OSCEs Parlamentariske Forsamling 2011-12

OSCE Alm.del Bilag 45

Offentligt

GENDER BALANCE REPORTOSCE PARLIAMENTARY ASSEMBLY

JULY 2012

Women as National, Ethnic, Linguistic, Racial andReligious Minorities

Presented ByDr. Hedy Fry, Special Representative on Gender Issues of the OSCE PA

Table of ContentsI.II.Introduction………………………………………………………………………..2Women Minorities ………………………………………………………………...2a. Framing the Issue……………………………………………………………...2b. Women Minorities in the OSCE Region………………………………………5i. Racial minorities……………………………………………………………….6ii. Migrant Women…………………………………………………………….....8iii. Indigenous Women………………………………………………………..….10iv. Roma and Sinti Women…………………………………………………..….13c. OSCE initiatives……………………………………………………………...15i. Migrants……………………………………………………………………....18ii. Roma Sinti……………………………………………………………………19Gender in the OSCE Governmental Institutions…………………………………22a. OSCE Secretariat……………………………………………………………..24b. Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR)…………....25c. Office of the High Commissioner on National Minorities (HCNM)………...26d. Office of the Representative on Freedom of Media………………………….26e. Seconded Posts in the Secretariat, Institutions and Field Operations…….….27f. Field Operations: Gender Balance of Local Staff……………………………28g. Gender in OSCE Documents…………………………………………………29Gender in the OSCE PA………………………………………………………….29a. Member Directory Statistics………………………………………………….29b. Initiative to Boost Women’s Participation……………………………..…….30c. Gender in the Assembly Bureau……………………………………………...31d. Female Presidents and Vice-Presidents in the OSCE PA…………………....31e. Officers of the OSCE PA General Committee……………………………….32f. Participation in the OSCE PA Meetings……………………………………..32g. Participation in OSCE PA Election Monitoring 2011/2012………………....33h. Permanent Staff of the OSCE PA International Secretariat……………..…...34i. The International Research Fellowship Programme…………………………35j. Female Representation in National Parliaments of OSCE Countries………..35Annexes………………………………………………………………………….36

III.

IV.

V.

1

I. IntroductionSince 2001, the Special Representative on Gender Issues of the OSCE ParliamentaryAssembly (OSCE PA) has issued an annual report including an analysis of a special topic aswell as a study of the OSCE’s gender disaggregated statistics. The topic chosen for the 2012Gender Report is women as national, ethnic, linguistic, racial and religious minorities. Thetopic is all the more fitting in light of the 20thanniversary in 2012 of the United NationsDeclaration on the Rights of Persons Belonging to National or Ethnic, Religious andLinguistic Minorities.The 2012 Gender Report concludes that, despite continuing efforts, the OSCE Gender ActionPlan from 2004 has had little discernible success so far in increasing the number of women intop management positions. The top leadership is still dominated by men, with the number offemale professionals in management positions increasing from 30 per cent in 2010 to 31 percent in 2011. All but one Head of OSCE Institutions and all but two Heads of FieldOperations are men.

II. Women Minoritiesa. Framing the Issue1In order to formulate appropriate legislation and polices to address the challenges andconcerns related to gender equality and the protection and promotion of women’s rights, it isimportant to appreciate the diversity of women and the multiple and intersecting barriers andsources of discrimination they face that prevent them from fully enjoying their rights andfrom enhancing their political, economic and social participation.

1

Material in this section was drawn primarily from the following sources: Report of the Independent Expert onMinority Issues, United Nations Human Rights Council, 3 January 2012; Recommendations of the Forum onMinority Issues: Guaranteeing the Rights of Minority Women and Girls, United Nations Human RightsCouncil, 3 January 2012; Note by the Independent Expert on Minority Issues on Guaranteeing the Rights ofMinority Women, United Nations Human Rights Council, 13 September 2011; Minority Rights: InternationalStandards and Guidance for Implementation, Office of the United Nations High Commissioner on HumanRights, 2010; Democratic Citizenship, Languages, Diversity and Human Rights: Guide for the Development ofLanguage Education Policies in Europe from Linguistic Diversity to Plurilingual Education, 2002.

2

In this respect, women minorities, i.e. women with a national or ethnic, linguistic, racial,cultural or religious identity that differs from that of the majority population and who are in anon-dominant position,2are double-burdened in that they face barriers as women and asmembers of a minority group.3Their life experiences differ from those of men, from

majority women, and from minority men.For decision-makers and legislators, addressing the challenges that emerge from thisintersection of women’s and minority concerns is complex, requiring both a gendering ofminority rights and the valuing of the diversity of women. Adding to the complexity is thediversity among minorities and the varying types and degrees of disadvantages faceddepending on the visibility of their identity; their knowledge of the local language; if they arean indigenous people, native born, migrants, or first, second or third generation; their socio-economic status; and the traditional gender roles in their community and culture.The

experience of members of minority groups vary in relationship to their geographicconcentration, sense and strength of identity, and the characteristics that constitute thatidentity. Thus, a one-size fits all approach to enhancing gender equality and addressingminority concerns is unlikely to be effective.Moreover, an internationally agreed definition of minority does not exist nor does agreementas to which groups constitute minorities, although there is a general understanding thatmembership in a minority group comprises objective and subjective factors and members aremotivated by a concern to preserve together that which constitutes their common identity. Inthis respect, some individuals are assigned minority status without identifying as such, andsome states deny the existence of a minority on their territory despite members of the groupseeing themselves as such.4

2

Minority Rights: International Standards and Guidance for Implementation, United Nations Human RightsOffice of the High Commissioner, 2010.3

In many instances, religious, racial, linguistic, ethnic, cultural or national identities overlap, compounding thediscrimination.4

Report on the Integration of women belonging to ethnic minority groups, Committee on Women’s Rights andGender Equality, European Parliament, 30 June 2010; Mandate of the OSCE High Commissioner on NationalMinorities,http://www.osce.org/hcnm/43201

3

Many women minorities remain vulnerable to many disadvantages, despite their rights aswomen, minorities, and indigenous peoples being enshrinedinter aliain the UniversalDeclaration of Human Rights, the International Covenant of Civil and Political Rights(ICCPR), the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, theConvention on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), the BeijingDeclaration, the Declaration on the Rights of Persons Belonging to National or Ethnic,Religious and Linguistic Minorities, the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms ofRacial Discrimination, and the Universal Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.5The most prominent and impacting disadvantages include inadequate access to qualityeducation, the labour market and employment (including pay equity, promotions, hiring),justice and legal protection, housing and basic services, health services, and financialservices. Many have limited if any knowledge of the local language and of information andsupport services.Many women minorities are vulnerable to poor socio-economic conditions due to a lack ofeconomic independence, resulting in higher levels of impoverishment for them and theirfamilies relative to the majority population. They are more likely to live in segregated low-income and overcrowded housing and neighbourhoods, often with limited access to basicservices.Their health risks are higher and outcomes are worse.They are also more

vulnerable to trafficking and domestic violence.

Some women minorities are stateless,

unable to obtain documentation because of the barriers they face, and are thereby deprived ofcitizenship and the legal rights contained therein.Other disadvantages include barriers

concerning the use of their own language in private and public, as well as the practice of theirreligion in private and public.Ultimately, many women minorities are politically, economically and socially alienated.Their isolation and marginalization from the majority population is compounded by society’sintolerance and negative treatment of them, systemic discrimination, and prejudice andmisinformation concerning their differences and values. They are frequently victims of

5

Twelve OSCE participating States did not vote, abstained or voted against the Universal Declaration on theRights of Indigenous People: Azerbaijan, Georgia, Canada, the United States, Russia, Ukraine, Romania,Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Montenegro.

4

extremism and targets of hate crimes. Under difficult economic conditions and politicaluncertainty, they also become scapegoats. Without knowledge of the local language orculture, or access to support services, they are unable to negotiate their interests and demandrespect for their rights.Their alienation and access to political, economic and social life is complicated further asthese women may also face discrimination within their communities.Because of the

persistence of traditional domestic and gendered roles, they may face internal cultural,traditional, and religious barriers from within their group to their participation in decision-making, their economic empowerment and mobility, thereby resulting in lack of social andeconomic contact, lack of access to child care, health services, education, and inability to ownproperty. Women in marginalized groups are often unable to access justice when they arevictims of domestic violence if such incidents are not recognised as a crime within theircommunity; they may also be unaware of what protection and legal services are available tothem.Moreover, as women belonging to a minority group, their gendered concerns

frequently receive a lower priority than those related to the rights of the group in general.Ultimately, women minorities are caught in a vicious circle whereby the discrimination andprejudice they face leads to their political, economic, and social alienation within and outsidetheir communities, and limits their ability to participate in decision-making bodies, whetherin formally elected offices or informal bodies of their community, on issues that concernthem as women and as members of a minority. This in turn renders them unable to affectmeaningful change and to enjoy their human rights.

b. Women Minorities in the OSCE Region6Women minorities within the participating States of the OSCE have made great strides interms of their political, economic and social achievements and contributions to their own

6

The material in this section was drawn primarily from Data in Focus Report: Multiple Discrimination,European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2010; Ethnic Minority and Roma Women in Europe: A Casefor Gender Equality? European Commission, 2010. For additional information, see Democratic Citizenship,Languages, Diversity and Human Rights: Guide for the Development of Language Education Policies in Europefrom Linguistic Diversity to Plurilingual Education.

5

communities as well as society at large. However, such achievements vary widely and manywomen in marginalized groups face disadvantages and discrimination as described in thepreceding pages, with some facing considerably more than others. Given that an adequateand comprehensive presentation of these experiences is beyond the scope of this report, thedisadvantages and vulnerabilities of four groups in the region will be highlighted asparticularly noteworthy for parliamentarians and decision-makers alike:women; migrant women; indigenous women; and Roma and Sinti women.It bears noting that a proper evaluation of the state of women minorities in the OSCE regionis made significantly more difficult because of the absence of consistent and standardizedsex-disaggregated data of minorities across the participating States.Law enforcementracial minority

agencies are noted to be especially weak in collecting data on women in marginalized groups.Indeed, data collection is central to identifying, comparing and taking steps to remedy formsof discrimination against women in general and women minorities in particular that otherwisemight go unnoticed.

i.

Racial Minorities7

Racial minority women in the OSCE region are diverse in their life experiences and theextent to which they face disadvantages and discrimination. They include women of Africandescent, Latinas, Asians, and South Asians. They are diverse not only in terms of race, butalso in terms of status in the country as native-born or migrants, country of origin and thenumber of generations established in the country, level of education, age, language skills,religious identity and ethnicity, their demographic proportion relative to members of thedominant racial group and the pace at which the proportion is changing, socio-economicstatus, level of political participation, access to affirmative action or positive measures to

7

Material for this section was drawn primarily from Visible Minority Women, Statistics Canada, 2011; ThePersistence of Racial and Ethnic Profiling in the United States: A Follow-Up Report to the U.N. Committee onthe Elimination of Racial Discrimination, American Civil Liberties Union, 2009; Singled Out: Exploratory studyon ethnic profiling in Ireland and its impact on migrant workers and their families, Migrant Rights CentreIreland, March 2011.

6

remedy their disadvantages, urban or rural settlement, life expectancy, health risks, and theirrate of employment and in what sectors.However, as a group they are more vulnerable to discrimination and the violation of theirrights than racial majority women because of the visibly identifiable characteristic of theirrace. Accordingly, throughout the OSCE region, they are more likely than racial majoritywomen to face prejudice, intolerance or unfair treatment in the workplace, particularlyconcerning applications, hiring, or promotion; in education, health care, social services andwelfare, and financial institutions; in public transportation and at border crossings. They alsoface greater risk of being victims of hate crimes.Many racial minority women throughout the OSCE region face particular disadvantages inthe form of racial profiling by state institutions such as law enforcement and border security.While there are many dimensions and manifestations of racial profiling, one particularconcern related to its violation of human rights is its tendency to investigate and question aperson of interest or potential suspect of a crime – committed or planned - based onsubjective characteristics rather than on evidence. Such investigations rely on race as a proxyfor presumption of a crime committed.8They are profiled under a range of circumstances,including as commercial sex trade workers, drug traffickers or drug users, and alcoholics. Asa result, racial minority women have encounters with law enforcement disproportionate totheir share of the general population and are also over represented in the criminal justicesystem. According to one report, they are more likely to be victims of police misconduct andbrutality, including rape, sexual harassment, assault, overly invasive and abusive andhumiliating searches, which often go unreported by the women.9Racial minority women are frequently profiled as illegal migrants or are targeted forunwarranted arrests in order to uncover evidence of not being documented. In some cases,there is also a disproportionate number of arrests of racial minority women for documentation

8

The Persistence of Racial and Ethnic Profiling in the United States: A Follow-Up Report to the U.N.Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, American Civil Liberties Union, 2009.9

The Persistence of Racial and Ethnic Profiling in the United States: A Follow-Up Report to the U.N.Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, American Civil Liberties Union, 2009.

7

reasons during the course of domestic violence investigations, creating a disincentive forreporting domestic violence.For women minorities, racial profiling undermines their trust in state institutions and policeenforcement, as well as their sense of equal protection under the law. Such conditions can beparticularly dangerous for victims of domestic violence who stay in a violent situationbecause of a sense of having no choice or recourse to justice. Racial profiling compounds thesense of alienation, exacerbates racism and xenophobia, and deepens their social, political,and economic marginalisation.

ii.

Migrant Women10

The conflation of belonging to a national, ethnic, religious, racial or linguistic minority andbeing a migrant renders a woman particularly vulnerable to multiple discriminations and topolitical, economic and social alienation. Migrant women in the OSCE region, however, arenot a monolithic group and vary according to numerous distinctions in addition to theirminority identity or identities, such as their motivation for migration, country of origin, levelof education, employability in their profession, and whether migration was voluntary orinvoluntary, temporary or permanent, legal or illegal. They also differ in terms of theiraccess to training and education and to support for integration and language skillsdevelopment. Their experiences with respect to the violation of their human rights will varyaccordingly.

10

Maria Kontos, “Between Integration and Exclusion: Migrant Women in European Labour Markets,”Migration Information Source,Migration Policy Institute, 23 March 2011; “Care to Care? Addressing thechallenges of integrating migrant women into Europe’s labour force,” RAND Europe, 2009; Kathleen Ferrier,Special Representative on Migration OSCE PA, Remarks on Peace and Confidence-Building ThroughEconomic and Environmental Co-operation, OSCE Parliamentary Assembly Economic Conference –FosteringEconomic Co-operation and Stability in the OSCE region,Batumi, Georgia, 12 May 2012; Kathleen Ferrier,Special Representative on Migration OSCE PA, Remarks at the Trans-Asian Parliamentary Forum, Almaty,Kazakhstan, 15 May 2010; Kathleen Ferrier, Special Representative on Migration, OSCE PA, Winter Meeting,Vienna, Austria, 24 February 2011; Hedy Fry, Special Representative on Gender issues, OSCE PA, GenderBalance Report, 2011.

8

Women minorities who migrated for economic or employment reasons are less wellintegrated into the labour market than native-born or majority women and migrant men.They are commonly employed in marginal, gendered positions and in irregular sectors.These include domestic work, caregiving, health care, agriculture and food processing, thehospitality and restaurant industry, as well as the sex trade. Some of these sectors areespecially sensitive to economic downturns as is any support for training or social programs,making many of these women additionally vulnerable.Women migrants belonging to a minority group and who are undocumented; lack a legitimateresidency status; have limited access to reliable information, support, and legal protection;and are without knowledge of the local language are particularly vulnerable. If they weretrafficked, they are completely dependent on those who exploited them and are morevulnerable to conditions of enslavement because of the apparent absence of any viableoptions.While the predominant image of the minority migrant woman in the OSCE region is of aneconomic migrant, it is important to note the different life experience of those minoritymigrant women who are refugees or internally displaced persons. Some of these women aredisplaced because of long-standing and unsettled conflicts in the OSCE region. Many moreseek resettlement and asylum from conflicts outside the region. According to the UnitedNations High Commission on Refugees, there are some 4.8 million persons falling under itsmandate in the OSCE region. They include some 2.5 million refugees and asylum-seekers,1.4 million internally displaced persons, and some 880,000 returnees, stateless and otherpersons of concern.11Accordingly, migrant women minorities are more likely to be economically disadvantaged, inlow-paying, unskilled, part-time, unprotected, informal positions, regardless of theireducation or qualifications, and to lack access to access to child care, training and education.Coupled with their marginalization because of limited knowledge of the local language andaccess to information services, they are more vulnerable to danger, exploitation and abuse,

11

http://www.osce.org/home/71530.

9

sexual harassment, lack of access to justice and protection, and victimisation. Their potentialpolitical, economic and social contribution is thereby seriously constrained.It is important to note that the OSCE participating States vary significantly in terms ofmigration management measures and the impact of these measures on migrant women,including the regulation of many of these sectors, the administration of work permits formigrant workers, support and protection services, recognition of foreign credentials andeducation, criminalization of traffickers, management of the commercial sex trade, and theenforcement of these measures.

iii.

Indigenous Women12

While no internationally agreed definition of indigenous peoples exists, they are generallyconsidered a non-dominant group with a distinct identity who inhabited lands beforecolonialism and the establishment of state borders and who have a strong and long termattachment to those ancestral lands and the natural resources contained therein. The rights ofindigenous peoples are protected as minority rights under international law as well asmechanisms and mandates relating to them directly.In the OSCE region, indigenous peoples live in particular in Canada and the United States,and the circumpolar states of Denmark (Greenland), Sweden, Norway, Finland and Russia.The diversity among these indigenous populations is evident particularly in terms of languageand culture, but also in location. Whether residing in southern, central or northern regions, orlocated in urban centres, indigenous peoples face challenges and threats to their way of lifethrough the degree of control, ownership and development of natural resources, access to and

12

Material in this section was primarily drawn from Arctic Human Development Report: Gender Issues,Stefansson Arctic Institute, Iceland, 2004; Tonina Simeone, “The Arctic: Northern Aboriginal peoples,” Libraryof Parliament, Parliament of Canada, October 2008; Clara Morgan, “The Arctic: Gender Issues,” Library ofParliament, Parliament of Canada, October 2008; Briefing Note 1: Gender and Indigenous Peoples, PermanentForum on Indigenous Issues, United Nations, 2010; Briefing Note 2: Gender and Indigenous Peoples’Economic and Social Development, Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, United Nations, 2010; BriefingNote 3: Gender and Indigenous Peoples’ Education, Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, United Nations,2010; Briefing Note 4: Gender and Indigenous Peoples’ Environment, Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues,United Nations, 2010; Briefing Note 5: Gender and Indigenous Peoples’ Human Rights, Permanent Forum onIndigenous Issues, United Nations, 2010;

10

level of education, and employment rates. Accordingly, they differ across and within theparticipating States in terms of the disadvantages and discrimination experienced.Indigenous women in the OSCE region share many concerns about disadvantages anddiscrimination with minority women relating to their cultural, racial and linguisticdistinctions from the majority female population, but also have many specific considerationsstemming from their history with colonialism and attachment to their ancestral lands and theirnatural resources.13In this respect, it is important to note that some indigenous cultures weregenderless, having developed a distinct form of gender relations that were consideredcomplementary before contact with non-indigenous populations and their hierarchical view ofgender roles transformed these structures.Accordingly, the disadvantages and

discriminations indigenous women face stem in large part from being placed in a non-dominant position vis à vis indigenous men by outside forces and from being politically,economically, and socially subordinate to the men in their communities.14Disregard for their human rights as women, as minorities, and as indigenous people has comein many forms. In many instances, they and their communities were forcibly removed fromtheir traditional lands to remote areas with little connection to their lifestyle or little to offerin terms of sustenance and sustainability, deliberately excluded from mainstream political,economic and social spheres, and, according to some analysts, experienced genocide.15Theforced physical dislocation was particularly traumatic for indigenous children who wereuprooted from their families in order to receive formal education in a foreign language andaccording to a foreign culture and values, with the deliberate intent of diminishing theiridentity and language, and alienating them from their culture and way of life. Many werephysically and sexually abused, which in later years led to social marginalisation, lack of self-esteem and value, substance abuse, and domestic violence. In part because of limited access

13

Minority Rights: International Standards and Guidance for Implementation, United Nations Human RightsOffice of the High Commissioner, 2010.14

Arctic Human Development Report: Gender Issues, 2004.

15

Robert A. Williams, “Encounters on the Frontiers of International Human Rights Law: Redefining the Termsof Indigenous Peoples' Survival in the World,” Duke Law Journal, Vol. 1990, No. 4, Frontiers of Legal ThoughtIII (Sep., 1990), pp.660-704.http://www.jstor.org/stable/1372721.

11

by many indigenous communities to resources and health care services to address thesesituations, the survivors of such abuse have perpetuated these activities.Among the most disadvantaged indigenous peoples, their marginalisation has been mostobvious in its physical form because of the remoteness and isolation of their communities andwhereby they are required to reside apart from mainstream society on designated land wherehousing, education and basic services are in extremely short supply.The situation is

compounded by poor health; high infant mortality rates; low life expectancy; highunemployment; high suicide and attempted suicide rates; limited education; poverty; and insome cases high rates of fetal alcohol syndrome.For many of the most disadvantaged indigenous women, these life experiences have resultedin sexual exploitation, human trafficking, and violence. They experience higher rates ofunemployment and limited access to education than the majority population. Due to theprejudice and indifference they experience from law enforcement institutions, many of thecrimes of which they are victims, including rape, domestic violence, and murder, are notinvestigated or taken to trial.16In many cases, law enforcement does not respond effectivelyto indigenous women because they pre-judge the reliability and credibility of these women aswitnesses due to the fact they are indigenous, often discounting legitimate reports of violenceand other crimes. As well, their over-representation in the criminal justice system and theirhigh levels of interactions with law enforcement generate indifference within the criminaljustice system.While indigenous women are severely disadvantaged by the development of the naturalresource economy that favours jobs traditionally occupied by men, many of the additionalvulnerabilities faced by indigenous women, particularly in the circumpolar north, relate to theeffects of climate change and environmental contamination on their traditional lifestyle andculture and in light of their strong bond with the environment and their natural surroundings.

16

See Stolen Sisters: Discrimination and Violence Against Indigenous Women in Canada, AmnestyInternational, 2009.

12

It is noteworthy that some indigenous women play significant decision-making roles and canhave tremendous authority in their societies and local communities. This influence hastransferred into the formation of their representative organisations such as the Pauktuutit InuitWomen’s Association and their leadership in international indigenous organisations, such asthe Inuit Circumpolar Conference, and in international fora more generally in order to raiseawareness of indigenous women’s issues and concerns, including environmental stewardshipand climate change. However, their influence has not transferred to strong representation informal and higher levels of institutional structures of decision-making, including electedoffice.Neither have they had significant representation on priority issues facing their

communities, such as natural resource development and management.

iv.

Roma and Sinti Women17

The condition of Roma and Sinti women is another high profile dimension of minoritywomen in the OSCE region. As with other categories of minority women, the Roma andSinti are a heterogeneous group with wide-ranging differences among them depending inparticular on where they reside. While the majority are sedentary, they will differentiateaccording to the duration of settlement and in which country, the legal status of theirresidency, their language, socio-economic status, and whether they are asylum seekers orrefugees.

17

See Council of Europe, Roma and Travellers Glossary (2006) for an outline of the terms used to refer toRoma and Sinti, and their distinctions. Material in this section is drawn primarily from Ethnic minority andRoma Women in Europe: A Case for Gender Equality? European Commission, 2010; World Bank, RomaInclusion: An Economic Opportunity for Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Romania and Serbia, September 2010;Parallel Report to the Human Rights Council, European Roma Rights Centre, Life Together and the Group ofWomen Harmed by Forced Sterilization concerning the Czech Republic, 2012; European Roma Rights Centre;Breaking the Barriers: Romani Women and Access to Public Health Care, European Centre on Racism andXenophobia, Council of Europe, 2003; Political Participation of Roma with Emphasis on Political Participationof Roma Women in the Countries of the Region, K-factor Ltd., Croatia, 2011; Implementation of the ActionPlan on Improving the Situation of Roma and Sinti within the OSCE Area, Status Report 2008, OSCE/ODIHR;Review of EU Framework National Roma Integration Strategies (NRIS), Open society Foundations, 2012;Action Plan on Improving the Situation of Roma and Sinti within the OSCE Area, OSCE, 2003; HCNM’sReport on Roma in the CSCE Region, HCNM, 1993; The ODIHR Contact Point for Roma and Sinti Issues: AnOverview, OSCE/ODIHR.

13

Because of their cultural differences and the misunderstandings surrounding them, asmembers of the Roma and Sinti minority the women experience high levels of prejudice andintolerance by the majority population and even state institutions, such as law enforcement.As a result, they are politically, economically and socially segregated and marginalised.They are at higher risk of being victims of violence and hate crimes by the majoritypopulation, and are vulnerable to being scapegoats for political and electoral purposes.Accordingly, they are severely disadvantaged in terms of their access to housing and tend tolive in shanty camps.Under such poor living conditions, which includes severe

overcrowding, lack of basic facilities such as running water and electricity, the Roma areparticularly vulnerable to poor health. These risks are compounded by limited access toadequate health services and reduced access to information in general. The health concernsfor Roma women are further aggravated by the high rate of early and multiple pregnancies,which in some countries where they reside has led to cases of state-imposed forcedsterilization. Moreover, efforts to offer compensation and redress and to safeguard againstfuture such action have been inadequate. Their life expectancy is significantly lower thanthat of majority women.Roma women are more likely to be unemployed or inactive in the labour market than Romamen. Those that are employed are more likely to be so in the informal economy. The lack ofdocumentation is a particular barrier faced by many Roma women to obtain formalemployment or even to access social benefits. Nevertheless, the generally high rates ofunemployment among the Roma population are associated with the high levels of poverty;according to one source, as many as 90% of Roma in Europe live below the poverty line.18Another significant barrier faced by Roma women are the traditional gender roles within theircommunity that enforce a patriarchal system and a view of women as subordinate. Thisresults in more limited access to employment, health, education, property and social servicesthan Roma men. Indeed, education of Roma women is undervalued, and girls and youngwomen are more likely to leave school because of family responsibilities and early

18

Data in Focus Report: Multiple Discrimination, European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2010.

14

marriages.19What education they might receive is taught at segregated or special schools forRoma and is of poor quality compared to non-Roma schools. Divorce is not common andmany women endure violent marriages as a result.Accordingly, the socio-economic status of Roma women is significantly lower than majoritywomen and Roma men. With limited access to employment and education, many resort tobegging and are at higher risk of carrying out criminal activities, prostitution anddelinquency, and trafficking.

c. OSCE InitiativesA brief review of OSCE initiatives concerning the situation of women minorities in theOSCE region reveals that it has well-established mechanisms and institutions by which to acton its mandate regarding promoting human rights, including women’s rights and minorityrights. These include the Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR -which includes programs on tolerance and non-discrimination; combating racism, xenophobiaand discrimination; freedom of religion or belief; hate crime; migration; gender equality; anda contact point for Roma and Sinti issues), the Gender Advisor, the Special Representative ofthe Chairperson in Office (CIO) on Gender issues, the High Commissioner on NationalMinorities (HCNM), the Personal Representative of the CIO on Combating Racism,Xenophobia and Discrimination, also focusing on Intolerance and Discrimination againstChristians and Members of Other Religions, and the Personal Representative of the CIO onCombating Anti-Semitism.For its part, the OSCE Parliamentary Assembly has such

mechanisms as the Special Representative on Migration and the Special Representative onGender Issues.Their activities and mandates are based in large part on the commitments made by theparticipating States in theFinal Actof the Conference on Security and Cooperation inEurope, the OSCE participating States committed themselves to respect “human rights andfundamental freedoms ... for all without distinction as to race, sex, language or religion.”

19

Ethnic minority and Roma Women in Europe: A Case for Gender Equality? European Commission, 2010.

15

Other notable documents related to women’s rights, national minorities, cultural, linguisticand religious identity, and race include the 1990 Document of the Copenhagen Meeting ofthe Conference on the Human Dimension of the CSCE, the 1990 Charter of Paris for a NewEurope, the 1991 Report of the CSCE Meeting of Experts on National Minorities, the 1992CSCE Helsinki Document: The Challenges of Change, among other subsequent documents.More recently, Ministerial Council decisions including 10/11, 08/09, 9/09, 10/09, 06/08,10/07, 13/06, 10/05, 14/05, 15/05, list commitments related to gender equality, nationalminorities, and ethnic, religious, racial, and cultural groups, as well as tolerance, non-discrimination, the promotion of mutual respect, and combating hate crimes.20For its part, the OSCE Parliamentary Assembly’s Edinburgh Declaration, Kyiv Declarationand Oslo Declaration, and the Belgrade Declaration also highlight the importance ofcommitments in these areas and urge participating States and their parliaments to continue toincrease their efforts to safeguard and promote equal opportunities for women and minorities.With respect to women minorities specifically, the2004 OSCE Action Plan for the Promotionof Gender Equalityspecifically calls on the HCNM to “address specific issues relating to theparticipation in public and private life of women belonging to national minorities and, inpolicies and projects developed by his/her office, take steps necessary to counter the doublediscrimination suffered by these women, as appropriate within the context of his/her conflictprevention mandate.”21The 2011Annual Evaluation on the Implementation of the 2004 Action Plan for thePromotion of Gender Equalitynotes several overlapping initiatives concerning genderequality and minorities and which highlight efforts to improve the situation of the mostdisadvantaged. In particular, ODIHR continued to mainstream issues related to gender-baseddiscrimination into its Tolerance and Non-Discrimination Information System (TANDIS),which also provides links to reports from non-governmental organizations pertaining to

20

For a complete list of these commitments organized according to themes, please refer to OSCE HumanDimension Commitments, Volume 1, Thematic Compilation, 3rdEdition (2011),http://www.osce.org/odihr/76894?download=true.21

2004 Action Plan for the Promotion of Gender Equality, OSCE.

16

gender-based violence or discrimination.

The report also highlighted the work of the

Advisory Council of the OSCE/ODIHR Advisory Panel of Experts on Freedom of Religionor Belief in applying a gender perspective to its review of draft legislation on freedom ofreligion or belief and in the preparation of the second edition of theGuidelines for Review ofLegislation Pertaining to Religion or Belief.ODIHR also assisted the Personal

Representatives of the Chairperson-in-Office on tolerance and non-discrimination issues byidentifying key NGOs addressing gender mainstreaming or women rights in relation to hatecrimes and other forms of intolerance, and providing input concerning minority women whomay experience aggravated discrimination. The 2010 OSCE Review Conference held inadvance of the 2010 Astana Summit highlighted various forms of gender discrimination; theplight of refugee women and children in conflict areas; efforts to strengthen gender-sensitiveoutreach initiatives in relation to hate-motivated crimes and incidents; and the developmentof gender-sensitive, rights-based educational methodologies which take into account specificforms of intolerance faced by migrant women.22The mandate of the HCNM is specific to national minorities and early warning and earlyaction regarding immediate tensions involving national minority issues and their long-termroot causes. While he works on the basis of confidentiality in order to build confidence withstakeholders, many of his activities have focused on issues directly related to minoritylanguage rights and citizenship. While he is not mandated to implement projects specificallyaimed at promoting gender equality and resolving various gender-related issues, recentHCNM projects have highlighted themes relating to gender relations in society. When theHCNM makes country visits, he regularly meets with different NGOs and minorityrepresentatives, including women's groups and male and female minority representatives, inorder to exchange information as well as to encourage interethnic dialogue within a State.23Notwithstanding these initiatives, OSCE efforts to address the specific yet diversedisadvantages and vulnerabilities experienced by women minorities in the region are

22

2011 Annual Evaluation Report on the Implementation of the 2004 Action Plan for the Promotion of GenderEquality.23

2011 Annual Evaluation Report on the Implementation of the 2004 Action Plan for the Promotion of GenderEquality.

17

undermined by three areas of weakness in particular. First, women and minorities areunderrepresented in the leadership and management positions at the OSCE. Second, theplight of indigenous peoples is explicitly referred to only in the 1992 Helsinki Document:Challenges of Change, i.e. “The participating States (29) Noting that persons belonging toindigenous populations may have special problems in exercising their rights, agree that theirCSCE commitments regarding human rights and fundamental freedoms apply fully andwithout discrimination to such persons,” and otherwise not included in the mandate of theOSCE’s mechanisms and institutions, notwithstanding the distinct challenges that indigenouspeoples experience.Third, collaboration across the various mechanisms and institutions on issues concerningwomen minorities could be strengthened in order to reinforce the multidimensional issues atplay. In other words, because of the cross-cutting nature of and multiple discriminationsfaced by women minorities, greater effort is required to consider gender equality andminorities as overlapping issues.Nevertheless, some of the more prominent recent initiatives carried out by these mechanismsand institutions warrant reference, particularly regarding migrants and Roma/Sinti.

I.

Migrants

While not specifically addressing the issue of women minorities as migrants, among the mostrecent initiatives undertaken by OSCE bodies concerning women migrants, the Office of theCo-ordinator of Economic and Environmental Affairs, in co-operation with the OSCE Centrein Astana, the Government of Kazakhstan, IOM, ILO and UNWomen promoted gender-sensitive labour migration policies through a regional training event in Astana in September2010. A total of 60 government officials and policymakers from Central Asian countries tookpart in the training designed to raise awareness of the main challenges faced by female labour

18

migrants, highlight some of the gender gaps in migration policies, and provide possiblesolutions.24In addition, the OSCE published in 2009 aGuide on Gender-SensitiveLabour MigrationPolicies in order to raise awareness about good practices and to provide tools on how to shapegender-sensitive labour migration processes in accordance with OSCE commitments.25The 2009 Ministerial Council in Athens adopted a decision which encouraged theparticipating States to work on migration management by, in part, respecting the rights ofmigrants and increasing efforts to combat discrimination, intolerance and xenophobiatowards migrants and their families, and to continue working on gender aspects of migration.

II.

Roma and Sinti

Since being the first international organization to recognize the particular problems of theRoma, the OSCE and its bodies have worked continuously to raise awareness of thediscriminations they face and to promote initiatives that would improve their situation.Among others areas of recent activities undertaken by OSCE bodies, the HCNM recentlywarned against the rise of anti-Roma violence in the region.26In addition, the ODIHRrecently launched with the European Union a two year, EUR 3.3 million project entitled“Best Practices for Roma Integration” in the Western Balkans to promote their socialinclusion and combat the discrimination they face.27

24

2011 Annual Evaluation Report on the Implementation of the 2004 Action Plan for the Promotion of GenderEquality.25

http://www.osce.org/eea/37228

26

“OSCE High Commissioner on National Minorities warns against rise of anti-Roma violence and extremenationalism in Europe,” 10 October 2011. The HCNM identified as early as 1993 concerns about the challengesand disadvantages the Roma and Roma women in particular face.27

http://www.osce.org/odihr/91077

19

The OSCE and its bodies have also taken action specifically regarding Roma women andgirls. For instance, the 2003OSCE Action Plan on Improving the Situation of Roma and Sintiis explicit in its recommendations on initiatives regarding Roma women and girls. In thecontext of efforts by participating States and relevant OSCE institutions to develop policiesand implementation strategies, it recommends that “the particular situation of Roma and Sintiwomen should be taken into account in the design and implementation of all policies andprogrammes. Where consultative and other mechanisms exist to facilitate Roma and Sintipeople’s participation in such policy-making processes, women should be able to participateon an equal basis with men. Roma women’s issues should be systematically mainstreamed inall relevant policies designed for the population as a whole.” In order to counter prejudiceagainst Roma and Sinti and to effectively elaborate and implement policies to combatdiscrimination and racial violence, the report also recommends that, in the context oflegislation and law enforcement, participating States “take into account in all measures andprogrammes, the situation of Roma and Sinti women, who are often victims of discriminationon the basis of both ethnicity and sex.” In the context of unemployment and economicproblems, it recommends that participating States “develop policies and programmes,including vocational training, to improve the marketable skills and employability of Romaand Sinti people, particularly young people and women.” In the area of health care, itrecommends that participating States pay special attention to the health of Roma women andgirls, particularly regarding the provision of health care information and improving access togynecological, maternal and natal health care. In other respects, it calls on participatingStates to guarantee the equal voting rights of Roma women and to promote Roma women’sparticipation in public and political life.In light of the multiple forms of discrimination faced by Roma women, ODIHR takes care toensure that Roma women are represented in human dimension meetings. In this context,Roma women presented their views during the High Level Conference on Tolerance andNon-Discrimination in Astana in June 2010. In addition, Roma women actively contributedto a Working Session of the OSCE Review Conference in Warsaw in October 2010 and acorresponding side event on migration and freedom of movement coorganized by ODIHR,the European Roma Rights Centre and Amnesty International. ODIHR has provided smallgrants to Roma organizations to raise awareness in Roma communities and among Romawomen of the importance of the voting process and voting procedures. ODIHR supports20

activities organized by partner institutions and civil society actors that have a gender-specificfocus. For example, in April 2011 ODIHR participated in the conference “Roma Women inFocus – Roma Women in Central and Eastern Europe”, organized by the European Women’sLobby in Budapest. On International Women’s Day, 8 March 2011, ODIHR staff gave apresentation on the situation of Roma women in Europe at a meeting of the AustrianWomen’s Council in Vienna.Furthermore, ODIHR promotes the adoption of a gender-sensitive approach within thebroader human rights discourse among Roma and Sinti civil society, including withtraditional community leaders. In this regard, ODIHR works closely with local authoritiesand civil society organizations to ensure that attention is paid to the issues of non-participation in education and the high drop-out rate of Roma girls from schools and theirparticular vulnerability with regard to the right to education, connected to the practice ofearly marriage.28Particular attention is paid to address the disadvantages Roma and Sinti girlsface in accessing educationThe 2010 manualPolice and Roma and Sinti:Good Practices in Building Trust and

Understandingincludes several references to the particular impact of police misconduct onRoma women and the role that Roma women can play in enhancing trust. In this respect, itsuggests policies and programmes that increase recruitment of Roma women into policeforces and that create a culturally sensitive environment in order to strengthen their retention.Moreover, on International Women’s Day 8 March 2012, the head of the OSCE ContactPoint for Roma and Sinti Issues highlighted the vulnerability of Roma women regardingaccess to health care, education, segregation, poverty, and the multiple forms ofdiscrimination they experience.29He also adopted a special mentor programme that focuseson the empowerment of Roma women.30

28

2011 Annual Evaluation Report on the Implementation of the 2004 Action Plan for the Promotion of GenderEquality.29

http://www.osce.org/odihr/88848http://www.osce.org/odihr/13996

30

21

III.

Gender in the OSCE Governmental Institutions

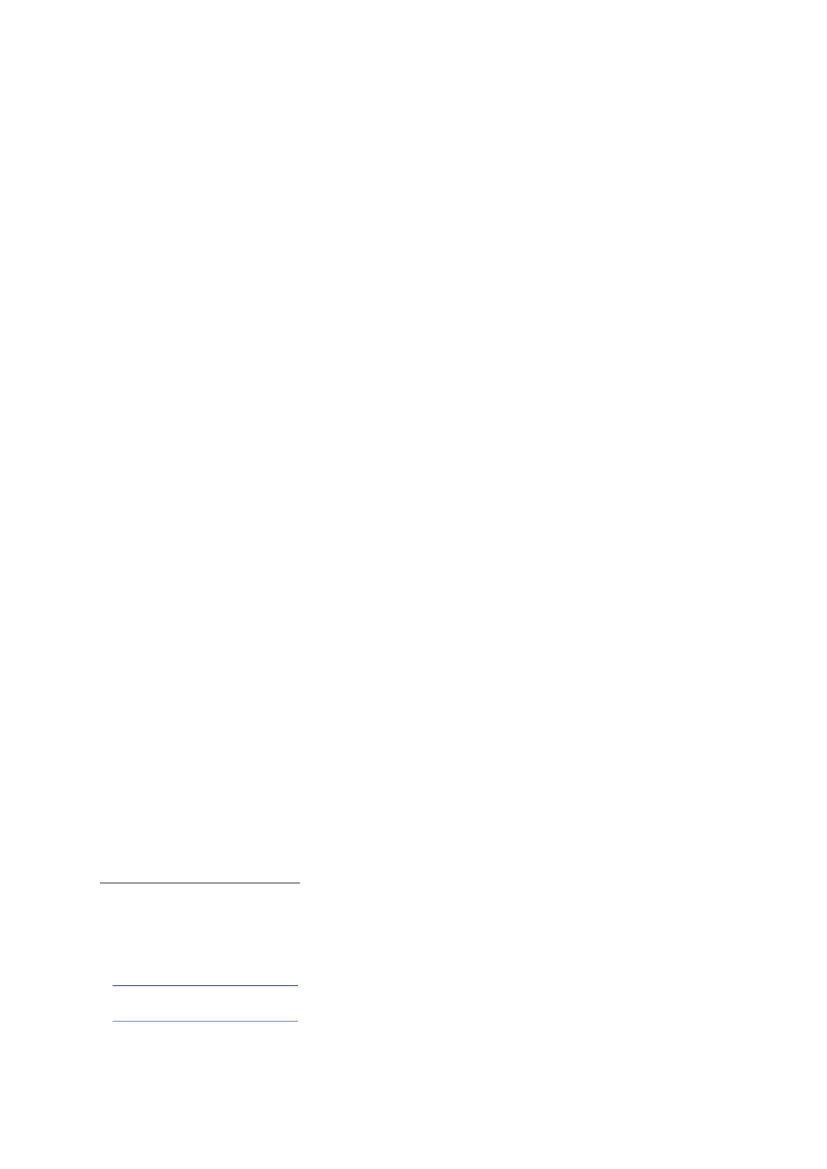

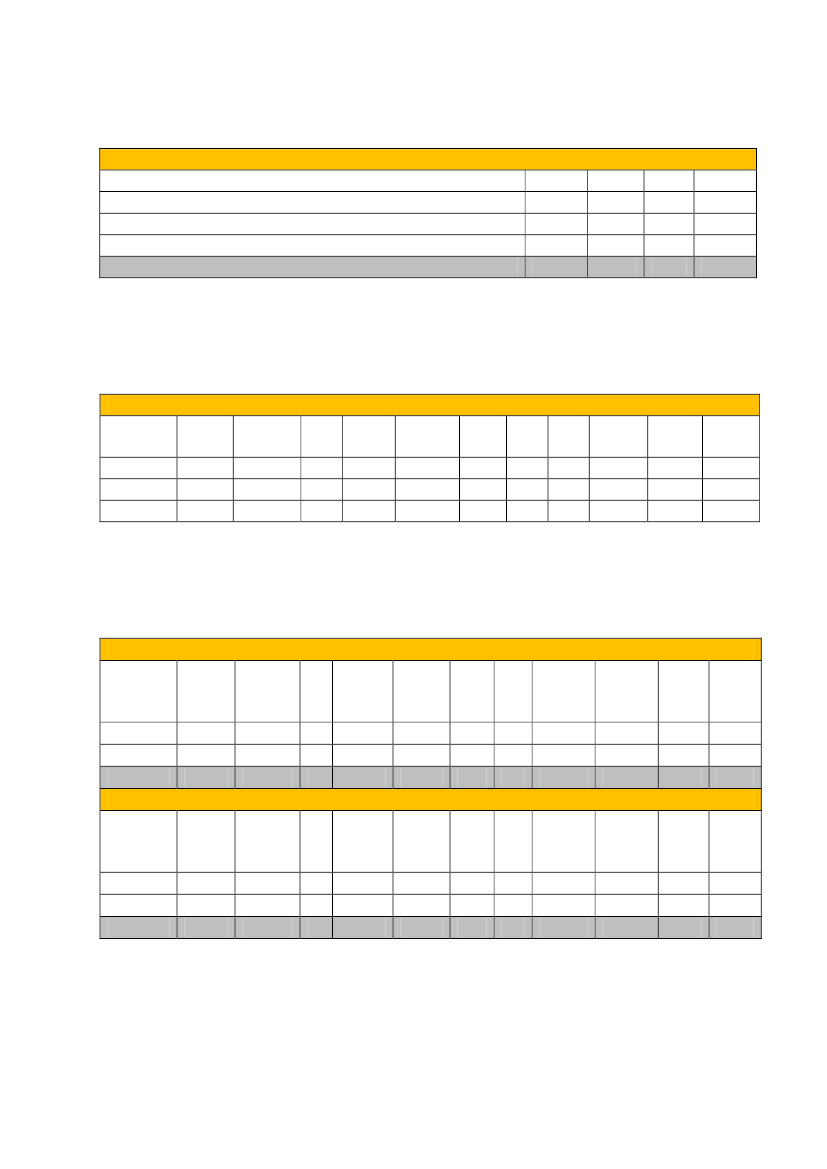

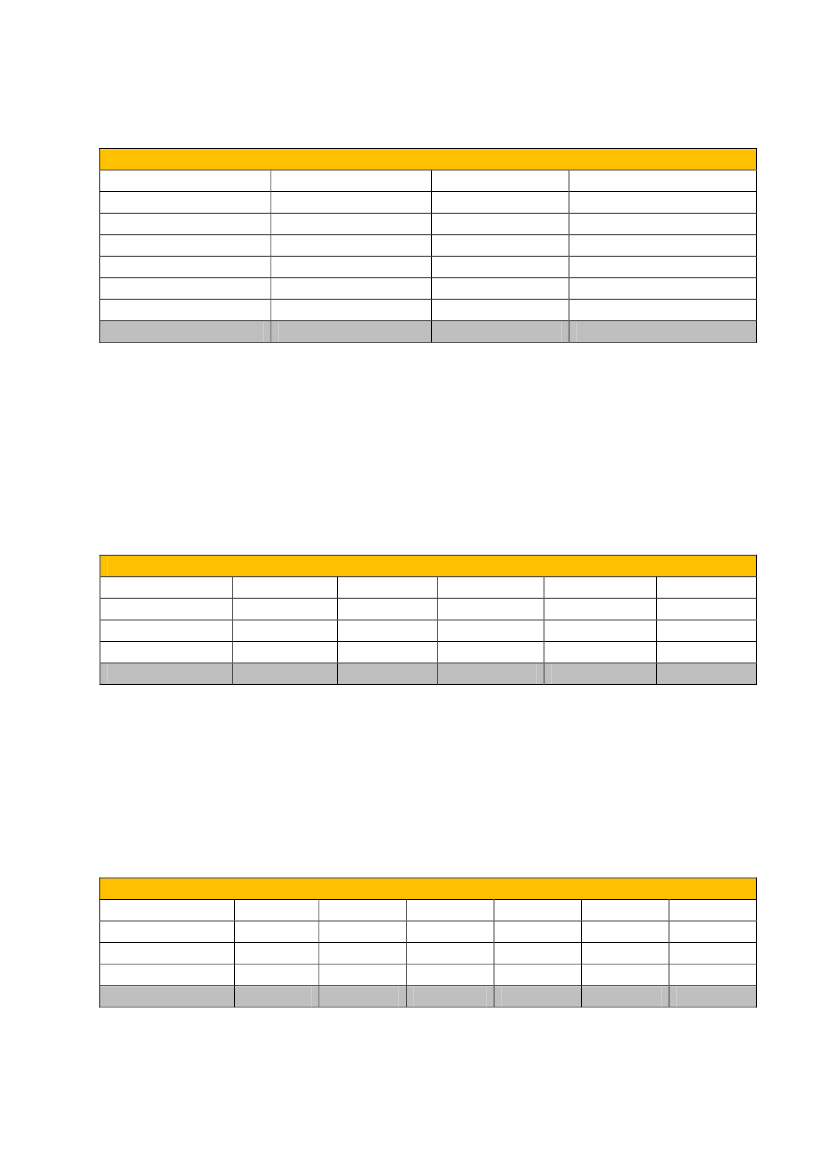

The progress of gender balance throughout the OSCE governmental structures—discussed inthe following pages— is measured by statistics published in the September 2011 SecretaryGeneral’s Annual Evaluation Report on the Implementation of the 2004 OSCE Action Planfor the Promotion of Gender Equality.As of 1 May 2011, the OSCE maintains a staff of 2,639, with women representing 46 per centof the total workforce. During the reporting period, the number of women holdingprofessional staff positions increased by two per cent. Women continue to be under-represented in management positions compared to the overall representation of women withinthe general service and professional staff sector.31

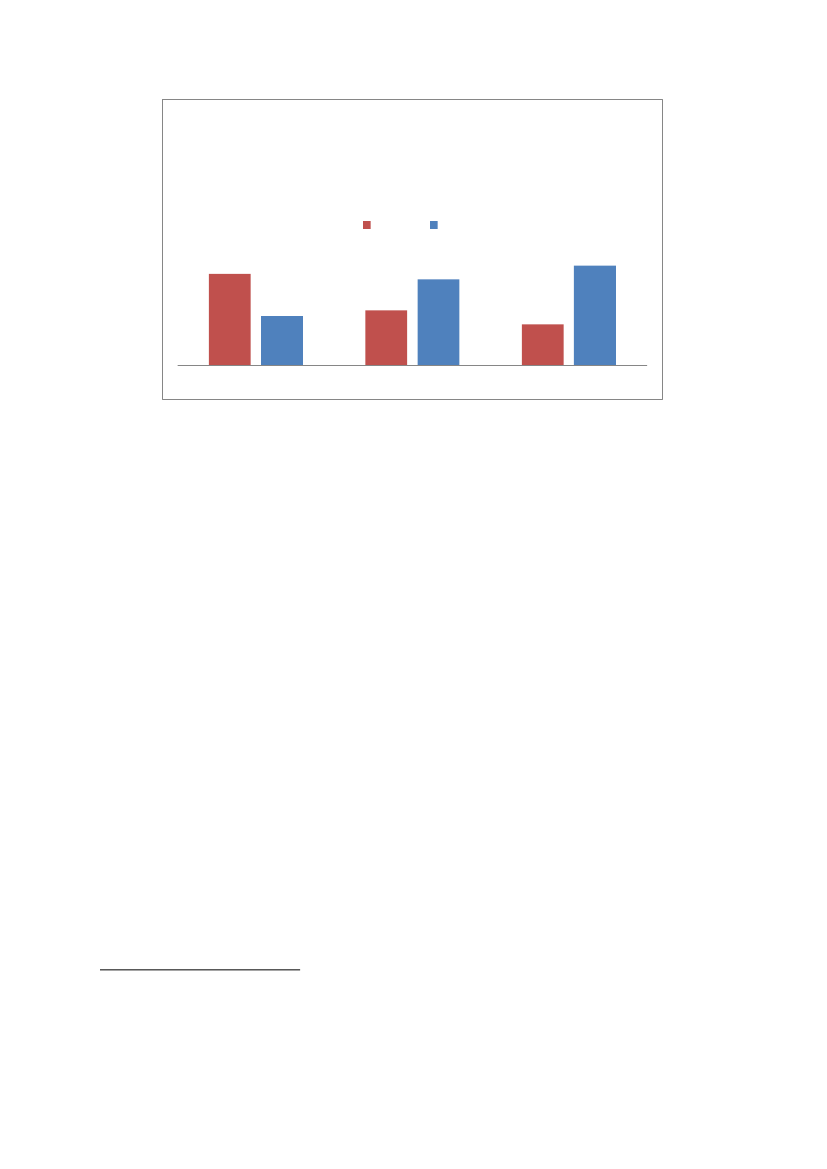

Positions Held by Women inthe OSCE (%)201046%47%46%201148%30%31%

General Service Staff

Professional Staff

Management

Gender balance within the Heads of Missions and Heads of Institutions has shifted since thepublication of the 2011 Secretary General’s Annual Evaluation Report with the appointmentof Ambassador Natalia Zarudna as Head of the OSCE Center in Astana in December 2011and Jennifer Leigh Brush as Head of the OSCE Mission to Moldova in April 2012.

31

See Table 1

22

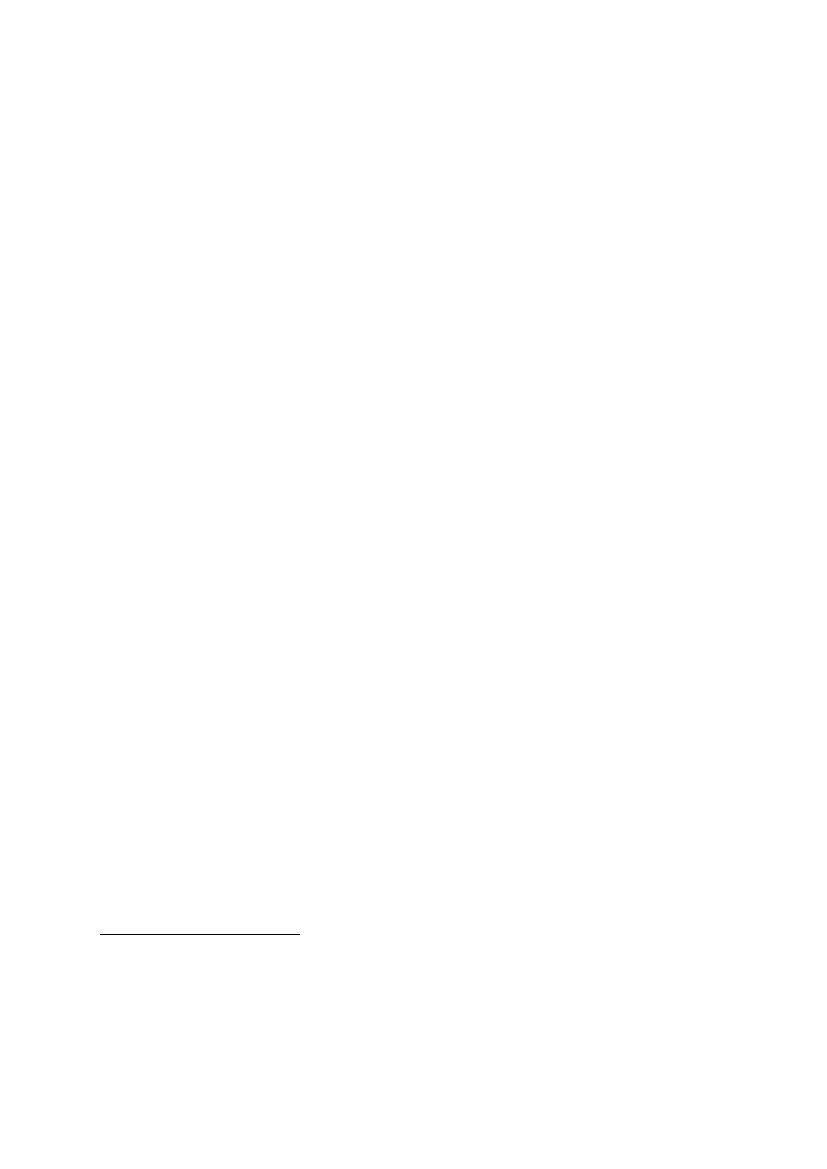

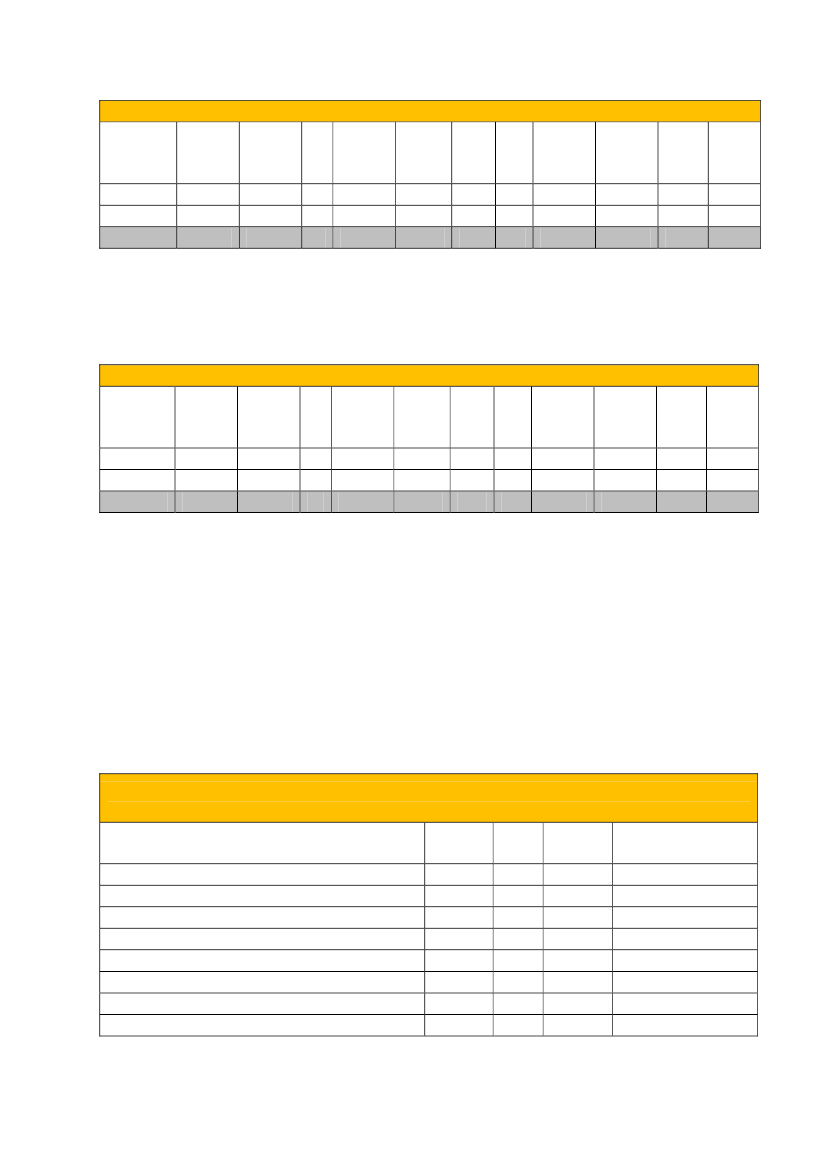

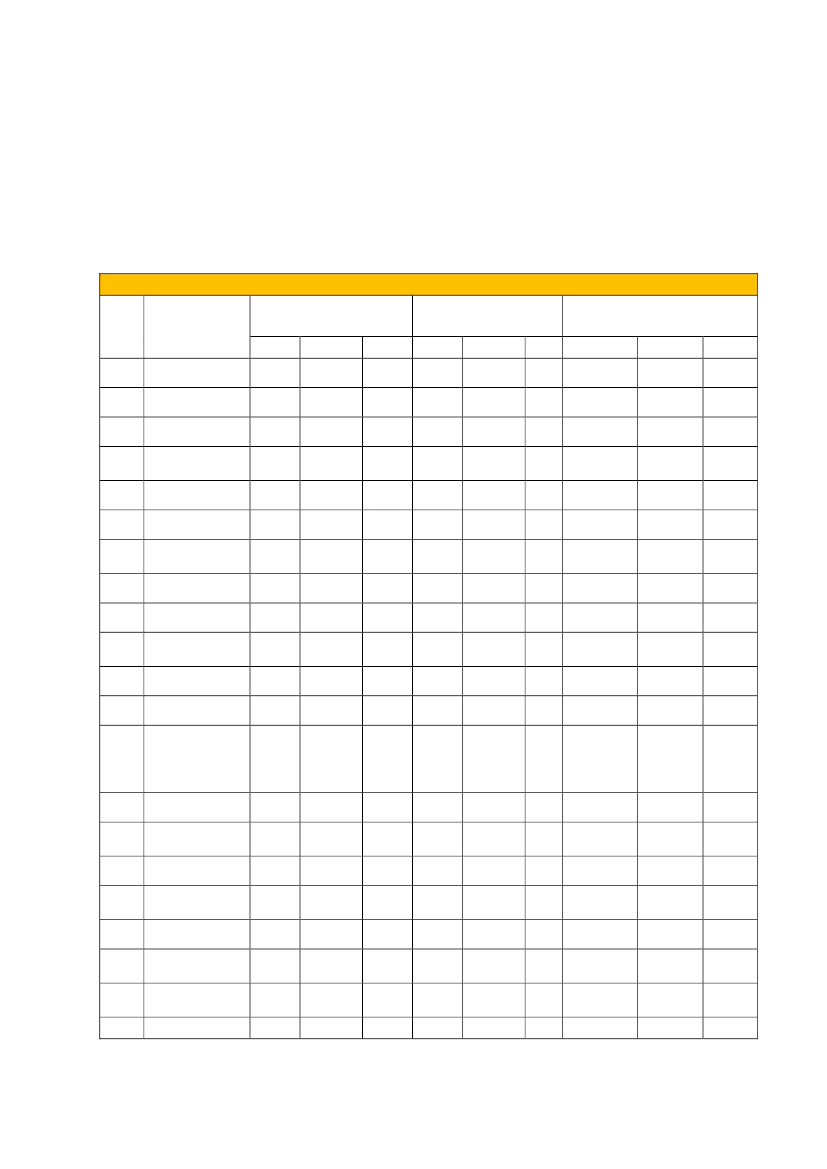

Within the Secretariat and Institutions female representation among professional posts hasgrown from the reported 38 per cent in 2010 to 44 per cent in 2011. The Secretariat andInstitutions have also seen an increase in women holding management positions, with 15 outof a total of 38 positions are now held by women.32Field operations have seen a slight increase in the percentage of female representation withinthe ranks of international professional staff. However, this increase is not due to a rise inwomen hired for vacancies within international professional positions, but rather because of adecrease in overall staffing. At the time of reporting, 50 per cent of international professionalpositions held within field operations are occupied by women.Female representation in management positions within field operations has seen a slightdecline. Representation slid from 29 per cent in 2010 to 28 per cent in 2011, due to one fewerwoman holding a management position than in 2010.Among the field operations with the highest number of seconded staff, the OSCE Mission toBosnia and Herzegovina remains the most consistently gender-balanced presence withwomen representing 52 per cent of the overall seconded positions. The OSCE Missions toKosovo and Skopje are not far behind with 46 per cent and 44 per cent of positions held bywomen, respectively.33

32

See Table 2See Table 3

33

23

Women Represented in the OSCEField Operations by Seconded PositionsOSCE Mission to Bosnia and Herzegovina342411149565313S41OSCE Mission to KosovoOSCE Mission to Skopje

S1

S2

S3

The number of female Deputy Heads of Mission has increased to four with the appointmentof Nina Soumalainen, Deputy Head of OSCE Mission to Bosnia and Herzegovina on 12 May2012. The Deputy Head of Mission at the OSCE Centre in Astana, the OSCE Office in Bakuand the OSCE Mission in Skopje are all female.On the other end of the gender balance spectrum, the OSCE field presences in Bishkek andSerbia are lagging far behind, with 23 per cent and 25 per cent of positions held by women.

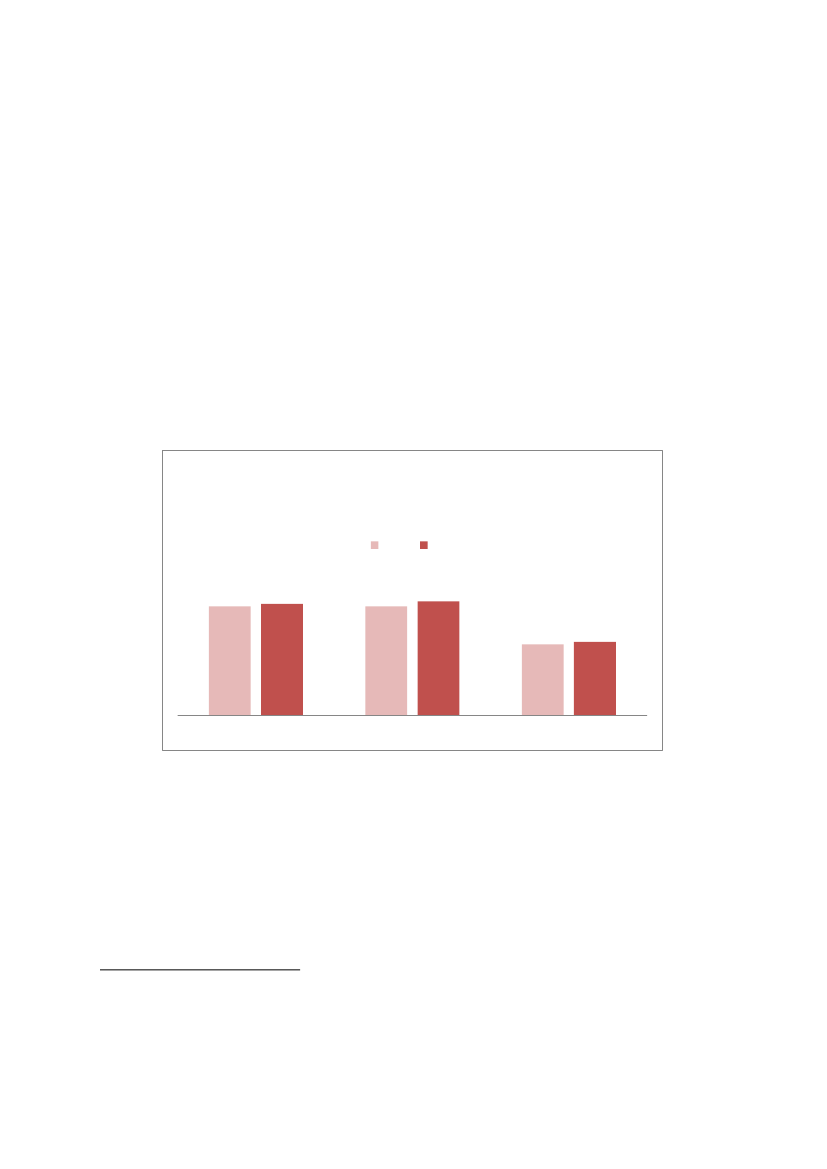

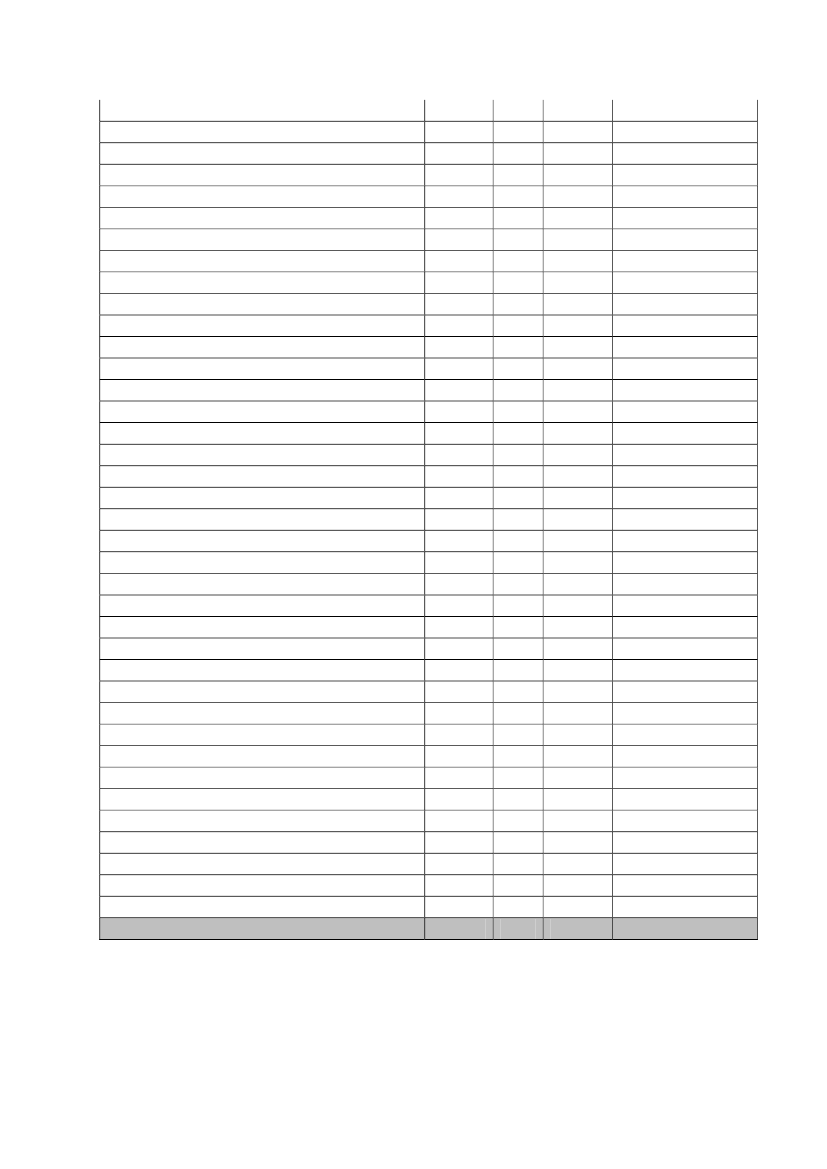

a. OSCE SecretariatIn total, women represent 53 per cent of the OSCE Secretariat workforce in Vienna. This isan increase of two per cent since last reporting. However, further analysis reveals that theincrease in female representation is due to a shift in overall staffing numbers. As detailed inlast year’s report, men remain in that majority among P-level positions with a representationof 61 per cent, while women make-up over 66 per cent of the G-level workforce. Womenoccupy of 2 out of the 7 high level (D+) positions.34

34

See Table 4

24

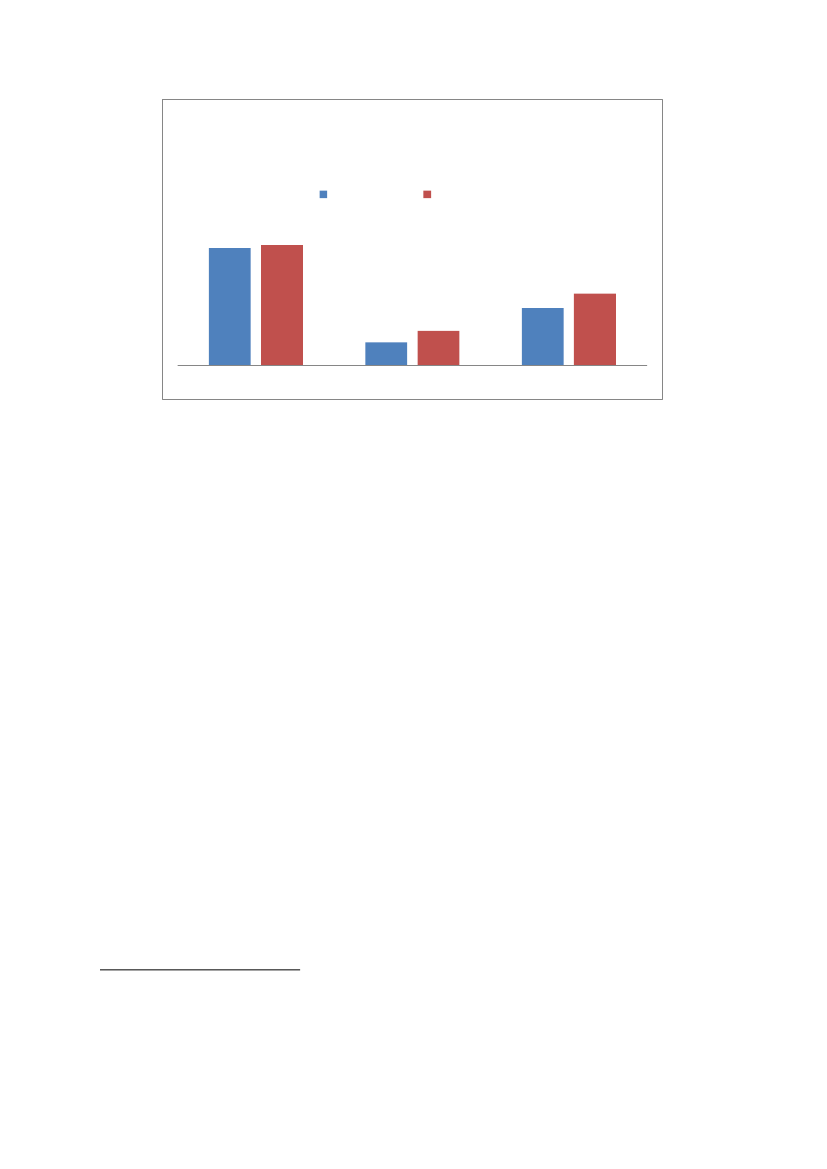

Post Distribution of the OSCESecretariat(%)Women65%35%39%29%Men71%61%

G

P+

D+

b. Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR)The Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) has seen a growth in jobswithin the past year resulting in the addition of 13 positions. The most significant shift inrepresentation is the number of seconded women within ODHIR which has jumped fromeight in 2010 to 12 in 2011. This has resulted in a two per cent reallocation in favour ofwomen.35

35

See Table 5

25

Post Distribution of Women inODIHR: Annual ComparisonWomen 20104142Women 2011

2520812

G1-G7

S

P1-P5

c. Office of the High Commissioner on National Minorities (HCNM)The Office of the High Commissioner on National Minorities has tipped the scales in favor ofthe overall percentage of women working within the commission. 63 per cent of theworkforce is represented by female employees. However, when breaking down the numbersby position, men continue to dominate the upper echelons of the P-level positions holding 13out of 17 positions. On the other hand, ten out of ten positions within the G-level pay-gradeare occupied by women. This further emphasizes the gender inequality among high-rankingpositions within HCNM and on a larger scale with in the OSCE in its entirety.36

d. Office of the Representative on Freedom of the MediaThe Office of the Representative on Freedom of the Media (ROFM) has been highlighted asthe most gender-aware Institution within the OSCE and the only Institution of the OSCEheaded by a woman. While relatively small with only 12 posts, two fewer than the previousyear, the majority of the posts are filled by women. However, the recent shift in the overallpercentage of female representation is slightly altered by the vacancy of two posts, which

36

See Table 6

26

brought the percentage up from 64 per cent to 75 per cent without actually increasing thenumber of women occupying posts within the ROFM.37

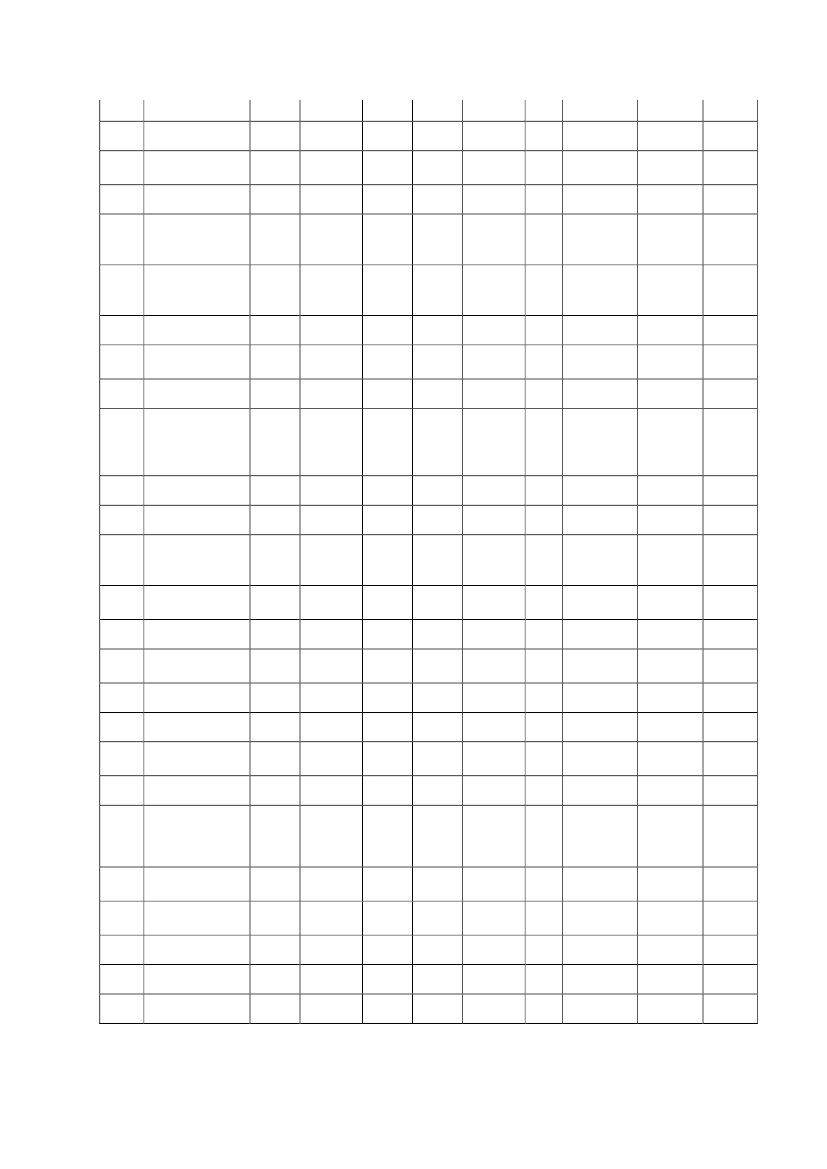

e. Seconded Posts in the Secretariat, Institutions and Field OperationsAs denoted in the Secretary General’s Annual Report, the seconded staff positions within theSecretariat and Institutions are not classified and therefore not included in the standardsystem of grading. In 2011, 455 staff members were seconded by 44 participating States ofthe OSCE. Azerbaijan and Switzerland are not currently sponsoring seconded positions andthus the number of participating States has dropped from last year’s 46 to 44.Surprisingly, when evaluating the gender balance of seconded positions by country, Denmarkfalls in the same category as Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Malta, the Republic of Moldova andSerbia with zero female representation among seconded staff. This is in stark contrast tocountries such as Finland, Latvia and Uzbekistan, whose representatives are entirely female.France, the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Czech Republic, Georgia, Portugal,Slovenia, Estonia, Belgium and Montenegro have an equal 50/50 gender representationamong seconded positions. The United States of America stretches the gender balance with52 per cent of its seconded positions occupied by women.Overall, there is a 42 per cent female representation within the seconded staff of the OSCE.This is an increase of three per cent from the previous reporting year. However, it is alsoimportant to note that there has been an overall decrease in seconded positions, the majorityof which have been from positions held by men. The results are a change in genderdistribution through a decrease in male representation by 18 posts; women gained 11positions with a total loss of seven positions.38

37

See Table 7See Table 8

38

27

d.

Field Operations: Gender Balance of Local Staff

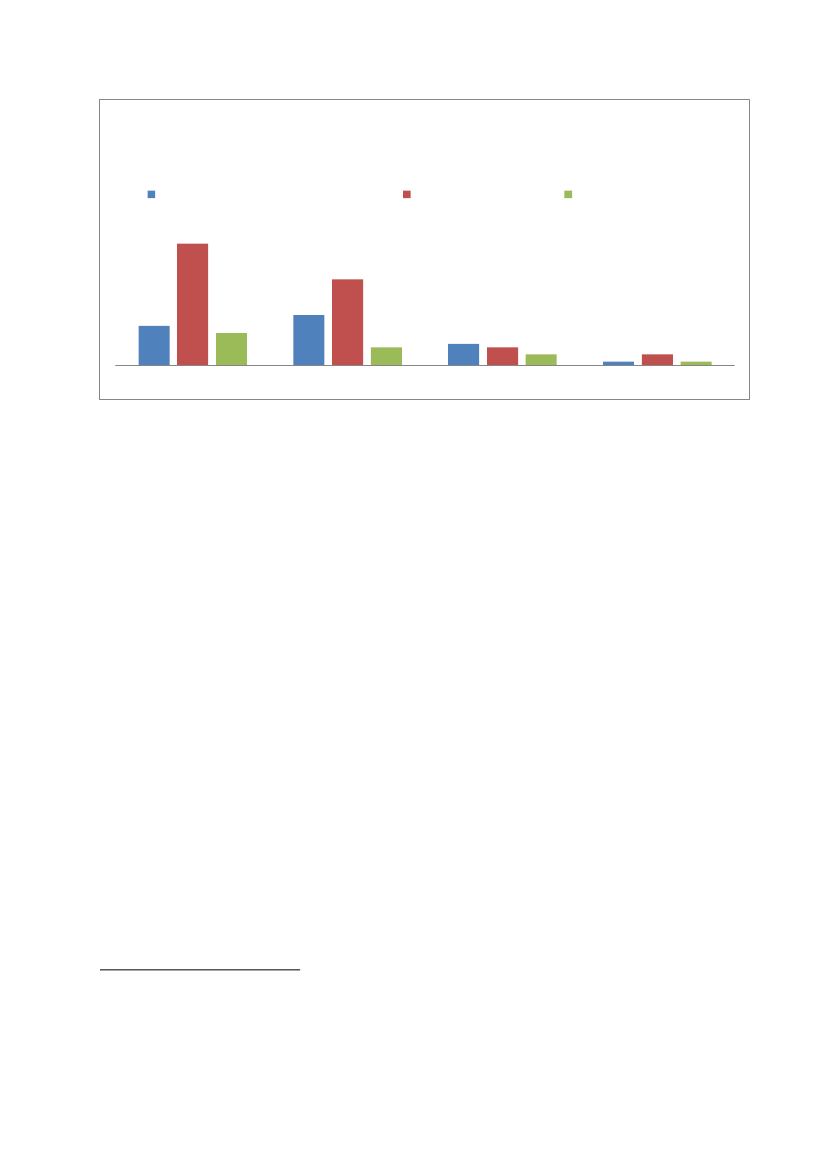

The number of locals staffing field operations varies according to the size of the operationand its mandate. The OSCE Mission to Kosovo continues to be the largest staffed fieldoperation within the OSCE with 474 local staff. Thirty per cent of the overall workforce ofthe OSCE Mission to Kosovo is female. This is the lowest percentage of local female staffwithin a field operation. The OSCE Mission to Bosnia and Herzegovina, the second largestfield operation with 432 local staff, 231 of which are women thus, occupying 53 per cent ofthe local staff positions within the mission.Overall, the field operations tend to be on an even keel with regards to gender distributionamong local staff. The OSCE Presence in Albania boasts a 51 per cent gender balance with atotal of 71 local positions whereas the OSCE Office in Zagreb and the OSCE Project Co-ordination in Uzbekistan maintain an equal 50/50 gender distribution.

Women in OSCE Field Operations and GeneralServices Staff in the OSCE Secretariatand Institutions 2011 (%)InstitutionsSecretariatPrs. Rpr. CiO Conflict dealt with by the Minsk ConferenceOffice in ZagrebOffice in YerevanProject Co-ordinator in UzbekistanProject Co-ordinator in UkraineMonitor Mission to SkopjeOffice in TajikistanMission to SerbiaMission to MontenegroMission to MoldovaMission in KosovoOSCE Mission to Bosnia and HerzegovinaOSCE Centre in BishkekOSCE Centre in BakuOSCE Centre in AstanaOSCE Centre in AshgabatOSCE Presence in Albania010203078.564.754.55064.15059.543.638.753.559.355.230.153.449.353.868.14750.74050607080

28

a.

Gender in OSCE Documents

Annually, the Secretary General of the OSCE presents the Evaluation Report on theImplementation of the 2004 OSCE Action Plan for the Promotion of Gender Equality. Thereports provided by the OSCE field operations in 2011 show that efforts continue to be takento mainstream gender perspectives in projects across all three dimensions. However, as inprevious years, the initiatives to integrate a gender perspective in projects were observedprimarily in the human dimension of the OSCE’s work. Nonetheless, a growing number offield operations have focused on integrating a gender perspective in the second and firstdimensions.Most of the results achieved in countries hosting field operations are linked to the adoption oflegislative frameworks on gender equality, implementation of existing frameworks,promotion of participation of women as candidates for elective office and support forprevention of violence against women.

IV.

Gender in the OSCE PA

During the Vilnius Annual Session 2009, the Standing Committee amended the OSCE PA’sRules of Procedure, agreeing to introduce a new sub-clause to Rule 1 stating that, “Eachnational Delegation should have both genders represented.”Over the past two years therehave been significant changes by States in efforts to meet this goal, though not all countriesare in compliance.

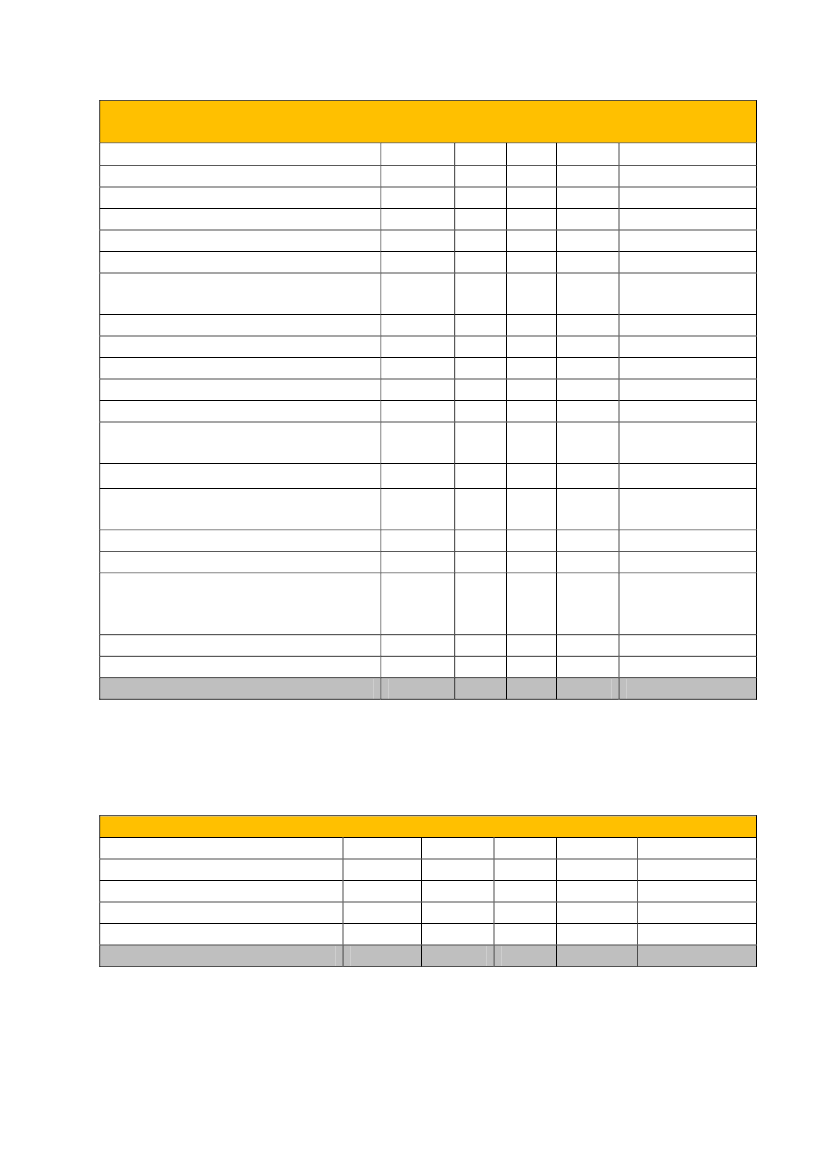

a.Member Directory Statistics39There is an overall male majority within the OSCE Parliamentary Assembly, with 222 menand 83 women. Women outnumber men, however, within the Secretaries and Staff sectors.Among the OSCE PA Secretaries of Delegations, 39 out of 71 are women; representing a 55

39

The OSCE PA Member Directory is available on request from the International Secretariat.

29

to 45 per cent gender distribution among Secretaries of the OSCE PA. Women also dominatethe staff sector, holding 13 out of 16 posts.40

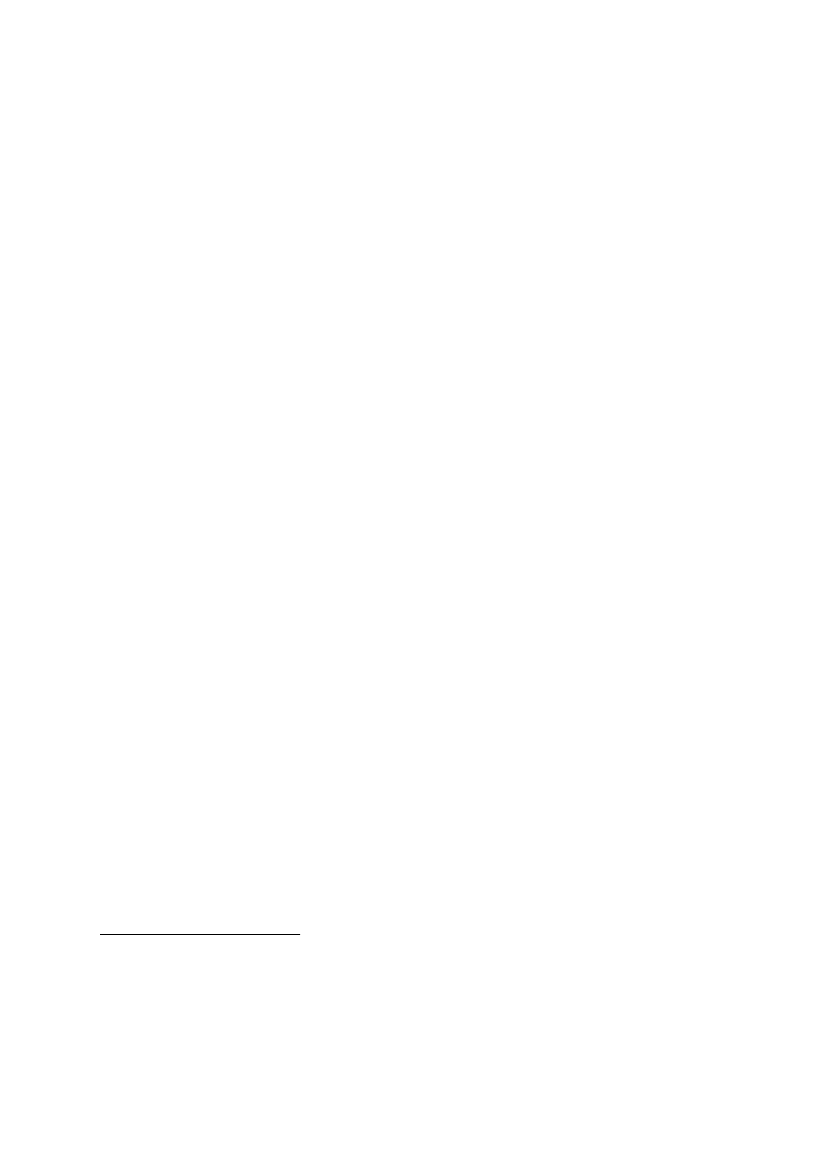

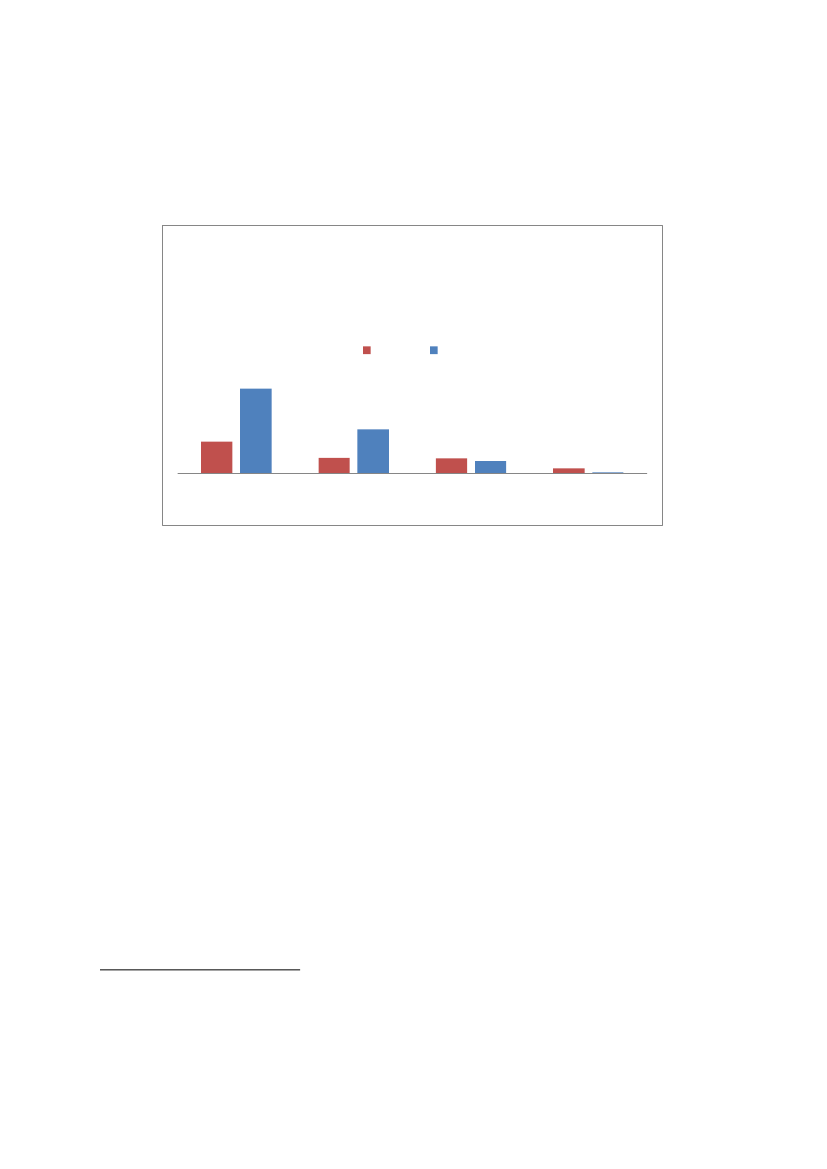

Gender Balance of the OSCEParliamentary Assembly as ofFebruary 2012Women222115413932133Men

83

OSCE PA Members OSCE PA Alternate OSCE PA Secretaries Staff of DelegationMem.

In contrast, the majority (73 per cent) of regular Members of the OSCE PA and 74 per cent ofAlternate Members are men, holding a combined number of 337 out of 460 positions. Thereis an encouraging improvement among women occupying regular Member positions, with anincrease from 75 positions to 83 delegates this year.

b. Initiative to Boost Women’s ParticipationEqual gender representation among national delegations has increased over the year. In 2011,15 OSCE PA delegations consisted exclusively of men. In 2012, 10 delegations are in thisposition.

40

See Table 10

30

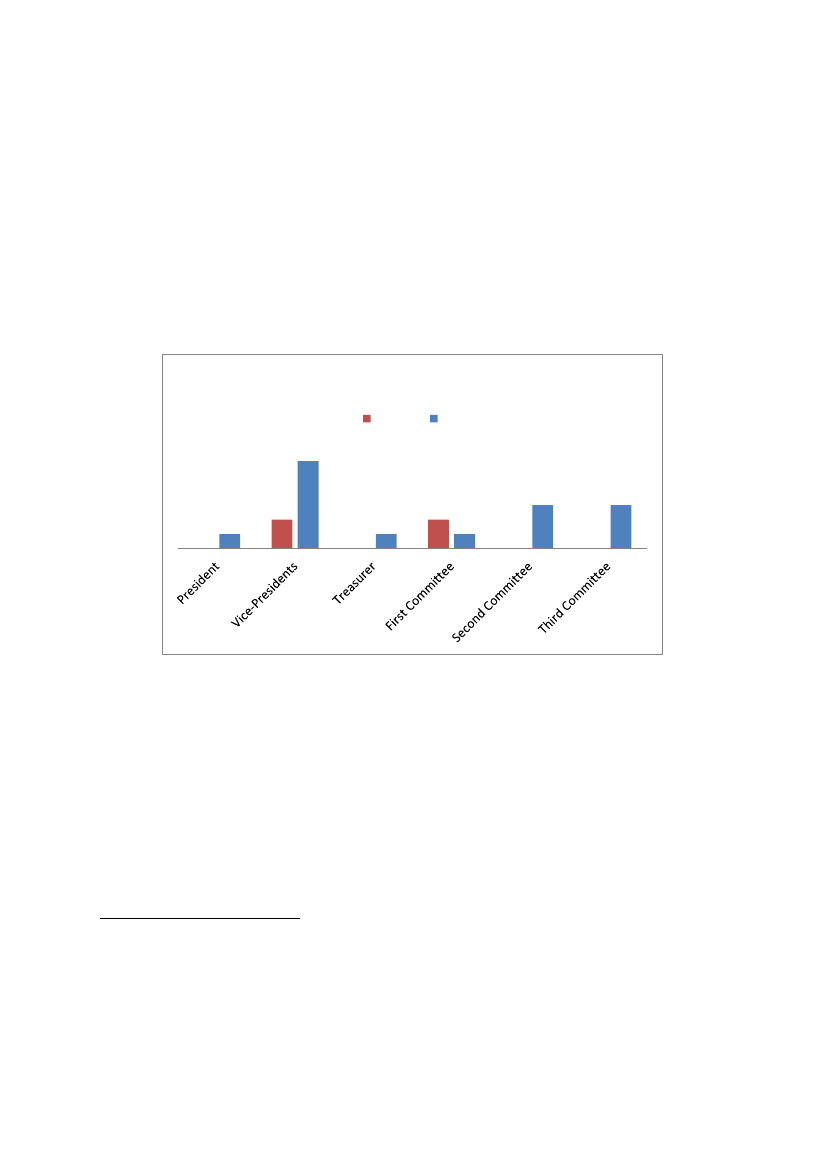

c. Gender in the Assembly BureauThe Bureau is composed of the President, nine Vice-Presidents, the Treasurer and thePresident Emeritus, as well as three Officers of each of the General Committees. The Bureauis currently comprised of 20 members— 4 of whom are female— providing for an 80 percent to 20 per cent ratio in favor of men. This falls short of the targeted goal of 30 per centestablished by the OSCE PA’s Special Representative on Gender Issues, Dr. Hedy Fry.41

Gender Balance of Bureau MembersWomen63211213Men

d. Female Presidents and Vice-Presidents in the OSCE PAThe statistics regarding female Presidents and Vice-Presidents remains unaltered from theprevious reporting year. There are currently two female Vice-Presidents, Isabel Pozuelo(Spain) and Walburga Habsburg Douglas (Sweden).42

41

See Address by Dr. Hedy Fry, Special Representative on Gender Issues to the OSCE ParliamentaryAssembly, 10thWinter Meeting, 24-25 February 2011. Vienna, Austria42

See Table 11

31

e. Officers of the OSCE PA General CommitteesThe overall gender balance of the General Committees has remained unchanged since 2011;there remain two women among seven men. In contrast to previous years, however, theGeneral Committee on Political Affairs and Security is comprised of two women, with afemale Vice-Chair and a female Rapporteur. Both the General Committee on EconomicAffairs, Science, Technology and Environment and the General Committee on Democracy,Human Rights and Humanitarian Questions are entirely male.

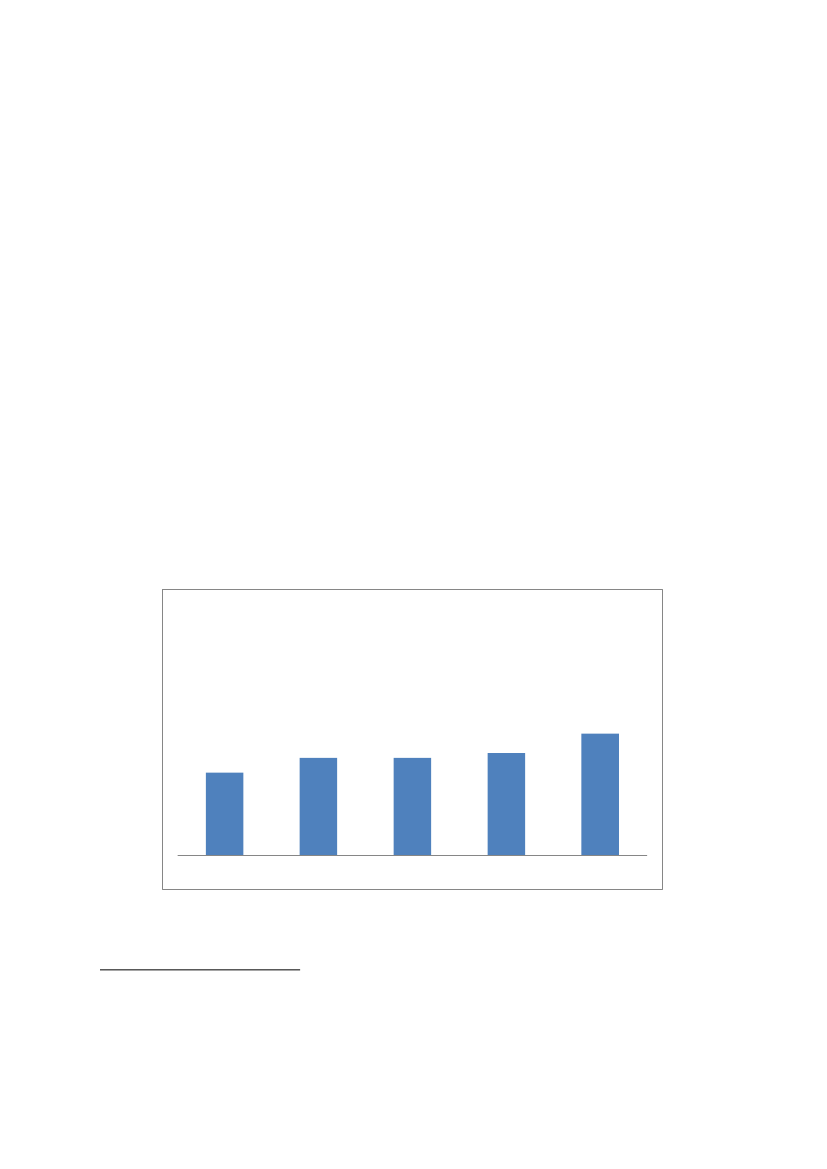

f. Participation in OSCE PA MeetingsThe following charts show the general attendance at the OSCE PA’s Meetings and thepercentage of female Members of Parliament who participated.The 2011 Annual Session observed an increase in female participation by four per cent fromthe previous year. As demonstrated by the figures below, there is an encouraging rise infemale participation. The numbers have leaped from 17 per cent in 2007 to 25 per cent in2011.43

Female Parliamentarian Participationin OSCE PAAnnual Session (%)25%20%17%20%21%

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

43

See Table 12

32

The overall percentage of female participation remains at 25 per cent.participants in nine years.45

44

This indicates a

slowing of momentum, as last year’s Winter Meeting boasted the highest number of female

Female Parliamentarian Participationin the OSCE PAWinter Meeting (%)25%22%21%20%22%25%

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

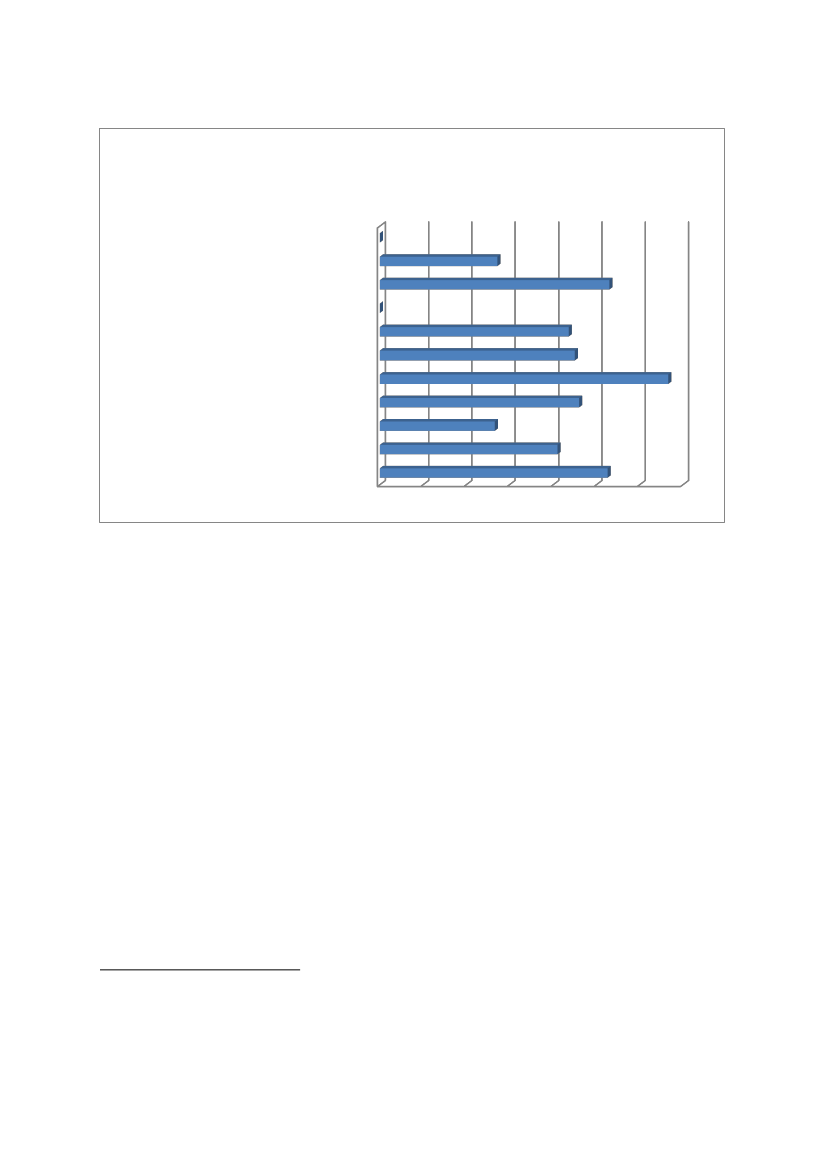

g. Participation in OSCE PA Election Monitoring 2010-2012The graph below shows the Assembly’s female Members’ participation in electionobservations missions over the 2011-2012 period:

44

See Table 13See OSCE PA Gender Balance Report; July 2011

45

33

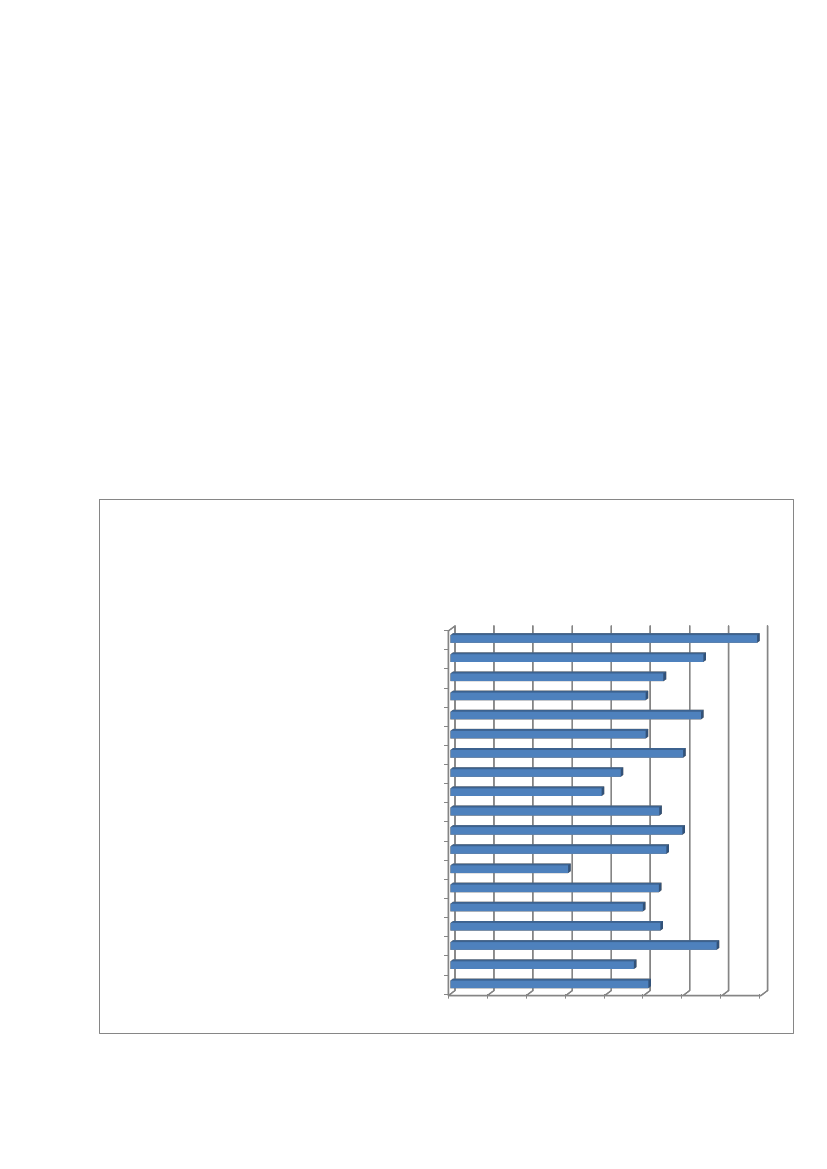

Female Delegate Participation in ElectionMonitoring 2011-2012 (%)Serbia 16 May 2012(2nd round)Serbia 6 May 2012(1st round)Armenia 6 May 2012Russian Federation 4 March 2012Kazakhstan 12 January 2012Russian Federation 4 December 2011Kyrgyzstan 30 October 2011Tunisia 23 October 2011Turkey 12 June 2011The former Yugoslav Republic of Macadonia 5 June 2011Kazakhstan 3 April 2011

0.0%13.6%26.5%0.0%21.8%22.5%33.3%23.0%13.3%20.5%26.3%5.0% 10.0% 15.0% 20.0% 25.0% 30.0% 35.0%

0.0%46

The figures concerning female participation in OSCE PA election monitoring show that overthe 2011-2012 period the highest number of female participants occurred within CentralAsian elections—Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. Out of the 11 observations listed, 2 were ledby female Heads of Delegations, Turkey and Kyrgyzstan. The calculations exclude Staff ofDelegation and Secretariat personnel thus, diminishing the female participation levels inSerbia and Russia to zero. The average for the period is 20 per cent.Interesting to note that in recent EOMs, there have been more women participating inelection monitoring than in the OSCE PA meetings.

h. Permanent Staff of the OSCE PA International SecretariatThe permanent staff of the OSCE PA International Secretariat, including the Vienna LiaisonOffice, is comprised of 18 individuals of whom 8 are women. The two appointed Deputy

46

Calculations for female participation were done excluding staff of delegations.

34

Secretaries General represent an equal gender balance with one women and one man. Thecurrent office of the OSCE PA Secretary General is held by a man.

i. The International Research Fellowship ProgrammeThe International Secretariat of the OSCE Parliamentary Assembly has a ResearchFellowship Programme in which it engages graduate students for a period of six-months eachto gain practical experience in the field of international affairs.There are currently five research fellows working at the International Secretariat inCopenhagen, and three in the Vienna Liaison Office— four women and four men— showingan equal gender distribution among the research fellows.

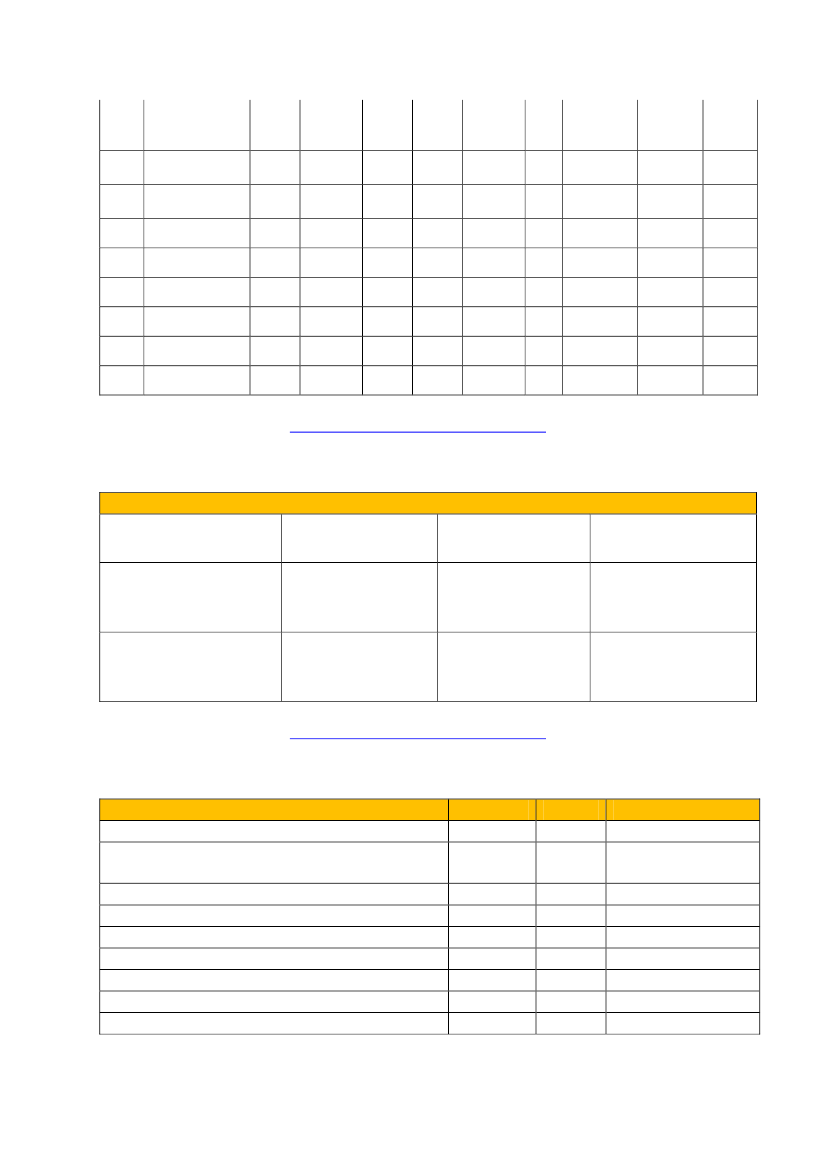

j. Female Representation in National Parliaments of OSCE CountriesWithin the OSCE participating States, those with the least amount of female representationwithin national parliaments are Georgia with only 6.6 per cent of female representationwithin the “Lower or single House”, as well as Ukraine, Armenia, Malta, and Hungary whichmaintain a ratio of between 8.0-8.80 per cent.47It is important to note that the results of the 6May elections in Armenia brought about an increase in female representation by two per centfrom previous years. This amounts to a total female representation of 10.69 per cent.Collectively, female representation among national Parliaments within the OSCE region is22.4 per cent, combining Upper House or Senate and Single or Lower Houseparliamentarians. This is higher than the national average in Europe.48

47

See Table 14See Table 15

48

35

V.

Annexes

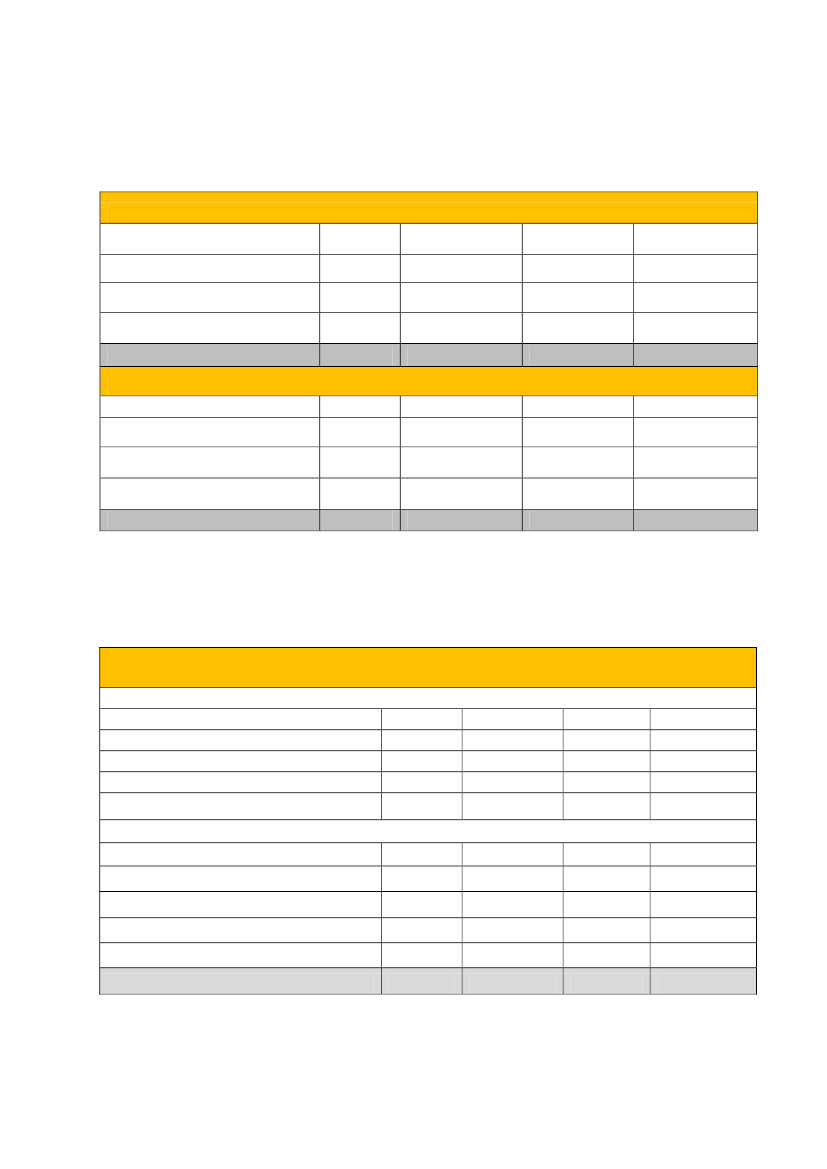

Table 1

Post Distribution of Staff in the OSCE 2011CategoryGeneral Service StaffProfessional StaffManagementTotalCategoryGeneral Service StaffProfessional StaffManagementTotalMen8434701031416Women740436461222Total15839061492638Total16269191492694% Women47%48%31%46%% Women46%46%30%45%

Post Distribution of Staff in the OSCE 2010MenWomen8745001051477754419441217

Note: figures as of May 2011 and May 2010 respectivelyTable 2

Post Distribution of the OSCE Staff, in OSCE Secretariat, Institutions and field operations 2011Secretariat and Institutions StaffCategoryMenWomenTotal% WomenGeneral Service Staff8117625768%Professional Staff13010123144%Higher Management23153839%TotalCategoryGeneral Service StaffProfessional StaffHigher ManagementTotalGrand TotalNote: figures as of 1 May 201136234292Field Operations StaffMenWomen7623408011821416564335319301222526Total13266751112112263856%% Women43%50%28%44%46%

Table 3Post Distribution of Seconded Staff in the OSCE Field Operations 2011CategoryS1S2OSCE Mission to Bosnia and Herzegovina1114OSCE Mission to Kosovo3424OSCE Mission to Skopje95Grand Total5443Note: figures as of 1 May 2011Table 4Post Distribution in the OSCE Secretariat 2011S inG in %S% P1-P5D1 D2 SG65% 15 38%4702035% 24 62%72131100% 39 100%119151

S365314

S41315

CategoryWomenMenTotal

G1-G712166187

P+in%39%61%100%

Total185167352

Totalin %53%47%100%

Note: figures as of 1 May 2011Table 5Post Distribution in the Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights 2010HeadG1-ofCategoryG7 G in % S S in % P1-P5D1 D2Inst. P+ in% TotalWomen4172% 889%2000038%69Men1628% 111%3110162%50Total57100% 9 100%51101100%119Post Distribution on the Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights 2011HeadG1-ofG7 G in % S S in % P1-P5D1 D2Inst. P+ in%TotalCategoryWomen4274% 1286%2500041%79Men1526% 214%3410159%53Total57100% 14 100%59101100%132Note: figures as of 1 May 2010 and 1 May 2011 respectivelyTable 637

Totalin %58%42%100%

Totalin %60%40%100%

Post Distribution in the Office of the High Commissioner on National Minorities 2011HeadofTotalCategory G1-G7 G in % S S in % P1-P5 D1 D2Inst. P+ in% Total in %Women10100% 480%410033%19 63%Men00% 120%1300167%11 37%Total10100% 5100%17101100%30 100%Note: figures as of 1 May 2011Table 7Post Distribution in the Office of the Representative on Freedom of the Media 2011HeadofTotalS S in % P1-P5 D1 D2Inst. P+ in%Totalin %CategoryG1-G7 G in %Women3100% 267%300167%9 75%Men00% 133%200033%3 25%Total3100% 3100%5001100%12 100%Note: figures as of 1 May 2011

Table 8Seconded Staff in the OSCE Secretariat, Institutions and Field Operations by Seconding Countryand Sex 2011Total Seconded%Seconded AuthorityStaffWomenMenWomenUnited State of America52%283058Italy47%201838Spain65%91726Germany38%231437France50%111122Austria33%16824Canada64%4711United Kingdom32%1572238

PolandSwedenCroatiaBulgariaGreeceIrelandMacedonia, former Yugoslav Republic ofCzech RepublicGeorgiaPortugalSloveniaBosnia and HerzegovinaNetherlandsHungaryTurkeyFinlandLatviaArmeniaEstoniaRomaniaSlovakiaNorwayRussian FederationUzbekistanBelgiumMontenegroBelarusLithuaniaAzerbaijanDenmarkKazakhstanKyrgyzstanMaltaMoldova, Republic ofSerbiaSwitzerlandTajikistanUkraineGrand TotalNote: figures as of 1 May 2011Table 939

60%38%63%42%44%33%50%50%50%50%50%30%30%25%14%100%100%67%50%40%33%22%18%100%50%50%25%20%0%0%0%0%0%0%0%0%0%0%42%

4103758333337791800123479011340211131011265

66554433333333322222222111110000000000190

10168129126666610101221223456911122450211131011455

Gender Balance of Local Staff in OSCE field operations and General Services Staff in the OSCESecretariat and Institutions 2011Field OperationWomen In % MenIn %TotalOSCE Presence in Albania36 51%3549%71OSCE Centre in Ashgabat8 47%953%17OSCE Centre in Astana15 68%732%22OSCE Centre in Baku14 54%1246%26OSCE Centre in Bishkek36 49%3751%73OSCE Mission to Bosnia andHerzegovina231 53% 20147%432OSCE Mission in Kosovo143 30% 33170%474OSCE Mission to Moldova21 55%1745%38OSCE Mission to Montenegro19 59%1341%32OSCE Mission to Serbia68 54%5946%127OSCE Office in Tajikistan48 39%7661%124OSCE Spillover Monitor Mission toSkopje52 44%6756%119OSCE Project Co-ordinator in Ukraine25 60%1740%42OSCEProjectCo-ordinatorinUzbekistan9 50%950%18OSCE Office in Yerevan25 64%1436%39OSCE Office in Zagreb8 50%850%16Personal Repr. Of the CiO on theConflict dealt with by the MinskConference6 55%545%11Secretariat121 65%6635%187Institutions55 79%1521%70Grand Total940 49% 99851%1938Note: figures as of 1 May 2011Table 10OSCE Parliamentary Assembly as of February 2012CategoryWomenIn %MenIn %OSCE PA Members8327%22273%OSCE PA Alternate Members4126%11574%OSCE PA Secretaries3955%3245%OSCE PA Staff1381%319%Grand Total17632%37268%

Total3051567116548

Note: figures as of February 2012, representatives of the Holy See not included in the figures40

Table 11Gender Balance of Bureau MembersWomenMen12612133415

CategoryPresidentVice-PresidentsTreasurerFirst CommitteeSecond CommitteeThird CommitteeGrand TotalNote: figures as of May 2012

Total18133319

Table 12Parliamentarian Participation in the OSCE PA Annual Session20072008200920104145435020018217018617202021241227213236

CategoryWomenMen% WomenGrand Total

20115516925224

Note: figures were calculated using only Members and Alternate members of countrydelegations, Staff of Delegations and the OSCE PA Staff, along with the OSCE Secretariat,Observers, Guests, International Parliamentary Organizations and Partners for Co-operation were excluded from these calculations

Table 13Parliamentarian Participation in the OSCE PA Winter Meeting200720082009201020115143484958180164192174172222120222523120724022323041

CategoryWomenMen% WomenGrand Total

20126018025240

Note: figures were calculated using only Members and Alternate members of countrydelegations, Staff of Delegations and the OSCE PA Staff, along with the OSCE Secretariat,Observers, Guests, International Parliamentary Organizations and Partners for Co-operation were excluded from these calculationsTable 14Women in Parliament in OSCE countriesLower or singleUpper House orHouseSenateSeats

Women

141568561256770571262042935

CountryAndorraSwedenFinlandNetherlandsIcelandNorwayDenmarkBelgiumSpainGermanySloveniaBelarusThe F.Y.R. ofMacedoniaPortugalSwitzerlandAustriaLuxembourgCanadaKazakhstanLiechtensteinCroatia

%

50.00%44.70%42.50%40.70%39.70%39.60%39.10%38.00%36.00%32.90%32.20%31.80%30.90%28.70%28.50%27.90%25.00%24.70%24.30%24.00%23.80Seats

---------5 20---------6 2011 2N.A.11 27 20Women

---------75---------71263694058%

---------27---------298819119Women OSCE PADelegate Members%Members Women

28683668101326366557623252302451504123411111100%62%33%37%0%33%67%62%10%38%0%67%33%33%50%80%20%14%7%50%33%

2468101113161821"24

283492001506316917915035062090110

26

123

38

---

---

---

283031""434546

2302001836030810725151

665751157626636

---10 2N.A.---N.A.8 20------

---4661---10347------

---919---392------

42

%474950"PolandKyrgyzstanLatviaUnitedKingdomCzechRepublicSerbiaUzbekistanItalyBosniaandHerzegovinaBulgariaEstoniaRepublicMoldovaLithuaniaMonacoTajikistanFranceGreeceSan MarinoSlovakiaof460120100650109282314523.70%23.30%23.00%22.30%22.00%22.00%22.00%21.60%21.40%20.80%19.80%19.80%19.10%19.00%19.00%18.90%18.70%18.30%17.30%16.90%16.00%16.80%15.70%15.10%14.20%10 2------N.A.100------82713------181

83313740133533333136231630368

2013030105111100101220221

25%0%33%23%0%75%0%8%0%100%33%33%33%33%0%0%17%0%33%12%67%0%67%33%12%

56""57

200250150630

445533136

10 2---1 204 20

81---100321

15---1561

59

42

9

6 20

15

2

6164"6768"69717276

240101101141216357730060150

50202027412109561126

---------------3 209 20---------

---------------34347---------

---------------577---------

78

UnitedStatesofAmericaAzerbaijanTurkmenistan

432

73

11 2

100

17

81798386"

125125140166550

2021222578

---------4 20---

---------60---

---------18---

AlbaniaIrelandTurkey

43

9299104108116"120"128

RussianFederationMontenegroRomaniaCyprusHungaryMaltaArmeniaUkraineGeorgia

450813305638669131450137

611037634611369

13.60%12.30%11.20%10.70%8.80%8.70%8.40%8.00%6.60%

N.A.---11 2------------------

169---136------------------

8---8------------------

1437363383

202010000

14%0%29%0%17%0%0%0%0%

Note: figures obtained fromhttp://www.ipu.org/wmn-e/classif.htm(accessed5 May 2012)Table 15Women in Parliament in OSCE CountriesSingle House orUpper House orlower HouseSenate22.70%21.10%

CategoryEurope - OSCE membercountriesincludingNordic countriesEurope - OSCE membercountriesexcludingNordic countries

Both Housescombined22.40%

20.90%

21.10%

20.90%

Note: figures obtained fromhttp://www.ipu.org/wmn-e/classif.htm(accessed5 May 2012)Table 16OSCE PA Election Monitoring 2010-2012Kazakhstan 3 April 2011Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia 5 June2011Turkey 12 June 2011Tunisia 23 October 2011Kyrgyzstan 30 October 2011Russian Federation 4 December 2011Kazakhstan 12 January 2012Russia 4 March 2012Armenia 6 May 201244MPs Women % of women571526.3%3430652171325497415716701320.5%13.3%23.0%33.3%22.5%21.8%0.0%26.5%

Serbia 6 May 2012(1st round)Serbia 16 May 2012(2nd round)Note: figures as of 21 May 2012Image on cover page courtesy of Shutterstock

225

30

13.6%0.0%

45