Transportudvalget 2011-12

TRU Alm.del Bilag 232

Offentligt

18 Jan 2012

European Aviation Safety AgencyCOMMENTRESPONSEDOCUMENT(CRD)

CRDTONPA 2010-14RMT.0322 (FORMER OPS.055)Draft Opinion of the European Aviation Safety Agencyfor a Commission Regulation establishing the Implementing Ruleson flight and duty time limitations and rest requirementsfor commercial air transport (CAT) with aeroplanesanddraft Decision of the Executive Director of the European Aviation Safety Agencyon Acceptable Means of Compliance and Guidance Material related tothe Implementing Rules on flight and duty time limitations and rest requirementsfor commercial air transport (CAT) with aeroplanes

‘Implementing Rules and Certification Specificationson flight and duty time limitations and rest requirementsfor commercial air transport (CAT) with aeroplanes’

R.F010-02 � European Aviation Safety Agency, 2012. All rights reserved. Proprietary document.

CRD 2010-14EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

18 Jan 2012

This Comment Response Document (CRD) provides updated draft rule documents andresponses to comments received on the NPA 2010-14 on flight and duty time limitations andrest requirements for commercial air transport (CAT) with aeroplanes.The objective of task OPS.055, as required by the legislator, was to update the flight and dutytime limitations and rest requirements (FTL) for CAT with aeroplanes taking into accountrecent scientific and medical evidence. To fulfil this objective:the flight and duty time limitations and rest requirements specified in EU-OPS1Subpart Qhave been reviewed;the provisions for areas in EU-OPS Subpart Q currently subject to national provisions inaccordance with Article 8.4 of Regulation (EC) No 1899/2006 (e.g. extended flight dutyperiods with augmented flight crew, split duty, time zone crossing, reduced rest andstandby) have been suggested; andthe use and role of fatigue risk management (FRM) and individual flight time specificationschemes have been considered.

The Review Group which was set up to give expert advice to the European Aviation SafetyAgency (hereafter referred to as the ‘Agency’) on this task met seven times during thecomment review process to discuss the comments received on the NPA. The Agency alsocontracted three independent scientists to provide scientific input on the questions raised inthe NPA and on a number of additional questions agreed upon with the Review Groupmembers. Furthermore, a special meeting with the Advisory Group of National Authorities(AGNA) was convened in accordance with Article 7 of the Rulemaking Procedure2.The Agency has included in this CRD all existing Subpart Q FTL requirements as ImplementingRules (IRs). The changes to Subpart Q have been minimal and limited to issues wherescientific evidence had identified a clear need for safety improvement.As a result of the analysis of more than 49 000 comments received on the NPA, theconsultation of the Review Group, the scientists’ reports and the conclusions from the ad hocAGNA meeting, the following changes to the initial proposals of the NPA are proposed:Unlike in the NPA, the CRD proposes Certification Specifications (CSs) for all theelements that were at the discretion of the Member States under EU-OPS (the so-calledArticle 8 provisions).The maximum daily flight duty period (FDP) for the most unfavourable starting times hasbeen limited to 11 hours.A far more comprehensive set of rules addressing the effect of significant time zonecrossing.The NPA’s Guidance Material recommending spreading out duty periods evenly byincluding a cumulative duty limit for any 14 consecutive days has been upgraded and abinding limit of 110 hours in any 14 consecutive days has been introduced.Provisions to mitigate cumulative fatigue due to disruptive schedules have been added.Annex III to Commission Regulation (EC) No 859/2008 of 20 August 2008 amending CouncilRegulation (EEC) No 3922/91 as regards common technical requirements and administrativeprocedures applicable to commercial transportation by aeroplane.Management Board Decision concerning the procedure to be applied by the Agency for the issuing ofopinions, certification specifications and guidance material (‘Rulemaking Procedure’), EASA MB 08-2007, 13.6.2007.

1

2

R.F010-02 � European Aviation Safety Agency, 2012. All rights reserved. Proprietary document.

Page 2 of 103

CRD 2010-14

18 Jan 2012

An additional type of standby — the so-called ‘long-call standby’ — has been introduced.To cater for unforeseen circumstances in actual flight operations arising before crewmembers have reported for duty, requirements for ‘delayed reporting’ are replacing theinitially proposed rules for ‘short-term re-planning’.The requirements for the extensionrefined. The rules for the extensionbeen simplified; the time needed asFDP is now simply a function of theplanned extended FDP.of an FDP due to augmented flight crew have beenof an FDP due to in-flight rest for cabin crew havein-flight rest for cabin crew to achieve the extendedtype of in-flight rest facility and the duration of the

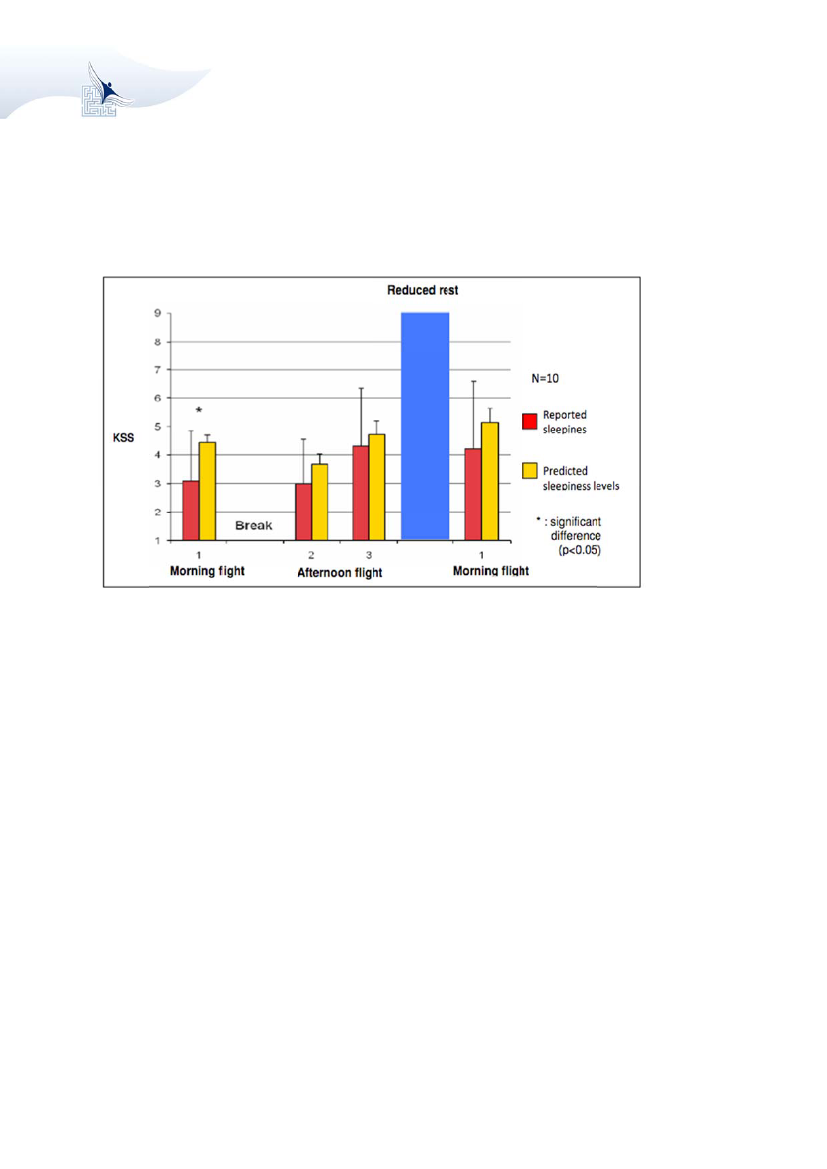

Specific rules concerning home base are addressed in a CS. Initially the proposed ruleforesees that the home base is a single airport location; however, deviation from the ruleis permitted under Article 22.2 of the Basic Regulation3.Finally, reduced rest provisions have been tightened. The CRD proposal mirrors thecurrent national practice of several Member States. Since the provisions are reflected in aCS, deviation will be possible under Article 22.2 of the Basic Regulation.

The Explanatory Note provides detailed information explaining the proposals as a support topotential commentators. Therefore, it should be read before placing reactions.

3

Regulation (EC) No 216/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 February 2008 oncommon rules in the field of civil aviation and establishing a European Aviation Safety Agency, andrepealing Council Directive 91/670/EEC, Regulation (EC) No 1592/2002 and Directive 2004/36/EC(OJ L 79, 19.3.2008, p.1), as last amended by Commission Regulation (EC) 1108/2009 of theEuropean Parliament and of the Council of 21 October 2009 (OJ L 309, 24.11.2009, p. 51).

R.F010-02 � European Aviation Safety Agency, 2012. All rights reserved. Proprietary document.

Page 3 of 103

CRD 2010-14TABLE OF CONTENTSA.EXPLANATORY NOTEI.II.III.IV.V.B.I.II.INTRODUCTIONSCOPEUPDATE ON THE PROCESSOVERVIEW OF THE CHANGES PROPOSEDHOW TO SUBMIT REACTIONS

18 Jan 2012

556686970717373848485

PROPOSED RULEDRAFT OPINION — DRAFT COVER REGULATION TO REGULATION ON AIROPERATIONSANNEX III, PART-ORO (ORGANISATION REQUIREMENTS)SUBPART— FLIGHT AND DUTY TIME LIMITATIONS AND REST REQUIREMENTS

III. DRAFT OPINION — ANNEX II, PART-ARO (AUTHORITY REQUIREMENTS)SUBPART OPS — AIR OPERATIONSIV.V.DRAFT DECISION — CERTIFICATION SPECIFICATIONS, FLIGHT TIMESPECIFICATION SCHEMES

DRAFT DECISION — ACCEPTABLE MEANS OF COMPLIANCE (AMC) ANDGUIDANCE MATERIAL (GM) TO PART ORGANISATION REQUIREMENTS (PART-ORO)91SECTIONVIII — FLIGHT AND DUTY TIME LIMITATIONS AND REST REQUIREMENTS9197103103103103

VI. EU/JAR-OPS REFERENCE — EASA REFERENCEC.APPENDIXI.II.III.COMMENTATORSCOMMENTS RECEIVEDSCIENTISTS’ REPORTS

R.F010-02 � European Aviation Safety Agency, 2012. All rights reserved. Proprietary document.

Page 4 of 103

CRD 2010-14

18 Jan 2012

A.I.1.

Explanatory NoteIntroductionThis CRD contains a summary of the comments received on the Notice of ProposedAmendment (NPA) 2010-14 on flight and duty time Limitations and rest requirements forcommercial air transport (CAT) with aeroplanes, which was published on 20 December2010. This CRD also contains a revised rule text and an overview of the proposedchanges.The text of this CRD has been developed by the Agency, based on the commentsreceived on the NPA, on the input of the OPS.055 Review Group and on the reports fromthree independent scientists4. It is submitted for consultation of all interested parties inaccordance with Article 52 of the Basic Regulation and Articles 5(3) and 6 of theRulemaking Procedure.When developing rules, the Agency is bound to follow a structured process as required byArticle 52(1) of the Basic Regulation. Such process has been adopted by the Agency’sManagement Board and is referred to as the ‘Rulemaking Procedure’.The purpose of this Comment Response Document (CRD) is to develop an Opinion on theImplementing Rules on flight and duty time limitations and rest requirements forcommercial air transport (CAT) with aeroplanes as well as a Decision on the relatedCertification Specifications (CSs), Acceptable Means of Compliance (AMC) and GuidanceMaterial (GM). The scope of this rulemaking activity is outlined in the Terms of Reference(ToR) of rulemaking task OPS.0555, which is included in the Agency’s 2010–2013Rulemaking Programme.The Agency is directly involved in the rule-shaping process. It assists the Commission inits executive tasks by preparing draft regulations, and amendments thereof, for theimplementation of the Basic Regulation which are adopted as ‘Opinions’ [Article 19(1)]. Italso adopts Certification Specifications, including Airworthiness Codes and AcceptableMeans of Compliance and Guidance Material to be used in the certification process [Article19(2)].A Review Group of National Aviation Authorities (NAAs), airline, flight and cabin crewrepresentatives supported the Agency in the review of the comments and in thepreparation of the CRD. This Group was chaired by an independent advisor and includedan observer from the European Commission. It met seven times during the period fromApril to November 2011. During these meetings the Review Group discussed thecomments received on the NPA and the proposed changes to the rule.With a view to receiving scientific input on the NPA 2010-14, the Agency issued a call fortender and contracted three independent scientists who provided three scientific reportson the questions raised in the Explanatory Note of the NPA and on an additional set ofquestions that had been prepared by the Review Group. The three scientists and theReview Group convened a 3-day meeting in May 2011 where the draft scientific reports(that had previously been sent to all Review Group members) and the scientists’ answersto the questions where discussed in detail. Following these discussions, the threescientists submitted their final reports in late September 2011.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

45

The reports from the three independent scientists are annexed to this CRD in section C.II.http://www.easa.eu.int/rulemaking/docs/tor/ops/EASA-ToR-OPS.055(a)_OPS.055(b)-00-20112009.pdf

R.F010-02 � European Aviation Safety Agency, 2012. All rights reserved. Proprietary document.

Page 5 of 103

CRD 2010-148.

18 Jan 2012

The Agency has taken due account of the scientists’ advice contained in their reports.The scientists’ advice is separately listed in each of the comment summaries for each ofthe key topics of Section IV of this CRD.Due to the large number of comments received, this CRD does not follow the traditionalformat: it was not technically possible to generate a CRD using the Agency’s CommentResponse Tool (CRT). Therefore, the Agency used the alternative method for processingall comments posted via the CRT: this CRD does not contain a response to each of thecomments that have been sent to the Agency. Comments have been grouped accordingto subject together with a response to the grouped comments in Section IV of this CRD. Acopy of the individual comments and a list of the commentators are provided in SectionC.II and C.III of this document.

9.

II. Scope10.This CRD includes a proposal for Implementing Rules (IRs), Certification Specifications(CSs), Acceptable Means of Compliance (AMC) and Guidance Material (GM) on flight andduty time limitations and rest requirements for commercial air transport operations byaeroplanes other than air taxi, emergency medical service (EMS) and single pilotoperations. The FTL requirements in general are the same for flight and cabin crew withfew marginal differences.Today’s FTL requirements for commercial transportation by aeroplane are laid down inSubpart Q of EU-OPS6. They are the result of long-lasting negotiations based onoperational experience of former national legislation. Therefore, the European Parliamentand the Council when adopting Regulation (EC) No 1899/2006 specifically requested theAgency to conduct a scientific and medical evaluation of Subpart Q [ref.: Regulation (EC)No 3922/91, new Article 8(a)] and to assist the Commission in the preparation ofregulatory proposals, if required:‘By 16 January 2009, the European Aviation Safety Agency shall conclude a scientific andmedical evaluation of the provisions of Subpart Q and, where relevant, of Subpart O ofAnnex III. Without prejudice to Article 7 of Regulation (EC) No 1592/2002 of theEuropean Parliament and of the Council of 15 July 2002 on common rules in the field ofcivil aviation and establishing a European Aviation Safety Agency, the European AviationSafety Agency shall assist the Commission in the preparation of proposals for themodification of the applicable technical provisions of Subpart O and Subpart Q of AnnexIII.’

11.

III. Update on the process12.The related Notice of Proposed Amendment (NPA) 2010-14, dated 20 December 2010,was open for a 3-month public consultation. By the closing date 20 March 2011, theAgency had received 49 819 comments from 2 715 individuals and organisations,including National Aviation Authorities (NAAs), professional organisations and privatecompanies.46 957 comments out of the total 49 819 comments were placed by individuals. Of thoseindividual comments some 98.6 % (i.e. 46 340 comments) originated from individualcommentators who had identified themselves as crew members in airlines operatingAnnex III of Commission Regulation (EC) No 859/2008 of 20 August 2008 amending CouncilRegulation (EEC) No 3922/91 as regards common technical requirements and administrativeprocedures applicable to commercial transportation by aeroplane.

13.

6

R.F010-02 � European Aviation Safety Agency, 2012. All rights reserved. Proprietary document.

Page 6 of 103

CRD 2010-14

18 Jan 2012

under CAP 3717, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland’s (UK) flightand duty time and rest requirements. Of all individual comments 98.0 % (46 057individual comments) were duplicates or near duplicates and an important number ofcomments was either assigned several times or to paragraphs not corresponding to thecomment.14.Next to the comments from individuals, 1 518 comments were placed by 28 creworganisations, 748 comments by 30 individual operators, 199 comments by 9 operatororganisations and 397 comments by 12 NAAs.All comments received on the NPA 2010-14 were reviewed, analysed for their relevancewith regard to the proposed changes and summarised per rule paragraph. Due to theunprecedented high number of comments received, the Agency acquired an electronictext analysis toolkit designed by the University of Massachusetts for government agenciesto deal with large amounts of comments on legislative proposals. This tool was used toidentify duplicate comments and near duplicate comments and to sort commentsaccording to the relevant paragraph. Comment summaries, related responses tosummarised comments and the proposed revised rule text were discussed with theReview Group. The composition of the Review Group was based on the composition of theinitial Rulemaking Group as regards the distribution of group members from differentstakeholder groups. Group members that had resigned during the review phase werereplaced following the rules of procedure for the membership of rulemaking groups.Seven meetings of the Review Group took place on the following dates:16.18 and 19 April 2010;17, 18 and 19 May 2010;7 and 8 June;14 and 15 September 2010;19 and 20 October 2010;9 and 10 November 2010; and29 November 2010.

15.

A special meeting of the Advisory Group of National Authorities (AGNA) was convened inaccordance with Article 7 of the Rulemaking Procedure on 24 October 2010 because someNAAs had expressed concerns in their comments regarding the NPA proposals on themaximum daily flight duty period (FDP) during night hours, the need for an additional 14-day duty limit, the need for additional provisions to compensate the effects of disruptiveduty patterns, and on reduced rest provisions.During this meeting representatives of National Aviation Authorities provided guidance tothe Agency on the following 12 questions:The maximum allowable daily flight duty period (FDP) at the most favourable timeof the day.The maximum allowable daily FDP at night.The need to keep the 1-hour extension versus its integration into the basicmaximum FDP.The reduction of the maximum allowable daily FDP for more than 6 sectors (beyondSubpart Q).The impact of the window of circadian low (WOCL) on the extension due to in-flightrest.The impact of the number of sectors on the extension due to in-flight rest.The possibility of using economy seats for in-flight rest.

17.

7

CAP 371 The Avoidance of Fatigue In Aircrews, Guide to Requirements.

R.F010-02 � European Aviation Safety Agency, 2012. All rights reserved. Proprietary document.

Page 7 of 103

CRD 2010-14

18 Jan 2012

The need to put an additional cumulative duty limit every 14 days to mitigatecumulative fatigue.The need for extended recovery rest periods to compensate for irregular patterns ofwork.The added value of reduced rest provisions as compared to split duty.The maximum duration of home standby and related mitigating measures.How to best integrate the need for operational flexibility in this proposal.

IV. Overview of the changes proposed18.The responses to the comments were drafted by the Agency after consultation with theReview Group. The following paragraphs provide a summary of the comments andconclusions regarding the main topics that have been identified in the consultationprocess. All changes resulting from these main topics as well as from the other commentsare provided in Section B, which includes the newly proposed rule. Given the largenumber of comments, Section C of this CRD refers to the link placed on the Agency’swebsite which includes a document of all the comments placed. Section C also providesan overview of the commentators who placed their comments in the Comment ResponseTool (CRT).Implementing Rules and Certification Specifications19.20.In the proposal of this CRD the Agency has included all the elements of the existing FTLrequirements under Subpart Q as Implementing Rules (IRs).The changes to Subpart Q have been minimal. The Agency proposed changes only tothose parts of Subpart Q where scientific evidence has identified a clear need for safetyimprovement.Subpart Q of EU-OPS did not harmonise all FTL provisions. Some elements of Subpart Qare currently left by Article 8(4) of EU-OPS to the national legislator ‘until Communityrules based on scientific knowledge and best practices are established’, therefore leadingto different national legal provisions across Europe. Unlike in the NPA, the Agency in thisCRD proposes Certification Specifications (CSs) for all elements that were governed bynational rules under EU-OPS. Therefore, the proposed rule for ‘standby other than airportstandby’ and the definition of the relationship between airport standby and the assignedflight duty, split duty, additional rest to compensate for time zone differences, reducedrest and the extension of flight duty period due to in-flight rest foresees CertificationSpecifications (CSs) and is inspired by existing national rules, operational experience andscientific principles.Since both Implementing Rules (IRs) and Certification Specifications (CSs) have to becomplied with in their entirety, the proposed rule structure promotes a level playing field.Both the IRs and CSs will be the basis of operators’ FTL schemes. In those cases wherethe operator can demonstrate an equivalent level of safety, and provided that the requestfor individual flight time specification scheme proposed by the operator has beenendorsed by its competent authority and has passed the Agency’s technical assessmentbased on a scientific and medical assessment, the CS provides for ‘controlled flexibility’.This process is described in detail in Article 22 point 2 of the Basic Regulation.This CRD foresees the CS approach in those areas where European harmonisation did notexist previously and where national rules differ widely. The prescriptive limit contained ina CS must always contain a reference to an Implementing Rule. This approach ensuresfor the first time a harmonised rule in those areas that were previously governedexclusively by national rules.The CS approach is the result of the discussions of the Review Group and is in principlesupported by the majority of the group members, including those representing NationalAviation Authorities (NAAs).Page 8 of 103

21.

22.

23.

24.

R.F010-02 � European Aviation Safety Agency, 2012. All rights reserved. Proprietary document.

CRD 2010-14Rule structure25.

18 Jan 2012

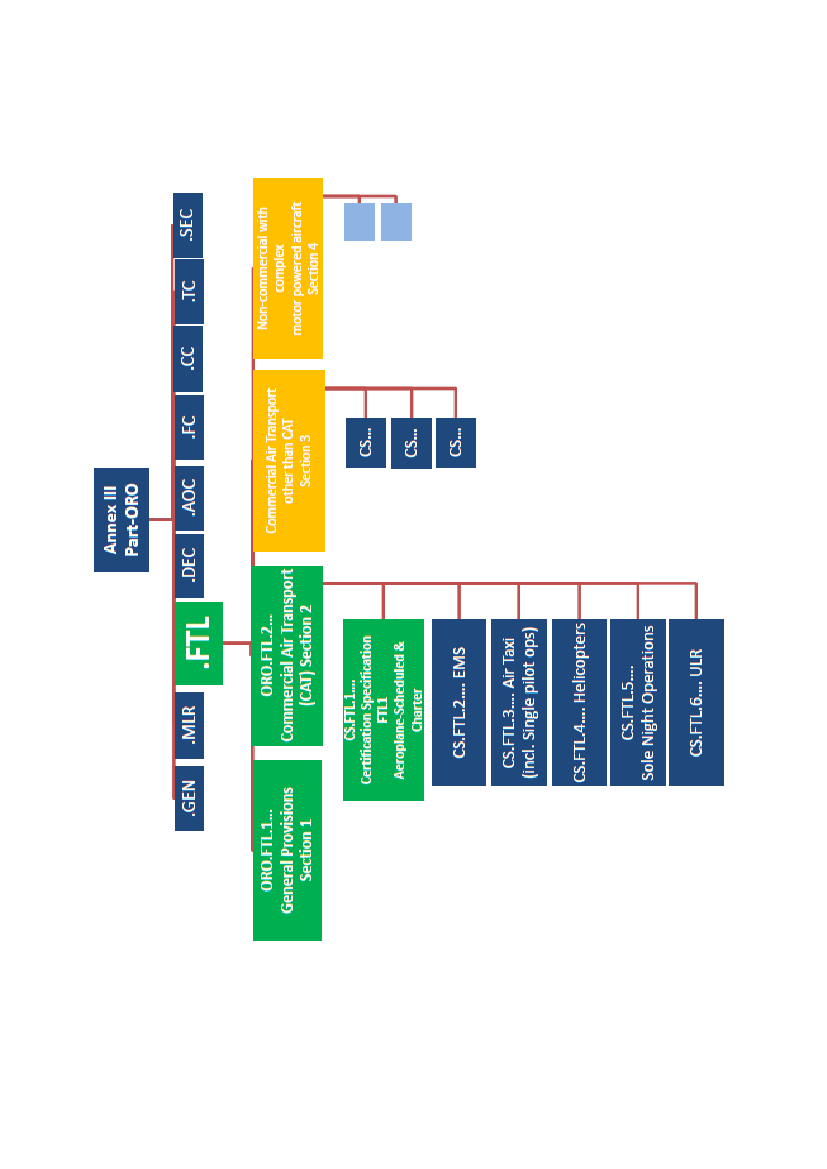

All Organisation Requirements for Air Operations (Part-ORO) are contained in Annex IIIto the Regulation on Air Operations8. Annex III contains a subpart on flight and duty timelimitations and rest requirements (Subpart-FTL).Subpart-FTL, Section 1 of Annex III (Part-ORO) includes general provisions applicable toall commercial operators as well as non-commercial operators with complex motor-powered aircraft. It includes a definition section, addresses general operators’responsibilities and includes provisions on fatigue risk management.Subpart-FTL, Section 2 of Annex III (Part-ORO) includes general provisions applicable tocommercial air transport (CAT) operators with all aircraft types. It addresses in particulargeneral requirements on home base, flight duty period, flight times and duty periods,positioning duty, split duty, standby duty, rest periods, nutrition and records.Certification Specification (CS) FTL 1 contains specific flight and duty time limitations andrest requirements for commercial air transport by aeroplane — scheduled and charteroperations. It includes the prescriptive details of the requirements contained in Section 2and covers the requirements for the so-called ‘Article 8’ provisions.The structure of the AMC and GM follows the structure of the IR; additional AMC and GMare proposed for CS-FTL 1.It is important to note that Subpart-FTL, Section 2, as well as the CertificationSpecification FTL 1 does not apply to the following CAT operations:a.b.c.air taxi operations meaning non-scheduled on demand commercial operations withan aeroplane with a passenger seating configuration of 19 or less;emergency medical service operations;single pilot operations and helicopter operations.

26.

27.

28.

29.30.

These operations are therefore exempted from the proposed rules. Until the relatedImplementing Rules are adopted for such operations, Subpart Q of EU-OPS, the relatednational exemptions, as well as the Member States’ national requirements will apply.31.Additional rulemaking tasks will address detailed requirements for:a.b.c.32.emergency medical services — RMT.0346 [former OPS.071(a)];air taxi (including single pilot operations) — RMT.0429 [former OPS.071(b)]; andcommercial airOPS.071(c)].transportoperationswithhelicopter—RMT.0430[former

Further rulemaking tasks for Sole Night Operations and Ultra Long Range Operations(ULR) will follow.

8

Opinion No 04/2011 of the European Aviation Safety Agency of 1 June 2011 for a CommissionRegulation establishing Implementing Rules for Air Operations.

R.F010-02 � European Aviation Safety Agency, 2012. All rights reserved. Proprietary document.

Page 9 of 103

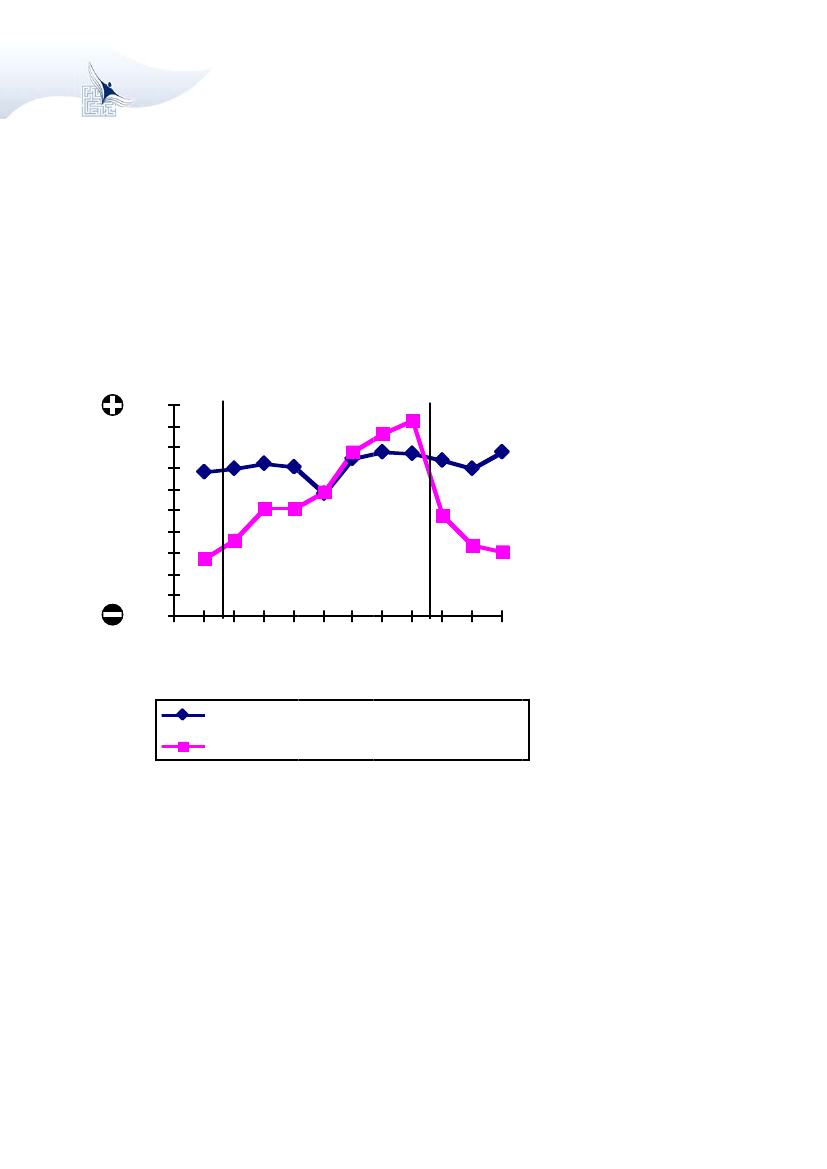

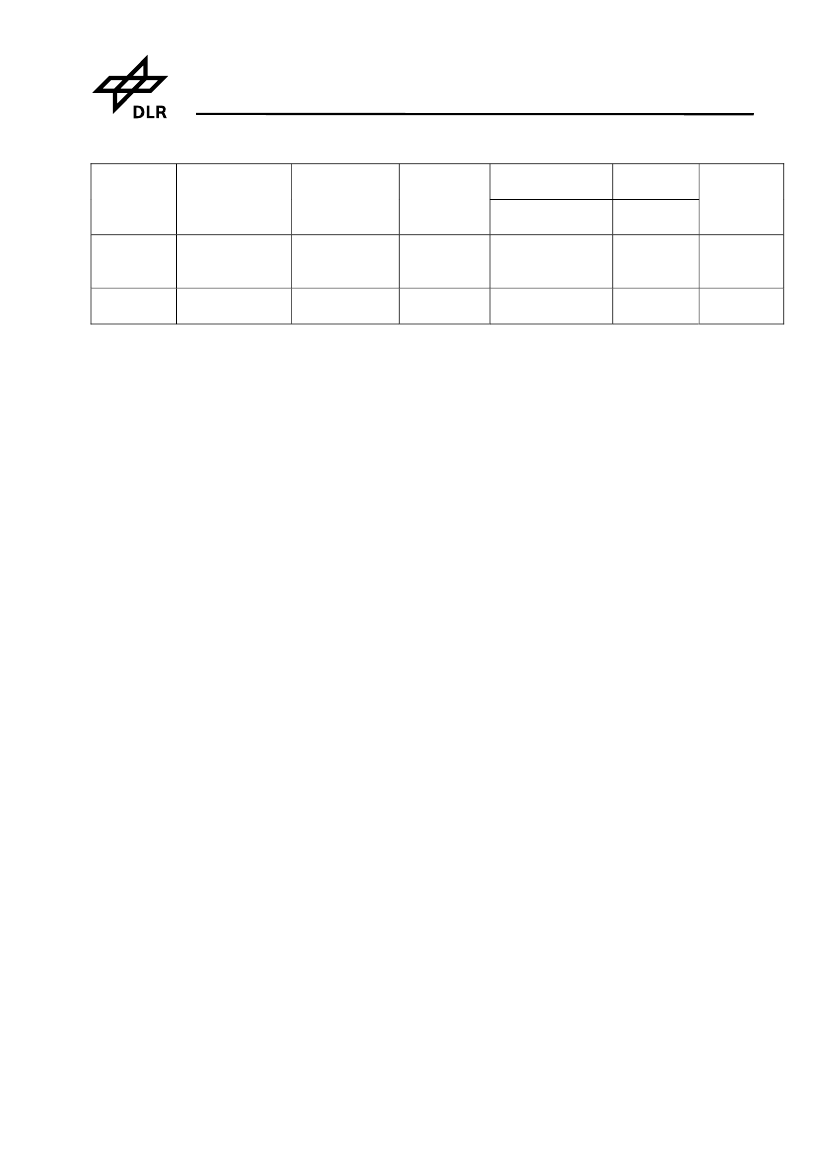

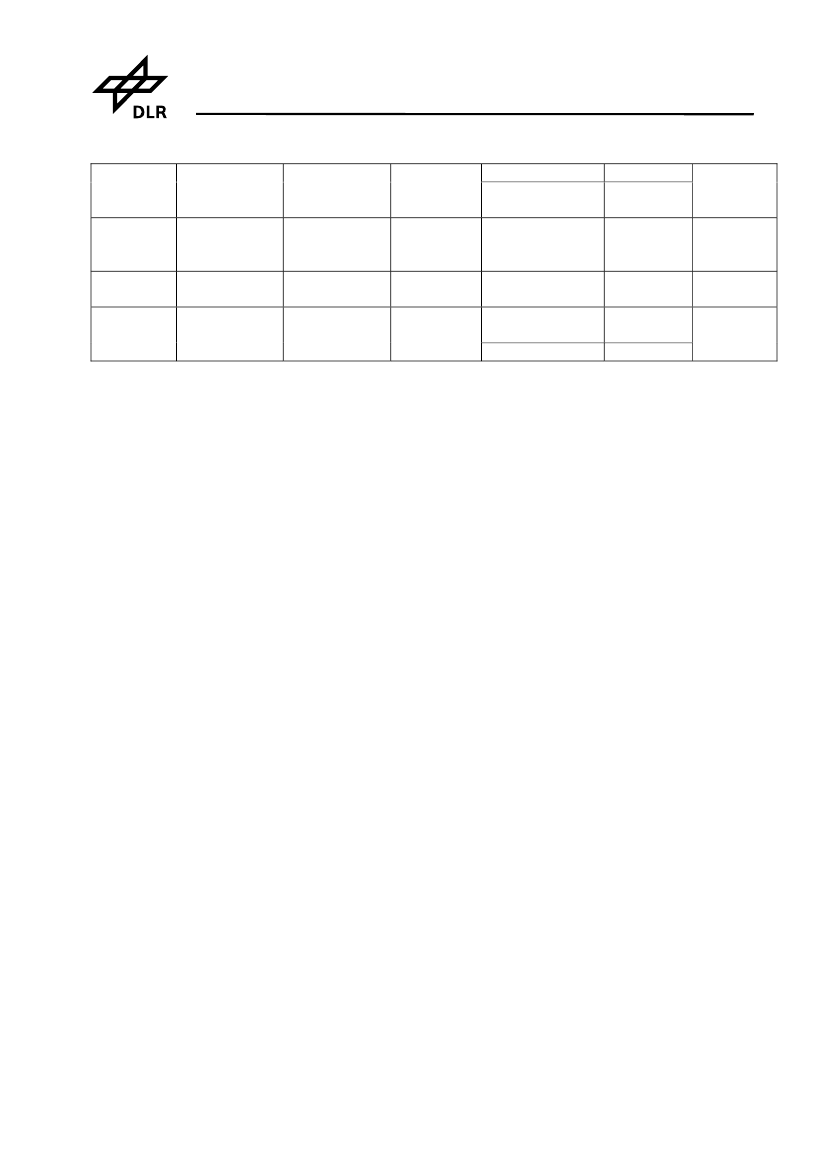

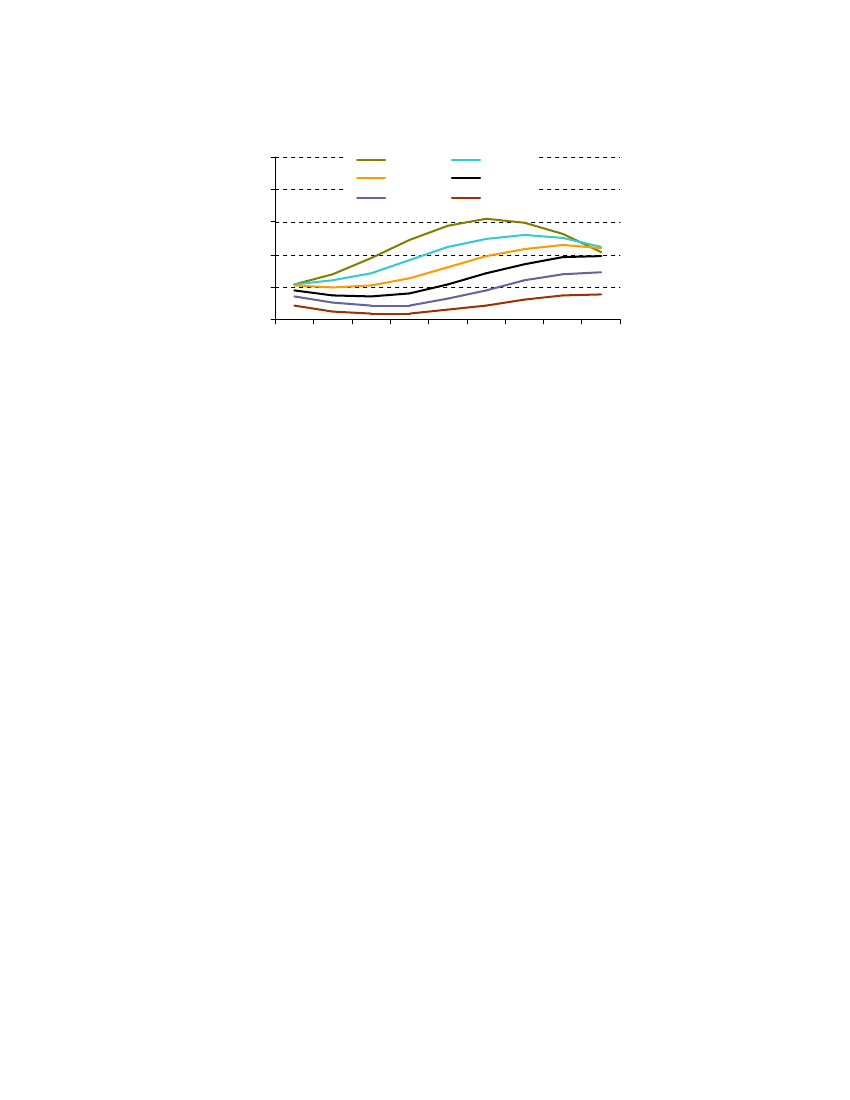

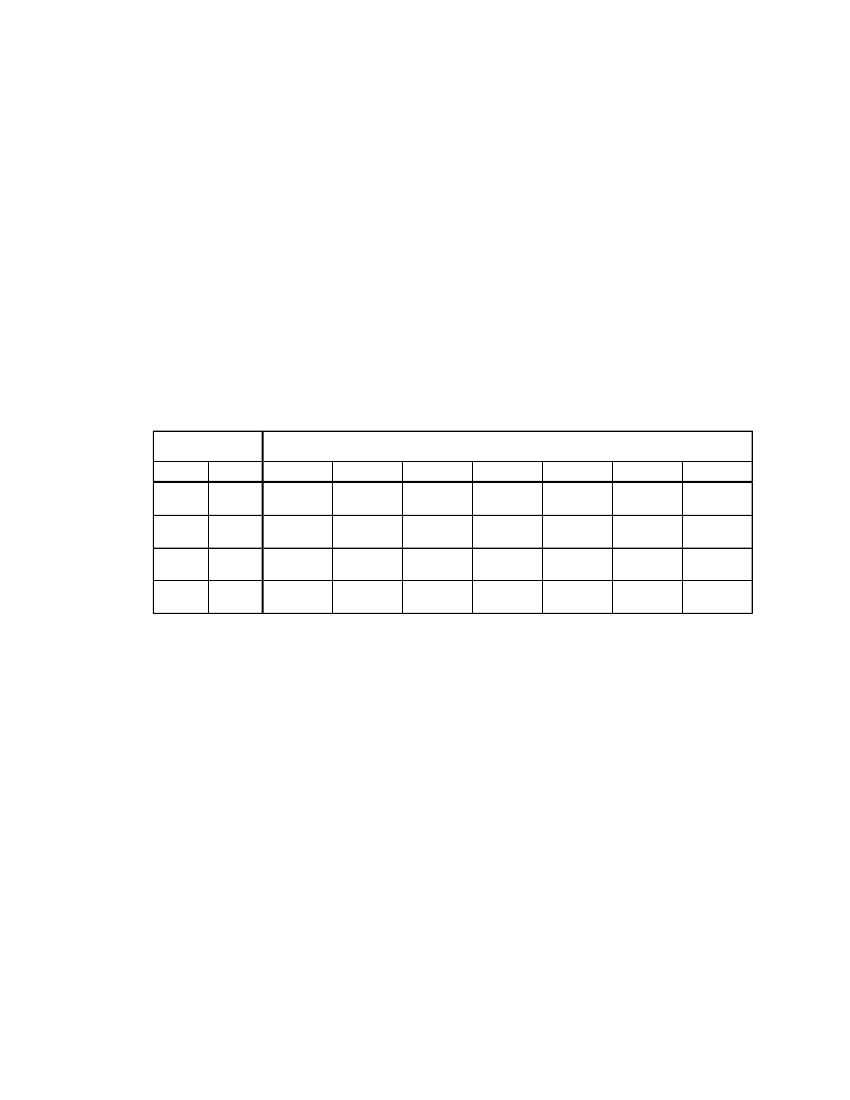

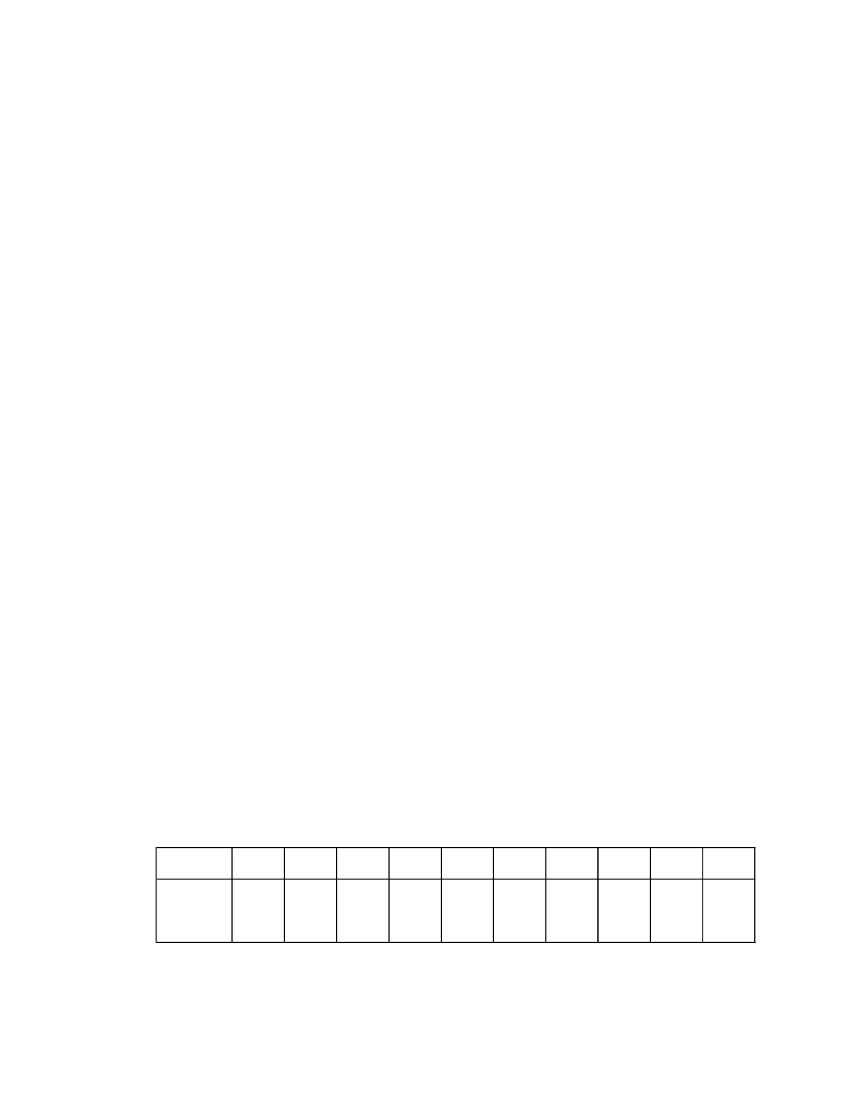

CRD 2010-14Table I.1: Overview of the rule structure ‘Regulation on Air Operations’

18 Jan 2012

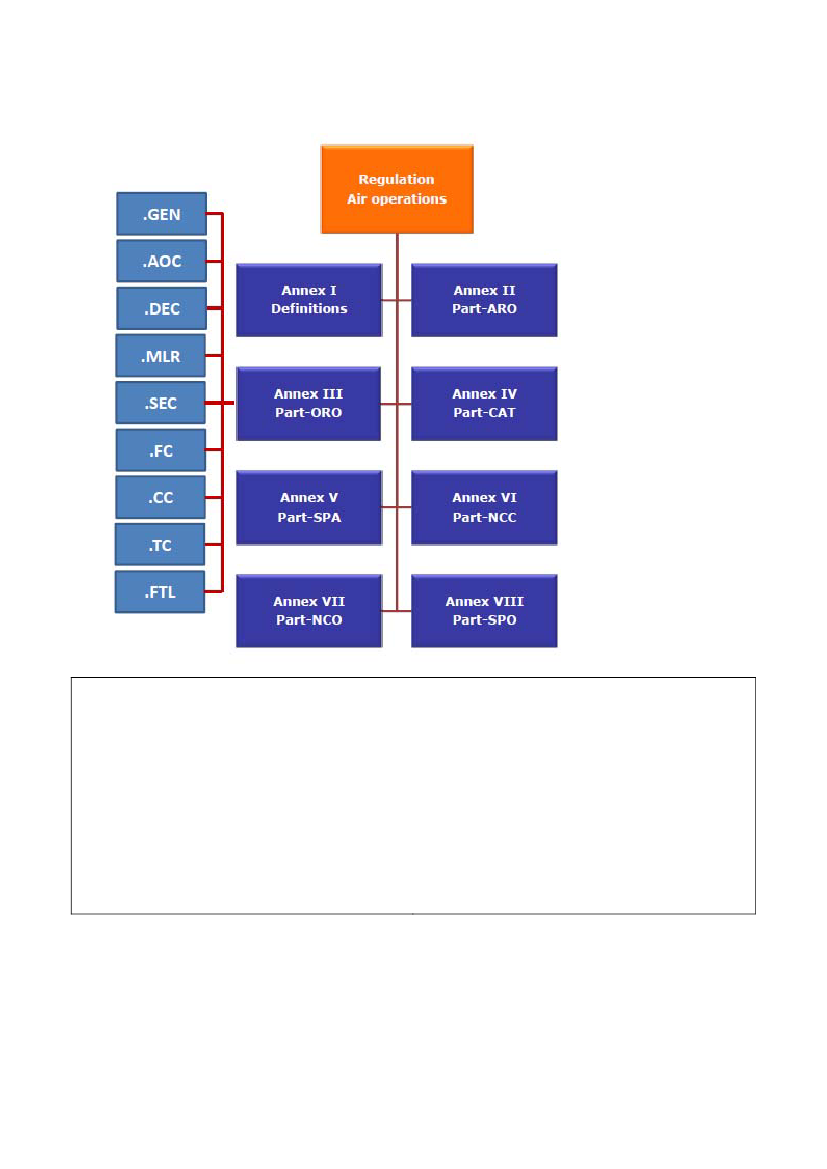

.GEN: General requirements.AOC: Air operator certification.DEC: Declaration.MLR: Manuals, logs and records.SEC: Security.FC:.TC:Flight crewTechnical crew in HEMS, HHO or NVIS.CCC: Cabin crew.FTL: Flight and duty time limitations and restrequirements

Part-ARO: Authority requirementsPart-ORO: Organisations requirementsPart-CAT: Commercial Air TransportoperationsPart-SPA: Operations requiring specificapprovalsPart-NCC: Non-commercial operations withcomplex motor-powered aircraft(CMPA)Part-NCO: Non-commercial operations withother than CMPAPart-SPO: Special operations, e.g. aerial work

R.F010-02 � European Aviation Safety Agency, 2012. All rights reserved. Proprietary document.

Page 10 of 103

CRD 2010-14

18 Jan 2012

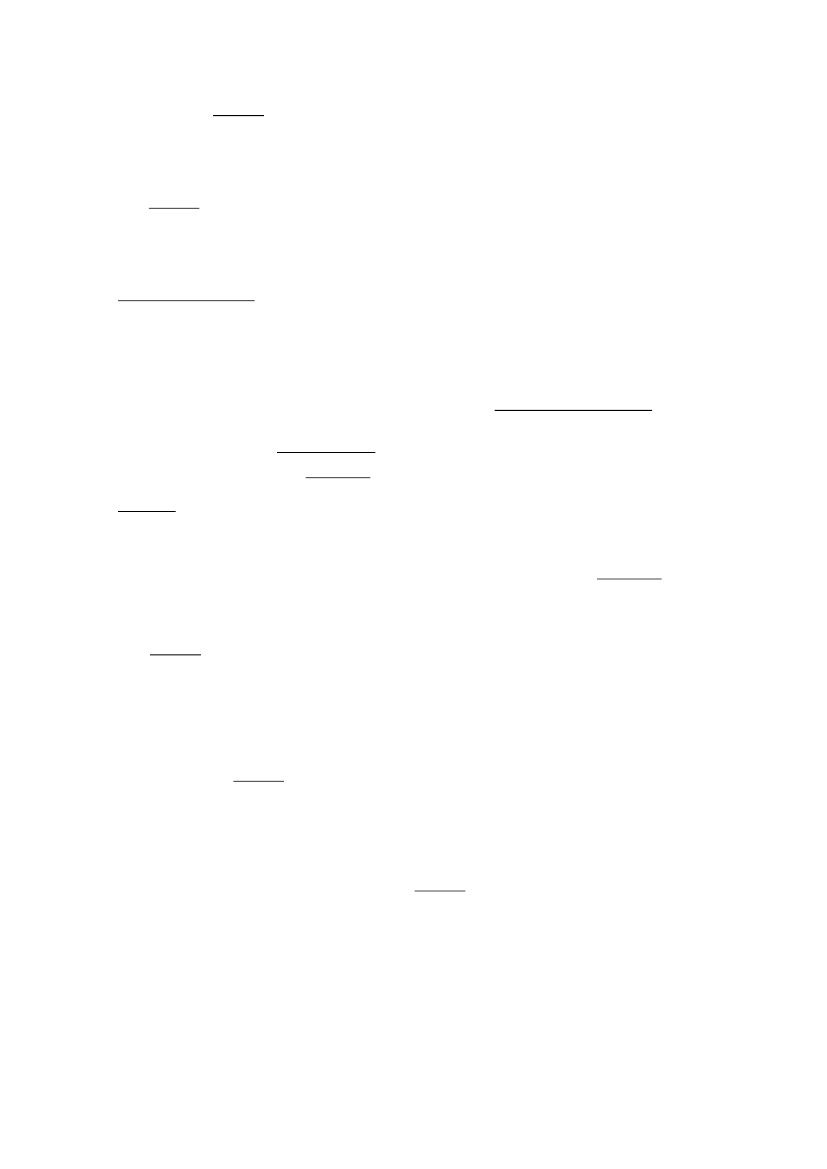

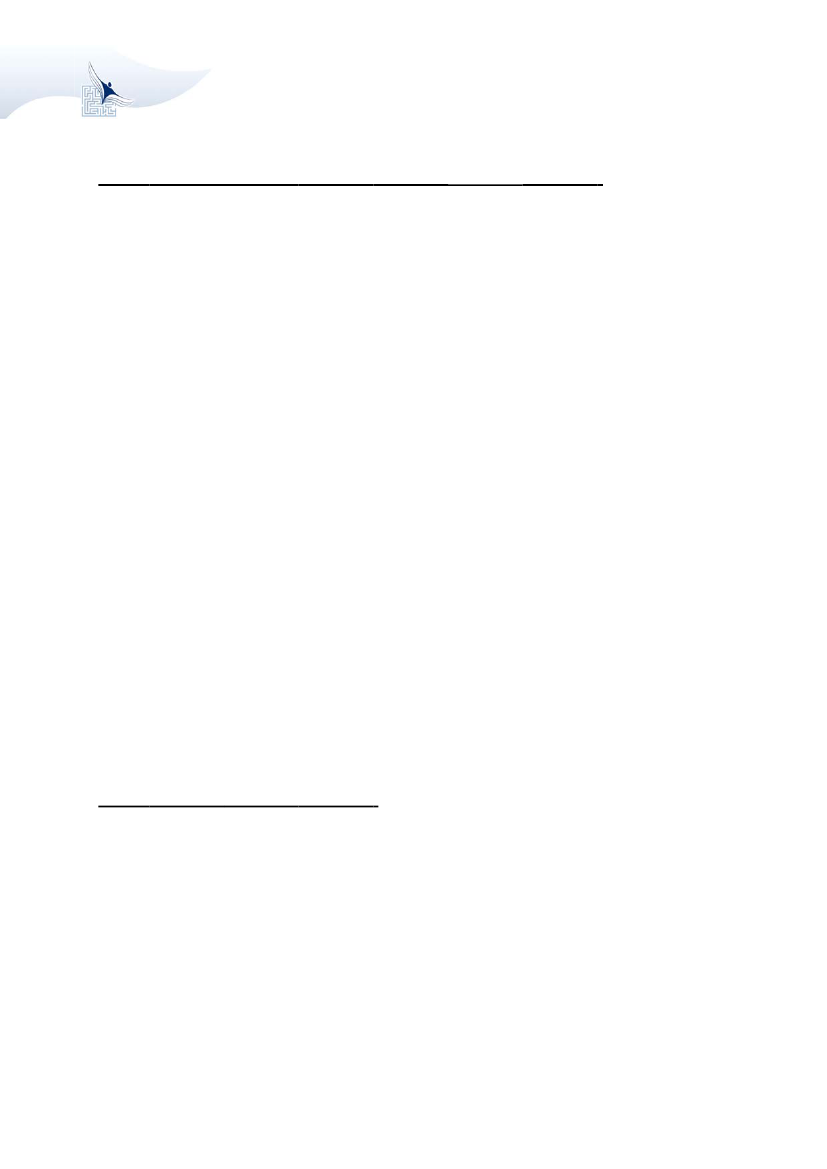

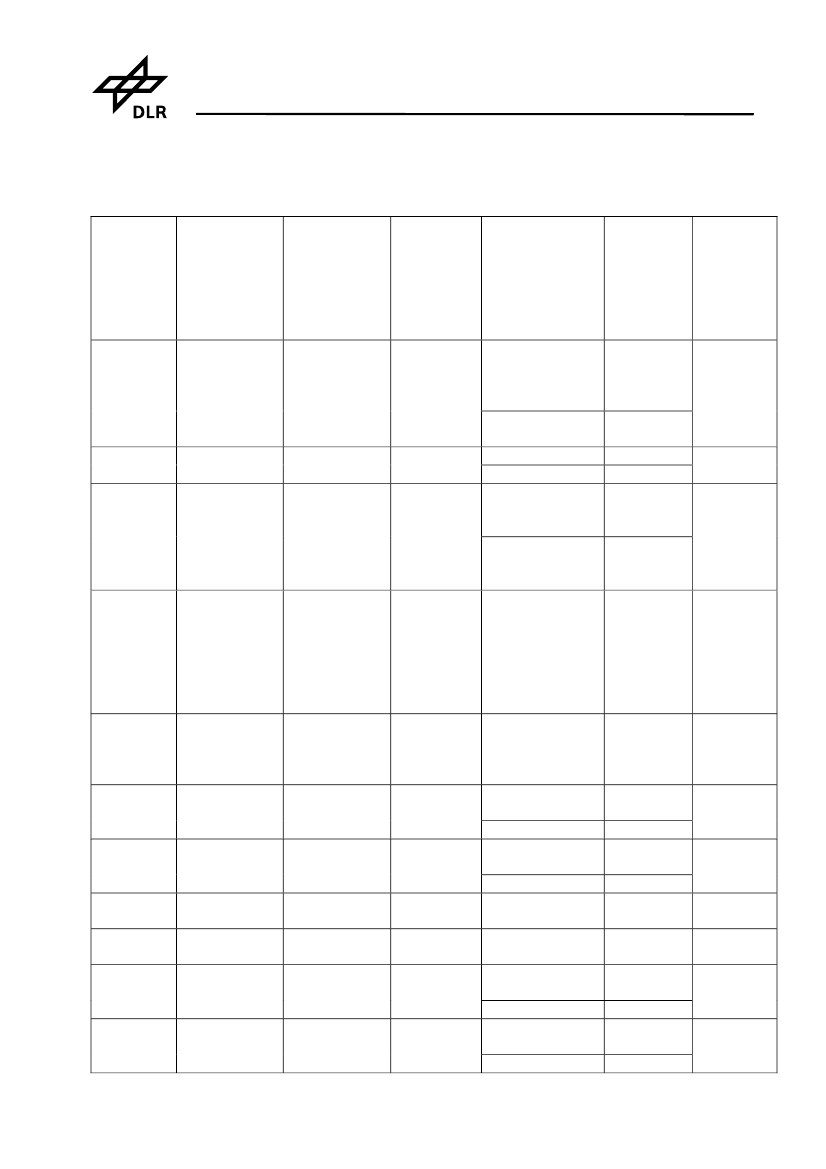

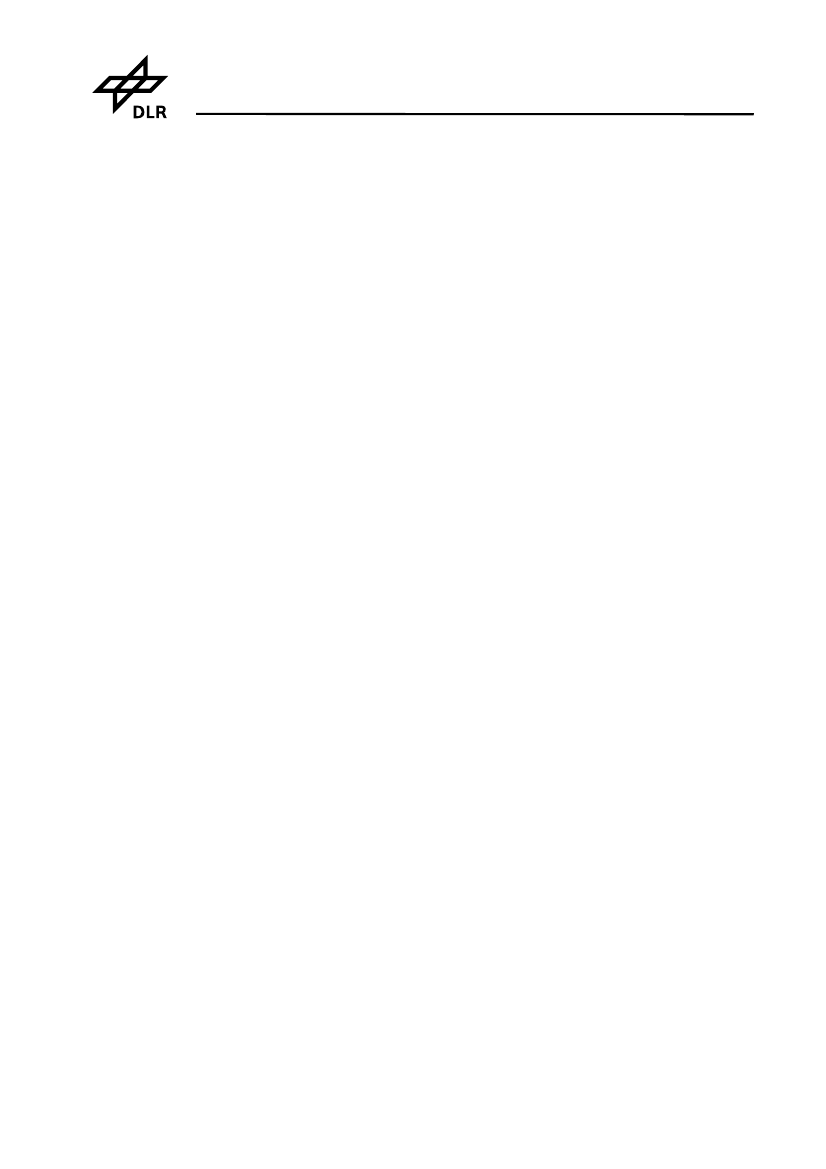

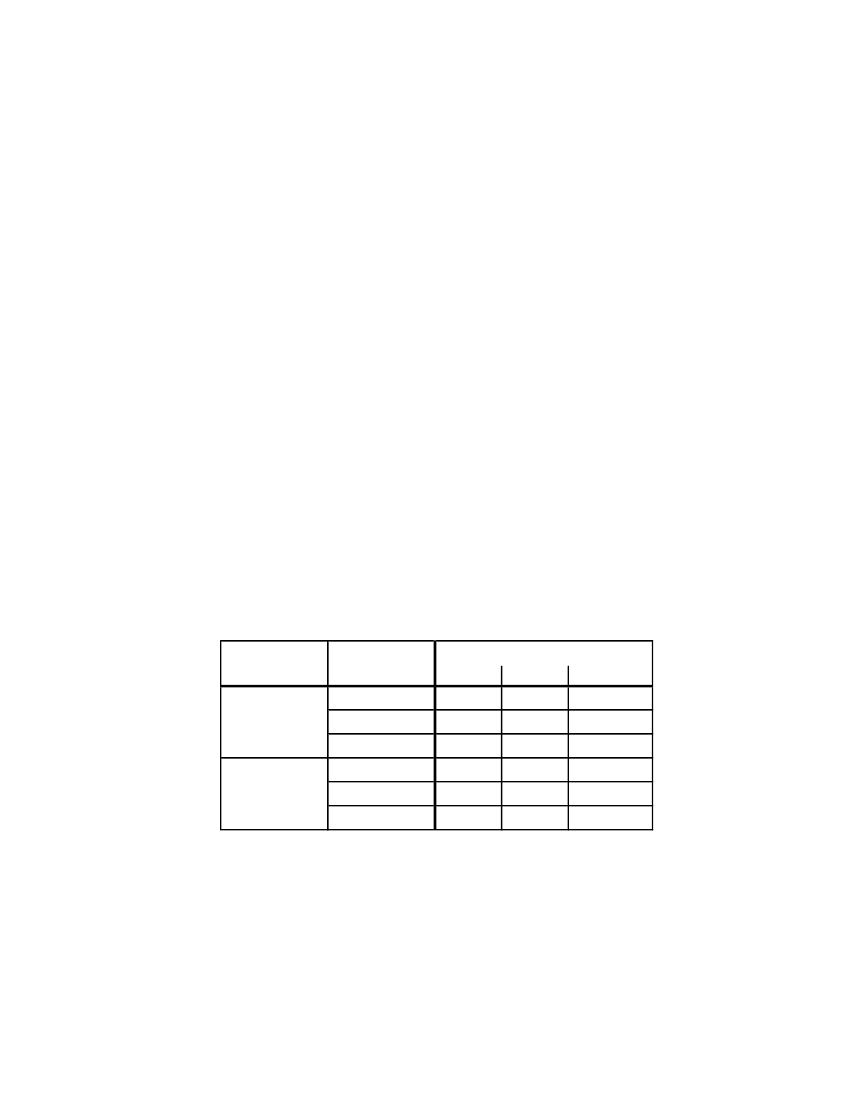

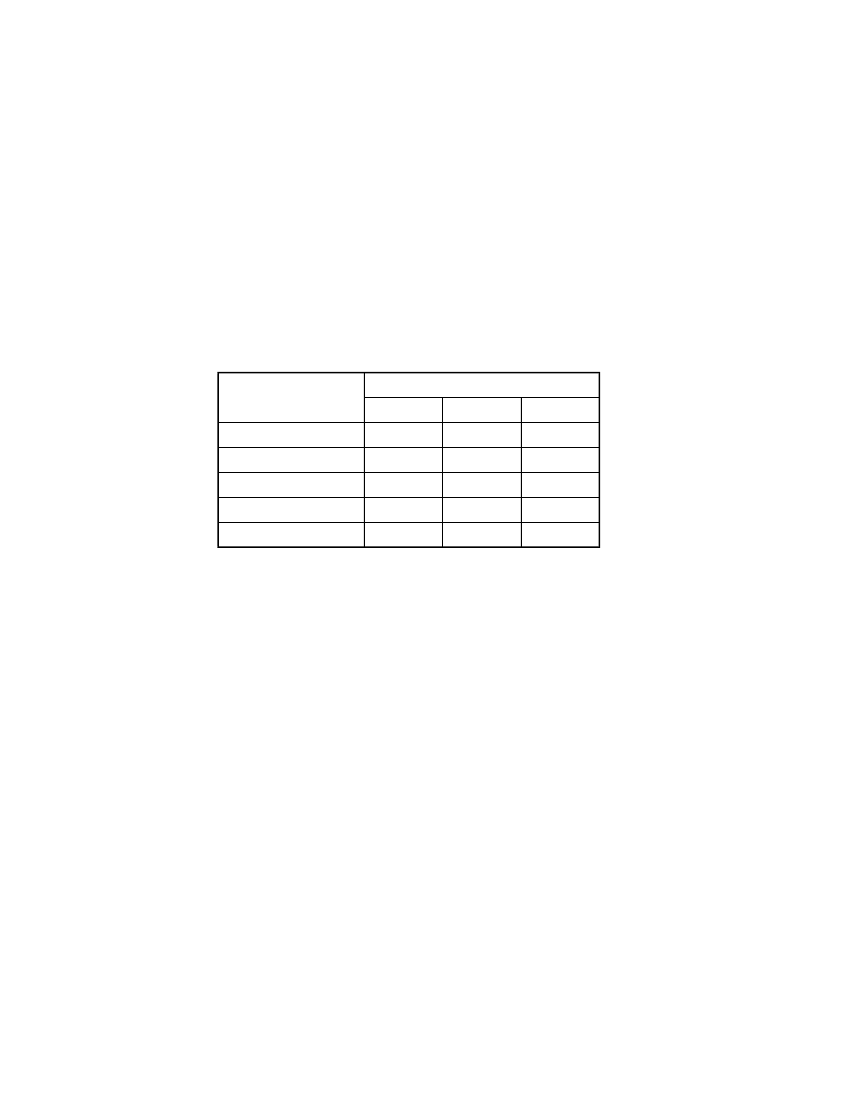

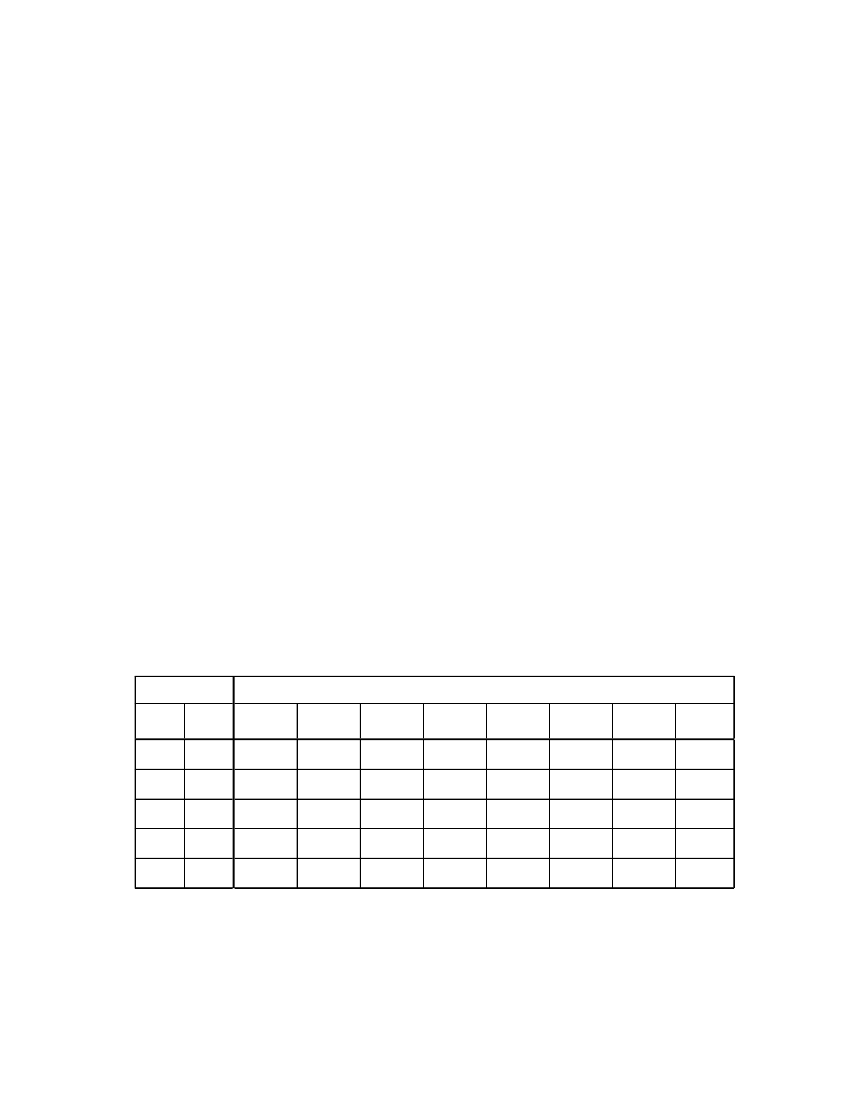

Table I.2: Overview of t he r ule structu re ‘flight and duty ti me li mitations and r estrequirements’

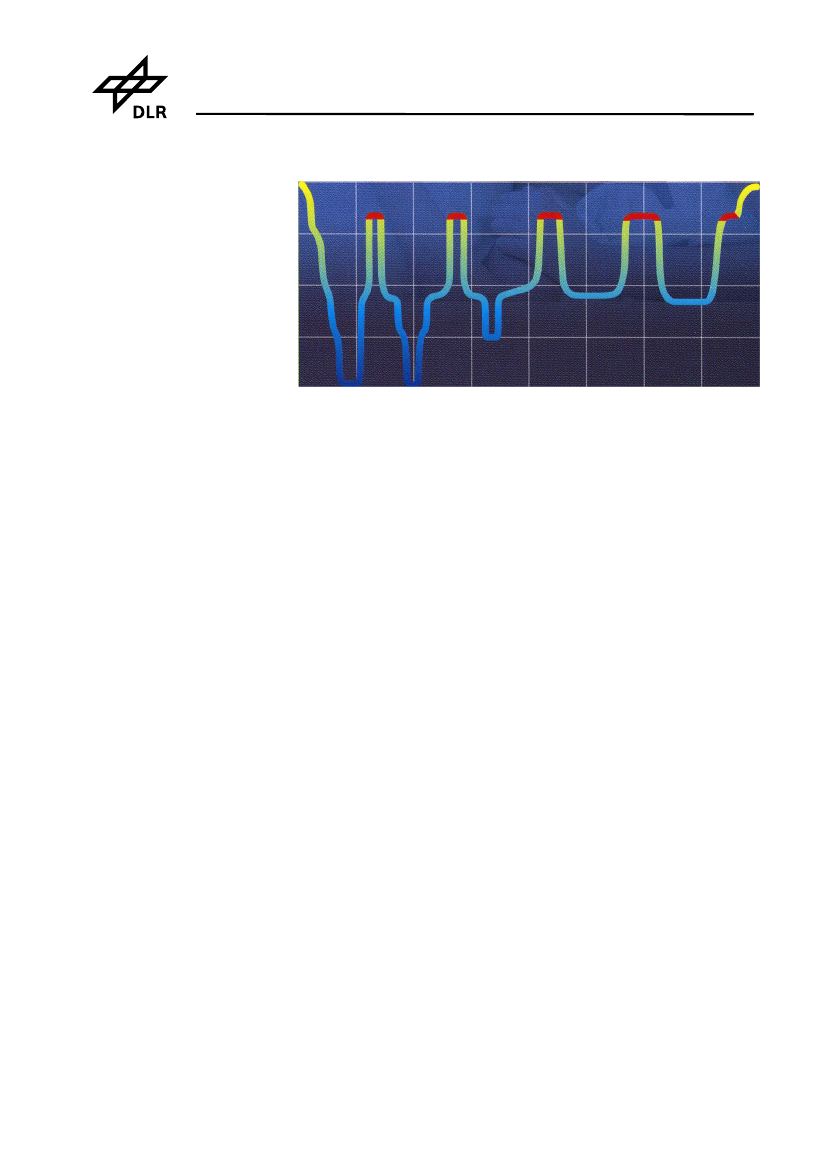

R.F010-02 � European Aviation Safety Agency, 2012. All rights reserved. Proprietary document.

Page 11 of 103

CRD 2010-14Definitions33.

18 Jan 2012

The paragraphs of the Explanatory Note dedicated to definitions and the definitionsthemselves attracted many comments by all stakeholder groups. Especially individualcommentators and crew organisations requested a number of additional definitionsarguing that numerous sections of the proposed rules contained wording that lacked cleardefinitions. They particularly demanded definitions for the terms ‘short-term re-planning’,‘operational need’, ‘unforeseen circumstances’, ‘sufficiently in advance’, ‘satisfactorily freefrom fatigue’, ‘spread as evenly as possible’ and ‘satisfactory level of safety’.Acclimatised

34.

Commentators from all stakeholder groups criticised the proposed definition for‘acclimatised’ for not being clear enough or not properly describing the phenomenon ofcircadian misalignment inherent to substantial time zone crossing. Since none of thecomments had been substantiated with scientific or medical data, only little conclusionscould be drawn from individual commentators’ comments, crew organisations’ commentsor operator organisations’ comments.The scientific reports coincided that adaptation to the new time zone would not becomplete after spending 36 hours free of duty or 72 hours conducting duties at thelayover destination. The three scientists agreed in their reports that acclimatisationoccurs gradually and depends on the time difference and the direction of the time zonetransition. Normally adaptation to westward time zone transitions is easier.The CRD takes account of the scientists’ advice applying conservative maximum FDPlimits whenever the state of acclimatisation is unknown.If layovers at one destination are planned to be less than 36 hours it should be possiblefor crew members to remain acclimatised to their home base time zone.Only for planned layovers of more than 36 hours, and depending on how many timezones have been crossed, un-acclimatisation or acclimatisation to the destination timezone shall be taken as reference for the maximum FDP values. Acclimatisation is onlyassumed after more than 60 hours of permanence in the case of 4 eastward or 5–6westward time zone transitions or even longer permanence if more time zones arecrossed.If crew members change time zones with every flight and do not spend enough time atone layover destination to become acclimatised to the new time zone, they are assumedto be unacclimatised during the entire rotation.The Agency believes that the complex context of acclimatisation is best reflected in atable that describes the state of presumed acclimatisation after time zone crossing takinginto account the duration of the layover, the direction of time zone transitions and thetime zones crossed.Accommodation

35.

36.37.38.

39.

40.

41.

Diverging views were expressed by commentators as regards the value of having adefinition foraccommodationand the content of the definition itself. While creworganisations insisted on introducing the clarification that an empty aircraft could notqualify as accommodation, operator organisations requested to explicitly include thepossibility to use an empty aircraft as accommodation as long as all other criteria aremet.Only one Member State expressed that there was a clear need to exclude an emptyaircraft as accommodation for the purpose of split duty or standby.Many comments were received requesting to replace the ‘possibility’ with ‘ability’. Theintention of the definition is that the place should possess temperature control and thepossibility to be obscured or illuminated as a minimum standard.Page 12 of 103

42.43.

R.F010-02 � European Aviation Safety Agency, 2012. All rights reserved. Proprietary document.

CRD 2010-1444.45.

18 Jan 2012

Individual commentators requested clarification that accommodation should be equippedwith furniture to allow a comfortable stay of all crew members.The Agency believes that there is no need to exclude an empty aircraft asaccommodation as long as all other criteria are met. Accommodation should be equippedadequately to allow a comfortable stay of all crew members making use of the facility atone time. Therefore, the Agency amends the definition including a reference to aminimum standard of furniture in accommodation. The word ‘possibility’ has beenchanged to ‘ability’ in the CRD.Air taxi operations

46.

Very few comments were received regarding the definition of ‘air taxi operations’. Oneoperator organisation supported the definition as proposed. Two Member States askedfor clarification if the mentioned 19-seat configuration was referring to themanufacturer’s certified seating configuration of the aeroplane or the seatingconfiguration in use by the operator. One Member State stated that the seatingconfiguration was not relevant for the type of operation and that therefore therequirement related to the seating configuration should be removed.This CRD does not include proposals for ‘air taxi operations’. They will be addressed bythe future rulemaking task RMT.0429 [former OPS.071(b)]. Therefore, the Agency doesnot see the need to change ‘air taxi operations’ before RMT.0429 starts.Augmented flight crew

47.

48.

Comments regarding the proposed definition of ‘augmented flight crew’ should beanalysed in connection with the definitions of operating crew member and the rulesconcerning in-flight rest.Crew organisations and one Member State claimed that cabin crew should be included inthe definition of ‘augmented crew’. They stated that augmented cabin crew had to becarried to allow cabin crew members to leave their assigned post during the flight for thepurpose of in-flight rest. They argued that resting cabin crew members should bereplaced by suitably qualified cabin crew members and that as a consequence the cabincrew had to be augmented on flights with an extended FDP due to in-flight rest. Theyreasoned that cabin crew have responsibilities for maintaining safety within the cabinduring all phases of a flight and that the minimum number of cabin crew for theoperation of an aircraft is established by the aircraft certification.The Agency disagrees that the scope of the proposed definition of augmented crew has tobe broadened to include cabin crew. The number and composition of cabin crew isestablished in Annex III, Organisation Requirements for Air Operations (Part-ORO),ORO.CC.100. Therefore, the proposed definition remains unchanged.Break

49.

50.

51.

Crew organisations and one Member State suggested the word ‘duty’ in the definition ofbreak to be replaced by the term ‘flight duty’ for more clarity. The word ‘crew’ should becomplemented by ‘member’ to make clear that a break might also apply to a single crewmember and not to full crews only. It was also suggested that a break should always bepre-planned. The extent to which pre-planning shall be a requirement for a period of timeshorter than a minimum rest period to count as a break or flight duty is defined in thesections where rules on split duty use the term ‘break’.The Agency agrees and has amended the definition of ‘break’ for more clarity.Crew member

52.

53.

One crew organisation suggested that the types of crew members, flight, technical andcabin crew should have their specific individual definitions.Page 13 of 103

R.F010-02 � European Aviation Safety Agency, 2012. All rights reserved. Proprietary document.

CRD 2010-1454.

18 Jan 2012

The terms ‘crew member’, ‘cabin crew member’ and ‘technical crew member’ are definedin Annex I, Definitions for Terms used in Annexes II–IX. Therefore, the Agency concludesthat there is no need to repeat the definitions of different types of crew members.Duty

55.

One operator pointed out that a duty a crew member had volunteered for should alsocount for cumulative limits and should be counted as duty. The word ‘required’ could beunderstood to exclude activities a crew member volunteers to perform for the operator.Crew organisations and one Member State suggested the explicit inclusion of ‘giving andreceiving training’ and ‘checking’ in the list of activities that should be considered asduty. One crew organisation suggested removing completely the list of activities. It wastheir view that any activity for the operator should be considered duty. Operatororganisations and one Member State proposed specifying that only some elements ofstandby count as duty while crew organisations maintained that all standby types shouldcount in full as duty.The definition of duty has been changed by removing the word ‘required’ for more clarity.There should not be room for any doubt that a duty a crew member has volunteered forshall count as such.The list of activities that shall count as duty is to be considered enumerative but notrestrictive and gives indication of what are the typical tasks that shall be considered asduty. Any task that is not mentioned in the definition will count as duty.The extent to which standby shall be counted as duty is regulated in the paragraphscorresponding to ‘standby’.Duty period

56.

57.

58.

59.

60.

No comments were received.Early start

61.

Crew organisations and individual commentators proposed considering a wider time bandfor the definition of early start. There was no agreement amongst the commentators onthe range of such a wider time band; the suggestions covered reporting times between05:00 and 06:59 or 06:00 and 09:00 at home base and 06:00 and 08:00 out of base.Individual commentators and crew organisations also criticised that the definition of earlystart was not used to limit the number of early starts in a defined period of time.Operator organisations expressed that the definition was superfluous because the effectsof window of circadian low (WOCL) encroachment on the maximum FDP were alreadyaddressed.Member States indicated that the definition of early start had to be linked to the timezone where the crew member is acclimatised. It was also suggested to make reference to‘crew member’ instead of ‘crew’.Two Member States stated that the definition of early start should not only relate to flightduty periods but also to duty periods. They argued that reporting times before 07:00, ifnot 08:00, should be included to take better account of sleep reduction due to having torise in the WOCL.The three scientists concurred in their reports that the definition of early start shouldinclude reporting times between 05:00 and 06:59.The Agency has amended the definition of ‘early start’ taking into consideration thescientists’ recommendations to include a wider time band.The word ‘crew’ has been replaced by ‘crew member’ to make clear that this definitionrefers to the individual and not to the entire crew.Page 14 of 103

62.

63.

64.

65.66.67.

R.F010-02 � European Aviation Safety Agency, 2012. All rights reserved. Proprietary document.

CRD 2010-1468.

18 Jan 2012

Since the definition should be used to manage fatigue-related risks and not only flightduties that are fatiguing, the amended definition covers all duty periods starting in thedefined time band. For more clarity reference is made to the time zone.Eastward-Westward and Westward-Eastward transition

69.

Two crew organisations asked for this definition to be removed. One operator suggestedincluding also a definition for the term ‘rotation’ used in the definition. One Member Statesuggested making reference to the time zones crossed and not to the hours of timedifference. It was also criticised that the reference point between alternating rotationswas not clearly defined. Two Member States and one operator requested defining thehome base as reference point between alternating rotations and to clarify that theadditional night of rest as a consequence of such a transition should be taken at homebase.The Agency agrees that a new definition for the term ‘rotation’ is useful for betterunderstanding. The definition of ‘Eastward-Westward and Westward-Eastward transition’has been changed to make reference to the time zones crossed. Also home base hasbeen introduced as the transition point.Flight duty period (FDP)

70.

71.

Crew organisations requested including a certain amount of time at the end of any FDPfor safety tasks to be completed after the end of the last flight. They also suggestedincluding positioning, general training, administrative duties, airport standby andsimulator training into the same duty period before a flight as an operating crewmember.As regards the relation between FDP and split duty, crew organisations argued that thedefinition of FDP should also cover the break in a split duty. Operator organisations,Member States and crew organisations expressed that the definition should make clearthat an FDP always has to include a flight or series of flights. One Member Statesuggested aligning the definition with Subpart Q.Post-flight duties are counted as cumulative duty and have an impact on the minimumrest after an FDP. The Agency does not see the need to include post-flight duties in FDP.The Agency also believes that the definition of FDP is in line with the definition in SubpartQ. For more clarity the word ‘operating’ has been added when referring to the crewmember.Flight time

72.

73.

74.

Two Member States requested aligning the definition of ‘flight time’ with the definition of‘block time’ in Subpart Q. They argued that the definition in Subpart Q had been in linewith the definition of ‘block flying time’ in the Council Directive 2000/79/EC (WorkingTime Directive for Mobile Workers in Civil Aviation). They claimed that any minor changewould lead to operators having to keep two sets of records. The change consists in factthat under the NPA definition ‘flight time’ would only have to be recorded if an actualtake-off and landing (a flight) had taken place.Crew organisations recommended establishing a link between ‘sector’, ‘block to block’and ‘flight time’. They argued that taxiing for a remote holding position should beregarded equally as taxiing with the purpose of taking off and after landing. Theydefended that any time during which engines are running should count as flight time forthe purpose of cumulative flying time limits.The Agency concludes that an additional administrative burden should be avoided foroperators. The definition of ‘flight time’ should therefore be in line with the definition of‘block time’ used in Subpart Q. The definition has been amended.

75.

76.

R.F010-02 � European Aviation Safety Agency, 2012. All rights reserved. Proprietary document.

Page 15 of 103

CRD 2010-14Home base77.

18 Jan 2012

Crew organisations requested the words ’normally’ and ‘under normal circumstances’ tobe removed from the definition. They also requested to mention the permanent characterof home base in the definition. They recommended home base to be a ‘single airportlocation’. A number of crew organisations suggested to define ‘normal circumstances’through the exception, that means the only case when an operator would have to providesuitable accommodation at home base for so-called back-to-back operations coveredunder FTL.1.235(b). One operator suggested including that also positioning and not onlyflight duty could start or end at home base.One Member State proposed home base to be ‘apermanentsingle location nominated bythe operator from where the crew member starts and ends a duty period or a series ofduty periods’.The definition of home base remains unchanged. Conditions as regards permanency andchanges of home base are given in the corresponding rules.Late finish

78.

79.

80.

Operator organisations pointed out that there wasn’t any reference to ‘late finish’ in anyof the rules in Chapter 2 or Appendix X, Section 1; they therefore recommended deletingthe definition. As regards the restrictions that should apply to FDPs encroaching theWOCL, they argued that the reduction of FDP due to reporting time was covering thepossible fatigue impact.Crew organisations requested including arrivals between 23:00 and 01:59 at home baseand arrivals between 00:00 and 01:59 out of home base into the time window of the latearrival. One crew organisation proposed to widen the window to start at 22:00; theysubstantiated their suggestion with the fact that the hours between 23:00 and 02:00 areconsidered to be the most valuable night hours for recuperative sleep.One Member State recommended making reference to a crew member and not to ‘thecrew’ for better understanding.The three scientists agreed in their reports that the definition of late finish should start at00:00 in order to properly take into account the sleep loss resulting from a late finish.The Agency has amended the definition of late finish in line with the scientists’ advice. Inorder to clarify that the definition refers to individual crew members, ‘crew’ has beenreplaced by ‘crew member’.Local day

81.

82.83.84.

85.

No comments were received regarding the definition of local day.Local night

86.

Crew organisations proposed changing the definition of local night to 10 hours between22:00 and 10:00. They argued that the intention of defining a local night was to allow fora full night’s sleep of 8 hours. A definition of 8 hours between 22:00 and 08:00 wouldallow for starting times as early as 06:00. Starting as early as 06:00 could lead to asleep loss of an average of over 90 minutes, reducing the recuperative effect of the nightsleep.The term ‘local night’ is used in rules related to the recurrent extended recovery restperiod or in rules related to additional rest requirements related to disruptive schedules.Those rules provide compensation for cumulative sleep loss. The Agency concludes thatthere is no need to change the definition.Page 16 of 103

87.

R.F010-02 � European Aviation Safety Agency, 2012. All rights reserved. Proprietary document.

CRD 2010-14A single day free of duty88.

18 Jan 2012

One Member State pointed out that the Working Time Directive for Mobile Workers inCivil Aviation9(WTD) mandates 98 days off duty. One operator suggested standardisingthe terminology and avoiding non-defined terms such as ‘day off’.Crew organisations claimed that this definition suggested that days free of duty couldonly be assigned individually. They therefore requested renaming the definition to ‘dayoff’ or ‘day free from duty’.One operator recommended including a requirement for a number of days off per monthor per 28-day period; they also encouraged to follow the CAP 371 model of defining aminimum duration of 34 hours for a day off. It was also requested to somehow combinethe definitions of ‘local day’, ‘single day free of duty’ and ‘minimum recurrent extendedrecovery period’. A different proposal suggested defining a single day free of duty as‘a time free of all duties consisting of a single day and two local nights and which mayinclude a rest period as part of the day off. The minimum length of which is 30 hours’.The Agency believes that it is helpful to include a reference to the WTD for completeness.The purpose of this proposal is the management of fatigue-related risks. Days off andannual leave are socially negotiated conditions that have an impact on fatigue; therefore,the Agency concludes that it is reasonable to include a reference to a single day free ofduty although the rule text itself does not establish further requirements related to asingle day free of duty.Long-call standby

89.

90.

91.

92.

A new definition for long-call standby has been included (see also paragraphs 408 to 467on ‘other standby’).Night duty

93.

Some crew organisations suggested aligning the definition of night duty with thedefinition of WOCL, proposing a time window that would overlap with the one definingearly start. One operator stated that this definition should somehow make reference to aflight duty. A number of operators requested to delete the definition as it is useless,arguing that the effects of WOCL on FDP were reflected in the limitations of FDPaccording to the reporting time of an FDP.Fatigue-related risks due to finishing late, starting early or working throughout the nightmust be managed. The Agency believes that clear definitions of what is anearly start,alate finishor anight dutyare relevant and should therefore remain in Section 1. In orderto enable appropriate fatigue risk management it is also important to clearly distinguishthe three different types of duties that might lead to sleep loss. Any night duty will leadto sleep loss, no matter if flight or other duty. Therefore the Agency concludes leavingthe definition as proposed initially.Operating crew member

94.

95.

One crew organisation requested that a crew member carrying out any type of trainingon a flight simulator should be considered as an operating crew member. A number ofcrew organisations asked for an additional definition of ‘resting crew member’ to makeclear that a crew member during in-flight rest should not be counted as operating crewmember.Council Directive 2000/79/EC of 27 November 2000 concerning the European Agreement on theOrganisation of Working Time of Mobile Workers in Civil Aviation concluded by the Association ofEuropean Airlines (AEA), the European Transport Workers' Federation (ETF), the European CockpitAssociation (ECA), the European Regional Airline Association (ERA) and the International Air CarrierAssociation (IACA).

9

R.F010-02 � European Aviation Safety Agency, 2012. All rights reserved. Proprietary document.

Page 17 of 103

CRD 2010-1496.

18 Jan 2012

The definition, as proposed, covers any type of duty a crew member might be carryingout on board an aircraft. Therefore, the Agency does not see the need to amend thedefinition. In-flight rest is considered FDP and duty, therefore a crew member is still anoperating crew member during in-flight rest. The Agency concludes that the definition asproposed is clear enough.Positioning

97.

Two Member States suggested changing the word ‘request’ back to the initial word usedin the Subpart Q definition ‘behest’. They argued that the wordbehestis stronger anddoes not imply that there is an option as opposed torequestwhich implies thatcompliance is optional. They also proposed including an additional definition for‘travelling time’ in order to keep the Subpart Q definition.Crew organisations pointed out that the excluded time for local transfers from a place ofrest outside the home base and vice versa should not exceed 1 hour for a round trip. Anytime exceeding this 1-hour limit should be counted as positioning and has therefore animpact on the maximum FDP if taking place before the crew member acts as operatingcrew member and should count as duty if taking place after the last flight of that crewmember performing as acting crew member.The Agency agrees that the word ‘behest’ as in Subpart Q describes more clearly thatcompliance is not optional. Further details are reflected in the corresponding ruleparagraphs.Rest facility

98.

99.

100. Some Member States suggested clarifying in the definition that only in-flight rest wasreferred to with the definition ofrest facilityas opposed to ‘accommodation’ or ‘suitableaccommodation’ for the purpose of breaks in split duty or as used in airport standby.They therefore proposed changing the name of the definition to ‘in-flight rest facility’.Another Member State emphasised that reference should be made to in-flight restspecifying that a ‘class 2 rest facility’ should at least recline 60�, they furthermorerequested to exclude the possibility that a ‘class 3 rest facility’ could be located on theflight deck.101. Operator organisations explained their need to include a definition for an additional‘class 4 rest facility’ to allow for in-flight rest in common tourist class seats, providedthey are separated from the passengers by a curtain and the adjacent seats up to theaisle are left un-occupied by passengers. One operator organisation suggested defining‘class 3 rest facilities’ as a common economy seat in a special configuration as describedand currently in use in one Member State for in-flight rest on board single aisle aircraftswith neither bunks nor business class seats nor any other seats that meet the criteria ofclass 3 rest facilities. One operator also requested adding that the curtain to separate therest area from the rest of the cabin was only needed when passengers are carried.Another operator pointed out that in occasions light controls in bunk rest facilities couldbe unserviceable. They suggested changing the wording in a way that would allow for theflight to operate with an extension if the light control was not available. Operatororganisations also stated that the definitions in the proposal were not fully in line withthe definitions given in the TNO report.102. Some operators’ comments stated that the Agency had not produced scientific evidenceagainst the use of economy seats for in-flight rest for cabin crew and that such practicescould be subject to FRM.103. Crew organisations criticised that the definition did not include the requirement for therest facility to be free from any disturbance from passengers or operating crew members.One crew organisation commented that any reference to rest should be avoided for class2 and class 3 rest facilities because the likelihood to sleep in such a seat is minimal.

R.F010-02 � European Aviation Safety Agency, 2012. All rights reserved. Proprietary document.

Page 18 of 103

CRD 2010-14

18 Jan 2012

104. The scientists agreed in their reports that there was no scientific evidence to support thatrest taken in ordinary economy seats would allow for restorative sleep and couldtherefore justify an FDP extension.105. In line with the scientists’ view the Agency is not convinced that in-flight restarrangements in economy seat allow for recuperative sleep in order to allow for an FDPextension due to in-flight rest. The Agency revises the definitions to be in line with theTNO report. In the amended definition a reference to the rest facility being on board anaircraft has been included.Rest period106. Individual commentators requested clarification of the link between ‘a single day of dutyand a rest period’. One Member State suggested keeping the wording from Subpart Q,emphasising in the definition that a rest period has to beuninterrupted.107. The definition of a single day free of duty has only been included for completeness and asa reference. The important concept in terms of fatigue risk management is rest. TheAgency agrees that rest should be uninterrupted and accepts re-introducing the word‘uninterrupted’ as in Subpart Q.Rotation108. A new definition for rotation has been added following the request made by acommentator in comments on the definition of Eastward-Westward and Westward-Eastward transition.Short-call standby109. A new definition for short-call standby has been added.Agency’s conclusions on definitions110. A more conservative limit for maximum FDP shall be applied when the state ofacclimatisation is unknown. The state of acclimatisation shall be reflected in a tablereplacing the definition.111. An empty aircraft is not excluded for use as accommodation as long as all other criteriaare met. The criteria for adequate equipment are refined in the revised definition.112. The definition of ‘augmented crew’ remains unchanged.113. Editorial changes have been made to the definition of ‘break’.114. The different types of crew members are defined in Annex I to the Regulation onAir Operations.115. The extent to which standby shall count as duty is established in the paragraphsdescribing ‘standby’. The definition has been amended for clarity but remains unchangedin substance.116. The definition of ‘early start’ has been amended followingrecommendation. Editorial changes have been made for more clarity.thescientists’

117. A new definition for ‘rotation’ has been included. The amended definition of ‘Eastward-Westward and Westward-Eastward transition’ uses the home base as reference point andrefers to ‘time zones crossed’ instead of ‘hours’.118. The word ‘operating’ has been added to the definition of ‘flight duty period’ whenreferring to crew members for more clarity.119. The definition of ‘flight time’ has been amended to avoid additional administrative burdenfor operators.

R.F010-02 � European Aviation Safety Agency, 2012. All rights reserved. Proprietary document.

Page 19 of 103

CRD 2010-14

18 Jan 2012

120. The definition of ‘home base’ remains unchanged; clarifications as regards the conditionsthat shall apply are given in the corresponding rule paragraphs.121. The definition of ‘late finish’ has been amended according to the scientists’ advice. Aneditorial change has been introduced for clarity.122. The definition of ‘local night’ remains unchanged.123. The definition of a ‘single day free of duty’ remains unchanged.124. A new definition for ‘long-call standby’ has been added.125. The definition for ‘night duty’ remains unchanged.126. The Agency does not see the need for an additional definition of ‘resting crew member’;the definition of ‘operating crew member’ remains unchanged.127. The wordrequestin the definition of ‘positioning’ is replaced bybehest.128. The revised definition of ‘rest facility’ has been aligned with the specifications given in theTNO report10. It has also been included that the rest facility is on board an aircraft.

129.The Agency accepts the proposal to re-introduce the worduninterruptedin the definitionof ‘rest period’.130. The Agency has added a new definition for the term ‘rotation’.Operator responsibility131. Crew organisations stated that operator responsibilities should be applicable for all typesof CAT operations; they therefore suggested deleting ‘where applicable to the type ofoperation’. This view was shared with one Member State. One operator organisation onthe other hand endorsed the wording as proposed.132. Crew organisations also criticised that the Subpart Q binding requirement for operationalrobustness had been moved to AMC. In addition to their request to upgrade AMC1-OR.OPS.FTL.110 (i) Operator responsibilities to be an IR, they suggested including a newGM stating that flight should be planned allowing for at least a buffer of 30 minutesbetween the maximum FDP and the planned duration of the flight to ensure that minordelays do not require an excessive and repeated use of commander’s discretion. Theyalso stated that the 33 % criterion was not effective; they suggested refining AMC1-OR.OPS.FTL.110 (i) and requiring corrective action to be taken earlier.133. One crew organisation suggested amending the provisions including a requirement foradequate timing of the rest periods to enable recuperative sleep in point (f)OR.OPS.FTL.110 Operator responsibilities. They furthermore requested extending theobligation to provide appropriate rest to crew members not only before undertaking thenext flight duty but also before any other type of duty.134. Many crew organisations requested operator responsibilities to be regulated moreprescriptively. They also suggested including a catalogue of the Agency’s sanctions forthose operators not fulfilling their responsibilities. Crew organisations found theexpression ‘sufficiently in advance’ vague and proposed replacing it with a prescriptivelimit, namely ‘14 days in advance’.135. The Agency’s proposal for IR and AMC describing operator responsibilities triggered awide range of operators’ comments. Operator organisations stated that the AMC toOR.OPS.FTL.110 Operator responsibilities (a) was driven by a social agenda. They alsorequested to distinguish between monthly rosters, and rolling weekly and monthlyrosters. Another operator claimed that roster changes should be possible with a 72-hournotification period.10

Extension of duty period by in-flight relief, M. Simons & M. Spencer, 20007

R.F010-02 � European Aviation Safety Agency, 2012. All rights reserved. Proprietary document.

Page 20 of 103

CRD 2010-14

18 Jan 2012

136. One Member State stated that there was no safety case or scientific evidence to maintainOR.OPS.FTL.110 Operator responsibilities (a), and also requested to keep Subpart QOPS 1.1090 2.3.137. Crew organisations and one Member State on the other hand found that the publicationof rosters 14 days in advance should be a firm requirement in the IR.138. Two operators from different countries supported the text of OR.OPS.FTL.110 Operatorresponsibilities as proposed.139. One operator recommended using only one definition of ‘day off’ throughout the entiredocuments referring to the requirement in OR.OPS.FTL.110 Operator responsibilities (g).They suggested using the CAP 371 definition of single day off as 34 hours including 2local nights. One Member State suggested replacing ‘local days free of duty’ by ‘extendedrecovery rest period’.140. One operator proposed an alternative AMC to AMC1-OR.OPS.FTL.110 (a) to suit theirspecific type of operation.141. Another operator claimed that the proposal did not acknowledge the difference betweenscheduled and on demand operations.142. One Member State found the expression ‘sufficiently free from fatigue’ subjective andproposed deleting point (b) OR.OPS.FTL.110 Operator responsibilities to avoidmisinterpretation. Another Member State recommended defining the term ‘well-rested’,used in OR.OPS.FTL.110 Operator responsibilities (f). Member States also stated that‘seasonal period’ and ‘significant proportion’ should be defined or explained in AMC toenableobjectiveregulatoryoversightofAMC1-OR.OPS.FTL.110 (i) Operatorresponsibilities.143. Another Member State suggested including a requirement for operators to includeapplicable maxima for FDP and duty in published rosters to facilitate the commander’sassessment in the case of commander’s discretion.144. Stakeholders from all stakeholder groups suggestedOperator responsibilities (b) for better understanding.Agency’s conclusions on operator responsibility145. The Agency agrees that operator responsibilities shall apply to all types of CAToperations; however, rules shall be proportionate. Therefore, the first sentence ofORO.FTL.110 Operator responsibilities remains unchanged.146. ORO.FTL.110 (b) has been amended for better understanding.147. The Agency does not see the need to define the term ‘well-rested’; however, in order toavoid misunderstandings, ORO.FTL.110 Operator responsibilities (f) has been amendedand ‘well-rested’ has been replaced with ‘rested’.148. Although an ORO.FTL.110 Operator responsibility (g) has been transposed from SubpartQ, the Agency agrees that additional undefined terms should be avoided. Therefore, ‘localdays free of duty’ has been replaced by ‘recurrent extended recovery rest period’.149. The prescriptive requirement to change a schedule or a crewing arrangement if theactual operation exceeds the maximum flight duty period on more than 33 % of theflights during a scheduled seasonal period stems from Subpart Q. The Agency hastherefore transposed this requirement into an implementing rule. The requirement hasbeen moved from AMC to IR, therefore ORO.FTL.110 (i) has been amended accordingly.150. The Agency maintains the requirement to publish rosters 14 days in advance as an AMC.The principle of this rule stems from Subpart Q, meaning that this is not a newrequirement. The AMC proposes one (but not the only one) means to comply with therule. AMC1-ORO.FTL.110 (a) Operator responsibilities remains unchanged.rephrasingOR.OPS.FTL.110

R.F010-02 � European Aviation Safety Agency, 2012. All rights reserved. Proprietary document.

Page 21 of 103

CRD 2010-14

18 Jan 2012

Crew member responsibility151. Operator organisations criticised that crew member responsibilities had not beenmentioned in Chapter 1 of ORO.FTL. They emphasised on the individual responsibility forcrew members not to perform duties whilst unfit due to fatigue11.152. Crew member responsibilities include the obligation to comply with the appropriate flighttime limitations of the operator based on paragraph 7.f and 7.g of the EssentialRequirements. Crew members are required not to perform duties on an aircraft if theyknow or suspect that they are suffering from fatigue. At the same time, crew memberswho are subject to the FTL limitations of more than one operator are required to informeach operator about their activities. Crew member responsibilities have been transposedinto CAT.GEN.MPA.100 Crew responsibilities of Annex IV Part-CAT of the Agency’sOpinion 04/2011.153. In addition to the crew member responsibilities established in CAT.GEN. MPA.100, crewmembers should make optimum use of the opportunities and facilities for rest providedand plan and use their rest periods properly.154. The Agency accepts that crew member responsibilities should be reflected. Therefore, anew paragraph ORO.FTL.115Crew me mber responsib ilitieshas been introduced inChapter 1. This paragraph refers to CAT.GEN.MPA.100 and introduces an additional pointtransposing the requirement ‘to make optimum use of the rest opportunities and facilitiesfor rest provided and plan and use their rest periods properly’, stemming from EU-OPS.Fatigue risk management & fatigue management trainingFatigue risk management155. The proposed Implementing Rules and corresponding AMC and GM regarding fatigue riskmanagement (FRM) triggered numerous comments from stakeholders. While the generalidea of implementing FRM to deviate from prescriptive rules is widely supported, onlycrew organisations from one Member State reject the use of FRM. It is their view thatprescriptive FTL schemes based upon scientific principles and knowledge are supposed tobe safe. They do not see the need to additionally monitor the risk(s) arising from crewmember fatigue with FRM. They also believe that the provisions laid down in Article 14 ofthe Basic Regulation provide a sufficient level of flexibility.156. The majority of operator organisations defended that FRM had no place within operationsunder a prescriptive FTL scheme. However, stakeholders from all stakeholder groupswidely suggested a ‘copy-paste’ inclusion of the ICAO Annex 6 provisions on fatiguemanagement. Only when deviating from the prescriptive FTL schemes, according to theirview, FRM as an integral part of the operator’s management system should be used tomanage the operational risk(s) of an operator arising from crew member fatigue. Someoperator organisations also suggested applying FRM provisions only to the specificelements of the FTL scheme (or specific flights) which deviate from the prescriptive FTLrules.157. Crew organisations questioned the effectiveness of FRM managing fatigue-related risk(s)applying FRM in isolation to just some of the specific elements proposed in the NPA to beallowed under FRM.158. Crew organisations and one Member State requested to fully incorporate the ICAO’sAnnex 6, Part I, Chapter 4, Article 4.10.6 into OR.OPS.FTL.115. Some crew organisationsalso suggested exactly copying the ICAO Guidance on Fatigue Risk Management SystemRequirements into the corresponding IRs. Another crew organisation and one operator11

Point 7.f & g of Annex IV to the Basic Regulation.

R.F010-02 � European Aviation Safety Agency, 2012. All rights reserved. Proprietary document.

Page 22 of 103

CRD 2010-14

18 Jan 2012

criticised that ‘self-reporting of fatigue risks’ had been omitted when reproducing thepossible identification methods of hazards in AMC1-OR.OPS.FTL.115(d)(2)(i).159. Where the NPA envisaged FRM to manage the potential risks arising from crew memberfatigue identified with mathematical fatigue modelling in certain types of operations (e.g.extended FDP overlapping the WOCL), some operator organisations recommendedadditional mitigating measures such as extended pre and post-flight rest instead of FRM.160. A number of Member States commented on the proposals concerning FRM. Some of thembelieve that FRM, as an execution programme of an operator’s SMS, should bemandatory. They requested this to be reflected in hard law in order to fulfil the ICAOstandards.161. Member States defending this view agree that an FRM needs to be approved andmonitored by the competent authority. Some Member States even propose consideringthe possibility to enforce the establishment of aFatigue Risk Policyon all CAT operators ifa full FRM is not required for operations within the prescriptive limits.162. The following aspects of a flight time specification scheme were identified by stakeholdersas potential areas where FRM would be necessary to operate outside conservativeprescriptive limits:consecutive early starts;consecutive night duties;extended duties between 18:00 and 06:59; anddeviation from a 100-hour duty in a 14-day limit.extension of FDP due to in-flight rest for cabin crew; andreduced rest.

163. In addition, two areas were highlighted where FRM would be a useful tool:

164. Other Member States insisted on the requirement for FRM only to deviate from theprescriptive limits or as an additional tool to assess complex flight time specificationschemes.165. The scientific assessment of the NPA resulted in general agreement amongst the threescientists that:FRM should play a more important role in FTL; andtraining for all crew members was a core element of FRM.

166. Two scientists advocated the use of FRM also within the prescriptive limitations as a wayto manage safety in the framework of the Airline Safety Management System. Theyespecially highlighted that the following fatigue-related risks could efficiently beaddressed through FRM:commander’s discretion;short-term re-planning;some aspects of standby;extended FDP due to in-flight rest;time-off-day effects on the effectiveness of in-flight rest in augmented crewoperations;number of sectors in augmented crew operations;split duty;reduced rest;extended FDP in general; andPage 23 of 103

R.F010-02 � European Aviation Safety Agency, 2012. All rights reserved. Proprietary document.

CRD 2010-14consecutive early starts and night duties

18 Jan 2012

167. The scientists also supported the ICAO approach of allowing deviations from prescriptivelimits only under an authority-approved FRM.Fatigue management training168. The NPA requirement for fatigue management training was welcomed by creworganisations and Member States.169. Crew organisations suggested prescribing a minimum duration of 5 hours for the initialfatigue management training. One crew member organisation also proposed adding apoint concerningresponsible commutingto AMC1-FTL.1.250.170. Two Member States suggested an additional requirement to keep records of the fatiguemanagement training including a measure of competence. The same Member States alsorecommended recurrent training at least every 24 months.171. Operator organisations did not see at all the need for fatigue management training. Theystated that fatigue management training was only justified when a deviation fromprescriptive FTL made FRM necessary. In that case, they argued, the fatiguemanagement training should be comprised of detailed instructions to crew, operationsand rostering staff on the application of the elements of the FTL system for which FRMwas applicable. The Agency’s proposal to extend fatigue management training to crewrostering personnel and concerned management personnel was also opposed by operatororganisations. They stated in their comments that they could not see the safetyjustification for such a training to be delivered to personnel qualified to apply FTL rulesand collective labour agreements in order to produce legal rosters.172. Other operator organisations suggested re-naming the paragraph concerning fatiguemanagement training to ‘fatigue management awareness’ in order to avoid falseexpectations from crew members.173. One operator found it illogical to mandate comprehensive FRM training for operatorsoperating within the limits of prescriptive FTL without requiring the means to put theknowledge into effective practice.Agency’s conclusions on fatigue risk management and fatigue managementtraining174. The Agency believes that FRM provisions are an indispensible part of this proposal.Although FRM is only mandatory when operators intend to benefit from more relaxedlimits in limited areas of the proposed flight time specification scheme, the conditionsthat have to be complied with in order to do so have to be described in detail.175. The Agency accepts that its FRM provisions should assist Member States to comply withthe ICAO requirements. ORO.FTL.120 has been amended to reflect the ICAOrequirements.176. The content of the ICAO Appendix 8 is reflected in the AMC. Although the AMC is oftenreferred to as soft law, regulated persons should apply AMC to demonstrate compliancewith the IR.177. Opinion 04/2011 ORO.MLR.115 Record-keeping (c) contains requirements regardingpersonnel records. Crew member training, checking and qualifications shall be stored for3 years and the last 2 training records of other personnel for whom a trainingprogramme is required shall be stored.178. Self-reporting of fatigue risks has been included under (a) in AMC1-ORO.FTL.120(d)(2)(i)Fatigue Risk Management (FRM) to match the ICAO requirements.179. Operators are responsible to manage all operational risks, including those arising fromcrew member fatigue. The Agency believes that compliance with prescriptive FTL is notalways enough to guarantee that crew members remain sufficiently free from fatigue soR.F010-02 � European Aviation Safety Agency, 2012. All rights reserved. Proprietary document.

Page 24 of 103

CRD 2010-14

18 Jan 2012

that they can operate to a satisfactory level of safety under all circumstances. Fatiguemanagement training will increase awareness and shall help identify possible fatigue-related hazards, even in operations entirely compliant with prescriptive FTL.180. The wording of ORO.FTL.250 Fatigue management training has been adapted for editorialreasons. A reference to the recurrent character of the training has been included.Home base181. The elements on home base and in particular the issue of multiple home bases attractedmany comments. The main concerns expressed by the commentators were on theconcept of a home base within a multiple airport system as opposed to a single homebase and the possibility for operators to change crew members’ home base several timesper year. Most commentators criticised the possibility of multiple home bases. In theirview a single home base would still enable the operator to assign crews to differentairports, but this would require crew members to travel in their own time and duringtheir own minimum rest period leading to decreased rest time and increased fatigue.Those commentators did not see any justification for multiple airport systems and areworried about changes of the home base, which in their view would mean that the crewmember would have to sacrifice part of their rest time in-between duties to travel to thenext home base. This, they argue, would decrease rest time and ultimately increasefatigue.182. The majority of the commentators requested that there should be a limit of changing ahome base of once a year, and that there should at least be an AMC to establish howmany changes of home base per year are acceptable. Those commentators referred tothe ICAO Annex 6 (4.4.5) which states that the home base should be assigned with adegree of permanence.Current definition of home base in EU-OPS is sufficient183. Few commentators from operator organisations argued that the existing definition of ahome base contained inOPS 1.1095is fully sufficient and that the additions contained inthe NPA are of no safety benefit and should therefore be decided by collective bargaining.Member States stated that the current home base definition in EU-OPS is a core elementfor any FTL regulation and that today’s Subpart Q definition is open to diverginginterpretations and implementations.184. All scientists agreed that excessive travelling time combined with early reporting raisessafety concerns.Advantages and disadvantages of multiple home base185. Those commentators being critical of the concept of a multiple home base wereconcerned that multiple airport home bases would increase travelling times for crewmembers and would thus have an impact on fatigue. In some Member States where crewmembers have a single home base some operators can require crew members to livewithin a distance of 50 km from the airport so that they can reach the airport at all timeswithin 1 hour. Those commentators argued that in the case of a multiple airport systemthe home of the crew member could be further away from the second airport, whichcould lead to travelling times of more than 2 hours. From a safety point of view thiswould be unacceptable, they argued. One operator, who is applying the multiple airportsystem approach, proposed that each crew member should be nominated with a mainhome base and one or more satellite home bases, if necessary, and provided that thetravelling time to a satellite home base is less than or equal to the travelling time to themain home. The operator argued that multiple airport systems can be beneficial in termsof reducing travelling time and fatigue from the crew member’s point of view.186. One operator explained their operational need to cater for a pool of volunteer cabin crewmembers who ordinarily conduct other non-flying duties. They may live and/or work atR.F010-02 � European Aviation Safety Agency, 2012. All rights reserved. Proprietary document.

Page 25 of 103

CRD 2010-14

18 Jan 2012

places or stations away from the multiple flying bases and commute to their home basein order to commence flying duties. On this particular example the Agency notes that it isa crew member’s personal decision on where to establish their residence; however, asstated in the NPA, it is a shared responsibility of the operator and the crew membersconcerned to ensure that they arrive well-rested for duty. The concept of sharedresponsibility is described in GM1-ORO.FTL.235 Minimum rest periods, where it is statedthat well-rested means physiologically and mentally prepared and capable of performingassigned in-flight duties with the highest degree of safety.187. The scientists stated that in the case of multiple airport systems the integrity of thehome base could be at risk and that excessive travelling times, especially those linkedwith early starts, are of concern. Multiple airports should not be used to extend thetravelling time beyond a reasonable limit (e.g. 1.5 hours). According to the scientists, ifthis limit is exceeded due to the provision for multiple airports, the additional time(whether before or after the FDP) should count as positioning. The frequency of homebase changes should be monitored by FRMS.188. With respect to Member States, the opinion was split. Some Member States agreed thatthe safety impact of multiple airport systems is negligible even with a somewhat greaterdistance, the economic consequences for the operator can be substantial and the possiblesocial consequences for the crew members are compensated by the fact that therepositioning is considered duty time and thus compensated financially and in time.189. Other Member States are concerned that the impact on fatigue as a result of multipleairport systems and increased travelling times is substantial and that the final proposalshould include adequate mitigating measures by including a clearer definition of‘travelling’ and ‘positioning’, to ensure that in the case of multiple home bases travellingtime counts as positioning.190. A third group of Member States stated that for the most normal EU operations a singleairport would be a home base rather than multiple airport locations. Nevertheless, theneed for an operator, particularly a larger operator, to have the flexibility to ask crewmembers to report to one of a few nearby airports is understood. While those MemberStates support the requirements for the distance and travelling time between themultiple airport locations, there is the additional risk of the increased travelling timetaken by the crew members to reach all the airports in the multi-airport location.Role of the competent authority in approving multiple home base191. Some Member States suggested adding separate Guidance Material which would remindcrew members of their responsibilities to report for duty fit and rested. Where the crewmembers’ travelling time to their home base exceeds 90 minutes they should makealternative arrangements for accommodation closer to their base.192. A considerable number of Member States requested an addition to FTL.1.205(a) tostipulate that where the operator uses a multiple airport location the multiple airportlocations are approved by the competent authority. This additional requirement shouldensure that multiple airport locations have been realistically assessed and preventexcessive travelling times and journeys to work. In addition, they suggested that wherethese multiple airport locations are used the operator should only use them for crewmembers that volunteer for the multi-base as this would ensure that the crew memberscan reach all the airports within a reasonable travelling time and won’t have an excessivejourney to work due to having to drive for a further hour to reach the airport for report.193. Industry stakeholders did not comment on the role of the competent authority inapproving a multiple airport home base.194. One scientist stated that in the case of multiple airport systems the integrity of the homebase could be at risk and that further provisions should be included in the regulations toprotect the integrity of the home base and to avoid that multiple home bases are used toevade the requirement for a positioning flight.R.F010-02 � European Aviation Safety Agency, 2012. All rights reserved. Proprietary document.

Page 26 of 103

CRD 2010-14Distance and travelling time limitations

18 Jan 2012