NATO's Parlamentariske Forsamling 2011-12, Forsvarsudvalget 2011-12, Det Udenrigspolitiske Nævn 2011-12

NPA Alm.del Bilag 14, FOU Alm.del Bilag 57, UPN Alm.del Bilag 102

Offentligt

The Secretary General’sAnnual Report2011

Foreword

M

any will remember 2011 as a year ofausterity. But it has also been a year ofhope. The international community unitedin its responsibility to protect. Much of theArab world took a new path forward. And the EuropeanAllies showed they were willing and able to lead a newNATO operation.

For NATO, 2011 was one of the busiest years ever. FromLibya to Afghanistan and Kosovo, from the Mediterranean Seato the Indian Ocean, the Alliance was committed to protectingits populations and active in upholding its principles andvalues. We enabled the Afghan security forces to start takingthe lead for security for over half of the Afghan population.We successfully concluded our training mission which hascontributed to improving Iraq’s security capacity. 2011 wasalso a benchmark year for reforms. We took significant stepsto further streamline our structures, enhance our effectivenessand reduce our costs. At the same time, we strengthened ourcapabilities in many areas, including the prevention of cyberattacks. And we enhanced our connectivity by increasingcooperation with our partner countries in the Euro-Atlanticarea, the Middle East, North Africa and the Gulf, as wellas with many other countries across the globe. This is atransatlantic Alliance that, despite the economic crisis,has once again demonstrated its commitment, capabilityand connectivity.In 2011, our new Strategic Concept was put to thetest. This report – the first of its kind – shows that wesuccessfully met that test.At the start of the year, few would have imagined NATOwould be called to protect the people of Libya. But on31 March, NATO took swift action on the basis of thehistoric United Nations Security Council Resolution 1973.We saved countless lives. And seven months later, wesuccessfully completed our mission. When I visited Tripolion 31 October, Chairman Jalil of the National TransitionalCouncil told me, “NATO is in the heart of the Libyan people.”Operation Unified Protector was one of the most remarkablein NATO’s history. It showed the Alliance’s strength and

flexibility. European Allies and Canada took the lead; theUnited States provided critical capabilities; and the NATOcommand structure unified all those contributions, as well asthose of our partners, for one clear goal. In fact, the operationopened a completely new chapter of cooperation withour partners in the region, who called for NATO to act andthen contributed actively. It was also an exemplary missionof cooperation and consultation with other organizations,including the United Nations, the League of Arab States, andthe European Union. Throughout, NATO proved itself as aforce for good and the ultimate force multiplier.These achievements give me great confidence as I lookforward to 2012. Clearly, economic challenges are likely toremain a dominant factor and decisions taken today mayshape our world for decades to come. Our task is to makesure we emerge stronger, not weaker, from the crisis weall face. But we can draw great strength from an enduringsource: the indivisibility of security between North Americaand Europe. NATO is a security investment that has stoodthe test of time for over six decades and continues to deliverreal returns for all Allies, year after year.2012 will be marked by our Chicago Summit in May.This will be an opportunity to renew our commitment tothe vital transatlantic bond between us and to redouble ourefforts to share the burden of security more effectively.We will take important decisions to keep NATO committed,capable and connected.Afghanistan remains by far our largest operation, withover 130,000 troops as part of the broadest coalition inhistory. 50 Allies and partners are determined to ensurethe country will never again be a base for global terrorism.Afghanistan is moving into the right direction and transitionto Afghan security lead is on track to be completed bythe end of 2014. As Afghan security forces grow moreconfident and capable, our role will continue to evolveinto one of support, training and mentoring. But theChicago Summit will show our commitment to a long-termpartnership with Afghanistan, together with the wholeinternational community, beyond 2014.

2

At Chicago, we will also take measures to improve ourcapabilities. During our operation in Libya, the United Statesdeployed critical assets, such as drones, precision-guidedmunitions and air-to-air refuelling. We need such assetsto be available more widely among Allies. In the currenteconomic climate, delivering these expensive capabilitieswill not be easy. But it can be done, and it is critical if weare to respond effectively to the challenges of the future.The answer lies in what I call “smart defence”: doing betterwith less by working more together. In Chicago, we willdeliver real “smart defence” commitments, so that everyAlly can contribute to an even more capable Alliance.NATO’s missile defence system to defend European Allies’populations, territory and forces against the growing threatof ballistic missile proliferation is “smart defence” at its bestand it embodies transatlantic solidarity. We have alreadymade considerable progress. Along with a prominent andphased US contribution, a number of Allies have madesignificant announcements, including Turkey, Poland,Romania, Spain, the Netherlands and France. Thesedifferent national contributions will be gradually broughttogether under a common NATO command and controlsystem. Key elements of it have already been tested

successfully and I expect the initial components of thesystem to be in place by the time of the Chicago Summit.NATO has invested heavily in its network of partnerships.Continued NATO-Russia cooperation is vital for thesecurity of the Euro-Atlantic area and the wider world.Twenty-two partner countries have troops or trainers onthe ground in Afghanistan. And our successful operationto protect the people of Libya could not have takenplace without the political and operational support of ourpartners in the region and beyond. At Chicago, we willrecognize the contribution made by our partners who arewilling and able to share the security burden with us.Chicago is about delivering important commitments.Personal commitment, too, has been key to the Alliance’ssuccess. Dedicated civilian and military staff are workingin operational theatres and in headquarters to protect our900 million citizens. They work under demanding anddangerous conditions. This report is a tribute above all totheir sacrifice, bravery, and professionalism.■

Anders Fogh RasmussenNATO Secretary General

3

NATO operations –progress and prospectshe tempo and diversity of NATO operations haveincreased considerably since the Alliance’s firstmilitary interventions in the early 1990’s. Today,over 140,000 military personnel are engaged inNATO-led missions on three continents, managing complexground, air and naval operations in all types of environment.Afghanistan constitutes the Alliance’s most significantoperational commitment to date. 2011 was, however,marked by NATO’s commitment to Libya, which showedthat the Alliance is prepared, equipped and able to intervenein such crises – and must continue to be able to do so.NATO is also helping to provide peace and security inKosovo, and is playing a key role in the stability of the entireWestern Balkans region. Off the Horn of Africa and in theGulf of Aden, the Alliance is making a significant contributionto counter-piracy efforts, helping to protect a vital waterwaythrough to Europe and the East for the global economy.

T

security operations in coordination with the AfghanNational Security Forces (ANSF) and assists in thedevelopment of Afghan National Security Forces andstructures, including training the Afghan National Armyand the Afghan National Police. Currently, more thana quarter of the world’s countries are participating inISAF – a true measure of the unwavering internationalcommitment to Afghanistan’s secure, stable anddemocratic future.The fundamental reason for ISAF’s presence is to ensurethat the country never again becomes a safe haven forterrorists.2011 has been a year of consolidation, reinforcingthe achievements made in 2010 with ISAF’s counter-insurgency strategy, especially in the south of thecountry, and commencing the gradual transition ofresponsibility for the security of the country from ISAFtroops to Afghan forces. In 2011, over half the populationsaw their army and police beginning to take the lead inproviding them with security. In addition to conductingsecurity operations, ISAF has continued to help buildup the Afghan army and police force through the NATOTraining Mission-Afghanistan (NTM-A). In parallel, ISAF

AfghanistanThe main focus of the UN-mandated, NATO-ledInternational Security Assistance Force (ISAF) remainsthe provision of security for Afghanistan. ISAF conducts

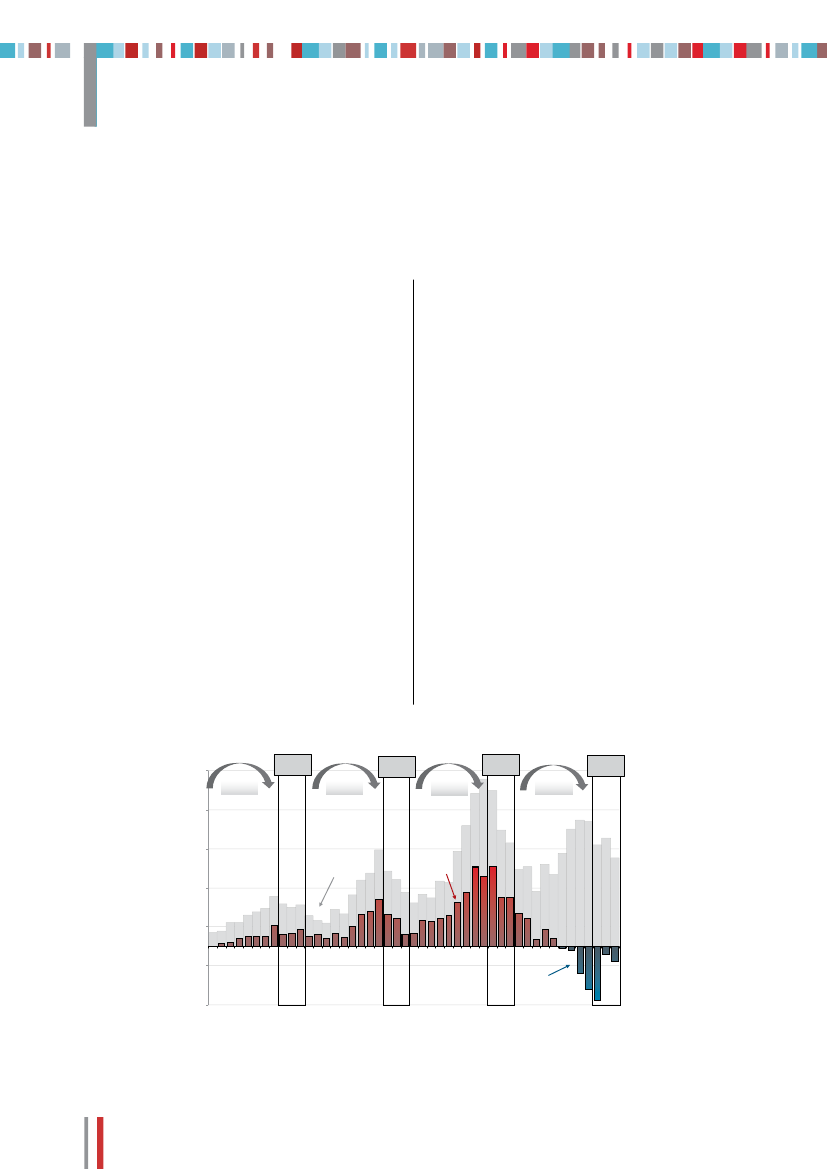

Enemy-initiated attacks country-wide4500

Sep-Nov2008

Sep-Nov2009

Sep-Nov2010

Sep-Nov2011

+52%3500

+59%

+94%

-21%

Number of Incidents

2500

Enemy-InitiatedAttacks1500

Increase fromYear Before

500

-500

Decrease fromYear Before

4

Jan 08Feb 08Mar 08Apr 08May 08Jun 08Jul 08Aug 08Sep 08Oct 08Nov 08Dec 08Jan 09Feb 09Mar 09Apr 09May 09Jun 09Jul 09Aug 09Sep 09Oct 09Nov 09Dec 09Jan 10Feb 10Mar 10Apr 10May 10Jun 10Jul 10Aug 10Sep 10Oct 10Nov 10Dec 10Jan 11Feb 11Mar 11Apr 11May 11Jun 11Jul 11Aug 11Sep 11Oct 11Nov 11

-1500

Data source:Afghan Mission Network (AMN)Combined Information DataNetwork Exchange (CIDNE)Database, as of 16 Dec 2011.

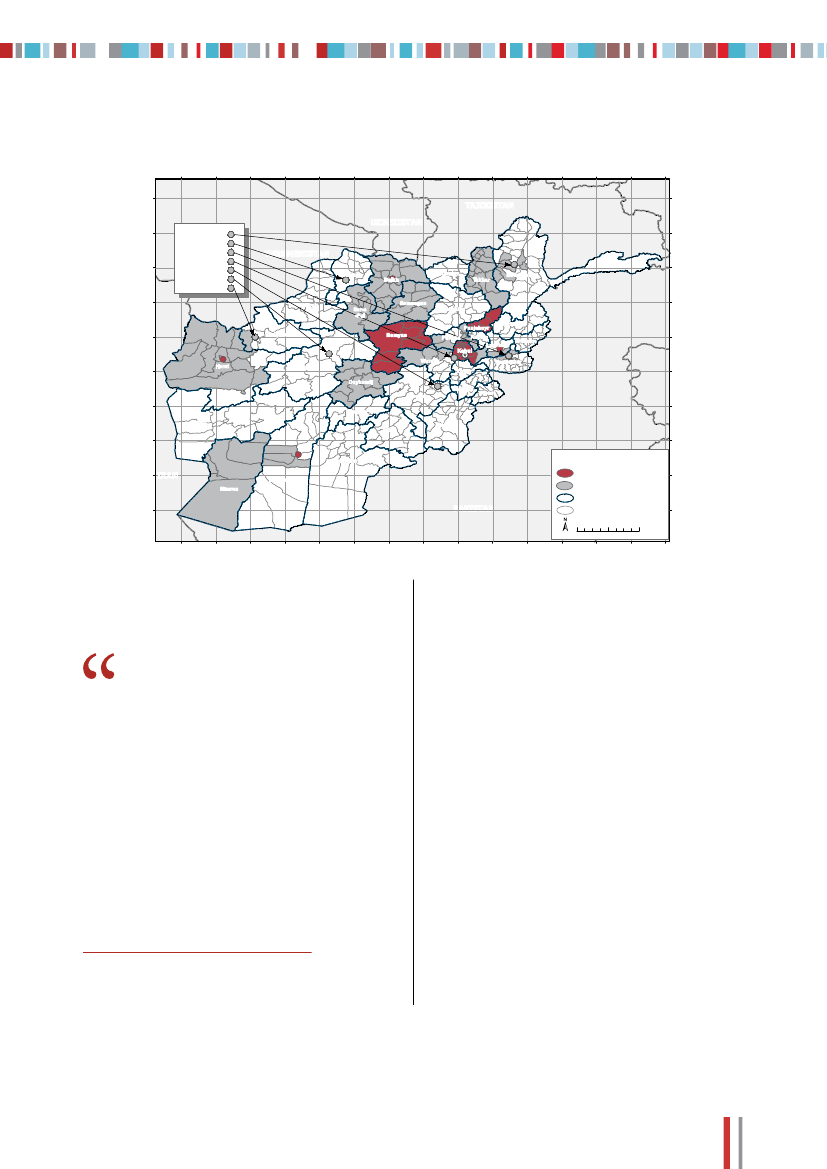

Afghanistan transition map for tranche 1 and 261�E62�E63�E64�E65�E66�E67�E68�E69�E70�E71�E72�E73�E74�E75�E

39�N

TAJIKISTANCities of:FaizabadShebreganJalalabadMaidan SharTURKMENISTANGhazniCheigh CharanQalai Naw

UZBEKISTAN38�N

38�N

TURKMENISTANJowzjanBalkhKunduzTakharBadakhshan37�N

36�N

37�N

Faryab

Sar-e-Pul

Samangan

BaghlanPanjshayrParwanKapisaLaghmanNuristanKunar

35�N

Kabul34�N

LogarDaykundiGhazniPaktiya

Khost33�N

33�N

UruzganFarahZabulPaktika

32�N

Kandahar

LegendTranche 2Province BoundaryDistrict Boundary050100200 km30�N31�N

IRANNimroz

31�N

Helmand

Tranche 1

32�N

34�N

Herat

Ghor

Wardak

Nangarhar

35�N

Badghis

Bamyan

36�N

39�N

30�N

PAKISTAN

Afghanistan Provinces and Districts updated as of July 201061�E62�E63�E64�E65�E66�E67�E68�E69�E70�E71�E72�E73�E74�E75�E

Produced bySITCEN GeoSection inDecember 2011

is also directly involved in facilitating the developmentand reconstruction of Afghanistan through ProvincialReconstruction Teams throughout the country.

greater stability has enabled progress on all frontsOver time, greater stability has enabled progress on allfronts. Access to basic healthcare is improving and infantmortality is falling; school enrolment of children – includinggirls – has increased from under 1 million in 2001 toaround 8 million in 20111; and 5.7 million refugees havereturned from Pakistan and Iran, representing nearly aquarter of Afghanistan's population2.Stability continues to improve. In 2011, overall enemy-initiatedattacks decreased and the insurgency was weakened.1 World Bank figures2 Figures from the Office of the United Nations High Commissionerfor Refugees

Indeed, attacks were down 8 per cent country-widecompared to 2010. In Helmand, attacks decreased by30 per cent and in some districts by 80 per cent. Whilespectacular attacks dominate the media, the insurgency hasdeclined, rather than intensified. Combined Afghan NationalSecurity Forces and ISAF-led operations placed persistentpressure on the insurgency, in areas such as the South, whereit was at its strongest.Despite this momentum, much work remains to be done.Insurgents continue to conduct high-profile attacks andintimidation campaigns. They have targeted high-rankinggovernment officials as well as influential political andreligious leaders.

Transition: ‘A new era of stability, security andresponsibility for Afghanistan’Progress in Afghanistan, in particular with regard to thetraining of the Afghan army and police force, has enabledthe start of transition to full Afghan security lead. Transitionis the process by which responsibility for Afghanistan’ssecurity is gradually transferred from ISAF to Afghan lead,with an ISAF presence maintained but the role of troopsevolving from a “combat” to a “support” role.

5

The process started in July 2011. By the end of 2014, it isexpected that Afghan authorities will have taken the leadthroughout the country. At the 2012 Summit in Chicago,NATO leaders, together with the Afghans, will decide whatadditional support needs to be given to the ANSF to helpthem fulfil their fundamental tasks. In concrete terms,this will mean what further training and education arenecessary to ensure that the Afghan forces and authoritieshave the skills and the support they need to keep theircountry secure.Afghan and NATO authorities have been assessingthe readiness of areas for transition. On 21 March, theAfghan New Year, President Karzai announced the firstAfghan districts to start transition; implementation of thisfirst tranche began in July 2011. On 27 November, thePresident announced the second tranche of areas to initiatetransition, with implementation begun in December 2011.As a result of these decisions, over 50 per cent of thepopulation will live in areas under Afghan security lead. Thetransition process will continue until the end of 2014.

34,000 Afghans in training at these sites. In order toprotect this investment in professionalism, the quality ofANSF equipment has also been significantly improvedand Afghan soldiers and policemen are now paid aliving wage salary which meets or exceeds the nationalstandard of living.On average, there are 6,000 Afghan army recruitsscreened and placed into training each month, but only14 per cent of them are literate. In order to address this,a mandatory literacy programme for the ANSF has beeninstituted. By November 2011, some 136,000 personnelhad completed some combination of first, second or thirdgrade literacy exams and another 90,000 were in trainingwith the aim of the ANSF achieving over 60 per cent firstgrade literacy by the end of January 2012. The ANSF iswell on track to reach and even exceed this target.While significant progress has been achieved, challengesremain. For example, continued literacy training will beessential to enable further professionalization of theforce, the retention rate needs to be improved to sustainthe growth and cohesion of the force, and buildingeffective leaders in sufficient numbers will be crucial insolving the most difficult challenges. In this regard, itis important for the broader international community,including ISAF contributing nations, to reconfirm theircommitment to provide financial, material and trainingsupport for the ANSF and continue to help sustain theANSF beyond 2014.

Afghan National Security Forces – NATO TrainingMission-AfghanistanNATO’s main effort in Afghanistan has increasinglyfocused on the training and development of the AfghanNational Army (ANA) and the Afghan National Police(ANP), known collectively as the Afghan National SecurityForces (ANSF). In January 2010 the Afghan Government,in discussion with the international community, agreed togrow the ANSF towards 305,600 personnel by October2011. Increased training support to the ANSF, mainlythrough the NATO Training Mission-Afghanistan (NTM-A),enabled Afghans to reach this ceiling, as planned. As aresult, the insurgency is now facing an ANSF which has,since the beginning of 2010, grown by 110,000 soldiersand police. With this growth in both size and capability,Afghan army and police will continue to replace ISAFtroops and assume an ever-increasing lead in providingsecurity across the country.The growth in size of the Afghan security forces has beenmatched by an improvement in the capabilities of Afghanforces. NTM-A has taken significant steps to improve andmaintain quality: institutional training across Afghanistannow follows a standardized programme of instructionfor the army and the police; ANSF leaders are enteringthe force with better training than their predecessors;there are now some 62 different training sites acrossAfghanistan and, at any one time, there are more than

Afghanistan will one day stand on its own, but itwill not be standing aloneWith the conclusion of the transition process, theinternational community’s commitment to Afghanistan doesnot come to an end. As reinforced during the InternationalConference on Afghanistan held in Bonn in December 2011,the international community will remain strongly engagedin support of Afghanistan beyond 2014. And NATO willplay its part. At the NATO Summit in Lisbon in November2010, NATO and the Government of the Islamic Republicof Afghanistan signed a Declaration on an EnduringPartnership. This partnership is the framework on whichNATO will build its long-term engagement with Afghanistan,designed to continue after the ISAF mission. As NATO’srole shifts from a lead combat role to one of support, Alliesand ISAF contributing countries have stressed they remaincommitted to Afghanistan. NATO will continue to stand bythe Afghan people throughout transition and beyond.

6

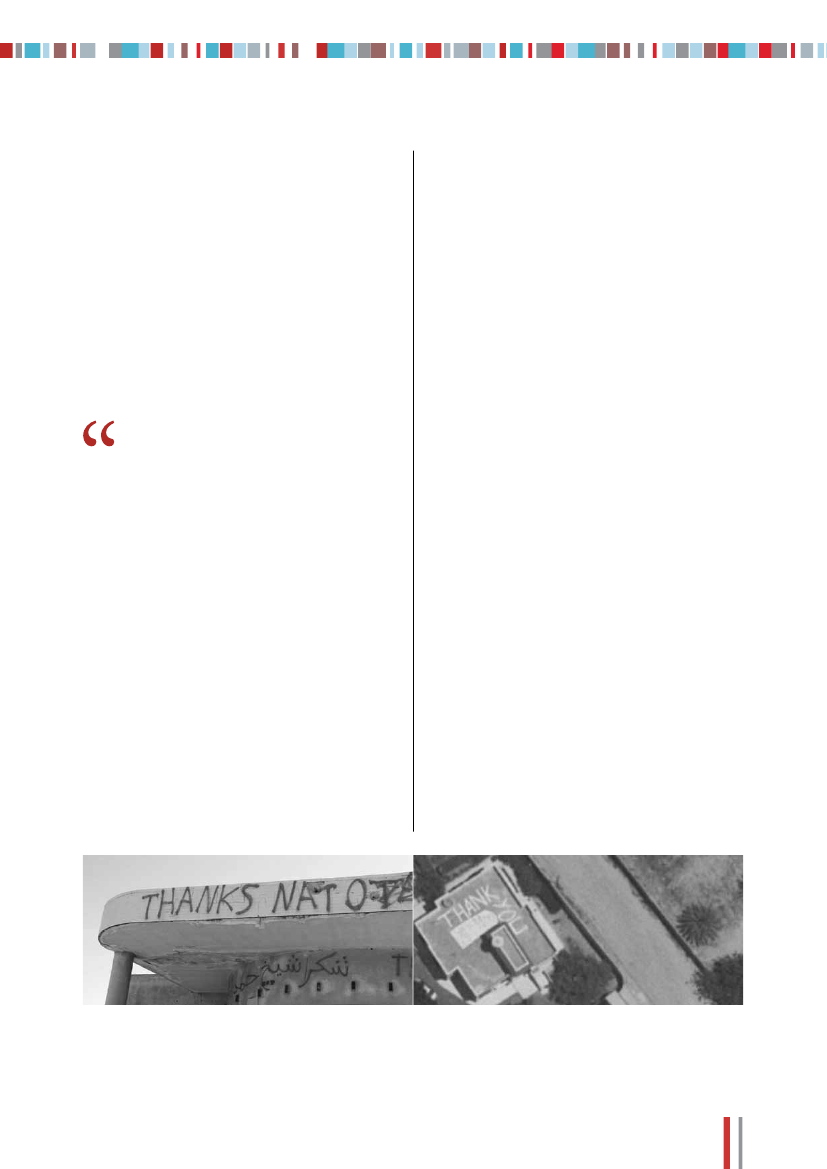

Operation Unified Protector in LibyaMuch of the world’s attention in 2011 was focused on thecrisis in Libya where NATO played a crucial role in helpingprotect civilians from attack or threat of attack. NATO’sintervention to enforce a historic UN mandate was swift andwas brought to a successful conclusion seven months afterits start. This was one of the few occasions in which the UNSecurity Council has authorized the international communityto intervene militarily to protect civilians from, in particular,their own government. The widespread and systematic actsof violence and intimidation committed by the Libyan securityforces against pro-democracy protesters, as well as thegross and systematic violation of human rights brought theinternational community to agree on taking collective action.

of events in Libya in March 2011 met these criteria. With theadoption of UNSCR 1973, several UN member states tookimmediate military action. NATO followed by enforcing theno-fly zone only six days later.NATO took over sole command and control of allmilitary operations for Libya on 31 March. It acted in fullaccordance with the UN mandate and consulted closelythroughout with the UN, the EU, the League of Arab Statesand other international partners.The NATO-led “Operation Unified Protector” had threedistinct components:-the enforcement of an arms embargo on the high seasof the Mediterranean to prevent the transfer of arms,related material and mercenaries to Libya;the enforcement of a no-fly zone in order to preventany aircraft from bombing civilian targets; andair and naval strikes against those military forcesinvolved in attacks or threats to attack Libyan civiliansand civilian-populated areas.

use “all necessary measures” to protect Libyan civiliansIn February 2011, a peaceful protest in Benghazi againstthe 42-year rule of Colonel Muammar Qadhafi was met withviolent repression, claiming the lives of dozens of protestorsin a few days. As demonstrations spread beyond Benghazi,the number of victims grew. The UN Security Counciladopted Resolutions 1970 and 1973 in support of the Libyanpeople, “condemning the gross and systematic violationof human rights, including arbitrary detentions, enforceddisappearances, torture and systematic executions.” TheResolutions introduced active measures including a no-flyzone, an arms embargo, and the authorization to memberstates, acting as appropriate through regional organizations,to use “all necessary measures” to protect Libyan civilians.In support of broader international community efforts, theAlliance’s decision to undertake military action was basedon three clear principles: a sound legal basis; strong regionalsupport; and a demonstrable need. The particular context

--

At its peak, the NATO-led operation involved over 20 NATOships in the Mediterranean, over 250 aircraft of all types, andwas conducted in an area more than 1,000 kilometres wide.Of particular significance, it involved a coalition of NATOAllies and five non-NATO countries, including Sweden andmainly countries from the region (Jordan, Morocco, Qatarand the United Arab Emirates), thereby highlighting the strongregional support for NATO’s operation.NATO’s strategy was defined by the mission, namely to takeall necessary measures to prevent attacks and threats ofattack against civilians and civilian areas. The most pressingand immediate task was to prevent attacks with tanks andheavy artillery on Benghazi. It also meant engaging witharmed units that were attacking the city of Misrata. And itmeant degrading ammunition supplies and command andcontrol networks so that the regime’s military commanderscould not conduct or coordinate such attacks.

7

Overall, NATO conducted over 3,000 hailings at sea, almost300 boardings for cargo inspection with 11 vessels beingdenied access to their next port of call. NATO flew over 26,000sorties, of which 42 per cent were strike sorties damagingor destroying approximately 6,000 military targets. NATOassets flew an average of 120 sorties per day. In support ofhumanitarian assistance, NATO deconflicted nearly 4,000 air,sea and ground movements to allow missions by the UN, non-governmental organizations and others to proceed unhindered.There was an absolute requirement to minimize collateraldamage and civilian casualties. Air strikes were thereforecarried out with the greatest possible care and precision.Civilian infrastructure, such as water supplies and oilproduction facilities, was never targeted. At no time werethere any forces under NATO command on the groundin Libya. The UN mandate was carried out to the letter,as stated by the UN Secretary-General, Ban Ki-moon, inDecember 2011: “This military operation done by the NATOforces was strictly within (resolution) 1973.”The cumulative effect of NATO action to protect civilians wasthat the regime forces were gradually degraded to a point thatthey could no longer carry out their campaign country-wide.The successful termination of the NATO-led operation andthe fall of the Qadhafi regime have opened up a new chapterin Libya’s history. For the first time in more than 40 years,the Libyan people have a unique opportunity to shape theirown future. But the hard work of creating a new country andembarking on genuine reconciliation has only just begun.While there is no further operational role for NATO followingthe conclusion of Operation Unified Protector, NATO standsready to assist the new Libyan authorities, upon request, inareas where it could provide added value. The new Libyanauthorities have set up an interim government and electionswill be held in 2012. In short, a period of transition has begun.The NATO-led force in KosovoThroughout 2011, the NATO-led force in Kosovo – KFOR –has continued to provide peace and security in Kosovo. Underthe mandate provided by UN Security Council Resolution 1244of 10 June 1999, KFOR contributes towards a safe and secureenvironment in Kosovo and the freedom of movement for allpeople in Kosovo, irrespective of their ethnicity.KFOR has continued to create the necessary conditionsfor other international actors and stakeholders to effectivelyperform their respective roles in Kosovo. In particular, thegeneral improvement in the security situation in Kosovo greatlyassisted in the deployment of the European Union Rule of Law

Mission in Kosovo, with which NATO cooperates very closelyon a daily basis. It has also allowed the Alliance to graduallyadjust KFOR’s military presence. Following a decision by NATOdefence ministers, a reduction from 10,000 to 5,500 troopswas successfully implemented by the end of March 2011.

The “unfixing process”In parallel, KFOR has continued with the unfixing process ofthe original nine “Properties of Designated Special Status”in Kosovo. These sites have a particular religious, culturaland symbolic value and, over time, responsibility for theirprotection is handed over to the Kosovo police. Followingthe successful unfixing of five “Properties of DesignatedSpecial Status” to the Kosovo police in 2010, KFOR alsoimplemented the handover of guarding responsibilities for theArchangel’s site on 10 May 2011, and on 15 January 2012for the unfixing of the seventh site, the Devic monastery.ˇ

The situation in Northern KosovoWhile KFOR has been successful in carrying out its UNmandate, the security situation abruptly deteriorated inNorthern Kosovo in July 2011 over a customs dispute.Clashes ensued, resulting in two major spikes of violencein July and September, followed by a third in November,prompting the Alliance and its partners to adapt their postureon the ground. In this context, the NATO OperationalReserve Force was deployed in August, with a troopcontribution of around 600 soldiers, in order to help bolsterKFOR’s deterrent presence in the North.Amid the heightened tensions and clashes in NorthernKosovo, KFOR acted carefully, firmly and impartially, witha view to guaranteeing the people of Kosovo a stableenvironment, freedom of movement and security. Meanwhile,at the political level, NATO has continued to support thedialogue between Belgrade and Pristina under EU auspices,which is the only way out of the crisis. Both parties needto find a sustainable solution to a number of importantissues as well as contribute to both the reconciliation andnormalization process in the area.These developments have prompted NATO to adjust itsplanned calendar. With the Operational Reserve Forcedeployed in order to strengthen NATO’s deterrence posture,the reduction of KFOR has been delayed with the aim toensure the ability to maintain a safe and secure environmentif tensions arise. The Alliance will assess the situation at thebeginning of 2012 and decide at what stage KFOR forcescan be reduced to a lower level.

8

Counter-piracyPiracy continues to be a serious security threat. Of the attacksreported in 2011, Somali pirates are responsible for overhalf of them according to the International Maritime Bureau(International Chamber of Commerce). Throughout 2011,NATO has remained actively engaged in combating piracy andarmed robbery at sea off the Horn of Africa – and will continuedo so at least until the end of 2012 – in line with the relevantUN Security Council Resolutions and in close cooperationwith other key organizations and countries involved.

However, the international community continues to be facedwith increasingly well-armed, violent and bold Somali pirategangs who are operating in a wider area.There are, however, limitations to the effects of navaloperations in rooting out piracy. It is important to helpcountries in the region build the capacity to fight piracy,and NATO is willing and able to assist in these efforts,within means and capabilities given the current economicclimate. NATO is also aiming to develop its capacity-building activities, for instance working with the UN SupportOffice for the African Union Mission in Somalia and theInternational Maritime Organization.Ultimately, there is a need to address the root causesonshore. NATO is making a contribution to this effortby supporting the African Union Mission in Somalia, atthe African Union’s request, by providing subject matterexpertise and participating in meetings of the InternationalContact Group on Somalia.

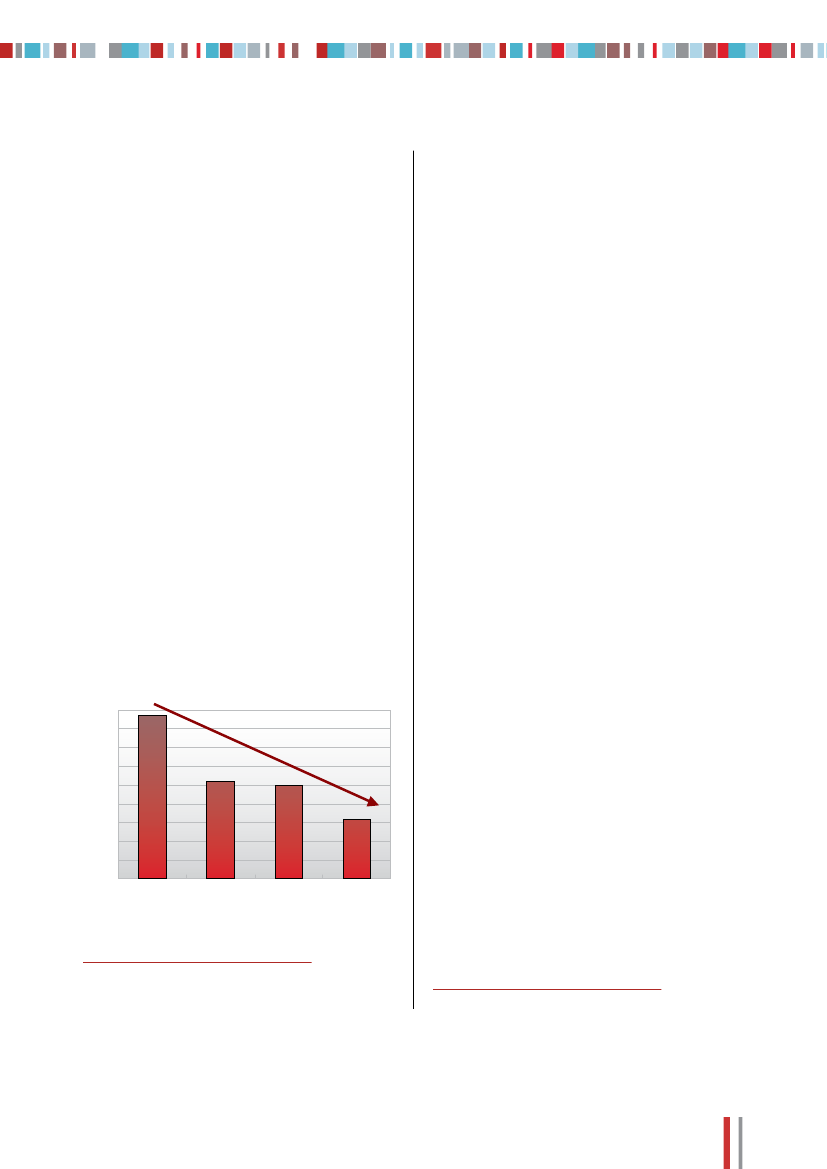

Operation Ocean ShieldIn 2011, NATO had on average 4-5 ships deployed in thearea as part of Operation Ocean Shield, focused primarilyon naval escorting and deterrence. It also provided threemaritime patrol aircraft for a period of three months eachtime. This deployment of patrol aircraft – of which there is anoverall shortfall – was of great value, especially in light of thelimited availability of ships in the area and the expansion ofpirates’ activities deep into the Indian Ocean.NATO ships have contributed to disrupting pirate actiongroups. Throughout 2011, there have been a total of 154attacks in the Gulf of Aden, Somali Basin and the ArabianSea. In the same period, naval forces disrupted 96 piratevessels and only 24 vessels were pirated. The success rateof piracy incidents decreased in 2011 compared to 2010.3This has been recognized by the UN Secretary-General in his25 October 2011 report on piracy to the UN Security Council.Pirate attack success rate

Training missionsNATO conducted a training mission in Iraq for severalyears. Although small-scale, the NATO Training Mission-Iraq (NTM-I) played an important role in training, mentoringand providing assistance to the Iraqi Security Forces inorder to contribute to the development of Iraqi trainingstructures and institutions. Since its launch in 2004, ittrained over 5,200 commissioned and non-commissionedofficers of the Iraqi Armed Forces and around 10,000Iraqi police.4These achievements have helped the IraqiGovernment develop a baseline of enduring capability fortheir security forces and build a credible security sector.The mission ended its work on 31 December 2011.However, NATO remains committed to developing along-term relationship with Iraq through its structuredcooperation framework and, in April 2011, the Alliancedecided to grant Iraq partner status.

45%40%35%30%25%20%15%10%5%0%2008(41/94)44%

■

2009(45/175)

2010(45/177)

2011(24/154)

3 Statistics provided by NATO’s Maritime Command HQ,Northwood, United Kingdom – the command leading NATO’scounter-piracy operation.

4 Statistics provided by Allied Joint Force Command, Naples, Italy.

9

Tackling emerging security challengeshe security environment continues to change ata rapid rate and NATO has invested in 2011 toensure that the Alliance is capable of meetingthese emerging security challenges. Cyberattacks, the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction,terrorism and other emerging threats such as energyvulnerabilities increasingly affect the security of NATO’salmost 900 million citizens.

T

Missile defenceOver 30 countries have or are acquiring missiles thatcould be used to carry conventional warheads andeven weapons of mass destruction. The proliferation ofthese capabilities does not necessarily mean there is animmediate intent to attack NATO, but it does mean thatthe Alliance has a responsibility to protect its populations,territory and deployed forces. For several years, NATO hasbeen pursuing a theatre missile defence programme for theprotection of deployed NATO troops against ballistic missilethreats with ranges of up to 3,000 kilometres. At the 2010Lisbon Summit, NATO leaders decided to expand thisprogramme to include the protection of NATO Europeanterritory, populations and forces.A ballistic missile defence action plan was approved inJune 2011 to outline how to achieve the NATO territorialballistic missile defence. Efforts in the second half of 2011were especially focused on implementing steps that willallow NATO to declare an interim NATO ballistic missiledefence capability by the time of the Chicago Summitin May 2012. This objective is ambitious and will requirefurther work to ensure that appropriate Allied commandand control mechanisms are in place.A key contribution to this capability comes from theUnited States through its sensors and interceptorsdeployed in Europe. To make the system trulycomprehensive, other Allies also need to contribute similarassets, as they are already doing for the protection ofdeployed troops. These national elements will then beintegrated into a single NATO network. It is the transatlanticelement of NATO’s missile defence system that makes it sosignificant both militarily and politically.At the same time, NATO invited Russia to cooperateon the ballistic missile defence. As Russia could alsobe threatened by ballistic missiles, it makes sense forNATO and Russia to cooperate in defending againstthem. NATO’s vision is of two separate systems with thesame goal, which could be made visible in practice byestablishing two joint missile defence centres, one forsharing data and the other to support planning.

Cyber defenceIt is in the Alliance’s interest to reduce nationalvulnerabilities, as well as anticipate crises and preparefor their management. Cyber attacks, for instance, canparalyze a country. They also have the potential to becomea major component of conventional warfare. This realizationhas increased the urgency to strengthen cyber defencesnot only at NATO, but across the Alliance as a whole.In 2011, NATO approved a new cyber defence policyand an Action Plan that will upgrade the protection ofNATO’s own networks and bring them under centralizedmanagement. The new policy also makes cyber defencean integral part of NATO’s defence planning process,offering a coordinated approach with a focus on preventingcyber attacks and building resilience.Since the cyber attacks against Estonia in 2007,NATO has been looking beyond the protection of itsown communication systems to assist Allies seekingNATO support. The new policy, for instance, introducesthe possibility for NATO’s Rapid Reaction Teams tobe dispatched, on the demand of individual membercountries, for cyber incidents. Education and trainingcapabilities will also be developed, principally throughthe Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence inTallinn, Estonia, a NATO-accredited Centre of Excellencesince 2008. The most recent Cyber Coalition 2011exercise included six partners: Finland and Sweden wereplayers, and Australia, Austria, Ireland and New Zealandsent observers, as did the European Union. The interestpartners take in NATO’s cyber security activities isconstantly rising and is an integral part of the new policy.

10

This cooperation is being developed in the spirit of the1997 NATO-Russia Founding Act, by which both partiesagreed to refrain from the threat or use of force againsteach other. The work on the two objectives set in Lisbonto develop a Joint Analysis of a framework for futuremissile defence cooperation and to resume theatre missiledefence cooperation, has been challenging, with differencesimpeding rapid progress. While trying to build trust, progresswith Russia in this field has not been as substantial ashoped. Theatre missile defence work has focused on thedevelopment of a computer-assisted exercise. A relatedevent is planned for March 2012, with a possible follow-upevent later in the year. The development of the Joint Analysisis progressing, however, at a slow pace.

TerrorismIn 2011, NATO remained engaged in developing measuresto defend against terrorism. The Alliance supported scienceand technology work in the fields of explosives detection,

in particular, with a unique project involving Russia andNATO. The project, known as Standex, aims to counterthe threat of attacks by improvised explosive devices onindividuals circulating in large public areas such as airportsor metro stations. It integrates a combination of differenttechniques and technologies for the detection of explosivesand the localization, recognition, identification and trackingof potential perpetrators of attacks. In 2011, NATO alsofocused on the protection of critical infrastructure, includingharbour security and route clearance. Moreover, theAllies made significant progress in developing a systemwith Russia that will help prevent terrorist attacks whichuse civilian aircraft – such as the 9/11 attacks againstthe United States. This new airspace security system willfunction by sharing information on airspace movementsand by coordinating interceptions of renegade aircraft. Itsoperational readiness was declared in December 2011.■

11

Modernizing NATO

A

t a time of financial crisis, governments arefaced with difficult budgetary choices. For mostAllies, this has meant rapidly seeking solutionsto bring budgets back into balance, with aninevitable impact on defence spending.

level of ambition, which is defined as NATO being able toprovide command and control for two major joint operations(such as the NATO-led operation in Afghanistan) andsix smaller military operations (such as Operation ActiveEndeavour in the Mediterranean) at any one time.Beyond the Alliance’s three essential core tasks – collectivedefence, crisis management and cooperative security –which were highlighted in the 2010 Strategic Concept, thereform of the Command Structure also takes into accounta number of new tasks and requirements such as missiledefence and civil-military planning. The new NATO CommandStructure should reach Initial Operational Capability by theend of 2013 and be fully implemented by end 2015.

At the Lisbon Summit in November 2010, the Allies reactedcollectively to the effects of this crisis and launched aNATO-wide reform process not only reflecting austeritymeasures taken in member countries, but seeking to makethe Alliance more modern, efficient and effective. Each andevery one of NATO’s political and military structures is beingstreamlined. The acquisition of critical capabilities is beingreassessed to ensure that the Allies can acquire capabilitiesand ensure greater security with more value for money.

Modernizing structuresReform of the military command structureThe NATO Command Structure is the backbone of theAlliance. It enables the implementation of political decisionsby military means, providing for the command and control ofNATO’s military operations, missions and activities. As such,it underpins the credibility of the North Atlantic Treaty.The Command Structure has been thoroughly reviewedwith the objective of making it more effective, leaner andaffordable. In June 2011, defence ministers agreed a revisedstructure that will reduce manning by one third, from over13,000 to 8,800. In addition to these reductions, there isalso a new emphasis on deployability. Both of the joint forceheadquarters in Brunssum and Naples (“joint” implying theparticipation of all three forces: land, air and naval) and airoperations centres (in Germany, Italy and Spain) can deployas need be to respectively exercise command and controlover, as well as support, operations in theatre.The new structure also places increased reliance on nationalcommand and control capabilities and the NATO ForceStructure, which comprises the organizational arrangementsthat bring together national forces placed at the disposalof the Alliance. This is necessary for the Alliance to meet its

NATO Agencies reformNATO Agencies employ 6,000 people working inseven countries with a total business volume of over10 billion Euro in 2010. They are essential to NATO,providing critical support to current operations, includingAfghanistan, and managing the procurement of majorcapabilities such as Eurofighter.NATO Agencies are being consolidated and rationalizedto enhance efficiency and effectiveness in the deliveryof capabilities and services, to achieve greater synergybetween similar functions and to increase transparencyand accountability. A detailed implementation plan wasapproved in June 2011 and significant steps have beentaken to transfer functions and services of a majorityof the 14 agencies into three new agencies, which willfocus on communications and information; support; andprocurement. These are expected to be set up by theNorth Atlantic Council in June 2012.As the reform moves forward, the specific needsof multinational programmes are being guaranteedthroughout the process, and capability and service deliveryare being preserved, especially where operations areconcerned. Savings resulting from the reform should bein the region of 20 per cent of the running and personnelcosts. In view of the level of estimated transition costs,

12

additional savings will become more apparent in the longerterm, as is the case with all such reforms.

Integration of structures involved in crisis managementAlliance crisis-management procedures were rationalizedduring 2010 and proved effective in the Libya crisis.In particular, since Lisbon, new working methodshave been introduced for a more effective, integratedapproach, which reflects NATO’s commitment to a trulycomprehensive approach to crisis management.Two complementary elements of a civilian crisis-management capability have been formed within NATOstructures. A Civil-Military Planning and Support Sectionwas set up within the International Staff at NATOHeadquarters. It supports analysis, planning and conductof operations; it injects the civilian dimension in theplanning phase, ensuring that the views and concerns ofother actors and organizations are considered and that thenecessary operational interaction is achieved throughoutthe entire crisis spectrum. Additionally, NATO civil andmilitary bodies are also moving forward in their adaptationof relevant planning procedures. In support of these efforts,work continues to refine the non-military expertise availableto NATO and to enable its effective use.

spending gap between the United States and other Alliesis deepening. To counter this trend, NATO continues to“spend better” through what has been coined “smartdefence”. NATO continues to prioritize the Alliance’s mostpressing capability needs, set targets for forces and toassess how and where Allies use their resources to helpthem ensure maximum value for money.

NATO continues to prioritize the Alliance’s most pressing capability needsImpact of the economic crisis on defence spendingand capabilitiesThe effects of the current economic crisis on defencespending have been considerable. In 2011, the annualdefence expenditures of 18 out of 28 Allies were lowerthan they had been in 2008. Further reductions have beenannounced or can be anticipated and this at a time whenthe defence spending and military capabilities of a numberof countries outside the NATO area are increasing.Allies continue to pursue the transformation of their forces tobe able to meet future risks more efficiently by modernizingand restructuring their forces, and making them moredeployable, sustainable and interoperable. Allies agree thatthis requires adequate defence spending, including on themodernization of equipment. However, cuts in defencespending have entailed significant delays or cancellationof major equipment projects in many countries, therebyputting into question equipment recapitalization andtransformation efforts at a time when existing equipmentis ageing and is subject to increased wear as a result ofits use during current military operations. There have alsobeen widespread reductions in training rates. A numberof countries have also cut military and civilian personnelnumbers and have reduced pay and allowances forpersonnel.The Alliance does still retain sufficient forces and capabilities.However, this assessment is based on the over-reliance ona few member states, especially the United States, for theprovision of costly and advanced capabilities. Concerns

Headquarters reformAgainst a backdrop of changing priorities and realbudgetary pressures, efforts are underway to modernizeand streamline working practices at NATO Headquarters.Major steps have been taken to reduce the committeestructure and to enhance the sharing of information.The International Staff and the International Military Staffworking at NATO Headquarters are being collocatedaccording to their area of responsibility, helping to ensurea coherent and joint approach to policy development andimplementation. As part of these changes, the InternationalStaff are evolving towards a leaner, more flexible workforcesharply focused on NATO’s priority areas. All of thesechanges are designed to ensure that with the inaugurationof the new headquarters in 2016, a new NATO will moveinto a new headquarters.

Modernizing capabilitiesThe crisis in Libya clearly demonstrated the importanceof maintaining modern capabilities in an unpredictablesecurity environment. However, in the current economicclimate, defence budgets are being severely cut and the

13

over the provision of adequate levels of some capabilities5for recent operations have brought this imbalance intosharper focus. In the decade since 2001, the United States’share of total Alliance defence expenditures has grown from63 to 77 per cent, resulting from both an 82.4 per centincrease in defence expenditures for the United States anda 5.7 per cent decrease in defence expenditures for NATOEuropean nations, in real terms.The defence spending6of only three Allies is projectedto be at or above 2 per cent of GDP in 2011 – therecommended level of defence spending agreed by Allies;15 Allies are expected to spend less than 1.5 per cent ofGDP on defence. Only eight Allies are expected to havespent 20 per cent or more of their defence expenditures onmajor equipment in 2011 – also the recommended level ofspending agreed by Allies – while six will likely spend lessthan 10 per cent. The majority of Allies are facing difficultyin maintaining the proper balance between short-termoperation and longer-term investment expenditures in lightof decreasing defence budgets and increased expendituresrising from the cost of contributions to current operations.

decisions transparently within the Alliance so that NATOretains collectively the capabilities needed to address the fullrange of missions.Instead of pursuing purely national solutions, Allies havedecided that where it is efficient and cost-effective, theywill seek out more multinational solutions, including foracquisition, training and logistic support. By these means,Allies will improve the delivery of capabilities while fairlydistributing the defence burden. To that end, defenceministers have agreed the need to deliver a range ofsubstantive multinational projects by the 2012 ChicagoSummit with a view to making the resulting capabilitiesavailable to NATO. This work is being closely coordinatedwith European Union staffs to avoid overlap with the EUinitiative on pooling and sharing.“Smart defence” should also provide a long-term vision fora new way of delivering capabilities. NATO is not startingfrom scratch. The Strategic Airlift Capability brings together12 nations to procure and operate huge C-17 transportplanes. By doing this together, they have acquired animportant capability that individual members of theconsortium could not obtain individually. And the ballisticmissile defence programme allows national systems tooperate jointly under NATO command and share earlywarning and data on the threat of incoming missiles.

“Smart defence”To address these concerns, a new approach is needed.In 2011, NATO began to vigorously pursue a new way ofacquiring and maintaining capabilities, captured by theterm “smart defence”. It is about member states buildinggreater security – not with more resources, but with greatercollaboration and coherence of effort. The way forward liesin prioritizing the capabilities needed the most, specializingin what Allies do best, and seeking multinational solutionsto common problems. Priorities and shortfalls are wellestablished through NATO’s extensive and robust defenceplanning mechanisms. At the Lisbon Summit in 2010, Alliescommitted to focus their investment on 11 areas of themost critical needs, including missile defence, counteringroadside bombs, medical support, command and control,and intelligence and surveillance. Specialization is sensitivebecause it touches on sovereignty, but in reality it is anessential management tool exercised by member states ona continuous basis. The key is for Allies to coordinate such5 For instance, combat search and rescue, suppression of enemyair defences, air-to-air refuelling, airborne early warning, signalsintelligence and unmanned attack platforms are highly dependenton the United States, which provides approximately 75 per cent ormore of these capabilities.6 Data in this paragraph are based on current prices and updatedGDP as at November 2011.

Lisbon package of critical capabilitiesPrevious capability initiatives7have helped generate new oradditional capabilities for NATO but proved unable to rectifycertain capability shortfalls. At the Lisbon Summit, NATOleaders agreed a new approach, centred on a package ofthe most pressing capability needs.8These were carefullyselected to help the Alliance meet the demands of ongoing7 Defence Capabilities Initiative; Prague Capabilities Commitment.8 Current priority shortfalls for operations, including the AfghanistanMission Network, with emphasis on capabilities that will endurebeyond current needs, such as the Countering ImprovisedExplosive Devices (C-IED), strategic and tactical airlift, andcollective logistics contracts, including for medical support;capabilities to deal with current, evolving and emerging threats- expansion of Active Layered Theatre Ballistic Missile Defence,protection against cyber attacks, and possible capabilityrequirements associated with the needs of a ComprehensiveApproach and Stabilisation and Reconstruction; and selectedlong-term critical enabling capabilities – Bi-SC (StrategicCommand) Automated Information Systems (Bi-SC AIS), the AirCommand and Control System (ACCS) and Joint Intelligence,Surveillance and Reconnaissance (JISR) including the AllianceGround Surveillance (AGS) system.

14

operations, face emerging challenges and acquire keyenabling capabilities. In general, implementation is proceedingsatisfactorily, although not all of the financing aspects of theAlliance Ground Surveillance (AGS) programme have yet beenagreed. This key transatlantic programme aims at procuringGlobal Hawk drones and associated systems, which withsophisticated radars, provide a broad and unfolding pictureof what is happening on the ground. Operational experiencehas confirmed the importance of the package and particularlythe need for an enduring NATO capability for joint intelligence,surveillance and reconnaissance.

deployed operations, including out-of-area and at strategicdistance. The deployability of forces is the number offorces Allies are able to send out that are prepared andequipped for an operation. The sustainability of forces isthe overall land force strength that can be sustained ondeployed operations for an extended period of time (thisperiod being defined as a total of 18 months).Between 2004 and 2010, the number of land forces thatcan be deployed and sustained has increased: the numberof deployable troops has risen by just over 6.5 per centand the number of sustainable troops by over 21 per cent.However, there are signs that this improvement is levellingoff. While over half of NATO Allies now meet or exceedthe target for the sustainability of land forces, NATO willcontinue to seek further improvements in the usability ofAllies’ forces.To ensure that NATO and Allies get the best output(capabilities and forces) for the input (money and otherresources) available, NATO is developing a set of indicatorsthat will provide a more comprehensive picture of how andwhere Allies utilize their resources. These indicators willcomplement the reporting on the usability of Allies’ forces.They are designed to help encourage further burden-sharing between Allies and reveal best practices that canbe used for others to follow.■

UsabilityAlliance forces need to be adequately structured,prepared and equipped for crisis-response and out-of-area operations. Prior to the current economic downturn,shortfalls in the availability of forces for Allied purposeshave already manifested themselves from time to time.A variety of measures have been used to tackle thisproblem such as, from 2004, a new focus on the so-calledusability of Alliance forces. Under this initiative, targets areset for the deployability and sustainability of Allies’ landforces9, with a view to making more of them available for9 40 per cent of land forces to be deployable and the abilityto sustain 8 per cent on operations or other high-readinessstandby; these targets were later raised to 50 per cent and 10per cent respectively. In addition, they were supplemented in2009 by targets for air forces (40 per cent deployable; 8 per centsustainable).

15

Cooperative security –multinational solutions to global issueshe 2010 Strategic Concept highlightedcooperative security as one of NATO’s three coretasks. The logic of this is clear. Today’s securitychallenges are increasingly transnational andthe most effective responses include the broadest range ofpartners, countries and international organizations alike.While reaffirming that the Alliance is committed tomaintaining its “open door” policy for other Europeancountries to become members, the Strategic Concept setthe goal of enhancing partnerships through flexible formatsthat bring NATO and its partners together – across andbeyond existing frameworks. Throughout 2011, NATOmade substantial progress in implementing this goal.The Libya operation demonstrated the Alliance’s commitmentto giving its operational partners a structural role in shapingdecisions in NATO-led missions. From the day the Alliancebegan its UN-mandated operation to protect civilians inLibya, NATO’s operational partners, including from the region,were around the table helping to shape and then endorseall political and operational decisions. The contribution ofpartners to all aspects of the mission was essential and willserve as a model for future operations.The Strategic Concept underlined NATO’s willingnessto develop political dialogue and practical cooperationwith any nations and relevant organizations across theglobe that share NATO’s interest in peaceful internationalrelations. Looking beyond existing partnership structuresand employing a flexible format that allowed for theinclusion of a broad group of countries who sharedthe same security concerns, a meeting was held oncounter-piracy in September 2011. Representatives from47 countries and organizations involved in counter-piracyin the Indian Ocean attended that meeting. More meetingswith a wide range of nations and organizations on criticalshared security concerns are expected to follow.The development of NATO-Russia relations remaineda priority in 2011. Following on from NATO’s offer inLisbon, intensive negotiations are underway to developcooperation with Russia to defend Europe against thegrowing threat of missile attack. Even as those discussions

T

continue, NATO has stepped up cooperation with Russiato fight the flow of drugs from Afghanistan and to helpbuild the capacity of the Afghan Army. For the first timeever, a Russian submarine participated in a submarinerescue exercise in 2011, as well as Russian fighter jets in alive counter-terrorist exercise. While NATO and Russia stilldo not see eye to eye on all issues, the level and scope ofNATO-Russia cooperation continues to grow in areas ofshared concern.Regarding relations with other international organizations,the assessment is mixed. The strategic partnership withthe European Union has not yet fulfilled its potential, whilethe pace has accelerated with the United Nations due tothe wide range of operational cooperation undertaken.The Libya crisis also led to unprecedented contactsbetween the Alliance and the League of Arab States,whose support for the overall international efforts wasessential. These relations should form the basis for a deeperengagement in the future. Indeed, NATO will seek a strongerrelationship with the broader Middle East and North Africaregion, principally by strengthening the MediterraneanDialogue and Istanbul Cooperation Initiative. Allies willwork closely with partners from the region to see how theycan work better together to address common securitychallenges. Membership of the Mediterranean Dialogue willbe open to Libya, if the country so desires, as a frameworkfor political dialogue and focused practical cooperation.

■

16

NATO Public Diplomacy Division1110 Brussels – Belgiumwww.nato.int

1954-11 NATO Graphics & Printing - SGAR11ENG