;Rima Salah,Deputy Executive Director;Gordon Alexander,Director,Office of Research; NicholasAlipui,Director,Programme Division; Louis-Georges Arsenault,Director,Office of Emergency Programmes; Colin Kirk,Director,Evaluation Office; Khaled Mansour,Director,Division of Communication; Richard Morgan,Director,Division of Policyand Practice; LisaAdelson-Bhalla; Christine De Agostini; Stephen Antonelli; Maritza Ascencios; LakshmiNarasimhan Balaji;GerritBeger; Wivina Belmonte; Rosangela Berman-Bieler; Aparna Bhasin; Nancy Binkin; Susan Bissell; ClarissaBrocklehurst;MarissaBuckanoff; Sally Burnheim; Jingqing Chai; Kerry Constabile; HowardDale; Tobias Dierks; KathrynDonovan;PaulEdwards; Solrun Engilbertsdottir; Rina Gill; Bjorn Gillsater; Dora Giusti; JudyGrayson; AttilaHancioglu;Peter Harvey; Saad Houry; Priscillia Kounkou Hoveyda; Robert Jenkins; Malene Jensen; TheresaKilbane; JimmyKolker;JuneKunugi; Boris De Luca; Susanne Mikhail Eldhagen; Sam Mort; Isabel Ortiz; Shannon O’Shea; Kent Page;NicholasRees; MariaRubi; Rhea Saab; Urmila Sarkar; Teghvir Singh Sethi; Fran Silverberg; Peter Smerdon; Antony Spalton;Manuela Stanculescu; David Stewart; Jordan Tamagni; Susu Thatun; Renee Van de Weerdt; and NataliaElenaWinder-Rossi.Special thanks to Catherine Langevin-Falcon,Chief,Publications Section, who oversaw the editing and production of thestatistical tables and provided essential expertise, guidance and continuity amid changes in personnel.Finally, a particular debt of gratitude is owed to David Anthony,Chief,Policy Advocacy, and editor of this report for the pastseveneditions, for his vision, support and encouragement.

REPORT TEAM

EDITORIAL AND RESEARCHAbid Aslam, Julia Szczuka,EditorsNikola Balvin, Sue Le-Ba, Meedan Mekonnen,Research officersChris Brazier,WriterMarc Chalamet,French editorCarlos Perellon,Spanish editorHirut Gebre-Egziabher,Lead,Yasmine Hage, Lisa Kenney,AnneYtreland, Jin Zhang,Research assistantsCharlotte Maitre,Lead,Anna Grojec,Carol Holmes,Copy editorsCeline Little, Dean Malabanan, Anne Santiago,Judith Yemane,Editorial and administrative supportPRODUCTION AND DISTRIBUTIONJaclyn Tierney,Chief,Print and Translation Section;Germain Ake; Fanuel Endalew; JorgePeralta-Rodriguez;Elias Salem; Nogel S. Viyar; Edward Ying Jr.

EM28BAFebr RGua Ory ED2012

STATISTICAL TABLESTessa Wardlaw,Associate Director,Statistics andMonitoring Section, Division of Policy and Practice;PriscillaAkwara; David Brown; Danielle Burke;XiaodongCai; ClaudiaCappa; Liliana Carvajal; ArchanaDwivedi; AnneGenereux; ElizabethHorn-Phatanothai;ClaesJohansson; RouslanKarimov; Mengjia Liang;RolfLuyendijk; NyeinNyeinLwin; Colleen Murray;HollyNewby; KhinWityeeOo; Nicole Petrowski;ChihoSuzuki; Danzhen YouONLINE PRODUCTION AND IMAGESStephen Cassidy,Chief,Internet, Broadcast andImage Section; Matthew Cortellesi; Susan Markisz;KeithMusselman; Ellen Tolmie; Tanya TurkovichDesign by Green Communication Design inc.Printed by Brodock Press, Inc.

Acknowledgements

iii

ACTION

PUTTING CHILDREN FIRST IN AN URBAN WORLDThe experience of childhood is increasingly urban. Over half the world’s people – including more than abillion children – now live in cities and towns. Many children enjoy the advantages of urban life, includingaccess to educational, medical and recreational facilities. Too many, however, are denied such essentials aselectricity, clean water and health care – even though they may live close to these services. Too many areforced into dangerous and exploitative work instead of being able to attend school. And too many face aconstant threat of eviction, even though they live under the most challenging conditions – in ramshackledwellings and overcrowded settlements that are acutely vulnerable to disease and disaster.The hardships endured by children in poor communities are often concealed – and thus perpetuated – by thestatistical averages on which decisions about resource allocation are based. Because averages lump every-one together, the poverty of some is obscured by the wealth of others. One consequence of this is thatchildren already deprived remain excluded from essential services.Increasing numbers of children are growing up in urban areas. They must be afforded the amenities andopportunities they need to realize their rights and potential. Urgent action must be taken to:• Better understand the scale and nature of poverty and exclusion affecting children in urban areas.• Identify and remove the barriers to inclusion.

• Ensure that urban planning, infrastructure development, service delivery and broader efforts to reduce poverty and inequality meet the particular needs and priorities of children.• Promote partnership between all levels of government and the urban poor – especially children and young people.• Pool the resources and energies of international, national, municipal and community actors in support of efforts to ensure that marginalized and impoverished children enjoy their full rights.These actions are not goals but means to an end: fairer, more nurturing cities and societies for all people –starting with children.

iv

THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S CHILDREN 2012

EM28BAFebr RGua Ory ED2012

FOREWORDWhen many of us think of the world’s poorest children, the image that comes readily to mind is that of achild going hungry in a remote rural community in sub-Saharan Africa – as so many are today.But asThe State of the World’s Children 2012shows with clarity and urgency, millions of children in citiesand towns all over the world are also at risk of being left behind.In fact, hundreds of millions of children today live in urban slums, many without access to basic services.They are vulnerable to dangers ranging from violence and exploitation to the injuries, illnesses and deaththat result from living in crowded settlements atop hazardous rubbish dumps or alongside railroad tracks.And their situations – and needs – are often represented by aggregate figures that show urban children to bebetter off than their rural counterparts, obscuring the disparities that exist among the children of the cities.This report adds to the growing body of evidence and analysis, from UNICEF and our partners, that scar-city and dispossession afflict the poorest and most marginalized children and families disproportionately.It shows that this is so in urban centres just as in the remote rural places we commonly associate withdeprivation and vulnerability.The data are startling. By 2050, 70 per cent of all people will live in urban areas. Already, 1 in 3 urbandwellers lives in slum conditions; in Africa, the proportion is a staggering 6 in 10. The impact on childrenliving in such conditions is significant. From Ghana and Kenya to Bangladesh and India, children livingin slums are among the least likely to attend school. And disparities in nutrition separating rich and poorchildren within the cities and towns of sub-Saharan Africa are often greater than those between urban andrural children.Every disadvantaged child bears witness to a moral offense: the failure to secure her or his rights to survive,thrive and participate in society. And every excluded child represents a missed opportunity – because when soci-ety fails to extend to urban children the services and protection that would enable them to develop as productiveand creative individuals, it loses the social, cultural and economic contributions they could have made.We must do more to reach all children in need, wherever they live, wherever they are excluded and leftbehind. Some might ask whether we can afford to do this, especially at a time of austerity in nationalbudgets and reduced aid allocations. But if we overcome the barriers that have kept these children fromthe services that they need and that are theirs by right, then millions more will grow up healthy, attendschool and live more productive lives.Can we afford not to do this?Anthony LakeExecutive Director, UNICEFForewordv

EM28BAFebr RGua Ory ED2012

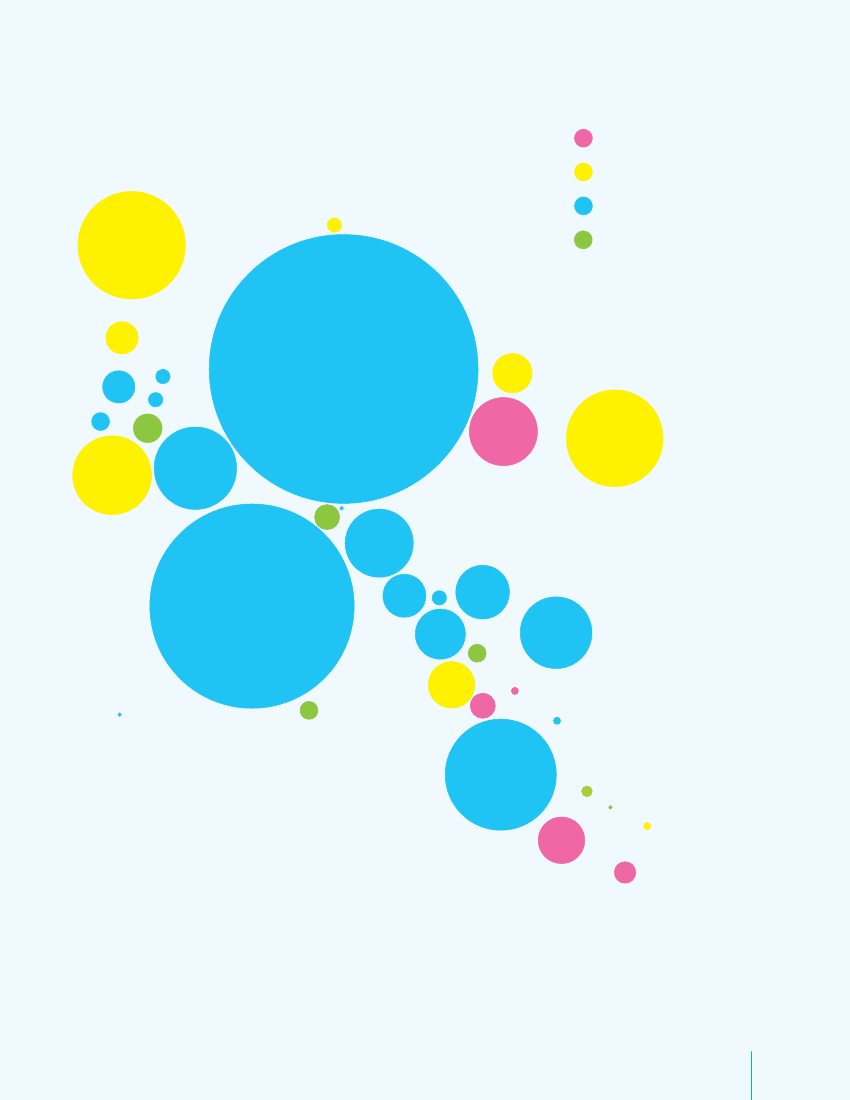

AN URBAN WORLDThis graphic depicts countries and territories with urbanpopulations exceeding 100,000. Circles are scaled inproportion to urban population size. Where space allows,numbers within circles show urban population (in millions)and urban percentage of the country’spopulation.NorwaySweden7.9FinlandEstoniaIcelandNetherlands13.883%Belgium10.497%

Denmark

LatviaLithuania

Canada27.481%

Ireland

UnitedKingdom49.480%

Germany60.874%

Poland23.361%CzechRepublicSlovakia7.7

Belarus7.2

EM28BAFebr RGua Ory ED2012Spain35.777%Italy41.468%AlbaniaMaltaPortugalBahamas

United Statesof America255.482%Mexico88.378%Cuba8.5

France53.585%

Luxembourg

Ukraine31.369%

AustriaHungaryRomania Republic ofSwitzerlandMoldova12.3Slovenia57%Croatia SerbiaBulgariaBosnia andHerzegovina The formerYugoslavMontenegroRepublic ofMacedonia

GreeceCyprus

Turkey50.770%LebanonSyrian ArabRepublic11.456%Jordan

GeorgiaAzerbaijanArmenia

Morocco18.658%

Algeria23.666%

Tunisia7.1

OccupiedPalestinian Territory

Iraq21.066%Kuwait

Libya

Mauritania

Niger

Chad

Egypt35.243%Sudan17.540%

Israel

Guatemala BelizeHaiti Dominican7.1RepublicHondurasJamaicaEl SalvadorNicaraguaCosta RicaPanama

Cape Verde

Senegal

Mali

Saudi ArabiaUnited Arab22.5Emirates82%EritreaYemen Oman7.6

BahrainQatar

Gambia

Guinea-Bissau

BurkinaFasoGhana12.651%

Nigeria78.950%

Colombia34.875%Ecuador9.7

Venezuela(BolivarianRepublic of)27.193%

BarbadosTrinidad and TobagoGuyanaSuriname

Guinea

Sierra Leone

CôteLiberia d’Ivoire10.051%

CentralAfricanRepublic

DjiboutiEthiopiaSomalia13.817%Kenya9.0

Togo Benin

Cameroon11.458%

UgandaRwanda

Peru22.477%

Bolivia(PlurinationalState of)Paraguay

Brazil168.787%

Equatorial GuineaGabonSao Tome and Principe

Burundi

United Republicof TanzaniaDemocraticCongo11.8Republic26%of the Congo23.235%MalawiComoros

Angola11.259%BotswanaNamibia

MauritiusMozambiqueZambia9.0MadagascarZimbabweSwaziland

Chile15.289%

Uruguay

SouthAfrica30.962%

Lesotho

Argentina37.392%

Source:United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA), Population Division special updated estimates of urban population as of October 2011, consistent withWorld Population Prospects: The 2010 revisionandWorld Urbanization Prospects: The 2009 revision.Graphic presentation of data based onThe Guardian,27 July 2007.This map is stylized and based on an approximate scale. It does not reflect a position by UNICEF on the legal status of any country or territory or the delimitation of any frontiers.

vi

THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S CHILDREN 2012

Above 75% urbanBetween 50% and 75% urbanBetween 25% and 50% urbanMongolia

RussianFederation104.673%

Below 25% urban

ChinaUrban population in millions

Kazakhstan9.4

629.847%

KyrgyzstanUzbekistan10.036%TajikistanTurkmenistan

Democratic People’sRepublic of Korea14.760%

Afghanistan7.1

Iran(IslamicRepublic of)52.371%

Pakistan62.336%

India367.530%Maldives

EM28BAFebr RGua Ory ED2012Percentage urbanNepalBhutan

Republicof Korea40.083%

Japan84.6

Canton67%14.5

Bangladesh41.728%

Lao People’sDemocraticRepublicMyanmar16.134%

Viet Nam26.730%

Thailand23.534%

Cambodia

Philippines45.649%

Malaysia20.572%

Brunei Darussalam

Sri Lanka

Singapore

Timor-Leste

Indonesia106.244%

Papua New GuineaSolomon Islands

Australia19.889%New Zealand

Fiji

Notes:Because of the cession in July 2011 of the Republic of South Sudan by the Republic of the Sudan, and its subsequent admission to the United Nations on 14 July 2011,data for the Sudan and South Sudan as separate States are not yet available. Data presented are for the Sudan pre-cession.Data for China do not include Hong Kong and Macao, Special Administrative Regions of China. Hong Kong became a Special Administrative Region (SAR) of China as of 1 July 1997;Macao became a SAR of China as of 20 December 1999.Data for France do not include French Guiana, Guadeloupe, Martinique, Mayotte and Reunion.Data for the Netherlands do not include the Netherlands Antilles.Data for the United States of America do not include Puerto Rico and United States Virgin Islands.

An urban world

vii

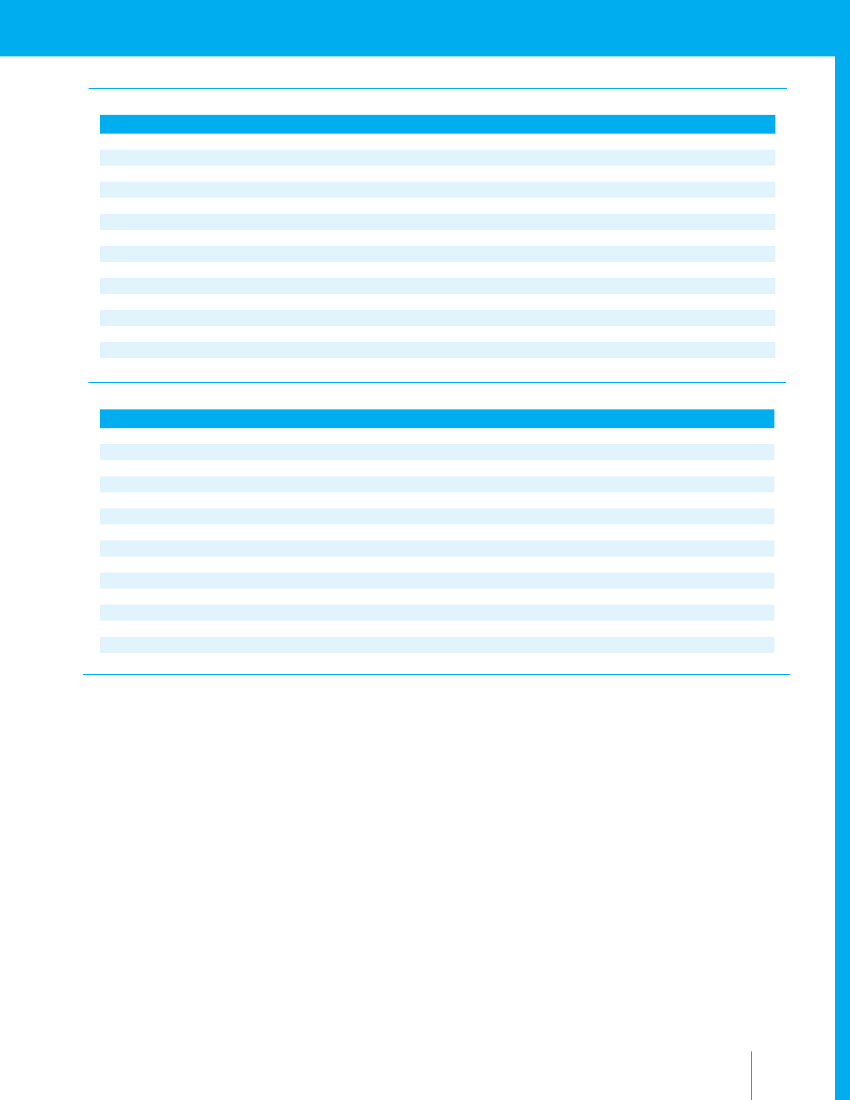

CONTENTSACkNOWLEDGEMENTS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . iiiACTION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ivFOREWORDAnthony Lake, Executive Director, UNICEF . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .vCHAPTER 1Children in an increasingly urban world . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1An urban future . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2Poverty and exclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .3Meeting the challenges of an urban future . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .8CHAPTER 2Children’s rights in urban settings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .13An environment for fulfilling children’s rights . . . . . . . . . . .14CHAPTER 4Towards cities fit for children . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .49Policy and collaboration . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .49Participatory urban planning and management . . . . . . . . . .50Child-Friendly Cities . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .55Non-discrimination . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .55Nutrition and hunger . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .55Health . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .57HIV and AIDS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .57Water, sanitation and hygiene . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .58Education . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .58Child protection . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .60Housing and infrastructure . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .60Urban planning for children’s safety . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .61Safe cities for girls . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .61Safe spaces for play . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .62Social capital . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .62Cultural inclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .62Culture and arts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .63Technology . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .63CHAPTER 5Uniting for children in an urban world . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .67Understand urban poverty and exclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .68Remove the barriers to inclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .70Put children first . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .73Promote partnership with the urban poor . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 74Work together to achieve results for children . . . . . . . . . . . . 74Towards fairer cities . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .75

Health . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .14Child survival . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .14Immunization . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17Maternal and newborn health . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .18Breastfeeding . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .18Nutrition . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .19Respiratory illness . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .22Road traffic injuries . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .22HIV and AIDS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .22Mental health . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .24Water, sanitation and hygiene . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .25Education . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .28Early childhood development . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .28Primary education . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .29Protection . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .31Child trafficking . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .31Child labour . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .32Children living and working on the streets . . . . . . . . . . . . . .32CHAPTER 3Urban challenges . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .35Migrant children . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .35Economic shocks . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .40Violence and crime . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .42Disaster risk . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .45

viii

THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S CHILDREN 2012

EM28BAFebr RGua Ory ED2012PANELS

Social determinants of urban health . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .4Slums: The five deprivations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .5Definitions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10The Convention on the Rights of the Child . . . . . . . . . . . . . .16The Millennium Development Goals . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .33Agents, not victims . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .38Armed conflict and children in urban areas . . . . . . . . . . . . .42

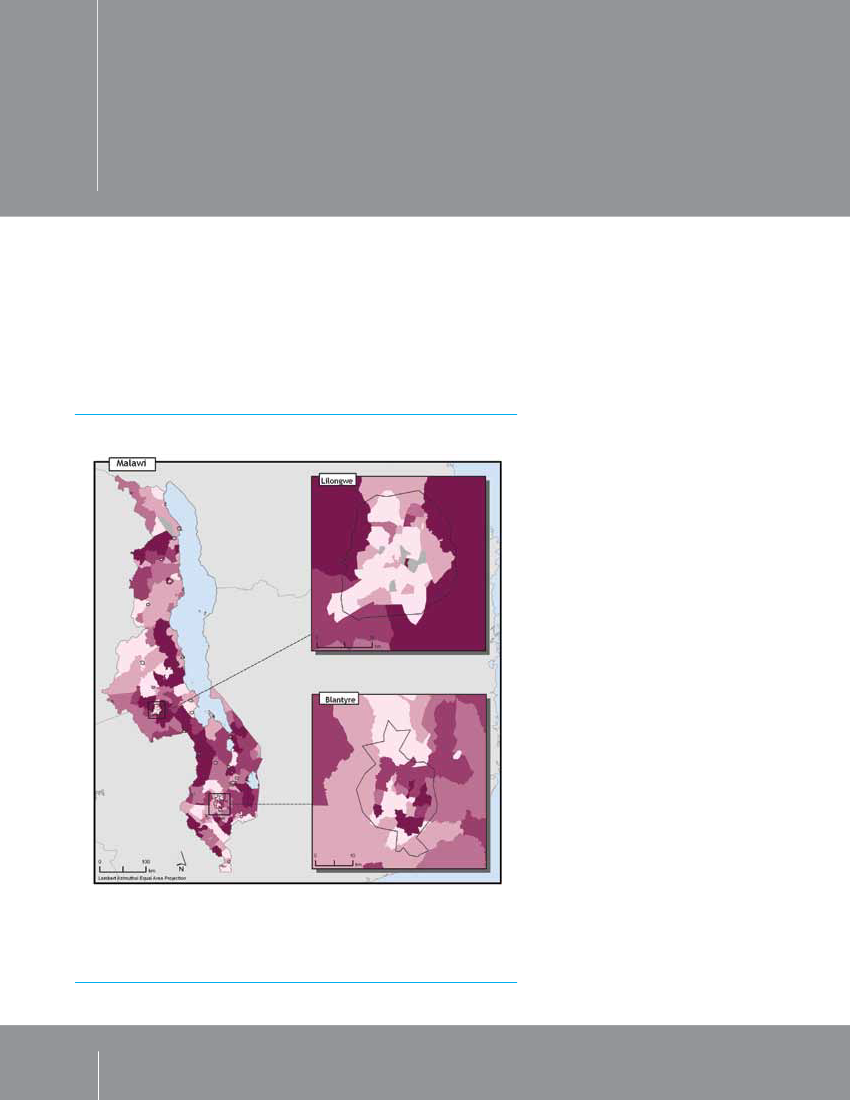

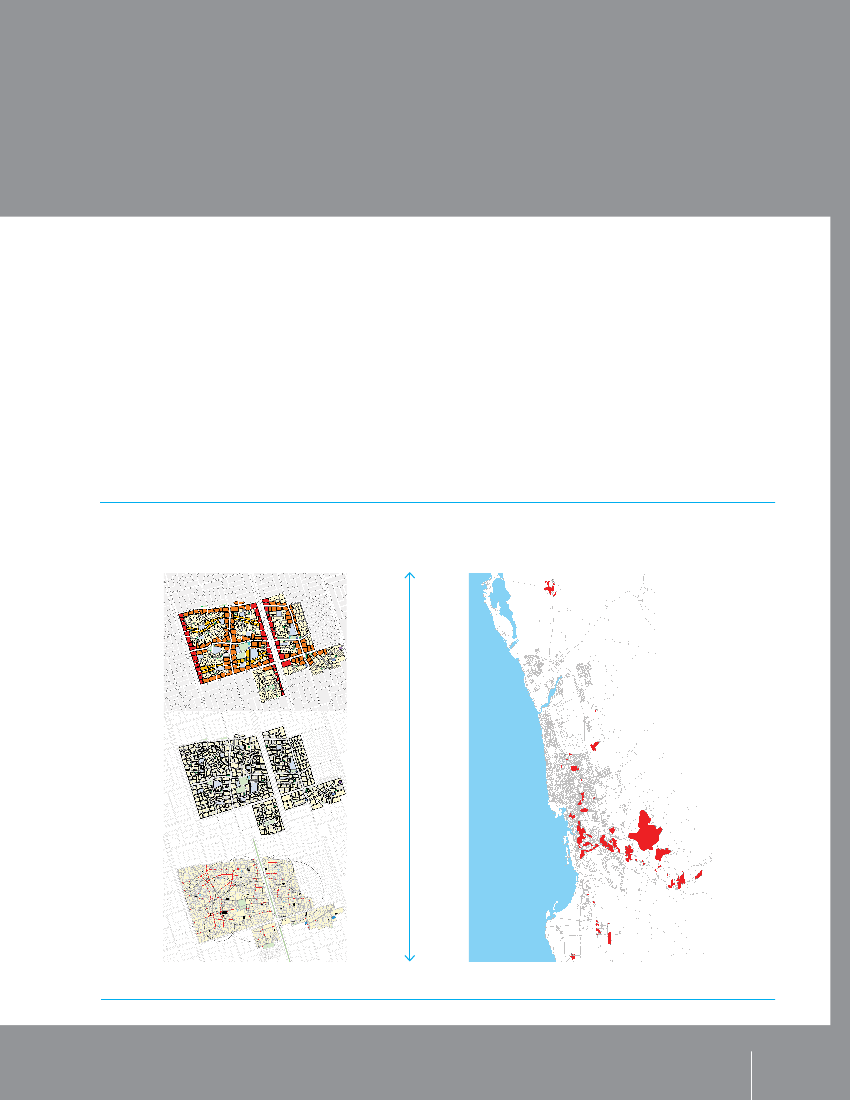

FOCUS ONUrban disparities . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .6Maternal and child health services for the urban poor:A case study from Nairobi, kenya . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .20Mapping urban disparities to secure child rights . . . . . . . . .26Helpful strategies in urban emergencies . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .39Women, children, disaster and resilience . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .41Urban HEART: Measuring andresponding to health inequity . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .52The Child-Friendly Cities Initiative:Fifteen years of trailblazing work . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .56Upgrading informal settlements in Jeddah . . . . . . . . . . . . .64The paucity of intra-urban data . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .69PERSPECTIVE

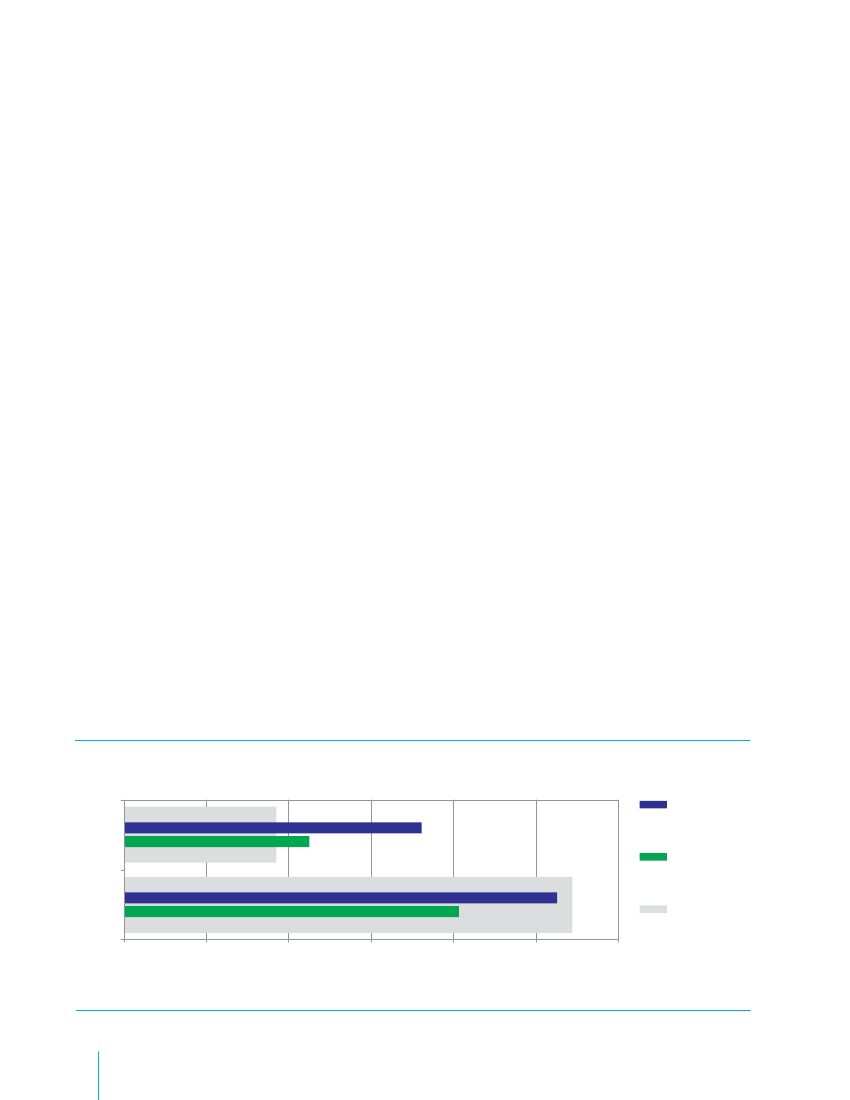

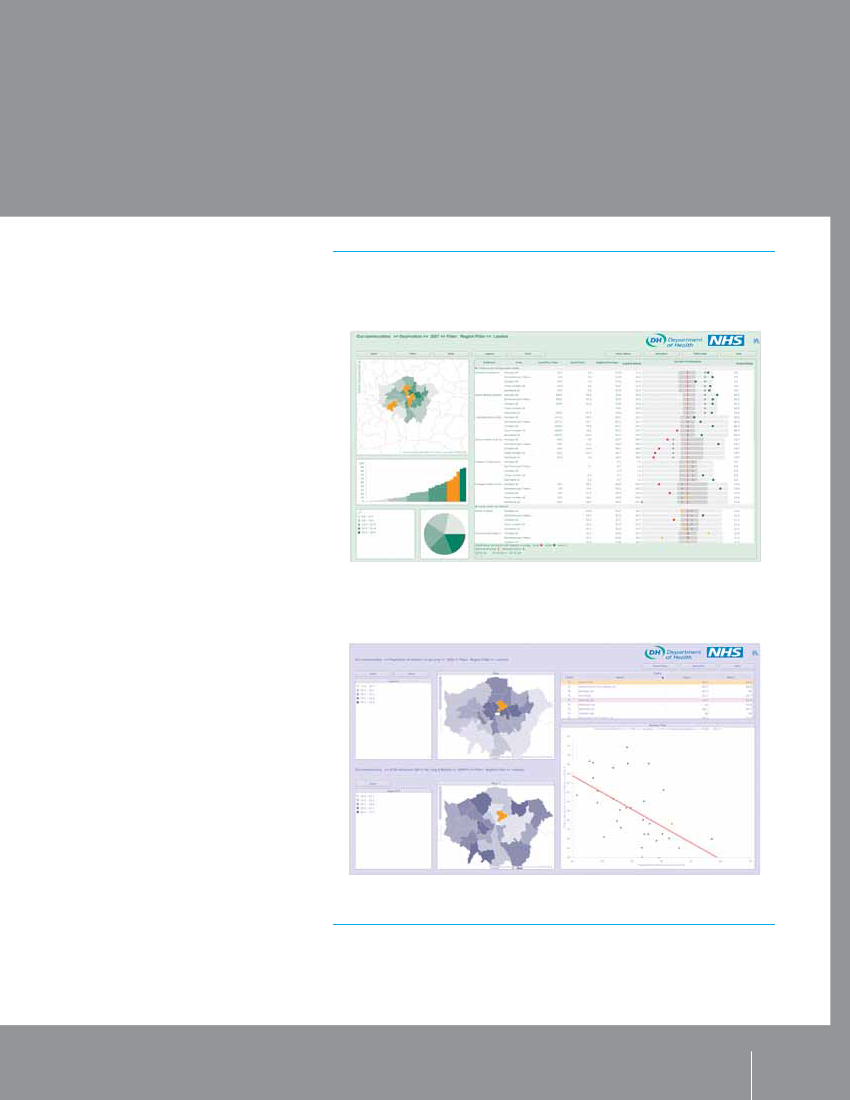

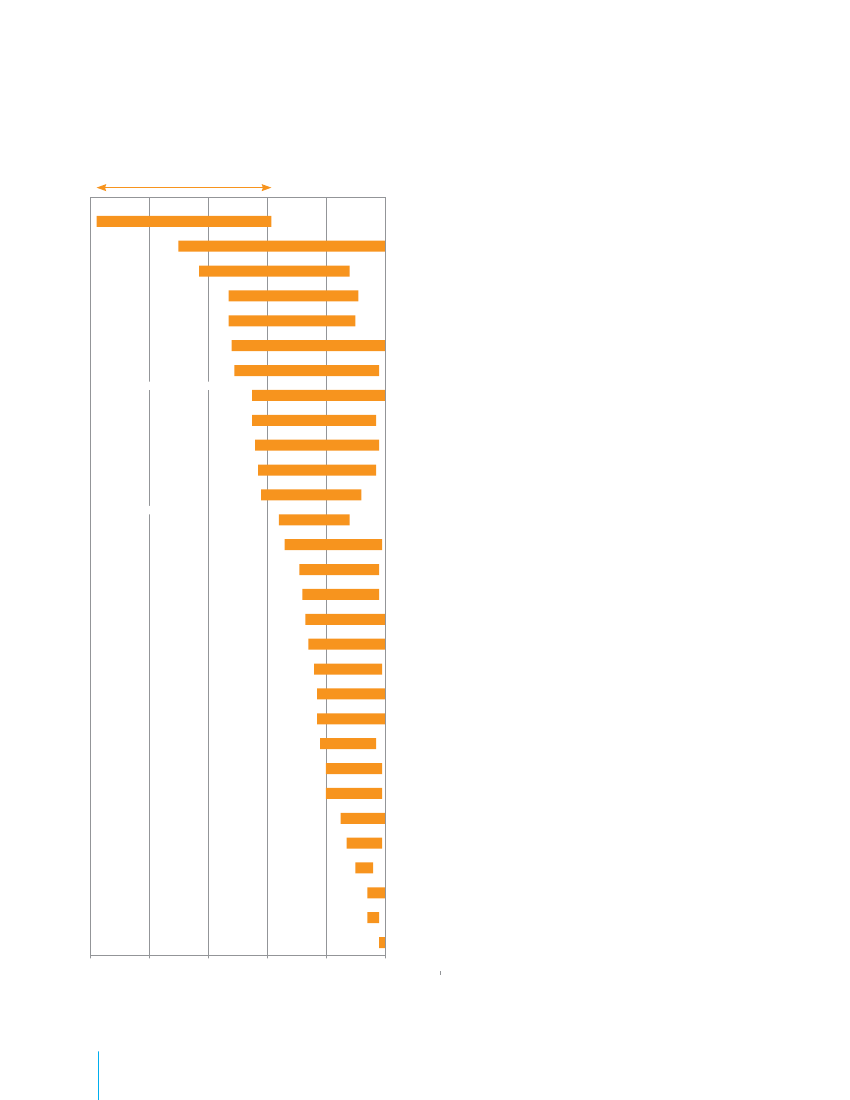

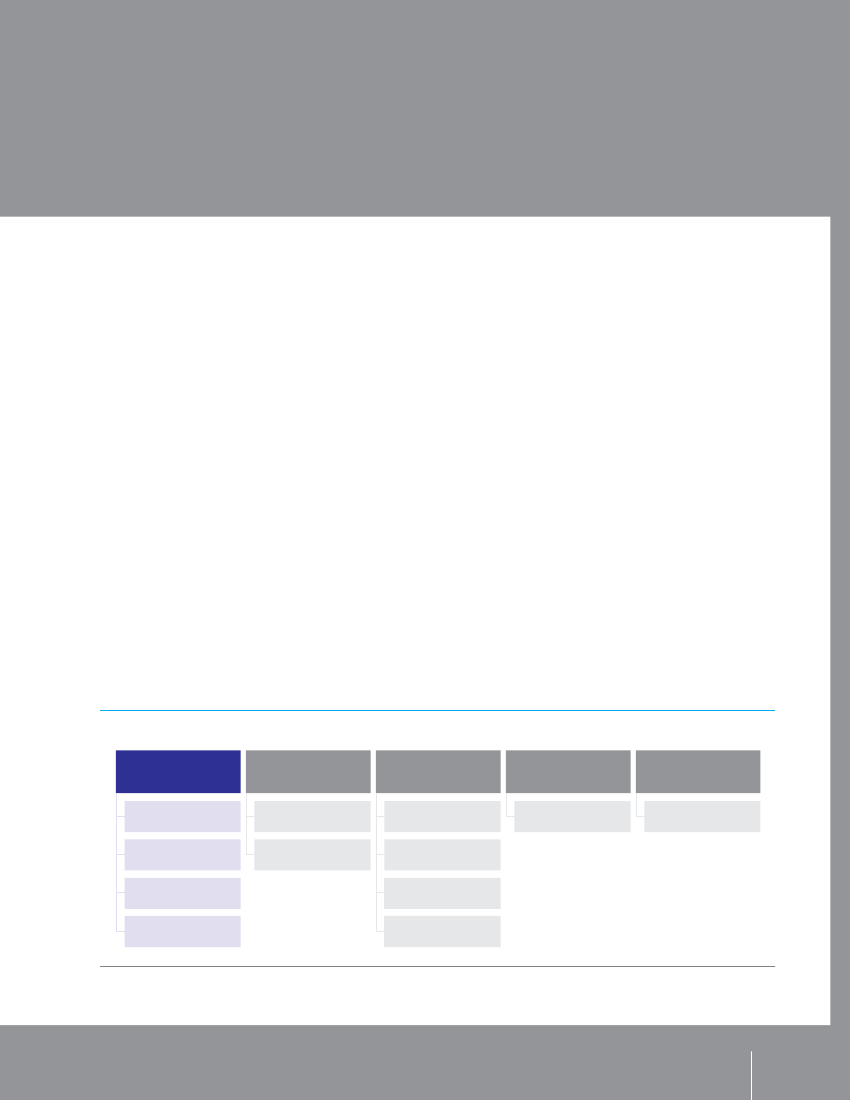

1 .5 Half of the world’s urban population lives in citiesof fewer than 500,000 inhabitants . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 112 .1 Wealth increases the odds of survival for childrenunder the age of 5 in urban areas . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .182 .2 Children of the urban poor are more likelyto be undernourished . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .192 .3 Stunting prevalence among children under3 years old in urban kenya . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .212 .4 HIV is more common in urban areas andmore prevalent among females . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .222 .5 In urban areas, access to improvedwater and sanitation is not keeping pacewith population growth . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .242 .6 Mapping poverty in Lilongwe and Blantyre, Malawi . . .262 .7 Tracking health outcomesin London, United kingdom . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .272 .8 Urban income disparities also mean unequalaccess to water . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .282 .9 School attendance is lower in slums . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .304 .1 Urban HEART planning and implementation cycle . . . .524 .2 Twelve core indicators . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .534 .3 Design scenarios for an informal settlement . . . . . . . . .65REFERENCES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .76STATISTICAL TABLES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .81

Her Majesty Queen Rania Al Abdullah of JordanOut of sight, out of reach . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .15Amitabh BachchanReaching every child: Wiping out polio in Mumbai . . . . . . .23Eugen CraiA world apart: The isolation of Roma children . . . . . . . . . . .37ATD Fourth World Movement Youth Group, New York CitySpeaking for ourselves . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .43Tuiloma Neroni SladePacific challenges . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .46José Clodoveu de Arruda Coelho NetoBuilding children’s lives to build a city . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .51Ricky MartinTrafficked children in our cities:Protecting the exploited in the Americas . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .54Celine d’Cruz and Sheela PatelHome-grown solutions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .72FIGURES

An urban world . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . vi1 .1 Almost half of the world’s children live in urban areas . . . .21 .2 Urban population growth is greater in lessdeveloped regions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .31 .3 Educational attainment can be mostunequal in urban areas . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .61 .4 Urban populations are growing fastest inAsia and Africa . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .9

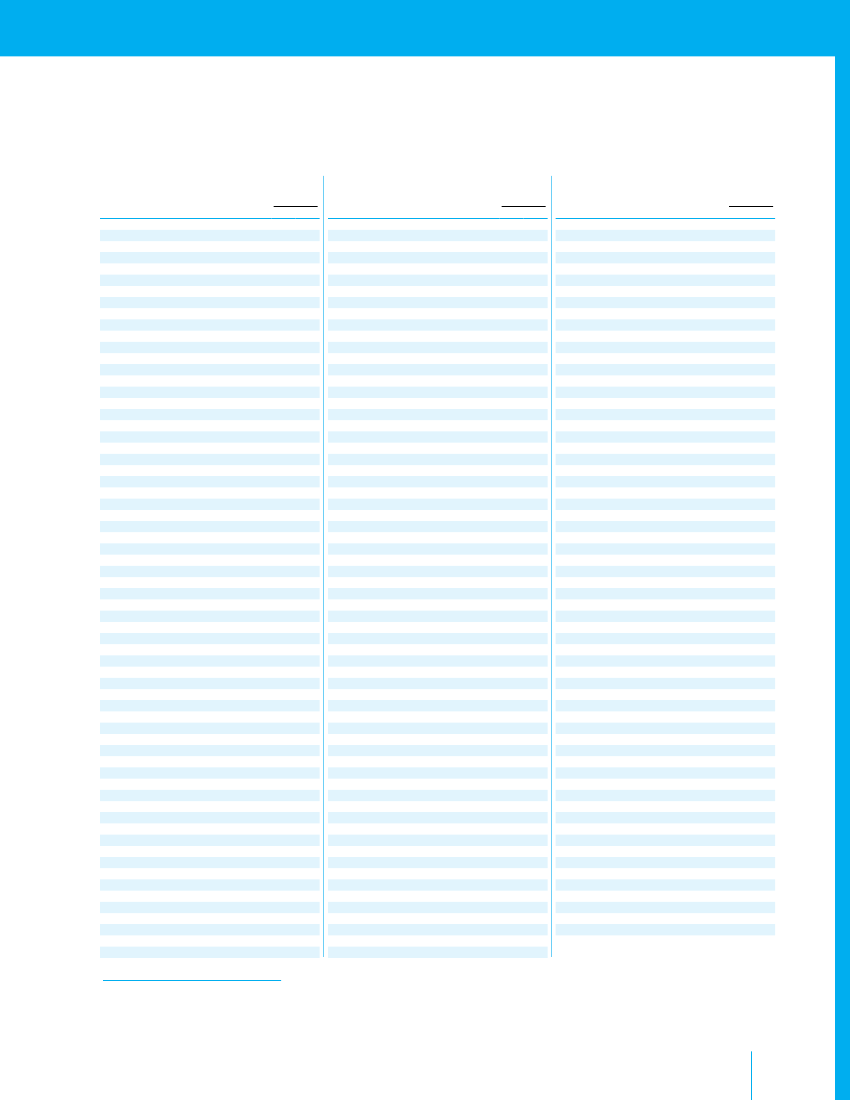

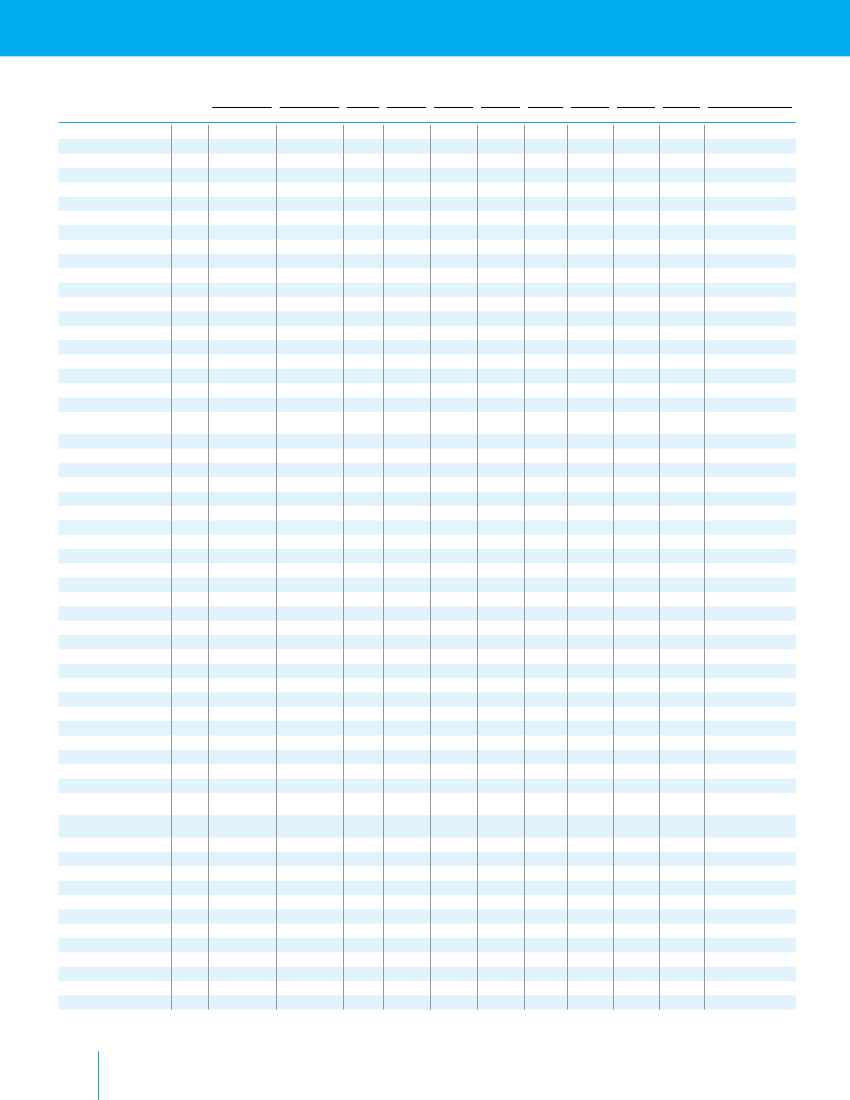

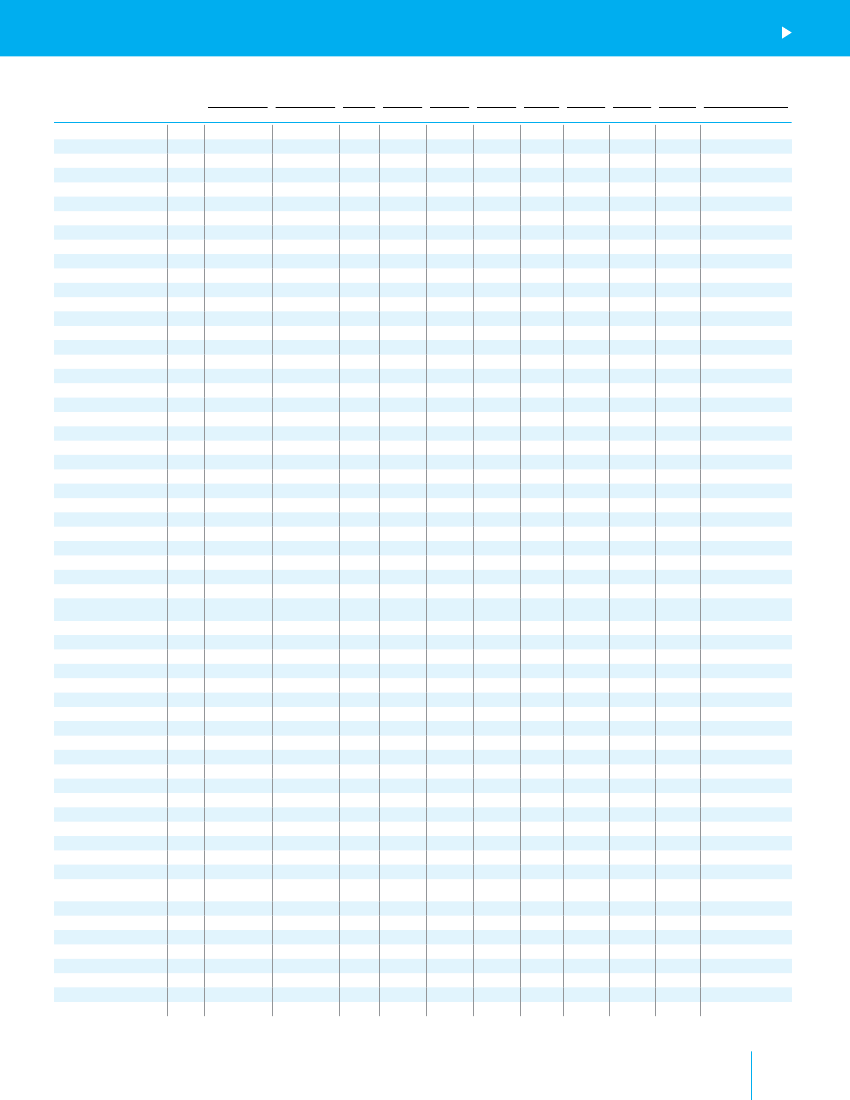

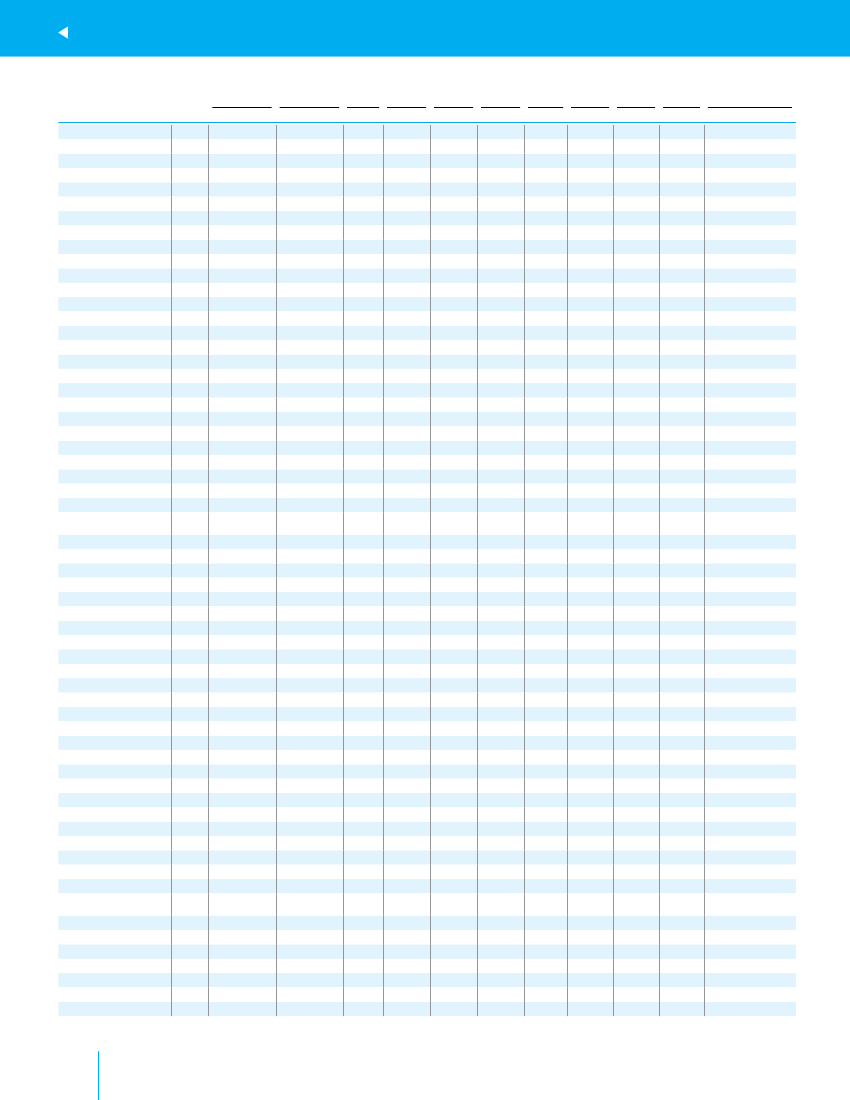

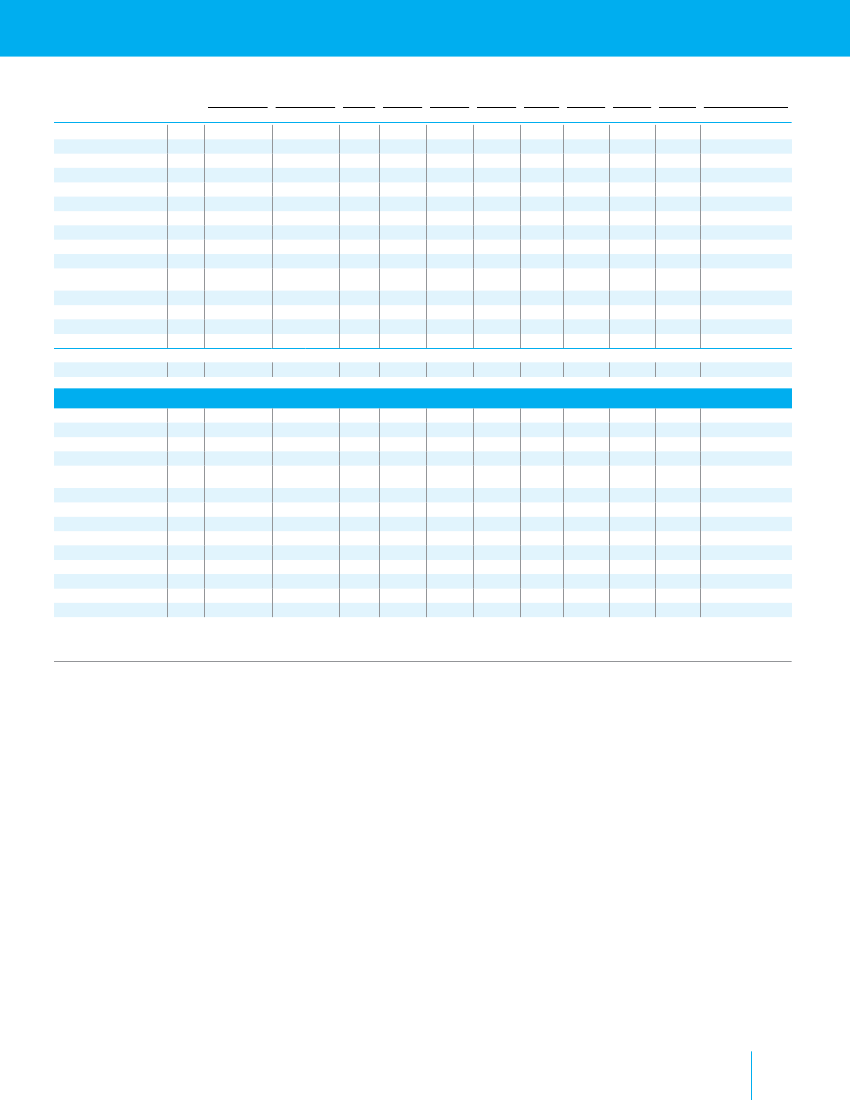

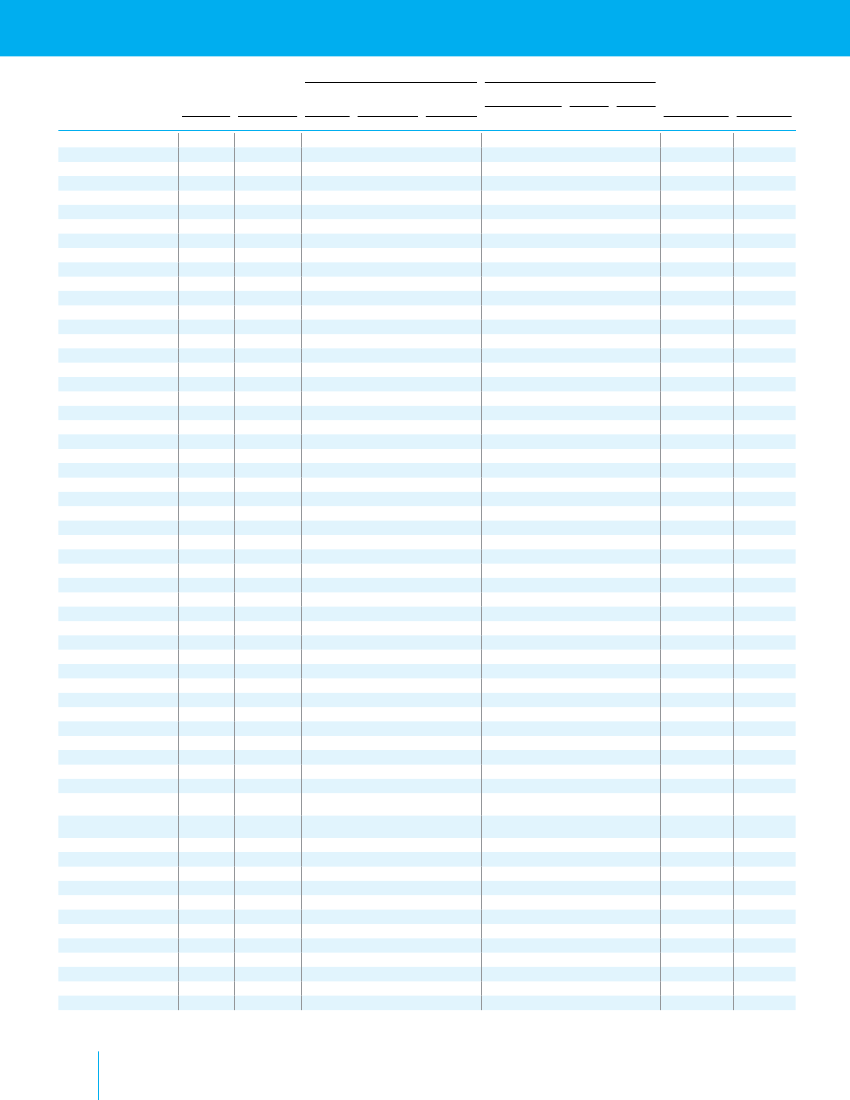

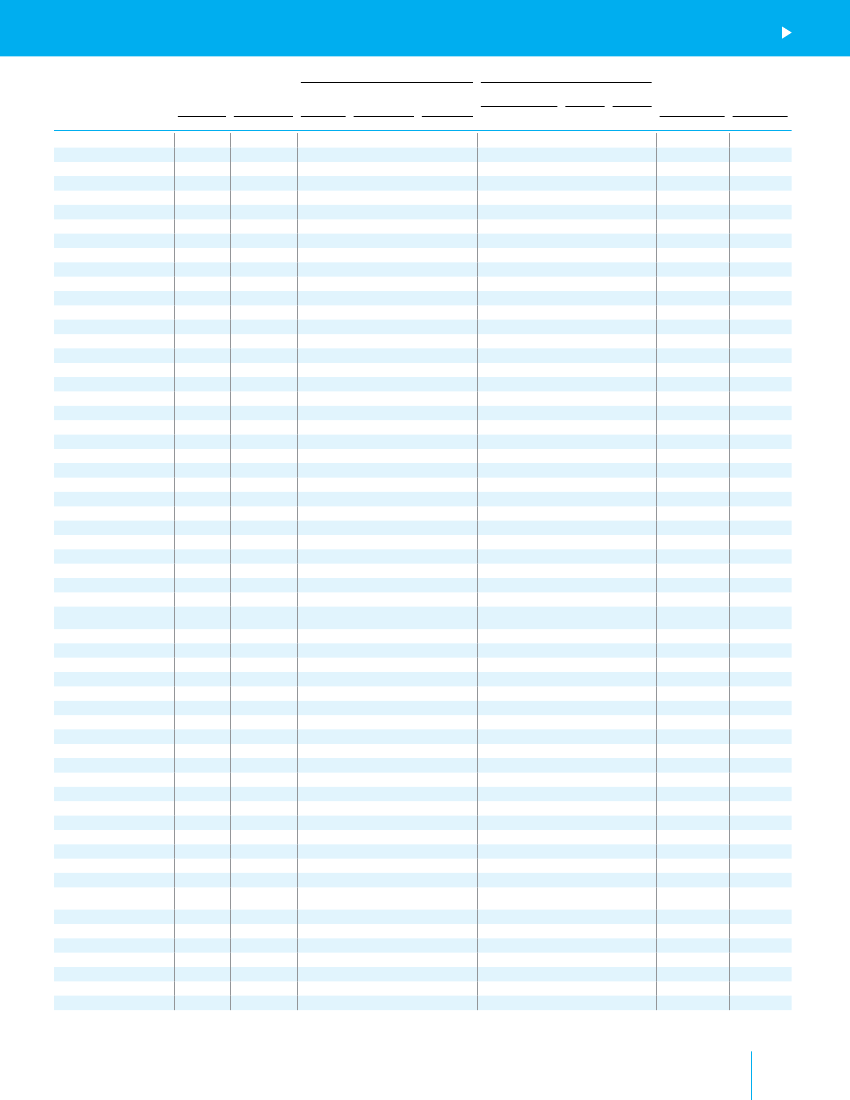

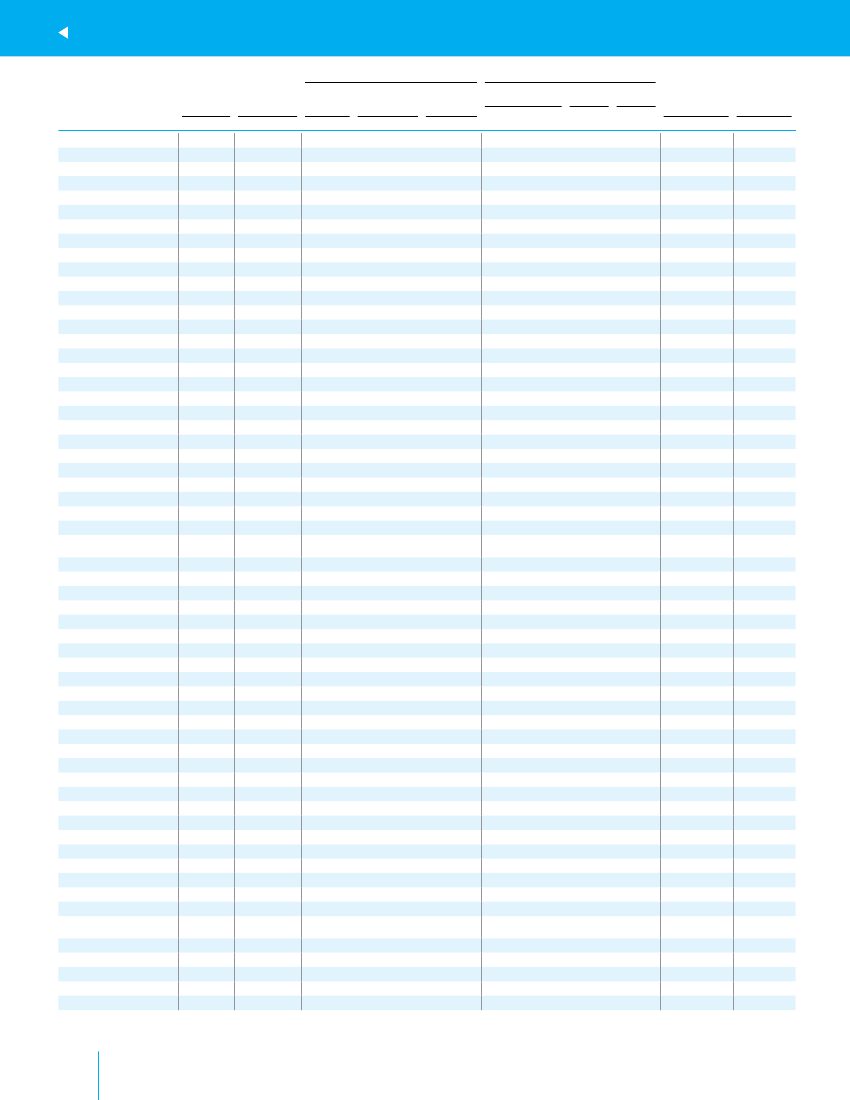

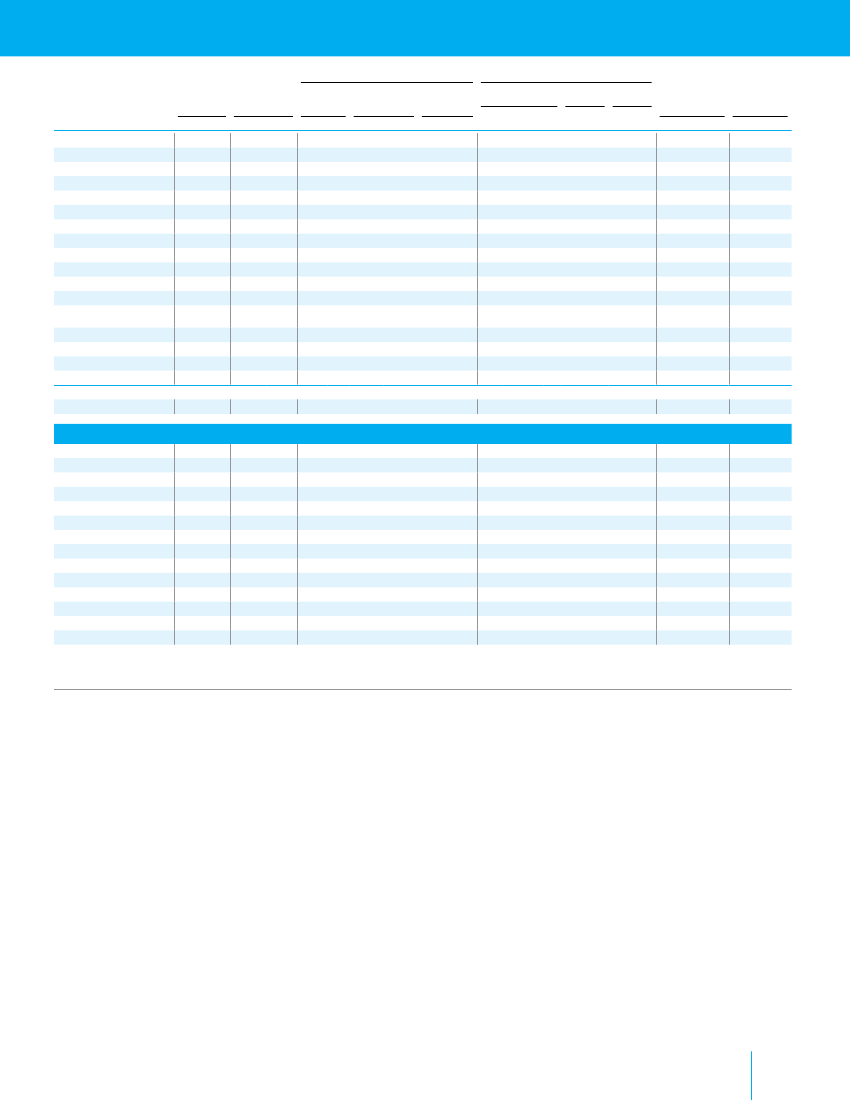

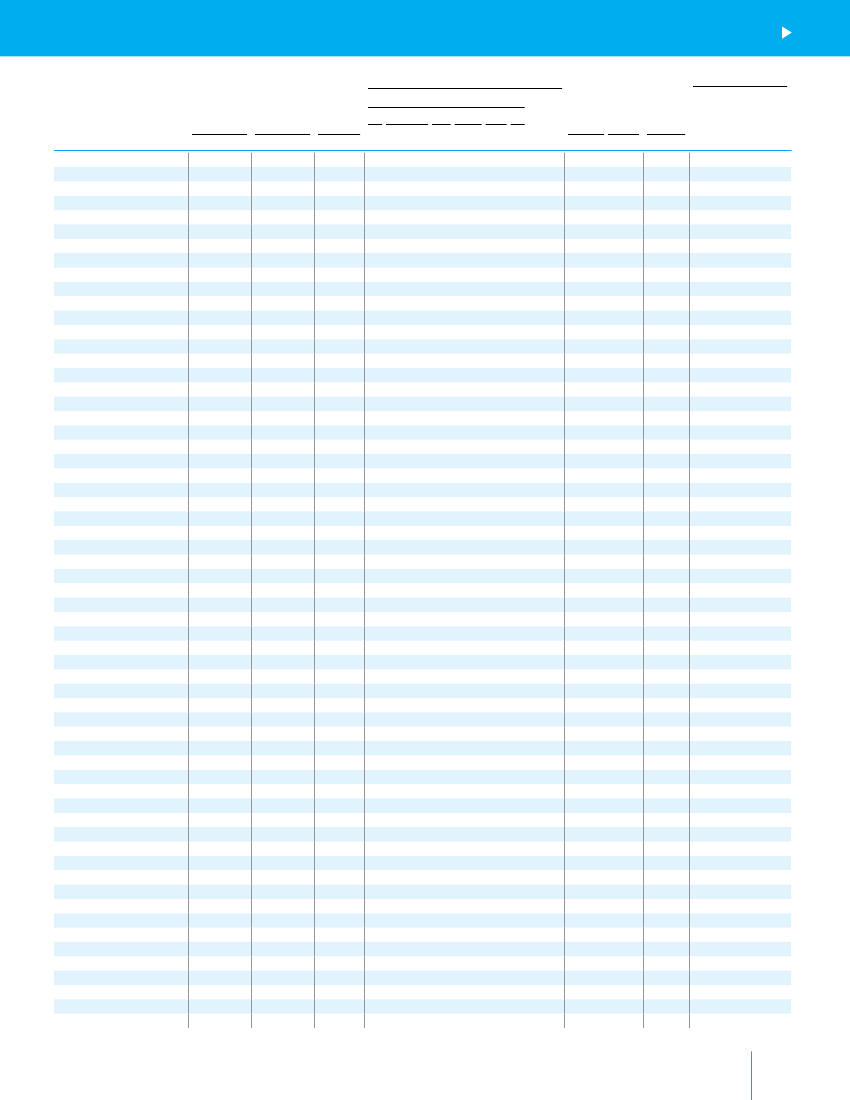

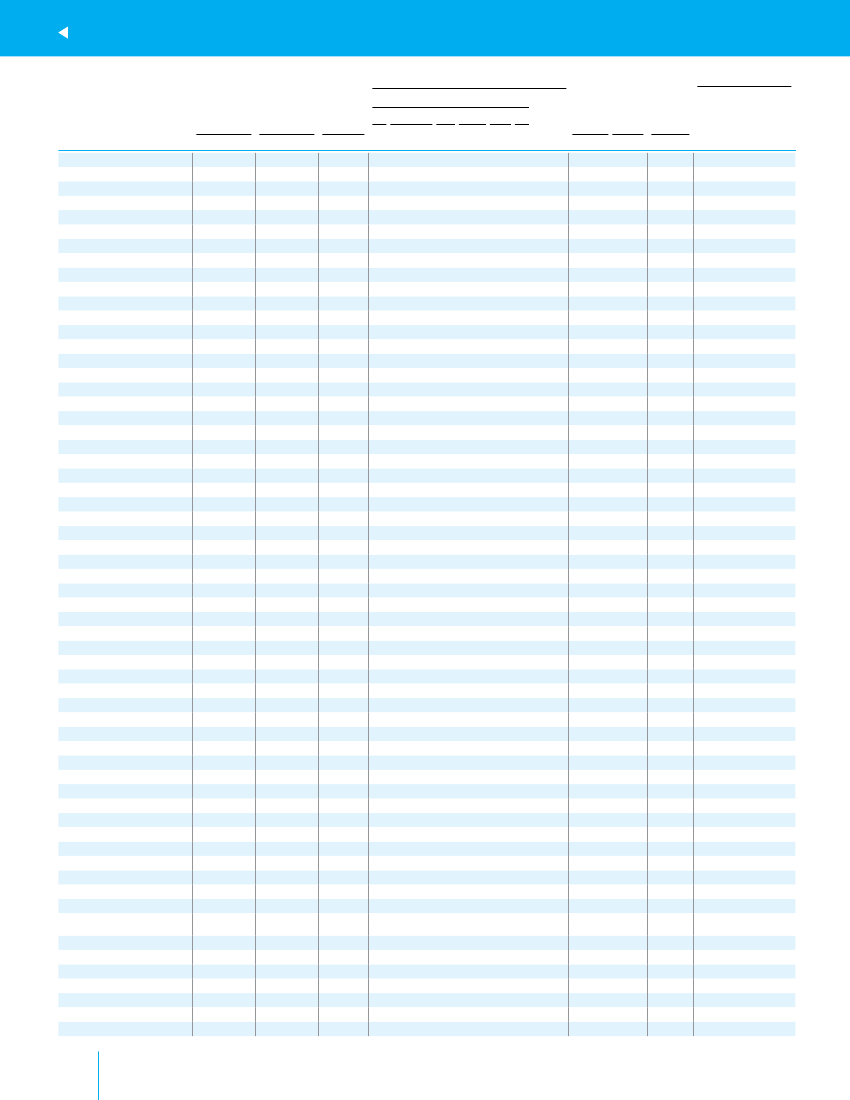

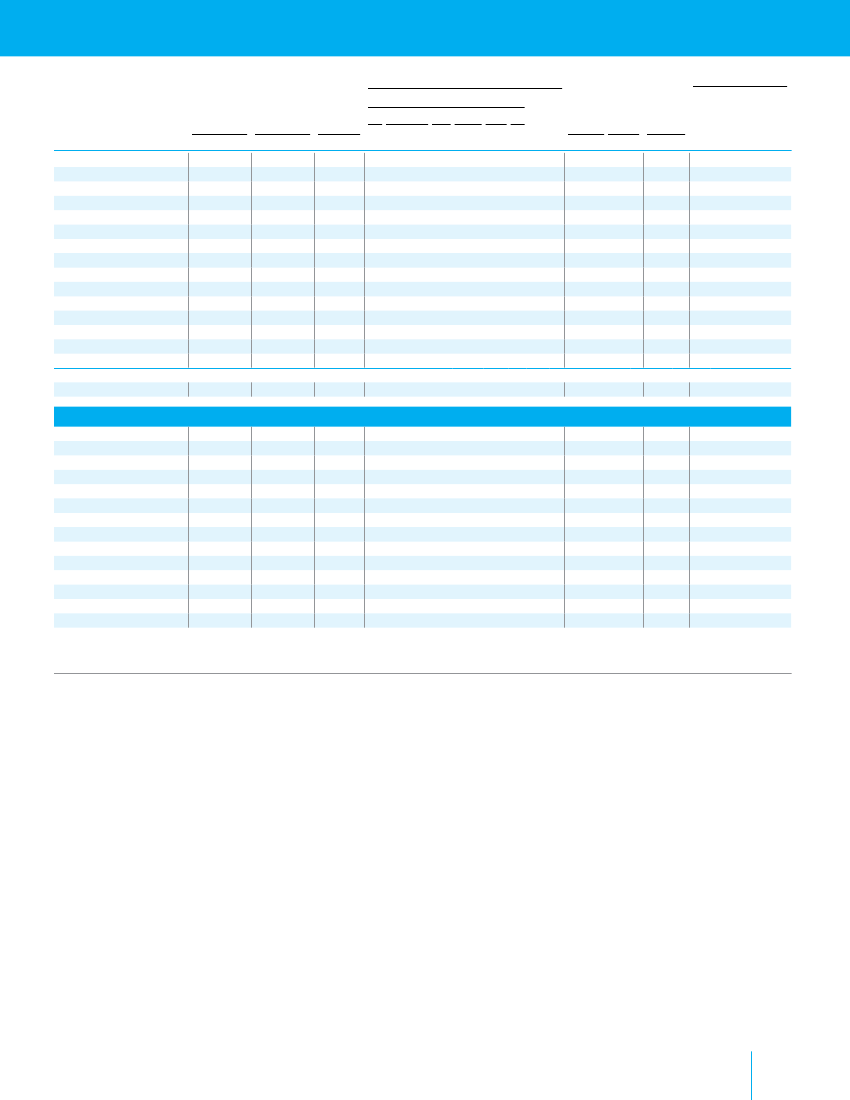

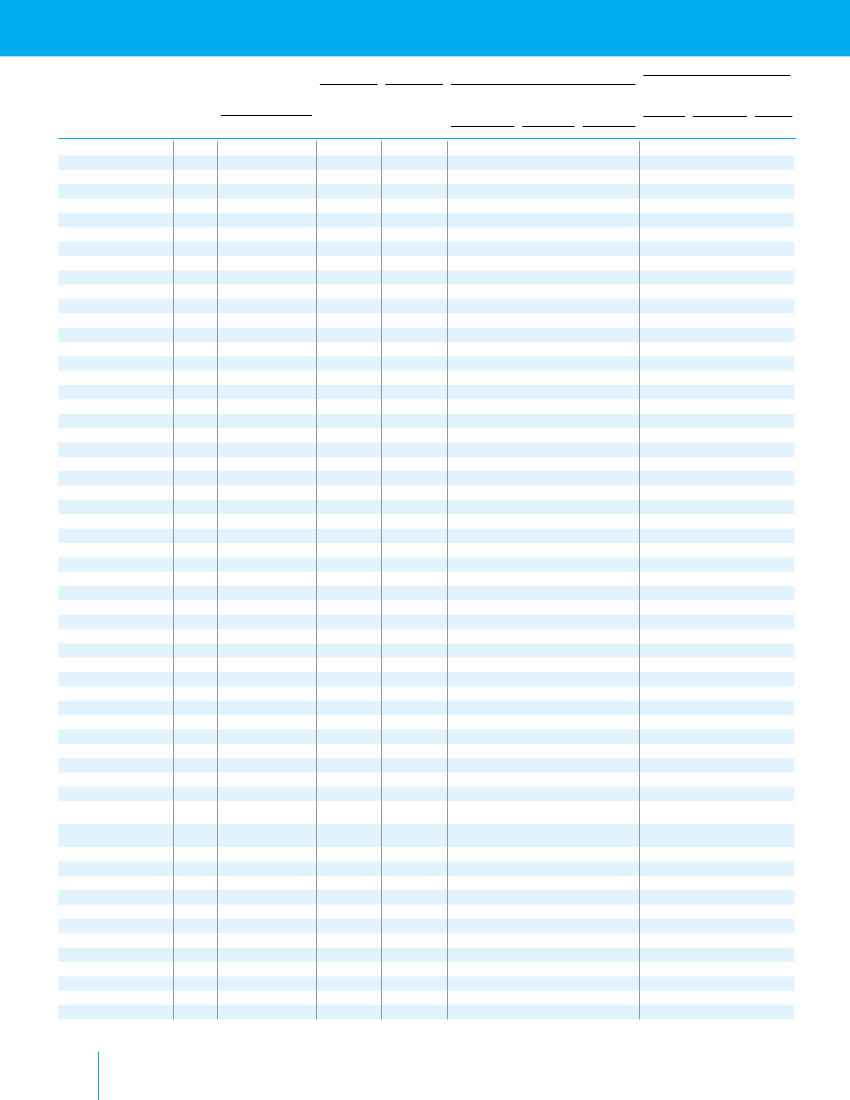

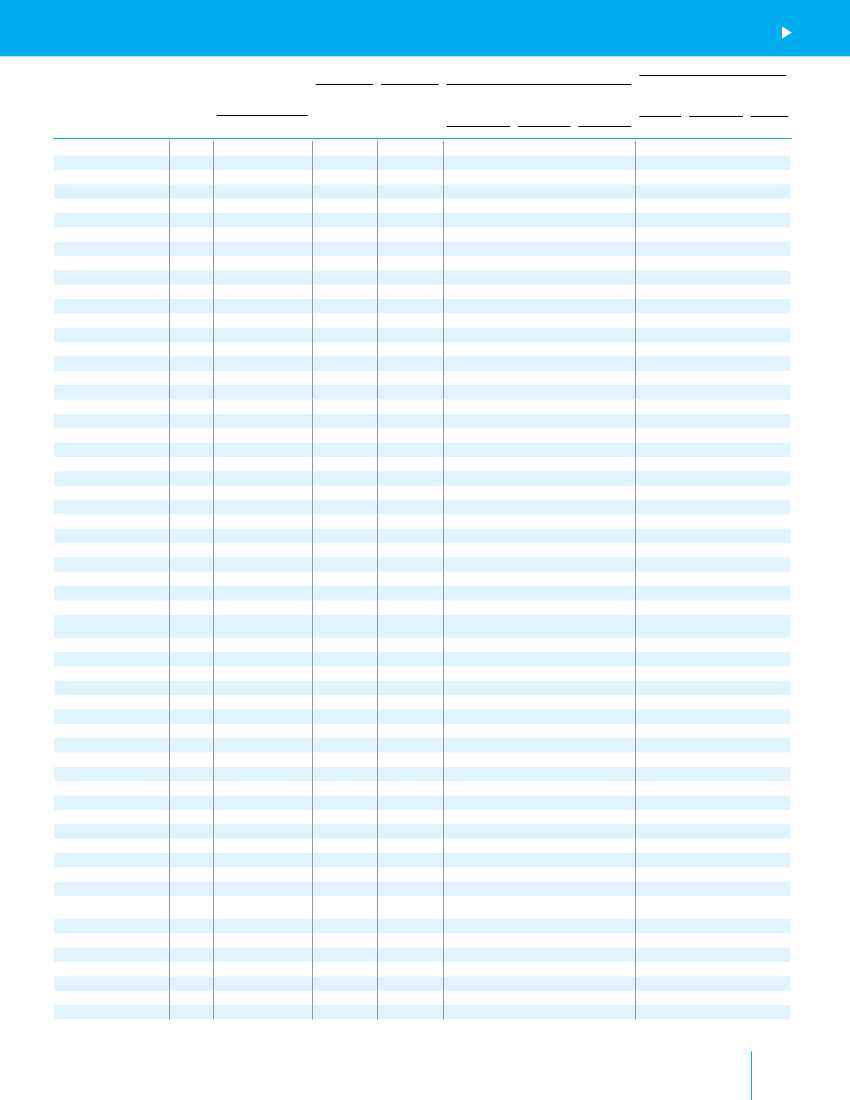

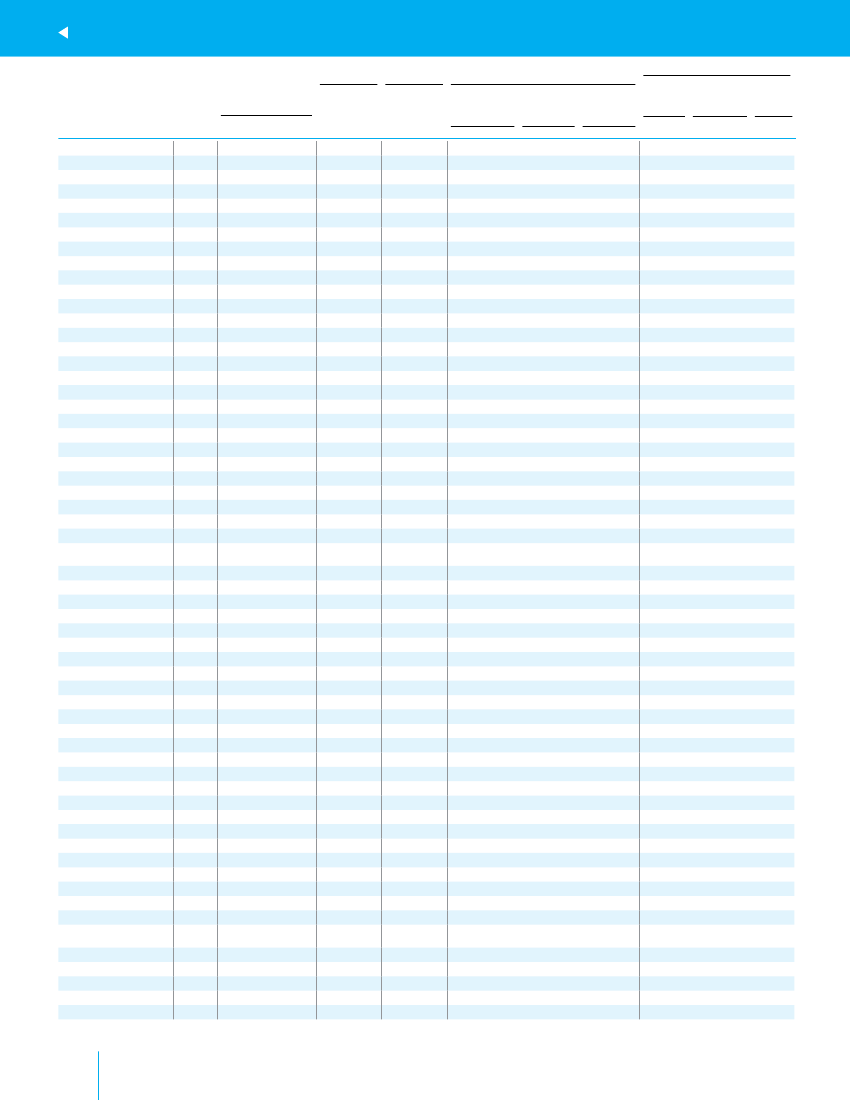

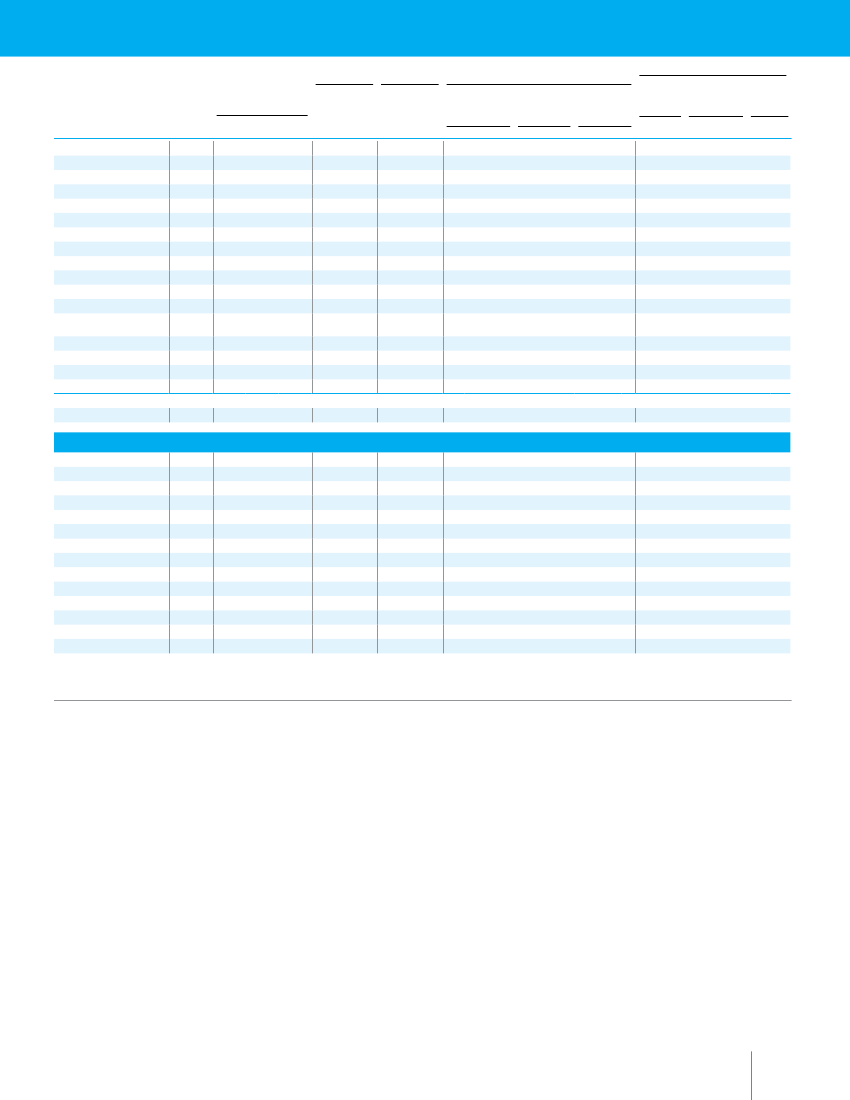

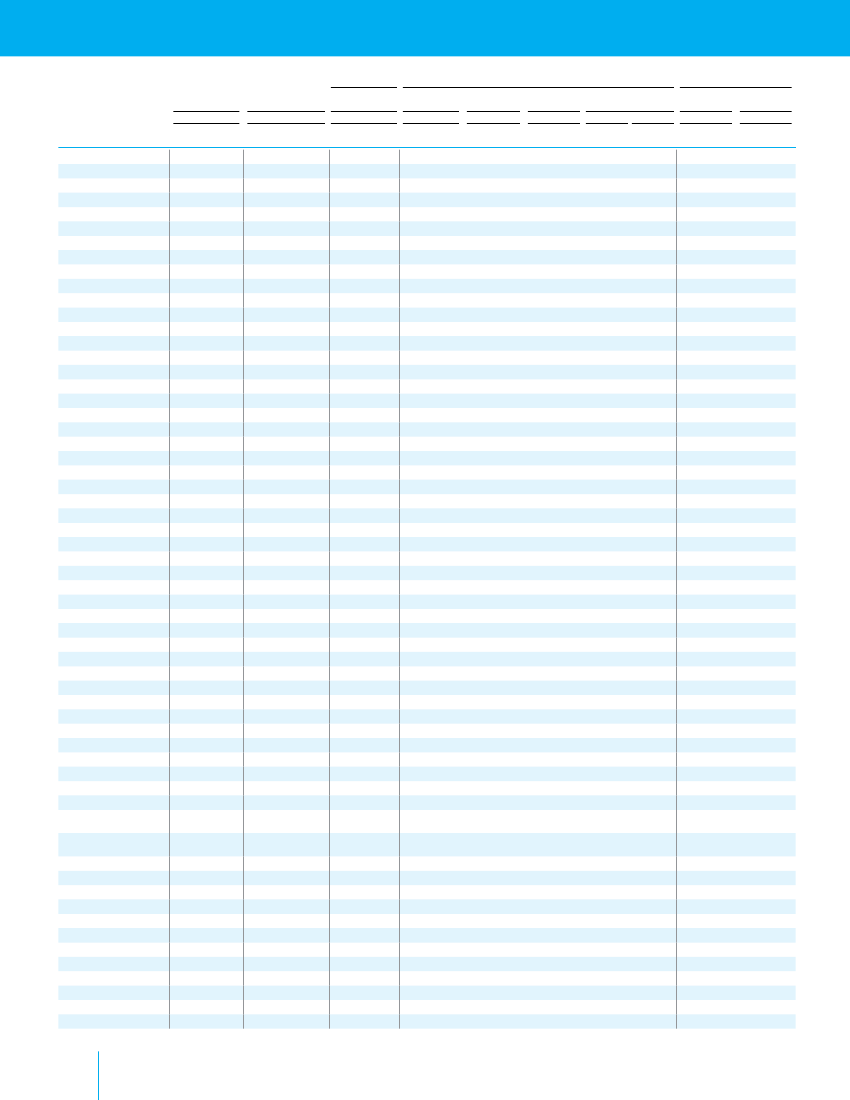

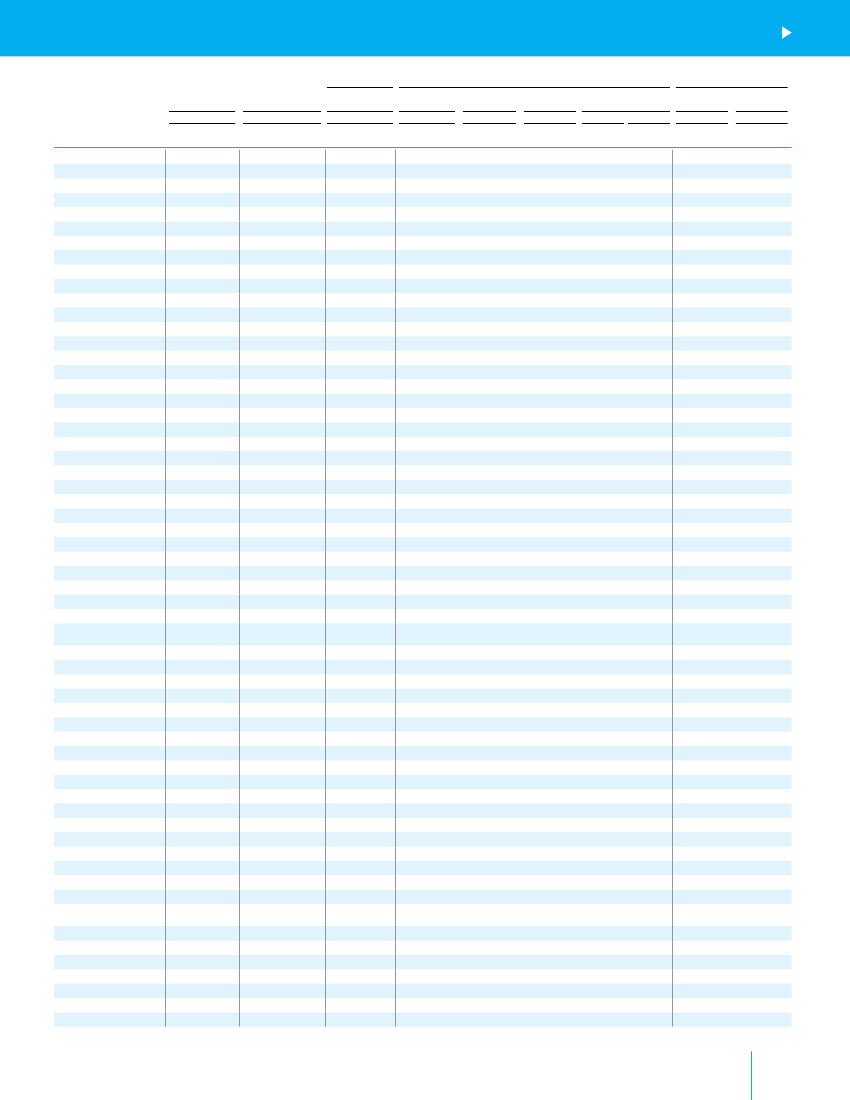

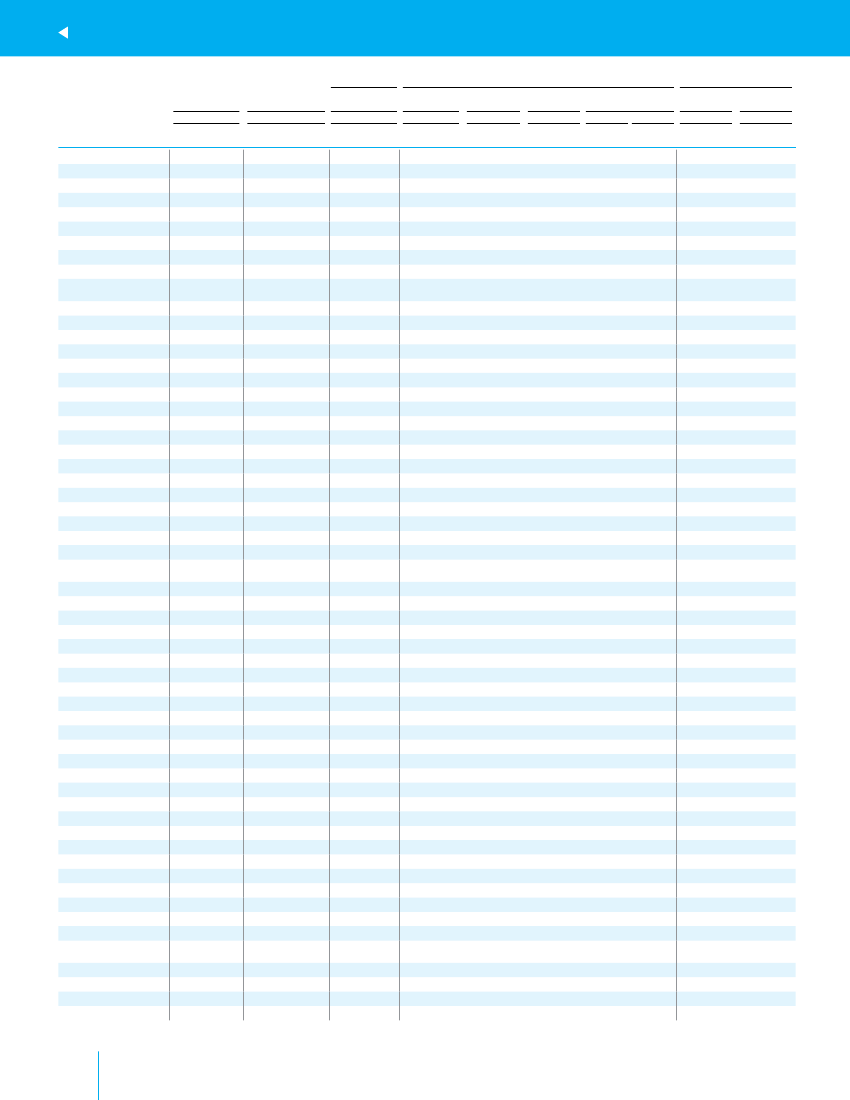

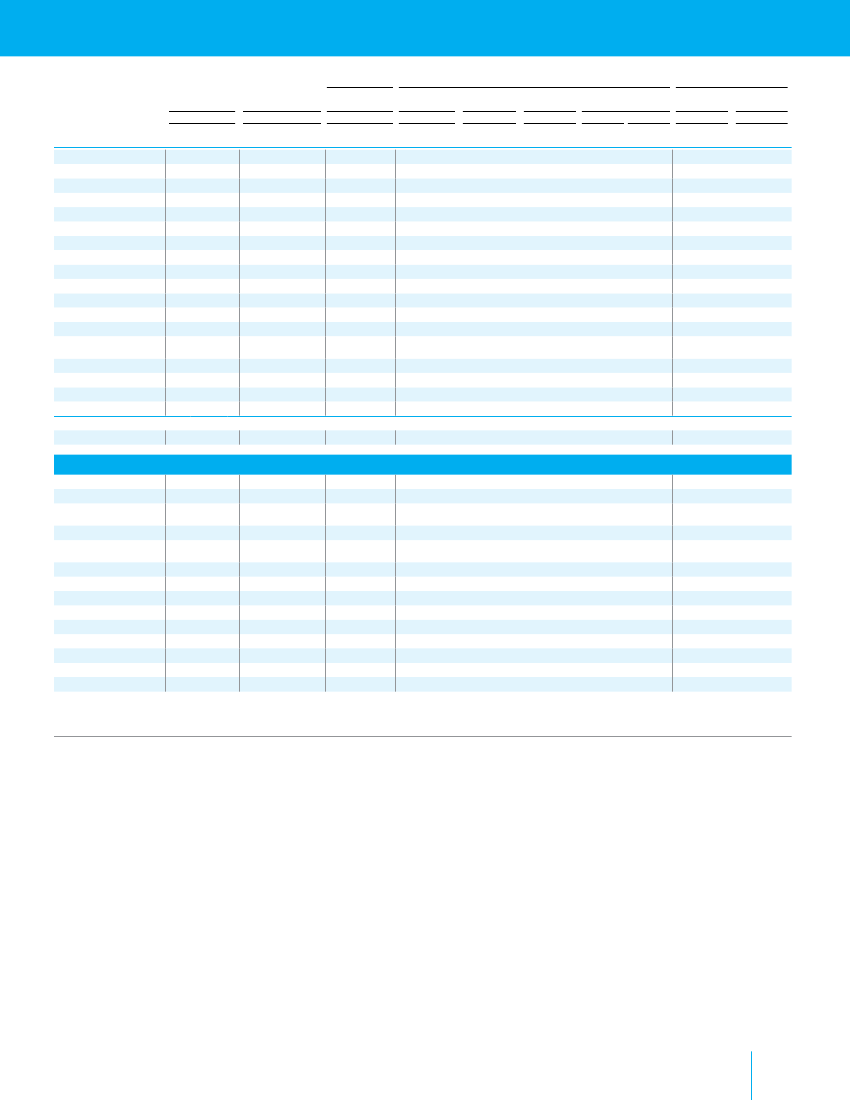

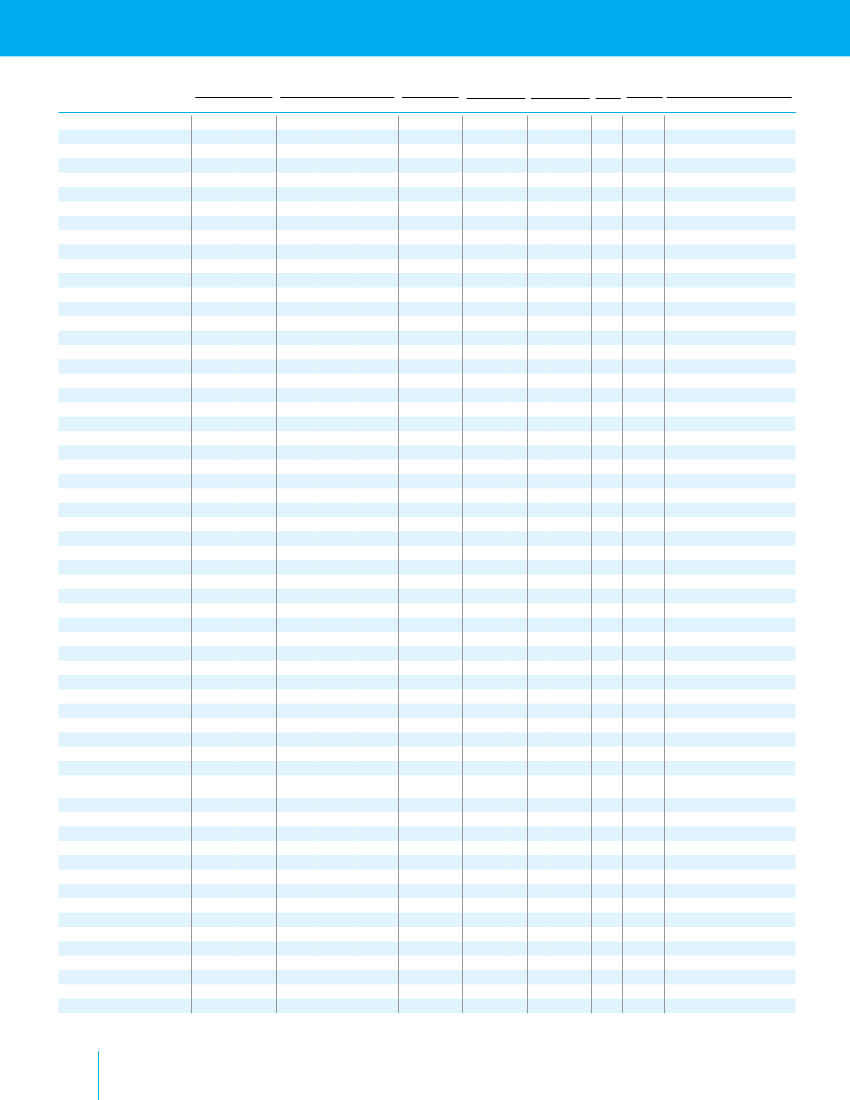

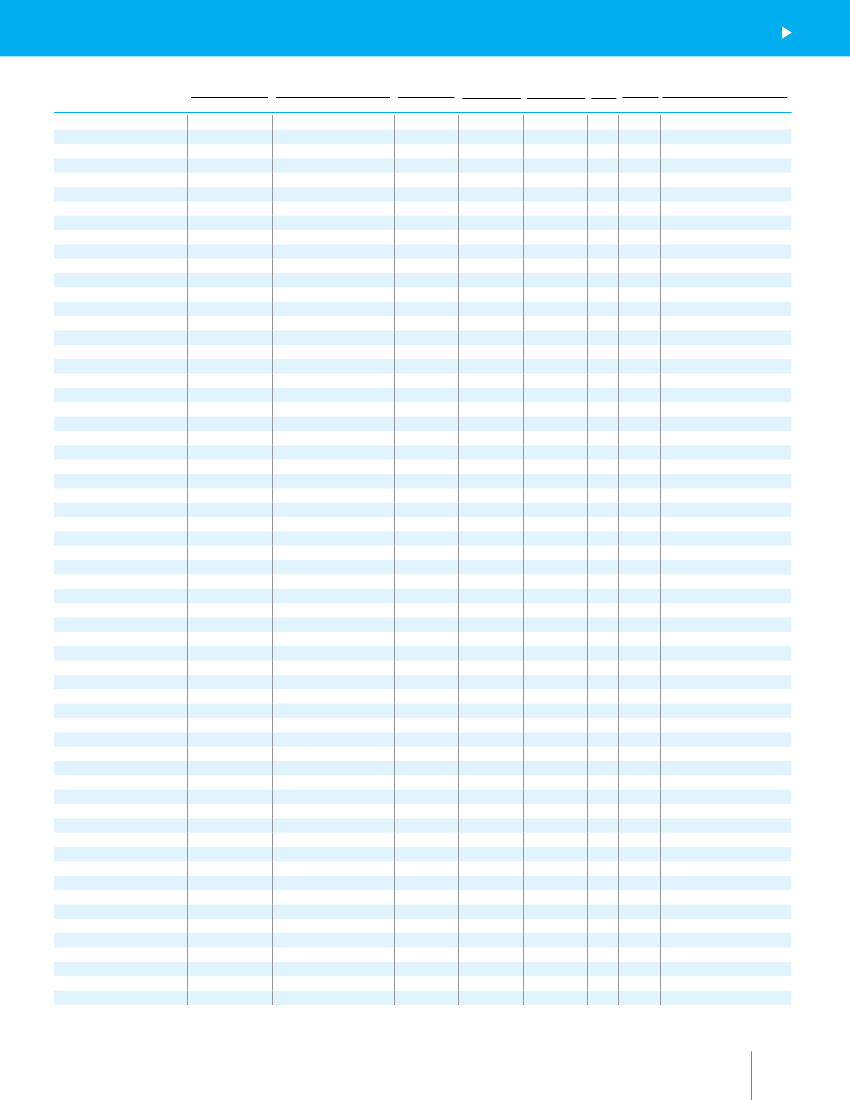

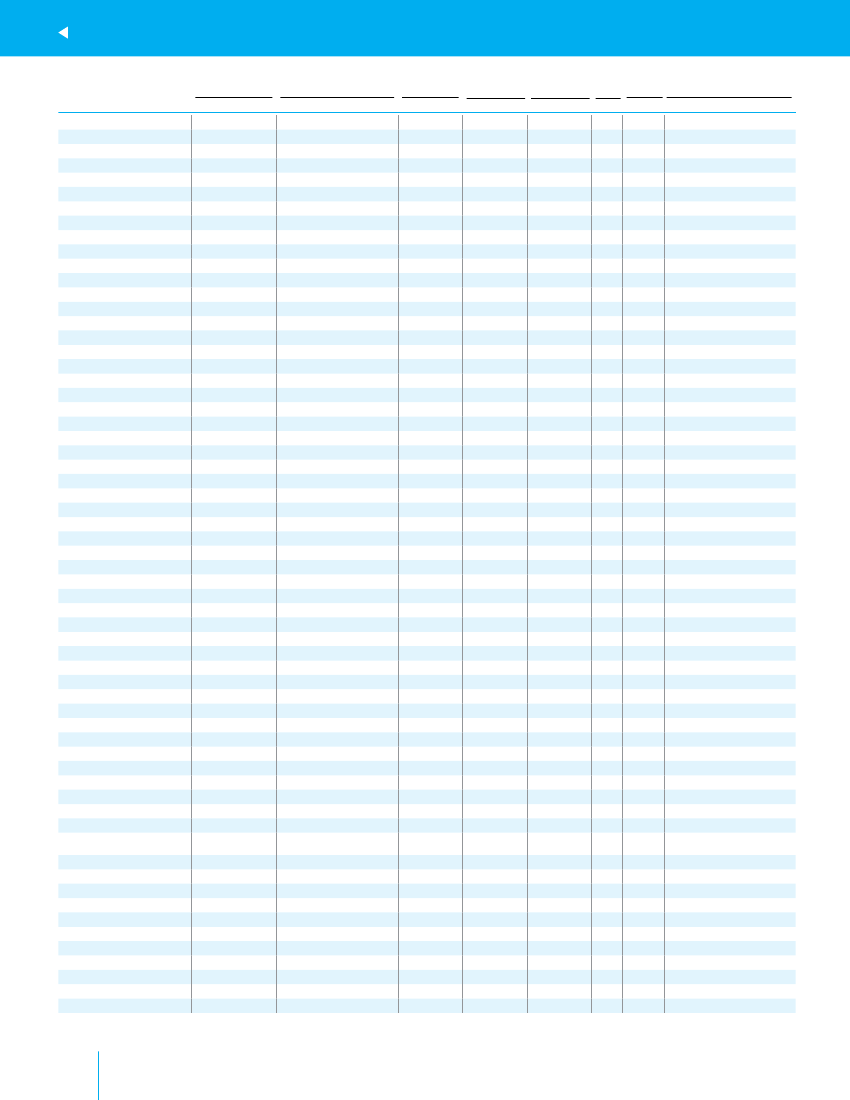

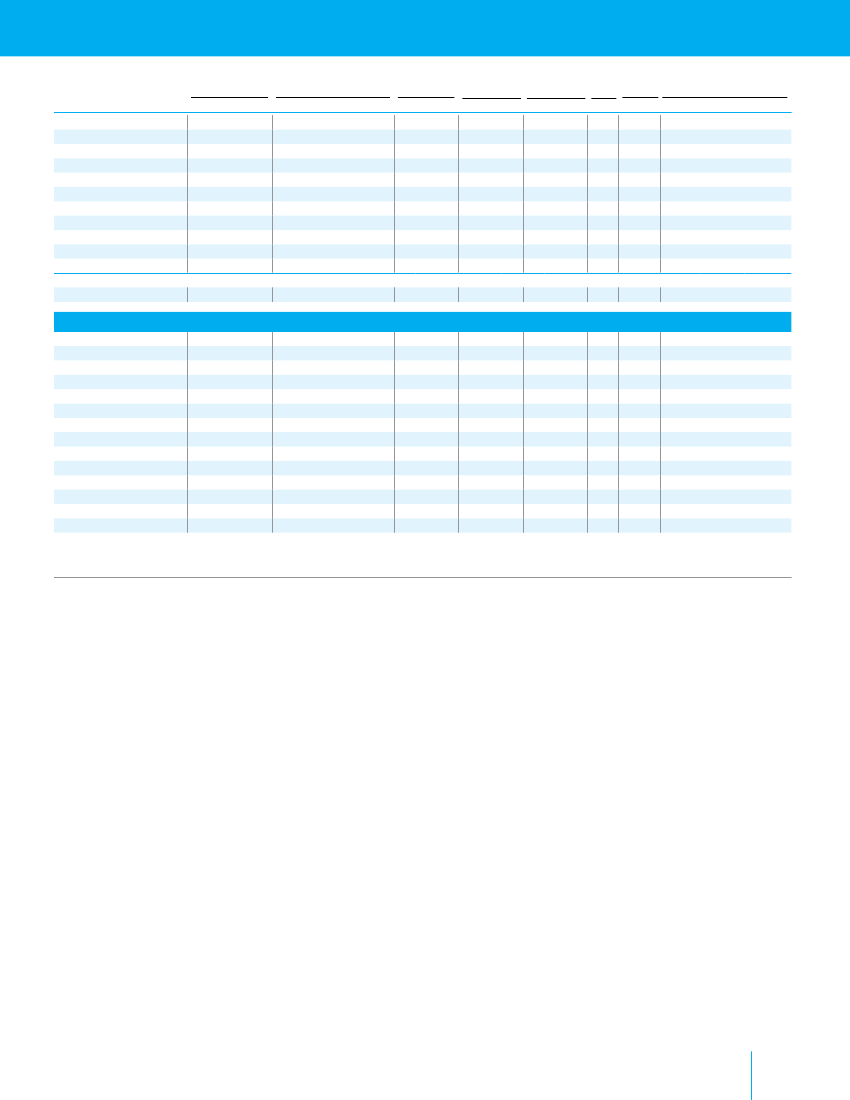

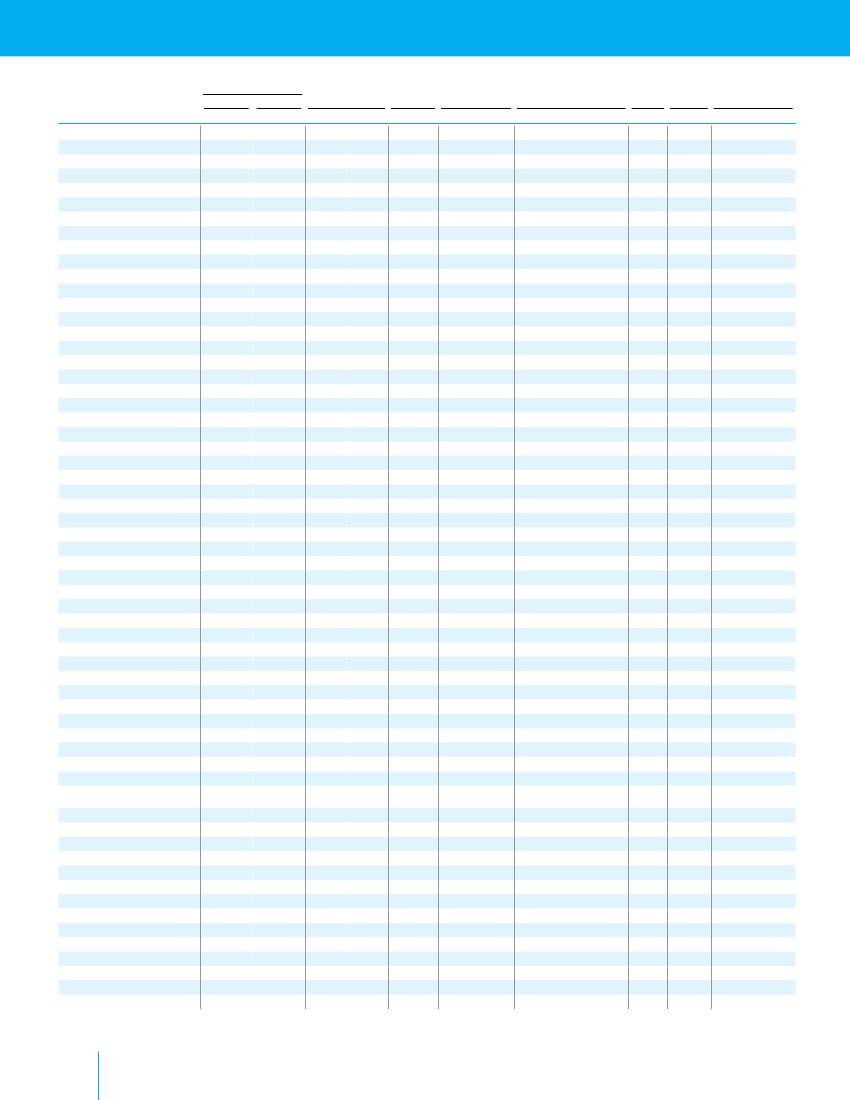

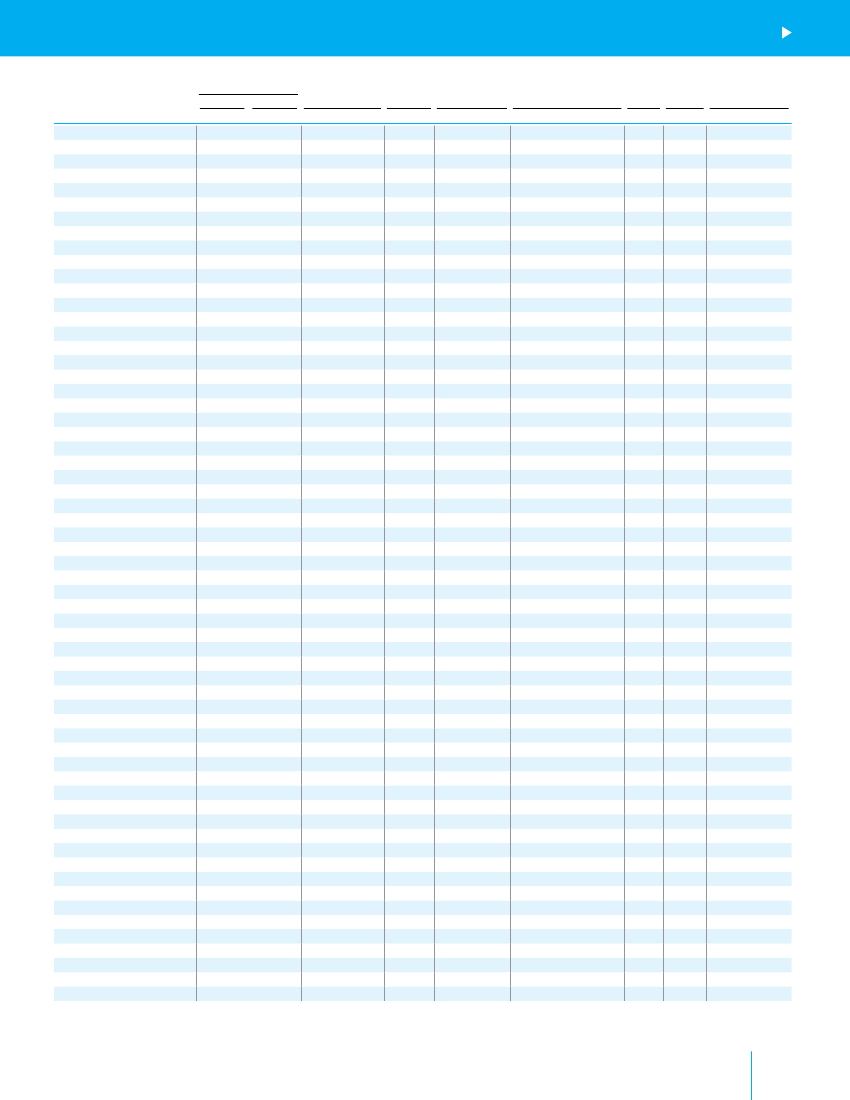

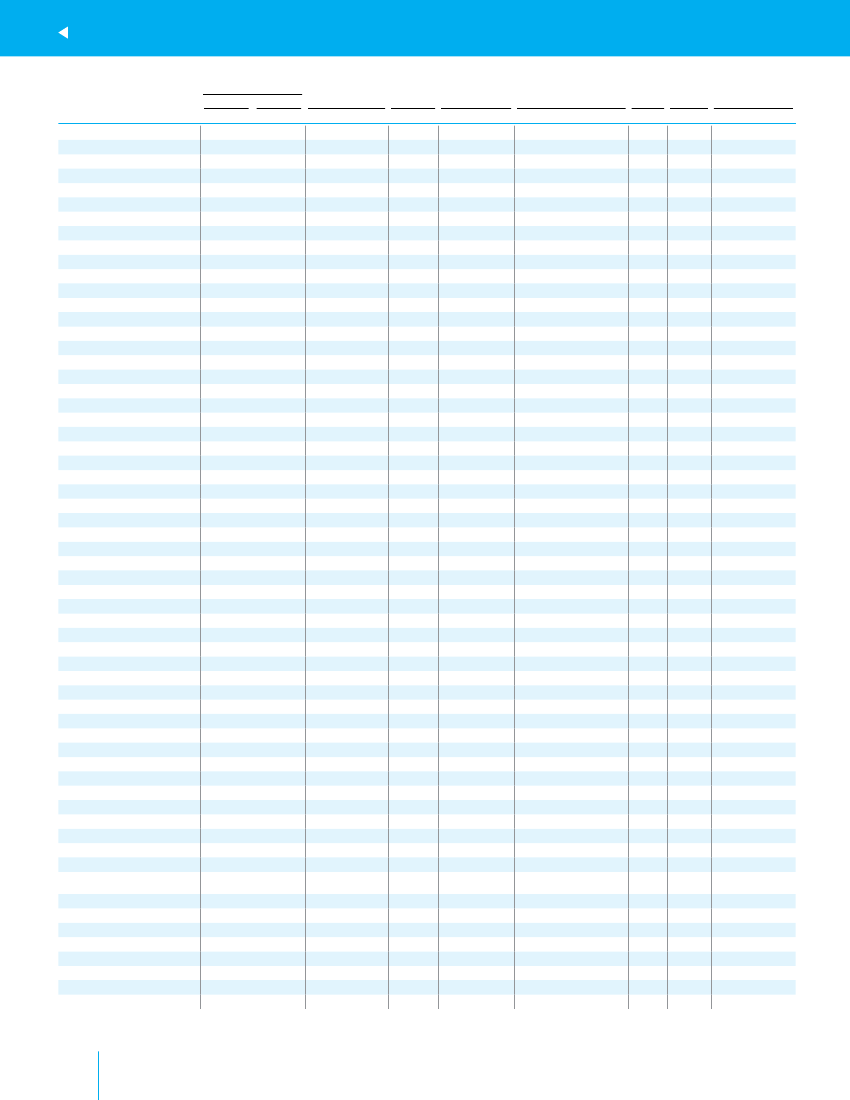

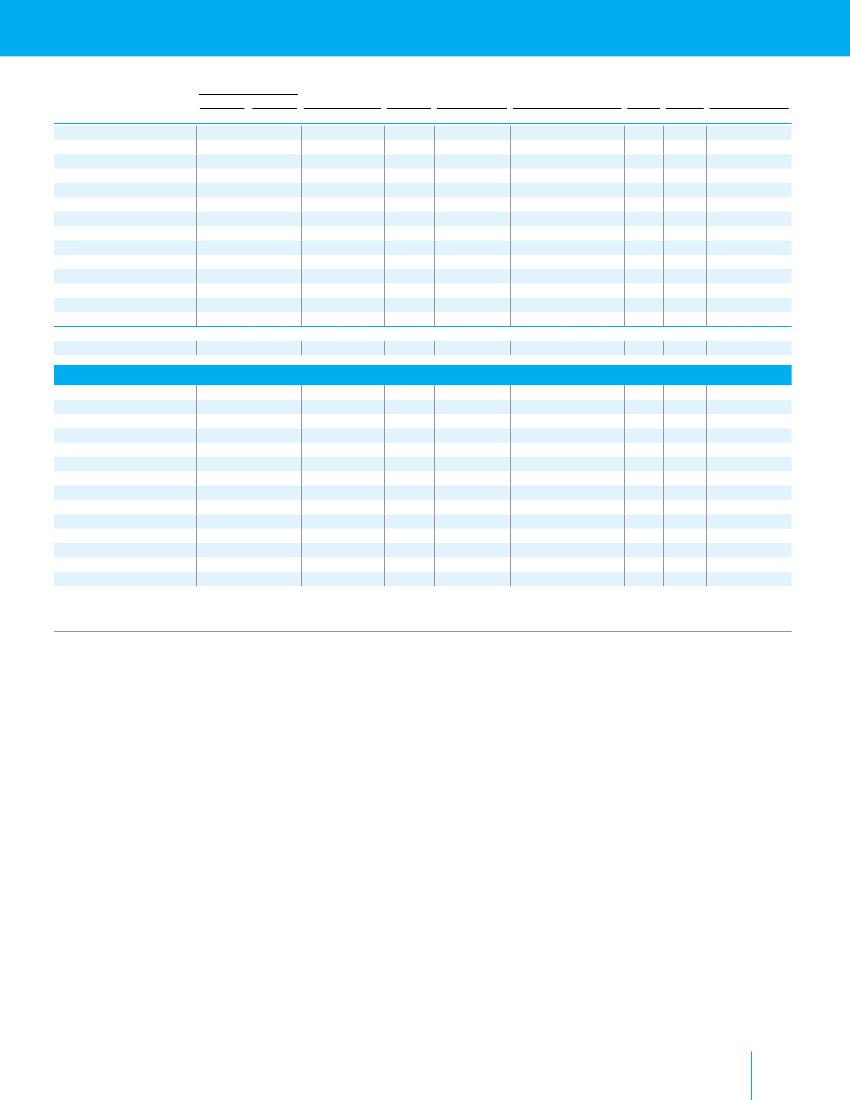

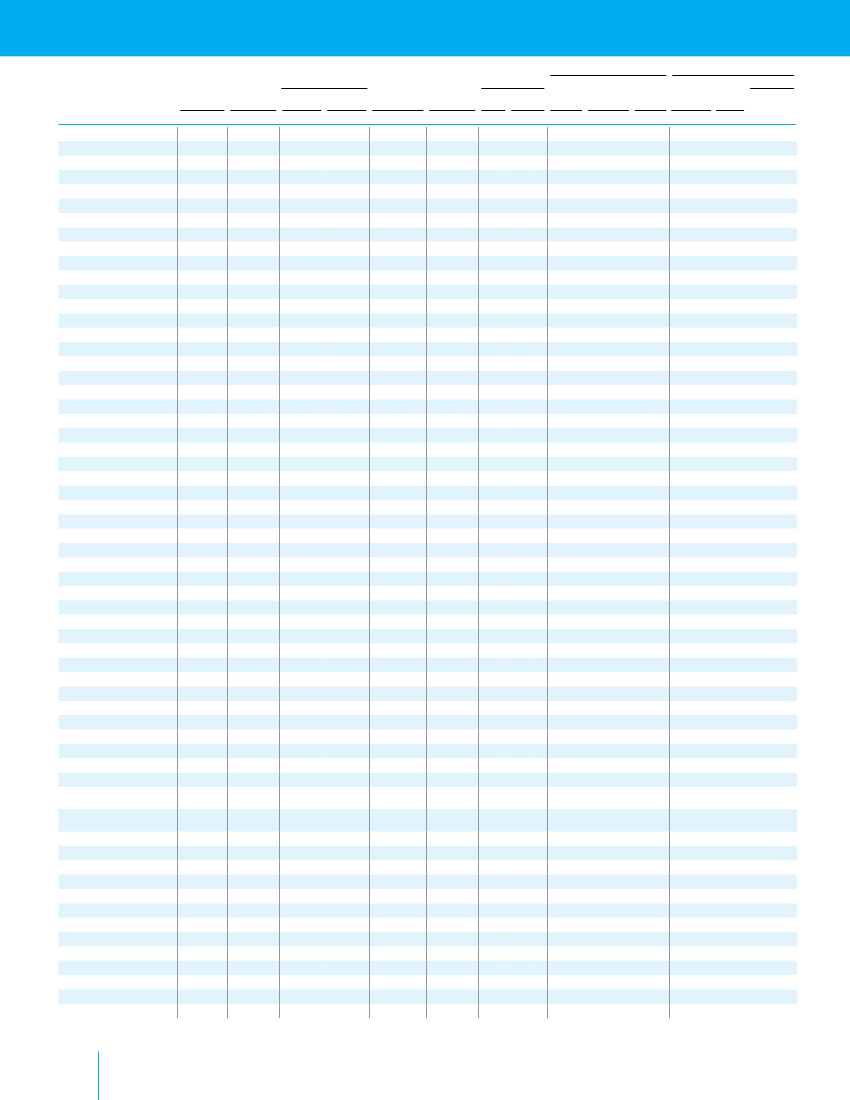

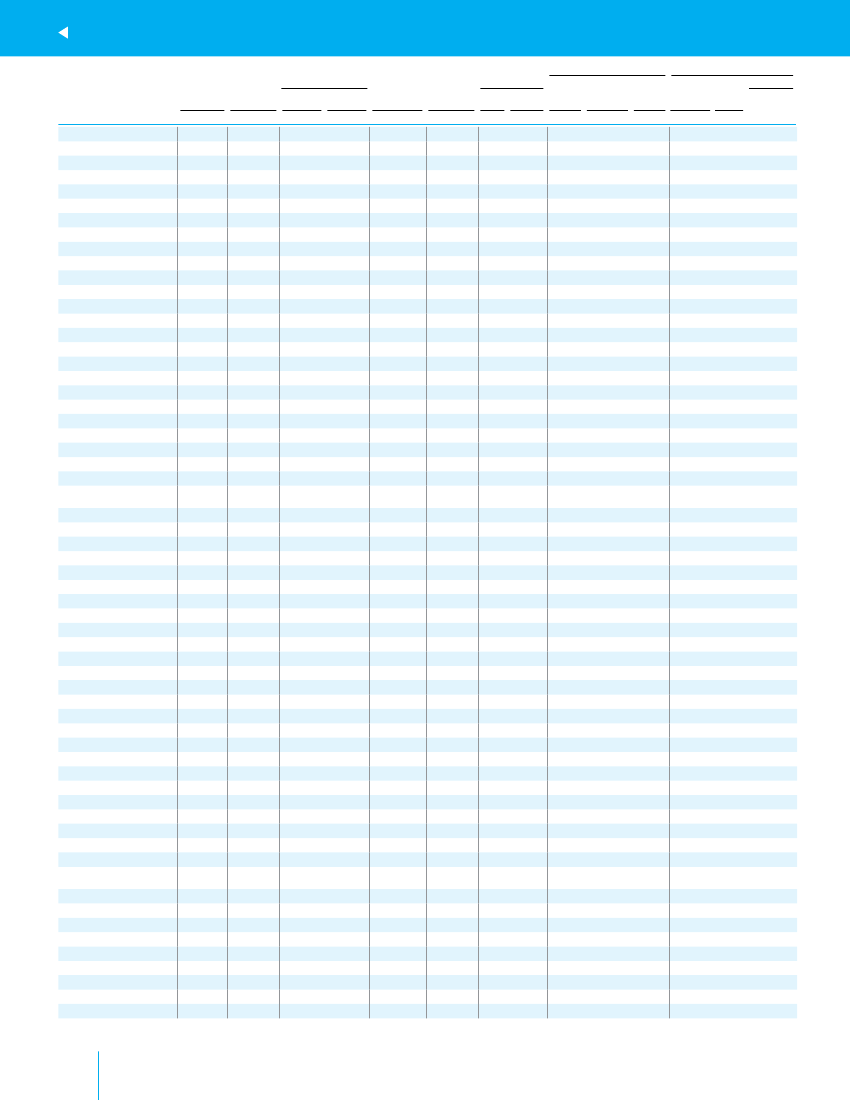

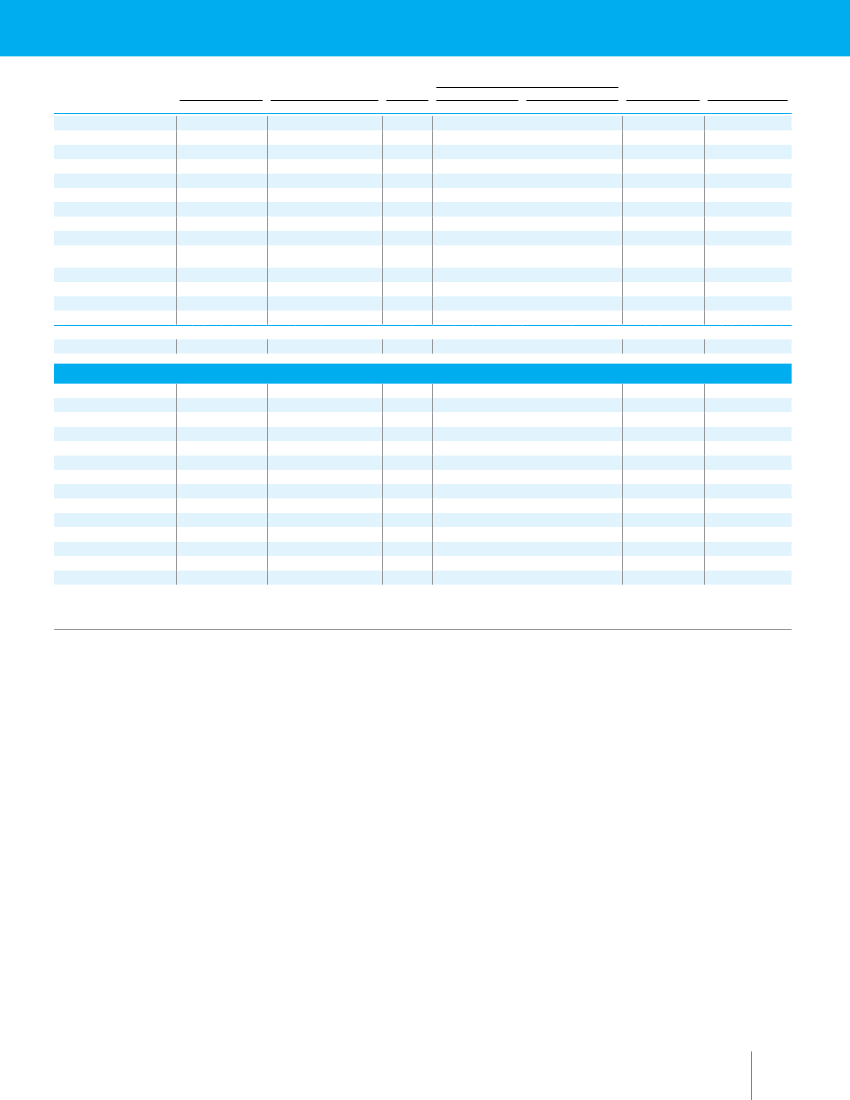

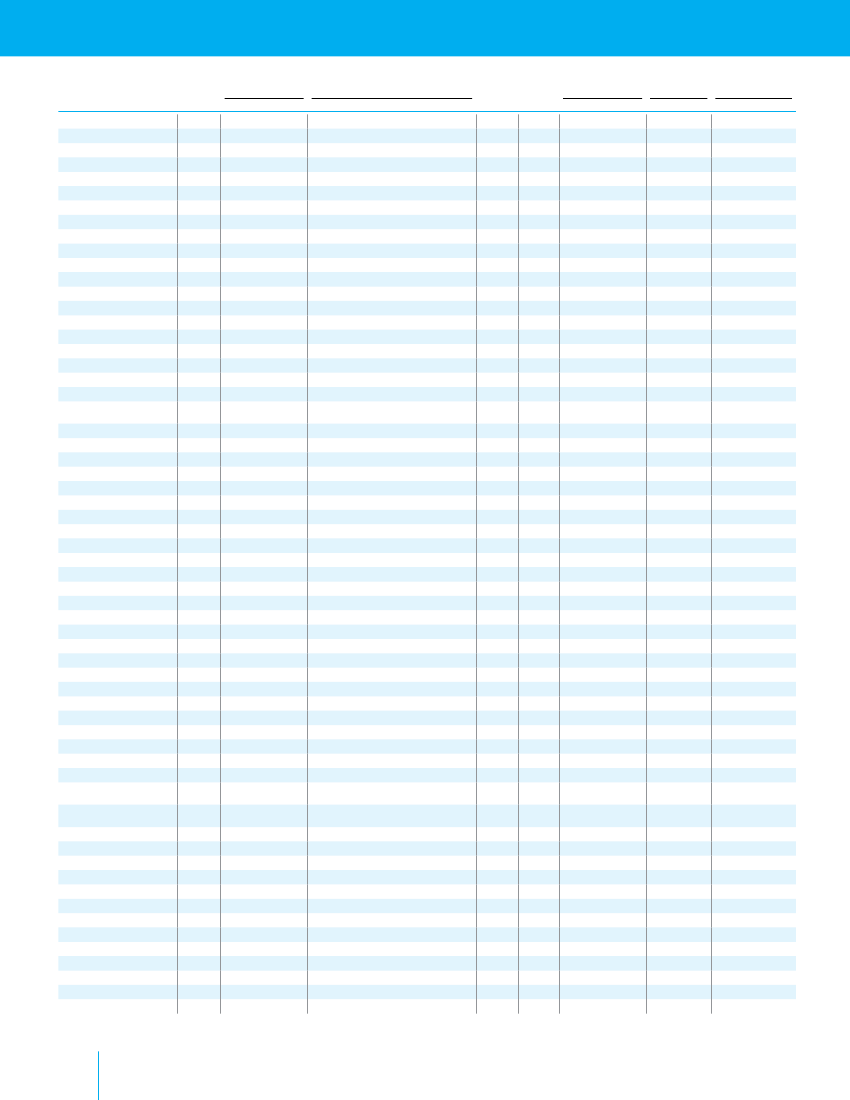

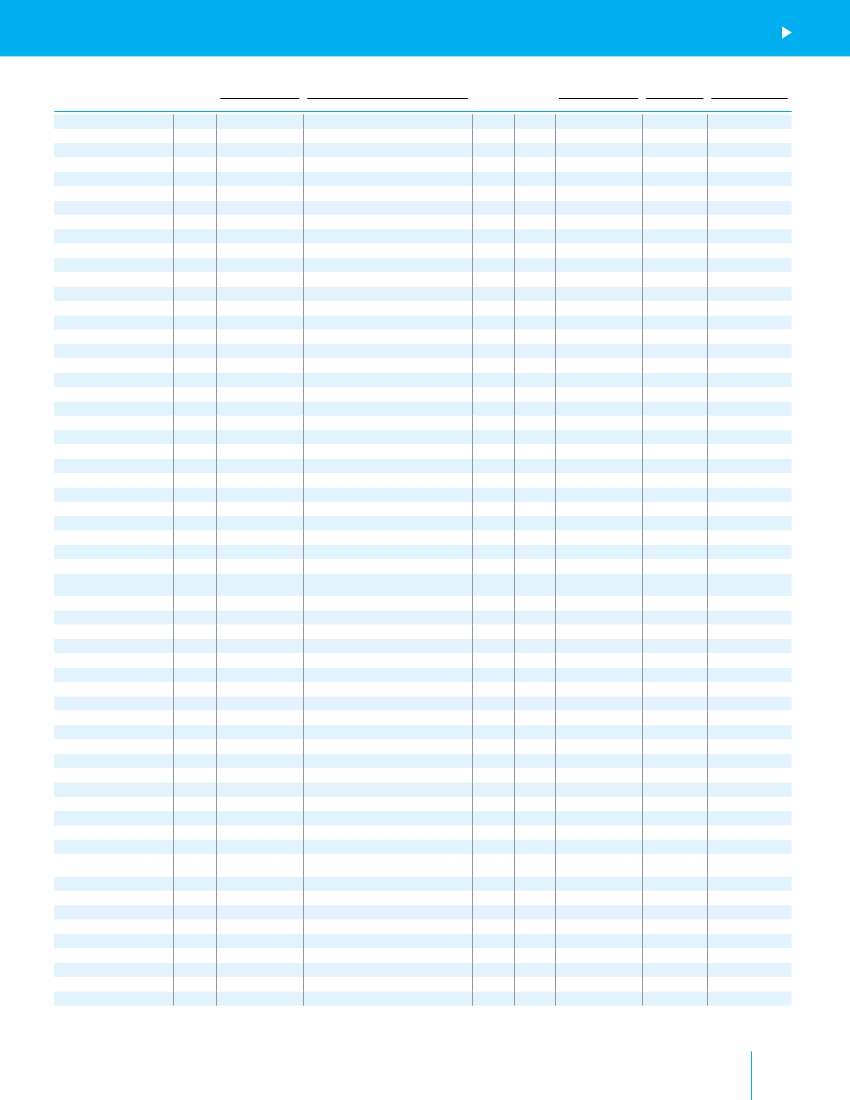

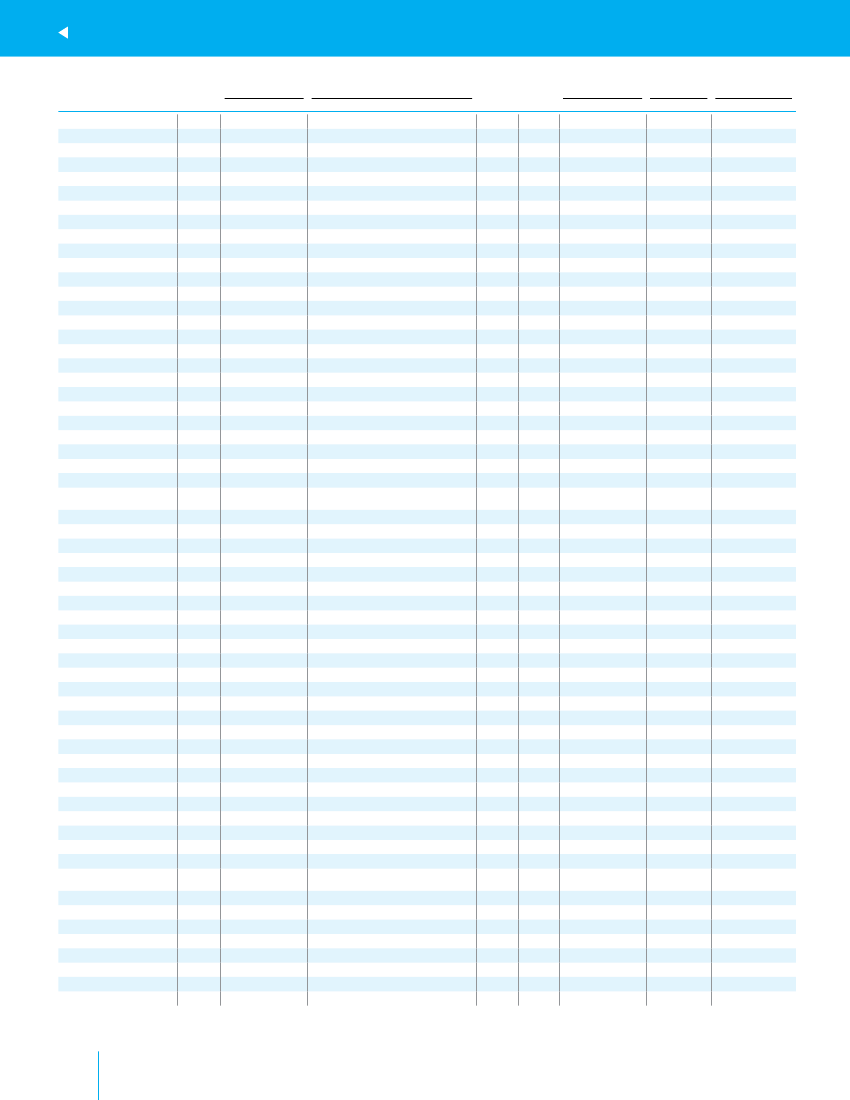

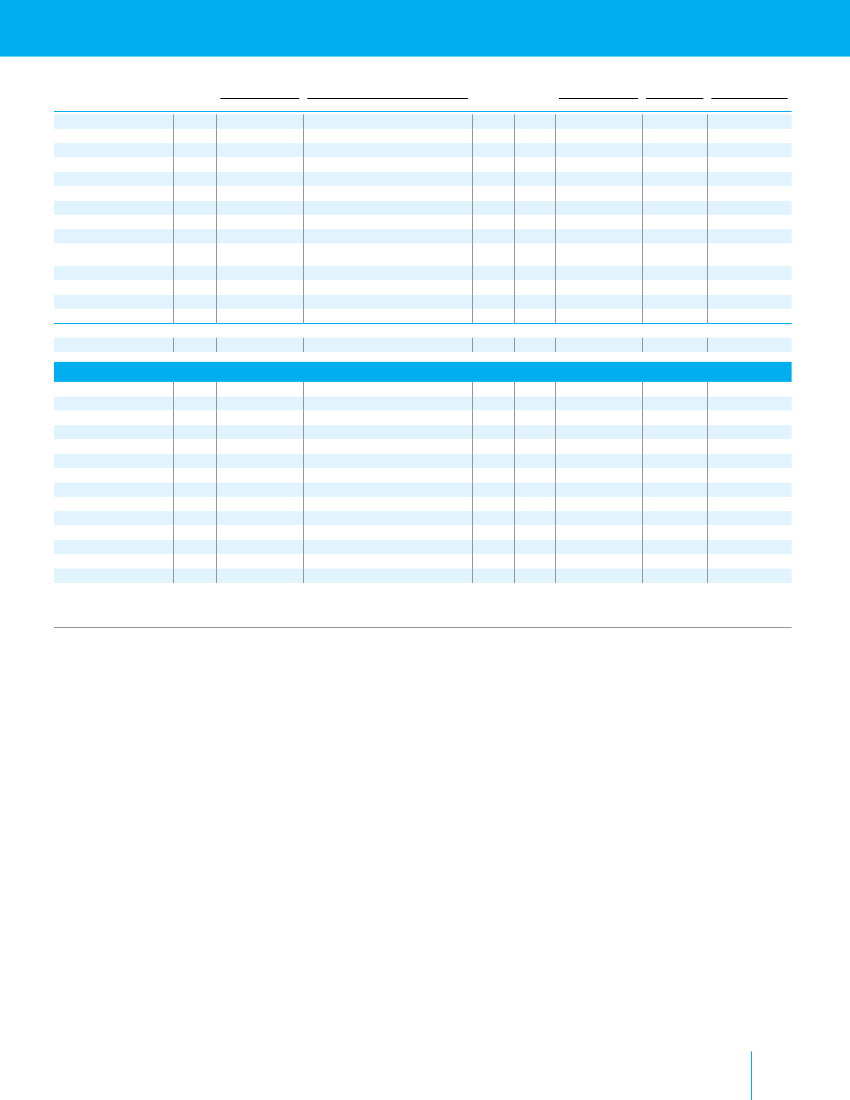

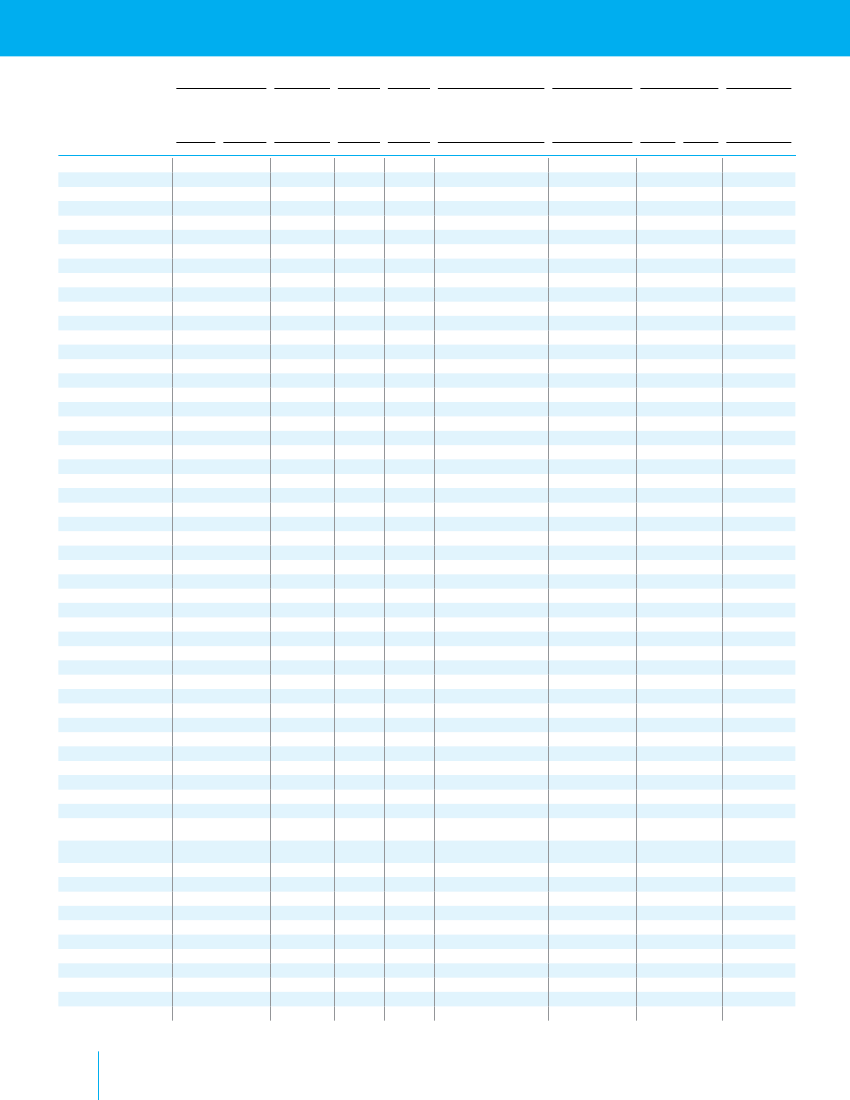

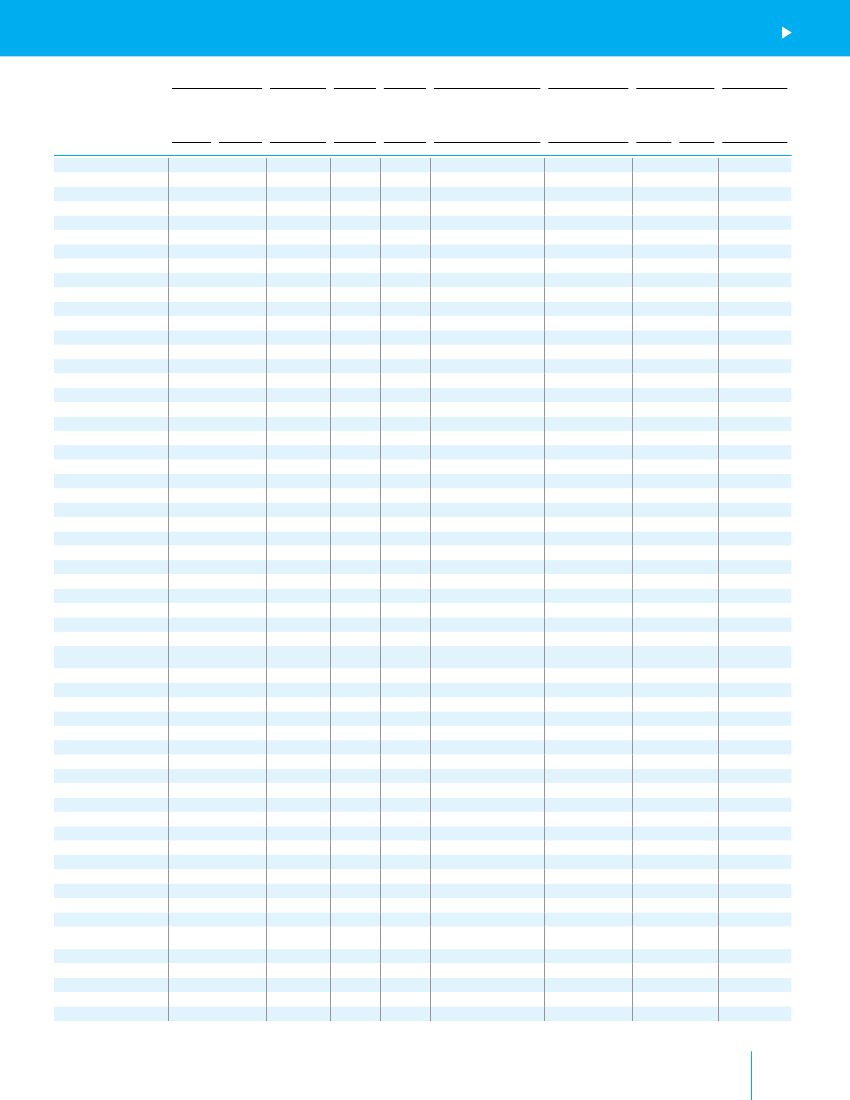

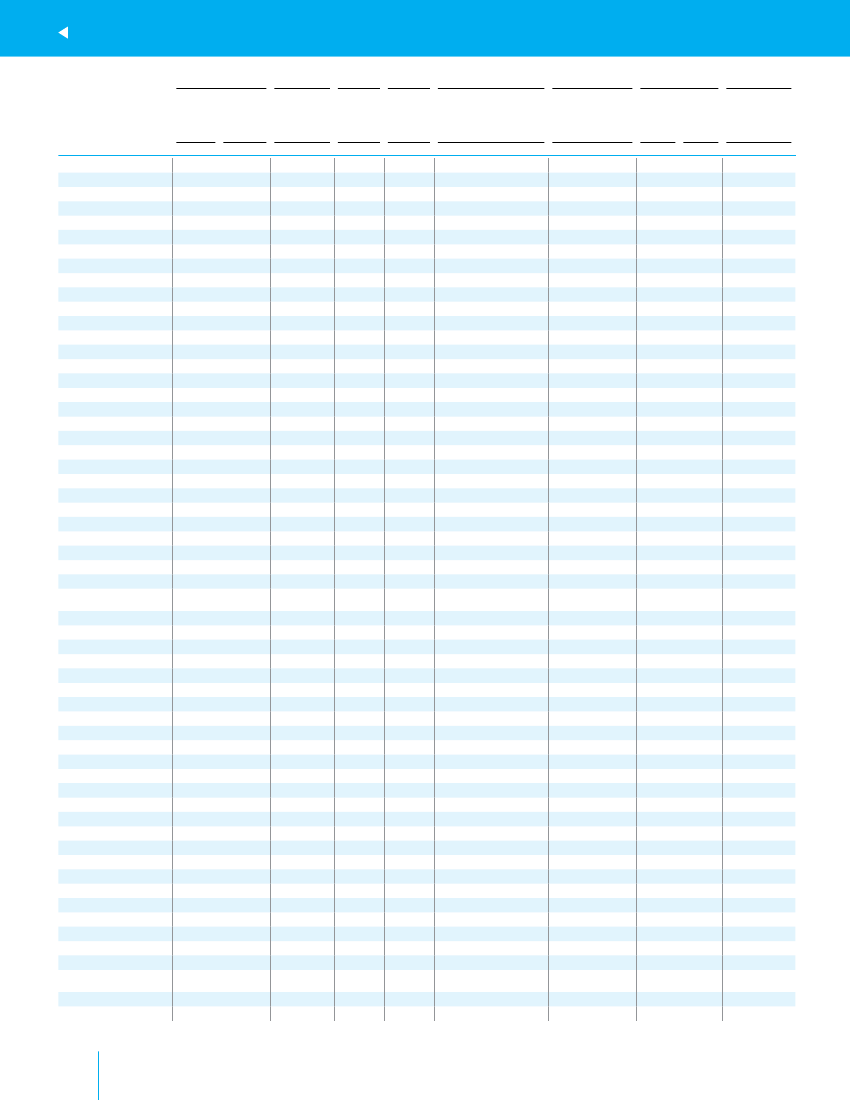

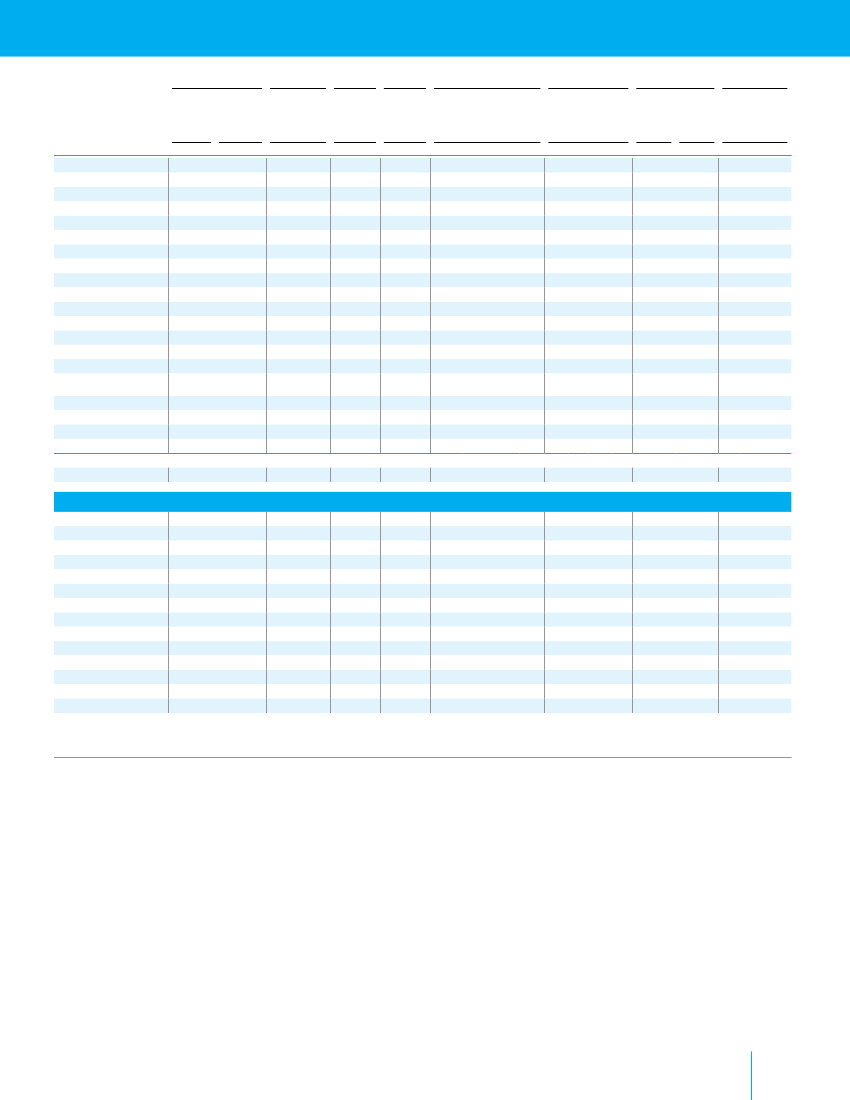

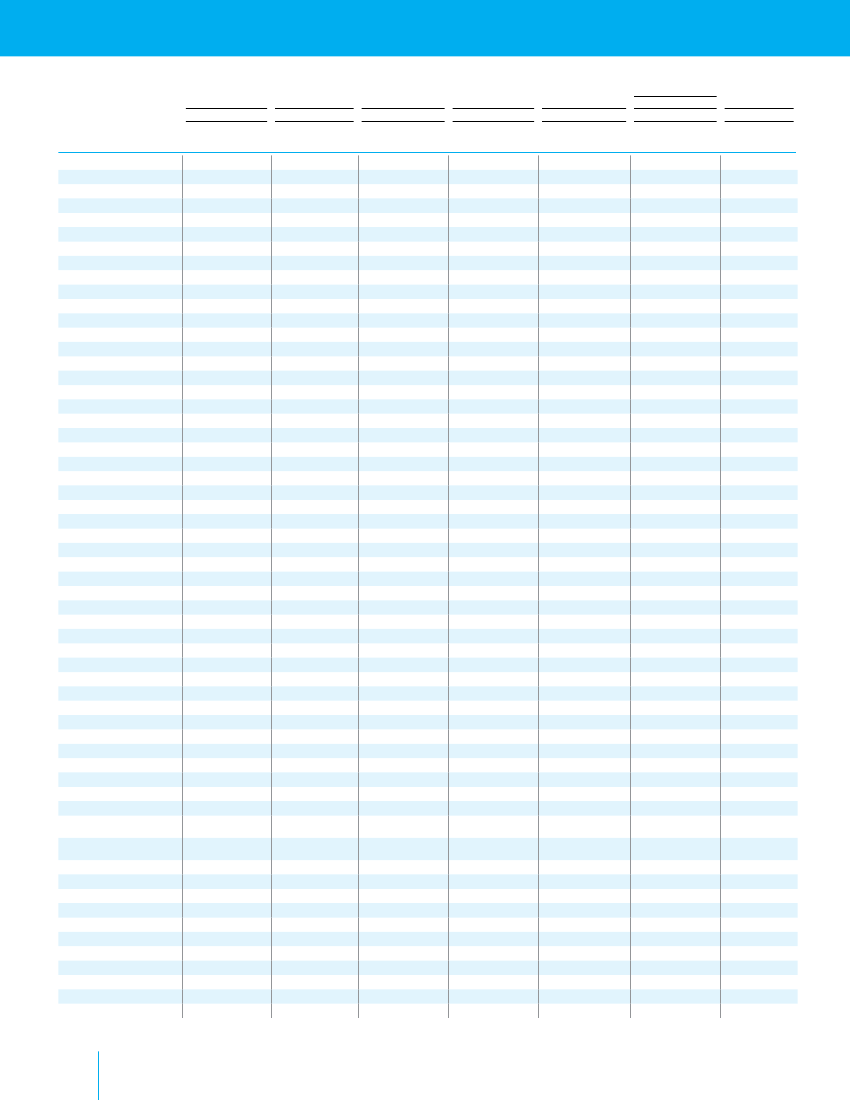

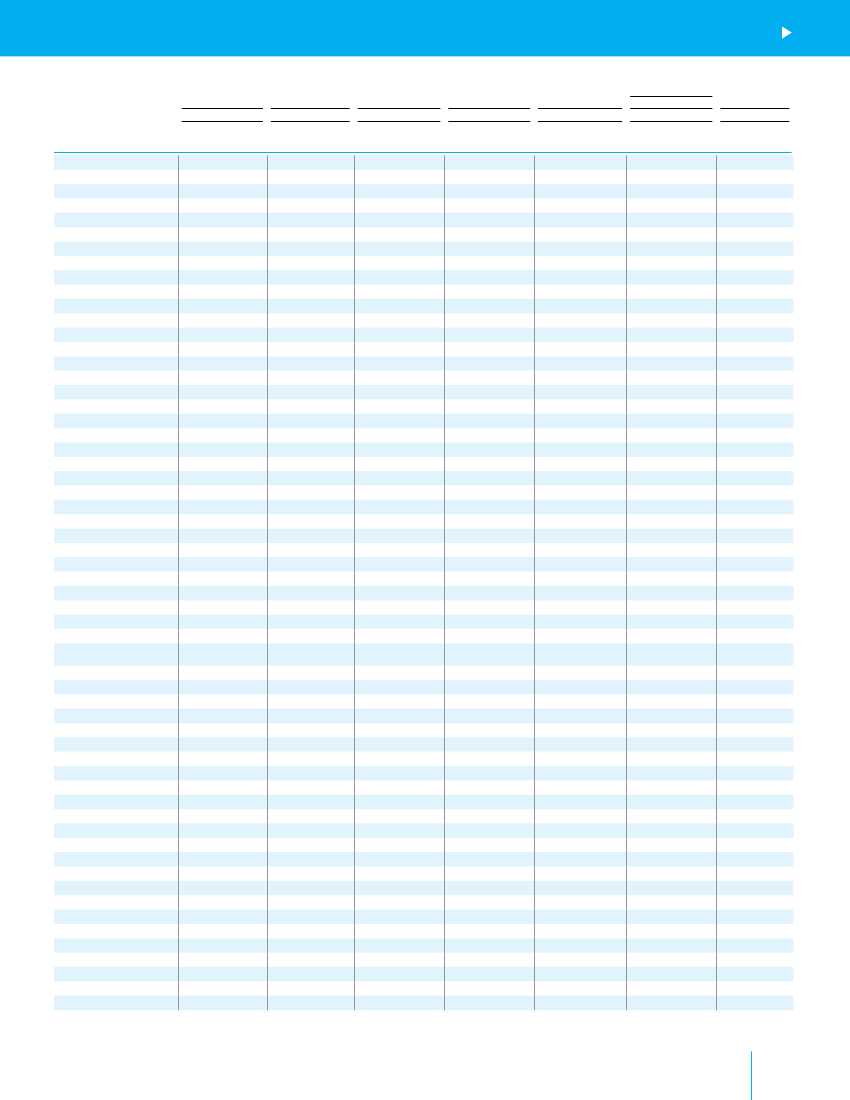

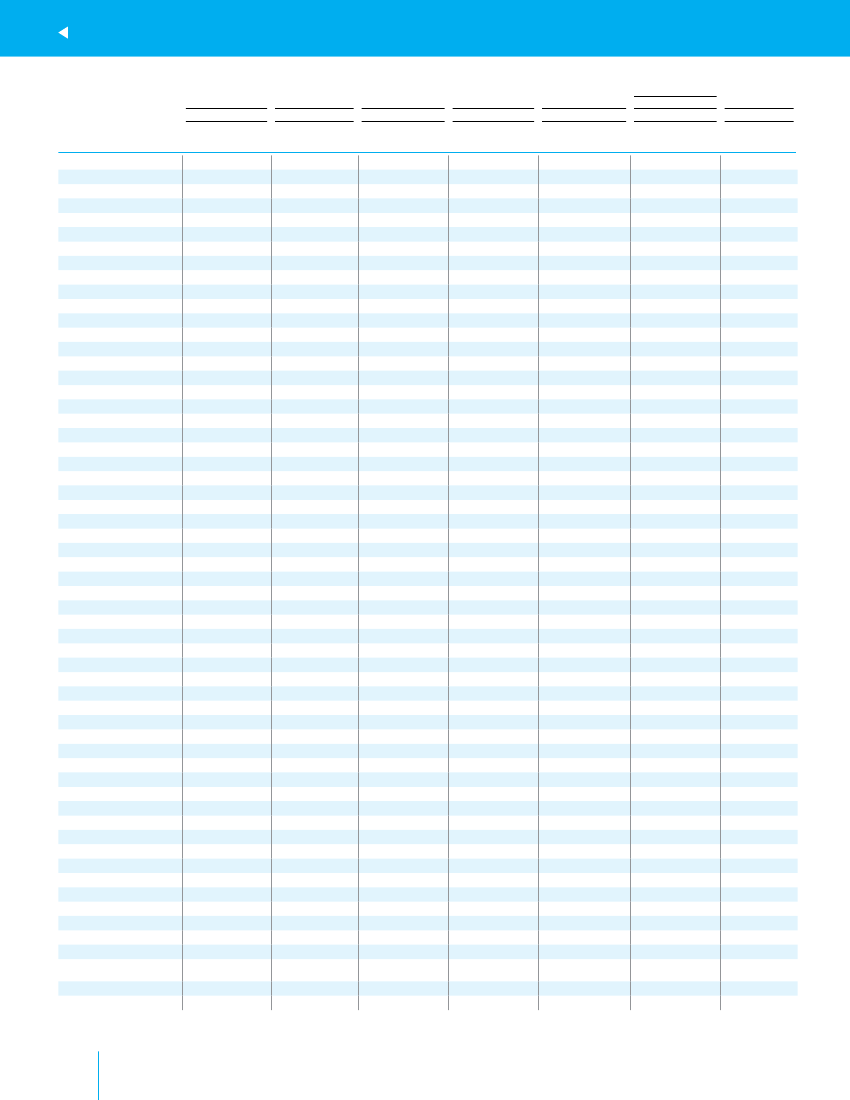

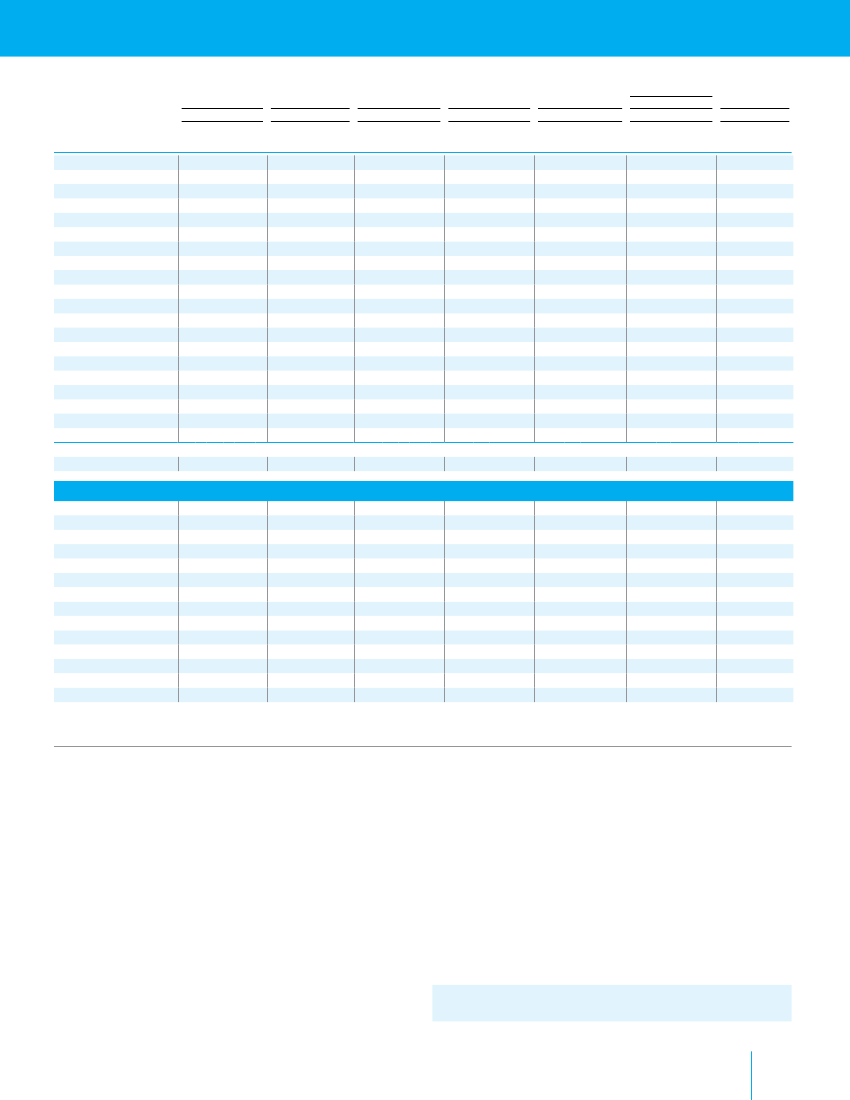

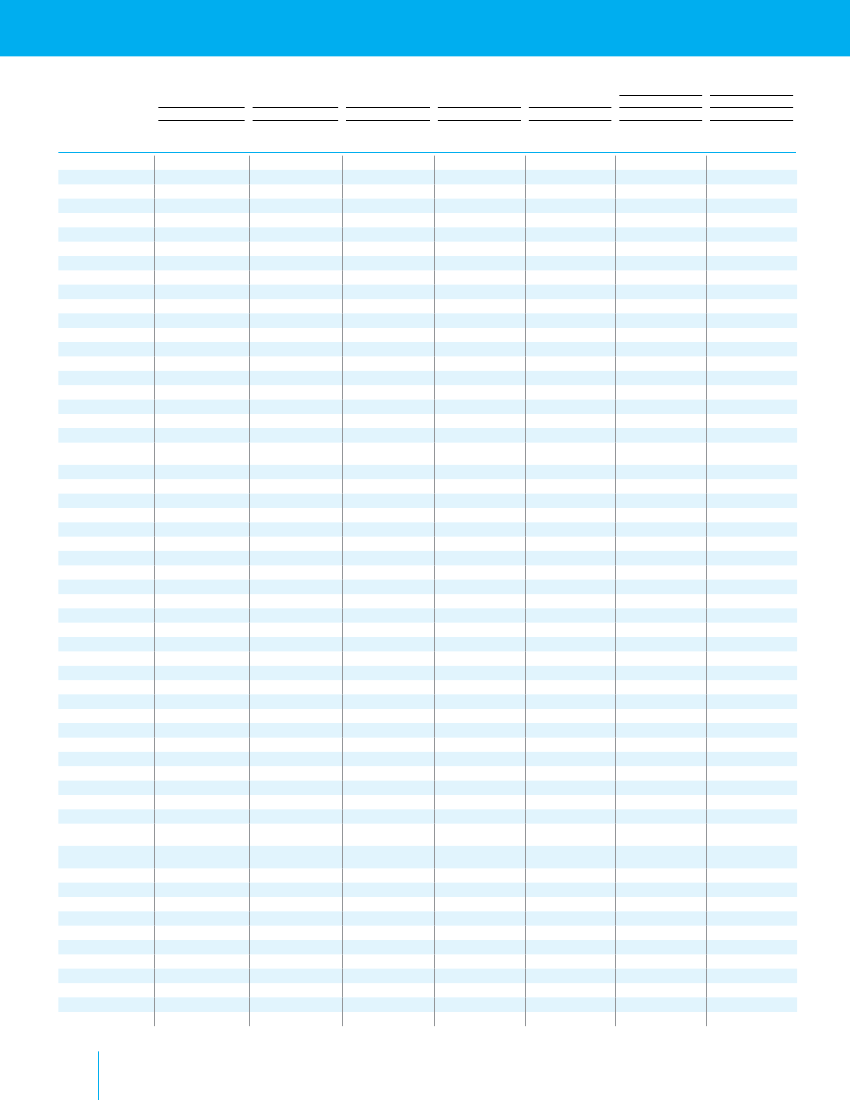

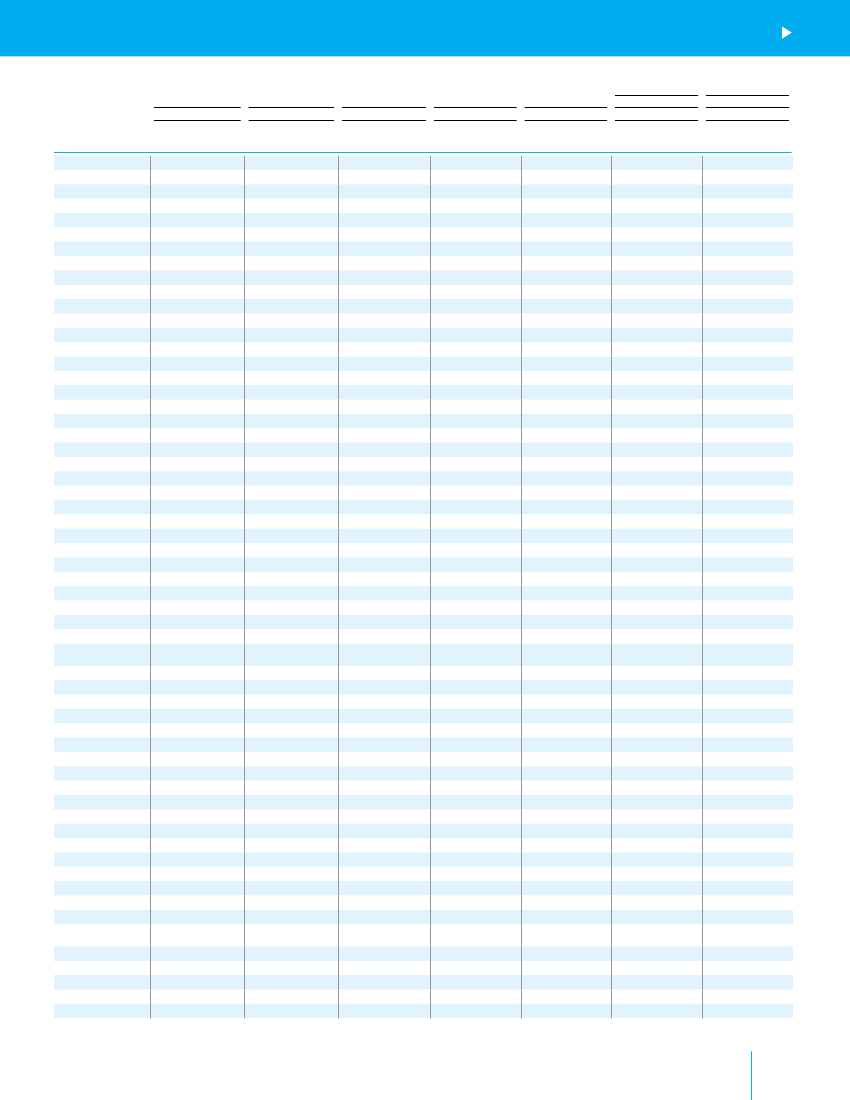

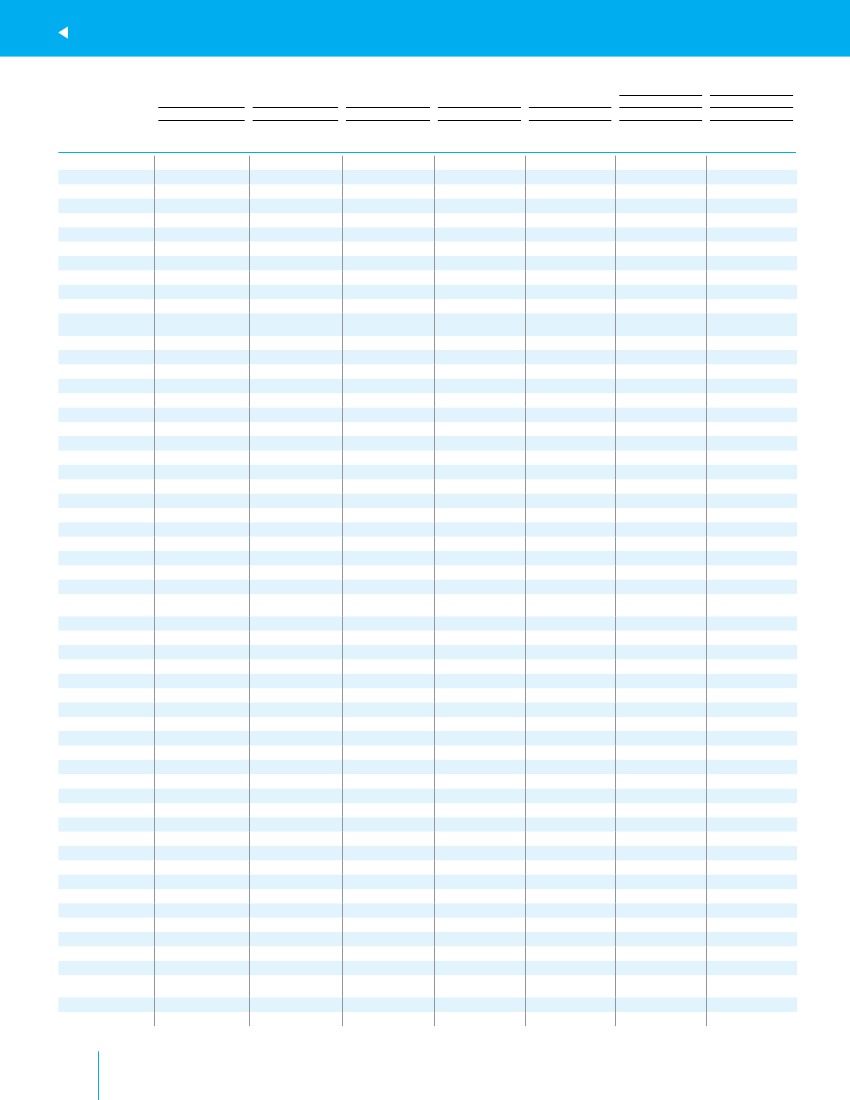

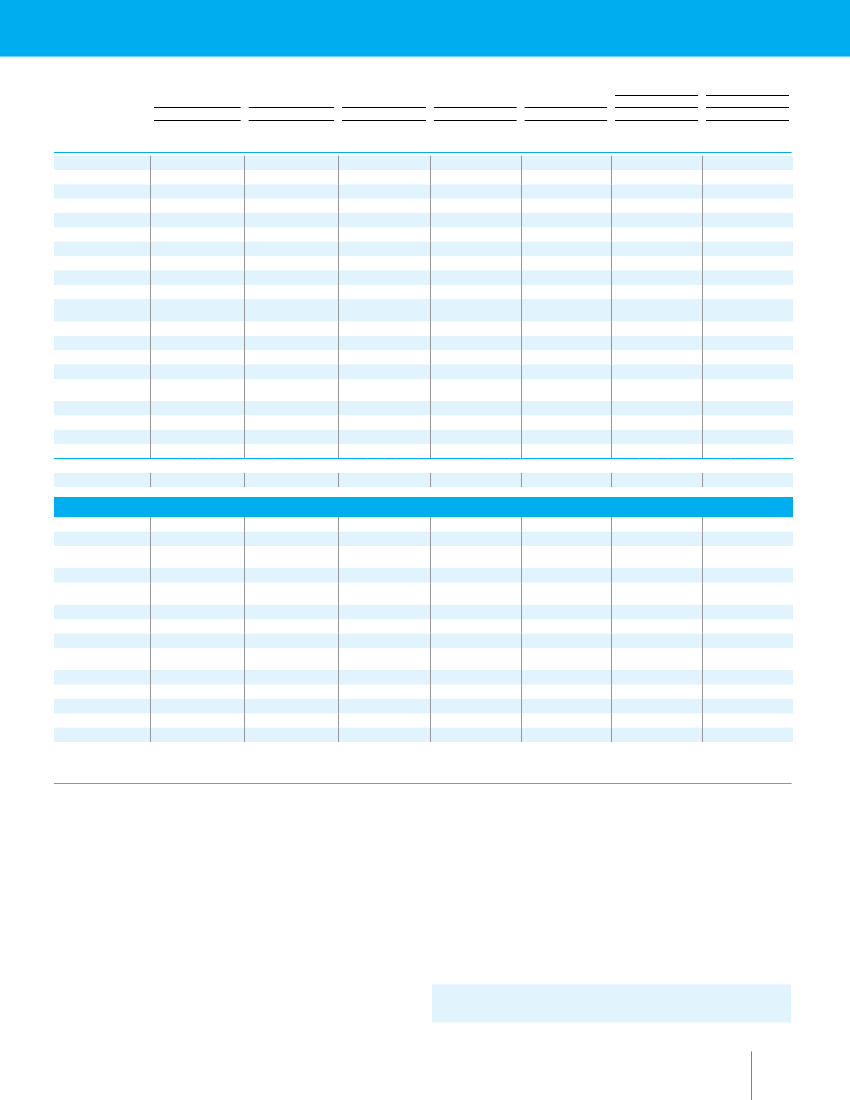

EM28BAFebr RGua Ory ED2012Table 7 .

Under-five mortality rankings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .87Table 1 . Basic indicators . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .88Table 2 . Nutrition . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .92Table 3 . Health . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .96Table 4 . HIV/AIDS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 100Table 5 . Education . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 104Table 6 . Demographic indicators . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 108Economic indicators . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 112Table 8 . Women . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 116Table 9 . Child protection . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .120Table 10 . The rate of progress . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .125Table 11 . Adolescents . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .130Table 12 . Equity – Residence . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .134Table 13 . Equity – Household wealth . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .138ABBREVIATIONS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .142

Contents

ix

CHAPTER

1

EM28BAFebr RGua Ory ED2012� UNICEF/NYHQ2005-1185/Roger LeMoyne

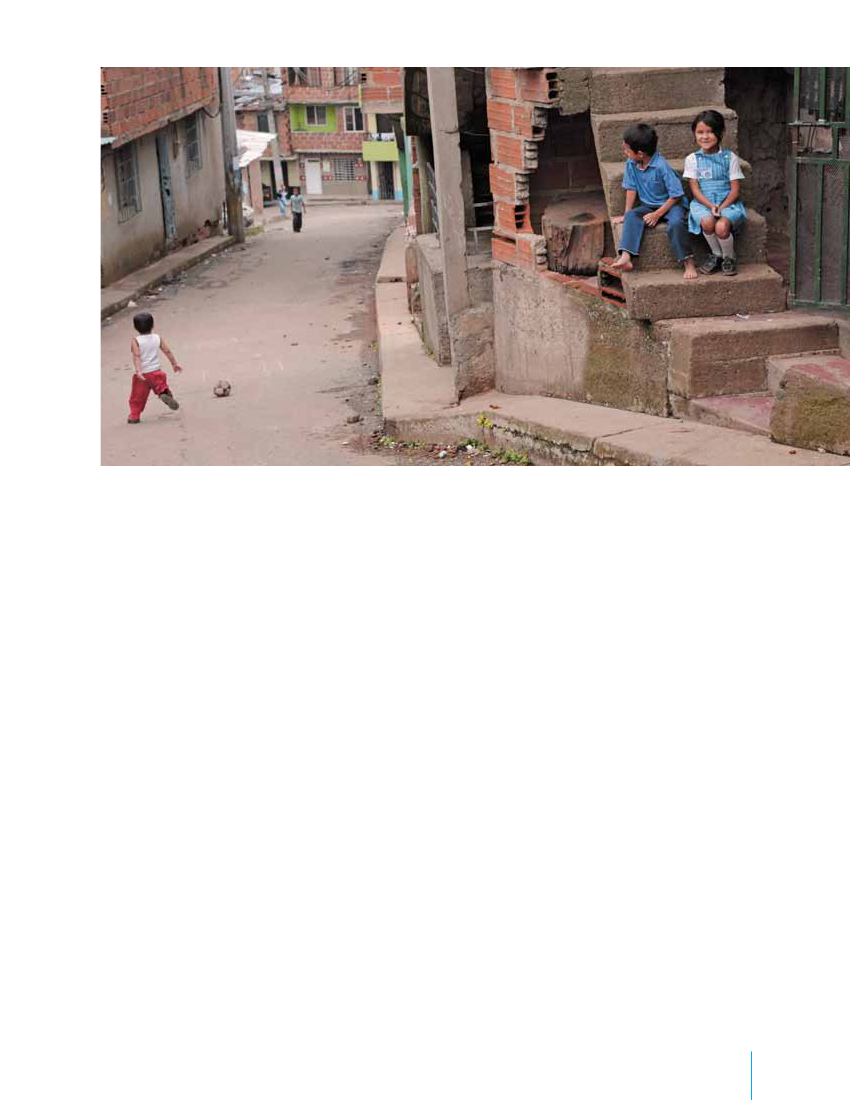

The day is coming when the majority of the world’schildren will grow up in cities and towns. Already, halfof all people live in urban areas. By mid-century, overtwo thirds of the global population will call these placeshome. This report focuses on the children – more thanone billion and counting – who live in urban settingsaround the world.

Urban areas offer great potential to secure children’srights and accelerate progress towards the MillenniumDevelopment Goals (MDGs). Cities attract and gener-ate wealth, jobs and investment, and are thereforeassociated with economic development. The moreurban a country, the more likely it is to have higherincomes and stronger institutions.1Children in urbanareas are often better off than their rural counter-parts thanks to higher standards of health, protection,education and sanitation. But urban advances have

EM28BAFebr RGua Ory ED2012

Children inan increasinglyurban worldbeen uneven, and millions of children in marginalizedurban settings confront daily challenges and depriva-tions of their rights.Traditionally, when children’s well-being is assessed, acomparison is drawn between the indicators for chil-dren in rural areas and those in urban settings. Asexpected, urban results tend to be better, whether interms of the proportion of children reaching their firstor fifth birthday, going to school or gaining access toimproved sanitation. But these comparisons rest onaggregate figures in which the hardships endured bypoorer urban children are obscured by the wealth ofcommunities elsewhere in the city.Where detailed urban data are available, they revealwide disparities in children’s rates of survival, nutritionalstatus and education resulting from unequal access to

Children in an increasingly urban world

1

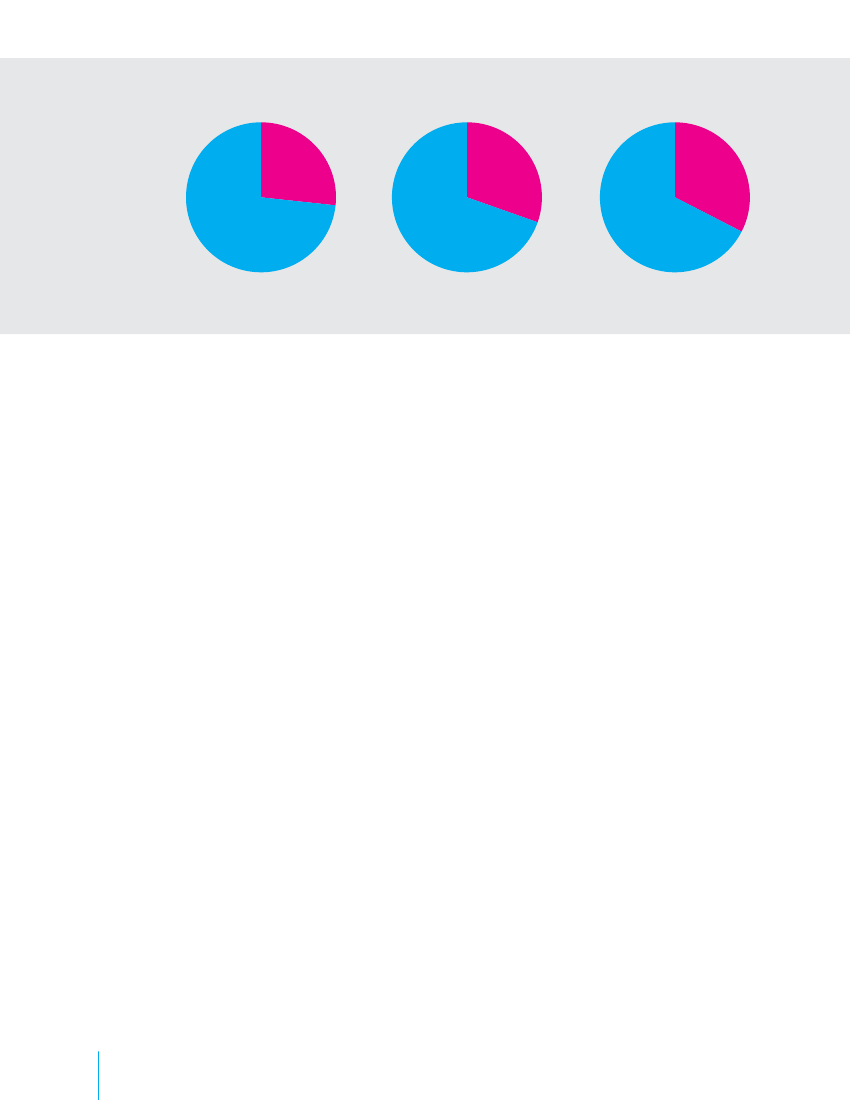

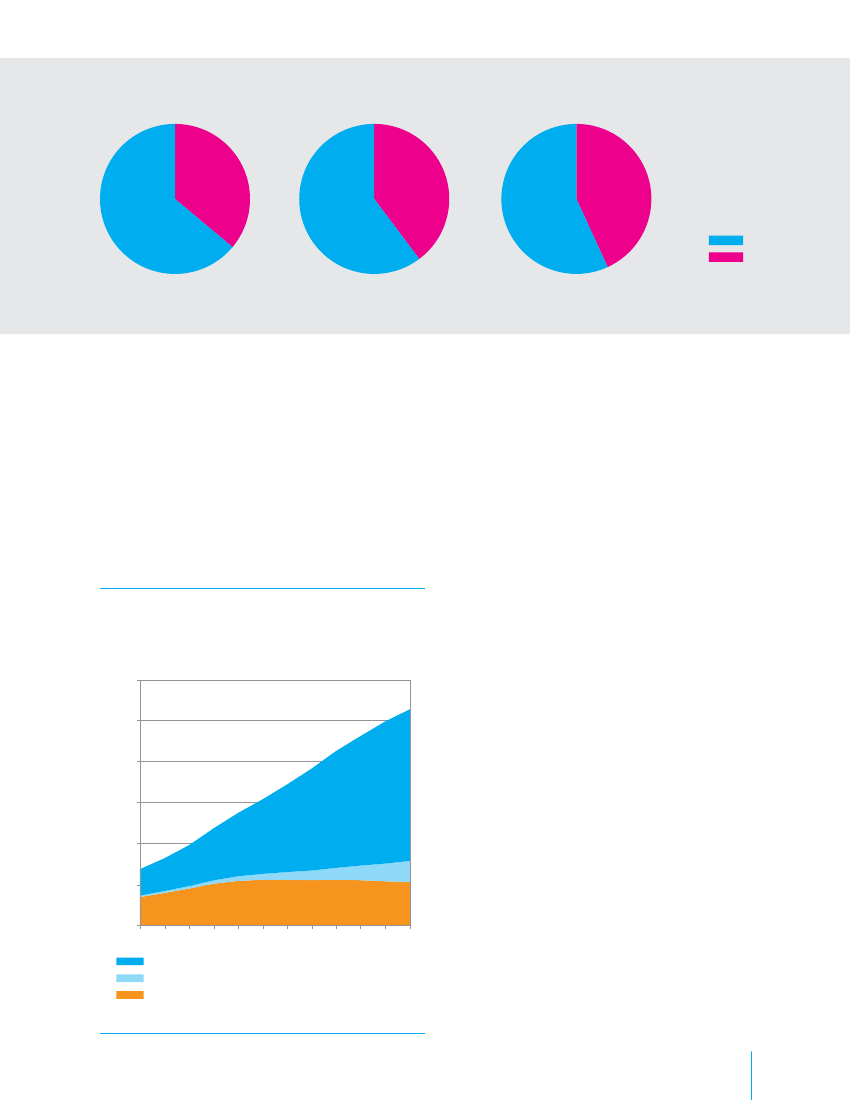

Figure 1 .1 . Almost half of the world’s children live in urban areasWorld population (0–19 years old)

27%

30%

33%

1955

1965

1975

This report focuses mainly on those children in urbansettings all over the world who face a particularlycomplex set of challenges to their development and thefulfilment of their rights. Following an overview of theworld’s urban landscape, Chapter 2 looks at the statusof children in urban settings through the lens of inter-national human rights instruments and developmentgoals. Chapter 3 examines some of the phenomenashaping the lives of children in urban areas, from theirreasons for coming to the city and their experience ofmigration to the challenges posed by economic shocks,violence and acute disaster risk.Clearly, urban life can be harsh. It need not be. Manycities have been able to contain or banish diseases thatwere widespread only a generation ago. Chapter 4 pre-sents examples of efforts to improve the urban realities2THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S CHILDREN 2012

EM28BAFebr RGua Ory ED2012An urban future

services. Such disaggregated information is hard to find,however, and for the most part development is pursued,and resources allocated, on the basis of statistical aver-ages. One consequence of this is that children livingin informal settlements and impoverished neighbour-hoods are excluded from essential services and socialprotection to which they have a right. This is happen-ing as population growth puts existing infrastructureand services under strain and urbanization becomesnearly synonymous with slum formation. Accordingto the United Nations Human Settlements Programme(UN-Habitat), one city dweller in three lives in slumconditions, lacking security of tenure in overcrowded,unhygienic places characterized by unemployment,pollution, traffic, crime, a high cost of living, poorservice coverage and competition over resources.

that children confront. These instances show that it ispossible to fulfil commitments to children – but onlyif all children receive due attention and investmentand if the privilege of some is not allowed to obscurethe disadvantages of others. Accordingly, the finalchapter of this report identifies broad policy actions thatshould be included in any strategy to reach excluded chil-dren and foster equity in urban settings riven by disparity.

By 2050, 7 in 10 people will live in urban areas. Everyyear, the world’s urban population increases by approx-imately 60 million people. Most of this growth istaking place in low- and middle-income countries. Asiais home to half of the world’s urban population and66 out of the 100 fastest-growing urban areas, 33 ofwhich are in China alone. Cities such as Shenzhen, with a10 per cent rate of annual increase in 2008, are doublingin population every seven years.2Despite a low overallrate of urbanization, Africa has a larger urban populationthan North America or Western Europe, and more than6 in 10 Africans who live in urban areas reside in slums.New urban forms are evolving as cities expand andmerge. Nearly 10 per cent of the urban population isfound in megacities – each with more than 10 millionpeople – which have multiplied across the globe.New York and Tokyo, on the list since 1950, havebeen joined by a further 19, all but 3 of them in Asia,Latin America and Africa. Yet most urban growth istaking place not in megacities but in smaller cities andtowns, home to the majority of urban children andyoung people.3

36%

40%

43%RuralUrban

1985

1995

2005Source:United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA), Population Division.

Migration from the countryside has long driven urbangrowth and remains a major factor in some regions.But the last comprehensive estimate, made in 1998,

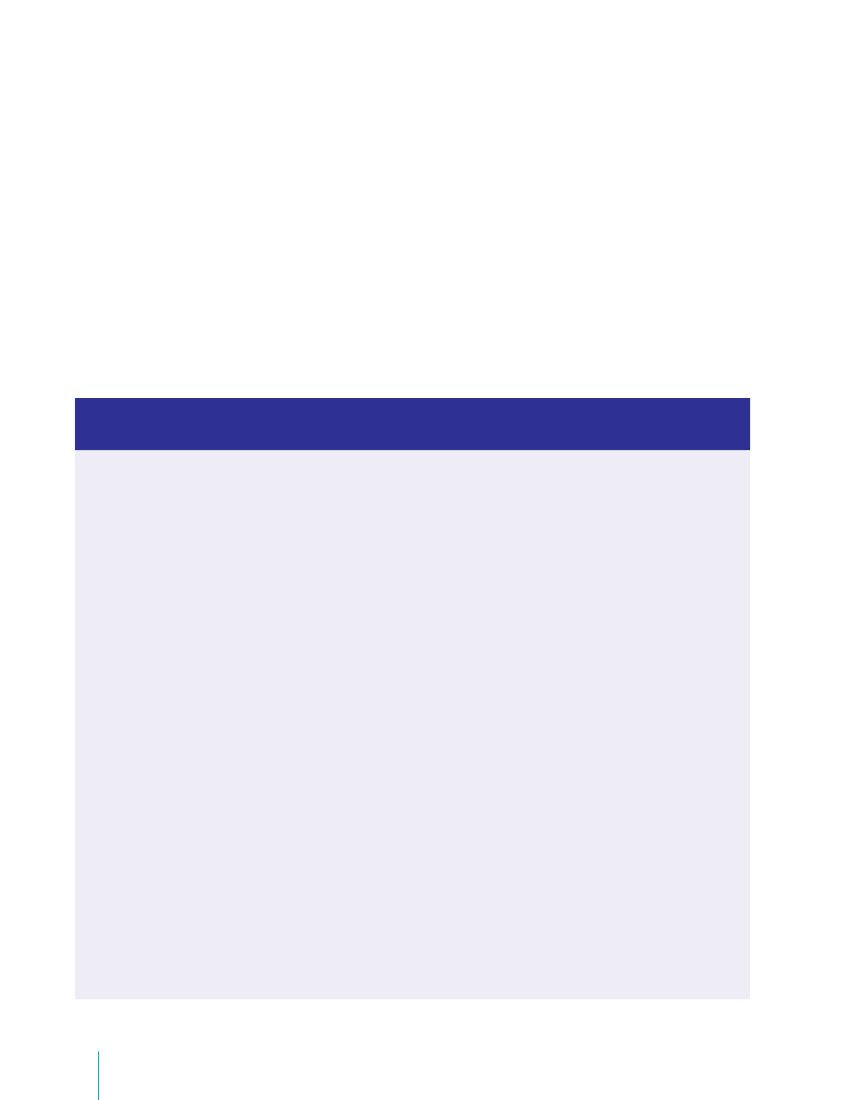

Figure 1 .2 . Urban population growth is greater inless developed regionsWorld urban population (0–19 years old)Millions1,200

1,000

800

600

400

200

0195019551960196519701975198019851990199520002005

Less developed regionsLeast developed countries (a subset of less developed regions)More developed regionsSource:UNDESA, Population Division.

EM28BAFebr RGua Ory ED2012

In contrast to rapid urban growth in the developingworld, more than half of Europe’s cities are expectedto shrink over the next two decades.4The size of theurban population in high-income countries is projectedto remain largely unchanged through 2025, however,with international migrants making up the balance.5

suggests that children born into existing urban popula-tions account for around 60 per cent of urban growth.6

Poverty and exclusionFor billions of people, the urban experience is oneof poverty and exclusion. Yet standard data collec-tion and analysis fail to capture the full extent of bothproblems. Often, studies overlook those residents of acity whose homes and work are unofficial or unreg-istered – precisely those most likely to be poor orsuffer discrimination. Moreover, official definitions ofpoverty seldom take sufficient account of the cost ofnon-food needs. In consequence, poverty thresholdsapplied to urban populations make inadequate allow-ance for the costs of transport, rent, water, sanitation,schooling and health services.7Difficult urban living conditions reflect and are exac-erbated by factors such as illegality, limited voice indecision-making and lack of secure tenure, assetsand legal protection. Exclusion is often reinforced bydiscrimination on the grounds of gender, ethnicity, raceor disability. In addition, cities often expand beyondthe capacity of the authorities to provide the infrastruc-ture and services needed to ensure people’s health andwell-being. A significant proportion of urban popula-tion growth is occurring in the most unplanned anddeprived areas. These factors combine to push essen-tial services beyond the reach of children and familiesliving in poor urban neighbourhoods.Physical proximity to a service does not guaranteeaccess. Indeed, many urban inhabitants live close toChildren in an increasingly urban world3

schools or hospitals but have little chance of using theseservices. Even where guards or fees do not bar entry, poorpeople may lack the sense of entitlement and empower-ment needed to ask for services from institutions perceivedas the domain of those of higher social or economic rank.Inadequate access to safe drinking water and sanita-tion services puts children at increased risk of illness,undernutrition and death. When child health statis-tics are disaggregated, it becomes clear that evenwhere services are nearby, children growing up inpoor urban settings face significant health risks. Insome cases, the risks exceed those prevalent in ruralareas.8Studies demonstrate that in many countries,children living in urban poverty fare as badly as or

worse than children living in rural poverty in terms ofheight-for-weight and under-five mortality.9Children’s health is primarily determined by the socio-economic conditions in which they are born, grow andlive, and these are in turn shaped by the distributionof power and resources. The consequences of havingtoo little of both are most readily evident in infor-mal settlements and slums, where roughly 1.4 billionpeople will live by 2020.10By no means do all of the urban poor live in slums –and by no means is every inhabitant of a slum poor.Nevertheless, slums are an expression of, and a practi-cal response to, deprivation and exclusion.

Social determinants of urban healthStark disparities in health between rich and poor havedrawn attention to the social determinants of health, orthe ways in which people’s health is affected not onlyby the medical care and support systems available toprevent and manage illness, but also by the economic,social and political circumstances in which they are bornand live.

The urban environment is in itself a social determinantof health. Urbanization drove the emergence of publichealth as a discipline because the concentration ofpeople in towns and cities made it easier for communicablediseases to spread – mainly from poorer quarters to wealth-ier ones. An increasingly urban world is also contributing tothe rising incidence of non-communicable diseases, obesity,alcohol and substance abuse, mental illness and injuries.Many poor and marginalized groups live in slums andinformal settlements, where they are subjected to amultitude of health threats. Children from these commu-nities are particularly vulnerable because of the stressesof their living conditions. As the prevalence of physicaland social settings of extreme deprivation increases, sodoes the risk of reversing the overall success of diseaseprevention and control efforts.The urban environment need not harm people’s health.In addition to changes in individual behaviour, broader

Source:World Health Organization; Global Research Network on Urban Health Equity.

4

THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S CHILDREN 2012

EM28BAFebr RGua Ory ED2012

social policy prioritizing adequate housing; water andsanitation; food security; efficient waste managementsystems; and safer places to live, work and play caneffectively reduce health risk factors. Good governancethat enables families from all urban strata to accesshigh-quality services – education, health, public trans-portation and childcare, for example – can play a majorpart in safeguarding the health of children in urbanenvironments.Growing awareness of the potential of societalcircumstances to help or harm individuals’ health hasled to such initiatives as the World Health Organization’sCommission on Social Determinants of Health. Its recom-mendations emphasize that effectively addressing thecauses of poor health in urban areas requires a rangeof solutions, from improving living conditions, throughinvestment in health systems and progressive taxation, toimproved governance, planning and accountability at thelocal, national and international levels. The challengesare greatest in low- and middle-income countries, whererapid urban population growth is seldom accompanied byadequate investment in infrastructure and services. TheCommission has also highlighted the need to address theinequalities that deny power and resources to margin-alized populations, including women, indigenous peopleand ethnic minorities.

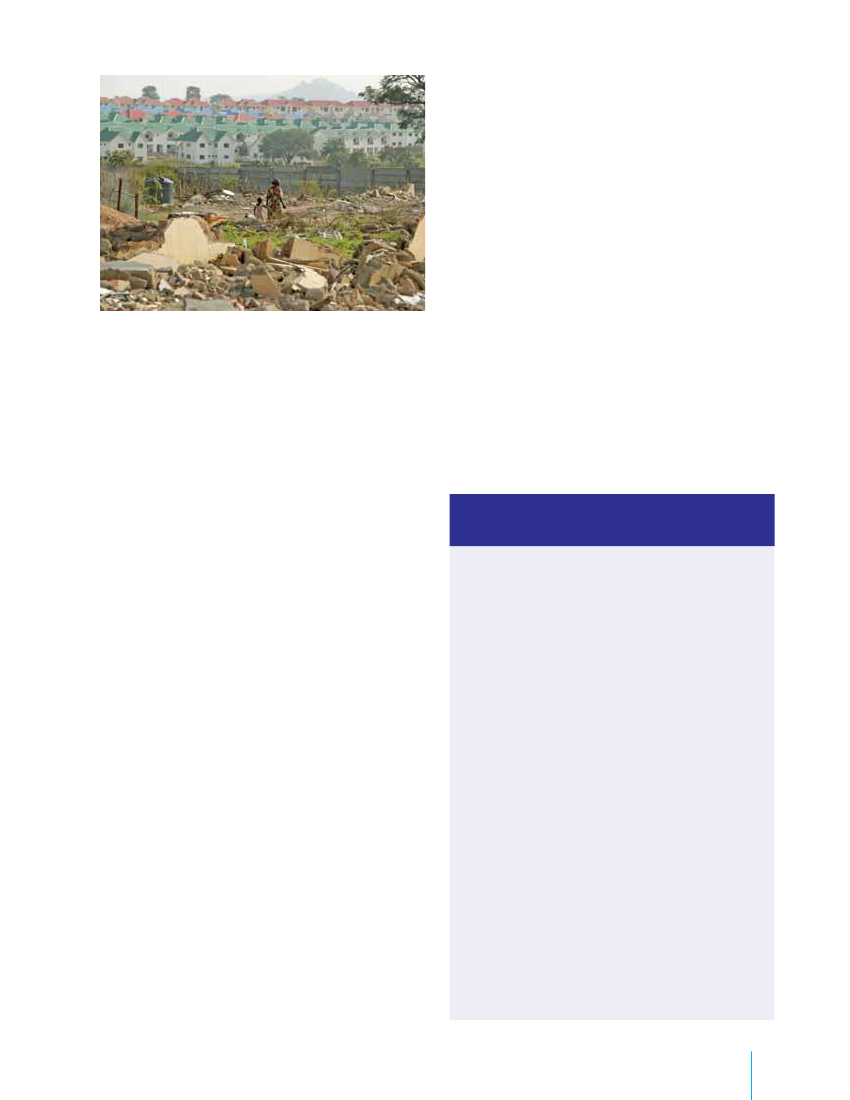

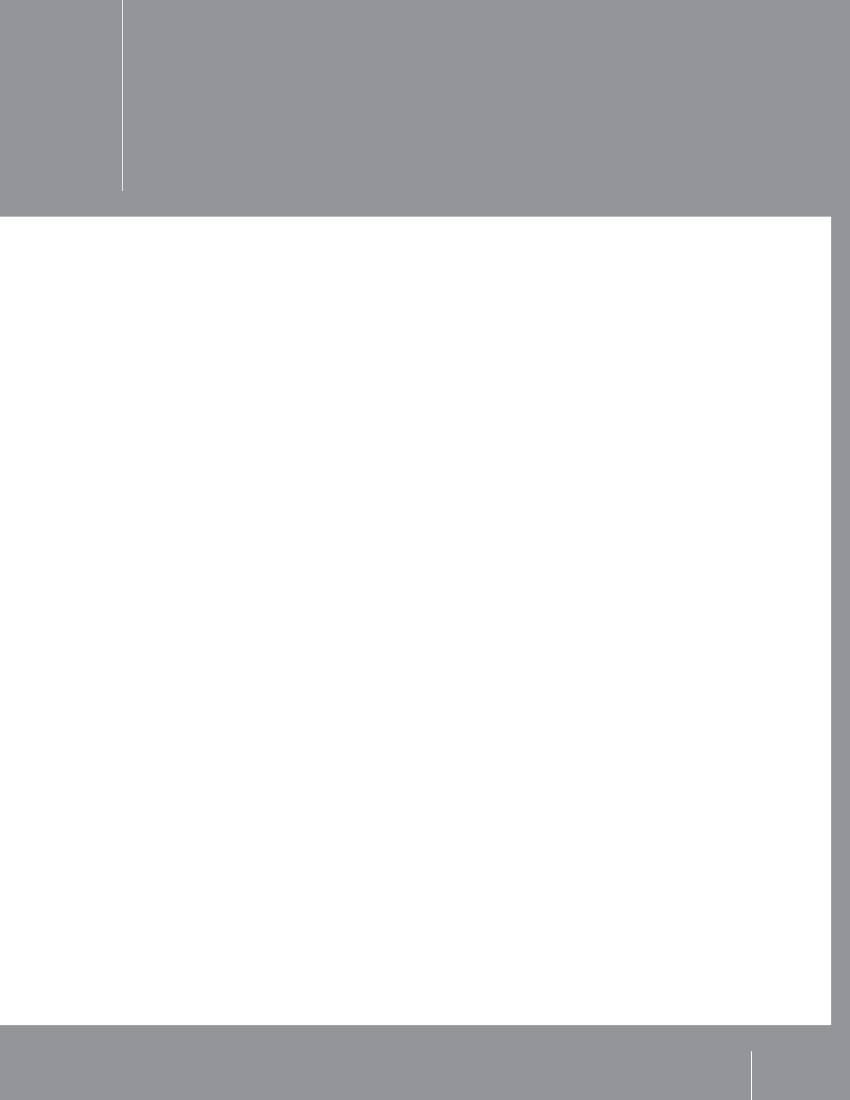

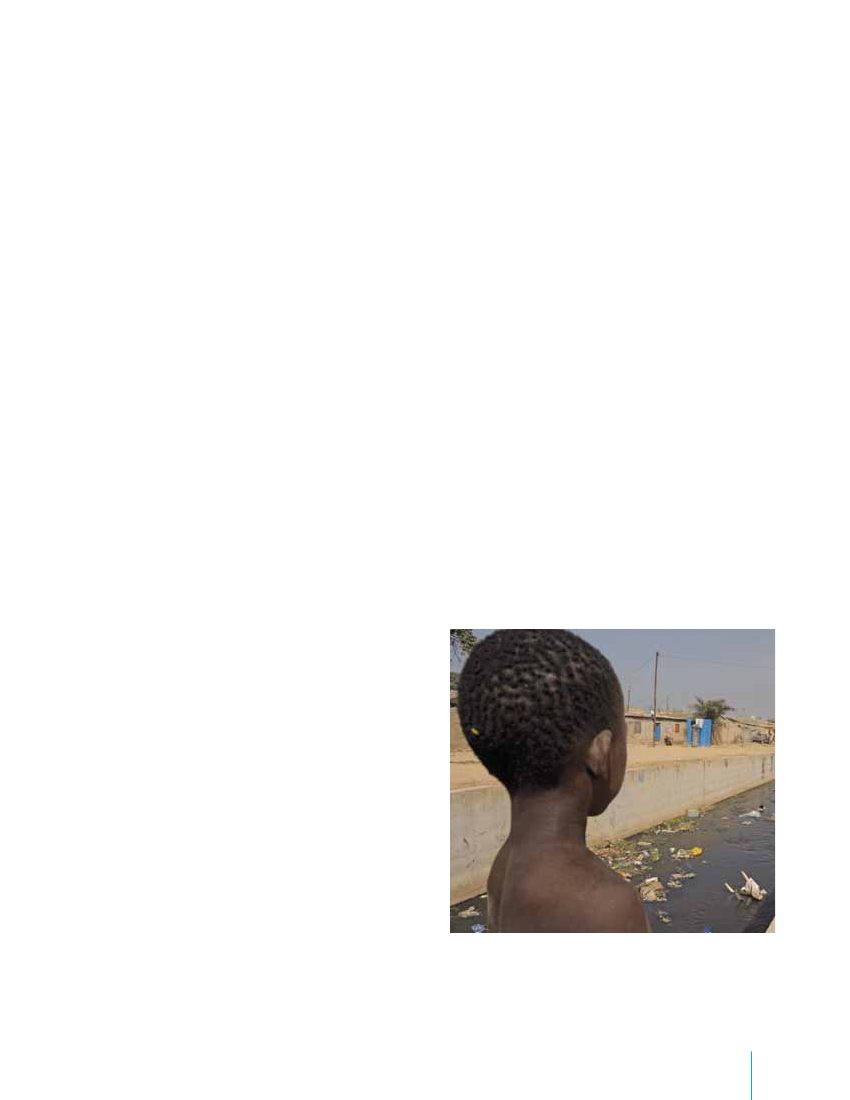

A woman and child walk among the ruins of a low-income neighbourhoodalongside a new residential development in Abuja, Nigeria.

the slum stands in the way of a major redevelopment.They may come without warning, let alone consulta-tion, and very often proceed without compensation orinvolve moving to an unfeasible location. The evictionsthemselves cause major upheaval and can destroy long-established economic and social systems and supportnetworks – the existence of which should come as nosurprise if one ponders what it takes to survive andadvance in such challenging settings. Even those whoare not actually evicted can suffer significant stress andinsecurity from the threat of removal. Moreover, theconstant displacement and abuse of marginalized popu-lations can further hinder access to essential services.Despite their many deprivations, slum residentsprovide at least one essential service to the very soci-eties from which they are marginalized–labour. Someof it is formal and some undocumented, but almostall is low-paid – for example, as factory hands, shopassistants, street vendors and domestic workers.

� UNICEF/NYHQ2006-2606/Michael Kamber

Illegal dwellings are poor in quality, relatively cheap –though they will often still consume about a quarter ofhousehold income – and notorious for the many hazardsthey pose to health. Overcrowding and unsanitary condi-tions facilitate the transmission of disease – includingpneumonia and diarrhoea, the two leading killers of chil-dren younger than 5 worldwide. Outbreaks of measles,tuberculosis and other vaccine-preventable diseasesare also more frequent in these areas, where popula-tion density is high and immunization levels are low.In addition to other perils, slum inhabitants frequentlyface the threat of eviction and maltreatment, not just bylandlords but also from municipal authorities intent on‘cleaning up’ the area. Evictions may take place becauseof a wish to encourage tourism, because the countryis hosting a major sporting event or simply because

EM28BAFebr RGua Ory ED2012

Impoverished people, denied proper housing and securityof tenure by inequitable economic and social policies andregulations governing land use and management, resortto renting or erecting illegal and often ramshackle dwell-ings. These typically include tenements (houses that havebeen subdivided), boarding houses, squatter settlements(vacant plots or buildings occupied by people who donot own, rent or have permission to use them) and ille-gal subdivisions (in which a house or hut is built in thebackyard of another, for example). Squatter settlementsbecame common in rapidly growing cities, particularlyfrom the 1950s onward, because inexpensive housingwas in short supply. Where informal settlements wereestablished on vacant land, people were able to buildtheir own homes.

Slums: The five deprivationsThe United Nations Human SettlementsProgramme (UN-Habitat) defines a slum householdas one that lacks one or more of the following:• Access to improved waterAn adequate quantity of water that is afford-able and available without excessive physicaleffort and time• Access to improved sanitationAccess to an excreta disposal system, eitherin the form of a private toilet or a public toiletshared with a reasonable number of people• Security of tenureEvidence or documentation that can be usedas proof of secure tenure status or for protec-tion from forced evictions• Durability of housingPermanent and adequate structure in anon-hazardous location, protecting its inhabit-ants from the extremes of climatic conditionssuch as rain, heat, cold or humidity• Sufficient living areaNot more than three people sharing thesame room

Children in an increasingly urban world

5

FOCUS ON

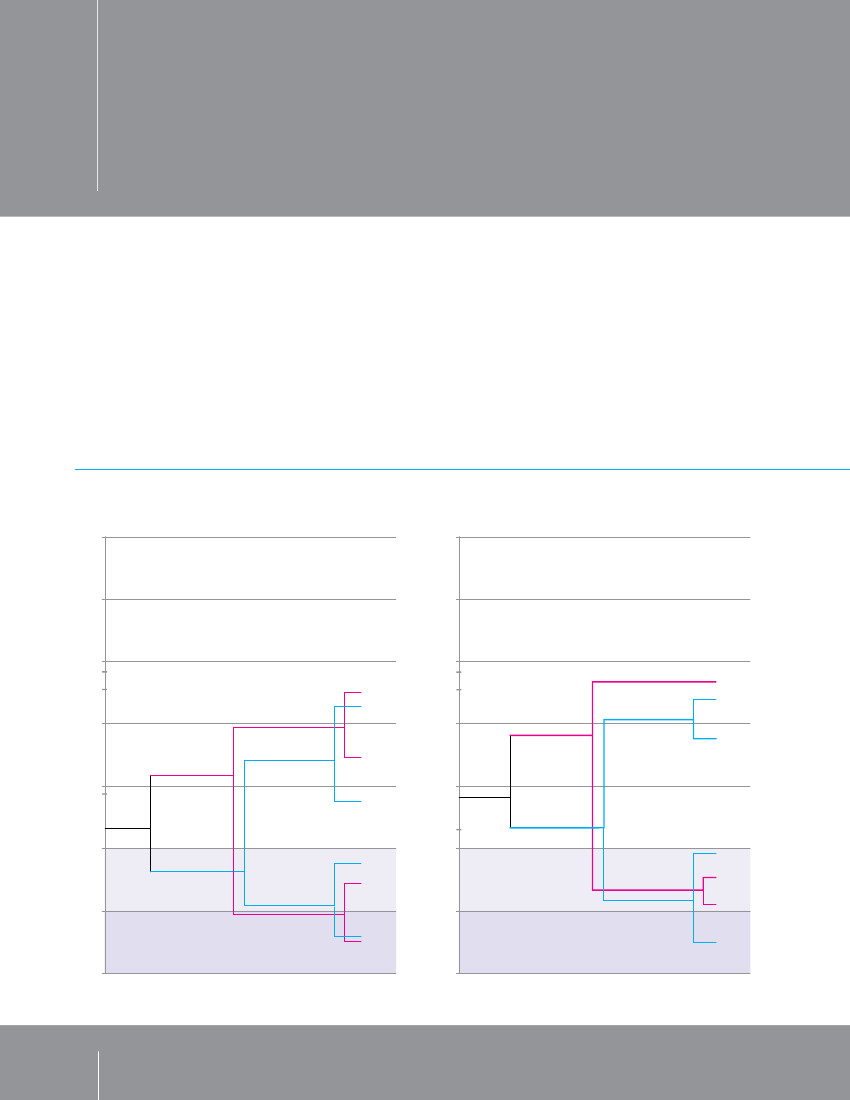

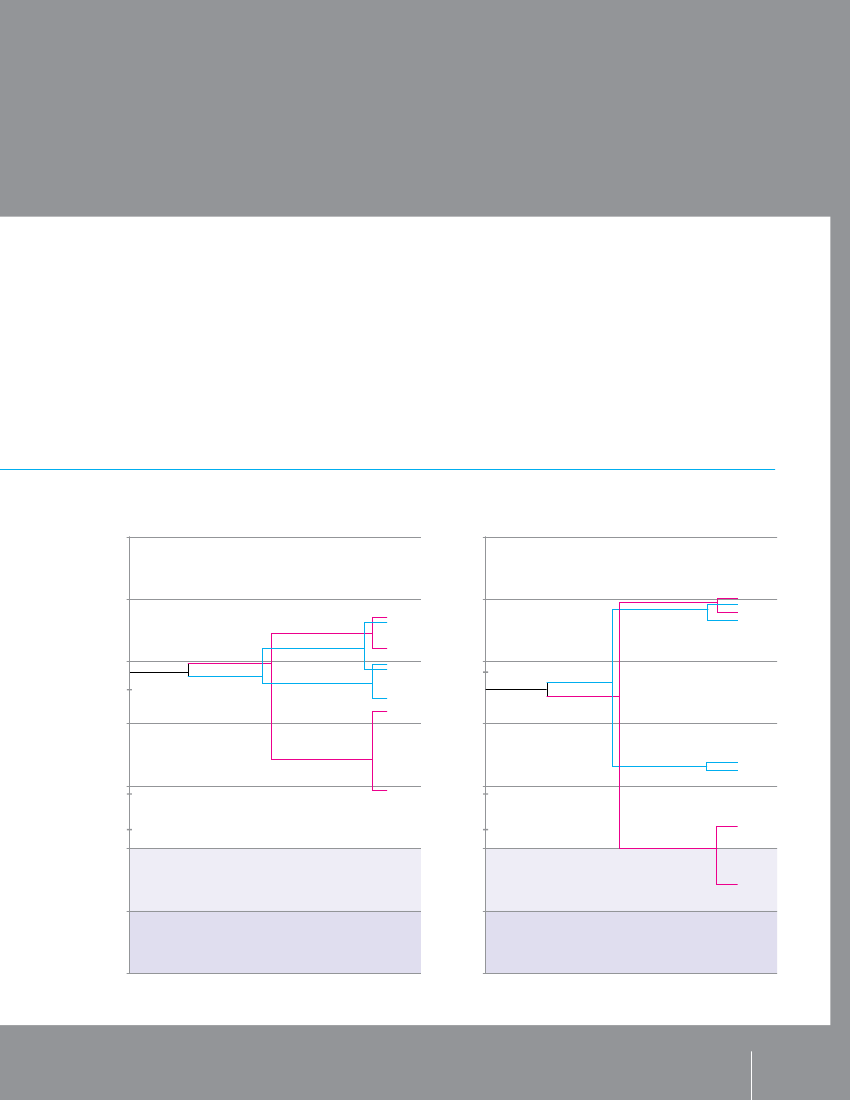

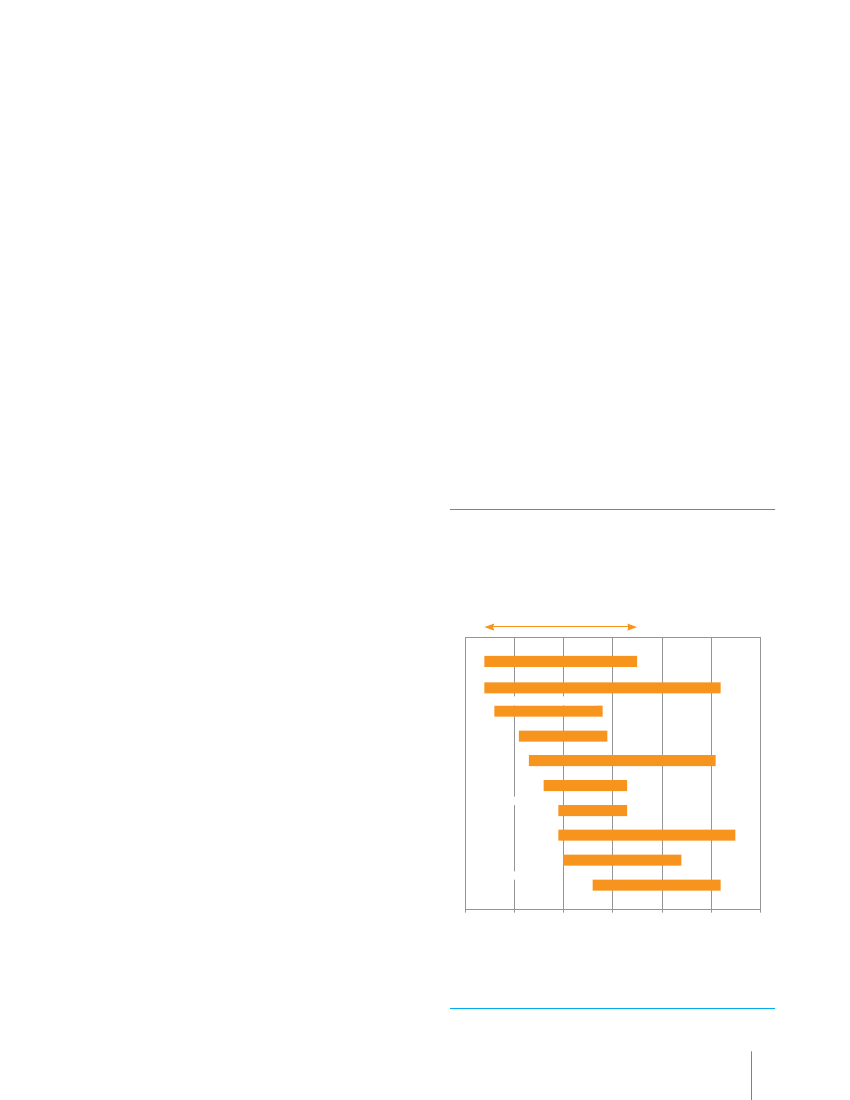

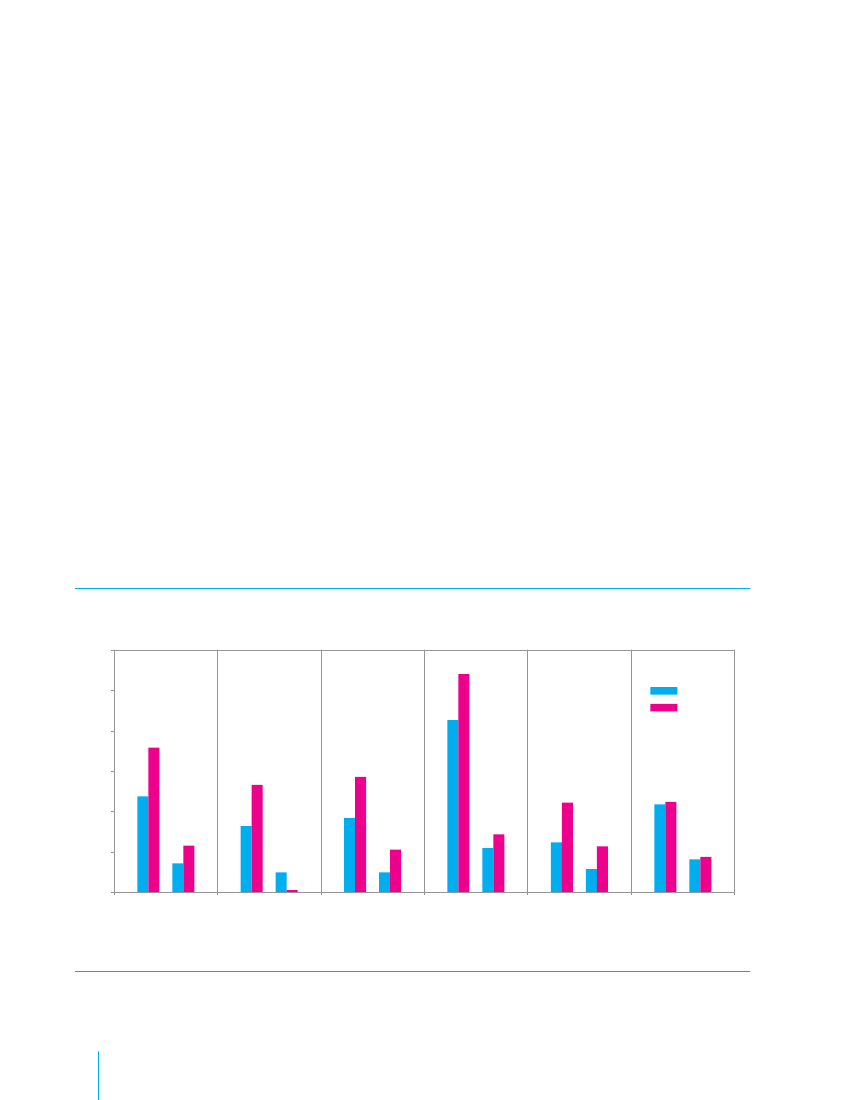

URBAN DISPARITIESnational averages are disaggregated, itbecomes clear that many children living inurban poverty are clearly disadvantagedand excluded from higher educa-tion, health services and other benefitsenjoyed by their affluentpeers.The figures below, called ‘equity trees’,illustrate that, while vast disparities exist inrural areas, poverty also can severely limita child’s education in urban areas – in somecases, more so than in the countryside.In Benin, Pakistan, Tajikistan andVenezuela (Bolivarian Republic of), theeducation gap between the richest 20per cent and the poorest 20percent isgreater in urban than in rural areas. Thegap is widest in Venezuela, where pupilsfrom the richest urban families have, onaverage, almost eight years more school-ing than those from the poorest ones,compared with a gap of 5 years betweenthe wealthy and poor in rural areas. InBenin, Tajikistan and Venezuela, children

On average, children in urban areas aremore likely to survive infancy and earlychildhood, enjoy better health and havemore educational opportunity than theircounterparts in rural areas. This effect isoften referred to as the ‘urban advantage’.Nevertheless, the scale of inequalitywithin urban areas is a matter of greatconcern. Gaps between rich and poor intowns and cities can sometimes equal orexceed those found in rural areas. When

Figure 1 .3 . Educational attainment can be most unequal in urban areasAverage years of schooling among population aged 17–22, by location, wealth and gender14

12

10

TajikistanVenezuela (BolivarianRepublic of)

EM28BAFebr RGua Ory ED2012Benin14

Pakistan

12

10

Tajikistan

urban richest 20%rural richest 20%

Average years of schooling

8

urban richest 20%rural richest 20%

Average years of schooling

malemale

Venezuela (BolivarianRepublic of)

femalemalemale

8

urban

female

urban6

female

PakistanBenin

6

female

Pakistan

Benin4

ruralmale

4

ruralEducation poverty

malemale

urban poorest 20%2Education poverty

malefemale

rural poorest 20%urban poorest 20%femalefemale0

2

rural poorest 20%

femaleExtreme education poverty

0

Extreme education poverty

Source:UNICEF analysis based on UNESCO Deprivation and Marginalization in Education database (2009) using household survey data: Benin (DHS, 2006);Pakistan (DHS, 2007); Tajikistan (MICS, 2005); Venezuela (Bolivarian Republic of) (MICS, 2000).

6

THESTATE OF THE WORLD’S CHILDREN 2012STATE OF THE WORLD’S CHILDREN 2012

from the poorest urban households arelikely to have fewer years of school-ing not only than children from wealthierurban households but also than theirrural counterparts.Some disparities transcend location.Girls growing up in poor households areat a great disadvantage regardless ofwhether they live in urban or rural areas.In Benin, girls in urban and rural areaswho come from the poorest 20 per cent

of the population receive less than twoyears of schooling, compared with threeto four years for their male counterpartsand about nine years for the richest boysin urban and rural settings. In Pakistan,the difference in educational attain-ment between the poorest boys and girlsis about three years in rural areas andabout one year in urban areas.The gender gap is more pronounced forpoor girls in urban Tajikistan. On average,

14

EM28BAFebr RGua Ory ED2012Tajikistan1412

they receive less than six years of educa-tion, compared with almost nine years forpoor girls in rural areas. Butthe gendergap is reversed in Venezuela, where thepoorest boys in urban areas receive theleast education – less than threeyearsof schooling, compared to four and ahalfyears for the poorest girls in urbansettings and about six and a half years forthe poorest boys and girls in rural areas.

Venezuela (Bolivarian Republic of)

12

urban richest 20%rural richest 20%

urban richest 20%rural richest 20%rural poorest 20%

malemale

femalefemalemalemale

10

Tajikistan

urbanrural

femalemalefemale

10

Average years of schooling

8

Average years of schooling

Venezuela (BolivarianRepublic of)

femalemale

TajikistanVenezuela(BolivarianRepublic of)

ruralurban

8

urban poorest 20%

rural poorest 20%

malefemale

6

PakistanBenin

female

6

PakistanBeninfemale

4

4

urban poorest 20%

male2Education poverty2Education poverty

0

Extreme education poverty

0

Extreme education poverty

Children in an increasingly urban worldChildren in an increasingly

7

Children juggle to make money on the streets of Salvador, capital of the eastern state of Bahia, Brazil.

Meeting the challengesof an urban future

Children and adolescents are, of course, among the mostvulnerable members of any community and will dispro-portionately suffer the negative effects of poverty andinequality. Yet insufficient attention has been given tochildren living in urban poverty. The situation is urgent,and international instruments such as the Conventionon the Rights of the Child and commitments such asthe MDGs can help provide a framework for action.The fast pace of urbanization, particularly in Africa andAsia, reflects a rapidly changing world. Developmentpractitioners realize that standard programmingapproaches, which focus on extending services to morereadily accessible communities, do not always reachpeople whose needs are greatest. Disaggregated datashow that many are being left behind.Cities are not homogeneous. Within them, and partic-ularly within the rapidly growing cities of low- andmiddle-income countries, reside millions of childrenwho face similar, and sometimes worse, exclusion anddeprivation than children living in rural areas.In principle, the deprivations confronting childrenin urban areas are a priority for human rights-based8THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S CHILDREN 2012

EM28BAFebr RGua Ory ED2012

development programmes. In practice, and particu-larly given the misperception that services are withinreach of all urban residents, lesser investment has oftenbeen devoted to those living in slums and informalurban settlements.For this to change, a focus on equity is needed – one inwhich priority is given to the most disadvantaged chil-dren, wherever they live.The first requirement is toimprove understandingof the scale and nature of urban poverty and exclu-sion affecting children.This will entail not only soundstatistical work – a hallmark of which must be greaterdisaggregation of urban data – but also solid researchand evaluation of interventions intended to advancethe rights of children to survival, health, development,sanitation, education and protection in urban areas.Second, development solutions mustidentify andremove the barriers to inclusionthat prevent marginal-ized children and families from using services, exposethem to violence and exploitation, and bar them fromtaking part in decision-making. Among other neces-sary actions, births must be registered, legal statusconferred and housing tenure made secure.

� UNICEF/NYHQ2006-1335/Claudio Versiani

Fourth, policy and practice mustpromote partner-ship between the urban poor and government at all itslevels.Urban initiatives that foster such participation –and in particular those that involve children and youngpeople – report better results not only for children butalso for their communities.Finally, everyone mustwork together to achieve resultsfor children.International, national, municipal andcommunity actors will need to pool resources andenergies in support of the rights of marginalized andimpoverished children growing up in urban environ-ments. Narrowing the gaps to honour internationalcommitments to all children will require additionalefforts not only in rural areas but also within cities.

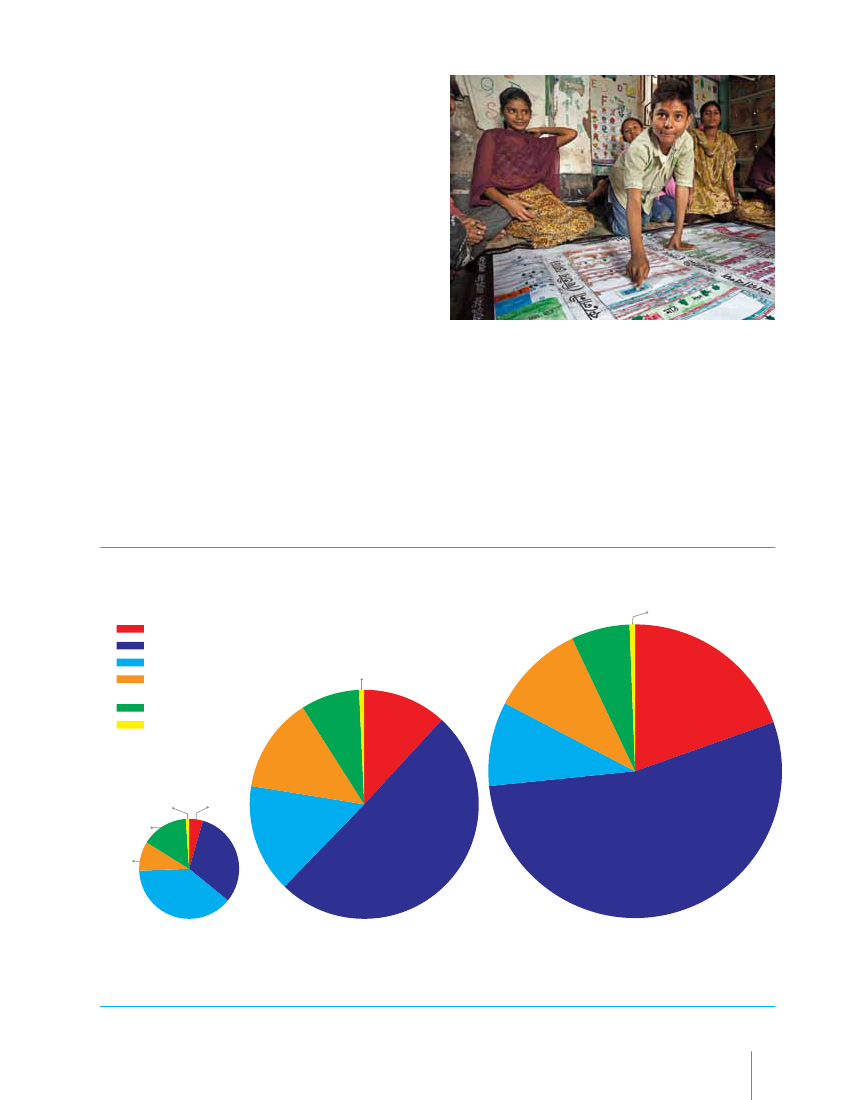

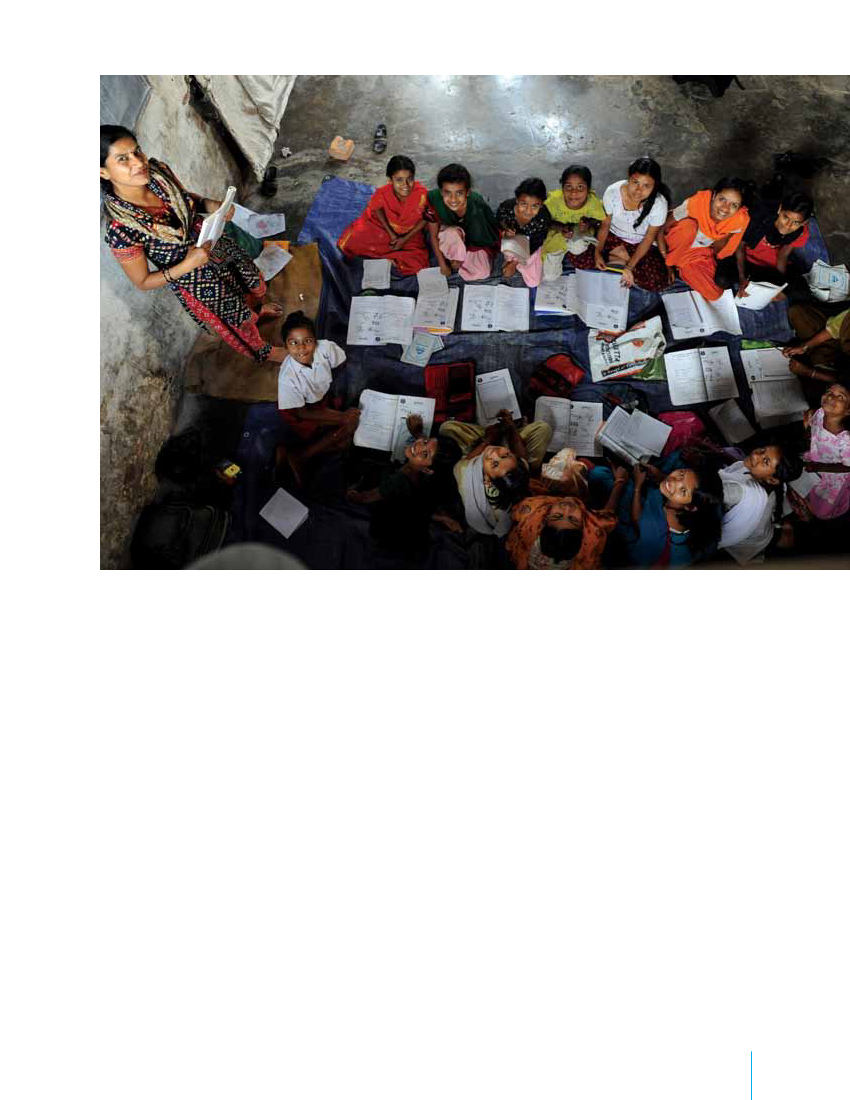

Children put their sprawling slum on the map – literally. The data theyhave gathered about Rishi Aurobindo Colony, Kolkata, India, will beuploaded to Google Earth.

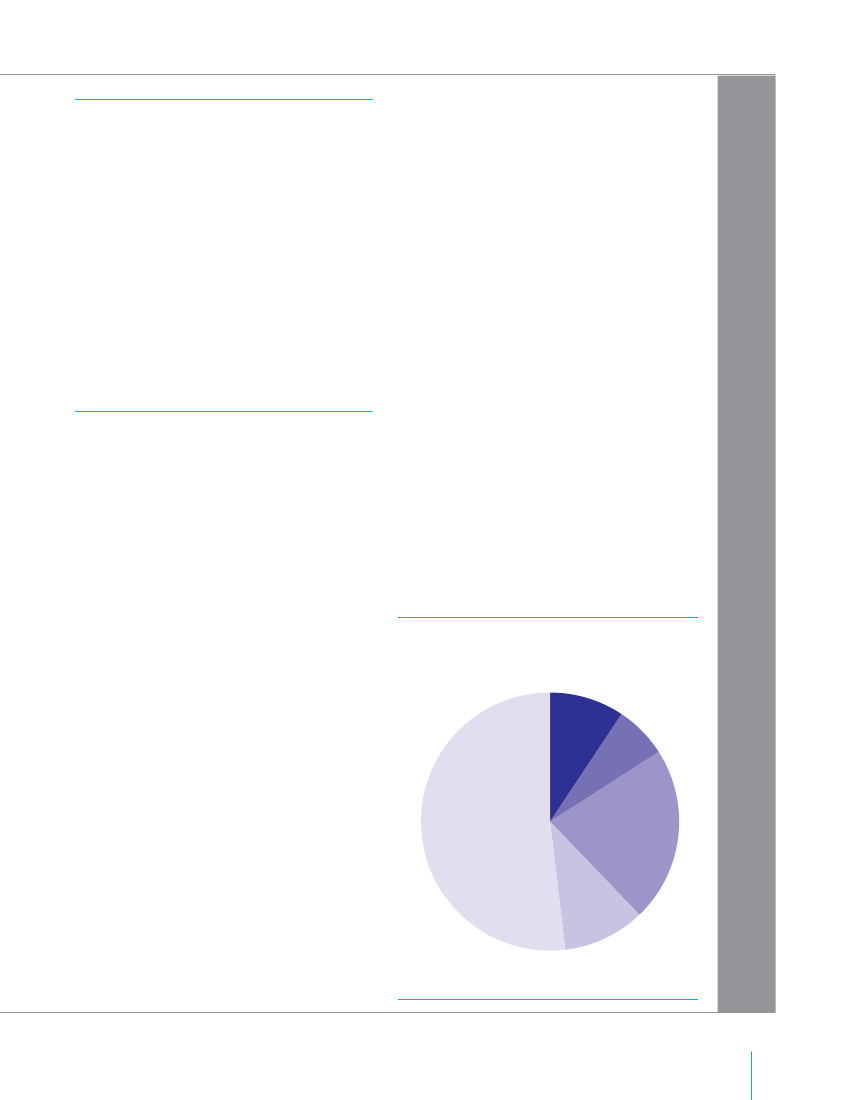

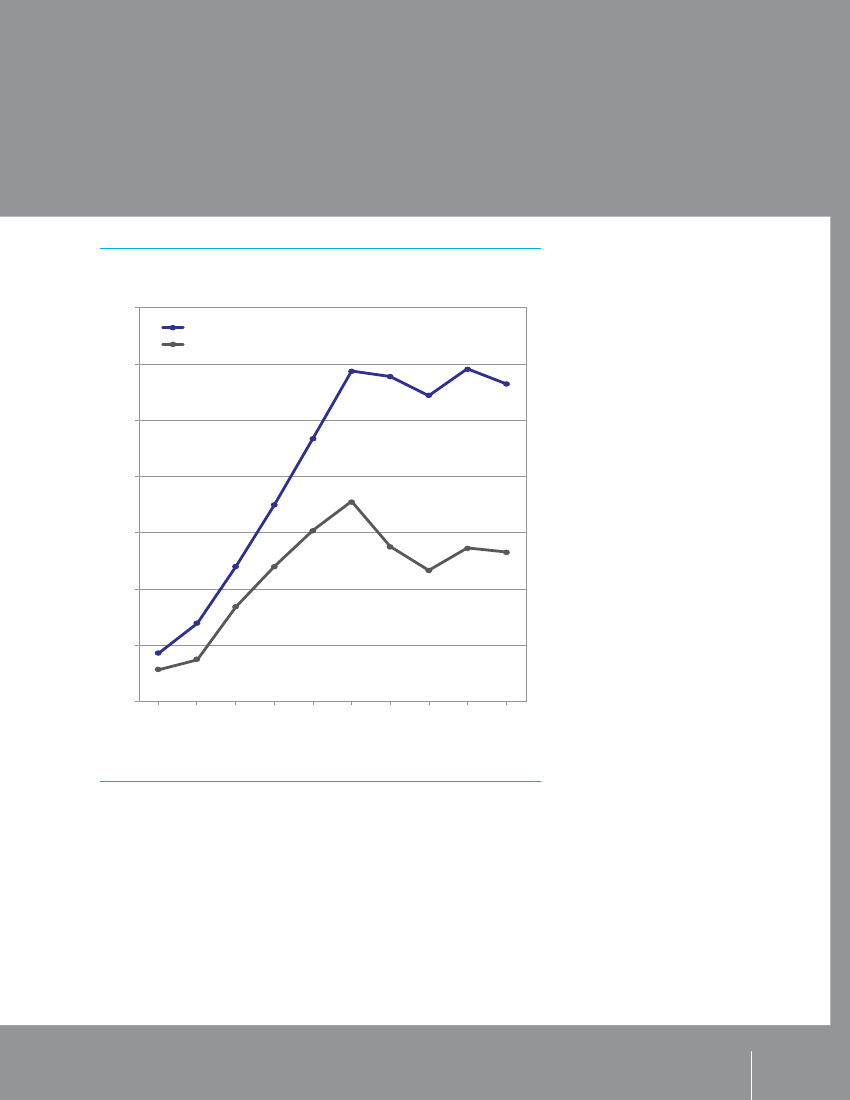

Figure 1 .4 . Urban populations are growing fastest in Asia and AfricaWorld urban population 1950, 2010, 2050 (projected)

EM28BAFebr RGua Ory ED2012

Clearly, children’s rights cannot be fulfilled and protectedunless governments, donors and international organi-zations look behind the broad averages of developmentstatistics and address the urban poverty and inequalitythat characterize the lives of so many children.

1%

AfricaAsiaEurope

Latin Americaand the CaribbeanNorth AmericaPacific

1%

6%

10%

20%

8%

12%

14%1% 5%15%10%38%19500 .7 billionSource:UNDESA, Population Division.

9%

15%31%

50%

54%

20103 .5 billion

2050 (projected)6 .3 billion

Children in an increasingly urban world

9

� UNICEF/INDA2011-00105/Graham Crouch

Third, asharp focus on the particular needs andpriorities of childrenmust be maintained in urban plan-ning, infrastructure development, service delivery andbroader efforts to reduce poverty and disparity. Theinternational Child-Friendly Cities Initiative providesan example of the type of consideration that must begiven children in every facet of urban governance.

URBAN (AREA)The definition of ‘urban’ varies from country to country, and,with periodic reclassification, can also vary within one coun-try over time, making direct comparisons difficult. An urbanarea can be defined by one or more of the following: admin-istrative criteria or political boundaries (e.g., area within thejurisdiction of a municipality or town committee), a thresholdpopulation size (where the minimum for an urban settle-ment is typically in the region of 2,000 people, although thisvaries globally between 200 and 50,000), population density,economic function (e.g., where a significant majority of thepopulation is not primarily engaged in agriculture, or wherethere is surplus employment) or the presence of urban char-acteristics (e.g., paved streets, electric lighting, sewerage).In2010, 3.5 billion people lived in areas classified as urban.

containing the city proper, suburbs and continuouslysettled commuter areas or adjoining territory inhabited aturban levels of residential density.Large urban agglomerations often include several adminis-tratively distinct but functionally linked cities. For example,the urban agglomeration of Tokyo includes the cities ofChiba, Kawasaki, Yokohama and others.METROPOLITAN AREA/REgIONA formal local government area comprising the urbanarea as a whole and its primary commuter areas, typicallyformed around a city with a large concentration of people(i.e., a population of at least100,000).In addition to the city proper, a metropolitan area includes

DEFINITIONS

The (relative or absolute) increase in thenumber of peoplewho live in towns and cities. The pace of urban populationlation and the population gained by urban areas throughrural settlements into cities and towns.URBANIzATION

growth depends on the natural increase of the urban popu-both net rural-urban migration and the reclassification of

The proportion of a country that is urban.RATE OF URBANIzATION

The increase in the proportion of urban population over

time, calculated as the rate of growth of the urban popu-lation minus that of the total population. Positive rates offaster rate than the total population.CITy PROPER

urbanization result when the urban population grows at a

The population living within the administrative boundariesof a city, e.g., Washington, D.C.Because city boundaries do not regularly adapt to accom-modate population increases, the concepts ofurbanagglomerationandmetropolitan areaare often used toimprove the comparability of measurements of city popula-tions across countries and over time.URBAN AggLOMERATIONThe population of a built-up or densely populated areaIn 2009, 21 urban agglomerations qualified as megacities,accounting for 9.4 per cent of the world’s urban popula-tion. In 1975, New York, Tokyo and Mexico City were the onlymegacities. Today, 11 megacities are found in Asia, 4 in LatinAmerica and 2 each in Africa, Europe and North America.Eleven of these megacities are capitals of their countries.MEgACITyAn urban agglomeration with a population of 10 millionor more.

10

THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S CHILDREN 2012

EM28BAFebr RGua Ory ED2012URBAN SPRAWLPERI-URBAN AREA

URBAN gROWTH

both the surrounding territory with urban levels of residen-tial density and some additional lower-density areas thatare adjacent to and linked to the city (e.g., through frequenttransport, road linkages or commuting facilities). Examples ofmetropolitan areas include Greater London and Metro Manila.

Also ‘horizontal spreading’ or ‘dispersed urbanization’. Theuncontrolled and disproportionate expansion of an urbanarea into the surrounding countryside, forming low-density,poorly planned patterns of development. Common in bothhigh-income and low-income countries, urban sprawl ischaracterized by a scattered population living in separateresidential areas, with long blocks and poor access, oftenoverdependent on motorized transport and missing well-defined hubs of commercial activity.

An area between consolidated urban and rural regions.

Megacities, 2009 (population in millions)1Tokyo, Japan (36.5)2Delhi, India (21.7)3Sao Paulo, Brazil (20.0)4Mumbai, India (19.7)6New York-Newark,United States (19.3)7Shanghai, China (16.3)8Kolkata, India (15.3)9Dhaka, Bangladesh (14.3)10Buenos Aires,Argentina (13.0)11Karachi, Pakistan (12.8)12Los Angeles-Long Beach-Santa Ana,United States (12.7)13Beijing, China (12.2)15Manila, Philippines (11.4)16Osaka-Kobe, Japan (11.3)17Cairo, Egypt (10.9)18Moscow, RussianFederation (10.5)19Paris, France (10.4)20Istanbul, Turkey (10.4)21Lagos, Nigeria (10.2)

spark business and change the nature and function ofindividual towns and cities, promoting regional economicgrowth but also often reinforcing urban primacy andunbalanced regional development.Examples include the industrial corridor developingbetween Mumbai and Delhi in India; the manufacturingand service industry corridor running from Kuala Lumpur,Malaysia, to the port city of Klang; and the regionaleconomic axis forming the greater Ibadan-Lagos-Accraurban corridor in West Africa.CITy-REgIONAn urban development on a massive scale: a major citythat expands beyond administrative boundaries to engulfsmall cities, towns and semi-urban and rural hinterlands,sometimes expanding sufficiently to merge with othercities, forming large conurbations that eventually becomecity-regions.

5Mexico City, Mexico (19.3)14Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (11.8)

Sources:UNDESA, Population Division; UN-Habitat.

METACITy20 million people.

A major conurbation – a megacity of more than

As cities grow and merge, new urban configurations arecity-regions.MEgAREgION

formed. These includemegaregions, urban corridorsand

A rapidly growing urban cluster surrounded by low-density hinterland, formed as a result of expansion,

growth and geographical convergence of more than onemetropolitan area and other agglomerations. Commonin North America and Europe, megaregions are nowexpanding in other parts of the world and are charac-

terized by rapidly growing cities, great concentrationssignificant economic innovation and potential.

of people (including skilled workers), large markets and

Examples include the Hong Kong-Shenzhen-Guangzhoumegaregion (120 million people) in China and the Tokyo-Nagoya-Osaka-Kyoto-Kobe megaregion (predicted toreach 60 million by 2015) in Japan.URBAN CORRIDORA linear ‘ribbon’ system of urban organization: cities ofvarious sizes linked through transportation and economicaxes, often running between major cities. Urban corridors

EM28BAFebr RGua Ory ED2012current population of over 17 million.10 million +

For example, the Cape Town city-region in South Africaextends up to 100 kilometres, including the distancesthat commuters travel every day. The extended Bangkokregion in Thailand is expected to expand another 200 kilo-metres from its centre by 2020, growing far beyond its

Figure 1 .5 . Half of the world’s urban populationlives in cities of fewer than 500,000 inhabitantsWorld urban population distribution, by city size, 2009

9%

5 to 10million

7%Fewer than500,0001 to 5 million

52%500,000 to1 million

22%

10%

Source:Calculations based on UNDESA,World Urbanization Prospects:The 2009 revision.

Children in an increasingly urban world

11

CHAPTER

2

EM28BAFebr RGua Ory ED2012� UNICEF/NYHQ2008-1027/Christine Nesbitt

Children’s rightsin urban settingsChildren whose needs are greatest are also those whoface the greatest violations of their rights. The mostdeprived and vulnerable are most often excluded fromprogress and most difficult to reach. They requireparticular attention not only in order to secure theirentitlements, but also as a matter of ensuring therealization of everyone’s rights.

Children living in urban poverty have the full rangeof civil, political, social, cultural and economic rightsrecognized by international human rights instruments.The most rapidly and widely ratified of these is theConvention on the Rights of the Child. The rights ofevery child include survival; development to the fullest;protection from abuse, exploitation and discrimina-tion; and full participation in family, cultural and sociallife. The Convention protects these rights by detailingcommitments with respect to health care, education,and legal, civil and social protection.All children’s rights are not realized equally. Overone third of children in urban areas worldwide go

EM28BAFebr RGua Ory ED2012

unregistered at birth – and about half the children inthe urban areas of sub-Saharan Africa and South Asiaare unregistered. This is a violation of Article 7 of theConvention on the Rights of the Child. The invisibil-ity that derives from the lack of a birth certificate or anofficial identity vastly increases children’s vulnerabilityto exploitation of all kinds, from recruitment by armedgroups to being forced into child marriage or hazard-ous work. Without a birth certificate, a child in conflictwith the law may also be treated and punished as anadult by the judicial system.1Even those who avoidthese perils may be unable to access vital services andopportunities – including education.Obviously, registration alone is no guarantee of accessto services or protection from abuse. But the obliga-tions set out by the Convention on the Rights of theChild can be easily disregarded when whole settle-ments can be deemed non-existent and people can,in effect, be stripped of their citizenship for wantof documentation.

Children’s rights in urban settings

13

Inadequate living conditions are among the mostpervasive violations of children’s rights. The lack ofdecent and secure housing and such infrastructure aswater and sanitation systems makes it so much moredifficult for children to survive and thrive. Yet, theattention devoted to improving living conditions hasnot matched the scope and severity of the problem.Evidence suggests that more children want for shelterand sanitation than are deprived of food, educationand health care, and that the poor sanitation, lack ofventilation, overcrowding and inadequate natural lightcommon in the homes of the urban poor are responsi-ble for chronic ailments among their children.2Manychildren and families living in the urban slums of low-income countries are far from realizing the rights to“adequate shelter for all” and “sustainable humansettlements development in an urbanizing world”enshrined in the Istanbul Declaration on HumanSettlements, or Habitat Agenda, of 1996.3Since children have the rights to survival, adequatehealth care and a standard of living that supports theirfull development, they need to benefit from environ-mental conditions that make the fulfilment of theserights possible. There is no effective right to play with-out a safe place to play, no enjoyment of health withina contaminated environment. Support for this perspec-tive is provided by such treaties and declarations asthe International Covenant on Economic, Social andCultural Rights; the Convention on the Eliminationof All Forms of Discrimination against Women; theHabitat Agenda; and Agenda 21, the action planadopted at the 1992 United Nations Conference onEnvironment and Development. The Centre onHousing Rights and Evictions, among others,documents the extensive body of rights relatedto housing and the disproportionate vulnerabil-ity of children to violations of these rights. Inrecent years, practical programming aimed atfulfilling rights has been focused on the pursuit ofthe Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), all ofwhich have relevant implications for children in urbanpoverty. One of the targets of MDG 7 – to ensureenvironmental sustainability – focuses specificallyon improving the lives of at least 100 million of the

A mother holding a one-year-old infant obtains micronutrient powderfrom social workers in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Micronutrient deficienciescan lead to anaemia, birth defects and other disorders.

14

THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S CHILDREN 2012

EM28BAFebr RGua Ory ED2012HealthChild survival

world’s slum dwellers by 2020. This is only a smallpercentage of those who live in slums worldwide; thetarget does not address the continuing growth in thenumber of new slums and slum dwellers.This chapter looks at the situation of children inurban settings and considers in particular their rightsto health; water, sanitation and hygiene; educationandprotection.

Article 6 of the Convention on the Rights of theChild commits States parties to “ensure to the maxi-mum extent possible the survival and developmentof the child.” Article 24 refers to every child’s right tothe “enjoyment of the highest attainable standard ofhealth and to facilities for the treatment of illness andrehabilitation of health.” The Convention urges Statesparties to “ensure that no child is deprived of his or herright of access to such health care services.”

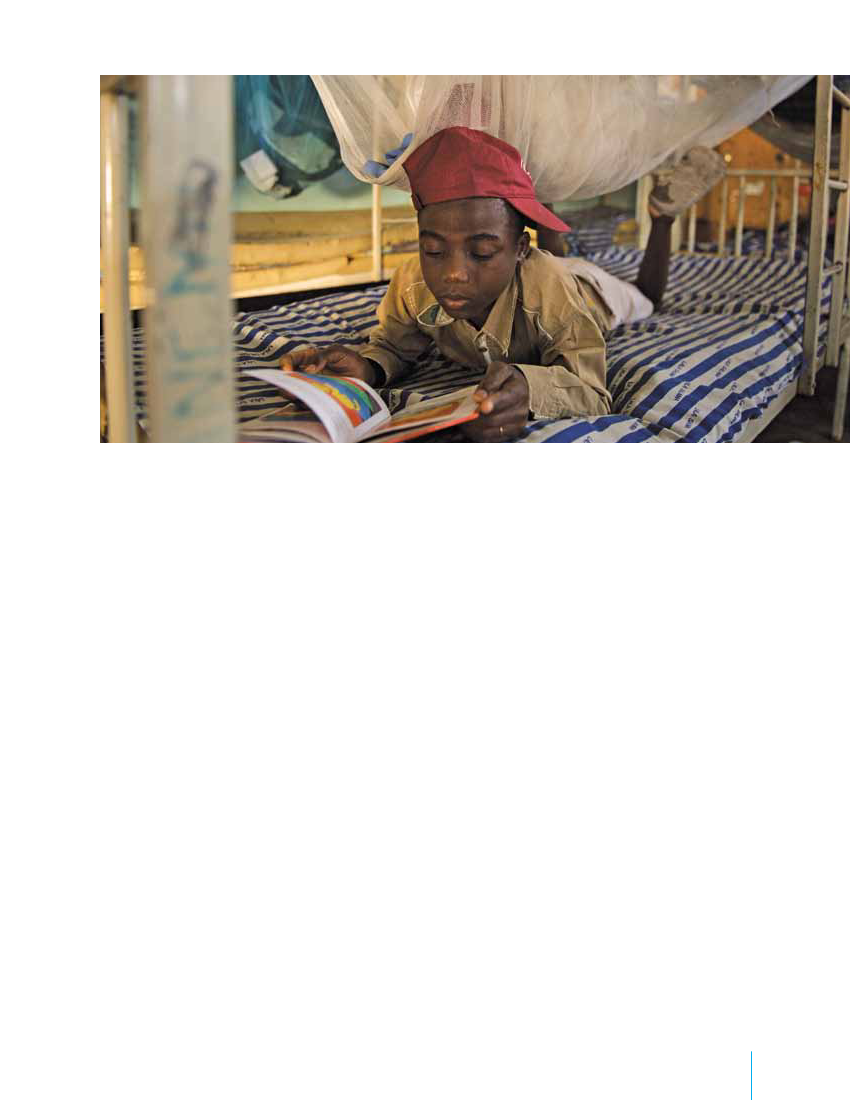

Nearly 8 million children died in 2010 before reach-ing the age of 5, largely due to pneumonia, diarrhoeaand birth complications. Some studies show thatchildren living in informal urban settlements areparticularly vulnerable.4High urban child mortal-ity rates tend to be seen in places where significantconcentrations of extreme poverty combine withinadequate services, as in slums.

� UNICEF/NYHQ2009-0609/Shehzad Noorani

An environment for fulfillingchild rights

PERSPECTIVE

OUT OF SIGHT,OUT OF REACHby Her Majesty Queen Rania Al Abdullah of Jordan,UNICEF Eminent Advocate

The contrast could not be more ironic.Cities, where children flourish with goodschools and accessible health care, arewhere they also suffer greatly, deniedtheir basic human rights to an educa-tion and a life of opportunity. Side byside, wealth juxtaposed against poverty,nowhere else is the iniquity of inequity asobvious as in a city.

Over the course of a decade, the state ofthe world’s urban children has worsened.The number of people living in slumshas increased by over 60 million. Theseare mothers and fathers, grandmothersand grandfathers, sons and daughters,scratching out a life in shantytowns theworld over. With the direct disadvan-tages of urban poverty – disease, crime,violence – come indirect ones, social and

EM28BAFebr RGua Ory ED2012In the Arab world the facts are clear:More than one third of the urbanpopulation lives in informal settlementsand slums. These environments arehazardous to children; a lack of adequatesanitation and drinkable water poses amajor threat to their well-being. In someless developed Arab countries, over-crowding in makeshift houses furtheraggravates the precarious health condi-tions of these vulnerable families.For Palestinian children, city life can bea grim life. Too often, it represents gunsand checkpoints, fear and insecurity.Yet their greatest hope is their nationalpride: a deep-seated belief in education,which they know is essential for build-ing a life and rebuilding their country. Yet,since 1999, across Occupied PalestinianTerritory, the number of primary-school-aged children who are out of school hasleapt from 4,000 to 110,000, a staggering2,650 per cent increase. In Gaza, amongthe world’s most densely populated areas,access to and quality of education havedeteriorated rapidly. For the sake of thesechildren’s futures and of the all-important

Half the world’s population now lives incities. Throughout history, urban life, soconcentrated with humanity, has beena catalyst for trade, ideas and opportuni-ties, making cities engines of economicgrowth. Today, living in a city is widelyregarded as the best way to find pros-perity and escape poverty. Yet hiddeninside cities, wrapped in a cloak of statis-tics, are millions of children struggling tosurvive. They are neither in rural areas norin truly urban quarters. They live in squa-lor, on land where a city has outpaceditself, expanding in population but notin vital infrastructure or services. Theseare children in slums and deprived neigh-bourhoods, children shouldering the manyburdens of living in that grey area betweencountryside and city, invisible to theauthorities, lost in a hazy world of statisti-cal averages that conceal inequality.

cultural barriers, like gender and ethnic-ity, that deny children from the slumsthe chance to enrol in and completeprimary school. Education is pushed outof reach because there are not enoughpublic schools or the costs are too high.Religious groups, non-governmentalorganizations and entrepreneurs try to fillthe gap but struggle without governmentsupport or regulation. As the best chanceto escape their parents’ destinies eludesthese children, the cycle of destitutionspins on.

search for regional peace, we must setaside our anger and angst and give themthe childhoods they deserve, childhoodswe expect for our own children, filled withhappy memories and equal opportunities.In a few Arab countries, the fates ofdisadvantaged urban children are beingrewritten. In Morocco, the governmentprogramme ‘Cities without Slums’hopes to raise the standards of nearly300,000homes. By engaging banksand housing developers, a ‘triple win’scenario is possible for poor people,the government and the private sector.Jordan, too, is making strides. Amman isone of the region’s leading child-friendlycities, with over 28,000students partici-pating in children’s municipal councils toprioritize their needs, rights and interests.The results have been impressive: parks,libraries, community spaces, educationalsupport for children who dropped out ofschool, campaigns against violence andabuse, and information and communica-tion technology centres for the deaf.Yet for Arab children – forallchildren – tothrive, nations have to work together. Wehave to share resources, adopt and adaptsuccessful initiatives from around theglobe and encourage our private sectorsto engage with disadvantaged families sowe can catch those falling through thecracks. In cities across the world, chil-dren out of reach are too often out ofsight. If we are to raise their hopes andtheir prospects, we have to dig deep intothe data, unroot entrenched prejudicesand give every child an equal chance atlife. Only in this way can we truly advancethe state ofallthe world’s children.

Children’s rights in urban settings

15

The Convention on the Rights of the ChildThe Convention on the Rights of the Child, adopted in 1989,was the first international treaty to state the full range of civil,political, economic, social and cultural rights belonging tochildren. The realities confronting children can be assessedagainst the commitments to which it holds States parties.Legally binding on States parties, the Convention detailsuniversally recognized norms and standards concerning theprotection and promotion of the rights of children – everywhereand at all times. The Convention emphasizes the complementar-ity and interdependence of children’s human rights. Across its54 articles and 2 Optional Protocols, it establishes a new visionof the child – one that combines a right to protection throughthe State, parents and relevant institutions with the recognitionthat the child is a holder of participatory rights and freedoms.All but three of the world’s nations – Somalia, South Sudan andthe United States of America – have ratified the document.This broad adoption demonstrates a common political will toprotect and ensure children’s rights, as well as recognitionthat, in the Convention’s words, “in all countries in the world,there are children living in exceptionally difficult conditions,and that such children need special consideration.”The values of the Convention stem from the 1924 GenevaDeclaration of the Rights of the Child, the 1948 UniversalDeclaration of Human Rights and the 1959 Declaration of theRights of the Child. The Convention applies to every child,defined as every person younger than 18 or the age of major-ity, if this is lower (Article 1). The Convention also requiresthat in all actions concerning children, “the best interests ofthe child shall be a primary consideration,” and that Statesparties “ensure the child such protection and care as isnecessary for his or her well-being” (Article 3).Furthermore, “a mentally or physically disabled child shouldenjoy a full and decent life, in conditions which ensuredignity, promote self-reliance and facilitate the child’s activeparticipation in the community” (Article 23). This extends tothe right to special care, provided free of charge wheneverpossible, and effective access to education, training, healthcare, rehabilitation services, recreation opportunities andpreparation for employment.ParticipationOne of the core principles of the Convention is respect forand consideration of the views of children. The documentrecognizes children’s right to freely express their views in allmatters affecting them and insists that these views be givendue weight in accordance with the age and maturity of thechildren voicing them (Article 12). It further proclaims chil-dren’s right to freedom of all forms of expression (Article 13).Children are entitled to freedom of thought, conscience andreligion (Article 14), to privacy and protection from unlawfulattack or interference (Article 16) and to freedom of associationand peaceful assembly (Article 15).Social protectionThe Convention acknowledges the primary role of parentsor legal guardians in the upbringing and development ofthe child (Article 18) but stresses the obligation of the Stateto support families through “appropriate assistance,” “thedevelopment of institutions, facilities and services for thecare of children” and “all appropriate measures to ensurethat children of working parents have the right to benefit fromchild-care services and facilities for which they are eligible.”Of particular relevance in the urban context is the recognitionof “the right of every child to a standard of living adequatefor the child’s physical, mental, spiritual, moral and socialdevelopment” (Article 27). The responsibility to secure theseconditions lies mainly with parents and guardians, but Statesparties are obliged to assist and “in case of need providematerial assistance and support programmes, particularlywith regard to nutrition, clothing and housing.” Children havethe right to benefit from social security on the basis of theircircumstances (Article 26).Health and environmentStates parties are obliged to “ensure to the maximum extentpossible the survival and development of the child” (Article6). Each child is entitled to the “enjoyment of the highestattainable standard of health and to facilities for the treat-ment of illness and rehabilitation of health” (Article 24). Thisincludes child care; antenatal, postnatal and preventive

Every child has the right to be registered immediately after birthand to have a name, the right to acquire a nationality and topreserve her or his identity and, as far as possible, the right toknow and be cared for by her or his parents (Articles 7 and 8).

Non-discriminationStates parties also take on the responsibility to protect childrenagainst discrimination. The Convention commits them torespecting and ensuring rights “to each child within their juris-diction without discrimination of any kind, irrespective of thechild’s or his or her parent’s or legal guardian’s race, colour, sex,language, religion, political or other opinion, national, ethnic orsocial origin, property, disability, birth or other status” (Article 2).Children belonging to ethnic, religious or linguistic minoritiesand those of indigenous origin have the right to practise theirown culture, religion and language in the community (Article 30).

16

THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S CHILDREN 2012

EM28BAFebr RGua Ory ED2012

care; family planning; and education on child health, nutrition,hygiene, environmental sanitation, accident prevention andthe advantages of breastfeeding. In addition to ensuring provi-sion of primary health care, States parties undertake to combatdisease and malnutrition “through the provision of adequatenutritious foods and clean drinking water, taking into consid-eration the dangers and risks of environmental pollution.”Education, play and leisureThe Convention establishes the right to education on the basisof equal opportunity. It binds States parties to make “availableand accessible to every child” compulsory and free primaryeducation and options for secondary schooling, includingvocational education (Article 28). It also obliges States partiesto “encourage the provision of appropriate and equal oppor-tunities for cultural, artistic, recreational and leisure activity”(Article 31).ProtectionStates parties recognize their obligation to provide for multipleaspects of child protection. They resolve to take all appro-priate legislative, administrative, social and educationalmeasures to protect children from all forms of physical ormental violence, injury or abuse, neglect or negligent treat-ment, maltreatment or exploitation, even while the childrenare under the care of parents, legal guardians or others(Article 19). This protection, along with humanitarian assis-tance, extends to children who are refugees or seekingrefugee status (Article 22).

Under the Convention, States are obliged to protect childrenfrom economic exploitation and any work that may interferewith their education or be harmful to their health or physical,mental, spiritual, moral or social development. Such protec-tions include the establishment and enforcement of minimumage regulations and rules governing the hours and condi-tions of employment (Article 32). National authorities shouldalso take measures to protect children from the illicit use ofnarcotic drugs and psychotropic substances (Article 33) andfrom all forms of exploitation that are harmful to any aspect oftheir welfare (Article 36), such as abduction, sale of or trafficin children (Article 35) and all forms of sexual exploitation andabuse (Article 34).

The Convention’s four core principles – non-discrimination; thebest interests of the child; the right to life, survival and devel-opment; and respect for the views of the child – apply to allactions concerning children. Every decision affecting childrenin the urban sphere should take into account the obligation topromote the harmonious development of every child.

EM28BAFebr RGua Ory ED2012Immunization