Forsvarsudvalget 2011-12

FOU Alm.del Bilag 141

Offentligt

Computer Therapy for the Anxiety and DepressiveDisorders Is Effective, Acceptable and Practical HealthCare: A Meta-AnalysisGavin Andrews1*,Pim Cuijpers2, Michelle G. Craske3, Peter McEvoy4, Nickolai Titov51School of Psychiatry, University of New South Wales, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia,2Department of Clinical Psychology, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam,Amsterdam, The Netherlands,3Department of Psychology, University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California, United States of America,4Centre for ClinicalInterventions, Perth, Western Australia, Australia,5School of Psychiatry, University of New South Wales, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

AbstractBackground:Depression and anxiety disorders are common and treatable with cognitive behavior therapy (CBT), but accessto this therapy is limited.Objective:Review evidence that computerized CBT for the anxiety and depressive disorders is acceptable to patients andeffective in the short and longer term.Method:Systematic reviews and data bases were searched for randomized controlled trials of computerized cognitivebehavior therapy versus a treatment or control condition in people who met diagnostic criteria for major depression, panicdisorder, social phobia or generalized anxiety disorder. Number randomized, superiority of treatment versus control (Hedgesg) on primary outcome measure, risk of bias, length of follow up, patient adherence and satisfaction were extracted.Principal Findings:22 studies of comparisons with a control group were identified. The mean effect size superiority was0.88 (NNT 2.13), and the benefit was evident across all four disorders. Improvement from computerized CBT was maintainedfor a median of 26 weeks follow-up. Acceptability, as indicated by adherence and satisfaction, was good. Research probitywas good and bias risk low. Effect sizes were non-significantly higher in comparisons with waitlist than with activetreatment control conditions. Five studies comparing computerized CBT with traditional face-to-face CBT were identified,and both modes of treatment appeared equally beneficial.Conclusions:Computerized CBT for anxiety and depressive disorders, especially via the internet, has the capacity to provideeffective acceptable and practical health care for those who might otherwise remain untreated.Trial Registration:Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry ACTRN12610000030077Citation:Andrews G, Cuijpers P, Craske MG, McEvoy P, Titov N (2010) Computer Therapy for the Anxiety and Depressive Disorders Is Effective, Acceptable andPractical Health Care: A Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 5(10): e13196. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0013196Editor:Bernhard T. Baune, James Cook University, AustraliaReceivedJune 18, 2010;AcceptedSeptember 7, 2010;PublishedOctober 13, 2010Copyright:ß2010 Andrews et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permitsunrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.Funding:GA, NT, PM, MC hold a grant for research on Internet Treatment from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council registration#630560.The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.Competing Interests:The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.* E-mail: [email protected]

IntroductionAnxiety disorders and major depressive disorders are common,costly and debilitating [1,2]. Remarkably, less than half the peoplewith these disorders see a physician and only a quarter receiveappropriate treatment [3]. Effective treatments for these disordersexist (i.e., selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) andcognitive behavior therapy (CBT) [4,5]. However, the publichealth impact of these remedies is limited for a number of reasons.Specifically, these disorders often are unrecognized [3,6], theefficacy of SSRIs may be limited to very severe cases [7], CBT isnot widely available, in part because of insufficient numbers ofadequately trained clinicians [8], and patients do not or cannotadhere to the costs and demands of face-to-face CBT treatment.Almost one third of individuals attending an anxiety disordersPLoS ONE | www.plosone.org1

clinic did not start treatment [9], and attrition from randomizedcontrolled trials for anxiety and depression can reach 50% [10].Internet and computer-based delivery formats could improveaccess to CBT. There have been two recent meta-analyses ofinternet-based and other computerized psychological treatmentsfor depression and anxiety states [11,12]. They included studies ofparticipants at risk, with sub-threshold symptoms, or with DSMdisorders. In anxiety states, the effect size superiority over controlconditions was large (23 studies, Cohen’s d = 1.1), and indepressive states the effect size was moderate (12 studies,d = 0.41). Two transdiagnostic programs included in these meta-analyses, one aimed at panic and phobias – Fearfighter [13] – andthe other aimed at depression and anxiety states - Beating theBlues [14] – were sufficiently powerful to be recommended forroutine use in the UK National Health Service [15].October 2010 | Volume 5 | Issue 10 | e13196

iCBT Anxiety and Depression

Recent research on computerized CBT delivered over theinternet (iCBT) or by computer in the clinic (cCBT) hasemphasized programs in which a predetermined syllabus presentsthe principles and methods of CBT in a series of lessons, usuallywith homework assignments and supplementary information. Themajority of newer programs are designed for individual anxiety ordepressive disorders. Computerized CBT can be self-guided,supported by reminders from a non-clinical technician or practicenurse, or guided by a clinician who makes telephone calls, sendsemails or posts comments on a private forum. The majoradvantages of iCBT are accessibility and convenience for bothpatients and clinicians, but equally important is that treatmentfidelity in both iCBT and cCBT is guaranteed by thecomputerized delivery. If these treatments are to become part ofhealth care we need to know if such programs benefit patients whomeet criteria for anxiety or depressive disorders in the short- andlong-term, and if they are acceptable to such patients.

interest were also examined. Finally, we wrote to researchers toidentify any unpublished studies meeting the inclusion criteria.

Study selectionAll studies of adults with the relevant diagnoses that randomizedsubjects to computerized CBT versus treatment as usual or controlcondition were included. We additionally examined studies inwhich computerised CBT was compared with face to face CBT.Items extracted in each study were as follows: Number of subjectsrandomized; basic results (details of treatment condition, details ofcontrol group, significant differences in outcome, Hedges g andnumber needed to treat (NNT), adequacy of bias minimizationscored 0 = complete minimization, 5 = no minimization (ade-quacy of sequence generation, allocation concealment, adequateblinding, missing data addressed, no selective reporting [17]);follow-up duration and stability, acceptability to participants(percent adherent to the full course, percent satisfied). Theseacceptability and bias ratings were independently conducted bytwo researchers, with differences resolved following discussion.

RationaleWe restricted the present review to studiesdesignedasrandomized controlled trials of computerized CBT forparticipantswho met diagnostic criteria for either major depressive disorder,social phobia, panic disorder with or without agoraphobia, orgeneralized anxiety disorder (GAD). Computerized CBT wasrequired to be the majorinterventionthat wascomparedto treatmentas usual, or to control conditions such as placebo or waitlist. Weconfined the analysis ofoutcometo self report measures of theprincipal characteristic of each disorder; to the magnitude andstability of the outcome; and to the acceptability of computertherapy as estimated from the level of adherence to the course andthe satisfaction upon completion.

Meta-analysisWe followed a described method [12, p197–198]. In brief, wecalculated the effect size (Hedges’ g) indicating the differencebetween the two conditions at post-test, as the difference betweenthe mean of the treatment condition and the mean of the controlcondition, divided by the pooled standard deviation and adjustedfor small sample bias [18]. We only used instruments that relatedto the principal measure of the disorder to generate a mean effectsize. Because the effect size is not easy to interpret from a clinicalpoint of view, we also calculated the NNT by transforming theeffect sizes based on Z scores using the formulae provided byKraemer and Kupfer [19]. The NNT is defined as the number ofpatients one would expect to treat to have one more successfuloutcome.The effect sizes for each study were pooled according to therandom effects model, and differences between subgroups ofstudies tested using the mixed effects model. As indicators ofheterogeneity of pooled effect sizes, we calculatedI2, whichindicates the heterogeneity in percentages, and we tested whetherthe level of heterogeneity was significant using the Q statistic.Small study bias was tested by inspecting the funnel plot on theprimary outcome measures (effects on depression or anxiety atpost-test) and by a trim-and-fill procedure [20], which yields anestimate of the pooled ES after taking bias into account. Allanalyses were conducted using the computer program Compre-hensive Meta-Analysis (version 2.2.021) [21].

MethodThis review was registered (www.ANZCTR.org.au/ACTRN12610000030077.aspx). All English language randomized con-trolled trials of iCBT or cCBT that used participants who metDSM criteria (established by structured diagnostic interview) foreither major depression, social phobia, panic disorder or GAD,and that compared iCBT or cCBT with treatment as usual,placebo or waitlist control groups, were included. All papersanalysed were either published or in press and the investigatorshad copies of all final manuscripts.

Information sourcesThe search strategy followed that of the previous meta-analyses[11,12] that used a database of studies on psychological treatment[16] (www.psychotherapyrcts.org) and other general data bases toinclude RCTs of computer-aided psychotherapy that werepublished after the cut off dates for previous meta-analyses (fromMarch 2008 for anxiety disorders and January 2009 fordepression). The search was conducted on the 31stof December2009. A total of 2670 abstracts were examined from the followingdatabases: PubMed (N = 308), Cochrane Database of SystematicReviews and Register of Controlled Trials (N = 719), Cinahl(N = 88), PsychINFO (N = 78), Medline (N = 171), Social SciencesCitation Index (N = 1155), and Embase (N = 155). We identifiedabstracts by combining terms indicative of psychological treatmentand depression, anxiety, and anxiety disorders (both MeSH termsand text words). In addition, these terms were paired with theterms ‘internet or computer or online’ to identify papers relating tointernet or computer treatment in particular. Reference lists for allidentified reviews and meta-analyses of computer-aided psycho-therapy, as well as those of included studies, for the time period ofPLoS ONE | www.plosone.org2

ResultsThe previous meta-analyses [11,12] were taken as having beencomprehensive for the period covered by their search strategy.Nine studies included in those meta-analyses met the newinclusion criteria, (focus on one of the four specified diagnoses,iCBT or cCBT the principal treatment). Thirteen additionalstudies were identified making 22 studies in all. Minimization ofresearch bias was assessed [17]. All studies reported data using theintention to treatmethod and all usedself report measuresof themainoutcomethereby obviating the need for blinding. Three studies onlymet these basic criteria, 13 studies also met themethod of sequencegenerationorallocation concealmentcriteria and six studies satisfied all 5criteria.Results of the meta-analysis of the 22 studies [22–43] aredisplayed in Table 1: grouped by diagnosis, listing author and dateof publication, N randomized, effect size of intervention comparedOctober 2010 | Volume 5 | Issue 10 | e13196

iCBT Anxiety and Depression

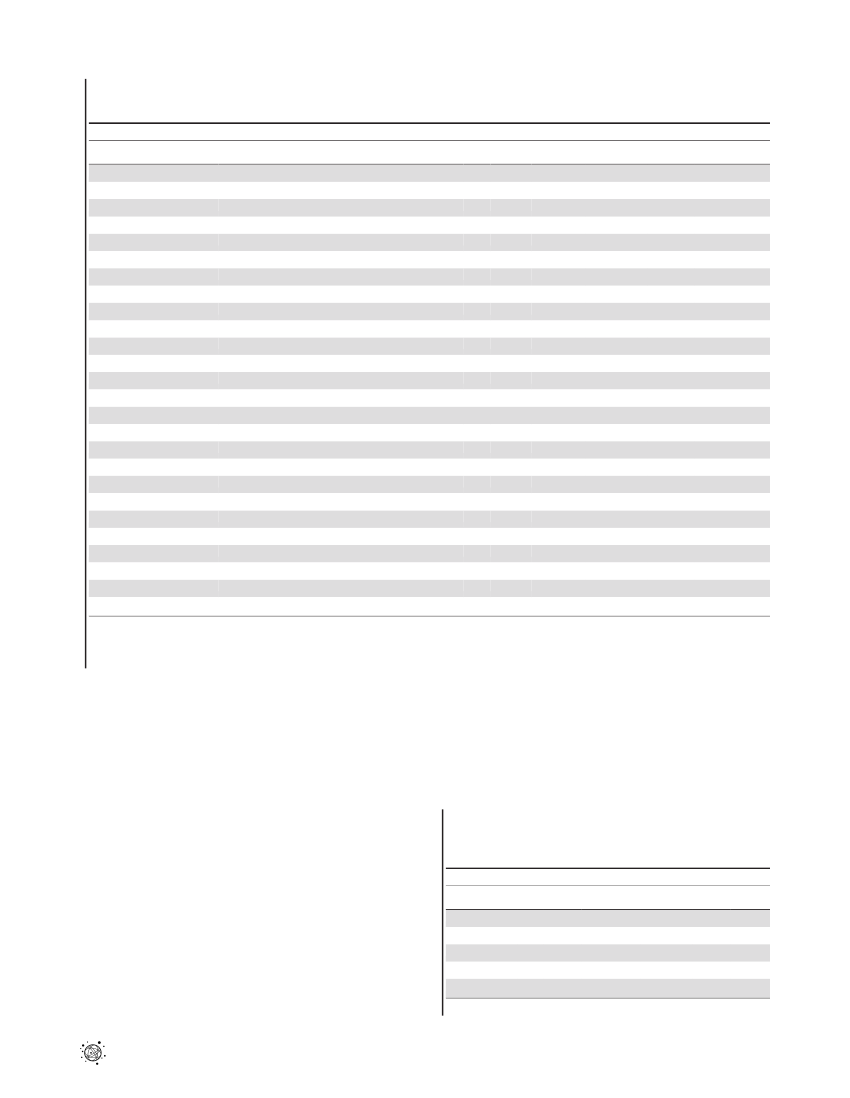

Table 1.Selected characteristics and results of randomized controlled studies examining the effects computerized and internet-based cognitive behaviour therapy for adult depression and anxiety disorders.

StudyMAJOR DEPRESSIONAndersson, 200522Kessler, 20092523

Conditions

N

g

NNT

Bias Risk

F-U

Adhere/Satisf

iCBT+therapist support.waitlist+discussion groupiCBT+therapist support.TAU by GPiCBT+therapist support.waitlistcCBT.waitlistiCBT+therapist support.waitlistcCBT+therapist support.waitlist

75297483614145

0.870.610.561.260.991.10

2.162.993.251.591.941.77

001211

26w16w-9w-26w

63/-73/-74/82100/-70/8787/-

Perini, 200924Selmi 1990Titov 20102627

Wright 2005

PANIC DISORDERCarlbring, 200128Carlbring, 2006Klein, 2001Klein, 200630313229

iCBT.waitlistiCBT.waitlistiCBT.Self-monitoring controliCBT.Information controliCBT.Information controliCBT+therapist support.waitlist

416023553259

0.991.130.391.490.740.28

1.941.744.591.412.506.41

102101

-39w-13w13w4w

80/8580/9790/-90/-82/-79/-

Richards, 2006Wims 201033

SOCIAL PHOBIAAndersson, 200634Berger et al. 200935Botella et al. 2009Carlbring, 200739403736

iCBT.waitlistiCBT.waitlistiCBT.waitlistiCBT.waitlistiCBT+therapist support.waitlistiCBT+therapist support.waitlistiCBT+therapist support.waitlistiCBT+therapist support.waitlistiCBT+therapist support.waitlistiCBT+therapist support.waitlist

645252571201058898

0.760.641.071.070.670.941.181.02

2.442.861.821.822.752.021.681.89

01210111

52w-52w52w52w26w26w-

56/-90/8548/-93/-97/7078/10081/10077/-

Furmark et al 200938Titov, 2008 I

Titov, 2008 II

Titov, 2008 III41GADTitov 200942Robinson 201043

48150

1.081.13

1.811.74

11

--

75/8574/87

N, number randomized; g, Hedges g; NNT number needed to treat; Bias risk (0 = no risk, 5 = high risk) inadequacy of sequence generation, no allocation concealment,inadequate blinding, missing data not addressed, selective reporting; F-U, follow-up in weeks; Adhere/satisfaction, percent adhering to whole course/percent satisfiedwith course; iCBT, CBT over the internet; cCBT, CBT over computer in clinic; GAD, Generalized Anxiety Disorder.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0013196.t001

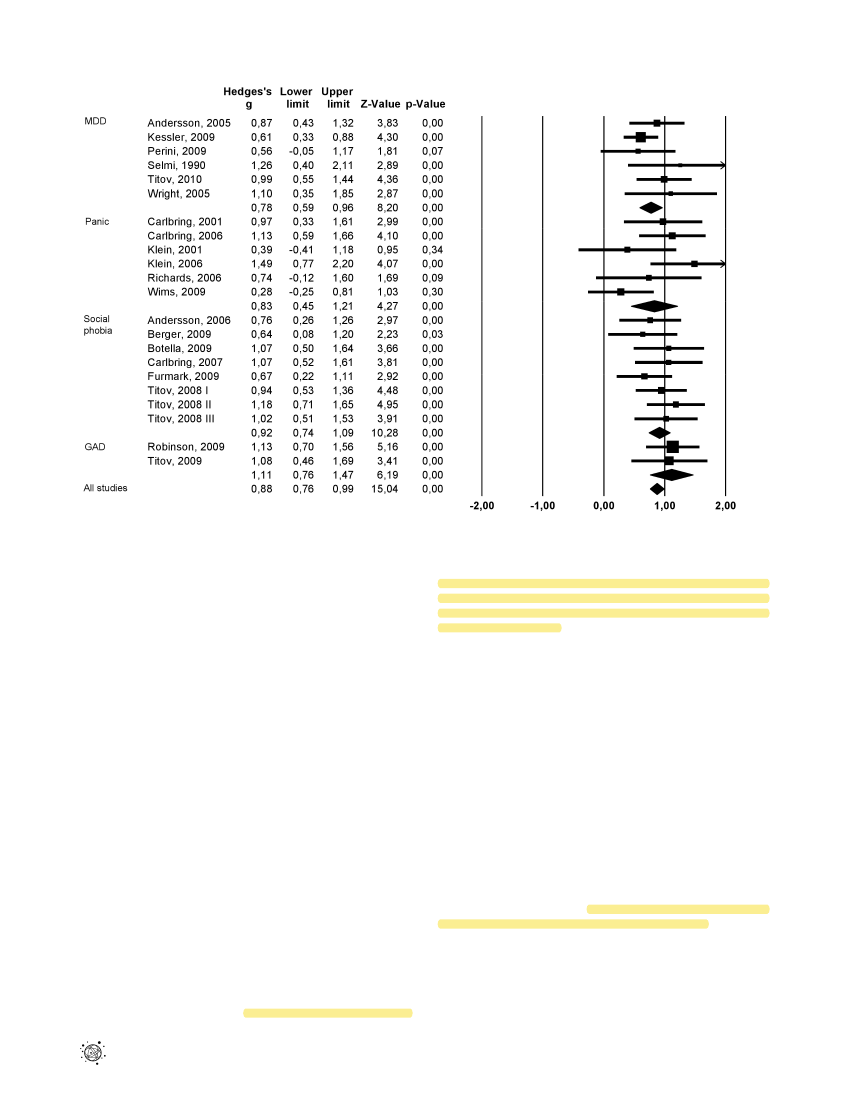

to control condition (Hedges g), NNT, risk of bias; length of follow-up; and adherence and patient satisfaction as a proxy foracceptability. Summary data are in Table 2 and a funnel plot ofstudies ranked by disorder shows the confidence limits around theeffect sizes for each study (Figure 1).The overall effect sizesuperiority of computerized CBT over control group across allfour disorders was 0.88 and the confidence limits did not includezero (p,0.001). Similar results were obtained for major depression(g = 0.78, 95% CI 0.59–0.96), social phobia (g = 0.92, 95% CI0.74–1.09), panic disorder (g = 0.83, 95% CI 0.45–1.21) and GAD(g = 1.12, 95%CI 0.76–1.47). Heterogeneity was non-significantfor each disorder and for all studies together. There was a small,non-significant indication for small sample bias (adjusted effect sizeg = 0.80). Although the effect size for studies using a waitlistcontrol group (g = 0.94; 95% CI: 0.81–1.07) was somewhat higherthan for treatment as usual and other control groups (g = 0.75;95% CI: 0.51–0.98), this difference was not significant (p.0.1).Fourteen of the 22 studies reported follow-up data that rangefrom 4 to 52 weeks post-treatment (median 26 weeks), and in nonewas there evidence of relapse. Adherence and satisfaction areindicators of acceptability of computerised CBT to patients. Allstudies measured one or both. Adherence was good, and a medianPLoS ONE | www.plosone.org3

of 80% of people who began these programs completed all lessons(range 48%–100%). Ten of the 23 studies provided data on patientsatisfaction and a median of 86% (range 70%–100%) of patientsreported that they were satisfied or very satisfied.There were two studies [25,27], in which computerized CBTwas also compared to face-to-face CBT for depression and three

Table 2.Summary results of meta-analyses examining theeffects of internet- and computerized CBT for depression andanxiety disorders.I20049.7707.84

DisorderMDDSocial phobiaPanicGADAll disorders

N686222

g0.780.920.831.120.88

95% CI0.59–0.960.74–1.090.45–1.210.76–1.470.76–0.99

Z8.20 ***10.28 ***4.27 ***6.19 ***15.04 ***

NNT2.392.072.261.752.15

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0013196.t002

October 2010 | Volume 5 | Issue 10 | e13196

iCBT Anxiety and Depression

Figure 1. Effect sizes of Computerised CBT versus control conditions at post-test.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0013196.g001

comparison trials, not included in the main meta-analysis as therewas no control group, in which the comparison betweencomputerised CBT and face to face CBT was in patients withdepression or panic disorder [44–46] (total number of patients inthe five studies was 567; 300 in the computerized and 267 in theface-to-face conditions). The effect size indicating the differencebetween computerized-treatments and face-to-face treatments wasnon-significant g = 0.09 in favour of computerized treatments(95% CI:20.34,17),with zero heterogeneity. In the computercondition therapist time was reduced compared to face-to-facetherapy for depression by 50% [27] and 79% [44], and in panicdisorder by 35% [46] and 70% [45]. Treatment satisfaction wasreported as good in both computerised and face-to-face treatmentgroups [27,45,46].

DiscussionTwenty two RCTs of computerised CBT for major depression,social phobia, panic disorder or generalized anxiety disordershowed superiority in outcome over control groups. The effectsizes are substantial, and the results indicate both short term andlong term benefits. Furthermore, patients adhered to and weresatisfied with computerised CBT, despite the significantly reducedamount of contact with the clinician. Thus, computerised CBT isan efficacious and acceptable treatment, and by increasingconvenience and reducing clinician time that would otherwise berequired by face-to-face treatment, it offers increased access totreatment for those suffering from anxiety and depression.The results come from 9 different groups working indepen-dently in 7 different countries. Similar results were obtained forPLoS ONE | www.plosone.org4

each disorder and heterogeneity was non-significant for eachdisorder and for all studies together. It is as though there is a coreset of CBT skills that is of benefit in the internalising disordersincluded in this analysis.Most patients had been recruited as volunteers, largely aftermedia publicity, but a minority were referred by their clinician.This raises the question, ‘are these patients comparable to patientswho seek face-to-face treatment?’ In a large study (n = 774),internet patients with one of these four disorders were as severewhen assessed by symptom, distress and disability measures asthose attending a face-to-face clinic, and both groups weresignificantly more severe than cases identified in an epidemiolog-ical survey [47]. Another index of severity is treatment history.Three studies reported this. In one study of iCBT for depression ina primary care setting, three quarters of patients had a history ofprevious episodes [23]. The chronicity was similar in two iCBTstudies for depression in community volunteers. In the first [24]70% had sought prior help and 51% were currently takingmedication for their depression. In the second study [26] helpseeking and medication rates were comparable and 72% said theironset of depression was before the age of 21, 78% said they hadhad more than 5 episodes and 78% said that they had had noremission in the last 2 years. Thus, it appears that participants inthese trials resemble people who attend regular clinics. There werefew data on treatment history in the studies of anxiety disorders.The mean effect size, indicating the superiority of the comput-erized intervention over the control group, was 0.88, NNT 2.15. Themost common control group was waitlist, with treatment for themdelayed until the intervention group had completed treatment.Placebo or active treatment control groups are preferable, but areOctober 2010 | Volume 5 | Issue 10 | e13196

iCBT Anxiety and Depression

difficult to arrange when there is no face to face contact with theparticipants. Interventions compared to waitlist controls have shownincreased effect sizes compared to interventions compared to thetreatment as usual studies [12] and the null finding in the presentmeta-analysis may be due to insufficient power. There were nostudies comparing computerised CBT and medication. Five studiescompared internet therapy directly with face-to-face CBT fordepression or panic disorder, and while all found strong pre-posttreatment effects, none found differences between the two modes ofdelivery. We conclude that computerized CBT, with clinician ortechnician assistance which can be as brief as one hour per patient,can work as well as face-to-face CBT.Adherence to computerized CBT was good; in the medianstudy, 80% of individuals who began these programs completed allstages. This rate of completion suggests that computerized CBTwas well accepted by participants. The programs containedbetween five and nine ‘lessons’. Conceivably, some participantswho do not complete all the lessons may have gained all they needfrom the program. More research is needed regarding the tailoringof computerized programs to the needs of individuals. Ten of the22 studies provided data on patient satisfaction; in the medianstudy 86% of patients were satisfied or very satisfied with thecomputerized CBT program. Participants noted the advantages ofcomputerized therapy, including convenience (such as completionof the program in the evening when there are no competingdemands), ability to proceed at one’s own pace to master thematerial, low cost and privacy. We conclude that computerisedCBT is acceptable to patients.There is a need for more extensive follow-up assessment as only14 of the 22 studies provided follow-up data, at a median 26 weeks(range 4–52). As with face-to-face CBT [5], the benefits lasted andno significant relapse was reported.The majority of studies identified measures of distress, disability,quality of life, or work force participation as secondary outcomemeasures. While changes in these secondary outcome measureswere not as large as in the primary outcome measures, they weresignificant and demonstrate that internet treatment has thecapacity to change health status not merely reduce specific

symptoms. One study pooled data from three RCTs of socialphobia and showed significant improvements in comorbidsymptoms of depression and generalized anxiety even thoughthe treatment was focused solely on the social phobia [48].The benefits described are substantial yet the content of theprograms is relatively simple and the therapist or techniciancontact brief. For example in the Andersson [22] study (g = 0.87),the treatment group had access to five weekly text ‘lessons’ aboutrecovering from depression – behavioural activation, cognitiverestructuring, sleep and physical health, and relapse preventionand future goals. This raises an issue of whether we presentlyconceptualise the nature of these four disorders correctly, either asrelated to temperament [2] or to neurotransmitter abnormalities[49] neither of which could be expected to yield to relatively briefsessions of skills based teaching about controlling worryingthoughts and confronting feared situations. The mechanism bywhich these programs produce benefit needs to be explored.In sum, the 22 identified computerized CBT programsgenerated a large effect size superiority over control groups withmaintenance of gains at follow-up and good patient adherence andsatisfaction. As the programs become more sophisticated, theclinician or technician time required seems to be decreasing to theorder of 10 minutes per week per patient [26,43,50].Is it possible to integrate these internet services with existingmental health services so that people who do not recover withinternet therapy can, in a stepped care design, receive face to facecare? We now, it seems, are beginning to know enough about theefficacy, applicability and potential cost savings from the internetprograms for people with anxiety and depressive disorders to beginto integrate these internet services with existing mental healthservices.

Author ContributionsConceived and designed the experiments: GA PC MGC PM NT.Performed the experiments: PC PM. Analyzed the data: GA PC MGCPM NT. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: NT. Wrote thepaper: GA PC MGC PM NT.

References1. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Walters EE (2005) Prevalence, severity, andcomorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National ComorbiditySurvey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 62(6): 617–621.2. Goldberg DP, Krueger RF, Andrews G, Hobbs MJ (2009) Emotional disorders:Cluster 4 of the proposed meta-structure for DSM-V and ICD-11. Psychol Med39: 2043–2059.3. Andrews G, Issakidis C, Sanderson K, Corry J, Lapsley H (2004) Utilising surveydata to inform public policy: comparison of the cost-effectiveness of treatment often mental disorders. Br J Psychiatry 184: 526–533.4. Roy-Byrne PP, Cowley DS (2007) Pharmacological treatments for panicdisorder, generalized anxiety disorder, specific phobia and social anxietydisorder. In: Nathan PE, Gordon JM, eds. A guide to treatments that work. 3rded. New York: Oxford University Press. pp 395–427.5. Butler AC, Chapman JE, Forman EM, Beck AT (2006) The empirical status ofcognitive-behavioral therapy: A review of meta-analyses. Clin Psychol Rev 26:17–31.6. Weisberg RB, Dyck I, Culpepper L, Keller MB (2007) Psychiatric treatment inprimary care patients with Anxiety Disorders: A comparison of care receivedfrom primary care providers and psychiatrists. Am J Psychiatry 164: 276–282.7. Fournier JC, DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, Dimidjian S, Amsterdam JD, et al.(2010) Antidepressant drug effects and depression severity: A patient-level meta-analysis. JAMA 303(1): 47–53.8. Weissman MM, Verdeli H, Gameroff MJ, Bledsoe SE, Betts K, et al. (2006)National Survey of Psychotherapy training in psychiatry, psychology, and socialwork. Arch Gen Psychiatr 63(8): 925–934.9. Issakidis C, Andrews G (2004) Pretreatment attrition and dropout in anoutpatient clinic for anxiety disorders. Acta Psychiat Scand 109(6): 426–433.10. Haby MM, Donnelly M, Corry J, Vos T (2006) Cognitive behavioural therapyfor depression, panic disorder and generalized anxiety disorder: a meta-regression of factors that may predict outcome. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 40(1):9–19.11. Cuijpers P, Marks IM, Van Straten A, Cavanagh K, Gega L, et al. (2009)Computer-aided psychotherapy for Anxiety Disorders: A meta-analytic review.Cogn Behav Ther 38(2): 66–82.12. Andersson G, Cuijpers P (2009) Internet-based and other computerizedpsychological treatments for adult depression: A meta-analysis. Cogn BehavTher 38(2): 196–205.13. Marks IM, Kenwright M, McDonough M, Whittaker M, Mataix-Cols D (2004)Saving clinician’ time by delegating routine aspects of therapy to a computer: Arandomized controlled trial in phobia/panic disorder. Psychol Med 34: 9–18.14. Proudfoot J, Ryden C, Everitt B, Shapiro DA, Goldberg D, et al. (2004) Clinicalefficacy of computerised cognitive-behavioural therapy for anxiety anddepression in primary care: randomized controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry 185:46–54.15. National Institute for Clinical Excellence: Computerised cognitive behaviourtherapy for depression and anxiety: Technology Appraisal 97. http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/TA097guidance.pdf. Accessed 2009 November 24.16. Cuijpers P, Van Straten A, Warmerdam L, Andersson G (2008) Psychologicaltreatment of depression: a meta-analytic database of randomized studies. BMCPsychiatry 8: 36.17. Higgins JPT, Green S, eds (2009) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviewsof Interventions Version 5.0.2 [updated September 2009]. The CochraneCollaboration, Available: www.cochrane-handbook.org..18. Hedges LV, Vevea JL (1996) Estimating effect size under publication bias: smallsample properties and robustness of a random effects selection model. J EducBehav Stat 21(4): 299–332.19. Kraemer HC, Kupfer DJ (2006) Size of treatment effects and their importanceto clinical research and practice. Biol Psychiatry 59: 990–996.20. Duval S, Tweedie R (2009) A nonparametric ‘‘trim and fill’’ method ofaccounting for publication bias in meta-analysis. J Am Stat Assoc 1(104):1338–1350.

PLoS ONE | www.plosone.org

5

October 2010 | Volume 5 | Issue 10 | e13196

iCBT Anxiety and Depression

21. Borenstein M, Hedges L, Higgins J, Rothstein H (2007) Comprehensive MetaAnalysis Version 2. Englewood, NJ: Biostat.22. Andersson G, Bergstrom J, Hollandare J, Carlbring P, Kaldo V, et al. (2005)��Internet-based self-help for depression: randomized controlled trial. Br JPsychiatry 187: 456:451.23. Kessler D, Lewis G, Kaur S, Wiles N, King M, et al. (2009) Therapist-deliveredinternet psychotherapy for depression in primary care: a randomized controlledtrial. Lancet 374: 628–634.24. Perini S, Titov N, Andrews G (2009) Clinician-assisted internet-based treatmentis effective for depression: randomized controlled trial. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 43:571–578.25. Selmi PM, Klein M H, Greist JH, Sorrell SP, Erdman HP (1990) Computer-administered cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression. Am J Psychiatry147(1): 51–56.26. Titov N, Andrews G, Davies M, McIntyre K, Robinson E, et al. (2010) Internettreatment for depression: a randomized controlled trial comparing clinicianversus technician assistance. PLoS ONE 5(6): e10939. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0010939.27. Wright JH, Wright AS, Albano A, Basco MR, Goldsmith LJ, et al. (2005)Computer-assisted cognitive therapy for depression: maintaining efficacy whilereducing therapist time. Am J Psychiatry 162(6): 1158–1164.28. Carlbring P, Westling BE, Ljunstrand P, Ekselius L, Andersson G (2001)Treatment of panic disorder via the internet: a randomized trial of a self-helpprogram. Behav Ther 35: 751–764.29. Carlbring P, Bohman S, Brunt S, Buhrman M, Westling BE, et al. (2006)Remote treatment of panic disorder: a randomized trial of internet-basedcognitive behavior therapy supplemented with telephone calls. Am J Psychiatry163: 2119–2125.30. Klein B, Richards JC (2001) A brief internet-based treatment for panic disorder.Behav Cogn Psychother 29: 113–117.31. Klein B, Richards JC, Austin DW (2006) Efficacy of internet therapy for panicdisorder. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry 37: 213–238.32. Richards JC, Klein B, Austin DW (2006) Internet cognitive behavioural therapyfor panic disorder: does the inclusion of stress management information improveend-state functioning? Clin Psychol 10(1): 2–15.33. Wims E, Titov N, Andrews G, Choi I (2010) Clinician-assisted internet-basedtreatment is effective for panic: a randomized controlled trial. Aust N Z JPsychiatry. in press.34. Andersson G, Carlbring P, Holmstrom A, Sparthan E, Furmark T, et al. (2006)�Internet-based self-help with therapist feedback and in vivo group exposure forsocial phobia: a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol 74(4):677–686.35. Berger T, Hohl E, Caspar F (2009) Internet-based treatment of social phobia: arandomized controlled trial. J Clin Psychol 65(10): 1021–1035.36. Botella C, Gallego MJ, Garcia-Palacios A, Banos RM, Quero S, et al. (2009)˜The acceptability of an internet-based self-help treatment for fear of publicspeaking. Br J Guid Counc 37(3): 297–311.

37. Carlbring P, Gunnarsdottir M, Hedensjo L, Andersson G, Ekselius L, et al.´�(2007) Treatment of social phobia: randomized trial of internet-deliveredcognitive-behavioural therapy with telephone support. Br J Psychiatry 190:123–128.38. Furmark T, Carlbring P, Hedman E, Sonnenstein A, Clevberger P, et al. (2009)Guided and unguided self-help for social anxiety disorder: randomizedcontrolled trial. Br J Psychiatry 195: 440–447.39. Titov N, Andrews G, Schwencke G, Drobny J, Einstein D (2008) Shyness 1:distance treatment of social phobia over the internet. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 42:585–594.40. Titov N, Andrews G, Schwencke G (2008) Shyness 2: treating social phobiaonline: replication and extension. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 42: 595–605.41. Titov N, Andrews G, Choi I, Schwencke G, Mahoney A (2008) Shyness 3:randomized controlled trial of guided versus unguided internet-based CBT forsocial phobia. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 42(12): 1030–1040.42. Titov N, Andrews G, Robinson E, Schwencke G, Johnston L, et al. Clinician-assisted internet based treatment is effective for generalized anxiety disorder:randomized controlled trial. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 43: 905–912.43. Robinson E, Titov N, Andrews G, McIntyre K, Schwencke G, et al. (2010)Internet treatment for generalized anxiety disorder: a randomized controlledtrial comparing clinician versus technician assistance. PLoS ONE 5(6): e10942.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0010942.44. Kay-Lambkin FJ, Baker AL, Lewin TJ, Carr VJ (2009) Computer-basedpsychological treatment for comorbid depression and problematic alcohol and/or cannabis use: a randomized controlled trial of clinical efficacy. Addiction 104:378–388.45. Carlbring P, Nilsson-Ihrfelt E, Waara J, Kollenstam C, Buhrman M, et al. (2005)Treatment of panic disorder: live therapy vs. self-help via the internet. BehavRes Ther 43: 1321–1333.46. Kiropoulos LA, Klein B, Austin DW, Gilson K, Pier C, et al. (2008) Is internet-based CBT for panic disorder and agoraphobia as effective as face-to-face CBT?J Anxiety Disord 22: 1273–1284.47. Titov N, Andrews G, Kemp A Robinson E (2010) Characteristics of adults withanxiety or depression treated at an internet clinic: comparison with a nationalsurvey and an outpatient clinic. PLoS ONE 5(5): e10885. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0010885.48. Titov N, Gibson M, Andrews G, McEvoy P (2009) Internet treatment for socialphobia reduces comorbidity. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 43(8): 754–759.49. Licinio J, Wong M-L (2010) Pharmacogenomics of antidepressants: what is next?Mol Psy 15: 445. doi:10.1038/mp.2010.58.50. Titov, N, Andrews G, Schwencke G, Solley K, Johnston L, et al. (2009) An RCTcomparing effect of two types of support on severity of symptoms for peoplecompleting internet-based cognitive behaviour therapy for social phobia.Aust N Z J Psychiatry 43(10): 920–926.

PLoS ONE | www.plosone.org

6

October 2010 | Volume 5 | Issue 10 | e13196