Grønlandsudvalget 2011-12

GRU Alm.del Bilag 50

Offentligt

MEGAPESCA Lda

CONTRACTCADREFISH/2006/20SPECIFICCONVENTIONN�35:EX-POSTEVALUATION OF THECURRENTPROTOCOLTO THEFISHERIESPARTNERSHIPAGREEMENTBETWEEN THEEUROPEANUNION ANDGREENLANDFINALREPORTSeptember 2011

This report has been prepared with the financial support of the European Commission.The views expressed in this study are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of theEuropean Commission or of its services. This report does not seek to establish the Commission’s futurepolicy in this area.The content of this report may not be reproduced, or even part thereof, without explicit reference to thesource.

Oceanic Développement & MegaPesca Lda (2011).Framework Contract for performing evaluations, impact analyses and monitoring services in the context ofFPAs concluded between the European Union and non-EU member statesNo.Fish/2006/20).DOCUMENT INTERNE : DROITS DE DIFFUSION RESERVES A LA C.E.

Contact des auteurs :

OCEANIC DEVELOPPEMENTZ.I. du Moros, 29900 Concarneau, FranceTel :Fax :Email :URL :+33 2 98 50 89 99+33 2 98 50 78 98[email protected]http://www.oceanic-dev.comVersion : Final ReportRéf. rapport: FPA 35/GRL/11/NCDate de publication :September 2011

Final Report

Fisheries Partnership Agreement FPA 2006/20

FPA 35/GRE/11

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS USEDACAPADAPIAIDCOAMAPAoILVETARVIATQCAFFCETACFPCPUEArctic Contaminants Action ProgramAssocia§ão dos Armadores da Pesca Industrial.EuropeAid Co-Operation OfficeArctic Monitoring and Assessment ProgrammeAgency of Industry, Labour Market and Vocational Education and TrainingCooperativa de Armadores de Buques de Pesca del Puerto de VigoAutonomous Tariff QuotaConservation of Arctic Flora and FaunaComprehensive Economic and Trade AgreementCommon Fisheries PolicyCatch Per Unit Effort

DAMOCLES Developing Arctic Modelling and Observing Capabilities for Long-termEnvironmental StudiesDFHADFODGDGPADKKDVFAEEAEEZEMODNETEPPREUEURFIDESFPAFTEGAGPBGDPGEPDepartment of Fisheries, Hunting and AgricultureDepartment of Fisheries and Oceans CanadaDirectorate-GeneralDirec§ão Geral das Pescas e Aquicultura.Danish KronerDanish Veterinary and Food AuthorityEuropean Economic AreaExclusive Economic ZoneEU Marine Observation and Data NetworkEmergency Prevention, Preparedness and ResponseEuropean UnionEuroFishery Information Data Exchange SystemFisheries Partnership AgreementFull-time EquivalentsEmployers AssociationBritish PoundGross Domestic ProductGreenland Education Programme

Final Report

Fisheries Partnership Agreement FPA 2006/20

FPA 35/GRE/11

GFLKGHLGHRGGINRGISGRTGRLHACCPHRGHSIAICESISKITITQIUUIWCJCKNAPKKPLTUMAPMFNMoCERCMoFFAMoHFAMoILMMOUMPAMSMSCMSYNAFO

Greenland Fishery and Licence ControlGreenland HalibutGreenland Home Rule GovernmentGreenland Institute of Natural ResourcesGeographical Information SystemsGross Registered TonnageGreenlandHazard Analysis and Critical Control PointHome Rule GovernmentHarmonised SystemInuit AtaqadigiitInternational Council for the Exploration of the SeIcelandic KronerInformation TechnologyIndividual Transferable QuotaIllegal, Unreported and UnregulatedInternational Whaling CommissionJoint CommitteeFishermen and Hunters associationA Greenland political party known by its initials “KP”LithuaniaModified Atmosphere PackagingMost Favoured NationMinistry of Culture, Education, Research and the ChurchMinistry of Finance and Foreign AffairsMarket Ministry of Health and Family AffairsMinistry of Industry and LabourMemorandum of UnderstandingMarine Protected AreaMember StatesMarie Stewardship CouncilMaximum Sustainable YieldNorthwest Atlantic Fisheries OrganizationFinal Report

Fisheries Partnership Agreement FPA 2006/20

FPA 35/GRE/11

NEAFCNGONOKNWWGOCTOSPARPDSPRGSDWGSSBSTECFTACsUKUNUNCLOSUSUSDVMEVMSWKREDS

North East Atlantic Fisheries CommissionNon Governmental OrganisationNorwegian KronerNorth Western Working GroupOverseas Countries and TerritoryConvention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the NE AtlanticProgramming Document for the Sustainable Development of GreenlandRoyal GreenlandSustainable Development Working GroupSpawning Stock BiomassScientific Technical and Economic Committee on FisheriesTotal Allowable CatchesUnited KingdomUnited NationsUnited Nations Convention on the Law of the SeaUnited StatesUnited States DollarVulnerable Marine EcosystemsVessel Monitoring and SurveillanceWorkshop on Redfish Stock Structure

Final Report

Fisheries Partnership Agreement FPA 2006/20

FPA 35/GRE/11

CONTENTS

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY................................................................................................................. IRÉSUMÉ EXÉCUTIF.....................................................................................................................VII1INTRODUCTION.........................................................................................................................11.11.222.12.22.32.42.52.62.72.833.13.23.33.43.53.63.73.83.944.14.24.355.15.25.3675

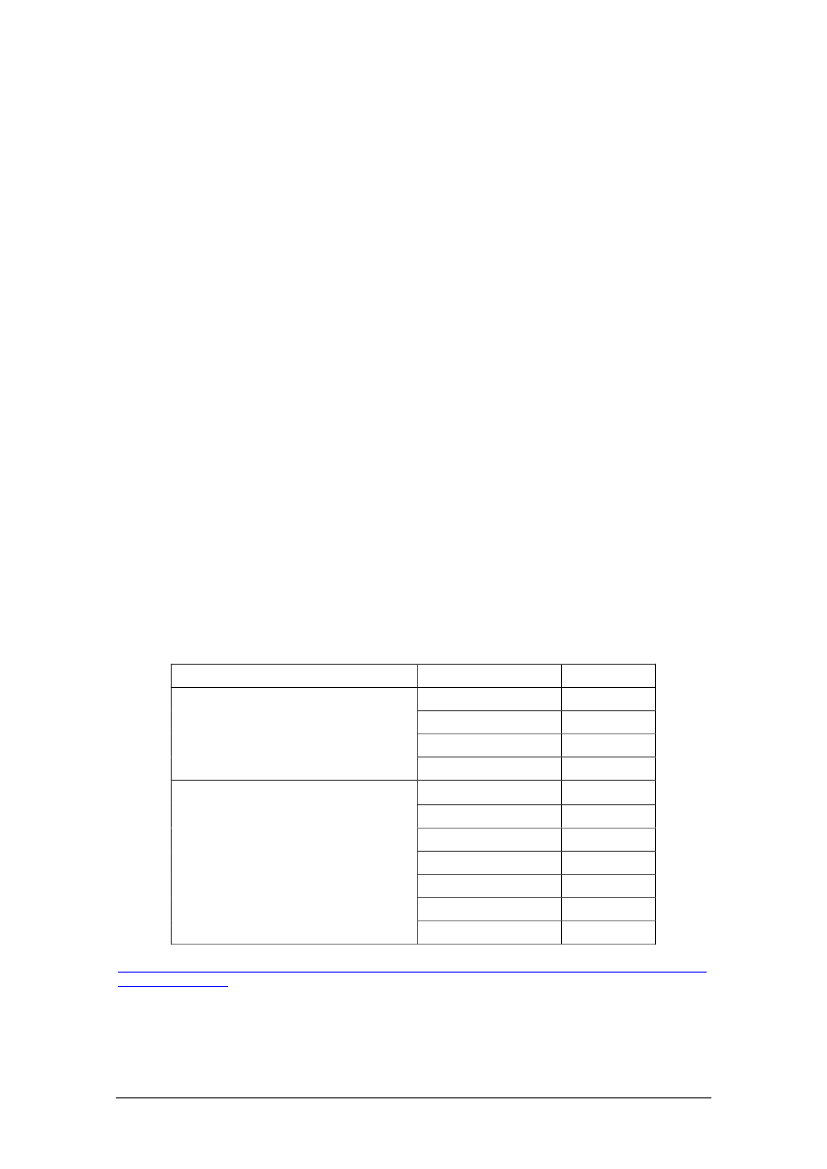

BACKGROUND..........................................................................................................................1METHODOLOGY.......................................................................................................................1POLITICAL SITUATION.............................................................................................................2ECONOMIC SITUATION...........................................................................................................3FISHERY SECTOR....................................................................................................................3OTHER SECTORS.....................................................................................................................4INTERNATIONAL TRADE..........................................................................................................5MARITIME BOUNDARIES.........................................................................................................6MEMBERSHIP OF THEARCTICCOUNCIL..........................................................................8EUPOLICIES WITH RESPECT TOGREENLAND................................................................9FISHINGFLEET.......................................................................................................................15GREENLAND CATCHES.........................................................................................................17PROCESSING INDUSTRY......................................................................................................22HEALTH AND HYGIENE CONDITIONS.................................................................................24EMPLOYMENT IN FISHERIES...............................................................................................25INTERNATIONALTRADE INFISHERIESPRODUCTS......................................................25FISHERY SECTOR ORGANISATIONS..................................................................................31FISHERIESAGREEMENTS WITH OTHER THIRD COUNTRIES.......................................32FISHERIESMANAGEMENT INGREENLAND....................................................................36FISH STOCKS..........................................................................................................................39NON-TARGET IMPACTS OF FISHERIES ACTIVITY...........................................................56MARINEPROTECTEDAREAS.............................................................................................58THEEU-GREENLANDFISHERIESPARTNERSHIPAGREEMENT...............................60AVAILABILITY OF QUOTA AS PERPROTOCOL................................................................63UTILISATION OF FISHING OPPORTUNITIES.....................................................................65

POLITICAL AND ECONOMIC CONTEXT......................................................................2

GREENLAND’S FISHERY SECTOR..............................................................................15

GREENLAND’S FISHERY RESOURCES AND MANAGEMENT....................39

EU-GREENLAND FISHERIES PARTNERSHIP AGREEMENT........................60

FINANCIAL AND ECONOMIC IMPACTS OF THE EU- GREENLAND FPA6.16.26.36.4MARKET VALUES OF SPECIES SUBJECT TO THEFPA................................................75FINANCIAL AND ECONOMIC IMPACTS ONEU.................................................................77FINANCIAL AND ECONOMIC IMPACTS ONGREENLAND...............................................81FINANCIAL AND ECONOMIC IMPACTS ON THIRD COUNTRIES....................................84

7

IMPACTS OF THE FISHERIES SECTOR POLICY SUPPORT MEASURES84

7.1

SOURCE OF DATA ON PROGRESS AGAINST INDICATORS...........................................84

Final Report

Fisheries Partnership Agreement FPA 2006/20

FPA 35/GRE/11

7.27.37.47.57.6898.19.19.29.39.49.59.61011

OVERALL OBJECTIVES OF THE MEASURES....................................................................84AREA1: ADMINISTRATION FOR THE FISHERIES2007-2012....................................85AREA2: CONTROL AND ENFORCEMENT.........................................................................89AREA3: BIOLOGICAL ADVICE............................................................................................91SUMMARY OF PROGRESS ON IMPLEMENTATION OF THE MEASURES.....................94IMPACTS ON TARGET FISHERY RESOURCES..................................................................96RELEVANCE..........................................................................................................................100EFFECTIVENESS..................................................................................................................100EFFICIENCY...........................................................................................................................101SUSTAINABILITY AND ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTS.......................................................101COHERENCE AND COMPLEMENTARITY.........................................................................102EUADDED VALUE................................................................................................................102CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS....................................................103ANNEXES...............................................................................................................................104

RESOURCE AND ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTS....................................................96FINDINGS OF THE EX-POST EVALUATION..........................................................100

ANNEX1: QUOTASDELIVERED UNDER THEEU-GREENLANDFISHERIESPARTNERSHIPAGREEMENT.........................................................................................................104ANNEX2: ANNUAL CATCHES AND VALUES OF CATCHES.....................................................109ANNEX3: DEPENDENCY OFEUBILATERAL EXCHANGES WITH THIRD COUNTRIES ONTHEEU GREENLANDFPA...........................................................................................................110ANNEX4: SCIENTIFIC ADVICE,ADOPTEDTACS,AND CATCHES FOR STOCKS OFRELEVANCE TO THEFPADURING THE PERIOD OF THE CURRENT PROTOCOL(2007-2011).................................................................................................................................................113

Final Report

Fisheries Partnership Agreement FPA 2006/20

FPA 35/GRE/11

TABLES

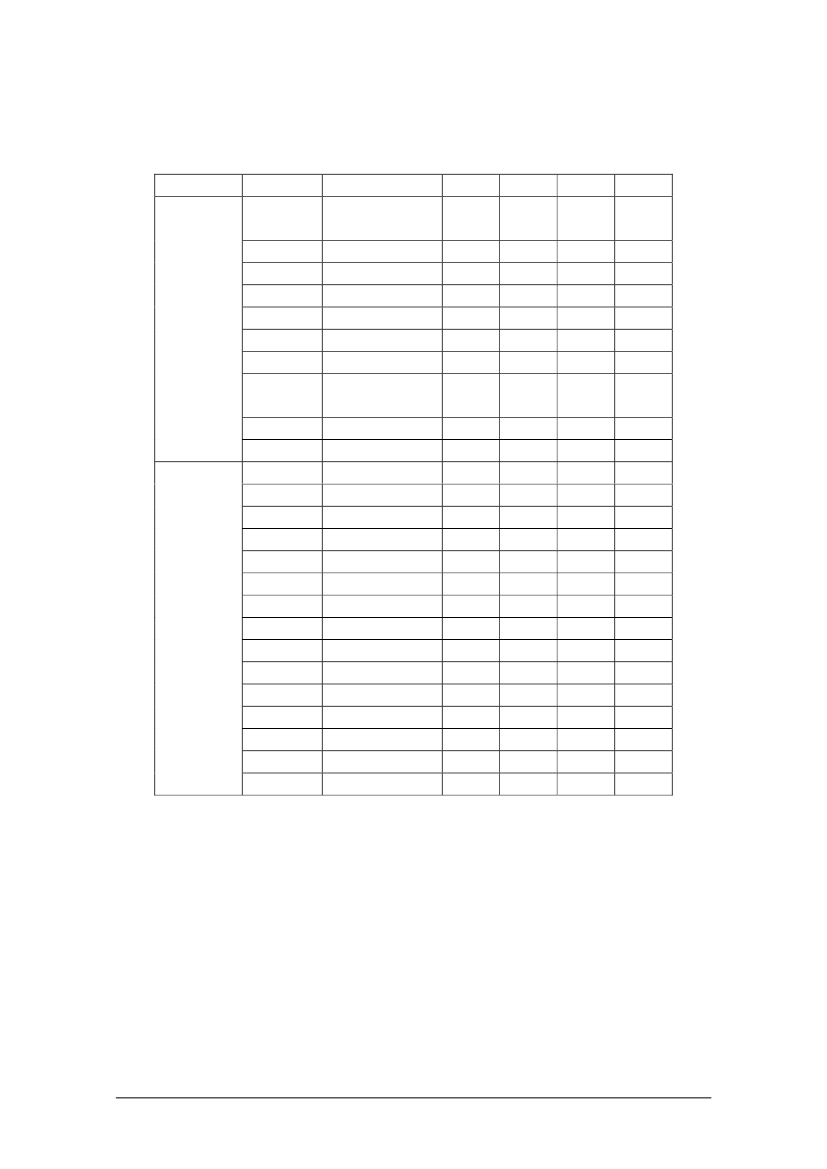

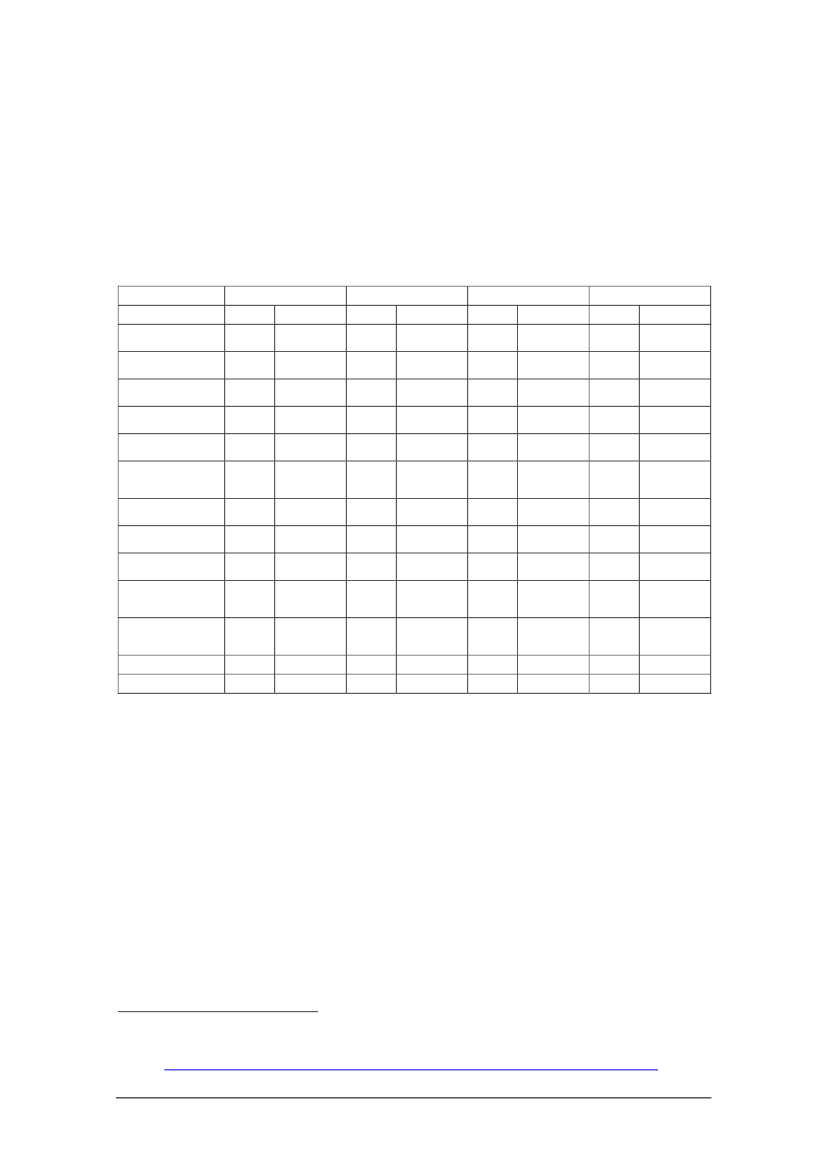

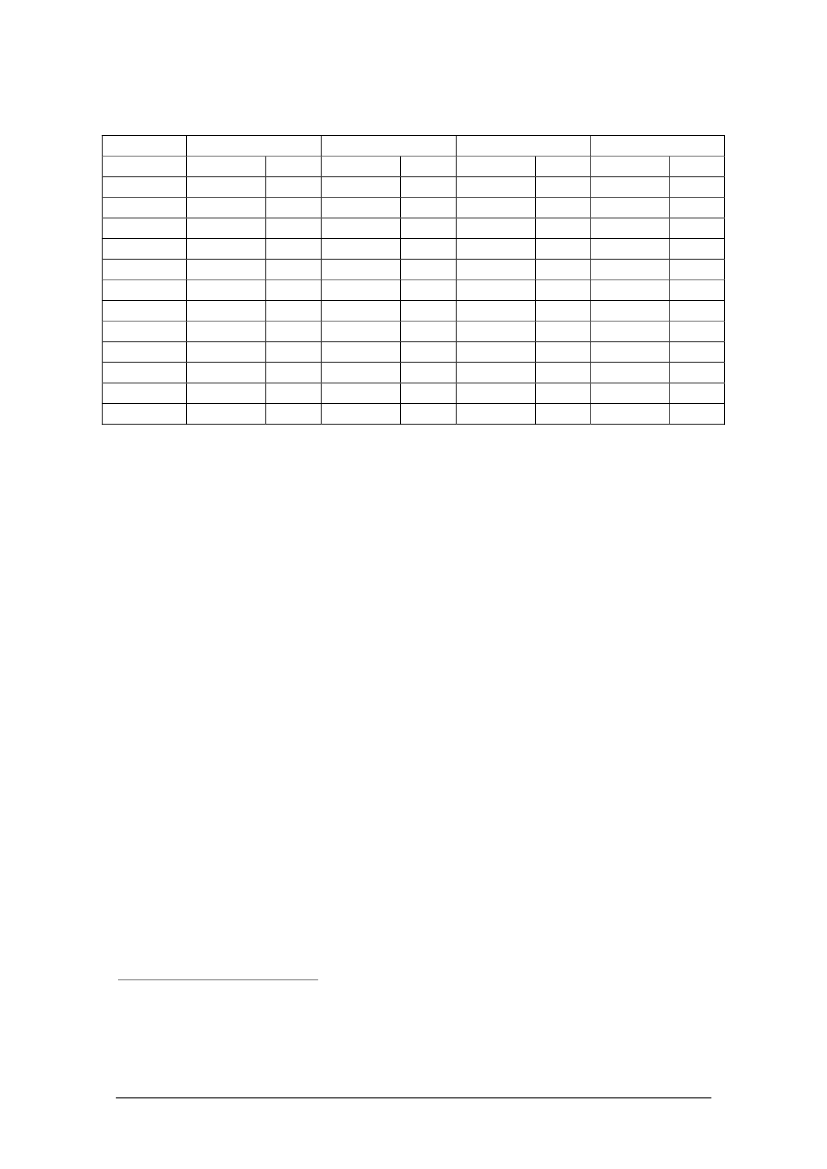

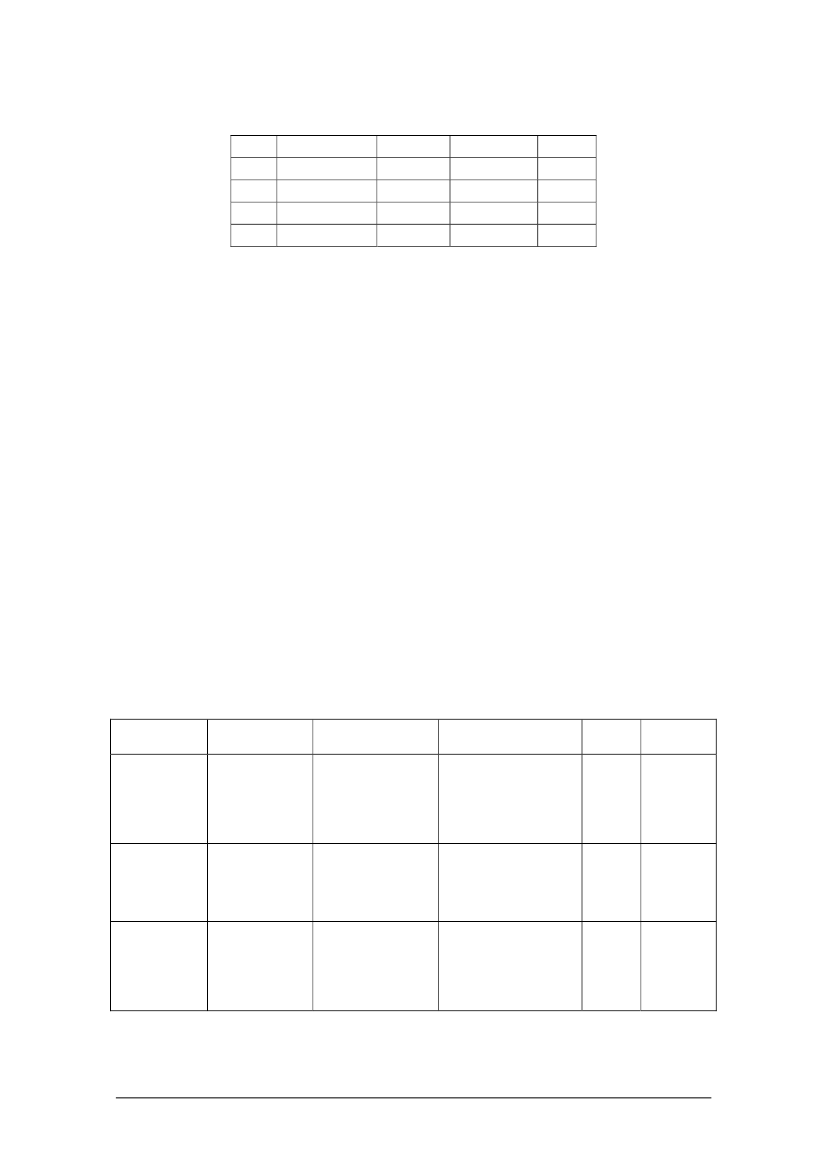

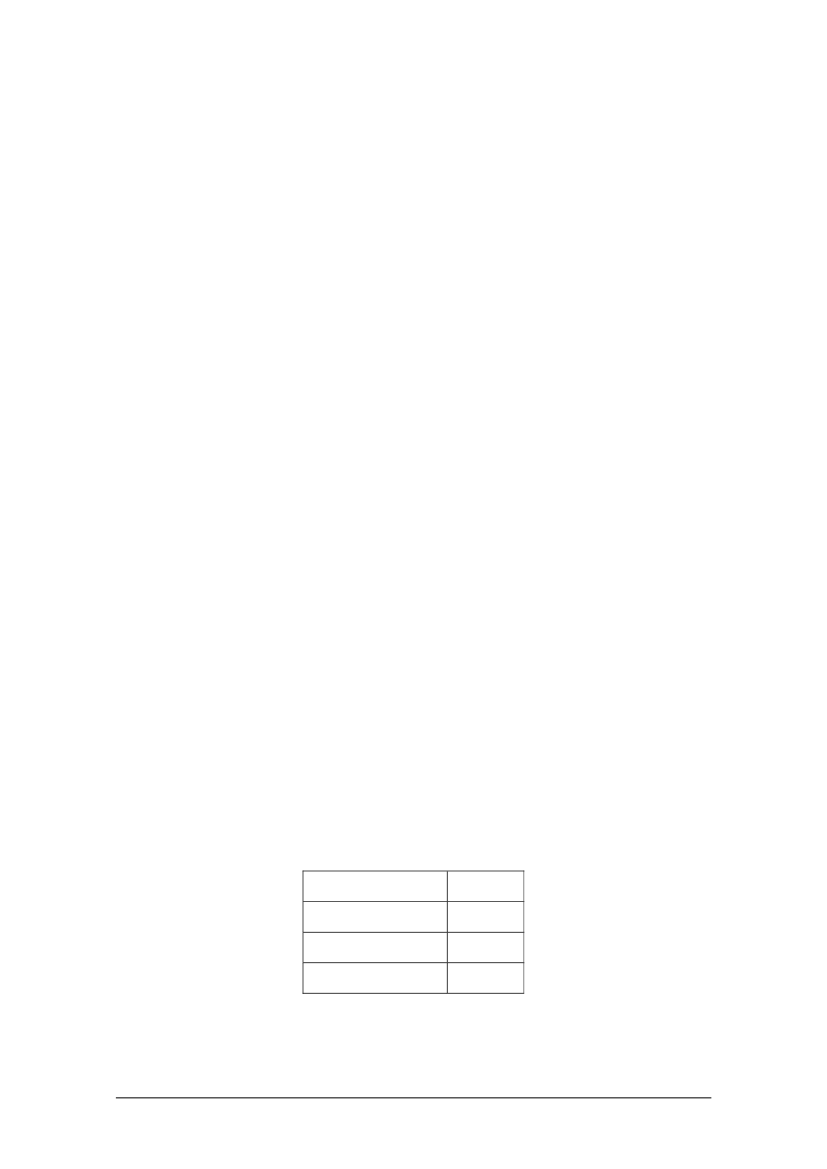

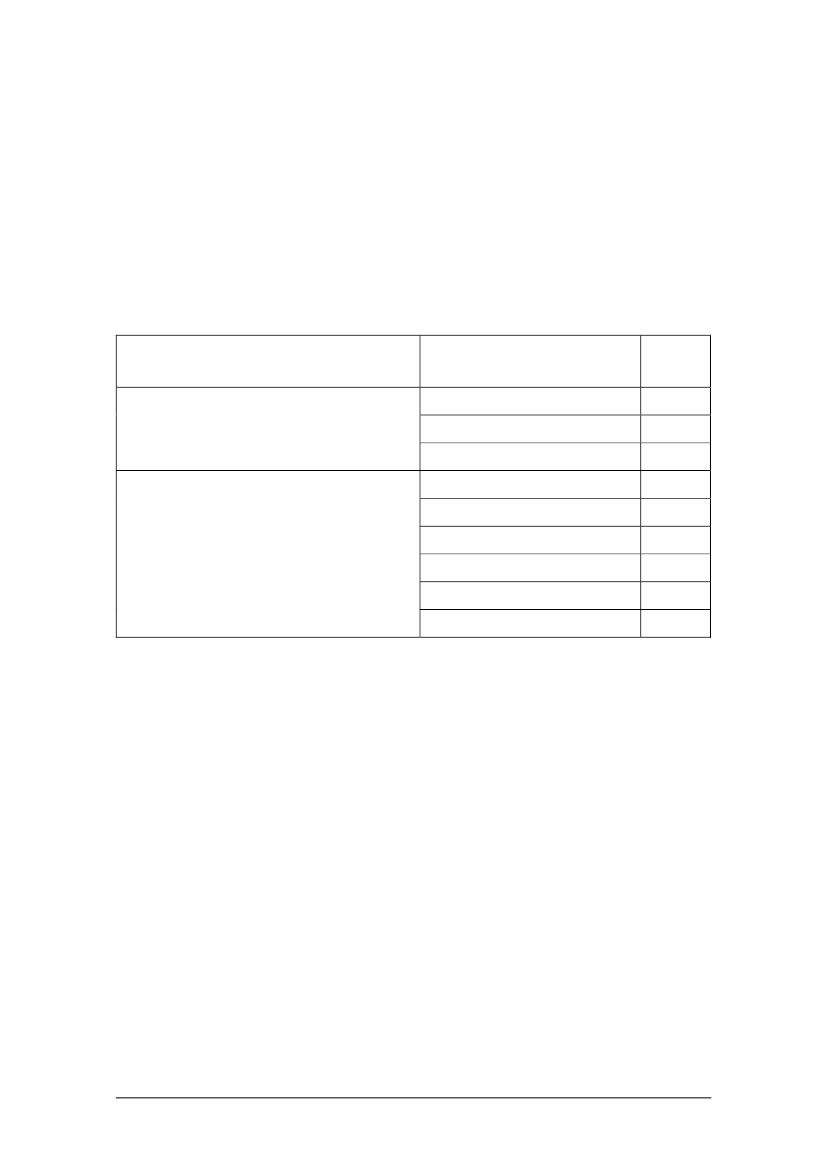

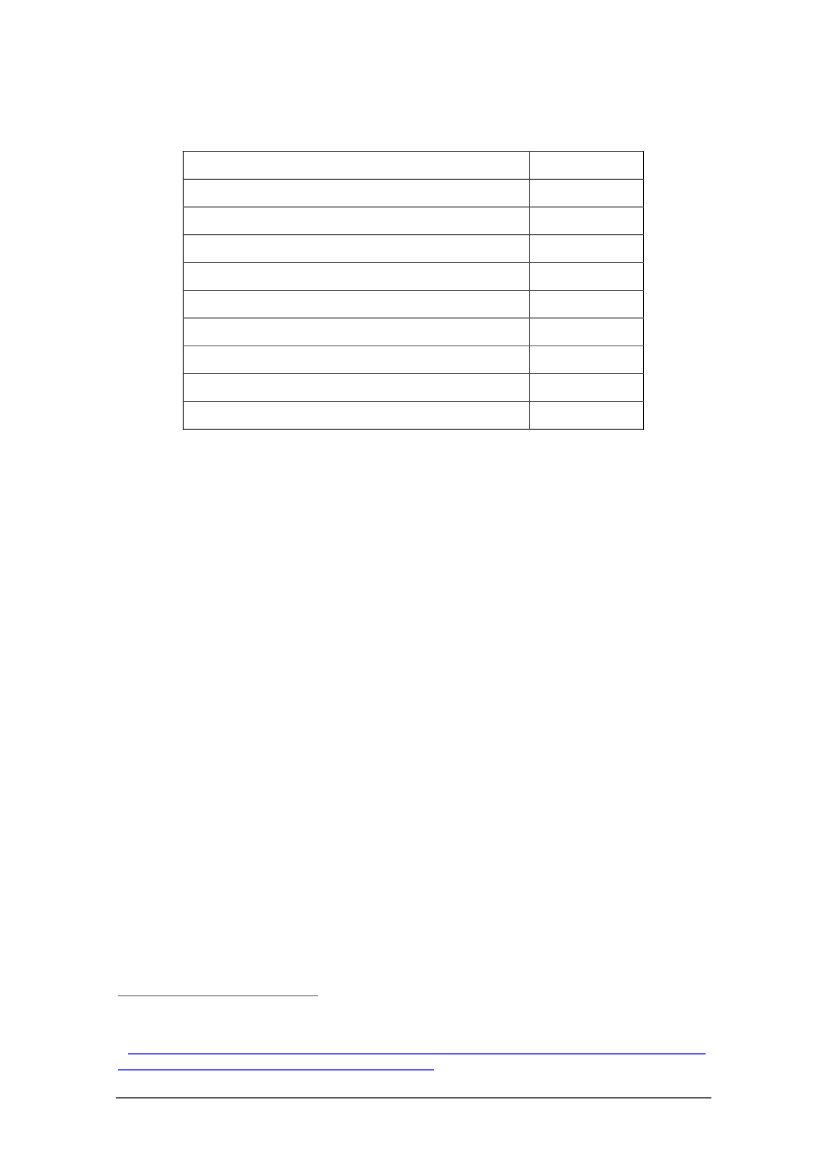

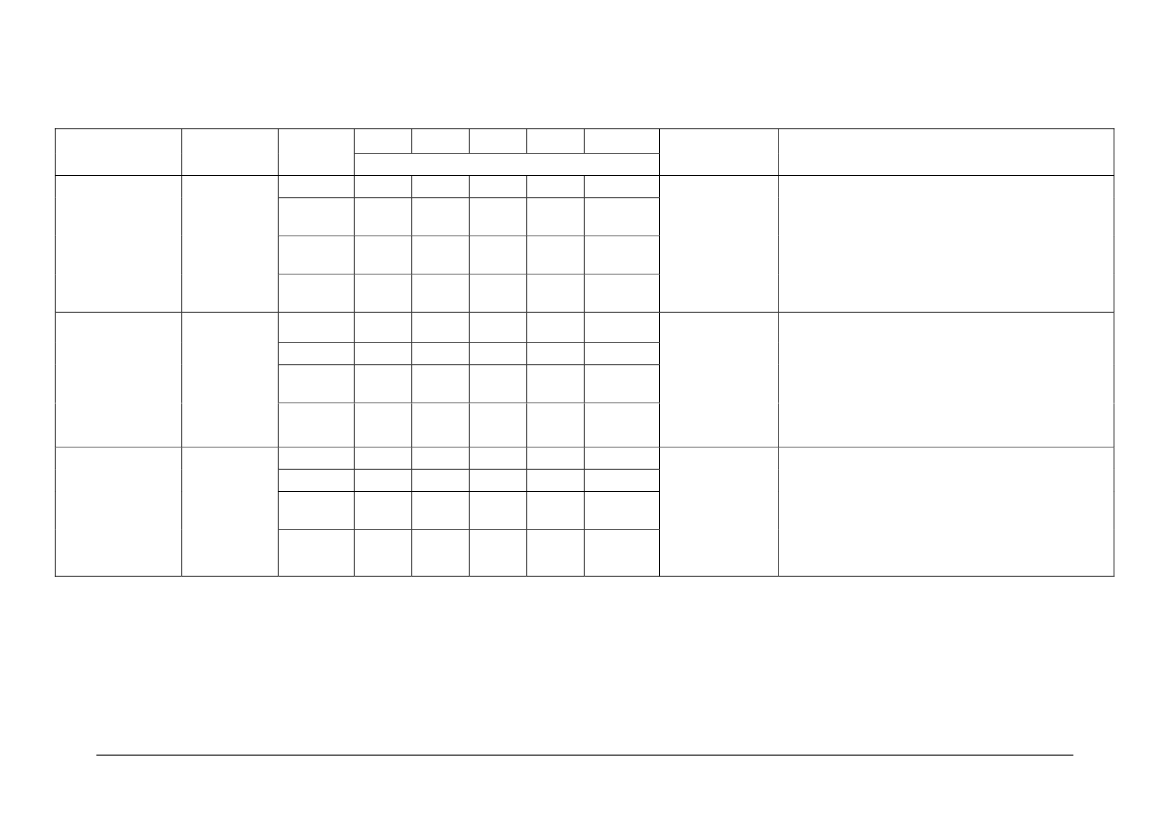

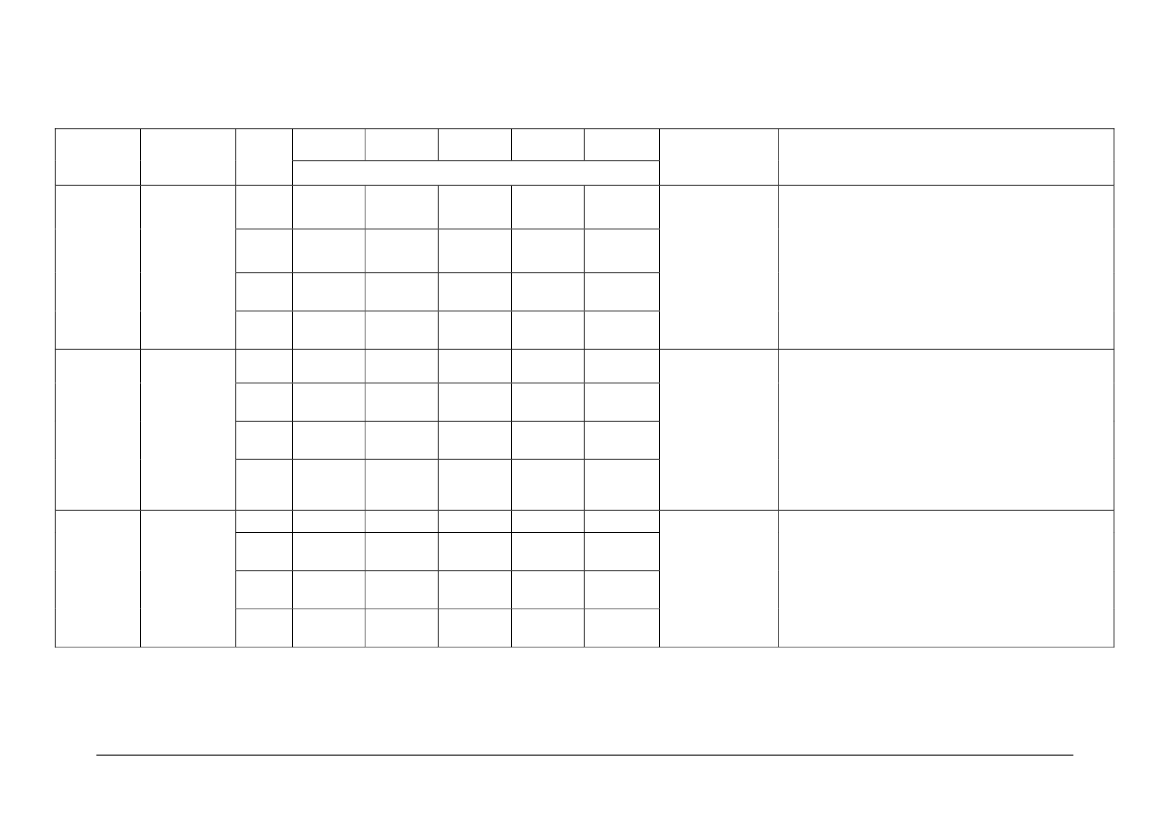

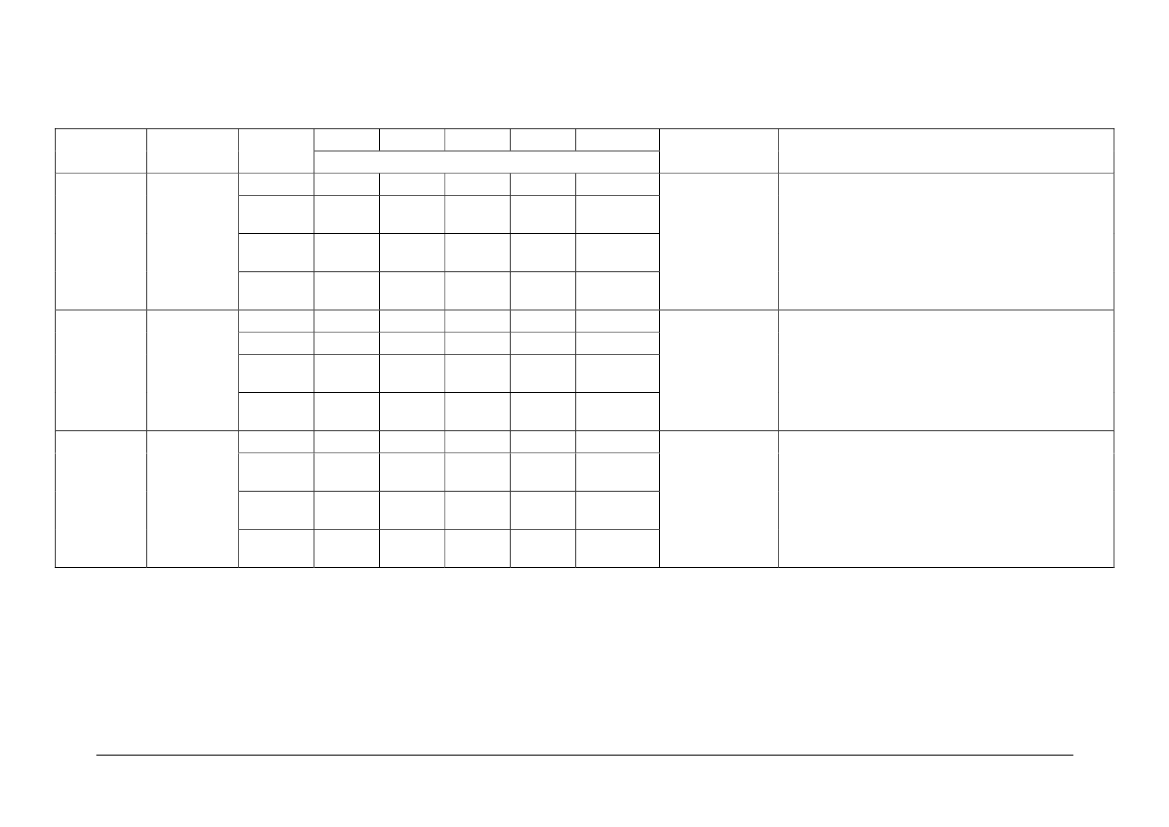

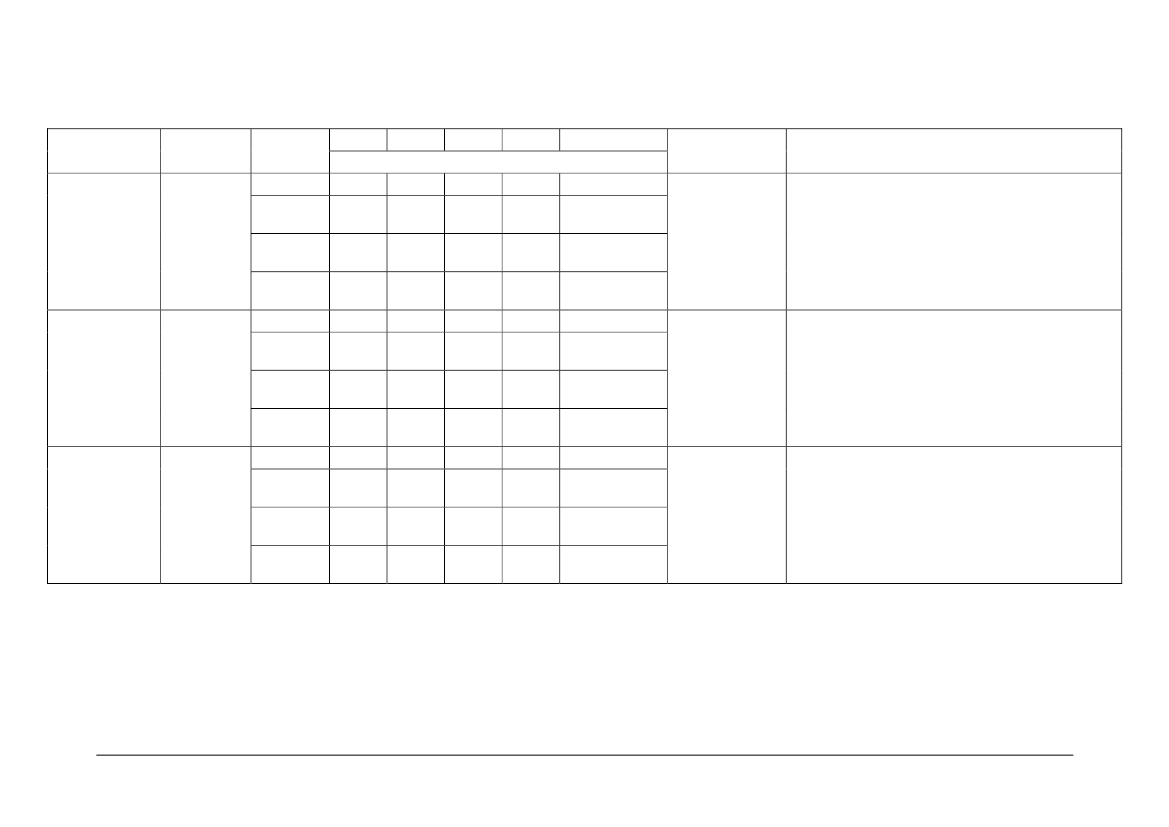

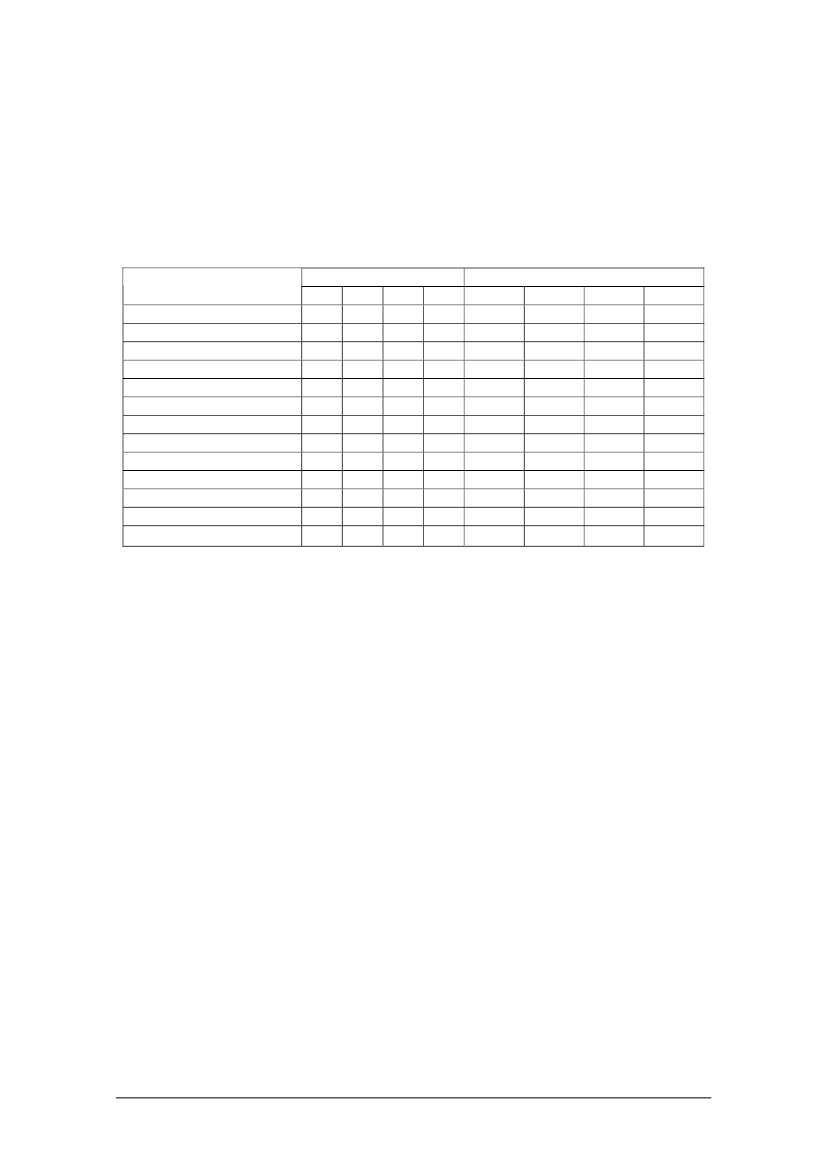

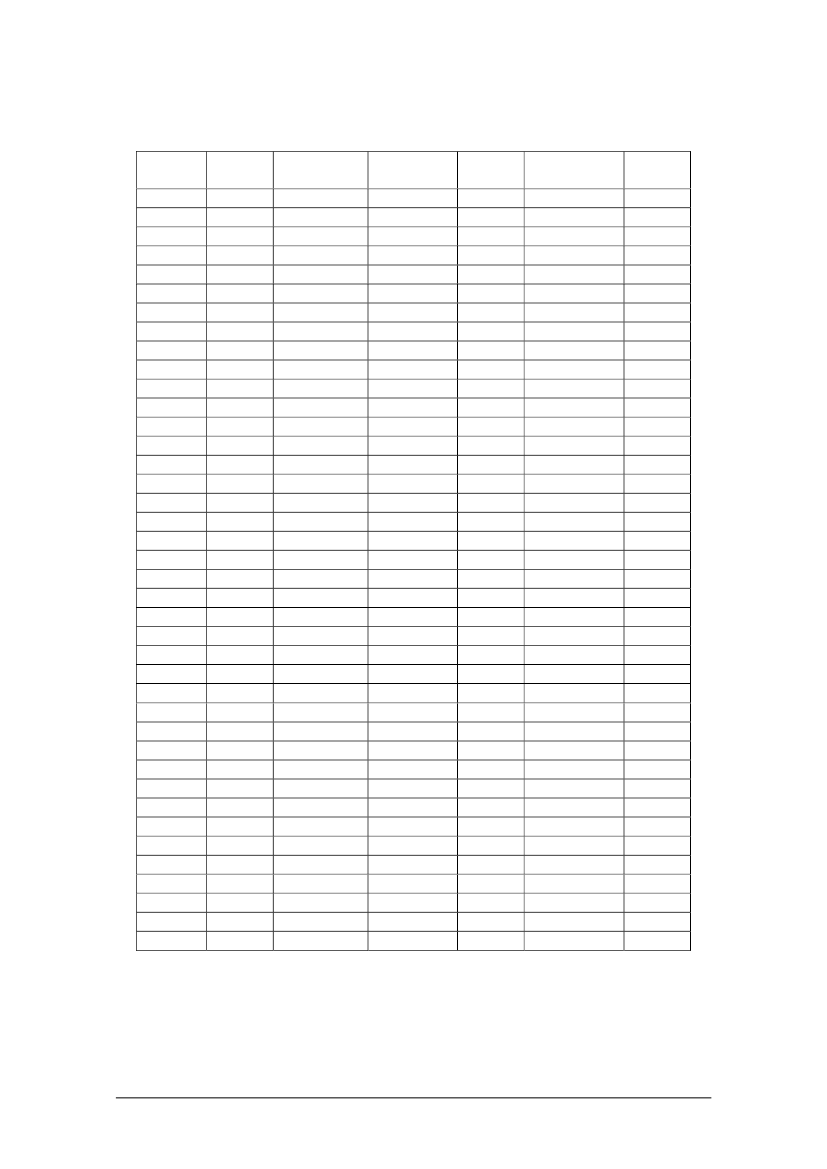

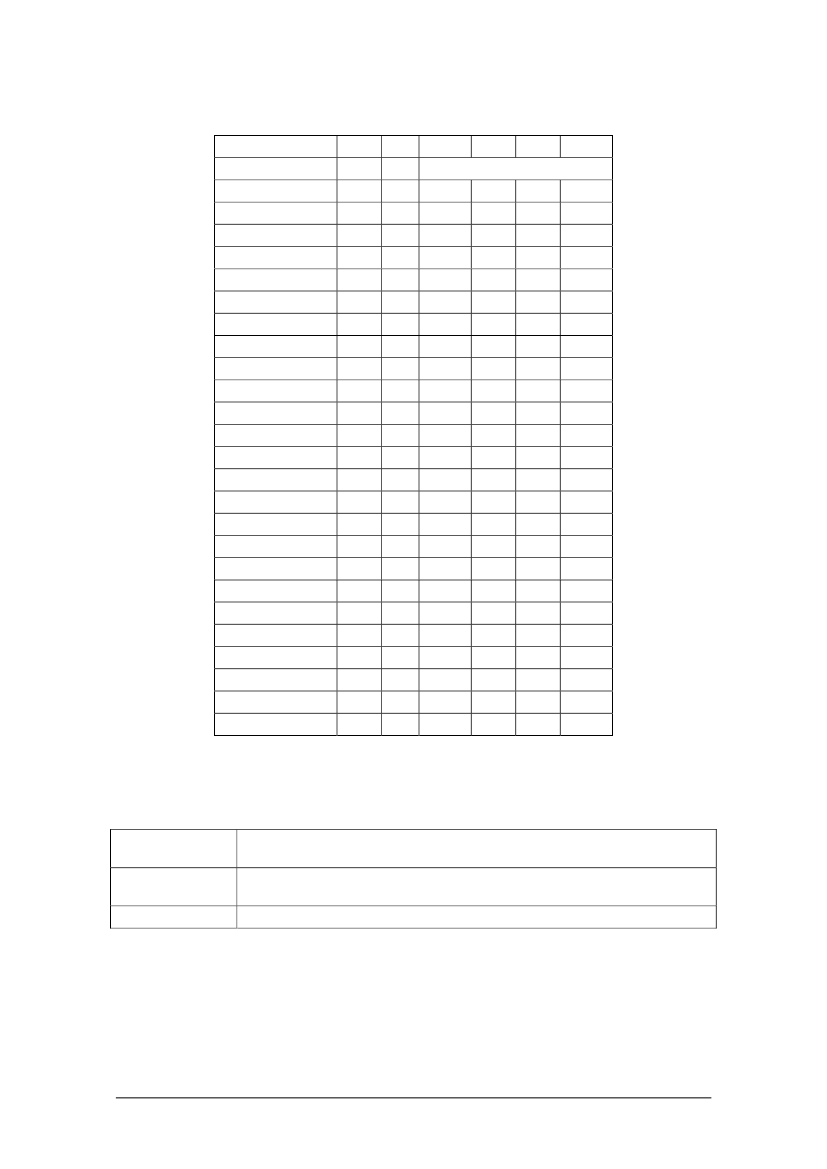

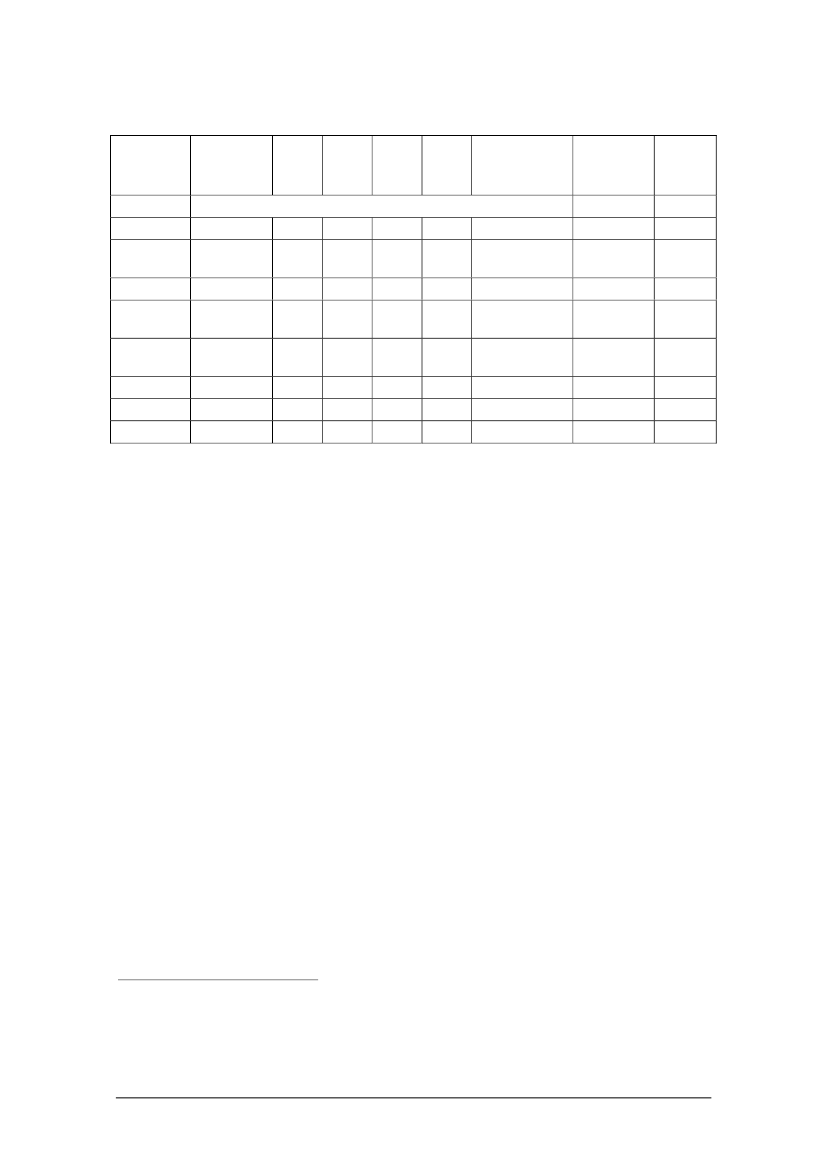

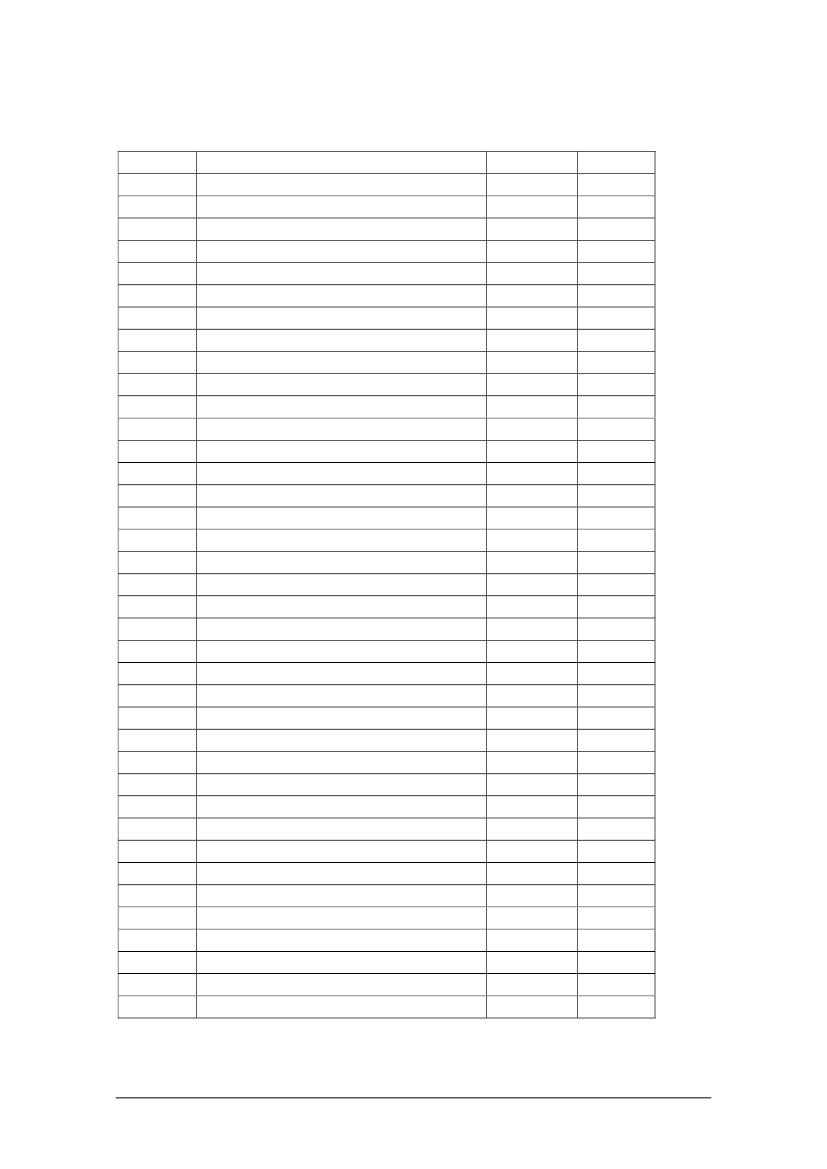

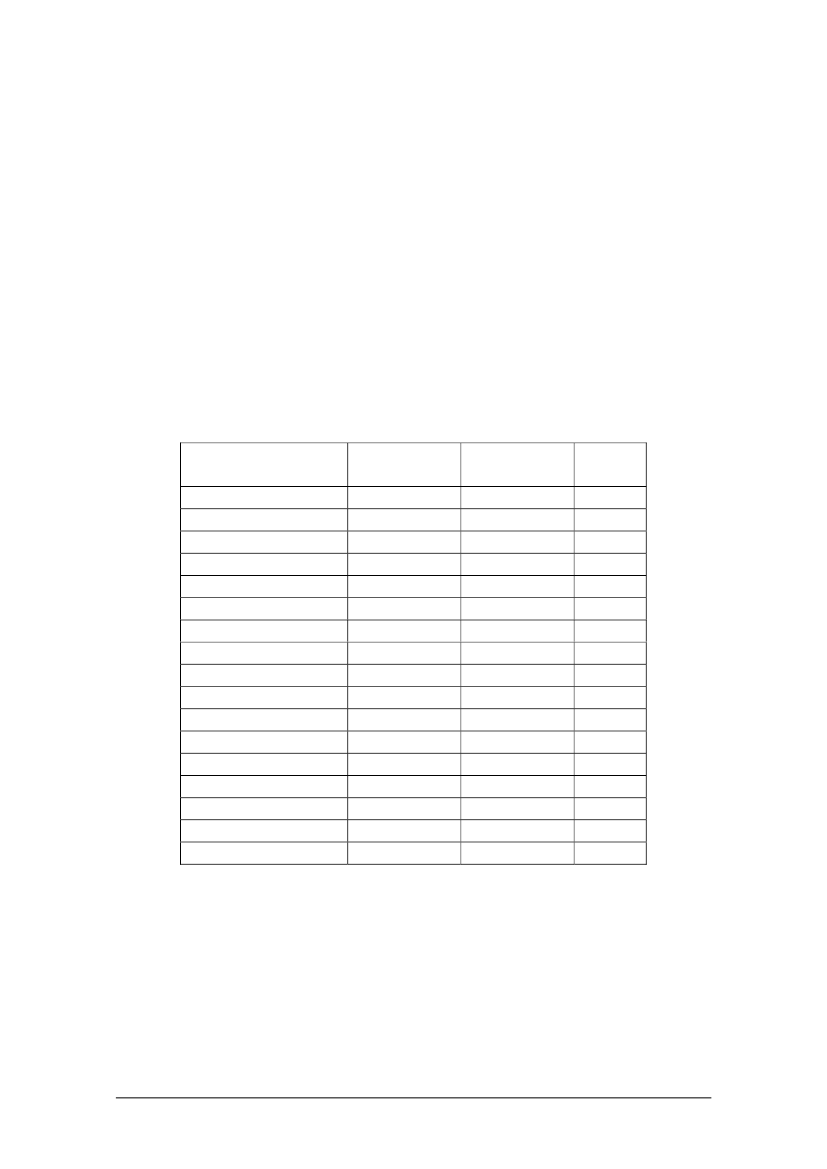

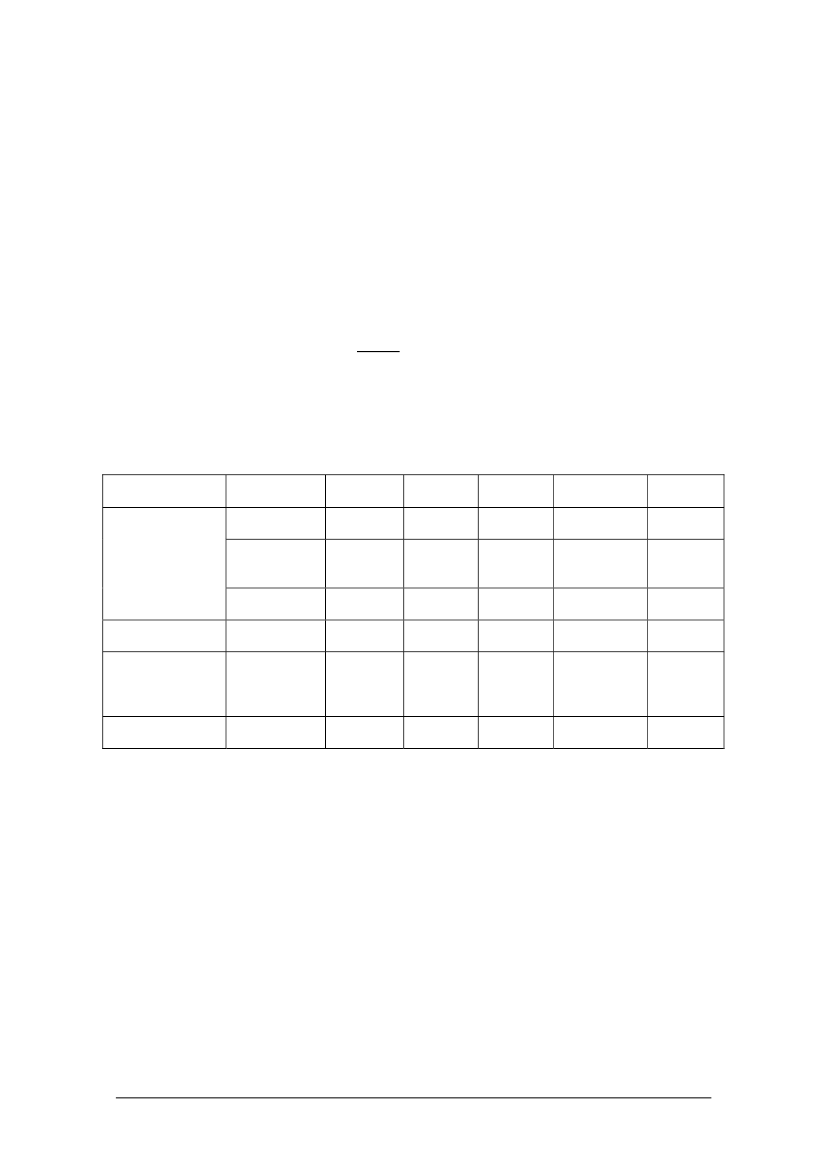

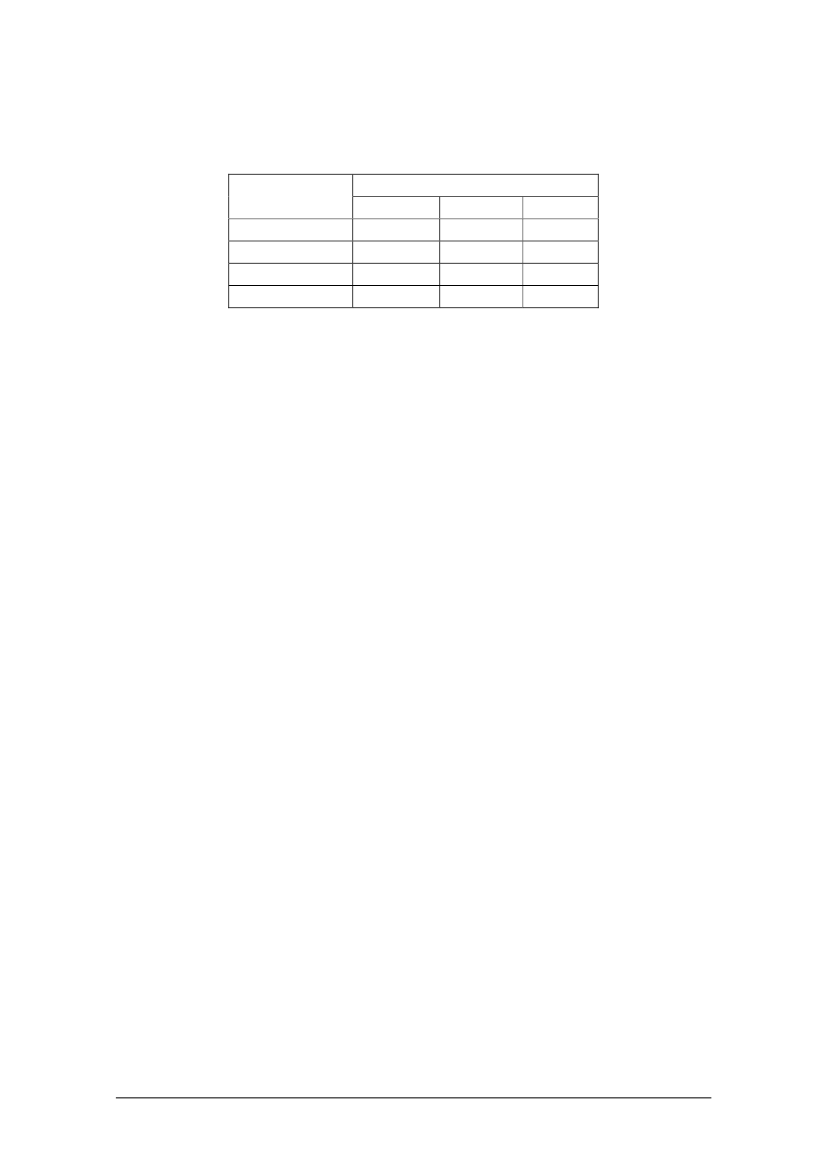

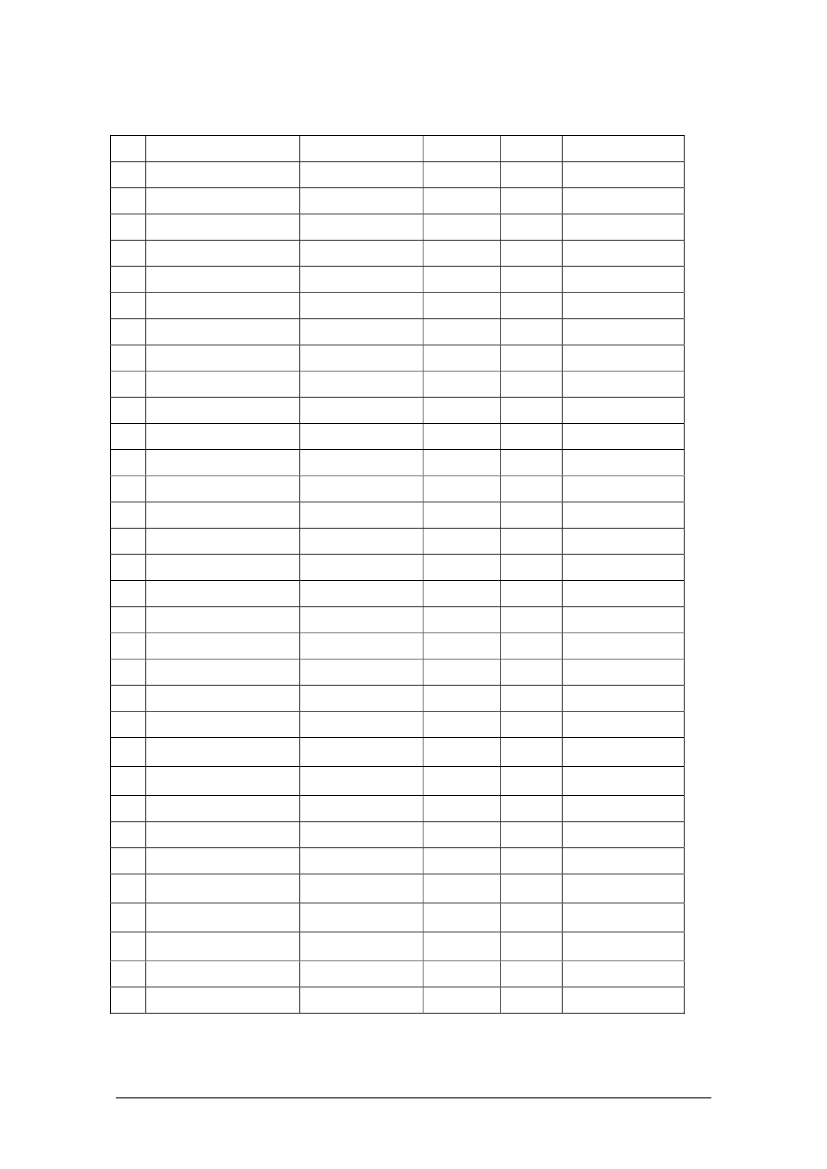

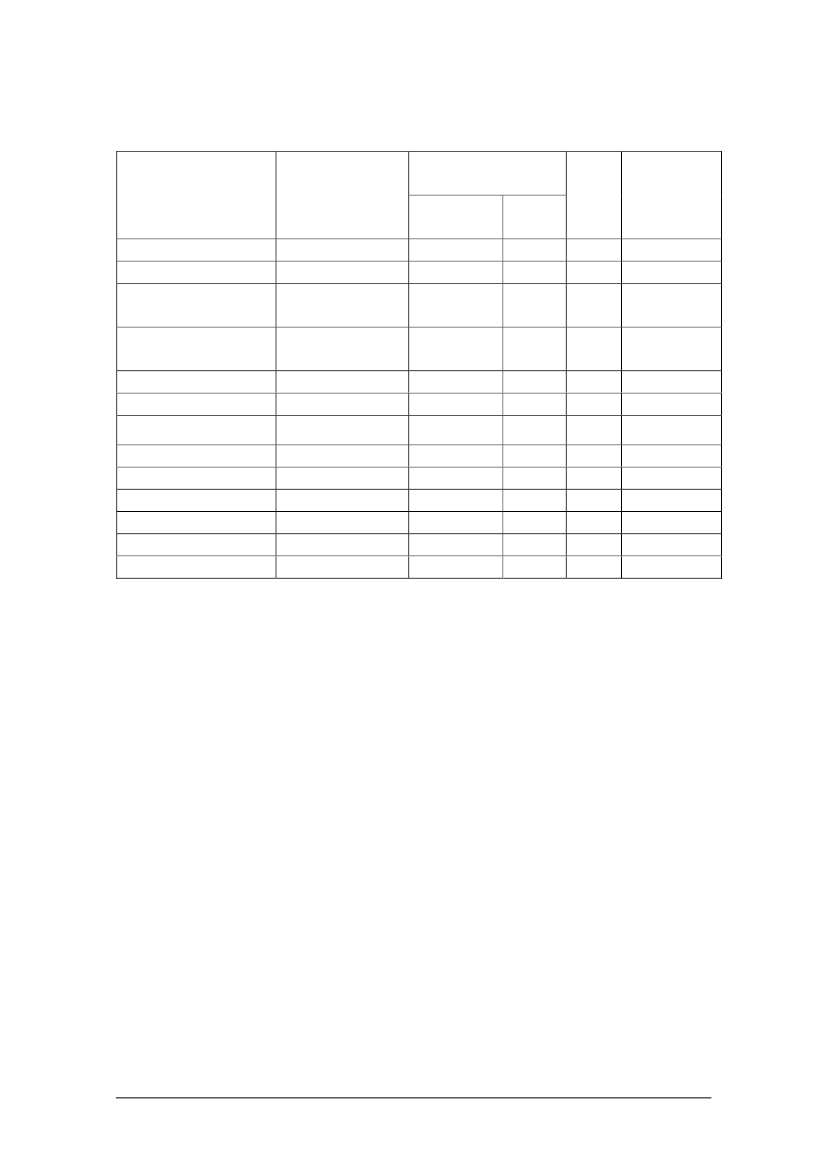

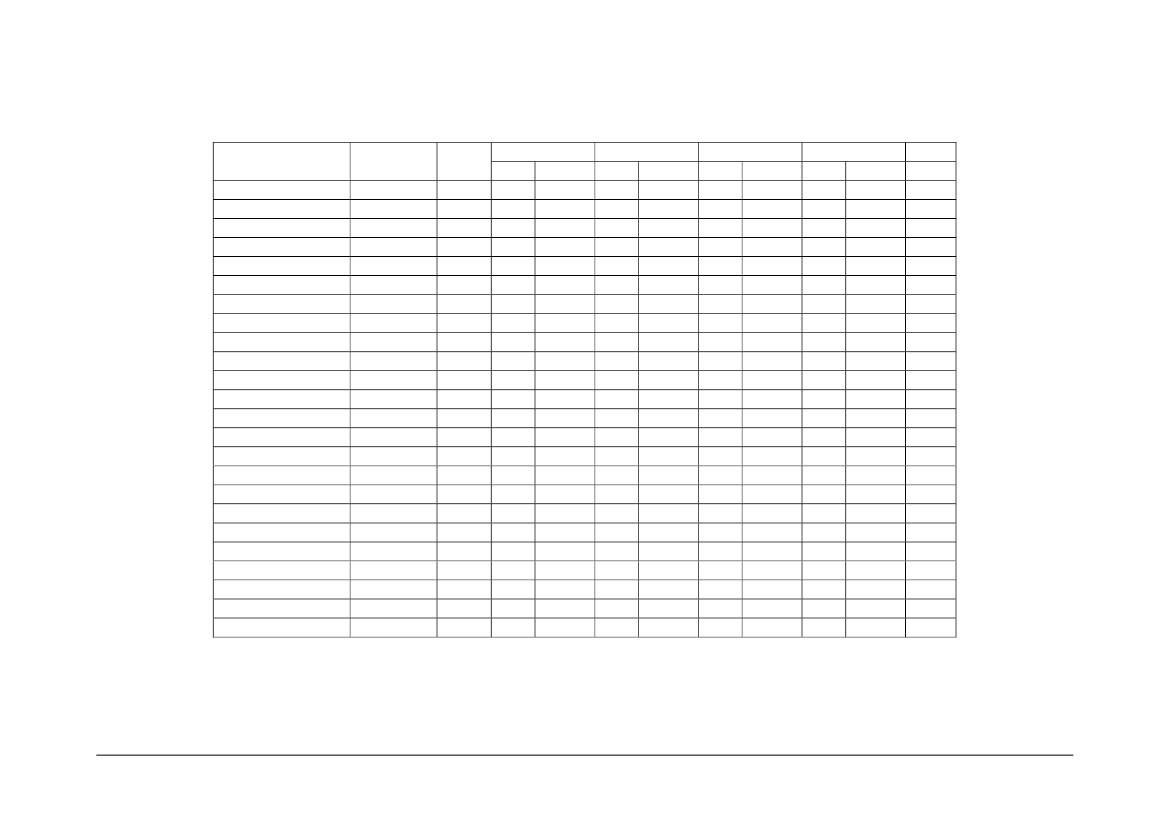

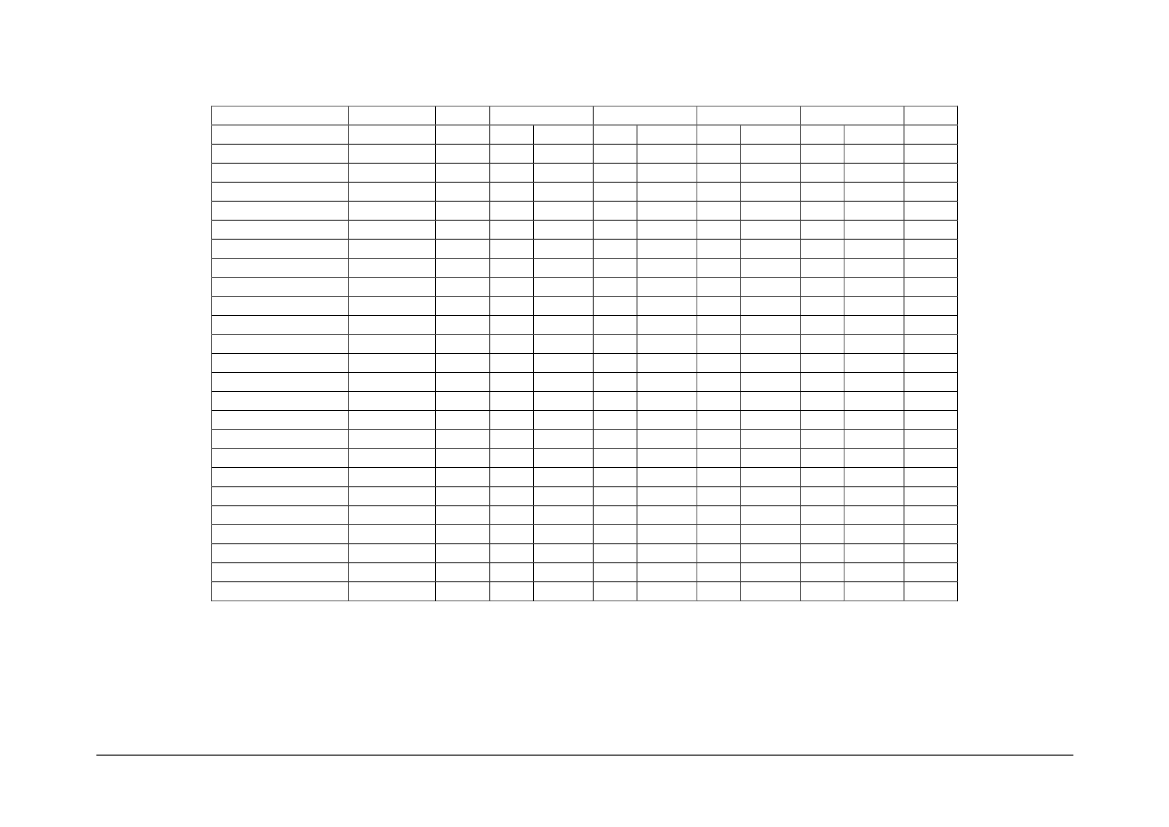

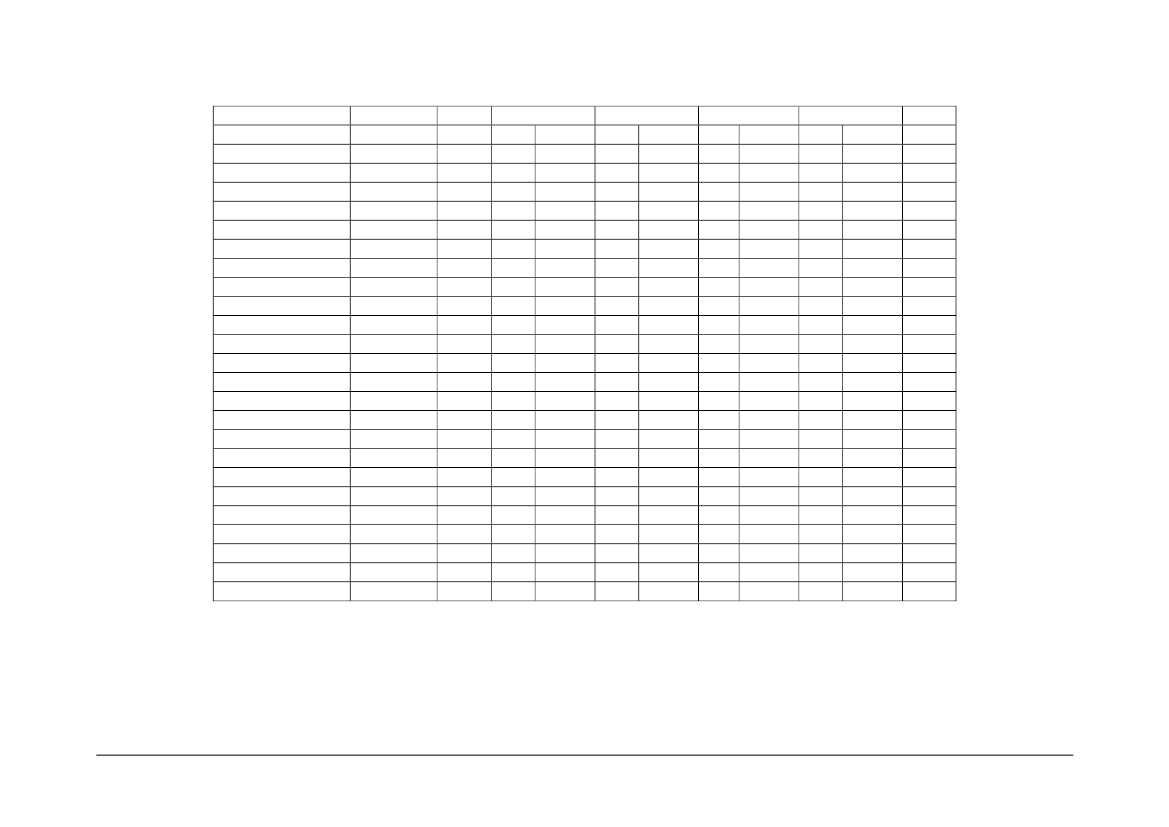

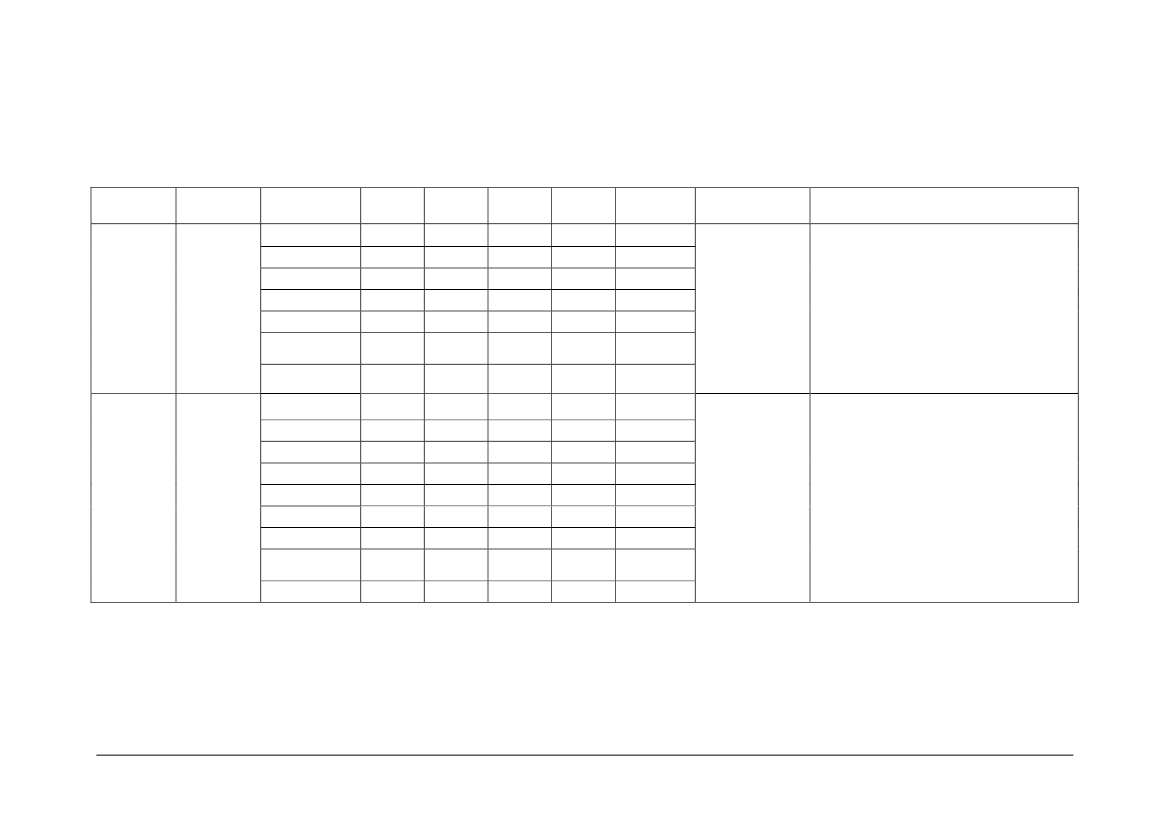

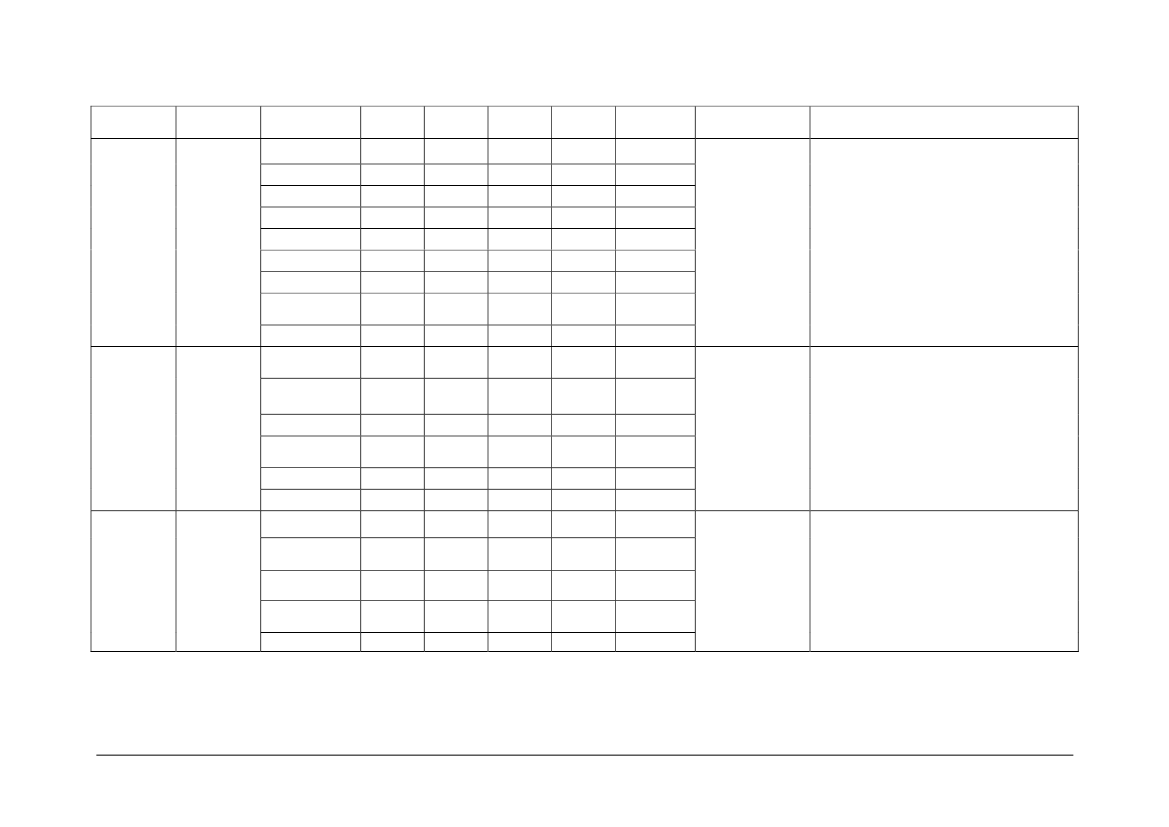

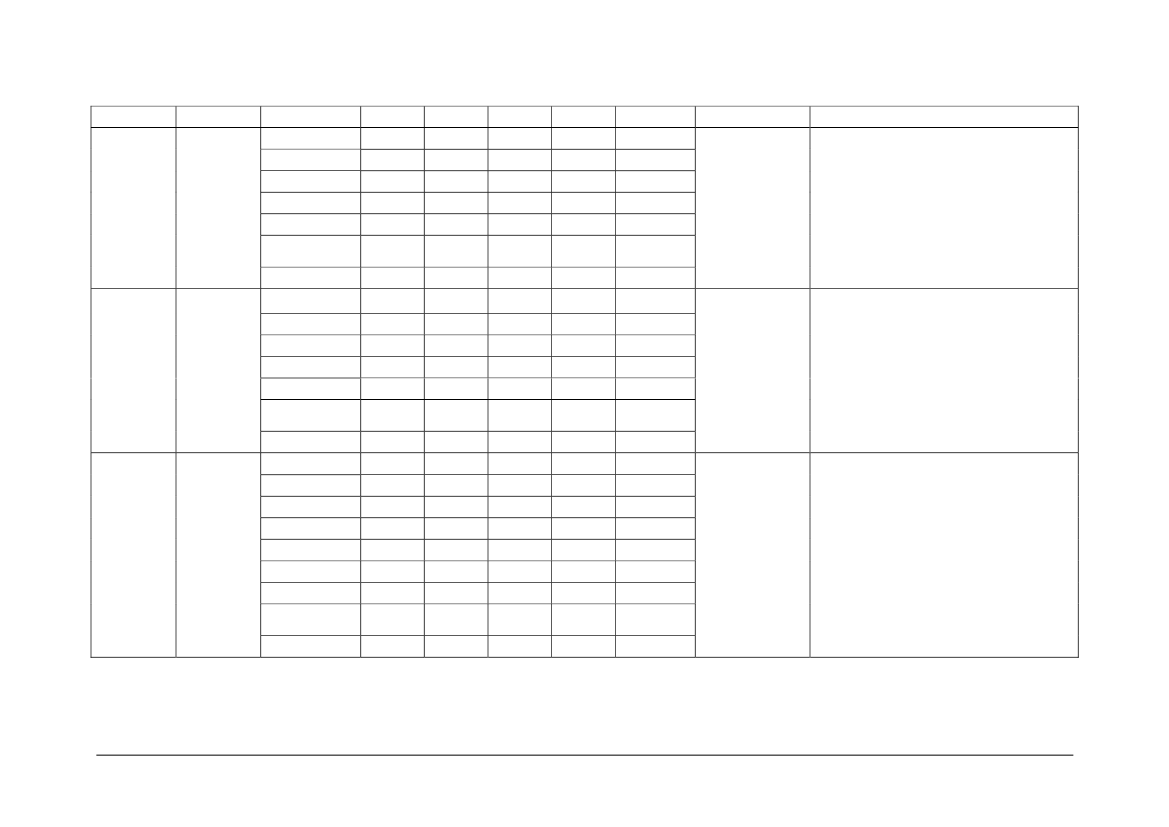

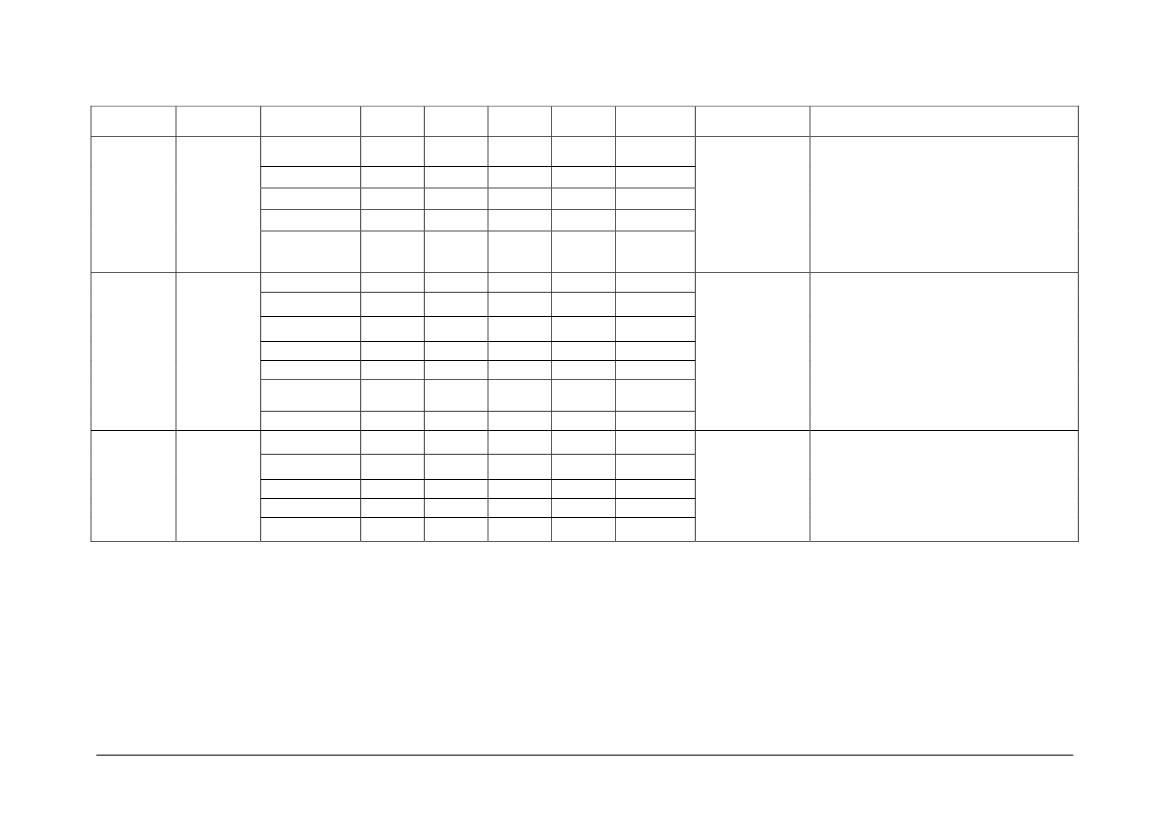

Table 1:Greenland Exports................................................................................................... 6Table 2: Summary of Greenland responsibilities to Arctic Council WorkingGroups................................................................................................................................ 9Table 3: Characteristics of and trends in dimensions of Greenland fishing fleet16Table 4: Total catches in GRL waters (including foreign vessels).......................... 18Table 5: Catches of cod in Greenland (including foreign vessels)......................... 19Table 6: Other catches taken by Greenland vessels inside and outside theGreenland EEZ............................................................................................................... 20Table 7: Catches of foreign fleets operating in Greenland waters........................ 21Table 8: Numbers of small scale fishermen in four municipalities.......................... 25Table 9: Imports of fishery products from Greenland to the EU.............................. 26Table 10: Principal EU market destinations................................................................... 27Table 11: Utilisation of EU’s erga omnes import tariff quota on cooked andpeeled shrimp................................................................................................................. 28Table 12: Zero duty tariff quotas of non-originating products exported fromGreenland to the EU..................................................................................................... 28Table 13: Utilisation by Greenland of the tariff quota for non-originating fisheryproducts............................................................................................................................ 29Table 14: Modifications to tariff regime impacting upon trade in fishery productsfrom Greenland............................................................................................................... 29Table 15: Allocation keys for capelin............................................................................... 32Table 16: Exchange of fishing opportunities under the Greenland-NorwayFisheries Agreement (2011)....................................................................................... 33Table 17: Exchange of fishing opportunities under the Greenland-RussiaFisheries Agreement (2011)....................................................................................... 34Table 18: Exchange of fishing opportunities under the Faroes-GreenlandFisheries Agreement..................................................................................................... 35Table 19: Distribution of ITQ rights in the offshore shrimp fishery of Greenland37Table 20: Sustainability of Greenland fisheries subject to the EU-GreenlandFisheries Partnership Agreement............................................................................. 52Table 21: Level of indicative fishing opportunities established by the Protocol.. 62Table 22: Quotas Delivered under the EU-Greenland Fisheries PartnershipAgreement 2007-2010................................................................................................. 64

Final Report

Fisheries Partnership Agreement FPA 2006/20

FPA 35/GRE/11

Table 23: No. and capacity of EU vessels drawing licences under the FisheriesPartnership Agreement................................................................................................ 66Table 24: Average annual utilisation of fishing opportunities and catches underthe EU-Greenland Fisheries Partnership Agreement *...................................... 67Table 25: Composition and quantity of bycatch declared by EU vessels in theGreenland EEZ (2008)................................................................................................. 72Table 26: Greenland quotas exchanged between EU Member States 2007-2010............................................................................................................................................. 74

Table 27: Latest release dates for intra-community quota swaps (shrimp andredfish).............................................................................................................................. 74Table 28: Exchange of issued fishing licences for Greenland opportunitiesbetween Member States.............................................................................................. 75Table 29: Market values of fish caught under the EU-Greenland FPA................. 77Table 30: Average annual costs and benefits to the EU and Greenland of theEU-Greenland FPA....................................................................................................... 78Table 31: Average annual value of the catches under the Fisheries PartnershipAgreement....................................................................................................................... 79Table 32: Dependency on Greenland quota of bilateral exchanges of fishingopportunities with third countries.............................................................................. 81Table 33: Licence fees paid by EU vessels operating under the EU-GreenlandFPA.................................................................................................................................... 82Table 34: Greenland budget allocations specified in the context of FPA fisherysector support................................................................................................................. 83Table 35: Structural adjustment projects supported in 2007 / 2008....................... 88Table 36: Training courses undertaken by Greenland Fisheries Officials 2008-2009................................................................................................................................... 89Table 37: Expenditure on Control and enforcement functions................................ 90Table 38: Production of management advice for commercially important fishstocks................................................................................................................................ 93Table 39: Overview of impacts on stocks of relevance to the EU GreenlandFisheries Partnership Agreement during the period of the current protocol(2007-2011)..................................................................................................................... 97

Final Report

Fisheries Partnership Agreement FPA 2006/20

FPA 35/GRE/11

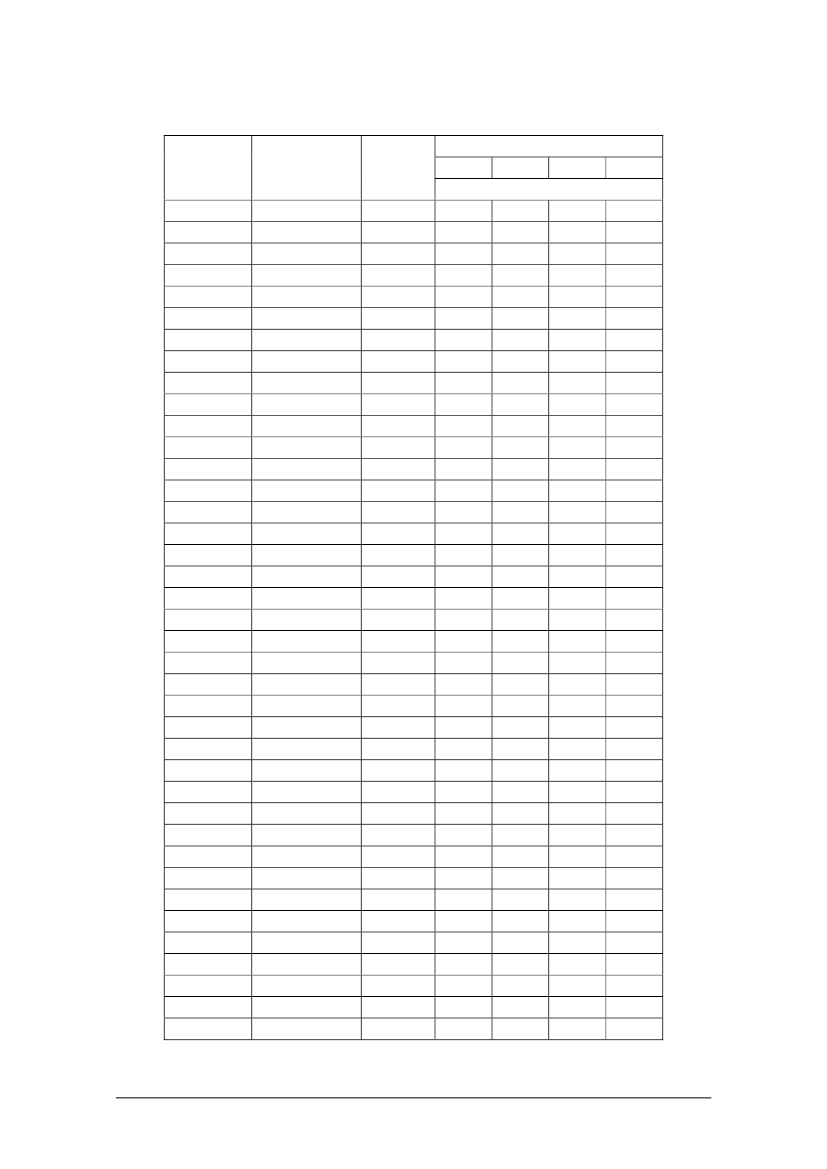

FIGURES

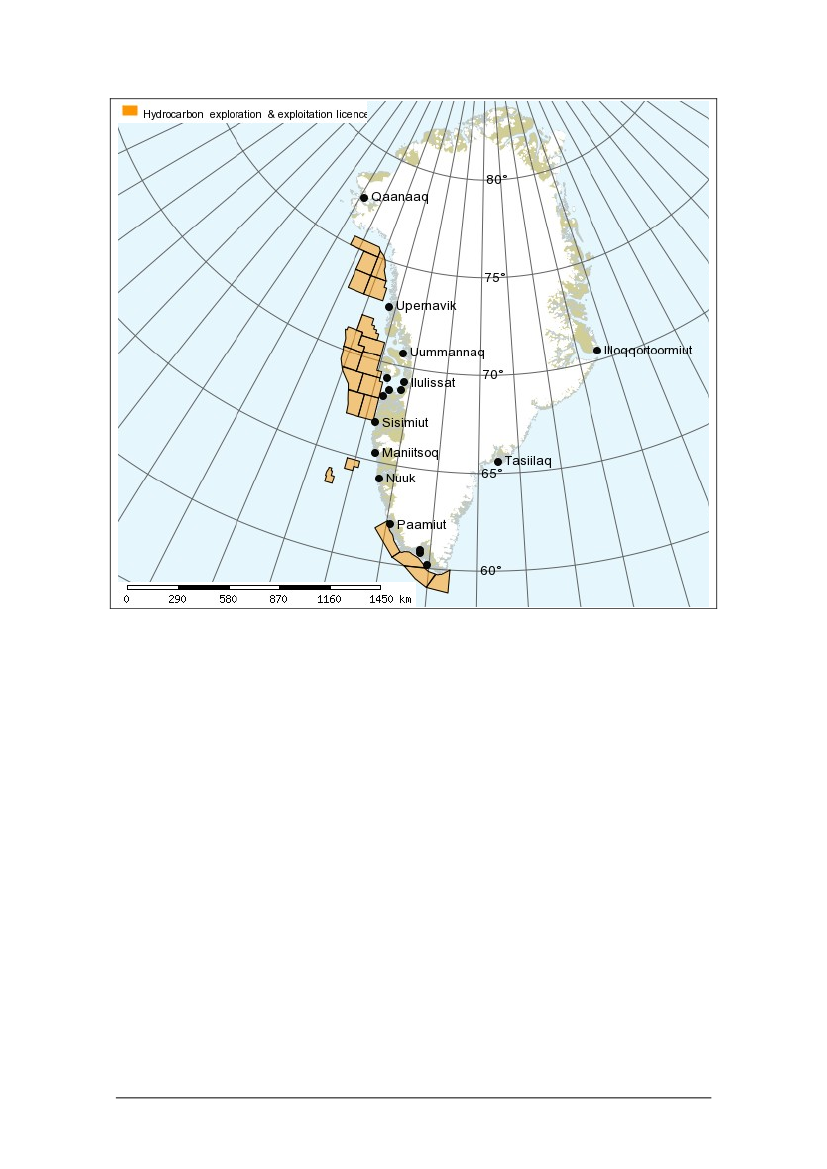

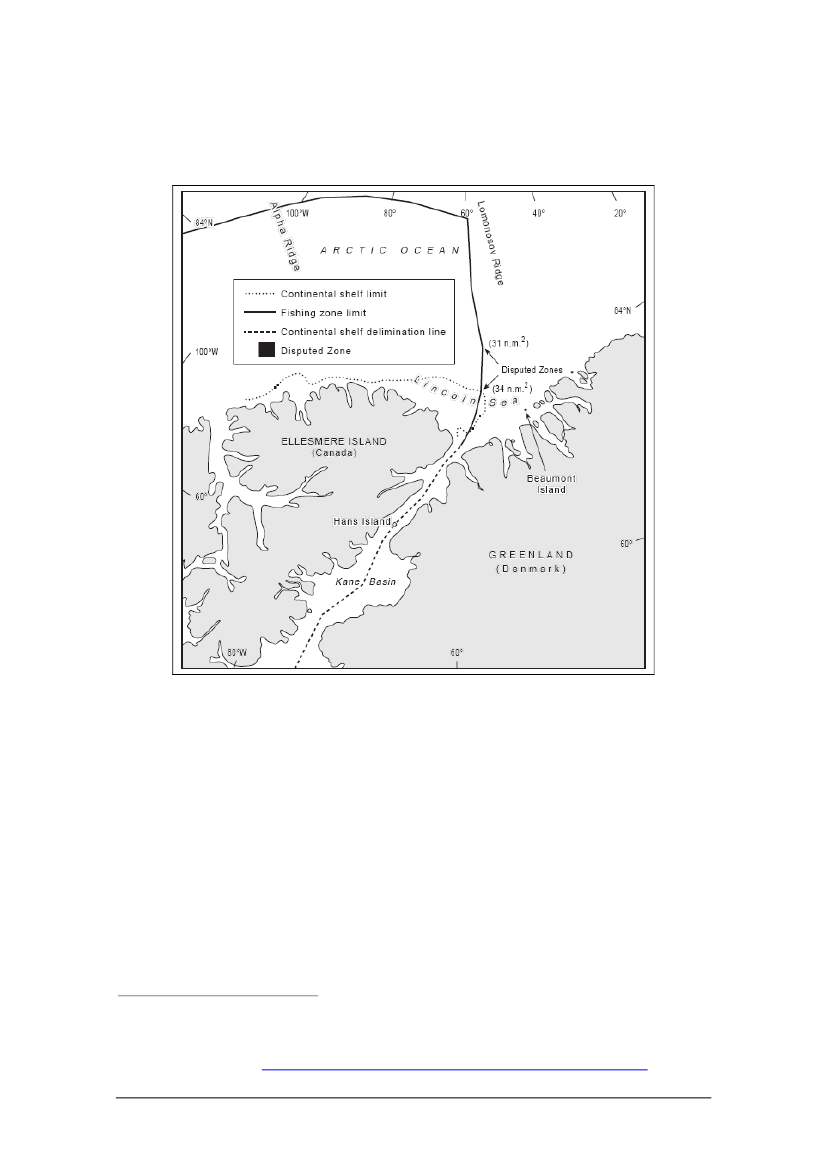

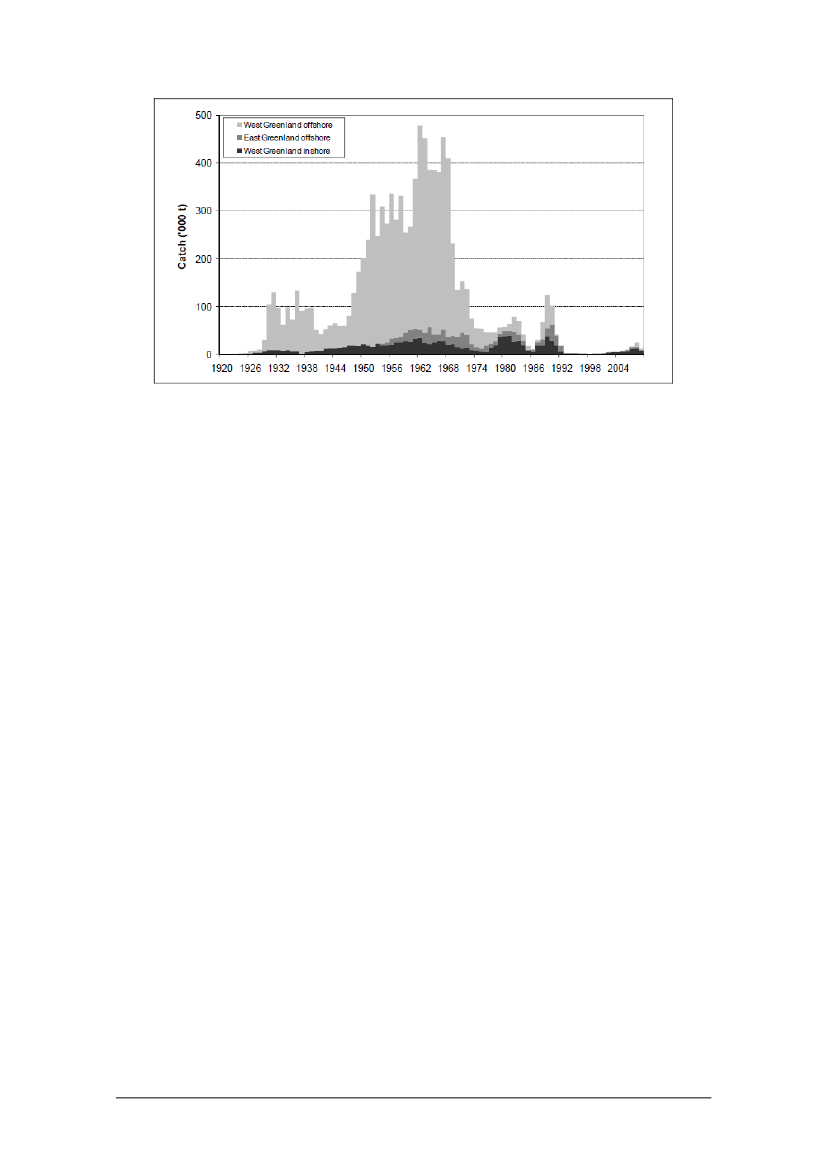

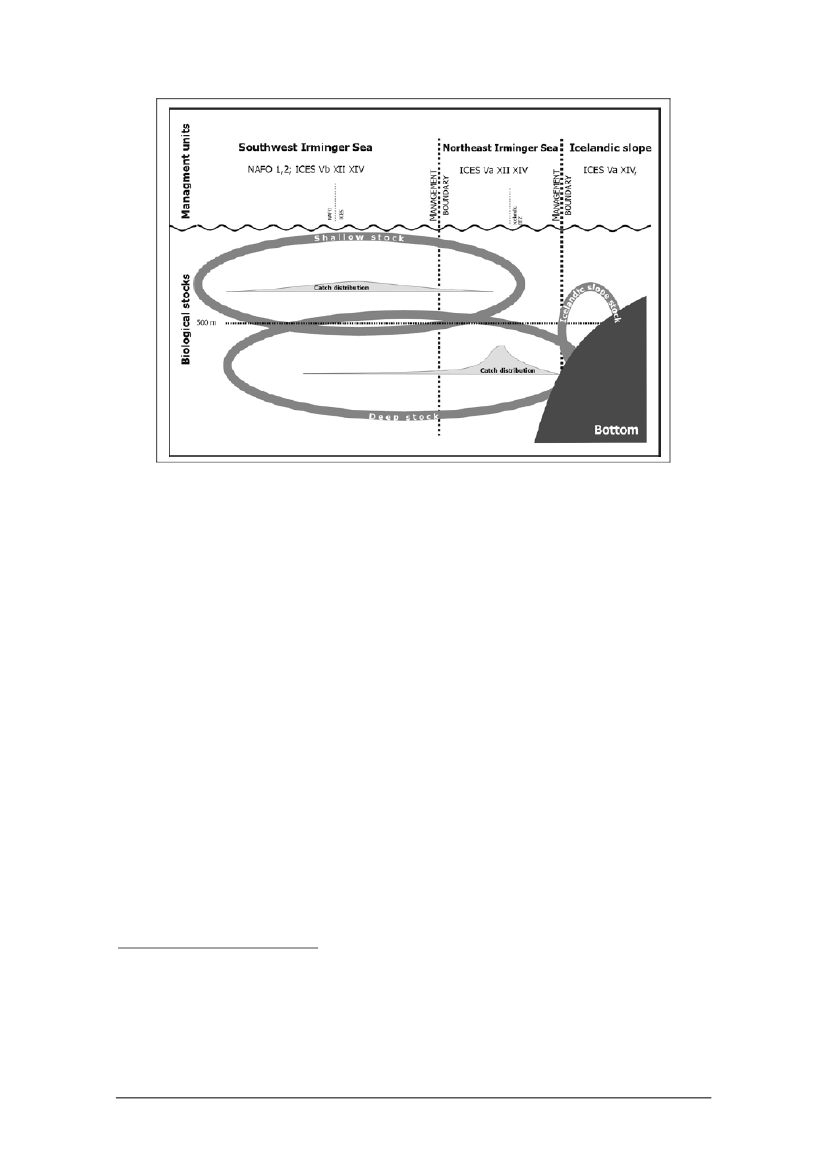

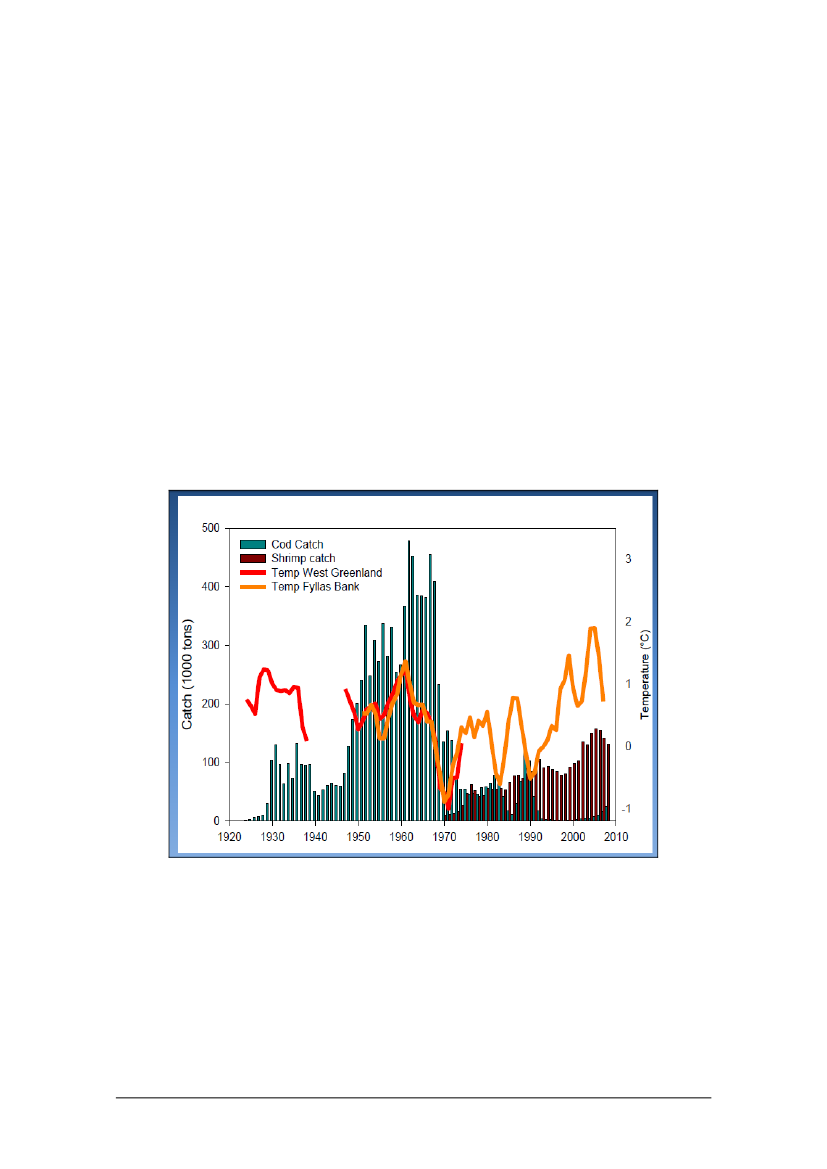

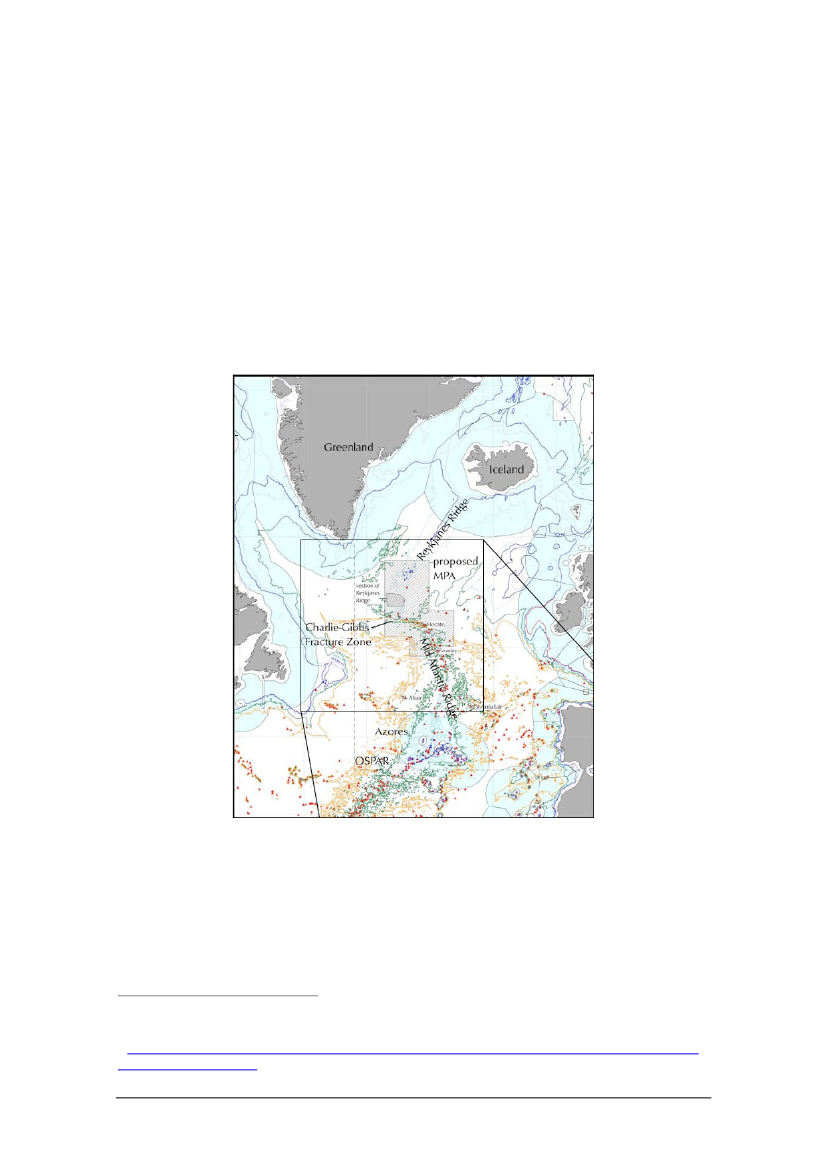

Figure 1: Oil and gas exploration concessions in Greenland..................................... 5Figure 2: Greenland- Canada maritime boundary disputes in the Nares Straitand Lincoln Sea................................................................................................................ 7Figure 3: Catches of cod in East and West Greenland since the 1920s.............. 40Figure 4: Schematic representation of biological stocks and adoptedmanagement units of S. mentella in the Irminger Sea and adjacent waters.............................................................................................................................................. 43

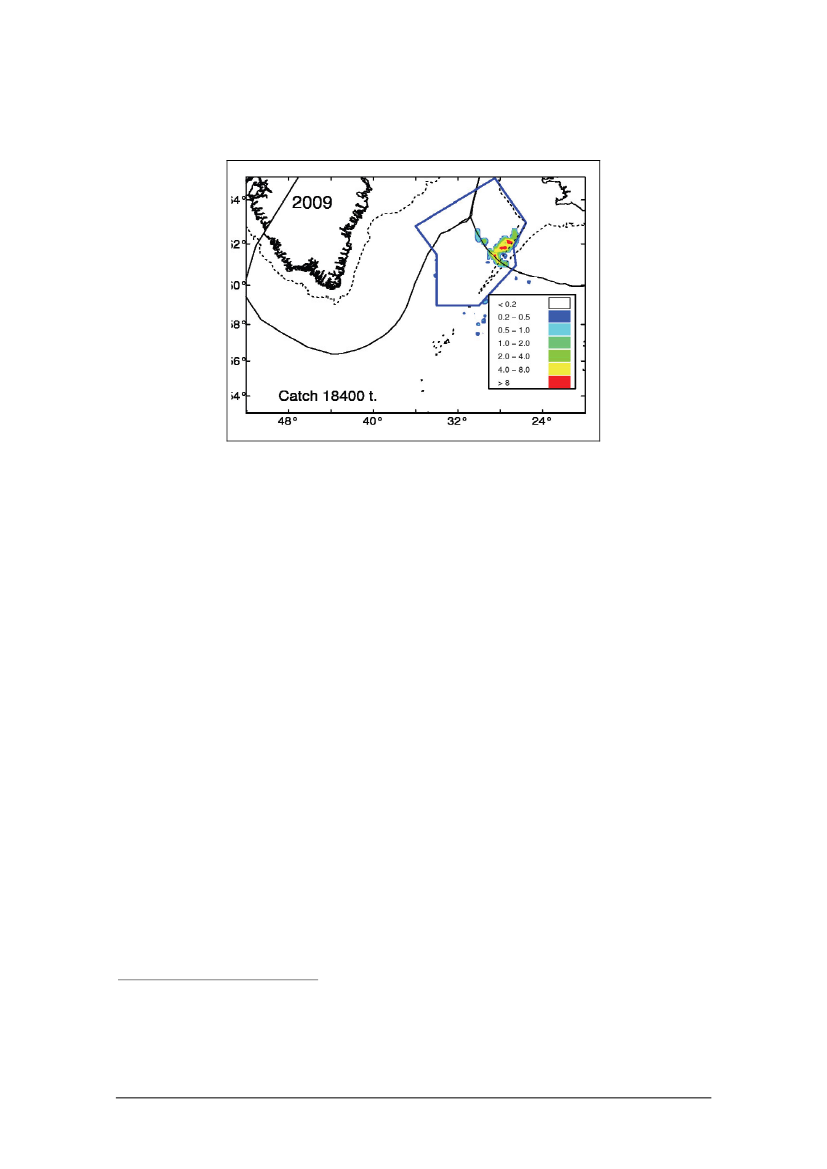

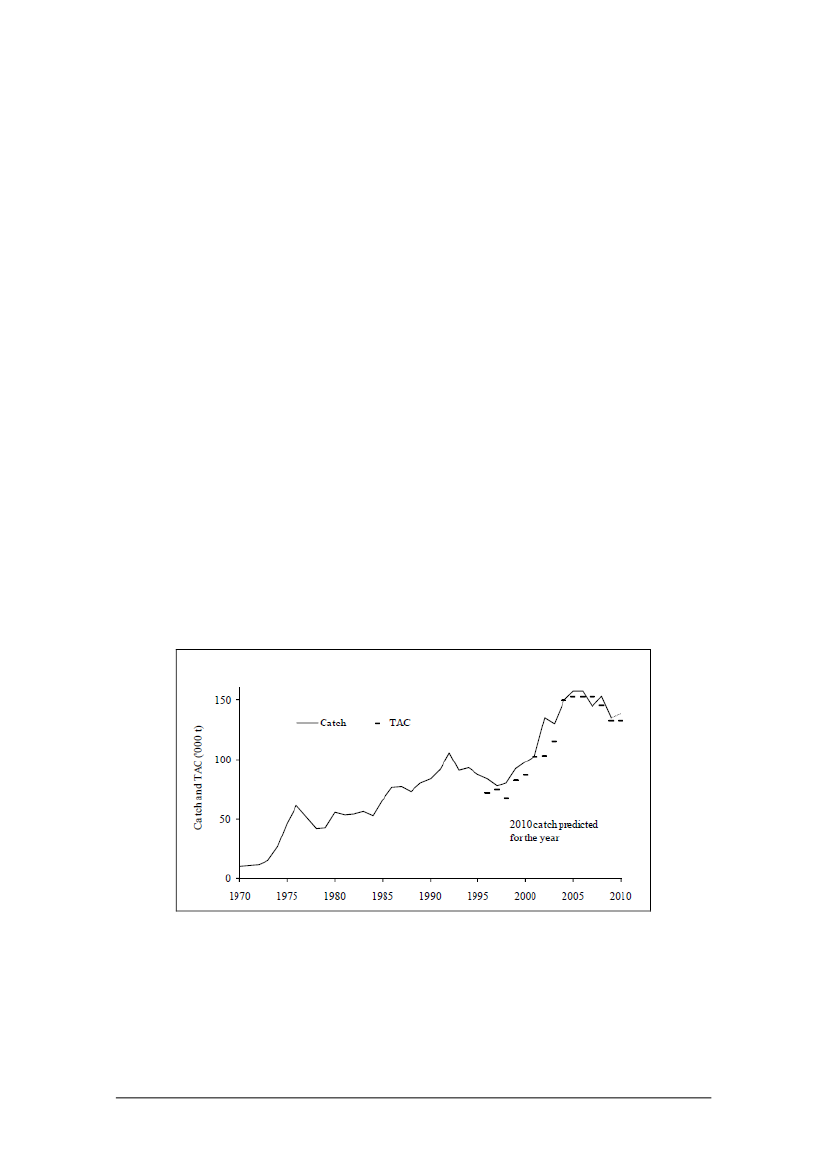

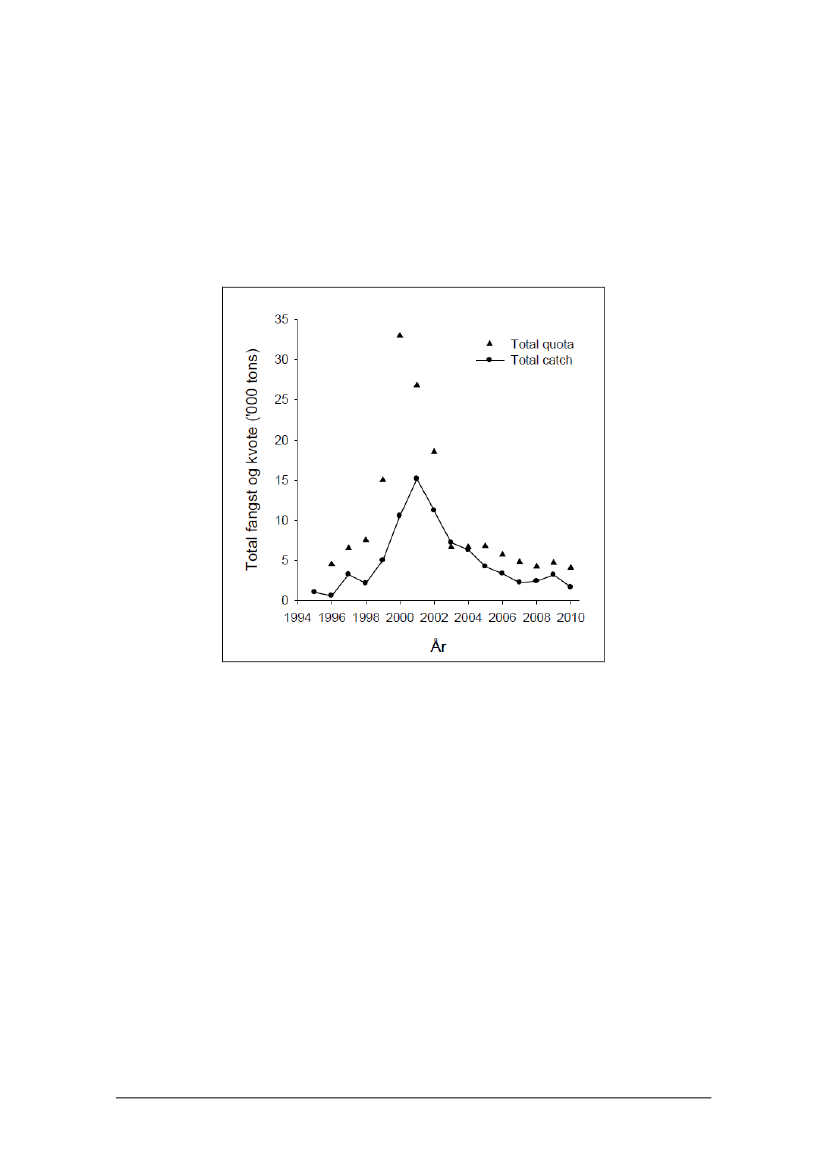

Figure 5: Fishing areas and total catch of pelagic S.mentella from therecommended northeast management unit in the Irminger Sea and adjacentwaters in 2009................................................................................................................ 44Figure 6: Catches and TACs of the shrimp fishery in NAFO SA 0+1, off WestGreenland. Source: NAFO.......................................................................................... 47Figure 7: Catches (fangst) and quota (kvote) in the Greenland offshore andinshore fisheries for snow crab from 1994 to 2010 (year: aar)........................ 49Figure 8: Historical catches of cod and shrimp off West Greenland. Bycatchesand discards.................................................................................................................... 56Figure 9: Location of the proposed MPA in the Charlie Gibbs Fracture Zone.... 59

Final Report

Fisheries Partnership Agreement FPA 2006/20

FPA 35/GRE/11

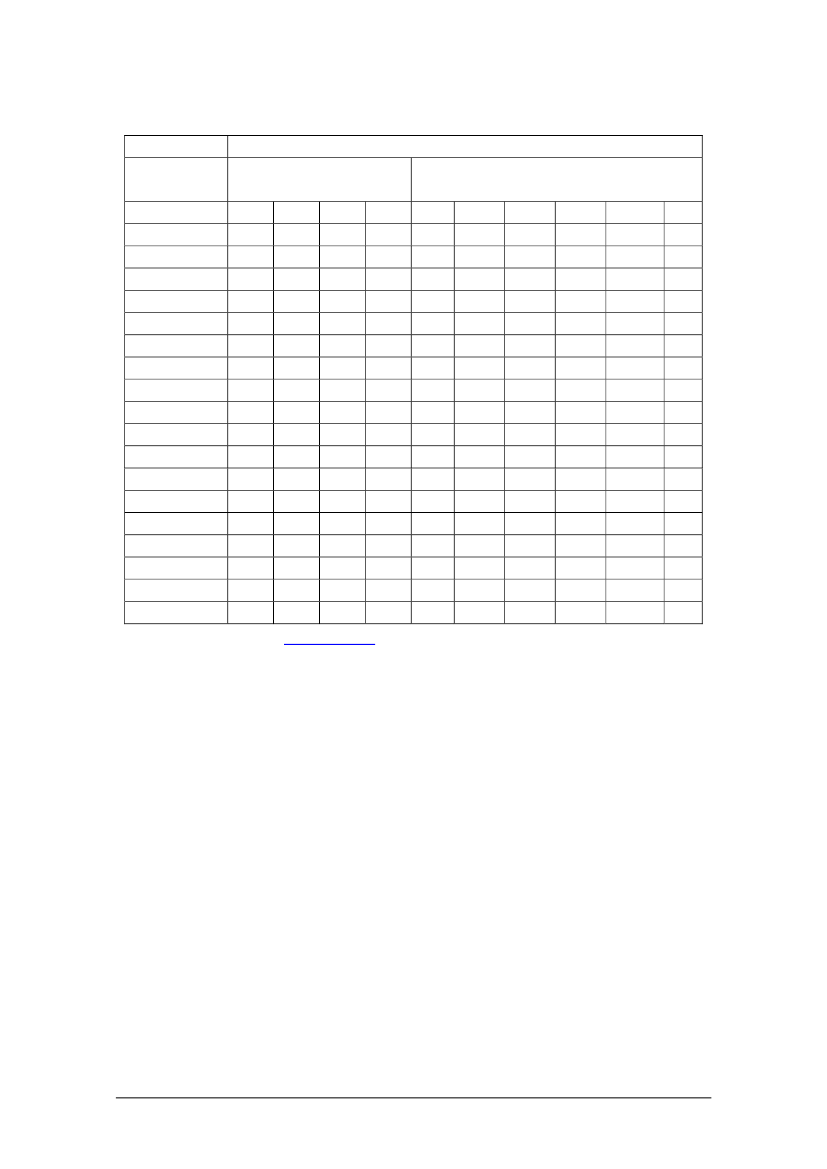

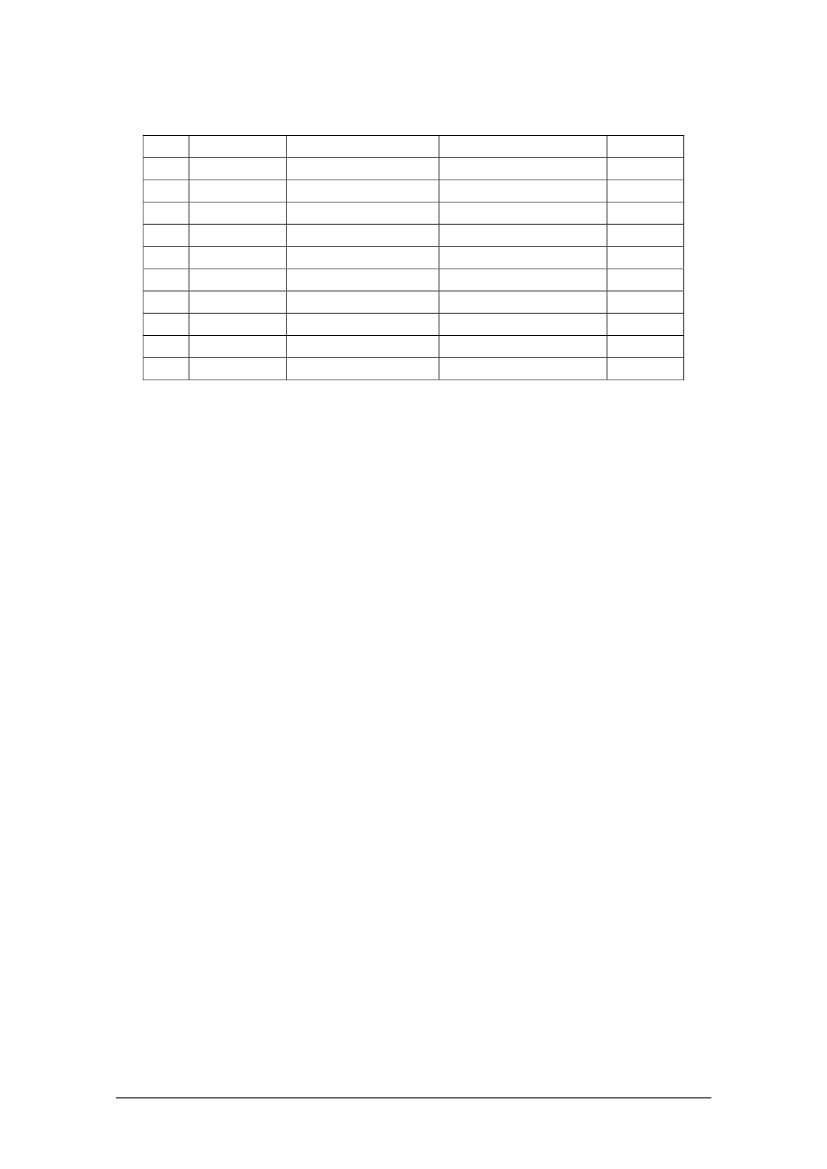

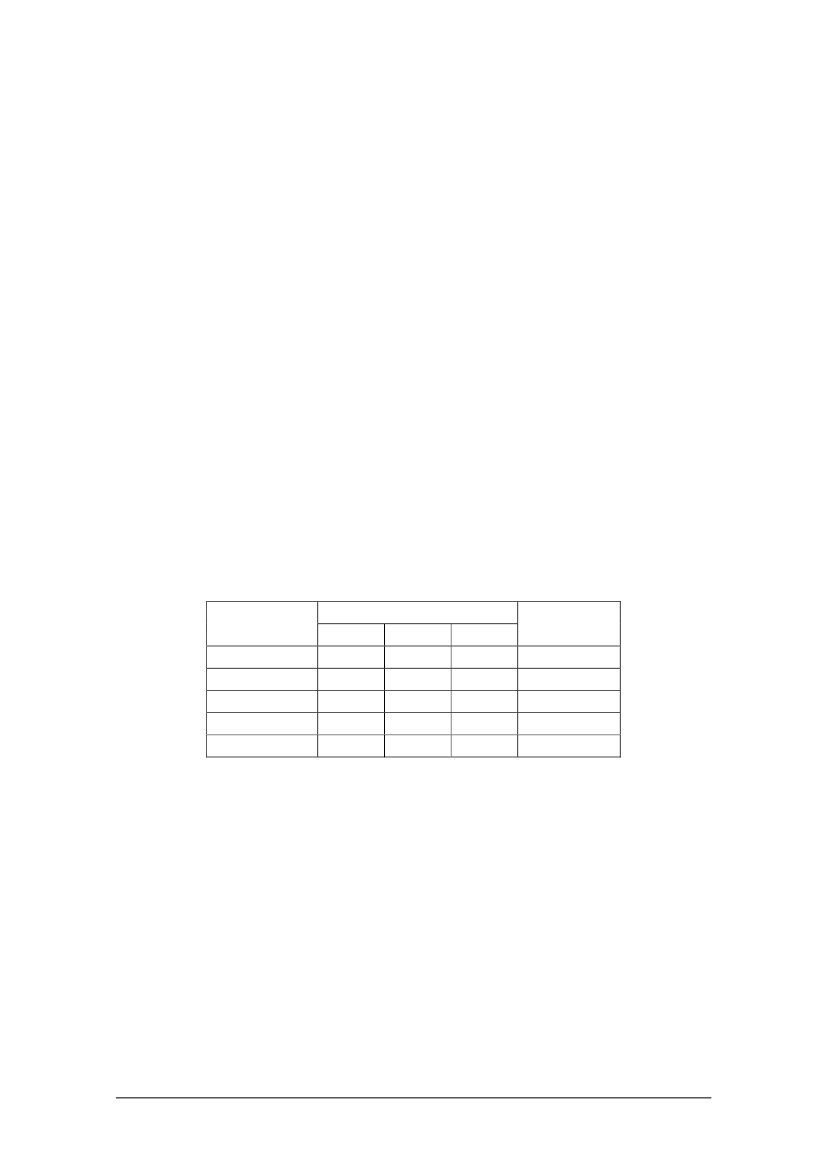

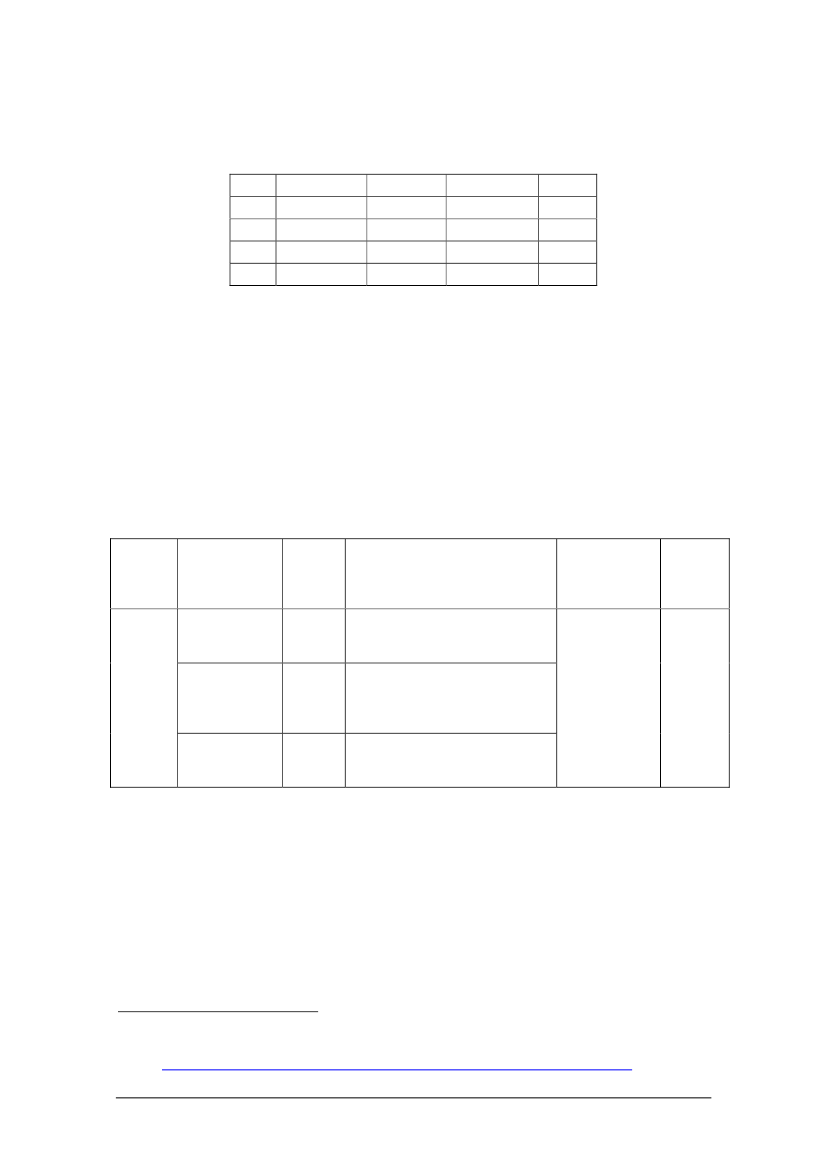

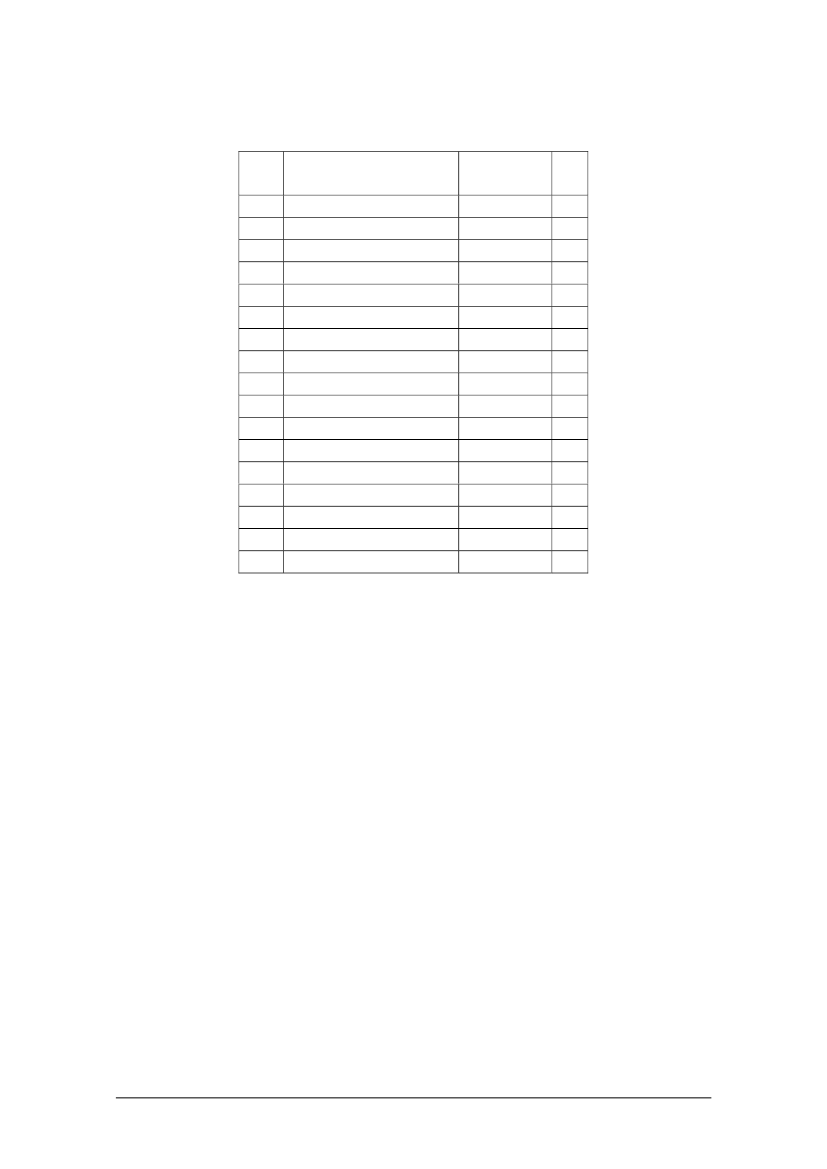

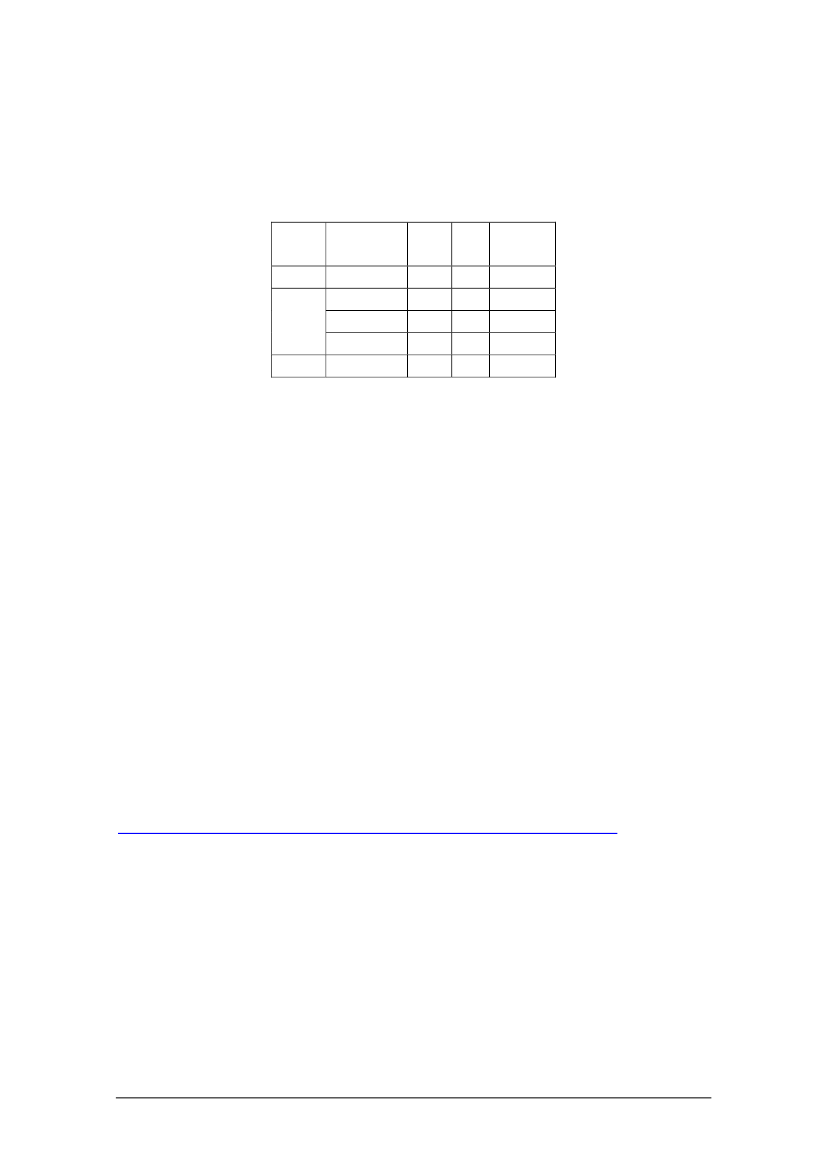

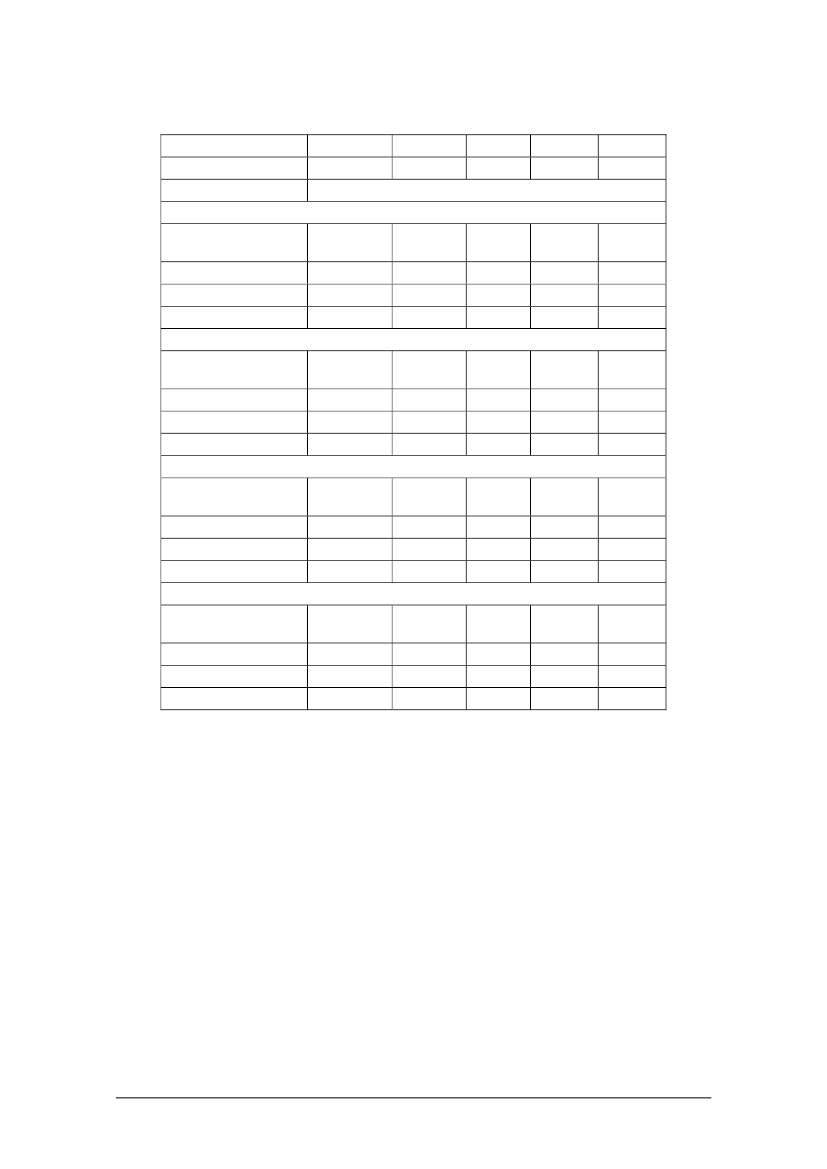

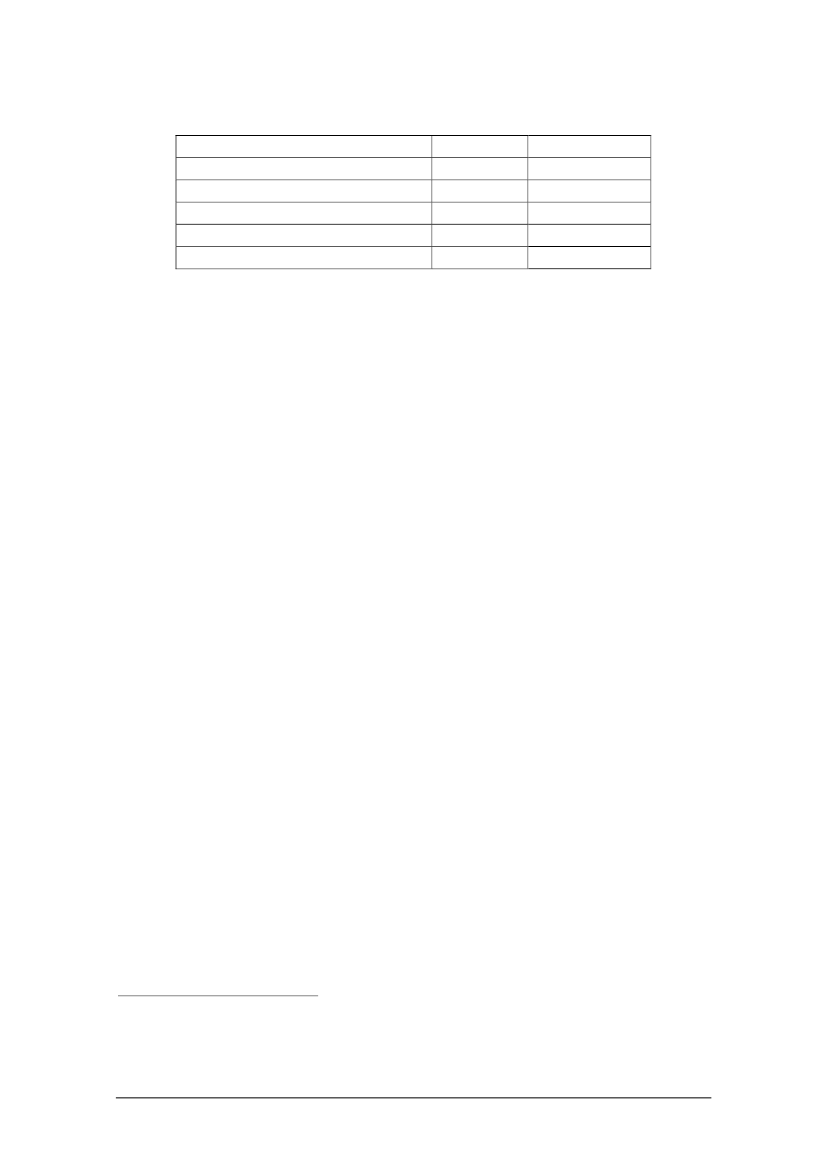

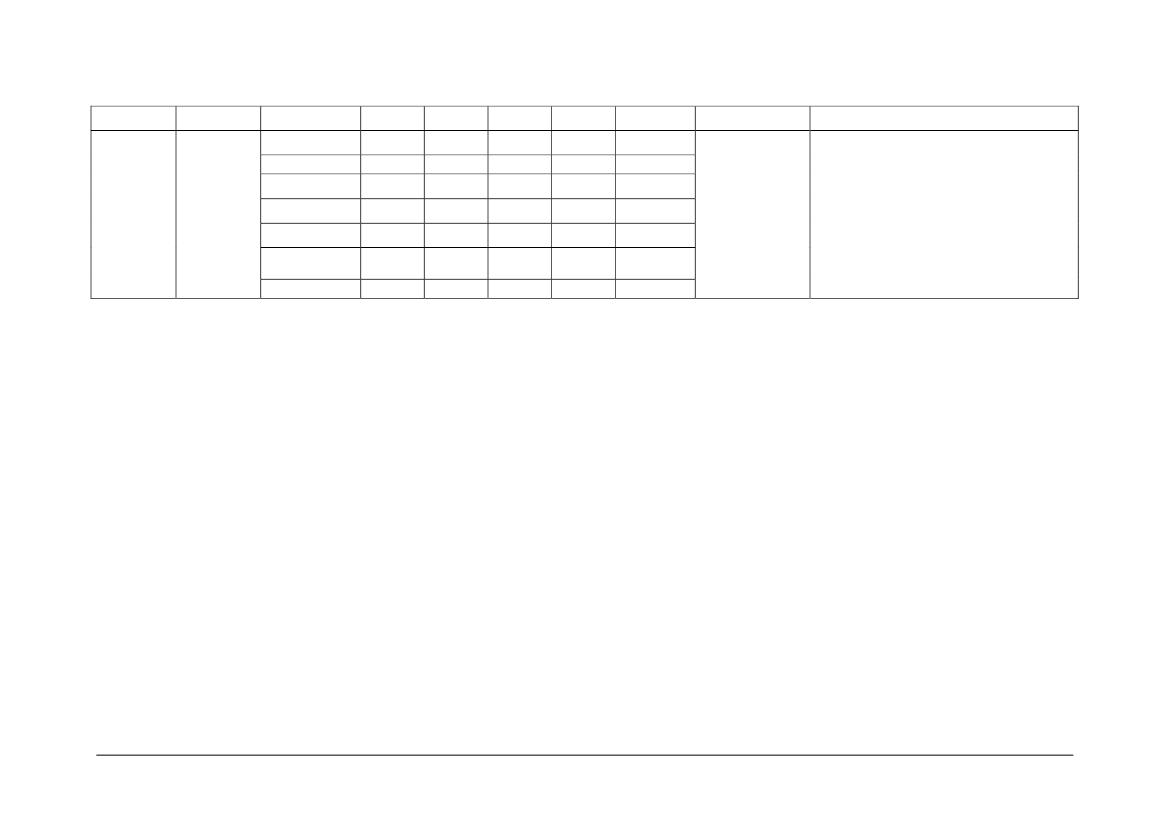

EXCHANGE RATESYear2007200820092010Euro1111USD1.371.481.391.33DKK7.457.467.457.447NOK8.0598.128.828.04ISK87.43145.14172.73164.103GBP0.68190.780.90.86

Source: InforEURO Exchange Rates, European Commission

Final Report

Fisheries Partnership Agreement FPA 2006/20

FPA 35/GRE/11

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY1. This report provides the findings of a study comprising an ex-post evaluation of theFisheries Partnership Agreement between the European Union and Greenland. The studywas commissioned by the Directorate General for Maritime Affairs and Fisheries of theEuropean Commission under a framework contract “for performing evaluations, impactanalyses and monitoring services in the context of Fisheries Partnership Agreements(FPAs) concluded between the European Union and non-EU member states (No.FISH/2006/20)” operated by a consortium comprising Oceanic Développement (France) andMegapesca Lda (Portugal). The study commenced on January 14th2011 and wascompleted on 13thMay 2011.2. The Fisheries Partnership Agreement between the parties was initialled in June 2006, andentered provisionally into force on 1stJanuary 2007 for a period of six years (until 31stDecember 2012). At the time of the study the Fisheries Partnership Agreement hastherefore been operational for just over four years, and the period of evaluation covers theyears 2007 to 2010 inclusive. The methodology involved review of documentation, analysisof quota, licence and catch data from different sources, and interviews/contacts with keystakeholders, including Greenland Government and industry, EU fleet interests, EuropeanCommission, European Member State and Norwegian and Faroe Island Governments(since they receive exchanged quota from the EU, supplied under the Fisheries PartnershipAgreement).3. Greenland is the World’s largest island; the northernmost point lies just 740 km from theNorth Pole. From north to south, Greenland extends 2,670 kilometres. In 1979 Denmarkgranted “Home Rule” to Greenland, which provided for autonomy over most policy areas,with the exception of foreign policy, defence and a number of other functions which wereperformed by Denmark, as the sovereign state. Following a referendum in 2008 a new lawon Self-Government took effect on 21 June 2009, furthering devolution of powers to thenewly entitled Naalakkersuisit (Government of Greenland). Denmark retains functions ofdefence, fishery inspection outside the territorial waters, constitutional affairs, currency andmonetary policy.4. The population of Greenland is 56,452. This includes around 6,300 resident Danes. Thepopulation is stable. The labour force in 2010 was 28,510, with an unemployment rate of7.1%. Greenland’s has low inflation (1.4% in 2009) but suffers from a high structuralunemployment rate, along with an aging population. Gross National Income was EUR29,286/capita in 2006 but has not risen in real terms in recent years. The Government is thelargest employer, accounting for 44% of all jobs. The country relies heavily on the annualblock grant provided by Denmark, accounting for an estimated 32% of GDP.5. The domestic fishery sector is the economy’s most significant earner accounting for 13% ofdirect Gross Value Added and 17% (5,500) of employment (including processing and otherlinked activities). The fishery sector accounts for 88% of tangible exports, almost all ofwhich are to the EU (87% via Denmark). The fishery sector has witnessed a reduction intrade prices for its main export industry (frozen shrimp) as well as decline in other exportssuch as snow crab. The cod fishery, a major resource up to the early 1980s, has failed torecover, despite promising signs. Minerals and tourism remain only marginal contributors toincomes and employment, although there are significant hopes attached to extractiveindustries, offshore oil, hydro-electric schemes and aluminium smelting operations. Severalmajor investment proposals are being considered by Government.6. Climate change and impacts on the Greenland ice sheets bring the possibility of mineralexploitation and new maritime routes with associated costs and benefits. Greenland’s Arcticlocation makes it a strategically important country within the Kingdom of Denmark, and forthe EU. It is an active member of the Arctic Council (currently under the chair of Denmark)and has territorial claims in the Arctic. Greenland and Canada have two unresolvedterritorial disputes, over Hans Island and the maritime boundary in the Arctic Ocean.

Final Report - pagei

Fisheries Partnership Agreement FPA 2006/20

FPA 35/GRE/11

7. In 1953 Greenland ceased to be a Danish colony and became an integral part of Denmark,thus joining the then European Community with Denmark in 1973. Greenland subsequentlyseceded from the EU in 1985. The Fisheries Agreement was established then as an integralpart of Greenland’s negotiations for withdrawal from the EU. The result was that the EU’straditional fishing rights were sustained, and in return, Greenland was able to continuereceiving financial support from the EU.8. Greenland’s status as one of the Member States’ Overseas Countries and Territories (OCT)is guaranteed by the Greenland Treaty negotiated on secession from the EU. This confersthe benefit of tariff free access for its fishery products exported to the EU (sincesupplemented by tariff quotas for non-originating fishery products ). The OverseasAssociation Decision governing the EU’s relations with the OCTs has been extended andexpires at the end of 2013.9. Until 31 December 2006, all EU financial assistance to Greenland (EUR 42.8 million peryear) was channelled through the Fisheries Agreement between the EU and Greenland. Anew approach was adopted with the introduction of the Fisheries Partnership Agreementsfrom 1stJanuary 2007, which focus on fisheries only. An alternative instrument was requiredto facilitate Greenland’s development, and from 1stJanuary 2007 the EU and Greenlandtherefore also entered into a Partnership Agreement for the sustainable development ofGreenland. This Partnership Agreement will expire at the end of 2013. The PartnershipAgreement has delivered budgetary support to Greenland valued at EUR 25 million/year,programmed via a “Programming Document for the Sustainable Development ofGreenland”, which focuses support on the Greenland Education Programme. A mid-termreview of the programme found that it had acceptable levels of efficiency, effectiveness andsustainability, and recommended extending the areas of cooperation, to includeenvironment, climate and indigenous peoples, thus establishing clearer links to the EU’sCommunication on the European Union and the Arctic Region.10. Greenland’s marine EEZ is 2,184,254 km2and can be divided into two zones: EastGreenland and West Greenland. Both have rich fishery resources and fall within the remit ofICES and NAFO respectively. Around 220,000 tonnes of fish have been caught annually inthe Greenland fishery in the years 2007-2010, of which 65% were shrimp, emphasising theimportance of this resource to the Greenland economy. The other principal fisheries areGreenland halibut, cod, redfish, snow crab and capelin. The EU and other third countryfishers (Norway, Russia, Faroes and Iceland) fish predominantly in East Greenland. SomeGreenland quotas for straddling and migratory stocks (redfish and capelin) are taken ininternational or Icelandic waters.11. The Greenland fishing fleet comprised some 757 vessels in 2007. Most vessels are small.There are an estimated additional 3,000 to 5,000 dinghies and sledges which are used forfishing and hunting at different times of year. The industrial fleet comprises 47 vesselsoperating in the EEZ and in international, Faroese and Norwegian waters.12. The fish processing industry comprises some 56 processing establishments and 4 coldstores. The sector is dominated by two large multi-national processing and exportingcompanies, Royal Greenland and Polar Seafoods, which operate the industrial shrimp fleetand the 5 main shrimp processing establishments. They specialise in processing, includingvalue added processing, of shrimp, Greenland Halibut and cod and have significantprocessing interests in the EU and global sales and marketing operations. The 100% state-owned company, Royal Greenland, made a loss of EUR 5.8 million in 2009/2010, andcarries EUR 265 million of debt. In 2009, the company had to raise an additional capitalinjection of EUR 66 million, from the Government of Greenland. The Company is reported tohave returned to profit in 2010. Government policy is to stabilise the company, reduce itsdebt and consider privatisation.13. The fish catching sector provided employment for about 2,000 full-time equivalents (FTE) in2004 while the processing industry provided 3,500 FTE. The fishery sector providesemployment for 17% of the workforce, about half of the jobs provided by the fishing industryin the 1970s. The rate of decline in fisheries employment in the inshore fishery is about 6%due to lack of profitability and retirement.

Final Report - pageii

Fisheries Partnership Agreement FPA 2006/20

FPA 35/GRE/11

14. Exports of fishery product to the EU over the period 2007-2009 have averaged around EUR290 million per year. Greenland is the largest global producer of coldwater shrimp(Pandalusborealis).Frozen shrimps account for about 62% of the export value of fisheryproducts, and Greenland halibut, accounts for about 27%. Cod accounted for only 4% oftotal export value. Greenland enjoys full access to the EU market for fishery products as aresult of its status as an OCT country. The EU duty applied to whole frozen Northern shrimpfrom other sources is 12% (20% for cooked and peeled shrimp). The Greenland preferenceis supplemented by the provision of a tariff quota of 10,000 tonnes of non-originatinghalibut, Greenland halibut and frozen shrimp (hardly utilised by Greenland), and anadditional tariff quota of 2,100 of prepared and preserved shrimp (fully utilised) to allowcontinuity of activity of the Greenlandic processing sector. However, these preferenceshave been eroded to a degree by the granting by the EU of anerga omnestariff quota forfrozen shrimp (currently 20,000 tonnes per year).15. The key elements of the Fisheries Partnership Agreement are that Greenland grants accessto EU vessels to fish in its EEZ in return for a financial contribution. Fishing opportunities inthe form of indicative quotas for different species are set out in the Protocol. From 2008onwards these comprised 55,000 tonnes of capelin and 36,700 tonnes of other speciesincluding cod, shrimp, Greenland halibut, redfish, Atlantic halibut and snow crab. Provisionis made that the EU may employ the fishing opportunities in exchanges between the EUand other third countries, specifically Norway, Iceland and Faroe Islands. EU and thirdcountry vessels may only fish in the Greenland EEZ when they hold a valid licence, forwhich fees (for EU vessels only) are set in the Protocol at 5% of a specified reference price.The EU undertakes to pay Greenland EUR 85,852,464 over a six year period, payable inannual tranches of EUR 14,307,244. Each year Greenland commits to applying EUR3,261,449 of this (slightly less in 2007) in favour of implementing a sectoral fisheries policywith a view to securing continued responsible fishing, to be managed in the light ofobjectives identified by mutual agreement within the frame of the joint committee.16. Because of resource limitations, on nine occasions over the four year period from 2007 to2010 inclusive Greenland has not been able to deliver all of the fish quotas set out in theProtocol. Deficits were in quotas for capelin in all years, halibut (both East and WestGreenland) in 2009 and 2010, and cod in 2010. The average annual deficit was 35,530tonnes, which corresponds to 39% of the annual quantity. A compensation mechanism (toallow Greenland to offer alternative opportunities) has worked well for small fluctuations inavailability of quota, but has not been able to cope with the “debt” for larger quantities ofcapelin (a resource with a known high degree of natural variation). In 2010 the partiesagreed that the debt (valued at EUR 2.6 million) should be resolved by i) reduction of the2011 compensation payment by EUR 1.6 million and ii) expansion of the sectoral policymatrix by Greenland, to include purchase of research vessel valued at EUR 1.1 million.17. During the period a total of 37 EU flagged vessels have benefited from the FisheriesPartnership Agreement, including 5 from Germany, 13 from Spain, 4 from UK, 6 fromPortugal, 1 from Denmark, 3 from Lithuania and 2 each from Poland and Estonia(accounting for 3% of the EU fleet tonnage). A concession by Greenland to allow groups ofvessels from a single Member state to purchase blocks of licence for subsequentdistribution between them has significantly facilitated uptake of licences. As a result overalluptake of opportunities has been good, averaging 75% during the period. If quotastransferred by the EU in bilateral exchanges with other third countries (Norway, FaroeIslands and Iceland) are included, then overall utilisation, in terms of licences drawn, isabout 90% of the available quota.18. Quotas for EU vessels are allocated according to relative stability keys, which do not fullymeet the pattern of current demand. A system of intra-community quota exchangesbetween Member States is well used, and has helped to maintain the level of utilisation ofthe Fisheries Partnership Agreement. In the first two years, some fleet segmentscomplained about quota being released too late in the year to allow effective planning, but asystem of regular and earlier swaps has evolved.

Final Report - pageiii

Fisheries Partnership Agreement FPA 2006/20

FPA 35/GRE/11

19. There are significant differences in utilisation depending on the quota. Fishing opportunitiesfor shrimp in W.Greenland, Greenland halibut and cod are in high demand. Theintroduction of management measures has limited the utilisation of cod opportunities to 91%overall. Only 45% of the annual quota of 7,000 tonnes of shrimp quota in East Greenland isused, and only 46% of redfish quotas. The snow crab fishing opportunities under the FPAhave never been utilised by Spain. Atlantic halibut quota allocated to Portugal has proven tobe virtually unfishable to EU vessels, and of limited interest to Norwegian ones. Bycatchesunder the Fisheries Partnership Agreement have been minimal.20. Overall, in an average year, the Protocol has delivered catches of 48,502 tonnes/year, ofwhich 16,472 tonnes were caught by EU vessels, and 32,030 tonnes by third countryvessels (these averages exclude years in which no capelin were caught). The annualcatches taken in the Greenland zone by EU vessels are estimated to correspond to about0.3% of total EU catches. On average EU vessels caught 63% of the quotas available tothem, and third country vessels 88%.21. Based on fish prices published in Iceland, the average revenues derived from the FisheriesPartnership Agreement were EUR 45.6 million/year, of which EU vessels derived EUR 31.9million (70%) and third country vessels EUR 13.7 million (30%). In fact since EU vesselsobtain access to fishing opportunities in a balanced exchange of Greenland quota withNorway, Faroe Islands and Iceland, the EU benefits of the Fisheries Partnership Agreementmay be considered to include these latter revenues (assuming that the balanced exchangeis cost/benefit neutral). The EU Member states which benefit the most are Germany (42% ofthe revenues under the Fisheries Partnership Agreement), Denmark (11%), Poland (7%)and UK (4%).22. Quota obtained from Greenland has contributed respectively 89%, 37% and 100% of thequota supplied in the EU’s annual balanced exchange with Norway, Faroe Islands andIceland (the balance being from EU stocks). Overall Greenland contributed 70% of thesesexchanges in cod equivalent terms. Access of EU vessels to important resources,particularly in Norway and Iceland (in the context of the EEA Agreement) has thereforebeen highly dependent on the EU’s agreement with Greenland (although EU and Icelandwere not able to agree on the terms of the exchange in 2009 and 2010). Without theseopportunities it is unlikely that many vessels in the distant water fleets of UK, Spain,Portugal and Germany could continue to operate.23. For the EU, the Fisheries Partnership Agreement has delivered net value added benefitsestimated at EUR 20.3 million/year, for an outlay of EUR 15.8 million, suggesting a costbenefit ratio of 1.3 (i.e. returning EUR 1.30 for every EUR 1.00 invested). This is a positivereturn, and equivalent to that of the Fisheries Partnership Agreements with Mauritania(which is also a “mixed” agreement). It has accounted for approximately 330 full time jobs atsea, suggesting around a total of around 500 EU jobs are dependent on fishing inGreenland under the Fisheries Partnership Agreement (but considerably more taking intoaccount the supported activities in other third countries).24. Therefore whilst the Fisheries Partnership Agreement has been effective in promoting EUfishing in Greenland and other third country waters, it has only been a marginally efficientmeans of achieving these ends, and its viability remains sensitive to externalities. Thesystem of licence allocation is inefficient, with rigid annual limits requiring that EU vesselspurchase more quota than is required (on averaging catching 16,472 tonnes out of 19,783tonnes of quota taken, with17% of purchased quota remaining unused at the end of theyear). Third country vessels suffer no penalty by over-drawing quota.25. Overall, including the sector support, the EU has contributed a relatively high EUR286/tonne of fishery products produced (30% of the sales value). Moreover the EU financialcontribution and licence fees represent almost 70% of the budgetary income generated bythe Greenlandic fishing sector, while accounting for only 12% of the total value of thecatches in the EEZ. Of the overall access costs to the resource (compensation plus licencefees, estimated at EUR 259/tonne) the EU has contributed 85% and the fleet operators15%, which is more or less the same level of public contribution applied by EU policy in theEU’s other mixed Fishery Partnership Agreements (for example 87% in Mauritania) butFinal Report - pageiv

Fisheries Partnership Agreement FPA 2006/20

FPA 35/GRE/11

considerable more that the EU’s “tuna agreements” where the targeted split is typically65/35.26. For Greenland, the Fisheries Partnership Agreement has been an effective measure togenerate income from several fishery resources which it may not otherwise have been ableto exploit. In 2011 the amount of compensation was adjusted downward to partly accountfor the cancellation of the capelin debt accrued during the period 2007 to 2010(corresponding to EUR 0.4 million/year). Therefore the Fisheries Partnership Agreementgenerated on average EUR 15.8 million per year in financial contributions, comprising EUR13.9 million in adjusted contribution and EUR 1.9 million in licence fees. This incomeaccounted for 1.3% of the state budget in 2010. The resource rent achieved isapproximately EUR 326/tonne (35% of vessel revenue, which is high by internationalstandards).27. The Fisheries Partnership Agreement has not been effective in delivering any significantadditional economic benefits to Greenland (such as joint ventures, employment on board, orlandings into processing). A programme of sector support measures valued at around EUR4.0 million/year has been implemented by the Ministry of Fisheries Hunting and Agriculture,in line with Article 4 of the Protocol. The FPA-linked financial contribution accounts for some70% of the state budget contribution to the fisheries sector. About half of the money hasbeen spent on fisheries research. The programme was found to have relevant objectives,and has achieved positive results on measures related to fisheries research, training ofstaff, and fisheries control, thus contributing to the improved sustainability of the Greenlandfisheries sector. However, it has failed with regard to structural adjustment of coastalfisheries, and it is not always clear that the budgetary support has been used forinvestment, rather than current, expenditure.28. There are concerns regarding sustainability of the three of the ten fishing opportunitiesspecified in the Fisheries Partnership Agreement. There is clear evidence that cod,Greenland halibut in E.Greenland and redfish (deep pelagic stocks) are subject toexcessive and unsustainable levels of exploitation, and that the Fisheries PartnershipAgreement has contributed respectively 11%, 30% and 8% of the overall exploitation duringthe period of the evaluation. For cod, some management measures have been introducedin line with a cod management plan developed by Greenland, but this plan needs furthermodification if it is to deliver long term sustainability. For redfish, an Agreement signed inMarch 2011 by Greenland, the EU and other states regarding management of this speciesin the Irminger Sea will progressively reduce TACs and should bring sustainability in future.For Greenland halibut (East), another straddling stock, there is no Agreement between thecoastal states (Greenland, Iceland and Faroe Islands); each sets autonomous TACs andcatches exceed scientific advice by a factor of 5. Although there are also concernsregarding the sustainability of the levels of exploitation of shrimp in W.Greenland(considered to be at risk), here the Fisheries Partnership Agreement has contributed lessthan 3% of the exploitation, and an effective management plan was introduced in 2010.There is also a risk that exploitation of the Atlantic halibut has not been sustainable,although there is insufficient evidence for a definitive analysis. Other quotas (shrimp inE.Greenland, Greenland halibut in W.Greenland, capelin and snow crab) are all consideredto be subject to sustainable management. All fisheries are known to have low rates ofbycatch. All demersal trawl fisheries are subject to sorting grids, and discarding isprohibited. There are no known negative non-target or ecosystem impacts.29. In general the Fisheries Partnership Agreement is coherent with EU development, trade andpolicies, which together deliver a range of benefits to the Government of Greenland andGreenlandic stakeholders. Except for the lack of sustainability of three key stocks, it isbroadly coherent with the Common Fisheries Policy. The Fisheries Partnership Agreementis potentially coherent with the EU’s emerging policy framework with regard to the Arcticregion. In respect of EU trade measures in relation to seal products, which has had anegative impact on livelihoods of small scale fishers/hunters, the policy framework haslacked coherence. Overcapacity in inshore fisheries and lack of alternative employmentopportunities are critical structural problems in the Greenland fishery sector, which remainto be properly addressed in future through a strengthened structural adjustment programme

Final Report - pagev

Fisheries Partnership Agreement FPA 2006/20

FPA 35/GRE/11

under the sectoral policy support measures supported by the Fisheries PartnershipAgreement.30. Overall, the study concludes that the Fisheries Partnership Agreement has been ofimmense mutual benefit to the parties, and therefore recommends that the parties enternegotiations for the renewal of the protocol. It is recommended that a new protocol be for aperiod of just three years, to allow for a subsequent protocol to be adjusted to ensure fullcoherence with any renewal of the Overseas Association Decision and the GreenlandPartnership Agreement. This will also allow for new measures within the reformed CommonFisheries Policy to be reflected in the design of a new Fisheries Partnership Agreement andProtocol, which are coherent with other EU policy areas, including the EU’s Arctic Policy inrelation to maritime and environmental matters.

Final Report - pagevi

Fisheries Partnership Agreement FPA 2006/20

FPA 35/GRE/11

RÉSUMÉ EXÉCUTIF1. Ce rapport présente les résultats d’une étude d’évaluation ex-post de l’accord departenariat dans le domaine de la pêche entre l’Union Européenne et le Groenland.L’étude a été lancée par la Direction Générale de la Pêche et des Affaires Maritimes dela Commission européenne sous un contrat cadre « pour la réalisation d’évaluations,d’études d’impact et des services de suivi dans le contexte des accords de partenariatdans le domaine de la pêche conclu entre l’Union Européenne et Pays non-membresde l’UE ref. FISH/2006/20 » dont le titulaire est le consortium composé d’OceanicDéveloppement (France) et Megapesca Lda (Portugal). L’étude a débuté le 14 janvier2011 et s’est terminée le 13 mai 2011.2. L’accord de partenariat dans le domaine de la pêche entre les deux parties a étéparaphé en juin 2006 et est entré provisoirement en vigueur le 1erjanvier 2007 pour unepériode de six années (jusqu’au 31 décembre 2012). Au moment de cette étude,l’accord a donc été opérationnel pendant un peu plus de quatre années, et l’évaluationcouvre la période 2007-2010 inclus. La méthodologie mise en œuvre comprend unerevue de la documentation disponible, une analyse des données sur les quota, leslicences et les captures issues de différentes sources, and des contacts / interviewsavec des parties prenantes clés dont les autorités du Groenland et son industrie de lapêche, les intérêts de l’UE dans l’armement de navires, la Commission européenne, lesEtats membres de l’UE ainsi que les autorités de Norvège et des Faeroe dans lamesures où ces entités re§oivent des quota de l’UE qui les obtient sous cet accord).3. Le Groenland constitue la plus grande île du monde. Son point le plus septentrional està 740 m du Pôle Nord. Du Nord au Sud, le Groenland s’étend sur 2 670 km. En 1979, leDanemark a accordé au Groenland une part d’autonomie sur la plupart des domaines,à l’exception de la politique étrangère, de la défense et de quelques autres fonctionsrégaliennes. A la suite d’un référendum tenu en 2008, l’autonomie a été élargie par uneloi qui a pris effet le 21 juin 2009 et qui donne au nouvellement nommé Naalakkersuisit(Gouvernement du Groenland) davantage de pouvoir. Le Danemark continue d’assurerla défense, l’inspection de produits de la pêche en dehors des eaux territoriales, lesaffaires constitutionnelles et la politique monétaire.4. La population du Groenland est de 56 452 habitants, incluant environ 6 300 résidentsdanois. La population est stable. Le nombre de personnes en âge de travailler était de28 510 en 2010 avec un taux de chômage de 7,1%. Le taux d’inflation au Groenland estbas (1,4% en 2009) mais souffre d’un taux de chômage structurellement élevé ainsi qued’une population vieillissante. Le Produit Intérieur Brut était de 29 286 € par personneen 2006 mais n’a pas marqué de croissance en termes réels sur ces dernières années.Le Gouvernement est le plus grand employeur, absorbant 44% des emplois. Le paysest très dépendant de la subvention annuelle accordée par le Danemark qui représente32% du PIB.5. Le secteur de la pêche national est le premier secteur économique représentant 13%de la valeur ajoutée directe et 17% (5 500) de l’emploi (incluant la transformation et lesautres activités connexes). Le secteur de la pêche est à l’origine de 88% desexportations avec une destination pratiquement exclusivement vers l’UE (87% vers leDanemark). Le secteur de la pêche a subi les effet d’une baisse de prix à l’exportation(crevettes congelées), ainsi que sur d’autres produits comme le crabe des neiges. Lapêcherie de cabillaud, une ressource majeure jusqu’au début des années 80, ne s’estpas restaurée en dépit de signes prometteurs. Le minerai et le tourisme restent dessecteurs faiblement contributeurs à l’emploi et aux revenus. Toutefois, il existe desperspectives pour les secteurs des mines, du pétrole offshore, de l’énergiehydroélectrique et de la fusion d’aluminium. Plusieurs projets d’investissements sontexaminés par le Gouvernement.6. Le changement climatique et son impact sur la couverture glacière du Groenland faitapparaître des possibilités pour l’exploitation du minerai et la création de nouvellesroutes maritimes avec des coûts et des bénéfices associés. La localisation arctique duFinal Report - pagevii

Fisheries Partnership Agreement FPA 2006/20

FPA 35/GRE/11

Groenland lui donne un avantage stratégique à l’intérieur du Royaume du Danemark etpour l’UE. Le territoire est un acteur majeur du Conseil de l’Arctique (présidé en cemoment par le Danemark). Il existe des revendications territoriales dans l’Arctique. LeGroenland et le Canada ont deux cas non résolus, l’un sur l’île de Hans et l’autre sur leslimites maritimes dans l’océan arctique.7. En 1953, le Groenland a cessé d’être une colonie du Danemark et a été intégré aupays, rejoignant ainsi l’UE avec le Danemark en 1973. Le Groenland s’est séparé del’UE en 1985. L’accord de pêche a fait partie intégrante des négociations vers le retraitde l’UE. Le résultat a été que les droits de pêche traditionnels de l’UE ont étéconservés, et en retour, le Groenland a pu continuer à recevoir un soutien financier del’UE.8. Le statut du Groenland en tant que Pays et Territoires d’Outre-Mer (PTOM) est garantidans le Traité négocié lors de la séparation de l’UE. Ce statut confère au Groenland lebénéfice d’un accès à tarif nul au marché de l’UE pour les produits de la pêche(complété depuis par des quotas tarifaires pour les produits non-originaires). Le Traitéencadrant les relations entre l’UE et les PTOM a été prorogé et doit expirer à la fin de2013.9. Jusqu’au 31 décembre 2006, toute l’assistance financière de l’UE au Groenland (42,8M€ par an) a été délivrée sous l’accord de pêche. Une nouvelle approche a ensuite étéadoptée avec l’introduction d’un accord de partenariat dans le domaine de la pêche envigueur depuis le 1erjanvier 2007 qui ne concerne que ce secteur. Un nouvelinstrument était nécessaire pour soutenir le développement du Groenland et depuis le1erjanvier 2007, l’UE et le Groenland ont conclu un accord de partenariat pour ledéveloppement durable du Groenland. Cet accord expirera fin 2013. L’accord departenariat apporte un soutien budgétaire de 25 M€ par an mis en œuvre par ledocument de programmation pour le développement durable du Groenland. Leprogramme se concentre sur le secteur de l’éduction. Une revue à mi-parcours amontré que ce programme est raisonnablement efficient, efficace et durable, et arecommandé l’élargissement du partenariat vers les secteurs de l’environnement, duclimat et des populations indigènes ,créant ainsi un lien clair avec la Communication del’UE sur la région arctique.10. La superficie de la ZEE du Groenland est de 2 814 254 km� et peut être divisée en deuxzones Est et Ouest. Les deux zones disposent de ressources naturelles et sont dansles zones couvertes par le CIEM et la NAFO respectivement. Environ 220 000 tonnespar an de poissons ont été capturées par les pêcheries groenlandaises entre 2007 et2010, dont 65% de crevettes, ce qui souligne l’importance de cette ressource pourl’économie du pays. Les autres principales pêcheries sont celles de flétans, cabillauds,sébastes, crabe des neiges et capelan. L’UE et les autres flottes étrangères (Norvège,Russie, Faeroe) exploitent principalement la zone Est-Groenland. Quelques quotas duGroenland pour des espèces migratoires et chevauchantes (sébastes, capelan) sontpêchés dans les eaux internationales ou sous juridiction de l’Islande.11. La flotte de pêche du Groenland comptait quelques 757 navires en 2007, dont la plupartsont de petite taille. On estime qu’il y a en plus entre 3 000 et 5 000 canoes utiliséspour la chasse et la pêche à différentes périodes de l’année. Le segment industriel estcomposé de 47 navires travaillant dans la ZEE, ainsi que dans les eaux internationalesou celles sous juridiction des Faeroe et de la Norvège.12. Le secteur de la transformation des produits de la pêche compte quelques 56 unités et4 entrepôts frigorifiques. Ce secteur est dominé par deux grandes multinationales,Royal Greenland et Polar Seafoods qui arment la flotte de pêche crevettière etcontrôlent les 5 plus grands établissements de transformation. Ces sociétéstransforment de crevettes, du flétan et du cabillaud et ont des intérêts dans dessociétés sur le territoire de l’UE faisant de la transformation et du négoce. La sociétéRoyal Greenland contrôlée à 100% par l’Etat a affiché une perte de 5,8 M€ en2009/2010, et accumule 265 M€ de dettes. En 2009, la société a du injecter 66 M€dans son capital, apportés parle Gouvernement. La société serait redevenue profitable

Final Report - pageviii

Fisheries Partnership Agreement FPA 2006/20

FPA 35/GRE/11

en 2010. La politique du Gouvernement est de stabiliser la société, réduire ses dette etd’examiner la possibilité d’une privatisation.13. Le secteur de la capture donnait de l’emploi à environ 2 000 personnes équivalenttemps plein (ETP) en 2004, plus 3 500 ETP dans le secteur de la transformation. Lesecteur emploie 17% de la force de travail, soit environ la moitié des emplois dans lesecteur au cours des années 70. Le taux de décroissance de l’emploi dans le secteurde la pêche côtière est d’environ 6% du fait d’un manque de rentabilité et de retraites.14. Les exportations de produits de la pêche vers l’UE se sont monté à environ 290 M€ paran en moyenne sur la période 2007-2009. Le Groenland est le premier producteurmondial de crevettes nordiques (Pandalusborealis).Les crevettes congeléesreprésentent environ 62% de la valeur des exportations, devant le flétan avec 27%. Lecabillaud ne représente plus que 4% des exportations. Le Groenland a un accès àdroits nuls au marché de l’UE pour les produits de la pêche du fait de son statut dePTOM. Le droit appliqué à la crevette nordique congelée de pays tiers est de 12% (20%pour les crevettes cuites et pelées). La préférence tarifaire accordée au Groenland estcomplétée par un quota tarifaire de 10 000 tonnes pour du flétan et de la crevettenordique non-originaire (peu utilisé par le Groenland), ainsi qu’un quota tarifaireadditionnel de 2 100 tonnes pour des crevettes préparées et en conserves (totalementutilisé). L’intérêt de ces préférences a été érodé par la décision de l’UE d’accorder unquota tarifaireerga omnespour la crevette congelée (actuellement 20 000 tonnes paran).15. Le principal élément de l’accord de partenariat dans le domaine de la pêche est que leGroenland autorise l’accès à des navires de l’UE pour pêcher dans sa ZEE en échanged’une contribution financière. Les possibilités de pêche sous la forme de quotasindicatifs sont définies dans le protocole d’accord. Depuis 2008, elles sont constituéesde 55 000 tonnes de capelan et 36 700 tonnes d’autres espèces dont du cabillaud, dela crevette, du flétan, de la sébaste, du flétan noir et du crabe des neiges. Le protocoleprévoit que l’UE puisse utiliser certaines possibilités de pêche négociées sous cetaccord dans ses échanges de quotas avec d’autres pays tiers, et plus précisement laNorvège, l’Islande et les Faeroe. Les navires de l’UE et ceux d’autres pays tiers nepeuvent exercer dans la ZEE que si ils détiennent une licence de pêche dont le coûtpour les armateurs de l’UE est fixé dans le protocole à 5% d’un prix de référencespécifique. Sous le protocole, l’UE s’engage à payer au Groenland un montant de85 852 464 € sur une période de six années, payable par tranche annuelle de14 307 244 €. Chaque année, le Groenland s’engage à utiliser 3 261 449 € (un peumoins en 2007) au financement de la mise en œuvre de sa politique sectorielle visant àassurer la durabilité de l’exploitation, en ciblant des objectifs qui dont définis de manièreconjointe dans le cadre de la Commission Mixte de l’accord.16. Du fait de limites sur la disponibilité des ressources, le Groenland n’a pas été enmesure d’octroyer les quotas prévus sous l’accord pour 9 espèces entre 2007 et 2010inclus. Les déficits concernent les quotas de capelan (chaque année), le flétan (à l’Estet à l’Ouest du Groenland) en 2009 et 2010, et le cabillaud en 2010. Le déficit annuelmoyen est de 35 530 tonnes, ce qui correspond à 39% des quantités annuelles. Unmécanisme de compensation qui permet au Groenland de proposer des possibilités depêche alternatives a bien fonctionné pour de petites fluctuations annuelles dans ladisponibilité des quotas, mais n’a pas pu être utilisé pour résoudre le problème de la« dette » pour de plus grandes quantités de capelan (une ressource dont l’abondanceest connue pour varier naturellement de manière importante d’une année à l’autre). En2010, les parties se sont accordées sur le fait que la dette (évaluée à 2,6 M€) pourraitêtre apurée i) par une réduction de la compensation financière de l’accord de 1,6 M€ etii) l’inscription par le Groenland de l’achat d’un navire de recherche évaluée à 1,1 M€dans la matrice des mesures sectorielles.17. Pendant la période, 37 navires de l’UE ont bénéficié des possibilités de pêche, dont 5navires de l’Allemagne, 13 de l’Espagne, 4 du Royaume Uni, 6 du Portugal, 1 duDanemark, 3 de Lituanie, et 2 du Portugal et de l’Estonie. Ces navires représentent 3%

Final Report - pageix

Fisheries Partnership Agreement FPA 2006/20

FPA 35/GRE/11

de la capacité en jauge de la flotte de l’UE. Une concession du Groenland pourautoriser des groupes de navires d’un même Etat membre d’acheter en bloc deslicences pour les redistribuer ensuite entre eux a grandement facilité la procédure dedélivrance des licences. Le taux d’utilisation des possibilités de pêche négociée a étébon, de 75% en moyenne sur la période. Si l’on inclut les quotas transférés par l’UEdans le cadre de ses échanges avec d’autres pays tiers (Norvège, Islande, Faeroe),l’utilisation globale mesurée en nombres de licences utilisés se monte à 90% dunombre disponible.18. Les quotas pour les navires de l’UE ont été distribués suivant les clés de la stabilitérelative qui ne correspond pas totalement avec la demande constatée. Un systèmed’échanges intra-communautaire de quotas entre les Etat membres est utilisé demanière satisfaisant et a contribué à maintenir le taux d’utilisation de l’accord. Pendantles deux premières années, quelques segments de flotte ont évoqué des disponibilitéstardives de quotas qui ont gêné la planification des activités, mais le système a évoluédepuis pour permettre des échanges plus tôt.19. Il existe des différences significatives dans l’utilisation suivant les quotas. Lespossibilités de pêche pour la crevette dans l’Ouest du Groenland, du flétan duGroenland et du cabillaud sont très demandées. L’introduction de mesures de gestion alimité l’utilisation globale des possibilités de pêche sur le cabillaud à 91%. Seulement45% du quota annuel de 7 000 tonnes de crevettes dans l’Est du Groenland est utiliséainsi que seulement 46% du quota de sébastes. Les possibilités de pêche pour le crabedes neiges sous l’accord n’ont jamais été utilisées par l’Espagne. Le quota de flétanatlantique alloué au Portugal est pratiquement impossible à pêcher et se révèle d’unintérêt limité pour la Norvège. Les prises accessoires sous l’accord sont minimales.20. Au total, sur une année moyenne, le protocole d’accord a permis de capturer 48 502tonnes par an, dont 16 472 tonnes sont capturées par des navires de l’UE et 32 030tonnes par des navires de pays tiers (ces moyennes excluent les années pendantlesquelles aucun capelan n’a été capturé). Les captures annuelles prélevées par lesnavires de l’UE sont estimées équivalentes à 0,3% des captures totales de l’UE. Enmoyenne, les navires de l’UE ont capturé 63% des quotas disponibles, et les navires depays tiers 88%.21. Sue la base des prix des poissons publiés en Islande, le chiffre d’affaires annuel moyenréalisé sous l’accord a été de 45,6 M€ par an, dont 31,9 M€ (70%) par les navires del’UE et 13,7 M€ (30%) par les navires de pays tiers. Depuis que les navires de l’UEobtiennent des possibilités de pêche dans le cadre d’un échange équilibré des quotadans la zone Groenland avec la Norvège, l’Islande et les Faeroe, les bénéfices del’accord pour l’UE doivent intégrer ces éléments (en faisant l’hypothèse que l’échangeéquilibré est neutre d’un point de vue coût-bénéfice). Les Etats membres qui bénéficientle plus sont l’Allemagne (42% du chiffre d’affaires sous l’accord), le Danemark (11%), laPologne (7%) et le Royaume-Uni (4%).22. Les quotas obtenus sous l’accord avec le CRL ont contribué à respectivement 89%,37% et 100% des quotas mis à disposition avec la Norvège, les Faeroe et l’Islandedans le cadre des échanges (le solde étant des quotas sur des stocks dans les eux del’UE). Au total, le Groenland contribue à 70% de ces échanges en termes d’équivalentcabillaud. L’accès de navires de l’UE à des ressources importantes en Norvège et enIslande (dans le cadre de l’Accord EEE) est par conséquent très dépendant de l’accordentre l’UE et le Groenland (bien que l’UE et l’Islande n’aient pu s’entendre sur leséchanges en 2009 et 2010). Sans ces possibilités de pêche, il est improbable que lesnavires de pêche lointaine du Royaume-Uni, de l’Espagne, du Portugal et del’Allemagne puisse continuer à travailler.23. Pour l’UE, l’accord a apporté une valeur ajoutée nette de 20,3 M€ par an pour uninvestissement annuel de 15,8 M€, suggérant un rapport coût-bénéfice de 1,3 (i.e.chaque 1 € investi rapporte 1,3 €). Le rapport est positif et est comparable avec celuiobtenu sous l’accord avec la Mauritanie (qui est aussi un accord mixte). L’accordpermet de soutenir 330 postes de travail embarqués, avec environ 500 emplois dansFinal Report - pagex

Fisheries Partnership Agreement FPA 2006/20

FPA 35/GRE/11

l’UE directement dépendants de l’activité de pêche sous l’accord avec le Groenland(mais probablement sensiblement plus en tenant compte des activités liées dans lesautres pays tiers).24. En conséquence, si l’accord a été efficace pour soutenir la pêche par des navires del’UE dans les eaux du Groenland et d’autres pays tiers, il n’a été que marginalementefficient pour atteindre cet objectif, et sa viabilité reste dépendante d’externalités. Lesystème de distribution des licences n’est pas efficace avec des limites annuellesrigides qui exigent que les navires de l’UE achètent plus de quota que nécessaire (enmoyenne, pêcher 16 472 tonnes sur un quota total de 19 783 tonnes, avec 17% duquota acheté qui reste inutilisé à la fin de l’année). Les navires de pays tiers ne sontpas pénalisés par des achats de quota en excédent.25. Globalement, en intégrant les montants en soutien à la politique sectorielle, l’UE acontribué à la hauteur élevée de 286 € par tonne de produits capturés (30% de lavaleur commerciale). De plus, la contribution de l’UE et les paiements des armateursreprésentent pratiquement 70% des recettes budgétaires générées par le secteur despêches groenlandais alors que les captures ne représentent que 12% en valeur du totaldes captures dans la ZEE. Sur le coût total de l’accès à la ressource (compensation etredevances pour licences estimés à 259 € par tonne), la contribution de l’UE représente85% et celle des armateurs 15%, ce qui est similaire à la répartition mesurée sousd’autres accords mixtes (par exemple 87% en Mauritanie) mais supérieure à larépartition sous les accords thoniers de l’UE sous lesquels la répartition recherchée estde 65/35.26. Pour le Groenland, l’accord a été efficace pour générer des recettes à partir deplusieurs pêcheries qui n’auraient pas pu être valorisée autrement. En 2011, le montantde la compensation a été ajusté à la baisse de manière à annuler une partie de la dettesur le capelan accumulée entre 2007 et 2010 (correspondant à 0,4 M€ par an). Enconséquence, l’accord a généré en moyenne 15,8 M€ par an comprenant 13,9 M€ encompensation ajustée et 1,9 M€ en redevances licences. Ces recettes représentent1,3% des recettes de l’Etat en 2010. La rente obtenue est d’environ 326 € par tonne(35% du chiffre d’affaires des navires, ce qui est haut par rapport aux standardsinternationaux).27. L’accord n’a pas été efficace sous son objectif de générer des bénéfices économiquesadditionnels pour le Groenland (comme des sociétés mixtes, de l’emploi embarqué oudes débarquements locaux à des fins de transformation). Un programme de soutien àdes mesures sectorielles d’environ 4 M€ par an a été mis en œuvre par le Ministère dela Pêche, de la Chasse et de l’Agriculture suivant l’article 4 du protocole. La contributionde l’accord représente 70% des dépenses du budget de l’Etat au bénéfice du secteurde la pêche. Environ la moitié des montants ont été investis dans la recherche. Leprogramme est estimé correspondre à des objectifs pertinents et a donné des résultatspositifs pour les mesures concernant la recherche, la formation des cadres et lecontrôle des pêcheries, contribuant ainsi à l’amélioration de la durabilité du secteur dela pêche. Cependant, les mesures concernant l’ajustement structurel de la flotte côtière,et il n’est pas toujours clair de distinguer si le soutien budgétaire a été utilisé pourl’investissement ou le fonctionnement courant.28. Il existe des inquiétudes sur la durabilité de trois des dix possibilités de pêchespécifiées dans l’accord. On dispose d’éléments clairs indiquant que les stocks decabillaud, de flétan du Groenland dans l’Est de l’île et de sébaste (poisson pélagiqueprofond) sont sujets à des niveaux de pêche excessifs non soutenables, avec l’accordqui contribue à respectivement 11%, 30% et 8% du niveau global d’exploitation pendantla période couverte par l’évaluation. Pour le cabillaud, des mesures de gestion on étéintroduites dans le cadre d’un plan de gestion du cabillaud mis en œuvre par leGroenland, mais ce plan devrait être modifié pour réussir à garantir la durabilité dans lelong terme. Pour la sébaste, un accord signé en mars 2011 par le Groenland, l’UE etd’autres pays concernant la gestion de l’espèce dans la Mer d’Irminger diminueraprogressivement les TACs et devrait aboutir à la durabilité dans le futur. Pour le flétandu Groenland (stock Est) qui est un autre stock chevauchant, il n’existe pas d’accordFinal Report - pagexi

Fisheries Partnership Agreement FPA 2006/20

FPA 35/GRE/11

entre les Etats côtiers (Groenland, Islande et Faeroe). Chaque partie fixe des TACsautonomes et les captures dépassent les recommandations scientifiques d’un facteur 5.Bien qu’il existe des inquiétudes sur la soutenabilité des niveaux d’exploitation de lacrevette dans l’Ouest du Groenland (considéré comme à risques), l’accord n’a concernéque 3% des captures, et un plan de gestion efficace a été introduit en 2010. Le risqueque l’exploitation du flétan atlantique n’ait pas été soutenable existe, mais les donnéesmanquent pour s’en assurer. Les autres quotas (crevettes dans l’Est du, flétan duGroenland dans l’Ouest, capelan et crabe des neiges) sont tous considérés commeétant sujet à une gestion durable. Toutes les pêcheries sont connues pour avoir destaux élevés de prises accessoires. Toutes les pêcheries démersales au chalut doiventêtre équipées de grilles de tri et les rejets sont interdits. Il n’y a pas d’impacts négatifsconnus sur les espèces non-ciblées ou sur les écosystèmes.29. En général, l’accord de partenariat dans le domaine de la pêche est cohérent avec lespolitiques de l’UE concernant le développement et le commerce qui ensembleapportent des bénéfices au Gouvernement du Groenland et aux parties prenantesnationale. A l’exception de l’absence de durabilité dans l’exploitation de trois stocksclés, l’accord est globalement cohérent avec la politique commune de la pêche.L’accord est potentiellement cohérent avec la politique en développement de l’UE pourla région arctique. Concernant les mesures prises par l’UE pour les produits à base dephoques, le cadre politique manque de cohérence. La surcapacité dans les pêcheriescôtières et l’absence de possibilités d’emplois alternatifs sont l’un des problèmesstructures critiques du secteur de la pêche du Groenland, qui doit être traité dans lecadre d’un programme renforcé d’ajustement structurel à introduire dans le programmedes mesures de soutien sectoriel considérés par l’accord de partenariat dans ledomaine de la pêche.30. L’étude conclut que globalement, l’accord a été très bénéficiaire pour les deux parties,et recommande par conséquent que les deux parties négocient un renouvellement duprotocole. Le futur protocole devrait avoir une durée de 3 années de manière à garantirune parfaite cohérence avec tout renouvellement de la décision relative à l’associationdes PTOM et de l’accord de partenariat avec le Groenland. Cette durée permettraégalement de prendre en considération dans un prochain accord de nouvelles mesuresprises sous une politique de la pêche réformée, en cohérence avec d’autres initiativescommunautaires incluant la politique pour l’arctique sous ses aspects maritimes etenvironnementaux.

Final Report - pagexii

Fisheries Partnership Agreement FPA 2006/20

FPA 35/GRE/11

1 INTRODUCTION1.1 BackgroundThis report provides the findings of a study comprising an ex-post evaluation of the FisheriesPartnership Agreement between the European Union and Greenland. The study wascommissioned by the Directorate General for Maritime Affairs and Fisheries of the EuropeanCommission under a framework contract “for performing evaluations, impact analyses andmonitoring services in the context of Fisheries Partnership Agreements (FPAs) concludedbetween the European Union and non-EU member states (No. FISH/2006/20)” operated by aconsortium comprising Oceanic Développement (France) and Megapesca Lda (Portugal).The Fisheries Partnership Agreement between the parties was initialled in June 2006, andentered provisionally into force on 1stJanuary 2007 for a period of six years (until 31stDecember 2012). It was adopted into EU law by Council Regulation (EC) No 753/2007 of 28June 2007. At the time of the study the Fisheries Partnership Agreement has therefore beenoperational for just over four years, and the period of evaluation covers the years 2007 to 2010inclusive.The main objective of this report is to provide the parties to the Fisheries Partnership Agreementwith an analysis to help understand the associated costs and benefits, consider the progressmade so far in meeting its objectives and suggest ways in which the Fisheries PartnershipAgreement could better serve their mutual needs, whilst meeting policy objectives forsustainable fisheries. This information will assist the parties the negotiation of any new protocolwhich they may decide to enter into.This report is broadly divided into four sections. In the first section it presents a brief descriptionof the general political and economic context of the EU – Greenland Fisheries PartnershipAgreement, which includes a detailed review of the relationship between the EU and Greenland,as well as general background of relevance, including maritime boundary issues. The secondsection describes Greenland’s fisheries resources and its sector. The third section describes theimplementation of the EU-Greenland Fisheries Partnership Agreement (FPA), and assesses itsimpacts on the EU fleet, the European Union and Greenland (including the implementation ofGreenland’s fishery sector policy supported by the Fisheries Partnership Agreement. The finalsection presents the overall conclusions and recommendations for the parties.

1.2 MethodologyThe methodology adopted by the consultants included the following activities:••••Review of documentation provided by the Commission (catch data, quota swaps, AgreedRecords and legal basis for the Fisheries Partnership Agreement).Literature review regarding Development Policy, Maritime Policy and the Arctic DimensionReview of work programmes of the working groups of the Arctic Council, and analysis ofGreenland obligations in this respectMeetings and phone discussions with EU fishery sector stakeholders and EU Member Statefishery administrations (in Estonia and Denmark, UK, Germany, Poland, Spain andPortugal)Field mission to Greenland and consultation with Greenland stakeholders (fisheriesadministration, fisheries control, fisheries and environmental research, fishing andprocessing industry interests, NGOs);Collection and review of data on implementation of sectoral policy measures implementedunder the FPA;

•

•

Final Report - page1

Fisheries Partnership Agreement FPA 2006/20

FPA 35/GRE/11

•

Contact with Norwegian and Faroese stakeholders regarding utilisation of fishingopportunities and implementation of the access arrangements for opportunities received asa result of the EU-Greenland Fisheries Partnership AgreementMeetings and discussions with European Commission Services, including DG MaritimeAffairs and Fisheries, DG DevelopmentAnalysis of licence and catch data relating to EU, Norwegian, Icelandic and Faroe Islandfishing vessels, and calculation of values of catches made.Assessment of impacts on Greenlandic and EU fishing sectors, and economies

•••

The methodology has drawn on relevant elements of the “Specific Methodological Guidelines forEvaluation of Fisheries Partnership Agreements” prepared by the Consultants in February 2008,and reflects the approaches set out in “EvaluationStandards and Good Practice (C/2002/5267,23.12.2002)”and “EvaluatingEU activities: A practical guide for Commission services (July2004)”.The findings are considered in the context of the objectives of the Fisheries PartnershipAgreements as set out in COM(2002) 637 Final, “Communication from the Commission on anIntegrated Framework for Fisheries Partnership Agreements with Third Countries”.

2 POLITICAL AND ECONOMIC CONTEXT2.1Political situationGreenland became a Danish colony in 1814 and became a part of the Kingdom of Denmark in1953, with the passage of the new Danish constitution. In 1979 Denmark granted “Home Rule”to Greenland, which provided for autonomy over most policy areas, with the exception of foreignpolicy, defence and a number of other functions which were performed by Denmark, as thesovereign state. The devolution established a Home Rule Government with an electedparliament of thirty-one members. The head of government is the Prime Minister. As part of therealm of the Kingdom of Denmark, Greenlanders also elect two representatives who sit in theParliament of Denmark.A Joint Greenlandic-Danish Commission considered devolution of powers during the period2004 to 2008, and proposed a new Law on Greenland Self-Governance1in May 2008.Following a referendum on 25 November 2008 the new law took effect on 21 June 2009. Thisprovides for Greenland to have the option of taking over responsibility for 32 functions currentlyperformed by Denmark, including police, justice and border control. Under the Law, Denmarkretains functions of defence, fishery inspection outside the territorial waters, constitutionalaffairs, currency and monetary policy. The first areas (administration of mineral resources andimmigration) were taken over in 2010. Danish Ministry of finance has estimate that the cost ofthese functions is more than EUR 40million/year. In the meanwhile, Denmark has undertaken tocontinue supporting the Greenland budget with an annual block grant of EUR 469 million in2010.Also with the passing of the new Law on Greenland Self Government on 21 June 2009, the title“Greenland Home Rule Government (GHRG/Groenlands Landsstyre) was amended to becomethe Naalakkersuisit (Government of Greenland).In the meanwhile following a General Election in June 2009, the centre-left Inuit Ataqadigiit (IA)party won the election and formed a coalition. The current Naalakkersuisut therefore consists of

Lov Nr. 473 af 12. Juni 2009 om Gronlands Selvstyre (Act No 473 of 12 June 2009 onGreenland Self Government. Lovtidende 13.06.2009)

1

Final Report - page2

Fisheries Partnership Agreement FPA 2006/20

FPA 35/GRE/11

nine Members. Six are the from Inuit Ataqatigiit party, two from the Democrats, and one fromKattusseqatigiit Partiaat. The Coalition Agreement 2007-2013 was signed on 10 June 2009.Under the theme of Fisheries and Hunting the Coalition Agreement of 10 June 2009 indicatedthat, “a politically independent organ will be established for the allocation of fish and shellfishquota”. Until now this has not been established. One notable aspect is that the FPA is notmentioned in the Coalition Agreement, although it is stated that Greenland will continue tocooperate with the EU in the context of the Partnership Agreement and Greenland’s OCTstatus.

2.2

Economic situation

The population of Greenland is 56,452 (20102). This includes around 6,300 resident Danes. Thepopulation is stable. The labour force in 2010 was 28,510, with an unemployment rate of 7.1%.Greenland’s has low inflation (1.4% in 2009) but suffers from a high structural unemploymentrate, along with an aging population. Its Gross National Income was EUR 29,286/capita in 2006.However, GDP has not risen in real terms in recent years.The Government is the largest employer, accounting for 44% of all jobs. There are 18communes, the largest concentration of the population being in the South and Western region ofGreenland. All transport between settlements is by air or sea. This all leads to high transportcosts and an inflexible and immobile labour market. The system of production is characterisedby significant public intervention, with an underdeveloped private sector and reliance ontransfers from Denmark.The country relies heavily on the annual block grant provided by Denmark, accounting for anestimated 32% of GDP. Substantive difficulties facing the country include a) high dependencyon fisheries b) direct and indirect subsidies to government owned enterprises c) high wagelevels d) ageing population d) lack of skilled manpower e) marginalisation of the indigenouspopulation f) slow private sector development. Significant opportunities for economicdevelopment are emerging, with oil and minerals, transport services (in relation to a potentialfuture opening of the north west passage to the Pacific), aluminium smelting and energy. Thecountry faces significant challenges in managing environmental and social impacts of economicdevelopment.

2.3

Fishery sector