Forsvarsudvalget 2011-12, Det Udenrigspolitiske Nævn 2011-12

FOU Alm.del Bilag 23, UPN Alm.del Bilag 47

Offentligt

POLITICAL185 PCTR 11 E rev 1 finalOriginal: English

N AT O P a r l i a m e n t a r y As s e m b l y

SUB-COMMITTEE ONTRANSATLANTIC RELATIONS

AFGHANISTAN – THE REGIONAL CONTEXT

REPORT

JOHNDYRBYPAULSEN (DENMARK)RAPPORTEUR

International Secretariat

October 2011*

*

This report was prepared for the Political Committee in August 2011and adopted at theNATO PA Annual Session in Bucharest, Romania in October 2011.Assembly documents are available on its website, http://www.nato-pa.int

185 PCTR 11 E rev 1 final

i

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Map of PakistanPakistan: Map of ConflictsGlobal Heroin Flows of Asian Flows

I.II.

INTRODUCTION.........................................................................................................1AFGHANISTAN AND NEIGHBOURING COUNTRIES ...............................................2A. PAKISTAN ..........................................................................................................2B. IRAN ...................................................................................................................4C. CENTRAL ASIAN REPUBLICS ..........................................................................5D. RUSSIA...............................................................................................................7E. INDIA ..................................................................................................................8F. CHINA.................................................................................................................8CONCLUSION: PURSUING A REGIONAL APPROACH TO AFGHANISTAN .........10

III.

185 PCTR 11 E rev 1 final

ii

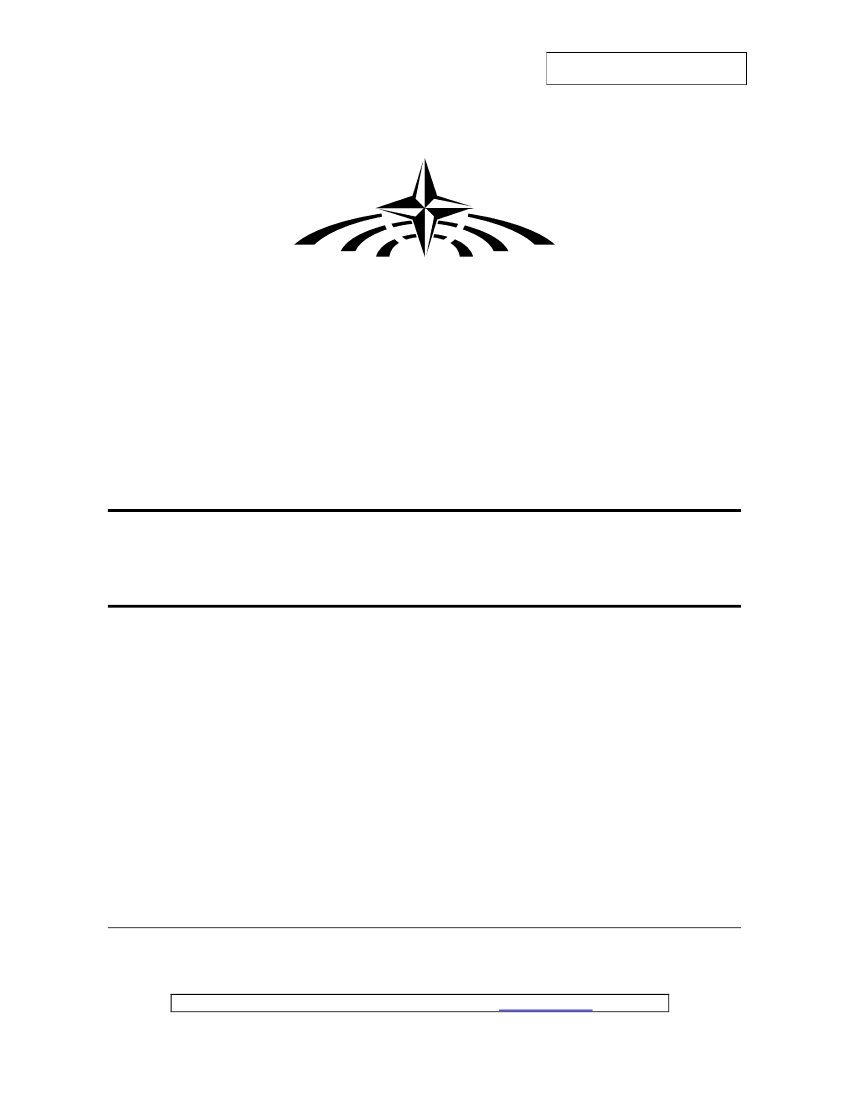

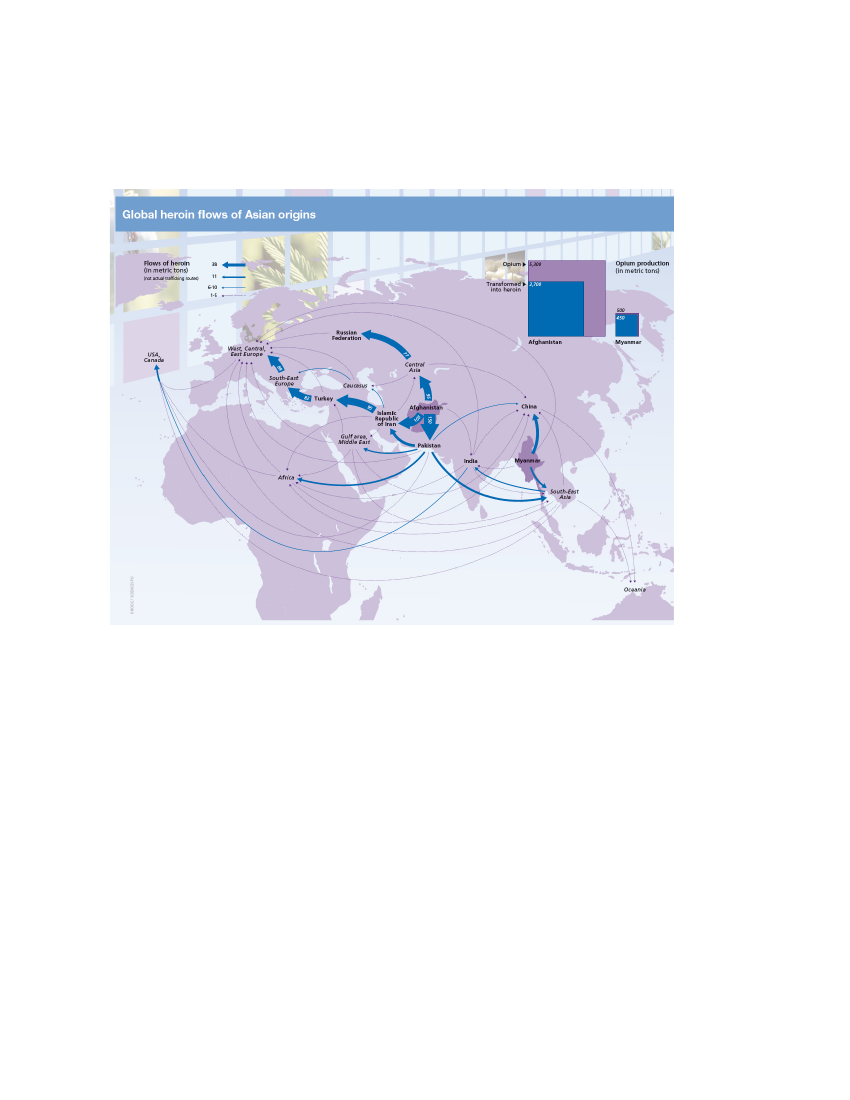

MAP OF PAKISTAN

Source: US Congressional Research Service (CRS)

185 PCTR 11 E rev 1 final

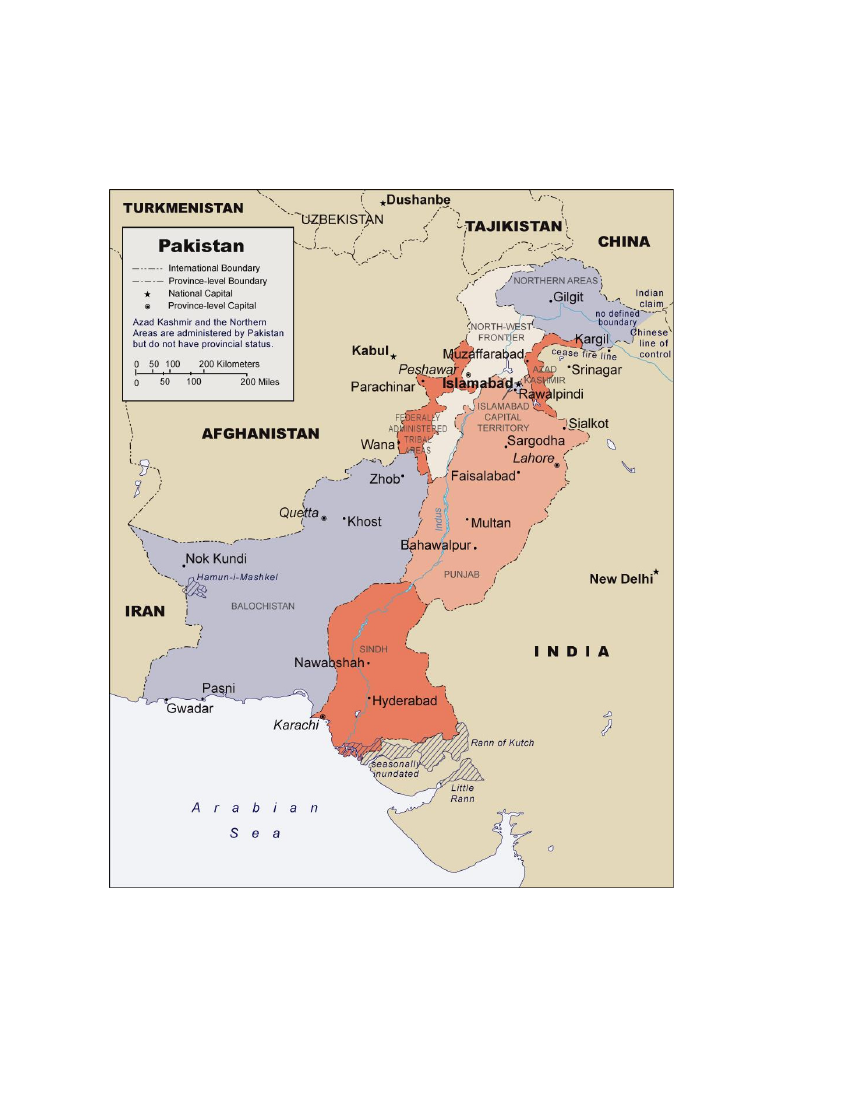

iiiPAKISTAN : MAP OF CONFLICTS

Source: BBC News

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/8046577.stm

185 PCTR 11 E rev 1 final

iv

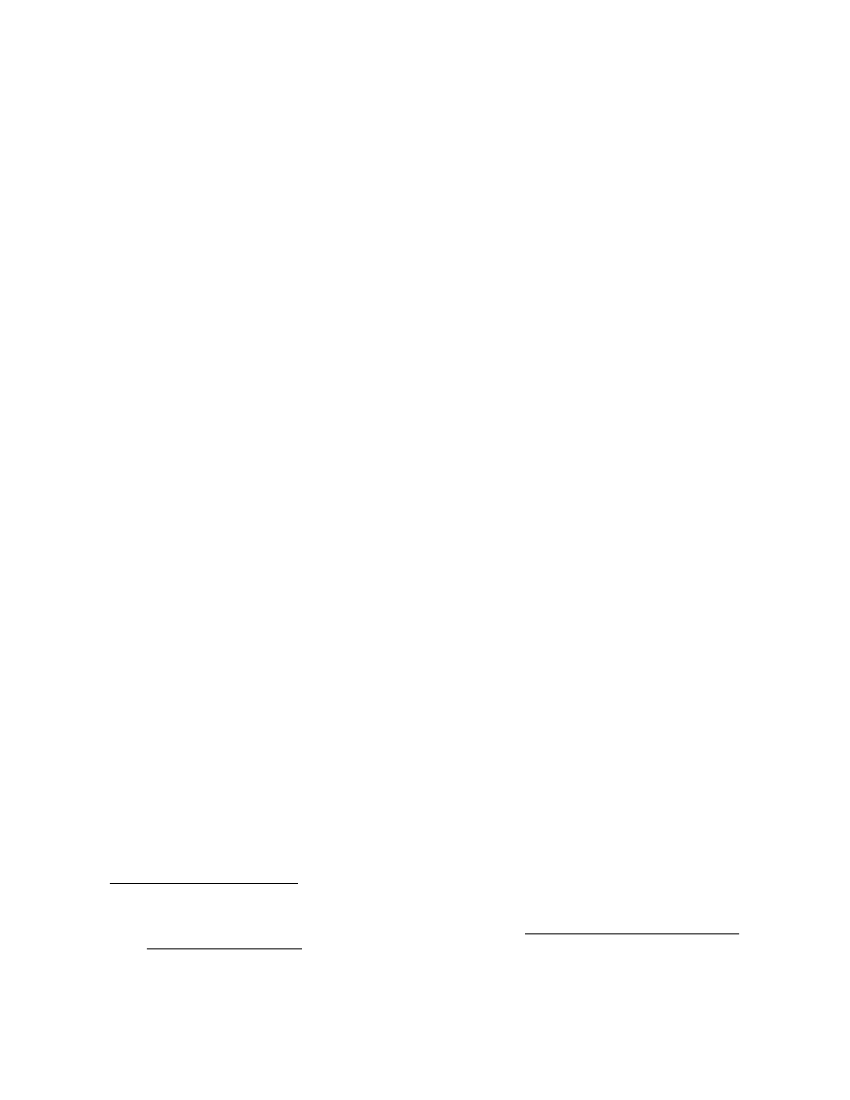

Fig. 3 Global heroin flows of Asian origins 2010. Source UNODC World Drugs Report 2011

185 PCTR 11 E rev 1 final

1

1.As manifest in the evolving policies on both sides of the Atlantic, the growing conviction thatthe conflict in Afghanistan can only be resolved by addressing the complex interstate relationshipsin the region necessitates an in-depth analysis of the situation in Afghanistan from a regionalperspective. This regional constellation has been shaped by numerous forces that have been atplay for decades. The Sunni/Shia divide, remnants of Cold War allegiances, the Islamic Revolution,the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, the Afghan Jihad and the rise of the Taliban constitute some ofthe forces that left their mark in the region, as Afghanistan has become an arena for competingrivalries. With the imminent transfer to Afghan authority, the necessity for a regional approach iseven more pressing as regional powers are likely to compete in carving out their own space inAfghanistan, following the gradual withdrawal of the international military presence, particularly thatof the United States, the first phase of which is scheduled to be completed by December 2011.2.Indisputably all countries of the region have a stake in Afghanistan’s well-being, and thelatter’s future is likely to have an impact on the region at large. In 2002, the Kabul Declaration wassigned by the neighbouring states of China, Iran, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan andUzbekistan, reaffirming their commitment to constructive and supportive bilateral relationshipsbased on the principles of territorial integrity, mutual respect, friendly relations, co-operation andnon-interference in each other's internal affairs. Similarly, the 26 January 2010 Istanbul “Heart ofAsia” Declaration commits the signatory countries (Afghanistan, Pakistan, Turkey, Iran, China andTajikistan) to the sovereignty, independence, territorial integrity and national unity of Afghanistanas well as of each of the other signatories. The importance of regionally-owned solutions is beingincreasingly recognised, as seen more recently at the London Conference that was held on30 January 2010. Nevertheless, the situation in the region remains complex and rife with tensions.Despite the increased resort to regional organisations, such as the South Asian Association forRegional Co-operation, the Economic Co-operation Organization and the Shanghai Co-operationOrganization (SCO), unresolved issues such as Kashmir impede their full capacities. Thus, theinternational community needs a well-calibrated regional approach that includes the relevantcountries/actors, addresses their concerns, seeks to reconcile differences and builds uponcommon opportunities. An integral part of the regional approach has to include the strengtheningof the Afghan security forces and institutions. Without a functioning Afghan government,development of a regional approach will be very difficult, if not impossible to achieve.3.While there are various interpretations of what a regional approach would entail, a commontheme is the effort to align all of Afghanistan’s neighbours and vital stakeholders into aco-operative framework resting on counter-terrorism, counter-narcotics, reconstruction andstate-building, which would ultimately lead to a stabilised Afghanistan. US President BarackObama has urged for such an approach since the early days of his presidency, when he publiclyannounced a new US strategy for Afghanistan and Pakistan in March 2009. A prominent elementof that strategy was to bring “together all who (…) have a stake in the security of the region - ourNATO allies and other partners, but also the Central Asian states, Gulf nations and Iran, Russia,India and China”.1One notable expression of that approach is the fact that, in the operationalrealm, Afghanistan and Pakistan are currently treated as a common theatre. Similar expansionhas occurred in the policy dimension, and has prompted the emergence of relevant institutions andstructures. For example, soon after the appointment of Richard Holbrooke as the US SpecialRepresentative to Afghanistan and Pakistan, other involved nations appointed counterparts toHolbrooke’s position to form what President Obama has termed as the “Contact Group forAfghanistan and Pakistan”. The group is an informal arrangement that provides room fordiscussion and dialogue on Afghanistan, but experts, including Ashley J. Tellis, point out that itssize has not been conducive to effectiveness.1

Jesse Lee, “A New Strategy for Afghanistan and Pakistan,”The White House Blog,27 March 2009,http://www.whitehouse.gov/blog/09/03/27/A-New-Strategy-for-Afghanistan-and-Pakistan/

185 PCTR 11 E rev 1 final

2

4.These developments are indicative of the regional stance assumed by the internationalcommunity in Afghanistan. Nevertheless, efforts to mitigate crucial rivalries have achieved little,largely because of the incompatible alignment of national interests in the region and thecross-cutting nature of the security dilemmas that hold neighbours in an intractable deadlock.Experts such as Ashley J. Tellis, claim that recent announcements by NATO Allies on troopwithdrawal between now and 2014 may have contributed to hardening the positions ofneighbouring states. Convinced of the imminent allied exit, they may, in fact, focus even moreclosely on pursuing their national interests. The announced timetable for the withdrawal of theinternational military presence, most notably that of the United States which provides the bulk ofthe International Security Assistance Force (ISAF), is likely to prompt a recalculation andrecalibration of all interests and players involved, making the achievement of a regional approachan infinitely more difficult, but increasingly more crucial, task.5.If cracking the core issues of conflict in the region is a daunting task in the short-term,encouraging economic integration is, perhaps, one viable channel for aligning the various interestsinvolved. Experts, including Frederick Starr and Haroun Mir, have suggested efforts andprogrammes towards reviving the old Silk Road or engaging the region in a common watermanagement mechanism, since Afghanistan can serve as a major water supplier for Pakistan,Iran, and the Central Asian Republics. Other cross-national economic issues that have a largepotential comprise electricity, minerals, oil and gas, including their exploitation and transit. Suchinitiatives can function as key confidence-building measures. The majority of Afghan trade occurswith its neighbours. This creates a network of economic interdependence, which unfortunately hasnot yet encouraged actors to focus on accumulating absolute economic gains rather than relativepolitical gains. Instead, many states have been more focused on using Afghanistan as a playingfield in order to gain relative political advantage vis-à-vis critical rivals. It seems evident that forregional economic co-operation to work, the necessary security guarantees need to be in place.

AFGHANISTAN AND NEIGHBOURING COUNTRIES

PAKISTAN6.Among the neighbouring states, Pakistan’s fate is the most intertwined with that ofAfghanistan, as the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA), Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa (KP, theformer North-West Frontier Province - NWFP) and Balochistan function as the main refuge andsupply-route into Afghanistan for the insurgents.7.Approximately 1.7 million officially registered refugees from Afghanistan are currently living inPakistan, most of them in KP, the FATA, and in Balochistan. It is estimated that another millionnon-registered Afghan refugees have sought refuge in Pakistan. Pakistan is crucial for theprovision of logistical support to ISAF in Afghanistan. It remains the principal artery for transportingsupplies and fuel to Afghanistan, even though an increasing part of supplies to ISAF forces is nowdirected through the “Northern Distribution Network” (NDN).8.As extremists continue using the Afghan-Pakistani border areas as a safe haven,Islamabad’s co-operation in the allied efforts against insurgents as well as in a potential settlementbetween the insurgents and the Afghan government remains of crucial importance. In the past,however, Pakistan’s counter-terrorism approach has been anything but uniform. While thePakistani government has formally denounced religious extremism and Islamist terrorist groups, ithas been criticised by British Prime Minister David Cameron, among others, for “looking bothways” on terrorism.2The fact that Osama Bin Laden has been hiding inside Pakistan for several2

Alex Barker, James Lamont and Farhan Bokhari, “Cameron Warns Pakistan Over Terror,”FinancialTimes,28 July 2010.

185 PCTR 11 E rev 1 final

3

years has raised further questions about Islamabad’s commitment to fight al-Qaeda and theinsurgency. Elements of the Pakistani security services have been suspected of secretly aidingthe various terrorist and insurgent groups that attack Afghan and ISAF forces in Afghanistan.Moreover, these elements have also been accused of supporting militant extremists in Kashmirand in India proper. Senior Pakistani officials, including Prime Minister Gilani, have regularlydismissed such criticisms.9.Although Pakistan has often turned a blind eye on certain extremist groups on its territory, ithas increasingly recognised that the insurgency poses a growing threat to the Pakistani state itself.While the number of terrorist attacks declined in 2010, the overall security situation in the countrycontinues to deteriorate; violence has spread from the border areas in the North West toBalochistan, Punjab and the major cities. Recently, Islamabad has begun to act more decisivelyagainst extremist groups. For example, it started military offensives against the Taliban in Bajaur,the Swat Valley, and South Waziristan in 2009. However, the results have been mixed andsectarian rivalries in these areas persist. Pakistan has exercised only indirect control, mainly viathe elders. However, since 2006 as many as 1,000 tribal leaders have been targeted and killed byinsurgents and Pakistani Taliban, thus further limiting Islamabad’s control over the border regions.10. While Afghanistan and Pakistan share a lot of similarities, their bilateral relationship has oftenbeen uneasy. Afghan officials have repeatedly accused Islamabad of meddling into their internalmatters and of openly supporting the Taliban and other extremist groups. Moreover, both sideshave accused each other of not doing enough to prevent the insurgency from crossing into theirterritories. To a large extent, the tensions are rooted in the long-standing territorial dispute overthe Durand Line which separates both countries. Neither Pakistan nor Afghanistan have ratifiednor formally agreed the 2,640km-long border. The issue is further complicated by the fact thatPashtun tribes live on both sides of the porous border. Pashtuns make up 40% of Afghanistan;however, there is a larger number of Pashtuns living in Pakistan, where they constitute 15% of thepopulation.11. While divisive issues remain, lately the bilateral relationship between Afghanistan andPakistan has improved. During a recent visit to Afghanistan by Pakistani Prime Minister Gilani, thetwo countries agreed on the establishment of a Joint Commission tasked to promote the peaceprocess with the Taliban. In June 2011, President Karzai was on a two-day visit to Islamabad todiscuss reconciliation efforts. At the same time, the beginning of the transition to Afghanleadership and the tense relations between Islamabad and Washington following the Bin Ladenraid raise serious questions over Pakistan’s own stability and its future policy towards Afghanistan.12. The two countries are closely linked economically: Pakistan is the largest trading partner ofAfghanistan, while the latter is the third largest importer of Pakistani goods after the United Statesand China. To promote trade, the two countries established a joint chamber of commerce inNovember 2010. Earlier on, in July of that year, both signed the Afghanistan-Pakistan TransitTrade Agreement (APTTA), which succeeds the Afghanistan Transit Trade Agreement (ATTA).The new agreement allows Afghan exports to India using the land border between Pakistan andIndia, although Afghan trucks are not allowed to pick up Indian goods and have to return empty.Moreover, it envisages the use of Afghan territory for trade between Pakistan and the CentralAsian countries. Implementation of the agreement began in June 2011 and signifies great successfor the Canada-brokered “Dubai Process” whose aim was to build understanding and co-operationbetween the two countries in a number of key areas, such as infrastructure, trade, customs,counter-narcotics, and law enforcement, among others.13. Pakistani officials have expressed criticism over what they see as NATO Allies’ (and theinternational community) inability to articulate a desired end-state for Afghanistan, much less astrategy to achieve it. Pakistan’s main objective has long been to limit India’s influence inAfghanistan and to establish a regime that is friendly to Pakistan.

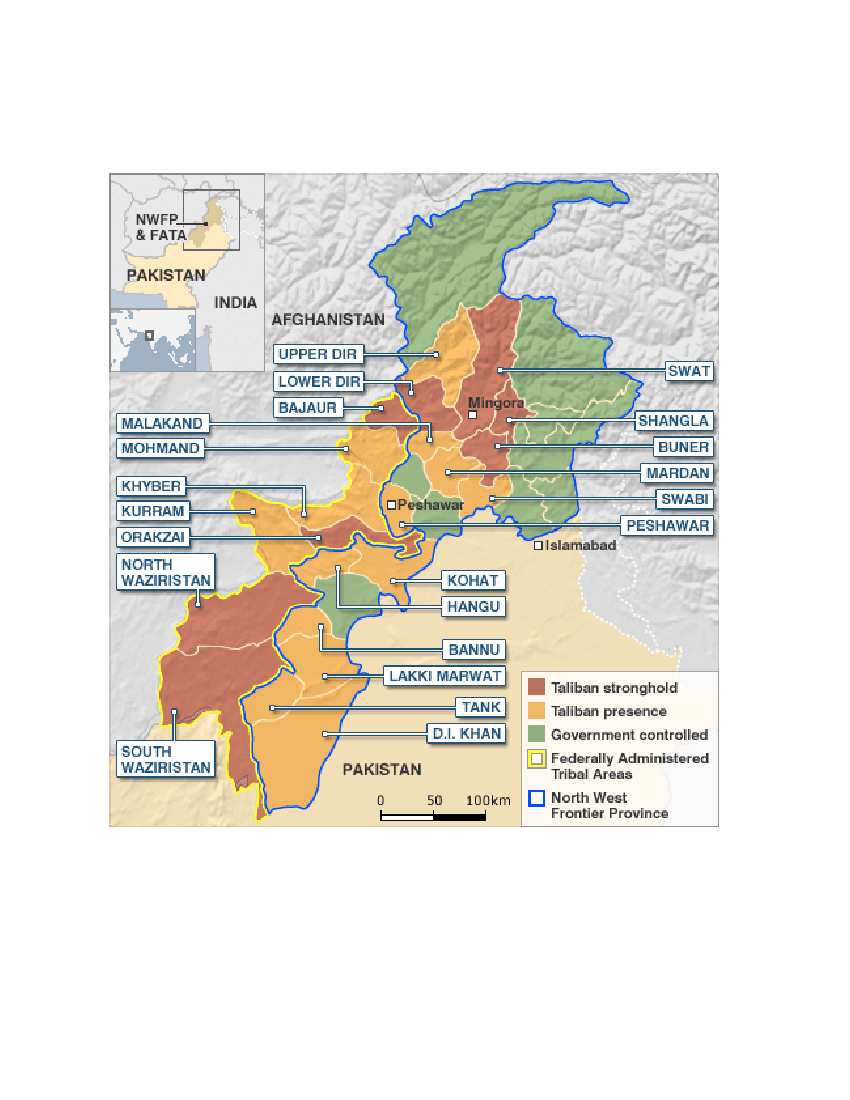

185 PCTR 11 E rev 1 final

4

14. Pakistan has long seen Afghanistan through the lens of its on-going rivalry with India. Fearfulof being “encircled” by rival India and Afghanistan, Pakistan is suspicious of India’s growingpresence and aid to Afghanistan. The strong perception of the Indian threat dates back to thepartition of the Indian subcontinent in 1947, which left behind a legacy of bitterness and mistrust.India and Pakistan fought three wars, in 1947-48, 1965, and 1971. Tensions rose again after theterrorist attacks at the Kashmir Assembly and the Indian Parliament in late 2001 and after theMumbai attacks in 2008. Both New Delhi and Islamabad seek to ensure a friendly regime inAfghanistan, following an eventual ISAF withdrawal.15. While bilateral relations with India have recently improved, the continuing tensions betweenthe two countries have resulted in a disproportionately high Pakistani defence budget. Moreover,the country suffers from sluggish economic growth, high inflation, rampant corruption, highunemployment and a weak tax collection system. These factors severely limit Islamabad’s abilityto provide basic services to its population, which, in turn, poses a serious challenge for thegovernment. Many families depend on the remittances of workers that have sought employmentelsewhere, notably in the Gulf and other Muslim countries. The growing Pakistani populationfurther complicates the country’s internal situation. Approximately half of the country’s populationis below the age of 20, according to a 2009 British Council study; its population is estimated togrow by 85 million in the next 20 years.16.Moreover, the increasing urbanisation of the country heightens ethnic tensions, providingrife opportunities for radical organisations to recruit new followers among the impoverished inPakistan. Pakistan’s ranking in the United Nations Development Programme’s (UNDP) HumanDevelopment Index slipped from 120 in 1991, to 138 in 2002, and to 141 in 2009, below Congo(136) and Myanmar (138). There is considerable underinvestment in education. According toindependent expert Stephen P. Cohen, “extremist movements have displaced the Pakistani armyas the largest recruiter of young Pakistani males”.3As a result of these developments, there is anincreasing radicalisation of society, as demonstrated by, among other developments, theassassinations of representatives of minorities and other political figures. The 2005 Kashmirearthquake and the catastrophic consequences of the 2010 floods have made matters worse.17.In sum, Pakistan views its relations with Afghanistan, first and foremost, through the lens ofits relations with India and its efforts to avoid a strategic “encirclement”. To that end, Islamabad hasa vested interest in maintaining a weak government in Kabul that it can easily control with itsforeign policy interests in mind. In order to achieve a negotiated settlement with the Taliban,Pakistan’s co-operation would be crucial. To that end, Pakistan’s reputation, damaged by theBin Laden raid, needs to be recovered and viable confidence-building measures need be pursued.

B.

IRAN

18. Iran has deep economic, historical and cultural links to Afghanistan and the two countriesshare a border stretching close to 1,000km. They have maintained frequent high-level contactsand economic ties since 1979, a critical year in their bilateral relations when the Islamic Revolutionunravelled in Iran and Afghanistan was invaded by the Soviet Union. Tehran lent heavy support tothe anti-Soviet resistance and absorbed millions of refugees from Afghanistan. Fiercely opposedto the Soviet presence in Afghanistan, Pakistan and Iran partnered in forming the interim post-communist Afghan government following the Soviet withdrawal. Nevertheless, their allegiancesquickly diverged thereafter – with Pakistan supporting the Pashtun communities and the Taliban.In contrast, Tehran, perceiving a threat from the militant Sunni vision of the Taliban, gave itssupport to the Northern Alliance, which became the anti-Taliban stronghold in the North. While thetwo countries had regular disputes regarding the rights of water supply from the Helmand river,their current bilateral relationship is good. However, a number of critics allude that Iran is stifling3

Stephen P. Cohen,The Future of Pakistan(Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution,January 2011).

185 PCTR 11 E rev 1 final

5

economic expansion of Western Afghanistan -by cheap exports, for example- to maintain aneconomic grip over its Eastern neighbour.19. As Iran has been directly affected by the sharp increase in drug consumption among itsyouth and because its territory provides the main route for exporting Afghan drugs to the West,Tehran does share the Allies’ concern regarding the drug issue. Similarly, Iran has an interest inthe emergence of a stable and inclusive regime in Kabul. However, Tehran or elements of theIranian security establishment, are reportedly acting to undermine coalition goals and operations inAfghanistan. Even though it remains wary of the emergence of an anti-Shia government inAfghanistan, Tehran or elements of the regime’s security services, are reported to be providinginsurgent groups, including the Taliban, with lethal weapons and training. Independent observershave suggested that Tehran’s tactical support for the Taliban, who are mostly Pashtun, is largely atodds with its own long-term interests and is primarily motivated by its tense relationship with theUnited States.20. Iran played a constructive role in overthrowing the Taliban regime in 2001. Since thebeginning of Operation Enduring Freedom in 2001, Iran has absorbed more than2 million immigrants from Afghanistan, putting a severe strain on its tenuous social welfare system.Iran has pledged over US$1 billion in aid to Afghanistan, though this commitment has largelyremained unmet. Nevertheless, it has invested considerably in agriculture, infrastructure and otherrebuilding efforts as well as in general development projects, mostly in Herat Province. While itmaintains economic and cultural ties with Persian-speaking and Shia minorities and sustains closerelations with the leading Shia cleric Ayatollah Mohammad Mohseni, Iran is also careful in hedgingits position vis-à-vis all political, ethnic and religious groups in the eventuality of a sudden changeof power. Moreover, Iran has issued joint statements with India on co-operation and stabilisation inAfghanistan, committing to fighting terrorism, in addition to partnering on transportation,infrastructure and energy projects. A number of high-level visits between Tehran and Kabul havetaken place in 2011 to discuss efforts to combat drug trafficking and organised crime. Mostrecently, an Afghanistan-Pakistan-Iran trilateral summit meeting was held in Tehran in lateJune 2011, with the aim of strengthening cooperation in the political, security and economic areas.21. Even though it has an interest in the emergence of a stable and inclusive regime in Kabul,Iran’s relations with the United States are the main determinant of its policy towards its Easternneighbour and the region.

C.

CENTRAL ASIAN REPUBLICS

22. The repercussions of the conflict in Afghanistan, particularly in terms of drug trafficking, poseserious security challenges to the Central Asia countries (Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan,Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan). The region’s borders with Afghanistan are treacherously porous,thereby providing an open door for drug trafficking to Russia and to Europe. Additionally,traffickers have gained wide-ranging influence over state institutions, particularly in the two mostfragile states of the region, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan. Another key challenge is religiousfundamentalism, and in particular the destabilising influence of the Pakistani Taliban. There areindications that a growing number of Central Asian militants are trained in Pakistan and sent tofight in Afghanistan, before they disappear into the neighbouring Central Asian countries.23. All five Republics of Central Asia see security and stability in Afghanistan as vital to theirnational security. Though their interests and concerns with regard to Afghanistan differ, there arecertain themes, threats and opportunities that present a common denominator. Nevertheless,there are variations in their positions on three basic, and largely interdependent, points: perceptionof core threats and vital national interests; relations with Russia; and engagement with the UnitedStates and ISAF. The Central Asian Republics share a concern regarding the threat posed by

185 PCTR 11 E rev 1 final

6

al-Qaeda, terrorism and, to varying degrees,4drug trafficking. Nevertheless, as experts point out,the Republics differentiate between the threats posed by al-Qaeda and the Taliban, being deeplyconcerned about the former but not viewing the latter with particular urgency. Instead, theRepublics are considerably more worried regarding the prospect of a premature, in their opinion,ISAF withdrawal.524. To varying degrees, the Central Asian Republics, short of Turkmenistan’s “positiveneutrality”, are aiding the allied effort in Afghanistan, including through participation in the NorthernDistribution Network, which provides a vital, and increasingly important, alternative supply route forISAF. Currently, about half of the ground cargo for the U.S. forces in Afghanistan is transferredthrough the NDN. Moreover, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan provided ISAF with airfields.Engagement with the United States and ISAF has been carefully sequenced and calibratedvis-à-vis relations with Russia. Russia retains a strong influence in the region, particularly throughits links with the political and security establishments. However, Moscow’s diplomatic prestige wastarnished by the 2008 Georgia war and, in particular, by its recognition of Abkhazia andSouth Ossetia. In this context, the Central Asian Republics remain suspicious of Russian foreignpolicy goals in the region.25. So far, Kazakhstan has been the only state of the region to provide foreign assistance toAfghanistan. The Central Asian Republics are engaged in a number of regional initiatives onborder management and local law enforcement such as the “Caspian Sea Initiative(The Violet Paper)”, as well as the “Security Central Asia Borders (The Yellow Paper).” Overall,co-operation between the five states remains limited and regional agreements often remainunimplemented. For instance, despite regional agreements on the free movement of goods acrossborders, Uzbek authorities have imposed, for alleged security reasons, a permanent blockade oftheir border with Tajikistan. Overall, the Central Asian Republics’ contribution to efforts to stabiliseAfghanistan have been primarily motivated by economic self-interests of the ruling regimes; theyhave made no real attempt to provide aid or development.26. In addition to the challenges emanating from Afghanistan, another challenge stems from thevery nature of the regimes in power in Central Asia. The suppression of opposition movements bythe autocratic regimes, often justified by the threat of terrorism, creates a situation in which theIslamic opposition is the only structured, capable alternative to the regimes. In addition, the lack ofprospects for the young, particularly in Uzbekistan where approximately 70% of the population isunder the age of 30, provides a fertile ground for recruitment by fundamentalists. According toAlain Délétroz, Vice-President Europe of the International Crisis Group, the hard line assumed bythe Central Asian regimes, the drug and weapon trafficking, the free-moving extremists, and thehigh youth unemployment rates could bring down any one of the regimes, which would have acatastrophic impact on all states involved.27. While differentiating between the threats posed by al-Qaeda and the Taliban, theCentral Asian Republics are particularly concerned about a premature Western withdrawal fromAfghanistan. Dreading the possibility of any ensuing instability, the Republics display a vividinterest in developing economic links in the region, but also seek to tailor their engagement with aview to balancing Russia’s influence in the region.

4

5

Drug trafficking poses a much bigger threat for Tajikistan, which is also vested in Afghanistan’s futurein lieu of the large numbers of ethnic Tajiks in Afghanistan.Martha Brill Olcott, “Central Asian Republics,” in Ashley J. Tellis and Aroop Mukharji (ed.),Is aRegional Strategy Viable in Afghanistan?(Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for InternationalPeace, 2010), p. 58.

185 PCTR 11 E rev 1 final

7

D.

RUSSIA

28. Since mid-19thcentury, Afghanistan’s relations with Russia have varied betweenco-operation and confrontation. In modern times, their relationship hit its lowest point following the1979 Soviet invasion and the ensuing decade of war. And while the Soviet invasion and the warare still remembered in both countries and limit Moscow’s ability to engage more actively withKabul, relations have gradually improved in recent years, evidenced most notably byHamid Karzai’s first official visit to Moscow in January 2011. Similarly, RussianPresident Medvedev is scheduled to visit Kabul for the first time later this year. This improvementstems partially from Moscow’s recognition that a possible failure of the international coalition inAfghanistan would ultimately destabilise Central Asia and undermine its own security. As a result,Moscow has put Afghanistan high on its priority list.29. One upshot to that has been the Afghanistan Air Transit Agreement, signed in 2009, whichallows Russian territory to be used for the transit of NATO supplies, thus offering a vitaldiversification for ISAF supply routes. The material transported through the NDN, mostly non-lethalcargo comprised of food, fuel, and other supplies, makes up 50% of all ground cargo toAfghanistan. However, there are discussions underway between Russia, the Central AsianRepublics and NATO regarding the possibility of including weapons in the list of transit supplies.Financed by the United States, Russia has also delivered 24 helicopters to the Afghan air force. Atthe recent NATO-Russia Council meeting in Berlin in mid-April 2011, NATO and Russia agreed toestablish a Helicopter Maintenance Trust Fund that would provide training, spare parts and tool kitsfor Afghan helicopters. Moreover, Russia has pledged to train Afghan police and military forcesand offered assistance with rebuilding vital infrastructure and industry complexes that wereoriginally constructed by Russian engineers in the 80’s. Russia has expressed readiness toparticipate in the financing and construction of important regional energy projects such as projectsfor power transmission from Tajikistan to Pakistan (Central Asia-South Asia electricityscheme CASA-1,000). This might also be include the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-Indiagas pipeline (TAPI), although a number of observers argue that Russia would not be interested inTAPI as it would give alternative economic outlets to the Central Asian Republics, which wouldreduce its economic and political sway over them.30. Russia has tried to limit and reverse Western military presence in Central Asia, which itconsiders its sphere of influence. One manifestation of that are the two “quadrilateral summits”between Pakistan, Russia, Afghanistan and Tajikistan, aimed at curtailing drug trafficking andsmuggling. These constitute a major concern for the Russian Federation and the latter has beenvocal in criticising NATO for not doing enough to tackle drug production in Afghanistan. However,while it is trying to contain U.S. power, Moscow nevertheless also recognises that the interests ofthe Allies and ISAF in Afghanistan coincide with its own. Russia sees a stable Afghanistan as amain prerequisite for securing its Southern border.31. To that end, Moscow has engaged in training Afghan and Central Asian counter-narcoticspersonnel -more than 1,000 officers have been trained at the Domededovo Counter-NarcoticsTraining Centre since 2005. The establishment of a second training centre in St. Petersburg wasagreed upon by the NATO-Russia Council during the Lisbon Summit. Most recently, Russiancounter-narcotic officials participated in raids that eliminated four illegal drug labs in Afghanistan.In sum, Russia has gradually expanded its contribution to the stabilisation of Afghanistan.However, it seems unlikely that it would be willing or able to make any military contribution tofighting the insurgency.32. In brief, Russia’s current stance on Afghanistan and the region needs to be understoodagainst the backdrop of its painful memories from Afghanistan, its aspirations for influence inCentral Asia as well as its efforts to demonstrate at least token support for NATO and the UnitedStates. That said, Russia is genuinely interested in a stable Afghanistan and has strengthened itscontributions to ISAF.

185 PCTR 11 E rev 1 final

8

E.

INDIA

33. With the exception of Pakistan, India shares the interests of all relevant stakeholders in theregion. Its focus in Afghanistan is on preventing the rise of Islamic fundamentalism in the region.To that end, it stands against the prospect of a Taliban return to power and has investedsignificantly in boosting the capacities of Afghan institutions, businesses and human capital.India-Pakistan relations are a key factor in New Delhi’s reluctance to contribute to the developmentof the Afghan security forces, even though it is cognizant of its vital importance for the internalstability of the country. On the economic front, India is interested in strengthening its position inthe region as well as in reaching into Central Asia, where it is being outpaced by its main economicrival -China.34. India maintains high level contacts with Afghanistan and has reaffirmed its commitment topartnership with Kabul. It is the fifth largest state contributor to Afghan reconstruction, havingpledged US$ 1.2 billion on civilian development, infrastructure and economic developmentprojects. Currently working on the Salma hydroelectric dam in the Herat Province, India had alsopartnered with Iran in the construction of a highway connecting Afghanistan’s ring road to theIranian ports, thus by-passing Pakistan’s monopoly on access to sea routes. India openedconsulates in a number of key Hindu and Sikh-populated Afghan cities, located near the Pakistaniborder, prompting Pakistani accusations that it is planning to use them against Islamabad. InMay 2011, India’s Prime Minister made his first visit to Afghanistan since 2005, pledging moreeconomic support.35. The Kashmir question is probably the single most sensitive issue for India. New Delhi isbitterly opposed to any international efforts to mediate the dispute, which stems from the conflictingclaims over the Kashmir region. The relationship between Islamabad and New Delhi has beentense, particularly following the 2008 Mumbai terrorist attacks. However, there has been a thaw inbilateral relations, as indicated by a recent meeting in India between Prime MinisterYousuf Raza Gilani and Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, which took place during a WorldCup cricket game between the two countries.36. Striving to prevent the rise of Islamic fundamentalism, India has focused its efforts oncapacity-building and strengthening economic ties with Afghanistan. Its political/strategic rivalrywith Pakistan and economic rivalry with China invariably play a strong role in its policy calculations.

F.

CHINA

37. China’s involvement in Afghanistan is closely related to its larger interests in Pakistan andCentral Asia: internal counter-terrorism issues, bilateral relations with the United States; and theacquisition of foreign goods, energy and mineral resources. Geographically, China shares aborder with the North-Eastern sliver of Afghanistan known as the “Wakhan Corridor”. The strategicWakhjir Pass connects the Chinese Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region (XAR) with this Easterntip of Afghanistan. With renewed international focus on Afghanistan and due to their commonborder, Chinese interest in Afghanistan has increased in the last decade. Thus far, however,China has been reluctant to become involved in any multilateral fora and has preferred to pursue abilateral approach towards Afghanistan.38. Beijing has made concerted efforts to maintain co-operation with other regional actors,including Pakistan and India,6in order to sustain its economic growth. Overall, however, Chinaviews Afghanistan in terms of its wider alliance with Pakistan and relations with its economic rivalIndia. Beijing does not want its Afghanistan policies to strain its long-standing, privilegedrelationship with Islamabad. Independent observers, especially those in India, perceive Chinese6

People’s Daily, “China-India Relations Maintain Healthy, Steady Momentum of Development,”People’s Daily,14 December 2010.

185 PCTR 11 E rev 1 final

9

support for Pakistan as a key aspect of Beijing’s policy of “encirclement” of India. This, theybelieve, is a means of preventing or delaying New Delhi’s ability to challenge Beijing’s regionalinfluence.7Lingering mutual distrust between India and China, and the rise of both nations’geo-political power over the last decade, strengthen the credibility of such views.39. China, like Western countries and India, is deeply concerned by the growth of Islamistmilitancy in Pakistan and the training of Chinese Muslims in militant camps. Moreover, a risingIslamic terrorist threat to China has made increased security co-operation with Kyrgyzstan,Kazakhstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan a priority of the Shanghai Co-operation Organization(SCO). China is also creating economic partnerships with the Central Asian Republics, and theregion is a growing market for Chinese consumer goods.840. A badly destabilised Afghanistan presents a threat to Chinese security. China is worriedabout increasing threats from domestic insurgents, drug smugglers and other criminals viaconnections between groups operating in Afghanistan and those in the XAR. Like Russia, Chinadoes not want Afghanistan to become the base for a long-term, sizeable Western political,economic, and military presence in Central Asia. Many Chinese observers believe that along-standing US presence would cement Washington’s “strategic encirclement” of China andweaken China’s influence among other Central Asian states, in much the same way as India fearsChinese encirclement. However, as it has considerable economic interests in Afghanistan, Chinadoes not want ISAF (and the international community) to fail in Afghanistan. However, itseconomic and other interests in Afghanistan have, thus far, not prompted Beijing to become amore active actor (and contributor?) to the stability of Afghanistan.41. China has made limited contributions to training the Afghan National Security Forces(ANSF). In March 2010, military ties were strengthened after a number of meetings between theChinese and Afghan Defence Ministers. Chinese Defence Minister Liang Guanglie pledged thatthe “Chinese military will continue its assistance to the Afghan National Army (ANA) to improvetheir capacity of safeguarding national sovereignty, territorial integrity and domestic stability”. Bothcountries have strong Police links, particularly in the realms of counter-narcotics andcounter-terrorism. There is further evidence that China is developing border access routes,communication networks and supply depots near the Wakhjir Pass to facilitate possible increasedChinese involvement in Afghanistan.942. While the deployment of Chinese police forces to Afghanistan remains a possibility, anyfuture involvement by the People’s Liberation Army is less likely.10Nevertheless, Chinese efforts tomodernise and upgrade infrastructure in the region bordering the Wakhan Corridor make itincreasingly obvious that Beijing sees a need to safeguard its interests in the region, especially asits strategic and economic interests in Afghanistan grow.43. China’s involvement in Afghanistan needs to be understood in the framework of its widerobjectives in Pakistan and Central Asia. Its main interests concern counter-terrorism and securityissues, its bilateral relationship with the United States, trade, as well as energy and mineralresources.

7

8

9

.

10

Jamal Afridi,China-Pakistan Relations(6 July 2010), Council on Foreign Relations Backgrounder,http://www.cfr.org/china/china-pakistan-relations/p10070.Edward Wong, “China Quietly Extends Footprints into Central Asia,”The New York Times,2 January 2011.Russell Hsiao and Glen E. Howard, “China Builds Closer Ties to Afghanistan Through WakhanCorridor,”China Brief of The Jamestown Foundation,vol. 10, no. 1,http://www.jamestown.org/single/?no_cache=1&tx_ttnews[tt_news]=35879.Geoff Dyer, “Obama to Press China on Afghanistan,”Financial Times,12 November 2009.

185 PCTR 11 E rev 1 final

10

CONCLUSION: PURSUING A REGIONAL APPROACH TO AFGHANISTAN

44. In addition to the issues raised above, the production and trafficking of narcotics fromAfghanistan remain a key challenge that requires a regional approach. The drug flows emanatingfrom Afghanistan have had immense impacts on its neighbours. With 1.2 million drug-dependentusers, Iran has one of the most severe addiction problems in the world. Opiate addiction isequivalent to 2.26% of the population aged 15-64 years. In Pakistan, the number of opiate usershas reached 628,000 of which 77% are chronic heroin abusers.11Tajikistan may have up to 75,000drug addicts, 80% of whom are opiate abusers. In Uzbekistan, an estimated 0.5% of the adultpopulation are injecting drug users, and Kazakhstan and Kyrgystan together have over 60,000registered drug users. China has an estimated 2.3 million registered addicts, over 80% of whomare heroin users. Given the fact that Afghanistan accounted for 74% of global opium production in2010 and supplied 380 metric tonnes, or 83% of the world’s heroin, reducing these flows intoAfghanistan’s neighbouring countries is a regional priority.45. There are many regional counter narcotic initiatives currently being pursued. The Paris Pactis an international partnership to combat trafficking and abuse of Afghan opiates and in accordancewith the pact, the UNODC is leading the Paris Pact Initiative, a project that facilitates periodicalconsultations at the expert and policy level and also aims to strengthen data collection andanalytical capacities in and around Afghanistan. This project also provides partners with the use ofa secure, automated internet-based tool for the co-ordination of technical assistance in the field ofcounter-narcotics. The Triangular Initiative (TI) is another tool that aims to enhance cross-borderco-operation in the field of counter-narcotics enforcement between Afghanistan, Pakistan and Iran.The TI has been a major stimulus in enabling senior officials from Afghanistan, Pakistan and Iranto agree upon measures to improve cross-border co-operation in countering narcotics traffickingand the smuggling of precursor chemicals into Afghanistan. There are also several otherinitiatives, such as the Rainbow Strategy for constructive engagement with prime regional actors,and the Central Asian Regional and Information Coordination Centre (CARICC) which co-ordinatesinformation sharing for counter narcotics operations. CARICC has also co-ordinated a number ofbilateral and multilateral operations between member states and CARICC partners which haveresulted in narcotics seizures.12Despite these international efforts, the results of these initiativeshave not led to a significant reduction of opium production in Afghanistan. Drug production andtrafficking remain serious challenges not only for the countries in the region but the internationalcommunity at large. Even though Afghanistan’s heroin production dropped by an estimated 40% in2010, mainly due to disease13, and is expected to be relatively static in 2011/1214, the fact thatAfghanistan still supplies the world with 74% of its opiates indicates that there is some way to go insolving the narcotics problem emanating from the country. International efforts to combat theproduction and trafficking of Afghan drugs must therefore continue and made more effective.Closer regional and international co-operation is essential to make progress in these areas.46. While NATO’s military engagement in Afghanistan remains crucial, it is important to point outthat there can be no purely military solution to the stabilisation of Afghanistan. To that end, NATOpursues a comprehensive approach that emphasises the integration of civilian and military efforts,capacity-building and economic development, as well as the training of the ANSF. However, itremains unclear if the withdrawal of NATO forces and the transfer of responsibility to Afghanauthorities can be successfully concluded by 2014 or what residual forces would stay thereafter.11

12

13

14

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime,Illicit Drug Trends in Pakistan(Pakistan: United NationsOffice on Drugs and Crime Country Office, April 2008).United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime,Central Asia(2011), http://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/drug-trafficking/central-asia.html.United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime,World Drug Report 2011(Vienna: United Nations Office onDrugs and Crime, 2011), p. 61.United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime,Afghanistan Opium Survey 2011: Winter RapidAssessment All Regions, Phases 1 and 2,(Vienna: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime,April 2011), p. 2.

185 PCTR 11 E rev 1 final

11

We are presently at a critical juncture of the international engagement in Afghanistan and the raidagainst Bin Laden is likely to impact the future trajectory of this engagement. Experts, such asShahrbanou Tadjbakhsh, point to a number of possible scenarios: 1) a light military footprint tocombat terrorist groups such as al-Qaeda; 2) a continued US presence in Afghanistan with theview of maintaining a stabilising foothold in the region; 3) the possibility for a negotiated agreementwith the Taliban and their reintegration in political life.15Nevertheless, a recurring theme in all thesescenarios is the need to pursue regional diplomacy and regional reconciliation in an effort to avoidfurther Afghan fragmentation along ethnic lines.47. One logical conclusion is that stronger emphasis on co-operation with Afghanistan’sneighbours is needed. The Allies recognise the importance of having a regional approach to thestabilisation of Afghanistan. Since late 2001, a number of NATO decisions and statements havestressed the need to deepen relationships with Partner countries neighbouring Afghanistan, mostnotably Russia, the Central Asian states and Pakistan.48. If NATO has systematically underscored the need for regional co-operation in Afghanistan,achieving this has proven to be far more difficult. Co-operation has grown and improved in somecases, such as with Russia, but progress with key countries such as Pakistan has remaineduneven. That relationship hit a new low in the spring of 2011, following new demands byIslamabad to limit or terminate US drone strikes in Pakistan’s border areas. Furthermore, as anAlliance, NATO has developed only limited political dialogue with China and has no point of contactwith Afghanistan’s Western neighbour Iran. Moreover, although all neighbouring states have avested interest in a stable and secure Afghanistan, the assistance of Afghanistan’s neighbours forISAF has been only fitful and not driven by a genuine effort to help NATO succeed.49. At the political-diplomatic level, the Alliance has addressed Afghanistan’s regional context invarious fora, such as the NATO-Russia Council (NRC), the Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council(EAPC), numerous meetings of ISAF troop-contributing countries, and the Tripartite Commission,among others. While these initiatives provide useful momentum, NATO’s role in generating policyconsensus among Afghanistan’s neighbours is, at best, limited, especially in view of the upcomingtransition. The neighbours have different, in part conflicting, interests in Afghanistan and someneighbours consider NATO with suspicion.50. After a late start, the European Union increasingly demonstrates that Afghanistan andPakistan constitute a legitimate area of EU engagement. The European Security Strategy of 2003explicitly states that the Union has interests outside of its immediate neighbourhood and assertsthat the most serious global threats emanate from distant places, such as Afghanistan andPakistan. To date, the EU has invested more than €8 billion in Afghanistan’s reconstruction effort,making the latter the largest recipient of EU Commission aid in Asia. At present, EU memberstates’ troops make up to 30,000 of the ISAF presence on the ground. Nevertheless, the EUpresence in Afghanistan has been chaotic, deprived of a clear strategy and plagued by poor co-ordination among the various EU actors. The Rapporteur hopes that the EU will apply the “lessonslearned” and bring its considerable expertise in reconstruction, development and peace-building tobear more effectively.51.By virtue of its almost universal membership, the United Nations (UN) is an eminentlyimportant actor in this context. It provides the legal framework for the ongoing NATO mission inAfghanistan and has held numerous conferences aiming to refine the form and shape of theinternational engagement in Afghanistan. The United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan(UNAMA) and Turkey now co-chair the Regional Working Group initiative, which brings togetherrepresentatives from neighbouring countries and interested parties to promote political, economicand security co-operation. This will culminate in a conference in Istanbul in early November 2011.15

For more information, see Sharbanou Tadjbakhsh,Post-war On Terror? Implications from a RegionalPerspective(Oslo: Norwegian Peacebuilding Resource Centre, 2011).

185 PCTR 11 E rev 1 final

12

The mission is also actively engaged in peace-building through the Salaam Support Group,working alongside the High Peace Council at the strategic level and at the grass-roots levelthrough various council representatives, religious and civic leaders, aiming to engage oppositiongroups, create confidence-building measures as well as to produce civilian effects. The UN is alsomonitoring the Afghan Government's programme attempting reintegration of insurgents which hasreported an increase in the number of individuals who have registered in the programme.52.Given the complexity of the task and the different, partially conflicting interests and agendasof its neighbours, developing a common, positive approach towards Afghanistan among theneighbouring countries will be a cumbersome, long-term process. Moreover, the weaknesses ofstate structures within the different countries are likely to limit the effectiveness of a regionalapproach. Here, too, with its different sub-structures the UN can play a leading role in assisting thecountries of the region in developing their infrastructures and decent living conditions for theirpopulations, which could, over time, help overcome existing antagonisms and rivalries. Moreover,the UN can play the important role of bringing the Iranians into the same tent as the Unites States.53.Looking ahead, it is only logical that the UN will take on a more prominent role inAfghanistan after the withdrawal of ISAF forces. The UN must also have a leading role in theefforts directed at engaging Afghanistan’s neighbours. A concrete step to that end would be aUN-led initiative to settle the disputed border between Afghanistan and Pakistan.The Rapporteur hopes that the Afghan government will not continue to use it as a bargaining chipin their relationship with Pakistan but that it will show greater willingness to reach agreement onthis issue. In a broader context, it would be helpful if the Istanbul conference of the RegionalWorking Group Initiative would agree on a document similar to the Kabul Declaration of GoodNeighbourly Relations. In addition, a mechanism designed to start confidence-building measuresfor regional security, trade, development, economic and cultural relations would be anotherimportant positive step forward. It would be crucial, however, that governments follow up on theagreements made. Regrettably, there has been much talk and only very little, if any, action. WhileAfghanistan’s neighbours have repeatedly expressed their willingness to co-operate and assistKabul to stabilise the country they have actually done little to help in practical terms. This onlyunderlines the need for international engagement. It is important to try to get the countries torealise that there are benefits to all from interdependence. Until now they tend to view it as a zerosum game: if someone wins, someone else must lose. The Rapporteur hopes that theinternational Bonn conference on Afghanistan in early December 2011 will help overcome existingsuspicions and lead to more effective international co-operation, particularly among Afghanistan’sneighbours.54. A viable regional approach to Afghanistan is stymied by numerous complicating factors,including the Kashmir conflict, Iran’s nuclear programme and contested border issues, to name buta few. As stated above, co-ordinating the policies of the neighbouring countries does not fall underNATO’s remit. Nevertheless, NATO member states need to align their policies vis-à-visAfghanistan’s neighbours. In this context, NATO should expand its existing partnerships withneighbouring countries. The Alliance should initiate political dialogue with the countries with whichit currently has no formal contacts. Such efforts are crucial for the achievement of a lasting politicalsettlement and the consolidation of hard-won political gains.55. It falls to national governments to consider which channel or organisation can better serve inthe formulation of a coherent diplomatic and political strategy regarding Afghanistan’s neighbours.The bilateral relations of individual NATO member states with the countries of the region willremain important, but NATO governments should use the Alliance as the primary forum forconsultation and policy co-ordination regarding Afghanistan and the region. The NATOParliamentary Assembly has a crucial role to play here. Its role as a forum for parliamentaryexchange between senior representatives from NATO member and partner countries isincreasingly relevant for building awareness and understanding as well as confidence and,eventually, consensus. What is more, by closely monitoring international developments which

185 PCTR 11 E rev 1 final

13

impact the security of NATO member and partner states, the Assembly, primarily through itsmembers and their national parliaments, provides meaningful input into the decision making of itsmember states. As Afghanistan and the stability in the region remain key issues for our security,the Assembly will continue to focus its activities in the country.