Socialudvalget 2011-12

SOU Alm.del Bilag 318

Offentligt

UNICEFInnocenti Research CentreReport Card 10

Measuringchild povertyNew league tables of child povertyin the world’s rich countries

Innocenti Report Card 10was written by Peter Adamson.Two background papers from the UNICEFInnocenti Research Centresupport this Report:1.Bradshaw, J., Y. Chzhen, C. de Neubourg, G. Main, B. Martoranoand L. Menchini (2012), ‘Relative Income Poverty among Children inRich Countries’,Innocenti Working Paper2012-01, UNICEF InnocentiResearch Centre, Florence.www.unicef-irc.org/publications/pdf/iwp_2012_01.pdfde Neubourg, C., J. Bradshaw, Y. Chzhen, G. Main, B. Martoranoand L. Menchini (2012), ‘Child Deprivation, MultidimensionalPoverty and Monetary Poverty in Europe’,Innocenti Working Paper2012-02, UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre, Florence.www.unicef-irc.org/publications/pdf/iwp_2012_02.pdf

2.

The UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre would like to acknowledge thegenerous support forReport Card 10provided by the Andorran,Belgian, Swiss and United Kingdom National Committees for UNICEF.Any part of thisInnocenti Report Cardmay be freely reproduced usingthe following reference:UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre (2012), ‘Measuring Child Poverty:New league tables of child poverty in the world’s rich countries’,Innocenti Report Card 10,UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre, Florence.

Which countriesare included?

TheReport Cardseries is designed to monitor and compare theperformance of economically advanced countries in securing the rightsof their children.The Innocenti Research Centre (IRC) was established in Florence, Italyin 1988 to strengthen the research capability of the United NationsChildren’s Fund (UNICEF) and to support its advocacy for childrenworldwide. IRC is the dedicated research hub of the UNICEF Office ofResearch (OOR), which provides global leadership for the organization’sstrategic research agenda around children. The Office aims to set out acomprehensive framework for research and knowledge within theorganization, in support of its global programmes and policies. Throughstrengthening research partnerships with leading academic institutionsand development networks in both the North and South, the Officeseeks to leverage additional resources and influence in support ofefforts towards policy reform in favour of children.The Centre's publications are contributions to a global debate on childrights and help facilitate full implementation of the Convention on theRights of the Child in low-, middle- and high-income countries. Theviews expressed are those of the authors and researchers and do notnecessarily reflect the policies or views of UNICEF.

Data on child deprivation ratesare drawn from the 2009 roundof theEuropean Union Statisticson Income and Living Conditionsand are therefore available for 29countries, i.e. all 27 countries ofthe European Union plus Norwayand Iceland. Most of these (23out of 29) are also members ofthe Organisation for EconomicCo-operation and Development(OECD). The exceptions areBulgaria, Cyprus, Latvia,Lithuania, Malta and Romania,which are EU member states,but not members of the OECD.Data on relative child povertyrates are also available for sixadditional OECD countries(Australia, Canada, Japan,New Zealand, Switzerland, andthe United States). The analysisof relative child poverty thereforeincludes the following 35countries:Australia, Austria, Belgium,Bulgaria, Canada, Cyprus,Czech Republic, Denmark,Estonia, Finland, France,Germany, Greece, Hungary,Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Japan,Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg,Malta, the Netherlands,New Zealand, Norway, Poland,Portugal, Romania, Slovakia,Slovenia, Spain, Sweden,Switzerland, United Kingdom,United States.

� United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), May 2012ISBN: 978-88-8912-965-4ISSN: 1605-7317UNICEF Innocenti Research CentrePiazza SS. Annunziata, 1250122 Florence, ItalyTel: (+39) 055 2033 0Fax: (+39) 055 2033 220[email protected]www.unicef-irc.org

I n n o c e n t I

R e p o R t

c a R d

1 0

1

UNICEFInnocenti Research Centre

This report sets out the latest internationally comparable data onchild deprivation and relative child poverty. Taken together, thesetwo different measures offer the best currently available pictureof child poverty across the world’s wealthiest nations.Previous reports in this series have shown that failure toprotect children from poverty is one of the most costly mistakesa society can make. The heaviest cost of all is borne by thechildren themselves. But their nations must also pay a verysignificant price – in reduced skills and productivity, in lowerlevels of health and educational achievement, in increasedlikelihood of unemployment and welfare dependence, in thehigher costs of judicial and social protection systems, and inthe loss of social cohesion.The economic argument, in anything but the shortest term, istherefore heavily on the side of protecting children from poverty.Even more important is the argument in principle. Becausechildren have only one opportunity to develop normally in mindand body, the commitment to protection from poverty must beupheld in good times and in bad. A society that fails to maintainthat commitment, even in difficult economic times, is a societythat is failing its most vulnerable citizens and storing upintractable social and economic problems for the yearsimmediately ahead.It is for these reasons that this comparative snapshot of childpoverty in the industrialized nations is presented for theattention of political leaders, press and public.

2

I n n o c e n t I

R e p o R t

c a R d

1 0

T W O

VI E W S

OF

CHILD

POV ER TY

New league tables of child povertyin the world’s rich countries

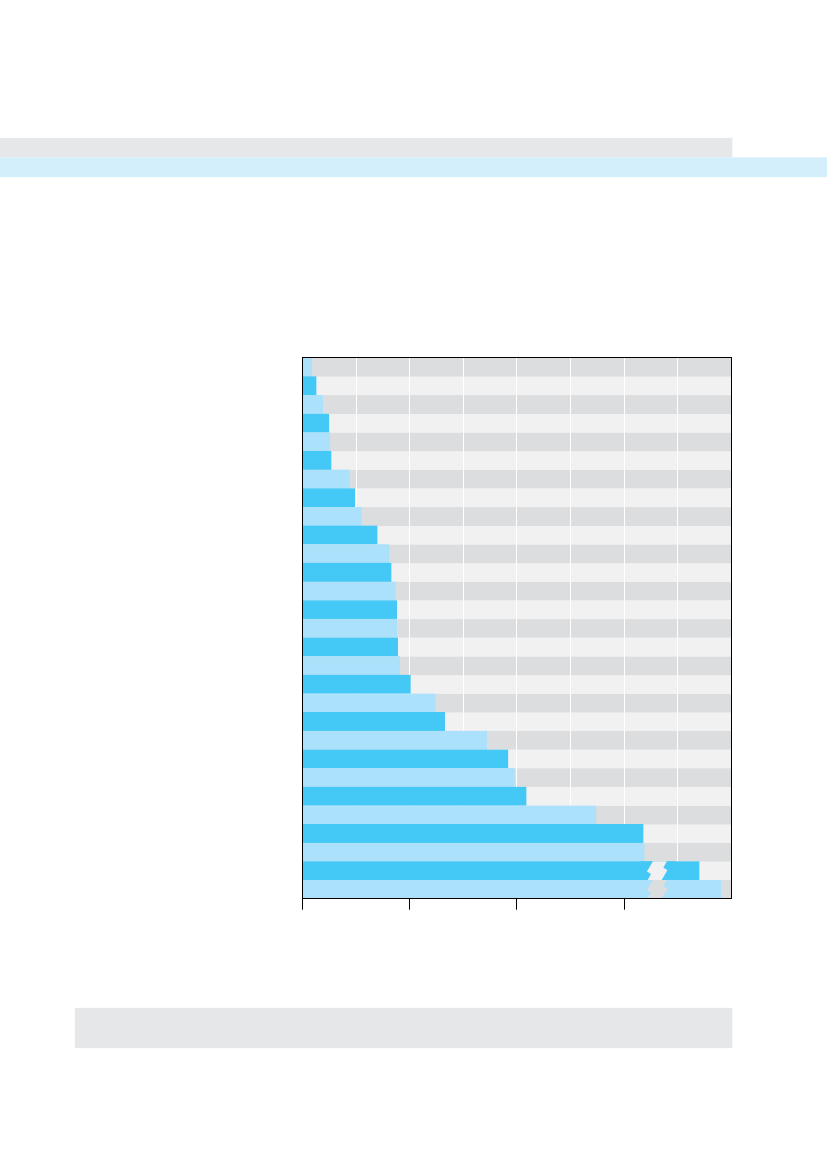

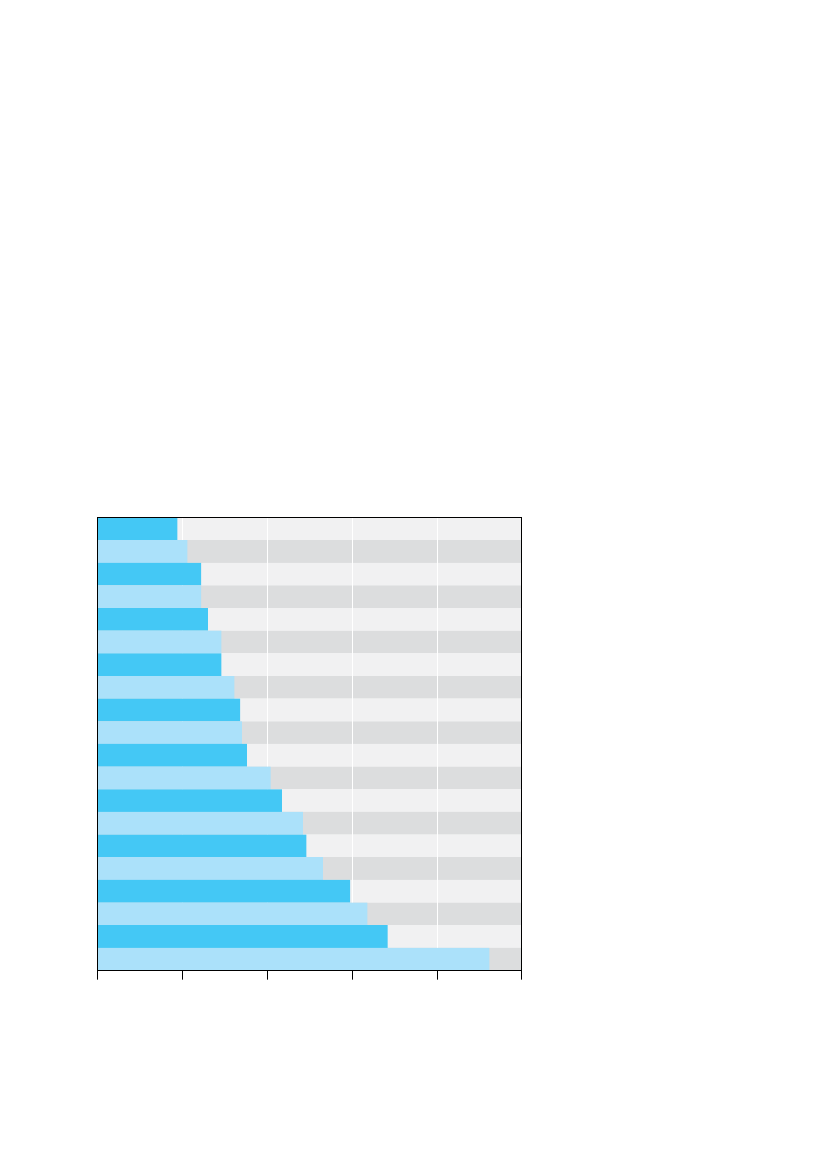

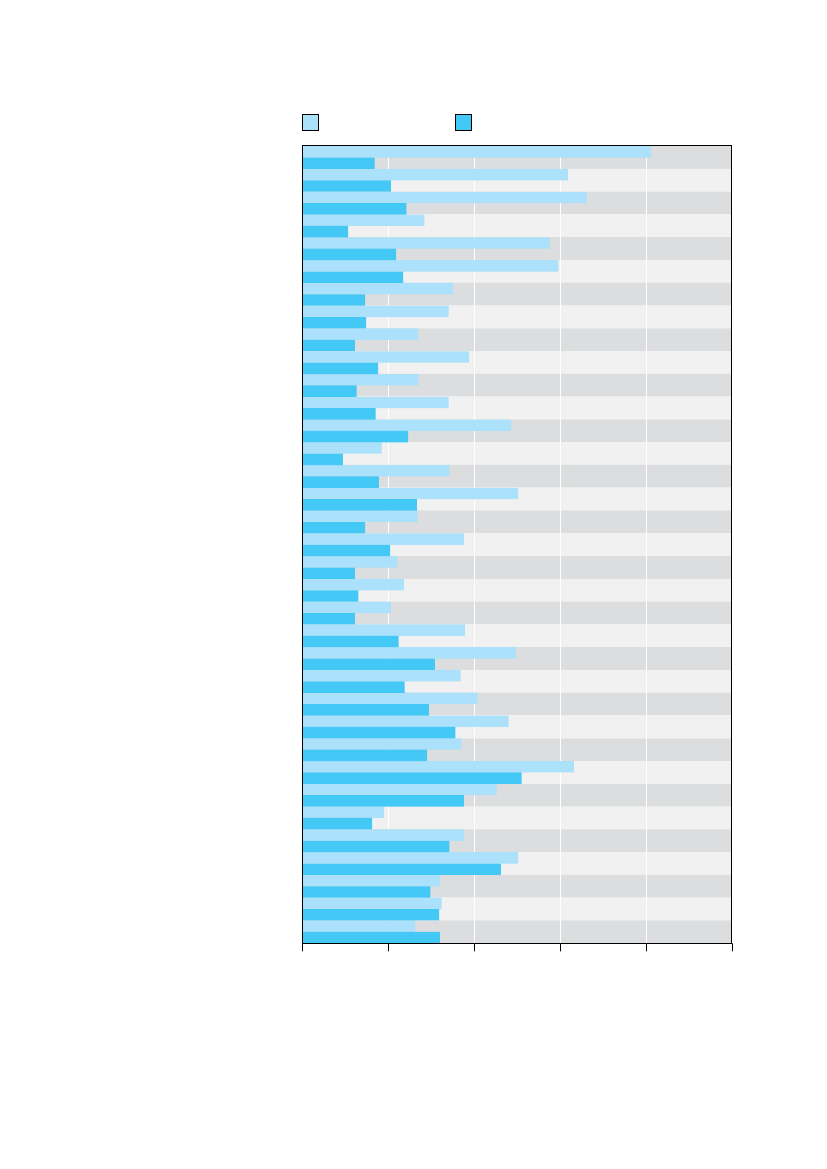

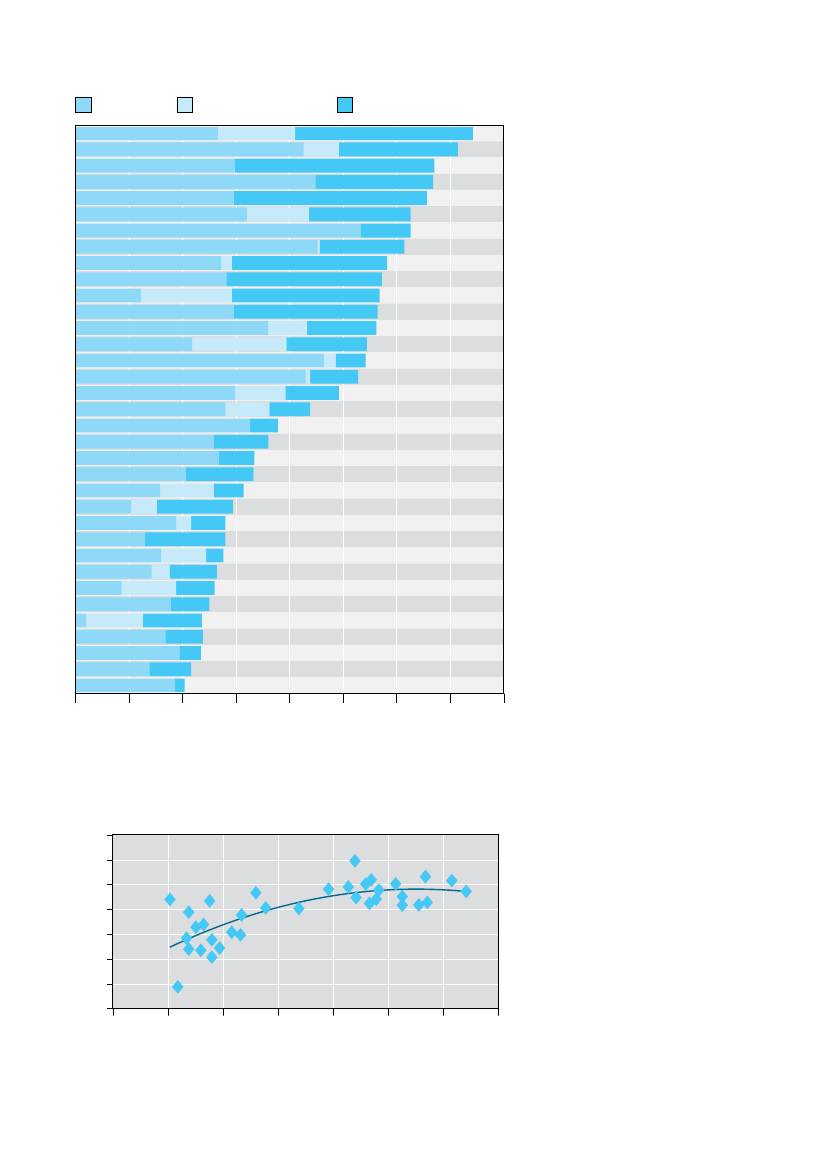

Fig. 1aA league table of childdeprivation, 29 economicallyadvanced countriesFigure 1a shows the percentage of children(aged 1 to 16) who lack two or moreof the following 14 items because thehouseholds in which they live cannotafford to provide them.1.2.Three meals a dayAt least one meal a day with meat,chicken or fish (or a vegetarianequivalent)Fresh fruit and vegetables every dayBooks suitable for the child’s age andknowledge level (not includingschoolbooks)Outdoor leisure equipment (bicycle,roller-skates, etc.)Regular leisure activities (swimming,playing an instrument, participating inyouth organizations etc.)Indoor games (at least one per child,including educational baby toys,building blocks, board games,computer games etc.)Money to participate in school tripsand eventsA quiet place with enough roomand light to do homework

0.91.31.92.52.62.74.44.95.57.08.18.38.78.88.88.99.110.112.413.317.219.219.820.927.431.831.956.672.601020Child deprivation(% of children lacking two or more items)Note:Data refer to children aged 1 to 16.Source:Calculations based on EU-SILC 2009.

IcelandSwedenNorwayFinlandDenmarkNetherlandsLuxembourgIrelandUnited KingdomCyprusSpainSloveniaAustriaCzech RepublicGermanyMaltaBelgiumFranceEstoniaItalyGreeceSlovakiaLithuaniaPolandPortugalLatviaHungaryBulgariaRomania30

3.4.

5.6.

7.

8.9.

10.An Internet connection11.Some new clothes (i.e. not allsecond-hand)12.Two pairs of properly fitting shoes(including at least one pair ofall-weather shoes)13.The opportunity, from time to time, toinvite friends home to play and eat14.The opportunity to celebrate specialoccasions such as birthdays, namedays, religious events, etc.

The data are drawn from the 2009 round of theEuropean Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions(EU-SILC)and are not available for non-European countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

I n n o c e n t I

R e p o R t

c a R d

1 0

3

IntroductionThe league tables on these pagespresent the latest available data on childpoverty across the world’s rich nations.Figure 1a, made available here for thefirst time, shows the proportion of

children in each country who aredeprived – i.e. ‘lacking two or more’of 14 items considered normal andnecessary for a child in aneconomically advanced country(see opposite for the full list).

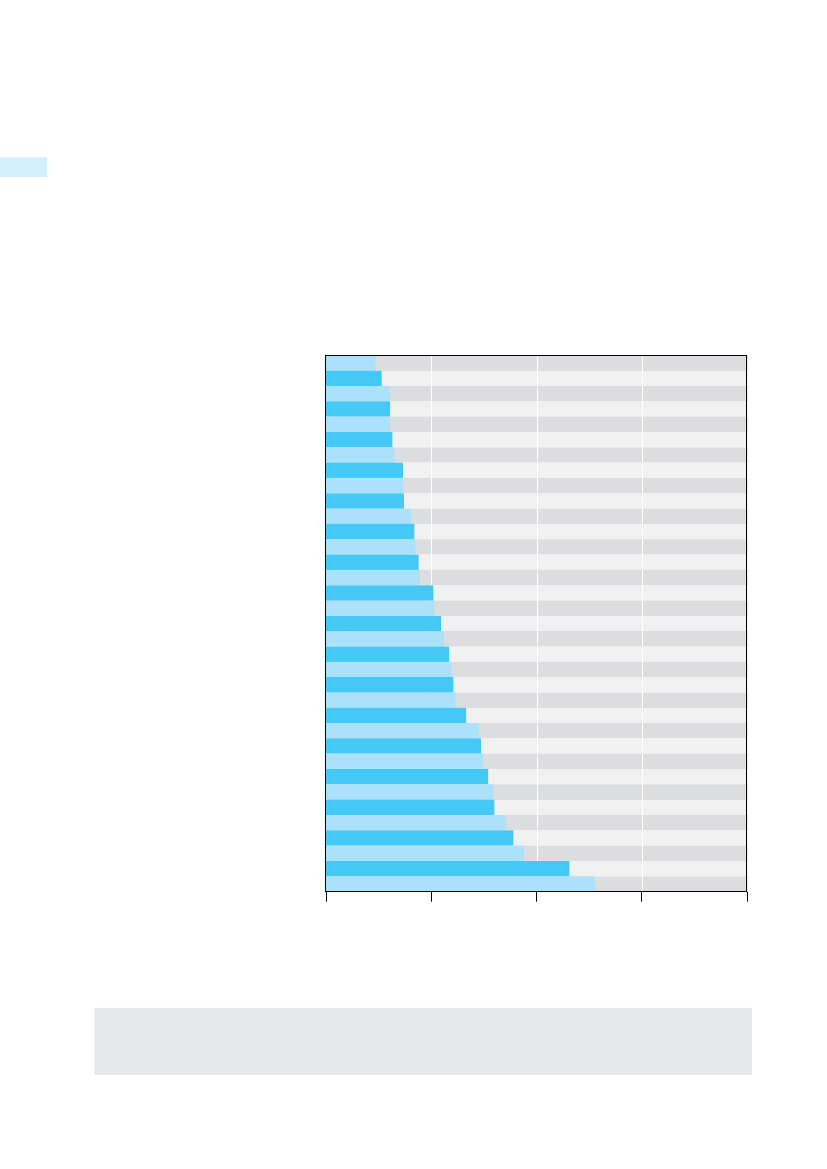

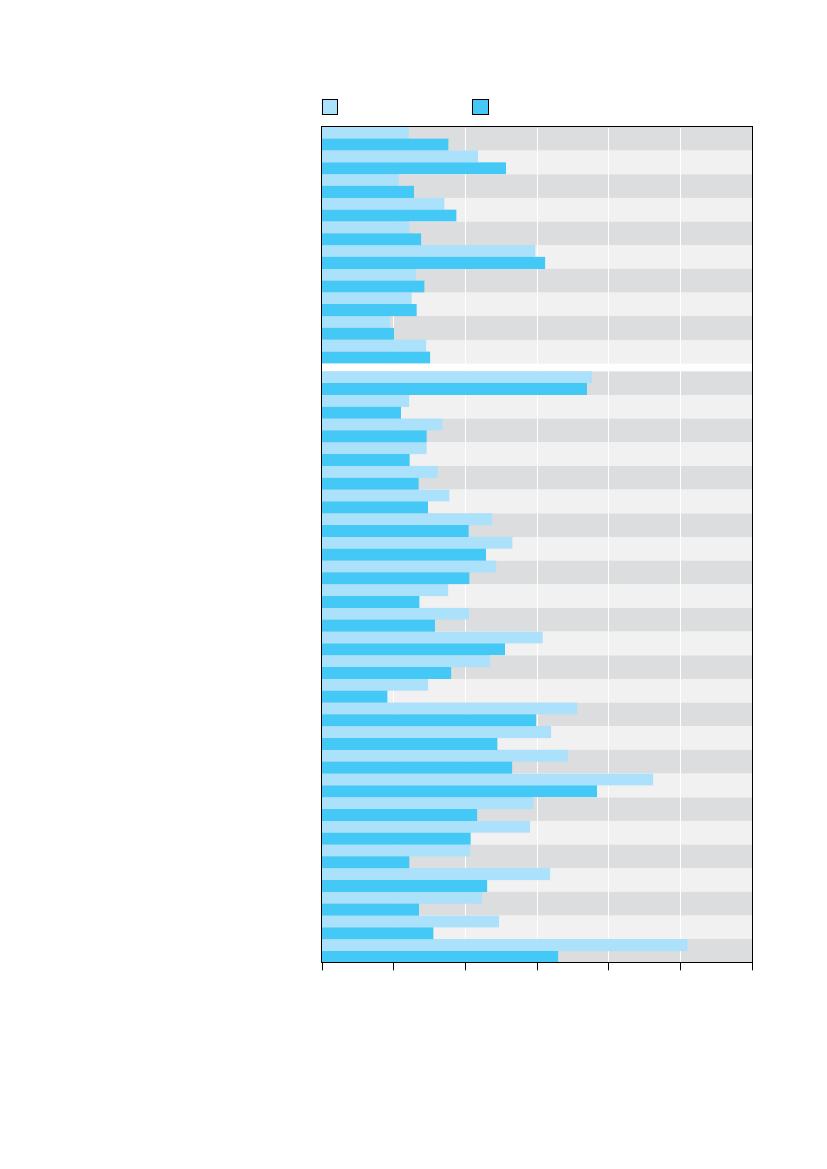

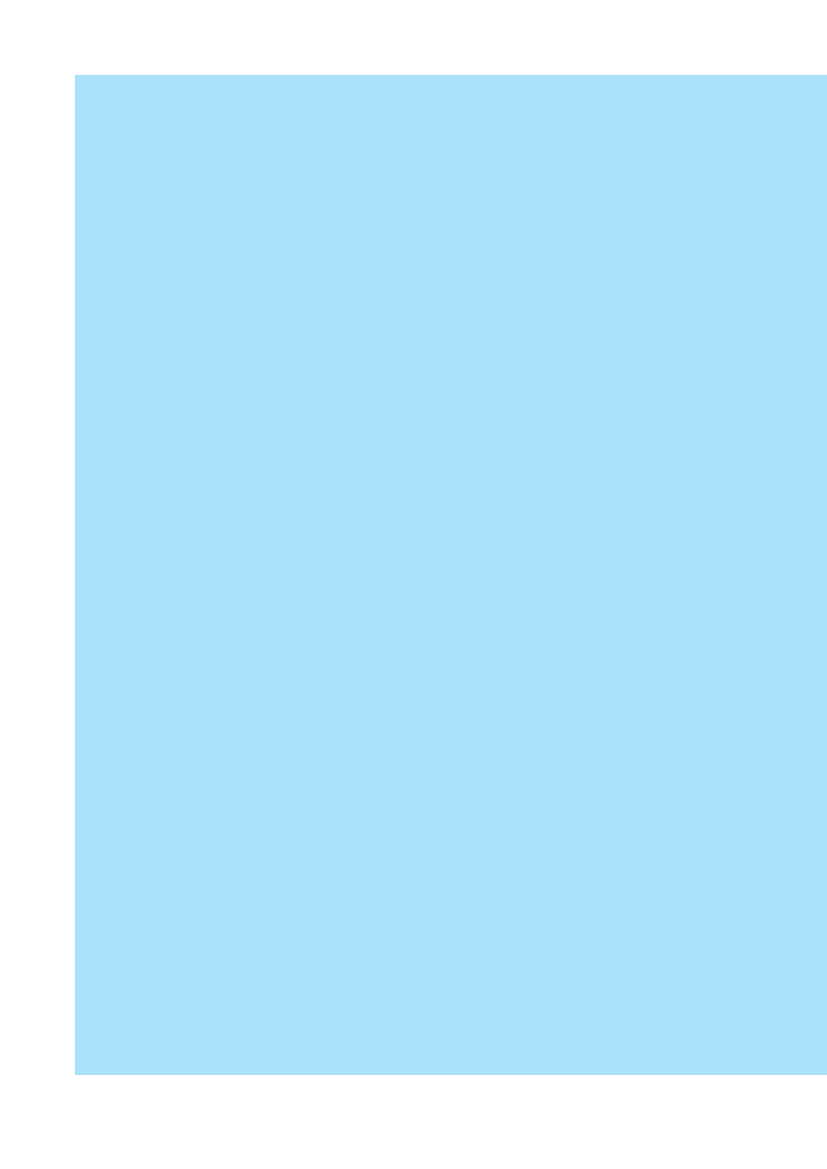

Figure 1b shows the percentage ofchildren living in relative poverty,defined as living in a household whoseincome, when adjusted for family sizeand composition, is less than 50% ofthe median income for the country inwhich they live.

Fig. 1bA league table of relative childpoverty, 35 economically advancedcountriesFigure 1b shows the percentage of children(aged 0 to 17) who are living in relativepoverty, defined as living in a household inwhich disposable income, when adjustedfor family size and composition, is lessthan 50% of the national median income.

4.75.36.16.16.16.36.57.37.37.48.18.48.58.88.910.210.310.911.211.711.912.112.313.314.514.714.915.415.916.017.117.818.823.125.5010

IcelandFinlandCyprusNetherlandsNorwaySloveniaDenmarkSwedenAustriaCzech RepublicSwitzerlandIrelandGermanyFranceMaltaBelgiumHungaryAustraliaSlovakiaNew ZealandEstoniaUnited KingdomLuxembourgCanadaPolandPortugalJapanLithuaniaItalyGreeceSpainBulgariaLatviaUSARomania40

2030Child poverty rate(% of children living in households with equivalent income lower than 50% of national median)

Note:Data refer to children aged 0 to 17.Sources:Calculations based on EU-SILC 2009, HILDA 2009, SLID 2009, SHP 2009, PSID 2007. Results for New Zealand are from Perry(2011). Results for Japan are from Cabinet Office, Gender Equality Bureau (2011).

Some OECD countries – Australia, Canada, Japan, New Zealand, Switzerland and the United States – are included in the league tableof relative child poverty (Figure 1b) but could not be included in the league table of child deprivation (Figure 1a) because relevantdata are not available. Child deprivation data are drawn from theEuropean Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditionsand aretherefore only available for the 27 EU countries plus Iceland and Norway.

4

I n n o c e n t I

R e p o R t

c a R d

1 0

As may be seen at a glance, the twoleague tables project two very differentpictures of child poverty in the world’srich nations. What these differentpictures mean – the relationshipbetween them and the controversiessurrounding them – is the subject ofthisReport Card.

the child poverty rate is one of themost important of all indicators of asociety’s health and well-being. For thehere and now, it is a measure of whatis happening to some of society’s mostvulnerable members. For the years tocome, it is a pointer to the well-beingand cohesion of society as a whole.Previous reports in this series havepresented the evidence for the closeassociation between child povertyand a long list of individual and socialrisks – from impaired cognitivedevelopment to increased behaviouraldifficulties, from poorer physical healthto underachievement in school, fromlowered skills and aspirations to higherrisks of welfare dependency, from the

Slipping down the agendaIn the wake of statistics following thepost-2008 economic crises, the childpoverty rate has rarely surfaced.“In a downturn,”says Sharon Goldfeld,National Director of the AustralianEarly Development Index,“the firstthing that happens is that children drop offthe policy agenda.”Yet it is arguable that

greater likelihood of teenagepregnancy to the increased probabilityof drug and alcohol abuse. That thereare many exceptions – many childrenwho grow up in economically poorfamilies who do not fall into any ofthese categories – does not alter thefact that poverty in childhood isclosely and consistently associated withmeasurable disadvantage both forindividuals and for the societies inwhich they live.iA commitment to protecting childrenfrom poverty is therefore more thana slogan or a routine inclusion in apolitical manifesto; it is the hallmarkof a civilized society.

Box 1Children and recession

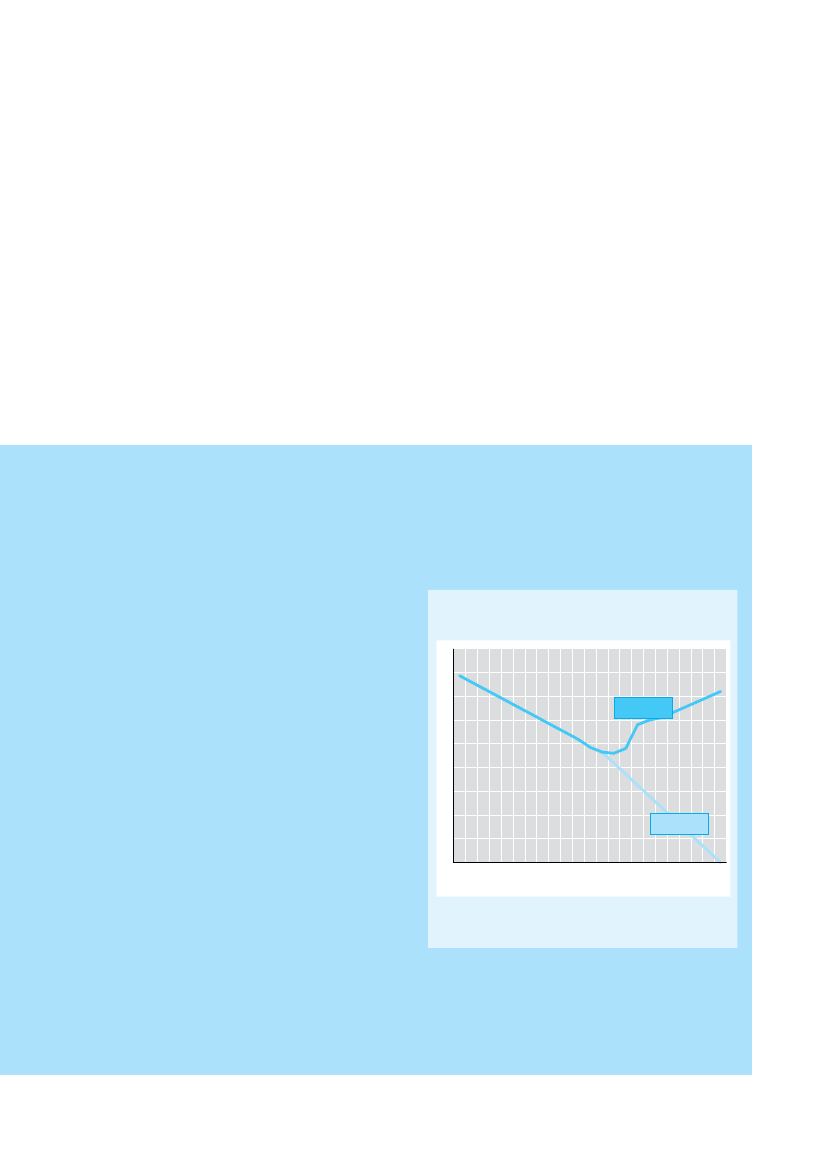

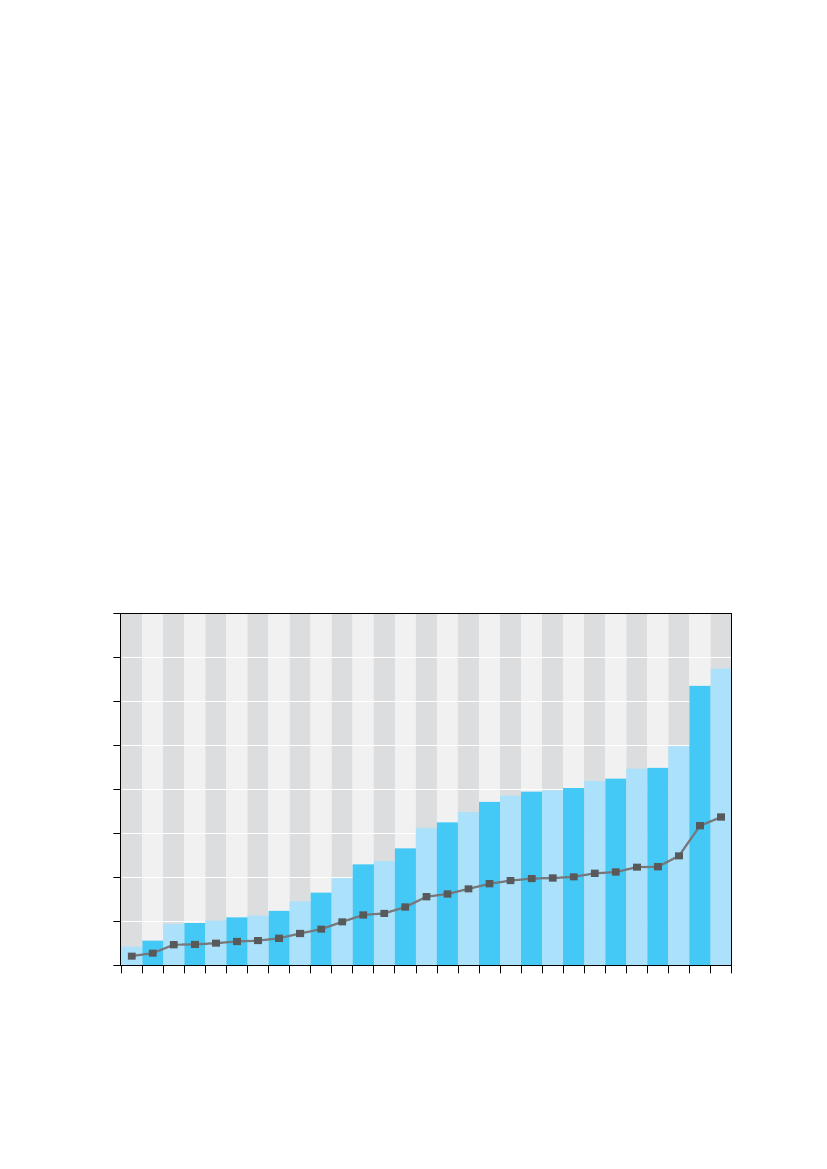

There are almost no internationally comparable data onwhat is happening to child poverty as a result of theeconomic downturn of the last three years.It is nonetheless evident that front-line services forfamilies are everywhere under strain as austeritymeasures increase the numbers in need while depletingthe services available. It is also clear that the worst isyet to come. Many families, even those on low incomes,have some form of ‘cushion’ – whether in the form ofsavings, assets, or help from other family members – bywhich to maintain spending during difficult times. Thereis therefore almost always a time lag between the onsetof an economic crisis and the full extent of its impact.CommitmentIn Ireland, a leader in both the theory and practice ofmonitoring child poverty, some data are available toestimate the effects on children and families of asevere contraction in the national economy. Between2009 and 2010, for example, Ireland’s own childdeprivation index showed a rise of almost 7 percentagepoints, from 23.5% to 30.2%.1Over the same period,falling median incomes meant that relative child povertyrose by less than one percentage point – again showingthe value of using the two different measuresdiscussed in this report.

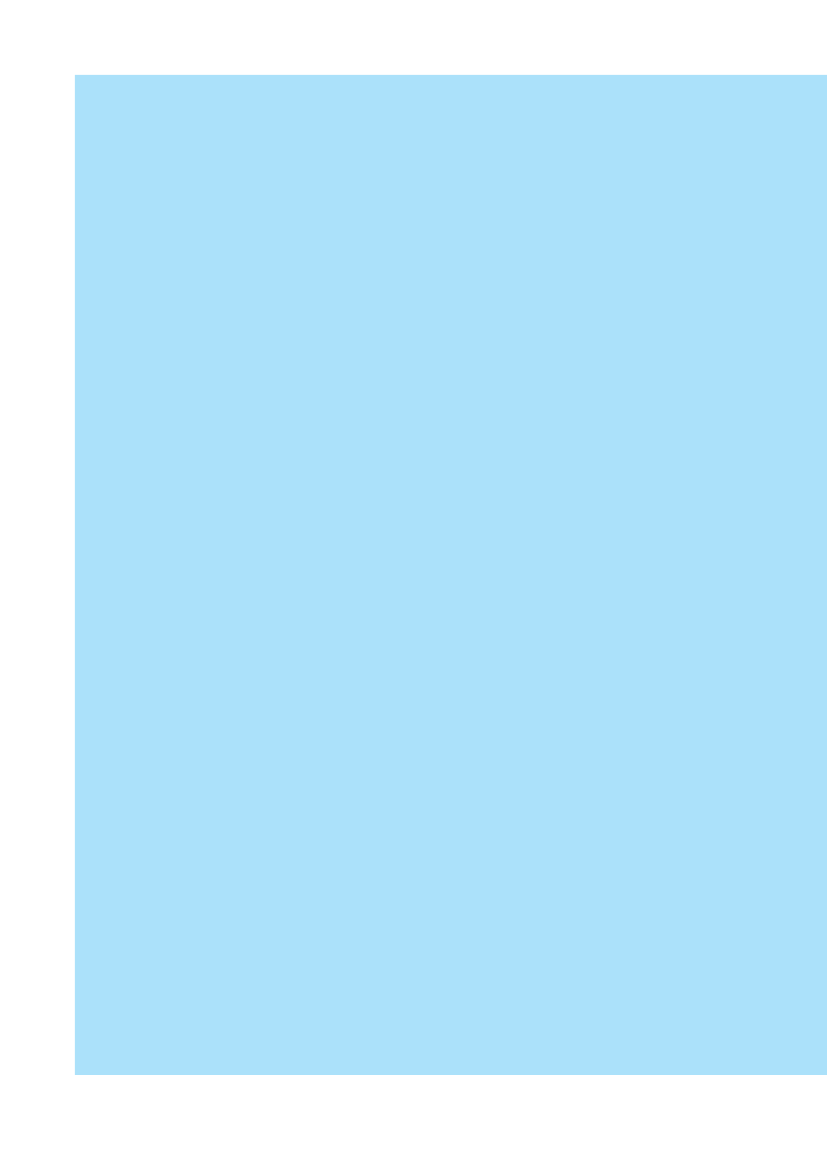

The possible impact of the economic downturn onefforts to reduce child poverty rates has also recentlybeen estimated for the United Kingdom, where theChild Poverty Actof 2010 has set legally binding targetsfor reducing child poverty. By 2020, the relative childpoverty rate is to be halved to no more than 10%.(‘Absolute income poverty‘ – defined as living onan income below 60% of the median income forthe benchmark year 2010 and updated only for inflation– is to be cut from 20% to 5%.)But as the Act came into force, the economic crisiswas already beginning to threaten social protectionprogrammes. Child benefits, for example, have beenfrozen for three years – meaning that in real termsthey will fall in value. Child tax credits and otherprogrammes designed to protect the poorest childrenhave been cut back.What difference are such changes likely to maketo the UK’s long-term efforts to bring down childpoverty rates?ReversalAccording to an October 2011 report from the Institutefor Fiscal Studies (IFS),2the likeliest prospect is that theprogress of recent years will be thrown into reverse.Although currently thought to be stable, the childpoverty rate is predicted to begin rising again in 2013.

I n n o c e n t I

R e p o R t

c a R d

1 0

5

A crisis of monitoringIn practice, making good on thiscommitment is impossible withoutclose monitoring of what is happeningto children’s lives. It is monitoring thatmakes possible evidence-based policy,political accountability, informedadvocacy and the cost-effective use oflimited public resources. Theavailability of timely data is thereforein itself an indicator of whether thecommitment to protecting children isbeing taken seriously or not.The two league tables, Figures 1a and1b, therefore reveal more than thepercentages of children living indifferent kinds of poverty. They also

reveal a crisis of monitoring. In bothcases the data they present, althoughthe latest available, are mostly drawnfrom surveys conducted in 2009. Theyare therefore at least two to three yearsold.*This would be bad enough at thebest of times. But these are not the bestof times. And it is a significant failing,on behalf of many governments ofOECD countries, that the available dataon children’s lives do not yet reflect theimpact of the economic downturn(see Box 1: Children and recession).Underlying weak monitoring is thelack of any robust public or politicalconsensus on how child povertyshould be defined and measured.

“The discourse on poverty is very confusing,”says Jonathan Bradshaw, Professor ofSocial Policy at the University of Yorkand one of the authors of the statisticalanalysis on which this report draws:ii“Wetend to mix up concepts and measuresand use different words to describe the samething and the same words to describedifferent things.”iiiMany of the questions and confusionsabout the measurement of childpoverty are encompassed by the twoleague tables with which this reportbegins. It may therefore be helpful tosummarize the principal differencesbetween them.

Looking further ahead, levels of ‘relative’ and ‘absolute’child poverty are expected to reach 24% and 23%respectively by 2020/21 – compared to the target figuresof 10% and 5%. This would mean a return to the relativechild poverty levels of two decades ago.Such forecasts, says the IFS, are“always highlyuncertain.”In particular, they cannot accurately predictthe impact of, and responses to, the tax and benefitchanges currently in the pipeline. They are nonethelessthe best available independent estimate of“what mighthappen to poverty under current government policies.”Since these forecasts were made, the commitment toincrease child credits by more than the rate of inflation in2012 and 2013 has been abandoned. According to IFScalculations, this decision alone is likely to mean thatanother 100,000 children will fall below the relativepoverty line.

Relative child poverty rate,United Kingdom, 1998–202028262422201816141210199820002002200420062008201020122014201620182020Target

Predicted

Source:Data from the Institute for Fiscal Studies, London, October 2011. The graph showsthe percentage of children living in households below 60% of equivalized median incomebefore housing costs. For illustrative purposes, the 'Target' line assumes linear progresstowards the 2020 goal.

1Central Statistics Office Ireland, Government of Ireland, 2011.2Brewer, M., J. Browne and R. Joyce (2011).Child and Working-age

Poverty from 2010 to 2020,Institute for Fiscal Studies, London.

*EU-SILC 2009: data on income refers to 2008, other data to 2009. Poverty data was released in early 2010.

6

I n n o c e n t I

R e p o R t

c a R d

1 0

A deprivation indexFigure 1a, a League Table of ChildDeprivation, represents a significantnew development in the internationalmonitoring of child poverty. For thefirst time, theEuropean Union Statisticson Income and Living Conditions,sampling more than 125,000households in 29 European countries,has included a section on the lives ofchildren aged 1 to 16. Using this data,the UNICEF Innocenti ResearchCentre has constructed the 14-itemChild Deprivation Indexon whichLeague Table 1a is based.The 14 items in the indexencompass the ability ofhouseholds to afford:1.2.

5.6.

Outdoor leisure equipment(bicycle, roller-skates, etc.)Regular leisure activities(swimming, playing aninstrument, participating in youthorganizations etc.)Indoor games (at least one perchild, including educational babytoys, building blocks, boardgames, computer games etc.)Money to participate in schooltrips and eventsA quiet place with enough roomand light to do homework

Overall, the league table shows thatapproximately 85% of the almost85 million children (aged 1 to 16) in29 European countries have at least 13of the 14 items in the deprivationindex and are therefore ‘not deprived’.The second most obvious feature ofthe table is that the highest rates ofdeprivation are to be found in someof the newest and poorest membercountries of the European Union.Over 30% are seen to be deprived inHungary and Latvia, over 50% inBulgaria and over 70% in Romania.For Central and Eastern Europeancountries, therefore, the league table ofchild deprivation makes grim reading.Among the richest 15 countries, allexcept France and Italy have childdeprivation rates below 10%. Butclearing a bar that is set so low doesnot warrant any great applause. Inthe world’s wealthiest nations theproportion of children lacking twoor more of these basic items shouldbe at or close to zero. Yet in practiceonly Denmark, Finland, Iceland, theNetherlands, Norway and Sweden have

7.

8.9.

10.An Internet connection11.Some new clothes (i.e. not all

second-hand)12.Two pairs of properly fitting

Three meals a dayAt least one meal a day withmeat, chicken or fish (or avegetarian equivalent)Fresh fruit and vegetablesevery dayBooks suitable for the child’sage and knowledge level(not including schoolbooks)

shoes (including at least one pairof all-weather shoes)13.The opportunity, from time to

3.4.

time, to invite friends home toplay and eat14.The opportunity to celebrate

special occasions such as birthdays,name days, religious events etc.

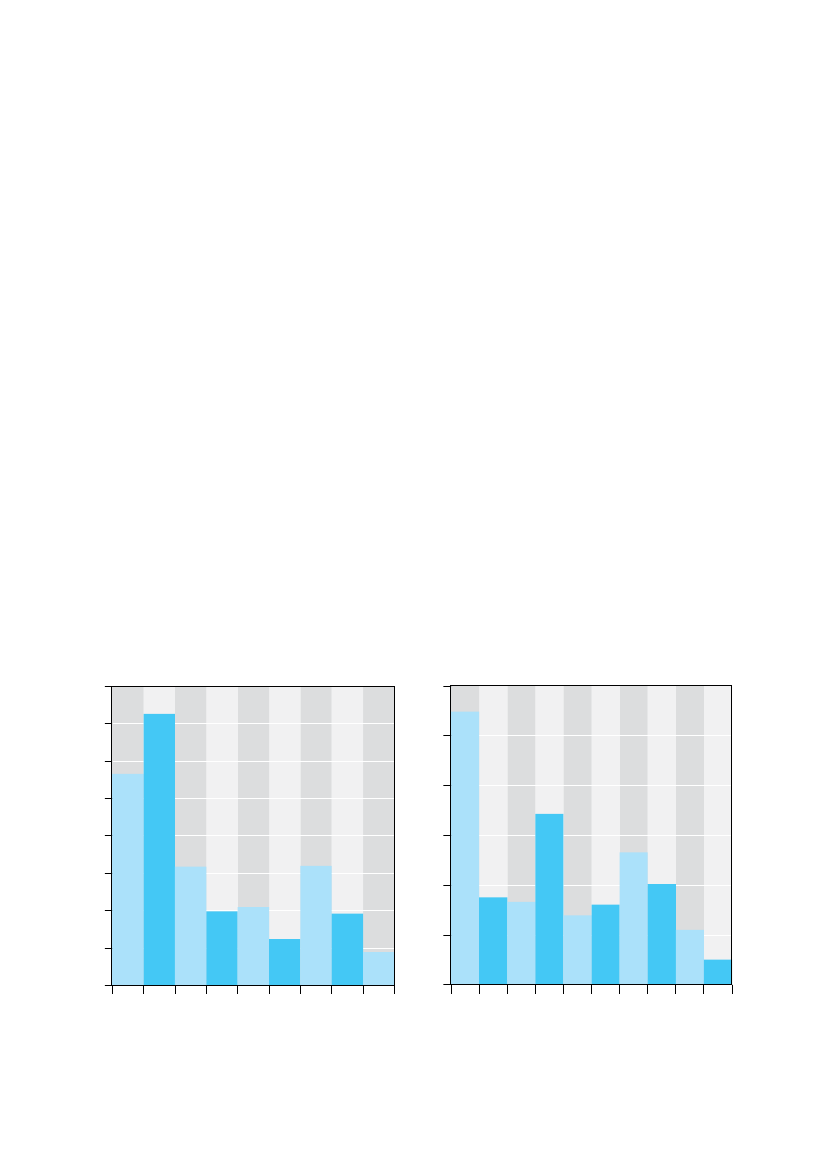

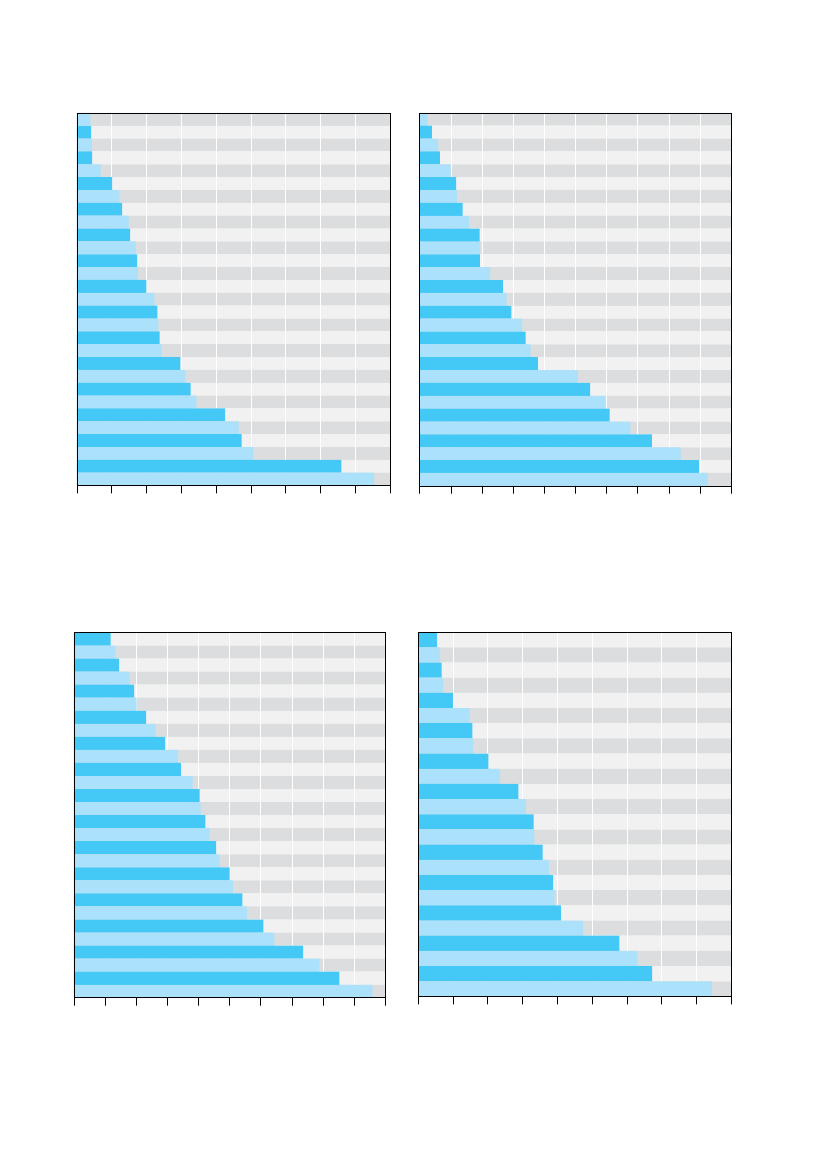

Fig. 2aPercentage of children deprived in countries withGDP per capita between $13,000 – $25,000 (PPP)8072.67060504031.83020100Lithuania($17,059)($18,925)

Fig. 2bPercentage of children deprived in countries withGDP per capita between $25,000 – $36,000 (PPP)3027.425

56.620% Children deprived

% Children deprived

17.215

13.310.18.88.37.08.15.5

31.9

1019.820.912.48.919.25

2.50United KingdomGreece($25,058)($27,556)

Slovenia

($29,303)

($30,728)

($32,262)

($32,413)

($25,572)

($33,349)

Czech Republic

($19,690)

($22,875)

($13,764)

($14,216)

($16,166)

Romania

($20,275)

($24,804)

(per capita GDP in parentheses)

(per capita GDP in parentheses)

($35,145)

($35,254)

Portugal

Slovakia

Bulgaria

Estonia

Hungary

Finland

Cyprus

Spain

Italy

Poland

France

Latvia

Malta

I n n o c e n t I

R e p o R t

c a R d

1 0

7

child deprivation rates below 3%. ForAustria, Belgium and Germany, the rateclimbs to 8% or more. In France andItaly the rate rises above the 10% mark.

Relative poverty leagueThe second of the two league tables(Figure 1b) paints a very differentpicture of child poverty in the world’sadvanced economies.It includes six OECD countries thatdo not participate in EU-SILC(Australia, Canada, Japan,New Zealand, Switzerland and theUnited States), and is based on thedefinition of relative poverty used bythe OECD. Under this definition, achild is deemed to be living in relativepoverty if he or she is growing up in ahousehold where disposable income,when adjusted for family size andcomposition, is less than 50% of themedian disposable household incomefor the country concerned.*By thisstandard, more than 15% of the 200million children in the 35 countrieslisted in Figure 1b are seen to be livingin relative poverty.The top five positions in the leaguetable are occupied by Iceland, Finland,Cyprus, the Netherlands and Norway(with Slovenia and Denmark close

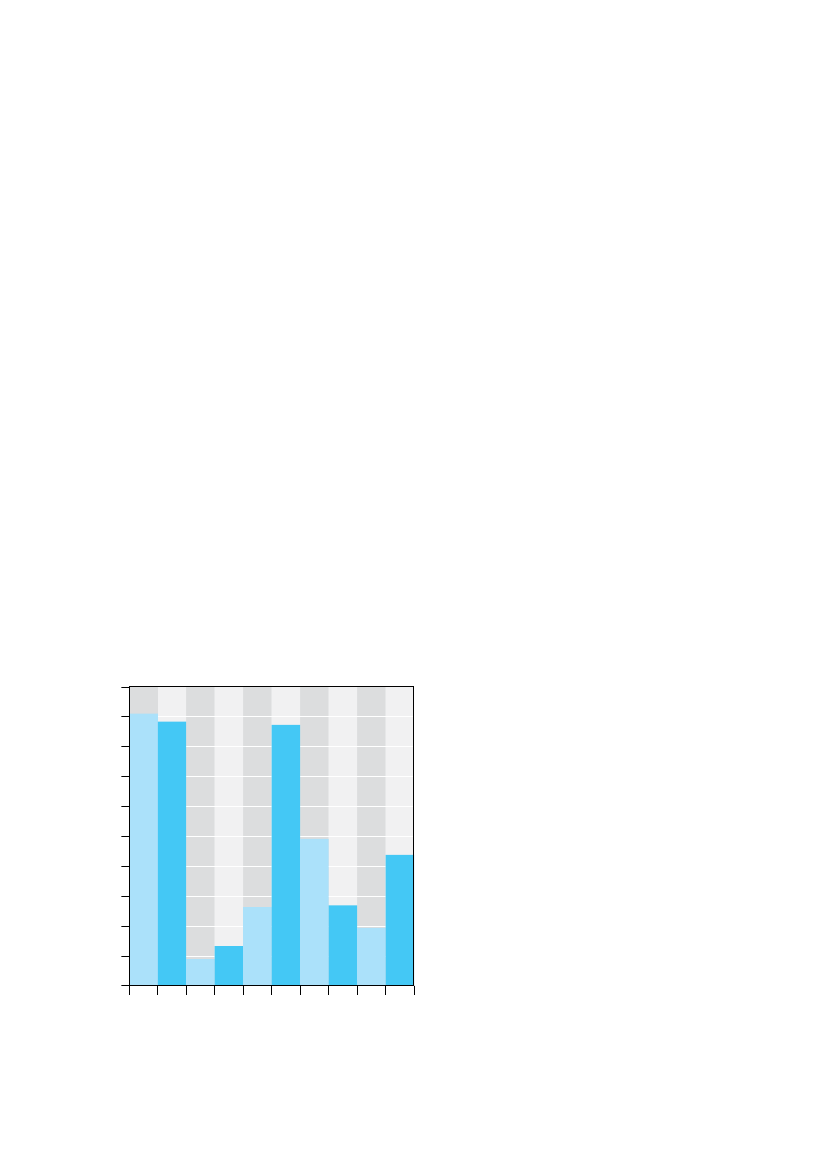

More with lessLooked at as a whole, the childdeprivation table may therefore seemto present little more than a blurredreflection of each country’s level of percapita income. But a closer look revealsthat some countries are in factachieving much more – and somemuch less – than their income levelswould predict. Estonia, Hungary andPoland, for example, have roughlyequivalent per capita incomes butwidely varying rates of childdeprivation (see Figure 2a). Portugaland the Czech Republic both have percapita incomes of about PPP $25,000,but Portugal’s child deprivation level isthree times higher (see Figure 2b).Belgium and Germany have similarper capita incomes to Denmark andSweden – but child deprivation ratesthat are about three and seven timeshigher (see Figure 2c).

behind). All of these countries haverelative child poverty rates below 7%.Another eight countries including twoof the largest – Germany and France –have rates between 7% and 10%. A thirdgroup, including Australia, Canada,New Zealand and the United Kingdom,post rates of between 10% and 15%.A further six, including populous Italyand Spain, show rates of between 15%and 20%. In only two countries aremore than 20% of children living inrelative poverty – Romania and theUnited States.Overall, the divide between thewealthy and not-so-wealthy nations ismuch less clear-cut. Hungary, Slovakiaand Estonia, for example, are seen tohave a smaller proportion of childrenliving in relative poverty than theUnited Kingdom, Italy, Spain, or theUnited States. Clearly, this is notbecause a smaller proportion of theirchildren are poor in an absolute sense;it is because the incomes of most poorhouseholds in these former centrally-planned economies do not fall as farbehind the median level of income forthe nation as a whole.Finally, it is worth noting that – despitethe very different measures of child povertyemployed in these two league tables – sevencountries are ranked in the top 10 in both– Cyprus, Denmark, Finland, Iceland,the Netherlands, Norway and Sweden.

Fig. 2cPercentage of children deprived in countries withGDP per capita between $36,000 – $85,000 (PPP)10987% Children deprived

9.1

8.8

8.7

ControversyWhat are we to make of these twovery different pictures of child povertyin the world’s richest nations?First, it is important to resist thetemptation to see the two differentviews presented in Figures 1a and 1bas contradictory or mutually exclusive.Both are valid. Both can inform policy.And both make it clear that somecountries are doing a much better jobthan others at protecting their childrenfrom poverty.Note:Data refer tochildren aged 1 to 16.Sources:Calculationsbased on EU-SILC 2009for child deprivation andon World DevelopmentIndicators (2011) for GDPper capita, PPP (currentinternational $).

6543210($36,279)

4.94.4

2.61.30.9

2.71.9

Belgium

Germany

($36,320)

($36,733)

Iceland

Sweden

Denmark

($39,643)

Austria

Ireland

Netherlands

($37,157)

($37,672)

($38,804)

($55,717)

($40,796)

Luxembourg

($84,766)

Norway

*Most European Union countries draw the relative

(per capita GDP in parentheses)

poverty line at 60% of national median income. Forpurposes of international comparison, the OECD (andthisReport Cardseries) uses a relative poverty linedrawn at 50% of median income.

8

I n n o c e n t I

R e p o R t

c a R d

1 0

The two measures are, however,profoundly different in concept.The most important difference betweenthem is that the child deprivation tableuses a fixed measure for all 29 countriessurveyed; the criterion applied (lackingtwo or more from the same list of 14items) is exactly the same for Swedenor the United States as it is for Bulgariaor Romania. Inevitably, therefore, itputs the emphasis on the differencesbetween richer and poorer countries.The criterion used to measure relativechild poverty, by contrast, changes withthe median income of each country; ittherefore transfers the emphasis to thegap between the bottom and themiddle in the living standards ofchildren within each country.It is because of this difference that thepoorer countries in Figure 1a tend tohave significantly higher rates of childdeprivation but may or may not havehigher rates of relative income poverty.For the same reason, the two differentmeasures tend to respond to economicand policy changes in very differentways.ivIn periods of sustainedeconomic growth, for example, theproportion of a nation’s childrendefined as ‘deprived’ will almostcertainly fall as overall incomes rise.The proportion living inrelativeincomepoverty, on the other hand, may eitherrise or fall depending upon whethertheir household incomes grow by moreor less than the median income for thenation concerned. To take a famousexample, a decade of sustainedeconomic growth in the Ireland of the1990s more than doubled the nation’smedian income, but the proportion ofchildren living in relative poverty alsorose because the incomes of householdsbelow the poverty line rose moreslowly than the median income for thecountry as a whole.Such examples bring us to the heartof one of the principal controversiessurrounding the measurement ofchild poverty.

‘Real’ povertyIt is often argued that relative povertyisn’t ‘real poverty’. Real poverty, it issaid, means lacking basics - enoughfood to eat, adequate clothing, a dryhome, an indoor toilet, hot water, anda bed to sleep in. Once you leave suchbasics behind and start drawingpoverty lines based on statisticalnotions like median income, it isargued, you end up with results thatfail to make intuitive sense and sofail to convince either politicians orpublic. Can the child poverty ratereally be said to be rising, for example,at a time when the incomes of thepoor are also rising? And can therereally be more children in povertyin the United Kingdom or theUnited States than in Hungary orLithuania (as shown in Figure 1b)?Or are these findings just statisticalartefacts produced by a definition ofchild poverty that is in effect basedon a concern not with poverty butwith inequality?Such are the arguments that pushmany to reject the relative incomemeasure and to embrace instead thedirect measurement of deprivation.Does the child have three meals a day?A few books in the home? And a roofthat doesn’t leak? Isn’t this a muchmore intuitive measure, and one thatis more capable of winning publicunderstanding and support?Direct measures of outcomes likedeprivation do have advantages overindirect or ‘input’ measures such ashousehold income (see Box 2: Theproblem with incomes). But the troublewith the argument that deprivationmeasures ‘real poverty’, whereas relativeincome does not, is that the intuitivelyappealing idea on which it rests is thatpoverty should be measured in anabsolute rather than a relative sense.And from here it is but a short step tothe belief that the deprivation indexpresented in Figure 1a is an absolutemeasure whereas the median incomemethod used for Figure 1b is ‘only’ arelative measure.

This is a mistake. Both are relativemeasures.The deprivation index is based on thekind of possessions, services andopportunities that most people wouldconsider normal for a child growingup in a wealthy country today. Inother words, it is relative to both timeand place. Twenty years ago, forexample, such a list would not haveincluded an Internet connection. Goback a little further in time and‘having at least one meal a day withmeat, chicken or fish’ would not havebeen regarded as normal. In fact thelonger the historical view the moreobvious it becomes that poverty is anessentially relative concept. Anypoverty line intended to represent aminimum acceptable standard of livingin the industrialized world todayimplies higher standards of food,clothing, housing, water supply,sanitation, health care, education,transport and entertainment than wereavailable to even the wealthiesthouseholds of previous eras.The whole idea of defining childpoverty in an absolute sense thereforerests on shaky ground. Unless we wishto argue that the threshold should beset at the minimum income necessaryfor sheer physical survival then therecan in fact be no such thing as anabsolute poverty line.The real debate, therefore, is notwhether poverty lines should beabsolute or relative, but how and howoften they should be updated to reflectchanges in the living standards ofsociety as a whole. If the decision istaken, for example, to draw an‘absolute’ poverty line at some fixedpoint and to update it only forinflation, then this means that a relativepoverty line is being anchored to anarbitrary point in time. As the yearspass and incomes rise, such a povertyline is likely to fall further and furtherbehind the norm for the society andto become less and less useful. This isessentially what has happened over the

I n n o c e n t I

R e p o R t

c a R d

1 0

9

Box 2The problem with incomes

Relative child poverty rates are usually estimated byassuming that household income is a reasonable guideto the material resources available to the child. But thisassumption is beset by problems.1Among the concerns:σσ

σσ

Income measures cannot reflect the fluctuations inincome experienced by many households (for exampleas a result of overtime, bonuses, working shorterhours, becoming unemployed, or taking retirement).Calculating a poverty rate from household incomedata requires that some method be used to converthousehold income into equivalent individual incomes(see Box 3: Do children have incomes?). To achievethis, an ‘equivalence scale’ must be used. But suchscales are not based on any scientific understandingof the different patterns of need in households ofdifferent size.Household income measures cannot reflect the factthat some families may be much more competentthan others in managing income or in prioritizingspending (for example by putting children’s needsfirst). The child of a high-income household, forexample, will not be counted as poor even if most ofthe income is spent on drugs, gambling or alcohol;conversely a child in a low-income household will becounted as poor even if the parents make enormoussacrifices to ensure that the child has the sameadvantages and opportunities as his or her peers.

σσ

Data on incomes may not be reliable, especially ifderived from surveys, or if a significant proportion ofthe working population is self-employed or employedin informal work. Under-reporting of earnings variesfrom country to country, and tends to be greatertowards the bottom end of the income scale.Most countries measure household incomesbeforehousing costs. In practice, a family’s capacity tomeet children’s needs is more likely to be dependenton incomeafterhousing costs (which can varysignificantly within as well as between countries).Income does not always reflect the real level ofresources available. A family’s economic capacity, itssecurity and spending power, are based not only onhousehold income at a single point in time but alsoon savings and debts, on home ownership and housevalues, on previous earnings and future expectations,on the help that may be available from other familymembers, and perhaps on the value of home-produced goods such as food and clothes.When used to compare child poverty in differentcountries, income measures cannot take into accountthe fact that services such as health care and childcare may be subsidised or free in some countries butnot in others. This may make a substantial differenceto real ‘disposable household income’.Similarly, whether or not education, and particularlypre-school education, is free or subsidised may makea substantial difference to disposable incomes. Inmost advanced economies, primary and secondaryeducation is usually available free of charge. But earlychildhood education is subsidised to differentdegrees in different countries. The same is true oftertiary or college education, which may mean thatparents in some countries must try to put asidesignificant sums even when their children are stillyoung. Both of these factors affect real disposableincomes to different degrees in different countries.σσ

σσ

σσ

σσ

σσ

Some or all of these problems combine to introducedoubts about household incomes as a measure of thereal resources available to the child. And they help toexplain why surveys have sometimes found thatmeasures of household spending do not correspond tomeasures of household incomes. At any given level ofhousehold income, for example, material livingstandards tend to vary substantially according towhether they are assessed by incomes or byexpenditures.2In most advanced economies, householdincomes are easier to monitor than expenditures. Butexpenditure measures would in most cases provide amore reliable guide to the real level of resourcesavailable to the household.

1See for example, Fusco, A., A-C. Guio and E. Marlier (2010).

’Income Poverty and Deprivation in European Countries’,EurostatMethodologies and Working Papers,European Commission, Luxembourg.2Bradshaw, J. and N. Finch (2003). ‘Overlaps in Dimensions of Poverty’.

Journal of Social Policy,32 (4): 513-525.

1 0

I n n o c e n t I

R e p o R t

c a R d

1 0

last half century in the United States(see Box 10: The United States:redrawing the line).The obvious alternative is to updatenational poverty lines in such a way asto track the norms and living standardsof the society. But how often, and bywhat method? Should the line beupdated irregularly in an ad hoc way,subject to political pressures and thecompeting influences of differentinterest groups? Or should it beupdated in a regular and systematic wayin order to preserve its relationship withcontemporary living standards? Inwhich case, setting the poverty line at apercentage of each nation’s medianincome and updating it every yearmight, after all, be a strong contender.This is why theInnocenti Report Cardseries, in common with both theEuropean Union and the OECD,continues to use a child poverty linebased on a percentage of medianhousehold income.

Why, then, is it necessary tocomplicate the picture by adding asecond measure? Why introduce theChild Deprivation Index?

Relative weaknessThe answer is that, for all its strengths,the relative income measure has twoprincipal weaknesses.First, even those who support theprinciple of measuring child povertyin a relative way would concede thathousehold income may not always bea reliable proxy for the real resourcesavailable to the child (see Box 2: Theproblem with incomes). It is, at best,an indirect measure, leaving open thepossibility that children may bedeprived in households that are notincome-poor and not deprived inhouseholds that are income-poor.Second, when comparing relativechild poverty rates in differentcountries, a poverty line drawn at a

percentage of median income onlyworks well if the countries beingcompared have broadly similar levelsof income and living costs. Otherwise‘relative poverty’ comes to mean verydifferent living standards in differentcountries: a household with 50% ofmedian income in Bulgaria has anactual income of11,400a year; ahousehold with 50% of medianincome in Norway has an incomeof117,000a year.One may argue that this doesn’t reallymake any difference – that relativepoverty means ‘relative to one’s ownparticular society’ and not to thenorms of some other country. But thisargument is only fully convincing forthe wealthier countries of the OECDwhere living on an income below50% of the median is a plausiblemeasure of what it is intended tomeasure – the sense of falling so farbehind the norms of one’s society asto be at risk of social exclusion

Fig. 3Poverty lines and median incomes, European countries140,000

135,000

130,000

125,000

120,000

115,000

110,000

15,000

Czech Republic

Slovakia

Estonia

Malta

Greece

Slovenia

Spain

Italy

Cyprus

Germany

Belgium

France

Austria

Netherlands

Finland

Sweden

Iceland

Ireland

Denmark

United Kingdom

Luxembourg

Portugal

Lithuania

Romania

Bulgaria

Hungary

Note:Income figures for non Euro-zone countries are converted using purchasing power parity (PPP) exchange rates.Sources:Elaboration of 2009European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditionsdata and Eurostat.

Norway

Poland

Latvia

0

I n n o c e n t I

R e p o R t

c a R d

1 0

1 1

(see Box 8: The public view). Life at50% of median income in poorercountries like Bulgaria and Romaniamay not signify the same level ofdifference, or imply the same degreeof social exclusion, as it does inDenmark or Norway. That said, itshould also be noted that at very lowlevels of income even small differencescan make a significant difference toopportunities and living standards.Since the enlargement of theEuropean Union to 25 countries in2004 and then to 27 countries in2007, this problem of ‘the meaning ofthe median’ has become more pressing.Cross-national comparisons in theEuropean Union must now span agroup of countries whose annual percapita incomes range from less than

$14,000 to around $85,000. A relativeincome poverty line based on 50% ofmedian incomes will inevitablystruggle to reflect this new diversity.Figure 3 illustrates the problem. Thisshows, for example, that the 10 richestcountries havepoverty linesthat arehigher than themedian incomesof the10 poorest countries. This means thatchildren who are below the relativepoverty line in France or Germanymay be significantly better off in actualliving standards than children who areliving at the median income level inPoland or Portugal.vOr to takeanother example, a child living at therelative poverty line in the Netherlandshas double the income of a childliving at the median income level in acountry like Hungary (Figure 3).

Finally there is the worry thatcomparing relative child poverty rateson the basis of household incomescannot take into account significantdifferences between countries in thecost of living and especially in thecosts of essential goods and servicessuch as health and child care. Anincome of $30,000 in country A,where such services are free or heavilysubsidized, may imply a very differentstandard of living from the sameincome in country B where suchitems must be paid for at market rates.In sum, a relative poverty line drawn at50% of median income is an attempt todefine a concept of poverty on whichthere is widespread agreement inprinciple – a concept which says thatthe poor are those who do not haveaccess to the possessions, amenities,activities and opportunities that areconsidered normal by most people inthe society in which they live (seeBoxes 6, 8 and 9). But when using thisyardstick to make comparisons betweencountries, it is probably better to restrictthe comparison to those generallywealthier countries where living onincomes below 50% of median impliesa similar level of risk of social exclusion.Figure 4, for example, restricts thecomparison of relative child povertyrates to the 20 OECD countries withannual per capita incomes of morethan $31,000.

Fig. 4A league table of relative child poverty, selected OECD countries4.75.36.16.16.57.37.38.18.48.58.810.210.912.112.313.314.915.917.123.105101520Child poverty rate (% of children living in households with equivalent incomelower than 50% of the national median)IcelandFinlandNetherlandsNorwayDenmarkSwedenAustriaSwitzerlandIrelandGermanyFranceBelgiumAustraliaUnited KingdomLuxembourgCanadaJapanItalySpainUSA25

Deprivation doubtsThese concerns and problems have ledto increasing pressure for the relativeincome measure to be supplemented bya more direct measure of child poverty.Within individual economicallyadvanced countries, direct measures ofchild deprivation are sometimesavailable. They have been deployed, forexample, in Finland, Germany, Greece,Ireland, the Netherlands, Sweden, andthe United Kingdom.viInternationally,theChild Deprivation Indexpresented inFigure 1a is the first attempt to meetthis need. As already noted, it is made

Note:Data refer to children aged 0 to 17.Sources:Calculations based on EU-SILC 2009, HILDA 2009, SLID 2009, SHP 2009, PSID 2007. Results for Japanare from Cabinet Office, Gender Equality Bureau (2011).

1 2

I n n o c e n t I

R e p o R t

c a R d

1 0

possible by the decision of theEuropean Union to include a specialsection about children’s lives in theEU-SILC survey (see Box 7: TheEuropean Union: 2020 vision).At first glance, this alternative soundsquite straightforward: draw up a list ofitems that most people think of asnecessary for a child and conduct asurvey to find out what proportion ofthe child population of each countrylacks each of the items.In practice, this too has its problems.First, deprivation statistics gleanedfrom surveys may also be unreliable.What people consider to be necessaryfor their children, for example, mayvary with income and aspiration.Presented with a list of items whichcorresponds to one’s own familypossessions, it is likely that most itemswill be judged as ‘necessary’. A list thatincludes items that are not affordable,on the other hand, may attract fewerticks in the ‘necessary’ box. Thetendency for what is considerednormal to increase with incomes, andto decrease with persistent poverty, hasoften been observed. And it is notdifficult to see how this might affectthe results of surveys about childdeprivation. Parents in poorhouseholds may decide that certainitems are unnecessary because they areembarrassed or ashamed to admit thatthey are unable to provide them.viiThe published survey results may havethe appearance of objective data, butbehind every statistic of childdeprivation is an individual parentanswering a survey question aboutwhether or not they can afford toallow their child ‘to participate inschool trips and events’, or ‘to invitefriends home to play and eat’, or ‘tohave a quiet place with enough roomand light to do homework’.Then there is the problem of whatitems should be included in adeprivation index and whatimportance should be attached to each.How do we know that the list reflectsa minimum acceptable standard of

living for a given group of countries ata given time? And who should decide?Should the items be chosen byexperts? Or by opinion polls to findout which items are regarded asnecessary by the population at large?Or should they be selected (andweighted) by investigating whatpercentage of the population alreadypossesses the items? Giving no‘weighting’ to the individual items isnot a neutral approach – it is ajudgement that all the items on thelist are of equal importance and thatthis is true for all of the countriesbeing compared.

Further, there is the problem of thedifferent needs of different agegroups. A personal computer, forexample, was originally included in alist of necessities proposed by theEuropean Union but subsequentlydropped when it was shown that only30% of the population considered acomputer to be ‘absolutely necessary’or ‘necessary’.viiiIf the poll had beenconducted among young people, asopposed to the population as a whole,it is reasonable to suppose that amuch higher proportion would havecategorized a computer as a necessity.

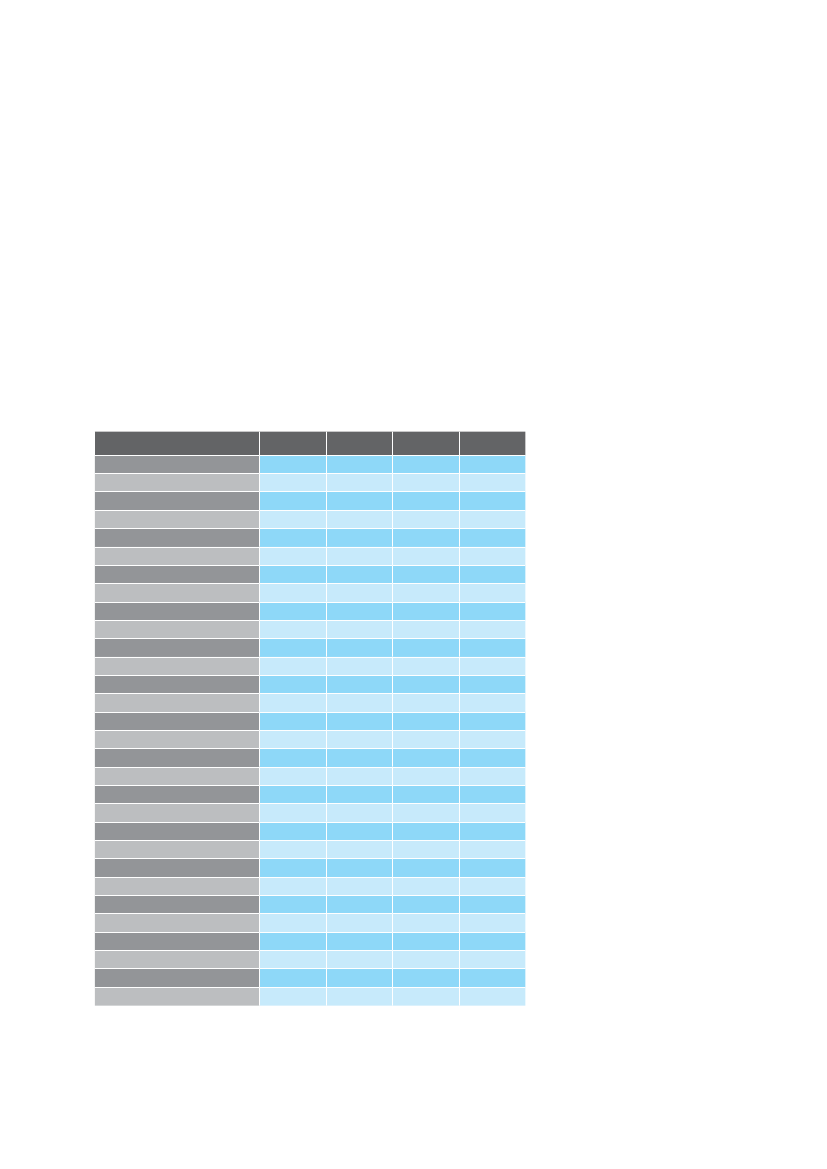

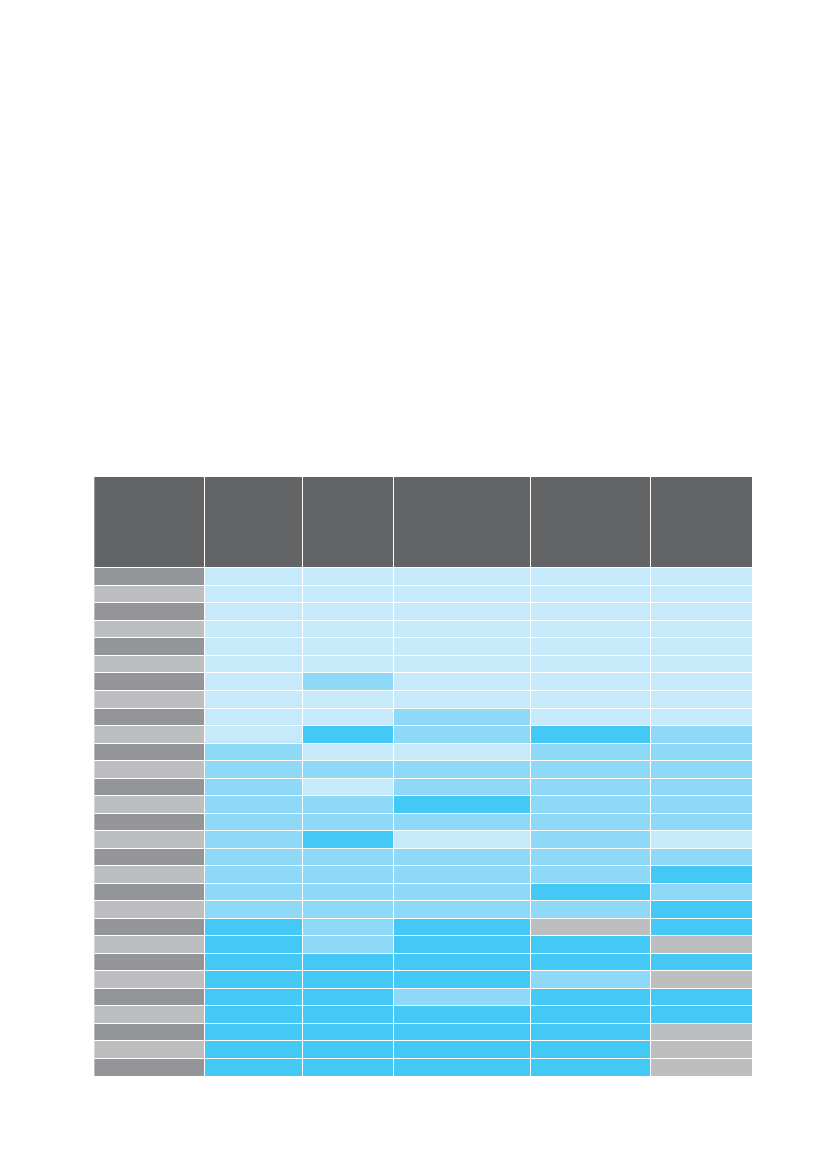

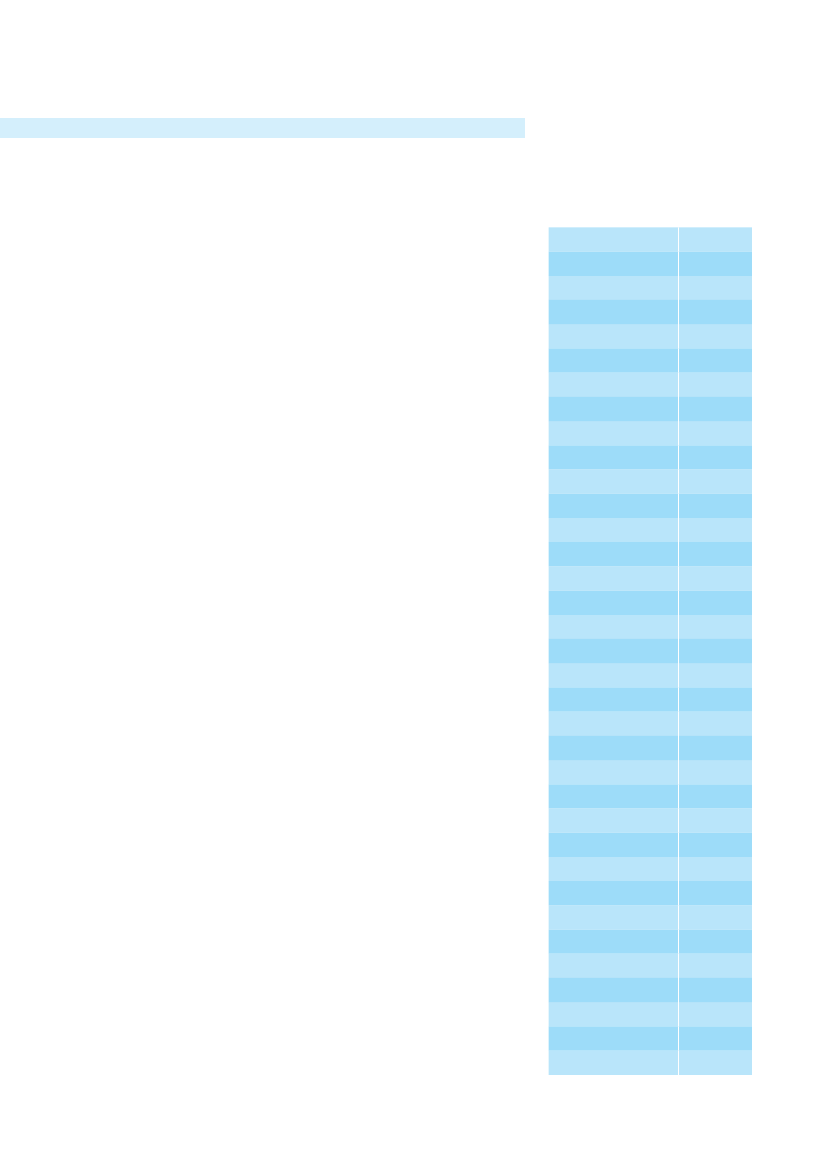

Fig. 5Child poverty rates by different relative poverty linesCountryIcelandFinlandCyprusNetherlandsNorwaySloveniaDenmarkSwedenAustriaCzech RepublicSwitzerlandIrelandGermanyFranceMaltaBelgiumHungaryAustraliaSlovakiaNew ZealandEstoniaUnited KingdomLuxembourgCanadaPolandPortugalJapanLithuaniaItalyGreeceSpainBulgariaLatviaUSARomaniapoverty line at 50%4.75.36.16.16.16.36.57.37.37.48.18.48.58.88.910.210.310.911.211.711.912.112.313.314.514.714.915.415.916.017.117.818.823.125.56.15.64.27.37.59.69.68.89.78.111.512.212.816.617.8poverty line at 40%1.91.51.82.93.12.93.63.73.23.83.23.54.63.72.94.13.04.36.6poverty line at 60%10.111.912.115.411.311.111.412.713.613.017.918.914.916.820.316.620.617.617.019.420.620.822.421.922.922.720.524.324.223.523.624.425.031.132.3

Note:The shading in the last three columns indicates whether a country ranks in the top third (light blue), middle third(mid-blue), or bottom third (dark blue) of the relevant league table.Sources:Calculations based on EU-SILC 2009, HILDA 2009, SLID 2009, SHP 2009, PSID 2007. Results for New Zealandare from Perry (2011) and refer to 2010. Results for Japan are from Cabinet Office, Gender Equality Bureau (2011).

I n n o c e n t I

R e p o R t

c a R d

1 0

1 3

Choosing a thresholdFinally, in this summary of the strengthsand weaknesses of the differentmeasures used in the two league tablesof child poverty, it should be noted thatthere are problems common to both.First, both the child deprivationmeasure and the relative incomemeasure must confront the questionof where and how the thresholdshould be drawn.In the case of relative income poverty,for example, should the line be drawnat 60% of median household income

(as in the European Union) or at 50%(as used by the OECD for purposes ofinternational comparison)? By way ofreassurance, Figure 5 shows that thereis little change to the relative childpoverty rankings when the line isdrawn at different percentages ofmedian income. (It should also beborne in mind that in practice theremay be little difference between lifejust below and just above whicheverpoverty threshold is chosen.)In the case of the deprivationmeasure, should the threshold beset at ‘lacking two or more’ of the

14 items in the deprivation index?Or at ‘three or more’ or ‘four ormore’? For the league table of childdeprivation in this report (Figure 1a),the line is drawn at ‘lacking two ormore’. But this decision is essentiallyopportunistic: drawing the line at‘lacking one or more’ would havegiven arbitrary emphasis to just oneitem on the list. It would also haveproduced extremely high childdeprivation rates for the poorest EUcountries. Setting the line at ‘lackingthree or more’, on the other hand,would have produced extremelylow deprivation rates for thewealthier countries.Secondly, both the deprivationmeasure and the relative incomeleague table tell us what proportion ofeach nation’s children fall below theselected thresholds, but they tell usnothing abouthow far below.In the case of the deprivation measure,the question of ‘how far below’ can inpart be answered by setting a lowerthreshold for the Child DeprivationIndex. Figure 6, for example, showsthe proportion of children in eachcountry who lack 2, 3, 4 and 5 ormore of the 14 items.In the case of the relative child povertymeasure, the question ‘howfararethose below the poverty line allowedto fall?’ finds an approximate answer inFigure 7 which compares 35 countriesby the depth of their poverty gaps –the difference between the medianincome of households below thepoverty line and the poverty line itself.The findings of this table will beconsidered under the headingAssessinggovernment performance(p.19).

Fig. 6Proportion of children in each country lacking 2, 3, 4 and 5 items or moreon the deprivation indexCountry29 European countriesAustriaBelgiumBulgariaCyprusCzech RepublicDenmarkEstoniaFinlandFranceGermanyGreeceHungaryIcelandIrelandItalyLatviaLithuaniaLuxembourgMaltaNetherlandsNorwayPolandPortugalRomaniaSlovakiaSloveniaSpainSwedenUnited KingdomNote:Data refer to children aged 1 to 16.Source:Calculations based on EU-SILC 2009.

2+13.38.79.156.67.08.82.612.42.510.18.817.231.90.94.913.331.819.84.48.92.71.920.927.472.619.28.38.11.35.5

3+9.85.36.649.25.06.11.57.70.66.56.211.725.10.32.510.325.213.83.15.41.20.715.323.062.015.24.45.30.72.8

4+7.43.74.741.13.84.71.24.50.23.93.98.420.60.01.48.320.711.61.73.50.60.310.817.853.812.12.63.20.41.7

5+5.82.43.136.32.13.10.73.30.02.62.86.116.70.00.66.215.910.41.32.50.40.18.513.846.810.31.52.10.01.3

OverlapsGiven the strengths and weaknesses ofthese two very different ways ofmeasuring and comparing childpoverty, there is an obvioustemptation to combine them in someway in order to construct a singleoverarching measure which wouldhave the strengths of both and the

1 4

I n n o c e n t I

R e p o R t

c a R d

1 0

weaknesses of neither. It has beensuggested, for example, that a singlemeasure of child poverty might beconstructed by counting as poor onlythose children who are poor underboth definitions – i.e. those who lacktwo or more of the items on thedeprivation index and who live inhouseholds where incomes are lessthan 50% of the national median. Butthis would be to ignore theunderlying incompatibility – the factthat the deprivation measure is basedon a definition which does not varyacross countries, whereas the relativeincome poverty measure is based on adefinition which changes from nationto nation. To make the two measuresconceptually compatible, it would benecessary to adjust the deprivationindex so that both the list of items itcontains and the threshold chosenwould reflect a standard of living thatis considered normal or necessaryineach individual country.This could bedone, either by surveys to establishwhat proportion of the populationconsiders which items to be‘necessary’ (consensus weighting) orby weighting each item according towhat proportion of households ineach country already own or haveaccess to each item (prevalenceweighting). But this procedure wouldraise more problems than it solveswhile at the same time jettisoning thesimplicity and the intuitive appeal ofthe deprivation index.When used for internationalcomparison the two measures aretherefore separate in concept andshould remain so in practice. Both thechild deprivation rate and the relativechild poverty rate are useful topolicymakers, to social scientists, to themedia, and to advocates for child well-being. Combining them into acommon measure would be likecombining oil and water, in that thewhole would be less useful than thesum of the parts.Withinindividual countries, on theother hand, it may be useful tocombine the two measures by

focusing on the overlap between them– asking what percentage of a nation’schildren are both deprivedandlivingin relative income poverty. Thisapproach, currently used for examplein Austria, Ireland and the UnitedKingdom, helps to ease some of theworries surrounding the measurementof poverty by means of householdincomes. As Professors Brian Nolanand Christopher Whelan, contributorsto the development of Ireland’s officialpoverty measure, have written:

“Given two relevant pieces of informationabout the household–income anddeprivation–each with limitations fromboth conceptual and measurementperspectives, incorporating both into themeasurement process is one way to seek toimprove reliability in identifying the poor.”ixIn practice, household income remainsa principal determinant of whether ornot the needs of children areadequately met. But it is not the onlydeterminant. Public spending can also

Fig. 7The poverty gap10.911.812.812.913.614.615.016.016.116.216.317.617.817.918.418.820.320.620.620.721.021.121.422.323.527.129.829.931.131.332.032.833.134.737.505101520253035

FinlandHungaryIcelandIrelandAustraliaLuxembourgFranceNew ZealandAustriaSwitzerlandMaltaSloveniaBelgiumCyprusNetherlandsUnited KingdomEstoniaCzech RepublicPolandGreeceNorwaySwedenCanadaGermanyLithuaniaSlovakiaItalyPortugalJapanLatviaBulgariaDenmarkSpainRomaniaUSA40

Child poverty gap(gap between the poverty line and the median income of those below the poverty line)Notes:The poverty gap is the distance between the poverty line and the median income of those below thepoverty line (expressed as a percentage of the poverty line). Calculations are based on a poverty line set at50% of the national median income. Countries are ranked by increasing levels of the child poverty gap.Sources:Calculations based on EU-SILC 2009, HILDA 2009, SLID 2009, SHP 2009, PSID 2007. Results forNew Zealand are from Perry (2011) and refer to 2010. Results for Japan are from Cabinet Office, GenderEquality Bureau (2011).

I n n o c e n t I

R e p o R t

c a R d

1 0

1 5

help parents to meet children’s needs.And for this reason it is not axiomaticthat falling household income mustalways mean rising levels of childdeprivation. The governments that aremost successful in protecting childrenfrom poverty are likely to be thosethat strive to reduce the number oflow-income householdsandhelp toprovide essential goods, services andopportunities for children growing upin such households. This strategymakes it possible to offer a significantdegree of protection to children evenin times of economic crisis. And it alsoillustrates the usefulness of deployingboth a relative income measure and adirect measurement of deprivation inthe struggle to monitor and mitigatethe impact of economic forces on thelives of children.

The argument that the use of thisrelative poverty measure may misleadthe public because it inevitably carrieswith it a suggestion of ‘absolutepoverty’ is a genuine concern. But thisis a problem not so much in theconcept as in its communication. Itcan and should be addressed bysticking strictly to the term ‘relativechild poverty’ when that is what ismeant. To say that ‘child poverty levels’are higher in the United States than inthe Czech Republic is to invite public

misunderstanding and rejection. To saythat ‘relative child poverty levels’ arehigher risks no such misunderstanding;there is nothing either misleading ormeaningless about the statement that agreater proportion of children areallowed to fall significantly below thenorms of their societies in the UnitedStates than in the Czech Republic.When presented for what it is – anapproximate measure not of absolutepoverty but of falling so far behind the

Box 3Do children have incomes?

How should it be done?How, then, is child poverty bestmeasured, monitored, and compared?In previousReport Cards,some basicprinciples for the cross-nationalmonitoring of child poverty have beenproposed. They are summarized andupdated here.1. Continue to monitor relativechild poverty based on nationalmedian incomesMost poverty lines are based on household incomes. But to calculatehow many individuals live below the poverty line, household incomesmust be converted to equivalent individual incomes (including‘incomes’ for children).This cannot be done by simply dividing household income by thenumber of people in the household. It may not be true that ‘two canlive as cheaply as one’, but the amount required to maintain a givenstandard of living does not rise in direct proportion to the number ofpeople in the home. The cost of heating, or a television or an Internetconnection, for example, does not double if there are four peoplerather than two. Many such economies of scale – including being ableto buy food or cleaning materials in bigger quantities – are available tolarger households.Unfortunately there is no scientific way of converting household incomeinto individual incomes. Rough and ready methods must therefore beused, of which the most common is the ‘modifiedOECD equivalencescale’by which the first adult in each household is counted as 1.0, thesecond adult as 0.5, and each child under the age of 14 as 0.3. The totalthen becomes the number of ‘equivalent individuals’ by which householdincome must be divided. For example, a household with an income of$46,000 for two adults, one 15-year-old, and one pre-school child wouldbe counted as having the equivalent of 2.3 individuals and their‘equivalized’ individual incomes would be $20,000. It is this figure that isused to establish the median income for the nation as a whole (the pointat which exactly half have more and half have less – see Box 4: Themedian is the message). The relative poverty line is then drawn at acertain percentage of that median. In the European Union, the line isdrawn at 60% ofequivalizedmedian income.The number of children estimated to be living in poverty is thencalculated as the number of individual children living in households inwhich the equivalized income is below this line.

Median income is“a strong indicator ofwhat is considered normal in contemporarysociety.”xIt should therefore continueto be used as a basis for identifyingthose at risk of social exclusion (seeBoxes 4 and 6).Most countries have data on incomes,and these data can be used both tocompare countries and to monitorchanges over time. Tracking theincomes of those at the bottom endof the distribution in relation to theincomes of those at the median showshow the benefits of economicprogress or the pain of economicrecession are being distributed. It isnot a measure of overall inequality inthe society; it is a measure of how thepoorest are faring in relation to thosein the middle.

1 6

I n n o c e n t I

R e p o R t

c a R d

1 0

normal standard of living in the societyas to be excluded from the advantagesand opportunities that the majoritytake for granted – the idea of relativechild povertydoesmake intuitive sense.2. Measure deprivation directly

to define and defend the simultaneoususe of the relative child poverty rate.xiThe special module on childdeprivation, included as a one-offexperiment in the latest round ofEU-SILC, should therefore bedeveloped into a regular andpermanent feature of future surveys.3. Measure depth and duration

advanced economies in the form ofa ‘poverty gap’ league table.Ideally, the monitoring of childpoverty would include its timing andduration as well as its breadth anddepth. The earlier the privation andthe longer its duration, the greater thepotential impact on the child. This istrue both because of the inherentvulnerability of the earliest years oflife and because the longer a familystays poor the harder it may becometo maintain essential expenditures(as savings and assets run down, forexample, or as borrowing and othersources of help reach their limits).In other words, child poverty should

Child poverty also needs to bemonitored by direct measurement ofdeprivation. The proportion of childrenwho lack an adequate diet, or a quietplace to do homework, or suitablebooks and an Internet connection, isthe kind of measure that allows actualliving standards to be compared acrossnations. It makes immediate sense to awide public and contributes towards amore rounded understanding of childpoverty. And in so doing, it also helps

As already noted, it is also importantto measurehow farbelow the povertyline the poor are being allowed to fall.For this purpose, the median incomeof those below the poverty line, as apercentage of the poverty line itself, isa useful measure. Figure 7 haspresented this calculation for 35

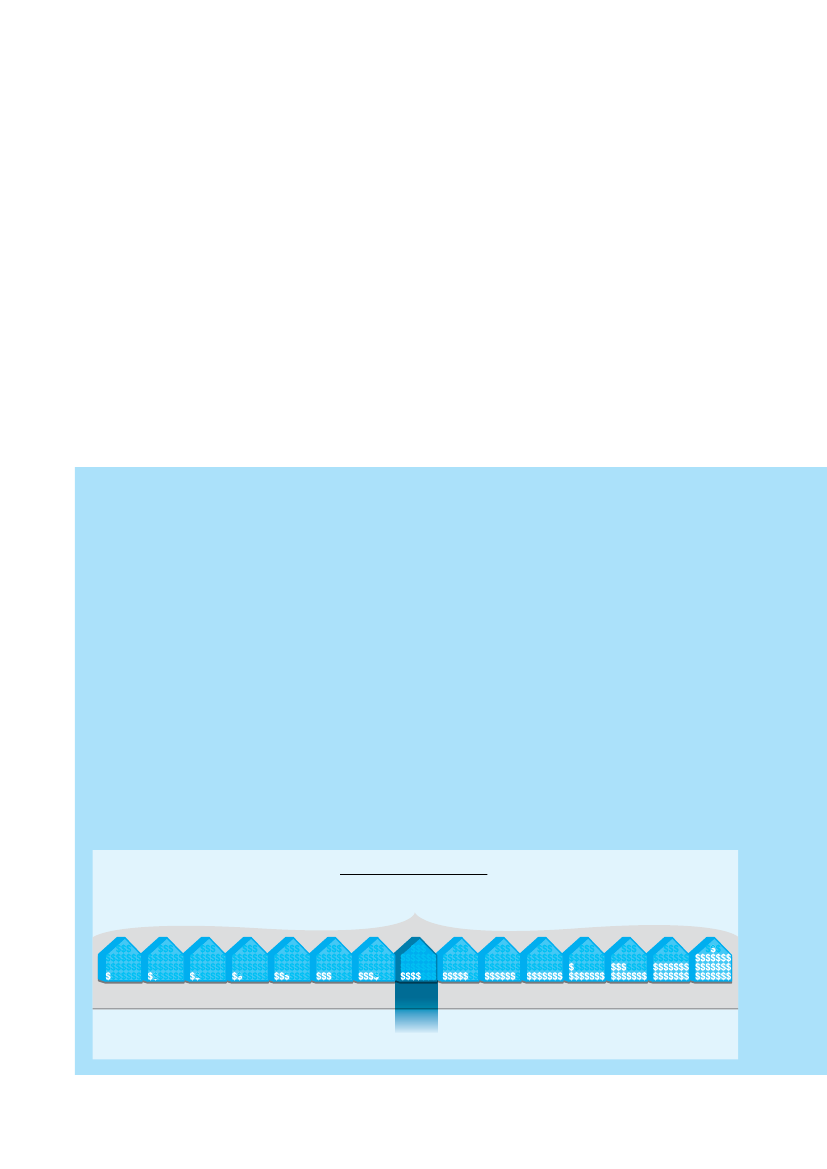

Box 4The median is the message

The words 'average' and 'median' can still causeconfusion in public discourse and even in policy-making.The difference between the two is illustrated in thediagram below.Imagine a street with a single row of houses numbered1 to 15. The household with the lowest income in thestreet lives at number 1, the second poorest householdlives at number 2, and so on up to the richest householdin number 15.The average household income is calculated bydividing the total income of the street by the totalnumber of households. In the example given here, thiscomes to $60,000.

The median household income is the income of thehousehold in the middle of the income scale – the pointat which half of the households have more and half haveless. In this example, the median income is $40,000 (theincome of house No. 8).As the example shows, there can be significantdifferences between the average and the median.The two also respond to change in different ways.Imagine, for example, that the two richest people in thestreet, living in houses Nos. 14 and 15, were to moveout and be replaced by Bill Gates and Warren Buffett. Inthis event, the average household income of the streetwould rise to several billion dollars. But the median

Total income of all houses$900,000Number of houses15

Average household income$60,000

No. 1$10,000

No. 2$12,000

No. 3$14,000

No. 4$16,000

No. 5$27,000

No. 6$30,000

No. 7No. 8$35,000$40,000

No. 9$50,000

No. 10$60,000

No. 11$70,000

No. 12$80,000

No. 13No. 14No. 15$100,000 $140,000 $216,000

7 houses with lower income

Median household income$40,000

7 houses with higher income

I n n o c e n t I

R e p o R t

c a R d

1 0

1 7

be monitored in three dimensions –asking not onlyhow manychildren fallbelow national poverty lines buthowfarand forhow long.4. Maintain a close monitoringsystem

development are happeningnow.All OECD countries have the capacityto track key economic indicators –growth, inflation, unemployment, tradebalances – on a quarterly basis. It istherefore unacceptable that basicinformation on what is happening tochildren’s lives should be so out ofdate. Key data on basic aspects of childpoverty and child well-being shouldbe made available not every four yearsbut every year.5. Set time-bound targets andbuild support

Most governments of economicallyadvanced countries are committed inprinciple to the monitoring of childpoverty and social exclusion. But itmust be said that collecting and makingavailable the necessary data every fewyears is not monitoring. It cannotadequately inform policy or alertgovernments, the media, the public, thechildren’s organizations, or the academiccommunity to the problems being facedby children whose years of growth and

Report Card 6(2005) recommendedthat all OECD countries should aimto reduce relative child poverty rates to

below 10%. Countries that had alreadyachieved this were challenged toemulate the Nordic countries byreducing the rate still further – to 5%or less. Since that time, relative childpoverty rates have risen in almostevery OECD country*(an increasethat does not as yet reflect the impactof the post-2008 economic downturn).As Figure 1b shows, only Iceland nowachieves a relative child poverty rate ofless than 5%, though Finland remainsclose at 5.3%. The latest nationallyavailable data suggest that Iceland, too,has allowed its relative child povertyrate to drift above the 5% mark.This upward trend in relative childpoverty rates over recent years is in

income would stay the same: the middle house in theincome distribution would still be No. 8, and its incomewould still be $40,000.For the same reason, it is quite possible to increase theincomes of all the houses with incomes above themedian (Nos. 9 to 15) without affecting the medianincome of the street as a whole.It is sometimes said that relative poverty, defined as thepercentage of households below a certain percentage ofmedian income, can never be abolished because thetarget is always moving. As incomes rise, the povertyline also rises, and so ‘the poor will always be with us’.But this is not the case. In the above example, thoseliving in houses 1, 2, 3 and 4 are below the poverty linebecause their household incomes are below 50% of themedian for the street as a whole. But if the incomes ofthose households were to rise to $20,000 then therewould be no houses with incomes below 50% ofmedian. Relative poverty would have been abolished.And the median itself would not have changed.

Illustrating the normalThis distinction between average and median cansometimes be critical. For example, the argument overwhether pay is generally higher in the public or privatesector may well depend on whether the average or themedian is used when making the comparison. If theaverage is chosen, then pay in the private sector maywell be higher – because the average can besubstantially increased by a small number of peoplewith very high earnings (the equivalent of Gates andBuffet moving into the street). If the median is selected,on the other hand, then pay in the public sector may behigher – because the median level of pay in the privatesector is not increased by the incomes of those at thevery top of the income distribution.Many economists now argue that it is the median,rather than average, that should be used to illustratewhat is normal in a given society. Nobel prize-winningeconomist Joseph Stiglitz, for example, points out thatin the United States, “median and average behavedifferently…real median household income has actuallydipped since 2000. But G.D.P per capita has gone up.”1.

1Quoted in ‘The Rise and Fall of the G.D.P by Jon Gertner, New York Times,.’

13 May 2010.

*The relative child poverty rates published inReport Card 6are not strictly comparable with the rates given inReport Card 10(See Figure 1b andBox 3: Do children have incomes?)

1 8

I n n o c e n t I

R e p o R t

c a R d

1 0

large part the result of global economictrends. But that does not mean that it isinevitable. It is within the power ofevery government in the OECD to setrealistic targets for reducing relativechild poverty and to put in place thepolicies and the monitoring systemsrequired to meet those targets.xiiFigure1b shows that a realistic target for thecountries with relative child povertyrates below 10% would be to renewthe struggle to reduce the rate to 5% orlower. Similarly, the 12 countries withrates between 10% and 15% should aimat lowering relative child poverty below10%. The 8 countries currently withrates of 15% to 25% have the capacityto bring the rate below the 15% levelas an essential first step.Announcing such targets is of course notenough. It is now more than 20 years,for example, since the Government ofCanada announced that it would“seek toeliminate child poverty by the year 2000.”Yet Canada’s child poverty rate is highertoday than when that target was firstannounced.xiiiIn part this is becausethe commitment was not backed by acompelling political and public consensusor by any firm agreement on howchild poverty should be defined andmonitored. Targets can only be afirst step.In the past, the European Commissionhas done much to help EU countriesto develop common indicators forthe measurement of child poverty andto develop plans for its reduction (seeBox 7: The European Union: 2020vision). But since the economic crisisbegan, child poverty appears to haveslipped down the Commission’s agenda.Children barely feature, for example, inthe Europe 2020 strategy. In particular,the Commission appears reluctant topublish cross-national data on fallinggovernment expenditures for childrenand families. Later this year (2012), theCommission is due to make proposalsto member states on child well-being.Those proposals should include targetsfor specific reductions in child povertyby the end of this decade.

Fig. 8Relative child poverty rates before taxes and transfers (market income) and aftertaxes and transfers (disposable income)before taxes and transfersafter taxes and transfers

IrelandHungaryUnited KingdomFinlandAustraliaNew ZealandAustriaCzech RepublicNorwayFranceSloveniaGermanyLuxembourgIcelandMaltaCanadaSwedenBelgiumNetherlandsDenmarkCyprusSlovakiaLithuaniaEstoniaPortugalBulgariaPolandRomaniaLatviaSwitzerlandSpainUSAJapanItalyGreece01020304050

Child poverty rate(% of children living in households with income lower than 50% of the national median income)Notes:For each country and for both income definitions, poverty calculations are based on a poverty line set at 50% ofthe national median disposable income. Countries are ordered by decreasing percentage of poverty reduction achieved.‘Taxes and transfers’ takes into account all income taxes paid by households and all benefits that directly affect householdincomes (i.e. not including in-kind or near-cash benefits).Sources:Calculations based on EU-SILC 2009, HILDA 2009, SLID 2009, SHP 2009 and PSID 2007. Results for New Zealandare from Perry (2011) and refer to 2010. Results for Japan are from Cabinet Office, Gender Equality Bureau (2011).

I n n o c e n t I

R e p o R t

c a R d

1 0

1 9

Fig. 8aChild poverty rates before taxes and transfers (market income) and after taxes and transfers, selected countriesbefore taxes and transfersafter taxes and transfers

25

3025.123.125.1

2017.515

20

19.4

2518.817.120

17.0

17.0

16.2 15.9

1515108.813.3

107.3

8.57.4

10

5

55

0FranceSpain

0USACanada

0AustriaGermanyCzechRepublicItaly

Sources:Calculations based on EU-SILC 2009, SLID 2009 and PSID 2007.

6. Avoid unnecessary complexity

The more complex the measure ofchild poverty, the less useful it is likelyto be.7. Measure well-being broadly

Child poverty is about more thanincome or the lack of items on a givenlist. Children can be poor in love andattention, in parental time and skills, inrelationships and community, in publicservices and environmental quality. It istherefore also necessary to continue todevelop ways of monitoring childwell-being in the round.It was for this reason thatReport Card 7(2007) developed an initial measure ofoverall child well-being for OECDcountries. Bringing together a total of40 indicators for which internationallycomparable data were available, thereport compared child well-being across21 OECD countries under theheadings of material well-being, healthand safety, education, peer and familyrelationships, risk behaviours, and youngpeople’s own subjective sense of well-being. This experiment will be refinedand repeated with new data in the nextissue in this series (ReportCard 11).8. Focus on disparity

There will always be children who fallbehind the average, whether in materialcircumstances or educationalachievement. The critical question is‘how far behind?’ Is there a pointbeyond which ‘falling behind’ is notunavoidable but unacceptable? This wasthe issue examined inReport Card 9(2010), which offered a practical guideby looking at the gaps – whether inmaterial well-being, or in health or ineducational achievement – between thechildren at the bottom and thechildren at the median point in eachcountry. If, for example, the gap ineducational achievement is significantlywider in country A than in country B,then this suggests that young people incountry A are falling further behindthan is necessary. Put positively, thevarying child disparity records ofcountries at similar levels of economicdevelopment offer a real-worldmeasure of the scope for improvement.

inevitable result of global economic pressuresor demographic transitions.”says JonathanBradshaw.“Governments can and do takesteps that are remarkably successful incounteracting child poverty.”xivIt would therefore also be useful tohave some measure ofhowsuccessful.The principal league tables of childpoverty with which this report beganprovide one overview of the record ofdifferent governments in helpingfamilies to protect children from thesharpest edges of poverty. But theavailable data also allow more specificcomparisons to be made.Figure 8 presents one such comparison.Drawing on data from 35 advancedeconomies, it shows what the relativechild poverty rate would be ifgovernments did not intervene withtaxes and transfers (light blue bar). Itthen compares this with the actualrelative child poverty rate after all taxesare deducted and benefits paid (bluebar). The difference may be seen as onemeasure of the efforts and effectivenessof different governments in reducingrelative child poverty.Such a presentation is of course biasedin favour of those countries with highinitial rates of relative child poverty(the higher the starting level, thegreater the scope for reduction).Nonetheless, it furnishes some striking

Assessing governmentperformanceThe extent and depth of childdeprivation and relative child povertyin different countries is the result of acomplex interaction between culturaland historical factors, demographictrends, labour market conditions, andglobal economic forces. Butgovernment policies and expendituresare also critical.“Child poverty is not an

In addition to monitoring averagelevels of child well-being, it is alsoimportant to focus specifically on thechildren left behind.

2 0

I n n o c e n t I

R e p o R t

c a R d

1 0

Box 5Invisible childrenBoth measures of child poverty used in this report arebased on household surveys or household income data.But some of the children and young people most at riskof poverty do not live in households; they live ininstitutions, in children's homes, in temporaryaccommodations, in hostels or hospitals, in prisons, inhouses for refugees or asylum seekers, in mobilehomes, or on the streets. It is also possible that some ofthe most at-risk children may be not represented inhousehold surveys because they live in remote areas orin families and communities whose presence may beillegal and unregistered.All of these ‘non-mainstream’ groups are likely to bestatistically invisible.A notable example are the 4.5 million Roma childrenwho live in the European Union.In 2005, 12 governments (6 of them members of theEU) committed to a ‘Decade of Roma Inclusion’.At the mid-point of the ‘Decade’, a report from theOpen Society Foundations concluded that, “Thelack ofdata about Roma communities remains the biggestobstacle to constructing any thorough assessment ofhow governments are meeting their Decadecommitments.”1The Czech Republic, Hungary, Slovakia and Spain, forexample, have no data to track even such basicindicators as infant mortality rates and primary schoolcompletion rates for Roma children. “Withoutcomprehensive data to evaluate government efforts andguide policies,”says the report, “thesituation…is likelyto remain dire.”2

1McDonald, M. and K. Negrin (2010). ‘No Data – No Progress: Country

findings, data collection in countries participating in the Decade of RomaInclusion 2005-2015’, Open Society Foundations, Budapest. Available at:www.soros.org/initiatives/roma2Ibid.

Box 6Relative agreementThe idea of defining poverty in a relative rather than anabsolute sense is not new.In the 18th century, Adam Smith famously argued thatpoverty is the inability to afford, “notonly thecommodities which are indispensably necessary for thesupport of life, but whatever the custom of the countryrenders it indecent for creditable people, even of thelowest order, to be without.”1A century later, and froma different ideological perspective, Karl Marx foundhimself in agreement, “Ourneeds and enjoymentsspring from society; we measure them, therefore bysociety and not by the objects of their satisfaction.Because they are of a social nature, they are of arelative nature.”2In 20th-century America, the liberal economistJ. K. Galbraith argued (1958) that, ”Peopleare poverty-stricken when their income, even if adequate forsurvival, falls markedly behind that of their community.”3In the early 1960s, the conservative Rose Friedman,also argued that the definition of poverty changes asgeneral living standards change; people living at theend of the twentieth century who are labelled poor, shewrote, “willhave a higher standard of living than manylabelled not poor today.”4Republicans at the timeendorsed the relative idea: ”Noobjective definition ofpoverty exists,”said a Republican Congressionalresponse in 1964: “Thedefinition varies from place toplace and time to time. In America as our standard ofliving rises, so does our idea of what is substandard.”5By the early 1960s, sociologists and economists likeVictor Fuchs in the United States and Peter Townsendin the United Kingdom were arguing that governmentsshould recognise the essentially relative nature ofpoverty by setting national poverty lines at a fixedpercentage of national median income (see Box 9:The poverty line: a short history).Today, the most commonly used poverty definition inthe developed world is a definition ofrelativepoverty,and most OECD countries now calculate their headlinepoverty rates by the percentage of the populationwhose incomes fall below 50% or 60% of nationalmedian income.

1Adam Smith,An Enquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations,

Book 5, Chapter 2, 1776.2Karl Marx,Selected Works,Volume 1, 268-269, Lawrence and Wishart,

London, 1946.3Galbraith, J. K. (1958).The Affluent Society,Houghton Mifflin, Boston.4Friedman, R. D. (1965). ‘Poverty: Definition and Perspective’, American

Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research, Washington, D.C.5Minority [Republican] views, p. 46 in U.S. Congress, Report of the Joint

Economic Committee on the January 1964 Economic Report of the Presidentwith Minority and Additional Views, US Government Printing Office,Washington, D.C., 1964.

I n n o c e n t I

R e p o R t

c a R d