Miljøudvalget 2011-12

MIU Alm.del Bilag 349

Offentligt

United Nations Development Programme

CASE STUDIES OFS U S TA I N A B L E D E V E LO P M E N T I N P R AC T I C E

TRIPLE WINS FORSUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT

United Nations Development Programme

C A S E S T U D I E S O F S U S TA I N A B L E D E V E LO P M E N T I N P R AC T I C E

TRIPLE WINS FORSUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT

United Nations Development ProgrammeMarch 2012Copyright � 2012 United Nations Development Programme. All rights reserved.This publication or parts of it may not be reproduced, stored by means of any system or transmitted,in any form or by any medium, whether electronic, mechanical, photocopied, recorded or of any othertype, without the prior permission of the United Nations Development Programme. The views andrecommendations expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily representthose of UNDP, the United Nations or its Member States.

Design and production:Kimberly Koserowski, First Kiss Creative LLC

Table of ContentsFOREWORD..................................................................................................................................................................................3INTRODUCTION: THE THREE STRANDS OF SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT..............................................4SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT SINCE 1990: WHERE ARE WE NOW?...............................................................6WHAT HAS WORKED?.............................................................................................................................................................8WHAT NEEDS TO BE DONE?................................................................................................................................................9THINGS CAN BE DIFFERENT............................................................................................................................................. 11RESETTING THE AGENDA: WHAT IS NEEDED?......................................................................................................... 13From Millennium Development Goals to Sustainable Development Goals................................................ 13Green is not enough: ‘triple-win’ development is the future ............................................................................ 14Better governance and capacity development matter ....................................................................................... 16Revisiting finance for sustainable development ................................................................................................... 20Beyond GDP and the bottom line: new metrics for sustainable development .......................................... 21Leveraging knowledge and innovation to deliver results.................................................................................. 23WHAT DO UNDP AND THE UN BRING TO THE TABLE?......................................................................................... 24WHY RIO+20 CAN MAKE A DIFFERENCE.................................................................................................................... 26CASE STUDIES OF SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT IN PRACTICE................................................................... 27Brazil: making sustainable development happen................................................................................................. 28Croatia: energy efficiency............................................................................................................................................... 36Nepal: decentralized renewables ................................................................................................................................ 39Mongolia: inclusive finance for sustainable development ................................................................................ 43Namibia: community-based resource management ........................................................................................... 46Niger: reforesting the Sahel through ‘farmer-managed natural regeneration’........................................... 48South Africa: ‘Working for water’ ................................................................................................................................. 51Bhutan: sustainable development .............................................................................................................................. 53REFERENCES............................................................................................................................................................................. 55

Triple wins for sustainable development

1

2

Triple wins for sustainable development

ForewordSustainable development is synonymous in the minds of many with the colourgreen—and for good reason. Twenty years ago at the firstEarth Summitin Rio deJaneiro, leaders set out what today is conventional wisdom: human progress—bothsocial and economic—cannot be divorced from environmental protection. Unlessboth are advanced together, both will flounder or fail.Green is not enough. Sustainable development is about health, education, and jobs,as much as ecosystems. It is about ever widening inclusion and movement awayfrom decisions that erode democratic space and do not address social inequality,intolerance, and violence. Sustainable development is about change that transformsimpoverished peoples, communities, and countries into informed, educated, healthy and productive societies.It is about wealth creation that generates equality and opportunity; it is about consumption and productionpatterns that respect planetary boundaries; it is about increasing tolerance and respect for human rights.Building on the human development legacy that originated with Amartya Sen and Mahbub Ul Haq and wascaptured by the firstHuman Development Reportin 1990, UNDP has long promoted alternative approaches tomeasuring human progress, including with the Human Development Index. Today, we are building on this legacyby exploring how to adjust the index to reflect environmental sustainability, so that governments and citizensmight better track real progress towards truly sustainable development. This must be our collective objective.As countries prepare for the ‘Rio+20’United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development,UNDPis pleased to share this report. After suggesting what it takes to move towards sustainable development, thereport sets out national examples of progress toward sustainable development, from developing countries likeNepal and Niger, as well as emerging economies like South Africa and Croatia. These examples show how social,environmental, and economic progress can be integrated to make a more sustainable future. They illustrate whatthe future of development programming should look like.Instead of focusing on the tradeoffs between the three strands of development, this report highlights the rangeand significance of the complementarities between them. It describes ‘triple-win’ development policies andprogramming that regenerates the global commons by integrating social development with economic growthand environmental sustainability.UNDP invites policy-makers and practitioners preparing for ‘Rio+20’ to consider this report as a contribution tothe debate on how to make sustainable development happen.As is our underlying mission, UNDP will continue to support countries in translating the principles of sustainabledevelopment into practice in the 177 countries and territories in which we work—empowering lives andadvancing resilient nations—and to share their experiences for the benefit of others.

Olav KjørvenAssistant Administrator and Director, UNDP Bureau for Development PolicyMarch 2012

Foreword

3

Introduction:the three strands ofsustainable development“We all aspire to reach better living conditions. Yet, this will not be possibleby following the current growth model . . . We need a practical twenty-firstcentury development model that connects the dots between the key issuesof our time: poverty reduction; job generation; inequality; climate change;environmental stress; water, energy and food security.”UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moonDevelopment is not just about growth. Likewise, sustainability is not just about protecting the environment. Bothdevelopment and sustainability are primarily about people living in peace with each other and in equilibrium withthe planet. Their rights, opportunities, choices, dignity and values are (or should be) at the centre of everything.Sustainable development is about meeting the needs of people today without compromising the abilityof future generations to meet their needs. Inter-generational equity—avoiding the unjustified transferof development risks from present to future generations, without sacrificing reductions in poverty andinequality today at the altar of future environmental concerns—is implicit in this approach to development.Current patterns of consumption and production risk breaching planetary boundaries. If the natural environmentundergoes significant degradation, so too does the potential to improve people’s lives—both in this andsubsequent generations. This is especially true for the world’s poorest—most of whom rely directly upon naturefor their livelihoods, and whose prospects are therefore most directly affected by the threats to ecosystems.Unless issues of equity and sustainability are properly addressed, current development trajectories could grindto a halt, or even go into reverse. Avoiding such outcomes will be the great challenge of the 21st century.The report suggests six key principles that are needed to reset the global development agenda. It thenuses country case studies that describe policy measures, programmes, and efforts that can support amore robust and sustainable human development model. This method is used to illustrate examplesof enlarging people’s freedoms and opportunities that can be achieved while safeguarding the naturalenvironment for future generations. It also suggests that sustainable development requires that itseconomic, social, and environmental ‘pillars’ be thought of as synergistic and integrated ‘strands’ that lendthemselves to inter-weaving and linkages.This publication is devoted to development policy and practice as the art and craft of weaving these strandstogether in order to make sustainable development real. It looks at the ‘how’ of sustainable development. Itconsiders what can happen whengreen growth—thenexus of the ‘economic’ and ‘environmental’ strandsof sustainable development—is combined withinclusive growth—thenexus of the ‘economic’ and ‘social’strands. In this way, the report provides concrete examples of policies, programmes, and projects from

4

Triple wins for sustainable development

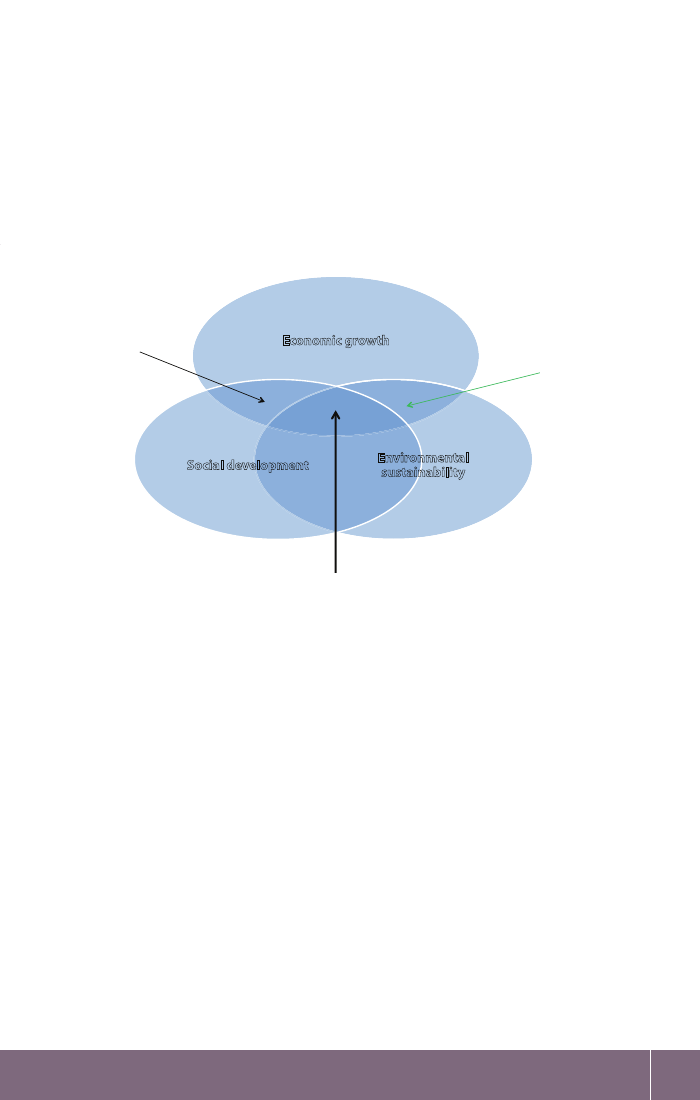

different countries and across different sectors that are helping to restore the global environmental commonswhile also providing employment, energy, and other basic services to vulnerable people whose legitimatedevelopment aspirations must not go unmet.Without denying their existence or importance, this publication does not focus on the trade-offs betweeneconomic, environmental, and social development objectives. It emphasizes instead ‘triple wins’ that expandthe sustainable development ‘sweet spot’ where its strands intertwine (Figure 1). The more we gear policytowards that intersection the more it expands, and the less daunting the trade-offs become.

Figure 1—The sustainable development “sweet spot”wth”ro

“Gr

siveg

Economic growth

een

“Inclu

economy”

Social development

Environmentalsustainability

“Sweet spot”: Outcomes that strengthen all three sustainable development strands

This report complements UNDP’s 2011‘Sustainabilityand Equity: A Better Future for All’Human DevelopmentReport,which provides an analytical tour de force of the links between sustainable development, povertyreduction, and equality; andUNDP’s official submission to the Rio conference,which focuses on key issues inthe inter-state negotiations.

Triple wins for sustainable development

5

Sustainable development since1990: where are we now?

In 1992, world leaders gathered for the first Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro and agreed on the ‘Rioprinciples‘which recognized the importance of integration across the environmental, social, and economic strandsof sustainable development. However, the modern day story of sustainable development started inearnest two years earlier.“People are the wealth of nations”—so began UNDP’s first Human Development Report in 1990. This wasa groundbreaking step. The concept of human development was born, defined as a process of enlargingpeople’s choices to lead lives they value. The 1990 Human Development Report also launched theHumanDevelopment Index.Designed to move beyond the traditional GDP measure to assess the state of humanwell-being, the Human Development Index incorporated indicators for a long and healthy life, knowledge,and a decent standard of living.Ten years later in 2000, building on a decade of major United Nations conferences and summits, worldleaders adopted the United Nations Millennium Declaration, committing their countries to a new globalpartnership to reduce extreme poverty. The Millennium Declaration made possible the design andimplementation of the eightMillennium Development Goals(MDGs)—a series of time-bound goals (withquantified targets and indicators) for reducing extreme poverty, with a deadline of 2015.

Box 1: Progress towards achieving the MillenniumDevelopment Goals (MDGs)••The world as a whole is on track to reach MDG1 (the target for cutting extreme poverty in half ).By 2015, the global poverty rate should fall below 15 percent—well under the 23 percent target.Some of the poorest countries have made the greatest strides in education (MDG2). Forexample, Burundi, Rwanda, Samoa, Sao Tome and Principe, Togo, and Tanzania have achievedor are nearing the goal of universal primary education.The number of deaths of children under the age of five declined from 12.4 million in 1990 to 8.1million in 2009 (MDG4). This means nearly 12,000 fewer children die each day.Increased funding and more intensive control efforts have cut deaths from malaria by 20percent worldwide (MDG6), from nearly 985,000 in 2000 to 781,000 in 2009.New HIV infections have declined steadily (MDG6). In 2009, some 2.6 million people were newlyinfected—a 21 percent drop since 1997, when new infections peaked.The numbers of people receiving antiretroviral therapy for HIV or AIDS increased 13-fold from2004 to 2009 (MDG6), thanks to increased funding and expanded programmes.Some 1.1 billion people in urban areas and 723 million people in rural areas gained access toimproved drinking water sources during 1990-2008 (MDG7).

•••••

Source:‘Major progress towards Millennium Development Goals,but the most vulnerable are left behind, UN reportsays’, UN Department of Public Information, July 2011

6

Triple wins for sustainable development

Considered together, the Earth Summit’s sustainable development principles, the definition andmeasurement of human development, the Millennium Declaration, and the Millennium DevelopmentGoals—these constitute significant progress towards a holistical approach to development, and tomeasuring progress toward that end.Significant progress towards sustainable development has certainly been made in the last two decades.Despite this, programmes and policies that focus on the ‘triple-win’ space are not yet standard practice,not yet the habit of policy-making.

Triple wins for sustainable development

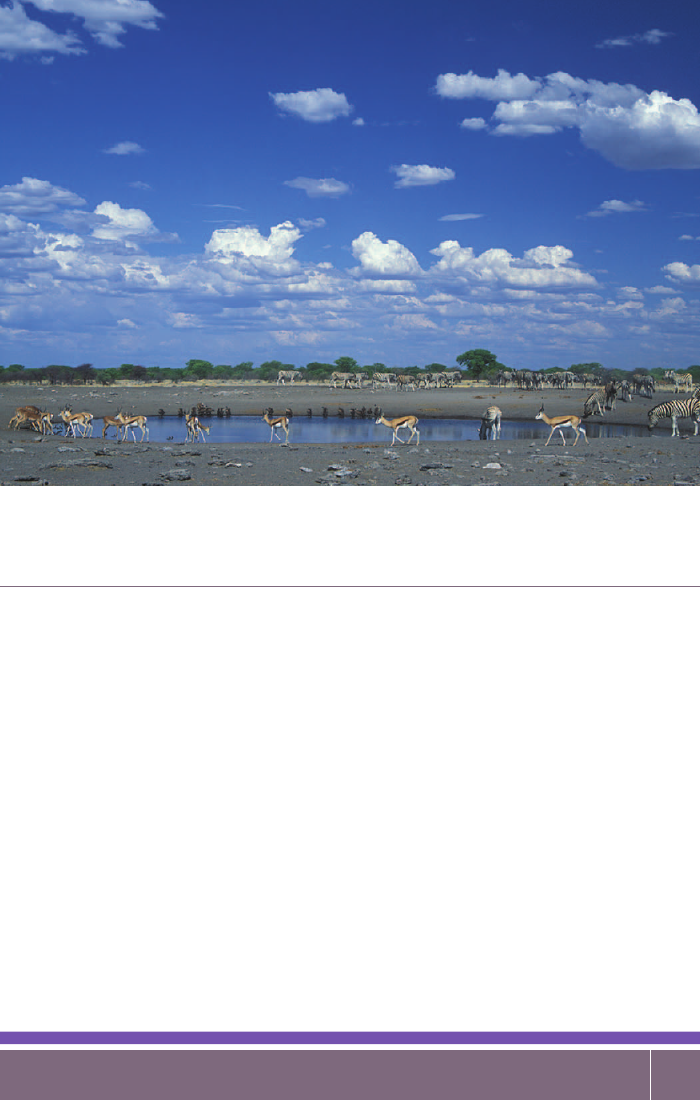

7

What has worked?Trends over the past 40 years document significant improvements in human development, especiallyamongst the poorest countries (Box 1, page 6). Countries in the lowest 25 percent of the humandevelopment index rankings improved their overall HDI by 82 percent over the period—twice the globalaverage. Since 1990 (the baseline against which progress toward attaining the Millennium DevelopmentGoals is measured), hundreds of millions of people have been lifted out of poverty. The world is withinreach of seeing every child enrolled in primary school. Fewer lives are being lost to hunger and disease.The world overall is healthier, wealthier, and better educated than ever before.Progress has likewise been made in repairing the ozone layer (Box 2 below), in reducing pollution inmajorriver basins,in reducing technical losses in the use of energy, water, and other natural resources,in expanding the land and coastal regions covered by protected areas, and in extending basic services.

Box 2:Repairing the ozone layerDepletion of the atmosphere’s protective ozone layer was a key global environmental concern in thelate 1980s, following the discovery of a major ozone ‘hole’ over the Antarctic. The Earth was thoughtto have been on track to lose two thirds of its ozone layer by 2065, leading to dramatic increases inskin cancer. But thanks to theMontreal Protocolto the Vienna Convention for the Protection of theOzone Layer (which entered into force in 1989), global chlorofluorocarbon production was completelyphased out by 1996. Since then, the ozone layer has begun to recover; Antarctic ozone is expected toreturn to pre-1980 levels sometime between 2060 and 2075.Adapted fromResilient People, Resilient Planet(2012), report of Secretary General’s High Level Global SustainabilityPanel

The work of global institutions and treaties whose roots can be traced to Rio 20 years ago—theGlobalEnvironment Facility,the global conventions onclimate change, biodiversity,anddesertification—havemade concrete improvements in environmental quality for people all over the world. These conventionshave made possible the mobilization of billions of dollars for investments in the global environmentalcommons. The ‘think globally, act locally’ slogan, which was popularized at Rio, has taught us the importanceof civil society and community empowerment. Growing numbers of banks and corporations issue annualsustainability reports, showing how ecological concerns have become part of ‘business as usual’.

8

Triple wins for sustainable development

What needs to be done?As important as this progress has been, trends of the past 20 years show that, in many respects,development has not been sustainable—either environmentally or socially.Growth in global output (from US$11 to US$63 trillion, according toIMF data)and population (from 4.6to seven billion people) have placed new demands on the planet—particularly the global commons, themanagement of which can not be left to the invisible hand of the market. The atmosphere’s ability to absorbgreenhouse gases (without significant temperature increases), the oceans’ abilities to generate bionutrients,the world’s forest cover, the earth’s soil nutrients—these are among the common property resources thatare increasingly overtaxed by the march of progress. Local communities—particularly in coastal areas andarid regions—are facing growing threats from floods, droughts and increasing competition for dwindlingresources. Relative prices of food, energy, and many primary products have risen sharply.The world’s ecosystems are under great stress. One fifth of the world’scoral reefshave been damagedbeyond repair. Desertification in regions such as the Sahel threatens livelihoods in thedrylands,whichare home to a third of the world’s people. By 2003, nearly a third of theworld’s fisherieshad collapsed.The social dimension of sustainable development is a mixed picture. Despite the progress made inachieving theMDGs,results have been uneven within and between countries, and there are still too many people being leftbehind. Progress tends to bypass those who are lowest on the economic ladder or are otherwise disadvantagedbecause of their sex, age, disability or ethnicity. Disparities between urban and rural areas remain daunting.In 2009, nearly a quarter of thechildren in the developing worldwere underweight, with the poorestchildren most affected. Children from the poorest households in the developing world are more thantwice as likely to die before their fifth birthday as children in the richest households. RecentUNICEFresearchfinds that some four million young children die each year—more than 10,000 per day—due tohunger, malnutrition, and unsafe drinking water.Some 1.5 billion people do not haveaccess to reliable electricity services;some 2.4 billion do nothave reliableaccess to modern heating and cooking technologies.Approximately 900 million peoplelackaccess to safe water,and nearly three billion lack access to modern sanitation systems. The socio-economic consequences of inadequate access to improved water and sanitation services are substantial.Annual GDP losses associated with inadequate access to water have been assessed at 6.4 percent, 5.2percent, and 7.2 percent inIndia, Ghana, and Cambodia,respectively.Harsh gender-based inequalities persist in many societies, despite evidence showing a positive correlationbetween closing gender gaps and more favourable development outcomes. Women lack access to land,property and inheritance rights in large parts of the world, violence is a brutal reality for millions of womenand girls in many countries, women’s access to basic reproductive health services is too often denied, andin many developing countries girls continue to lag behind boys in school enrollment and completion.Despite much progress since theWorld Conference on Womenin Beijing in 1995, women continue to bepoorly represented within the public service, in particular in leadership and decision-making positions.

Triple wins for sustainable development

9

Children who are poor, female, or living in a conflict zone are less likely to be in school. Worldwide, amongchildren of primary school age not enrolled in school, 42 percent—28 million—live in poorcountriesaffected by conflict.As we have witnessed again and again the last 20 years, conflict is an absoluteshowstopper for sustainable development. Successful conflict prevention and peacebuilding areprerequisites for development progress. A balanced and holistic sustainable development agenda is themost effective approach to preventing conflict and securing peace.Poverty, demographic pressures, and access to basic services have traditionally been seen as predominantlyrural problems. This may now be changing. A recent World Bank study finds that, as of 2010, the majorityof the world’s population was living in cities. According to the Making Cities Work initiative, the world’spopulation by 2050 will grow by an additional 2.2 billion people—2.1 billion of whom will be born incities, and 2.0 billion of whom will be born in theworld’s poorest cities.The development challenges of the future will therefore increasingly wear an urban face. Rapid, unplannedurbanization is already producing new and exacerbating some old social problems. Violent crime in urbanareas is one of these, particularly among youth living in informal peri-urban settlements facing uncertainemployment prospects in the formal economy.Recent UNDP researchdescribes and analyzes disturbingincreases in violent crime in the Caribbean: during 1990-2010, for example, the homicide rate (per 100,000population) in Jamaica rose from 21 to 51; in Trinidad and Tobago it rose from 5 to 35. Rural developmentprospects continue to be challenging: many communities suffer from underinvestment in agriculture,energy and transport infrastructure, increased competition for land, water and other resources, climatechange impacts, and devastation from AIDS, malaria, and other diseases.At least thirty million jobs were lost globally during 2007-2009, and labour markets have yet to fullyrecover from the impact of the global financial crisis. Global unemployment is now estimated at 200million. Another 400 million jobs will be needed to keep up with new labour-market entrants. In addition,900 million workers—around 30 percent of the global labour force—are ‘working poor’, living on lessthan two dollars a day. In many countries, job prospects for the young are at their least favourable in years.Income poverty, gender gaps, unequal access to resources, basic services, and decent work, heightenedexposure to disaster and environmental risks—these all go together. This confluence is not a coincidence:the human costs of environmental degradation and social underdevelopment are born predominantly bythe poor, whose livelihoods and welfare are most closely linked to natural resources and social protection,and who are therefore most likely to bear the social costs of unsustainable environmental practices.The ‘ArabSpring‘shows how these linkages are not academic. Real and perceived social inequities inthis region have interacted with high food prices and governance concerns to create deep-seated socio-political instability, conflict, and crisis—even in upper-middle income countries.

10

Triple wins for sustainable development

Things can be differentAs we look towards ‘Rio+20’ and beyond, to the post-2015 development framework that will succeed theMillennium Development Goals, we face the question: ‘What do we want our future to look like?’A succinct response to this question was captured in a recent speech by Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff(Box 3): “Wewant the word ‘development’ always associated with the term ‘sustainable’…We believe that it ispossible to grow and to include, to protect and to conserve.”

Box 3: Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff on sustainabledevelopment, and ‘Rio+20’“We want the word ‘development’ always associated with the term ‘sustainable’. Together with theMillennium Development Goals, we need to set the goals for sustainable development. These goals,including commitments and targets for all countries in the world, should have at its core the fightagainst poverty and inequality, as well as environmental sustainability.In my government, when we talk about sustainable development we mean accelerated growth ofour economy in order to distribute wealth, in order to create formal jobs and to increase the incomeof workers. We mean income distribution to eradicate extreme poverty and to reduce poverty,including public policies to improve education, health, public safety and all public services providedby the Brazilian government. We mean balanced regional growth so as to correct the inequalitybetween the regions in Brazil. We mean creating a vast market of mass consumption goods, whichwill provide the internal support to our development. We mean that Brazil is becoming, and wewill become, a country of middle classes. We mean development with environmental sustainabilityas a prerequisite. Sustainable development also means strengthening social participation anddemocracy, encouraging and defending our values, our culture, and our cultural diversity.We believe that it is possible to grow and to include, to protect and to conserve.Rio+20 will discuss a development model capable of linking growth and job creation, povertyeradication and inequality reduction, social participation and expansion of rights, education andtechnological innovation, sustainable use and preservation of environmental resources.”Taken from an unofficial translation of herspeech delivered to the World Social Forumin Porto Alegre, 26 January2012.

Triple wins for sustainable development

11

Brazil’s development experience shows that the future can indeed be different. In the last two decades,Brazil has benefitted from a combination of:••••••Rapid economic growth;Significant declines in income poverty and inequality;The attainment of near universal access to basic energy, water, and sanitation services;Very high shares of renewables in electricity generation;Important social policy innovations;Balancing rural development needs with progress in protecting the country’s natural capital.

Just as the Earth Summit set a new direction for our world 20 years ago, so now policy-makers, experts,and civil society and advocacy groups must learn from such experiences to revisit the premise of currentdevelopment models and see what works, why, and where we can and must do better.It is time to reset the global development agenda.

12

Triple wins for sustainable development

Resetting the agenda:what is needed?The 1992 Rio sustainable development principles offer a vision for combining economic growth withenvironmental and social sustainability. Twenty years later, questions about the implementation of theseprinciples have risen to the fore. As the international community prepares for ‘Rio+20’, and works to definean agreeable outcome, progress towards this vision in six areas is particularly important:1.From MDGs to Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): progress towards attaining the MDGs mustbe accelerated and sustained, and the post-2015 global development goals must evolve into SDGs.2.Green is not enough. ‘Triple-win’ policies and programming are the way forward.3.Better governance and capacity development matter.4.Finance for development must be revisited.5.Beyond GDP and the bottom line—new metrics for sustainable development are needed.6.Leveraging knowledge and innovation to deliver results.

1.

From Millennium Development Goals toSustainable Development Goals

Attaining theMillennium Development Goalsis the first step towards a sustainable future—even as theconversation on what the post-2015 development framework should look like begins in earnest.Accelerating progress.During 2010-2011, UNDP together with other UN agencies developed and pilotedtheMDG acceleration frameworkto do just that. This framework has now been deployed in some 30countries, and demand for its use is growing. The framework brings governments, development partners,and other stakeholders together to analyze why—often despite a range of strategies and plans—progresstowards achieving specific MDGs is proceeding too slowly. Bottlenecks and constraints are identified, actionplans to address them are designed and implemented, and the necessary resources are mobilized.Across four countries in the Sahel—Niger, Burkina Faso, Chad, and Mali—this framework is focusing onMDG1, in terms of food security and nutrition. Priority actions have been identified to widen access toseeds and fertilizer, and decentralize the services that provide them; improve nutrition; expand socialprotection; and enhance the technical know-how of small-scale farmers.Sustaining progress.Progress already achieved toward meeting the Millennium Development Goalscan be set back, if not reversed, by the shocks of disasters, macroeconomic instability, food shortages,or socio-political unrest. Once progress is reversed, the impacts are multiple and can span generations.If instability—and the social and economic unrest it can generate—has become an enduring, systematiccharacteristic of the global economy, then countries must be better prepared for the waves to come. Theyneed to safeguard and sustain progress already made.

Triple wins for sustainable development

13

For many poor households, the impact of crises depends on what governments do with their budgets: howmuch do they spend to fight the crisis, protect the poorest, and finance progress towards meeting the MDGs?This underscores the need for participation and local solutions as well as direct interventions—such asdeveloping and extending social protection systems, clarifying and strengthening property rights, andthelegal empowerment of the poormore broadly. Such interventions help build societies’ resilience toshocks and sustain MDG progress.Moving towards Sustainable Development Goals.Reaching the Millennium Development Goals willnot automatically shift the world onto a sustainable development trajectory, partially because the MDGsare weaker on environmental concerns. In a number of respects, progress in meeting MDG 7 (‘ensureenvironmental sustainability’) has been relatively modest, in part because of governance shortcomings, inpart because of difficulties with measuring and monitoring progress towards environmental sustainability.More holistic Sustainable Development Goals should therefore evolve from the MDGs, and serve as thebasis for a new, post-2015 development framework.The Sustainable Development Goals should be one set of global development goals that:•••Reflect the entirety of the sustainable development agenda, including the continuing importance ofpoverty reduction;Are universal in character, pertaining to developed and middle-income countries, as well as to low-income and less developed countries; andAddress all three strands of sustainable development in each of the goals.

To the extent possible, the Sustainable Development Goals should seek to build on the MDGs and usequantified indicators to monitor progress. The post-2015 development framework should also be firmlygrounded in the other core values besides poverty reduction expressed in theUN Charterand reaffirmedin theMillennium Declaration—humanrights, justice, peace and security. Such an approach can helpensure that national transitions to sustainable development are aligned with broader understandings ofpeople’s welfare, enlarging their opportunities.

2.

Green is not enough. ‘Triple-win’ policies andprogramming are the way forward

‘Triple-win’ policies and programming, integrating and finding synergies between social development,economic growth, and environmental sustainability, are the future of development. Many countries arealready implementing programming that integrates the social, environmental, and economic strands ofsustainable development. For example:•The government of India has adopted several rights-based laws to address inequity, protectthe vulnerable, and ensure sustainable development. These include laws to protect the right toeducation and information, national food security legislation, and theMahatma Gandhi NationalRural Employment Guarantee Act.In addition to containing the world’s largest wage guaranteeprogramme—providing employment to approximately 54 million households—this integratedframework reduces food insecurity by conserving water, soil fertility, and biodiversity; it alsosequesters carbon. Almost 50 percent of the programme’s workers are women; 43 percent are fromhistorically disadvantaged groups.

14

Triple wins for sustainable development

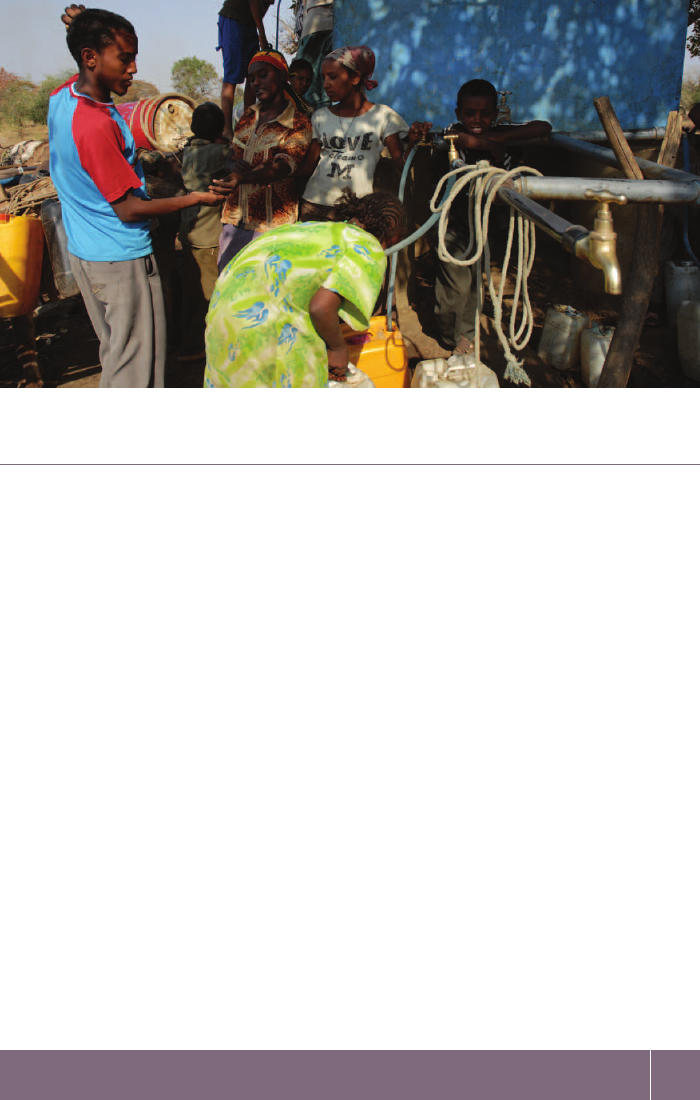

The UN Capital Development Fund is helping the Government of Ethiopia to provide basic social andeconomic infrastructure and improve the natural resource base of local communities.� UNCDF/Adam Rogers

•

Under Brazil’sBolsa Famíliaprogramme, 11 million households—some 25 percent of the population—receive conditional cash transfers to raise incomes above the poverty line, at a cost of less than onepercent of annual GDP. Recipient households are required to have their children in school and toensure they receive regular medical attention. The imperatives of rural development and protectingthe country’s natural capital are aligned via theBolsa Verdeprogramme, which offers conditional cashtransfers to 73,000 smallholder and indigenous households living in environmentally sensitive areas,who pursue ecologically sustainable livelihoods.South Africa’s ‘Workingfor Water’programme employs 20,000 people per annum, to remove water-intensive alien tree and plant species from local habitats. Since its inception in 1995, the programmehas cleared more than one million hectares of alien plant species, releasing fifty million cubic metersof additional water per annum. Much of this water is used for irrigated agriculture, reducing local foodinsecurity. The programme targets marginalized groups as potential employees: it seeks to ensure that60 percent of its staff are women, 20 percent are youth, and five percent are living with disabilities.Ethiopia’sProductive Safety Net programmehas reached over eight million beneficiaries in 300food-insecure districts, providing cash and predictable food supplies in return for participation inpublic works in such areas as environmental conservation, water management, and terracing. It hasincreased caloric intake by 19 percent among recipient households, and nearly half of beneficiariesreported a greater use of health facilities.In Niger’s southern regions, reforestation based on ‘farmer-managednatural regeneration’,and supportedby local communities, has reforested five million hectares (about four percent of the country’s land area),with the affected areas benefitting from rapidly growing parkland in forest and vegetation cover density.These efforts increased cereal yields by 100 kilograms per hectare in 2009, improving livelihoods and foodsecurity for some 2.5 million people. The primary beneficiaries have been residents of rural communities,with particular attention to vulnerable communities and indigenous people.

•

•

•

Triple wins for sustainable development

15

Sustainable energy for all.Energy offers clear opportunities for better integrating the three strands ofsustainable development. By expanding access to sustainable energy supplies, progress can be advancedalong all three dimensions:•Economic: billions of under-served consumers can be brought into the global market place, andbusiness- and employment creation could accelerate—particularly in rural areas, where such energysupplies are most likely to be lacking.Social: women and children can be liberated from the drudgery of gathering biomass for fuel; healthand education could be improved by reducing indoor pollution from poorly designed stoves, and byproviding health clinics and schools with the heat and power needed for uninterrupted service delivery.Environmental: deforestation, and the emissions created by burning soft coal and biomass thatcontribute to climate change, could be reduced.

•

•

The UN Secretary General’sSustainable Energy for Allinitiative, to be launched at ‘Rio+20’, is designed togenerate global momentum to achieve three specific energy targets by 2030, namely:•••Achieving universal access to modern energy services;Doubling the rate of improvement in energy efficiency; andDoubling the share of renewables in the global energy mix.

The sustainable development potential of this initiative is illustrated by Nepal’sRural Energy DevelopmentProgramme.Since its introduction in 1996, this programme has brought decentralized renewable energyservices to some one million people living in the most remote parts of the country. It has provided reliable,low-cost electricity to rural communities via the construction of micro hydropower stations, and hasraised living standards. Average incomes in beneficiary households have increased due to improvementsin electricity access, while average annual household spending on energy fell to US$19 compared toUS$41 spent by non-electrified households.As of 2010, the programme had connected 59,000 households to micro hydropower installations, constructed317 new micro hydropower plants (with 5.7 megawatts of installed capacity), and installed nearly 15,000improved cooking stoves, 7,000 toilet-attached biogas plants, and 3,200 solar home heating systems.

3.

Better governance andcapacity development matter

Country experiences indicate that public finance is usually not the binding constraint on nationalprogrammes that make a difference for sustainable development.Bolsa Famílialifts millions of people outof poverty in Brazil every year at the cost of less than one percent of GDP. Croatia’s public sector energyefficiency programme leveraged US$4 million in initial seed funding into US$30 million in private sectorinvestments.Instead, it is usually the quality of governance and the capacity to govern well that matter.Capacity development is needed to help developing countries absorb innovative technologies and avoidhigh-carbon development paths, while also reducing poverty and inequality.

16

Triple wins for sustainable development

Just five years ago, Cerro Santa Ana was a slum. Today, thanks to community participation in renova tion,it is a tourist destination that attracts more than 20,000 visitors each week.� Elder Bravo / UNDP Ecuador

Effective lawmaking, oversight, and representation—the three chief functions of parliaments—along with accessto justice, are fundamental to ensuring that all branches of government are accountable and transparent beforethe public. Parliaments can be powerful agents of change for sustainable development. But they often needstrengthened capacity, whether to legislate for sustainable development or to promote institutional reform.Decentralization, local and inclusive governance, and social mobilization are needed for empowered citizensto ‘think globally while acting locally’. The transformations now taking place in the Arab world illustrate thispoint. There, people have come out onto the street to express their desire for dignity, opportunity, andjustice alongside a meaningful say in the decisions that affect their lives, and an end to corruption, abuseand repression. They remind us that, to be sustainable, development must provide for human rights, justice,the rule of law, accountability, equity and—crucially—gender equality and women’s empowerment.Democratic governance cannot be fully achieved without the participation of women at all levels. This isnot only a good in itself; there is also growing evidence that greater participation of women in institutionsincreases responsiveness to women’s priorities and needs and in determining the manner in whichservices are provided.Governance: the glue that holds sustainable development together.In the words of the SecretaryGeneral’s High Level Global Sustainability Panel: “democratic governance and full respect for humanrights are key pre-requisites for empowering people to make sustainable choices”. Seen in this light,governance serves as the glue that binds together efforts to more closely integrate the three strands ofsocial, economic, and environmental development in policy and in practice.

Triple wins for sustainable development

17

This is particularly true when it comes to:•Clear land and natural resource rights for local communities,to generate incomes and jobs, strengthenlocal incentives to sustainably manage the resources on which local livelihoods depend, and helpensure equity of such rights between women and men. UNDP’sLegal Empowerment of the Poorinitiative offers many good examples of what can be done in this respect.Institutional capacityto design and implement integrated development policies and programmesthat address all three sustainable development strands; and which benefit from partnershipsbetween central and local governments, private companies, civil society organizations, andinternational organizations. Creating this institutional capacity often requires a combination of publicadministration reforms—structural reviews, civil service reform, use of e-governance tools, finding theright balance of decentralization, deconcentration, and centralization—and ‘collaborative’ capacitydevelopment initiatives, emphasizing the expansion of capacities for brokerage, partnerships, andnetwork development and management.Social programmingthat integrates social protection with social service provision, environmentalprotection, and crisis prevention and recovery; that improves access to energy, water, sanitation andother basic services; and which protects the poor and vulnerable by taking rights-based approachesthat reflect the global conventions and the UN’s universal values.

•

•

For example, growing numbers of large metropolitan areas are moving towardssmart growthin cities,which also offers an abundance of opportunities for grass-roots innovation and creating pro-poor greeneconomies—as envisioned byAgenda 21at Rio in 1992. Important public investment—and income-and employment-generation—opportunities are presentinter aliain the construction, refurbishing, andmanagement of public infrastructure and programming, whether for energy-efficient buildings and masstransit systems, or for urban agriculture to help address urban poverty and hunger.For many smaller cities, taking advantage of these opportunities requires significant investments incapacity development. This is particularly true for improving governance and financial managementsystems (interaliathrough public-private partnerships), and engaging with, and responding to the needsof, poor and vulnerable households and communities, including women, migrants, and the residents ofinformal settlements.Principles for ‘triple-win’ policies and programming.The country case studies below show thatsustainable development happens at country—often at the community—level. Better support is thereforeneeded for efforts to develop ‘triple-win’ policies and programming that integrate the three strands ofsustainable development, while at the same time strengthening coordination across and between allactors for increased effectiveness.Certain principles should underline all ‘triple-win’ policy and programming if sustainable development isto be realized. The focus should be on:•Strengthening inter-ministerial coordination,including via the lead of high level government officeswith appropriate institutional capacity and authority in development policy. As the UN SecretaryGeneral’s High Level Global Sustainability recommends, governments should adopt whole-of-government approaches under the leadership of the head of state or government, and involvingall relevant ministries, in order to address issues across sectors and improve policy coherence.Governments and parliaments should incorporate the sustainable development perspective intotheir strategies, their legislation and, in particular, their budget processes.

18

Triple wins for sustainable development

•

Getting the incentives right through aligned and integrated national, sub-national, local and sectoraldevelopment strategiesthat are tied to medium-term expenditure frameworks. Synergies betweendevelopment strategies allow all levels of government to get the incentives right for attracting public andprivate sector investment. The same institutions should have the capacity needed to effectively designand implement these strategies, at the level of the individual, institution, and broader environment.

Box 4: Mechanisms for policy coherenceOptions for improving policy coherence—allowing governments to break silos and better integratethe three strands of sustainable development—include the following:•Institutions:High-level coordination bodies, either within the state—such as India’s PlanningCommission, China’s National Development and Reform Commission, and South Africa’sNational Planning Commission—or of a multisectoral nature, such as Barbados’s SocialPartnership initiative (which brings together ministers, employers, and trade unions to addressmajor economic, social and environmental challenges under the leadership of the PrimeMinister).Instruments:National sustainable development plans and strategies, which:–––––––seek to integrate the three strands of sustainable development;are championed by the head of state or government;receive broad political support in parliament;bring together all relevant stakeholders (sub-national governments, private sector, civilsociety);have time frames that are long enough to address development challenges, but shortenough to influence behavior today;are aligned with national budgets, sectoral development programmes, and donor activities;andcontain monitorable indicators for assessing progress toward meeting strategic objectives.

•

Adapted from the 2012Resilient People, Resilient Planetreport of the Secretary General’s High Level GlobalSustainability Panel, p. 68.

•

Ensure meaningful participationof the private sector, representatives of parliaments and sub-nationalgovernments, and civil society actors—particularly those representing vulnerable groups, includingwomen, children, indigenous peoples, ethnic minorities, people living with disabilities or HIV andAIDS, or low-skilled workers.Be informed by the latest global and local scientific data and knowledge,with carefully designedaccountability and regulatory frameworks and enforcement mechanisms.Raise public awarenessabout the links between governance, poverty reduction, gender equality,and environmental sustainability—possibly through the global application of the environmentalgovernance principles of theAarhus Convention.Promote resilience to crisis and shocks,regardless of whether they are associated with disasters,macroeconomic instability, high food or energy prices, or armed conflict. More accurate targeting of

••

•

Triple wins for sustainable development

19

social assistance, the expansion of crop insurance, and better use of early warning systems can boostresilience among vulnerable households, helping them to invest in their future and take moderaterisks, and ultimately drive productivity gains and inclusive growth.Global governance.Addressing governance at theglobal levelis also important. This could meanimproving the functioning of the United Nations Economic and Social Council, possibly by turning theCommission on Sustainable Development into a Sustainable Development Council. It could also mean thepossible introduction of a voluntary sustainable development peer review mechanism or a periodicglobalsustainable development outlookreport, to monitor progress and encourage development coherence.So far, however, the discussion of how governments can more strongly bring together the three strandsof sustainable development and drive implementation at the national and sub-national level, is lessconcrete. This is an area in which the United Nations has a wealth of accumulated experience, and canplay a critical role in supporting countries in accelerating progress towards sustainable development.‘Rio+20’ provides an opportunity to strengthen UN Country Teams and the Resident Coordinator systemto bring support and services from across the UN system to programme countries in a way that canfacilitate integrated action across the three strands of sustainable development.

4.

Revisiting finance for sustainable development

Financing for sustainable development needs to increase. At the same time, fiscal tensions inOECD-DACcountriesare squeezing the fiscal space for traditional development cooperation. While overall globalaid spending hit its highest level ever in 2010, a near-term decline in OECD-DAC aid flows seems likely.Longer term, estimates of the volume and shape of other forms of development assistance (e.g., climatefinance) face considerable uncertainty.The costs of shifting towards a sustainable future are real, however. A relatively low estimate of the totalannual climate change mitigation and adaptation costs through 2030 is US$249 billion, for example; andthis addresses only one threat (global warming) to the global environmental commons. By contrast, officialdevelopment assistance (ODA) constitutes a relatively small pool of finance, at approximately US$130 billionannually. Most of the investments in regenerating the global commons will therefore be owned, managed,and financed, by the private sector. Helping create the appropriate enabling environment, to direct theseflows—ODA, domestically available public finance, other sources—to the projects where they can deliverthe largest transformational impact, is a critically important task for the public sector. No less important,however, is the need to ensure that the public funds that are available to support national transitions tosustainable development are able to leverage and catalyze larger pools of private finance.A number of possible new public financing mechanisms merit serious consideration.Tobin taxes—leviesonfinancial transactions with which financial market instability or other negative externalities may be associated—are one such category. Thanks in part to recent changes in the payments systems for foreign exchangetransactions, UNDP’s 2011 ‘’Sustainabilityand Equity: A Better Future for All’Human Development Reportfoundthat a 0.005 percent tax on foreign exchange transactions would yield some US$40 billion annually.There are other options:•Governments spend nearly US$1 trillion annually onenvironmentally unsustainable subsidies,including for fossil fuel production. Abolishing or curtailing such subsidies would promote botheconomic and environmental sustainability. The savings could finance investments in sustainabledevelopment—including in social protection to shield those most vulnerable to higher energyprices, as well as in expanding clean and renewable energy solutions.

20

Triple wins for sustainable development

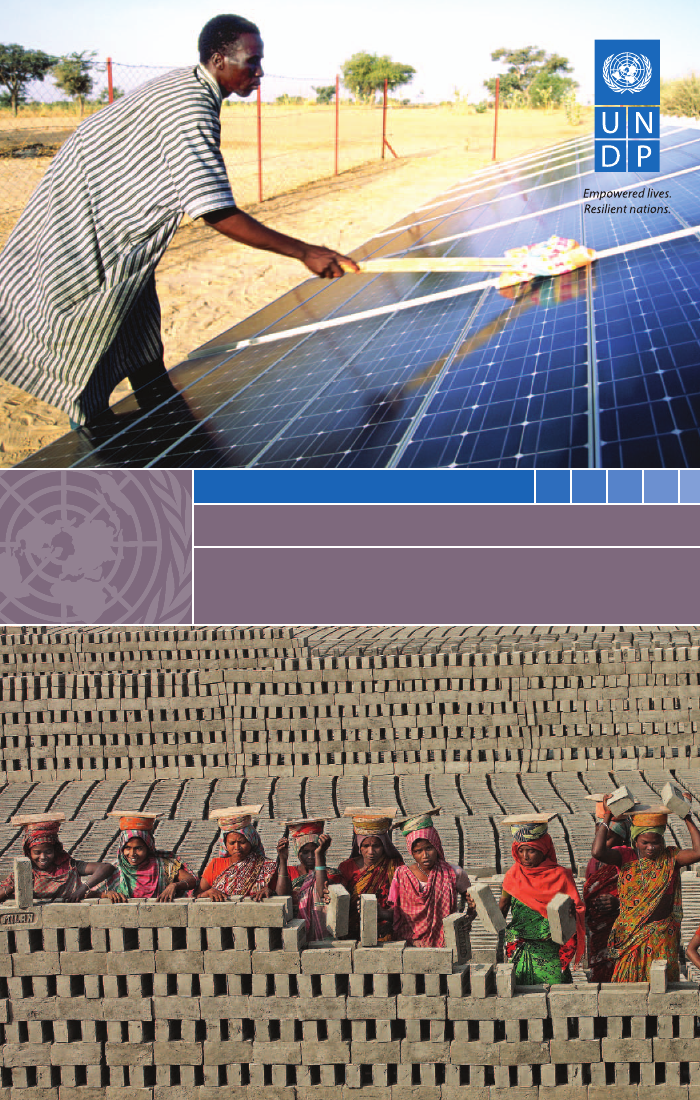

Men and women inspect a solar panel. � Jorgen Schytte / UNDP Egypt

•

Governments also spend nearly US$5 trillion annually onpublic procurement(10-20 percent of GDP in mostdeveloping countries). If one fifth of these expenditures were to be managed in accordance with sustainabledevelopment criteria, another US$1 trillion in financing for sustainable development would appear.

These points show that financing for sustainable development is available. They also show that—ifgenerated correctly—the process of generating these resources can help to reset the global developmentagenda and regenerate the global environmental commons.

5.

Beyond GDP and the bottom line:new metrics for sustainable development

The metrics by which progress is assessed poorly serve the cause of sustainable development, in both thepublic and private sectors.In the public sector,‘Rio+20’ should be the beginning of the end of measuring development progressmainly in terms of GDP growth. The ‘Rio+20’ final document is an opportunity to request that the UNsystem and the Bretton Woods institutions to build on theSystem of Environmental-Economic Accounting(the introduction of which started in Europe, for air pollutants, environmental taxes, and material flowaccounts, in 2012), to jointly develop metrics that could include gross national income for sustainabledevelopment, a sustainable development index, or both.

Triple wins for sustainable development

21

An Indian woman works with handmade paper destined for foreign markets. � UNDP India

These metrics, which could be taken up by the UN Statistical Commission for consideration in thediscussions around the post-2015 global development agenda, should seek to measure:•Progress in ‘greening’ key sectors, such as environmental investments, the sales of ‘green’ goods andservices and green jobs; improvements in energy and resource efficiency; re-use, recycling, and othermeasures of doing more with less; andChanges in welfare that reflect holistic, integrated trends in natural capital, poverty, and social inclusiveness,as well as output—indicators of how well the economy is delivering across all three strands of sustainabledevelopment. Work to develop a sustainability-adjusted human development index could be accelerated.

•

In theprivate sector,important progress has been made in corporate social responsibility duringthe past two decades. The private sector is the driver of economic growth and highly responsive toincentives provided by all levels of government. ‘Triple wins’ will invigorate the private sector and multiplydevelopment gains. However, further steps are needed—particularly in terms of:•moving toward standardized ‘triple bottom line’ corporate reporting frameworks that can monitorthe links between commercial behavior and sustainable development, reflecting social andenvironmental, as well as financial criteria;requirements that all publicly traded companies regularly report on their social and environmental(as well as financial) sustainability; and that key financial data be reported on a country-by-countrybasis, in all jurisdictions in which companies operate, in order to improve the quality of informationabout global development finance and reduce illicit financial flows.

•

These innovations could support the monitoring of progress towards sustainable development, includingthrough theglobal sustainable development outlook reportproposed by the Secretary General’s HighLevel Global Sustainability Panel.

22

Triple wins for sustainable development

6.

Leveraging knowledge and innovationto deliver results

The case studies below point to many successful examples of sustainable development. Importantlessons have been learned from both the successes and the mistakes made in the process. But the hard-won benefits produced are typically isolated, even though their broader application could produceexponential benefits and contribute vital ideas to the evolution of sustainable development.As the section on governance and capacity above points out, one of the principles that should underpinall ‘triple-win’ decisions is that they should beinformed by the latest global and local scientific data andknowledge.National transitions to sustainable development should be based on relevant innovation,knowledge, capacity, and experience from around the world, leveraging south-south and other forms ofcooperation for increasingly effective development results.As ‘Rio+20’ approaches, a globally recognized home for this function—a Global Centre for SustainableDevelopment—should be found. Such a Centre could catalyze innovation, act as a repository ofinitiatives, a global knowledge-sharing platform, and an analytical hub, as well as broker links betweenthe demand for, and supply of, sustainable development initiatives. It could promote collaborative andinterdisciplinary research and create linkages across researchers, policy-makers, and the private sector;and identify, disseminate, and scale-up successful models.There is a clear need for organizations with the mandate and capability to gather information on theseinitiatives, analyze their effectiveness and political feasibility, and broker their adoption throughout theworld. While global centers exist for green growth, inclusive growth, and social innovation, they do notsystematically pull the green, the social, and the economic together into coherent frameworks, analysis,and actionable policies.

Triple wins for sustainable development

23

What do UNDP and the UNbring to the table?

On the ground in more than 177 countries and territories, UNDP since 1966 has been partnering withpeople in all walks of society to help empower lives and build resilient nations. As the UN agency witha mandate to promote democratic governance, UNDP encourages transformational change to helpcountries move towards a sustainable future. It does so with particular experience and expertise in howto build and strengthen institutional capacity.UNDP’s track record in supporting sustainable development is reflected in its mandated expertise in eachstrand of development—and in its ability to see across and integrate all three strands. The UNDP-UNEPPoverty-Environment Initiativeis an example of how this can take place (see Box 5). At the national level,this work takes place within the framework of the UN Resident Coordinator system and its conveningpower—ideally under a ‘One UN’ framework.In particular, UNDP promotes sustainable development through supporting:•inclusive and sustainable growth,advancing economic opportunities via equitable access to socialservices, protecting the environment and embracing low-emission, climate resilient development;anddemocratic governance for inclusion, resilience and peace,advancing equality, the rule of law,human rights, and accountable, effective institutions in times of stability and of crisis, with theparticipation of all peoples—including women, girls, youth and marginalized groups—in politicaltransitions and processes.

•

UNDP is committed to a global partnership for achieving UN Secretary General’sSustainable Energyfor Allinitiative by 2030. Wherever there is a demand from governments, UNDP will capitalize on theconvening power of the Resident Coordinator system to help strengthen governance arrangementsand ‘triple-win’ policy and programming at the national and sub-national level, bringing policy options,financing, technology, and capacity development together to create conditions to scale up what works.UNDP continues to advocate strongly for the achievement of the Millennium Development Goals,including via:••••theMDG acceleration framework;coordinating the UN’s efforts to respond to national priorities;providing policy and technical advice to countries as they work to achieve the MDGs; andworking with countries on in-depth analyses and reports on MDG progress.

24

Triple wins for sustainable development

Working within the wider UN family, UNDP is leveraging this experience to help countries to determinewhat the global development framework should look like after the 2015 MDG deadline.As it strives to always be better, UNDP will:••••accelerate progress in greening its own programming and facilities, particularly in programme countries;use human development indicators and data to better monitor national transitions towardssustainable development;mainstream low-emission, climate-resilient development principles across its work; andleverage traditional and non-traditional partnerships and forms of development finance, to supportnational transitions toward sustainable development, particularly viasouth-south cooperationandpublic-private partnerships.

Box 5: TheUNDP-UNEP Poverty and Environment InitiativeThe Poverty-Environment Initiative is a UN-led global programme that supports country effortsto reduce poverty by strengthening environmental sustainability—and vice versa. It focuses inparticular on ensuring that poverty-environment linkages are appropriately reflected in national andlocal development planning, from policy-making to budgeting, implementation and monitoring.The Poverty-Environment Initiative:•••••was launched in 2005 and significantly scaled-up in 2007;is funded by the Governments of Belgium, Denmark, Ireland, Norway, Spain, Sweden, the UnitedKingdom, and the United States of America, and by the European Union;works inAfrica, Asia-Pacific, Eastern Europe and Central Asia,andLatin America and theCaribbean;has full programmes in seventeen countries, and is providing advisory services in a number ofothers; andprovides supra-national support for ‘Deliveringas One’and other measures to increase theUN’s development effectiveness at the national level, in the areas of poverty reduction andenvironmental sustainability.

Triple wins for sustainable development

25

‘Rio+20’ can make a differenceWith a global population of seven billion and expected growth of a further two billion by 2050, there isno time to lose in securing a sustainable future. ‘Rio+20’ offers a timely moment for politicians, policy-makers, the private sector, experts, and civil society and advocacy groups to revisit the premise of currentdevelopment models and see what works, why, and where we can and must do better.It offers a moment to set a course of enlarging people’s freedom, opportunty, and choice to lead lives theyvalue, while safeguarding the natural environment for generations to come.For this to happen, silos must be broken down, institutions strengthened, capacities developed, policiesadjusted, markets developed, and democratic governance fortified.Most importantly, behavior must change.We know why. This report illustrates how. ‘Rio+20’ should help the world answer when.

People lining up to cast their votes at a polling station in Mozambique. � P. Sudhakaran / UN Mozambique

26

Triple wins for sustainable development

Case studies of sustainabledevelopment in practiceProgress towards sustainable development does not happen in the abstract; it occurs with the contextof individual countries, sectors, and communities. Useful explanations of how sustainable developmentis done must therefore be based on descriptions of concrete policies and programmes that integrate theeconomic, social, and environmental strands and then scale up these activities for broader impact.Eight such case studies are briefly presented in the pages below. The countries profiled come from variousregions (Latin America, Europe, Asia, Africa) and from contrasting developing countries and emergingeconomies—Bhutan, Brazil, Croatia, Mongolia, Namibia, Nepal, Niger, and South Africa. Many of theprogrammes and policies profiled have strong sectoral characteristics (e.g., ‘energy’, ‘water’, ‘inclusivefinance’, or ‘food security’). However, all these case studies satisfy two criteria:•Irrespective of their sectoral origins, the programmes described have integrated the economic, social,and environmental strands of sustainable development in a meaningful way—they have generated‘triple wins’; andThe programmes have been scaled up, creating national impact.

•

In addition, the case studies on Brazil and Bhutan provide a more macro view of sustainable development.The Brazilian study in particular describes how Brazil during the past two decades has managed to achievesignificant development successes in terms of economic growth, reductions in poverty and inequality,and extending basic services, while also dramatically expanding the share of the Amazon rainforestcovered by protected areas.Taken together, these stories provide a brief but compelling narrative to show that sustainabledevelopment can, in fact, be made to happen; and how it can be made to happen.

Case studies of sustainablesustainable developmentTriple wins for development in practice

27

Brazil: making sustainabledevelopment happen

Country context.The world’s fifth largest country by territory and seventh largest by GDP, Brazil hasabundant natural, human, and economic resources. Like many developing countries, Brazil during the pasttwo decades has enjoyed rapid economic growth: per-capita GDP increased by nearly 50 percent during1992-2011. Nonetheless, Brazil has historically faced a number of grave social challenges, including highlevels of income inequality and social exclusion, large regional disparities, and lack of universal accessto basic social services. The Amazon rain forest and other components of Brazil’s biodiversity have comeunder growing threats.Fortunately, Brazil during the past two decades has made great progress in combining economic growthwith significant social gains, while moving to strengthen the protection of its natural capital. In additionto rapid GDP growth, Brazil during the past two decades has benefitted from:••••••Large declines in income poverty;Reductions in income inequality;Achieving near universal access to basic energy services;Very high (by international standards) shares of renewables in electricity generation;Important social policy innovations; andThe rapid expansion of forests in the Amazon basin that are included in protected areas.

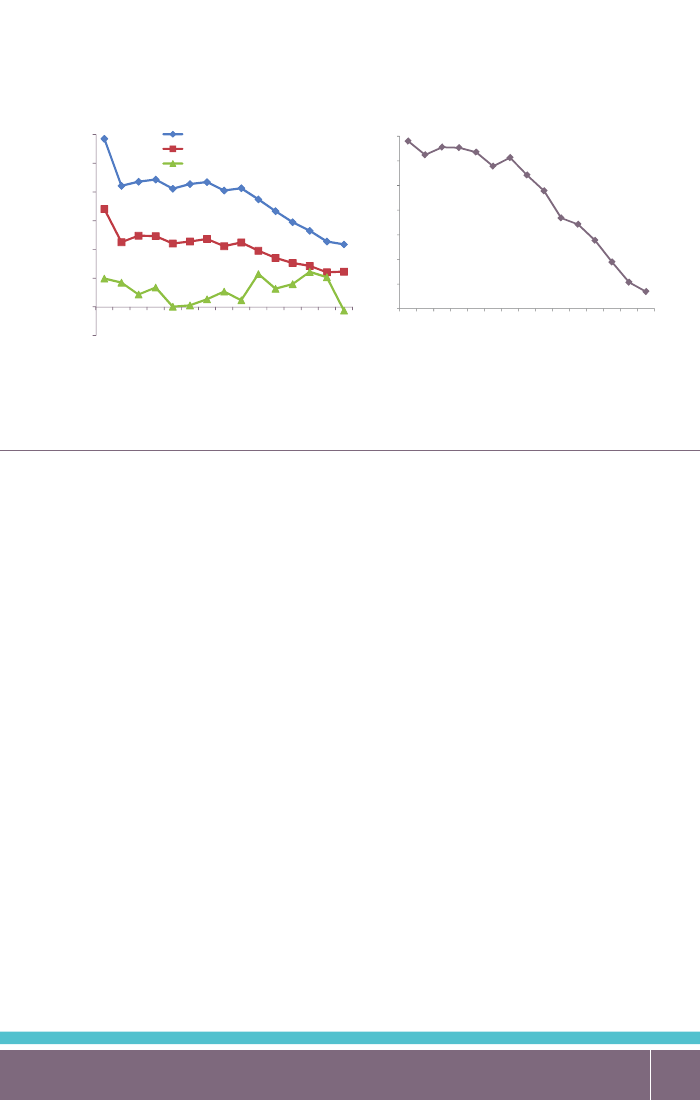

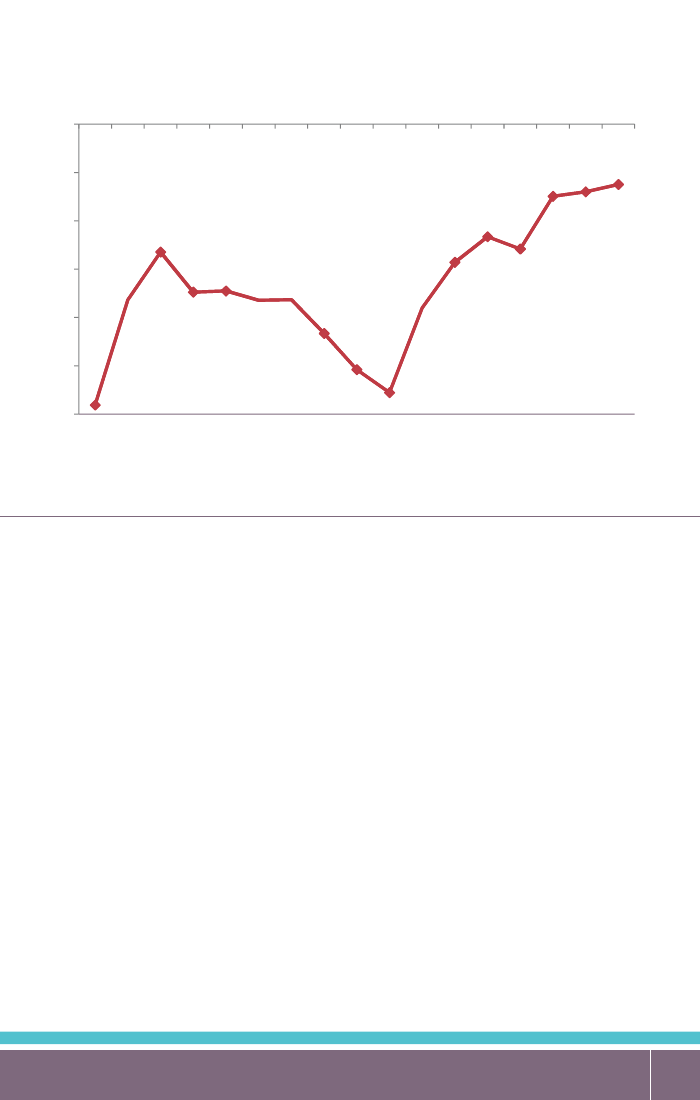

These developments did not happen by accident: they result from measures taken by the Braziliangovernment—and supported by civil society and the private sector—to achieve sustainable and inclusivegrowth, to address the economic, social and environmental strands of sustainable development in anintegrated manner. Brazil’s experience shows that rapid progress in national transitions to sustainabledevelopment is possible.Reductions in income poverty and inequality.Internationally comparableWorld Bank datashowrates of income poverty and extreme income poverty (measured against daily per-capita thresholds ofUS$2 and US$1.25, respectively) dropping sharply during the 1993-2009 period (Chart 1). Thanks to thisprogress, the numbers of people living in poverty dropped by more than half (from 45 to 21 million forincome poverty; from 26 to 12 million for extreme income poverty) during this time. While economicgrowth certainly contributed to this result, a very important role was played by reductions in inequality:the Gini coefficient for income inequality, which was close to .61 in 1993, had dropped to under .55 by2009 (Chart 2). In contrast to many developing and developed countries, Brazil has managed to make itseconomic growth increasingly inclusive.

28

Case studies of sustainable development in practice

Chart 1: Income poverty, annual GDPgrowth rates, Brazil (1993-2009)30%25%20%15%10%5%0%Income Poverty*Extreme Income Poverty**Annual GDP growth

Chart 2: Gini coefficient of incomeinequality, Brazil (1993-2009)0.610.600.590.580.570.560.550.54

19919 3919 5919 6919 7919 8920 9020 1020 2020 3020 4020 5020 6020 7020 809

-5%

* Income-based measure, at US$2/day.** Income-based measure, at US$1.25/day.Source: World Bank POVCALNET database, based on 2005 purchasing-power-parity exchange rates.

Because income inequality in Brazil fell during 2008-2009, severe income poverty continued to declineeven during the global financial crisis (Brazil’s GDP shrank in 2009). Brazil was thus able to shield manyof the most vulnerable households from the effects of the crisis. On the other hand, Brazil’s levels ofincome inequality remain among the world’s highest, and reflect continuing challenges of poverty, socialexclusion, and regional disparities.2010 census dataindicate that the extremely poor are concentratedin rural areas and in the Northeast region, are disproportionately young, and mostly of African descent.Many are illiterate.These reductions in income poverty and inequality have been matched by important progress inalleviating non-income poverty:••••••Theunder-five mortality ratedeclined from 59 in 1990 to 19 in 2010 (per 1000 live births);Theinfant mortality ratedropped from 50 in 1990 to 17 in 2010 (per 1000 live births);Thematernal mortality ratefell from 120 in 1990 to 58 in 2008 (per 100,000 live births);The share of the population suffering frommalnutritiondropped from 11 percent in 1991 to 6 percentin 2007;The share of the population withaccess to safe drinkingwater increased from 89 percent in 1990 to98 percent in 2010; andThe share of the population withaccess to improved sanitation facilitiesrose from 68 percent in 1990to 79 percent in 2010.

Brazil: making sustainable development happen

19919 3919 5919 6919 7919 8920 9020 1020 2020 3020 4020 5020 6020 7020 809

29

Jair dos Santos says harvesting the cerrado fruit is more money and less work. With the extra incomefrom the wild fruit, Mr. Santos is able to buy new furniture, tools and running water for his home.� David Dudenhoefer / UNDP Brazil

These trends reflect the fact that Brazil has invested heavily in social as well as economic development.Believing that poverty is a multi-dimensional problem that goes well beyond the lack of income, thegovernment has designed and implemented a number of integrated programmes for social protection,extension of basic services, and food security that have helped break vicious circles of social exclusion,lack of opportunity, low incomes, and poor health.Launched in October 2003, theBolsa Família(FamilyBenefit)programmehas become the Government’sflagship social protection initiative. UnderBolsa Família,four different cash transfer programmes, whichhad previously been operated by separate ministries, were merged. Byconditioning cash transfersonbeneficiary compliance with requirements for school attendance, vaccinations, and pre-natal visits,BolsaFamíliaincreases poor household use of basic services while also strengthening their human capital—both of which are essential to escaping from poverty.Complementary initiativesthat are administeredfor beneficiary households include programmes for literacy, vocational training, microcredits (for smallfarmers), and theBolsa Verdegreen benefits programme (see below).A large body of evidence indicates that a significant share of the reductions in poverty and inequalitymentioned above can be attributed, in part, toBolsa Família.For example:•Bolsa Famíliahas been taken to scale: more than13 million households(covering nearly 30 percent of thepopulation) receive benefits under this programme. Depending on per-capita income and the number andage of children in the household,monthly benefitsreceived under this programme can range from US$55 toUS$530 per family. These benefits are rather large vis-à-vis the extreme poverty line at US$120 per householdmember (which is above the international poverty threshold of PPP US$1.25 per day). That is,Bolsa Famíliaprovides relatively large benefits for relatively large numbers of vulnerable households.

30

Case studies of sustainable development in practice

•

UNDP researchfound that about one fifth of the 4.7 percentage point decline in the Gini coefficientduring 1995-2004 could be attributed toBolsa Família.Likewise, research by the Funda§ão GetúlioVargas found thatBolsa Famíliaalone was responsible for one sixth of the reduction in poverty andinequality (as measured by changes in the Gini coefficient) during 2003-2009.

Bolsa Família’ssuccesses reflect in part Brazil’s long experience with conditional cash transfers. It was the firstsuch programme to be introduced in Latin America (in 1985), and has had an impact on the global expansionof conditional cash transfer programmes. It also reflects the importance of partnerships with civil societyorganizations, which help the government to reach out to vulnerable households and communities. This hasallowed the government to undertake a number of steps toimproveBolsa Família’stargeting accuracyover time.These include:•••Developing the appropriate division of responsibilities for managing the programme across thenational government, states, districts, and municipalities in Brazil’s decentralized context;Improving the quality of the information in thenational beneficiary registry(in which 19 millionfamilies are currently included); andImproving cross-ministerial monitoring of beneficiary compliance with programme conditionalities,and of integration with other complementary programmes.

Bolsa Família’s‘infrastructure’ also facilitates the implementation of other targeted programmes. Forinstance, the debit card through which payments are made to beneficiaries is also being used for makingpayments to beneficiaries under complementary programmes. As a result of this targeting accuracy andmanagerial economies,Bolsa Família’sfiscal implications have been kept at relatively moderate levels.UNDP researchfinds that, in 2009, the programme absorbed only about 0.9 percent of total publicspending, about 0.35 percent of GDP.As part of theBrasil Sem Miseria(BrazilWithout Poverty)social programme launched by President DilmaRousseff in 2011, the government is now extending (by 2013)Bolsa Famíliato over 800,000 families thathave the right to the benefits, but have not yet taken them up. To increase the efficiency in fighting extremepoverty and protecting children, the number of eligible beneficiary children per household will be increasedfrom three to five. This expansion will allow for the extension of coverage to 1.3 million additional childrenand adolescents whose families comply with programme conditionalities for keeping them in school andin good health. Currently, 40 percent of the population living in extreme poverty is under 14 years of age.Fome Zero.When former Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s (‘Lula’) started his first term inJanuary 2003, he designated the eradication of hunger as one of his top priorities—famously statingin his inauguration speech that, if at the end of his term, every Brazilian will have three meals a day, hewould have accomplished his life’s mission. TheFome Zero(Zero Hunger) food security initiative, whichwas launched in 2003, was intended to do just this. Together withBolsa Famíliaand support for familyagriculture through the state food procurement programme (Programade Aquisi§ão de Alimentos), FomeZerois widely credited with raising the income of the poorest families in Brazil, improving child health, andreducing the scale ofmalnourishment.This helped make possible the inclusion of theright to adequatefoodin the Brazilian constitution in February 2010.Recognizing that eradicating hunger requires a comprehensive, multi-sectoral response,Fome Zerofocuses both on the demand side of food security issues—via cash transfers (e.g., underBolsa Família),targeted food deliveries (for vulnerable households and groups such as indigenous peoples and schoolchildren), and access to information—and on the supply side,inter aliavia support of food productionfrom small-scale and family farmers.

Brazil: making sustainable development happen

31