Udvalget for Landdistrikter og Øer 2011-12

ULØ Alm.del Bilag 202

Offentligt

European UnionRegional Policy

Guide to broadband investment

September 2011

Guide to broadband investmentFinal report

September 2011

FOREWORDEurope is facing an investment challenge in the financing of high speed internet infrastructure. High amounts of investmentsare needed to achieve ubiquitous coverage of state-of-the-art competitive broadband networks, yet “the benefits for society asa whole appear to be much greater than the private incentives to invest in faster networks “In its Digital Agenda for Europe, the European Commission showed its commitment to overcome this challenge and make“every European digital”, irrespective of geographic location or social and economic condition. Information and CommunicationTechnologies (ICT) empower individuals to bring innovation at work and in the daily lives of their families, to improve their lifechances and to bring change in society. Therefore, the Commission is convinced that from the households in sparsely populatedareas of north Sweden or in rural Bulgaria, to the SMEs in mountainous areas, islands and other remote regions in south of Italy,Poland or Spain, no one should be left behind, as concerns Internet connectivity, irrespective of the short-term commercial vi-ability of the investment.To achieve such ambitious targets, Europe needs to invest in an infrastructure of quality that is universally accessible and whichprovides services at an affordable price level. The important role of public funding initiatives is to complement the insufficientprivate investments by selecting those investment models that catalyse interest from a variety of private investors and fosteropen competition among all market players.The EU’s Cohesion policy and agricultural policy for Rural Development can contribute to this EU pledge by joining up effortswith the Connecting Europe Facility in supporting investment in high speed networks and services and in stimulating demandfor ICT.This guide is the results of a joint effort from Analysys Mason, various Commission services, the European Broadband Portaland the Bottom up Broadband initiative born under the Digital Agenda for Europe. It represents the first attempt by the Com-mission to advise public authorities managing EU funds on the strengths and weaknesses of different models of investment inhigh speed internet infrastructures and on the technological, regulatory and policy issues that are at stake in the case of eachof these models.With cooperation by all stakeholders, the European Broadband Portal will endeavour to complete this guide by exploring otherinnovative investment models developed at national, regional or local level. Ultimately the Portal will develop into a live toolbox at the disposal of public authorities to help them planning their interventions and maximising the absorption of EU funds.In the context of its proposals for the future Cohesion Policy, the Commission recommends the development of innovationstrategies for smart specialisation. ICT and the Digital Agenda being enablers for innovation and growth are key componentsof these strategies.

Johannes HahnCommissioner for Regional Policy

Dacian CiolosCommissioner for Agricultureand Rural Development

Neelie KroesVice-President

Joaquín AlmuniaVice-President

12

European Broadband: investing in digitally driven growth COM(2010) 472.As proposed within the Multiannual Financial Framework for 2014-2020.

Contents11.11.21.31.41.522.12.22.333.13.244.14.24.34.455.15.25.35.45.566.16.26.36.46.577.17.2Executive summaryIntroduction and aims of the guideBasis and content of the guideGuidance on different investment modelsNext steps following preparation and planningConclusions and recommendationsIntroductionBackgroundAims of this documentApproach used to compile the guideWhy should I invest in broadband?IntroductionOverview of the regional benefits that broadband can provideWhat type of network infrastructure should I invest in?IntroductionAccess networkThe backhaul and core networkOther factors to consider when assessing possible network architecturesHow should I invest?Bottom-up modelPrivate design, build and operate (DBO) modelPublic outsourcingJoint venturePublic design, build and operate (DBO) modelHow do I manage/monitor the outcome?Why are period monitoring and management so important?What are the characteristics of the monitoring undertaken by different organisations?What commercial aspects need to be monitored?What non-commercial aspects need to be monitored?What governance mechanisms are available?What can be done to ensure demand for services?How do I understand the level of demand?How can I ensure that the required level of demand is reached?1124810141414182424242828313435373839404143454545474850525253

Error! Unknown document property name.

Guide to broadband investment

88.18.28.399.19.29.31010.110.2

What can be done to reduce the cost and manage risks?IntroductionMeasures to reduce costsMeasures to manage risksWhat are the next steps that need to be taken?EU funding applicationState aid complianceProcurement and deliveryFurther work by the ECKeeping the guide up to dateOther actions from broader feedbackGlossary of termsBibliographic and other referencesAims and results of example projectsInfrastructure choices from example projectsInvestment models used in example projectsDemand activities from example projects

5656565759596266737373

Annex AAnnex BAnnex CAnnex DAnnex EAnnex F

The European Union has the full ownership including copyright of this guide.The guide has been supported by the contributions of the European Broadband Portal, ERISA(European Regional Information Society Association), Commission services and the members ofthe "Bottom Up Broadband Initiative" set up under the Digital Agenda for EuropeAnalysys Mason LimitedBush House, North West WingAldwychLondon WC2B 4PJUKTel: +44 (0)845 600 5244Fax: +44 (0)20 7395 9001[email protected]www.analysysmason.comRegistered in England No. 5177472

Error! Unknown document property name.

Guide to broadband investment | 1

1 Executive summary1.1 Introduction and aims of the guideThis document sets out best practice examples in planning an investment of public funds inbroadband projects. The guidance provided is targeted at all Managing Authorities1in theEuropean Union (EU). The guide has been prepared by Analysys Mason on behalf of the EuropeanCommission (EC), and details the issues associated with investment planning and procurementthat must be considered by any Managing Authority that is aiming to implement an EU-fundedbroadband project.The EC has recognised that Member States will need to make significant investments in broadbandinfrastructure to meet the objectives set out in the Digital Agenda for Europe (DAE): by 2020, allEuropeans should have access to the Internet at speeds above 30Mbit/s and 50% or more ofEuropean households should have subscriptions above 100Mbit/s.The EC considers this guide a particularly important resource for Member States whichhave the facility to use funds from the current (2007-2013) and the future programmingperiod (2014–2020) to assist in the deployment of new broadband and high speed broadbandinfrastructure. Those Member States are urged to use this guide to develop an action planthat will ensure the DAE targets for 2020 are met.The EU’s aims of regional policy are to achieve social, economic and territorial cohesion2.Territorial balance and improved quality of life in rural areas are other objectives underlying theEU rural development policy3. Access to an affordable, good-quality and open ICT infrastructurefor all citizens will contribute to cohesion and rural development policy aims and to increaseinnovation and productivity of regional and rural actors. As a result, it is of primary importance forManaging Authorities to be aware that access to affordable broadband has a positive effect interms of meeting the most basic needs of the households, communities, public administrations andbusinesses in a territory.By ensuring that ICT services are available to as many people as possible, Member States willcontribute to cohesion, to innovation, and to social, economic and political change. Most of thebenefits of new ICT services will be derived from outside the ICT sector. Since large amounts of1

For the purpose of this document and for simplification reasons, Managing Authority should be understood as publicauthorities (national, regional, local) responsible for supporting the deployment of high speed networks in thecontext of the EU Structural (ERDF) and Rural Development funds (EAFRD). In the context of this guide, it alsorefers to agencies (e.g., intermediate bodies such as regional/rural development agencies) delegated to providepublic support to these networks and even Paying agencies under the Common Agriculture Policy..Managing Authorities should consult the EC cohesion guidelines, available at:http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/docoffic/2007/osc/l_29120061021en00110032.pdfManaging Authorities should consult the EC rural development guidelines, available at:http://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/rurdev/leg/index_en.htm

2

3

Guide to broadband investment | 2

public funds are involved, it is important for Managing Authorities to keep the goals of deliveringsocio-economic benefit to entire territories in mind, and prioritise the long-term benefit of allsocio-economic actors of regions and rural areas over short-term gain of any specific socio-economic actor.

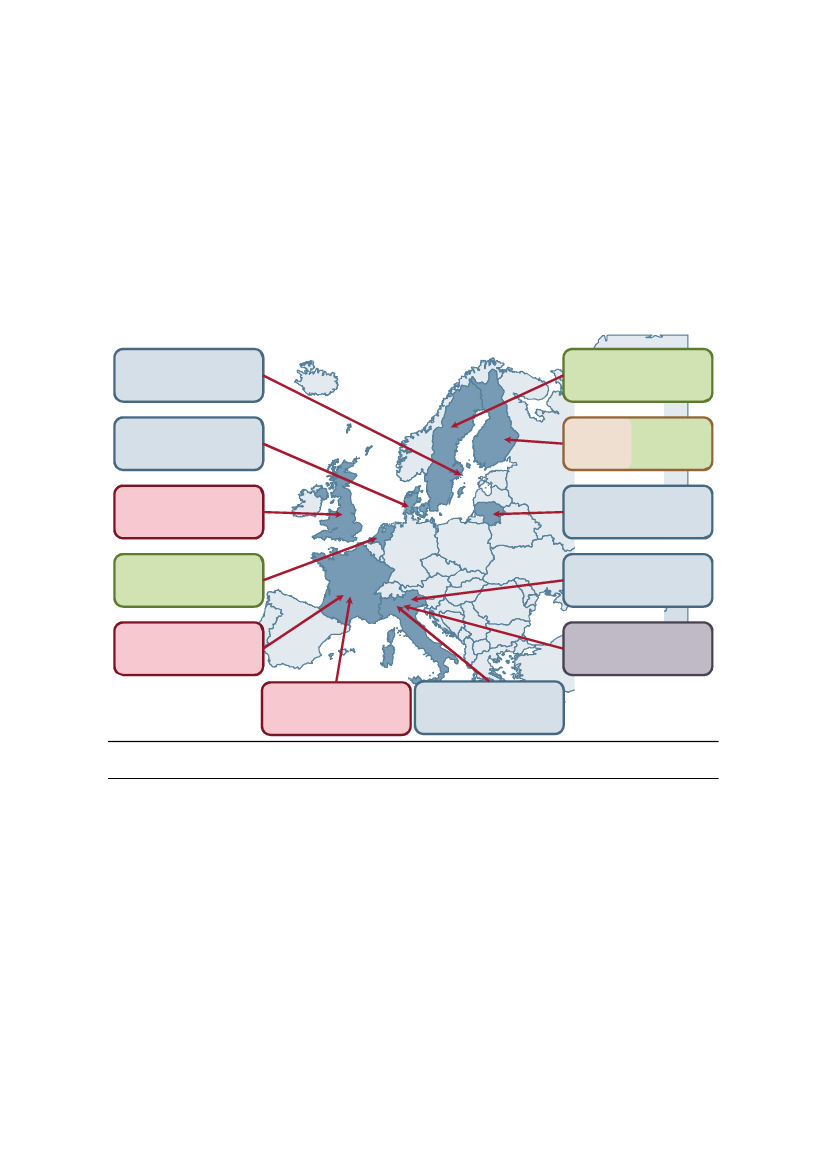

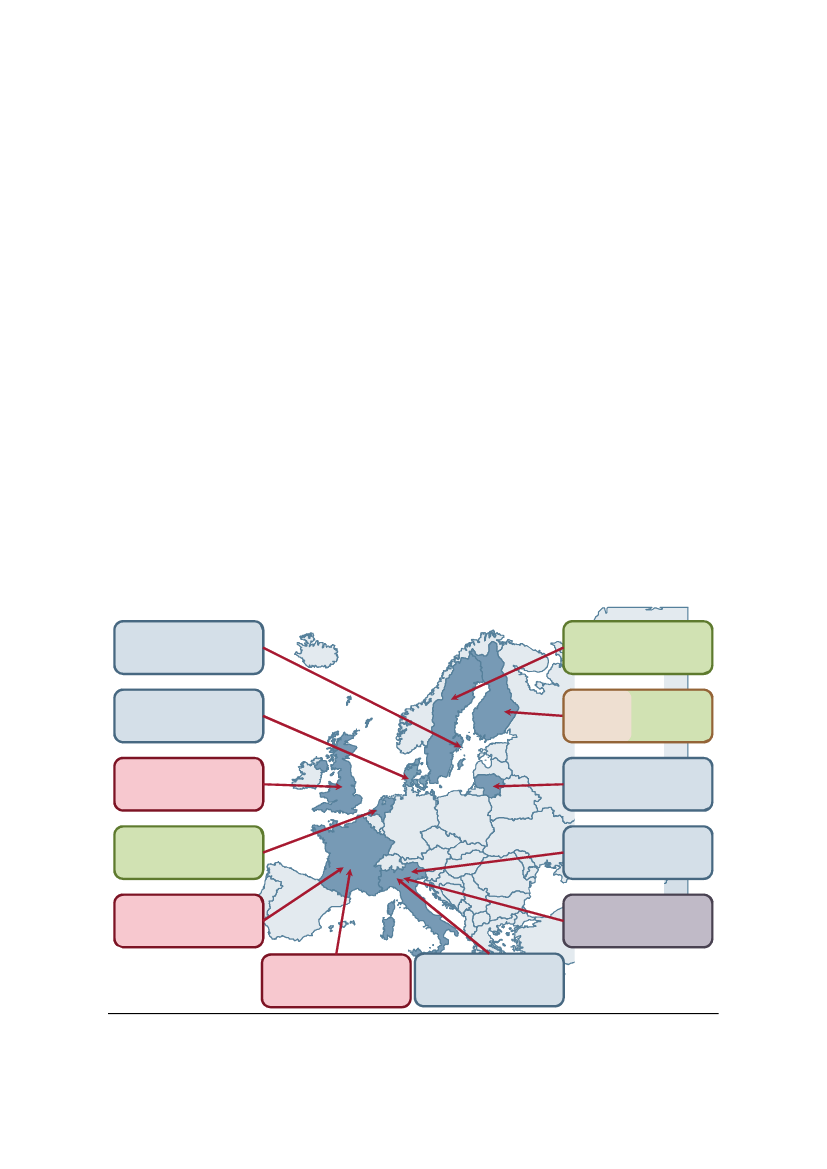

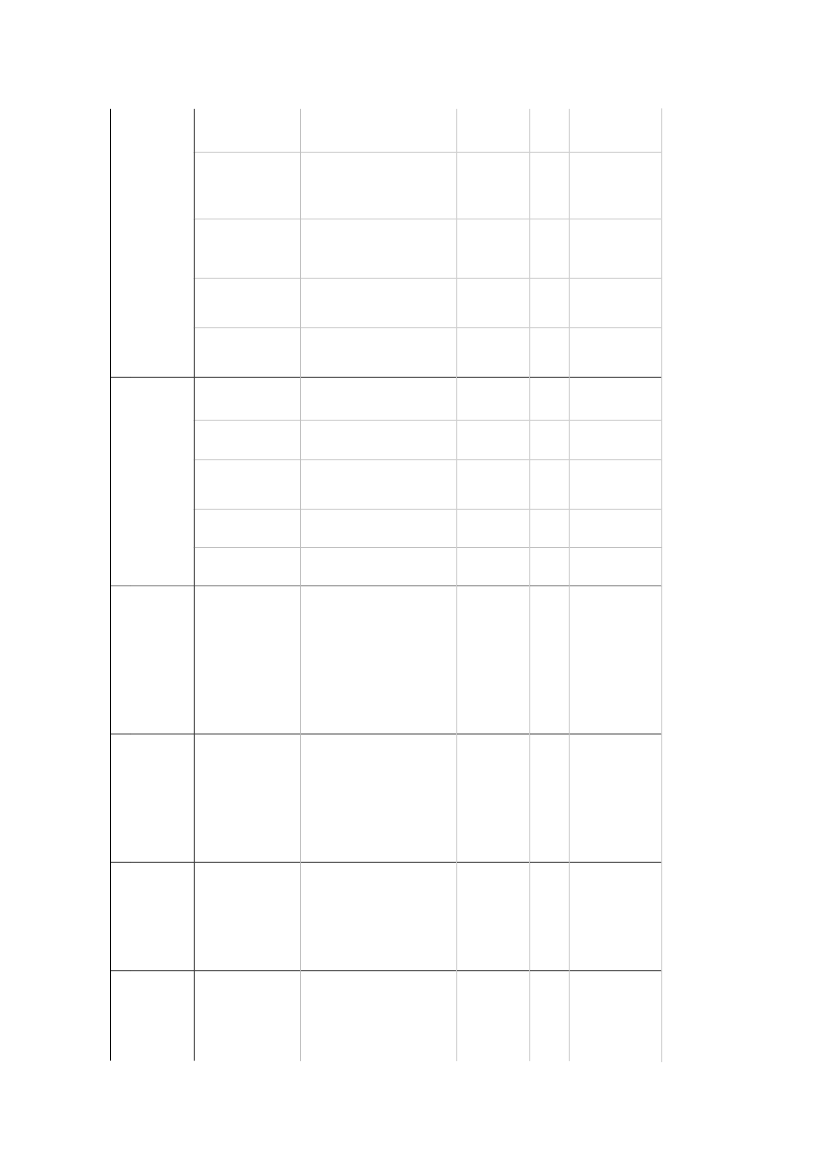

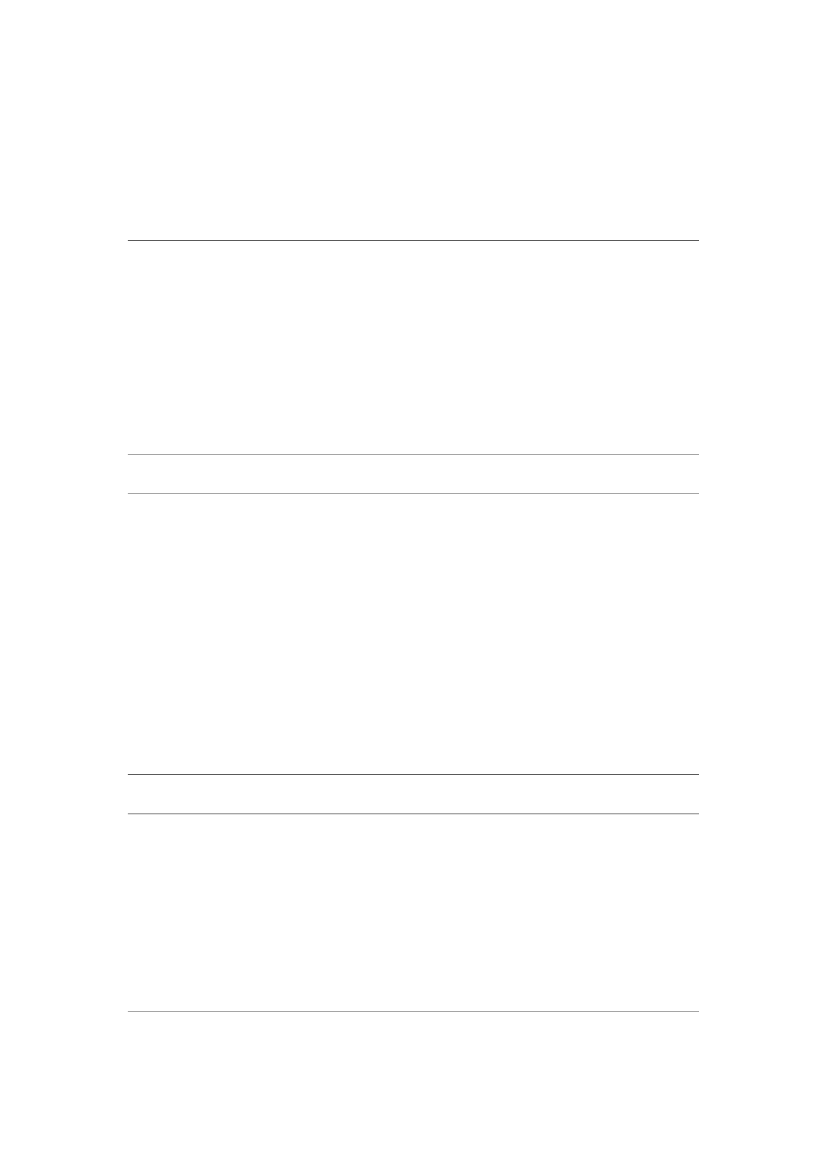

1.2 Basis and content of the guideThe main basis for the recommendations presented in this guide is a series of interviews withstakeholders from example projects which have already been successfully implemented. Theseexample projects are summarised in Figure 1.1.STOKAB, SwedenPublic DBOCity-based FTTHmeshed networkMidtsoenderjylland, DenmarkPublic DBOPartnership withelectricity providerSouth Yorkshire, UKPublic outsourcingPartnership arrangementfor network managementNuenen, NetherlandsBottom upCo-operative-based FTTHDORSAL, FrancePublic outsourcingInvestment in backbone,DSL and WiMAXAuvergne, FrancePublic outsourcingCabinet-based ADSLfor very long linesPiemonte, ItalyPublic DBOInspired privateinvestmentRural developmentprogramme, SwedenBottom upState-funded co-operativesNorth Karelia, FinlandPrivate DBO and bottom upGrant to build to within2km of homesRAIN, LithuaniaPublic DBONationwide backhauland core networkAlto Adige, ItalyPublic DBOWireless to homes andbusinesses; fibre to publicGeorgiaAzerbaijanArmeniaLombardia, ItalyJoint venturePlanned FTTH to 50%Turkeyof homes

Malta

Cyprus

Note: DBO = design, build and operate; FTTH = fibre to the homeFigure 1.1:Summary of example projects [Source: Analysys Mason]

Due to the complexity and unique circumstances of each broadband investment, this guide is notintended to provide a rigid, prescriptive framework within which investment decisions should bemade. Instead, it gathers together insights from the example projects to help Managing Authoritiesunderstand each of the key issues they must consider as they move through the investmentpreparation and planning process, and to help them make informed decisions.In addition to the interviews with stakeholders from the example projects, our research has alsoincluded insights from the following sources:

Guide to broadband investment | 3

••••

feedback from the eris@ annual conference regarding a range of possible financial models forbroadband investmentModels for efficient and effective public-sector interventions in next-generation broadbandaccess networks,Analysys Mason report for the Broadband Stakeholder Group, 9 June 20084a blogosphere consultation co-ordinated by eris@feedback from the first Digital Agenda Assembly held in Brussels on 16 and 17 June 2011.

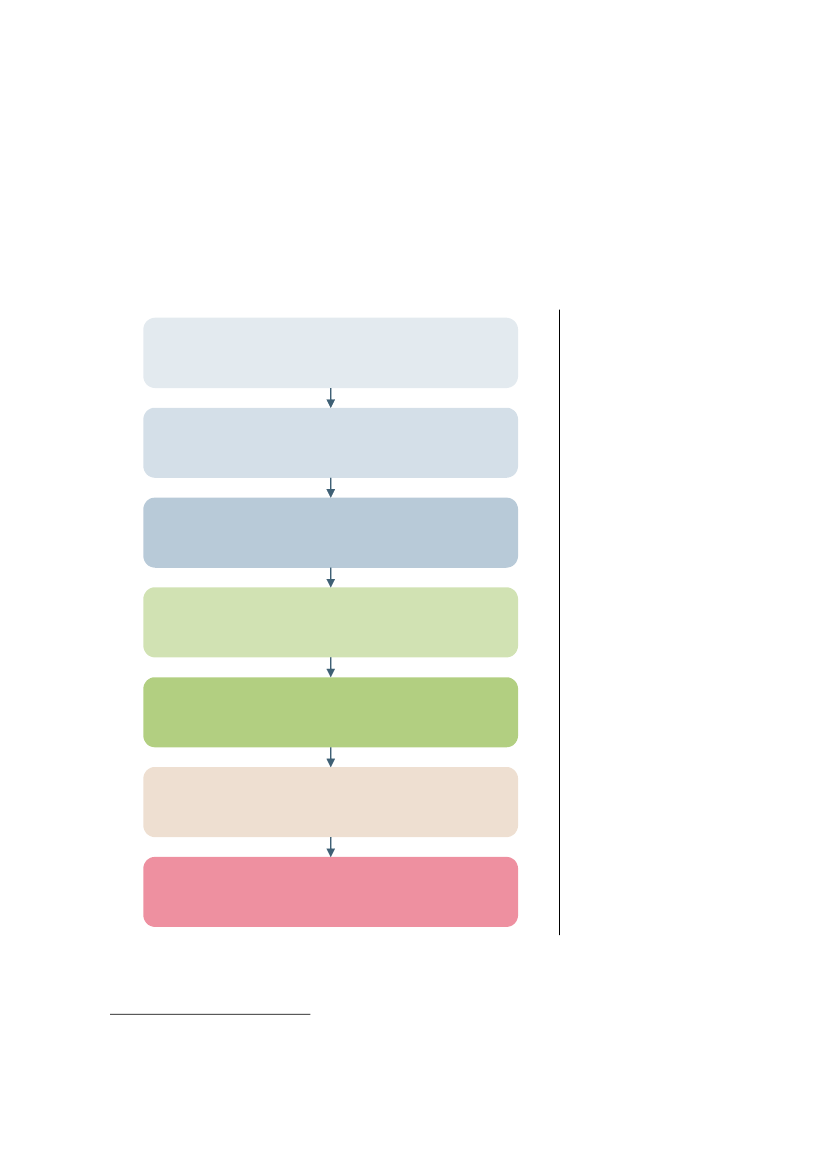

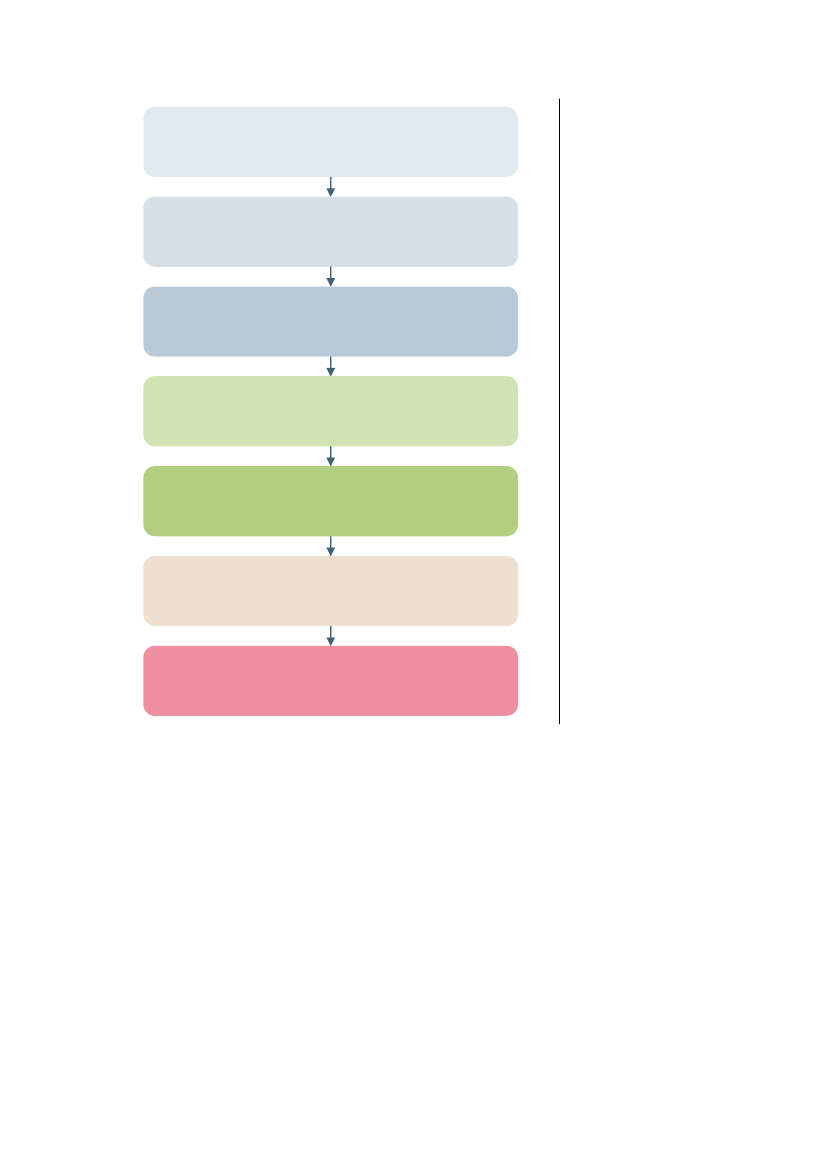

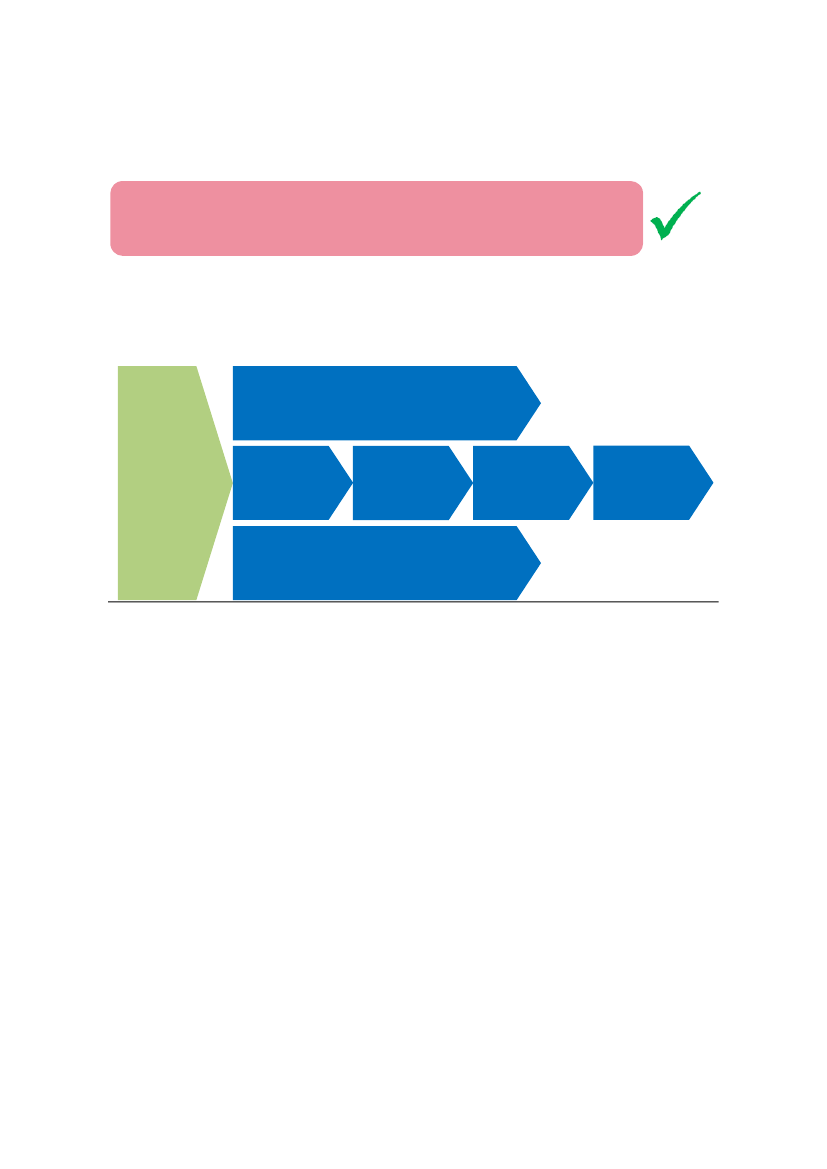

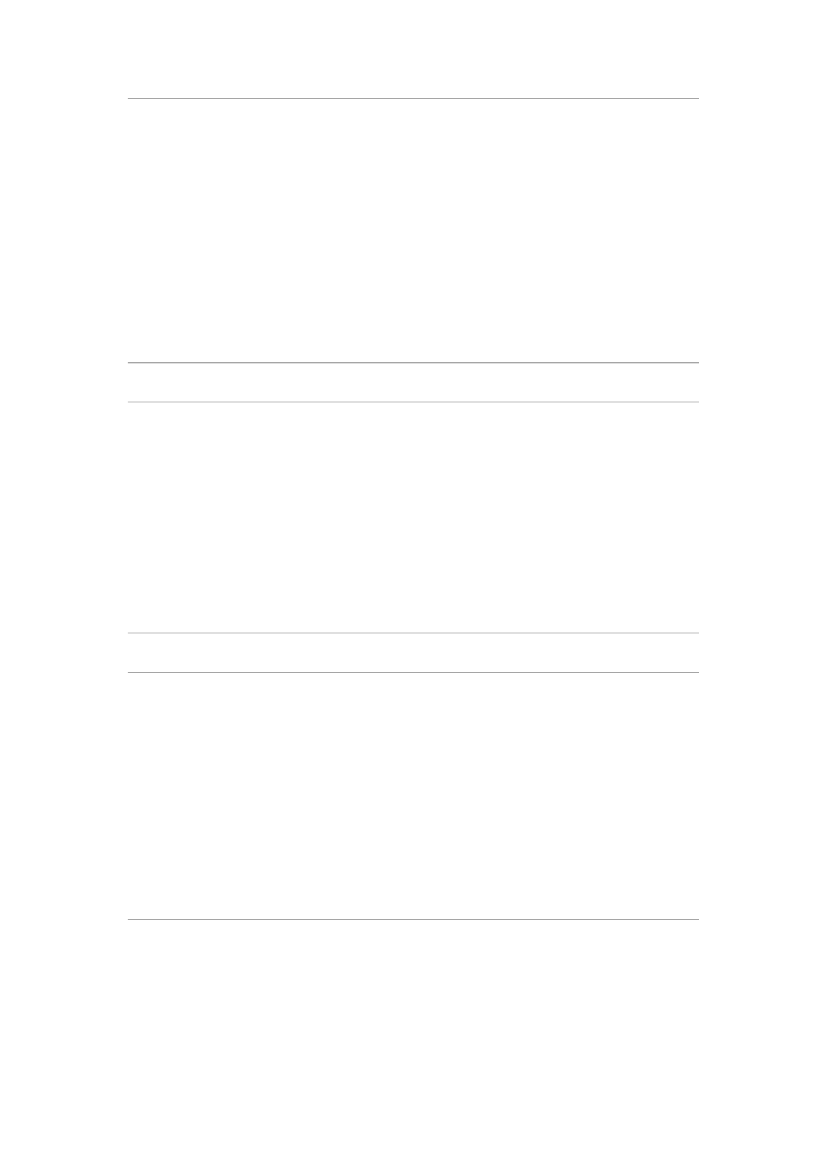

The guide is structured as a series of questions that a Managing Authority must ask itself whenplanning a broadband infrastructure investment. The structure of the guide is shown in Figure 1.2.Why should I invest in broadband?Define project aims to tackle market failures and/or deliver socio-economic benefits

Figure 1.2: The sevenstages of planning abroadband investment[Source: AnalysysMason]

What type of network infrastructure should I invest in?Understand the costs and benefits of different kinds ofinfrastructure

How should I invest?Understand the merits of each investment model and what mightwork best for you

How do I manage/monitor the outcome?Ensure successful delivery and operation, and provide evidencefor audit

What can be done to ensure demand for services?Understand the commercial case and your potential role on thedemand side

What can be done to reduce the cost and manage risks?Include measures to reduce costs and manage risks

What are the next steps that need to be taken?Contribute to hitting the DAE targets by using EU funds quicklyand effectively

This guide is complementary to existing guidance material which is publicly available, including:

4

Available at http://www.broadbanduk.org/component/option,com_docman/task,doc_view/gid,1008/Itemid,63/

Guide to broadband investment | 4

•••

Guide to Regional Broadband Deployment (1st edition)5Check List of Actions for Public Authorities Considering Broadband Interventions in Under-served Territories6FTTH Business Guide (2nd edition)7.

Additional guidance for the implementation of each investment model will be made available onthe European Broadband Portal8.The guide should be read in conjunction with the following important European Policy areas:•

The implementation of the EU’s cohesion policy, as outlined in theStrategic report 2010 onthe implementation of the programmes 2007–20139The implementation of the EU's rural development policy, as outlined in the report on theimplementation of the national strategy plans and the Community strategic guidelines for ruraldevelopment (2007-2013)10;The EC Communication onRegional Policy contributing to smart growth in Europe 202011and the accompanying Staff Working Document12The EC Communication onDigital Agenda for Europe13The EC Communication onEuropean Broadband: investing in digitally driven growth14Policy actions aimed at the achievement of EU targets for broadband networks15.

•

•

•••

1.3 Guidance on different investment modelsA key aspect of the investment preparation and planning phase is the choice of investment model.

5

Available at http://www.broadband-europe.eu/Lists/Competences/Guide%20to%20regional%20broadband%20development%20-%201st%20edition.pdfAvailable at http://www.broadband-europe.eu/Pages/checklist.aspxAvailable at http://www.ftthcouncil.eu/documents/Reports/FTTH-Business-Guide-2011-2ndE.pdfSee http://www.broadband-europe.eu/Pages/Home.aspxAvailable at http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/policy/reporting/cs_reports_en.htmAvailable at: http://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/rurdev/publi/index_en.htmAvailable athttp://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/docoffic/official/communic/smart_growth/comm2010_553_en.pdfAvailable athttp://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/docoffic/official/communic/smart_growth/annex_comm2010_553.pdfAvailable at http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2010:0245:FIN:EN:PDFAvailable at http://ec.europa.eu/information_society/activities/broadband/docs/bb_communication.pdfAvailable athttp://ec.europa.eu/information_society/newsroom/cf/pillar.cfm?pillar_id=46&pillar=Very%20Fast%20Internet

67891011

12

131415

Guide to broadband investment | 5

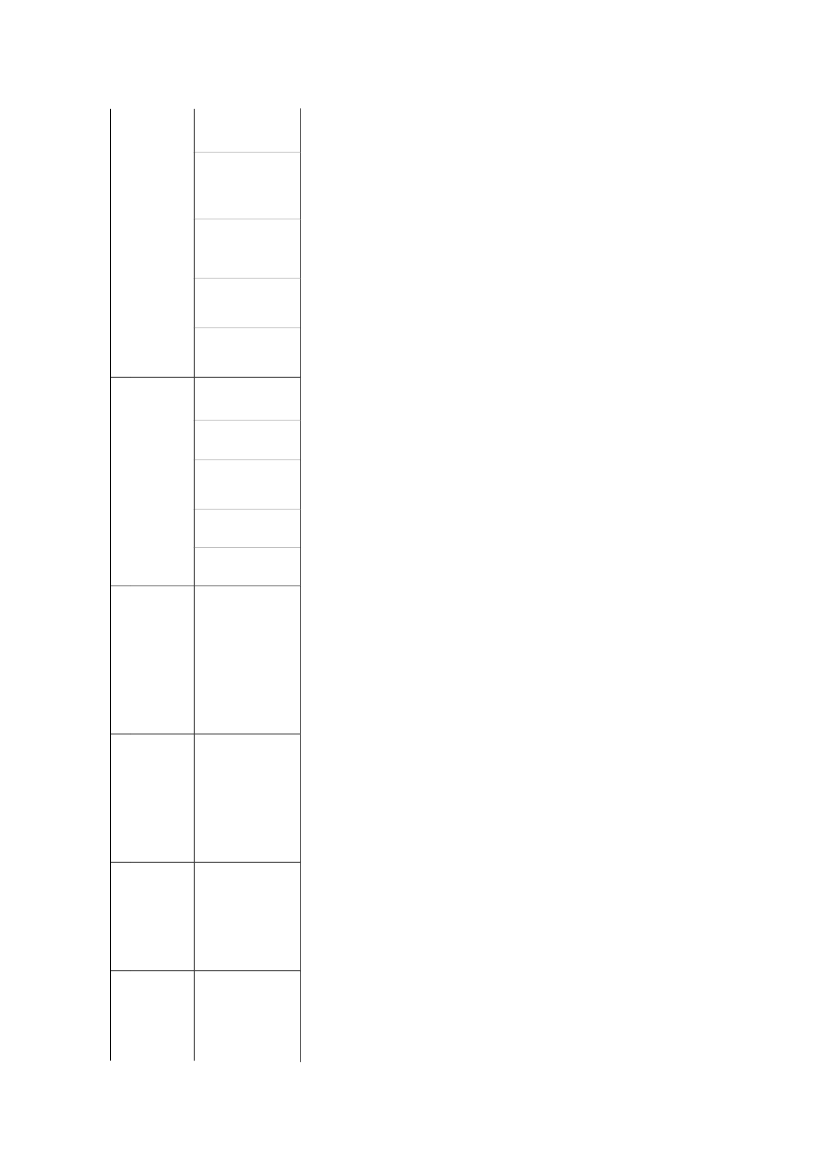

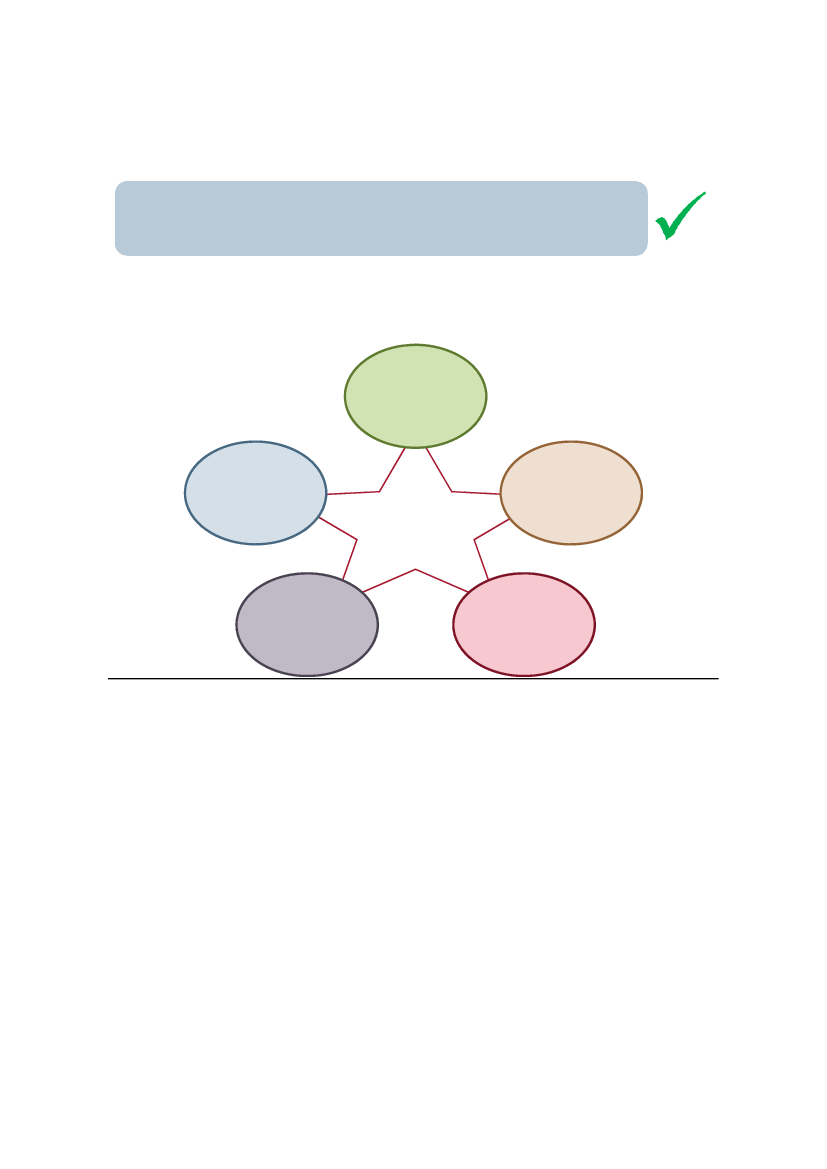

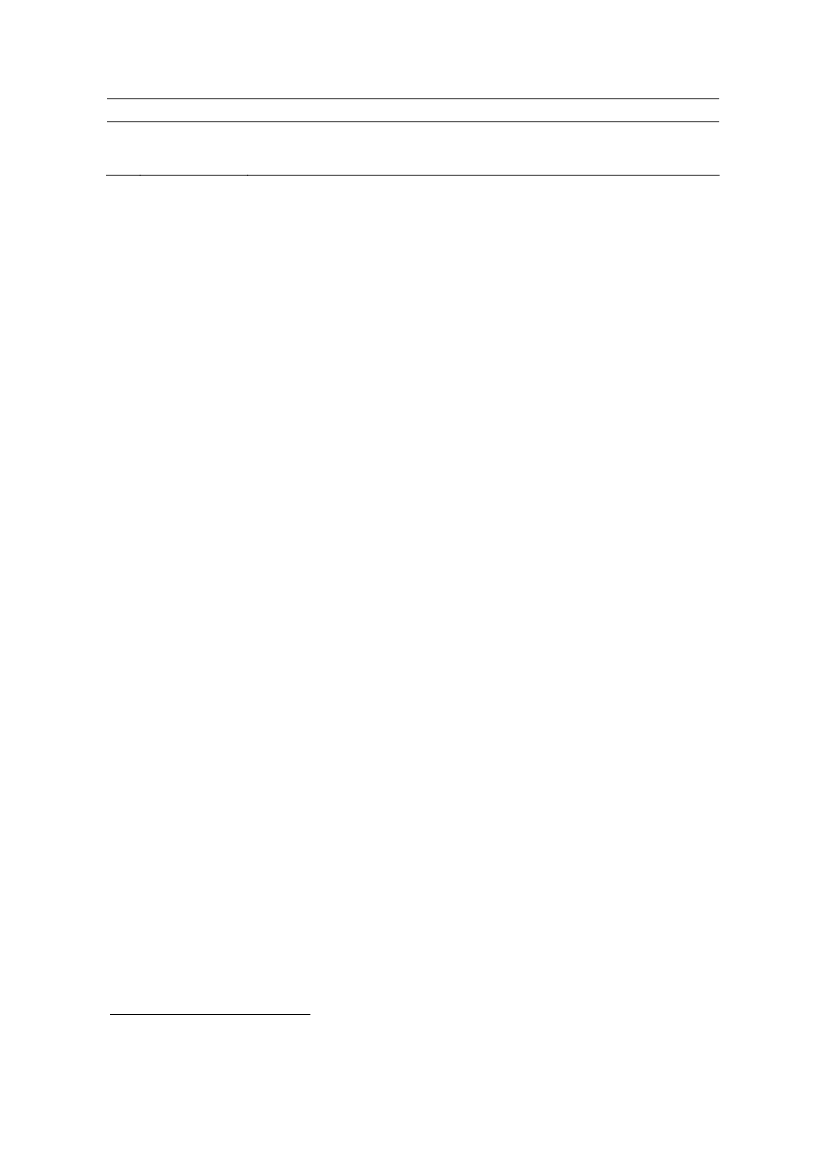

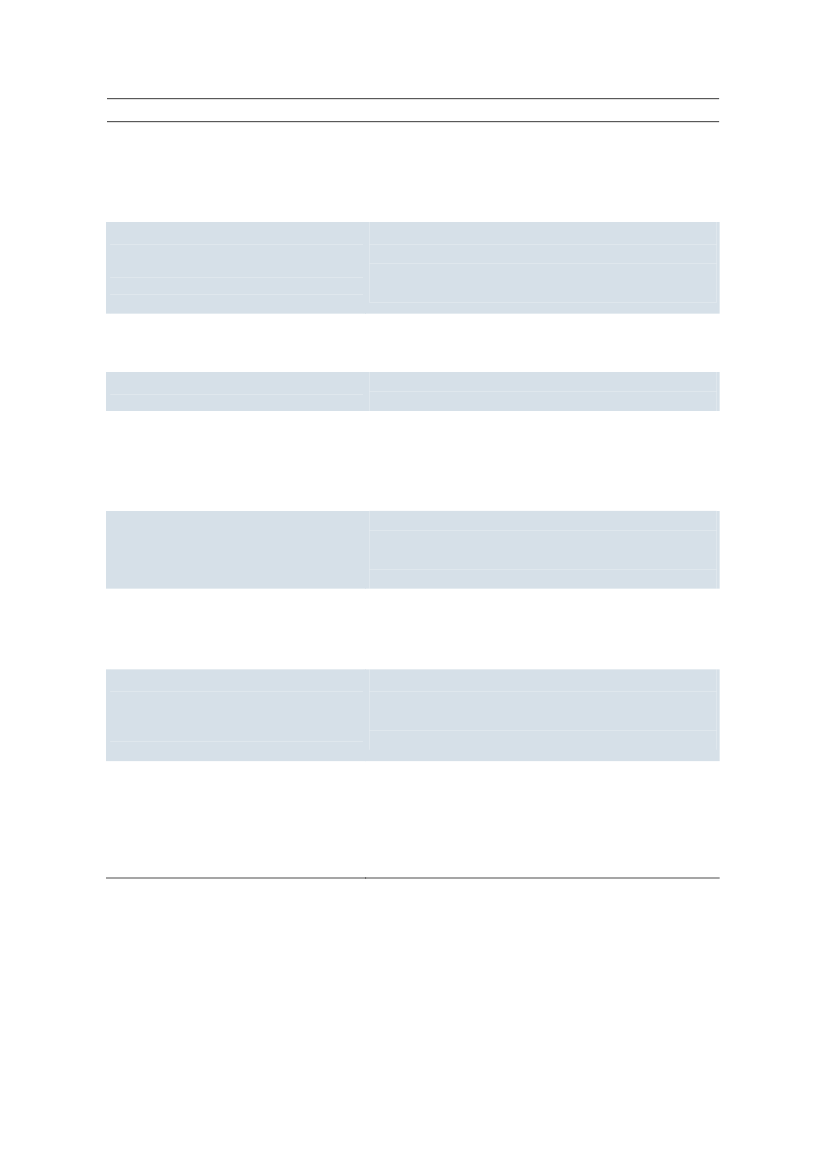

The investment models presented in this guide have been selected on the basis of public data onbroadband projects from around Europe, and input from DG REGIO and eris@. The modelsrepresent a range of options for combining public and private investment, and are presented inincreasing order of involvement by the Managing Authority. Each model is applicable in differentcircumstances, depending on the scope of the required infrastructure, the specific aims of theManaging Authority, and the investment/risk appetite of potential private sector partners. The fiveinvestment models are shown in Figure 1.3 and summarised below.

Bottom-up

Publicdesign, buildand operate

Fivemodels

Privatedesign, buildand operate

Joint venture

Publicoutsourcing

Figure 1.3:

Summary of available investment models [Source: Analysys Mason]

Bottom-up model16

The bottom-up, or local community, model involves a group of end usersorganising themselves into a jointly owned and democratically controlledgroup (frequently a co-operative) capable of overseeing the contract to buildand operate their own local network.The private design, build and operate (DBO) model involves the ManagingAuthority issuing funding (often in the form of a grant) to a private sectororganisation to assist in its deployment of a new network. The public sectorhas no specific role in the ownership or running of the network, but mayimpose obligations in return for the funding.

Private design,build and operate(DBO) model

16

In this context, 'bottom-up' does not refer to the LEADER intitiative.

Guide to broadband investment | 6

Public outsourcingmodel

Under a public outsourcing model a single contract is awarded for allaspects of the construction and operation of the network. The majorcharacteristic of this model is that the network is run by the private sector,but the public sector retains ownership and some control of the network.A joint venture is an agreement under which ownership of the network issplit between the public and private sector. Construction and operationalfunctions are likely to be undertaken by the private sector.

Joint venture model

Public design, buildA public DBO model involves the public sector owning and operating anetwork without any private sector assistance. All aspects of networkand operate modeldeployment are managed by the public sector. A public sector operatingcompany may operate the entire network, or may operate the wholesalelayer only (with private operators offering retail services).Guidance regarding the advantages and disadvantages of each investment model and the suitabilityof each to different circumstances is given in Figure 1.4.ModelBottom upAdvantages•Long-term, non-profitview, suitable for high-cost infrastructure(e.g. FTTH)Focuses demand andencourages localsocial cohesionLarger scale (thanbottom up)Low public burden,which can lead tofaster deployments•There is a minimumfunding threshold toattract privateinterestLimited control overoperations, whichmay reduce thesocio-economicimpactReduced financialbenefit to privatesector (compared toprivate DBO)AdditionalbureaucracyFor larger-scale investments, wheresufficient funding is available toattract private interest in rural areas,and where the operations (and risk)of the network can be confidentlytransferred to a private operatorDisadvantages•Localiseddeployments, withrisk of differingtechnologiesRecommended useFor targeting localised areas and forgaining the most benefit from smallamounts of funding

•

PrivateDBO

••

•

Publicoutsourcing

•

Public financialstability with privateexpertiseGreater control (thanprivate DBO)

•

•

•

Where the Managing Authorityrequires a high level of control overthe network, and where the privateoperator has a more conservativerisk profile than the private DBOmodel

Guide to broadband investment | 7

ModelJointventure (JV)

Advantages•Potential financialbenefit for bothparties, based on risksharingThe creation ofspecial-purposevehicles (SPVs) canmake the model veryscalable, and allowalternative investmentsourcesManaging Authorityhas full control topromote competitionand enforce standardsManaging Authoritycan ensure socio-economic benefits areprioritised

Disadvantages•Potential conflicts ofinterest must beresolved and mayblock creation/successfuloperation of the JVFew examples ofimplemented JVs toindicate bestpracticeSize and scopelimited by publicexpertisePotentially excludesprivate sectorexpertise

Recommended useWhere the interests of the publicand private sectors can be closelyaligned

•

•

Public DBO

•

•

•

•

Where a Managing Authority needsto have absolute control over theoperations of the network, or wheresmall targeted investment willinspire investment from privatesources

Figure 1.4:

Summary of advantages, disadvantages and recommended uses of the investmentmodels [Source: Analysys Mason]

In terms of the choice of investment model, a Managing Authority should consider the delivery ofbenefits to end users over thelong termas a key criterion in making that choice. The EC believesthat from a cohesion perspective, longer-term investment models work best for financing highspeed infrastructures, promote competition and allow the delivery of cheaper and better-qualityservices for end users. This is particularly the case when an investment focuses on future-proofpassive or backhaul infrastructure, which supports effective competition among a wide range ofservice providers. Issues associated with the long-term management of end-user benefits andeffective competition are discussed in more detail in Section 1.5.However, the EC wishes to encourage innovation in the choice of investment models, and is keento stress that there is no one model that is preferred above all others. Indeed, it is an important roleof a Managing Authority to use an appropriate combination of investment models from differentstakeholders to match their needs and to deliver a long-term solution for end users.A Managing Authority also needs to be innovative in terms of both the sources of funding and theavailable financial instruments for investment. It must consider private investment from bothwithin and outside the telecoms sector, including operators, institutional investors, utilities, endusers, content providers and equipment providers. In terms of financial instruments available to thepublic sector, the European Investment Bank (EIB) has developed examples of innovativeproducts and services,17such as:17

See http://www.eib.org/products/index.htm for more information.

Guide to broadband investment | 8

•••••

Individual loansIntermediated loansStructured finance facilitiesRisk sharing finance facilitiesGuarantees.

Regardless of the mix of public and private investment, a Managing Authority should choose theinvestment model on the basis of its ability to offer end users a range of affordable, high-qualityservices on a long-term basis.

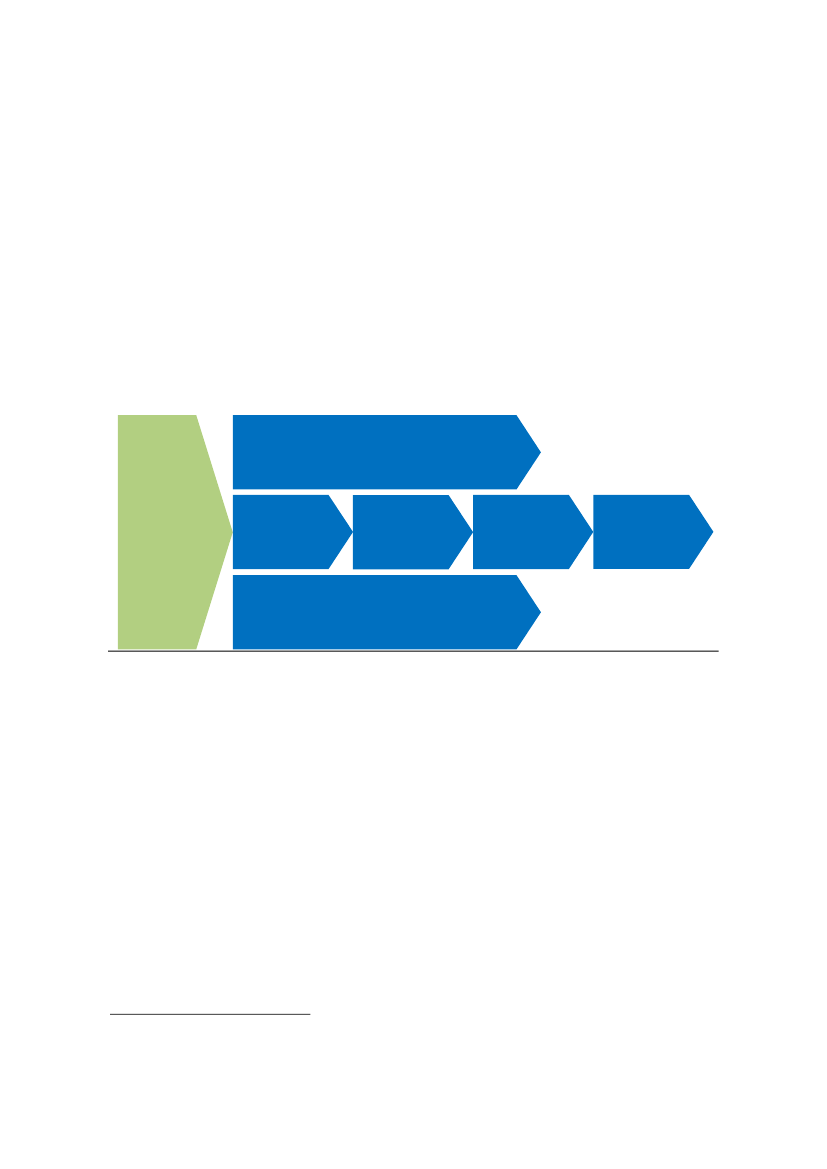

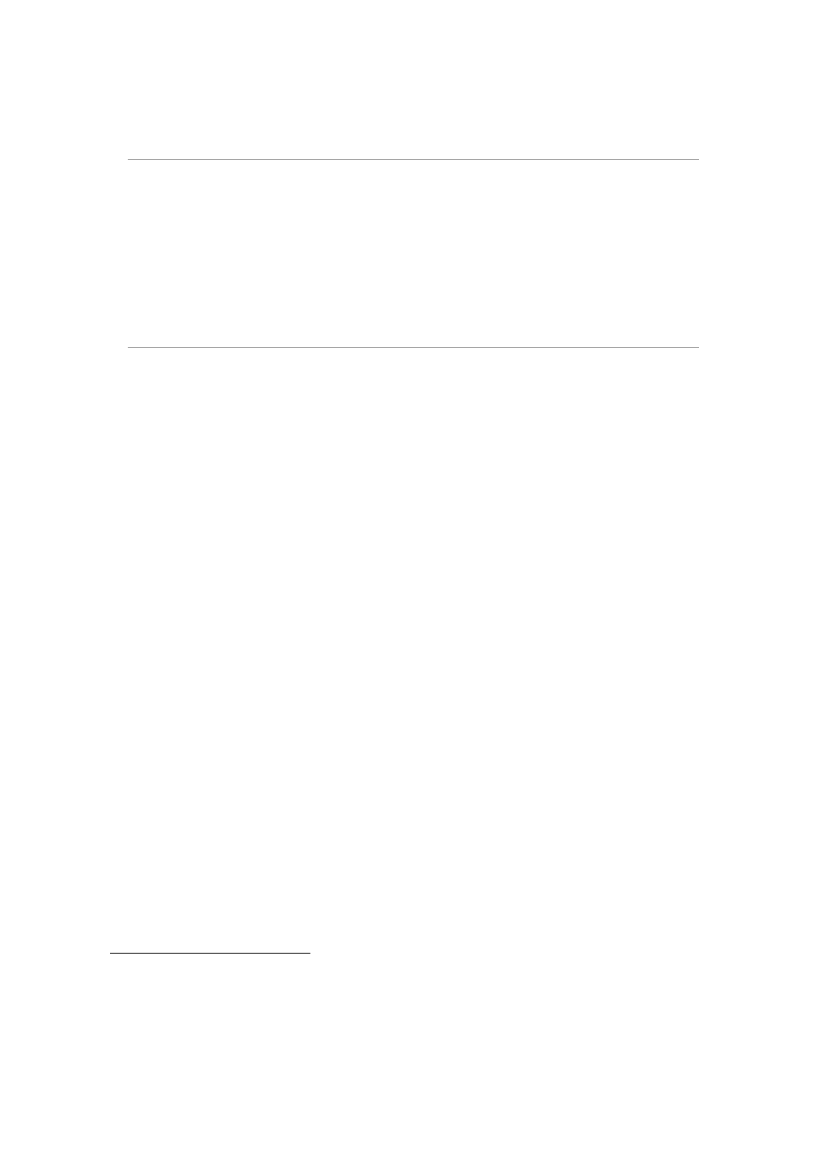

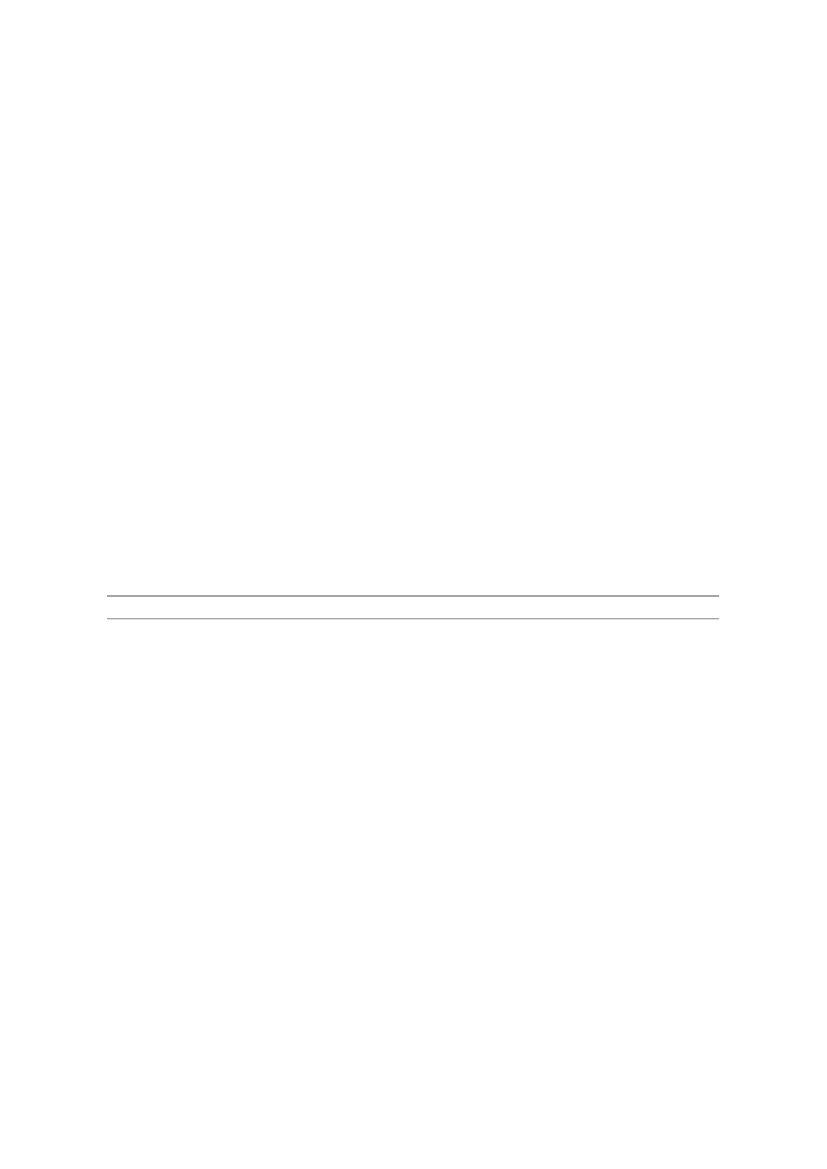

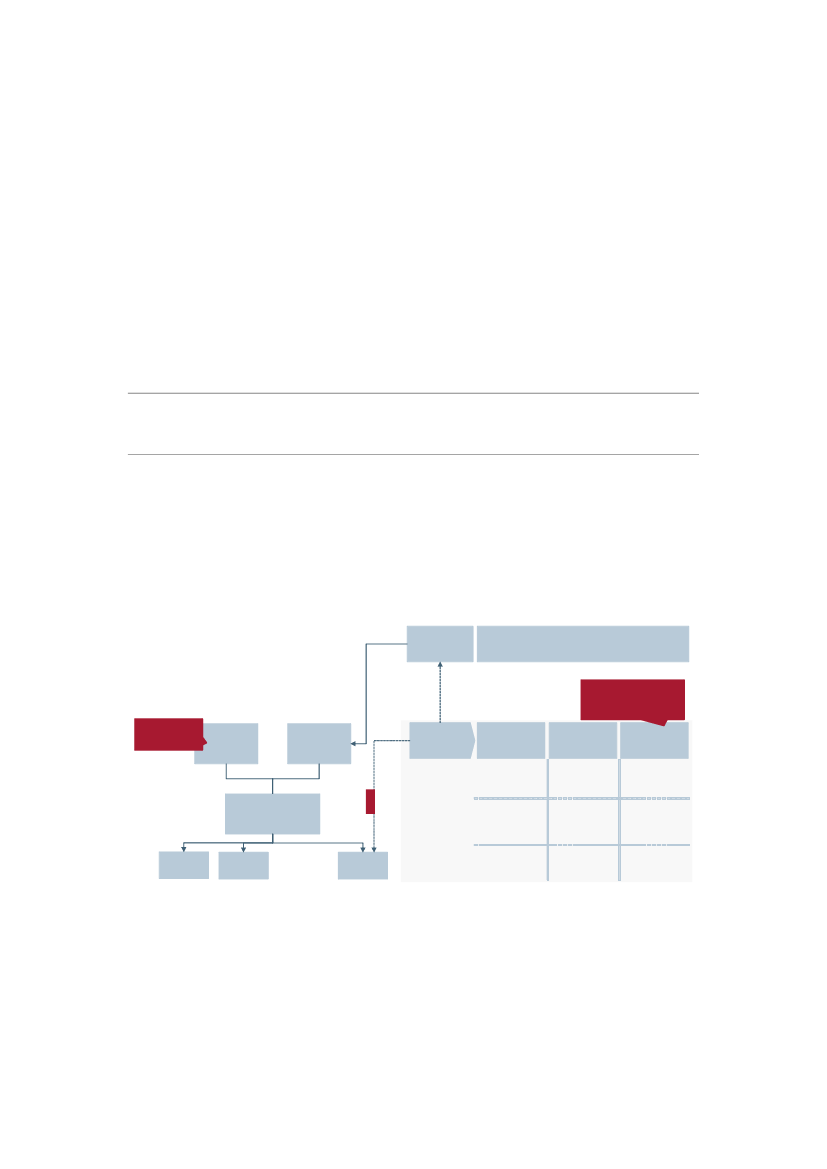

1.4 Next steps following preparation and planningThe guide also includes detailed guidance on the next steps that need to be taken, following theinvestment preparation and planning phase, as shown in Figure 1.5.

EU fundingapplicationPreparationandplanning

Procurementdesign

Procurementactivity

Contractaward

Broadbanddelivery

State aidcompliance applicationFigure 1.5:Next step activities [Source: Analysys Mason]

There are three key activity flows that follow preparation and planning: the EU fundingapplication, complying with State aid regulations18, and the four separate activities that contributeto procurement and delivery. These three activity flows are carried out broadly in parallel, and asummary description of each activity is provided below.1.4.1 EU funding applicationTo complete an EU funding application, or any other relevant funding application, a ManagingAuthority will need to assess the funding application guidelines and application form(s), andideally check that its understanding is consistent with that of the funding body, through the use ofmeetings and dialogue.

18

Under the State aid regime, projects developed under the "de minimis" rule do not need a state-aid clearance.

Guide to broadband investment | 9

There are a variety of sources of EU funding, and these can be combined with national or localsources of public sector funding, before being leveraged with private sector financing whereappropriate, as discussed in Section 1.3.1.4.2 Complying with State aid regulationsThe EC monitors the investment of public funds to ensure that State aid is not used to undulyfavour one or more private entities in a way that would distort a market. The key activities forachieving compliance with State aid regulations relate to justifying the need for publicintervention19. However, there are four situations in which a State aid notification isnotrequired:•If the investment is made on terms that are equivalent to those available to the market•If the level of aid is below a threshold of EUR200 000•If the broadband network is only used for public services•If the broadband project is being implemented as part of a national framework scheme whichhas already received State aid approval.If none of the above conditions is met, an individual State aid notification must be submitted to theEC. A Managing Authority should prepare a State aid pre-notification paper in consultation withthe relevant government department.In addition to describing the project objectives and approach in the State aid pre-notification paper,the Authority will need to gather and prepare evidence about the broadband demand and supplysituation in the localities of interest for the project. This includes a requirement for detailedmapping and coverage analysis, to determine whether infrastructure has already been (or is aboutto be) deployed on the supply side, as well as a mapping of the expected service requirement onthe demand side.Other inputs to the State aid process are derived from the project design, the procurementrequirements specifications and the responses from bidders during the procurement process. Inparticular, the requirements specifications and questions posed by bidders during the procurementshould be designed to help satisfy the EC’s guidelines on State aid for broadband.1.4.3 Procurement design, procurement activity, contract award and broadband deliveryThe procurement design is shaped by a number of factors and options that should be assessedmethodically by a Managing Authority and developed into a coherent, agreed procurementstrategy. Due to the wide range of factors involved in procurement design, a Managing Authorityis likely to need specialist procurement and technical support to ensure the procurement will bothmeet its objectives and comply with procurement legislation and State aid guidelines.

19

For more detail, seeCommunity Guidelines for the application of State aid rules in relation to rapid deployment ofbroadband networks,available at http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:C:2009:235:0007:0025:EN:PDF

Guide to broadband investment | 10

Each procurement route will include a specific set of activities. For example, the OJEUCompetitive Dialogue procedure includes the following steps:••••••

market awarenesspre-qualification questionnaire (PQQ)invitation to participate in dialogue (ITPD)dialogue processinvitation to tender (ITT)contract award.

A Managing Authority may award the contract to the winning bidder, once the key dependenciesof State aid approval and funding confirmation have been achieved.The broadband delivery stage is a complex undertaking and presents the contracting Authoritywith a variety of challenges. Many areas will require close monitoring and management, includingchecking the functionality/performance of the network, checking deployment costs and checkingthe services offered / prices charged to wholesale and retail customers.

1.5 Conclusions and recommendationsBased on research of the example projects and analysis of the steps that need to be taken towardseffective broadband delivery, we have derived the following conclusions and recommendations forany Managing Authority that is planning a public broadband investment.Socio-economicbenefit must bemanaged alongsideprojectsustainability todeliver long-termbenefitsDue to the large investment required to deploy broadband networks, publicinvestment of some kind will often be required (particularly in rural areas).When large amount of public funds are involved to deliver thesocio-economic aimsof EU policies, thelong-termneeds of territories must beprioritised over the commercial aims of specific private companies.For this reason, a Managing Authority might favour those models whichprovide long-term control over the operations of the project to ensure thatthe needs of the entire territory are met. Effective control of the project bythe Managing Authority will also help to ensure that access to the networkinfrastructure is made available on anopenandnon-discriminatorybasis (asdiscussed in more detail below). Effective control of the project will alsoallow the Managing Authority to ensure that the network is operated in away that supports the delivery of long-term socio-economic benefits (e.g. byensuring that service availability and performance meet minimumrequirements, and also ensuring that the desire for commercial returns doesnot overtake the need to provide affordable services).However, the private sector can bring invaluable expertise to broadbandprojects, and commercial discipline that can ensure projects are deliveredefficiently. The involvement of large-scale private operators can help to ensure

Guide to broadband investment | 11

the sustainability of the project, as their expertise and experience can help inadapting to changes in the market or embracing technological developments.It is therefore essential for a Managing Authority to engage with potentialprivate partners at an early stage of the procurement planning process to gaugetheir appetite for different investment models, while keeping the procurementprocess transparent and non-discriminatory.The bottom-upmodel may often besuitable for small-scale fibre projectsFibre to the home (FTTH) provides the very highest connection speeds toend users, but is usually very expensive to deploy. Our research suggeststhat the bottom-up model is a suitable complement to small-scale FTTHdeployments, as co-operatives can take a long-term not-for-profit view ofthe investment. Larger-scale deployments may be possible, where anexisting large-scale co-operative exists (e.g. a local utility company). In theexample projects we observed bottom-up models being deployed both on asmall scale (e.g. Nuenen and Swedish Rural Development Programme) andon a larger scale (e.g. the local co-operative electricity companies deployedfibre in Midtsoenderjylland, Denmark).However, Managing Authorities may face a challenge in leveraging thebottom-up model for a project involving widespread deployment (if large-scale co-operatives do not already exist). They should explore measures toaggregate discrete co-operative areas and promote common technicalstandards to enable major players in the industry to participate and hencedeliver benefits to end users, particularly regarding the choice andaffordability of services.Small investmentscan provide acatalyst throughinnovativepartnershipsNone of the example projects incorporates a formally established jointventure (the Lombardia project is still at the planning stage). However,particular elements of some projects were undertaken using a collaborativeapproach. In many cases, small investments led to innovative partnerships,and provided a catalyst for further investment from other sources.These examples included the Managing Authority in Piemonte, Italyinvesting in services in return for investment in infrastructure by theincumbent. And in North Karelia, many end users were inspired to committo the bottom-up funding of the network once they saw cable being installedalong their street.Managing Authorities should engage with potential private partners toexplore the possibility of innovative partnerships to catalyse investment.Open access toinfrastructuresupports effectiveAs discussed above, a Managing Authority should aim to ensure that thebroadband investment delivers a choice of affordable, innovative servicesfrom a range of retail suppliers over the long term. This aim is supported by

Guide to broadband investment | 12

competition

promoting effective and sustainable competition on the network, which inturn is supported by providing open and non-discriminatory access foroperators to use the infrastructure to provide services.Infrastructure access is possible on two broad bases:••

Access to thepassiveinfrastructure, such as underground ducts, darkfibre and terrestrial wireless sitesAccess to theactive infrastructure,which refers to the active electronicssuch as those attached to fibre or copper cables, or terrestrial wirelessand satellite electronic equipment.

The concept ofopenandnon-discriminatoryaccess refers to a situation inwhich any operator can interconnect with the network on the same terms asany other. The infrastructure operator must ensure that it does not undulyfavour any service provider(s) over any others. For this reason it isadvantageous to use a model under which the infrastructure operator is notalso a service provider, as this reduces any incentive for favouritism. It is acondition of granting State aid approval that the recipient of the aid providesopen wholesale access, regardless of the presence of significant marketpower (which is determined by national regulatory authorities through anestablished ‘market review’ process).It is generally accepted that if an operator has access to the passiveinfrastructure (e.g. copper, dark fibre or underground ducts) it will havemore freedom to develop innovative services, and therefore compete withother operators and hopefully deliver lower prices to consumers. However,access to passive infrastructure generally requires a higher level ofinvestment both from the access provider (which must ensure sufficientcapacity in ducts, dark fibre, cabinets, etc.) and from the access seeker(which must provide its own active equipment). In areas where the businesscase for next-generation access (NGA) broadband networks is alreadychallenging (such as rural areas), the additional investment required by theaccess seeker may mean that passive infrastructure access may be less likelyto support effective and sustainable competition, unless alternative and moreinnovative investment models are used which could mean lower cost andlower access charges (e.g.: bottom up model)20.Therefore, a Managing Authority should plan an investment with a view to20

The majority of costs are associated with deploying the passive infrastructure. Under apassive access model,theaccess seeker needs to deploy its own active electronic equipment relatively close to the end user, in order toconnect with the passive infrastructure. Although this cost is small when compared to the passive investment, it maystill be enough to create an unviable business case in very sparsely populated areas. The alternative is anactiveaccess model,which allows the access seeker to interconnect via active electronics from a more centralisedlocation, which provides lower control, but requires less upfront investment.

Guide to broadband investment | 13

ensuring that any new network infrastructure is opened at as many levels aspossible, thus allowing all market players to operate in a level playing field.Also, by investing in infrastructure rather than directly in services, aManaging Authority will help to ensure that it does not distort the market,which could be detrimental to end users.These considerations will encourage effective and sustainable competition,which will help to create an environment that stimulates the availability ofinnovative services at low prices, offered by a range of retail providers toconsumers and businesses.

Guide to broadband investment | 14

2 Introduction2.1 BackgroundTheDigital Agenda for Europeis one of the flagship initiatives of the EC’sEurope 2020 Strategyfor a smart and sustainable economy. The agenda provides a framework for Member States toachieve the 2020 strategy’s objectives for broadband deployment: that is, broadband access for allin Europe by 2013 and at least 30Mbit/s connections for all by 202021.The EC recognises that significant funding will be required in order to achieve these objectives,and all Member States have, or are developing, broadband plans to deliver the required connectionspeeds to their population. However, only around half of the broadband plans that include roll-outof superfast broadband networks set out the specific measures that will need to be implemented torealise the targets for broadband access.Due to rapid developments in technologies and business models for broadband services, there is arisk that rural areas will get left behind as commercial operators focus on urban areas that are morecost effective to serve. In order to limit the emergence of a ‘digital divide’ between urban and ruralareas, it is essential that local and regional authorities are able to use public funding effectively tosupport the roll-out of new broadband networks.The EC has also recognised that the sharing of best practice in terms of broadband investment hasplayed a key role in improving the outcome of ICT investment programmes in some regions.The EC considers this guide a particularly important resource for Member States who havethe facility to utilise EU funds from the current programming period (2007-13) to assist inthe deployment of new broadband infrastructure. Those Member States are urged to use thisguide to develop an action plan that will ensure the DAE targets are met.

2.2 Aims of this documentIn order to promote the sharing of best practice in implementing broadband investment, thisdocument aims to provide reliable and independent guidance on planning a broadband investment.Overall, the aims of the guide are as follows:•••

To help ensure that the Digital Agenda for Europe (DAE) targets are metTo support the aims of EU's regional policy for affordable high-quality broadband for allTo support the aims of EU's rural development policy for better quality of life and improvedprovision of basic services in rural areas;

21

These are the coverage objectives. There is also a take-up objective (for at least 50% of households to use servicesof at least 100Mbit/s).

Guide to broadband investment | 15

••

To help some Member States exploit EU funds more effectivelyTo learn from other projects which have been implemented and spread best practice.

The guide has been prepared on the basis of research into publicly available information,interviews held with stakeholders from several example projects which have already beenimplemented, and feedback gathered from an online consultation and from a workshop at theDigital Agenda Assembly in Brussels.The guide is aimed at Managing Authorities (and other implementing agencies) with responsibilityfor preparing projects to fund broadband, including calls for public procurement. The guide thereforeexamines a range of possible investment models and other issues that Managing Authorities need toconsider in order to successfully leverage public funds for broadband investment.Structure of the documentThis guide has seven sections, addressing each of the stages that a Managing Authority needs to gothrough when planning a broadband investment. The seven stages are shown in Figure 2.1 below.

Guide to broadband investment | 16

Why should I invest in broadband?Define project aims to tackle market failures and/or deliver socio-economic benefits

Figure 2.1: The sevenstages of planning abroadband investment[Source: AnalysysMason]

What type of network infrastructure should I invest in?Understand the costs and benefits of different kinds ofinfrastructure

How should I invest?Understand the merits of each investment model and what mightwork best for you

How do I manage/monitor the outcome?Ensure successful delivery and operation, and provide evidencefor audit

What can be done to ensure demand for services?Understand the commercial case and your potential role on thedemand side

What can be done to reduce the cost and manage risks?Include measures to reduce costs and manage risks

What are the next steps that need to be taken?Contribute to hitting the DAE targets by using EU funds quicklyand effectively

The content of each of the seven sections is summarised below.•

Why should I invest in broadband?This section looks at the drivers for investing inbroadband networks and how public funds can, if used effectively, help to deliver socio-economic benefits. It is essential that Managing Authorities define their aims at the start of theinvestment planning process. This section also considers the aims of past broadband projects,and how successfully they were achieved, as well as including some of the unexpectedbenefits that have arisen from these projects.What type of network infrastructure should I invest in?This section looks at the choicesavailable to a Managing Authority with regard to different parts of a broadband network (e.g.access vs. transport/backhaul networks), and the ways in which various elements of thenetwork support different aims of broadband investment. Additionally, although the majorityof the example broadband projects considered specify requirements that are technologicallyneutral, this section aims to explain the reasons for the particular technology choices, and

•

Guide to broadband investment | 17

assess their appropriateness for meeting various goals. A Managing Authority must considerthe pros and cons of each available technology, in order to choose the option that meets itsaims in the most cost-effective manner.•

How should I invest?Managing Authorities must choose the right investment model for theirparticular circumstances. This section gives details of five different models of investment thata Managing Authority could follow. It considers the advantages and disadvantages of eachmodel, and their suitability for different types of network investment. More detail on theseinvestment models is given below.How do I manage/monitor the outcome?It is essential for Managing Authorities tomanage/monitor the outcome of the investment to ensure that funding is being usedappropriately. This section looks at various methods that a Managing Authority can use tomonitor the implementation of projects and the appropriateness of each method for differentcircumstances. It is important for a Managing Authority to consider these issues as part of theplanning process, as any public or private partners in the investment project will need tocommit to managing and monitoring provisions upfront.What can be done to ensure demand for services?This section considers the relationshipbetween demand for services and the overall impact of the Managing Authority’s networkinvestment, based on insights from the research into example projects.What can be done to reduce the cost and manage risks?This section considers themeasures that can reduce the cost of a broadband deployment (e.g. re-using existinginfrastructure) and manage risks (e.g. through detailed planning).What are the next steps that need to be taken?In this section we consider the three parallelactivity streams that need to be initiated following the investment planning process: funding,procurement and delivery, and State aid.

•

•

•

•

Focus of the guide: broadband investment modelsThe main focus of the guide is to consider five high-level investment models for broadband, all ofwhich are available to Managing Authorities for funding broadband network deployment. Themodels below represent a spectrum of increasing involvement and commitment from theManaging Authority:•

Bottom up– a group of end users (frequently organised as a ‘co-operative’) decide to invest inthe deployment of a network. Public involvement is usually limited to issuing grants orguaranteeing loans, and/or facilitating access to publicly owned infrastructure such as ducts.Private design, build and operate– a private company receives funds (often in the form of agrant) from the public sector to assist in network deployment, but the private company retainsfull ownership.

•

Guide to broadband investment | 18

•

Public outsourcing– a public sector body outsources network build and operation to theprivate sector under a long-term agreement, but the public sector body retains ownership of thenetwork.Joint venture– public and private sector bodies both retain a stake in the network.Public design, build and operate– the public sector constructs and operates the networkitself, retaining full control and offering services on a retail or wholesale basis.

••

In addition, we are aware that (as part of preliminary analyses) some Managing Authorities haveconsidered other models, such as public-private partnership (PPP) models of the kind used forother major infrastructure projects, where availability payments are made over a long period.However, we have not yet identified any broadband projects that have used this model for a realdeployment, and this model is not considered in detail in this guide.

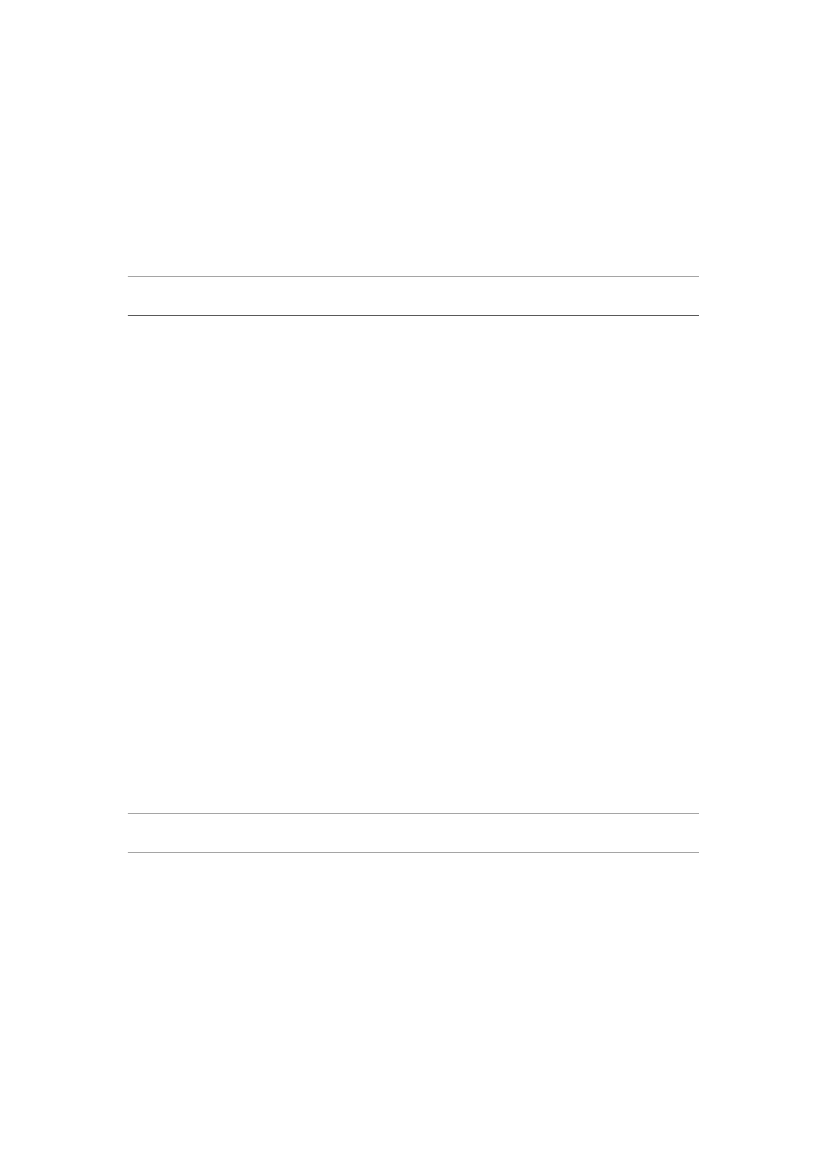

2.3 Approach used to compile the guideIn order to provide comprehensive information to support each section of the document, andtherefore create a useful guide for Managing Authorities, we conducted detailed research intoexisting broadband investment projects around Europe. As a result, we have built up an evidencebase of case studies from previous successful projects to deploy next-generation broadband (whichcan be found in Annex A). Figure 2.2 provides a summary of the example projects on which wehave conducted detailed research.STOKAB, SwedenPublic DBOCity-based FTTHmeshed networkMidtsoenderjylland, DenmarkPublic DBOPartnership withelectricity providerSouth Yorkshire, UKPublic outsourcingPartnership arrangementfor network managementNuenen, NetherlandsBottom upCo-operative-based FTTHDORSAL, FrancePublic outsourcingInvestment in backbone,DSL and WiMAXAuvergne, FrancePublic outsourcingCabinet-based ADSLfor very long linesPiemonte, ItalyPublic DBOInspired privateinvestmentRural developmentprogramme, SwedenBottom upState-funded co-operativesNorth Karelia, FinlandPrivate DBO and bottom upGrant to build to within2km of homesRAIN, LithuaniaPublic DBONationwide backhauland core networkAlto Adige, ItalyPublic DBOWireless to homes andbusinesses; fibre to publicGeorgiaAzerbaijanArmeniaLombardia, ItalyJoint venturePlanned FTTH to 50%Turkeyof homes

Malta

Cyprus

Figure 2.2:

Summary of example projects [Source: Analysys Mason]

Guide to broadband investment | 19

In addition to this detailed research, the guide includes insights from the following sources:••

feedback from the eris@ annual conference regarding the proposed financial modelsModels for efficient and effective public-sector interventions in next-generation broadbandaccess networks,Analysys Mason report for the Broadband Stakeholder Group, 9 June 200822a blogosphere consultation co-ordinated by eris@feedback from the first Digital Agenda Assembly held in Brussels on 16 and 17 June 2011.

••

When selecting projects for detailed analysis, we aimed to collect a range of examples, including(where possible): various examples of each investment model, and examples of a number of typesof infrastructure deployment. Where possible we have identified the outcomes of each project, interms of supporting competitive broadband provision and delivering socio-economic benefit.Figure 2.3 provides a summary of the examples considered in detail for the guide.

22

Available at http://www.broadbanduk.org/component/option,com_docman/task,doc_view/gid,1008/Itemid,63/

Guide to broadband investment | 20

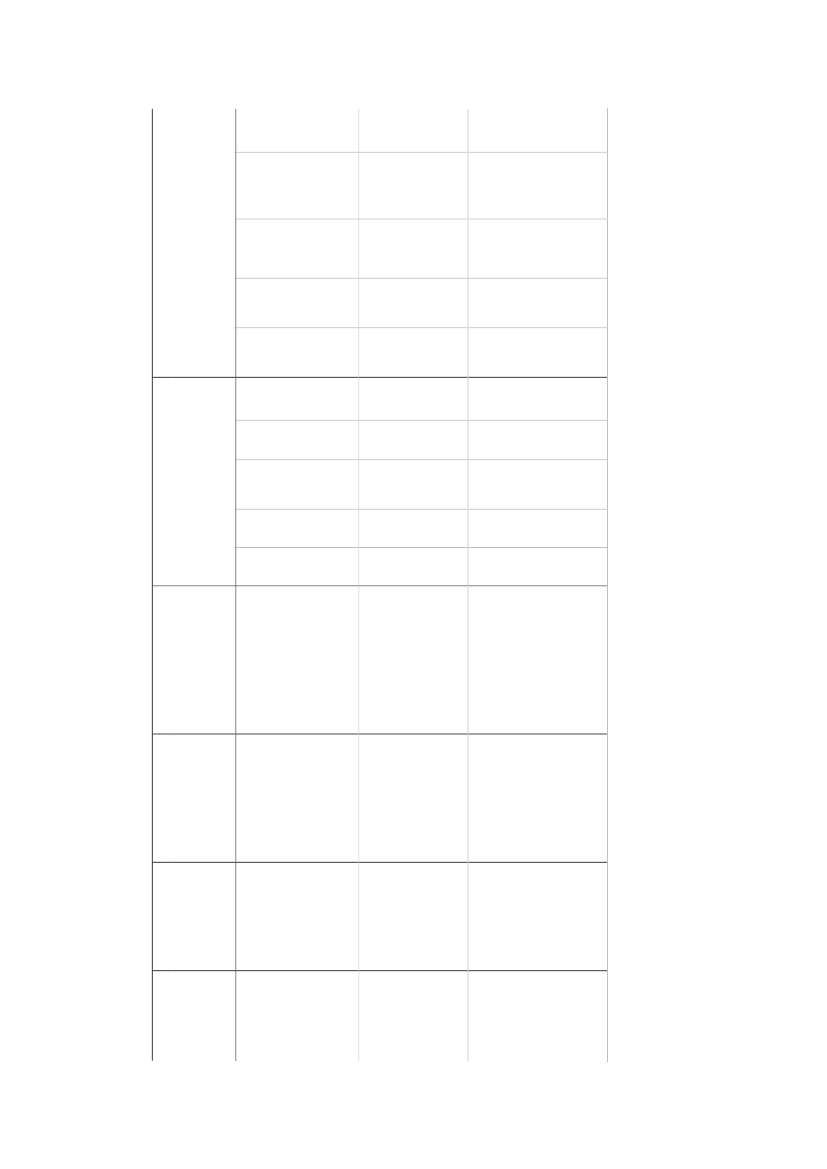

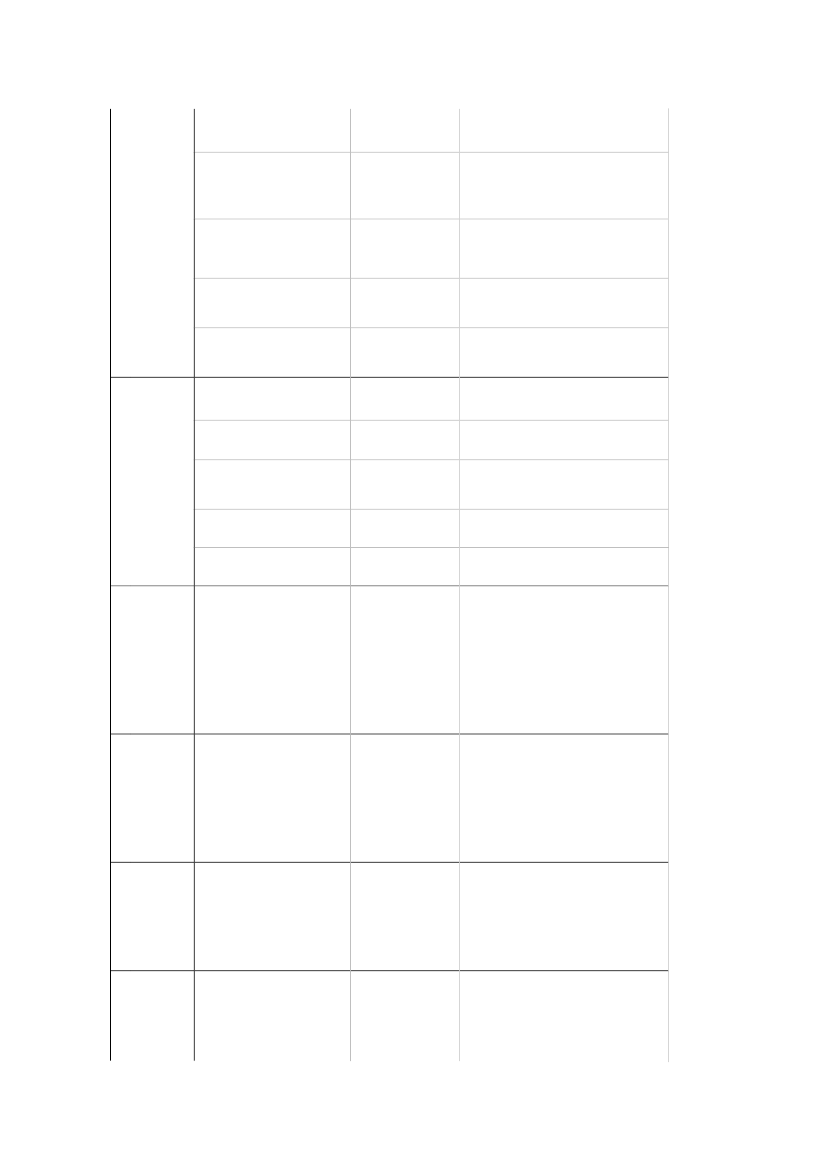

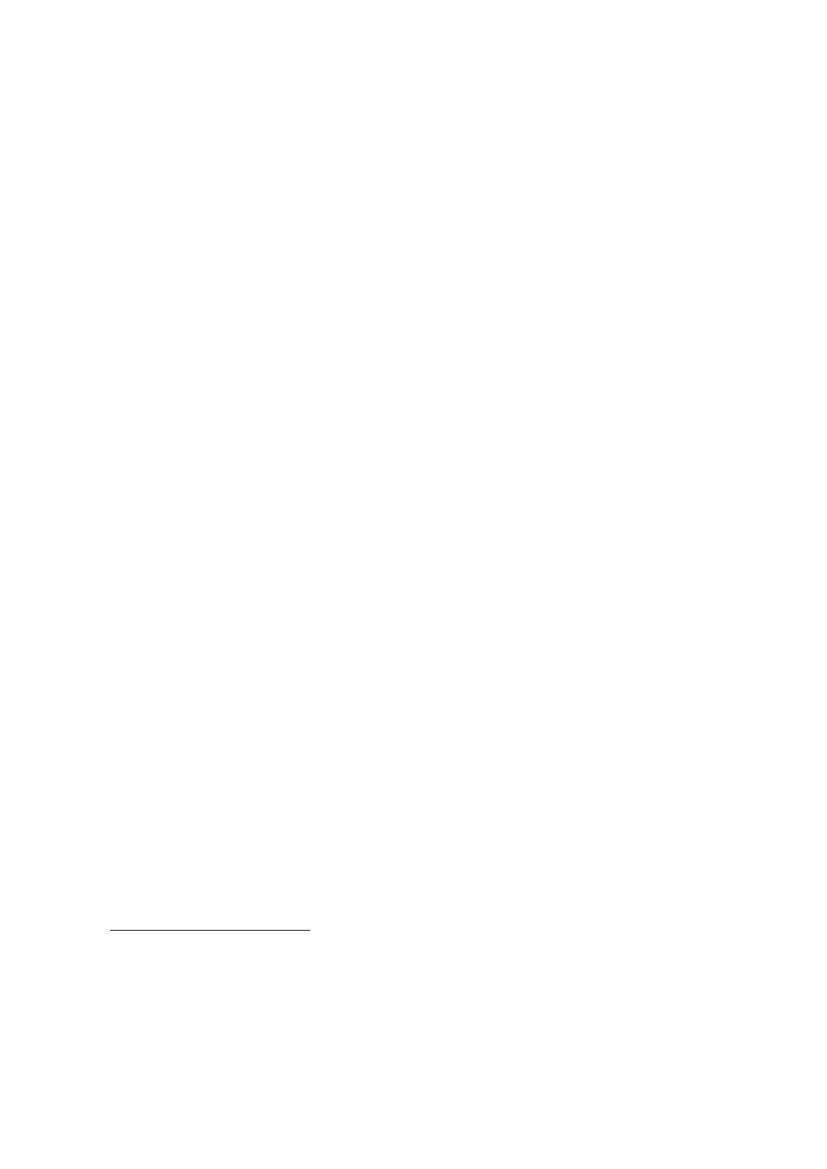

Figure 2.3:Investment valueInfrastructureFTTH FTTCInvestment model

Summary of example projects [Source: Analysys Mason]

Project

ManagingAuthority

Summary ofinvestment

Wire- ADSL Core & Bottom- Private PublicPublicJointless &back-upDBOout-ventureDBOsatellitehaulsourcing (partnering)**

Piemonte,Italy

Public ICTadministrationorganisation

Multipleinfrastructure toinspire privateinvestment

EUR 21 million fromERDF; EUR 7 millionfrom provincial funds;EUR 7 million fromnational funds; EUR15million from regionalfundsPublic investment ofEUR 6 million andprivate investment ofEUR 8 millionPublic funding fromnational governmentPublic investment ofSEK173.0 million andprivate investment ofSEK23.3 million andEUR 21 million from theEuropean EconomicRecovery Package(EERP).

( )

OnsNet,Nuenen,Netherlands

Close the gap(privatecompany)

Co-operative-basedinvestment in FTTHwith some backhaul

RuralDevelopmentProgramme,Sweden

Swedish Boardof Agriculture

National fundingmade available tolocal co-operativesfor FTTH

Guide to broadband investment | 21

ProjectFTTH FTTC

ManagingAuthorityInvestment valueInfrastructureInvestment model

Summary ofinvestment

Wire- ADSL Core & Bottom- Private PublicJointPublicless &back-upDBOout-ventureDBOsatellitehaulsourcing (partnering)**

Midtsoenderjylland,Denmark

VejenMunicipality

Investment in fibreconnection betweencity halls;partnership withelectricity companyfor FTTH

Total investment of EUR83, 6 million. Out ofwhich privateinvestment of EUR 81.6million and publicinvestment of EUR 2million which includesEUR 143300 ERDFsupport.Public investment ofEUR38 million andprivate investment ofEUR30 millionEuropean funding ofEUR13 millionPublic investment ofEUR6.2 million(including EuropeanRegional DevelopmentFund (ERDF) funding)and private investmentof EUR3.1 millionSuccessor projectincluded EUR66 millionfrom government, andEUR25 million from theEERP funds.

( )

DORSAL,Limousin,France

Collective oflocal authorities

Investment inbackbone, DSL andWiMAX services

NorthKarelia*,Finland

Regional council

Grant to local telcoto build backbone towithin 2km ofhousehold; bottom-up model for finaldrop

Guide to broadband investment | 22

ProjectFTTH FTTC

ManagingAuthorityInvestment valueInfrastructureInvestment model

Summary ofinvestment

Wire- ADSL Core & Bottom- Private PublicJointPublicless &back-upDBOout-ventureDBOsatellitehaulsourcing (partnering)**

DigitalRegion,SouthYorkshire, UK

Local authorities,regionaldevelopmentagency

Public investment inFTTC network, withpartnershiparrangement fornetworkmanagementPublic investment ofEUR38,5 million out ofwhich: EUR 10 millionERDF support, EUR 4.8million in nationalauthority funding andEUR 23,7 million in localand regional authoritiesfunding.Total investment of EUR50,1 million, out ofwhich ERDF support isEUR 42,6 million.Total investment ofEUR 450 millionTotal investment of EUR58,5 million, out ofwhich ERDF support is:EUR 7,9 million.

Total investment of EUR101,9 million, out ofwhich ERDF support is:EUR 37,6 million EUR

( )

Auvergne,France

Local authority(Auvergne EUoffice)

Deployment ofcabinet-based DSLservices to reduceline lengths andprovide basicbroadband

RAIN,Lithuania

Non-profit publicenterprise

Nationwidebackhaul/corenetwork

STOKAB,Sweden

Municipalityowned

City-based FTTHmeshed network

Lombardia,Italy

RegioneLombardia

Planned FTTHinvestment to 50%of homes

Guide to broadband investment | 23

ProjectFTTH FTTC

ManagingAuthorityInvestment valueInfrastructureInvestment model

Summary ofinvestment

Wire- ADSL Core & Bottom- Private PublicJointPublicless &back-upDBOout-ventureDBOsatellitehaulsourcing (partnering)**

Alto Adige,Italy

Bolzano LocalCouncil

Wirelessconnections tohomes; fibreconnections topublic sector andbusinesses

Total investment of EUR6 million, out of whichERDF contribution is:EUR 2.1 million.

*

The interview also considered the successor project to the North Karelia investment,Broadband for all in Eastern and Northern Finland.

**

A number of individual projects were undertaken as part the programme on a similar basis. Individual projects were not discussed separately, instead, the overallapproach was analysed.

*** ( ) refers to examples of partnering that do not fit the strict definition of a Joint Venture, but were felt to align with the philosophy of this investment model.

Guide to broadband investment | 24

3 Why should I invest in broadband?

Define project aims to tackle market failuresand/or deliver socio-economic benefits3.1 IntroductionAs a first stage in the investment planning process, it is essential for a Managing Authority todefine the aims of the broadband investment project. These aims will includewhatthe projectneeds to achieve, andwhy.Once a clear set of aims have been defined these will guide the rest ofthe project (and influence decisions throughout the planning process). A Managing Authorityshould consider the appointment of a ‘champion’ to drive the project aims forward.This section looks at a selection of reasons why a Managing Authority may decide to makebroadband investments, primarily associated with delivering socio-economic benefits (creatingstronger community relationships, supporting regional development, promoting competition andattracting/retaining investment). A Managing Authority may also derive benefit from using thenetwork for its own services (including playing the role ofanchor tenant,which could help tosupport the business case).Above all, it is important for a Managing Authority to be aware that access to affordable broadbandhas a positive effect in terms of meeting the most basic needs of the individuals, communities andbusinesses in a territory. It is important for a Managing Authority to keep these goals in mind, andprioritise the long-term benefit of individuals over short-term gain for private entities.The majority of the example projects which were studied for this guide were considered to be a successby the stakeholders who were interviewed. However, several interviewees, including those for NorthKarelia (Finland) and the Digital Region (UK) project, commented that it was too early to objectivelymeasure the impact of the broadband project on the region’s economy, and also highlighted that it wasdifficult to exclude the effects of the recent economic crisis on such a measurement.The aims of the example broadband projects, and how successfully they were achieved, are set out inAnnex C (which also highlights some of the unexpected benefits that have arisen from these projects).

3.2 Overview of the regional benefits that broadband can provideThe key regional benefits of broadband investment that were identified through our interviews andfurther research are: supporting economic development, minimising the digital divide andimproving social cohesion, as discussed below.

Guide to broadband investment | 25

Supporting economic developmentThroughout our analysis, three main project aims relating to economic development were identified:•

Contribution of broadband to GDP growth and productivity gains.This has been shownin academic work for the World Bank by Christine Qiang23(2009), who demonstrated that a10% increase in basic broadband penetration enlarged GDP growth by an additional 1.21%when looking at 66 high-income countries; and by 1.38% in the remaining 120 low- andmiddle-income countries. In some cases, the aim is to prevent a decline in GDP. For example,the DORSAL project in France “wasmotivated by regional enterprises threatening to leavetheir local premises and move to another region, where telecommunications services would becheaper and have higher quality”.The creation of new jobs or businesses,which may be directly linked to the telecoms sectoror may be from other sectors using the infrastructure that the programme has put in place. Adirect example of this was seen in the Piemonte project in Italy where a developmentprogramme was run by the exchange created through the project. The programme consists ofaround 100 participating enterprises, which are given hardware and resources (such asbandwidth) at a discount, with the successful enterprises being spun off as new independentbusinesses.An increase in consumer surplus,or the amount that consumers pay for a service, comparedto the value they feel they receive from the service outcomes. In the case of broadband, serviceoutcomes can range from quick access to large amounts of information (e.g. learning andhealth services), to access to the world’s largest portal for social and entertainment services.While none of the interviewed projects has measured this gain directly, a paper by ShaneGreenstein and Ryan McDevitt24(2009) showed that the consumer surplus gain generated bybroadband adoption in the USA between 1999 and 2006 was approximately USD7.5 billion.

•

•

In some projects, specific reports were issued that analysed the individual region and linked thepossibility of economic advancement of the region to an increase in broadband capabilities. Forexample, in the Digital Region project in South Yorkshire, UK, a report produced at the start of theproject helped to generate initial interest and buy-in from all the project stakeholders.Minimising the digital divideOne of the more crucial aims of broadband investment projects for rural areas is to minimise the‘digital divide’, a distributional objective25to ensure that all regions within a country enjoy similar23

Qiang, C. Z. and Rossotto, C. M.,Economic Impacts of Broadband, Information and Communications forDevelopment: Extending Reach and Increasing Impact,World Bank (Washington, DC, 2009), pp. 35–50.Greenstein, S. & McDevitt, R. (2009),The Broadband Bonus: Accounting for Broadband Internet’s Impact on USGDP(NBER Working Paper 14758).A distributional objective in this context is the attempt to promote equality of welfare between regions (with acomparison either nationally or internationally), frequently through wealth distribution.

24

25

Guide to broadband investment | 26

levels of digital connectivity. Minimising the digital divide is one of the main targets that the EC’sDirectorate General for Regional Policy (DG REGIO) tries to promote through the distribution ofits available funds. Given the rate of development of broadband in urban areas throughout Europe,these divides are becoming more marked.Below we consider some of the specific situations that can cause a digital divide, and hence theareas where public investment in broadband networks will have the most impact. The situationsdescribed below will make a commercial business plan more challenging, and so discourageinvestment in the area by commercial operators.•

Difficult geographical characteristics.Broadband network development can be restricted bychallenging geographical characteristics, such as the mountainous terrain of an area (ashighlighted in the Piemonte and DORSAL projects) or the sparsity of population (ashighlighted in the South Yorkshire project). These factors greatly increase the cost andfinancial risk of developing broadband services in an area, especially fibre solutions, and sodiscourage commercial investment.Low affluence of an area.A low level of disposable income in a region is likely to reduce thedemand for more expensive (newer) services, and so reduce the potential return on investment.There may be various reasons why a region has a lower affluence level, such as historicaleconomic factors. For example, in South Yorkshire where the Digital Region project issituated, the area suffered from the loss of the two core industries of the region (coal andsteel), and is now classified as an ‘Objective 1’ area by the EU26.Investment inertia.This occurs in regions that are able to provide some financial return, butare often overlooked by a commercial operator in favour of the more obvious investmentopportunities, or lower-risk opportunities available in other regions. This was demonstrated inthe Piemonte region of Italy: the region was suffering from investment inertia and required apublic investment catalyst to inspire confidence, and highlight the potential of the area. Thepublic sector invested in a new core network, a new Internet exchange and new services, andthis attracted investment from the incumbent to upgrade local exchanges.

•

•

If a Managing Authority can use an innovative investment model to fund the deployment ofinfrastructure, so that commercial operators only have to develop a business case for providingservices, then the effects of a digital divide can be minimised. Furthermore, broadband projectscan act as catalysts either to demonstrate demand for broadband in the region (as in the RuralDevelopment Programme in Sweden), or to stimulate a reaction from the market in the region (aswas seen in both Piemonte and the Digital Region projects).

26

An EU Objective 1 region is a region debilitated from any of: low level of investment; higher than averageunemployment rate; lack of services for businesses and individuals; and poor basic infrastructure.

Guide to broadband investment | 27

Improving social cohesionOur research highlighted a number of projects whose aims included strong social drivers. Theseprojects aimed to achieve a range of benefits from the social impact of broadband. A report byUniversity of Siegen (2010) report on the social impact of ICT classified the benefits as follows:•

Provision of e-health services.The ability to access information on healthcare is often listedas a major reason for obtaining access to the Internet. The availability of better health-relatedinformation has led to an improvement in the perception of healthcare in both the USA andCanada. In the Nuenen project in the Netherlands, the initial concept for the project was drivenby a local housing company’s wish to install e-health services, including videocommunications, in new-build homes for the elderly and disabled.Improved contact with community and family.A number of social researchers haveconcluded that the Internet promotes contact with friends and family, and allows people tomaintain contact with people who share similar interests. Indeed in the OnsNet example,recent research demonstrated that the project had helped to promote social cohesion amongmembers of the co-operative.Remote working.Access to ICT enables flexible working practices, in terms of both time andlocation. This provides benefits for both employers and employees (e.g. parents with youngchildren, who may be unable to work away from home, can now join the workforce). Theintroduction of remote working is one way in which the Rural Development Programme inSweden may achieve its objective of promoting entrepreneurship, employment and helping tosustain Sweden’s sparse rural population.Education and lifelong learning.While there is little evidence that e-learning is likely toreplace traditional face-to-face interaction between teaching staff and students, increased ICTpenetration can provide large sections of the community with the opportunity to engage inlong-term, informal learning.Projects can become targets for further research into the effects of broadband on varioussocio-economic factors,as occurred in OnsNet and Midtsoenderjylland, and it can be hopedthat this research will help to inspire and guide future projects. The existence of strong linkswith the local university was highlighted as a key success point in the Midtsoenderjyllandproject, and so by providing universities with access to data for research, a ManagingAuthority may be able to benefit from similar links in future projects.

•

•

•

•

Guide to broadband investment | 28

4 What type of network infrastructure should I invest in?

Understand the costs and benefits ofdifferent kinds of infrastructure4.1 IntroductionThe second stage of the investment planning process is for a Managing Authority to consider thetype of network infrastructure in which it is going to invest. Investing in infrastructure, rather thaninvesting directly in services, will help to ensure that a Managing Authority does not distort themarket, which could be detrimental to end users.The Managing Authority must consider the type of infrastructure along three dimensions: thescope of the network, the performance of the network, and the ability of the network to supportcompetition.4.1.1 Scope of the networkThis section looks at the options available for a Managing Authority to invest in different parts of abroadband network, and the various technologies available for each part.There are two main options for investing in broadband infrastructure:•

The access network,which comprises the connection between the end user and the nearestnetwork node (e.g. local exchange or central office). Various options are available forproviding broadband connections in the access network, depending on the requirements andavailable funding (including existing copper lines, new fibre-optic cables and wirelessnetworks).The backhaul and core network,which provides links between network nodes to allowconnectivity over large distances (e.g. between towns and cities). Because traffic from a largenumber of end users is aggregated as it passes through the backhaul and core networks, fibre-optic cable is often the technology of choice due to its high capacity. High-capacity wirelessmicrowave links are also used.

•

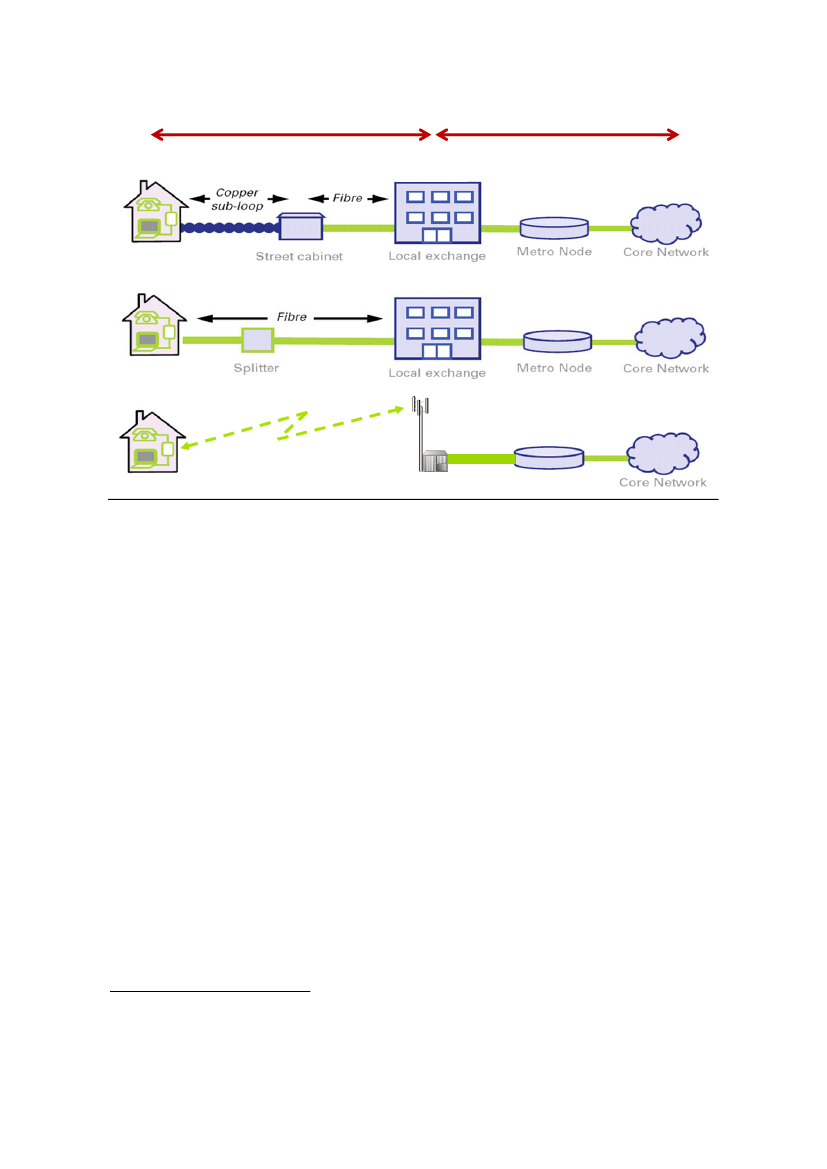

The extent of the access and backhaul/core portions of the network is shown in Figure 4.1 for threeexample NGA technologies.

Guide to broadband investment | 29

Access networkFibre to the cabinet

Backhaul and core network

Fibre to the premises

Terrestrial wireless

Radio base station

Figure 4.1:Extent of access and core/backhaul networks for some NGA technologies [Source:Analysys Mason]

Sections 4.2 and 4.3 examine which of these network components and technologies have beenused in the example projects, to identify different circumstances which lend themselves to aparticular choice.4.1.2 Performance of the networkIt is essential that a Managing Authority has at least a broad understanding of the candidatetechnologies and architectures that can be used to meet its requirements, so that it has anappreciation of the trade-off between cost and performance. Analysys Mason has conductedstudies which are available in the public domain on the cost and capabilities of both wireline27andwireless28technologies.However, EU State aid rules mean that a Managing Authority must specify its networkrequirements in a technology-neutral way. For example, a Managing Authority may specify that abroadband network must provide connections at a certain speed, and be able to be upgraded tosome higher speed over time, but it must not specify which technology is used to deliver thatspeed.2728

Available at http://www.broadbanduk.org/component/option,com_docman/task,doc_details/gid,1036/Available at http://www.broadbanduk.org/component/option,com_docman/task,doc_view/gid,1246/Itemid,63/

Guide to broadband investment | 30

It should be noted that a complementarymixof technologies may be appropriate in a particularregion. While fibre-optic cable usually delivers the highest connection speed, it is expensive todeploy over wide areas, and wireless and satellite technologies are likely to have a role to play inproviding cost-effective wide area coverage.4.1.3 The ability of the network to support competitionAnother important consideration is the impact that technology will have on competition.A condition for granting State aid is the obligation for the aid recipient to provide open wholesaleaccess, regardless of the presence of significant market power. It is generally accepted that if anoperator has access to the passive infrastructure (e.g. copper, dark fibre or underground ducts), itwill have more freedom to develop innovative services, and therefore compete with otheroperators and hopefully deliver lower prices to consumers.Under State aid guidelines29, the access obligations imposed on the infrastructure operator mustinclude access to both passive and active infrastructure level for at least seven years withoutprejudice to any similar regulatory obligations that may be imposed by the national regulatoryauthority (NRA). The subsidised network has to be designed in a way that guarantees that severalalternative operators can have access to the subsidised infrastructure at all levels: the supportedinfrastructure will have to offer sufficient place in the ducts, shall have sufficient dark fibrecapacity, place in the cabinets, and capacity on active access equipment. In the case of NGAnetworks, an argument may be put forward that in low-density areas access to the passive levelwill not result in additional competition since it may be not economically feasible to create analternative network. Therefore the State aid guidelines for broadband require that the new networkshould be opened at as many levels as possible, thus allowing market forces to decide whichaccess products suit them best.It is also essential to ensure that the infrastructure access (at which ever point it is offered) is openand non-discriminatory. This will require the Managing Authority to design wholesalerequirements which ensure that operators can compete effectively, regardless of who actually ownsand operates the network. The design of wholesale requirements is discussed in more detail inSection 9.3.1.Competition considerations will influence the choice between the two main options for providingfibre to the home. A ‘point-to-point’ network provides a dedicated fibre connection to each home.This means that an operator can easily access an end user by connecting to the relevant fibre. Analternative network is a ‘GPON’ architecture, whereby some of the access network is shared like acable network, but each customer has their own connection into their premises. A GPON networkmay involve lower costs than a point-to-point network, but the options for competition are less

29

State aid to broadband: primer and best practices,Filomena Chirico / Norbert Gaál, Directorate-General forCompetition, forthcoming

Guide to broadband investment | 31

straightforward as access to different customers must be managed electronically by the networkoperator30.

4.2 Access network4.2.1 Fibre to the home (FTTH)Fibre to the home (FTTH) involves laying a fibre-optic cable all the way from the central office /local exchange (or suitable local access node, such as a public sector building) to the home. FTTHis the technology with the highest capacity, and therefore provides the highest degree of futureproofing. However, due to the long distances involved in deploying a connection all the way to thehome, the deployment costs of FTTH can be very high. To date, commercial deployments ofFTTH have been limited due to this high cost.There are two main options for an FTTH architecture: GPON and point to point (P2P).GPON networks may require less capital expenditure (CAPEX) to be deployed (in particular inless densely populated, rural areas). Previous studies have shown that the cost of deploying a PTParchitecture is on average between 10-20% more than an equivalent GPON architecture31. The costdifference is higher in rural (less dense) areas than in urban (more dense) areas.However, as discussed above, the benefit of point-to-point networks is that they allow all operatorsto have full use of a fibre between the local exchange and the end user, hence allow fullunbundling, thus they tend to be viewed more favourably from a competition point of view. Stateaid policy (see section 9.4) also emphasizes that pro-competitive broadband architectures willresult in "lower prices and higher level of services for end user" which in turn can help to deliverbetter penetration rates in areas affected by cohesion problems.In contrast, the primary method of competition on GPON networks is via an electronic interface,which may restrict the level of control that an alternative service provider has over its services.The use of wavelength unbundling on PON networks may in the future offer a similar level ofcontrol as a dedicated fibre on a P2P network, but at the time of writing of this guide, thistechnology was still being standardised.Point-to-point networks may also be better suited to providing symmetric services and are able toprovide higher capacities to the end-users hence they are considered to be more future proofsolutions, particularly taking in the prospect of both households and businesses moving graduallytowards cloud-computing.30

It is often stated that point to point readily allows for passive (infrastructure-level) access whereas GPON readilyallows for active (service-level) access. As GPON technology evolves over time this distinction is likely to becomeless clear as access to individual wavelengths becomes viable.Pleaseseehttp://www.broadbanduk.org/component/option,com_docman/task,doc_view/gid,1036/,andhttp://www.vodafone.com/content/dam/vodafone/about/public_policy/position_papers/vodafone_report_final_wkconsult.pdf.

31

Guide to broadband investment | 32

It should be strongly emphasized that, in the case of both architectures, the cost of deployment tothe managing authority is much more dependent on the ability to re-use existing infrastructure andthe model of investment than on the choice of technology. This issue is discussed in more detail inSection 8. Furthermore, the sustainability of the project (and therefore the ability to deliver longterm socio-economic benefits) is more dependent on the choice of business model and theexpertise of project partners, than the choice of technology.In terms of the projects reviewed in the development of the guide, those projects which havealready deployed FTTH infrastructure have used PTP architecture. Project interviewees gave avariety of reasons for choosing PTP infrastructure, including the ability to support high speedconnections, the ability to provide symmetric services, the more future proof nature of PTP and theability to more easily support competition from multiple service providers. One project (which wasstill in the planning phase) was considering the use of GPON, due to this technology being thefavoured technology of the incumbent, who was involved in the project.A number of the example public projects researched for this guide have featured investments inFTTH in the access network. The example projects which deployed FTTH were as follows:••••••

OnsNet, Nuenen, Netherlands:for delivery of new video-based e-health servicesRural Development Programme, Sweden:to help meet a national target to provide100Mbit/s broadband to 90% of homesMidtsoenderjylland, Denmark:FTTH infrastructure was deemed important for economicdevelopmenteRegio, North Karelia, Finland:to help meet a national target to provide 100Mbit/sconnectivitySTOKAB, Sweden:FTTH was chosen as the most future-proof technologyLombardia, Italy:different FTTH architectures will be deployed (GPON and P2P),influenced by the preferences of both the incumbent and alternative operators.

Further details of these examples of FTTH deployment can be found in Annex D.4.2.2 Fibre to the cabinet (FTTC)Fibre to the cabinet (FTTC) involves laying fibre from the central office (or local exchange) to astreet cabinet or basement of an apartment block. Because the fibre is only laid for some portion ofthe distance to the home, significant cost savings can be realised relative to FTTH. However, asthe copper network is used for the last part of the connection to the home, the speeds available onan FTTC network are also significantly lower than with FTTH (around 80% in terms of the cost toconnect a home). As with FTTH technologies, the cost is strongly affected by the ability to reuseexisting infrastructure.We observed two examples of projects that featured FTTC infrastructure:

Guide to broadband investment | 33

••

Digital Region, South Yorkshire, UK:FTTC infrastructure was chosen for its ability todeliver significant increases in connection speeds, without the high cost of FTTHAuvergne, France:FTTC infrastructure was used to provide basic broadband, as there werestill a number of houses that were some distance from the cabinet.

Further details of these projects can be found in Annex D.4.2.3 Terrestrial wireless and satelliteTerrestrial wireless technologiesprovide a link between the home and the nearest network nodewithout the need for a physical wireline connection. Terrestrial wireless networks arecomplementary to fixed networks, and can be advantageous in areas where the installation of awireline network is difficult and/or expensive (e.g. in mountainous terrain). However, becauseseveral users access the network via the same last-mile link (i.e. the wireless link), thecontention32for services can be much higher than on wireline networks, and the realised speed may be muchlower than the maximum speed quoted by the service provider. In order to ensure an end userreceives anassuredlevel of service more base stations will have to be added, which will increasecosts. It should also be noted that demand for high-speed rates from a large number of users on awireless network tend to require additional investment in the fixed infrastructure that supports thewireless network.Satellite networksoffer a useful solution for areas that are not covered by terrestrial networks(either wireline or wireless), e.g. where the existing networks have left ‘not-spots’. Satellitetechnologies can contribute to reaching the Digital Agenda’s target of 100% coverage by 2013. Aswith terrestrial wireless technologies, many users are accessing the same node (i.e. the satellitetransponder) and so the effects of contention may have a greater impact than on fibre networks.Wireless technologies which could provide effective next-generation broadband services includeterrestrial wireless broadband technologies such as the 3GPP LTE-advanced or IEEE 802.16mWiMAX standards, and high-capacity satellites, using Ka-band multi-spotbeam technology.The costs of terrestrial wireless technologies vary according to a number of factors, including theterrain over which they are deployed, the data rate that must be delivered at the furthest point fromthe base station and the overall traffic demand. Indeed, for both terrestrial wireless and satelliteaccess technologies, the cost of deployment depends very heavily on the traffic demand to besupported. This is in contrast to the fibre technologies, for which costs do not vary as strongly withtraffic demand.Three of the example projects included wireless and satellite networks to complement the fixedinfrastructure. In these projects, terrestrial networks were used to cover most of the more rural32