Det Udenrigspolitiske Nævn 2011-12

UPN Alm.del Bilag 6

Offentligt

THE BATTLEFORLIBYAKILLINGS,DISAPPEARANCES ANDTORTURE

Amnesty International PublicationsFirst published in September 2011 byAmnesty International PublicationsInternational SecretariatPeter Benenson House1 Easton StreetLondon WC1X 0DWUnited Kingdomwww.amnesty.org� Amnesty International Publications 2011Index: MDE 19/025/2011Original Language: EnglishPrinted by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United KingdomAll rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by anymethod without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but notfor resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered withthem for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances,or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior writtenpermission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable.To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact[email protected]

Amnesty International is a global movement of more than3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150countries and territories who campaign to end grave abusesof human rights.Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrinedin the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and otherinternational human rights standards.We are independent of any government, political ideology,economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by ourmembership and public donations.

CONTENTSAbbreviations and glossary .............................................................................................5Introduction .................................................................................................................71. From the “El-Fateh Revolution” to the “17 February Revolution” .................................132. International law and the situation in Libya ...............................................................233. Unlawful killings: From protests to armed conflict ......................................................344. Enforced disappearances, detentions and torture........................................................575. Abuses by opposition forces .....................................................................................706. Foreign nationals: Abused and abandoned .................................................................797. Conclusion and recommendations.............................................................................91Endnotes ...................................................................................................................96

4

The battle for LibyaKillings, disappearances and torture

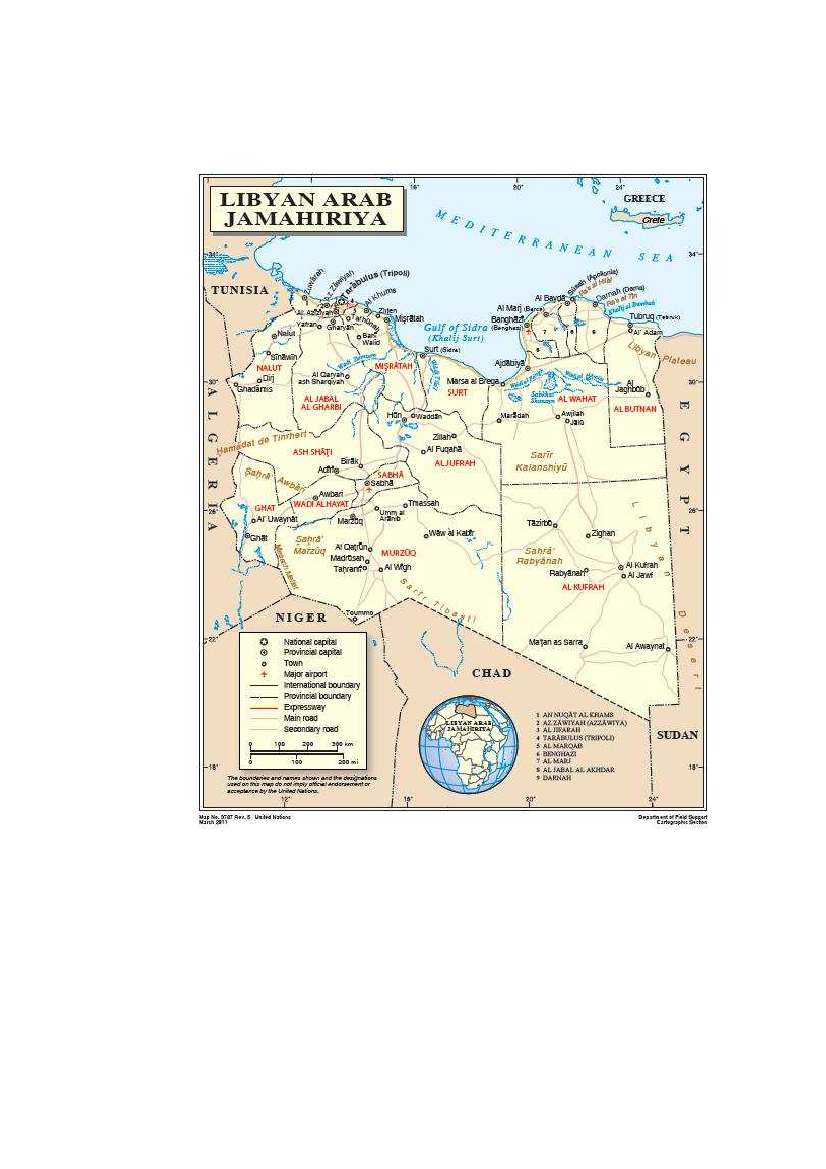

Libyan Arab Jamahiriya, No. 3787 Rev. 4 June 2004 � UN Cartographic Section

Amnesty International September 2011

Index: MDE 19/025/2011

The battle for LibyaKillings, disappearances and torture

5

ABBREVIATIONS AND GLOSSARYAl-Gaddafi forcesMilitary and security forces loyal to Colonel Mu’ammar al-GaddafiGeneral People’s Committee for Foreign Liaison and International Co-operationLibya’sequivalent to a Ministry of Foreign AffairsGeneral People’s Committee for JusticeLibya’s equivalent to a Ministry of JusticeGeneral People’s Committee for Public SecurityLibya’s equivalent to a Ministry of theInteriorEUEuropean UnionKata’ibPopular name for Colonel al-Gaddafi’s armed brigadesKateebaPopular name for the Kateeba al-Fodhil Bou ‘Omar military barracks inBenghaziICCInternational Criminal CourtICCPRInternational Covenant on Civil and Political RightsIOMInternational Organization for MigrationISAInternal Security Agency, an intelligence agency associated with some of the worsthuman rights violations under Colonel al-Gaddafi’s ruleNATONorth Atlantic Treaty OrganizationNTCNational Transitional Council, the Benghazi-based leadership of the oppositionRevolutionary CommitteesBodies created by Colonel al-Gaddafi to “protect” the 1969“El-Fateh Revolution”Revolutionary GuardsSecurity militia under Colonel al-Gaddafi’s ruleRPGRocket-propelled grenadeThuuwarPopular name for opposition fighters, literally meaning “revolutionaries”

Index: MDE 19/025/2011

Amnesty International September 2011

6

The battle for LibyaKillings, disappearances and torture

Amnesty International September 2011

Index: MDE 19/025/2011

The battle for LibyaKillings, disappearances and torture

7

INTRODUCTIONInspired and emboldened by anti-government protests sweeping across the Middle East andNorth Africa region, Libyans called for 17 February 2011 – the fifth anniversary of a brutalcrackdown on a public protest in Benghazi – to be their “Day of Rage” against ColonelMu’ammar al-Gaddafi’s four-decade long repressive rule. Until opposition forces finallystormed the capital, Tripoli, in late August, Colonel al-Gaddafi had controlled Libya for overfour decades.Desperate to maintain their grip on power in the wake of the uprisings in neighbouringTunisia and Egypt which led to the toppling of long-standing presidents, the Libyanauthorities arrested a dozen activists and writers in the lead-up to the “Day of Rage.”However, the arrest of prominent activists in Benghazi and al-Bayda had the opposite of theintended effect – it triggered a public outcry of anger and prompted demonstrations ineastern Libya ahead of the scheduled date.Security forces greeted the peaceful protests in the eastern cities of Benghazi, Libya’s secondcity, and al-Bayda with excessive and at times lethal force, leading to the deaths of scores ofprotesters and bystanders. When some protesters responded with violence, security officialsand soldiers flown in from other parts of the country failed to take any measures to minimizethe harm they caused, including to bystanders. They fired live ammunition into crowdswithout warning, contravening not only international standards on the use of force andfirearms, but also Libya’s own legislation on the policing of public gatherings.The crackdown in eastern Libya did not discourage people in other regions from joining theuprising. Protests flared up across the country from Nalut and Zintan in the Nafusa (western)Mountain region, and al-Zawiya and Zuwara in the west; to Tripoli; to Kufra in the south-east.Such protests were met with tear gas, batons and live ammunition. In the face of governmentbrutality, the protesters’ determination to topple Colonel al-Gaddafi grew. Anti-governmentprotests quickly escalated into armed clashes with Colonel al-Gaddafi’s security forces (al-Gaddafi forces).In some areas, opponents of Colonel al-Gaddafi’s rule quickly overpowered the security forcesand seized abandoned weapons. They burned many public buildings associated with staterepression, including premises of the Revolutionary Committees, a body entrusted with“protecting” the principles of the “El-Fateh Revolution” that brought Colonel al-Gaddafi topower in 1969; and the Internal Security Agency (ISA), an intelligence body implicated ingross human rights violations in past decades. By late February, most of eastern Libya, partsof the Nafusa Mountain and Misratah (Libya’s third city, located between Benghazi andTripoli) had fallen to the opposition. The unrest rapidly evolved into an armed conflict, andthe civilian population increasingly suffered as the battle for Libya raged on.In the unrest and ongoing armed conflict, al-Gaddafi forces committed serious violations ofinternational humanitarian law (IHL), including war crimes, and gross human rights violations,which point to the commission of crimes against humanity. They deliberately killed andinjured scores of unarmed protesters; subjected perceived opponents and critics to enforced

Index: MDE 19/025/2011

Amnesty International September 2011

8

The battle for LibyaKillings, disappearances and torture

Tripoli Street, Misratah � Amnesty International

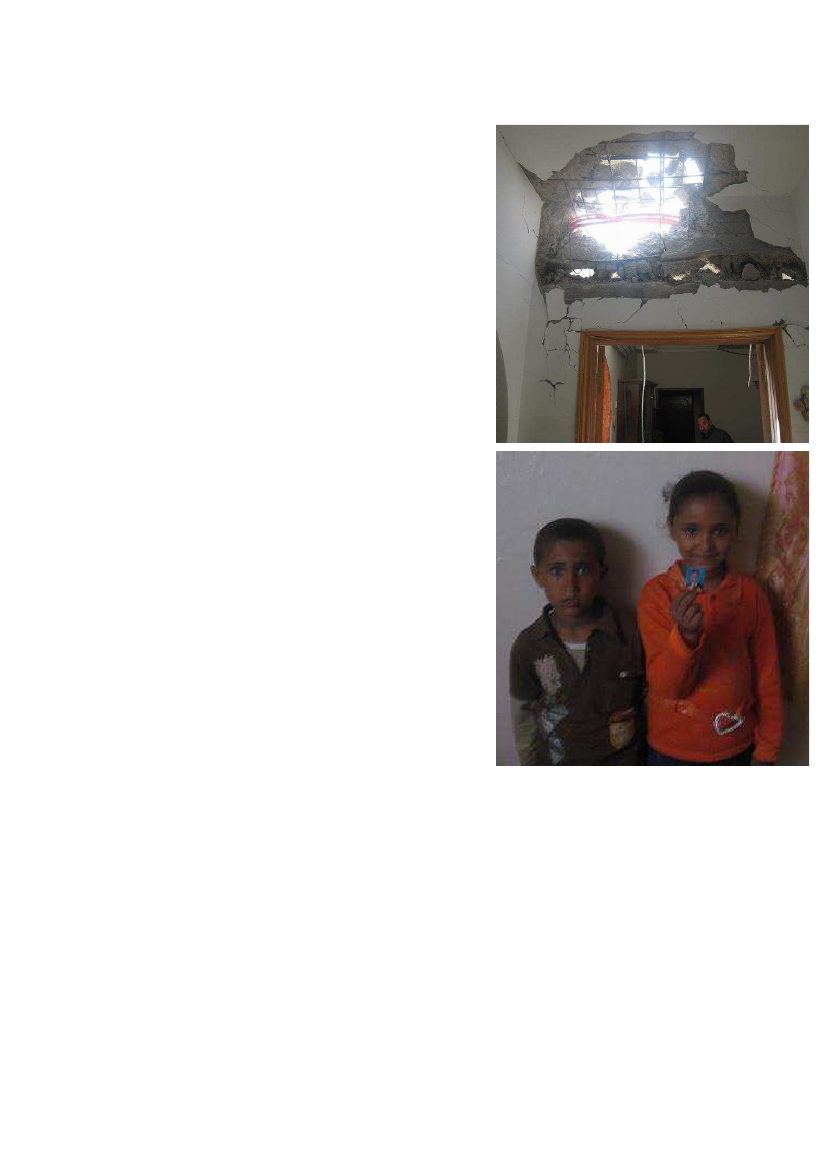

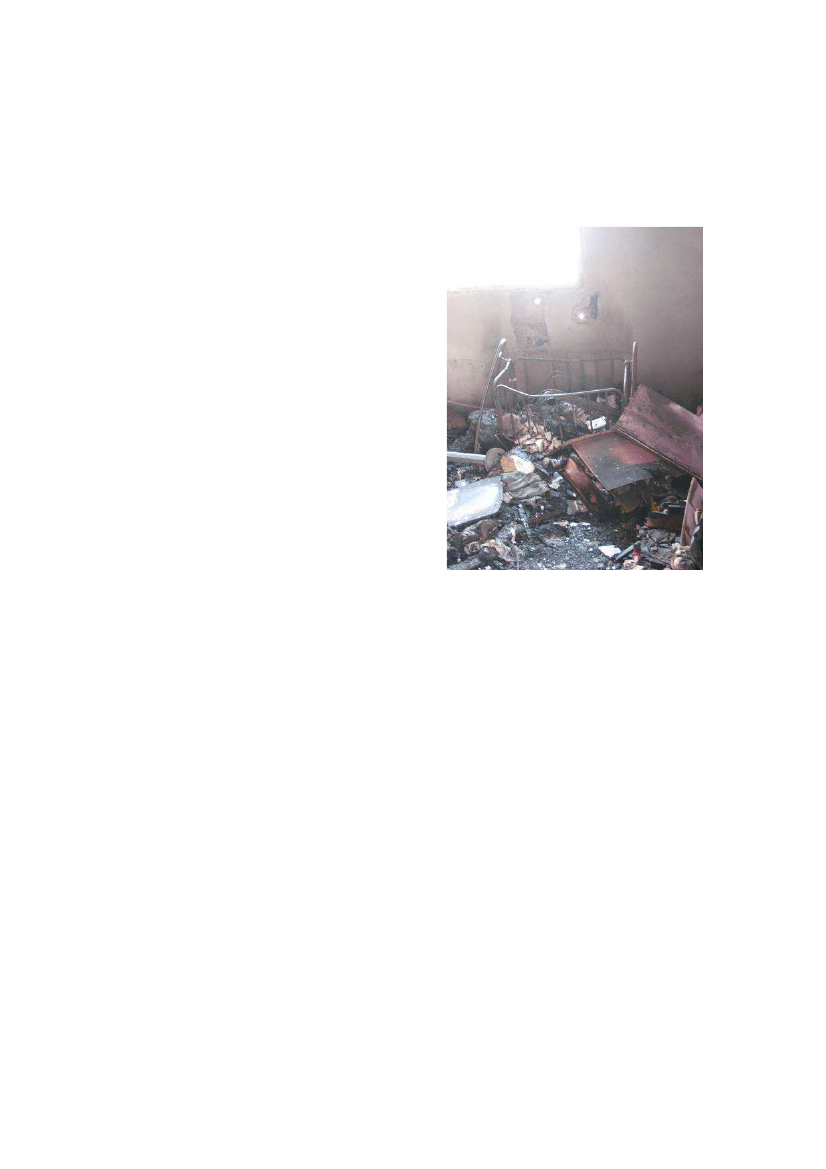

disappearance and torture and other ill-treatment; and arbitrarily detained scores ofcivilians. They launched indiscriminateattacks and attacks targeting civilians intheir efforts to regain control of Misratahand territory in the east. They launchedartillery, mortar and rocket attacks againstresidential areas. They used inherentlyindiscriminate weapons such as anti-personnel mines and cluster bombs,including in residential areas. They killedand injured civilians not involved in thefighting. They extra-judicially executedpeople who had been captured andrestrained. They concealed tanks and heavymilitary equipment in residential buildings,in a deliberate attempt to shield them frompossible air strikes by the North AtlanticTreaty Organization (NATO) forces.1

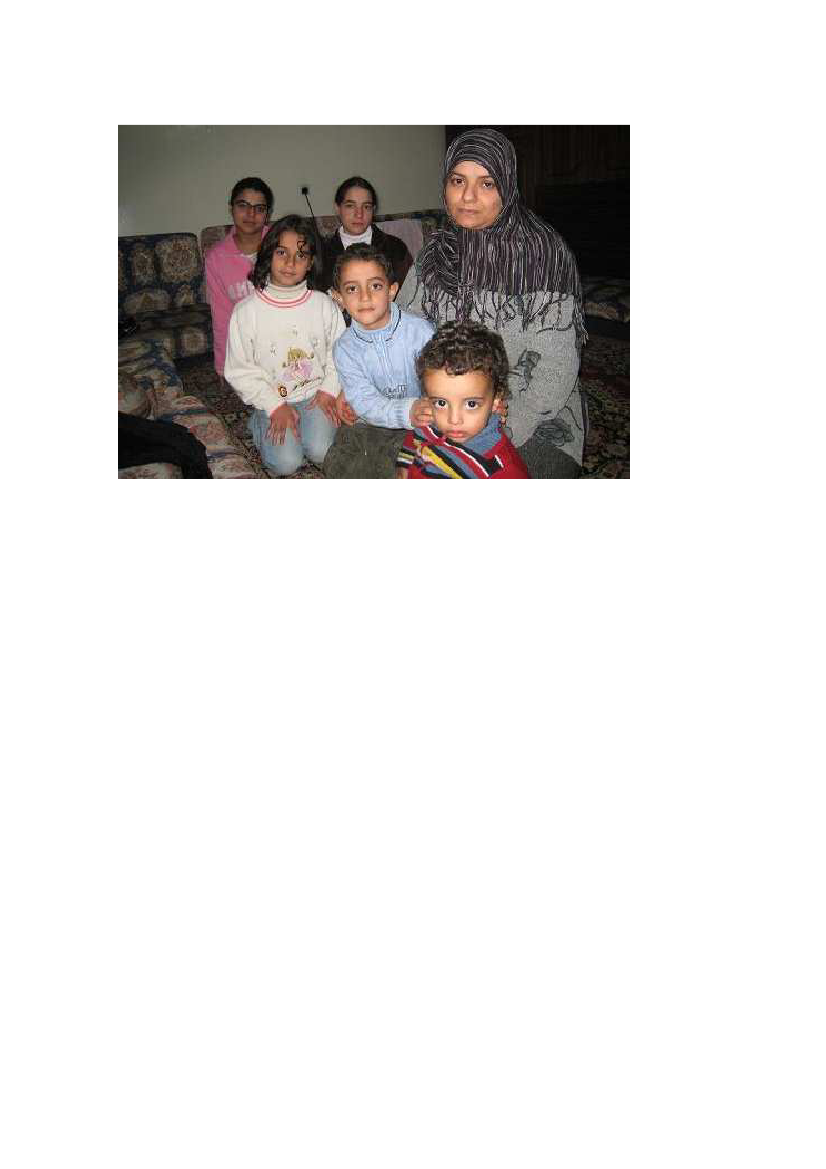

The siege by al-Gaddafi forces of opposition-held territory, notably Misratah but also areassuch as Zintan in the Nafusa Mountain, aggravated humanitarian crises there as residentswere living without or with only limited access to water, electricity, fuel, medicine andessential foodstuffs. As al-Gaddafi forces shelled opposition-held areas, civilians had nowheresafe to hide.Those who could flee from Ajdabiya, 160km west of Benghazi, and the Nafusa Mountain didso. Others, such as residents of Misratah, particularly from late March to early May, weretrapped as the city was besieged from all sides but the sea and relentlessly shelled. EvenMisratah’s port came under fire by al-Gaddafi forces in a clear attempt to cut the city’s onlyremaining escape route and lifeline for humanitarian supplies.Al-Gaddafi forces also engaged in an extensive campaign of enforced disappearances ofperceived opponents across the country, including journalists, writers, on-line activists andprotesters. Thousands of Libyans were abducted from their homes, mosques and streets, orcaptured near the front line, frequently with the use of violence. Among the disappeared werechildren as young as 12. The fate and whereabouts of many of those abducted remainedunknown until detainees escaped, or were freed, by opposition forces in Tripoli, and theirfamilies’ anguish continued for months. Earlier this year, some of the disappeared appearedin broadcasts “confessing” to carrying out activities against Libya’s best interests orbelonging to al-Qa’ida.Testimonies of some of those released from detention in Tripoli and Sirte, which throughoutthe conflict were strongholds of Colonel al-Gaddafi, confirm fears that the disappeared andother individuals abducted and detained by al-Gaddafi forces have been tortured or evenextra-judicially executed. The most frequently-reported methods of torture and other ill-

Amnesty International September 2011

Index: MDE 19/025/2011

The battle for LibyaKillings, disappearances and torture

9

treatment include beatings with belts, whips, metal wires and rubber hoses on all parts of thebody; suspension in contorted positions for prolonged periods; and the denial of medicaltreatment, including for injuries sustained as a result of torture or shooting.Such violations took place against the backdrop of the al-Gaddafi authorities’ severerestrictions of independent reporting in territories under their control; and violent attacks andassaults on Libyan and international media workers. Dozens of journalists have been detainedduring the unrest and at least seven have been killed near the front line. The government ofColonel al-Gaddafi also severely disrupted telephone communications and Internet access, ina vain attempt to halt the spread of information about the uprising and the governmentcrackdown.Members and supporters of the opposition, loosely structured under the leadership of theNational Transitional Council (NTC), based throughout the conflict in Benghazi, have alsocommitted human rights abuses, in some cases amounting to war crimes, albeit on a smallerscale. In the immediate aftermath of taking control in eastern Libya, angry groups ofsupporters of the “17 February Revolution” shot, hanged and otherwise killed throughlynching dozens of captured soldiers and suspected foreign “mercenaries” – and did so withtotal impunity. Such attacks subsequently decreased, although Sub-Saharan Africannationals continued to be attacked on what have proved to be largely unfounded suspicionsthat they were foreign “mercenaries” hired by Colonel al-Gaddafi.Opposition supporters targeted suspected al-Gaddafi loyalists and former members of some ofthe most repressive security forces. Between April and early July, for example, more than adozen such individuals were unlawfully killed in Benghazi and Derna (including at least threemembers of the ISA in Benghazi). They also tortured and ill-treated captured soldiers,suspected “mercenaries” and other alleged al-Gaddafi loyalists.Foreign nationals, particularly from Sub-Saharan Africa, have been particularly vulnerable toabuses by both al-Gaddafi and opposition forces, including arbitrary detention and torture,and found themselves caught in the crossfire. In a climate of racism and xenophobia stirredup by both sides, they have also been increasingly targeted for violent attacks, robbery andother abuses by ordinary Libyans across the country. As a result, many have fled across thenearest border or have been evacuated. While neighbouring countries, most notably Tunisiaand Egypt, have received hundreds of thousands of third-country nationals fleeing Libya,member states of the European Union (EU) continued to enforce their border control policiesand failed to guarantee safety for those escaping conflict. Since March, more than 1,500fleeing men, women and children have perished at sea trying to cross the Mediterranean toEurope.2As the violence in Libya escalated, the international community responded by setting-up aUnited Nation (UN) Human Rights Council Commission of Inquiry, referring the situation inLibya to the International Criminal Court (ICC) and authorizing “all necessary measures” –including the use of force, but short of a ground invasion – to “protect civilians”. Colonel al-Gaddafi’s government accused the international coalition (and then NATO after it took controlof military operations in late March) of killing over 800 civilians, although there is littleevidence available to corroborate such claims. NATO did admit to committing a number offatal mistakes, including one on 19 June in Tripoli that led to civilian deaths. Like all parties

Index: MDE 19/025/2011

Amnesty International September 2011

10

The battle for LibyaKillings, disappearances and torture

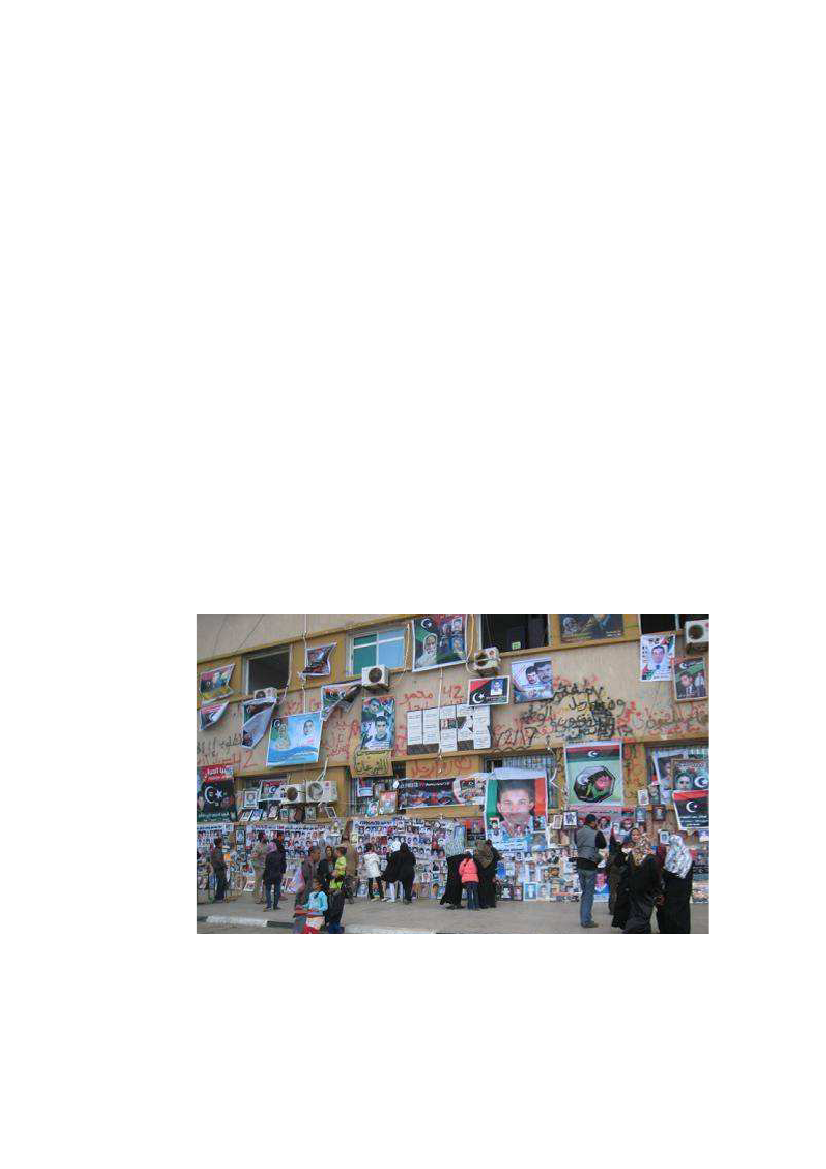

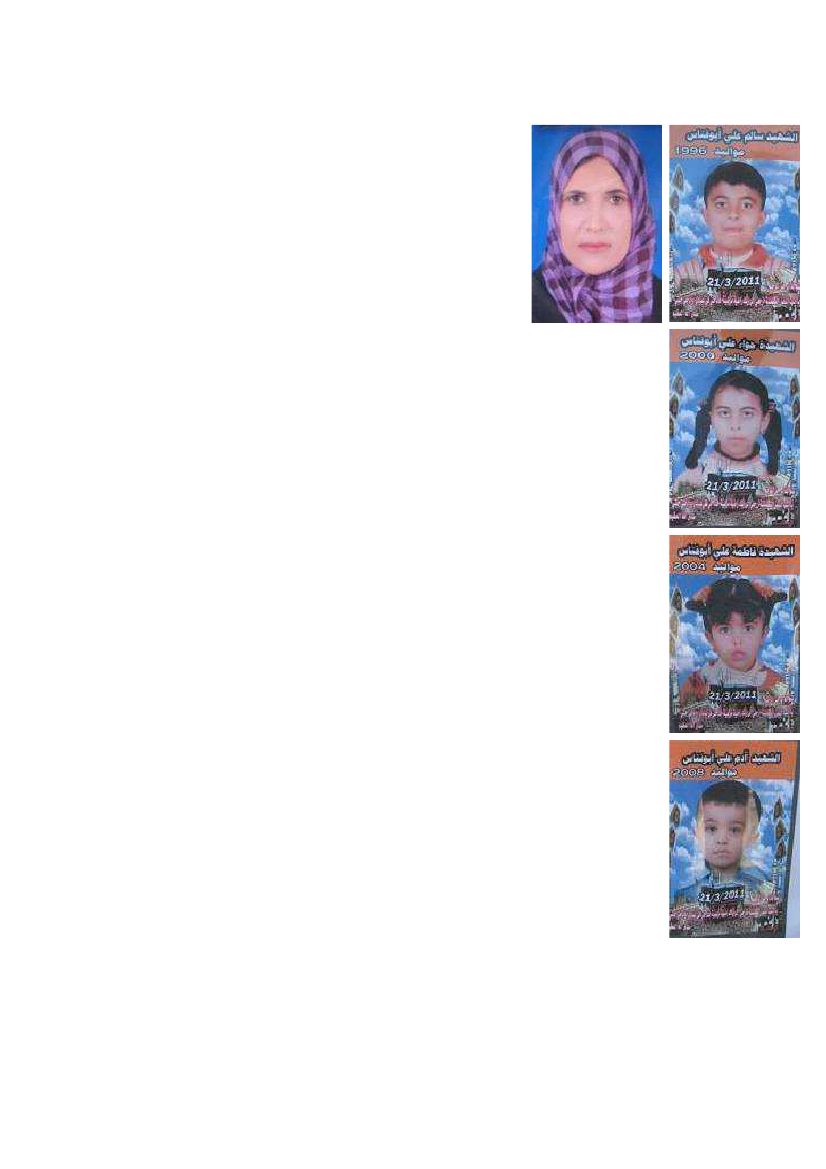

to the conflict, NATO is bound by IHL and must take all necessary precautions to sparecivilians and civilian objects.On 27 June, ICC judges approved arrest warrants for Colonel al-Gaddafi and two of his closeassociates, his son Saif al-Islam al-Gaddafi and his intelligence chief Abdallah al-Senussi foralleged crimes against humanity, including murder and persecution. This is an important stepin the fight against impunity in Libya and throughout North Africa and the Middle East.It is crucial that impartial and thorough investigations are carried out into all allegations ofserious human rights violations and violations of IHL. Wherever there is sufficient admissibleevidence, suspected perpetrators should be prosecuted in proceedings that fully respectinternational fair trial standards and with no imposition of the death penalty.Steps to prosecute those responsible are essential, not only to secure justice for victims andtheir families, but also to halt the repetition of such crimes in Libya and beyond. All victimsmust obtain redress, including reparation proportional to the gravity of the violation and harmsuffered.In order to build a new Libya on the basis of respect of human rights and the rule of law, allsuspected perpetrators must be brought to justice, regardless of their rank or affiliation –both supporters and opponents of Colonel al-Gaddafi. Those who have been found to beresponsible for abuses must not be allowed to hold positions from which they can againviolate human rights. Furthermore, comprehensive legal and institutional reforms must beintroduced to ensure respect for all human rights in law and in practice. Such reforms mustenshrine safeguards against human rights violations, such as arbitrary detention, torture andPhotos of the disappeared outside Benghazi North Court � Amnesty International

Amnesty International September 2011

Index: MDE 19/025/2011

The battle for LibyaKillings, disappearances and torture

11

enforced disappearances. They must also put in place mechanisms to ensure independent,non-partisan oversight and accountability of the security forces.To combat the legacy of four decades of human rights violations and abuse of power,guarantees must be introduced to build an independent judiciary that ensures that no one isabove the law and that no one is beyond its protection. Only then will Libyans be able toregain trust in national institutions and believe that the page has truly been turned on morethan four decades of repression and abuse.

ABOUT THIS REPORTThe bulk of the findings in this report cover developments up to late July 2011, when theconflict was still tightly contested between al-Gaddafi and opposition forces. They are largelybased on an Amnesty International fact-finding visit to Libya between 26 February and 28May 2011, including to the cities of al-Bayda, Ajdabiya, Brega, Benghazi, Misratah and RasLanouf. During the visit, the organization’s delegates interviewed victims and victims’families, eyewitnesses, medical professionals, lawyers, media workers, prosecutors,opposition fighters and others. They visited hospitals, morgues and areas affected by thefighting, including the front lines. They met several officials of the NTC and local councils,including NTC Chairman Mostafa Abdeljalil. They also visited several detention centresadministered by opposition authorities in al-Bayda, Benghazi and Misratah, where theyinterviewed detainees in private and detention officials.The report also draws on information collected by Amnesty International’s fact-finding visitsbetween 6 and 20 April and 12 and 20 June to Tunisia near the Ras Jdir and Dhehiba bordercrossings into Libya. There, the organization’s delegates met individuals who had fled Libya,including third-country nationals and Libyans from the Nafusa Mountain area. In addition,the delegates interviewed people receiving medical treatment in Tunisia for injuries sustainedas a result of fighting in Misratah, the Nafusa Mountain region, al-Zawiya and elsewhere. Thereport also draws from testimonies of third-country nationals who fled eastern Libya to Egypt,collected during a fact-finding visit to Saloum in July 2011.From 25 March, Amnesty International repeatedly requested to visit areas then under thecontrol of Colonel al-Gaddafi’s forces, including Tripoli and al-Zawiya. The organization hadhoped to assess the human rights situation there and to investigate alleged violations of IHLby all parties to the conflict, including NATO forces. The last such request was sent to theGeneral People’s Committee for Foreign Liaison and International Co-operation on 28 July.Amnesty International’s requests went unanswered. Amnesty International was thereforeunable to monitor and document in detail human rights violations and other crimescommitted in areas controlled by al-Gaddafi forces, including Tripoli and much of westernLibya.This report documents serious and widespread human rights violations committed by al-Gaddafi forces, including extrajudicial executions and excessive use of force against anti-government protesters; torture and other ill-treatment; and the enforced disappearances ofperceived opponents. It presents prima facie evidence of war crimes, including deliberateattacks against civilians and indiscriminate attacks. The report also documents abusescommitted by opposition forces and their supporters, including unlawful killings, torture and

Index: MDE 19/025/2011

Amnesty International September 2011

12

The battle for LibyaKillings, disappearances and torture

other violent attacks against captured soldiers, Sub-Saharan Africans suspected of beingmercenaries, and former members of the security forces.The report does not include information on allegations of sexual violence against womenduring the Libyan conflict. To gather information on such violations, Amnesty Internationaldelegates interviewed Libyan and foreign women in opposition-controlled territories, as wellas women who fled to Tunisia and Egypt; medical professionals, including gynaecologists andpsychologists; women’s groups activists and others; and reviewed some documentaryevidence, including video footage of women being subjected to sexual abuse. Theorganization was not able to collect first-hand testimonies and other evidence to verify theclaims, and is continuing its investigations.Amnesty International delegates returned to Libya in late August, days before oppositionforces stormed Tripoli. In al-Zawiyah, now under opposition control, they collectedtestimonies of people who had been injured in the battle for Tripoli and former detaineesfreed from military camps and other detention centres controlled by al-Gaddafi forces. Theyalso visited detention centres where those believed to be members of the al-Gaddafi forcesand suspected foreign mercenaries were being held.Cases highlighted in this report provide emblematic examples of wider patterns of abusescommitted since mid-February in Libya. Names of some individuals whose cases are includedhave been withheld to protect them and their families from reprisals, or on their request.

Amnesty International September 2011

Index: MDE 19/025/2011

The battle for LibyaKillings, disappearances and torture

13

1. FROM THE ‘EL-FATEH REVOLUTION’TO THE ‘17 FEBRUARY REVOLUTION’

Women demonstrate in Benghazi � Amnesty International

Inspired by the toppling of long-standing presidents in neighbouring Tunisia and Egypt,Libyans used social-networking websites to call for anti-government protests on 17 February2011. The significance of the date goes back to 17 February 2006, when security forceskilled at least 12 people and injured scores more in a protest in Benghazi, a protest that wasnot calling for political change, but simply expressing anger over cartoons of the ProphetMuhammad printed in Europe.A year later, in 2007, about a dozen activists announced plans for a peaceful demonstrationin Tripoli to commemorate the tragic event. The authorities arrested them and the protest didnot take place. After months in incommunicado detention, the activists were eventuallysentenced to prison terms ranging from six to 25 years for “attempting to overthrow thepolitical system”, “spreading false rumours about the Libyan regime” and “communicatingwith enemy powers”.3The crackdown on the 17 February 2006 protest, the silencing of any criticism of the actionsof the security forces, and the failure to bring those responsible for the deaths of protesters tojustice, typified the al-Gaddafi government’s record of repression of dissent, bans on anygatherings unless sanctioned by the government, and impunity for serious human rightsviolations.

Index: MDE 19/025/2011

Amnesty International September 2011

14

The battle for LibyaKillings, disappearances and torture

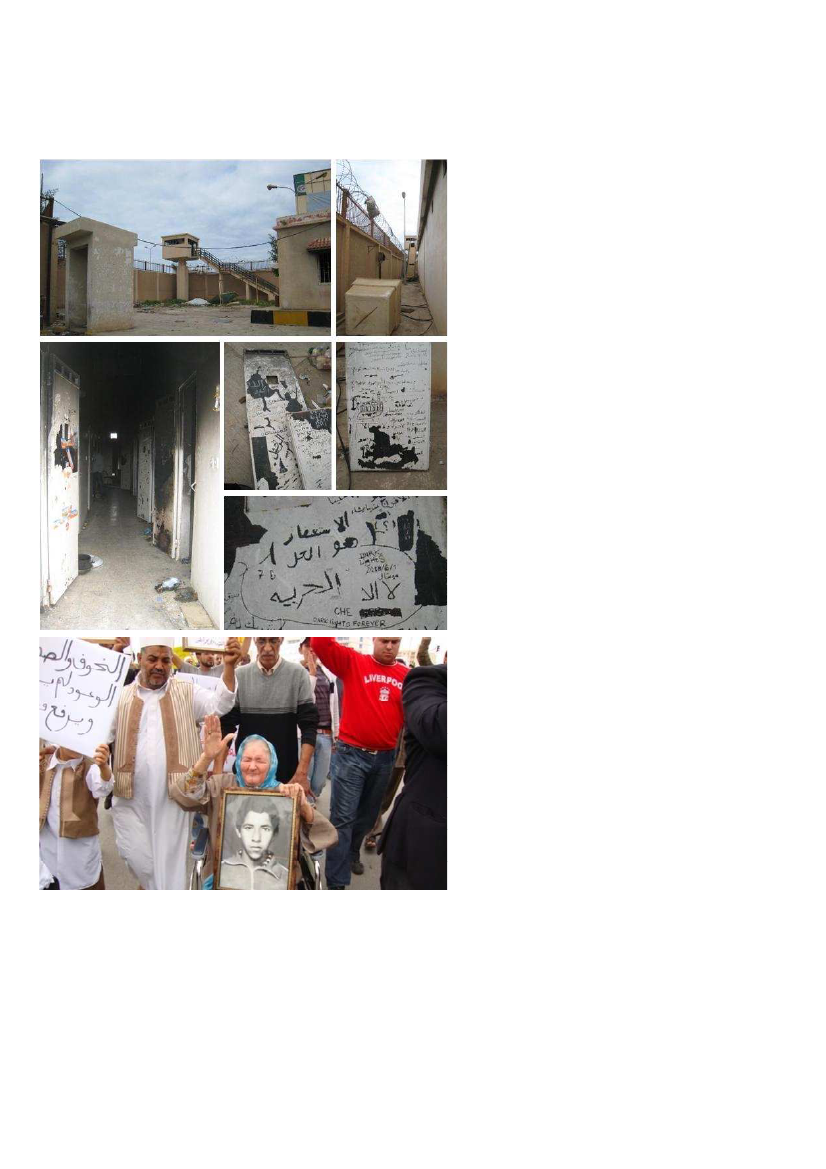

In power since 1969, Colonel Mu’ammar al-Gaddafi portrayed himself as the country’sguide rather than ruler.4Yet he relied onsevere reprisals against any perceivedopponents, through political killing –including of Libyans in exile – imprisonment,torture and other ill-treatment, harassmentand intimidation, not only of his perceivedcritics but also of their families. Suchviolations were among the reasons for the2011 revolt and calls for political reform.Despite Libya’s relative economic securitycompared to other restive North Africancountries, unemployment and other socio-economic grievances also propelled the “17February Revolution” and helped to rallyLibyans en masse. Protesters and otheropposition supporters say that corruption,unemployment and inequality were amongthe key triggers of the uprising. Many toldAmnesty International delegates that “thecountry is rich, but its people are poor”because under Colonel al-Gaddafi thecountry’s wealth had been distributed to thebenefit of his supporters. Many also pointedto the poor state of the country’sinfrastructure, education and health services,standing in stark contrast to its oil wealth.Serious human rights violations were ahallmark of Colonel al-Gaddafi’s rule. Certaingroups were particularly targeted, includingindividuals seen as critics of the authoritiesor the principles of the “El-Fateh Revolution”;those deemed to be a security threat; andforeign nationals in an irregular situation,particularly from Sub-Saharan Africa. Theviolations were facilitated by the absence ofadequate legal safeguards, particularly incases deemed to be political. In such cases,the much-feared ISA, whose remit, mandateand structure were opaque and unclear,acted above the law and was implicated inthe worst violations. The ISA controlled twomajor prisons, Abu Salim and Ain Zara,5in

Top: ISA facility in Benghazi, including details of graffiti on cell doors; Above: Families of those killed in1996 in Abu Salim Prison protest in Benghazi � Amnesty International

Amnesty International September 2011

Index: MDE 19/025/2011

The battle for LibyaKillings, disappearances and torture

15

addition to a number of unrecognized places of detention outside the remit of any judicialauthority. Those detained by the ISA were frequently held incommunicado for long periods inconditions sometimes amounting to enforced disappearance, exposing them to the risk oftorture or other ill-treatment.Colonel al-Gaddafi’s rule was also characterized by repressive legislation outlawing politicalparties and independent organizations, and heavy-handed reprisals against anyone who daredto criticize the authorities or to organize anti-government protests. The space for civil societyand independent media was virtually non-existent, although in recent years the authoritieshad shown more tolerance to some dissenting voices, as long as they did not cross certain“red lines”, such as direct criticism of Colonel al-Gaddafi or the ideological foundation of hispolitical system. Neither political parties nor independent human rights organizations wereallowed. The Gaddafi International Charity and Development Foundation (GaddafiDevelopment Foundation, GDF), headed by the leader’s son Saif al-Islam al-Gaddafi, was theonly organization permitted to address human rights issues, but clearly lacked independence.While Libyan law guaranteed peaceful freedom of assembly, in practice public meetings anddemonstrations were generally tolerated only when the participants were supporting thegovernment. However, public protests had been held in Benghazi since 2008 by families ofvictims of the Abu Salim Prison killings, where up to 1,200 detainees were extra-judiciallyexecuted in 1996 by security forces following a riot by detainees protesting against appallingprison conditions.6In June 2008, the Benghazi North Court of First Instance ruled that the authorities mustreveal the whereabouts and fate of 33 individuals believed to have died in Abu Salim orelsewhere in custody. Encouraged by the ruling, families then gathered almost every Saturdayoutside the People’s Leadership7premises in Benghazi holding pictures of their loved ones

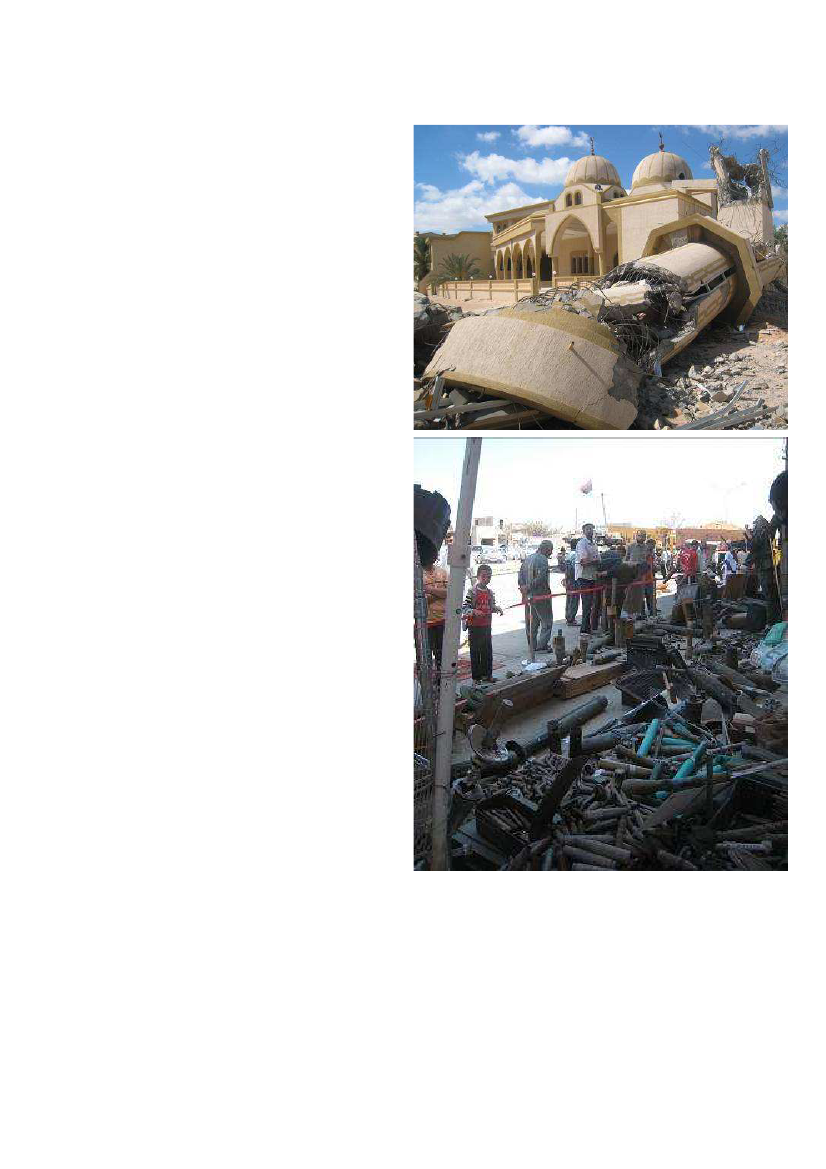

Destroyed “Green Book” statue in Misratah � Amnesty International

Index: MDE 19/025/2011

Amnesty International September 2011

16

The battle for LibyaKillings, disappearances and torture

and posters calling for the end of their suffering. Several were harassed as a result.8The relatives’ persistence no doubt helped to break the wall of silence and contributed to the“17 February Revolution”. Indeed, the arrest on 15 February of Fathi Terbil and Faraj al-Sharani, both prominent members of the Organizing Committee of Families of Victims of AbuSalim in Benghazi, was a catalyst for anti-government protests in Benghazi in the run-up tothe scheduled “Day of Rage” on 17 February.The authorities dispersed the protesters using non-lethal weapons, injuring scores of people,but nonetheless swiftly released the two men. Neither strategy worked as protests swelled inBenghazi on 17 February and then spread to other cities, including Zintan in the NafusaMountain; the remote Kufra in the south-east; al-Zawiya and Zuwara in the west; and al-Bayda, Derna and Tobruk in the east.Within days, protesters across eastern Libya overpowered the security apparatus, burneddown public buildings associated with the government, and seized weapons abandoned byfleeing security officials. In Benghazi alone, at least 109 people died as a result of gunshotwounds sustained during anti-government protests and clashes with security forces,according to local medical sources, including peaceful protesters and others not posing athreat to the security forces.The use of excessive force and firearms by al-Gaddafi forces in eastern Libya inflamed angerand triggered protests elsewhere in the country, including Tripoli, Misratah and the NafusaMountain. For instance, Misratah residents told Amnesty International that they initially tookto the streets on 19 February in solidarity with the victims in Benghazi and that they onlystarted calling for the “fall of the regime” during the funeral of Misratah’s first victim, KhaledAbu Shahma, shot by security forces on 19 February.The protest movement in Tripoli lagged behind that in other cities. It culminated in theconvergence of several marches on 20 February in the central Green Square – the symbolicseat of power adorned by huge posters of Colonel al-Gaddafi. According to witnesses, securityforces waited for the protesters to reach the square before opening fire, reportedly causingmany deaths and injuries. Smaller protests erupted elsewhere in Tripoli, including in SouqEl-Jum’a, Fashloum and Tajoura, in the following days, and were also reportedly met by liveammunition.In his first public speech after the unrest started, Colonel al-Gaddafi appeared on statetelevision on 22 February and described the protesters as “rats” manipulated by foreignerswishing to harm Libya’s interests. He threatened to use all means necessary to “purge Libyainch by inch, room by room, household by household, alley by alley, and individual byindividual until the country is purified”.9Two days earlier, his son Saif al-Islam al-Gaddafi, who despite not having an official role waswidely seen as influential and dubbed by some as a “reformer”, had also made a televisedspeech. He blamed Libyans living in exile for instigating anti-government protests andadmitted that the authorities had sought to prevent the demonstrations by carrying out arrests.

Amnesty International September 2011

Index: MDE 19/025/2011

The battle for LibyaKillings, disappearances and torture

17

He lamented the evolution of “small protests” into“a separatist movement… and a threat to thecountry’s unity”.10Maintaining that the reports ofthe casualty toll were exaggerated, Saif al-Islam al-Gaddafi admitted that protesters had been killed.He partly blamed soldiers poorly trained in crowdcontrol, but also said that protesters wereintoxicated when they violently attacked publicbuildings. He alleged that armed Islamist groupsand individuals were driving the uprising. Hepresented two options to Libyans: either standbehind the current political system, which wouldlift restrictions on freedoms and introduce otherreforms; or be prepared for a protracted war inwhich “we will fight to the last man, woman andbullet”.11Government opponents vehemently denied theinvolvement of foreigners or the influence ofIslamist armed groups, maintaining that themovement was a popular uprising. On 2 March,opposition forces announced the establishment ofthe NTC headed by Mostafa Abdeljalil, formerSecretary of the General People’s Committee forJustice (equivalent to the Justice Minister), whohad defected on 21 February in protest over theuse of lethal force against protesters by securityforces. The NTC declared itself to be the “solelegitimate representative of the Libyan people” andpresented its vision of a “democratic Libya” builton the foundations of good governance and therespect of the rule of law and human rights.12TheNTC also vowed to abide by Libya’s obligationsunder international human rights law.By late February, violence escalated as anti-government protesters took up arms and clashedwith al-Gaddafi forces. At alarming speed, theunrest evolved into a fully-fledged armed conflict,and confrontations intensified as al-Gaddafi forcesattempted to regain control of cities that had fallento the opposition forces, while the latter tried togain new ground.In response to the escalating violence andpersistent reports of widespread human rightsviolations, on 26 February the UN Security Councilpassed Resolution 1970 referring the situation in

Top: A destroyed minaret in Misratah; Above: A display of munitions in Misratah � AmnestyInternational

Index: MDE 19/025/2011

Amnesty International September 2011

18

The battle for LibyaKillings, disappearances and torture

Libya to the Prosecutor of the ICC, imposed sanctions and an arms embargo, and ordered thefreezing of assets of the country’s leaders.Colonel al-Gaddafi’s government became increasingly isolated diplomatically. In addition todefections by members of his inner circle, it was abandoned by former regional andinternational allies. Governments that had not long ago ignored the Libyan government’sappalling human rights record to seek its collaboration in the control of migration andcounter-terrorism and to exploit lucrative business opportunities in the country, suddenlyturned on it, damning its human rights record and in some cases recognizing the NTC as thesole government authority in Libya.13On 17 March, as fighting intensified in eastern Libya as well as in Misratah, the UN SecurityCouncil adopted Resolution 1973 authorizing the establishment of a no-fly zone over Libyaand the implementation of all necessary measures, short of foreign occupation, to protectcivilians. On 19 March, the international alliance14launched its first military attacks againstal-Gaddafi forces, which had by then reached the opposition stronghold of Benghazi. Thismeant that there was now an international armed conflict (between the Tripoli governmentand the UN-mandated international alliance) alongside the non-international armed conflictthat had begun in late February.NATO assumed control of international military operations in Libya on 27 March.15By theend of August, it had carried out over 7,500 strike sorties. Colonel al-Gaddafi’s governmentalleged that NATO strikes killed over 800 civilians, but such allegations are impossible toindependently verify (see About This Report).NATO did, however, admit that a “weapons systems failure” on 19 June might have causedthe loss of “innocent civilian” life and expressed its regret over the incident, confirming itsintention to take all necessary precautions to avoid civilian casualties.16In letters sent on 11April and 2 August, Amnesty International urged NATO to take the utmost care to avoidcivilian casualties, including in their choice of means and methods of attack. Theorganization called for full and impartial inquiries into any incidents that led to civiliancasualties, the publication of their results, and adequate reparation for victims.At the time of writing, NATO strikes and fighting between al-Gaddafi forces and oppositionfighters were ongoing. The battle for Tripoli, which opposition forces entered on the night of20/21 August, was continuing, with large parts of the city reportedly falling under oppositioncontrol. However, the armed conflict did not directly affect the whole country. Fighting wasfocused in particular areas, including between Ajdabiya and Ben Jawad in the east; and theNafusa Mountain area, al-Zawiya (now in opposition control), Misratah and Zliten in the west.Some areas experienced few battles until cities fell under the control of the opposition, aswas the case in Kufra in the south-east, or were quickly retaken by al-Gaddafi forces, as wasthe case in Zuwara in the west. Other areas witnessed protracted battles as opposition forcesresisted attacks launched by al-Gaddafi forces in early March. In particular, Misratah’spopulation lived under siege and under fire for nearly two months, until the front lines movedfurther to the east and west, away from densely-populated residential areas.

Amnesty International September 2011

Index: MDE 19/025/2011

The battle for LibyaKillings, disappearances and torture

19

The fighting led to the internal displacement of tens of thousands of civilians, many fleeingAjdabiya and surrounding areas. There was also a large exodus of Libyans and foreignnationals to neighbouring states. At the time of writing, over 672,000 foreign nationals hadfled Libya and not returned, including over 337,000 who fled home to neighbouringcountries and over 304,000 third-country nationals.17Also at the time of writing, anestimated 4,500 Libyans had crossed into, and remained in, Egypt and a further 187,000were in Tunisia, many of the latter having fled fighting in the Nafusa Mountain.Colonel al-Gaddafi’s government also clamped down on the media and communicationchannels. On 18 February, it blocked access to Facebook and Twitter, and soon afterdisrupted Internet access across Libya, leaving the vast majority of people without satellitetechnology, in both government- and opposition-controlled territory, with no Internetservices.18In the third week of February, the authorities severely disrupted telephonecommunications. People in opposition-controlled territory could not place international callsor calls to other parts of Libya. People in Tripoli and other territories at the time controlled byal-Gaddafi forces could receive international calls or calls from satellite phones, but few didso with ease as they suspected that the authorities could monitor their discussions. Thearrest of Syrian journalist Rana al-Aqbani on 28 March on accusations of “communicatingwith enemy bodies during wartime”, based on bugged phones conversations she had withpeople in eastern Libya and abroad, served as a cautionary tale.19The al-Gaddafi authorities’campaign of harassment of, and attacks against, journalists and restrictions on their freedomof movement in the government stronghold of Tripoli, coupled with the isolation of residentsof areas under the control of Colonel al-Gaddafi’s forces, meant that little was known aboutviolations committed in such areas.

Displaced residents of Ajdabiya stranded in the desert for weeks � Amnesty International

Index: MDE 19/025/2011

Amnesty International September 2011

20

The battle for LibyaKillings, disappearances and torture

JOURNALISTS UNDER FIREFrom the onset of the unrest, Colonel al-Gaddafi’s government waged a media war aimed at discreditingopponents and impeding negative coverage of its conduct.It sought to control the content of the coverageand block regular access to damning information, and attacked global media for inciting violence andspreading “rumours and false information”.20At the same time, it welcomed international journalists intoTripoli to transmit the “truth”, as long as they did not venture beyond government-sanctioned excursions orthe Rixos Hotel in Tripoli, where they were housed.Those who defied these rules were expelled, detained,

assaulted or worse. From mid-February, dozens of journalists – Libyan and foreign – suffered reprisalsfor attempting to independently monitor and report events in Libya. According to the Committee toProtect Journalists, at least 50 journalists were detained.21Many were seized in areas close to fighting,particularly near Brega, or in western parts of Libya controlled by al-Gaddafi forces.Mohamed Nabus � AmnestyInternational

On 23 February, the Libyan authority for External Communications, a body belonging to the al-Gaddafiauthorities responsible for dealing with foreign media, warned that the authorities were not responsible for thesafety of journalists working “without supervision” or entering illegally. At the same time, the al-Gaddafigovernment spokesman, Moussa Ibrahim, justified restrictions on journalists’ freedom of movement in Tripoliand other parts of western Libya as necessary for their own protection against “armed gangs”. Many foreignjournalists were detained incommunicado. Several were beaten or otherwise ill-treated.Lyndsey Addario,aphotographer withThe New York Times,was captured near Ajdabiya with three colleagues on 15 March by al-Gaddafi soldiers. She said that several of her captors groped her and at least one threatened to kill her.22ThreeBBC crew members reported being beaten, insulted and subjected to mock executions after they were capturedon 7 March near al-Zawiya.23Others journalists continued to be detained by al-Gaddafi forces. US freelance journalistMatthew VanDykewas taken by al-Gaddafi forces after heading to Brega from Benghazi in mid-March. Some four months later,Matthew VanDyke’s family finally received information that he was detained in Tripoli, at the time in the handsof the al-Gaddafi authorities. He was finally freed when Tripoli fell to opposition fighters.24While many foreignmedia workers have been released, the fate and whereabouts of at least six Libyan journalists and otherLibyans assisting media crews remain unclear and there are great concerns for their safety.25At least three Libyan and four foreign journalists or media workers have been killed near areas of fighting,some in unclear circumstances. They include Al Jazeera cameramenAli Hassan Al Jaber,who was killed bygunfire in an ambush near Benghazi on 13 March, in what appeared to be a deliberate and targeted attack,26andMohamed Nabus,who from the beginning of the protests became “the face of citizen journalism”,setting-up the first independent TV station on-line, bypassing the Internet shutdown by the Libyan authoritiesand sending raw information about the repression of the protests to the outside world.27He was shot dead on19 March in Benghazi, reportedly by al-Gaddafi forces, in an area where armed clashes had taken placebetween al-Gaddafi forces and opposition fighters.South African photojournalistAnton Hammerlwas killed on 5 April by al-Gaddafi forces at the front line nearBrega. News of his fate only emerged when the Libyan authorities released on 18 May three other foreignjournalists captured during the same incident. Two photographers, UK nationalTim Hetheringtonand USnationalChris Hondros,were both killed, by what appeared to be a projectile fired by al-Gaddafi’s forces on18 April while covering heavy fighting between opposition fighters and al-Gaddafi’s forces in the centre ofMisratah. Two of their colleagues were injured in the same incident.

Amnesty International September 2011

Index: MDE 19/025/2011

The battle for LibyaKillings, disappearances and torture

21

INTERNATIONAL MECHANISMSThe deteriorating human rights situation in Libya prompted the UN Human Rights Council tounanimously adopt on 25 February a resolution condemning the “recent gross and systematichuman rights violations committed in Libya, including indiscriminate armed attacks againstcivilians”, and establishing a commission of inquiry to investigate all alleged violations ofinternational human rights law in Libya.28Within days, the UN General Assembly suspendedLibya’s membership of the UN Human Rights Council.This followed the UN Security Council’s referral of the situation in Libya to the ICC on 26February.29On 27 June the Pre-Trial Chamber of the ICC issued arrest warrants for Colonelal-Gaddafi, his son Saif al-Islam al-Gaddafi and his head of military intelligence Abdallah al-Senussi for “crimes against humanity (murder and persecution) allegedly committed acrossLibya from 15 February 2011 until at least 28 February 2011, through the State apparatusand Security Forces”.30On 9 June, the UN Human Rights Council discussed the Commission of Inquiry’s report. TheCommission found evidence that the crackdown on protests in the first days of the unrestamounted to “a serious breach of a range of rights under international human rights law,including the right to life, the right to security of person, the right to freedom of assemblyand the right to freedom of expression”. The Commission also found that the authoritiescarried out widespread arbitrary arrests and engaged in a campaign of enforceddisappearances.After the situation in Libya developed into an armed conflict, the Commission interpreted itsmandate more broadly to additionally consider breaches of IHL by all parties to the conflict.The Commission found that:“[T]here have been many serious violations of IHL committed by Government forcesamounting to “war crimes”. Under the listing of “war crimes” in the Rome Statute applicableto non international armed conflict, the commission has identified violations involvingviolence to life and person, outrages upon personal dignity in particular humiliating anddegrading treatment, intentionally directing attacks against protected persons and targetsincluding civilian structures, medical units and transport using the distinctive emblems ofthe Geneva Conventions.”The Commission also noted that while it had registered fewer cases that would amount tocrimes under international law by opposition forces, it nonetheless had concerns about thetorture and other ill-treatment of captured soldiers and foreign nationals suspected of beingmercenaries.The Commission requested the extension of its mandate by a year given the large scope ofthe work, the ongoing violations in Libya, and the need to further delve into certainallegations it had not yet been able to confirm, such as the use of sexual violence and rapeon a large scale.31Various regional mechanisms also raised their concerns regarding the conduct of the Libyanauthorities. For instance, the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights unanimouslyordered provisional measures against Libya on 25 March. The Court described the situation in

Index: MDE 19/025/2011

Amnesty International September 2011

22

The battle for LibyaKillings, disappearances and torture

Libya as one of “extreme gravity and urgency”, and called on the al-Gaddafi authorities toimmediately cease any actions leading to the loss of life or violations of “physical integrity”.32The case against Libya was referred to the Court by the African Commission, which qualifiedthe violations in Libya as “serious and widespread”. On 22 February, the League of ArabStates suspended Libya from its sessions because of the crackdown on anti-governmentprotests.33

Amnesty International September 2011

Index: MDE 19/025/2011

The battle for LibyaKillings, disappearances and torture

23

2. INTERNATIONAL LAW AND THESITUATION IN LIBYASeveral bodies of international law apply to the situation in Libya.International human rights law, including on civil, cultural, economic, political and social rights, appliesboth in peacetime and during armed conflict and is legally binding on states, their armed forces and otheragents. It establishes the right of victims of serious human rights violations to remedy, including justice, truthand reparations.IHL, also known as the law of armed conflict, is a special body of international rules that apply alongsidehuman rights law to provide additional protection in situations of armed conflict. IHL includes rules protectingcivilians and other individuals who are not taking part in combat (“horsde combat”),as well as rulesregulating the means and methods of warfare. It also includes rules imposing obligations on states or otherentities militarily occupying a territory. IHL binds all parties to an armed conflict, including non-state armedgroups.International criminal law establishes individual criminal responsibility for certain violations and abusesof international human rights and IHL, such as war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide, as well astorture, extrajudicial executions and enforced disappearance.

2.1. OBLIGATIONS UNDER INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS LAW AND LIBYAN LAWLibya is a state party to some of the major international human rights treaties, including theInternational Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR); the Convention against Tortureand Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (UNCAT); the Conventionon the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW); the InternationalConvention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD); and the AfricanCharter on Human and Peoples’ Rights. Libya is legally bound by its obligations under theseinternational treaties, as well as by relevant customary international law.International human rights law applies in time of armed conflict as well as peacetime; some(but not all) rights may be modified in their application, or “derogated from” or limited insituations of armed conflict, but only to the extent strictly required by the exigencies of theparticular situation and without discrimination.34At the start of the unrest in Libya, there wasno armed conflict, and the lawfulness of conduct of Libyan security forces under Colonel al-Gaddafi was to be assessed against human rights standards alone.The NTC, which has been recognized by over 40 states as the government authority in Libyaand is, at time of writing, increasingly the de-facto authority in Libya, has declared that it willrespect “IHL and human rights declarations”. The NTC also declared: “We recognise withoutreservation our obligation to...guarantee and respect the freedom of expression through media,peaceful protests, demonstrations and sit-in and other means of communication”. The NTChas proclaimed that the state to which it aspire will respect “human rights, rules andprinciples of citizenship and the rights of minorities and those most vulnerable”.35

Index: MDE 19/025/2011

Amnesty International September 2011

24

The battle for LibyaKillings, disappearances and torture

There is no doubt that the NTC is legally bound by applicable rules of IHL, including those onthe treatment of prisoners, as a party to the non-international armed conflict in Libya (seesection on IHL below).Of particular relevance to this report are Libya’s international human rights law obligationsrelating to the right to life, the prohibition of torture and other cruel, inhuman or degradingtreatment (“other ill-treatment”), the prohibition of enforced disappearance, the prohibitionof arbitrary detention and the right to freedom of assembly.36Certain violations, such astorture and enforced disappearance, amount to crimes under international law that statesmust criminalize in domestic legislation.37States must ensure that those responsible forthese and other human rights violations of a criminal nature, including extrajudicialexecutions, are brought to justice.38

2.1.1. ENFORCED DISAPPEARANCES AND OTHER VIOLATIONS OF THE RIGHT TO LIBERTYArticle 2 of the International Convention for the Protection of all Persons from EnforcedDisappearance defines an enforced disappearance as “the arrest, detention, abduction or anyother form of deprivation of liberty by agents of the State or by persons or groups of personsacting with the authorization, support or acquiescence of the State, followed by a refusal toacknowledge the deprivation of liberty or by concealment of the fate or whereabouts of thedisappeared person, which place such a person outside the protection of the law”. Libya isnot party to the Convention, which came into force in December 2010; however, any act ofenforced disappearance as defined in the Convention will violate a range of rights under theICCPR and constitute a crime under international law.As a state party to the ICCPR, Libya is under an obligation to prevent arbitrary arrest anddetention and to allow anyone deprived of liberty an effective opportunity to challenge thelawfulness of their detention before a court (Article 9). It must ensure that those arrested arepromptly informed of any charges against them, and that those charged are brought beforethe judicial authorities within a reasonable time. Enforced disappearances also violate theright to humane treatment of detainees and the prohibition of torture and other ill-treatment(articles 7 and 10 of the ICCPR); and can violate the right to life (Article 6 of the ICCPR) andthe right to recognition as a person before the law (Article 16 of the ICCPR).Libyan legislation includes some safeguards against enforced disappearance and arbitrarydetention. For instance, Law No. 20 of 1991 on the Promotion of Freedom includes anumber of principles intended to guarantee the protection of human rights in theadministration of justice, such as Article 14 which stipulates that: “No one can be deprivedof his freedom, searched or questioned unless he has been charged with committing an actthat is punishable by law, pursuant to an order issued by a competent court, and inaccordance with the conditions and time limits specified by law”. According to the samearticle: “Accused persons must be held in custody at a known location, which shall bedisclosed to their relatives, for the shortest period of time required to conduct theinvestigation and secure evidence”.

Amnesty International September 2011

Index: MDE 19/025/2011

The battle for LibyaKillings, disappearances and torture

25

When committed as part of a widespread or systematic attack directed against a civilianpopulation, with knowledge of the attack, enforced disappearances constitute crimes againsthumanity.39

2.1.2. TORTURE AND OTHER CRUEL, INHUMAN OR DEGRADING TREATMENT OR PUNISHMENTLibya is a party to the ICCPR and the UNCAT. The authorities under Colonel al-Gaddafi failedto meet key obligations under these treaties regarding prevention, investigation,criminalization and reparations, when it comes to torture and other forms of ill-treatment.The Libyan authorities under Colonel al-Gaddafi failed to amend domestic legislation todefine torture in line with international law and to explicitly introduce an absolute prohibitionof torture (particularly, to ensure defences such as superior orders or “necessity” or otherexceptional circumstances are not available).The authorities under Colonel al-Gaddafi also failed to uphold their obligations to investigateallegations of torture and other ill-treatment; to bring those responsible for torture to justicein proceedings meeting international standards of fair trial; and provide all victims of tortureor other ill-treatment with redress including reparation.The Libyan authorities are also required to take concrete measures to prevent the occurrenceof torture and other ill-treatment, including by granting independent bodies the right tomonitor, including by means of visits, the situation of detainees in all prisons and otherplaces of detention. Some safeguards have been incorporated into Libyan laws. In addition toArticle 14 of Law No. 20 of 1991, mentioned above, these include the need for securityofficers to hold a warrant from the competent authority when arresting or detaining a suspect(Article 30 of the Penal Code); the requirement to detain suspects only in “prisons designedfor that purpose” (Article 31); and the right of detainees to challenge the legality of theirdetention (Article 33).However, the limited safeguards that exist in national law have been routinely flouted by theal-Gaddafi authorities and security forces, particularly in cases deemed to be political – aswitnessed in the crackdown against real or perceived government opponents and critics. Ifanything, the al-Gaddafi authorities increased their use of practices that facilitate torture andother ill-treatment, including secret detention, enforced disappearances, and prolongedincommunicado detention. Libya under Colonel al-Gaddafi strongly resisted internationalscrutiny and, despite repeated requests, did not extend an invitation to the UN SpecialRapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.

2.1.3. DEMONSTRATIONS AND EXCESSIVE USE OF FORCEStates have a duty to uphold the right to freedom of assembly. According to Article 21 of theICCPR, any restrictions on the right to freedom of assembly must be in accordance with thelaw and strictly necessary to preserve national security or public safety, public order, publichealth or morals, or protect the rights and freedoms of others. Any such restrictions must beproportionate to a legitimate purpose and without discrimination, including on grounds ofpolitical opinion. Even when a restriction on the right to protest is justifiable underinternational law, the policing of demonstrations (whether or not they have been prohibited)must be carried out in accordance with international standards. These prohibit the use offorce by law enforcement officials unless strictly necessary and to the extent required for the

Index: MDE 19/025/2011

Amnesty International September 2011

26

The battle for LibyaKillings, disappearances and torture

performance of their duty, and require that firearms are only used when strictly unavoidablein order to protect life.Article 1 of the Libyan Law on Public Assemblies and Demonstrations of 1956 stipulates:“Individuals have the right to meet peacefully. Policemen are not to attend their meetingsand they do not need to notify the police about such gatherings”.The law also provides for the right to hold public meetings in accordance with the regulationsset by the law. However, in practice, public assembly was never permitted during Colonel al-Gaddafi’s rule, unless the protestors were demonstrating in support of the government’spositions. Libyan legislation also severely constrains the right to freedom of expression, andprescribes harsh punishments for activities merely amounting to the exercise of that rightincluding life imprisonment and the death penalty.40While the Libyan authorities, like all governments, are responsible for ensuring public safetyand maintaining public order, including through the use of force when necessary and justified,it is clear that the al-Gaddafi security forces went far beyond what is permissible underinternational law and standards; and even under Libyan legislation. Force may only be usedby security forces in very limited and particular conditions, in response to activities thatgenuinely threaten lives and public safety. Even then, such force must be governed by theprinciples of necessity and proportionality as set out in international law and standards. Inresponding to anti-government demonstrations which started across Libya around 16February, al-Gaddafi security forces used excessive force, in contravention of relevantinternational standards as described below.

2.1.4. INTERNATIONAL STANDARDS ON THE USE OF FORCE BY LAW ENFORCEMENT OFFICIALSThe Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials and theCode of Conduct for Law Enforcement Officials are UN standards aimed at ensuring thatpolice and security forces carry out their duties in a manner that respects human rights.41The two documents specify obligations with respect to the right to life, the prohibition oftorture and other ill-treatment.42The process of the standards’ development and adoptioninvolved a very large number of states and at least the substance of Article 3 of the Code ofConduct and Principle 9 of the Basic Principles reflects binding international law.43Libyan security forces under Colonel al-Gaddafi did not meet these standards in the eventscovered by this report. Indeed, they failed even to comply with the more limited safeguardsprovided for under Libyan domestic standards (i.e. the Decision of the Minister of Interior inrelation to the necessary procedures for security forces to undertake before using firearms,published in the Official Gazette on 15 September 1965), which themselves were notconsistent with the UN Basic Principles. Under those domestic standards, security forceswere supposed first to issue an audible verbal warning for protesters to disperse, using aloudspeaker if necessary. According to those domestic standards, the head of the securityoperation could order the use of tear gas or water cannon, and allow for the use of batons andrifle butts to disperse the crowd, only if protesters failed to disperse after two such warnings.The domestic standards authorized security forces to use firearms only if such measures

Amnesty International September 2011

Index: MDE 19/025/2011

The battle for LibyaKillings, disappearances and torture

27

failed, or if protesters attacked persons or public property, in which case any use of firearmswould initially be authorized only if aimed at the feet of protestors.The al-Gaddafi security forces’ unnecessary and excessive use of force in response todemonstrations violated the State’s obligations to respect the right to life, to respect theprohibition of torture and other ill-treatment, and to respect the rights to freedom of assemblyand expression.

2.2. APPLICABLE RULES OF INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW

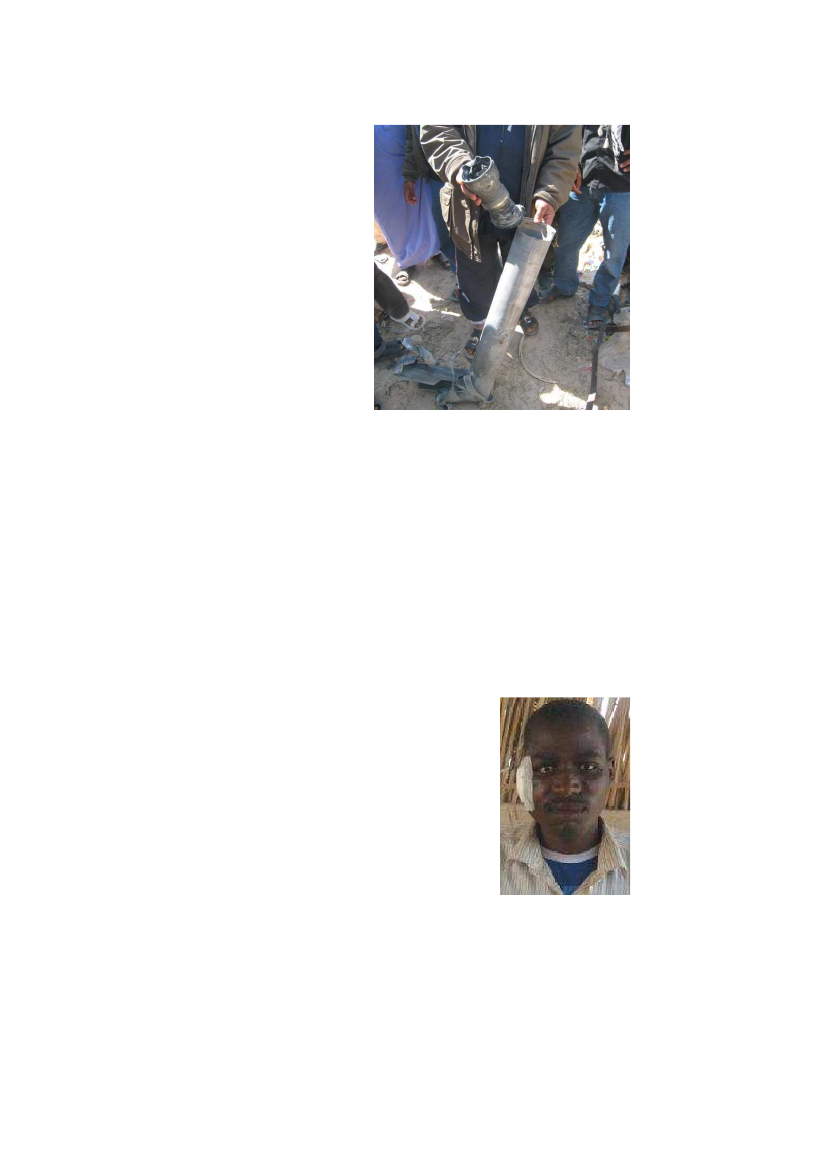

Cluster bomb, Misratah, 15 April. Text on side reads: “SMM MAT-120 LOT 2-07” � Amnesty International

At time of writing there is in Libya a non-international armed conflict between al-Gaddafiforces and opposition fighters. There is also currently an international armed conflict betweenthe NATO-led coalition forces and the al-Gaddafi forces. The overwhelming majority ofviolations documented by Amnesty International have occurred as part of the non-international armed conflict.While international human rights law applies at all times, IHL applies only in situations ofarmed conflict. It contains the rules and principles that seek to protect anyone who is notactively participating in hostilities: notably civilians and anyone, including those who werepreviously participating in hostilities, who are wounded or surrender or are otherwise captured.It sets out standards of humane conduct and limits the means and methods of conductingmilitary operations. Its central purpose is to limit, to the extent feasible, human suffering intimes of armed conflict.

Index: MDE 19/025/2011

Amnesty International September 2011

28

The battle for LibyaKillings, disappearances and torture

The four Geneva Conventions of 1949 and their two Additional Protocols of 1977 are amongthe principal IHL instruments. Libya is a state party to the 1949 Geneva Conventions and toProtocols I and II. Many of the specific rules included in these treaties, and all of those setout below, in any event also form part of customary IHL and are thus binding on all parties toany type of armed conflict, including on armed groups.44Violations of many of these rulescan constitute war crimes. States are obliged to ensure that anyone responsible for warcrimes is brought to justice.

2.2.1. CONDUCT OF HOSTILITIES RULESA fundamental rule of IHL is that parties to any armed conflict must at all times “distinguishbetween civilians and combatants”, especially in that “attacks may only be directed againstcombatants” and “must not be directed against civilians.”45A similar rule requires parties todistinguish between “civilian objects” and “military objectives”. These rules are part of thefundamental principle of “distinction”.For the purposes of distinction, anyone who is not a member of the armed forces of a party tothe conflict is a civilian, and the civilian population comprises all persons who are notcombatants.46Civilians are protected against attack unless and for such time as they take adirect part in hostilities.47(In this report, the term “civilians” is used to refer to civilians whoare not taking a direct part in hostilities.)Civilian objects are all objects (i.e. buildings, structures, places and other physical propertyor environments) which are not “military objectives”, and military objectives are “limited tothose objects which by their nature, location, purpose or use make an effective contributionto military action and whose partial or total destruction, capture or neutralisation, in thecircumstances ruling at the time, offers a definite military advantage”.48Civilian objects areprotected against attack, unless and for such time as they become military objectivesbecause all of the criteria for a military objective just described become temporarilyfulfilled.49In cases of doubt whether an object which is normally dedicated to civilianpurposes, such as a place of worship, a house or other dwelling, or a school, is being used formilitary purposes, it is to be presumed not to be so used.50Intentionally directing attacks against civilians not taking direct part in hostilities, or againstcivilian objects (in the case of non-international conflicts, medical, religious or culturalobjects in particular), is a war crime.51The principle of distinction also includes a specific rule that “acts or threats of violence theprimary purpose of which is to spread terror among the civilian population are prohibited”.52The corollary of the rule of distinction is that “indiscriminate attacks are prohibited”.53Indiscriminate attacks are those which are of a nature to strike military objectives andcivilians or civilian objects without distinction, either because the attack is not directed at aspecific military objective, or because it employs a method or means of combat that cannotbe directed at a specific military objective or has effects that cannot be limited as requiredby IHL.54“Area bombardments”, meaning attacks by bombardment of any kind which treatsas a single military objective a number of clearly separated and distinct military objectives

Amnesty International September 2011

Index: MDE 19/025/2011

The battle for LibyaKillings, disappearances and torture

29

located in a city, town, village or other area containing a similarconcentration of civilians or civilian objects, are particularlyprohibited.55The use of inherently indiscriminate weapons such asanti-personnel land mines and cluster munitions violates theprohibition on indiscriminate attacks; the misuse of weapons thatmay have legitimate military purposes in appropriate circumstances,such as artillery, mortars and rockets, to attack objectives in civilianareas also is likely to violate the prohibition on indiscriminate attacks.IHL also prohibits disproportionate attacks which are those “whichmay be expected to cause incidental loss of civilian life, injury tocivilians, damage to civilian objects, or a combination thereof, whichwould be excessive in relation to the concrete and direct militaryadvantage anticipated”.56Intentionally launching an indiscriminateattack resulting in death or injury to civilians, or a disproportionateattack (i.e. knowing that the attack will cause excessive incidentalcivilian loss, injury or damage) constitutes a war crime.57The protection of the civilian population and civilian objects is furtherunderpinned by the requirement that all parties to a conflict takeprecautions in attack and in defence. In the conduct of militaryoperations, then, “constant care must be taken to spare the civilianpopulation, civilians and civilian objects”; “all feasible precautions”must be taken to avoid and minimize incidental loss of civilian life,injury to civilians and damage to civilian objects.58Everything feasible must be done to verify that targets are militaryobjectives, to assess the proportionality of attacks, and to halt attacksif it becomes apparent they are wrongly-directed ordisproportionate.59Parties must give effective advance warning ofattacks which may affect the civilian population, unlesscircumstances do not permit.60Forces must also take all feasible precautions in defence to protectcivilians and civilian objects under their control against the effects ofattacks by the adversary.61In particular, each party must to theextent feasible avoid locating military objectives within or neardensely-populated areas, and remove civilian persons and objectsunder its control from the vicinity of military objectives.62

2.2.2. FUNDAMENTAL GUARANTEESIHL also provides fundamental guarantees for civilians, as well asfighters or combatants who are captured, injured or otherwiserendered unable to fight (horsde combat).Between them, commonArticle 3 and other provisions of the 1949 Geneva Conventions, the1977 Protocols and customary IHL include among others thefollowing fundamental rules applicable to all sides in all types ofarmed conflict: humane treatment is required; discrimination in

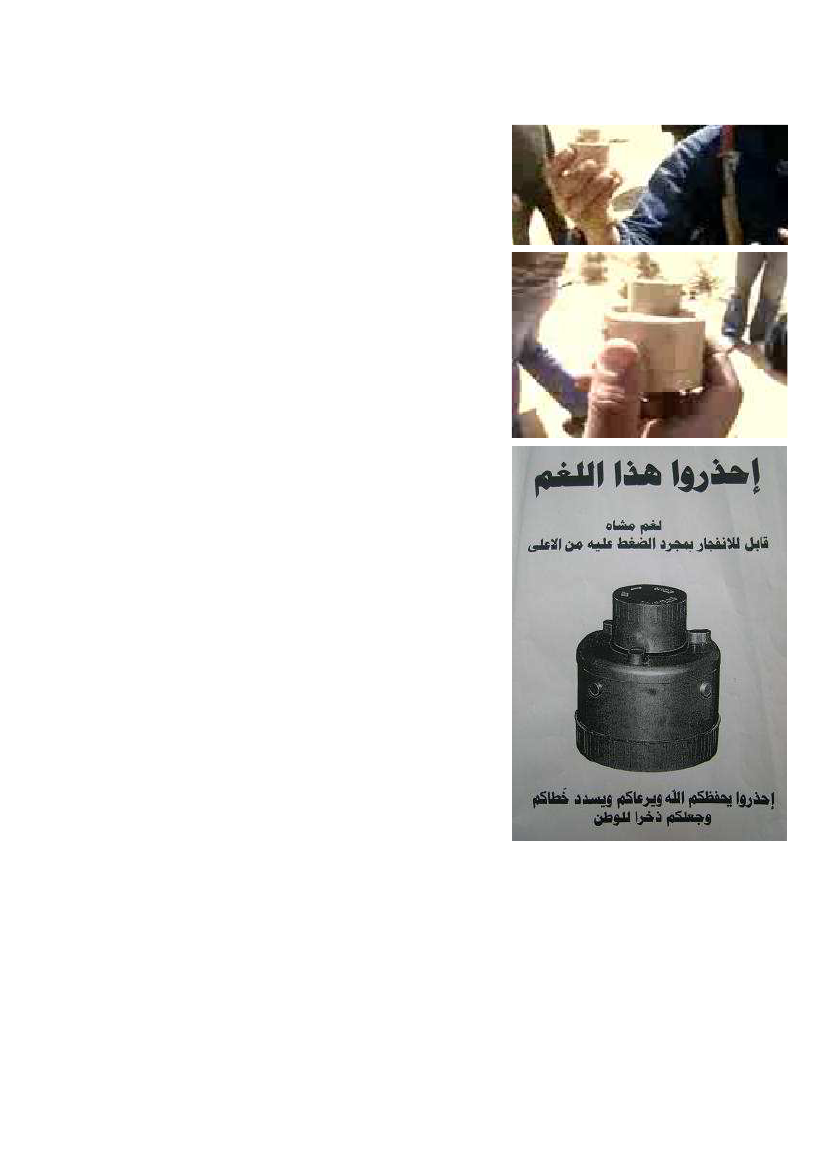

Anti-personnel mine found in the outskirts of Ajdabiya, and warningposter, March � Amnesty International

Index: MDE 19/025/2011

Amnesty International September 2011

30

The battle for LibyaKillings, disappearances and torture

application of the protections of IHL is prohibited; torture, cruel or inhuman treatment andoutrages on personal dignity (particularly humiliating and degrading treatment) are prohibited,as are enforced disappearance, murder, the taking of hostages, the use of human shields,and arbitrary detention; no one may be convicted or sentenced except pursuant to a fair trialaffording all essential judicial guarantees; and collective punishments are prohibited.63Depending on the particular rule in question, many or all acts that violate these rules will alsoconstitute war crimes.64As noted above, IHL also prohibits the use of “human shields”. This means intentionallybringing civilians or other persons who arehors de combatinto proximity with a militaryobjective, or locating a military objective in proximity to civilians or other personshors decombat,with the specific intent of trying to prevent the targeting of the military objective.65Use of human shields does not automatically immunize an otherwise valid military objectivefrom attack, but the people being used as human shields must be taken into account indetermining whether any attack is proportionate, and in the obligation to take precautions tominimize their death or injury.

2.3. INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL LAW

Safe/arming devices for MAT-120 cluster munitions � Amnesty International

Individuals, whether civilians or military, can be held criminally responsible for certainviolations of international human rights law and IHL. State officials must be particularlydiligent in seeking to prevent and repress such crimes.All states have an obligation to investigate and, where enough admissible evidence isgathered, to prosecute genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes, as well as othercrimes under international law such as torture, extrajudicial executions and enforceddisappearances.

2.3.1. WAR CRIMESGrave breaches of the Geneva Conventions and Additional Protocol I and most other seriousviolations of IHL are war crimes. Definitions of some of these crimes are included in theRome Statute of the International Criminal Court (Rome Statute). The list of war crimes inArticle 8 of the Rome Statute basically reflected customary international law at the time of

Amnesty International September 2011

Index: MDE 19/025/2011

The battle for LibyaKillings, disappearances and torture

31

its adoption, although they are not complete and a number of important war crimes are notincluded. Additional war crimes are listed in the ICRC Customary IHL study.66States areobliged to investigate all alleged war crimes, and to bring prosecutions where the evidenceallows.67

2.3.2. CRIMES AGAINST HUMANITYAccording to the Rome Statute, certain acts committed as part of a widespread or systematicattack directed against any civilian population, where the attack is part of a state ororganizational policy, constitute crimes against humanity if committed with knowledge of theattack. Such acts include murder, extermination, enslavement, deportation or forcibletransfer of population, imprisonment or other severe deprivation of physical liberty inviolation of fundamental rules of international law, torture, rape and other sexual crimes, andenforced disappearances.Crimes against humanity can be committed in either time of peace or during an armedconflict.

2.3.3. OTHER CRIMES UNDER INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS LAWWhether or not committed in the context of an armed conflict, certain acts such as torture,extrajudicial executions and enforced disappearances constitute crimes under internationallaw. For instance, the UNCAT requires that states investigate and prosecute (if they do notextradite for prosecution), anyone who commits, or who attempts, is complicit in, orotherwise participates in any act that falls within the treaty’s definition of torture.Extrajudicial executions and enforced disappearances are also recognized in internationalinstruments as being crimes in respect of which states have international obligations to bringthose responsible to justice.68The Human Rights Committee has said that, under the ICCPR,where investigations “reveal violations of certain Covenant rights, States Parties must ensurethat those responsible are brought to justice”, explaining:“As with failure to investigate, failure to bring to justice perpetrators of such violations couldin and of itself give rise to a separate breach of the Covenant. These obligations arise notablyin respect of those violations recognized as criminal under either domestic or internationallaw, such as torture and similar cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment (article 7), summaryand arbitrary killing (article 6) and enforced disappearance (articles 7 and 9 and, frequently,6).”The Committee has also said that states should “assist each other to bring to justice personssuspected of having committed acts in violation of the Covenant that are punishable underdomestic or international law”.69

2.3.4. RESPONSIBILITY OF SUPERIORS AND COMMANDERSMilitary commanders and civilian superiors can be held responsible for the acts of theirsubordinates.70Article 86 (2) of Protocol I, which imposes a single standard for militarycommanders and civilian superiors, reflects customary international law.71It states:“The fact that a breach of the Conventions or of this Protocol was committed by asubordinate does not absolve his superiors from penal or disciplinary responsibility, as thecase may be, if they knew, or had information which should have enabled them to conclude

Index: MDE 19/025/2011

Amnesty International September 2011

32

The battle for LibyaKillings, disappearances and torture

in the circumstances at the time, that he was committing or was going to commit such abreach and if they did not take all feasible measures within their power to prevent or repressthe breach.”

2.3.5. SUPERIOR ORDERSSuperior orders cannot be invoked as a defence for crimes under international law, but theymay be taken into account in mitigation of punishment. This principle has been recognizedsince the Nuremberg trials after World War II and is now part of customary internationallaw.72

2.4. ACCOUNTABILITYStates have an obligation to respect, protect and fulfil the right of victims of human rightsviolations to an effective remedy.73This obligation includes three elements:Justice: investigating past violations and, if enough admissible evidence is gathered,prosecuting the suspected perpetrators (in line with the obligations outlined above);Truth: establishing the facts about violations of human rights that occurred in the past;Reparation: providing full and effective reparation to the victims and their families.

2.4.1. JUSTICEThere are several possible means for bringing to justice those responsible for crimes underinternational law, in proceedings which meet international standards of fairness and do notresult in the death penalty.1.The Libyan authorities have an obligation to investigate all crimes under internationallaw and, whenever there is sufficient admissible evidence, prosecute the person suspected ofthose crimes.2.Other states: Other states should exercise their obligations to conduct prompt, thorough,independent and impartial criminal investigations of anyone within the State’s territory orjurisdiction who is accused or otherwise suspected of crimes under international law. If thereis sufficient admissible evidence, states should prosecute the suspect, or extradite him or herto another state willing and able to do so in fair proceedings which do not result in theimposition of the death penalty, or surrender him or her to an international criminal courtwhich has jurisdiction.3.The International Criminal Court: Libya has not ratified the Rome Statute. However, theUN Security Council, in accordance with Article 13(b) of the Rome Statute, has referred thesituation in Libya to the ICC Prosecutor.

2.4.2. REPARATIONSInternational law requires that the victims of human rights violations be provided withremedies that are not only theoretically available in law, but are actually accessible and

Amnesty International September 2011

Index: MDE 19/025/2011

The battle for LibyaKillings, disappearances and torture

33

effective in practice. Victims are entitled to equal and effective access to justice; adequate,effective and prompt reparation for harm suffered; and access to relevant informationconcerning violations and reparation mechanisms. Full and effective reparation includes acombination of the following elements: restitution, compensation, rehabilitation, satisfactionand guarantees of non-repetition.74The ICRC notes that armed groups are themselves required to respect IHL.75While thequestion as to whether armed groups are under an obligation to make full reparation forviolations of IHL is unsettled, practice indicates that such groups may be required to provideappropriate reparation.76

Index: MDE 19/025/2011

Amnesty International September 2011

34

The battle for LibyaKillings, disappearances and torture

3. UNLAWFUL KILLINGS: FROMPROTESTS TO ARMED CONFLICT“All I want is to see those who killed my son being arrested and tried.”Neesa al-Wirfally, mother of Ramadan Salem al-Mokahel who was killed in Benghazi on 19 February